M3_ METABOLIC MARKETPLACE MARGAO

A project report submitted to the Goa University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Architecture

Guide:

Arch. Fernando Dias Velho

Designer:

Ashley Alexandre D’Costa

Goa College of Architecture

T. B. Cunha Complex, Altinho, Panaji, Goa June, 2022

GOA COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE

T.B. CUNHA EDUCATION COMPLEX ALTINHO, PANAJI

CERTIFICATE

The following project is hereby approved as a creditable work on the approved subject, carried out and presented in the manner sufficiently satisfactory to warrant its acceptance as a pre-requisite for the award of degree for which it has been submitted.

It is understood that by this approval the undersigned does not necessarily endorse or approve any statement made, opinion expressed or design drawn therein, but approves the project only for the purpose for which it has been submitted and has satisfied themself as to the requirements laid down by the college.

Name of the Student: Ashley Alexandre D’Costa

Thesis Title: M3 Metabolic Marketplace_Margao

Guide: Arch. Fernando Dias Velho

Principal: Dr. A. K. Rege

Dated: 20 June 2022

Place: Altinho, Panaji

UND ERTAKING

I, Ashley Alexandre D’Costa, the designer of the thesis titled: “ M3_ Metabolic Marketplace Margao”

Hereby declare that this is an independent work of mine, carried out towards partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Architecture at Goa College of Architecture, Goa University, Panaji, Goa. This work has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of any Degree/Diploma; no material from other sources has been used without proper acknowledgment.

Sign:

Place: Altinho, Panaji

Date: 20 June 2022

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The story of the M3 began years ago- a blurry vision of a city centre every citizen could be proud of. I express my heartfelt gratitude to all those who have encouraged me to continue imagining a better future for Margao over the years. I thank Ar. Fernando Velho, my guide over the last two semesters, for helping lay the foundations for this project through rigourous research in the past semester, and whose constant encouragement and constructive criticism these past few months has propelled this thesis to fruition. I will remain grateful to him for having a lasting impact on the way I perceive the urban environment and my future approach to research and design.

My professors Ar. Amey Korgaonkar, Ar. Rohit Nadkarni, Ar. Suhas Gaonkar, Ar. Snehalata Pednekar and Ar. Jacob Mullamangalam have been extremely supportive throughout, and their valuable feedback and insights at every stage of the research, documentation and design has helped a great deal in the pursuit of the best design strategies for the M3

I am grateful to our Principal Dr. Ashish K.S. Rege for his support and speedy resolution of our thesis related issues. I also thank Dr. Vishvesh Kandolkar, Ar. Noah Fernandes, Ar. Rajiv Ribeiro, Ar. Kriselle Afonso, Ar. Vibhavari Shirodkar, Ar. Rita, Engr. James Afonso and Engr. Sarvesh Bandekar for their valuable insights Special thanks to Mr. Agnelo, Chief Officer, MMC and other MMC personnel for their assistance in my documentation of the New Market, Margao, and I also thank cousin Nirmala for making the necessary introductions.

The project would’ve been far less appealing without the assistance of Pauras Narvekar, whose beautiful sketches brought the market to life on the drawing board, Oum Kunvelkar, whose drone footage was a very helpful documentation tool, and the assistance of Dulcio, Enrica, Harsh, Kamya, Tanvi, Arnold, Shravan, Shubham, Akshay, Runal, Rojan and cousin Keith.

Many thanks to my buddies Aslesha and Vedanka for having made this semester so much easier to go through, with their contagious mischief and wholesome positivity.

I am also thankful to Saurabh Tubki, Sanad, Manguesh, Pankaj , Parth, Rucha, Raveena and Senia for their support, Vijay Bhai( Ben Cad Works) and Shankar (Siddharth Computers) for accommodating me at odd hours and obliging whenever I needed help. I thank Classic Printers for the high quality print job, and Martins Laser Cutting for their fantastic laser cutting services.

Many thanks to the helpful souls who’ve helped with transportation and sourcing of material, and the many unnamed persons who have contributed to the design effort in various ways.

My parents and sister Amanda have been incredibly helpful, generous and understanding throughout the five-year course, especially during this semester. I am eternally grateful for their constant support.

Finally, I thank God, who makes all things possible.

CHAPTER 1. CURiOSiTY

1.1 Origins

This is an architectural manifesto for a vision of change in the commercial heart of a small South-Central Asian city

This city has grown unchecked.

This city has stagnated.

This city has an interesting colonial history.

This city has an uncertain neoliberal future.

This city is chaotic.

This city is my home.

The city of Margao is a major commercial hub for most of South Goa. Its status in the south is akin to that of the cities of Panjim and Mapusa in the north. The city centre in particular, is known for gold, apparel, and general provisions. Once a commercial hotspot, retail in the inner city is now observed to be on the decline. We took a closer look to understand what drove inner city decay- the causes and effects. Congestion in the inner city caused by increased vehicular traffic, and lack of large single-owned retail spaces, drives large format retail to the suburbs; vehicles on the street push pedestrians inside the built environment, and colonnades morph into atriums; signages evolve to suit fast moving traffic, and street interfaces grow into visually striking elements, competing for attention.

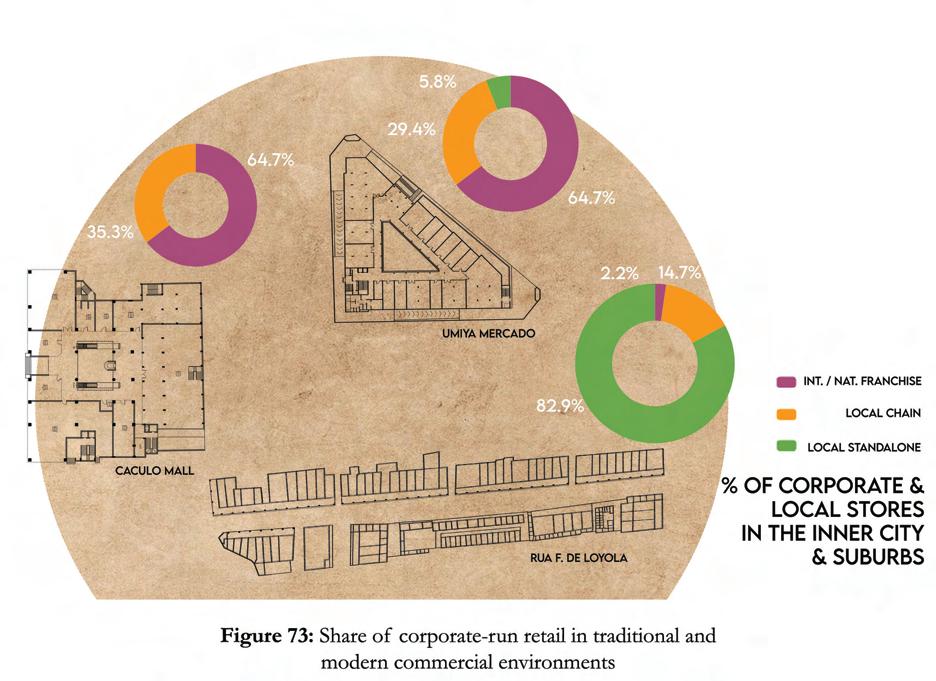

Our studies indicated that corporates have set up large format retail outlets in the suburbsparticularly in malls, and that traditional shopping streets are mainly comprised of small-scale local retailers. The graphs of the scale and ownership patterns of suburbs v/s inner city retail are the inverse of each other.

Drawing from this, large format retail moving towards the suburbs is not necessarily a terrible thing. It presents the unique opportunity of developing a local, community-driven city centre, giving back control of the inner city to its residents. A space that can be everything the mall strives to be, but cannot for want of a connection to the heart of the city.

Thus is born the M3. The antithesis of the shopping mall.

1.2 Exigency

Retail environments all over the world are in a constant state of flux. Our endless search for “the new” leads to the emergence of trends, which influence street interfaces and ultimately the character of the urban public realm itself. The marketplace- a manifestation of the needs and dreams of the city, is an ideal place to both- begin the search for what should remain constant; and set the tone for a future that embraces flux.

There is a need for a city centre- with the marketplace at its core, which empowers the local community, while also increasing the aspirational value of local goods and services in an increasingly consumerist world. As the antithesis of the shopping mall, the M3 is intended to serve as a hub for all stakeholders of the city, in a space that is comfortably Goan with cosmopolitan styling to keep its people inspired.

1.3 A Brief History of Mismanagement

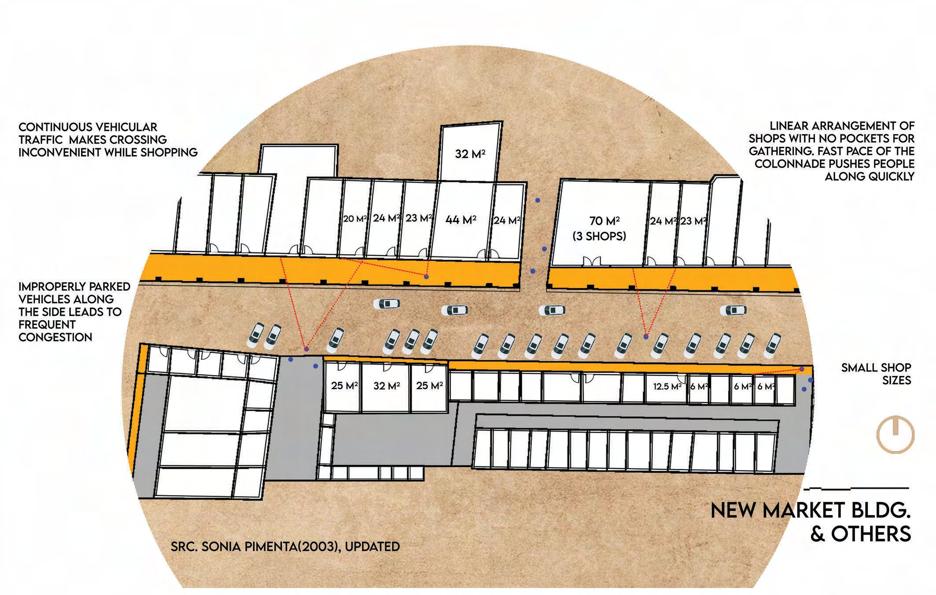

A study of the new market and adjoining blocks- the beating heart of the city, revealed that 202 shops and 333 stalls(less than 5m2) operated out of the New Market and adjacent blocks, as indicated in the plan below. The shops owned by the municipality are leased to businesses under a long-lease agreement, and are protected by the Goa, Daman & Diu Buildings (Lease, Rent & Eviction) Control Act 1968. Due to this, the municipality collects a paltry rent from all assets in the area, and hence continues the vicious cycle of mismanagement; less rent equals poor upkeep equals poor image equals talks for maintaining status quo on rentals.

The sopos or stalls within the market complex, were originally merely spaces allocated to vendors who came to peddle their wares, on a first-come-first-serve basis daily. A daily tax was levied by the municipal corporation, collected from each vendor by a representative of the MMC (Camara Municipal then)

Over time, these temporary stalls began taking root in the market- with partition walls, and eventually steel shutters coming up to define each vendor’s “private property” within the marketplace. The practice of sub-letting, though forbidden by law, continued to be carried out, with several tenants even selling their spaces. All this came at the expense of the municipal corporation, which gained virtually nothing from this prime commercial real estate.

1.4 Locale

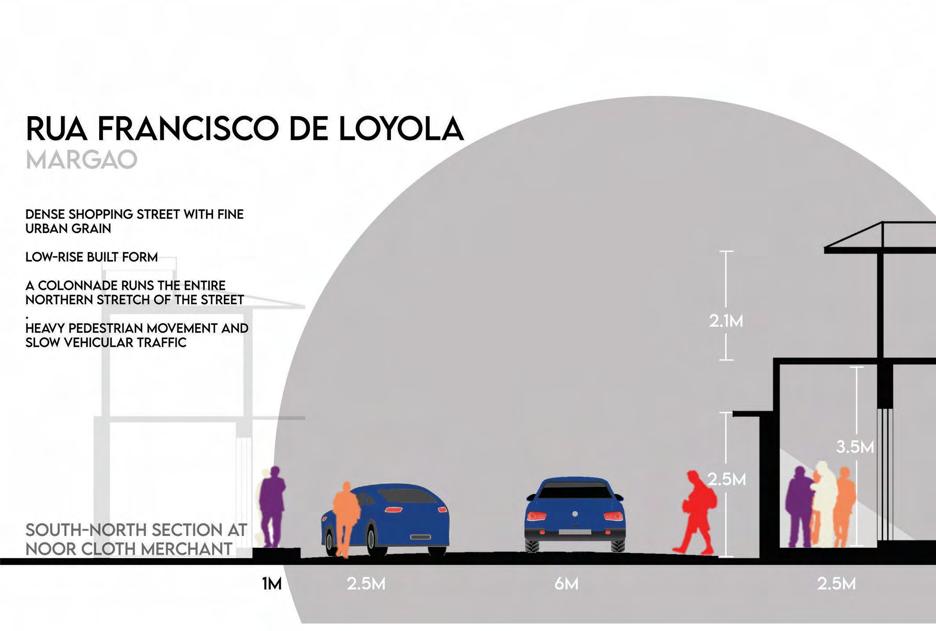

The site is situated on a C1 commercial plot of land, measuring 27662m2 , which includes the Rua Francisco de Loyola. The max permissible area under FAR, considering a buildable area of 17254 m2 is 34508 m2, of which 35.6% is presently utilized (8281.8m2). The maximum height as per current bylaws is 24m, and the minimum setback required on all sides based on municipal area concessions is 1.5m. The present ground coverage is 90%, but a coverage of 40% has been chosen for the proposed M3

The site of the old wholesale fish market- to the north-east of the New Market, is presently used as a parking lot for large service vehicles. Two interior streets connect Rua Francisco de Loyola to the Old Station Road. The nearest bus stop is at the Communidade Building, to the north-west.

Two-wheeler parking is available along Rua Francisco de Loyola, but is the cause of severe congestion along this road. Traffic congestion is exacerbated by the high density of commercial establishments in the area, served by narrow streets.

1.5 Pre-Design Objectives

The following is an objective completion chart for the research and methods employed to achieve the pre-design objectives.

1 To document and analyse the New Market and surrounding blocks in Margao, identifying stakeholders, their needs and grievances and key user groups.

2 To analyse the city of Margao at a macro level, understanding traffic movement, key commercial hotspots, residential zones etc. in order to make responsible urban level decisions.

3 To study established theories on the commercial realm, in order to obtain substantial knowledge of cause and effect of macro and micro design decisions.

4 To study successful models of commercial environments and distill the appropriate philosophies and features of design.

Photographs, Architectural drawings, info on user groups, stakeholders needs

Photographs, maps, plans, movement patterns

Established theories on the retail environment and commercial public realm.

Case studies of successful commercial buildings.

MMC archives, store owners, past students’ research, retailers, vendors.

Past students’ research, MMC archives, firsthand experience.

Books, Research Papers, Websites, Reports.

Web documentation, first-hand experience, secondary data sources.

Site visits, mapping, photography, interviews, secondary data sources.

Observational studies, photography, note-making.

Reading, note making.

Reading, note making, site visits, photography.

1.6 Broad Design Philosophy

This model of empathetic design philosophy stems from an understanding of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats which present themselves upon an analysis of the site, as listed below.

An empathetic model is not one that disregards scientific data in favour of the whims of the designer, but rather one that keeps in mind that- at the heart of any public infrastructure, are the people who make the space what it is. The aspirations, insecurities and concerns of all user groups must be considered when designing for the masses, in order to balance out design sensibilities with practical day-to-day functionality.

1.7 Operational Definitions

A list of frequently used terms and their specific definitions in the context of this study:

Neoliberalism: An economic ideology that advocates the use of free-market policies and reduced government control over commerce, as defined by Hayek and von Mises (1938).

Neoliberalisation: (Of India) becoming neoliberal in nature.

The Neoliberal Age: Used to describe the period from 1991 to the present day in India, during which neoliberal economic reforms have come into force and their effects felt.

Retail Environment: Used to refer to a large format freestanding store, a group of shops, a shopping street, commercial building, or a mall.

Public realm: Areas to which the public has access. Includes buildings, streets, squares, parks etc.

Commercial realm: Parts of the public realm that are engaged in commercial activity i.e. buying and selling of goods and services (for the purpose of making profit). Includes standalone shops, vendors, shopping streets, malls etc.

Internalisation: The process of making formerly external activities internal- to bring the activities carried out in the exterior parts of the built form into the interior spaces.

Privatisation: Of a public space, to become either partly or wholly privately owned.

Corporates: Large companies/ Business corporations with a minimum turnover of Rs.100cr that have interests in nationwide or international markets.

Large format retail: Retail stores with a net area of more than 1000 sqm. For the purpose of this study stores with a net area of more than 400 sqm have been considered as large format retail.

Inner City: The area within a 300m radius from the municipal square of the given city (Panjim/Margao).

Suburbs: Outlying parts of a city or town. Suburbs may also be defined as smaller communities adjacent to or within commuting distance of a city, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary (2021).

Signage: A visual element indicating the name of a shop or information related to one or many products/services sold there.

Landmark: Refers to any uniquely identifiable element, marked by clear form and contrast, as defined by Lynch (1960).

F&B: (abbreviation) Food and Beverage.

1.8 Scope and Limitations

The search for a solution to Margao’s problems has led to the realisation that it is prudent to approach such a problem with a pluralistic view. The multiple issues highlighted in the previous sections have varied solutions, the outcomes of which tend to raise conflict at times. The site identified spans private as well as public property, with well over 500 stakeholders. As discussed with my guide, our faculty members, as well as other professionals in the field, the practical realization of a project such as the M3 would be a mammoth task. It would perhaps require a Haussmanian approach- one that would be met with much resistance, as is currently observed in the case of any proposal put forward in the context of the New Market.

Upon careful documentation of the site, it has become apparent that the rehabilitation of all stakeholders in-situ would come at a huge cost to the local government, with little promise of financial profit in the near future. However, if financial profit is not the sole aim of such a development, and one were to view it as a public welfare project, in the direct interest of the citizens of Margao, then the M3 would be wholly justified.

It is a project the city desperately needs, but would perhaps be too afraid to embark on. The fear of loss of what is in hand, while in uncertain anticipation of what could be, often limits such a proposal to the confines of the drawing board. It is our hope that an intervention of its kind sees the light of day- purely in the interest of the citizens of Margao.

CHAPTER 2. REFLECTiONS ON A CiTY HERMAGORAS IN MARGAO

2.1 The Roots of Discord

In order to understand the origins of our problems, we turned to the colonial past of the market.

Quoting Linschoten (1583), Saldanha writes of the bazaars of Goa, where goods from all parts of the east were displayed; ‘Separate streets were designated for different classes of goods: Bahrain pearls and coral, Chinese porcelain and silk, Portuguese velvet and piece-goods, and drugs and spices from the Malay Archipelago. Fine peppers came from the nearby Malabar coast’ (2011).

As Trichur writes, the marketplaces of Goa flourished at the zenith of the Portuguese rule in the east, and subsequently lost prominence as Portuguese influence decreased in the Indian subcontinent (2013) Goa, he says, was a globalised economy with a free port in the last two decades of her colonial era- after the Indian government imposed trade barriers. He adds that post joining the Indian union in 1961, Goan markets began to resemble their Indian counterparts (2013).

In the Portuguese era, as stated by Rege, the area around the Holy Spirit Church originally developed as the most important quarter of Margao, with the Camâra Municipal building, the municipal market and the Church making it the centre of administrative, commercial and religious activity. He further adds that Rua Abade Faria developed as an important street here, featuring several prominent houses (2001).

Rege further states that the Camâra Municipal was eventually shifted to the present location of the

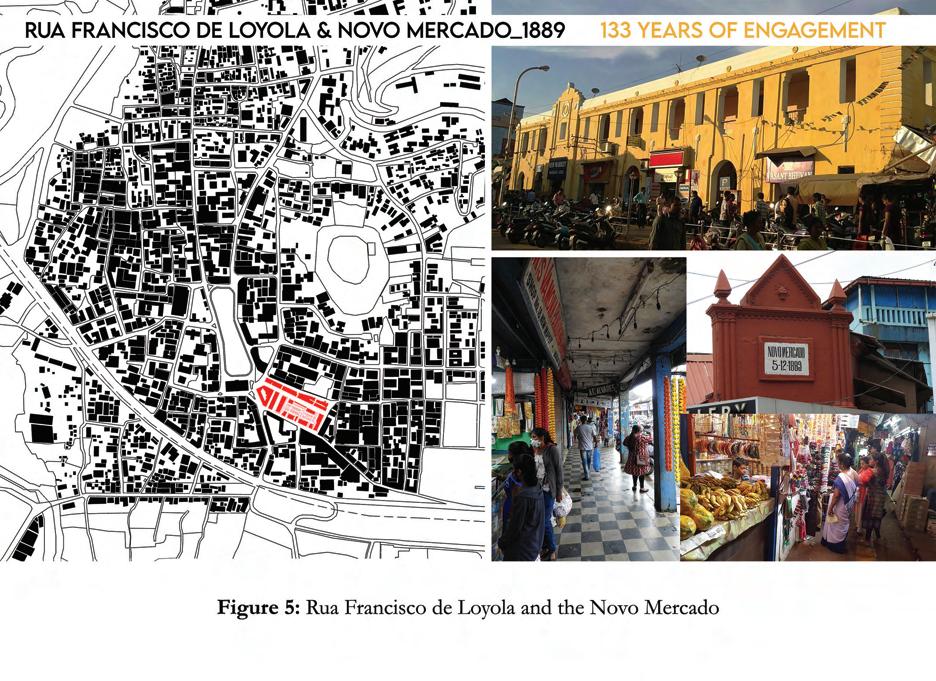

Margao Municipal Council building in 1914, prior to which a new market complex was constructed in 1889 between Rua Francisco de Loyola and the old station road (2001), as is corroborated by Coelho (2021). With the shifting of the municipal council building and the market, the area known today as central Margao rose to prominence. As stated in an article for the Times of India, the municipal garden and the adjoining Aga Khan Children’s park were constructed in 1959, creating a sizeable green space in the heart of Margao (Deshpande, 2016).

During several invigorating discussions of the Urban Design Studio 2020, mentored by Prof. Fernando Velho, Prof. Salvin Dias and Prof. Anup Gadgil, the question concerning the root cause for the decay of the inner city of Margao was a recurring one. Drawing from our discourse, is quite possible that the following factors contributed to inner city decay and the dismal state of commerce in the area:

The Margao Municipal Garden, which is actually made up of The Aga Khan Children’s Park and the Municipal Garden, both generously endowed upon the MMC by magnanimous residents, is at the very heart of Margao. However, instead of being a space for the community to pour into- thereby fostering a strong sense of community and strengthening relationships, the garden’s perimeter fencing gives it the impression of the yard of a penitentiary rather than that of a lively park in the city centre. Since the only ways in are those opposite the municipal council building and the post office (both of which are dangerous crossings, with high vehicular traffic movement) along with access from a single footpath that cuts through the shorter axis of the garden, most of the city’s commuters do not end up entering the garden purely because to do so would be a waste of one’s time. Additionally, due to its enclosed nature, the garden provides the perfect spot for a large number of vagabonds to call its relatively peaceful grounds home, thereby further dissuading the general public from seeing it as a space to spend quality time with family and friends. The automobile boom post ’91 further exacerbated this problem, creating a veritable ring of fire (motor exhaust) around the central garden.

On the commercial front, the city centre was a bustling locus of commercial importance, as indicated in the references cited earlier in this section. It has now been 133 years since the establishment of the New Market, and its obsolescence is in direct proportion to that of the city centre. This can be attributed to three factors;

a) The sizes of shops in the city centre have historically been small- catering to only a few patrons, and meant to be accessed by pedestrians off the street. Since each little shop is owned by a different party, the chance of a large shop under single ownership opening up in the city center is slim.

b) The automobile boom post the neoliberal reforms of ’91 changed the streets from slow pedestrian networks to fast paced avenues for machines of steel & glass. Pedestrians were now pushed into buildings (atriums), and the large spaces in front of shops- formerly filled with people on foot, began to be populated with cars and scooters. Commercial signages also grew larger as a result, due to the increasing size of visuals required to catch the eye of consumers in vehicles.

c) Supply chains managed by large corporations deemed the narrow streets of the inner city to be unfit for easy distribution of goods, in addition to the lack of parking space available and the absence of warehousing space. These unfavourable conditions pushed corporate houses away from the fine fabric of the inner city.

What we’re therefore looking at is the rise of the suburbs of Margao, which directly contribute to inner city decay, which in turn sets in motion the ugly cycle of declining patronage, low sales, poor maintenance of spaces, and a continued decline in patronage.

The signages that are now a ubiquitous feature of the elevations of all buildings in Margao, have also grown uglier over the years, competing for a larger share of the customers’ line of sight. Larger visuals evolve to catch the eye of the fast moving vehicle-bound consumer. Margao has become a city of ACP boards and Coca-Cola visuals. The imagery of the city gradually grows characterless, with price often being the only deciding factor. Low cost paving options dominate hardscapes, and Vinyl or acrylic signages line building facades.

On the management front, the standard practice in the new market area was such that the municipal corporation collected a tax from each sopo daily, allocating a table to each vendor under one common roof. Post the liberation of Goa, with inconsistent checks and poor accountability, stall owners began asserting their rights over these formerly temporary spaces, eventually going to the extent of building brick walls and enclosing their spaces with steel shutters. Today the New Market Complex appears a grid of miniscule shops, all privately owned, with the common spaces and passages in a terrible mess, often stinking of refuse strewn there by stall owners.

2.2 What Makes Popular Culture Popular?

In their book Learning from Las Vegas (1972), Scott-Brown, Venturi and Izenour put forward a fresh perspective through which one may view commercial architecture. The “commercial vernacular”, as described by them, was an overlapping of disciplines, set to tackle the complex problems of the 20th century through a combination of media. They further describe it as being driven by the desire to attract people, rather than to hold them in awe, and favouring ‘bold communication over subtle expression’ (1972). Las Vegas, they argue, is the pinnacle of the commercial vernacular- a style born of the need to attract consumers and boost sales, distinctly anchored to its place of origin, sans architectural expertise. They defined it as an architecture that ‘abandons pure form in favour of mixed media’ (1972).

In Goa, the influx of corporates and the development of the automobile industry (both catalysed by neoliberal economic reforms), caused stakeholders in the real estate industry to adopt new building styles that suited the rapid commercialisation of neoliberal Goa, as discussed by Inacio Coutinho, director of Reliance Builders, Margao (personal interview, September 2021).

The success of the commercial vernacular lies in its mass appeal. We live in a visual-centric society, and people are drawn by symbolism and imagery. The balustrade, as featured on the upper floor of the newly reconstructed Casa Bento Miguel, is a part of Goan colonial symbolism, as is evident in the vintage photographs catalogued by Pinho (2009). The balustrade, clubbed with white, yellow or red external walls and a Mangalore-tiled roof, incorporate a sense of ‘Goan-ness’ to even the most exotic building styles. This is an example of the Goan commercial vernacular- an aesthetic employed to appeal to the masses and thereby foster commercial growth.

Aside from the rampant use of colonical-era design elements in homes, the most common commercial typology in the neoliberal age is the ACP-clad façade or the synthetic board. An increasing number of commercial buildings in the neoliberal age adopt an ACP-clad façade for flexible branding options and easy maintenance, creating whole streets of unparalleled ugliness.

As noted by Scott-Brown et al, this new commercial aesthetic of large signs, glowing boards and aluminium facades emerged in the late 20th century in Las Vegas and was a direct product of the rise in automobile production and the spread of road networks (1972). They continue to describe the large billboards and neon signs of Las Vegas as being specifically designed to attract the attention of fast moving cars on the highway. The visuals, they add, needed to be explicit in nature so their meaning was absorbed quickly, and the distance between buildings was large so each structure could be comprehended at high speeds. They also observed that several shops featured false fronts that would enhance the shop’s importance, ‘enhancing quality and unity on the street’ (1972).

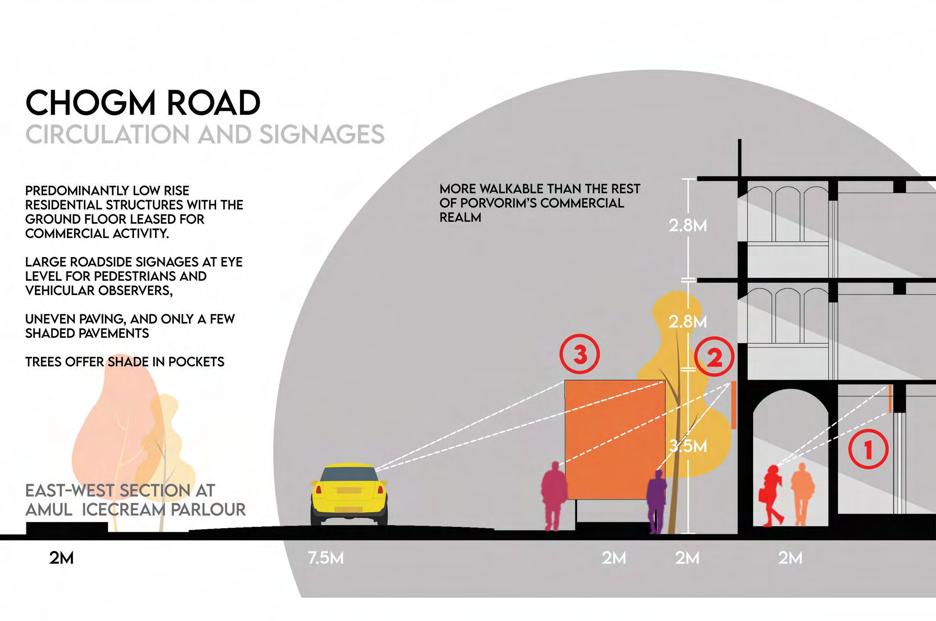

Unfortunately, this aesthetic has been rampantly used in even the most delicate pedestrian environs. We are constantly bombarded with tacky visuals and taglines. In Goa where most commercial environments are situated in dense urban settings where eye-level signages are far more effective than tall signs, one still finds the use of large flashy signages disproportionate to the scale of the street. It is an endless battle for the customer’s attention.

One commercial zone that offers justifiable potential for tall signs is the stretch of NH-66 passing through Porvorim. The layout of this stretch renders it rather hostile to pedestrians, with no footpaths on either side or crossings in between, as one expects of a highway. Given that this is almost exclusively the realm of the automobile, one can perhaps make the case for large signages that make a brief but lasting impact. Croma’s six-meter high signage and the numerous roadside signages of liquor stores in Porvorim are examples.

Now that I’ve made my dislike for the ubiquitous synthetic signages apparent, let’s move to the more interesting takeaway from the Scott-Brown-Venturi-Izenour study.

Although the shopping street is seen as a messy, unorganised environment; dependent upon explicit symbolism; featuring big signs by commercial artists and the product of slow development with an irregular aesthetic, it is- most importantly- the artistic expression of the masses.

Are the masses educated in design? Are the masses educated in design? Are the masses educated in Mostly not.

Are masses largely influenced by new materials presented to them by eager vendors? Generally, yes Generally, yes.

In my informed opinion as a design professional, do I enjoy viewing the commercial vernacular? Most certainly not.

The problem here lies less with the intentions of the general masses, and more with their exposure to good design. As a design fraternity, we have constantly failed our community.

We have kept our knowledge of design a closely guarded secret, known only to those who enter the Fort Knox of our education system to access it. Instead of spreading awareness about colour theory, proportions in design, space-making and cultural symbolism, we bask in the Quercitron light of the intellect of our snobbish peer groups.

We need to expose our communities to distilled versions of the same design theory we have been exposed to. Ads, films, music, instagram reels etc. are all powerful tools to initiate the masses into the wonderful world of design, and bring with it endless possibilities for the future of our cities. The uninitiated often mistake soulless character for sophistication. It is this that contributes to the allure of malls. Malls, which are generally perceived as a contemporary, trendy structure; with a control over explicit symbolism; featuring signs approved by corporates; and a construction process that renders a finished product within months, are actually everything a community needs to keep away from- commercially speaking. The mall promotes corporate brands, which are owned by entities that are far removed from the localities they are selling to (more on this in 2.3). They drain the local community of funds that would’ve otherwise been circulated locally. Apart from this, they perpetuate the narrative that exotic goods and trends trump local ones. People are encouraged to idolize foreign icons and this leads to poor cultural identity.

The physical manifestation of a cultural identity for the people of Margao could take form as its city centre- one that is commercial as well as cultural, with the former being a more important aspect in our local context.

From here onwards, we will refer to the M3 as this hypothetical entity that serves as the solution to the pressing problems of the inner city, and as the inspiration for the growth of its community.

As discussed by Kostof in The City Assembled, the inner city would traditionally have a central open space for commerce- the space was either purposefully framed or irregularly defined, but its purpose remained the same- a partnership between public and private interests (1992). He goes on to discuss how government works and business would be carried out within the same space- something akin to the functions of the municipal squares of Margao and Panjim in the pre-automobile age. In Margao, prior to the building of the garden as it stands today, the area between the Municipal Council Building and the Post Office was a social centre, flanked by important government buildings and commercial establishments.

Kostof goes on to discuss the nature of public space- spaces that the people are free to use, as opposed to privately owned spaces like homes and shops. The essence of the space is one’s freedom to act as they please (within the law), or to alternatively remain inactive if they so choose. A ‘public space’, as seen in the context of Kostof’s writings- and here also- is a well-defined place of sociocultural importance. Unlike the street or pier, which are transitional spaces open to public use, the public space is ‘ a destination; a purpose-built stage for ritual and interaction’ (1992). The public space- or public square as we shall refer to it- is necessarily a democratic space. It may be seen as a flexible space that everyone has a right over, while at the same time a space that no one has an absolute right over. The right of the citizens to hold demonstrations, conduct social affairs, or just take a nap on the bench, are to be respected, while at the same time maintaining that no persons or organisations may assume complete control of the space, denying others their right to use it.

In Goa, we have observed that the role of the city square as a public space is diminishing, and with commerce spreading to the suburbs it seems but natural for one to look for public spaces in suburban areas. However, unless community spaces are specifically planned for suburban areas, the only typologies that are likely to rise here are those of housing, institutional buildings and commercial establishments as is the case in Porvorim. What made the city square a special public space was its centrality to various buildings of importance. The chief public space was the generator of activity around it, and not merely the product of surrounding functions.

And this is exactly what the M3 strives to be. As the chief public space in the heart of the city of Margao, the M3 would cater to the immediate needs of the New Market i.e. calculated reorganization of spaces, the addition of utilities and parking, and a new sense of commercial identity. Additionally, the M3 would further augment the city centre to function as a recreational hub too. The addition of cafes, spas, arcades, fitness arenas and a multiplex contribute to a revamped image and provide the necessary ignition for a new brand of lifestyle for the residents of Margao. While suburban spaces tend to develop in a reactionary manner and historic city centres have been seen to develop sans context, the M3 is birthed into a hybrid cocoon at the heart of the city. It is both- along an important commercial strip, as well as an extension to preexistent functions

It would marry key features of a Goan market with cultural symbolism like the rotaçao weave pattern, kaavi art, colloquial scripts; Romi Konkani, English and Portuguese, and even local artist’s signature works. A purposefully designed public space for growth and community development. A pop cultural icon for and by Goans.

2.3 Why Do Dreams Die of Old Age?

Everybody wants it all today.

Humanity has never felt such a collective burning desire to be known and appreciated as it does now. The advent of social media networks, video sharing platforms, smartphones with in-built cameras, and high-speed internet services rocketed us into an era of mass stardom. Pretty much everybody has now begun documenting their lives in some form or the other, and a lot of this selfdocumentation is often content for the perusal of others.

To keep it less preachy, as a community- and I don’t speak for the outliers, we are all eager to build an image we can be proud of.

And it is this image that is at the heart of the problems the New Market is currently facing, and one that will continue to eat away at it in the years that follow.

When interviewed whether they would consider spending time with family or friends in the New Market complex, an unsurprising 95% of persons interviewed responded with a very clear and emphatic ‘NO’. The littered corridors, poorly lit spaces, lack of proper ventilation, frequent rat infestation, myriad foul smells, all contribute to a persistent assault on the senses of all those brave enough to venture into the Market. It is a space for the procurement of essential goods, and nothing more. The cafes within exist mainly to support the shopkeepers and their staff.

Upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that the vast majority of shopkeepers here are middle aged. A few older shopkeepers have even shut shop. The root cause of this problem is the image of the stalls and smaller shops. As shopkeepers in the area flourish, they are able to give their children a good education, and help them aspire to find employment in areas of their choice. Due to this exposure and the allure of jobs that have been romanticized in the media & pop culture, the next generation of Margao’s shopkeepers/retailers find their parent’s business to be of a rather poor image for their newfound stature. Money alone is no longer the chief motivator of a people that are so heavily influenced by the movies, Instagram, TikTok and other social media platforms.

What happens when the next generation of shopkeepers wish to be shopkeepers no longer?

In most cases, one of three things;

1. The owner gets old and eventually shuts the shop due to their inability to run it, and it goes back to the municipality.

2. The owner sells or sublets the shop, albeit illegally, to a party that is keen on running it.

3. The owner gets into a partnership with a party keen on running the shop.

The second scenario is the most common one, resulting in a large number of vendors who are not local, and hence do not possess the same connection to the local community as their predecessors did. Given that a large number of them are from distant towns and villages, and return there periodically with the profits they make all year round, this is an inherently bad system for the local community, as these vendors spend their profits elsewhere, and money that was pumped in from the locals of Margao, empties itself in an alien community.

Also, since the new persons running the shop/stall are not Goan themselves, they are less keen on preserving local customs and traditions, which ultimately die out, resulting in a massive cultural dilution.

This also gives rise to the influx of corporate entities into local markets. They are generally able to penetrate these markets simply due to the fact that locals shy away from taking up retail spaces that come with a high level of complexity involved. A shop may either be too small, or too large for the requirements of a local vendor, and hybrid agreements present too much difficulty for the average local retailer. A mall, on the other hand, is able to take over several small spaces to create larger ones if required, in addition to being perfectly capable of buying/renting out a very large space.

The chief problem with a mall is that promotes corporate brands, which as discussed in the previous chapter, are owned by entities that are far removed from the localities they are selling to. Apart from the drain of funds from the local community where they would’ve otherwise been circulated, corporates further bolster the narrative of how the foreign and exotic trumps the local. This causes further dilution of culture and heritage.

A direct response to this, as seen in the case of the M3, is the reimagination of the 300+ stalls of the market and its immediate surroundings. Each stall has been envisioned as a modular 2x2x2m capsule, with several customisations possible, depending on each vendor’s product category. These new stalls can be clubbed together to form larger ones in the case of multiple ownership, and most importantly, due to their trendy build quality and visual appearance, support the image of prosperity that the next generation of local retailers crave.

Think of them as year-long pop-up markets, with the possibility for weekly reinventions due to the extremely versatile structure of the individual stalls. Due to the dynamic nature of the stalls, the market’s image in the eyes of its people ceases to be static, and instead evokes the same sort of mystery the mazes of the erstwhile New Market complex did, albeit in a hygienic, logically organized setting. Consumers in such a setting experience a different sort of nostalgia in the market- a mix of wonder shaped by the complexity of the stalls and layouts, a sense of satisfaction with the ease of finding the products they are looking for due the logical organization of the market, and a connection with local culture through the use of colloquialisms for retail categories, indigenous patterns in the design language, and the works of local artists with high recall value for all functional signages.

The market doesn’t have to undergo a change of management to ensure its doesn’t go out of style.

2.4 The [Old] Kid on the Block

As the commercial heart of Margao, the M3 is set in a locale that has undergone barely any change over the decades. Lawmakers and local unions have fought hard to maintain the status quo in the area, pressured by the hundreds of stakeholders who are fearful of the disruption any development in the area would cause to their livelihoods. The wholesale fish market, formally situated on the northern side of the market, was shifted to another part of the city, but it’s site became a parking lot for large vehicles that would formally only drop-off/pick up fish to/from the area. The New Market Complex and surrounding buildings, all protected by perpetual lease agreements, have barely changed, even as most of the superstructures have eroded into mere husks. ACP cladding is used to hide this decay in several parts, but the whole area is really a dying horse that is being flogged to move one foot in front of the other.

Public transport connectivity is also poor, with the nearest bus stop 200m away, at Kamat restaurant in the also derelict Communidade Building. In addition to this, public restrooms are woefully inadequate for the massive hordes they cater to, with a pitiful 4 urinals and two stalls in the gents section and 5 stalls in the ladies section. Vendors are hard-pressed for storage as well, with no storage facilities available in close proximity, given how high the cost of commercial spaces in the area is.

The M3 is a proposal for a sensitive intervention across this whole area of 27,662m2, spanning the whole of Rua Francisco de Loyola and the surrounding blocks. The present ground coverage all along Rua F.de Loyola is nearly 100%, and this presents an added layer of complexity to our problem of de-densification and rehabilitation in the area.

To state our primary problem quite plainly;

The M3 needs to provide a solution that works towards the decongestion of the New Market complex and surrounding areas, while preserving the rights of retailers to conduct business from positions that are as commercially advantageous to them as is the case currently. This solution must necessarily uphold the indigenous nature of the market, keep corporate control to a minimum, maintain the humane scale of operations, improve and facilitate the upkeep of hygiene standards, facilitate sustainable revenue-collection models for the municipal corporation, empower the local workforce and entrepreneurs, increase quality of socio-economic life in the area, and in doing all this, preserve the complexity of the city centre.

2.5 Resilience Antifragility

In our search for a system of construction that endures both time and careless user groups (the latter being far harsher than the former), the architectural community often seeks to create resilient buildings- in other words buildings that die slower.

Because as a society, our methods of interacting with our built environment and the exploitative nature of our relationships with everything around us, leaves us with spaces on a detonation timer. It is only a matter of time before we outgrow a home, leave an office building desolate, or avoid an outdated mall.

But how does one go about creating a space that grows with its community? Is it even possible to achieve a space- a commercial one at that, which grows in benefits and progressively gets better instead of the more obvious contrary scenario?

Enter Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Taleb’s book Antifragility(2013) is a study on how certain things take on a property that puts them in a state of continued improvement or increasing value over time, as opposed to virtually everything else in our physical environment.

To quote Taleb, “Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.”

Taleb explains that the antifragile loves chaos. In the face of the unknown, the antifragile helps tackle a problem without even understanding it fully. It is a system of redundancies, heterogeneity, and fragmentation among others. But more important than anything else is perhaps the antifragile entity’s ability to get better with the introduction of stressors. Taleb cites the mythological examples of Damocles, The Phoenix, and The Hydra. Damocles, with a sword suspended above his head, is fragile, given that his fate depends on the slightest stresses applied to the string the sword is suspended from. The Phoenix is resilient or robust, given that upon exposure to stressors it is always reborn as it was before- all parts restored. The Hydra however, grows twice the number of heads that have been cut off- it actually benefits from stressors, and emerges even stronger than before.

A strong example of everyday antifragility Taleb uses is that of an options contract. For example when one purchases an option to buy a particular stock for a predefined price at a later date, the buyer has the right, but not the obligation to exercise use of said option at that later date. The seller, on the other hand, has the obligation to sell the stock at the predefined price to the buyer should they choose to exercise their right to buy. The critical takeaway here is that the option is of a far lesser value than the stock itself, and the buyer typically has low lowside, and high highside. It is important to note, as Taleb adds, that this is not a freely obtained option as some other opportunities in life, as someone is selling the option to someone to profit from it.

In the case of the M3, the principles of antifragility are applied through very simple logic. It can be observed that malls in Goa (and perhaps in several other parts of the world) are symbols of fragility in commercial infrastructure, owing to the fact that they are generally owned by individuals. The mall is a cohesive unit- homogeneous in its nature as a commercial space.

Apart from the anchor stores, which are the only part that is distinct from the rest of the mall, the rest is seen as one large store with several items available under one roof. When the lighting and finishes of the common spaces of the mall get jaded, all stores are seen in poor light (pun not intended).

Additionally, the mall may be shut at any time if the owner deems it necessary to do so, thereby rendering all stores within the mall closed. This relationship between the whole and the part is a fragile one, where the fate of so many rests in the hands of a few.

If instead, the retail stores of the mall operated as an agglomeration of stores with the only common management being that which is commonly funded and responsible for maintenance, it would weather any number of personal incidents and maintenance failures (which would promptly result in a change of maintenance personnel).

Heterogeneity and fragmentation are features of the antifragile, but their value is not apparent in the above examples unless one understands how the M3 actually applies them. Through its rehabilitation of the 396 sopos or stalls operating in the area within the new complex itself- giving each vendor a space of collective prominence, and ensuring a healthy number of stalls in each product category, the M3 ensures that individual issues that would prompt certain stalls being shut, only serves to enhance business in the competitors’ stalls. The vendors are also allowed to make changes to their stalls due to the flexible modular nature of the units, which- over time, will make for a dynamic visual environment, preventing the marketplace from becoming a jaded shopping centre like most

malls are doomed to become. Instead, given this constant microsurgery, the market will continue to be a place of wonder and inspiration- a pluralistic commercial stage for the people of Margao.

The M3 is also designed with the possibility of the addition of six floors of office space along with 2 levels of a multiplex at the very top. While the office levels allow for a model that can increase revenue for the municipal corporation, the multiplex offers the possibility for increased recreational and social interaction space after revenue goals have been met. All of this will take place in an incremental manner, so as to cater to the changing needs of the city.

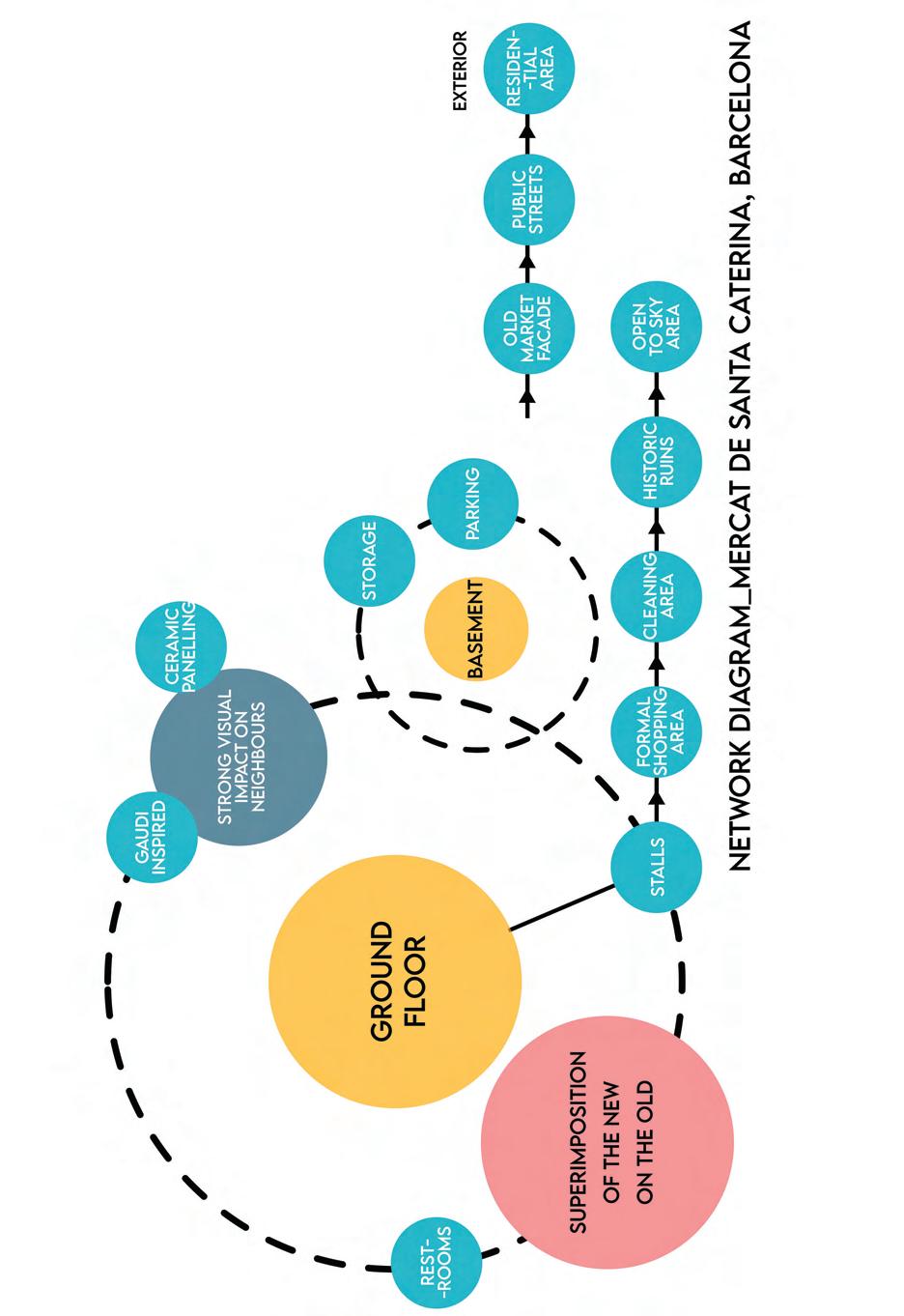

CHAPTER 3. ANTECEDENTS

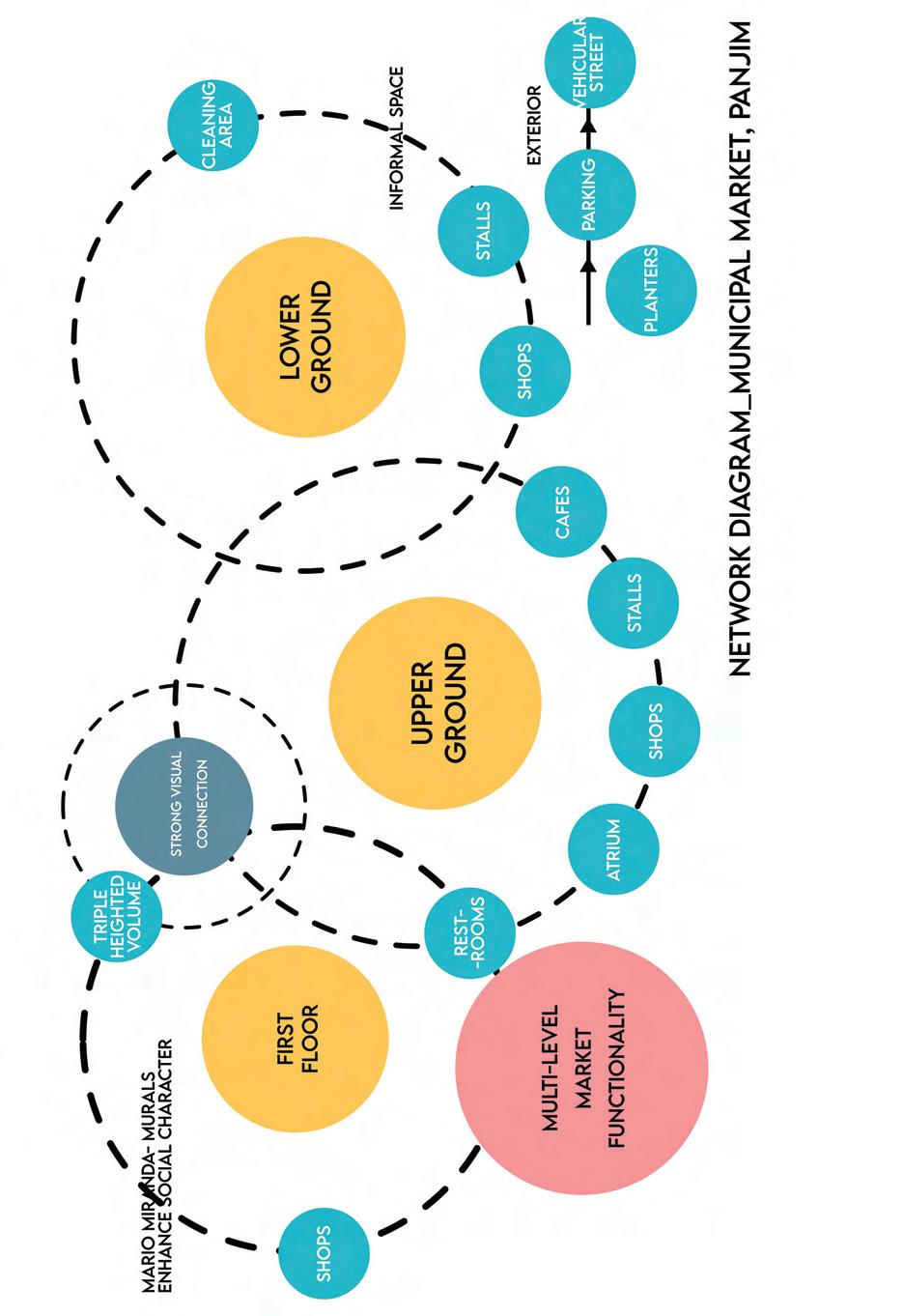

Case studies of markets from around the world, employed for their design intent and unique features- several of which have been suitably adapted for the M3