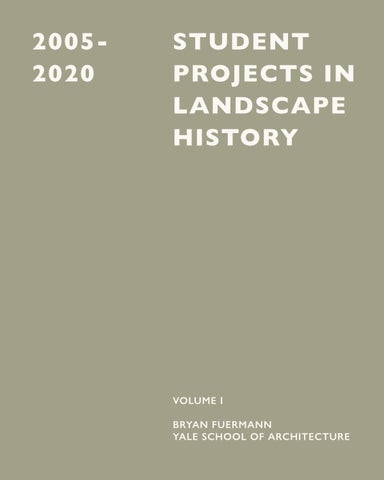

STUDENT PROJECTS IN LANDSCAPE HISTORY 20052020

VOLUME I

BRYAN FUERMANN YALE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

STUDENT PROJECTS IN LANDSCAPE HISTORY

2005-2020

VOLUME I

YALE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

BRYAN FUERMANN

VOLUME I

INTRODUCTION

HORTUS CONCLUSUS

SITE PLANS

LANDSCAPE TYPOLOGIES

BUILDINGS IN THE LANDSCAPE

LANDSCAPE INCORPORATED INTO BUILDINGS

MODELS OF LANDSCAPE GARDENS

COLOR IN LANDSCAPE

ERUDITE FUN

DRAWING THE LANDSCAPE

VOLUME II

ANALYZING

TREES

MOUNDS

ARTIST BOOKS

SOUNDSCAPES

PHOTOGRAPHY & CINEMA

APPENDIX

Zack Lenza

Millie Yoshida

Alex Kruhly

Meghan Royster

Michelle Gonzales & Clarissa Luwia

David Langdon

Melissa Shin

Stephen Gage

Maya Sorabjee

Drawing of Courtyards from Peristyle to the 1940s

House of the Tragic Poet

Three Cloisters

Through the Plan of St. Gall

Certosa del Galluzzo

Secret Gardens of the Italian Renaissance

The Edge of Paradise

The Landscape of the University

Bawa’s Horti Conclusi

II. SITE PLANS

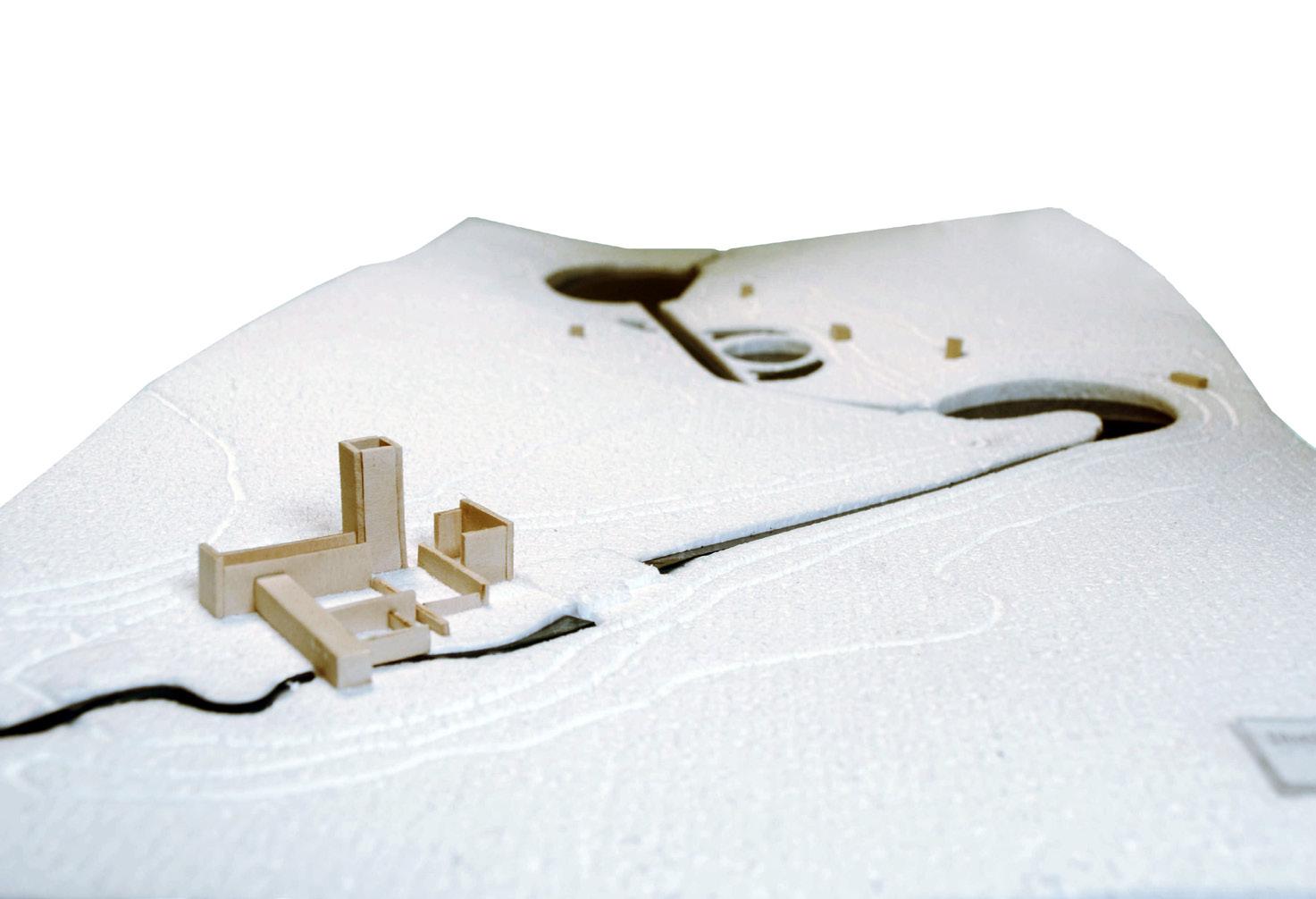

Haelee Jung

Shiyan (Nancy) Chen

Michelle Gonzales

Stephen Gage

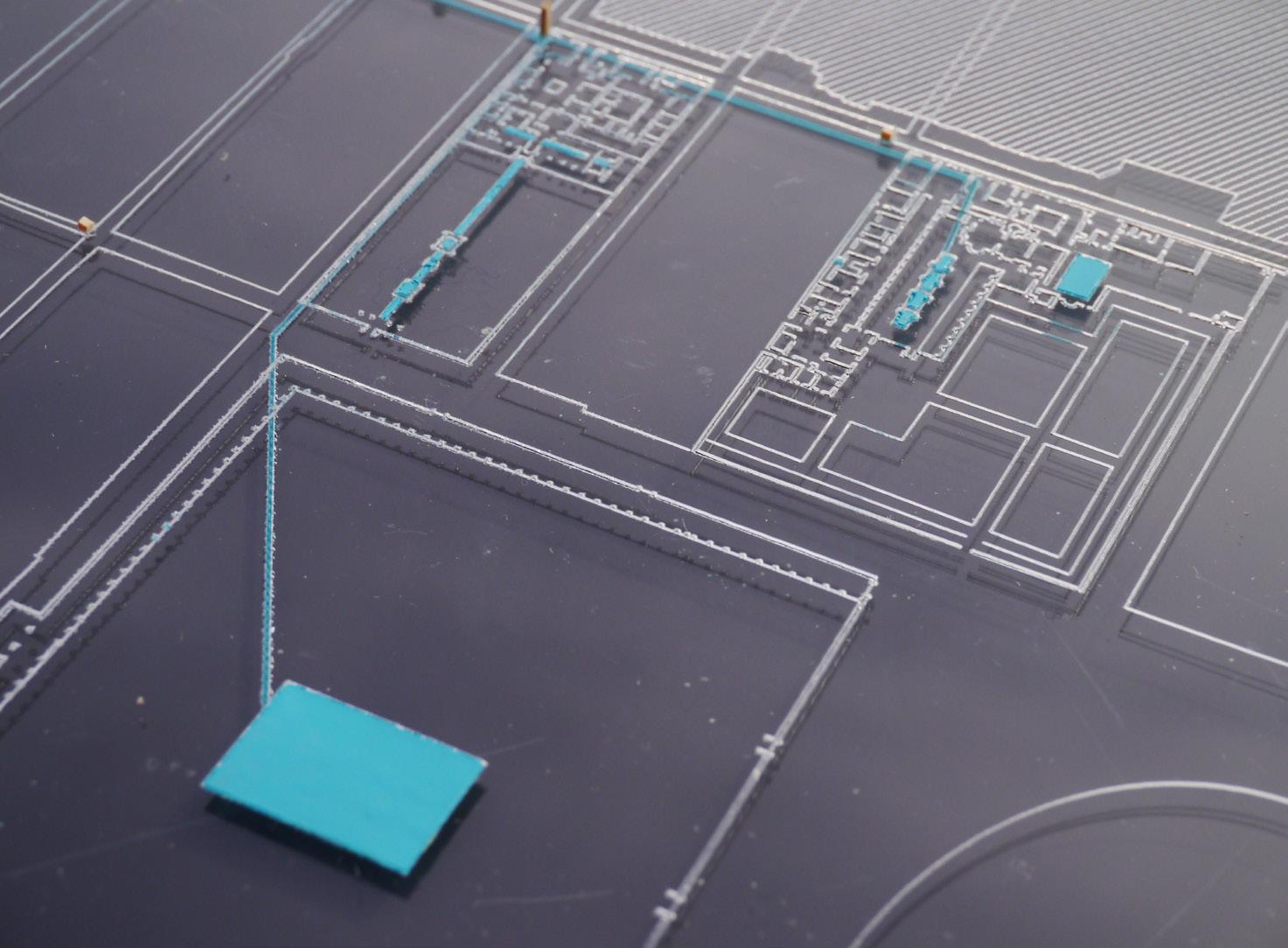

Model of the Public and Private Water Works in Ancient Pompeii

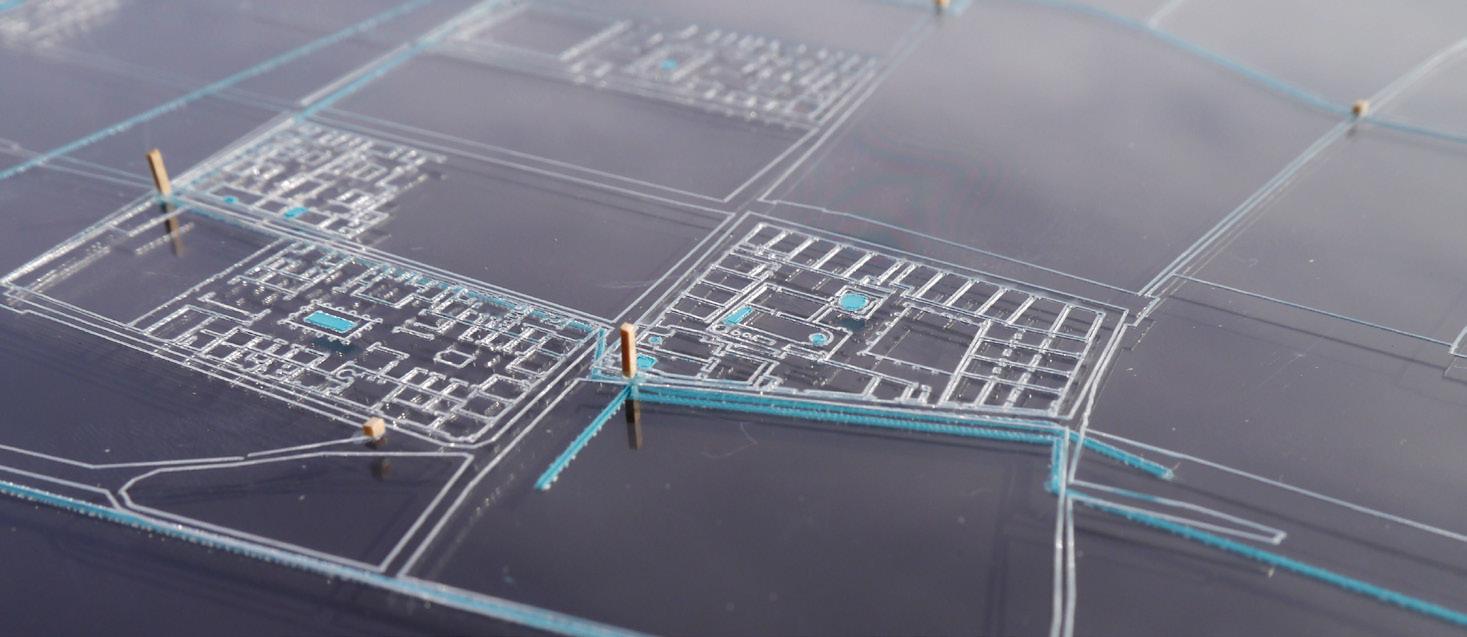

Site Model of Hadrian’s Villa

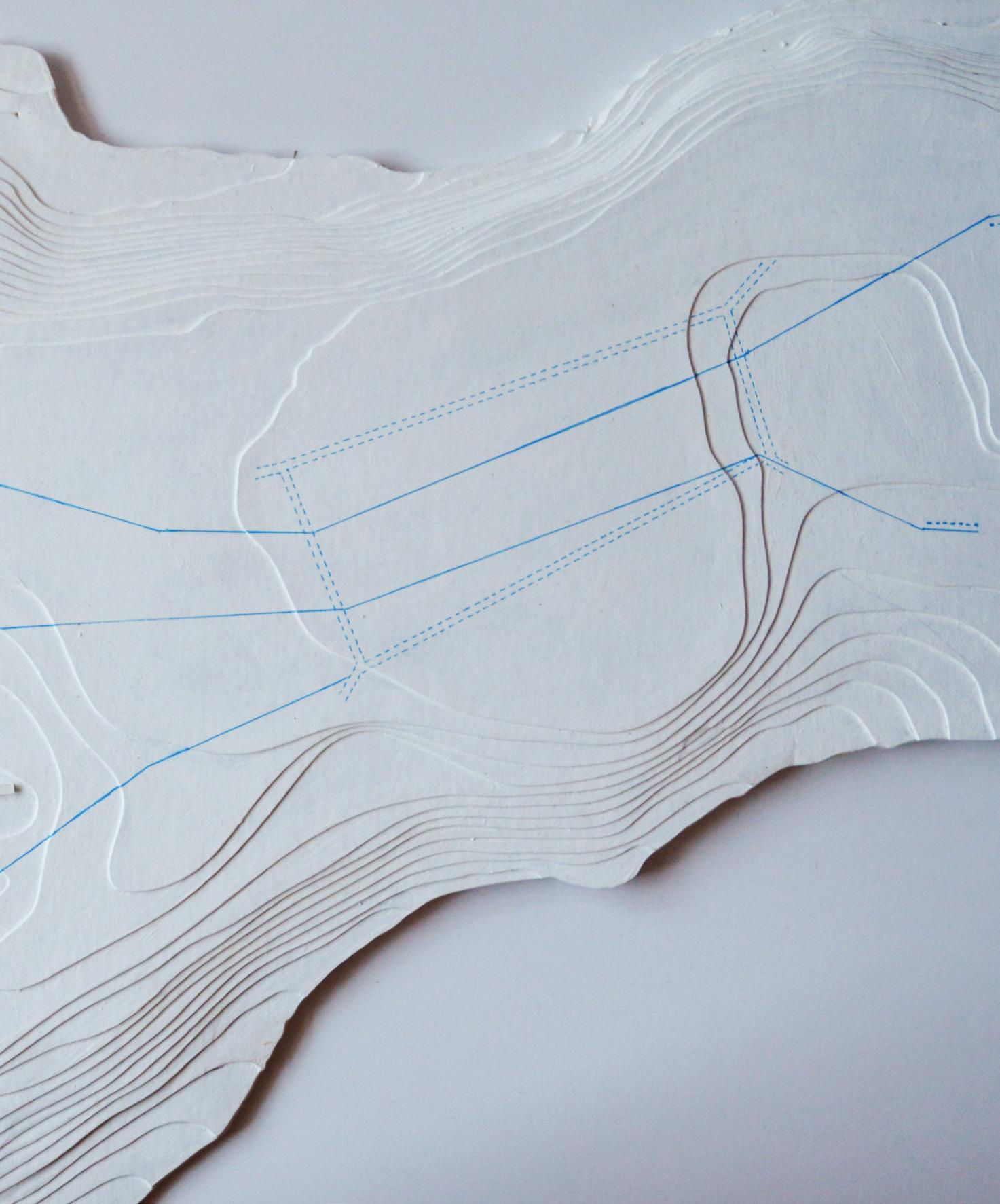

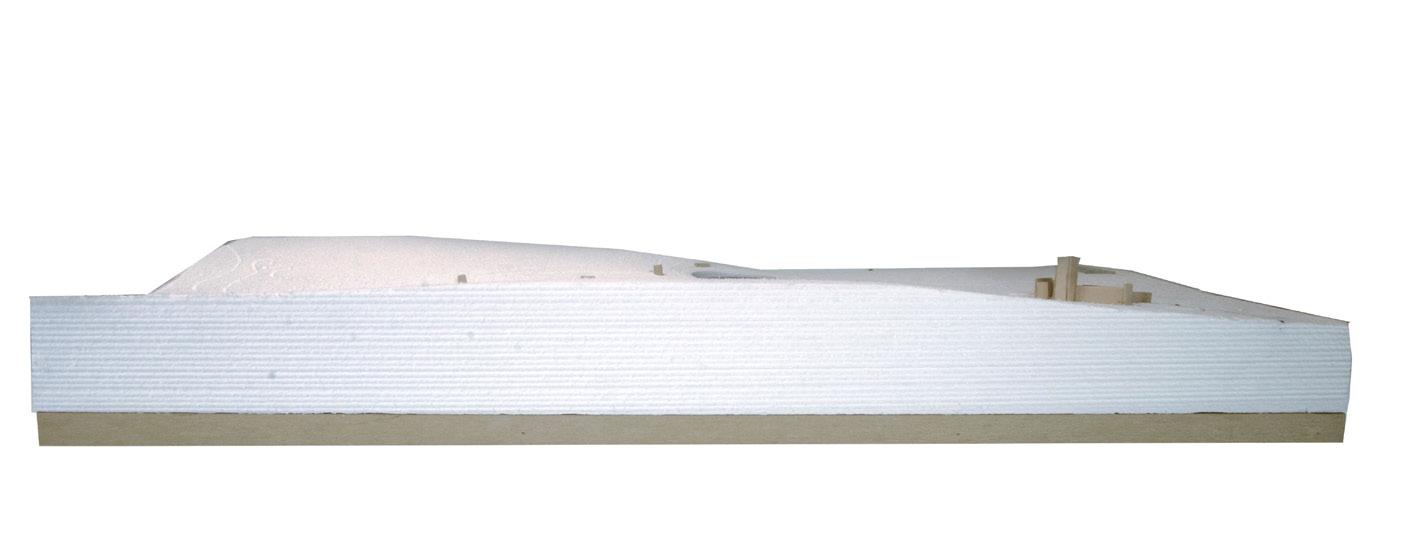

Topographic Model of the River Skell at Studley Royal, Fountains Abbey

Uniformity and Multiplicity

III. LANDSCAPE TYPOLOGIES

Michael Moriano

Aude Jomini

Elizabeth Nadai

Wesley Hiatt

Stephanie Jazmines

The Hippodrome Garden into the 20 th Century

The Euripus in Landscape History

The Euripus in Drawing and Model

The Monumental Stair

Monumental Landscapes

James Tate Bridge

IV. BUILDINGS IN THE LANDSCAPE

Luke Studebaker

From the Vernacular to the Formal Filipp Blyakher

Justin Hedde

Kola Ofoman

Ava Amirahmadi

Kin-Tak Yu

Benjamin Smith

Shuo Zhai

Melissa Weigel

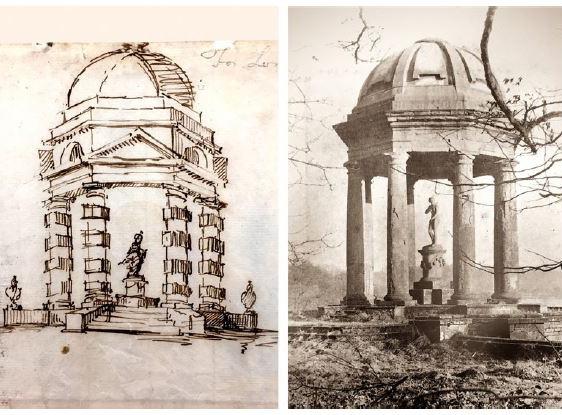

Hawksmoor’s Temple of Venus at Castle Howard

Hawksmoor’s Unbuilt Temple of the Four Winds at Castle Howard

Hawksmoor’s Alternative Schemes for the Mausoleum at Castle Howard

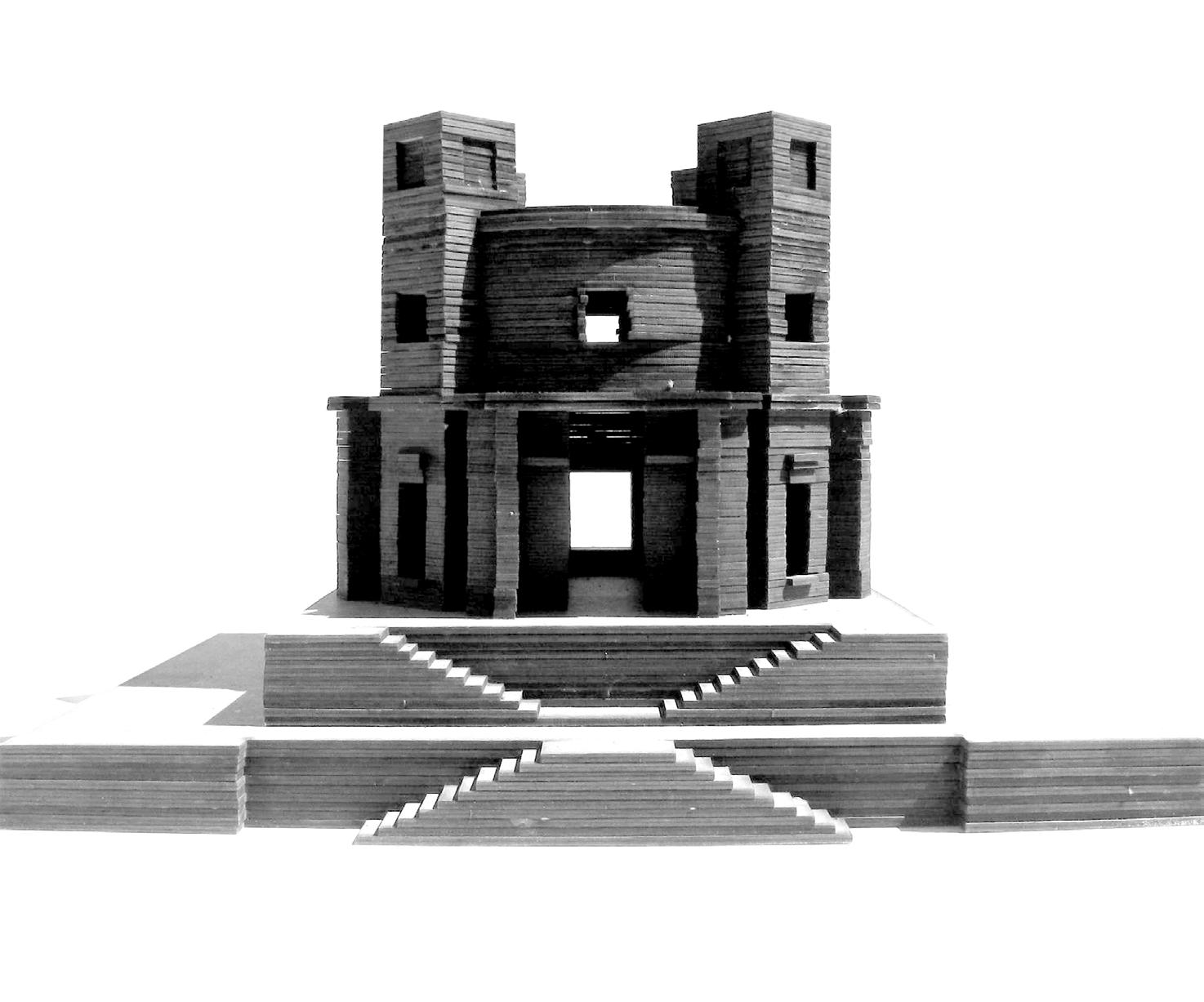

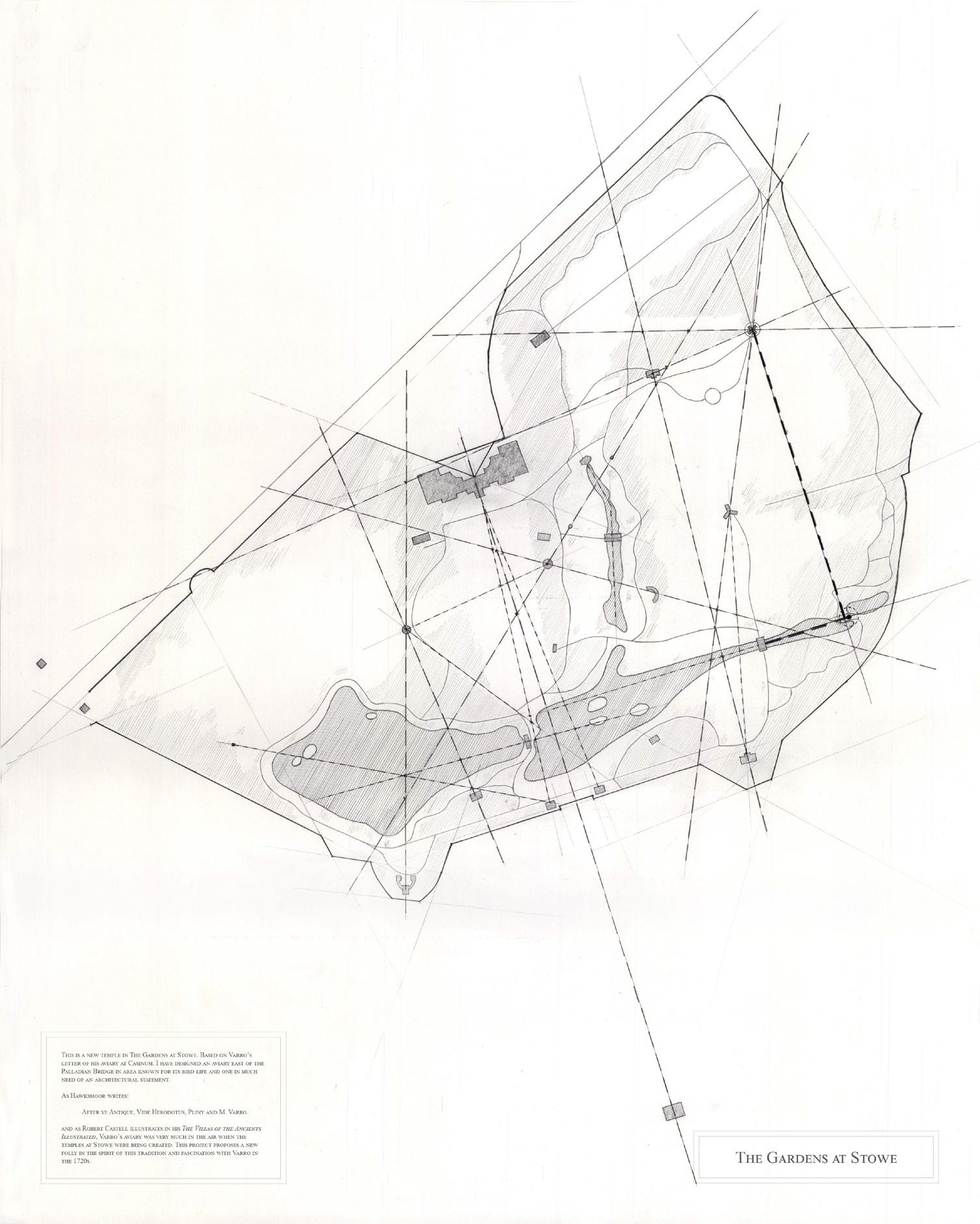

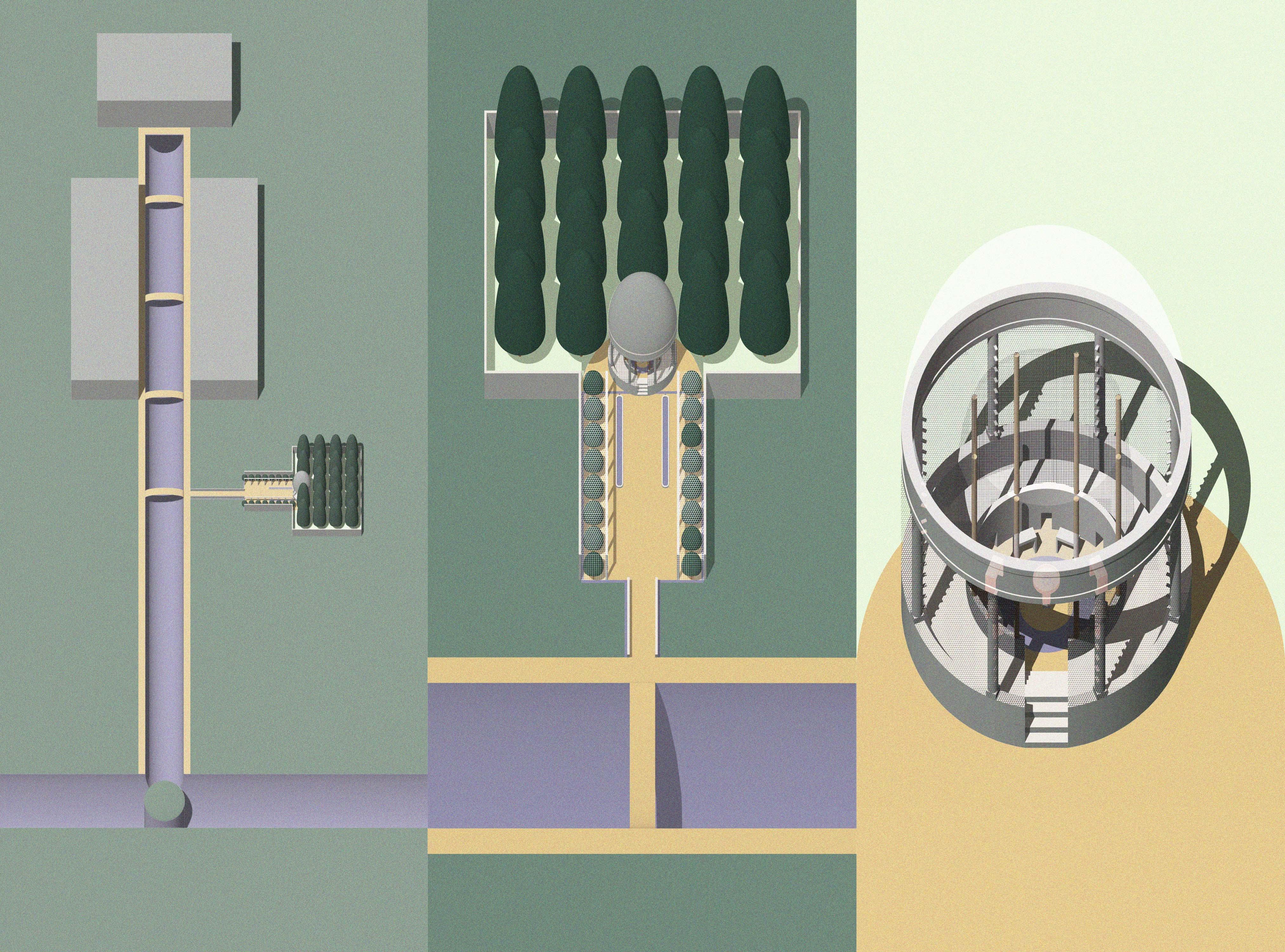

Aviary at Stowe

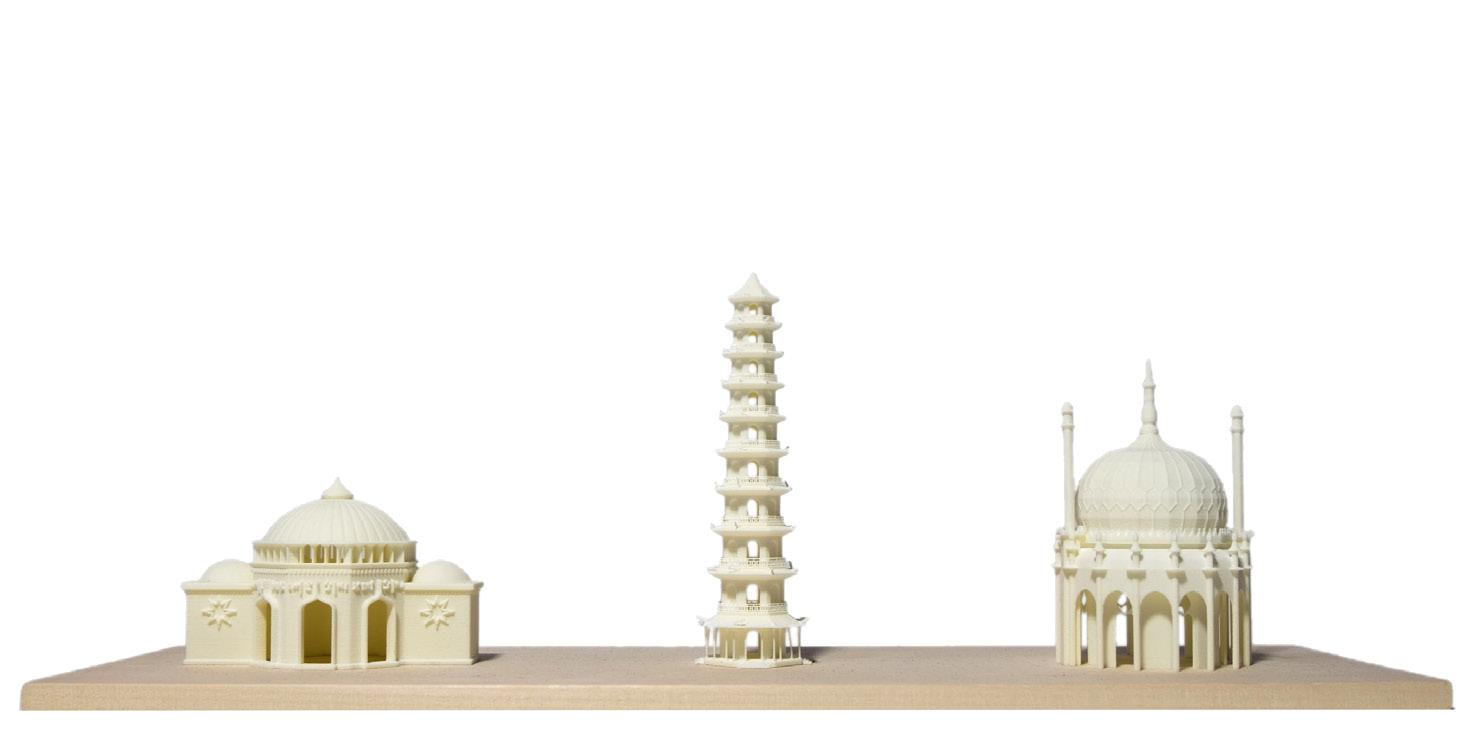

William Chambers’ Follies at Kew Garden

Animal Architecture in the British Landscape

Models of Chiswick House and Villa Rotunda

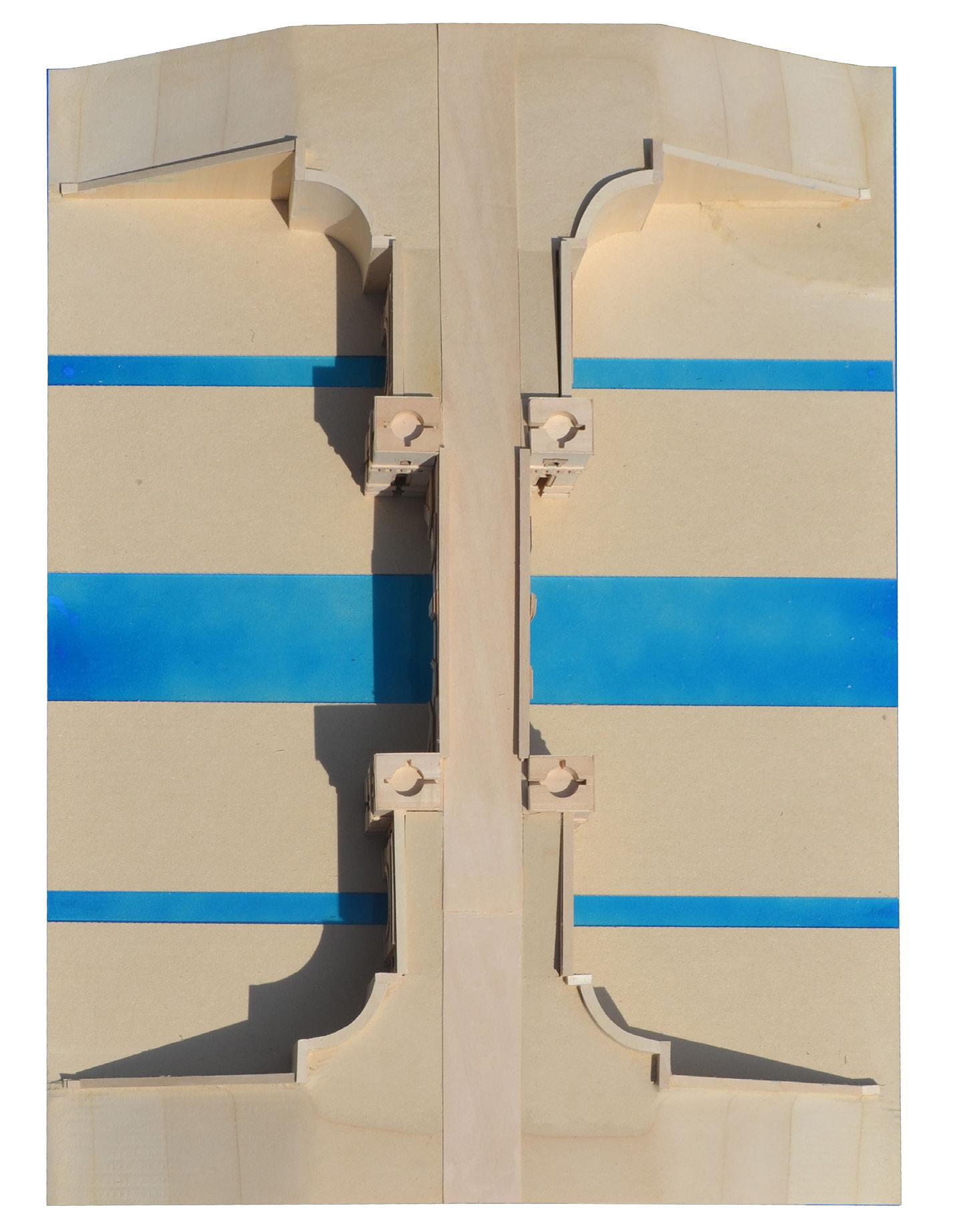

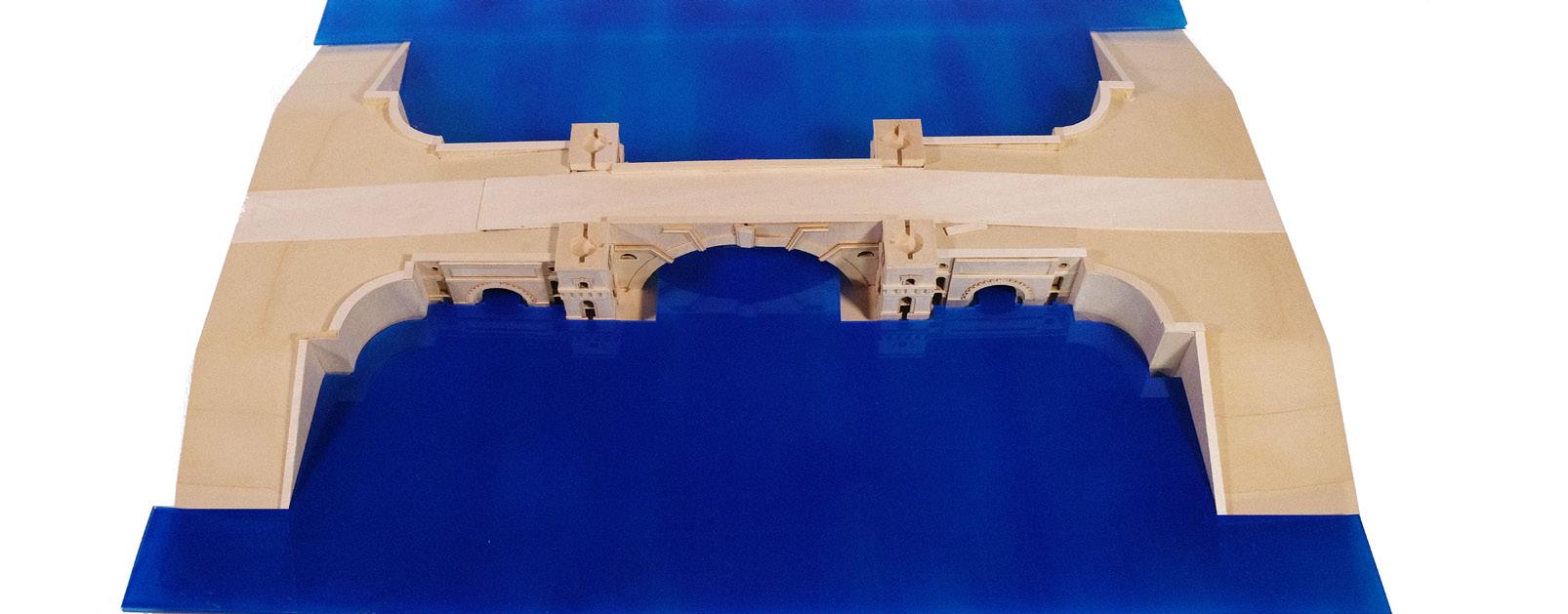

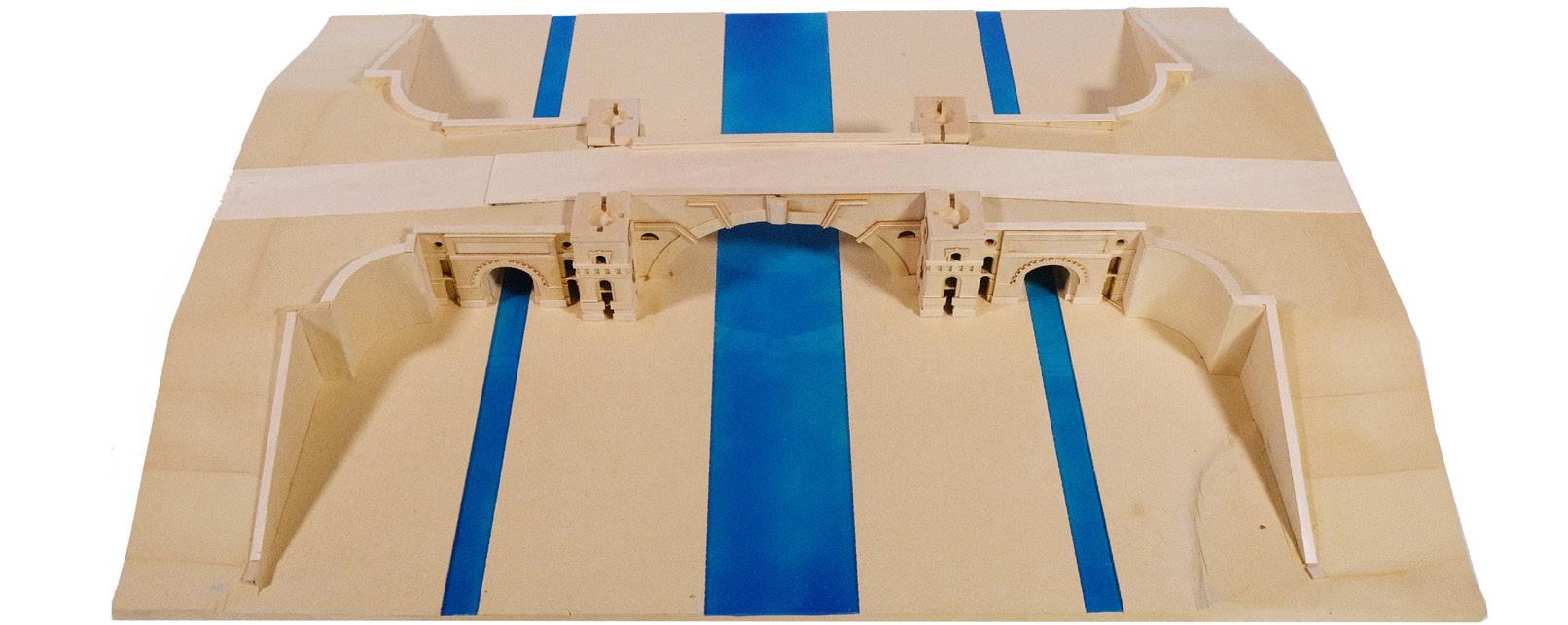

Sir John Vanbrugh’s Bridge at Blenheim

V. LANDSCAPE INCORPORATED INTO BUILDINGS

Jenna Ritz

Bobby Cheng

Laélia Vaulot

The Island Enclosure, Hadrian’s Villa

The Smaller Baths at Hadrian’s Villa

The Scenic Triclinium at Hadrian’s Villa

VI. MODELS OF LANDSCAPE GARDENS

Jason Roberts

Amir Mikhaeil

Michelle Chen

Aude Jomini

Jamie Edindjiklian

Yu Wang

Scarpa’s Brion Cemetery

Evolution of the King’s Privy Garden at Hampton Court

The Great Parterre at Hampton Court

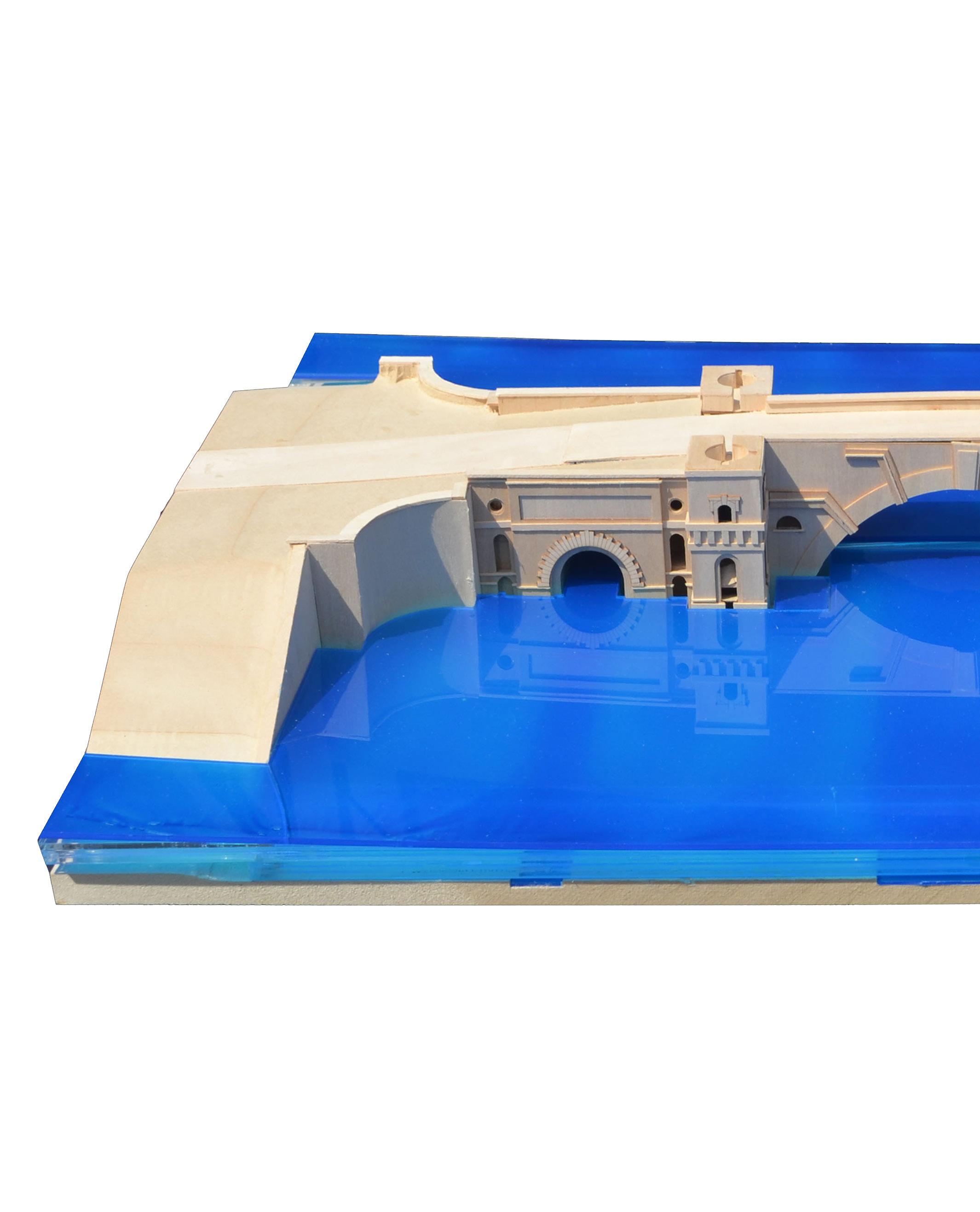

The Hexagonal Fortified Garden at Blenheim

All Green Garden

Model of Williams’ Chambers’ Landscape at Kew

VII. COLOR IN LANDSCAPE

Denisa Buzatu

Peter McInish

Colors in the Main Flower Border by Gertrude Jekyll

Chroma

VIII. ERUDITE FUN

Filipp Blyakher

Nicholas Miller

Alan Knox

Ha Min Joo

Madelynn Ringo

Richard Green

Talley Burns

Kristin Mueller

Cecily Ng

Anthony Gagliardi & Pearl Ho

Matthew Zych

Cecily Ng

IX. DRAWING THE LANDSCAPE

Naomi Darling

Leah Abrams

Maureen Ponto

Ilana Simhon

Lang Wang

Gina Cannistra

Stephanie Jazmines & Belinda Lee

Shannon McGoldrick

Garrett Hardee

Christine Pan

Christine Pan

Elizabeth Nadai

Kelsey Rico

David Schaengold

Hunter Hughes

Elise Barker-Limon

The Letters of the Younger Pliny

Ancient Roman Tea Service Set

Stourhead Walk Board Game

Coloring the British Landscape

A Kit of Temples

Castle Howard Model Kit

Through the Gates at Castle Howard

Constructing Landscapes with Alexander Cozens

Surprising Scenes from Oriental Gardens

Animated Drawing

Follies: A Field Guide to Madness

Kit for Laying Out Your Own Parterre de Broderie

Twelve Perspective Views of Stowe

Picturesque Landscape of the Garden Bridge Over the Thames

The Ha-Ha in British Landscape

A Drawing of Rousham

Statues of Rousham

Drawing of a Painted Wallpaper Frieze of the British Landscape

Stage Set of an English Garden

Temple, Follies, and Pavilions in the British Landscape: A Watercolor Drawing

Hunt for Britannia (30” x 125”)

Botanicum Imperatoria

Botanicum Imperialis

Drawing the British Landscape

Bridges in the British Landscape

Postcards of Ruins

Painting the British Sky

When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow

X. ANALYZING THE LANDSCAPE

Vittorio Lovato

Michael Krop

Bo Crockett

Ian Mills

Kelsey Rico

Kelsey Rico

Jolanda Devalle

Jolanda Devalle

Kassandra Leivia

Melissa Shin

Garrett Hardee

Seokim Min

John Kleinschmidt & Andrew Sternad

Aurora Farewell

Anthony Gagliardi

Constance Vale

Labor / Leisure

Lessons Learned

A Pattern Book of British Gardens and Manors to Scale

Templescapes

The Roman Aqueduct Book

Aqua Marcia

Conduits of Pratolino

Conduits of Villa D’Este

Internalizing Nature

Follies: Object & Morphology

The Garden Parterre

Communal and Individual

Landscape Lines

Drawing of the Smaller Baths, Stadium Garden, and Island Enclosure at Hadrian’s Villa

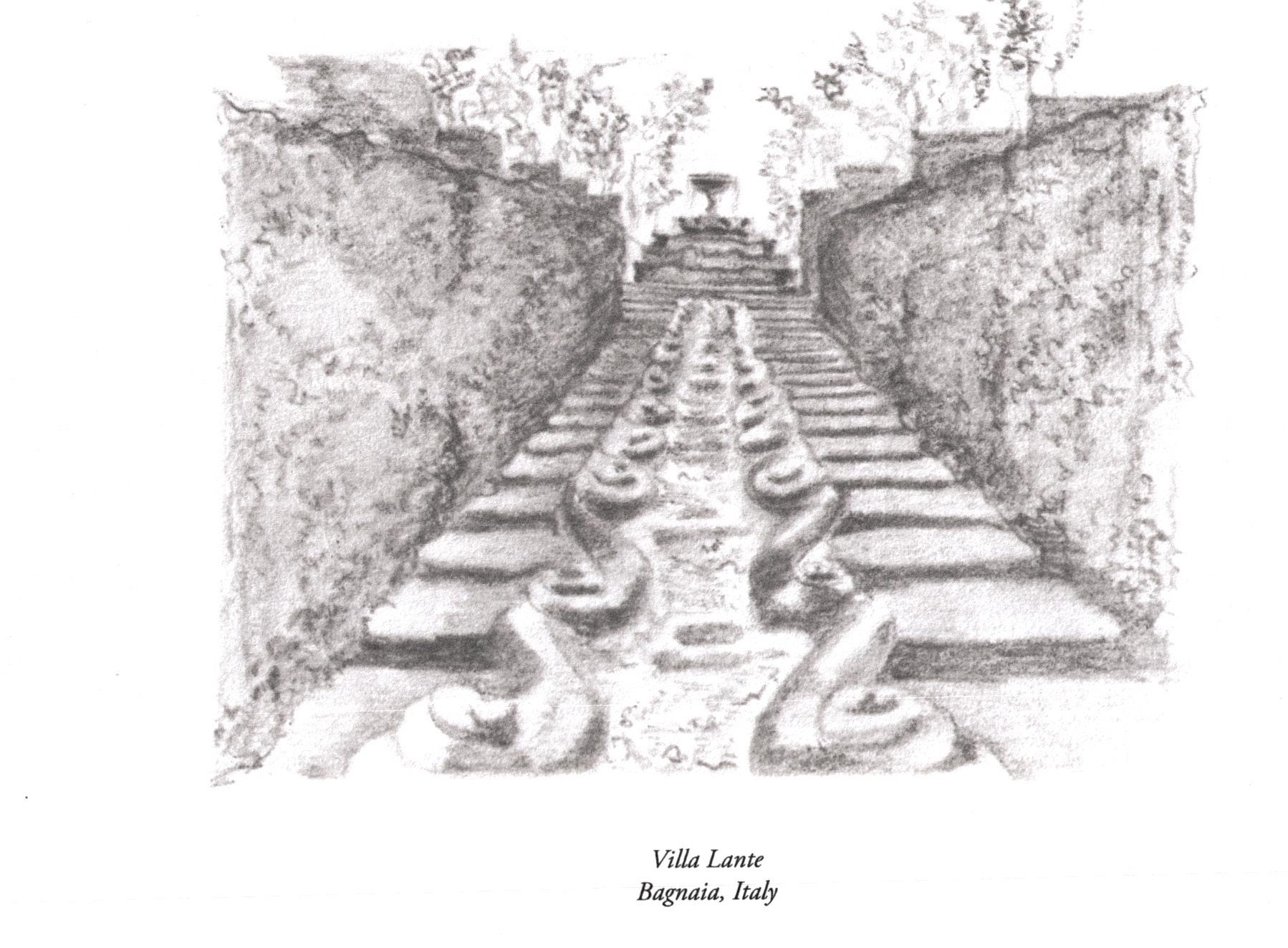

Planimetric Model of the Villa Lante, Bagnaia

Villa d’Este Water & Will

XI. TREES AND ROCKS

Daniel Jacobs

Maya Alexander

Naomi Ng

Daniel Marty

Louisa Nolte

Pomological Architecture

The Tree and the Column

The Edge of Forestscapes

The Power of Stone

The Use of Stone in the British Landscape

XII. MOUNDS

Isaiah King

Owen Howlett

Constance Vale

Mounds in the Landscape

Land Forms in the British Landscape

Typology of Mounds

XIII. ARTIST BOOKS

Alice Tai A British Landscape Primer

Haelee Jung & Melody Song Red Book of Sidley Park

Isaac Southard & Sarah Kasper Observations on Several Parts of England

Alex Kruhly Lines in the Landscape

Jonathan Molloy Lessons from Landscape

Boris Morfin-Defoy Replicating the Various Sounds of Water at the Villa d’Este

Ava Amirahmadi Soundscapes

XV. PHOTOGRAPHY & CINEMAS

Andrew Dadds Cinematic Garden

Marc Guberman Lordship of the Eyes

Daria Solomon Time Overwhelms the Works of Man

Ian Spencer Between and Beyond

Hiuki Liu Animating LeNotre at Vaux-le-Vicomte

For my students.

INTRODUCTION BY BRYAN FUERMANN

Student Projects in Landscape History, 2005-2020 documents work made by students in the Yale School of Architecture as their final projects in the two seminars in Italian and British landscape history I have taught at Yale since 2001. It emanates from a visit to my office by Christopher Ridgway who had come to Yale to give a talk on Castle Howard of which he is Chief Curator. Upon seeing in my office all of the projects I had saved and kept in drawers, on the top of my desk, on shelves, window sills, and leaning against the office wall, he asked: who sees this work. When I replied only those who stop by my office, he said they should not languish there but be seen by a much wider audience. And that is what this book aims to do.

When I first began teaching landscape history at Yale, I required the standard three thousand word essay as part of the course requirements. A few years in, however, I realized that many of my Yale students were more eager to undertake making projects in various mediums than to write papers, projects which often took considerably more time and effort than the traditional final paper. And so, beginning in 2005 I let students choose to write a paper or undertake a project that would express what interested them most in learning about the landscape history of Western Europe from ancient Rome to the present. Most chose projects. As seem throughout the pages of this book the projects extend to large scale hand-drawings, site plans, topographic models, planimetric models, building models, artist books, paintings, analytic investigations, photography, studies in sound and film, games, small books on landscape typologies, and animated videos. To contextualize them some remarks on the two courses I teach and the trips to Rome and to England my students take bear mentioning.

My fall seminar is an introductory survey of the history of landscape architecture and the wider, cultivated landscape in Western Europe from the Ancient Roman period to seventeenth-century Rome. The focus is primarily on Italian landscape history, in particular the townhouse gardens and villas of Pompeii and Herculaneum, the imperial residences of Ancient Rome, specifically Nero’s Golden House and Hadrian’s villa, the monastic gardens of late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, including the gardens of Islam, the Medici villas of Florence, sixteenth-century Roman city and villa gardens, Palladian villas, and the villa parks of Baroque Rome.

The course examines chronologically the evolution of several key elements of landscape architectural design: the concept of the Three Natures — Wilderness, the Agrarian and Infrastructural, which John Dixon Hunt calls the cultural landscape,1 and the designed landscape — garden typologies, architectural typologies relating to the garden, various uses of water in the garden and in public fountains, including an examination of the Roman aqueduct system, the organization and availability of plant materials, the role of sculpture and of garden ornamentation in landscape, and the representations of landscape in paintings, plans, maps, prints, and other media in each of the four periods under discussion--Ancient Roman, Medieval, early to late Renaissance, and Italian Baroque. A central theme of the course designed for architecture students but applicable to students of landscape architecture as well is the blurring of boundaries between inside and outside, the extension of architecture into the landscape and the insertion of landscape into buildings.

Where appropriate, parallels are drawn with landscape architecture in later periods in France, England, and America, principally by tracing the adaptation of landscape typologies over various periods and geographies in landscape history up to the present.

Additionally, I need to note the Robert A.M. Stern seminar in drawing, Rome Continuity and Change, which occurs late spring every year in Rome. The aim of this program is to teach Yale students how to improve their skills at drawing architecture and landscape by hand rather than by computer which now dominates the field of representation. For every year since 2001, but

1 See: John Dixon Hunt, “The Idea of a Garden and the Three Natures,” in Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory, Philadelphia, 2000, 32-75, hereafter cited as Hunt.

2020 and 2021 when the pandemic canceled the drawing seminar, I have served as an on-site lecturer, taking students to various sites based on logistical proximity: Hadrian’s villa in the morning and the Villa d’Este in the afternoon on one day, the Villa Lante and the Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola on another, the Villa Farnesina and the Villa Giulia still another, and more recently walking across Rome from the Trevi Fountain to the Piazza Navona, lecturing on the hydrology of Renaissance fountains.2 I mention this because many of the Rome students enroll in my Italian landscape history class, and I have no doubt their visit to and drawing in Rome informed and gave impetus to their projects. What follows are brief remarks on projects in the book based on material taught in the Italian course.

PROJECTS IN ITALIAN LANDSCAPE HISTORY

The Enclosed Gardens or Hortus Conclusus

The course begins with an examination of the ancient Roman house in Pompeii and the idea of the Hortus Conclusus or Enclosed Garden exemplified in the Peristyle garden. Zack Lenza’s beautifully rendered, large scale drawing of Enclosed Gardens which opens this book captures the long history of this important landscape typology from antiquity to the present. Reading from top to bottom in his drawing are the Peristyle gardens of the House of the Vettii and the House of the Golden Cupids; the East-West terrace at Hadrian’s villa; the monastic cloister of the Cistercian monastery at Fossanova and that of the Certosa of Galluzzo; the sequence of Ammannati’s courtyards at the Villa Giulia; Mies van der Rohe’s study for courtyard housing; Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Cemetery; Philip Johnson’s ‘thesis house’, Cambridge, Ma; and Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion The drawing captures the connectivity and variance of a type established in Ancient Rome that continues to the present.

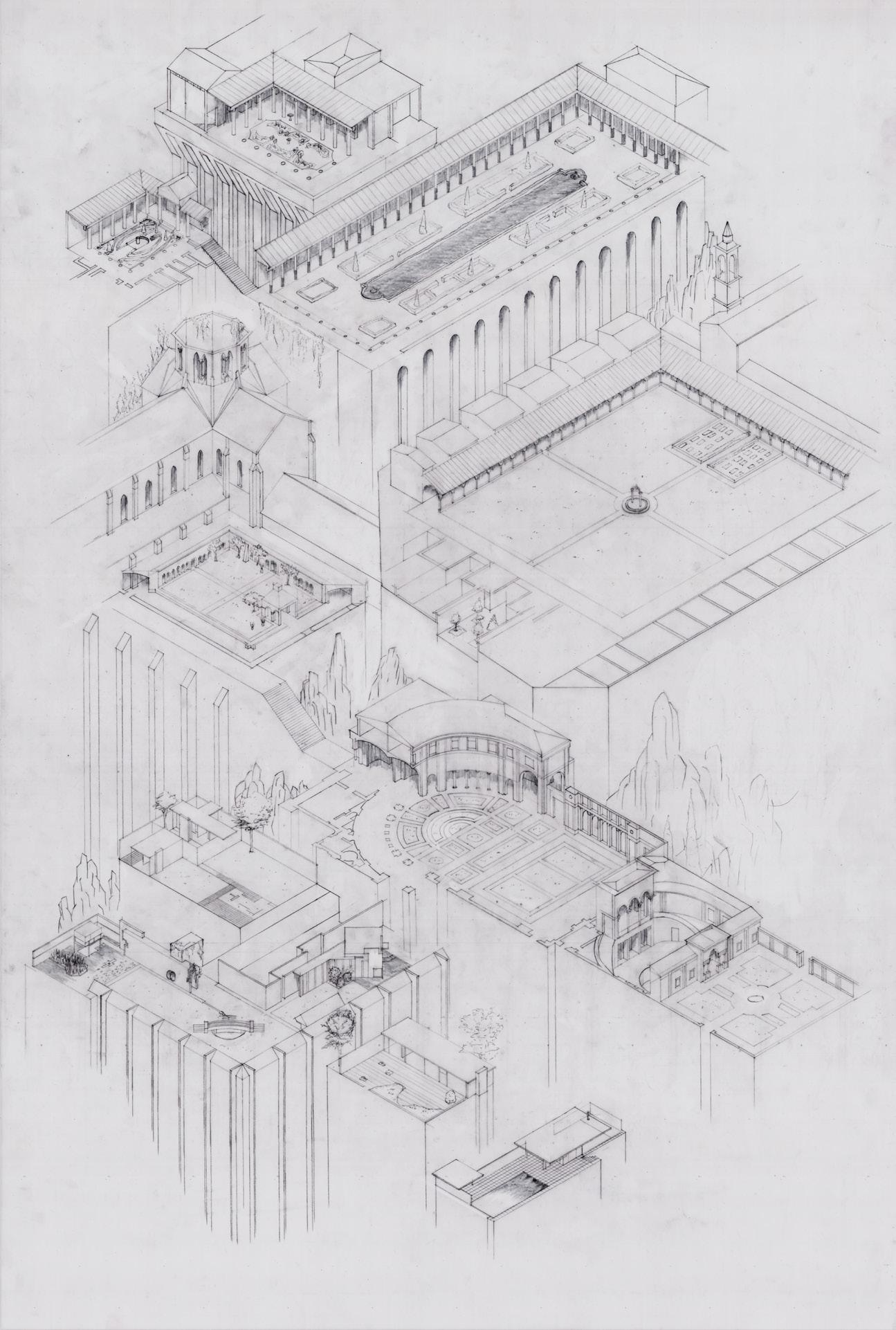

Within that long history Millie Yoshida chose to make a model of the House of the Tragic Poet and to convey three-dimensionally the light emanating at the end of the long axis of the house in the Peristyle garden. With Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of stark, white movie screens in mind as well as Le Corbusier’s description in Towards a New Architecture of light seen from the street spreading out from the peristyle of the ancient Roman house, Millie photographed the light captured in the interior of her model. To this she made a graphite drawing of her photograph that abstractly reveals the layering of the rhythms of light and dark in her model, a sequence that characterizes the ancient Roman house.

In shifting from ancient Rome to late antiquity and the Middle Ages, the course focuses on the importance of the enclosed cloister garden or garth and the religious meaning of its quadripartite divisions. Three projects address the transformation of the Peristyle to the monastic Garth.

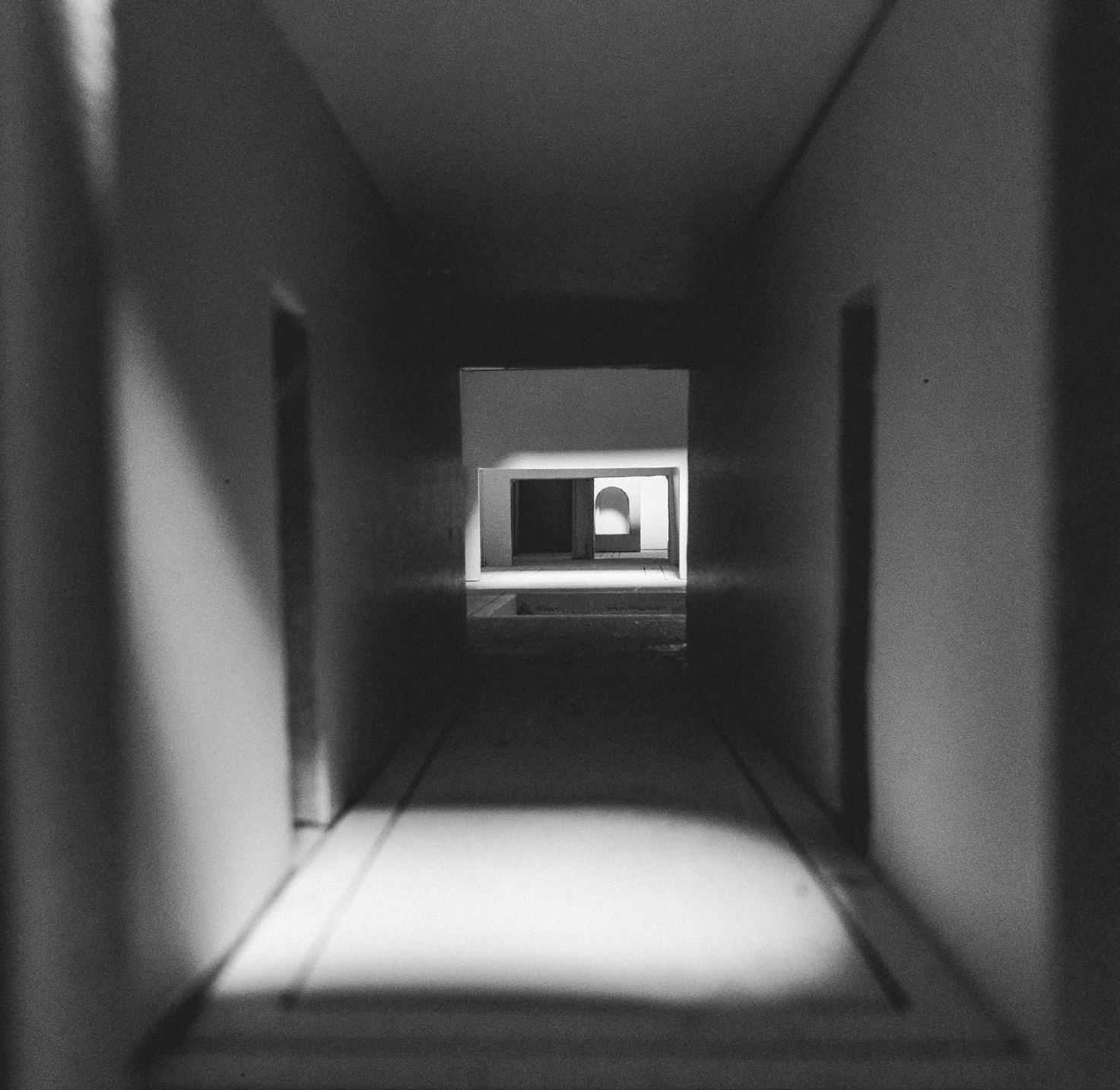

Alex Kruhly’s three wooden models of the monastery of Le Thoronet Abbey, France, 1160-1230, of Le Corbusier’s Sainte Marie de la Tourette, France, 1953-1961, and John Pawson’s Monastery of Novy Dvur, Czech Republic, 2009-2014, render these monastic buildings minimally but in so doing emphasizes with striking clarity the idea of solids surrounding landscape voids in the story of the architecture of the cloister garden.

2 This walk is primarily based on the work of Katherine Wentworth Rinne, The Waters of Rome, New Haven and London, 2010, in particular 56-108

Meghan Royster in her axonometric renderings of the Plan of St. Gall, based on Walter Horn’s study of the 9th century plan,3 details where and how landscape appears in various forms in the Utopian world of this Benedictine monastery, including that of the cloister garth, foursquare with four paths leading to the Juniper tree, symbol of the Cross, situated at the very heart of this idealized late antique complex.

Conversely Michelle Gonzales’ and Clarissa Luwia’s model of the Certosa del Galluzzo, 1341, superbly reveals how the cloister garden spatially dominates the architecture of the monastery in which surrounding the garth are the monks’ duplex cells. It is within these cells that each monk lives individually, attending to prayer and to his private garden, captured in the model’s pullout of one monk’s cell.

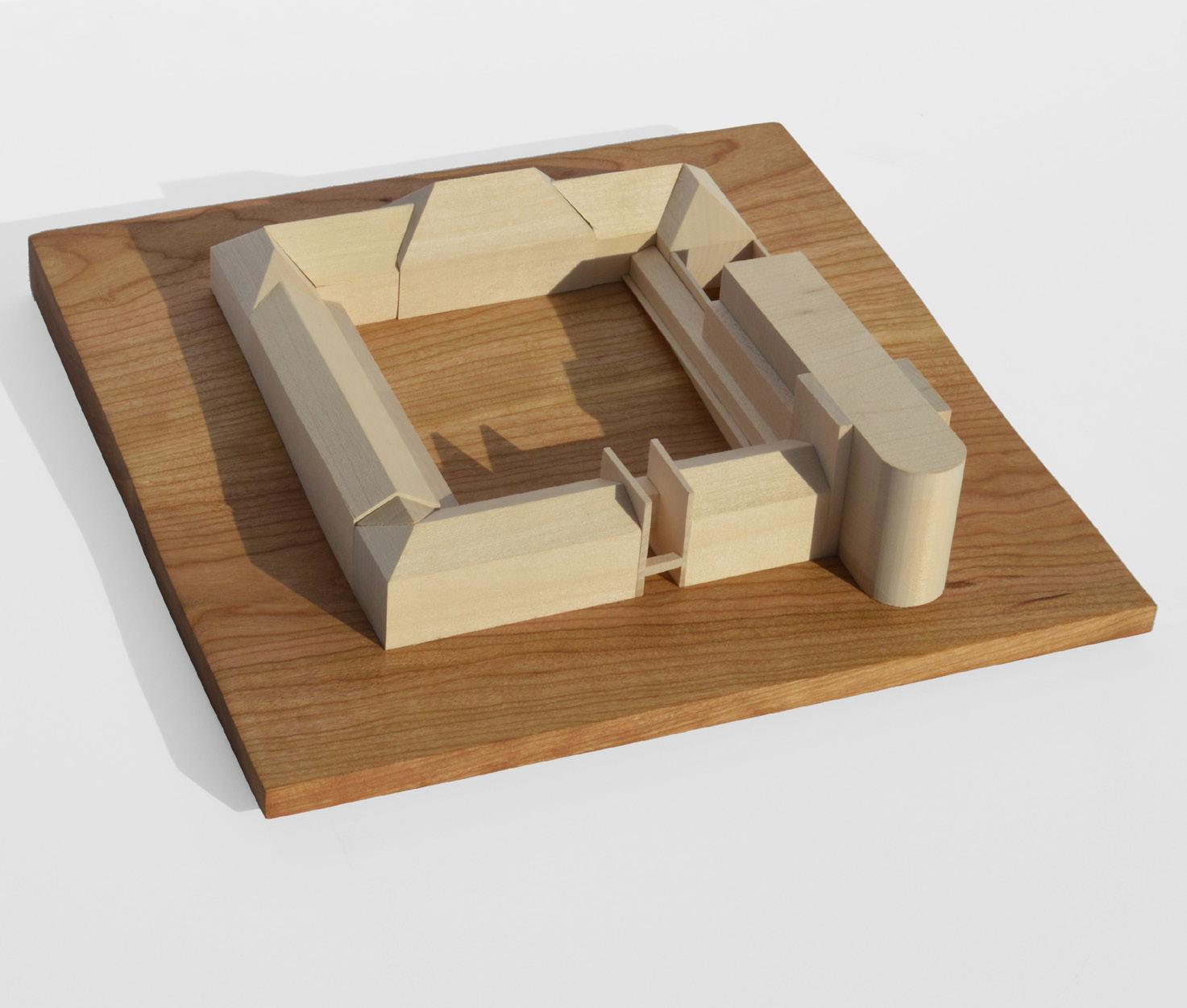

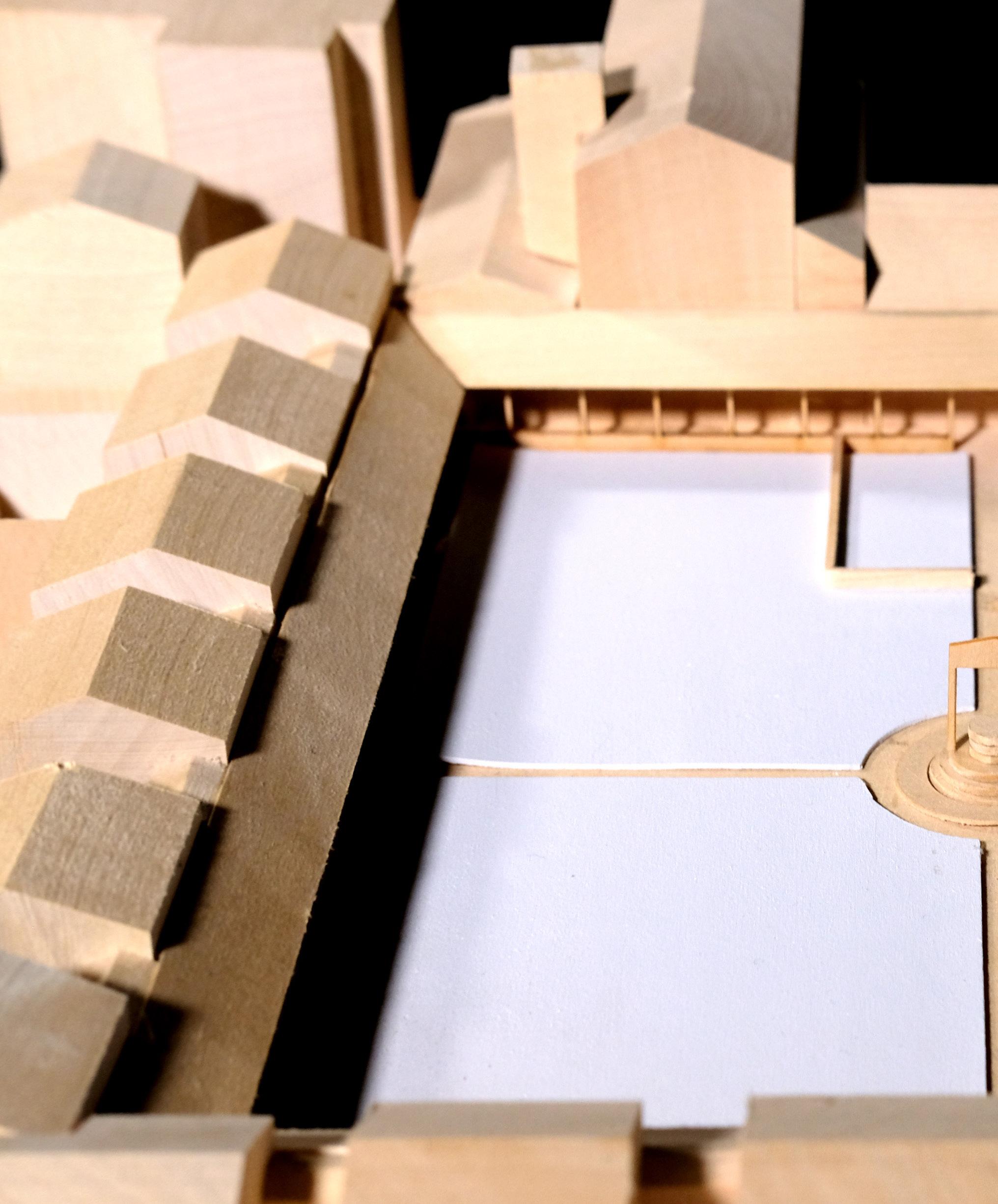

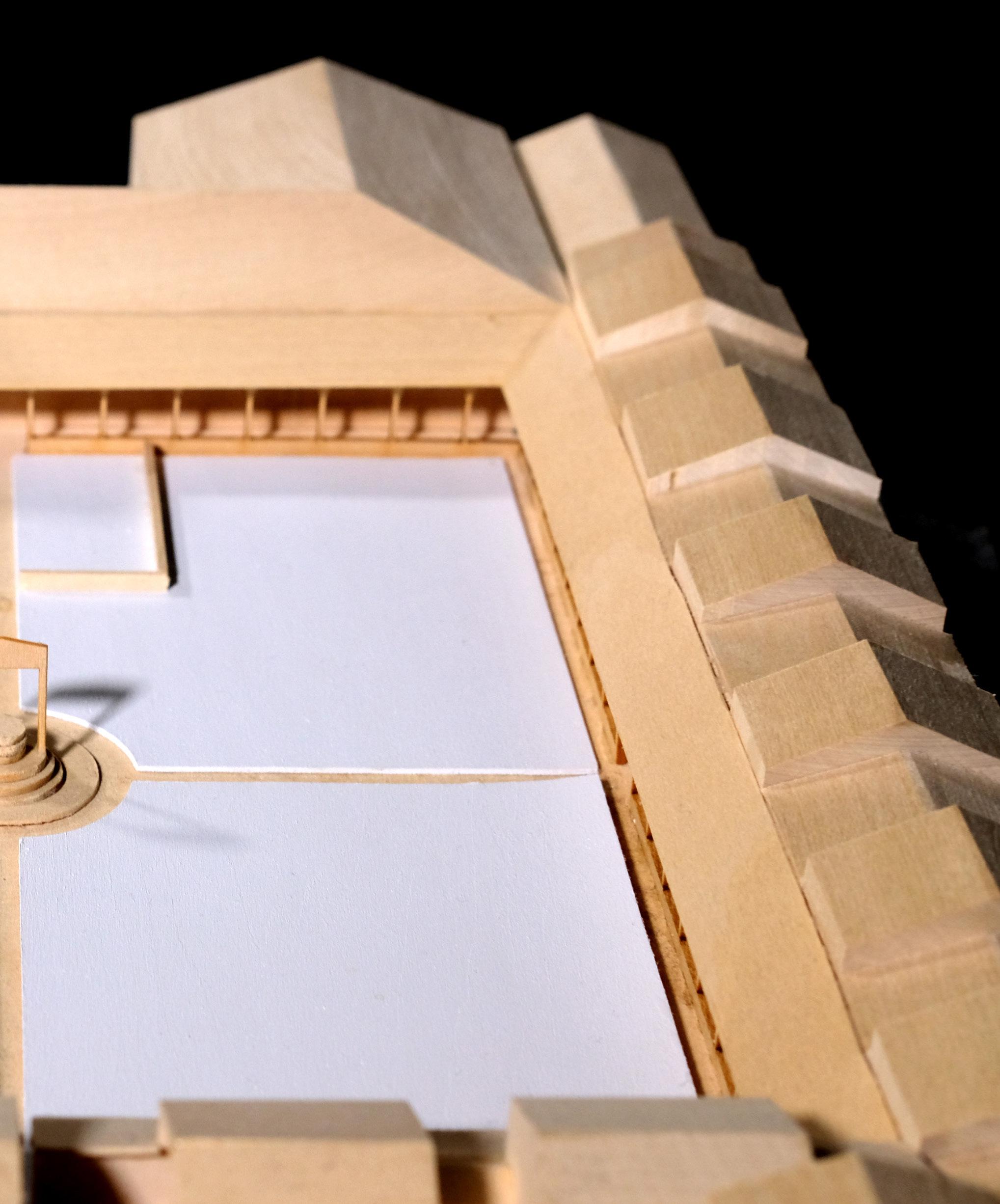

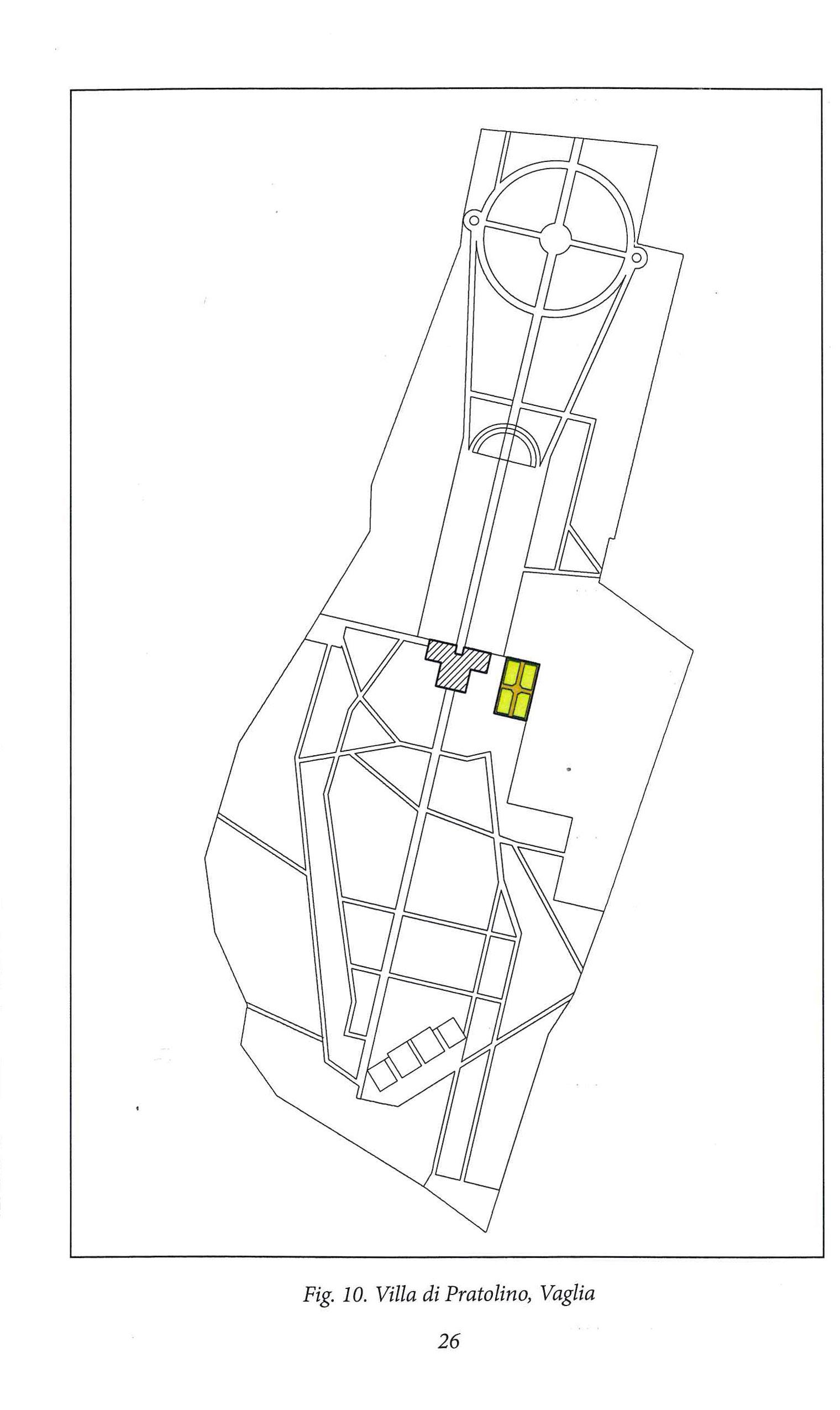

David Langdon’s Secret Gardens of the Italian Renaissance focuses solely on the secret or hidden gardens of the Florentine and Roman Renaissance, known as the Giardini Segretti, one period in the history of the typology of the Enclosed Garden.4 The project in the form of a bound booklet offers a short introduction accompanied by a list of eleven characteristics that define the secret garden, including Intimacy and Scale, Proximity to Residence, Perimeter walls, Privater use, Rare and expensive plants among others; a map of the secret gardens in and around Florence and Rome, and plans of sixteen villa gardens in which the enclosed garden is identified in color and accompanied by a brief description of its unique characteristics. Presented for readers are a few examples: the Medici villa at Castello; the Villa Corsini Mezzomonte, Florence; Villa Gamberaia, Settignano; the Medici villa at Pratolino, and the Palazzo Barberini with its famous bulb garden.5

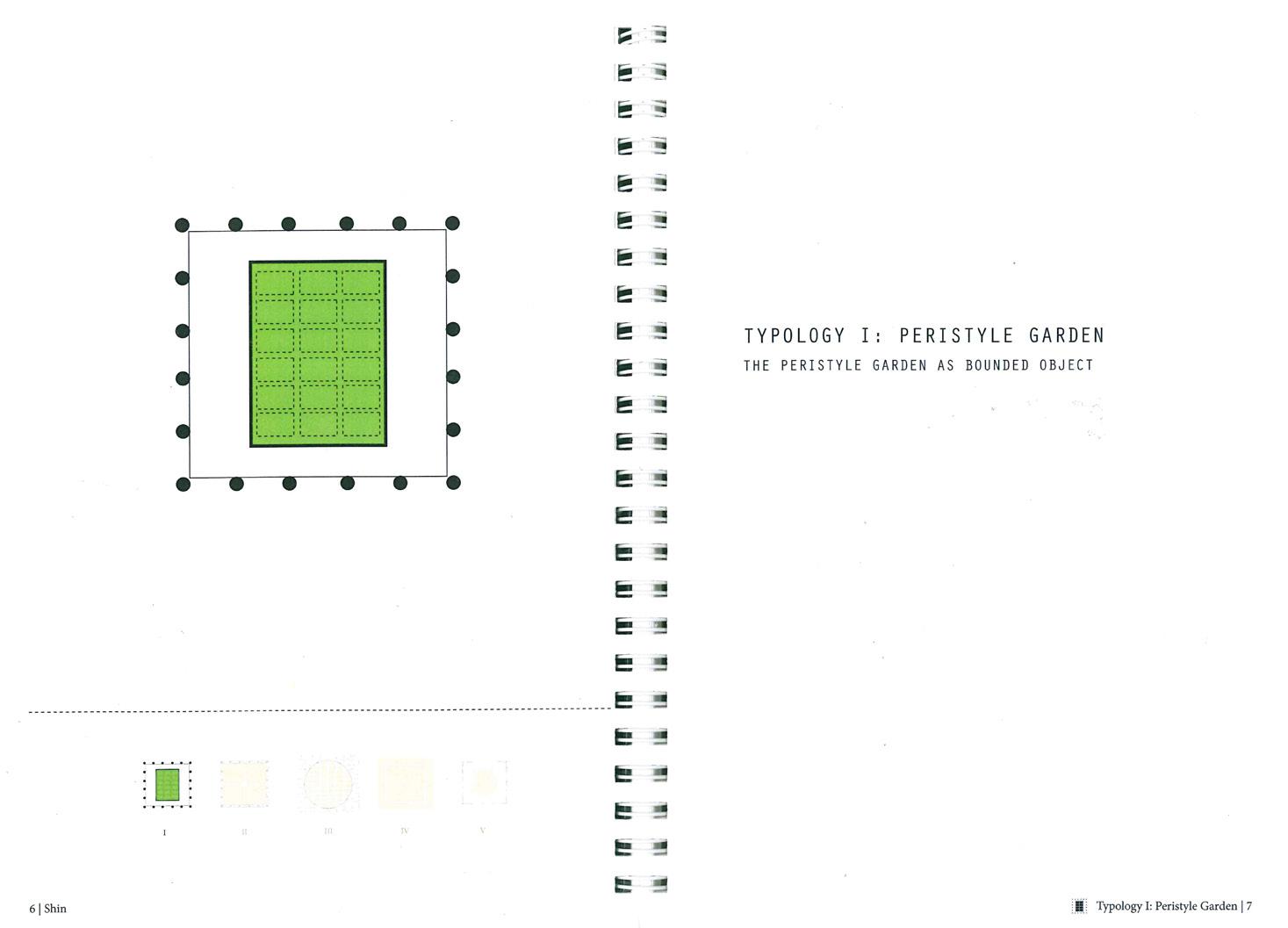

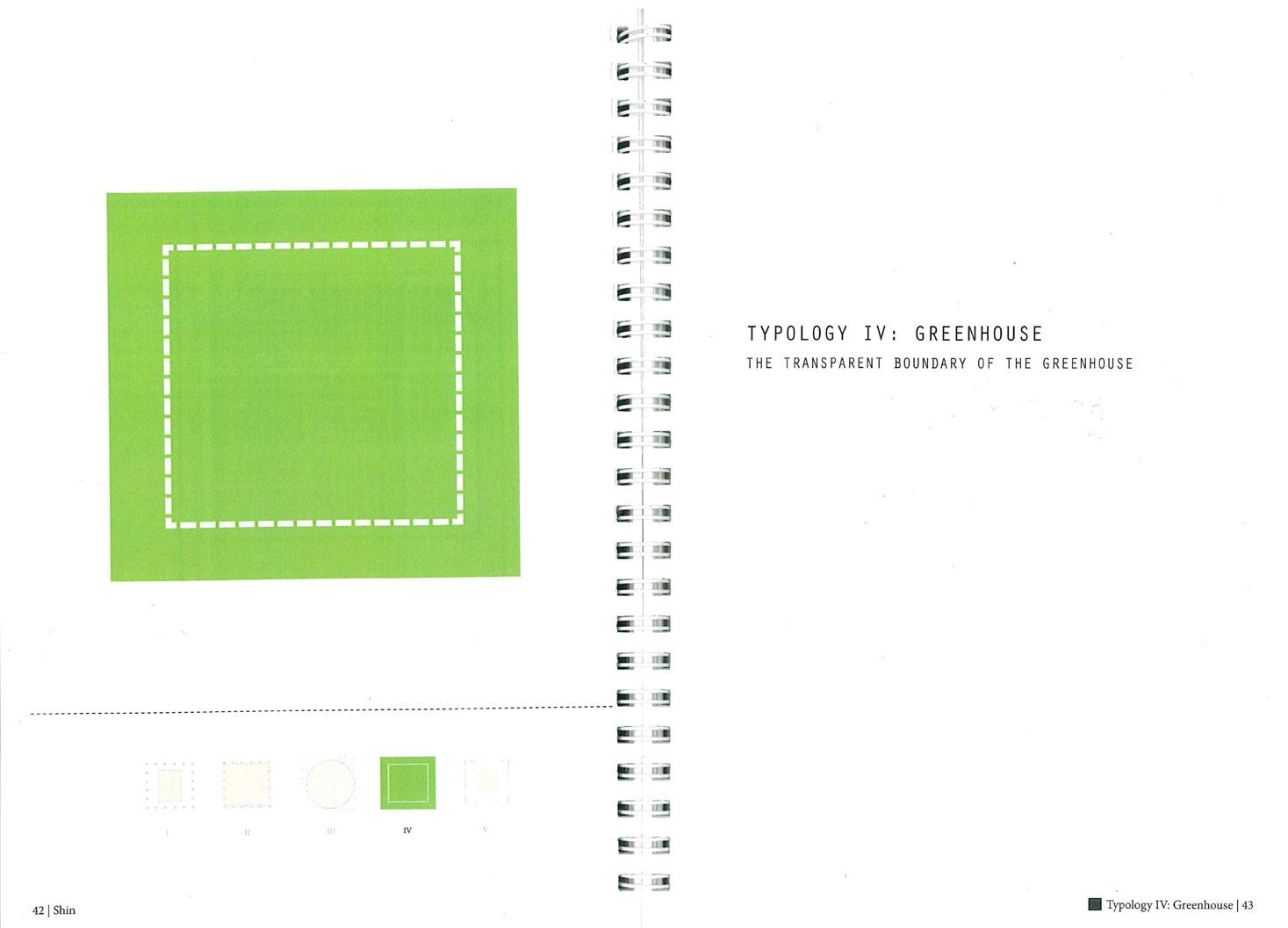

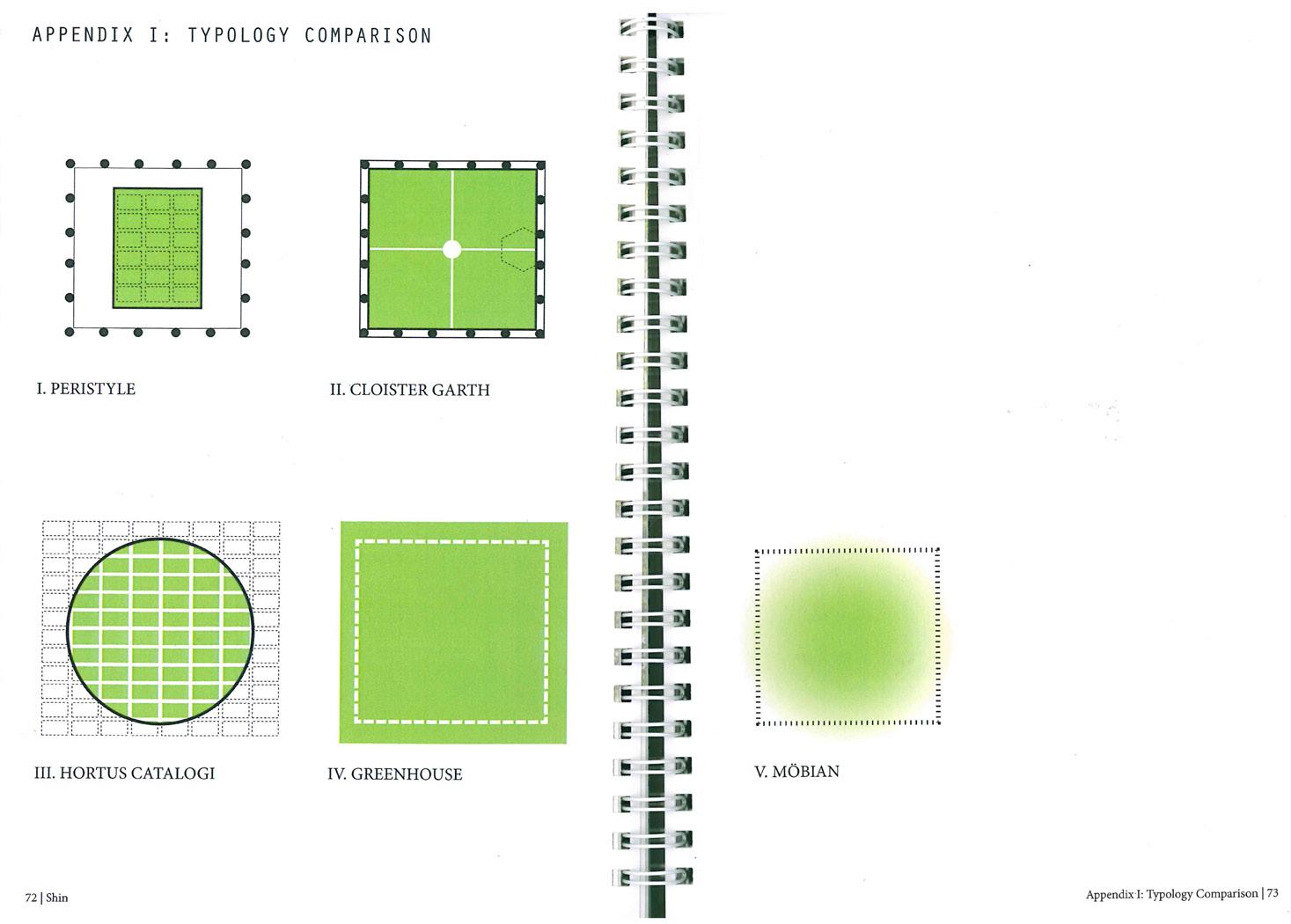

Melissa Shin’s project, The Edge of Paradise Interiorized Landscape and the Ambiguity of Space, is also in the form of a booklet that traces in text, diagrams, and images the typology of the Enclosed Garden over five periods in which she focuses on the ever-softening boundaries that encompass the garden: the Peristyle as a Bounded Object; the Cloister Garth and its expanded boundaries; the Botanic Garden of the Italian Renaissance; Greenhouses and transparent glass boundaries in the nineteenth century; and Mobius,6 a term applied to the twentieth century focus on the in-between, the intermingling of interior and exterior. After a detailed, well-informed Introduction to this landscape typology, Melissa provides a clearly defined diagram for each of her five categories, short, well researched texts, and multiple examples of each period for which in a diagrammatic format she isolates the green space within or to the edge of the architecture which encloses it. She concludes her study of the Hortus Conclusus with a comparison of scale of all gardens presented in her project which offers students a visually compelling diagram of the ways architecture encloses landscape from antiquity to the present.

Stephen Gage’s project shifts the history of the Enclosed Garden from its sacred, monastic moorings in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance to the secular in his indexical study of the history of the University Quadrangle. Organized as a bound book with introduction and detailed texts on one page and historic images and landscape plans on the other, Gage traces the quadrangle

3 See: Ernest Born and Walter Horn, The Plan of St. Gall: A Study of the Architecture & Economy Of & Life in a Paradigmatic Carolingian Monastery, Vol. 19 of California Studies in the History of Art, University of California, 1979.

4 See: Elizabeth Blair MacDougall, “A Cardinal’s Bulb Garden: A Giardino Segreto at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome,” in Fountains, Statues, and Flowers: Studies in Italian Gardens of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., 1994, 221-222.

5 Ibid, 219-347.

6 Melissa Shin writes: “A Mobius strip is a three dimensional object formed by cutting a strip of paper, twisting it once, and fixing both ends back together. It is a non-orientable surface, essentially meaning that it doesn’t have a clearly defined top and bottom.”

from its Italian and British collegial roots to the present in twenty case studies, concluding his investigation with a comparison of scale and of variations in the designs of the enclosed, quadrangular green spaces. It is a richly detailed document.

Lastly, Maya Sorabjee turned her interest in the enclosed garden from Western examples of the Hortus Conclusus to one in the East. She made a model of Geoffrey Bawa’s residence in Colombo, Sri Lanka, a house that became a series of interlocking enclosed courtyard gardens, assembled as contiguous bungalows became available to buy. Maya writes in Retrospecta 43 that each “Hortus Conclusus presents a different method of bringing landscape into the dwelling — from the roots of a tree that line a corridor to the leafy patios outside the bedrooms,” clearly conveyed in her depiction of sixteen individual spaces within the house. “Bawa’s house,” she concludes,” fragments the relationship between interior and exterior, creating a contained arrangement of landscape and architecture.”

Projects on the Infrastructure of Water

Essential to introducing students to landscape history is to demonstrate the variety of ways in which water plays a key role in the design of gardens and in the infrastructure of the city. Numerous projects in several mediums of representation focus on this all-important landscape element.

Three projects examine water as infrastructure.

Kelsey Rico constructed two compelling pull-out drawings, using unfolding strings to convey how water flowed in aqueducts to ancient Rome generally and in the Aqua Marcia in particular. As you unfold the strings the feeling of water moving through the channels is remarkably sensed.

As she writes of her two projects: “The Roman Aqueduct Book I provides an overview of the elements that make up a Roman aqueduct through a long, continuous drawing. A white thread representing the flow of water stitches its way through the entirety of the aqueduct and holds the accordion booklet together. Aqua Marcia: Water Channels catalogues the sizes and types of water channels found at several excavation sites along the aqueduct. Through this visualization, one can see the variation of building methods used to construct the Aqua Marcia over time, including vault, gable, and flat roofing. This time, the continuous string that binds the booklet together tracks the height of the water above sea level from the source and along the aqueduct until it reaches the distribution site in Rome.”

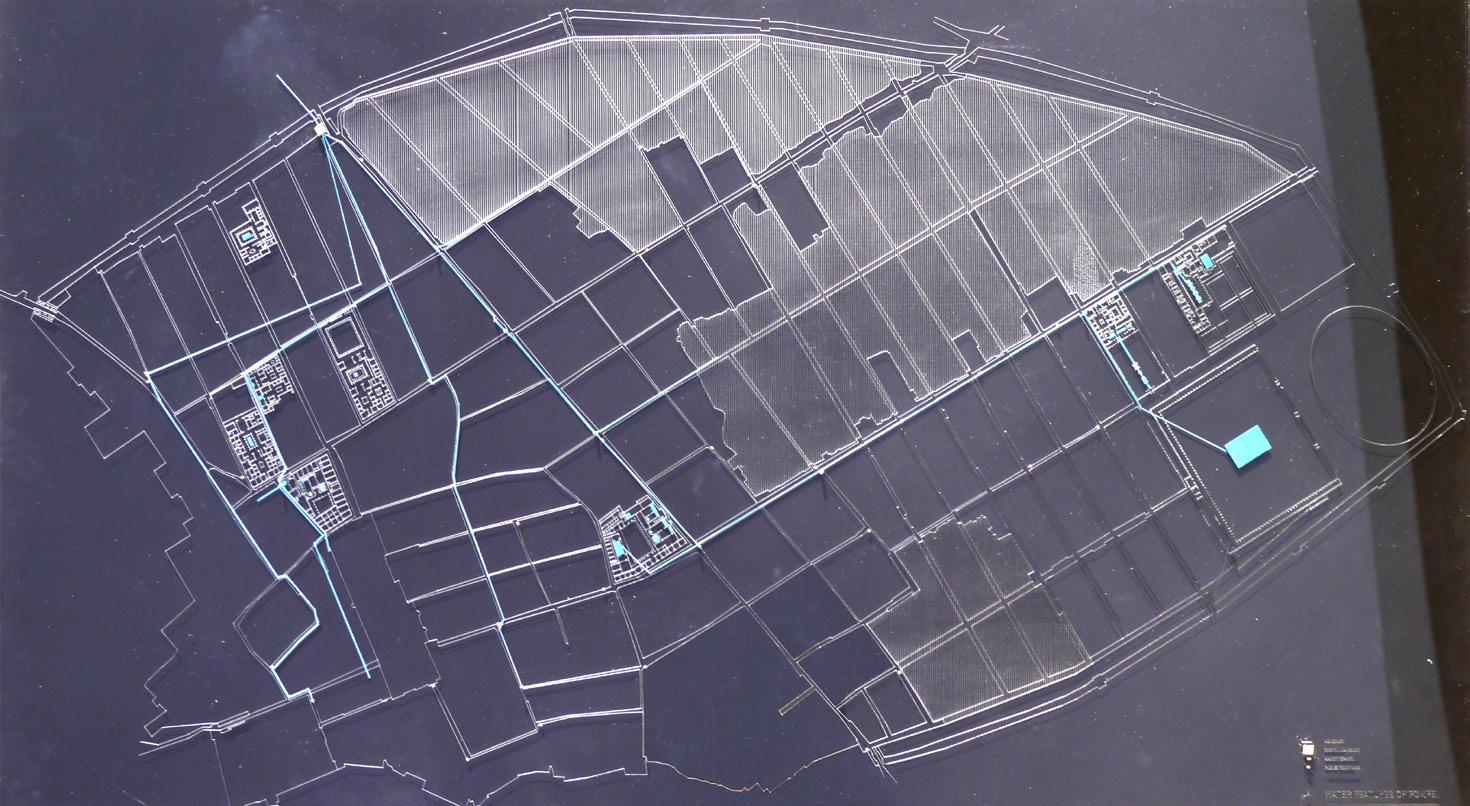

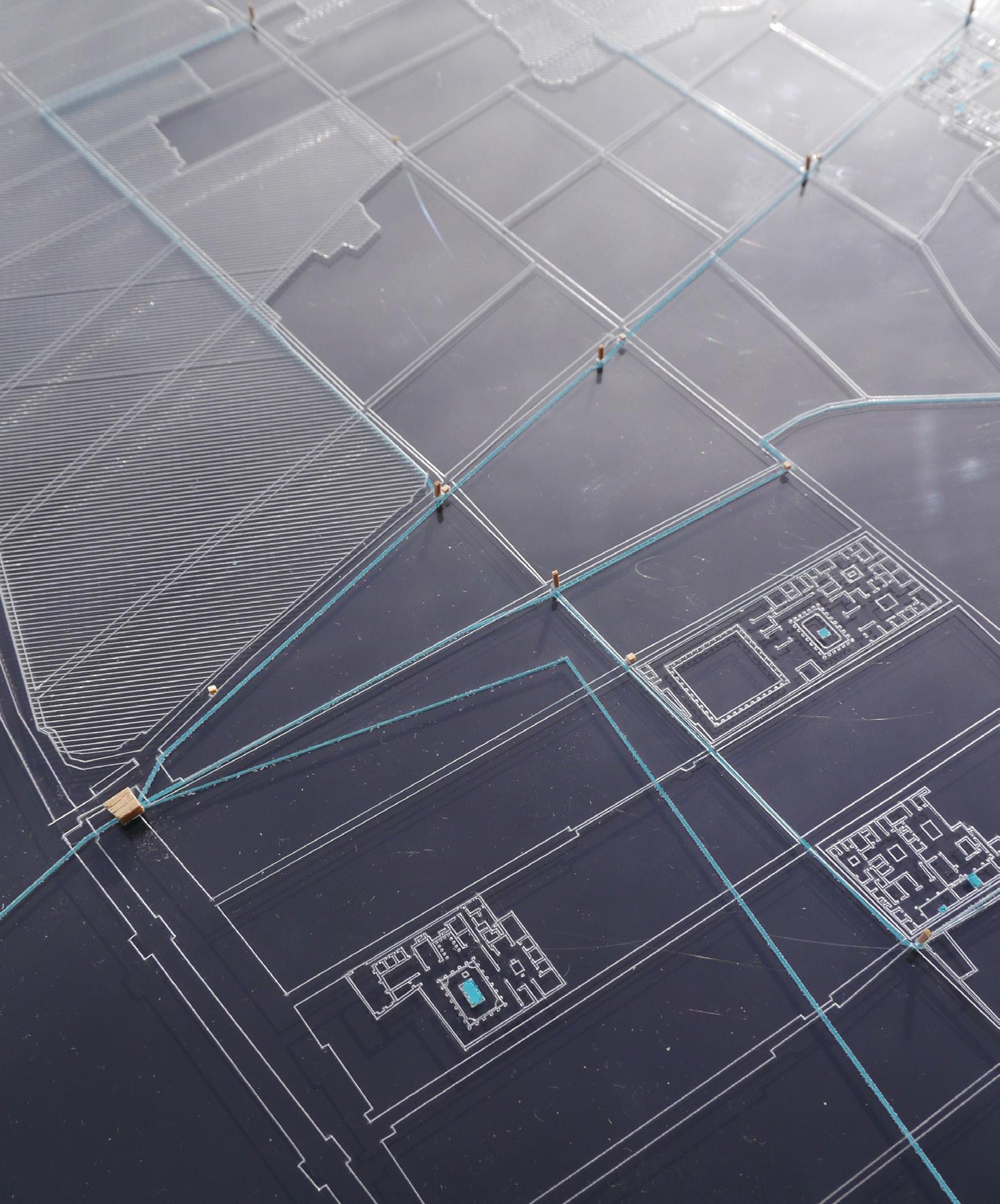

Haelee Jung also examined the channeling of water in urban engineering, but her attention was to the city of Pompeii. Her project is a superb site plan in acrylic of the entire town in which she shows in great detail the three paths of water which flowed gravitationally downward from the castellum acquae along Pompeii’s northern wall to various parts of the city.7 Included in the Pompeian water system were fourteen water towers, displayed in Haelee’s model in balsa wood, which were built to maintain a continuous flow of water throughout the city.

The model clearly indicates key sites within the city where water appeared in the form of fountains or pools in private houses, at inns, public baths, and civic spaces. I would call attention to the lower left or southeastern section of the model, for example, to view the cross-axial channels of water in the House of Octavius Quartio (formerly labeled the House of Loreius Tiburtinus)

7 Haelee’s source for her design is based on Jan Wiggers, “The urban supply system of Pompeii,” in Cura Aquarum in Campania 1994, eds. Nathalie de Haan and Gemma Jansen, Leiden, 1996, 29-32.

and further to the southeast to the four connecting pools of water in the House of Julia Felix. It is from this model that students can clearly visualize how water flowed through the city and was then shaped as a garden element in the ancient Pompeian house.

Three further projects focus on the hydrology of water: one in ancient Roman and the other two in Italian Renaissance gardens. Nancy Chen made a topographical model of Hadrian’s Villa in which she renders the ridges to the southeast and northwest between which in a relatively flat valley the villa is sited. Within the parameters of the villa she traces the tentative paths, marked in blue lines, of channeled water that flowed continuously from one of the four aqueducts that passed to the east of the villa,8 situated beyond the upper right of the model, downward on the northwest path in a drop of 24 degrees to the Scenic Triclinium and a further 36 degrees to the villa’s northern perimeter where it flows out and downward into the Aniene river.9

Although the diversions taken in channeling the water to various cisterns, buildings, and landscape elements such as fountains remain speculative,10 the model demonstrates where known water channels enter built structures such as the Scenic Triclinium, the landscape garden of the Stadium Garden, garden pools as seen in the East West Terrace, and fountains exemplified in the nymphaeum of the Water Court. The model allows students to gain an overall idea of the complex water infrastructure of the villa, reinforcing the argument that a plan of the villa was made prior to construction in 118 AD.11

Jolanda Devalle’s project consists of two detailed drawings of the system of conduits that brought water to and within the Italian Renaissance gardens of the Medici Villa at Pratolino and the Villa d’Este, Tivoli. Using an historical document of 1740-65, which Jolanda uncovered and translated from the Italian, she shows on a large site-plan of the region surrounding Pratolino how Francesco I de Medici “built seven kilometers of terracotta conduits to connect the twelve-spring sources of the Monte Senario…to three cisterns ‘Conserve’ located on the highest grounds of the garden.”

On her plan Jolanda shows in remarkable detail the location of the twelve springs, clearly marked in a legend provided in her drawing, from which water flowed into the conduits that descended in various routes from Monte Senario to the villa. It is a project that contributes significantly to our understanding of how Francesco engineered bringing water to his villa and by implication the efforts made by laborers (contadini) in constructing the system employed.12

Jolanda Devalle’s second drawing is an accompaniment to her drawing of the extensive effort to which Francesco de Medici I went to bring water to his fountains, grottoes, and cascading, mortared ponds at Pratolino. To obtain water for his gardens in Tivoli, Cardinal d’Este tapped directly into the Aniene river which ran by his villa. From here, as Jolanda’s drawing shows, river water was channeled through an underground conduit, cut out of the travertine rocks of the city’s substrata, running approximately 250

8 See: William MacDonald and John Pinto, Hadrian’s Villa and Its Legacy, New Haven and London, 1995, 26.

9 Ibid, 26.

10 MacDonald and Pinto write: “Parts of the distribution system remain unknown, but solid evidence for the results survive throughout the site. After crossing the East valley, the main supply ran northwest, and as the density of construction increased with the fall of the ground, the ever expanding number of secondary branches and local pipelines created a largely subterranean pattern of deltafication; that the principal elements were probably in place early on has already been mentioned.” Ibid, 170-171. For further discussion of water, see MacDonald and Pinto, “Waterworks and Landscape,” Ibid, 170-182.

11 Ibid, 32-38.

12 On labor used in the construction of conduits at Pratolino, see Suzanna B. Butters, “Pressed Labor and Pratolino: Social Imagery and Social Reality at a Medici Garden,” in Villas and Gardens in Early Modern Italy and France, eds. Mirka Benes and Dianne Harris, Cambridge, 2001, 61-87.

meters through the city of Tivoli, and directly into the cistern or holding tank of the villa garden behind the Oval Fountain from which water in the fountains continuously flowed gravitationally downhill and transversally across the villa gardens. That Cardinal d’Este achieved a spectacle of water unrivaled in the Italian Renaissance by any other garden, including that at Pratolino, is due to having a river flow directly into, across, and gravitationally down a steep hill within his garden.

Additionally Jolanda shows that to bring clear drinking water to his residence, Cardinal d’Este channeled the newly discovered Rivellese Spring to the town of Tivoli, bringing fresh water to the city populace as well to his Villa and to the upper cross-axial terrace of his garden.

Jolanda’s two analytic drawings contribute greatly to our understanding of the infrastructure necessary to create two of the great water gardens of the Italian Renaissance, in the environs of Rome and Florence.

Projects on the Interrelation of Water and Architecture at Hadrian’s Villa

The presence of water in three sites at Hadrian’s Villa---the Smaller Baths, the Stadium Garden, and the Island Enclosure, is the subject of Aurora Farewell’s final project. It is a large hand drawing which includes for purposes of location Piranesi plan, 1778, in which the three buildings are colored in red, over which she imposes villa zones taken from William MacDonald and John Pinto’s divisions of the Villa13 and a topographical overlay of the whole. Each of the three buildings are drawn in section, plan, and axonometric, based on her visit to the Villa as part of the Rome seminar and her careful reading of William L. MacDonald and Bernard M Boyle’s essay, “The Small Baths at Hadrian’s’ Villa,,”14 and Eugenia Salza Prina Ricotti’s essay, “The Importance of Water in Roman Garden Triclinia.”15

For the Stadium Garden Aurora draws in section the paths of water that enter and run above and below ground in the Garden and places the sectional rendering of it as an overlay of Ricotti’s axonometric drawing of the Stadium. Similarly, she draws the Small Baths in plan, indicating where the presence of water can be found within the building and as axonometric overlay. And for the Island Enclosure she provides both plan and an half axonometric rendering of it. Zone lines are identified16 and site lines are provided which show how these three buildings relate to one another. In faded gray are other parts of the Villa to which these three interconnect. It is a remarkable drawing, full of detailed information and informed speculation on how and where water enters, flows through, and connects each of the three buildings.

Other students made models of individual structures at the Villa. Jenna Ritz constructed one of the Island Enclosure (Maritime Theater) which she, too, had seen on the trip to Rome. The model details the colonnade with annular vault that surrounds the moat that in turn surrounds on all sides the multi-roomed island retreat with its two draw bridges. To view the interior space of the rooms on the island Jenna designed her model to split in two, allowing us to imagine how the interior and open spaces on the island might have looked, something only a now inaccessible walk on the island would convey.

13 Op cit, 38.

14 See: William L. MacDonald and Bernard M. Boyle, “The Smaller Baths at Hadrian’s Villa,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 39, No. 1 (March, 1980), 5-27.

15 See: Eugenia Salza Prina Ricotti, “The Importance of Water in Roman Garden Triclinia,” in Ancient Roman Villa Gardens, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., 1987, 135-184.

16 MacDonald and Pinto, 38.

Bobby Chen made a model of the Smaller Baths for which he documents the process of making the model, its location at the villa, and the geometry of the plan. He constructed the model as retractable in three layers which allows us to see the interior locations where the bowl-shaped pools of water can be found, the interior volumes seen when his retractable roof lifts off, and the elevation of the structure as a whole. Bobby’s project purposefully designed to lift the roof off of the Smaller Baths to view its interior recalls Gandy’s drawing of Sir John Soane’s Bank of England. Like the Gandy drawing his project allows students to examine details that a solid model would not convey. Conversely it turns the highly complex ruin back to its original form.

The third model of a specific building complex at Hadrian’s villa is that of Laelia Vaulot’s Scenic Triclinium facing out to the long canal (121 m) . With great detail Laelia models the semi-domed stibadium surrounded by channels of water, a semicircular pool at its base, and water stairs within niches around and above it. She furthermore captures the receding crypt built into the hillside, with its roofed platform and terminal apse. The model is a clear manifestation of how in this building water and architecture are intertwined. It also shows that to the traditional rhythms of light and dark and high and low, that characterize ancient Roman architecture, Hadrian added the sequence of land, water, land, water from the terminal apse to the long canal as a feature of Roman architecture. As conveyed in Laelia’ model water and architecture are seamlessly interwoven.

By placing alongside Nancy Chen’s topographical model, those of the Scenic Triclinium, the Island Enclosure, and the Smaller Baths, laid out on a table in the classroom students gain not only a sense of what these buildings at Hadrian’s Villa are like but also how water, conveyed in each structure, plays a pivotal role in the architecture of the Villa. It is the connective tissue which unites the Villa parts into a whole.

Projects on Water at the Villa d’Este

Three remarkable projects focused on water as garden element at the Villa d’Este of which two focused on the variety of sounds made by the villa’s fountain.

Boris Morin-Defoy constructed a sound machine, inspired by the works of Ned Khan and Zimoun, which uses bead-boards on moving rollers and computer coding to create a simulacrum of sound. As the machine turns the beads one can hear the changes in sound orchestrated by the variance in the volume of water and drop in grade in the fountains and water stairs at the Villa. To capture the sounds at the villa Boris has transmitted them onto Vimeo for all to hear.

Ava Amirahmadi, on the other hand, modeled a topography of sound determined by the fall of water in the villa’s fountains in which loudness is conveyed in her model’s highest peaks and near silence at their lowest levels. Her project is accompanied by two other soundscapes, one of the Fountain House in the cloister garden at the Cistercian monastery, Fossanova, and the other of the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. For each model Ava provided drawings which, when rearranging the placement of water in these gardens, scores the sounds of water based on the music of Vivaldi, John Gage, and Leonard Bernstein respectively.

Constance Vale’s project, Villa d’Este Water & Will, examines the fountains at the Villa d’Este in the form of a booklet which provides remarkably rendered and well researched sectional drawings of the waterworks, tracing the flow of water from one fountain to the other. For most fountains, Constance draws a broad view of them along the central cross axes in the garden. These are followed with a mylar overlay under which she draws sectionally the fountain itself for which she assigns a specific theme to identify each fountain’s unique properties or iconographic importance within the waterscape of the villa: Water and

Power for the Oval Fountain, an identity attributable to Cardinal d’Este’s ability to channel water from the Aniene River directly into the garden’s cistern located just behind the Oval Fountain; Water and Axiality for the Alley of the Hundred Fountains, a reference to the long cross-axis of the garden which the Alley follows; Water and Empire for the Rometta Fountain which signals the importance which ancient Rome played in the history of the waters of Tivoli; Water and Verticality for the Fountain of the Dragons, Water and Sound for the Fountain of the Dragon; Water and Magnitude for the Fountain of Nature; Water and Silence for the Fish Ponds; and Water and Nature personified in the Fountain of Diana of Ephesus.

Projects on the Typology of the Euripus

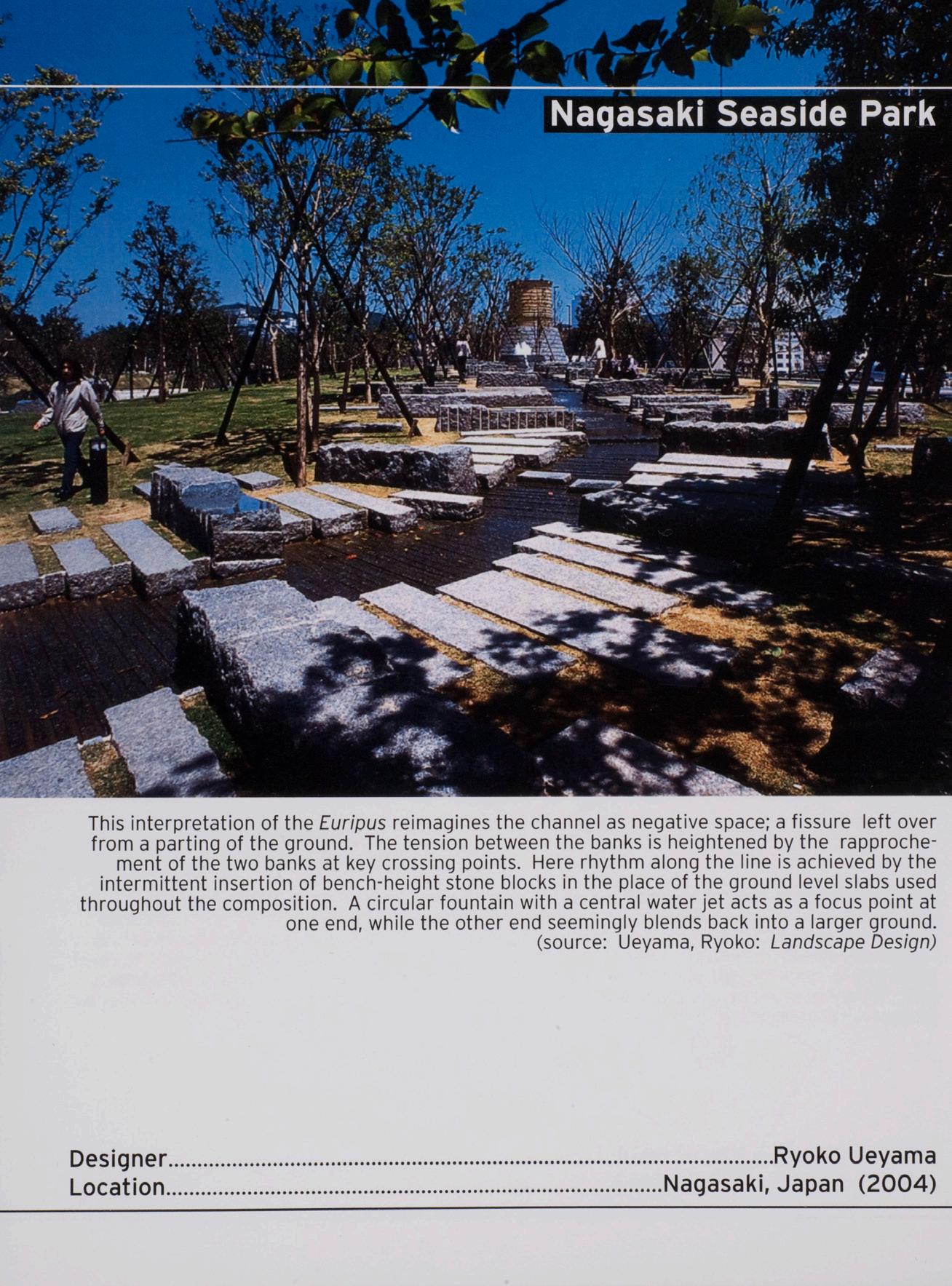

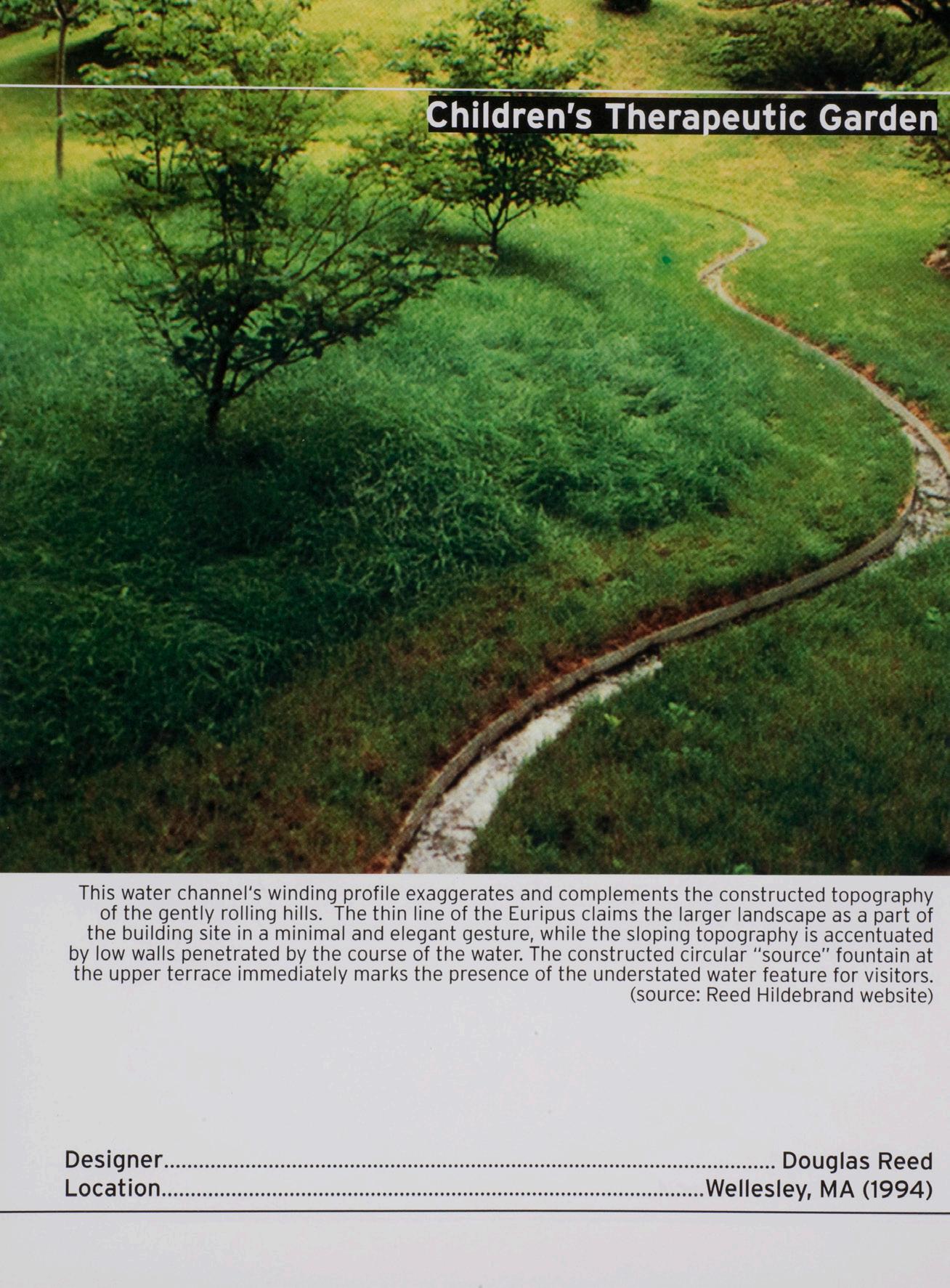

Two projects detail the landscape typology of the Euripus, the name Agrippa gave to the mile-long channel of water which he constructed and which flowed from his Baths to the Tiber across the Campus Martius.17 It is a term which I use in both courses to identify man-made channels of water constructed to emulate water found naturally in rivers, streams, and rivulets, a typology which I trace in multiple case studies from ancient Rome to the present.

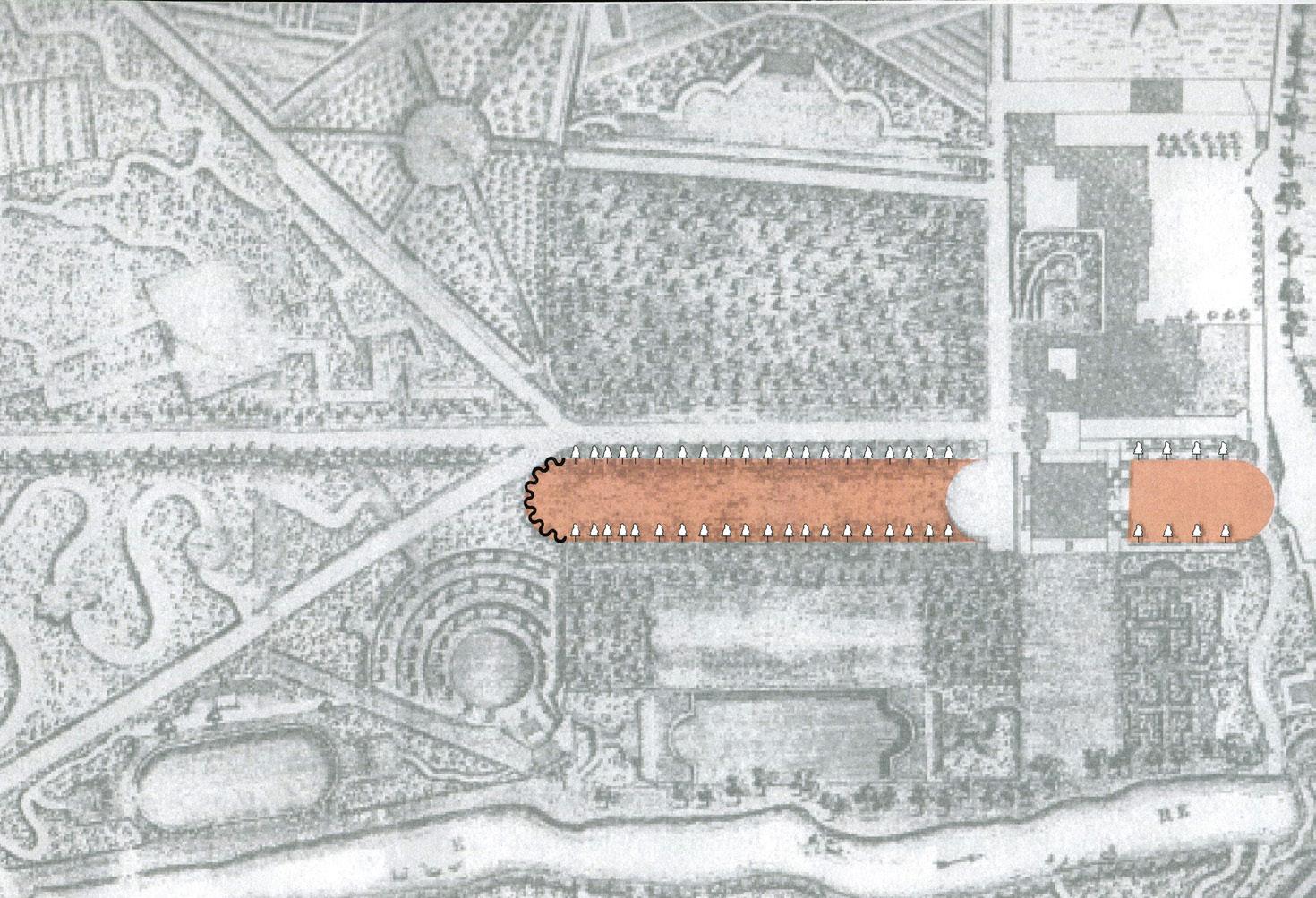

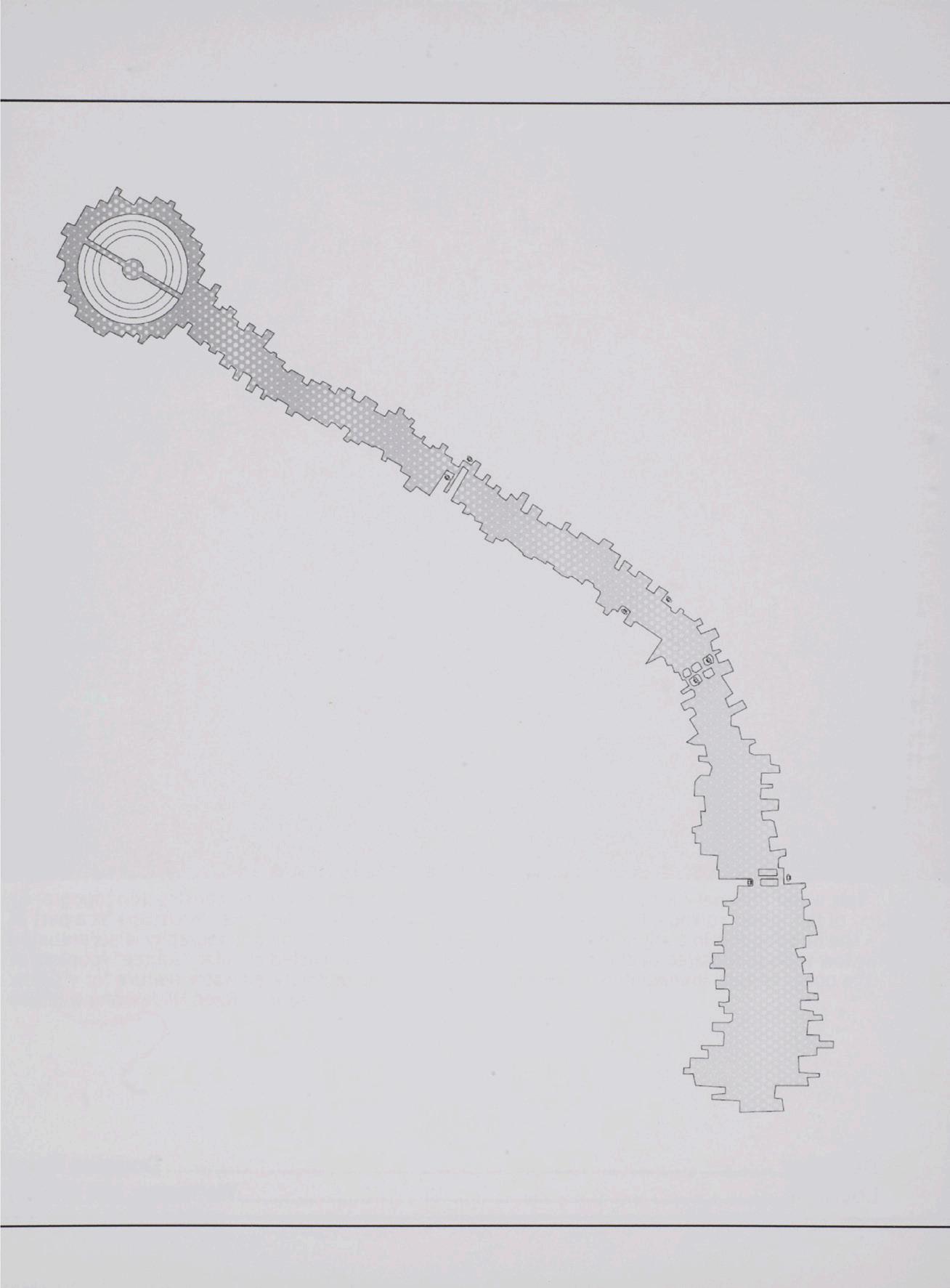

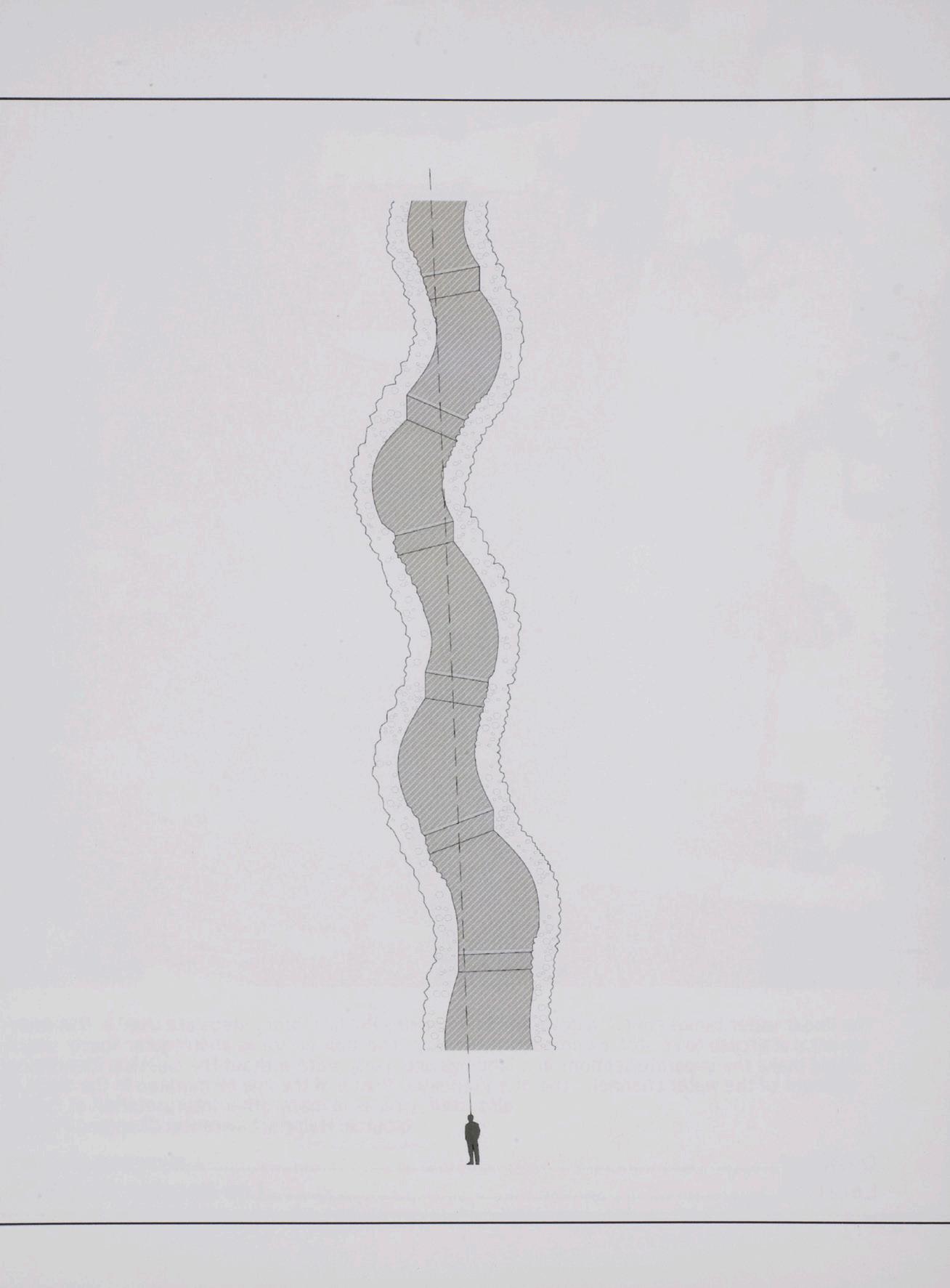

Audi Jomini investigates the Euripus in a book format, introducing the reader to its history, providing several historical examples such as the water channels in the Pompeian house of House of Octavius Quartio (formerly labeled the House of Loreius Tiburtinus) or William Kent’s meandering stream at Rousham and its use in modern landscape design, seen in Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Cemetery and Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute. But the majority of case studies in her book focus on contemporary examples, many of which were new to me, accompanied by her diagrammatic drawing for each of them. It is an amazingly thorough document and confirms the idea of the Euripus as a landscape typology still being used by landscape architects today.

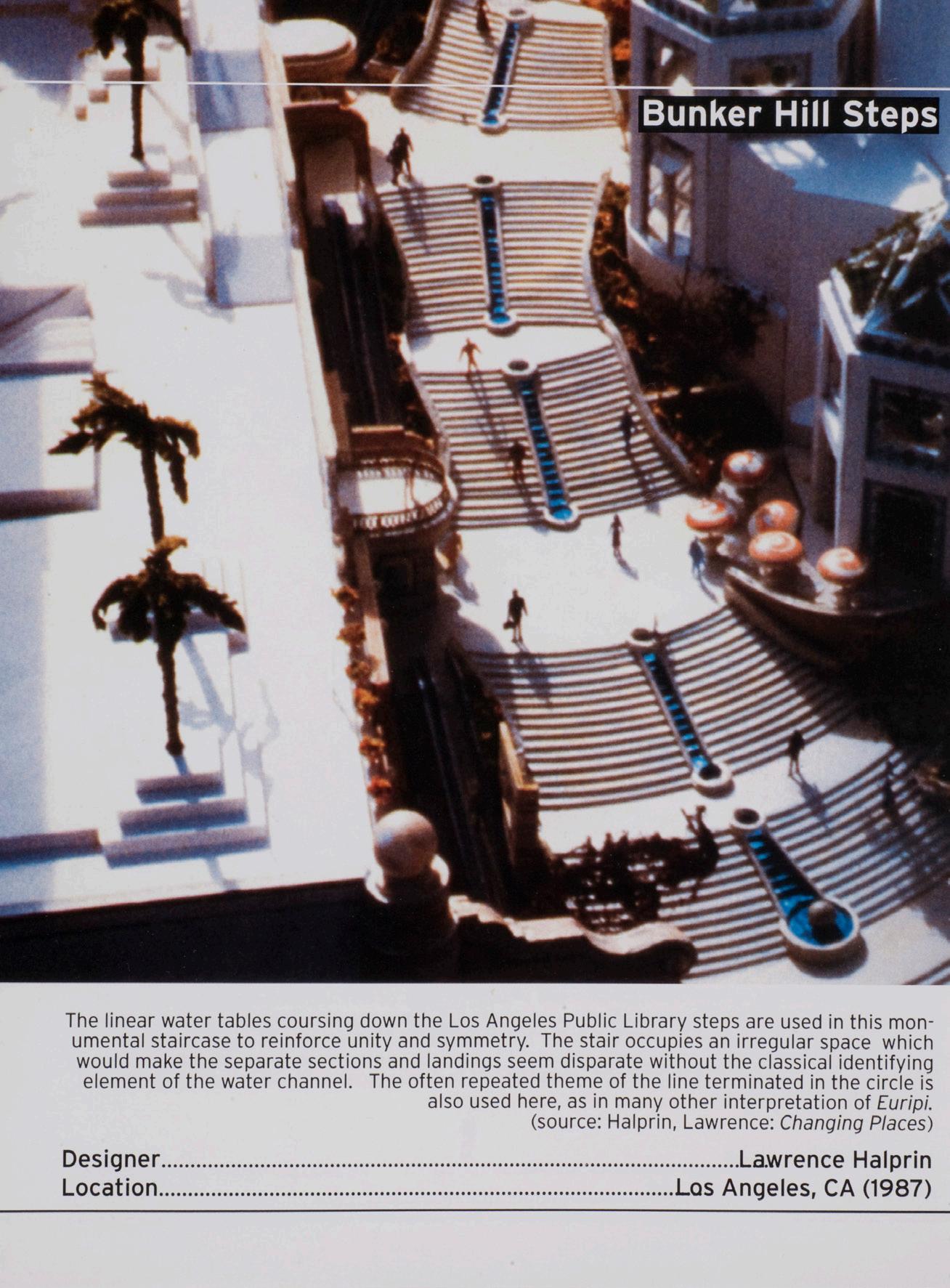

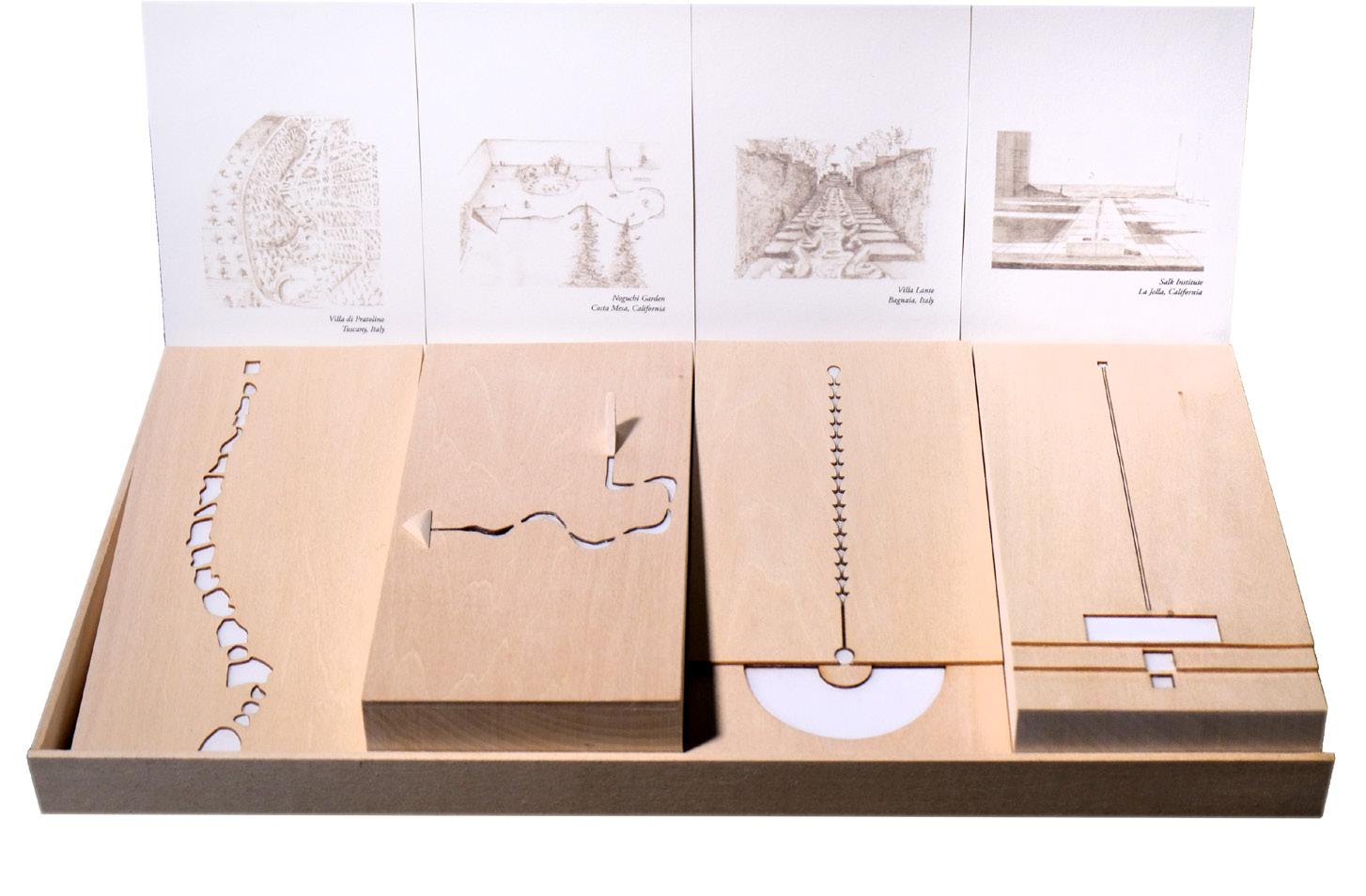

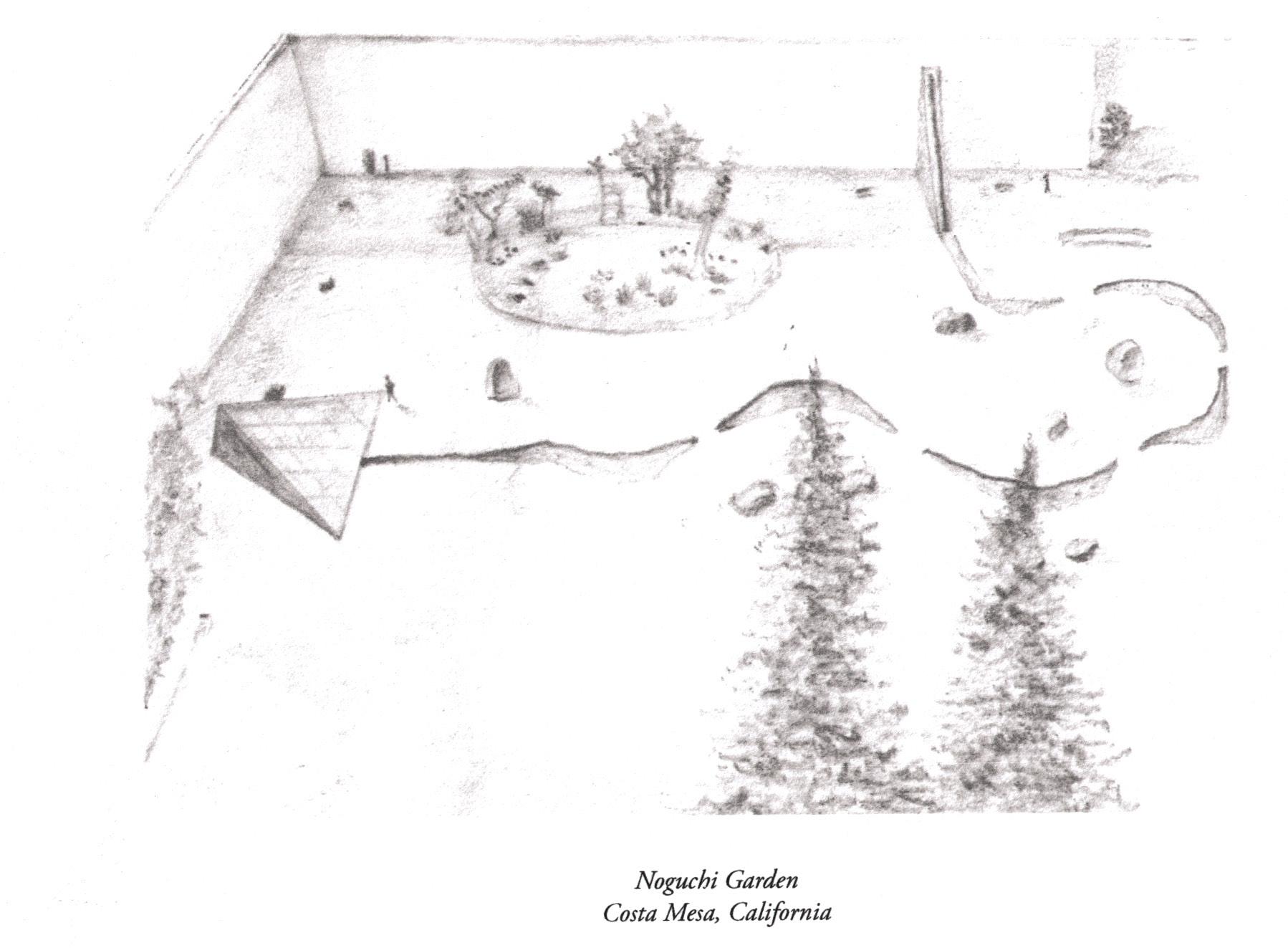

Elizabeth Nadai chose a different method of representation. She combines four, small, beautifully rendered drawings with four appropriately small wooden models that depict the Euripus in both modes of representation with great clarity. She chose two Italian Renaissance and two modern gardens where the presence of the Euripus is paramount: the Villa Lante, Bagnaia, the Villa Medici, Pratolino, the courtyard of the Salk Institute, LaJolla, Ca. and the Noguchi Garden, ‘California Scenario,’ Costa Mesa, Ca. By having the small drawings inserted into a sill above its complementary modeled form, the project is both a study of a typology as well as a dual presentation of landscape representation.

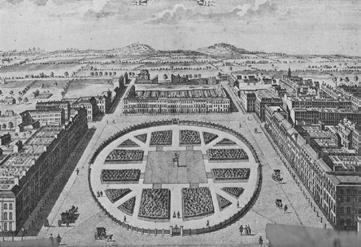

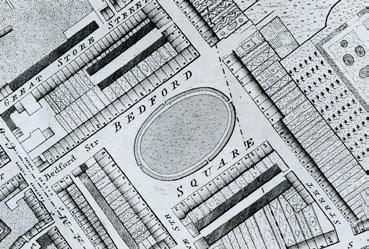

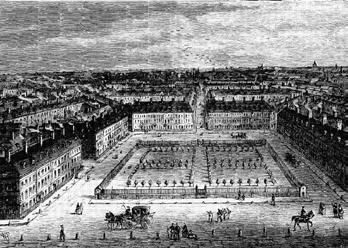

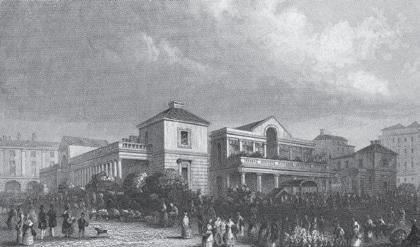

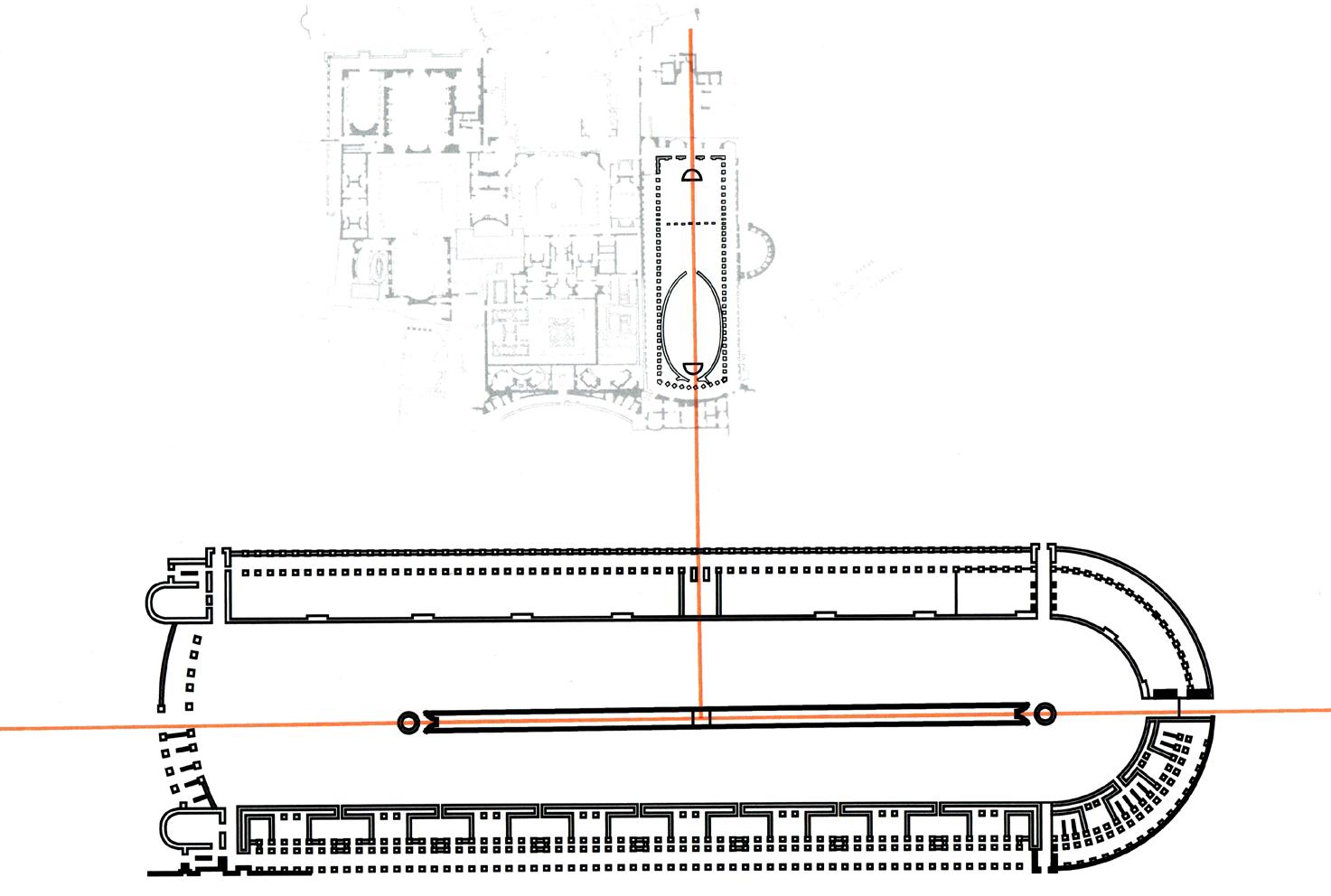

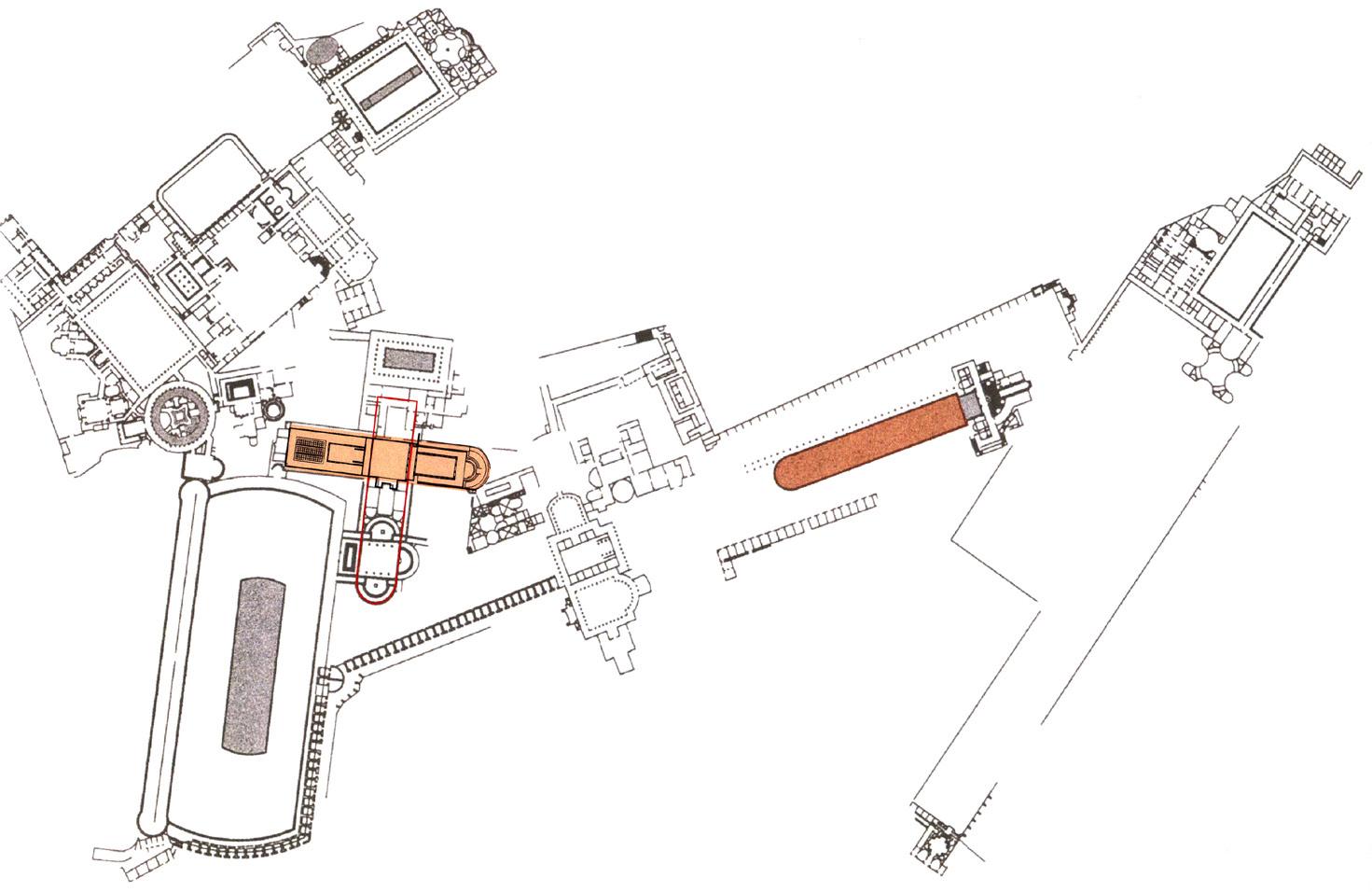

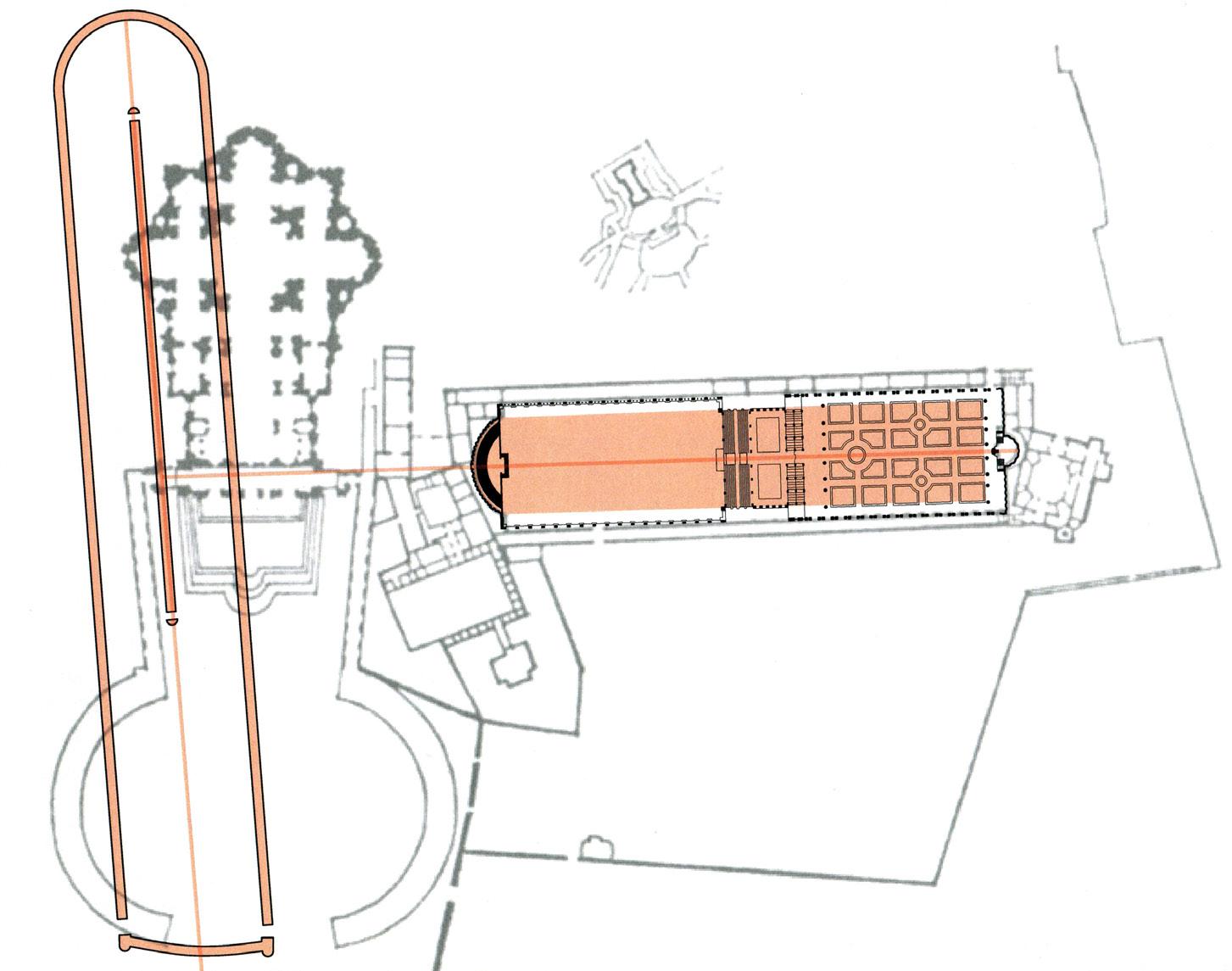

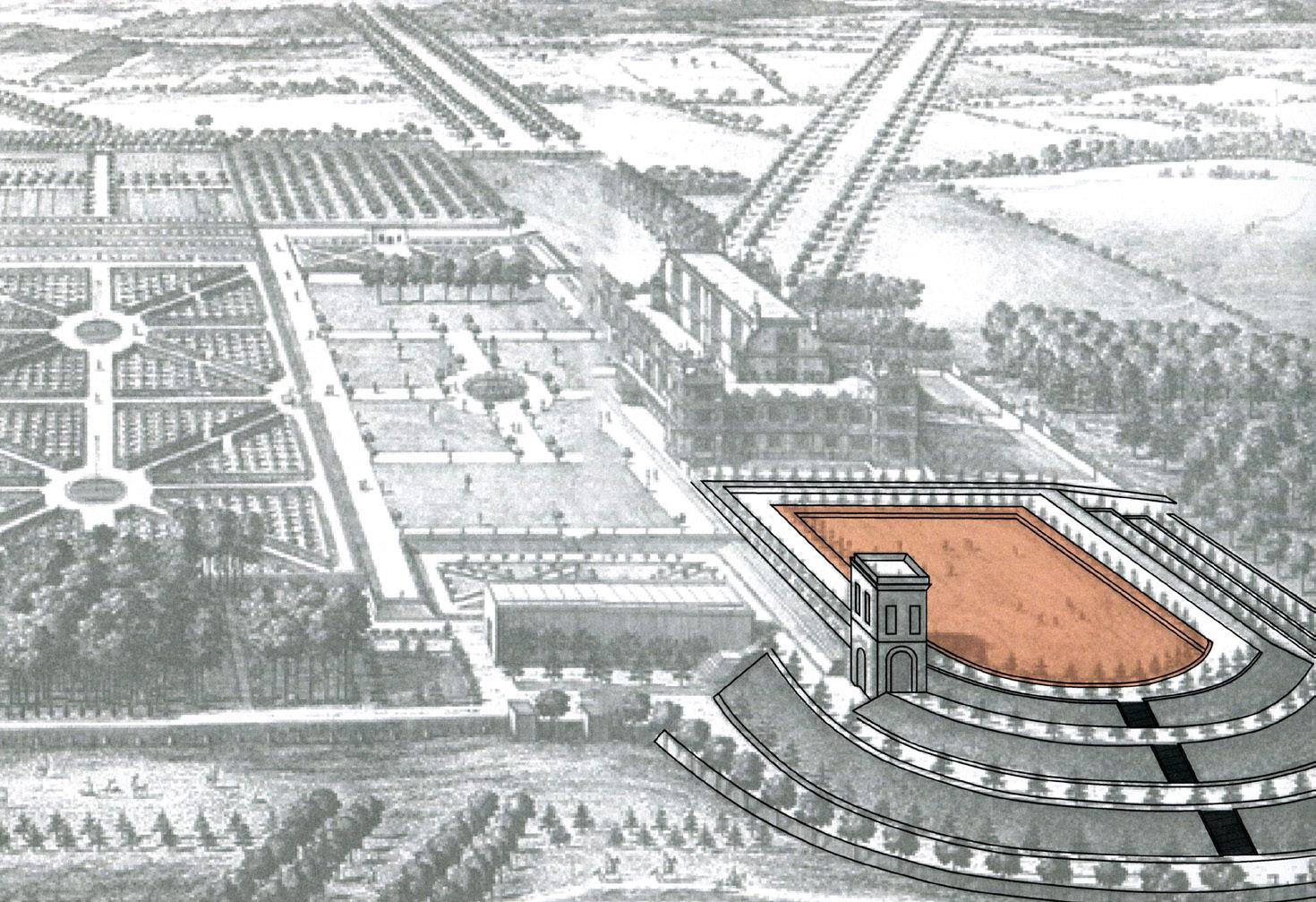

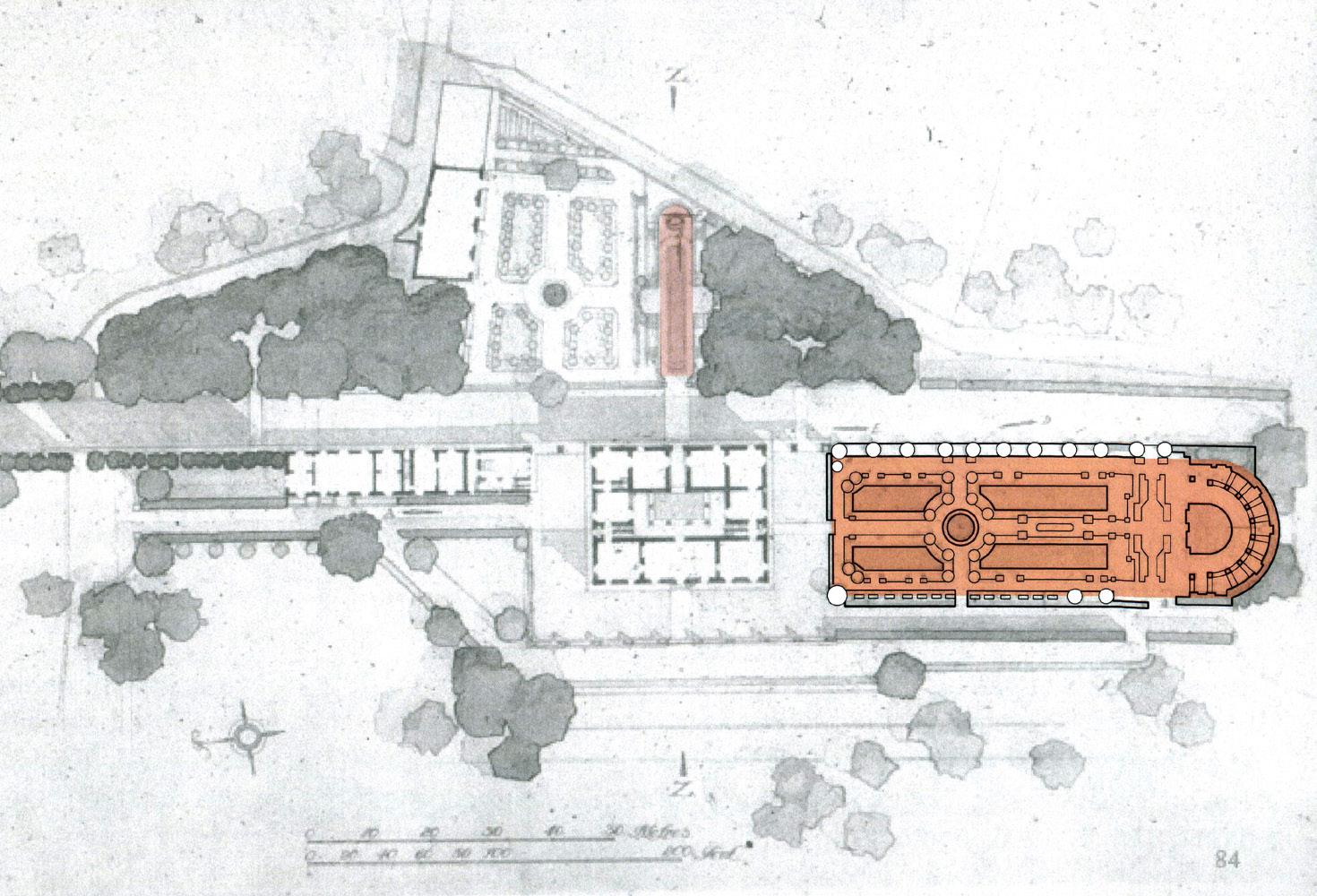

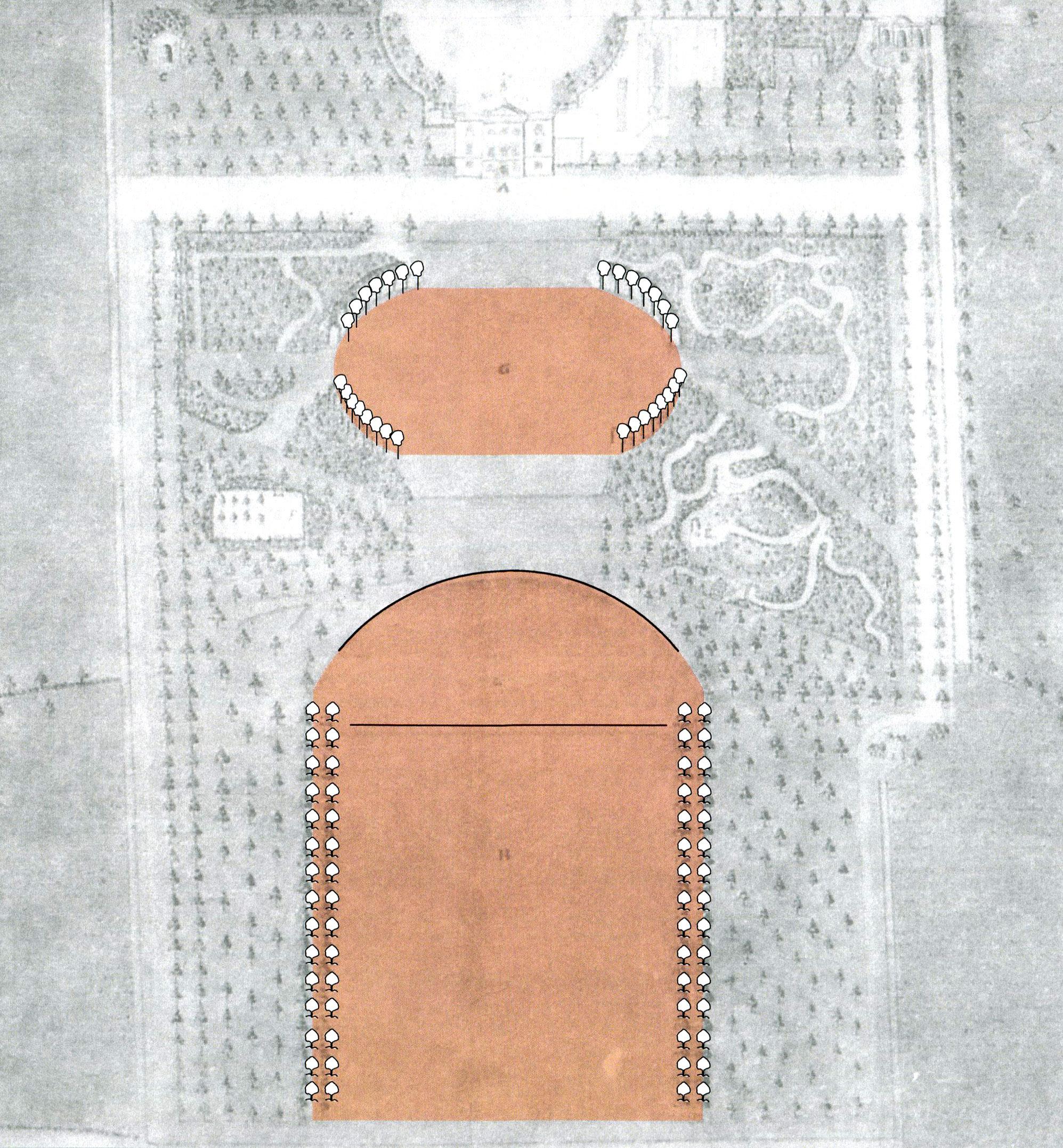

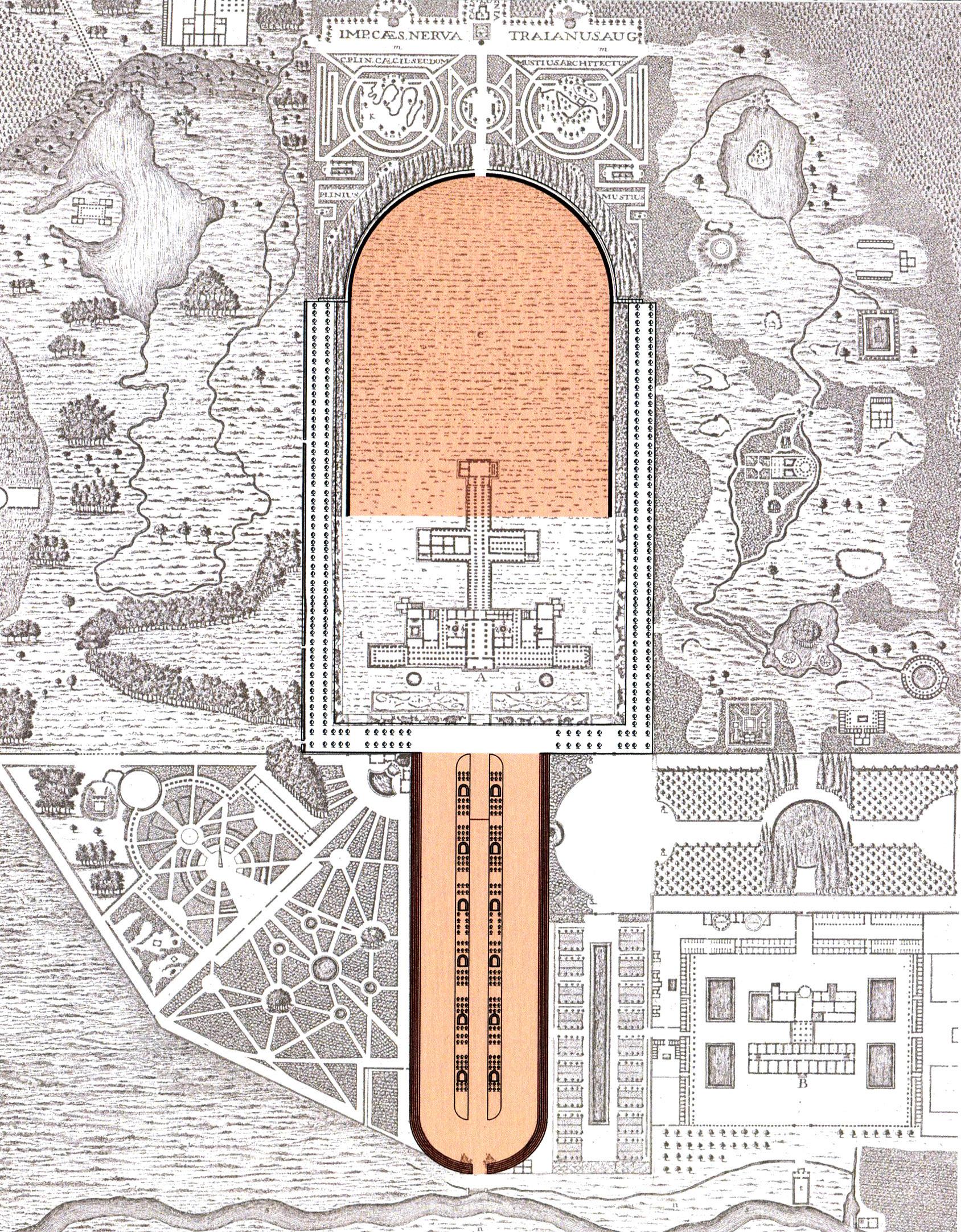

The Typology of the Hippodrome

In examining details of Pliny’s Tuscan villa, attention is drawn to his famous Hippodrome garden. From this ancient Roman example we trace in class the long history of the hippodrome as a formal shape in landscape design. Michael Moriano’s project captures this discussion in a well-researched indexical book that graphically articulates with numerous examples provided in the book the rectangle with curved end as a historically recurring form of landscape design. Beginning with the Circus Maximus and followed with Domitian’s Stadium garden Michael outlines with graphic clarity the reappearance of the hippodrome shape in the Villa d’Este, the Villa Giulia, the Luxembourg Gardens, William Kent’s design for the exedral garden behind Lord Burlington’s Chiswick villa, Pliny’s hippodrome reinterpreted by Robert Castell in his book Villas of the Ancients Illustrated, Schinkel’s exedral

17 See: Evans, Harry B, “Agrippa’s Water Plan,” AJA, Vol. 86, no. 3, July, 1982, 401-411 and Lloyd, Robert B. “The Aqua Virgo, Euripus and Pons Agrippae,” AJA, Vol. 83, no. 2, April, 1979, 193-204.

terrace at Charlottenhof, Potsdam, strikingly similar to Harold Peto’s longitudinal terrace at Iford Manor, and others. Michael’s book demonstrates that the hippodrome in form is a classic typology in landscape history.18

The Typology of the Round Temple

Shannon McGoldrick also used the format of a booklet, this one tracing the typology of round temples in the landscapes of antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and 17th to 19th century England. Beginning with the Tholos at Delphi, Shannon provides a clear image of each monument, to which she adds further images and historical descriptions. Her investigation traces the architectural form from its religious and ceremonial roots in Greek antiquity to its use as a garden pavilion at Hadrian’s Villa, an Aviary at Varro’s country estate in Casinum, the mausoleum of Cecilia Metella on the Via Appia. Its reemergence as a sacred structure in the Italian Renaissance is exemplified in Bramante’s Tempietto. And, as she documents, it is a form carried forward as architectural background in a stage set by Inigo Jones and ubiquitously adopted as a building type in the landscapes of 18th century England, including the Mausoleum at Castle Howard, the Temple of Venus at Stowe, the Temple of Ancient Virtue also at Stowe, the pavilion at Duncombe Park, and a proposed project by Humphry Repton at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Her booklet ends with a diagrammatic chart that traces the longue duree of the typology of the Round Temple in the landscape history of Western Europe. Like so many projects made by my Yale students Shannon’s shows how an architectural form once established in antiquity survives into the Renaissance and thereafter.

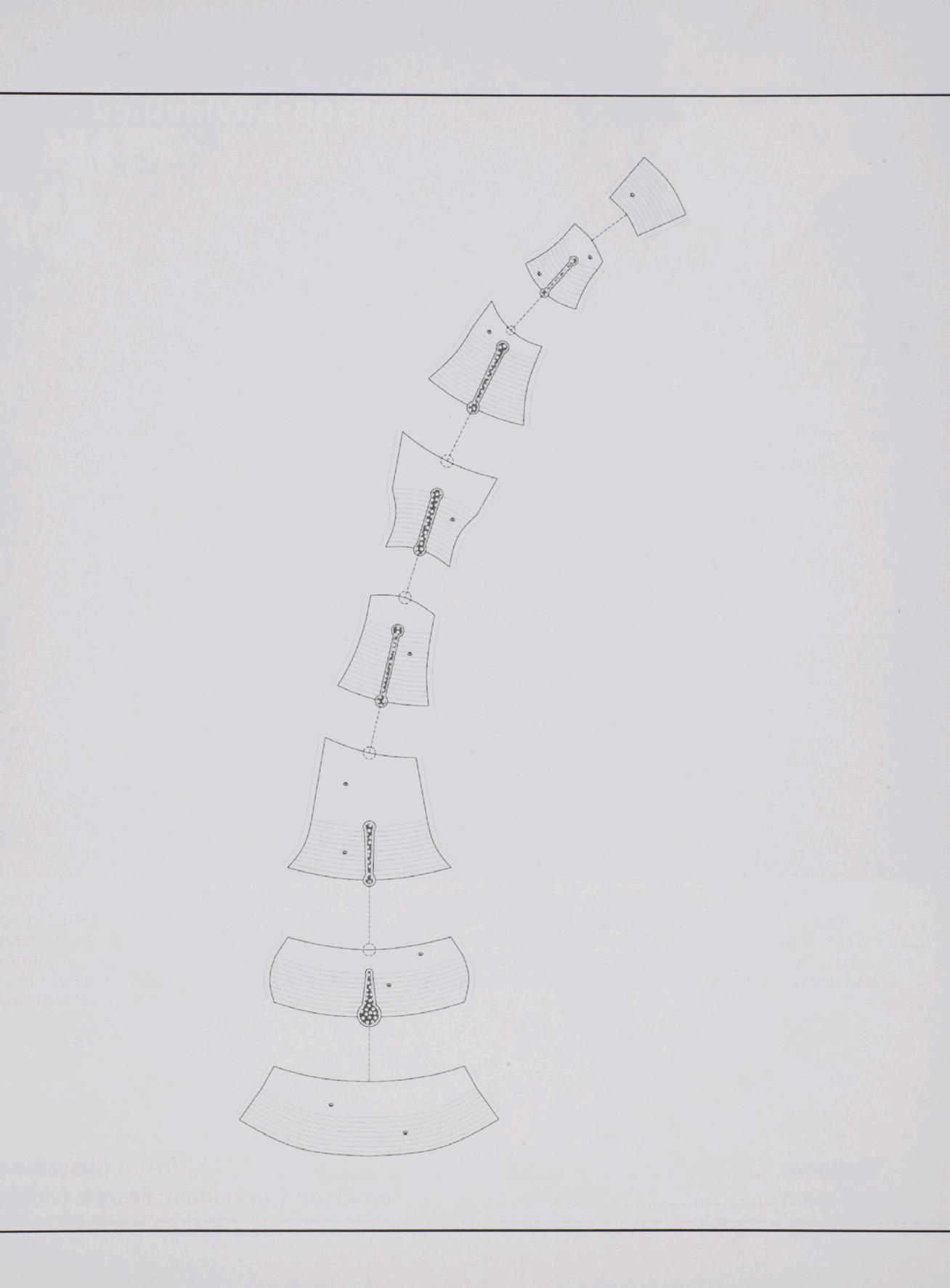

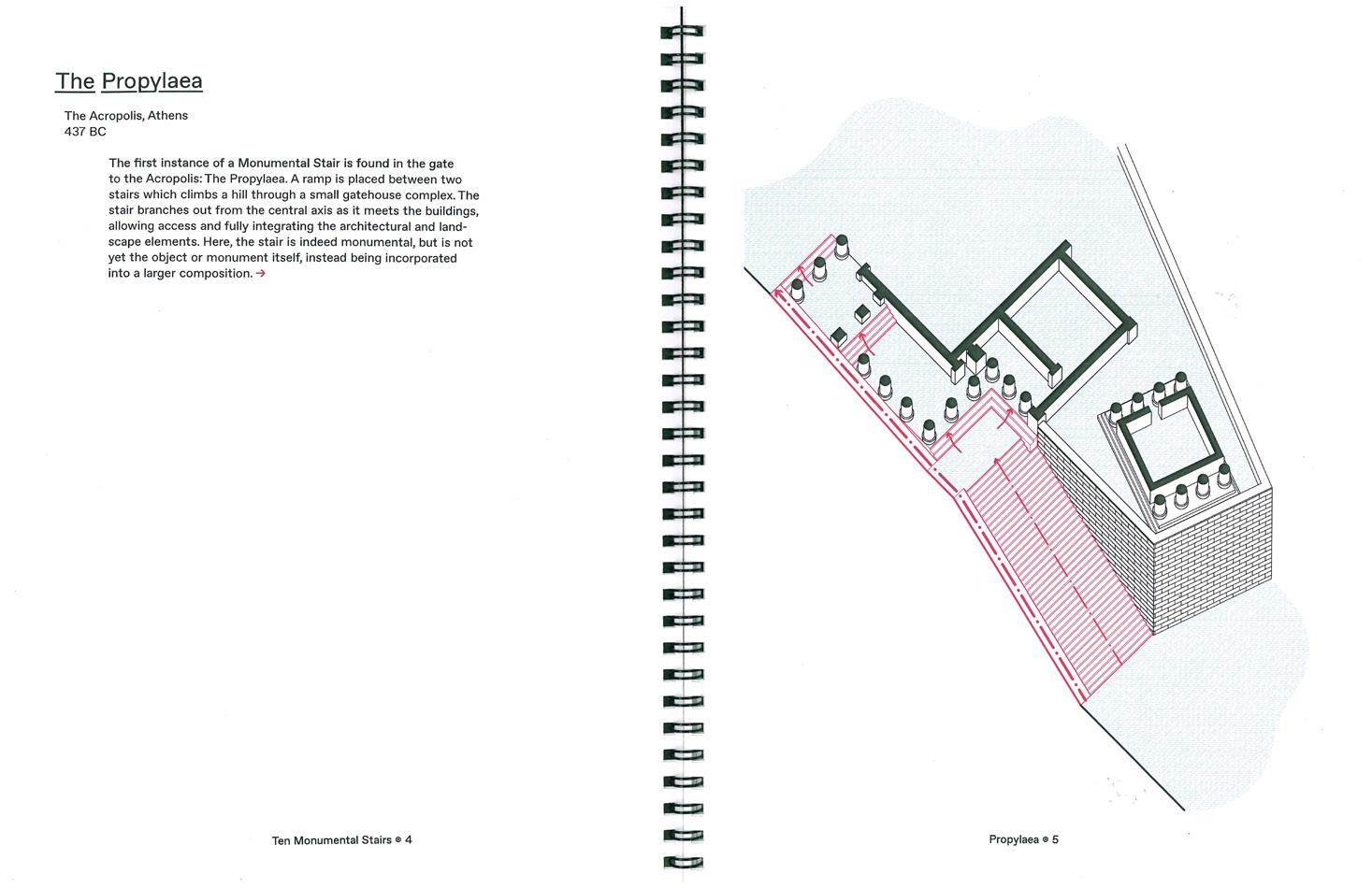

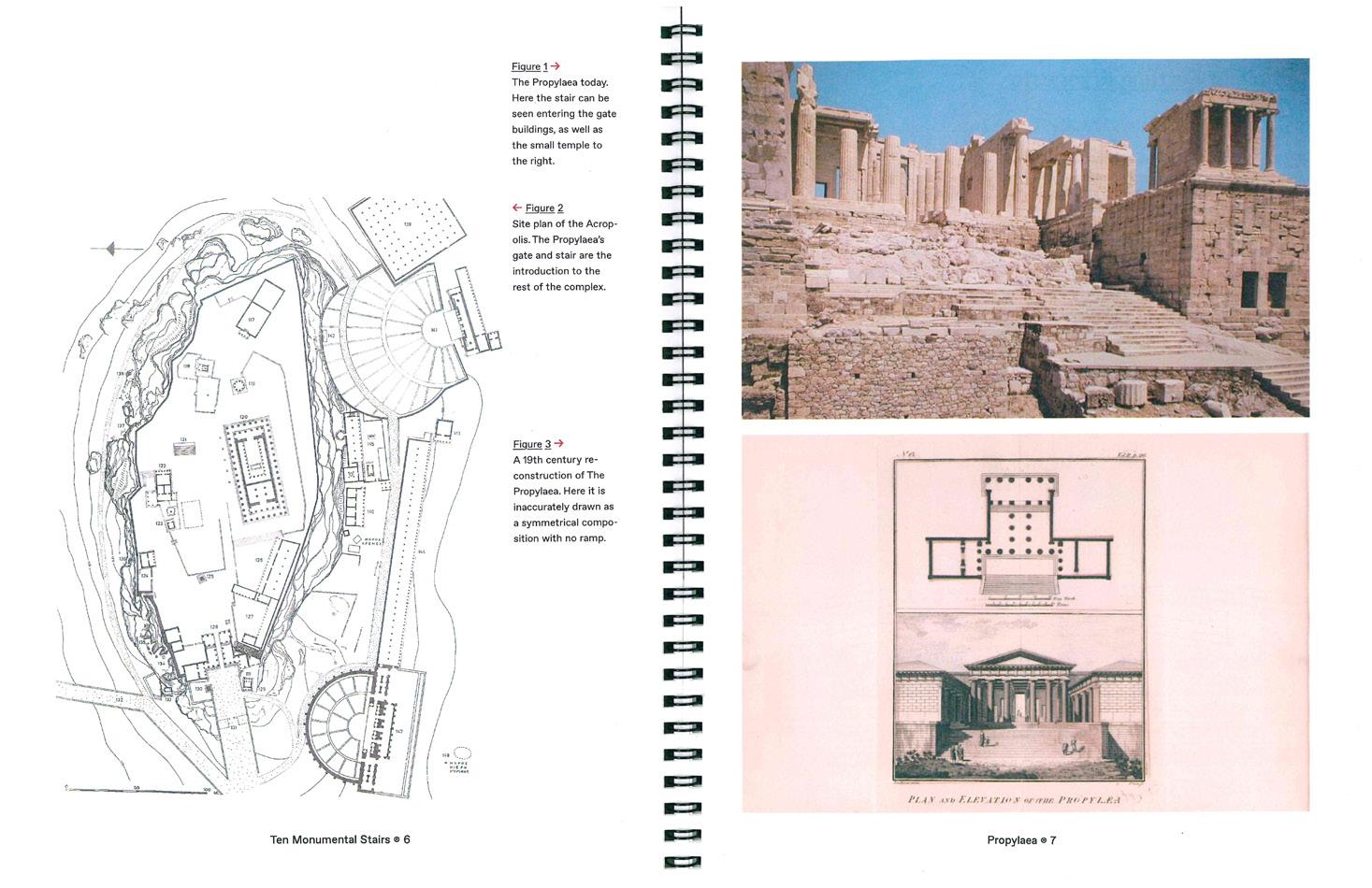

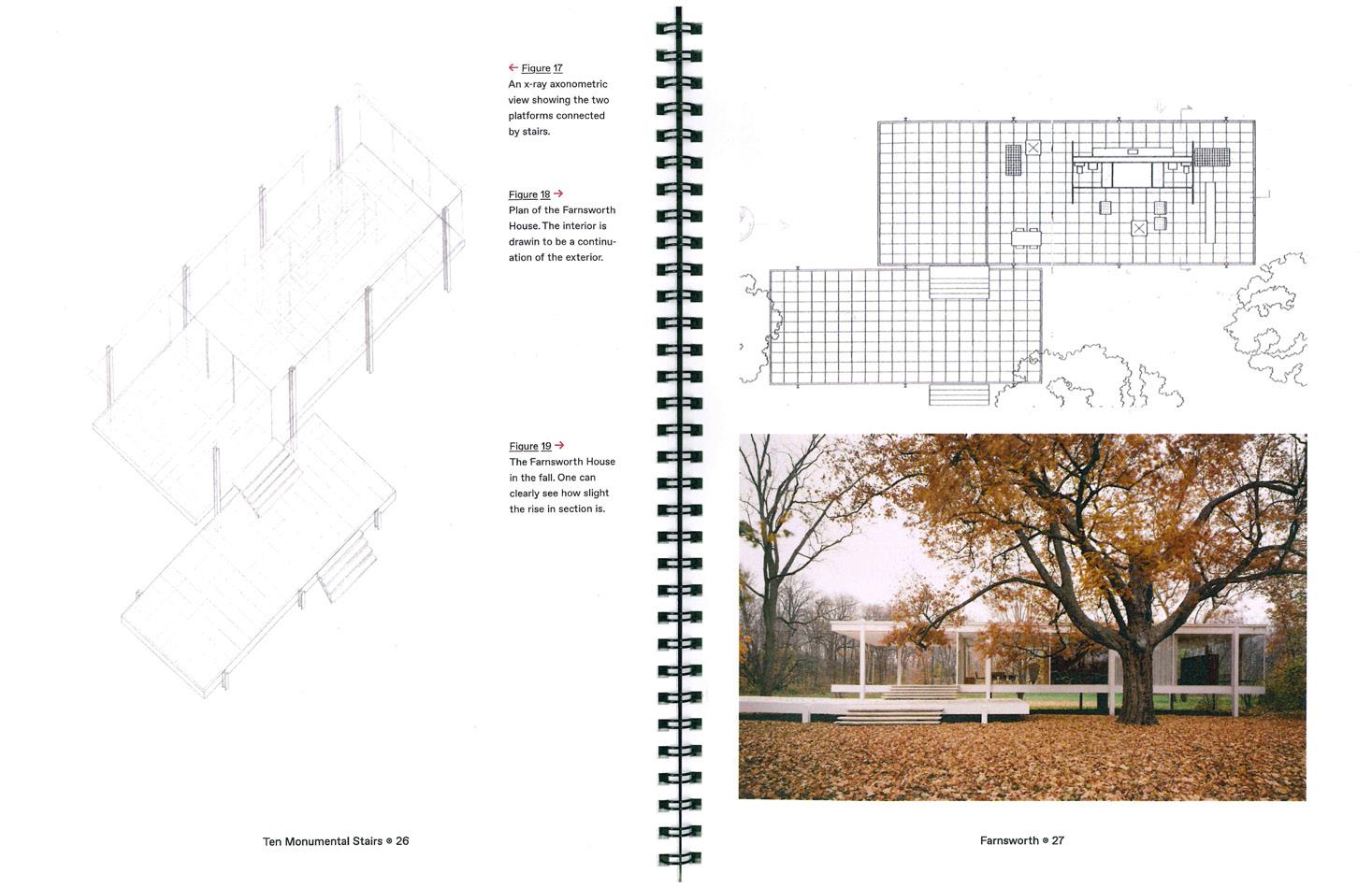

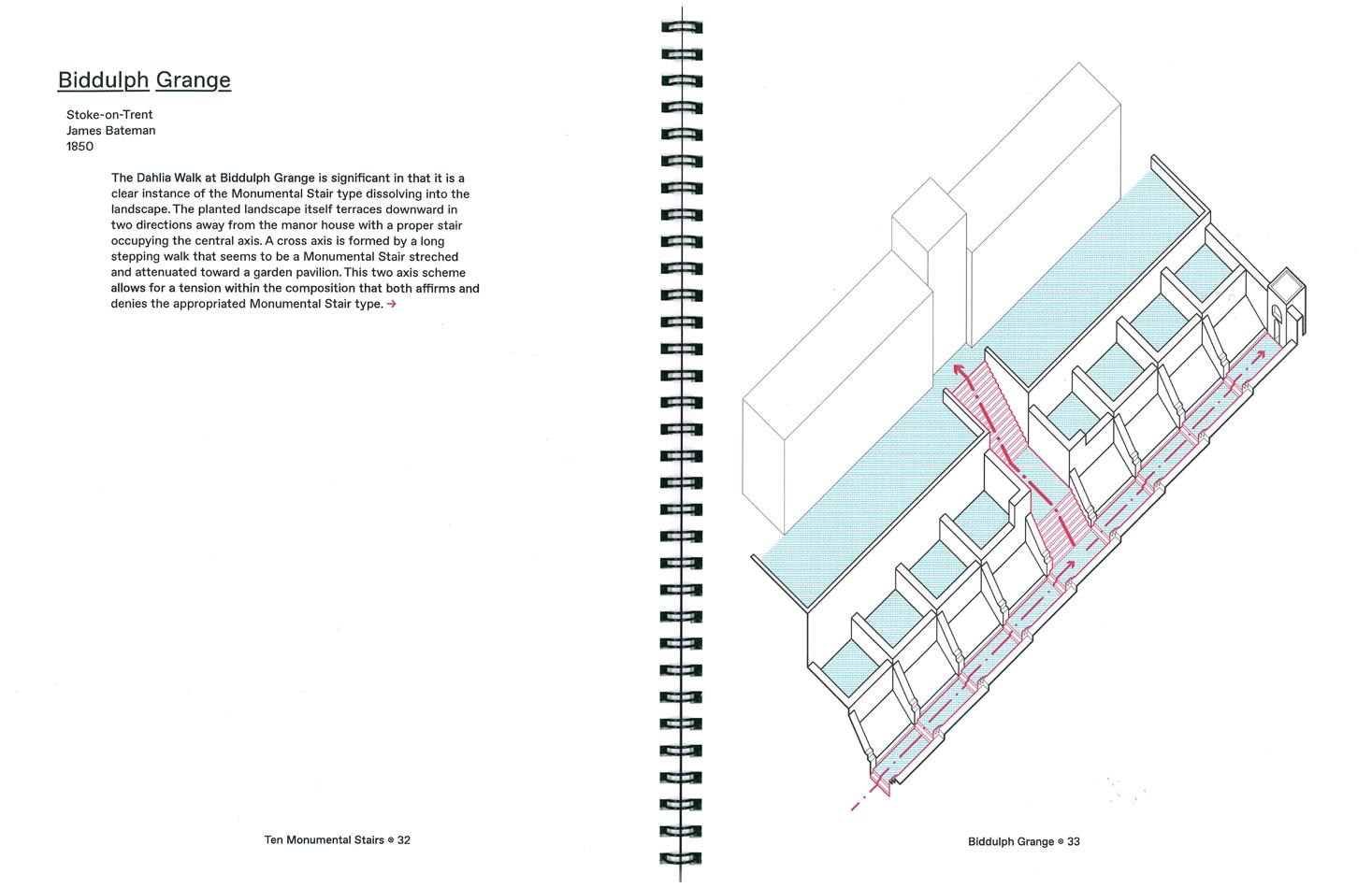

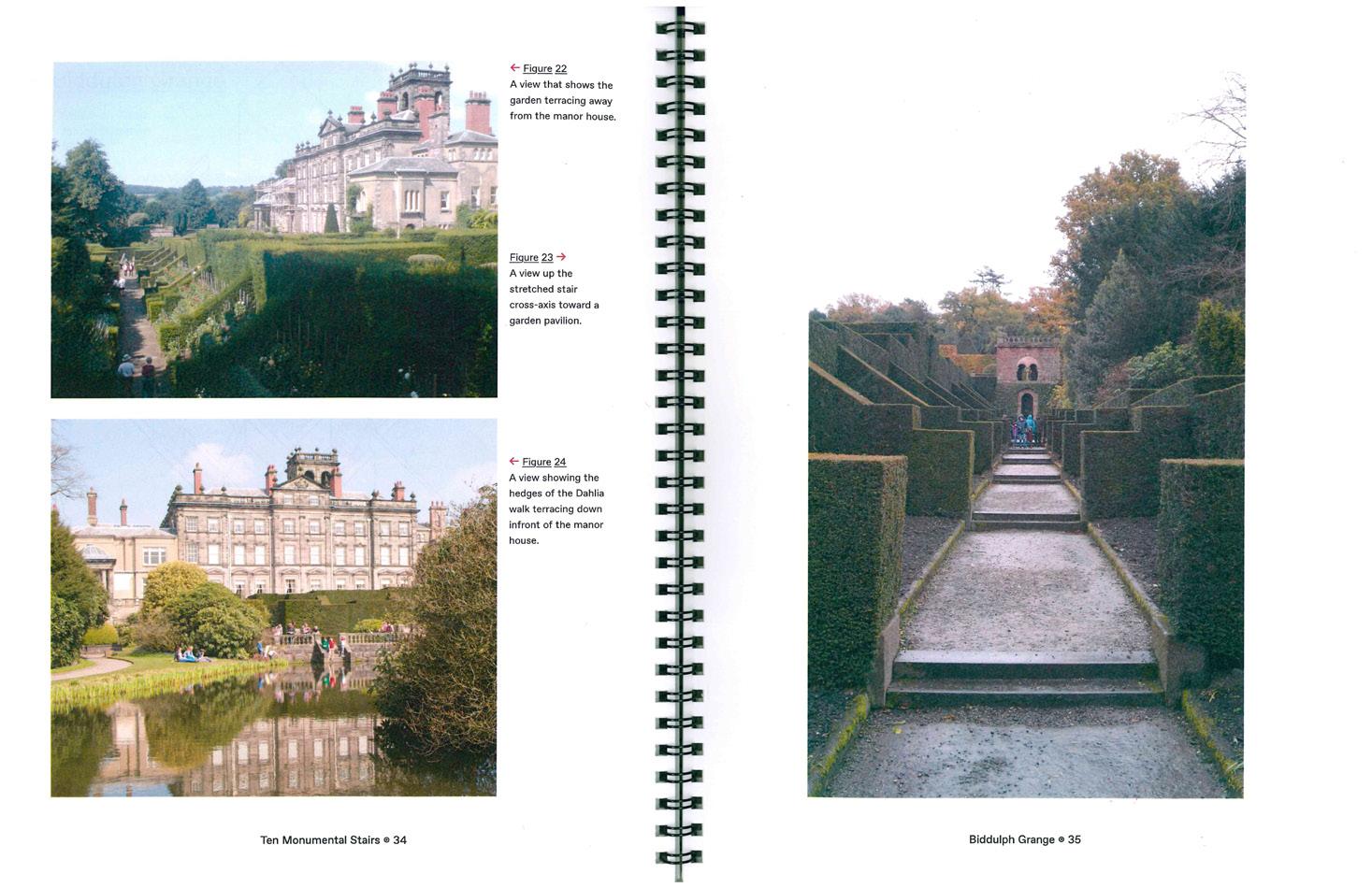

The Typology of the Monumental Staircase

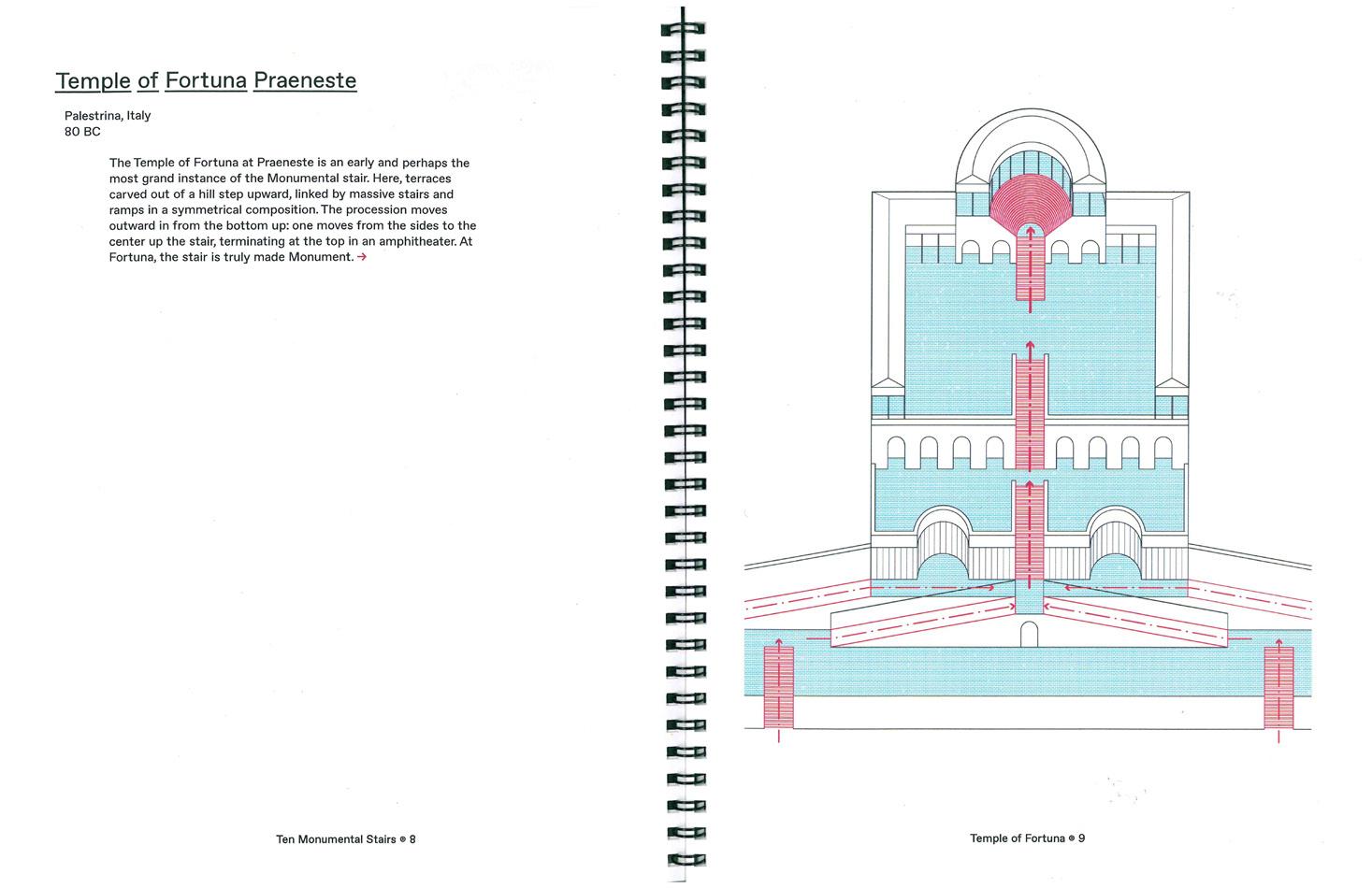

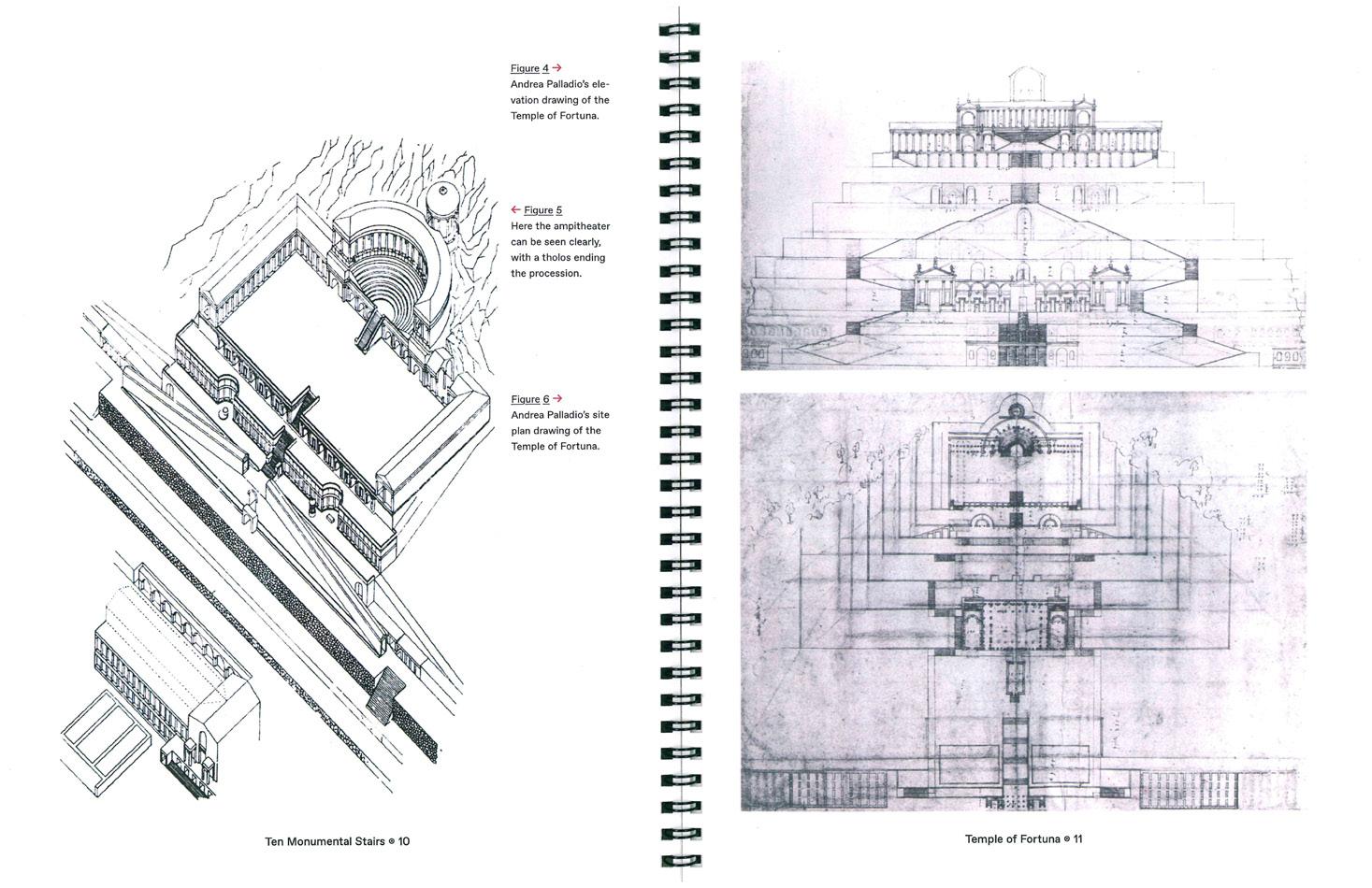

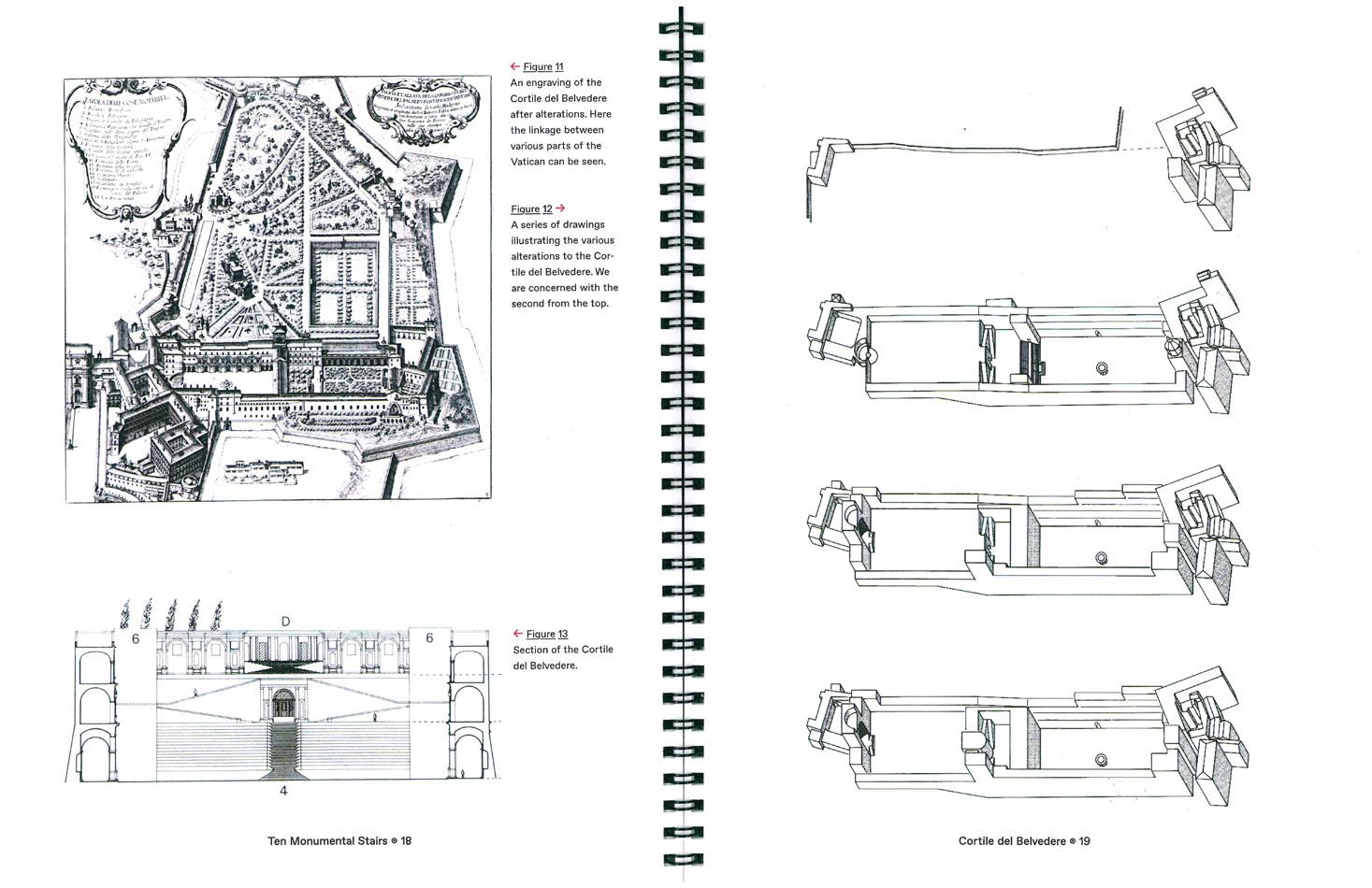

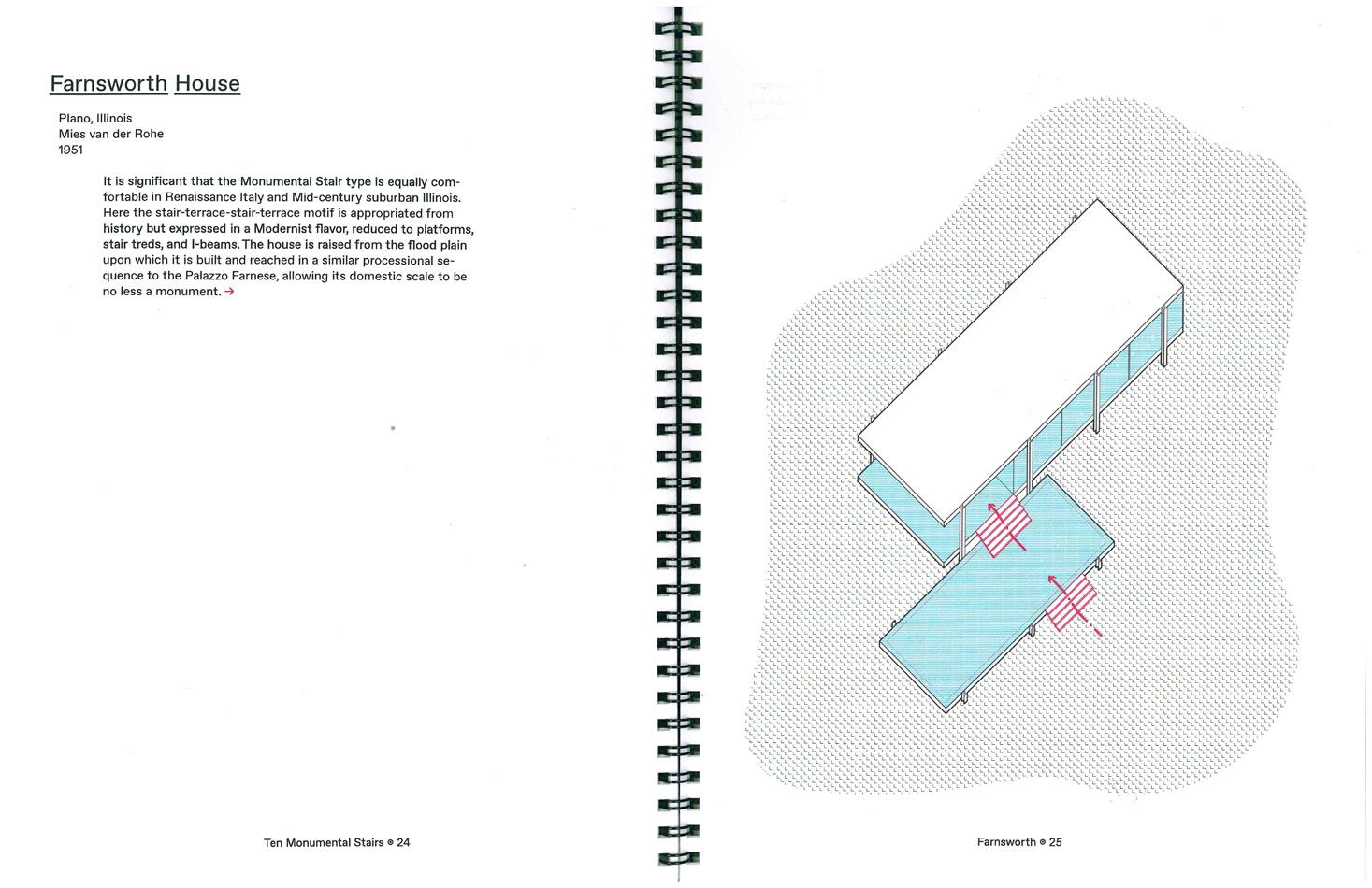

When in the course we come to analyzing Bramante’s design for the Cortile del Belvedere, I focus in part on his use of a monumental staircase, an important typology in landscape history.19 Wes Hiatt’s project, The Monumental Stairs, traces the history of this typology in ten case studies: the Propylaea, the Temple of Fortuna Praeneste, the Palazzo dei Papa di Viterbo, the Cortile del Belvedere, the Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, the Villa Lante, Biddulph Grange, Stroke-on-Trent, England, the Farnsworth House, Fletcher Steele’s Naumkeg, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and Fiole. In the introduction to his booklet, he writes: “Each monumental stair is drawn in a similar manner so that they may be compared. Common parts are found between all stairs: the horizontal ground, coded in blue, is deployed like a plateau between each piece of vertical circulation, coded in red, which can be a ramp or a stair.” For each of his studies Wes provides a short description and visual documentation, including drawings, plans, and photographs which inform his diagrammatic analyses. Several of Wes’s case studies are included in the book.

18 William L MacDonald in The Architecture of the Roman Empire, Volume I: An Introductory Study, New Haven and London, 1982 writes: “The word hippodromos was sometimes used by Latin writers to describe a garden or park laid out more or less upon the lines of a circus, such as the one at Pliny’s Tuscan villa. This connection between a palace or a villa and a circus shape was common in later antiquity and was revived or continued by Renaissance architects.” See also, ibid, n.70, 68. 19 Claudia Lazzaro writes: “Monumental garden staircases, like those of the Villa Carlotta, are symbolic forms that recall ancient Roman precedents and evoke the grandeur of antiquity through the intermediary of the Renaissance. A distinctive feature of Italian gardens, since much of the peninsula is hilly, they first appeared in sixteenth-century Roman gardens, chief among them the Villa d’Este at Tivoli. Inspired by Bramante’s Belvedere Court and Michaelangelo’s Capitoline Hill, the monumental staircases in Italian gardens also allude to the sites of the imperial Roman villa of Lucullus and the Temple of Fortune at Palestrina.” See: Claudia Lazzaro, “Italy Is a Garden The Idea of Italy and the Italian Garden Tradition,” in Villas and Gardens in Early Modern Italy and France, eds Mirka Benes and Dianne Harris, Cambridge, 2001, 54-55.

Projects Based on Ancient Roman Letters

In my fall seminar I ask students to read the ancient Roman letters of Pliny the Younger on his Tuscan and Laurentine villas, of Varro on his Aviary complex at Casinum, and Raphael on his Villa Madama. Based on these readings each student is asked to draw one of the buildings and landscapes described in the letters. Having been assigned Varro’s letter, Nicholas Miller chose for his final project to make a maquette of a tea service set based on Varro in the manner of the Swid Powell post-modern tea service sets of the 1980s.20 For his tea set Nicholas constructed a Tholos to hold the hot water; a reproduced Ancient Roman cup into which to pour the tea; a bird cage to hold the tea bags; a balum for sugar; and an herm figure out of whose mouth one can pour cream. Accompanying his maquette are his class drawing of the Aviary and a drawing of the maquette, both rendered in Nicholas’ bold, idiosyncratic style. It is a terrific project..

Fillip Blyakher’s project also drew on ancient Roman letters. He made a well-executed and playful pop-up book of Pliny’s Tuscan villa with Pliny’s stibadium, hippodrome garden, topiary gardens, and villa building based on Schinkel’s drawing of it, emerging from the pages. It too is a project of great fun.

The Organization of Plants in Landscape History

In the course, I introduce the story of how plants are organized over a long period of time. We begin with an examination of Livia’s garden room at Prima Porta, analyze the geometric shapes, the scale of compartments, and the rigid ordering of plants in the Italian Renaissance garden, the enlargement of scale and the loosening of form in the parterre de broderie in seventeenth century France, the beginnings of the gardenesque in late eighteenth century England, carpet bedding in juxtaposition to the wild in late nineteenth century England, the introduction of the herbaceous border in the work of Gertrude Jekyll and Beatrix Farrand, and conclude with contemporary examples in the works of Bernard Lassus. From this history of planting patterns two students made wonderful projects.

Garrett Hardee undertook to study the geometry of forms in Italian, British, and French gardens through a series of hand drawn and hand painted plans. For each individual garden plan, she provides a mylar overlay which, when lifted, depicts in its drawn outlines the geometric pattern that determines the organization of plants underneath in which they form compartments (compartementi), knots, or parterre de broderie. Her project is one that shows historic plant design in great clarity.

Cecily Ng focused solely on the parterre de broderie by creating a large, three-shelf box in which is contained a kit for making your own parterre de broderie. On the top shelf of the box is a card board, divided into four squares and four square panels in rust or gray, representing the colored earth or gravel of the parterre to be placed over the board. In the second shelf are green-cut outs of box and four yellow panels over which the box are to be placed to display a French garden in loose formatting. The third or bottom shelf contains numerous white cut-outs of parterre de broderie in intricate design to be placed over the colored boards as one sees fit. The project allows users to mix and match in making their own gardens in French plant formations.

20 On the Swid Powell post-modern tea service sets, see Annette Tapert, Swid Powell: objects by architects, New York, 1990.

Denise Buzata was fascinated by the planting plans and organization of color in Gertrude Jekyll’s herbaceous borders. For her final project she undertook to make an eight-foot long model of one of Jekyll’s borders.21 To construct it, Denise first chose a plan in which Jekyll identified the shape and color of each flower planted in her border. To isolate the color, Denise created a book in which each flower is shown and its primary color or corollae identified in monochrome next to it. The shape of each flower as drawn by Jekyll was redrawn by Denise in the computer and then color coded based on her monochrome studies. The varying height of each flower was identified and rendered by mounting her flower petals on wooden sticks. Denise then assembled her flowers following Jekyll’s plan, setting their wooden stakes in place on a solid wooden base. The result is a long, vibrant, and glorious model of one of Jekyll’s herbaceous borders.

The Organization of Trees

In the fall course we examine the importance of trees in ancient Roman landscape history. These include an assigned drawing of Varro’s Aviary based on his letter which describes how trees and columns are used in the construction of his bird cages, a review of the design of the Porticus Pomieana, the first public park in Rome22 where the imported trees or numbi act as natural correlatives to the colonnade that surrounds the open garden space of the park and temple/theatre complex, and the meaning of the Sacred Grove. It is the latter which is compared to Peter Walker’s use of the zelkova tree in his project, Keyaki Plaza, Saitama City, Japan,23 to Daniel Libeskind’s willow-olive grove in the Garden of Exile at the Jewish Museum, Berlin, and to Erik Gunnar Asplund’s and Sigurd Lewerentz’ Meditation Grove at Woodland Cemetery.24

Maya Alexander’s The Tree and A Column: Nature Defining Architecture is a booklet divided into two parts. Part one references the juxtaposition of trees and architecture in ancient Rome, in 16th century Lucca, and in the twentieth century. Part two lays out six typologies of grid formats in which trees, acting as natural correlatives to the built form, are consciously planted in different grided formats in conjunction with the architecture they inhabit or surround. The illustrated types are Fields, Field Mimics, Contained Fields, Contained Single, Soft Contained, Separated Dialogue, and Mixed Dialogue. Two examples of each typology are presented in her project with only one of each shown in this book.

Naomi Ng’s project, The Edge of Forestscapes: 5 Projects, looks at the edge conditions of five vastly different forest landscapes which convey five different styles of landscape design. In chronological order are Naomi’s model for LeNotre’s Vaux-le-Vicomte which illustrates the hard-edge of a single lined hedge planted between the formal garden of topiary cones and the unruly forest behind. For Asplund and Lewerentz’ Woodland Cemetery Naomi displays in her model the landscape’s soft edges, lined with weeping willows in front and Scots pine at the back with tombstones laid under pine trees. Lawrence Halprin’s Sigmund Stern Grove is modeled to convey the gradient edge that runs as a natural continuation from stoned hardscape to forest-scape. For the Bloedel Reserve she focuses on the formal, geometric Reflection pool with its hard-edge of clipped yew hedges that enclose it and which acts in juxtaposition to the wilder forest that surrounds the whole. And, for the 9/11 Memorial, Naomi models the

21 See: Gertrude Jekyll, Colour Schemes for the Flower Garden, London, 1982, in particular Chapter VI, “The Main Hardy Flower Border,” 124-141.

22 See: Kathryn Gleason, “Porticus Pompeiana: a new perspective on the first public park of ancient Rome,” Journal of Garden History, Vol. 14, No 1, Spring, 1994, 13-27.

23 See: Peter Reed, Groundswell, New York, 2005, 58-63.

24 See: Caroline Constant, The Woodland Cemetery: Toward a Spiritual Landscape, Stockholm, 1994

hard edge of Peter Walker’s gridded urban forest of over four hundred swamp white oaks surrounding Michael Arad’s highly geometric pools of water.

The models convey five different approaches to the presence of trees in the designed landscape: the French preference in formal gardening to the hard-edge; Asplund and Lewerentz’s relaxation of the edge with the retention of mixed plantations for burials within the forest floor; Lawrence Halprin’s graduated blurring of the edge into the naturalist forest; Richard Haag’s juxtaposition of hard-edged clipped yews to the wilder forest that encompasses them; and Peter Walker’s design for the 9/11 Memorial with its emphasis on trees planted in a rigid, minimalist grid in harmony with and as backdrop to Michael Arad’s giant voids of cascading water within them.

In a small booklet, “Pomological Architecture: Temptation Breeds Control,” exceedingly engaging because of its graphic design, Daniel Jacobs examines the presence of fruit trees in biblical texts and in gardens in the period from the Old Testament to the seventeenth century in Western Europe, focusing in particular on Spanish and Moorish gardens with which he has had a personal connection. He begins with a very useful lexicon of Fruit/Nut trees listed in the Old Testament and the Qur’an, followed by quotations from both sacred texts, in English and Arabic, which convey parallels of pomological references in each culture. What then follows are three ways in which Daniel identifies how fruit trees have been planted within this time frame: Single Points or isolated trees in the Pompeian Peristyle and Spanish courtyard gardens; Point Grids and Fields as illustrated in the orchard cemetery of the St. Gall plan and in Moorish plazas planted with citrus trees; and Total Control exemplified in the use of espalier and early European orangery. His project is a visual delight.

Analytic Projects

In the Yale School of Architecture Peter Eisenman taught for many years a course on Diagrammatic Analysis. This course informed Anthony Gagliardi’s project.

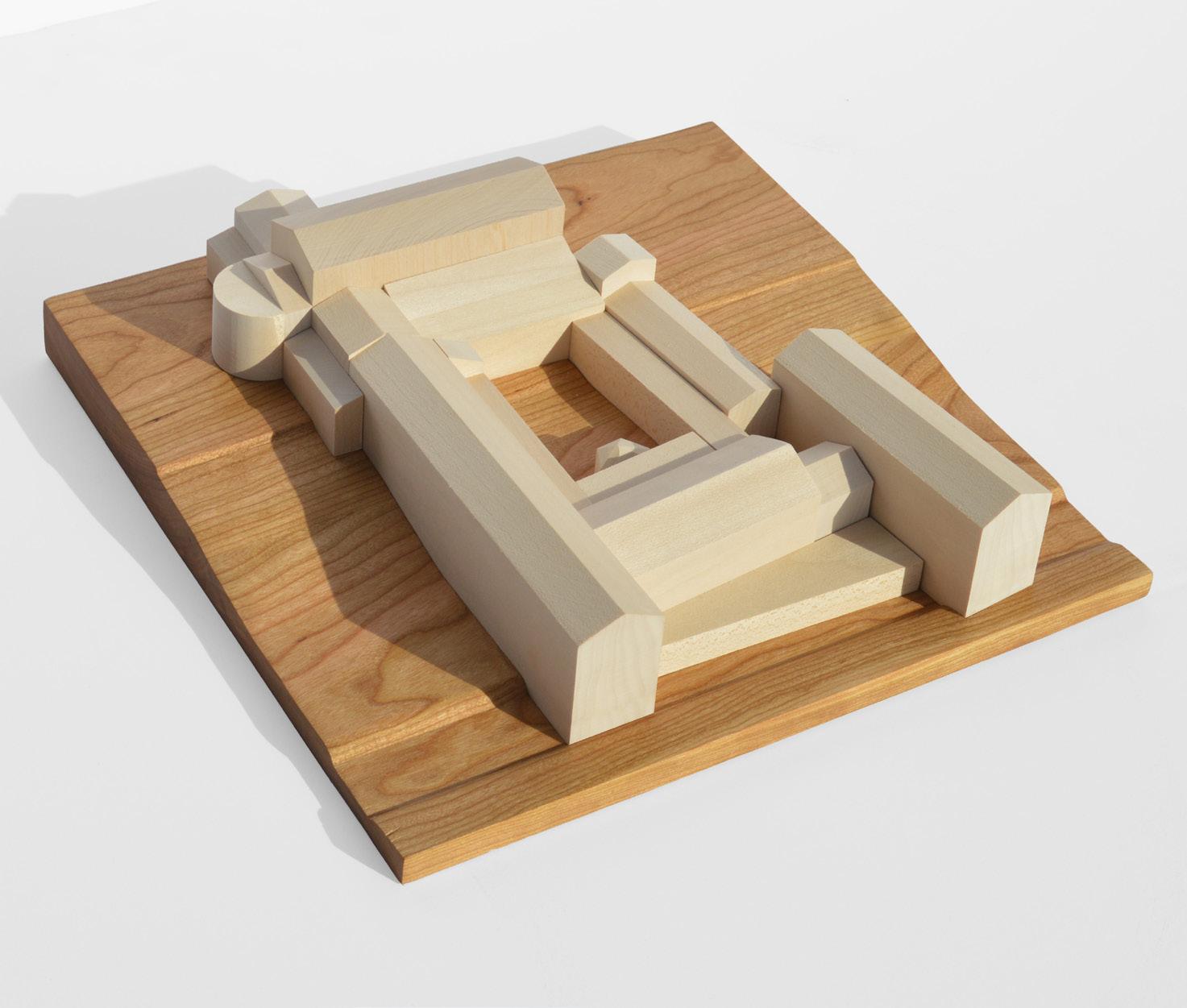

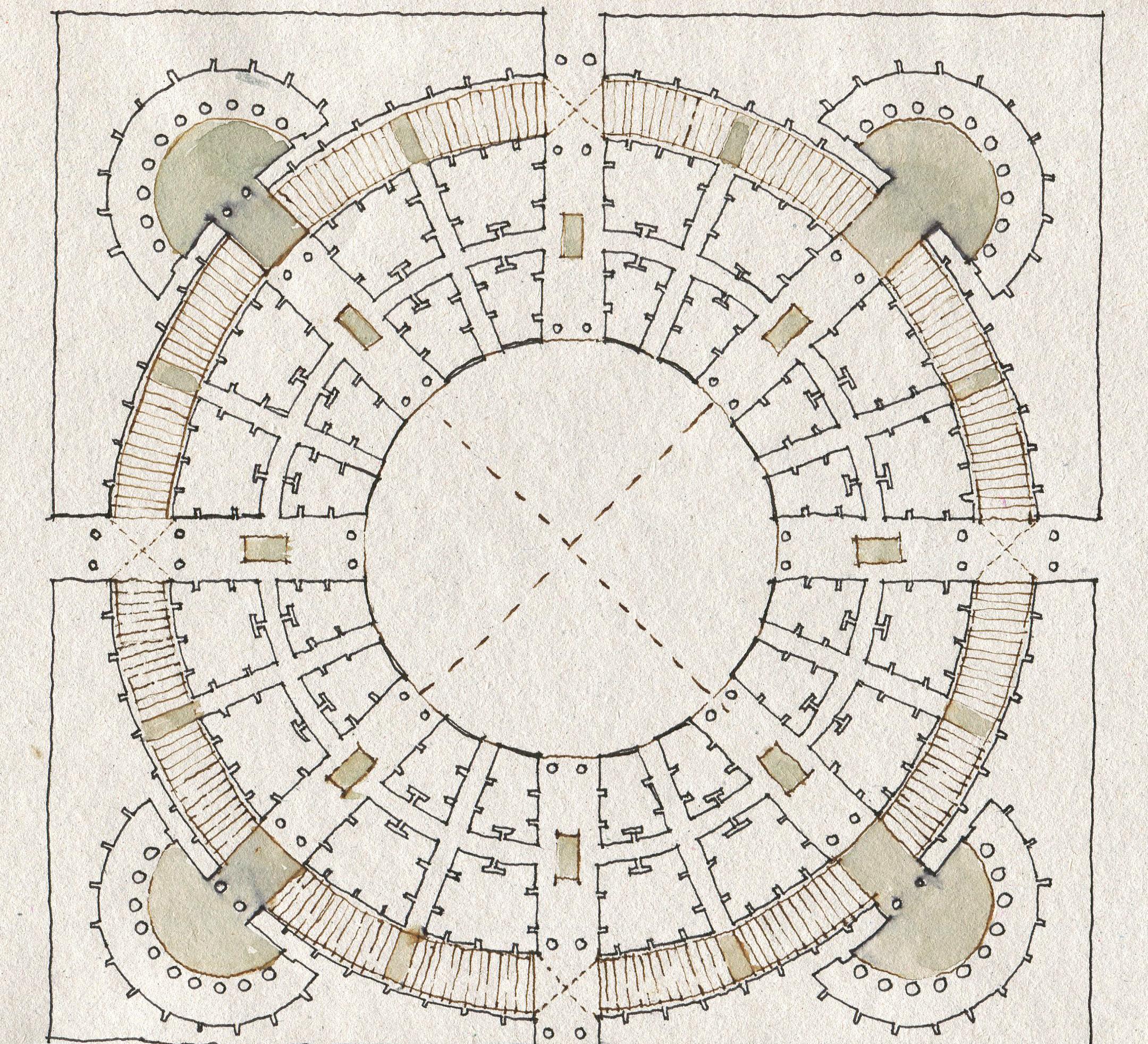

Anthony made two planimetric models of the site plans of two Italian Renaissance villas in Lazio: one of the hillside garden of the Villa Lante, shown in the book, and the other of the Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola, including that of the Casino built in the woods behind the pentagonal villa. The virtue of these models is the distillation of the design of gardens to their elemental forms, in the case of the Italian Renaissance garden to that of the geometry of square, circles, and semi-circles and clear alignment of parts. The two models make for a fine corollary to Garrett Hardee’s drawings of the underlying geometries in the planting compartments of the Italian Renaissance garden, previously mentioned.

Seokim Min’s project, Communal and Individual, is a well-made booklet of nine projects, beginning in the 1390s and ending in the 1970s, which focuses on individual housing in relation to the communal landscaping to which it is connected. These include the Certosa di Galluzzo, Florence, Italy; Jules Hardouin Mansart, Charles Le Brun, and Andre Le Notre’s Chateau de Marly, Versailles; Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s Royal Saltworks, Arc-et-Senans, France; John Nash’s Blaise Hamlet, Bristol, England; Joseph Paxton’s Birkenhead Park, Birkenhead Merseyside, England; Vaux and Olmsted’ town of Riverside, Illinois; Clarence S. Stein’s and Henry Wright’s Radburn, New Jersey; Aldo Rossi’s Cemetery of San Cataldo, Modena, Italy; and Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens, London.

To organize her study Seokim introduces a brief explanation of each project, accompanied with historical images. She then provides superb axonometric drawings of each case study to ‘better illustrate the relationship between communal green space

and individual housing.” It is these axon drawings with housing outlined in black and landscape in green which bring heightened clarity to the plans, scales, and interconnections of architecture and landscape of these comparative projects in the history of mass housing, whether for Carthusian monks, Royal guests, estate workers, suburbanites, or in Rossi’s case, the Dead.

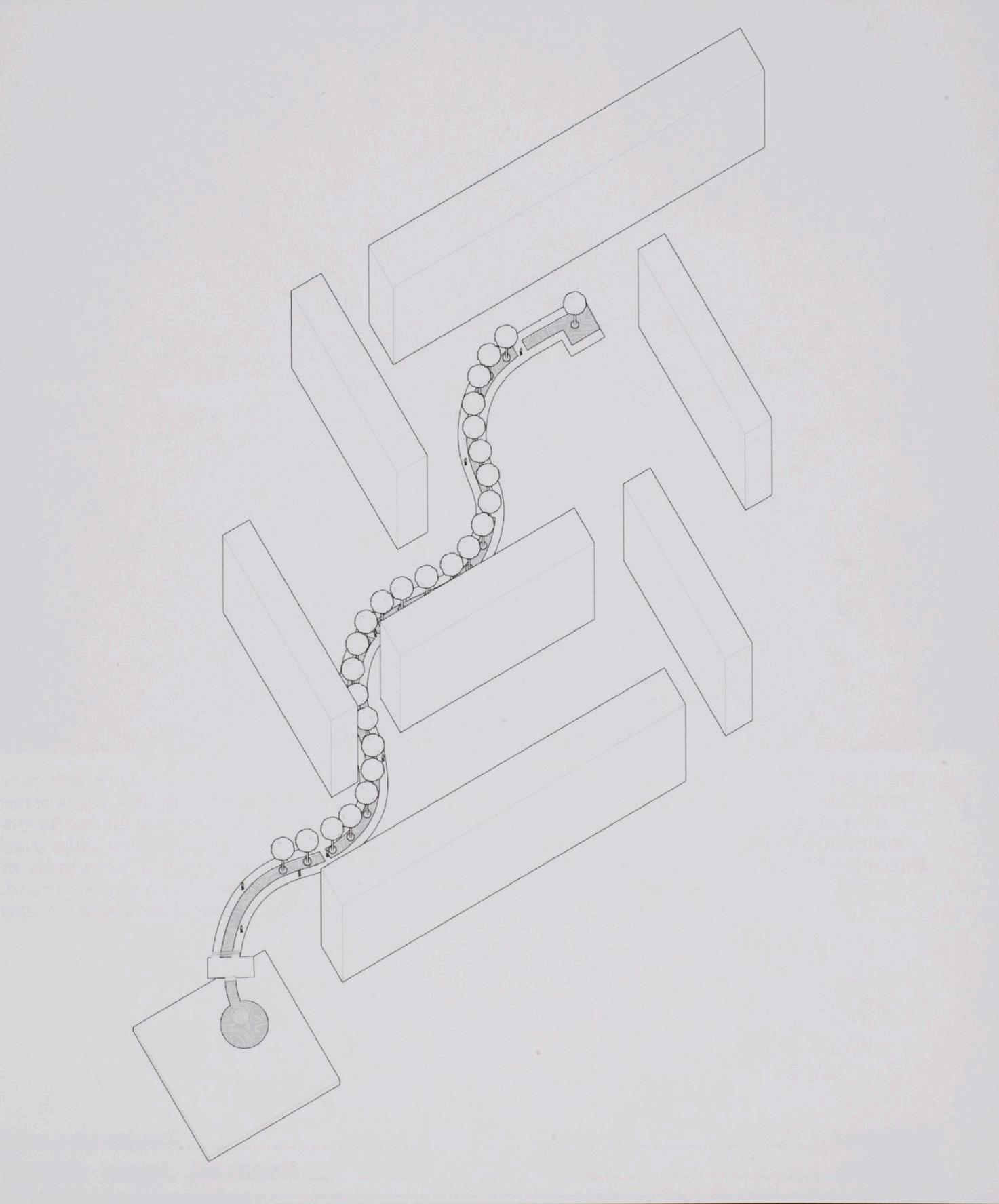

John Kleinschmidt’s and Andrew Sternad’s Landscape Lines is a book that dissects six seminal water gardens from antiquity and Renaissance Rome by lines and end-spaces which are catalogued for comparison. These include the House of Octavius Quartio ( formerly the House of Tiburtinus ), Hadrian’s Villa, the Villa Lante, Tiberius’ villa at Sperlonga, the Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, and the Villa d’Este. For each garden an analytic drawing is made of the main axis from a starting point to a perceived end point, a short text with accompanying images of the gardens is given, and key points along the line are identified and drawn in a third page. New imaginary water gardens are then re-composed from these fragments in order to “strain the joints and test whether a new balance can be created from disparate parts.” The project conveys an important theme in the fall course: the interrelationship of water and architecture from circa 79 AD to 1570s in the history of Italian gardens. It is a project which also shows students experimenting with their own designs of landscape.

From the Vernacular to the Formal in Villa Architecture

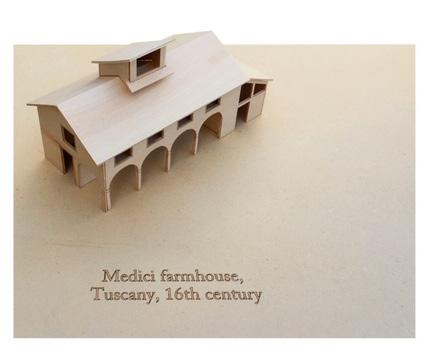

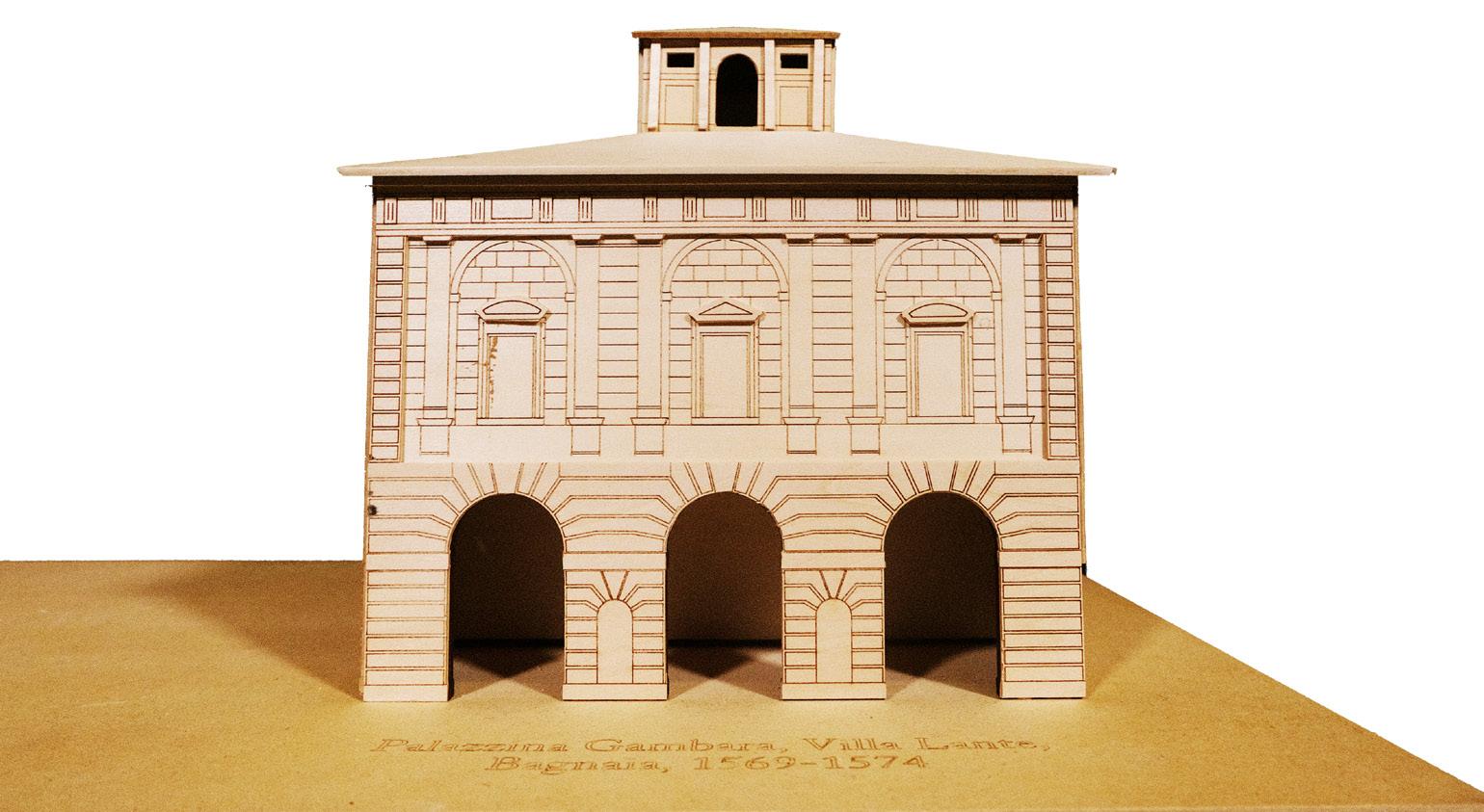

Luke Studebaker also examines the Villa Lante. But in his project the focus is on Vignola’s design of the Palazzina, a compact cube with hipped roof with an enclosed belvedere with hipped roof above. Its source, according to Claudia Lazzaro25 is vernacular farm buildings in Tuscany as seen in Luke’s model of the Medici farmhouse with hipped roof and dovecote with hipped roof above. The two models, side by side, firmly grounded on board, afford students the opportunity to view three dimensionally what James Ackerman describes as a potential fifth typology in the history of the villa.

The

Landscape of Cemeteries

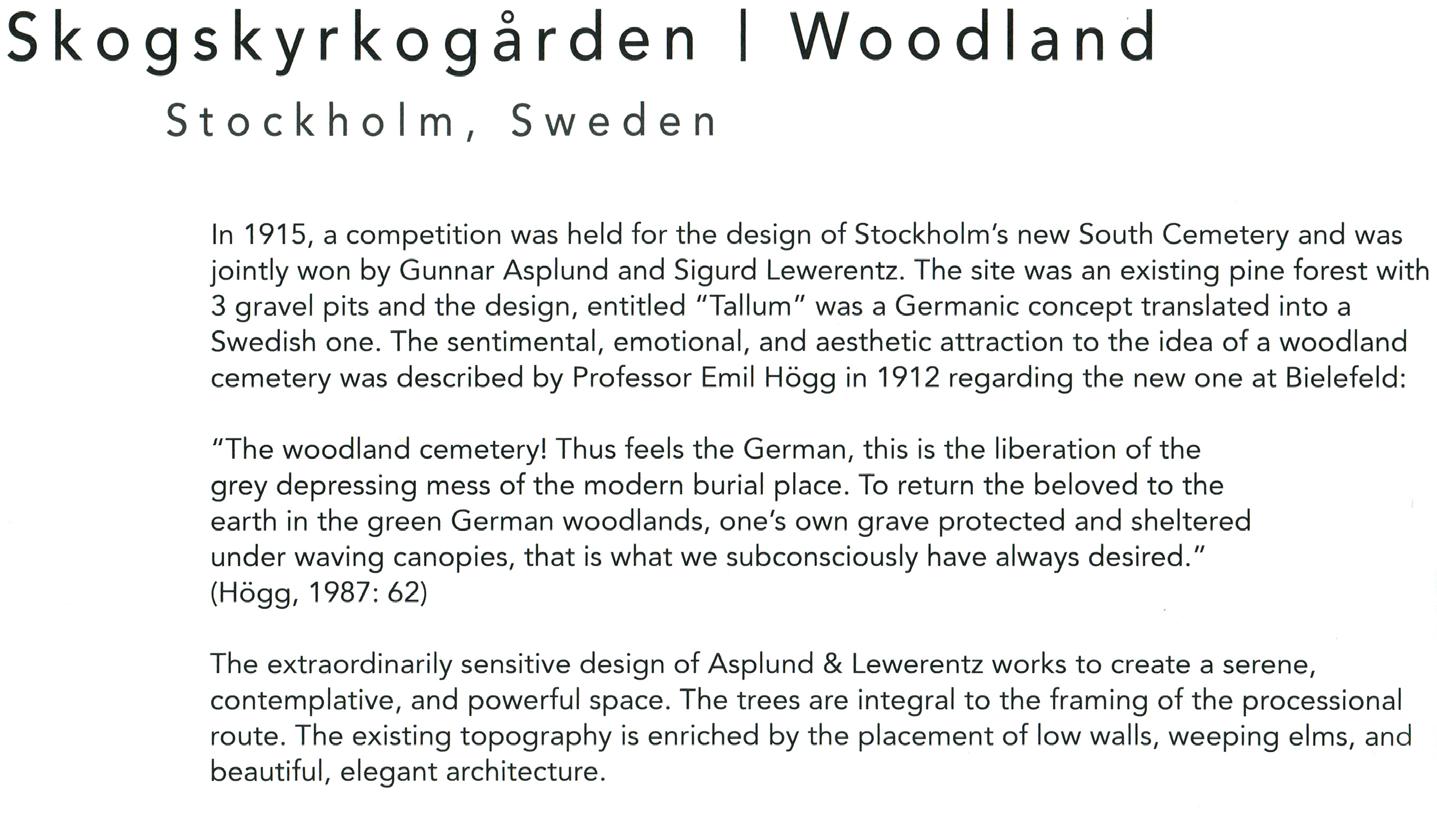

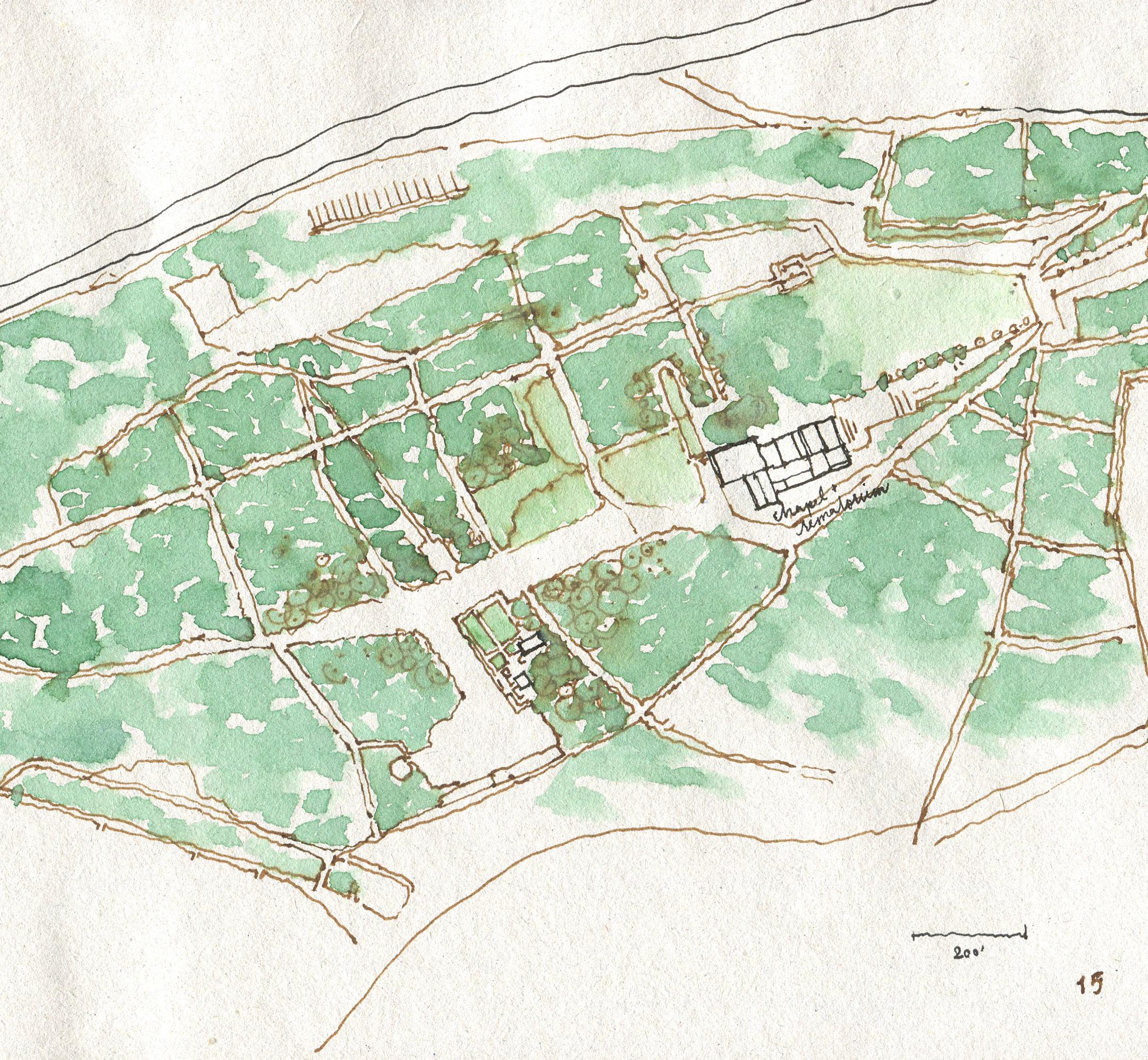

An essential feature of landscape history is that of the cemetery. In the course, students view the detailed drawing of the cemetery in the St. Gaul plan in which the graves of the monks are set in a garden of fruit trees surrounding the Cross which, written on the plan, states: “The holiest of the trees of the field is the Cross, Fragrant with the fruits of Eternal Salvation,” with futher lines as Wolfgang Braunfels points out, “Let the bodies of the departed brothers lie round this Cross and through its radiance attain the Kingdom of Heaven.”26 This plan of late antiquity begins a detailed look at four case studies of the history of cemeteries in Western Europe: the Campo Santo, Pisa; Carlo Scarpa’s design of the Brion Cemetery, San Vito d’Ativole; Aldo Rossi’s Post-Modern, unfinished addition to San Cataldo cemetery in Modena; and Erik Gunnar Asplund’s and Sigurd Lewerentz’s masterwork, Woodland Cemetery, Stockholm. The lecture resulted in two exceptionally well executed projects.

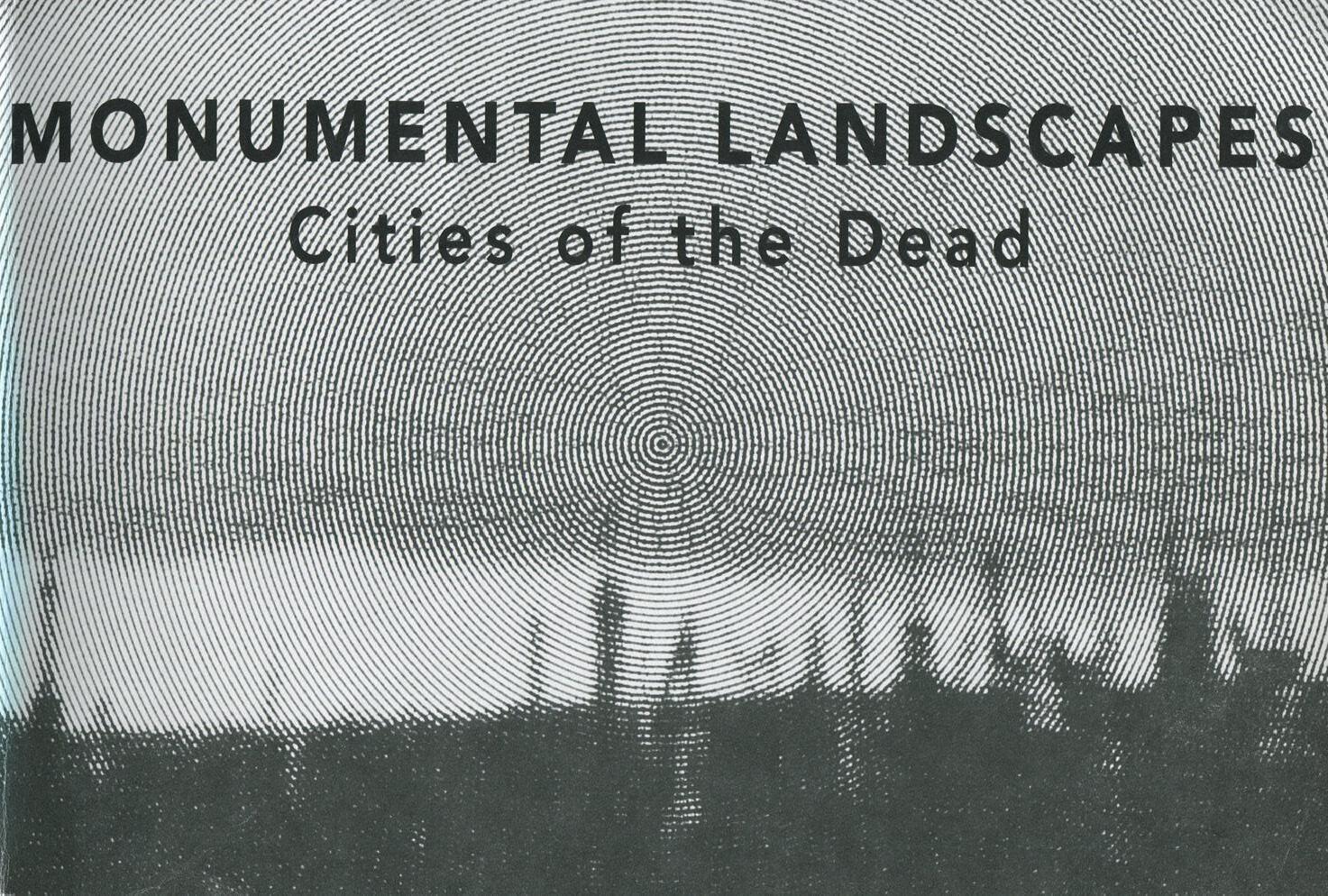

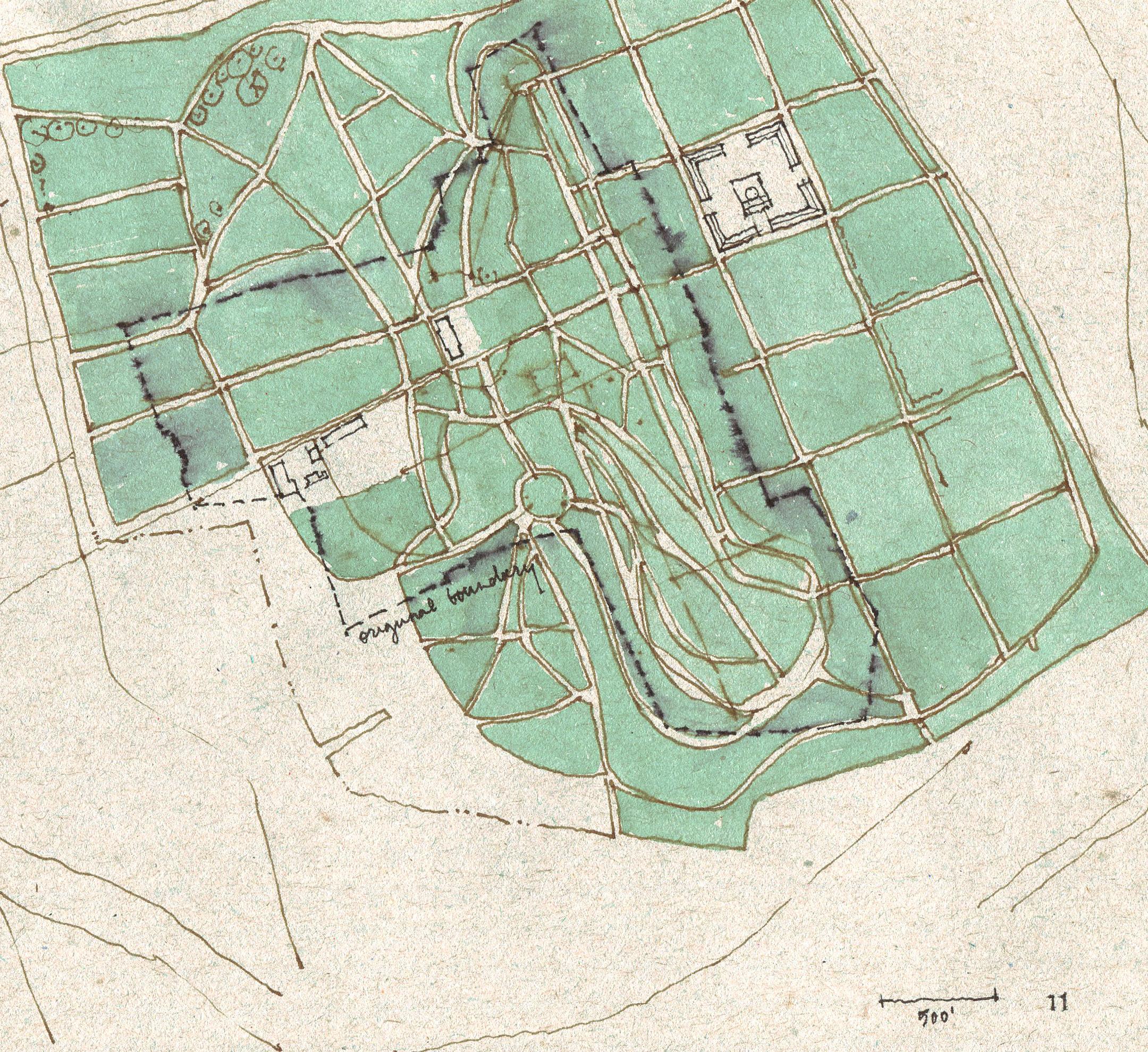

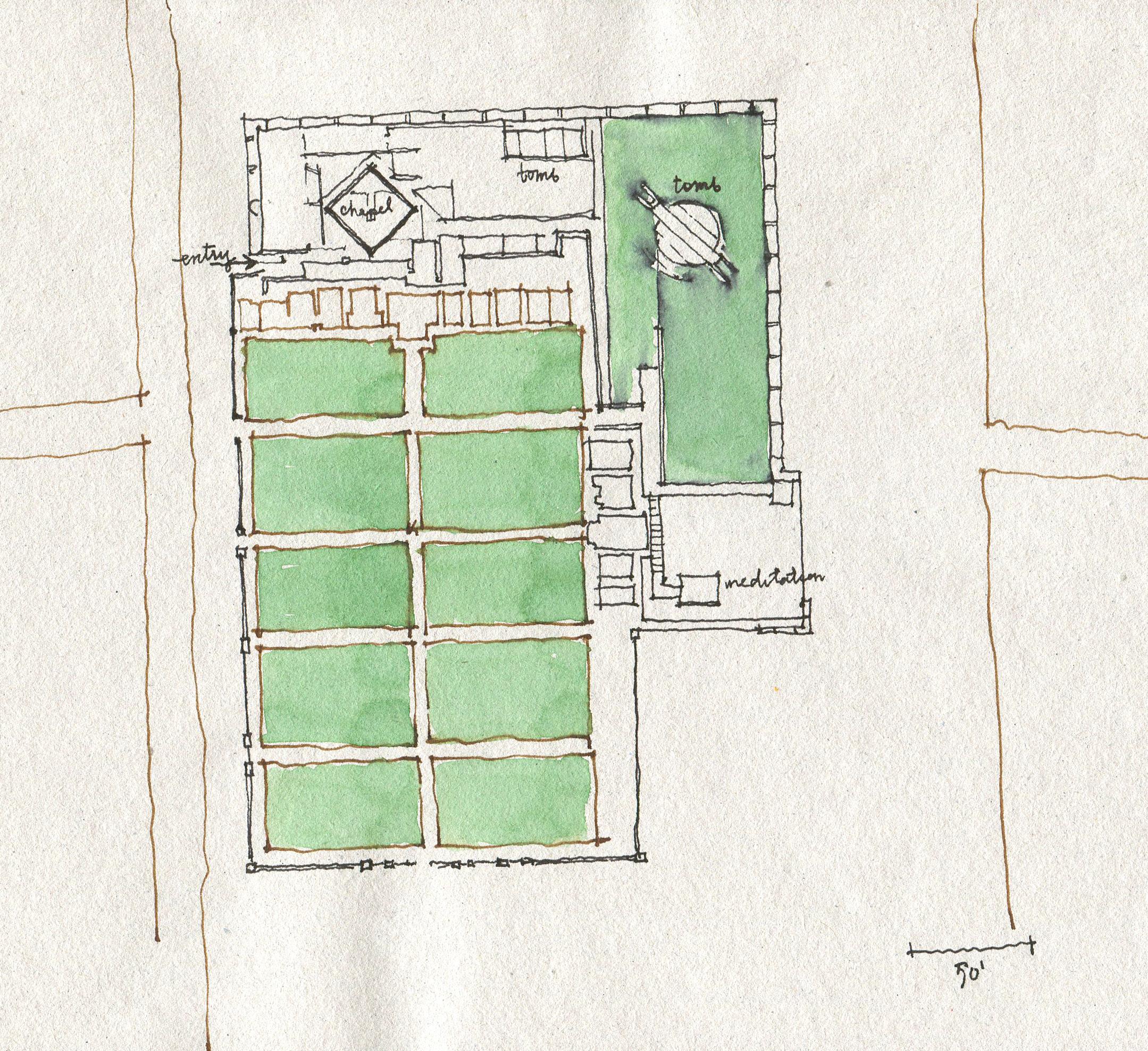

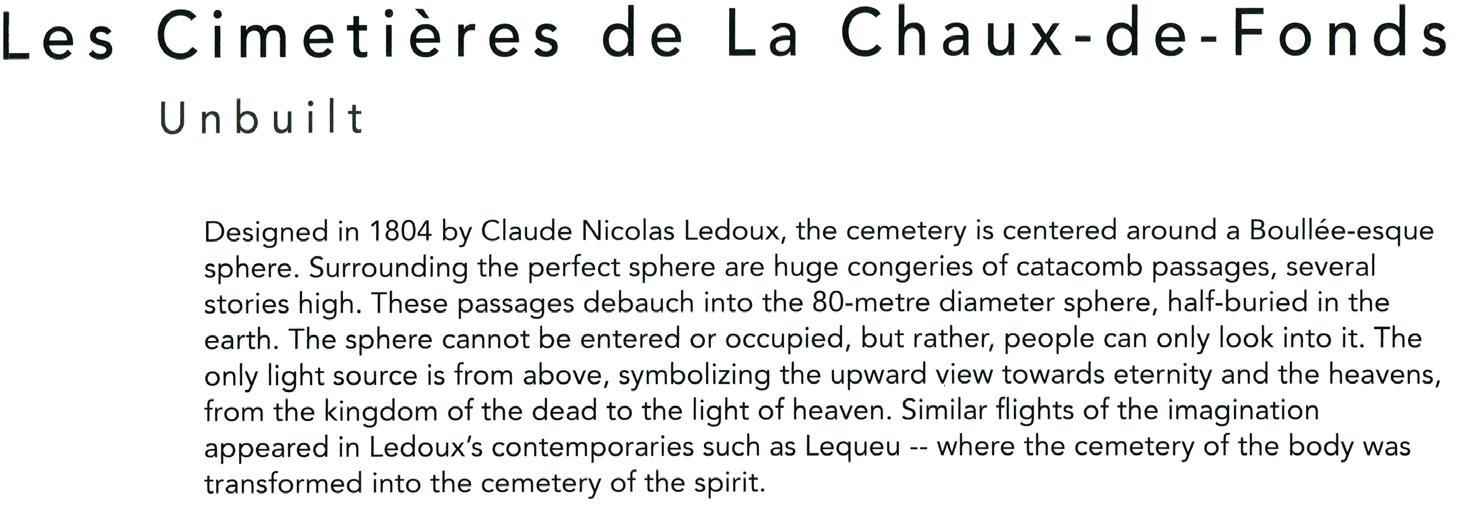

One is Jason Robert‘s superb, 3D printed model of the Brion Cemetery which presents in minute detail Scarpa’s idiosyncratic design. The other is Stephanie Jazmines’ Monumental Landscapes Cities of the Dead, a paper bound book, with historical texts and hand colored, loosely-drawn plans of ten case studies of cemetery designs. Included in the book are her texts and plans of Pere-Lachaise exemplifying Garden and Rural Cemeteries; Skogskyrkogarden, better known as Woodland Cemetery, representing Lawn-Park Cemeteries; the Brion-Vega Cemetery, identified by Jazmines as Speciality Cemeteries; and Les Cimetieres de la Chaux-de-Fonds, Ledoux’s unbuilt, visionary design.

25 See: Claudia Lazzaro, “Rustic Country House to Refined Farmhouse; The Evolution and Migration of an Architectural Form,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, XLIV, 4 (Dec, 1985), 346-367.

26 Wolfgang Braunfels, Monasteries of Western Europe, London, 1972, 37.

Drawing Second and Third Nature in the Italian Garden

The second lecture of the course focuses on the concept of the Three Natures in landscape history, of which two projects illustrate prime examples.

Cicero’s writes in his treatise, De natura deorum: “We sow corn, we plant trees, we fertilize the soil by irrigation, we dam the rivers and direct them where we want. In short, by means of our hands we try to create as it were a second nature within the natural world.”27 Cicero, as John Dixon Hunt duly notes, is describing “the cultural landscape: agriculture, urban developments, roads, bridges, ports and other infrastructures.”28 In looking at agriculture in antiquity the lecture focuses on the history of the plough which made possible the tillage of the land and for the Ancient Romans resulted in the division of agrarian land into what Emilio Serini describes as the centuratio “on whose landscape it made what even today remains perhaps the greatest and most lasting imprint.”29

To illustrate the lasting imprint of the centuratio on the Italian landscape a contemporary bird’s-eye view of the land surrounding Palladio’s Villa Emo is shown and discussed in class. Elise Barker-Limon, a Bass Scholar 2020/22, was struck by this image and decided for her final project, entitled “When tillage begins other arts follow”,30 to render it in the form of a textile. Her work, in the form of checkerboard patterns made from pieces of cut cloth, were stitched together into a whole. Elise then sewed a small model of the Villa Emo onto her textile and photographed her project in the landscape of Norfolk, England. Her project is the only one in twenty-one years of teaching at Yale which represents landscape in cloth, a time-honored tradition in textiles, to which Elise chose to adhere.

Shuchen Dong renders with an iPencil on an iPad a remarkable series of drawings of the two ways in which to walk the gardens of the Villa Lante, each with their own narrative, entrance gates, and fountains, and each embodying the concept of the Three Natures.

At the top right of her drawing is the public entrance into the large park or barco, drawn in plan just below it. A former hunting park, the barco represents the Golden Age when man lived in harmony with nature. At its entrance is the Fountain of Pegasus with nine caryatids representing the role of the arts in the making of the bifurcated villa garden. The path in the barco ends at the reservoir and announces the fall of man and the flooding of the earth. The barco was in narrative an example of First Nature and as a hunting park that of Second Nature.

The garden’s narrative continues with man having to recreate a world in which he can survive and thrive. That story begins at the top of the garden, also drawn in plan on the lower right. Here the flood, a metaphor of First Nature, is presented in the Fountain of the Grotto with dolphins from which the water flows gravitationally into the octagonal Fountain of the Oceans with its carved double-faced dolphins. From the oceans water courses downhill through natural streams represented in the garden by an elongated crayfish, a reference to Cardinal Gambara’s surname but also a preeminent example of the typology of the Euripus

27 See: Hunt, 33.

28 Ibid, 33.

29 See: Emilio Sereni, “The Roman Form of the Italian Agricultural Landscape,” in History of the Italian Agricultural Landscape, trans. R Burr Litchfield, Princeton, 1997, 32.

30 The quote is by Daniel Webster and is included in a drawing by Grant Wood, “Study for Breaking the Prarie,” 1935-1939 in the collection of the Whitney Museum of Art.

in landscape history. It continues over the top of a balustraded terrace and falls into the Fountain of the Rivers, represented in the form of two River Gods embodying the Arno and the Tiber. From the rivers water flows into the draught of a stone water table around which the Cardinal and guests could dine al fresco on the fruits of man’s labors, celebrated in the statues of Flora and Pomona, set in niches on either side of Fountain of the Rivers. Here Second Nature in the form of cultivated flowers and fruits is presented.

The journey of water continues its path into the Fountain of Lights in the form of Bramante’s exedral staircase with small reproduced ancient Roman oil lamps gurgling water out of them. It concludes its narrative flow at the bottom of the garden into a large square pool, divided into four parts, in the center of which is a round fountain with four statues of the moors holding up pears, mountains, and a star, emblems of Cardinal Montalto-Peretti seen in the upper right of Shuchen’s drawing. Here Third Nature, turning nature into Art, is presented.

It is at this point in the garden that one may exit the Villa through the private portal, drawn on the upper left, or start the journey in the garden uphill and into the park, that is from the Italian Renaissance to the mythical Golden Age.31

The narrative that informs the Villa Lante is one that depicts the Three Natures through the art of fountains: First nature implied in the fountains of the Barco and the story of the flood that overwhelmed man; Second nature or the agrarian landscape that provided the Cardinal with food and drink for his water table; and Third nature or man’s control over nature in the rigid, symmetrical, and geometric design of the garden in which Vignola’s design for twin palazzini are set. The Villa Lante is an Italian Renaissance villa garden that always delights students on the trip to Rome, and it is one that inspired Shuchen’s desire to draw it for her final project.

British Landscape History

The second course I teach at Yale is “Introduction to British Landscape History, 1500-1900 and to the Yale Center for British Art”. Taught spring term, it is designed to introduce students to the landscape and architectural history of Great Britain from the Age of the Tudors, c. 1500 to the end of the Victorian era, c. 1900 as well as to the collection of works, largely assembled by Paul Mellon, that relate specifically to the course in the Yale Center for British Art. In addition a trip to England over spring break to visit several gardens, landscape parks, and country houses shown in class is included. The trip divides the material of the course in two parts.

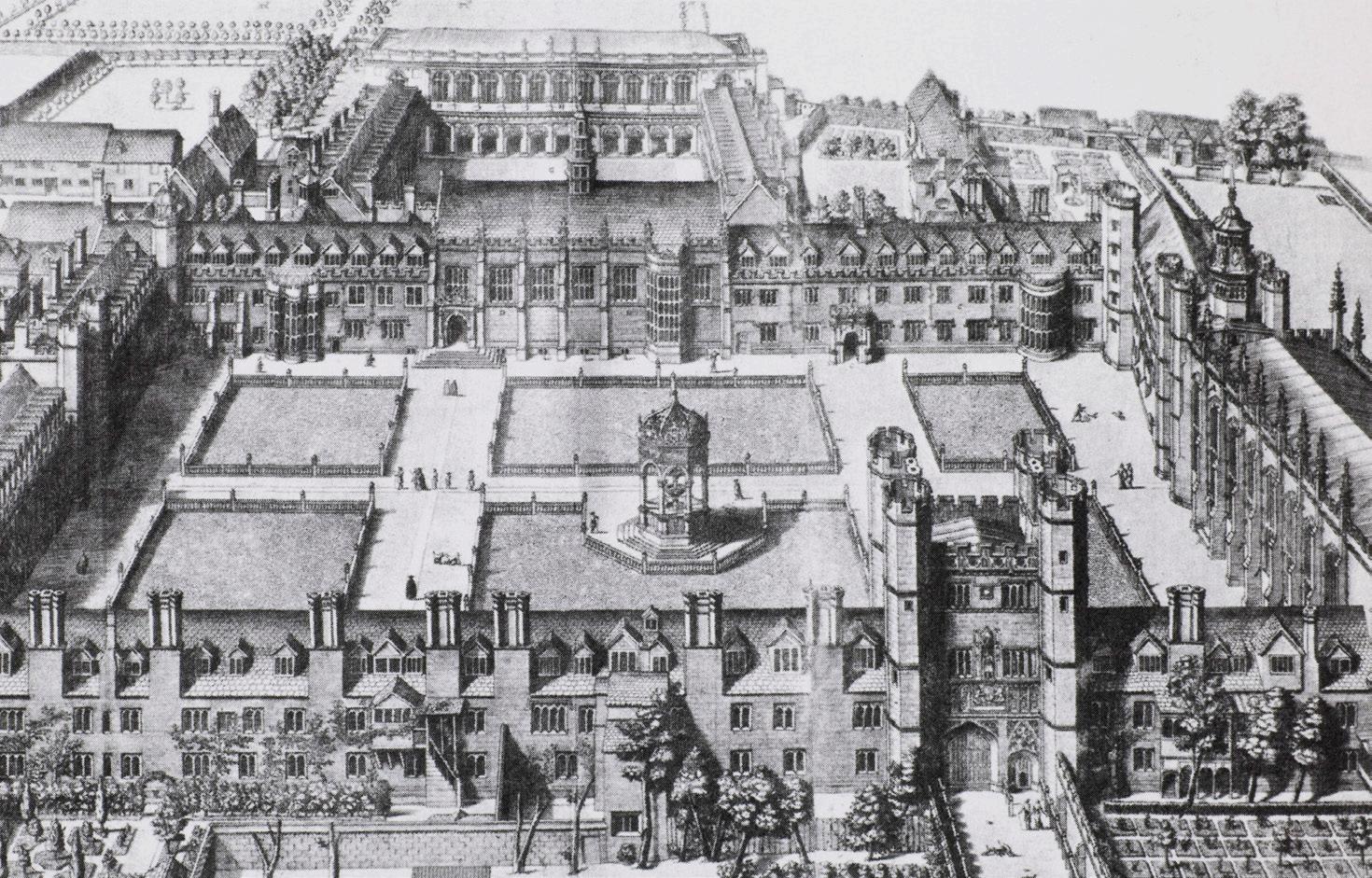

The first half of the course examines in chronological order the following topics studied in advance of the trip to England: an introduction to the architectural typology of the Castle, beginning with the Normans, including its interior landscape with moat, motte and militarily embanked walls designed for defense; Tudor architecture, including castellated elements, at Henry VIII’s Hampton Court and Tudor garden design as shown in Henry VIII’s Privy Garden; the emergence of classicism in the country houses and buildings of Robert Smythson and Inigo Jones at the turn of the seventeenth century and the role of ‘Types” on rooftops to view the landscape; the importation

31 See: Claudia Lazzaro, “The Villa Lante at Bagnaia: An Allegory of Art and Nature,” Art Bulletin, LIX: 4 (Dec, 1977), 553-560 and “The Flower of Them All: the Villa Lante at Bagnaia,” in The Italian Renaissance Garden From the Conventions of Planting, Design, and Ornament to the Grand Gardens of Sixteenth Century Central-Italy, New Haven, 1990, 243-269.

of Italian and French ideas of garden design conveyed through the stage sets of Inigo Jones in the early to mid seventeenthcentury; the implementation of Dutch and French formal garden elements, including canals, parterre de broderie, and gazon coupe, into British gardens at the end of the seventeenth-century as seen at Hampton Court under William and Mary and in several houses and gardens shown in Knyff & Kip’s Britannia Illustrata, 1707; the application of military gardening and the revival of castle architecture in the work of the English Baroque architects Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor at Castle Howard and Blenheim; by contrast, the birth of the Palladian villa and garden in Britain, both on the small scale at Chiswick and the large scale at Holkham; the Templescape of Stowe in all four phases of its design; the beginnings of ‘Naturalism’ first in the application of the meandering walk or wiggle as I call it, then in the use of the ha-ha as landscape device, and finally in the role of eye catchers that lead the eye beyond the garden to the agrarian fields in the work of William Kent in the 1730s; the emergence of British imperialism in landscape architecture as exemplified in Sir William Chambers’ circuit walk through world architecture for Kew Gardens, c 1750-70s; and Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown’s creation and development of the landscape park, 1740s-70s, in particular its primary elements of design, its ecological underpinnings, and its influence on the nineteenth-century design of English and American parks.

After the trip to England, the course examines the theory and practice of the Picturesque in four phases of its evolution— creating a landscape to look like a painting as seen at Stourhead; the writings, drawings, and use of optical instruments in the work of William Gilpin and his Picturesque tours; the theory of the Picturesque as a third aesthetic to be included alongside Edmund Burke’s the Sublime and Beautiful in the writings of Sir Uvedale Price and viewed in connection to the drawings and paintings of Sir Thomas Gainsborough in the collection of the British Art Center; and the theory of associationism in the work of Richard Payne Knight; a focus on the role of ruins in the landscape, both then as visited on-site at Fountains Abbey and now as exemplified in Peter Latz’s design for Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park, Duisburg, Germany, 1990-2002; the beginnings of landscape architecture as a profession and the concept of ‘deceit’ in landscape design in the published works of Humpfry Repton and applied to the ideas underpinning the creation of Freshkills, Staten Island, New York; the pursuit of the Alpine Sublime in the works of British artists, most particularly Alexander and John Robert Cozens, Francis Towne, and J.M.W. Turner, and lastly the transportation of the Sublime to America in the formation of the National Parks in America and the establishment through landscape of a national identity.

Throughout the term the course investigates the idea of nature in Britain within a wide cultural arena: the practical and pleasurable uses of landscape in farming, hunting, and field sports; the politics and economics that impacted the shape and size of landscape parks, including a detailed investigation of the Enclosure Acts; shifts in the philosophy of Nature over the eighteenth century; the use of mechanical devices to view landscape and books, including Country House guide books, to interpret landscape; and the role of commerce, imperialism, and colonialism in British landscape history, in particular in the seed, plant, and tree trade.

Where appropriate, connections between gardens of the past and those of the present are presented, including the works of contemporary land artists and Britain’s walking artists Richard Long and Hamish Fulton.

Additionally, as in the fall course I spend considerable time looking at architecture. After all, my students are studying to be architects, and I have found that a good way for them to begin to learn landscape history is to see how it relates to the history of their chosen profession.

The course is also designed to introduce students to the Yale Center for British Art which has the largest and most comprehensive collection of British art outside the United Kingdom. It is an unparalleled resource amongst American universities. Students of the

course view firsthand British painting and sculpture in the galleries and prints, drawings, maps, rare books, country house guide books, and optical devices,in the Print and Drawing Room, as described in Appendix 1.32

THE CLASS TRIP TO ENGLAND

Viewing the collection at the British Art Center offers students the opportunity to examine several modes of representation of British landscape history. However, to engage with the British landscape as it was meant to be experienced by walking it, students travel to England over spring break and visit several of the principle gardens, landscape parks, and country houses studied in the classroom. Because the trip informs so many projects in this book and confirms the importance of travel in the teaching of landscape history, I want to comment at length on it.

Day One

The itinerary, based on geographic logistics, begins on the first day at Stonehenge with its surrounding ancient burial mounds, one of several types of mounds examined in the class, and continues to Stourhead. Here students complete the circuit walk of the garden, including the side walk down the Combe to St. Peter’s Pump, a visit to the house, an introduction to the their first ha-ha behind the house, separating the west garden from Or Pasture, and end the visit at King Alfred’s Tower, the last and largest of follies Henry Hoare designed.

Stourhead resulted in many projects. As with contemporary films and television series where Stourhead often serves as a scenic backdrop, several students also made use of Stourhead as one example in their projects. Ha Min Joo includes a handdrawing of the iconic view from the Palladian bridge across the man-made, serpentine lake to Henry Flitcroft’s Pantheon in her coloring book. Michael Krop sketches site lines across the lake and outlines the difference between Henry Flitcroft’s Pantheon with its ancient Roman precedent; Ian Mills includes Flitcroft’s temples in his study of scale in the templescapes of the British landscape; Mark Guberman specifically chose Stourhead to argue that walking its circuit walk is an experience akin to cinema, particularly montage. And Alan Knox made an outstanding project: Stourhead Walk, a game in which the circuit walk around the man-made curvilinear lake is translated into a game board.

Day Two

Next day the class walks John Wood the Elder’s and the Younger’s designs for city planning in Bath. We congregate in Queen’s Square, walk uphill to the Circus, and on to the Royal Crescent, noting the use of geometry in town planning, the idea of creating country house architecture as town housing, and seeing their second ha-ha, this one separating the architecturally continuous facades of the thirty townhouses in the Crescent from what had been open grazing fields in the eighteenth century but which today forms Victoria Park. Here the typology of rus in urbe, introduced in the fall seminar when the class studies Nero’s Golden House, is carried forward into eighteenth century town planning.33

32 Among the works shown are those by Isaac de Caus, Salomon de Caus, Stepher Swizter, Colen Campbell, Sir John Vanbrugh, William Kent, Lord Burlington, James Gibbs, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, Jacques Rigaud, Sir William Chambers, Jacques Rigaud, Jean Baptiste Claude Chatelain, J. Seely, Sir William Hamilton, William Gilpin, Thomas Gainsborough, Richard Payne Knight, several of Humpfy Repton’s publications, drawings by Alexander and John Robert Cozens, Francis Towne, J.M.W. Turner, Samuel Palmer, and John Ruskin.

33 See: Michael Forsyth, Bath, 2003, 19.

From Bath the group continues late morning to Iford Manor, Harold Peto’s home and hillside garden, strewn with his collection of religious and architectural artifacts and his creation of his own personal cloister in the Romanesque style. The Peto garden with its central axis extends behind the centuries-old house through the hillside to the monument to Edward VII and the Great War and is bifurcated by the long cross-axis that ends with an exedral bench, like the nave of a basilica or Schinkel’s terrace at Charlottenhof. The organization is reminiscent of the plan of axis and cross-axis at the Villa d’Este, an English nod to Italian Renaissance garden design. Since the trip to England first began, the Cartwright-Hignett family, who have faithfully maintained Peto’s gardens, have graciously invited the Yale students into their home for refreshments, a visit the students very much enjoy as do I.

From Iford Manor the itinerary takes us to Oxford where, before checking in to Magdalen College for a three-night stay, the class visits the Oxford Museum of Natural History. After viewing the neo-Gothic details in the Ruskinian manner of the buildings’ elevation, the class explores inside the extraordinary stone carvings of the ground-floor capitals, the iron spandrels with their vegetal carvings, and the arcade on the second story where each labeled column is a different stone from the British Isles. The Ruskin Museum is a prime example of landscape documented and transformed into architectural ornament inside.

It is the carvings of its floriated capitals that became the basis of Kassandra Levia’s important final project, wholly in keeping with the taxonometric spirit of the Museum which serves as a parallel in time and Victorian interest in documenting nature to Decimus Burton’s Palm House, Kew, visited at the end of the trip.

Day Three

Day three begins at Rousham where students walk, surprisingly nearly always without any other visitors, the multiple paths of William Kent gardens, experiencing their third ha-ha which separates the field of Longhorn cattle from the bowling green at the end of which, beyond Scheemakers’ sculpture of the Lion attacking the Horse, students view Kent’s eye catchers placed across the Cherwell River in the distant agrarian landscape.

It is at this point students wander on their own on the multiple paths Kent has laid out in the garden that lead to his many garden experiences: the upper walk along the ha-ha to Kent’s castellated barn; the framed views between the arches of Kent’s Praeneste; the Vale of Venus with its rusticated cascades; Kent’s mortared Euripus that meanders rather than wiggles through the low shrubs in the woodlands; Townsend’s building from which the triangulated terminus of the garden at Hayford’s bridge is made; Apollo’s Walk under the carefully pruned canopy of trees; the stroll along the irregular Cherwell River; the steep climb up the concave lawn to Rousham’s great hedge; Rousham’s flower and kitchen gardens; its dovecote and Kentian-designed stables.

Rousham is a landscape of multiplicity of experiences which has been the source for many projects included in this book, in particular Lang Wang’s watercolors of the sculpture in the garden and Ilana Simhon drawing of the Kent landscape in multiple perspectives.

After lunch in Woodstock the class proceeds through Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Woodstock Gate and in a state of great surprise, what I call the wow moment, view the wide, enormous expanse of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown’s landscape park at Blenheim and the east elevation of Sir John Vanbrugh’s equally enormous bridge or viaduct as it is often called, now half sunk

due to Brown’s damming the River Glyme which runs through the park. From the Woodstock Gate we make the long walk to the Column of Victory dedicated to John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, and look back down the long axis between trees planted enfilade, across the Vanbrugh bridge, and into the courtyard of Vanbrugh’s and Hawksmoor’s Baroque Palace of Blenheim, whose stone walls carved in military decoration, reach out accessionally to the long, axial gaze. After taking in the carved military ornamentation of the north façade, students tour the interior of the house and end the visit to Blenheim with a walk through the early twentieth century formal gardens designed by Achille Duchine to the great south lawn under which lies the original hexagonal bastion garden, designed in the military fashion, by Henry Wise, c 1705-170834 but now covered over by Brown’s lawn.

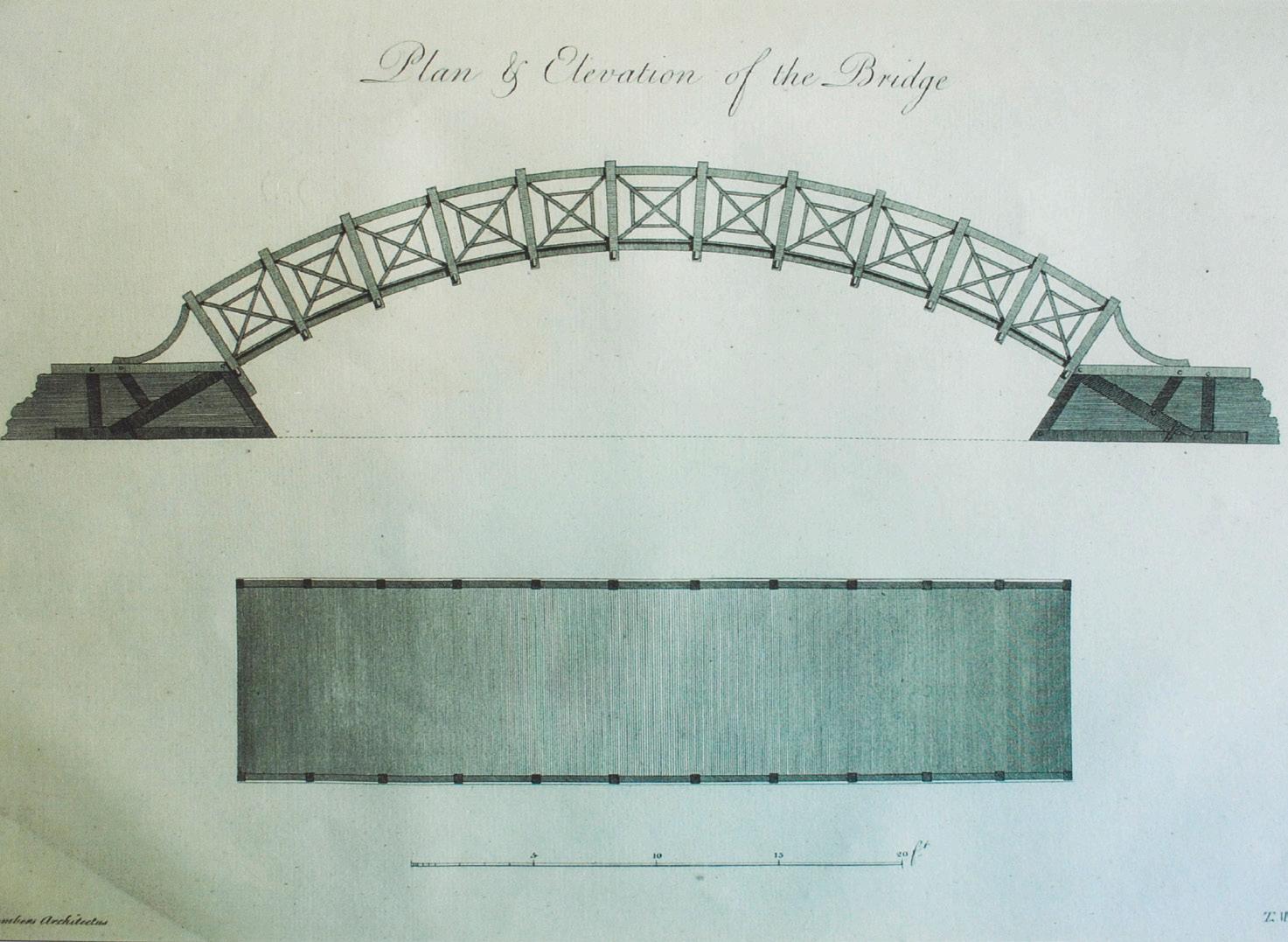

Blenheim yielded two projects: Melissa Weigel’s large-scale, interactive model of Vanbrugh’s bridge, showing it both in full elevation and half submerged under Brown’s lake and Aude Jomini’s carved, wooden model of Henry Wise’s hexagonal bastion garden. From this model one can sense how the garden, Brobdignagian in scale, must have dwarfed the Palace.

Day Four

The next day, all day, the class visits the Templescape of Stowe, including a short time spent in the Marble Saloon from which with the south doors opened students are able to look down the sloping lawn, across the lake, beyond the fields of grazing sheep to the Corinthian arch, all points on direct axis to each other and extending beyond, as seen when first arriving at Stowe, to the two mile-long tree-lined drive from the Arch to the town of Buckingham. The great view gives students a sense of the vast expanse of the four hundred acre park, its outer territory, and its over-riding geometric underpinnings.

So too does the walk through the Templescape at Stowe with its numerous follies, small to large, Gothic to Classical, whimsical to serious. It is this garden that illustrates the key role the folly plays in eighteenth century British landscape history, a subject which captured the attention of Ian Mills, Ava Amirahmadi, and Naomi Darling in their final projects.

Day Five