These Two Hands

TheseTwoHandsisaten-partstorytelling initiativethatexploresthelivesofindividuals throughthelensoftheirhands—symbolsof work,creativity,care,andresilience.Each narrativeoffersaglimpseintoahuman experience,reflectingthemanywayswe connectwithoneanotherinour communities.

PhotographedandnarratedbyKateDuff.

I didn't make this for you. I made this for me. It's really the only way I know howtobe.

Butifyouglimpsemyinnerworldand find something that mirrors your own experience, then maybe we can share a connection for a brief but shining moment. This is the magic of art - the ability to distill what it means to be human,thenshareitwithkindredsouls. It is the ephemeral mingling with the eternal.

“To work with your hands is service. To work with your hands and your head is craftsmanship. To work with your hands, your head, and your heart is art.”

— Saint Francis of Assisi

Pamela has run the corner store for nineteen years. We used to shop there regularly, back when we lived on that side of town. But in a small place like this, even a short move can change your routine. You switch shops—not out of disloyalty, just convenience.

Still, I pop in from time to time. Pamela and her husband are the kind of people who make you feel welcome the moment you step through the door. It wasn’t a hard decision to ask her to be the first subject in this series.

“Are you sick of running a corner store after all these years?” I asked. “I get tired of the early starts,” she replied.

Fair enough. Seven days a week, from 7am to 7pm—that’s a rhythm that wears on anyone. And yet, Pamela shows up. Quietly, steadily, her hands hold the shop—and a small piece of the town—together.

DoIcreatetoexist, orexisttocreate?

I first met Glenda at the front desk of the library. She looked warm, approachable—so I mustered the courage to share the elevator pitch for this new project.

Thankfully, she said yes. And she was so fascinating, I could have talked with her all day.

Glenda has used her hands in many ways. She’s been an art teacher for five and a half years, an illustrator for seven, a librarian for over two decades, and a photographer for the now-defunct Western Star newspaper.

Though she’s lived elsewhere—including more than three years in Doomadgee—Glenda was born in Roma. And it’s here she returned to live.

(Doomadgee is a town and locality in the Aboriginal Shire of Doomadgee, Queensland. It’s a mostly Indigenous community around 140 kilometres from the Northern Territory border, and 93 kilometres west of Burketown.)

When I asked which roles she loved most, Glenda replied without hesitation: illustration and photography.

For her portrait, she chose a small stack of favourite books—ones that held meaning for her. A quiet reflection of the stories her hands have held, and helped shape.

If you’re looking for a friendly local, it’s your butcher. We smile. Talk about the weather. I choose what I want, pay, we smile again, and say goodbye.

Shopping banter.

That’s usually as far as it goes. I didn’t even know his name. I do now— but it doesn’t matter. A name is just another label. What stays with me is the moment someone becomes real.

Even a small story can do that—dig a person out of the background and bring them into focus.

There are two butcheries in our town, plus the Woolworths meat section. It’s a rural place with a healthy appetite for meat, so there’s no shortage of butcher’s stories. I decided to ask this man. I’m still building up the courage to approach strangers, but he smiled at me.

Encouragement, even a small smile, helps.

I always feel sorry for butchers in winter—all that cold meat. As a kid, I helped pack and separate meat after home kills on our property. Not a favourite memory. Cold fingers, raw and red, slowly going numb.I said as much to my butcher. He laughed.

“It’s the freezers that get you. When I worked as a slaughterman, we had massive freezers—huge things. Now they were cold.” And so, our conversation continued. What else have these hands done?

They’ve been wrapped around helicopter controls, crop-dusting out of Gatton. They’ve shorn sheep out west. They’ve slaughtered, skinned, and hauled carcasses. The callouses on his fingertips speak for themselves.

“You never lose those once you’ve got them,” he said.

These hands—firm, skilled—slice cleanly through meat most people would never associate with the animal it came from. They’ve been both foreman and worker. Hands that have seen higher altitudes and grounded grit. They’ve done, grown, and learned.

I asked him what role he liked best.

“Flying, definitely,” he said. “I always wanted to do it. Wasn’t allowed, so as soon as I could, I got my commercial pilot’s licence.”

“So why go back to butchering?” I asked.

He grinned and turned his palms upward. “Ah, well, I got married— and now the boss is happy.”

I take it crop-dusting in a helicopter wasn’t her favourite idea. It doesn’t take much for a face—or a life—to become threedimensional. A five-minute chat. A story told in passing. And now, when I walk into that shop, I see him differently. Human to human.

Don't forget to copyright yourcontentandletreaders know where they can find moreofyourwork!

These are the hands of a man who’s done many things.

John spent years in the oil and gas industry as a driller and derrickman.

When the industry crashed in 1989, he found himself working in meatwork starting on the floor and eventually rising to become manager of Moorex Meats.

But the thread that’s run through it all—the constant—has been music.

John has been a DJ for 44 years, spinning tracks at weddings, pubs, and clubs from Melbourne to the Gold Coast, Brisbane to Birdsville, and everywhere in between. His hands have turned dials, loaded gear, cued the next song. They’ve read crowds and carried sound through decades.

They’ve also spent plenty of time on the wheel—especially last year, when he drove back and forth to Brisbane to check on his wife and newborn son, Jack, who was born premature and stayed in hospital for several months.

John was the DJ at my wedding over 30 years ago. He was also the DJ at my son and daughter-in-law’s wedding earlier this year. Some things don’t change—his professionalism, his instinct, and his knack for getting people dancing. The floor was packed all night.

Over the years, John, his father, and his brother also worked in fibreglass pool building. These days, he maintains pools and pump systems around town. But his hands still return to the rhythm.

When I asked John what he loved most about all he’s done, he paused just briefly.

“Probably being a DJ,” he said. “Though I also like to sit in the studio and work on my music and remixes.”

Helen’s whip might be verbal, but it’s highly effective.

These curated elements can make your zine even more awesome.Happycreating!

Admin folk know what I mean—sometimes it feels like it would be easier to just beat people with a stick than chase them for forms, plans, signatures, and follow-ups. I complain about the drama in my office, but at least I work alone. Helen is surrounded by engineers and draftsmen. So yes—she’s in administration, not the circus. But sometimes, it’s the same thing.

We’ve had many shop-floor chats over the years, as I’ve ducked in to ask for plans or paperwork. But I’d never asked to photograph her hands before.

That part was awkward. Just for a minute.

“My hands? But they’re awful,” she said. They’re not, and I told her so.

I often say my own hands are very ordinary—short nails, blunt fingers— but that’s exactly the point. The beauty isn’t in the polish; it’s in what they’ve done.

Once I explained, Helen relaxed. We got down to business.

“Have you always been in admin?” I asked.

“Well, yes. Very boring life really,” she replied. “I’ve always done admin —but in different places.”

“Like where?”

“We ran a few motels. The Mandalay, Bryant’s.” “The Mandalay—isn’t that the one with the sign ‘Slim Dusty slept here’?”

“Yes! That’s the one. Slim stayed with us when we ran the motel—with his daughter and the band. We had a barbecue. They were lovely.”

(Note to reader: If you don’t know who Slim Dusty is, please go and Google him. He’s an Australian legend. His songs are stories set to music, and he’s deeply loved across the country.)

Looking forward, looking back… we’ve come a long way down the track. (Sorry. If you know Slim, you know exactly where I just went.)

“Why did you leave the motel business?” I asked.

Helen didn’t flinch. “Well, my husband died suddenly, so I couldn’t run both the motels by myself.”

I hadn’t known. My heart sank.

Helen is very direct.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“That’s alright. It was fifteen years ago.”

She told me what happened.

They had a daughter at university and a son finishing high school. Her husband died of a heart attack while they were on a two-week holiday. “It left a huge hole,” she said. “My daughter came back from uni for six months. I took time off. Sold the leases. My son finished school.” Helen’s husband was just fifty.

I’m fifty-two, and my husband is fifty-four. I couldn’t help but imagine. The hole it would leave. A crater. It had done the same to Helen.

But she picked herself up. And her family followed.

“I often wonder if I should’ve got the kids some counselling,” she said. “We just kept rolling at the time. But now, well… I think I failed them there.”

“No, you didn’t,” I said. “You were in shock yourself.”

Do we mothers ever stop beating ourselves up? I remember a quote: Forgive your parents. It’s their first time here, too.

I didn’t tell Helen that. I only thought it later. But if you’re a mother, reading this: forgive yourself.

Helen worked downstairs for a soil testing company, eventually moving upstairs to the engineering office. She told me:

“I think I’m a bit hard on people now. I think, if you’ve had fifty years, that’s a good life. That’s more than some.”

But Helen isn’t hard. Not really. She’s resilient. Grounded. Practical. She has little patience for people who don’t take care of themselves or recognise the gift of being alive.

She also loves to garden. I know that because one Christmas I gave her some of my handmade essential oil hand cream—and she told me it was the only one that ever stopped her hands from cracking. I should make another batch. It might’ve been the avocado oil. Or the blue tansy. Maybe the chamomile.

Sometimes it’s the right mix of things that makes something so good, so memorable.

Like Helen.

These are the hands of one of the hardest-working electricians I know.

Jett is exceptional at what he does—and that alone would be worth writing about. But there’s more. It’s rare for a pair of young hands to hold much of an autobiography. Jett’s already do.

When they’re not on the tools, his hands are wrapped around the handlebars of a motorbike.

For the past two years, Jett has competed in the notorious Finke Desert Race—a two-day, off-road race through red desert country, stretching from Alice Springs to the small Aputula (Finke) Community. The route crosses the Finke River, believed to be the oldest in the world.

Racing bikes and cars side by side at breakneck speeds of 160 km/h (and beyond) across shifting dunes takes more than skill. It takes guts.

Last year, Jett placed 63rd. This year? He climbed to 45th.

Training starts months in advance and means letting go of plenty most people—young or old—would struggle to part with. If you’re getting the sense that Jett isn’t your average small-town twenty-something, you’re absolutely right.

He also co-hosts a podcast with Isabella. It’s not just about racing and bikes—it’s about life. Honest, funny, thoughtful. They speak from the perspective of young adults navigating their twenties, and they invite great guests along the way. It takes courage to launch something like that in a small town —and to do it well.

When I asked Jett what he sees in his hands’ future, he didn’t hesitate. “Bikes,” he said. “That’s all I see right now.” Fair enough. Finke is a hard cloud to come down from. Jett is one of the most grounded, humble humans I’ve met —young or old, in any field. As always, it’s hard to keep these stories short when the people in them are so worth knowing.

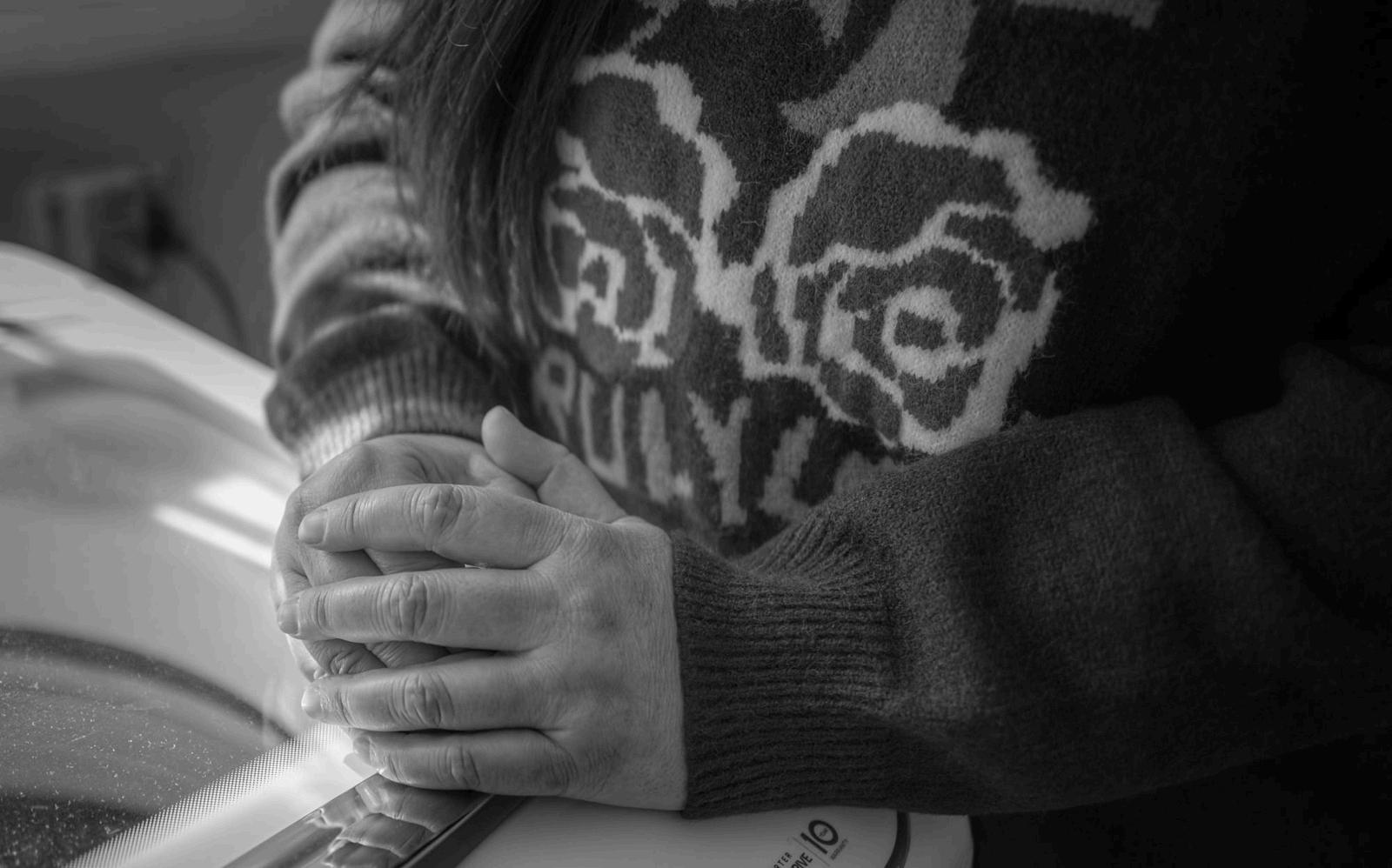

These are Maggie’s hands.

On a windy, cold day, I stepped into her home and was greeted by the scent of woodsmoke and a table set with tea. What followed was one of the most remarkable stories I’ve ever had the privilege to hear.

Maggie grew up in a remote village in China. Her family was very poor. Until the age of fourteen, she had never travelled more than 6km from home—and only then to visit her grandmother.

But Maggie was bright. She studied hard, graduated at the top of her class, and won a scholarship to university. She moved to Beijing, earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and a master’s in geophysics. She captained her university basketball and soccer teams, wrote for the campus radio station, and was one of the few students granted access to the university’s internet—where she met Joe, her now-husband.

When Joe got a job with Weatherford in Roma, Maggie moved with him. At first, she worked in a local Chinese restaurant, navigating a new country and a language barrier. But soon, she spotted an opportunity: a job opening in an engineering firm. Maggie applied, got the job, and never looked back. She began helping other Chinese women new to the area, translating, helping them find jobs—but it came at a cost. She was missing work hours to assist them.

Her solution? Start a business. With no background in cleaning or entrepreneurship, Maggie founded MW Cleaners. She made plenty of mistakes in the beginning.

“When a client first asked for a quotation,” she told me, “I didn’t even know what that was. But I learned. Every mistake taught me something. I call it paying the tuition—and I’ve paid a lot.”

She later launched a massage business to create even more opportunities for immigrant women—and trained herself so she could step in when needed.

Then came the motels.

When the lease for the Starlight Motel came up, Maggie and Joe jumped in. The landlord hesitated, unsure if they had the experience. Maggie secured a reference from Col Vaughan, a local motellier she had previously worked with—and won them over. Within six months, they’d learned the software, mastered the business, and expanded. They took on a second lease—this time, a much more run-down property, the Mandalay. And then COVID hit.

“It wasn’t too bad here in Roma,” Maggie said. “Just quieter.”

“So a bit more time on your hands?” I asked. “Yes,” she smiled. “I decided to get my plots licence”

Col, her old reference, also taught flying. He took Maggie up in a plane and she fell in love. Between motel shifts, she trained early in the mornings. Within a year, she was a licensed pilot, landing on remote airstrips from the outback to the coast. Her first time at Redcliffe? “Terrible,” she laughed. “Traffic control couldn’t understand me—and I couldn’t understand them. But now, it’s much easier.”

Maggie’s hands have done extraordinary things—and that’s still only half the story.

She’s led since childhood, when she filled in for her school’s only teacher. She’s organised charity drives, captained sports teams, mentored new arrivals, and transformed obstacles into opportunities.

Her leadership is grounded in gratitude. Her energy is contagious.

After two cups of tea, we wandered into her garden. Sunflowers —her favourite—danced in the breeze. The vegetables were thriving. Succulents lined the fence, many of them ribboned with show prizes.

Maggie is 45, but you wouldn’t guess it.

“I think I’m very young in spirit,” she told me. “I’m interested in so many things. I think our lives are measured by what we do and what we give back. I’m so grateful. We had nothing growing up, but it was a great life. We played in the creek, we ran free.”

As we spoke, Joe walked in the door. Their faces lit up like candles. It was one of the sweetest moments of all.

Maggie deserves a novel. But this is a zine—and a two-minute read will have to do.

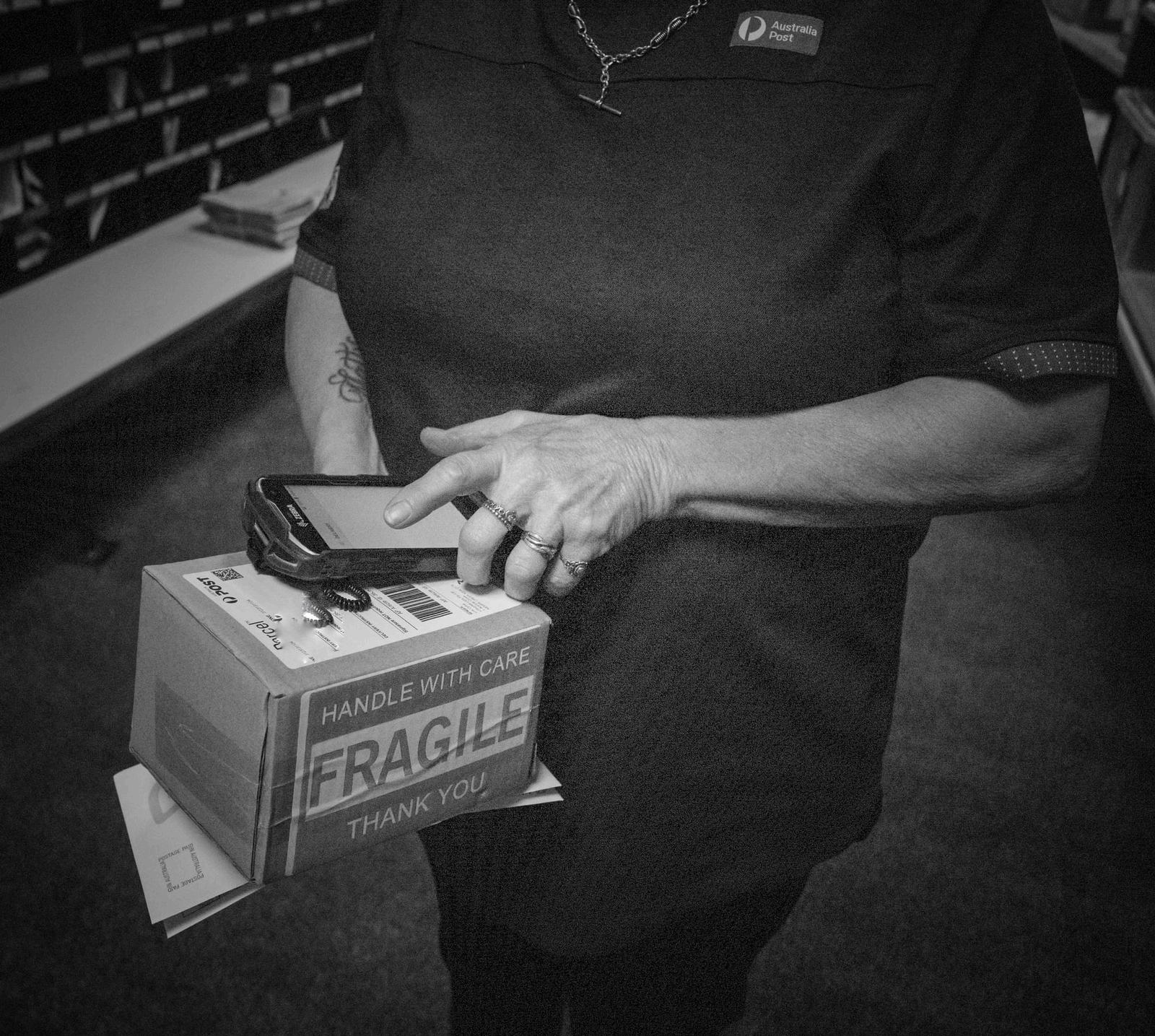

Lee-Anne’s hands hold great power. They’re the ones wrapped around that package you’ve been obsessively tracking on the Australia Post app.

“It’s here.”

“It’s not here.”

“No, it’s definitely not here.”

That kind of power.

Lee-Anne was one of the first people I approached when this project began. I pitched the idea… and then didn’t see her again for a while. I thought I’d scared her off. (Fair enough. I probably seemed a little intense.)

But when I saw her again, she told me she’d thought about it— and agreed. To my delight.

Lee-Anne has worked with Australia Post for over twelve years. Her days start early—5:00am on Mondays, 6:30 the rest of the week. She finishes by mid-morning, around 10:30am. And she loves it.

After her Monday shift, Lee-Anne volunteers at the local St Vincent’s store, sorting clothing in the back room. Her other favourite thing to do with her hands? Puzzles.

It’s these quiet, simple details I love—the small things that bring depth to our everyday interactions. Knowing them makes the smiles we share at the counter go that little bit deeper.

These are Jo’s hands.

Jo is a vet in a rural mixed practice—which means her days are rarely predictable. One moment she might be assisting a pregnant cow or horse, the next performing surgery on a dog, a cat, or whatever small creature comes through the door. The morning I met her, Jo had already desexed three dogs and investigated a concerning case involving a French bulldog. Just another start to the day.

She’s been a vet for seventeen years, twelve of them here in Roma. Originally from Goondiwindi, Jo travelled around Australia for eighteen months after graduating, gaining experience in vet surgeries of all shapes and sizes. She thrives on the variety, the problem-solving, and the hands-on nature of rural practice.

One of her former patients—pictured above—is Mindy the cat. Mindy was brought in with severe injuries after being hit by a car. A kind stranger had found her and brought her to the clinic. Jo’s skilled hands saved her life, though her leg couldn’t be salvaged.

A month later, Jo performed the amputation. Mindy made a full recovery and found her forever home as the surgery cat. These days, she welcomes visitors at the door with grace—and no shortage of attitude.

“Checkout chick”—that’s how we often refer to the women scanning our groceries at Woolies or IGA. I’m not sure what we call the men. Operators, maybe?

As I write this, it feels... off. Dismissive, even. I never meant it that way—it just hadn’t occurred to me until this morning. Sarah was beautifully presented. My eyes flicked to her hands: an impeccable manicure. I tucked my own scruffy fingertips into my back pockets as I waited in line.

She was chatting to the customer ahead of me, scanning items, packing them into bags, telling him how she was working at Woolworths to pay off her car. You could tell she loved it.

“My husband took it into the Bunnings car park the other day,” she sighed, “and now it has a dent.”

Her face fell just a little. That was all it took—I was in the conversation. The man finished up and it was my turn at the register.

I suddenly wished I had more groceries. I quickly explained the project and asked if I could take a photo of her hands. She smiled and said yes—immediately game.

Then a customer queued up behind me, so we jumped into a rapid-fire round:

“What sort of car is it?” I asked.

“A Suzuki Grand Vitara,” she replied proudly. “We use it to travel around Australia. When we stop somewhere, it has to be a town with a Woolies—then I work for a while.”

“How long until it’s paid off?”

“September,” she beamed. “I’ll be done. We’re sort of retired, you see. My husband worked on a dairy farm since he was fourteen. I told him—now it’s my turn to work.”

These Two Hands was never just about hands. It was about people. The ones we pass in the supermarket aisle, wave to at the counter, nod at on the street. It was about noticing—really noticing—what someone holds, builds, carries, and lets go of, every single day. Each pair of hands in this collection tells a story of effort, resilience, memory, and care. Some hands heal. Some create. Some lift. Some endure. Some hold the steering wheel through long nights or the scalpel with steady precision. Some make coffee, clean motel rooms, fix engines, stock shelves, write, sew, grow, build, hug, wave, mend. These stories reminded me that we all live so much deeper than what we present on the surface. That everyone is carrying something rich and real. That connection often begins in the smallest moment—a conversation, a glance, a hand reaching out.

Thank you for taking the time to meet these people. And thank you, too, for everything your own hands have done.

— Kate Duff

Ground Water Publishing