GOA COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE

T.B. CUNHA EDUCATION COMPLEX ALTINHO, PANAJI

CERTIFICATE

The following study is hereby approved as a creditable work on the approved subject, carried out and presented in the manner sufficiently satisfactory to warrant its acceptance as a pre-requisite for the award of degree for which it has been submitted.

It is understood that by this approval the undersigned does not necessarily endorse or approve any statement made, opinion expressed or conclusion drawn therein, but approves the study only for the purpose for which it has been submitted and has satisfied himself/herself as to the requirements laid down by the college.

UNDERTAKING

I, Ashley Alexandre D’Costa, the author of the dissertation titled:

“The Evolution of Goan Retail Environments in a Neoliberal Economy”

Hereby declare that this is an independent work of mine, carried out towards partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Architecture at Goa College of Architecture, Goa University, Panaji, Goa. This work has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of any Degree/Diploma; no material from other sources has been used without proper acknowledgment.

Sign:

Place: Altinho, Panaji-Goa

Date: 13 December 2021

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I express my deep gratitude to Ar. Fernando Velho, who has been a dedicated guide and the voice of reason throughout this semester. It was he who suggested an investigative approach to the evolution of retail, when the research was originally a mere documentative study. I am grateful to him for his time and patience, and wish future researchers the good fortune of having a guide like him.

My professors Ar. Rohit Nadkarni, Ar. Suhas Gaonkar, Ar. Snehalata Pednekar and Ar. Amey Korgaonkar have been extremely supportive throughout, and their valuable feeback and insights at every stage of the dissertation has helped a great deal in shaping my understanding of my research area.

I am grateful to Mr. Coutinho and Mr. Fernandes of Reliance Builders for their immense help with drawings for my case studies. Mr. Cacodkar of Rabindra Sinai Kakodkar & Associates was also very kind to provide me with necessary drawings. I express my gratitude to Ar. Siddha Sardessai, who provided invaluable assistance in my study of Caculo Mall. I also thank Ar. Arsekar in a special way for the time he spent with me, and the tremendous amount of effort he put in to search for old drawings.

I also thank Mr. Bhuvanish Sheth and the management of Mall de Goa, Mr. Surendra Naik of Umiya Builders, Ar. Gurudutt Sanzgiri, Ar. Sameith Khan and Mr. Royston Costa for their help in understanding the commercial environments of Goa, and Mr. Mohammed Arif, Mr. Ali Raza, Mr. Sebastian Mascarenhas and Mrs. Simi Panakal for their help in understanding corporate retail models.

Many thanks to Mr. Abhijeet Gayatonde, Mr. Jayesh Nadkarni, Mr. Michael & Mrs. Ziska D’Costa, and other store owners for their time and assistance.

I am extremely grateful to Chinmay Soman and Mrinal Sathe for their original drawings and research that feature in this dissertation. Their work laid the foundation for a deeper understanding of the Goan commercial realm.

My deep thanks to Joan and Ayesha for their assistance in proofreading this lengthy document and providing valuable crits.

I am also thankful to Saurabh Tubki, Raveena, Pankaj, Tahir, Rucha and Parth for their support, Classic Printers & Siddharth Computers for the high quality print job, and Amey Computers for supplying me with a laptop in record time when my old one malfunctioned.

Many thanks to the helpful souls who took the various consumer surveys that formed an integral part of my research, and the many unnamed persons who have contributed to the study in various ways.

My parents have been incredibly helpful and understanding throughout the semester, and I am eternally grateful for their constant support.

Finally, I thank God, who makes all things possible.

CHAPTER 1. AN INTRODUCTiON TO THE STUDY

1.1 Introduction

On a walk around Margao’s municipal square, one encounters several age-old commercial buildings that are a testament to centuries of trade in Goan markets. Goa, as written by Pinto, has since times immemorial held the reputation of being ‘a great commercial centre and a transit port of considerable significance, central to the active western littoral of India.’ (1994). Pinto further writes of Goa’s importance to mercantile activities for several centuries in the Portuguese Estado da India, and its trade with surrounding regions (1994).

Trade in Goa flourished in the initial phase of Portuguese colonial rule, but subsequently hit its nadir in the mid 18th century as stated by Trichur (2013). He goes on to write of how the Goan economy was radically transformed in the last two decades of colonial rule. India, Trichur says, ‘severed her political and economic ties with the administration in Portuguese Goa in 1954’ (2013). A direct result of this, he goes on to explain, was the declaration of Goa as a free port, in order to boost selfsufficiency and insulate the Goan economy against the harsh impact of Indian economic policies (2013).

The establishment of the free port meant that Goa was open to global trade much before the rest of the Indian subcontinent, which- as pointed out by Chithathoor (2021), was heavily focused on industrial production, and had imposed heavy restrictions on imports. This period of globalisation came to an end in 1961, with Goa’s commercial activities now controlled by the Indian government.

The economic neoliberalisation of 1991 catalysed a change in the Goan commercial realm- as it had in the rest of India (see Amaya, 2020), opening up Goan markets to global brands and once again changing the way Goan consumers moved, shopped and perceived retail environments. This study aims to understand the evolution of Goan retail environments in a neoliberal economy i.e. post 1991, in the urban context of the cities of Panjim and Margao.

1.2 Rationale

In the past, undergraduate researchers of the Goa College of Architecture have studied the morphology of traditional Goan markets, the adaptability of commercial signages, and the urban fabric of Goan cities (see Pimenta, Sonia (2003); Gehlot, Abhijeet (2010); Gracias, Donovan (2013); Antao, Sigmund (2015); Saglani, Priyanka (2016) and others). These studies have largely focused on colonial era trade and commerce, and the visual character of shopping streets thereafter.

Goa has witnessed profound changes in the structure of its economy- both in the twilight years of colonialism and in the three decades following liberation as noted by Trichur (2013), and further in the three decades of neoliberalism as observed by Chitathoor (2021). The emergence of malls- a new retail typology in the state post 2011, has further reshaped the Goan commercial realm.

Neoliberalism has catalysed several major changes in the commercial realm, and an investigative approach is required to uncover what these are in the architectural context These changes in the commercial realm justify a study on the evolution of Goan retail environments and the need to understand the trajectory of commercial developments and retail in the state. This dissertation examines what neoliberalism meant in the Goan context first, and then illustrates its impact on the Goan urban commercial realm.

1.3 Aim and Objectives of the Study

Aim: To study the transformation of the urban commercial realm in Goa, with a focus on retail in the age of neoliberalism.

Objectives:

1) To study the development of commercial environments in key Goan cities pre neoliberalism from 1961-1991 and post neoliberalism from 1991 to the present day.

2) To identify and analyse the changing and emerging physical retail trends in the cities of Margao and Panjim over time.

3) To understand the influences of specific commercial elements and their impact on consumers in the neoliberal age.

1.4 Central Argument

Neoliberal economic reforms and the influx of cash-rich corporates post 1991 have catalysed the development of large format retail away from the city core and led to the internalisation and privatisation of the Goan urban commercial realm.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

The Evolution of Goan Retail Environments in a Neoliberal Economy

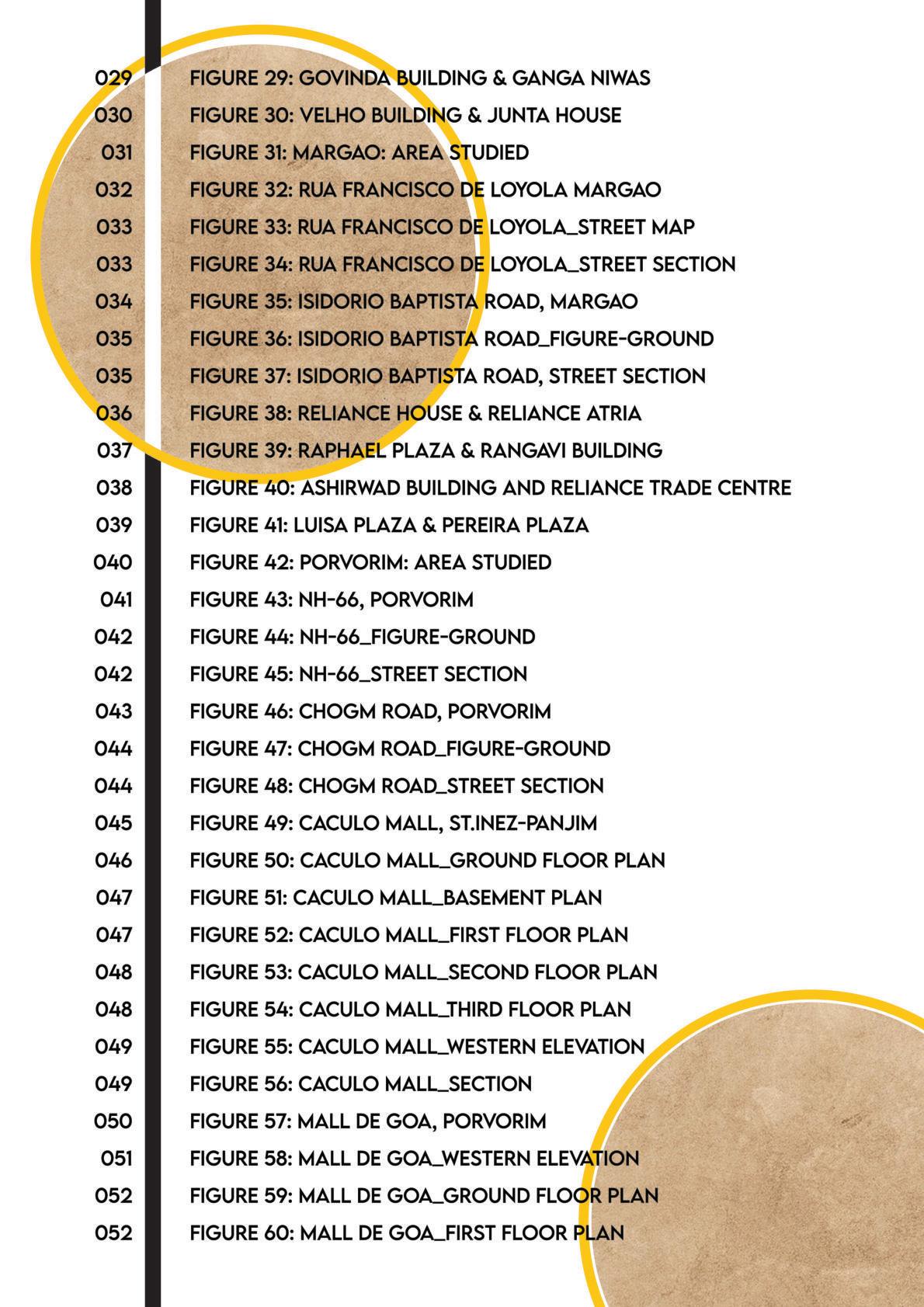

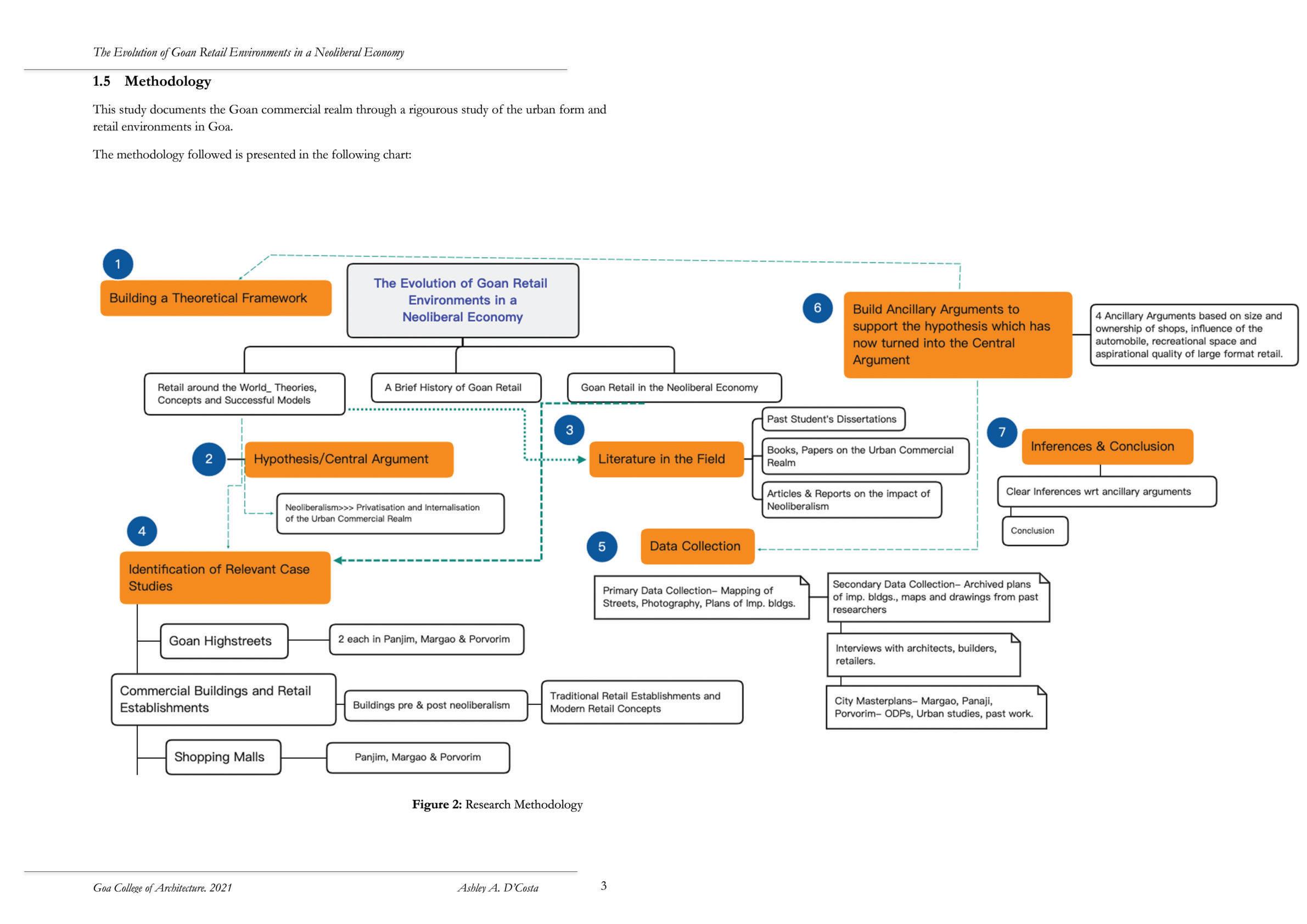

The following is a data collection chart for the research and methods employed:

No. Objective Type of Information Required

1 To identify and document Goan highstreets, malls, commercial buildings and retail outlets.

Photographs, Architectural drawings Site measurements, Info on age, nature of business, etc.

Source of Information Method of Collection

Builders, architects, archives, store owners, past students’ research.

Reading, photography, interviews, site visits, secondary data sources.

2 To study established theories on the retail environment, critical variables, and successful/failed models.

3 To understand the influences of specific retail elements and their impact on consumers in the neoliberal age.

Figure 3: Data Collection Table

1.6 Operational Definitions

Established theories on the retail environment and commercial public realm.

Books, Research Papers, Websites, Reports.

Reading, note making.

Statistical data on degree of impact of elements, architectural drawings

Goan consumers, store owners, architects

Surveys, questionnaires for brand reps., site visits.

A list of frequently used terms and their specific definitions in the context of this study:

Neoliberalism: An economic ideology that advocates the use of free-market policies and reduced government control over commerce, as defined by Hayek and von Mises (1938).

Neoliberalisation: (Of India) becoming neoliberal in nature.

The Neoliberal Age: Used to describe the period from 1991 to the present day in India, during which neoliberal economic reforms have come into force and their effects felt.

Retail Environment: Used to refer to a large format freestanding store, a group of shops, a shopping street, commercial building, or a mall.

Public realm: Areas to which the public has access. Includes buildings, streets, squares, parks etc.

Commercial realm: Parts of the public realm that are engaged in commercial activity i.e. buying and selling of goods and services (for the purpose of making profit). Includes standalone shops, vendors, shopping streets, malls etc.

Internalisation: The process of making formerly external activities internal- to bring the activities carried out in the exterior parts of the built form into the interior spaces.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Privatisation: Of a public space, to become either partly or wholly privately owned.

Corporates: Large companies/ Business corporations with a minimum turnover of Rs.100cr that have interests in nationwide or international markets.

Large format retail: Retail stores with a net area of more than 1000 sqm. For the purpose of this study stores with a net area of more than 400 sqm have been considered as large format retail.

Inner City: The area within a 300m radius from the municipal square of the given city (Panjim/Margao).

Suburbs: Outlying parts of a city or town. Suburbs may also be defined as smaller communities adjacent to or within commuting distance of a city, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary (2021).

Signage: A visual element indicating the name of a shop or information related to one or many products/services sold there.

Landmark: Refers to any uniquely identifiable element, marked by clear form and contrast, as defined by Lynch (1960).

F&B: (abbreviation) Food and Beverage.

1.7 Scope and Limitations

The study is focused on changes in retail in the urban commercial realm before and after neoliberalisation. It looks at commercial streets, commercial buildings and retail enterprises over the last few decades, illustrating emerging trends and changes in typologies. A considerable part of the research involves observational studies and architectural drawings of commercial streets and buildings by the author. Interviews with architects and builders of commercial buildings have been helpful in developing an understanding of why specific decisions are taken in the commercial realm While considerable data is available on post-neoliberal buildings, finding drawings that pre-date ’91 proved to be challenging, considering a majority of the drawings are not digitised.

The study has not included marketplaces i.e. traditional retail environments, as this is beyond the scope of the research. Superstores and automobile showrooms have not been included either due to limited availability of drawings that pre-date ’91.

Due to the short three-month duration of the study, limited case studies were chosen, and the depth of the research was limited to ensure that the study could be concluded in the given time. The COVID-19 S.O.Ps made physical interviews challenging, and several retailers and other industry stakeholders were uncomfortable having lengthy physical discussions and allowing persons into their premises.

The retail industry is competitive in nature, and stakeholders are understandably reluctant to share drawings, allow measurements or permit photography of their establishments.

This research has worked around these constraints as far as possible, but it would be prudent to note that not all the case studies will reveal the same level of detail.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

1.8 Chapter Outline

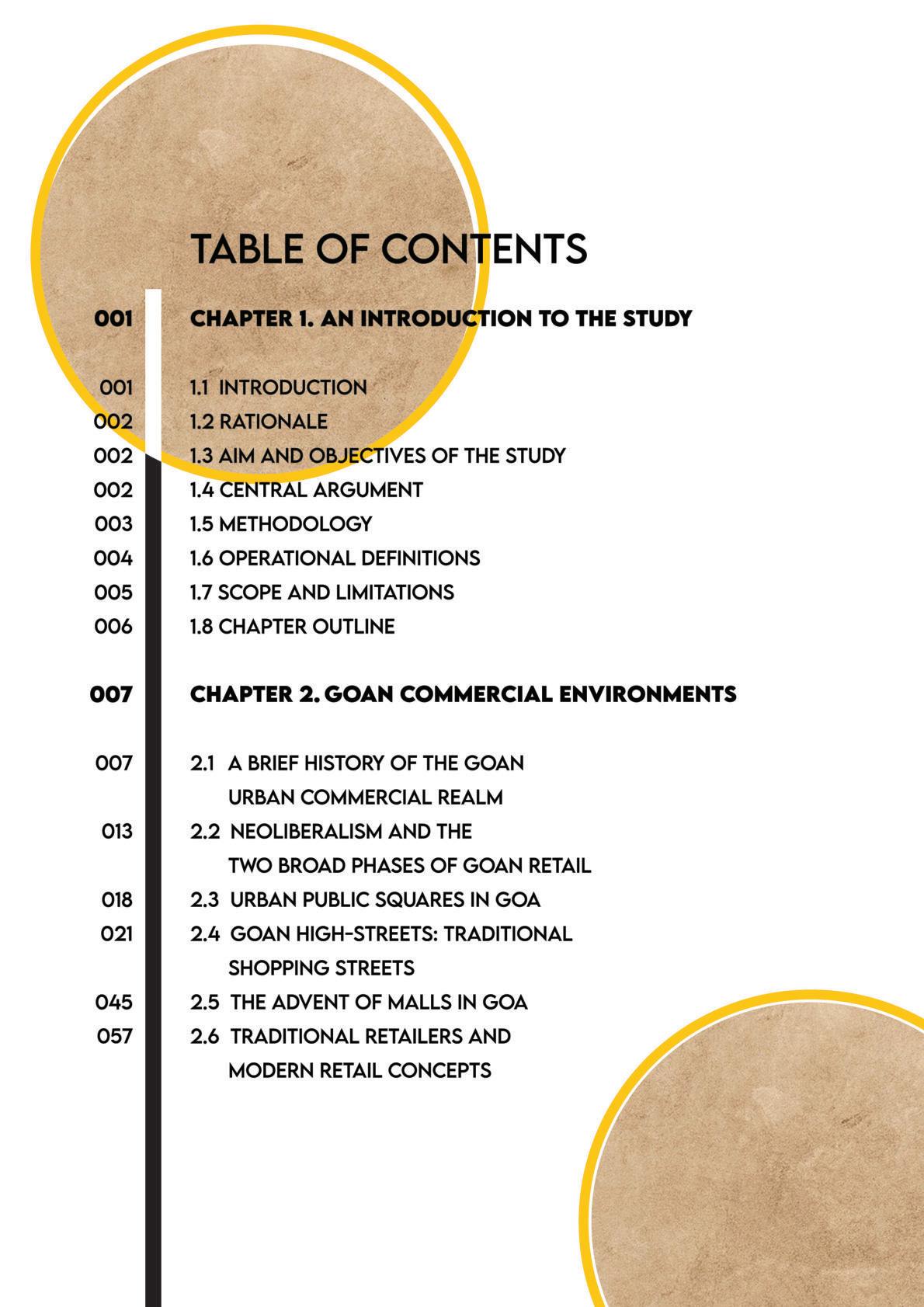

The bulk of the study is contained in three main parts, which form chapters 2, 3 and 4 of this dissertation. The first chapter is an introduction to the study, and the last chapter contains the inferences and conclusion. The following is an outline of all five chapters:

Chapter 1

The first chapter features an introduction to the dissertation that highlights the need for the study and orients the reader towards the aim and objectives of the research. The central argument is put forth in this chapter, and the research methodology is also defined.

Chapter 2

This chapter features an introduction to Goan commercial environments, starting off with a brief history of the commercial realm in the state and going on to explain the importance of neoliberalism to retail in Goa and why the central argument has been centred on its effects on Goan commerce. The Chapter then features a documentation of city squares, high-streets, commercial buildings, malls and finally individual retail enterprises in different retail segments, in Panjim, Margao and Porvorim.

Chapter 3

This chapter features established theories by experts in the fields of architecture, urban design and retail, in an attempt to analyse how different elements of the urban realm have been documented and studied. It then draws parallels to the Goan urban commercial realm and Goan retail environments from these studies, to understand how the Goan retail environment is to be observed and studied objectively. The literature studied was helpful in forming an opinion about the nature of Goan retail environments before proceeding to analyse them.

Chapter 4

In this chapter a set of four ancillary arguments are put forth to support the central argument on the effects of neoliberalism on Goan retail environments. Each argument has been substantiated. Upon proving all four arguments, the final inferences are drawn in the next chapter.

Chapter 5

The fifth chapter features the inferences drawn by the author on the basis of the evidence gathered in support of the four arguments of chapter four. A final conclusion follows, summarising the evolution of Goan retail environments in a neoliberal economy.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

CHAPTER 2. GOAN COMMERCiAL

ENViRONMENTS

2.1 A Brief History of the Goan Urban Commercial Realm

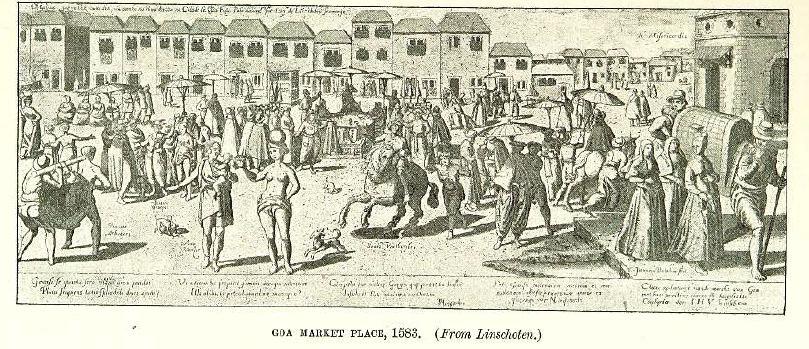

Quoting Linschoten (1583), Saldanha writes of the bazaars of Goa, where goods from all parts of the east were displayed; ‘Separate streets were designated for different classes of goods: Bahrain pearls and coral, Chinese porcelain and silk, Portuguese velvet and piece-goods, and drugs and spices from the Malay Archipelago. Fine peppers came from the nearby Malabar coast’ (2011).

Figure 4: A Marketplace of Goa, 1583 by Linschoten

As Trichur writes, the marketplaces of Goa flourished at the zenith of the Portuguese rule in the east, and subsequently lost prominence as Portuguese influence decreased in the Indian subcontinent (2013). Goa, he says, was a globalised economy with a free port in the last two decades of her colonial era- after the Indian government imposed trade barriers. He adds that post joining the Indian union in 1961, Goan markets began to resemble their Indian counterparts (2013).

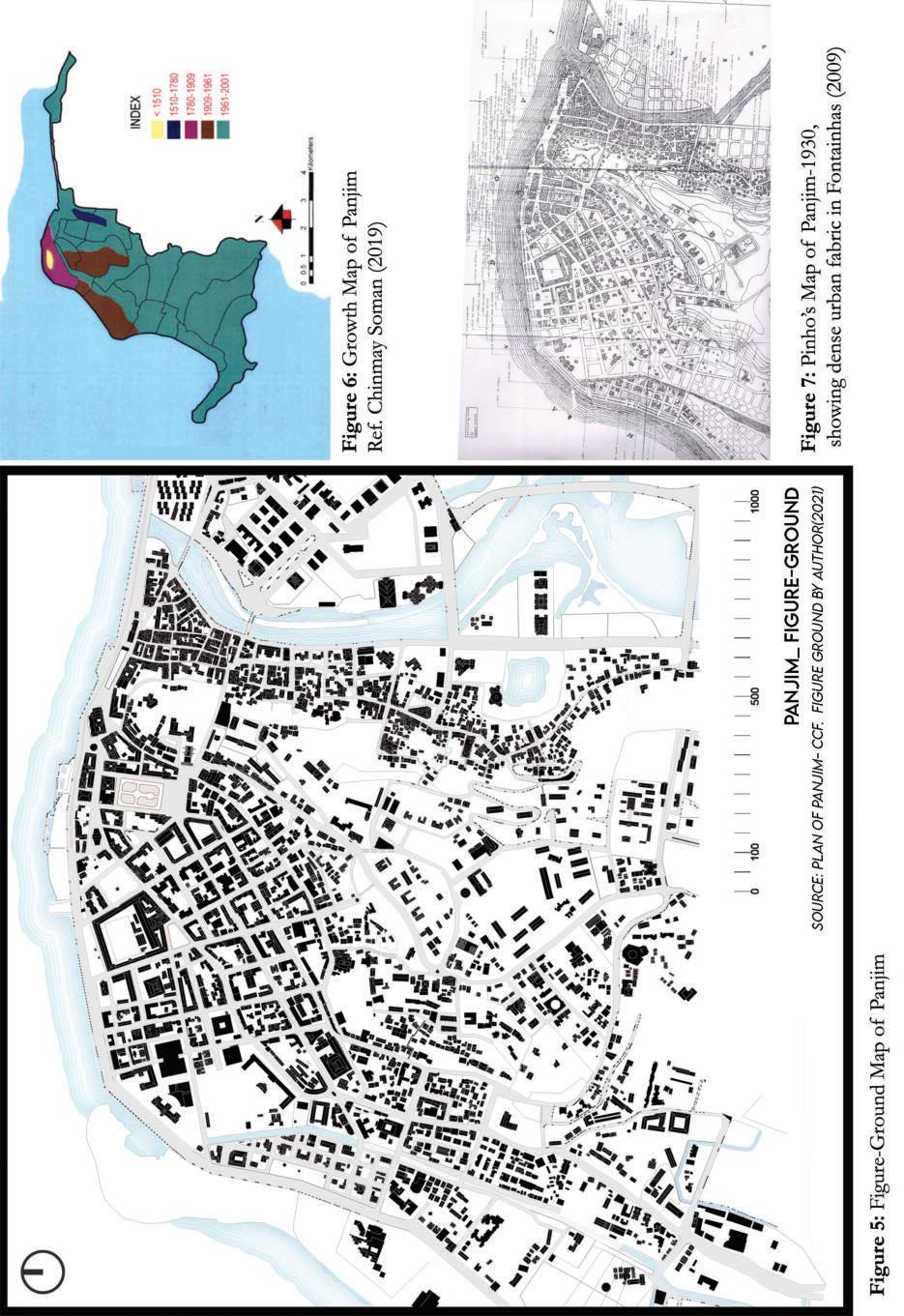

The city of Panjim, as stated in a report by Imagine Panjim, was formerly a fishing settlement that developed along the Mandovi riverfront. It goes on to illustrate that the areas of Mala and Fontainhas developed into the primary residential zone, (as corroborated by Pinho, 2009) while the parts around Garcia de Orta and the church square developed commercially (History of Panaji | Imagine Panaji, n.d.).

The city, as written by Pinho (2009), was the last of several capitals of Goa, earning the title in 1759. Pinho writes of the growth of Panjim as being slow, and initially unplanned. He adds that the city developed into an ‘administrative cum residential city, devoid of industries, with a moderate level of commerce, [and] a refined educational and cultural life.’ (2009).

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Pinho also points out that large areas of Panjim were originally built on reclaimed land, and streets were built alongside pavements, which was a feature not found in many Indian cities. He further adds that the city saw fast urban growth from the last quarter of the 19th century to the first quarter of the 20th century (2009).

The report by Imagine Panjim also adds that a beautification plan was put in place for the Church square, 18th June Road and other areas in 1940, and in 1952 the city received an overall face-lift for the exposition of St. Francis Xavier (History of Panaji | Imagine Panaji, n.d.).

Figures 5, 6 and 7 illustrate the figure ground map and growth of Panjim.

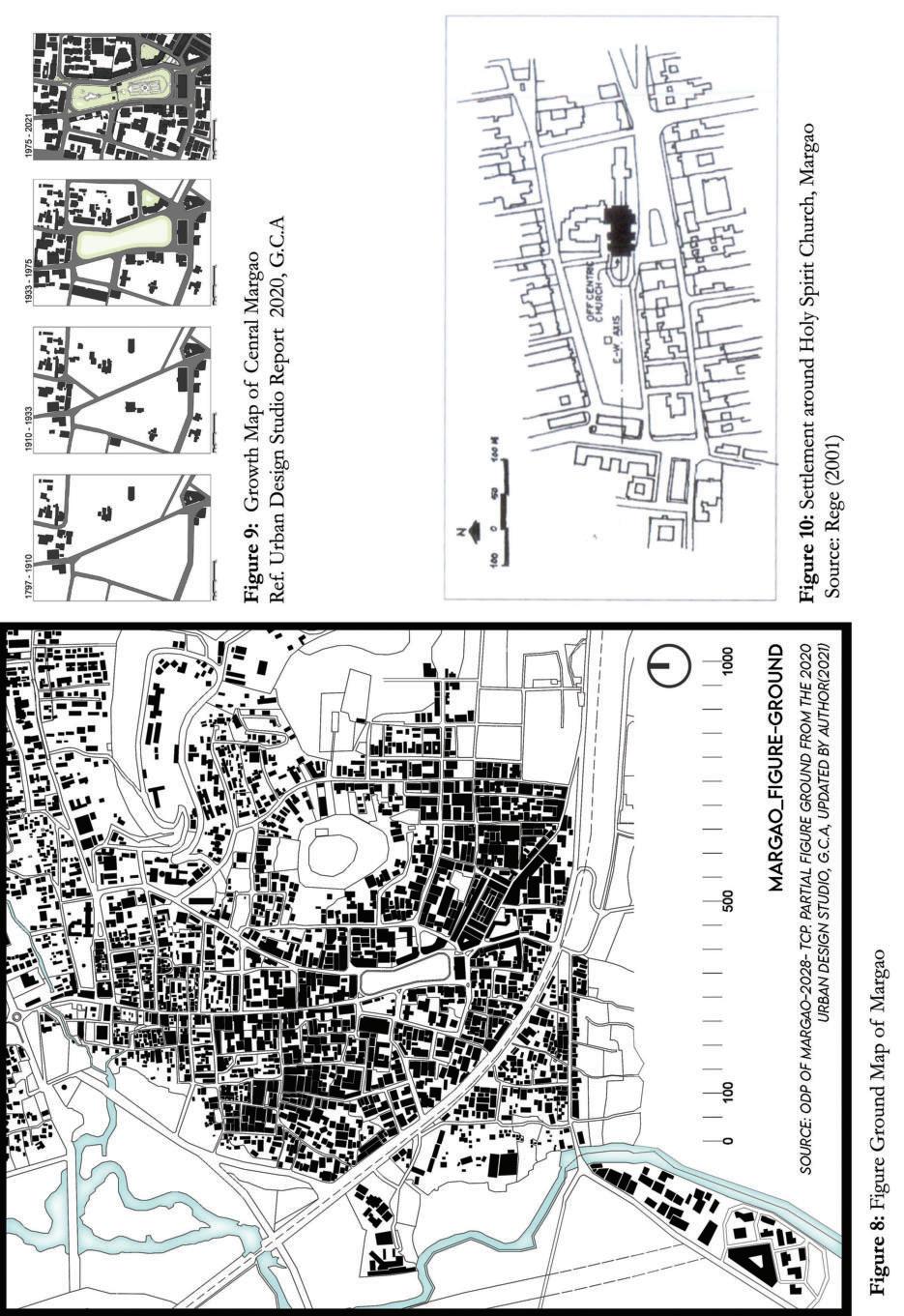

As Coelho writes, the city of Margao grew from a rural settlement, to eventually become the seat of the Camâra Municipal de Salcete in 1778, which was the administrative body overseeing all the villages in Salcete until the establishment of the Goa Municipalities Act of 1968 (2021). He also adds that the Camâra Municipal eventually became the Margao Municipal Council in post-liberation Goa, with the building in the heart of the city retaining its importance (2021).

As stated by Rege, in the Portuguese era, the area around the Holy Spirit Church originally developed as the most important quarter of Margao, with the Camâra Municipal building, the municipal market and the Church making it the centre of administrative, commercial and religious activity. He further adds that Rua Abade Faria developed as an important street here, featuring several prominent houses (2001).

Rege further states that the Camâra Municipal was eventually shifted to the present location of the Margao Municipal Council building in 1914, prior to which a new market complex was constructed in 1889 between Rua Francisco de Loyola and the old station road (2001), as is corroborated by Coelho (2021). With the shifting of the municipal council building and the market, the area known today as central Margao rose to prominence. As stated in an article for the Times of India, the municipal garden and the adjoining Aga Khan Children’s park were constructed in 1959, creating a sizeable green space in the heart of Margao (Deshpande, 2016)

Figures 8, 9 and 10 illustrate the figure ground map and growth of Margao

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021

Ashley A. D’Costa

Ashley A. D’Costa

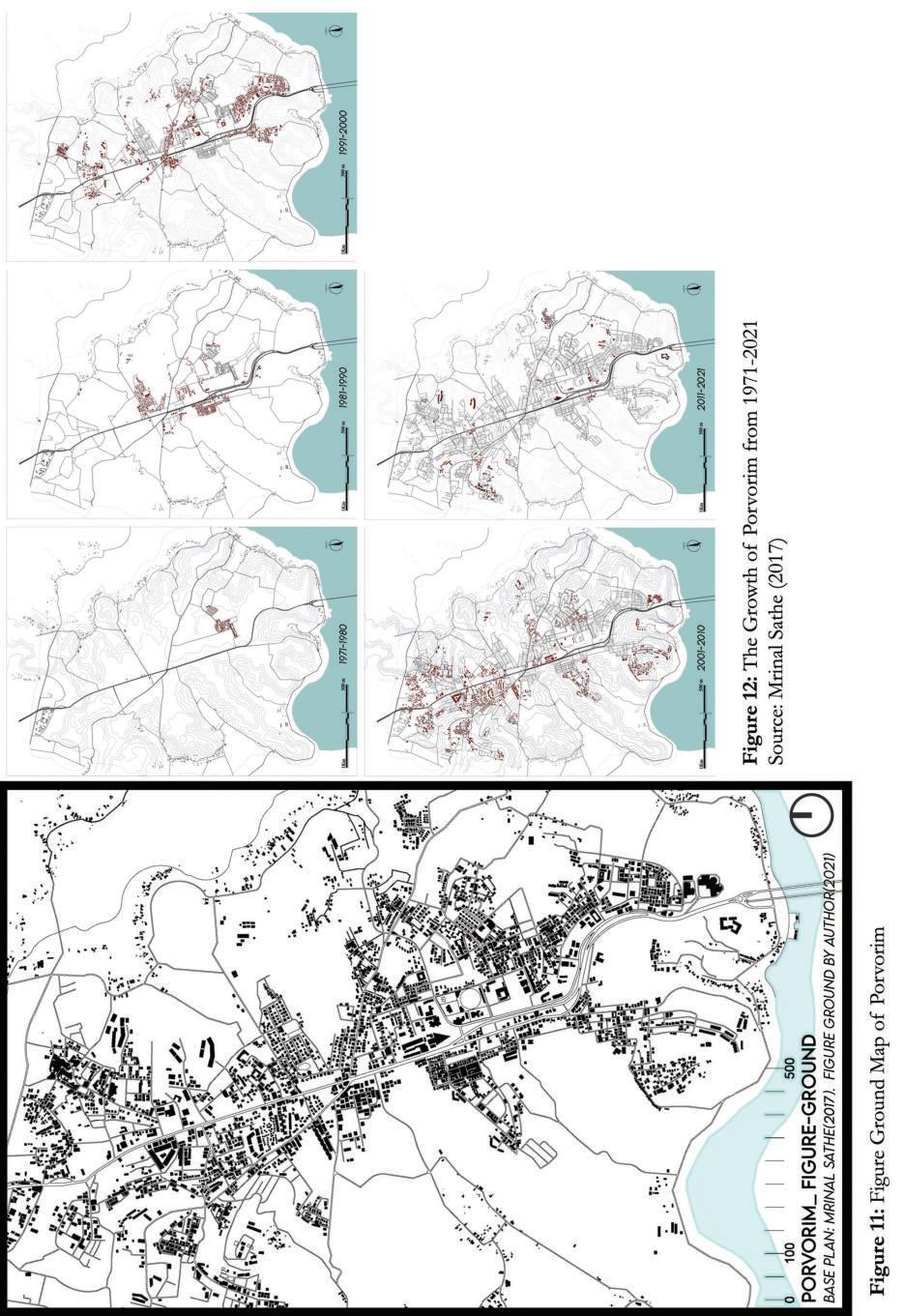

As Goan cities grew, surrounding areas developed as suburbs to support the urban realm, as put forward by Sathe (2017). Porvorim is perhaps the most prominent example of the growth of Goan suburbs; with Sathe writing of its transformation from a sparsely populated hamlet on the north bank of the Mandovi, to a bustling commercial centre by itself, now drawing people across the river from the capital city (2017).

Porvorim is the de facto legislative, executive and judicial capital of Goa, with all three arms of the government shifting their buildings there from Panjim in recent years, as observed by the author. As illustrated by Sathe in figure 12, it has witnessed rapid growth over the last few decades- not only due to the rise in institutional buildings, but also the emergence of several housing complexes, which in turn led to the development of commerce in the area Sathe notes that the construction of bridges across the Mandovi and the development of the national highway have greatly contributed to Porvorim’s growth (2017).

This development of Porvorim as a suburban environment is leading to the hollowing out of the city of Panjim. As important institutional buildings shift out of the city core, and large format retail establishments and housing colonies follow- as observed by the author- the city will lose its importance to its suburbs, and a reversal of roles is imminent, with real estate costs in the suburbs surpassing those of the inner city in the near future.

Figures 11 illustrates the figure-ground map of Porvorim.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

2.2 Neoliberalism and the Two Broad Phases of Goan Retail

As described by Chithathoor, neoliberalism has been used by several world governments- notably Great Britain, New Zealand, Chile, Brazil and India, in the hope of rescuing their countries out of high fiscal deficit via neoliberal economic reforms favouring foreign investment (2021).

On neoliberalism in India he says, ‘Economists describe 1991 as a watershed moment in India's history. Through the 60s and 70s India had a growth rate of 3.5%. Licence-raj or the permit system defined the pre-liberalisation era. Companies would have to procure a series of licences and permits to manufacture products and the system was extremely inefficient. The licence-raj regulated supply in every sector and ended up creating oligopolies. Companies had limited production runs and the competition was more or less non-existent.’ (2021)

Salvador Amaya, in a 2020 report for UFM Market Trends, stated that in the neoliberal age, the government restricted imports, and directed investment towards the production of capital goods (those used to make finished goods e.g. machinery, equipment etc.) in a bid to encourage industrialisation and domestic production (2020). He added that given the low per-capita income ($447 in 1985), the Indian government- unable to raise funds for development through taxationturned to financing via public debt. Amaya then stated that the country eventually racked up $70 billion dollars of debt by 1991, and was on the brink of declaring bankruptcy (2020).

A report by the Free Press Journal stated that the economic liberalisation of 1991 came at a time when India was reeling under the pressure of an acute balance of payments crisis. It further wrote that the country’s fortunes made an incredible turnaround in the years post liberalisation, with a strong economic growth of 15%, and added that neoliberalism catalysed a series of reforms that opened up the Indian economy, taking India from a $266 billion to a $ 3 trillion economy (FPJ Web Desk, 2021).

When the Indian government threw the economic ‘Hail Mary’ of neoliberalism, it opened the doors to a ‘free market’ commercial realm. As observed by the author, the effects of neoliberal reforms are being felt to this day. International brands in Goan shops; a wide range of options to choose from; and trendy shopping malls are all the direct result of neoliberalism, and are explored in the following chapters.

2.2.1 Pre-Neoliberalism (<1991)

Since Goa was already a part of the Indian Union in 1961 as affirmed by Pinho (2009), the retail scenario in pre-neoliberal Goa of the 80’s was similar to that of the rest of India at the time. It was an era of dirigisme, as pointed out by Chithathoor, where the state exerted direct control over the economy. He writes of how companies with monopolies such as those in the automobile and aviation industries operated very inefficiently, and did not act in the interest of the consumer. He further states that the private sector suffered greatly as a result of these monopolies, coupled with antitrust laws and a complicated process of opening new businesses (2021).

‘The approval of up to 80 government departments needed to be obtained when opening a new business, making entrepreneurship a gruelling challenge.’ (Chithathoor, 2021).

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

An article published by The Print stated that the availability of manufactured products was scarce in the pre-neoliberal age, and consumers would find themselves waiting for many months post placing orders. It added that the cost of products was extremely high too, and beyond the reach of the common man. ‘A standard 21-inch TV, which was introduced after the 1982 Asian Games, would then cost a customer Rs. 3000-4000, which inflation-adjusted, would be around Rs. 45000-50000 now. Same is the story with refrigerators and flights tickets.’(Misra and Rampal, 2021). As gathered from field interviews by the author, very few branded articles were available in Goan markets in the period from 1961-1991, and those that were, were beyond the purchasing power of the masses.

2.2.2 Post-Neoliberalism (1991- Present day)

A major difference that has been noticed between pre and post neoliberal Goa, is the huge variety of goods and the multitude of international brands that stock retail shelves on Goan streets today (based on field studies by the author). Consumers have myriad styles to choose from, and retailers are engaged in cutthroat competition to grab market share, much to the delight of the customer.

This variety is largely due to the end of retail monopolies. In the neoliberal age, monopolies are not awarded by the government, but increased market share is instead the product of a company’s consistent efforts to better its competitors. The consumer benefits immensely from this, as observed by the author.

A 2016 article in The Guardian describes competition and consumerism as critical to neoliberal ideology; ‘Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency.’ (Monbiot, 2016).

This competition among retailers (healthy or otherwise) was only possible due to the reforms enforced by the government post ’91. As Amaya notes in his report for UFM Market Trends, the government reversed its stance on the private sector in order to pull the nation out of financial crisis. This, he says (as stated earlier) was done through the introduction of the neoliberal policies of 1991. He further elaborates on how most sectors had their industrial license requirements eliminated, and relaxations on import licenses, tariffs, and most importantly foreign investment came into effect. He adds that the minimum requirements for bank reserves and restrictions on interest rates were also reduced, and limits on capital accumulation were removed (2020).

The reforms that Amaya noted were immensely beneficial to the consumer and to new entrepreneurs, as noted in field interviews by the author. With the increased ease of opening a business, many entrepreneurs opened retail outlets in the state, which gave the Goan consumer a kind of variety they had never experienced in the state since liberation (see Trichur, 2013). In the neoliberal age, the customer is no longer at the mercy of the retailer- “the choices are plenty and waiting time is negligible” (stated by a customer at Allen Solly, Margao).

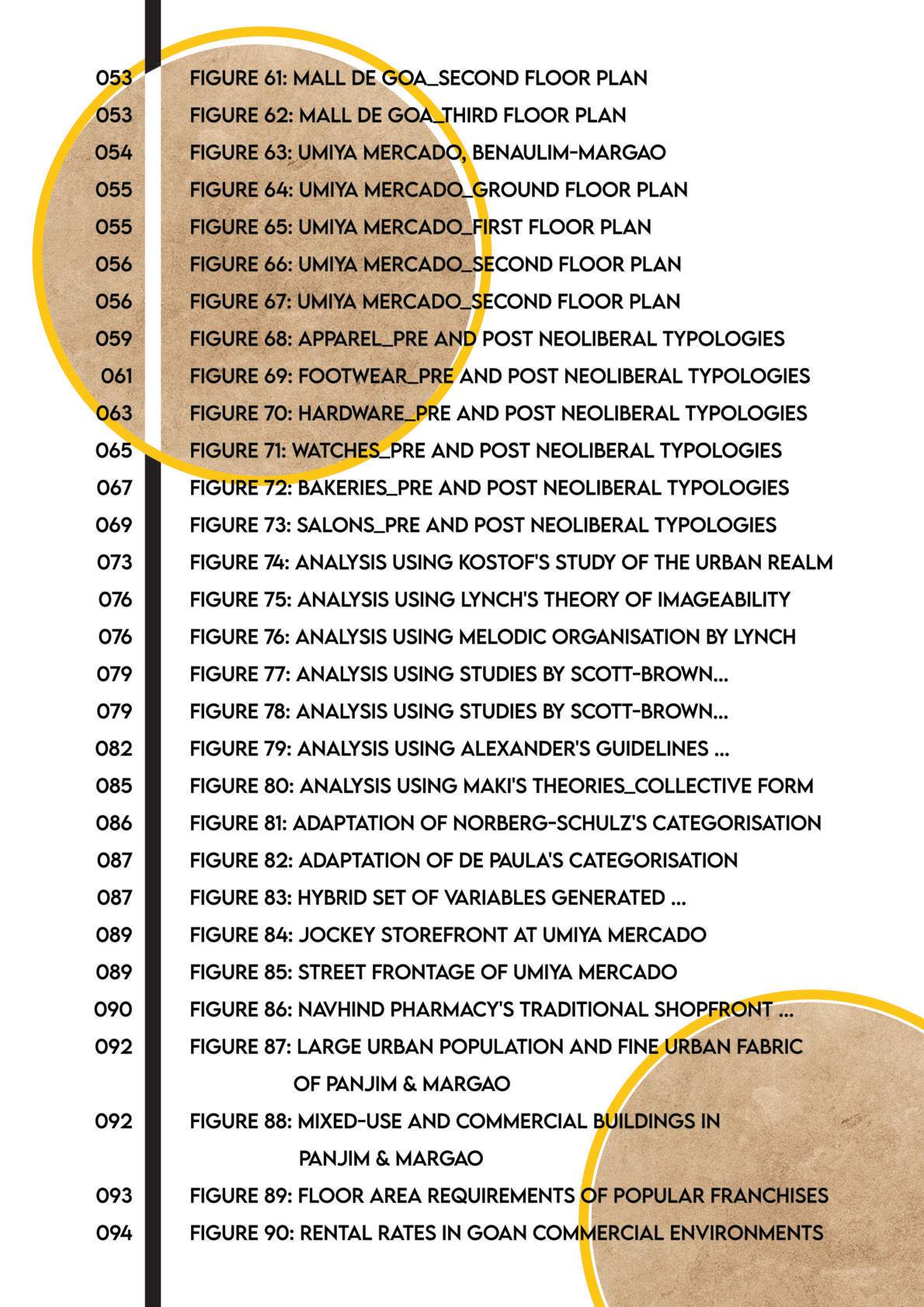

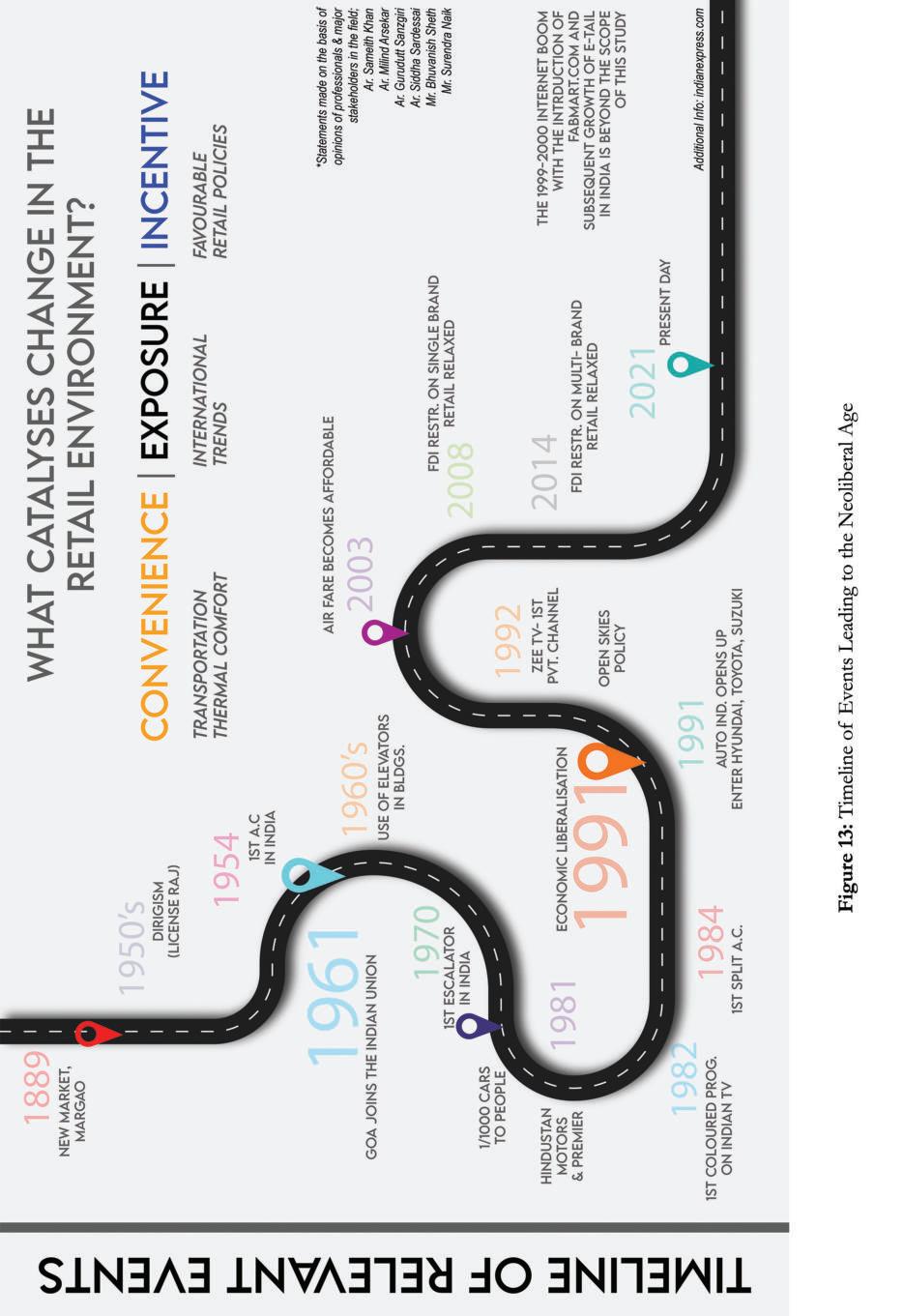

The charts below indicate the series of events that led to the present retail scenario in Goa (ref. Fig.13 & 14). Architect Milind Arsekar commented that elevators began being used from the 1960s onwards in many commercial buildings that were more than four stories high, as the bylaws dictated (personal interview September 2021). With the introduction of the escalator in the 1970s as discussed by Ar. Sameith Khan, the need to press buttons or open doors with shopping bags in ones hands was done away with. He also commented on how air conditioning- developed in the ‘50salthough its widespread use he said was limited until the 90s- greatly increased thermal comfort in

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

commercial buildings, adding a luxurious element to shopping (personal interview, September 2021). The open skies policy of ’91 as reported by the Free Press Journal, eventually led to a rapid increase in air travel, exposing Indian consumers to global products and trends. It further reported that post relaxation of FDI regulations, ‘foreign investment in India increased from $132 million in 1991, to $5.3 billion in 1996’ (FPJ Web Desk, 2021).

While Fig.13 is a timeline of relevant events, Fig.14 focuses on the key aspects of convenience, exposure and incentive, which have ultimately led to the present day retail scenario and the emergence of the latest retail typology in Goa- malls. Convenience for the consumer- through the development of air conditioning, transport and vertical access technology- added a luxurious element to retail, setting up the large experiential shopping concepts of today, as observed by the author. Exposure to international trends and brands- made possible by cheap airfare and televisioneducated the Goan retailer, creating brand awareness and setting the tone for the coming of global brands to Goan streets as observed in field studies featured in the next chapters. Finally, incentive for foreign corporates to set up businesses in India through reductions in taxes and increase in permissible FDI provided the final necessary impetus for global franchises to set up retail outlets in Goan (Indian) markets, as observed by the author. The mall- as indicated in the timeline- is in the author’s opinion, the culmination of neoliberal ideology; suburban, leased commercial space that is primarily run by corporates, featuring extensive visual branding, clear shop fronts and leisurely shopping experiences.

Section 2.3 features an objective study of certain Goan commercial environments, understanding their characteristics pre and post neoliberalism. An analysis of the same is featured in chapter 4.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A.

D’Costa

D’Costa

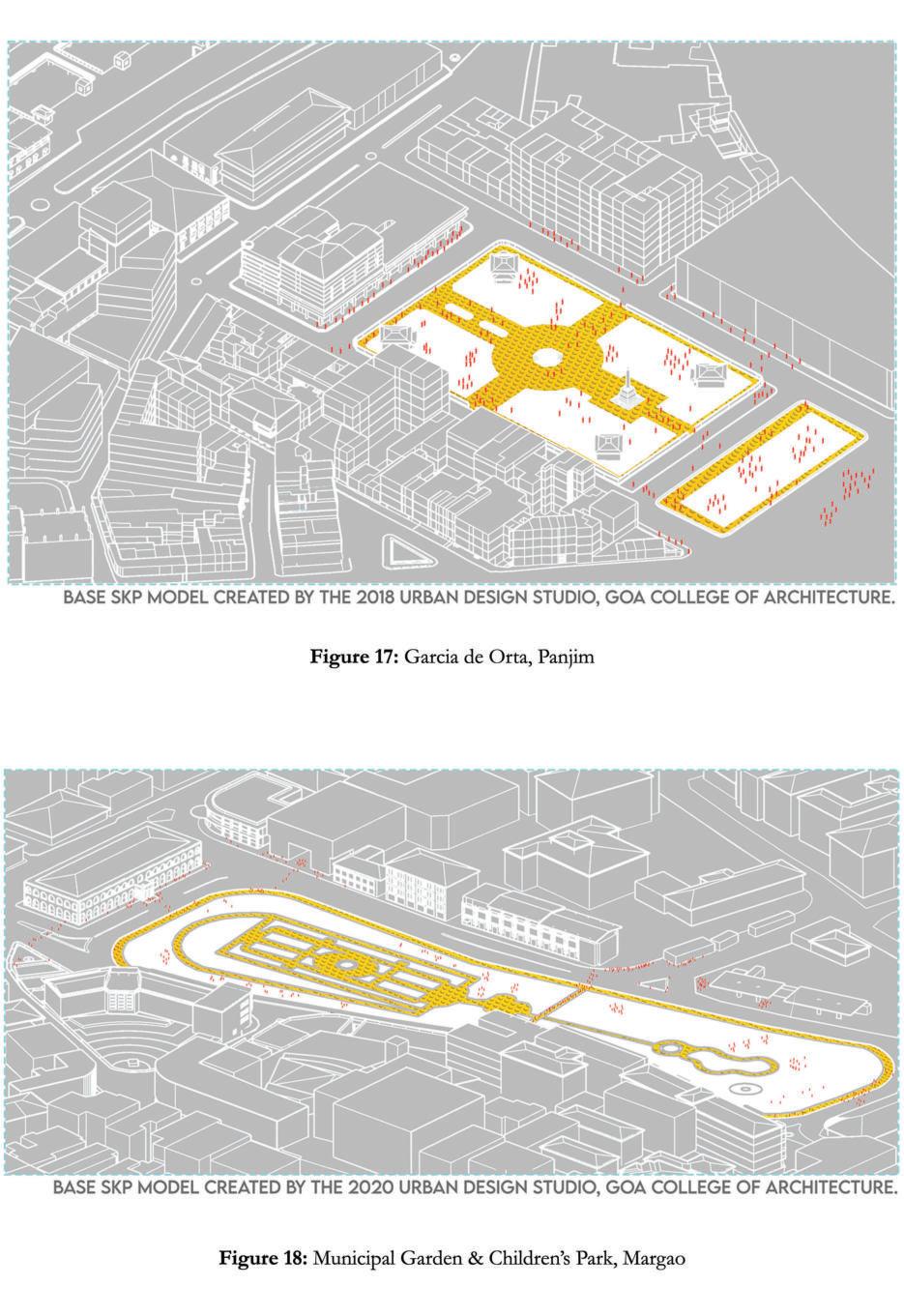

2.3 Urban Public Squares in Goa

The municipal squares of Panjim and Margao had functioned as socio-cultural spaces in colonial Goa, as illustrated by Pinho (2009). Over the years, they have been transformed into formal garden spaces that now serve as important recreational spaces rather than as commercial centres, as observed by the author.

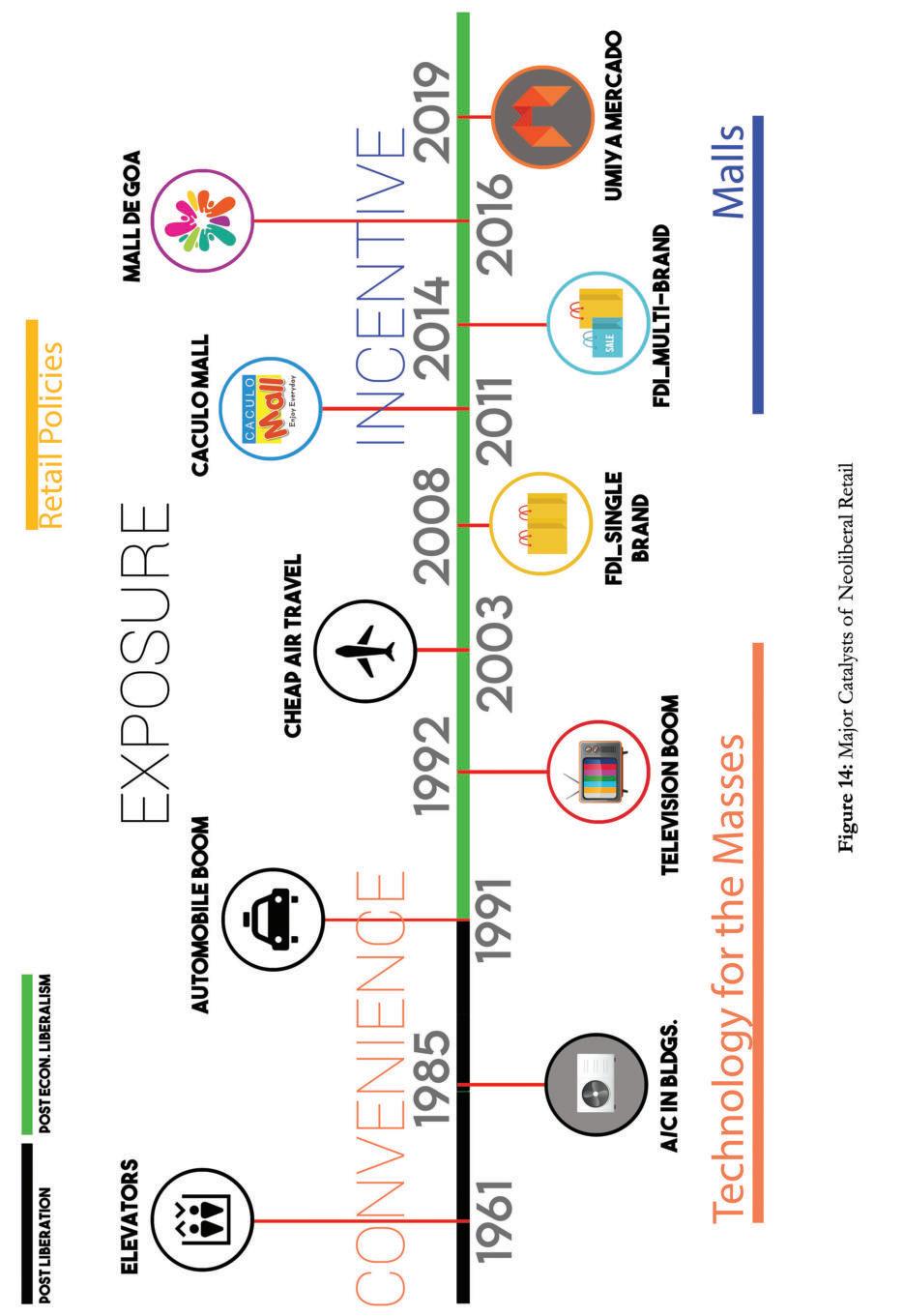

2.3.1 Garcia de Orta, Panjim

Garcia de Orta or the Panjim Municipal Garden, was built in 1855 (as observed on the plaque at the entrance by the author). An article in The Times of India states that it was named after the Portuguese herbalist Garcia da Orta who worked extensively in Goa in the 16th century (Sayed, 2016). As stated by Pinho, the garden, along with the adjoining church square, made up Panjim’s city square or the Largo das Flores- a large space in the heart of the city, that functioned as its socio-cultural centre (2009). The surrounding buildings are commercial in nature, featuring many colonial era businesses like Velho e Filhos, Mr.Baker, Casa J.D. Fernandes, Tarcar’s, Hindu Pharmacy and others, as observed by the author. Over the years the square has lost much of its commercial significance, but remains an important recreational green space in central Panjim. The garden was renovated in 2010 (as observed on the plaque at the entrance by the author).

The relevance of Garcia de Orta to this study is its supporting role to the surrounding commercial establishments.

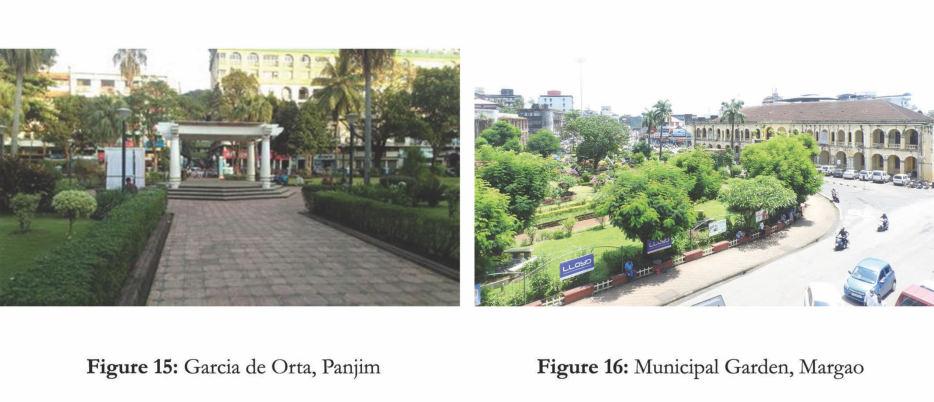

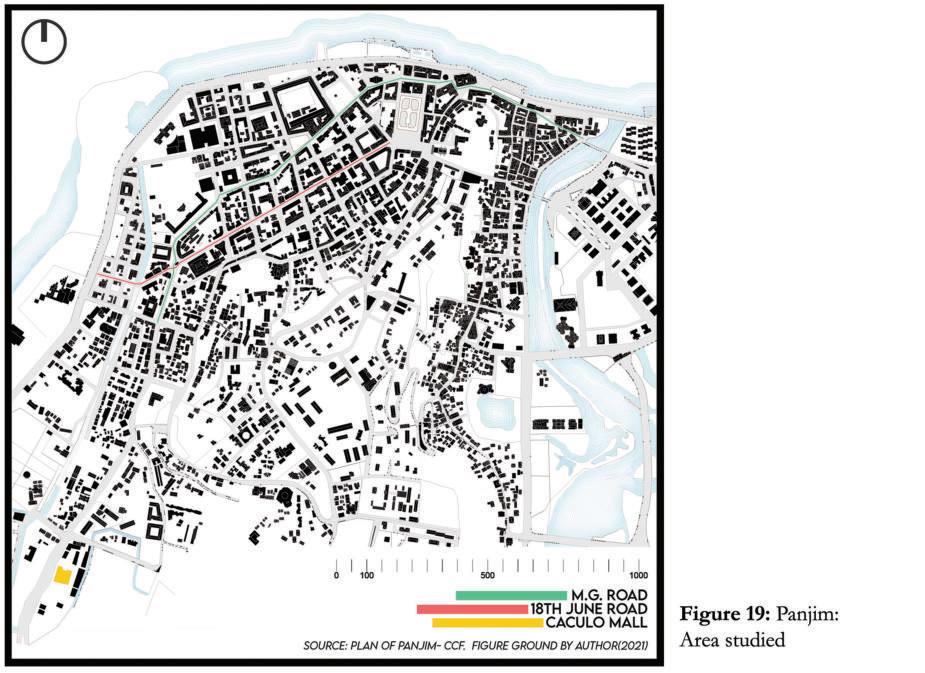

2.3.2 Margao Municipal Square

Margao Municipal Square, as written by Rege, was planned between 1890-1910 as part of a locus ‘between the railway line and the depression of land known as Pajifond’ (2001). He adds that the garden (as we know it today) was built in close proximity to the new ‘wholesale cum retail market’, along with the double storied Municipal Council Building (2001). An article in The Times of India stated that the Aga Khan Children’s Park was constructed on the northern side of the municipal garden in 1959, with the Municipal Park on the southern side (Deshpande, 2016). The parks are separated by a 2.5 meter-wide footpath, along which several vendors sell vegetables, flowers and small items. This middle path experiences heavy footfalls throughout the day, as observed by the author.

As Rege states, the area was originally a space of socio-cultural importance- surrounded by the new market, a theatre, the old Fazenda, and the now derelict Communidade building (2001). The space eventually turned into a recreational green space post its conversion into a park. Annual Carnival and Shigmo parades were held around the garden, but have now been moved to Fatorda, as observed by the author.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

The municipal garden is surrounded by a mix of institutional and commercial buildings. Commercial buildings include the Rangavi building, Costa-Pereira building, Mabai building and the Our Lady of Grace Church Complex- which houses commercial establishments on the street level, with the church and its surrounding property elevated above the shops due to the sloping topography (author’s field studies).

The relevance of Margao Municipal Garden to this study is its supporting role to the surrounding commercial establishments.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

2.4 Goan High-Streets: Traditional Shopping Streets

Goan highstreets have undergone extensive urbanisation since the colonial era, as analysed through a comparison of old and new photographs, documented by Pinho (2009) Streets such as Isidorio Baptista Road in Margao and 18th June Road and M.G. Road in Panjim feature several pre-colonial residential buildings whose ground floors were converted into commercial establishments; more recent residential buildings that were built with commercial spaces on the lower levels; and the most recent buildings on the street that are entirely commercial in nature, as observed by the author. Few streets such as Rua Francisco de Loyola in Margao are purely commercial, being specifically designated as shopping streets.

Goan’s shopping streets were the dominion of local businesses in the colonial and pre-neoliberal age, as indicated in the writings of Pinto (1994). Post neoliberalism- as observed by the authorseveral national and international franchises have entered the market, changing the pace, image and quality of retail on Goan high-streets.

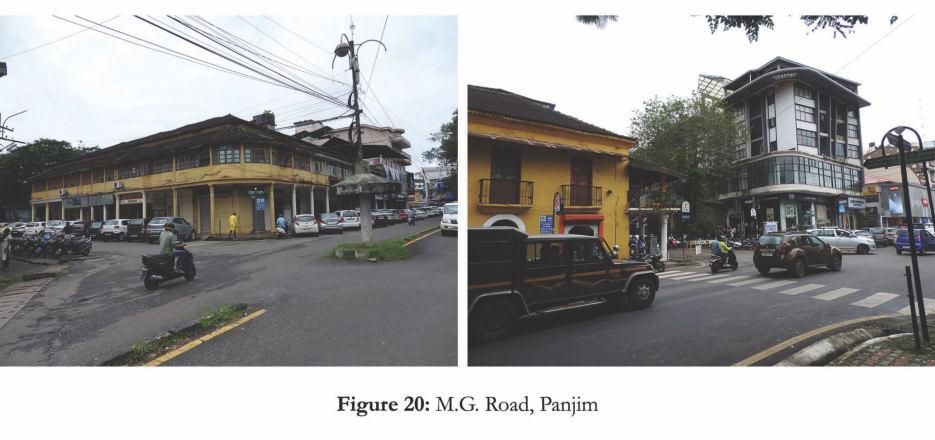

2.4.1 Panjim

The state capital sees the highest floating population among any Goan city, with over 100,000 people present on any given day (census2011.co.in). Panjim has preserved a considerable part of its colonial heritage, and commercial establishments are nestled within or in-between rich architectural edifices, as observed by the author. Its high-streets see a large number of national and international tourists, further boosting commerce. The city’s primary high-streets- M.G. Road and 18th June Road have been chosen for this study.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

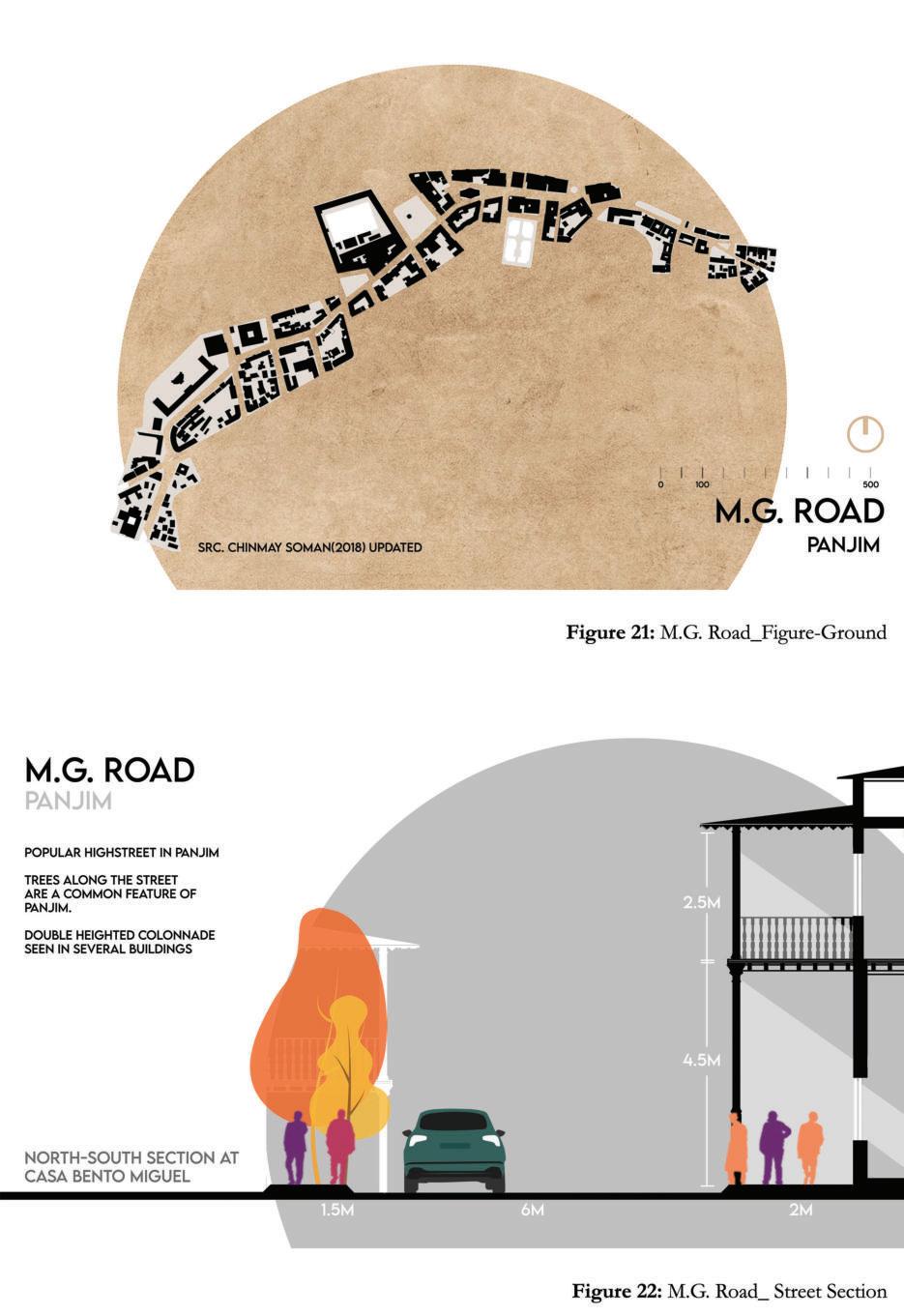

2.4.1.1

M.G. Road, Panjim

Mahatma Gandhi Road stretches from the Divja circle to the St. Inez junction. For the purpose of this research the stretch from the Old Patto Bridge to St.Inez junction has been studied. M.G. Road, as observed by the author, extends from east to south-west, winding past several commercial and institutional buildings such as the District and Sessions Court, Post Office, Don Bosco High School and others, eventually ending at Hotel Vivanta. The street is fairly walkable, but lacks adequate paving in certain parts, inconveniencing pedestrians.

M.G. Road is primarily a one-way street, briefly widening at St. Inez circle and Magnum Centre into a two-way street. Double heighted colonnades are present in certain buildings along the road, providing shelter from the elements. Large trees are seen only in a few pockets, and the rest of the street is exposed to the harsh sun and rain.

The street features several colonial era structures, a number of which have been adapted for modern day retail by popular national and international franchises such as Subway, Peter England, Skechers, U.C.B., Nike, The Body Shop, and Levi’s, among others, as observed during field studies by the author. A healthy mix of retail segments is observed here, with plenty of apparel stores, jewellery stores, electronics shops, wine shops, restaurants and food outlets.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

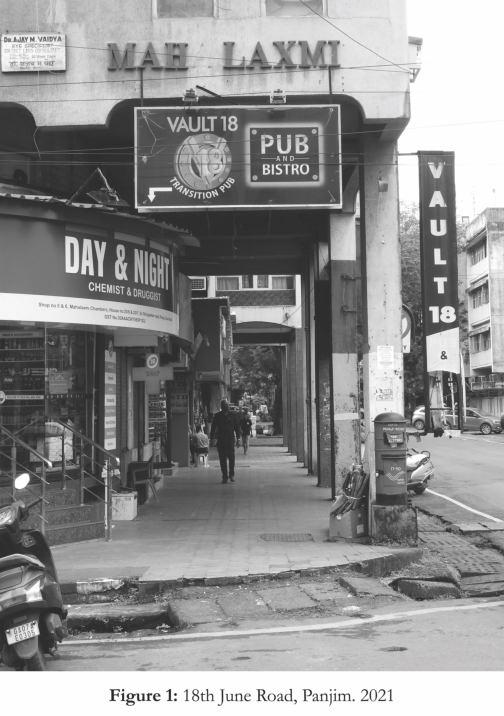

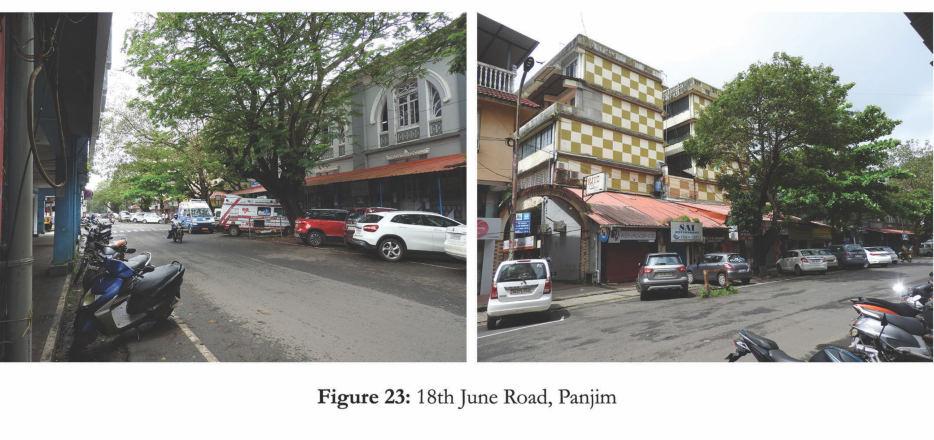

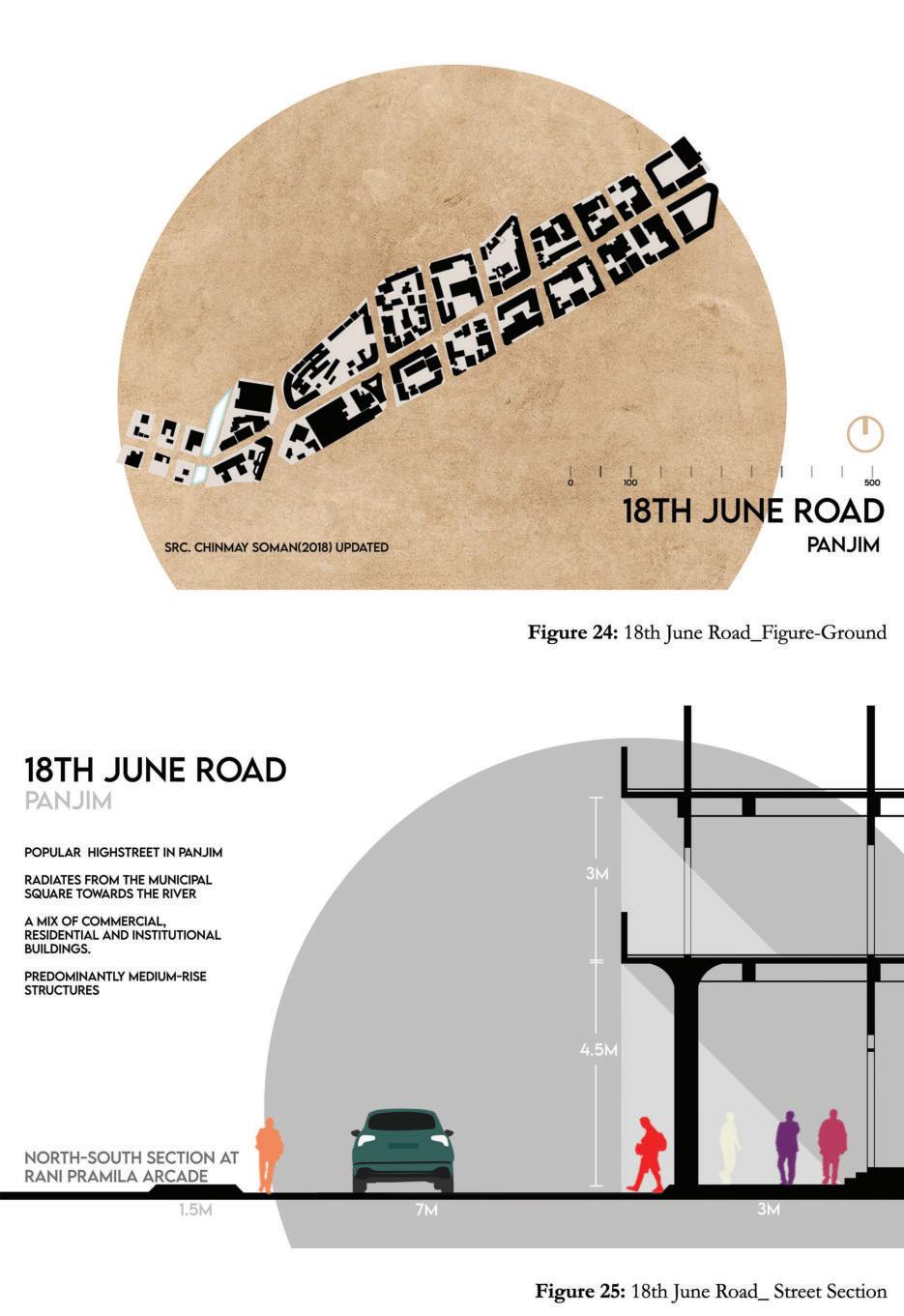

2.4.1.2 18th June Road, Panjim

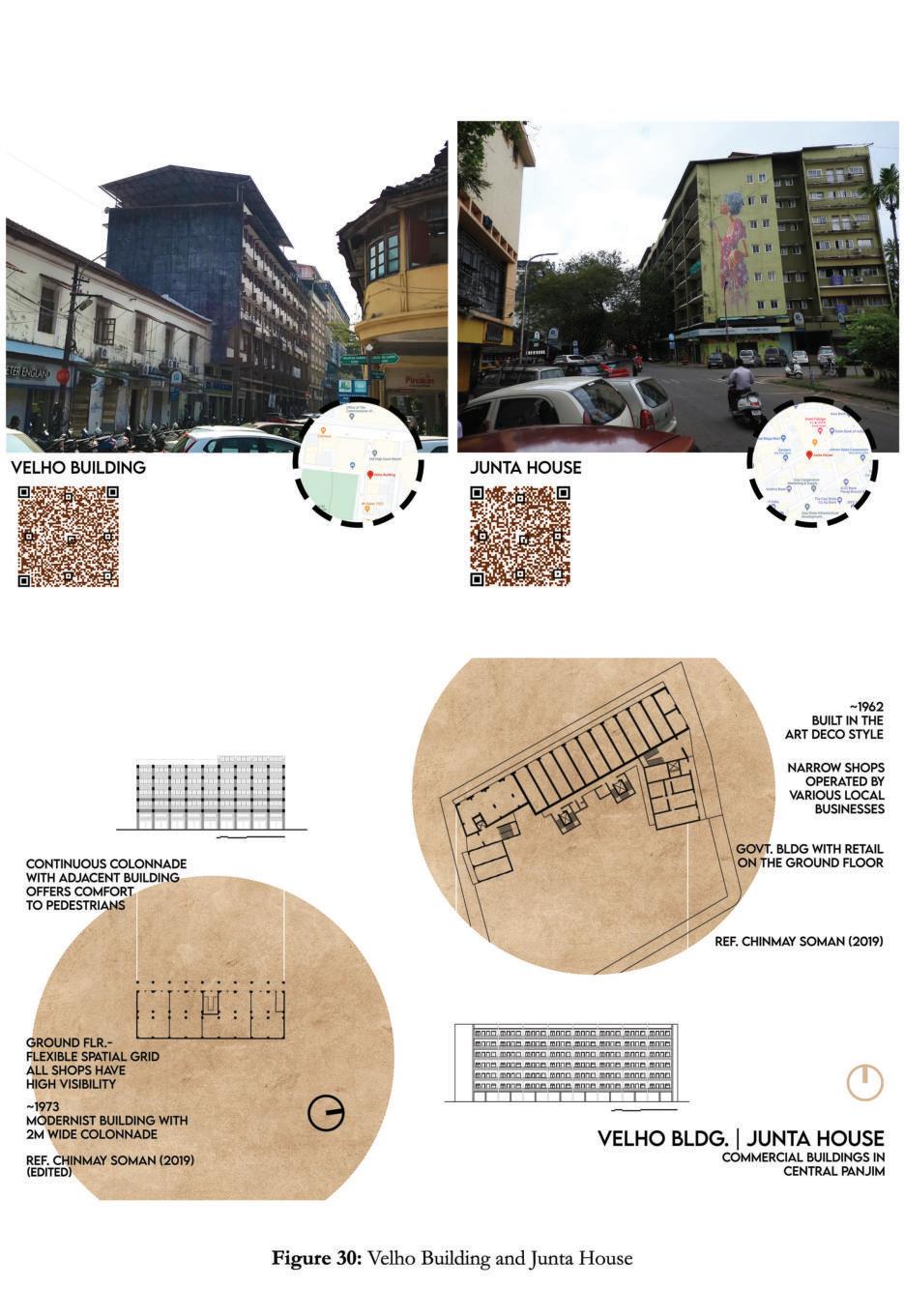

18th June Road extends from the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church Square to Mahavir Park in Campal. As observed by the author, the street is fairly straight as it extends from northeast to southwest, featuring a mix of commercial and institutional buildings such as the urban health centre, BSNL area office, Hotel Fidalgo, Junta House, Z-square cineplex (which now houses national superstore chain Vishal Megamart), and Goa Pharmacy college among others.

The street is one-way throughout, and is of roughly uniform width from end to end. 18th June Road is pedestrian friendly due to the presence of large trees with broad canopies along the pavement, as observed by the author. The street also features several buildings with colonnades, which provide additional relief from the elements.

Several residential buildings flank either side of the street, with the lower levels functioning as shops and offices, as observed by the author. Only a few global franchisees such as Domino’s Pizza and Bata are seen here, and a majority of the stores are local concepts. The retail mix is not as varied as that of M.G. road, with most outlets here belonging to the F&B segment.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

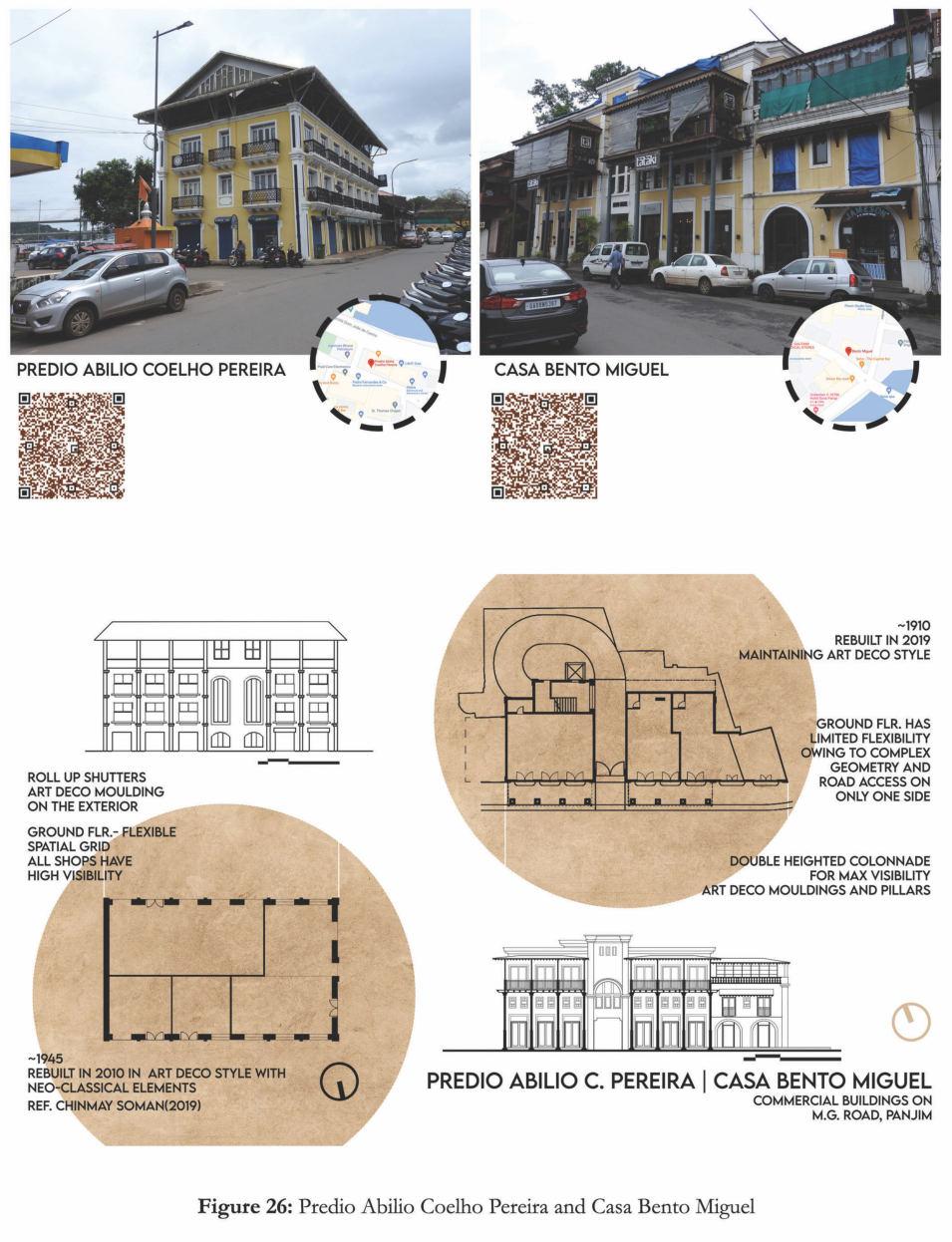

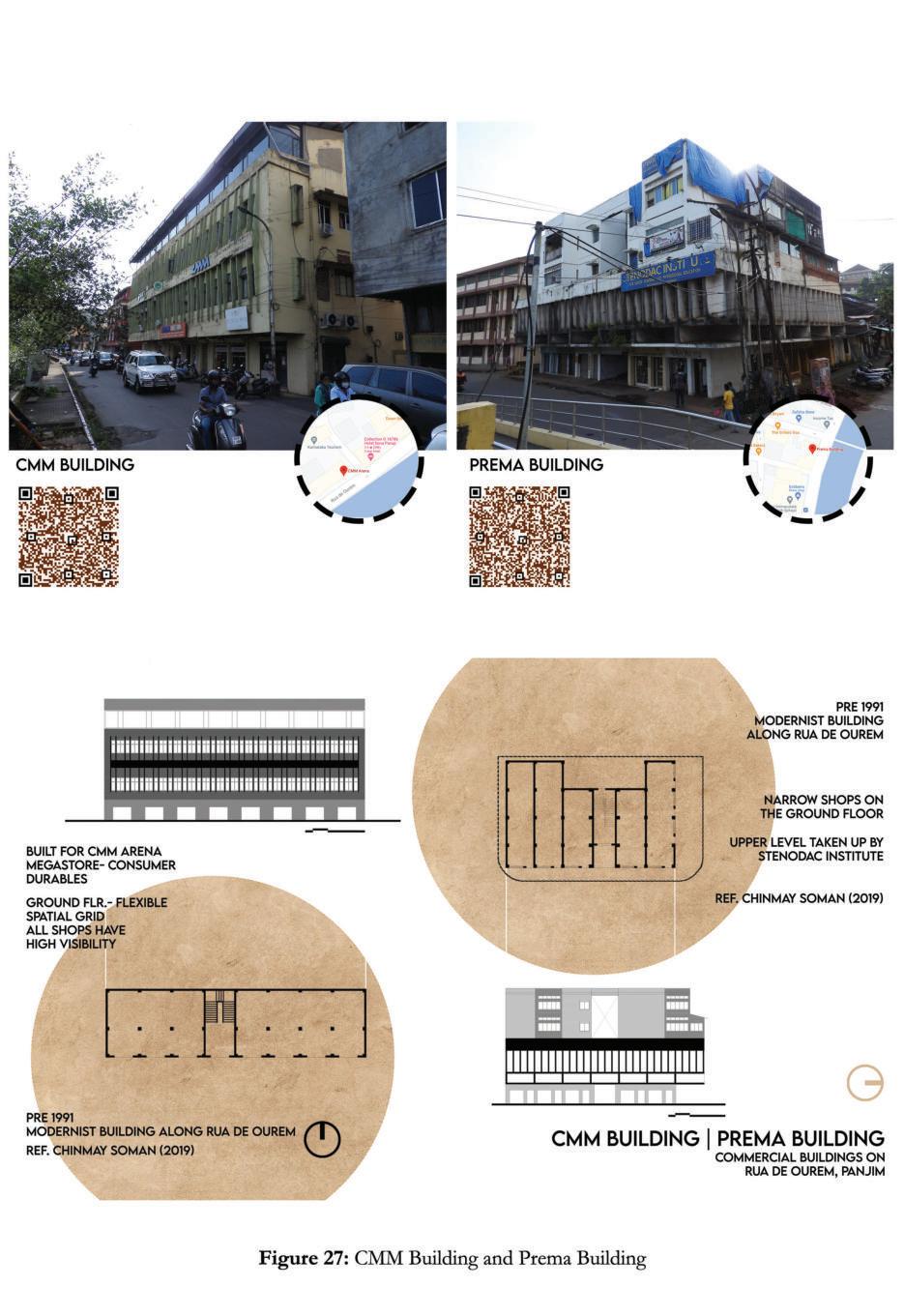

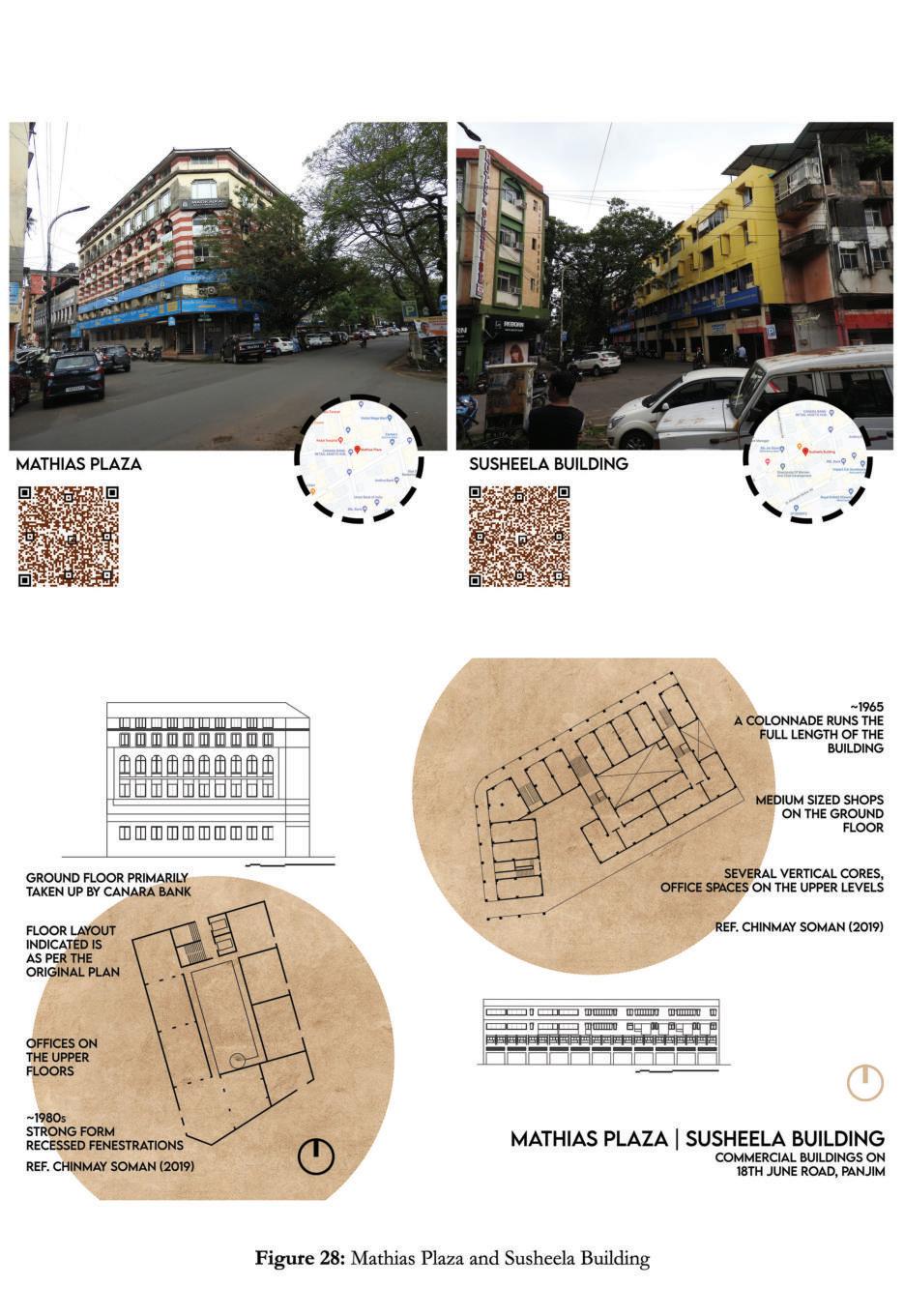

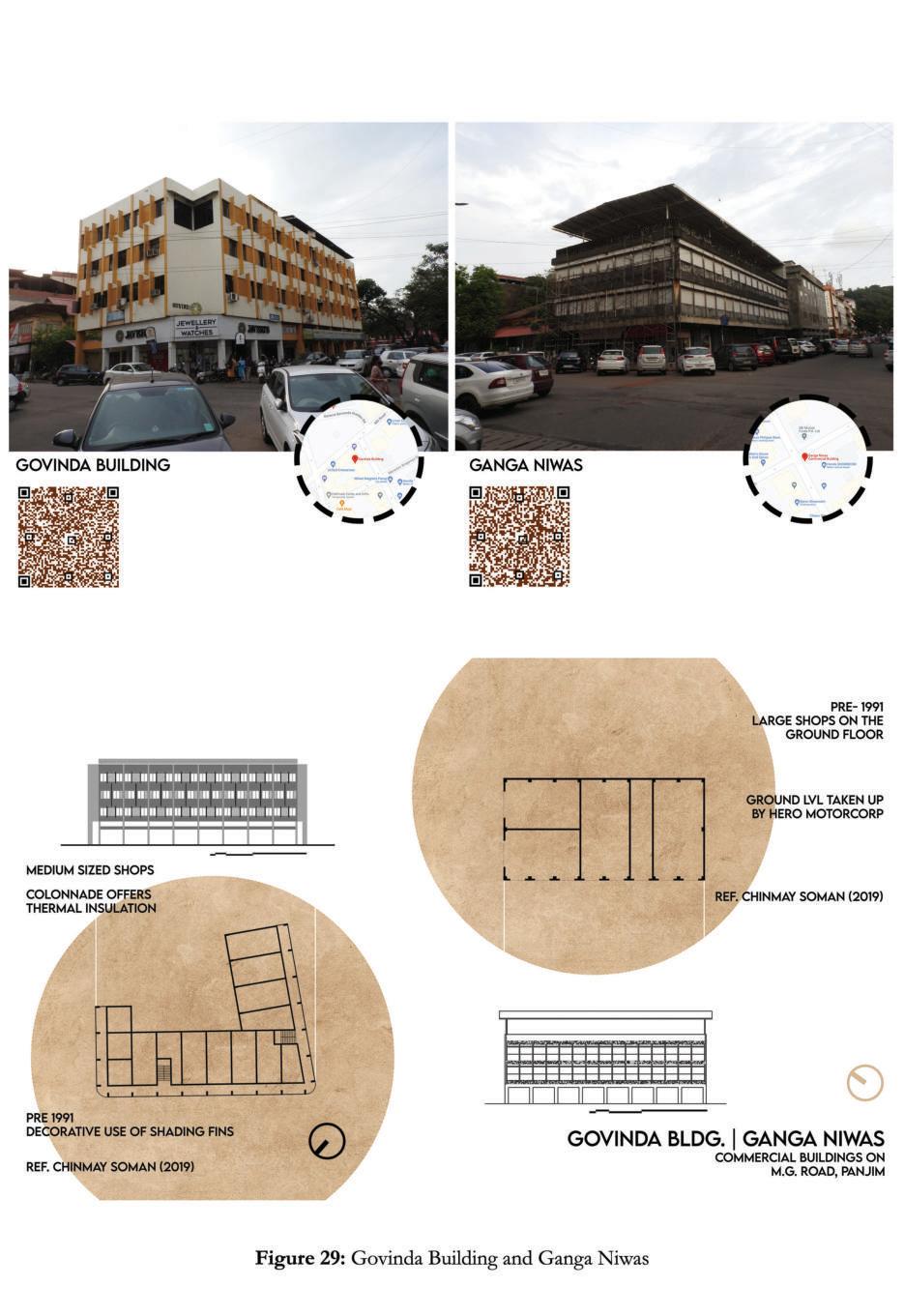

2.4.1.3 Commercial Buildings, Panjim

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture.

2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture.

2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

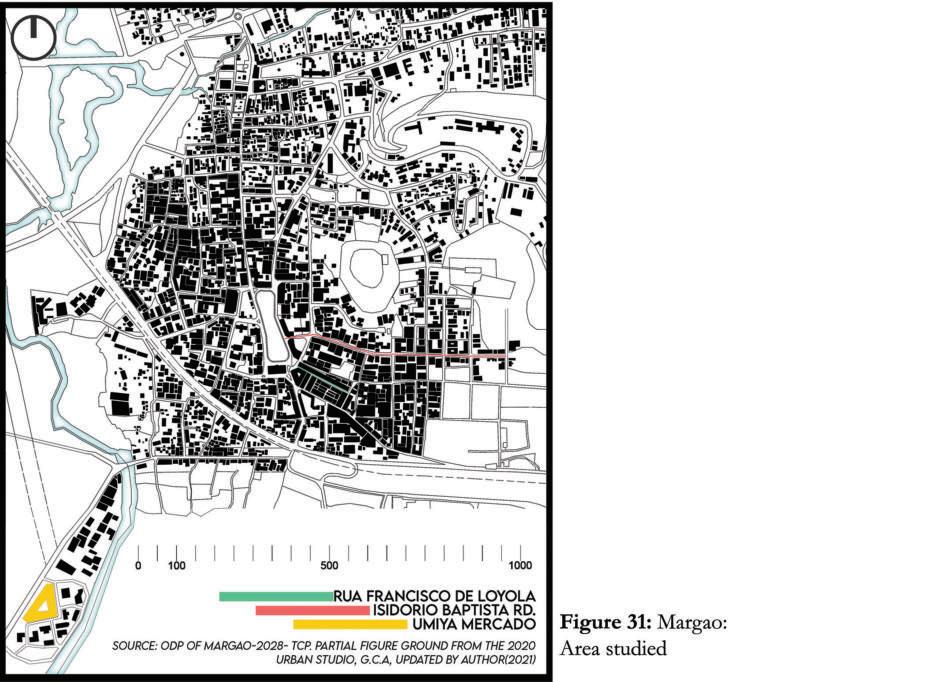

2.4.2 Margao

Margao is popularly referred to as Goa’s commercial capital. As stated in an article for The Navhind Times, the city has served as an important centre for trade since the colonial era, when it was used as a goods hub- given its good connectivity via road and rail. The article further states that the markets of Margao attract customers from all over South Goa, and are especially known for their goldsmiths, cloth, textiles and fish (Almeida, 2012). The shopping streets of Isidorio Baptista Road and Rua Francisco de Loyola have been chosen for this study.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

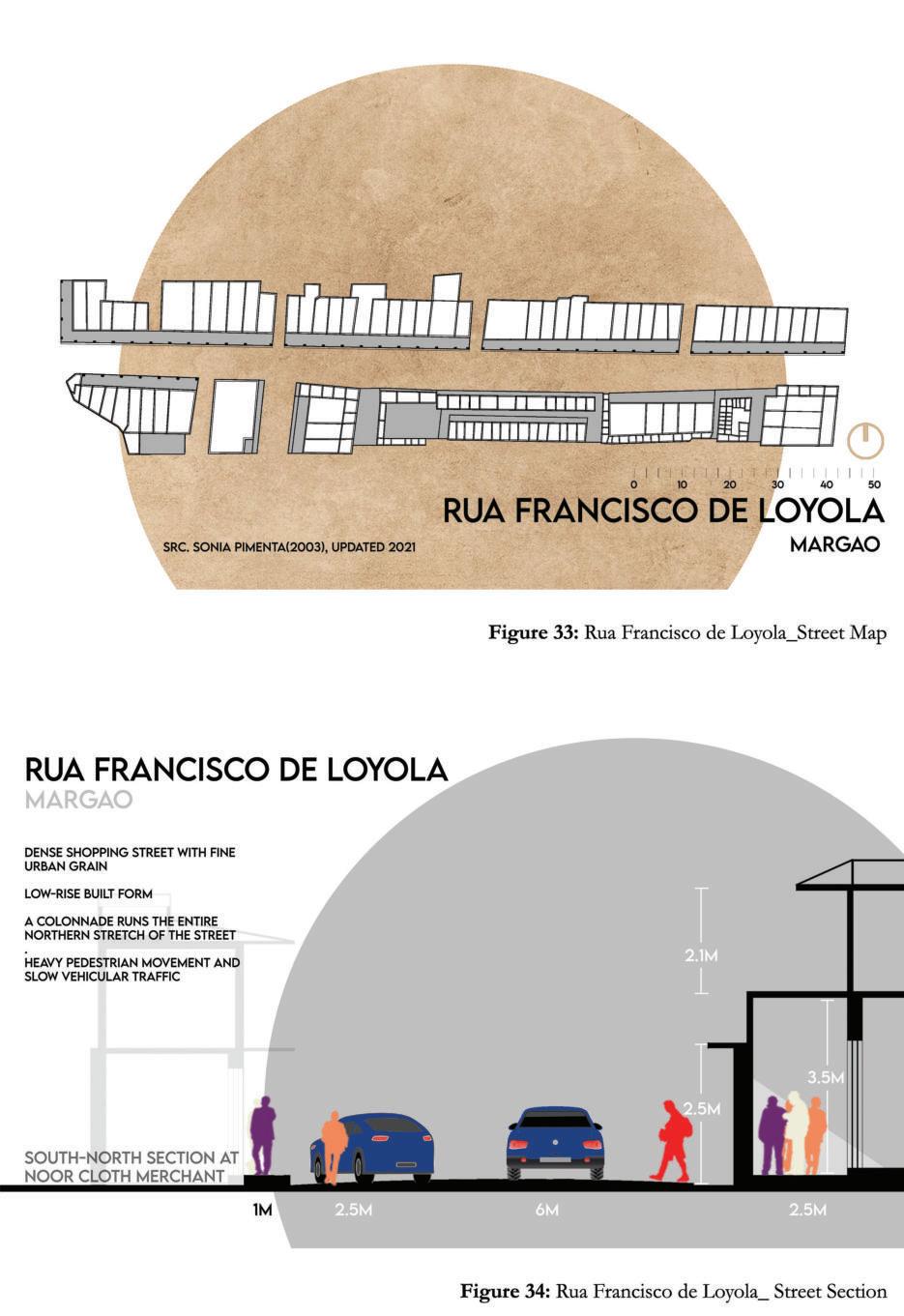

2.4.2.1 Rua Francisco de Loyola, Margao

Rua Francisco de Loyola is a purely commercial street in the heart of Margao, extending from the now derelict Timblo building to the circle at the Margao Municipal Council Building, from east to west. As observed by the author, the street- which is linear in nature- primarily features local business ventures, with jewelers being among the highest in number, as observed by the author.

Rua Francisco de Loyola features a colonnade along the entire northern length, providing shelter from the elements, and providing the adjacent shops with additional space into which several of them spill out. It is a single-lane, uni-directional street, with two-wheeler parking provided on the southern stretch. The street is extremely busy and congested with pedestrian and vehicular traffic alike all through the year, as observed by the author. With three market entrances opening onto the street, there is a constant ingress and egress of shoppers at the three nodes, further adding to the congestion.

The street features primarily low-rise colonial era buildings, with Ulhas Jewellers’ diamond showroom building being the only significant change on the street over the decades. The street also flanks the New Market- a dense network of micro enterprises and vendors. Most shop areas are less than 12 sqm., as observed by the author, and the urban fabric along this 150 meter stretch is incredibly dense.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa

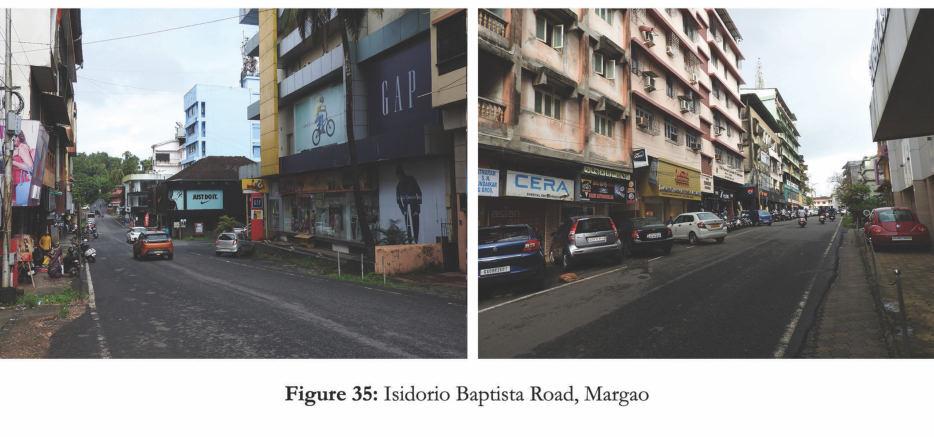

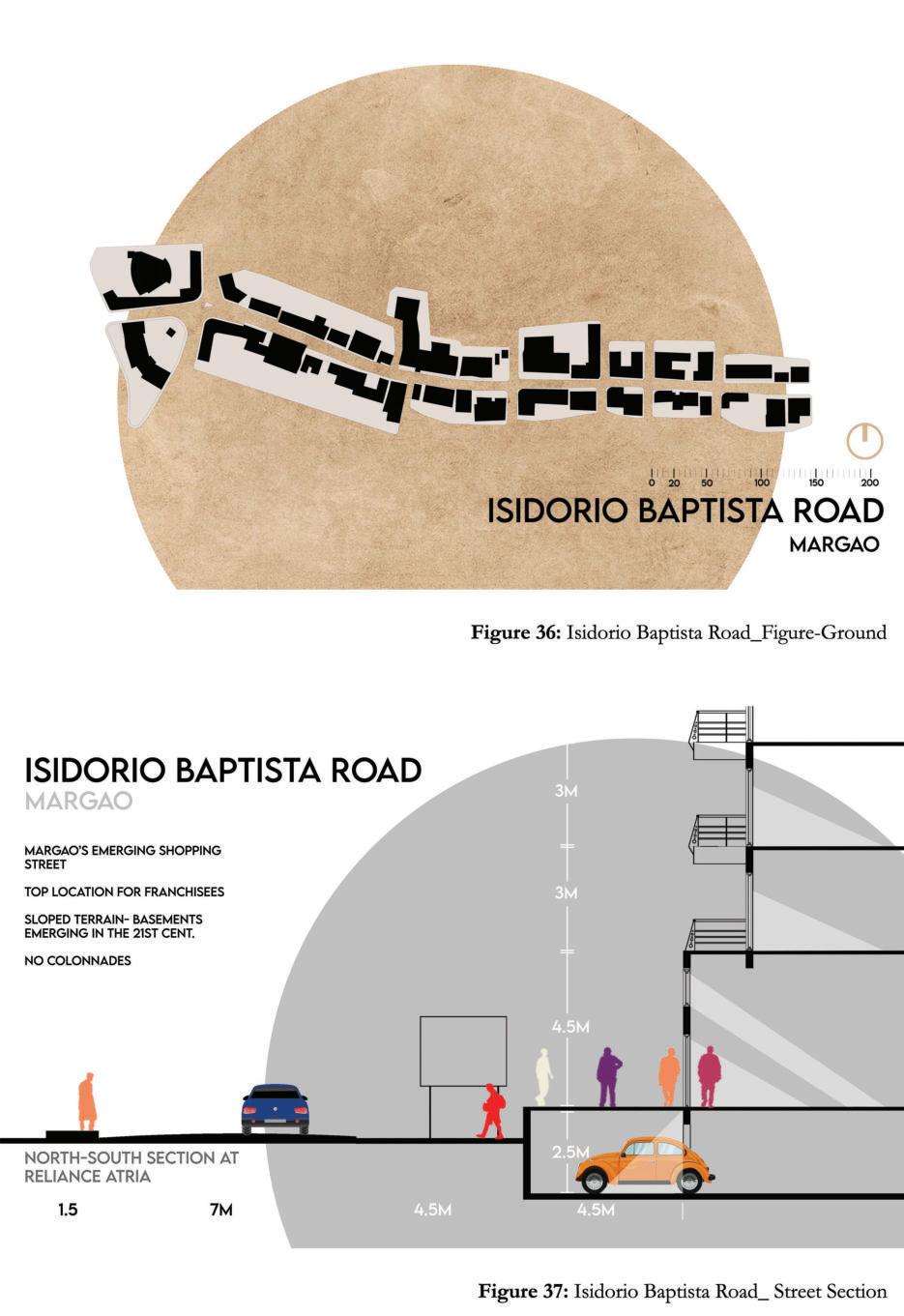

2.4.2.2 Isidorio Baptista Road, Margao

Isidorio Baptista Road stretches from the Margao Municipal Garden to Pepper’s restaurant in Pajifond, extending from west to east, over sloping terrain. As observed by the author through field studies and interviews, the street is presently a much sought after destination for retail franchises in Margao, and the presence of several apparel stores like Nike, Raymond, U.C.B, Louis Philippe and jewellery stores such as PNG Jewellers and J.G. Pednekar Jewellers affirms this.

The street is void of any colonnades or vegetation, exposing pedestrians to the vagaries of the weather, and climbs a few inclines along its course, making it rather challenging for pedestrians to walk along, as observed by the author. Isidorio Baptista Road is a one-way street, and parking is available along shopfronts.

Most buildings on the street are mixed-use in nature, featuring shops on the ground levels, offices on the upper floors and residential apartments above. The street features a healthy mix of retail segments as observed by the author, with plenty of apparel stores, jewellery stores, restaurants, food outlets and other retail categories present.

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley A. D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture. 2021 Ashley

A. D’Costa

A. D’Costa