By Michael S. Dosmann

I’ve been celebrating the life, and mourning the loss, of the centenarian silver maple (Accession 12560*C) that grew along Meadow Road. After almost a century and a half in this spot, this magnificent specimen was removed due to its deteriorating health. But oh, the many ways it served! Its precocious spring flowers supplied nectar for bees. The canopy shaded and cooled the air. MIT chemists gathered its flowers to study the polymers (sporopollenin) that compose its pollen. Instructors used its cut twigs for an International Society of Arboriculture identification test. But most important of all, this giant sentinel welcomed every one of us who walked below. Strolling tourists marveled at its sheer mass, children measured the twisty trunk’s diameter, and generations of staff and docents greeted it like an old friend. What if Benjamin Watson had never provided those seeds back in 1881? What would the Arboretum have been like these past 140 years without it?

Some twenty years before our silver maple was planted in the ground, great things were afoot in Washington, D.C. and in states across the country: the USDA was founded and the Morrill Act (the legislation that established land-grant universities) was signed in 1862. Good things resulted from these and other public initiatives to follow (Yellowstone was created in 1872, and the National Park Service was established in 1916). Through these, the US has preserved natural lands, curated irreplaceable collections, conducted research on woody plants, and educated student and lay person alike. Although the Plant Hardiness Map originated at the Arnold in 1927, it was the USDA that improved it in 1960 and, with updates every decade or so, provides an essential tool used by gardeners everywhere. How can one argue that these very good and very great things are not worth public support (i.e., tax dollars)?

Public support permeates the Arboretum: by my tally, over 1600 plants (10%) representing 600 taxa alive in the permanent collection are the result of it. We have Metasequoia glyptostroboides trees collected from wild populations in China in 1990 and donated by John Kuser, professor at Rutgers (a publicly supported, land-grant university). There are a half-dozen Malus accessions collected by Frank Meyer (explorer-botanist for the USDA) in China a hundred years ago, and over a dozen Malus sieversii (which gave rise to the domesticated apple) collected from Central Asian populations by a host of USDA scientists several decades ago. Incredible plants, all of them. Just as some came from the wild, others were made. Scientists at the US National Arboretum (USNA) hybridized

Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ in 1963 and released in 1980. We received our original accession in 1974, and its huge, purply-magenta flowers have been part of our cavalcade of color every spring since. More recently, we have been growing hybrid hemlocks from the USNA that tolerate that scourge, the hemlock wooly adelgid. These crosses between resistant Tsuga chinensis and susceptible T. caroliniana include ‘Traveler’ (hybridized in 1992, introduced in 2020) and ‘Crossroad’ (hybridized in 1998, introduced in 2022). Tree breeding is a slow affair, with progress measured in decades. Thank goodness for places like the USNA, one of the few places in the US still employing tree breeders, where generations of hybrids have been created, evaluated, and introduced by generations of scientists and curators, all to society’s benefit.

Speaking of hybrids, the Plant Collections Network (PCN, to which the Arnold Arboretum’s eight Nationally Accredited Collections belong) is a collaboration between the American Public Gardens Association and USDA. PCN benchmarking has helped us take our collections of Acer, Carya, Fagus, Forsythia, Ginkgo, Stewartia, Syringa, and Tsuga from great to exemplary, and I know it has been the same for other North American gardens.

In 2011, I joined staff from USDA’s North Central Regional Plant Introduction Station in Ames, Iowa (home of the National Plant Germplasm System [NPGS] repository responsible for ash) on expeditions to collect three species (Fraxinus americana, F. nigra, and F. pensylvanica) in Pennsylvania and New York. We collected enough seed from enough mother plants to capture entire populations’ worth of genetic diversity, enough to completely rebuild them in the future. It was timely, as emerald ash borer—which kills trees after a few years— had just arrived. Those populations, devastated in nature, are preserved (at least for now). This and other repositories possess incredible facilities, expertise, and longterm commitment to maintain wild and crop germplasm. And because NPGS is the largest germplasm-repository system in

the world, it serves a public good of global significance.

The US has preserved natural lands, curated irreplaceable collections, conducted research on woody plants, and educated student and lay person alike.

Since 2007, I have been a member of the Woody Landscape Plant Crop Germplasm Committee, which comprises university and garden scientists, members of the nursery industry, and USDA curators and researchers. We advise on matters related to the acquisition, curation, and research use of woody plant accessions held among the many repositories, often in response to biotic and abiotic threats. Last fall, members of our committee published a call-to-action paper, “Seeing the Forest for the Trees,” in HortScience, which described the litany of challenges woody plants face—threats in the wild and in our urban forests and managed landscapes. We highlighted exploration, conservation, and research solutions to real-world problems, and hoped that our report could serve as a playbook for government and university scientists to direct future work. And who knows, maybe it would spark new public and private investments to safeguard against future threats. I was unprepared for a new threat, one from within (DOGE), which would brutally girdle tree research and stewardship initiatives of vital public funding—funding I would say was already insufficient. The callous cutting of our nation’s programs will devastate not just the existing canopy (literally and figuratively), but also future replacements. Even if funding is restored at some point, the damage is going to last for a long time.

I know our late silver maple will be replaced by another great tree doing good things—our nursery is a constant pipeline of them. But imagine an indiscriminate clearcut through the Arboretum’s collections, without understanding the repercussions or having plans for any replacements. It might be like the Hurricane of 1938, an unplanned and unprepared for disaster that ripped some 1,500 of our trees asunder. Make no mistake, such a storm is rising.

—Orville Daniels, Arnold Arboretum Member

44

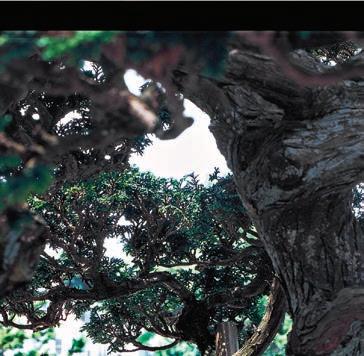

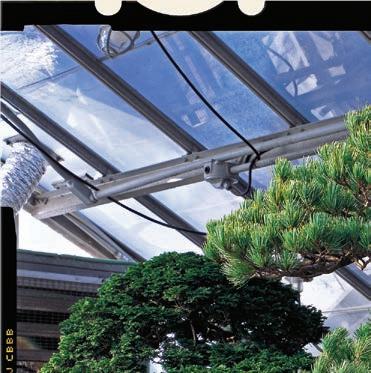

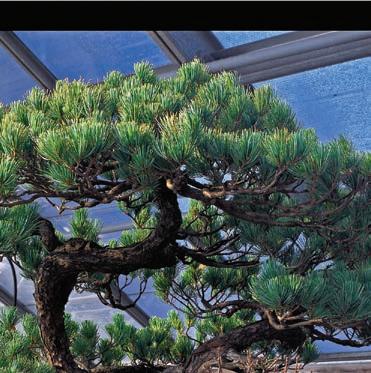

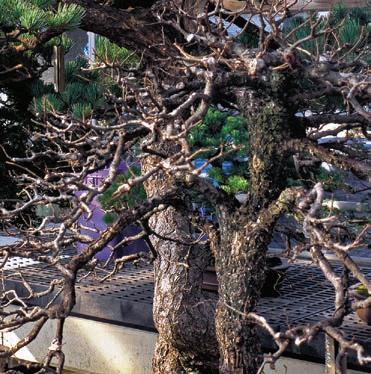

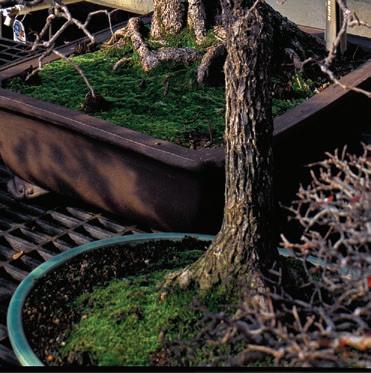

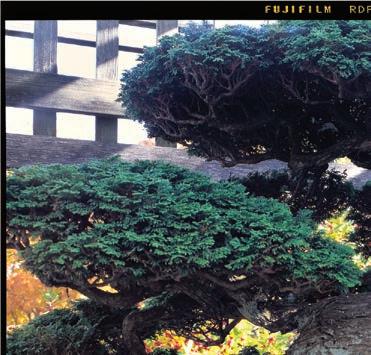

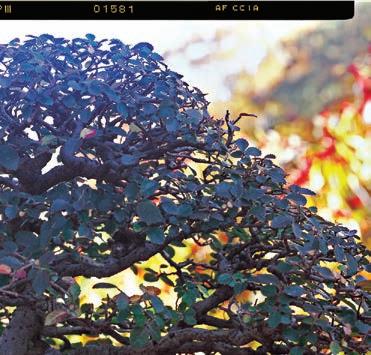

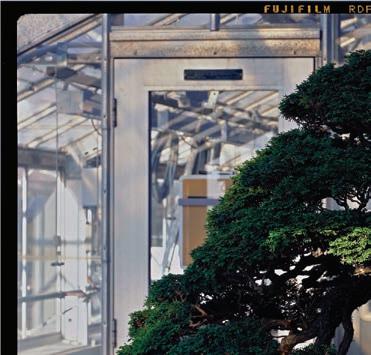

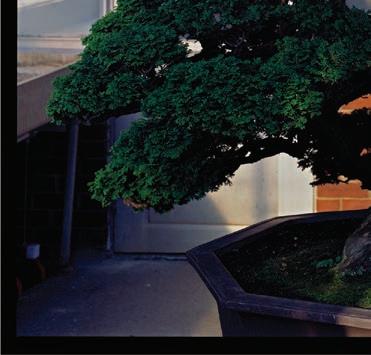

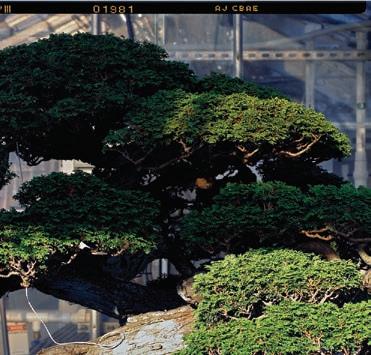

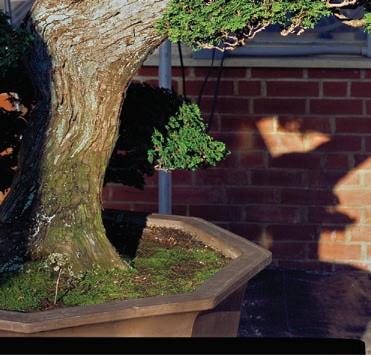

Carefully examined, bonsai can look as big as they feel. Photograph by Stephen Longmire

By Michael S. Dosmann

Nicholas Anderson plants ideas about successional horticulture and future flourishing amid the ruins of an old airfield; Benjamin Swett collects images that reveal the extraordinary ways urban trees show up in our everyday lives; Eve Farrell and her colleagues bring decades of carbon data in the Quabbin Watershed to life. 18 Plant Portrait

Rhododendron calendulaceum

By Michael S. Dosmann

A Maple in Memoriam

By Maureen Danahy and Claire Neid IN REVIEW

The Accidental Garden by Richard Mabey

Review By Shuchi Saraswat

Binsey Poplars

By Gerald Manley Hopkins

By Kyle Port

By David Foster, Rick Lewandowski, Rebecca Oreskes, Seana K. Walsh, Kenneth R. Wood, and Rohan Press

By Juan Rogelio Aguirre-Rivera, Eleazar Carranza-González, and Juan Antonio Reyes-Agüero

By Stephen Longmire

Cover

View of Meadow Road ca. 1986. Gift of Katherine Poole; courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design (54448).

Inside front and back covers Illustration by Shyama Golden

Editor

Matthew Battles

Designer Andy Winther

Editorial & Production Assistant

Claire Neid

Editorial Committee

Anthony S. Aiello

Yota Batsaki

Peter Del Tredici

Michael S. Dosmann

Rosetta Elkin

William (Ned) Friedman

Jon Hetman

Jonathan Shaw

Creative Consultants

Point Five

Arnoldia (ISSN 0004–2633; USPS 866–100) is published quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Massachusetts. Subscribe to Arnoldia by becoming a member of the Arnold Arboretum. For more information, visit arboretum.harvard.edu/support/membership or contact the membership department at 617.384.5766 or membership@arnarb.harvard.edu. Send all other Arnoldia communications to Circulation Manager, Arnoldia, Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130-3500. Telephone 617.384.5011; fax 617.524.1418; email arnoldia@arnarb.harvard.edu.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Arnoldia Circulation Manager The Arnold Arboretum 125 Arborway Boston, MA 02130–3500

Copyright © 2025. The President and Fellows of Harvard College

Arnoldia welcomes your ideas, questions, and feedback. Letters should be sent with the writer’s name, address, and phone number via email to arnoldia@arnarb. harvard.edu. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Find us online

ArnoldiaMag ArnoldArboretum ArnoldArboretum. Harvard

I feel moved to share with you and with readers of Arnoldia why my sons and I were inspired to establish a research award to support an early-career scientist at the Arnold Arboretum. As we all know, the Arnold Arboretum brings together a unique combination of world-class living collections, research facilities, a dedicated library and archives, all housed in a beautiful open-access free public park. The Maria Amalia Carvão Research Award gives early-career researchers a unique opportunity to jump-start their research and guide the direction of their future work with the support of the Arnold Arboretum. Talent is everywhere. However, not everyone has access to the resources to enable this talent to flourish. We intend the award to act as a bridge between talent and these resources.

My late wife, Maria Amalia Carvão, and I both grew up in Brazil, in middle-class families that focused on their children’s education. Early on, Maria developed an interest in science, which led to a career as a physician, where she coupled her scientific prowess with a keen interest in listening and supporting others. She also had a profound interest in nature, the environment, and plants’ role in preserving a healthy planet. A science career path, the environment, and supporting early professionals came together naturally to inspire us to want to focus on supporting environmental research.

Of course, we did not know in late 2024, at the time we established this philanthropic gift to support young scientists at the Arnold Arboretum, that the historic federal funding of basic and applied sciences would be disappearing. We now understand that our endowment gift is a way for the Arboretum in perpetuity to protect and support young scientists who are caught in the crosshairs of what is happening. As director Ned Friedman wrote to me: “Every endowment for research at the Arboretum now

really is a lifeline for the next generation of scholars who study the natural world.”

Let me also add as a point of inspiration that I had a career in business and technology, and I believe in science for good. I also believe in diversity of talent and equality of opportunity while recognizing that not everybody comes from the same circumstances. I was given opportunities to fulfill my ultimate potential, and I have had the privilege to mentor several others from diverse backgrounds in their quest for excellence. Research is about creativity (and a lot of hard work!). Creativity benefits from diversity. It is a direct correlation.

Early career scientists are still exploring options. If their work at the Arboretum can help reaffirm their passion for the field, then we have taken the first step. This award we have created is in perpetuity, meaning that we will have an early career scientist every year. Over time, I hope the award can represent a small contribution to the community of biologists, botanists, and environmentalists who will help us better understand, nurture, and preserve our plant species and how we interact with them.

I encourage younger scientists from around the globe to apply. Dream big, follow your dreams, work hard, and make an impact. For those who consider philanthropy, education is the foundation for everything: from civics to science. There is no better place to make a lasting impact than investing in those researching and building our future. My sons and I are so pleased we can honor Maria’s legacy through the next generation of researchers. We hope others will join us.

With best regards,

Paulo Carvão

I never thought that I would make the cover of a magazine, but I am pretty sure that I am the guy shown walking along Meadow Road in the lower left-hand corner of the cover of the Spring 2025 edition of Arnoldia

I had my doubts until I noticed that there are glasses tucked in to the neck of my shirt. That is how I carry my glasses and I don’t know anyone else that does. Since this is a 1982 photo, it shows me before I became an Arboretum docent.

The photo on the cover of Arnoldia , along with the sad news that my beloved silver maple is about to come down, has made this an eventful time. I cherish my past connections with the Arnold Arboretum and will continue to follow Arboretum news from Maine.

My best to everyone at the Arboretum, David Tarbet

Nicholas Anderson cultivates ideas about successional horticulture and future flourishing amid the ruins of an old airfield.

Nicholas Anderson is an ecological land manager, consultant, and arborist in Massachusetts, where he is a founding member of the Creating Commons Collective of Cape Ann.

I’ ve been lost in conversation and haven’t even noticed that we’ve left the city behind and are reaching our destination. We pull off to the shoulder by a fence fringed with wisps of little bluestem grass. We get out of the car and into the late morning air that feels indifferent to our presence. It’s midMarch, overcast, and the landscape is muted and emphatically flat in all directions.

We’re at Floyd Bennett Field in southeast Brooklyn at a site used to propagate native beach grasses for dune restoration. My companions are Matthew Morrow, the director of horticulture for NYC Parks, and his wife, Regina, who has just informed me that the beach on Dead Horse Bay, historically covered with antique bottles, has recently been closed due to radiological contamination.

Along with us is my dog Astra, who leaps out of the car and bolts gleefully into the field before I can get a leash on her.

We’re on an informal site visit to a spot where Matthew plans to enact a nursery/meadow roughly in keeping with my method of planting great quantities of tough native plants together in close proximity and then using their naturalized offspring to expand outward to new locations. But it’s also just an opportunity to poke around and botanize in this unique locale.

We walk past the fence and into the propagation fields, which are largely covered with black plastic fabric. Matthew and I have been talking about possible species for such a project, and immediately I spot one of my top suggestions. Frost aster is already visible

Illustrations by Matt Huynh

on the ground as weatherworn rosettes that will emerge and expand towards profusions of white flowers in the fall.

The soil is sandy but appears to be fairly dark and rich. We walk to the area where Matthew wants to establish the meadow and see that it’s already densely colonized by mugwort. Gardeners know this plant as a formidable Eurasian perennial that forms masses anchored by determined networks of rhizomes. But seeing them now, dormant with their feathery, seafoam leaves just visible at the surface, they resemble continents of coral. I bend down and pinch some leaves, and the oily perfume calls to mind the plant’s rich cultural history, but they also smell like sweaty work with subtle notes of futility. We discuss the prospect of putting black plastic over the mugwort to burn out the roots, or whether it might be better to just manually pull it out as the project moves forward.

Further along we see Yucca filamentosa with its needle-sharp leaves adorned with dry, curling strands that gesture at its specific epithet. Nearby we find a desiccated

The oily perfume calls to mind the plant’s rich cultural history, but they also smell like sweaty work with subtle notes of futility.

seed head of mullein emerging from the center of its exhausted basal foliage. These species are deemed native to different continents and are far apart on the tree of life. Nevertheless, they both feel deeply appropriate in this setting, as their similar morphologies—low, thick leaves with flowers atop a stalk—connote the capacity to make do in lean times. They fit perfectly within this scrubby, desolate landscape. Jamaica Bay is barely out of sight, but it’s easy to put it out of mind and imagine oneself in other parts of the world. There’s little here that suggests Brooklyn.

I first met Matthew almost a decade ago when I worked as a NYC Parks gardener out of Prospect Park. He was an early mentor for me, as he had a wealth of horticultural knowledge and was willing to endure my relentless questions. We became friends over the years and stayed in dialogue about all matters growing and green even after I left New York in 2019 for Cape Ann, Massachusetts, where I grew up. Matthew took on his new leadership role at Parks around that same time.

Urban trees are crucial to global carbon sequestration, yet forest-based metrics are often applied to urban spaces, resulting in misestimations of carbon stores. A recent study out of the Republic of South Korea developed urbanbased metrics to study stem volumes in urban tree species Ginkgo biloba, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, Platanus occidentalis, Prunus spp., and Zelkova serrata. The team applied these metrics across street trees, urban parks, and other categories such as residential areas and school campuses, finding that street trees have lower stem volumes than those in other urban land-use categories, and that DBH-height relationships in G. biloba and M. glyptostroboides varied most substantially across categories. These findings underscore the necessity of urban-based metrics to produce better-fitting models, leading to enhanced understanding of and planning for carbon sequestration in urban trees.

Back home, I had access to great quantities of what I call charismatic native “weeds”: species that are so fecund and/ or aggressive that their supply can always outstrip demand. I began experimenting with planting roots and rhizomes in overwhelming quantities directly into turf grass and compacted bare soil to see if the plants could be made to be the agents of their own destiny without much in the way of weeding or maintenance. Design and premeditation forsaken for a planting strategy that’s like a squirrel with a surplus of nuts, always on the lookout for new spots in the yard to bury them. I was driven to work in this way in imitation of the roadside meadows that inspired me, but I also felt that this could be a way to enact beauty, ecological flourishing, and resilience on public land in New York and elsewhere. If dense and diverse nurseries could be planted as the first order of business, public gardeners could learn to work with the naturalized surplus of these projects. They could get to know the plants as the weird living entities that they are, rather than as sentimentalized and decorative objects in plastic pots. For all of my reading about plants over the years, most of my knowledge has come down to working with intimacy at the intersection of my eyes and fingertips with soil, roots, and shoots, year after year. I want to invite people to this point of entry with plants, without all of the baggage of conventional horticulture.

To my delight, Matthew has been receptive to these ideas, and we’ve talked increasingly about implementation on NYC Parks land, but today is the first time we’ve looked at a space together with such intentions. On Cape Ann, I have around a dozen meadow projects, whose floristic components shift over time as they knit together with evergreater integrity. Meanwhile, these landscapes allow me to continuously fill buckets with divided plants while they cast seeds to the wind. My hope is that, however modestly this new project begins, within a couple of years the ground will be a diverse fabric of vegetation that works on its own terms while spreading outward at an assisted pace, always at sufficient density that the

entangled plants do the bulk of the work for themselves. I like to imagine this space as a cartoon volcano spewing hunks of undifferentiated meadow far and wide, forming new, flowering islands and archipelagos on neglected landscapes in the city.

Within a couple of years, the ground will be a diverse fabric of vegetation that works on its own terms.

We walk farther along, and now Astra bounds up beside us, proudly displaying the old stalk of mullein in her teeth, which she saw us admiring. Perhaps she picked up on our discussion of how this is a favorite species for Regina. The edges of the propagation fields are an inviting mosaic of bunch grasses, including the tawny tufts of little bluestem as well as blond fountains of a grass I don’t immediately recognize. We walk closer and marvel at the delicacy of its foliage, cascading perfectly like the hair of a 1970s teenage heartthrob. I decide that it’s probably prairie dropseed, but discover later that it’s African weeping lovegrass, a species extensively planted for erosion control and now deemed invasive. But in the moment, they conjure Sam Eliot’s narration in the opening of The Big Lebowski: they’re the right plants for their time and place. They fit right in there.

Past the grasses, the landscape gives way to short trees, mainly shining sumac and red cedar with scattered oaks and white pine. And pushing out from under the trees and into the grasses are menacing tendrils of poison ivy tipped with ghostly white berries. Bittersweet is also visible as threefoot whips. The modest length of these vines indicates that the area is periodically mowed, though such management is likely to be infrequent and arbitrary.

Floyd Bennett Field opened as an airport in the early 1930s, and also hosted the Navy and Coast Guard for much of the twentieth century. Now it exists under the umbrella of the federal government as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area, with an alphabet soup of agencies and interests that make use of the space, including the police, the city’s parks department, and the US Marine Corps Reserve. Numerous proposals to develop the site have been put forward over the decades, but none have come to fruition. So many powerful interests have

a claim on this landscape, yet they are all but invisible on this grey day. The land has so many stakeholders that it feels disowned, its ecology defiantly feral.

We move on to an adjacent area, an abandoned parking lot, which appears to connect to an old piece of the airstrip. Asphalt and sectioned concrete are visible in places, but much of it is covered in mosses and the remains of last year’s weed growth. We’ve come to find northeastern prickly pear cacti, which have naturalized on the site. Horticulturists are drawn to the species as a novelty, though they tend to look ridiculous in New England gardens. When I’ve seen them in the wild, they’re typically on exposed rocky outcroppings, where they look ecologically credible. But here they are so numerous that they appear to have been illegally dumped onto the composite surface like offcuts of rubber from a shoe factory—sections of wrinkled cactus lying haphazardly on top of one another, some breaking off and forming new colonies. In a sense, this is what I hope becomes of this nascent meadow project and others like it. Naturalized abundance radiating out without fanfare, certainty, or authorship. These cacti are a coveted native species, but they’re lying on asphalt atop soil dredged from the bottom of the bay. Plants don’t need to be brought into our Edenic fantasies to flourish. They’re more than happy to colonize our ruins.

Last winter, arborist Andrew (AJ) Tataronis noticed that one of the Arboretum’s weeping hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis forma pendula, 1514-2*A) seemed close to uprooting. AJ leads the Arboretum’s veteran-tree care efforts and was familiar with this 144-year-old specimen, a beloved fixture on Hemlock Hill Road.

To help this tree age gracefully, AJ and his colleague, Logan Nutter, constructed a crutch from a previously-felled Arboretum false cypress. Set into an 18-inch-deep hole with a six-inch foundation of gravel, it barely touches the limb above, and is padded with softened hemlock bark to prevent wear. The crutch also echoes a Japanese technique called hoozue ( ほおづえ , “chin resting”), in which branches are propped to both support and honor important plants.

Even with the support, this beautiful hemlock is in its twilight years. Every tree must fall, and the crutch is not intended to prevent this. Until it does, the support will highlight its aging beauty, as well as the passion of the those who care for it.

—Brendan Keegan, arboretum horticulturist

Benjamin Swett wanders the parks of New York city, collecting images that reveal the extraordinary ways urban trees enhance our everyday lives.

My best photography has always grown out of the ordinary life I lead. It starts almost without starting, not through special efforts or travel to distant places; not through expenditures of vast sums or courting other people, but almost by chance during the course of my regular preoccupations and activities.

I had received a fellowship from the New York Botanical Garden to make landscape photographs in The Bronx. One morning early in the fellowship year I got on the #2 subway, rode five stops to 149th Street and Grand Concourse, switched to the #4, rode nine stops to Kingsbridge Road, descended from the elevated station, and walked one block south to St. James Park.

It was the time of redbuds. You could see them from the entrance of the park, glowing like purple firebrands here and there back among the pathways and trees—trees on which the leaves were just coming out, bright green bristles on dark branches,

making the park look shaggy and friendly, as if it needed a shave.

Eleven-acre St. James Park, along Jerome Avenue in the Kingsbridge section of The Bronx, is more of a square than a park, and like a square it was, under the shaggy trees that day, full of people shooting basketballs, talking with friends, sitting on benches and scrolling through their phones, running this way and that in the playground, or passing through with shopping bags on the way home from the store. When I had first visited St. James many years before, in the mid-1990s, I had come as part of my job at the Parks Department to make a brochure that neighbors could use to fundraise and advocate for the park. One of our most successful and original brochures, The People of St. James Park had consisted almost entirely of square-format black-and-white portraits of park users going about their various activities.

As I wandered into the park today,

Benjamin Swett is a writer and photographer whose books include Route 22 and New York City of Trees, which won the 2013 New York City Book Award for Photography. His most recent book is The Picture not Taken.

though, it was not people but trees that were attracting my attention, and the one that I noticed first was a honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos).

New York City is full of honey locusts, but this one—halfway into the park on a central walkway—stood out for the dark massiveness of its lower trunk, from which the rest of the tree arched up and away to join neighboring trees in a twisted canopy of interlocking branches overhead.

There seemed something unusual about the tree, and as I approached to measure it I saw that it was a “true” honey locust, by which I mean a honey locust with thorns. All of the honey locusts now planted in the city, and most other places for that matter, are a thornless cultivar. So successful has the city been in replacing the thorny original (whose vicious spikes, growing around the trunk and branches like razor wire, were thought to have evolved millennia ago to protect the sweet bark from the teeth of mastodons) that to find one today is rare, and usually a sign of age; and though park workers had carefully clipped back the barbs around this one (and evidently, from the dark buildup around the base, had been doing so for decades), a sufficient number remained to identify the tree.

As I recorded the honeylocust’s diameter, 43 inches, in my notebook, and moved back and began photographing it from different angles, I again became aware of the people passing by, because I was using them as elements in the photographs. It occurred to me that, in my recent photography of trees, the relation of trees to people had changed. Increasingly, in the way I was photographing now, the trees were larger and the people smaller. This of course had a lot to do with the wide angle lenses I was using, but it also, I thought, came from something else. But what was that exactly?

As I was finishing with the honeylocust, a London plane growing nearby—all by itself on an otherwise empty lawn— diverted my attention, but not until I had made half a dozen exposures of this lovely but not particularly unusual tree did I realize that what had attracted me was not the

What do landscape paintings, tree physiology, and mathematics have in common? Fractals. A mathematical phenomenon in which shapes repeat themselves with increasing detail at finer scales, fractals have generated marvel and intrigue for centuries in art and nature. Though their aesthetic qualities have long been studied, using fractals to enhance our understanding of what makes beauty pleasurable has proven difficult. A recent PNAS Nexus study took up this question, analyzing trees depicted in artworks ranging from a sixteenth-century mosque in India to Piet Mondrian’s Gray Tree (1911). Researchers found that the trees depicted in these artworks were recognizable as “trees” because of how their branches scaled—a feature which is explainable through biological mechanisms, tree physiology, and fractal dimensions. Specifically, if the diameter and radius of tree branches scale within certain values of the so-called Hölder exponent (α) characterizing the fractal space, they are both recognizable as trees in artworks and more aesthetically pleasing to viewers. The complementary nature of scientific, mathematical, and artistic perspectives regarding the complexities of tree structures offers a lesson in the value of interdisciplinary dialogue, and an example of the boundless ways to appreciate the beauty of trees.

Gray Tree (1911) by Piet Mondrian. Kunstmuseum Den Haag (0334314) via Wikimedia

tree itself but the figure of a person in the background. The figure, all dressed in black, or perhaps rendered a silhouette from the angle of the sun, was doing yoga exercises or prayers behind a rock outcropping across the lawn—a coordinated series of bodily moves and gestures all culminating, in a regular way, in a raising of the arms to the sun.

While waiting for the person to raise their arms again I noticed a much larger London plane over by the southern wall of the park, and, nearby it, a super-bright redbud. A few minutes later I walked over to the bigger London plane and discovered it to be hollow at its base and, when I measured it, to have a diameter of 53 inches (why I keep measuring trees I can’t exactly say, except that I enjoy noting their changes if and when I come back to them). Growing from a ridge of ancient litter mixed with leaves along the wall, this London plane was a grand old tree, something to celebrate for itself but also, I decided as I kept photographing it from different angles, to enjoy in relation to everything else around it, not only the bright redbud (I was standing now with my back up against the park wall, keeping both trees in the frame) but a person in a blue dress and black parka with a fur-lined hood who happened to stroll by.

From the London plane it was to the redbud I went, and from that redbud to another growing at the top of the steps at the eastern entrance to the park—the very tree and steps, I remembered, that we had included on the cover of our brochure all those years before. I took some shots of steps and tree from the same dramatic angle from which I’d taken the previous one, again with a person walking up the steps (different camera now, and in color) and then climbed the steps and took some photos from under the canopy of the tree itself, back through the purple blossoms into the park and up the central walkway toward the park house.

I kept going like that, collecting images of the trees, gradually making a counterclockwise circle around the tennis, basketball, and handball courts at the center. I lingered, adjusted, waited, shot, adjusted,

In parks like this and in cities, people and trees would always be part of each other’s lives.

waited, shot. If I could include a person in the shot, no matter how small, so much the better. Eventually I came back around to a tall oak that grows at the northwest entrance of the park. It’s like a portal, this oak, one branch shooting out to create an arch through which you pass from the busyness of Jerome Avenue to the shaggy world of the trees and people inside the park—and out again. I took some shots of this tree with the elevated tracks and a passing subway behind it, and then got on a subway myself and went home.

Later, after I’d uploaded the pictures to my computer, I discovered that my favorite shot of the day was one of my first. I had been about to move on from the honeylocust when, noticing a line of schoolchildren approaching up the central walkway, all holding onto a rope, with one teacher leading and another following, I had raised the camera again and made one more exposure of the tree, slightly cockeyed from my haste to include the schoolchildren underneath. I had nearly forgotten this image, but seeing it enlarged on my screen—the enormous trunk jutting up in the foreground, the tiny children underneath in their jackets and shoes, holding onto the rope—I remembered what had been bothering me earlier about the scale of people in my pictures in relation to trees. I realized that of course this relationship would always be cockeyed because of the very different sizes and ages of the trees in relation to the people, and that this was something to celebrate. But in parks like this and in cities, people and trees would always be part of each other’s lives; they couldn’t escape each other—and that was how it should be. As I sat there at my computer I remembered a man with a huge smile on his face who had been observing me as I photographed one of the brilliant redbuds that morning. “Nature, huh?” he not so much asked as declared as he passed by.

Eve Farrell and colleagues bring decades of carbon data in the Quabbin Watershed to life.

Eve Farrell is a PhD student in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University researching plant-mycorrhizal responses to global change.

On a mid-January morning earlier this year, a team of forest experts and I bumped down a frozen gravel road in a state forestry truck to visit plots in the Quabbin Reservoir Watershed Forest. The Quabbin Forest, an 88-percent forested assemblage primarily of Pinus strobus, Quercus rubra, Acer rubrum, and Tsuga canadensis, is 23,000 acres of transition hardwood forest surrounding the largest body of water in Massachusetts. This would be my first time seeing any of the 283 Continuous Forest Inventory (CFI) plots scattered throughout the area—plots which, until this point, I had only known in the form of data frames and spreadsheets.

I was introduced to the Quabbin’s CFI plots as part of an internship project in the winter weeks between the fall and spring semesters of my first year in graduate school. I was the newcomer to a crew of foresters and ecologists from the Harvard

Forest—Audrey Barker-Plotkin, Jonathan Thompson, and Danelle LaFlower. My primary role on the team at the time of the Quabbin visit was data crunching: exploring the robust and uniquely longterm data that had been collected in these Quabbin plots since they were established in the 1960s. I had come to know these trees through spreadsheets, individuals represented by rows of data: basal area, aboveground biomass, status, and species name. But our field visit offered the chance to become acquainted with them in a new way, to encounter their features not as numbers but as physical attributes—stories told in real time.

The central questions of our project explore how disturbance—from light thinning to stand-replacing events—impacts total carbon storage and rate of sequestration relative to an undisturbed forest. Many of these Quabbin plots had undergone

disturbance through timber harvest, primarily via mild thinning but in rare cases through extensive cuts. We are interested in how the severity of this disturbance influences the forest’s carbon future. After a harvest, do surviving trees experience accelerated growth and increased sequestration, as is commonly believed? If so, for how long are these elevated growth rates sustained? How does total biomass in the plots 10, 20, 30, or 40 years after harvest compare to that of a plot that was never harvested? Our analyses aim to disentangle the timescales and trajectories of carbon recovery following varying disturbance intensity.

While our investigations are still ongoing, they provide insights into how timber harvests–and other disturbances such as storms, herbivory, fires, and droughts–may influence forest carbon dynamics over time. Our findings could inform silvicultural practices that balance forest productivity with carbon storage. More broadly, this work could contribute to a growing understanding of how temperate forests, increasingly subject to disturbance, store and recover carbon in decades to come.

Our findings could inform silvicultural practices that balance forest productivity with carbon storage.

Back in the field, a light layer of snow dusted the forest ground, and the understory was sparse—in part due to winter dormancy and in part due to extensive deer browsing in the area. Brian Keevan, a natural resource analyst from the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, organized the inventory of these plots for many years and was our guide for the day. Having donned warm layers, we climbed out of the truck and grabbed clipboards stacked with plot maps. Before heading into the woods, Brian showed me his outfitted field work vest. It was veteran forester gear: a worn-down Carhartt in which every forestry gadget imaginable was secured to prevent them from dropping to the ground and being lost in the understory.

Guided both by the plot map coordinates and Brian’s memory of where each plot is situated in the watershed, we wandered off the trail and into the woods. As we walked, young white pines, between two and four feet tall, were speckled about. Above them, much taller, older pines and some red oaks defined the canopy. We were searching for a pop of color in the

Lightning strikes in forests predominantly have been studied for their negative impacts to trees. Less is known about what positive effects lightning may have on a tree’s life history and forest biodiversity generally. Recent NSFfunded research by the Smithsonian’s Evan Gora and colleagues, published in New Phytologist, looked at lightning’s effects on Dipteryx oleifera, a large-statured rainforest tree native to Central and parts of South America. In central Panama’s mature tropical rainforest, researchers found that D. oleifera (and a few other species) did not experience damage to their canopies and trunks, while lightning damage to neighboring trees and lianas benefited D. oleifera by removing competitive neighbors. The research raises questions about whether the ability to survive lightning strikes is a strategic trait of long-lived and large-statured tree species.

cold landscape: a bright-red post or a tree labeled with paint. Soon, we spotted the marked post that indicated the center of a plot. Our crew gathered around it and took in the surrounding area. Each tree within 50 feet of where we stood was painted with a unique identifier at breast height, about 4.5 feet tall. Looking down at my clipboard, the plot map showed the exact location of these trees, their species code, and their status: live, standing dead, or fallen dead. A red dot on the sheet indicated the exact spot where we stood.

Using the plot map as a guide, I homed in on each tree within the plot’s perimeter. To my left was a worn stump. I glanced down at my clipboard and found an orange circle with an “x” in the center: “fallen dead.”

To my right stood a red oak. I searched for its position on the plot map and found an orange circle: “standing dead.” From where I stood, it resembled its winter-dormant relatives closely enough that I likely wouldn’t have known it was no longer alive. As I continued this exercise, the map and the stand came into alignment. Green circles dotted the map, each representing the live trees which stretched before me into the tall canopy.

The longer I matched the map to the landscape, the more the plot came into focus. I was simultaneously observing a richly textured woodland and a landscape of recorded growth. The CFI dataset reveals not only the stand’s current condition, but also its history. Through it, we could glimpse back in time to when these trees grew most or least, hinting years of flourish or struggle. Even trees that died decades ago, leaving few visible traces in the forest now, persisted in the form of data collected prior to their death. If a tree was young enough, we even knew roughly when it germinated and became a sapling (with at least a 6cm diameter, to be exact). I recognized that I could peer into the lives of these trees with precision that would be impossible without the multi-decadal work of foresters who created it. It was a collision of dimensions: data, time, and ligneous life overlaying one another to paint a striking

It was a collision of dimensions: data, time, and ligneous life overlaying one another to paint a striking picture of a forest ecosystem.

picture of a forest ecosystem. In my hand I held one picture of the forest mapped with orange and green circles. In my head I stored an image of the forest in spreadsheet form, cells denoting the status of trees over time. In front of me, and most powerfully, was the real forest, a present-tense snapshot of an ecosystem changing every day, every season.

We visited several other plots that day, each indicating a story like the one told through its data, but with its own texture and nuance. One plot had undergone a shelterwood cut in 1993, in which select mature trees were removed to promote the establishment of seedlings beneath their cover. Another plot had been lightly thinned in 1968 and patch cut in 2020, leaving behind a sunlit clearing now filled by raspberry bramble and early successional seedlings. Another, previously dominated by red oak and red pine, had experienced a mass mortality event in the 2010s—likely due to a moth outbreak and defoliation leading to timber salvage. Though I could infer each plot’s history from the dataset, walking among them gave the numbers more depth. Dense, shadow-cast plots indicated high biomass, while sunny, open plots indicated low biomass—a glance which, in some ways, serves just as well as a value in a spreadsheet does.

While I had come to know these trees as individuals represented by rows of data, our field visit offered the chance to become acquainted with them in a new way, to encounter their features not as numbers but as physical attributes. As I looked more closely at their bark, gazed up at their branches, and listened to my colleagues share observations about the plots in which we stood, the forest came into sharper focus. Each carefully marked and measured tree bridged decades of growth and data history—a quiet merging of time, sylvan matter, and a few scientists trying to make sense of the forest’s existence and regeneration.

By Michael S. Dosmann

Just as summer days start to sizzle, the flame azaleas start to spark. There are over 80 Rhododendron calendulaceum plants scattered throughout the Arboretum landscape. Although ‘Smokey Mountaineer’ on Meadow Road is an intense conflagration, my favorites are the bonfires—the good kinds to find in a tree collection—that ignite Bussey Hill’s southwestern side, from the oak understory up to the Explorers Garden.

About half were collected from various parts of the native range in the southeastern US, among them accession 479-81, which came to us by way of the University of Vermont. In 1978, the late Norman Pellett, professor of horticulture at UVM, collected seed that would become these plants from the Blue Ridge Mountains near Pisgah, NC, at almost 5000’ in elevation. This was part of his broader research initiative—funded by USDA—to study the low-temperature tolerances of azalea species native to Appalachia.

Norman targeted populations that were the most northern in latitude and highest in elevation; his exploration efforts led to collections of over 60 different provenances. Experiments like these can answer questions like “What limits a species’ range in nature?” or “How do the flower and leaf buds tolerate exceptionally low temperatures?” These projects can lead to new plant introductions for the managed landscape—perhaps those that are more ornamental, or for gardeners in Vermont in denial of their USDA Hardiness Zone, more tolerant of frigid temperatures. About a decade ago I visited Norman—long since retired—up at UVM’s Hort Farm. It was a treat to see plants he had collected, grown, evaluated, and introduced for the benefit of science and for the citizens of Vermont and beyond.

When I see those impossibly orange blooms trussed up in the species’ canopies in June, I’m reminded of creamsicle bars from my childhood. When I see them on one of this accession’s plants (we have eight individuals strewn about), I’m reminded of Norman and countless other horticultural yeoman employed at land-grant universities to teach, conduct research, and extend the knowledge to the public. Justin Smith Morrill, the nineteenth-century Vermont senator, championed some pretty radical ideas, things like public and accessible education. I’m grateful his ideas caught fire and led to the land-grant acts that bear his name and established over 100 public colleges and universities. Without them, this flame azalea wouldn’t be at the Arboretum, and neither would I.

Michael S. Dosmann is keeper of living collections in the Arnold Arboretum.

With its fiery flowers, 479-81 marks the calendar of the seasons on Bussey Hill. Photograph by Kyle Port

By David Foster, Rick Lewandowski, Rebecca Oreskes, Seana K. Walsh, Kenneth R. Wood, and Rohan Press

The magnitude of federal funding in landscapes, ecosystems, and communities is measurable, but its effects can be hard to feel firsthand. The occasional headline about an endangered species; the broad brim of the rangers’ hat on vacation; the agency stamps at the bottom of a wildlife-refuge sign glimpsed along a highway— these are occasional impressions, which rarely endurably register. As the first federal funding cuts landed in March of 2025, it struck us that the power of this tradition of federal stewardship (for it is a tradition, as well as a matter of law and policy) lies in this very transparency, familiarity, and ubiquity.

The Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act; the New-Deal commitment to federally-funded horticulture, conservation, and landscape work;

Forest Fire Control in New England, a diorama at Harvard Forest, part of a series depicting land-use history, ecology, and conservation of New England Forests, created in the 1930s by Guernsey and Pittman Studios, M. C. Hutchins, and John P. Crowe. Photograph by John Green

the Organic Act of 1897, which laid the groundwork for the National Forest Service and the National Park Service: down through this history, one finds expressed—first fitfully and then with great force—a commitment to doing the work of the land together. Taken as a whole, federal funding isn’t a list of programs on a spreadsheet; it’s a world of beautiful landscapes and thriving ecosystems, of extraordinary trees not only in managed and preserved landscapes, but in our own gardens. It is a world of intergenerational commitment to preservation, interpretation, and care—one which, though we take it for granted, is worthy of our celebration and, in the midst of its loss, our grief.

Current federal funding for basic science at Harvard has been terminated, including work on response of trees to climate change done here at the Arnold Arboretum. (This situation is highly fluid, subject to litigation and policy change, and may be different by the time we go to press). As Michael Dosmann points out in his column at the front of this issue, the Arnold is part of the world federal stewardship has made, through federal support for

longstanding collections, horticultural work, archival programs, and basic science. How to make this world of stewardship visible before it is damaged irreparably? How to highlight the importance of federal support of collections, research resources, landscapes, and ecosystems? To help us grapple with these questions, we invited some of the people who’ve done the work of this world to share stories that epitomize the importance of federal stewardship, indicate the richness and impact of the work, and suggest the scale of possible loss, especially in the realms of ecology, forest management, horticultural research, and basic science. —Arnoldia

Friends Day September 1985 was the darkest day at the Harvard Forest. To gathered supporters, alums, students, and staff Director John Torrey unveiled a contingency plan to “shutter the Forest as a department,” move the administration and research to

Cambridge, and manage the Petersham facilities as a field station. Beginning the third year of a five-year junior faculty appointment, I absorbed the explanation: termination of fifty years of funding from the Cabot Foundation, waning support from Harvard, and aging senior faculty. We needed grants, donors, or divine intervention.

Lacking connections to advance the last two options, I concentrated on convincing the National Science Foundation (NSF) that the unrivaled knowledge accumulated through seventy-five years of study on 3000 acres in central Massachusetts provided the ideal laboratory to address critical questions on the future of forest ecosystems. A year later, the rejection of my first grant proposal was still weighing heavily on my mind when opportunity literally walked in the back door of Shaler Hall.

Jerry Melillo, Director of the Ecosystem Center in Woods Hole, had been conducting studies on nitrogen and carbon cycling in our forests for a decade, but this was our first encounter. He sat down with John Torrey, Ernie Gould, and me to gauge the Forest’s interest in a longshot—to compete nationally to become one of a handful of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites sponsored through renewable six-year NSF grants. Melillo was heading to a twoyear stint at NSF and had good insights into the program. He viewed the Harvard Forest’s deep archive of data, facilities, and land base as ideally suited for integrated ecological studies. Moreover, he could envision the perfect team to complement his work and our Forest group: John Aber, ecosystem scientist and modeler at University of New Hampshire; Steve Wofsy from Harvard, atmospheric scientist with novel technology to measure forest carbon dynamics; Fakhri Bazzaz, to investigate plant-environment interactions; and Richard Forman, leader of the new field of landscape ecology. John Torrey agreed to lead this major proposal, and that afternoon I called each of my new Harvard colleagues and began reworking that rejected NSF proposal.

The project to contrast the responses of forest ecosystems to physical disturbances such as hurricanes and logging and to novel anthropogenic stresses such as acid rain and climate change was funded in 1988 and is just entering its final year (editor’s note: this termination occurred before the current administration took office). That series of seven grants fueled a transformation of the Harvard Forest from a delightful-but-struggling backwater to one of the world’s leading ecological research centers. Yet it was not the

size of the award that mattered. The initial grant of $600,000 was modest when split among more than a half dozen major research groups. Instead, it was the sustained commitment by the agency and the scientists that fueled cohesion, novelty, and growth.

As a department, the Harvard Forest pivoted and integrated all its programs and staff to support the LTER theme. As faculty retired, we created senior scientist positions, hiring superb colleagues who sought to collaborate, complement, and integrate into a team addressing major scientific questions that had tangible relevance to land management, conservation, and planning. Each of the outside research groups operated independently but with a strong focus on our collaborative goals. The collective power of all these researchers and the scientific infrastructure they built attracted hundreds from around the world to add studies, magnifying the effort.

The LTER program became a magnet attracting scientists, students, and practitioners to Petersham. It became the glue that held all comers and the institution together. It also became a multiplier, increasing NSF’s annual investment more than an order of magnitude through state, federal, foundation, and philanthropic funds. To young scientists like me, LTER brought mentors, superb colleagues, and students who shaped our careers. And every year the researchers and Harvard Forest community celebrate with an uplifting annual meeting that offers great promise for the future.

david foster is former director of the Harvard Forest. He is an editor of From the Ground Up, the online publication of Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands, and Communities, a conservation collaborative based in New England. Existing LTER programs have not been in the first round of direct spending cuts. On April 30, however, NSF staff were ordered to cancel all future program allocations. The Trump administration’s proposed budget for FY 2026 would cut funding for the NSF by about 55 percent.

In 1990, in the early years of my US Forest Service career, my then-boss sat me down to talk about the Forest Service mission. I was a young Public Information Specialist and he wanted to be sure I understood the idea of “multiple-use”—that the Forest Service was here to balance many different aspects of the land, and that while the land comes first, that didn’t mean forsaking the community. Our job was

I come back to the idea that my work was always about relationships: with the land, and with each other as citizens.

to listen to people, to understand their concerns and, somehow, to juggle the conflicts in a great dance, balancing both long and short-term benefits. It was also important to keep in mind that the multiple-use mission didn’t mean that every acre of land had to be treated the same: some areas might be appropriate for harvesting timber; other places were best stewarded for recreation use or designated wilderness. He made clear that the mission wasn’t easy. But it was rewarding.

I learned this lesson continually over my 25-year career in the Forest Service and on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF). From seasonal employment as a campground attendant, and a wilderness and backcountry ranger; to permanent work in recreation and timber marking, to a public affairs specialist and recreation and wilderness program leader for the WMNF. Beyond the borders of New England, I was chair of the chief’s national wilderness advisory group and part of the FS international disaster assistance support team in cooperation with USAID. I ended my career as a staff officer on the White Mountain National Forest Leadership team. What every position had in common was a sense

of relationship. Relationship between people and the land we all “own.” My boss was right to tell me early in my career that the FS multiple-use mission wasn’t an easy one. For every citizen who wants more designated wilderness, there is someone who wants more timber production. For everyone who wants more opportunities to recreate, there is a voice asking for more consideration for wildlife. And clean water amid human use doesn’t just happen—it takes care to protect the watersheds in which national forests exist.

Over my career, I also saw that it’s possible to look at multiple use as a purely transactional endeavor. We can get this many board feet, this many miles of hiking trail, this many miles of snowmobile trail. But I come back to the idea that my work was always about relationships: with the land, and with each other as citizens. We can look at national forests not just as producers of commodities, but as a shared responsibility in caring for what helps give us clean water, places to recreate, homes for wildlife, wilderness, and wood products.

I have another memory from my early days of Forest Service work. A co-worker and I were leading

a group of adjudicated youth in building cairns above treeline on the eastern slope of Mt. Washington. The cairns were meant to help hikers find the trail and to keep them from trampling fragile alpine flowers. For these young men, working with us was an alternative to juvenile prison. It was a perfect, clear day with what felt like unlimited visibility. As we took a break from the demanding work of moving heavy rocks, one of the young men asked, “How much does it cost to buy a mountain?”

The mountains had touched him just as they’d touched me only a few years earlier. We tried to answer his question by explaining that he was looking out over public land. It was land all of us owned together.

When hikers are sweating their way up to the iconic White Mountain alpine zone, they’re unlikely to think about the work that went into making the trail, about the young man who helped move rocks to build cairns. They’re not likely to think much about the habitat for the birds they hear or the unglamorous planning and monitoring done to protect both the land and the experiences they are having. They’re not thinking about the physical work of picking up trash

and cleaning toilets. Mostly, the work gets celebrated quietly, in the satisfaction of a job well done, juggling the many demands of multiple-use land management. Still, I hope people can notice how much effort it takes to care for public land. And I hope we notice before it’s gone.

rebecca oreskes retired from 25 years in the Forest Service in 2013. In February, the White Mountain National Forest lost 11 staff members; in April, the USDA issued a memo directing the USFS to increase timber harvest in some 60 percent of the lands they manage, and to eliminate most environmentalassessment and public-comment measures in the process.

After more than 35 years of fieldwork across the eastern and southern United States, I am continually amazed by the extraordinary plant diversity found in nature. These efforts would not be possible, though, without the guidance of dedicated experts and professional colleagues at USDA who have opened doors to gain access to locations where this diversity still thrives.

Much of this work—conducted in support of USDA conservation and horticultural efforts—has focused on documenting and collecting seed of plants for representation in living collections across the US, distribution to researchers and industry, and for long-term ex situ seed storage. Recent expeditions to the southeastern US and Gulf Coast have allowed us to gather under-represented plant diversity, especially from populations on the outer margins of their native ranges.

There remains so much to learn about genera such as Aesculus, Calycanthus, Clethra, Hydrangea, Kalmia, Hamamelis, Ilex, Lyonia, Pieris, Rhododendron, Stewartia, Styrax, Tamala (formerly Persea), Xanthorhiza, Zenobia, and many others. For example, recent fieldwork has resulted in numerous collections of Ilex ambigua, I. cassine, I. coriacea, I. decidua, I. glabra, I. laevigata, I. longipes, I. myrtifolia, I. opaca, I. verticillata, and I. vomitoria. This work also led to the discovery and seed collection of a new population of the state-rare Ilex amelanchier in western Florida.

Several plants—some common or only marginally available in horticulture—deserve further study

for their hardiness and adaptability. A few include: Aesculus parviflora, Chionanthus virginicus (ecotypes), Cornus alternifolia, Hydrangea quercifolia, Hydrangea cinerea, Illicium floridanum, Kalmia carolina, Kalmia latifolia, Leucothoe fontanesiana, Lyonia ferruginea, Magnolia pyramidata, Pieris phillyreifolia, and Zenobia pulverulenta, just to mention a few.

Additionally, we have documented and shared locations of rare taxa—including Pinckneya bracteata, Litsea aestivalis, Sideroxylon spp., and Fothergilla spp.—with state natural area specialists. Many plant populations at the edges of their ranges are at risk of disappearing, though, without the continued commitment of state and federal partners to conserve biodiversity ex situ.

As we continue to explore the habitats of our native flora, it becomes increasingly clear that we must document and preserve North America’s precious plant diversity with the same dedication we have historically applied to agronomic crops. This is not only an opportunity to conserve valuable genomic variation but also to support efforts to identify regionally adapted native taxa for the

horticultural industry—an industry that continues to rely on USDA-led research.

rick lewandowski has been a leader at the Morris Arboretum, Mt. Cuba Center, and the Shangri-La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center. The administration’s 2026 budget proposal cuts USDA funding by 18 percent of its current level. According to Reuters, the department has lost more than 15,000 employees to the administration’s incentivization to leave federal employment, nearly 15 percent of the workforce.

On the Hawaiian island of Kaua‘i, a rare, single-island endemic tree species is receiving a much-needed lifeline thanks to a collaborative conservation effort and support from the APGA–USFS Tree Gene Conservation Partnership. Ochrosia kauaiensis or hōlei in Hawaiian, a member of the Apocynaceae (milkweed) family, has a confirmed fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the wild. These scattered subpopulations—found in remote valleys, ridges, and slopes in the island’s north and northeast regions— face increasing pressure from invasive plants and

animals, likely contributing to the species’ decline and lack of natural regeneration.

In response to these threats, the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) launched a multi-phase, multi-institution conservation initiative to safeguard this beautiful, rare tree. Because O. kauaiensis produces recalcitrant seeds—meaning they do not survive drying or freezing for conventional seed storage—ex situ collections must be maintained as living plants in nurseries and botanical gardens or in tissue culture labs.

Over the course of seven field expeditions, NTBG and partners—including the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife and the Plant Extinction Prevention Program—journeyed into remote areas to map, tag, and collect seeds and DNA samples from 30 individual trees. Each tree was documented using Hawai‘i’s standardized population reference code system, ensuring accurate provenance for long-term tracking and monitoring. Seeds were propagated at NTBG’s Conservation and Horticulture Center, with plants established at NTBG’s McBryde and Limahuli Gardens on Kaua‘i and at Kahanu Garden on Maui. Seeds

were also sent to the Montgomery Botanical Center in Miami, Florida. In a few cases, immature fruits were collected—particularly when regeneration at the site was unlikely due to severe habitat degradation—and sent to the Micropropagation Laboratory at Lyon Arboretum’s Hawaiian Rare Plant Program on O‘ahu. These collaborative efforts have contributed to building a robust metacollection designed to safeguard the species from extinction.

Living plants from the collections continue to be maintained both in Hawai‘i and Florida as a future seed source for restoration efforts, and these metacollections are contributing to further innovations in applied conservation work. NTBG’s Plant Records Manager is adapting and testing a database tool for gap analysis as part of his master’s thesis at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. By overlaying wild collection points and existing ex situ data, the tool helps identify which subpopulations are underrepresented in current collections and prioritize future efforts, including targeted reintroductions. Additionally, living collections of O. kauaiensis are now being used in pollen conservation research, led by NTBG’s scientific curator of seed conservation, to determine how long viable pollen of the species can be stored—a crucial step toward enabling strategic breeding across space and time among metacollection holdings. Field data from the expeditions also informed a long-overdue update to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species assessment, conducted by NTBG staff, which reclassifies O. kauaiensis as Critically Endangered.

The story of Ochrosia kauaiensis is a powerful example of how federal conservation programs—like the APGA–USFS Tree Gene Conservation Partnership—can empower institutions to protect our planet’s species. Thanks to these collaborative efforts, there is renewed hope that this critically endangered tree may one day flourish again in its native forest, supported by the continued dedication of conservationists, scientists, and federal partners.

seana k. walsh is conservation scientist and curator of living collections and kenneth r. wood is research biologist at the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

I spent the last two summers working with the Colville National Forest in the Pend Oreille Valley of Washington’s northeast corner, a river valley which has since become the most intimate place to me on

earth. I’ve driven nearly its every road and visited its every trailhead. And yet, even then, I feel like something in it, now and ever, eludes me. Maybe that’s partially because I’ve seen it strictly in its splendid summers—not the red and yellow glow of heather and tamarack in autumn, not the fragile eruptions of lanceleaf springbeauty in April, nor least of all the utter transubstantiation of its smothered landscape in winter, Pend Oreille County receiving the most annual snowfall in the state. But it certainly also has something to do with the fact that I won’t be able to return to the Valley for the third time around, this summer, nor for any season in the foreseeable future, due to the paucity of federal funding. I can try to console myself by remembering that no one can ever really know a place fully, and that maybe the distance we will always have from it is part of what keeps us enchanted by it. Nonetheless, it’s a strange feeling, to carry a place so close to my heart that I know I only partially belong to, but which I cling to even more desperately in my absence from it, and doubly so in the face of my estrangement from any cultural world in which it might be shared and recalled. Indeed, the Valley is forgotten even to most Washingtonians, especially those westsiders who seem to believe that everything east of the Cascade crest is an apple-producing, nuclear-testing desert. Now that I’m living in Massachusetts, the lower Pend Oreille country seems even more infinitely unintelligible: I’ve not met a soul, out here, who knows of it, or who understands its ecology and geology—who understands that it is home to the only population of woodland caribou in the Lower 48, and to Washington’s only grizzly bears; who understands what it means to live in a valley pointed and oriented northbound, all its water destined for Canada—a place where downstream, paradoxically, means more rugged topography, means a rushing, furtive gorge, means higher flanking peaks, until you hit the lonesome Salmo-Priest Wilderness, nestled up against the Idaho and Canadian lines; who understands that when you get close enough to Idaho, the big cedars and hemlocks start up again—North America’s only inland temperate rainforest. I’m now attending a University with triple the population of the entire Pend Oreille County (a county, I like to say, so rural that it doesn’t even have a single traffic light)—and everything about that University is asking me to forget that the Pend Oreille Valley even exists, asking me to renounce it, and some days, and maybe more and more often, lately—as a sort of defense mechanism

We all affix ourselves to romantic myths, and the Forest Service was one to which I thought I was willing to dedicate my life.

against its evaporation—I think I’ve been tempted to renounce it. But I could spend this whole essay disowning it, and it would still be abundantly clear that it isn’t yet ready to disown me. Once you see those giant cedars down the South Salmo drainage, you’re a changed man, and something of them you’ll just never be able to let go.

Maybe the Valley hasn’t let go of me, but the world has told me I can’t really return to the Valley. And yet the thing is—even if the Colville would have me back, I’m not sure I’d want to go back. One of my deepest lessons working for the Forest Service is that a landscape is only as good as the people in it. But the people are all gone: Mitchell and Adrian, from the fire crew, with whom I’d play guitar at night and wax philosophical about life; Sam and Amelia, up at Sullivan Lake, who’d bake with me and swim with me and make me feel like I belonged, like I had a home; Carol, with whom I could be so vulnerable, with whom I loved to talk about my romantic hopelessness, and who connected me back to New England’s northern hardwoods; Micah, from Texas, reticent, but with whom I always felt a kind of deep spiritual connection, especially through his tremendous music taste (Boz Scaggs, Charley Crockett); Ken,

in his sixties, with his “Washington Wildlife” license plates, who’d worked for the Colville his whole life, who loved Black Sabbath’s debut, and who would tell me endless stories of camping out in the Salmo as a wilderness ranger (a job that was cut during the Bush administration); Sarah, the wildlife biologist, exceedingly kind and a mother to boot, who had once lived in a school bus at the top of a mountain—and Rianna, who would commute up from Spokane every morning—an hour’s drive north in a series of cars and vans that would always seem to break down before long, but which she would always find time to adorn with a wall of stickers on the back window; Rianna, who became, out of all of them, the person I was closest to, and with whom I could share with equal comfort both frank words and tender silence. I worked with Rianna most every day, scoping out damaged meadows and illegal OHV stream crossings, building fences, felling trees, hiking closed roads, collecting grizzly bear hair samples, and calling for endangered goshawks. It’s a rare kind of closeness that comes from working with someone ten hours a day, four days a week, for months at a time. But Rianna—and Sarah—and Micah—and all of these dear, dear friends—they’re all gone from the Colville now, even though many of them thought they were hired as permanent employees. Some of them finished the season with me and are, unlike me, moving on with their lives; some of them were let go by the Forest Service under the new administration; and some of them, like Rianna, left of their own accord, preemptively (she left to work for the state)—escaping the caprice of the federal government before it was too late. They’re all gone— and there’s no getting them back—and so, there’s no going back.

I have always thought of American federal land management as the best, most romantic, and most enduring form of conservation, maybe in the world. I never thought I would use that word, “caprice,” to describe it. For me, the Forest Service always carried the ring of such a noble history, through Roosevelt, Pinchot, Muir, Powell, etc., of course, but then also through a second layer of names, in the literary circuit—Norman Maclean, Aldo Leopold, Gary Snyder, William Stafford, all of whom worked with the National Forest system. My sense of federal lands as “secure” in their conservation, of federally-designated wilderness as the noblest and most immutable form of protection, of the National Forest system as the symbol of mixed-use land management in a way that could bridge political and economic

divides—that whole way of thinking has now come unmoored. Rianna’s intuition that there was more security in state management, rather than federal management, goes against every intuition I have ever had, but that is self-evidently the new way of things. We all affix ourselves to romantic myths, and the Forest Service was one to which I thought I was willing to dedicate my life. But like Thomas Wolfe said: you can’t go home again. To go back to the Forest Service, even if I could, would just to be to succumb to an illusion that I could achieve a kind of intimacy with that valley that I’ll never be able to achieve— especially in the face of the loss of the people that made that place what it is. Without them, the valley isn’t really the valley; its cedars may still beckon, but they can’t really keep their promise; they can’t really hold me anymore. And so I really do think it’s time to move on—to keep a sort of anchoring in that valley, yes, but also to not cling to it or pretend that it could be the way it was, again; and I’ve been trying to think about the lack of government funding as the push I need so as to not fall back onto the consolation and temptation of old myths. Maybe I should mourn the withdrawal of that funding more emphatically—but, the fact of the matter is, I’m trying to see it for myself

as something really needful, the closing of one door as the prerequisite for the opening of another. That doesn’t mean I don’t miss it like hell, and won’t continue to; it doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try to hold on. When I think back to it, I feel like I could have done it forever, working with Rianna and with the rest of them—learning my Inland Northwest trees and flowers by heart; spying on black bears up the Shedroof Divide every weekend. But then again, I feel sure that I will be doing it forever, in their name and in their absence, even as I carve out the contours of a new life here in Massachusetts, because of the unfinished and unfinishable business I will always have with that valley, no matter how much more time I am able to spend there, and no matter whether I’ll ever work for the Forest Service again. Whatever my day job, wherever I’m living—my heart’s work, and the work meant for my hands, will ever echo with the sound of that lost river, the glassy, Canada-bound Pend Oreille.

rohan press is an alumnus of the Harvard Divinity School (MTS 2025). This summer, he will serve as an interpretive ranger at Great Brook Farm in Carlisle, MA.

By Juan Rogelio Aguirre-Rivera, Eleazar Carranza-González, and Juan Antonio Reyes-Agüero

Arboreta are created to study and safeguard tree species and germplasm of interest; they are also attractive for recreation, aesthetics, and education, and provide many ecosystem services as well, moderating temperature and water runoff. Parking lots, by contrast, are installed on paved surfaces, exposed to and concentrating energy from the sun’s rays. In 2014, the parking lot of the Desert Zones Research Institute of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí (UASLP) was inaugurated, with the intent to create a tree-lined parking lot that also functions as an arboretum, with benefits such as furnishing shade, offering recreational space, and advancing knowledge. Garden plots were created between the spaces for the cars, in which native and exotic trees were planted. Each plant was identified with its scientific name. In an area comprising 1479 m2 with parking for 50 cars, 99 individual trees of 59 species now stand. As the evidence compiled here demonstrates, the arboretum is a model for converting parking lots into groves of trees, conferring benefits on cities, residents, and the broader environment.

The purposes of arboreta are varied, such as protecting species under some degree of threat and serving as reservoirs and sources of germplasm (seeds or cuttings); if the arboretum is established in relics of natural ecosystems, it is useful for preserving those areas that were left as ecological islands in rural, urban or suburban environments. For the community at large, arboreta are attractive for recreation, aesthetics, and education (Dunn 2017, Esparza-Olguín et al. 2020).

Western arboreta trace their history to the Trsteno Arboretum, near Dubrovnik in Croatia, which is recorded to have existed since 1494 (Plenković-Moraj and Jasprica 2000). In the United States of America, perhaps the two most important arboreta are the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts, which was established in 1872, and the United States National Arboretum,

Figure 1. Sketch of the IIZD-UASLP parking lot arboretum, with numbers indicating species in the collection as listed in Table 1. Courtesy of the authors