Flagship Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

Issue 4

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk

Issue 4

Published by Aylesbury Grammar School 2022

Aylesbury Grammar School

Walton Road

Aylesbury

Bucks

HP21 7RP

Assistant Headteacher

Vanessa Beckley

vbeckley@ags.bucks.sch.uk

AGS Research Team @AGSResearchEd

AGS Headmaster @AGSHeadmaster

www.ags.bucks.sch.uk

Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

2

Engaged Practice

Flagship Journal for Evidence

Front cover artwork by AGS A Level art student.

Foreword by the Headmaster

‘These institutions have a collective purpose, a shared set of rituals, a common origin story. They nurture thick relationships, and demand full commitment. They don’t merely just educate, they transform.’ David Brooks, The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life.

In his book, David Brooks reflects on the concept of a society of hyper-individualism characterised by unfulfillment and alienation - which is in stark contrast to the relationships, community and commitment displayed on these pages. For each researcher and research project, there are connections, professional growth, impact, and the relentless desire to improve the lives of our families and community.

This isn’t the first Flagship, and this isn’t the first publication based on educational research. However, it is the first since the historic disruption to education across the globe. It marks a fully-fledged approach to collaboration, a stability and creativity to the progress of our professional practice and the education of our young people.

In an academic year that has seen the return to a richness of musical performance, to emotion and creativity across the arts, as well as a speed and strength in the sporting arenas, 2021-2022 has seen many firsts and many triumphant returns.

Our students re-entered the examination halls in May and June 2022 to sit their qualifications for the first time in three years. They did so with preparation and resilience. Whilst an evolution of Remote Learning marked an end to School closures for snow events, the impact of climate change and the arrival of Storm Eunice in February and the extreme heat of July challenged this position, delivering unique, unprecedented closures and disruptions to learning. However, we were prepared. Prepared both to continue to learn, but also to be agile and flexible in the face of change. Something developed because of the pages you are about to read.

‘Everything must change so that everything can remain the same’, says Tancredi in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (Il Gattopardo), but the ‘same’ for us is hidden by a relentless desire to improve and an undeniable focus on ensuring certainty even when all around us we see and experience uncertainty.

To all the trailblazers and pathfinders, to the editing team, and the constant desire to transform, thank you. This is certainly our Flagship.

Mark Sturgeon Headmaster AYLESBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL

In a landscape where so much is unpredictable, it is human nature to seek facts on which it can rely. Perhaps that is why this edition of Flagship is our most extensive.

The audience – excited, apprehensive, maybe a little unnerved in what is probably their first large crowd since the restrictions – adjust masks, shuffle in their seats, back away apologetically from their neighbours. Mr Nathan, in his characteristic smart waistcoat and suit, styles his way to the front of the crowd and puts everyone at ease: smiling, benevolent, impressive. “Welcome to our first musical event since Lockdown,” he beams, the joy palpable. He turns to face his musicians and the miracle begins. The Hall, starved of sound, delight, laughter, joy for so many months, erupts into a cacophony of unleashed notes ricocheting off walls, glancing across the crowd, rebounding from the sound crew, burrowing into the names of our great Aylesburian heroes etched onto the memorial stone to the right of the audience, before flashing across the delighted and hopeful faces of our musicians. The pandemic is cruel but our School is stronger.

And what a calendar of exciting events followed. Whilst this is the fourth edition of Flagship, our Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice, in so many ways it has been a year of firsts. Like the whimsical initial notes of House Music, hesitant and delicate, we started again. Faces on screens became jostling students; WhatsApp groups dissolved into teachers collaborating over a coffee; House Art was tangible, concrete, three dimensional; hopeful Heads of Department buried thoughts of teacher assessed grades like a forgotten nightmare; students assembled bright and early in our Hall. Working groups started to meet, busily planning initiatives to support students with their literacy, their careers, their character. The PE department jammed their diary with fixtures. And Mr Crapper, Head of Modern Foreign Languages, unfolded his map of France and picked up his phone…

On Friday 27th May 2022, forty Y8 students departed for Burgundy in the first overseas curriculum trip since the start of Covid. The same month saw some four hundred dedicated students write their way to success in public exams with courage, optimism and determination. There were some unusual firsts too. Storm Eunice emptied the playgrounds, rubbish bins leashed down with rope, the School Hall defending itself as the wind buffeted its windows trying to break its resolve. The new Reception door twisted on its hinges. The Tower Block groaned at its mistreatment. Then came the Heatwave. The Met Office red warning kept students at home for the first time as roads melted. The Hall looked on wryly.

In a landscape where so much is unpredictable, it is human nature to seek facts on which it can rely. Perhaps that is why this edition of Flagship is our most extensive. We ask how we can support students to develop character to prepare them for an uncertain future; we question how we can support a more positive masculinity against the unhealthy Man Box that has been handed down by societal norms and consider the value of role models; we connect as humans across cultures examining ethnomathematics and diverse textbooks. In Flagship we do this rigorously and always from an evidence base.

Our staff are dedicated to a collective endeavour on behalf of our students. And like the gradual flourishing of music following the pandemic, the spirit of AGS swells and our great Hall beams down.

Vanessa Beckley Research Lead AYLESBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 4 EDITOR’S NOTE

From the back of the Hall the first few hesitant squeaks of a clarinet signal the arrival of our students. A little chatter from the front. An overloud boom from a microphone. Hurried steps to the sound board to check the connections.

VANESSA BECKLEY

Vanessa Beckley has been teaching English at AGS since 2009 and alongside this is Assistant Headteacher for Professional Learning. Deeply concerned and saddened by the dramatic fall in new teachers to the profession and the challenges of retention, she sees autonomous and purposeful professional learning, a collaborative School culture and staff interaction as essential steps in the journey towards better wellbeing for all. She is therefore excited to edit this fourth journal as a celebration of the commitment of its contributors and their exceptional talent. This year’s recommended read is “Running the Room” by Tom Bennett, a book which is simultaneously colourful, hyperbolic and witty, and practical, sage and outspoken. Definitely Marmite.

RACHAEL JACKSON

Rachael Jackson has been teaching French at Aylesbury Grammar School since 2019 and is also a Digital Learning Leader for the School and newly appointed to the role of Professional Tutor.

Rachael has been selected by the International Boys’ Schools Coalition (IBSC) to conduct an action research project on “Shattering Stereotypes: Helping Boys Cultivate Healthy Masculinity” and recently attended the IBSC conference on “The Path to Manhood” in Dallas, Texas with 500 educators from around the globe.

Rachael’s recommended reading on the topic of masculinities has to include the work of Raewyn Connell. She would also encourage the reading of Reiner’s (2021) book “Better boys, better men: The new masculinity that creates greater courage and emotional resiliency” which is a difficult book to read in terms of the suffering described but one which lingers in one’s thoughts and highlights the importance of this work.

HARRY DUDMISH

Harry Dudmish is a teacher of P.E., starting at Aylesbury Grammar school as an NQT in 2020, joining a very experienced department. Together with the new Director of Sport, and as part of the Character Development Working Group, alongside his research project in character, Harry looks to help develop an ever progressing PE curriculum. With an extensive background in team sports, Harry understands the range of benefits sports can offer students, but also seeks to continue exploring how far the mind can go. Much of the reading Harry does revolves around psychology and character, with recent books including “The Art Of Resilience” by Ross Edgley and “The Chimp Paradox” by Steve Peters.

JAMES TAYLOR

James Taylor has been teaching at Aylesbury Grammar School since 2019, and is a teacher of History and Classics. He has just completed his NQT+1 year, as well as supervising students for EPQ and acting as Head of House. This year, he has been conducting research on student perceptions of role models and leadership, enhancing the work he has been doing in both the Research and Character working groups. James always enjoys reading, both for historical curiosity and with an interest in educational and pastoral issues, so can recommend both “America on Fire: the Untold Story of Police Violence and Black Rebellion since the 1960s” by Elizabeth Hinton and “The Boy Question” by Mark Roberts.

5 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

ALEX GRUAR

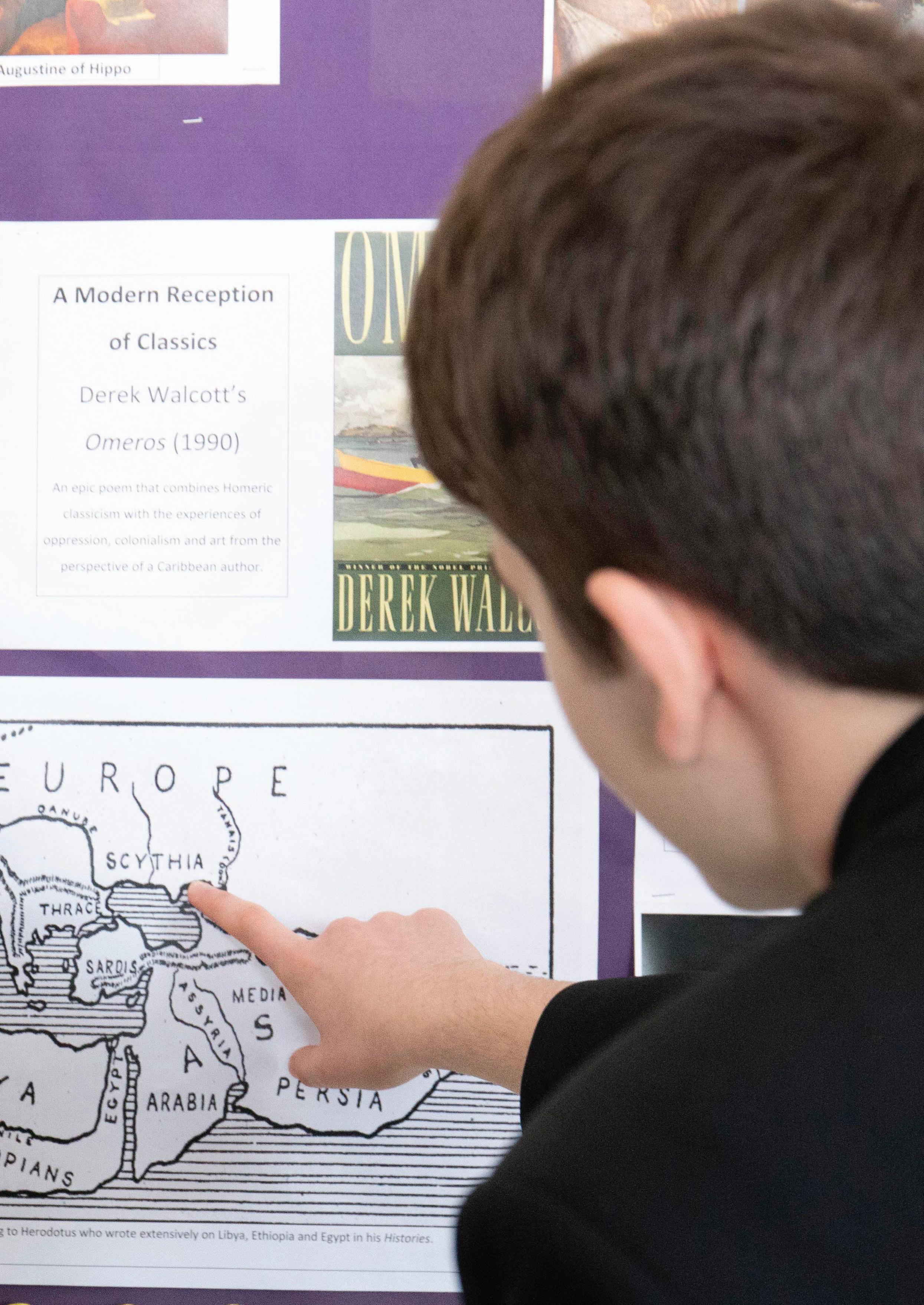

Alex Gruar is a teacher of Classics at Aylesbury Grammar School. She believes that the study of the ancient world is for everyone and has previously been involved in a project for the University of Oxford providing Latin GCSE lessons for teenagers who would not otherwise have the opportunity. For the past two years, she has been focussing on how changing to a more representative coursebook can improve student awareness of the existence of BAME people in the Roman world, and how teachers can optimise this. She recommends the Radio 4 programme “Detoxifying the Classics” as an introduction to why this should matter for all of us.

ALI MANJENGWA

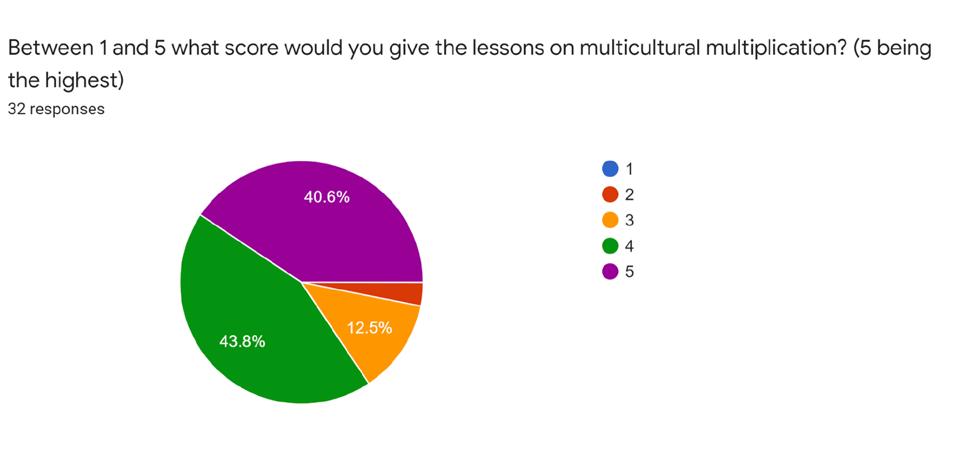

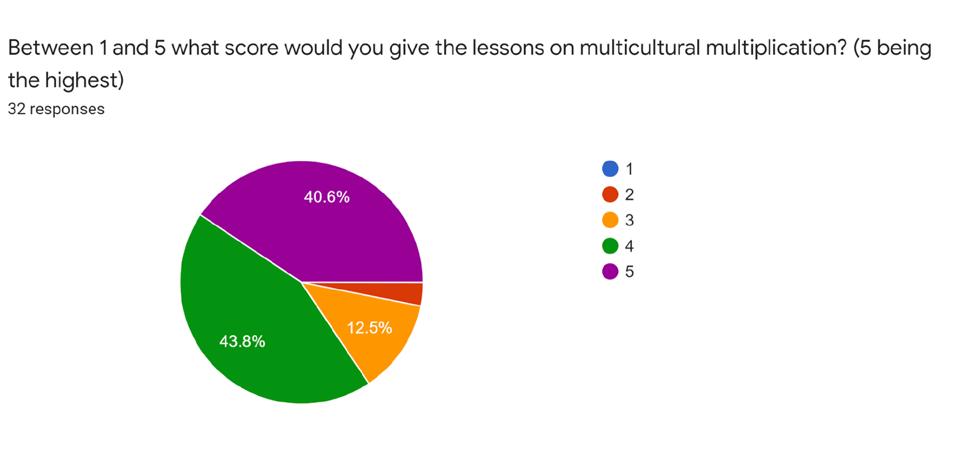

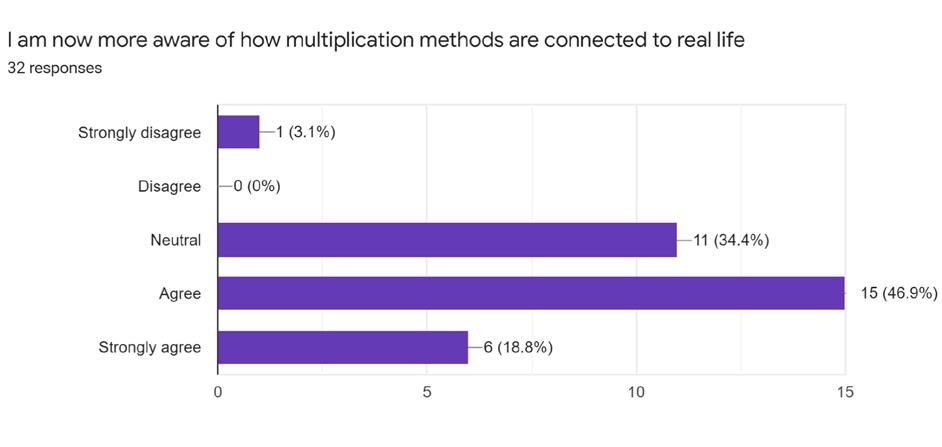

Ali Manjengwa is teacher of Mathematics at AGS having joined in 2008. He has been a member of the Diversity working group and the Research working party and has delivered presentations to staff on decolonising the curriculum. A diversity champion for the Maths department, he has an interest in curriculum change and has been researching ways to decolonise the Maths curriculum at AGS to make it more inclusive and interculturally responsive. This year he has focussed his research on implementing and evaluating an ethnomathematics strategy on students’ learning and understanding of multiplication.

ANDREW SKINNER

Andrew Skinner has been Head of English at AGS since 2014. This year, as part of completing his NPQSL, he explored the effect of a wider ranging induction summer camp on how students coped with the transition from primary to secondary school. John West-Burnham’s “Moral Leadership”, centred around ethical and value driven leadership in school communities, was influential and a springboard into many interesting discussions and further reading.

AMBER FINN

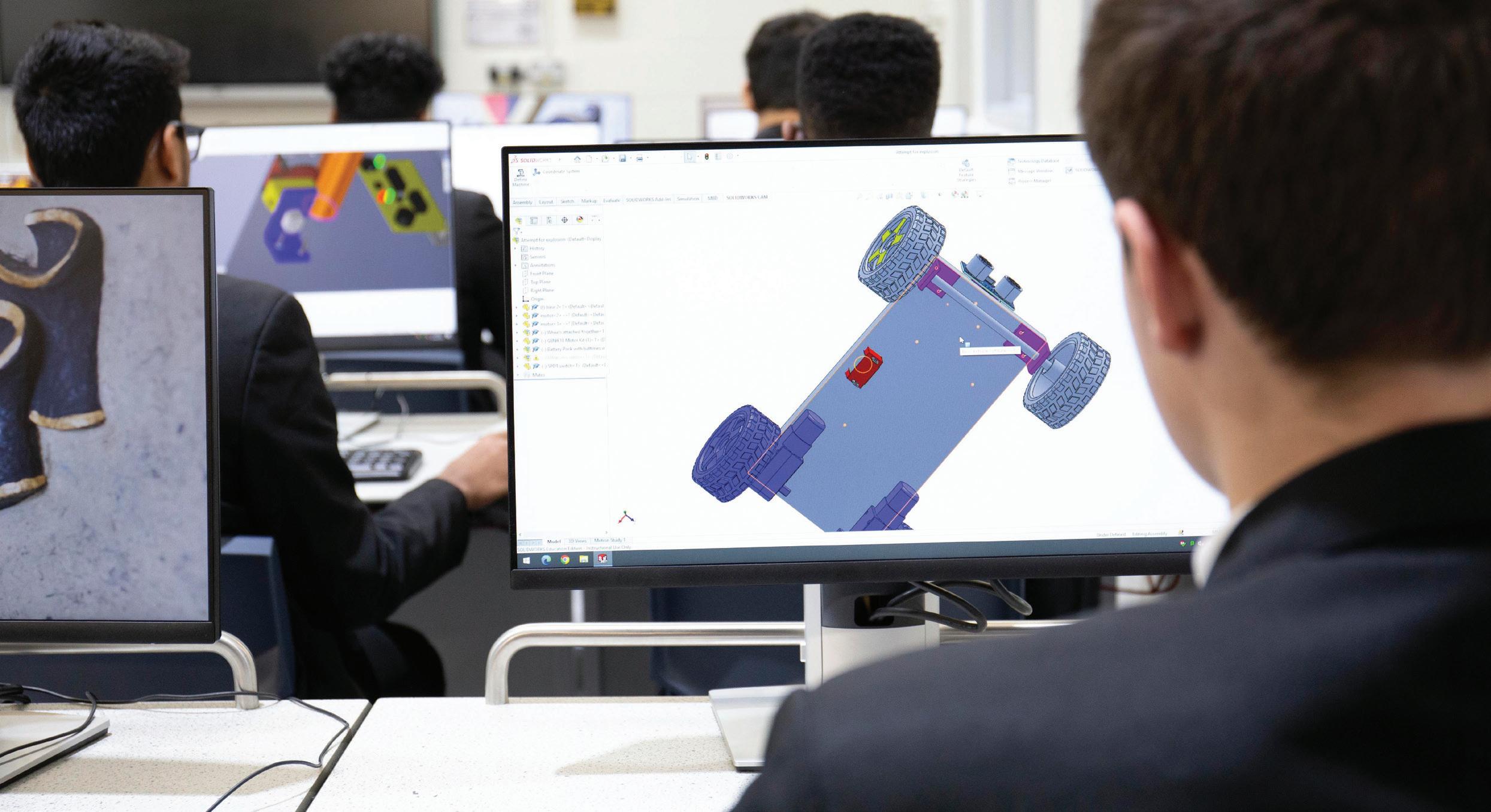

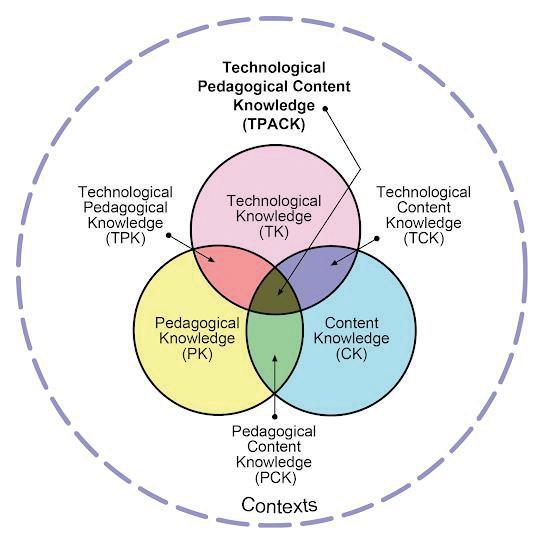

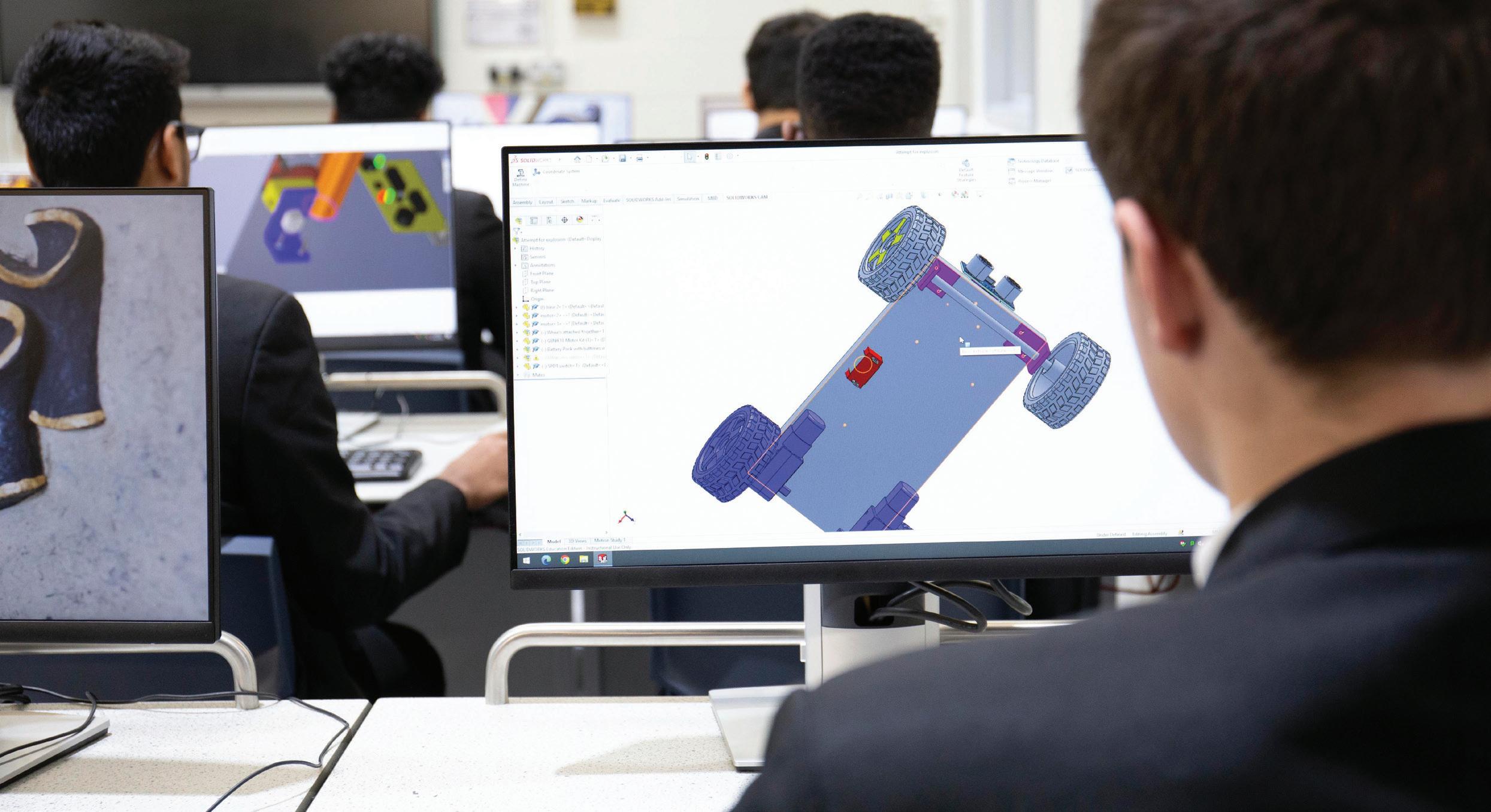

Amber Finn is a physics and computer science teacher who has been teaching at AGS for six years. She is particularly interested in the use of technology in education and is part of the School’s group of Digital Learning Leaders. When the International Boys’ Schools Coalition (IBSC) announced in 2019 that their upcoming theme for action research would be Boys and Technology: New Horizons, New Challenges, New Learning, she was excited to apply to be part of the cohort of teachers from around the world taking part. After multiple delays and obstacles due to COVID the research went ahead and the findings were presented at the annual IBSC conference in July 2022. A useful place to start when looking for research informed improvements is the Education Endowment Foundation’s (EEF) Guidance reports. Amber found the EEF’s report on Using Digital Technology to Improve Learning particularly useful.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 6

Meet The Research Team

Contents

9

RACHAEL JACKSON

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

21

HARRY DUDMISH

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

31

JAMES TAYLOR

To what extent can Year 9 students’ perceptions of role models be broadened and challenged within teacher and peer-led Personal Development sessions?

43 ALEX GRUAR

The impact of a change to a more diverse KS3 Latin course book in student perceptions of BAME people in the Roman world, and how to optimise this: an update.

55 ALI MANJENGWA

Assessing the effectiveness of an ethnomathematics teaching strategy on students’ understanding of mathematics.

63 ANDREW SKINNER

How might a broader and more inclusive transition process from Year 6 to Year 7 develop student confidence and attitude to learning in Autumn term for Year 7?

73 AMBER FINN

Using technology to support self-paced learning in physics and the effect on self-efficacy

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

ABSTRACT

Masculinity or masculinities is a subject that has been gathering attention dramatically since 2017. At the same time, it is often poorly defined, misunderstood and provokes strong feelings and opinions, or retreats into a silent taboo. In March 2022, I began an action research project with one class of Year 8 students to uncover their thoughts and feelings on masculinity. In this paper, you will hear their voices and you will be able to share in the privilege of listening to their innermost and most authentic thoughts. A privilege and also a great responsibility of really listening to them and hearing them. We all have a tremendous opportunity to learn and reflect and play a part in defining a world of limitless masculinities.

Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

Rachael Jackson Teacher of French, Digital Learning Leader, Professional Tutor

CONTEXT

In recent years, the term “Masculinity” has percolated conversation in schools, whether informally across playgrounds and through corridors or more formally. There are many terms used today and they are not always fully understood or helpful. You may have heard of some of these terms, such as “Positive Masculinity” and “Healthy Masculinity” or “Toxic Masculinity” and “Hypermasculinity”. The terms “Toxic Masculinity” and “Hypermasculinity” carry some unhelpful connotations as deficit models (Waling, 2019; Maricourt & Burrell, 2022) and it might be more constructive and accurate to talk in terms of “multiple masculinities” (Messerschmidt, 2018; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005).

Listening to young people about their experiences and perspectives on “multiple masculinities” has never been so important as it is today and we have an opportunity (and arguably an obligation) to guide and support them.

The voice of our young people became much more visible from 2017 onwards, following the high-profile legal case against Harvey Weinstein. The #MeToo hashtag provided a social platform for people to share their experiences of sexual abuse and very quickly went viral.

Then in 2020, a spotlight was shone on abuse specifically in schools and amongst young people, with the social platform, Everyone’s Invited. Survivors of sexual harrassment and abuse were able to anonymously share their story, and revealed the extent of sexual harrassment and sexual abuse in schools. Ofsted responded with a report in June 2021 which found that issues around sexual harassment are “so widespread that they need addressing for all children and young people” and advised schools “to act as though sexual harassment and online sexual abuse is happening to them” (Safer Schools, 2021).

Everyone in society is negatively impacted until we progress to a society that is better at accepting, supporting and championing “multiple masculinities”. Society today is seeing a crisis of masculinity with high and rising rates of loneliness, prison numbers, “despair deaths” (where men abuse alcohol or drugs to induce death) and suicide (Reiner, 2021; Pitts-Tucker, 2012; Lythcott-Haims, 2022; David Brooks, 2022).

Aylesbury Grammar School recognises the opportunity and the responsibility we have to support and guide our young people and has highlighted Positive Sexual Citizenship and Positive Masculinity as a priority in its School Development Plan this year. In support of this School priority, I have developed a Masculinity Programme that I am currently piloting with one Year 8 class.

LITERATURE REVIEW

For too long a narrow version of masculinity has harmed how boys feel about themselves and made them question where they fit (Brozo, Walter & Placker, 2002, p.531). For boys who do ‘not fit’, then life as an outsider is fraught with insults of being feminine, gay or odd (Nye, 2005, p.1941). For boys who manage to ‘fit themselves’ into the narrow version of masculinity, their experience is just as unhappy, sometimes unable to express their sensitive side, achieve academically or pursue their sexuality (Reiner, 2021; Legewie & DiPrete, 2021, p.466; Connell, 1989, p.293; Connell, 1992, p.742).

Hegemonic masculinity is the dominant construct of masculinity that prevails across the globe and has the typical characteristics of heterosexuality and physicality that undermine so many men who do not fit this profile. The Man Box concept (Porter, 2010) and exercise (Hurst, 2018) is a powerful visual reminder of today’s restrictive narrow definition of masculinity, where boys will eliminate “eighty percent of human emotions” to fit in the Box (Reiner, 2021). Boys say they cannot share their vulnerabilities and emotions for fear of being shamed by both boys and girls (Reiner, 2021). Boys and men will self-police themselves and each other on the strict hegemonic masculinity traits (Willer et al., 2013; Martino, 1999) and girls and women, as schoolmates, colleagues and mothers also play a formative role in constructing masculinities (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.848).

The concept of hegemonic masculinity emerged in the 1980s (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.830) but discussions of the male personality under tension can be found in Freud’s work from the 1950s (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.832). Hegemonic masculinity is not fixed; it evolves over time according to social and cultural change (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.835) and nor is it easily confined or defined; “is it John Wayne or Leonardo DiCaprio; Mike Tyson or Pele?” (Whitehead, 1998, p.58).

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 10

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

Hegemonic masculinity is not the majority or the norm, but it is the normative and the model against which all males are measured (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.832) and it positions itself as superior to all other subordinate non hegemonic masculinities. Simply put, there are a plurality of masculinities and hegemonic masculinity seeks to dominate them all (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.846).

If we box diversity into such narrow terms, some departments will see it as a box to be ticked (Bradshaw, 2009).

The traditional hegemonic masculinity contrives men as successful, responsible leaders and the financial breadwinners (Connell, 2016; Lu & Wong, 2013) and disseminates a belief that you are “either dominated or the dominator” (Reiner, 2021). Sportiness and sport is often used as a means to constrain boys into a narrow masculinity (Martino, 1999, p.240) and there are strong associations with alcohol, sexual accomplishments and involvement in “sexually crude conversations” with no space for anything other than heterosexuality (Pinkett & Roberts, 2019, p.104; Hurst, 2018, 6:00; Harper, 2004; Lu & Wong, 2013).

Physicality is another hegemonic lever, favouring superior, strong and muscular physiques (Nye, 2005, p.1947). Rich (2014) explores how race can also unhelpfully play out in establishing hegemonic masculinities and Lu and Wong (2013) highlight the additional stresses on different ethnic physicalities, for example slim-framed Asian Americans.

Being seen to be nerdy, a book-reader or a documentarywatcher can contradict hegemonic masculinity (Lu & Wong, 2013, p.357) and many boys seek to protect their masculinity in the classroom by looking like they ‘tried to fail’ rather than look like they ‘tried and failed’ (Pinkett & Roberts, 2019, p.11; Reiner, 2021, p52).

“The standards of true masculinity are so exacting as to be virtually unattainable” (Willer et al., 2013, p.983)

“The standards of true masculinity are so exacting as to be virtually unattainable” (Willer et al., 2013, p.983) and the additional constant risk of losing masculinity drives men to strive, protect and police their sense of masculinity (Willer et al., 2013). The overcompensation thesis says that where men feel their masculinity lost or threatened, they seek to demonstrate more strongly the

hegemonic masculinity traits, which at the moderate end of the scale could be disassociating with housework and at the more worrying end of the scale lead to harassment or violence towards women and those that threaten their sense of masculinity (Willer et al., 2013, p.984).

RESEARCH QUESTION

The overarching question for this research is:

To what extent can the delivery of a Healthy Masculinity Programme to a Year 8 class in registration, over a 12-week period, dismantle the “Narrow Masculinity” that pervades today and, in its place, construct a “Limitless Masculinity” ?

This research question and programme is still active and the findings will not be known until later in 2022 and the work will continue into 2023. In the interim, I can share the following:

WHAT DOES POSITIVE MASCULINITY MEAN TO YEAR 8 STUDENTS TODAY?

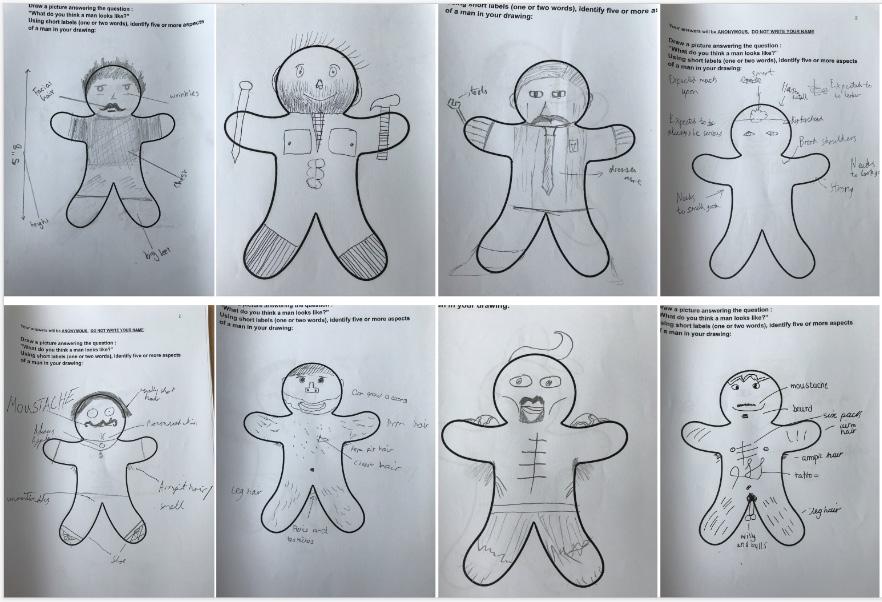

Based on the initial questionnaires completed by one Year 8 class, I am able to share what they think about masculinity today. Through their words and Gingerbread drawings they share what masculinity means to them.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This “action research” is practitioner-based qualitative research and seeks to evidence the theory within one Year 8 classroom using inductive reasoning (Mertler, 2019). I chose a Year 8 class as an optimum age for understanding the complexities we would debate and, at the same time, hopefully before they have concreted in their perspectives (Reiner, 2020).

“Research occurs in the ivory towers, whereas practice takes place in the trenches” (Parsons & Brown, 2002)

Research ethics requires honesty and openness and I therefore ensured all students participated on a strictly voluntary basis and with complete anonymity and confidentiality assured for every student.

11 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

I felt that in order to truly hear what Year 8 students really think and feel about masculinity today, and knowing how personal, private and sensitive this could be, that anonymous data would be a more authentic voice.

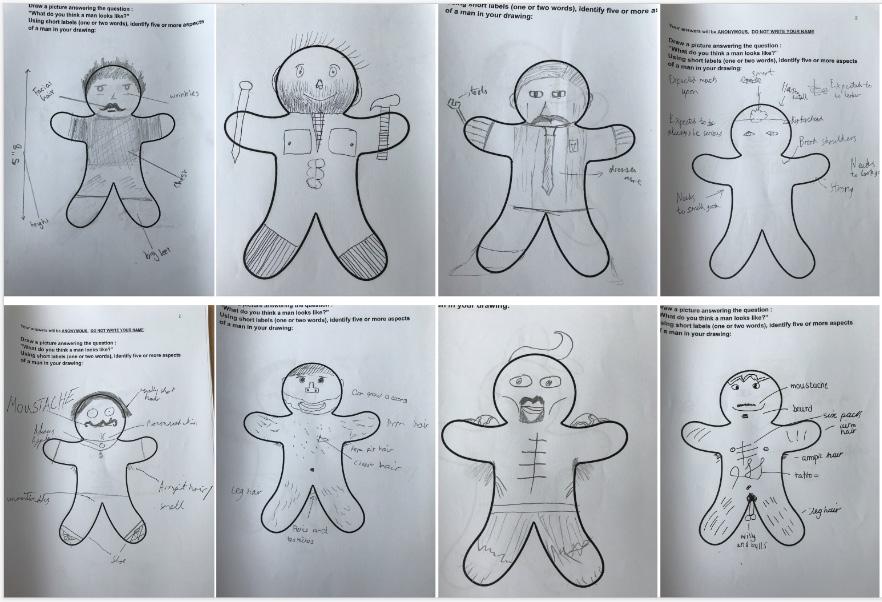

In March, I invited one Year 8 class to the library where they could spread out and find a quiet and private space to complete two questionnaires. The first questionnaire I asked them to complete was a Gingerbread Man. Without explaining what the word “man” meant (because I did not want to lead them in any way), I simply gave each student a Gingerbread Man sheet which included the instructions:

“Draw a picture answering the question: “What do you think a man looks like?”. Using short labels (one or two words), identify five or more aspects of a man in your drawing.”

The 12-week Masculinity Programme that I selected is based on an analysis of a number of well-researched and established programmes originating predominantly from the UK and US. These programmes included The Good Men Project, Manhood 2.0, Beyond Equality, The Representation Project, The Being Mankind and A Call to Men.

I chose the “Live Respect” programme developed by A Call to Men because it is designed for secondary schools and has been widely used in the US across schools, universities, the US Department of Justice, US Military, National Football League, Major League Baseball and corporations such as Deloittes and Uber. Founded in 2002 by Tony Porter, who is renowned for his 2010 TED talk, I engaged with their Director of Youth Initiatives to adapt the materials and to design a bespoke Masculinity Programme for Aylesbury Grammar School.

In recognition of my role as a teacher and being female, I wanted to reflect the boys’ gender and age more closely into our facilitation. I therefore asked the Head Boys to co-deliver the Masculinity Programme with me. Our Year 8 class were incredibly fortunate to have the three Head Boys of 2021-2022 and the three Head Boys of 2022-2023 co-run the sessions each week and lead the student discussions.

We are now nearing the end of the 12-week Masculinity Programme and following the completion, I will ask the Year 8 students to complete the same two questionnaires in the same way and hope to be able to see to what extent their perspectives have changed.

I will then review and revise this Masculinity Programme and feed forward the findings into an iterative and in-depth study starting September 2022 and completing Summer 2023.

I then collected in the Gingerbread Man questionnaire, again ensuring students’ anonymity by asking them to turn their drawing over and repeatedly shuffling the papers as I collected them.

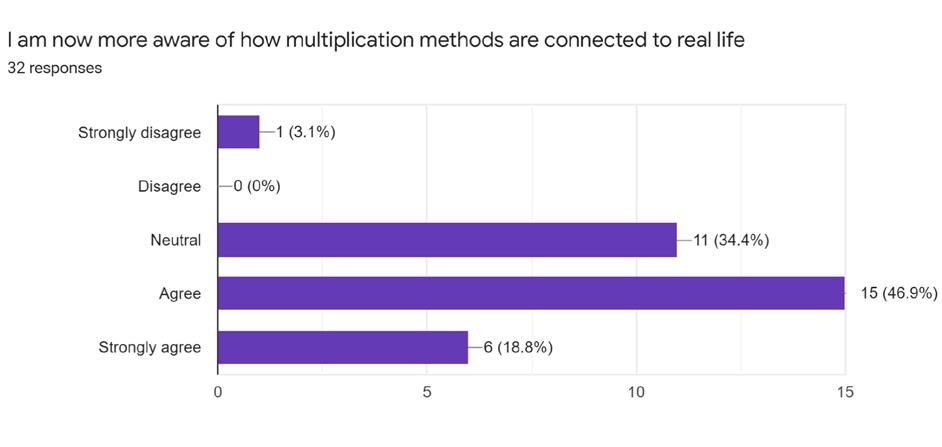

The Gingerbread Man questionnaire was designed to be very open and capture their thoughts without any leading questions. I then wanted to be able to drill down into specific questions that reflected the literature and therefore designed a second questionnaire using a Google Form, with a series of likert scale and free-format response questions. Together, the Gingerbread Man and the Google Form questionnaires provided rich data and a clear insight into their thoughts on masculinity, before I began the Masculinity Programme with them.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 12

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

FINDINGS

The most poignant finding from the two questionnaires was how important and yet taboo this subject is for the Year 8 boys. One student said they found it “hard as it is uncomfortable” and another said “I found it difficult because no one talks about things like this in or out of school”. This is confirmation of how important and welcome this open dialogue on masculinities is for our students.

“I found it difficult because no one talks about things like this in or out of school.” (Student E)

“I have never been asked theese (sic) questions before so it was preety (sic) hard.” (Student G)

The Gingerbread Man questionnaire findings revealed a strong reflection of the literature on traditional hegemonic masculinity. Thematic coding of the students’ annotated drawings revealed strong associations to physicality, responsibility and leadership. In a class of 32 students, 17 referenced puberty (drawing and labelling facial and body hair, and genitals), 10 referenced muscles (drawing and labelling six packs, pecs and biceps), 2 referenced being tall, and 7 referenced roles of responsibility, leadership and emotional strength.

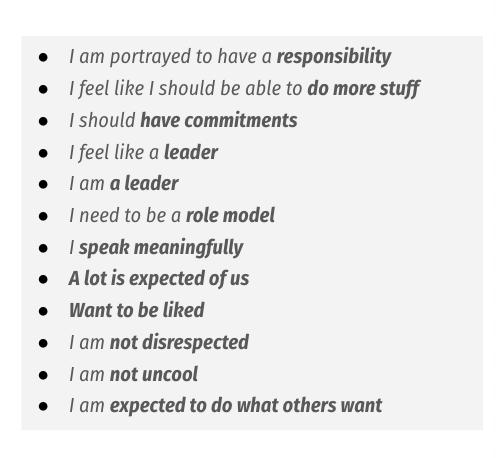

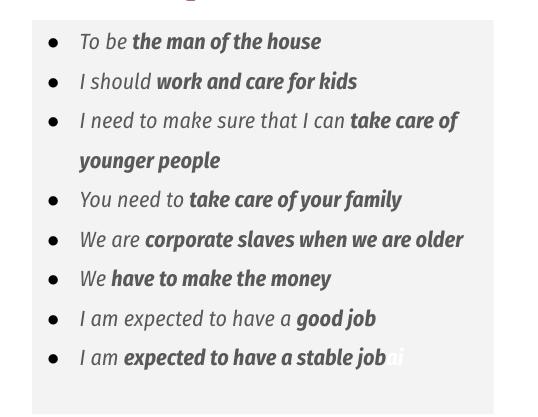

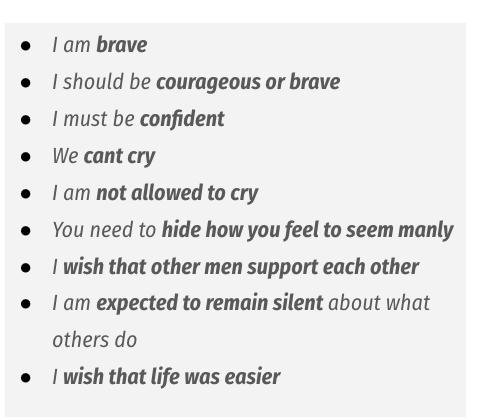

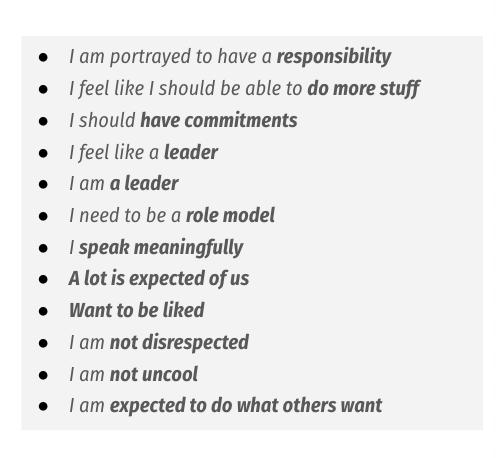

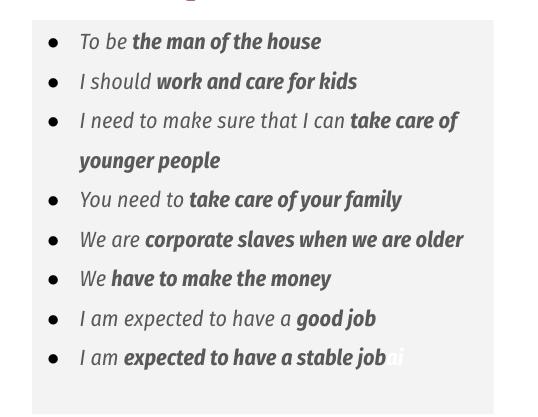

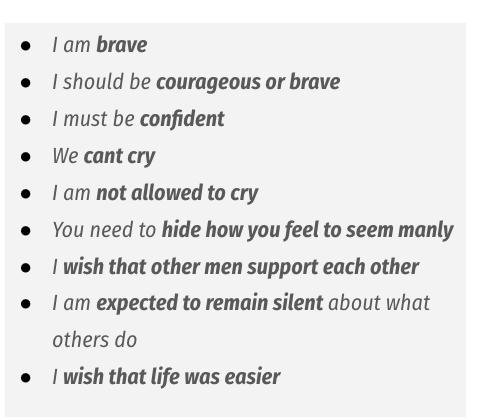

Following the Gingerbread Man questionnaire, the first question in the Google Form questionnaire for students to answer was to finish the sentence “As a man …” and to do this 10 times. The intention of this question was to probe deeply into their understanding of what it means to be a man (or boy). The responses revealed again a strong reflection of the traditional hegemonic masculinity. Students’ number one reference on the question of the role of a man, according to thematic coding, was to lead, care and provide financially for his family. Students said that “As a man I should work and care for kids” and that I am “to be the man of the house”. They described the responsibilities they saw: “we have to make the money” and “I am expected to have a good job” and “we are corporate slaves when we are older”. In their own words “a lot is expected of us”. The second largest category according to thematic coding centred around emotional strength. Students voiced the narrow masculinity that deprives boys of their full set of emotions granted to them at birth. They said, “I should be courageous or brave” and “I must be confident”. They said, “We cant (sic) cry”, “I am not allowed to cry ‘’ and “You need to hide how you feel to seem manly”. At the same time they know and feel this to be wrong in saying, “I wish that men support each other” and “I wish that life was easier”.

13 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

Hegemonic masculinity is not the majority or the norm, but it is the normative and the model against which all males are measured (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005, p.832) and it positions itself as superior to all other subordinate non hegemonic masculinities.

Students’ third largest category focused on physicality. Students said, “I am expected to be attractive”, “We want to be handsome”, “We want to be tall” and “I should be physically and mentally strong”.

A small number of students were able to voice a broader set of emotions and vulnerabilities in challenge to the narrow hegemonic masculinity. They said, “I should be able to ask people for help”, “I am kind”, “I respect” and “I am not perfect”.

15 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

Students voiced the narrow masculinity that deprives boys of their full set of emotions granted to them at birth.

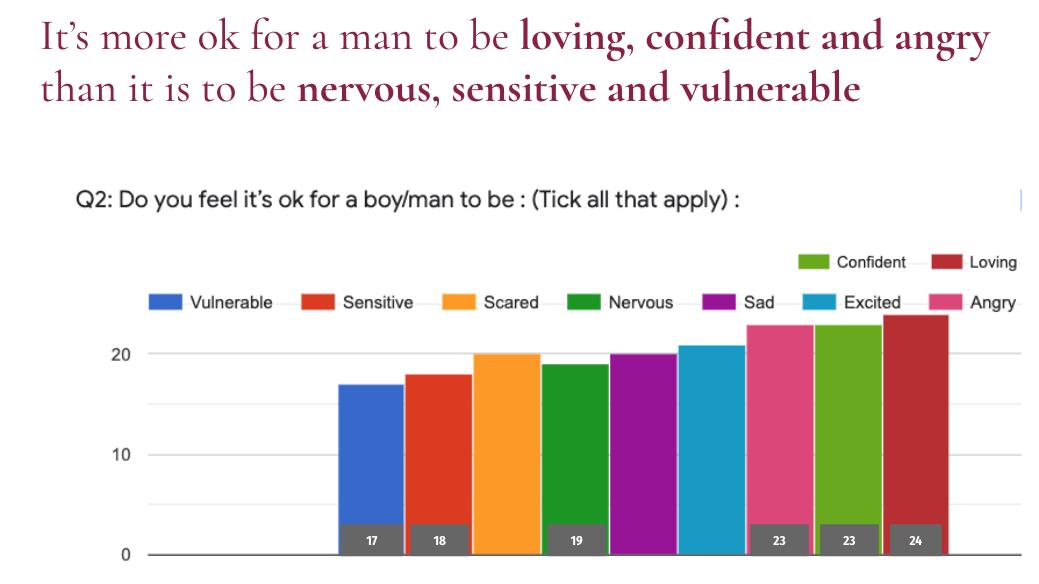

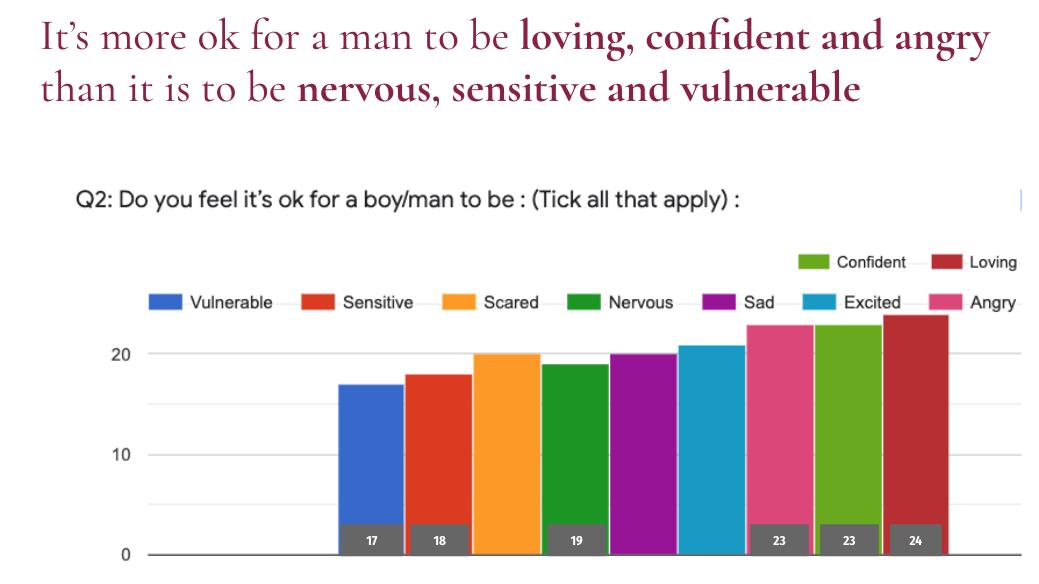

After the “As a man …” questions, students were presented with a series of likert scale and similar questions. These questions were designed to test to what extent the hegemonic masculinity described by the literature might be reflected in their answers. The Man Box literature states that boys start to exclude emotions and vulnerabilities as they grow up, based on what they see and learn about them on what it means ‘to be a man’. Our Year 8 students were asked to select all the emotions that they felt it was ok to feel as a man/boy. They articulated that it was ok to feel loving (24 responses), confident (23 responses) and angry (23 responses). At the other end of the scale there were just 19 responses for feeling nervous, 18 responses for feeling sensitive and the lowest score was 17 for feeling vulnerable. In summary, their answers are starting to reflect the narrowing of hegemonic masculinity. Some students added comments to this question and added the additional feelings of “lonely” and “depressed”.

One student positively wrote, “a man can feel anything that he wants” and at the other end of the spectrum another student wrote, “I don’t want to be seen as vulnerable, sensitive, scared, nervous, sad or angry”.

“i (sic) man can feel anything that he wants.” (Student B)

“I don’t wanna be seen as vulnerable, sensitive, scared, nervous, sad or angry.” (Student C)

“When we don’t like a girl, that’s our problem, when a girl doesn’t like us, that’s also my problem.” (Student F)

Students were asked if they felt comfortable crying in front of friends and two-thirds said no, compared to one-third who said yes. Contrast this with the question if students felt comfortable seeing two men kiss each other and just over one-half of students said yes and just under one-third said no. In short, Year 8 boys are more comfortable seeing two men kiss each other than crying in front of their friends. It may be that these results reflect the efforts in society and schools to champion tolerance of sexual orientation. It may also be that these results reflect the work still to do in society and schools to dismantle the constraints of narrow hegemonic masculinity.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 16

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

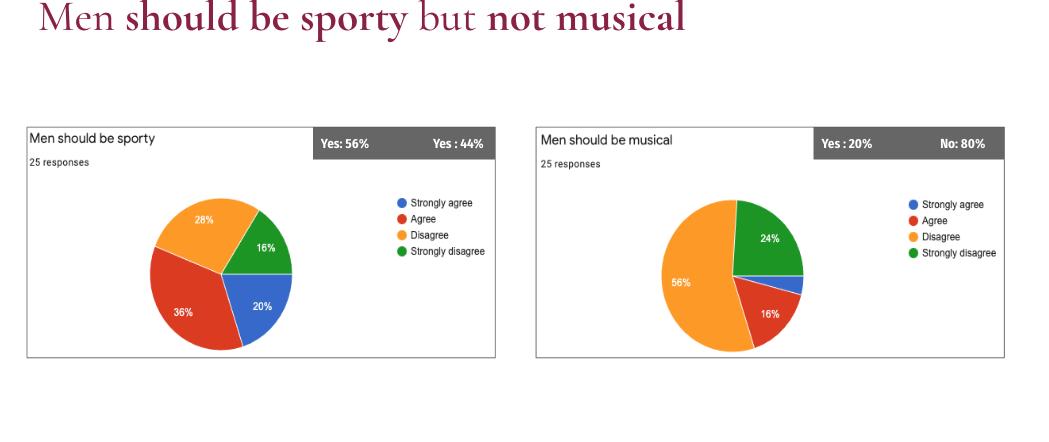

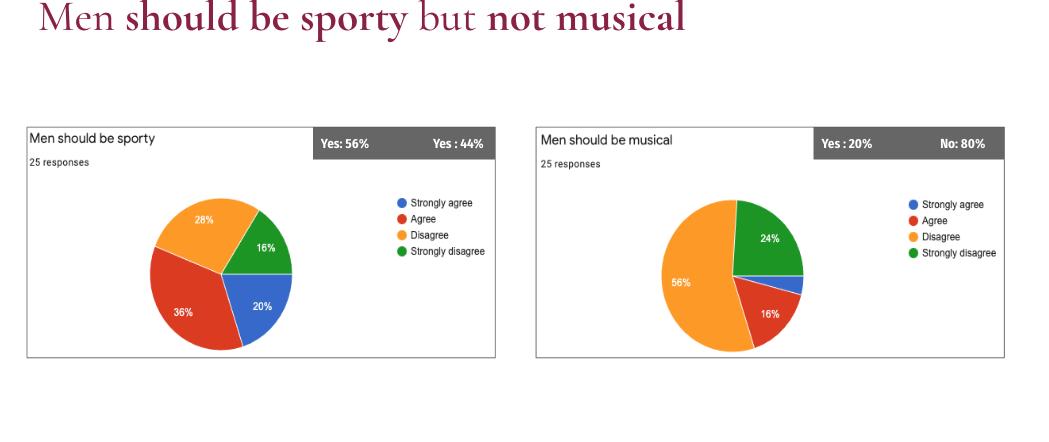

Students were asked a series of questions designed to see what associations they would make between masculinity and sport, music and intellectualism, to see whether the literature was borne out in the voices. Over half of students agreed “men should be sporty”, compared to less than a quarter of students who thought that “men should be musical”. Interestingly more than three-quarters of students disagreed that “men should be musical”. Responses on “men should be nerdy/intellectual” also showed weak association with masculinity, with two-thirds disagreeing and onethird agreeing with the statement. The boys’ responses to all three questions show some reflection of the narrow hegemonic masculinity.

CONCLUSION

When embarking on this action research, I did not know what I would find out, and in particular, I had no sense of what boys thought about masculinity. Yes, I see boys in the classroom and the playground and yes, there are snippets of conversation that I pick up on. But in terms of their deep, inner, private and personal thoughts on this topic, I had absolutely no idea.

The more I researched the literature, the more I reflected on a multitude of levels. I realised how starkly important it is to help boys have open conversations on masculinity. I realised the immense opportunity to lead and support these conversations, together with the terrifying burden of getting it right (or at least, not getting it wrong).

Informed by the literature, I created the Year 8

Students were given free-format questions to be able to add anything they wanted to say, so that the questionnaire could capture their complete and accurate voice as far as possible. One positive free-format response is shared below and it is both erudite and brings optimism.

Questionnaires so that I might capture their voices and see whether and to what extent their thoughts and ideas reflected the literature. I found out that yes, already in Year 8, their voices do reflect the literature and the dominant hegemonic masculinity of today’s society. They already ‘know’ that the full set of emotions gifted to them at birth is slowly being eroded by societal constructs of what it means to be a ‘man’. They already feel a sense of pressure to conform and the negative feelings that go with this.

I hope that the work I am doing with students today and into 2023 will help them take some steps towards dismantling the narrow hegemonic masculinity that pervades today, and allow them to talk more freely and openly. I hope that it will allow them to construct limitless masculinities for themselves and become the new norm for how they see the world around them.

17 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

“I (sic) just want to say that men can be whatever they want and do whatever they want unless they are harming others.” (Student H)

I realised how starkly important it is to help boys have open conversations on masculinity. I realised the immense opportunity to lead and support these conversations, together with the terrifying burden of getting it right (or at least, not getting it wrong).

REFERENCES

A Call to Men. (2021). The Live Respect Middle & High School curriculum. https://www.acalltomen.org/liverespect/

Anderson, E. (2005). Orthodox and Inclusive Masculinity: Competing Masculinities among Heterosexual Men in a Feminized Terrain. Sociological Perspectives, 48(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2005.48.3.337

Beyond Equality. (2021). Beyondequality.org. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://www.beyondequality.org/blog-posts/imagine-toolkit-involving-boysin-preventing-street-harassment.

Brooks, D. (2022). How to Treat Others with Respect. IBSC Conference. The Path to Manhood. Dallas, Texas. 26 June 2022.

Brozo, W. G., Walter, P., & Placker, T. (2002). “I Know the Difference between a Real Man and a TV Man”: A Critical Exploration of Violence and Masculinity through Literature in a Junior High School in the ’Hood. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(6), 530–538.

Connell, R. (2016). Masculinities in global perspective: hegemony, contestation, and changing structures of power. Theory and Society, 45(4), 303–318. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/44981834

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859. http://www.jstor. org/stable/27640853

Connell, R. W. (1992). A Very Straight Gay: Masculinity, Homosexual Experience, and the Dynamics of Gender. American Sociological Review, 57(6), 735–751.

Connell, R. W. (1989). Cool Guys, Swots and Wimps: The Interplay of Masculinity and Education. Oxford Review of Education, 15(3), 291–303.

GQ (2019). The State of Masculinity Now (A GQ Survey) https://www.gq.com/ story/state-of-masculinity-survey accessed 19Jan2022.

Edley, N., & Wetherell, M. (1997). Jockeying for position: the construction of masculine identities. Discourse & Society, 8(2), 203–217. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/42888109

EDUCATION - Being ManKind. (2021). Being ManKind. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://beingmankind.org/education/.

Farrell, A.D., & Meyer, A.L. (1997). The effectiveness of a school-based curriculum for reducing violence among urban sixth-grade students. The American Journal of Public Health, 87, 979-984.

Gilpin, C., & Proulx, N. (2018). Boys to Men: Teaching and Learning About Masculinity in an Age of Change (Published 2018). Nytimes.com. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/12/learning/lessonplans/boys-to-men-teaching-and-learning-about-masculinity-in-an-age-ofchange.html.

Harland, K., & McCready, S. (2012). Taking boys seriously - a longitudinal study of adolescent male school-life experiences in Northern Ireland. Department Of Education, 59. Retrieved 30 December 2021, from https://dera.ioe. ac.uk/16385/7/taking_boys_seriously_final.docx_Redacted.pdf.

Harper, S. (2004). The Measure of a Man: Conceptualizations of Masculinity among High-Achieving African American Male College Students. Berkeley Journal of Sociology. Vo.48, pp.89-107.

Hurst, B. (2018, December). Boys won’t be boys. Boys will be what we teach them to be. [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/ben_hurst_boys_won_t_ be_boys_boys_will_be_what_we_teach_them_to_be?language=en

Legewie, J., & DiPrete, T. A. (2012). School Context and the Gender Gap in Educational Achievement. American Sociological Review, 77(3), 463–485.

Lu, A., & Wong, Y. (2013). Stressful Experiences of Masculinity Among U.S.-Born and Immigrant Asian American Men. Gender & Society, 27(3), 345-371. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0891243213479446

Lythcott-Haims, J (2022). How Not to Mess Up Your Boys. IBSC Conference. The Path to Manhood. Dallas, Texas. 27 June 2022.

Maricourt, C. de and Burrell, S. R. (2022) ‘#MeToo or #MenToo? Expressions of Backlash and Masculinity Politics in the #MeToo Era’, The Journal of Men’s Studies, 30(1), pp. 49–69. doi: 10.1177/10608265211035794.

Martino, W. (1999). “Cool Boys”, “Party Animals”, “Squids” and “Poofters”: Interrogating the Dynamics and Politics of Adolescent Masculinities in School. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 239–263.

Mertler, C., 2019. Action research. 6th ed. California: SAGE.

Messerschmidt, J.W. (2018). Multiple Masculinities. In: Risman, B., Froyum, C., Scarborough, W. (eds) Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3319-76333-0_11

Namy, B.H, Stitch, S., Crownover, J., Leka, B. & Edmeades, J. (2015). Changing what it means to ‘become a man’: participants’ reflections on a school-based programme to redefine masculinity in the Balkans. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17:sup2, 206-222

Norland, S., James, J., & Shover, N. (1978). Gender Role Expectations of Juveniles. The Sociological Quarterly, 19(4), 545–554. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/4105654

Nye, R. A. (2005). Locating Masculinity: Some Recent Work on Men. Signs, 30(3), 1937–1962.

Parsons, R., & Brown, K. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researcher. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Pinkett, M., & Roberts, M. (2019). Boys don’t try? Routledge.

Pitts-Tucker, T. (2012). Pressure to keep up macho image may drive men to suicide. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 345(7876), 4–5. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/23278637

Porter, T., (2021). Live Respect: Gender and racial equity curriculum. Acalltomen.org. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://www.acalltomen. org/resources/liverespect-gender-and-racial-equity-curriculum-for-youngpeople-ages-10-24/.

Porter, T., (2010). A Call to Men. TED Talk. Retrieved 9 July 2022, from https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_porter_a_call_to_men

Promundo-US and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (2018). Manhood

2.0: A Curriculum Promoting a Gender-Equitable Future of Manhood. Washington, DC and Pittsburgh: Promundo and University of Pittsburgh.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 18

What does Positive Masculinity mean to Year 8 students today?

Safer Schools (2021) Everyone’s Invited – Ofsted Update - Safer Schools. [online] Available at: <https://oursaferschools.co.uk/2021/06/17/everyonesinvited-ofsted-update/> [Accessed 6 July 2022].

Reiner, A. (2021) Better boys, better men: The new masculinity that creates greater courage and emotional resiliency. New York, NY, USA: HarperOne.

Rich, C. G. (2014). Angela Harris and the Racial Politics of Masculinity: Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman, and the Dilemmas of Desiring Whiteness. California Law Review, 102(4), 1027–1052. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23784359

Shover, N., Norland, S., James, J., & Thornton, W. E. (1979). Gender Roles and Delinquency. Social Forces, 58(1), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.2307/2577791

Sinacore, A., Shaofan, B., & Cheng, P. (2020). Responsible Sexual Citizenship in Today’s World: The Challenges Confronting Boys. IBSC.

Swain, J. (2000). “The Money’s Good, the Fame’s Good, the Girls Are Good”: The Role of Playground Football in the Construction of Young Boys’ Masculinity in a Junior School. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(1), 95–109. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/1393361

The Children’s Society (2021). How toxic masculinity affects young people. https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/what-we-do/blogs/how-toxicmasculinity-affects-young-people

The Representation Project. (2021) The Representation Project. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://therepproject.org/about.

Waling, A. (2019) Problematising ‘Toxic’ and ‘Healthy’ Masculinity for Addressing Gender Inequalities, Australian Feminist Studies, 34:101, 362-375, DOI: 10.1080/08164649.2019.1679021

Wang, Z., Chen, X., & Radnofsky, C. (2021). China to teach masculinity to boys because of changing gender roles. NBC News. Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/china-proposes-teachingmasculinity-boys-state-alarmed-changing-gender-roles-n1258939.

Wilkinson, K. (1985). An Investigation of the Contribution of Masculinity to Delinquent Behavior. Sociological Focus, 18(3), 249–263. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/20831367

Willer, R., Rogalin, C. L., Conlon, B., & Wojnowicz, M. T. (2013). Overdoing Gender: A Test of the Masculine Overcompensation Thesis. American Journal of Sociology, 118(4), 980–1022. https://doi.org/10.1086/668417

Whitehead, S. (1998). Hegemonic masculinity revisited. Gender, Work, and Organization, 6(1), 58-62.

19

ABSTRACT

Schools are a place where students have the opportunity to receive and experience lessons, ranging from moral, personal and educational (Ryan and Lickona, 1992; Lerner, 2018), but do students really gain more than academic progress from lessons? The national curriculum for Physical Education identifies the requirement for students to become physically confident alongside building their character (Department for Education, 2012), which in turn should further promote and reinforce the wider development of our students than a single aim of educational achievement through their school lives. This research explores what lessons can offer aside from the academic progress from the perspective of the students themselves, with a focus on character development, particularly ownership.

Despite there being a clear vision and required desire to teach more than just the subject content, historically there has been a “hesitation” among the educational community to steer away from a “traditional” teaching programme. These concerns stem from a dominant ideology that lessons may “detract from the focus” of “increasing academic performance” (Benninga et al., 2006, p.448-452), suggesting that content knowledge not only holds a higher priority than developing young people, but also that both character and personal development can not occur alongside the learning of the subject. Fortunately, this view is becoming increasingly outdated, with a number of schools developing character education models, such as the AGS Learner. These models underpin key characteristics that shape young people in preparation for their future, but hold no overruling structure on how these are integrated or experienced for the student. Again, as previously stated, this project focuses on character development within lessons, but will further explore the impact a student centred teaching style has on exposing aspects of the AGS Learner to students, with ownership being the prioritised focus.

Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

Harry Dudmish Teacher of P.E.

Mosston and Ashworth (1990, 2002) for a number of years have been academics within the field of education, creating the “spectrum of teaching styles”. This spectrum indicates the broad range of teaching methods that can be used to deliver subject knowledge to the students. Despite there being multiple styles across the spectrum, there are two opposing agendas that encompass these: a student centred and teacher centred approach. Since then, there has been a magnitude of research surrounding the spectrum and methods within, indicating positives such as character development around student centred styles (Kaput, 2018). However, this project does not seek to debate which style of teaching is greater or holds more value, but rather to examine the impact a student centred approach has on the character development of students in P.E., while still exposing students to the school and national curriculum in lessons.

In summary, this research will look at clarifying three aims around the topic of character development.

1) Do P.E. lessons allow students to build their character as required in the national curriculum, and expose them to aspects of the AGS Learner?

2) Does a student centred approach, as suggested by academics, have an impact on character development?

3) Following on from the previous aims, how much is the ownership of the students enhanced and nurtured within P.E.?

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

CONTEXT

There are a number of reasons this project was carried out, which include investigating methods of integrating the AGS Learner into lessons, offering more to students than just the curriculum and subject knowledge, and gaining an understanding of the students’ perspective of physical education and teaching styles. All of these were underpinned by an ever present factor of still providing a valuable sequence of lessons following the department’s scheme of work, with an effort of nurturing character throughout.

Aylesbury Grammar School has been nurturing character since 1598, and can proudly demonstrate the development of character all the students experience throughout their school lives, while obtaining outstanding GCSE and A Level results. This combination results in students leaving AGS as young adults well prepared for their future, both academically but also in wider society. However, students are also required to develop wider skills and characteristics effectively in the younger year groups, just as much as the senior students. For a number of years the Year 7 cohorts have been formed by a spread of differing primary schools, with many new students joining AGS as a single student from their previous school, and not knowing anyone in their form, year or the school community. In 2022/23 the Year 7 body will include boys from 75 primary schools across neighbouring counties, highlighting the diverse group of young students joining, but also the immediate need for students to have suitable social and personal skills to cope with such change.

achieve their next step in education and their future careers. More specifically, P.E. at both GCSE and A-level also matches the school trend of high grades, alongside multiple students forming successful careers within the sport industry. However, despite the successes AGS P.E. provides within education and careers, the uptake of students selecting GCSE P.E. over recent years ranges between 20-30 boys, which equates to 14%. Equally, for A Level, student numbers range between 5-10 for P.E., which is 4% of the year. With over 80% of boys not selecting P.E. as an option, is there a need for such a dominant skill development focus for all students in KS3? Or can P.E. offer more by using physical activity as a vehicle to teach sport alongside wider skills and benefits?

LITERATURE REVIEW

For many years it has been known that schools are a great facilitator for young people to experience multiple developmental benefits which include character (Ryan and Lickona, 1992; Lerner, 2018), yet there has been a consistent reluctance to veer away from anything that is not curriculum focused (Benninga et al., 2006). However, more recent studies can suggest that this view within education is becoming increasingly outdated (Hellison, 2010; Arthur et al., 2016; Pike, et al., 2021), with frameworks such as character development models being in place nationwide, and school structures and environments lending themselves to support students in wider enrichment (Lavy, 2020). In addition to this, when looking into the specific topic of sport, historically there are clear indications that a sporting environment too provides fantastic opportunities to enhance these factors (Shields and Bredemeier, 1995; Gould and Carson, 2008). Despite academics highlighting the huge positive scope around personal development within schools and sport, there is limited indication of which methods best enhance the opportunities for these developments to occur.

Similar to the pattern of the Year 7 intake, is the display of excellent GCSE and A-level results students achieve from Aylesbury Grammar School. Throughout the School, in each subject, students obtain fantastic grades to help them

Research from Solomon (1997) and Rahman (2007) opened up two significant views on delivering P.E. to students and how sports can holistically be taught. The first, and arguably most obvious, is known as “teaching of the physical”. This very much relates to the “traditional” way of teaching, which involves teaching skill acquisition and seeking performance development and sporting understanding. The second approach is “teaching through the physical” which allows for broader learning to take place, while using the sport as the vehicle for learning to occur. New research indicates

23 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

For many years it has been known that schools are a great facilitator for young people to experience multiple developmental benefits which include character.

that these applications can be blended together to allow students to develop their sporting ability alongside their character, social and life skills (Suherman, Supriyadi and Cukarso, 2019; Pennington, 2019), which could be a factor in why there is now less reluctancy in character development within lessons. However, none of these academics were able to expand on teaching styles and methods for best delivering these approaches. Only in the last decade has there been any definitive research into specific teaching styles that are proposed to support character development alongside educational learning within lessons. Prior to this, academics could only offer looser suggestions in what can be incorporated to aid with wider enrichment of students, such as offering students a range of experiences within the same lesson (Siedentop, 1994; Hanif, 2006); lessons that utilise different motivational aspects (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Rahman, 2007); competition (Shields and Bredemeier, 1995) and social/team activities (Tutkun, Görgüt and Erdemir, 2017). In comparison, much more recent literature proposes that a student centred approach, and more specifically, a Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) approach is well suited to enhance character, particularly due to the use of conditioned games (Harvey, Kirk and O’Donovan, 2014; Sujarwo et al., 2021). Sujarwo et al. (2021) further expands on this, with an understanding that by providing clear parameters for students to work in, while not dictating on a specific technical focus, students will be able to find a range of successful ways to achieve the goals set out, and ultimately learn through this process and be exposed to social and personal developmental opportunities. However, there is a requirement for consistent reinforcement with aims and for lesson objectives to be clear, otherwise the focus of the lesson can become lost, and students may not receive any benefits from this style of teaching (Griffin and Butler, 2005; Mitchell, Oslin and Griffin, 2013). This limitation to TGfU can be directly linked back to Solomon (1997) and Rahman (2007), where using sport as a vehicle for learning, rather than a direct skill acquisition focus, can allow for students of differing ability to learn at different rates, alongside having different experiences to enhance characteristics. This integrated approach of blended learning for all has been supported for a number of years, particularly when it comes to the inclusion of character development (Berkowitz and Bier, 2005; Felderhof and Thompson, 2014; Pike, 2015).

METHODOLOGY

This project focused solely on KS3 students, across four support classes ranging from Year 7 to 9. With a wide sample of students being exposed to this research, there was an aim to be able to collate data from an array of perspectives, providing a true reflection on the impact a student centred approach has. The objective of accumulating accurate data from research within the character development field can provide challenges, as personal development can be difficult to assess externally (Mambu, 2015; Halonen et al., 2020). With this in mind the data collection process concentrated predominantly on questionnaires to provoke a self reflection process, which is suggested to hold greater value (Elias, Ferrito and Moceri, 2015). Although this collection method relies heavily on student comprehension and honest self reflection, the use of such a broad sample size should allow for anomalies to become filtered out.

As one of the aims within this research was to gain an understanding of the impact a student centred approach has on character development, students were required to complete an initial questionnaire, as an opening reference point for future comparisons to take place. The methodology had two data collection points, one before the TGfU unit of work started, and then one at the end. As suggested by Pike et al. (2021), this framework will offer suitable opportunities to assess each collection point separately, alongside comparing the impact the student centred approach had, using thematic analysis. Both of these data points used the same questionnaire to allow for more accurate comparisons, but with the final questionnaire also having extended probing questions around ownership, to enhance the search for specific understanding within this characteristic.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 24

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

In addition to the questionnaires, students who were unable to participate in P.E., due to no kit or injuries, would be completing a live observation and reflection sheet on the lesson taking place. This provided an added lens to the research allowing for students to express their views during the unit of work, in addition to the two collection points. This ‘non-doer sheet’ in conjunction with the questionnaire provided both quantitative and qualitative feedback, which now offered some reasoning behind the numbers that would be gathered.

This streamlined data collection method had the single focus of clarifying the three aims previously mentioned, with little deviation. With two assessment points, one initial and one final, alongside the non-doer sheet there was a specific focus on quantitative data, with some qualitative to provide context.

FINDINGS

The initial and final questionnaires provided a source of discussion not only around the particular topic of ownership, but also the general topic of character development within P.E. This section will aim to break down the questions asked in the questionnaire, with an analysis from the results gathered.

25 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

The first is known as “teaching of the physical”... which involves teaching skill acquisition and seeking performance development and sporting understanding. The second is “teaching through the physical” which allows for broader learning to take place, while using the sport as the vehicle for learning to occur.

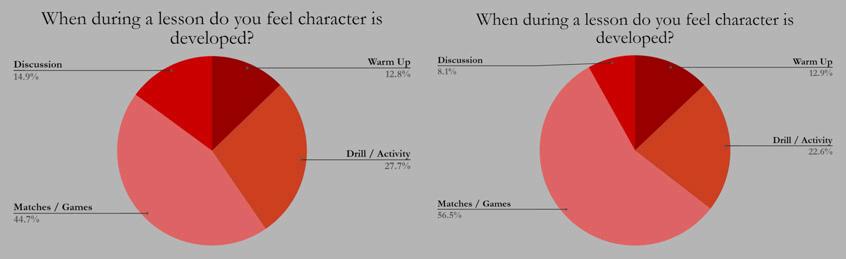

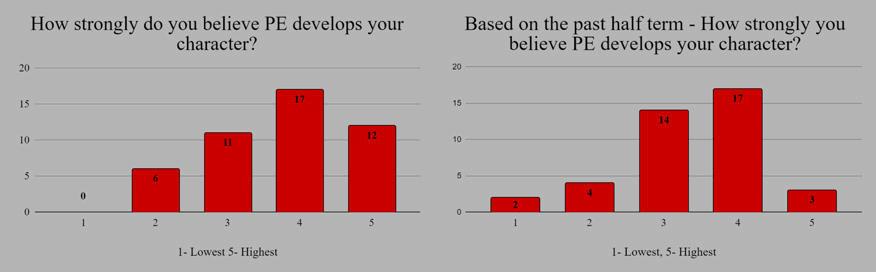

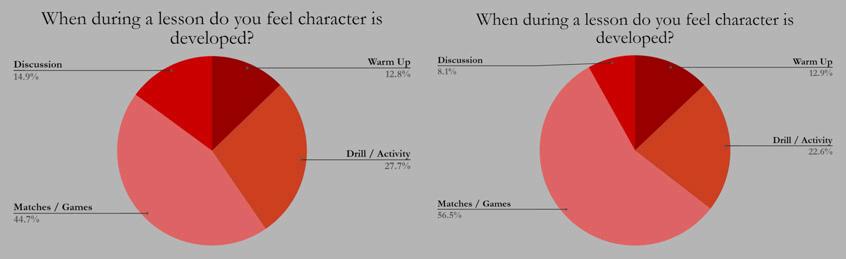

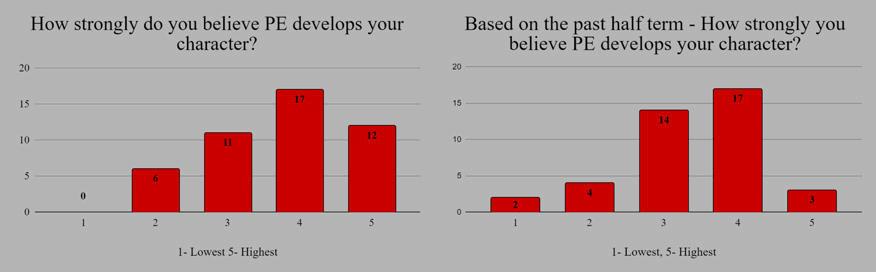

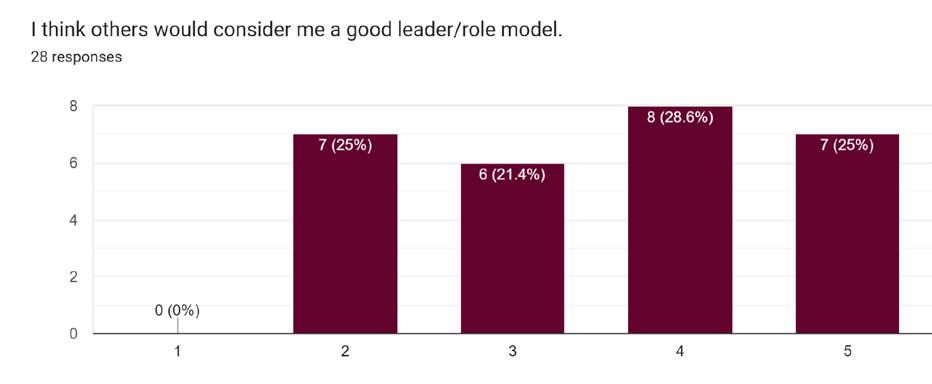

Both charts above highlight that there is a general consensus within the sample group that P.E. does have an impact on the development of character. Both assessment points showed four as the highest response, which corresponds to students thinking P.E. has an impact on character, indicating that sports does offer opportunities for personal development to occur. This supports the research from Shields and Bredemeier (1995), Gould and Carson (2008), which stated how effective a positive sporting environment can be.

When comparing the two results, it is initially clear to see that fewer students, after experiencing a TGfU unit, strongly believe P.E. developed their character, yet the remaining categories hold similar numbers between the sets of data. This could imply that on the surface, a unit of work on TGfU has little differing impact in comparison to a varied format of teaching, however when diving deeper into the questioning, this view starts to change.

Immediately, on both graphs it is clear that a large proportion of students feel that the games aspects of lessons have a significant impact on their character development. Also, it is interesting to see that between the two sets of data, there is both an increase in the perceived impact games have on character, in addition to a drop off in the impact of drill activities. This clearly highlights that students themselves, upon reflection, believe their personal development is most likely to be enhanced most during game situations, rather than drills. These findings directly coincide with research from Harvey, Kirk and

O’Donovan (2014) and Sujarwo et al. (2021), indicating that in fact conditioned games do enhance the development of young people’s character. Although there was both an increase in responses for games, and a decrease in drills, around a fifth of students believe drill activities support their character development. This can suggest that using a mixed approach would cater for a wider range of students, but would this then affect the majority of the class that selected games, or dilute the amount of opportunities to develop character by blending methods?

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 26

HOW STRONGLY DO YOU BELIEVE P.E. DEVELOPS YOUR CHARACTER?

WHEN DURING A LESSON DO YOU FEEL CHARACTER IS DEVELOPED?

What

P.E.

is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during

lessons?

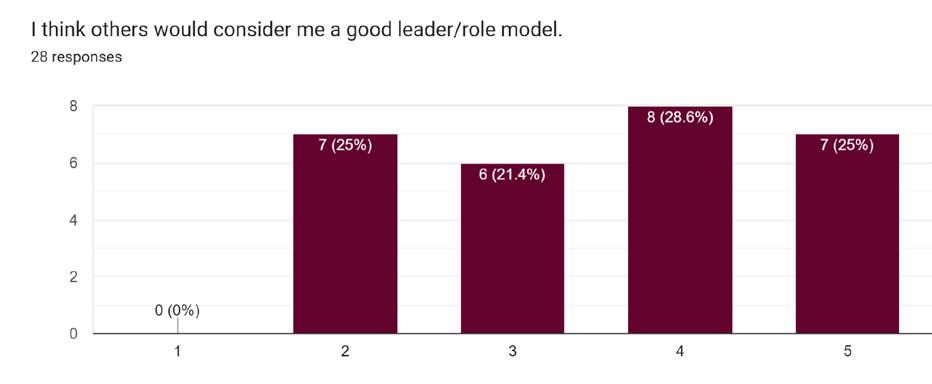

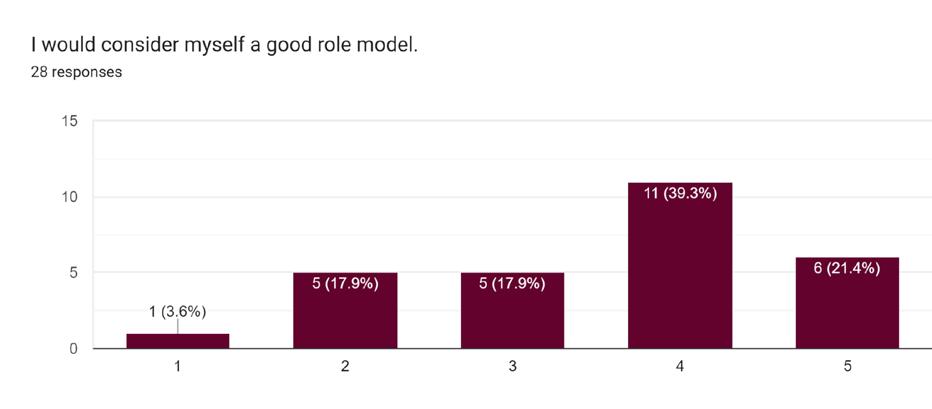

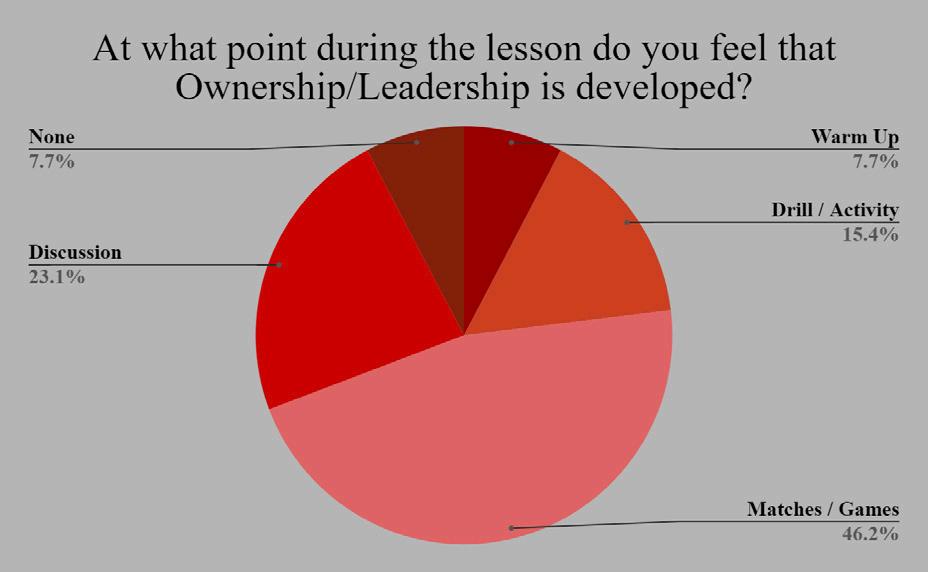

Firstly, with the students, the term ownership was interchanged frequently with leadership, resulting in discussions and data collection requiring to group the two terms together. From the data collected, it was evident that the student body was equally split with how they felt ownership was developed using a TGfU approach to the unit. The majority placed themselves in the middle ground (3), with a fairly equal proportion leaning towards they believed/strongly believed (4 and 5) conditioned games enhanced ownership in comparison to not believing/ strongly not believing (1 and 2). The fact students exchanged ownership and leadership could imply there is a misunderstanding with the terminology, which has then resulted in the majority selecting option 3. However, these results could also suggest that ownership is not a considerable factor that is developed through games from the students’ perspective, and that they believe other characteristics are enhanced more through the use of games. It is evident from previous graphs that students believe characteristics are developed through conditioned games, although maybe not ownership/leadership as much.

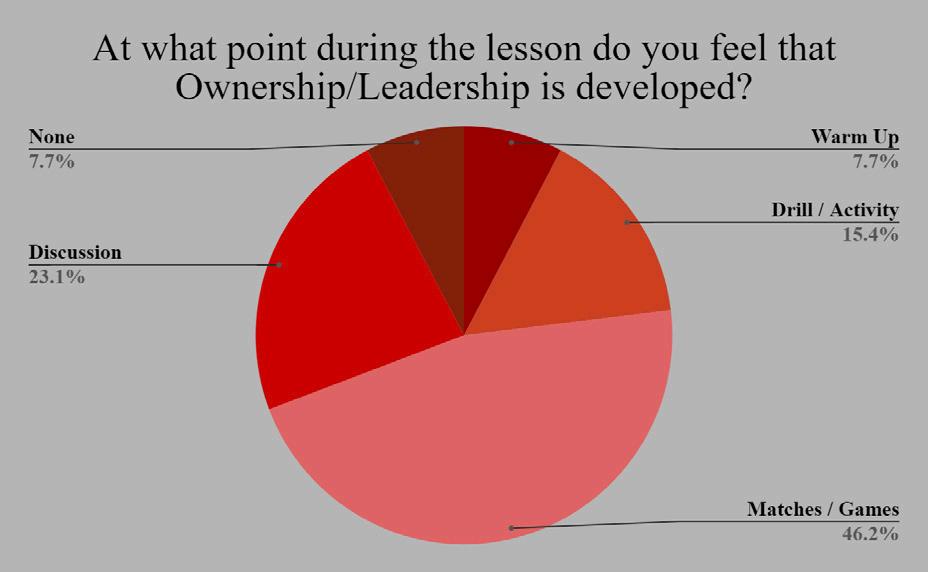

Although the previous graph indicated no suggestions that a TGfU approach impacts ownership, further questioning would rather suggest that the topic of work, or P.E. itself, has little effect on ownership development. This is because, when students were asked when ownership is developed during lessons, games again received the greatest response. In addition to this, drills received a huge drop off in comparison to games and discussions, and in previous questioning regarding wider characteristics. This highlights that a TGfU approach could offer some support with ownership being enhanced in comparison to reciprocal or command focus teaching styles, as only 15% of students stated drills as a response.

When students were further questioned into when specifically they felt the characteristic of ownership was most apparent for them, responses signal more reinforcement around the research of Harvey, Kirk and O’Donovan (2014) and Sujarwo et al. (2021) on TGfU.

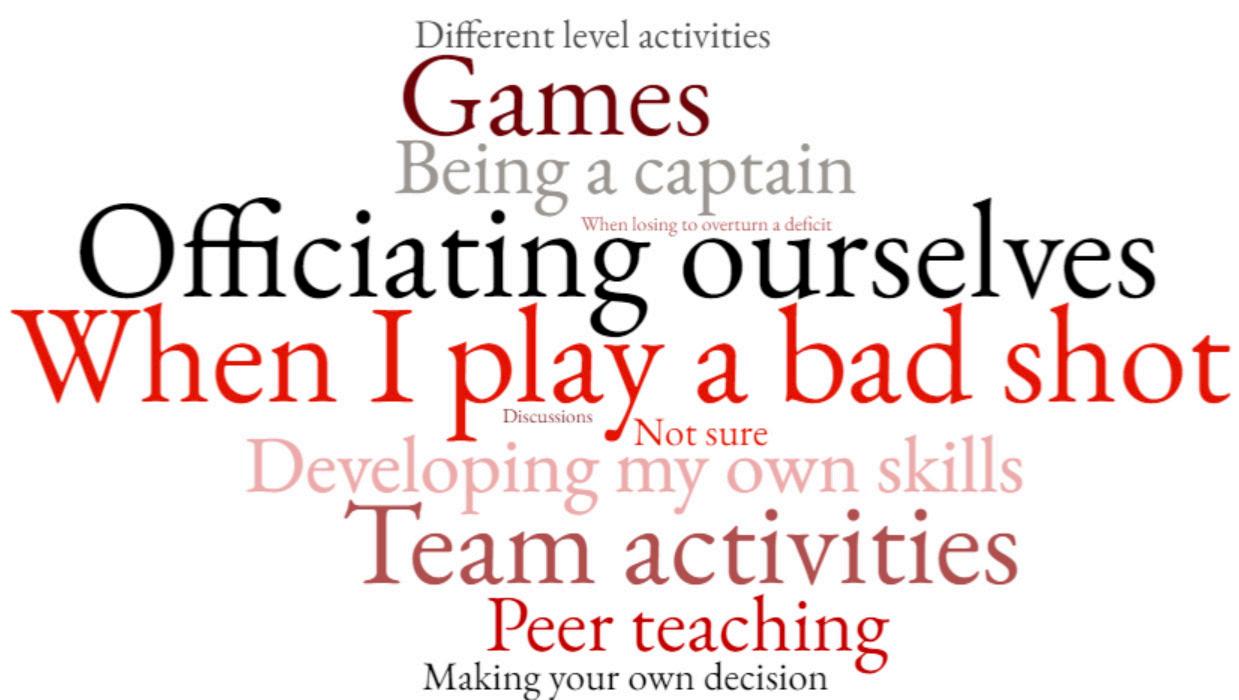

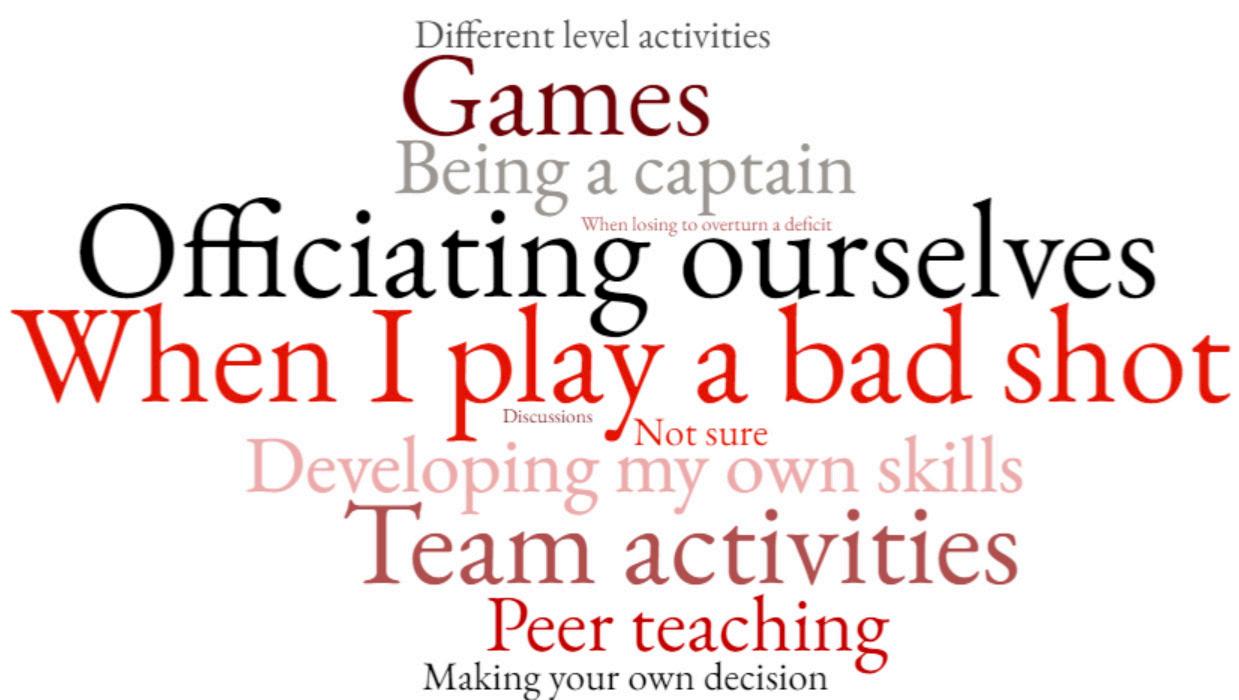

The image above shows the written responses of students, with the use of thematic analysis to group like-minded statements together to build a picture of the students’ thoughts - the larger the words, or phrases, the more common the response was. Many of these responses circulate around the theme of matches or gameplay, hinting that it is during a game when most students take ownership of their actions, learning or activity.

27 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

HOW STRONGLY DO YOU BELIEVE OWNERSHIP/ LEADERSHIP WAS DEVELOPED DURING THE TGFU UNIT?

WHEN DURING A LESSON DO YOU FEEL OWNERSHIP/LEADERSHIP IS DEVELOPED?

In 2022/23 the Year 7 body will include boys from 75 primary schools across neighbouring counties, highlighting the diverse group of young students joining, but also the immediate need for students to have suitable social and personal skills to cope with such change.

This correlates not only with research previously stated, but also ties together the previous graphs from the quantitative data, evidencing that students can not only identify what activities best support their personal development, but when specifically during these lessons characteristics are being practised.

STUDENT OBSERVATIONS

What teaching style was predominantly used in the lesson?

Centered 3

CONCLUSION

In summary, this project offered reinforcement to many of the academics stated within the literature review, with a comprehensive understanding of what P.E. and a TGfU approach can provide for students away from skill acquisition. Throughout this research were three aims that underpinned the focus, and which structured this report.

1) Do P.E. lessons allow students to build their character as required in the national curriculum, and expose them to aspects of the AGS Learner? When reflecting on both the initial and final data collection points, it seems apparent that P.E. certainly can offer, and does offer, the opportunity to develop aspects of the AGS Learner to the overwhelming majority of students.

In addition to the student reflections, any non-doer was required to provide live observations, indicating their thoughts on the teaching style being used, and then the characteristics being exposed during the lessons. These observations demonstrate, and further support, both previous findings from this research and academics, as the students observing the lessons noted that a teacher centred approach provides the fewest opportunities to develop characteristics. In addition to this, the observations also indicate that there is no opportunity for students to take ownership during a teacher centred delivery of a lesson. In comparison, a student centred approach, and an equal combination, offers many more opportunities for personal development, with ownership being stated in both styles.

2) Does a student centred approach, as suggested by academics, have an impact on character development? Certainly. A student centred approach provides a magnitude of opportunities for character to be enhanced and developed. There is, however, certainly a suggestion that an equal combination of both teacher and student centred approaches could offer richer value to a wider range of learners.

3) How much is the ownership of the students enhanced and nurtured within P.E.? Ownership is a factor that is involved with P.E., and based on the observations, significantly more so when delivered with a student centred style. However, it seems that other characteristics are developed more within P.E., and that student understanding of ownership, and possibly other characteristic terminology requires clarity and further learning and defining.

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 28

Student

Teacher

Equal

Centered 2

combination 3

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

REFERENCES

Arthur, J., et al., 2016. Teaching character and virtue in schools. Routledge

Benninga, J., et al., 2006. Character and academics: What good schools do. Phi Delta Kappan, 87(6), pp.448-452.

Berkowitz, M. and Bier, M., 2005. What works in character education: A research-driven guide for educators. Washington, DC: Character Education Partnership.

Deci, E. and Ryan, R., 1985. Motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. NY: Plenum Publishing Co.

Department for Education, 2012. Physical education programmes of study: key stages 3 and 4.

Elias, M., Ferrito, J. and Moceri, D., 2015. The Other Side of the Report Card: Assessing Students’ Social, Emotional, and Character Development. Corwin Press.

Felderhof, M. and Thompson, P., 2014. Teaching Virtue The Contribution of Religious Education. London.

Gould, D. and Carson, S., 2008. Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. International review of sport and exercise psychology, 1(1),

Griffin, L and Butler, J., 2005. Teaching Games for Understanding: Theory, Research, and Practice. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Halonen, J. et al., 2020. The Challenge of Assessing Character: Measuring APA Goal 3 Student Learning Outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 47(4).

Hanif, A., 2006. Sport. Ed @ Zhenghua Secondary School. Physical Education Newsletter, 20, 6-7.

Harvey, S., Kirk, D. and O’Donovan, T., 2014. Sport education as a pedagogical application for ethical development in physical education and youth sport. Sport, Education and Society, 19(1).

Hellison, D., 2010. Teaching personal and social responsibility through physical activity. Human Kinetics.

Kaput, K., 2018. Evidence for Student-Centred Learning. Education evolving.

Lavy, S., 2020. A review of character strengths interventions in twenty-firstcentury schools: Their importance and how they can be fostered. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2).

Lerner, R., 2018. Character development among youth: Linking lives in time and place. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 42(2).

Mambu, J., 2015. Challenges in assessing character education in ELT: Implications from a case study in a Christian university. TEFLIN Journal, 26(2).

Mitchell, S., Oslin, J. and Griffin, L., 2013. Teaching Sports Concepts and Skills: A Tactical Approach for Ages 7 to 18. Human Kinetics: Leeds.

Mosston, M. and Ashworth, S., 1990. The Spectrum of Teaching Styles. From Command to Discovery. Longman, White Plains, New York. Mosston, M., and Ashworth, S., 2002. Teaching physical education (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Benjamin Cummings.

Pennington, C., 2019. Creating and confirming a positive sporting climate. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 90(4).

Pike, M. et al., 2021. Character development through the curriculum: teaching and assessing the understanding and practice of virtue. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(4).

Pike, M., 2015. Ethical English – Teaching and Learning in English as Spiritual, Moral and Religious Education. Bloomsbury, London.

Pike, M., et al. 2021. Character development through the curriculum: teaching and assessing the understanding and practice of virtue. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(4).

Rahman, H.A., 2007. The zhenghua PE experience: A constructivist approach to character development through physical education.

Ryan, K. and Lickona, T., 1992. Character development in schools and beyond (Vol. 3). CRVP.

Shields, D. and Bredemeier, B., 1995. Character development and physical activity. Human Kinetics Publishers.

Siedentop, D., 1994. Sport education: Quality PE through positive sport experiences. Human Kinetics Publishers.

Solomon, G., 1997. Does physical education affect character development in students?. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 68(9).

Suherman, A., Supriyadi, T. and Cukarso, S, 2019. Strengthening national character education through physical education: An action research in Indonesia. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(11).

Sujarwo, S. et al., 2021. The Development of Physical Education Learning Models for Mini-Volleyball to Habituate Character Values among Elementary School Students. Sport Mont, 19(2).

Tutkun, E., Görgüt, İ. and Erdemir, İ., 2017. Physical Education Teachers’ Views about Character Education. International Education Studies, 10(11).

29 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

What is the impact of either a student centred or games approach on key stage 3 students’ character development, particularly ownership, during P.E. lessons?

To what extent can Year 9 students’ perceptions of role

and challenged within teacher and peer-led Personal Development sessions?

ABSTRACT

One of the key aims of education is to build character and help build young people into adults prepared to contribute to society, and we would like to think in doing this we are building role models. There is, however, a lot of debate and discussion around how students understand what a role model is or should be, and more interestingly where students might identify role models. As teachers, we often like to think of ourselves as role models, but how else can we help our young people to develop themselves into positive role models for society?

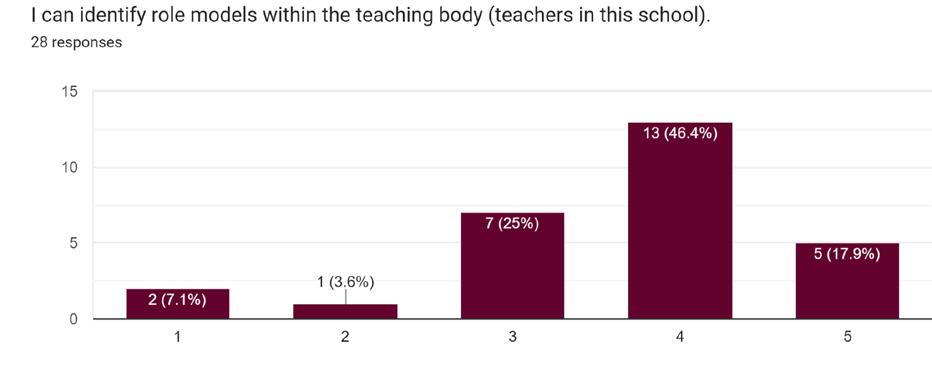

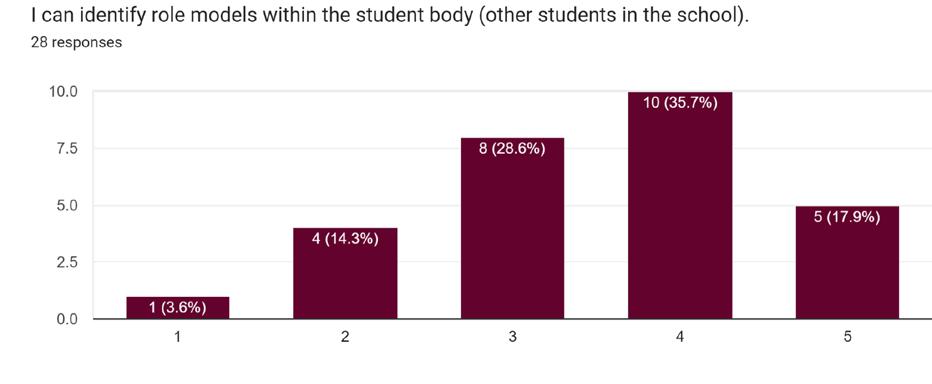

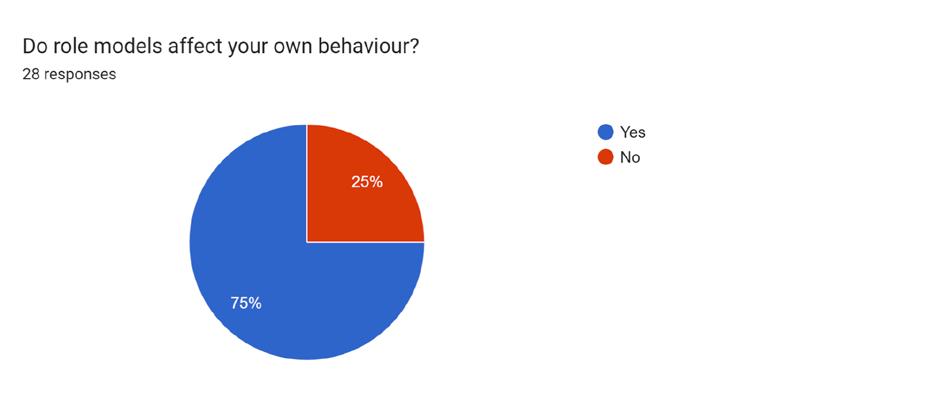

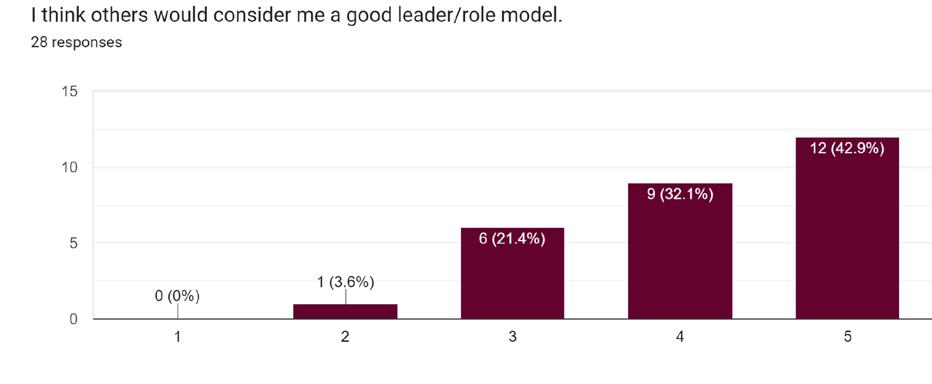

The aim of this research project is to investigate how our students perceive role models, their characteristics and where they view themselves within this. It then seeks to consider how teacher and peer intervention can be used to broaden and challenge these notions, and create greater discussion in the classroom of what makes a good role model. Within this, it evaluates the success of a series of Personal Development sessions in AGS with Year 9 that is one such example of this intervention in action. By assessing their engagement, attitudes and ideas, the research provides some interesting results, highlighting the potential benefits of peer discussions and sessions across a wider cohort.

31 Flagship: Journal for Evidence Engaged Practice

models be broadened

James Taylor Teacher of History

CONTEXT

Aylesbury Grammar School is a selective boys’ grammar school in Buckinghamshire, founded in 1598. It prides itself on not only achieving outstanding results at both GCSE and A Level, but offering a wide ranging extra-curricular provision to encourage access to a full and expansive curriculum. This is underpinned by a commitment to nurturing character development through the wider AGS Learner ideal, comprising the five broad characteristics of Ownership, Courage, Resilience, Innovation and Motivation.

As part of the wider development of character education in school, Personal Development sessions were introduced as part of a form tutor’s responsibilities during extended registration with their form group. These sought to discuss a series of issues, and encourage students to reflect upon their own character, values and attitudes. This also took place in a wider focus more recently on positive masculinity, with Positive Sexual Citizenship and Positive Masculinity both forming key foci in the School Development Plan for the year. This research sits alongside these priorities, as issues of role models and masculinity, research suggests, can be addressed alongside one another and are in many ways intertwined issues.

Across the academic year 2021-22, I have been a form tutor for a Year 9 group, and this seems a clear juncture in their school journey. They have transitioned fully into secondary school life, are a year group affected by Covid and during this year also begin to make choices down their future pathways by picking their GCSE options. This is also a key moment in which ideas of role models, masculinity, and leadership can be embedded - these students in the next year or so may be aspiring to Junior Prefect positions, taking on increased responsibilities, as well as facing potential challenges and barriers as they embark on GCSEs.

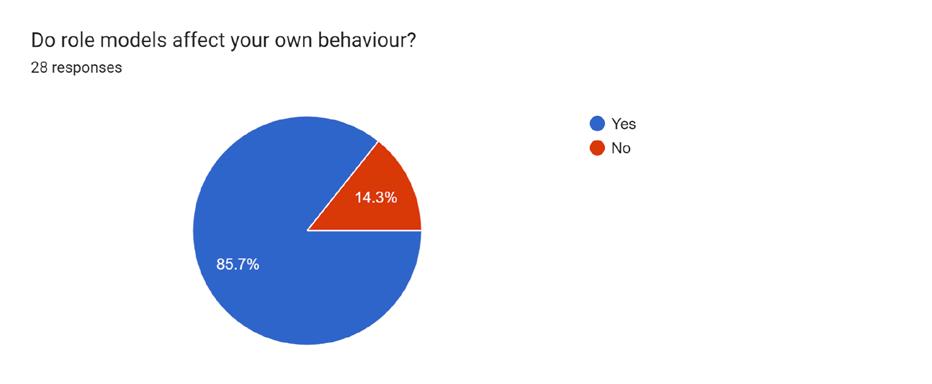

Therefore, this six week series of Personal Development sessions sought to both gain insight into their perceptions of role models, and thus what might influence their behaviour, values and attitudes towards masculinity and leadership. It also aimed to instil greater confidence in these students in themselves as potential role models for the future, and encourage them to seek to be positive role models.

LITERATURE REVIEW WHERE DO WE FIND ROLE MODELS?

Role models are discussed throughout society, with the term itself now to an extent amalgamated with other ideas, such as leadership, masculinity and achievement. This is something that Carrington and Skelton (2003) support, arguing:

“a role model today is most often equated with ‘a symbol of achievement’ and is sometimes conflated with being a ‘star’ or ‘idol’”

This seems, most obviously, to explain the idolisation and admiration of celebrities and famous individuals today, which is a factor that is worth discussing when it comes to how young people may view, and indeed misinterpret, role models.

Understanding role models, and how they are developed, can be discussed within traditional learning theories, particularly social learning theory (Bandura, 1986). Within this, Bandura argues that attitudes, values, and beliefs are formulated and learned through observation of others and experiences. Thus, the importance of role models cannot be understated, if this will lead others to transform their own behaviours in response. Role models are likely to be key to the socialisation process, and a great source of learned behaviour.

Thus, education is one area in which role models are sought, and there is a suggestion that young people have a narrowed view of role models that needs addressing by schools, as research suggests young people rarely challenge themselves on where attitudes come from, nor easily find reference points to change their outlook and values (Odih, 2002). Schools absolutely can tackle this, but the fact that this often then leads to more prescriptive solutions of ‘role models’ to address underachievement and ‘laddish’ behaviour in particularly young boys is interesting. suggesting an assumption that purely increasing the presence of role models within schools might be the solution (Francis, 2000). Whether this is achievable is one thing, but whether it is even necessary, for example, for male teachers to act as role models specifically for young boys is an assumption that research can challenge.

When it comes to where young people find role models, parents are cited frequently in research to be pivotal and

w: ags.bucks.sch.uk 32 To what extent can Year 9 students’ perceptions of role models be broadened and challenged within teacher and peer-led Personal Development sessions?

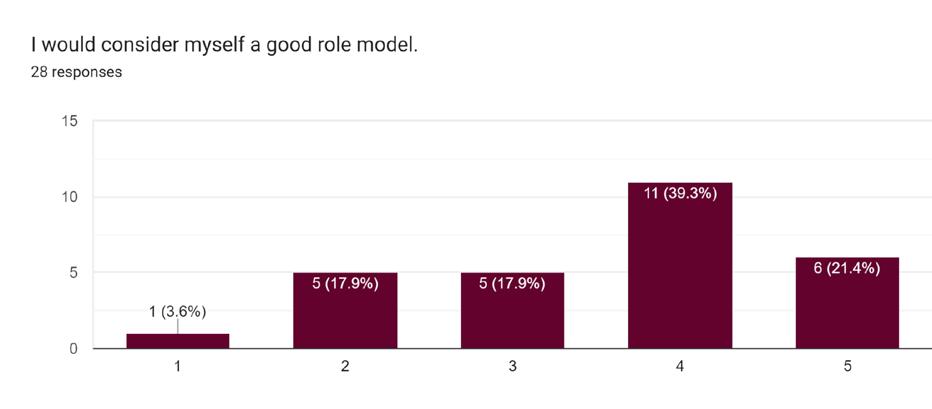

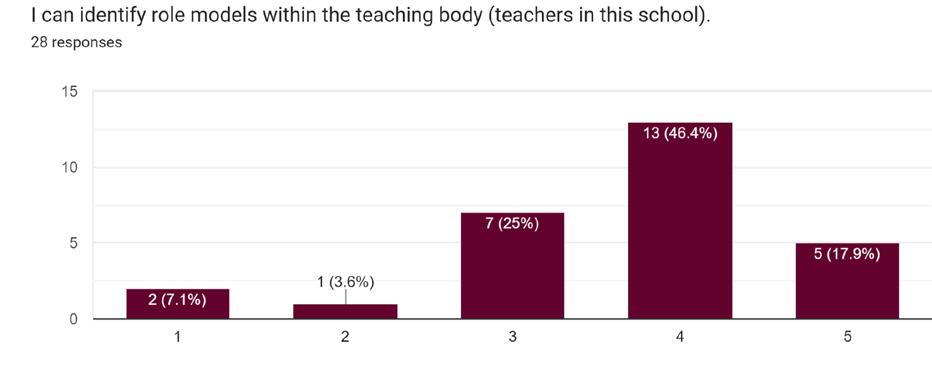

main role models (Stephens, 2006; Wiese and Freund, 2011). The idea that young people would emulate their parents is not surprising given Bandura’s socialisation theories, but the fact that further studies have continued to highlight this, and especially the lack of teacher presence in young people’s choice of role models, poses interesting questions - one that my research intended to unpick with our students.

WHY ARE ROLE MODELS IDENTIFIED?