THE GOLF COURSES OF NEW ENGLAND

WRITTEN

BY

JAMES SITAR

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK KOENIG

BY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK KOENIG

A! a !#$ #% $&' &$()a$d , I feel great affection for this part of the country. Start with its history, particularly that of the early European settlers and the communities they created in the New World and later the colonists who led the breakaway from the British and birthed a nation.

The natural beauty of the region is also something to behold— from the mountainous woodlands of Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and sun-drenched beaches of Connecticut and Rhode Island to cultural and commercial hubs like Boston, Portland and Burlington.

I also admire the hardworking people of New England and the rugged individualism they possess. Its denizens tend to be a frugal, modest breed. Taciturn, too, and generally not given to wild bursts of emotions. But as the British discovered during America’s War of Independence, they are not afraid to rise up if their lives and livelihoods are threatened in any significant way.

Then, there is the golf.

In many ways, New England is the cradle of the game in America. It is where many of the first golf associations in the country were established in the late 1800s. And the Scottish immigrant professionals who toiled at those places, such as Willie Campbell, Willie Anderson, and Willie Davis, helped grow the game by teaching people the rules of golf and how to swing a niblick or brassie.

The area is also home to some of the most influential and intriguing tracks in the U.S. Many of those were designed by Golden Age greats such as Donald Ross, William Flynn, Walter Travis, and Seth Raynor. But modern maestros like Bill Coore, Ben Crenshaw, and Gil Hanse have made their marks as well.

In addition, New England has produced a slew of top players,

World Golf Hall of Famers: Francis Ouimet, Julius Boros, and Glenna Collett-Vare to name but three. And as a place for the competitive game, it has few peers. The inaugural U.S. Amateur and U.S. Open were staged on successive days at the Newport Country Club in October 1895, for example. And by the end of 2024, the USGA had held 86 of its national championships on 30 different sites in New England, including 11 U.S. Opens. The Ryder Cup was first contested in 1927 at the Worchester Country Club in central Massachusetts. And the USGA has seen fit to organize three Walker Cups in the region. Two of those were at Brookline (in 1932, with Ouimet serving as a playing captain for the U.S. squad, and 1973) and a third in 1953 at Kittansett Club.

The area also happens to be where I played golf for the first time, as a teenager on the Seth Raynor-designed track at the Country Club of Fairfield in southwest Connecticut. It did not take long for me to fall hard for the royal and ancient game.

The Scottish burg of St Andrews may be the home of golf. But New England is my golf home.

It was the setting of the course at Fairfield that first appealed to me. Raynor had routed his layout on a rather snug, 100-acre tract bordered to the south by Long Island Sound and the west by an estuary. Much of that land had been a malodorous marsh before the architect filled it with soil he had shipped across Long Island Sound on barges, and most of the site was as flat as a ball marker. But the track nonetheless boasted plenty of character, thanks to well-positioned bunkers and fairways and greens that featured subtle humps and bumps. Raynor also crafted a couple of holes along a ridge on the east side of the property that overlooked the rest of the course as well as the waterways that abutted it.

The linksy, Old World character of what essentially was a treeless course when it fully opened for play in 1921 wowed me as well, and so did the template holes that Raynor had fashioned on the property, among them Bottle and Plateau as well as Eden and Redan. The wind was often up, which meant that golfers were often compelled to be creative with their shots. And it was an easy track to walk.

The Country Club of Fairfield could not have provided a better introduction to the sport, and the more I played it, the more I came to appreciate other aspects of the game, from course design and agronomy to the intricacies of match-play.

It was a wonderful education, and I found that the more I teed it up in other parts of the golf world, the deeper my knowledge appreciation of the sport became.

Not surprisingly, New England was a favorite place for field trips. There were games at classic seaside gems such as the Kittansett in Marion, Massachusetts; the Misquamicut Club in Watch Hill, Rhode Island; and Sankaty Head Golf Club on Nantucket island. And matches at deftly routed inland tracks, like Ekwanok in Manchester, Vermont, and Old Sandwich in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Those adventures exposed me to the

work of the game’s greatest course designers as well as to the history of golf and how it grew and prospered in this part of the world. In time, the game became almost all-consuming. It was not only the increasing number of rounds I recorded each year but also the leadership positions I came to assume at CC of Fairfield, first as a member of the men’s golf committee and then as its chairman. A stint as chairman of the greens committee followed soon after, and while I found the in-fighting and back-biting that were inherent parts of those roles distressing, I still relished the many ways they allowed to immerse myself further in golf.

The same can be said about the caddie scholarship trust I helped create and then run at Fairfield and the very meaningful ways that organization impacted the lives of local loopers.

Then, I started writing full-time about the sport, happily leaving behind the worlds of business and politics I had been covering for a beat that felt nobler and much more agreeable.

Twenty-five years later, I continue to write regularly about golf as I also manage to accrue some 60 or 70 rounds a year. It’s been a great gig that has enabled me to cover on 33 major championships, including 22 Masters; report on developments and trends in course design on five continents; savor the hospitality of some of the finest destinations in the world, from Turnberry to Tasmania and back again; and spend meaningful time with some of the most interesting characters in the game, whether hunting quail with Davis Love III in the Georgia low country or dove with Craig Stadler in Argentina; hanging out with Willie Nelson on his bus; hitching a ride from Waterville Golf Club to Shannon Airport on Hugh Grant’s helicopter in southwest Ireland; and playing a nine-hole rounds inside the walls of a palace owned by the King of Morocco.

As I think of these grand adventures, I am reminded that all I have been able to experience in the game has flowed out of New England, beginning with those first rounds at Fairfield and continuing with those trips I took—and still take—to the region’s best courses and clubs. It has given me so much.

—JOHN STEINBREDER

My favorite place to be in the world is on a golf course. ere is something about being among the nely manicured grass that gives me a great sense of joy. It is not just the grass, but all of the surroundings.. the history, the architecture, the crisp morning dew or the nal glimpses of a sunset splashing across the fairway that inspire me to preserve the moment. Photographing started as a way for me to take those moments and the golf course home with me. Over time, it has turned into a career, and one of the greatest joys of my life.

When I look at a golf course, I always start to nd out what makes this golf course special and then gure out how to capture that in a photograph. It might be something simple—like a unique depression in the middle of the green—or it might be something more signi cant like a body of water that borders the golf course. Every golf course has something special about it, and the courses featured in this book have an abundance of outstanding characteristics.

As I selected these photographs that were taken over a period of 7 or 8 years, it is a true pleasure to see how I have progressed as a photographer. My earlier photos focus more on subject and composition, while my later e orts add in an insatiable desire for spectacular lighting. My technical expertise and attention to detail has also expanded greatly and while it might not be obvious to the viewer, the task of composing this selection of photographs turned into a time line of my progression over the years. It was a great pleasure to compose this group of photographs that I am quite proud of.

e photographs of e Golf Courses of New England have been especially remarkable for several reasons. e variety and history is some of the most robust in the country. ere are so many interesting features and golf courses in New England that you simply will not nd anywhere else. e quality of architecture and the ambiance of New England is truly special. In this book, you will nd my best attempts to share that special feeling with you.

—PATRICK KOENIG

August 2024

Ma!!a+,-!&..! /! ',&0& $&' &$()a$d 1&(a$ . As the largest state (ahem, not a state, but a “commonwealth”) in the region, with the longest history, the greatest amount of industry, it sits at the unofficial head of the table. Suffice to say, it’s a good place for us to start.

As golf grew in the U.S., its centers were around New York City and Boston. These cities, steeped in shipping commerce, looked eastward to Britain culturally well after the American Revolution. Like all of the English town names that cover “New England,” the inhabitants here were still often under the influence of British culture. It’s no wonder that the game of golf was largely imported through these two ports.

Though Massachusetts is home to some of America’s most passionate (and aggressive and annoying) sports fans, it’s also home to many who made significant contributions to golf in America. As we’ll see, The Country Club (Brookline) is the origin of many firsts, host of many tournaments, and forger of many important relationships. Other clubs in the early days of American golf, including Myopia Hunt Club and Essex County Club, played formative roles as well.

Many great golfers come from Massachusetts, including the legendary Curtis Sisters (namesakes of the Curtis Cup), the hard-toforget Francis Ouimet, the legendary Pat Bradley, as well as Bob Toski, Scott Stallings, Tim Petrovic, Peter Uihlein, Megan Khang, James Driscoll, Michael Thorbjornsen, and Alexa Pano. Even though you’ve heard Paul Azinger’s Southern accent over countless hours, he’s actually a son of Massachusetts (he moved to Florida sometime before finishing high school). Massachusetts is also where the great golf writer Herbert Warren Wind is from, and where Donald Ross lived when he first arrived in the U.S., and where we introduced countless Americans to high-quality golf design.

Golf across Massachusetts is ridiculously good, not just around Boston. The western hills are home to Taconic and GreatHorse. The sandy, seaside soil of Cape Cod has yielded a number of outstanding courses, among them Kittansett and Eastward Ho! (We’ll explain the exclamation point later.) And golf on the islands—especially Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard—are a special treat. But first, on the next page, let’s show you all of the courses in Massachusetts, with the ones we’ll visit in red.

131. Heritage Country Club

132. Hickory Hill Golf Course

133. Hickory Ridge Country Club 134. Hidden Hollow Country Club

135. Highfields Golf and Country Club 136. Highland Country Club 137. Highland Links Golf Course

138. Hillcrest Country Club

139. Hillside Country Club 140. Hillview Country Club 141. Holden Hills Country Club 142. Holly Ridge Golf Club 143. Holyoke Country Club 144. Hopedale Country Club 145. Hopkinton Country Club

146. Hyannis Golf Course

147. Hyannisport Club

148. Indian Meadows Golf Course

149. Indian Pond Country Club

150. Indian Ridge Country Club

151. International Golf Club

152. Ipswich Country Club

153. John F. Parker Golf Course

154. Juniper Hill Golf Course Inc

155. Kelley Greens Golf Course

156. Kernwood Country Club

157. Kettle Brook Golf Club

158. Lakeview Golf Course

159. Lakeville Golf Club

160. LeBaron Hills Country Club

161. Ledgemont Country Club

162. Ledges Golf Club

163. Leicester Country Club

164. Leo J. Martin Memorial GC

165. Lexington Golf Club

166. Little Harbor Country Club

167. Locust Valley Country Club

168. Longhi’s Driving Range

169. Longmeadow Country Club

170. Long Meadow Golf Club

171. Lost Brook Golf Club

172. Ludlow Country Club

173. Maplegate Country Club

174. Marion Golf Course

175. Marlborough Country Club

176. Marshfield Country Club

177. Maynard Golf Course

178. Meadow Brook Golf Club

179. Merrimack Valley Golf Club

180. MGA Links at Mamantapett

181. Miacomet Golf Club

182. Middlebrook Country Club

183. Middleton Golf Course

184. Milford Country Club

185. Mill Valley Golf Links

186. Millwood Golf Course

187. Milton Hoosic Club

188. Mink Meadows Golf Club

189. Monoosnock Country Club

190. Mount Hood Golf Course

191. Mount Pleasant Country Club

192. Mt Pleasant Golf Club

193. Myopia Hunt Club

194. Nabnasset Lake Country Club

195. Nantucket Golf Club

196. Nashawtuc Country Club

197. Needham Golf Club

198. Nehoiden Golf Club

199. New England Country Club

200. New Meadows Golf Course

201. Newton Commonwealth GC

202. Norfolk Golf Club

203. Northampton Country Club

204. North Andover Country Club

205. Northfield Golf Course

206. Northfields

207. North Hill Country Club

208. Norton Country Club

209. Norwood Country Club

210. Oak Hill Country Club

211. Oakley Country Club

212. Oak Ridge Golf Club

213. Oak Ridge Golf Course

214. Ocean Edge Resort & Golf Club

215. Olde Barnstable Fairgrounds GC

216. Olde Salem Greens Golf Course

217. Olde Scotland Links

218. Old Sandwich Golf Club

219. Ould Newbury Golf Club

220. Oyster Harbors Club

221. Pakachoag Golf Course

222. Patriot Golf Course

223. Paul Harney Golf Club

224. Pembroke Country Club

225. Pine Brook Country Club

226. Pinecrest Golf Club

227. Pine Grove Golf Club

228. Pinehills Golf Club

229. Pine Knoll Golf Course

230. Pine Meadows Golf Course

231. Pine Oaks Golf Course

232. Pine Ridge Country Club

233. Pine Valley Golf Club

234. Pleasant Valley Country Club

235. Plymouth Country Club

236. Pocasset Golf Club

237. Ponkapoag Golf Course

238. Pontoosuc Lake Country Club

239. Poquoy Brook Golf Club

240. Presidents Golf Course

241. Quaboag Country Club

242. Quail Hollow Country Club

243. Quail Ridge Country Club

244. Quashnet Valley Country Club

245. Red Tail Golf Club

246. Reedy Meadow Golf Course

247. Rehoboth Country Club

248. Renaissance Golf Club

249. Reservation Golf Club

250. Ridder Farm Golf Club

251. River Bend Country Club

252. Robert T. Lynch Municipal

253. Rochester Golf Club

254. Rockland Golf Course

255. Rockport Golf Club

256. Round Hill Community Golf Club

257. Royal Crest Country Club

258. Sagamore Spring Golf Club

259. Saint Anne Country Club

260. Salem Country Club

261. Sandwich Hollows Golf Club

262. Sandy Burr Country Club

263. Sankaty Head Golf Club

264. Sassamon Trace

265. Scituate Country Club

266. Segregansett Country Club

267. Settlers Crossing Golf Course

268. Shaker Farms Country Club

269. Shaker Hills Golf Club

270. Sharon Country Club

271. Shining Rock Golf Course

272. Siasconset (Old Sconset) GC

273. Skyline Country Club

274. Southampton Country Club

275. Southers Marsh Golf Club

276. South Shore Country Club

277. Southwick Country Club

278. Springfield Country Club

279. Spring Valley Country Club

280. Squirrel Run Golf & Country Club

281. St. Marks Golf Club

282. Sterling National Country Club

283. Stockbridge Golf Club

284. Stone-E-Lea Golf Club

285. Stoneham Oaks Golf Course

286. Stone Meadow Golf

287. Stonybrook Golf Course

288. Stow Acres Country Club

289. Stowaway Golf Course

290. Strawberry Valley Golf Course

291. Sun Valley Golf Course

292. Swansea Country Club

293. Swanson Meadows Golf Course

294. Taconic Golf Club

295. Tatnuck Country Club

296. Tedesco Country Club

297. Tekoa Country Club

298. Templewood Golf Course

299. Tewksbury Country Club

300. The Back Nine Club

301. The Bay Club at Mattapoisett

302. The Bay Pointe Club

303. The Black Swan Country Club

304. The Blandford Club

305. The Brookside Club

306. The Captains Golf Course

307. The Country Club at New Seabury

308. The Country Club (Brookline)

309. The Crosswinds Golf Club

310. The Golf Club at Southport

311. The Golf Club at Yarmouthport

312. The Harmon Club

313. The Kittansett Club

314. The Meadow at Peabody

315. The Orchards Golf Club

316. The Ranch Golf Club

317. The Ridge Club

318. The Woods of Westminster

319. Thomas Memorial Golf & Country Club

320. Thomson Country Club

321. Thorny Lea Golf Club

322. Touisset Country Club

323. Townsend Ridge Country Club

324. TPC Boston

325. Trull Brook Golf Course

326. Turner Hill Golf and Racquet Club

327. Twin Hills Country Club

328. Twin Springs Golf Course

329. Tyngsboro Country Club

330. Unicorn Golf Golf Course

331. Vesper Country Club

332. Veteran’s Memorial Golf Course

333. Village Links Golf Club

Wampatuck

Waverly

343. Weathervane Golf Club

344. Wedgewood Pines Country Club

345. Wellesley Country Club

346. Wenham Country Club

347. Wentworth Hills Golf Club

348. Westborough Country Club

349. Westminster Country Club

350. Weston Golf Club

351. Westover Municipal Golf Course

352. Whaling

354. White Pines Golf Course

355. Whitinsville Golf Club

356. Wianno Golf Club

357. Widow’s Walk Golf Course

358. William Devine GC at Franklin Park

359. Willowbend

360. Willowdale Golf Course

361. Winchendon Golf Course

362. Winchester Country Club

363. Winthrop Golf Club

364. Woburn Country Club

365. Wollaston Golf Club

366. Woodland Golf Club

367. Woods Hole Golf Club

368. Worcester Country Club

369. Worthington Golf Club

370. Wyantenuck Country Club

371. Wyckoff Country Club

T,& +#-$.02 +)-1 is one of the oldest clubs in the U.S., and it’s one of five charter members of the USGA. As for why it was simply named “The Country Club,” when it was proposed in 1860—near the beginning of the Civil War—there were no other country clubs in the country, so there was no reason to differentiate it in name.

The club was founded to be a place for members to relax in the countryside … and to watch some horseracing. TCC founder James Murray Forbes, bought an existing racetrack and hotel (which would become the clubhouse), and the club was opened in 1882. The club had lawn tennis, bowling, a shooting range, and croquet, but horses remained the most popular attraction: with at least four different kinds of racing, as well as polo. Golf would only come 10 years later. While there are no horses or track today—the 1st and 18th fairways generally follow the inner curve of the original track—TCC boasts many sports, including tennis, platform paddle tennis, squash, swimming, curling, fitness, skeet shooting, ice skating, and hockey. About curling: TCC’s facility may be the first of its kind in the U.S. devoted to the sport.

A few members had the idea of creating a few golf holes, and play began in 1892. The very first shot attempted, by member Arthur Hunnewell, resulted in a hole-in-one. The onlookers, uninitiated to golf’s extreme difficulty, were reportedly nonplussed, thinking this must have been a normal result. It may be the worst reaction and reception to a hole-in-one in the history of golf. Willie Campbell was hired to be the club professional, and he laid out an additional nine holes, bringing the total to 18 in 1899. The course’s design would continue to evolve from a hodgepodge of members’ ideas. TCC’s member course may be the most stunning and influential course designed by many non-architects.

Speaking of members, some families go back six generations, but there is no pretense here: you’ll find more Subarus in the parking lot than BMWs. Given the size of the facilities, TCC can manage a much larger membership than its sister club, Myopia Hunt; there are over one thousand, with hundreds of additional national members.

The nine-hole Primrose course was designed by William Flynn, and it’s a lovely place to go out for a solo nine, or to bring a family member who’s learning the game, to enjoy the western part of this property. Four of the Primrose’s holes are included in the composite routing—its 1st and 2nd holes are combined into one longer par four—which has been used for major competitions since the 1957 U.S. Amateur. It’s common to hear people say that the composite

The very first shot at TCC, attempted, by member Arthur Hunnewell, resulted in a hole-in-one. The members watching were non-plussed.

course is much longer and demanding than the member course, and it’s difficult to beat the charm of the routing that members play daily. It’s a walking-only course, with special exception given only to those with an actual doctor’s note, medically requesting to ride in a cart. As a result, pace of play is a point of pride, and the use of caddies is essential. Typically, only twosomes are allowed before 8:15am, and you’re expected to scoot around in three hours or fewer, and caddies are mandatory until 1:30 in the afternoon. The author can vouch for the caddie crew, having been an alum of that ragtag bunch in the mid 2000s.

The 3rd hole—a longish par four with a fairway that dips and bends between two sizeable hills right at the landing area—was purportedly Arnold Palmer’s favorite par four in the world.

The 11th, a long par five, is appropriately called Himalayas, as it gains and loses elevation several times, playing over a large ridge of exposed granite, dropping down toward a creek, and then steeply uphill to a green guarded by ample rough for the last 60 yards of approach.

The 17th hole is a famous dogleg left par four, which is where Francis Ouimet settled the famous U.S. Open playoff in 1913, and where Justin Leonard made a long, uphill putt to seal the U.S.’s comeback in the 1999 Ryder Cup.

TCC has hosted 17 USGA championships, more than all but one other club. Most famously, the 1913 U.S. Open, won by amateur Francis Ouimet, a caddie who lived across the street, which began the golf boom in America; the 1999 Ryder Cup that featured the U.S. team’s dramatic Sunday comeback. The club has also hosted two U.S. Women’s Amateurs (1902, 1941), six U.S. Amateurs (1910, 1922,

The Country Club’s course grew in several stages, so it’s not the result of any one architect. The first six holes were laid out by three club members in March 1893.

1934, 1957, 1982, 2013), a Girls Junior Amateur (1953), two Walker Cups (1932, 1973), and four U.S. Opens (1913, 1963, 1988, 2022).

While the course was built by members and the early Club professionals, a number of golf course architects have left their mark on the property over the last century through consulting, designing and restoring— notably, Walter Travis, Donald Ross, William Flynn, and Geoffrey Cornish touched the course between 1913 and 1963. The course was updated by Rees Jones before the 1988 U.S. Open, and since 2006, Gil Hanse has been the Club’s consulting architect and has worked closely with TCC to renovate and restore the course for the 2013 U.S. Amateur, 2022 U.S. Open, and future championships. A course that was already great has become even better.

The yellow clapboard clubhouse is an old hotel and farmhouse, which was renovated to become an elegant building with dining, card and billiard rooms, and accommodations for those who wished to sleep over. In the grill room, an oil painting of Francis Ouimet looks over the diners. There’s a wood-paneled library and many small rooms on the first and second floors, whose walls each carry the story of TCC’s history. You can admire an original Stimpmeter, which was invented by TCC member Edward Stimpson.

The locker rooms and golf shop are in a separate brick building, featuring a double-decker men’s locker room, lined with old metal lockers. It was through a second-story window where the U.S. Ryder Cup team famously crawled and celebrated their epic comeback victory in 1999, on the roof of the bar area. Speaking of the bar, this is where the famous bartender Fernando made his signature drink. It doesn’t get much better than sipping a Fernando out on the patio, watching matches come down to the 18th green. Stick to just one Fernando, and you’ll still feel it; go for a second, call a car and good luck.

I! a +)/+,& .# !a2 that some country clubs can make you feel like you’re stepping back in time, but if one place earns that moniker more than any other, it’s Myopia Hunt.

The Myopia Hunt Club was founded by nine people—all former players on the Harvard baseball team, including four Prince brothers with notably poor eyesight—in 1875. Despite being a slight minority of founders, the club was named after their troubles with vision.

In 1882, some members wanted to move the club closer to Boston. But they didn’t move: they split. Some Myopia members broke off and founded The Country Club, just southwest of Boston, in 1882, and the Myopia Club itself moved to a much larger property in South Hamilton: it’s current and third location. TCC founders wanted to incorporate fox hunting in Brookline, but this proved too difficult, so they instead re-founded Myopia as Myopia Hunt Club, in its current location. Myopia Hunt was primarily focused on … hunting. The club also constructed a polo field in 1888, and it’s now one of the oldest continually running polo fields in the country. To this day, it’s not uncommon to see a horse and rider out somewhere on the property.

Golf originated here at the club in 1894, after members witnessed the game at The Country Club, 30 miles south, in Brookline. As with most early courses in the U.S., the course evolved slowly over time. R.M. Appleton laid out nine holes. Today’s course was designed and modified by Herbert C. Leeds, who worked at the club for over 30 years.

The course features small greens, challenging elevation changes, and deep bunkers that are often hidden from view. The avid golfer, President Taft—who summered in nearby Beverly while in office— got stuck in one on the 10th hole, and draft horses had to pull him out. The fescue is remarkably thick, as it hasn’t been burned in many years … some say not in 100 years.

Myopia was the only golf course to have two holes on Golf Magazine’s “Top 100 Holes in America ” list (compiled by Tom Doak in 1986).

The 1st hole, an uphill dogleg par four, features a blind tee shot. When you stand on the 1st green, which is perched atop a hill, much of the course open up for view. The par-five 2nd rewards you with a downhill tee shot, but a blind approach awaits, with a trench-like bunker that can gobble up a second shot you had hoped would run up to the green. The par-four 4th is often cited as a great hole: a slight dogleg left with plenty of trouble left. The 9th hole, Pond, is a very short par three with a very small, narrow green (perhaps only 10 yards wide), guarded by deep bunkers. The 4th and 9th holes were both named Golf Magazine’s Top 100 Holes in America (compiled by Tom Doak, 1986); Myopia was the only course to have two holes on that list.

Myopia hosted the U.S. Open four times arpund the turn of the century (1898, 1901, 1905, 1908). The winning score in 1901 of 331 (an average of almost 83 strokes per round) is still the highest total winning score in U.S. Open history. Not a single player broke 80 in any of the four rounds that year. The final day fell on a Friday, and there was a tie at the top, which would require a playoff, but the playoff participants had to wait until Monday, as Saturdays and Sundays were reserved for members.

There’s still hunting here, but it’s drag hunt style, meaning no live foxes anymore.

Yellow clapboard clubhouse has an old-fashioned bar and men’s locker room. This converted farmhouse wraps around the putting green, has low ceilings, screen doors, and a self-serve bar with brass footrests, with private liquor lockers for members. Its locker room, housed in a separate building, is the original. The locker room has remarkably tall ceilings, letting in lots of natural light. A golden eagle is perched above the bathroom entrance and contrasts well with the dark wood lockers and red carpeting.

Famed novelist John Updike was a longtime member of Myopia Hunt Club. Gil Hanse restored the course in 2011.

Manchester-by-the-Sea, MA • 1893

E!!&3 /! a !.#0/&d +)-1 , situated on equally fantastic land, that can boast one of Donald Ross’s greatest designs.

Ross was the head pro, superintendent, and architect at the Essex County Club from 1909 to 1917, and he redesigned the nine existing holes and expanded the course to 18. The house he lived in from 1909 to 1913 sits on the edge of the property, just 10 feet from the 15th tee. Perhaps only Pinehurst #2 can claim to have had Ross’s attention longer. Essex is Ross’s first great design, and when you consider how he used this remarkably undulating property, it’s not a stretch to consider it to be actually his best.

Founded in 1893, the club had the first nine-hole course in New England. When the five charter members of the USGA started inviting additional clubs to join, Essex County Club received their first invitation.

The course is known for its wild greens and design variety. The par-five 3rd’s green is thought to be the oldest existing green in the U.S., and it features a submerged “bathtub” feature in the left center of the green. The 11th hole is often cited as one of the best uphill par threes in the U.S.: a semi-Redan green that is said to resemble the deck of a sinking ship, with punitive bunkers left and right. The par-four 17th hole, which plays 72 vertical feet up a steep granite hill to a blind green approach, creates late-round drama, as does the 18th: a downhill par-four, with a fairway that snakes its way through two massive hills, and is easily one of the most picturesque par fours in New England. When Ross was around, this was the 4th hole, but it’s safe to say it makes for a perfect finishing hole. As a whole, Essex’s course exhibits the finest of early Ross’s more bold ideas and quirky features, which make it stand out against Ross’s late greats. The drive in passes the club’s grass and clay tennis courts before revealing the red-brick clubhouse, which features a small men’s

locker room on the second floor, with old metal lockers and classic showers. This old Andrews, Jacques, and Rantoul-designed clubhouse fits well into Essex’s remarkable rolling property.

Essex County Club is notable for admitting women from the outset, and it has been an important place in women’s golf. Essex hosted the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1897 and 1912, and the Curtis Cup in 1938 and 2010. Harriot Curtis and Margaret Curtis—the sisters and golf phenoms who founded the competition—were members at Essex. Their uncle was Laurence Curtis, who was one of the

founding representatives of the USGA (for The Country Club), and the USGA’s second president. The 2010 Curtis Cup played only 180 yards longer than the 1938 edition.

Bruce Hepner has made renovations to the course since 2001, with assistance from superintendent Eric Richardson. Many thousands of trees have been removed, including many from the rocky hills, revealing Essex’s rugged and natural beauty once again.

donald ross was born in 1872 in the small town of Dornoch, Scotland, home to one of the best courses in the world: Royal Dornoch. As a young man, he worked as a greenskeeper there, and spent a year apprenticed to Old Tom Morris in St Andrews. He also made clubs and served as a head pro.

While Ross designed over 400 courses in the U.S., he got his start in New England, where he lived for many years. His first design was at Oakley Country Club outside of Boston, where he was hired as the head pro in 1899. It was here that he met the Tufts family, owners of a new resort in the sandhills of North Carolina called Pinehurst, and he landed a job with them to design four of those courses, including the famed Pinehurst #2.

Ross would design courses in New England in the summer months, where he kept two offices: one in Little Compton, Rhode Island, and a satellite office in North Amherst, Massachusetts. As a result of his proximity, New England courses received the benefit of Ross’s extra attention and time on property. Due to the volume and difficulty of travel in the early 1900s, it’s believed that of the 400+ courses that he designed, he did not actually visit or walk roughly 100 of them, and another 100 or so he only saw once or twice. But Ross surely paid more visits to almost all of his creations in New England.

According to Ross expert Brad Klein, Ross designed or redesigned 91 courses in New England: 50 in Massachusetts, 12 in New Hampshire, 11 in Rhode Island, 11 in Maine, 5 in Connecticut, and 2 in Vermont. Among the very best of his designs in New England are Wannamoisett, Metacomet, Salem, Winchester, Concord, Bald Peak, Lake Sunapee, Vesper, Oyster Harbors, Belmont, Whitinsville, Hooper, Charles River, and his masterpiece, Essex County Club. He spent seven years at Essex—including four when he lived on the property—where he continued to meticulously hone his work.

Ross was also a good player in his own right, winning the Massachusetts Open twice, and the North and South Open three times. He also finished in the top 10 of the U.S. Open four out of the six times he played, and finished T8 in the 1910 British Open at the Old Course, edging out notable names such as J.H. Taylor, Harry Vardon, Willie Auchterlonie, John Ball, and Willie Park Jr.

Ross died in 1948. As of 2024, more than 100 national championships have been played on his designs. So much has been written about Ross—going far deeper than we can here—so if you’re further interested, we recommend Brad Klein’s landmark study, Discovering Donald Ross.

D&d,a4 +#-$.02 a$d 5#)# +)-1 has a unique name. While several New England clubs offered both golf and polo, few chose to include polo in its name. Originally the Dedham Polo Club was just polo. It was located nearby, and when its clubhouse was destroyed by fire in 1910, they decided to merge with a local club called Norfolk Country Club. The result is Dedham Country and Polo Club, which is located on the old Norfolk property today. Though theere is no longer polo, the club continues to honor its origins in its name and its logo: a polo player riding a horse at full gallop.

Dedham's course design has a strong lineage. Donald Ross designed the original nine-hole course in 1915. Then in 1920, the club then hired Herbert Fowler, who made some changes. When the club wanted to add another nine holes a few years later, they reached out to a third architect, named Seth Raynor. The 18-holes that Raynor designed opened in 1925. Raynor died three years later, and Dedham remained his only design in Massachusetts. Raynor’s beautiful bunkering—as well as the native fescue areas and exposed rock—provide the strong aesthetics at Dedham. There is also considerable elevation change throughout the property, but the elevated first tee offers a great view of what is to come: holes that climb and fall between two large hills, with a creek running in between. The first few holes run diagonal, using these features in different ways. These opening holes teach you to expect more uphill approach shots later in the round as well. The par-three 3rd is a demanding Redan template, followed by an uphill par five with indimidating fairway bunkers and a cross bunker that narrow the field of play. The par-three 5th is a Short template, with eight bunkers guarding this green. Center-line bunkers create the strategy on the par-five 6th: play safe, and it’s a three-shot hole for sure, but if you take on those bunkers on the inside dogleg, you can have a

chance to reach in two. The 7th and 8th play a bit along marshland, before the short, par-four 9th—an Alps template—forces players to make two precise shots on a hole with a semi-blind green.

Raynor’s beautiful bunkering—as well as the native fescue areas and exposed rock—provide the strong aesthetics at Dedham.

The back nine begins its return toward the clubhouse with a long par five, with a creek bisecting the fairway about 30 yards in front of the green. The par-four 11th rises over a hill and then turns, before rising again to a green perched on top of another hill. A three-putt can creep in on 13th green, which may be the largest on the course: a Punchbowl shape, guarded by a large Lion’s Mouth bunker front-center: if that sounds intimidating, that’s because it is. The long par-three 14th features a long Biarritz green: 70 yards long from front to back, so depending on the pin position, the hole can play from a mid-iron to a 3-wood. The 17th is a unique reverse Redan design, making it the second Redan on the course. The closing hole is a difficult par-four that plays uphill, while turning a bit to the left, back to the clubhouse.

Brian Silva created a master plan for the club in 2005 that sought to return the course to Raynor’s vision. In 2018, that major restoration was complete, allowing Dedham to shine once again. Dedham has hosted one USGA event: the 1975 USGA Girls Junior Amateur.

SETH RAYNOR HAD A SHORT CAREER as a golf course architect, but his distinct style has become one of the most influential in recent design. Not nearly as much is known about Raynor, compared to his Golden Age contemporaries however. With a background in engineering and little to no experience in golf, Raynor helped propel modern golf course design in the United States.

Seth Jagger Raynor was born on May 7, 1874. He grew up at the far eastern end of Long Island, in the area now known as the Hamptons. Educated at Princeton in the late 1890s, he returned to his hometown of Southampton to become a village engineer. This was how he met a well-connected man and leader in American golf: Charles Blair Macdonald. Macdonald wanted to build what he called the “ideal golf course,” on a difficult tract of land in Southampton. He needed a local man to survey the property and advise on all kinds of matters related to building in this area and soil. Macdonald was so impressed with Raynor’s skills that he asked him to continue on with the construction project, and then to work on more golf course design projects in the future.

In Raynor, Macdonald found a highly competent engineer, highly knowledgeable about matters that Macdonald had no background in. On the other hand, Raynor had no background in golf, so there was no threat of butting heads with the famously prickly Macdonald. The results of their collaboration on their first project together—the National Golf Links of America— still speak for themselves over 110 years later.

Macdonald had Raynor continue helping on Long Island projects, starting with Piping Rock, on Long Island, nearer Manhattan. They’d continue their work together on courses ranging from The Creek (NY), St. Louis CC (MO), Mid Ocean (Bermuda), and The Lido (NY). But Macdonald didn’t want to become a full-time architect—he was only designing courses for his friends and for clubs where he was a member—so soon enough, Raynor was receiving commissions through his association with Macdonald and based on their strong work together. Raynor started his own design firm.

Since working for Macdonald gave Raynor all of the ideas he knew about golf holes, Raynor was heavily influenced by Macdonald. Raynor continued using the concept of Ideal holes (often referred to as template holes), which were design principles based on some of the best strategic holes in (mostly) Scotland and England. Some of these templates include the Redan, Biarritz, Road Hole, Punchbowl, Alps, Valley, Eden, and Cape holes. But Raynor was certainly no copy cat or pre-fabricator: each of his holes are different from each other, based on how the land available dictated their placement and further strategy. Raynor also designed completely original holes as well, but he’s best known for the holes that take inspiration from the best in the world.

What many people will remember most vividly from Raynor courses are the bunker styling—often deep and steep—and the green contours. He often built rather large greens, with swales, dips, and hollows that not only affect putts and demarcate interesting pinnable areas, but also solve issues related to drainage. Whether it’s a Biarritz green or Redan or a Double Plateau, you’ll be able to recognize the concepts that Raynor helped to make greens around America more unique and strategic.

Raynor’s courses in New England include Wanumetonomy, Misquamicut, Dedham Country & Polo Club, CC of Fairfield, Yale, and Hotchkiss. In New York, the list is even more impressive: Sleepy Hollow, Fishers Island, Southampton, and Westhampton. His masterpieces elsewhere include Chicago Golf Club (IL), Shoreacres (IL), Camargo (OH), Yeamans Hall (SC), CC of Charleston (SC), Fox Chapel (PA), Mountain Lake (FL), and Blue Mound (WI). Overall, Raynor worked on or designed roughly 70 courses, though only 35 or so are still in existence.

Raynor died at age 51, in January 1926, while many of his projects were still being built, including Lookout Mountain (GA), Camargo (OH), and Essex County CC (NJ). The outstanding work was completed by Raynor’s associate, Charles Banks, who learned from Raynor for many years. Raynor kept few records, so it’s difficult for clubs to document and restore many of his courses. Thankfully, a number of them have discovered original plans and drawings, and/or historic photos that show contours and scale.

Many of the existing Seth Raynor courses have been faithfully restored over the past 25 years, by architects such as Brian Silva, Gil Hanse, Tom Doak, Bruce Hepner, and Tyler Rae, among others.

Want to learn more about Seth Raynor? Be sure to check out our other book, The Golf Courses of Seth Raynor (2023). MASSACHUSETTS

L#+a.&d a1#-. 67 4/)&! '&!. of Boston, Worcester (pronounced WUH-ster) is rich in history. John Adams once lived and worked here as a teacher, and it was a thriving manufacturing town from the late 1800s until World War II. Worcester today is still the second largest city in Massachusetts.

Founded in 1900, Worcester Country Club had great aspirations. Thirteen years later, the club moved to a larger property and commissioned a course by Donald Ross, The club hosted the inaugural Ryder Cup in 1927, as well as the 1925 U.S. Open and 1960 U.S. Women’s Open. Over the many years, the club has kept much of its classic feel.

In the first round of the 1925 Open, Bobby Jones called a one-shot penalty on himself when he felt his ball move at address. He would end up tying for the lead after 72 holes and lost in the 36-hole playoff, so the penalty cost him the title. When people commended him for calling the penalty, he famously replied, “You might as well praise me for not robbing a bank.”

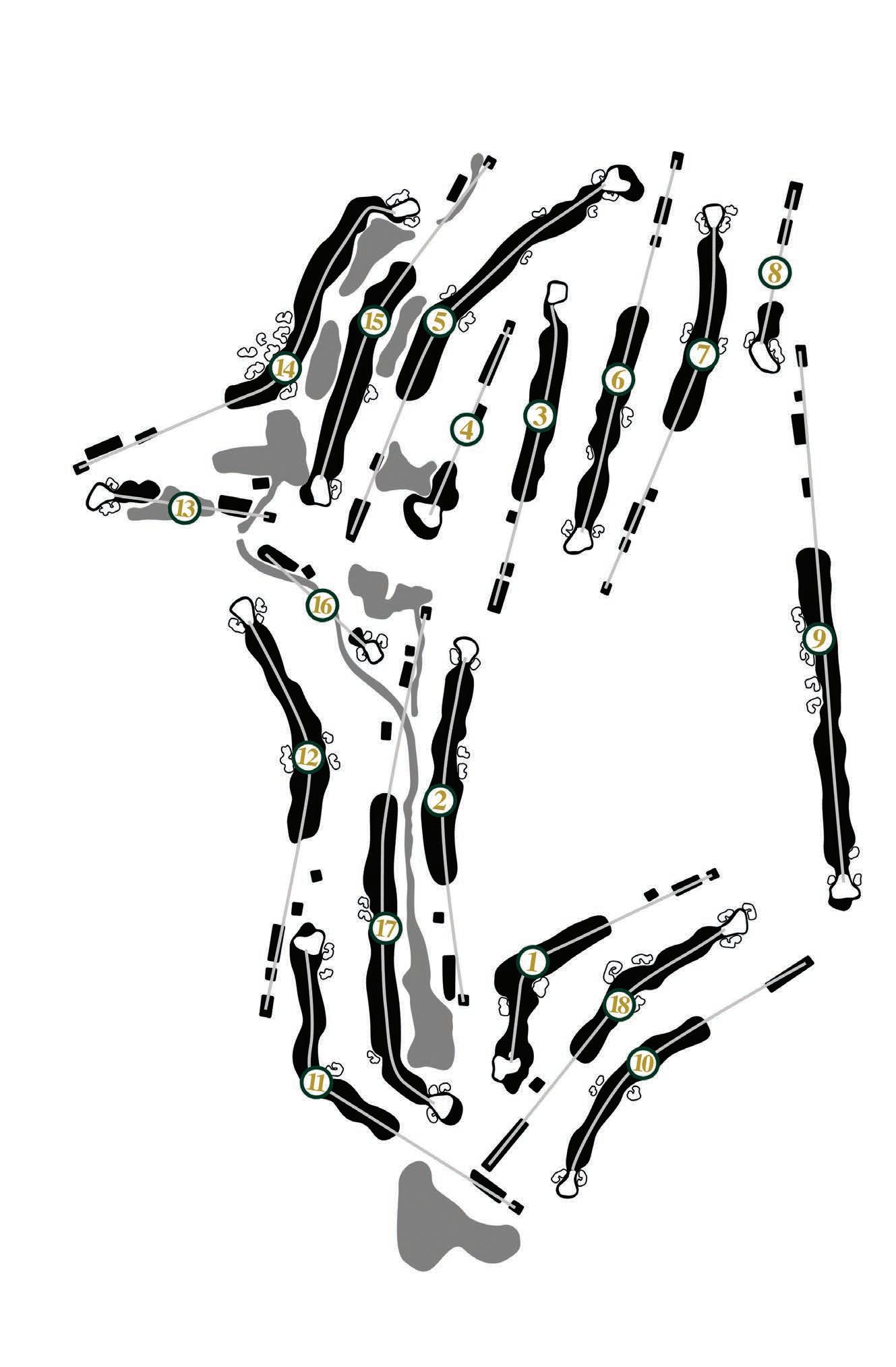

Ross routed this course over hilly terrain, which produces many uneven lies, among open vistas and native grass framing many of the holes.

The course is split by railroad tracks, with the holes to the south (1-7, 17-18 playing around a creek and pond, and the northern ones (8-16) meandering through heavily wooded territory. The course is kept in great condition. The collection of par fours here are excellent, and the par-three greens are wild. The back nine here is known for being one of the most compelling and entertaining in New England.

T,& +/.2 #% 1#!.#$ came to own a parcel of land on its southern edges, and some leaders decided to build a golf course here, thanks to some federal funding. Designed by Donald Ross, George Wright Golf Course was built in the 1930s as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project, and it opened in 1938. It’s a fantastic course—and value—as a municipal course.

The course is named after a Boston legend: George Wright was an early Hall-of-Fame shortstop for the Boston Red Stockings. When playing in Boston in the 1870s, he helped the team win six league championships in an eight-year span. After his playing years, he went into the sporting goods business, and he was also influential in introducing golf to Boston. In late 1890, Wright and some friends obtained a permit and chopped nine holes in the frozen ground of Boston’s Franklin Park, playing two rounds. Six years later, a public golf course was laid out in Franklin Park (now known as William J. Devine Golf Course), and it became only the second public course in the country. He also employed a young man in his Wright & Ditson store who himself would be come a legend: Francis Ouimet.

There’s also a more direct reason why the city named this Hyde Park course after Wright: he donated the land to the city. The land was extremely hilly and covered in rock, making it nearly impossible to develop for housing, but Wright and others knew it would be great for golf.

The land posed a number of challenges, mostly involving rock and drainage. All told, the work crews had to use roughly 60,000 pounds of dynamite to excavate a ledge, 72,000 cubic yards of dirt to raise the ground above the swamp level, and 57,000 feet of drainage pipe to drain the property. The project is said to have cost roughly $1 million, which is over $21 million in 2024 money. The Norman-style clubhouse is massive and is original to the 1938 opening.

64 | THE GOLF COURSES OF NEW ENGLAND

Sadly, the course fell into disrepair in the 1970s and ‘80s, before the City of Boston decided to take over operations again in 2004. They have brought the course back to its former glory, with some of the most interesting greens in the Boston area.

George Wright’s reputation is firmly back. Golf Digest named it the best muni in Massachusetts, GolfWeek ranked it the 14th best muni in the country, and Golf Magazine rated it the 3rd best muni in the U.S.

Much of this return to life is thanks to architect Mark Mungeam, who has performed restoration and renovation work here over many years. His work on muni courses around Boston has been pivotal in not only improving—but actually saving—great local golf.

Originally intended as a private development for a group of investors in the early 1930s, the land of George Wright Golf Course ended up with the City of Boston when the Great Depression hit and the investors disappeared.

A1#-. 87 4/)&! !#-., #% B #!.#$ , a relatively young club has been carved out of the granite hills and has quickly become one of the best modern courses in New England. It’s easy to miss the entrance. Only a simple stone stake—with the number “19” carved into it—marks the turn into Boston Golf Club. The club’s logo, a redand-white striped flag of the Sons of Liberty, further connects the club to Boston’s history and emphasis on independence.

The club famously has no rules or policies; it simply defers to common sense and reason. With no other sports, and no pool, golf is the focus here. And there are no tee times. The simple clubhouse caters to a laid-back feel, with a beautiful but simple, modern men’s locker room.

Gil Hanse routed this original design through a former rock quarry, featuring significant land movement and elevation changes. His contouring here feels extremely natural, as if the course was just here as-is. Native grasses frame many of the bunkers, and trees border the wide playing corridors, reminding players that danger is lurking. It’s a beautifully rugged, well-maintained test of skill among isolated holes carved out of dense forest. For these reasons, some refer to it as a sort of modern-day Pine Valley.

The short-but-difficult par-four 5th hole—appropriately named Shipwreck, with its super narrow green—has ruined many a scorecard. The next hole, a 160-yard par three, is equally difficult; the narrow green is guarded by natural-looking bunkers. The par-four 12th, named Gate, requires a drive over a stone wall, an accurate uphill approach to a saddle-shaped green. The 15th features a Great

The short-but-difficult parfour 5th hole, appropriately named Shipwreck, with its super narrow green, has ruined many a scorecard. 74 | THE GOLF COURSES OF

Hazard, nicknamed Hell’s 1/3rd Acre (reminiscent of Pine Valley’s own as well as Hanse’s similar constructions or restorations on other courses). The iconic view on this well-forested course comes on the 16th tee, looking back down the 15th. The course ends on another strong par three: the 18th plays uphill to a large green, where a long putt may win a match.

The club endured several hardships, including the death of its original owner in 2007, the recession in 2008, and a potential buy-out from Donald Trump. The membership rallied and bought the club and land, ensuring its democratic values of liberty and independence for the future.

Plymouth, MA • 2004

T,/0.2 4/)&! !#-., #% 1#!.#$ (#)% +)-1 is another modern course that opened up 20 years ago, one that has become one of New England’s best. Situated on a hilly, quiet, country road that winds around cranberry bogs, lakes, and meadows “has been in use for over 350 years, making it the oldest continuously used, still partially unpaved road in the United States.” This road was once a path used by the Wampanoag tribe. In fact, this road leads to the country’s very roots: Plymouth, where the Pilgrims arrived in 1620. The club occupies 3,000 acres of pine forest that were formerly the Talcott estate, and the Talcotts were descendents of a person on the Mayflower.

The sandy soil and dunes lend themselves to golf, and Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw have routed a fun layout through this pine tree forest. It was their first opportunity to work in the Boston area, and the results will not disappoint. You’ll find their trademark wide fairways and large, uniquely undulating greens, endless variety of hole lengths, directions, and shots required, rugged bunkers and natural vegetation, and subtle contouring: everything looks so natural that you swear this must’ve been here since Colonial times. While there’s width, better players will look to more specific, strategic locations, where they can better and more safely attack greens from more favorable angles. The fairways are a combination of fescue and bentgrass, and there’s no irrigation off of the fairways. You’d be hard pressed to find another course that plays as fast and firm in New England.

The fairways are a combination of fescue and bentgrass, and there’s no irrigation off of the fairways. You’d be hard pressed to find another course that plays as fast and firm in New England.

The short par-four 5th calls for an accurate drive over a forced carry to a narrow, angled fairway that follows the edge of a ridge,

MASSACHUSETTS | 81

with a hill that can kick and roll a drive down toward the green. It’s a kind of dogleg-left Cape hole that can entice long hitters to cut off more of the ravine than is prudent. The 5th may be considered a half-par hole, but don’t be surprised if you end up with double bogey or worse. The 7th is another par four with a unique green surrounded by sand. The downhill, par-five 13th plays to a wildly sloped green. Overly ambitious approaches can easily run through the green and into treacherous back bunkers, which make bigger numbers a real possibility. The 16th and 18th holes both play over a

massive hill, with downhill approaches, where players should likely land it short of the green and let it bounce up.

Like at Boston Golf Club, there are no other sports at Old Sandwich, but its clubhouse and cottages give off a more elegant, but comfortable, feel. The clubhouse—set down near a lake, with no great vistas—feels like a large retreat or lodge. The entire place is a home run.

When you walk around Old Sandwich, you absorb its natural beauty. It feels like it’s been here a very long time.

T,& 9/..a$!&.. +)-1 sits at the end of a peninsula, at a place called Butler Point, and is one of the few seaside courses in New England. The club took its name from two Native American words, kittan-sett, which mean “near the sea.” Pilgrim settlers were known to inhabit this area, which sits just 20 miles south of Plymouth Rock.

Kittansett has weathered financial hardships, endured U.S. military occupation during World War II, and has survived vicious natural disasters. Massive hurricanes have flooded the area, in 1938 and again in 1954. The pro shop, three club cottages, and some other buildings were washed away. These devastating storms are commemorated by a famous sign on the 7th hole, which shows the elevation the water reached: over 8 feet in 1954, and 7.5 feet in 1938.

The course was designed by William Flynn, and it was constructed by founding member Frederic C. Hood. A reported 100,000 tons of glacial rock was detonated, and rather than pay for costly removal, this rock was adjusted around the property and

covered with dirt, creating the imposing mounds.

The club took its name from two Native American words, kittansett, which mean “near the sea.” Pilgrim settlers were known to inhabit this area, which sits just 20 miles south of Plymouth Rock.

The course has two distinct sections: the wind-blown, linksy land of holes 1-3 and 16-18, and the inland 4-15, which are routed through thick woods and recall the English heathland. A unique feature—cross rough—occurs on six holes and helps to define Kittansett’s unique features. The par-three 3rd hole features an “island” green surrounded by sand, which becomes beach to the right of the green. The 11th is a blind par three with a mound and cross bunker 35 yards short of the green. Holes 16 and 17 play in different directions as they open up again to the winds off Buzzards Bay, offering challenging conditions—with opposite wind directions—down the stretch. The 1st and 18th holes, which play side-by-side on this narrow stretch of land, recall the dramatic opening and closing holes of the Old Course at St Andrews.

Kittansett hosted the 1953 Walker Cup and the U.S. Senior Amateur Championship in 2022. In the early 2000s, it also hosted the Harvard-Dartmouth matches, which saw the author of this volume making a 40-foot putt on the 18th green to secure the winning point for the Big Green—the last stroke of his short and unstoried competitive career. Sadly, there is still no commemorative plaque.

Kittansett exudes a simple charm and a vibe that’s all about golf. The clubhouse had to be rebuilt after record flooding, and has been expanded in recent decades. It features a very small men’s locker room and a comfortable dining room and a beautiful new outdoor bar and deck. The separate golf shop sits next to the 1st tee. The old clubhouse, which sits to the right of 18 green, has been preserved and is now used for small special events and housing on the second floor.

Gil Hanse has consulted on restoration efforts beginning in the 1990s. When William Flynn’s original drawings were later discovered, Hanse and Jim Wagner focused their efforts accordingly in significant work that took place in 2003, 2014, and 2019.

W/., %&!+-& - )/$&d ,#)&! , rolling hills, and views of Buzzards Bay and Quissett Harbor, Woods Hole Golf Club is a stunner. Many travelers to Martha’s Vineyard—who may take a ferry there out of Woods Hole Harbor—will drive by this course and might slow down to take in the view. Situated at the upper tip of Cape Cod, you can smell the ocean all around this seaside course.

Woods Hole began with nine holes, designed by Alexander Findlay in 1898. In 1899, the nine-hole golf course opened for play, and the club was incorporated in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1919, Thomas Winton added nine golf holes and routed the new 18-hole links. It’s a small property, but the dramatic land movement offers a lot of variety and a decent dose of challenge.

A 1919 Boston Transcript review noted: “The course is at the edge of Buzzards Bay, with one of the greens located only a few yards from a beach of smooth white sand which fairly entices the golfer to give up his golf for a swim.”

Woods Hole’s course draws some comparisons with another Cape Cod classic—Eastward Ho—but perhaps a bit less wild, with less interaction with the coast, and more trees.

Woods Hole tips out at just under 6,200 yards, but its small, undulating greens are its defense. All of the par threes are short here, but they require accuracy. Sidehill lies and significant elevation changes will test everyone’s iron game. In terms of standout holes, the king is the par-three 17th, which sits right on Buzzards Bay.

Woods Hole’s gray-shingled clubhouse is a relatively new construction, with stunning views and interior design. There’s a lot of charm here, on and off the course.

100 | THE GOLF COURSES OF NEW ENGLAND

THOUGH NOT KNOWN BY MANY TODAY, Alexander H. Findlay (1866-1942) was a true legend of his time. While many of his designs no longer exist, in part or whole, whether the course is lost to time or had been redesigned by figures such as Donald Ross, his evangelism for the game spread through much of the United States—including extensively across New England, and all the way to Montana, Nebraska, Texas, and South Florida—much of it before 1900. Findlay he laid the groundwork—quite literally—for the game of golf to take root in America. Along with C.B. Macdonald and Donald Ross, Findlay is one of the handful of people considered to be a “father” of American golf. And if all of the newspaper reports of his time were correct, he may have been one of the most interested men in America.

Alexander Findlay was born on a ship between England and Scotland to two English parents. He grew up in Cornwall, England and then in Montrose, Scotland (between Carnoustie and Aberdeen). He played golf from the age of 8, with a set of clubs that his mother got him, and he taught everyone he knew how to play. It’s said he met the young British royals Prince Albert and Prince George V (who would become King of England in 1910) near Balmoral

and got into a skirmish with them, but they soon became friends. By the mid-1880s, he was winning competitions in Scotland, playing with just three clubs; he is said to be the first person to ever shoot a 72 in an 18-hole competition. When his mother died in 1887, he left Scotland for America, and he secured a job as a ranch hand and cowboy in Nebraska. It’s believed that he laid out the first course in the Midwest, at least: a six-hole effort in Fullerton, Nebraska, around 1887.

Oil magnate Henry Flagler hired him to design some courses in Florida, and he used the opportunity to also design courses up and down the eastern seaboard. A year later, sporting goods company Wright & Ditson hired him to become an ambassador for golf clubs, sending him across the country to build courses and play in exhibitions to showcase the game of golf to those unaware of the game. The company would be acquired by Spaulding, with whom Findlay developed a line of hickory golf clubs (marked “A.H. Findlay”).

Beginning in 1900, Findlay enlisted his friend Harry Vardon—arguably the best player in the world at that time—to join him on many further exhibition trips across America, and together they marketed the Vardon Flyer, a new-technology golf ball made out of a resilient and rubbery material called gutta percha, that would revolutionize the game. These exhibitions may have done more to spred the game of golf across the country than any other campaign.

In the 1910s up until his death in 1942, he was a well-known golfer of his time who played with every U.S. president in his time in the States, and even taught the Pope how to hold a club (but failed to convince him to build a golf course in the Vatican City). He met and worked with a young Francis Ouimet and encouraged him to learn how to play. Findlay even allegedly counted both Teddy Roosevelt and Buffalo Bill Cody as friends. (This is a good time to note that our factchecker could not verify these claims.)

By most accounts, Findlay laid out over 100 courses across the U.S. Among those courses in this book, he contributed layouts at Hyannisport, Woods Hole, Dedham, Brae Burn, Vesper, Salem, Cape Arundel, Belgrade Lakes, Portsmouth, Miacomet, Siasconset, and Wannamoisett. Again, little or none of his work exists at these courses, but his work led to opportunities to pick up where he left off.

Findlay’s other courses in New England include Bass Rocks CC (MA), CC of Greenfield (MA), Portland CC (ME), Framingham CC (MA), Mount Pleasant (NH), and many others. Elsewhere, he was known for his work at the Greenbrier Resort (WV), Pittsburgh Field Club (PA), Llanerch CC (PA), Walnut Lane (PA), Basking Ridge CC (NJ), Tavistock CC (NJ), and San Antonio CC (TX).

Chatham, MA • 1922

T,/! )a$d 'a! #$+& 'a)9&d by two major figures in early colonizing history. According to the club, “in 1622, William Bradford, the leader of the Plymouth Colony, came to Cape Cod in the ship ‘Swan’ to trade with the Indians whose settlement was in the area now occupied by the Eastward Ho! Country Club. The Plymouth Pilgrims were in dire need of food, and Governor Bradford hoped to bargain for beans and corn. Accompanying him as pilot was the Indian known as Tisquantum, or Squanto. Unfortunately, shortly after the expedition entered what is now Pleasant Bay, Squanto died. Bradford had planned a rather lengthy visit in this area, but Squanto’s death made it necessary for him to return to Plymouth since no other pilot was available to guide the ship through the shoals south of the bay. Before leaving for Plymouth, the members of the expedition buried Squanto’s body, and it almost certainly rests within the bounds of today’s country club.” It is also believed that these waters off of the course saw the only combat near U.S. soil during World War I, when a German U-Boat was spotted and sunk.

The course was designed by William Herbert Fowler, and it opened for play on July 3, 1922. The club was named Great Point Golf Club, and then Chatham Golf/Country Club, before its current name stuck in the 1920s. Clearly its name is a nod in the easterly direction to the golf course Westward Ho!, due east in England. This course is Fowler’s only design on the east coast: he was a prolific designer in the U.K, and built several courses in California, but playing Eastward Ho! offers Americans a unique opportunity to see the work of one of the greatest British architects of the early 20th century.

As one of the most breathtaking and exhilirating courses in New England, the exclamation point in Eastward Ho! is well-deserved. Indeed, the location of Eastward Ho!, bordered by ocean on three sides—with the accompanying sand, heather, and ever-present wind—is one of the few New England courses that can called a true links course.

Many of the holes showcase stunning elevation changes, with holes routinely maneuvering the hilly landscape in ways that require accuracy off the tee and in the changing winds, as well as accurate approaches off of almost-certain uneven lies. The front nine heads—you guessed it—east, using much of the peninsula’s land to its advantage. The uphill 3rd hole, a short par four, may tempt long hitters to try driving the green, but the green is so small—and well-guarded with sharp falls on the left, right, and back—that a lost ball is more likely than a putt for eagle. The downhill 6th— a par four that navigates around competing hills—plays to a valley, and then a pitched-up green that sits next to the water, with dunes in the distance. The back nine heads mostly westward, onto the (relatively) flat section of the property and back around into the more undulating areas over the final holes. The par-three 15th is a favorite for many, known for being draped next to a gorgeous bay that lurks just six feet off of the green. Go long, and the hazard line greets you just three feet off of the back.

Eastward Ho! is the kind of course where even the most well-traveled golfers would be content to play every day. The wind directions and conditions make this course play differently daily, and you’re almost guaranteed to not have the same lie twice. The beautiful gray clubhouse fits the Cape Cod aesthetic on this remarkable piece of land. This sprawling clubhouse, sitting between the 9th and 18th greens, offers stunning views from the back patio.

The course was renovated by Keith Foster in 2004. Upon completion of construction, Herbert Fowler, said, “I am quite certain that this course will compare favorably with the leading courses in the United Kingdom and will be second to none of them. ”

, MA • 1923

L#+a.&d #$ .,& &a!.&0$ !,#0&! of Nantucket, in the village of Siasconset, far from the relative bustle of the downtown, you can find a calm and quiet while looking out onto Sankaty Head, with the Atlantic Ocean beyond, and no other land before Europe. Looking out toward Ireland and the U.K. may feel fitting here, at one of the U.S.’s true links course. There are few better places to find yourself around sunset, when the fescue seems to catch fire in the day’s dying light.

In the early 1920s, a wealthy man named David Gray donated 280 acres for the golf course, as well as a house to function as its clubhouse. The course was designed by a local golfer named H. Emerson Armstrong, and it opened in 1923. A few years later, Eugene “Skip” Wogan added bunkers and made other alterations. As a young boy, Wogan was Donald Ross’s personal caddie at Oakley Country Club, and then Ross hired Wogan to go with him to Essex County Club, and when Ross left Essex for Pinehurst, he picked Wogan as his replacement as head pro and greenskeeper at Essex. The mounded, grass-faced bunkering provides Sankaty Head’s great strategy, and a lot of its aesthetics.

A day at Sankaty Head—commonly referred to simply as Sankaty (pronounced SANK-a-tee)—is tough to beat. Thanks to its close proximity to the unfettered breezes off the Atlantic Ocean, a round at Sankaty can be quite windy. It can also play quite differently dayto-day, or even hour-to-hour. The course routing takes ever-changing directions, and is fashioned somewhat in the same of a figure eight, ensuring that the winds affect shots differently, forcing players to constantly adjust. Nantucket is nicknamed the Gray Lady because of its fog, and when it rolls in at Sankaty, all bets are off. The course today tips out at just under 6,800 yards. The front nine plays along the coast and lighthouse, and the back nine moves inland a bit, before rewarding players with ocean views again on the

last four holes. The 1st hole is a medium-length par four, with a green tucked to the left, with two cross bunkers protecting the bail-out right. The undulating green on the par-three 3rd is guarded on both sides by deep bunkers, and there’s native grass long. The long, uphill par-five 4th has cross bunkers jutting out on the left side of the fairway. The par-four 5th is shorter and runs downhill (and a bit sidehill, left to right). The difficult par-three 6th is well-guarded by bunkers left, short, and right. The par-five 8th can play incredibly long, so it’s nice that it’s followed by a short par-four 9th, where bunkers guard the favored angle of approach in the fairway, and around this pitched-up green.

The 10th is a great, dogleg-right par four with no fairway bunkers, but a devilish green. Players will want to favor the right side of the 11th fairway, which offers the best angle into this triangle-shaped green, with pot bunkers short and right. The par-three 14th is relatively short, and this partial punchbowl green can help slightly wayward tee shots from ending up in the difficult bunkers that largely surround this green. The par-five 17th runs uphill, with a fairway canted right to left. The closing hole is a straightaway par four, where players must avoid the fairway bunkers left and right to set up a short uphill approach to the final green.

The famous Sankaty Head lighthouse, guarding the eastern edges of Nantucket, forms a beautiful backdrop to this charming course. Its thick, red paint stripe has made it an iconic standout among the great lighthouses of New England. The lighthouse dates back to 1849, and it’s still in operation (automated in 1965). It serves as the club’s logo, with a few seagulls flying around it.

The clubhouse was restored recently, opening full, 360-degree views of the course and surrounding areas.

A.W. Tillinghast made some revisions to the course in the late 1920s, and the club’s committees tinkered with the course off-and-on for several decades. In 2016, the club hired Jim Urbina to restore Sankaty’s true links feel and fast-and-firm conditions. Urbina and Sankaty’s superintendent restored the original size of the greens, rebuilt bunkers, moved tee boxes, and removed excessive trees.

Sankaty hosted the USGA’s Mid-Amateur Championship in 2021.

Nantucket, MA • 1963

S/.-a.&d .,0&& 4/)&! !#-., of Nantucket town, and just one mile from the beach, Miacomet is a true public gem. This land was inhabited by the Wampanoag tribes, who referred to it as Miacomet, which meant “the meeting place.” A man named Ralph P. Marble bought these 400 acres in 1956, hoping to begin a dairy farm. Four years later, he realized the land was perfect for a golf course, and in 1963, the course opened.

The course’s bunkering, waste areas, vegetation, and fescue create a beautiful landscape for golf. These same features provide a good amount of challenge and variety, and the relatively small greens will test one’s short game on nearly every hole.

The opening hole features a large waste area on the left, and the road out-of-bounds on the right. Approaches to this small green must clear the false front, but also avoid going long, where out-of-bounds lurks again. The short par-four 2nd features that same waste area on the left, with an additional waste area to the right, closer to the green. A forced carry is required to this green, which is guarded by native grasses in front. The 3rd is a long par three, but the green is open in front for run-up shots. The par-five 4th hole bends to the right, around two waste areas, to a smallish, double plateau green. The 5th is another par five, with a wide fairway and uphill approach. The par-four 6th shares the 5th’s fairway, before it doglegs right, to a well-guarded green that features a spine running through the middle. Favor the left-side of the fairway on the long par-four 7th, as the green opens up from there. The 8th is a long par three, followed by the short par-four 9th, which snakes a bit to the left.

On the back, the dogleg-right par-four 10th is framed by stunning bunkers. The par-four 11th twists just a bit to the left, and the par-three 12th plays to a diagonal green with plenty of bunkers to the left and short-left. Cross bunkers define the strategy on the par-four 13th, where the tricky green lacks any bunkering beside it. The par-five 14th bends left, and the fairway gets interrupted by native grasses before dipping down to a lay-up area riddled with bunkers. The 15th is the shortest par three here, followed by the excellent par-four 16th that takes a turn left, with a waste bunker protecting the short-cut line toward another bunkerless, well-contoured green. The 17th takes a turn toward home, and the closing hole is a par five that features a center-line bunker near the ideal lay-up point. If you want to go for the green in two, you’ll have to carry the native areas in front of the green, and navigate the contours of this tricky green.

In the opinion of those who’ve played Miacomet, it can easily rank among the top public courses not only in New England, but in the U.S. overall. Howard Maurer expanded the course to 18 holes in 2003, and he returned in 2008 to renovate the original nine holes. Nantucket Golf Management runs the course, which is owned by the Nantucket Land Bank. In 2021, Miacomet was cohost for the USGA’s Mid-Amateur Championship stroke play rounds.

MASSACHUSETTS

Siasconset, MA • 1997

A1#-. 87 4/$-.&! %0#4 Nantucket town, southeast on Milestone Road, is Nantucket’s youngest but most exclusive golf club. It’s also one of the island’s most charitable organizations. Founded by Ed Hajim in 1997, Nantucket Golf Club took its name from the first club devoted to golf on the island, which dissolved in 1949. It’s draped over gorgeous sandplain grassland and coastal heathland that’s unique to Nantucket, and its construction was a study of marrying golf with the natural beauty of a landscape, while preserving much of the land as it was, and as it should remain. They not only built a golf course in the most environmentally sensitive fashion, they also built a rare-plant nursery, and an off-site habitat for the Northern Harrier Hawk.

The course is a Rees Jones design, with help from Greg Muirhead. No wetlands were disturbed or lost. The property is much flatter than its neighbor just a few hundred yards to the northeast: Sankaty Head Golf Club. The property also abuts Audubon Society conservation land, so there are plenty of birds and wildlife to spot. The club uses extremely low amounts of herbicides and pesticides, and they monitor the groundwater to ensure no negative effects.

The course opened in 1998, and the course has a naturalist feel. A par-72 layout, it can stretch over 7,000 yards. Jones purposely moved as little dirt as possible and built many greens as extensions of the fairways. The bunkering is natural-looking—links-like—in this area prone to high ocean winds: they are smaller and deeper, and sometimes clustered where strategy calls for more defense. The property is somewhat M-shaped, so the holes change direction often. The course plays very differently based on wind direction.

The par-four 1st hole is straightaway, but the two bunkers protecting the center and right edges of the green mean that the preferred angle is near the fairway bunker on the left. The 2nd and 3rd holes both twist a bit left, with a cluster of bunkers protecting the inner dogleg on the par-five 3rd. The next par five—the 6th—

features unique, small bunkers placed at both natural and strategic points, including two center-line bunkers 20-50 yards short of the green. The parthree 8th features a carry over a pond: the only water on the course.

In its early days, the club established the Nantucket Golf Club Foundation, which offers a variety of scholarships. They also organize the Children’s Charity Classic, a two-day golf tournament and fundraiser gala. In total, the foundation has raised roughly $60 million for local youth.

The back nine begins with a stout par four, with bunkers right of the landing area, and guarding both the left and right sides of the green. The par-five 12th plays to a diagonal fairway that turns left. The longish par-three 13th features a pear-shaped green. The par-four 14th may be short, but players need to place their tee shot between a series of bunkers spread out on both sides of the fairway. The long par-four 15th snakes around bunkers before reaching a long, narrow green. The 17th is another shorter par four, but bunkers guard the front-center of this green. The 18th is a very long par five, with conservation land running down the entire left side. It’s hard to beat a day at Nantucket Golf Club, which Golf Digest named the best new private course of 1998.

L#+a.&d #$ .,& +a45-! of Williams College, deep in the Berkshire Mountains, Taconic may be one of the top-five college courses in the country. The original seven-hole layout opened in 1896, and was expanded to 18 holes in 1928 by Wayne Stiles and John Van Kleek. The course got even better when Gil Hanse came to town in 2008 and made adjustments to this classic mountain course. If you like golf courses with long mountain vistas, maybe a little leaf-peeping, and/or old New England college campuses, you should get yourself to Williamstown. The course is hilly but compact, allowing spry golfers to play in under three hours. To remind players that Williams is a good liberal arts college, the scorecard quotes the classical Latin poet Ovid, who wrote “medio tutissimus ibis,” which translates loosely as “you’ll be safer down the middle” (though no translation is provided on the scorecard.) Less poetic—and less pretentious—there’s an old sign outside the pro shop that says, “No Preferred Lies, We Play Golf Here!” Indeed, the middle of the holes and greens are good places to be at Taconic. Many holes are lined with tall pines, requiring accuracy off the tee. The par-three 14th measures 173 yards from the back tees, and the green is guarded by six bunkers (some more tightly, some more loosely). The finishing holes here are particularly stout: after playing the long 15th and 16th holes, you might not be happy standing on the 17th: a 245-yard par three. And then the finisher is a 550-yard par five. Those final four holes are quite the final exam.

Taconic hosted the U.S. Junior Amateur in 1956, where a 16-year-old upstart named Jack Nicklaus reached the semifinals (he made a hole-in-one on the 14th). The club also hosted the 1963 U.S. Women’s Amateur and the 1996 U.S. Senior Amateur, and the NCAA Division-III Championships in 1958, 1972, and 1999.

Gil Hanse said, “Taconic Golf Club has outstanding greens, [and they] possess all of the bold undulations and imagination that mark greens built by classic golf course architects.”

Gil Hanse said, “Taconic Golf Club has outstanding greens, [and they] possess all of the bold undulations and imagination that mark greens built by classic golf course architects.”

ARCHITECT SPOTLIGHT