The Asbury Journal

From the Editor

Robert A. Danielson

11 New Additions to the Archives and Special Collections: John Wesley Letter and Possible Samuel Wesley Letter

Robert A. Danielson

21 Knowing What to Eat and When to Eat: Reading the Food Offering Text (1 Corinthians 8:1-11:1) from a Myanmar Christian Perspective

Hram Hu Lian

Hram Hu Lian

86 Freemasonry and the Methodist Episcopal Church in the Nineteenth Century

Nicholas M. Railton

139 Theory and Practice in John Wesley’s Critique of Calvinism: A Philosophical Examination

Walter Stepanenko

162 Defying Death: Abraham and Moses in Jewish Antiquity

David Zucker

179 Irene Blyden Taylor: God’s Apostle to Nevis

Robert A. Danielson

215 Charles Wesley and the Jews

Nicholas M. Railton

Features

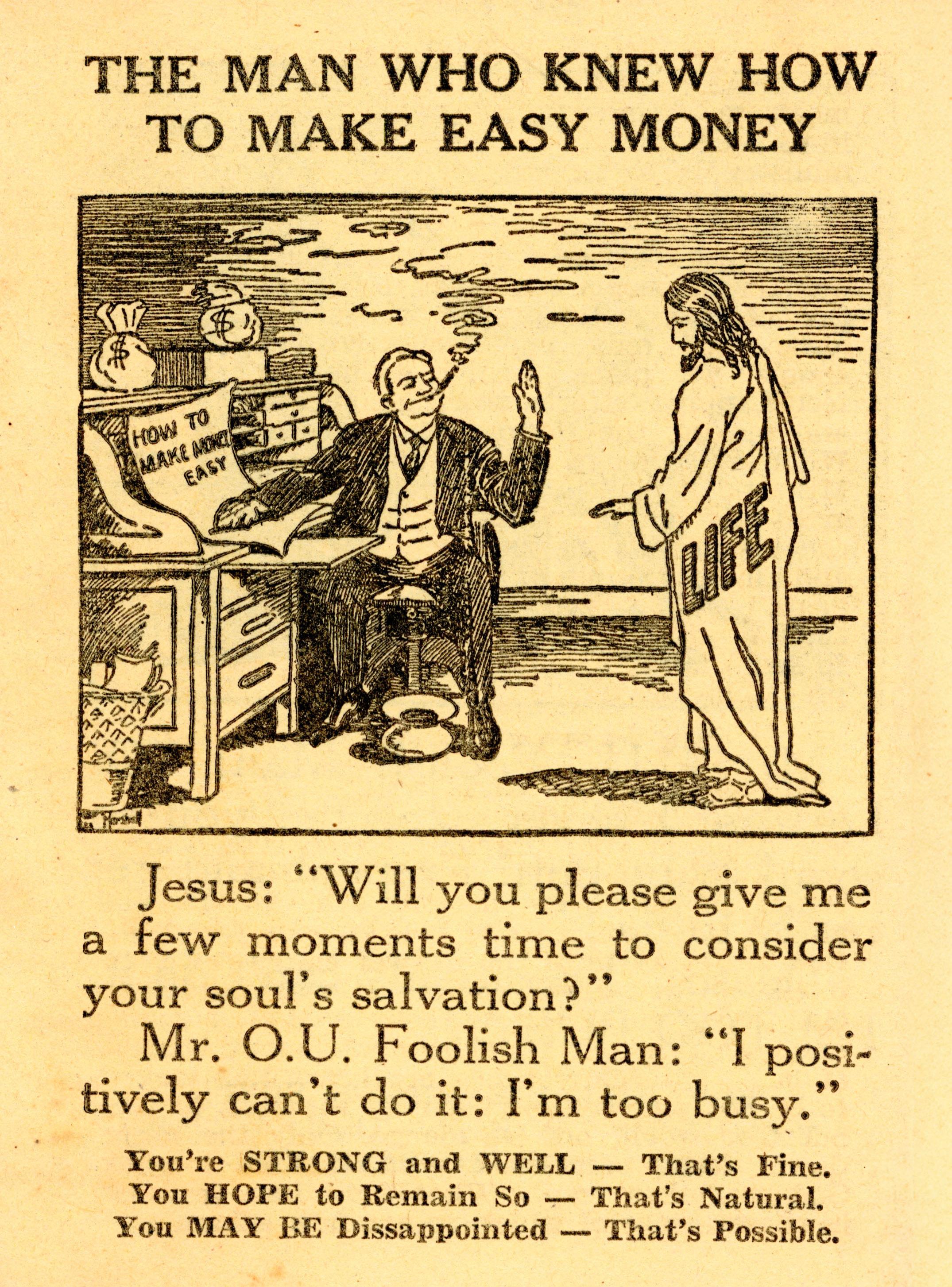

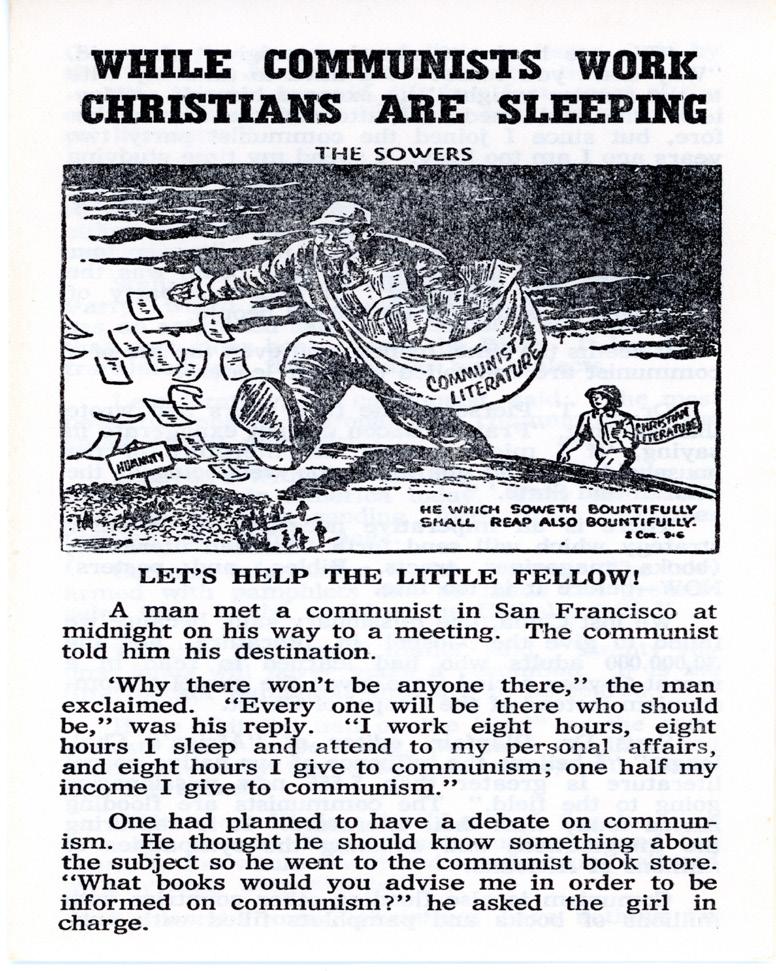

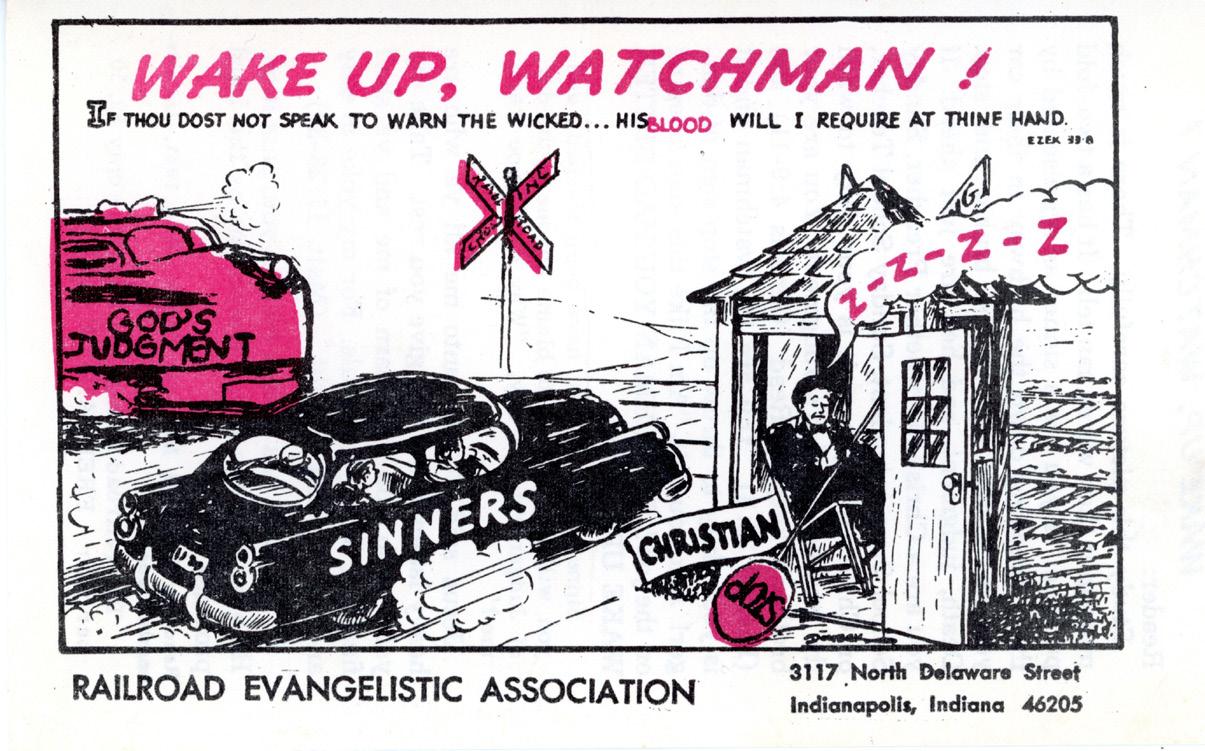

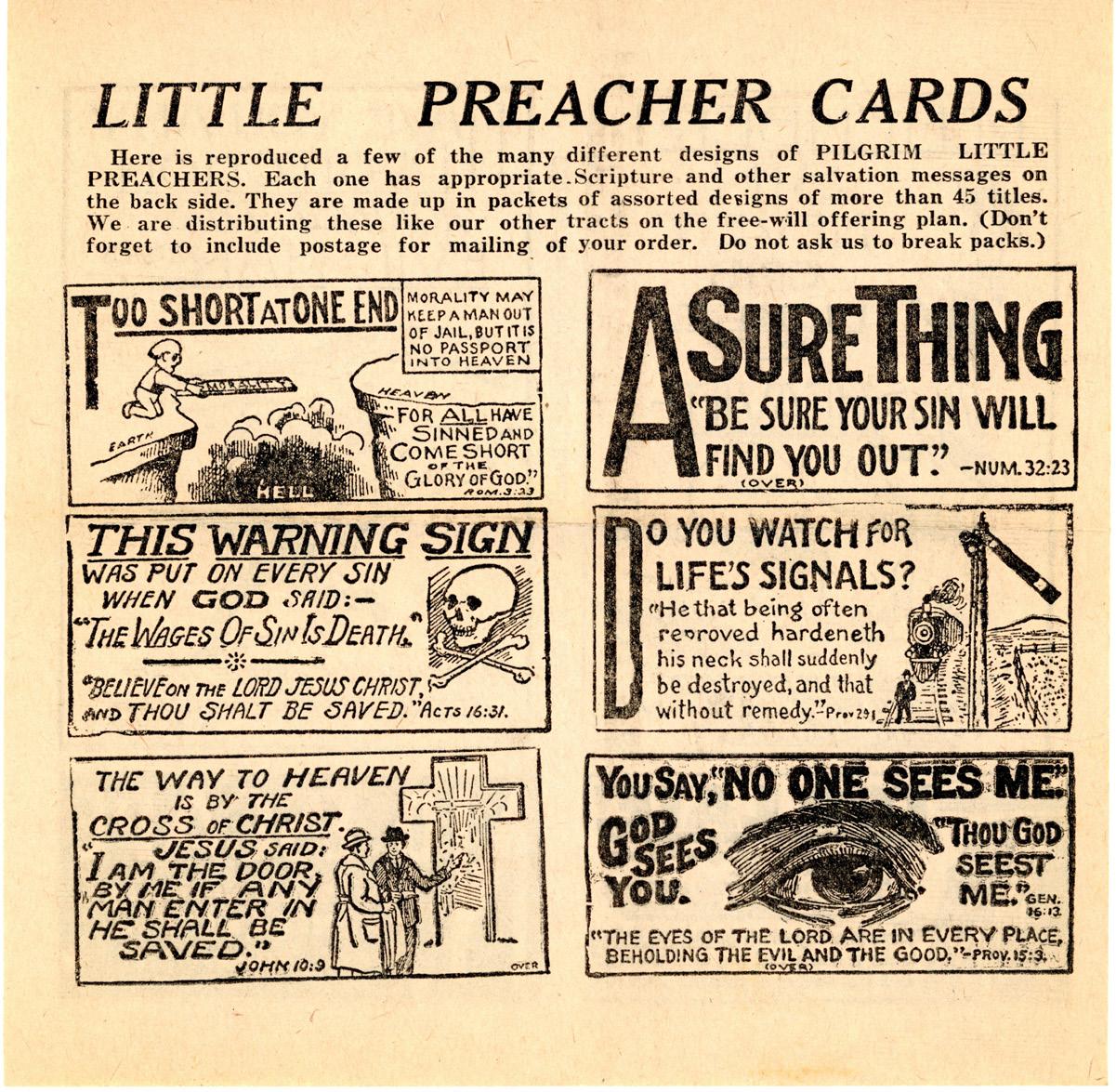

254 From the Archives: The Robert A. Danielson Collection of Christian Tracts and Pamphlets- “Little Preachers” of the Gospel Message

270 Special Book Essay: Thomas Oord on “The Death of Omnipotence”: “Not Born of Scripture”: Dwight D. Swanson

285 Book Reviews

291 Books Received

David

J.

Gyertson

Interim President and Publisher

John Ragsdale Interim Provost

The Asbury Journal is a continuation of the Asbury Seminarian (1945-1985, vol. 1-40) and The Asbury Theological Journal (19862005, vol. 41-60). Articles in The Asbury Journal are indexed in The Christian Periodical Index and Religion Index One: Periodicals (RIO); book reviews are indexed in Index to Book Reviews in Religion (IBRR). Both RIO and IBRR are published by the American Theological Library Association, 5600 South Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, and are available online through BRS Information Technologies and DIALOG Information Services. Articles starting with volume 43 are abstracted in Religious and Theological Abstracts and New Testament Abstracts. Volumes in microform of the Asbury Seminarian (vols. 1-40) and the Asbury Theological Journal (vols. 41-60) are available from University Microflms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106.

The Asbury Journal publishes scholarly essays and book reviews written from a Wesleyan perspective. The Journal’s authors and audience refect the global reality of the Christian church, the holistic nature of Wesleyan thought, and the importance of both theory and practice in addressing the current issues of the day. Authors include Wesleyan scholars, scholars of Wesleyanism/Methodism, and scholars writing on issues of theological and theological education importance.

ISSN 1090-5642

Published in April and October

Articles and reviews may be copied for personal or classroom use. Permission to otherwise reprint essays and reviews must be granted permission by the editor and the author.

The Asbury Journal 80/1: 6-10

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2025S.01

From the Editor

This issue of The Asbury Journal is dedicated to the memory of Hram Hu Lian (May 22, 1982 – June 2, 2024). Hu Lian was a Ph.D. student at Asbury Theological Seminary in the area of Biblical Studies with a concentration in the New Testament. He was from the country of Myanmar and also worked in the Archives and Special Collections of the B.L. Fisher Library. I knew Hu Lian from his work in the archives, but also as a student. When he was almost fnished with his coursework, he needed one more class during the summer, and so he arranged to do an independent study with me on the Anthropology of Food and Buddhism in Myanmar. He was hoping to make this a key part of his Ph.D. dissertation. Part of his work for that study was to produce a publishable article. I told him at the time that I would like to publish it in The Asbury Journal, but it needed a little editing work. Sadly, he never had time to do that work, and so I have done some basic editing and his paper is in this issue of The Journal, both in English and translated into Burmese, the principal language of Myanmar, by a friend and classmate, David Lian. (Special thanks to David for this work in honor of Hu Lian.) I feel this article can help perpetuate some of what Hu Lian was trying to accomplish with his Ph.D. work, and I pray that his work will continue to strengthen the work of the Church in Myanmar.

Perhaps more than this paper though, I remember our weekly meetings when Hu Lian was so worried about the state of his country, Myanmar, which was involved in civil unrest, and the safety of his wife and children. He was working hard to get them out of the country, and so we often prayed for their well-being in those meetings. I remember the joy in his face when I saw him in the parking lot after the class and he introduced me to his wife and children, after they had arrived safely. It was a wonderful answer to our prayers.

I also remember Hu Lian’s work in the archives, where he had become the person who knew how to do everything. He was the expert when you needed something. Often, many of the images you see in the “From the Archives” essay for the past few years, were scanned by Hu Lian.

When he became unexpectedly ill and was hospitalized, the entire archives had to fgure out how to do many things which had always fallen to Hu Lian. We still grieve his loss as a co-worker and as a friend. Our prayers and thoughts continue to go out to his family, and especially his children who he deeply loved and cared about.

In Memory of Hram Hu Lian (May 22, 1982 – June 2, 2024)

It is somehow suitable, given Hu Lian’s work in the archives, that we start this issue of The Journal announcing some important new gifts to the Archives and Special Collections, including a signed letter of John Wesley’s and a possible letter of Samuel Wesley, along with other Wesleyana. This is followed by Hram Hu Lian’s paper in English, followed by the same paper translated into Burmese. In this paper, he is seeking to relate Paul’s advice on eating meat offered to idols with the real practical theology of Christians in Myanmar who often interact with their Buddhist neighbors, and these interactions often involve issues of eating together at

social events, many of which have religious connotations. Hram Hu Lian is aiming to fnd biblical support to encourage increased interactions between Christians and Buddhists, while also remaining true to scripture.

Nicholas Railton presents the next article which examines the history of Freemasonry within Methodist circles in the 18th century. While some groups, like the Free Methodists rejected ties to secret societies, the Methodist Episcopal Church appears to have embraced these connections. Railton raises the types of concerns these connections caused, and in a well-documented article seeks to increase research interest in this topic.

Walter Stephanenko uses the debates between Wesley and Calvinist opponents to examine how Wesley’s view of theory and practice worked together in terms of his theology. He is less concerned with the traditional theological arguments and more interested in the process which Wesley used to both address theological and practical concerns among the Methodists.

Rabbi David Zucker joins The Asbury Journal again in this issue with a fascinating examination of Jewish rabbinic sources regarding the death of Abraham and Moses. While only briefy touched on in scripture, understanding the Jewish sources on this topic better helps us understand Jewish views about death in historic times. These rabbinic stories have many similarities as Abraham and Moses both seek to avoid death, and even refuse to go with God’s angels who are sent to bring them to heaven. This look into the topic can help Christians seeking to understand possible early Jewish infuences on Christian views of death as well.

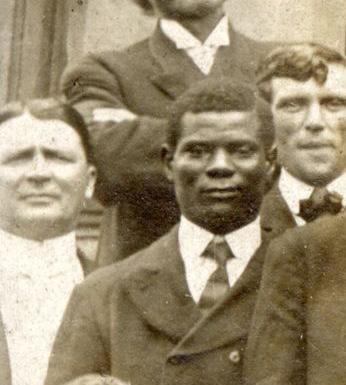

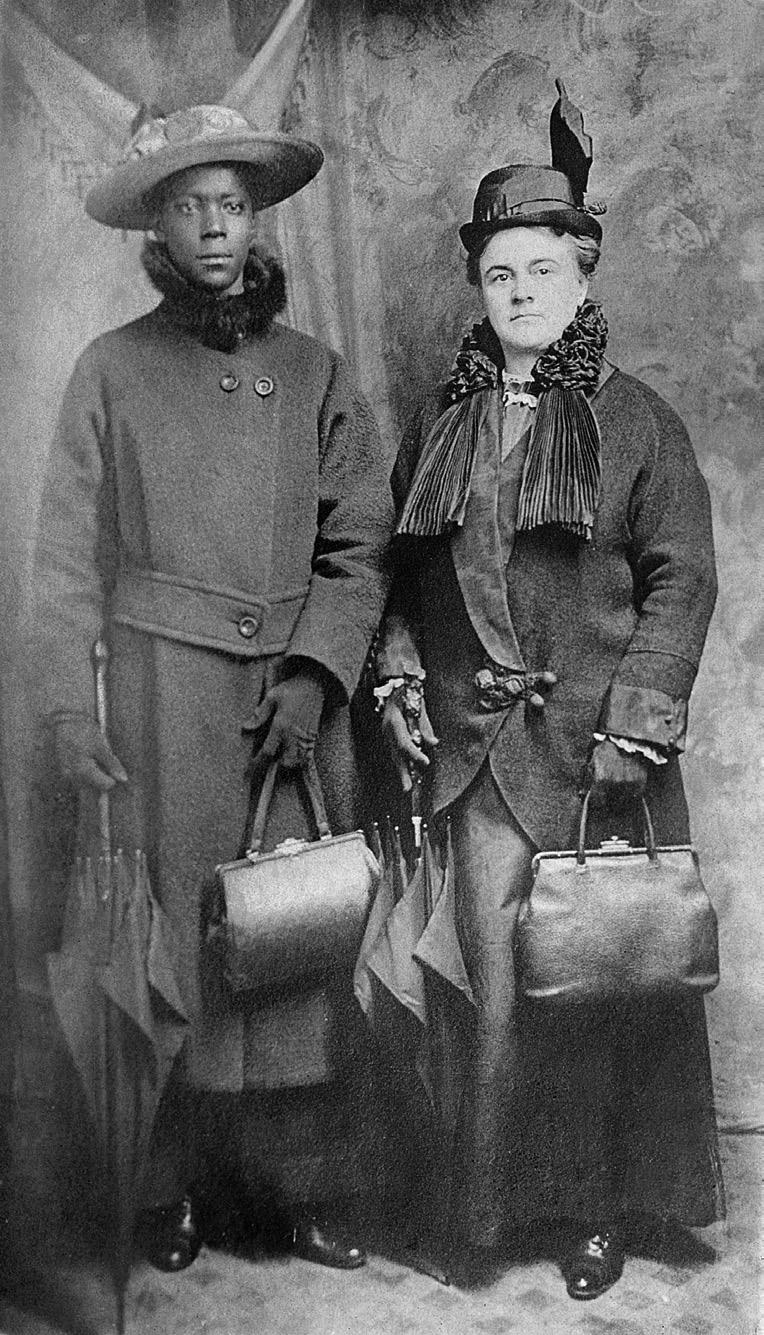

The story of Irene Blyden Taylor is told by Robert A. Danielson in the next article. This little-known story of an early African-American Holiness missionary to the Caribbean is insightful in understanding key missiological principles. Irene worked on the island of Nevis, and due to her work no foreign missionary was ever needed to live on the island. Her work demonstrates the complexity of early Holiness missions in the English-speaking Caribbean, but also shows how God laid the foundation for the Wesleyan Church in the islands through the work of ordinary people who did extraordinary things.

Nicholas M. Railton presents a second article on the views of Charles Wesley of the Jewish people of his day. In particular, he analyzes the anti-Jewish protests of 1753 (triggered by a law to allow citizenship for Jews in England), and a political cartoon from the time which seems to suggest Charles Wesley’s agreement with these sentiments. However, as

Railton points out, the infuence of Samuel Wesley and Charles’ own work suggests that their theology toward the Jewish people was not against the Jews, but rather saw the restoration of the Jewish people to the Holy Land as part of the eschatological views of scripture, and therefore Railton suggests that while some Methodists clearly held anti-Semitic views, it is unlikely that these views were held by Charles or Samuel Wesley. Railton is also encouraging modern Methodists, in Britain especially, to be more refective on their modern views toward Israel in light of the historical theology of the Wesleys.

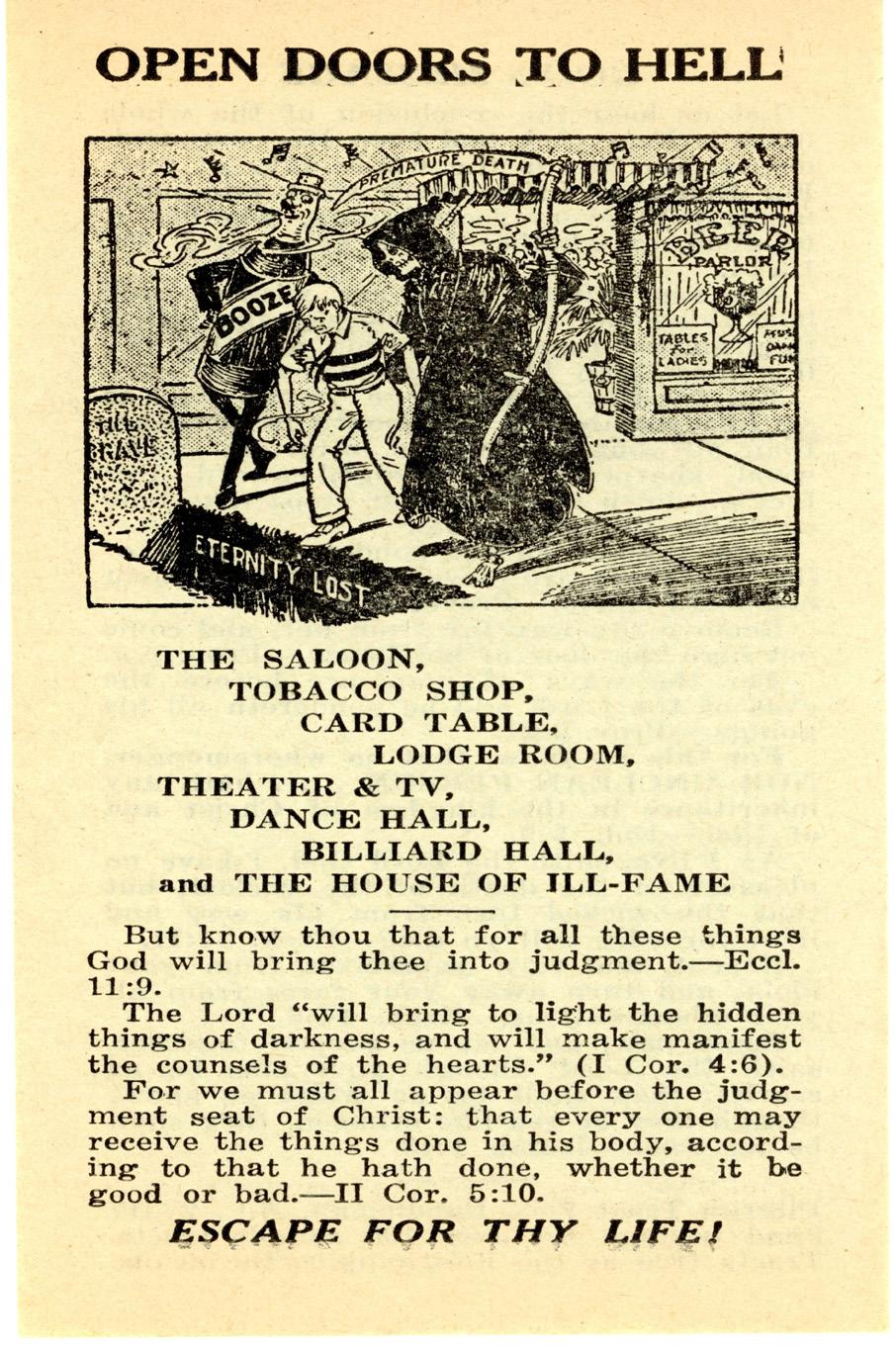

In the From the Archives essay for this issue, I examine the development and use of tracts and their importance for understanding lay theology, especially from the 1920s through the 1970s. This in an area rich for potential research which provides insight into the concerns of ordinary Christians and their spiritual needs. Finally, Dwight D. Swanson presents a special book essay focused on dealing with issues raised in Thomas Oord’s book, The Death of Omnipotence and Birth of Amipotence. Swanson presents strong evidence countering some of the principle themes taken by Oord, particularly in regard to confusing etymology with meaning and translation with interpretation. The use of El Shaddai in Genesis and Job is especially important in Oord’s view for understanding concepts on the omnipotence of God. Swanson argues that Oord’s conclusions lack appropriate scholarly support.

In many ways, this issue of The Asbury Journal is about speaking from the margins. Whether it be from the Church in distant Myanmar and the island of Nevis in the Caribbean, to Methodists opposed to Freemasonry, to Jewish views of scripture and Methodist views of Jews, it is always important to hear points of view from the margins and not just the centers of the Christian world. Even the article on Calvinism is speaking from the academic margins of the philosophy of religion instead of the theological center. The issue of tracts also forces us to examine issues of concern to ordinary Christians, which are often sidelined in academic circles. The margins are an important place in scripture and in the Jewish and Christian traditions. The Jewish people themselves were on the margins of the empires of the ancient world. God chose a people who were slaves in Egypt, defnitely a marginalized people, to form a new nation. The prophets frequently supported the people on the margins. Jesus cared for those on the margins in his day, whether they be despised tax collectors, or lepers,

or sinners rejected by the local religious elite. In his description of the fnal judgement in Matthew 25, Jesus points out that actions done for “the least of these,” those who were hungry or thirsty, strangers, naked, sick, or in prison, would be actions done to Christ himself. Being true Christians means being able to hear and respond to the voices of the poor, the immigrant, the excluded or rejected of society, and bring them the Good News that God loves and cares for them, just as much as for the people at the center. Christian theology and practice must always include the people on the margins. As Jesus quoted from Isaiah in announcing his message in Luke 4:18-19 (ISV),

“The spirit of the Lord is upon me; He has anointed me to tell the good news to the poor. He has sent me to announce release to the prisoners and recovery of sight to the blind, to set oppressed people free, and to announce the year of the Lord’s favor.”

This continues to be our message, even as academics and theologians. We must never become so captured by the center of power that we forget we are sent to the margins, and I pray our academic work as well as our practical ministry will never fail to remember this essential truth.

Robert Danielson Ph.D

The Asbury Journal 80/1: 11-20

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2025S.02

Robert A. Danielson

New Additions to the Archives and Special Collections: John Wesley Letter and Possible Samuel Wesley Letter

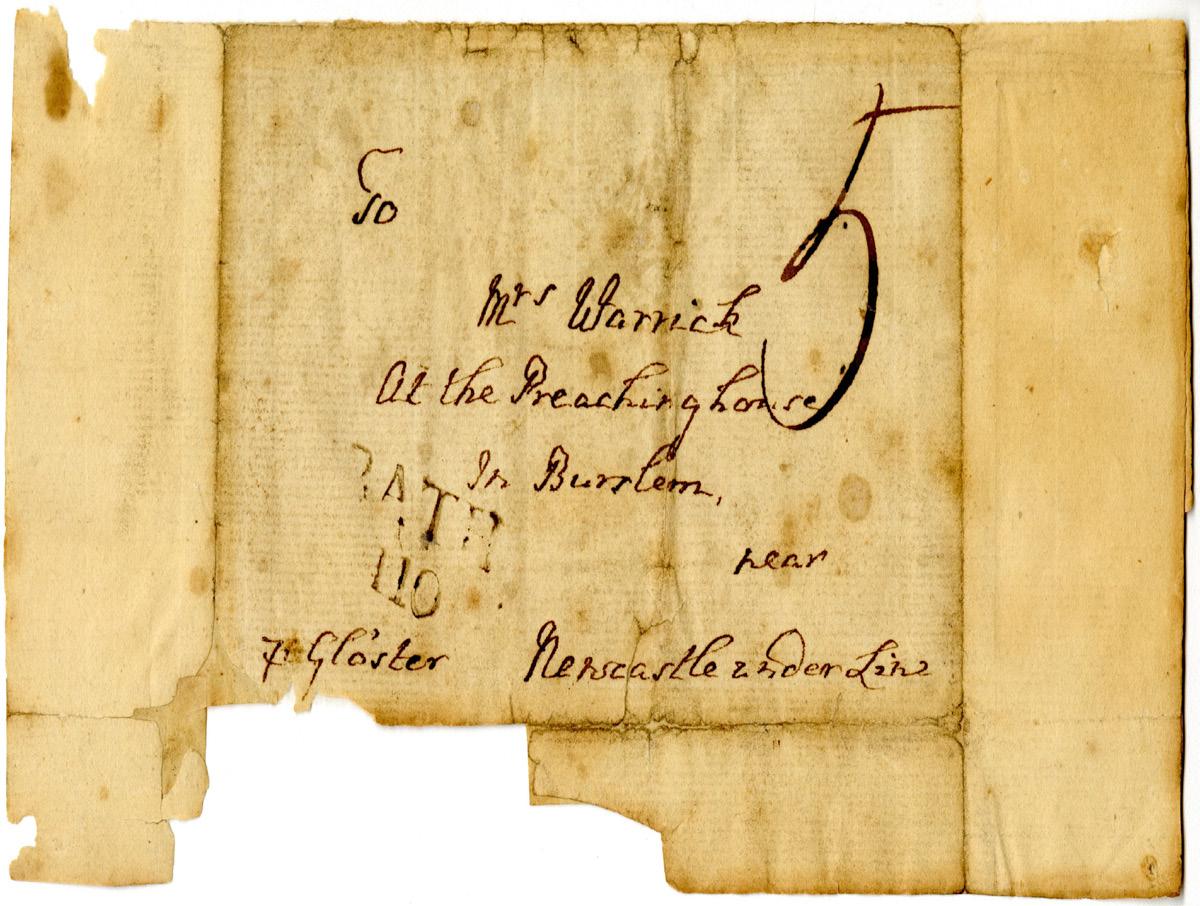

In a generous gift to Asbury Theological Seminary this past winter, Rev. George S. Rigby, Jr. donated a collection of Wesleyana and rare books which he had collected over a lifetime. Of particular signifcance, this collection contained an original letter from Rev. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. This particular letter is well documented and was purchased in 1971 from Charles Sessler, Inc., a noted dealer in rare books and manuscripts. Rev. Rigby shared the letter with Dr. Frank Baker in 1981, when he was the editor-in-chief of The Oxford Edition of Wesley’s Works. In Baker’s correspondence with Rigby, he indicates that Thomas Warrick came as an assistant to Burslem in Staffordshire in August of 1785. Two other young men (one a Samuel Edwards and the other possibly John Robotham) had also turned up as preachers. The two younger men were arguing about who should remain, and one of them, who was married, wanted a house for his wife. Baker noted, “Like Asbury, however, who learned it from him, Wesley didn’t really favour married preachers, and although he did support them from Conference funds, that support was mainly limited to the ‘regulars.’” This letter was also printed in John Telford’s The Letters of the Rev. John Wesley, A.M. (Epworth Press, London 1931, reprinted 1960) volume eight, page 168; however in that publication the year is wrong, listed as 1789. The transcript of the letter records,

Bath Sept 10 1785

My Dear Sister

I know not what to do, or what to say; this untoward man so perplexes me! It is not my business to fnd Houses for Preacher’s wives; I do not take it upon me. I did not order him to come to Burslem: I only permitted what I could not help. I must leave our Brethren to compromise these matters among themselves: they are too hard for me. A Preacher is wanting in Gloucester Circuit. One of them may go thither. I am, with Love to bro. Warrick

My Dear Sister, Your Affectionate Brother

J Wesley

Image of the John Wesley Letter Donated to Asbury Seminary (Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

Addressed: To Mrs Warrick At the Preaching House In Burslem, near Fr Glo’ster Newcastle under Lain (possibly Newcastleunder-Lyme)

Image of the Cover of the John Wesley Letter (Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

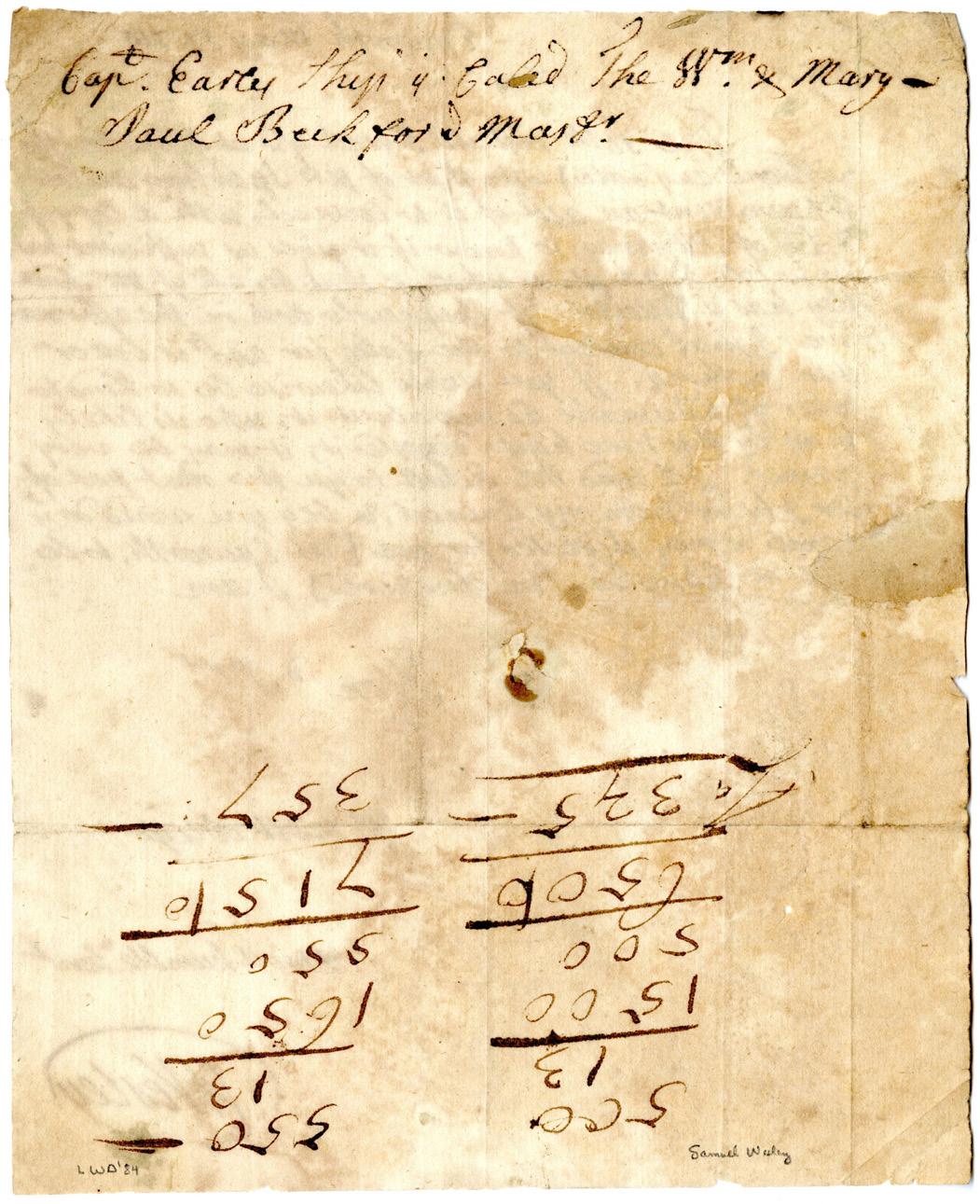

The other letter with possible historical signifcance is a letter reportedly from Samuel Wesley, although it has not been authenticated. It appears to have come from the collection of autograph letters and historical documents of Alfred Morrison, who was a well-known collector of such materials in the 19th century. It is the documentation from Morrison that attributes the letter to Samuel Wesley. The letter is sent to “Capt. Early Ship is called The Wm & Mary- Paul Beckford Mastr.”

Image of the Back Page of the Possible Samuel Wesley Letter (Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

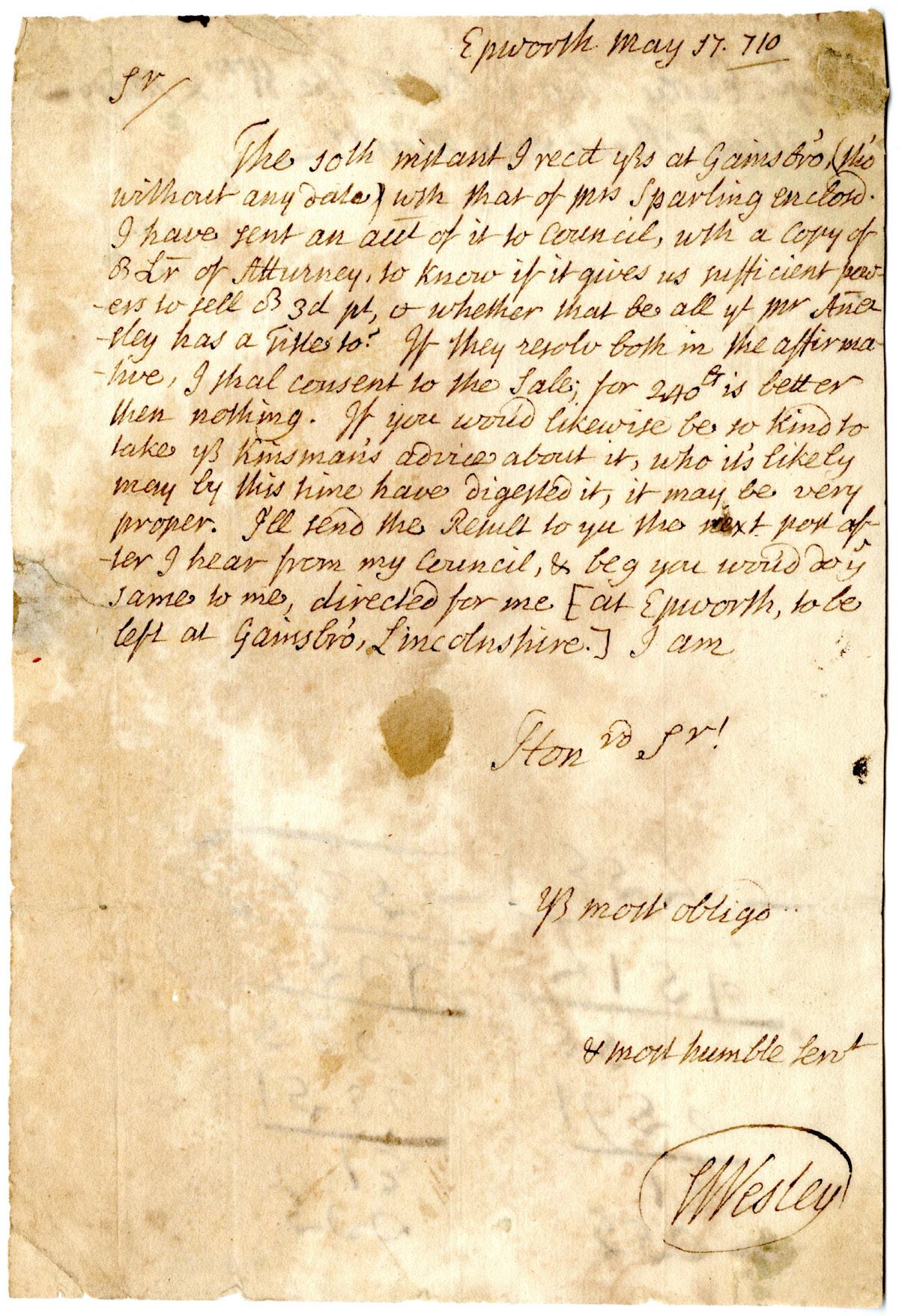

Epworth May 17, [1]710

Sir

The 10th instant I recd yrs at Gainsbro’, (tho’ without any date) with that of Mrs. Sparling enclosd. I have sent an acct of it to council, with a copy of our Ltr of Atturney, to know if it gives us suffcient pow-ers to sell our 3d pt, or whether that be all yr Mr. Ana-sley has a Title to? If they resolv[e] both in the affrma-tive, I shall consent to the sale; for 240 £ is better then nothing. If you would likewise be so kind to take yr Kinsman’s advice about it, who it’s likely may by this time have digested it, it may be very proper. I’ll send the Result to you the next post af-ter I hear from my council, & beg you would do as same to me, directed for me [at Epworth, to be left at Gainsbro’, Lincolnshire.] I am

Honrd Sir!

Yrs most obligd

& most humble servt

S Wesley

Image of the Main Page of the Possible Samuel Wesley Letter (Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

(2025)

Some internal evidence that might support a letter from Samuel Wesley can be seen in the date of 1710, since Samuel became the rector at Epworth in Lincolnshire in 1695. By 1700, Samuel was in serious debt, and this was followed by a number of catastrophes, including the rectory burning in 1702, a crop of fax burning in 1704, being imprisoned for debt in 1705, and the rectory burning again in 1709 with its contents and almost with his son, John. So, a concern about funds makes sense as well. Also of interest, his wife Susanna was the daughter of Samuel Annesley, and the name “Anasley” in the letter could refer to that family and the possibility of selling some type of property for an inherited part.

(Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

Enoch Wood Bust of John Wesley (circa 1800)Gift from Rev. George Rigby

Rev. Rigby’s gift also included around 100 books (with about half of these being older rare texts), several prints, and at least nine older porcelain Staffordshire fgures of Wesley and other collectable items of Methodist ephemera. Of particular note is the Staffordshire bust of John Wesley done by Enoch Woods. The Woods family of Staffordshire potters were followers of John Wesley, and Wesley sat for Enoch Woods in Burslem in 1781 for this image. It was frst released for sale in Leeds at the Methodist Conference in 1781. Wesley considered this likeness by Woods to be one of the best done of Wesley. The bust gifted to the Seminary is inscribed, noting Wesley’s death in 1791. A second issue was made at the time of Wesley’s death, so this bust is from this period or slightly later.

(Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

Black Wedgewood Bust of John Wesley (circa 1904)Gift from Rev. George Rigby

Some Other Staffordshire Figures of Wesley Given by Rev. George Rigby (Used with the permission of the Asbury Theological Seminary Archives and Special Collections)

The Archives and Special Collections, along with the B.L. Fisher Library and Asbury Theological Seminary in general, are grateful for Rev. Rigby’s collection and hope it will continue to encourage scholars studying the Wesleyan Movement in the future.

The Asbury Journal 80/1: 21-40

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2025S.03

Hram Hu Lian

Knowing What to Eat and When to Eat: Reading the Food Offering Text (1 Corinthians 8:1–11:1) from a Myanmar Christian Perspective

Abstract:

Food offerings play a vital role in the socio-religious life of the people of Myanmar. This is mainly because food is served as a part of worship in religious settings (Nat worship, Ahlu pwe, and religious festivals), as well as a part of regular interactions in a social setting (workrelated dinner parties, dinner parties at a Buddhist neighbor’s house, and non-religious social gatherings). In this context, knowing what to eat, and when to eat, becomes crucially important for Myanmar Christians as often times a person encounters various questions in regard to food offerings such as; Should a Christian participate in Buddhist religious festivals? Can he/she partake of food offered the Nats? Can he/she participate in the neighbor’s dāna offering ceremony to witness and share the joy on their meritorious occasions? In the case of a religiously mixed family, should Christian family members share or refrain from both the food and meritorious acts of other Buddhist family members? With these questions in mind, this article is an attempt to read the food offering text of 1 Corinthians 8:1–11:1 from a Myanmar Christian perspective.

This article is divided into three parts. The frst part discusses the socio-religious context of food offerings in Myanmar, highlighting the food offering practices in Nat Worship, popular Buddhism, and religious festivals. The second part discusses the rationale behind the food offering practices in Nat worship (propitiation) and Buddhist religious offerings (merit producing dāna). In the fnal part, the text of 1 Cor. 8:1–11:1 will be examined from a Myanmar Christian perspective, highlighting what types of foods are prohibited, and what types of foods are permitted in various occasions, both in Corinth and Myanmar.

Key Words: Myanmar, food offerings, Buddhism, Nat worship, contextualization

Hram Hu Lian (May 22, 1982 – June 2, 2024) was a Ph.D student at Asbury Theological Seminary from Myanmar in the area of Biblical Studies with a New Testament concentration. This paper was one of his last papers, written for an independent study and focused on the topic he hoped to develop into his Ph.D. dissertation. His unexpected death impacted those who knew him and those he worked with in the Archives and Special Collections of the B.L. Fisher Library. His kind nature, devotion to his family, and his love of God remain a constant memory for those who interacted with him as fellow students, staff, and professors. He will be missed. This article is published in his memory.

Introduction

Food offerings play a vital role in the socio-religious life of the people of Myanmar. This is mainly because food is served as a part of worship in religious settings (Nat worship, Ahlu pwe, and religious festivals), as well as a part of regular interactions in a social setting (workrelated dinner parties, dinner parties at a Buddhist neighbor’s house, and non-religious social gatherings). In this context, knowing what to eat, and when to eat, becomes crucially important for Myanmar Christians as often times a person encounters various questions in regard to food offerings such as; Should a Christian participate in Buddhist religious festivals? Can he/she partake of food offered the Nats? Can he/she participate in the neighbor’s dāna offering ceremony to witness and share the joy on their meritorious occasions? In the case of a religiously mixed family, should Christian family members share or refrain from both the food and meritorious acts of other Buddhist family members? With these questions in mind, this article is an attempt to read the food offering text of 1 Corinthians 8:1–11:1 from a Myanmar Christian perspective.

This article is divided into three parts. The frst part discusses the socio-religious context of food offerings in Myanmar, highlighting the food offering practices in Nat Worship, popular Buddhism, and religious festivals. The second part discusses the rationale behind the food offering practices in Nat worship (propitiation) and Buddhist religious offerings (merit producing dāna). In the fnal part, the text of 1 Cor. 8:1–11:1 will be examined from a Myanmar Christian perspective, highlighting what types of foods are prohibited, and what types of foods are permitted in various occasions, both in Corinth and Myanmar.

The Socio-Religious Context of Food Offerings in Myanmar

Nat Worship

Nat worship is one of the primal religions of Myanmar1 which still dictates much of the religious thought and behavior of the people. The failure of a powerful king, like Anawrahta, who tried to wipe out the religious practices of Nat worship and replace it with Theravada Buddhism in the eleventh century C.E, indicates how deeply Nat worship is rooted in the minds of the people of Myanmar.2 According to Khin Maung Nyunt, Nat worship is broadly defned as the worship of spiritual beings because “‘Nat’ is a derivative from a Pali word ‘Natha’ which means ‘a resplendent being

(2025)

worthy of veneration.’ Nat generally applies to all spiritual beings- devas, gods, goddesses, deities or spirits who deserve worship by human beings for their favor.”3

Traditionally, there are believed to be thirty-seven Nats who intervene with the welfare of human beings. However, various scholars have pointed out that the number can be much higher as the term “Nat” can apply to all spiritual beings.4 In fact, one Burmese scholar placed the number of earthbound-Nats alone around 3705 and there are various kinds of Nats in the Burmese pantheon. Moe Moe Nyunt has classifed them under four categories, namely:

(1) Tasay-Taye or evil spirits who haunt, bring curses, hardships, dangers, and cause mischief in people lives,

(2) Deva-Nats who save and protect good people from danger and other calamities,

(3) Nature Nats who reside in trees, waterfalls, hills, paddy felds, etc.,

(4) Earthbound Nats who are the lords, kings, governors, and rulers of individuals or groups of people, or a set of objects, or certain places.6

The Nat worshippers in Myanmar pay homage, bring offerings/ sacrifces, or sing songs to the Nats in order to appease them. Shrines in the form of spirit houses are erected in various places depending upon the location of the Nats’ habitation (e.g, under trees, on the hills/mountains, etc.).7 There is also a Nat shrine on the family altar (alongside the Buddha image) for the household Nats who oversee the personal and domestic events of the inhabitants such as: health, wealth, marriages, and births, etc. Every Nat shrine is provided with offerings.8 There are also special Nat festivals where the thirty-seven Nats are worshipped.9 Nat-kadaws (spirit mediums)10 are the main practitioners, who are spiritually married to the Nats11 and according to Melford E. Spiro they play various roles in regard to Nat worship; namely they (a) arrange the public Nat ceremonies, (b) present the offering to the Nats, (c) take good care of the Nat shrine (mostly the village Nat shrine at the gate of the village), (d) dance as a service to the Nat, (e) perform private rites on behalf of the clients, and (f) serve as a medium. Thus, he calls them “an oracle, a medium, a diviner and a cult offciant.”12

The Nat devotees present food offerings at every Nat worship or festivals. The devotees offer food and drink at the family Nat shrine or village Nats shrine as a daily ritual. They would also participate in annual regional Nat festivals where devotees from the nearby town/village gather together to present offerings and participate in the propitiation of the regional Nats Most importantly, the devotees would also participate in the annual national Nats festivals such as Taung-pyone pwe, Popa Medaw festival, and Mingun Nat festival (also known as Shwe Kyun Pin Nat pwe).13

Popular Buddhism

Although Myanmar is known as a country which adheres to Theravada Buddhism, it is the scholarly consensus that the majority of the population practices folk or popular Buddhism.14 Popular Buddhism by defnition is a syncretistic religion which incorporate animistic elements with Buddhist beliefs and practices.15 In the case of Myanmar, Nat worship, which is mentioned above, serves as the central element of Myanmar popular Buddhism. Spiro asserts that Buddhism and Nat worship coexist in Myanmar while complementing each other and also conficting with each other.16 In the case of the former, Buddhism and Nat worship co-exist because they provide for two different psychological needs of the people, i.e, Buddhism provides the means to achieve otherworldly goals, Nat worship offers solutions to the day-to-day mundane matters, which are irrelevant to Buddhism.17 Despite the complementary nature, the two traditions are clearly distinguishable, as both operate on different doctrines and ethos.18 Hence, he describes the relation between the two religious’ practices in terms of an Apollonius-Dionysius dichotomy.19

Apart from Nat worship, the popular Buddhists also practice astrology (Badin-Yadayar), Bodaw, or Weikza and other superstitious rituals. According to Maung Htin Aung, “Astrology to the Burmese meant not only the methods of tracing the courses of the planets and their infuence on mortals, but also the ritual by which the planets were appeased and made to withdraw their baneful infuence. In other words, it involved a worship of the planets.”20 The astrologers are believed to be able to tell one’s fortune, prevent misfortune, bring good luck, and solve various kinds of problems.21 Bodaw or Weikza is another person who is believed to possess supernatural spiritual power, have control over aulan saya22 and is able to help the poor and the oppressed. Last but not least, the popular Buddhist also believes in superstitious practices such as an obsession with getting good luck, or luck

associated objects (e.g, a lucky charm bracelet, special necklace, etc,), and the number nine.23

When it comes to food offerings, the popular Buddhist offers food to (1) the Nats in order to appease the Nats in Nat shrines, (2) the family altar in front of the statue of Buddha, (3) the monks in the morning as a daily ritual, (4) the monks on special occasions, and (5) as a communal feast. In the case of food offerings on the family altar, the Buddhist always sets aside the frst portions of rice and vegetables they have cooked for the family altar, where the statue of Buddha is placed. The early morning or dawn food offering is usually performed in light of a deep reverence for the Buddha, as well as the frst act of a good deed, which earns merit. Food offerings to the monks on special occasions and ahlu24 are done to gain merit and ensure better prospects in his/her next life. Zon Paan Pwint records U Nay Main Da from Nanda Gone Yi Monastery in Yangon, who said that, “after offering the food in the early morning, Buddhists feel they have done a good deed for the day.”25 He further states that a “Buddhist believes the person who eats the food which is offered to the Buddha is free from danger and will possess good health.”26 Buddhists also expect their food offering to be reciprocated, as they are believed to received back abundant and delicious foods in their life in exchange.27

Religious Festivals

The Myanmar lunar calendar is flled with festivals as there are festivals which are celebrated throughout the year. These festivals play a signifcant role in the lives of the people of Myanmar, because they not only provide the occasion to earn merit (dāna), but also serve as the time to celebrate communal ceremonial feasts.28 Among the most popular festivals are: the harvest festival (February), Thingyan water festival (early April), the full moon days of the months of Kason (April/May), Waso (June/July), the Nat festival (August/September), and Thidingyut (September-October).

Commemoration of the above festivals take various forms. For instance, the Burmese cook htamane, a special sticky rice made with sesame seeds, peanuts, and ginger to commemorate the Harvest festival. The Thingyan water festival is held in early April to mark the Burmese New Year. The sprinkling of water symbolizes cleansing of past sins and bad luck. During this festival, people go to the pagodas to offer food for alms, and the housewives at home prepare food and gifts to presents to their neighbors.29

The Kason festival is celebrated to announce the auspicious birth of Buddha, and for the celebration of this occasion people pour water on the sacred Bodhi tree and scented water in the pagoda. The Burmese also celebrate the full moon day of Waso which marks the beginning of Buddhist Lent and the anniversary of Buddha’s frst sermon on the Four Noble Truths. People donate robes to the monks on this occasion and shinbyu ceremonies are held as well.30 The Burmese celebrate the Taungpyone Nat Festival, where they offer three bunches of bananas, coconuts, rice, eggs, vegetables, fruits, sweets, and drinks (mineral water or alcohol) to the Nats.31At the end of the ceremonies, on the full moon day, the Burmese celebrate the festival of light (Thidingyut), where they pay respect to the elders and light candles.

The Rationale of Food Offerings in Myanmar

Propitiation

This concept of appeasing the deity with food offerings is prominently seen in Nat worship and there are at least two reasons for performing a food offering to the Nats. First, the Burmese perform food offerings mainly out of fear. This is mainly because Burmese believe that if Nats are not properly propitiated they will not only fail to protect them, but can also bring illnesses and curses. Hence, fear is the motivational factor for performing that duty. Second, people also offer food to the Nats because they want to receive assistance, blessings, and good luck. This is particularly true in regard to Deva Nats and Earthbound-Nats.

There are various levels of propitiation.32 First, at a personal or private level, the devotees offer food and drink at the family Nats shrine every morning seeking protection, guidance, and good luck. When the supplication is answered, the devotee will invite nat-kadaw/s to celebrate a thanksgiving ceremony called nat-kana pwe with food, orchestra music, and dances.33

Second, devotees participate in a local Nat pwe which are mostly seen in the rural areas, because every Burmese village has a Nat shrine for its village Nat. Spiro states that three times a year, in the months of Waso (June/July), Thadingyut (September-October), and Tagu (April), the village Nat is propitiated with a ritual offering of food to the Nat at sunset. In addition to the food, candles are lit, and a prayer is chanted by the local Nat expert, while the village orchestra plays music to sooth the Nats. 34 He further describes the treatment of the food after the service as follows:

This offering, like all offerings of food to the nats, is later distributed among, and eaten by, the participants. The nats, it is believed, consume the spiritual essence of the food by smelling it. Thus the saying, nathma angwei, luhma atwei, ‘a smell (on the part) of a nat (is like) a touch (on the part) of humans.’35

Third, there is also an annual regional Nat Pwe where devotees from the nearby town/village gather to present offerings and participate in the propitiation of the regional Nats. Spiro mentioned of the annual festival of Sedaw Nat Pwe where the Sedaw Thakinma and her brothers are propitiated as an example.36 In this regional Nat Pwe, devotees offer bananas, the images of the Nat shrine are ritually bathed in the river and returned to the Nat shrine. Throughout the ceremonies the orchestra plays a repertoire of Nat music where the Nat dakaws and other spirit-possessed devotees dance before the Nats. 37

Lastly, the devotees would also participate in an annual Nats festivals such as Taung-pyone pwe, Popa Medaw festival, and Mingun Nat festival (also known as Shwe Kyun Pin Nat pwe). Taung-pyone pwe is the most famous Nat festival in Myanmar which last for a full week and the festival honors the Nat brothers Shwepyingyi and Shwepyinge (popularly known as the Taungpyone Min Nyinaung or Taungpyone Brothers). The festival draws tens of thousands each year and, while many come to propitiate these Nats because of hereditary obligations, others are participatory observers of the Nats pwe who still made their offerings to the Nats 38 The festival is presided over by Nat-Ouk with four principle female Nats kadaws and four principal male Nats kadaws. The role of these eight principal Nats kadaws is to lead the processions, performing Nats dances.39 The core propitiation mainly falls under two forms: dancing and other ritual activities performed by Nats kadaws, and offerings which consist of coconuts, bananas, cloth, money, liquor, and bouquets of fowers and ferns made by the devotees.40 Additionally, one can seek the service of Nats kadaws with a fee to solve a problem which is within the competence of the Nats such as business, illness, marriage, divorce, and so on.41 Popa Medaw Nat festival is another popular Nat festival which is held a week after the Taungpyone Nat festival to honor Popa Medaw (the Mother of Popa), who was the mother of the Taungpyone Min Nyinaung. Mingun Nat festival, which last six days, is held in Mingun village in central Myanmar to pay homage to the brother and sister of Shwe Kyun pin, “who became nat spirits when the tree under which they were hiding from their uncle fell on them, killing them.”42

Religious Offering or Dāna

Dāna, according to Hiroko Kawanami, is “the religious practice of generous offering [given] to members of the monastic community.”43 Dāna offering is regarded as an essential meritorious deed in both Mahayana and Theravada Buddhist traditions. In Myanmar, the Buddhists offer dāna for two reasons. First, dāna is offered to the monks in order to receive religious merit. According to Spiro, this merit-producing dāna is mainly done in two ways; (1) by offering special meals to the monks, and (2) by purchasing domestic animals in order to save them from slaughter.44 It is normative for Buddhist monks (and nuns) to express their gratitude and to publicly recognize gifts offered to them by reciting blessing chants or by public proclamation of the donor’s meritorious acts in gratitude.45 Second, Myanmar Buddhists offer dāna to the monastic community when they encounter life crises: terminal illnesses, accidents, business losses, family problems, or any event they consider inauspicious, to offset bad karma by conducting a meritorious deed.46

When it comes to food offerings as merit-producing dāna, Buddhist monks in Myanmar are not vegetarians so they eat whatever is offered.47 As Spiro states, “the more elaborate the meal and the greater the number fed, the greater the merit.”48 Thus, people offer them the most prestigious item of food, which is meat and usually chicken or pork.49 Attached to this offering is the practice of sharing ahlu which is commensality in the form of communal feasts. Here the wider community witnessed and shared the joy of the individual or family’s meritorious occasion. After the communal feasts, the community would join the second part of the ceremony which consists of two main parts.50 The frst part consists of the recitation of awkatha51 by the congregation, the response and confrmation by the offciating monk, and the taking of the Five or Eight precepts. The second part consists of a sermon by the chief monk, a collective recitation of paritta, 52 the confrmation of the meritorious value of the donors by the principal monk, the pouring of water or water libation ritual (yezet-cha), the collective recitation of ahmyá we53 (three times), and the congratulatory proclamation of sadhu (three times).54

Reading 1 Corinthians 8:1–11:1 from a Myanmar Christian Perspective

Given the socio-religious signifcance of food offerings in Myanmar, the text of 1 Corinthians 8:1–11:1 is very relevant for the

(2025)

Myanmar Christian community. Often times, one encounter various questions in regard to food offerings such as; Should a Christian participate in Buddhist religious festivals? Can he/she partake food offered the Nats? Can he/she participate in the neighbor’s dāna offering ceremony to witness and share the joy of their meritorious occasion? In the case of a religious mixed family, should the family member/s share or refrain from both the food and meritorious deeds of other family members? Having these questions in mind, we will be reading the text of 1 Cor. 8:1–11:1 from a Myanmar Christian Perspective. Since Paul mainly deals with the issue of food offerings in the sacred places (temple precinct and at the table of pagan gods) and social location (marketplace meals and meals at home), we will discuss our text under these headings.55

Partaking in A Sacred/Cult Meal (8:1–13; 10:1–22)

In the frst reported issue in relation to food offerings in 1 Corinthians is the idea that some of the church members, who belong to the higher strata of the community, are actively participating in a sacred meal and partaking εἰδωλόθυτα at a pagan temple in the name of possessing gnosis (πάντες γνῶσιν ἔχομεν) and authority (ἐξουσία).56 In addition to their participation, the strong group also pressures the weak to follow suit, so that they will “build up” (οἰκοδομεω) the conscience of “the weak” (ἡ συνείδησις αὐτῶν ἀσθενὴς) in the church. The weak, on the other hand, perceive the action of the strong as idolatry because of their weak conscience and this in turn causes them to fall in their faith.

The issue at stake in the text of 1 Cor. 8:1–13 and 10:1–22 is idolatry, and scholars like Derek Newton and Richard Liong-Seng Phua have demonstrated that the question of what constitutes idolatry (in regard to food offerings) can be a tricky one, since idolatry can take various forms in both the Greco-Roman as well the Diaspora Jewish context.57 In the case of the former, Newton points out that the ancients perceived sacrifce in various levels; some were considered meaningless, some customary, and some recognized the presence of the god/s who could either help or harm the worshipper. They also attended and participated in communal meals for various reasons; some attended to demonstrate their socio-economic status, some to build friendships, and for some, to fulfll their sociopolitical obligations. Thus, meals in temple contexts were multidimensional and multi-functional.58 In a similar vein Phua’s study show that idolatry can take various forms in the Diaspora Jewish context, such as; actual

idolatrous behavior in visiting pagan temples and invoking pagan gods; cognitive error in terms of confusing the true God with nature or other gods; misrepresenting Yahweh with an object; and open abandonment of the Jewish ancestral tradition.59

Despite the existence of a range of perspectives and viewpoints on idolatry in regard to food offerings, what is clear from the text is that Paul is concerned with two things, Corinthians Christian participation of cultic meals in the temple precincts which was a partnership with demons (8:10; 10:20–21) that can cause harm to the brothers/sisters’ conscience (8:9, 12). These two issues are important for Myanmar Christians, because when it comes to food the main concern lay in the issue of the power behind the food. Our study on the socio-religious context of food offerings in Myanmar has demonstrated that devotees of the Nats and popular Buddhists believed in the transformative power of the food after it is offered to the deity. It is one of the reasons that both traditions promote partaking of food which is offered to the Nats and Buddha for the purpose of protection, healing, and bringing good luck to the business and the family. Additionally, partaking in food offerings would also bring harm to the conscience of other believers because they are accustomed to fear the Nats and partaking of the food would indicate the believer’s sharing a partnership or allegiance with the Nats or the Buddha.

Since Paul has consistently opposed Christians attending, eating, and getting involved in sacrifcial offerings of temple festivals, Myanmar Christians, likewise, should refrain from attending Nats pwe and partaking fo food offered to the Nats. In addition, they should also avoid attending and partaking in some of the Buddhist merit-producing dāna offerings, because they are highly religious in nature. In the case of harming the brothers/ sisters’ conscience, Paul’s advice according to Newton, is that “knowledge must be superseded by love and individual self-interest must be set aside for the sake of others and of the whole body of Christ.”60 Christians in Myanmar, likewise, should set aside their self-interest and practice love for God and for the brothers/sisters in Christ, so that they will not become a stumbling block.

Partaking in A Social Meal (10:23–11:1)

When it comes to a social meal, Paul discusses two types of food; (1) food (meat) purchased in the market (1 Cor. 10: 25) and a homecooked meal for dinner (1 Cor. 10:27). Various scholars have established that all of

the meat products sold in the market for public consumption came from the temple, as the surplus meat from temple sacrifces were sold to the merchants in the meat market.61 Since all the meat passed through the sacrifcial ritual of the temples, all meat purchased from the market and the homecooked meat for any dinner were technically “the meat offered to the idol” (ἱερόθυτόν). This situation is closely paralleled to the food offerings in Myanmar, where the Buddhists will offer a portion of every food, whether it be food sold in the market or food cooked for a meal, on the family altar or to the monks. Hence, all foods eaten by Buddhists are technically a food offering to the deity.

It is a puzzle for many Christians in Myanmar when they read about Paul’s permission for Christians to partake in food offered to idols without raising questions on the origin of the meat (10:25; 27). Therefore, it is important to ask the question, what prompts Paul to permit the Corinthians to partake of meat offered to idols in the social setting, but not in the cultic setting? Based on the different terms used for idol-meat in 1 Cor. 8–10 (εἰδωλόθυτον [8:1, 4, 7, 10] and ἱερόθυτόν [10:28]) Ben Witherington argues that εἰδωλόθυτον is a polemical Christian term denoting “something sacrifced to an idol or idols” whereas the term ἱερόθυτόν refers to meat sacrifced in a temple, but not eaten in the temple.

62

John Fotopoulos, who did a socio-rhetorical study on 1 Cor. 8:1–11:1, further points out that there are at least three reasons for Paul to allow Christians to partake in the social meal.63 First, Paul allows the purchase of meat sold from the macellum because there does not seem to have been any clear way to make a distinction between sacrifcial and non-sacrifcial food.64 Second, Paul’s allowance of food sold at the macellum also served his rhetorical strategy as an accommodation to the strong, one of who may have been Erastus, who as aedile (city treasurer), would have had oversight of the macellum.65 Third, Paul also allows the strong to accept invitations to meals extended by pagans on social grounds. He instructs them to eat whatever was put before them, without raising questions on the grounds of moral consciousness. Paul’s instructions allowed the consumption of all food being served, as long as the Corinthians were not aware that sacrifcial food was being served, an approach which allowed continued social relations with pagans.66

Based on the close parallel of socio-religious signifcance of food offerings in Corinth and Myanmar, one can conclude that Christians in Myanmar can partake of food that they purchased in the market and

participate in a social meal, such as a business-related dinner party, a dinner party at a Buddhist neighbor’s house, and even to participate in the communal feast of ahlu pwe without raising the origin of the food. While participating in ahlu pwe, a Christian should avoid attending the second part of the ceremony, which is very religious in nature. However, if someone brings up the religious nature of the food, or in the case that one is aware that this action would harms the conscience of other Christian neighbors or church members, then the concerned Christian should avoid participation in social meals for the sake of the conscience of Christian brothers/sisters, as well as that of the host.

Conclusion

As we have observed in our study above, Paul was mainly concerned with Christians’ participation of food offerings to the deities in the cultic setting, and not their participation in social settings. In the case of the former, he has consistently opposed Christians attending, eating, and getting involved in sacrifcial offerings in the temple, or in the temple precincts. Whereas in the case of the latter, he allowed Christians to purchase food from the market and partake in social meals with caution. Since many of the food offering issues in Corinth have close parallels with the socio-religious context of food offerings in Myanmar, this paper proposes that Myanmar Christians refrain from attending Nats pwe and partaking of food offered to the Nats. In addition, they should also avoid attending and partaking in some of the Buddhist merit-producing dāna offerings because they are highly religious in nature. In the case of purchasing food and participating in a social meal, Christians in Myanmar can freely partake of food that they purchased in the market, and participate in a social meal, such as a business-related dinner party or a dinner party at a Buddhist neighbor’s house.

In order to maintain good social relations with Buddhist friends, Christians may also participate in the communal feast of ahlu pwe without raising the origin of the food. While participating in ahlu pwe, a Christian should avoid attending the second part of the ceremony due to its very religious nature. However, if one brought up the religious nature of the food, or in the case that one is aware that this action would harm the conscience of other Christian neighbors or church members, then the concerned Christian should avoid participation in the social meal for the

sake of the conscience of other Christian brothers/sisters, as well as for the sake of the host.

End Notes

1 According to Maung Htin Aung, other important and popular primal religions of Myanmar include Astrology and Alchemy. While the practice of Astrology is still relevant to modern Myanmar Buddhist, the practice of Burmese alchemy seems to die out as the Burmese alchemist aiming to attain an eternally youthful body through alchemy seems to be impractical for the Popular Buddhist who are more concerned with their day to day socio- economic and spiritual hardship. See, Maung Htin Aung, Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism (Rangoon: The Religious Affairs Department Press, 1979), 1; Moe Moe Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response to the Burmese Nat- Worship (Yangon: Myanmar Institute of Theology, 2010), 48.

2 Pau Khan En, “Nat Worship: A Paradigm for Doing Contextual Theology for Myanmar” (Ph.D diss., University of Birmingham, 1995), 7.

3 Khin Maung Nyunt, “Traditional Nat Festivals of the month Nattaw (December),” Myanmar Digital News, December 29, 2020, https:// www.myanmardigitalnewspaper.com/en/traditional-nat-festivals-monthnattaw-december (accessed March 23, 2022).

4 See, En, “Nat Worship,” 73; Melford E. Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: With A New Introduction by the Author (London/New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1966, exp. ed.1996), 52; Khin Maung Than (Seik-Pyin- Nya), A-Yu-The-Hmu, Nat-Koe-Kwe-Hmu hnint SeikPyin-Nyar Shu-Daunt (The Superstitions in Nat Worship: A Psychological Perspective) (Yangon: Pin-war-yone, 2006), 143 (In Burmese).

5 Than, A-Yu-The-Hmu, 143.

6 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 27–33.

7 En, “Nat Worship,” 73; Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 48–49.

8 Robert L. Winzeler, Popular Religion in Southeast Asia (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefeld, 2016), 92.

9 One of the most famous annual Nat festivals is Taung-pyone festival which was held on the full moon day of December at Taungbyone village in central Myanmar.

10 For want of a better term, Spiro refers to nat-kadaw as shamans. See, Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 205–229.

11 Nat-kadaw literally means nat-wife or one who married a nat in Burmese. While many of them are female, Spiro mentioned that 3 to 4 percent are male. Cf. Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 205.

12 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 206.

13 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 108–125; Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 44–45.

14 See, John Brohm, “Buddhism and Animism in a Burmese Village,” The Journal of Asian Studies 22 (1963): 155–167; Winston L. King, A Thousand Lives Away: Buddhism in Contemporary Burma (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964), Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 247–263; Aung, Folk Elements, 1–6; Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 22–46; Donald K. Swearer, The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010), 1–3; Winzeler, Popular Religion, 91–115.

15 Winzeler, Popular Religion, 90–91.

16 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 266–280.

17 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 266.

18 For the detail discussion in confict, see Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 253–263.

19 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 297; cf., Winzeler, Popular Religion, 93.

20 Aung, Folk Elements, 1.

21 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 49.

22 Aulan saya is the person who is believed to have powers to control evil spirits and power to use the evil power to achieve malevolent end. See Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 51.

23 The Burmese associated the number 9 with success and in order to get success in life, the popular Buddhist will offer 9 kinds of tendrils or fruits, or fowers, or candles. See Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 53.

24 Ahlu basically mean religious offering and the term is always associated with commensality in the form of communal feasts. See Hiroko Kawanami, The Culture of Giving in Myanmar: Buddhist Offerings, Reciprocity and Interdependence (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 40.

25 Zon Pann Pwint, “Making Merit: On the Business of Buddhist Offerings,” Myanmar Times, July 8, 2013, https://www.mmtimes.com/ special-features/168-food-and-beverage/7442-food-for-buddhist-thought. html (accessed March 31, 2022).

26 Pwint, “Making Merit.”

27 Pwint, “Making Merit.”

36 The Asbury Journal 80/1 (2025)

28 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 123–124.

29 C. Duh Kam, “Christian Mission to Buddhists in Myanmar: A Study of Past, Present, and Future Approaches by Baptists” (D.Miss diss., United Theological Seminary, 1997), 242.

30 The Shinbyu is the ceremonies celebrate for the entrance of the Burmese boy into the novitiate of the Buddhist monkhood. See, Brohm, “Buddhism and Animism,” 161.

31 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 44; King, A Thousand Lives Away, 51.

32 While both Spiro and Ngunt classifed the propitiation as three level, I think the four-level classifcation fts better because a personal or private level propitiation at the family Nat sin is different from participating in a local Nat pwe.

33 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response, 44.

34 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 110.

35 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 110.

36 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 110–112.

37 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 112.

38 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 116.

39 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 117.

40 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 119.

41 The Nat-dances are performed while dancing to the music at the state of Nat-possession. During this trance, the Nat-kadaw obtains relevant information for the clients and delivered it to them. See, Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 118, 207.

42 Than Naing Soe, “Shwe Kyun Pin Nat Festival Draws Annual Believers,” Myanmar Times, September 3, 2015, https://www.mmtimes. com/lifestyle/16302-shwe-kyun-pin-nat-festival-draws-annual-believers.html (accessed April 1, 2022).

43 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 6.

44 Melford E. Spiro, Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and its Burmese Vicissitudes (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), 271.

45 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 9.

46 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 158, n. 32

47 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 159, n. 8.

48 Spiro, Buddhism and Society, 271.

49 Although eating beef is not forbidden in Myanmar, most monks do not eat beef, probably due to the close association villagers have with cattle in their daily life. See Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 159, n. 8.

50 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 40–43.

51 awkatha is a devotional chant recited at Buddhist ritual in Myanmar.

52 Paritta is a protection prayer which is believed to have benefcial functions such as curing illnesses and injuries, inviting good fortune, pacifying restless spirits, soliciting protection from devas and deities to achieve a peaceful balance. See, Kawanami, The Culture of Giving, 41.

53 ahmyá we basically mean the sharing meritorious deeds and it is a recitation to send out loving kindness to everyone in the planet.

54 sadhu mean well done.

55 Since 1 Corinthians 9 deals mainly with Paul’s apostolic authority, we will not discuss the text in this study.

56 For the elites of Corinthians, see David W. J. Gill, “In Search of the Social Elite in the Corinthian Church,” TynBul (1993):323-37).

57 See, Derek Newton, Deity and Diet: The Dilemma of Sacrifcial Food at Corinth, JSNTSup 169 (Sheffeld: Sheffeld Academic Press, 1998); and Richard Liong-Seng Phua, Idolatry and Authority: A Study of 1 Corinthians 8.1-11.1 in the Light of the Jewish Diaspora. LNTS 299 (London/ New York: T&T Clark, 2005).

58 Newton, Deity and Diet, 175–242.

59 Phua, Idolatry and Authority, 35–124.

60 Newton, Deity and Diet, 22.

61 See, Gerd Theissen, “The Strong and the Weak in Corinth: A Sociological Analysis of a Theological Quarrel,” The Social Setting of Pauline Christianity: Essays on Corinth, ed. and trans. by John H. Schütz (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982), 121–143. Wendell Lee Willis, Idol meat in Corinth: The Pauline Argument in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10, SBLDS 68 (Chico, CA: Scholar Press, 1985), 230; Ben Witherington, Confict & Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 189–190; Jerome Murphy O’Connor, St. Paul’s

(2025)

Corinth: Texts and Archaeology, 3rd rev. and expanded edn. (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2002), 186.

62 Ben Witherington, “Not So Idle Thoughts about Eidolothuton,” TynBul 44 (1993): 238–242.

63 John Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols in Roman Corinth, WUNT 151 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003), 239–250.

64 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols, 240.

65 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols, 240.

66 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols, 243–247.

Works Cited

Aung, Maung Htin

1979 Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism. Rangoon, Myanmar: The Religious Affairs Department Press.

Brohm, John

1963

En, Pau Khan

“Buddhism and Animism in a Burmese Village.” The Journal of Asian Studies 22 (1963): 155–167.

1995 “Nat Worship: A Paradigm for Doing Contextual Theology for Myanmar.” Ph.D Dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Gill, David W. J.

1993 “In Search of the Social Elite in the Corinthian Church.” TynBul (1993): 323– 37.

Kam, C. Duh

1997 “Christian Mission to Buddhists in Myanmar: A Study of Past, Present, and Future Approaches by Baptists.” D.Miss Dissertation., United Theological Seminary.

Kawanami, Hiroko

2020 The Culture of Giving in Myanmar: Buddhist Offerings, Reciprocity and Interdependence. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

King, Winston L.

1964 A Thousand Lives Away: Buddhism in Contemporary Burma. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Murphy O’Connor, Jerome

2002

Newton, Derek

1998

St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology. 3rd rev. and expanded edition. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

Deity and Diet: The Dilemma of Sacrifcial Food at Corinth, JSNTSup 169.Sheffeld, England: Sheffeld Academic Press.

Nyunt, Khin Maung

2020

Nyunt, Moe Moe

“Traditional Nat Festivals of the month Nattaw (December),” Myanmar Digital News, December 29, 2020, https://www.myanmardigitalnewspaper.com/en/ traditional-nat-festivals-month-nattaw- december (accessed March 23, 2022).

2010 A Pneumatological Response to the Burmese NatWorship. Yangon, Myanmar: Myanmar Institute of Theology.

Phua, Richard Liong-Seng

2005

Pwint, Zon Pann

2013

Soe, Than Naing

2015

Spiro, Melford E.

1971

Idolatry and Authority: A Study of 1 Corinthians 8.1-11.1 in the Light of the Jewish Diaspora. LNTS 299. London/ New York: T&T Clark.

“Making Merit: On the Business of Buddhist Offerings,” Myanmar Times, July 8, 2013, https://www.mmtimes. com/special-features/168-food-and-beverage/7442food-for-buddhist-thought.html (accessed March 31, 2022).

“Shwe Kyun Pin Nat Festival Draws Annual Believers,” Myanmar Times, September 3, 2015, https://www. mmtimes.com/lifestyle/16302-shwe-kyun-pin-natfestival-draws-annual-believers.html (accessed April 1, 2022).

Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and its Burmese Vicissitudes. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

1996 Burmese Supernaturalism: With A New Introduction by the Author. London/New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, (1966), expanded edition.

Swearer, Donald K.

2010

The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Than, Khin Maung (Seik-Pyin-Nya)

2006 A-Yu-The-Hmu, Nat-Koe-Kwe-Hmu hnint Seik-Pyin-Nyar Shu-Daunt (The Superstitions in Nat Worship: A Psychological Perspective). Yangon, Myanmar: Pin-waryone. (In Burmese.)

Theissen, Gerd

1982 “The Strong and the Weak in Corinth: A Sociological Analysis of a Theological Quarrel.” Pages 121–143 in The Social Setting of Pauline Christianity: Essays on Corinth. Edited and translated by John H. Schütz. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress.

Willis, Wendell Lee

1985 Idol meat in Corinth: The Pauline Argument in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10, SBLDS 68. Chico, CA: Scholar Press.

Winzeler, Robert L.

2016 Popular Religion in Southeast Asia. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefeld.

Witherington, Ben

1993 “Not So Idle Thoughts about Eidolothuton,” TynBul 44 (1993): 238–242.

1995 Confict & Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

The Asbury Journal 80/1: 41-85

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2025S.04

Hram Hu Lian

ကက�င်းမက�သလခပ�သည

ပါ၀ငဆငနသင်ပါသလ�း။

hram hu lian

မည်သညအစ�းအစ�မို�းကု� ခွင််ခပ�ရမည်ဟူကသ�

ကနွးသွ�းမည်ခဖစကပသည်။

Hram Hu Lian

B.L. Fisher

(Archives and Special Collections)

အခမ်းအန�းမိ�းတွင

ဤကဆ�င်းပါးကု�

စ�းပွမိ�းမိ�းနှင်

hram hu lian

ကက�င်းမက�သလခပ�သည

ပါ၀ငဆငနွသင််ပါသလ�း။

အသင်းကတ�် နှင်

မို�းကု�

မည်သညအစ�းအစ�မို�းကု�

ကနွးသွ�းမည်ခဖစကပသည်။

အစ�းအစ�ပက��်ခခင်းနှင်သက်ဆင်သည

hram hu lian :

ကခ်ဆု�ကပသည်။

hram hu lian

၊ ပ�ပ�းမယကတ�် ပွနှင် မင်းကန်းနတပွ (ကရှကွန်းပင်နတပွဟူ၍ လည်းကခ်ဆု�ကပသည်)13 က်သု

ကသ� နှစစဉကိင်းပသည

လကခးကိင််သး�ကက�က�င်း

ကကု�က်နစ်သကကသ�

ဗ�ဒဘ�သ�၀ငမိ�း၏

မုဆငရ�

သကဘ�တရ�းမိ�းကု�ပါ

သကဘ�တရ�းမိ�းအ�း

hram hu lian : မည်သညအစ�းအစ�ကု�

စ (Apollonius-Dionysius)

သကဘ�တရ�းအခဖစ

နကတကဗဒင

ကု� ကဆ�င�ကဉ်းကပးနင်ခခင်းတု�ကု� ခပ�နင်သည်သ�မက အမို�းမို�းကသ�

ခပဿန�မိ�းကု�လည်း

Bodow) သု�မဟ�တ

hram hu lian

(ဧပပးလအကစ�ပု�င်း)၊ လမိ�းတွင

hram hu lian :

အကလးအခမတ��းကသ�

မက ကစတးပ��ုးမိ�း၌လည်း ကမွးကကု�ငကသ�

ခမနမ�လူမို�းတု�သည်

Taungpyone

hram hu lian

သည နတကန�းပွ (nat-kanapwe)

အစ�းအစ�တုပါ၀င

hram hu lian

(Shwepyingyi

(Shwepyinge)

(Taungpyone Min Nyinaung)

Taungpyone Brothers

ကငွက�ကး၊

ခပ�န်းမင်းညးကန�င (Taungpyone Min Nyinaung)တု�၏

မင်းကန်း (Mingun) နတပကတ�်မှ�

ကွန်းပင (Shwe Kyun pin)၏ အစ်မကတ�်

ကရ

hram hu lian

Hiroko Kawanami

ရန ကက�င်းမခပ�လ�ပ်ခခင်းခဖင်

အ၀င်းသု

မမက�က�းခခင်းတု

ရတ်ဆု��ကခခင်း၊

hram hu lian :

Derek Newton

Richard Liong-Seng Phua

hram hu lian

ဘ�သ�ကရးဆု�ငရ�

အကခခအကနမို�းတွင

hram hu lian

Ben Witherington

hram hu lian :

Erastus

အက�က�င်းတရ�းမှ�

ဝုည�ဉကရးရ�အ�းကကးကသ�

ကသ�

ကု� အနရ�ယခဖစကစသည

hram hu lian

သည ဗ�ဒဘ�သ�ဝငတ�အတကမ

See, Maung

Htin Aung, Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism (Rangoon: The Religious Affairs Department Press, 1979): 1; Moe Moe Nyunt, A Pneumatological

Response to the Burmese Nat- Worship (Yangon: Myanmar Institute of Theology, 2010): 48.

hram hu lian : မည်သညအစ�းအစ�ကု�

2 Pau Khan En, “Nat Worship: A Paradigm for Doing Contextual

Theology for Myanmar” (Ph.D diss., University of Birmingham, 1995): 7.

3 Khin Maung Nyunt, “Traditional Nat Festivals of the month Nattaw (December),” Myanmar Digital News, December 29, 2020, https://www. myanmardigitalnewspaper.com/en/traditional-nat-festivals-month-nattawdecember (accessed March 23, 2022).

4 See, En, “Nat Worship,” 73; Melford E. Spiro, Burmese

Supernaturalism: With A New Introduction by the Author (London/New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1966, exp. ed.1996): 52; Khin Maung Than (Seik-Pyin- Nya), A-Yu-The-Hmu, Nat-Koe-Kwe-Hmu hnint Seik-Pyin-Nyar

Shu-Daunt (The Superstitions in Nat Worship: A Psychological Perspective) (Yangon: Pin-war-yone, 2006): 143 (In Burmese).

5 Than, A-Yu-The-Hmu: 143

6 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response: 27–33.

7 En, “Nat Worship,”: 73; Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 48–49.

8 Robert L. Winzeler, Popular Religion in Southeast Asia (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefeld, 2016): 92.

9

Supernaturalism: 205–229

Spiro, Burmese

Supernaturalism: 205.

12 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 206.

13 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 108–125; Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response: 44–45.

14 See, John Brohm, “Buddhism and Animism in a Burmese Village,”

The Journal of Asian Studies 22 (1963): 155–167; Winston L. King, A Thousand

Lives Away: Buddhism in Contemporary Burma (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964), Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 247–263; Aung, Folk

Elements: 1–6; Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response: 22–46; Donald K. Swearer, The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010): 1–3; Winzeler, Popular Religion: 91–115.

15 Winzeler, Popular Religion: 90–91.

16 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 266–280.

hram hu lian : မည်သညအစ�းအစ�ကု�

17 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 266.

18

See, Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 253–263.

19 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 297; cf., Winzeler, Popular Religion: 93.

20 Aung, Folk Elements: 1.

21 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response: 49.

22

Pneumatological Response:

Pneumatological Response: 53.

See Hiroko Kawanami, The Culture of Giving in Myanmar: Buddhist

(2025)

Offerings, Reciprocity and Interdependence (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020): 40.

25 Zon Pann Pwint, “Making Merit: On the Business of Buddhist Offerings,” Myanmar Times, July 8, 2013, https://www.mmtimes.com/specialfeatures/168-food-and-beverage/7442-food-for-buddhist-thought.html (accessed March 31, 2022).

26 Pwint, “Making Merit.”

27 Pwint, “Making Merit.”

28 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 123–124. 17

29 C. Duh Kam, “Christian Mission to Buddhists in Myanmar: A Study of Past, Present, and Future Approaches by Baptists” (D.Miss diss., United Theological Seminary, 1997): 242.

30

(Shinbyu)

Brohm, “Buddhism and Animism,”: 161.

31 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism, 44; King, A Thousand Lives Away: 51.

32 Spiro and Ngunt

33 Nyunt, A Pneumatological Response: 44.

34 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 110.

35 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 110.

36 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 110–112.

37 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 112.

38 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 116.

39 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 117.

40 Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 119. 41 နတ်အက(Nat-dances)

(Natkadaw)က အ�ကးအဉ�ဏကတ�င်းခးသ�းမ သင််ခမတကလိ�်ကနမုရှုကသ� သတင်းအခိက်အလကမိ�းကု�

See, Spiro, Burmese Supernaturalism: 118, 207.

42 Than Naing Soe, “Shwe Kyun Pin Nat Festival Draws Annual Believers,” Myanmar Times, September 3, 2015, https://www.mmtimes. com/lifestyle/16302-shwe-kyun-pin-nat-festival-draws-annual-believers.html (accessed April 1, 2022).

43 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 6.

44 Melford E. Spiro, Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and its Burmese Vicissitudes (New York: Harper and Row, 1971): 271.

45 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 9.

46 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 158, n. 32 18

47 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 159, n. 8.

48 Spiro, Buddhism and Society: 271.

49

See, Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 159, n. 8.

50 Kawanami, The Culture of Giving: 40–43. 51 �သက�သ(awkatha)

Giving: 41.

56 For the elites of Corinthians, see David W. J. Gill, “In Search of the Social Elite in the Corinthian Church,” TynBul (1993):323-37).

57 See, Derek Newton, Deity and Diet: The Dilemma of Sacrifcial Food at Corinth, JSNTSup 169 (Sheffeld: Sheffeld Academic Press, 1998); and Richard Liong-Seng Phua, Idolatry and Authority: A Study of 1 Corinthians 8.111.1 in the Light of the Jewish Diaspora, LNTS 299 (London/New York: T&T Clark, 2005).

58 Newton, Deity and Diet: 175–242.

59 Phua, Idolatry and Authority: 35–124.

60 Newton, Deity and Diet: 22.

82 The Asbury Journal 80/1 (2025)

61 See, Gerd Theissen, “The Strong and the Weak in Corinth: A Sociological Analysis of a Theological Quarrel,” The Social Setting of Pauline Christianity: Essays on Corinth, ed. and trans. by John H. Schütz (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1982): 121–143. Wendell Lee Willis, Idol meat in Corinth: The Pauline

Argument in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10, SBLDS 68 (Chico, CA: Scholar Press, 1985):

230; Ben Witherington, Confict & Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical

Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995): 189–190;

Jerome Murphy O’Connor, St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology, 3rd rev. and expanded edn. (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2002): 186. 19

62 Ben Witherington, “Not So Idle Thoughts about Eidolothuton,”

TynBul 44 (1993): 238–242.

63 John Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols in Roman Corinth, WUNT

151 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003): 239–250.

64 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols: 240.

65 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols: 240.

66 Fotopoulos, Food Offered to Idols: 240.

Works Cited

Aung, Maung Htin

1979 Folk Elements in Burmese Buddhism. Rangoon, Myanmar: The Religious Affairs Department Press.

Brohm, John

1963 “Buddhism and Animism in a Burmese Village.” The Journal of Asian Studies 22 (1963): 155–167.

En, Pau Khan

1995 “Nat Worship: A Paradigm for Doing Contextual Theology for Myanmar.” Ph.D Dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Gill, David W. J.

1993 “In Search of the Social Elite in the Corinthian Church.” TynBul (1993): 323– 37.

Kam, C. Duh

1997 “Christian Mission to Buddhists in Myanmar: A Study of Past, Present, and Future Approaches by Baptists.” D.Miss Dissertation., United Theological Seminary.

Kawanami, Hiroko

2020 The Culture of Giving in Myanmar: Buddhist Offerings, Reciprocity and Interdependence. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

King, Winston L.

1964 A Thousand Lives Away: Buddhism in Contemporary Burma. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Murphy O’Connor, Jerome

2002 St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology. 3rd rev. and expanded edition. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

Newton, Derek

1998 Deity and Diet: The Dilemma of Sacrifcial Food at Corinth,JSNTSup 169. Sheffeld, England: Sheffeld Academic Press.

Nyunt, Khin Maung

2020 “Traditional Nat Festivals of the month Nattaw (December),” Myanmar Digital News, December 29, 2020,https://www.myanmardigitalnewspaper.com/en/ traditional-nat-festivals-month-nattaw- december (accessed March 23, 2022).

(2025)

Nyunt, Moe Moe

2010 A Pneumatological Response to the Burmese NatWorship. Yangon, Myanmar: Myanmar Institute of Theology.

Phua, Richard Liong-Seng

2005

Idolatry and Authority: A Study of 1 Corinthians 8.1-11.1 in the Light of the Jewish Diaspora. LNTS 299. London/ New York:T&T Clark.

Pwint, Zon Pann

2013 “Making Merit: On the Business of Buddhist Offerings,” Myanmar Times, July 8, 2013,https://www.mmtimes. com/special-features/168-food-and-beverage/7442food-for-buddhist-thought.html (accessed March 31, 2022).

Soe, Than Naing

2015 “Shwe Kyun Pin Nat Festival Draws Annual Believers,” Myanmar Times, September 3, 2015,https://www. mmtimes.com/lifestyle/16302-shwe-kyun-pin-natfestival-draws-annual-believers.html (accessed April 1, 2022).

Spiro, Melford E.

1971 Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and its Burmese Vicissitudes. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

1996 Burmese Supernaturalism: With A New Introduction by the Author. London/New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, (1966), expanded edition.

Swearer, Donald K.

2010 The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Than, Khin Maung (Seik-Pyin-Nya)

2006 A-Yu-The-Hmu, Nat-Koe-Kwe-Hmu hnint Seik-PyinNyar Shu-Daunt (The Superstitions in Nat Worship: A Psychological Perspective). Yangon, Myanmar: Pin-waryone. (In Burmese.)

Theissen, Gerd

1982 “The Strong and the Weak in Corinth: A Sociological Analysis of a Theological Quarrel.” Pages 121–143 in The Social Setting of Pauline Christianity: Essays on Corinth. Edited and translated by John H. Schütz. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress.

Willis, Wendell Lee

1985 Idol meat in Corinth: The Pauline Argument in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10, SBLDS 68. Chico, CA: Scholar Press.

Winzeler, Robert L.

2016 Popular Religion in Southeast Asia. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefeld.

Witherington, Ben

1993 “Not So Idle Thoughts about Eidolothuton,” TynBul 44 (1993): 238–242.

1995 Confict & Community in Corinth: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

The Asbury Journal 80/1: 86-138

© 2025 Asbury Theological Seminary

DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2025S.05

Nicholas M. Railton

Freemasonry and the Methodist Episcopal Church in the Nineteenth Century

Abstract: Virtually nothing has been written on the presence and impact of Freemasonry within the Methodist Episcopal Church. This article begins to fll this lacuna by shedding some light on the topic. It has been claimed that John Wesley was himself a Freemason. In his journal he briefy discusses a book by an ex-Mason.

In this article some of the similarities and differences between the two systems are highlighted. The Morgan Affair temporarily weakened the position of Freemasonry in the Methodist Episcopal Church and in broader American society. Twelve short biographies of Methodists who joined the lodge show that the infuence remained. Freemasonry played a role in the schism in New York between 1858 and 1860, which led to the formation of the Free Methodist Church. In the second half of the nineteenth century newspapers like The Christian Cynosure, Der Lutheraner and Leaves of Healing highlighted the continuing infuence of Freemasonry on decisionmaking within the MEC.

At the end of the nineteenth century the Freemason William McKinley became the frst Methodist President of the USA. Right up to World War II Freemasonry continued to spread within the MEC. Two hundred years after the Morgan abduction Freemasonry needs to be seriously discussed again. Wesley’s remarks on Freemasonry provide the starting-point for Methodist refection on the subject.

Keywords: Freemasonry, Methodism, William Morgan, Methodist Episcopal Church, lodge

Nicholas M. Railton, M.A., PhD., is a retired university lecturer and school teacher. His email is: nicholasrailton@gmail.com

Introduction

On 30 November 1798 an eighteen-year-old theology student registered for membership in St. Vigean Lodge No. 101 in the small Scottish town of Arbroath.1 Following fve preparation sessions he was formally admitted to Freemasonry on Christmas Eve 1798 and acquired the degree of Master Mason.2 The student’s name was Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847), the founder of the Free Church of Scotland. He had matriculated at St. Andrews University in November 1795 and, from 1843 onwards, worked to establish a union of all Protestants in the United Kingdom. That body, the Evangelical Alliance, was founded in Freemasons’ Hall in London.3

It was a not uncommon occurrence for theology students, candidates for ministry and clergymen to seek membership in a Masonic lodge. Why Thomas Chalmers wanted to join a lodge is unknown. In all likelihood a relative of his will have suggested to him that lodge membership enabled a young man to gain important contacts in bourgeois society. In a letter to his older brother James, dated 1 January 1821, Chalmers claimed he had never attended a lodge since the turn of the century.4 It seems as if the teenager had become a Mason for egotistical and material reasons, inspired by a hope that lodge membership would be useful in obtaining his frst pastorate. His conversion following his reading in 1811 of William Wilberforce’s Practical View of Christianity (“a great revolution in my thinking”, as he described the change in a letter dated 14 February 1820) led to a strictly evangelical understanding of the Bible.5 His Masonic career suddenly came to an end.6

In 1797 the philosopher and Freemason John Robison (17391805) published a book in Edinburgh.7 In the preface to his book the author declared he had become a Master Mason in his youth and had visited many lodges all over Europe, from Belgium to Russia. Robison came to believe that reformers and revolutionaries, men without religious principles, were utilizing lodges for their political purposes. Indeed, the “leaders of the French Revolution” were all Masons. The book sparked interest amongst readers in North America8 and Chalmers probably heard of the book’s success in Edinburgh. He actually got to know Professor Robison at the University of Edinburgh where his philosophical convictions were profoundly shaped by his teacher.9

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Freemasons were not only active in the Church of Scotland, but also in British Methodist churches. Rev. Jacob Stanley was shocked in 1813 when Methodists told