2 ND - 3 RD CENTURY BC | 21 CM SOLID CAST BRONZE

Provenance

With Edward Safani (1912-1998), New York Collection of Christos G. Bastis (1904-1999), New York

Antiquities from the Collection of the late Christos G. Bastis, Sotheby’s, New York, 9 December 1999, Lot 121 Collection of Kenzo Takada (1939-2020)

Kenzo Takada - La Collection d’un Citoyen du Monde, Aguttes, Paris, 17 June 2009, Lot 440

Exhibited

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 20 November 1987 - 10 January 1988, as part of the Christos G. Bastis Collection

Published

Antiquities from the collection of Christos G. Bastis, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mainz on Rhine: P. von Zabern, 1987, no. 110, p.198 (ill.)

A superb example of the artistic heights achieved by Hellenistic bronze casters. Depicting a follower of the wine god Dionysus in a moment of drunken revelry, it is a particularly wonderful sculpture, full of pathos

C . 80 - 120 BC 125 g CAST, TWISTED AND FILIGREE GOLD

Provenance

British private collection, collected during or just after World War II

Thence by descent

With Barnard and Moore, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, acquired from the above in April 1997

British private collection, acquired from the above in April 1997

The present gold brooches are an exquisite and unparalleled example of Celtic gold-working from late Iron Age Britain. Surpassing even the British Museum’s Winchester Hoard in technique, design and configuration, they are an outstanding and enigmatic example of ancient craftsmanship.

A Masterpiece of Ancient Craftsmanship

Preserved in exceptional condition, the present brooches are an exquisite and unmatched example of gold-working from late Iron Age Britain. The ornate scrolls of beaded wire filigree, the connecting chain constructed by a loop-in-loop technique, and pendant with the helicoid wire, are particularly fine examples of intricate metalworking rarely seen in England. The combination of three chains, three brooches (the end of the third chain likely once held a third brooch) and a pendant in a single piece of jewellery is similarly unique, and possibly reminiscent of Hellenistic and Roman body-chains. The present pendant was also perhaps once adorned with further embellishment, such as pearls, coloured glass or even coral inlaid into the top and middle recesses. The brooches’ exquisite decoration and unique configuration suggest that they were likely made in a Mediterranean workshop and later brought to England, either through Celtic trade with the empire or via migration from France, driven by the violence of Caesar’s Gallic Wars.

As one of an exceedingly rare few examples of pure gold brooches from Iron Age Britain, the present example can be compared only with the famous Winchester Hoard. One of the most significant Iron Age treasure finds in Britain, the hoard consists of four gold brooches, with one chain remaining (unattached), two gold necklace-torcs, and two gold bracelets. At the time of their discovery in 2000, they were the most intricate examples of gold Iron Age brooches known, and swiftly acquired by the British Museum. However, while the loop-in-loop technique of the necklace-torc and the chain parallels that of the present example, the present brooches display a more advanced and intricate design. In particular, the filigree decoration (unseen in the Winchester Hoard) and the unique overall configuration presents an extraordinary and unparalleled example of goldworking from this period.

While pairs of brooches joined by chains are known from both sides of the Channel in the first century BC, these tend to be silver rather than gold. As such, the present brooches are further notable for their high gold content, equating to about 39 Corieltauvi gold staters - an enormous and so far unparalleled value for such an item of jewellery. Made for a high-ranking noble or member of the ruling elite and perhaps later valued as a source of highly-concentrated wealth in times of hardship, they were possibly even concealed in times of turmoil for safekeeping, as the archaeological evidence from the discovery of the Winchester Hoard suggests.

Left

The Winchester Hoard, Iron Age, c.75-25 BC, The British Museum.

Right

Reconstruction of how the brooches might have been worn

3 RD MILLENNIUM BC | LARGEST 6.8 CM KNAPPED OBSIDIAN

Provenance

Collection of Jean-Henri Hoffmann (1823-1897), Paris, by 13 March 1877

Published

Comptes-rendus de la Société Française de Numismatique et D’Archéologie, Vol. 1, 2nd Series (Paris, 1877), p. 93, 263.

A remarkable group of early Bronze Age obsidian cores and lamellae, from the island of Milos, in the Cycladic Islands.

‘Among the various kinds of glass, we may also reckon Obsidian glass... which Obsius discovered in Æthiopia. This stone is of a very dark colour, and sometimes transparent … Many persons use it for jewellery, and I myself have seen solid statues in this material of the late Emperor Augustus...’

6 TH - 5 TH CENTURY BC 37 CM | CARVED LIMESTONE

Provenance

Discovered by Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904) at the sanctuary of Aphrodite at Golgoi, Cyprus, around 1870

Collection of Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904)

Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired from the above by subscription c.1872

Cypriote & Classical Antiquities, Duplicates of the Cesnola & Other Collections (Part 1), Sold by order of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Anderson Galleries, New York, 1928, Lot 294 (ill.)

With Bruno Cooper Works of Art, Norwich Collection of Michael Rosenfeld, London, acquired from the previous in 2007

Published

Cesnola, Luigi Palma di, A Descriptive Atlas of the Cesnola Collection of Cypriote Antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1885, No. 569.

A recently rediscovered monumental votive head from the foremost sanctuary of Archaic art in the Mediterranean world. An outstanding example of the fusion of the Assyrian, Egyptian and Greek artistic traditions, this work is one of very few important Archaic Cypriot sculptures remaining in private hands. Unearthed during the groundbreaking excavations of Luigi Palma di Cesnola in the 1860s-70s, it later formed part of the founding collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

In the sixth century BC, exploitation of an abundance of chalky, soft and easily workable limestone on the Mesaoria plain provided Cypriot sculptors with the perfect medium. Able to be modelled with precision, the stone’s fine grain and workability resulted in an apogee of sculptural production on the island. Located near a thriving quarry, the sanctuary of Golgoi became a key centre of artistic production, and functioned as a major centre for worship and veneration. Limestone sculptures were a crucial part of the visual and ritual landscape of the sanctuary, with their elaborate headdresses, such as the laurel or myrtle wreath of the present head, and garments of complete statues indicating their rank and piety, as well as their participation in cult activities.

Discovered in 1870 during the groundbreaking excavations by Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832- 1904), the temple of Aphrodite at Golgoi near Athienou is renowned today for being home to some of the finest examples of Cypriot stone sculpture in the world. The cultural diversity of the island is particularly notable in these sculptures, with the archaic smile and large almond-shaped eyes reminiscent of Greek kouroi, and the corkscrew beards and hairstyles typical of Assyrian sculpture. Rediscovered and reidentified as being from that same expedition, the present votive head is an exceptional over life-size example of CyproArchaic limestone sculpture. Expertly carved and from one of the richest artistic traditions of the ancient Mediterranean, it is a particularly enigmatic example of the island’s early culture.

The Cesnola Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Trained as a soldier and diplomat, Luigi Palma di Cesnola was appointed as the US Consul based in Larnaca in 1865. Despite arriving in Cyprus with no prior knowledge of ancient history or archaeology, over the next few years, he amassed an unrivalled collection of Cypriot antiquities through extensive excavations. Numbering 35,000 objects, this included the finest group of Cypriot limestone sculptures in the world.

After exhibiting these works in London, officials and rulers around the globe sought to acquire the objects for their national museums. But it was the newly formed Metropolitan Museum of Art that was to win the collection. Cesnola accompanied his pieces to New York, and devoted himself to supervising their installation and publication. In 1877, he accepted a place on the Museum’s board of trustees, and served as its first director from 1879 until his death in 1904.

The Cesnola Collection is still regarded today as the most important and comprehensive collection of Cypriot material in the world. As the founding collection of the Metropolitan Museum, it did much to establish the museum’s reputation, which endures to this day.

Left The present head published in A Descriptive Atlas of the Cesnola Collection... no.569, 1885.

Right Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904) in Cyprus, c.1865-1877.

‘This wonderful collection is especially preeminent in that it illustrates the growth of ancient art more fully than any other. It therefore attracts great attention in Europe, where it is considered one of the most important discoveries of the centuries...’

1872.

40,000 - 10,000 YEARS OLD | 11.5 CM HIGH BONE IN TAR MATRIX

Provenance

Collected by George Lee of Costa Mesa, California in the late 1970s, with permission of the land owners, at Maricopa, California

Asphalt block containing the claws and bones of several raptors, most likely bald eagles. An example of the unique preservative qualities of the asphalt seeps in Western North America.

6 TH - 4 TH CENTURY BC 30 CM | CAST, HAMMERED AND PUNCHED BRONZE

Provenance

Collection of Axel Guttmann (1944-2001), Berlin Antiquities including pieces from the Axel Guttmann Collection, Hermann Historica, Auction 60, 13 October 2010, Lot 2169 (part)

An enigmatic ancient Greek bronze trophy of war, once a greave worn by a hoplite in battle and later nailed to a wooden support and incised with a dedication to the gods, the partial inscription in Doric Greek reading, ‘I am sacred to the god’. An icon of warfare and warrior culture from a pivotal era in Western civilisation.

Emerging from the Dark Age, the Greek world in the seventh and sixth centuries BC was defined by a period of expansion, discovery and innovation, underpinned by the renowned and revered military units of the city-states. The economic prosperity of the polis brought about the rise of the fully armed Greek infantrymen - the hoplites - who funded their own armament. With a full panoply of armour costing between 75 and 100 drachmas, or the equivalent of 3-5 months pay for a skilled artisan or mercenary, his armour was his pride and joy, a marker of his economic status and the difference between life and death in the heat of battle.

From the early seventh century BC, greaves formed an integral part of the hoplite’s panoply. Developing from the earlier Mycenaean type, the greave was a metal shin-guard, running from the kneecap to the instep, with perforations around the edge from which to attach a fabric lining, cushioning any blow sustained by the wearer. Throughout the 6th century, they developed into beautiful pieces of workmanship, and like the present example, were sculpted perfectly to reflect the anatomy of the wearer’s leg. Beaten to a flexibility which allowed them to be sprung on, they were a sleek, streamlined and effective addition to the soldier’s protection in battle.

The present example, with beautifully sculptural form and muscular indentation, is a finely made greave which would have been worn on the hoplite’s left shin. Elevated by the enigmatic inscription, denoting its use and dedication in antiquity, it is an icon of ancient Greek warfare and warrior culture.

The dedication of armour at a sanctuary was a profound act of thanksgiving, marking the victor’s gratitude for divine protection in battle. Plucked from a fallen enemy soldier, the armour would have then been taken from the battlefield on the long pilgrimage to a temple or sanctuary, such as those at Olympia and Delphi, which became pre-eminent depositories of such dedications. The present trophy is one of approximately 18 inscribed greaves known to exist and was likely dedicated by a soldier, or group of soldiers, on behalf of a city-state, perhaps to the god Zeus. At the top, the square-shaped hole still survives, the metal around it splayed outward from the force of the hammer blow that drove it into a wooden post or rafter. There it would have remained on proud display, perhaps for decades, before being laid to rest.

Worn into battle, this greave may have been present at some of the most renowned military campaigns of the age. The early decades of the 5th century BC in particular saw the battles of Marathon (490 BC), Thermopylae and Salamis (480 BC), conflicts which are widely recognised as having had profound consequences on the course of Western civilisation and its foundational ideals. During these conflicts, a hoplite had to rely on his well-made armour - as well as the protection of his gods - to ensure victory. With the inscription and dedication, the present greave is a particularly rare and enigmatic example of this crucial part of the hoplite’s panoply.

Right Line drawing of the inscription on the present greave.

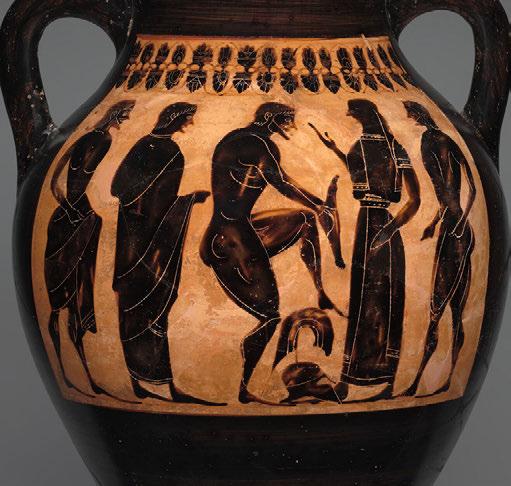

Left

Amphora with Herakles fighting Geryon, and an arming scene of a warrior, c.540-530 BC. Harvard Art Museum, 1972.42.

700,000 - 300,000 BC 12.7 CM PATINATED GREY FLINT

Provenance

From the collection of Guy Dubois, Rouen, France

Subsequently, French art market, 2023

With early 20th century collection label, ‘Abbeville, Somme’

A fine example of the first human technology, knapped from a nodule of grey and cream flint.

C . 2100 - 1900 BC 28 CM BURNISHED POTTERY

Provenance

Collection of David Goodman (d. 2001), acquired in Cyprus between May 1965 and January 1969, exported under license no. 5754 (item no. 25) granted by the Government of Cyprus’ Department of Antiquities [dated 24th January 1969]

Thence by descent

Cypriot plank figures are among the most iconic, abstract representations of the human form in prehistoric art. The present piece is probably the largest and most impressive plank figure of this type known in private hands. Belonging to a rare, ambitious group showing infants being held at the chest, she is a particularly compelling display of motherhood and fertility. An icon of ancient Cyprus, legally exported in 1969 with a license from the Government of Cyprus’ Department of Antiquities.

Artistic interpretations of the female form were produced by nearly all prehistoric civilisations around the world. With many emerging during the Bronze Age, a formative period in human history, the prevalence of such figures reveals the shared importance placed on women and their position in these early societies. While each depiction is unique to the culture that made them, the common abstraction of form and exaggeration of female attributes - such as the breasts and hips - highlights the significant role of women as childbearers and nurturers. From the steatopygous figures of Anatolian and Near Eastern art to the elongated, minimalist figures of the Cycladic Isles, many have been seen as symbols of the ‘Great Mother Goddess’, embodying ideas of fertility, regeneration and the cycle of life from birth to death, all crucial to the survival of these early communities. Of all these depictions, it is the timeless aesthetic of the Cypriot plank figures that is among the most compelling. Characterised by simplified, geometric shapes and incised patterns, they are strikingly modern in their abstraction. Of those identified as female, several have breasts modelled in relief, while a rare few are depicted holding a child. In their clear emphasis on motherhood, these types of figures are a particularly powerful symbol of the shared values of these early societies.

Stylised images of the human form are icons of early Cypriot art. In modifying the body, Cypriot artists established their own artistic identity, distinct from those of neighbouring civilisations such as Egypt or Mesopotamia. During the prosperity of the Early and Middle Bronze Age (2400-1600 BC), the geometric and decorated statues known as ‘plank figures’ became the preferred form of representation. Characterised by their flat, rectangular bodies and incised decoration, the single figures are the most common type known today.

Left

Cycladic female figure, 4500- 4000 BC, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Acc. no. 1972.118.104)

Right

Steatopygous Figure, Amlash, late 2nd-early 1st millennium BC. Private Collection.

As the only identifying features given to these simplified forms are female, they have generally been identified with the fertility cult of the ‘Great Mother Goddess’. Sometimes found in tombs, their archaeological context appears to support the argument of their religious significance as symbols of regeneration and rebirth. However, as highly expressive and enigmatic objects, it is clear that they were also intended to be viewed and appreciated in day-to-day life. Indeed, the ambiguous nature of the figures (for not all have female attributes), and their appearance at a time of significant cultural change, has also led to the conclusion that they were designed as a marker of group identity with particular reference to ancestral authority. Whether conspicuous symbols of fertility, family or even social prestige, the wear on the bottom end of the figures appears to confirm that they were likely displayed standing upright in settlements as important symbols in early Cypriot culture.

Previously regarded as ‘clumsy’ and ‘barbaric’, their simplified, geometric forms are now seen as evidence of the remarkable skill of the ancient artist to define and redefine the parameters of human representation. Indeed, while emerging at a crucial time in the island’s early history, to today’s viewer, these plank figures are intriguingly modern in their abstraction.

Acquired by collector David Goodman (d.2001) when he was working for the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) between 1965 and 1969, the figure was also granted an export licence by the Government’s Department of Antiquities. Today, such licences are exceptionally rare, but crucially serve to confirm the object’s legal status. When coupled with the rarity of the motif itself, the present plank figure is an outstanding and notably well-provenanced example of early Cypriot art.

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 30.7 KG L5 CHONDRITE

Provenance

Discovered in Northwest Africa (exact coordinates unknown)

Detached from its parent body by a mighty impact, this large, oriented meteorite travelled over a hundred million miles through space before falling to Earth in the North African desert. Moulded into a rounded boulder during its fall, with beautiful regmaglypts radiating along its edges. These elongated dimples formed when streaks of superheated molten rock streamed off the surface as it blazed through the atmosphere. The entire piece is coated in a glossy, umbercoloured fusion crust.

‘This meteorite is a spectacular example of an oriented ordinary chondrite; flow lines radiate away from the nose, generating the appearance of a handheld fan. A portion of the surface is filled with irregular ridges and depressions – this is secondary fusion crust, formed after a minor fragmentation event in the lower atmosphere.’

Dr Alan E. Rubin, Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA

2 ND - 3 RD CENTURY AD 15 CM | CARVED AND POLISHED MARBLE

Provenance

Collection of Bo Ive (1922-1981), Denmark

Thence by descent

An extremely fine marble head of a satyr, depicted with ivy wreath, curly hair and pointed goat’s ears, the full lips slightly parted to reveal the creature’s clenched teeth. Given the visible fragmentation on the left side, this head was once part of a relief. Almost completely worked in the round and carefully polished, the skill of the sculptor is particularly remarkable given the confined working space available for a relief carving, such as this.

500 - 520 BC 23 CM | CAST, HAMMERED AND INCISED BRONZE

Provenance

Gifted to General Maurice Sarrail (1856-1929), Commander of the Armée d’Orient (1915-1917), around the period of his retirement, c. 1917

Thence by descent

An exceptionally well-preserved and well-provenanced example of one of the most iconic artefacts of ancient Greece - the Illyrian Helmet. Once worn by a hoplite or Macedonian warrior in antiquity, and two and a half millennia later gifted to General Maurice Sarrail, a renowned French General and the Commander of the Armée d’Orient during the First World War.

The sixth century BC was a time of continual technological and artistic improvement, with Greek armoursmiths spearheading the advance. Recognisable by its sleek and streamlined design, the present helmet is a particularly fine and well-preserved example of the Illyrian type, displaying the simple yet elegant form associated with the zenith of the helmet’s production. A recent x-ray has also revealed for the first time that the helmet bears an inscription, ‘Γ Π’, in the corner of the proper right cheek piece. This was perhaps a ‘maker’s mark’, identifying the skilled bronzesmith or workshop in which it was cast, although it is also possible that the inscription could have been added after the helmet was made, to identify the owner.

As the mainstay of the soldier’s panoply during the early stages of hoplite warfare, the Illyrian helmet would have been worn by soldiers fighting in the Graeco-Persian Wars, at the Battles of Marathon (490 BC) and Thermopylae (480 BC). While falling out of favour with the Greek hoplite, who favoured the greater protection of the closed-face Corinthian helmet, the Illyrian remained the preferred choice in the north of Greece, and in particular, in Macedonia. Here, the visibility afforded by the open face suited independent and fastmoving warriors and cavalry, and soon became symbolic of the militaristic culture of the kingdom, featuring prominently on the coinage of Macedonian kings such as Alexander I (498-454 BC) and Perdiccas II (454-413 BC).

The Macedonian Front, 1914-1918

Two millennia later, in September 1915, General Maurice Sarrail (1856-1929), Commander of the Armée d’Orient during World War I, left France for the Macedonian Front to relieve the Serbian soldiers under attack by the German and Bulgarian armies. But his arrival of merely entrenched a stalemate. To support their continued presence, soldiers began to dig trenches, lay lines of communication, and establish infrastructure necessary to their survival. In doing so, they unearthed tombs and sarcophagi of warriors from the fifth and sixth centuries BC, bringing French soldiers face-to-face with their ancient predecessors. Fearful that any destruction of antiquities could jeopardise the Allies’ already-shaky relationship with the then-neutral Greek state, and aware of the need to document and research discoveries for posterity, Sarrail issued a series of orders. L’Instruction sur la Conservation et la Recherche des Antiques (February and April 1916) provided soldiers with a forward-thinking and comprehensive approach to archaeology on the battlefield. In addition to reporting finds and recording data, soldiers were ordered to set up a temporary museum - ‘just a stone’s throw from the front line’. Aware of the need to do more, on 20 May 1916, Sarrail set up a specific archaeological division dedicated to the safeguarding of sites and artefacts, The Service Archéologique de l’Armée d’Orient (SAAO).

Left

The temporary museum at Salonika, c.1915-7.

Right (top)

X-Ray of the present Illyrian helmet showing a newly discovered inscription.

Right (bottom)

General Maurice Sarrail (1856-1929).

A in Zeitenlik, 22 May 1917.

Diagram of the contents of Sarcophagus A from Zeitenlik, in Léon Rey, Albania 2(6), 1927, p. 34.

The Gardeners of Salonika

In need of expertise, archaeologists, archivists, architects, painters and photographers who had been called up for military service elsewhere were swiftly redirected to work with the SAAO. Turning their attention to safeguarding Greece’s cultural heritage, they excavated major sites such as Zeitenlik (Stavroupolis) and Mikra Karaburun (Karabournaki), in a methodical manner that was extremely progressive for the time, and published their findings in archaeological journals such as the Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique.

General Sarrail himself took an active role in the work of the SAAO. In particular, his visit to the ancient city of Pella was reported in British newspapers. That day, the General rose early to read through the excavation reports, and later he ‘explored the ruins with the energy of a boy.’ He had ‘question after question’ for the officer in charge, and took ‘delight’ in learning of a new find - so much so that soldiers working there would ‘hardly have suspected that on those shoulders rested the responsibility for the most complicated campaign in which the Allies [had] engaged.’

While derided by the French Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau (1841-1929) as the ‘Gardeners of Salonika’, the work of the SAAO was crucial to safeguarding Greek cultural inheritance. The army provided transportation, tools, manpower, as well as funding. Indeed, French archaeologist Gustave Fougères (1863-1927) acknowledged the importance of this assistance, reporting that the manpower provided for the archaeological work at St George’s Rotunda in Salonika would have cost at least 200,000 francs in peacetime. Moreover, with the help of military technology, the SAAO were able to pioneer the use of aerial photography in mapping and surveying archaeological sites - an important practice still used today. Without Sarrail’s support and the SAAO, many archaeological sites on the Macedonian front would have been lost to a devastating conflict.

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 5.6 CM 339 g | PALLASITE

Provenance

Discovered in the Magadan District, Russia, 1967 (62° 54’ N, 152° 26’ E)

Published Meteoritical Bulletin, no.43, Moscow (1968)

Comprising less than 0.2% of all meteorites, pallasites, made up of an iron-nickel matrix interwoven with amber-coloured olivine gemstones, are perhaps the most dazzling of all. This piece, cut from the Seymchan meteorite discovered in 1967 in the bed of the Jasačnaja River by geologist F. A. Mednikov, has been fashioned into a mirror-polished sphere, to provide a threedimensional view into the core of this stunning, extraterrestrial specimen.

1420 - 1460 AD 90.4 CM | FORGED AND TEMPERED IRON

Provenance

Found in the bed of the river Dordogne near Castillon-la-Bataille, France, mid-1970s Fine Arms and Armour, Christie’s, London, 8 July 1980, Lot 37 Collection of David Oliver, (d. 2021) acquired from the above sale Thence by descent

Published

Ewart Oakeshott, ‘A River-Find of 15th Century Swords’, in Blankwaffen, 1982, pp. 1732, no. 4

Ewart Oakeshott, ‘The Swords of Castillon,’ in The Tenth Park Lane Arms Fair, 1993, pp. 7-16, p. 10, no. B (ill.)

Clive Thomas, ‘Additional Notes on the Swords of Castillon’, in The Park Lane Arms Fair, 2012, pp. 40-63, p. 47 (ill.)

Ewart Oakeshott, Records of the Medieval Sword, 1991, p. 134, no. XV.8

Ewart Oakeshott, ‘Further Notes on a River-Find of 15th Century Swords’, in The First Park Lane Arms Fair 1984, pp. 7-12, pp. 7-8 (ill.)

One of the most exceptional medieval swords in private hands, from the legendary Castillon Hoard recovered from the bed of the Dordogne River in the mid-1970s. Widely published as the ‘finest’ and ‘most handsome’ of the entire group, almost certainly wielded in the Battle of Castillon — the final and most decisive battle of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453). An iconic knightly weapon, and one of the rare few medieval swords directly linked to a specific battle, it is an exquisitely crafted and perfectly balanced arming sword, embodying the essence of medieval chivalry and the knightly class.

The Mystery of the Castillon Swords Sparked by feudal and territorial disputes between the kingdoms of England and France, The Hundred Years War has come to be known as the longest, most significant conflict of medieval Europe. Spanning over a century from 1337 to 1453, the conflict saw five generations of rulers, the rise and subsequent fall of knightly chivalry, the emergence of national identities, and the evolution of military technology and strategy. Romanticised in later ages, the conflict has endured in the popular imagination as the epitome of chivalrous warfare, heroic tales and epic battles, with figures like Joan of Arc, the Black Prince and Henry V becoming legendary icons of their country’s history.

The Castillon swords emerge from the end of the conflict, and their story is a particularly enigmatic one. On 17 July 1453, the famed English general, John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, led a small contingent ahead of his main army, annihilating an enemy-French detachment nearby to the town of Castillon-sur-Dordogne. By this time, the English and the French had been locked in a devastating war for over a century, yet Talbot, assured of victory, pressed on. Soon faced with the full force of 9,000 French soldiers, well-prepared with entrenched artillery, the English forces were decimated. While contemporary commentators noted the ‘great valour’ with which each side fought, the battle lasted only an hour, with a Breton counter-attack eventually sending English soldiers fleeing across the Dordogne River. The English were routed, and Talbot was dragged from his horse and killed. With the destruction of Talbot’s army, French authority soon returned to the country. Unknown to the soldiers at the time, the battle marked a decisive turning point in history, and the end of one of the most devastating conflicts of medieval Europe.

On 26 April 1977, over five hundred years on from the end of the Hundred Years War, six medieval swords came up for sale at Christie’s, Geneva, and with eleven more appearing in other sales all over Europe, they were quickly snapped up by institutions all over the world. Said to have been dredged from the bed of the Dordogne River, close to the ancient town of Castillon-sur-Dordogne, experts began to consider the provenance of this remarkable find. Theories began to circulate that the swords were abandoned by English men-at-arms fleeing across the river on that fateful day in 1453. As more information emerged, it was revealed that the swords - numbering 81 in total - had been part of the cargo of a sunken barge. As the main supply-route for the English in Aquitaine, perhaps it was an English ship, carrying weapons to arm their men on the ground? Or was it a French vessel, taking arms, stripped from the dead or captured English soldiers, after the battle itself? As some of the rare few medieval swords that can confidently be linked to the battle in which they were used, they are an unparalleled icon of medieval warfare and epic tales of knightly valour.

Of all the weapons of the Castillon hoard, the present sword has been widely acknowledged as the ‘finest’ and ‘most handsome’ example. Visually well-proportioned, the wheel-house pommel with recessed decoration complements perfectly the weight of the tapering blade. Indeed, it has been identified by medieval arms and armour expert, Ewart Oakeshott, as the ‘perfect cut-and-thrust weapon, light and quick in the hand and beautifully balanced’. This sentiment has been similarly echoed by expert Clive Thomas, who described it as an ‘outstanding weapon’. During the course of the Hundred Years War, both sides saw dramatic innovations in military technology and strategy. While soldiers often had their own preferences for their primary weapon, whether a longsword, mace or axe, the ‘arming sword’ (developed in the fourteenth century to pierce plate armour) was the chief sidearm for knights all over Europe. While such swords could be made relatively cheaply, or indeed plucked from enemy-dead after battle, a well-proportioned, well-balanced sword, such as the present piece, was expensive to acquire, indicating that it was likely made for a wealthy patron or knight.

As an important signature of quality and craftsmanship, the sword was also inlaid with a maker’s mark on both sides of the blade towards the forte. This mark would have identified the swordsmith or the workshop where the sword was forged, and was crucial in the trade of high-quality weapons. The smith’s mark on the present piece is similar to one on the blade of a sword in the Wallace Collection (A462), also found in France, as well as a sword found in 1743 in the River Thames now in the Museum of London (52.12.1).

66 MILLION YEARS OLD | 12.6 CM PES II-2, ACHERORAPTOR TEMERTYORUM

Provenance

Found by Bryan Clark, 3 September 2019 on Escott Ranch, Perkins County, South Dakota, USA

An extremely rare and remarkably well-preserved ‘killing claw’ of an Acheroraptor temertyorum from the Velociraptorinae subfamily, dating to the Late Cretaceous and from the famed Hell Creek Formation.

The Thief of the Underworld Acheroraptor temertyorum was a terrifying predator of the Late Cretaceous. Literally meaning ‘hell plunderer’, the name of the species is a fitting hybrid. As one of the last dinosaurs to roam the floodplains of western North America around 66 million years ago, Acheroraptor stood alongside some of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, counting among its contemporaries the iconic meat-eater, Tyrannosaurus rex, as well as the herbivores,Triceratops and Edmontosaurus.

Belonging to the Velociraptorinae subfamily - commonly known as ‘raptors’Acheroraptor was a small but ferocious predator. Growing to approximately three metres long and weighing about 40 kg, it was a bipedal and feathered carnivore, with an extended tail, a long-snouted skull and dagger-like serrated teeth. Examination of its bite force suggests that its jaws inflicted rapid, slashing bites to the victim, just like its close cousin, Velociraptor mongoliensis. A crucial feature of the Acheroraptor was the oversized sickleshaped claw on the second digit of each hindfoot. Commonly known as the ‘killing claw’, it is thought to have been used in slashing and restraining prey. While the victim struggled, positioning and balance would be maintained by its long, beam-like tail, as well as ‘stability flapping’ - itself an important and independent step in the origin of flight. This process, aptly called the Raptor Prey Restraint - or ‘ripper’ - method, remains used by extant Accipitridae today, such as hawks and eagles.

Inspiring Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park, raptors were further immortalised through Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film adaptation, where the ‘killing claw’ took centre stage as the dinosaur’s signature weapon. In reality, the fossil record for Acheroraptor is extremely sparse, and fossils of the iconic sickle-shaped claw are rarer still. With these examples surviving only in fragmentary form, this specimen is remarkable for both its completeness and impressive size. As such, it is an iconic symbol of both the prehistoric predator and its enduring fame in popular culture.

Left Reconstruction of Acheroraptor temertyorum in the Hell Creek environment.

Right

The discovery of the present claw on Escott Ranch, 2019.

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 1544 g 246 g 425 g IRON, COARSEST OCTAHEDRITE

Provenance

Discovered in Maritime Territory, Siberia, Russia (46° 9’ N, 134° 39’ E)

An exceptional group of iron meteorites from the largest witnessed meteorite shower in recorded history.

On the morning of 12 February 1947, a colossal iron meteor exploded over the Siberian mountains, creating a fireball brighter than the sun. Witnesses described the event as a terrifying spectacle, marked by deafening explosions and shock waves, with a massive 20-mile-long smoke trail across the sky. P. J. Medvedev, an artist who witnessed the fall while sketching, immortalised this dramatic scene in a now-famous painting.

Originally weighing around 100,000 kg and travelling through space at 14 km per second, the main mass fragmented upon entering Earth’s atmosphere, exploding into thousands of pieces. The meteorites recovered from the 4.5 km strewn field can be divided into two main types; individual specimens that broke off early in the meteorite’s fall, and shrapnel, ripped apart at a much lower altitude. The finest specimens, like these, bear the unmistakable marks of their descent; thumbprint-like impressions created by atmospheric ablation, and trailing flow lines formed as molten metal streamed across their surface during their fall.

Fragments from this famous impact are housed in the world’s major natural history museums, such as the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the Natural History Museum in London.

‘The sky was ablaze with blinding light, and the sound that followed was like thunder from a dozen storms combined. The ground shook as if the Earth itself was convulsing.’

Left P. J. Medvedev, eyewitness painting of the Sikhote-Alin impact, February 1947.

Caption Eyewitness account of the SikhoteAlin impact.

C . 332 BC | 23 CM WIDE | CARVEDRED-BROWN QUARTZITE

Provenance

Collection of Arthur Sambon (1867-1947)

Objets d’art et de haute curiosité de l’antiquité, du Moyen Âge, de la Renaissance et autres... formant la collection de M. Arthur Sambon, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, 2628 May 1914, Lot 5 (ill.)

Collection of French furniture designer, Georges Geffroy (1906-1971)

Thence by descent

Published

J. Malek, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, no. 804-075-390

A. Ostier, Plaisir de France, N° 394, November 1971, p. 43

One of the most exquisite hardstone reliefs known, from one of the most extraordinary collections of ancient art ever formed - the Arthur Sambon collection. Depicting a regional personification surrounded by hieroglyphs in sunken relief.

Of all the relief work produced in Pharaonic Egypt, those carved in hardstones - granite, basalt, and quartzite - are the most rare. These materials were significantly more difficult to quarry and carve than softer stones like limestone or sandstone. As a result, hardstone reliefs were more expensive to produce and typically reserved for elite contexts, such as royal temples and tombs. Synonymous with elite commissions, hardstone also played an important role in the display of wealth, secular power and even divine authority. Among these hardstones, quartzite was the most challenging to work, but also the most beautiful, being particularly treasured for its unique colour. Hailing from the quarry at El-Gabal el-Ahmar near the ancient city of Heliopolis, the cult centre of the sun god Ra, its warm, golden hue was considered sacred. When used in royal statuary, it stressed the solar aspect of kingship, emphasising the pharaoh’s divine authority. First used for colossal royal sculpture in the 18th Dynasty, red quartzite soon became synonymous with the most exquisite statuary and temple decoration Egypt had ever seen. The ultimate expression of its beauty can be seen in the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut at Karnak, made almost entirely of red quartzite, and carved in intricate sunken relief, just like the present example. As an ingenious technique invented by the Egyptians, sunken relief was usually for the outside of the temple, intended to increase the shadows cast by the strong north African sun and resulting in greater visibility of the beautifully carved figures.

The present piece is a relief of truly exquisite craftsmanship, and parallels of this quality in quartzite are difficult to locate. Ptolemaic hardstone reliefs are particularly well-known from Behbeit El-Hagar, built by Nectanebo II and completed by Ptolemy II. However this relief exceeds even the lofty quality produced at this renowned site. On account of its depiction - the personification of one of Egypt’s regions (or nomes) - we can infer that the original scene likely contained a procession of similar personifications, all bearing agricultural produce from their regions as offerings to the gods. The figure here wears a wig topped by a nome standard, once representing the god Andjety of the ninth nome of Egypt, Andjet. In front of him, he would have held a tray carrying various offerings, while the hes vase, holding a lotus flower, is the offering of the figure behind him. A crucial feature in royal temple decoration, such depictions represented the unity of Egypt’s constituent parts under the pharaoh.

The Arthur Sambon Collection

By the 20th century, the present quartzite relief formed part of the most distinguished collections of ancient art ever formed - the Arthur Sambon collection. The first auction of Sambon’s collection was held in 1914, at Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. On offer were many masterpieces that are now the key highlights of museum collections around the world today. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York boasts about thirty items from the Sambon collection, including an impressive bronze Roman portrait head, traditionally attributed to Marcus Agrippa (MMA acc. no. 14.130.2), as well as Donato de’ Bardi’s early Renaissance masterpiece, Madonna and Child with Saints Philip and Agnes (MMA acc. no. 37.163-1-3). Other museums to house pieces from the Sambon sale of 1914 today are the Musée du Louvre, the Walters Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the British Museum, to name a few. Yet, from the many masterpieces in that sale, the renowned art advisor to J. P. Morgan, Belle da Costa Greene, wrote to Renaissance scholar, and lifelong friend, Bernard Berenson, that she ‘should love to have [the] Egyptian plaque...’

Above

The present relief in the 1914 catalogue of the Sambon Collection, Galeries Georges Petit, Paris.

C . 575 - 500 BC 22.3 CM | CAST, HAMMERED AND PUNCHED BRONZE

Provenance

Private collection, mid-20th century based on restoration techniques

Subsequently, private collection, Zurich Antiquities Sotheby’s, New York, 12 June 2001, Lot 12

Private collection, London, acquired from above sale Cahn Auktionen AG, Basel, Auktion 4, 18 September 2009, Lot 190

Exhibited

Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins, South of France, June 2011 to 2020 (Acc. no. MMoCA. 430)

Published

M. Burns, ‘Graeco-Italic Militaria,’ M. Merrony (ed.), Mougins Museum of Classical Art, France, 2011, p. 199, fig. 50

R. Hixenbaugh, Ancient Greek Helmets: A Complete Guide and Catalogue, Hixenbaugh Ancient Art, 2019, no. C440, p.397

The archetypal ancient Greek helmet, emblematic of hoplite culture. Prominently exhibited and published as part of the renowned Mougins Museum collection of arms and armour.

C . 380 - 380 BC 14 CM WIDE | CARVED LIMESTONE

Provenance

Collection of Dr. Jacob Hirsch (1874-1955)

Bedeutende Kunstwerke aus dem Nachlass, Dr Jacob Hirsch, Adolphe Hess, Lucerne, 7 December 1957, Lot 7 (ill.)

Collection of Dr. Ady (1925-2021) and Gilberte Steg (1924-2021)

A unique and unparalleled sculptor’s model, owned by one of the most important ancient art dealers of the 20th century. The most diverse tablet known, depicting four full and one partial animal, all of great significance to Egyptian culture. A remarkable insight into the artistic development of an Egyptian sculptor during a period of intense political upheaval.

Small and easily transportable stone slabs featuring various, seemingly-disjointed compositions, such as the present piece, were in fact an essential part of the teaching and learning process in the sculptors’ workshop of ancient Egypt. Serving as artistic exemplars, they were key in demonstrating the successive steps in order to achieve a finished product. By copying the model, students would have practised their technique, and committed to memory the Egyptian artistic canon. This was particularly crucial in the Late and early Ptolemaic period, as successive waves of invasion and foreign rule resulted in increased artistic production to visually legitimise one ruler over another.

The range of subjects of these pieces is varied. Animals feature heavily on account of their importance to the hieroglyphic alphabet, as complete mastery of their form and execution was paramount. Here, the barn owl denotes the sign for M, and the bull, ka However, the latter’s depiction might also be due to the symbolic value of the creature as representative of strength and masculine virtue. In Egyptian culture, the bull had particularly strong ties to kingship and monarchical identity, making it a crucial symbol in a time of political and cultural upheaval.

Representations of vultures and baboons however are considerably less common. Vultures similarly appear in the hieroglyphic alphabet, as the symbol for the letter A. However, believed to be conceived by the female alone, they also symbolised purity and motherhood, and were considered sacred to the pharaohs. Baboons were also held in high esteem by the ancient Egyptians, playing a significant role in religion and cosmology. The baboon was best known as a manifestation of the moon god, Thoth, who in addition to being the god of writing and knowledge, also recorded the ‘weighing of the heart’ ceremony after death.

The present piece, with its variety and lack of formal composition, suggests a dynamic and exploratory phase in the sculptor’s creative process - a sort of ‘sketch pad’differentiating it from more typical Egyptian sculptors’ models. The only piece known from this period that presents a similar varied study (although with only four figures) is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago (acc. no. 1920.253).

As highly important components of the wider cultural policy of the ruling dynasty, sculptors’ models present the point at which art and politics converge. Consideration of this context provides an important insight into their various depictions, and in particular, endows them with greater cultural significance.

Left

Figure of a Baboon, Late Period, Dynasty 26, c. 664-525 B.C. 8.8 cm high. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Acc. No. 26.7.874).

Right

Sculptor’s model with hieroglyphs, early Ptolemaic Period, c. 300 BC Granite, 23.4 x 14 cm. Art Institute Chicago. Museum (No. 1920.253).

Caption E. H. Gombrich.

‘One Egyptian word for sculptor was... He-Who-Keeps alive.’

67 MILLION YEARS OLD 12.5 CM | FOSSILISED TOOTH

Provenance

Found in Butte County, South Dakota, USA, Summer 2021

An extremely large and extraordinarily well preserved tooth of one of the most iconic prehistoric predators - Tyrannosaurus Rex - with a remarkable video capturing the moment of its discovery.

The King of the Dinosaurs

Found in Butte County, South Dakota, this fossil comes from the Hell Creek ecosystem, where T. rex fossils were first unearthed in 1902 by Barnum Brown, a palaeontologist with the American Museum of Natural History. The genus was first classified as Tyrannosaurus rex in 1905. As Henry Fairfield Osborn, President of the American Museum of Natural History, said, the name befits ‘its size, which greatly exceeds that of any carnivorous land animal hitherto described...’ Deriving from the Greek and Latin for ‘tyrant lizard king’, it was by no means undeserved. At its largest, the Tyrannosaurus rex reached heights of 12 metres in length and weighed between 5,000-7,000 kilogrammes. Dubbed the ‘largest flesh-eater that ever lived’ by Brown in 1915, the T. rex jaw, lined with 60 saw-edged teeth, would have had spectacular strength, capable of delivering up to 6 tonnes of pressure and being able to crush bone easily. The present specimen with its perfectly preserved serrated edge and spider web-like surface is an iconic symbol of one of Earth’s greatest prehistoric predators.

2 ND - 4 TH CENTURY AD | 19.9 CM | CAST BRONZE AND FORGED IRON

Provenance

Excavated in 1936 at Chtaura (Lebanon) near Baalbeck, in the ruins of a Roman temple

Collection of Maurice Bérard (1891-1985), acquired from a dealer in Beirut Collection de Monsieur B., Drouot Richelieu, Paris, 6 November 1992, Lot 173 Antiquities, Christie’s, New York, 15th December 1993, Lot 116

Published

H. Seyrig, ‘Un Couteau de Sacrifice,’ Iraq, Vol. 36, No. 1/2 (1974): 229-230

L. Hopfe, ‘Archaeological Indications on the Origins of Roman Mithraism,’ Uncovering Ancient Stones, Eisenbrauns Publishers, (1994), p.147-156

W. Haase, Religion (Heidentum: Die religiösen Verhältnisse in den Provinzen [Forts.]), Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2016, p.3321-3323

E. Friedheim, ‘The Mithrakana in the Yerushalmi—A Historical Note’, MAARAV, 21:1-2 (2014): 319-328

An important, widely published ceremonial dagger, likely once used in religious rituals and sacrifices, and adorned with the rich iconography of one of the most fascinating mystery cults of antiquity, the cult of Mithras.

Mithras and the Sacred Bull

In the second century AD, a new religion - Mithraism - spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire. Taking root among soldiers, officials and merchants, it was practiced by small, fraternal groups in candlelit subterranean temples, offering a unique and intimate religious experience, unlike the more typical public rites of the Graeco-Roman world. In further contrast to prevailing religion, the symbolism and rituals of Mithraism were only revealed to its members, who had to go through various initiations to progress up the ranks. Transported by Roman soldiers to the Empire’s far-flung frontiers, Mithraism soon had a strong following, and was one of the main ‘alternative’ religions, along with Christianity, that were vying for influence over the Roman world.

With limited written descriptions of the Mithraic cult, our understanding of the religion is mainly derived from the visual landscape of their subterranean temples, known as the Mithraea. Funded by wealthy members, decoration of the Mithraeum was likely under the direction of the Pater (the highest rank in the cult). From Kriton’s famous depiction of the tauroctony in the round (usually rendered in relief or fresco) at Ostia, to its depiction on silver plates likely used in feasts, at Poetovio and Stockstadt, the Mithraic cult presented a unique source of artistic inspiration. The possibilities associated with the cult were so great that in the second century BC a group of artists established a workshop near a cult centre in modern-day Strasbourg, in the hope of benefiting from their patronage.

The present dagger is a remarkable and so far unparalleled example of the artistic production that resulted from the spread of this fascinating extinct religion. It would likely have been displayed in the temple or used in its secret ceremonies and rituals. Imbued with particular symbolic significance, it is a unique rendering of the central myth of the religion - the tauroctony. Usually shown in relief or fresco above the central altar, the tauroctony was the focal point of every cult temple. Often interpreted as the moment of creation, Mithras, wearing a cloak and Phrygian cap, is seen kneeling on the back of a bull, pulling back his head and stabbing it in the neck with a dagger. Below, a scorpion, the symbol of evil, attacks the bull’s testicles while a dog and a snake drink blood from the wound. In various interpretations, Mithras’s sacrifice is surrounded by a range of animals, such as the lion and boar, which are interpreted astrologically as representing Mithras’s control over the cosmos.

Adorned with rich and complex iconography, this was clearly an important object in antiquity, imbued with the spiritual meaning of one of the most era-defining mystery religions of the ancient world.

Left

Marble group of Mithras slaying the bull, 2nd century AD. Marble. The British Museum, London.

75 MILLION YEARS OLD 42 CM FOSSILISED SHELL

Provenance

Discovered in the Blood Reserve, Alberta, Canada

A magnificent example of one of the most spectacular fossil types known. Many of the extraordinary ammonites recovered from the Bearpaw Formation suffer from compression and losses, requiring reconstruction from multiple individuals. This specimen is notable for its original condition and intense, unenhanced rainbow iridescence.

‘The Horn of Ammon, which is among the most sacred stones of Ethiopia, has a golden yellow colour, and is shaped like a ram’s horn. The stone is guaranteed to ensure without fail that dreams will come true...’

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 4.4 KG CHONDRITE

Provenance

Reputedly found in the Saharan region of Northern Mali

A strikingly sculptural oriented meteorite, its surface shaped by the intense heat and motion of its fiery descent through Earth’s atmosphere.

C . 664 - 330 BC | 26 CM WOOD, BRONZE, ELECTRUM AND GLASS INLAY

Provenance

Found at Tuna el-Gebel, Egypt

Egyptian, Greek, Roman and other Antiquities, belonging to an Eastern Art Museum, Various New York Private Collectors, and other Owners, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, April 1953, Lot 88 (ill.)

Collection of John F. Lewis Jr. (1899–1965) and Ada Lewis Jr. (1900–1967), Philadelphia, likely acquired at the above sale

Thence by descent

An extraordinary example of the moon god, Thoth, in one of his most symbolically charged forms. This remarkably ambitious statue, rendered by separate artists working in tandem, displays exquisite wood carving together with masterful bronzeworking. This so far unparalleled votive originates from the foremost cult centre of the god at Tuna el-Gebel where it would have stood out among a sea of figures.

One of the most poignant episodes in Pharaonic religion is the healing of the Eye of Horus, known as the Wadjat While locked in an epic battle for Egypt’s throne, Horus’s eye is torn from him by Seth, before Thoth, the god of wisdom, writing, and lunar balance, intervenes. With his divine insight and restorative power, he retrieves and reconstitutes the Eye, not merely mending a physical injury, but restoring harmony to the cosmos itself. It is in this role that Thoth is shown here: healer and restorer of Ma’at - the divine order - through the resurrection of what was lost.

To the Egyptians, the baboon, Papio hamadryas, was the embodiment of Thoth on Earth (alongside the ibis). They saw the agitated chattering of baboons at dawn as a greeting to the rising sun by the creatures of the moon-god, reflecting his position as mediator between the gods. With an intimate connection to Thoth, the animal itself formed a central part of the worship of the god. Their veneration was particularly concentrated on cult centres, where they were worshipped in life, mummified and commemorated in elaborate ceremonies after death.

Revered and worshipped throughout Egypt, from the predynastic period through to the Roman occupation, the figure of the baboon remained a consistent archetype in Egyptian religious iconography for over three millennia. From as early as Dynasty I, the Thothbaboon was traditionally depicted sitting upright, with his hands on his knees and a sundisc or crescent above his head. The addition of the Wadjat eye to this depiction emerged in the Late Period as a reminder of Thoth’s conciliatory and healing role in returning Horus’ eye to him, following the conflict with his rival, Seth.

The Cult of Thoth at Tuna el-Gebel

Active from the time of the Old Kingdom, the foremost centre for the veneration of Thoth was the ancient city of Hermopolis Magna. Located on the border between Upper and Lower Egypt, it was an important religious centre, with the city’s necropolis at Tuna elGebel, the largest in Graeco-Roman Egypt, renowned for the animal cult that thrived there. Over the centuries, it developed from an exclusive burial place of the high priests of Thoth, into a vast, village-like complex and burial place for the Hermopolitan elite, with numerous temples, subterranean galleries and animal sanctuaries open for public veneration. In the temple forecourt, monumental, thirty-tonne sculptures of baboons, carved from quartzite and commissioned by Pharaoh Amenhotep III, dominated the landscape as eternal reminders of the object of their worship. While not native to Egypt, baboons were imported from abroad at vast expense to live in the temple, underscoring their importance to cult veneration.

Drawing pilgrims from all over Egypt, dedication of votive statues of baboons, such as the present example, contributed to this rich and symbolic landscape. Likely commissioned for a member of the wealthy elite, the present statue is a remarkable example from Tuna el-Gebel. In its harmonious, composite form, it would have stood out among its many counterparts, placed there over the centuries as an outstanding piece of craftsmanship. With the body skilfully carved from wood, the delicately modelled and lifelike execution of the snout betrays the Egyptian devotion to naturalism in the depiction of their sacred animals, more so than any other culture throughout the Levant and Mediterranean.

Above Statue of god Thoth as a baboon, reign of Amenhotep III (1400-1353 BC), at Hermopolis (modern day Ashmunein).

‘The baboons that announce Re when this great god is to be born again… they dance for him, they jump for him, they sing for him, they sing praises for him... they shout for him… They are those who announce Re on heaven and on Earth.’

Karnak Temple Texts

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 149 g ANORTHOSITE, NWA 14685

Provenance

Found in Northwest Africa in 2020

A beautiful cross section of a lunar meteorite from Northwest Africa. It reveals a magnificent greyish-white brecciated interior, evoking the surface of the Moon as seen by the eye on a clear night.

‘A stunning fragment of lunar meteorite NWA 14685. The uncut surface of the rock is a hummocky otherworldly landscape of ridges and valleys. This meteorite reflects the unceasing bombardment of the lunar surface by errant projectiles – from micrometeorites to multi-kilometer asteroids.’

Dr Alan E. Rubin, Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA

6 TH - 7 TH CENTURY AD 5-8 CM BRONZE, BLUE GLASS ANDRED ENAMEL

Provenance

British collection, by repute found in Norfolk

Subsequently UK art market, Bury St. Edmunds

DRG Coins & Antiquities, Hertfordshire, purchased from the above, early 1990s

British private collection, thence by descent

A masterpiece of Celtic metal and enamel work, originally forming part of a hanging bowl, one of the most enigmatic and prestigious artefacts of early medieval Britain, representing the pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon ritual luxury and status. This group, rendered in enamel and bronze, is one of only two known examples to preserve an internal fish sculpture, a feature otherwise known only from the royal ship burial at Sutton Hoo, the richest Anglo-Saxon burial ever discovered.

The hanging bowls of the migration period are a particularly distinctive object type. Celebrated today for the elaborately decorated mounts, hooks and escutcheons that would have been attached to the circumference of the bowl, these thin-walled bronze vessels were meant to have been suspended from a central fulcrum or tripod. However, their intended use remains somewhat of a mystery, with suggestions from oil lamps to drinking vessels both for ceremonial and functional use. On account of the rare few which feature an additional decorated escutcheon on the inside of the bowl (notably the present and Sutton Hoo examples), it seems likely that any liquid carried was intended to be water, allowing this ornamentation to be seen.

Richly decorated and often found in high-status graves, hanging bowls came to be considered as the status symbol of the Anglo-Saxon elite. Yet, their intricate metalworking and signs of ancient repairs hint at earlier Celtic manufacture. Whether crafted by Celts and acquired by Saxons through trade, as loot or as diplomatic gifts, or made by Germanic manufacturers in the Celtic style, they are a fascinating example of the fusion of the two cultures in the period following the fall of the Roman Empire.

The often elaborately decorated escutcheons of early medieval hanging bowls feature a range of motifs that are a unique development of the religio-political context of the British Isles during this period. On a red enamelled background, the present example’s curvilinear designs and zoomorphic motifs reflect the long-standing tradition of high-quality Celtic metalwork. In particular, the three external escutcheons bear unique iterations of the distinctive trumpet-scroll pattern, which was adopted and developed by Irish missionaries for use in some of the most iconic illuminated manuscripts of the age. The additional central escutcheon here, which would have decorated the inside of the bowl, also features two hound motifs, important in Celtic mythology as symbols of loyalty, protection and healing. Moreover, the rotating fish is a particularly rare and enigmatic example of hanging-bowl decoration. Likely mounted on a rotating pin, if the bowl was indeed filled with water, it would have given the illusion of a swimming creature. Aside from the present piece, the only other extant hanging bowl featuring an internal fish decoration - itself a rare example of sculpture in the round from this period - is from the famous royal ship-burial found at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia.

Believed to be the final resting place of King Redwald of the East Angles (d. 625-6 AD), the Sutton Hoo ship is the greatest early medieval treasure found. The hanging bowl found there was suspended in antiquity on the end wall of the burial chamber, near the ceremonial sceptre, a crucial emblem of the power of the deceased. Its notable position in the ship reflects the particular extravagance of its decoration, as well as the important position given to these bowls in Anglo-Saxon society. Comparable only to the Sutton Hoo example, the present hanging-bowl escutcheons are masterpieces of early medieval metalwork.

Left

Hanging bowl and central fish escutcheon from Sutton Hoo, 6th-7th century AD. The British Museum, London.

‘But to table, Beowulf, a banquet in your honour; Let us toast your victories, and talk of the future... Then Hrothgar’s men... yielded benches to the brave visitors and let them feast. The keeper of the mead came carrying out the carved flasks, and poured that bright sweetness.’

Beowulf, Lines 489-495.

4.5 BILLION YEARS OLD 53 CM 34.68 kg IRON - COARSE OCTAHEDRITE

Provenance

Discovered in the Magadan District, Russia, 1967 (62° 54’ N, 152° 26’ E)

Published Meteoritical Bulletin, no. 43, Moscow (1968)

A magnificent and extremely sculptural specimen of the Seymchan meteorite, recovered from Eastern Siberia. A striking extraterrestrial sculpture, preserving the patinated and partially melted exterior of the meteorite, together with the mesmerising pattern of iron-nickel crystals on the cut face interior.

The interior section of the present meteorite reveals the beautiful interlocking crystal structure of two nickel-iron alloys. Formed by the supercooling of the parent body from a molten state in the vacuum of space around 4.5 billion years ago, this mesmerising and reflective pattern is indicative of the meteorite’s extraterrestrial origin, as this structure can only occur in outer space. Believed to have hailed from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and flung into space by an enormous impact, this extraordinary specimen would have travelled over 100 million miles before falling to Earth. As it plunged through the Earth’s atmosphere at cosmic velocity, the surrounding air was heated to 1,700°C resulting in an intense fireball. The outer surface of the rock would have melted away, exposing a new surface also affected by the adverse temperatures. During this process, streaks of molten metal vaporised off the exterior, causing the scars and indentations now visible on the surface.

As fascinating messengers from space, meteorites are immensely important to scientific research today. Not only do they carry the building blocks of our Solar System, but they have even changed the course of evolution itself. While advancing planetary science, meteorites are also imbued with an ethereal quality, deriving from their beauty and otherworldly origins. Formed over billions of years, and perfected by the intense heat of atmospheric entry, they are entirely natural sculptures, symbolic of the incredible forces of our universe.

‘The meteorite hardly seen was lying among the stones of a brook-bed... The smaller specimen was found by I. H. Markov with a mine detector in October 1967...’

Left

The recovery of the Seymchan meteorite, 1967.

Caption Meteoritical bulletin, no. 43.

‘This sculptured piece of the Seymchan pallasite has an interior window featuring olivine-free metallic iron-nickel. The sample has a coarse Widmanstätten pattern indicative of slow cooling at the top of the molten core of a differentiated asteroid. The metal grains forming this pattern are bent, due to shearing during violent break-up in the atmosphere.’

Dr Alan E. Rubin, Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA

Published by ArtAncient Ltd

June 2025

ArtAncient 31 Imperial Rd London

SW6 2FR

info@artancient.com +44 (0)20 3621 0816

ISBN 978-0-9930370-7-8

Published by ArtAncient Ltd

Text & Design: Olivia Longhurst

Photography: Costas Paraskevaides

Jethro Sverdloff

Printer: Gemini Print Solutions