BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Summer 2025

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Summer 2025

“Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

When Theodore Roosevelt spoke those words, he wasn’t just giving a pep talk. He was laying down a challenge to future generations of Americans: to live boldly, to act decisively, and to fight for the ideals that define our national character. For those of us who hunt, fish, and find purpose in wild places, there may be no mightier principle than defending America’s public lands.

Our public lands are the foundation of our history and culture and essential to the American ideal. They’re where we learn resilience, humility, and personal renewal in the high country. They’re where we teach patience—in a duck blind or trout stream—to the next generation of conservation leaders. They’re where we fail, try again, and sometimes, gloriously, succeed.

But those lands—640 million acres of national forests, wildlife refuges, BLM parcels, and more—are under attack in ways that demand we live up to Roosevelt’s charge and BHA’s promise to defend our public lands legacy against seemingly insurmountable odds.

In the dead of an early May night, a provision that would open the door to the sale of nearly half a million acres of public land in Nevada and Utah was quietly slipped into the House Budget Reconciliation Bill. Contrary to the gaslighting effort by elected leaders willing to sell us out, this wasn’t about improved management, affordable housing, or fiscal responsibility. It was calculated to privatize our national legacy, converting public treasure into private gain, and turning a birthright into a balance sheet.

When the bill, along with language to sell off public lands, was reported by the House Natural Resources Committee on May 6, 2025, the BHA community, as it always does, mobilized without a moment of hesitation. We activated the BHA network of grassroots warriors, launched a campaign under the banner of United We Stand for Public Lands, and mobilized tens of thousands of passionate public lands advocates across the country. Volunteers flooded congressional offices with calls, emails, and messages demanding elected officials reject the language to sell our public lands. The response was overwhelming, building momentum to become BHA’s third-most responsive call to action a matter of days. Our voices were heard, and the House measure was ultimately defeated.

But that was just the beginning. In June, the Senate’s version of the budget reconciliation bill was released, proposing the sale of more than 3 million acres across the West. The battle for our public lands had become a full-blown war. Many of our peer organizations joined the cause, and BHA members once again heeded the call. At Rendezvous, the energy was palpable. We were there to celebrate wild public lands and waters—but while we celebrated, we also united. This was our time to rise. By late June, when this magazine issue was finalized, our action alert was nearing 100,000 actions.

Let’s be clear: public lands are not a partisan issue. They are an American one, rooted in the very principals of democracy, where it’s all equal ground—on trailheads and mountain peaks, in trout

streams and grasslands, and in the campfires that invite us to share in the backcountry experience.

And yet, too many of our elected leaders ignore the overwhelming passion for public lands voiced by the vast majority of Americans, hoping no one is watching as they cave to private interests. Whether it’s Utah’s lawsuit to undermine the very foundation of federal land management, the erosion of bedrock conservation policy, or this latest maneuver in the budget bill, the message is clear: Public lands are nothing more than assets on a balance sheet, not opportunities to be cherished.

Backcountry Hunters & Anglers rejects that cynical and selfserving vision, and we refuse to sit back and hope someone else will do the work. We are resolved to defend our public lands legacy because we know what’s at stake: access and opportunity, wildlife habitat and clean water, rural economies and sustainable jobs, and a uniquely American form of freedom. The freedom to roam. The freedom to belong. The freedom to pass on these experiences to our kids.

At BHA, we have clarity of purpose. We call our lawmakers. We show up to commission meetings. We organize pint nights, plant trees, pull fences, and clean up trash. We mentor new hunters. We share meals of a wild-game harvests and celebrate stories of wildland moments. And we fight.

We fight because we know that once a piece of public land is gone, it’s gone for good. And we fight because the stakes have never been higher.

Roosevelt didn’t shy from controversy or conflict. He understood that conservation was hard, messy work—but necessary, nonetheless. He understood that daring mighty things means sometimes taking shots from those who stand on the sidelines. But it also means we stand a chance at winning glorious triumphs.

We can choose to live boldly. To act decisively. To speak truth to power. We can dare mighty things.

Because if we don’t, who will?

Let your voice be heard. Take action at backcountryhunters.org and join us in defending what makes this country great.

United We Stand for Public Lands.

-Patrick Berry, President & CEO

“Do eat food that is honorably harvested, and celebrate every mouthful.”

~ Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

Ryan Callaghan (Montana) Chairman

Dr. Christopher L. Jenkins (Georgia) Vice Chair

Jeffrey Jones (Alabama) Treasurer

Katie Morrison (Alberta) Secretary

Ed Anderson (Idaho)

Patrick Berry, President & CEO

James Brandenburg (Arkansas)

Bill Hanlon (British Columbia)

Jim Harrington (Michigan)

Hilary Hutcheson (Montana)

Ray Penny (Oklahoma)

Nadia Marji, Vice President of Marketing and Communications

Frankie McBurney Olson, Vice President of Operations

Katie DeLorenzo, Western Field Director

Britney Fregerio, Director of Finance

Chris Hennessey, Eastern Field Director

Kaden McArthur, Director of Policy and Government Relations

Dre Arman, Regional Stewardship and Habitat Connectivity Manager

Brian Bird, Chapter Coordinator

Chris Borgatti, Eastern Policy and Conservation Manager

Kylee Burleigh, Digital Media Lead

Tiffany Cimino, Membership and Community Development Manager

Trey Curtiss, Strategic Partnerships and Conservation Programs Manager

Bard Edrington V, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Contributors in this Issue

On the Cover: BHA Alaska chapter board member Paul A. Foward absorbs the inclement weather during a traditional bow sheep hunt. Photo by Colin Arisman, Grand Prize Winner of the 2024 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

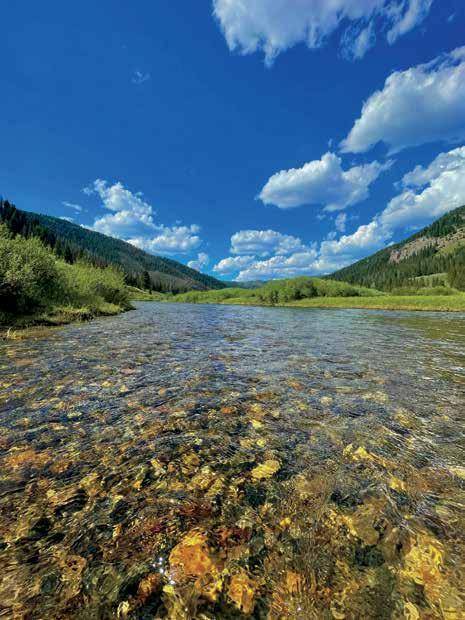

Above Image: Fresh trout from a narrow stream. BHA Member Kyle Klain, 2024 Public Lands and Waters Photo Contest

Troy Basso, Thomas Baumeister, Charlie Booher, Zach Brady, Kevin Colburn, Frank DeSantis Jr., Micah Fields, Nolan Fregerio, Jim Gates, Jacob Greenslade, Robert Graham, Jim Harris, Brian Halchak, Ted Hansen, McKenna Hulslander, Ken Huxtable, Marcus Jacobson, Joshua Jackson, Chip Jawstrong, Chuck Kartak, JJ Laberge, Ben Long, Kaden McArthur, Dustin McKenna, Jeff Mishler, Marianne Nolley, Wendi Rank, Kelly Reynolds, Damia Siebenahler, Joseph Sigurdson, Sarah Snipes, Jonathan Wilkins, Mike Wintroath

Journal Submissions: williams@backcountryhunters.org

Advertising and Partnership Inquiries: mills@backcountryhunters.org

General Inquiries: admin@backcountryhunters.org

Don Rank (Pennsylvania)

Matt Shilling (Minnesota)

Peter Vandergrift (Montana)

J.R. Young (California)

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus

Brady Fryberger, Office Manager

Mary Glaves, Chapter Coordinator

Makayla Golden, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Andrew Hahne, Habitat Stewardship Coordinator

Aaron Hebeisen, Chapter Coordinator

Jameson Hibbs, Chapter Coordinator

Bryan Jones, Armed Forces and Stewardship Programs Manager

Josh Mills, Corporate Conservation Partnerships Coordinator

Devin O’Dea, Western Policy and Conservation Manager

Brittany Parker, Chapter Coordinator

Max Siebert, Operations Coordinator

Joel Weltzien, Chapter Coordinator

Zack Williams, Editorial and Brand Manager, Backcountry Journal Editor

Intern: Maisie Kroon

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807 www.backcountryhunters.org admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, a North American conservation nonprofit 501(c)(3) with chapters in 48 states and the District of Columbia, two Canadian provinces and one Canadian territory. Become part of the voice for our wild public lands, waters and wildlife. Join us at backcountryhunters.org

All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher.

Published July 2025. Volume XX, Issue III

BY MARCUS JACOBSON

The birds’ songs break the stillness of the early morning as water laps the shoreline of our campsite. A hint of last night’s campfire still hangs in the air. As I take in the peaceful morning, I roll onto my side to see if anyone else in the tent is awake.

My 5-year-old son, Sawyer, is sleeping peacefully in his sleeping bag, his grandfather on his other side. I smile at the young boy, who was exhausted by the time we crawled into the tent the previous night after a day full of excitement for his first trip to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. My father lies on his back, eyes closed, his gray hair becoming visible in the newly developing morning light. This would be roughly his 65th trip to the Boundary Waters, having visited its wild country multiple times a year since his first church trip as a youngster. Since then, he has traveled the entire BWCA from west to east, paddling and portaging countless miles and experiencing nearly every wild animal encounter the ecosystem has to offer.

I was fortunate to have a dad who shared his passion for this wilderness with me at a young age. My first trip was at 3 years old, and I quickly developed a passion for the Boundary Waters that rivals his. Those early experiences, paddling alongside my father and absorbing his deep respect for the wilderness, developed my desire to conserve this special place. Witnessing the untouched beauty of the BWCA as a child instilled in me a lifelong responsibility to protect and advocate for it. Growing up exploring the BWCA, I have some of my fondest childhood memories there. It helped shape me as a person and taught me invaluable lessons that I carry into my personal life. To me, the BWCA isn’t just a place to escape the hustle

and bustle of the industrialized world; it is a spiritual connection and a reset. As Edward Abbey once said, “Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit.” That couldn’t be truer for my spirit, and I dare say for everyone’s.

Sawyer awakens with as much enthusiasm as when he started the trip, ensuring we are awake and ready for another exciting day. A pearly fog, burned off by the morning sun, greets us as we exit the tent. After taking in the morning views, it doesn’t take long for Sawyer to express his hunger. We head back to the spot in the woods where we had found two large pine trees and showed Sawyer how to suspend a line across them to hang our food pack the night before. As I start on breakfast, Sawyer explores our campsite and claims an old stump next to the fire grate as his breakfast table. We all agree that you couldn’t find a better spot for breakfast.

With a 5-year-old, every camping activity is a learning experience full of questions. Tasks take longer, but both my dad and I know that is exactly why we are here. Each moment presents an opportunity for Sawyer to engage with the wilderness, fostering curiosity and independence. Whether it’s learning to tie a secure knot, understanding how to balance a canoe, or simply observing the way a turtle moves across the rocks, these moments lay the foundation for a lifelong connection with nature. Our agenda is simple: to spend time with Sawyer and foster his interest in the outdoors. We spend the rest of the day making “pinecone soup”—a concoction of pinecones, rocks, pine needles, sticks, and various other items Sawyer finds around camp—as well as swimming, watching a garter snake sunning itself in our camp, and fishing in the evening. The night ends with Sawyer feeding a crackling campfire as we watch the sun set behind the trees of the western sky.

By conserving this wilderness, we can show that the human race is capable of learning—and growth—by placing pristine wild country and a perpetual outdoor economy over permanent environmental destruction and temporary financial gain.

As the campfire glow lights the faces of my dad and my son, I am filled with gratitude for those who came before me and saw the importance of protecting this wilderness, ensuring that it remains intact. That foresight has allowed me to share this wild and untouched landscape with my father and now with my own son.

The BWCA, located in the Superior National Forest in the northeast corner of Minnesota, spans over one million acres. It consists of more than 1,200 miles of canoe routes, 12 hiking trails, and over 2,000 campsites. Given that motorized access is not allowed and that many visitors practice the “leave no trace” ethic, the BWCA is home to some of the cleanest water in the world. In many places, you can fill your water bottle straight from the lake and safely drink it.

However, the most visited wilderness in the United States faces a serious threat from a proposed copper mine along the Rainy River watershed, which flows north into the Boundary Waters. Supporters claim it will create jobs and boost the local economy, but the hidden costs tell a different story. While mining has been conducted safely in this region for years, copper mining differs significantly from the more common iron ore mining. Extracting copper from

sulfide ore produces sulfide tailings, which, when exposed to water, form sulfuric acid and other acid mine drainage. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the metal mining industry is the largest toxic polluter in the country, with every U.S. copper mine polluting its surrounding environment. On average, copper mines generate 99 tons of waste rock for every ton of copper, and acid mine drainage can contaminate water sources for centuries with heavy metals like mercury, arsenic, and lead.

Cleaning up abandoned hard rock mines falls to taxpayers, with the U.S. Forest Service estimating in 2017 that remediation costs nationwide could exceed $50 billion. In stark contrast, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness contributes about $77 million annually to northeastern Minnesota’s economy and supports more than 1,000 jobs tied to outdoor recreation and tourism.

I recall the proverb: “When the last tree has been cut down, the last fish caught, the last river poisoned, only then will we realize that one cannot eat money.” By conserving this wilderness, we can show that the human race is capable of learning—and growth—by placing pristine wild country and a perpetual outdoor economy over permanent environmental destruction and temporary

financial gain. Recognizing the severity of this threat emphasizes the importance of experiences like ours in the Boundary Waters—not only for personal growth but also for inspiring future advocates who will carry on the fight to protect our last remaining backcountry.

As my dad and I paddle the canoe toward our exit portage, my son drags his paddle in the water, watching the wake it creates as he changes its angle. Although his experiment slows our forward progress, I smile, remembering doing the same thing as a boy on my early trips. I am filled with hope as I watch the next generation develop a passion for our natural world. We tie the canoe on the truck, and I buckle Sawyer into his car seat. I smile, knowing that the next generation of wilderness advocates is already falling asleep, a stuffed-animal loon in his lap, commemorating his first trip to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Marcus Jacobson is a Minnesota resident and BHA member who loves to share his passion for the outdoors with his three kids and wife as much as possible.

Legislation passed by the House of Representatives on May 22, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, includes provisions that would reverse the 20-year mineral withdrawal that prohibits mining in this watershed and reinstate mining leases for Twin Metals. Visit the BHA Action Center to voice your support for the Boundary Waters at backcountryhunters.org/take_action#/324

Make a meaningful impact on the future of our wild public lands, waters, and wildlife by giving to BHA. Every contribution, regardless of size, plays a crucial role in protecting the wild spaces that enrich our lives!

ONE-TIME OR RECURRING DONATION

JOIN THE CAMPFIRE SOCIETY

APPRECIATED SECURITIES OR STOCK

RETIREMENT PLAN BENEFICIARY

REQUIRED MINIMUM DISTRIBUTIONS

MEMORIAL OR HONORARIUM

“OUTDOORS FOR ALL” SCHOLARSHIP

A late-May amendment to the House budget reconciliation bill triggered national outcry and fierce opposition from Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. The amendment, quietly inserted without public input, authorized the sale of nearly 500,000 acres of public lands in Utah and Nevada—a move that bypasses conservation safeguards and threatens critical wildlife habitat and recreational access.

“This isn’t about partisanship. This is about principle,” said Ryan “Cal” Callaghan, BHA’s North American Board Chair. “Our public lands are not surplus, not bargaining chips, and absolutely not for sale.”

Initially hailed for excluding land sale provisions, the House Natural Resources Committee’s original budget framework gave BHA and other advocates reason for optimism. But the late-stage amendment shattered that hope—revealing a backdoor attempt to sidestep bipartisan laws like the Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act (FLTFA). That law, which BHA helped make permanent, requires that proceeds from any land sale be reinvested in public access and conservation. The amendment ignored it entirely, reducing public lands to mere budget pay-fors.

“This is a full-scale breach of public trust,” said BHA President & CEO Patrick Berry. “It’s a deliberate move to hide from public accountability. The American people overwhelmingly oppose selling off the lands they own.”

In response, BHA launched its United We Stand for Public Lands campaign and mobilized tens of thousands of grassroots advocates. Volunteers flooded congressional offices with tens of thousands of calls and messages. In late May, public lands sales in the House budget bill were removed, but the fight was far from over.

When the Senate released its version in June—proposing the sale of a staggering 3 million-plus acres—BHA members rose again: phone calls, emails, op-eds, and a flood of social media posts. By mid-June, the action alert had become the most utilized in the organization’s history, surpassing 100,000 actions. And we won’t stop there.

Through 2025 and beyond, BHA will continue to double down on its efforts to defend access, stewardship, and the shared legacy of public lands. Through United We Stand, the organization is elevating public lands and waters as central to the American ideal— uniting hunters, anglers, and citizens across the political spectrum to oppose land grabs, confront misinformation, and demand real leadership from elected officials.

With every call made and every voice raised, BHA is proving that public lands are not just places on a map—they are the beating heart of American freedom. And we intend to keep them that way.

Keep up to date on the United We Stand for Public Lands campaign at backcountryhunters.org

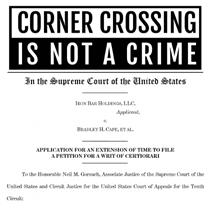

BHA reaffirms its position: Corner crossing is not a crime.

In late May, Iron Bar Holdings petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to review a major 10th Circuit ruling that upheld the rights of four Missouri hunters who used a ladder to legally move between two checkerboard parcels of public land without touching private property.

BHA has supported the hunters from day one, helping raise more than $220,000 for their defense and filing two amicus briefs in federal court. The case has become a national flashpoint in the fight for access to landlocked public lands.

“If the Supreme Court takes this case, we’ll be ready,” said BHA President and CEO Patrick Berry. “Because access for all is worth fighting for—all the way to the highest court in the land.”

BHA remains committed to ensuring commonsense access solutions that respect private property and defend America’s public lands legacy.

BHA is proud to partner with Elkhorn Coffee and announce the new Public Grounds roast, showcasing BHA’s fierce defense of our most American freedom: public lands and waters. One dollar from every bag sold goes to support BHA’s mission. Public Grounds is coming soon to elkhorncoffee. com, at select BHA events and through the BHA website.

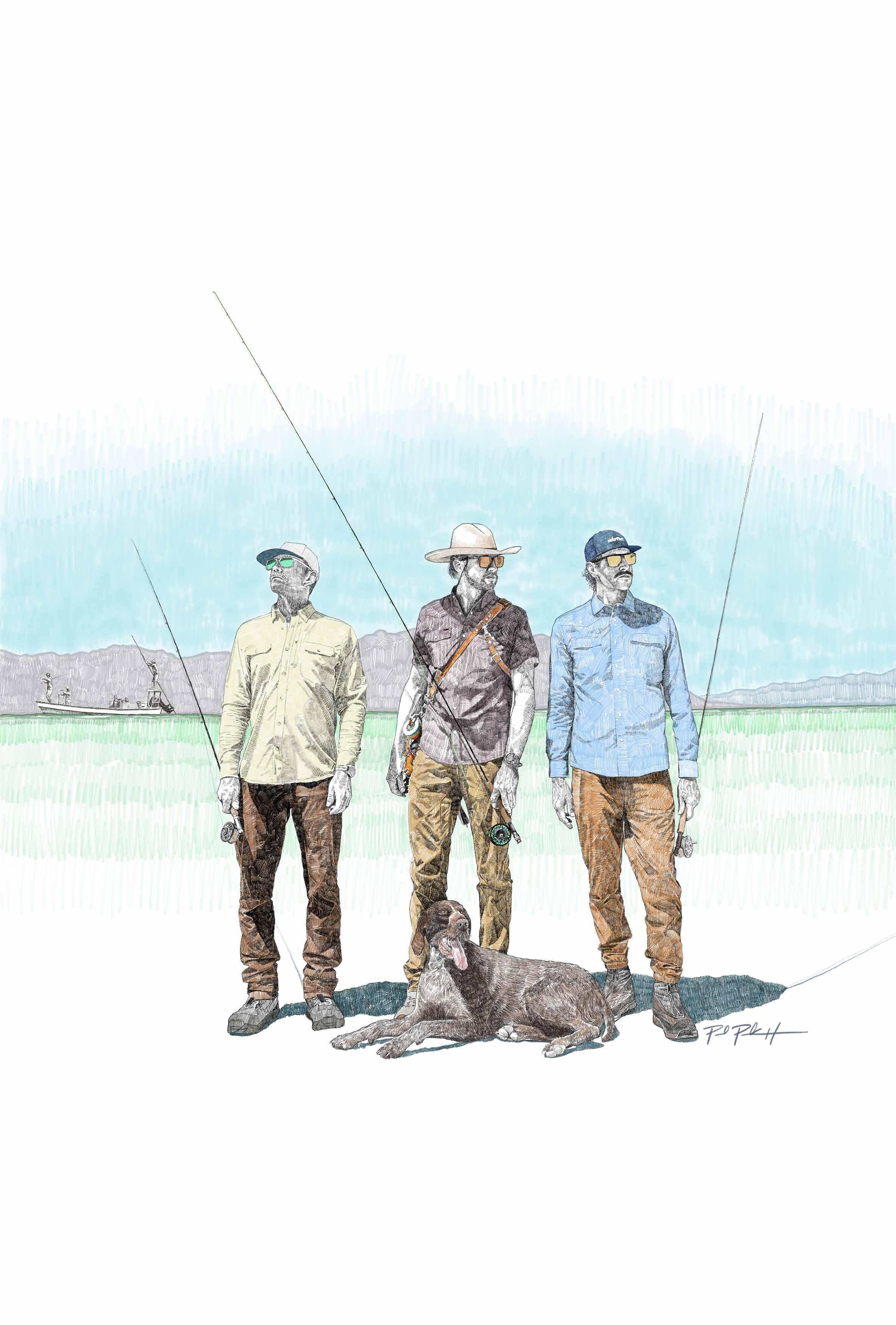

Trey Curtiss, a native son of Montana, is BHA’s Strategic Partnerships and Conservation Programs Manager. Trey is also among a very small group of public lands’ elk hunters who have successfully filled a bull tag now for 10-plus years in a row. Ponder that, for a moment, especially for those of us who have hunted bulls in the backcountry and think we know exactly what that entails. Do we know, really? What are we missing? What does it take in time, gear, commitment, preparation? Join us for one of the most in-depth talks on public lands elk hunting you’ll ever encounter.

Before diving into the nitty gritty from one of the best elk hunters you’re yet to hear of, Trey and Hal ponder the future of hunting, conservation, and the wild places we rely on for sustenance and spirit —and BHA’s critical role in it all—in this not-to-be-missed episode of BHA’s Podcast & Blast.

Ed Anderson: Boise, Idaho. A Minnesota native who found his way West with the U.S. Air Force, Ed is an artist and entrepreneur who has been part of the hunting and fishing space for more than 15 years. As an outfitter, guide and lodge owner, his path in the outdoors has crossed public managers, biologists and ranchers (among others). Those unique relationships and experiences have grown a deep-rooted demand to see the legacy of our country’s public lands live on.

Ed’s home and studio in east Boise, but he’s also at home in South Florida where his family has been for 60 years. He and his twin daughters are just as easily on a skiff in Florida or rowing a raft down a wild river. Either way, protecting America’s wild spaces binds close to his art, business and life.

Matt Shilling, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Matt Shilling is an entrepreneur with a deep passion for wild places. He carries experience in the private sector as an advisor, board member, executive, and founder of multiple companies and nonprofit organizations. Shilling also had the honor of serving at the highest levels of the public sector. Among other roles, he served in The White House where his portfolio included agriculture, energy, the environment, and homeland security. An ardent believer in giving back to the community, Shilling served as a volunteer firefighter for 13 years. He and his family reside in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

WASHINGTON, D.C.

Why are you a BHA member and staffer?

I was born and raised in Utah—actually less than a mile from a wilderness area—a state with abundant hunting and angling opportunities on public lands and waters. Early on, I realized these resources were taken for granted by many decision-makers in the state. During my time in college studying political science, I learned about BHA and quickly became a member. A few years later, early in my career as a conservation lobbyist in Washington, D.C., I was incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to join the BHA government relations team. Joining the BHA staff was a no-brainer for me, as someone who cares deeply about the future of our remaining wild places and the opportunities they provide to hunt and fish.

Government relations at the Capitol and White House are a mystery to many of us. What does your typical day advocating for BHA priorities entail?

As the sole government relations staffer at BHA, my role entails a broad set of responsibilities. But on a typical day, I spend most of my time doing two things: meeting with congressional or administration staff to educate them on the issues BHA is prioritizing; and coordinating with the many other entities that share BHA’s policy goals. Meeting with decision-makers can mean either asking them to take a specific position or perhaps attempting to influence their position on an issue, but also strategizing with champions of BHA’s policy goals and supporting the work they are doing. In order to be most effective, conservation organizations often coordinate on policy work.

What’s one thing that might surprise us about the inner workings of D.C. politics?

The conservation advocacy world is a small one. Despite the seemingly vast expanse of suits in Washington, D.C., and countless lobbying interests, when it comes down to it, there are only so many individuals working on public lands and conservation issues. It is a tight-knit community, where many folks are close friends outside of work, across the political spectrum, and everyone communicates. This makes it immensely important to approach this work intentionally and build allies, rather than reinforce enemies. Any good, durable policy work is done in a bipartisan fashion. And given that the party controlling the agenda changes frequently, it is important to cultivate support on both sides of the aisle in order to weather any storm.

2025 has been incredibly active on the policy front for BHA. How can your average BHA member best have an impact on policy at the Capitol?

Engaging with your local BHA chapter and field staff is the easiest way to understand what threats and opportunities BHA is facing when it comes to public lands and waters conservation and access, even at a national level. All politics start local, and that ground-level understanding is a critically important foundation for reaching out to your elected officials, educating your community, and building additional support for the causes that BHA works on. For each of these things, sharing your own personal story is just as important as properly conveying policy goals, because it provides the context for your audience.

2025 has been incredibly active on the policy front for BHA. How can your average BHA member best have an impact on policy at the Capitol?

Springtime on the Potomac River is special as the American and hickory shad spawn brings these anadromous fish in from the Atlantic Ocean to my backyard. Weighing between 1 and 6 pounds, these herring are a blast to catch with a fly rod, using a sinking line to get your fly down on the river bottom. On a good day, you would be hardpressed to pull me away from the river—the bite can be so hot that you just have to decide when it is time to leave, because the fish don’t tell you when to go.

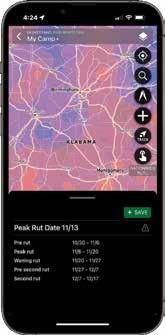

WHITETAIL RUT MAP Unlock the most extensive Rut Map in the country

WHITETAIL ACTIVITY FORECAST Plan your hunt around peak movement times

Join millions of hunters who use HuntStand to view property lines, find public hunting land, and manage their hunting property. Enjoy a powerful collection of maps and tools — including nationwide rut dates and a 7-day whitetail activity forecast with peak deer movement times.

WHITETAIL

Download and map for FREE!

BHA’s Backcountry Bounty is a celebration not of antler size but of BHA’s values: wild places, hard work, fair chase and wild-harvested food. Send your submissions to williams@backcountryhunters.org or share your photos with us by using #backcountryhuntersandanglers on social media! Emailed bounty submissions may also appear on social media.

Hunter: : Jameson Hibbs, BHA chapter coordinator (staff)

Species: wild turkey | State: Kentucky| Method: shotgun |

Distance from nearest road: three miles | Transportation: foot

Hunter: Bridger Long (son of Nick Long, PA chapter treasurer) | Species: whitetail State: Pennsylvania | Method: rifle| Distance from nearest road: two miles | Transportation: foot

Hunter: Jason Shroeder, BHA member

Species: wild turkey State: California

Method: shotgun

Distance from nearest road: four miles

Transportation: foot

Hunter: Matt Rogers, BHA Member | Species: elk State: Colorado | Method: rifle | Distance from nearest road: four miles | Transportation: foot

Hunter: Felix Rodriguez (age 13), BHA Member | Species: Merriam’s turkey State: Idaho | Method: shotgun Distance from nearest road: one mile Transportation: foot

Find:

Rotten log

Animal bone

Seashell Deer scat

Animal print

Campfire ring

Crawdad

Old man’s beard

Canada geese

A bird’s nest

The Little Dipper constellation

Yellow flower

Flying insect

Spider web

Tree with bark that is NOT brown

Smooth skipping stone

Collect and dispose of three pieces of trash from public land

Something you think is a treasure

Nolan Fregerio is the 7-year-old son of BHA Director of Finance Britney Fregerio. Residing in Montana, Nolan loves camping, chopping firewood, tending to the campfire ... and s’mores and hot chocolate of course!

BY JIM HARRIS

An acre of land that might seem meaningless to most people can have an incalculable value in the grand scheme of things. Such is the case of an acre — actually slightly less — that came into the possession of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission recently with the help of Arkansas Backcountry Hunters and Anglers.

That acre eased the concern over access to Cedar Creek Wildlife Management Area’s 103 acres in Scott County, about 18 miles southeast of Waldron. The gravel road over that acre connects Arkansas Highway 28 with a new gate leading into the WMA and provides parking for visitors.

“Point-nine (0.9) acres doesn’t seem like much, but when you look at it, we use the (WMA) as a base for multiple research projects,” Jason Mitchell, an AGFC wildlife biologist who works in the area, said. “The (USDA) Forest Service uses it as a helipad for its controlled burns, instead of having to fly to Mena to get the fuel and fly back. We also use it as a base for our equipment and our supplies working on Forest Service co-op areas. Getting blocked out of this (acquisition), we would have had to back up and punt.”

“There is no other access into Cedar Creek WMA without building a road through Forest Service land,” Mitchell says. When that was mapped out, the AGFC was looking at 8.5 miles of dirt road “instead of the 250 to 300 feet it is now,” Mitchell said.

Land acquisition for a state agency is difficult and timeconsuming. A volunteer national group with an Arkansas chapter, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, luckily was looking for a project like this that could help the agency. The parcel in question had been through several owners, and for a while the AGFC secured an easement with one of the owners beginning in 2015.

However, there were complications with the easement, and when the land changed hands again, that went away. Depending on who owned that tiny parcel in the 33 years since the foreclosed farmland came into the AGFC’s possession, access to the WMA could be blocked. The parcel’s most recent owner, Thomas Steele, informed Mitchell he wanted to sell to the AGFC.

Instead of the AGFC going through all the hoops required to buy the land, and seeing another acquisition attempt fall through as it had before, BHA made its first purchase as a national organization and gave the acre to the AGFC.

The deal closed in August of 2023 and after a lot of ancillary work and the gate was put in place, the AGFC, members of BHA’s Arkansas chapter and a few other interested parties dedicated the land Nov. 22, a bright fall day.

“It’s the first land acquisition for the whole organization,” Brad Green, a recent BHA Arkansas chapter board member, said. “We were real excited when the opportunity came up to be able to partner and just preserve public access to public lands. A huge deal. That’s what we’re about and that’s what we all do here and we want to do more.”

That sentiment courses throughout BHA.

“We want to find some more places to do these types of projects on, open up more access,” Larry Haden, the Arkansas BHA chapter’s newest board chairman, said. “Everybody has their own species that they’re pursuing, whether it’s quail, ducks, elk or whatever. BHA’s focus is public land, the land we’re actually on, and the ability to kind of adopt an area, and not only state but federal, around refuges and so forth. The focus on the land is kind of what separates BHA from a lot of other folks.”

James Brandenburg, who is on BHA’s North American board and has led the Arkansas chapter, says the opportunity to work with partners is key. “Where we’re breaking new ground for our organization, it helped us as a chapter to be able to taste success,” Brandenburg said. “That’s very much appreciated. And I think

that from our side, we would say thank you to y’all as an agency for using your professional expertise to help folks like us do good work.”

Easy access to Cedar Creek WMA makes it easier for hikers and hunters to reach the west end of the 150,000 acres of Muddy Creek WMA to the south, about an 800-yard jaunt from Cedar Creek’s gate. Muddy Creek is managed cooperatively by the AGFC and the Forest Service.

The BHA board members say the money used to purchase the parcel came from Black Bear Bonanza, the Arkansas chapter’s annual fundraiser. This year’s event, its fourth, is scheduled for 9 a.m.-5 p.m., March 1, at Benton County Fairgrounds in Bentonville. Last year’s event drew 1,500 people, and probably 600 to 700 or those were youngsters, according to Green. “It’s a family-friendly event,” Green said. The shindig celebrates the reintroduction of black bears in Arkansas by the AGFC and includes presentations and discussions with black bear biologists.

Jim Taylor, formerly with the Arkansas Wildlife Federation board and a life member of BHA, purchased land adjacent to Cedar Creek WMA. He uses the access road to enter his property through an agreement with the AGFC. He helped pay for the new, yellow gate across the road leading into the WMA, according to Matthew Warriner, AGFC Wildlife Management Division assistant chief. Access into Cedar Creek WMA is by foot only from the gate.

Special regulations for the small WMA are outlined in the AGFC’s annual Arkansas Hunting Guidebook, available at agfc.com and across the state in sporting goods stores and elsewhere.

The AGFC obtained the WMA’s 103 acres in 1991. Research projects studying bats, spotted skunks, eastern wild turkey, black bear and other species have been based on the WMA over the years, Mitchell says, especially turkey research with its proximity to Muddy Creek WMA and the Ouachita National Forest. A Missouri Department of Conservation team stayed on the WMA to conduct nuthatch surveys one year. 2024 was the second year of a project to transplant birds to restored habitat in Missouri’s Mark Twain National Forest.

“I wasn’t aware of all the research and everything that goes on here,” Green said. “I thought we were just opening up public access. But, no, there’s a lot of research that goes on up here. It’s an important property.”

At one point in its life as a WMA, cattle grazed on the land, and later, hay was farmed to keep the fields open. That resulted in a lot of fescue and Johnsongrass growing on the property.

“So, when we started trying to manage it, you could hide a tractor up there in the Johnsongrass and fescue,” Mitchell said. “We’ve done multiple burns on the area, done some hack and squirt (using chemicals to kill unwanted tree species), some (wildlife stand improvement) work, some herbicide work and we’re looking to do some more things like cedar removal … trying

to get the cedar down is a challenge.”

Since beginning the habitat work, AGFC staff have seen a couple of broods of turkeys on the property.

“We’ve done prescribed burning on the entire unit, one field system at a time,” Mitchell said. “We’ve actually watched quail come off from areas we just lit to move to other areas. It’s been interesting just to see the transition. It’s kinda getting more of an open woodland look to it. When I started 15 years ago, I wouldn’t have sent a beagle through it. It looked like a south Arkansas thicket.”

In clearing the acreage of overgrowth, staff have stumbled upon a trash dump or two left by previous residents, such as chicken housing material and more that will have to be hauled out. BHA has offered to help with that in the coming months.

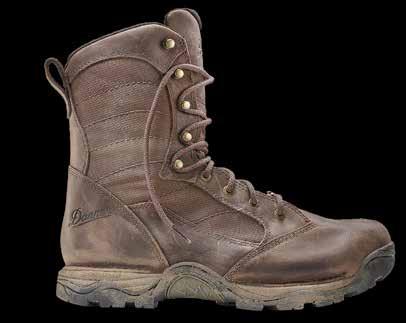

“We’re not afraid to get in there and do the work, get our boots dirty,” Green said. According to Green, the Cedar Creek project became a priority “because Matt (Warriner) brought it to us.”

Warriner said he and AGFC Deputy Director Brad Carner, who was chief of the Wildlife Management Division during 2009-21, had been working on a landlocked parcel initiative with OnX and BHA when the Cedar Creek opportunity came up.

“We’ve been trying to get this for many years because we didn’t have secure access to the WMA, and we were concerned access could be shut off to the public and us at any time,” Warriner said. “Brad and I talked to Brad Green, it was like a spark, and within BHA it just ignited, and they ran with it. It was impressive. I didn’t realize until later on that as far as a national organization, this was their first land acquisition.”

Green said the owner, Thomas Steele, “was willing to let us purchase it and donate it to y’all. He was a big part of it, too.”

Warriner gave the biggest share of credit to BHA. “We had to work through a number of things, and y’all did, too, y’all through your national organization,” Warriner said to Green on dedication day. “Y’all never gave up, which we very much appreciate.”

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of Arkansas Wildlife, the official magazine of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

• INDUSTRY STANDARD HUB MOUNT

• 5/8 x 24 DT MOUNT INCLUDED

• 6.4” OR 8.17” LONG

• 1.5” DIAMETER

• 9.5 OR 12.4 OUNCES

The BANISH 30-V2 is shorter, lighter and quieter than its predecessor. Configurable length and high-quality titanium construction. Rated up to .300 WBY and now HUB mount compatible.

• MULTI-CALIBER SUPPRESSOR

• 100% TITANIUM

• LENGTH CONFIGURABLE

LENGTH 6.4” OR 8.17”

DIAMETER 1.5”

CALIBER 7.62MM/.308

FINISH CERAKOTE

LIFETIME YES

WARRANTY Black Tan

Since Hurricane Helene hit Southern Appalachia, BHA members have delivered supplies, defended wild waters, and fought for a sustainable rebuild.

BY SARAH SNIPES

It’s late September, and I’m sorting camping gear for a weekend deer hunt when my husband breaks my concentration.

“Have you looked at the weather lately?”

I know we’re expecting rain, but I’m trying to be tough. Besides, last weekend, they completely missed the forecast.

I check the update and see Hurricane Helene looming, threatening flash floods in Western North Carolina. The campground I booked is on the river, so I cancel my reservation, reminding myself there are three more months of deer season.

It rains all week. By Thursday, the ground is saturated, and emergency alerts buzz our phones every half hour. The county sets a 7:00 p.m. curfew.

On Friday morning, hours before dawn, Helene finally hits, and I wake to a violent, relentless wind. I hear the sharp crack of trees breaking and feel it in my bones when they fall to the ground.

At first light, we peer into the meadow below our house. The culvert that usually trickles into the yard is blasting muddy water, flooding a row of white pines and nearly covering the driveway.

When the storm recedes, we check on our neighbors. The couple next door had a massive oak fall on their house while they were sleeping, springing leaks in their bedroom ceiling.

A few miles away, a woman watched helplessly as a landslide buried her husband while he dug a trench to divert floodwaters from their home. He died days later in the hospital.

Hurricane Helene hit North Carolina as a tropical storm and became the worst natural disaster in the state’s history.

Rain totals reached 20 to 30 inches in Western North Carolina, with winds topping 100 miles per hour.

At least 230 people died across the seven states affected by Helene.

Washed-out roads and bridges isolated communities, leaving them without electricity, running water, or cell service.

Within days, North Carolina BHA members were among the first to load supplies and head into the hardest-hit areas.

“Being only a few hours away and watching the devastation unfold broke my heart,” says Zach Brady, BHA’s North Carolina chapter leader for the Mountain and Piedmont region. “We decided to find the places not yet receiving aid by five or six days after the storm. We knew we could backpack in supplies—all of us are experienced outdoorsmen and wanted to use those skills.”

Zach and his fellow BHA members gathered supplies and donations from their network and traveled to Newland, North Carolina, to deliver shelf-stable food, water, baby supplies, hygiene products, batteries, fuel, and first aid kits.

They’ve since returned multiple times, bringing space heaters and warm clothing as winter set in and many people were still without electricity.

At first, the focus was on the human impact of Helene, and rightly so. Soon it became clear that the forests and rivers of Southern Appalachia had also been profoundly affected.

Land managers said recovery could take up to a decade, but those estimates didn’t factor in the ongoing damage from rushed infrastructure repairs in sensitive areas like the Nolichucky Gorge.

Chris Lennon, a fishing guide, paramedic, and BHA Tennessee chapter board member, was among the first to sound the alarm.

Just two weeks after the storm, Chris and others returned to the Nolichucky, shocked to find out-of-state contractors with heavy equipment already repairing the 40 miles of railroad tracks damaged by Helene.

Excavators were mining rock from the riverbed to rebuild the rail line and damming tributary streams that hold native Appalachian brook trout. And this was in a river that supports the endangered Appalachian elktoe mussel and a thriving outdoor economy.

Chris and his community formed a grassroots group, Nolichucky Witness, to document the damage and raise their concerns with CSX Transportation—the rail operator—and the federal agencies responsible for overseeing the work.

When their attempts were met with silence, they coordinated with advocacy groups American Whitewater and American Rivers, which filed a lawsuit through the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“The lawsuit was filed against the public land managers—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—who failed us,” says Chris.

In December, the group celebrated when the Army Corps and the Tennessee Department of Conservation ordered CSX and its contractors to stop excavation of the riverbed.

Now, CSX is repairing parts of the same rail line in North Carolina, where Chris says the state agencies have put stricter guidelines in place, in part because of the success of the lawsuit.

“BHA’s North Carolina chapter played a significant role in getting the word out about what CSX did in Tennessee,” says Chris. “That has helped keep the mining in the North Carolina section of the gorge to a minimum.”

Chris and BHA’s Tennessee chapter board are still fighting

for the Nolichucky, pressing the U.S. Army Corps to hold CSX accountable as it decides how the company must repair the damage done to the river.

The Nolichucky is just one of many Southern Appalachian rivers impacted by Helene.

Heath Cartee, owner of Pisgah Outdoors and a BHA North Carolina chapter corporate partner, guides anglers on the nearby French Broad River. He says past development has made the area more prone to flooding.

“I’m not a hydrologist; I just work on the water, and I see things,” says Heath. “This floodplain that is used for growing sod or corn should be a swamp where water would sit and percolate into the river. These creeks should meander, but they’ve been straightened using an excavator. Now, the water gains a lot of velocity as it drains into the river, and that causes flooding.”

Heath adds that historic interventions, like the late 1800s dredging by the French Broad Steamboat Company, further increased the river’s vulnerability.

The company blasted bedrock to deepen the river’s channel for transporting passengers and freight, disrupting its natural flow and reducing its capacity to absorb water, making it more conducive to flooding.

Recently, some have proposed damming the French Broad to create a reservoir as a solution to these heightened flood risks.

“But that’s looking for a man-made solution to a man-made problem,” Heath says. “We have a history of trying to control something that’s not controllable. This river isn’t going anywhere

except where it wants to go, and we’re going to have to work with that.”

As on the Nolichucky, the infrastructure on and around the French Broad was badly damaged by Helene. In a region that relies on outdoor recreation for its economic vitality, these repairs are critical.

At first, Heath hoped the rebuild would be handled with the sustainability and care that was missing from past development patterns. But recently he shared that his optimism has been shattered.

On the French Broad and in surrounding watersheds, the U.S. Army Corps and contractors are removing storm debris with heavy equipment, where Heath says they’re violating ecological guidelines, destroying wildlife habitats, and disregarding community concerns in a rush to secure federal funds.

As this story was going to press, Heath shared that he and a coalition of area residents, business owners, and advocacy groups recently met with U.S. Representative Chuck Edwards (NC-11) to voice their concerns and request federal support.

Hurricane Helene left a trail of destruction but also revealed the grit and resilience of these Southern Appalachians who not only defend public lands and waters but also support their communities long after the storm. Whether through advocacy or delivering essential aid, they’re committed to rebuilding and protecting what matters most.

BHA member Sarah Snipes is a writer and communications professional from North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, where she hunts whitetails and wild turkeys and fishes for native brook trout.

• The Alaska chapter started its first scholarship in May to help graduate students studying fish, wildlife, or natural resource conservation in Alaska. They prioritize applicants who are hunters or anglers and are working on projects related to animal populations or outdoor recreation.

• In April, the Alaska chapter partnered with the Audubon Society, Juneau Audubon, and Southeast Alaska Land Trust (SEALT) at Devil’s Club Brewing Co. to learn about eBird, a tool for birders and conservationists. The next morning, they went on a bird walk in the Mendenhall Wetlands.

• In May, the Alaska chapter worked in the Canoe Lake Chains in the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge to clear the area for recreation, including with the U.S. Forest Service and Kenai River Stream Watch to install fencing to guide anglers and protect the riverbanks.

• In March, the Alaska chapter sponsored Paige Drobny from Squid Acres, who finished third in the 40th Iditarod Race, which takes place on public lands.

• The 4th Annual Black Bear Bonanza was a roaring success, drawing participants from multiple states to celebrate Arkansas’s bear recovery and raise tens of thousands of dollars for conservation.

• The chapter made a $3,000 donation toward an Arkansas Game and Fish Commission K-9 unit for law enforcement and search and rescue.

• In April, Chapter Legislative Chair Kip Kruger advocated for crucial Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) funding with legislators in Washington, D.C., before turning his focus to state legislators to successfully amend SB290, a bill threatening protections for America’s first national river.

• The British Columbia chapter continues as a stakeholder on the provincial CWD committee, discussing and advocating for sound CWD management using best practices to stop the spread.

• Members represented BHA at a number of outdoor shows across the province. Look out for more events in your region.

• We’re looking for more volunteers to help out on a regional and provincial level. If you’re interested in helping the chapter, get in touch at britishcolumbia@backcountryhunters.org.

• In response to the much-anticipated release of the California Black Bear Conservation Plan, the chapter has submitted a petition to the Fish and Game Commission advocating for a second bear tag. We will be participating in the commission meeting to help expand hunting opportunities for black bears in the Golden State.

• The chapter completed yet another successful turkey camp, with almost 30 volunteers, many of whom were firsttime hunters. Stories, techniques, and laughs were shared, and several birds were harvested.

• The Armed Forces Initiative hosted a successful pig hunt, bringing members of our military community with a wide range of hunting experience to spend a weekend talking about conservation and chasing pigs.

• We welcomed ten new volunteer leaders, including Damon DeGraw, Jacob Kinnard, Steve Bridges, John Young, Cade Kloberdanz, Sid White, Jason Judge, Ben Monarch, Aidan McCormick, and Kassi Smith.

• On March 13, the Colorado Senate passed Joint Resolution 25-009, “Protection of Colorado’s Public Lands,” which reaffirms the state’s dedication to conserving our public lands.

• We joined the Colorado Stream Access Coalition, working to change/improve some of the worst public access laws in the West.

• The chapter has continued to work actively on an initiative to reinstate bear hunting in Florida. A limited bear hunt was opened in 2015 and has been closed since.

• On May 10, the chapter hosted a cleanup event on Citrus WMA in Inverness.

• The chapter hosted its annual scouting workshop in Jupiter on June 28.

• Join us for a Public Land Packout Pop-Up event in North Idaho this summer. These events will occur during the evening on the first Tuesday of the summer months. Please see our chapter web page for more details.

• The Idaho chapter wrapped up a long legislative session full of advocacy and testimonies both in favor of and against a large number of public lands, hunting, and wildlife bills.

• We will be conducting Learn to Hunt classes in North and South Idaho this summer and are actively seeking mentors to pair with our eager students.

• The Illinois chapter had a great spring, hosting a Turkey Talk event in partnership with Sitka Gear at their new store. Chapter Coordinator Aaron Hebeisen, along with members, educated many people on how to hunt turkeys.

• The chapter also hosted the grand opening of a public archery park at Lake Shelbyville in a one-of-a-kind partnership with the Corps of Engineers.

• Finally, we continue to push the Muddy Waters Tour event focused on getting clear legislation on public water access for our great state.

• The Indiana chapter hosted a wood duck box installation at JE Roush Fish and Wildlife Area in northeastern Indiana. This was a follow-up from an event last year when we used a Bendix grant to purchase supplies and host a duck box build.

• In collaboration with the BHA’s Indiana State University Collegiate Club, the chapter held a grassroots workday at Wabashiki FWA in west-central Indiana for the fourth year in a row. This year, the chapter planted native shrubs on a recently acquired 80-acre parcel and also continued invasive removal.

• The Iowa chapter had a very successful 2025 Iowa Deer Classic, with strong engagement from patrons of the show.

• The Iowa chapter hosted the 2nd Annual Bluegill Bash on June 7 at Hickory Grove Lake.

• The Iowa chapter was awarded an Iowa governor’s deer tag for 2025. All funds raised from the 2024 tag were allocated to help purchase public lands in the state.

• On March 5, the chapter welcomed BHA North American Board Chair Ryan Callaghan to discuss legislation at The Barn at Kill Creek Farm, where 120-plus members attended.

• On March 22, the chapter hosted the annual Lenexa Clay Shoot.

• In February, March, and April, the chapter hosted its first Legislative Breakfasts at the Capitol with SCI.

• The chapter “dug in” to conservation — planting trees, building birdhouses, and boosting pollinator habitat.

• Murray State’s collegiate club planted cypress, ran trapping workshops, and showed up big for Earth Day.

• Save the date for our Bourbon, Bands & Public Lands event on Sept. 13.

• The chapter hosted a Brews and Brookies pint night at Ore Dock Brewing in Marquette with Dr. Troy Zorn (MI DNR Fisheries) to discuss coaster brook trout fishing and conservation.

• Hosted a Talking Turkey Pint Night at Heights Brewing in Farmington with Jenn Davis from the National Wild Turkey Federation, covering habitat and hunting in Michigan.

• The Tamarack SGA Fence Pull was held June 20 near Sunfield—helping improve wildlife access by removing outdated fencing.

• The Mid-Atlantic chapter continues to work behind the scenes with state agencies, partner organizations, and elected officials from across the region.

• The chapter is working with the Armed Forces Initiative to support oyster restoration work on the Chesapeake Bay with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

• Hosted our 2nd Annual Big Truck Farm Brewery 3D Archery Shoot, and it was a huge success. We’re looking forward to continued expansion of the event next year.

• The Minnesota chapter thanks Eli Mansfield for serving as our board chair for three years, and he is now transitioning to our policy lead!

• The chapter partnered with the Trust for Public Land to host a Learn to Hunt Turkey event with 15 new hunters.

• The chapter held a Public Lands Pack-Out in Grand Rapids, cleaning up a heavily used access point to hundreds of acres of Northern Minnesota public land.

• The chapter welcomed new board members Colleen Foehrenbacher and Jon Duesterhoeft.

• The chapter hosted a Gun Dog Social with local Quail Forever and North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association chapters in June. Sportsmen and four-legged friends were invited to hang out and learn about the organizations, as well as win sweet dog-specific gear.

• Join us on July 18 and 19 for Squadfest 2025 in Hazelwood, Missouri. Hope to see you there.

• Be on the lookout for archery nights throughout the summer all around the Saint Louis area.

MONTANA

• Montana chapter board members worked diligently in the latest state legislative session to protect Montana’s public lands, waters, and wildlife.

• The chapter welcomed new board members Beth Brennan, Steve Matzker, and Kyle Mitchell.

• The chapter hosted a wild game dinner in Red Lodge at Black Canyon Bistro and a meet-and-greet with BHA President and CEO Patrick Berry at the MeatEater flagship store in Bozeman.

NEBRASKA

• The chapter hopes you were able to join us at this year’s Trashy Cat at Twin Rivers SRA—a great weekend of fishing and cleaning up public lands.

• In June, the chapter worked at East Willow Island Wildlife Management Area west of Cozad for an exotic woody plant control and habitat restoration project.

• July 31 to August 3, join chapter members in Halsey National Forest to take part in the Nebraska Bowhunters Association Jamboree.

NEVADA

• The Nevada chapter tabled at both the Elko and Reno Sportsman’s Expos.

• Nevada Department of Wildlife honored our chapter leaders with outstanding volunteer awards.

• The chapter provided input and support for several bills that are moving forward in the legislature involving: water resources for wildlife, roadkill salvage, wildlife crossings, and edible portions for bear and lion.

NEW ENGLAND

• In New Hampshire, BHA submitted comments on the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department’s 10-year Game Management Plan.

• The New Hampshire team tabled at a sportsman’s show and at the NHFG’s Discover WILD day.

• In May, the Massachusetts team hosted a great storytelling night at the Filson store in Boston.

• The chapter continued through the spring with their virtual mentor series. Stay tuned to our social channels for the next installment.

• The chapter will be hosting a stop on the Full Draw Film Tour. It will be the only stop in the NY metro area. Stay tuned for the date and details.

• The chapter participated in a Public Land Pack-Out. Members and friends cleaned up three separate wildlife management areas across the state.

• New Mexico AFI members held the third annual Lincoln NF habitat restoration project and turkey hunt. Participants and youth hunters hunted in the mornings and then built beaver dam analogs to help restore riparian habitat.

• The chapter participated in the New Mexico Outdoor Adventure Show and the Santa Fe Brewing Spring Runoff event, where they sold merchandise and spoke to current and prospective members.

• Chapter members cleaned up trash and debris near Peña Blanca along the Rio Grande River alongside Ducks Unlimited and Adobe Whitewater Club members.

• The chapter tracked and provided input/support on multiple bills during this year’s legislative session, including Senate Bill 5, which overhauls the game commission and fees and was signed into law by the governor.

• The chapter ran four pack-outs in April across the state. We worked on Three Rivers Wildlife Management Area, Cranberry Mountain WMA, East Otto State Forest, and teamed with Vermont on Lake Champlain WMAs and boat launches.

• The chapter kicked off turkey season with Pint Nights at Rusty Nickel Brewing in western New York and Common Roots Brewing in Albany.

• Chapter volunteers are supporting the Department of Environmental Conservation’s Trek for Trout with volunteers and a Pint Night in Saranac Lake. The project is studying backcountry brook trout ponds in the Adirondacks.

• At our Spring Round-Up camping event, members enjoyed perfect weather, instructive programs, fine dining, and lots of camaraderie and storytelling. See you next year!

• The North Carolina AFI Inshore Fishing Camp hosted 10 service members at Hammocks Beach State Park for a weekend of angling instruction.

• We celebrated the removal of Section 4 of Senate Bill 220 that would have made it illegal to launch a boat from state roads to access public waters.

• The North Dakota chapter concludes the 2025 legislative session, celebrating the results on nine out of 10 bills, including a big win to restructure landowner pronghorn tags, giving more tags to the public—a bill the chapter drafted.

• The Dakota Prairie Grasslands will be opening the scoping period for the first-ever Travel Management Plan for the Little Missouri National Grasslands. The chapter has been pushing this since its inception in 2018.

• The annual gun raffle drawing was held on May 29 at the Broadway Grill and Tavern in Bismarck.

• Here in Ohio, the chapter is watching swollen rivers and reminiscing about our recent fly-tying event in Milford. State sponsor Whuff Rod Co. provided a rod to raffle, and all had a great time!

• The chapter is working on summer events, including skills events around the state, an archery hike in southeast Ohio, and the Mobile Hunting Expo in southwest Ohio.

• The chapter continues to advocate for the inclusion of H2Ohio funds in the Ohio state budget. This critical water quality effort funds a variety of projects benefiting Ohio citizens.

• In March, the Oklahoma chapter board hosted a Hunting and Fishing Fellowship event at Roughtail Brewery in Oklahoma City. The family-friendly event brought about a great discussion about conservation.

• The chapter assisted the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation in building wood duck boxes at Copan Wildlife Management Area in May.

• The chapter will be collaborating with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation and Quail Forever to do a legacy habitat improvement project on Spavinaw WMA.

• The chapter hosted its first springtime Bustin’ Clays event fundraiser. This is the first in a series of three clay shoots for 2025. Stay tuned for details.

• The chapter has also participated in numerous habitat workdays, removing litter, planting, and removing invasive

species in partnership with the Pennsylvania Game Commission and other conservation agencies.

• On the legislative front, our top priority is the passage of a bill that removes the prohibition on Sunday hunting. This legislation has been a priority for several sessions, and we have high hopes for passage this year.

• The Southeast chapter has joined ten other conservation groups to oppose Alabama HB509, which would designate deer possessed by a licensee as personal property of that licensee and prohibit state agencies from killing, testing or prohibiting the transfer of captive deer due to disease, except under certain circumstances. This bill seeks to privatize public resources and will stifle efforts to control CWD and other diseases in Alabama’s deer herd.

• The chapter is investigating the deer and hog gun-hunting closure in the Mobile Tensaw Wildlife Management Area. The chapter would like to hear from any member who has traditionally accessed the Ghost Fleet Tract in the nowclosed area.

• The chapter has opposed the closure of Big Creek Lake in Mobile County, Alabama. The lake, which has been open to public recreation for decades, was recently closed to the public citing safety concerns. While the chapter supports actions meant to protect a sensitive ecosystem and resource, the method of protection must be balanced with traditional uses and avoid privatization of the public resource. For more information on this and other current efforts, please reach out to chapter leadership.

• The chapter opposed a baiting bill that would allow baiting for whitetail deer and wild swine on privately owned/ leased land.

• The chapter also opposed an amendment to the Tennessee Wetlands Act that would designate non-federal regulated wetlands as real property and loosen protection.

• The chapter sent a formal letter to USACE Nashville opposing CSX’s recommended remediation plan for the Nolichucky River through Cherokee and Pisgah National Forests. Listen to BHA’s Podcast & Blast episode “Compounding Damage with Destruction” for the backstory on this issue.

• The chapter signed on to a coalition statement sent to the legislature along with 13 other conservation groups supporting bills that would increase oversight of the captive-deer breeding industry in Texas.

• The chapter is preparing to launch the Adopt an Access program for the 2025 hunting season to help keep our public lands clean.

• The chapter held a campout and squirrel hunt in the Sam Houston National Forest in late spring.

UTAH

• The chapter hosted its first Wild Game Dinner & Fundraiser, welcoming new faces to the organization and raising impactful funds to support our advocacy and stewardship work.

• Board members engaged in the Division of Wildlife Resources public input process in April to provide a BHA perspective on proposed rule changes related to CWD, permit allocations, and harvest reporting.

• The chapter ramped up its work on the “Utah is Not For Sale” campaign through education and local advertising.

• The chapter held two incredible wild-game processing events—one featuring a cougar on the East Side and another with a black bear on the West Side—giving over 30 participants hands-on butchering experience.

• The chapter knocked out five conservation and habitat projects so far this year, including community favorites like the 7th Annual Methow Valley Fence Pull and the 2nd Annual Yakima Canyon Recreation Area Clean-Up.

• Chapter representatives attended an in-person commission meeting, inviting all WDFW commissioners to join us at upcoming conservation events—we’re excited to build stronger connections and show them our impact firsthand.

• On April 24, the chapter assisted the West Virginia DNR and First Energy in planting 288 trees on Coopers Rock State Forest and Snake Hill Wildlife Management Area near Morgantown.

• On May 17, the chapter assisted the Greenbrier River Fly Fishing Classic, mentoring children from the West Virginia Children’s Home Society in fly fishing and outdoor skills near Lewisburg.

• On May 31 and June 1, the chapter set up a booth at the Appalachian Fly Fishing Festival in Thomas.

• The Wisconsin chapter continues to invest in our strong outdoor heritage through Learn-to-Hunt/Fish events for spring turkey, trout, and bear hunting with hounds.

• Our UW-Stevens Point branch hosted a successful Gear & Beer Bash, with 19 student volunteers welcoming more than 200 attendees.

• Chapter members put their passion for conservation to work at the Mead Wildlife Area, Goose Lake Wildlife Area, and the Lulu Lake State Natural Area for habitat workdays and Public Land Pack-Outs.

• Lobbying efforts continue for a sandhill crane hunt as the chapter continues to work with conservation partners, as well as host thematic pint nights.

• On April 10, the chapter hosted a Thankful Thursday fundraiser with My Country 95.5 at The Beacon Club. We raised over $11,000! Thank you to all who donated and came out and supported us.

• The Wyoming chapter hosted the Little Sunlight Trail Cleanup on May 17.

• Sabrina King will be continuing her policy work for the chapter in and beyond Cheyenne, engaging with priority topics like corner crossing and transferable landowner licenses.

Find a more detailed writeup of your chapter’s news along with events and updates by regularly visiting www.backcountryhunters.org/chapters or contacting them at [your state/province/territory/region]@backcountryhunters.org (e.g. newengland@backcountryhunters.org).

Spread out the map and circle those little-explored waters that ignite your imagination. The Approach 138 expands your access to harder-to-reach fisheries with a design that’s easy-to-launch, adaptable for flat and moving water, and fully featured for angler comfort and convenience. Every inch is crafted for versatility, rowing performance, and stealth, with quality backed by decades of craftsmanship. The NRS Slot Rail frame system lets you fine-tune seat, oar, and gear placement for balance, comfort, and control. Welded PVC construction, continuous-curve tubes, and a high-pressure drop-stitch floor provide a stable casting platform and reduce drag, excelling even in shallow, technical water. Padded dry box seats, rod holders, anchor system, and motor mount come standard. Whether you’re running a full-luxury setup on a finger lake or stripping it down for a backcountry mission, the Approach adapts to how you fish. Where you Catch the Adventure™ is up to you.

A single person—and action—results in the establishment of a Veteran Waterfowl

BY DUSTIN McKENNA

Thankfully, sometimes a single action—such as a cold call—can catalyze significant change. A notable success was achieved in March 2024, when the Nebraska Game and Parks Commissioners unanimously approved the establishment of a Veteran Waterfowl Season and further when the Nebraska Legislature passed LB 867, amending state statute to formally mandate this season. Scheduled for the weekend preceding each zone’s opening for duck season, this initiative marks a crucial development in supporting veterans.

The groundwork for this season was laid in July 2023 when I initiated a partnership with Commissioner Rick Brandt. My initial outreach was a cold call, inspired by the public contact information on the Game and Parks Commissioner website. Commissioner Brandt, a Navy veteran and conservationist, was enthusiastic and eager to assist. Our collaborative efforts involved biweekly meetings to strategize and establish a timeline for integrating the season into the 2024 schedule. Notably, Commissioner Brandt facilitated a meeting with Tim McCoy, director of Nebraska Game and Parks, to refine the legislative proposal.

During a pivotal meeting in March 2024, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission recommended the establishment of the Veteran Waterfowl Season as part of the 2024 waterfowl regulations.

Simultaneously, I collaborated with Nebraska State Senator Danielle Conrad, whose familial ties to the military fueled her commitment to supporting the veteran community. Together, we drafted LB 1001, legislation to mandate the annual occurrence of the Veteran Waterfowl Season. Senator Conrad introduced the bill, which was set for discussion in the Natural Resources Committee on February 14. In preparation for the hearing, we convened with key stakeholders, including Alicia Hardin, Nebraska Game and Parks Wildlife Division administrator, and Ryan McIntosh, legislative chair of the National Guard Association of Nebraska, to address mi-

nor revisions to the bill. These amendments were incorporated into a white copy presented at the hearing, ensuring the most current version was discussed. During the hearing, I, along with McIntosh and veteran Evan Egger, voiced our support for the bill. Ultimately, the committee chair opted to merge LB 1001 with LB 867, prioritizing it for legislative consideration.

The successful passage of LB 867 enshrined the Veteran Waterfowl Season in Nebraska law, culminating over a year of advocacy and collaboration. This achievement was made possible through the steadfast support of Commissioner Brandt, Senator Conrad, and the dedicated staff at Nebraska Game and Parks.

Thanks to the bill’s passage, in September 2024, the Nebraska chapter of the Armed Forces Initiative hosted its second annual Waterfowl Camp. This event provided six veterans with an enriching weekend of waterfowl hunting from both shore and boat. Despite warm weather conditions, participants enjoyed memorable experiences, including one veteran’s notable accomplishment of harvesting his first banded goose. This camp fostered camaraderie among veterans and volunteers while enhancing understanding of waterfowl and public land management in Nebraska.

The journey from a simple cold call to the enactment of a state statute underscores how just one person can affect meaningful change in conservation policy.

BHA member Dustin McKenna is a cavalry officer in Nebraska’s National Guard and BHA’s Armed Forces Initiative secretary. He divides his free time chasing waterfowl, upland game, and deer in his home state and spending time with his wife, Megan (also a Nebraska National Guard soldier), and his two children, Keavy (7) and Forrest (4).

BY CHARLIE BOOHER

Our nation is in the midst of what will likely be recorded as the largest government restructuring effort since FDR’s New Deal. In the early weeks of the second Trump Administration, federal employees were relieved of their duties en masse, with more reductions in force on the horizon. There’s much to be said about how and why this is being done, as well as the merits of doing it at all. The reality is that the federal agencies that manage the public lands and waters of our country, and aid in the research, management, and conservation of our fisheries and wildlife, have lost thousands of employees—the full scope of which is still unclear months later.

All this is personal for me. As a wildlife biologist by training, many of the folks who have lost their jobs were classmates, are peers and friends, and many have been mentors to me and many others over decades-long careers in public service. It’s hard to see these folks— many of whom have mortgages to pay, growing families, and parents who rely on their help—now out of work. These firings, and the precedent they set, create uncertainty. And that uncertainty makes it harder, at the individual and family level, to justify pursuing the current menu of careers in wildlife or natural resource management. Many good, smart, hardworking people will leave the field for good or choose not to enter it in the first place.

These layoffs, firings, and overall reduction in force poses an immediate problem of essential work falling by the wayside. Tomorrow and in the decades to come, it poses challenges and, if we are willing and capable of rising to the occasion, some opportunities.

For now, to state the obvious, these scopes of work will no longer be accomplished. Trails on our national forest lands will go uncleared. Pit toilets at our national parks may go uncleaned. And

seasonally closed BLM and Forest Service gates may remain locked, for there is no one to open them. Many of these tasks are essential; the reductions in force pose an immediate or imminent threat to our wild public lands, waters, and wildlife—and the success of BHA’s work.

BHA continues to advocate both in D.C. and on the ground for our public land managers to have the resources and personnel they need to properly steward our shared lands and waters.

For some, it may be an open question as to whether an employee of the federal government is necessary to accomplish these tasks, or whether these tasks need be done at all to achieve the congressional charters of these agencies, but it should be universally accepted that those decisions ought to be made deliberately and with respect for the folks who have been doing these jobs.

In some instances, contractors, state employees, or other professionals may now be relied on to accomplish these tasks. And if they can accomplish high quality work for a lower cost, it would be good for all of us. But we must remain vigilant to ensure that this is the case.

Public land stewards, whether we see it as forced or created, must find opportunities to rethink and retool what it means to be a wildlife biologist, manager, or researcher. Hunters and anglers— direct and communal descendants of those who set up this whole thing in the first place—are well prepared for this new landscape.

Every agency, institution, or policy has a story. And an intimate understanding of the history and evolution of that body is integral to understanding what it was meant to and can achieve, as well as formulating a plan for its future. We must be clear about our priorities for public land, water, and wildlife, and advocate for the most efficient and effective means of achieving those goals.

First and foremost, we must continue to ensure that the multiple use mandate of our public lands remains intact. Agencies like the BLM and Forest Service are tasked with balancing the production of our nation’s food, fuel, and fiber alongside recreational, wilderness (and Wilderness), and wildlife habitat. This will remain true unless Congress decides otherwise. However, as advocates for our own interests and equities, we must ensure that this balance is dutifully executed, and that there are enough of the right kind of personnel to do just that.

Further, this occasion also requires some understanding of the current landscape of workforce development in natural resource management. Today, the practical reality of becoming a “wildlife biologist” or a natural resource manager is years, if not decades, of school to achieve advanced degrees and credentials that are rooted in conducting academic research, rather than a training focused on the skills required of those professions on a daily basis. Those skills are often taught, or perhaps more appropriately, learned, on the job. Which raises an important question about what skills future members of this workforce will need, and what kind of training will be necessary to gain those skills.

As somebody with a handful of those degrees, I can say with confidence that I wouldn’t be where I am today without the theoretical knowledge and laboratory experiences gleaned from professors at Michigan State University and the University of Montana. However, it’s clear that our field’s biggest gaps in coverage are not folks with advanced degrees. The gaps and vacancies in our field are folks who can actively identify plants, who are willing to work long days fixing fences, clearing trails, and spraying weeds,

and those who can interface with a public who is increasingly disconnected from the natural world. These folks, just like those who are skilled in other trades, need to be heavily recruited, trained to hone the skills necessary for the job, respected, and paid a living wage.

In navigating the redefined future of our nation’s most fundamental public land and resource institutions, we must consciously center the resources on which we rely, while also respecting the time, training, and expertise of a workforce that has made significant personal and professional investments in these agencies. It will not be easy, just as it has not been easy for many individuals and families who have been part of this process thus far. But it is still up to us to ensure that our public lands and waters and the agencies tasked with stewarding them are left better than we found them.