Urban Design is one of the ways in which we help to support the everyday lives of people in public places. The professional practice of urban design emerged from the disciplines of landscape and architecture as an extension of the traditional concerned with the arrangement of, and relationship between built elements and functional design to place a far greater focus on the in uence of design on people and city life. Over time the professional scope has expanded to include an appreciation of the economic, functional, detail social and use aspects of place. This report provides a contemporary summary of urban design considerations. It uses these to analyse a number of prominent and emerging case studies to investigate the ways in which urban design is being used to facilitate social participation in the public realm. How can we use our contemporary understanding of urban design to analyse the social performance of public places and then use this to recommend tactics for future projects?

People in public spaces

Urban design tactics to facilitate social participation in the public realm

© Australian Urban Design Research Centre

2015

People in Public Places

Urban design tactics to facilitate social participation in the public realm

AUDRC | University of Western Australia

Contents

List of Figures

Figure 1 Principles of social participation

Figure 2 Urban design elements

Figure 3 Analytical framework

Figure 4 Design criteria

Figure 5 Tactics

Introduction | 6 / Research Project Structure | 8 // Case Studies | 20 P1 - P6 Urban Plazas | 22 T1 - T7 Transit | 56 S1 - S5 Social Incubators | 92 /// Tactics Summary | 114 //// Recommendations | 116 References | 124

Credits | 128

| 130

Image

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Urban design has continually engaged with the social life of the city, informing the way in which the public realm is considered and configured.

People in Public Places is intended as a contemporary compendium. It is a document which has taken on a relatively complex task in attempting to bridge the relationship between design and the social ‘performance’ of public places. Urban design is however a discipline which spans disciplines; it is concerned not just with arranging the physical framework of the city but also understanding and shepherding the forces and actions which underpin this spatial configuration to achieve a people-focussed outcome.

Rather than simply facilitating the arrangement of space lie the objectives of urban design, the people-focussed values which underpin the designer’s intentions to produce a certain form or structure. Specific approaches to achieving these may vary from designer to designer but

there is a general agreement that those involved in shaping the urban environment are doing it to enable liveable cities for all. This effectiveness can be about many aspects: promoting economic turnover, maintaining the health of its citizens, inspiring civic pride, responsibly managing resources, accommodating populations, keeping citizens safe or providing the territory for the social lives of the populace.

The research and findings contained within this document are mostly concerned with this last aspect – the territory of the social happenings of the city, the public realm. In particular the research has been designed to help the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority of Western Australia (MRA) ensure that its public realm projects of the future are broadly appealing to the citizens who will use them

and to promote social wellbeing. As Richard Rogers exclaims in his foreword to Jan Gehl’s book Cities for People ‘Everyone should have the right to easily accessible open spaces, just as they have the right to clean water’1

The MRA is a government redevelopment authority which operates in the Perth metropolitan area and has a range of urban redevelopment projects. It often takes on the planning, design and delivery of substantial public realm projects – streets, plazas, parks etc, as part of these activities. In parallel the Department of Planning and Western Australian Planning Commission continues to work towards a compact city model, the chief elements of which are a series of high density urban nodes arranged around public transport, brownfield redevelopment projects and activity corridors along key public transport routes. The vision for these precincts to provide exceptional liveability confirms an important and diversified role for the public realm – it must cater for a greater number and wider range of uses and users. Therein lies part of the challenge — what can be done to ensure that the public realm elements of these ‘new’ project types are suitable and support the social needs of a diverse demographic?

It is a significant challenge for one document to answer as it must comprehend the complex, dynamic and continually evolving and continuously studied relationship between urban design practice and the social functioning of space and then apply this to specific project types. Confounding this is the role of context which means every project must be considered in relation to its geographic, historical, functional, climatic and economic circumstance. The appreciation of the importance of contextual parameters makes

the generalisation of design aspects difficult to achieve whilst also highlighting the risks of going too far with a generic approach. The challenge for this research is to navigate the tension between the general and the specific and provide useful guidance without resorting to simplistic mimicry. Each project should be judged on its merits but this research aims to highlight some fundamental urban design principles which can be adopted.

While much of the attention and research in urban design focuses on overall levels of use, and correlates this to economic benefits and experiential satisfaction levels, this study is focused on the social impact The study approaches this through a research method which establishes a series of principles based around the concept of social participation. Social participation is a meaningful basis for an analytical framework related to the social performance of urban design as it has direct links to other social ‘performance’ territories2. If people participate in a collective or shared setting or activity then this makes civic engagement or the formation of social capital more likely3. This effect has been measured by such means as membership in voluntary organisations and public realm studies.

The principles are connected then related to the contemporary elements of urban design practice. This framework is then applied to a series of relevant case study project types which illustrate the different ways (tactics) in which social participation can and has been facilitated through design. Finally the analytical efforts are summarised into a series of general principles which seem to be supported across many of the projects investigated and could be

2 Shortall, Sally. (2008). Are rural development programmes socially inclusive? Social inclusion, civic engagement, participation, and social capital: Exploring the differences. Journal of Rural Studies, 24, 450-457.

3 Ibid.

1 Rogers, Richard. Foreword in Cities for People, Gehl, Jan. (2010) Island Press, Washington DC

Introduction | 76 | People in Public Places

/ Research Project Structure

The research project documented in this report has been designed to address the objective of informing social particpation outcomes in the design of the public realm.

Research question

The research question stems from the definition of the overall study objective to conduct research and development of design responses/solutions to maximise social participation in urban development projects. Further in achieving this international precedents and research, including delivery and implementation mechanisms were considered. Following initial scoping the research question was defined as:

‘what urban design tactics are suitable to enhance the potential for social participation in state-led public realm projects in new and regenerated urban centres, such as Transit Oriented Developments?’

This is a question of multiple parts. Firstly to understand the relationship between urban design and social participation.

Secondly to apply this knowledge to inform the design of the specific project contexts that have been identified.

Objectives

The research objectives arising from consideration of the research question are:

i.Investigate and define the relationship of urban design practice to enhancing the potential for social participation.

ii.Document tactics which can be employed in the urban design of public realm projects to potentially enhance social participation.

iii.Define principles which can be used to inform the potential for social participation in state led public realm projects.

Method

The research method is split into three parts to address the objectives.

Part 1

Theoretical and case study research is used to establish an understanding of the different ways in which urban design practice contributes to achieving social participation.

This is done by building a definition of social participation, in the context of built environment projects, as a foundation. This identifies 4 key principles.

Following this a survey of urban design theory and practice identifies a series of design elements which can be used to organise the different aspects of the organisation and execution of urban design projects. Each design element consists of a number of design criteria which collate the more specific actions which can be undertaken toward meeting the research objectives related to social participation.

The specific relationships between the design elements and the principles are then established. This is done to understand how the design elements relate to the universal ‘territories’ of social participation and identify any overlaps or shortfalls.

The design elements and their constituent criteria establishes the analytical framework though which existing projects can be interrogated with respect to contributing to social participation.

Part 2

Specific design tactics under each criterion are extracted for a number of case studies from desktop project review and publication. The case studies are chosen to illustrate a range of methods of achieving social participation in public realm projects whilst also providing direct feedback on the specific project types of new and regenerated urban centres, such as Transit Oriented Developments.

The tactics are then presented using key project images and discussed, where appropriate, in relation to their demographic context. The tactics are arranged in an approximate sequential order, as a kind of story-board, which moves from the tactics which establish the social participation aspects of each project through to the more supporting actions.

Part 3

As referred to in the introduction it is difficult to make formulaic recommendations for urban design process and practice as each case has its own specific context which will influence the choice and order of tactics. Following the application of the analytical framework to the case studies however the tactics are reviewed and summarised into design principles which provide a widely applicable set of guidelines for considering the organisation and execution of the urban design of public realm projects to improve their potential to facilitate social participation.

/ Research Project Structure | 98 | People in Public Places

Definitions & Principles of social participation

Social participation refers to people’s social involvement and interaction with others. Social participation builds social networks, social capital and sense of belonging and is directly related to health and quality of life outcomes1. Facilitation of social interaction in transit-oriented public spaces that serve large volumes of people also requires consideration of catering to a diverse demographic range wherever possible. An ideal urban design response includes attracting different users and groups and encouraging and supporting different types and intensities of interaction. Some key demographics considered in this research include age, gender and cultural background.

Social participation is a widely used term and there is no commonly held definition. A review of literature on social participation however was able to identify the following 4 key principles2 which highlight the socio-spatial territories associated with the design, development and operation of the public realm which support social participation generally:

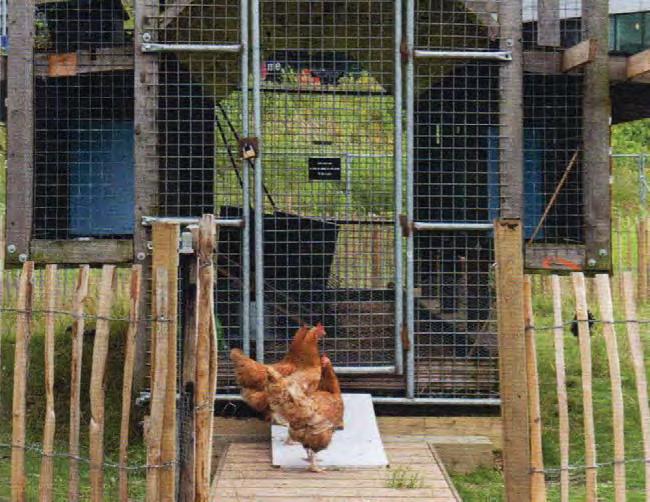

Sharing

Formal and semi-formal forums and processes for exchange and transfer of knowledge and skills, e.g. men’s shed, community gardens.

1 Levasseur, M., Richard, L., Gauvin, L. & Raymond, É. 2010. Inventory and analysis of de fi nitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 2141-2149.

2 Lindström, M. 2005. Ethnic differences in social participation and social capital in Malmö, Sweden: a population-based study. Social science & medicine, 60, 1527-1546. Mars, G. M. J., Kempen, G. I. J. M., Mesters, I., Proot, I. M. & van Eijk, J. T. M. 2008.

Characteristics of social participation as de fi ned by older adults with a chronic physical illness. Disability and rehabilitation, 30, 1298-1308.

RMIT University 2006. Evaluation of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy 2000-2004. Melbourne VIC.

Working

Provide paid or voluntary employment opportunities including family and carer responsibilities.

Decision Making

Enable existing community members, representatives and organizations in decision-making process across different project stages including design, activity planning, and place management.

Engagement

Events, activities and their environments which attract different users and groups, encourage and support different types and intensities of interaction, e.g. leisure, recreation, hanging out.

Thus social participation is multi-faceted involving groups, families and individuals in both structured and informal activities and environments, connecting with people in various degrees of intimacy and familiarity and taking part in the organisation and decision making processes which affect their social life and that of the others around them. The literature review has also pointed out the cultural and demographic specificity of certain aspects of social participation. Therefore any learnings from particular projects need to be qualified in terms of this context. Accordingly subsequent work in the presentation of case studies acknowledges their social and demographic context.

Figure 1

The principles are the core actions and behaviours which support the potential for social participation

W ORKING S H ARING

DECISIONMAKINGENGAGEMENT

/ Research Project Structure | 1110 | People in Public Places

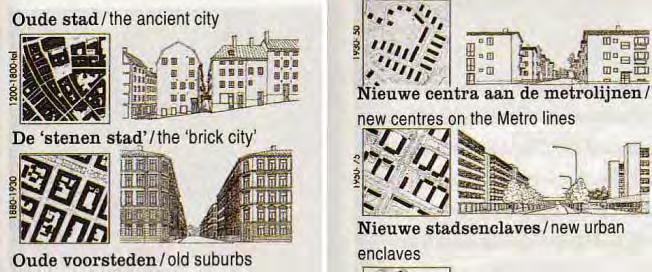

Design Elements

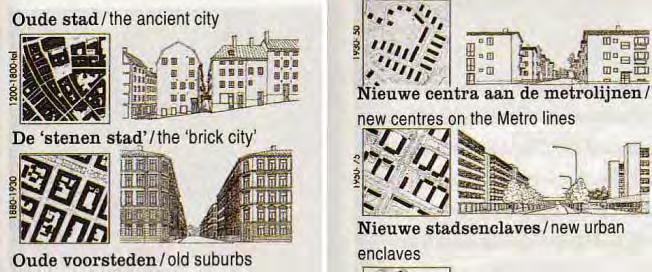

Design elements were described which represent the key territories of contemporary urban design practice. These were derived from urban design literature and theory as well as project case studies. Each design element is comprised of a number of more specific possible actions. The relationship of these actions to the overall research objective is discussed in subsequent steps however the design elements are defined below.

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Aspects of the organization of the project which relate to community involvement and empowerment in the design process and outcome

PROGRAMMING

The organization and implementation of specific uses.

URBAN STRUCTURE

Aspects which inform the configuration of the fundamental structure of the physical environment

URBAN CHARACTER

Aspects of tradition, style, pattern, form and/or use which

contribute to the arrangement of the built environment. Fundamentally these elements could be understood in relation to two meta-categories: software and hardware.

‘Soft’ aspects relate to establishing a structure for communication, exchange and specific activities within the design process. Typically this is done during the early parts of the project. It often directly informs the programming and enables authentic and enduring participation in the use of the space. It is specific to the situation and may or may not follow conventional top-down engagement practices. Both Networks & Exchange and Programming design elements could be categorised as software.

The ‘hard’ physical elements of the built environmenttraditional urban design components which may or may not take on traditional forms depending on the context and process. The criteria are well understood but the important challenge is to try and understand how the hardware has responded to, or supports the local context. Urban Structure, Urban Character and Programming all deal with the hard physical frameworks of constructed space.

Figure 2

The design elements are the key areas of practice related to the organisation and execution of urban design.

PROGRAMMING URBANCHARACTER

W

S H

NETWORKS&EXCHANGE URBANSTRUCTURE DECISIONMAKINGENGAGEMENT

ORKING

ARING

/ Research Project Structure | 1312 | People in Public Places

Analytical framework 1

The analytical framework provides a way of connecting the theoretical and practical dimensions of the inquiry to help tackle the research question. It allows identification of which urban design elements operate on the key principles of social participation.

For example the principle of Decision Making is substantively connected to the urban design elements of Programming and Networks and Exchange. Both of these elements involve people coming together to organise and manage aspects of the project. For instance being involved in forums to discuss the types of spaces and / or programme of activities they would like to see in their community. They are involved in a collaborative manner to make decisions which impact on either or all relevant stages of the project - planning, design and operation.

This exercise confirms that all of the design elements are in some way related to the principles and validates their consideration in respect of achieving the research objectives.

Networks and Exchange was related to all of the principles endorsing its important position and substantial potential in the design process with respect to achieving the objective of social participation.

Programming also presents a significant connectivity to the principles illustrating its potential importance and efficacy with respect to the research objectives.

Urban Structure is strongly related to Engagement as it provides the physical framework through which activities and events are able to take place both in terms of space and attractivity.

Similarly Urban Character is substantially related to Engagement as it provides aspects of the physical condition with which people and groups identify, which can create an attractive setting to enable a range of different social activities.

Development of the analytical framework indicates that the ‘soft’, or non-traditional aspects of urban design are very important with respect to supporting the principles of social participation. This tends to back up the recent focus on tactical and temporary urban design in practice where ‘bottom-up’ methods have been employed. These designs are generated through the establishment of community and self-directed groups with common interests who largely take on the role of decision making and curating activities.

Figure 3

The analytical framework identifies how the principles relate to the design elements.

ENGAGEMENT W ORKING AHS R I NG DECISIONMAKING

PROGRAMMING URBANCHARACTER NETWORKS&EXCHANGE URBANSTRUCTURE

/ Research Project Structure | 1514 | People in Public Places

Analytical framework 2

All of the design elements were validated with respect to the research objective. Further research was undertaken to identify the key criteria within these design elements which relate to providing the conditions for social participation. This research drew on both traditional and contemporary perspectives.

The practical observations of William Whyte, Clare Cooper Marcus and Jan Gehl provide a useful link between the role of physical elements and conditions in supporting social activity. The writings of Lynch, Cullen and the Joint Center for Urban Design at England’s Oxford Polytechnic Institute provide a robust framework for considering urban structure in relation to providing attractive and comprehensible settings for human interaction. More contemporary publications such as We own the City and Tactical Urbanism explore new paradigms of urban design activity in a digital, socially and governmentally fragmented age. A full list of the publications which have been used to extract the design criteria are presented in the references.

The design criteria are described below under their relevant elements. This research has demonstrated that their are substantially more design criteria under urban structure than the other elements. This is not to say that it is more important but identifies that it is better understood and has received more attention in professional discourse to date.

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Collaboration

Organisation of project or infrastructure to facilitate involvement in various stages of project design, including operation and management.

Productivity

Organisation of project or infrastructure to facilitate employment and/or volunteering for a shared or individual purpose/outcome for community members,

Learning & engagement

Organisation of project or infrastructure to facilitate educational or skills-development for community members.

PROGRAMMING

Social & cultural diversity

Use and activation strategies that facilitate the engagement of different cultural and ethnic groups.

Health, wellbeing & play

Use & activation strategies aimed at increasing the health

and wellbeing of all users. Including walkability, increasing green space, and opportunities for passive and active recreation.

URBAN STRUCTURE

Accessibility

Design approaches to ensure accessibility for all users, with special consideration for those who are differently-abled, elderly, or parents with children/prams. Including ramps, lifts (if appropriate), and wide access paths, etc

Flexibility

Design approaches which give users a choice of use and occupation - allowing multiple group and individual combinations and respecting user’s preferences with respect to their willingness to engage.

Amenity & Comfort

Design approaches to support necessary and optional passive activities in a space. Including seating, shading, and materiality.

Connectivity

Design approaches that connect the public realm with its surroundings. Generally the permeability of the public realm including pathways, streets and open space networks.

Legibility

Design approaches that aim to create a coherent set of identifiable elements in the public realm, which have clear formal boundaries. Elements would include landmarks, paths, nodes and edges.

Safety

Design approaches to ensure safety for all users, with special consideration to gender, age, and ethnicity. Including lighting, activation, passive surveillance, visibility of pathways, and ground floor activation etc.

URBAN CHARACTER

Imageability

Design approaches aimed at drawing upon, enhancing, and integrating specific elements of the existing landscape or built form to contribute to a sense of place and attachment that is positively cogitated (attractive).

Complexity

Design approaches which contribute to establishing a sense of diversity and richness in the perception of a place which is interesting and inviting.

COLLABORATION

LEARNING & ENGAGEMENT

PRODUCTIVITY

FLEXIBILITY

ACCESSIBILITY

SAFETY

LEGIBILITY

AMENITY & COMFORT

CONNECTIVITY

SOCIAL & CUTURAL DIVERSITY HEALTH, WELLBEING & PLAY

IMAGEABILITY

COMPLEXITY

Figure 4

The design criteria are the more detailed aspects of each of the design elements which relate to the potential for social participation in the public realm.

W ORKING AHS R I NG DECISIONMAKING

ENGAGEMENT

PROGRAMMING URBANCHARACTER NETWORKS&EXCHANGE URBANSTRUCTURE

/ Research Project Structure | 1716 | People in Public Places

// Case Studies

The case studies have been chosen to best inform the multiple aspects of the research objective.

The analytical framework was applied to a number of case studies to determine what tactics which had been employed under the different design criteria to contribute to the principles of social participation. A range of case studies were selected based on the expectations of the research, both to clarify the understanding of the role of urban design in facilitating social participation in the public realm, and to extend this to inform the future configuration of specific types of projects (state led projects in urban centres such as TODs).

The research adopted 3 types of case studies to inform the research objectives - urban plazas, transit oriented developments and social incubators.

Type 1 – Urban Plazas

Exemplary public realm design projects across a range of locations, budgets, urban contexts and scales. These projects were selected based on their documented ambitions or performance with respect to social participation.

Type 2 – Transit Public realm projects which are specifically related to tran-

sit stations and more intense urban development in the immediate location. These projects were selected based on development maturity, reputation and availability of adequate documentation.

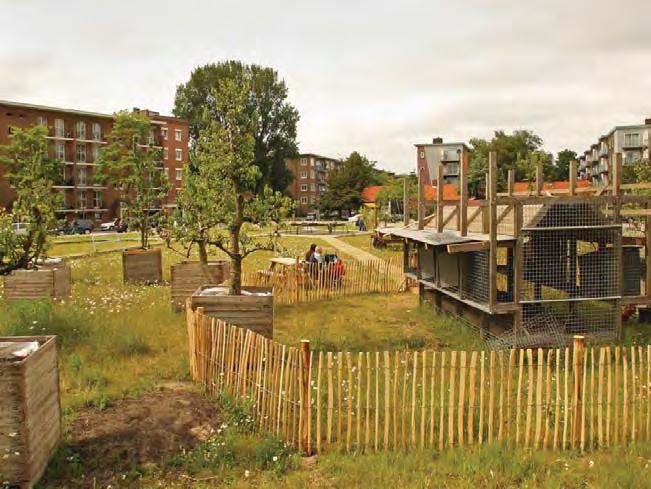

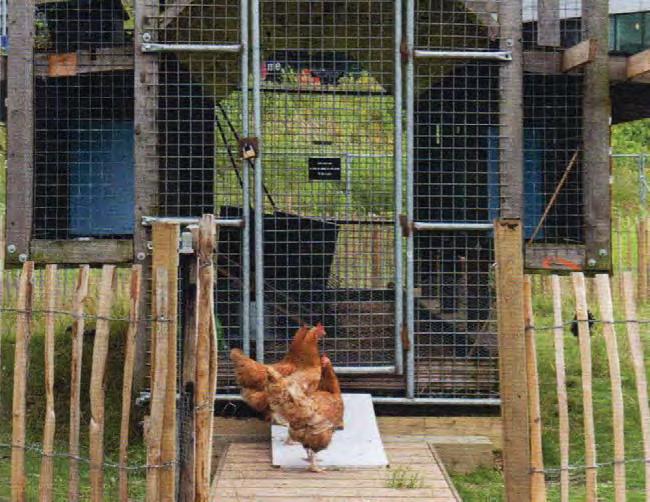

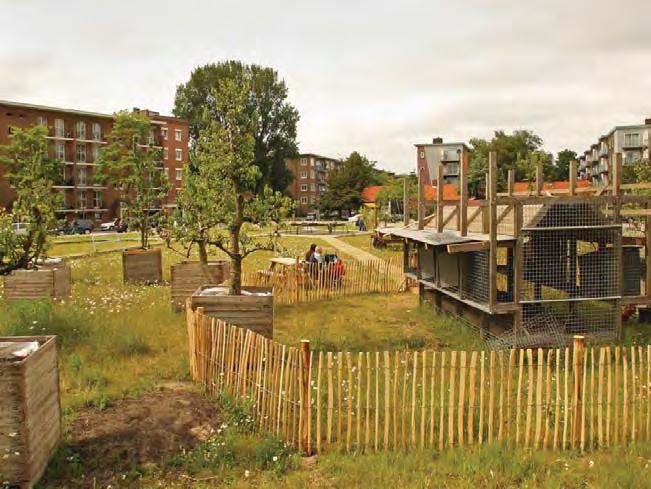

Type 3 – Social incubators

These are a ‘loose’ collection of projects which demonstrate innovative practice - experimental ways of organising urban projects in a contemporary urban context to engender social participation. These projects were selected from current publications.

The case studies include information on user group, ethnicity and status contexts. The notes highlight where the project was specifically focused on bringing isolated groups together. Where possible the definitions for each project are taken directly from sources in the location of the project. For example in a project located in the US definitions of ethnicity are taken from the US Census Bureau, however these may have been simplified for reporting. It should be qualified that these definitions may differ between countries and so should be considered in their local context.

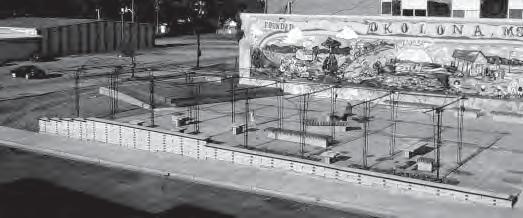

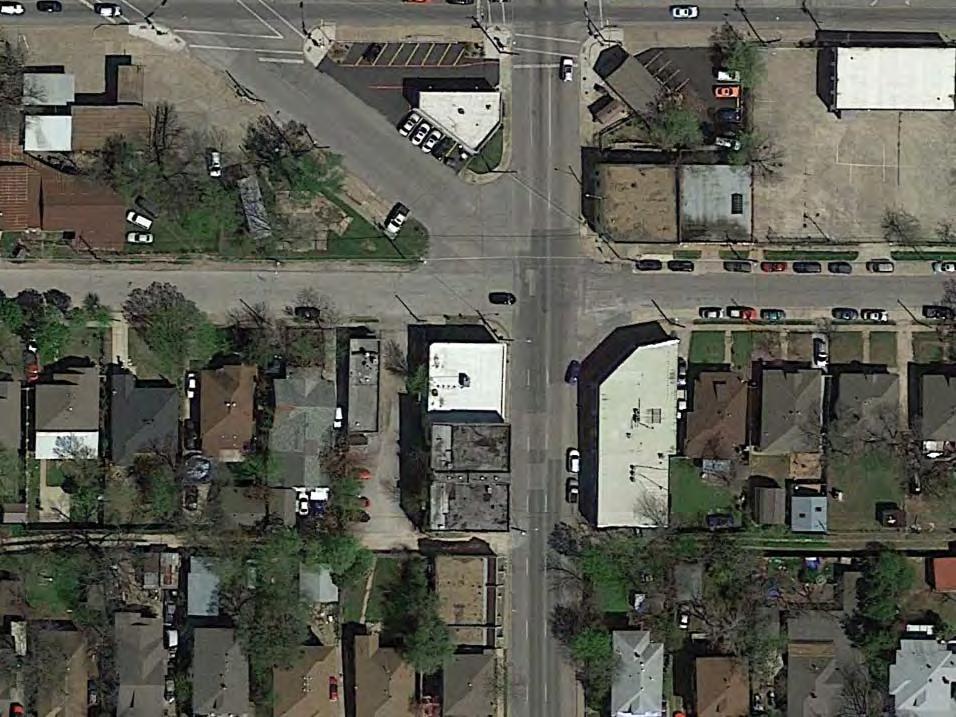

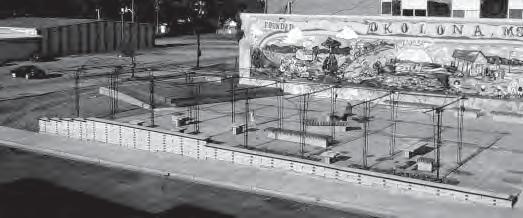

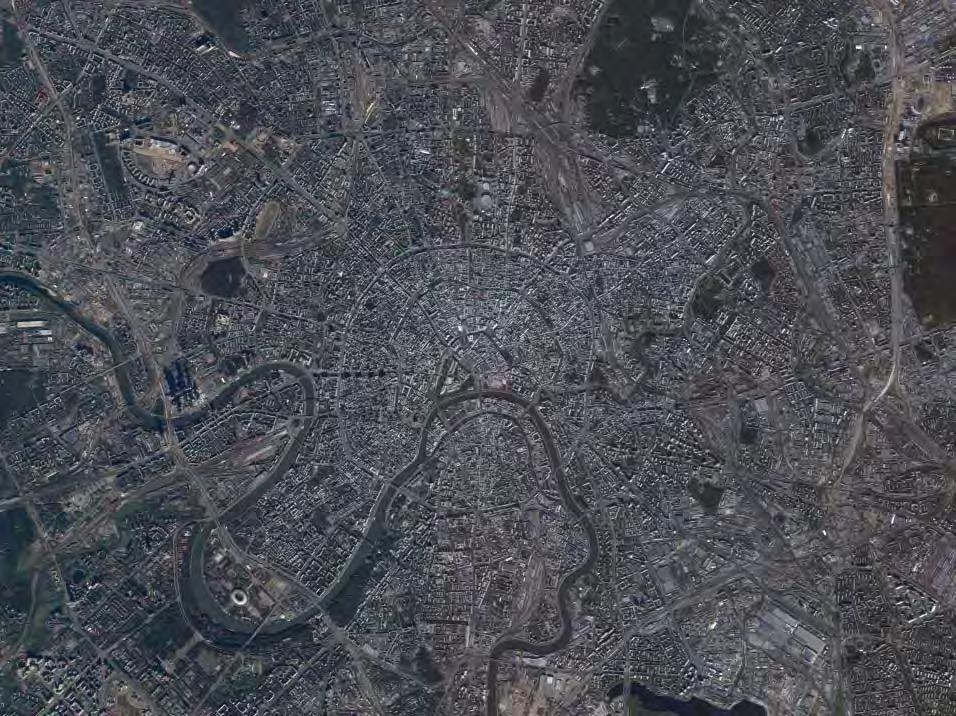

Urban Plaza P1 Okolona Downtown Park Okolona, MS M M S

Transit Social Incubators P2 Putnam Triangle Plaza Brooklyn, New York NY T5 Courthouse Square Arlington, VA P3 Charlotte Ammundsens Square Copenhagen, DK P4 Fly the Flyover Kwun Tong, HK T4 Contra Costa Transit Village Contra Costa, CA P5 Marsupial Bridge Milwaukee, WI P6 Nicolai Cultural Centre Courtyard Kolding, DK P7 Civic Space Phoenix, AZ T1 Pioneer Courthouse Square Portland, Oregon US T6 Del Mar Transit Village Pasadena, CA T7 Hammarby Sjostad Stockholm, SWE S1 Build a better block Dallas, TX S2 Delai Sam Moscow, Russia S3 Garden of Eden Fort Greene Brooklyn NY S4 Roosevelt Road Green Life Axis Taipei, Taiwan S5 Cascoland Kolenkitburt Amsterdam, NL L T3 Arlington Heights Village Arlington, IL T2 Thornton Place Seattle, WA S M M M M L L L L XL S S S S M Local Centre Regional Centre Regional Centre CBD City Centre District Centre CBD City Centre Local Centre Regional Centre CBD Local Centre City Centre Local Centre Regional Centre Regional Centre CBD Local Centre City Centre 22 // Case Studies 70 64 50 44 38 34 30 26 60 56 102 98 92 86 82 76 110 106 | 1918 | People in Public Places

TypeProject ScalePage Context

P1 Okolona Downtown Park

Okolona, MS

Type: Urban Plaza

Context: Local Centre

User Groups: Families Individuals Youth

Ethnicity context: White (26%)

Hispanic (3%)

Black (71%)

Status: Residents

Local business Workers

Students

Key Aspects:

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Collaboration

Productivity

Learning & Engagement

PROGRAMMING

Social & Cultural diversity

Health/ wellbeing & play

Okolona is a town with a population of around 3000 people and a history of racial segregation. A substantial vacant site in the middle of the downtown area was identified as suitable for a public space project to serve the civic and economic development needs of the community.

Social participation context:

This project is notable as it is a small urban centre attempting to create a public space which can be used to bring the community together and build relationships and trust. How does a project attempt to unify a historically divided community whilst still meeting the functional needs of a public space in an urban centre?

URBAN STRUCTURE

Accessibility

Flexibility

Amenity & Comfort

Connectivity

Legibility

Safety

URBAN CHARACTER

Imageability

Complexity

S

0’17.02”N

34°

88°44’57.10”W

910 m2

// Case Studies | 2120 | People in Public Places

50 m

Collaboration

▶ Community led project

A diverse group of citizens including local business owners initiated the idea of a downtown public space project which could build social capital.

Productivity

▶ Student enterprise

The detailed design and construction management was undertaken by architecture students as part of their course.

Productivity

▶ Student enterprise

Local high school students were invited to design and paint a mural on the blank side wall of the neighbouring building which addressed the site.

Collaboration

▶ Citizen involvement in design process

The design team spent several weeks in the town and conducted face to face interviews and surveys and were helped by a special ‘committee’ of diverse residents.

Productivity

▶ Participation in building

Local workers and other citizens, including children became interested in the project and provided labour and shared skills.

Legibility

▶ Defining paths & edges

The new retaining wall on the boundary which doubles as a seat and the alignment of the wisteria arbor clearly demarcate the public territory.

Flexibility

▶ Diversity of Occupation

The capping on the retaining wall doubles as an informal seat which is shaded but is suitable for ‘hanging out’ on the street. This peripheral, streetside occupation of formal public space is often preferebale for some users such as youth.

Flexibility

▶ Flexible community gathering spaces

The open nature of the park and small stage provide flexibility to host a range of different types and scales of events.

Imageability

▶ Community identification in built elements

The new brick paving used to fill in the gaps of previous floors contains handprints and markings of children who were involved in the project.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

A wisteria arbor was incorporated to meet the wishes of local residents and workers for a shady place in the downtown area where it would be possible to rest or eat lunch.

Flexibility

▶ Multiple aspect seating

Seating is wide enough and distributed carefully to allow a variety of different scales of groups to use the space whilst respecting privacy.

Imageability

Learning & Engagement

▶ Community management of public space

Local community members who were involved in providing skills and support for the project became unofficial caretakers of the site.

▶ Familiar materiality & Form Materials are familiar yet used in non-conventional ways to create a unique theme and reflect the resourceful nature of small towns.

// Case Studies | 2322 | People in Public Places

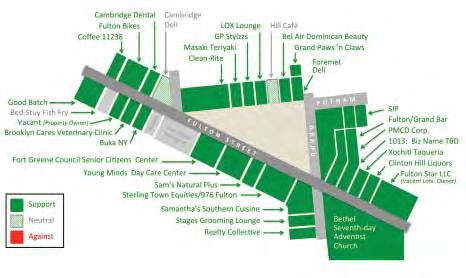

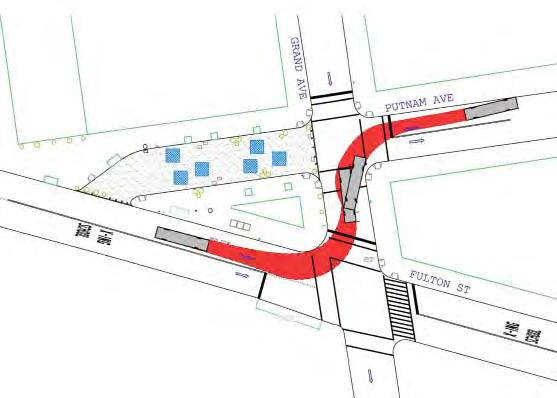

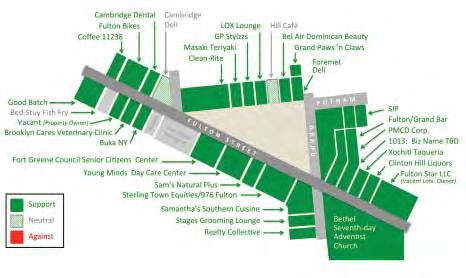

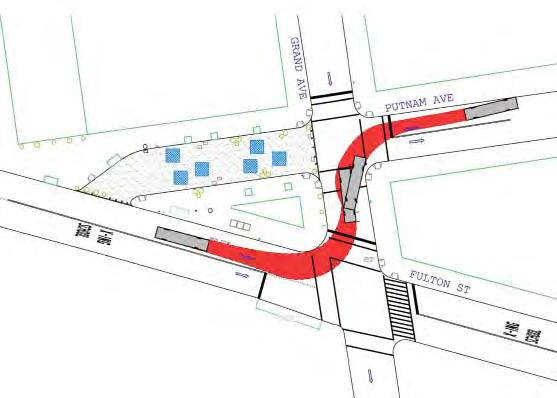

P2 Putnam Triangle Plaza

Brooklyn, New York NY

Type: Urban Plaza

Context: Local Centre

User Groups: families elderly social groups - small

Ethnicity context: African American (40%)

White (30%)

Hispanic (10%)

Key Aspects:

Status: residents residents-new local business NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Collaboration

Productivity

Social & Cultural diversity

Putnam Triangle Plaza was installed as a temporary public space along the Fulton Street commercial and metro corridor in the neighbourhood of Clinton Hill. The juncture of the street grids had created an awkward road intersection with a large triangular traffic island isolated from the streets and sidewalks. The local business alliance saw an opportunity to create a much needed neighbourhood open space which improved the public realm offering and supported the opportunities for local business.

Social participation context: The area is on the front of a ‘white wave’ out of New York city which is sweeping over the areas of Brooklyn which are well connected to downtown areas. What kind of public space can help support local business and the traditions of local residents promoting a sense of respect and integrating the new residents?

Amenity & Comfort Connectivity

Lear ning & Engagement PROGRAMMING

Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN STRUCTURE

Accessibility Flexibility

Legibility Safety URBAN CHARACTER

Imageability Complexity

S

40°40’57.64”N 73°57’42.68”W 1,060 m2 75 m // Case Studies | 2524 | People in Public Places

Collaboration

▶ Community led project

Fulton Area Business (FAB) coalition was formed from local business owners intent on improving local conditions including the public realm.

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

The urban centre/high street lacked a true public space such as a plaza and there was little opportunity for the local community to gather and meet.

Amenity & comfort > Scale

The public area has increased from 300m2 to 1,060m2 which allows a diverse range of uses to be considered being large enough to accomodate many of the existing community groups in the area involved in active pursuits.

Connectivity

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

DOT NYC works with selected not-for-profit organizations to create neighbourhood plazas throughout the City to transform underused streets into vibrant, social public spaces.

Legibility

▶ Defining paths & edges

Paving changes help reinforce the transitions between different functions in the public realm and unite public territories.

Safety

▶ Pedestrian improvement

The oblique intersection with bus turning meant poor sight distances and road position for vehicles as well as compromising the safety of pedestrians.

▶ Transport & traffic relocation

An existing bus route was changed allowing the reclamation of roadway for public use adjacent to the traffic island and retail outlets giving patrons a generous and safer forecourt whilst consolidating and simplifying bus traffic movements

Amenity & comfort > Shelter

The consolidation of the bus routes allowed a shelter to be installed where previously patrons waited at a stop on a traffic island - they are now integrated with the public relm and provide an additional use profile.

Productivity

▶ Local business enhancement

Improved public space was seen as a driver for increasing local business activity.

Flexibility

▶ User specific furniture

After trialling the temporary installation seniors requested seating with arm rests and backs to be included in the future design.

Flexibility

▶ Interim project

In order to convince the local community, test the main ideas and leave space for refinement without significant upheaval a temporary interim stage was implemented.

Flexibility

▶ Flexible equipment

Furniture is lightweight and can be moved by the public depending on their needs.

Legibility

▶ Defining public territory

Planters and granite blocks created a border to an otherwise poorly contained residual open space.

Amenity & Comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

In the second stage of the project new tree planting is proposed to improve permanent shade and offset the predominance of hard materials.

Programming

▶ Event Management & Coordination

Now that the space is officially ‘created’ local groups can apply to use the space for events through the citywide event & coordination management office.

Learning & engagement

▶ Community management of public space

Volunteers from local businesses maintain and clean the square, and put out tables and chairs each day.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Colour & Surface

The dark asphalt surface was replaced with a light gravel which brightens the area and unites the previously distinct public territories of the sidewalk and traffic island.

// Case Studies | 2726 | People in Public Places

P3 Charlotte Ammundsens Square

Copenhagen, DK

Type: Urban Plaza

Context: City Centre

User Groups: families youth elderly social groups – small social groups - large

Ethnicity context: Danish (77%)

Non-western (15%)

Status: residents

IIn a fast growing city area a traditional square adjacent to a cultural centre which had been colonised by parked vehicles is reimagined to cater for the diverse population that surrounds it. The formerly passive public space is designed and reprogrammed to welcome different types of visitors and residents.

Social participation context: The adjacent cultural centre is used by a wide variety of inner city residents and social groups and also has a youth focus. How can a relatively small urban plaza accommodate a variety of different functions such as markets, hanging out and dance classes with different sized groups and age profiles?

Key Aspects:

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Collaboration

Productivity

Lear ning & Engagement

PROGRAMMING

Social & Cultural diversity

Health/ wellbeing & play

Accessibility

Flexibility

Amenity & Comfort

Connectivity

Legibility

Safety

Imageability

Complexity

URBAN STRUCTURE

URBAN CHARACTER

M

// Case Studies | 2928 | People in Public Places

55°41’1.25”N 12°33’49.98”E 1,700 m2 60m

Collaboration

▶ Local community based organisation

The square is immediately adjacent to an existing cultural centre and can augment the existing social and cultural functioning of this location in the city.

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

Previously the square was used for parking vehicles and now they are excluded.

Learning & engagement

▶ Community management of public space

Programming

▶ Tradition informing use

Elements of a traditional urban typology – the Copenhagen Square informed the design.

Safety

▶ Colocation

The cultural centre and its cafe directly open onto the square and can ensure the park is active as well as provide passive surveillance.

The adjacent community centre manages the space as part of its overall business operation.

Legibility

▶ Form

The square retains an overall legible form and some traditional elements whilst low scale interventions provide a secondary level of organisation and intrigue.

Connectivity

▶ Maintain through routes for pedestrians

Wide steps allow pedestrians to navigate in a direct fashion between the two street levels at either end of the square without upsetting the place function.

Programming

▶ Civic/Arts anchor

The existing civic and arts function of the community centre can open out into the square.

Complexity

▶ Diversity of type

The square provides traditional elements such as paved courtyards and benches for conventional uses whuich seniors appreciate but which can also be adapted to a variety of uses.

Safety

▶ Openness and sightlines

The square maintains visibility and sightlines by keeping built elements to a low scale.

Programming

▶ Recreational & sporting infrastructure

A sunken surface allows multiple courts for sports use favoured by youth and is collocated with junior play equipment however the scale of the level court surfaces allows larger groups to congergate for a range of active and passive functions such as dancing classes.

Flexibility

▶ Multiple aspect seating

Peripheral benches allow users to orient to the square or the court and can be used for spectating or relaxing.

Accessibility

▶ Integrated universal access design

The sunken playing surface can be reached by a ramp which is integrated into the ‘cliff’ architecture.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

An ‘urban cliff’ wanders through the square and provides a dynamic and adaptable surface which can be adapted for a range of youth activities.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

Additional tree planting is used to provide seasonal colour, shade and to generally soften a highly urban environment.

Imageability

▶ Community identification in built elements

Blank walls are utilised by local artists to create a continuously changing colourful backdrop.

// Case Studies | 3130 | People in Public Places

P4 Fly the Flyover

Kwun Tong, HK

Type: Urban Plaza

Context: CBD – infrastructure

User Groups: families youth individuals

Ethnicity context: Chinese HK (97%)

Status: residents workers new workers

Kowloon East was once a dense manufacturing hub. When large parts of this industry moved to the mainland the result was a remnant fabric of industrial buildings and transport infrastructure. The area is however planned to become a second CBD. EKEO was established to mediate between the policy interests of government and the public interests of the area to help ‘kick-off’ the public realm necessary to support this transition. Fly the flyover was a scheme to try and make use of ‘redundant’ space underneath an elevated expressway.

Social participation context: The area is very high density and has a history of working class occupation and dwelling but is now earmarked for transition to a modern business district. How can the existing long term residents be brought along during the transition and avoid the development of an ‘us’ and ‘them’ community?

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE Collaboration Productivity Learning & Engagement

Aspects: PROGRAMMING Social & Cultural diversity Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN STRUCTURE Accessibility Flexibility Amenity & Comfort Connectivity Legibility Safety URBAN CHARACTER Imageability Complexity M

Key

22°18’41.85”N 114°13’4.74”E

// Case Studies | 3332 | People in Public Places

5,900 m2

170m

Collaboration

▶ Local community based organisation

EKEO established a local office, and was locally branded and focussed, despite having the resources of a government office, and was set up with the specific goal of tapping into and foregrounding the existing and yet unrecognised strong community networks in the area.

Learning & Engagement

▶ Community involvement in vision setting

Prior to any formal plans or projects community members were engaged in workshops to help develop a vision for the waterfront area and understand what all of the constraints and opportunities may be.

Programming

▶ Removing space restrictions

Traditionally the areas under the bridge were fenced off and subject to a number of restrictions on use. Through the mediation and consultation process EKEO was able to align interests and broker agreements to test removal of these barriers.

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

Previously access to the area was simply restricted by security fencing. This has been removed.

Amenity & Comfort

▶ Weather Protection

The flyover provides a ‘natural’ canopy and allows a range of events to take place protected from the elements.

Safety

▶ Colocation

The office of EKEO is situated at one of the project which allows passive surveillance of the space in a continuous manner.

Amenity & Comfort

Productivity

▶ Community enterprise

Local community groups have the ability to program the space, to exhibit and promote their activities and skills through the colocated office of EKEO.

Legibility

▶ Defining public territory

New paving, paths, surfacing and landmark structures clearly claim and signify the territory under and adjacent to the flyover as public realm.

▶ Scale

The height and dimensions of the flyover provide a large volume, of cathedral like proportions, which can be itself an uplifting and special experience.

Connectivity

▶ Public space to overcome infrastructure barrier

The project has opened up a previously ‘forbidden’ territory which acts as a stepping stone to realising the vast potential of the abandoned waterfront as a defining feature of the future public realm.

Connectivity

▶ Integrated public connections

The path networks and public space connect directly to the local street network and integrate the space physically with the local community allowing pedestrian access.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

Flexibility

▶ Flexible equipment

A range of furniture and ‘props’ are provided which can be moved to facilitate a variety of events and uses and can be managed and storedby the local EKEO office.

Rather than a predetermined use the large volume under the flyover was designed to be able to stage a diverse range of community events and installations.

Safety

▶ Infrastructure for non-essential activities

A variety of activities can now take place on the site involving a wide range of users which creates a positive perception and passive surveillance.

// Case Studies | 3534 | People in Public Places

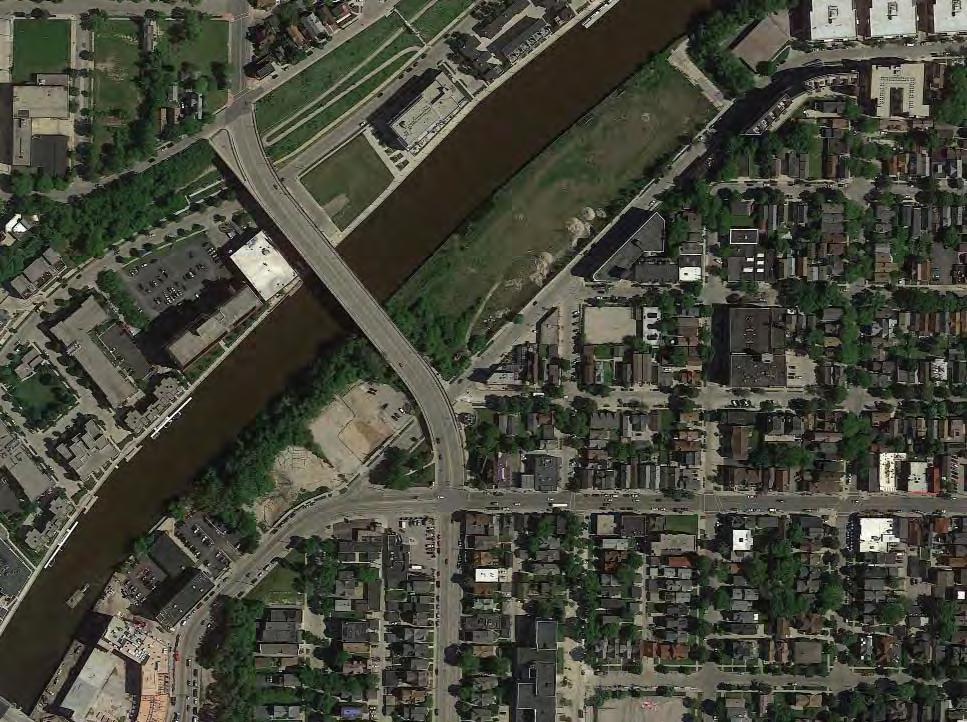

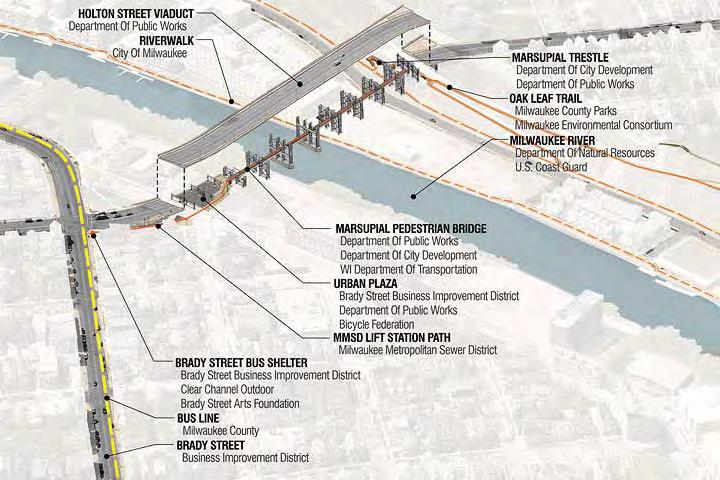

P5 Marsupial Bridge

Milwaukee, WI

Type: Urban Plaza

Context: District Centre – infrastructure

User Groups: families social groups – small cyclists

Ethnicity context: European (Polish, German, Italian) White

Status: residents residents - new long-term migrants local business

Key Aspects: M

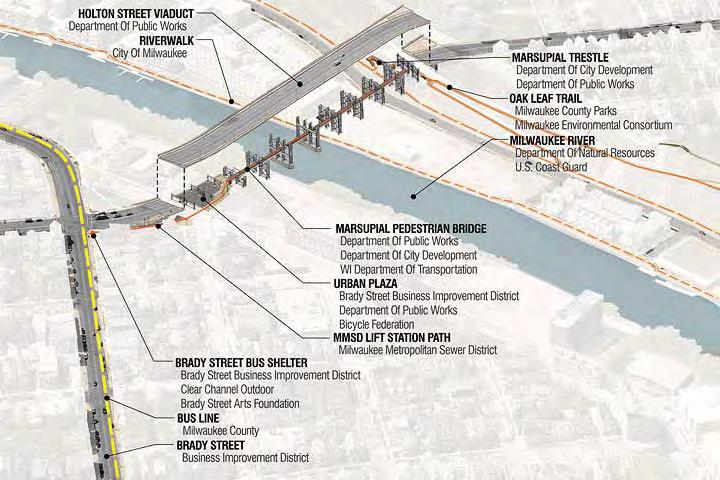

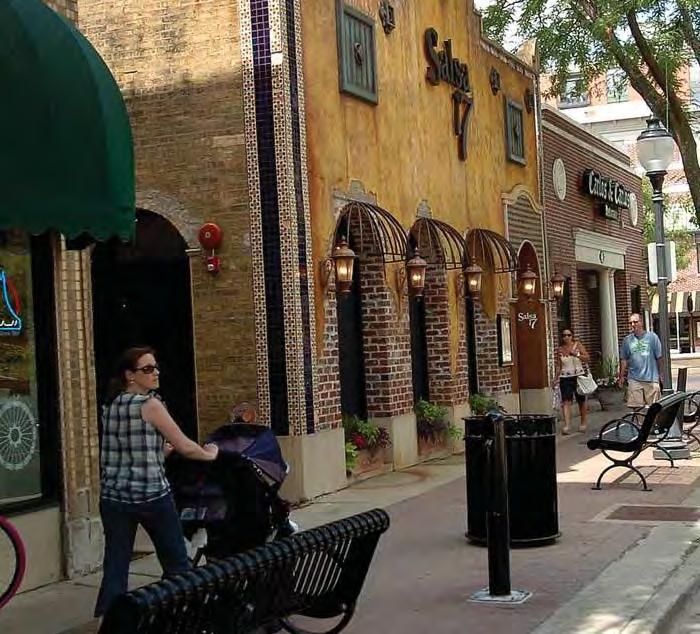

Marsupial Bridge is a project which seeks to connect communities and provide a unifying element for non-motorised traffic. Typically areas beneath infrastructure have been abandoned or avoided however this project looks to adapt the positive aspects of such places. It draws on the cultural and social diversity of the adjacent Brady Street neighbourhood which is one of the city’s best known and surviving ethnic commercial strips.

Social participation context: The bridge provides a link to the historical Brady Street high street precinct from the new neighbourhoods to the north and is in that sense a device to broaden the social and cultural base of this popular area. The project is a ‘hinge’ between these areas and defines a new civic relationship. How does a project which is all about linear connectivity manage this transition, being more than just a path, and provide an asset in this ‘vague terrain’ for the public life of both communities?

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE Collaboration Productivity Learning & Engagement PROGRAMMING Social & Cultural diversity Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN STRUCTURE Accessibility Flexibility

& Comfort Connectivity Legibility Safety URBAN CHARACTER Imageability Complexity

Amenity

3’13.35”N

43°

87°54’11.95”W 2,800 m2 230m

// Case Studies | 3736 | People in Public Places

Brady Street

Collaboration

▶ Community led project

The project responds to needs identified by communities on the opposite side of the river to the Brady Street Improvement District.

Produtivity

▶ Local business enhancement

The new connection across the river offers new customers to the Brady Street commercial area.

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

The project works across and with a host of partners including the local arts foundation, local business and Milwaukee Bicycle Federation as well as city, state and federal bodies.

Imageability

▶ Thematically Integrating surrounding uses

The sewer lift station forms a feature of the access path whereas the bridge and plaza utilise the viaduct structure as a ‘host’.

Connectivity

▶ Integrated public connections

Amenity & comfort

▶ Scale

The lofty area under the bridge is adapted to provide a generously scaled covered public realm.

The project stitches together a number of existing and new connections between neighbourhoods, streets and public amenities such as the Milwaukee River walk and Oak Leaf trail.

Connectivity

▶ Public space to overcome infrastructure barrier

The urban plaza provides a place for people to stop and rest or gather which provides activity in a relatively uninhabited area and breaks the long path.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

Local community members have appropriated the space for a variety of personal and public events such as film screenings, weddings and plays. Its peripheral character suits more minority and experimental programmes.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Weather protection

The bus shelter and bridge deck provide protection from the weather for both stationary and active users

Accessibility

▶ Streetscape improvements

A uniquely designed bus shelter sets a new quality standard for street furniture and defines the corner of the commercial district.

Legibility

▶ Defining paths & edges

Honed concrete surfacing is a unifying element of the shelter, pathways, ramps and landings.

Learning & engagement

▶ Interpretive content

The bus shelter also acts a specially designed information stand which can be used for project and community information.

Imageability

▶ Familiar materiality & Form

The new bus shelter design was based on the traditional shelters across the city which are distinctive and offer protection from the elements.

// Case Studies | 3938 | People in Public Places

Safety

▶ Infrastructure for non-essential activities

The swings create room for playful occupation of the space and encourage a variety of users to incidentally occupy the plaza.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

The urban plaza component occupies the protected territory under the bridge and provides a basic framework of benches and lighting to support multiple uses.

Legibility

▶ Integrated lighting

Lighting is integrated into the structure at close intervals to avoid high contrast environments and ensure the public areas are visible from a variety of locations and distances.

Connectivity

Accessibility

▶ Formalise paths

A number of informal routes in the semi-industrial location have been formalised and enhanced as part of the overall project.

▶ Maintain through routes for pedestrians

The project maintains and extends the bridge crossing for pedestrians to join into the commercial area and connect the neighbourhoods.

Flexibility

▶ Multiple aspect seating

Benches can be used for a variety of seating arrangements and user group sizes. Their variable spacing, lighting and indeterminate orientation make them highly adaptable for performance and play.

Programming

▶ Recreational & sporting infrastructure

Local artists installed swings in the plaza to take advantage of the large void and these have been formalised by the local authority.

Legibility

▶ Defining public territory

A crushed gravel (non-trafficable) surface to the plaza clearly demarcates a public area for non-traffic activities and is inviting for children and others as a play surface.

Amenity & comfort

Programming

▶ Active transport management

The project is deliberately aimed at improving cycling conditions through the dimensions of the pathways and has been adopted by bicycle users as a meeting place.

▶ Use of natural materials

The bridge deck , railing and bus shelter use wood to humanise the pedestrian and cyclist environment and offset the grand but imposing industrial context.

Safety

▶ Openness and sightline

Low height furniture, semi-transparent railings and a straight, gradual path alignment ensure that sightlines along the length of the pathway and across the plaza are preserved.

// Case Studies | 4140 | People in Public Places

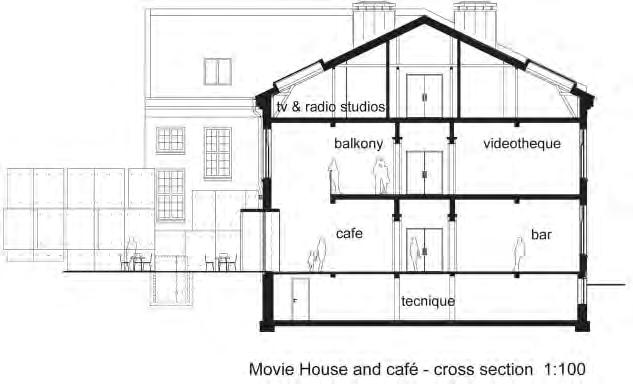

P6 Nicolai Cultural Centre

Courtyard

Kolding, DK

Type: Urban Plaza Context: City Centre

User Groups: families children social groups – small social groups - large

Ethnicity context: Danish (88%)

Non-European (5%)

Status: visitor/tourist residents local business

This urban plaza project is located directly in the city centre and is framed by a number of historical buildings. The challenge for this project was to repurpose a surface car park and create a Cultural Centre which accommodates and weaves together a variety of different uses and user types as well as create a coherent public realm.

Social participation context:

The public space for this project is framed by a number of cultural uses which support different programmes and age groups. Children feature heavily and the centre serves a regional population base. How can the public realm be designed to respond to its rich heritage, accommodate the day to day needs of the children and other uses and users and still provide a gathering place for up to 1000 people for regional events?

Key Aspects:

Collaboration

Productivity

Learning & Engagement PROGRAMMING

Social & Cultural diversity

Health/ wellbeing & play

Accessibility

Flexibility

Amenity & Comfort

Connectivity

Legibility

Imageability Complexity

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

URBAN STRUCTURE

Safety URBAN CHARACTER

M

m2

m // Case Studies | 4342 | People in Public Places

55°29’28.08”N 9°28’16.08”E 3,800

70

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

The project was partly sponsored by RealDania who are a member-based philanthropic organization that supports social objectives of projects in the built environment which placed the social agenda very much in the foreground of the design process.

Learning & engagement

▶ Learning centre incorporated into project

The House of children’s culture is supported by the LOA foundation and is an open program were the children of Kolding can do different cultural activities, drama, theatre, dance and movement in the different workshops

Programming

▶ Civic/Arts anchor

There are five civic buildings/functions framing the square and one is available for arts residencies and as a general studio tenancy for local artists. The civic nature consolidates activity and avoids the risk on over dependency on commercial enterpriises.

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

The project was also sponsored by the Danish Foundation for Culture & Sports facilities which seeks innovation in relation to the design and planning of culture and sports facilities that is rooted in changes and new patterns in everyday life. This further enhanced and diversified the social ambitions of the proect.

Programming

▶ Tradition informing use

The site was originally a group of school buildings and the themes of the schoolyard, learning and occupation by children have been incorporated into the different functions.

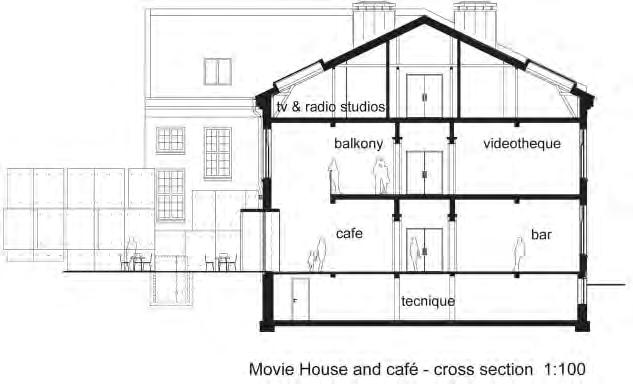

Productivity

▶ Community enterprise

The Cinema House is occupied by a not for profit art cinema with an accompanying café which contributes to a consistent use profile.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

The large courtyard is relatively free of permanent fixtures and can be adapted to a range of large scale activities and uses.

Flexibility

▶ Diversity of Occupation

The large open aspect with well spaced furniture allows different users and functions within the space to congregate and interact.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Scale

The sense of generous scale of the courtyard is preserved and reinforced by a lack of clutter and a continuous surface treatment.

Legibility

▶ Form

The territory is mostly orthogonal and easily understood through uniting of different elements, consistent surfacing and the placement of thresholds and gateways at the most public locations.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

Tree planting has been grouped to soften the repetitive elements and existing trees have been carefully preserved and integrated into the buildings.

Legibility

▶ Defining paths & edges

A high steel wall clearly defines, contains the public realm running along what was previously a poorly defined section of the perimeter.

Complexity

▶ Richness & Intrigue

Patterned surfaces are used to overcome the potential monotony of the asphalt surface and suggest a sequence of movement without obstruction.

// Case Studies | 4544 | People in Public Places

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

The courtyard had been used for parking and vehicle access however the decision to create a public territory excluded traffic.

Complexity

▶ Diversity of Type

Whilst the overall ‘schoolyard’ is open subtle variations allow the creation of different’rooms’ for both traditional and inventive use allowing different sized groups and functions to inhabit the area without comprimising larger gatherings.

Safety

Safety

▶ Repetitive use elements

The café, theatre and other perimeter functions provide a routine programme which ensures consistent and varied use profiles.

▶ Maximum adaptability of ground floor

Ground floor openings of the surrounding civic buildings have been redesigned to address the courtyard in key locations to ensure a regular pattern of surveillance and interaction on the public space perimeter.

Accessibility

▶ Universal access design

All of the public realm and buildings are wheelchair accessible and the smooth, level surface of the courtyard is easily negotiated by different users.

Imageability

▶ Repurposing historic structures

The old school buildings have been repurposed for civic functions and the ‘schoolyard’ has been reinstated for play and a range of activities.

Programming

▶ Concerts and Events

The combination and concentration of different civic uses combined with the multi-functionality and scale of the open space allows a diverse range of events to take place.

Imageability

▶ Familiar materiality & Form

The new elements have colours and forms which are sympathetic to the brickwork grounding the design in the local context and encouraging an adoption of the new elements by the existing community.

Connectivity

▶ Integrated public connections

The courtyard provides a pedestrian connection between two perimeter streets whilst the public buildings provide a permeability across their ground floors to integrate the street and open space and avoid an exclusive realm.

Safety

▶ Openness and sightlines

The courtyard is open and space transitions are dealt with in subtle ways through surfacing patterns, trees, voids in structures and low height furniture which maintains sightlines.

// Case Studies | 4746 | People in Public Places

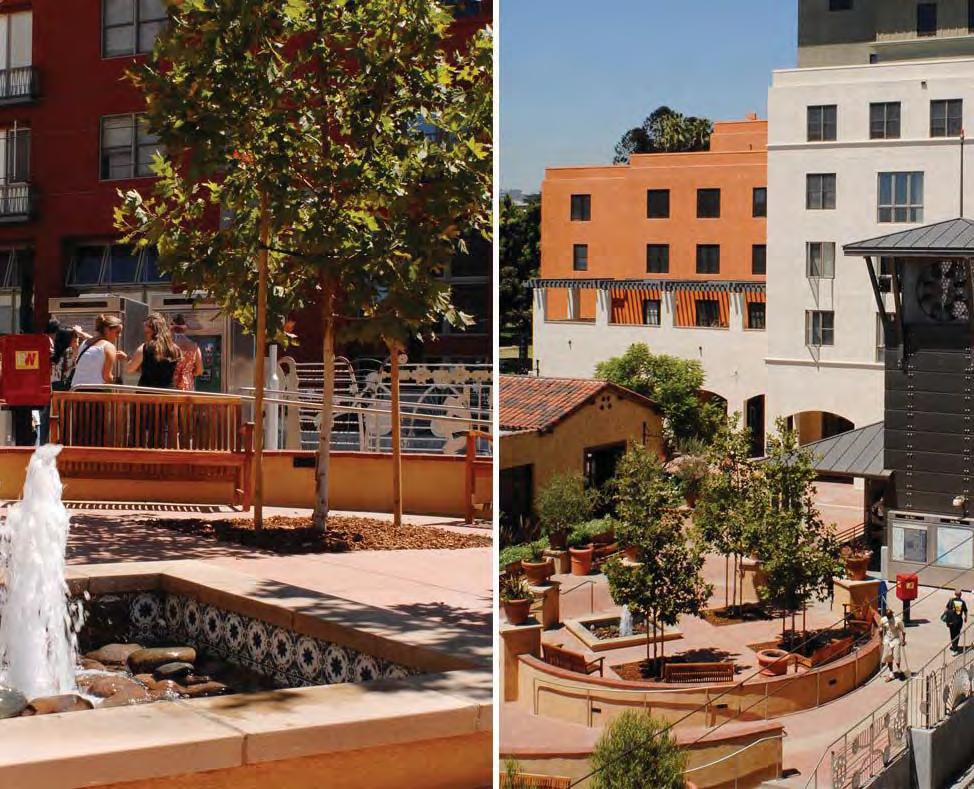

P7 Civic Space

Phoenix, AZ

Type: Urban Plaza Context: CBD

User Groups: all

Ethnicity context: White (66%)

*Hispanic (41%)

African American (6.5%)

Asian (3.2%)

Status: visitor/tourists residents – low income students commercial business

Civic Space Park is nestled in the heart of downtown Phoenix, Arizona . This park, developed in partnership between the City of Phoenix and Arizona State University, brings to the surrounding downtown community a vibrant mix of storefront and respite environment. The park concept weaves together an urban fabric. Various programmable spaces meet the needs of a wide variety of ages and user profiles. Seventy percent of the site will ultimately be shaded with trees and unique undulating shade structures. The park is exclusively for pedestrian use, and it is adjacent to the Central Station Transit Centre.

Social participation context:

Civic Space Park occupies a social nexus in the downtown area. The perimeters are variously occupied by university students, transit patrons, boarding houses and institutional buildings and its central location and scale means a regional civic role. The challenge is for the park to provide a united place with enough flexibility to adapt to its varying functions and mix the passive and active recreation demands of different ages.

Key Aspects:

Collaboration

Productivity

Accessibility

Flexibility

Connectivity

Legibility

Imageability

Complexity

*Note: Hispanic is identi fi ed as a separate ethnicity category in the US census, and may also identify as white in the race category. Hence proportions reported here may exceed 100%.

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Learning & Engagement PROGRAMMING

Social & Cultural diversity

STRUCTURE

Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN

Amenity & Comfort

Safety URBAN CHARACTER

L

4’26.56”W

230 m

// Case Studies | 4948 | People in Public Places

33°27’12.37”N 112°

21,500 m2

ASU

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

The University of Arizona saw benefits to its downtown campus profile and functionality in a new public space in this location and partnered with the City of Phoenix local authority

Cultural diversity

▶ Civic/Arts anchor

The project is bounded by tertiary education establishments, a transit hub and a YMCA – the existing building on site was re-purposed for exhibitions and community use.

Collaboration

▶ Collaborative partnership and funding

The project was financed using bonds issued by the city and approved by constituents which gave a wide sense of ownership.

Safety

▶ Colocation

The university and other adjacent functions such as the YMCA gymnasium provide a diverse and continuous user profile.

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

Previously the majority of the site was in private ownership and used for parking vehicles, the city acquired the land for public purposes.

Collaboration

▶ Citizen involvement in design process

Community groups were thoroughly engaged in the vision setting process and a collaborative concept ‘the weave’ was generated.

Learning & Engagement

▶ Learning centre incorporated into project

Arizona State University Parks & Management students use the park as a learning laboratory which provides diversity to the use profile and gives adjacent functions an interest in the design and management of the space.

Productivity

▶ Digital Compatibility

The basement and gallery building provide free Wi-Fi which makes it a popular spot with students from the adjacent campus.

Productivity

▶ Retail strategy

A basement level tenancy provides opportunity to take advantage of the destination nature of the park.

Connectivity

▶ Transit connection

The project is directly adjacent to the Downtown Central Station and is bordered by light rail.

Complexity

▶ Diversity of type

A traditional peaceful shaded park area was incorporated into the design at the request of seniors who lived in the area.

// Case Studies | 5150 | People in Public Places

Programming

▶ Children’s attractions

A splash pad allows children to play in an unstructured fashion and is playfully illuminated so that it can be used at night.

Safety

▶ Openness and sightlines

Despite its expansive size the refined lightweight structures and gradual level changes maintain an open aspect and ensure the public realm is visually permeable.

Imageability

▶ Repurposing historic structures

A large 1920s showroom on the site was restored and upgraded to provide community functions. This provides an anchor to the public functioning of the park.

Legibility

▶ Defining paths & edges

The materiality and alignment of the adjacent Taylor Street pedestrian corridor is continued through the site integrating surrounding uses and movement networks particularly the university.

Connectivity

▶ Integrated public connections

The public and open terrain across an entire block acts as an urban connector between the fringing private, public and civic functions.

Accessibility

▶ Pedestrian prioritisation

Vehicles and parking are completely excluded from the park.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

Shade canopies and tree planting are critical elements in achieving comfort in the large open space in a desert climate. The spacing of the trees and their placement on the gentle ‘hills’ allows small social groups to form independent of one another.

Programming

▶ Concerts and Events

A stage was incorporated into the design to allow structured events and performances.

Programming

▶ Event Management & Coordination

The event programming is informed by community and focus group interviews and research and funded through a number of local downtown partners.

// Case Studies | 5352 | People in Public Places

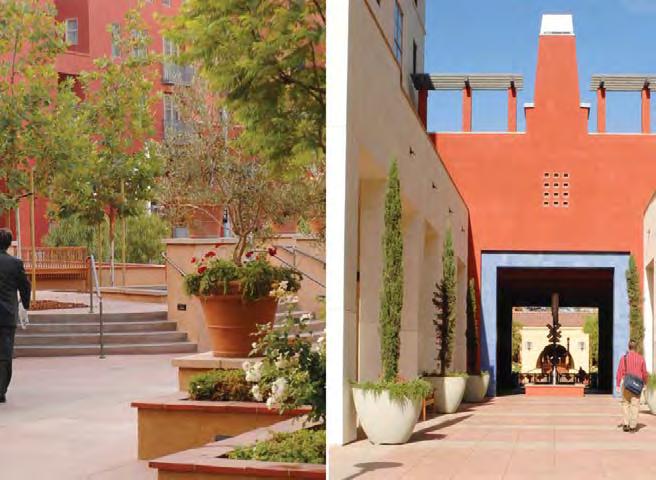

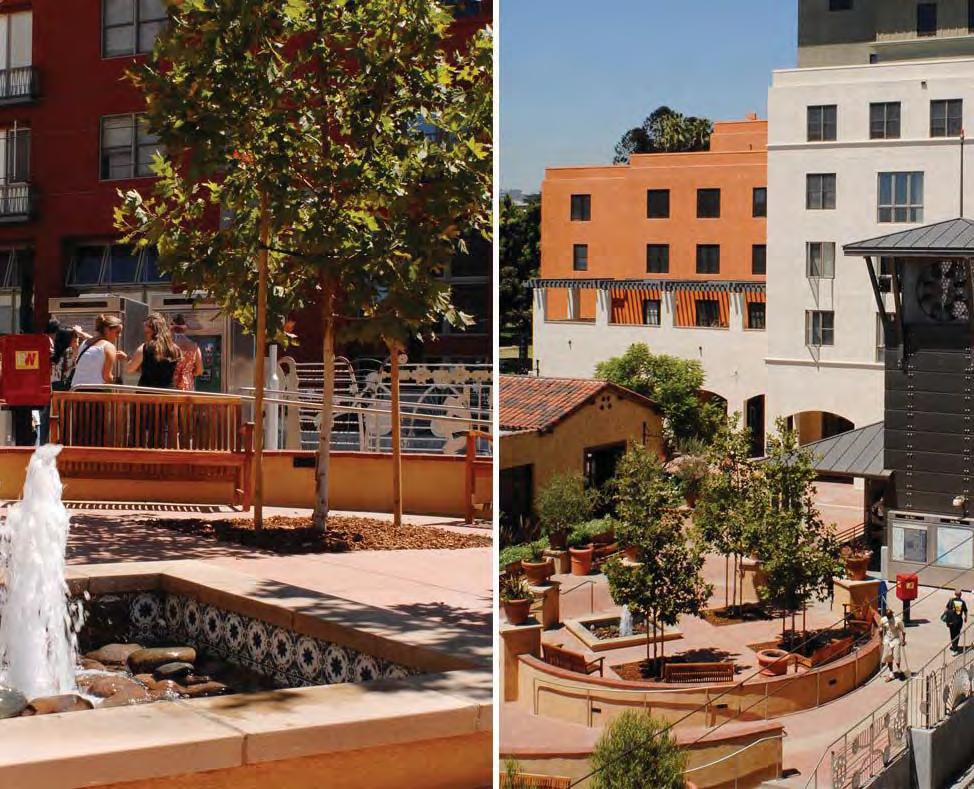

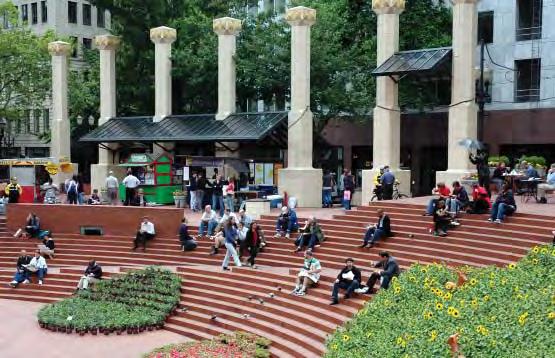

T1 Pioneer Courthouse Square

Portland, Oregon US

Type: Transit Context: CBD

User Groups: all

Ethnicity context: White (70%)

Hispanic (9%)

Asian (7%)

African American (6%)

Native American (1%)

Status: visitors/tourists transit patrons commercial business

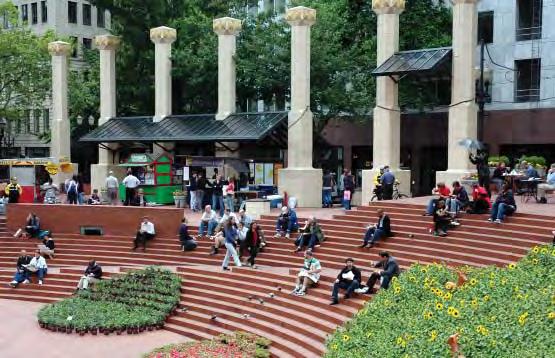

Pioneer Courthouse Square was formerly a 2 storey parking garage located on a strategically significant site where surface transit routes intersected. It was transformed into a public square via a design competition in 1980 and has often been held up as an exemplar of transit integrated public realm design.

Social participation context: The downtown location and transit context mean that the space must accommodate the whole diversity of the City. Some users pass through for transfer, others congregate for formal and informal meetings whilst structured programming focusses on large gatherings. How does the spatial design of such a place respond to the diverse demands of social interaction?

Key Aspects:

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE

Collaboration

Productivity

Lear ning & Engagement

PROGRAMMING

Social & Cultural diversity

Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN

Accessibility

Flexibility

Amenity & Comfort

Connectivity

Legibility

Imageability

Complexity

STRUCTURE

Safety URBAN CHARACTER

M

m // Case Studies | 5554 | People in Public Places

45°31’7.10”N 122°40’47.40”W 5,300 m2 75

Collaboration

▶ Community led project Community members called Friends of Pioneer Square raised significant funds to keep the project developing in the face of institutional problems.

Collaboration

▶ Citizen involvement in design process

Extensive citizen involvement in concept development and design selection criteria to remove aesthetic and political bias.

Imageability

▶ Community identification in built elements

Programming

▶ Tradition informing use

The hotel which was originally on the site was once the city’s most popular meeting space.

Community members who supported the project had their names engraved onto paving bricks and furniture which are used in the project.

Legibility

▶ Form

The square form of the block is easily understood and reinforced with built elements whilst opposing edges and corners are visible.

Connectivity

▶ Transit connection

The square sits at the crossroads of the downtown transit routes ensuring it is both convenient for a large variety of users and well activated.

Legibility

▶ Defining public territory

Trees, columns, planters, low walls, bollards and transit stops clearly demarcate the extent of the public realm without obstructing sightlines or restricting access and permeability.

Programming

▶ Civic/Arts anchor

The square is home to the downtown Visitor and Travel Information Centre, a Theatre and a studio which broadcasts daily TV news programmes.

Accessibility

▶ Integrated universal access design

The main plaza can be reached by the footpaths and a disabled ramp is integrated into the theatre steps rather than a separate element.

Programming

▶ Indeterminate use

Rather than a predetermined use the large level open area within the square allows a diverse range of community events, stalls and installations.

Safety

▶ Openness and sightlines

The square maintains visibility by recessing building functions and not installing structures which would obstruct sightlines.

Safety

▶ Repetitive use elements

Repetitive daily activities particularly around transit ensure that there is a continuous use profile and passive surveillance.

Flexibility

▶ Multiple aspect seating

Peripheral benches allow back to back seating giving visitors a choice to engage with either street or square depending on their prefernce.

Flexibility

▶ Diversity of Occupation

The wide arc of theatre steps allow many individuals and different sized groups to congregate in different locations preserving their privacy and providing them with choice over engagement.

Imageability

▶ Familiar materiality & Form

Bricks, terracotta and neo-classical elements draw on the built heritage whilst providing inviting and familiar textures.

// Case Studies | 5756 | People in Public Places

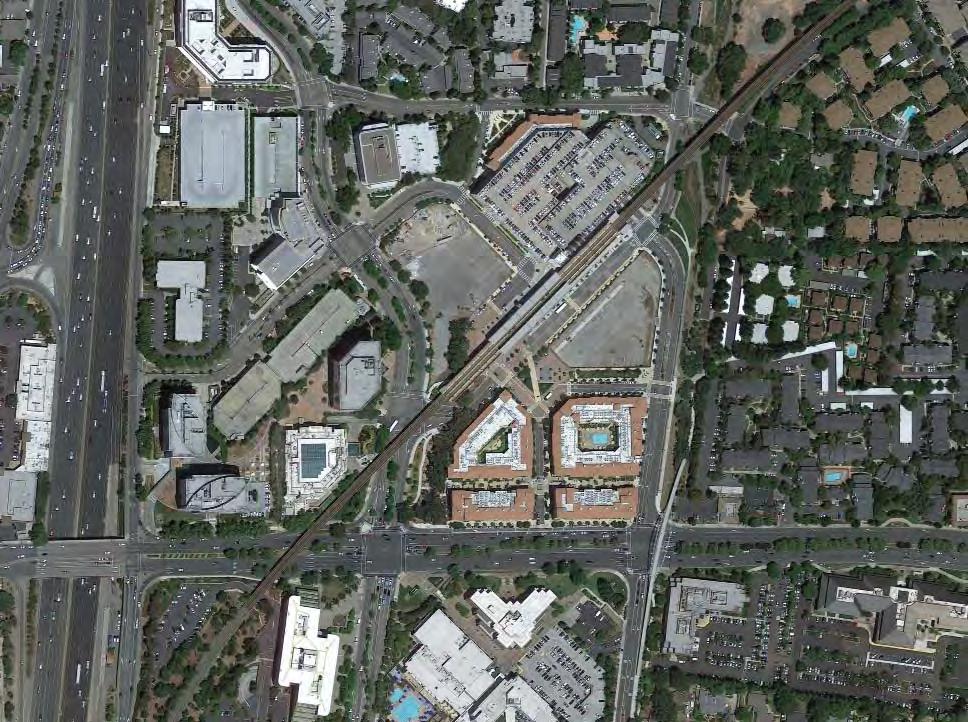

T2 Thornton Place

Seattle, WA

Type: Transit Context: Regional Centre

User Groups: families individuals

Ethnicity context: White (56%)

Hispanic (12%)

Black (3%)

Asian (24%)

Status: Residents

Key Aspects:

Local business Transit patrons NETWORKS

Collaboration

Productivity

Social & Cultural diversity

Thornton Place establishes a new paradigm for urban development in an area which has traditionally catered for commuter parking. The project establishes a high density mixed use environment but makes strong commitments to the public realm both for the use of the new residents immediately adjacent but also as an asset and amenity for the broader neighbourhood. It is a project which sets a benchmark for the transit oriented development pattern that this area will sustain in the future and places the public realm as an integral part of this.

Social Participation Context:

The population is ethnically diverse although within the context of a modern city. The project presents a new type of urban development within a broader transitional frame. How can the public realm contribute to the needs of the existing and future neighbourhood whilst providing for the new local residents and business visitors?

Accessibility

Flexibility

Amenity & Comfort

Connectivity

Legibility

Imageability Complexity

& EXCHANGE

Learning & Engagement PROGRAMMING

Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN STRUCTURE

Safety URBAN CHARACTER

M

// Case Studies | 5958 | People in Public Places

47°42’8.85”N 122°19’29.25”W 32,000 m2 180 m

Learning & Engagement

▶ Community involvement in vision setting

A public open day and online survey for the broader neighbourhood helped identify the key constraints to retrofitting an automobile dominated neighbourhood and establish local values for a new urban centre.

Programming

▶ Civic/Arts anchor

A new library and community centre have been constructed in the vicinity within walking distance of Thornton Place with a street frontage to establish a new form of pedestrian oriented urbanism in the neighbourhood.

Connectivity

▶ Public open space network structure

The public areas form part of a broader open space network which has been established for the whole precinct.

Complexity

▶ Diversity of experience

The project incorporates a range of public realm typologies such as formal retail plaza, internal streets, mews and creekside paths.

Legibility

▶ Logical and human scaled public realm

The block dimension of 200m was broken down into smaller parts with public access to create a more pedestrian scaled fabric.

Connectivity

▶ Integrated public connections

The large open space along the creek extends to the borders of the project integrating with existing and future public pedestrian movement networks. This ensures that this part of the site remains truly public.

Connectivity

▶ Transport & traffic relocation

Surface park-and-ride parking spaces have been integrated into a parking structure which reciprocates with the evening and weekend demand patterns of a cinema complex.

Accessibility

▶ Liberating public space

The project has chosen to open a new public green link along the creek line rather than a completely internal semi-public perimeter block arrangement.

Flexibility

▶ Diversity of Occupation

The public pathway along the creek is wide enough to accommodate a range of both active and passive use profiles.

Amenity & comfort

▶ Tree planting & shade

Safety

▶ Colocation

A cinema complex and ground floor retail address the internal street providing a continuous ground level use profile within the block.

Imageability

▶ Natural features and landmarks

The culverted Thronton Creek which is an important Salmon stream has been reimagined as a natural feature which is clearly distinctive in the urban context.

The natural environment of the creek provides a restful outlook for contemplative behaviours.

// Case Studies | 6160 | People in Public Places

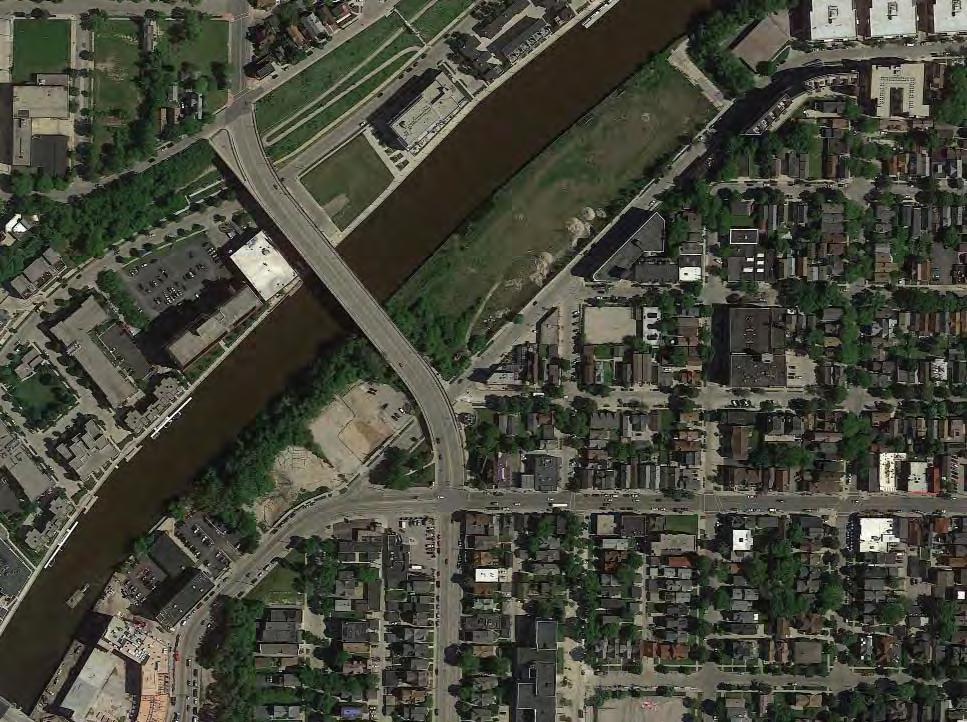

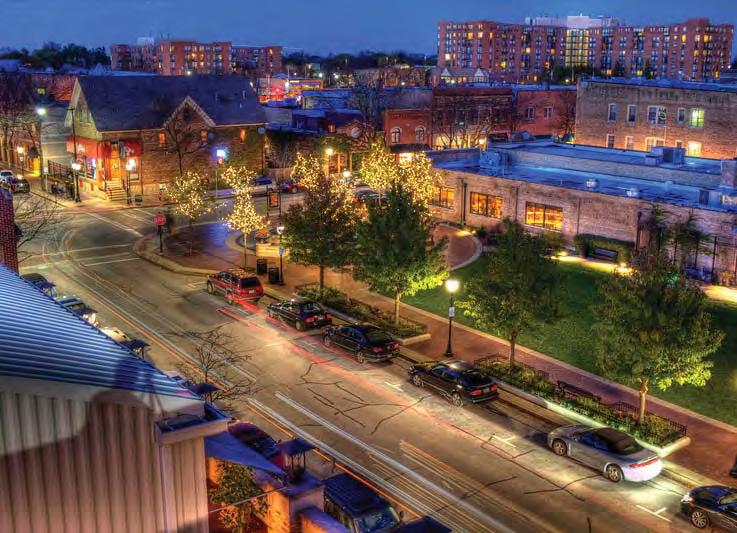

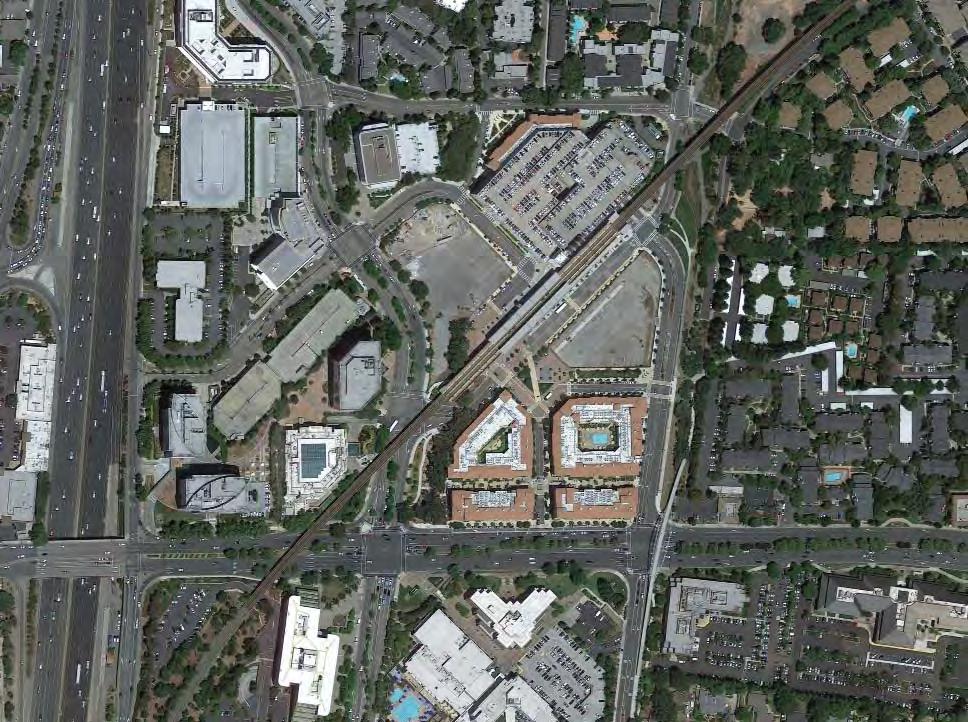

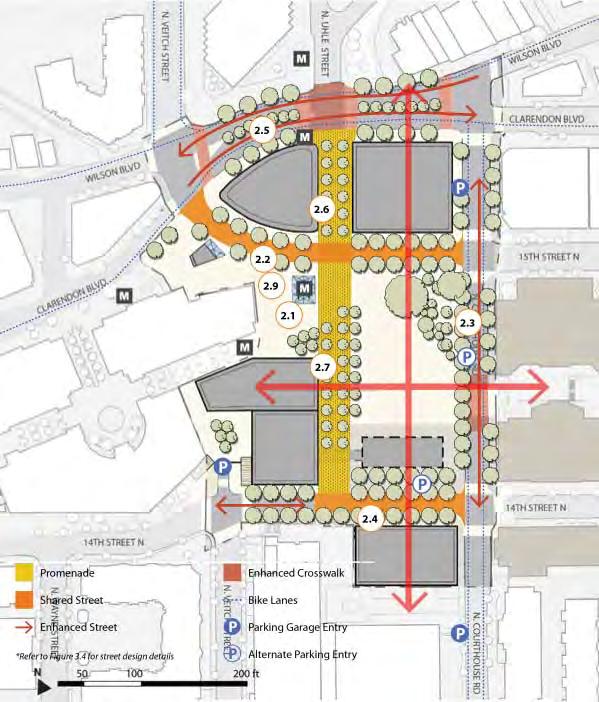

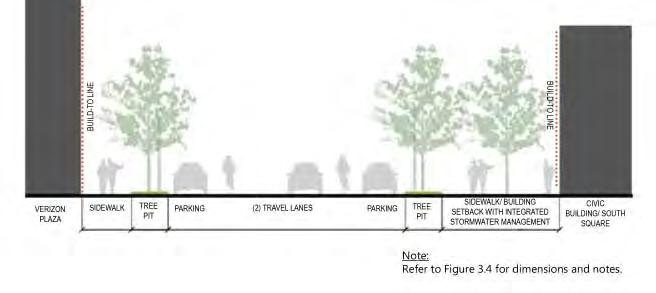

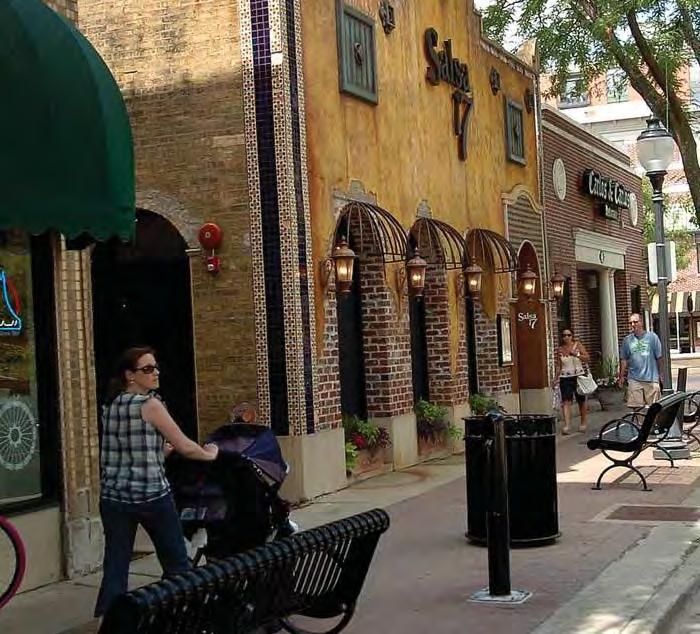

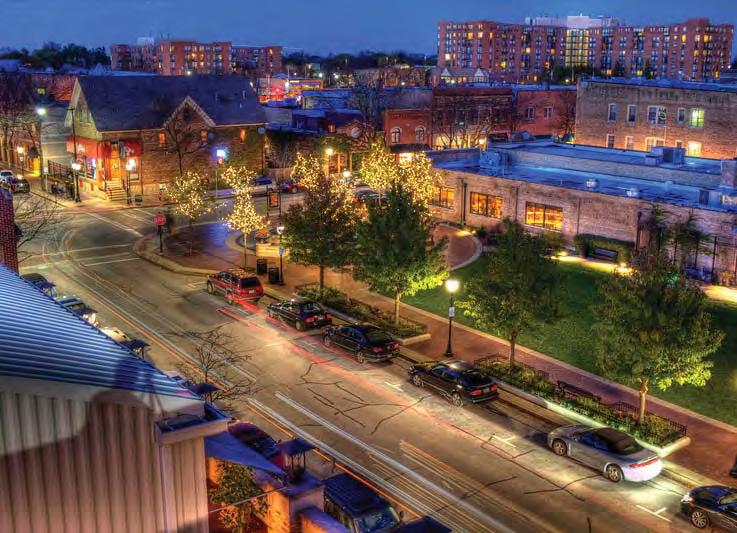

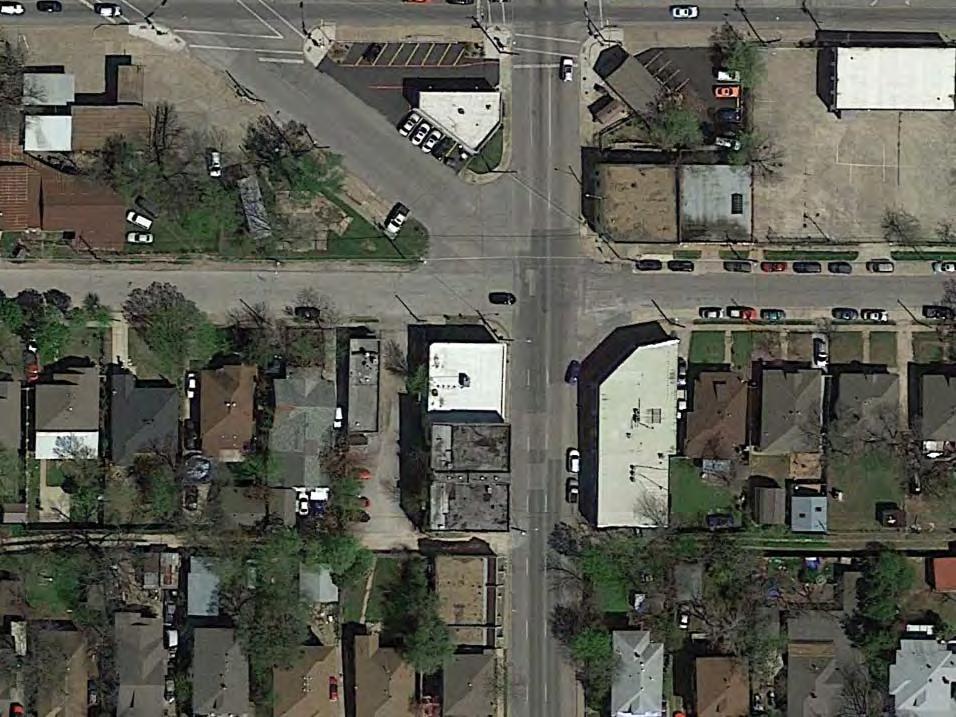

T3 Arlington Heights Village

Arlington, IL

LType: Transit

Context: Regional Centre

User Groups: families individuals elderly social groups – small social groups - large

Ethnicity context: US white (88%)

Status: residents workers local business transit patrons

Arlington Heights was a peripheral village NW of Chicago which became a commuter suburb in the 1970s. Following some isolated downtown redevelopment in the 1980s the relocation and upgrade of the Metra commuter rail station to more closely coincide with the downtown area precipitated coordinated TOD efforts. A significant early challenge was to overcome the dangerous arrangement and barrier effect of the parallel at-grade rail, carpark and highway infrastructure for pedestrians.

Social participation context: Arlington heights is a typical North American urban centre for a large suburban catchment – overrun with asphalt and vehicular priority. The demographics are relatively homogenous and oriented toward white middle class families. With all that said these commuter nodes are attempting to transition into activity centres to try and provide a variety of experiences and business opportunities and cater for an emerging demographic of ‘non-traditional’ households and modern enterprise.

Key Aspects:

NETWORKS & EXCHANGE Collaboration Productivity Learning & Engagement PROGRAMMING Social & Cultural diversity Health/ wellbeing & play URBAN STRUCTURE Accessibility Flexibility Amenity & Comfort Connectivity Legibility Safety URBAN CHARACTER Imageability Complexity

42° 5’2.62”N 87°58’57.68”W

// Case Studies | 6362 | People in Public Places

23.2 Ha

500 m

Collaboration

▶ Local community based organisation

The project was directed by a specially commissioned Task Force comprised of members from the Village Board (council), plan commission, design commission, economic alliance, chamber of commerce, downtown business association, downtown business owners, and residents.

Connectivity

▶ Public space to overcome infrastructure barrier

Improved connectivity between the north and south sides of the new station area, was achieved by creating a public park adjacent to the station to break up the journey across the parallel railway and highway ‘obstacles’ and also introduce a pleasant forecourt to the station area. This staged crossing is particularly important for elderly and any users who may struggle with negotiating complex crossings.

Collaboration

▶ Planning & Design community & stakeholder charrettes

Design charettes and workshops have been used to involve stakeholders including the local community in the planning and preliminary urban design process.

Learning & engagement

▶ Community involvement in vision setting

In a 2 year period during the development of the masterplan the Task Force held 31 public meetings to to gather input, identify issues, formulate recommendations and define the vision and objectives for future development downtown.

Connectivity

▶ Transport & traffic relocation

Learning & engagement

▶ Community involvement in vision setting

Development of a steering committee including community members to review the performance of other TODs and improvement of downtown areas.

The train station was relocated west such that the access movements and pedestrian flows coincide more closely and integrate with the downtown precinct improving the leginilityof the downtown area.

Legibility

▶ Legible town centre

Overall streetscape improvements and a park/plaza on one of the quadrants of the central crossroads builds on the opportunity afforded by the traditional street grid pattern to establish a legible town centre character.

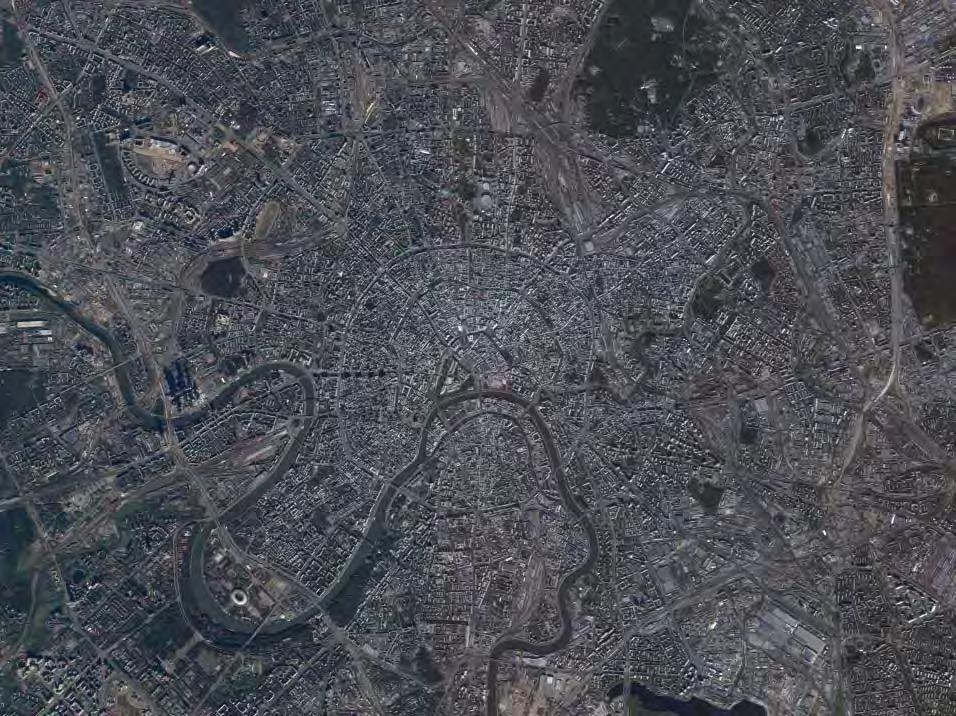

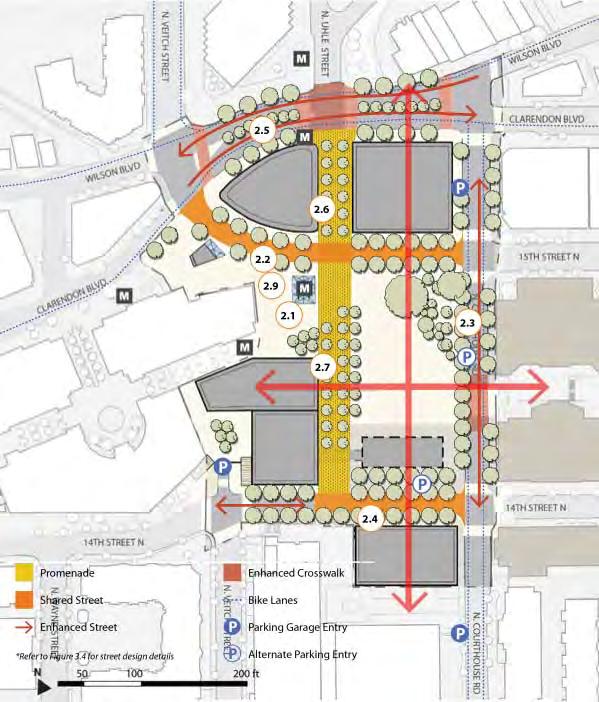

Amenity & comfort