19 minute read

Onstage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Nicolas Kendall

ONSTAGE

Advertisement

Cathy also enjoys taking a little credit for the great success of violinist Nicolas Kendall’s first performance in Asheville. After the dress rehearsal, she said to him, “You need to play a fiddle tune for an encore, this audience would love it.” He said, “Oh, we can do that.” Kendall started improvising and the orchestra joined in. “He was fiddlin’, the orchestra gets into an A minor groove as the back-up band,” Cathy says, “and the audience did love it.”

Music for Important Occasions

For these Asheville Symphony musicians, the music matched the emotion.

The importance of music in our lives is nowhere more obvious than when we choose it to accompany important occasions. Sometimes joyous (for a wedding), sometimes solemn (for a funeral), music celebrates and comforts.

Several Asheville Symphony musicians remember concerts when the music matched their own joy or sadness.

Bass player Vance Reese’s father was in the hospital the week Vance was preparing for a performance of Carmina Burana. “In fact he died the weekend of this particular concert,” Vance says. “It was one of Daniel’s first concerts and we were doing the first part, ‘O Fortuna.’”

Vance didn’t know all the words, but he knew the gist: “O Fortune, like the moon, you are changeable, ever waxing and waning.” He says he was sensing “in a very palpable way the ticking of the clock, how we are alive one moment, dead the next, healthy one day, not healthy the next. And here’s this unrelenting music that drives that.”

Vance remembers feeling angry and “wanting to fight fate, fight that cycle.” Then he realized that the rest of Carmina Burana “does support life. There’s love and laughter and drinking and bawdiness and funniness.” It was a performance, he said, that “stuck in my head for the changes in my family.”

Baby music

An earlier performance also marked a change in Vance’s family, this one happy. His wife Jean played the cello for the Symphony, starting about the time he began playing bass. She was pregnant with their son, Jonathan, during a November 1999 concert. “We were playing the 1812 Overture about a month before he was born,” Vance remembers, “and she felt Jonathan kick inside her when the drums went off. She realized that was her last concert for awhile. That ‘awhile’ has been ten years now.”

Horn player Michael Brubaker recalls his wife had a similar experience. He was playing with the Savannah Symphony and she was the personnel manager. They were awaiting their first child during a performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. “My son was kicking along to the beat,” Mike says.

Cellist Patricia Koelling Johnston may take the “Playing While Pregnant” prize. She’ll never forget the Symphony’s 1981 Valentine concert, when they were featuring Stravinsky’s The Firebird. She was expecting her first child.

“I remember this very clearly,” she says, “as I started having mildish contractions every five minutes late in the afternoon before the concert. Being good Lamaze parents-to-be, my husband and I had the hospital bag packed.” They arranged a signal: Pat would drop a handkerchief on stage if things progressed, and he would retrieve the car.

She was confident, she says, because the principal horn, Tom English, was a surgeon, so care was close if necessary. The contractions continued and strengthened through The Firebird. “The cello part is difficult enough to create distractions!” Pat says. “Thankfully, Jay allowed me to finish the concert before making his entrance into the world.” She and her husband went to the hospital about midnight, and Jay was born Sunday afternoon.

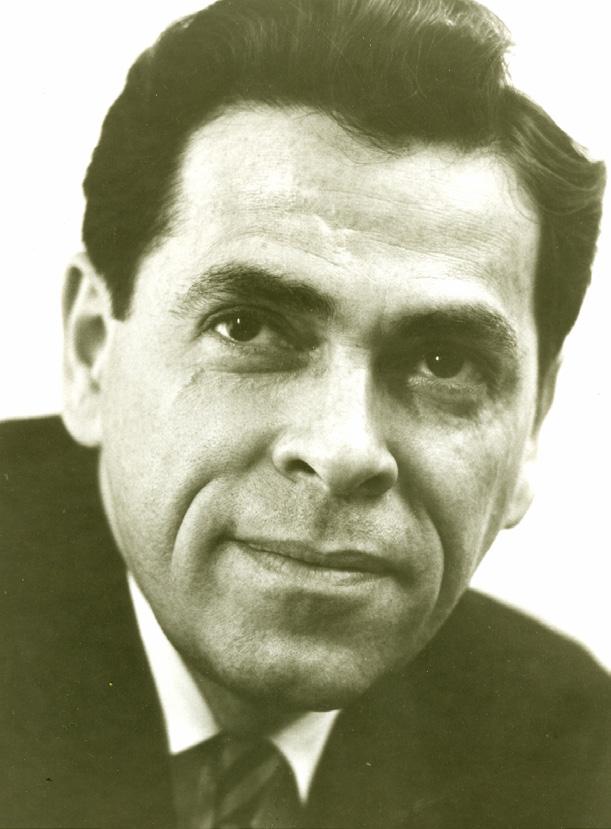

Robert Hart Baker

Conversations with Conductors: Part I

Robert Hart Baker talks about his 23 seasons as Music Director of the Asheville Symphony and why he wears a moustache.

Robert Hart Baker became the Asheville Symphony’s first full-time music director and conductor in residence in 1981 and guided its musical coming-of-age for 23 seasons. During his tenure, he took the Symphony from a semi-professional orchestra of about 40 players to a fully professional ensemble of some 80-100 members. He became Conductor Laureate at the end of the 2004 season.

A cum laude graduate of Harvard University, Bob studied privately with Leonard Bernstein. He then received master’s and doctoral degrees from the Yale School of Music. He also studied with Herbert Von Karajan at the Salzburg Mozarteum in Austria. Before he came to Asheville, he was living in New York City and conducting the New York Youth Symphony at Carnegie Hall and the Connecticut Philharmonic Orchestra, which he helped found.

Bob recalls that after he applied for the Asheville position, two members of the Symphony’s search committee, Tom Bolton and Mack Day, came to New York to interview him and hear him conduct in Connecticut. They then invited him to Asheville to participate in auditions.

As Bob tells the story, his father’s insurance agent was also the agent for Aaron Rosand, a famous violinist and something of a rival to Isaac Stern in the concert world. The agent knew Rosand had recently played in Asheville and suggested Bob go see him for advice.

“So,” Bob says, “I went and said, ‘Mr. Rosand, I’m a young conductor and I would like to get a professional orchestra outside of New York. I’m reaching the point where I can’t spend the time building my own Connecticut orchestra, and the youth symphony is the kind of job you should move on from.’” He asked Rosand if the violinist would give him a coaching session.

Rosand said, “You don’t need any lessons from me, you’ve got good training. But you just don’t look the part. You’re 24 years old, you look like you’re 16, they’re never going to hire you.”

Bob said, “What do I do?”

“Look at me,” Rosand said. I’m a so-so looking guy, but I have a beard and a goatee, I look very European. When people look at me they think I’m an artist right away, because I look the part. You need to grow some facial hair. How about a moustache?”

Bob said, “Fine, if that’s what it takes, I’ll grow a moustache.”

So he grew the moustache and joined four candidates for auditions in Asheville. Each had about 30 minutes to rehearse the Symphony with a section of Handel’s Water Music. The piece, Bob says, “has string parts that are not really hard, you just have to play them in tune. But it has outrageously hard French horn parts. So we were all conducting, and the horns were having a problem. Nothing sounded very good.”

As the candidates were leaving Thomas Wolfe Auditorium, they passed members of the board and other players seated at the back. Bob heard a whispered, “Well, which one did you like?” The whispered reply: “I like the one with the moustache.”

So the one with the moustache got the job. “I swore at that point,” Bob says, “that if I got the Asheville Symphony job with my moustache, I would not shave it off. And as long as I had a conducting job, I would not shave it off. That would be a bad luck sign.”

Abbey Simon

First concert

The moustache may have brought him good luck, but Bob might have wondered if his luck was holding when two near mishaps almost derailed his first full concert here.

Pianist Abbey Simon was to be the guest soloist. Bob says, “I worked out with his agent to do the Brahms First Piano Concerto, which is a major, major work. I sent a note out to the airport saying, ‘Welcome to Asheville, Mr. Simon, looking forward to our Brahms.’” Unbeknownst to Bob, Simon had written down in his schedule book that he was to play Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto.

In those days before cell phones, Simon went immediately to an airport payphone and called the Symphony office. “This is Abbey Simon. I want to talk to this Baker guy.” Bob got on. Simon said, “What do you mean sending me a note saying we’re playing Brahms. We’re doing Beethoven.”

Bob said, “Mr. Simon, if you’ll look at your contract, it says we’re doing Brahms’ First Concerto.”

“No, it doesn’t. I’m going to call my agent on this other pay phone.”

Still connected to the Symphony office, he called New York. Bob heard him say, “This is Abbey Simon. What town am I in and what am I playing?” The agent said, “You’re in Asheville and you’re playing Brahms.” Bob heard Simon say, “Holy – .” Then he got back on the line with Bob: “What do we do?”

Bob said, “Mr. Simon, you have a choice, either the Asheville Symphony can try to learn the Beethoven Fourth Piano Concerto in one night, or you can relearn the Brahms Concerto in one night. Take your pick.”

Simon said, “Can you get me the sheet music to the Brahms?”

“Yes.”

“Ok, have it delivered to my hotel room and I’ll play the Brahms.”

As Bob remembers it, the orchestra’s pianist drove to Charlotte to pick up a copy of the Brahms Concerto, Simon refreshed it, and he did the concert. “This was a guy who was famous for having a temper,” Bob says,”but we got along fine, he was lovely.”

Simon did manage to have a little fun at Bob’s expense. At the reception after the concert, Bob introduced him as “a man who plays everywhere from London to Oshkosh.” Simon replied, “Robert, I don’t want you to put Oshkosh at the back end of that equation. I’ve played Oshkosh, it’s a very nice city, it’s the complete equal of Asheville and you shouldn’t put it down.”

Bob’s second hurdle for his first concert was an Asheville policeman who stopped him on the way to the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. “I had burned up the engine in my Volkswagen driving from New York to Asheville,” he says, “so I had a big old renta-wreck with bald tires.” He was driving down Merrimon Avenue at dusk, about 7:30, dressed in his tails for an 8:15 performance.

“There was a blue light behind me,” Bob says, “and a policeman stops me. The policeman came over and said, ‘You’ve got bald tires and you’re kind of weaving down Merrimon, so I think you’ve been drinking.”

He asked Bob to get out of the car and walk a straight line. Then he said, “Touch your nose.” Then, “Breathe into my nose.” “They didn’t have breathalysers then,” Bob says, “so I blew into his nose and there’s no alcohol.” The policeman said, “You haven’t been drinking. So why are you wearing a party suit?”

Bob said, “It isn’t a party suit. In about a half an hour I’m supposed to be giving the downbeat for the opening of the Asheville Symphony season at the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium.”

The policeman said, “We don’t have a symphony around here.”

Bob said, “Oh, yes, you do, you have an Asheville Symphony.”

“Why are you driving a car with bald tires?” Bob showed him the rental agreement and said, “I don’t mean to rush things, but if I don’t get going, I’m going to have a thousand people mad at me for being late to my own concert.”

The officer said, “Well, I’m going to write you a citation. Now you don’t drink and drive.”

“No, sir, I certainly won’t.”

“Because if you keep driving like you’re driving, you’re going to pick up more cops between here and there.”

First challenges

Other than a pianist who came prepared for the wrong piece and a policeman who wondered why a guy in white-tie-and-tails was driving an old car with bald tires, what were the first challenges for the Symphony’s new music director?

“There were three things we had to do right away,” Bob says. The first was to let the 40 or so players, some of whom had different ideas about how the Symphony should progress, know there would be a single vision for the group. “I let them know that they would be paid, that we were going to professionalize the orchestra and that we would have professional standards.

This meant re-auditioning all the musicians. “The new kid on the block gets one chance to reaudition everybody,” Bob says, “before you start having baggage or the feeling that somebody knows somebody or it’s fixed. I had a clean slate.”

He heard everybody play and placed them where he thought they should be. “I was very objective because I was brand new,” he says. “So that gave everybody a sense that we would have a musical clean start.”

Bob found a mix of professional-level players and amateur players. The next thing was to establish technical standards for each of the instruments so the orchestra could play the full range of the concert repertoire.

“For instance,” Bob says, “in the violins, I insisted that everybody learn how to balance the bow so they could play staccato music.” This was preparation for the first concert’s performance of Rossini’s Semiramide Overture, which requires balancing the bow. “After that overture, which was our first piece,” Bob says, “the place went nuts, because all of a sudden it sounded like a real orchestra. It wasn’t perfect, but that was a new thing.”

Robert Hart Baker addressing the Symphony

In the brass section,” he says, “We were insisting that people play in a way that they weren’t missing notes all the time. They had to improve their accuracy. These were all the nuts and bolts part of the Symphony that we had to get going right way.”

Did he have to weed people out?

“I didn’t actually throw anybody out,” he says, “but we did what is called reseating, where the weaker players went to the back of the section. If they couldn’t learn the music in time for the concert, they wouldn’t play.” To help the process, he began holding rehearsals every Monday, whether there was a concert or not. The players could in effect take lessons on music new to them, so they could master it by concert week.

When he began, Bob says, the Symphony sounded like a typical community orchestra. “Nobody likes to be called a typical community orchestra,” he says, “meaning that when you came to a concert, you’d hear funny notes in the violins, you’d hear funny notes in the horns, you’d just hope they’d get through the pieces. Sometimes we’d kill a Mozart piece, sometimes we’d play a Mozart piece alright.”

Bob took the long view. He knew it would take 10 to 15 years of training to get to a level of consistency that marks a professional orchestra. There was no music school in Asheville, so the Symphony became its own training ground for its players. “That’s what we had to do,” he says.

When did the Symphony reach the professionalism he aimed for? How did he know they were there?

“We reached that point in this orchestra by the early 90s,” he says. “When we started playing certain pieces for the second time, when we started doing pieces like Beethoven Nine, Carmina Burana, the Mahler symphonies, the Prokofiev symphonies, things that were really big time repertoire, then I knew that we had made it.” Another test, he said, was when people heard the Symphony on recordings broadcast on WCQS. “If you heard us on the radio,” he says, “we sounded like a real orchestra.”

More challenges

While bringing the musicians up to a professional level, Bob’s second challenge was to expand the repertoire. “To build an orchestra,” he says, “you have to cover all of the major pieces by all the major composers over time. That’s the way the orchestra really learns how to play in style. When the orchestra can handle the Classics, Hayden, Mozart, Beethoven, then you move into the Romantics, then you move into the Moderns. Then you have the ability to really play.”

Knowing the major repertoire, Bob says, gives the orchestra what he calls “a residual memory.” The music is “in their blood,” he says. “That gives you that sense of confidence in the concert.”

While the broadened repertoire helped the players’ musicianship, it also increased the audience’s expectations. “My job in the first two-thirds of the time I was here,” Bob say, “was to train the orchestra and also to expose our audience to a great variety of great music, so that they were more sophisticated listeners.”

Again, he took the long view. “The idea when I came here was that we would perform over the course of time the nine Beethoven symphonies, the four Brahms, the major Dvoraks, the major Tchaikovskys, the Strauss tone poems. We ended up doing five of the Mahler symphonies. I had the luxury here of being able to program as I wanted to so that we would cover the gamut.”

While he was honing the orchestra’s skills, expanding its repertoire and increasing the audience’s musical sophistication, he also helped build the audience’s size. “Thomas Wolfe is a large auditorium,” he says. “Filling it is like trying to fill Carnegie Hall without being in the same-sized city. And that’s a task. Music is so expensive to do, you’ve got to really fill the place to make it go.”

In planning his concerts, Bob stuck to the standard format of overture, concerto and symphony, “like a typical three-course meal,” he says. But he always tried to have a theme or connection between the pieces. After a while, the Symphony started giving each concert a thematic name. “But even before we named them,” he says, “I would find a program, for instance, where one composer had studied with another or one was friends with another.”

He also looked for music with a connection to Asheville and Western North Carolina. “Over the years we did three or four pieces by Caryl Florio, the resident composer at the Biltmore House at the turn of the 20th century. We did some Lamar Stringfield. Béla Bartók lived in Asheville, so we made sure we did some Bartók. Anything that showed the audience we cared about this area and their cultural environment, we would try to work into a concert.”

When Bob began in Asheville, there was a strong core audience for the Symphony of about 600 people. By the time he left, that core had grown to about 1,500. “And we were getting attendance up close to 2,000 for some concerts,” he says.

To build that base, the Symphony improved the ways it reached out to the community. “We improved our brochures, we did much bigger mailings,” he says. “There was an ongoing campaign where I and others would go around and talk to groups. I would visit Lions Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, garden clubs. I would let them know the Asheville Symphony is your symphony.”

He says it was a little like a political campaign. “You’d meet two, three, five, ten people at a time, you’d shake hands with them and you’d say, ‘I’d like to see you at the Symphony.’ We’d also say things like, ‘You’ve probably heard great classical music in movies and on television but you didn’t know you’d like it. You need to give the Symphony a try.’”

Memorable music

Ask Bob what his most memorable musical moments are from his time with the Asheville Symphony and he quickly lists choral concerts: an opera highlights concert (“We had a wonderful tenor singing Nissan Dorma”), Carmina Burana, Beethoven’s Ninth and Verdi’s Requiem, which he conducted twice.

The choral concert came in the spring, during allergy season, which made one program memorable for another reason. “Some of the out-of-town singers would come and get all full of the yellow pollen,” he says. “It wasn’t too good for the vocal chords.” British-born soprano Lindsey McKee was guest soloist along with a mezzo soprano that Bob does not name. “The mezzo could not get a single note out of her throat in the concert,” Bob says, “so Lindsay sang both the roles, soprano and the alto. The other singer lip-synced and no one was the wiser. It was one of the most amazing vocal performances I’ve seen.”

Bob says that many guest soloists are among his great memories. His list of favorites includes a young Paul Neubauer, who later became principal violist for the New York Philharmonic; cellist Carter Brey, Bob’s Yale classmate who became principal cellist of the New York Philharmonic; mezzo-soprano Jennifer Larmore who sang with the Symphony in the early 80s before she went on to become a star at the Metropolitan Opera; pianist Eugene Istomin who brought his own piano in a truck; pianist Ruth Laredo; and Aaron Rosand, the violinist responsible for the Baker moustache.

He also enjoyed solists from the pops and jazz world. When Dizzy Gillespie was guest artist for Bob’s first pops concert, the young conductor wasn’t as familiar then with jazz as he is now. (His wife, Barbara Duvall Baker, is a flutist and jazz vocalist.) “It was quite daunting to put together his progressive be-bop jazz charts with the Symphony,” he says. Although I like jazz, at the time it was pretty new to me.”

The concert was to include Gillespie’s big numbers: “Night in Tunisia” and “Salt Peanuts.” Gillespie said, “All right, Robert, start ‘em up.”

Bob recalls, “I gave what was basically a classical-looking upbeat to the music. And he just looked at me.”

Gillespie said, “What was that? You can’t expect me to play after you do that.”

“What do you mean?”

He said, “You’ve got to count it off. You’ve got to go, ‘a-one, ‘a-two, ‘a-one-two-three four.”

“So I got my little dressing down from Dizzy Gillespie,” Bob says, “and everything was fine after that.”

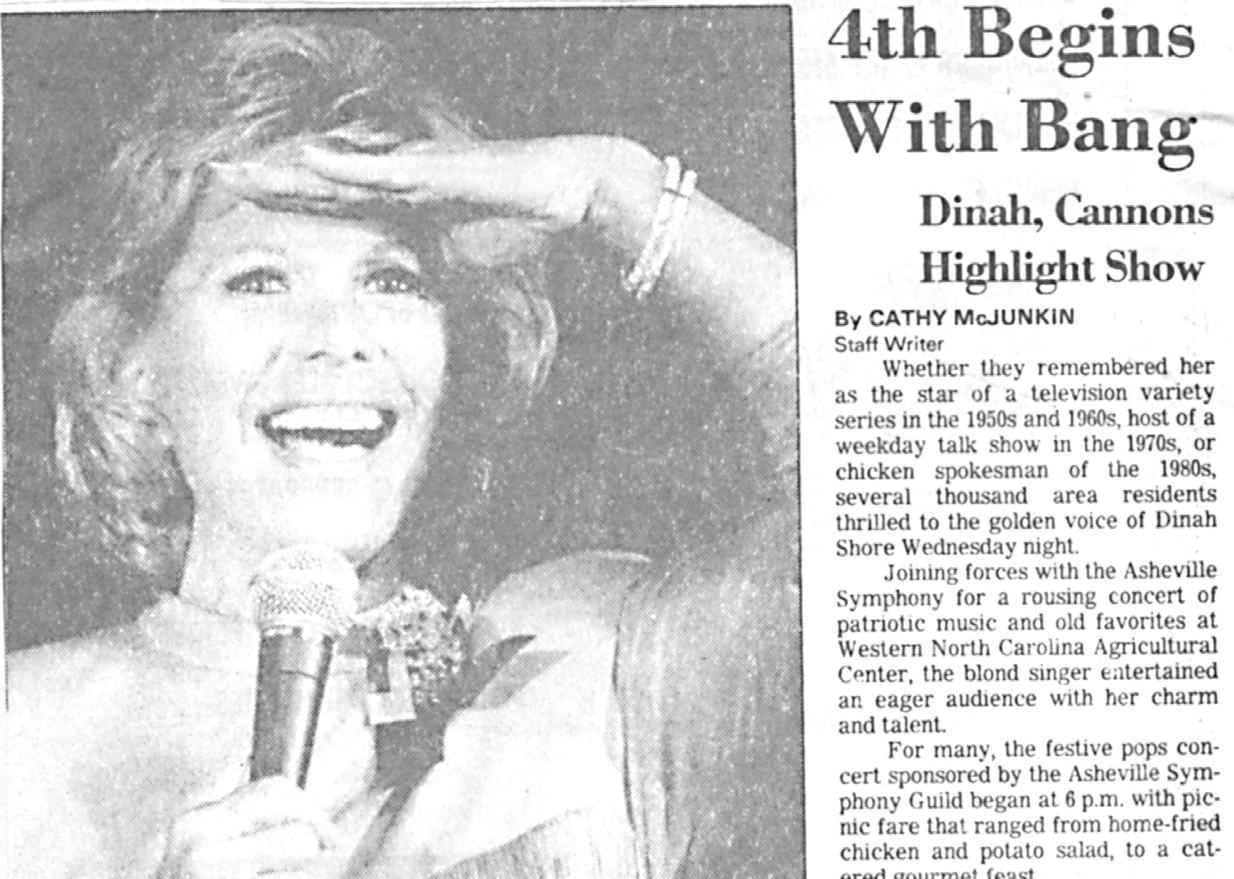

His experience with Dinah Shore was more reassuring. At the time of her pops concert with the Symphony at the Western North Carolina Agricultural Center, she had an ongoing relationship with Burt Reynolds, 20 years her junior. Shore took some questions from the audience, one of which was, “How’s Burt, and what do you think of younger men?” She replied, “I think younger men are great,” and leaned over and gave Bob a big kiss.

With all the guest artists, Bob says, “it was always a great musical education for the orchestra and for me. We would invite them to give us feedback, to tell us how they wanted to play it, how to shape it, so that our musicianship would be improved.”

The Guild produces a hugely successful concert, “Picnic with Dinah” Courtesy of Asheville Citizen-Times