Adam Summers

BSc/MArch Architectural Studies

W.S.A. Cardiff University Print Portfolio 2024

Neath Abbey, in the former industrial heartland of South Wales, has been occupied since the 13th century, from a Tudor mansion, to a plundered ruin and then a copper smelting foundry. The history of the site is visible in the artefact of Neath Abbey itself, with the lichen from times less polluted, now blackened and fossilised against the backdrop of the Port Talbot steelworks.

Human industry has had a great impact on the material of the site, as in the sulphate crystals from copper smelting and the teetering stonework left by the abbeys plunderers. It occured to me that through Aldo Rossi’s concept of urban morphology, that human industry and social formations changing over time, has had a direct impact on the very urban fabric of the conceptual city, in this case at Neath Abbey. On a study trip to Dublin, I observed that the bottle caps, NOS canisters and broken bottles of the Temple Bar area, fitted between the stones pavers of the street, with human habitation making an impact on the city, and the city making an impact on humanity, feeding into each other to create our urban areas.

The land at Neath has been throughly mined of its resources, historically this valuable land brought jobs and identity to the area, so thte new building must reflect this legacy of plundered, valuable earth and rework it in modern context. My solution to the constraints of the site and the urban theories of Aldo Rossi, was to design the Neath Abbey Workshops, a series of rammed earth and timber workshops and studios surrounding a central Hall of Materials, where archaeology, raw materials, used coffee mugs from the cafe and works of art produced in the studios are displayed by racks of structural timber columns. This space removes the hierachy that we impose on certain objects and materials, asking provocative questions about what is worth saving for posterity and what is better altered.

The landscape of the site morphs through channels dug across site, forming new water ways off the nearby River Clydach, the water irrigating the site for new plant life as well as eroding the soil slowly and continually, exposing new archaeology at the abbey and continuing the process of dissolving and reforming the site fabric. A carbon sink cloister and meadow covers the site, offsetting more than the total operational Carbon requirements for the new buildings.

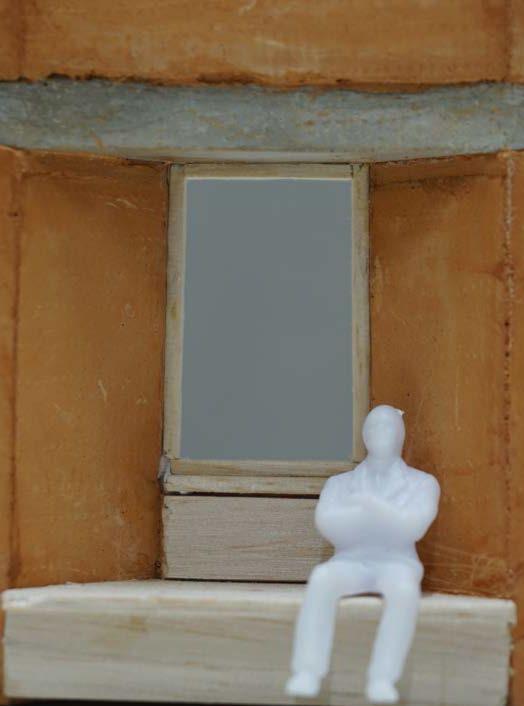

These models were part of my attempt to find practical ways of building within historic ruins, such as the ones at Neath Abbey.

Model 1 was made by firstly creating the existing stone structure using modelling concrete with a much lower percentage of water in its mixture, which increased it’s viscosity and therefore allowed the concrete to be handmoulded into shape. Then a mixture of plaster of Paris, concrete and red mortar dye was combined to create the proposed rammed earth layer, which was achieved by hand cutting balsa wood moulds that went with the contours of the stone and were waterproofed using PVC tape. This striking model then had balsa windows and openings added.

Model 2 is a small maquette of a rammed earth vaulted doorway, achieved by creating an inverted mould made up of layers of greyboard covered in PVC tape to achieve a smooth effect. Plaster of Paris mixed with mortar dye was then added to create the model.

Model 3 shows how stone lintels might be used to create openings in rammed earth walls, with modelling concrete used to create a precast rectangular block, which was then added inside an additional mould with pieces of PVC tape used to both waterproof and preserve the colour of the exposed concrete. With the plaster dried, the mould was then dismantled to reveal the stone lintel seemlessly fixed to the plaster and balsa portions were added to create a window and seating.

The section design for the new vernacular of lime stabilised rammed earth and Oak timber initially rejected the more philosophical concepts behind the design, that being chiefly about the ground floor earth walls forming a thick thermal barrier that both stitched seemlessly onto the existing fabric and created a simplistic structural plinth that evocatively weathers as time passes. Instead this section inserts insulation between two tied earth walls, reducing the effectiveness of the thermal mass and increasing embodied Carbon. A concrete raft foundation also seems to reject the principal of Carbon reduction and circular life of buildings.

The final section instead utilised only lime stabilised rammed earth for the ground floor walls, both achieving a regulation U-Value of 0.14 W/m²K for the fabric of a new non-dwelling and forming a strong structural plinth for the insulated first floor structure. The new ground floor also features a Ty Mawr Limecrete patented and approved system, using sandstone spread plinths underneath the earth walls, echoing the traditional foundation method of the abbey updated for a modern usage.

During my time as a Part 1 Assistant from 2022-2023, I was given the opportunity to work on a variety of projects, from an infill project adjacent to Gloucester Road tube station, designing a mews house conversion and a rural new-build.

The most common project type was office retro-fit and extension, the most rewarding of these being the extensive redesign of a prominent building on Tottenham Court Road. With a complete redesign of the facade, interior, endof-trip facilities and plans.

My involvement with the project spanned Stages 0-3 of the RIBA Plan of Work, where I began by surveying the existing steel and concrete structure and producing 3D and 2D CAD of the structure, which was crucial to understanding our building constraints from the very beginning. I progressed onto producing a variety of options for the internal layout and facade, allowing the project to progress whilst a new project architect could be appointed.

After fully modelling the building, including surrounding context, I was tasked with producing high-quality external and internal renders as quickly as possible for design team and planning meetings, which had to have a consistent aesthetic between design changes.

The project went through a variety of changes in terms of program, possible tenant, facade aesthetic, until eventually achieving planning approval with a brick and stone approach in image 3.

My Fifth year unit titled ‘The Regenerative Vision’, was concerned with regenerating the St Philip’s Marsh area of central Bristol, adjacent to Temple Meads, and also questioning what we mean when we try and regenerate an urban area.

We were tasked with understanding how to regenerate an area of central Bristol with high land-values, few existing assets and derelict structures ripe for demolition. The simple option would have been demolition and sweeping redevelopment, but as a unit we came to the conclusion that the outward appearance belied an area crucial to the success of Bristol as a regional centre, with the Bristol fruit and vegetable market being the largest in the country and positioned dead centre of St Philip’s Marsh.

Our groupwork began site analysis in collaboration with Bristol City archaeologist Pete Insole, studying what made St Philip’s unique and how it came to be this industrial pocket on an artificial island in the heart of Bristol.

Through collaborative urban planning, we were able to work at a scale none of us had experience in before, providing insight into the importance of masterplanning and the impact it can have on the socio-economics of the places we live and work.

We undertook a several day trip to Lisbon before we began our individual proposals, visiting the radical flooding infrastructure and historic preservation that makes Lisbon what it is.

An immunodeficiency clinic that harnesses freshwater wetland ecosystems to restore the biodiversity, flood defences and health outcomes of the St Philip’s Marsh community

Regeneration of St Philip’s Marsh is not a point in time, but an ongoing process. The medicine of ‘Salutogenesis’ offers a system for not only designing healthy environments for people, but for reinterpreting and strengthening the way we design healthy communities and regeneration schemes; both literally health conscious and resilient against the passage of time.

The challenge of this architectural proposal, was using both form and function to manage the positive and negative impacts upon immune system health that arise from integrating the changeable, seasonal and tidal landscape of the freshwater wetland, with the absolute clinical necessity of a medical space that is controllable, consistent and cleanable.

The resolution to this dialectic comes through architecture and ecology, creating a unique typology for St Philip’s Marsh based on seeing nature and site geography as assets, not hindrances or boxes that need ticking. Designing in such a holistic manner, will lead to all encompassing improvement at St Philip’s Marsh, from the smallest microbe, to individual health improvement, to providing a template for national and global redevelopment.