LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN CLUB

The First 100 Years

BACK NINE PRESS

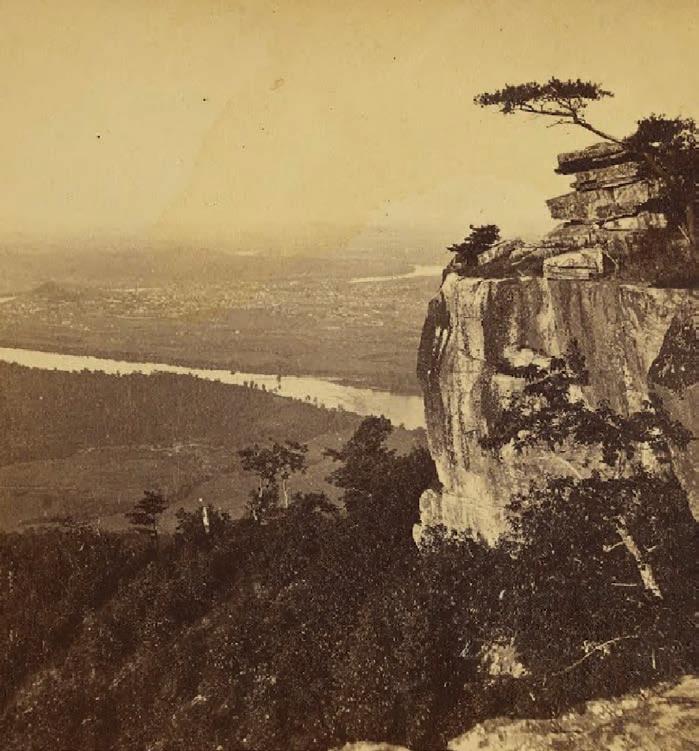

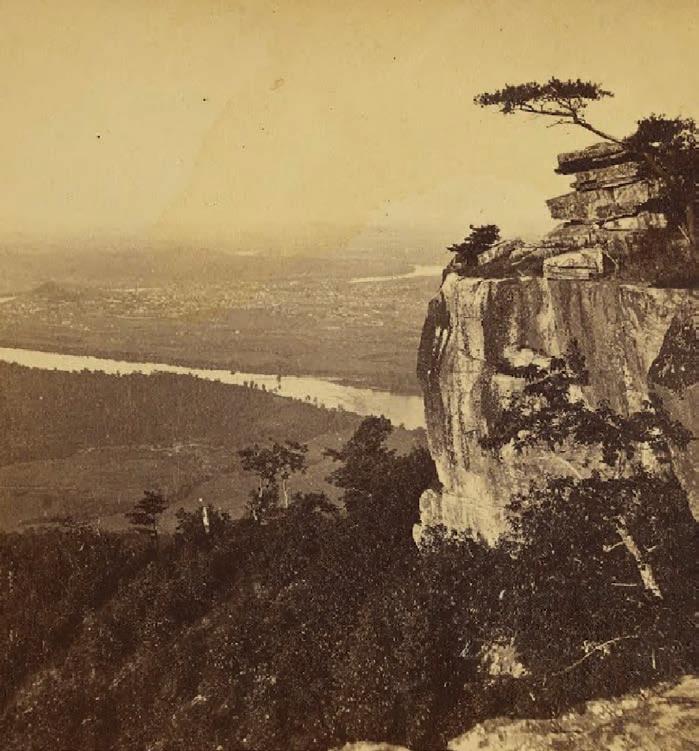

The story of Lookout Mountain began 240 million years ago, when the collision of tectonic plates forced up the stretch of sandstone rock that today towers more than 2,000 feet above the river valley below. Lookout Mountain is part of the Cumberland Plateau, the southernmost section of the Appalachian Plateau. The Tennessee River curves in front of the northern brow of the mountain.

Lookout Mountain will always be best known for its spectacular outcroppings of rock, but the mountain is surprisingly hollow in spots. Centuries of rain and dripping water, which found its way slowly through the top layer of sandstone rock, has worn away some of the limestone deposits that are inside Lookout Mountain, in the process creating several large caves. Mother Nature took her time building Lookout Mountain.

The earliesT evidence of humans living around what is today Chattanooga is moundwork believed to be from the Mississippian/ Muscogee tribe of Native Americans. The Muskogean period stretches back as far as 1,000 years. The Muskogean word for rock was pronounced “chato,” and it’s theorized they may have used the regional sufx “-nuga” when describing a place of dwelling. In the Creek language spoken by the Muskogeans, the phrase “Chat-to-to-noog-gee” translates to Rock rising to a point, which probably referred to Lookout Mountain.

Members of the Cherokee tribe of Native Americans were living in the area as early as 1776. The name “Lookout Mountain” is used on at least one map as early as 1795. By 1816—and likely much earlier—there was a permanent Cherokee Nation settlement in the Chattanooga area around what is today Broad Street. The Cherokee were removed from Chattanooga and the rest of South in 1838 as part of the U.S. government’s decision to forcibly resettle the tribes on a newly created reservation in Oklahoma.

The city of Chattanooga was incorporated in 1839. The arrival of a railroad in 1850 combined with the city’s location along the Tennessee River made Chattanooga a natural magnet for trade. Soon the phrase “where corn meets cotton” was being used to reference Chattanooga’s role as a gateway between the North and South. A decade later, Chattanooga’s location would make it an important strategic holding during the Civil War.

Right: Closeup of 1884 map of former Cherokee territories, with Lookout Mountain in lower-center area. This corner of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama would be the latest area held by the Cherokee tribes before removal.

Below: Depiction of local Cherokee villages during the Pisgah period (1000-1500 AD).

The cherokee were using Lookout Mountain as a hunting ground and game preserve when the frst white settlers began living on the mountain. The two groups seem to have lived without major confict for almost a century.

The Cherokee had maintained a system of trails up to Lookout Mountain, but they purposely kept the trails too narrow to be used by the wagons of white settlers. Colonel James Whiteside built the first road up to Lookout Mountain when he arrived in 1838. Whiteside charged a $0.50 toll for wagons to use his road. Travelers on horseback paid half. The Colonel also acquired several large tracts of land on top of the mountain through the Cherokee Land Lottery.

By the 1850s, the Whiteside family built and operated the original Lookout Mountain Point Hotel under the East bluff. The hotel was built near one of the many natural springs that are found on the mountain. The availability of clean drinking water was a major factor in the steadily increasing number of settlers living on Lookout Mountain by the second half of the 19th century. Life on top of the mountain was still hard work. Anyone wishing to live their year round would have to be almost entirely self-sufficient. The Mountain had no electricity, running water, septic systems or law enforcement. The density of the trees and lack of usable topsoil prevented any large-scale farming.

Deciding to live on top of the mountain was not for the faint of heart.

After the Cherokee were forcibly relocated in 1838, much of the land on top of Lookout Mountain was divided and given by grant to white settlers through a process known as the Cherokee Land Lottery. Known beneficiaries included William Rieves of Halls County and Ovid Sparks of Outnam County, Georgia.

left: Painting of Colonel James Whiteside (1803-61) and family, with servants, at their summer home atop Lookout Mountain. This area is now Point Park.

(James Cameron, c. 1858, courtesy of the Hunter Museum)

top: Colorized 1864 photograph of Moccasin Bend of Tennessee River. (Matthew Brady)

Bottom: 1864 drawing, perhaps of the Twin Sisters rocks. (William Cullen Bryant’s Picturesque America, 1879)

The firsT posT office was esTablished on Lookout Mountain on June 11, 1867. The first school on the mountain opened in 1878. The town of Lookout Mountain, Tennessee was incorporated in 1890, and by 1914 the earliest version of a Lookout Mountain Club had a clubhouse at 109 Highland Avenue.

The McCallie, Drinnon, and Jackson families were some of the earliest documented occupants of the land that became Fairyland. The Masseys and Hixons are recorded as living near Lula Lake. It’s not known whether these families lived on the Mountain all year. The top of the mountain was still without most of the advantages of living in the city below. Lookout’s lack of significant farming and industrial opportunities left few options for earning money. Anyone wishing to live on Lookout Mountain full time would either need to arrive with a source of income already established or learn to live on the limited resources found on the mountain at the time.

Arthur Thomas, Colonel A.M. Johnson, and Colonel Tomlinson were the early owners of the land around Rock City. Colonel Johnson’s daughter, Mrs. Douglas Everett, inherited the land.

Garnet Carter and O.B. Andrews eventually bought the property from Mrs. Everett for what would become their Fairyland project. Carter and Andrews acquired additional land from the Thomas and McFarland families that was used for Fairyland.

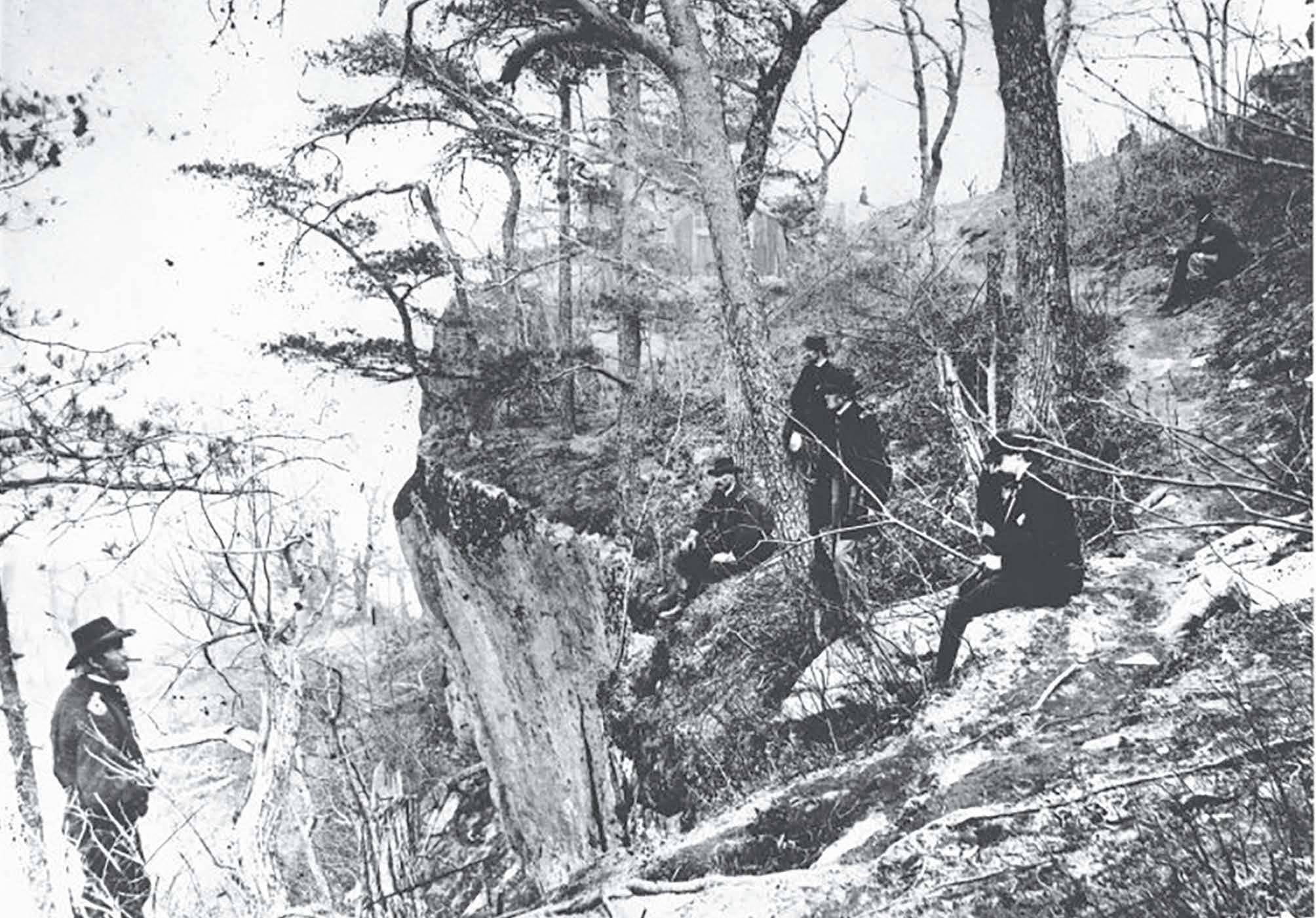

on november 24, 1863, the name “Lookout Mountain” was permanently written into the history of the United States. On that day, Union forces led by Major General Joseph Hooker captured Lookout Mountain from the Confederacy. The Battle Above the Clouds, as it became known, marked a signifcant shift in momentum during the Civil War.

Just two months earlier, the outlook for the Union had been bleak. Following their defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga, 40,000 Union soldiers had retreated back into Chattanooga during the fnal week of September. Confederate General Braxtron Bragg followed close behind. In an attempt to besiege the city, Bragg quickly positioned his Army of Tennessee atop Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge.

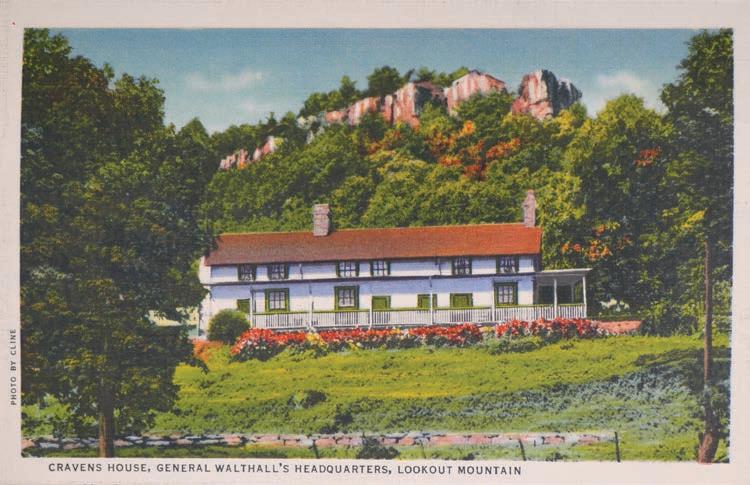

The Confederate Army used the home of local industrialist Robert Cravens as a lookout. The Cravens family continued to live in their home even though it had become the confederate’s main line of defense against a potential attack. Eventually, the constant shelling by Union cannons forced the family to leave their home. These correspondents set up their camp in the Cravens House front yard, where they wrote, sketched, and photographed. Though the “White House,” as the soldiers referred to it, had been repeatedly hit by cannon and small arms fre, it was intact after the battle. But during the days that followed, the house was almost completely stripped away by Union forces and used

as tent fooring and frewood. (The Cravens family would rebuild after the war.)

Faced with the very real threat of having one of his key armies starve, President Abraham Lincoln transferred command of the situation to General Ulysses S. Grant on October 17. Within 10 days, Grant launched a surprise attack at nearby Brown’s Ferry. This successful move reopened the Tennessee River as a supply line for the North. By early November 1863, General William Sherman arrived with 20,000 Union reinforcements.

Grant’s planned counterofensive called for a three-pronged attack, with the majority of Union forces concentrated on taking out the core of Bragg’s army stationed along Missionary Ridge. Joseph Hooker was given 10,000 men for his assignment to attack Lookout Mountain. Hooker’s assault began in the early hours of November 24, but high water, fog, and mist kept his troops from reaching the lower slopes on Lookout Mountain until well after dawn.

Finally around 10 a.m., Hooker’s men made their frst contact with the Confederate front

line, at a spot one mile southwest of Lookout Point. Badly outnumbered and confused by the poor visibility, the Confederate troops were soon in retreat. By nightfall, Bragg withdrew his men back to help defend Missionary Ridge. Lookout Mountain was back in Union hands for good.

Casualties from the Battle of Lookout Mountain totaled 671 for the Union, and 1,251 for the Confederacy: those fgures are just a fraction of the carnage that occurred when Bragg’s entire Army of Tennessee was defeated on Missionary Ridge the following day. Chattanooga served as a major Union supply hub for the remainder of the Civil War. Sherman’s march to Atlanta and beyond was made possible by the provisions forwarded through Chattanooga. For the Confederates, the defeats at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge were the start of a continuous retreat that would not end until the fnal surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

Today, several locations on Lookout Mountain are part of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. Point Park is a ten-acre memorial park that overlooks the Lookout Mountain Battlefeld and the city of Chattanooga. The paved walking path in the park takes visitors by several monuments, Confederate artillery positions, and a scenic overlook. The largest monument is the New York Peace Memorial, which was donated by the state of New York as a tribute to peace and reconciliation between Union and Confederate veterans of the war. Inside Point Park, at the point of the mountain, is the Ochs Memorial Observatory.

IT was during The Third week of November 1924 that the news broke. Two local Chattanooga businessmen named Oliver Burnside “O. B.” Andrews and Garnet Carter were planning to develop a large tract of land on top of Lookout Mountain into a residential community. On November 22, a Chattanooga newspaper reported that the new project would straddle the Rock City and Rock Village sections of the mountain, and that the new development would be named Fairyland. The day before, an application for the new company’s charter had been filed with the county clerk. The application stated that the initial capitalization of the project would be $300,000.

While initial reporting on Fairyland quoted the size of the project at 400 acres, in reality Carter and Andrews had already arranged to acquire more than 700 acres. Much of the land that became Fairyland was purchased from families that had acquired the land after it had been seized from the local Cherokee tribe as part of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

There had been rumors for decades about new projects that were allegedly slated for Lookout Mountain. None had even reached the starting line. Someone wishing to build anything of signifcant size on top of the mountain would need to provide their own roads, utilities, and other resources. Despite these challenges, news of a Fairyland development was taken seriously from the frst moment that the plans were made public. Andrews and Carter, both in their early forties in 1924, were already well established in Chattanooga business and social circles. A decade earlier, the same pair had founded the Chattanooga Lookouts franchise baseball team, and they had demonstrated a knack for getting big things done. For the optimistic citizens of Chattanooga, the Fairyland development was further validation that their city was continuing to grow.

For Carter and Andrews, Fairyland would be the realization of an idea that had been taking shape for several years. The pair made trips to places like French Lick, Indiana, and Miami, Florida, to scout for new business opportunities. During the trips the two men noticed the positive efects that several real estate projects were having on the local population.

Carter and Andrews sensed the time was right for a similar project in Chattanooga. Both men had previous success in business, but they would be taking on a large risk with the Fairyland project. Finding and acquiring the land on Lookout Mountain was only the frst step. Developing Fairyland into a livable community required roads, sewers, and electricity. For their plan to succeed, Carter and Andrews would have to sell Fairyland housing lots fast enough to fnance the signifcant investment in infrastructure. The catch was that selling lots usually required infrastructure. Most prospects expected at least a road leading to the land they were being sold.

The two men were gambling that their fellow Chattanoogans trusted them enough to buy lots based on the idea of Fairyland rather than the current reality. They had made a big bet, but it was one that would quickly prove sound.

Previous Page: L.C. Smallwood Contracting Company works on the construction of the Fairyland roadway, circa 1924.

above: Tree clearing for Fairyland development, locations unknown.

It’s appropriate that the creation and formative years of the Fairyland development are most often associated with Garnet Carter and his wife Frieda. The couple did spend their entire adult lives creating, building, marketing, and living on Lookout Mountain. But there was another man who was highly involved and infuential, who should also be remembered.

oliver burnside andrews—“O.B.” to most who knew him—was Garnet Carter’s partner in the founding of Fairyland.

Born on July 23, 1882, O.B. was the youngest of Garnett and Roaslie Andrews’ seven children. The Andrews were already a prominent family of early Chattanooga by the time O.B. arrived. Garnett Andrews served as mayor of Chattanooga from 1891 to 1893, and the family’s prosperity allowed O.B. to be educated at the newly founded Baylor School and then the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, which is now Auburn University.

O.B. Andrews began his professional career working as an insurance inspector in Philadelphia.

Andrews was living in Philadelphia in late 1903 when he married his wife Stevie Campbell, but the young couple moved back in Chattanooga by 1905. It was in 1905 that Andrews founded the Acme Box Company. Acme was successful from the start, and O.B. reinvested his paper profits into a wide variety of civic, philanthropic, and investment projects. In 1908, Andrews spearheaded a group of investors that brought minor league baseball to Chattanooga. The new baseball team’s first stadium was named Andrews Field, and the Chattanooga Lookouts would make East Third Street their home for most of the next century.

Acme Box eventually became Andrews Paper Box Company, then Consignees Favorite Box Company. Andrews also served as director of Hamilton National Bank, secretary of Richmond Mills, and vice president of the National Box Makers Association.

Andrews was also a committed supporter of Chattanooga throughout his life. His name appears on descriptions of countless civic and charity projects throughout the first four decades of 20thcentury Chattanooga history. In most of the endeavors, Andrews is listed alongside still-familiar names such as Lupton, Probasco, and Carter.

Garnet Carter was Andrews’ main partner on the Chattanooga Lookouts deal, and baseball was only the beginning of their shared interests. The two young men were the same age, both had left Chattanooga as teenagers but returned by their early twenties, and both had married within a year of each other. Carter and Andrews had enough early financial success to gain them entry into the top tier of Chattanooga society. Carter and Andrews also shared an entrepreneurial spirit—or at least enough of an innate curiosity to continue to explore new potential opportunities throughout their lives. It seems almost inevitable that the duo would team up to investigate the potential of capitalizing on the exploding returns in real estate development during the 1920s. Carter and Andrews witnessed the Florida land boom up close during one of their research trips, but the pair decided their hometown of Chattanooga was a better bet.

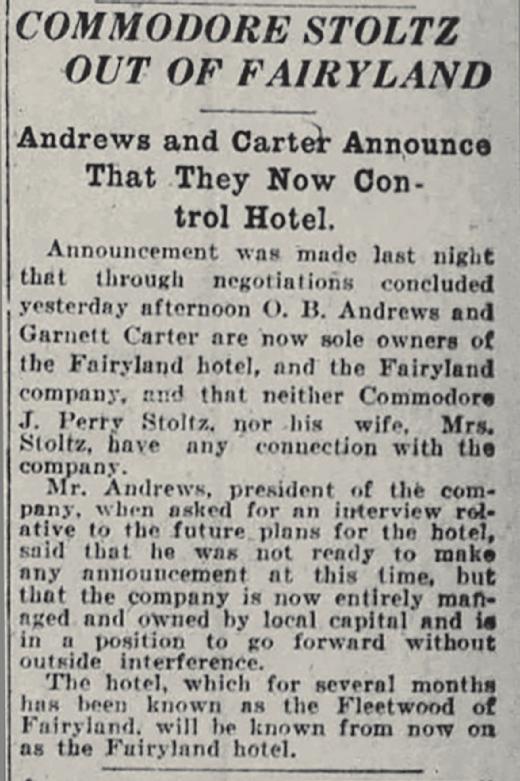

O.B. would sell his interest in Lookout Mountain in early 1928, prior to the Great Depression. He died unexpectedly on January 22, 1937, due to a heart attack while at work. He was 54 years old.

duplicate the Fleetwood model in other locations across the southeastern United States, and Lookout Mountain would be one of the first to launch.

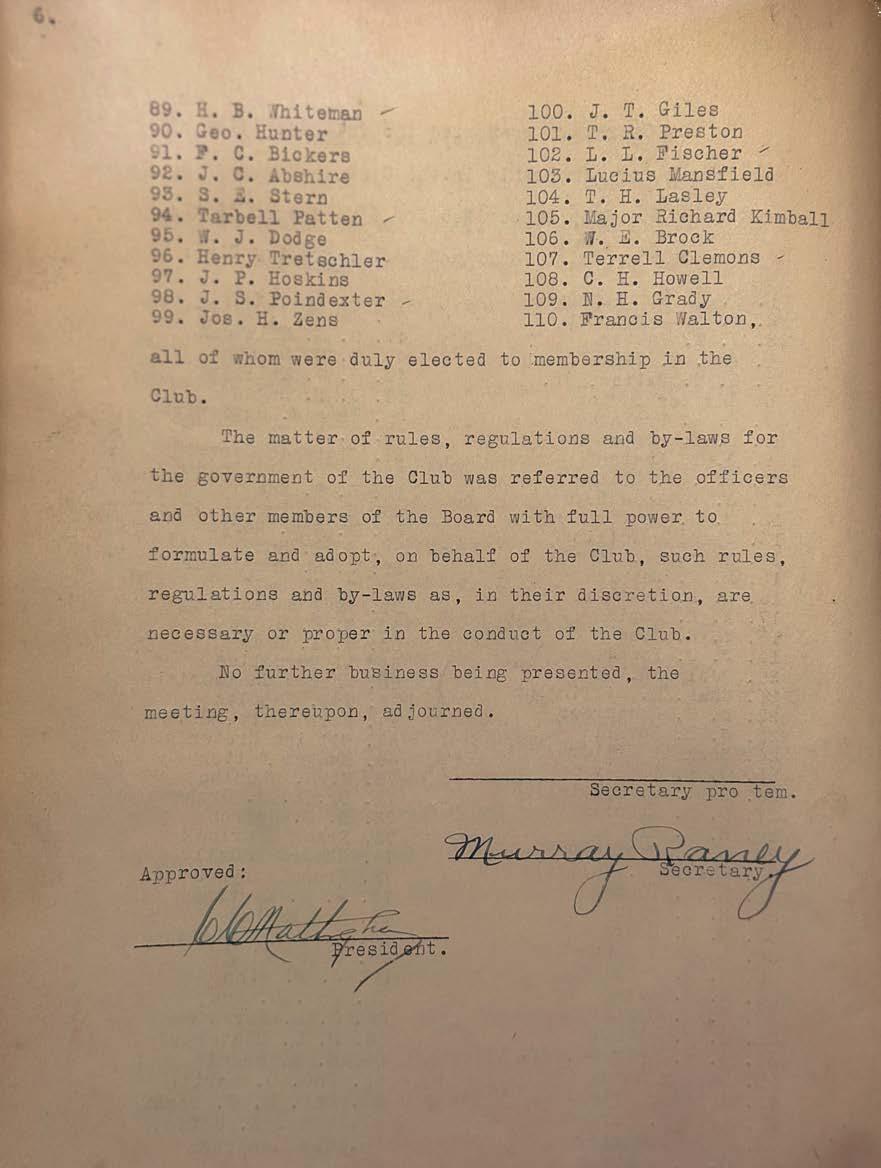

The next news to break about the plans for the Lookout development came when Carter and Andrews announced their intention to form what was briefly called the Fleetwood-Fairyland Golf and Country Club. A golf course fit well with Stoltz’s plans for attracting customers to fill the Fleetwood’s 300 rooms, and Carter and Andrews knew that a golf course would make the land surrounding it more attractive to buyers. Fortunately for the trio, many of Chattanooga’s leading citizens were eager to get involved. The planned golf course was announced by Andrews during a dinner with local businessmen. By the end of the night, the attendees had pledged a total of $100,000 toward building a golf course and clubhouse. Andrews and Carter agreed to donate 100 acres for the golf course. The initial newspaper reports said that Donald (but mislabeled “Duncan”) Ross would design the course.

The newly formed club already had 110 members who had committed $250 each before its first meeting on the night of August 13, 1925.

On May 2, 1926, the Fairyland Company placed a notice in the Sunday edition of the Chattanooga Times, stating that all subdivided lots within the Fairyland development had been sold. The notice stated that total sales had already reached $1.45 million. According to the statement, the remaining land in Fairyland would not be subdivided or offered for sale before May 1927.

were iT noT for one extremely bad break, Perry Stoltz might have completely altered the game of golf, while simultaneously preventing the future rise of Paris Hilton. A brief explanation:

Jacob perry sTolTz was born in Ohio in 1870. As a young man Stoltz made his frst fortune by creating an early version of a pinball machine. Stoltz used his pinball profts to invest in apartment buildings in New York City, which of course proved to be successful. Somewhere along the way—possibly after he joined the New York Yacht Club— Stoltz began referring to himself as “Commodore” J. Perry Stoltz, though he had not earned any such designation in the Navy, but rather simply had a penchant for sailing boats. The Commodore’s next winning development was the Fleetwood Hotel, a 15-story luxury hotel he built on the bay side of Miami Beach in 1913. From the top of the building, Stoltz ran Miami’s frst radio station, WMBF. By all accounts, Stoltz’s businesses were performing well, when in 1925 he suddenly attempted to dramatically expand his hotel business. Within six months, Stoltz announced plans to build new hotels in Augusta, Georgia, in Hendersonville, North Carolina, and on Lookout Mountain. All of the hotels would feature the same 15-story, 300-room design, they would all carry the Fleetwood name, and the hotels would all be topped with transmitters that would help Stoltz blanket the South with his radio stations. Stoltz believed that he’d be able to attract visits from customers who already enjoyed the original Fleetwood. Conrad Hilton was just beginning to expand using this same model. Hilton had bought and built a number of hotels in Texas, and he was plan-

ning to expand into the Southern states, and for a brief moment in time it appeared Stoltz might outpace him.

Stoltz’s projects seemed to all be progressing. The Augusta hotel—on the site of the former Fruitland Nursery—broke ground on February 2, 1926. Construction of the hotel in Henderson grew 12 stories high that same year. For publicity, Stoltz brought heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey to train in Hendersonville for his next bout.

Stoltz even announced he was building another Fleetwood Hotel in Florida: this one as part of a subdivision he planned to call Fairyland Point.

Then it was suddenly all over for Stoltz, just as quickly as it had begun. A devastating series of hurricanes slammed into Florida in 1926. The original Fleetwood was heavily damaged, leaving Stoltz with no income at the exact moment he had taken on large amounts of debt. The “Commodore” had lost everything. He moved back to Ohio, where he lived out the fnal 20 years of his life.

The fallout afected Lookout Mountain and elsewhere. The Fleetwood in Henderson, North Carolina, was never completed, and the construction site was eventually demolished. The Fairyland Point subdivision in Florida had barely begun. In Georgia, the Fleetwood site would sit fallow for several years, before a group headed by Bobby Jones eventually acquired the property now known as Augusta National Golf Club.

Today the only noticeable reminder of Perry Stoltz on Lookout Mountain is Fleetwood Drive—named after Stoltz’s proposed project— which still winds its way through the middle of Fairyland.

sTarTing in The summer of 1925 and continuing through 1926, Fairyland was slowly coming to life. Roads and utilities were installed and paid using the proceeds from lot sales. Some houses were being built for families that wanted to move onto the mountain. Other homes were going up for out-of-state owners planning to stay at Fairyland to escape the summer heat in their hometowns. There was also speculation taking place. Lots were being bought and sold by investors looking to proft from rising prices. Homes were also being built by smaller developers betting that potential buyers would overpay for one of the frst completed homes at Fairyland.

Freida Carter used the growth of Fairyland as an opportunity to try her hand at developing homes. Mrs. Carter designed, scaled, and oversaw the construction of 16 Fairyland homes, the original Fairyland gas station, a small snack shop adjacent to the Inn, and the Carter’s own home that was known as “Robinwood.” Mrs. Carter would later develop the Fairyland Club’s Mother Goose Village and the elaborate gardens that are now known as Rock City. Contemporary reviews of Freida Carter’s work confrmed the talent and knowledge of someone who was extraordinarily capable.

above & ToP righT: Construction on the Fairyland’s ballroom area, in 1924.

boTTom righT: Completed ballroom area in 1925.

LefT Page, ToP: The Fairyland living room, with original golf course map on display on far wall.

LefT Page, boTTom LefT: Inside the ballroom and dining room.

LefT Page, boTTom righT: The living room, with Peter Pan fresco.

The fairyland clubhouse was designed by Chattanooga architect William Hatfeld Sears (1875-1951). Sears was also infuential in founding the Chattanooga chapter of the Boy Scouts in 1914, and was a committed leader of its council and board across fve decades. He also designed the 1928 Tudor Revival-style Grandview estate that was built for Peyton Carter, Garnet Carter’s uncle; the Chapin family purchased the house in 1999, and it’s still owned by the Chapin family today, who have been running the adjacent Rock City since the 1950s.

The Fairyland grounds were designed by the famous landscape architect Warren Henry Manning (1860-1938). Manning hailed from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had worked for many years for the legendary Frederick Law Olmsted. Manning was responsible for the horticultural displays of the famous Chicago Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) of 1893, as well as the landscaping at the sprawling Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, and the modernized city plan for Birmingham, Alabama in the late 1910s.

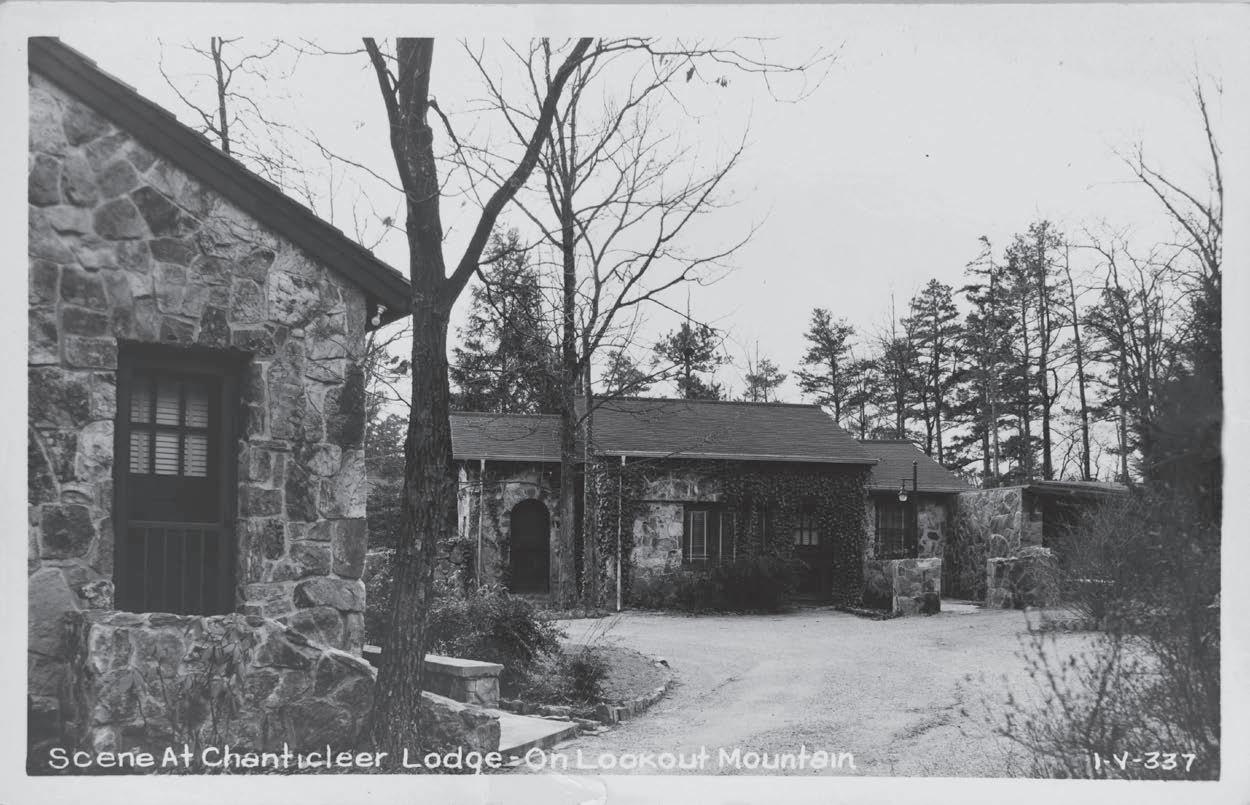

ofTen misTaken as parT of the original Fairyland plans, what’s now the Chanticleer Inn was built as a private residence in 1927 for a Richard and Annalee Watkins. Mrs. Watkins began renting out her spare bedrooms after the death of her husband in 1929.

Although never ofcially part of the Fairyland development, the Chanticleer has been housing visitors to Lookout Mountain on a continual basis for almost a century.

Additional rooms were added in 1935. The pool was built in the late 1950s. Annalee Watkins sold in the 1960s, and ownership changed hands four times in the next half century. In 2002, Rock City purchased Chanticleer Inn and completed a renovation of its rooms. Michael and Teresa Turner have operated the Inn since purchasing it in 2018.

LefT, beLow: Postcard of the Chanticleer Inn, date unknown.

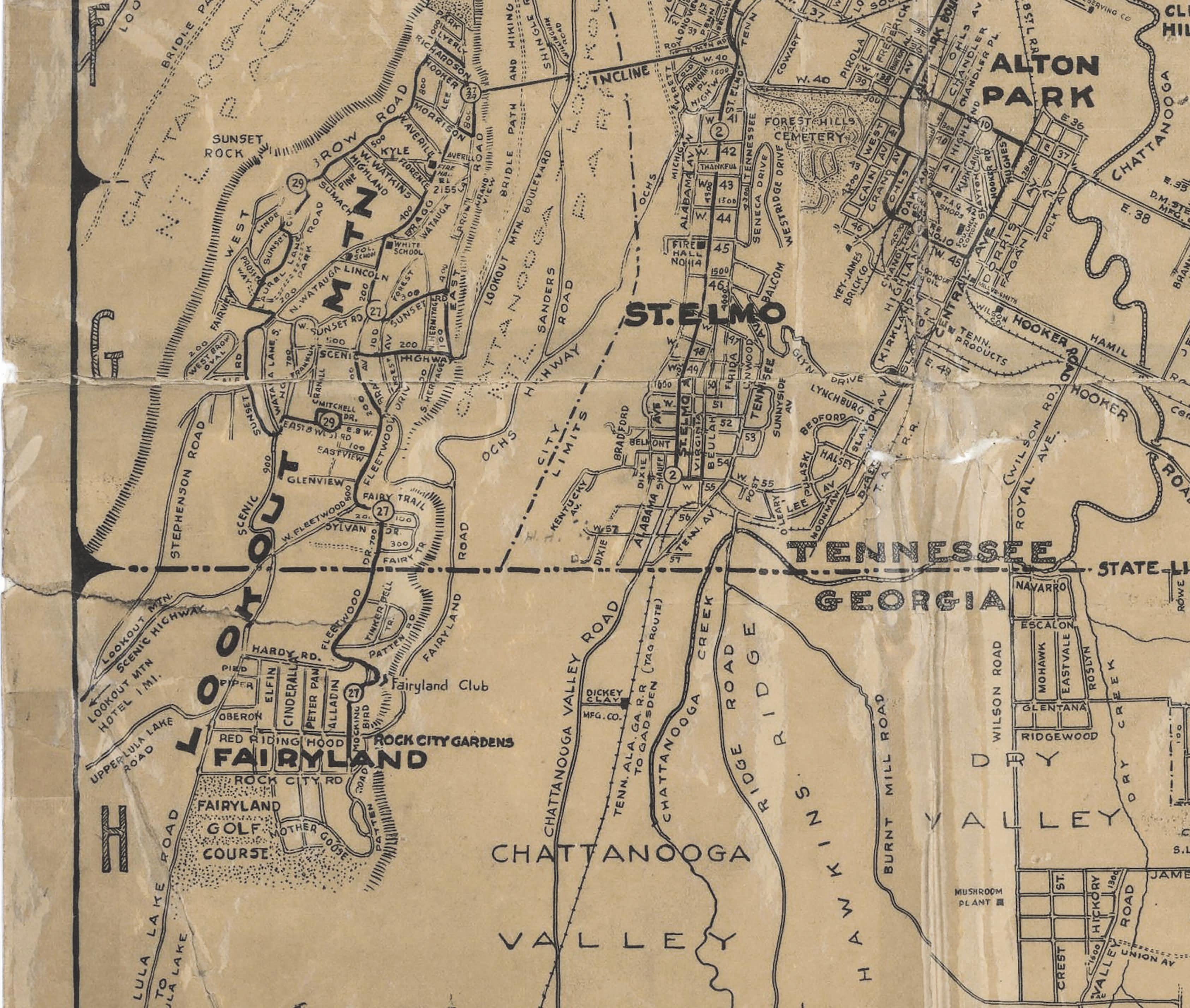

righT: Closeup of Rudolph Shutting’s street map of Chattanooga, 1938.

Frieda Carter’s vision for Fairyland extended to the naming of streets, which helped to complete the special feel of the development. Streets named after children’s book characters, such as Cinderella, Tinker Bell, Aladdin, Red Riding Hood, and Pied Piper, intersect with local names such as Patten and Hardy, and with development names such as Fleetwood and Fairyland.

Roughly five miles of roads were paved by February 1926, including Hardy Road, Patten Road, Mockingbird Lane, Wood Nymph Trail, Mother Goose Trail, Cinderella Road, Elfin Road, and Red Red Riding Hood Trail. And note that some roads are not yet represented on the map, such as Robin Hood Trail, Princess Trail, and Wendy Trail, and many south of the “Fairyland Golf Course,” including Wood Nymph Trail, and Rainbow Drive.

forTunaTely for carTer and andrews, the Fairyland project on Lookout Mountain had already achieved great momentum by the time of Stoltz’s downfall. Now the pair would need to find a way to sustain that momentum as the project faced its first headwinds. In hindsight, it’s interesting to speculate if the May 1926 grand announcement halting new Fairyland lot sales until the following year might have coincided with Carter and Andrews first learning of the severity of Stoltz’s financial collapse. Another clue that big changes were happening behind the scenes was the September 27, 1926 announcement of the Crest Lodge Club. It stated that this new Crest Lodge Club would have a national membership, and its home would be a new $500,000 separate clubhouse planned for the site immediately to the right of the 3rd tee box on today’s Lookout Mountain golf course. The Crest Lodge announcement listed Andrews, Carter, J.B. Pound, and Alexander Chambliss among its organizers. Stoltz’s name was notably absent.

Few mentions at all are made of Stoltz in Fairyland records or newspaper reports beyond the first half of 1926. This must have been an incredibly stressful time for Andrews and Carter. The pair would have been scrambling to juggle the economics of paying for the recent Fairyland Inn expansion, launching the Crest Lodge, opening the golf course, and completing the infrastructure for the residential streets of Fairyland—all without the capital they had counted on from Stoltz. They knew that word of Stoltz’s downfall would eventually go public, and once it did, questions would arise about the stability of their projects, which in turn would hurt lot sales.

Carter and Andrews were no longer hoping for Fairyland to make them rich, they were scrambling to keep it from ruining them.

The developmenT on Top of a mountain would become more attractive with the addition of a golf course. As previously mentioned, Andrews and Carter donated the 100 acres of land. They would break ground, hoping for a quick opening. There was buzz for a new golf course in the area, whic actually created buzz in national golf magazines before it had opened, which touted Seth Raynor’s pedigree and successes elsewhere before his untimely death. Though its construction took much longer than expected, the future course would not disappoint.

Fairyland was off To a successful sTarT, but Garnet Carter and O.B. Andrews knew that they would need to add more amenities if they wanted their new community to continue growing. Sales of residential lots were proceeding well, but the pair knew that their remaining potential buyers would need to see proof of more progress before deciding to put money down to move up onto the mountai. Public officials in Chattanooga agreed that the road up to Lookout Mountain was in need of expansion and improvement. How to do it—and who should pay for it—was another matter.

News and debates about the road up the mountain appeared on the front page of local newspapers on an almost daily basis since the Fairyland development was first announced. Carter and Andrews’ proposal for a new golf course on Lookout Mountain received a much better reception. If there was enough interest in forming a new club, the Fairyland partners announced that they were willing to contribute a 107-acre lot that straddled both sides of Lula Lake Road. When completed, the pair would have another amenity to attract potential Fairyland residents and hotel guests.

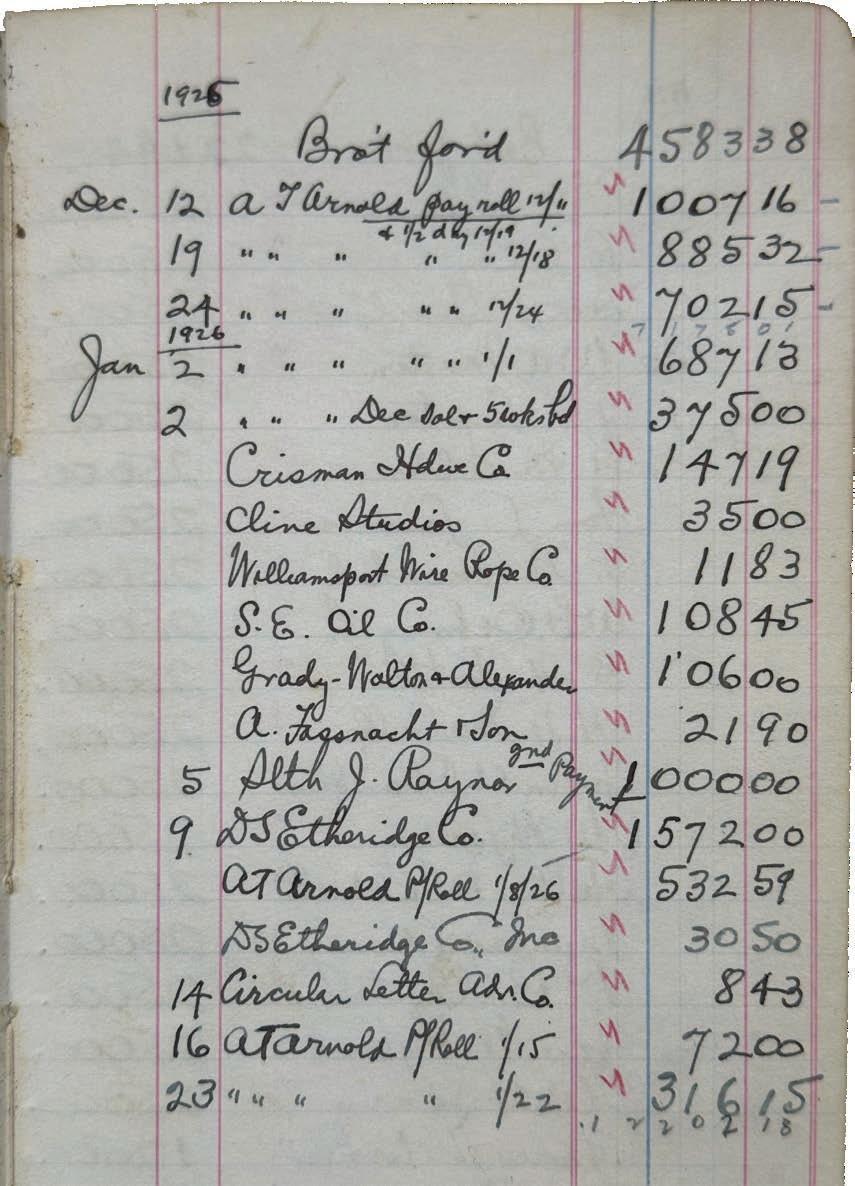

ToP LefT: The ledger of golf club treasurer Scott Probasco Sr.

ToP righT: January 1926 payments to vendors, including Seth J. Raynor.

boTTom LefT: October 1925 payments for maps and other items.

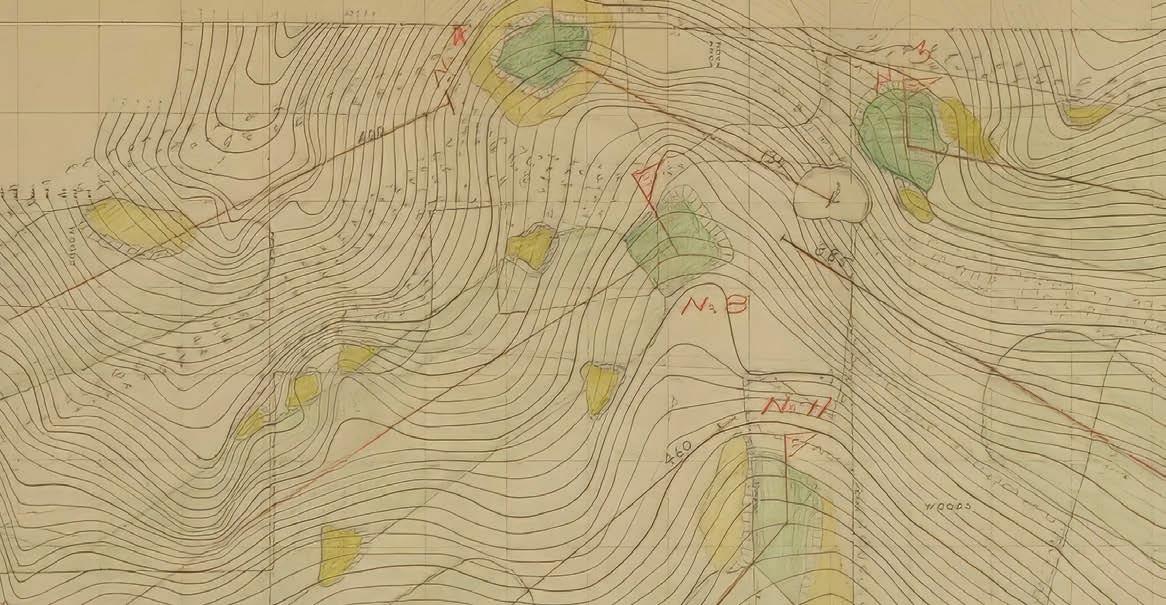

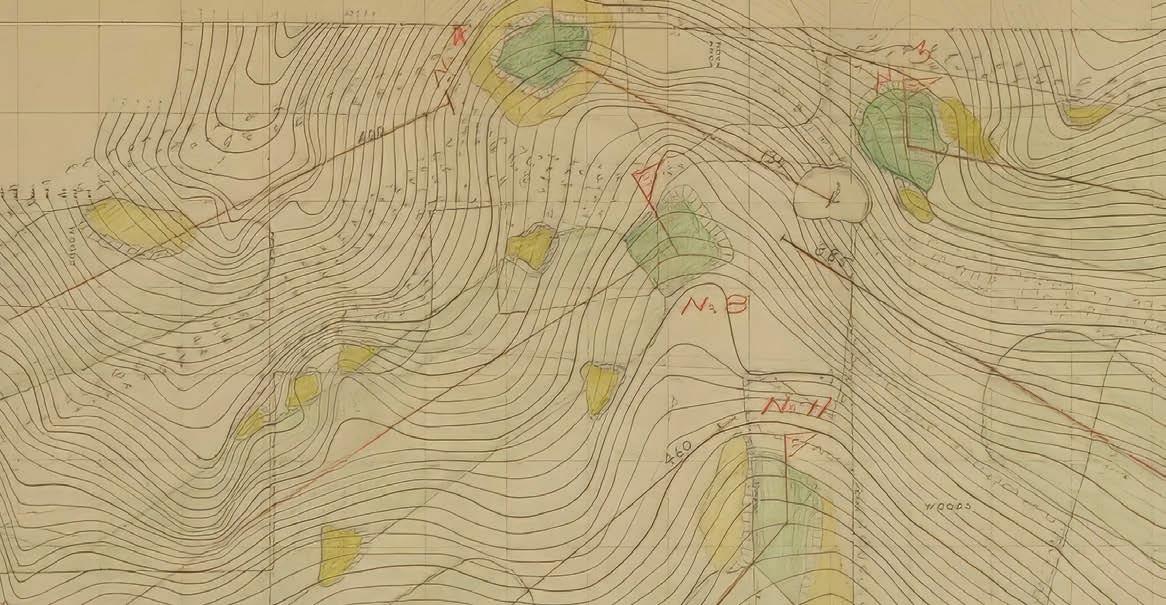

mosT of whaT we know about Seth Raynor’s time at Lookout Mountain is confirmed in the treasure trove of documents the club has preserved. Records show they paid Chas Baird $541.94 on October 9, 1925, and the Edward Betts Engineering Company $625 the following day. Both payments are listed for “topographical map” in the original Fairyland Golf ledger. The maps were prepared ahead of Raynor’s visit to Lookout Mountain in mid-October 1925. The club’s first payments to Raynor and Banks occurred on November 25: $1,000 to Raynor, and $246 to Banks. A note appears in the ledger next to Raynor’s payment that explains the terms: it’s the first of five $1,000 payments Fairyland had agreed to pay Raynor for his “fee as architect.” Banks’ payment was classified as an expense reimbursement. The ledger shows that Raynor was paid the second installment of $1,000 on January 5, 1926.

The surviving documentation of Raynor’s work at Lookout Mountain is among the strongest of any project that Raynor was involved with. The polite and reserved man from Southampton, New York gave almost no interviews or public remarks during his short but prolific career, and Raynor kept almost no records for himself of his own work. He either underestimated the value that his workpapers would have to future generations, or more likely: he was far too busy at the time to consider the matter for posterity.

This 1926 news article tells of of Raynor’s visit to Lookout that was part of that day’s announcement of the Crest Lodge Club.

Raynor’s work on the Lookout Mountain project is consistent with what historians have been able to confirm about his other projects. By 1925, Raynor was crisscrossing the country, working on more than a dozen new golf designs at a time. Getting a topographical map drawn of the course’s property was the first step. It was not unusual for Raynor to outsource the task of mapping the land to a local vendor, as long as there was confidence in their abilities.

It was also not unusual for Raynor’s first visit to survey a future golf course to also be his last. He traveled almost nonstop—mostly by train—for most of his two-decade career. Raynor preferred to walk a new property as much as possible while visiting his clients. When he ran out of daylight, he would begin working out possible routings for the course.

Routing a golf course isn’t dissimilar to assembling a piece of furniture without the instructions: it might be obvious where some of the pieces should go, but the skill is in putting every piece together without having to start over, or to backtrack too many times.

above: The 1st green. righT: Location unknown.

sTudenTs and fans of golf course architecture will never satisfy their curiosity with Seth Raynor’s routings. For his entire career, Raynor never strayed far from what Macdonald taught him starting at the National Golf Links of America. The pair mostly relied on versions of just two dozen hole designs for every course that either had built: including the same four designs for the short holes of virtually every course. What remains a tantalizing mystery is the process by which Raynor was able to find the combination of holes that unlocked the best design for each property, across wildly different terrains and topographies. Any detailed analysis of his work fails to yield any recognizable pattern of where or why he uses any specific template where he does. With his unique engineering background, he somehow just made them all seem to fit right at every course.

If Raynor was staying in a location for multiple days, he would work on the routing back at his hotel at night, while that day’s observations were still fresh in his mind. Raynor would work on his routings on his train rides, if he was traveling overnight to his next appointment. Raynor is believed to have also designed several golf courses without having visited them first, particularly if a trusted associate had prepared a detailed and reliable topographical map for him to work from.

Once Raynor finalized a design, he often had models produced—often made out of a clay putty substance called plasticine—of each hole or putting green. These models weren’t just for show. Modern architects often bring their own teams of shapers and earthmovers from project to project. But in Raynor’s era,

the best designers had to be, by necessity, good teachers. He used the plasticine models to help explain to local blue-collar laborers—most of whom had never constructed a golf course—what they were supposed to build after the architect had moved on. The models were often nailed to posts near where the hole was to be built. Sadly, almost none of these clay models remain.

The work of shaping the holes, installing irrigation and drainage lines, and eventually planting grass was done almost entirely by crews of local laborers and construction crews. The responsibility for managing the onsite work varied from project to project, but it was almost never witnessed by Raynor for any significant length of time. Like his contemporaries, he often never saw the completed version of many of the courses he built. Travel was just too difficult.

Raynor almost certainly only made that one visit to Lookout Mountain in October 1925. Seth and his wife Mary spent the final two months of the year traveling to California—and then out to Hawaii for two weeks— before making the long return back to New York at the year’s end. He would never return from his trip to Florida in January 1926. He died there at age 51.

Charles Banks later wrote, “I went with him to Lookout Mountain, Tennessee where we worked together for a week on the layout of the Fairyland Golf Course. Mrs Raynor accompanied Mr Raynor on this trip and we had a most delightful time together, though we worked steadily in the field by day and on the maps by night, often up to midnight.”

righT: Boyd and Oakes Jr. hitting approaches from the 5th fairway.

The course ThaT raynor designed and Banks constructed for Lookout Mountain includes most of the features Raynor commonly used, with just enough of the notable exceptions that make each one of his courses feel unique. Keeping in mind that Raynor’s plan assumed that rounds would start on what is today’s 3rd hole, Lookout is the only one of the 100 or so courses Raynor routed to end with two sharply downhill holes. The Principal’s Nose fairway bunker was usually a feature on Raynor’s Maiden holes, but at Lookout Mountain he used the Principal’s Nose to help create the bespoke design that is the 8th hole today. Raynor

still found just the right place to build a Maiden that Charles Banks thought was the finest hole on the property.

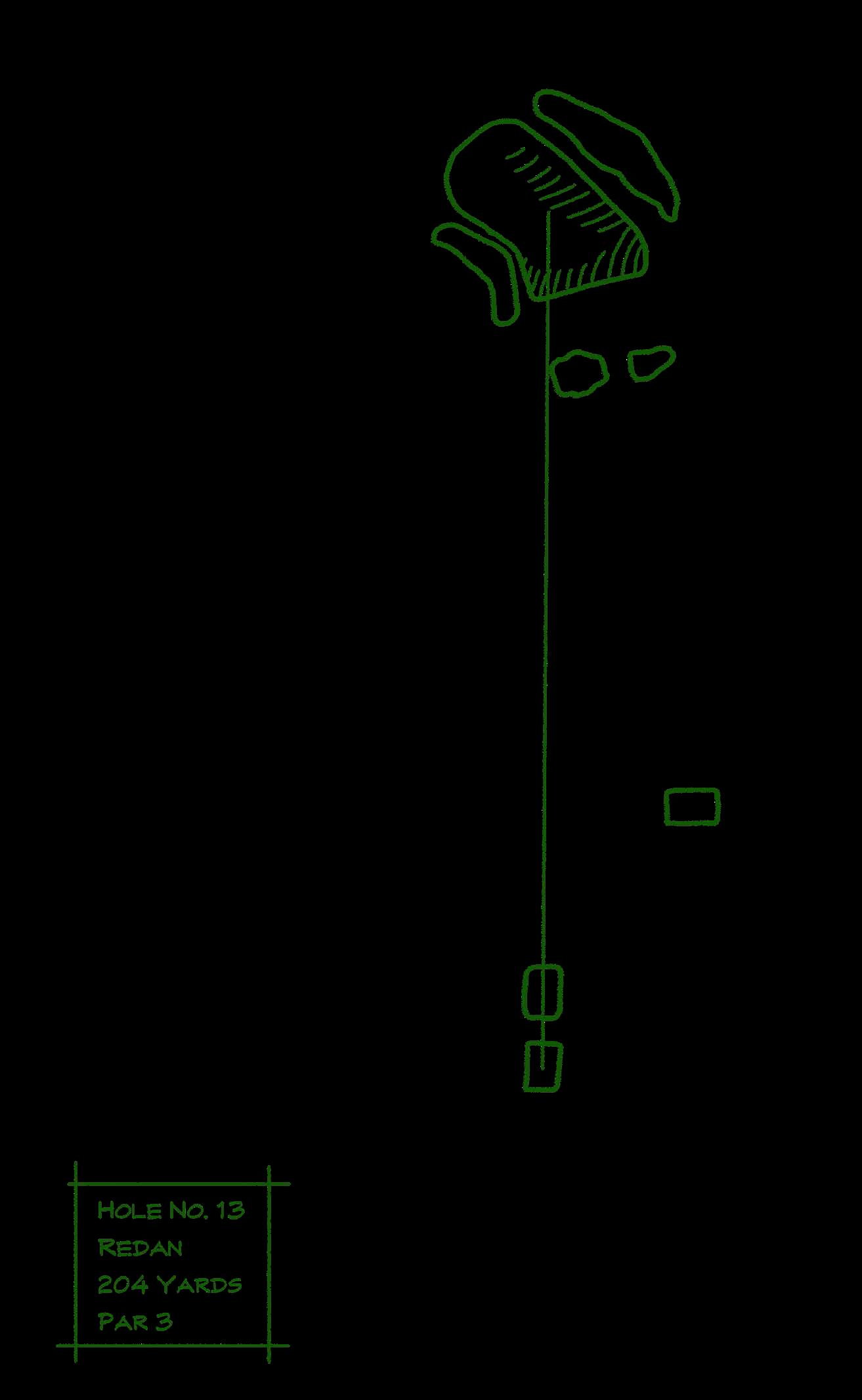

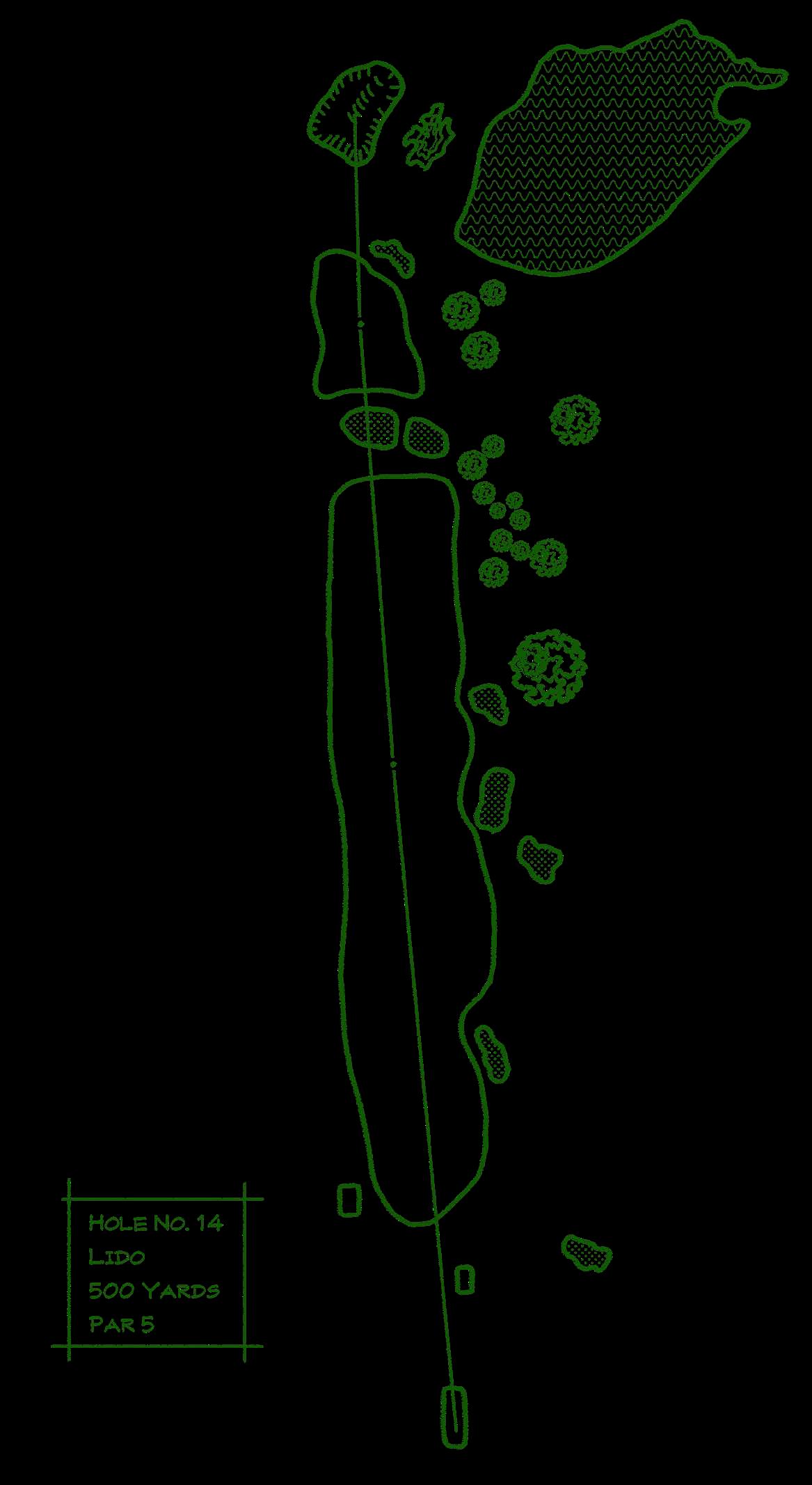

Rather than trying to force copies of his same holes into all of his projects, Raynor had a rare talent for incorporating the unique features he found at each site he worked at into his designs for that location. Lookout’s four par-three template designs—Biarritz, Short, Redan, and Eden—are almost always all found at Raynor courses, but nowhere else can you find one with a tee box like Lookout’s 6th hole, or views like the 13th, or exposed rock like the 16th.

raynor’s physical plan for the Lookout Mountain course is dated November 13, 1925 (see pages 114-15). The plan is notable for carrying Banks name just below Raynor’s—a detail that would soon take on added importance.

When Seth Raynor died unexpectedly on January 23, 1926, he had more than a dozen projects in various stages of development. Alister Mackenzie was chosen to replace Raynor at Cypress Point—although Raynor is thought to have sketched out a hole routing for Cypress that’s not much different than what was built. At some clubs like Camargo, the club members who oversaw the completion of Raynor’s work. But more than anyone, it was his assistant Charles Banks who took on the difficult task of trying to do justice to his mentor’s work.

Banks’ highest priority in the immediate aftermath of Raynor’s death was to complete construction at Lookout Mountain. Banks lived in the Fleetwood Inn while working closely with Scott Probasco Sr. to finish construction. It was likely Probasco’s relationship with Banks and the Hotchkiss School that helped keep Banks focused on Lookout at a time when he was juggling a dozen other unfinished Raynor projects. Fairyland records show payments to Banks in November 1925, and then in April, June, August, September, and December of 1926. Fairyland paid Banks well for his efforts: it appears Banks’ compensation included the outstanding $3,000 from Raynor’s agreement. Banks received his final payment from Fairyland in the form of two $1,000 interest-bearing bonds issued to him in 1930.

Work to complete the course went well into the first half of 1926. Banks sounded upbeat in an interview he gave that summer, discussing the recent completion of a well that struck water at 230 feet. Banks also discussed the clover

overseed that was almost ready to be plowed over in preparation for planting the grass seed. Rail cars would bring the topsoil to Fort Oglethorpe, where it would be mixed with Bermuda grass seed, then transported up the mountain and distributed downhill from the highest point of the golf course.

Alas, Mother Nature did not cooperate. In those years, Chattanooga had averaged about 50 inches of combined rain and snow precipitation annually. But in 1926, rains were well above average. No one had ever seen anything like the storms that arrived in 1926: a record six major hurricanes measuring Category 3 or more in intensity made landfall on the Atlantic coast. The storms pushed a pressure zone filled with moisture onto Chattanooga and held it there for months. The resulting storms washed out the work being done on Lookout’s course almost as quickly as it was completed. Trying to complete the Lookout Mountain golf course in the summer of 1926 was like reading a newspaper in a carwash.

More bad news arrived when work began on building the bunkers for the course. Workers often hit bedrock with their shovels as soon as they dug just inches below the surface. There were no good options to solve this problem. Raynor depended on bunkering to introduce strategy into many of his hole designs, but construction was already behind schedule and over budget because of the constant rain showers. The club had already gone over budget to build the course, making it one of the most expensive ever built—and it still wasn’t finished. The club’s leadership made the decision to complete the construction and seeding as quickly as possible, and without most of the 81 bunkers that Raynor had designed.

plans for whaT by Then was being called the Crest Lodge Club were officially announced on September 26, 1926. The announcement stated that work on a $500,000 clubhouse would begin on January 1, 1927. The clubhouse was shown to overlook both the Raynor-designed golf course and the Chattanooga Valley.

It’s likely that this was the same location for the clubhouse that Raynor had been told when he was working out the routing for the golf course, but there is no evidence of any efforts made toward building a golf clubhouse in that spot. It’s possible that Andrews and Carter had always intended for a Crest Lodge clubhouse to be built on the spot shown on Raynor’s plan, but it’s more plausible that the idea for a separate Crest Lodge club was born of necessity during the scramble to overcome Commodore Stoltz’s sudden exit. Either way, no progress was ever made, and the golf course was never played in the order of holes that Raynor had planned.

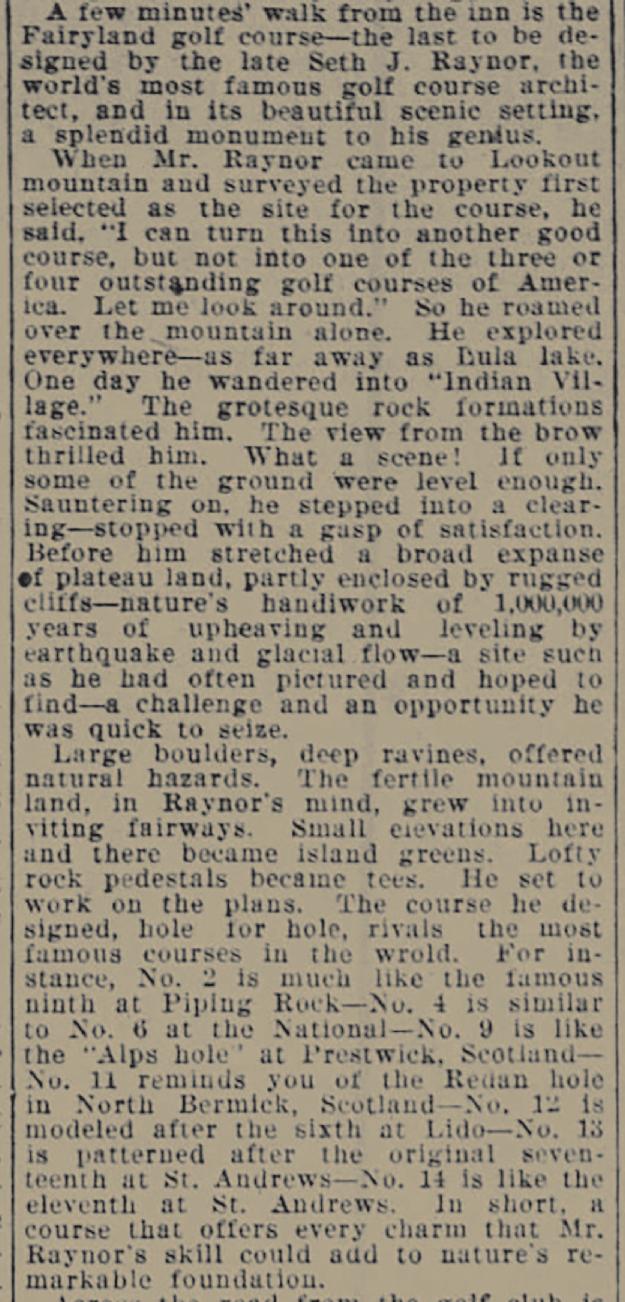

The newspaper coverage of the Crest Lodge announcement included some of the earliest details about the golf course:

“When Mr. Raynor came to Lookout Mountain and surveyed the property frst selected as the site for the course, he said, “I can turn this into another good course, but not one of the three or four outstanding golf courses of America. Let me look around.

“So he roamed over the mountain alone. He explored everywhere—as far away as Lulu Lake. One day he wandered into ‘Indian Village.’ The grotesque rock formations fascinated him. What a scene! … sauntering on, (Raynor) stepped into a clearing—stopped with a gasp of satisfaction. Before him stretched a broad expanse of plateau land.

—No. 2 is much like the famous ninth at Piping Rock

—No. 4 is similar to No. 6 at the National

—No. 9 is like ‘The Alps’ hole at Prestwick, Scotland

—No. 11 reminds you of the Redan hole in North Berwick, Scotland

—No. 12 is modeled after the sixth at Lido

—No. 13 is patterned after the original seventeenth at St. Andrews

—No. 14 is like the eleventh at St. Andrews.

In short, a course that offers every charm that Raynor’s skill could add to nature’s remarkable foundation.”

The article confirms Raynor’s plan for Lookout included many of what are now known as his template holes.

Almost none of Seth Raynor’s bunkers had been constructed when the Lookout Mountain course was finally ready for an Opening Day tournament on July 1, 1927. Only 10 holes were open for the event, which featured 38 players and was won by A. Pollack Boyd. Weather delays and depleted finances kept the full 18 holes from being ready for play until 1929. By then, any hope of installing the rest of Raynor’s bunkers had been abandoned due to rising costs and lack of resources. Aside from the missing bunkers, there were only a few small differences between Raynor’s design and the golf course that his associate Charles Banks completed.

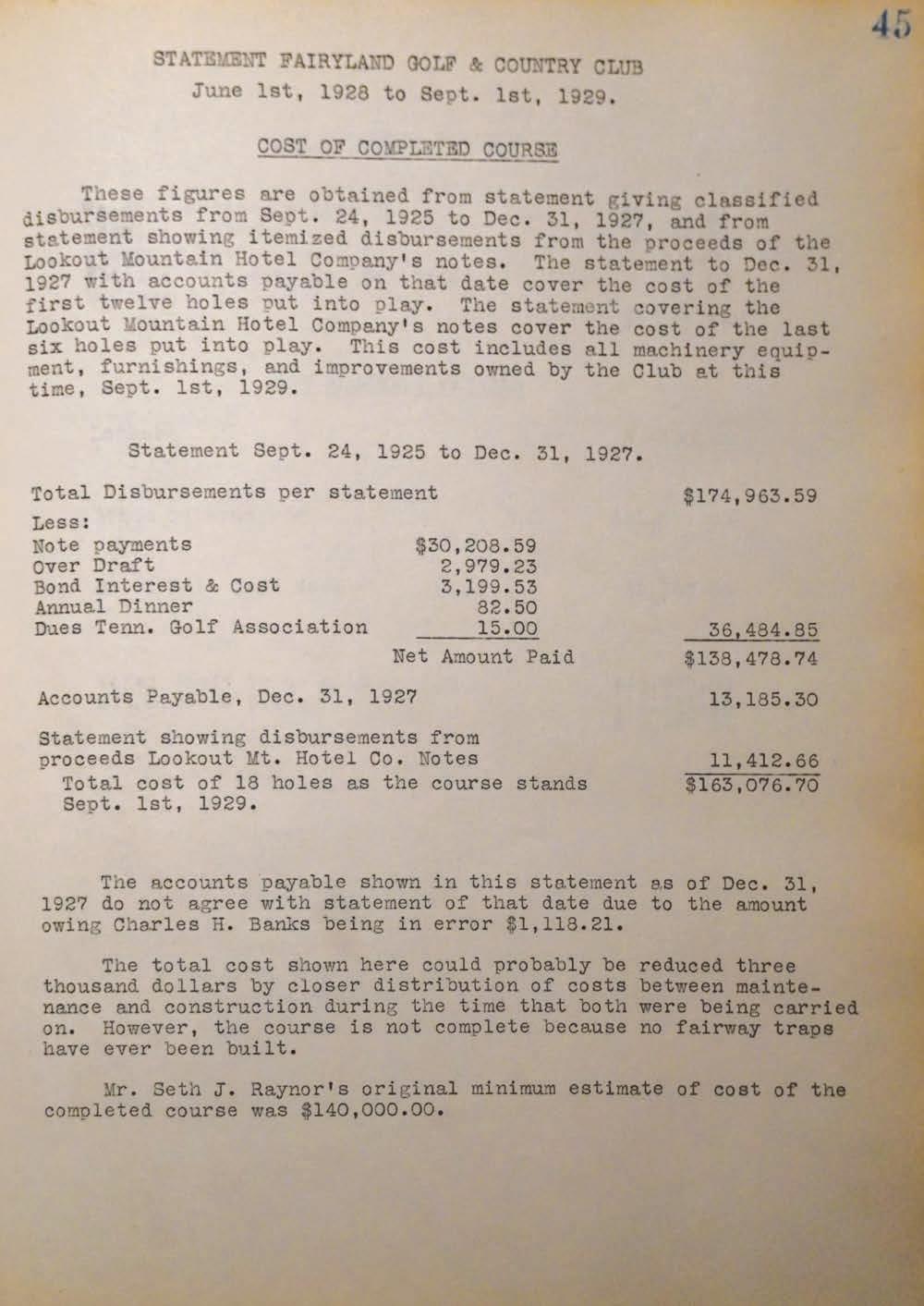

According to early club records, the final cost for the completed golf course was $163,076.70. Those same records state that Seth Raynor’s original estimate to build the course was $140,000. The land donated by Carter and Andrews to build the course was listed on the club’s 1930 balance sheet with a value of $120,000.

CHAPTER 5

Before fairyland, there was a Lookout Mountain Club on Highland Avenue, in what would eventually become the home of Henrietta and Durwood Sies. In the early 1900s, this club was one of the few places on Lookout Mountain where young women and their mothers could gather to lunch, play cards, and catch up on the news.

Today’s Fairyland clubhouse began as a cornerstone of Garnet Carter and O.B. Andrews’ original 1924 strategy for developing the large tract of land they had recently acquired on Lookout Mountain. A large residential neighborhood was the centerpiece of their plan, but Carter and Andrews knew that before they could sell most people land, you’d first have to provide them a way to get to it, and some place to stay and eat and recreate once they arrived.

The Two men invesTed in a bus company to shuttle potential buyers up the mountain. Their plan for keeping them on the mountain was more ambitious. The first public announcement of the Fairyland development in November 1924 included an English-style tavern, which would be constructed first. True to their word, Carter and Andrews had hired noted architect William Hatfield Sears by the following month and settled on the building’s design. The clubhouse would be built primarily of moss stone and stretch out for 200 feet along the very edge of the eastern brow of the mountain. The tavern—soon renamed the Fairyland Inn—was designed with a kitchen, dining room, and public rooms on the first floor, and 50 overnight rooms on the two higher floors. It was noteworthy at the time that each guest room would contain its own private bathroom. The intention, Sears said, was to build the Inn at a standard that would preview the high quality of the rest of the future development.

Work began on the Inn by the end of the year and continued almost nonstop throughout the winter, thanks to a circus tent that Sears erected to keep the construction site warm and dry. Carter and Andrews wanted the Inn completed by April 1, 1925, just in time to welcome snow-bird visitors who were about to migrate back north from their winter homes in Florida.

Sears had the building well under roof by February, and two months later the building was ready to receive its first guests, albeit with only 30 of the guest rooms completed. The Inn was well received by early visitors and became the marketing tool for the entire Fairyland project as Carter

and Andrews had envisioned. Plans for expanding the Inn were put in motion even as the initial construction phase was being completed in early 1925. They wanted to add a large dance pavilion to the east side of the Inn, separate from the ballroom in today’s Fairyland clubhouse. Sears described the plan as a dance floor that would ramble in and out of the trees. They also planned for a billiard room in the basement. That same announcement shared that they would construct four small cottages in close proximity to the clubhouse. Sears would also design the two- and three-bedroom cottages, which would be completed in time to rent for the following summer.

Future plans for the Fairyland Inn changed dramatically when Perry Stoltz entered the picture. Carter and Andrews had met Stoltz during a trip to Miami a few years earlier. Seeing the success of Stoltz’s Fleetwood hotel had helped to inspire Carter and Andrews to begin developing their own plans for Lookout Mountain. Now they were bringing in Stoltz as a partner on Fairyland.

The Commodore’s arrival in Chattanooga was not a quiet one. Front page headlines on July 31, 1925 repeated Stoltz’s big plans for Fairyland. He announced he would be spending $2 million to build a 300-room, 15-story hotel on Lookout Mountain that would closely resemble his Fleetwood hotel in Miami, in both name and appearance. Stoltz also had plans for the newly renamed Fleetwood Fairyland Inn. The recently completed Inn had cost Carter and Andrews a reported $375,000 to build. Stoltz now wanted to spend another $600,000 to add a ballroom, 115 more guest rooms, a large terrace, and a swimming pool. They also added the tennis courts around this time.

Construction on the additions to the Inn began almost immediately, though Stoltz’s plans for his huge new hotel would continue to change.

As detailed in Chapter 2, Stoltz’s days in Chattanooga were finished long before any of the commitments he had made. Stoltz’s financial implosion and O.B. Andrews’ sale of his interests in Fairyland in December 1926 left Garnet Carter as the sole operator of the Fairyland company, busline, and hotel, which was now once again known as the Fairyland Inn.

The newly added ballroom, swimming pool, and terrace were all well received by guests, but their costs to build and maintain would now make it extremely difficult for Carter to operate the Inn at a profit. The ongoing struggle to complete Fairyland’s golf course meant fewer visitors, racking up even more losses for Carter at a time when he must have already been under enormous financial pressure. A news article from February 13, 1927 reported that the Fairyland Golf Club had agreed to a multi-year lease of the Inn from Carter, but there is no record of such a lease or any lease payments in Fairyland Golf Club’s records, nor does there appear to be any change in the way the Inn was operated.

The next several years would be difficult ones for Garnet Carter and the Fairyland Inn. Guests continued to enjoy staying at the Inn, but over the next five years, Carter took operating losses of more than $100,000. Carter was only able to cover the losses by taking a mortgage on the property, and by February 1931 he was in default on the loan. By then, the worst of the Great Depression had reached Lookout Mountain. Just a few years earlier, the Inn had played a starring role in the red-hot launch of Fairyland. Now Carter was unable to find anyone to help save the beautiful Fairyland Inn from being auctioned off to outof-town investors for pennies on the dollar.

Carter was understandably bitter on the day of the sale. He remarked, “We would have been better off if we had given the Inn away five years ago; we would be $100,000 off. We have been operating the Inn at a loss because there are not enough moneyed people in Chattanooga to support it,” Carter said. “People come up to the Inn and want to get a Coca-Cola for a nickel and a sandwich for a dime.

They want dances, but they aren’t willing to pay for them.”

The Fairyland Inn was auctioned off on the steps of an Atlanta courthouse on March 3, 1931. A lawyer representing a group of Atlanta investors made the winning bid of $68,000. Despite the hard feeling he’d expressed a day earlier, Garnet Carter was present at the auction and participated in the bidding until it reached $67,500. The Fleetwood Inn, which had cost an estimated $500,000 to build, would now have its future decided in Atlanta. At the time of the sale, it was widely assumed that the Fairyland Inn would need to be expanded if it was ever to become profitable. Most agreed that more guest rooms were needed to help underwrite the cost of the pool and other amenities. For the next three years, the Inn sat empty while Lookout’s residents waited for news from its new Atlanta owners.

Finally, the Inn reopened on May 19, 1934. A newly formed Lookout Mountain Fairyland Club reached an agreement was reached to lease the Inn from its Atlanta owners. The Inn’s hotel rooms would remain mothballed, but people would be able to enjoy the pool and common areas once again.

The reopening of the Inn also meant the return of the horses that were boarded in stables underneath the back of the Inn. Exploring Lookout Mountain’s trails and streams on horseback had been a popular activity of visitors staying at the Inn. Some of the owners of new homes in Fairyland formed their own riding society. The homeowners enjoyed exploring their new neighborhood on mounts they kept at their own residences or boarded at the Inn. The riding program at the new Lookout Mountain Fairyland Club was overseen by the popular Miss Giltner. Giltner was responsible for the care of the horses, which were imported for the summer season from the Jungle Club in Tampa, Florida. Miss Giltner was remembered fondly by many of the girls she taught to ride during Fairyland Club summer camps. The boy campers enjoyed learning to fire shotguns at targets flung off the brow of the mountain.

Over the next decade, membership in the Lookout Mountain Fairyland club grew to 300 families. Many—but not all—were also members of Fairyland Golf Club. By 1945, the Lookout Mountain Fairyland Club’s finances were healthy enough to negotiate an agreement to buy the Inn for $100,000. The purchase price included the clubhouse, the Mother Goose Village, the swimming pool and tennis courts, and the 17 acres of land surrounding the club.

The club has remained a focal point of life on the mountain since it was repurchased. Horses and target shooting eventually yielded to busier streets and denser housing in the neighborhood, but the spectacular views from the club’s porches, pool, and patios will never go out of style. For more than eight decades, the Fairyland Club has been the place on the mountain where friends are made, marriages are proposed, and Christmas Eve is celebrated together.

Building a club and golf course are arduous Tasks . Bringing both to life is both physically gruelling and mentally stressful. Over time, and through eras of economic hardship, many clubs and courses don’t survive their initial buzz.

For the golf course atop Lookout Mountain, its path to a secure future was rockier than most. The members of Fairyland Golf Club had already beaten the odds by the time that 38 of them gathered on July 1, 1927 for an opening-day tournament. The young club had to overcome Perry Stoltz’s financial implosion, the sudden death of Seth Raynor—as well as construction issues and historic rainfall—just to reach this point.

And yet, very few members of the club and golf course could have imagined in 1927 that the worst was yet to come. What follows is a story of strong will and sheer survival.

over The course of his short career, golf course architect Seth Raynor was involved in the design of about 100 golf courses. Only 64 of those designs were ever completed, and Lookout Mountain is one of just 39 that survive today. That’s not unusual: Raynor’s contemporaries—such as George Thomas, Alister Mackenzie, and Donald Ross—have had their work disappear in similar ratios. (The current generation of elite golf course architects aren’t fairing much better. Half of Tom Doak’s first 10 original courses are already gone.) The Raynor golf courses that are gone were just as good as the ones that remain. The members of the clubs that no longer exist were just as wealthy as the members of the ones that have survived. Sure, some of Raynor’s projects had worse luck than others. All clubs face challenges from time to time.

The only common trait of clubs that last a century is a membership that loves its golf course, its club, and its fellow members. At all of these clubs, there have been successive generations of members who have refused to throw in the towel when times got tough.

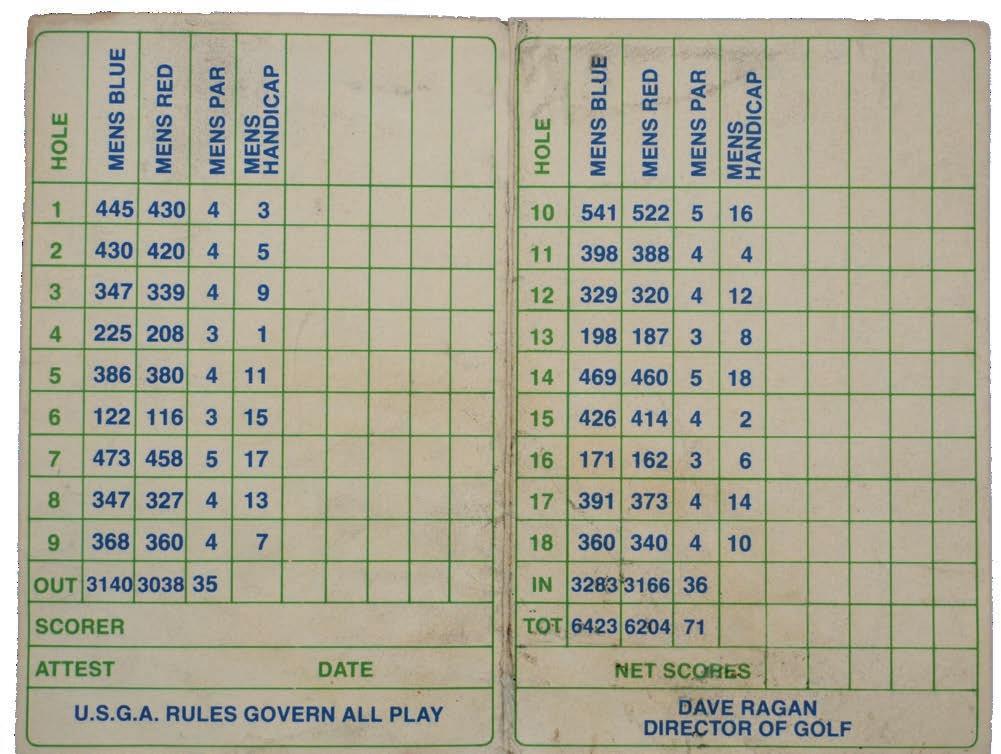

The name of the Fleetwood Fairyland Golf and Country Club was changed before the club even opened. The young club was now known as Fairyland Golf Club. A separate holding company, named Fairyland Golf and Country Club, held the long-term lease of the land and had full control over the golf club for the next several decades (see early, undated scorecard). Members of Fairyland GC technically owned equity in Fairyland G & CC, not Fairyland GC. The Fairyland balance sheet carried debts of $57,000 from expenses to build the golf course and the operating losses incurred while the club prepared the course for opening play. One of the first expenses recorded on Fairyland’s checkbook was an expenditure of $15 for the club to join the Tennessee Golf Association.

In 1929, the club borrowed $5,300 at 7% interest and used the proceeds to pay off the expenses incurred from building the first

Fairyland golf clubhouse. The modest two-story clubhouse sat to the right of today’s 8th tee box. Rounds began there on today’s 8th tee and ended on today’s 7th green.

The first clubhouse had a room around the back that served as the caddyshack. On the first floor were bathrooms, a sitting room, and a room to store golf bags. The upstairs of the clubhouse featured living quarters for the family of Alex Balfour. The club hired Balfour in 1928, becoming the first employee to oversee the golf course, pro shop, and caddyshack.

By the middle of 1929, there were already 15 delinquent member accounts. The good news was that the final six holes of the golf course were finally ready to open that summer. By the end of 1929, 8 members had been suspended for nonpayment of debts, and 18 additional members were now delinquent on their club dues. The Great Depression may not have reached everyone’s wallet immediately, but its timing was awful for a young private club that hadn’t had time to strengthen its balance sheet.

membership numbers wenT into freefall beginning in early 1930, and it soon became obvious the club would only survive if members were willing to fight to keep it alive. Lookout Mountain made some important, prescient changes to stay afloat. The board voted in May 1930 to offer women full-member privileges for $60 per year. The board also reworked the land lease between Fairyland GC and Fairyland Golf and Country Club. In February 1931, four Chattanooga clubs announced a new reciprocity agreement: any member of these four clubs could play Chattanooga G&CC the first Thursday of each month. Fairyland would welcome reciprocal play on the second Thursday, Meadow Lake on the third Thursday, and Signal Mountain G&CC on the fourth Thursday. Still, from September 1930 to September 1931, 48 members resigned from Lookout Mountain. Membership at Fairyland had fallen from 196 to 145 over the past year, and the survival of the club was in doubt.

The board was forced to take drastic actions in early 1932. Bondholders were informed that Fairyland was cutting interest payments from 7% to 3% on its original, outstanding bonds (totalling $50,000). Employee pay was cut by 10%. The club offered new memberships with no initiation fee paid up front, but the offer had no takers. Another wave of resignations brought Fairyland to 101 members.

Board minutes from 1933 indicate there were discussions with Chattanooga G&CC about a potential merger. With no new initiation payments coming in, and the dues for paying members cut in half, the club’s total revenue in 1933 totaled just $7,544.

The year ended with 90 members still paying dues—fewer than any other time since the night the club was first proposed in 1925. There were now 85 members suspended from the club because of failure to pay past dues.

Rock bottom came in 1934: membership dropped to as few as 80 members, prompting the board to suspend interest payments on all debt. Junior memberships were offered for the first time and assessed annual dues of just $10.

Finally in 1935, a few small hopeful signs of light began to emerge. Membership rolls increased to 90, then up to 101 in 1936. The club was able to start making token payments of 1% to bondholders: an important gesture as the expiration of the original 10-year bonds approached.

In 1937, Fairyland’s board was successful in negotiating a 20-year extension with its bondholders. By 1939, the worst effects of the Depression had passed. The club enjoyed 120 members, and it reinstated the initiation fee for new members. Fairyland’s caddies even received a pay increase to $1 per bag.

above: Women enjoying lunch on the outdoor patio at the Fairyland Club, overlooking the valley.

During this timeframe, not much changed on the golf course or in the small clubhouse. Alex Balfour did his best to maintain the golf course with the meager budget afforded him. The caddies complained about the members, and the members complained about the caddies. Rules were slowly evolving into games that resemble today’s Dogfight games. The annual Calcuttas were taking on traditions that only come from the passage of time. And a local teenager named Lew Oehmig was beginning to draw attention with his golf game.

Since iTs earliesT days, Lookout Mountain has witnessed many competitions, whether it’s been on the golf course or tennis courts, or in the pool. Whether it’s a club championship, the Swing Ding, or a friendly Friday match, a lot of the club’s history—and camaraderie—is on full display in these events. The clubs have also produced some wonderful competitors who have not only won local and state tournaments, but have excelled on the national level. Lookout members have performed well in Junior Olympics and on high-profile NCAA teams, as well as in state and USGA championships. Two legends have even won state competitions in five or six different decades. Many of these accolades may already be known, but all of them are worthy of being remembered and celebrated.

golf was firsT played on Lookout Mountain in 1928. Only ten holes of the new golf course were ready on opening day, but members of the fledgling Fairyland Golf Club can be forgiven for being eager to get started, after experiencing so many setbacks. Now at long last, their golf course—part of it anyway—was ready.

A large group of members and curious locals showed up to watch golf on opening day. The field of 38 players was made up of notable local golfers and members. Play on opening day began on today’s 8th hole, then skipped over to today’s 17th and 18th, and continued on today’s 1st through 7th holes. Dr. C.E. Byington and Murray Raney won the best ball competition after surviving a scorecard playoff, with five other teams who matched their gross score of 78 and a net of 71. A. Pollack Boyd claimed the singles prize with his low round of 78. As a nationally known player, Boyd’s victory was unsurprising. It’s also unsurprising that in Boyd’s opening day foursome was another player whose name will still sound familiar to today’s Lookout members. Like Boyd, W.G. Oehmig Jr. was already a Chattanooga city champion by the time the Fairyland plans were announced. Oehmig Jr. quickly agreed to join the new golf club and by opening day, he was already serving as Fairyland’s first tournament chairman.

Oehmig is just one of several family names that are intertwined with golf on Lookout Mountain throughout the past century. Scott Probasco Sr. had been president of the Chattanooga Chamber of Commerce when he was elected vice president at the new golf club’s first meeting (then served as treasurer). He is almost certainly responsible for hiring Seth Raynor to design the course. A longtime personal friend of Walter Hagen, Scott Sr. played in many local and regional competitions in the 1920s. When Raynor died, it was Scott Probasco Sr. who worked with Charles

Banks to oversee its completion. Scott’s wife, Peggy, learned to play golf after getting married, was a good player, and an even better advocate for local competitive golf. She was an active member of the Women’s Tennessee Golf Association, serving as its president twice. In her first year as president, she revived the Tennessee Women’s Amateur, which hadn’t been played in many years; her husband Scott Sr. donated a trophy, which is still in use today. Peggy played in the tournament that year and finished second.

A few names down is Pollack “Polly” Boyd, the winner of the opening day round. He was a member of the Dartmouth golf team that won the national title in 1921, and he was runner-up for the individual title. A year later, Boyd was the individual medalist before winning the individual intercollegiate championship in 1922 (winning the 36-hole championship match 12 up with 11 holes to play). He won the Tennessee Amateur in both 1921 and ‘22. Later in 1922, He actually beat reigning British Open champ Walter Hagen in a local exposition. Boyd competed in amateur tournaments among the likes of Bobby Jones, Chick Evans, Francis Ouimet, and Jesse Sweetser, and in the early 1920s he

appeared on lists of top U.S. amateurs while winning three Tennessee Amateur titles in a row. Boyd was one of four golfers selected to represent the U.S. in the 1920 Olympics, alongside Bobby Jones, but there were not enough entries from other countries for the competition to run that year.

Boyd served as a longtime director of the Southern Golf Association, and as its president in the early 1950s.

Boyd’s friend Ewing Watkins (son of R.M. Watkins) was often referred to in local papers as the “Chattanooga Shark.” Watkins had played golf at Georgia Tech—playing on its golf team, in fact, in 1918, the year when Bobby Jones himself matriculated there. In 1920, Watkins finished second in the Southern championship, behind only an 18-yearold man named Bobby Jones. Then in 1924, he won the Tennessee Amateur tournament. In 1928, Watkins and Boyd played in a local charity match against Bobby Jones and Watts Gunn at Chattanooga G&CC; local papers did not print the results, so it’s unlikely that the local boys pulled off the upset. Watkins made it to a semifinal of the U.S. Senior Amateur in 1955.

Thomas Cartter Lupton and his father J.T. Lupton are listed 6th and 9th on the list of the club’s 110 founding members. J.T. Lupton and two partners founded Coca-Cola Bottling in 1899. By the time Fairyland was founded, Lupton had already built the fortune he passed down to his only child, Cartter.

Jerome “J.B.” Pound is 19th on the Fairyland Golf Club founders list. Pound became Fairyland Golf Club’s second president in 1929 and helped keep the club alive during the tough times that soon followed. Pound was elected and served as mayor of the town of Lookout Mountain in 1926. Pound was also the president of the Patten Hotel in Chattanooga and two other hotels in Savannah, Georgia. As a result, Pound helped to clean up the scrambled business interests that Perry Stoltz left behind, and Pound is credited with helping to save what had been the Fleetwood Hotel project.

LefT Page, ToP: From left to right: J.T. Lupton, J.B. Pound, and Scott L. Probasco Sr.

righT Page, ToP: At a 1928 charity match, from left to right: Pollack Boyd, Bobby Jones, Watts Gunn, and Ewing Watkins.

Paul Carter, Garnet’s brother, was also a founding member of the golf club. Paul became the first manager of the original Lookout Mountain Hotel when it opened in 1928. Paul Carter later married Ann Lupton, niece of J.T. Lupton, and became an executive at Coca-Cola Bottling.

a fitting tribute to a woman who was invited to play on the 1956 Curtis Cup team, but had to decline because she was in late pregnancy. The breadth of her golf career is astonishing, considering that she was able to maintain such a high quality of play even while raising four children. Remarkably, she won her first and last Tennessee state state titles 37 years apart.

Lew Oehmig and Betty Probasco are two of the many great players over the past century who have split their time between Chattanooga Golf and Country Club and Lookout Mountain Golf Club. Almost all of the Fairyland founding members were already members at Chattanooga G&CC, and golf competitions between the two clubs started and faded away for a half century, until Mike Jenkins and Lex Tarumianz founded a tournament called the Oehmig Cup in 1991, as a tribute to Lew Oehmig.

The Oehmig Cup is a Ryder-Cup style event contested annually by sides from Lookout Mountain and Chattangooga Golf and Country Club. The two clubs alternate hosting the match each fall. Played over three days, the 16-man sides play team matches the first two days before the traditional Sunday singles matches. The event took on added significance after the sudden death of Lew’s son, Henry King Oehmig, in 2015.

ToP LefT: Betty Rowland in 1946.

ToP righT: Betty and Scotty Probasco Jr. on their wedding day in 1953.

boTTom LefT: Betty holding a trophy, date unknown.

boTTom righT: Betty celebrating a winning putt, date unknown.

Among the longer running informal games at Lookout Mountain is The Bubble. Played on Friday afternoons or mid-morning on the weekends, Bubble games are usually matches using one or two best balls from each team of foursomes. The typical Bubble wager of a $2 front-$4 back-$4 overall nassau creates just enough post-round accounting that a beer or two can often be enjoyed before the outcomes are known.

The Balloon game has typically followed a similar format as Bubble games, with one notable exception: Balloon games are typically populated by some of Lookout’s best players. The Balloon game usually starts ahead of The Bubble game on weekend mornings.

Both the Balloon and the Bubble evolved from the Dogfight games that were held as often as four days a week in the early years. Records from a century of board meetings demonstrate that no other issue has received as much continuous debate from the membership as the rules and policies for the weekly games. USGA rules were adopted by the club in the 1930s, but the decision did little to slow debates over preferred lies, senior teeing grounds, and a steady stream of others.

Women and children were welcome to play at Lookout since the club’s founding. Naturally, policies addressing who could play, and how the course could be used, have evolved over the past 10 decades, especially when course traffic had risen or fallen sharply.

What hasn’t changed is the love that Lookout’s members have for the golf course on their mountain. Whether it’s a cool morning in the fall or a sunset round in the summer, there has been no other place Lookout golfers have wanted to be for the past century.

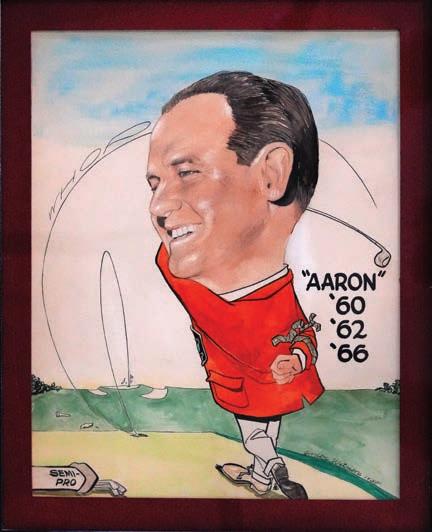

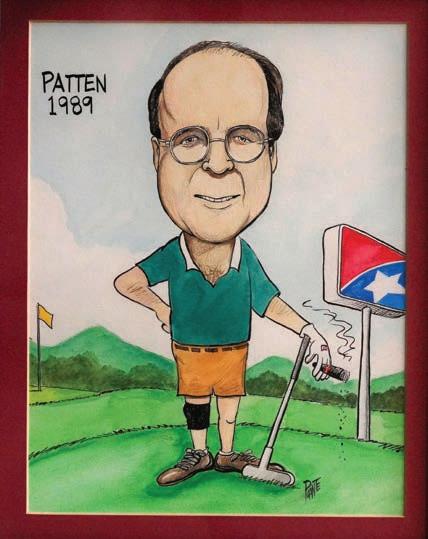

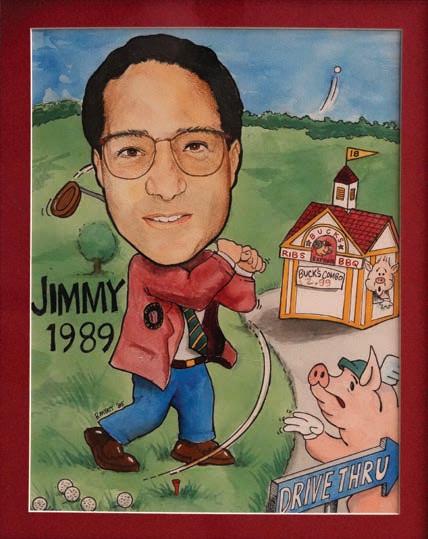

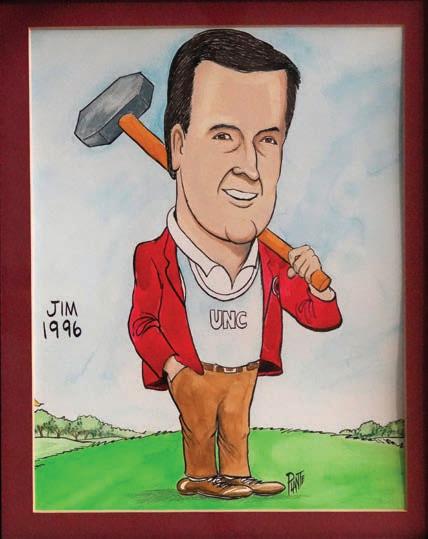

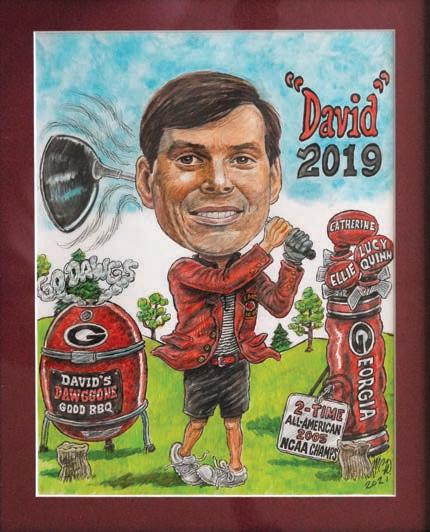

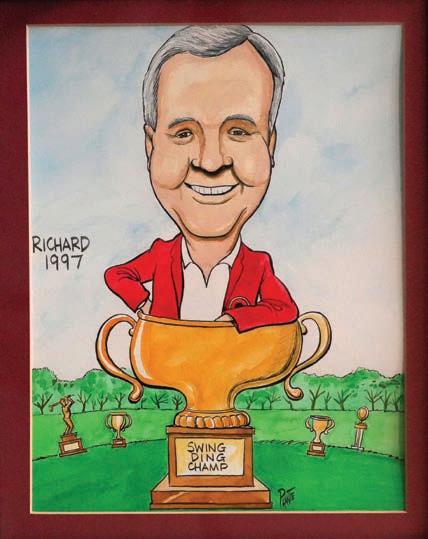

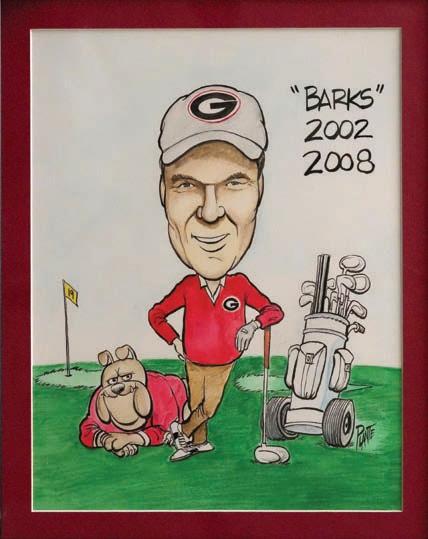

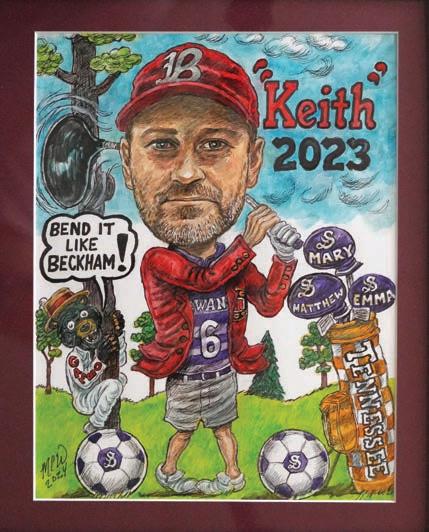

Started by Jack Lupton and John “Hollywood” Stout in 1959, the Swing Ding has been played now for 65 years.

It’s the biggest golf event at Lookout Mountain, and by far the most popular. More than 75 Lookout members and their guests compete for the red coats awarded to each year’s winning team.

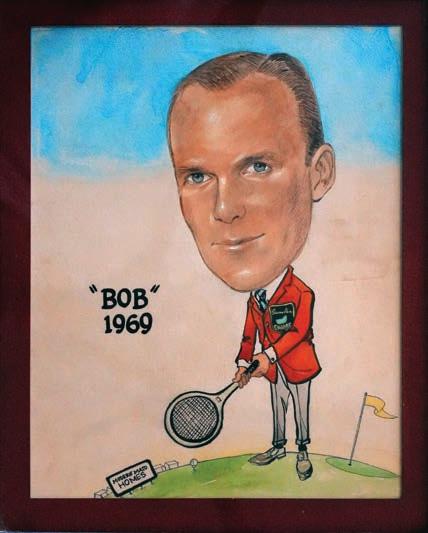

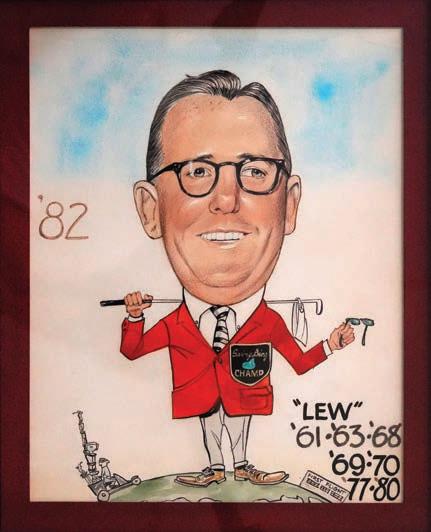

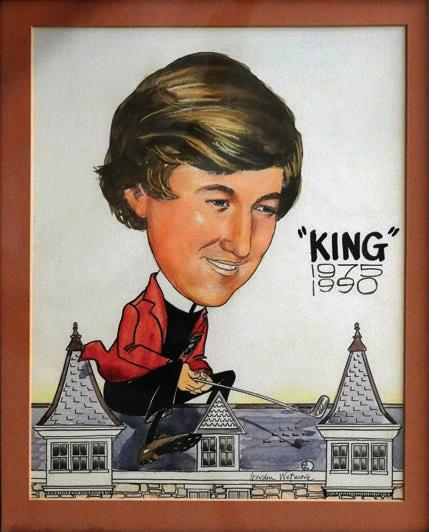

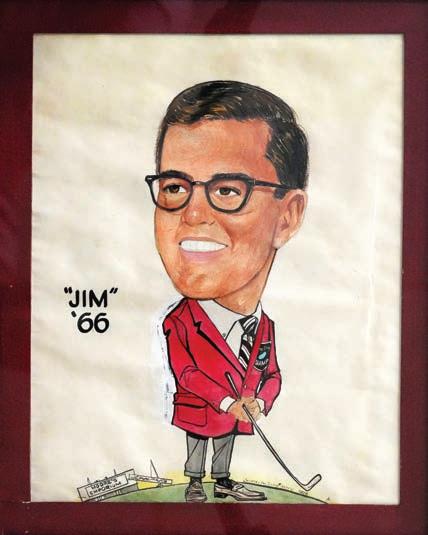

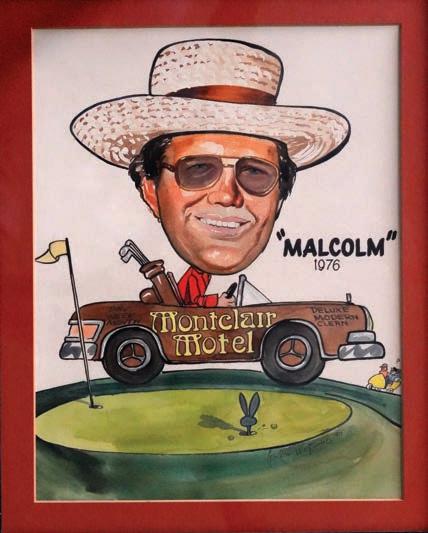

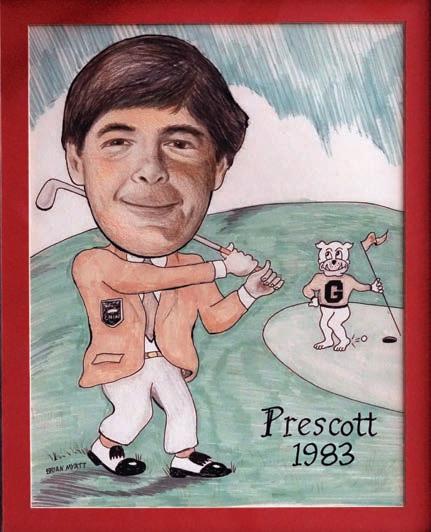

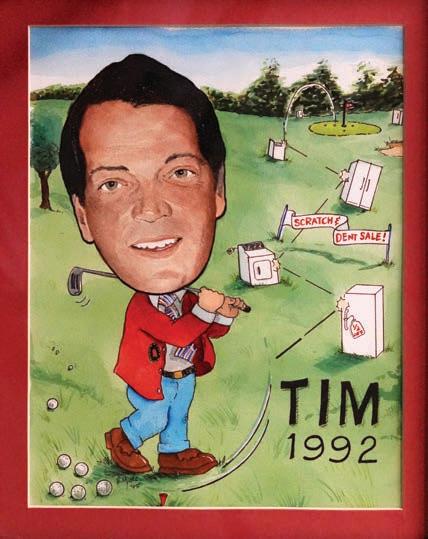

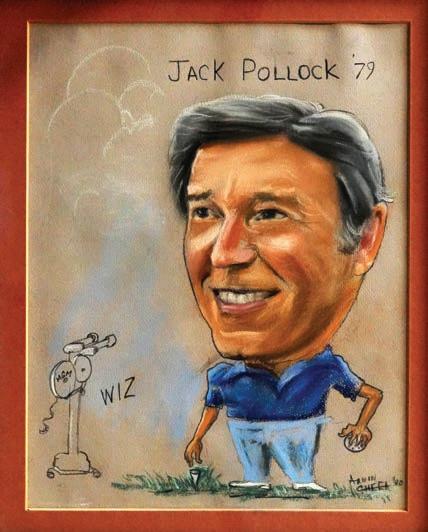

Lew Oehmig won the Swing Ding eight times with eight different partners. For good measure, he set the Lookout Mountain course record of 63 while playing in the event. Caricatures of each years’ winners adorn the walls of the men’s grill room in the golf clubhouse. Many of the earlier caricatures were drawn by Gordon Wetmore.

The Swing Ding has grown to much more than just a golf competition. It’s the event that multiple generations of Lookout Mountain families circle on their calendars each year.

The pool at the Fairyland Inn opened during its second summer of operation in 1926. The pool was a major attraction for the guests staying at the Inn. That original Fairyland pool was in approximately the same location as today’s pool, but was routed around the huge boulders that are still nearby.

The pool quickly became a popular neighborhood gathering spot when the Inn reopened as the private clubhouse of the new Lookout Mountain Fairyland Club in 1934. In early days, leaping from the top of the rocks into the pool was a test of courage for the children and grandchildren of members.

Hal and Gordon Atchley worked at the Fairyland pool as lifeguards during summers in the 1940s. The brothers spent their autumns playing football for the University of Tennessee.

The Fairyland Club’s swim team was started by Marilyn Doster, Mefran Campbell, and Bobby Davenport in the early 1960s. The early teams were coached by Mr. and Mrs. Richard Davenport. The swim team has a long tradition of competing well against much larger teams. The Fairyland Flash swim team now boasts over 100 members, from ages 5 to 18.

The swim team has produced some great swimmers and divers. In the late 1960s, Ellen Kovacevich Hanna was a city, state, and state-high school champion in diving for several years while at Girls Preparatory School.

Brothers Chris and Rick Bryant won city and state honors while at Baylor in the early ‘70s; Chris finished 6th in the 1973 Junior Olympics, and Rick was on the swim team at the University of Virginia. In the mid-’70s, Mark Williamson was city, state, and high school All-American

during his years at McCallie. In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, sisters Elizabeth Caulkins Bookout and Caroline Caulkins Bentley both became high school All-Americans at GPS, as well as city and state champions.

The pool has been renovated several times over the past 100 years. No records survive, but it appears that the most significant renovation to the pool occurred just after World War II, likely following the club’s purchase of the property in 1945 from the previous leaseholders.

The pool at the Fairyland clubhouse was just finishing another major renovation in 2024-25, when this book was going to print. Members are eager to put the new pool to use after going without swimming the previous summer. No matter the version, the pool has always been one of the most popular gathering spots on Lookout Mountain and one of the club’s most treasured features.

Then in The laTe 2000s, the prospect of a restoration again took fight. The golf club’s board began a search to identify who might be the best architect to execute the fnal phase of completing the golf course. They eventually settled on a polite young rising star named Gil Hanse.

Stein and Oehmig had been working with The University of the South in Sewanee to renovate their 1915 nine-hole course. Stein had discovered Hanse when Hanse was working for Tom Doak at Renaissance Golf Design, and Oehmig had loved the Capstone Club in Alabama, which was one of Hanse’s first designs. It was during this period that they suggested Hanse to finish the restoration of Lookout’s course. Hanse did complete the project at Sewanee in 2013.

In 2008, again at Betts, Stein found another original map of the golf course proposed for Fairyland/ Lookout Mountain. This second map was dated October 18, 1925, and Stein describes it as a working map (see previous page). This important discovery came at an opportune moment: while Hanse was developing his plan for improving Lookout.

The map was nine feet wide and four feet tall: large enough and full of enough detail that Stein could easily identify many of the hole and green designs that Raynor almost always employed when planning his golf courses. The map is labeled “Fairyland Golf Club,” lists Seth Raynor and Charles Banks as golf course architects, and lists the address of Raynor’s office in New York City. The scale of the contour lines is noted as two feet.

Finally in 2009, the issue was put to a vote of Lookout’s members. They approved the Hanse plan and incorpo-

ToP: The par-fve 11th hole, circa 1998, before the Silva renovation.

middLe: After Silva’s work, circa 2005.

boTTom: Post-Rae/Franz restoration in 2024.

rated it into the Club’s bylaws. But the timing couldn’t have been worse: within months, a severe recession was hurting pocketbooks everywhere. As the result, the club would need to shelve the Hanse project.

The economy eventually improved, but the members’ appetite for more work (and spending) on the golf course did not. This led to Hanse and Oehmig and Stein to turn elsewhere and work on other projects. Hanse was in high demand across the U.S. and beyond. Stein teamed up with Brian Silva to build Black Creek Golf Club: a modern, Raynor-inspired design that sits in a pretty valley just to the west of Lookout Mountain. Oehmig was consulting on the construction of the Sweetens Cove golf course in 2015 when he died. Sweetens architect Rob Collins named the 4th hole there for King; it’s the only hole on the course with a name.

By the time the Covid-19 pandemic shut down most of the world in spring 2020, the “Son of a Long Range Plan” could have been renamed “Long Shot Plan.” Many people assumed the financial shockwaves from the pandemic would be a serious challenge for clubs like Lookout Mountain.

Only a few months later, a much different scenario had developed: the country experienced a spike in interest in golf and gathering socially in safe ways. The Lookout leadership felt that the time was finally right to finish what Stein and Oehmig had started— and many others had helped with—over the previous four decades.

As detailed in Chapter 8, the members voted resoundingly to restart the previously postponed work on the course. For those who were familiar with the original pedigree of Lookout’s course, it was a promising development that could unveil a design that had not fully been carried out. Almost exactly a century after Seth Raynor had planned, his design for a golf course on top of Lookout Mountain would finally be completed.

Now with Gil Hanse’s time completely booked for the foreseeable future on other projects, the club turned to Tyler Rae and Kyle Franz to perform the latest work. Despite their youthful appearances, Rae and Franz both came into the Lookout project with more than 20 years of experience working on high-profile jobs, while learning from great modern architects such as Ben Crenshaw, Bill Coore, Gil Hanse, and Tom Doak.

For much of 2022 and the first half of 2023, Franz and Rae oversaw a talented team of shapers, laborers, technicians, and contractors.

The completed Lookout Mountain golf course officially reopened on June 20, 2023. Golf Digest named it the Best Restoration of the year.

Future generations of Lookout members will have the privilege—and responsibility—to protect what so many worked so long to finish building.

ToP: Tyler Rae and Kyle Franz survey construction work.

boTTom: Shaping of the 13th green and surrounds.

righT Page, ToP: The 5th hole, before and after tree removal and restoration.

righT Page, middLe: The iconic 11th green, from Silva’s work to Rae & Franz’s.

righT Page, boTTom: Evolution of restoration work on the 16th green, in 2022.

LookouT mounTain’s golf course has always been known as one of the most unique settings for a game. Today’s version is also now recognized as one of the best in the country. It’s a true original design by one of the greatest golf architects of the Golden Age of architecture, conceived by a man whose work has become more understood, appreciated, and celebrated in the past three decades. It’s also his only design on top of a mountain, with views that no one forgets.

With all that said, building and maintaining the golf course was a challenge from the start. Seth Raynor died just before construction began, and his associate Charles Banks would need to complete the course and all of Raynor’s other unfinished projects. Then, when construction began, historically bad weather and stubborn rock and soil, tested the wills and wallets of all involved. Just a year or two later came the Great Depression that would spell the end of many golf courses and country clubs across the 1930s.

The story of Lookout’s golf course is a story of steely determination. It’s also, now, a great story of restoration: in recognition for the club’s recent vision and leadership, and for the work of Tyler Rae and Kyle Franz, the course won the Best Restoration of 2023 award from Golf Digest. We’ll now explore each hole to showcase how they each contribute to the whole masterpiece that is Lookout Mountain.