This report outlines a process of Collaborative Place Design Meeting. to assist with the translation of the community reference group’s vision and principles into spatial ideas to be considered in the design of a conceptual masterplan for a significantly scaled inner urban regeneration area.

Principles to Place

Subiaco East Redevelopment

Collaborative Place Design workshop summary report to inform conceptual master planning

© Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Principles To Place

Subiaco East Redevelopment

Collaborative Place Design workshop summary report to inform conceptual master planning

Principal Authors: Dr Anthony Duckworth Grace Oliver

Prepared for: Development WA

AUDRC University of Western Australia

Introduction | 6 / Background | 8 // Methodology | 12 /// Results | 18 //// Activity Evaluation | 30 ///// Conclusion | 36 References | 38 Acknowledgements | 40 Contents

Introduction

This report outlines a process of Collaborative Place Design to assist with the translation of the community reference group’s vision and principles into spatial ideas to be considered in the design of a conceptual masterplan for a significantly scaled inner urban regeneration area.

This report outlines a process of Collaborative Place Design undertaken with a Community Reference Group (CRG) for the Subiaco East regeneration project. The Collaborative Place Design activity was undertaken as part of the community engagement phase of a project being undertaken by Ceating Communities Australia to help inform a conceptual built form and land use masterplan of the regeneration area.

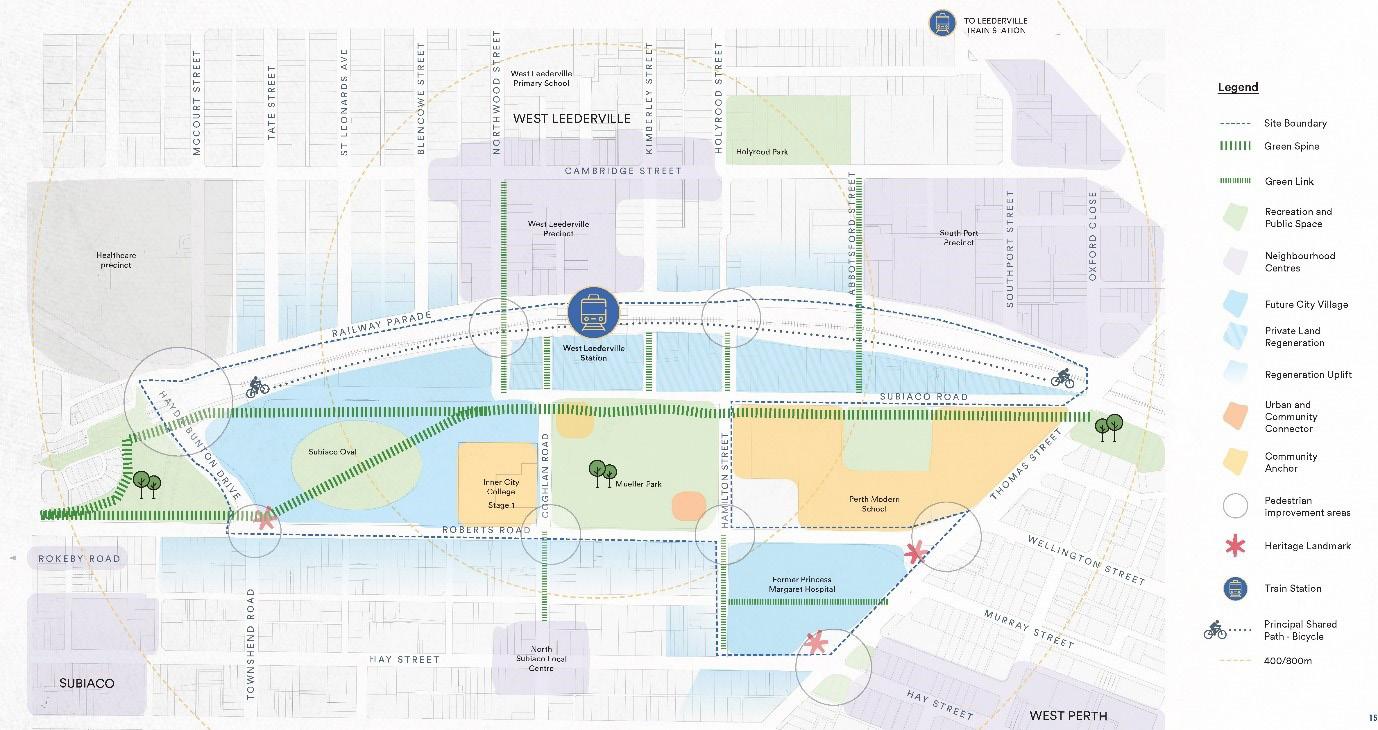

The Subi East project will see the rejuvenation of 35ha of land to create a vibrant new north-eastern gateway to Subiaco on the western edge of Perth CBD (the innerwest). Subi-East regeneration involves the reimagining, planning and design of significant areas of land under the control of state government. The Subiaco Oval and decommissioned Perth Children’s Hospital are the principal sites which are identified to be transformed into mixed-use development.

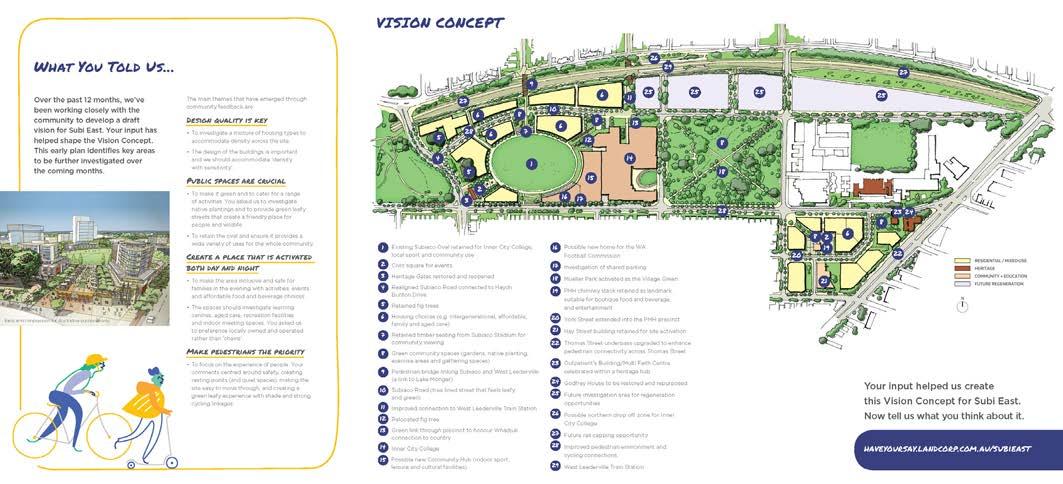

The Collaborative Place Design activity was focussed on helping to translate the community’s Vision and Principles for the future development of the area into spatial actions. These were captured in a ‘Masterplan Directions’ brochure which informed the Co-Design process.

The Collaborative Place Design workshop was conducted with the project Community Reference Group (CRG) set

up for the Subiaco East regeneration project. Collaborative Place Design uses physical interactive models in carefully facilitated workshops to engage stakeholders and communities in urban planning and design projects.

The method is aimed at bridging the gap between design experts, non-design professionals and community members. As stated in a recent UN Habitat report ‘While many upgrading projects adopt civic engagement activities, the transition phase between community needs and the expert designs is often lost in translation.’ (UN Habitat, 2020).

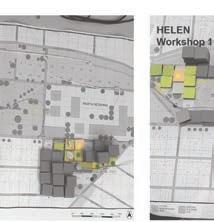

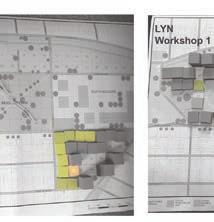

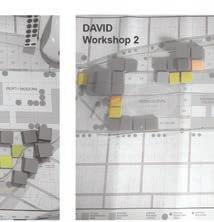

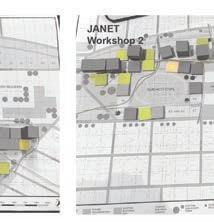

The process unfolded principally over two meetings of the project Community Reference Group over a six week period from April to May 2020. The main interactive Collaborative Place Design activity was conducted online via Zoom™ video conferencing software with five separate workshops held with groups of between four to six participants over the course of one day. Representatives from the client, Development WA acted as observers but did not participate. The results of the individual workshops were collated, analysed and communicated back to the entire Community Reference Group in a subsequent CRG Meeting.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Introduction 76 Principles To Place

/ Background

The Subiaco East project will see the redevelopment of 35 Ha of land on the western edge of Perth CBD formerly comprised of ageing medium density residential buildings, sporting facilities, the former state children’s hospital and associated health buildings.

The local community and the population more broadly within the metropolitan area have a strong emotional connection to the regeneration site. It was one of the first significant sporting venues following colonial settlement and the experiences of children and families attending the hospital.

The site, located in ‘Mooro Country’ is a place of ancient indigenous significance for the Whadjuk Noongar people, situated on high ground with spring water, a place of significance for birth, marriage and children (Communities 2020). This attachment fosters a strong sense of public ownership over the site and the willingness for a high level of community participation and involvement in the redevelopment project.

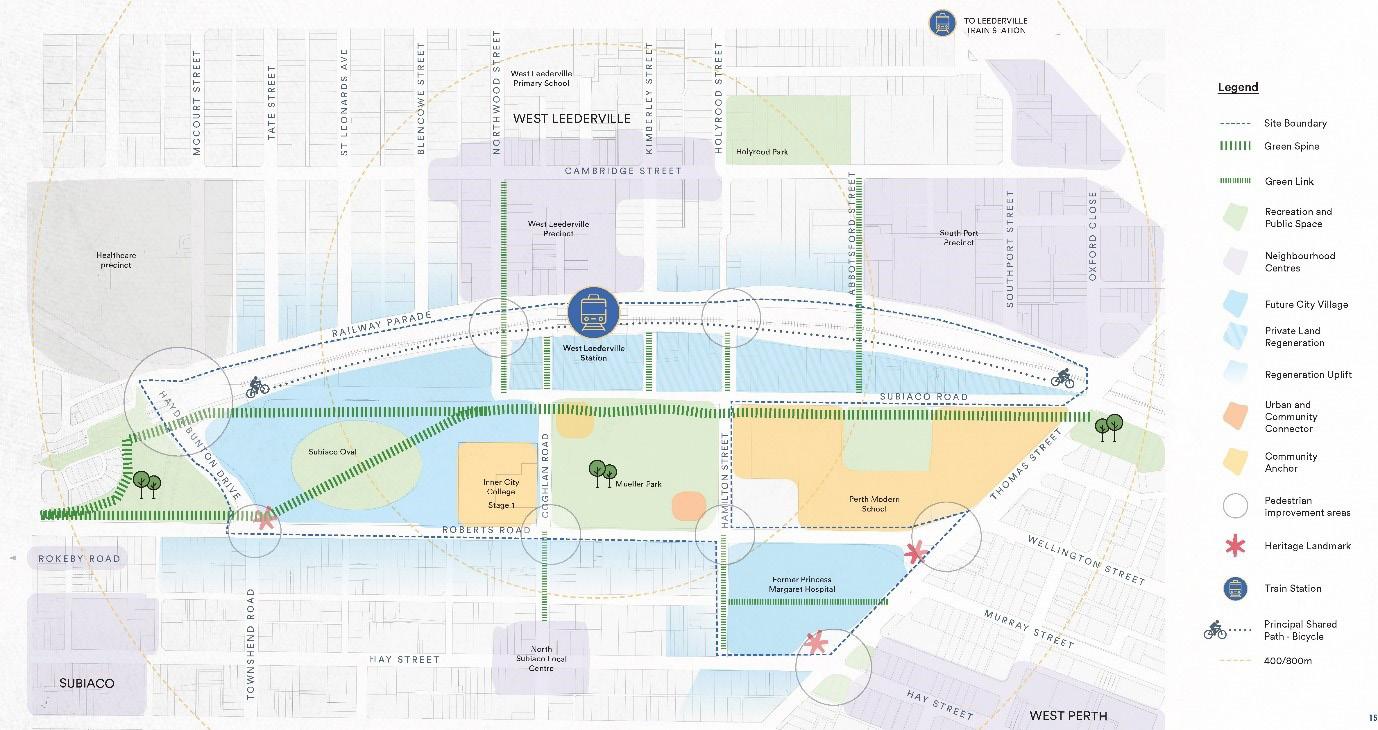

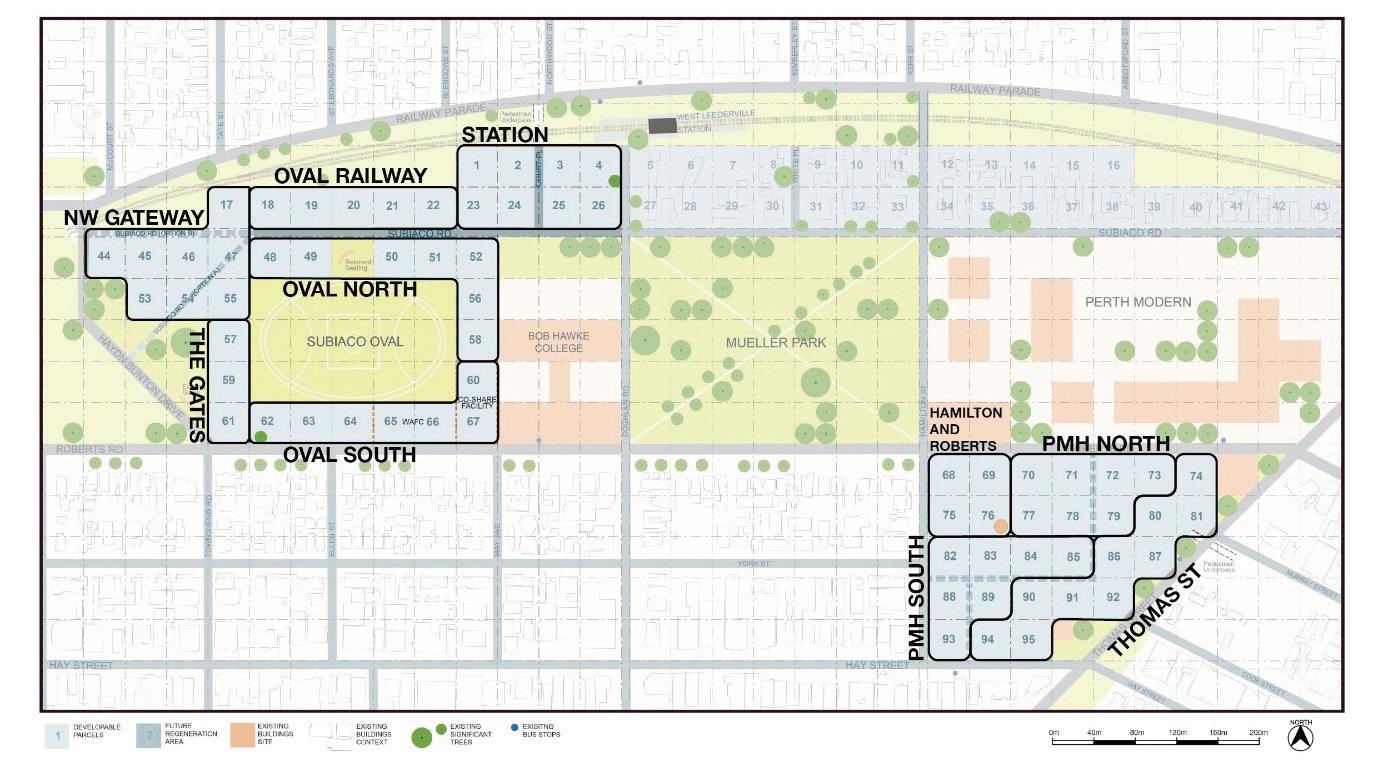

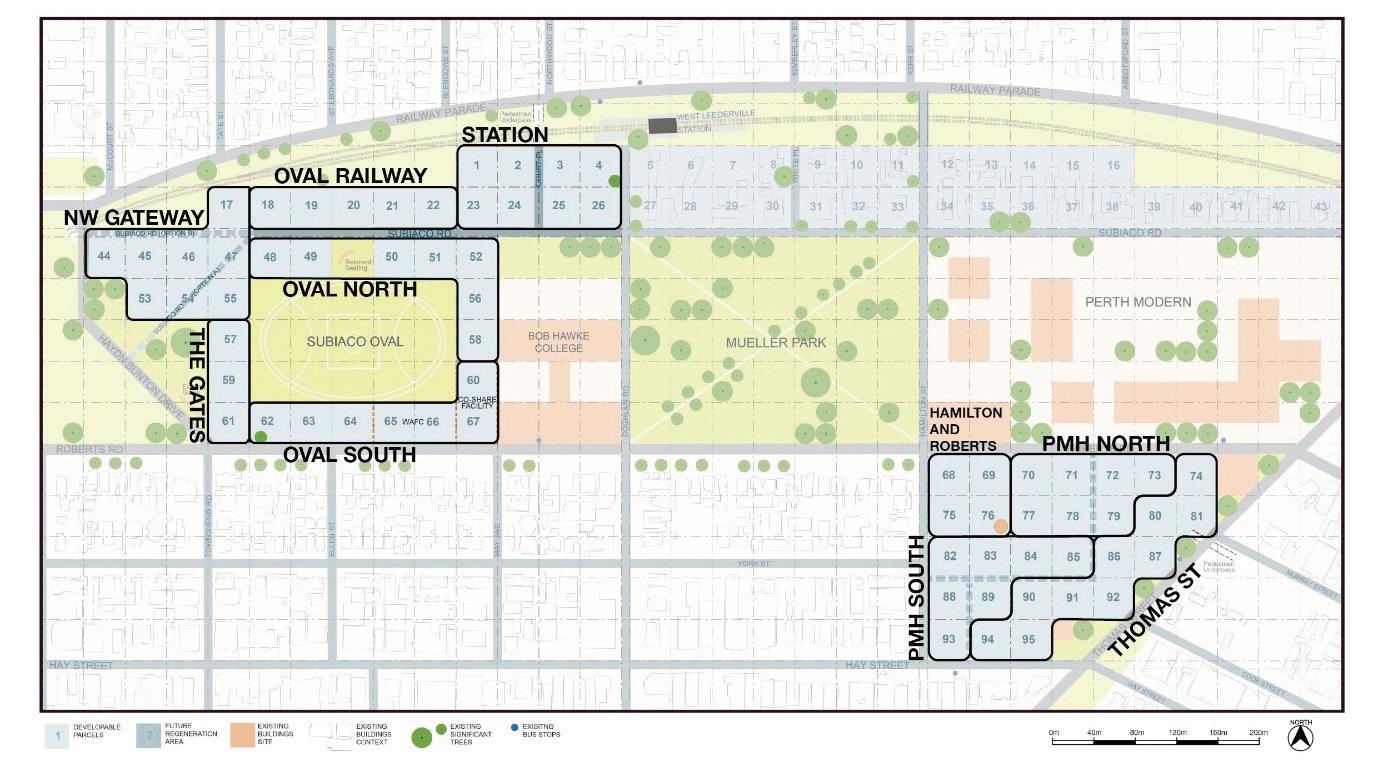

The Subiaco Oval and decommissioned Perth Children’s Hospital are the principal redevelopment sites which fall within a broader residential and educational context with a large public park (Mueller Park) sitting between the two locations, the Fremantle passenger rail line bounding the northern extremity with the West Leederville Station situated midway and Roberts Road (currently a two lane one-way distributor) flanking the southern extremity of the oval locale and the northern edge of the children’s hospital site (Figure 1).

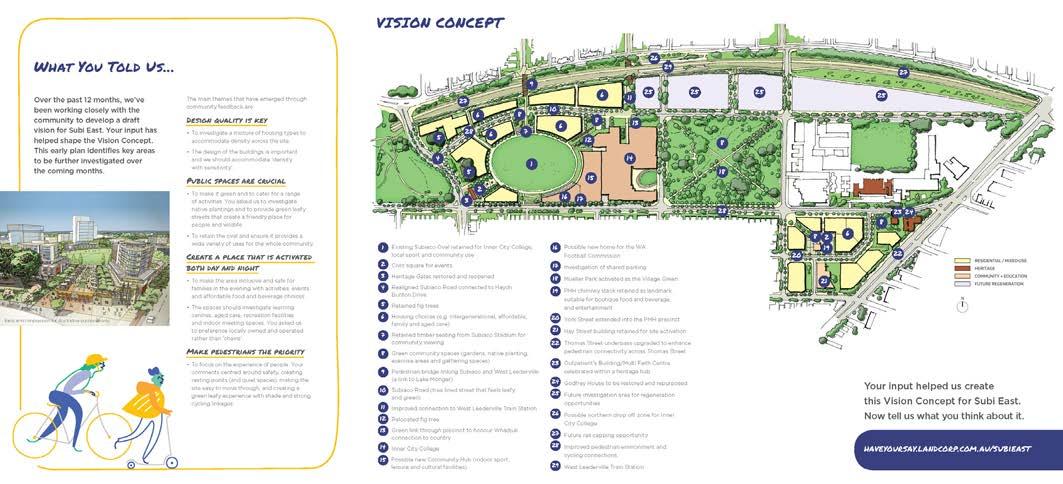

A draft concept vision was prepared in 2019 to support the business case. This concept vision presented a preliminary plan for the site and early artists impressions of the potential built form locations, scale and character (figure 2). Following this a planning and design team was

appointed to develop a more detailed masterplan concept in conjunction with further stakeholder and community engagement. This report details the collaborative design activity which was undertaken as part of this engagement process.

• Engagement with the Whadjuk Working Party.

• Formation of a Precinct Liaison Committee (principally organisational stakeholders - MRA, LC, DoE, DLGSCI, DPLH, DoC, DoF, CoS, ToC).

• Community Survey (Jul/Aug 2018) – 719 residents & business, 805 workers.

• Community feedback on Draft Project Vision (early 2019)

• Community Reference Group (CRG) formed.

The Subi East regeneration project has undertaken a wide range of stakeholder engagement activities. These range from broad community surveys to the formation and involvement of representative groups. The history of the sites and their context is diverse and of local and state-wide significance. Key elements of the engagement strategy have involved:

• Community Reference Group Engagement process

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Background

Figure 2: The Draft vision concept for the site, prepared for the business case (Landcorp, 2019)

98 Principles To Place

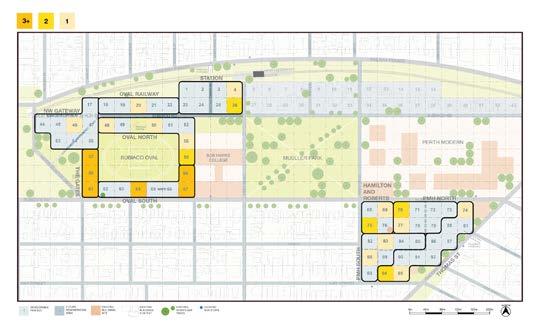

Figure 1: Subiaco East site context plan (source: Element 2019)

incorporating AUDRC collaborative design workshop (the subject of this report).

Engagement forums had led to significant stakeholder input in defining the nature of the design challenge for the masterplan. The Subi East Masterplan Directions pamphlet condensed the results of the stakeholder engagement process into relatively detailed statements of guidance for planning and design actions.

The following principles or ‘Project Pillars’ were captured and presented in the Masterplan Directions document (figure 3) and comprise the underlying themes which informed the spatial planning and design:

Connected City Village

The Gateway to a Great Life

A Connected Place with a Connected Community

Kaya Subi (Welcome Subi)

Respect for Aboriginal Culture and Heritage

A Rich and Diverse History

A Community of Reflection

A Spirited Community

A Green Pulse

A Place of Equilibrium

Connected to Nature

Collective Wellbeing

A Place of Learning

A Place for Children

A Growing Community

A Place of Wellness

Whilst a professional design team had been appointed the project proponents also intended that the CRG would participate in the part of the design process, particularly to input into the ideation and testing/evaluation of masterplan designs. A level of involvement or ‘mode’ of engagement (Reed, Vella et al. 2018) equivalent to Involve/Collaborate (International Association of Public Participation 2014) was envisaged. This mode of engagement suggests a moderate degree of power sharing in the design process ‘to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered’ and where appropriate or necessary ‘partner with the public in aspects of decision making’ (International Association of Public Participation 2014).

The ideation ambitions of the engagement process for the design phase were essentially investigating how the spatial

intents of the Masterplan Directions were envisgaed by the community members on the site. This meant that the activity had to be capable of taking this written knowledge and translating it into a spatial realm which could be used by the design team. A task which has often been ignored or misinterpreted - ‘While many upgrading projects adopt civic engagement activities, the transition phase between community needs and expert designs is often lost in translation.’ (Martinuzzi, C. and C. Lahoud, 2020). This is a critical phase in the engagement strategy where a poor translation risks undermining the precious vertical trust which has been established in the engagement process to date.

As part of this translation the activity needed to:

• educate with respect to spatial literacy/competency (understand the scale of the site in planning and design terms) in order to participate in the development of spatial ideas and provide appropriate feedback.

• enhance understanding and empathy with respect to the constrained nature of the spatial task of urban planning and design professionals particularly the relationship between the target for development yield related to economic feasibility, the amount of developable land, open space provision and the scale of built form (eg the need for trade-offs and to ‘walk a mile in the planners shoes’)

• help diffuse ‘us and them’ oppositional mindsets,

• foster collaboration and help reach agreements and compromises; and

• foreground and collectively compare the diversity of knowledge, experience and viewpoints within the CRG with respect to spatial preferences and priorities such as the range and patterns of preference for building intensity (density), building height, open space provision, community facilities, connectivity and active transport routes.

Considering these objectives a collaborative design activityPillars to Place: Collaborative Design Workshop was created and employed for community engagement for the Subi East regeneration project as part of the masterplan design stage.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Background 1110 | Principles To Place

Figure 3: The Draft vision concept for the site (Landcorp, 2019)

// Methodology

The Collaborative Place Design engagement methodology creates a customised interactive approach to ensure that the communities preferences and priorities are able to be integrated into the design process.

Methodology

Collaborative Place Design is a specific method of collaborative design (Co-Design) which uses a unique suite of scaled interactive physical models in carefully facilitated workshops, tailored to the needs of each project and the stakeholders and communities involved. It is a highly appealing and inclusive method suited to the effective involvement of diverse people and views into urban planning and design decisions such as new projects and policies. It is therefore a highly suitable approach for this particular engagement circumstance.

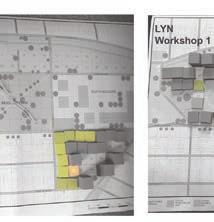

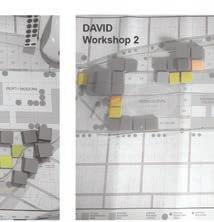

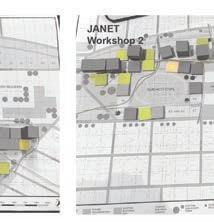

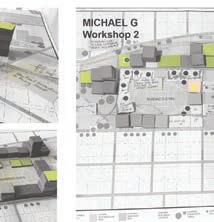

Typically Collaborative Place Design activities involve a number of small groups or individuals collectively engaging in a spatial challenge on a scaled site model which approximates the task of a professional conceptual design. Once the spatial challenge is completed groups present back to each other to enable collective reflection.

The project required participants to be involved in a ‘Principles and Place’ style activity. This is a scaled interactive physical model workshop typically applied during the start of concept design phases where participants are involved in a shared and parallel process of design and reflection to understand, interpret, explore and invent the spatial realities of projects.

The emphasis of this type of activity is not to necessarily solve a specific problem or produce a design but for participants to present a model outcome which best captures their values and principles using a spatial language which can be integrated into the decision making process.

The detailed design of the activity was linked to the specific objectives of this activity within the broader engagement and design project. The objectives were discussed

with members of the project team from Development WA (project owners and managers), UDLA (Urban and Landscape design consultants) and Hassell (Architecture and Built Form design consultants). The key objectives identified were:

• sourcing localised and specific values, experience and knowledge and translation and incorporation into project decisions,

• help moderate extreme positions, facilitate compromise, diffuse opposition and help align views by eliciting a broad range of values and preferences from participants,

• educate all participants about the complexity of projects and the need for trade-offs when making decisions; and

• help representatives and proponents better understand the key values and priorities of participants and conversely improve participants’ awareness of the constraints project proponents and regulators face.

Activity Design

The brief for the specific design of the activity was defined by the engagement objectives and the following:

• This was a spatial planning and design exercise and any interactive technique of the activity was to be capable of being understood by people with a range of baseline spatial and urban planning literacy. To be inclusive it needed to work for the lowest individual level of spatial understanding.

• The activity needed to be completed within a limited time period, workshop duration was limited to seventy five minutes which included time for collective reflection.

• Respond to the circumstance of COVID-19 which denied face to face contact and placed limitations on material choices for design of supporting tools.

The activity was designed to situate the participants within their current context. The selection of the scale of the model is a critical initial decision. A 1:2000 scale was chosen as it enabled the entire site to be represented at a dimension which could be relatively quickly understood and interacted with. The scale had also been used successfully in previous interactive collaborative design activities for master planning (Duckworth-Smith and Oliver 2019) and still allows an approximation of building height (the ‘z’ dimension) and hence representation and appreciation of overall urban form.

The structure of the interactive method for participants was

informed by the activity design constraints and the specific engagement objectives. Based on this four key urban design themes and associated elements were identified to be considered for the interactive component of the activity:

• MOVEMENT - as the internal road network was largely decided the elements considered were walking routes, bicycle paths and bus stops

• PUBLIC OPEN SPACE - interactive elements were presented as recreation, nature & conservation and urban plaza

• COMMUNITY - elements comprised community buildings, note flags for new ideas and trees

• BUILDINGS/DEVELOPMENT - organised as building envelopes with three intensities - low-rise (3/4 storeys), medium-rise (5/6 storeys). Individual pieces could be stacked to create higher intensities.

The interactive procedure of the activity was based on identifying preferences for public amenities and facilities within the context of a quantitative demand (a target floorspace area). The dynamics were structured such that participants were encouraged to sequentially identify movement, open space and community facilities preferences prior to massing development. This approach ensured that participants were initially focussed on public assets and that these would not be placed as an afterthought around the private development. This approach effectively foregrounded the communities input with respect to preferences and priorities related to public space, community facilities and connectivity.

Physical pieces for the interactive model including the base drawing, were designed considering the following criteria:

• An appropriate size of individual pieces/artefacts in terms of understanding the scale of the site and the ‘grain’ of urban development.

• An appropriate size of individual pieces/artefacts given the extent of the site, time limitations and the need to represent over two thousand apartments.

• Key urban design elements to be represented as interactive pieces were buildings, different public open space types, walking and cycling transport routes and community facilities.

• An appropriate size in terms of handling and placing pieces given potentially different physical abilities within the reference group.

• The need to allow multiple experiments/iterations.

• Constructing pieces to be sufficiently abstract to avoid detailing specific building types but still be understood as a scale of potential building.

• Identify materials which were appropriate given the

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Methodology Background Background 1312 | Principles To Place

risks of infectious disease transmission associated with COVID-19.

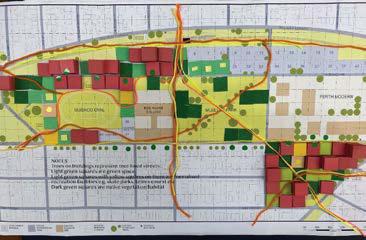

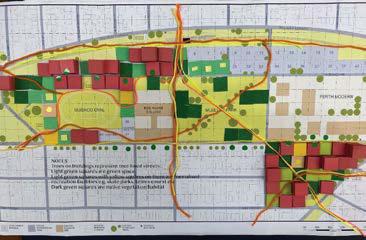

A modular and gridded approach was decided on as this simplifies placement of the pieces which was an important factor given the time constraints for the workshops and the increasing likelihood during project development that the feedback would need to be done via video (as the impacts of COVID-19 began restricting face to face gatherings). The grid allowed quick identification of location preferences both by the participant and the facilitator and allowed for efficiency during analysis of results. This meant that the base drawing needed to be carefully designed and drawn to both closely represent the scale of the site and accommodate a modular grid. A 40m x 40m grid was adopted as this corresponds closely to typical development parcels (or these can be combined to approximate larger sites), allows for suitably sized pieces at 1:2000 scale in terms of handling (2cm x 2cm) and can be integrated with the site dimensions.

Whilst the Base Drawing was to scale it was important to qualify that it was an approximation of the site (a scaled diagram) to enable the objectives of the activity to be met and that participants were not expected to create a final design (figure 3). In addition each of the 40m x 40m parcels was numbered for reference. Parcels east of Coghlan Road

adjacent to the rail reserve were included but identified for future regeneration and were not considered unable to be developed.

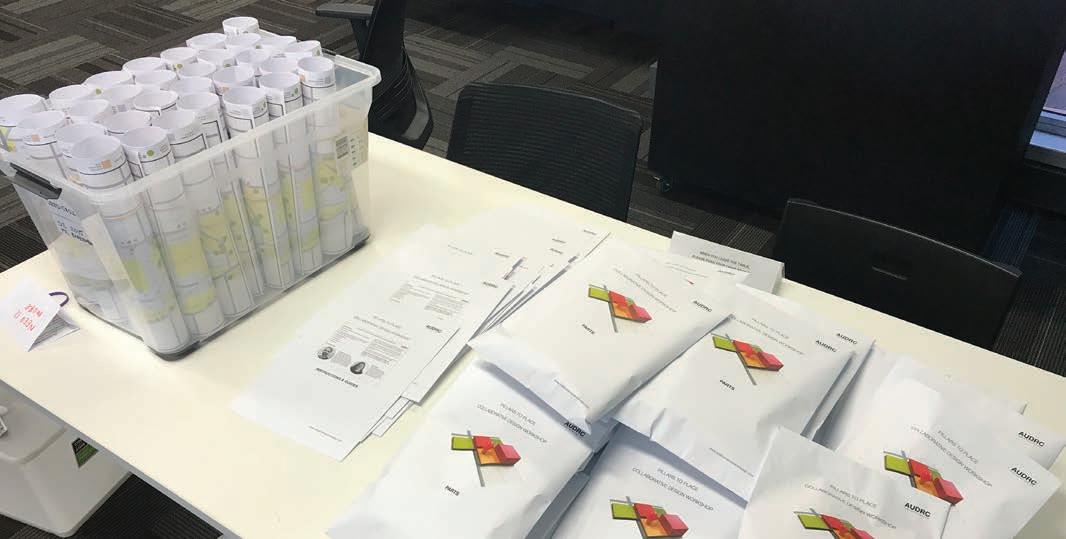

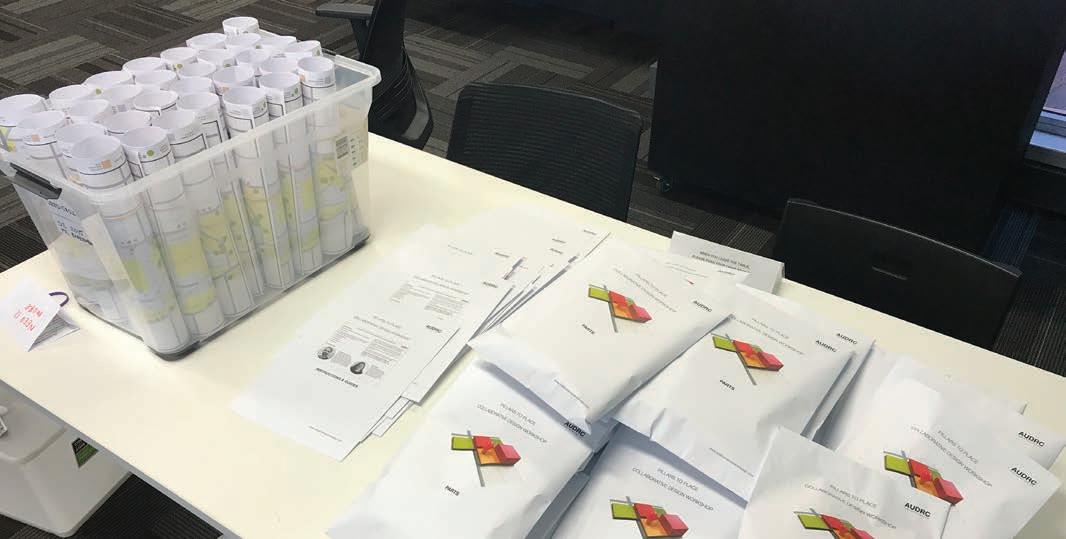

The majority of the interactive pieces were made from paper products – bond paper and laser cut screenboard as research showed that the COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2) did not survive beyond twenty four hours on cardboard (van Doremalen, Bushmaker et al. 2020). During development of the design activity it was apparent that individual models would need to be sent to each of the participants (The CRG had thirty five members). There was insufficient time or opportunity to engage a commercial supplier given the COVID-19 restrictions so the pieces were made, printed and packaged in-house by hand (figure 5).

The pieces which represented buildings were designed to occupy the entire 40m x 40m (2cm x 2cm) grid parcel. Two sizes were made so that a range of development intensities and building types could be constructed. The base pieces of Low-rise and Mid-rise equated to known building types but could also be stacked to create taller, more intense development proposals. It was important to qualify that the pieces approximated building envelopes rather than actual building footprints. The calculations of the dwelling yield for the pieces was based on the building footprint occupying 60% of the parcel.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

NORTH 0m 40m 80m 120m 160m 200m EXISTING BUILDINGS SITE DEVELOPABLE PARCELS EXISTING BUILDINGS CONTEXT EXISTING SIGNIFICANT TREES FUTURE REGENERATION AREA 1 2 EXISITNG BUS STOPS RAILWAY PARADE RAILWAY PARADE ROBERTS RD TSYELREBMIK TSRREK TSDROFSTOBBA TEERTSTROPHTUOS TSTRUOCcM TSETAT EVASDRANOELTS TSEWOCNELB YORK ST TSNOTLIMAH D RNALHGOC EVAYAM TSNELLE D RDNEHSNWOT .LPTRUOC .LPETIHW HAY STREET CHURCHILL AVENUE ROBERTS RD THOMASSTREET HAY STREET MURRAYSTREET OUTRAM STREET HAYSTREET WELLINGTONSTREET SUBIACORD (OPTIONA) Existing GatesHAYDNBUNTONDRIVE COOKSTREET SUBIACO RD SUBIACO RD Pedestrian Underpass Pedestrian Underpass SUBIACO RD (OPTION B) Retained Seating CO-SHARE FACILITY WAFC 12 3 456 7 89 10 11 12 1718 19 20 21 22 232425 2627 28 13 141516 2930 31 32 33 34 3536 37 3839 40 4142 43 4445 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 5354 55 56 57 58 59 60 616263 6465 66 67 68 697071 7273 74 75 7677 78 79 80 81 82 84 85 8687 88 8990 91 92 93 9495 83 PERTH MODERN SUBIACO OVAL MUELLER PARK BOB HAWKE COLLEGE WEST LEEDERVILLE STATION 0m 40m 80m 120m 160m 200m NORTH

Figure 5: Prototyping and constructing the interactive pieces for the activity design.

Figure 4: The 1:2000 gridded base drawing used in the interactive model activity (site 630 x 335mm)

Methodology 1514 | Principles To Place

Figure 6: Individual participant model packs, base drawing, guides & instructions prior to distribution.

A set of instructions, a background context map and guide sheets for the model pieces were printed and included to accompany the model pieces packs for each participant. Each set of printed material and model artefacts was identical. A participant feedback form was also included.

Implementation

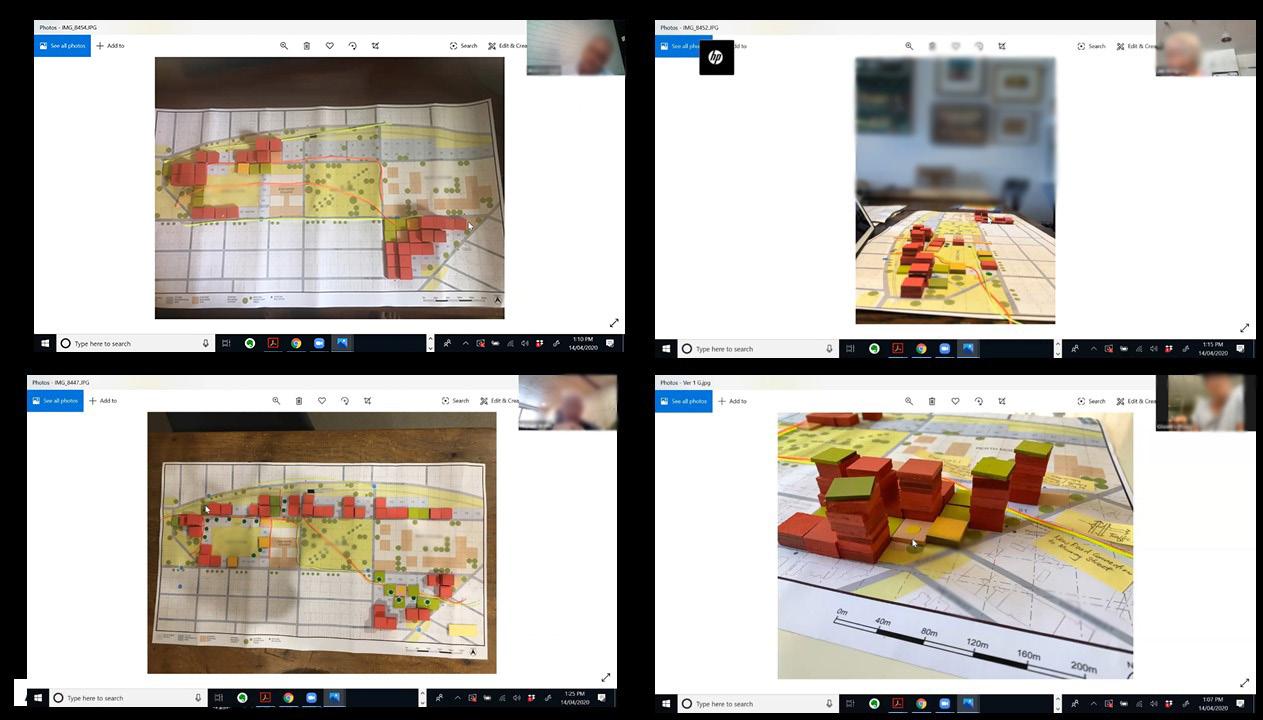

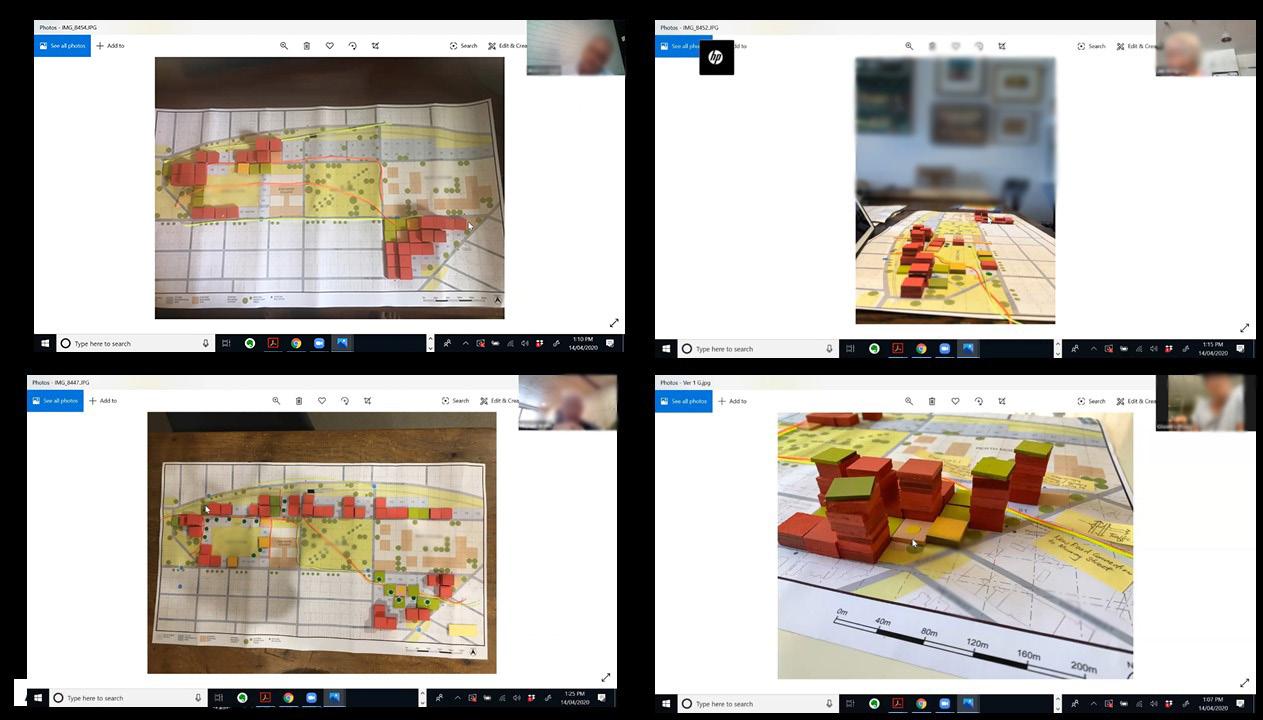

Owing to restrictions on face to face contact workshops were conducted electronically using Zoom™ video conferencing software. The workshop format consisted of five groups, which given time and management constraints were limited to six participants. The format of the workshops was a 15 minute introduction and explanation, 30 minutes of model building, 5 minutes for participants to photograph their arrangements and submit via text message or email, 5 minutes for collating and organising images, 20 minutes for individual presentation and group collective reflection.

Each participant received their individual model pack, guides and instructions (figure 6) prior to the workshop and

was encouraged to experiment with the physical interactive component of the activity so that they were familiar with the pieces and dynamics of interaction. This also potentially limited the amount of instruction needed during the workshop which was important as there were time constraints and the efficiency of communication via video was relatively unknown.

Five workshops were undertaken, facilitated by two AUDRC staff which engaged twenty six participants. Most of the participants were based at home during the workshop sessions. One participant who did not have access to a computer or the software was assisted via a purpose built office set up.

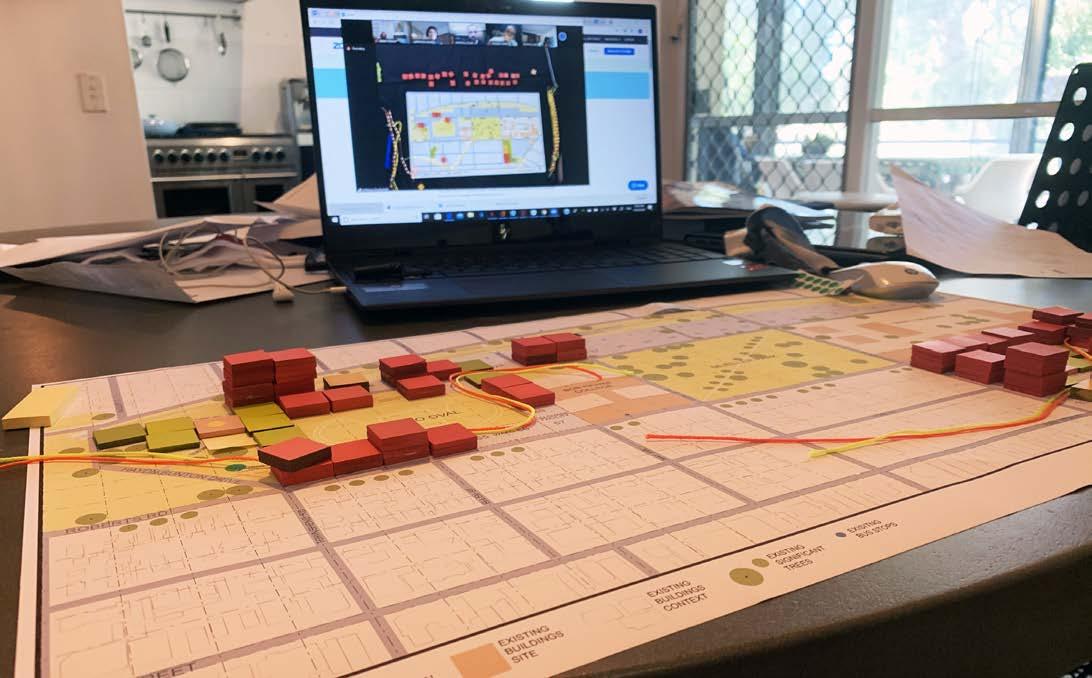

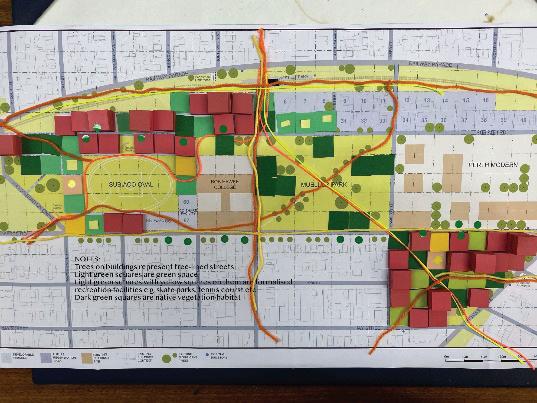

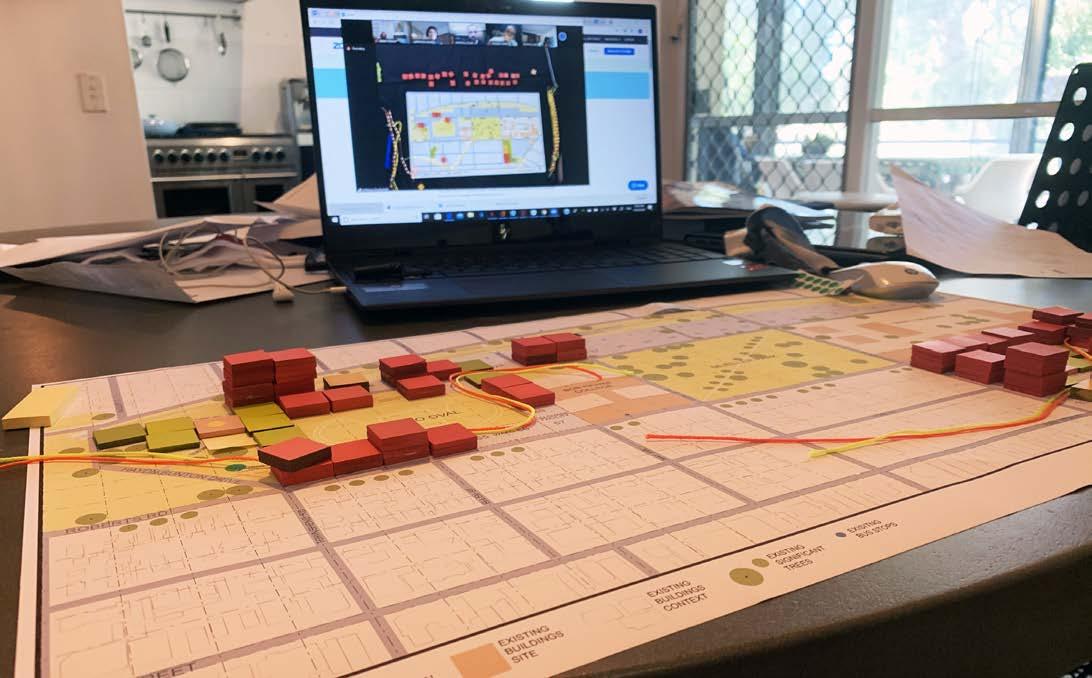

Thirty five models attempts were recorded as some participants made multiple attempts prior to and following the workshops. A plan view of a reference model was available during the workshop via a separate camera stream and this could be used by the AUDRC facilitators to highlight areas or clarify elements of the design activity (figure 7).

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Figure 7: Online facilitation arrangement with reference model between facilitators and overhead camera for live feed of reference model

Figure 9: Online workshop facilitation examples where individual models images submitted by participants are presented back to the group.

Methodology 1716 | Principles To Place

Figure 8: Image of participant working at home during the workshop with the reference model and other participants visible on the laptop screen.

/// Results

The results are presented under two categories:

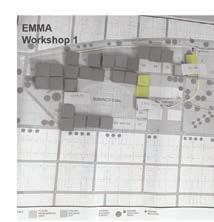

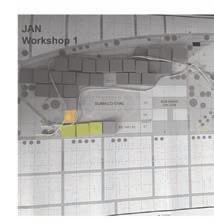

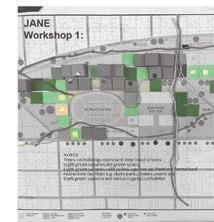

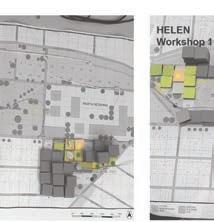

1. Workshop highlights – summaries of patterns and preferences from observation by the facilitators across all of the workshops in tables 1 to 4.

2. Quantitative Analysis – summaries of calculations of patterns of distribution of key elements from detailed analysis of models.

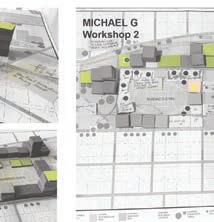

MOVEMENT EXAMPLE MODEL

Recognise extensions and connections of walking and cycling routes beyond the immediate site particularly:

• to Station Square/Rokeby Rd, across Thomas to Hay St/West Perth,

• continuation to Kings Park

• West Leederville Station/shopping, underpass to Mueller Park and across Mueller Park to PMH site

General permeability of the site – ensure clear and safe public walking routes through the development which prioritise foot traffic (eg Subiaco Road).

Possibility of public connections through/around Subi Oval and permeability across PMH site.

Possibility of reinforcing active transport routes along Roberts Road and the suitability of conversion to two-way traffic to improve permeability for pedestrian crossing.

Repeated suggestions ensure Subiaco Road is an active street suitable for walking and as a public realm as opposed to a vehicle thoroughfare (walking street).

Linking/strengthening connections between railway cycle path and site

Realignment of Roberts Road at eastern end to rationalise movement and create street environment adjacent to Perth Modern.

Table 1: Highlight results for MOVEMENT theme.

OPEN SPACE EXAMPLE MODEL

Repeated preference for public open space on PMH site either as a central area with potential integration of community facilities and urban plaza flanked by development or as part of a green corridor linking to Mueller Park.

Possibility of appending public space (recreation) to Subiaco Oval for additional public uses or high quality recreational/active elements that is available throughout the day. Potential for additional public open space around the retained seating to provide an appropriate setting for this community asset.

Prioritisation of open plaza/events space/gathering at the west end of Subi Oval potentially collocated with cultural facilities, markets and adjacent to the old gates which are recognised as an historical ‘jewel’

The experience of the underpass connection at West Leederville was mentioned including safety and there were suggestions to ‘open’ the approach on the southern side with public space to improve the amenity, surveillance and security

Contribution from Ecological Scientist participant

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Table 2: Highlight results for OPEN SPACE theme.

Results 1918 | Principles To Place

Workshop highlights

Repeated preference for high-rise/intensity development at the north-western extent of the site – to act as a gateway, minimise overshadowing of the public realm/oval and as a visual connection to Subiaco Square.

COMMUNITY EXAMPLE MODEL

Integration of cultural facilities/performing arts/markets on Western edge of Subi Oval

Incorporation of narrative (commemoration/reflection) of children’s stories/history on PMH site including acknowledgement of indigenous children.

BUILDINGS/DEVELOPMENT EXAMPLE MODEL

Generally there is a conceptual difference in approaches regarding the treatment of development in proximity to Subi Oval which can be summarised as:

• A desire to maintain the open and qualities of the oval and return to the public domain, particularly as it presents to Roberts Road as a visual connection. Mostly support very little or low-scale development immediately surrounding and avoid overlooking.

• A recognitionof the opportunity for more intense development around the oval to capitalise on the open qualities for apartment dwellers.

Repeated preference for high-rise/intensity development at the north-western extent of the site – to act as a gateway, minimise overshadowing of the public realm/oval and as a visual connection to Subiaco Square.

Repeated preference for high rise/intensity along the rail line and also clustered

station.

Repeated preference for high rise/intensity along the rail line and also clustered near the West Leederville station.

Repeated preference for high rise/intensity along Thomas Road on the PMH site

Contribution from Planning Professional

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Table 3: Highlight results for COMMUNITY theme.

near the West Leederville

Table 4: Highlight results for BUILDINGS/DEVELOPMENT theme.

Results 2120 | Principles To Place

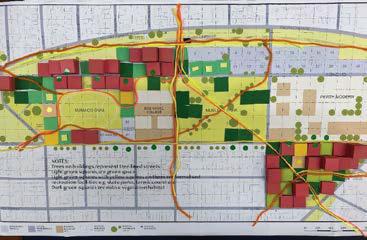

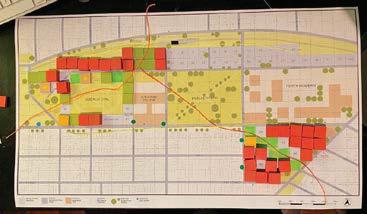

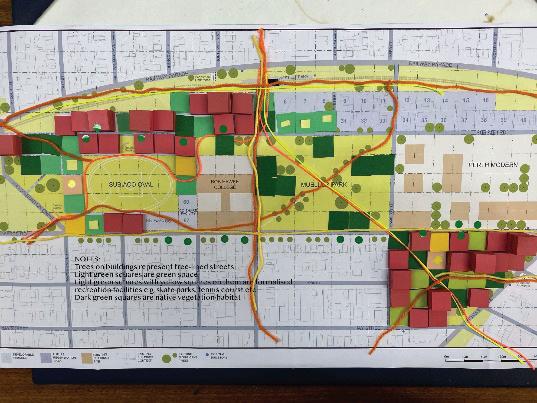

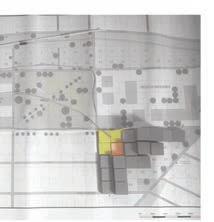

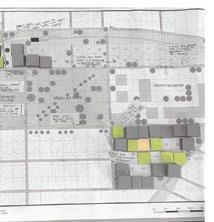

Figure 10: The six sub-precincts used for quantitative analysis.

Quantitative Analysis

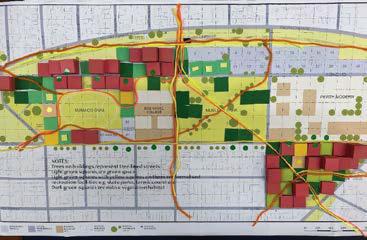

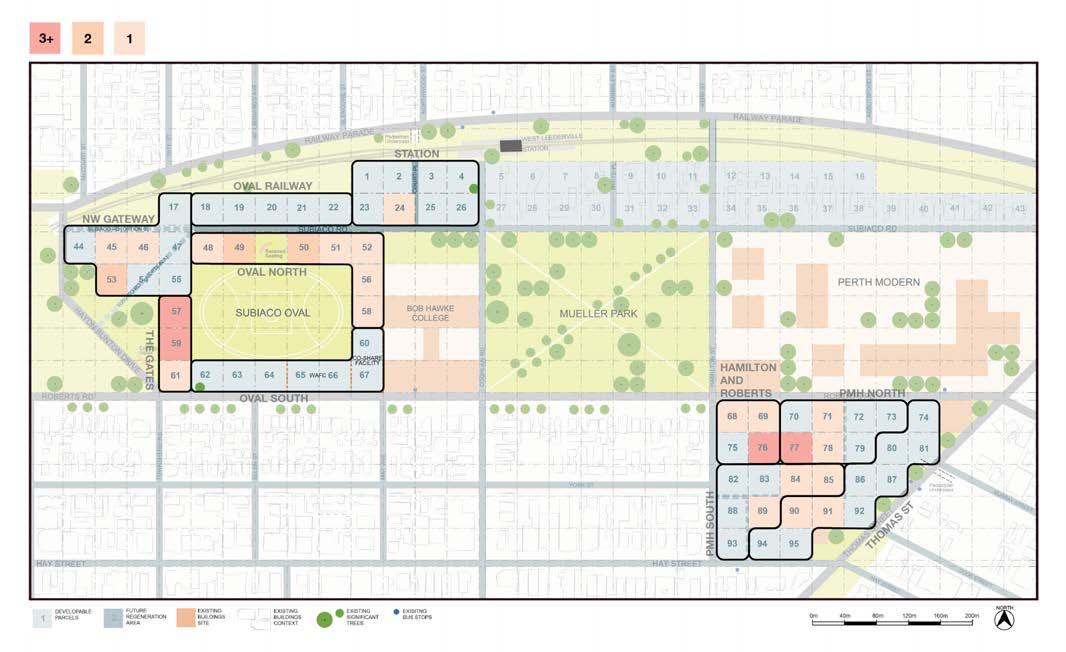

The quantitative analysis involved recording the location and number of OPEN SPACE, COMMUNITY and BUILDING/DEVELOPMENT pieces for each model.

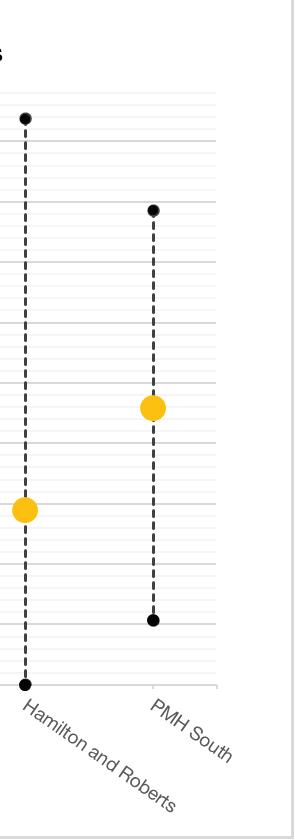

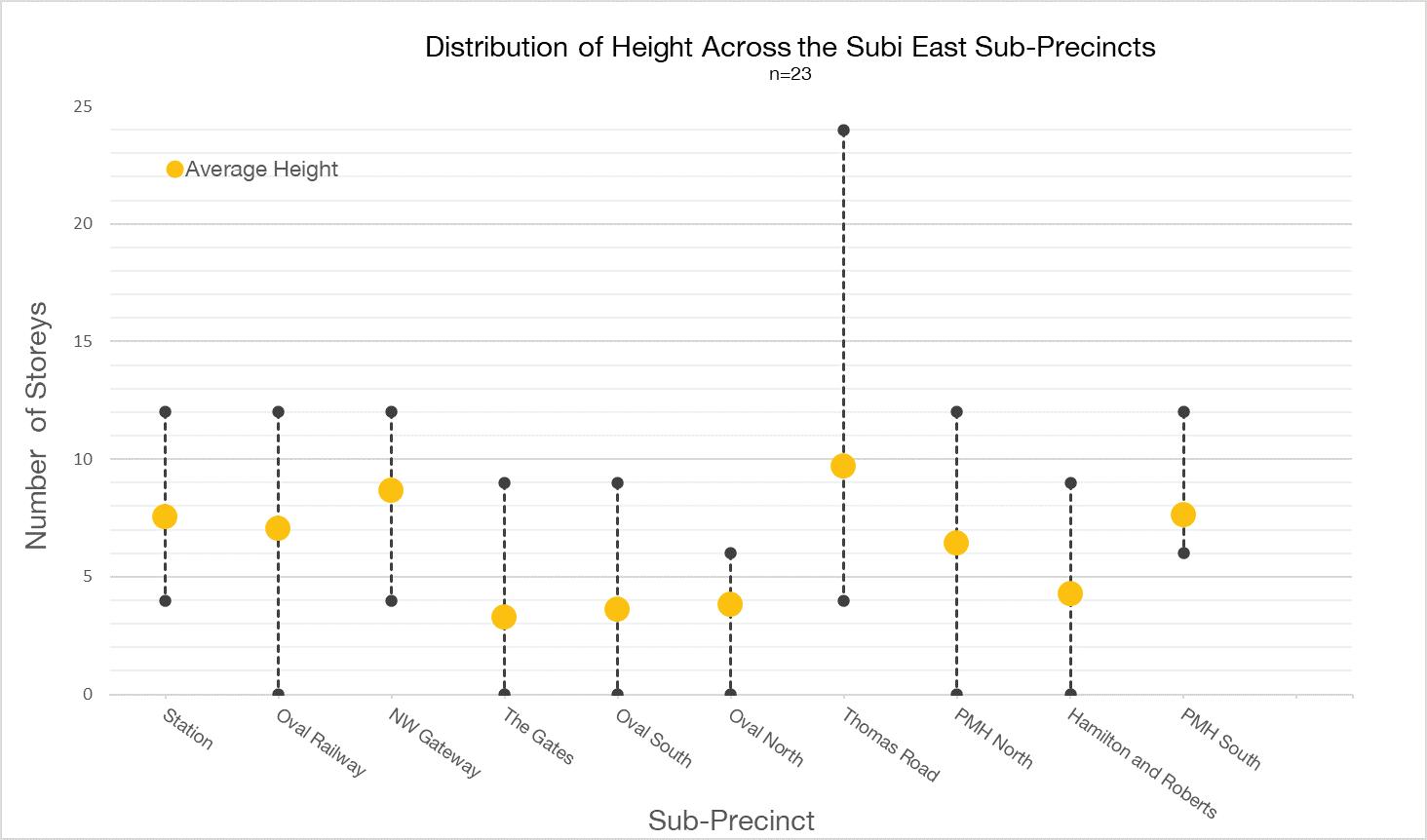

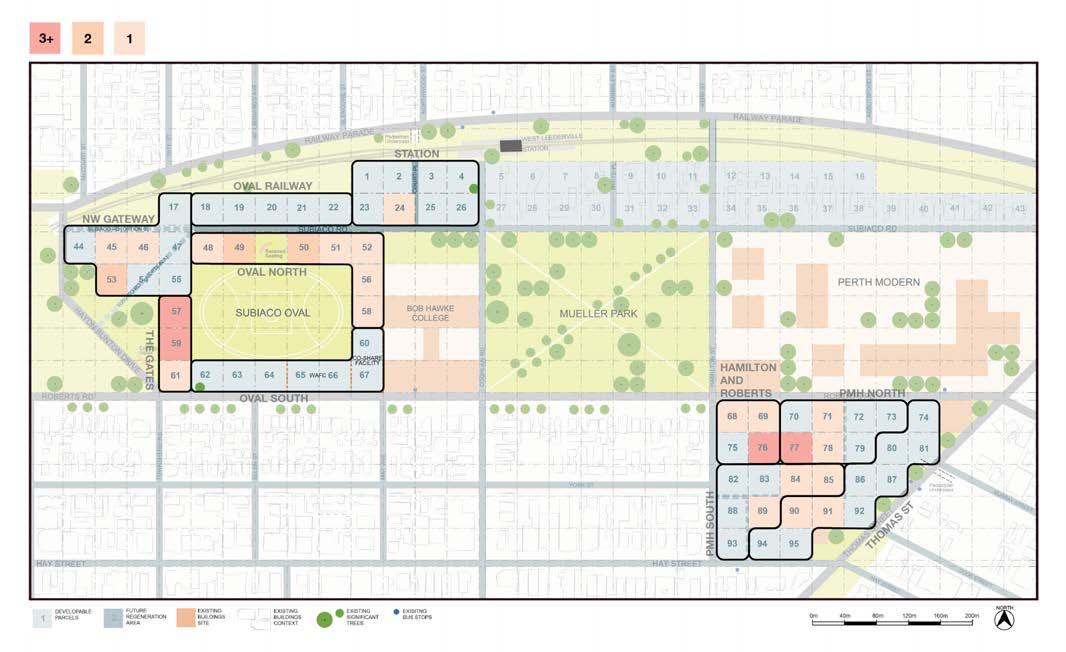

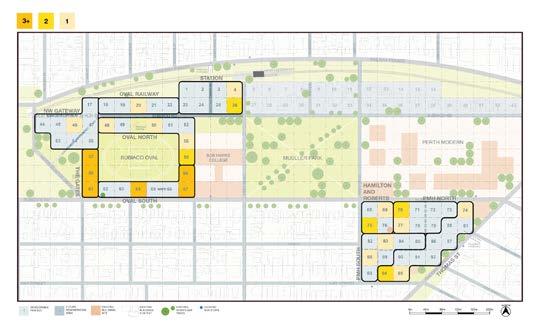

To be able to more accurately describe distribution patterns the developable parcels in the base drawing were split into a number of sub-precincts (figure 10). These sub-precincts approximated the way in which participants and other stakeholders had discussed more localised, fine-grained zones or microneighbourhoods. There were six sub-precincts in the Subiaco Oval area and four on the Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH) site.

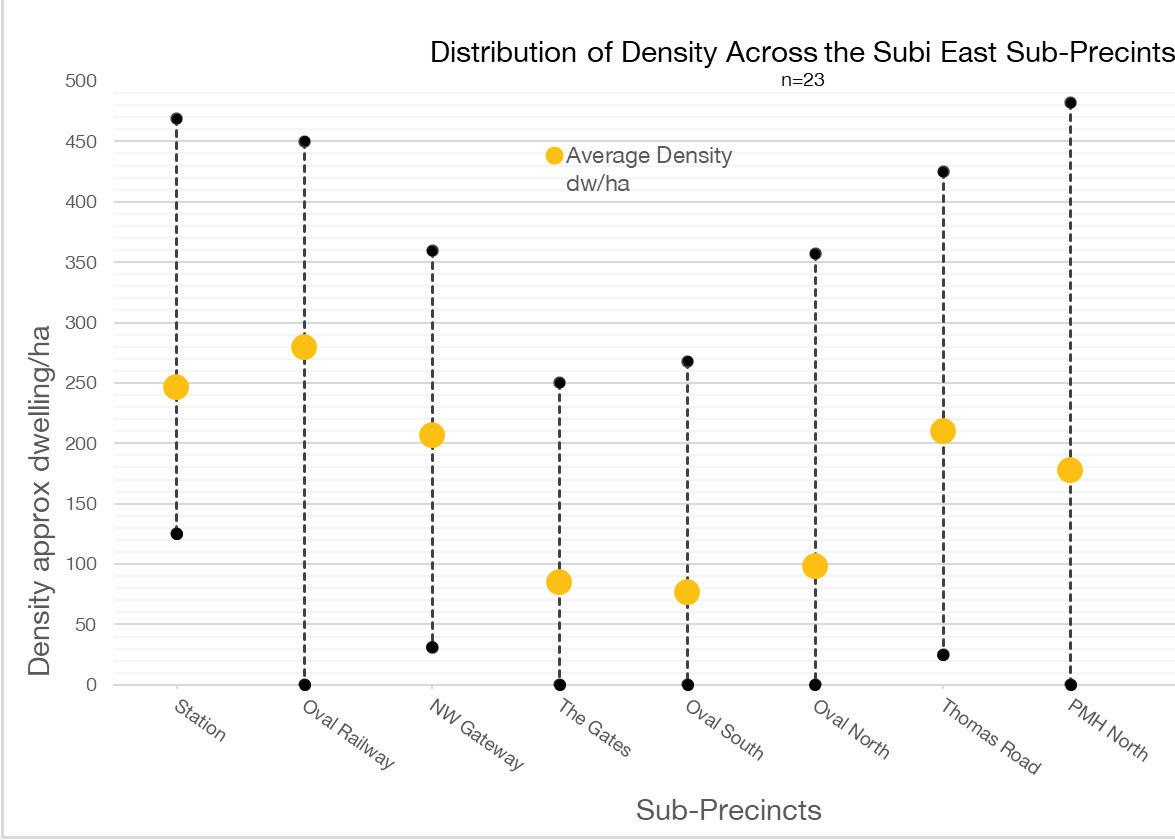

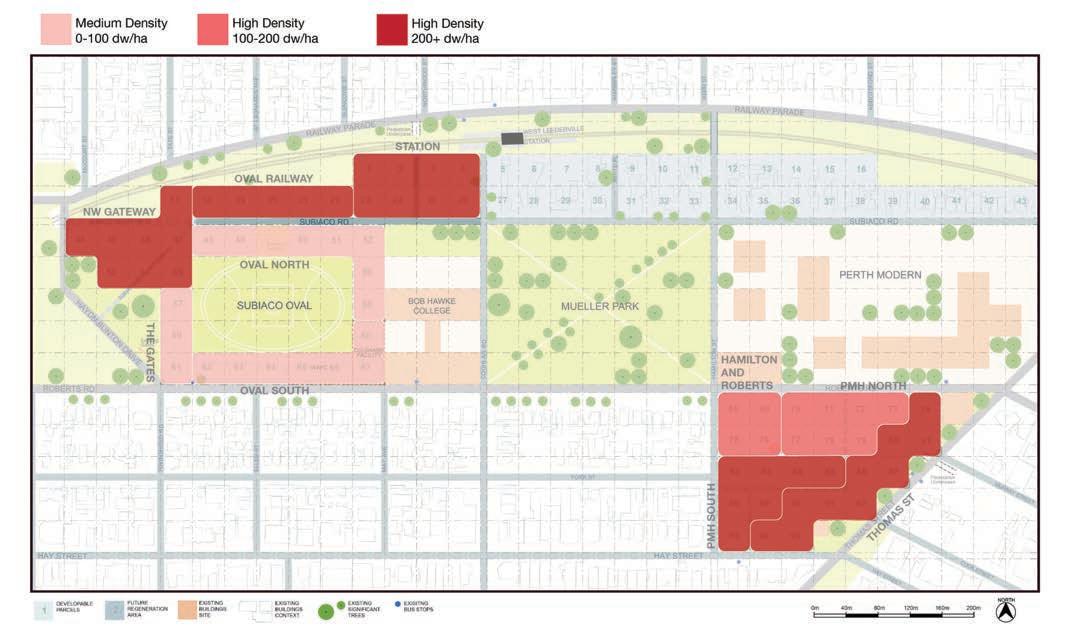

The key quantitative assessments undertaken for each sub-precinct were:

• minimum, maximum and average density

• minimum, maximum and average height

• minimum, maximum and average open space percentage

• percentage distribution of community facilities

• percentage distribution of urban plaza

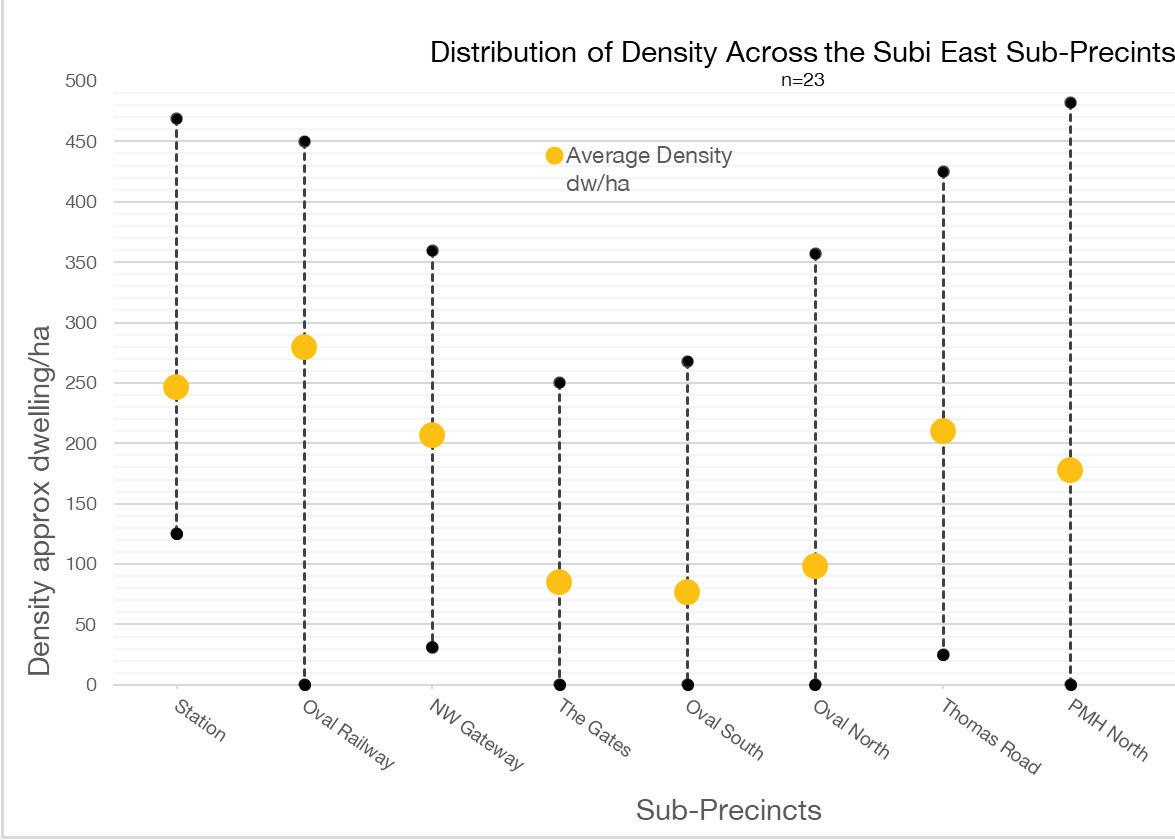

Density

Density results calculated the approximate intensity of the concentrations of dwellings across the site from

participant models. The building envelope pieces were converted into a net density figure of dwellings per hectare using a site coverage of 60%, useable floor area (UFA) ratio of 80% and average dwelling size of 80m2.

The exact figures should be treated with some caution with respect to suggesting prescriptive approaches as average dwelling size and the UFA conversion factor could be variable depending on building type and market response. Commercial premises could also occupy floor space and some covered parking may be contained within the above ground built volume. In addition the site areas were approximations of the actual site extents. The figures do however give an indication of the range of relative preferences of built intensity and average within each of the sub-precincts (Chart 1).

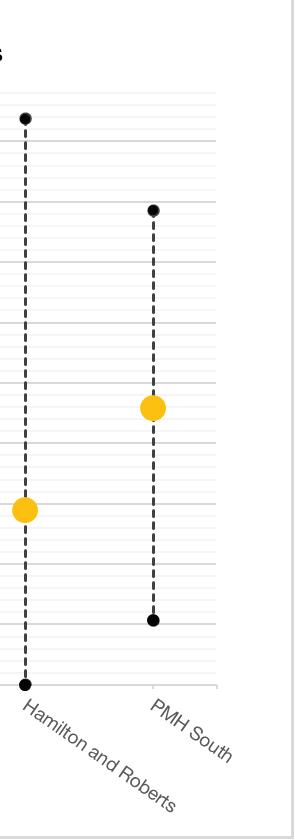

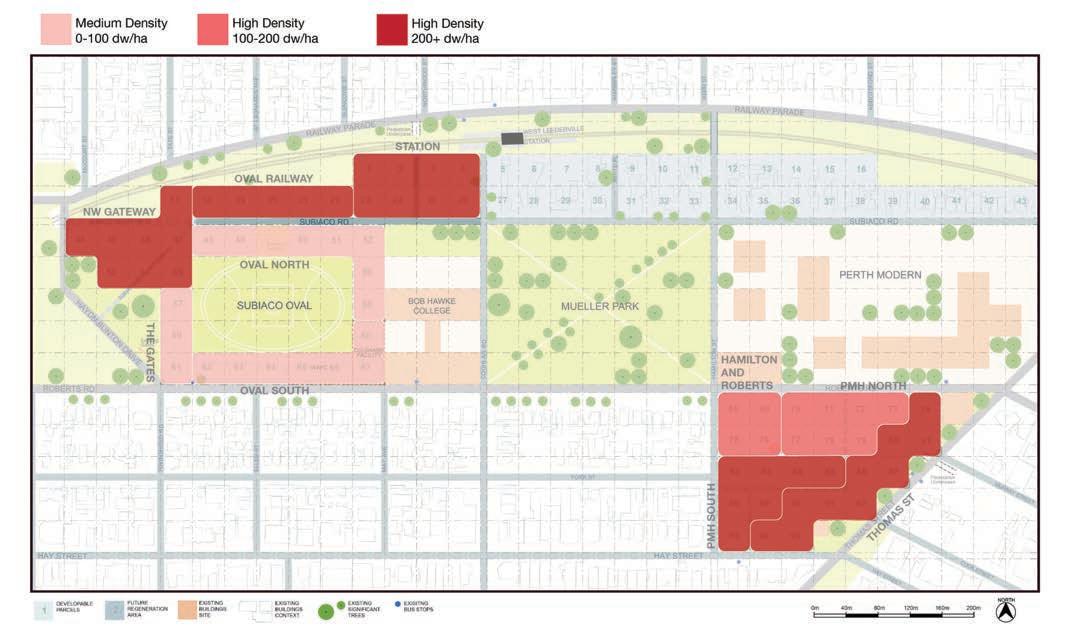

A series of ranges were established to represent average preferences for density – medium density (less than one hundred dwellings per hectare), high density band one (one hundred to two hundred dwellings per hectare) and high density band two (over two hundred dwellings per hectare). Figure 11 shows a picture of the relative concentrations of the average density across the completed models organised according to these ranges.

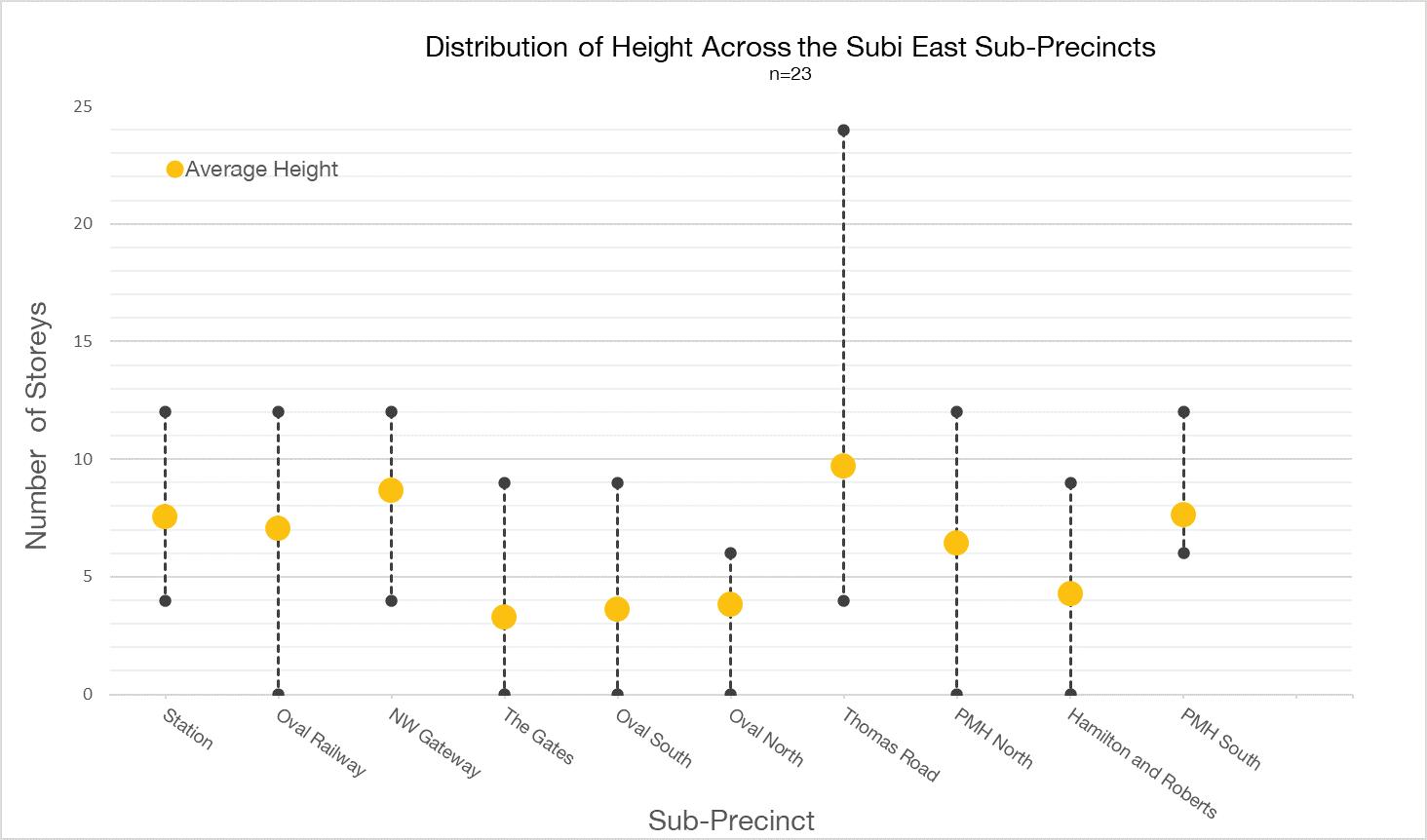

Height

The pieces provided were approximately to scale so that it was possible to calculate the variation of preferences

for building heights across the sub-precincts. Chart 2 shows the variation of individual responses and the group average for building height.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Chart 1: Individual minimum and maximum ranges and average of density modelled across the sub-precincts (CRG)

Figure 11: Average density modelled across the sub-precincts (CRG, n=23)

Results 2322 | Principles To Place

Chart 2: Individual minimum and maximum ranges and average of height modelled across the sub-precincts (CRG)

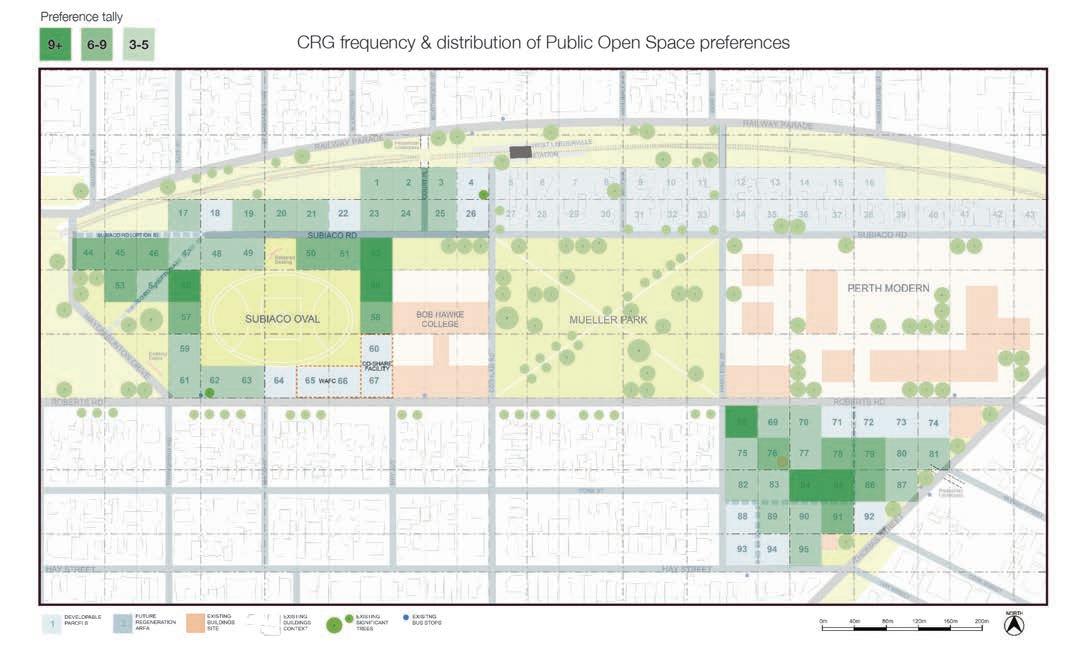

Open Space

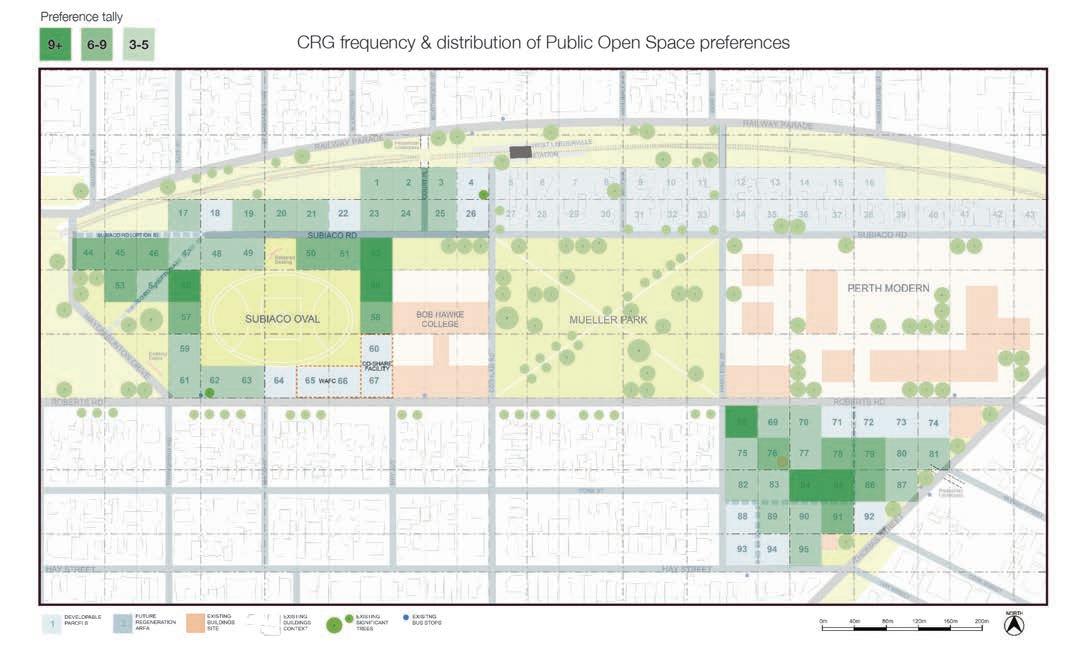

Open space was calculated by identifying the number and location of green spaces placed by participants in each of the sub-precincts. Participants were each provided with four each of two types of green spaces which were not

differentiated for this tally. The frequency of the placement preferences is shown on figure 12 organised into three bands denoting the number of times placement in that location was recorded.

Community

The distribution of preferences for community facilities was also recorded. Each participant was given two community facility tiles and the distribution and frequency of their location has been mapped on figure 13 organised into three bands denoting the number of times placement in that location was recorded.

Urban Plaza

Similar to community the distribution of preferences for the urban plaza facilities was also recorded. Each participant was given two urban plaza tiles and the distribution and frequency of their location has been mapped on figure 14 again organised into three bands denoting the number of times placement in that location was recorded.

Quantitative Analysis Discussion

The quantitative analysis revealed a number of distinct and general patterns. The charts for density indicate some wide variations in individual preferences across the sub-precincts. The position of the average in relation to

the extent of the ranges gives an insight into the level of agreement of a particular preference. For example even though there is substantial range in density modelled for The Gates, Oval South and Oval North sub-precincts the average is situated at the lower end of this range indicating that there was more of an overall preference for lower density in these locations.

Combining the open space data with the density preferences helps to give an indication of the preferred built form. For example a high average density with a moderate to high open space, such as the NW Gateway sub-precinct would indicate a preference for taller buildings set in more open grounds. Conversely low density with low open space would indicate a preference for larger footprint low-rise type development such as the Oval South area.

There is a consistent correlation between high density in the Oval Railway and Station sub-precincts indicating a preference for concentration of development in these

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Figure 12: Open space frequency and distribution preferences represented in individual models (CRG, n=23)

Figure 13: Distribution of preferences for location of community facilities (CRG, n=23)

Results 2524 | Principles To Place

Figure 14: Distribution of preferences for location of urban plazas (CRG, n=23)

locations. Similarly the Thomas Road sub-precinct attracted a preference for higher density.

The range of preferences for density indicates a wide variety of opinions amongst the group which makes it difficult to make any broadly consistent conclusions. The highest average building height was recorded for the Thomas Road sub-precinct and the NW Gateway. There is a strong preference for open space on the Oval North and Gates sub-precincts which also correlates with the preferences for the location of an urban plaza. This correlates with anecdotal discussion regarding the preference for an open, inviting and community focussed corner in this location echoing historical patterns of gathering. Also whilst there is an ambition for density on the PMH site this is somewhat counterbalanced by a preference for open space suggesting a blending of the two and the need for a built form response which acknowledges the public connection to the site.

The preference for the distribution of community buildings is strongly correlated with the Gates and Oval South subprecincts. There is also a preference for the North West and southern regions of the PMH site. The preference for the urban plaza locations is also correlated with the Gates sub-precinct and the Oval North area also received several preferences. In addition the idea of a central plaza for the PMH site emerged.

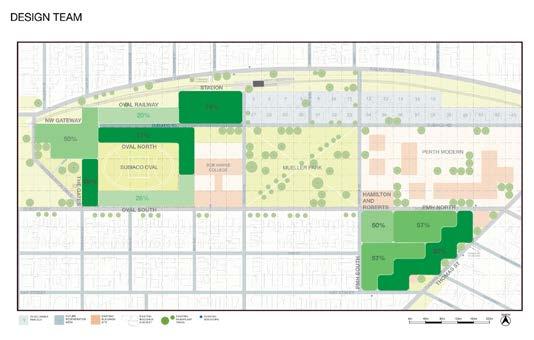

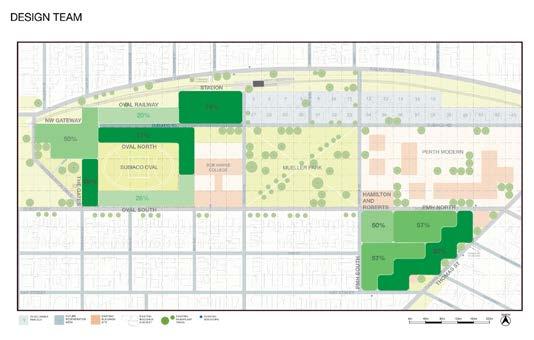

Design Team Conceptual Approach

Following completion of the initial collaborative design engagement activity AUDRC was approached to use the model to represent the professional design team’s initial conceptual approach to the master plan with the CRG. It was recognised by the project team that the interactive model had established a clear visual language related to core spatial concepts and would be an effective way to communicate the preliminary configurations.

The design team supplied locations of approximate building footprints, heights, key connections and open space locations and types. This was used to construct a model by AUDRC using the same approach that had been undertaken by CRG members. This model was provided to the design team for review and then finalised. The results of this model were analysed and represented using the same graphical approach so that comparisons with the CRG average could be completed.

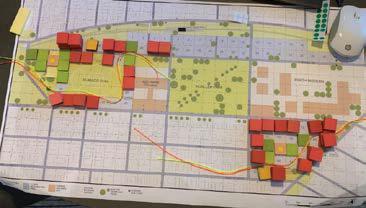

Comparative Analysis of Design Team Approach

Density

At a broad level the distribution of density (or intensity) proposed by the design team is similar to the average distribution calculated from the CRG. A notable difference is that the CRG tended to focus intensity along and adjacent to Thomas Road whereas the design team concentrated in a smaller area and to the rear of the old hospital site (PMH South and Hamilton & Roberts subprecincts). The design team also focussed a higher level of intensity on the NW Gateway sub-precinct identifying the capacity of this location to provide for taller buildings.

A key outcome is that the CRG expressed a consistent preference for low intensity development on the sporting oval perimeter and this was translated by the design team. There was general feeling that the oval was revered as a very public asset and that it should not be privatised by overlooking and the imposition of private development with minimal setbacks. This is in stark contrast to the original business case concept (figure 16) which hadn’t undertaken the depth of consultation, and made assumptions from a previous project. This approach was refuted and translated spatially by the CRG using the interactive modelling method.

Open Space

The comparison of open space distribution is correlated with development intensity (figure 18). The design team proposed a landscape setting along Thomas Road in response to the treatment of the heritage assets. The CRG generally supported greater intensity along and adjacent to Thomas Road so there is a discrepancy in that approach. This discrepancy is however driven by an overarching built form and landscape concept which is the remit of the professional design team if they recognise sufficient contextual evidence. It highlights that the community are not qualified designers and may not always be able to conceptualise complex constraints and the models have limitations in terms of being able to communicate these. As discussed during the methodology the process objectives are not to let the community design the project as such.

Distribution in the sub-precincts adjacent to the oval is mostly similar however the design team provides greater open space near the station. This is mostly as a result of the promotion of a taller and more slender building type which provides a smaller footprint and greater open space on the site.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Figure 15: Distribution of preferences for location of density, design team on left, CRG average on right (n=23)

Figure 16: Original business case concept showing development fringing the oval

Results 2726 | Principles To Place

Figure 17: Final masterplan (Hames Sharley for Development WA)

Community Building

The design team had a much more specific location for the community building as they effectively only had one vote whereas the CRG were able to distribute preferences across the site. There was also an expectation about the location of the community building from previous negotiations. CRG members also placed their preferences around the historic gates, not necessarily recognising this as a location for a building but acknowledging the community importance of this part of the site. This preference is recorded more in the landscape and public space design rather than as a specific building.

With this in mind the alignment between the community preference and the design team response is quite strong with the south east corner of the oval a consistent location. There was also recognition by the CRG of the important community role of the former hospital site and again whilst this is not recorded as a specific building it is something which is addressed through the landscape and public design approach and potentially the re-purposing of heritage assets.

Urban Plaza

Similar to the community building the design team effectively only have one vote with respect to location of urban plazas. This shows a very strong correlation with the CRG preferences.

The CRG distributions also indicate preferences for public space and there is particular emphasis on the northern edge of the sporting oval.

Comparative Analysis Discussion

The comparative analysis is both informative and instructive. It reveals that there are many similarities between the CRG and the design team response with respect to preferences for each of the elements. This could be attributed to careful listening from the proponents or the emergence of a relatively natural synthesis of constraints by both groups or a combination of both.

The analysis also revelas how the interactive exercise is used by the participants to express a range of values.

Whilst the pieces themselves are relatively specific, for example this is a community building, participants would

distribute pieces according to where they felt community needs should be represented. The preference map then presents as a kind of culture-scape, a recording of intention and feeling rather than a deliberate built environment (development) response. It suggests that the tool could be used more generally to record this kind of ‘value-scaping’ rather than direct participants toward a built outcome. In this respect the question for the exercise would be reframed as ‘Where do you think culture and community is most important, where should we take notice?’

The analysis also revealed the potential of overlaying different themes to inform design. For example combining the community building and urban plaza responses begins

to build a picture of focus for the public realm as both elements are striving toward the public life of the site and are complimentary.

Overall it should be restated that the objective is not to let the community design by consensus but to translate the community’s values and preferences into spatial information for consideration by the design team. There may be sophisticated reasons for the design team;s specific design approaches which may lead to different responses. The exercise however provides guidance for the design team and also allows them to investigate areas of discrepancy and identify areas which may need to be prioritised in terms of communication of the design concept.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Figure 18: Distribution of preferences for location of open space, design team on left, CRG average on right (n=23)

Figure 19: Distribution of preferences for location of community building, design team on left, CRG on right (n=23)

Figure 19: Distribution of preferences for location of urban plaza, design team on left, CRG on right (n=23)

Results 2928 | Principles To Place

//// Activity Evaluation

The Collaborative Place Design activity was well received by participants and led to significant achievements in terms of translating their ideas and meeting specific engagement objectives.

This part of the report reflects on the effectiveness of the Collaborative Place Design activity in meeting its specific objectives. This is informed by observation, written participant feedback (thirteen submitted forms) completed following the activity, written feedback from the two project managers and responses to an independent review of the overall engagement process conducted by Research Solutions.

This was the first undertaking of a completely on-line Collaborative Place Design workshop. All Participants were able to submit a design and most were fully completed. This indicated that the scope of the task was generally aligned with the workshop duration. Further refinement and improvements to the design of the model pieces and interactive dynamics of the activity are possible. Opportunity for collective reflection is a critical element to help achieve the engagement objectives and

this was limited by the on-line nature of interactivity, the arrangement of separate workshops and the time allowed for this. The exchange of tacit knowledge during critical reflection is restricted by the video format. Mechanisms of communication particular to tacit knowledge exchange such as body language and story telling are difficult to make apparent or encourage.

General Response

Respondent feedback indicated a high level of satisfaction with the workshop. Relevant comments from participant feedback forms included:

‘It was a small group and an efficient one – Anthony and Catherine were very helpful!’

‘Thanks for the workshop - it went really well. Clearly explained, well organised and engaging.’

‘Very good exercise’

‘Great tool!’

‘Yes, good facilitation and input by all.’

The authors of the Research Solutions report, who interviewed 28 of the 35 CRG members and received survey responses from 26 of them identified that:

‘Those who participated in the AUDRC modelling session really enjoyed the experience. Almost all raised it spontaneously and spoke about it in detail.’

Further participants described: ‘enjoying showing others their work and looking at other people’s designs’; and ‘developing a deeper appreciation for the decisions that need to be made’

Participant transcripts from the interviews also provided high levels of general support for the activity:

‘As an exercise, it was very powerful. The concept is phenomenal’

‘I liked the modelling exercise, I was expecting it not to work but It worked well

‘I felt it’s a very good exercise’

‘I think the modelling is interesting from a community’s perspective’

‘I liked the process following... I thought it was quite astounding – great job. The logistics of it – a great job.’

The two project managers were also asked a general question related to their overall perception of the success of the activity. Their responses are also provided below.

Any other comments about your perceived benefits of the activity?

PM1: ‘Admittedly, I was a little reluctant to use this approach, as it could present some level of risk if not done properly. My concern was that it could result in a ‘design by community’ who just don’t have all the required technical information. However, the way AUDRC approached the engagement, and the strict rules around the model, definitely added value to the process.’

PM2: ‘There were a number of benefits to this activity. I

think it allowed people the space to test their own ideas in a way that identified real constraints and challenges in the project. It allowed quieter voices in the room to have an equal say on where elements were placed. The activity also gave a very clear understanding to the project team on where the CRG was at in terms of their own preferences and drivers.’

Objective 1

• the need to learn spatial literacy/competency (understand the scale of the site in planning and design terms) in order to participate in the development of spatial ideas and provide appropriate feedback.

Generally nearly all of the participants participated in the activity and produced at least one completed design. This means that they oriented themselves spatially and understood the basic spatial concepts contained within the activity. Feedback question No.3 targeted this objective by asking:

Q3. Did you find that the activity allowed you to explore different spatial ideas effectively?

Of the thirteen respondents who provided written feedback twelve responded affirmatively to this question. Comments included:

‘Yes – great tool’

‘Yes but better face to face’

‘Yes – very helpful’

Transcripts from participant interviews conducted by Research Solutions also identified the following comments with respect to this objective:

‘I felt it’s a very good exercise if you’re not used to planning, to make them think about how the spacing went.’

‘As soon as you started placing blocks here and there, you really got a feel for how complex these decisions are.’

The two project managers were also asked a specific question with respect to this objective. Both responses are provided below.

Did you find that the activity allowed participants to easily translate written ideas and thoughts into spatial actions?

PM1: ‘Yes, with the exception of a few participants,

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Activity Evaluation 3130 | Principles To Place

most seemed to intuitively use the model to express their thoughts and ideas.’

PM2: ‘Yes – It was a well designed template and instructions. I noted all members enthusiastically participated in the activity and helped them to articulate why they moved tiles to certain locations.’

Objective 2

• enhance understanding and empathy with the constrained nature of the spatial task of urban planning and design professionals (eg the need for trade-offs) to help diffuse ‘us and them’ oppositional mindsets, foster collaboration and help reach agreements and compromises (‘walk a mile in the planners shoes’).

An interesting observation under this objective, which may be more of a hypothesis as it was not tested with the participants, is the ‘humanising’ influence of participants being situated in their home environments during the workshop. Casual observations of the domestic environments seemed to create a familiar and convivial atmosphere. This in contrast to a persona or role which could be adopted or perceived in a more formal environment. This has the potential to help build empathy between participants as each is understood as part of a household and/or family.

Feedback question No.5 targeted this objective by asking Q5. Did you find the activity allowed you to understand some of the competing needs and necessary trade-offs?

Of the thirteen respondents nine responded affirmatively to the question:

‘Yes – cant have everything’

‘I really didn’t have a great deal of conflict - there seemed enough room for all the elements I wished to include.’

‘Yes preference for higher rise in return for more open space’

‘The short time for the workshop didn’t allow us to explore this.’

Transcripts from the interviews also supported performance against this objective:

‘It showed similarities /differences between how you and others thought’

‘You can see the people who didn’t like high-rise could see the benefits… by doing the high-rise, it really reduced the building footprint’

‘if you didn’t like density, you had to have a high rise somewhere. So that made you really think where to put them’

‘As an exercise, it was very powerful. As soon as you started placing blocks here and there, you really got a feel for how complex these decisions are. ‘

A specific question targeting this objective was also asked on the two project managers and their responses are presented below.

Did you sense that participants were able to empathise and learn about the practicalities of the consultant’s urban planning and design challenge?

PM1: ‘Yes, those that wanted to genuinely participate were able to understand the challenges and practicalities of the design team. Some participants who had ulterior agendas chose to alter the rules to frustrate the outcome (i.e. not use all the building blocks)’

PM2: ‘Yes – Having to physically locate all of the tiles within the spaces and noting the constraints helped participants to understand the challenges and also to clarify their own preferences and reasoning.’

Objective 3

• foreground and collectively compare the diversity of knowledge, experience and viewpoints within the CRG with respect to spatial preferences and priorities to help diffuse dominant personalities and provide an inclusive opportunity to contribute.

There were demonstration of significant performance against this objective. Even though there was substantial effort in production and organisation the use of individual models meant that participants could each express their viewpoints. In addition, because the intercative model packs were delivered two days prior to the workshop the participants hade time to contemplate the task, experiment with the interactive components and reflect on their positions prior to the workshop. In some instances participants had multiple versions which showed evidence of critical analysis abd self-reflection.

The format and duration of the sequential workshops meant that collective reflection was limited to each of the workshop groups rather than the whole CRG. The on-line format also restricted interaction between group members as each participant took their turn presenting their outcome. This led to more of a presentation format rather than a discussion format which would potentially have promoted a higher level of participation in the activity.

Documenting individual models through photography and presenting the images meant that all group members could easily see and ‘read’ each others approaches. This perhaps allowed for better comparison than face to face workshops as there was a consistency in the way models were photographed and presented. The facilitator was also able to quickly move between submissions to highlight differences and similarities and generally make comparative analyses.

Feedback question No.4 targeted this objective:

Q4. Did you find the activity allowed you to understand some of the priorities and preferences of other community representatives?

Of the thirteen respondents ten provided an affirmative response to this question. Comments included: ‘Yes, this was great. I modified many of my ideas once I had seen what others had done’ ‘Yes, some great ideas’ ‘Yes. I got a lot of good ideas from other participants but also found a number of common principles.’ ‘Very beneficial and enabled me to consider new ideas and compromises’

Transcripts from the interviews conducted by Research Solutions also supported performance against this objective:

‘It showed similarities /differences between how you and others thought. You could pull out all the good ideas of everyone else’s…. with everyone doing that, kind of a synergistic development of the model. ‘

‘they broke us into small groups and we all got a chance to show off our maps, ample time to explain why we had placed things where’

There were a number of comments provided by the two project managers in their written feedback with respect to this objective. The first question which provided some

insight into this was related to inclusivity.

Was the process inclusive for the participants?

PM1: ‘Yes – I think having the individual packs may have even provided more benefit for individuals as it required them to take more responsibility for the overall design of their submission rather than through a codesign process as a group on a single activity board. It allowed the quieter voices in the room to express their sentiments more freely and on an equal level.’

PM2: ‘Yes, very much so.’

The second question targeted aspects of trust building.

Did you notice any developments in terms of building of trust (however small eg shared reflections, lack of hostility, conviviality) both between participants and vertically with the project team as a result of the activity?

PM1: ‘The activity allowed a range of views to be shared. Interestingly there were a number of times were participants had placed their markers in the same location but had different motivations for doing so. Voicing these drivers seemed to provoke more discussion within the groups on the motivations for placing items in certain spaces.’

PM2: ‘Yes, those that honestly wanted to participate were quite enthusiastic, and even seemed to have some fun. However, those that couldn’t get the model to support their position seemed to get a little agitated.’

Criticisms & Improvement

Despite a significantly positive response from participants generally there were some comments which suggested limitations and possible improvements with the activity. For example feedback from the project mangers noted:

PM1: ‘The drawback was the time and effort needed to produce the model pieces and get them to the participants. Acknowledging it was unusual times. It might be good (when time and funding permits) to convert this into an electronic game-like model.’

PM1: ‘Noting that time was a restriction with this activity, I would have liked to provide individuals with more time to undertake the pre-session activity.’

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Activity Evaluation 3332 | Principles To Place

The report from Research Solutions identified two points with respect to modifying the exercise:

• more time allowed for people to create their models; and

• clearer explanations of the parameters of the exercise.

Another important observation which could influence the way the interactive modelling activity could be framed related to being very clear on the level of influence the CRG had. Even though the activity was not identified as

a ‘design’ exercise it could be construed as such and attention should be reinforced with respect to clearly explaining the activity objectives.

Based on the activity designers and facilitators experience, discussions with the project mangers and participants a ‘Lessons Learned’ document was produced which focusses on opportunities and improvements for this type of engagement activity. These are shown in table 5.

Issue Suggestion

Greater timeline would have allowed participants more time to participate

Group sizes of up to 6were a good size to allow discussion

1hr 15 minutes were allowed for the session. This was quite rushed, all sessions took 1hr 30mins

Variation in participants familiarity with instructions and equipment

Grid format very useful for orientation but may be too restrictive for placement of some uses

Lack of opportunity for group reflection and discussion

Longer lead times

Repeat future sessions with similar size

Look at extending session times if conducting online in same format.

Longer lead times between delivery and event

Look at refinements to interactive dynamics and design of Base Drawing

Difficult given time – if models completed ahead of time then this would allow more collective reflection – so more lead time and instruction prior to sessionto allow models to be completed and submitted ahead of schedule

Successful in migrating discussions from text to spatial ideas

Lots of information presented with individual models as opposed to fewer collaborative models typical of face to face workshops

Participants would like greater numbers of open space pieces

Poor feedback completion

Greater resourcing for analysis and evaluation

Don’t limit this, allow community to place as many pieces as they would like to describe their priorities

Participants not having enough time and also overload of content due to compressed timeframe and switch to digital platform.

Confusion on blocks perceived as buildingsNeeds to be more explicit in instructions about use of ‘counters’ rather than building footprints.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Activity Evaluation 3534 | Principles To Place

Table 5: Summary of ‘Lessons Learned’ from reflection, analysis and observation.

///// Conclusion

The Collaborative Place Design activity was a prototype for conducting online engagement using tactile methods. It delivered a range of positive project outcomes as well as providing important lessons for future research and practice.

The Subiaco East redevelopment project provided a unique opportunity to trial and implement an online engagement opportunity using the Collaborative Place Design engagement method. Whilst typically this relied on a face to face environment the impact of distancing restrictions resulting from COVID-19 demanded a novel approach. The result was to create simpler interactive models which could be distributed individually to each of the participants.

The engagement objectives remained the same however and the success of the new approach needed to be explored as part of the project. Observation, facilitation and analysis of the results suggested a very high level of participation and that the approach was successful in enabling community members, many with limited spatial literacy, in translating their intentions into spatial actions. T

The use of individual models created a number of opportunities with respect to the interpretation and analysis of the spatial actions. It allowed averages across the group to be calculated and democratised the community design process. This allowed people to understand the range of views within their community , dispel assumptions and moderate dominating ‘voices’ within a representative group.

The results provided some clear spatial expressions of more widely held views, such as the attachment to the oval as a public asset and the cultural significance of the hospital site. The exercise provided a spatial ‘brief’ for the design team as remarked upon by one of the project managers ‘I note that the design team themselves were interested in the results of the activity more than think they expected and found it to be a useful activity in understanding CRG drivers on key elements of the design’

Being the first trial of this particular approach the evaluation of the activity was a critical element of the project. This, involving on the day participant feedback, observation and reflection from activity designers and workshop facilitators, post-workshop written feedback from key project managers and independent individual interviews and analysis conducted three months after the workshop. This provided an indication of the overall success of the project, allowed evaluation against specific engagement objectives and identified areas for improvement.

The evidence suggest overwhelmingly positive performance against the key objectives of this part of the engagement activity. All of the participants, except one, were highly engaged with the activity. It provided an important leap in the project from talking about ideas to representing them spatially. Feedback highlighted how the activity allowed participants to understand the complexity of the design process, the need for compromise and the range of views held within the CRG.

The best evidence of the achievements of this work comes from verbatim quotes and written feedback, for example:

‘You could pull out all the good ideas of everyone else’s…. with everyone doing that, kind of a synergistic development of the model’

‘As an exercise, it was very powerful. As soon as you started placing blocks here and there, you really got a feel for how complex these decisions are.’

‘There were a number of benefits to this activity. I think it allowed people the space to test their own ideas in a way that identified real constraints and challenges in the project. It allowed quieter voices in the room to have an equal say on where elements were placed. The activity also gave a very clear understanding to the project team on where the CRG was at in terms of their own preferences and drivers.’

The feedback also provided useful suggestions for areas to improve the practice and highlighted the benefits of an individual activity as opposed to a group one. Whilst an element of risk was unavoidable owing to the unique circumstances the novel approach was successful in meeting the objectives of this activity and provided a cognitive leap for community members into the ‘businessend’ of the urban planning and design project giving them both the opportunity to contribute and the capacity to absorb and reflect on the spatial plan that would ultimately guide urban redevelopment of the site.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Conclusion 3736 | Principles To Place

References

Creating Communities (2020). Subiaco East Redevelopment Project Cultural Context and Place Narrative. Perth WA, Development WA.

Duckworth-Smith, A. and G. Oliver (2019). AUDRC Research P4: A summary report on the research and development of innovative tools for community engagement, communication and collaborative design for planning and urban design policy. Perth WA, UWA (AUDRC).

Development WA (2019). “Subi East Masterplan Directions.” Perth WA, Development WA.

Evans, M. and N. Terrey (2016). “Co-design with citizens and stakeholders.” Evidence-based policy making in the social sciences: Methods that matter: 243.

International Association of Public Participation (2014). IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum. Louisville CO, IAP2 International Federation.

Landcorp, MRA (2018) “Subi East Vision Concept” Perth, WA.

Laurian, L. (2009). “Trust in Planning: Theoretical and Practical Considerations for Participatory and Deliberative Planning.” Planning Theory & Practice 10(3): 369-391.

Martinuzzi, C. and C. Lahoud (2020). Public space sitespecific assessment: Guidelines to achieve quality public spaces at neighbourhood level. UN Habitat. Nairobi KENYA.

Reed, M. S., S. Vella, E. Challies, J. de Vente, L. Frewer, D. Hohenwallner‐Ries, T. Huber, R. K. Neumann, E. A. Oughton and J. Sidoli del Ceno (2018). “A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work?” Restoration Ecology 26: S7-S17.

Research Solutions (2020). “Subi-East CRG Review.” Perth, WA.

Sanoff, H. (1985). “The application of participatory methods in design and evaluation.” Design Studies 6(4): 178-180.

Steen, M., M. Manschot and N. De Koning (2011). “Benefits of co-design in service design projects.” International Journal of Design 5(2).

The Australian Centre for Social Innovation. (2020). “Unpacking co-design.” Retrieved September 23 2020, 2020, from https://www.tacsi.org.au/unpacking-codesign/.

van Doremalen, N., T. Bushmaker, D. H. Morris, M. G. Holbrook, A. Gamble, B. N. Williamson, A. Tamin, J. L. Harcourt, N. J. Thornburg, S. I. Gerber, J. O. Lloyd-Smith, E. de Wit and V. J. Munster (2020). “Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1.” New England Journal of Medicine 382(16): 1564-1567.

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

References 3938 | Principles To Place

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Development WA.

The authors would like to acknowledge the input into the organisation of the activity from Creating Communities Australia who were the lead engagement consultants on the project, particularly Andrew Watt for his suggestions and guidance.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and guidance from Catherine Bentley of Development WA.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support staff who hand delivered the individual models to private residences on a Sunday to meet the time-frames in response to distancing orders. In the words of one participant:

‘A particular shout out to the person who delivered maps and models to every single person’s house. got up one morning, to find all these maps of Subi East…. It was about 10.15 on a Sunday night that they were delivered. I caught them on my camera. I thought the amount of work they put into getting all of those packs done was phenomenal’

© AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021 © AUDRC Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2021

Acknowledgements 4140 | Principles To Place