GREAT MUSIC GREAT MEMORIES

with the

GREAT MUSIC GREAT MEMORIES 50 Years 1960-2010 with the Asheville Symphony

Copyright © 2010 Asheville Symphony Society, Inc.

Asheville Symphony P.O. Box 2852, Asheville, NC 28802 828.254.7046 www.ashevillesymphony.org

Great Music, Great Memories is an apt title for this book which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Asheville Symphony. It helps us remember that music is first and foremost what we’re all about. Thanks to the orchestra and its talented musicians, we are proud to bring live symphonic music to our community.

An equally apt title might have been “Great People Make a Great Symphony.” This book describes the energetic, committed, tireless and talented people who created, sustained and continue to enrich the Symphony, not only over the 50 years since the first subscription season but also stretching back to 1927. We can rightly claim to be one of North Carolina’s oldest orchestras.

On behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to extend my thanks to some of those “Great People” who made this book possible:

J.K. MacKendrie (Mack) Day’s thought-provoking essay entitled “A Love Song—Its Role: Is It Worth The Effort” presented before the Pen and Plate Club on July 21, 1983, was the inspirational starting point for Arnold’s Wengrow’s research on this book. The Archives Team —Chloe Atkins, Beverly Briedis, Carole Roskind and Fran Sandfort—must be recognized for its outstanding work over the past one-and-a-half-years with the Symphony’s irreplaceable archival collections. These documents provided the exact historical materials necessary to produce this commemorative book and its companion DVD. Madelyn Bennett Edwards and Otis Philbrick are also to be saluted for co-producing the outstanding Anniversary DVD, enclosed herein, which distills the essence of the Symphony’s story, set to the music of our excellent orchestra.

My special thanks to my trusted teammate, Carole Roskind, for working side-by-side with me as we planned and developed on-going events celebrating our Golden Anniversary.

Finally, our thanks to Arnold Wengrow, who coordinated the research in addition to writing Great Music, Great Memories. He encouraged us to see the 50 years of the Asheville Symphony within the substantial musical and artistic history of our city and our region.

President,Great Music, Great Memories was produced for the Asheville Symphony’s 50th Anniversary under the direction of Carole Roskind and written and edited by Arnold Wengrow, with further editing by Carole Roskind and Jill Hurd. It was proofed by Sally Keeney and Elisabeth Varner. Leslie Shaw of Leslie Shaw Design was the designer.

It would not have been possible without the support and assistance of the staff, musicians, ASO Board president, Carolyn Hubbard and the Board of Directors, volunteers of the Asheville Symphony and the members of the Asheville Symphony Guild. We acknowledge them with gratitude. We also are grateful to those below who shared their recollections, answered questions, offered advice, supplied photographs and provided expertise. Many people helped during this two-year project, and we apologize if we have omitted any names.

Larry Adamson, Linda Alford, Susan Arnold, Catherine Arps, Chloe Atkins, Robert Hart Baker, Jane Beebe, David Beebe, George Bilbrey, Tom Bolton, John Bridges, Beverly Briedis, Michael Brubaker, Ron Clearfield, Carolyn Ray Cort, the Reverend Patricia Harris Curtis, Mary Byrd Daniels, J.K. MacKendree Day, Joyce Dorr, Madelyn Bennett Edwards, Joyce Farwell, Rosemary Fischer, Cherylonda Fitzgerald, May Jo Denardo Gray, Ginny Hayes, Emmet Hayes, William Henigbaum, Susan Hensley, Jill Hurd, Patricia Koelling Johnston, C. Robert Jones, Franklin Keel, Doug Keen, Dick Kowal, Margery Kowal, Sydney vom Lehn, Carol McCollum, Margie Metz, Fred Meyer, Daniel Meyer, Rob Neufeld, Wendy Newman, Beverly Ohler, Marcia Onieal, Ruben Orengo, Otis Philbrick, Gloria Pincu, Randal Pride, Karl Quisenberry, Vance Reese, Bill Roskind, Frank Rutland, Diana Sanderson, Fran Sandfort, Jack Sherman, Robert Sorton, Marty Stickle, Irene Stoll, Dewitt Tipton, Hobart Whitman.

We are grateful to the following organizations and individuals who have provided invaluable assistance.

Asheville Citizen-Times (Holly McKenzie, Phil Fernandez) , Asheville School (Diana Sanderson, Glenn Mayes), Asheville Symphony Staff (Steven Hageman, Sally Keeney, Michael Morel, Elisabeth Varner),The Biltmore Company ( Dini Pickering, Jill Hawkins, Kathleen Mosher, Erica Walker) , Brevard College Library (Mike McCabe, Director of the Library), Charlotte Symphony (Tanya Davis, Director of Artistic Planning), Converse College (Wade Woodward, Director of the Mickel Library), James Madison University (Brian Cockburn, Head of Music Library; Jeffrey Showell, Director, School of Music), LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts (Samson Lin, Administrative Assistant, Pack Memorial Library (Zoe Rhine, North Carolina Collection), Spartanburg Herald-Journal (Tom Priddy), University of Illinois Library (Ryan A. Ross, Lincoln and Illinois History Collection), University of North Carolina at Asheville, Ramsey Library,( Anita White-Carter, Helen Wykle).

We are grateful to the Asheville Citizen-Times, the Biltmore Company, the North Carolina Collection of Pack Memorial Library and the University of Illinois Library Lincoln and Illinois History Collection for permission to reprint photographs from their archives.

Arnold Wengrow is a theatre director and writer who covers arts and travel from his home in Asheville. He specializes in writing about contemporary theatre design and is a contributing editor of Theatre Design and Technology, the Journal of the United States Institute for Theatre Technology. He wrote the catalog essay for Mostly British: Scene and Costume Design of the 20th Century: Tobin Collection of Theatre Arts at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, in 2002 and was guest curator and catalog author for Observe and Show: The Theatre Art of Michael Annals at the Theatre Museum of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2003. He was founding artistic director of the theatre program at the University of North Carolina at Asheville in 1970 and retired as professor emeritus of drama in 1998. His articles have appeared in Entertainment Design, U.S. Airways Magazine, British Heritage, and The Spectator. He has written frequently about the arts for the Asheville Citizen-Times

Foreword from the President of the Asheville Symphony Board of Directors 1

Acknowledgements 2

Great Music Great Memories 5 - 11

Onstage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 - 20

Conversations with Conductors: Part I - Robert Hart Baker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 - 26

Conversations with Conductors: Part II - Daniel Meyer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 - 31

Gallery of Photos 32 - 33

Backstage 35 - 38

Photo Scrapbook: Robert Hart Baker 39

Out Front 41 - 47

Asheville Symphony: A Timeline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48 - 62

Conductors, Concertmasters & Managers Through the Years . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

Presidents of the Asheville Symphony Board of Directors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Presidents of the Asheville Symphony Guild 65

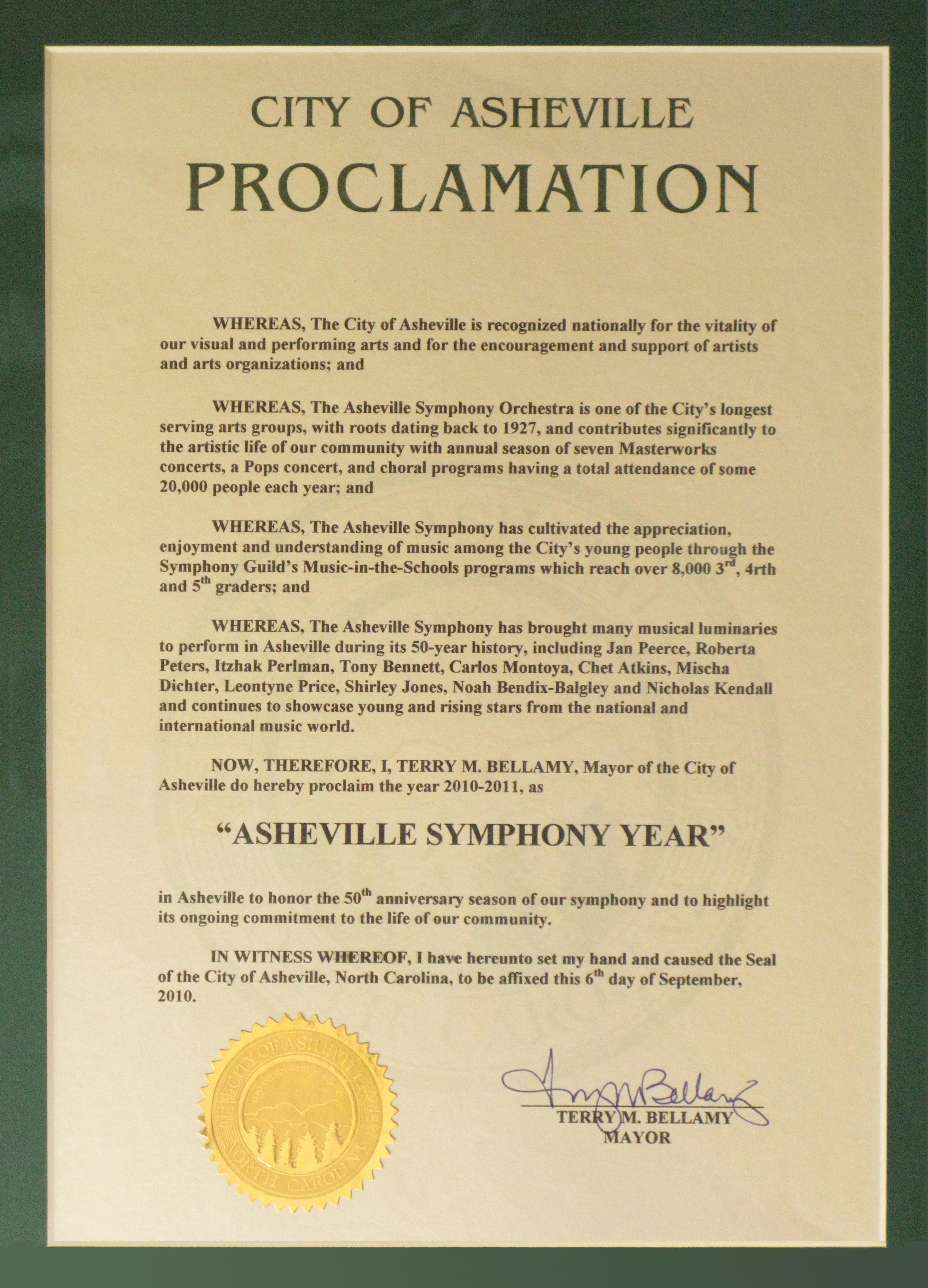

City of Asheville Proclamation of 2010 -2011 as “Asheville Symphony Year” 66

Great Music

Great Memories

Photo courtesy of Asheville Citizen-Times

Photo courtesy of Asheville Citizen-Times

Our brains are musically wired.

Music, like Proust’s madeleine dipped in tea, can bring sights, sounds, ideas and emotions flooding back. It’s one of our most potent keys to memory.

Neurorologists and psychologists have even proved this scientifically. Oliver Sacks, the eminent neurologist and author of Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for A Hat, says music and memory are deeply connected at the brain level. His 2007 book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain describes cases of people with devastating memory loss who are revitalized by melody and harmony.

Sacks became interested in music and memory, he told NPR’s Ira Flatow, when he saw “people who couldn’t take a step but who could dance, people who couldn’t talk, but could sing. Music somehow seemed to give them a flow they couldn’t initiate for themselves.” He was struck that people who had lost the powers of thought and language, “might recognize music, might sing along, might suddenly become lucid when they were exposed to music.”

“We are,” Sacks says, “a musical species, no less than a language species.”

Researchers have long studied the association of music and memory. Norman M. Weinberger at the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory at the University of California, Irvine, looked at some of this research in a 1995 article he titled “Threads of Music in the Tapestry of Memory.” His conclusion? Music that accompanies conscious learning “enters into memory for the material learned. Moreover, recall is better when the music present during learning is also present during recall.”

Psychologists Martin Conway and Catriona Morrison at the University of Leeds in England say music stimulates the release of dopamine, the neurotransmitter often called the brain’s “pleasure chemical.” “We’re better able to record memories when we’re in a positive frame of mind,” Morrison told Elizabeth Devita-Raeburn, a writer for the magazine More

So with all that science to back up what we probably already knew, we asked people who have known the Asheville Symphony from three perspectives – backstage, onstage and from out in the house, from the beginning to the present – to recall the great music and their great memories.

Asheville’s Symphony has a long genealogy.

The Asheville Symphony dates its 50th anniversary from its first subscription season in 1961-62. But Asheville can trace its symphonic aspirations back to 1927, when Lamar Stringfield, a 30-year-old Juilliard-trained flutist and conductor, formed what he called the Asheville Symphony Orchestra. He gathered a group of 24 Western North Carolina musicians for a summer afternoon concert of Beethoven, Schubert and Liszt on June 5 at the Plaza Theatre on Pack Square, now the site of Pack Place.

Born in Raleigh, Stringfield attended Mars Hill College and was already on his way to an important national career as a conductor and composer. He was awarded a traveling fellowship in 1928 by the Pulitzer Prize jury for a promising composition based on Appalachian folk tunes, From the Southern Mountains Suite

Stringfield had high ambitions for his Asheville Symphony. “I had a wild dream of an orchestra for Asheville, North Carolina,” he told a friend. After two more summer concerts, he envisioned a state-wide audience and went to Raleigh to ask Governor O. Max Gardner for a subsidy. But the Depression thwarted Stringfield’s plans, and he left Asheville for Chapel Hill and a position at the University of North Carolina.

There, in 1932, he became the founding conductor of the North Carolina Symphony, funded by the Works Progress Administration, the Depression-era federal program to put the unemployed to work. Eventually the State of North Carolina supported it as well.

If it had not been for Lamar Stringfield’s first Asheville Symphony, the North Carolina Symphony might not have come into existence when it did. Stringfield kept his ties to Asheville, retired here and continued to compose and perform until his death in 1959. He is buried in Riverside Cemetery.

One of Stringfield’s musical colleagues in Asheville, Joseph DeNardo, the longtime director of music for the Asheville City Schools, kept the area’s symphonic aspirations alive with a community orchestra. (DeNardo had taught Stringfield to play the flute when they served together in France in World War I.) DeNardo began his orchestra in 1932 as part of the same Federal Music Project that started the North Carolina Symphony. There were strong ties between the two groups; the Asheville orchestra was considered almost a branch of the North Carolina Symphony. By 1938, what was then called the Asheville Civic Orchestra was playing concerts with 42 musicians at Lee Edwards High School (now Asheville High), David Millard Junior High and the City Auditorium. It continued until at least 1950.

North Carolina’s oldest symphonies, the Charlotte Symphony and the North Carolina Symphony, were both founded in 1932. Winston-Salem began its symphony in 1946; Fayetteville and Greensboro founded theirs in 1956. Today’s Asheville Symphony, incorporated in 1958, is the fifth oldest full-season orchestra in North Carolina and one of the state’s senior musical organizations.

John Bridges, one of the keepers of Asheville’s cultural memory, was present at the creation of the Asheville Symphony, as well as many of our other long-running performing arts groups, including the Asheville Community Theatre, Asheville Bravo Concerts and the Asheville Chamber Music Society. A classical singer, actor and librarian, he grew up in Asheville and for a time managed the Steinway Concert Hall in New York. He wrote the program notes for the Symphony’s first subscription concert in 1961.

John recalls that in the mid-1950s a group of musicians, many of whom had played with the Asheville Civic Orchestra, began meeting to play symphonic music in the fellowship hall of the First Presbyterian Church. One of the instigators of the gatherings was Jane McIntire, a contralto soloist in the First Presbyterian choir, who worked as the parts manager for Hayes & Hopson Auto Supplies on Pack Square.

In the fall of 1955, Jane appears to have invited a newly arrived music teacher at the Asheville School to conduct the group. Sol B. Cohen, 64, was an Illinois native who had studied violin and composition in Europe before serving in World War I. After the war he settled in Los Angeles, where he wrote and arranged music for movies, played with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and conducted for modern dance pioneers Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. He then had a long career teaching music at a variety of public and private schools, including the Interlochen National Music Camp.

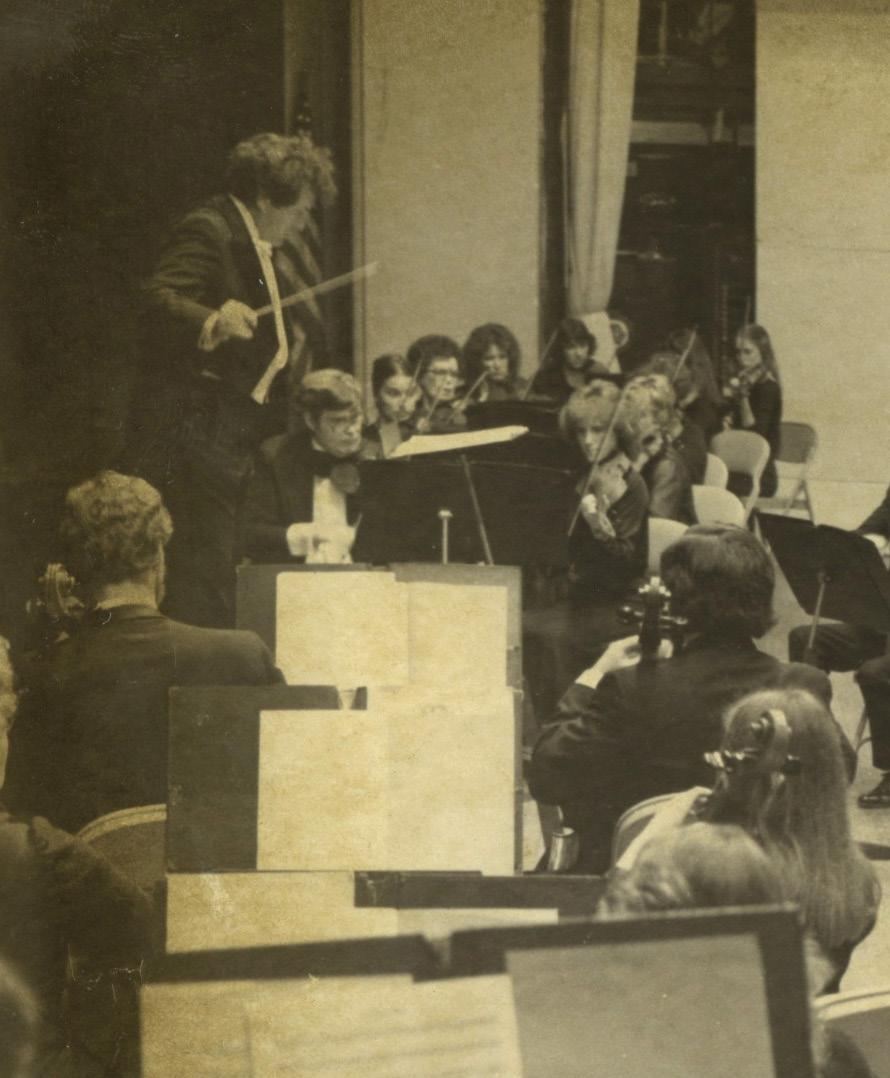

How did Asheville come to have its Symphony?John Bridges Photo by Roger Bargainnier Joseph DeNardo conducting the Asheville Civic Orchestra, City Auditorium, 1938 Courtesy North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library Jane McIntire

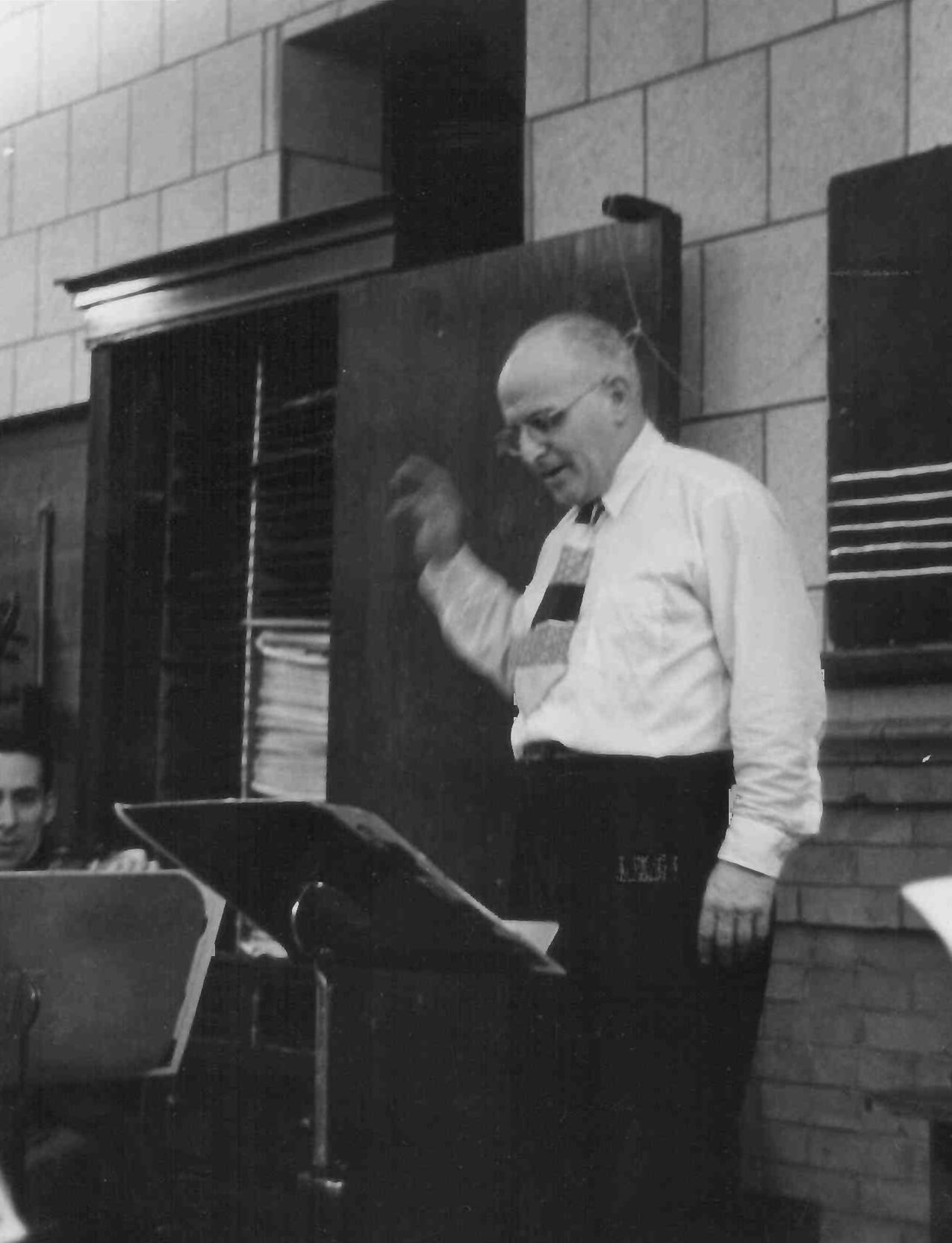

For the next three years, until shortly before he left for the Roosevelt School in Stamford, Connecticut, Cohen served as first conductor for what he and Jane called the Asheville “Little Symphony.” Cohen’s diaries, now in the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, give behind-the-scenes glimpses into those early years. They show that Asheville’s musical community and its leaders, including Joe DeNardo, were quick to recognize and embrace new artists of high caliber.

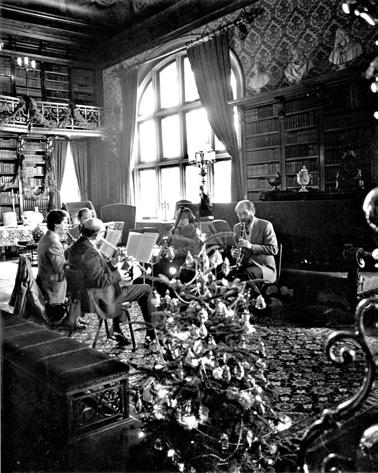

On Monday, October 31, 1955, Sol Cohen wrote above the printed date in the little “page a day” diary he used, “1st Orchestra Rehearsal! “ He knew something important was starting for Asheville. “This was indeed a triumphant day! “ he continued. “I went to the Presbyterian Church, where 20 of the orchestra players gathered for a rehearsal.” The group was preparing for a Christmas performance of Handel’s DeNardo had sent a group of his Asheville High band members to play with the older musicians. Cohen called them “wonderful high school boys” and soon added his own Asheville School students to the group. “It was a tremendously successful evening,” Cohen noted. Jane McIntire told him, “For the first time in years we have an orchestra in Asheville!” Other players thanked him as well. “A wonderful beginning!” Cohen concluded.

The next day Cohen went into town to buy music scores and stopped by to talk to Jane about a name for the group. Jane wanted to call it the “Little Symphony,” a popular name at the time for community orchestras. Cohen preferred the “Little Symphony Orchestra.” Jane prevailed.

For the Little Symphony’s second rehearsal the following Monday, the ensemble had grown to 25 players. It was “as lively a group as I have ever had,” Cohen noted. “The ‘old timers’ and the HS boys all combined to make scintillating music,” he wrote. “May Jo and her mother were a great help.” May Jo and her mother were May Jo and Tommsie DeNardo, Joe DeNardo’s daughter and wife, both violinists. At the next rehearsal, Cohen had “three trombone players and a brace of trumpeters that would have overthrown the gates of Jericho!”

Others in that early group were cellist Joan Day Beebe, a teacher at Allen High School, the private academy for African American girls; Agnes K. Whitman, a violinist and teacher at Mars Hill College; and Frank Rutland, an ardent amateur violinist who came to Asheville in 1956 to begin his career as a research engineer with American Enka. In 1958 Joan Beebe, Agnes Whitman and Frank Rutland became the incorporators of the present Asheville Symphony.

Of the founding mothers and fathers, Jane McIntire, Sol Cohen, Joan Beebe and Agnes Whitman are deceased. Frank Rutland, who was the Symphony’s first concertmaster, and David Beebe, Joan’s husband, remember those early years with great affection. Others who have recalled that time include Larry Adamson, who started playing French horn for the Symphony in 1960 when he joined the Warren Wilson College faculty to teach biology; Hobart Whitman, Agnes’s son, a French horn player; May Jo DeNardo Gray; Sydney vom Lehn, a violinist who was the Symphony’s second concertmaster; and two high school violin students at the time, Carolyn Ray, now Carolyn Ray Cort of Burnsville, and Mary Byrd Daniels, who also became a concertmaster of the Symphony. Mary Daniels still plays with the Symphony today, more than 50 years later.

By Fall 1958, the group decided it was time to become official. Jane McIntire had died unexpectedly, so the impetus may have come from Joan Beebe, who had administrative talents and later served as the dean of Warren Wilson College. She and Agnes would have realized that to stabilize, grow, raise funds and eventually hire a conductor, musicians and staff, they should incorporate as a nonprofit organization. “They needed to move on and do larger work,” David recalls. They asked William C. Moore of Patla, Straus, Robinson & Moore to draw up the documents for what they named the Asheville Little Symphony. Joan Beebe, Agnes Whitman and Frank Rutland signed.

The Asheville Symphony that emerged in 1958 had a long genealogy of classical musicians and music lovers, both in Asheville and Western North Carolina. The musicians and their audiences were a small but cosmopolitan community. Many of the musicians were conservatory trained. Some had come from Europe. They all knew each other. They played together. They saw each other at concerts.

From his position as band and choral director at Asheville High School, Joe Denardo was influential from the 1920s into the 1960s. Besides conducting the Asheville Civic Orchestra from 1932 until about 1950, he probably taught—or knew—every music student who came through the Asheville City Schools. In 1951, he conducted a high school chorus of 700 students for an audience of 3,000 at the City Auditorium when Roy Larsen, chairman of Time, Inc., came to present Asheville with its “All-American City” designation. Everyone who knew about in music in Asheville knew that Joe Denardo was a child prodigy in his native Italy and once played for Giuseppe Verdi.

Everyone interested in classical music also knew pianist and teacher Grace Potter Carroll, the second wife of Dr. Robert Carroll, the founder of Highland Hospital. She had studied with the famous European piano teacher Theodor Leschetitzky, who had taught Paderewski, and concertized there. Her husband built her a 1,500 square-foot music room with cherry walls at Homewood, their mansion in Montford. Here she held musical evenings, probably as early as the mid-1930s. It was here that Béla Bartók attended the only musical event of his stay in Asheville in 1943-44. And many of the Symphony’s early musicians, including Joan Beebe, Agnes Whitman, Hobart Whitman and Mary Byrd Daniels, were each invited to play at Homewood.

In nearby Brevard, the Transylvania Music Camp began in 1945. A summer music festival was added soon after. The camp and festival became the Brevard Music Center in 1955. Brevard, which also had an important music program at Brevard College, was an important destination for both the Asheville Symphony’s musicians and their audiences.

Since 1932, musical performances by visiting artists of international stature had been sponsored by the Asheville Community Concert Association (now Asheville Bravo Concerts). They certainly helped build an audience for classical music. The North Carolina Symphony was also a regular visitor. And the success of the recently formed Asheville Chamber Music Series must have encouraged Joan Beebe and Agnes Whitman that their new organization would find its place in the community. The Chamber Music Series began six years before the Symphony incorporated and had 800 subscribers for its first season. Joan and Agnes played music with the founder of the Chamber Music Series, Josef Vanderwart, a pianist and businessman who had escaped Nazi Germany.

Soon after the Symphony incorporated in September 1958, Sol Cohen began preparing his final concert with the Little Symphony for a live radio broadcast in November. On October 27, he notes in his diary that he asked Lamar Stringfield to conduct a portion of that evening’s rehearsal. Did Cohen or Stringfield recognize that they were taking Asheville’s orchestra full circle back to its beginning in 1927? Stringfield died the following January.

After the November broadcast, Cohen, perhaps anticipating that he would be leaving Asheville in the spring, turned the conductor’s position over to Richard Renfro of Western Carolina College in Cullowhee. He continued to play violin with the Symphony. After a rehearsal in February, he wrote, “I can see the old order vanishing into—absorbed into—The New. There are more players, there is more discipline, a new technical skill is developing. That the old ‘spirit’ is lacking is, I suppose, not important. Music—good music—is being played. Dr. Renfro is really doing fine work.”

The old order would become further absorbed into the new later that year. Sometime in 1959 Joan and David Beebe were introduced to Helen and John Sorton, who had moved from Charlotte that year. John was the new comptroller for the Celanese Corporation. (David was the comptroller of Warren Wilson College.) Both John and Helen had been active with the Oratorio Singers of Charlotte. John was an organist and singer; Helen, a graduate of the High School of Music and Art in New York City, was a pianist, string bass player and singer.

Helen attended a rehearsal of the Little Symphony at First Presbyterian Church. Larry Adamson recalls, “She gave us her background and her involvement in Charlotte,” and soon she was the newly-incorporated group’s manager. “I’m sure that Joan and Agnes were involved in offering the position to Helen,” Larry says.

Helen had formidable organizational skills, enormous energy and great personal flair. At the High School of Music and Art, her yearbook said,”Helen plays bass with a smile on her face.” She was runner-up to a future Miss America, Bess Myerson, as “prettiest person” in the school. Helen set about taking the group from a collection of musicians who played together to a fully-functioning orchestra. She drove a 1957 pink and white Chrysler Windsor with fins, the only car like it in town. Everyone knew when Helen Sorton was out on Symphony business.

Robert Sorton, Helen and John’s son, was about eight years old at the time and remembers that “out of the blue” his mother became the Symphony’s manager and sole employee. As a young man Robert studied oboe. When he was 13, he left Asheville for the newly-opened North Carolina School of the Arts in Winston-Salem but returned to play with the Asheville Symphony as second and then principal oboe from age 14 until 1974, when he finished graduate school.

As an accountant, John Sorton took care of the Symphony books and made sure the organization stayed solvent. “My mother was pushing music stands around, calling people in New York, contracting musicians and finding conductors,” says Robert, now professor of oboe at Ohio State University.

When she began, Helen’s goals for the new organization were first to get an on-going, part-time conductor and then to plan a subscription concert season. Before Helen joined the organization, the Asheville Little Symphony gave individual concerts under Richard Renfro’s direction. They performed a Sunday afternoon concert at William Randolph School auditorium with Richard Naff of the Mars Hill College music faculty as soloist for the Concerto No. 3 for horn and orchestra by Mozart. In December 1959 the Little Symphony accompanied a 100-voice chorus singing Handel’s The Messiah at the First Baptist Church. In March 1960 Renfro conducted a concert at Elizabeth Williams Chapel at Warren Wilson College, the group’s third out-of-town concert of the season.

By that summer or fall, however, Helen had found her conductor. He was M. Thomas Cousins, a member of the music faculty at Brevard College and a well-known composer of mostly choral and sacred music. Helen’s daughter, Carol, was studying music at Brevard, which may have cemented the connection. Cousins conducted his first public performance with the Little Symphony on December 4, 1960, with Bach’s Christmas Oratorio at Central Methodist Church.

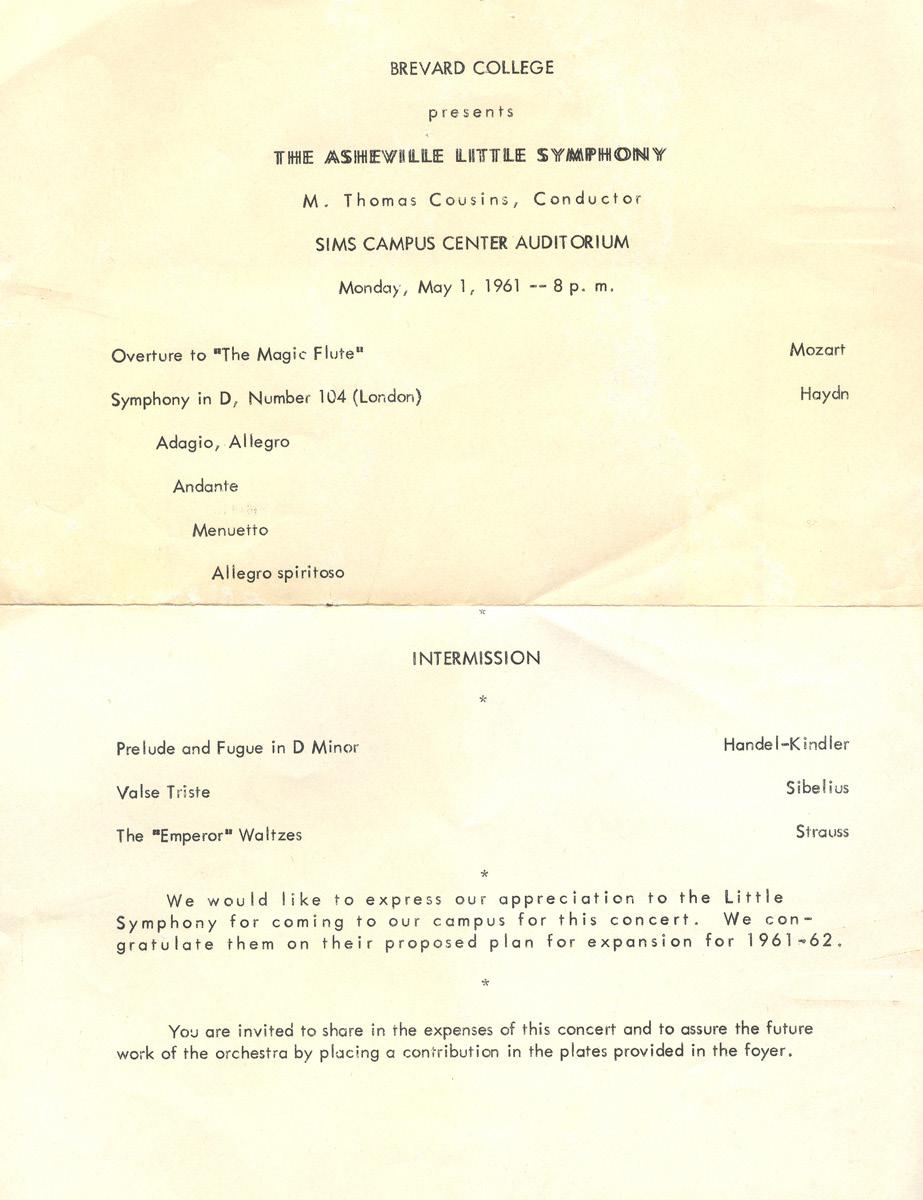

The Little Symphony then played its first full concert under Cousins’ baton at Brevard’s Sims Campus Center Auditorium on Monday, May 1, 1961. The ambitious program included Mozart’s Overture to The Magic Flute, Haydn’s Symphony in D, No. 104, Handel’s Prelude and Fugue in D Minor, Valse Triste by Sibelius and the Emperor Waltzes by Strauss. A note on the program said, “We would like to express our appreciation to the Little Symphony for coming to our campus for this concert. We congratulate them on their proposed plan for expansion for 1961-62. You are invited to share in the expenses of this concert and to assure the future work of the orchestra by placing a contribution in the plates provided in the foyer.”

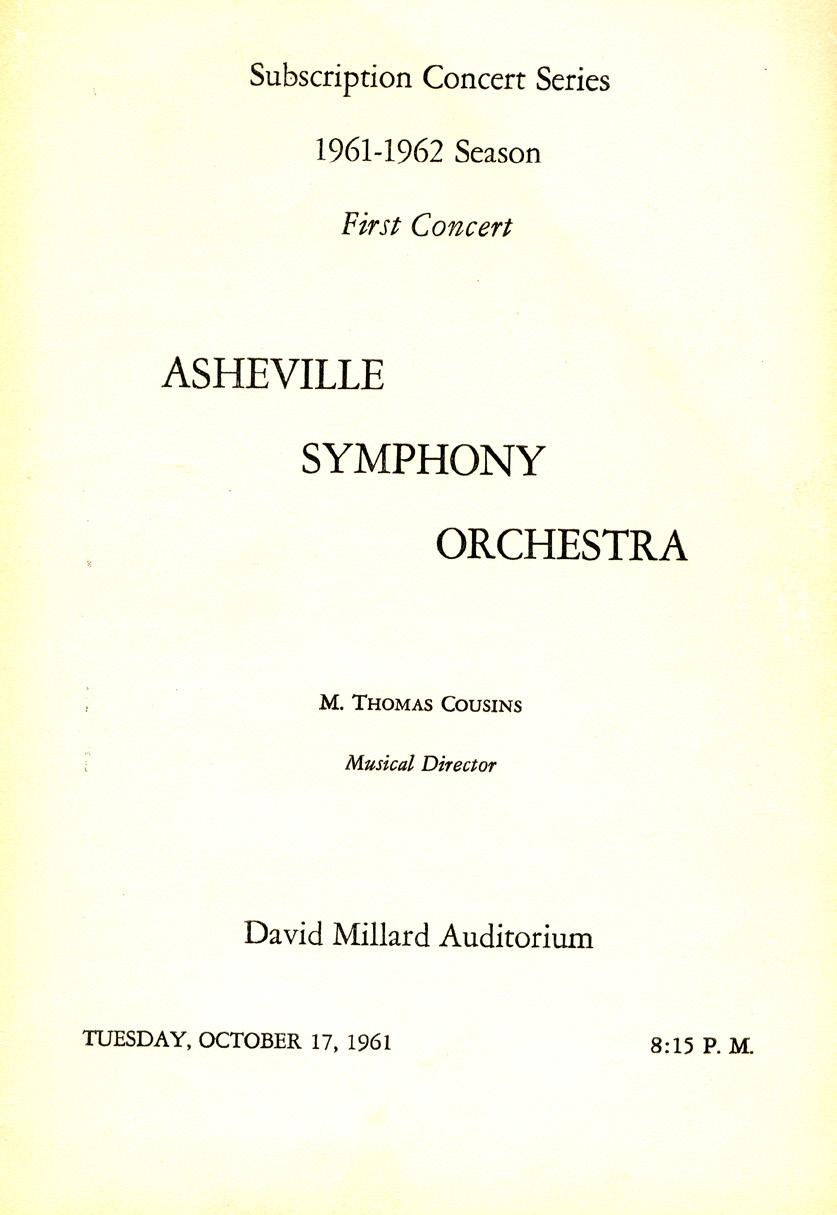

For the first subscription season, Helen scheduled four concerts from October 1961 to May 1962 in the auditorium of David Millard Junior High School, at Oak and College streets, across from the First Baptist Church. Season tickets were $5.00 regular, $2.50 for students and were on sale at Ivey’s, a major downtown department store (now the site of the Haywood Park Hotel). Individual concert tickets were $1.50 regular, 75 cents for students.

David Millard was one of Asheville’s most venerable buildings. It was built in 1916 as Asheville High, with an intimate auditorium seating about 750 on the main floor and a balcony. The auditorium was already the home of the Asheville Chamber Music Series. Most importantly, the auditorium’s abundant use of wood and its plaster walls painted with calcimine gave the hall lively acoustics. It would be the Asheville Symphony’s home for the next seven years.

Another one of Helen’s early goals seems to have been getting “Little” out of the Symphony’s name. There was nothing little about her ambitions for the orchestra. The program of the first concert in 1961 quietly dropped the diminutive. In 1963, the name was officially changed to the Asheville Symphony Society, Inc. Its purpose was “to form, develop, promote and operate an orchestra and related choral groups and to present public concerts, recitals and musical programs . . . in and outside the City of Asheville, North Carolina.” It would “foster, encourage and advance an appreciation of music . . . and promote public education in . . . classical music . . .” It would provide “an opportunity for students and musicians of promise to participate and gain experience in symphony orchestra playing.”

Program for first concert of first subscription season, October 17, 1961

It wasn’t long before Helen was attracting prominent members of the community to the Board of Directors. There were nine directors for the second season. There were 15 by the third season, including Weldon Weir, the powerful Asheville City Manager. And Helen had moved her office from her home on Brookwood Road to Room 311 in City Hall.

Helen was savvy enough to include not just the politically and socially well-connected but people with real musical knowledge. Joe DeNardo and Grace Potter Carroll were on the board by the third season.

For its first subscription concert, Musical Director Thomas Cousins had about 50 musicians from Asheville and surrounding communities, including Murphy, Sylva and Burnsville. They opened with Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture. As John Bridges wrote in his program notes, it has a “thunderous rendition” of “Gaudeamus Igitur” at the end. The audience’s reaction was thunderous as well and would not stop until the full orchestra stood for a bow.

They continued with Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 in B Minor (The “Unfinished”). After intermission came Handel’s Suite for Orchestra (from “The Water Music”). The final selection was Rimsky-Korsakoff’s The Russian Easter Overture. After the conductor and orchestra acknowledged the audience’s applause, Cousins introduced Helen Sorton to receive her share of the credit for making the new venture happen.

It was probably not a coincidence that Thomas Cousins chose to open the first concert of the first season of the new Asheville Symphony

with the celebratory Academic Festival Overture. It was probably also not a coincidence that he chose to close this opening concert with an overture. The entire concert was the overture to all that was to follow.

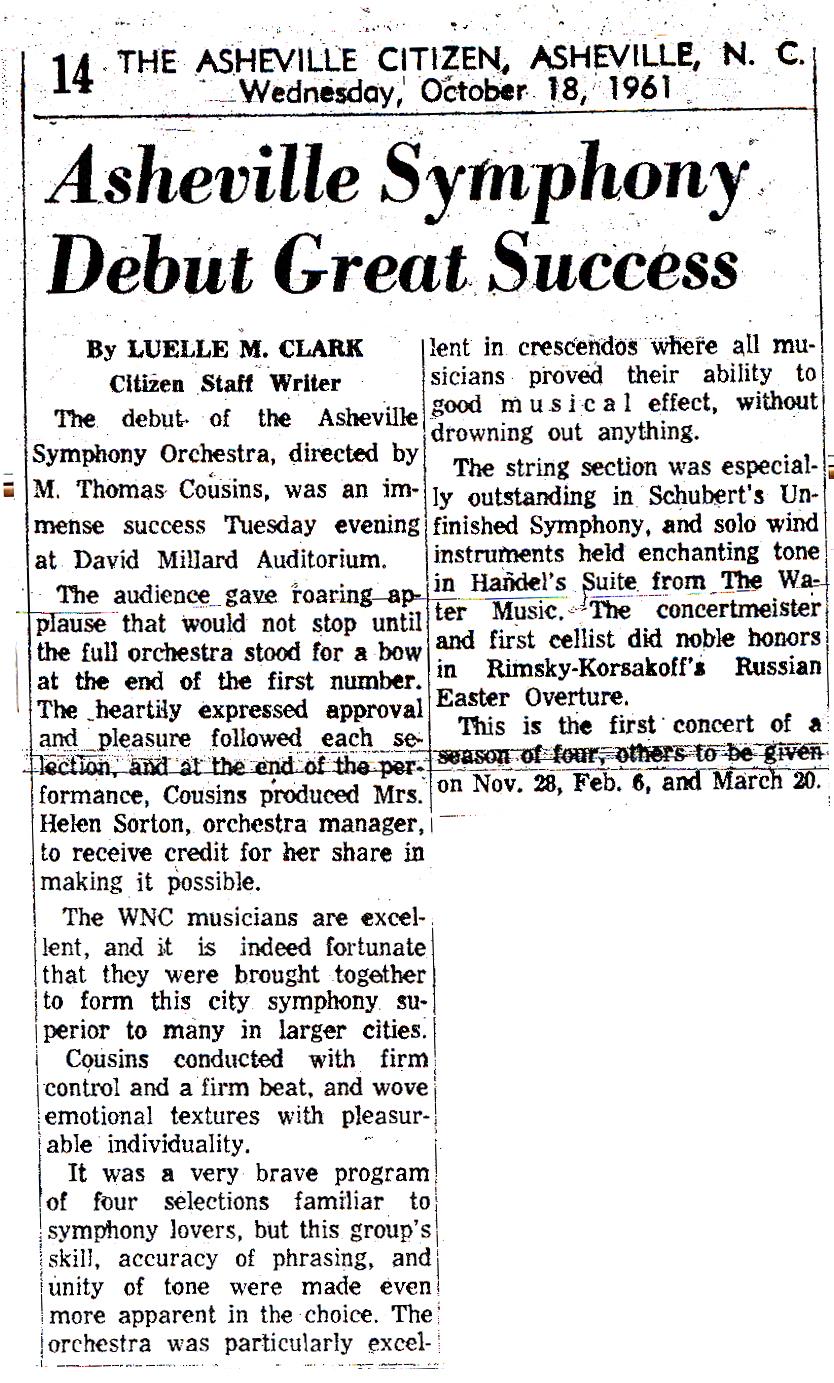

The concert started at 8:15 p.m. It was a short program, about 60 minutes of music. With an intermission, the evening was probably over by 9:30 p.m., time enough for Luelle Clark, a writer for the Asheville Citizen to travel the six or seven blocks from David Millard to the newspaper office and file her story before deadline.

She reported the next morning, “The debut of the Asheville Symphony Orchestra, directed by M. Thomas Cousins, was an immense success Tuesday evening at David Millard Auditorium . . . The WNC musicians are excellent, and it is indeed fortunate that they were brought together to form this city symphony superior to many in larger cities. Cousins conducted with firm control and a firm beat and wove emotional textures with pleasurable individuality. It was a brave program of four selections familiar to symphony lovers, but this group’s skill, accuracy of phrasing and unity of tone were made even more apparent in the choice. . . This is the first concert of a season of four, the others to be given on Nov. 28, Feb. 6, and March 20.”

The Asheville Symphony had begun.

Violinist Mary Byrd Daniels is the Symphony’s longest serving musician.

If violinist Mary Byrd Daniels were in a Broadway musical called Playing With the Asheville Symphony, she would be the show’s longest-running star. She is certainly one of the Symphony’s longest-serving musicians. She was 14 when her parents informed her she would join a group of seasoned musicians in a new symphony ensemble. That was in 1959, a year after the group incorporated as the Asheville Little Symphony. Mary played the Symphony’s first two seasons before graduating from high school in 1963. With time out for college, family and living away from Asheville, she has played with them ever since. And talk about long runs! She was the orchestra’s concertmaster, its “second-in-command,” for 25 years, 1982-2007.

Mary wasn’t daunted by older musical colleagues when she was a teen, since she had begun playing when she was five. She went to music camp at the Brevard Music Center every summer starting when she was 12. “I can’t remember a time when a violin wasn’t in my hands,” she says. She studied with Elizabeth Krauss, a beloved Asheville violin teacher, who lived and taught on the top floor of the Daniels home on Charlotte Street. “She would knock her cane on the floor every morning at 6:30 and my father would say, ‘Granny Krauss is waiting for you,’” Mary recalls.

Like many of the Symphony’s musicians, Mary teaches private pupils and plays with other orchestras, in her case the Greenville Symphony and the Hendersonville Symphony. One of Mary’s fondest musical memories is the time that Edvard Tchivzhel, now the music director and conductor of the Greenville Symphony, was invited by Robert Hart Baker to conduct Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 with the Asheville Symphony in 1992. Tchivzhel had just defected from the Soviet Union with the help of Greenville friends after a 1991 United States tour conducting the State Russian Symphony Orchestra.

“I remember thinking this is not the most technically accomplished performance,” Mary says, “but I have never heard the orchestra be so electric.” The fourth movement ends with a rousing series of cadence chords. Mary remembers them at the bottom left side of the page in her score. “The audience was on their feet and yelling before those chords were finished,” she says. “It still gives me chills.”

That performance reverberates for Mary as a turning point for what the Symphony could accomplish. It showed her “what our orchestra could do,” she says, “how enthusiastic they could be and how the audience received it so well. None of our music making is any good unless it speaks to our audiences.”

Another vivid memory gives Mary chills, but for a different reason. That was the time during a dress rehearsal for Liszt’s symphonic poem Les Préludes when she accidentally tossed her bow off the stage out into the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. She can still see the place in the score, where a very loose, rolling bowing is called for. “My bow hit my leg and took an enormous nose dive off the stage. It landed on the floor on its tip and then gently rolled over.”

To non-musicians, this might seem like a candidate for America’s Funniest Home Videos, but as Mary puts it, “Bows are exquisitely expensive.” Violinists seek out the most perfect bow they can afford, just as they do with vintage violins. Mary’s bow was made in the 18th century by Nicholas Lupot, known as the “French Stradivarius” and had been found for her by a friend in Montreal. “Violins and bows become such an intrinsic part of our bodies,” Mary says, “that you feel horrified if you’ve done damage to it. It’s as if you’ve done damage to yourself.”

Somebody out front picked the bow up and handed it back to Mary, but, she says, “For the next 30 minutes I was frozen; I wanted to cry. Bob just kept going, as if nothing had happened.” She used the Lupot bow for almost her entire tenure as concertmaster. Now she saves it for very special occasions.

In sports, business and music, it takes teamwork.

It’s more than a fun fluke of language that orchestra musicians and the members of a basketball team are called players. Could there be a game needing more intricate teamwork, individual skill and high-energy in a tight timeframe than a symphony performance? Is there any team sport more complicated than an orchestra?

Imagine almost 100 players covering some 20 different positions on the court at once. Our Symphony team is divided into five sub-teams (strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion and keyboard) and those sub-teams break into some 19 smaller miniteams (first violins, second violins, viola, cello, bass, etc). And each mini-team has a slightly different playbook!

Each player may not be fiddling, plucking, blowing, tooting or banging every moment, but each one is in play every second of the game. When the ball or the musical passage comes your way, you’ve got to be there to grab it. Every note from every player has to be on target and on time, every time. Think of 100 basketball players sinking 100 balls through 100 hoops at exactly the same moment, shot after shot after shot.

Sports and orchestras aren’t the only groups needing teamwork, of course. Peter Drucker, the father of modern management, often said that orchestras worked the way business teams should. “There are probably few orchestra conductors who could coax even one note out of a French horn,” Drucker wrote, “let alone show the horn player how to do it. But the conductor can focus the horn player’s skill and knowledge on the musicians’ joint performance. And this focus is what the leaders of an information-based business must be able to achieve.”

If executives draw management metaphors from orchestras, Asheville Symphony horn player Michael Brubaker takes his analogies for the musical team from the visual arts.

“A lot of music that we play in the Symphony,” he says, “is like a large landscape painting.” He cites a recent performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 4. The piece, he says, “is filled with enormous images and incredible detail. When you are inside the music on stage, you recognize that the part you have is only one part of the details of the painting. What I remember is that I’m in charge of blue.”

Mike says that the members of the team don’t have the view of the game the fans do. “The musicians don’t hear what the audience hears,” he says. “It’s very noisy on stage, especially in the brass section. What we hear is just the palette or the brush we are painting with.”

Team members are not always aware of what their teammates are doing. “The brass section can sometimes be playing and not realize there is another instrument in the orchestra playing our same part,” he says. “There have been a number of times we’re playing with the cellos and I’m surprised they are playing. I can’t hear them.”

How does he know they’re playing? “Ah,” he says, “that’s what rehearsals are for.”

Mike takes another example from Mahler’s Fourth of how the orchestra team works. “Mahler doesn’t write for my instrument the way he does in the other symphonies,” he says, “where we are a large army of brass instruments.” Here, the solo horn has passages the other horns don’t have. These were played by Terry A. Roberts, the team leader for the horns, known as the principal player.

“Terry has insight into the music and into the performance that I thought was very exciting,” Mike says. “It was like watching a great actor work. Our excitement comes from listening to our colleagues play well. It’s a team effort. We are obviously being led by our music director, but we are constantly listening to the art that our colleagues are producing.”

Mike’s strongest memory of team spirit among musicians and audience was the performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in September 2001 after 9/11. “It was electrifying,” he says.

He notes that Beethoven was writing during an artistic and political period that was causing him a great deal of personal turmoil. “Music has a power to convey the complex emotions of a time,” he says, “and Robert Hart Baker was aware that this was a piece of music written about the aspirations of humanity. I remember the performance because it allowed the musicians on stage to make an emotional statement. We were equally attuned to the audience in our desire to keep faith in the goodness of mankind.”

Former board members Carole and Bill Roskind remember the occasion vividly as well. “There was a lot of discussion about whether or not to even go ahead with the concert because of the nationwide fear of terrorism,” Carole says. She recalls that at the very beginning of the evening, Robert Hart Baker asked the audience to stand and sing America the Beautiful.

The next morning, former Symphony president Joyce Dorr was moved to write a letter to the Asheville Citizen-Times. Last evening Asheville Symphony’s performance, she said, “dedicated to those thousands suffering from this week’s tragedy, was indeed a stunning musical projection of Beethoven’s own resolution: ‘I will grapple with Fate; it will not overcome me.’ Every beat of this music was symbolic of a universal heartbeat quickened by a determination to alleviate pain and suffering throughout the world without being overcome by the struggle.”

For Mike Brubaker, “the importance of an orchestra is the way we can connect to an audience beyond politics. Bob Baker dedicated the Beethoven performance to an event and made it more than just a concert, he made it a collective act of faith in humanity.”

Why auditions for the Asheville Symphony are anonymous.

No one knows the origin of the famous joke about how to get to Carnegie Hall. Early versions were sometimes attributed to violinist Jascha Heifetz and sometimes to pianist Artur Rubinstein. The answer (“practice, practice, practice”) is also true for the question, “How do you get to the Asheville Symphony?”

But practice isn’t enough. Even the best-trained and most practiced musicians have to audition. Vance Reese, co-principal string bass player since 2002, recalls his audition and reveals a surprising Wizard-of-Oz experience.

“I’ve been on both sides of the screen,” Vance says, referring to the way musicians and the panel of judges at the audition are hidden from each other.

The 2002 audition for principal bass was held in the Civic Center Banquet Hall, above the lobby of the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. The players waited outside until Sally Keeney, the Symphony’s artistic administrator, ushered them in for their individual appointments.

“The player is instructed to say nothing to give himself or herself away,” Vance says, “and the conductor is the only one who speaks on the other side: ‘No 23, please start the first selection at rehearsal number 6.’”

The auditionees had been given a list of what Vance calls “particularly hard or famously tough excerpts from the orchestral literature.” In this case, the selections were from concertos by the 18th-century composer Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf and the 20th-century composer and Conductor Serge Koussevitzky.

Despite his PhD in music from Indiana University, Vance had to learn both pieces for the first time. “I had majored in organ, not bass,” he says, “so I didn’t learn some of the bass repertoire.” He studied bass starting in middle school in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. His teacher was the late Edgar Meyer Sr., director of the local schools system string orchestra (and father of the prominent bassist and composer Edgar Meyer). “He said if I studied bass, I would always assured of a job,” Vance says; “My first paying job was playing for The Mikado at the Clarence Brown Theatre in Knoxville. I was in 9th grade, before I could drive.”

One reason of course is to insure fairness to all the musicians, whether they are known or unknown to the conductor and other judges. Contending for the principal’s position were three local bass players from the Symphony, three from out of town and two others who occasionally played with the orchestra.

Another reason for the screen, Vance says, is to make the judges focus completely on the sound. “What they want to hear is whether a person can play out strongly and be a leader for the section. They want to hear the player’s dynamic and musical range.”

They can also tell if the musician is what Vance calls “a busy player, moaning, rustling, sighing.”

The audition lasted about 15 minutes. Vance expected to come in third after two fellow members of the Symphony he rated as better players. (He had been playing with them since 1999.) So he was surprised and pleased when he was asked to share the principal’s position with Lee Metcalfe.

French horn player Michael Brubaker recalls that for his 2000 audition he had an unusual level of anxiety. “I had just been recently bitten by a brown recluse spider,” he says,” and the back of my leg had an industrial level allergic reaction. I was on medication, and it was very difficult trying to concentrate on the audition.”

Both Vance Reese and Mike Brubaker had already been playing with the Symphony before their formal auditions. Sometimes the conductor will give a quick listen to a new player when he’s looking for a substitute or part-time player. “I played a Bach piece for Bob Baker after a rehearsal,” Vance remembers, “Bob was standing a couple of feet away. He was not terribly impressed as I recall. My bass needed some serious work at the time.”

Mike Brubaker says for the 10 or 15 minutes of intense concentration required by an audition, “we are polishing the music to a level that lets the committee hear that the performer is actually aware of the other parts. You have to convey the parts that are missing.”

Spider bites aren’t the only distractions Brubaker has had to deal with. He recalls a concert when he was suffering from a bout of poison ivy. “There is nothing much worse than being in white tie and tails and wanting to scratch during a very quiet passage of music,” he says.

For an audition in London for the principal horn position with a small Portuguese chamber orchestra, he made the mistake of trimming his moustache right before he played. “I had nipped my lip with the scissors,” he says, “and consequently was bleeding. I just kept playing with the blood running down.”

“Probably not,” he says. “In any case, they shouldn’t have scissors.”

Cellist Cherylonda Fitzgerald travels many roads to make her music.

Cellist Cherylonda Fitzgerald, one of the Symphony’s most recent additions, first began playing during the 2004-05 season. She and her husband had recently moved to Watauga, Tennessee, near Johnson City, where he teaches digital media at East Tennessee State University. Like all of the Symphony’s musicians, Cheryl goes to great lengths to practice her art. That includes traveling to teach at several locations and to rehearse and perform with multiple musical groups in different cities.

“Musicians have to piece together a career,” she says.

With a Master of Music degree from State University of New York at Stony Brook, Cheryl soon landed teaching positions at ETSU and nearby Milligan College. .She was introduced to the Asheville Symphony through former member Katie Hamilton, who was the previous cello instructor at Milligan. Cheryl’s first performance with the Symphony was shortly after Daniel Meyer’s audition concert. She later auditioned for him and has been playing with the Asheville Symphony ever since.

Besides teaching college students, Cheryl has her own studio with about 30 private students mostly from Kingsport and Johnson City. They range in age from five to “a doctor whom I’m not going to ask his age,” she says, with an infectious laugh that occurs frequently. “I even had a student who was 88,” she adds.

Her other orchestras are the Johnson City Symphony and the Symphony of the Mountains, which performs in Kingsport and other locations in Tennessee and Virginia. She is also a member of the Paramount Chamber Players, based in Bristol, and the Shelbridge Chamber Players, based in Johnson City.

How does she juggle three symphonies, a chamber ensemble, two colleges, 30 private students and five locations?

“I discovered Google Calendar and that saved my life,” she says with another laugh, and then adds, “It’s a very complicated schedule.”

Sally Keeney, the Symphony’s artistic administrator, says almost all of the musicians can tell a similar story. “I really can’t think of a musician who doesn’t play with at least one other orchestra,” she says.

There are about 15 other orchestras that share musicians and Sally knows most of them. The Symphony sets its schedule according to the availability of Daniel Meyer and the calendar of the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. “This year we did work with the Hendersonville Symphony,” Sally says, “to adjust our Holiday Pops schedule so our musicians could play both.”

There are often conflicts with many of the other orchestras, Sally notes. “The musicians will usually go where the money is,” she says, “unless they have a titled chair. And with that, they will most likely go where the title is as it comes with some responsibility, especially a principal chair.”

Asheville’s third horn, for example, is principal in Greenville, so she goes with Greenville every time there is a conflict. When that happens, “It is my job to replace the absent musician with an approved substitute,” Sally says. “If I have run out of approved substitutes, I will call other personnel managers and ask for recommendations.”

Cheryl makes the 130-mile, one-and-a-half-hour round-trip journey between Watauga and Asheville for two to three rehearsals before the Friday night rehearsal and Saturday dress rehearsal and performance. “On Fridays I stay overnight with violinist Alice Keith Knowles, who lives in Black Mountain,” she says. “In addition to playing with the Asheville Symphony, Keithie is the principal second violinist of Symphony of the Mountains and plays with me as a member of the Paramount Chamber Players.”

Even in her short time with the Symphony, Cheryl has collected many memorable musical moments. “I started around the same time Daniel did,” she says. “I was impressed with his rapport with the audience. That is something that is becoming more and more important with conductors. It’s a way of personalizing classical music, so it is more approachable to the audience.”

She recalls two of the Symphony’s unusual collaborations: Asheville’s Red Herring Puppets accompanying Stravinsky’s Petrushka with giant puppets in May 2008 and Pittsburgh’s Attack Theatre performing a dance interpretation of de Falla’s El Amor Brujo in May 2009.

She also has a vivid memory of cello virtuoso Zuill Bailey’s first appearance in Asheville. “I really do think that he is going to succeed Yo-Yo Ma as the next ambassador of cello,” she says.

Bailey was performing Dvorak’s Cello Concerto, and Cathy’s fellow Symphony cellist, Franklin Keel, was preparing the same piece for a competition at Appalachian State University. She overheard Bailey offer to give him a coaching session during the orchestra’s break.

“Do you mind if I listen in?” Cheryl asked.

She invited herself to their private lesson?

“Sure!” she says, with a big laugh.

Franklin remembers the occasion as well. “My tendency, especially with a piece as difficult as Dvorak’s Cello Concerto,” he says, “is to overthink and overcomplicate the execution of the instrument. Zuill quickly spotted areas where I was overthinking and was very helpful in simplifying my approach, which helped to improve my sound.”

“It says a lot about Zuill’s personality to take the time to do that,” Cheryl says. “Not every artist will. I can see Yo-Yo Ma doing things like that.”

Almost every member of Catherine Arps’ family has played with the Asheville Symphony.

Catherine Arps has played viola with the Asheville Symphony almost every season since she moved to Western North Carolina in 1972. There were no auditions in the early years, Cathy recalls. All the musicians were volunteers, led by part-time conductors whose primary responsibility was teaching at local colleges. “If a section member moved to town and you could play, they wanted you,” she says.

Cathy and her husband live in Sylva, where they grow vegetables, flowers and herbs for local markets, restaurants and community subscribers. Like many of the musicians who live away from Asheville, she has traveled many miles getting to and from rehearsals and performances. “I was bringing two college students who couldn’t afford to travel. I was instrumental in getting musicians paid a little bit for travel, maybe a nickel a mile back then,” she says. To save gasoline costs, players try to car pool. “When the cars stop and musicians get out with their instruments, it’s like the circus and all the clowns getting out,” she says. “It’s part of the adventure.”

Weather can also be part of the adventure. “If it snows hard, the place where it gets impassable is Canton,” she says. She drives with her father, William Henigbaum, a Symphony violinist. “My dad, being an Iowa driver, doesn’t stop for a snowflake,” she says. She remembers an occasion when the Interstate was closed. “We got off, took the old road and managed to get there,” she says, but they couldn’t get home. “We slept on the floor at Pat Johnston’s,” Cathy says, referring to a fellow cellist.

Cathy’s entire family is musical and may hold the record for number of members playing with the Asheville Symphony. In Iowa, where she grew up, her mother played violin and viola and her father directed a chamber music series. “All the rehearsals were in our house,” she says, “and after my sisters and I were sent to bed, we would sneak back downstairs and listen to these fascinating people.”

Her mother, Mary Henigbaum, moved to Western North Carolina first and joined the Asheville Symphony. Her father also moved here, joined the Symphony and at 89 is still playing with them. “My dad is still teaching, still conducting an orchestra, still mowing the grass” at his house “up the hill” from Cathy’s.

Her sisters, Jane and Nancy, have played with the Symphony, and Jane was the Symphony’s personnel manager for two years in the late 1970s. In 1985, Cathy’s daughter, Hannah, won a Young Soloist Competition when she was 11 and played as a violin soloist with the Symphony for a Children’s Concert. She played again as member of the second violin section for a concert or two in the fall of 1993 before she went off to college.

With Symphony rehearsals occasionally looking like a family reunion for Cathy, it’s not surprising that one of her favorite memories is about her father. “When my dad turned 80,” she says, “we were going to have a birthday cake after dress rehearsal. I asked Bob Baker if we could surprise him by singing Happy Birthday.”

The orchestra was rehearsing for Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, so there was a huge chorus and four soloists on stage. Robert Hart Baker turned to the soloists and said, in German so Bill Henigbaum would not understand, “We’re now going to sing Happy Birthday.” Cathy recalls, “The soloists turned and belted it out to my dad sitting in the first row,” where he was assistant principal.

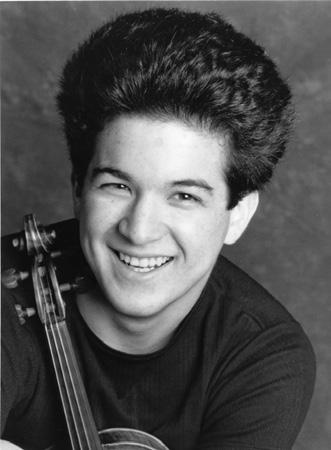

Cathy also enjoys taking a little credit for the great success of violinist Nicolas Kendall’s first performance in Asheville. After the dress rehearsal, she said to him, “You need to play a fiddle tune for an encore, this audience would love it.” He said, “Oh, we can do that.” Kendall started improvising and the orchestra joined in. “He was fiddlin’, the orchestra gets into an A minor groove as the back-up band,” Cathy says, “and the audience did love it.”

For these Asheville Symphony musicians, the music matched the emotion.

The importance of music in our lives is nowhere more obvious than when we choose it to accompany important occasions. Sometimes joyous (for a wedding), sometimes solemn (for a funeral), music celebrates and comforts.

Several Asheville Symphony musicians remember concerts when the music matched their own joy or sadness.

Bass player Vance Reese’s father was in the hospital the week Vance was preparing for a performance of Carmina Burana. “In fact he died the weekend of this particular concert,” Vance says. “It was one of Daniel’s first concerts and we were doing the first part, ‘O Fortuna.’”

Vance didn’t know all the words, but he knew the gist: “O Fortune, like the moon, you are changeable, ever waxing and waning.” He says he was sensing “in a very palpable way the ticking of the clock, how we are alive one moment, dead the next, healthy one day, not healthy the next. And here’s this unrelenting music that drives that.”

Vance remembers feeling angry and “wanting to fight fate, fight that cycle.” Then he realized that the rest of Carmina Burana “does support life. There’s love and laughter and drinking and bawdiness and funniness.” It was a performance, he said, that “stuck in my head for the changes in my family.”

An earlier performance also marked a change in Vance’s family, this one happy. His wife Jean played the cello for the Symphony, starting about the time he began playing bass. She was pregnant with their son, Jonathan, during a November 1999 concert. “We were playing the 1812 Overture about a month before he was born,” Vance remembers, “and she felt Jonathan kick inside her when the drums went off. She realized that was her last concert for awhile. That ‘awhile’ has been ten years now.”

Horn player Michael Brubaker recalls his wife had a similar experience. He was playing with the Savannah Symphony and she was the personnel manager. They were awaiting their first child during a performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. “My son was kicking along to the beat,” Mike says.

Cellist Patricia Koelling Johnston may take the “Playing While Pregnant” prize. She’ll never forget the Symphony’s 1981 Valentine concert, when they were featuring Stravinsky’s The Firebird. She was expecting her first child.

“I remember this very clearly,” she says, “as I started having mildish contractions every five minutes late in the afternoon before the concert. Being good Lamaze parents-to-be, my husband and I had the hospital bag packed.” They arranged a signal: Pat would drop a handkerchief on stage if things progressed, and he would retrieve the car.

She was confident, she says, because the principal horn, Tom English, was a surgeon, so care was close if necessary. The contractions continued and strengthened through The Firebird. “The cello part is difficult enough to create distractions!” Pat says. “Thankfully, Jay allowed me to finish the concert before making his entrance into the world.” She and her husband went to the hospital about midnight, and Jay was born Sunday afternoon.

For Pat, The Firebird will always be a reminder “of the joy of becoming a mother and not a small amount of pain.”

Robert Hart Baker talks about his 23 seasons as Music Director of the Asheville Symphony and why he wears a moustache.

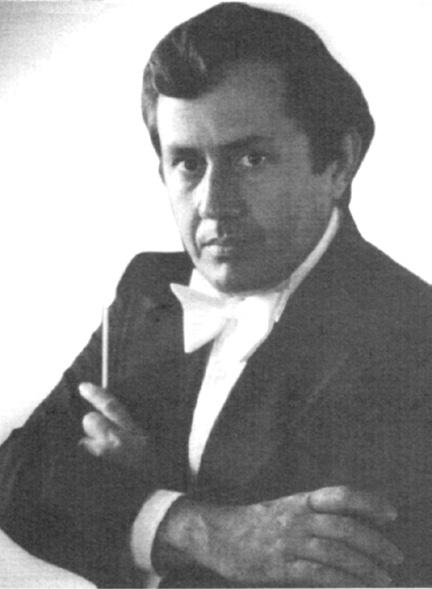

Robert Hart Baker became the Asheville Symphony’s first full-time music director and conductor in residence in 1981 and guided its musical coming-of-age for 23 seasons. During his tenure, he took the Symphony from a semi-professional orchestra of about 40 players to a fully professional ensemble of some 80-100 members. He became Conductor Laureate at the end of the 2004 season.

A cum laude graduate of Harvard University, Bob studied privately with Leonard Bernstein. He then received master’s and doctoral degrees from the Yale School of Music. He also studied with Herbert Von Karajan at the Salzburg Mozarteum in Austria. Before he came to Asheville, he was living in New York City and conducting the New York Youth Symphony at Carnegie Hall and the Connecticut Philharmonic Orchestra, which he helped found.

Bob recalls that after he applied for the Asheville position, two members of the Symphony’s search committee, Tom Bolton and Mack Day, came to New York to interview him and hear him conduct in Connecticut. They then invited him to Asheville to participate in auditions.

As Bob tells the story, his father’s insurance agent was also the agent for Aaron Rosand, a famous violinist and something of a rival to Isaac Stern in the concert world. The agent knew Rosand had recently played in Asheville and suggested Bob go see him for advice.

“So,” Bob says, “I went and said, ‘Mr. Rosand, I’m a young conductor and I would like to get a professional orchestra outside of New York. I’m reaching the point where I can’t spend the time building my own Connecticut orchestra, and the youth symphony is the kind of job you should move on from.’” He asked Rosand if the violinist would give him a coaching session.

Rosand said, “You don’t need any lessons from me, you’ve got good training. But you just don’t look the part. You’re 24 years old, you look like you’re 16, they’re never going to hire you.”

Bob said, “What do I do?”

“Look at me,” Rosand said. I’m a so-so looking guy, but I have a beard and a goatee, I look very European. When people look at me they think I’m an artist right away, because I look the part. You need to grow some facial hair. How about a moustache?”

Bob said, “Fine, if that’s what it takes, I’ll grow a moustache.”

So he grew the moustache and joined four candidates for auditions in Asheville. Each had about 30 minutes to rehearse the Symphony with a section of Handel’s Water Music. The piece, Bob says, “has string parts that are not really hard, you just have to play them in tune. But it has outrageously hard French horn parts. So we were all conducting, and the horns were having a problem. Nothing sounded very good.”

As the candidates were leaving Thomas Wolfe Auditorium, they passed members of the board and other players seated at the back. Bob heard a whispered, “Well, which one did you like?” The whispered reply: “I like the one with the moustache.”

So the one with the moustache got the job. “I swore at that point,” Bob says, “that if I got the Asheville Symphony job with my moustache, I would not shave it off. And as long as I had a conducting job, I would not shave it off. That would be a bad luck sign.”

The moustache may have brought him good luck, but Bob might have wondered if his luck was holding when two near mishaps almost derailed his first full concert here.

Pianist Abbey Simon was to be the guest soloist. Bob says, “I worked out with his agent to do the Brahms First Piano Concerto, which is a major, major work. I sent a note out to the airport saying, ‘Welcome to Asheville, Mr. Simon, looking forward to our Brahms.’” Unbeknownst to Bob, Simon had written down in his schedule book that he was to play Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto.

In those days before cell phones, Simon went immediately to an airport payphone and called the Symphony office. “This is Abbey Simon. I want to talk to this Baker guy.” Bob got on. Simon said, “What do you mean sending me a note saying we’re playing Brahms. We’re doing Beethoven.”

Bob said, “Mr. Simon, if you’ll look at your contract, it says we’re doing Brahms’ First Concerto.”

Abbey Simon

Abbey Simon

“No, it doesn’t. I’m going to call my agent on this other pay phone.”

Still connected to the Symphony office, he called New York. Bob heard him say, “This is Abbey Simon. What town am I in and what am I playing?” The agent said, “You’re in Asheville and you’re playing Brahms.” Bob heard Simon say, “Holy – .” Then he got back on the line with Bob: “What do we do?”

Bob said, “Mr. Simon, you have a choice, either the Asheville Symphony can try to learn the Beethoven Fourth Piano Concerto in one night, or you can relearn the Brahms Concerto in one night. Take your pick.”

Simon said, “Can you get me the sheet music to the Brahms?”

“Yes.”

“Ok, have it delivered to my hotel room and I’ll play the Brahms.”

As Bob remembers it, the orchestra’s pianist drove to Charlotte to pick up a copy of the Brahms Concerto, Simon refreshed it, and he did the concert. “This was a guy who was famous for having a temper,” Bob says,”but we got along fine, he was lovely.”

Simon did manage to have a little fun at Bob’s expense. At the reception after the concert, Bob introduced him as “a man who plays everywhere from London to Oshkosh.” Simon replied, “Robert, I don’t want you to put Oshkosh at the back end of that equation. I’ve played Oshkosh, it’s a very nice city, it’s the complete equal of Asheville and you shouldn’t put it down.”

Bob’s second hurdle for his first concert was an Asheville policeman who stopped him on the way to the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. “I had burned up the engine in my Volkswagen driving from New York to Asheville,” he says, “so I had a big old renta-wreck with bald tires.” He was driving down Merrimon Avenue at dusk, about 7:30, dressed in his tails for an 8:15 performance.

“There was a blue light behind me,” Bob says, “and a policeman stops me. The policeman came over and said, ‘You’ve got bald tires and you’re kind of weaving down Merrimon, so I think you’ve been drinking.”

He asked Bob to get out of the car and walk a straight line. Then he said, “Touch your nose.” Then, “Breathe into my nose.” “They didn’t have breathalysers then,” Bob says, “so I blew into his nose and there’s no alcohol.” The policeman said, “You haven’t been drinking. So why are you wearing a party suit?”

Bob said, “It isn’t a party suit. In about a half an hour I’m supposed to be giving the downbeat for the opening of the Asheville Symphony season at the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium.”

The policeman said, “We don’t have a symphony around here.”

Bob said, “Oh, yes, you do, you have an Asheville Symphony.”

“Why are you driving a car with bald tires?” Bob showed him the rental agreement and said, “I don’t mean to rush things, but if I don’t get going, I’m going to have a thousand people mad at me for being late to my own concert.”

The officer said, “Well, I’m going to write you a citation. Now you don’t drink and drive.”

“No, sir, I certainly won’t.”

“Because if you keep driving like you’re driving, you’re going to pick up more cops between here and there.”

Other than a pianist who came prepared for the wrong piece and a policeman who wondered why a guy in white-tie-and-tails was driving an old car with bald tires, what were the first challenges for the Symphony’s new music director?

“There were three things we had to do right away,” Bob says. The first was to let the 40 or so players, some of whom had different ideas about how the Symphony should progress, know there would be a single vision for the group. “I let them know that they would be paid, that we were going to professionalize the orchestra and that we would have professional standards.

This meant re-auditioning all the musicians. “The new kid on the block gets one chance to reaudition everybody,” Bob says, “before you start having baggage or the feeling that somebody knows somebody or it ’s fixed. I had a clean slate.”

He heard everybody play and placed them where he thought they should be. “I was very objective because I was brand new,” he says. “So that gave everybody a sense that we would have a musical clean start.”

Bob found a mix of professional-level players and amateur players. The next thing was to establish technical standards for each of the instruments so the orchestra could play the full range of the concert repertoire.

“For instance,” Bob says, “in the violins, I insisted that everybody learn how to balance the bow so they could play staccato music.” This was preparation for the first concert’s performance of Rossini’s Semiramide Overture, which requires balancing the bow. “After that overture, which was our first piece,” Bob says, “the place went nuts, because all of a sudden it sounded like a real orchestra. It wasn’t perfect, but that was a new thing.”

In the brass section,” he says, “We were insisting that people play in a way that they weren’t missing notes all the time. They had to improve their accuracy. These were all the nuts and bolts part of the Symphony that we had to get going right way.”

“I didn’t actually throw anybody out,” he says, “but we did what is called reseating, where the weaker players went to the back of the section. If they couldn’t learn the music in time for the concert, they wouldn’t play.” To help the process, he began holding rehearsals every Monday, whether there was a concert or not. The players could in effect take lessons on music new to them, so they could master it by concert week.

When he began, Bob says, the Symphony sounded like a typical community orchestra. “Nobody likes to be called a typical community orchestra,” he says, “meaning that when you came to a concert, you’d hear funny notes in the violins, you’d hear funny notes in the horns, you’d just hope they’d get through the pieces. Sometimes we’d kill a Mozart piece, sometimes we’d play a Mozart piece alright.”

Bob took the long view. He knew it would take 10 to 15 years of training to get to a level of consistency that marks a professional orchestra. There was no music school in Asheville, so the Symphony became its own training ground for its players. “That’s what we had to do,” he says.

When did the Symphony reach the professionalism he aimed for? How did he know they were there?

“We reached that point in this orchestra by the early 90s,” he says. “When we started playing certain pieces for the second time, when we started doing pieces like Beethoven Nine, Carmina Burana, the Mahler symphonies, the Prokofiev symphonies, things that were really big time repertoire, then I knew that we had made it.”

Another test, he said, was when people heard the Symphony on recordings broadcast on WCQS. “If you heard us on the radio,” he says, “we sounded like a real orchestra.”

While bringing the musicians up to a professional level, Bob’s second challenge was to expand the repertoire. “To build an orchestra,” he says, “you have to cover all of the major pieces by all the major composers over time. That’s the way the orchestra really learns how to play in style. When the orchestra can handle the Classics, Hayden, Mozart, Beethoven, then you move into the Romantics, then you move into the Moderns. Then you have the ability to really play.”

Knowing the major repertoire, Bob says, gives the orchestra what he calls “a residual memory.” The music is “in their blood,” he says. “That gives you that sense of confidence in the concert.”

While the broadened repertoire helped the players’ musicianship, it also increased the audience’s expectations. “My job in the first two-thirds of the time I was here,” Bob say, “was to train the orchestra and also to expose our audience to a great variety of great music, so that they were more sophisticated listeners.”

Again, he took the long view. “The idea when I came here was that we would perform over the course of time the nine Beethoven symphonies, the four Brahms, the major Dvoraks, the major Tchaikovskys, the Strauss tone poems. We ended up doing five of the Mahler symphonies. I had the luxury here of being able to program as I wanted to so that we would cover the gamut.”

While he was honing the orchestra’s skills, expanding its repertoire and increasing the audience’s musical sophistication, he also helped build the audience’s size. “Thomas Wolfe is a large auditorium,” he says. “Filling it is like trying to fill Carnegie Hall without being in the same-sized city. And that’s a task. Music is so expensive to do, you’ve got to really fill the place to make it go.”

In planning his concerts, Bob stuck to the standard format of overture, concerto and symphony, “like a typical three-course meal,” he says. But he always tried to have a theme or connection between the pieces. After a while, the Symphony started giving each concert a thematic name. “But even before we named them,” he says, “I would find a program, for instance, where one composer had studied with another or one was friends with another.”

He also looked for music with a connection to Asheville and Western North Carolina. “Over the years we did three or four pieces by Caryl Florio, the resident composer at the Biltmore House at the turn of the 20th century. We did some Lamar Stringfield. Béla Bartók lived in Asheville, so we made sure we did some Bartók. Anything that showed the audience we cared about this area and their cultural environment, we would try to work into a concert.”

When Bob began in Asheville, there was a strong core audience for the Symphony of about 600 people. By the time he left, that core had grown to about 1,500. “And we were getting attendance up close to 2,000 for some concerts,” he says.

To build that base, the Symphony improved the ways it reached out to the community. “We improved our brochures, we did much bigger mailings,” he says. “There was an ongoing campaign where I and others would go around and talk to groups. I would visit Lions Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, garden clubs. I would let them know the Asheville Symphony is your symphony.”

He says it was a little like a political campaign. “You’d meet two, three, five, ten people at a time, you’d shake hands with them and you’d say, ‘I’d like to see you at the Symphony.’ We’d also say things like, ‘You’ve probably heard great classical music in movies and on television but you didn’t know you’d like it. You need to give the Symphony a try.’”

Ask Bob what his most memorable musical moments are from his time with the Asheville Symphony and he quickly lists choral concerts: an opera highlights concert (“We had a wonderful tenor singing Nissan Dorma”), Carmina Burana, Beethoven’s Ninth and Verdi’s Requiem, which he conducted twice.

The choral concert came in the spring, during allergy season, which made one program memorable for another reason. “Some of the out-of-town singers would come and get all full of the yellow pollen,” he says. “It wasn’t too good for the vocal chords.” British-born soprano Lindsey McKee was guest soloist along with a mezzo soprano that Bob does not name. “The mezzo could not get a single note out of her throat in the concert,” Bob says, “so Lindsay sang both the roles, soprano and the alto. The other singer lip-synced and no one was the wiser. It was one of the most amazing vocal performances I’ve seen.”

Bob says that many guest soloists are among his great memories. His list of favorites includes a young Paul Neubauer, who later became principal violist for the New York Philharmonic; cellist Carter Brey, Bob’s Yale classmate who became principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic; mezzo-soprano Jennifer Larmore who sang with the Symphony in the early 80s before she went on to become a star at the Metropolitan Opera; pianist Eugene Istomin who brought his own piano in a truck; pianist Ruth Laredo; and Aaron Rosand, the violinist responsible for the Baker moustache.

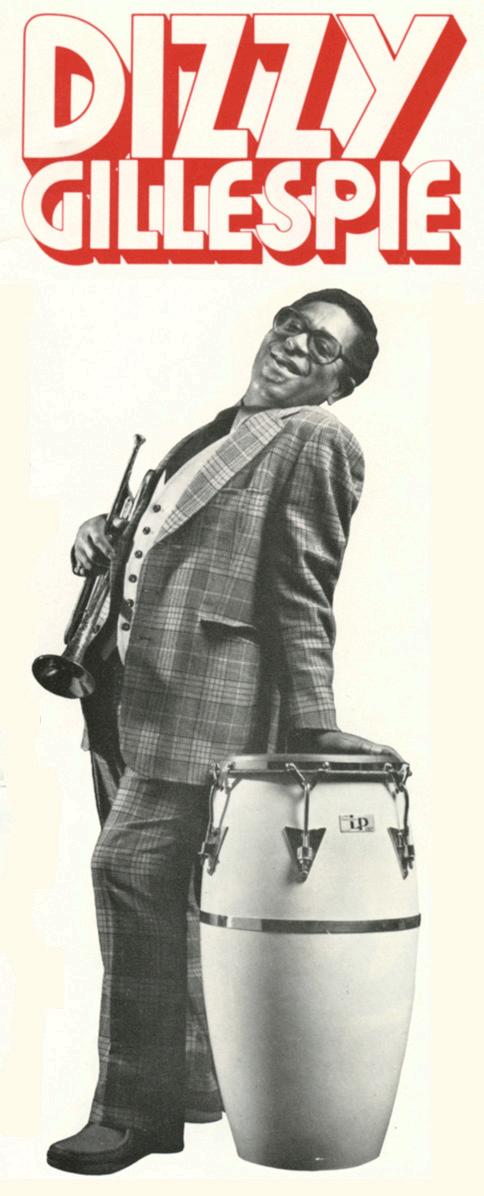

He also enjoyed solists from the pops and jazz world. When Dizzy Gillespie was guest artist for Bob’s first pops concert, the young conductor wasn’t as familiar then with jazz as he is now. (His wife, Barbara Duvall Baker, is a flutist and jazz vocalist.) “It was quite daunting to put together his progressive be-bop jazz charts with the Symphony,” he says. Although I like jazz, at the time it was pretty new to me.”

The concert was to include Gillespie’s big numbers: “Night in Tunisia” and “Salt Peanuts.” Gillespie said, “All right, Robert, start ‘em up.”

Bob recalls, “I gave what was basically a classical-looking upbeat to the music. And he just looked at me.”

Gillespie said, “What was that? You can’t expect me to play after you do that.”

“What do you mean?”

He said, “You’ve got to count it off. You’ve got to go, ‘a-one, ‘a-two, ‘a-one-two-three four.”

“So I got my little dressing down from Dizzy Gillespie,” Bob says, “and everything was fine after that.”

His experience with Dinah Shore was more reassuring. At the time of her pops concert with the Symphony at the Western North Carolina Agricultural Center, she had an ongoing relationship with Burt Reynolds, 20 years her junior. Shore took some questions from the audience, one of which was, “How’s Burt, and what do you think of younger men?” She replied, “I think younger men are great,” and leaned over and gave Bob a big kiss.

With all the guest artists, Bob says, “it was always a great musical education for the orchestra and for me. We would invite them to give us feedback, to tell us how they wanted to play it, how to shape it, so that our musicianship would be improved.”

Some of Bob’s memorable moments are mishaps he might prefer to forget. A performance of Schubert’s Mass in A Flat with the Asheville Symphony Chorus was the only time in 23 years in which he had to restart a piece in a concert. Bob explains, “The piece starts in cut time, which means you give a beat and the half note is the beat instead of a quarter beat.” However, the bassoon soloist who starts the piece, began in regular time, while Bob was conducting in cut time. “We couldn’t get off the ground,” Bob says. “I put my hands down, I didn’t say anything, just started it again. I thought maybe nobody would notice.”

But the next day, the critic for the Asheville Citizen-Times said, “It’s a shame they can’t start on time but it got better from there.” “That was the only time,” Bob says, “that I really wished I could take back something we did.”

Another occasion was less public but perhaps more painful. The Asheville Symphony Guild had started a young artist competition for area music students. “Without the Guild,” Bob says, “a lot of the activities and a lot of the money for the Symphony simply wouldn’t be there. It’s a very important organization.” The early competitions were held at Warren Wilson College or UNC Asheville. “At the time,” Bob says, “we were auditioning duo-pianists with a Mozart double concerto, so the two players needed equal pianos.”

In those days, Bob notes, “not every musical, technical aspect was communicated between me and the office and the Guild, so it turned out nobody ordered the pianos to be tuned.” When the two young pianists played their first chords, it was clear that one piano was down half a tone from the other. “One piano you’d hit the white key and it would be C major, and the other piano would be in B major,” Bob says. “It sounded like Charles Ives rather than Mozart.”

The pianists, in their early teens, were in tears. “Everyone was standing there, trying to figure out what to do,” Bob says. “I brought them tissues. We assured the music teacher they would get a fair shot.” Ultimately, they had to have each piano in a duo concerto play separately. “This is something nowadays I’m sure would never happen again,” Bob says. “But these are the kind of growing pains that happen when you want to run your own competition.”

Besides looking back at where the Symphony has been, Bob likes to look ahead. If he were coming in as a consultant for the Symphony’s next five to ten years, what would he see?

“One of the things I think should happen,” Bob says, “is that after they have perfected their monthly classical subscription season, which they’re doing a very good job with and getting good attendance, sooner or later the Symphony probably will want to return to the place where they do more alternative concerts, like pops concerts and concerts for young people.”