ESTHETICS

Pocket Guide to Esthetics

Robert Tracinski

The Atlas Society Press

© Copyright 2025

Published by The Atlas Society

1038 Miwok Dr.

Lodi, CA 95240

Cover design by Matthew Holdridge

Book layout by Lorence Olivo & Erin Redding

Proof editing by Donna Paris

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this booklet or portions thereof in any form. Manufactured in the United States of America.

ISBN 979-8-9885173-3-7

Our Mission

The Atlas Society’s mission is to inspire people to embrace reason, achievement, benevolence and ethical selfinterest as the moral foundation for political liberty, personal happiness and a flourishing society.

We build on Ayn Rand’s works and ideas, and use artistic and other creative means to reach and inspire new audiences. We promote an open and empowering brand of Objectivism; we welcome engagement with all who honestly seek to understand the philosophy, and we use reason, facts and open debate in the search for truth above all else; we do not appeal to authority or conflate personalities with ideas. We resist moral judgment without adequate facts, and believe disagreement does not necessarily imply evasion.

Pocket Guide to Objectivist Esthetics

Esthetics is the theory of art what art is, how it works, how it has the emotional effect on us that it does and why we need it.

Let’s start with an initial discussion of that “why.” Why study art? Why is it important?

We can start with the observation that art has a big impact on the world. Politics is the obsession of our day, which attracts a lot of the passion that used to be reserved for religion or art. But there’s an old saying: “Politics is downstream of culture.” Culture is in many respects more important than

politics, projecting and reaffirming a view of the world that is more personal and profound and drives the decisions we make about every aspect of how we live.

“Art” means all the different forms of art: painting, sculpture, novels, poetry, theater, films, music, dance, architecture, design. And it means both the refined achievements of high art and the simplified products of popular culture. Whatever its medium or its level of sophistication, art conveys an expectation of what we think is possible in life and what ought to be possible, and it does this in a form that is immediate and emotional and doesn’t

require us to read abstract theories or study philosophy.

Four Davids

To illustrate this, and to give some concrete grounding for a discussion of art, let’s start with scenes from a “culture war” in Europe about 600 years ago the period known as the Renaissance. We can see this cultural transformation in the form the people of the time mostly experienced it: in art.

Before this time, the dominant culture produced a whole genre of what was called the Man of Sorrows, often a portrayal of Christ (Fig. 1), which was devoted to the theme of abject human suffering.

Figure 1: Pieta from the Leubus Abbey, 1370. Wikimedia Commons

At about the same time, people were beginning to create very different art in Italy, especially in the city of Florence.

Around 1440, the sculptor Donatello created a statue of David (Fig. 2), from the Biblical story of David and Goliath.

Figure 2: Donatello’s David, c. 1440. Wikimedia Commons

David is a young shepherd who volunteers to take on a giant enemy warrior. He defeats him using his sling and cuts off Goliath’s head. In this sculpture, David is depicted as a young boy, wearing a typical shepherd’s hat from Donatello’s time, with the head of Goliath at his feet.

If we go forward about a generation, to 1475, we see a different version of this story from Andrea del Verrocchio (Fig. 3).

Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: David by Andrea del Verrocchio, 1475.

If we were to ask the age of the boy portrayed by Donatello, we might guess he is 10 or 12; there’s a smooth softness to his muscles. But in Verrocchio’s version, we see something that happens about the time boys hit puberty, when the musculature hardens and becomes more wiry.

Also consider the pose of the figure. In Donatello’s version, the pose of the body is fully relaxed and languid. In Verrocchio’s, the figure seems more active, and the way he puts his hand on his hip makes him look self-confident, maybe even cocky.

Now let’s move forward another generation or so, to 1504. This is the

most famous version of David, by Michelangelo (Fig. 4).

Wikimedia Commons

Figure 4: David by Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1504.

If we ask how old this young man is and young man is the right word we would put him at about 18. He has a fully grown musculature, but not the bulk we might expect in someone older, and his face is still smooth with the subcutaneous fat that tends to disappear with age.

If you see this sculpture in person, you’ll notice that there is fear in David’s eyes but as with the Verrocchio version, there is confidence in his pose. To get a sense of this, try assuming the same stance and project how you would have to feel to stand like that. This David is not just strongly built and athletic; he is confident of his power.

When this sculpture was completed, it was put in front of the main government building in Florence, facing in the direction of Rome. Florence was a smaller city, but it was the home of the new intellectual and artistic trends of the Renaissance, and it positioned itself as the David to Rome’s Goliath.

Now let’s look at Rome’s response: a version of David from the Roman sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1624 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: David by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1624. Wikimedia Commons

If we ask how old this young man is, we might guess he is at least 25. He has filled out into full adulthood, with the physique of an elite athlete. Notice also the determined set of his mouth and the twisting pose as he goes into the windup to deliver the fatal blow. The story of David and Goliath can be portrayed in two different ways. In one interpretation, David is a small shepherd boy who could not possibly be a physical match for the giant Goliath, so it must be only through divine intervention, because God is on his side, that he wins the fight. The other interpretation is that it is David’s own courage, intelligence, and strength that make it possible for him to win. The earliest version, from Donatello, gives

us the first interpretation. But by the time we get to Bernini, we have switched all the way over to the second interpretation.

If we look at these examples one after the other, in chronological order, they clearly tell a story. They show us a growing assessment of the power of man. Over less than 200 years, we can literally see the growth in stature, power, and maturity that is being attributed to the human form.

This gives us an answer to why art is important. These are some of the most famous sculptures of the Renaissance, a time when human knowledge was growing, modern science was being born, and technology was advancing rapidly. The art of the time reflected this

progress and also helped lead the way. It gave people inspiration and encouragement for everything else they were doing.

The Cognitive Psychology of Art

These sculptures give us a basis for understanding how art achieves its impact, and we can draw on them to concretize points made in Ayn Rand’s theory of art, presented in her 1969 book, The Romantic Manifesto.

Notice that every one of these sculptors made very specific decisions about how to portray the human figure: David’s age and muscular development, the way he’s dressed, the expression on his face, the pose of his body. Each of those decisions reflects the artist’s view of what he thinks is important, not just in this story from the Bible, but also what he thinks is important about human life in general. Then there is the choice of the subject itself. David and Goliath is a

story of human power, a story of triumph over seemingly insurmountable odds. Contrast that to the Medieval “man of sorrows” genre. Just the choice to portray one of those stories and not the other conveys something about the artist’s view of the world.

This is what Ayn Rand called a “selective re-creation of reality.” Art imitates life. The artist is imitating the real world, creating a fictional person in these sculptures, based on observation of real humans. But that re-creation is selective, requiring artists to make decisions that produce very different figures.

Here is how Ayn Rand put it.

Art is a selective re-creation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value-judgments.

By a selective re-creation, art isolates and integrates those aspects of reality which represent man’s fundamental view of himself and of existence. Out of the countless number of concretes of single, disorganized, and (seemingly) contradictory attributes, actions, and entities an artist isolates the things which he regards as metaphysically essential and integrates them into a single new concrete that represents an embodied abstraction.

What does it mean for the artist to pick things that are metaphysically essential? In philosophy, metaphysics refers to the widest, most basic ideas about the nature of the universe. Is the universe orderly, are there natural laws or is it chaotic and incomprehensible? Do we have control over our lives or are we at the mercy of fate or some larger force? And so on. We can see how different views on these topics would have a big impact on how artists choose, for example, to make a sculpture of David.

Rand insists that everyone does have a view on these big issues, even if they’ve never studied philosophy, and even if they can’t put their view of the world into words. That’s true especially if they can’t put it into words, because this gives them an even greater need for

some way of grasping it that isn’t in words which is exactly what they might get from one of these sculptures.

Humans are thinking beings. We’re constantly drawing conclusions and generalizations. Before we do our thinking in explicit terms, discussing sophisticated concepts in science or philosophy, we do it implicitly. We do our thinking in a form we can’t quite put it into words, and instead we hold it as a series of associations, which we experience on an emotional level.

The sum of all the conclusions and generalizations a person draws about life is what Ayn Rand calls a “sense of life.”

A

sense of life is a preconceptual equivalent of

metaphysics, an emotional, subconsciously integrated appraisal of man and of existence.

She adds that we might describe a “sense of life” in terms like: “This is life as I see it.” Or: “This is what life means to me.” That is what art is trying to capture, producing what she calls an “embodied abstraction.”

But why do we need an abstraction brought down into a concrete, specific, “embodied” form? The key role of art is that it takes very abstract issues and makes them available to us in a way that is concrete, immediate, and grasped automatically. You don’t have to read about it, you just see it.

This is what Ayn Rand describes as “the psycho-epistemological function of art.”

“Psycho-epistemology” is a term she coined to describe the connection between psychology and cognition. “Cognitive psychology” is the term more widely used today.

Here is what Ayn Rand had to say about the cognitive psychology of art.

Art brings man’s concepts to the perceptual level of his consciousness and allows him to grasp them directly, as if they were percepts.

That’s what she means by an “embodied abstraction.” The selective choices made by the artist create a concrete object that is stylized to represent an abstract view

of the world. Because this view of the world emerges from the details, it affects us directly. We are not necessarily told the message that the artist intends, and the whole point is that we don’t have to be told. The message gets through in a direct and immediate way. Let’s go back to Michelangelo’s David, looking at it from a different angle (Fig. 6.).

Figure 6: David by Michelangelo Buonarotti, 1504. Wikimedia Commons

From this angle, we can see real fear in David’s eyes, but also determination. This is consistent with the pose of the larger figure, which conveys his strength and confidence. So a central theme of this sculpture is courage, because that’s what emerges from a combination of fear and confidence. Michelangelo shows us what it looks like to have confidence and determination in the face of fear exactly what you would need as a David taking on a Goliath.

That is the abstraction that is embodied in the figure of David, so much so that he was used as a symbol for the whole city of Florence and is still universally recognized today, more than 500 years later.

There are three key elements of Ayn Rand’s theory of art.

1. Everyone has an implicit view of man and of the world, a sense of life.

2. We need to be able to grasp that view of the world in a direct, immediate, and concrete form, an embodied abstraction.

3. We do this through the selective re-creation of reality, the choices the artist makes in representing people or events.

Painting and Style

The examples we’ve used so far are from sculpture, so let’s look briefly at how this applies to other forms of art.

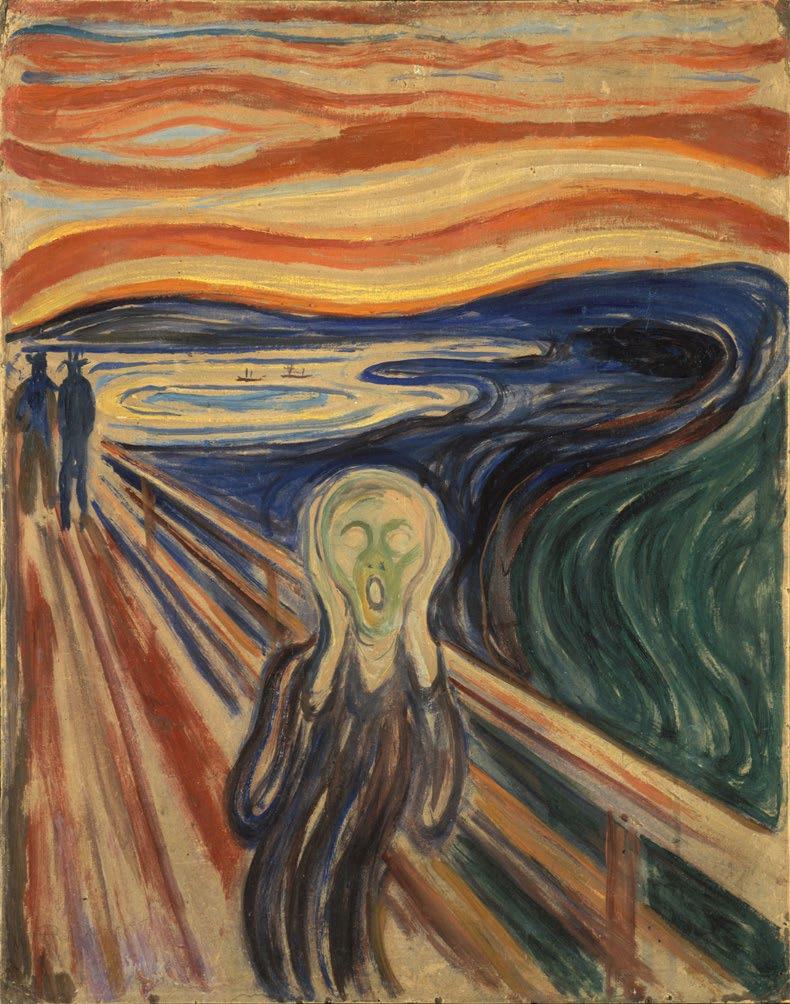

Painting is closest to sculpture, particularly when it portrays the human form. Consider the contrast between “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” by Johannes Vermeer, about 1665 (Fig. 7), and “The Scream,” by Edvard Munch, from 1893 (Fig. 8).

Figure 7: Girl with a Pearl Earring, Johannes Vermeer, 1665. Wikimedia Commons

Figure 8: The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893. Wikimedia Commons

These paintings obviously present very different estimates of life. One shows us a beautiful woman at the peak of youth and health, gazing serenely at the viewer. The other is a human figure distorted by some kind of fear or pain. One of these people is likely to be enjoying life and all it has to offer the other not so much.

It’s not just what the paintings portray, but how they portray it. The contrasting styles of these paintings imply very different things about how we, the viewers, are perceiving the figures they portray. Think what your consciousness would have to be like to see things as Vermeer shows them: a kind of serene, luminous clarity. Contrast this to what your brain

would have to be going through to see things as Edvard Munch shows them: in wild, distorted swirls. One shows us what the world looks like to a mind that is sharp and clearly focused, the other what it looks like in a mental state of panic and confusion.

A painting doesn’t have to show people. A landscape painting, for example, can show us just the world, giving us a message about what kind of world it is.

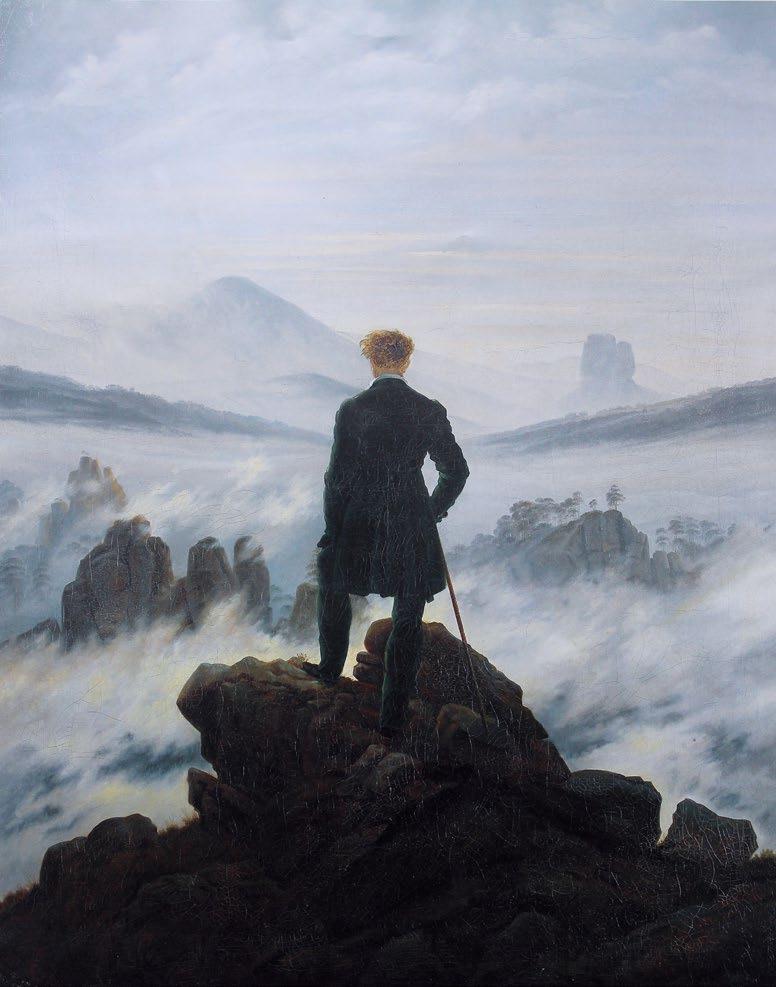

Consider an example that gives us a bit of both: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, painted in 1818 by Caspar David Friedrich (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich, 1818. Wikimedia Commons

There is a definite sense of drama in this landscape, with rugged mountains and fog below. But this is portrayed without any real sense of danger, which is reflected in the calm of the central figure, who does not seem to have suffered any traumatic hardship to get to the peak from which he surveys this scene. The combination gives us a sense of how dramatic and exciting the world can be, but also a sense of confidence in our ability to explore it.

Architecture Architecture is not about re-creating the world; the columns of a building, for example, are not meant to be imitations of trees. Architecture is about creating a new environment to live in, and that environment says something about how the architect thinks we should live.

There is a lot of debate right now about modern versus traditional architecture. Today’s conservatives insist on a simplistic view in which all traditional architecture is good and all modern architecture is bad. To understand architecture on a less superficial level, let’s look at examples from three very different schools of 20th Century architecture.

Consider the Toronto-Dominion Centre in Canada by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Toronto-Dominion Centre, Canada, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1967-69. Wikimedia Commons

This is typical of the mid-20th Century “International Style.” These buildings convey a sense of life in the choice of materials and shapes, using glass and steel in grid-like rectangles. It is a view of the world that is orderly and technological but also regimented, anonymous, collective. Every office or apartment is identical to every other, pared down to its bare essentials and stripped of any individuality. This was very much deliberate. The International Style was developed by European architects in the 1930s partly as an expression of industrial socialism.

Now contrast that to Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (Fig. 11).

These swirling shapes convey an exuberant kind of craziness, but they also deliberately upend any sense of order or comprehensibility. It’s almost a visual assault on reason. This is considered an example of the Postmodernist and Deconstructivist

Figure 11: Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, Frank Gehry, 1997. Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra. Wikimedia Commons

schools. Like their counterparts in philosophy, these approaches to architecture seek to break down and “deconstruct” any laws, rules, or principles used to bring order to human thought. Finally, look at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (Fig. 12).

Figure 12: Fallingwater, Pennsylvania, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1937. Photo by Robert Tracinski.

A central stone mass is structurally and visually balanced against cantilevered terraces that echo the stone ledges of the waterfall. This conveys a sense of order, comprehensibility, and integration with the natural world, combined with complexity, originality, and a sense of drama.

In The Fountainhead, which she began writing as Fallingwater was being built, Ayn Rand took inspiration from Wright’s architecture and the theories of his mentor, Louis Sullivan, who taught that “form follows function.” She championed Modern architecture that emphasizes a sense of logic in which the design of a building flows from its structural requirements, functional needs, and the conditions of its site—

and integration, in which all the details are consistent with one another.

Art Is an Imitation of What?

If art is an imitation of life, what is it imitating? In a case like the sculpture of David, this question is relatively easy to answer. It is an imitation in stone of a human figure. But what about music?

Music is about relationships between tones, between individual notes. These relationships have a well-defined mathematical basis, relating to the wavelengths of sound vibrations and the degree to which these wavelengths overlap. We don’t have to know this mathematics to experience the result. Our ears and our brains detect and respond to these differences and give us the result primarily in terms of consonance versus dissonance. If you hear two notes together, you will get a

sense that these notes go together, they are harmonious or that they don’t go together, they clash.

Notice that these terms, consonance and dissonance, are also terms used for cognition, for thinking. This implies that the relationship between tones can conjure up and represent a state of mind. Music can sometimes imitate sounds from the external world, but it is mostly about an internal state of mind, whether your thoughts are harmonious or whether they clash. Often, a piece of music starts with some form of tonal clash or tension and eventually moves toward a sense of harmony. When this is achieved, it is called a “resolution” another term that applies both to music and to cognition. We might talk of

finding the resolution of a problem in mathematics, but we would also apply it to the point in a piece of music where disparate sounds come together harmoniously.

If art is a selective re-creation of reality, what is being re-created in music is a state of mind, which is summoned forth, by way of our ears and brains, through the mathematical relationships between musical tones.

Art and Inspiration

A common view of art is that it is the opposite of mathematics or any other form of reasoning. The Romantic school of the 19th Century is associated with the view that art is created, and affects its audience, through some mysterious emotional inspiration that is outside the realm of rational understanding.

Against this viewpoint, we have the testimony of two giants of the Romantic era. In 1848, the painter Eugène Delacroix described a conversation with his friend, the composer Frédéric Chopin.

I asked him to explain what it is that gives the impression of logic in music. He made me understand

the meaning of harmony and counterpoint; how in music, the fugue corresponds to pure logic, and that to be well versed in the fugue is to understand the elements of all reason and development in music…. It gave me some idea of the pleasure which true philosophers find in science. The fact of the matter is, that true science is not what we usually mean by that word a part of knowledge quite separate from art. No, science, as regarded and demonstrated by a man like Chopin, is art itself. On the other hand, art is not what the vulgar believe it to be, a vague inspiration coming from nowhere, moving at random, and portraying merely the picturesque, external

side of things. It is pure reason, embellished by genius.

The power of art is not just that it summons up some one specific emotion or that it evokes a sense of beauty. The real power of art is that it is carefully, consistently constructed to convey a view of the world. Even if you don’t like an artist’s view of the world, you are still made to experience it, to live inside the world as the artist sees it for at least a few moments.

This is why people are so passionate about art. It can challenge your view of the world, change it, or confirm it. But it has this power because we are using our rational faculty to think about the world and draw generalizations about it.

Art and Abstraction

The theory we have discussed so far is opposed to some of the dominant theories of art. Most notably, it is a theory of representational art. We can see what this art has to say about human life and the world because it is representing or re-creating a human figure or a natural landscape. This is true of the whole history of art from prehistoric cave paintings up to the 19th Century. But around the turn of the 20th Century, a new theory of “abstract” art produced works especially in painting and sculpture that are nonrepresentational. They present shapes and colors and proportions without seeking to represent specific objects from the world.

This art is supposed to be “abstract” because it is abstracting away from any concrete object that would otherwise be represented and showing just the shapes and colors. A famous example is the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, a pioneering Modernist. Mondrian’s early paintings began by breaking down the visual shape of a tree into thick lines and vivid blocks of color. Over time, these lines and blocks of color were broken out more distinctly until his works lost any sense that they were portraying a real object. By 1930, the lines in his paintings became thick, black, and completely straight, enclosing rectangles in bright, primary colors. There is no longer any inspiration from a real object or any attempt to reproduce it.

The problem is that this is not actually more “abstract” in a cognitive sense. It is going in the other direction, breaking down a perception, in this case our perception of a tree, into individual sensations: a sensation of color here, versus another sensation of color there. In doing so, it empties the art of content, leaving us with no ability to draw a larger meaning out of it.

Compare this to the sculptures of David, where we start with concrete observation and move up to a wider meaning. Here is a young man with these particular features in this particular pose, and the artist’s choices prompt us to think: What kind of person would look like this, what kind of person would stand like this? This is what makes it possible for us to draw more

general ideas about what this person is like and what is possible to him in life.

This is how thinking actually works: We observe specific facts and use them as a basis to form generalizations. That’s what is actually “abstract” about art, in the sense of dealing with big ideas. But “abstract” art in the Modernist sense takes us in the opposite direction, breaks things down to sensations, and then to ever simpler sensations, bleaching them of all meaning.

The contrast between Modernism and other schools is really about clashing ideas of what “abstraction” means. One school, which originates with the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato, holds that observation of concrete, individual things is a distraction from the process

of thinking, and the way to progress to a higher level of abstraction is to sever our connection to these things. “Abstract” art in the Modernist sense is an expression of that view of cognition. It’s the idea that to be abstract, we have to eliminate representation of concrete things. Aristotle, by contrast, taught that we gain knowledge by immersing ourselves in observation of the world. Abstractions emerge from the observation of specific things, by comparing them and drawing general patterns. That’s the process of actual abstraction we experience when we look at a sculpture of David. Representational art offers us abstractions in this Aristotelian, inductive sense.

(Appropriately enough, you can see this philosophical contest in a work of art: Raphael Sanzio’s The School of Athens from 1511, in which the two central figures are Plato, gesturing upward, away from observation and toward a world of disembodied abstractions, and Aristotle, gesturing outward and encouraging us to draw abstractions from the observation of concrete facts.)

As a more general pattern, Modernism in the 20th Century often meant that innovation in art took the form of elimination removing something. Modernism offered poetry without meter and rhyme, painting without shading and perspective, music without consonance and harmony. In extreme cases, we got music without any music; John Cage famously wrote a piece that

58 is simply four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. This is an extreme example, but it’s where we end up when we assume that creativity is about removing basic elements from each medium of art.

A Theory of Literature

The last major branch of art to discuss is the one on which Ayn Rand presented her most detailed views. The Romantic Manifesto begins with a theory of esthetics in general and a brief overview of the different forms of art. But Ayn Rand was a novelist and playwright before she was a philosopher, and the book’s subtitle is “A Theory of Literature.”

In fiction, the artist’s view of the world is conveyed through the story. It’s conveyed through the thoughts and actions of the characters and especially through the choices they make.

Consider an example from the writer who influenced Ayn Rand, Victor

Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Misérables which has enjoyed a long influence and was adapted in recent decades into a musical and a film.

The setup of the story is that our hero, Jean Valjean, is an escaped convict who chooses to renounce hatred and reform himself. Eventually, he becomes a welloff and respectable citizen. But then he hears the news that another man is accused of being the fugitive ex-convict Jean Valjean and will go back to prison in his place. So far, he has been able to be a good man and have a respectable place in society. Now, it’s one or the other.

Hugo shows Valjean struggling with that choice, but he doesn’t stop there. When Valjean decides he has to go to

the courtroom to save this poor man, he rents a carriage. But the novel is set in the early 19th Century, when travel is difficult, and Valjean encounters a series of mishaps a carriage wheel breaks, a bridge has been washed out by a storm. So Valjean doesn’t just have to choose to do the right thing. He has to keep on choosing it. At any point, he could grab onto the excuse that he tried to do the right thing but fate intervened. Instead, he continues to make the right choice in the face of all obstacles.

This is something with obvious application to real life.

This is what Ayn Rand regarded as the essential issue in fiction. It is the approach she defined as Romanticism in fiction: a focus on the protagonist’s

choices. She contrasted this to Naturalism, a school of literature that emphasized, not heroes, but ordinary or average men who are victims of their circumstances, crushed under larger forces they can’t control.

Ayn Rand’s version of Romanticism, in her own work, added an extra twist. She portrayed the kind of hero Victor Hugo did, a man or a woman with the strength of character to do the right thing in the face of obstacles. But she portrayed them in the world of science, technology, and business. In The Fountainhead, in place of a knight in shining armor, we have an architect building a skyscraper and fighting for the originality and integrity of his designs.

In Atlas Shrugged, the equivalent of the scene with Jean Valjean and the carriage is a long flashback in which Hank Rearden recalls the years he spent developing a new and better alloy of steel.

He did not think of the ten years. What remained of them tonight was only a feeling which he could not name, except that it was quiet and solemn. The feeling was a sum, and he did not have to count again the parts that had gone to make it. But the parts, unrecalled, were there, within the feeling. They were the nights spent at scorching ovens in the research laboratory at the mills—the nights spent in the workshop of his home, over

sheets of paper which he had filled with formulas, then tore up in angry failure the days when the young scientists of the small staff he had chosen to assist him waited for instructions like soldiers ready for a hopeless battle, having exhausted their ingenuity, still willing, but silent, with the unspoken sentence hanging in the air: “Mr. Rearden, it can’t be done” the meals, interrupted and abandoned at the sudden flash of a new thought, a thought to be pursued at once, to be tried, to be tested, to be worked on for months, and to be discarded as another failure the moments snatched from conferences, from contracts,

from the duties of running the best steel mills in the country, snatched almost guiltily, as for a secret love the one thought held immovably across a span of ten years, under everything he did and everything he saw, the thought held in his mind when he looked at the buildings of a city, at the track of a railroad, at the light in the windows of a distant farmhouse, at the knife in the hands of a beautiful woman cutting a piece of fruit at a banquet, the thought of a metal alloy that would do more than steel had ever done, a metal that would be to steel what steel had been to iron the acts of self-racking when he discarded a hope or a sample,

not permitting himself to know that he was tired, not giving himself time to feel, driving himself through the wringing torture of: “not good enough...still not good enough...” and going on with no motor save the conviction that it could be done then the day when it was done and its result was called Rearden Metal these were the things that had come to white heat, had melted and fused within him, and their alloy was a strange, quiet feeling that made him smile at the countryside in the darkness and wonder why happiness could hurt.

This is a view of the innovative entrepreneur as a kind of crusader, driven by a commitment to moral excellence. The ten years of Rearden’s quest is interesting, because that’s how long the siege of Troy lasts in the Iliad and how long it takes Odysseus to return home. So this is an epic literally on a Homeric scale, but instead of being about battle and conquest, it’s about invention and production.

Ayn Rand gave us what you might call Romanticism for the industrial age, epic stories set in the world of capitalism.

Art and Didacticism

Ayn Rand’s themes have obvious political implications, and she does include overt political and philosophical messages in her novels. But when we say that art has a message, that it conveys a view of the world, we don’t mean that art is didactic.

Remember the idea of the “embodied abstraction.” The point of art is to take a view of the world and embody it in a concrete. Instead of telling you the message, it shows you. It gives you the experience of living in the world as the artist sees it.

Didacticism in art is strangely prevalent today. There is a lot of art, on both sides of our culture war, where it seems to be

more important to have the right message, and especially the right politics, rather than to tell a good story.

Ayn Rand was insistent that first you have to have a good story or a compelling artistic vision, and politics and philosophy are secondary. It’s not that you can’t have a political theme, because she certainly did, but that political slogans are not a substitute for a worldview.

My basic test for any story is: Would I want to meet these characters and observe these events in real life? Is this story an experience worth living through for its own sake? Is the pleasure of contemplating these characters an end in itself? It’s as simple as that.

The experience of seeing your view of the world, your sense of life, put into concrete form is rewarding as an end in itself.

The Model and the Fuel

This experience is rewarding because it fulfills two profound psychological needs. In Rand’s metaphors, art provides the model and the fuel for human life. She describes the artist as a kind of “model-builder.” The fictional people or settings or actions in art show us what kind of person we could be, how the world could be, what kind of life we could live. She wrote that each of us needs “an image in whose likeness he will reshape the world and himself. Art gives him that image; it gives him the experience of seeing the full, immediate, concrete reality of his distant goals.” We can all recall a fictional character we’ve encountered who had an influence on us,

someone we wanted to be when we grew up. Art also provides the fuel to get there. She wrote that every person “needs a moment, an hour, or some period of time in which he can experience the sense of his completed task, the sense of living in a universe where his values have been successfully achieved…. Art gives him that fuel; the pleasure of contemplating the objectified reality of one’s own sense of life is the pleasure of feeling what it would be like to live in one’s ideal world.”

Ayn Rand specifically championed the need for a sense of the heroic. In praising the very first James Bond film, Dr. No, which she described as “a brilliant example of Romantic screen

art,” she explained, “The obstacles confronting an average man are, to him, as formidable as Bond’s adversaries; but what the image of Bond tells him is: ‘It can be done.’”

This is the foundation for the emotional power and impact of art. It reaches people at the core of the motivations and choices that determine the whole course of their lives.

Understanding this helps us understand what kind of art we’re seeking out and what effect it has on us. For those who have the interest and ability, it can help you decide what kind of art you might make to embody your own vision of the world.

It also provides a context for what we call the “culture war” in America today. Our conflicting visions for the culture often involve scolding others for having the wrong views and even trying to ban them. But the best kind of culture war is one in which everyone offers their own competing vision for what the world could be and tries to lure us over by showing us what their view means in concrete reality, as embodied in great and powerful works of art.

That’s the kind of culture war where culture wins, because everyone offers us what is most inspiring in their view of the world and we can use this art as the model and the fuel to pursue what we think is the best way of life.

About the Author

Rob Tracinski studied philosophy at the University of Chicago and has been a writer, lecturer, and commentator for more than 25 years. He is a Senior Fellow for The Atlas Society, the editor of Symposium, a journal of political liberalism, is a columnist for Discourse magazine, and writes The Tracinski Letter. He is the author of So Who Is John Galt Anyway? A Reader’s Guide to Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

Our Work

Publications: From graphic novels to pocket guides, our books are available in multiple formats and languages.

Social Media: The Atlas Society has the largest and most engaged following on all social media platforms, engaging our audience with memes, video shorts, and weekly Instagram takeovers.

Videos: From animation to comedic features to music videos, our productions include Draw My Life videos, animated book trailers, and animated graphic novel series.

Educational Resources: With online courses, weekly live podcasts, webinars, campus speaking tours, and campus activism kits, we educate students of all ages.

Student Conferences: Our annual Galt’s Gulch conference welcomes hundreds of young people from around the world to engage with our faculty of scholars and take the next step in their journey of advanced intellectual engagement.

Commentaries: In addition to educational resources, our website offers commentaries on a wide range of political, cultural, and personal topics.

The Atlas Society is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. For additional information, or to support our work, please contact us via email info@atlassociety.org or via our website atlassociety.org.