BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

The first night my cousin and I set camp on the only semi-flat spot we could find. We wanted to go a bit farther, but the fading vestiges of light told us otherwise. The rocky finger ridge covered in snow would have to do.

We quickly worked to set up the teepee, an act made difficult by the terrain. After breaking a few stakes, we used paracord and rocks to secure our shelter. While I unpacked the stove, my cousin gathered wood, which was easy because we were in the middle of a burn. Luckily, we had somehow found the spot with no widow makers but plenty of dry timber. The first crackle of the fire warmed our bodies and our souls.

As we went to bed that night we were greeted by the wind. You could hear it come over the top of the ridge, whistle through the trees, and then hit the teepee with force. The powerful gale was both impressive and unnerving. Little sleep was had.

The next day we left camp and ventured into a spot new to us that held much promise. As we explored the nooks and crannies of one of the only areas with standing dark timber, however, we found nary a trace of elk track. Plenty of old sign was visible, but the wapiti had cleared out. What we thought would have been a refuge for wary bulls was a quiet landscape. We saw one bird that I failed to identify. A second cousin joined us that night, and once again we stoked the fire and settled in for the night.

The wind picked up again. But instead of coming in waves, it was constant. Snow had melted around the shelter, and gaps to the outside world were apparent.

The first time I heard the roar of gust as it came over the ridge, I thought it was an airplane buzzing the tower. The sustained winds whistled through the trees; the gusts roared. The teepee shook violently, walls collapsing and then springing back to form. With headlamps on we ventured outside and found more rocks to bolster our shelter … in one spot building a bit of a wall to cover the gap. Feeling satisfied with our extra security, we returned to the warm refuge.

All night the wind persisted, as well as the gusts. We extinguished the fire; the stovepipe kept being lifted off the stove as the wind brutalized our teepee. Even less sleep was had, but we made it through the night. With no sign of our quarry, we broke camp after breakfast and hiked out the four miles to the trailhead. In some ways we felt defeated; in others we were invigorated by facing the elements.

Many plans were laid on the walk out for future endeavors. Next year we will return earlier in the season and change our luck, hope being the eternal driver.

Similar to those nights I spent with my cousins on the edge of the Bob Marshall Wilderness, we all are emerging from the past twoplus years and the constant winds of covid. We’ve learned a lot and have many hopes and dreams for 2023.

Nothing like a Seek Outside teepee to weather the storm.

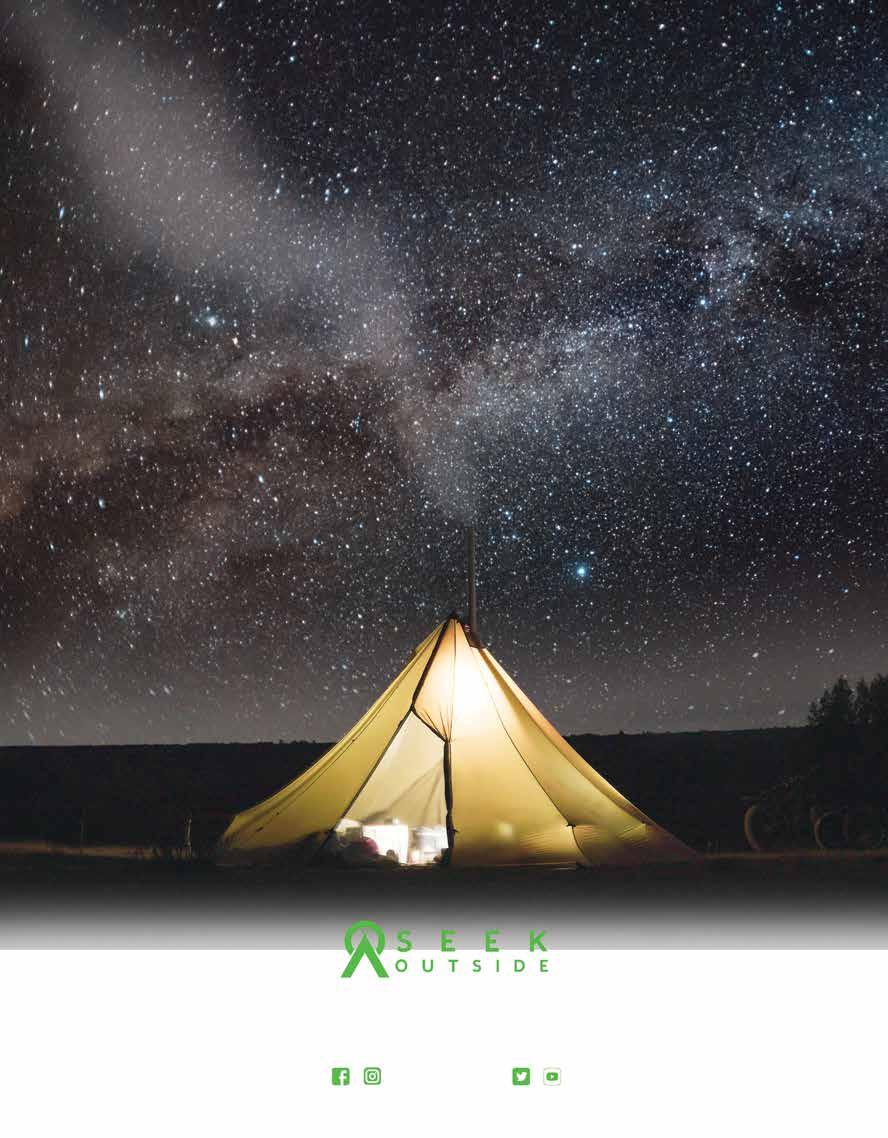

First and foremost, we’re looking forward to getting back together in person. At BHA, our energy is fueled by each and every one of you. Like my first night in the wilderness, I feel and hear the gusts we have met over the past few months. It’s high time to channel that force in support of the values we all share. Our 12th annual North American Rendezvous will take place in Missoula, Montana, March 16-18, 2023. Join us. What an occasion it will be!

Together we’ll generate energy to power our work – from our efforts on the ground on up to the halls of Congress. Restoring bison on our public lands and replacing the missing capstone of our conservation pyramid. Passing the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act and generating funding for at-risk species of wildlife. Pioneering a solution to the problem of feral horses and burros on public lands in the West. Resolving the conflict over corner crossing and opening up equal-opportunity access to all our lands and waters. Perpetuating and enhancing the North American Wildlife Model of Wildlife Conservation and securing the future of our cherished fish and wildlife populations. Continuing our battle to protect the special places in North America that are central to our identities as hunters, anglers and public lands advocates. These are just a few of the fights I’m excited to join you in the arena to tackle head on –and to win.

The time, talent and treasure you all give to this great organization are the rocks that secure our conservation legacy. None of it can be accomplished alone. As 2022 ends, I offer you a hearty thank you for your continued efforts – and look forward to continuing our work in the new year. Together we will carry the day.

Ted Koch (Idaho) Chairman

J.R. Young (California) Vice Chairman

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

T. Edward Nickens (North Carolina) Secretary

Land Tawney, President and CEO

Tim Brass, State Policy and Field Operations Director

John Gale, Conservation Director

Frankie McBurney Olson, Operations Director

Katie McKalip, Communications Director

Rachel Schmidt, Innovative Alliances Director

Dr. Keenan Adams (Puerto Rico)

Ryan Callaghan (Montana)

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia) Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Chris Borgatti, New York and New England Chapter Coordinator

Travis Bradford, Video Production and Graphic Design Coordinator

Veronica Corbett, Montana Chapter Organizer

Trey Curtiss, R3 Coordinator

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Regional Manager and Southwest Chapter Coordinator

Kevin Farron, Montana Chapter Coordinator

Britney Fregerio, Controller

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager and Executive Assistant to the President and CEO

Chris Hager, Washington and Oregon Chapter Coordinator

Andrew Hahne, Merchandise and Operations

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator (MN, WI, IA, IL, MO)

Chris Hennessey, Regional Manager

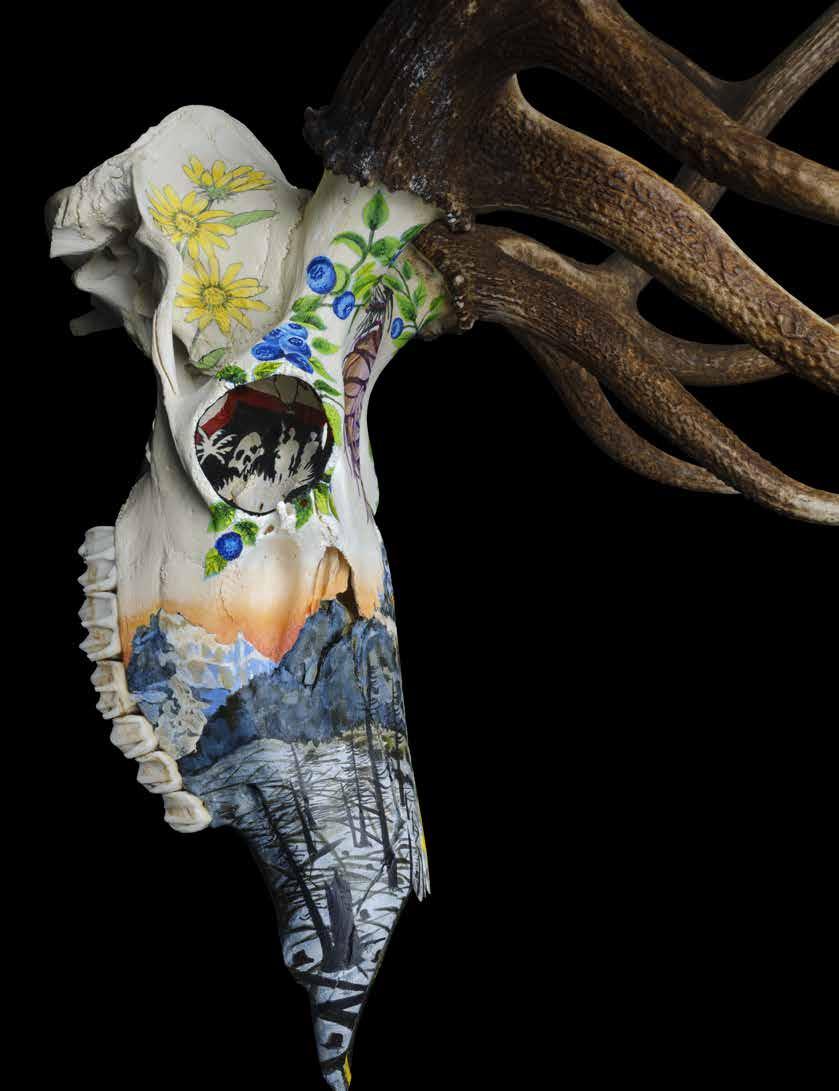

On the Cover: Artwork by

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia)

Ben O’Brien (Montana)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator (MI, IN, OH, KY, WV)

Trevor Hubbs, Armed Forces Initiative Coordinator

Josh Kaywood, Southeast Chapter Coordinator

James Majetich, Alaska Chapter Coordinator

Kate Mayfield, Operations Coordinator

Kaden McArthur, Goverment Relations Manager

Jason Meekhof, Events and Special Projects Coordinator

Josh Mills, Conservation Partnership Coordinator

Erin Nuzzo, Grants and Annual Giving Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, California Chapter Coordinator

Brittany Parker, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Thomas Plank, Communications Coordinator

Kylie Schumacher, Collegiate Program Coordinator

Ryan Silcox, Membership Coordinator

Brien Webster, Program Manager and Colorado and Wyoming Chapter Coordinator

Zack Williams, Backcountry Journal Editor

Interns: Marissa Acosta, Alexis Cichon, Sarah Garner, Jordyn Jackson, Jenna McCrorie, Faith Wells

Jackson,

by Jamil Fatti. Read “All the Right Words” on page 45 for the backstory.

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published Dec. 2022. Volume XVIII, Issue I

Kobe photo Above Image: Will Woodruff, 2021 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest Aaron Agosto, Andrew Bartoe, Cayla Bendel, Jeff Benda, Charlie Booher, Brandon Dale, Max Dickinson, Patt Dorsey, Marcy Fryt, Hudson Gardner, Melissa Hendrickson, Trisha Hedin, Kjell Hedström, Jamie Karambay, Drew Kazenski, Ed Kiokun, Jake Lunsford, Perrin Pring, Christopher Ross, Kyle Shaney, Cliff Shrader, A.R. Thompson, Barry Whitehill, Kai WhitehillJOIN THE CONVERSATION

“A TRUE CONSERVATIONIST IS A MAN WHO KNOWS THAT THE WORLD IS NOT GIVEN BY HIS FATHERS, BUT BORROWED FROM HIS CHILDREN.” -JOHN JAMES AUDUBON

Cattails rustled as my setter lowered stiffly into a crouch. Frozen in place, only his nostrils flared with the scent of wild pheasant. Flapping wings and color erupted from the vege tation. I shouldered my side-by-side and watched the rooster fold.

Wherever that scene took place, it’s far from here.

Wrestling a plastic bottle from the jaws of my young gun dog, ending his triumphant lap around the red dirt parking lot, was a vibrant reminder of that moment.

I was in the Piedmont of the Carolinas, far from pheasant. Here, quail are more of an old rumor than huntable game bird. While whispers of optimism surround Gentleman Bob, they’ve mostly disappeared along with the old farms and pine savannas that supported them.

As with most places, though, there are riches to be had for those able to donate time and tread.

Autoloader in hand, I listened for the “meep” of my red compact SUV, signaling it was locked. We began our hike. Dawn flooded the forest floor, and clouds of breath emanated from from my mouth and the mouth of my dog on this frigid morning commute.

Cold is a seasonal companion here, providing reprieve from snakes and biting insects. It made this trip feasible.

History taught me to put at least a mile or two between us and the car, or the dog and I wouldn’t be alone. The path is an old logging road that winds through the famed rolling red hills of oak, hickory and pine.

Steep timbered terrain transitioned into the flat, spongy to pography of our destination. Shrill cries of a wood duck wel comed us with the first glimpse of the river.

I commanded the dog to heel.

He sprinted off.

We both knew where he was going

No electric collar or whistle, not even the biting cold, keeps him dry for long. Nothing dissuades him from completing his performance – regularly leaping into the first stagnant puddle, oxbow or stream we come across. I’ve reluctantly learned to let him get it out of his system and dodge the dramatic wet shakes.

As with many areas in the eastern United States, the pivot from clearcutting forests in the mid-1900s to implementing policies of a limited timber harvest led to an overabundance of single-aged mature forests. The dams built to reduce flooding and efforts to snuff out forest fires have also contributed to

this. With no natural or artificial perforations in the canopy and limited sunlight released to the forest floor, vital young forests and cane break habitats have vanished from many areas.

Help, however, is on the way.

A revival of prescribed fires and increased timber harvests –aimed at reestablishing the long leaf pine savanna that is home to the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker – has led to a speckling of improved habitat across the Piedmont and coastal plain.

Cane breaks are a personal favorite, comprised of American riv er cane. It’s a native species of bamboo that grows in long riparian groves and was once used by Native Americans for various tools and blowguns here in the Southeast.

The Great Pee Dee, Saluda and Yadkin rivers drain great swaths of the region, where rain and mechanical releases push water in and out of cane and privet river bottoms like an erratic tide, leaving puddles and damp forests. These combine with late season acorns to provide a winter oasis for migratory species, which come in great numbers when snow blankets the upper reaches of the continent.

Despite my shortcomings in training, my dog’s merry nature evolved into focused work as we reached our first cane break. Head down, he plunged in and out of the dense foliage. A trail of ele vated leaves and swaying cane marked his passage, as his short legs kept him well below my line of sight. As he maneuvered through mid-story branches and ankle-deep water, I tried to keep an eye out for woodcock. They seemed to be nowhere, until suddenly fire works of brown and auburn launched from underfoot into the air.

I learned to trust that if there are birds to be had, the dog will put them in the air and retrieve them – not to hand, but close enough.

An armadillo was our initial discovery. Deeper into the wood land we went. I noticed the dog stop, turn 90 degrees and zigzag to ward an ambiguous location. The telltale sign of impending action was followed by gunshots, feathers and a few birds on a game clip.

After I cleaned the birds, I allowed them to cool during the re mainder of our walk. We continued, dissecting every patch of suit able habitat found along our route. Hours and miles passed with no more flushes. Eventually, the trail rounded a corner and signified the nearing conclusion of our hunt.

Finally willing to heel alongside me, we examined our last pros pect. Slipping along the perimeter of a flooded acre of privet and oak, our eyes scanned for the drakes and hens we’ve seen here be fore.

Not today. Our trophies were two-thirds the limit of timberdoo dle, sore legs and the liberation brought upon by a hard hunt in a southeastern wilderness expanse.

Few wall paintings or magazine covers depict the hunt for an obscure, often overlooked gamebird in a region ripe with humidity and reptiles. Nevertheless, the endless miles of forested creeks and streams, which run through the national forests and state lands, of fer rich opportunities and purpose to gun dog owners looking for wild quarry and a place to get lost.

Back at the car, I tossed the newly acquired soda bottle in the car for later disposal. An hour or two of pavement separated us from college football, hot showers and drinks.

BHA member Andrew Bartoe is a Great Lakes native living in the Carolinas. He’s a proud husband, gun dog owner, craftsman, angler and an engineer by trade.

It’s going to be another fantastic gathering of our BHA family from across North America!

This year’s Rendezvous will take place at a new venue, the Missoula County Fairgrounds, in Missoula, Montana, March 16-18, 2023. The fairgrounds’ historic buildings will hold vendors, seminars, panels, live Podcast & Blast recordings with Hal Herring and more. With a move to an indoor-outdoor venue, Rendezvous will be a have an amazing array of opportunities for learning and gathering with old and new friends alike.

Three focused seminar areas, Food, Field Skills and Policy, will feature presentations from chefs, experts in hunting, angling and foraging skills, as well as engaging policy discussions with thought leaders from around the continent.

The Minnesota chapter will seek to defend their repeat title in this year’s Wild Game Cookoff. You won’t want to miss this event; learn, watch and cheer on this year’s competitors as they seek to wrestle the Golden Bull Trophy from the defending champs.

Chefs, members and locavores will convene again for this year’s Field to Table dinner, widely referred to as the best wild game meal anywhere. Attendees will witness chefs from around the country showing their amazing skills with wild game and then feast on their sumptuous creations. This year James Beard Award winner, writer and chef Hank Shaw will be among the chefs preparing this not-to-bemissed repast.

On the final night of Rendezvous 2023 we will wrap with our signature event, Campfire Stories, featuring tales from the inimitable Randy Newberg, veteran and BHA Armed Forces Initiative member DJ Zor, Ray Penny of G&H Decoys and more! Listen, laugh and maybe even cry as these amazing storytellers tell captivating tails of their outdoor adventures.

This is the largest gathering of public land owners in North America. Come and partake in the revelry with new and old friends, and enjoy all that Rendezvous has to offer. Tickets are on sale now at backcountryhunters.org

BHA’s 2022 Membership Survey results again depict a membership that trends young, is politically diverse, and is motivated by a set of core values: conservation ethics, tradition and health.

BHA’s survey offers up a profile of today’s public lands hunter and angler: characterized by an affinity for wild foods, a desire to spend as much time as possible on public lands and waters and a commitment to public service.

Highlights from the 2022 BHA Membership Survey follow:

63% of BHA’s membership is 45 or younger; more than a quarter (28%) is between the ages of 25 and 34.

30% of BHA’s members identifies as Independent; 20% Republican, 20% Democrat, 6% Libertarian and 1% Green (21% identifies as none of these or prefers not to respond).

20% of BHA members are active duty military or veterans (the U.S. average is 7%).

54% of BHA’s members forages along with hunting and fishing.

88% of BHA’s members spends at least half of their time recreating on public lands and waters.

More at backcountryhunters.org/bha_s_member_survey_2022_ results

A life member of BHA, Doug Pineo was the embodiment of conservation. From his time at Washington State Game Department and Department of Ecology, Doug fought for the preservation of biodiversity, land conservation and public access to natural resources.

An avid angler and upland bird hunter, Doug also made his mark in the falconry world as a falconer himself as well as a product designer and craftsman. Additionally, Doug served on numerous nonprofit boards, including but not limited to North American Grouse Partnership, Inland Northwest Land Conservancy and as a founding member of the Peregrine Fund.

But what I will remember most about Doug was his infectious energy. His smile abounded every time I saw him, including trolling for walleye, calling for turkeys or when sharing stories and a beer at the BHA Rendezvous. He reveled sharing stories from the pheasant fields or describing the way his falcons worked, and he lit up about his family, their successes and his grandchildren.

Doug was the type of person who would instantly make you feel like a friend and buoyed your desire to fight for what we all hold dear.

Douglas Anderson Pineo passed away September 7, 2022, and is survived by his wife Trisha, his children Helen and Chris and many siblings, grandchildren and other close relatives.

-Josh Mills, BHA development coordinator

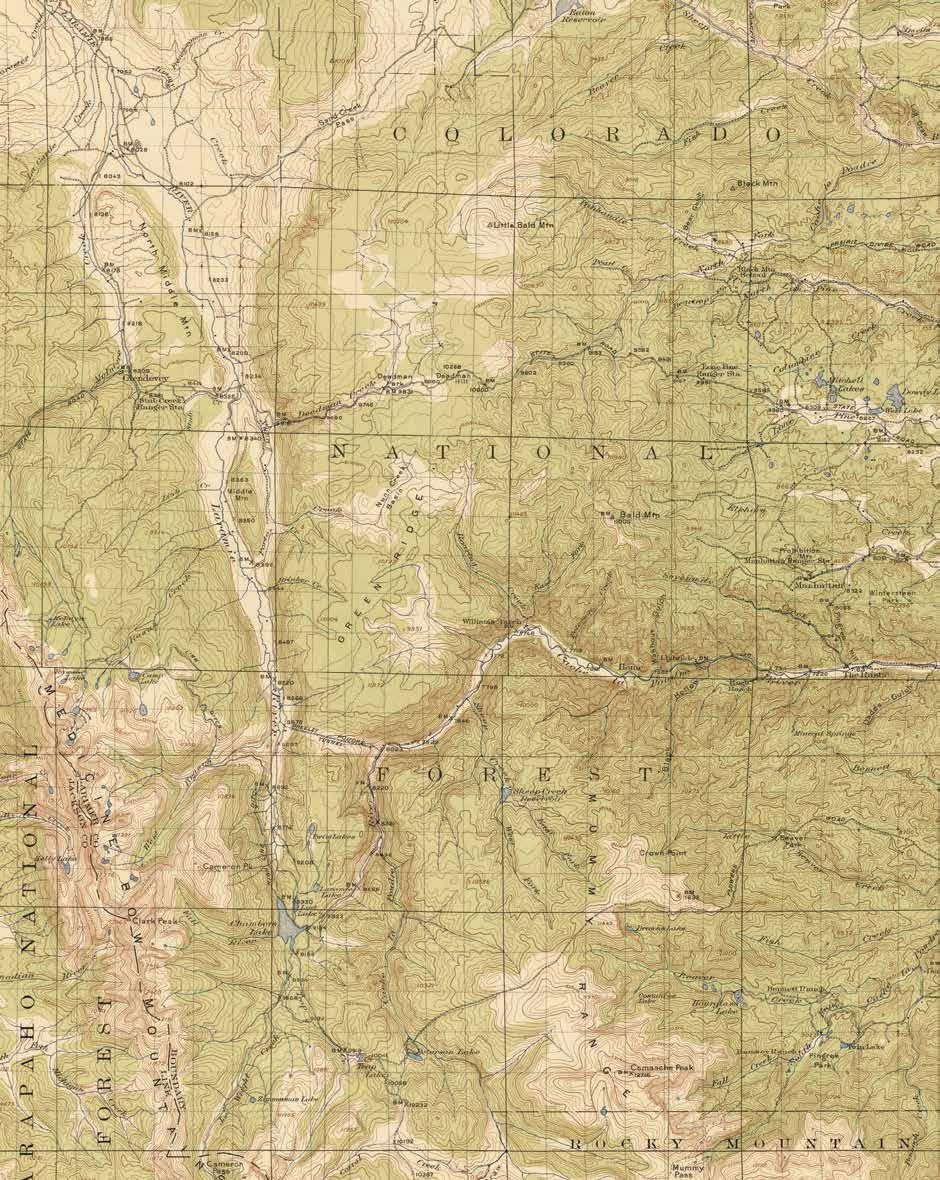

Valuable wildlife habitat in central Colorado will be permanently conserved following recent designation of Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument by President Joe Biden. Encompassing more than 10,000 acres of critical winter range for elk as well as mule deer habitat, migration corridors and headwaters fisheries, the area also is home to a historic military site, Camp Hale, a World War II-era training ground.

A broad coalition of hunting and fishing groups, including Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, has long advocated for the area’s long-term conservation. BHA staff were present today in Colorado where the president announced the designation and commended the administration’s decision.

“Hunters and anglers in Colorado have been working with local communities for more than a decade to permanently conserve these public lands and waters and important fish and wildlife habitat,” said BHA Conservation Director John Gale, who was on hand for the president’s announcement. “We’re pleased with the administration’s decision to heed the call of millions of citizens and undertake foresighted action in support of these irreplaceable landscapes.

“The Antiquities Act is a crucial tool to conserve large landscapes, secure important fish and wildlife habitat and uphold hunting and angling opportunities,” Gale continued. “Since it was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, it’s been used by 17 presidents, both Republicans and Democrats, to ensure the long-term conservation of places important to hunters and anglers.”

BHA has consistently advocated for America’s national monuments system and the judicious use of the Antiquities Act as a way to permanently conserve important large landscapes. Key to achieving this outcome is a process that adheres to specific tenets and is locally driven, transparent, incorporates the science-based management of habitat, and upholds existing hunting and fishing opportunities.

In 2016, BHA and a consortium of outdoor groups and businesses released a report on how national monument designations can sustain important fish and wildlife habitat while maintaining traditional hunting and fishing access, which can be read at backcountryhunters.org/national_ monuments_report

An editorial error resulted in the printing of an earlier draft of the story “Mother Wilderness,” in the Fall 2022 print issue. The correct, final version of this story appears in the digital version, which is readable at backcountryhunters.org/ fall_2022_issue_of_backcountry_journal

Ashley Peters grew up in rural Iowa, in a landscape of cornfields and monoculture agriculture. Looking for a wilder and wider life, she found her way to U.S. Forest Service trail jobs in the Minnesota Boundary Waters and in Alaska, to a degree in communications, and to conservation work ranging from the gator-bellowing swamps of Louisiana to the woodcock and grouse popple of the upper Midwest. Hal and Ashley talk the deep engagement and beginners’ mindset of adult-onset hunters and anglers, the challenges of finding one’s way to one’s passions, the swiftlychanging world of conservation, climate and wildlife diversity, and the business of somehow communicating it all clearly to a sometimes skeptical and indifferent public. That and more from the BHA Podcast & Blast wherever you get your podcasts.

Do you know an individual who deserves to be recognized for their outstanding contributions to conservation or our organization? This is your chance to help us honor their work with one of our 2023 awards! Award recipients are announced annually at the North American Rendezvous, set for March 16-18, 2023, in Missoula, Montana! The deadline for nominations is Feb. 3, 2023.

More information can be found and nominations can be made at backcountryhunters.org/2023_bha_awards_nomination_portal

BHA’s Outdoors for All scholarship assists young people with disabilities access to outdoors experiences by providing adaptive equipment or outdoor education. The scholarship, open to anyone ages 10-20, mitigates the expense of outdoor recreation and conservation education and expands experiences and opportunities for people with disabilities.

Applications for 2023 scholarships will be accepted from Oct. 1, 2022-Jan. 30, 2023.

Email submissions to admin@backcountryhunters.org, subject: Aidan Long/Outdoors For All Scholarship applicant.

Applications, written or video, should include the following: name, age, location, activity or gear you would like the scholarship to be applied to, articulation of financial burden, if any (not required), what is motivating the young person to participate in the outdoors, what being outdoors means to them, and how it makes them feel.

BHA’s North American Board of Directors will choose the recipients, and scholarship winners will be notified February 2023.

Great fly fishing, incredible scenery and the chance for an epic fishing story is what got me up early on a Saturday morning in May. That and a crowing rooster that lives on the farmstead next to the campground I was staying at along the Bitterroot River in Missoula, Montana.

I crawled out of my tent and made a pot of coffee on my camp stove, filled my travel mug, grabbed my camera and walked over to the only other human awake at this early hour. Brandon Dale was already dressed in waders and crouched down in the grass next to his tent, inspecting his fly-fishing gear. He looked up at me with an ear-to-ear smile that filled me with the same excitement and energy that surrounds him wherever he goes.

I met Brandon the day before at BHA’s North American Rendezvous, which gives attendees the opportunity to come together in support of public lands and waters. I was there to compete in the Wild Game Cookoff. Brandon was there in his role as a board member for BHA’s New York chapter, while also serving as the New York ambassador at Hunters of Color.

When he told me he intended to get up early the next day and go fly fishing before the day’s events began, I begged him for a chance to join – I’d only witnessed the unique overhead cast of a fly fisher on TV and in the movies.

I’ve always had the sinking feeling I’d be overwhelmed learning the fly-fishing basics. But Brandon is one of those natural mentors who has a zeal for both his work and outdoor passions – and it can inspire and motivate the rest of us to pursue our dreams.

I sipped on my mug of coffee as I followed Brandon to a spot he picked out on the banks of this south-to-north flowing river, lying under the watchful eye of Blue Mountain in Big Sky Country. In less than a minute, we witnessed our first “riser” – a trout rising to the surface. Then another, and another. These swirls, splashes and

winks in the water were often followed by a dorsal fin and a flick of a tail. My heart pounded harder in my chest every time one showed itself. It was the same excitement I get when I see the side-to-side swishing tail of a whitetail.

I watched Brandon fish with an easeful intention. His casts started with the rod tip low to the water, then paused on the backcast with the rod tip high. Finally, he finished with the rod tip low to the water again. The downward trajectory of how he casts is the opposite of how he lives his life.

Brandon is a medical student in New York City, but he grew up in Lafayette, Louisiana. Inspired by his mom’s work ethic while growing up poor in the South, he’s proud to say he’s the first in his family to attend college. His unyielding drive and determination have him studying for a Ph.D. in biomedical sciences and pharmacology – he wants to discover new cancer drugs. His goal is to be a physician researcher specializing in breast cancer.

I watched Brandon cast again, sending a delicate presentation of an artificial insect drifting along the surface of the river. Suddenly he set the hook. “Fish on?” I asked excitedly. “Is it a fish?”

“Just a log,” Brandon explained as the line broke off, dashing my dreams of a netted and photographed trophy trout.

He spent the next few minutes sitting across from me on the riverbank, tying on a new fly, picked out from his box of over 200 different sizes and patterns. Using his right thumb and forefinger, he slowly and carefully threaded the line through the tiny eye on the lure.

I believe you can tell a lot about a person by what kind of fishing knot they tie. Brandon chose a Trilene knot – strong and reliable. As he did so, he shared that, after years of study and passing his medical boards, his own mother, Emily, had been diagnosed with breast cancer just a few weeks ago.

My mouth felt dry in that moment as I considered how I would react if my own mother had such a diagnosis. But Brandon didn’t

skip a beat. He stood up tall, clutched his fly rod and stepped back toward the water. His eyes scanned the surface for another riser as he explained to me how they had found her cancer early and had successfully removed the tumor. He was optimistic his mother would have a full recovery. How I yearned for his type of confidence and trust about fishing – and life!

Brandon Dale is a fisherman who possesses the attributes of talent, knowledge and patience, which allow him to read a trout stream’s runs, pools, eddies and undercuts for the answers the rest of us seek but can’t seem to grasp. It’s his modest but determined character that helps him be successful in the outdoors. And it’s his commitment to conservation and mentoring underrepresented hunters and anglers that speaks loudly of his love of nature and his fellow man.

Just as he doesn’t lament over his mother’s breast cancer diagnosis, he also doesn’t sit with regret over the barriers of entry for new hunters and anglers. He volunteers his time and dedicates himself to teach others. Whether he’s wearing a lab coat or a pair of waders, Brandon Dale is on a mission to make things better.

BHA member Jeff Benda is a wild game chef, butcher, photographer, and outdoor writer (wildgameandfish.com). He lives with his wife and daughter in Fargo, North Dakota.

BRANDON, YOU ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT HELPING RECONNECT PEOPLE TO THEIR HERITAGE AND GROWING HUNTING AND ANGLING IN UNDERREPRESENTED COMMUNITIES. HOW ARE YOU WORKING TO ACCOMPLISH THAT? AND HOW CAN BHA MEMBERS AND THE ORGANIZATION PLAY A ROLE?

I’m the New York ambassador for Hunters of Color, and I’m a board member for the New York chapter of BHA. Through both roles, I coordinate year-round mentored hunting and outdoor skills education programs to increase the access and accessibility for new hunters and fishermen from underrepresented communities. Whether it’s a night on the indoor archery range, 3D outdoor archery courses, fly fishing outings, sausage-making demonstrations or online scouting and gear talk sessions, my goal is to holistically prepare mentees for all aspects of hunting and angling. These sessions culminate in two mentored deer bowhunting weekends, where the mentees are paired with mentors and hunt while building community to continue their journeys throughout the season.

Being based out of New York City, there are unique challenges to hunting and fishing that the mentees understand firsthand. However, I really enjoy being able to build community around hunting and angling for people who may have never left the concrete jungle. In many ways, once someone learns how to navigate hunting and fishing out of NYC, they are prepared to do it anywhere.

Most importantly, it is incredibly rewarding to foster the next wave of hunters, anglers, conservationists and, ultimately,

public land advocates, who will carry the flame to their communities while also making the outdoors more inclusive and accessible for everyone. Collaboration is key to the success of these programs, and I work closely with The Nature Conservancy in New York and BHA’s New York chapter.

The best way BHA members can get involved is to become a mentor or volunteer who spreads the word. Much of the cultural and technical know-how of hunting, fishing and outdoor recreation is familial. For folks who didn’t grow up with these mentors and experiences, the best thing we can do is to step up, teach others and pay it forward. We’ve got Hunters of Color (HOC) communities across the U.S., so reach out to your local ambassador and get connected to become a mentor. BHA, as an organization, should continue to be a key partner for HOC, and continue to help new hunters find community and mentorship.

I’m a BHA member because I fundamentally and unequivocally believe that we all have the right to recreate on and enjoy public lands. Being able to work with an organization that is dedicated to protecting that right is something that just makes sense. The folks in BHA are another huge reason of why I’m a member. The BHA community feels like family. We’re all united by a passion for hunting, fishing and conservation of our public lands, and I’m proud to be a part of this organization.

Connect with Brandon Dale: Instagram @bdale13 and @huntersofcolor Email: brandon@huntersofcolor.org huntersofcolor.org

“To have places we can access with the least amount of barriers. … It is the most democratic platform you can imagine. Everybody is welcome. … It is my job, and it is urgent for me to be the voice for these places.”

-Rue Mapp, Founder and CEO Outdoor Afro Vallejo, California

“I was introduced to BHA through the collegiate program. … I didn’t even know that public lands were a thing.”

-Madeline Damon, BHA U. of Montana collegiate club Missoula, Montana

“BHA is focused on a few things in conservation that no one else is focused on; specifically, the issue of access of public lands.”

-Ray Penny, owner G&H Decoys, veteran Tulsa, Oklahoma

“This is the most youthful organization, and it is a big tent – everyone is allowed to participate … that is generational (conservation) leadership.”

“This is the group that gives voice. It amplifies voice and action. We have found a way to leverage our relationship… I’ve never been involved in an organization that has this kind of ground up punching power.”

-Eddie Nickens, journalist, BHA North American board member, Raleigh, North Carolina

-Col. Mike Abell, BHA Kentucky chapter board Louisville, Kentucky

Species:

This is our workhorse, the ideal do-it-all option for most hunters. With each design decision, we sought the perfect balance: a shell that provides rugged protection without sacrificing flexibility; a true stealth fleece that’s still lightweight and breathable; all the technical details you want without the extras you don’t. Available as a jacket, vest, hoodie, and pants.

DuPage River, Illinois. Photo: istock.com/ EJ_Rodriquez

Conservation’s godfather, Theodore Roosevelt, once stated, “It is a good thing for us, by speech, to pay homage to the memory of Abraham Lincoln, but it is an infinitely better thing for us in our lives to pay homage to his memory in the only way in which that homage can be effectively paid, by seeing to it that this republic’s life, social and political, civic and industrial, is shaped now in accordance with the ideals which Lincoln preached.”

Roosevelt paid homage to Lincoln’s memory by protecting 150 million acres of accessible lands and waters for all people to enjoy, across the nation.

However, Lincoln’s home state, Illinois, currently has an accessibility problem in regard to its public waters.

Eight-hundred and eighty miles of the Illinois border is created by water flowing down the Mississippi, Wabash and Ohio rivers. In Illinois proper, there are 87,000 miles of waterways. But the Illinois Supreme Court confirmed in June 2022 that large areas of flowing water in Illinois are privately held by the landowners owning water frontage.

The court supported landowners along private waterways down to the middle of the waterway, including the water itself. The flowing water belongs to the landowner, the court found, and anyone floating along is trespassing.

This limitation stems from outdated laws and definitions. Federal law recognizes all waterways as public as long as they are considered “navigable,” floatable for means of commerce at any time in U.S. history. “Navigable” is a term open to interpretation and by Illinois state law is given a slightly different definition that does not align with federal law. Not all federally navigable waters in Illinois are open to the public due to Illinois law.

In the early 1900s, the DuPage River floated a wheel boat for public transportation, a clear representation of commerce and navigability, but by Illinois law, this river remains private. This is because the state of Illinois law designates public water, ignoring federal access laws. The water turns muddier, however, as the

a tube and float the DuPage, as long as you are content to risk the possibility of trespassing.

While I certainly respect property lines, borders drawn across moving water seem quite different from the ol’ fence row and give rise to a whole host of questions.

Is your water trespassing on your neighbor’s water? Who’s caring for the water? Who even knows?

As Roosevelt showed, if a resource is owned by everyone, it will indeed be left for generations to come.

Water, a building block of life, a resource so plentiful, so important, is inaccessible to most of us in Illinois – inaccessible to the angler looking to escape to the local stream or the family looking to float and connect outdoors. By contrast, accessible waterways create the opportunity for others to recognize the importance of natural resources, and in turn, they recognize the value of public lands and waters, not just for weekend adventures but for the future prosperity of all Illinoisans.

BHA’s Illinois chapter has been engaged with other organizations across Illinois to work on legislation changes that will align Illinois water access law with federal access laws, expanding water access opportunities for all. It is time to pay homage to Lincoln and Roosevelt and secure water access for all to enjoy for generations to come – or we will continue to float along in muddy waters.

Drew Kazenski resides in rural Central Illinois and serves as cochair of the Illinois BHA chapter. With a great passion for hunting, fishing, conservation and the future of it all, he believes we all take something from the land; therefore we should all give something back.

A version of this story also appeared in the Chicago Tribune on Sept. 6, 2022. Speak up for public water access in Illinois at backcountryhunters.org/take_action#/takeaction

Years ago, I was lucky enough to draw a bull elk tag in Utah’s Book Cliffs, where I enjoyed a tremendous hunt in the remote and rugged region. I harvested a mature bull with my father at my side and was hooked.

Since that hunt, I’ve explored canyon after canyon of the country on foot. Sometimes I’m hunting bison, elk or turkey – but often I’m trying to better understand the topography, hydrology and archaeology of this wondrous country.

In 1988, Utah’s Grand County Commission created a Special Service Road District whose sole purpose was to construct an 83-mile paved highway, named the Book Cliffs Highway, through the East Tavaputs Plateau, which is a remote region of southeastern Utah filled with archeological wonders and abundant big game, for the extraction of gas, oil and minerals.

In response, citizens from Grand County changed the three-person commission into a seven-member council and, in 1993, dissolved the board’s administrative authority to continue pursuit of the highway. The mineral lease funds allocated to the highway were redirected to recreation, hospitals and solid waste special service districts.

That was just the beginning.

In 2013, the Book Cliffs Highway reemerged under former Rep. Rob Bishop’s (R-Utah) public lands bill as a public utility corridor. And in 2014, the Grand County Council joined the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition (SCIC) – consisting of Utah’s Carbon, Daggett, Duchesne, Uintah, San Juan, Emery and Sevier counties – in a move to begin moving taxpayer dollars into the building of the illfated highway.

But then in January of 2015, after a new election, the newly appointed Grand County Council rescinded the previous council’s resolution to join SCIC over concerns for the proposed highway. Since this time, Grand County, no longer a member of the SCIC , has opposed the building of the highway.

Opposition to the highway, specifically in Grand County, lies on various foundations. Once proposed as a “fossil fuels” highway, and opposed as such, it is now being touted as a tourism corridor to move individuals from Yellowstone to the Mighty Five national parks in southern Utah. The alignment would save tourists approximately 15 to 25 minutes over taking existing routes and would leave those rural communities with a lack of revenue generated by the tourism industry.

The project has also been opposed by many – including Grand County, local NGOs and municipalities such as Helper and Dinosaur – due to the tremendous financial burden it would place on taxpayers.

It would cost approximately $6.6 million per mile (for about 35 miles) for construction of the highway, along with a yearly maintenance of approximately $1.35 million.

To note, these estimates are now years old and do not account for the escalating costs of building materials and fuels since the pandemic.

The most poignant impact to backcountry hunters and anglers is the irreversible destruction this route would cause to fish and wildlife habitat in the area.

The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources currently has a working group addressing the many issues faced by wildlife in this region. Extended drought leading to forage degradation, loss of perennial water sources, forage competition with livestock and feral horses, and elevated heat have led to either stagnant or declining elk, deer, pronghorn and bighorn sheep populations, not to mention upland game. The highway will add another burden for wildlife to shoulder, leading to direct vehicular loss, habitat fragmentation, invasive weed introduction and stressors to wildlife breeding and reproduction.

That’s why the Utah chapter of BHA has advocated against this highway by spearheading media campaigns both locally and nationally seeking to promote membership activism at a state legislative and local political level. BHA has also promoted the opposition of the highway at the Western Hunting and Conservation Expo, educating sportsmen and women on the effects of the highway on big game.

In March of 2022, the SCIC voted four-three to no longer pursue the highway, stating that they would rather invest in other large infrastructure projects such as the Uintah Basin Railway, which would run through pristine habitat in the central mountains of Utah. At this time, the executive director of SCIC, and the biggest proponent of the highway, has also resigned from his position.

The future of the Book Cliffs Highway is unknown. However, citizens of Utah and BHA members, those who find value in wildlife and wild places, should be ever vigilant of its potential return and be ready to hold strong in this almost 35-year-old battle.

Trisha Hedin is the director of an adult education program and a county commissioner in Moab, Grand County, Utah. Hedin also sits on working groups with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, representing both elected officials and sportsmen and women. She’s an avid rock climber and hunter, specifically enjoying hunting elk and turkeys. Trisha represents Utah’s southeastern region on the board for BHA’s Utah chapter.

• In October, the chapter partnered with TRCP and guest John Gaede ke (Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge) for a presentation about Brooks Range, its hunting and fishing qualities, and information about the Ambler Road EIS comment period.

• In September, the chapter partnered with the Midnight Sun Fly Cast ers to clean litter on the Chena Hot Springs Road.

• In August, approximately 70 people volunteered for the annual inva sive crawfish removal event in Kodiak, which removed over 1000 craw fish from critical juvenile salmon habitat.

• The chapter continues to publicize the proposed industrial road through the West Susitna Valley; as more Alaskans learn the specifics of the plan, enthusiasm for the project is waning.

• The Alberta chapter held an Armed Forces Initiative elk hunt at the Waldron Ranch to highlight cooperative conservation and steward ship practices on public and private land.

• Signed on as a partner on a “Shadow Coal Policy” to emphasize the

need for firmer legal protections for the Eastern Slopes.

• Sent a letter to the AEP Minister calling for restoration and reclama tion of public lands damaged during coal exploration since 2020.

• Partnered with the Ghost Watershed Alliance for an August cleanup in the Ghost PLUZ.

• The chapter held an annual family squirrel camp near Flagstaff in con junction with the Arizona Wildlife Federation and Arizona Fish and Game Department.

• Held the 3rd annual World Championship Dove Cook Off in Yuma, Arizona.

• Led a very successful mushroom hunt near Flagstaff.

• The chapter partnered with Ozark Beer Co. to release a limited-run of our very own beer: Bear State Golden Lager. A portion of the proceeds from this beer will directly benefit our fight for public lands, waters and wildlife here in Arkansas!

• In partnership with the Arkansas Game & Fish Commission and onX, we helped provide the agency data necessary to identify landlocked parcels of land throughout the state. The chapter board will be engaged in ongoing work to address access opportunities in Arkansas.

• AFI was approved as a Skillbridge partner for separating active duty mil itary members. We will have one active duty member working within AFI to increase members skills and lend assistance as they move toward separation.

• Kirtland AFB hosted a very successful antelope camp in New Mexico.

• AFI hosted 18 veterans on a wilderness canoe trip into the Boundary Wa ters Canoe Area Wilderness, which highlighted the need for permanent protections for the BWCA.

• Washington AFI hosted Grouse and Garbage, where 20 participants cleaned the Stoner Pit Shooting Range in the Elbe Hills. They success fully filled a 15 feet by 18 feet trailer with all the trash!

• A Colorado bear and elk camp was held in November for Colorado Armed Forces Initiative leaders.

• AFI established a new installation chapter at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina.

• The chapter participated in the Together for Wildlife Workshop to further progress of regional wildlife advisory committees, Wildlife Act review and Indigenous knowledge and shared decision-making policies.

• The chapter is involved in Provincial Hunting Trapping Advisory Team sub committees regarding the thinhorn sheep management plan and the Limit ed Entry Hunting system review.

• Members have been active and volunteering across the province with inva sive plant pulls, trail days, the WildCam project, an alpine lakes survey and holding pint nights with educational speaker presentations.

• Public Lands Month kicked off with a pint night and pack out on the Kern River, followed by a coho salmon restoration planting project with BLM in Point Arena, as well as a CSUF collegiate club Trabuco Creek cleanup.

• BHA also teamed up with the United States Marine Corps again to replace two guzzlers in Anza Borrego using helicopters and a volunteer ground team. Many groups came together to make this happen, but a special thanks goes out to the Marines (HMLAT 303), Scott Gibson, WSF, SCBS, ABDSP, ABF and the Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Na tion for purchasing the tanks.

• The Capital chapter hosted three WMA cleanups in September in sup port of Public Land Month. We were able to clear trails, cut shooting lanes for disabled hunting blinds and collect several dozen bags of trash.

• The chapter is running a mentored hunt program this fall and winter, where we will work with 10 new hunters. This will be a several day men tored educational event followed by a Virginia shotgun deer hunt.

• The chapter recently expanded its board to help further expand our re gion of engagement, and we are working on revamping the field represen tative volunteer team.

• The collegiate program awarded our third year of the Public Land Owner Stewardship Fund, which supports on the ground stewardship projects, to the University of Minnesota, Washington State University, University of Wisconsin Stevens Point and Murray State University

• Clubs showed up for Public Lands Month by packing out trash from their public lands. Washington State University picked up trash along the Snake River before hitting it for some fishing, and our emerging club at California State University Fullerton packed out trash from the Northwest Open Space.

• We hosted our final three learn to hunt workshops at Murray State (squirrels), University of Montana (waterfowl) and Northern Arizona University (rabbits and quail).

• The Colorado chapter published “Tag Allocation Observations” and a “Memo on Illegal Trails” on the BHA website.

• The chapter submitted comments for the BLM’s Colorado Big Game Resource Management Plan Amendment.

• The Seek Outside Podcast sat down with chapter co-chair Don Holm strom (Ep. 99) and chapter coordinator Brien Webster (Ep. 104).

• New chapter leaders include Nicholas Alfieri and David Brown as Cen tral Mountains Group assistant regional directors.

• Our 14th annual rendezvous will be held June 9-11, 2023, at the Soap Creek Corral/Coal Mesa Horse Camp west of Gunnison.

• The Georgia chapter submitted a petition to the governor, signed by thousands of Georgians, to urge the state to buy Pine Log WMA – a vital piece of public land that is currently for sale.

• The chapter has multiple events planned or in the planning stages for 2023.

• The chapter continues to build on the success of our Learn to Hunt pro gram, with mentors being assigned to all participants for what should be a great season.

• Idaho BHA is helping to build an information sharing coalition with other conservation organizations to better position our priorities for the next legislative session.

• The chapter donated $1,000 to Lake Shelbyville Fish Habitat Alliance for continued habitat improvements. Look out for more fish stocking, habitat builds and cleanups soon.

• The chapter is in the early stages of building the first BHA public 3-D archery trail in central Illinois. To become a sponsor of this project, reach out to Illinois@backcountryhunters.org

• Over 95% of Illinois waterways are not accessible to the public. The chapter continues to stay engaged in expanding stream access in Illinois. Please reach out to the chapter to organize events on water near you and continue to contact your legislators and ask them to be engaged in ex panding access. See the article on page 25 for more information.

• The Indiana chapter came together for their second annual chapter ren dezvous at Glendale FWA. The event was a great success, with events consisting of mourning dove and squirrel hunts, a public land pack out, special guest DNR presenters, an archery shoot, wild game cook-off and general conversation about where we are headed as a chapter.

• With funding supported by a grant from Bendix, the Indiana chapter was able to fund and assist Indiana DNR with the re-decking of the boardwalk at Pisgah Marsh Area.

• The chapter hosted its third annual state rendezvous in August at Saylor ville Lake near Des Moines.

• Partnered with two county conservation boards and others to contrib ute to the purchase of multiple tracts for public access in Ida and Lyon counties.

• Attended the Iowa Conservation Alliance annual meeting to lend Iowa BHA’s voice to legislative priorities for the upcoming 2023 legislative session.

• The Kansas chapter partnered with Friends of the KAW to do two sepa rate river cleanups in Manhattan and Desoto, along the Kansas River, in October.

• Trivia pint nights were held in Lawrence and another in Bonner Springs, which partnered with wildHERness at Outfield Beer Company.

• BHA helped with a cleanup project to remediate an illegal marijuana farm at Perry Lake near Topeka in September.

• In August the chapter accomplished a lot: held our annual summer at Pea body WMA by filling a dumpster with trash; held a Hack & Spray Day for invasive species on Higginson-Henry WMA; as part of a four-way partnership with Hunters of Color, Anderson County Sportsman’s Club and Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife, held a shotgun skills and pre-dove warmup.

• In September, the chapter did its part with Public Lands Month: a trash cleanup in Central Kentucky with Bluegrass Trout Unlimited at Hickman Creek, and to celebrate Public Lands Day, we went down to Eastern Ken tucky to Buckhorn Lake WMA and did a trash cleanup.

• After a two-year hiatus, we held our Michigan chapter rendezvous in Au gust – an amazing time with some incredible raffle prizes given away.

• Our policy group is closely following a proposed expansion of a military base, which could affect public access.

• Pint nights are in the works!

• The chapter will host the first annual North Country Icebreaker, Jan. 2729 at McQuoids Resort, on Mille Lacs Lake near Isle, Minnesota. This regional get-together will feature ice fishing, dark-house spearing, winter camping, wild game cooking and more!

• The Minnesota chapter partnered with the Minnesota DNR to host events in Eden Prairie and Grand Rapids that demonstrated lymph node extraction and discussed issues surrounding chronic wasting disease.

• The Minnesota chapter welcomes Keng Yang to the chapter board.

• The Missouri chapter, in celebration of Public Lands Month, donated $1,500 to the River Access Coalition legal fund, who we have partnered with to regain river access at Lindenlure on the Finley River.

• The chapter has also donated $1,500 to the Wyoming Corner Crossing Fund and $500 to the Bully pulpit fund. With matching donations, the three donations total over $6,500 in funds.

• The chapter organized a public land cleanup at Cooley Lake, outside of Kansas City.

• The chapter gained permission to intervene against a lawsuit that threatens Montana’s elk hunting heritage. Learn more at KeepElkPublic.org.

• Met with Senator Tester, Interior Secretary Haaland and USFWS Direc tor Williams to support and celebrate conservation efforts in Northwest Montana.

• The chapter testified before the Land Board, Fish & Wildlife Commision and the Private Lands/Public Wildlife Council to support public access, land acquisitions and equitable, fair-chase hunting opportunities.

• Sprayed invasive weeds, restored streambeds, maintained trails and cleaned up the Madison River and hosted events in Helena, Missoula, Butte, Kalispell, Lewistown, Billings and Bozeman.

• Nebraska chapter members attended the Nebraska Bowhunters Jamboree, sharing what BHA is all about with attendees.

• The Nebraska chapter board is meeting regularly to schedule events around the state.

• The chapter held an upland season kickoff pint night and raffled off an over-under shotgun, which was donated by chapter sponsor Imbib Cus tom Brews.

• The chapter is working toward the goal of selecting regional chapter leader representatives to better represent the membership in our huge state.

• The policy committee is very active in wild horse and burro management and is paying close attention to extraction and power projects in the state.

• During late October, the Vermont Armed Forces Initiative team held a turkey hunting camp at Wild Roots Farm in Bristol, with hunting in the Green Mountain National Forest.

• In Rhode Island, we partnered with the Department of Environmental Management fish and wildlife division to support a waterfowl workshop and mentored hunt during the state’s youth waterfowl season.

• Vermont BHA members are planning a wintertime apple tree release in several locations on public land; reach out if you’re interested in lending a hand.

• The New Jersey chapter, in partnership with NWTF, hosted a mentored archery deer hunt for six adults in cooperation with Wallkill River Na tional Wildlife Refuge in October. The hunters attended a safety and deer hunting workshop and hunted a full day with their mentor. The Newton High School Future Farmers of America invited the hunters to the school, and the students walked them through how to butcher and process a deer from start to finish.

• A passionate BHA member successfully stopped an unnecessary road clo sure in Grant County, which would have impacted 5,000 acres of BLM and state land access in mule deer country.

• In light of the New Mexico Supreme Court’s recent opinion re-affirming the public right to recreate in public waters, the chapter secured grant funding to execute stream access stewardship projects and educational events this fall.

• The chapter worked with NMWF to release a report outlining the extent of elk tag privatization in New Mexico based on the most recent data.

• The chapter teamed up with New York Hunters of Color and the Nature Conservancy of New York for an outdoor 3D archery and wilderness skills day. This event was prep for the mentored bowhunt coming up in No vember!

• The chapter partnered with the New york DEC at the Utica Marsh WMA, helping to refinish the observation tower overlooking the marsh.

• The chapter is helping new hunters up their game. Check out our new Instagram reels (@newyorkbha) on building arrows and packing for a backcountry big game trip out west.

• The Sundheim Boatramp renovation was completed in September. North Dakota Game and Fish matched chapter dollars to make this boat ramp operational again.

• Hosted our first Beer, Bands and Public Lands event in Fargo in late Au gust. We hope to grow this event into a major fund raiser going forward.

• Our 3rd non-motorized signage project was conducted in August. Volun teers replaced dozens of faded/defaced non-motorized signs in the Little Missouri National Grasslands.

• This year’s Badlands Classic, a 3D archery shoot that takes place entirely on the Little Missouri National Grasslands (aka The Badlands), was our 4th year partnering with the Roughrider Archers. We continue to work towards growing this event.

• The Ohio chapter had a very busy Public Lands Month, with a total of five recent events, including a “learn to fly fish” session, led by local leg end Jerry Darkes and the always fun Ohio Women On The Fly; a catfish jugging event on the scenic Little Miami River; and a cleanup at Alum Creek State Park. With various promotions at events, we were able to sign up nearly 80 new members and were honored as BHA’s September Chapter of the Month.

• The chapter supported the acquisition and rehabilitation of land along a mile-long section of one of Ohio’s beloved steelhead tributaries, the Chagrin. The chapter has previously pledged $5,000 to the effort and more recently submitted a letter of support for the Chagrin River Floodplain and Land Conservation Project.

• The chapter held its first “Cut and Cook” butchering and cooking class this fall. Alongside chapter sponsors and volunteers, the class broke down field dressing techniques and showed easy ways to prepare wild game once back home.

• Chapter leaders and volunteers helped to restore sagebrush and bitter brush habitat in Eastern Oregon, alongside Oregon Hunters Associa tion. Sagebrush and bitterbrush habitat is crucial to thriving mule deer populations, which have dwindled in Eastern Oregon and continue to decline.

• Several cleanups were held across the state, including one in which 40 contractor bags of trash and two sofas were removed from state game lands.

• The first annual Bustin’ Clays with BHA was successfully held in Carl isle. The event served as a fundraiser to support policy work in the state.

• The chapter engaged as the sole organization in a pilot “Adopt a Boat Access” program with the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission.

• Sunday hunting on public land remains the top priority for our chapter. We continue to communicate with policy makers and build relation ships with other local leaders to support the movement.

• The chapter launched a call to action based on a change made by the SCDNR to national forest land regulations in South Carolina, which reduced overall access by 67% for walk-in waterfowl hunting. Our chap ter leadership led members in messaging the SCDNR and lawmakers in opposition.

• From Dec. 1-4, the chapter held a campout hunt at the ever-threatened Yanahli WMA. The group camped at Henry Horton State Park and hunted at Yanahli, and a great time was had by all.

• This fall, the chapter held a cleanup at Percy Priest WMA. This WMA is near cities and subdivisions, and trash is dumped there regularly. We made a big difference and made important connections with the TWRA officer in charge of the WMA.

• The chapter continues to hold monthly pint nights in Nashville. At tendance is growing, and there is a lot of excitement for the mission of BHA in Tennessee.

• The chapter was awarded a grant by Gulf of Mexico Alliance to go to ward smooth cordgrass planting for shoreline resiliency and to prevent erosion of coastal marsh habitat at the Texas Mid-Coast Refuge Com plex

• The chapter launched the “Adopt a Public Dove Field” program, recruit ing hunters to be stewards of properties enrolled in Voluntary Public Access.

• The chapter continues to support Save the Cutoff, working to maintain public access on this stretch of the Trinity River.

• We wrapped up our inaugural five-week Hunting for Sustainability workshop with a hands-on field dressing and processing workshop. A dozen graduates are afield this fall, and we hope to hear successful stories soon. Thank you to Utah DWR for the support.

• This summer, the chapter heavily contributed to the statewide elk man agement plan, which will be in place for the next eight years.

• Utah chapter board member William Peterson helped a special needs youth hunter gear up for his once in a lifetime moose adventure in the fall. Will coordinated a guide and gear donation from Cabela’s. The hunt was a success and an unforgettable experience for this young pub lic land owner!

• The chapter has joined the Washington Sportsmen Coalition with several other hunting and angling organizations across the state. This effort was bred from the fight for and ultimate loss of Washington’s spring bear season earlier this year.

• The chapter was awarded the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Region 2 Organization of the Year. This comes after long efforts to restore hunting opportunities in Washington State.

• The chapter will have a booth and raffle at the West Virginia Hunting & Fishing Show in Charleston.

• Stay tuned to our e-newsletter and social channels for 2023 chapter events.

• The chapter will be tracking the 2023 West Virginia legislative session and will keep you posted on relevant bills via email and our social chan nels.

• The chapter successfully completed its annual learn to bow hunt pro gram in September. The program consists of participants learning the basics of archery, along with lessons around deer hunting, over the span of seven weeks, before a weekend mentored hunt.

• The chapter is funding a carcass dumpster at its adopted wildlife area, Goose Lake, to help fight stop the spread of CWD. The chapter is also donating $1,000 to Bayfield County to help fund carcass dumpsters.

• The chapter engaged in a Wisconsin Conservation Policy Summit to collaborate with other hunting and fishing organizations to advocate for pro-hunting and angling policies in Wisconsin.

• The chapter would like to thank MeatEater for its continued support on the Wyoming corner crossing issue. From sharing posts to encouraging donations and to donating $15,000 directly to the BHA campaign to cover the hunters’ legal fees – MeatEater’s support has been instrumen tal in our efforts during the last year. Thank you!

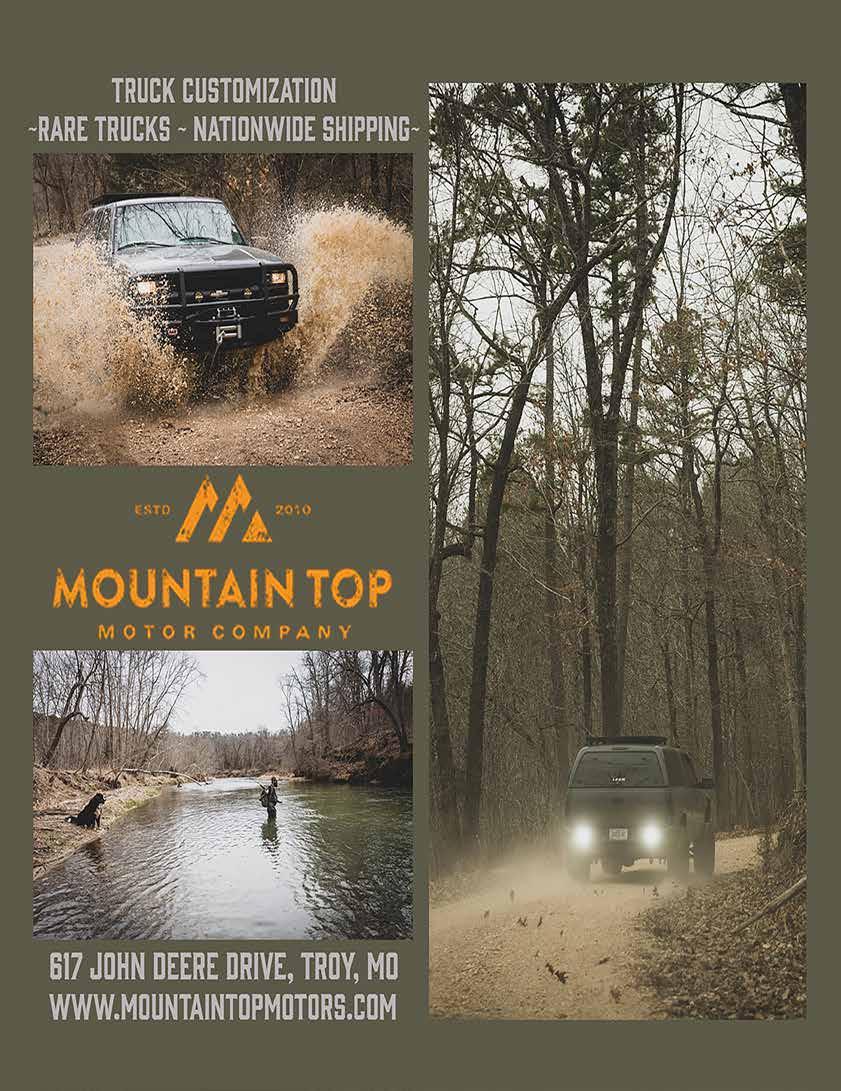

• Thank you to Jon Lang, owner of Mountain Top Motors, for his gen erous match donation of $5,000 to BHA’s September corner crossing campaign. Thanks to Jon and our amazing members, we raised $23,645 during the month of September, exceeding our fundraising goals, and raised over $111,000 total, ensuring the Missouri hunters will have the funds they need to cover remaining criminal defense fees and current civil defense fees.

• The chapter has contracted with a lobbyist and will be actively engaged during the 2023 legislative session to defend and expand public access opportunities.

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountry hunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org)

An overnight snowfall left an inch of fresh powder in the woods –perfect for tracking ruffed grouse on this wintry morning.

I came across a group of tracks that tiptoed their way up a draw and followed them while keeping an eye out ahead of me. Soon enough, I approached a stand of young hemlocks and heard the trill of a ruffed grouse. One flushed to the left. I quickly fired but missed. A second burst out of the thicket but never presented a shot. Finally, a third grouse launched out, and I swung the shotgun and connected.

Pursuing grouse in the late season is a rewarding experience for any hunter who enjoys being in the winter woods with a shotgun in hand. Grouse can be an elusive species no matter the time of year, but once snow starts falling, it can provide the hunter a unique opportunity to track and locate these clandestine birds.

When it comes to the late season, grouse gravitate toward habitat that meets their food and shelter requirements in a relatively small area.

Ruffed grouse have limited body fat, so they need food that is readily available all winter long.

For both western and eastern states, mature male aspen trees are a significant winter food source – and grouse fly up to the branches to eat the tree buds. If there is a lack of nearby mature aspen stands, you may be able to find grouse feeding in birch or younger aspens.

In western states, snowberries are another late season food source, while in eastern states, hazel brush is more important for ruffed grouse. Ruffed grouse may consume hazel brush catkins and snowberries earlier in winter when they are more prevalent. Both of these plants provide cover and concealment while the grouse feed.

Besides food, ruffed grouse need shelter from the cold, wind, predators and precipitation. Conifer trees can be excellent harbors for grouse as their large, sloping branches block snowfall and lend bare ground underneath. Young stands of hemlock are also sheltered areas that grouse use as travel corridors between roosting and feeding sites. While there may be a foot of powdery snow on the open ground, it could be only a dusting under hemlock stands, which makes for easy walking.

Finding food sources near conifers helps place you in potential late season grouse habitat. Look for hills and draws that buffer cold northerly winds, and sunny slopes that provide opportunity for sunbathing in trees. Draws also accumulate snow earlier on, which gives the grouse the added option of roosting in deeper snowpack when temps plummet well below freezing.

Although many hunters locate grouse with bird dogs, it can be beneficial to go solo into the snow-covered woods at times.

An ideal situation for tracking grouse is the morning after an overnight snowfall. If the temperature is not frigid, the grouse will be moving in the morning hours, trekking from their roosting sites to their food sources.

With fresh snow, you may spot their tracks, which resemble

miniature turkey prints. I like to walk trails and edges of cover to first find tracks. If I do not locate them there, I head farther into aspen stands or clumps of hemlock.

It is important to determine which direction the grouse was walking.

To do this, look at their long middle toe, which points to their direction of travel. However, in light powdery snow, it can be difficult to decipher. In this situation, check to see if the tracks cross under pines. There is usually less snow in the understory, and you should find more “readable” grouse tracks.

Once you have found tracks and know their direction, keep on them.

Not only could you be heading toward a nearby grouse, but you will also learn some of their habits and where they travel, shelter, roost and feed. If you come to a dead-end where a grouse took flight or the snow becomes patchy, you have to do some detective work and think about where the bird might have ventured.

If there are nearby conifers, hemlock thickets or aspen stands, those are places to check out, and you may relocate tracks or grouse in those spots. The birds generally do not travel far in winter, so tracking them is not a long ordeal.

Hunting ruffed grouse in the snow without a bird dog can be productive, but there is limited prior warning that a grouse is about to flush, so you must be ready for snap shots.

As you follow grouse tracks, it is important to keep the shotgun up and ready (port arms, for you military folks). In this position, you will be able to quickly swing the shotgun over to the bird, release the safety and fire a shot. Scan ahead as you track the grouse, because they may be on the ground and silhouetted against the snow.

Late season is also a time that grouse start to regroup. If you find one of these groups, they may give their position away by sounding off an alarm call. This alarm call gives you just enough time to approximate where the grouse are, position yourself for the flush and take aim. When in a group, grouse most often take to the air as individuals. If you miss one shot you may still have a second or third opportunity.

As is often the case, grouse dodge, dip and dive safely away from

your shots. When this happens maintain focus on the direction the grouse flew. They usually head for denser cover, and most ruffed grouse flush 100 yards or less before landing on the ground or in a tree. Work toward the area you think they landed, and slowly scout any dense patches of trees, especially conifers. Periodically look up because they may have landed in the branches. Take note of these locations where you flush grouse, which are areas to explore on return trips.

It can be downright impossible to snap shoot a shotgun with bulky gloves on, so I prefer to wear thinner gloves with hand warmers nested on top of my hands.

Gaiters are also very useful as they keep snow from falling into your boots while you wade through deep patches. Taller gaiters keep pants legs from getting soaked with snow.

Lastly, any shotgun from 12 to 28 gauge with 6 to 7.5 shot will work. A 20 gauge can pack the right amount of punch without the weight of a 12 gauge. The lighter 20 gauge can help you to draw the shotgun onto the target quicker in snap shooting scenarios.

For chokes, I tend use a double barrel shotgun with one barrel threaded with a modified choke, because the late-season woods have far less foliage on them, so shots on grouse can be quite far sometimes. As for the other barrel, I still like to have a skeet or improved cylinder choke for those in-your-face flushes.

Regardless of your gun of choice, a rewarding experience awaits in the late-season grouse woods.

Marc Fryt is a proud BHA member, fly fishing guide, upland hunter, outdoor writer and photographer currently living in Spokane, Washington.

By the time you’re reading this issue of Backcountry Journal, it will have been half a year since 58 members of Congress attempted to dismantle the American System of Conservation Funding.

The RETURN Act, introduced by Rep. Andrew Clyde (RGA), aims to repeal the Pittman-Robertson excise tax on firearms and ammunition and replace the source of the wildlife restoration account with royalties from offshore oil and gas development. This would functionally divorce hunters and recreational shooters from funding conservation and would destabilize the source of nationwide conservation funding.

As of this writing, seven of the sponsors have withdrawn their names from the bill, admitting that the proposal was misguided at best.

For the first time in recent memory, politicians from both sides of the spectrum are trying to divert permanently authorized monies away from wildlife conservation because these taxes either impede our ability to exercise our Second Amendment rights or because

they implicate wildlife conservation in any and all firearm violence that occurs in this country.

For those of us who think about conservation daily, removing these funding streams is a scary prospect – and one that would undo 85 years of efforts by hunters, anglers and trappers to pay for the restoration and conservation of wildlife.

The American System of Conservation Funding consists of a three elements: the sale of hunting, fishing and trapping licenses by each state; excise taxes collected on the manufacturing of firearms, ammunition and archery tackle under the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act; and excise taxes collected on fishing equipment under the Dingell-Johnson Federal Aid in Sportfish Restoration Act of 1950 and the Wallop-Breaux Aquatic Resources Trust Fund of 1984. These federal funds are all managed by the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration (WSFR; “wis-fer”) program at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These federal dollars are then matched at the state level by money collected from the sale of hunting, fishing, and trapping licenses, and they bankroll state fish and wildlife agencies. According to a recent survey of state fish

and wildlife agencies, these three sources make up more than 85 percent of dedicated agency revenue in nearly half of the states.

“Many Americans are unaware of the remarkable conservation impact of the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program,” said now-FWS Director Martha Williams in a press release. “State wildlife agencies dedicate WSFR funds to a variety of conservation projects and programs such as hunting and fishing education, fish and wildlife management, scientific research, habitat restoration and protection, land and water rights acquisition and hunting and boating access. Everyone benefits from these investments, which have ensured a legacy of wildlife and outdoor opportunities for all.”

The American System of Conservation Funding is often discussed alongside the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, but these two are not interchangeable. The North American Model is a set of principles – first aggregated and articulated by Valerius Geist, Shane Mahoney and John Organ (editor’s note: read Organ’s “The Origins and Purpose of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation” in the fall 2022 issue of Backcountry Journal) in the early 2000s – that in their collective application distinguish wildlife conservation in the U.S. and Canada from other forms worldwide. It is silent on funding and on specific laws or policies. The American System of Conservation Funding describes a specific set of policies that fund wildlife and fisheries conservation. It’s a nuanced distinction but an important one for the sake of this discussion.

The stories of conservation in this country we often hear and tell are critically intertwined with this model and this system. They often begin toward the end of the 19th century when market hunting was decimating large game populations and hunter-conservationists of the day leapt into action to stem these declines. A critical piece of this campaign to conserve wildlife was establishing a system of funding to ensure dedicated, future professionals would be able to make a living improving populations of public wildlife, restoring habitat and managing land for all of us to enjoy.

“The American System of Conservation Funding was developed by hunters and anglers nearly a century ago and generates nearly a billion dollars annually,” said Ted Koch, BHA’s North American board chair. “We chose to tax ourselves and have led conservation funding since. This is the foundation for the most successful approach to wildlife conservation in the world and is essential for maintaining public ownership of wildlife to avoid limiting access to only the wealthy who would gladly pay for the exclusive privilege.”

These funds facilitate the management of nearly 35 million acres of state lands, have sent more than 2 million individuals through hunter safety programs and over the last 85 years have bankrolled the recovery of iconic North American wildlife. We all benefit from this legacy, but it is under threat.

While the Dingell-Johnson program has remained untargeted, the Pittman-Robertson account has come under fire from both sides of the aisle.

“The RETURN our Constitutional Rights Act would recklessly unravel Pittman-Robertson funding as we know it,” said John Gale, BHA’s conservation director, in a press release. “Its passage would

have devastating consequences for our fish and wildlife agencies and would limit the role of sportsmen and women in funding conservation, diminishing our effectiveness as a constituency. This is a legacy of which we’re justifiably proud – and which we’re committed to continuing in perpetuity.”

Groups on the other side of the political spectrum are seeking to separate wildlife conservation from the firearm industry for other reasons. Namely, they have a desire to separate firearm-based violence from productive and good wildlife conservation efforts or to use those excise tax dollars for causes other than wildlife. Notably, they’d like to see those funds used to better equip urban hospitals that treat victims of gun violence, which is certainly an important cause and is deserving of durable funding. However, tearing down a successful program to stand up another is just poor policy.

Proposals like all of these are universally bad for wildlife and undermine our 85-year-old, bipartisan American System of Conservation Funding. However, they do force us to think about how we would fund wildlife conservation if these policies, or those who contribute to them, disappear.

As conservationists, we know that these funds are critical to the important work of state fish and wildlife agencies and must be protected at all costs. However, these policies may also be improved or diversified. Other items could be taxed. Tribal wildlife agencies could be made eligible for these funds. Monies from other sources could be made available. But if we want to maintain or improve this system, it’s up to us to do so.

“The numbers are substantial: Lifetime Pittman-Robertson contributions from gun and ammunition manufacturers total more than $15.3 billion. Last year, $1.5 billion was apportioned to the states for conservation. Of that, $1.1 billion is tied directly to sales of guns and ammunition.” said Land Tawney, BHA president and CEO. “These dollars are critical to our wild places, and they have led to the successful restoration of elk, mule deer and pronghorn populations in New Mexico and Montana, as well as species like wild turkey, waterfowl and white-tailed deer all across America.”

If you want to do something about this today, pick up the phone and call both of your senators and your representative in the House. Let them know that you support the Pittman-Robertson program and oppose any policies that would attempt to dismantle it. I’ll do the same, with as many offices as I can, and hopefully we can keep this system of conservation funding alive, well and diversified in the next 85 years.