c . 1349-1333 B c 13 c M HIGH RED QUARTZITE

Provenance

Collection of British archaeologist, Sir Cyril Fred Fox (1882-1967), thence by descent

A fragmentary base from a monumental statue bearing the cartouche of Queen Nefertiti with her epithet, 'Mistress of the Two Lands.'

c . 285-116 B c 43 c M HIGH cARVED AND POLISHED GRANITE

Provenance

European private collection since at least 1951 [as indicated by the wooden base by Kichizo Inagaki (1876-1951)]

Charles Dikran Kelekian (1900-1982), New York [possibly Inv. no. 4908]

Otto L. (1897-1966) and Eloise O. Spaeth (1902-1998), New York, before June 1955 Antiquities, Sotheby's, New York, 30 May 1986, Lot 70

Charles Pankow (1923-2004), San Francisco, acquired from the above

The Charles Pankow Collection of Egyptian Art, Sotheby's, New York, 8 December 2004, Lot 99

Subsequently, collection of Bassam Alghanim, New York, acquired from the above

Exhibited

The Spaeth Collection at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, June - September 1955, no. 1

Published (inter alia)

H. De Meulenaere and P. MacKay, Mendes II, 1976, pp. 185, 199, no. 60, pl. 24a-b. D. Klotz, 'The Statue of the diokêtês Harchebi/Archibios Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art 47-12,' BIFAO, vol. 109, 2009, p. 300, n. 143.

A finely modelled torso of Egyptian official, Hor-maa-kheru. Carved in hardstone - the preserve of elite commissions - it has been identified as one of the few sculptures of this style to hail from Mendes, the administrative and cult centre of the Nile Delta.

Once belonging to Otto and Eloise Spaeth, patrons of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art and the MoMA, and exhibited alongisde works by Pablo Picasso, Paul Gauguin, Marc Chagall and Paul Cézanne at the 1955 exhibition of their collection at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts.

The Prophet of Isis the Great Egyptian figural sculpture was conceived in a number of archetypal forms: striding, kneeling, enthroned, or bearing a naos or stela. Of these, the striding figure became the most iconic, enduring into the Ptolemaic period and exerting a lasting influence on the Western tradition, most notably in the striding kouroi of archaic Greece. Such statues were produced in a range of materials, from perishable wood and limestone to particularly durable granite and quartzite. Many were anonymous works but some were inscribed with the names and titles of their owners. The finest examples were carved in hardstone, such as the present piece, and enriched with elaborate hieroglyphs, preserving both the identity and the offices of the subject.

Depicting the official Hor-maa-kheru, it also belongs to a small group of such hardstone votive statues commissioned by local officials for the main temple of Mendes, one of the foremost administrative and religious centres in the Nile Delta. Identified by scholars

Herman De Meulenaere and Pierre MacKay as an addition to the corpus first assembled by renowned Egyptologist Bernard Bothmer, this work stands alongside such masterpieces as the torso of Amenpayom, now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, hailed by Bothmer as ‘the finest torso in Egyptian tradition of the Ptolemaic period’. With its refined modelling, elegant proportions, and association with the important Mendesian group, the present torso embodies the endurance of one of the most iconic Egyptian sculptural traditions.

As the capital of the 16th Nome of Egypt and home to the cult of the sacred ram-god, Ba-neb-djedet, Mendes was visited by successive generations of rulers from the time of the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. While great pharaohs such as Amasis II and Nectanebo I had consistently honoured the city, it was the homage paid by Ptolemy II and Arsinoë II, as seen in the celebrated Mendes Stela, that truly established the pre-eminence of Mendes as an administrative and religious cult centre. The wealth that poured into the city in turn encouraged the flourishing of the local aristocracy, who took a prominent role in religion and politics in the area.

Commissioned by one such member of the Mendesian elite, the masterful and elegant carving of the present torso, with the traditional pose and characteristic loincloth, is quintessentially Egyptian. The figure’s belt bears an inscription naming the owner, Hormaa-kheru, alongside that of his parents, Aset-em-akh-byt and Wen-nefer. The back-pillar is inscribed with vertical lines of hieroglyphs enumerating Hor-maa-kheru’s religious titles, which include ‘Prophet of Isis the Great, the Mother of the God, who resides in Mendes,’ as well as priest of the ram-god. His numerous titles also reflect the importance of Mendes as a religious and cultural centre under Ptolemaic rule. In addition to his priestly offices, Hormaa-kheru also held the secular title of Overseer of the Seal, or treasurer, indicative of his very important role within the local bureaucracy at the time of the city’s pre-eminence.

This torso first circulated the Paris art market in the early twentieth century. Handled by renowned artisan Kichizo Inagaki (1876–1951), and dealer, Dikran Kelekian (1900-1982), it was later acquired by New York collectors, Otto and Eloise Spaeth. As patrons of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, they were known for their skilled connoisseurship and discerning taste, amassing a collection that comprised works from antiquity to the modern day. While in their collection, the present torso was exhibited at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio from June to September 1955 (as revealed by a sticker found under a rubber pad on the base), where it was displayed as one of a few antiquities alongside the works of renowned artists of the 20th century such as Pablo Picasso, Paul Gauguin, Marc Chagall and Paul Cézanne. This torso is an exquisite example of elite Egyptian statuary with a particularly remarkable provenance.

Above

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Profile of Laval, now in the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Formerly the Spaeth Collection, exhibited alongside our torso at the Columbus Art Gallery in 1955.

‘Scribe of the White Crown, overseer of the seal, priest of Anet, priest of Khnum, priest of Banebdjedet, priest of Hat-Mehit, attendant [...] priest of Isis the great, mother of the god, who resides in Mendes, Hor-maa-kheru, son of Wen(-nefer)...'

Hieroglyphic inscription on the torso of Hor-maa-kheru

c . 8 TH - 9 TH c ENTURY AD | 4.6 c M HIGH GILT BRONZE, GLASS INLAY

Provenance

English Private Collection, acquired on the London art market pre-2000

An exceptionally fine gilt-bronze finial in the form of a beast’s head, once the terminal of a ceremonial drinking horn. Inlaid with glass eyes and retaining much of its original gilding, it is a rare survivor of elite Anglo-Saxon feasting culture.

c . 664-332 B c 6 c M HIGH cAST BRONZE

Provenance

Alexander Dobkin (1908–1975), New York, acquired prior to 1975

Thence by descent to his daughter, Katherine Dobkin, New York

A finely cast bronze cat head crowned with a scarab, uniting two of Egypt’s most powerful symbols. The cat embodies Bastet’s protective grace, while the scarab signifies rebirth and the rising sun. Formerly in the collection of the New York figurative painter, Alexander Dobkin.

c .300,000 - 30,000 YEARS OLD 114 x 107 x 34 c M SANDSTONE c ON c RETION

Provenance

Found whilst mining for sand, in the forest of Fontainebleau, 1988-1991

Subsequently with Jean-Paul Obeniche (1926-2020), circa 1991

Subsequently, ‘Masterworks of the Earth’ Collection, Richard Berger and Miriam Dyak, acquired from the above circa 1991

Exhibited

‘Masterworks of the Earth’, Seattle, Washington, 1991-2022

The finest concretion recovered from the most important discovery at the famed site of Fontainebleau. ‘The Gogotte’ challenges the boundary between nature and art. It is perhaps the most anthropomorphic natural formation known, epitomising the pinnacle of pareidolia – that innate human tendency to see meaningful shapes in abstract forms. It is inescapably a figure; a god, an idol or a warrior. From the collection that supplied almost all Fontainebleau concretions to America’s top natural history museums, ‘The Gogotte’ is the gem that Richard Berger chose to retain. For more than 30 years, it has remained the most publicised and impactful centrepiece of his ‘Masterworks of the Earth’ exhibition.

A Natural Sculpture

Gogottes are sandstone concretions believed to have formed between 300,000 and 30,000 years ago by the almost instantaneous cementation of silica-rich groundwater percolating through the pure quartz sand of the Fontainebleau desert. However, their sparkling white appearance is due to a geological process that occurred over 30 million years earlier. During this period, known as the Oligocene, continually retreating and flooding seas filtered the then sand dunes of the Paris Basin, leaving a remarkably fine, homogeneous sand with a particularly high silica content, often reaching above 99.7%. Unique to this region, the present specimen was the foremost gogotte to come from a considerable discovery of these concretions in 1988-1991.

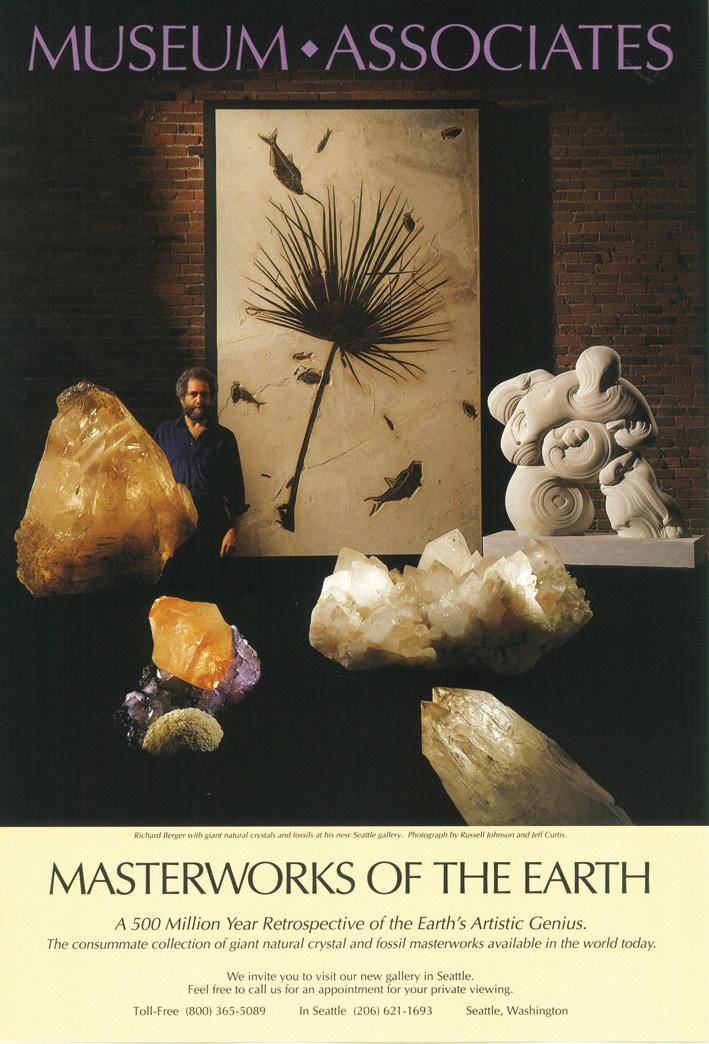

Fascinated by the recent discoveries in Fontainebleau and likening them to works by Michelangelo, Seattle-based mineral collector and dealer, Richard Berger sought to acquire as many gogottes as he could for his fittingly-titled exhibition, the ‘Masterworks of the Earth'. Home to remarkable geological specimens, from a 520-million-year-old crystal cluster from Namibia, to a giant ammonite fossil from the Chihuahuan Desert, the collection aimed to ‘awaken a new love and appreciation for the magnificence of planet Earth’.

The gogottes acquired from the sand dunes of Fontainebleau were its crowning glory. In particular, the present specimen was the centrepiece of the collection, singled out for use on promotional material.

As incredible ‘ambassadors of the Earth,’ gogottes have become a fundamental display piece of the natural history museum, with many acquiring theirs from Berger's collection.

The Houston Museum of Natural Science, the Yale Peabody Museum, and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, all acquired their specimens from 'Masterworks of the Earth'. Their prominent positioning within these institutions highlights their significance.

The Smithsonian's gogotte, for example, is displayed in the Harry Winston Gallery as one of six natural formations that surround arguably the most famous gemstone in the world, the Hope Diamond.

Left

Promotional advertisement for the 'Masterworks of the Earth' collection.

Cycladic figure, c.4500-4000 B.C. Marble. 21.4cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Acc. No. 1972.118.104.

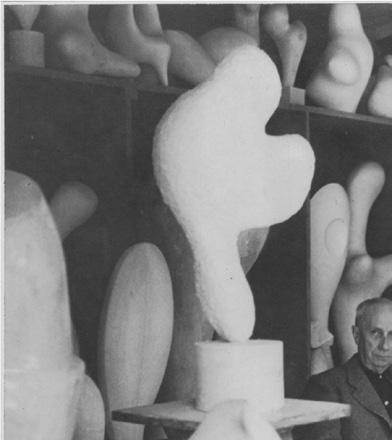

From the moment of their first discovery, gogottes have captivated all those who have come into contact with them. The Sun King, Louis XIV (1638-1715), was so enchanted by their shapes that he had several specimens excavated to decorate the gardens of the Palace of Versailles, under the direction of the celebrated architect and gardener, André le Nôtre (1613-1700). In the 20th century, gogottes inspired artists in their experimentation with abstraction, and they became a particular favourite of the Surrealists such as Henry Moore (1898-1986). Sculptor, Jean Arp (1886-1966) even reflected on their influence in his work, writing in 1958: 'Concretion signifies the natural process of condensation, hardening, coagulating, thickening, growing together. Concretion designates the solidification of a mass. Concretion designates curdling, the curdling of the earth and the heavenly bodies. Concretion designates solidification, the mass of the stone, the plant, the animal, the man. Concretion is something that has grown.’

Just as Shakespeare’s Antony sees shapes in shifting clouds, on seeing The Gogotte, it is natural to experience pareidolia, the innate desire to perceive a meaningful image in its random curves and shapes. Endeavouring to understand these geological specimens, we see in their folds a certain familiarity; in the present formation, an anthropomorphic figure, simultaneously a god, an idol and a warrior. Known to the ‘Masterworks of the Earth’ collection as 'The Sumo', this human-like concretion has captivated all since its discovery. In admiring its forms, we are perhaps also reminded of the Cycladic figures of the ancient Mediterranean, or the distorted and exaggerated proportions of Picasso’s portraits. Blurring the line between art and nature, this concretion, with its sparkling surface and anthropomorphic silhouette, embodies the meaning intended by the word terribilità As a term applied by contemporaries to Michelangelo’s sculptures, it denotes the sheer awe felt at the magnificence of an object’s creation. The Gogotte fulfils this in every aspect. It is a colossus, comparable to the sculptures of great artists, yet it is shaped entirely by the hands of Nature.

'Look at certain walls stained with damp, or at stones of uneven colour... you will be able to see in these the likeness of divine landscapes, adorned with mountains, ruins, rocks, woods, great plains, hills and valleys in great variety; and then again you will see there battles and strange figures in violent action, expressions of faces and clothes and an infinity of things which you will be able to reduce to their complete and proper forms.'

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Treatise on Painting

4 TH - 3 RD c ENTURY B c 33 c M HIGH POTTERY

Provenance

Collection of Julien Bessonneau (1842–1916), France; thence by descent Jean-Pierre Léveilley, Angers; acquired from the beneficiaries of the above collection in the 1970s–80s

An unusually large and finely proportioned lebes gamikos, the ceremonial nuptial vessel of ancient South Italian marriage rites.

c . 6 TH c ENTURY AD | 5.2 c M DIAMETER | GOLD, GARNET, GLASS

Provenance

With Achille Cantoni of Milan (1844-1914)

Marc Rosenberg (1852–1930) collection, Berlin, Germany, acquired from the above Hermann Ball & Paul Graupe, Berlin, Sammlung Marc Rosenberg, 4 November 1929, Lot 125

With Dr Wertheimer, Basel Collection of Ernst (1903-1990) and Marthe Kofler-Truniger (1918-1999), Lucerne (Inv. no. K 727 D), acquired from the above Private Collection, Lucerne, acquired from the above circa 1974, thence by descent

Published (inter alia)

H. Rupp, Die Herkunft der Zelleneinlage und die Almandin-Scheibenfibeln im Rheinland, Bonn, 1937, p. 76, pl. 21, no. 2, 5.

Exhibited

Kunsthaus, Zurich, Sammlung E. und M. Kofler-Truniger, Luzern, 7 June-2 August 1964.

A fine and well-provenanced example of one of the most striking emblems of the early medieval elite, displaying the fusion of Classical goldworking techniques with Germanic and Frankish tastes.

c .140 AD | 41 c M HIGH cARVED AND POLISHED MARBLE

Provenance

Thought to have been acquired by Sir John Inglis, Lord Glencorse (1810 - 1891) in Florence, Italy

Thence by descent to Sir Roderick John Inglis of Glencorse (1936-2018)

Lady Geraldine Inglis (1950 - 2022) of Glencorse by 1977, gifted from the above

Thence by descent

One of the finest and best preserved Roman Imperial portraits remaining in private hands. Recently rediscovered and identified as the biological son of Antoninus Pius (r.138-161 AD), Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus.

Coming from the estate of the Inglis family of Glencorse, and likely acquired by Sir John Inglis, Lord Justice-General of Scotland (1810-1891) in Florence during his travels to the continent in the 1850s and 60s.

The present bust is the finest and best preserved of a Roman Imperial portrait type known from only nine extant examples. Despite the type being previously identified as a young Commodus, classical archaeologist and renowned scholar, Professor Klaus Fittschen has convincingly argued that this is in fact a posthumous depiction of Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, the biological son of Antoninus Pius (r.138-161 AD), who died before his father's accession to the Imperial throne. To the six identified by Fittschen, we can now add a head in the Musée National du Bardo published in 2023, an additional head from the art market, and the present bust. Of these nine depictions, the ArtAncient bust is by far the finest and best preserved example, and by extension, one of the finest and best preserved portraits of an Imperial prince remaining in private hands.

The rule of the Antonine dynasty is often considered the apogee of the Roman Empire. Antoninus Pius ushered in an era of peace and prosperity, which was carried forward by his adoptive sons, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. While Verus expanded the Empire’s frontiers through military campaigns, Marcus Aurelius—sole ruler after his brother’s death—endures as the philosopher-king, with his Meditations famously reflecting the Stoic ideals of duty, discipline, and the pursuit of virtue and truth that defined his reign. While the assassination of Commodus brought the dynasty to an end following his infamous and turbulent rule, the Antonines remain one of the most famous Imperial dynasties, presiding over Rome at the end of the period famously known as Pax Romana

In this context of philosophical and political power, the Antonines also oversaw the emergence of an artistic style that has become uniquely associated with the Roman Imperial period. With their high polish, dramatic use of the running drill and articulated eyes, portraits of the Antonine period made use of novel techniques to maximise the effect of light, shade and reflection. This created a vivid, expressive style that defined the artistic identity of the dynasty, and had an enormous influence on the visual landscape of 18th and 19th century Neoclassicism.

When we acquired the present bust from Sworders auction house, there remained serious doubts as to its age. On account of the very few portrait busts that remain in a similar state of preservation, as well as the elaborate style of the drapery it preserved, it was dismissed by some as a copy by the likes of Neoclassical sculptor, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (1716-1799). However, as seen in the case of the bust of Emperor Commodus acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2008, such remarkable preservation and seemingly incongruent style alone cannot be considered strong enough evidence for a piece’s later dating. Ultimately the reason the style of the drapery was questioned, in both cases, is because drapery itself rarely survives. Indeed, complete portrait busts are extremely rare, with many fracturing at the neck (the weakest point), and becoming separated over time. Moreover, while Neoclassical copyists were indeed skilled imitators of the ancient form, the deeply-carved and angular drapery seen here is indicative of the Antonine style, as seen in the drapery on a female bust in the Metropolitan Museum (no. 13.115.2) . Other factors also point to the use of ancient carving methods. During the second century, the drill emerged as the favoured tool for accurately rendering elaborate curls of fashionable hairstyles, but it was also used to add depth to drapery, as well as figures' facial features. This novel carving method is visible here, both in the drapery and the hairstyle, which is typified by the extensively drilled curls, and the separation of locks by drilled channels. Even the corners of the mouth and pupils of the eyes here are drilled, as is typical with Antonine portraiture of this period. Most importantly, traces of two measuring points — small bosses of stone protruding from a carved surface — on the top of the head indicate that the piece was likely copied, in line with ancient techniques, from an original prototype. Close comparison with another head now in the Glyptotek in Copenhagen, identified by Fittschen, indicates that ours must have been produced in antiquity by a sculptor with intimate knowledge of a common model.

Above Head of Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, c.140 AD. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, no. 3358.

Below

Measuring point on the ArtAncient bust.

In addition to its remarkable preservation, the condition of the surface, relatively free from signs of age, was also noted. But cleansing the bust of dirt and modern paint revealed a waxy texture on the surface in some areas (notably the hair) indicating a modern cleaning technique. Indeed, restorers of the 18th and 19th century commonly used acid, bleach or poultice on ancient marbles to clean away burial encrustations. While thoroughly cleaned at some point during its lifetime, the less visible or more protected areas presented particularly clear remains of encrustations.

Upon receiving photographs, and extensive condition reports, Professor Klaus Fittschen, the leading authority on Antonine portraiture, confirmed that our bust was unequivocally ancient, and the eighth version of the Imperial prince known to him after the newly published head in the Musée National du Bardo.

The bust comes from the descendants of the Inglis family of Glencorse, and was likely acquired by Sir John Inglis (1810-1892), distinguished lawyer and politician, on one of his trips to the continent around the 1850-60s. Known for his illustrious legal career, which culminated in his appointment as Lord Justice-General of Scotland and Lord President of the Court of Session in 1868, he also had, according to his biography, 'a great love for and keen appreciation for art.’ This likely stemmed from his early studies of the ancient past under Sir William Hamilton (1788-1856). A collector and philanthropist, during his lifetime, Inglis actively supported exhibitions, lending his own works by the likes of Henry Raeburn (1756-1823) and William Shiels (1785-1857) to the Royal Scottish Academy, as well as sitting on the Board of Manufacturers, the institution that founded the National Gallery of Scotland and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

For much of his life he resided at 30-31 Abercromby Place, Edinburgh, purchasing Glencorse House in 1855-56, as well as inheriting his familial home, Loganbank, on the edge of the Glencorse estate, in 1883. Known to have ‘brought paintings and bronzes and other objects of art from all quarters for the ornamentation of his house,' his ‘taste was extremely good and pure, and educated as well as intuitive.’ Hiring the renowned architect of the age, Sir David Bryce (1803-1876), he oversaw the renovation of these three houses in line with the Neoclassical style of the day. The interior of his Edinburgh home at 30-31 Abercromby Place, redesigned by Bryce in 1857, included elaborate baroque-carved French walnut balustrades, Corinthian columns, and even a series of Parthenon reliefs. Meanwhile, Loganbank was outfitted with ‘mid-18th century furnishings’, ‘Rococo overmantelled chimney pieces of the finest quality’, and ‘17th century panelling.’ In particular, the ‘ownercollector contrived a little Empire Room,’ and lined it with grisaille wallpaper panels of Cupid and Psyche by Dufour of Paris. Inglis clearly had a strong interest in the classical past. Portrait busts of the family from this time by pre-eminent Scottish sculptor, Sir John Steell RSA (1804-1891), depicted with classical drapery similarly testify to this interest.

Between 1849 and 1852, Inglis made several trips to the continent, visiting ‘many German and Italian galleries,’ and preserving ‘a vivid recollection of the achievements of art which he had admired in continental centres.’ In particular, through his sister-in-law’s marriage, Inglis had close familial connections to Florence. It is possible that during one of these trips Inglis acquired the present bust, and also came to know the archaeologist and dealer, Wilhelm Helbig (1839-1915), who was an active dealer in Italy during this period. In the final years of Inglis’ life, his son, Alexander Wood Inglis (1845-1929) donated several objects, including antiquities, to the National Galleries of Scotland and other institutions.

Though the piece stayed in the family, it was eventually mistaken for a modern sculpture. The last owner, Sir Roderick, similarly lived in South Africa before leaving the dispersal of the estate and the family’s belongings - including the present bust - to his wife on their divorce in 1977.

25.5 c M HIGH, 19.5 c M WIDE | cALc ITE AND c HALc OPYRITE ON MATRI x

Provenance

Discovered at the Sweetwater Mine, Viburnum Trend, Ellington, Reynolds County, Missouri, USA, in 2019.

An exceptional and highly sculptural specimen from the famed 'Dragon Scale Pocket,' unearthed during a single, now legendary find in 2019 at the Sweetwater Mine. This dramatic cluster presents a striking spray of lustrous, dark golden-green calcite crystals, arranged in overlapping tiers, evoking dragon scales, after which the specimens are named.

c . 7 TH - 8 TH c ENTURY AD | 4.5 c M HIGH GILT SILVER WITH BLUE GLASS

Provenance

By repute found near Fyfield in Essex in the early 1990s

English Private Collection

A unique Anglo-Saxon depiction of Ragnarök, the cataclysm in Norse mythology that led to the destruction and rebirth of the gods and the cosmos. The wolf Fenrir is shown devouring Odin, who emerges from Fenrir's mouth to grab the underworld serpent, Jörmungandr.

c . 724-332 B c 8.5 c M HIGH | GREEN AND BLUE GLAZED FAIEN c E

Provenance

Collection of George Anastase Michaelidis (1900-1973) Fine Antiquities, Christie's, London, 13 July 1983, Lot 399 Subsequently, collection of Prof. Hermann A. Schlögl (1932-2023), Germany.

Published

H. A. Schlögl, Geschichte und Wege: Notizen zu ägyptischen Totenstatuetten und anderen Kleinfunden, Verlag Michael Haase, Berlin, 2012, p. 153-7 (ill.).

An inscribed fragment from the 'Bowl of the Traitor,' a unique ritual vessel attributed to Udjahorresnet, the eminent Egyptian admiral, priest, and chief physician who abandoned his pharaoh to serve the Persian kings, Cambyses and Darius.

‘Chief physician of Upper and Lower Egypt. Specialist in Syrian products...'

Translation of hieroglyphs on the 'Bowl of the Traitor.'

c . 7 TH - 6 TH c ENTURY B c 38.5 c M | cARVED LIMESTONE WITH PIGMENT

Provenance

Discovered by Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904) at the sanctuary of Aphrodite at Golgoi, Cyprus, around 1870

Collection of Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904)

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired from the above by subscription c.1872.

Published

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hand-Book no. 3, The Stone Sculptures, New York, 1904.

A fragment from a colossal Archaic Cypriot sculpture, preserving the sweeping eyes and characteristic smile of Cypro-Archaic art. Combining Near Eastern and Greek traditions at the crossroads of the Mediterranean, it was discovered by Luigi Palma di Cesnola in the 1860s–70s and later entered the founding collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

2 ND c ENTURY B c PENDANT 4.2 c M, c HAIN 75 c M | GOLD, GARNET, INLAID GLASS

Provenance

Reputedly found in Olbia, Ukraine Collection of Friedrich Ludwig von Gans (1833 -1920), Frankfurt with Kurt Walter Bachstitz Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands by 1921 until at least 1930 Collection of Ernst (1903-1990) and Marthe Kofler-Truniger (1918-1999), Lucerne, acquired prior to 1960 (Inv. no. K 728 A) Private Collection, Lucerne, acquired from the above, circa 1974, thence by descent

Published (inter alia)

R. Zahn, Galerie Bachstitz Gravenhage: Antike, byzantinische, islamische Arbeiten dei Kleinkunst und des Kunstgewerbes. Antike Skulpturen, vol II, Berlin, 1921. (p. 10, no. 28a, pl. 7).

H. T. Bossert, Geschichte des Kunstgewerbes, Band IV, Berlin & Zurich, 1930, p. 225.

Exhibited

Meisterwerke Griechischer Kunst, Kunsthalle, Basel, 19 June-13 September 1960 Sammlung E. und M. Kofler-Truniger, Zurich, Kunsthaus, Luzern, 7 June-2 August 1964

An ambitious work of Hellenistic jewellery, this pendant embodies the heights of goldworking and gem-cutting in the final centuries BC. Depicting an openwinged butterfly, symbol of the soul’s freedom, it unites Greek artistry with the techniques and materials of the wider eastern Mediterranean. Of the very few pendants of this type to survive, this is the earliest, the best known, and the most widely published in private hands.

Following Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian empire in 331 BC, unprecedented quantities of gold from the treasuries of Babylon and Persepolis flooded the Hellenistic world. The economic prosperity that followed established a new elite, who fostered a market for luxurious goods of unparalleled refinement and innovation, reflective of their newfound status. Goldsmiths in turn created detailed and intricate jewellery, that blended Greek artistry with Near Eastern techniques. At its height in the final few centuries BC, Hellenistic mastery of goldworking established a standard of craftsmanship and opulence that has echoed through the history of jewellery design ever since.

With its intricacy and ambitious design, the present pendant and chain is a particularly exquisite and enigmatic example of the heights achieved by these Hellenistic craftsmen. The butterfly is also a particularly poignant motif. To the ancient Greeks, butterflies were not just delicate creatures of the wind. They were the very essence of the human spirit, and an important symbol of its transformation after death. As the manifestation of the Goddess Psyche - a mortal woman granted immortality by Zeus - their fluttering was seen to embody the regeneration of the spirit, an idea inherently tied to the unique lifecycle of the insect. Just as the butterfly breaks free from the chrysalis, so the soul is set free from the body and from the shackles of mortality. Depicted on gemstones, vases and reliefs, it was a deeply entrenched symbol within ancient Greek society, reaching the far outposts of the Hellenistic world.

From the Black Sea

Elaborately decorated necklace pendants in the form of a butterfly are known today through a rare group from the region surrounding the Greek colony of Olbia on the northern coast of the Black Sea. The fact that these necklaces were all found within the same region suggests that they were produced locally, likely by the skilled artisans that settled in the region following its conquest by Zopyrion, a general of Alexander the Great in the 3rd century BC. On account of their enigmatic symbolism and elaborate design, they often accompanied their owners as prized grave goods, invoking ideas of the soul’s regeneration after death. Of the handful that survive today, the present, with its ambitious design and remarkable provenance, is the most well-known and widely published example remaining in private hands.

Its wings are expertly inlaid with colourful mosaic glassware using the cloisonné technique, which developed in the Near East, and finished with an outline of beaded wirework. A deep red, heart-shaped garnet indicates the head - a shape well-known from Hellenistic jewellery as a symbol of fertility and new life. The abdomen is indicated by another red garnet and a beautifully banded agate bead, whilst the spiralled wires used for the antennae and legs were similarly made with a Near Eastern technique known as the strip-twist method.

While the majority of these necklaces are in major museum collections around the world, from the British Museum to the Walters Art Museum in America, the present pendant is among the most well-known and widely published. Through comparison with the small gold flasks from Olbia found with the two necklaces now in the Walter’s Art Museum, our pendant has even been used to date the type, and has been identified as one of the first of this kind produced. The only piece of comparable quality is perhaps the pendant now in the Odessa Archaeological Museum, with the one in the British Museum being described as ‘simpler and much cruder’. Indeed, while in the Kofler-Truniger collection the present necklace was exhibited at the landmark exhibition fittingly titled Masterpieces of Greek Art, from 19 June to 13 September 1960.

17 TH c ENTURY OR EARLIER 31 c M HIGH SHELL

Provenance

Willy Boetschi (1911–1964), Fort-Dauphin, Madagascar, acquired in the region of Androy during his mining activities, circa 1930s–1950s

By descent to his wife, Irmy Boetschi (née Wassmer, 1906–1997), Fort-Dauphin and later South of France, following their divorce in 1953

Thence by descent to their daughter, Monique Journeaux (née Boetschi, b. 1939), Lausanne, 1997

An intact egg of the elephant bird, Aepyornis maximus, the largest egg ever laid by any animal.

c . 3000 B c 22 c M DIAMETER BANDED ALABASTER

Provenance

Collection of V. Everit Macy (1871-1930)

American Art Association, 6 January 1938, Lot 240 Collection of actress and socialite Doris Duke (1912-1993)

Christie's New York, The Doris Duke Collection 3-4 June 2004, Lot 237 Collection of Prof. Hermann A. Schlögl (1932-2022), Germany

Carved from a beautiful piece of banded stone, the natural veining exploited to form an abstract, almost anthropomorphic face. Formerly in the collection of V. Everit Macy (1871–1930), prominent American industrialist and philanthropist, and later Doris Duke (1912–1993), celebrated actress and socialite.

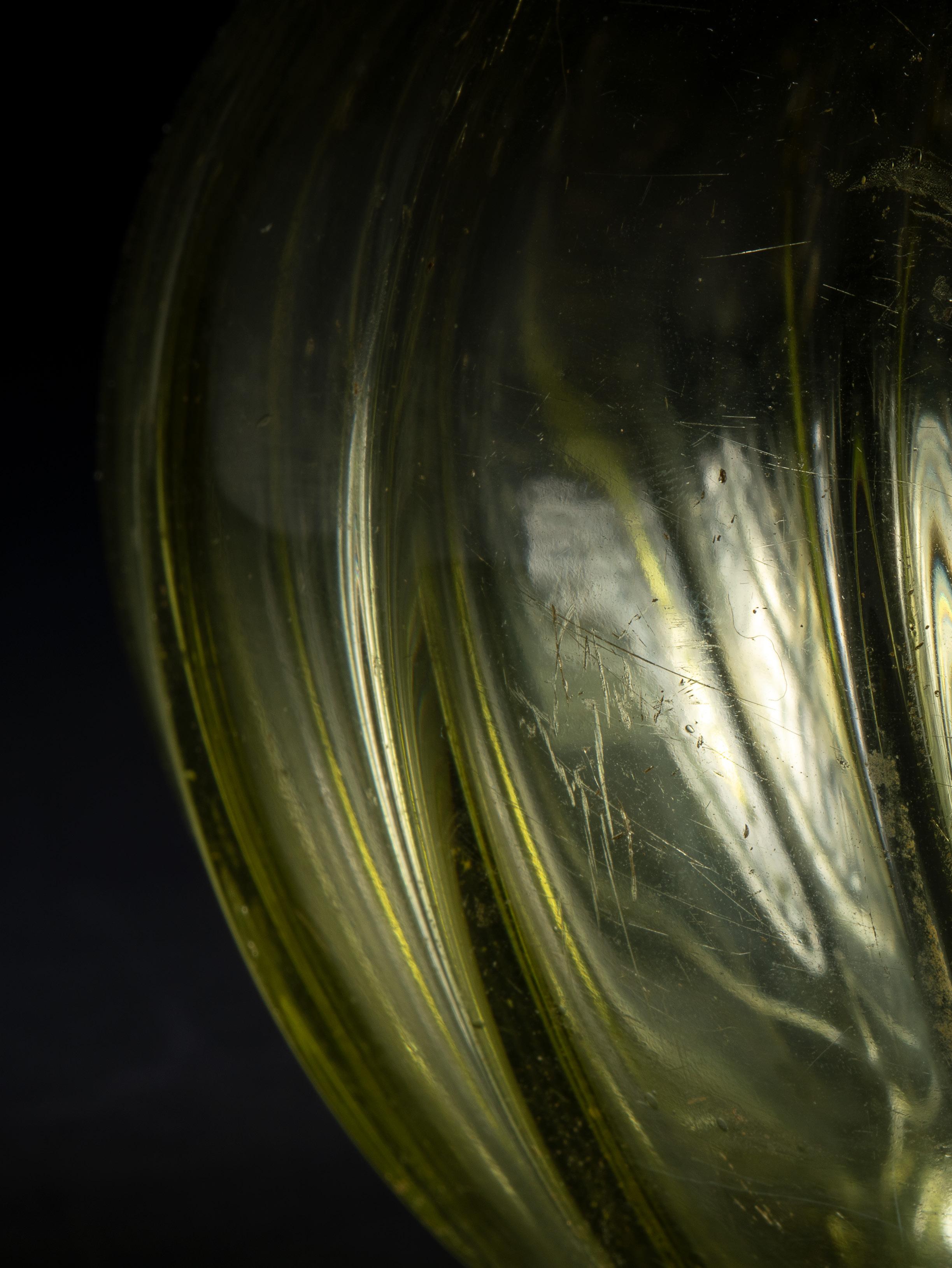

c MID -1 ST - MID -2 ND c ENTURY AD 15 c M HIGH GREEN GLASS

Provenance

Collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon (1819-1899), France, thence by descent; with label reading '107. St Victor', reputedly discovered there on 2 April 1843

Les Antiques de Louis-Gabriel Bellon, Jack-Philippe Ruellan, Vannes, France, 4 April 2009, Lot 184

Subsequently, Collection of Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al Thani (1966-2014), acquired at the above sale.

An immaculately preserved ribbed glass vessel discovered in Saint-Victor, France, in 1843. Subsequently in the famous 19th-century collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon and more recently in the collection of Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al Thani.

c . 1150-930 B c 59 c M LONG cAST BRONZE

Provenance

Likely found in the River Seine, France Philippe Missilier (1949-2022) Collection, Paris

With French cultural property passport, 255244 and export license no. 2025 DNF 1828 04092026

An exceptional ceremonial spear, the largest of its kind, known from only a handful of examples discovered in northern France and the British Isles. An extremely rare and highly important status symbol of Late Bronze Age warrior culture.

The rise of bronze-smithing in Europe brought with it not only technical innovation but also profound social change. Coinciding with the emergence of a new warrior elite, metalworkers began producing weapons of exceptional quality and beauty that were as much symbols of prestige as instruments of combat. Indeed, archaeological evidence from the period suggests that the mastery of arms - in particular the sword, spear, and axe - became cornerstones of society. With authority rooted in martial ability, these finely cast weapons became important markers of rank, displayed in life and interred in death as part of the lavish burial assemblages that have come to define the period today.

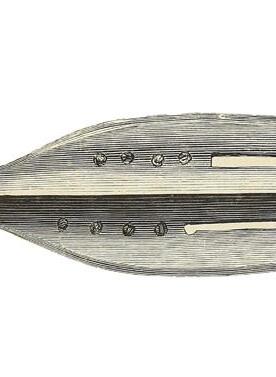

This elegant, leaf-shaped spearhead is the largest known and one of the best preserved examples of a remarkably sophisticated spear type identified from a handful of finds from northern France and the British Isles. The striking similarities between the surviving examples suggest production in a single workshop in northern France. The example found in the River Thames, near Bray, is perhaps evidence of a widespread cultural network, linking chieftains and kingdoms across the channel.

The remarkable, golden lustre of the present piece is further indicative of its importance in antiquity. This ‘river patina’ is the result of millennia submerged in freshwater, where the oxygen-depleted environment allowed for astonishing preservation. As an object of great significance and material value, it was likely cast into such a waterway as a votive offering to the gods, as is testified by the two other examples found in the River Seine, and one in the River Thames.

The craftsmanship of the present spear indicates that it was made for a very high-status individual. Indeed, the material and labour cost of such an object in prehistoric Europe would have been enormous, and the blade’s deliberate weakening in pursuit of beauty and ornamentation suggests that its aesthetic value was considered more important than its utility.

Illustration of a similar spearhead in the collection of Julien Gréau. From Collection J. Gréau : Catalogue des bronzes antiques et des objets d'art du Moyen Âge et de la renaissance, 1885.

c . 4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 23 x 25 c M STONY-IRON, PALLASITE

Provenance

Discovered in 1967, Magadan District, Russia (62° 54’ N, 152° 26’ E)

Published Meteoritical Bulletin, no. 43, Moscow (1968).

A magnificent cross-section from the pallasite meteorite, Seymchan, recovered from the bed of the river Hekandue in the Russian Far East, and revealing the honeycomb-like structure characteristic of pallasites, with gems of semiprecious olivine embedded in shimmering iron-nickel crystals.

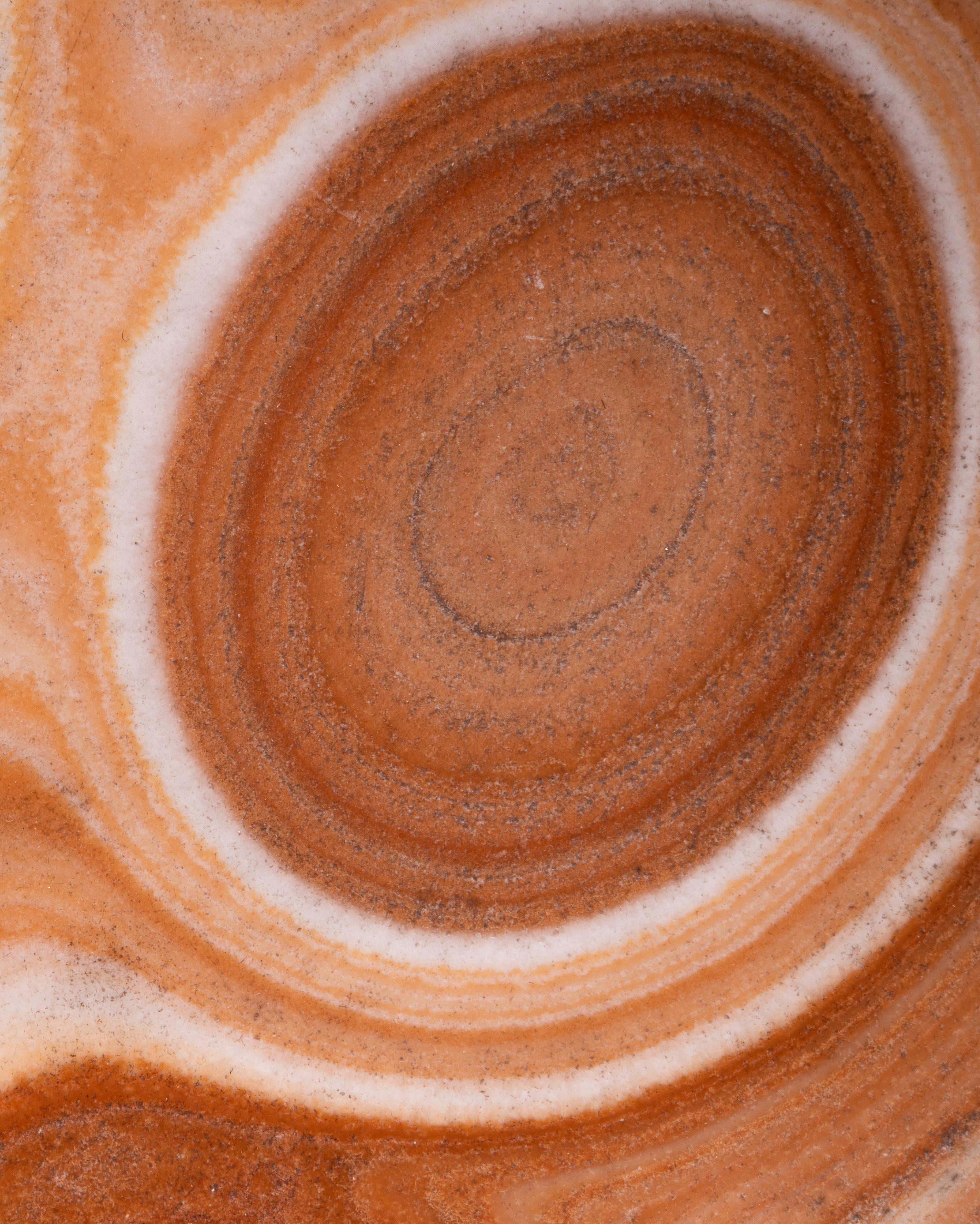

c . 1290 - 1270 B c | 34 c M HIGH | cARVED ORANGE QUARTZITE

Provenance

European private collection since at least 1951, as indicated by the previous wooden base by Kichizo Inagaki (1876-1951)

Maîtres Laurin, Guillox, Buffetaud, and Tailleur at Hôtel Drouot, Salle no. 6, 20 May 1987, Paris, Lot 315

Subsequently, the Thalassic Collection, Theodore (1932-2001) and Aristea S. Halkedis (1933-2014), New York

Acquired by Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al Thani (1966-2014) from the above.

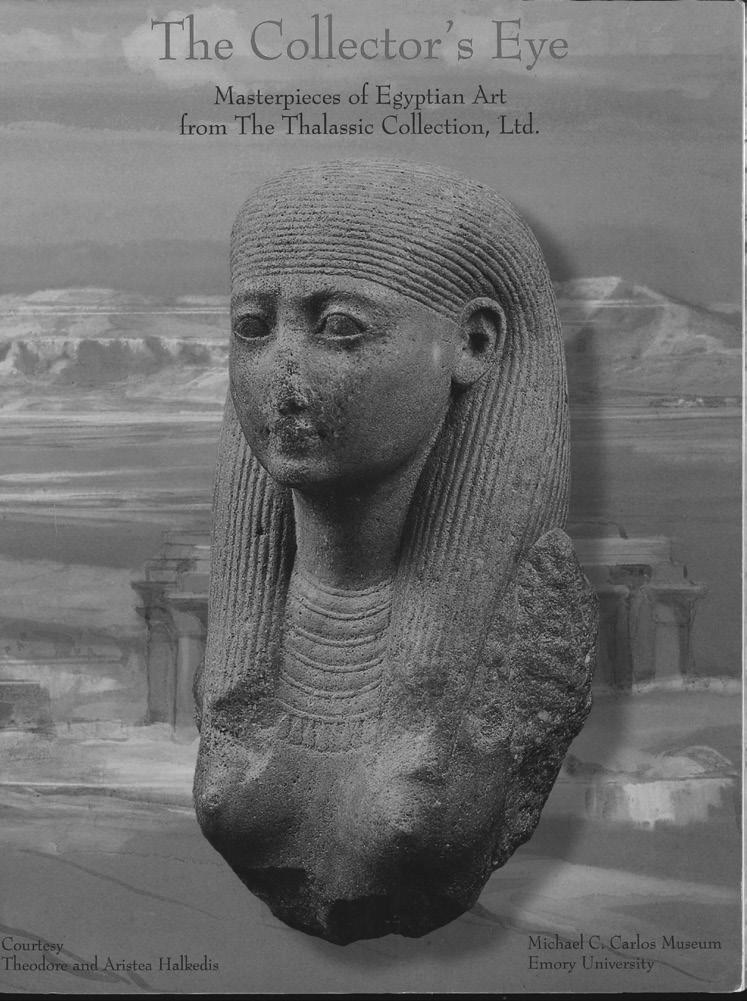

Published

The Collector's Eye, Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from The Thalassic Collection, Ltd. Michael C. Carlos Museum, Atlanta, 2002, p. 29-34, no. 16.

Exhibited

‘The Collector's Eye: Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from The Thalassic Collection,’ Michael C. Carlos Museum, 21 April 2001 - 6 January 2002.

An exquisite hardstone bust of a female deity, with tripartite wig and Usekh collar, displaying the best of early Nineteenth Dynasty art. Once belonging to two of the most important art collections of the twenty-first century: the Thalassic Collection and the Sheikh Al Thani Collection.

Described by the distinguished archaeologist and curator Dorothea Arnold as a ‘quartzite masterpiece’, this bust is an exquisitely modelled example of hardstone statuary from Egypt’s Nineteenth Dynasty. Carved from a block of rich orange quartzite, indicating an exceptionally wealthy patron, it was likely created as a votive, for display within a temple. In antiquity, the complete statue would have shown the goddess either standing or seated, presented alone or accompanied as part of a divine group. Typical of early Ramesside art, her naturalistic features reflect the post-Amarna artistic tradition, while also being paralleled in the statuary of Sety I and Ramesses II. With her tripartite wig and broad Usekh collar, she is an iconic and masterfully carved example of New Kingdom hardstone sculpture. The reign of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) saw a high point in the production of Egyptian hardstone statuary. Valued for its quality and durability, hardstones such as granite, basalt, and quartzite were significantly more difficult to quarry and carve than softer stones like limestone or sandstone. As a result, hardstone sculpture was more expensive to produce and typically reserved for elite contexts. Synonymous with such commissions, hardstone sculpture played an important role in the display of wealth, secular power and divine authority. The scale of Ramesside commissions was unprecedented, with colossal statues carved from Aswan granite being installed at Luxor, Karnak, Abu Simbel, and the Ramesseum.

Of all the hardstones carved by the ancients, orange quartzite was particularly treasured for its unique colour. Likely hailing from the quarry at El-Gabal el-Ahmar near the ancient city of Heliopolis, the cult centre of the sun god Ra, its warm, golden hue was considered sacred. With its brilliance thought to evoke the regenerative properties of the sun’s cycle, statuary and relief sculpture carved from the stone were endowed with particular significance. When used in royal statuary, it stressed the solar aspect of kingship, emphasising the pharaoh’s divine authority. Known as ‘the Red Hill,’ El-Gabal was the leading quarry for quartzite in Egypt, reaching its height under Ramesses II. First used for colossal royal sculpture in the Eighteenth Dynasty, quartzite soon became synonymous with the most exquisite statuary Egypt had ever seen. During the Amarna period in particular, royal statuary was frequently made of orange quartzite, as its potent symbolism reinforced Pharaoh Akhenaten’s religious focus on the Aten (the sun disk).

Sensitively carved from the same stone, the present bust is exquisitely modelled, combining the emerging predilection for hardstone sculpture with the enduring naturalistic style of the Amarna period. The fine modelling of the face, the smooth flesh, and rounded eyelids and brow ridges, combined with the detailed rendering of individual strands of hair in the wig, as well as the subtly modelled breasts, betray the hand of a master sculptor. The natural eye shape, without any stylised cosmetic lines, is well known from Amarna-era portraiture, such as the head of King Tutankhamun now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Acc. no. 50.6). The round face, full cheeks and upturned, smiling lips are paralleled in the portraits of Sety I (r. 1290-1279 BC), who sought to reestablish control after the upheaval of Akhenaten’s reign, while the simplicity of the head ornamentation is seen in divine images of the reign of his son, Ramesses II.

Above

The modelling of the eyes on the present bust betrays the Armana influences seen in this depiction of Tutankhamun now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, acc. no. 50.6

The quartzite bust has had a particularly illustrious collection history, forming part of two of the most important collections of recent years: the Thalassic Collection and the Sheikh Al Thani Collection. The Thalassic Collection of Theodore (1932-2001) and Aristea Halkedis (1933-2014), is known as ‘one of the finest collections’ of Egyptian art ‘in the world.’ Of all the masterpieces in their collection, the present bust was a particular highlight, selected as the cover piece for the famed exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum, The Collector's Eye, Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from The Thalassic Collection in 2002. The scholarly contribution to the catalogue is still consulted by academics and private collectors alike, with renowned archaeologist and curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dorothea Arnold, writing on the present bust.

In 2002, it was acquired for the collection of Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al Thani (1966–2014). Considered one of the most ambitious private art collections of modern times, the Sheikh assembled an extraordinary range of objects, from ancient manuscripts and antiquities to contemporary art, furniture, vintage cars, and fine jewellery - including the famed 70-carat Idol’s Eye diamond. Appointed Qatar’s Minister of Culture, Arts and Heritage in 1997, Sheikh Al Thani played a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s cultural identity, overseeing the establishment of landmark institutions such as the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and acquiring works to populate their collections. Known for his discerning eye and reputation as one of the world’s most active collectors, his acquisitions not only elevated Qatar’s standing on the global stage but also cemented his own legacy as a patron of the arts and cultural heritage.

2860-2521 B c | 16 c M | cARVED LIMESTONE

Provenance

With Mathias Komor (1909-1984), New York Antiquities and Islamic Art Sotheby's, New York, December 12th 1991, lot 23 Subsequently, Collection of Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al Thani (1966-2014)

An extraordinary limestone bowl, carved in the rare and striking form of a starfish.

c .664-525 B c 7 c M HIGH | FAIEN c E

Provenance

Collection of Brigitte Martin (b. 1955), Paris, acquired from the Mythologie Gallery, Paris, 1973

A finely modelled faience figure of a baboon, representing the god Thoth, patron of writing and wisdom, its naturalistic features beautifully rendered from the textured fur to the delicately placed hands and rounded haunches.

c . 246 - 221 B c 35 c M HIGH cARVED MARBLE

Provenance

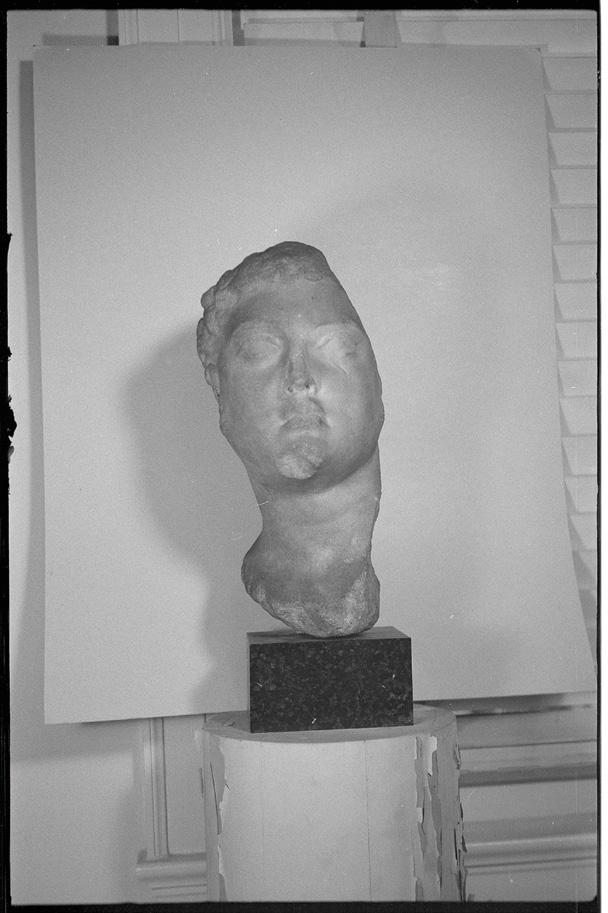

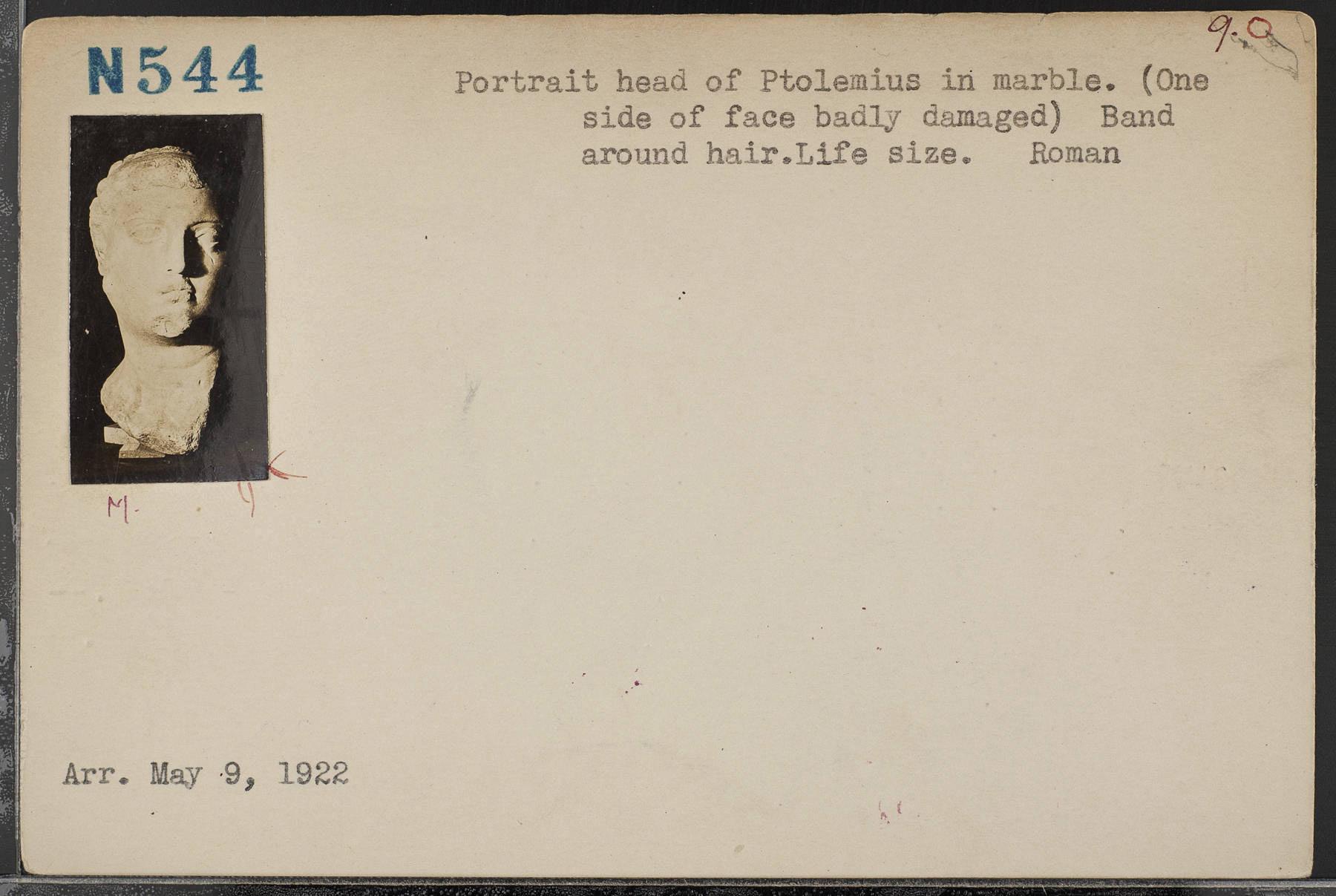

With Edgar Altounian, Paris, prior to 1922

Acquired by Ernest Brummer from the above on 25 April 1922

The Ernest Brummer Collection, Galerie Koller, 16 – 19 October 1979, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, Lot 622

European Private Collection, acquired from the above

Published (inter alia)

L. Baumer, ‘Vater oder Sohn?: Ein Nachtrag zu einem Ptolemäerbildnis’, Hefte des Archäologischen Seminars der Universität Bern, 13, (1990): pp. 5-8.

I. Jucker-Scherrer, ‘Ptolemaios III. Euergetes’, in Gesichter: Griechische und Römische Bildnisse aus Schweizer Besitz, Exhibition Catalogue, Bern, 1982, no. 2, pp. 18-19.

R. Smith, Hellenistic Royal Portraits, Oxford, 1988, no. 37, pl. 27 (6/7), p. 162.

Exhibited

‘Gesichter: Griechische und römische Bildnisse aus Schweitzer Besitz’, Historisches Museum, Bern, 6 November 1982 – 6 February 1983.

One of the finest surviving works of Alexandrian sculpture, the ‘Brummer King’ is the largest and most securely attributed of the twenty extant marble and terracotta heads considered by scholars to depict Ptolemy III Euergetes. Almost certainly part of an official monument in antiquity, it is further distinguished by the quality of its marble - a material scarcely available in ancient Egypt.

Of all the Ptolemaic marble and terracotta heads that survive today, only twenty are accepted by scholars to depict Ptolemy III of Euergetes. Of all these, the present head is the most securely attributed to the ruler. Writing about the present piece in 1983, classical archaeologist, Dr. Ines Jucker-Scherrer noted, ‘The narrow eyes under elongated, smooth eyebrows, the fine, small nose and the gently rounded, small mouth are characteristic of Ptolemy III.’ However, while many, including those portraits depicted on coins, are usually posthumous, and show the ruler as ‘exceptionally corpulent and overladen with divine attributes,’ the present piece, by contrast, ‘show[s] the ruler in a lifelike way.’ She concluded therefore, that ‘this representation of Ptolemy differs fundamentally from contemporaneous artworks ... due to his serenity and almost hieratic severity. '

The extant heads of Ptolemy III are commonly small and were most likely private statues or objects of worship as part of the Ptolemaic dynastic cult. The sheer size of the Brummer King (over 30 cm tall) as well as the superior material make it stand out among the corpus. Cut from a single block of marble - a material not readily available in Egypt - it was clearly once part of an official monument on public display. Specialist in Greek and Roman sculpture, Lorenz Baumer has identified this portrait as an example of the finest Alexandrian work. It most probably belonged to an official monument in the Ptolemaic capital, Alexandria, ‘where there is still a smaller, stylistically closely related Euergetes head.’ It seems that only the heads of full-body Greek-style statues were made of marble during this period. The bodies must have been crafted from more perishable materials, such as wood, thus explaining why only the heads have commonly survived.

Ptolemy III Euergetes

The Ptolemaic dynasty was founded in 305 BC, when the Macedonian Ptolemy (d. 282 BC), governor of Egypt after Alexander the Great’s death (323 BC), proclaimed himself pharaoh. As a foreign dynasty in Egypt, the Ptolemies were keen on seeking the approval of the local population. They produced official portraiture which showed them in a purely Egyptian - or as with this portrait, Greek manner - and sometimes in a style which fused elements of both cultures. Ptolemy III reigned from 246 to 222 BC. His epithet ‘Euergetes’ means ‘the benefactor’. Under his rule, the Ptolemaic Kingdom reached its apogee as the largest successor state of the Hellenistic kingdom. An enterprising builder, he notably ordered the construction of the Serapeum of Alexandria and the Temple of Horus at Edfu, the best-preserved masterpieces of Egyptian architecture.

The Ernest Brummer Collection

Our piece was bought by renowned art dealer, Ernest Brummer (1891-1964) from antiquities dealer Edgar Altounian of 34 Rue Saint-Lazare, on 25 April 1922 for 5,000 French francs. Arriving with Brummer on 9 May, it entered the collection of one of the foremost art dealers of the 20th century.

Born in Hungary, Ernest Brummer came from a family of art dealers who collected a wide range of pieces, from classical antiquity to modern art. Having studied music and art history, in 1906 Ernest moved to Paris and in 1912, founded, alongside his brothers, Joseph (1883-1947) and Imre (1889-1928), their first gallery, ‘Brummer Frères: Curiosités’, at 6, Boulevard Raspail. In 1914, Joseph and Imre moved to establish a U.S. branch in New York. Following World War I, Ernest reopened their successful business in Paris, as ‘E. Brummer: Objets d’art archéologiques’. The brothers worked closely together in a transatlantic partnership until the start of World War II, when Ernest fled occupied Paris and joined them in New York.

Above

Our

Above

Not only did they deal in masterpieces from antiquity, but they also held many exhibitions on French painters, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Rousseau. The Brummer archives, now with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holds documentation relating to a vast array of artworks hailing from China, Japan, Persia, Oceania and Africa, as well as Egyptian and Graeco-Roman antiquities and medieval art. Following Joseph’s death in 1947, Ernest remained at the helm of the New York gallery until his own death in 1964. Over these years, Ernest and then his widow, Ella Baché-Brummer organised several auctions of the collection. Today, works from the brothers' gallery can be found in museums around the world.

c . 2 ND - 3 RD c ENTURY AD 10 c M HIGH cARVED AND POLISHED MARBLE

Provenance

Dr. Henri Longrée (1922–2005), Brussels, acquired in the 1950s

Thence by descent to his son, Maxime Longrée (b. 1960), Brussels

Full of pathos, this finely carved head of Hercules shows the hero in a moment of introspection. His furrowed brow, parted lips and curling beard, with the head turned gently to the left, convey an unusual depth of expression for a work of this scale.

c . 380 - 200 B c 107 c M HIGH, 215 c M OVERALL | cARVED LIMESTONE

Provenance

Collection of Dr. Hans Hitzler, Bochum, Germany, acquired prior to 1944.

Ancient Sculpture and Works of Art, Sotheby's, London, 3 December 2019, lot 60.

The upper part of a monumental anthropoid limestone sarcophagus, finely carved and preserving several hieroglyphs from a spell for immortality from the Book of the Dead.

The elaborate funerary rites of the ancient Egyptians - mummification, the casting of spells, and rituals such as the Opening of the Mouth ceremony - were practiced over three millennia and believed to provide the deceased with safe passage to the afterlife. While specific customs and traditions adapted over time, the preservation of the body, as the eternal dwelling place for the ka (the life force), remained central. Beginning in the Old Kingdom with mummification and wooden coffins, as Egypt’s prosperity grew, the burial paraphernalia became more elaborate, resulting in richly decorated assemblages and sophisticated methods of embalming. Royal and elite burials saw tombs similarly decorated with protective spells from the Book of the Dead, and scenes of offering, worship or rebirth, reflecting not only the wealth of the individual but also Egypt’s deep-seated belief in life after death.

First seen in the royal burials of the Old Kingdom, large-scale stone sarcophagi developed from the wooden coffins of earlier periods, soon becoming common among priestly and administrative elites desiring to mimic the elaborate burial practices of their rulers. Wooden coffins still existed, often elaborately painted and nestled within their stone counterparts, but it was the monumental stone anthropoid sarcophagus that became an iconic marker of status and an enduring symbol of Egyptian culture. While their practical role was to safeguard the body, to the Egyptians, these enormous sarcophagi were seen as the temples of Osiris - the god of the underworld, resurrection and eternal life, into which the owner was transfigured after death.

So entrenched in Egyptian burial practice, their use continued under the Ptolemies, who sought to legitimise their rule through the adoption of the visual landscape of Egypt’s sacred traditions. Compared to their wooden predecessors, the sarcophagi of the late and Ptolemaic periods were carved on a particularly large scale, measuring generally around two metres and weighing multiple tonnes. Limestone was a popular medium for their creation. Its relative abundance and workability enabled broader sections of society, particularly the priestly and administrative elites, to commission elaborate burial paraphernalia once reserved for kings and the highest nobility. Limestone provided a durable medium that could be carved on an impressive scale, with many examples originally being carved from one slab of stone. Harder limestones also allowed for particularly fine carving of the features, as seen here in the contours of the cheeks, the detailed cosmetic lines and the lips. Originally, the surface might even have been painted to consolidate this lifelike depiction.

Inscriptions and spells on sarcophagi - a common feature of Egyptian burial practicealso became more standardised in the Late and Ptolemaic periods. This ultimately allowed the identification of the complete inscription on the present piece from just a handful of remaining hieroglyphs. Indeed, renowned American Egyptologist, Jonathan Elias, identified that the complete inscription of the present example originated from Chapter 154 of the Book of the Dead, and specifically a spell for ensuring the immortality of the body after death.

Above

The full spell from Chapter 154 of the Book of the Dead as inscribed on the sarcophagus.

'Hail to thee my father Osiris, I have come, that you may treat this flesh of mine (so that) this corpse of mine shall not pass away, for I am complete; complete, like my father Osiris-Khepri. He is like the one whose corpse does not pass away. ' Book of the Dead, Chapter 154

c . 3 RD c ENTURY B c 24 c M HIGH TERRAc OTTA, WHITE SLIP, RED PIGMENT

Provenance

Collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon (1819-1899), Saint-Nicolas-lez-Arras and Rouen, thence by descent

An exceptionally fine Tanagra terracotta, depicting a veiled young woman with head slightly turned and drapery falling in delicate folds. Once in the celebrated 19th-century collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon, among the earliest and most important assemblages of Tanagra figures.

66 MILLION YEARS OLD | 13 c M FOSSILISED BONE AND TOOTH

Provenance

Discovered on Reed Ranch, Lance Formation, Niobrara County, USA in 2022.

The partially preserved dentary (lower jaw) from an iconic prehistoric predatorTyrannosaurus rex - with serrated tooth.

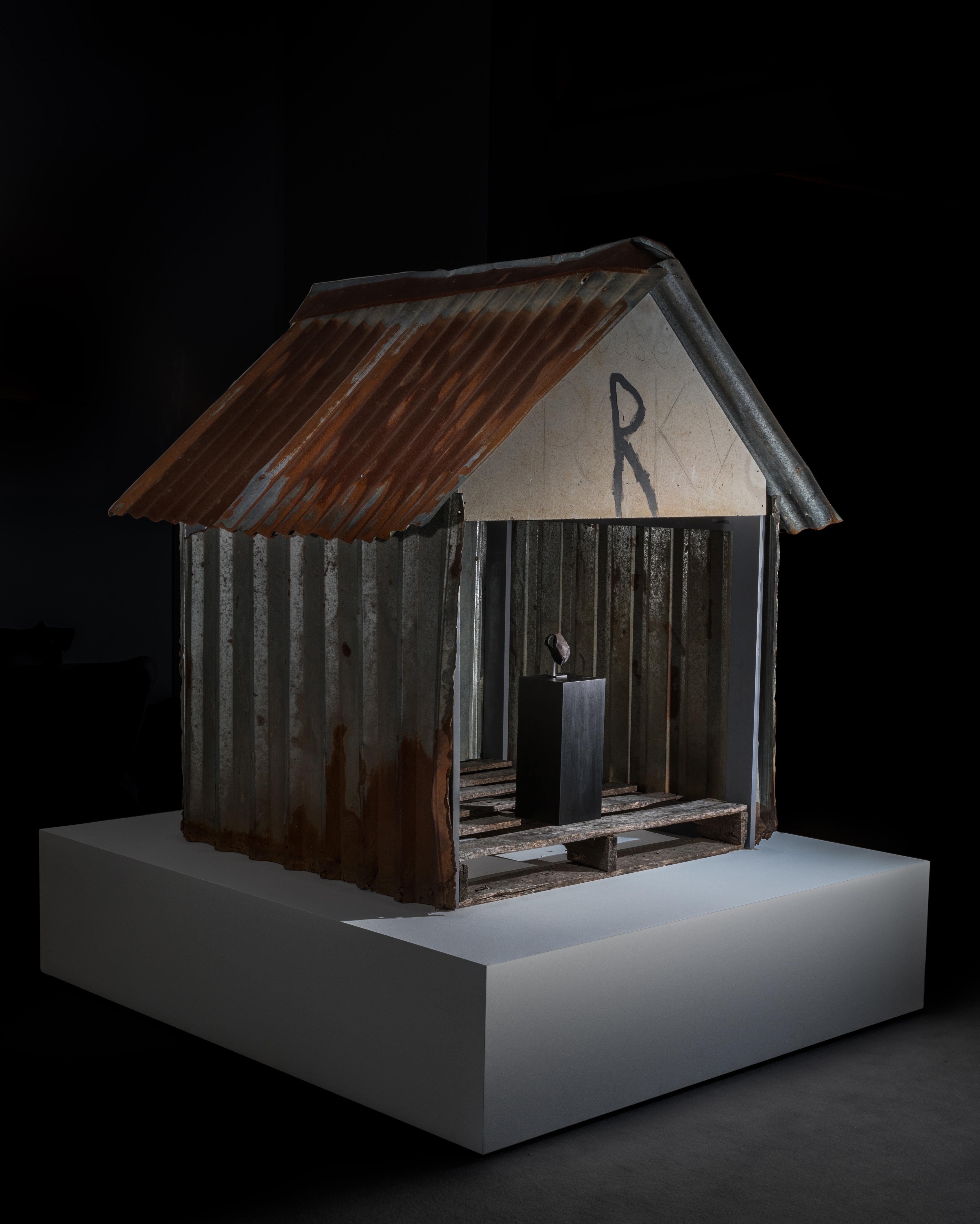

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 7.6 c M AND 146 c M c M2 METEORITE AND DOGHOUSE

Provenance

Alajuela, Costa Rica (10°23’29.03”N, 84°20’28.58”W)

Published Meteoritical Bulletin, no. 108 (2020) Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 55, 1146-1150.

The ‘La Esmeralda’ meteorite, displayed with the doghouse it struck, preserves a moment almost never seen: the instant an extraterrestrial object collided with a man-made structure. A unique display in the field of natural history.

On the evening of 23 April 2019, in the central Costa Rican town of Aguas Zarcas, a German shepherd named Roky was settling down for the night. At 9:07pm, a giant explosion sent shockwaves through the town. Captured on CCTV, dash cameras and mobile phones, the meteorite shower that ensued was one of the most scientifically important in recorded history.

Entering the atmosphere at colossal speed, the meteoroid exploded into a fireball, sending fragments hurtling towards the planet. With most landing unseen in the jungle, one crashed clean through the roof of Roky’s doghouse, barely missing him. Overnight, Roky’s iron shed joined the ranks of some of the world’s most remarkable storytelling objects. Within hours, news spread of the fall. Scientists, hunters, and collectors flocked to the small town to find specimens of the meteorites, and quickly, their price skyrocketed - surpassing even the price of gold. The present meteorite was purchased from the landowner by meteorite hunter Mike Farmer, who also bought the doghouse, recognising its newfound scientific importance.

Termed ‘black gold’ by the locals, the Aguas Zarcas meteorite, as a carbonaceous chondrite, CM2, is one of the most important meteorites known to researchers. But from the moment the meteoroid entered our atmosphere on 23 April 2019, the clock began to tick. Clay, one of the major constituents of a carbonaceous chondrite, is extremely porous. Earthly amino acids and other organic compounds can contaminate the delicate information preserved in the meteorite, and to make matters worse, Costa Rica was on the edge of the wet season. With their classification unknown at the time, only a handful of the meteorites were collected before the strewnfield was soaked with rain - the present example is one of the few that remains in remarkably pristine condition, and free from terrestrial contamination. Immediately taken to the Center for Meteorite Studies (CMS) at Arizona State University, it was classified as belonging to the same rare group as the famous Murchison CM2 meteorite that fell in Australia in 1969.

Carbonaceous chondrite CM2 meteorites are the stony fragments of primitive asteroids, which were broken apart from the parent body by a colossal impact. Rich in carbon, they have been extensively researched by scientists, revealing a wealth of information about the solar nebula and the potential origins of life on Earth. Indeed, as a CM2 meteorite, the present example contains organic molecules including complex amino acids - the building blocks of proteins - as well as large amounts of water, both crucial to the evolution of life forms.

As the first fall of a carbonaceous chondrite since the Murchison event, Aguas Zarcas is the most scientifically important meteorite fall in half a century. Over 144 different scientific studies of the meteorite have been published, with research still ongoing. But its importance is perhaps best encapsulated by the title of an article published in July 2020, called ‘The Aguas Zarcas (CM2) Meteorite: New Insights Into Early Solar System Organic Chemistry.’

The meteorite’s fusion crust bears a sienna-hued streak, remnants of its crash landing through the tin roof of Roky’s doghouse, and thumb-shaped impressions known as regmaglypts, formed when molten rock streamed off the meteoroid’s surface as it blazed through the atmosphere. As a scientifically important meteorite, it is a rare and powerful reminder of the forces of the universe. Together with Roky’s doghouse, the pair make up one of the most famed meteoritic displays in the world.

Above

Roky, with his owners and the meteorite hunter Greg Hupe (far right).

‘If I had to start a new museum collection for meteorites, and I could only select two, I would choose Murchison and Aguas Zarcas... If I could choose only one, I would choose Aguas Zarcas.’

Philipp Heck, Curator of Meteoritics and Polar Studies at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

Published by ArtAncient Ltd

Frieze Masters

October 2025

ArtAncient

31 Imperial Rd

London

SW6 2FR

info@artancient.com

+44 (0)20 3621 0816

ISBN 978-0-9930370-8-5

Published by ArtAncient Ltd

Text & Design: Olivia Longhurst

Photography:

Costas Paraskevaides

Jethro Sverdloff

Printer: Gemini Print Solutions