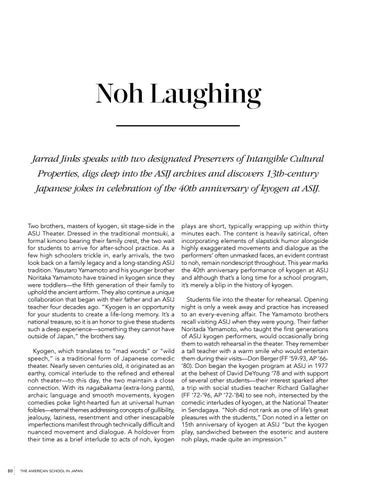

Noh Laughing Jarrad Jinks speaks with two designated Preservers of Intangible Cultural Properties, digs deep into the ASIJ archives and discovers 13th-century Japanese jokes in celebration of the 40th anniversary of kyogen at ASIJ.

Two brothers, masters of kyogen, sit stage-side in the ASIJ Theater. Dressed in the traditional montsuki, a formal kimono bearing their family crest, the two wait for students to arrive for after-school practice. As a few high schoolers trickle in, early arrivals, the two look back on a family legacy and a long-standing ASIJ tradition. Yasutaro Yamamoto and his younger brother Noritaka Yamamoto have trained in kyogen since they were toddlers—the fifth generation of their family to uphold the ancient artform. They also continue a unique collaboration that began with their father and an ASIJ teacher four decades ago. “Kyogen is an opportunity for your students to create a life-long memory. It’s a national treasure, so it is an honor to give these students such a deep experience—something they cannot have outside of Japan,” the brothers say. Kyogen, which translates to “mad words” or “wild speech,” is a traditional form of Japanese comedic theater. Nearly seven centuries old, it originated as an earthy, comical interlude to the refined and ethereal noh theater—to this day, the two maintain a close connection. With its nagabakama (extra-long pants), archaic language and smooth movements, kyogen comedies poke light-hearted fun at universal human foibles—eternal themes addressing concepts of gullibility, jealousy, laziness, resentment and other inescapable imperfections manifest through technically difficult and nuanced movement and dialogue. A holdover from their time as a brief interlude to acts of noh, kyogen

40

THE AMERICAN SCHOOL IN JAPAN

plays are short, typically wrapping up within thirty minutes each. The content is heavily satirical, often incorporating elements of slapstick humor alongside highly exaggerated movements and dialogue as the performers’ often unmasked faces, an evident contrast to noh, remain nondescript throughout. This year marks the 40th anniversary performance of kyogen at ASIJ and although that’s a long time for a school program, it’s merely a blip in the history of kyogen. Students file into the theater for rehearsal. Opening night is only a week away and practice has increased to an every-evening affair. The Yamamoto brothers recall visiting ASIJ when they were young. Their father Noritada Yamamoto, who taught the first generations of ASIJ kyogen performers, would occasionally bring them to watch rehearsal in the theater. They remember a tall teacher with a warm smile who would entertain them during their visits—Don Berger (FF ‘59-93, AP ‘66’80). Don began the kyogen program at ASIJ in 1977 at the behest of David DeYoung ‘78 and with support of several other students—their interest sparked after a trip with social studies teacher Richard Gallagher (FF ‘72-’96, AP ‘72-’84) to see noh, intersected by the comedic interludes of kyogen, at the National Theater in Sendagaya. “Noh did not rank as one of life’s great pleasures with the students,” Don noted in a letter on 15th anniversary of kyogen at ASIJ “but the kyogen play, sandwiched between the esoteric and austere noh plays, made quite an impression.”