Ryuji Tanaka ii

Ryuji Tanaka II

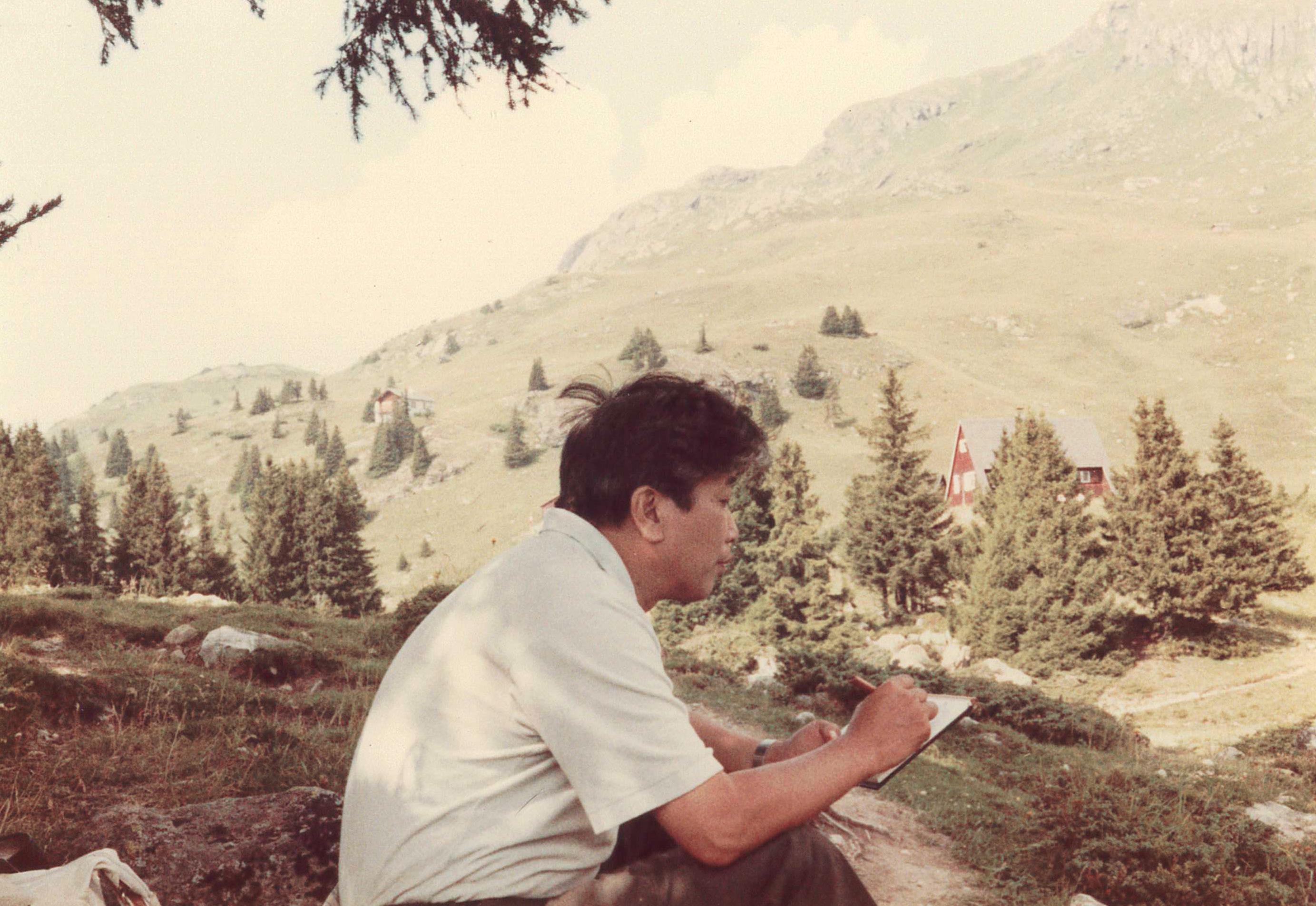

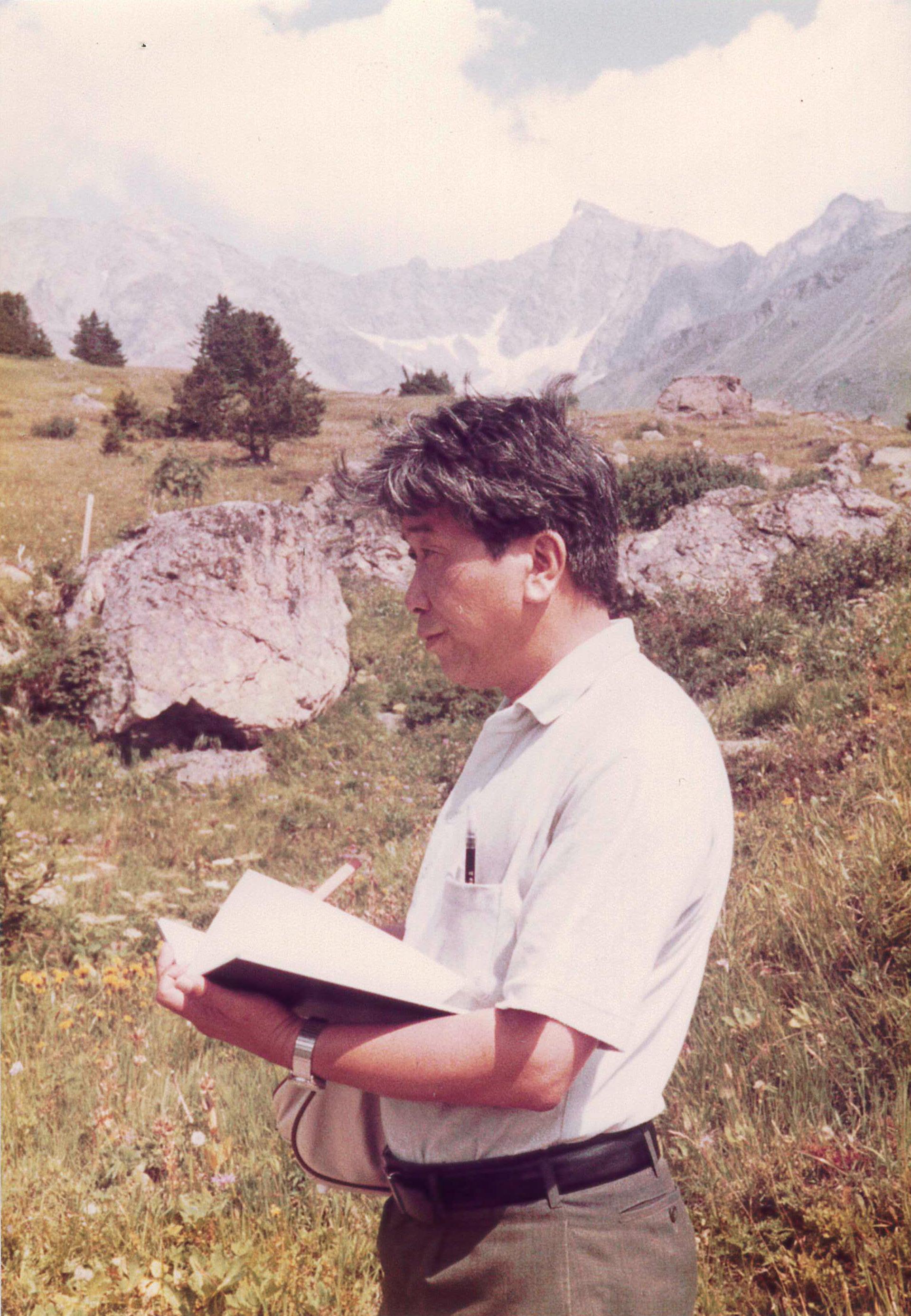

Tanaka sketching outdoors, ca. 1982.

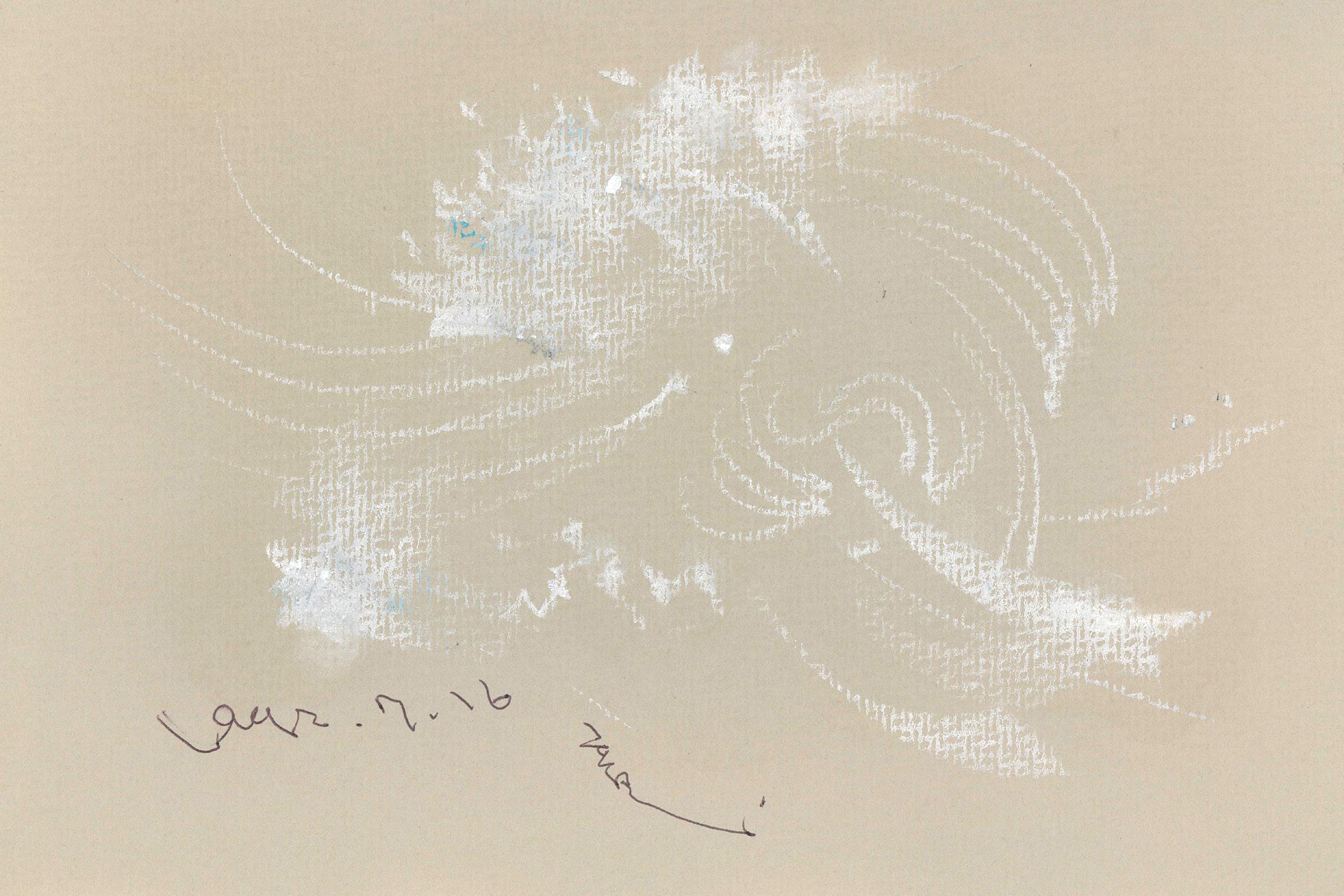

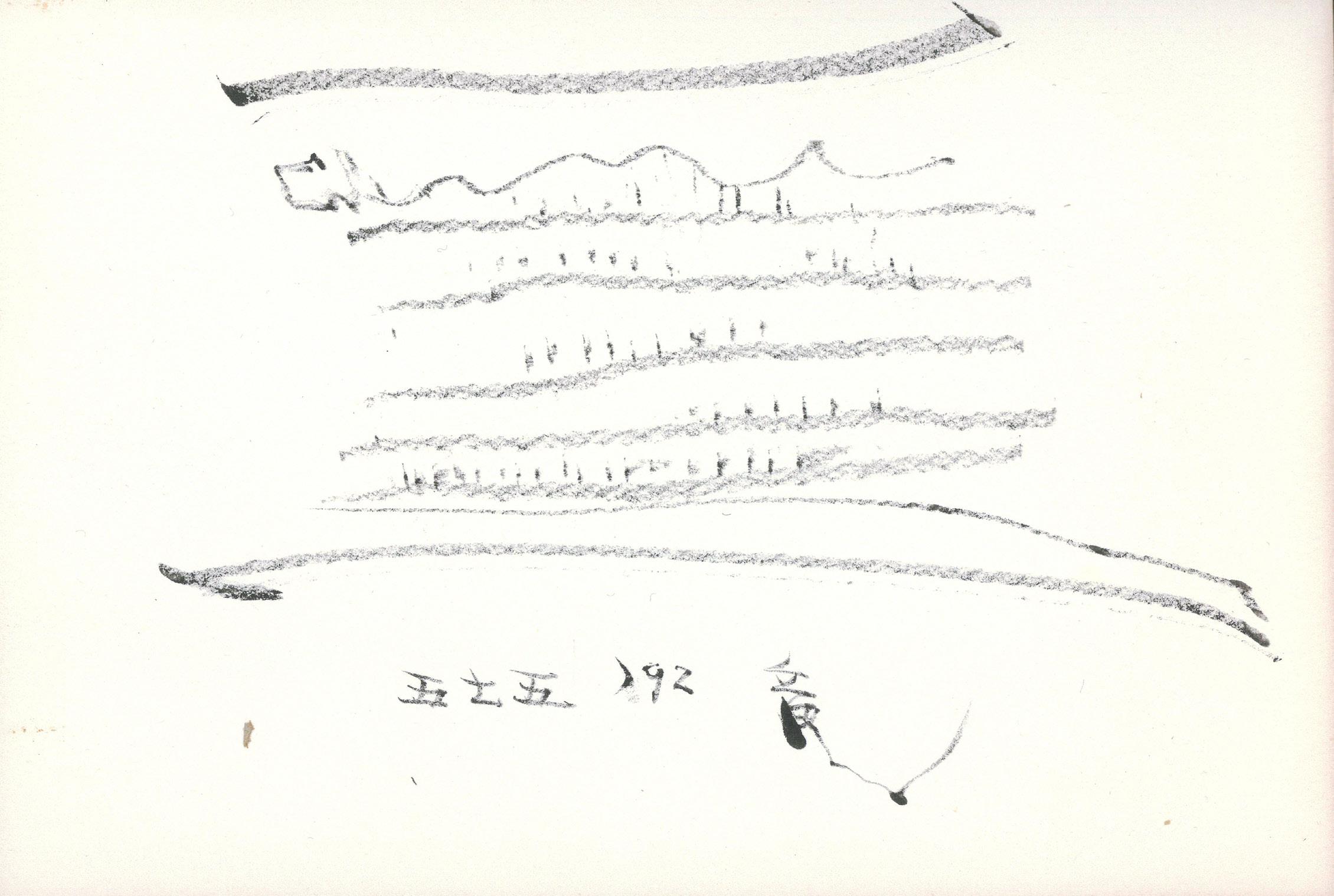

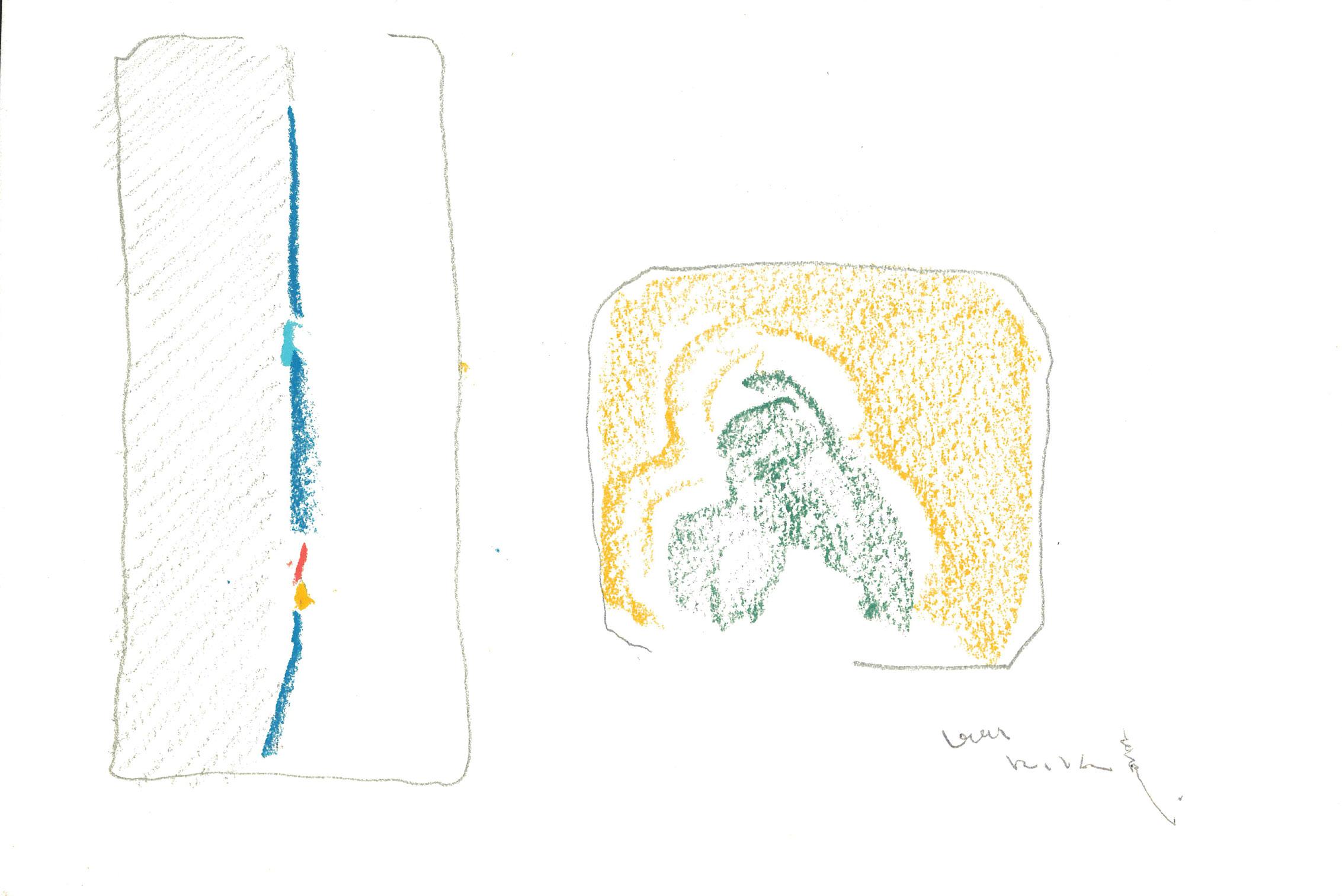

Preliminary sketch on paper, 16 July 1992.

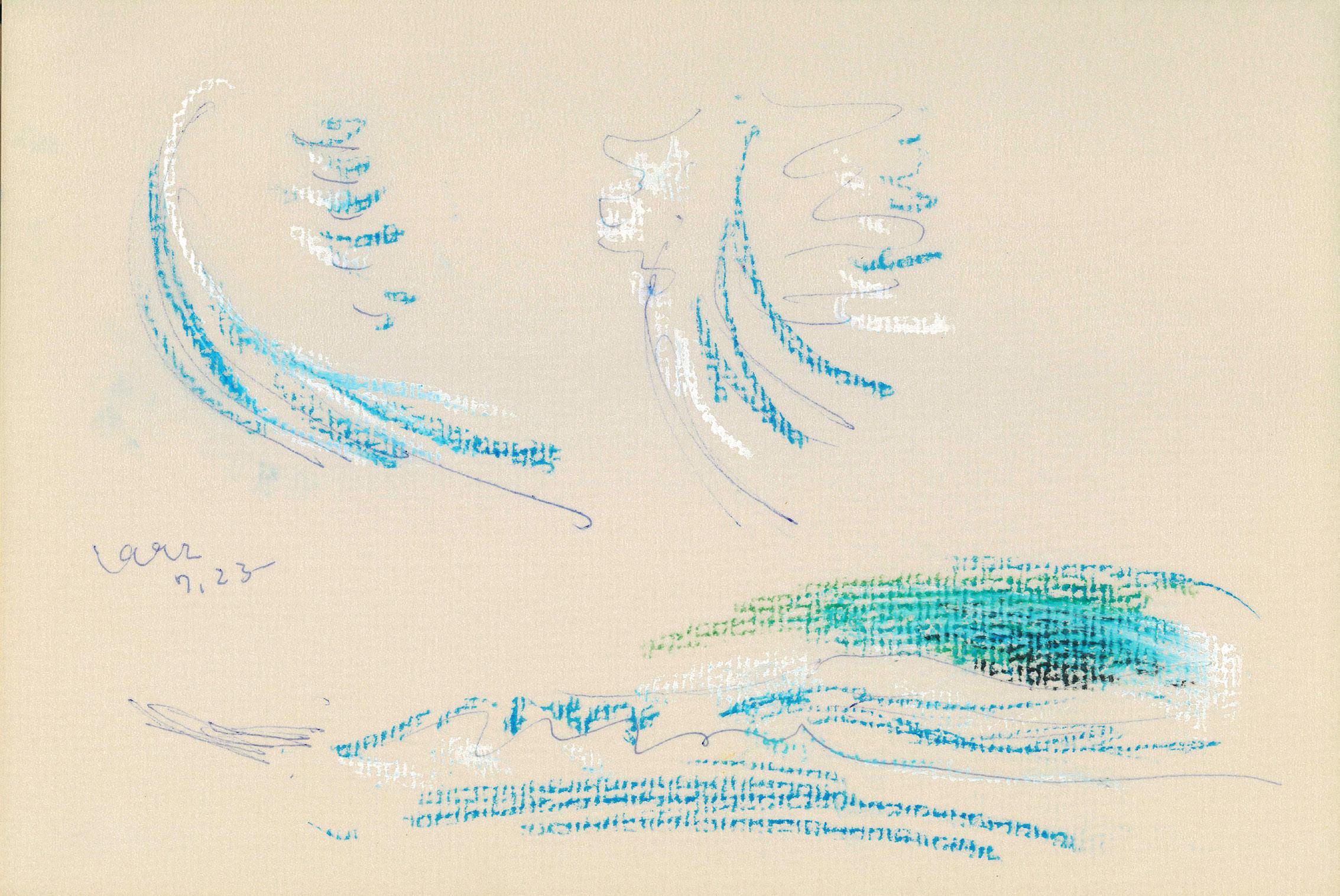

Preliminary sketch on paper, 23 July 1992.

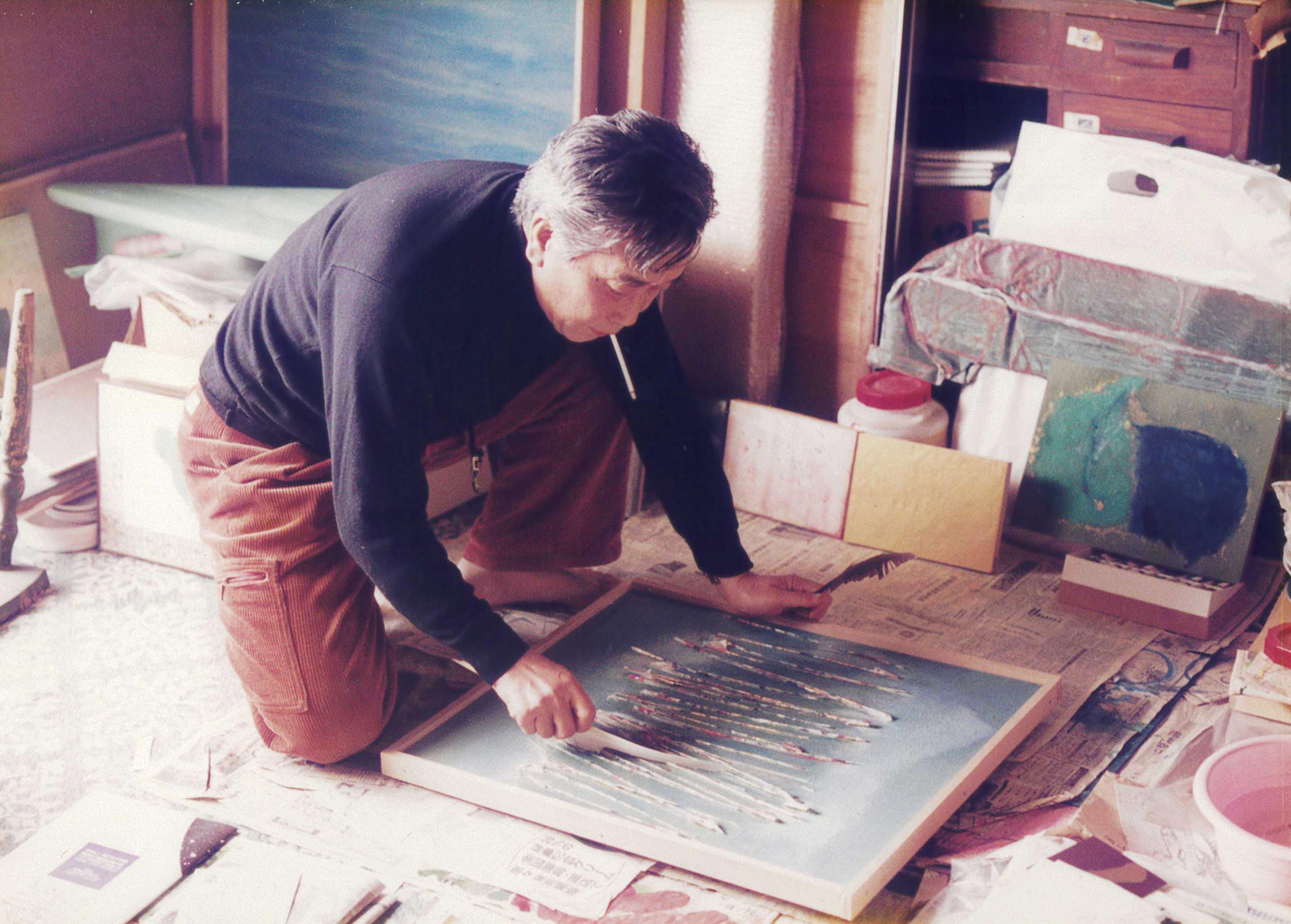

Tanaka working in his studio, ca. 1982.

Preliminary sketch on paper, 1992.

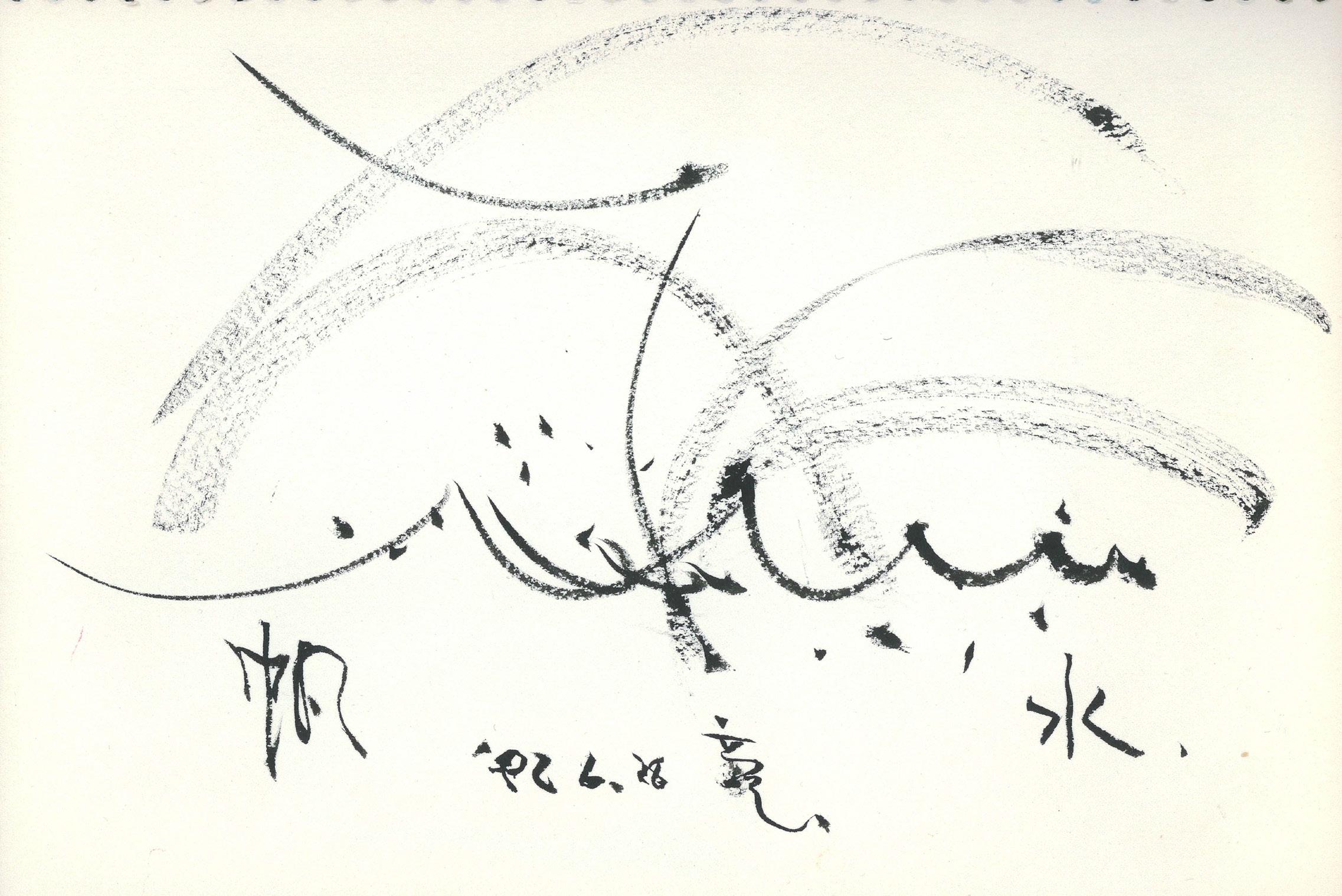

Preliminary sketch on paper, 28 June 1992.

Tanaka sketching outdoors, ca. 1982.

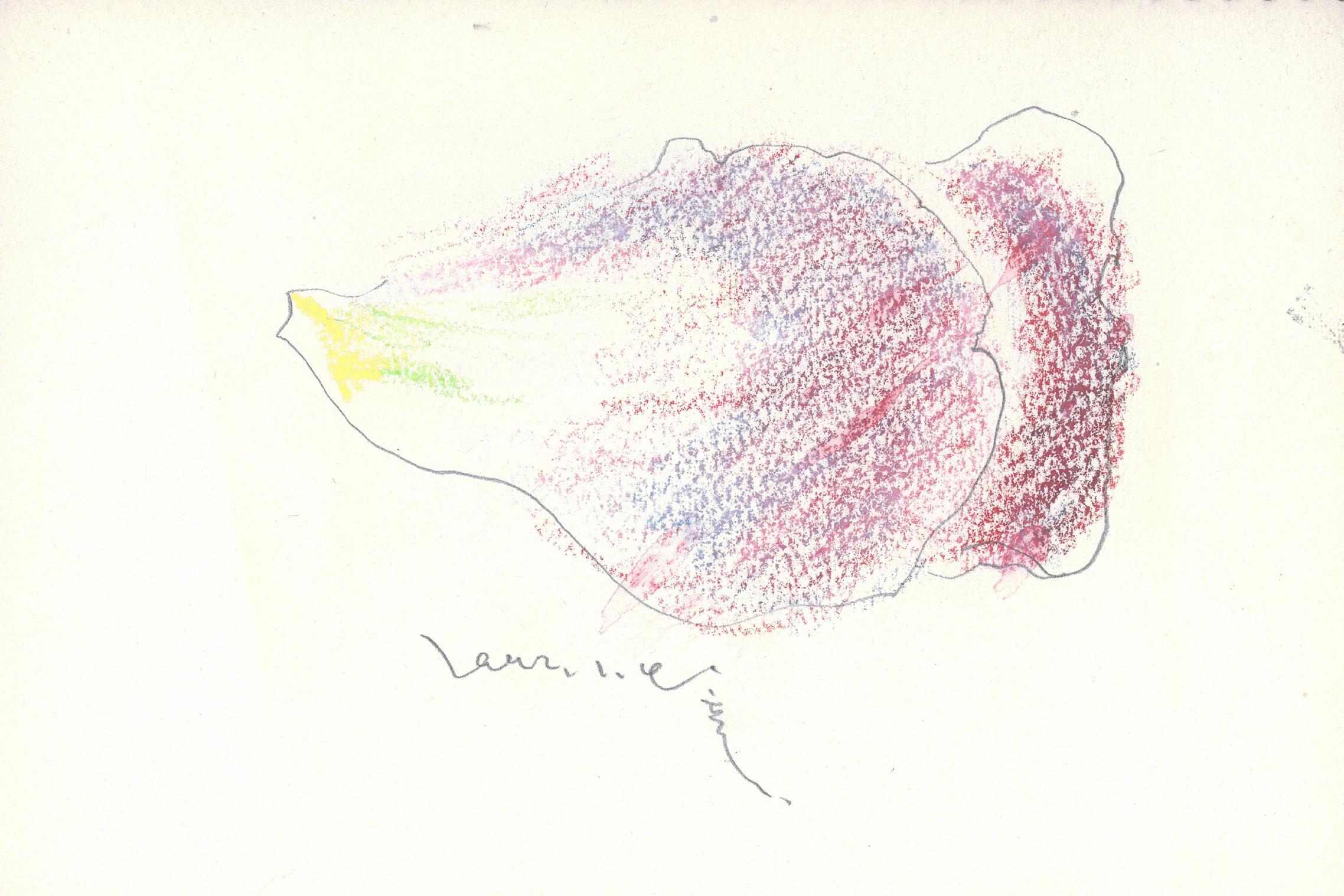

Preliminary sketch on paper, ca. 1991.

Preliminary sketch on paper, ca. 1992.

Preliminary sketch on paper, ca. 1992.

Preliminary sketch on paper, 29 June 1992.

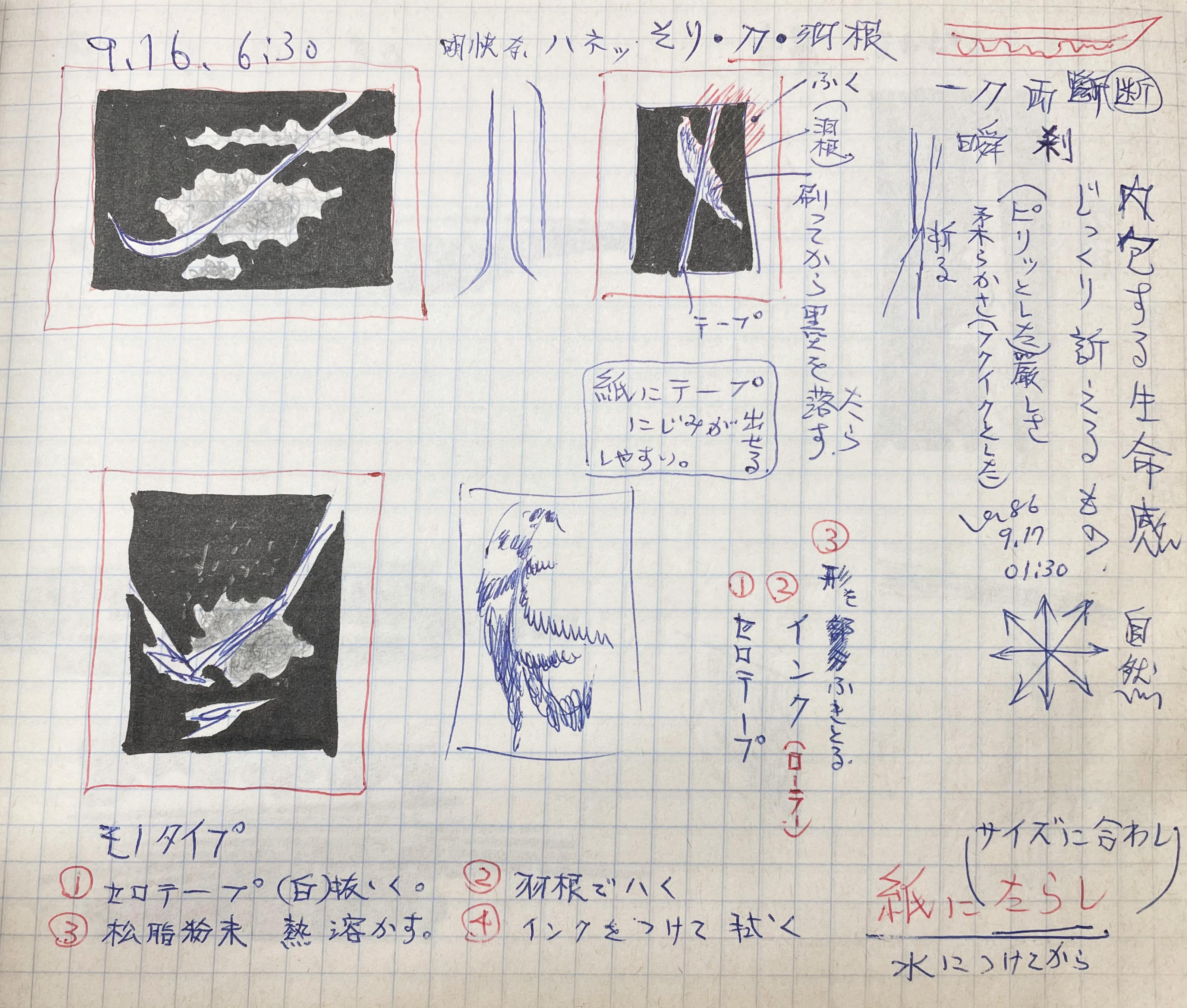

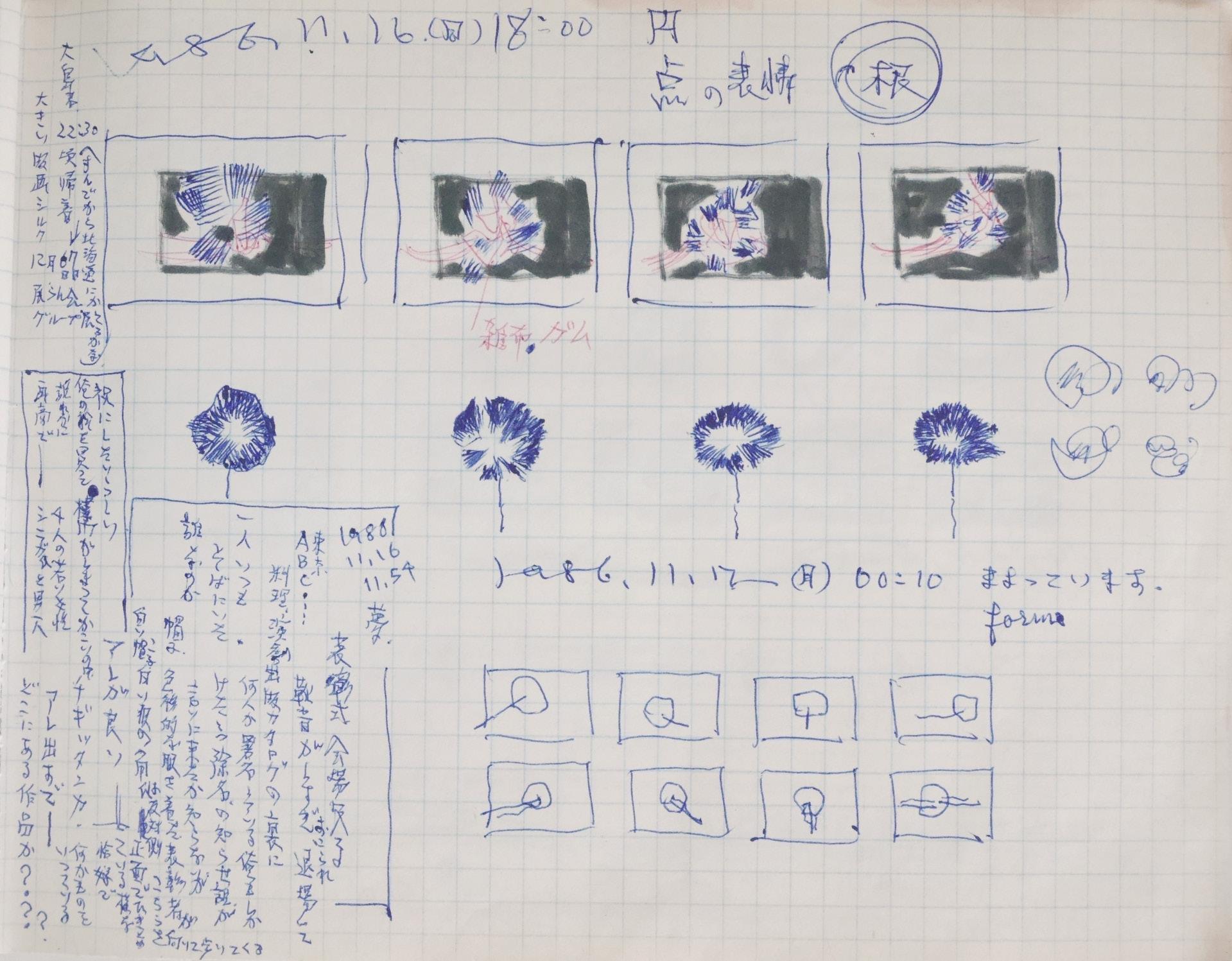

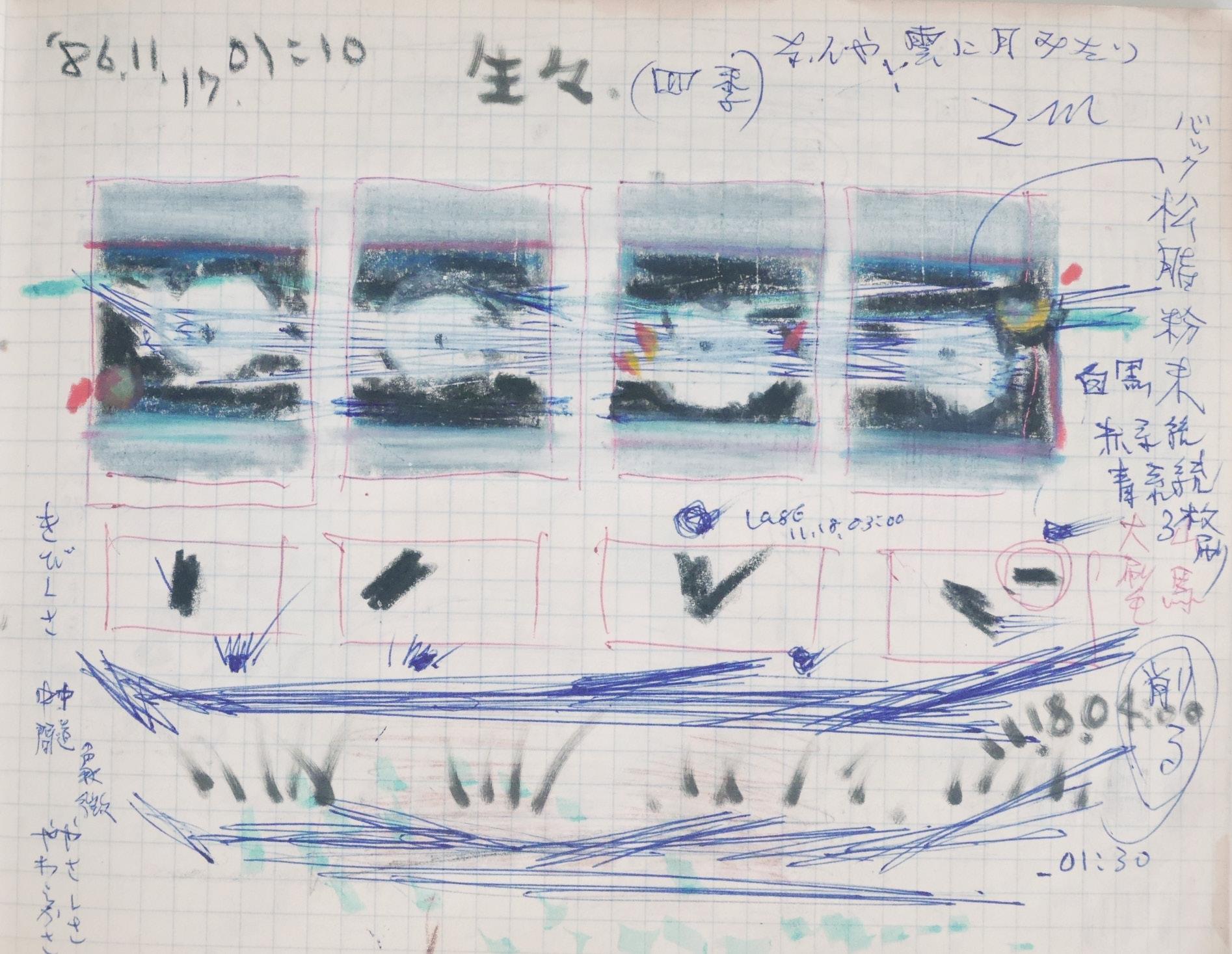

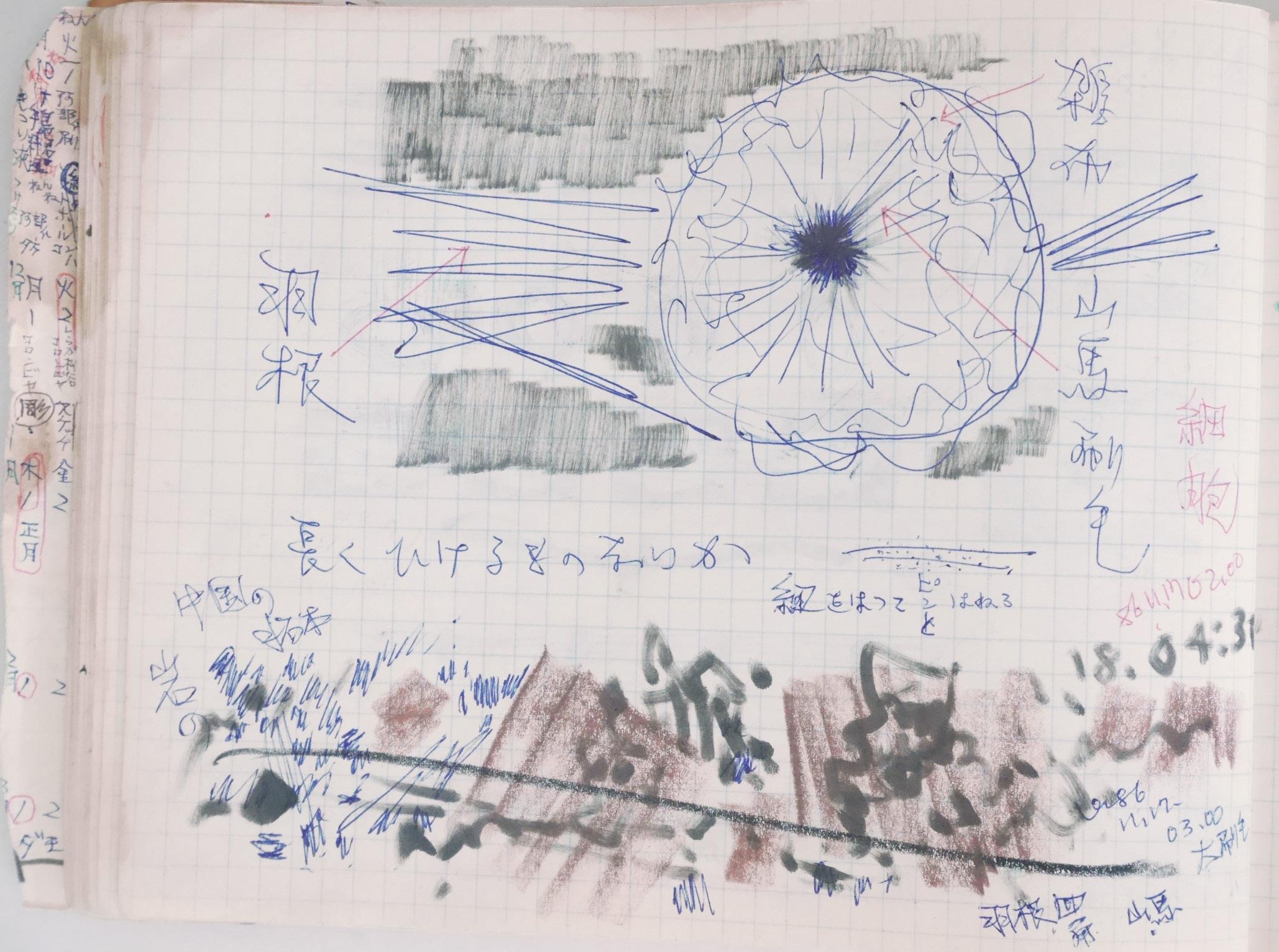

pp.10–17: In 1986–87, Tanaka stayed in Paris for eight months, where he studied contemporary printmaking at Atelier 17 with Stanley William Hayter. The following pages show diary extracts from this period during his European stay.

Tanaka solo show at Espace Japon in Paris in 1987.

Diary notes from September 16, 1986:

Liveliness that is kept inside

What appeals to you slowly and steadily

Softness

Nature

Clear splashes, arches, swords, and feathers

Severeness

Diary notes from November 17 and 18, 1986:

Four seasons

It turns out to look like Moon and the clouds.

Back / Powder resin

Black and white

A range of blue

A range of red

Three prints

Severeness

Middle way / Middle

Symbols

Tenderness / Softness

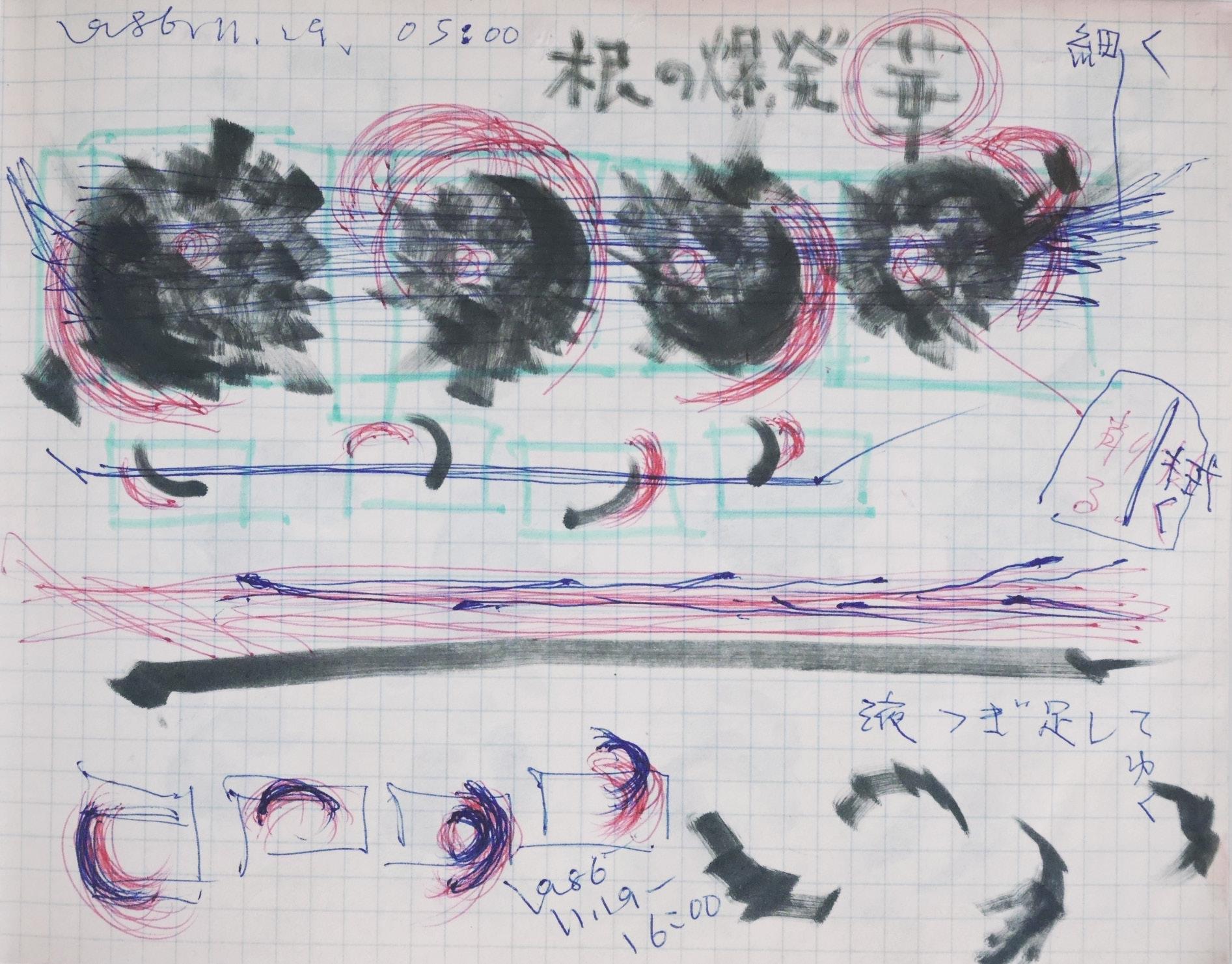

Diary notes from November 19, 1986:

Explosion of roots Flower

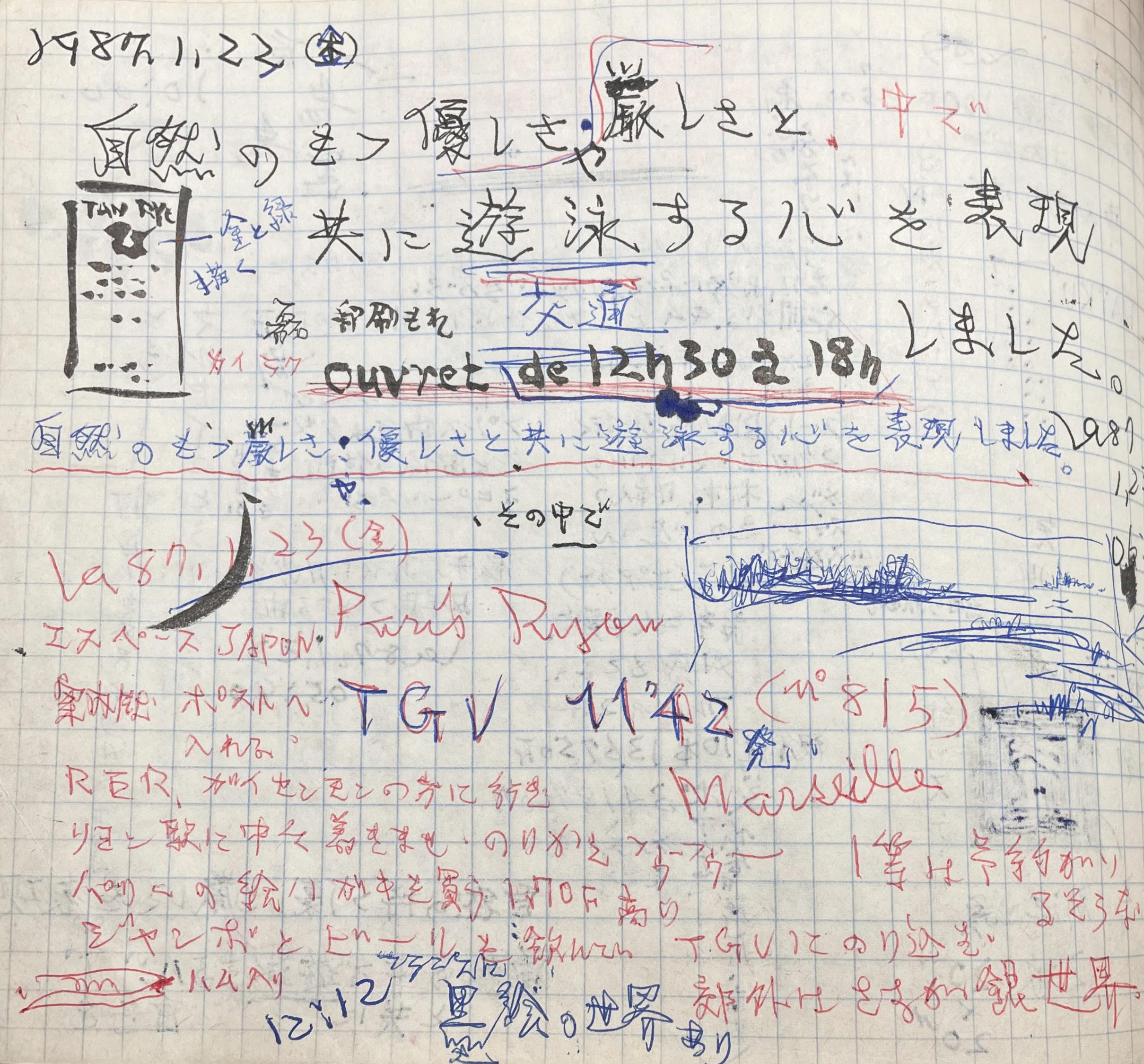

Diary notes from January 23, 1987:

I tried to express a spirit that freely swims together with the tenderness and severity of the natural world.

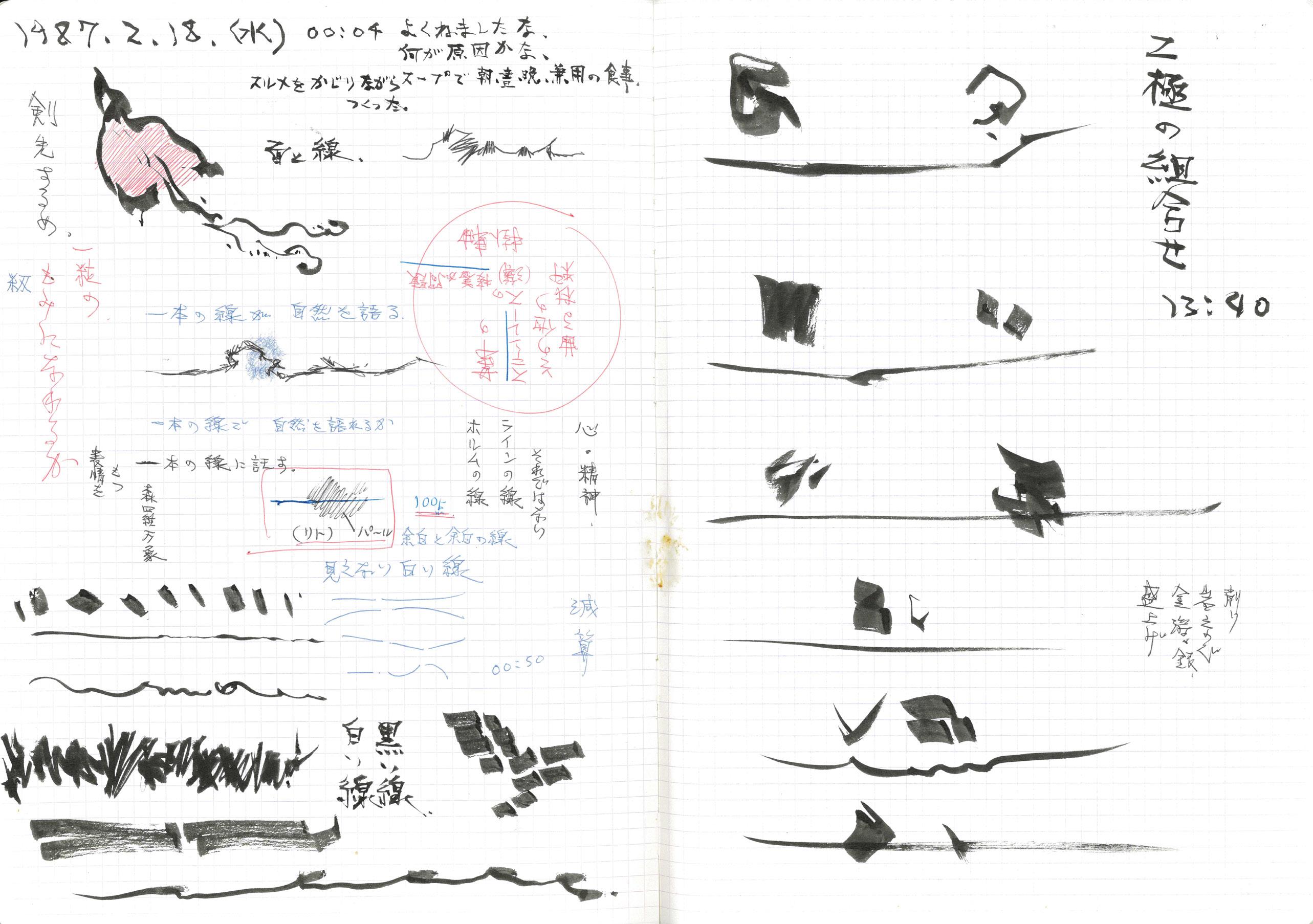

Diary notes from February 18, 1987:

A plane and a line.

Can you become a piece of grain?

A single line tells a story of nature.

Can you make a single line tell a story of nature?

Having expressions

Charge a single line with everything.

Universe Mind and spirit

It’s not that.

A line of line

A

Margin

An

A

A

Combination of the two

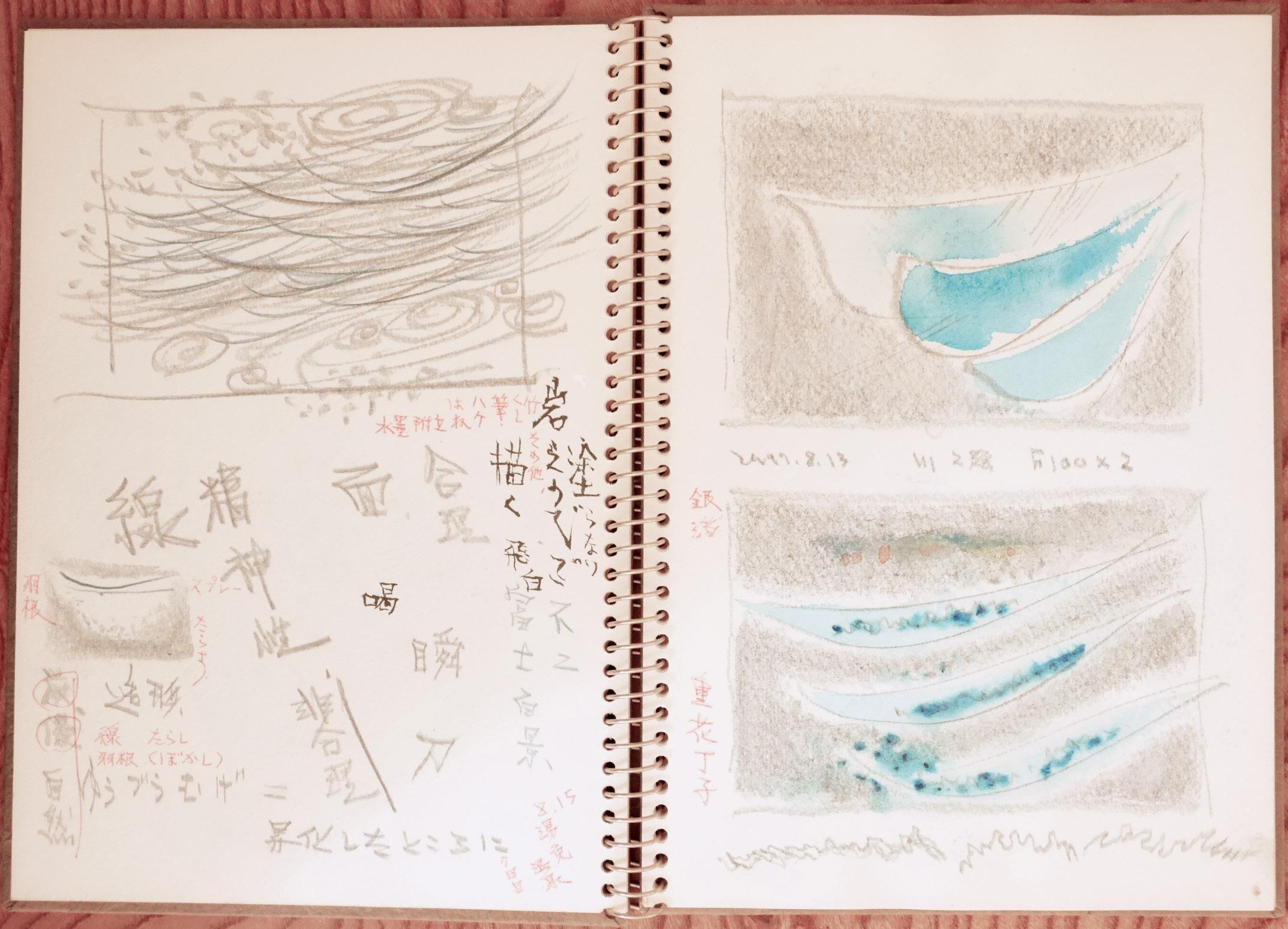

Tanaka’s notebook, dated 13-15 August 1997:

Line / Spirituality / Irrationality / Plain surface / Rationality / Blinking / Sword Shaping / Severity, tenderness / Nature

Line / Tarashi 1 / Feather (blurring) Free and flexible = at the point of sublimation

With mineral pigment / Paint / Not to paint / Expression with a dry brush

Ink Tsuketate 2 / Feather / Flat brush / Brush / Comb / Bamboo / etc. Fuji / One hundred views of Mt. Fuji

15 August / Yumen Onsen / Day 7

13 August, 1979 / Two subjects on the river / F100 × 2 Silver leaf /

2 In

Ju¯ka Cho¯ji 3

1 Here, the painter means Tarashikomi, a technique in Japanese painting of adding ink or paint of a

colour or density on top of another before the latter has dried.

Ryuji Tanaka ii

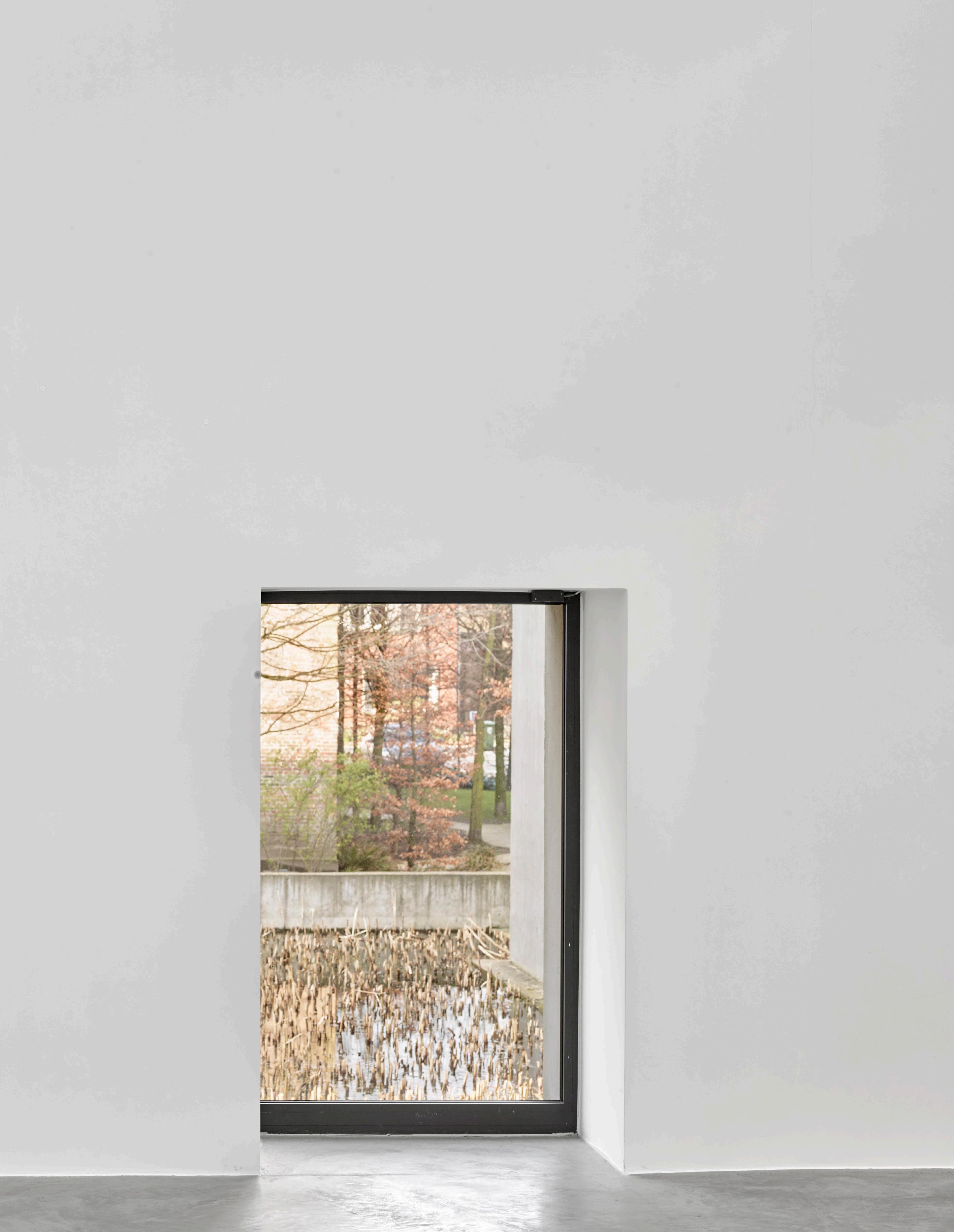

Publisher: Axel Vervoordt Gallery

Kanaal

Stokerijstraat 19 2110 Wijnegem, Belgium www.axelvervoordtgallery.com

Co-published by: MER. Paper Kunsthalle Geldmunt 36 B-9000 Gent www.merpaperkunsthalle.org

Managing editor: Anne-Sophie Dusselier

Texts: Shigeo Chiba, Boris Vervoordt

Translation from Japanese: Christopher Stephens and Sonoko Nakanishi

Proofreading: Michael James Gardner

Graphic design: Luc Derycke, Jeroen Wille, Studio Luc Derycke, Ghent

Photography of the plates: Jan Liégeois

The historical pictures were scanned from the private archive of the family of Ryuji Tanaka.

Research: Maki Tanaka, Toki Fujimoto, Ami Fukuda. (ARTCOURT Gallery)

Art © 2024 The Estate of Ryuji Tanaka

Texts © 2024 the authors

Photography © 2024 the photographers

All rights reserved © 2024 Axel Vervoordt Gallery www.axelvervoordtgallery.com

This publication was made possible thanks to the support of ARTCOURT Gallery, Osaka: Mitsue Yagi, Ami Fukuda

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders. If, however, you feel you have inadvertently been overlooked, please contact the publisher.

25 Ryuji Tanaka’s Masterful Devotion to Nature

Boris Vervoordt

31 In Pursuit of the Expanse of Nature: Tanaka Ryuji’s Quest

Chiba Shigeo

35 Plates

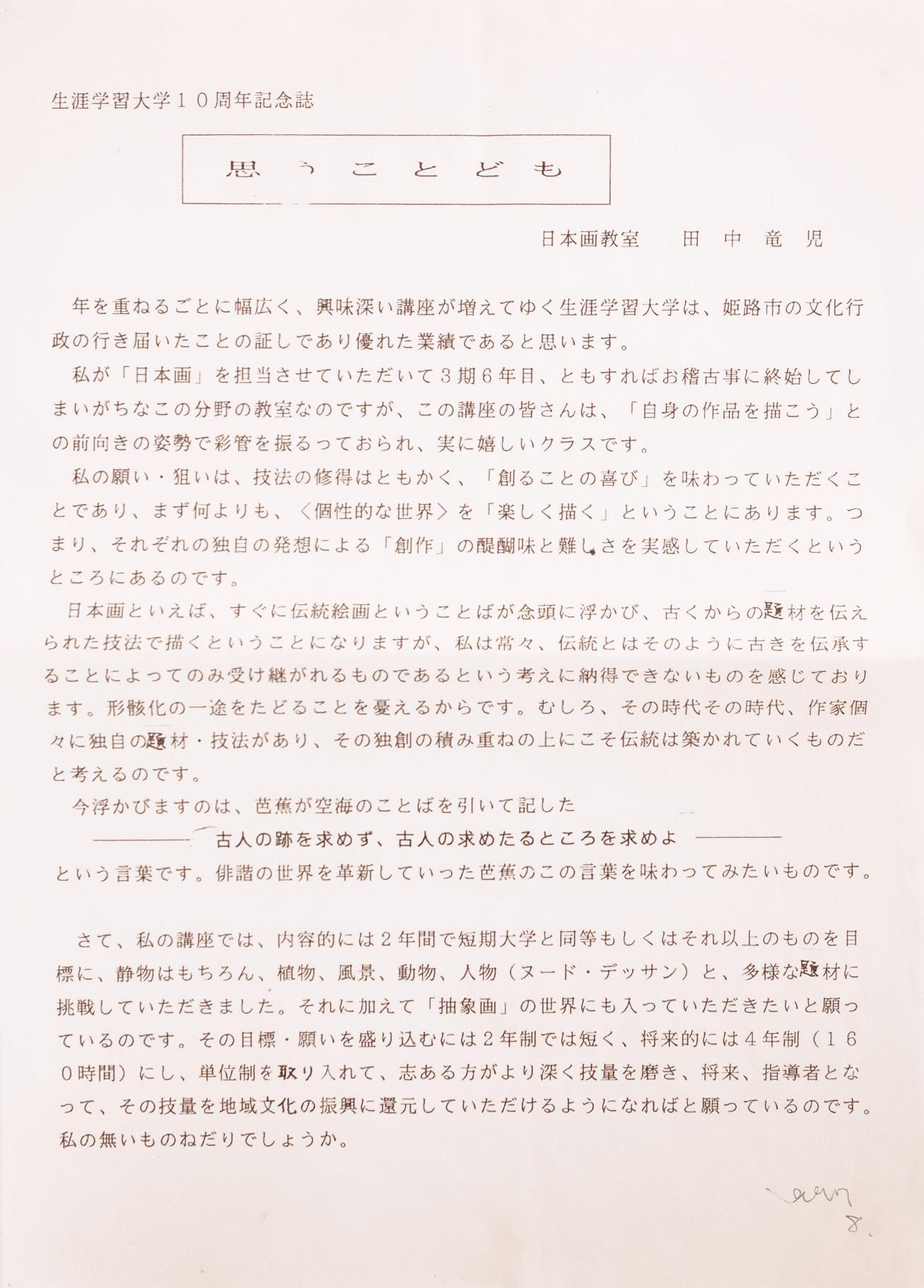

… When we think about Japanese painting, the term ‘traditional painting’ immediately comes to mind, which means painting conventional subjects using techniques that have been passed down from generation to generation. But I have never been convinced by the idea that tradition can only be passed down by handing down the conventions in that way as I fear that this would only lead to a mere formality. Rather, each artist has his or her own unique subject matters and techniques, and I believe that it is on the basis of the very accumulation of such originality that tradition is built.

This reminds me of some of Ku¯kai’s words cited by Basho¯: seek not the footsteps of the ancients, but seek what they sought. I would like to reflect on this saying by the revolutionary of the world of Haiku…

Ryuji Tanaka August, 1997

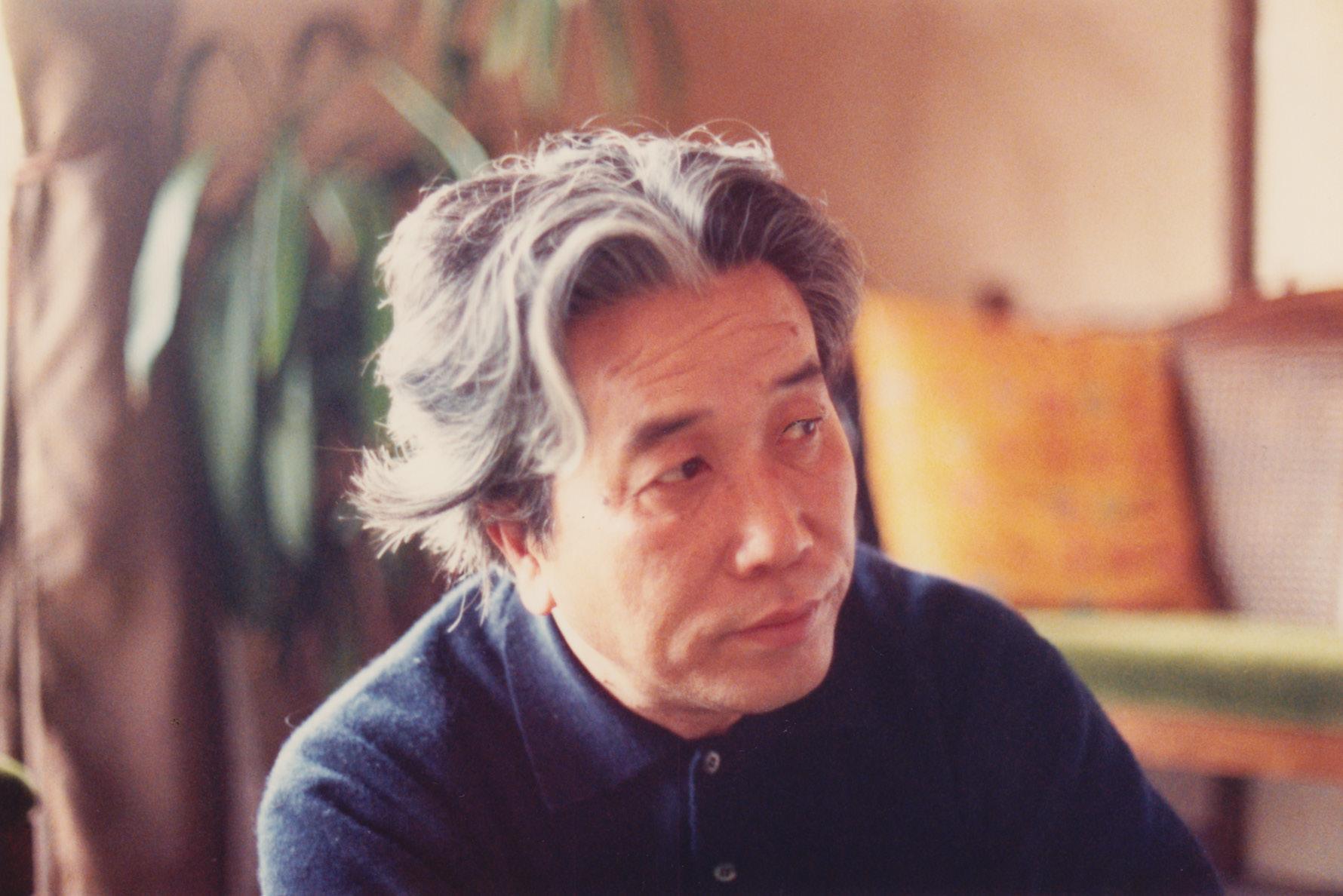

Ryuji Tanaka, 1990.

Ryuji Tanaka’s Masterful

Devotion to Nature

“Do not seek to follow in the footsteps of the ancients; seek what they sought.”

– Ku¯kai (Ko¯bo¯-Daishi)

Boris Vervoordt

Creation is not imitation. One cannot simply repeat what others have done before. The creative life is based on inspiration, study, and knowledge, but ultimately, the original path is your own. The saying, “One can never step in the same river twice”, is not only about the passing of time and the newness of adventure but also about creating a unique story. Define your individualism through singular intuition. Ryuji Tanaka was exactly this type of person and creative artist.

In a 1993 letter sent to those involved with the publication, Ryuji Tanaka: My Selection, he wrote: “A unification with nature—that is my artistic principle. Placing myself at the crossroads between the interwoven kindness and harshness of nature, I express the things I see and hear there through ‘myself’.”

Tanaka knew the ultimate test of the quality of his art depended on his unique way of seeing the world. Tanaka was, first and foremost, a nihon-ga (Japanese-style painting) artist. He deeply understood the techniques, concepts, and nihon-ga traditions He worked throughout his career to understand its borders while redefining its limits. For this reason, I believe in the contemporary relevance of his work and its great value in our understanding of the past, present, and future.

In 1948, Tanaka was twenty-one when he helped establish the Pan-real Art Association with other young artists who studied at the Kyoto Municipal School of Painting. It’s astonishing to think he wrote the following text nearly fifty years later in August 1997:

“… When we think about Japanese painting, the term ‘traditional painting’ immediately comes to mind, which means painting conventional subjects using techniques that have been passed down from generation to generation. But I have never been concerned by the idea that tradition can only be passed down by handing down the conventions in that way as I fear that this would only lead to mere formality.

Rather, each artist has his or her own unique subject matters and techniques, and I believe that it is on the basis of the very accumulation of such originality that tradition is built. This reminds me of some of Ku¯kai’s words cited by Basho¯: seek not the footsteps of the ancients, but seek what they sought. I would like to reflect on this saying by the revolutionary of the world of haiku… “

In this text, Tanaka grapples with some of the biggest questions in art-making. How does the art of today relate to the traditions (and rules) of the past? What is originality? What is tradition?

Even while he sought to express his manifesto, Tanaka was a creative who was very interested in other art forms. Like many artists of his time, he worked

as a teacher, but he was passionate about films, antiques, the work of his students, and he was passionate about haiku.

Think about the qualities of haiku and what comes to mind. Spareness, brevity, simplicity, depth, control, poetry, philosophy, and measured power. The same can be said of Tanaka’s art. They can be described by their spare materiality, but they are rich in expression. Even in their simplicity, they are deceptively deep, controlled, poetic, philosophic, and beautifully powerful. Tanaka’s paintings are lyrical representations of haiku: they are quiet but dynamic.

Building upon the foundations early in his career, the 1960s were a productive and influential period in Tanaka’s life. He began to hold solo exhibitions, win prizes for his work, and submit his paintings to various group exhibitions. His close friendship with Kazuo Shiraga, which began at the Kyoto Municipal School of Painting, led to his regular visits to the Gutai Pinacotheca. Tanaka joined the Gutai Art Association in 1965 and although he remained a member for only a couple of years, his experiences and particularly his friendship with Shiraga were influential. One hears echoes of the Gutai manifesto, “Do what no one has done before!” and the group’s constant quest for originality throughout much of Tanaka’s writing and work. I often think of Shiraga’s iconic performance, “Challenging the Mud” and the ways the artist very physically wrestles with nature in a way that both emerge transformed. Tanaka, in much of his work, seemed to be giving his paintings a physical embodiment of an idea—a poetic representation of nature or a landscape, transformed by his choice of materials and his gestures.

There is the material and there is the way that the material transcends its traits through the hand of the artist. Tanaka had specific, innovative ways of utilising pigments and incorporating silica, glass, adhesives, pebbles, and even metal in his work. I’m attracted to how he crushed minerals to use them like paint, and rather than a brush or even his own body, in some works, he used feathers to make soft, sweeping, powerful gestures to create blurry effects with the paint. As revolutionary as some of his ideas were about how to transform his genre, Tanaka was formally concerned with form and composition. In some of his writings—and there is one I found particularly fascinating—he addresses the challenges he had with a circular line in dialogue with a straight line and the “disorder of the gold leaf”. I’ve always found the expressiveness of his canvasses to be full of spontaneity and surprises—the happy accidents of material transformed by the artist’s energy and not his deliberate will alone. This note reminds me that he was always “shaking hands with the material” and the results were indicative of his interactions with the very nature of painting and what happens on the canvas. He may have planned his compositions in insightful ways, but he often let the material speak. His paintings, even when still, hold meaning and movement, like a brush of nature.

Tanaka was interested in duality. In other personal writings, he addressed concepts such as “consciousness and unconsciousness. Necessity and supply. The gentleness and harshness of nature.”

Shigeo Chiba’s new essay in this book helps us understand the nuanced connections between the East and West. He writes, “The West has its theories and practices, and Japan has its own. In general, the people of East Asia have the idea, or rather the sense, that everything is space and emptiness, but this

Boris Vervoordt

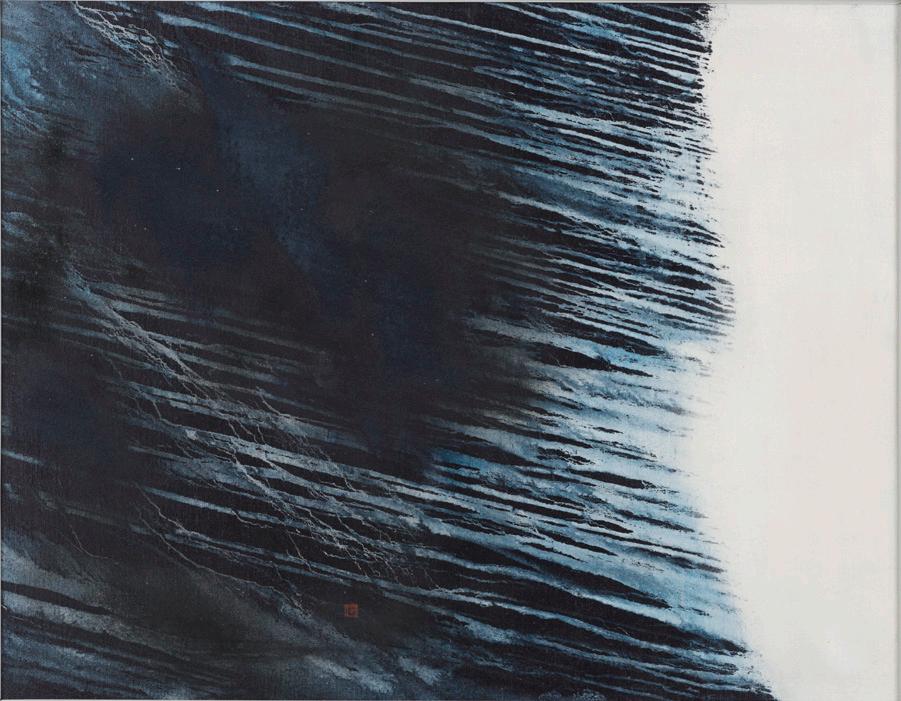

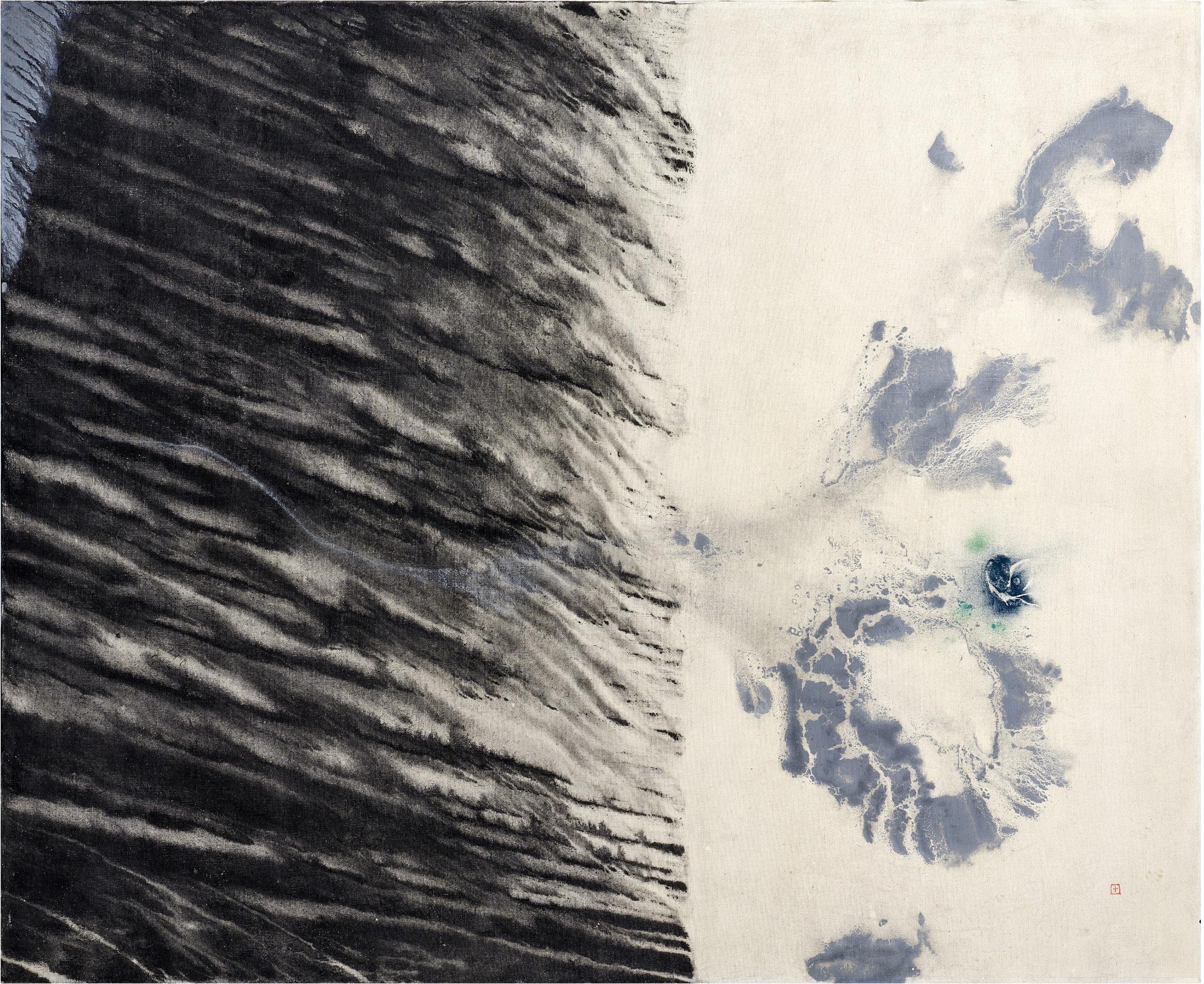

Fig. 1 Shizen ’01 (B), 2001, for which Tanaka received an award in 2002.

is not the same as a void or vacuum as conceived in the West.” Chiba helps me understand that in the context of Tanaka’s work, there are different ways of seeing. If we were to seek a balance between the Eastern and Western ways of seeing while thinking about Tanaka’s work specifically, we must consider that emptiness is not empty, and void is not nothing; there is the pregnant possibility of the void. There is always something constantly in motion, energy hidden beneath the surface—even in silence, there is space.

Considering Tanaka’s work, it’s important to keep in mind the Japanese Buddhist concepts of the five elements—earth (chi), water (sui), fire (ka), wind (fu), and void (ku). The elements are a way to look at the natural world to better understand our connection (and respect) for it. Void is often referred to as the sky, the space of stillness and silence, yet immense power. There are wonderful analogies to be drawn with Tanaka’s work, and I’m certain that he understood this because I feel the energy of matter becoming chi in his work.

Our gallery was founded in 2011, and our work is based on several key interests and ideas. For more than fifty years, my family has had a long-standing interest in seeking connections between East and West. We’ve always been fascinated by artistic explorations of the void. We’re drawn to artists who have the profound ability to express timelessness, originality, harmony, silence, and beauty, and to demonstrate the creation of energy through matter.

The gallery continues to serve as a platform for solo artists—living and those who have passed—by offering them space for the singular expression of their vision and sharing it with the world. We strive to do this work daily. The book is the second installment in a series. If the first book placed Tanaka’s work in the context of the Gutai Art Association, these pages serve to highlight the works that the artist produced later, primarily in the 1980s and ‘90s, and establish a balance for Tanaka’s entire oeuvre. The works from this period have a profound lyricism and demonstrate his increasing explorations and mastery of his craft. During this period from 1986-87, he spent most of the year in Paris. He was eager to find out what was happening in Europe and the West, continuing to gain knowledge and break free of strictly Japanese traditions. There, he studied printing techniques and visited his friend, another Gutai artist, Takesada Matsutani. These stories serve as an important reminder about Tanaka’s life. He was an important artist who was a member of significant movements and artistic groups, but it’s interesting to remember that he was beholden to no one. He stayed true to himself and that’s a trait I admire for his principled individuality. With gratitude to the Tanaka family, this book is a testament to our commitment to Ryuji Tanaka’s legacy and part of the ongoing scholarship necessary to deepen the art world’s knowledge and understanding of this truly original artist.

August 2024

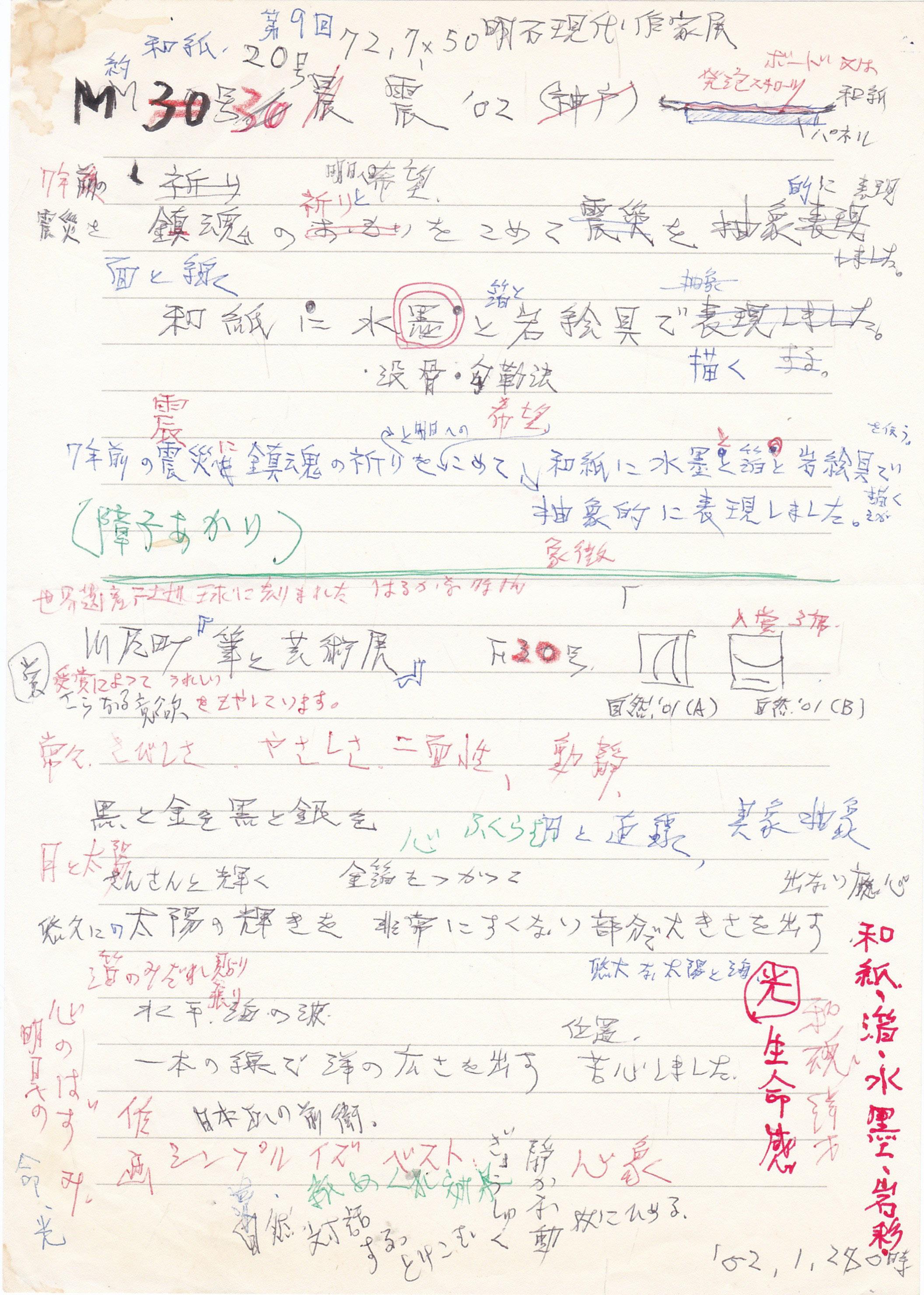

Note by the artist Ryuji Tanaka dated 28 January 2002, upon receiving the award Kawajiri-cho, third prize in the exhibition “Brush and Art”, for the work Nature ’01 (B):

I am delighted by the award. / This is motivating me further.

Always / Severeness / Tenderness / Two-facedness, movements and stillness

Black and gold / Black and silver

The Moon and the Sun / Shining brightly / Using gold leaf

Expressing the eternal shining of the Sun, largeness with extremely small parts / Struggling to express

Mind / Swells / Circles and lines, the figurative and the abstract

Grand Sun and sea

Rough application of gold leaf / Tension

Horizontality, waves of the ocean

Expressing the vastness of the ocean with a single line / I struggled to decide its position.

The leaping of spirit towards tomorrow / Life, light

Japanese avant-garde. / Composition / Simple is the best / A mental picture

The e]ect of peeling paper

Nature / Conversation. / Take in / Condensation / Quiet dynamism / Hide inside

Light / Liveliness / Wakon Yo¯sai 1

Japanese paper, gold leaf, ink, and mineral pigment

In Pursuit of the Expanse of Nature:

Shigeo Chiba Tanaka Ryuji’s

Quest

Ryuji Tanaka was a nihon-ga painter who came of age during World War II, when many students were drafted as the war effort intensified. Happily, he lived through these years, to the age of nearly ninety, and created a singular body of work over the course of his long career. He was largely forgotten for a long time, but today we are beginning to gain a clearer picture of the true nature of his achievements.

Tanaka was of the same generation as Kazuo Shiraga, and studied at the same art school in the nihon-ga department. Early on, he was among those seeking to revolutionise nihon-ga and participated in the 1948 establishment of a group called Pan-real, consisting largely of fellow students at the school who shared a similar understanding of the issues. Nihon-ga, literally “Japanese painting,” arose in the late 19th century amid a sense of crisis over the growing influence of Western art, and while building on Japanese traditions, is a relatively new genre. However, it gradually became more focused on traditional forms, materials, and themes, and for all intents and purposes, this did not change after World War II. While Western painting was evolving dramatically toward its logical conclusion, the “death” or “end” of painting (a progression not irrelevant to contemporary Japan), the world of nihon-ga remained oblivious, narrowly interpreting the same traditions and growing increasingly hermetic and ossified.* Pan-real started out with a policy of openness in terms of both style and theme, but soon there were schisms, and it stagnated over time. Tanaka evidently saw this coming early on and was quick to leave the group. His work while in Pan-real deals with diverse themes, including those evincing interest in social issues, and his style shows various influences such as Surrealism and Cubism, but it never departed from Illusionism (the attempt to represent reality). However, in the 1960s it underwent significant change. This does not appear to be the influence of Gutai, as Tanaka fundamentally differed from the Gutai members in terms of what he sought to paint. While Shiraga was a mentor in some ways, Tanaka wanted to realise in contemporary painting the same fundamentals of spatial expression that have always characterized East Asian art. In other words, in terms of revolutionising nihonga and the question of what nihon-ga truly means in the present age, it can be said that he took a most classical approach.

A painting generally consists of figure and ground. If there is only figure the result will be something like manga, while examples of ground alone can be seen in Colour Field Painting. As a rule, however, the two are not separate, with figure an isolated, cut-out shape and ground merely a background. In the East Asian traditions in particular, painting is only possible when figure and ground merge into one. However, this is not easy to achieve, whether using traditional Western perspective (which in essence produces a trompe l’oeil effect) or conventional East Asian three-point or six-point perspective. To produce a substantive space on a two-dimensional surface through a fundamentally different method and philosophy, something that cannot be achieved with perspective, i.e. Illusionism––Tanaka began pursuing this direction in the early 1960s, and thereafter developed it in increasingly abstract works. Examples from the early

stages of this exploration can be seen in works from his 1963 solo exhibition at Takegawa Gallery (Fig. 1–3): Sei, Sei (7), Untitled and others.

His exploration was a search for answers to two inextricably related questions: “What do I want to paint?” and “Can I do it without relying on Illusionism?” In 1965, when he joined Gutai, his mind was already firmly set on these issues, and it seems he did not have much to learn from Gutai. He withdrew from the group after about two years, struck out on his own at the age of forty, and followed what could be called a clear and consistent trajectory from the 1970s onward. He sought to depict, or better to express in pictorial space, the entirety of nature’s vastness unfolding before the eyes.

To do so required introducing a structure to the pictorial space, a different process from creating a composition on a planar surface. It meant putting in place a structure that gave substance to the expanse of the planar surface and make this a solid skeletal framework on which to build a painting. In practical terms, this involves selecting a figure and rendering it, while simultaneously giving shape to the ground on which it is rendered. Ideally (if possible), the ground should be painted in the same manner as the figure. Tanaka saw and felt such structures in the spaces of the natural world. His goal was to produce these structures on the picture plane while absorbing and processing all the sensations that people derive from nature, not only through the visual organs, but through the entirety of the body and mind. He was in pursuit of painting in which what was seen with the eyes expanded to fill and gain embodiment in the entire realm of the senses.

At the same time, Tanaka was searching for a way to deal with figure that did not evoke illusionistic form. He experimented with a wide range of subjects, but viewing his entire output without looking at the titles of works (referencing haiku, mandalas and so forth) or the year of production, all one can find in terms of likenesses of things in the real world are figures resembling mountains or clouds, and the vast majority do not constitute form but rather non-illusionistic figures. This is not abstract painting, but rather figuration with a high degree of abstraction—and this is a crucial point—but all have the sense of somehow belonging to nature. The figure is placed at the centre and is, so to speak, suspended in midair in the pictorial space.

Meanwhile, other works are based around interrelations between these figures and elements that are both like and unlike lines. Examples from the 1980s include Sei ’81 (A) (Fig.4) and Sei ’81 (C) (Fig. 5). As the interrelations themselves are at the core of the paintings, the integration of figure and ground is effectively achieved.

Comparing these two modes, what we find is that they represent two poles of Tanaka’s painting practice. This is a testament to his paintings’ stylistic breadth. And even in the former group of works where figure is clear, the figure (or form) is almost certain to have linear elements (like those of the latter group). Or rather, it is as if these linear elements are emanating from the figure. For example, Sitting (Black 100) features a figure resembling a mountain seated on the ground. (Fig. 6). Even in the former group of works, the interrelation of ground and figure is not neglected.

I have been using the term line here, but this does not mean line in the Western sense of a sharp boundary drawn between objects. Since ancient times, it has been understood in East Asia that there are no lines in the nat-

Chiba Shigeo

Fig. 1 Ryuji Tanaka. Solo exhibition at Takegawa Art Gallery, Tokyo, April 1963. First floor view. Tanaka sitting on the right.

Fig. 2–3 Ryuji Tanaka. Solo exhibition at Takegawa Art Gallery, Tokyo, April 1963. Second floor view. ‘Sei’ works from 1963

ural world, and nature has been depicted accordingly. Tanaka’s line is more correctly described as stroke, which is both figure and ground. Stroke in East Asian painting constitutes abstracted figure and ground, and one should have this in mind when viewing Tanaka’s work. In other words, his stroke elements are also simultaneously figure and ground, and if one accepts that, one can see this is also true of his painting’s figures. In the natural world, figure and ground are integrated without distinction. In this way, it is possible to embody in painting the entire vast expanse of nature itself.

What he sought was not “pictorial space as pictorial space” as East Asian people think of (or once thought of) it. He had no concept of “a painting as a painting.” He wanted to embody on a flat surface the vast expanse of nature itself, or “space itself,” the primal essence of which is found in nature. Of course, this means the “expanse of nature” as perceived by one individual, Tanaka. This highly personal endeavour, if it cannot be called global in scope, can at least stir empathy in all those who share land, water, air, climate, food, and by extension body, sensation, and thought.

Tanaka placed importance on using natural pigments because these have always determined the sensibility of Japanese (or East Asian) painting. In a humid climate, moisture forms the underlying basis of space itself and how it appears to us. One could say the world of water lies at the deepest level of the Japanese psyche, and the visual aspects of a work of art will not have validity or ring true unless the artist connects with the flow of water which also governs the whole of the human body. Tanaka grasped this on a sensory level. As a contemporary person, he experimented with various ideas, such as mixing sand and glass powder with mineral pigments and blending not only traditional nikawa glue but also modern adhesives with solvents. However, this experimentation always bore relation to the basic underlying world of water.

What Tanaka endeavoured to depict was not things in nature, but the spatial expanse of nature itself. Within nature there are mountains, rivers, trees, and vegetation, but more than discrete objects, they are all part of a natural space integrated with the sky and the atmosphere. What he practiced is described in Japanese as shizen ni narau, learning from nature. This does not mean copying nature, but following the essential ways of nature, and this formed the process of structuring that Tanaka conceived and practiced.

He aimed to express his ideas through structuring of ground, figure, and the relationship between them. Of course, this was not an easy task. However, during his middle and late career, while he alternated between the two poles of his practice, this process of alternation seemed to become less deliberate and to soften over time. No matter the circumstances, nature is always nature, and his work grew progressively closer to nature in its essential processes.

Modern painting, which emerged and evolved in the West, reached a watershed in the 1970s, and one great cycle ended. This is frequently described as the death, or the end, of painting, but it does not mean painting ended on a certain day, and in fact this terminal period went on for some time. Tanaka, who was between middle and old age at the time, could not have been unaware of it.

I seem to hear him saying: “My quest to depict the expanse of the natural world was valid. It was a great challenge, and the results may not have been

In Pursuit of the Expanse of Nature: Tanaka Ryuji’s Quest

Fig. 4 Sei ’81 (A), 1981, Mineral pigment on canvas, other materials. Private Collection.

Fig. 6 Sitting on (Black 100), ca. 1976, mineral pigment on canvas, other materials. Private Collection.

Fig. 5 Sei ’81 (C), 1981, Mineral pigment on canvas, other materials.

satisfactory, but it was not in vain. In fact, I now believe there can be no other meaningful endeavour in painting.”

In the end, what is the final theme or subject that painting can address? Is it not the “space itself” that we occupy and are all part of? It seems the most noble endeavour is to confront “the expanse of space itself” head on, to try to express it even if the task is impossible, neither relying on objects or occurrences in the real world to stand in for space, nor retreating into the formality of abstraction. If so, what is the essence of “space itself”? In the West it would probably be identified as light, but in the Japanese islands it is air and water. Vision is shaped by light, but light is shaped in turn by air and water.

The West has its theories and practices, and Japan has its own. In general, the people of East Asia have the idea, or rather the sense, that everything is space and emptiness, but this is not the same as a void or vacuum as conceived in the West. In the Japanese climate, moist air drifts, water flows, and space itself seems to waver as if constantly in motion. If Western viewers feel something special and intrinsic to Japanese painting, surely it comes from this fertile emptiness, this airy, moist expanse, the “vast expanse of nature itself”.

* Painting in Japan, including murals in burial mounds and Buddhist paintings, originated in China (sometimes coming via the Korean Peninsula). These various genres of painting were eventually “Japanised” (incorporated into the indigenous Yamato culture). “Japanised” Buddhist painting and classical yamato-e painting reached their pinnacles in the 12th century. It was between the late 16th and early 19th centuries that yamato-e developed dramatically into large-scale sliding-door paintings. Meanwhile, ink wash painting was

not introduced until relatively late, in the 12th century, with Japanese starting to produce their own ink wash paintings in the late 13th century, and the genre reaching a zenith in the late 15th and 16th centuries. Both yamato-e and ink wash painting were already moribund when the country opened its borders in the late 19th century. Nihon-ga from the Meiji Era (1868–1912) is a strange hybrid indeed, combining these two obsolete genres and giving the whole a partially Westernised flavor.

Chiba Shigeo

Plates

“Hen” (Transformation), 1950s Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 65 × 90,5 cm

Untitled, ca. 1962 Mineral pigments and mixed media mounted on wooden panel, 183 × 92 cm

Untitled, ca. 1962 Mineral pigments and mixed media mounted on wooden panel, 183 × 92,5 cm

D”, ca. 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 61 × 91 cm

“Sei (M)” , 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 53 × 32,5 cm

“Sei A”, ca. 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91 × 73 cm

Untitled, s.d. Mineral pigments and mixed media on paper, mounted on panel, 177,5 × 116 cm

Untitled, s.d. Mineral pigments and mixed media on paper, mounted on panel, 117,5 × 116 cm

Untitled, ca. 1962 Mineral pigments and mixed media on two wooden panels, 183 × 184 cm

“Sei FJ”, ca. 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91 × 72,5 cm

“Sei F (IV)”, ca. 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 65 × 91 cm

“Sei (San)”, 1963 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 38 × 46 cm

“Kishi no Fudo” (The Nature of the Knight), 1967 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

previous pages, from left to right

Untitled, n.d. Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 61 × 91 cm

Untitled, n.d. Mineral pigments, glass powder, and mixed media on canvas, 61 × 91 cm

“Kishi no Fudo” (The Nature of the Knight), 1967 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

Untitled, s.d. Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 54 × 46 cm

“Shiki ’78, Haru” (Four Seasons ’78, Spring), 1978 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

“Shiki ’78, Aki” (Four Seasons ’78, Autumn), 1978 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

Untitled, 1970s Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91,5 × 106 cm

“Chi” (Earth), 1978 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91 × 116,5 cm

“Chu” (Sky), ca. 1978 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91 × 116,5 cm

“Shizen (Hana) 20” (Nature (Flower) 20), 1977 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 60 × 73 cm

“Shiki ’78, Natsu” (Four Seasons ’78, Summer), 1978 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 130 × 162 cm

Untitled, 1977 Mineral pigments on canvas, 71 × 89,5 cm

San ’78, 1978 Mineral pigments on canvas, 91 × 117 cm

Untitled, late 1970s Mineral pigments on canvas, 130,5 × 161,5 cm

overleaf

Untitled, ca. 1980 Folding screen in four parts. Mixed media on paper, mounted on Japanese paper, mounted on panel, 180 × 362 cm

Untitled, ca. 1980 (four parts) Mixed media on paper, mounted on Japanese paper, each mounted on cardboard, with a stretcher, 180 × 90,5 cm (each)

Untitled, ca. 1980 Mixed media on paper, mounted on Japanese paper, mounted on cardboard, 90,5 × 180 cm

Untitled, 1980 Mixed media on paper, mounted on Japanese paper, mounted on cardboard, 90,5 × 180 cm

Untitled, 1983 Folding screen in four parts. Mixed media on paper, mounted on Japanese paper, mounted on panel, 180 × 362 cm

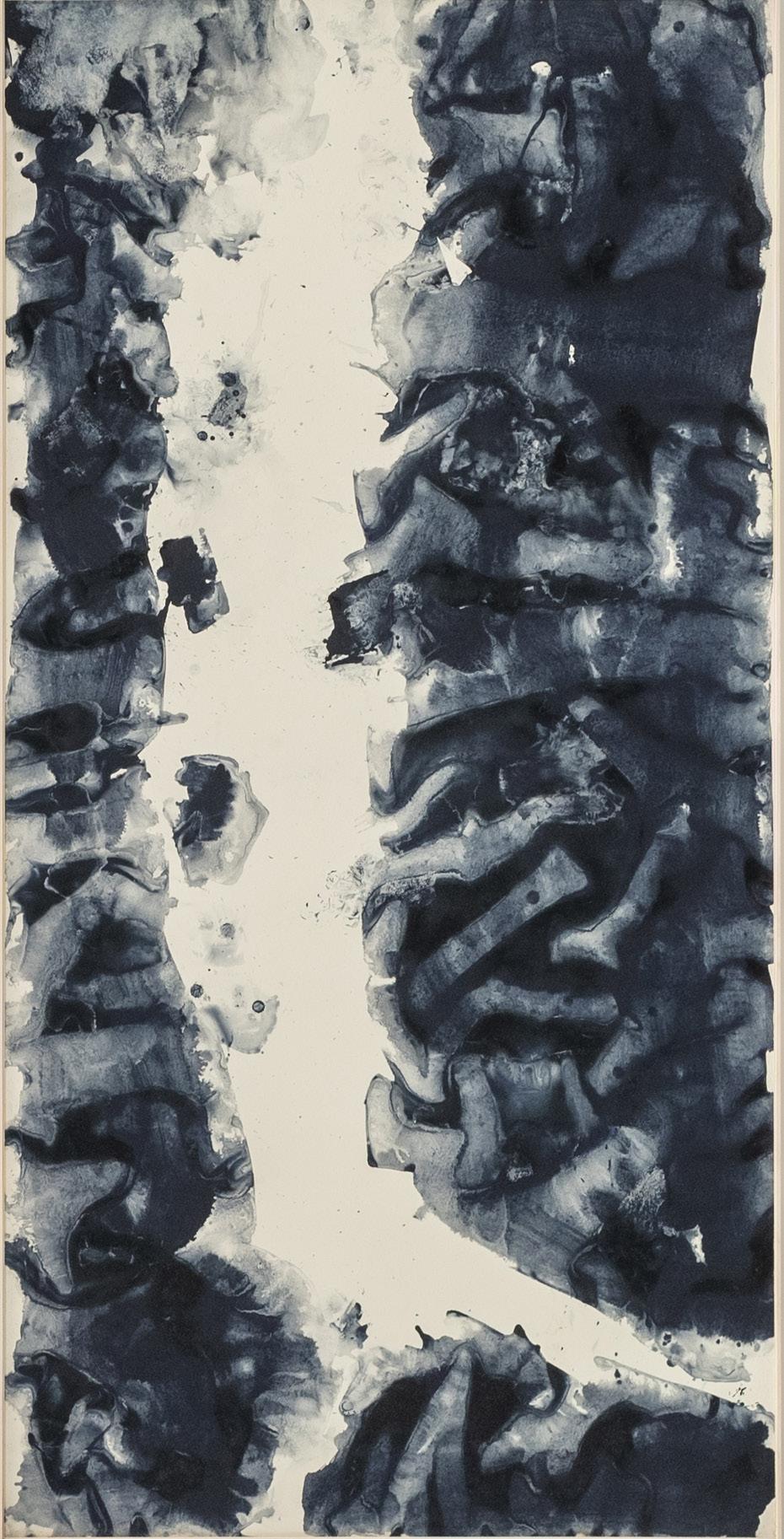

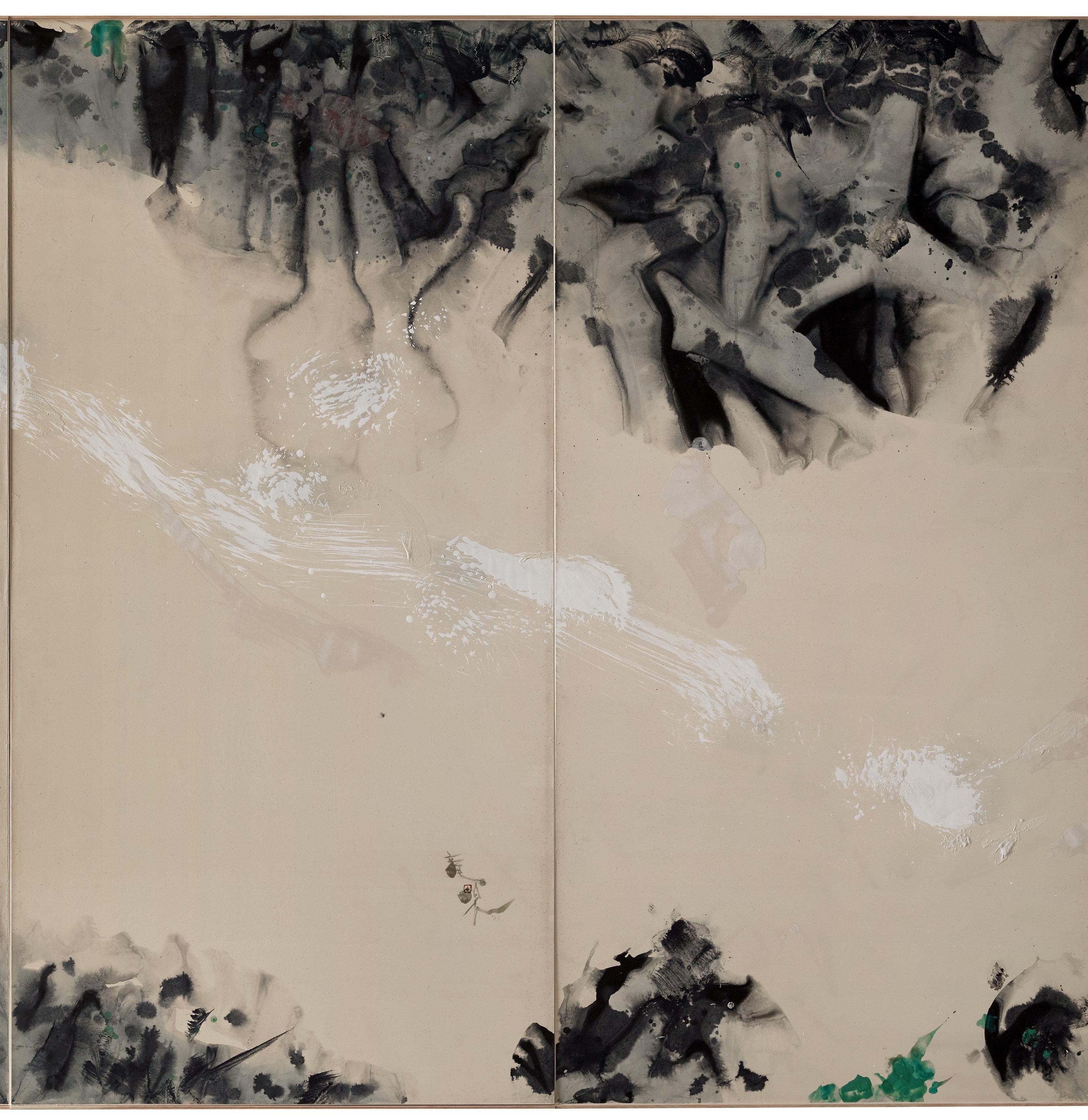

Untitled, 1983 (diptych) Ink, mineral pigments, and mixed media on paper, mounted on a cardboard, on a stretcher, 180 × 90,5 cm (each)

Untitled, 1986 Ink, mineral pigments, and mixed media on paper mounted on cardboard, 180 × 90,5 cm.

Collection Museum M+, Hong Kong

“Hikari ’90 Ryokai Mandara” (Light ’90 Mandala of the Two Realms), 1990 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 60 × 73 cm

“Hikari ’90 Ryokai Mandara F30 (Light ’90 Mandala of the Two Realms F30), 1990 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 73 × 91 cm

“Shizen ’90, Shaku” (Nature ’90, Shining), 1990 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 225 × 180,5 cm

Untitled, s.d. (Two panel folding screen) Mineral pigments and mixed media on paper, 85,5 × 185,5 cm

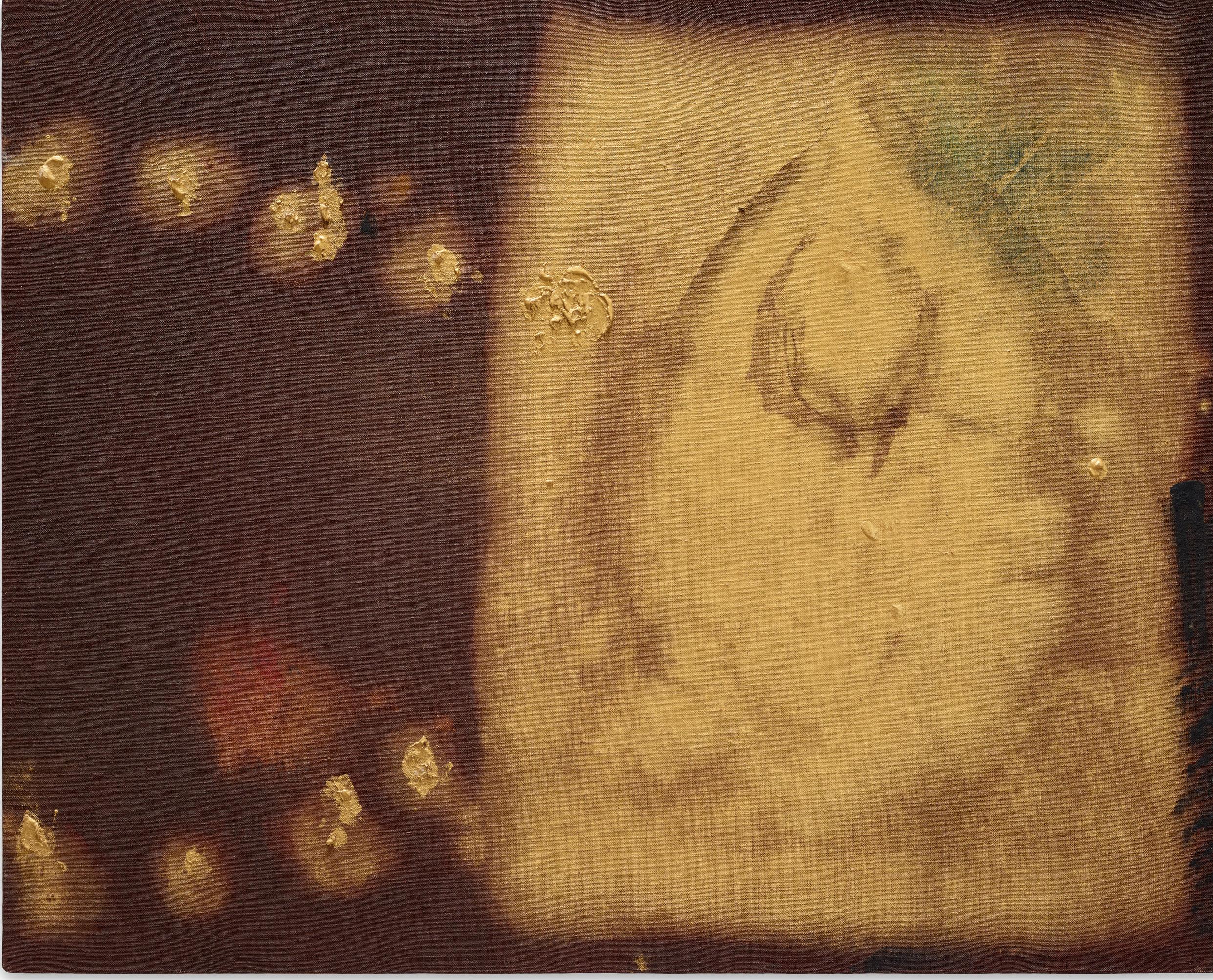

“Hikari Mandara ’90 (A)” (Light Mandala ’90 (A)), 1990 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 218 × 333 cm

“Hikari Mandara ’90 (A)” (Light Mandala ’90 (A)), 1990 Detail

“Hikari Mandara ’90 (B)” (Light Mandala ’90 (B)), 1990 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 218 × 333 cm

“Shizen ’91 (Hikari)” (Nature ’91 (Light)), 1991 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 182 × 227 cm

“Shizen ’91 (Kyo)” (Nature ’91 (Sounds)), 1991 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 182 × 227,5 cm

overleaf

“Shizen ’91 (Hikari)” (Nature ’91 (Light)), 1991 Detail

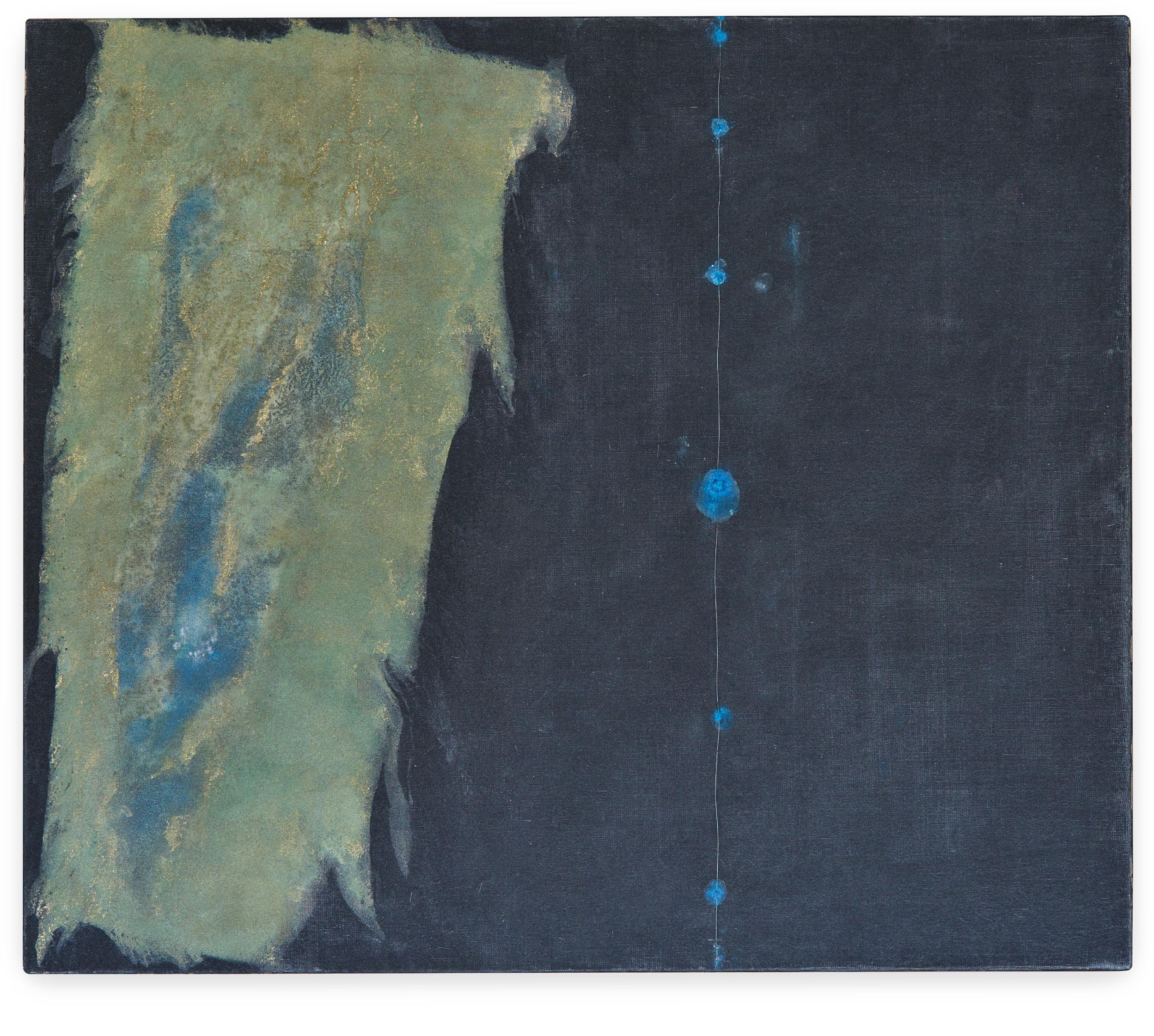

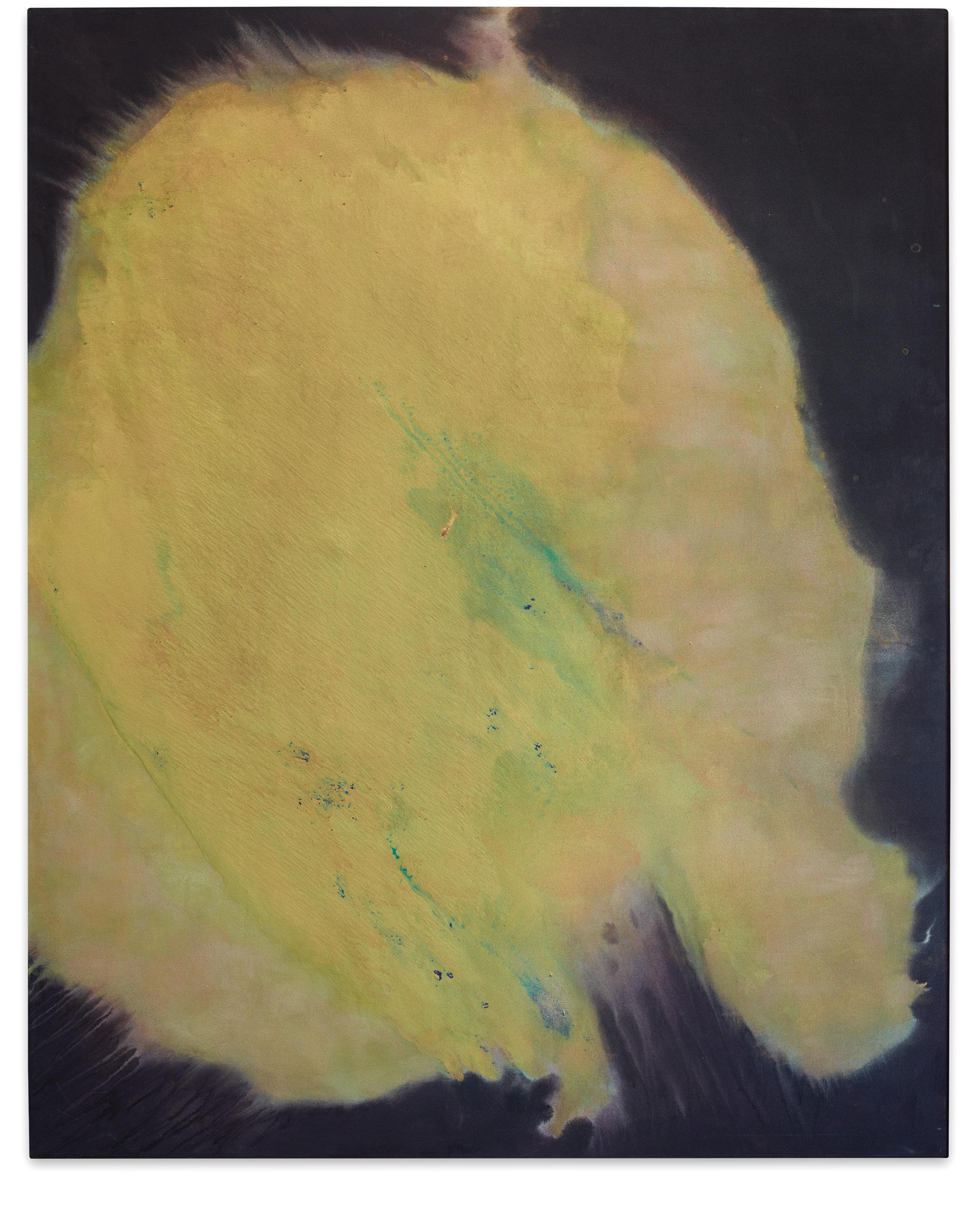

“Kaze ’91 (Ryuryoku)” (Winds ’91 (Green willows)), 1991 Oil and mineral pigments on canvas, 182 × 227,5 cm

“Kaze ’91 (Kako)” (Winds ’91 (Red blossoms)), 1991 Mineral pigments on canvas, 182 × 227,5 cm

overleaf

“Kaze ’91 (Kako)” (Winds ’91 (Red blossoms)), 1991 Detail

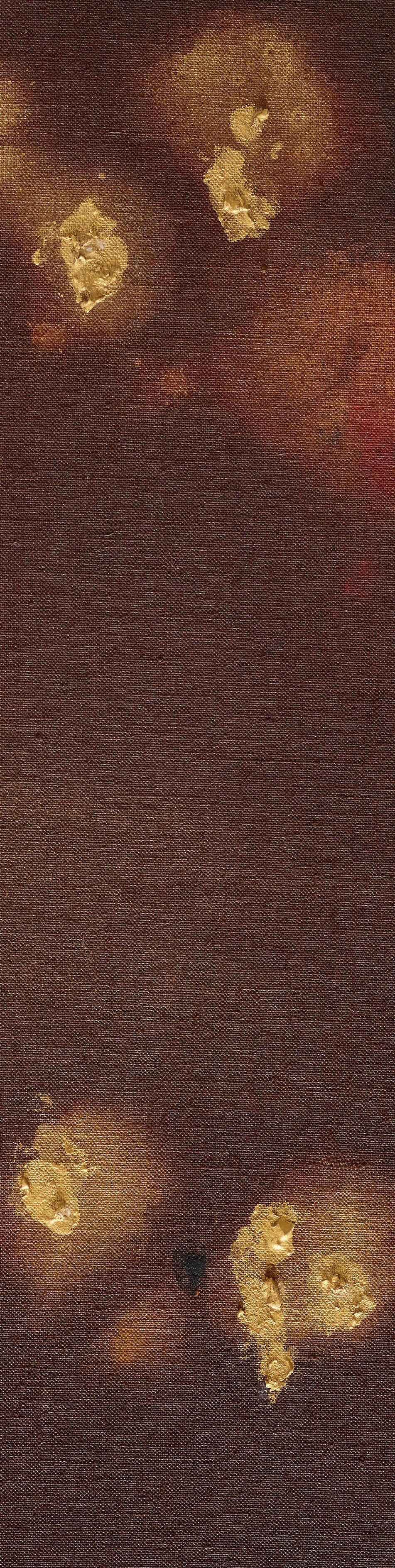

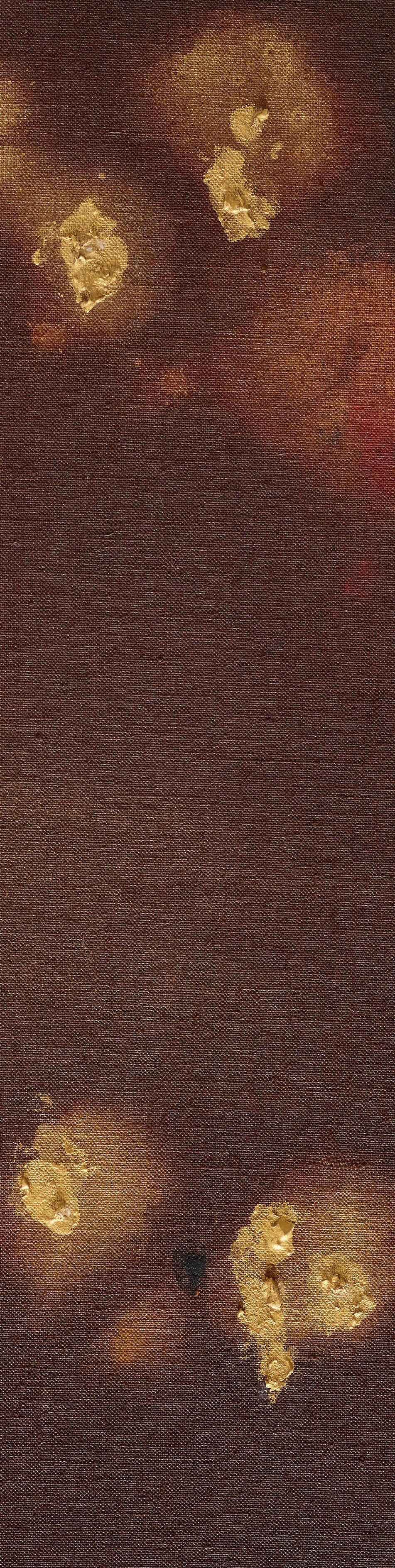

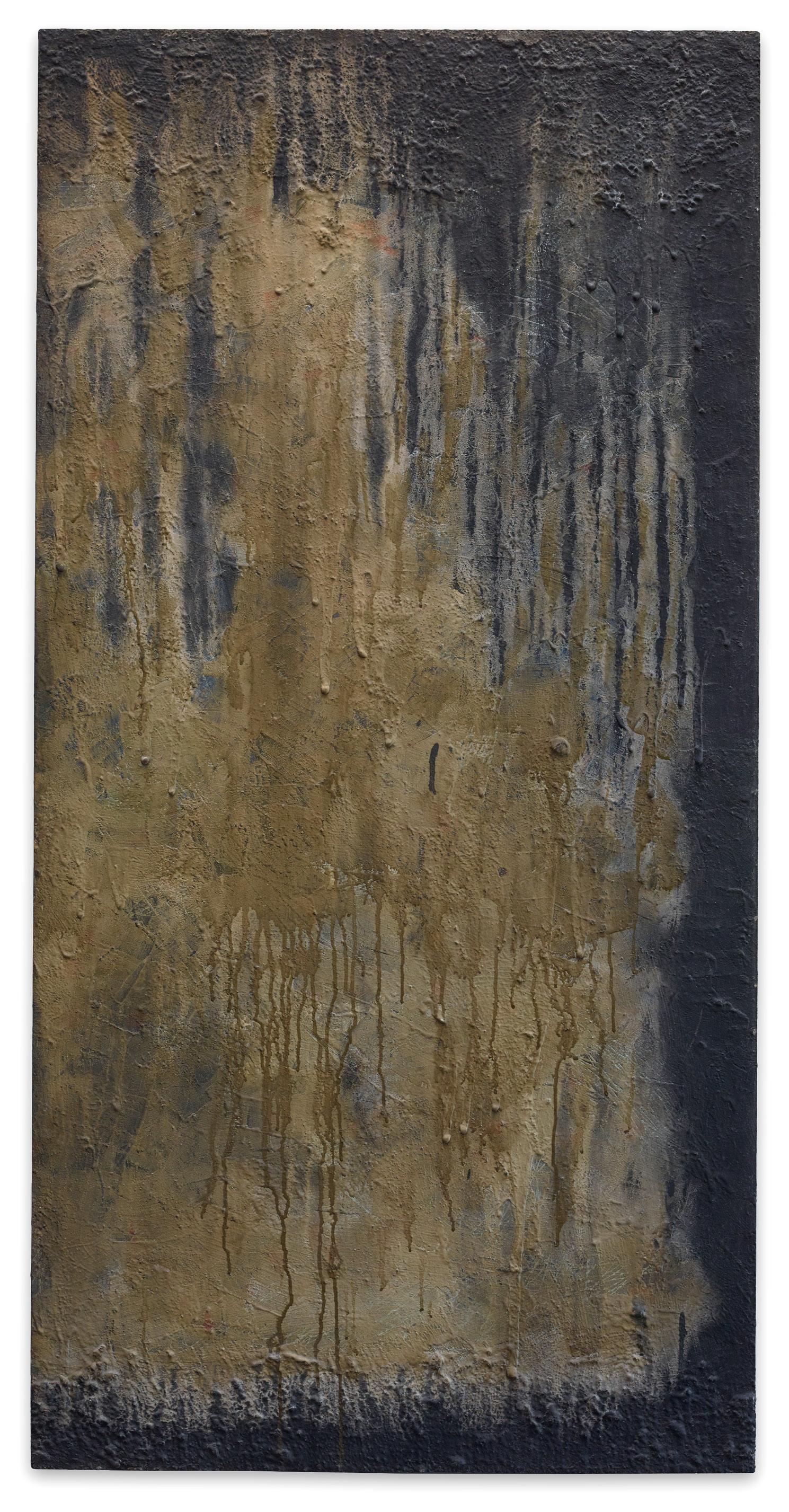

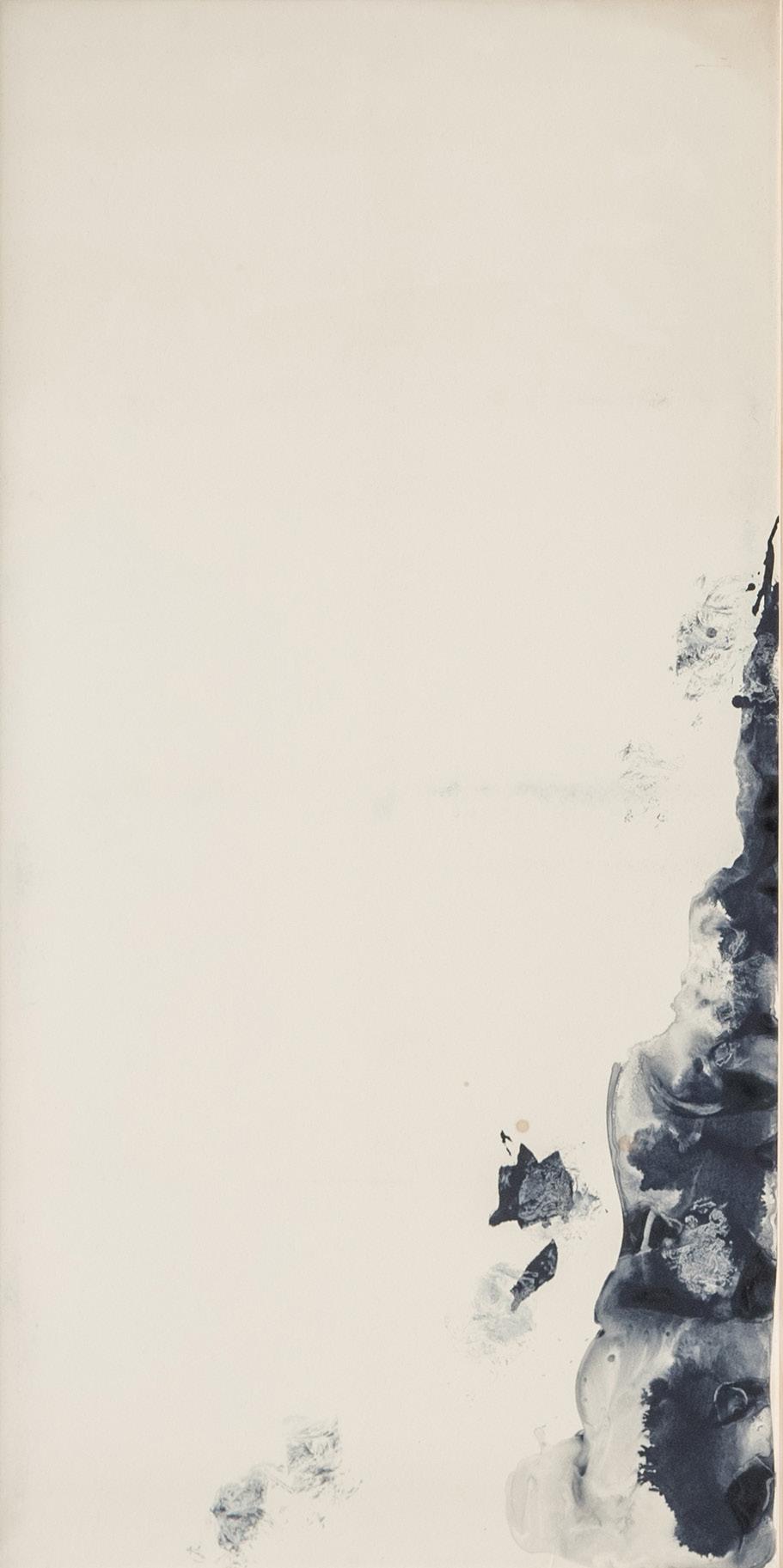

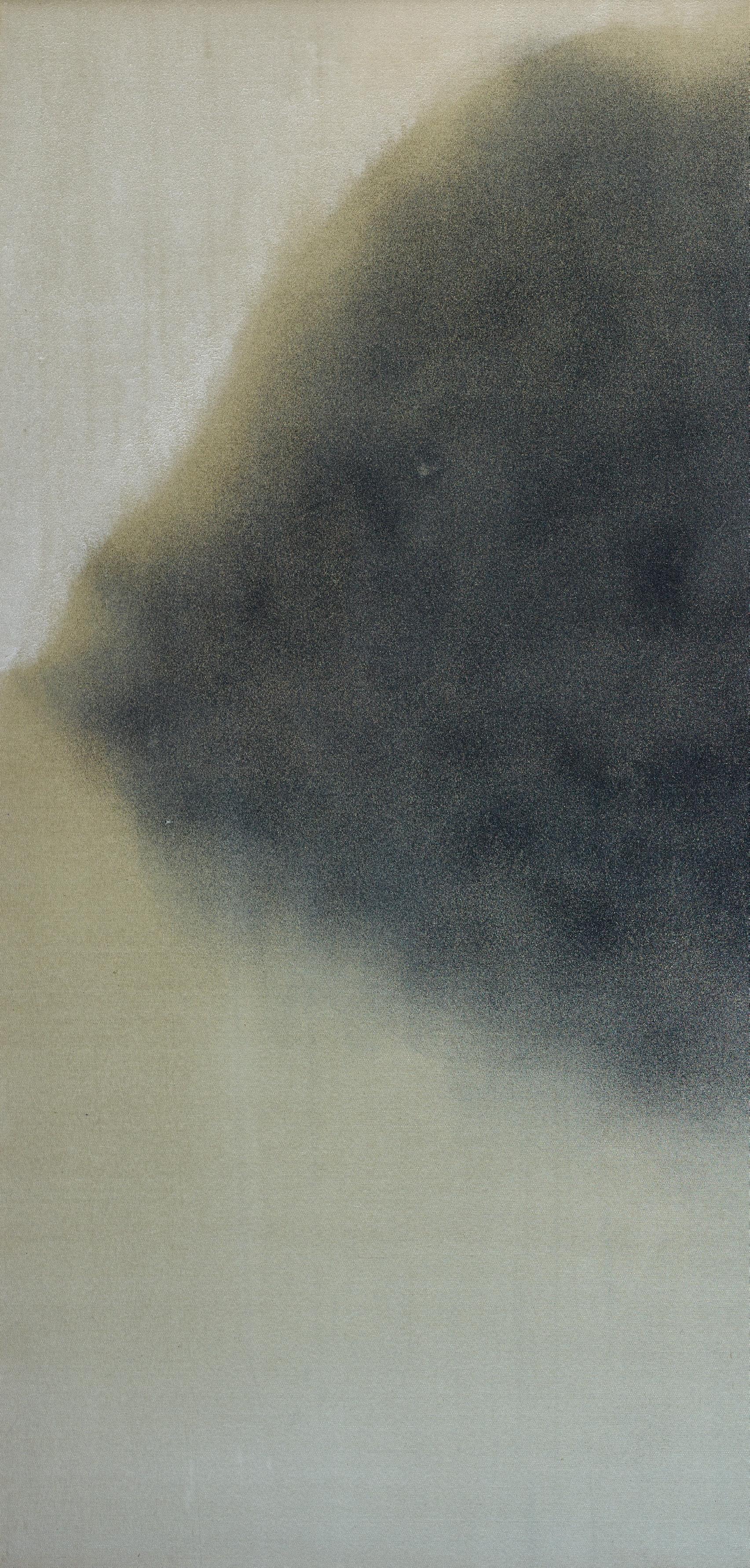

“Go, Shichi, Go (i) ’92” (Five, Seven, Five (i) ’92), 1992 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, mounted on panel, 182,5 × 91,5 cm

“Go, Shichi, Go (Ki no kaze) ’92” (Five, Seven, Five (Seasonal Wind) ’92), 1992 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, mounted on panel, 182,5 × 91,5 cm

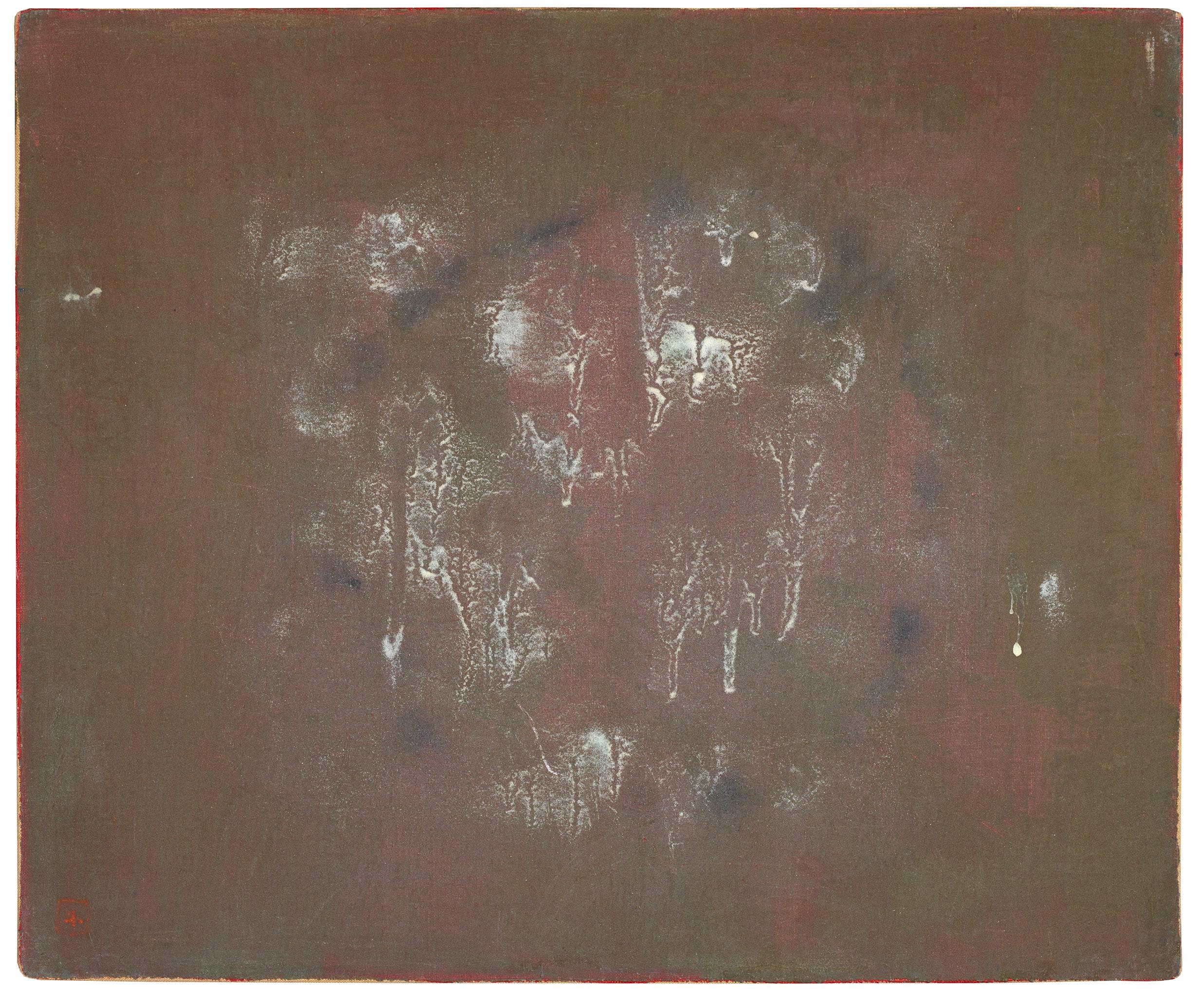

“Haiku ’92 (I)”, 1992 Mineral pigments on canvas, 162 × 130,5 cm

“Haiku ’92 (Ro)”, 1992 Mineral pigments on canvas, 162 × 130,5 cm

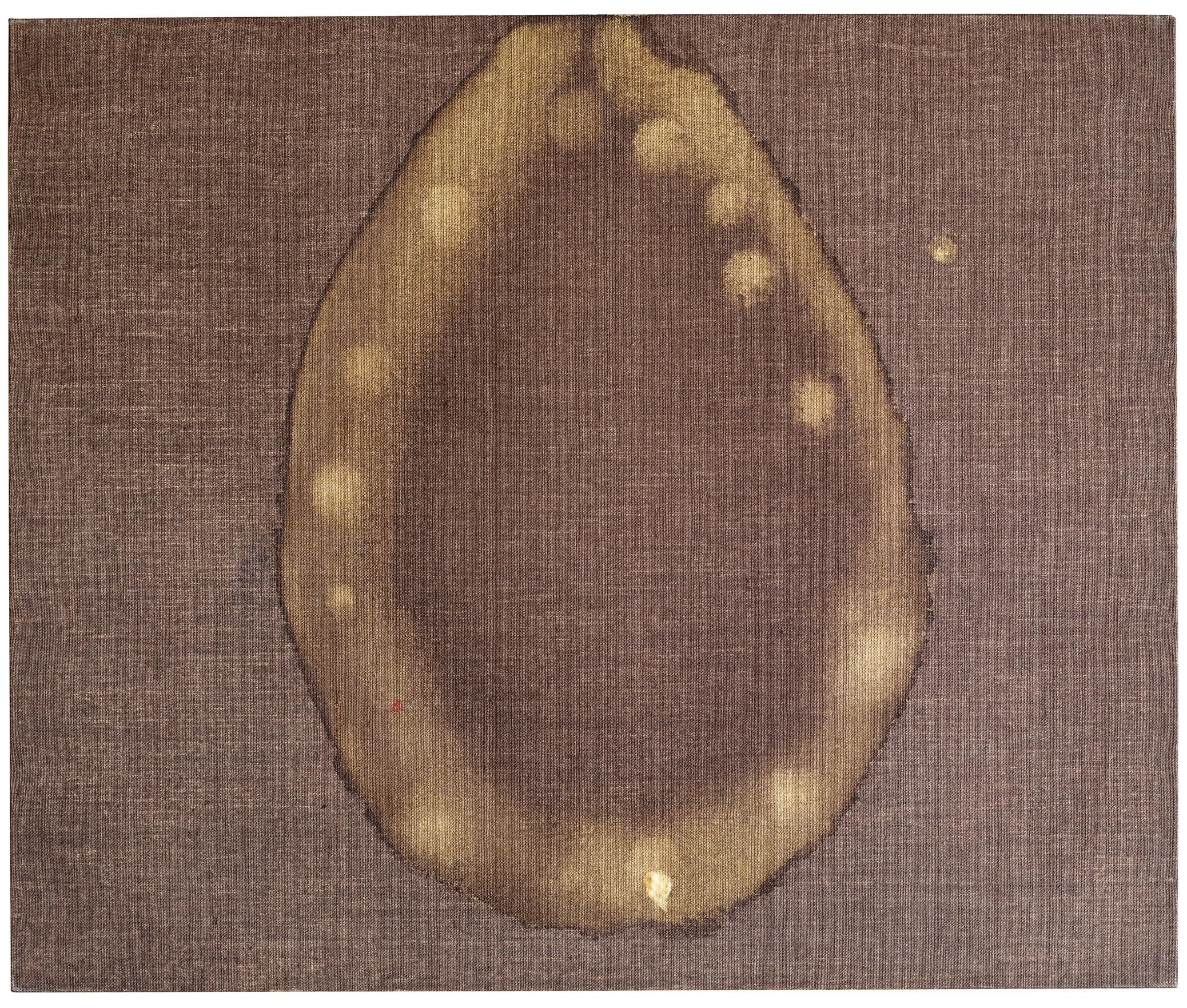

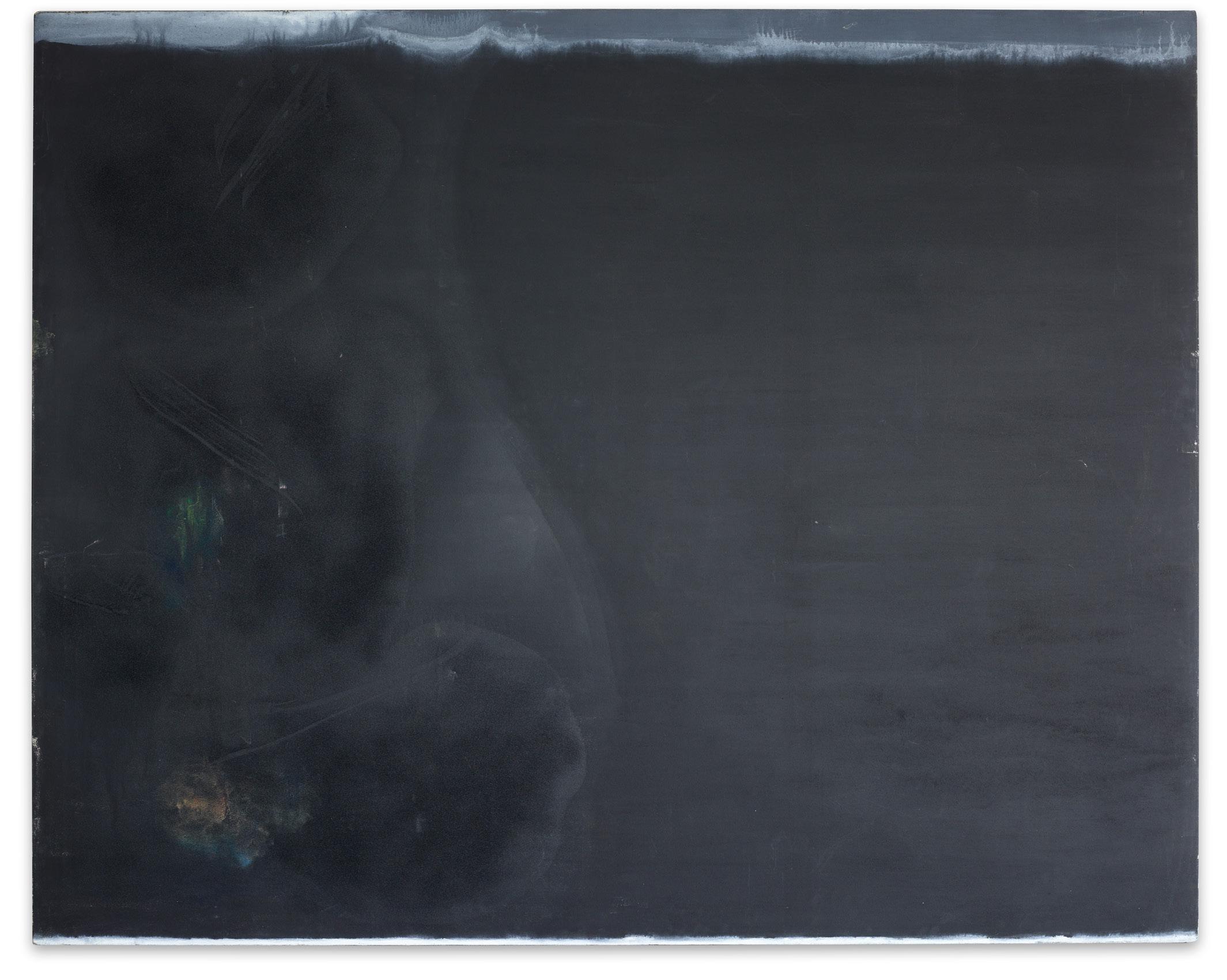

Untitled, ca. 1993 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 180,5 × 225 cm

Untitled, ca. 1993 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 180,5 × 225 cm

overleaf

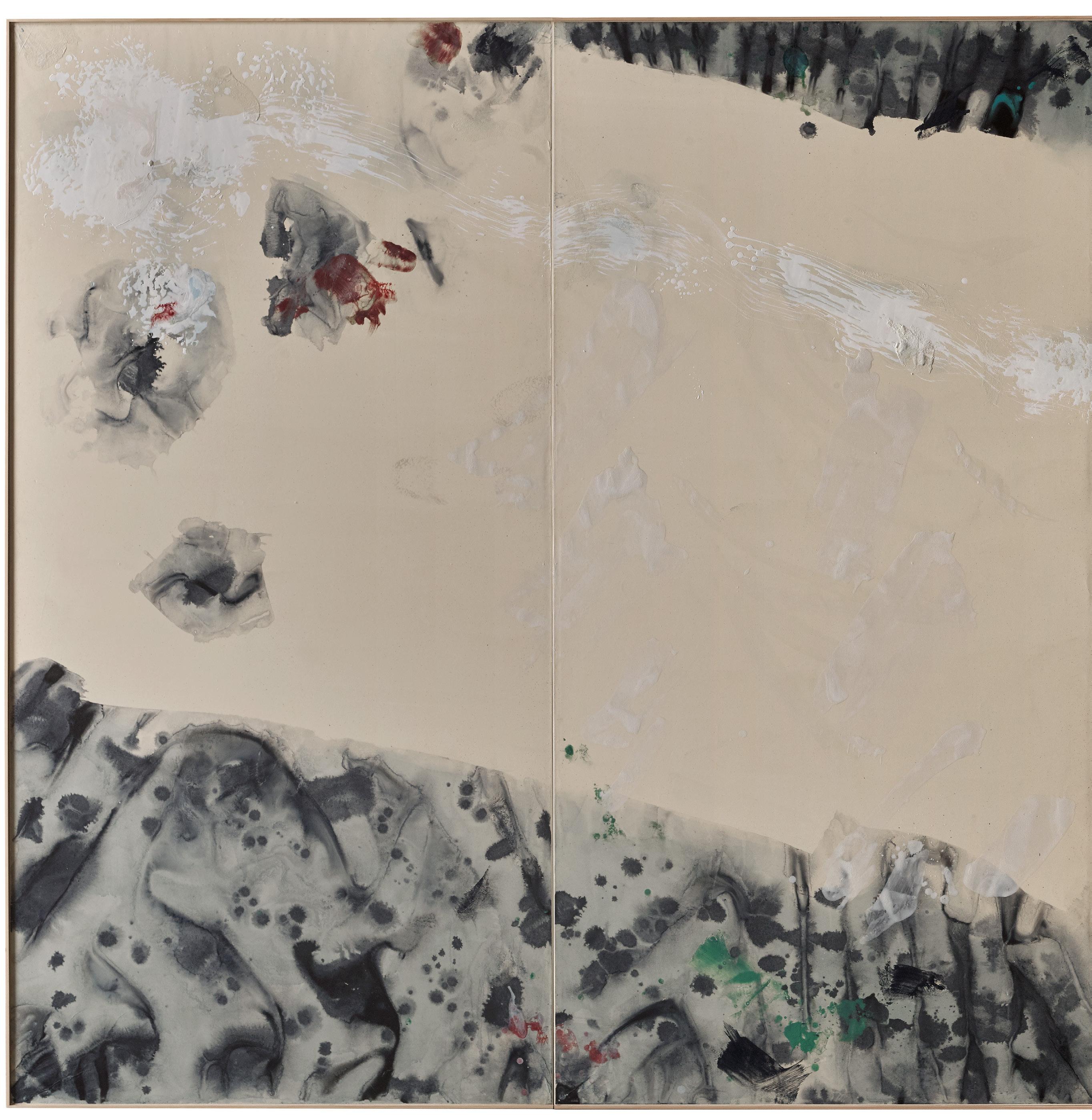

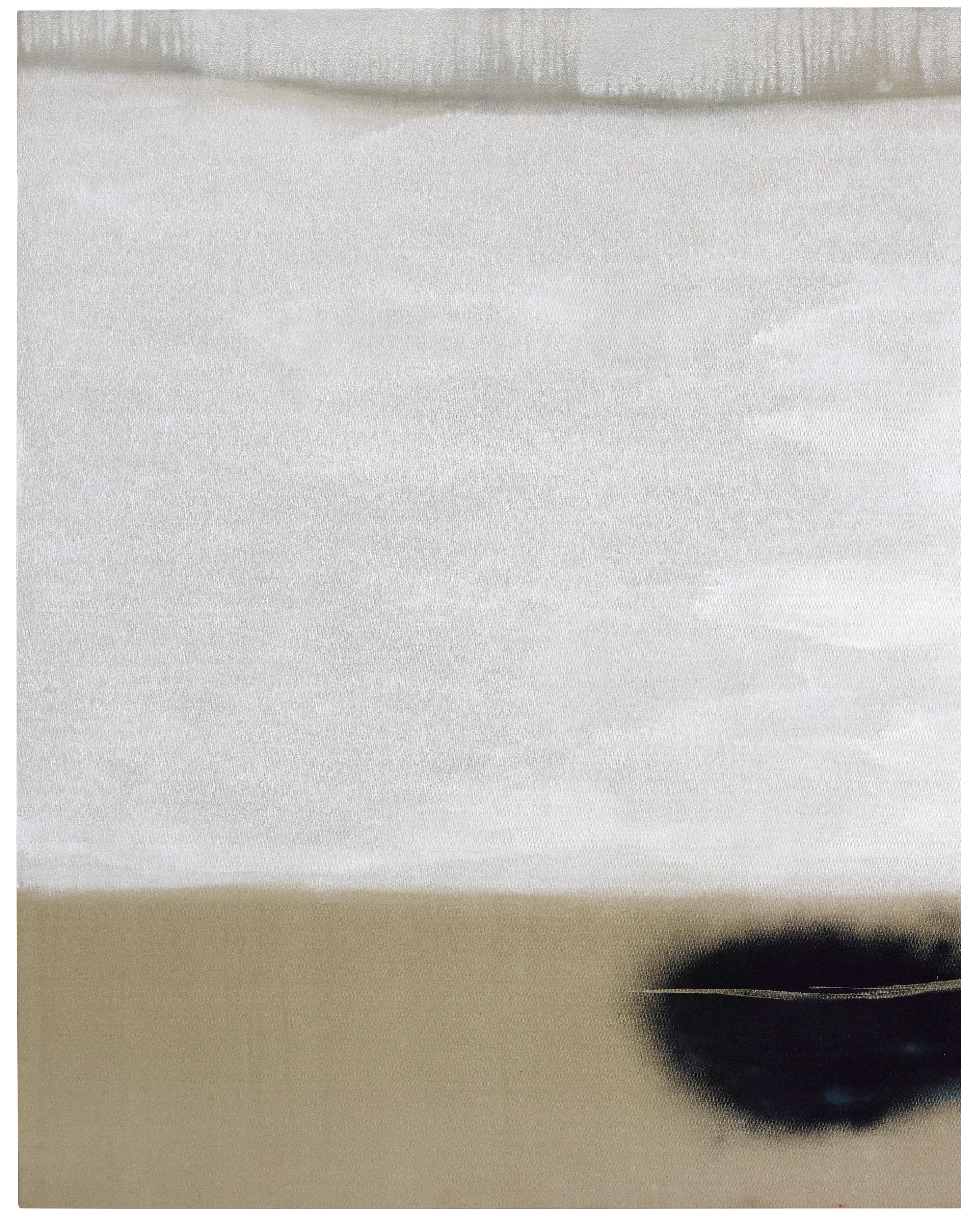

“So Nidai (A)” (Two Subjects of Expression (A)), 1993 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 182 × 227,5 cm

“So Nidai (B)” (Two Subjects of Expression (B)), 1993 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 182 × 227,5 cm

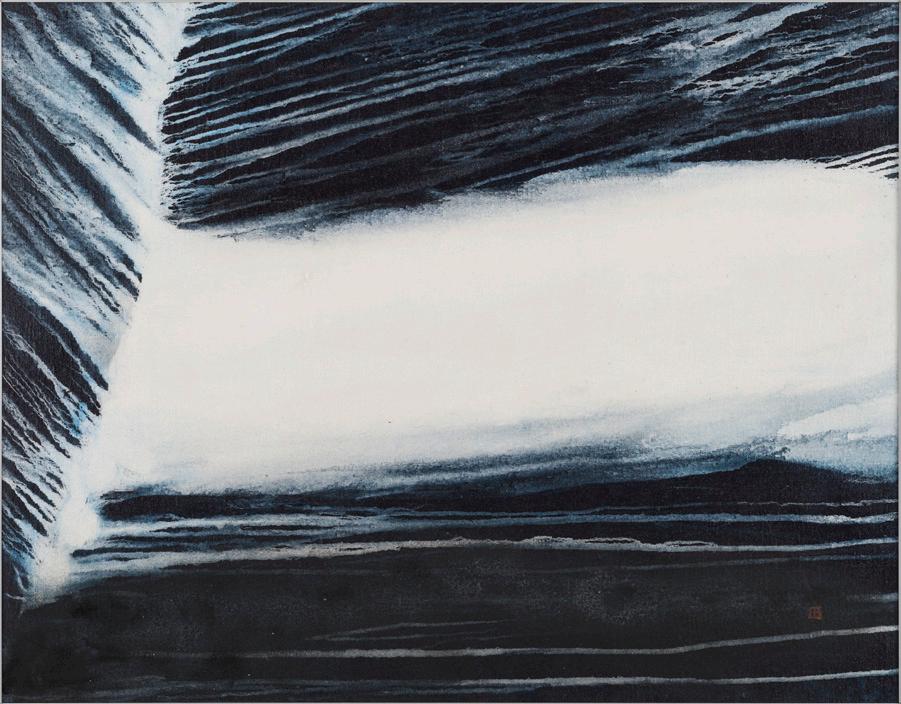

“Classic ’94 Light Arrangement Op. 3” (An Original Picture of a Wall Painting, Iguazú Falls: World Heritage), 1994 Mineral pigments and mixed media mounted on panel, 97 × 131 cm

“Shizen ’96 (Shiro)” (Nature ’96 (White)), 1996 Mineral pigments and mixed media on canvas, 91 × 116,5 cm

“Go Shichi Go (A) ’92” (Five, Seven, Five (A) ’92), 1992 Mineral pigment on canvas, 112 × 145,5 cm

overleaf

“Shun ’01”, 2001 Oil and mineral pigment on canvas, 162 × 131 cm