ARKANSAS WILD

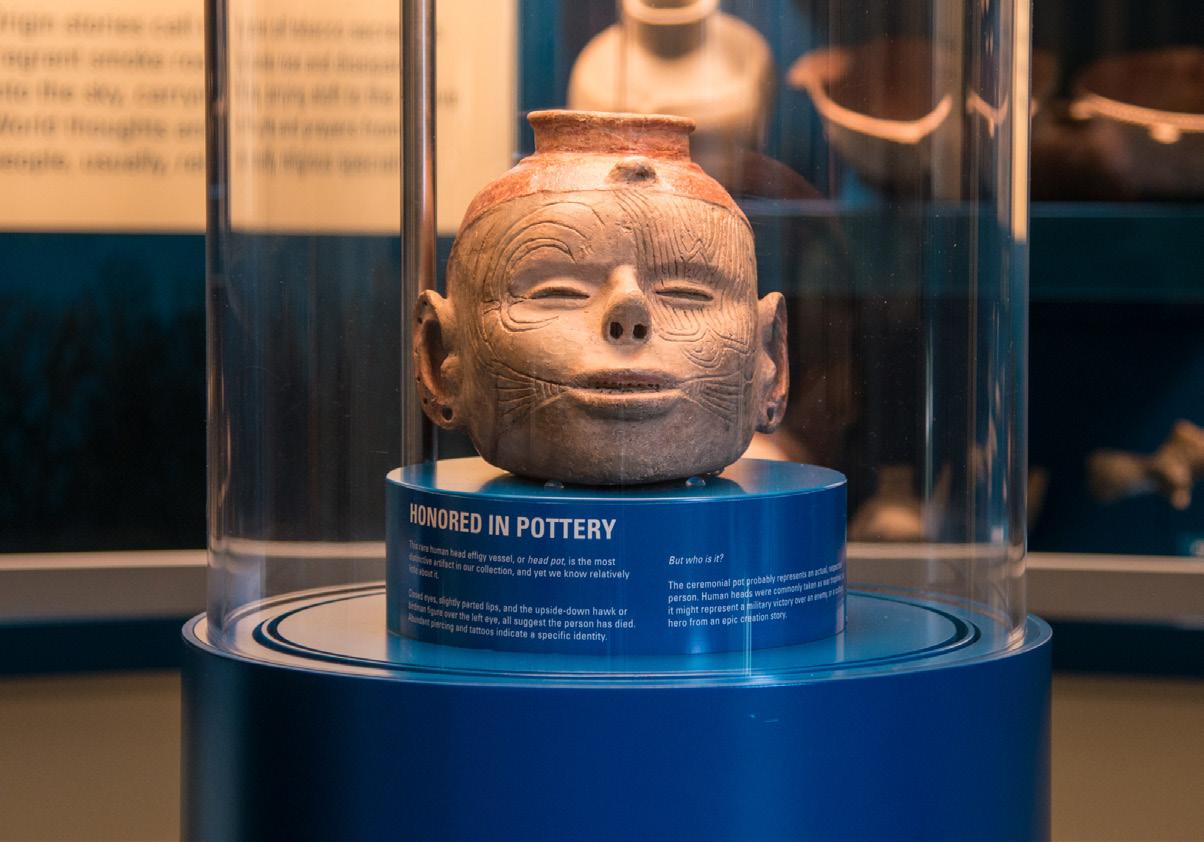

Hampson Archeological Museum State Park

AFTER SCHOOL SNACK

Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry expanding mission to public schools.

PASSPORT

State's museum parks offer a breath of fresh air inside or out.

Maintain and store gear, pack an adventure and more with this wonderful winter gear.

Arkansas artist Matt McLeod gave his heart to his hobby and found success after work.

Bonus gift ideas that won't fit under the tree!

"Bambi Bites" are a culinary tradition at Calhoun County's Jackson Hill Hunting Club.

Where truth is rarely accurate, and directions are always truthful.

ARKANSAS

THE COVER: Matt McLeod's bright and kinetic style is evident in landscape paintings such as "Mirror Lake, " shown here. Photography by Sara Reeves.

BROOKE WALLACE Publisher brooke@arktimes.com

KATIE HASSELL Art Director/Digital Manager

WENDY HICKINGBOTHAM Senior Account Executive

ANITRA LOVELACE Circulation Director

ARKANSAS WILD

MANDY KEENER Creative Director mandy@arktimes.com

LESA THOMAS Senior Account Executive

MIKE SPAIN Advertising Art Director

ROBERT CURFMAN IT Director

ALAN LEVERITT President

SARA REEVES

Sara Reeves is a commercial photographer based in Little Rock. She has been exploring Arkansas with her cameras for over 20 years, telling countless colorful stories of the places we roam and the fascinating people we meet along the way.

CONTRIBUTORS

PHILLIP POWELL

Phillip writes for the Arkansas Times as a Report for America Corps Member. He likes to learn about environmental issues and different kinds of farms in Arkansas, and is happy to be contributing to Arkansas Wild

Matt McNair Editor matthew.ryan.mcnair@gmail.com

LUIS GARCIAROSSI Senior Account Executive

ROLAND R. GLADDEN Advertising Traffic Manager

CHARLOTTE KEY Administration

RICH FAHR

Rick Fahr is a native of Northeast Arkansas. A longtime journalist and military veteran, he began hunting and fishing with his grandfather as a child. He is president of Jackson Hill Hunting Club, located outside of Hampton in Calhoun County.

FROM the editor

A little Help from our friends

Hello-ho-ho from the jolly heights of Catfish Tower, o ye faithful readers! I suspect that by the time you get your be-mittened mitts on this Winter 2025 edition of Arkansas Wild , yule be well and truly tired of Christmastime puns, and so that’ll be the last of’em from this here elfin editor, lest a lump of coal turn out to be the least of my worries.

And so here we are then, all of us still riding the same big rock, having successfully hung on for another cosmic gyre; completed, according to our reckoning, within a few weeks of this writing. (Not sure about this reading, as that is the future and I am not you.) But still, either way, not all of us hung on for the full turn. A few people in my life that flipped the calendar to January 1, 2025 aren’t going to see what’s above the fold come January 1, 2026 — some in the fullness of their time, one tragically not — and I’ve been around long enough to know the same probably applies to everyone reading this. If not, that is a blessing, but if so, flip the calendar in their stead, and hold them in your heart; hold them in it just as tightly as you hold in your arms the ones still here. And hold tight the hope that hugs pierce veils, just as sure as paper beats rock; and I will too, and if we all hope hard enough then perhaps we’ll will it so.

But while not enough of that — never enough of that, go ahead and keep that up — that’s also not the only business at hand in this letter, just as it’s not the only business at hand in the wintertime. As for the latter, along with remembering the gone-on it is a time for merrymaking with the still-around, in all its various forms. From holidays to true-blue Holy Days, feasting with the family you were gifted and the one that you’ve made, hunting seasons and sports seasons and parties of all stripes. We can’t fit all of it in here, but we can sure try.

As noted, this issue hits the stands right in the middle of the holiday season, which also means winter is properly setting in. Holidays are great and even wintertime has its charms, but if we’re being honest, there are some drawbacks. Christmas especially can be downright stressful, full of expectations and obligations (and the occasional bank overdraft), and while winter can be beautiful after its fashion and a great time to get out in the woods, the weather can also be a bummer and, far as forecasts go, partial to the ol’ rope-a-dope. With all that in mind, we’ve put together a list of state parks (and a couple other spots) that are great for quick trips and offer ample opportunity to get your Natural State fix even when the weather’s not cooperating.

We’ve got stories of people seeing beauty in the world and doing their best to share it with everyone else. In Little Rock, artist Matt McLeod is still plying his trade after more than two decades as a working artist, for the most part translating the splendor he sees in nature to color and canvas. He’s good at it, too, but the story of how he got in front of the easel full time is pretty neat in its own right.

There’s also a little crossword puzzle in this issue. The answers will be in the next issue (also online within a couple weeks), but there are also several hidden in this one; they’re tucked into another article.

It was my great pleasure this issue to write about Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry. If you’ve never heard of this worthy outfit, please do check out our profile of the organization and its director, Ronnie Ritter. If you have heard of it, go ahead and read it anyway. And think about filling an extra tag this season if you can.

If you’re reading this right now, there’s a good chance you’ve been to deer camp at least a few times in your life, maybe even this year. And while the prime deer camp season has come and gone yet again, we’ve got some deer camp stuff to send you to your slumber dreaming of next year’s trip, or dreaming up lies to tell about the ones in years past.

And that’s all for now. Thanks as always for reading, and we’ll be looking for you come March 2026.

See ya out that way, Matt McNair

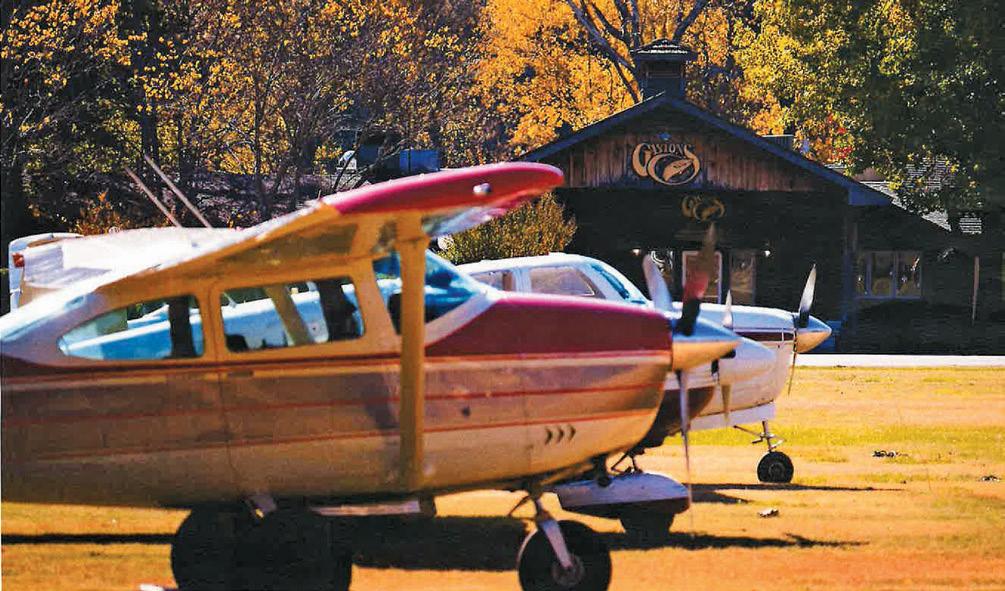

Writer and a hunting buddy strategize between outings.

An Ounce of Prevention

TREAT YOUR TOOLS AND YOURSELF RIGHT WITH THIS GREAT GEAR.

Sure, it can be a hassle running around looking for gifts during this special time of year when everybody else is doing the same thing, but for every person who swears this is the year they’re putting their foot down — saying “no” to conspicuous consumption, shouting “NO MORE!” from the reindeerinfested rooftop to the madding crowd below — there are exactly the same number of people climbing down from the rooftop and heading to the mall. (They’re the same people.) You’re going to do the same thing, trust us, but have no fear: We do not, and will not, judge. Instead, we’ll supply this Gear Guide so that you can find the middle ground, i.e., picking the perfect gift for someone from whom you can borrow that very same gift.

Stay charged up. Take advantage of that sweet, sweet modern technology without the extra step of building a fire with a portable battery. Central Arkansas outdoor emporium Fish 'N Stuff has a complete line of Dark Energy Poseidon Pro Power Banks. They’re built to withstand an Arkansas-grade beating and be good to go for three full phone charges (500 recharge cycles). Check it and other outdoor accessories out at Fish 'N-Stuff’s Sheridan location (7473 Warden Road) or in the ether at fishnstuff.com.

Get fired up. Find that sweet spot between “early adopter” and “basically a Luddite” with the Biolite Campstove 2+, a compact stove that burns organic material (i.e., twigs and leaves and such) to not only do normal campfire things — boil water, cook food, etc, — but also charge electronic devices like your precious cellular phone. Further complicate your triangular relationship with the Stone and Space ages with the Biolite Solar Panel 100, a compact and portable solar apparatus that harnesses the power of the very Sun in order to keep you Wordle streak alive. A host of Biolite’s paleo-modern wonders can be found locally at Ozark Outdoor Supply, or you can see a preview at bioliteenergy.com.

Pack of all trades, master of one.

Pack it up. Lots of different outdoors activities require lots of different and very specific kinds of gear, but a backpack is something that just about every outdoor enthusiast is going to need at some point. And while even a backpack can get to be awful specific to this or that activity, a backpack is way more likely to be useful across way more activities than just about any other part of an outdoor kit. And in our humble opinion, a hunting backpack is the most versatile type of this most versatile piece of gear, with one of the thickest intersections of this particular Venn diagram nicely accommodating the Trophyline C.A.Y.S. 2.0. While tailored to the needs of saddle hunters, the C.A.Y.S. 2.0 utilizes space, pockets, tie-down sites, durability and weather resistance in such a way to make it handy for any hunter, hiker, trekker, geocacher, student, or anyone else that might need to get out for the afternoon, or even a day or three. It’s also a moderately priced rig available locally at Fish 'N-Stuff. Hit them up and grab your newest, most versatile possession at 7473 Warden Road in Sheridan, or fishnstuff.com.

Bow up. If you’ve got a young Robin Hood or Katniss Evergreen on your list this year, think about placing an Easton Beginner Recurve Bow Archery Kit under the tree. This ambidextrous recurve bow is a lightweight 1.3 pounds and, more importantly, can be set at a 10-pound draw weight (maximum 20 ponds) suitable for the mighty-yet-tiny arrow-slinger on your gift list. The kit comes with three arrows and a quiver, finger protector and armguard, and a sight to go along with the bow; or, you can leave off the frills and get the bow by itself. No matter the setup, you’ll find it, and the expertise to get you started, at Fish 'N-Stuff, located in Sheridan and also at fishnstuff.com.

Start'em young.

You're all whet!

Good clean gun!

Get clean. There are three times when you should be prepared to clean, adjust, or otherwise maintain any firearm: just before you store it for the off-season, the second you retrieve it to prepare for the upcoming season, and every other time, ever. That’s pretty much all of the time(s), so it’s best to be prepared. Get yourself or someone on your list ready for responsible action with the Sportsmans’s Range Box Universal Gun Cleaning Kit from Otis Technology. A universal cleaning kit suitable for rifles, pistols, shotguns, and inline muzzleloaders, the Otis Range Box provides a portable go-to cleaning kit for any firearm enthusiast who is past the “3-in-1 and a rag” stage but well within the “they ain’t got that” stage. Check out this and other firearm accessories at otistec.com.

The dark winter months are a good time for making sure your gear is up to snuff, and the holiday season is a good time for gadgetry. Get a dose of both by boxing up a proper sharpening setup, such as the Work Sharp Precision Adjust knife sharpening system available at Bass Pro Shops (1 Bass Pro Drive, Little Rock, or basspro.com)

Or or a more traditional (and local!) take on knife sharpening, pick up a genuine Arkansas whetstone. Novaculite (whetstone) from what is now known as Garland and Hot Spring counties has been traded amongst native tribes since before recorded history and European settlers since their arrival. Pick up a piece of very useful history today at Historical Arkansas Museum Gift Shop in Little Rock, or any one of several Arkansas State Park gift shops (find parks and check for availability at arkansasstateparks.com).

Listen up!

Protect your hearing and get the drop on your quarry at with Axil TRACKR ear muffs. Axil ear muffs (or buds) amplify quiet sounds in the woods but block loud (82 decibels) sounds, and are also bluetooth-enabled. Survey the extent of this brave new world at goaxil. com and check local availability at Bass Pro Shops.

Legislative Roundup

A

REVIEW OF SOME OF 2025'S MOST CONSEQUENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION.

By Phillip Powell

As 2025 draws to a close, outdoors lovers should be on the lookout for a few major state and federal policy changes to public lands that could impact your next adventure around Arkansas.

Trails at Mena Project

In the push to expand the outdoor recreation economy in Arkansas, the little town of Mena — situated in the midst of the Ouachita National Forest at the base of Rich Mountain — is receiving some major state-funded upgrades to its public outdoor recreation infrastructure. Specifically, the state is helping to fund a new bike park on land overlapping Queen Wilhelmina State Park, the Ouachita National Forest, and the city of Mena. State senator Bart Hester, Republican leader from Cave Springs, sponsored a new law that clarified liability protections for a new bike lift system coming to the park. (A bike lift is just like a ski lift you might find in the tall, snowy mountains of Colorado– but you guessed it! They are for mountain bikers instead.)

As Hester explained, the new “Trails at Mena” project will include one of the state’s first bike lifts (there is a similar lift planned for a park in Bella Vista by the Walton-funded OZ Trails). With Hester’s new law on the books, bike lift construction is moving forward with clear rules for liability of operators, participants, and regulations on inspecting the new lifts well into the future. To read Act 155 in its entirety, go to arkleg.state.ar.us.

Flatside Wilderness Expansion

Expansion of the beautiful and centrally located Flatside Wilderness Area continues to wind its way through Congressional bureaucracy thanks to Congressman French Hill. The bill, which is titled the Flatside Wilderness Expansion Act, will expand the wilderness area by more than 2,200 acres. After the House of Representatives approved the bill in May, it was cleared by the Senate Agriculture Committee in October and appears likely to pass the full Senate in the upcoming session.

Buffalo National River

The bill has drawn praise from several environmental groups, including the Southern Environmental Law Center, the Ozark Society, and the National Wildlife Federation. Flatside was one of the original wilderness areas established in Arkansas back in the 1980s, and was previously expanded by Congress in 2019 through Hill’s efforts. As many outdoors enthusiasts know, a federal wilderness designation provides immense conservation and scenic protection to an area. An in-depth look at Flatside Wilderness Area, including ongoing efforts to increase its size, can be found in the September 2025 issue of Arkansas Wild.

Fix Our Forests Act

A controversial bipartisan bill authored by Arkansas Congressman Bruce Westerman and Senator John Boozman is also winding its way through Congress to streamline the permitting process and other bureaucratic hurdles associated with managing approximately 200 million acres of national forests, including around 2.9 million in Arkansas.

The bill has drawn significant backlash from many environmental groups like the Southern Environmental Law Center, the Sierra Club, and EarthJustice. But other groups like the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, the Nature Conservancy, and National Audubon Society support the legislation because of its efforts to tackle the growing threat of wildfires which has devastated communities in the Western United States. The bill would undeniably make it easier for timber companies to log more in national forests with less input from the public, especially in wet southern forests with little risk of wildfire, according to Anders Reynolds, Legislative Director at the Southern Environmental Law Center and a native of Wynne. But for advocates like Westerman and Boozman, along with their Democratic colleagues California Senator Alex Padilla and Colorado Senator John Hickenlooper, the bill opens up national forests to more active management with prescribed cutting and burns after decades of fire suppression and reduced management.

Buffalo River Industrial Farming Moratorium

The iconic Buffalo National River became a flashpoint in legislative debates this year, as a group of state legislators urged on by farm industry groups tried to pass a law putting the pause on permitting industrial hog farms near the river into question. Environmentalists drove the the Capitol week after week to implore legislators to choose a different path, and through the intervention of Governor Sarah Sanders — a major advocate of outdoor recreation — legislators came to a compromise to give themselves more oversight over future permit moratoriums while protecting the Buffalo River from hog farms far into the future. The bill, titled Act 921, did not substantively change state law, but tensions surrounding the bill were reminiscent of the earliest battles fought over the Buffalo River — between small generational farmers, back-to-the-land conservationists, state and federal government — and a reminder that the conversation, sometimes quite heated, continues.

Waters of the United States

The federal Environmental Protection Agency is moving forward with new regulations that will redefine which wetlands will receive federal protections in coming years. Specifically, the rule would redefine the term “Waters of the United States,” therefore redefining which bodies of water are protected by the federal Clean Water Act. A Supreme Court ruling in Sackett v. EPA has allowed the EPA to move forward with the deregulation, which could have major impacts on privately owned wetlands throughout the Arkansas Delta. If the rule goes into effect later this year as it’s written, landowners will be able to clear more wetlands without permits from the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Arkansas does not have state-level wetlands protections, and some researchers at the Environmental Defense Fund warn the rule could open up millions of acres of wetlands to unregulated development in coming years.

LOCAL FARE

Good to be (Kitchen) King

OF THE MANY TRADITIONS THAT WILL TAKE ROOT IN A WELL-ESTABLISHED DEER CAMP, THOSE REVOLVING AROUND FOOD CAN BE THE MOST DELIGHTFUL.

Recipes and Photography By Rick Fahr

Of the many traditions that will take root in a well-established deer camp, those revolving around food can be the most delightful.

The delegation of labor is an important component of any proper deer camp. While not many start with an official chore list, an unofficial and unwritten list is almost always established. Over time, those chores and duties are done by, and associated with, particular members of the camp. These chores and the people who do them become a part of the camp’s fabric, and eventually its lore. One might even get a bit of a reputation for doing something exceedingly well, and the chore becomes a little fiefdom, a miniature realm over which one particular camper has control and which becomes a source of great pride for the choredoer, and amusement for the rest of the camp.

Except for the most mundane of chores — somebody needs to keep up with and haul off the garbage, for instance, and there’s always something to clean or tidy up whether you’re in the fanciest of cabins or under the bluest and whippiest of tarps — deer camp tasks usually end up being pretty fun, and if you’re the person entrusted with a certain chore every year, well, you’re going to really get after it.

Thomas Parker shows off a tray of his famous Bambi Bites.

With few exceptions, the most glamorous and respected of these annual chores is that of Camp Cook. Taking a look inside a long-running deer camp and observing the kitchen scene — who cooks, and with what, and what it is that is getting cooked year in and year out — is akin to felling a tree and counting the rings. A spindly tree barely out of the sapling stage will not have many rings at all, while a great big knotted-up for-sure tree will have rings within rings within rings, and probably evidence of a fire or two, or maybe a borer infestation. Same thing with a deer camp: Find a bunch of young hunters in the woods just getting their camp established and you’re liable to find a bunch of cheap beef jerky, maybe a few cans of Beanee Weenees and a sleeve of off-brand saltine crackers for variety. (There will likely be a supply of beverages that is seemingly out of proportion to the meager food stores.) Stumble upon a veteran camp, however, and you will find a camp kitchen that might well have a Michelin star or two, if the Michelin Man hadn’t had a flat on the way out. The head of this kitchen is the king of the castle, at least for one day a year.

Which brings us to this issue’s “Arkansas Fare” piece, wherein we get a glimpse of the kitchen at Jackson Hill Hunting Club. Already a going concern when current camp president Rick Fahr joined in 1984, this Calhoun County outfit is a classic example of an old-school South Arkansas camp with its own set of traditions and lore and, of course, cooks. Thomas Parker is one such cook, and Fahr was kind enough to document for posterity as Parker whipped up his signature Jackson Hill dish, “Bambi Bites.”

— Matt McNair

Get To Know Thomas Parker

Having a native-born Lousianan in an Arkansas hunting club is a good news-bad news proposition.

Bad news: He gets regular opportunities to gloat a bit during most of the LSU-Arkansas football games, and the rest of us know more about the Tigers’ roster and game plan than we ever thought possible.

Good news: He likes to cook, as most Louisianans do. And he’s good at it, as most Louisianans are.

And so whenever Thomas Parker — now a transplant in Fouke — says he’s got supper handled, he gets no complaints from the rest of us at Jackson Hill Hunting Club, located in the middle of nowhere Calhoun County.

One of his signature dishes is Bambi Bites, a favorite after someone bags a deer.

They are great as heavy hors d’oeuvres or a main course. Using venison steaks along with cream cheese infused with diced jalapeños and bacon, these bite-sized treats are easy to prepare and packed with flavor.

Bambi Bites

INGREDIENTS:

1 venison back strap (5 pounds)

1 tub Philadelphia Cream Cheese (8 ounces)

10 slices of bacon (halved)

Jalapeno peppers (1 to 2 for the spice-intolerant, more adventurous palettes)

1/4 cup Worcestershire sauce

1/4 cup teriyaki sauce

2 tbs Tony Chachere’s Original Creole Seasoning

2 tbs lemon pepper

2 tbs black pepper

1 tbs garlic powder

Toothpicks

INSTRUCTIONS:

Cut the back strap into 1/4-inch-thick steaks.

Mix Worcestershire sauce, teriyaki sauce, creole seasoning, lemon pepper, black pepper and garlic powder to make marinade.

Put venison steaks in a 1-gallon plastic bag, and pour marinade over. Refrigerate four to five hours. Allow cream cheese to soften.

Dice jalapenos and add to cream cheese.

On each venison steak, put one tablespoon of jalapeno/cream cheese mixture.

Overlap steak and wrap with 1/2 piece of bacon. Secure bacon to steak with toothpicks.

On a preheated charcoal grill, place each bit 2 inches apart. Cook until bacon is done and steaks are at desired doneness — usually about five minutes per side. Roll bites to cook evenly.

Not Mad, Man

LITTLE ROCK ARTIST MATT McLEOD FOLLOWED HIS PASSION FROM THE ADVERTISING INDUSTRY TO THE ART WORLD

STORY By MATT McNAIR PHOTOGRAPHY By Sara Reeves

If you’ve spent much time at all in downtown Little Rock, you’ve no doubt seen Matt McLeod’s work. A fixture in Arkansas’s art scene for years, his pieces have hung on many a gallery wall in The Natural State, including for a time in his own downtown gallery; housed in the Arkansas Building, it was an early anchor on that stretch of Main Street between Riverfront and SOMA during a time when downtown Little Rock’s ongoing renaissance was really picking up steam.

His gallery is gone, replaced by another artist’s boutique and the space now flanked by an eclectic mix of galleries and services and shops, but McLeod’s presence remains, and that’s where you’ve seen his work if you’ve ever been down there, even if you’ve never set foot inside an art gallery.

It’s those great big koi, giant goldfishlooking carp swimming through a neon-bright hyperreal metallic pond, all shimmering across the northfacing entirety of the building that currently houses Oak Forest Vintage (purveyor of clothing and relics from the now-long-ago 1980s, impossibly bright and neon like the McLeod-authored fishpond on the side of their building), and that once, some years ago now but for many years just the same, was home to the legendary Bennett’s Military Supplies.

wooded, hilly area of Little Rock, the rest being interesting works by other artists, art he’s either acquired or received through the years. That’s not to say his own work is not in sight, but that his own work is just that: work. Work in progress, work in various stages and forms.

“I paint every day,” he says, stressing the importance of putting in the hard work of honing one’s craft, while also noting that up-and-coming artists can be thwarted by the most unartistic of realities: paying the bills.

“When artists fail, it’s because they run out of cash,” he says, noting that even today, as a successful full-time working artist, he maintains another business venture unrelated to painting.

I’ve wondered for years why McLeod didn’t paint catfish on the side of that building and was determined to ask once given the chance to interview him for this piece, but the question slipped my mind the second I walked into his studio and found myself fully transported by the first painting I saw, one that utilized that same incredibly sharp color palette to depict a northern landscape (I guessed Canada, it turned out to be Montana) so achingly real the air seemed to smell of spruce. Admirably enough, that seemed the only finished work of his own displayed in the home studio he inhabits in a

“It’s saved my bacon multiple times,” he insists, adding that he advises any aspiring artist to maintain multiple streams of revenue — waiting tables, working retail, anything at all — in order to have enough money coming in, and coming in steadily, to keep a roof over their easel.

“Put out a lot of traps,” he says, using an apt metaphor, purposefully or not, for this publication.

“Figure out a way to bring it in somewhere. Eat what you kill and store away the rest.”

Before he maintained a business venture as a

financial backstop for his art, McLeod lived his life the other way around, knocking about the workaday world and keeping art as a hobby. That work, however, was at least art-adjacent: After graduating from Southern Methodist University in 1987, McLeod landed a job with TraceyLocke, a large advertising firm. But “art-adjacent” is not “art,” of course, and while the firm’s creative teams were busy creating and composing high-stakes ad campaigns — they had the Pepsi Cola account during the so-called “cola wars” — McLeod was on the media communication side of the business, looking at cost-benefit ratios of ad buys and, he says, “basically crunching numbers.”

Beginning work on "Autumn Road, Baxter County."

Matt McLeod in his Little Rock home studio.

"Duck Dog." SOLD This piece, in progress here, was displayed at Art Group Gallery.

“For me, art was my greatest gift. And I was neglecting it as a hobby."

—Matt McLeod

While crunching numbers to optimize the effectiveness of an ad campaign’s rollout was not the career he had in mind when he went off to college, the advertising business itself was; he just imagined himself on a team dreaming up clever ads, not totting up ledger columns related to same. But he quickly found that the artistic aspect of advertising — graphic design — was not to his liking. The design classes he had most looked forward to did not dissuade him from the industry, but it did turn him away from what he had hoped would be his creative outlet, as the labor-intensive and rigid demands of pre-digital graphic design did not carry the joy of art for McLeod. Creating a concept was all well and good, but the execution of that concept was a slog of cutouts and layouts, with any mistake more or less sending the would-be designer back to square one.

By that same token, the form precluded improvisation of any kind. Shifting gears in the middle of a project would necessitate a do-over just the same as fouling it up, and it was this frustration, as much or more than any other aspect, that McLeod found untenable.

“It was not forgiving of changes,” he says of graphic design before the form pivoted to digital tools. And while that would happen even as McLeod was entering the industry, he had finished up his degree without the portfolio that might have afforded him the ability to make the transition to digital design on the job. “I did not build a portfolio,” he says of his focus on media communication after becoming disenchanted by the design classes, and so, he continues, “I never got a chance to go into the creative department because I did not have a portfolio.”

“I kind of fell through the cracks,” he says.

He didn’t fall too far though, and after a few years working in Dallas he landed an offer from the Arkansas advertising firm Cranford Johnson Robinson (now CJRW), which allowed him to continue his career in Little Rock, his hometown.

“Neat people,” he says of the venerable agency’s principals, recalling his time there fondly. “Nothing but respect for them.” And while he was happy to be back home after his years in Texas, and

though he liked his work and the people he worked for, McLeod felt like something was missing.

“All of these people that were my age were landing in Little Rock from the UA [University of Arkansas],” says the SMU grad, “and they all knew each other, and they didn’t really know me that well.” Finding it difficult to ingratiate himself with a peer cohort made up, for the most part, of friends from college, McLeod was looking for something to occupy his off-work hours.

“I just decided I needed a hobby,” he says. “I needed something to do after work.”

Happy (little trees) Hour

As a child, McLeod spent his days outside playing sports or roaming the woods around his house. But when the weather turned bad and kept him indoors, he enjoyed painting with a watercolor set his mother had given him; with those happy hours in mind — rather than the after-work kind he’d been skipping anyway — he headed to the Arkansas Arts Center (now the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts) and signed up for evening art classes.

“I just loved it right away,” he says of drawing, painting, and attending classes during those afterwork hours; and as he progressed in his studies, he began to find more fulfillment in front of the easel than he did in front of advertising reports. Advertising was his job, which he liked, and painting was just his hobby; though at the same time, painting began to feel like something more. “I was,” he says, “falling in love with my hobby.”

“And that all comes to a head,” he says of the process wherein his hobby began to outrank his vocation, “right after 9/11.”

McLeod recalls himself and “millions of other people” facing a new reality, an existential shift in everyday life that compelled a reassessment of just about everything that comprised everyday life. And like a lot of other folks, he began to think about what it was he’d like to do with the rest of his time on Earth besides just surviving. “The days after that shock,” he says of the attacks and their aftermath, “were days of taking stock.”

“What was important? What was I doing? And did I really want to be doing it? Why am I leaving this hobby, that I love, only a couple of hours a night a few nights a week?” Deep down he knew the answer: He was an artist, and so he needed to somehow truly become an artist.

“I knew I needed to do it,” he says of becoming a full-time, working artist. “I just needed to find a way to do it.”

Having made his decision, McLeod was determined to make the leap, but — as he is quick to point out in his advice to hopeful professional artists — there were bills to be paid, as there always will be. He was at this point working with another Little Rock advertising agency, Thoma Thoma, and despite his epiphany wasn’t ready to give up a steady paycheck. Fate intervened once again, however, as a series of acquisitions resulted in downsizing at Thoma Thoma; McLeod’s position was among those to be eliminated. When the boss called him in to break the news, McLeod took it well and told his now-former employer that it seemed as if “God or the universe” was telling him to become an artist.

The man holding the pink slip agreed.

“I think you’d be a really great artist,” McLeod recalls him saying, before adding a caveat. “And I want you to go be an artist right now. So I’m going to pay you for the rest of this month, but you leave right now and go start becoming an artist.”

So McLeod did just that, and while the rest is indeed history, as they say, to say it in this case is a little too neat, a little too pat.

“I’d love to tell you it’s been easy,” McLeod says of the journey from hobbyist to professional, “but it’s not.”

Realizing all too well that he had been presented with a choice

and a cosmic nudge tantamount to spiritual revelation — “I have my own faith, and I believe God was moving in that moment,” he says of his existential crossroad — he first set about making sure he had other ways of making enough money to keep the lights on as he established his practice, but in the main leaned headfirst and headlong into his art. And even now, though he is allowing himself to ease off the hustle a bit as he enters his sixth decade (as of this writing, he has a formal installation in only one gallery), he maintains a professional’s discipline, painting every day and always receptive to whatever inspiration might come for the next piece.

Inspiration can come from anywhere, but for McLeod it very often comes from the outdoors. While he honed his personal style in the Great North (studying under Canadian artist Mike Svob) and draws on that landscape for some of his most striking art — e.g., the painting that so grabbed me when I visited McLeod’s studio, which is titled “Mirror Lake” and happens to grace the cover of this issue — it is the out-of-doors within The Natural State that provides the most ready fodder for his imagination and canvas.

“I love to ride my bike, go for hikes, do anything outside; I’ve taken pictures from my kayak,” he says of his process, which most often begins with a simple sojourn through nature, sketch pad or camera in hand. Be it backcountry or backyard, he says, “I just like being outdoors and doing stuff.”

On the day I visited him, McLeod’s newest work, “Duck Dog,” was up on the easel. Though unfinished, it possessed enough life for even the most unschooled observer (present author very much included, though McLeod did his best to give me a brief primer on art theory during our visit) to perceive

Mixing oil paints on glass-topped palette.

“Theres been some really great people in my life... really great parents that supported me, and some professional people that really helped me make that transition.”

—Matt McLeod

a thrilling sense of life and movement, the swoop of feather and sharp slope of snout seeming to flow and breathe as a welltrained Labrador comes up out of the bayou with his prize.

“I have a fascination with working dogs,” says McLeod by way of explaining one of his favorite subjects.

It’s a sentiment with which a great number of our readers would no doubt agree. Even for those who don’t have a good working concept of what a good working dog — in this case a duck dog, but in any case a working dog bred for its work no matter the task — McLeod’s goal for this painting, as with all of his art, is to engage the audience to such a degree that “they feel what it was that I was feeling” when the idea came to him, a connection that, according to McLeod, “kind of completes the cycle.”

In McLeod’s tree-canopied studio — part workroom, part showroom, part living room — one gets the feeling that, for

him at least, the cycle has definitely been completed, or is at the very least rounding into form. From portraits of things familiar to most folks around here (Ozark farmsteads, happy and determined duck dogs) to some things that are maybe not so familiar (that vibrant, humidity-free Montana landscape), McLeod seems very aware that he is blessed in the ability to take it all in, and to make his way in the world by showing it to others through his talent and his distinct, vibrant style.

“We have a beautiful country,” he says, summing up his thoughts on inspiration and his duty to act on it and, through his art, convey it to others. “And we have a beautiful globe.”

Matt McLeod’s work is currently on display at Art Group Gallery in Little Rock (www.artgrouparkansas.com), and can be found online at www.mattmcleod.com.

Camp Talk

ACROSS

1. Some breech loaders,or what you get with a muzzleloader

4. Disease afflicting many a deer camp

5. Where the action is?

6. See 3 Down

8. An old-timer might prefer using one of these during 1 Down over an [3 Down + 6 Across]

9. With 12 Across, a newly-popular cartridge in Arkansas

11. 4 Across, to an old-timer (2-words)

12 . See 9 Across

14. Cause of too much screen time at deer camp? (2-words)

15. ________ Station(Opening Day hot spot before the AGFC app) (2-words)

DOWN

1. With "the," what a camp elder might take on an especially cold morning? (2-words)

2. Without doubt, the cause of much anguish in the deer woods (especially in October)

3. With 6 Across,Arkansas's newest hunting season

4. Loud snacks for big game out West?

5. Path through the woods that is rarely straight but always narrow? (2-words)

7. Reason that switching to trophy hunting really ticks someone off?

10 . One might come in handy when still on a 5 Down after sunset

13. Where the action is?

ARKANSAS. BE WELL ARKANSAS.

AFTER SCHOOL SPECIAL

ARKANSAS HUNTERS FEEDING THE HUNGRY EXPANDS ITS MISSION TO AID PUBLIC SCHOOLS.

STORY By MATT McNAIR PHOTOGRAPHY By Brian Chilson

Ronnie Ritter devotes a great many of his waking hours to solving the problem of hunger in Arkansas. As the current executive director of Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry, the nonprofit organization that helps to provide much-needed animal protein to the state’s food banks through donated venison, much of his time is spent conversing with volunteers across Arkansas who are working diligently to see that every Arkansan has enough food to eat on any given day, through his program or some other charity. But even with all of that day-in, day-out exposure to the realities of food insecurity, Ritter can still sound as if he’s seeing the breadth of this problem for the first time.

“You would not believe how many hungry kids are out there,” he says with wearied awe. “I couldn’t believe it, I had no idea.”

But, of course, Ritter is not seeing the breadth of this problem for the very first time. After 25 years with AHFH (16 of those as director), Ritter knows as well as anybody the immensity of Arkansas’s hunger crisis, and has probably done more to combat that crisis than any person you’re likely to meet on any given day.

Seemingly, though, the capacity for that kind of dedication comes packaged with a healthy capacity for unhappy surprise; after all, to lose one’s susceptibility to shock in the face of moral travesty is to court burnout, if not outright shack up with it. And while the hunger crisis in Arkansas — a global agricultural force, yet among the most food-insecure states in

the Union — is a shameful irony and a seemingly bottomless well of righteous outrage, looking at the problem of “hungry people” through the more exacting lens of “hungry children” perhaps has a way of dipping the draw-bucket deeper yet.

Not to say that feeding hungry kids was ever not a primary goal of the AHFH mission. The organization — which facilitates the donation by Arkansas hunters of ethically harvested deer to local food banks and other hunger-relief organizations through the cooperation of independent meat processors — was always set up as a means of feeding hungry people generally, but also optimized to feed hungry families, extended families, and community networks, all of which, of course, include children. But it wasn’t until around 2017 that an AHFH brainstorming session turned to another, different charitable effort: weekend backpack programs.

SPECIFIC NEED

For many children growing up in food-insecure homes, even in communities where AHFH and other like-minded organizations operate, public school is the only place they are assured of a full and adequate meal. For these kids, there is no guarantee of a square meal — or even two, which you might get at school, and forget about three — when school is not in session. (Emphasis on “in session,” i.e., even during the school year there are two full days per week that many Arkansas children can’t count on getting a real meal.) Backpack programs

Ronnie Ritter (right), on a recent pick-up at AHFH processing partner Kruse Meat Market, pictured with owner Joey Hutichinson.

attempt to mitigate this by sending eligible students home with a backpack containing not books, but food.

Often lacking in the backpacks, however, is true nutritional value (as opposed to merely caloric value); and of the nutritional shortcomings, the biggest gap is most likely protein. As protein is AHFH’s stock in trade, Ritter and his brainstorming partners naturally zeroed in on the protein gap. All well and good, but all that protein came in the form of burger, and one can’t very well fill up a child’s backpack with a few pounds of raw ground meat, no matter how much good the cooked version might do them.

Crucially, Ritter and his crew noticed that one of the primary means of getting some protein in those backpacks was by including as many processed meat snacks (think Slim Jims) as possible. These snack sticks — comprised of heavily processed meat, sketchily sourced — are better than nothing, but far from ideal.

“We just stumbled upon ’em,” Ritter says of the sodium-laden, preservative-saturated cholesterol accelerants hawked by Randy “Macho Man” Savage and beloved by loitering teens everywhere, figuring that if they could produce something similar in taste but locally sourced, made with more nutritious ingredients and ethically harvested, un-mysterious meat, they could get them to those very same kids and “just see if they like ’em.”

Thanks to the program’s reliance on a statewide network of independent meat processors and local food banks, hunters who donate their harvest can be confident their donation will help their own community.

“You would not believe how many hungry kids are out there.”

—Ronnie Ritter, executive director of Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry.

BUCKS TO BURGER, DOES TO DONATIONS

When the idea for the snack sticks came, Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry had been a going concern for nearly 20 years and, while a lot of work, was running just about as smoothly as a nonprofit of its size could.

Several things have contributed to AHFH’s success and efficiency. First and foremost, the underlying mission is an appealing and universal one: to feed the hungry. (One doesn’t have to be religious for this mission to resonate, but it almost certainly doesn’t hurt that Arkansas is an intensely religious state.) But the way that AHFH goes about accomplishing that mission — facilitating the redistribution of harvested venison — is, while perhaps not uniquely Arkansan, nonetheless ideally suited to Arkansas and Arkansawyers.

For one thing, deer hunting is deeply ingrained in the state’s culture, and while there are plenty of folks alive and hunting today who can remember a time when just seeing a deer — much less actually killing one — conferred bragging rights and storytelling privileges, past and ongoing efforts of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission and other stakeholders have resulted in a deer population that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago. It’s more than enough to feed hunters and their immediate families. For another, there is something ennobling — for both giver and recipient — in charity expressed as food rather than money, and food produced, rather than purchased, by the provider.

That last bit is key to AHFH’s system and also sets it apart from many other charitable organizations of similar size and scope. With more than 70 local processors operating across 54 Arkansas counties, AHFH has, for all intents and purposes, a statewide presence. To anyone who has donated a harvest to the organization or benefited from its efforts, this likely seems obvious; but for the many people in the state who have done neither, nor, not having ever bought a hunting license — likely a much higher number than the average reader of Arkansas Wild presumes — ever encountered the AHFH donation option at AGFC.com, the organization might well be completely unknown. While comparable charities certainly facilitate local action, the vast majority effect good works through charitable giving alone (e.g., targeted grants), so most charitable giving to them consists of monetary donations, and necessitates a centralized infrastructure. They also, crucially, run conventional public relations campaigns, including large, publicfacing fundraisers.

AHFH is different in that, while relying on monetary donations to fund operating costs, it does not distribute money, dealing only in the provision of specific food. Even in the case of that food, AHFH does not donate it so much as facilitate its collection and distribution, negotiating a set per-carcass processing fee with individual processors (all processors receive the same per-deer rate, though that rate may change from year to year) and providing each with the tools to document the donation for themselves (to be paid), AHFH (to make the payment), and the AGFC (to ensure all state game laws are followed by all parties). AHFH connects the processor with eligible local food banks — Ritter vets these organizations, though he does take suggestions for local food charities from the processor — and then largely steps aside, letting the local operators take care of their own affairs until it’s time to settle up at the end of the season.

“I don’t know and I don’t need to know,” he says of who exactly is receiving packages of AHFH-facilitated ground venison after the initial negotiation and setup with the processor, insisting that local control of the resource is key and that AHFH should not be in the business of passing out the donations. And, in an outfit that Ritter views as less an endeavor than a calling, he’s confident that everyone involved only wants to help out their neighbor, insisting he must, and does, “trust the processors to do the right thing.”

To date, those processors have done the right thing to the tune of 1.5 million pounds of ground venison, every ounce of which has gone to an Arkansas resident in need. Last season’s haul was a record 100,000 pounds; as of this writing, the 2025 hunting season is still in swing.

GOOD PROBLEM TO HAVE

Even though the tried-and-true AHFH policy of processing all donated venison into ground meat was a success, the example of after-school backpack programs highlighted a limitation: The meat being distributed was not shelf-stable. It had to be refrigerated and then cooked. While children certainly benefit from this system, many a hungry child is in that condition on account the adult responsible for them is unable,for whatever reason, to consistently do things like obtain raw ground meat from a food charity, store it properly, and ultimately prepare it as a meal.

Snack sticks, on the other hand, are shelf-stable. That means a hungry child can either eat that snack stick as soon as they clear the schoolhouse door or keep it in their backpack, their room or wherever else until they choose to eat it.

They taste good, too. As soon as the first batch was rolled out, Ritter knew AHFH had hit upon a special idea and a new opportunity to uniquely serve some of the state’s most vulnerable citizens: hungry children. But unlike the system in place for ground venison, which had become a well-oiled and relatively simple machine over AHFH’s existence, getting the snack sticks to the ones who needed them most presented new challenges for Ritter and his team.

The primary challenge is cost. While any local participating processor can safely and legally accept donated venison and process it for consumption, it takes a specialized facility to produce a shelf-stable snack stick that meets state and federal guidelines. And as of this writing, there is no such facility in Arkansas; the closest one is in Missouri, between Cape Girardeau and St. Louis.

Along with the obvious expense of transporting donated venison to the Missouri-based facility and then hauling the finished product back to Arkansas, there are also significant added production costs for the snack sticks, such as additional ingredients and commercial-grade packaging. Storage is a cost concern as well because the meat must remain refrigerated at the donation site until enough has been collected to fill a trailer for a run to Missouri. That last requirement alone — storage — makes it impossible for a large number of AHFH participating processors to accept harvest donations for the snack stick program.

“Processing costs are going up every year,” Ritter says while discussing the challenges of processors — small businesses that operate on thin margins and in small facilities — that, despite wishing to participate, can’t afford to commit to storing unforeseeable quantities of meat for uncertain lengths of time during peak deer season, a vital few weeks that for many local processors can make the difference between red and black ink come book-balancing time. “They just can’t do it.”

Despite the challenge snack stick production represents to AHFH and its existing partner network, the organization has been able to increase the number of sticks produced and distributed every year since its initial rollout. This success is largely attributable to a dynamic partnership between AHFH, the AGFC and several large hunting clubs throughout the state.

The AGFC, through its Deer Management Assistance Program (DMAP), has for years partnered with these large clubs — the kind of clubs with dozens and dozens of members, hundreds and hundreds of acres, and a sizable operating budget — to parlay the game management and habitat assistance offered by the agency into a collaboration

To learn more about Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry, go to arkansashunters.org or call 501-282-0006.

Club members or landholders interested in participating in DMAP, visit agfc.com/education/ deer-management-assistance-program-dmap.

Top: One of AHFH's trailers before a run to the snack stick facility in Missouri. Bottom: the shelf-stable snack stick provides needed protein for hungry kids.

with AHFH. Participating clubs — whose property is home to massive deer herds that club members generally wish to manage for trophy buck production — host special hunts each season with the sole purpose (aside from managing the herd) of donating every harvested deer to AHFH, and specifically to the snack stick program.

The AGFC helps by issuing special permits for these hunts (deer harvested and tagged under the program’s rules do not count against the tag limit included with the hunter’s standard license), and by providing an AGFC biologist qualified and equipped to perform on-site CWD testing. (Testing for chronic wasting disease, or CWD, is not required in Arkansas, though each deer harvested for snack sticks is tested before processing.) Arkansas Hunters Feeding the Hungry stations a refrigerated trailer for storage at each location, making it possible to perform every pre-shipment task — harvest, donation, registration, testing and storage — in one place.

The partnership has been a resounding success, with the meat harvested from DMAP hunts alone accounting for more than 115,000 packages of snack sticks distributed to 50 school districts in 2024, bringing the total of individual snack sticks donated to schools since the program’s inception to an estimated 600,000.

THE WORK CONTINUES

While the additional storage requirements and production costs associated with the snack sticks make them more difficult to fit into one of the most compelling and vital aspects of AHFH’s operation — local hunters donating their harvest to local processors for distribution in those immediate communities — Ritter has done his level best to assure that local agency is still a major part of the snack stick program. This includes efforts by

as AHFH to participate in the local school district’s student hunger relief program, such as a grant disbursed this year to AHFH from the Pine Bluff Area Community Foundation (an affiliate of the Arkansas Community Foundation) providing enough funding for a recent delivery of snack sticks to schools in the Pine Buff school district.

While the snack stick program is what really animates Ritter in conversation (“They just love ’em,” he says of the kids who find snack sticks in their take-home backpack, “I think it’s their favorite thing”), the original strategy of providing ground deer meat — with its lower operational costs, intensely local focus and broader distribution footprint — remains just as important to Ritter and AHFH. And though the organization makes strides in participation and production every year, the hunger crisis in Arkansas persists.

“Giving it away is easy,” says Ritter. “We could give away a million pounds if we had it.”

Beyond pounds of meat, the problem — as anyone involved in any charitable mission knows — will most likely be funding, or a shortfall thereof. But with AHFH’s dynamic system of volunteers, hunters and community-minded local processors — and, crucially, financial help from working-class hunters chipping in a few bucks when buying a license each year, along with larger donations from well-coined outdoorsmen — it is perhaps not naive to think AHFH can continue to grow and further tamp out the shameful state of food insecurity in The Land of Opportunity.

“I like to partner with people with passion,” Ritter says when reflecting on the qualities of the folks involved with AHFH and those he’d like to see contributing in the future, be it through financial savvy, woodcraft, or any other means.

DISCOVER

Off to the great indoors!

EXPLORE THE NATURAL STATE IN ANY KIND OF WEATHER

By MATT McNAIR

While the wintertime in Arkansas is in some respects great for getting outside — it takes a real doozy of a cold snap to be really cold, it’s neither too rainy nor all that dry, there’s plenty of hunting to be done and you can still fish for just about anything — winter can still make the darkest months of the year, for outdoors enthusiasts, a bit of a drag.

First, the “darkest months” bit. Not a whole lot of daylight to go around from December to March! Between work and every other thing, that 10 or so hours of sunshine we get this time of year rarely cuts it. And if you’re reading this fresh off the press, you’re smack-dab in the middle of the holidays, too.

And to that , then: the holidays. Our chances for an outdoor frolic already limited by diminished daylight and capricious weather, we’re also bound by obligations to family and friends, and probably an office party or church function or some mix of same. What’s more, children are usually involved, and as much as their holiday-kindled joy might triple-size the hearts of all the grown-up Grinches ferrying them around, Yuletide child-minding can still be … a lot They bore easily. They have no filter. Their moodiness defies emotional physics. They do not have their own money.

And on yet to that : money. The holiday season — despite sacred roots across cultures — has become very accommodating to the profane, inasmuch secular traditions and conventions undergirding the modern observation

of ancient spiritual ones tend also to undermine them; no matter your faith tradition or lack thereof, during the holidays a great deal of corporate energy is expended on the sole mission of separating you from your dollars. Resistance is not futile, but most of us cave eventually.

So what’s a hemmed-in nature lover to do? Glad you asked! Because we here at Arkansas Wild have got a few nifty ideas for scratching that outdoor itch while maximizing daylight, dodging inclement weather, entertaining the kiddos, and saving a few bucks if you need an extra gift or two. As is often the case, Arkansas’s top-shelf state park system figures prominently in your next good idea.

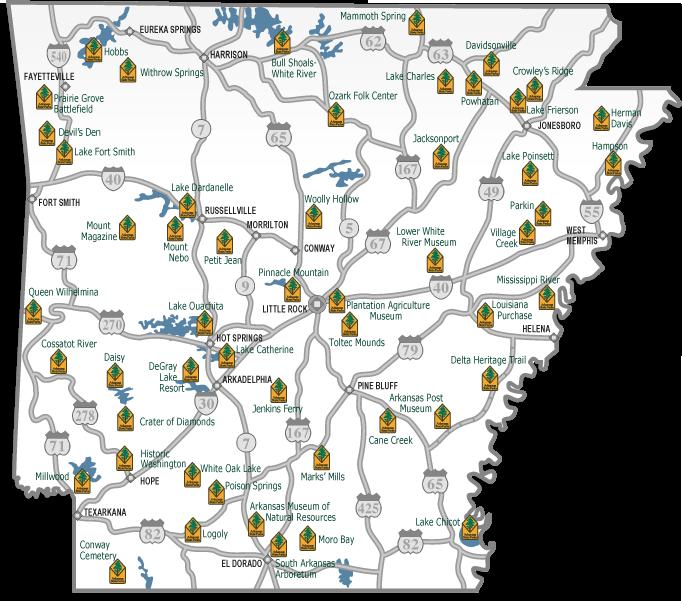

Among Arkansas’s state parks are several that are committed to the preservation and interpretation of our state’s material and cultural history. These archeological and museum parks can be enjoyed to great degree indoors, so crummy weather won’t be a problem (most also have a trail or outdoor exhibit, too). These outposts also tend to be relatively close to a town big enough to do a little Christmas shopping.

One thing: Museum parks are generally closed on Mondays and Tuesdays (as well as actual holidays , as opposed to the holiday season in general) Before you go check operating hours at arkansasstateparks.com.

So don a camouflage fleece and your jolliest thinking cap, and follow us around the state to some of the best outdoor recreation you’ll find under a roof. Happy holidays!

AGFC's Witt Stephens J.R. offers artifacts galore.

ARKANSAS MUSEUM OF NATURAL RESOURCES

Ask someone from elsewhere to name something they associate with Arkansas, and you’re liable to get any number of answers, from the hill culture of the Ozark Mountains to the Old South ghosts that haunt the state’s Delta landscape from stem to stern, from impressions of nature and people that range from inspirational to, occasionally, insulting. But in all that variety, it’s doubtful that more than a handful of folks from elsewhere — and probably not too many Arkansawyers either, especially in the hill country north of the Arkansas River — would answer that question with “oil.” But for a time in the early 20th century, southern Arkansas was the center of America’s fledgling petroleum empire.

If you count yourself among the Arkansas locals that aren’t fully aware of just how much black gold affected the history of our state, take a trip down to Union County and check out the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources. Easily accessible directly off Arkansas Highway 7 in Smackover, the museum tells the tale of Arkansas’s oil boom not only through the nuts-and-bolts of petroleum extraction, but also the boomtown culture that sprang up in the wake of those initial oil strikes and ensuing (black) gold rush.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

The roughnecks of yore didn’t have the option to dodge the elements when pulling oil out of the ground, but luckily you will have that option when learning about it. Boasting 25,000 square feet of climate-controlled exhibit space, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources includes a geology lesson that takes visitors on a trip through deep time, explaining the geological processes that culminated in

the petroleum boom of the early 20th century and, really, our entire modern world. There are also interactive exhibits sure to delight the youngest members of your crew, such as the (fully indoor) Dogpatch-esque recreation of a South Arkansas boomtown.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

The museum sits on 19 wooded acres, and the outdoors portion of the park is wound through with easily walkable trails that pass by numerous pieces of extraction equipment from the old oil fields, as well as a replica of a wooden oil derrick standing 112 feet tall.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

Located just 10 miles south of the museum on Arkansas Highway 7, El Dorado offers a continuing education of the oil boom with its numerous museums, including the outdoor Oil Heritage park and statue garden situated in the downtown historic district. The entirety of downtown El Dorado is a walkable portal to the region’s past and a window into its vibrant present, including the bustling Murphy Arts District. If there on a Thursday or Friday evening, indulge in fine dining and a show at MAD House 101 Restaurant and Bar, or fuel up with traditional American diner fare — breakfast on through to supper —seven days a week at Johnny B’s. To take full advantage of downtown El Dorado’s thriving coffee shop scene, spend the night at either the sleek new Haywood Hotel or in one of the retro-chic downtown spaces collectively operated by, and known as, the Union Square Guest Quarters.

ROAD TRIP BONUS

And finally, if the route works out, head home via U.S. Highway 82, which crosses through the Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge 35 miles east of El Dorado.

The Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources includes an indoor replica of a South Arkansas boomtown.

Oil Heritage Park in downtown El Dorado.

HAMPSON ARCHEOLOGICAL MUSEUM STATE PARK

If you’ve been leaving Northeast Arkansas off your to-do list of late, rectify that oversight by heading up to Mississippi County and visiting the Hampson Archeological Museum State Park. Located in Wilson and near the site of a settlement occupied by a people during a period of time archeologists now refer to as the Nodena Phase (c.14001650 CE), Hampson Archeological Museum State Park offers a fascinating look at the lives of people living in the Mississippi Delta long before European settlement and American expansion altered both the landscape and culture of the region.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

Although on the smallish side, the Hampson museum packs an outsize punch, offering a collection of Nodena artifacts staggering in their quality, detail, and ability to transport the visitor to a time and a world that is otherwise hard to fathom. Along with the stunning collection of Native American artifacts on display, the exhibit space offers carefully curated interpretive panels and activities (the latter well suited to younger visitors), as well as the fascinating story of Dr. James K. Hampson, who led the excavation of the archeological site and whose family ultimately donated the collection and original museum (since replaced by the current facility) they had built to house it.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

Hampson Archeological Museum State Park is a small museum and sits on a fairly small park site, but there is a paved walking trail that winds through the grounds. The real attraction outside of the museum, though, is the town of Wilson itself, the entirety of which is within walking distance — indeed, it is mostly within sight — of Hampson. Weather permitting, take a stroll through this Delta gem after taking in the museum, and if weather isn’t permitting, Wilson still has you covered.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

The town of Wilson is a destination in and of itself. Founded as a company town and styled after a 19th-Century English village, Wilson boasts a nationally-known eatery in the Wislon Cafe. For lodging, stay for a night as the landed gentry at The Louis, a luxruious downtown hotel that also operates the Louis Field Club, with offerings including sport shooting and guided hunts. Other shops and attractions abound on and around the Tudor square, and the Mighty Mississippi is just to the east ... ask the concierge at The Louis or one of the shopkeeps on the square about guided trips offered by outfitters that, while not based in town, maintain local contacts.

ROAD TRIP BONUS

If home is anywhere at all south of Wilson, it won’t be hard to make sure the route goes through Parkin, just 40 miles down Interstate 55 and a smidge to the west. While the shopping and lodging in Parkin might be a bit scant compared to Wilson, it does boast another fascinating look into Arkansas’s pre-European past at Parkin Archeological State Park.

Hampson Museum offers a glimpse into NE Arkansas' past.

The Willson Cafe is a must-see for foodies.

LOWER WHITE RIVER MUSEUM STATE PARK

Not many rivers in the United States vary in terrain, temperature, and all-around temperament on their course as does the White River. Probably better-known nationwide for its upper reaches in the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks, with its artificial lakes and resultant trout fisheries, the lower White of the Arkansas bottomlands is no less fascinating or historically significant. Get out of the cold and get a history lesson on this other side of the White River at the Lower White River Museum State Park in Des Arc.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

Learn about the White River’s incredible natural history and vital importance to the history of Arkansas’s pre- and post-European settlement and industry through recreations and interpretations of travel, shipping, fishing, and even button-making (via the oncethriving pearling industry) in the cozy confines of a small-butsignificant exhibition space.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

While there are no trails or outdoor exhibits at the half-acre site, the White River itself beckons just three miles away. Follow the main drag through Des Arc to Riverfront Park and take in a stunning view of the Des Arc Bridge, which spans the White via Arkansas Highway 38, as you walk the city’s two paved riverfront trails.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

After taking in the river views, head back down Main Street to check out White and Son Fish Market/ Kristi’s Kitchen, a one-two punch of classic river town food and vibes.

HISTORICAL ARKANSAS MUSEUM

Located in downtown Little Rock, Historical Arkansas Museum is both a museum and a living history facility that includes restored buildings that date to Arkansas’s territorial period, a period-appropriate garden maintained by volunteers from the Pulaski County Master Gardeners, and a working blacksmith shop (a recreation rather than a restoration, but functional and period-appropriate all the same). While not technically a state park, Historical Arkansas Museum (or “H.A.M.”, and pronounced “ham” by most folks in the capital city) is administered by the Department of Parks, Heritage, and Tourism, and like other state-run facilities it is open to the public free of charge.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

Along with typical museum fare — in this case, mostly artifacts and information pertaining to Arkansas’s territorial period and early statehood — H.A.M. regularly displays art that ranges from territorial to contemporary, including folk crafts and work from indigenous artists. There is a dedicated children’s area, and a knife gallery that displays, among other impressive and historically significant blades, “Bowie No. 1,” a James Black knife that is possibly the knife crafted by Black for its namesake, Jim Bowie.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

Outside of the H.A.M. building, visitors can tour grounds that feature the aforementioned territorial homestead, complete with restored dogtrot cabin and recreated blacksmith shop, as well as the Hinderliter House, a 19th-century dwelling and grog shop, and the oldest house still standing in Central Arkansas.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

H.A.M.’s River Market location in downtown Little Rock makes it an ideal home base for any number of outdoor/indoor adventures of a historical bent. To learn about Arkansas’s political life from early statehood on through the early 20th century, head to Old State House Museum just a few blocks from H.A.M., and a look at living memory on up to the present is just another mile and change away at the Arkansas State Capitol. And even visiting the big city — and regardless of weather conditions — you can get your true-blue Natural State fix at the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission’s Witt Stephens Jr. Central Arkansas Nature Center, also in the River Market. That’s an awful lot to see in one day and on an empty stomach, so it’s fortunate indeed that Little Rock offers a wide array of dining and lodging right downtown amid all the informative fun. To get your sleeping and snacking plan lined out pre-trip, go to littlerock.com.

ROAD TRIP BONUS

Sure, Little Rock is in the middle of Arkansas. Everybody knows that. But you'll know better if you can suss out the literal, geographic center of the state and go see the stone marker there. Here are some clues: Saline County, and a rural cemetery with a tree in its name. And one last clue, and a rewarding one at that: After you solve the mystery, you can celebrate success with a sandwich from the Olde Crowe General Store.

History is alive and hard at work at the Historic Arkansas Museum.

Examples of buttons on exhibit at Lower White River Museum State Park showcase a once thriving pearling industry.

PLANTATION AGRICULTURE MUSEUM

Located just a few miles south of the Little Rock metro in the community of Scott is the Plantation Agriculture Museum, a state park that preserves and interprets the industrial and cultural history of postCivil War commercial agriculture in the Arkansas bottomlands. The main exhibit space, built in 1912, was originally a general store; the 14.5 acre site itself, which includes the primary exhibition building as well as a seed warehouse and associated railroad spur, cotton gin, and numerous other outbuildings, has been a state park since 1989.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

The old general store contains numerous artifacts dating to the 19th century, all of which are used to demonstrate daily life in the homes and fields of a large cotton plantation in the decades after the Civil War. There are also numerous interpretive signs and pieces of literature that provide context to the remnants of plantation life on display in the museum.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

While there are no official trails on the park site, the grounds are fully walkable, bounded on the west by a small oxbow lake and chock-a-block with restored outbuildings and equipment. Combining the two is the historic tractor exhibit, an array of extremely early heavy industrial cotton equipment (including steam-powered rigs) housed underneath a large open-air shed.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

The Curve Market is a farm stand, cafe, and gift shop perfect for picking up a snack or a souvenir on either side of a trip to the park, and looks to be the most happenin’ spot in Scott.

Don't forget your pencil!

PAPERS, PLEASE.

In case you missed it (not sure why you would’ve, as there definitely wasn’t anything else of note going on at the time), back in 2020 Arkansas State Parks introduced Club 52, a program meant to encourage folks to visit all 52 of Arkansas’s excellent state parks. (These top-tier outdoor wonderlands recorded an epic uptick in visitation that year, almost certainly because of this passport program and for no other reason at all, there being not one single external factor encouraging people to get out-of-doors that year.) Five years later, the passport program is still a going concern and an excellent way to add yet another layer of fun to an already-fun enterprise: toodling around Arkansas and visiting our state parks! Each time you visit a park, head to the Visitor Center and get a stamp for that park (or, if it’s an unstaffed park such as Jenkins Ferry Battleground State Park, find the interpretive marker and make a pencil etching of the raised park symbol). Once you hit 25 parks visited, show the Visitor Center staff member and claim a deck of commemorative playing cards, (52 parks, get it?), and then a nifty T-shirt when you get stamped for the big Five-Two. Passport books are available at any staffed Arkansas State Park, and — just like admission to every single one of those parks — the book is free.

19th Century agricultural equipment on display at the Plantation Agriculture Museum.

BRIAN CHILSON

PLUM BAYOU MOUNDS

ARCHEOLOGICAL STATE PARK

One of the most impressive sites of indigenous moundbuilding in North America, Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park — formerly Toltec Mounds State Park — is just 4.5 miles southwest of the Plantation Agriculture Museum on U.S. Highway 165, and every bit as fascinating. Make a day of it by bundling both if you can, but be aware that Plum Bayou might take up all of the precious daytime hours allotted during the winter months. Not only is there a fascinating museum and amazing, preEuropean earthen mounds, there’s a mystery: No one knows exactly who lived at the site, why they built the mounds, or what became of them.

WHAT TO DO (INSIDE)

The museum portion of Plum Bayou Mounds Archaeological State Park delves into the mystery of the Plum Bayou people and chronicles modern efforts to find out exactly who they were and what exactly happened to them. There is also a massive dugout canoe on display that, while not from the Plum Bayou site itself (it was excavated in Saline County), is representative of boats made by other Central Arkansas peoples during the Plum Bayou period, and is quite something to behold regardless.

ROAD TRIP BONUS

From Plum Bayou Mounds, keep going southwest down U.S. Highway 165 for five miles to the town of Keo, where on Main Street you’ll find Charlotte’s Eats & Sweets, home of perhaps the most famous pie case in all of Arkansas. On second thought, maybe hit Charlotte’s first, as those pies go quick. Either way, call 501-842-2123 beforehand to gauge your chances.

WHAT TO DO (OUTSIDE)

Unfortunately, many of the mounds built by the Plum Bayou people were destroyed as white settlers moved into the Arkansas River bottomlands and set up large farms and plantations. Even though much was destroyed before the site’s cultural and scientific value were realized, however, a few still remain and the locations of many others have been found and marked. Two trails, both accessible and suitable for walkers of most abilities, weave through the site, and markers that correspond to brochures for each trail allow for an informative and self-guided tour.

WHAT (ELSE) TO DO

Less than a mile from Plum Bayou down Kesl Road sits the Willow Belle Mansion, a prime example of opulent plantation-era architecture that is now in the business of hosting events, particularly weddings. If Plum Bayou seems a little too spooky for a proposal, maybe pop the question at Willow Belle.

The sun sets over one of the Plum Bayou Nounds. Exactly who built the mounds and why remains a mystery.

My, my, gotta try Charlotte's Pie.

Give the Gift of experiencinG the Wild

By MATT McNAIR

Whether you’ve picked up this issue of Arkansas Wild fresh off the press — with just a precious few days before the underside of the tree or the inside of a stocking must be flush with consumerism’s merrily-wrapped spoils — or after all the big holidays have wound down and with our little magazine’s ink just as dry as (so we hear, anyway) January, you’ve likely got gifting on the brain one way or the other. So with that in mind, Arkansas Wild is happy to present our 2025 Holiday Bonus Gift Guide. As a companion to our standard Gear Guide, we’ve stocked the Gift Guide with gift ideas that prioritize living over loot and learning over lucre, all suitable for gifting on either side of the holiday divide. And as an added bonus, these experiential care packages are ideal for sharing, so go ahead and sign yourself up as well, and give your lucky recipient the gift of a plus-one!

TEACH SOMEONE TO FISH (OR START A FIRE, OR BUILD A SHELTER, OR) …

Even if one is looking to be more Bill Bryson than Bear Grylls, it never hurts to know a few things about getting along out in the woods and away from your pushbutton support system. And really, who doesn’t want to be the resourceful salt who can whip up a fire and set up camp without that last-minute trip to Walmart? To that end, you might look into booking a survival workshop from Arkansas Survival. Located near Houston, Arkansas (Perry County), Arkansas Survival offers several classes ranging from one-day navigation workshops to multi-day advanced survival training, as well as kid-friendly classes. If you’re ready to tell the beaten path to beat it, you can find out more about Arkansas Survival at arkansassurvival.com, or call 479-747-7056.

HI-HO, SWEETIE PIE! AWAY!

If you’re lucky enough to have ridden a horse in your life, you know how awesome it is; if you haven’t been so lucky to have ridden a horse, chances are you’d like to. Well, luck is with both camps at Dutch Acres Farm in Jacksonville. With a competition-level staff that specializes in multiple riding styles, riders of all sizes and skills (or lack thereof) can find something to learn at Dutch Acres, from kids as young as three (who can participate in the Tiny Tots program with Sweetie Pie the Welsh Pony) to advanced grownup riders who fancy themselves quite the horse master and ready to make the leap to competitive riding (though they’ll have to prove themselves to Quasar, a dressage veteran and notorious perfectionist). And if you ride till you get saddle-sore, you can tell your troubles to the cuddly gang of not-for-riding critters that make up Dutch Acres Farm’s Barnyard Buddies. To hone your riding skills and test your cuteness threshold, go to dutchacresfarm.net or text 501-453-2668.

A JACK (OR JILL!) OF ALL TRADES…