The aim of this research project is to understand the barriers developers experience in delivering medium density projects on infill sites in Perth, and subsequently to develop strategies to mitigate these barriers. The findings of this report indicate that the principle barriers to medium density infill are community resistance and lack of sizeable development sites.

In responding to these challenges, the report concludes that planners should critically appraise State and Local Government planning with respect to limiting the number of centres targeted for infill development and setting minimum site areas and residential densities for infill development. Without such measures in place, it will continue to be difficult for developers to corral the necessary impetus behind medium density development. Moreover, the reports concludes that State or Local Government should deploy pilot projects and protect urban forests to reduce community opposition to infill, and that designers should develop alternative car parking arrangements and construction methods to increase project feasibility.

Wow! Now I understand

Missing in action

© Australian Urban Design Research Centre 2018

‘missing middle’

Strategies for delivering the

in Perth

Contents 1. Introduction 6 2. The barriers to medium density in Perth 34 3. Mitigating the barriers to medium density in Perth 48 4. Site testing the mitigation strategies 86 5. Conclusions 122 Contributors 124 Bibliography 126

5

1. Introduction

From 2000 to 2015, in all regions of the world, the expansion of urbanised land outpaced the growth of urban populations, resulting in ‘urban sprawl’...

6

Currently, more than half of humanity –3.5 billion people – live in cities, and the United Nations project this number will continue to grow (United Nations 2016). At the same time, from 2000 to 2015, in all regions of the world, the expansion of urbanised land outpaced the growth of urban populations, resulting in ‘urban sprawl’ (United Nations 2017). In a bid to deal with the problems of sprawl, and to deliver ‘equitable, efficient and sustainable use of land and natural resources’ (United Nations General Assembly 2016) governments are striving to deliver urban infill development.

Australia is no exception. All Australian State and territory capital cities have planning to achieve urban infill development. Infill development is typically being mandated to safeguard both rural and biodiverse land in the peri-urban zones, and minimise infrastructure costs, commuting times, and the concentration of economic and social vulnerabilities on the fringes of our cities (Kelly and Donegan 2015). Across the nation, capital city planning policies, on average, stipulate that 60% of all new residential development should be infill, yet far less than that is typically achieved (Bolleter and Weller 2013). We attribute this deficit to several factors, including typically unplanned approaches to infill development, community resistance (the Not In My Back Yard factor), and economic feasibility issues. Given Australia’s population is projected to grow from 25 to 70 million by 2100, our failure to meet our infill targets has serious implications. At a regional scale, the failure of Australian cities to meet their respective infill targets, could mean

that they grow in what is recognised as a typically unhealthy, socio-economically stratified, unsustainable and unproductive manner (Kelly and Donegan 2015).

In pursuit of infill development, urban planning strategies have focused primarily on Transport Orientated Development (TOD) principles (Calthorpe and Fulton 2001) which include Activity Centres, and the possibility of increased residential density along Activity Corridors (City of Melbourne 2010, Woodcock, Dovey et al. 2010, Duckworth-Smith 2012). Indeed, in a national effort to transition from monocentric to polycentric urban systems, State and territory policies identify 343 Activity Centres for infill development nationwide (Bolleter and Weller 2013). While the principles of TOD are well established and valid, their application in Perth, Melbourne and Brisbane has proven a challenge (Goodman and Moloney 2004, Kelly and Donegan 2015). As Jago Dodson explains ‘…despite more than two decades of consolidation policy, across Australia’s major cities there are vast suburban regions of low density development’ (2010). Indeed, Australian cities have some of the lowest residential densities in the world –Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane averaging only 15.7, 13.8, 12.1, 9.2 people per hectare respectively (Hurley, Taylor et al. 2017). While these cities typically do not meet their urban infill targets, much of the infill development that is delivered is comparatively low density, dispersed ‘background infill’ (Monash University Department of Architecture 2011,

7

Bolleter 2016). This form of infill can have detrimental effects on urban forests, street interface and private open space provision (Bolleter 2016).

The missing middle in Australian cities

Because of their low-density suburban form, commentators identify that Australian cities experience a ‘missing middle’ – a term coined by American architect Daniel Parolek in 2010. The ‘middle’ refers to medium density ‘multi-unit or clustered housing types compatible in scale with single-family homes’ that help meet the ‘growing demand for urban living’ (Opticos 2018). It has since gained considerable traction as the disparity between low-density residential housing and high-rise apartments in Australian cities has grown.

8

The term medium density development, which constitutes the missing middle, is ambiguous. In this report, we have defined it to encompass 2-3 storey compact housing, terrace style housing, maisonette (manor) housing, dual occupancy housing, townhouse housing, through to five storey low-rise apartments. The related residential densities extend from R40 (40 dwellings per hectare net density) to R100 (100 dwellings per hectare net density). In other Australian cities, planners and communities often consider medium density both higher and denser than this. Nonetheless, the definition we have employed is higher than the Western Australian Residential Design Codes which define medium density as between R30 and R60 (Western Australian Planning

Commission 2015).

The literature explains the presence of a ‘missing middle’ in Australian cities by several factors, which can be grouped into three broad categories; resistant communities, development economics or regulatory hurdles.

The literature indicates that communities in Australian cities are resisting medium density infill in their neighbourhoods because:

• There is a lack of a Local and State Government leadership and communication strategies for medium density infill (Rowley and Phibbs 2012).

• Residents perceive Infill as degrading neighbourhood character, decreasing in open space amenity (Searle 2004), increasing traffic and parking hassles (Holling and Haslam McKenzie 2010), lowering house prices and introducing ‘undesirable’ people into traditional family orientated suburban areas.

In relation to development economics, the literature indicates the predominate barriers to medium density infill development in Australian cities are:

• Difficulties of obtaining finance

• Cost and uncertainties of service infrastructure provision (Rowley and Phibbs 2012)

• Land availability and lot amalgamation challenges (Murphy 2012)

• A lack of economic incentives for developers tackling complex medium density infill (Urban Development Institute of Australia 2011)

• High construction and labour costs for mid-tier developers

• ‘Excessive’ car parking requirements (Holling and Haslam McKenzie 2010)

• Sometimes problematic and unattractive sites (Spira 2013).

In relation to the regulatory environment, the literature indicates the predominate barriers in Australian cities are:

• A lack of State Government containment policies on the fringe (Alexander and Greive 2010)

• Local government opposition to infill (Dovey and Woodcock 2014)

• Ineffective Local Government community consultation frameworks

• Local government lacking the funding or training required to deal with medium density infill development (Dovey and Woodcock 2014)

• Planning approval delays and uncertainties (Rowley and Phibbs 2012).

These barriers to medium density are all set out in the diagrams overleaf.

9

Community barriers

The literature review identified the following principle community barriers to high amenity medium density density development in Australian cities.

Source: literature various

Community resistance to infill generally

Community resistance due lack of a communication strategy regarding urban infill

Community resistance due to built heritage and neighbourhood character concerns

Community resistance due to decrease in open space amenity

Community resistance due to poor quality medium density development

Community resistance due to increase in traffic and parking nuisance

Community resistance due to social concerns regarding residents of higher density development/ reduced house prices

Detached houses

(R12) Suburbs (R25-40)

Suburbs

The ‘missing middle’

Suburbs (R40-60)

Group dwellings

Duplex Manor houses Town houses

Lack of buyers of medium density product due to strata concerns and lack of traditional family suitable dwellings

11 Activity Centres (R60+) City centre (R100+) Terraces Apartments 3 storeys Apartments 5

Apartments 7

Apartments 20

storeys

storeys

storeys Apartments 2 storeys + maisonettes

Economic barriers

The literature review identified the following principle economic barriers to high amenity medium density density development in Australian cities

Source: literature various

houses

Detached

Suburbs

Suburbs (R12)

(R25-40)

Suburbs (R40-60)

The ‘missing middle’

Group dwellings

Duplex Manor houses

Town houses

Cost and uncertainties of service infrastructure provision Difficulties of obtaining finance

Land availability + lot amalgamation challenges

A lack of economic incentives for developers tackling complex medium density infill

Construction + labour costs for mid-tier developers

‘Excessive’ car parking requirements

Sometimes problematic/ unattractive sites

13 Activity Centres (R60+) City centre (R100+) Terraces Apartments 3 storeys Apartments 5 storeys Apartments 7 storeys Apartments 20 storeys Apartments 2 storeys + maisonettes

Regulatory barriers

The literature review identified the following principle regulatory barriers to high amenity medium density development in Australian cities

Source: literature various

A lack of a Local/ State Government leadership/ communication strategy for medium density infill

A lack of State Government containment policies on fringe

Local Government opposition to infill

Ineffective Local Government community consultation frameworks

Detached houses

(R12) Suburbs (R25-40)

Suburbs

(R40-60)

Suburbs

The ‘missing middle’

Group dwellings

Duplex Manor houses

Town houses

Onerous Local Government garbage truck requirements

Main Roads regulations regarding access on arterial roads

Local Governments not funded or trained to deal with medium density development

Planning approval delays/ uncertainties

15 Activity Centres (R60+) City centre (R100+) Terraces Apartments 3 storeys Apartments 5 storeys Apartments 7 storeys Apartments 20 storeys Apartments 2 storeys + maisonettes

The missing middle in Perth

16

While the above diagrams set out the predominate barriers to achieving medium density experienced in Australian cities, this report is specifically focussed on Perth – a city which differs from Melbourne and Sydney (for instance) in relation to population size, density and growth, economic conditions, and cultural identity. Indeed, Perth is one of the lowest density, most car dependent cities in the world. In response to its sprawling form, there have been repeated attempts by State Government to deliver medium density development in conjunction with public transport nodes. Perth’s ‘Metroplan’ strategy launched in 1990, the 2004 ‘Network City’ plan and 2010 ‘Directions 2031’ plan, all aimed to consolidate urban infill development in relation to public transport routes and nodes (Department of Planning and Western Australian Planning Commission 2015) in Activity Corridors and Activity Centres.

Despite Activity Centre and Activity Corridor policies being the flagships of State Government TOD planning, a significant amount of low density urban infill development is occurring through the subdivision of suburban backyards in Perth’s Central Sub Region –development which is controlled through the State Government administered R-Codes (West Australian Planning Commission and Department of Planning 2015) and Local Government planning schemes. This form of urban infill development we refer to as ad hoc subdivision or ‘background’ urban infill – namely, small projects yielding fewer

than five group dwellings (Department of Planning and Western Australian Planning Commission 2014). The issue with this density of urban infill development is that it delivers poor private open space amenity, erodes the urban forest, and is typically car dependent (Duckworth-Smith 2015, Bolleter 2018). Moreover, because of strata titling, it will be exceedingly difficult to redevelop these areas at a higher density in the longer term.

Despite the long term application of Activity Centre and Activity Corridor policies (and a comparatively low target for 47% of urban infill) Perth achieved 41% in 2016 which is higher than Perth’s historical average (Department of Planning 2017). Moreover, figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) show that, in Perth in 2017, 73% of all new residential development was single houses (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018). The national percentage for single houses in 2017 was much lower, at 53%. Only 13% of all new residential development was ‘medium density’ which the ABS classes as semidetached, townhouses and flats, units or apartments between one and three storeys (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018). This compares to the national percentage of 19%. In Perth 14% of all new residential dwellings were flats/ units/apartments, 4 storeys and above. The national percentage was 27% (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018). These figures are confirmed by data from Bankwest which shows that Western Australia, and Perth in particular has the lowest percentage of medium density dwelling approvals (28%) of any other mainland State

(Bankwest 2017). The ACT has 81%, NSW has 60%, Victoria 48%, and South Australia 31% (Bankwest 2017).

WA

building approvals 2012- 2017

This graph reveals a relative shortfall of 2-3 storey apartment development in Perth 2012-2017.Data courtesy of Housing Industry Forecasting Group

0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 Semi-detached 1 storey Semi-detached 2 storey Apartment 1-2 storey Apartment 3 storeyApartment 4+ storey 17

New Perth dwellings by type 2014- 2017

This graph reveals that developers delivered a declining amount of 2-3 storey medium density developments in Perth between 2014-2017. Data courtesy of the Australian Bureau of Statistics

Apartments 1-2 storeys

Apartments 4+ storeys

Flats/ units/ apartments (1-2 storeys)

Flats/ units/ apartments (3 storeys)

Flats/ units/ apartments (4+ storeys)

Apartments 3+ storeys

0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 3,000 3,500 4,000 2014201520162017

New lots since 2009 and Activity Centres/ corridors

This map reveals that much of the infill development occuring in Perth since the release of Directions 2031 in 2009 is not in designated Activity centre of Activity Corridor sites, or near to Regional Open Space or public transport. This map is indicative only. Data courtesy of Landgate + the DPLH

19

Suburban fabric prior to background infill

A visualisation of a R15 suburban area typical of Perth’s middle ring suburbs with generous private open space and leafy green amenity prior to background infill.

Suburban fabric post background infill

A visualisation of a typical R25-40 suburban area typical of Perth’s middle ring suburbs post background infill development.

While background infill leads to some increase in residential density it tends to occur at the cost of the urban forest and the ecosystem services it provides, as well as aggravating communities.

Moreover, the issue with this density of urban infill development is that, because of strata titling, it will be exceedingly difficult to redevelop these areas at a higher density.

21

Typical example of background infill

This plan shows a background infill subdivision typical of Perth’s middle ring suburbs. The issue with this density of urban infill development is that it generally delivers poor private open space amenity, erodes the urban forest, and is typically car dependent

Case Study 01

Number of Dwellings 6 Dwellings

Number of Lots Double Lot

Site Area 1578m2

Built Footprint 647m2 - 41%

Driveway 474m2 - 23%

Private Open Space 220m2 - 14% 0 5 10 15 25m

Site plan

Garage Entry Pedestrian Entry Private Open Space Driveway Road

Floor plan

23

Typical background infill

In such background infill examples almost 25% of the lot area (not including enclosed garages) is dedicated to the movement of vehicles. As a result the area of private open space is considerably reduced.

Site plan

Case Study 02

Number of Dwellings 2 Dwellings

Number of Lots single lot

- 23%

- 19%

Site Area 698m2 Built

334m2

Driveway 165m2

Private

133m2

0

Footprint

- 47%

Open Space

5 10 15 25m

Garage Entry

Pedestrian Entry

Private Open Space Driveway Road

Floor plan

25

Method

Given the challenges posed to delivering medium density infill development in Perth, the research question that forms the basis for the initial chapter is:

What community, economic, and regulatory barriers exist to developers delivering high amenity medium density urban infill projects in Perth?

As explained previously, we define medium density development as between 40 and 100 dwellings per hectare (net density) and a height of between two and five stories. We have chosen to focus on existing suburban areas fringing Perth’s Activity Centres which are typically zoned for a residential density of between R40 and R100. This reflects that these sites are where State Government planning aims to deliver medium density development. While shopping centre or heritage train stations form the heart of many of Perth’s Activity Centres, we considered these as requiring planning approaches that were less generalisable to the broader suburban condition of Perth, and Australian cities. Henceforth, we have excluded them from our scope.

The research question that forms the basis for the subsequent chapters is:

What strategies can government planners employ to mitigate the barriers to high amenity, medium density infill development in Perth, and how do these strategies relate to existing planning policies?

The reference to high amenity in this case means internal rooms and spaces that are adequately sized, comfortable,

with good levels of daylight, natural ventilation and outlook; complemented by well-designed external spaces that provide welcoming, comfortable environments with effective shade as well as protection from unwanted wind, rain, traffic and noise (Department of Planning 2016).

We generally focus on mitigating strategies that have a spatial dimension although we do also propose community or governance related strategies. We have visualised the mitigation strategies proposed by interviewees in the latter chapters of the report. In the visualisations, we have applied these strategies in a typical test site on the suburban edge of a greyfield, middle ring suburb, Activity Centre.

The reference to existing planning policies in this case means principally the State Government administered Residential Design Codes (R-Codes) which control the design of residential development in Western Australia, through dictating maximum building heights, lot boundary setbacks, privacy requirements, overshadowing, amongst others (West Australian Planning Commission and Department of Planning 2015), as well as the ‘Draft Perth and Peel @3.5 million’ which is the overarching plan for Perth (Government of Western Australia 2015, Department of Transport, Public Transport Authority et al. 2016). The State Government recently released a draft design guide for apartments (Department of Planning 2016), informed in part by NSW’s SEPP 65 Apartment Design Guide. However, for the duration of our project this document has been under review, as

26

part of a broader examination of Western Australia’s planning process, as such we have not made it a specific focus. Reference to existing planning policies also includes local planning schemes and supporting documents such as Activity Centre Structure Plans that designate residential densities and land use.

To answer both research questions we utilised an inductive, qualitative ‘descriptive’ research strategy (Swaffield and Deming 2011). Descriptive research strategies produce new knowledge by systematically collecting and recording data that is observable or tangible (Swaffield and Deming 2011). As such, to understand the barriers to medium density development, and possible mitigation strategies, we gathered data from interviews with:

• Private developers/ builders

• Development institutes

• Parliamentarians

• Architect/ developers

• State Government planners

• Local Government planners

• Councillors

• Community representatives

• Planners employed in the private sector

• Real estate experts

• Civil engineers, and

• Urban designers

We asked interviewees about feasibility, regulatory, and community barriers to

delivering medium density development in Perth. Subsequently, we asked interviewees about mitigation strategies for the barriers experienced. All interviews were semi-structured and open-ended, lasted 30-60 minutes, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim after completion, yielding hundreds of pages of text data. We then reviewed, and re-reviewed the interview transcripts to find key themes.

Complimenting this interview process was a comprehensive literature review regarding urban infill development and medium density development both in Australia, and internationally. However, we have emphasised the results of the interviews, as we believe that many of the barriers to medium density relate to a specific urban context, and its cultural, societal, economic and governance complexities – a level of geographic specificity that a literature review of national (and international) publications is unlikely to garner. This interview process updates important stakeholder engagement work conducted in Perth and Melbourne in 2012 by Steven Rowley and Peter Phibbs from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (Rowley and Phibbs 2012).

In the developed world, planning in the twentieth century was about designing and delivering ‘sprawl’ (Schneider and Woodcock 2008). Subsequently, the densification of this sprawl will be one of the major challenges for designers and planners in the twenty first century. While we have limited our focus to Perth, we have directed this report towards this broader challenge.

27

Research method

This diagram sets out the research method we use to examine the research question:

What community, economic, and regulatory barriers exist to developers delivering high amenity medium density urban infill projects in Perth?

Review literature on barriers to medium density nationally

Review current medium density in Perth

Interview stakeholders re barriers to medium density + mitigation strategies in Perth

Development industry

Literature review

Chapter 1

Mapping and data review

Design professions

Government

Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Develop strategies for medium density in Perth

Strategy 1

Strategy 2

Strategy 3

Chapter 3

Test strategies on a typical site in Perth

Conclude findings

Typical test site

Conclude findings

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

29

Typical study areas

We have chosen to focus on suburban areas fringing Perth’s Activity Centres which are typically zoned for a residential density of between R40 and R100. The choice of such sites reflects that these are where many of the barriers to medium density (such as community opposition and land amalgamation, are most pronounced).

Morley Primary Activity Centre

Data courtesy of DPLH and Landgate

Cannington Primary Activity Centre

Data courtesy of DPLH and Landgate

31

Whitfords Centre

Data courtesy of DPLH and Landgate

Maylands Activity Centre

Data courtesy of DPLH and Landgate

33

2. The barriers to medium density in Perth

The following chapter sets out the barriers experienced by developers in delivering medium density development

34

The following chapter sets out the barriers experienced by developers in delivering medium density infill in Perth in relation to three broad categories, community, economic, and governance. These barriers have been primarily discerned from the interview process described previously.

35

Dominant barriers to delivering high amenity medium density development in Perth

This graph idenitifies the dominant community, regulatory and economic barriers to medium density development identified by our interviewees. The most signficant barrier was community resistance. Others included a lack of local government expertise and support, and finally difficulties amalgamating lots. Please note, due to the difficulties of quantifying qualitative research this graph is indicative only.

(Source: interviews)

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%

Community barriers

Regulatory barriers

Economic barriers

37

Community barriers

Community resistance

Overall interviewees consistently rated community resistance as the most significant of all the barriers to medium density infill, because it created uncertain conditions for development. This tallies with the literature around urban infill development (Wheeler 2001). For example in 2011, 52% of suburban residents of Australia’s capital cities said they ‘would not like’ increased population in their neighbourhood and only 11% said they would like it (Productivity Commission 2011). As Wendy Sarkissian tells us: ‘A huge battle has been waging for more than two decades about this matter in Australia…’ (Sarkissian 2013) – and that a public ‘sullenness’ exists in relation to the densification of suburban neighbourhoods (Kelly and Donegan 2015).

Our interviewees identified several key reasons for this community opposition. These included fears related to perceived increased traffic and parking hassles (Local government planner 2018, Parliamentarian 2018), declining property prices (Development institute representative 2018), a lack of privacy, a lack of amenity (Parliamentarian 2018), and the destruction of greenery and in particular urban forests (Community Representative 2018).

Poor examples of low to medium density infill

Moreover, the interviewees regarded that poor examples of urban densification were fuelling resistance in existing communities (Parliamentarian

2018). This was particularly those arising from the ‘blanket re-zonings’ which produce background infill (Developer 1 2018, Real estate expert 2018) and essentially saw ‘shit behind shit, you know, triplex development’ (Developer 1 2018). Interviewees identified that such examples had not sensitively considered local context, streetscape and interface, lacked mature trees, greenspace and amenity and were dominated by paved surfaces (State government planner 2018). Interviewees regarded that such examples confirmed the worst fears of resistant communities. As a parliamentarian explained, ‘you make the job much easier for a NIMBY crowd when it’s a really poor design with poor amenity…’ (Parliamentarian 2018). Interviewees identified that the loss of mature trees arising from blanket up-zonings were a major issue for communities. As one interviewee explained ‘in my local experience a lack or a loss of canopy can be quite distressing for local people, and that can lead to them “getting their backs up”’ (Community Representative 2018).

The R-Codes were criticised for allowing such development to occur. As one interviewee explained, such projects may be ‘fully in compliance with the R-Codes, but it’s not necessarily contextually responsible, high quality, or responsive to the needs of the community…‘ (Urban designer/ planner 2018).

Established developers also cited poor quality urban infill as a major issue:

It makes me cringe when I see some of the developments of the last 40 years here... And that’s why it’s so important

38

we get it right this time cause otherwise it will take another generation to rebuild the trust that we lost ... people will say, ‘Oh no, see I knew it was a ghetto.’ Just like it did in the fifties (Developer 2 2018).

The interviewees perceived that poor examples of densification were particularly an issue because Perth residents had a deep-seated cultural affinity with suburbia. Interviewees stated that a significant ‘cultural shift’ was required for existing suburban residents to develop a ‘cultural appreciation of the benefits of medium density’ (Architect and developer 2018). To enable this shift, interviewees regarded that the built examples of urban infill needed to be not just average, but exemplary (Developer 2 2018).

39

Economic barriers

Low land values and profit margins

Ultimately, the development industry delivers medium density housing in return for a profit. ‘Without this, development simply will not happen’ (Rowley and Phibbs 2012). Accordingly, interviewees noted, that barriers to medium density in Perth included ‘flat’ economic conditions, comparatively low land values, (by Sydney or Melbourne standards) and reduced population growth. They noted that, as a result, medium density development is ‘going to struggle in most locations, unless you’re in a really prime apartment location’(State government planner 2018). Interviewees regarded that having the required economic conditions in place was fundamental to delivering medium density urban infill. As one interviewee put it, ‘if developers see the margins, then they will do it. The market will make it happen’ (Civil engineer 2018).

Compounding Perth’s relatively low land values was State Government planning for urban infill, which interviewees perceived, designated too many potential centres for densification. As one interviewee explained ‘... Just because you’ve drawn a box and said, “Insert good project here,” doesn’t mean that someone’s going to step in and do that’ (Architect and developer 2 2018). Perth’s Activity Centre network planning was (in particular) criticised by interviewees:

I mean there’s 93 of them or something. You’re trying to do it across too many centres and inevitably you can’t invest

as much as you would like, and really need to, to kick off a couple of the major ones (Developer 2 2018).

Some interviewees went as far as to describe Perth’s Activity Centre planning as a ‘complete mess’ (Civil engineer 2018) because of a lack of hierarchy, development priority, and in turn government funding. This is important because as Goodman and Moloney remind us:

Activity Centre planning requires an enormous commitment from government to provide infrastructure and incentives as well as the means required to assemble land. Without an appropriate level of funding and government co-ordination it is unlikely there will be any significant outcomes from Activity Centre planning (Goodman and Moloney 2004).

High construction costs

Interviewees identified other economic barriers to medium density development, such as construction costs – the cost of building medium density housing being ’considerably more per square metre’ than that of detached suburban dwellings (Architect and developer 2018). While the increased complexity of construction involved in medium density development is a significant factor in determining cost – E.g. multi-storey construction, shared party walls, lifts, stairs, and required fire separation between dwellings (Monash University Department of Architecture 2011) – there was a perception among interviewees that building medium density developments in Perth should be cheaper. In part, interviewees

40

perceived that this was due to the lack of experience of local builders in working with alternate, lightweight construction systems that could reduce the costs of building. As a developer explained:

…the cost of construction is still too high for medium density stuff. That’s why we end up leaning all the time down on the double brick single storey stuff. As soon as you get into any sort of density it just becomes very expensive (Developer 2 2018)...

A reliance on brick construction in Perth is both reflective of an oversupply in bricks and a relative surplus of brick layers (Developer 2 2018). Moreover, Perth was perceived to be lacking in carpenters, skilled in timber, light weight construction techniques, such as those employed to construct timber framed medium density dwellings in the ‘Lightsview’ project in Adelaide (Developer 2 2018).

Interviewees explained, that the result of expensive construction methods was that potential buyers ‘do the equation and calculate they’re going to get, 100 square metres in a medium density house compared with a 220 square metre house on a larger piece of land [on the fringe of the city]. To many, that equation doesn’t stack up’ (Architect and developer 2018). This in turn leads to difficulties in developers achieving the bank finance needed to construct medium density projects (Architect and developer 2 2018).

Land assembly challenges

Another factor inhibiting medium density development in suburban infill sites is the fragmented land ownership (Murphy

2012). As the interviewees explained, ‘most significant medium density typologies, such as low-rise apartments, require the amalgamation of sites to be feasible. The problem for developers is that lot amalgamation takes time; time they can’t or do not want to spend’ (Civil engineer 2018). As a State Government planner further elaborated:

They don’t view that long-term return on investing. They say, ‘Hang on, if we sold that for 200 houses, we’re going to make a few extra million. But if we wait to develop that over time with a whole bunch of apartments… it’s going to maybe take 10 years to do it all. Or we just chop it up into single lots, it will be sold in a year, and we’ll pocket the money.’ They take a very short-term view of the world (State government planner 2018).

The result of lot amalgamation challenges is that low density background infill is delivered indiscriminately throughout up-zoned areas. As one interviewee explained: ‘Every time there’s a lifting of the R codes we just subdivide the lots whereas really what we should be doing is trying to consolidate the lots and deliver a much better outcome’ (Development institute representative 2018). This reflects the situation where there are few restraints on subdividing suburban quarter acre lots for background, survey strata infill dwellings.

Service infrastructure uncertainties

Another key economic barrier to the delivery of medium density projects in suburban Activity Centre sites is the

41

cost of providing service infrastructure. This cost directly affects the feasibility of a development, and is compounded by uncertainties around developer contributions for infrastructure upgrades which all add to the perceived risk (Rowley and Phibbs 2012). As one interviewee explained ‘People say [about urban infill], ‘Oh, we want to make better use of the infrastructure we’ve got.’ Pipes and wires basically are what it comes down to, but they get full. Once they’re full, it’s an astronomical cost to upgrade them, particularly sewers… (Civil engineer 2018). This is an issue in Perth because there is no State Government ‘infrastructure funding mechanism… to be able to start funding some of that’ (Local government planner 2018) which means that Local Governments pay, or alternatively they pass the cost of infrastructure upgrades to developers. This uncertainty is a major impediment to medium density infill development and the costs of infrastructure upgrades are inevitably passed on to the end consumer (Rowley and Phibbs 2012).

Car parking requirements

State Government dictated car parking requirements are another significant economic barrier for medium density infill redevelopments, in that they limit developable areas (Monash University Department of Architecture 2011). Indeed, in background infill, vehicle access and parking constitute a substantial proportion (~25%) of the site (Bolleter 2016), not including garages. In Perth, requirements stipulate that 1 bedroom dwellings have between 0.75 and 1 bay, 2+ bedroom dwellings 1 to

1.25 bays, in addition to visitor car parking (Department of Planning 2016), requirements which are broadly aligned with buyer expectations. Nonetheless, one interviewee explained that such parking provision reduced development feasibility:

Parking is a huge thing. And not just parking, but then the need to cover the parking to make it as direct as possible, in terms of its relationship to units. The expectations we have in the community [around parking] really confound the potential for building design outcomes (Architect and developer 2018).

Onerous parking requirements on development sites also can limit the retention and propagation of mature trees that would help to moderate community resistance to medium density infill. Of course this needs to be balanced by community concerns regarding the parking hassles in adjacent streets, which existing residents perceive to go hand in hand with infill development (Local government planner 2018, Parliamentarian 2018).

42

43

Governance barriers

Compounding such economic barriers to medium density infill, interviewees perceived, was the inexperience and resistance of some of the Local Governments charged with delivering medium density infill in Perth. Rightly or wrongly, interviewees made this claim both with respect to councillor and officer level staff.

Resistance from Local Government

Resistance to urban infill can be significant at the Local Government level. This is reflective of a political structure which is ‘divided between local and state levels where the state holds all the power and the purse strings, yet local councils take much of the responsibility for development decisions’ (Dovey and Woodcock 2014). As Kim Dovey explains:

Much of the blame for inaction falls upon local councils who are often elected to enforce the anti-development views of their residents. The State Government does not want the electoral backlash that flows from urban intensification and is happy for Local Government to be seen as responsible. Yet local councils are not funded nor staffed to deal with the complexities of transit-oriented development (Dovey and Woodcock 2014).

The perception of interviewees was that Local Government councillors are being disproportionately affected by a ‘noisy minority’ of residents who are opposed to urban infill development. As one interviewee explained ‘the councillors all respond to the community voice… and as such minority groups, of 10 people,

are still winning because they’re voicing it through the council (Real estate expert 2018). Other interviewees explained that ‘until the community attitude to medium density softens’ it is going to mean ‘resistance from many elected members’ (Architect and developer 2018). In response, a Local Government councillor explained ‘I am a servant of the people, and Local Government is not like State Government. If I believe the majority of the people want X, that’s what I will support: X’ (Local Government Councillor 2018).

Partly because of this resistance some Local Governments have been slow to produce design guidelines to steer medium density development, relying instead on the generic R-Codes document prepared by the State Government to regulate development outcomes across the whole state (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015). As one interviewee explained:

I think there is some Local Governments that are being very naughty. There is nothing to have stopped them producing design guidelines to produce better design, and they haven’t. And they blame the state. No, you could’ve done that, and you haven’t (Parliamentarian 2018).

However, other interviewees explained that even where Local Governments had produced such planning, the statutory weight of the R-Codes meant planners assessing development applications were required to comply with the R-Codes (and its open space and lot size requirements) regardless

44

(Local government planner 2018); in effect over ruling local planning policies.

Moreover, interviewees also explained that where Local Governments had produced guidelines for medium density development there was little coherence or continuity between the planning frameworks (Architect and developer 2018), a situation which in turn results in uncertainty and decreases development feasibility. This situation, interviewees identified, was not helped by the ‘crazy number of local authorities’ in Perth (Real estate expert 2018)

A lack of expertise

Further to the influence of sullen communities on councillors, interviewees identified a ‘lack of competence’ and ‘courage’ in some councils in relation to delivering medium density infill development (Developer 1 2018). The interviewees alleged this lack of expertise took several different forms. Some criticism stemmed from the fact that the council officers approving medium density development were planners ‘with a complete lack of knowledge’ regarding the complexity of medium density projects (Architect and developer 2018). As one interviewee explained:

There is a lack of education on both the planning and consumer side, so people ring up the council and ask ‘Hey, what’s going on with this [development]?’ And the planner being like ‘Meh, I dunno.’ It’s either compliant or it’s not compliant, I don’t know whether it’s good or bad, it’s just compliant or not compliant… (Architect and developer 2018).

As interviewees noted, because there is

often ‘no one at council explaining what the ‘design move’ is, everyone is ‘in the dark’ (Architect and developer 2018) which leads to increased confusion and, in turn, community resistance. Partly because of an alleged lack of expertise, Local Government approval times for medium density projects can reputedly take ‘two years’ (Developer 1 2018) which obviously works against project feasibility.

Poor community engagement

Reflective of a lack of expertise is (sometimes) poor Local Government led community engagement processes. While Local Government’s set the zoned residential density of suburban areas, existing residents sometimes do not fully understand the implications of such zonings. As an interviewee explained:

…Local Governments are at fault in the sense that they… zone an area medium density or high density, then a developer comes along, rightly puts forward a proposal, and then the Local Governments do everything they can to slow it down or stop it. Because they get a bit of backlash, because, they didn’t explain to the community what the zoning meant [in terms of height], because they’re poorly engaged and advertised. And then the developers cop it (Parliamentarian 2018).

Often existing residents only find out about a medium density development adjacent when the council sends them a notification well into the design process. As another interviewee explains, ‘Part of the problem is people find out about it when they are sent the draft Development Application by the council,

45

46 that this is going to be built next door, and they flip out about it… [They feel] how could you be doing this without me knowing? Even though there’s a structure plan that was advertised two years before’ (Civil engineer 2018).

47

3. Mitigating the barriers to medium density in Perth

In this chapter we set out the strategies that interviewees identified could mitigate barriers to medium density...

48

While the previous chapter set out the barriers that developers experience in attempting to deliver medium density infill in Perth, in this chapter we set out the strategies that interviewees identified could mitigate these barriers (refer to the diagram overleaf for a summation).

Please note, we do not intend this section to be an overarching guide for the design of medium density infill development – this being available through the existing literature (Department of Planning 2011, Monash Architecture Studio 2012) . Rather it illustrates the key mitigation strategies that were identified by interviewees.

49

Mitigating strategies for delivering high amenity medium density development

Interviewees felt that high quality pilot projects in conjunction with mandating minumum densities and lot sizes for infill development were essential for mitigating the barriers to medium density development in Perth. Please note, due to the difficulties of quantifying qualitative research this graph is indicative only.

(Source: interviews)

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

Community mitigation strategies

Regulatory mitigation strategies

Economic mitigation strategies

51

Deploy

pilot projects to educate communities and test assumptions

Overall, interviewees felt that the most effective strategy was the deployment of pilot projects to help shift community resistance to infill. The interviews indicated that pilot projects were of importance, in dispelling the ‘myths, and fears’ about medium density living (Dovey and Woodcock 2014). As one developer explained ‘As we demonstrate good outcomes… I think the fearful [communities] will go, “ah okay, it wasn’t such a big deal”’ (Developer 2 2018), and community cynicism will be dispelled (Developer 2 2018). This highlights the need for more exemplar medium density infill projects such as Landcorp’s White Gum Valley development. The replication of such projects throughout Perth’s Local Government Areas – with the necessary adjustments to local character – has significant potential to reduce community resistance to medium density.

Future research projects should ultimately test the pilot projects in constructed form to understand the degree to which they deliver high amenity, feasible urban infill development. A ‘long-term longitudinal research project’ could assess the ‘design and liveability outcomes for the residents, transport usage’ amongst other aspects (Civil engineer 2018). As another interviewee explained:

I think one of the failings… is we don’t tend to do a review post development, so we can go back and say, ‘okay, what was the community concerned about? Did those fears eventuate or not or what

mitigation strategies were adopted in the design? Did they work or not?’ (Development institute representative 2018).

Interviewees believed that being able to provide such empirical, real world data could help to shift community sentiment by providing ‘evidence to comfort people’ who are worried about how medium density infill is ‘going to affect their wellbeing and their livelihood’ (Development institute representative 2018). The need for project evaluation that interviewees identified, certainly tallies with the related literature. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) propose that internationally comparable indicators can help measure compact city policy performance so that ‘metropolitan areas can benchmark their results and improve their policy actions’ (OECD 2012) – a crucial tool in engaging the community and moving towards ‘shared goals.’

52

Figure caption: The deployment of pilot projects can be used to reassure communities about built outcomes as well as test the assumptions behind infill development through longitudinal research projects.

As we demonstrate good outcomes… I think the fearful communities will go, “ah okay, it wasn’t such a big deal” (Interviewee)

53

Correlate medium density development with public domain upgrades

The interviewees felt that medium density development in suburban settings should communicate the kind of ‘community benefits’ that development could yield (Developer 1 2018). As one interviewee elucidated:

I think it has a lot to do with evolving community attitudes and demonstrating the benefits of medium density housing. I think much of that will come simply through the consistent delivery of it and understanding that it delivers better streets where people are able to commune with one another, it delivers better levels of service in terms of more shops within walking distance, cafes, bars, these kinds of things. The more population you have, the more intense population you have in a setting, the more that can be offered in the terms of those kinds of public amenities (Architect and developer 2018).

Interviewees considered that improvements should be particularly focussed on the public domain such as streetscapes where ‘proper’ tree planting can reduce the perceived density of urban infill and making it less ‘imposing’ (Real estate expert 2018). One interviewee cited the neighbourhood of Kingston in Melbourne which has ‘three, four, five storey apartment blocks’ but ‘you can hardly tell’ because they’ve got road reserves with these massive trees, well developed shoulders with landscaping and footpaths and cycle ways’ (Real estate expert 2018). Moreover,

interviewees felt that much better use could be made of road reserves:

When I was a kid, a long time ago, there were 16 kids in the street. There was four games of cricket and two games of soccer going on all the time… you don’t really see it happening anymore (Civil engineer 2018).

Interviewees identified the upgrading of local parks as a key strategy to both provide amenity to a densifying neighbourhood, but also to incentivise community acceptance of medium density development (Developer 2 2018, Local Government Councillor 2018) –although the difficulties of securing the support of local council parks department was noted (Urban designer 2018). Finally, interviewees also suggested that medium density developments could locate some of their ‘communal, private open space, say, on a corner, and giving this element back to the public realm’ (Urban designer/ planner 2018).

Such strategies have implications for Western Australia’s R-Codes as this document only dictates building, garage and carport setbacks from the street (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015), as opposed to requiring infill developers to upgrade the streetscape or local parks, or provide communal open space to the public.

54

After

Before

Figure caption: Medium density development can be incentivsed to local communities by improving the public domain.

Medium density developments could locate some of their communal, private open space, say, on a corner, and giving this element back to the public realm (Interviewee)

55

Typical background infill

Infill linked by an upgraded public domain

Figure caption: Medium density development should be correlated with upgraded streetscapes and new pedestrian connections between amalgamated lots. This can helpt to reduce the perceived density of development

Kingston in Melbourne which has three, four, five storey apartment blocks but you can hardly tell because they’ve got road reserves with these massive trees, well developed shoulders with landscaping and footpaths and cycle ways (Interviewee)

57

Mandate minimum lot sizes/ incentivise lot amalgamation

Interviewees felt that background, low density infill should be constrained through setting minimum lot sizes for urban infill development – a situation which interviewees believed would increase market demand for medium density development (Architect 2018, Local Government Councillor 2018). While an exact minimum was not generally provided one interviewee regarded this should be around ‘1,200 to 1,500 square metres’ (Development institute representative 2018), which would essentially preclude any suburban infill unless adjoining lots could be amalgamated- the typical suburban lot being 1000 square metres or less. This minimum would preclude the ‘mum and dad investor [who] without even thinking… can make money’ (Real estate expert 2018) on a ‘crappy little subdivision’ (Developer 1 2018) a situation which has led to only a ‘minimal increase in the dwelling yields’ of existing suburbs (Real estate expert 2018). It was noted however that the setting of minimum lot sizes would possibly incur a ‘huge political backlash’ (Civil engineer 2018). Short of mandating minimum lot sizes interviewees felt that greater incentives could be given to encourage land amalgamation (Architect and developer 2018, Real estate expert 2018). These could include density bonuses, ‘cash, opportunities, or swapping air rights’ (Developer 2 2018), and split zonings which allowed higher densities for amalgamated lots (Planner 2018).

The importance of lot amalgamation

was stressed by most interviewees and even referred to as the ‘holy grail’ in terms of achieving medium density infill development (Developer 2 2018). The need for lot amalgamation was explained in terms of it allowing the ability of designers to respond to the ‘site characteristics, the orientation… achieve higher buildings ... and a better density return and a much better outcome that the community would be accepting of’ (Development institute representative 2018). Other interviewees believed that lot amalgamation provided ‘more room to move’ which, in turn, made medium density infill ‘cheaper to build, as it improves the efficiency of the site,’ as well as reducing the perception of ‘imposing’ medium development (Real estate expert 2018).

Moreover, larger lots were linked to development feasibility, as one interviewee explained:

Developers just can’t get big enough slabs of dirt, so rezoning it all to R60, R80, R100, is meaningless unless you have framework that pulls these lots together to give developers a decent piece of Perth to work with… (Real estate expert 2018).

Conversely, on a small non amalgamated lot one interviewee explained the ‘overlooking, the design, everything gets complicated and you start annoying all your neighbours’ (Real estate expert 2018). As they reasoned: when you are trying to put ‘10, 15 units’ on a small lot ‘they’re all going to be really punky units, with tiny little balconies because we’re trying to maximize the yield to make it work’ (Real estate expert 2018).

58

No amalgamtion = no development

Locked

Amalgamtion = development

Figure caption: Mandating minimum lot sizes for infill could improve development outcomes

Unlocked

59

While the R-Codes document sets out minimum lot areas for medium density development, these are comparatively small and unlikely to preclude the ‘business as usual’ background infill development (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015).

60

61

Mandate minimum densities for infill

While interviewees regarded that minimum lot sizes should be set, they also strongly felt that minimum residential densities should be established, with possible rewards for developing above the minimum density (Real estate expert 2018, State government planner 2018). As one interviewee explained: ‘you need to mandate minimum densities before infill [in appropriate areas]. And don’t mess around with R30 or 40, but get it up to R80 or 100…’ (Community Representative 2018). As another interviewee explained the problem with schemes which merely incentivise density (in isolation) was that developers ‘don’t want to build apartments there. They want to build a hundred terrace houses, they don’t need your density’ (State government planner 2018).

Interviewees identified that once low-density background infill had occurred, and larger lots subdivided and strata titled, it was very difficult to adapt to a medium density outcome over time. As one interviewee elucidated;

You need to force the market to pause and not get away from itself… we have to stop these individual lots from being carved out because we’re all going to strata and trying to unwind those strata titled lots 20 to 30 years from now is going to be so much hard work (Real estate expert 2018).

Another interviewee argued that setting minimum lot sizes and minimum densities could actually constrain infill development in a ‘flat’ real estate market (such as Perth is currently experiencing), rather than lead to medium density

outcomes (Civil engineer 2018). In response other interviewees argued that it was important for those setting such controls to hold their nerve until market conditions improved and medium density outcomes were forced. This was also linked with the perception of there being too many Activity Centres and ‘too much land’ which means there is little uptake of medium density. As one interviewee expounded:

The most important thing is that planners need to have is courage and hold steady with their plans, and every time a plan doesn’t seem to be rolling out the way they want, to avoid going ‘let’s start again and reshape it.’ If we sit back and look at the property cycle, what doesn’t work today, will work in a few years … we live in a world of economic and market cycles… If Perth grows to a metropolitan population of three million by 2031, it will come back, it’s just at the bottom of the market now, which is just starting to come good again. If we are patient and we create the appropriate frameworks this will happen (Real estate expert 2018).

Other interviewees also made the point that community attitudes to urban infill would also likely soften over time, so it also may pay to wait on this front too. As one interviewee described ‘maybe we just need to take a stop at where we’re at and what we’re asking of people and just make sure that we have everything in place that we need, for when people are ready to live in a multi-unit [medium density development]’ (Local government planner 2018).

The setting of minimum densities

62

Figure caption: Mandating minimum densities for infill can avoid low density infill which often aggravates local communities and often does not deliver considerable increases in density.

Locked

63

Unlocked

Medium density infill Low density infill

contradicts existing Local Government zonings which typically stipulate only maximum residential densities (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015).

Population growth/ land values

Figure caption: It is important to set minimum density controls until population pressures increase, market conditions improve and medium density outcomes result.

If we sit back and look at the property cycle what doesn’t work today, will work in a few years … If we are patient and we create the appropriate frameworks medium density development will happen...

64

65

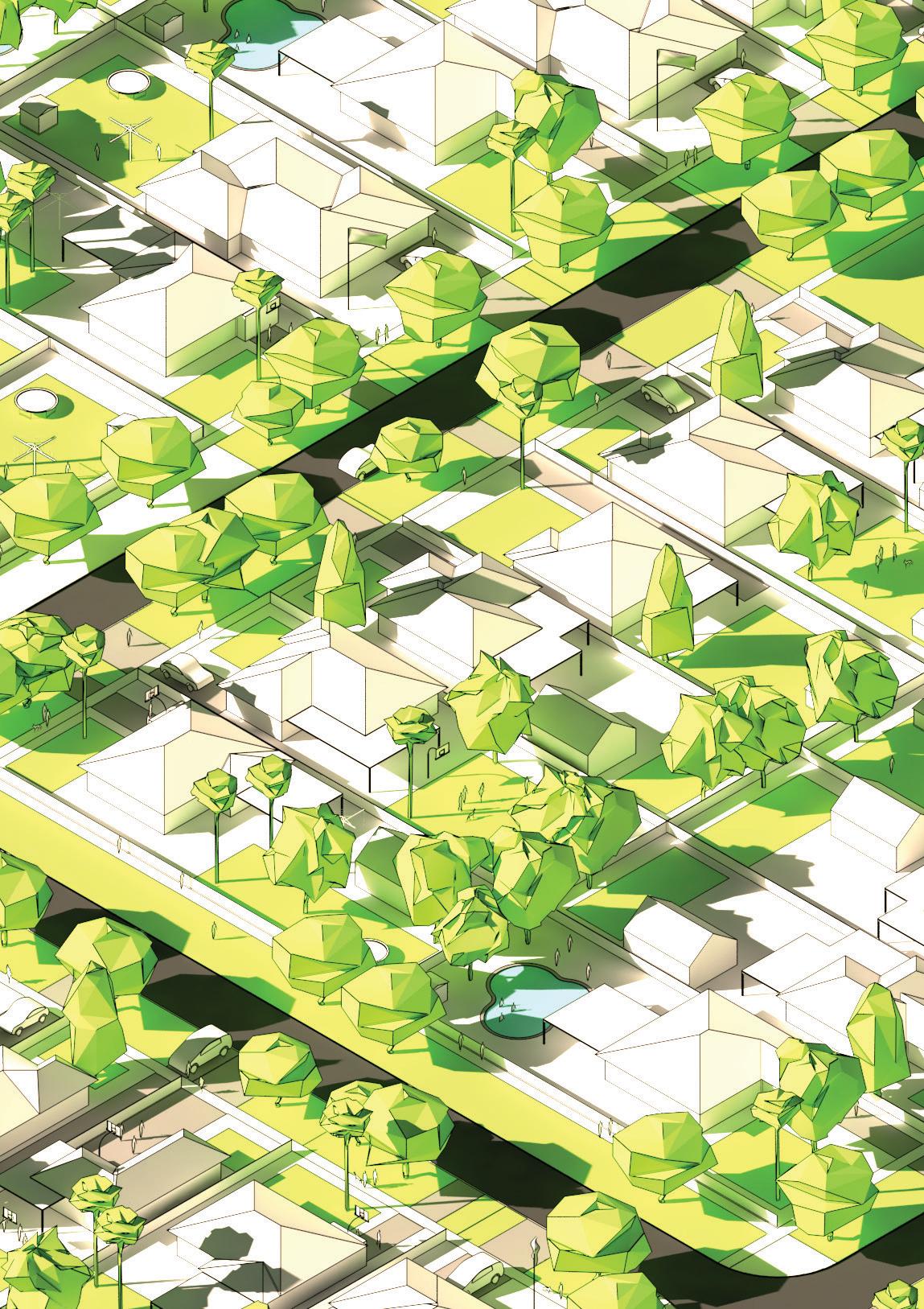

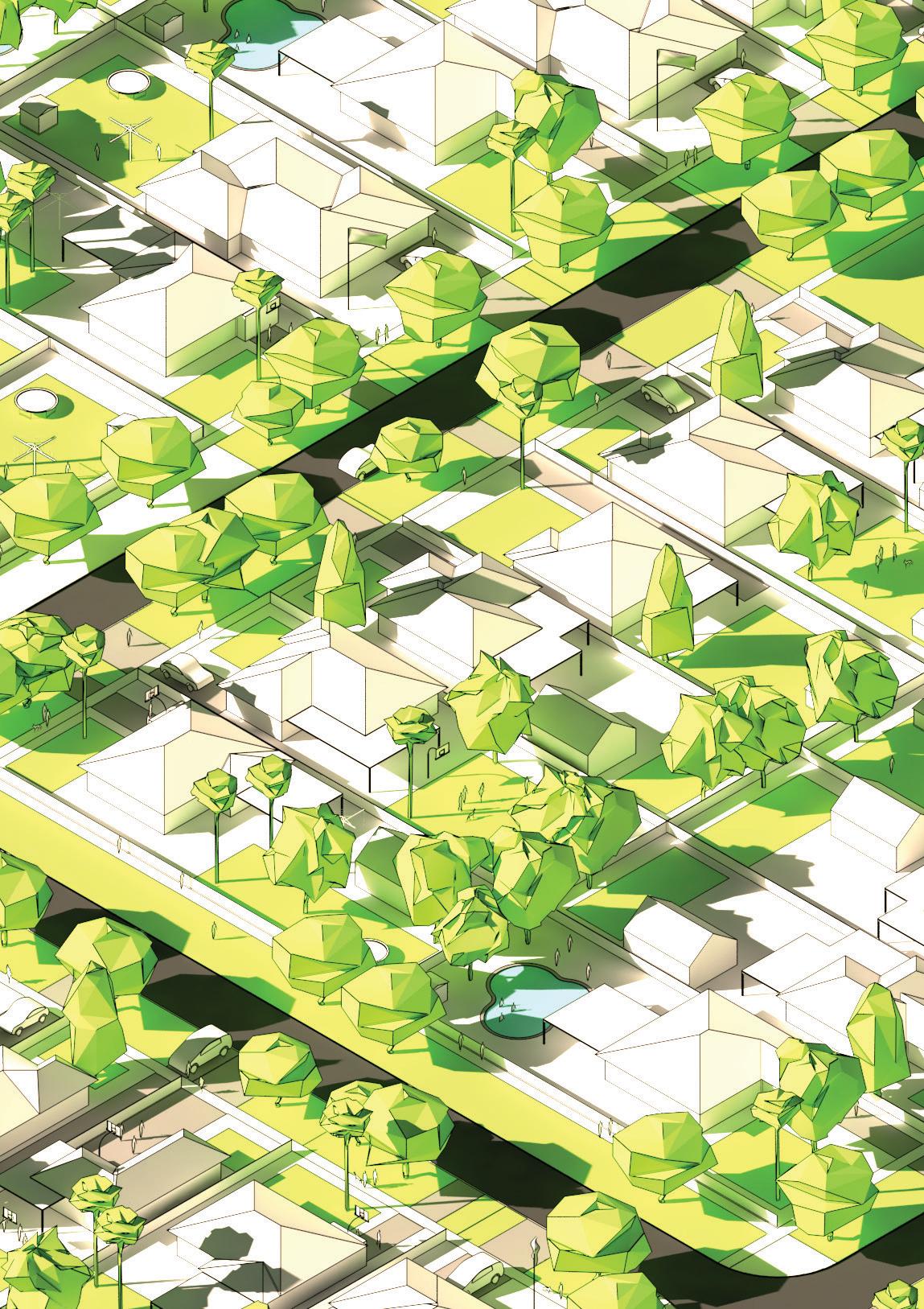

Protect

and densify the urban forest in

medium density infill

As the earlier sections of this report explained, one of the reasons existing communities were resistant to urban infill was because they perceived it to be an assault on the ‘leafy greenness’ of their neighbourhoods. In part, as a response, interviewees felt that there should be ‘minimum standards of amenity that need to be provided’ which relate to ‘privacy, solar access, sustainability, the protection of mature trees, minimum areas of deep soil zones, and the limiting of parking area’ (Architect and developer 2018).

Interviewees felt that one way of aiding this was to allow zero lot boundaries on a number of sides to produce more consolidated ‘courtyard’ areas of private open space for tree planting, rather than narrow ‘corridors’ of private open space produced by the building setbacks required by the R-Codes (Developer 2 2018) (Architect and developer 2018). Other interviewees suggested that designers and developers should deliver more slender buildings with smaller footprints that can then maintain existing trees, have deep root zones, and actually have an outdoor space for families… (Urban designer/ planner 2018). This could also be helped by placing outdoor living spaces on roof terraces- a shift which frees up the ground plain for tree planting. One planner also suggested that tree retention could be further incentivised by rewarding the retention of ‘certain amounts’ of trees on site with bonuses for ‘more height and more density…’ (Planner 2018). A Local

Government councillor also concluded ‘If you retain that tree, we’ll give you [developers] an extra two blooming apartments.’ (Local Government Councillor 2018).

The Victoria Park Town Team has even set a minimum target for 49 metres squared of tree canopy cover per resident, an aspiration which has been endorsed by the local council (Community Representative 2018). This will require the bolstering of the urban forest as population increases in this rapidly densifying area (Community Representative 2018). Given Australian communities’ unreceptive attitudes to ‘tall’ buildings, the use of mature trees to reduce the perceived density of infill development makes much sense (McMahon 2012).

Conversely, interviewees criticised the R-Codes, for its failure to regulate the protection of mature trees (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015), and the type of infill development it typically creates – ‘squat, flat development that takes up all of the communal open space opportunity’ (Urban designer/ planner 2018), and with it the chance of maintaining and growing mature trees.

66

Urban forest density

Urban form density

Figure caption: Local communities are often distressed by the loss of mature trees in the development of infill. Rather the urban forest should be ‘densified’ in conjunction with the urban form.

R25

R100

67

Figure caption: By providing private open space areas on roof decks ground level areas are freed up for tree planting.

...we need to actually pull them up and make them more slender buildings with smaller footprints that can then maintain existing trees, produce deep root zones, and actually have an outdoor space for families that are residing on these little three-twos, three-ones (Interviewee)

21st century Australian Dream

Before After

20th century Australian Dream

Before After

Figure caption: Modular courtyard dwellings with zero lot setbacks can be arranged efficiently around mature trees.

69

Educate Local Government about medium density

70

A key mitigation strategy interviewees identified was educating Local Government councillors and staff so that they can understand, appraise, and communicate the benefits of medium density development (Developer 2 2018, Real estate expert 2018). Some interviewees felt that the best way of elevating the level of design knowledge was for councils to employ a ‘council architect’ who could complement and enhance the skills of council planners who are not typically well-versed in spatial design (Architect and developer 2 2018). Moreover some interviewees regarded that council architects would be an asset because concerned residents could call up the architect who could explain in detail the design intent of medium density projects (Architect and developer 2 2018).

Other interviewees suggested that the best way of educating Local Government councillors and staff was to take them on tours of exemplar medium density projects. A developer who has conducted such tours said the predominate response has been ‘Wow, now I understand’ (Developer 2 2018). Interviewees believed such direct experience of medium density projects was the only way of dispelling the ‘nervousness and fear’ around medium density development in many Local Governments (Developer 2 2018).

Wow! Now I understand

Figure caption: Interviewees suggested that the best way of educating Local Government councillors and staff was to take them on tours of exemplar medium density projects

71

Provide consistent medium density policy

Interviewees generally felt that a consistent State Government policy for medium density design would help to improve development feasibility through reducing the complexity of navigating divergent Local Government policies and development incentives (Parliamentarian 2018, Real estate expert 2018). As one interviewee explained:

You know, developers and the Property Council aren’t gonna sign up for medium density unless there’s some more consistency across the board (Parliamentarian 2018).

interviewee explained, such projects may be ‘fully in compliance with the R-Codes, but it’s not necessarily contextually responsible, high quality, or responsive to the needs of the community…‘ (Urban designer/ planner 2018).

72

Interviewees generally regarded that the Design WA guide for medium density development – which the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage and a consultant are currently preparing –could help to ensure coherence across Perth’s ‘crazy number of local authorities’ (Real estate expert 2018). Although our interviewees generally supported the consistency potentially offered by the Design WA guide it was felt that Local Governments should be allowed some limited variation in relation to their local area (Parliamentarian 2018). Other interviewees felt that consistency would be best achieved by ‘merging all the councils’ (Developer 1 2018) however this would be likely to incur significant community backlash.

While the R-Codes do provide some consistency, in relation to medium density outcomes, they were criticised for allowing poor quality medium density development to occur. As one

Figure caption: Interviewees generally felt that a consistent state government policy for medium density design would help to improve development feasibility. This would enable ‘apple for apple’ comparisons...

73

Improve community engagement strategies for medium

density

The interviewees generally felt that strategies for engaging local communities regarding medium density development could be improved at both local and State Government levels. As one interviewee explained:

I think that is a massive failure of the State Government at the moment. Because you talk to most members of the community, particularly older generations, and they just don’t get the benefits of density. We need to sell it much better through really aggressive marketing, TV and newspaper (Urban designer 2018).

At a Local Government level, one interviewee identified CoDesign (Collaborative Design) engagement strategies as being ‘really useful’ for working with communities regarding infill development (Community Representative 2018). Anthony Duckworth-Smith at AUDRC has been progressively developing and refining a series of CoDesign toolkits. The toolkits are physical ‘game’ sets or flexible models which are designed for a specific urban context and spatial challenge, often infill development, and allow workshop attendees to understand, and engage with, the spatial implications of policy first-hand. One interviewee explained that the CoDesign approach worked well with communities because ‘there was real value in a hands-on approach’ (Community Representative 2018).

74

Figure caption: The AUDRC has been conducting hands-on community engagement exercises in a bid to positively engage with communities around the issue of infill development.

75

Develop medium density timber / light weight construction

Interviewees generally felt that the feasibility of medium density development could be improved through the adoption of modular, lightweight, timber construction, which interviewees believed could reduce construction costs (Architect 2018), and potentially lessen community resistance in that timber buildings are more aligned with the aesthetic and materiality of Perth’s suburbs (Community Representative 2018).

With respect to cost, one interviewee cited a medium density project in Adelaide which utilised timber frame, low-rise apartment buildings which had seen a cost reduction of ‘at least 30% below’ conventional masonry construction (Developer 2 2018).

Nonetheless, interviewees referred to the need to ‘build up capacity and experience in the [timber] industry itself’ (Civil engineer 2018), to get the pricing for timber frame construction to anywhere near what is being achieved in elsewhere in Australian cities (Developer 2 2018).

76

Timber construction

Masonry construction

Figure caption: Lightweight timber construction for medium density infill is potentially cheaper and more aligned with suburban aesthetics than masonry construction.

That kind of concrete masonry is exactly what the rest of the suburb isn't, right? (interviewee)

KG KG

= = = = 77

Improve adaptability of medium density building types

One advantage of timber construction that interviewees referred to, was its potential to be adapted over the longer term in relation to changing economic conditions, community sentiment, and its occupant’s lifestyles. This adaption could include the addition of rooms and the closing in of outdoor spaces; in effect, mirroring the flexibility that was a characteristic of traditional suburban dwellings. Interviewees regarded this a viable way of avoiding a situation where the residents of low-density infill development, built with traditional masonry construction, are unable to adapt their dwellings to higher densities over time. As one interviewee explained the benefits of adaptability are ‘you can buy, you can lease, you can live, you can run a business, you can run a shop’ and if you don’t like it’ you ‘change it for something else’ (Architect 2018).

The R-Codes do not contain any suggestions, or requirements, for building adaptability (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015), and some interviewees felt that restrictiveness of the R-Codes, in this respect, was unnecessary (Architect 2018).

78

6

1 2 3 4 5 Adaptable housing Phase Tree maturity Land values Community sentiment Occupants

Figure caption: Lightweight, modular buildings are potentially adaptable to changing conditions.

The benefits of adaptability are you can buy, you can lease, you can live, you can run a business, you can run a shop and if you don’t like it you change it for something else (Interviewee)

79

Develop alternative parking arrangements for medium density

Interviewees identified that car parking requirements for medium density development were overly onerous (Urban designer/ planner 2018), and reduced the feasibility and amenity of such projects. As one interviewee explained, ‘We’re totally destroying our opportunity for these places by insisting on these stupid rules for cars (Civil engineer 2018).’ Other interviewees opposed the designation of driveways on private lots as open space in the R-Codes: ‘It always annoys me that the driveway, is considered ‘public open space’ given it’s not usable’ (Local Government Councillor 2018).

To this end interviewees identified alternative car parking arrangements which reduce private car parking on medium density lots and utilised street verges for right angle car parking. As one interviewee explained ‘For those of us who have lived in Europe, our attitude to parking here is ridiculous. Force people onto the bloody street. They’re all about 50 metres wide, anyway, and get rid of the verges, which are using massive amounts of water’ (Civil engineer 2018). Others suggested that shared cars and car-bays, for medium density residents as a potential solution for parking issues (Architect and developer 2018).

The use of verges and streets for private parking contradicts the R-Codes which does not allow private car parking on street verges (Western Australian Planning Commission 2015). It also faces potential resistance from residents who ‘are quite attached to their cars’

(Community Representative 2018) and like to have them safely secured in private garages.

Figure caption: Background infill provides considerably more lot area per car than per person. We believe the area for cars should be reduced and the area for people increased.

80

Figure caption: Verges can be utilized to provide alternative car parking arrangements which minimise the amount of private lot area lost to car parking. Non densified lots could potentially rent out verge parking spaces to residents of medium density development.

For those of us who have lived in Europe, our attitude to parking here is ridiculous. Force people onto the bloody street. They’re all about 50 meters wide, anyway, and get rid of the verges, which are using massive amounts of water... (Interviewee

81

Limit infill and greenfield development sites

A strong theme which emerged from the interviewees was that State Government needs to exert more control to restrict greenfield development on the fringe of Perth. Interviewees believed that this could corral suburban development and increase the viability of medium density infill (Parliamentarian 2018). As one interviewee explained: ‘we say we want a denser city, and we’ve been doing that since Network City , but we don’t actually do anything to make it happen... we don’t hold the line at all’ (Civil engineer 2018). Interviewees believed that this could be achieved by implementing a greenbelt that constricts urban sprawl or by ‘dramatically increasing developer contribution charges for the extra cost of the infrastructure’ on the fringe. However, it was identified that while there is ‘a million ways you could do it, there’s no political appetite to do any of it’ and ‘the industry would go apoplectic’ (Civil engineer 2018).

While interviewees believed limiting urban development on the fringe was necessary for achieving medium density infill, they also felt that medium density infill should be only targeted in specific locations. As one interviewee explained: …it’s a hearts and minds game, you must be able to tell this community that you’re going to leave the fabric of the suburb fundamentally unchanged. The density needs to be targeted and properly placed. If you can sell that vision and leave the core of the suburb unchanged and only put the density where it’s logically needed you’ll get

better infill outcomes, and the community will support you instead of fighting you all the way… (Real estate expert 2018).

One interviewee suggested that one way of focussing medium density development was to concentrate on the limited areas that have significant infrastructure capacity (Civil engineer 2018). As the interviewee explained this ‘requires a complete shift of mindset, because the planners are always in denial about what’s under the ground. You actually start with that. You go, ‘This is where it’s opportunity’’ (Civil engineer 2018). Such opportune sites could then be targeted within planning strategies and schemes (Civil engineer 2018).

A refocussing of medium density development efforts on a limited number of sites has major implications on Perth’s overarching planning document which sets out a substantial 93 Activity Centres sites (Department of Planning and Western Australian Planning Commission 2015) – as well as the Metronet project which aims to introduce a host of new centres. By focussing these efforts interviewees felt that the government would then be able to afford to ‘kick off a couple of the major ones’ (Developer 2 2018).

82

Figure caption: Some interviewees believed delivering medium density infill is contingent on curtailing suburban expansion

We say we want a denser city, and we’ve been doing that since Network City , but we don’t actually do anything to make it happen... we don’t hold the line at all (Interviewee)

UGBGreenbelt/ Development impetous

impetousDevelopment

83

Current Activity Centres

Figure caption: Focussing urban development in limited centres could improve development feasibility.

Pilot project

Pilot project

Pilot project

Consolidated Activity Centres

85

4. Site testing the mitigation strategies

The following section tests the medium density mitigation strategies on a real site...

86

Site testing the mitigation strategies

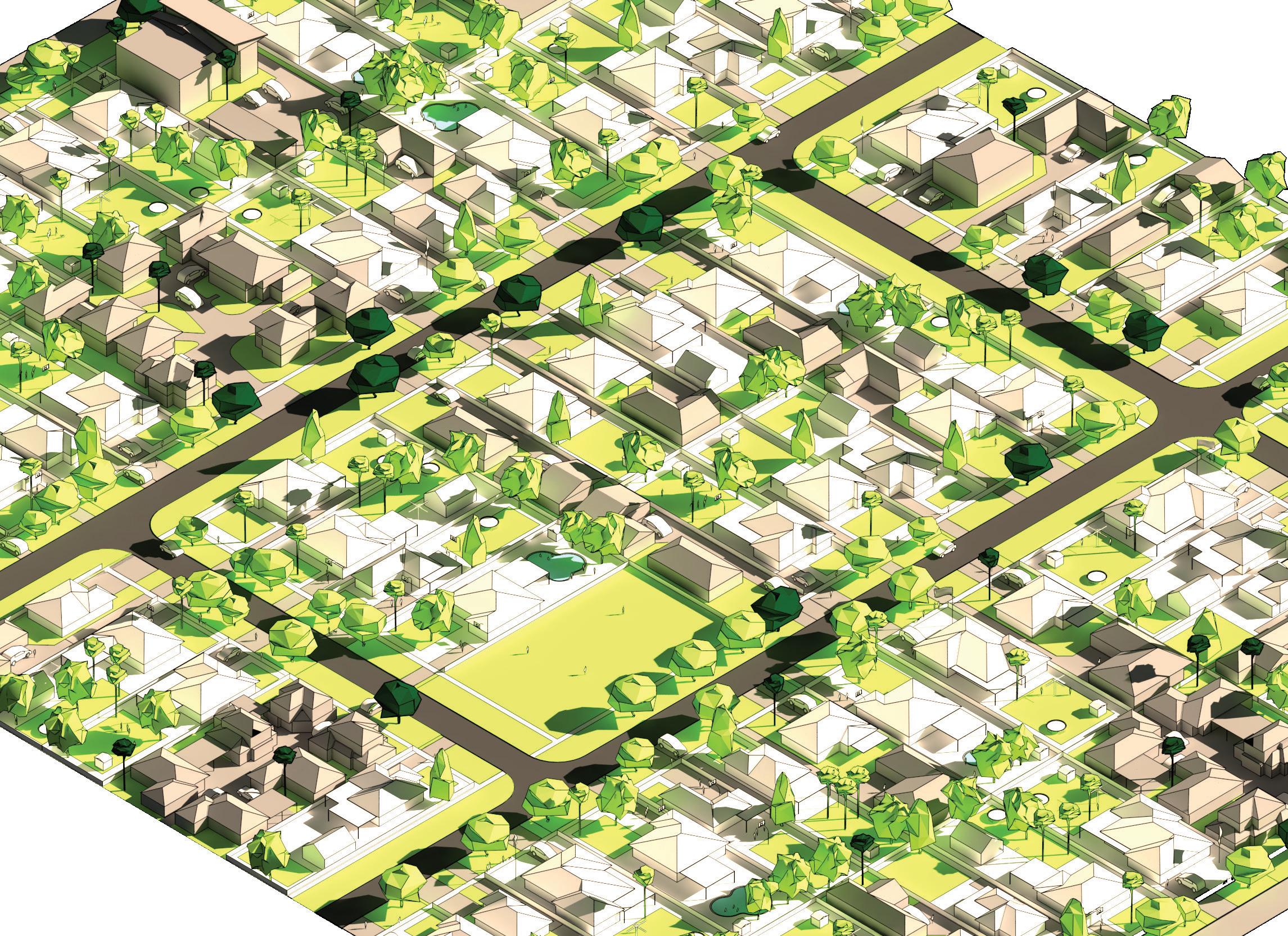

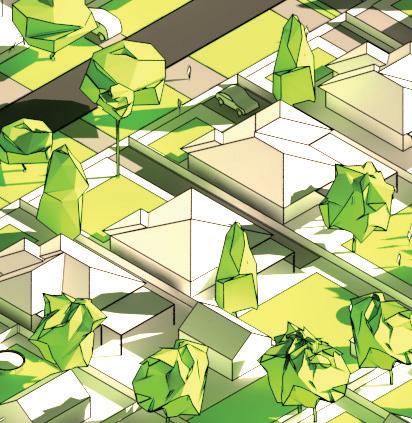

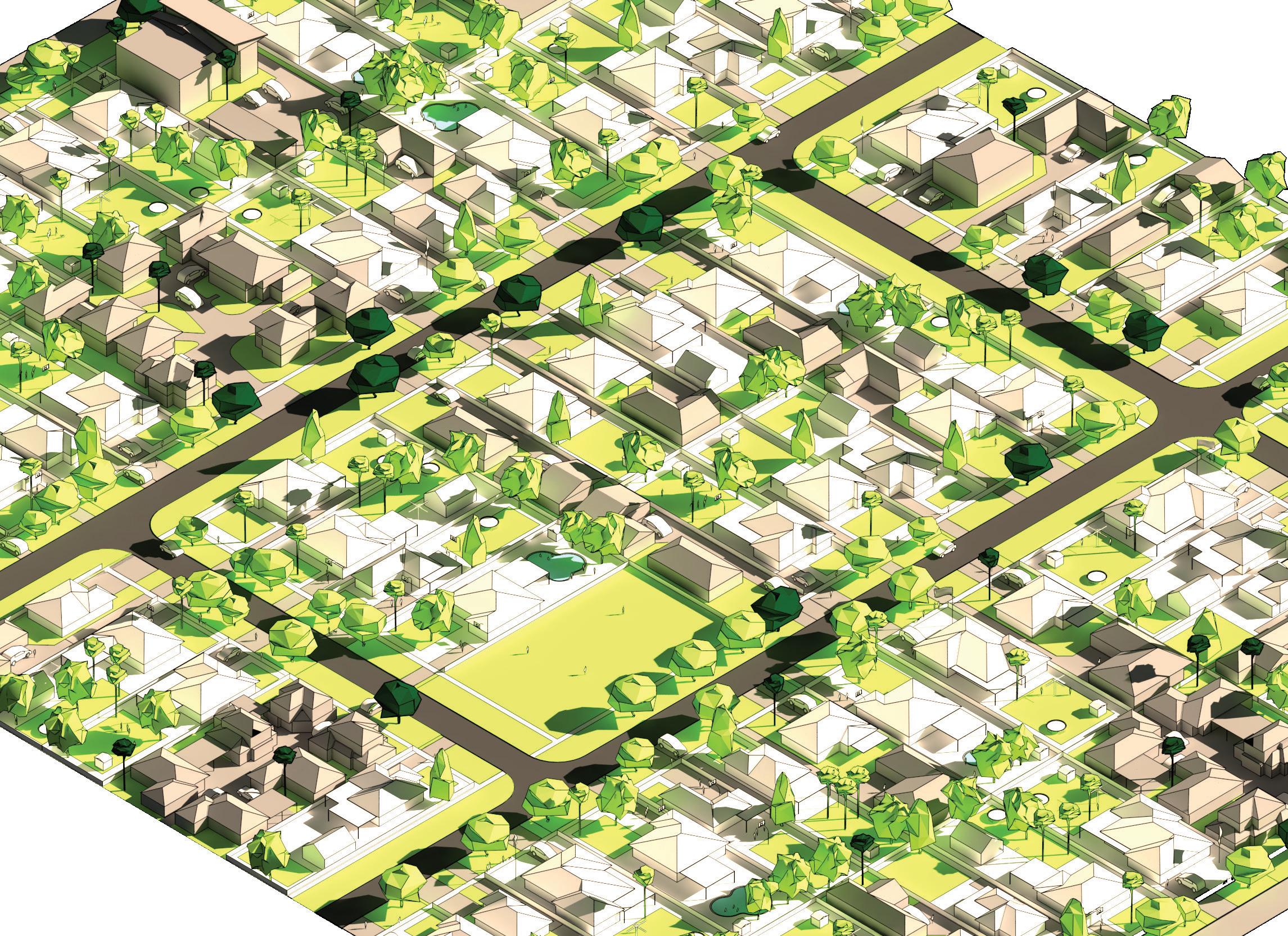

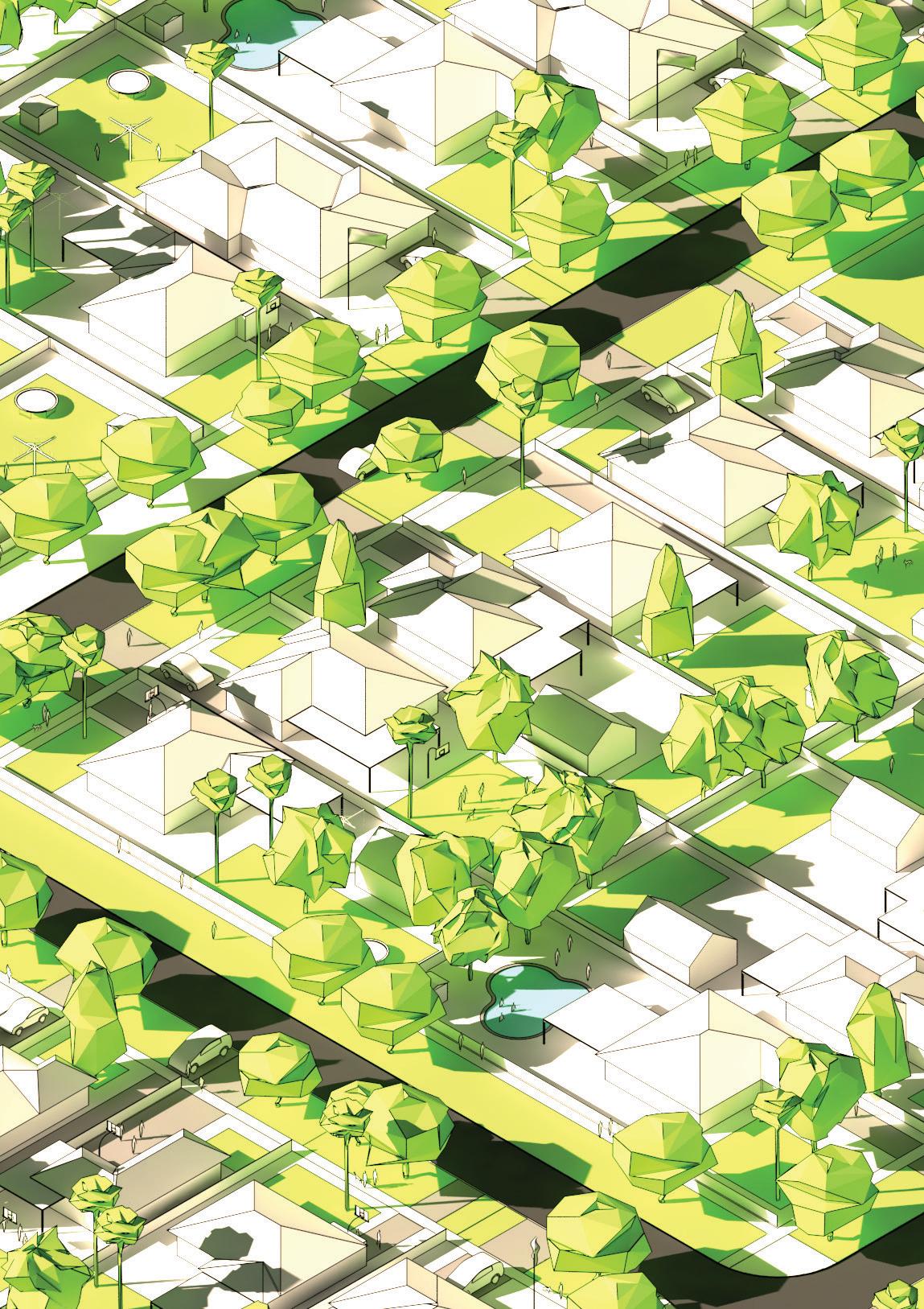

In this chapter we have applied the mitigation strategies in a typical lowdensity suburban setting fringing a designated Primary City Centre Activity Centre in Perth’s greyfield, middle ring suburbs. This setting is characterized by a gridded road network of local streets, detached residential housing at net density of approximately R15, typically large residential lots of 700-1,000 metres squared which sustain a substantial urban forest.