Lawyer The Arkansas

H A R L E Y

A C C O U N T

I N G

S

O

L U T I O N S

Let us take care of the bookkeeping, so you can focus on your business.

As a busy attorney, you have enough on your plate without having to worry about the nitty-gritty details of bookkeeping. That's where our experienced team of bookkeeping experts can step in and take the burden off of your shoulders

Our comprehensive bookkeeping services are designed specifically to meet the unique needs of law firms like yours

W H Y U S ?

With 18 years of corporate finance, accounting, and audit experience at Fortune 500 companies, I have managed billions of dollars in budgets for high-stakes clients such as the Department of Defense, the U S Navy, and the Department of State. I’ve also served on several boards as treasurer, overseeing financial strategy and budget management Now, as a business owner managing the books for my four companies, I understand firsthand the needs of small businesses. I specialize in bookkeeping for small businesses, particularly attorneys, and aim to provide financial clarity and peace of mind so you can focus on growing your business.

PUBLISHER

Arkansas Bar Association

Phone: (501) 375-4606 Fax: (501) 421-0732 www.arkbar.com

EDITOR

Anna K. Hubbard

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Karen K. Hutchins

PROOFREADER

Cathy Underwood

EDITORIAL BOARD

Caroline R. Boch

William Taylor Farr

Anton L. Janik, Jr.

Jim L. Julian

Tory Hodges Lewis

Drake Mann

Tyler D. Mlakar, Chair

Michael A. Thompson

Courtney K. Nosari Wall

Brett D. Watson

Amie K. Wilcox

David H. Williams

Nicole M. Winters

OFFICERS

President

Kristin L. Pawlik

President-Elect

Jamie Huffman Jones

Immediate Past President

Judge Margaret Dobson

President-Elect Designee

Representative Carol Dalby

Secretary Glen Hoggard

Treasurer

Brant Perkins

Parliamentarian

Brent J. Eubanks

YLS Chair

Frank LaPorte-Jenner

BAR ASSOCIATION STAFF

Executive Director

Karen K. Hutchins

Director of Operations

Kristen Frye

Finance Administrator/CPA

Staci Clark

Director of Government Affairs

Leah Donovan

Publications Director

Anna K. Hubbard

Executive Administrative Assistant

Michele Glasgow

Office & Data Administrator

Cynthia Barnes

Professional Development Coordinator

Lisa McCormick

Information Specialist

Rachel Henderson

Lawyer The Arkansas

features

Honoring Arkansas Bar Association Members Who Served in the U.S. Military

Specialist 5 (E-5) Fred Ursery 6th Battalion/77th Artillery in Cu Chi and Can Tho, Vietnam March 1, 1968-April 1, 1969 By Fred Ursery

UALR William H. Bowen School of Law Veterans Legal Services Clinic By Professor Rebecca Feldmann

Legislative Hearings: Playing by the Right Rules By Frank Arey and Emily White

Juvenile Circuit Court 101 By Brenda Stallings

From a Judge's Perspective: Things a Lawyer Might Think About When Practicing in Juvenile Court By Judge Thomas

to

The Arkansas Lawyer (USPS 546-040) is published quarterly by the Arkansas Bar Association. Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, Arkansas. POSTMASTER: send address changes to The Arkansas Lawyer, 2224 Cottondale Lane, Little Rock, Arkansas 72202. Subscription price to nonmembers of the Arkansas Bar Association $35.00 per year. Any opinion expressed herein is that of the author, and not necessarily that of the Arkansas Bar Association or The Arkansas Lawyer. Contributions to The Arkansas Lawyer are welcome and should be sent to Anna Hubbard, Editor, ahubbard@arkbar. com. All inquiries regarding advertising should be sent to Editor, The Arkansas Lawyer, at the above address. Copyright 2024, Arkansas Bar Association. All rights reserved.

Lawyer The Arkansas

Advertise in the next issue of The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

President: Kristin L. Pawlik; President-Elect: Jamie Huffman Jones; Immediate Past President: Judge Margaret Dobson President-Elect Designee: Carol Dalby; Secretary: Glen Hoggard; Treasurer: Brant Perkins Parliamentarian: Brent J. Eubanks; YLS Chair: Frank LaPorte-Jenner

Trustees:

District A1: Elizabeth Esparza, Geoff Hamby, William M. Prettyman, Lindsey C. Vechik

District A2-A3: Matthew Benson, Evelyn E. Brooks, Jason M. Hatfield, Christopher M. Hussein, Michelle Rene' Jaskolski, Sarah C. Jewell, George Rozzell, Russell B. Winburn

District A4: Kelsey K. Bardwell, Craig L. Cook, Brinkley B. Cook-Campbell, Dusti Standridge

District B: Randall L. Bynum, Mark Kelly Cameron, Thomas M. Carpenter, Tim J. Cullen, Bob Edwards, John A. Ellis, Bobby Forrest, Michael K. Goswami, Steven P. Harrelson, Michael M. Harrison, Jim Jackson, Anton L. Janik, Jr., Victoria Leigh, Skye Martin, Kathleen M. McDonald, J. Cliff McKinney II, Jeremy M. McNabb, Molly M. McNulty, Meredith S. Moore, John Ogles, Casey Rockwell, Lauren Spencer, Aaron L. Squyres, Caitlin Campbell Stepina, Jessica Virden Mallett, Danyelle J. Walker, Patrick D. Wilson, George R. Wise

District C5: William A. Arnold, Joe A. Denton, John T. Henderson, Brett D. Watson

District C6: Bryce Cook, Paul N. Ford, Jeffrey W. Puryear, Paul D. Waddell

District C7: Kandice A. Bell, Robert G. Bridewell, Sterling T. Chaney, Taylor A. King

Delegate District C8: Carol C. Dalby, Amy Freedman, Connie L. Grace, John S. Stobaugh

Ex-officio Members: Judge David McCormick, Judge Chaney W. Taylor, Vicki S. Vasser, Dean Cynthia Nance, Dean Colin Crawford, Denise Reid Hoggard, Eddie H. Walker, Jr., Christopher M. Hussein, Karen K. Hutchins

Strength & Experience

Class of 1999

Congratulations to Members Celebrating Their 25th Year of Practice

Justin T. Allen

Lisa L. Baker Gibbs

Madeline L. Bennington

Tameron C. Bishop

Dean Terrence Cain

Andrew L. Caldwell

Michael Carr

Jon B. Comstock

Gregory K. Crain

Shawn Bradley Daniels

William Lee Dawkins

Judge Margaret Dobson

Ruth Allison Dover

Bryan W. Duke

Missy McJunkins Duke

Angela Echols

Bob Edwards

John Andrew Ellis

Pamela Epperson

J. Carter Fairley

John A. Flynn

Jesse J. Gibson

David P. Glover

Thomas Daniel Goodwin

Julie D. Greathouse

Althea Hadden

J. Christopher Harris

Charlene Davidson Henry

James E. Hensley, Jr.

Matthew R. House

Brian Hyneman

Scott A. Irby

Martin A. Kasten

Ginger Kimes

M. Wade Kimmel

Chrissie Lamkin

M. Melissa Lee

Lana Gilmer Leger

Patrick W. McAlpine

Dustin B. McDaniel

Joseph P. McKay

Erin S. McKool

Melissa McManus

Robin Miller

Joseph G. Nichols

C. Ryan Norton

Shannon E. Padilla

Cameron Bunting Parker

Christopher B. Parkerson

Samuel J. Pasthing

Kristin L. Pawlik

Thomas Earl Pryor

Chris R. Reed

Gregory L. Smith

Robert Todd Smith

Stuart Larson Spencer

Jason Aaron Stuart

Jeremy Swearingen

Howard Todd Whatley

Patrick D. Wilson

Jennifer Wilson-Harvey

Robert Patrick Young

ArkBar 2024-2025 Committee Chairs

ArkBar President Kristin Pawlik appointed the following members to serve as committee chairs.

501(c)(3) Exploratory Committee: David Biscoe Bingham

Annual Meeting: Christopher M. Hussein and William J. Ogles

Arkansas Bar PAC: Lindsey Vechik

Artificial Intelligence Task Force: Meredith Lowry

Audit: Dan Young

Bar Center Task Force: Bob Estes

Editorial Advisory Board - The Arkansas Lawyer: Tyler D. Mlakar

Finance: Brant Perkins

Hall of Fame Selection Committee: J. Cliff McKinney II

Judiciary: Judge Margaret Dobson

Jurisprudence and Law Reform: Paul W. Keith

Law School: Harry A. Light

Legislation: Glen Hoggard

Mock Trial: Margaret K. Davis

Past Presidents: Judge Margaret Dobson

Personnel (ArkBar): Denise R. Hoggard

Political Speech and Activities Task Force: Aaron L. Squyres

ArkBar 2024-2025 Section Chairs

Thank you to the following members for leading the sections this year. Watch for additional chair elections.

Agricultural Law: Jordan P. Wimpy

Appellate Law: Tasha C. Taylor

Business Law: William P. Feland, II

Construction Law: William P. Feland, II

Corporate & In-House Counsel: William P. Feland, II

Debtor/Creditor: Mary-Tipton Thalheimer

Elder Law: Ashley Stepps

Environmental Law: Mitchell Alexander Dowden

Family Law: Amanda Nicole Williamson

Government Practice: Vincent C. Henderson, II

Natural Resources Law: Patrick Hickey

Probate & Trust Law: David Biscoe Bingham

Real Estate Law: J. Cliff McKinney, II

Section of Taxation: Hannah Van Horn

Solo, Small Firm & Practice Management: John S. Pickell

Young Lawyers’ Section: Frank LaPorte-Jenner

Oyez! Oyez!

APPOINTMENTS AND ELECTIONS

The Gaines House honored the Honorable Annabelle Imber Tuck and the Honorable Joyce Williams Warren with the Sandra Wilson Cherry Award. The Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program honored Dean Cynthia Nance with the Justice Robert L. Brown Community Service Award. UA Little Rock Bowen Alumni Association honored Judges Rita and Wayne Gruber with the Distinguished Alumni Awards; Colette Honorable with the Outstanding Alumni in Public Service Award; and Cara Butler with the Emerging Leader Award. Jim Wyly of Wyly Rommel, PLLC was selected for the Commitment to Justice award by the University of Arkansas Law school, Fayetteville and the law school Alumni Society. J. Cliff McKinney II of Quattlebaum, Grooms & Tull PLLC was inducted as a Fellow of the American College of Mortgage Attorneys.

WORD ABOUT TOWN

Taylor King Law announced that Thomas Odom and Kelsi Scarlett joined the firm. Wright Lindsey Jennings announced that Lauren Ator, Allie Barnes, Elizabeth Kimbrell, and Timothy Frith joined the firm. Rose Law Firm announced that Mitchell A. Dowden joined the firm. Quattlebaum, Grooms & Tull PLLC announced that Michaela D. Caudle, J. Houston Downes, David A. Gardner, Tyler C. Gillespie, and Falyn E. Traina have joined the firm.

Send your oyez to ahubbard@arkbar.com

2024 Mock Trial Competition Call for Volunteers

Single-Weekend, Round-Robin Competition Feb. 28-March 1

“High School mock trial is a unique opportunity that engages and introduces students in a fun way to the legal system and the judicial process—one that often inspires futures,” said Maggie King Davis, chair of the Mock Trial Committee. “Students continue to participate, in part, because of the positive interactions with members of our legal community. Every year, our students look forward to taking on the role of attorneys and witnesses and preparing for the case competition.” To this end, we seek judges and lawyers to serve as scoring and presiding judges during the competition. No mock trial experience is necessary, as we provide a brief orientation before the round.

We are pleased to continue hosting a single-weekend, round-robin competition, which will take place on Friday, February 28 and Saturday, March 1, 2025, in Little Rock. Because this is a single weekend of competition, where all teams will get to compete in four rounds of competition, we need as many volunteers as possible to hold a successful competition. To volunteer, go to www.arkbar.com/ARMockTrial or contact Davis at maggie11king@gmail.com. The Mock Trial Committee appreciates your support.

Representative Carol Dalby elected the new ArkBar President-Elect Designee

The Arkansas Bar Association (ArkBar) is pleased to announce Representative Carol Dalby as the new President-Elect Designee. Rep. Dalby, of Texarkana, was elected without opposition at the close of nominations on October 7, 2024. She will begin her one-year term as President-Elect in June 2025 and will assume the office of President at the 2026 ArkBar Annual Meeting.

A long-time active member of ArkBar, Rep. Dalby currently serves on the Board of Trustees and the Law School Committee. She has previously served on the Board of Governors and has been involved in several key committees, including Professional Ethics, Governance, Jurisprudence and Law Reform, Judicial Nominations, Juvenile Justice, Lawyers for Literacy, Legal Related Education Super Committee and Committee for a Modern Judiciary.

In addition to her work with ArkBar, Rep. Dalby is serving her fourth term in the Arkansas House of Representatives, where she represents District 100, covering Texarkana and part of Miller County. For the 94th General Assembly, she chairs the House Judiciary Committee and serves on the House City, County, and Local Affairs Committee, as well as the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee. She is also a practicing attorney in Texarkana.

Rep. Dalby earned her undergraduate degree from Ouachita Baptist University, a master's degree from East Texas State University (now Texas A&M), and her Juris Doctor from the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville.

Her leadership extends beyond the legislature. She has served as President of the Texarkana School Board, District Judge for Miller County, and Special Justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court. She has also led various community organizations, including Opportunities Inc., the Junior League of Texarkana, the Texarkana Regional Arts Council/ Women for the Arts, the Library Commission and the Red Cross. For her dedication to volunteerism, she received the Junior League's Outstanding Sustainer Award.

Rep. Dalby is a member of First United Methodist Church and resides in Texarkana with her husband, John. They have two grown children.

Reflecting on the Attorney Oath of Admission

Kristin Pawlik is the President of the Arkansas Bar Association. She is a partner at Miller, Butler, Schneider, Pawlik & Rozzell, PLLC in Northwest Arkansas.

On October 4, I had the honor to witness Chief Justice John Dan Kemp administer the Oath of Admission to Arkansas’s newest attorneys. It had been some time since I last heard the Oath read aloud, and as I listened, I felt goosebumps rise. In my 25th year of practice, the commitment we make to support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of Arkansas resonated deeply—not as a lofty ideal but as a call to action. The pledge of civility, too, feels more necessary than ever.

After administering the Oath, the Chief Justice offered his congratulations to the admittees, inviting each Justice to do the same. What followed was an unflinching acknowledgement of the challenges of our profession. I’ve included selected portions of their remarks for your reflection as you “endeavor always to advance the cause of justice.”1 Videos of the ceremony may be viewed at this link: https://www.arcourts. gov/courts/supreme-court/oral-argumentvideos/other.

❖

I urge you to safeguard and improve your reputation and the reputation of our profession. Conduct yourself with honor, respect the legal system and give courtesy due to courts of justice and judicial officers. Never compromise your integrity. Work hard, keep your word, speak the truth and keep your promises. Remember that civility is not inconsistent with being a zealous advocate.

—Chief Justice John Dan Kemp ❖

You’re required to always be a zealous advocate... Zealously representing your clients’ interests within the bounds of the law... And let justice be done or the heavens fall. Go forth and defend the constitution.

—Justice Karen Baker

Attorney Oath of Admission

I will support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of Arkansas, and I will faithfully perform the duties of attorney at law. I will maintain the respect and courtesy due to courts of justice, judicial officers, and those who assist them.

I will, to the best of my ability, abide by the Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct and any other standards of ethics proclaimed by the courts, and in doubtful cases I will attempt to abide by the spirit of those ethical rules and precepts of honor and fair play.

To opposing parties and their counsel, I pledge fairness, integrity, and civility, not only in court, but also in all written and oral communications.

I will not reject, from any consideration personal to myself, the cause of the impoverished, the defenseless, or the oppressed.

I will endeavor always to advance the cause of justice and to defend and to keep inviolate the rights of all persons whose trust is conferred upon me as an attorney at law.

Our democracy is fragile, and the rule of law is being tested like never before... So... if you are brave enough to try and if you enter the arena and you fight the good fight, I need to warn you that the world will not necessarily stand up and applaud. But I challenge you to march on anyway.

—Justice Courtney Rae Hudson ❖

You have graduated, you’ve passed the bar, you have all the knowledge to practice... But then don’t forget that as you’re climbing up that ladder to reach down below and teach one.

And so, for the generation that comes behind you, be that teacher, too.

—Justice Rhonda Wood ❖

Today, you have a power you didn’t have before. You have a power to help your clients... And so in the great words of the philosopher, Uncle Ben, from the Spider-Man movie, “With great power comes great responsibility.” And when you think of that responsibility—truthfulness, honor, character, integrity—those are the things that go into building your reputation.

—Justice Shawn A. Womack ❖

Your oath is also that you’ve been given an opportunity not just to serve your client, but to serve your community. So, look for opportunities where you can help either your family, your church, your schools, your community where you can give back.

—Justice Barbara Webb ❖

What you do as an attorney matters. It matters to other people... We have a responsibility, and you do need to be faithful to that duty and to that responsibility. But don’t lose sight of the quality of life and the people around you that need you. They need your time. Be sure to be intentional about spending time with your family and not letting the importance, the true importance of what you’re doing, get in the way of the family that needs you.

—Justice Cody Hiland

Endnote:

1. In re Attorney Oath of Admission, 2012 Ark. 82. ■

Rodney Moore

Scott Irby

Connecting and Engaging the Next Generation of Arkansas Lawyers

With the 2024-2025 year well underway, the Young Lawyers Section has hit the ground running. I was fortunate to be invited to speak at the new student orientations for both the University of Arkansas School of Law in Fayetteville and the William H. Bowen School of Law in Little Rock. These presentations were great opportunities to meet the incoming classes of law students to our state and introduce the Arkansas Bar Association to the next generation of our organization. It was also a great opportunity to explain to the students the value of membership in our association, especially when it costs them nothing.

It’s been a little while since I was in law school, so I had to be reminded that membership into the Bar Association is free for law students. This is a great value to the students, and it also presents a great opportunity to introduce new members to our organization. A student can join the association at any time for free and get full access to all the benefits that we enjoy every year with our membership. This allows the students to experience what it is like to be a member, and it gives them plenty of time to explore the resources that we provide. Because of this, it has become my goal to sign up every law student in Arkansas to the Bar Association. I would also ask you, dear reader, to keep this in mind if you attend an event with a law student this year. If you are visiting with any law students, please remind them that they too can join our organization today for the low cost of absolutely free.

Along with our outreach work this fall, YLS co-sponsored two clinics with the Arkansas Access to Justice Commission: one in Northwest Arkansas and one in Little Rock. I was able to join for the Little Rock clinic and am happy to say that we had a great turnout of both lawyers and students. At the event, I worked at a table with two law students answering questions on the

Free Legal Answers website. The event itself was a fun opportunity to work through legal questions that could rival bar exam hypos. It was also a good opportunity to provide some practical experience to the students, another important goal for the Young Lawyers Section this year.

I am often asked about what issues I see new attorneys are facing, and professional experience (or the lack thereof) is a topic that always comes up. There are many causes of this problem, but at the end of the day students and new attorneys are not getting

Frank LaPorteJenner is the Chair of the Young Lawyers Section. Frank is a managing partner of LaPorte-Jenner Law, PLLC.

enough opportunities to do meaningful legal work at the early stages of their career. Our goal is to make YLS a resource for providing those opportunities. For example, we started planning our annual Wills for Heroes clinic, and we plan to recruit students from both schools to join with our volunteer attorneys, making the clinic both a pro bono event and a professional development opportunity. We are going to continue to plan other professional development programs this year, but I will also turn once again to you, dear reader, for your help. If you have an upcoming pro bono event, please reach out so YLS can help recruit young attorneys and law students to join as well. Young professionals are always looking for ways to put their education into practice; they just need to know where to go.

Frank owns and manages LaPorte-Jenner Law, PLLC with his wife Kelli, and can be reached anytime at frank@LPJlaw.com ■

2024-2025 YLS Executive Council

Frank LaPorteJenner, Chair

Breanna Jordan McLaren Chief Engagement Officer

Justin W. Harper District B Rep.

William T. Harris District C Rep.

Grace Wewers

Fletcher At-Large Rep.

Samuel W. Mason, Chair-Elect & District A Rep.

Hayley Ferguson District B Rep. Brittany Hawkins District A Rep.

Will Hegi District C Rep.

Eli Cummins At-Large Rep.

Dominique D. Lane Secretary/ Treasurer & At Large Rep.

Marcus A. Priest District A Rep.

Syndey L. Rasch

District B Rep.

Ledly S. Jennings District C Rep.

Frank at the U of A law school orientation

Honoring Arkansas Bar Members Who Served

in the U.S. Military

Celebrating the Courage and Dedication of Our Military Members

We proudly honor the members of the Arkansas Bar Association who have served in the United States military. Their dedication and sacrifice have made a lasting impact on our nation, and we pay tribute to their commitment with deep respect. A detailed list of these members’ contributions, including posthumous recognitions, is available on our website. While this record celebrates their bravery, we recognize that it may not include all who have served. If you know someone who should be included in future publications, please contact the editor. Let us together ensure that their legacy of courage and sacrifice is always remembered.

Please visit ArkBar’s Tribute to Members who Have Served in the Military at the link below or scan the above code: https://www.arkbar.com/members/members-in-the-military

Overton Anderson

Philip S. Anderson

James A. Badami

Frank Bailey

Michael D. Barnes

Marilyn Dearien Barton

Zach Baumgarten

Jonathan W. Beck

Joe Benson

Ed Bethune

Allen W. Bird II

Sam N. Bird

Judge Denzil Keith Blackman

Daniel C. Blaney

John Dudley Bridgforth

Charles A. Brown

Major Natalie G. Brown

LeAnne Pittman Burch

William Jackson Butt, II

Anthony B. Cameron

Worth Camp, Jr.

Jennifer Carlisle

Charles L. Carpenter, Jr.

Jerry W. Cavaneau

John S. “Jack” Cherry

Murray Claycomb

Nathan Coulter

F. Thomas “Tom” Curry

Justice Paul Danielson

Thom Diaz

Jerry Dodd

Greg Downs

Don R. Elliott, Jr.

Bob Estes

Peter G. Estes, Jr.

John C. Everett

Judge Vic Fleming

William Charles Frye

Sam Gibson

Martin G. Gilbert

John P. Gill

Morton Gitelman

James C. Graves

Ron Griggs

Judge Wayne Gruber

Will Gruber

Judge David F. Guthrie

Stuart W. Hankins

Dick Hatfield

William D. Haught

Robert L. “Skip” Henry

Donald C. Hill

Randal Hobbs

Cyril Hollingsworth

James W. Hyden

Greg S. James

C. Cole Jeffries, Jr.

Glenn W. Jones

Robert L. Jones, Jr.

Dak Kees

Joseph M. Kraska

Tim Leathers

M. Melissa Lee

John C. Lessel

Fletcher C. Lewis

Stark Ligon

Phillip A. McGough

Joseph P. McKay

Cody A. McKinney

J. Conley Meredith

Cal McCastlain

James McMenis

Henry N. Means, III

Russ Meeks

George B. Morton

Lee Muldrow

J. R. Nash

Edward Nelson

Judge David Newbern

Jim Nickels

Alan J. Nussbaum

Richard C. Ourand, Jr.

Hugh Overholt

William L. Owen

Michael Parker

Eudox Patterson

Ellis Lamar Pettus

David Dero Phillips

John M. Pittman

George Plastiras

David M. Powell

Donald E. Prevallet

Joseph Purvis

Brian D. Rabal

John “Buddy” W. Raines

Gordon S. Rather, Jr.

Herbert Lynn Ray

Chris Rittenhouse

George Ritter

Fred Roberson

William S. Robinson

Adam M. Rose

James (Jim) A. Ross, Jr.

Thomas S. Russell

Marissa A. Savells

Corey Seats

Brenda Simpson

Damon C. Singleton

Berl S. Smith, Jr.

James E. Smith, Jr.

Judge Kim Smith

Richard H. Smith

Scott E. Smith

Paul Suskie

F. Mattison Thomas III

Lonnie C. Turner

Richard E. Ulmer

Fred Ursery

Glenn Vasser

Magistrate Judge Joe Volpe

Wyman R. (“Rick”) Wade, Jr.

Stan L. Warrick

John Dewey Watson

Todd C. Watson

Richard N. Watts

Phillip Wells

David H. Williams

W. Jackson Williams, Jr.

Wayne Williams

Judge Billy Roy Wilson

Jeffery D. Wood

Daniel H. Woods

Judge Wm. Randal Wright

Steven S. Zega

Bethune

Bird A. Bird S. Blackman

Brown Burch Butt Camp

Carlisle Coulter Curry

Anderson O. Anderson P. Badami Bailey Beck Benson

Bridgforth

Dodd Elliot Downs

Gitelman

Graves Griggs Gruber Wa. Gruber Wi. Guthrie

Barnes

Haught Henry

Hill Hobbs

Hyden James Jones Kees Leathers Kraska

Danielson Holt

Fleming

Baumgarten

Diaz Claycomb

Cameron

Pettus

Ursery

Ray Watts

Raines

Morton Meeks

McKay

McMenis

Meridith

McGough

Williams D. Wade

Suskie

Nussbaum

Purvis

McKinney

Parker

Muldrow

Vasser

Ligon

ArkBar’s Statement of Ownership for USPS is printed here. PS Form 3526 is required by the Post Office annually to show proof of continued eligibility for mailing under a Periodical Permit.

January 27th

Deadline for submission of completed nomination forms to the Arkansas Bar Association’s Secretary

A Call to Leadership Election Cycle Timeline

February 10th Deadline for mailing of ballots in contested races

March 3rd Deadline for receipt of signed ballots

Nominations are being collected for the Office of Secretary and American Bar Association Delegate positions. Nominating petitions for the office of President-Elect are due the first Monday in October 2025. The next President-Elect Designee will come from Bar District A. Contact Karen Hutchins at 501-801-5663 for information on these positions.

Boone, Carroll, Crawford, Franklin, Johnson, Logan, Madison, Newton, Sebastian B9-15 28 9 Pulaski

4 2 Baxter, Cleburne, Conway, Faulkner, Fulton, Independence, Izard, Jackson, Lawrence, Marion, Perry, Pope, Randolph, Searcy, Sharp, Stone, Van Buren, White, Yell

4 1 Clay, Craighead, Crittenden, Cross, Greene, Lee, Mississippi, Monroe, Poinsett, Prairie, St. Francis, Woodruff

Arkansas, Ashley, Bradley, Calhoun, Chicot, Clark, Cleveland, Columbia, Dallas, Desha, Drew, Grant, Jefferson, Lincoln, Lonoke, Ouachita, Phillips, Union

Garland, Hempstead, Hot Spring, Howard, Lafayette, Little River, Miller, Montgomery, Nevada, Pike, Polk, Saline, Scott, Sevier

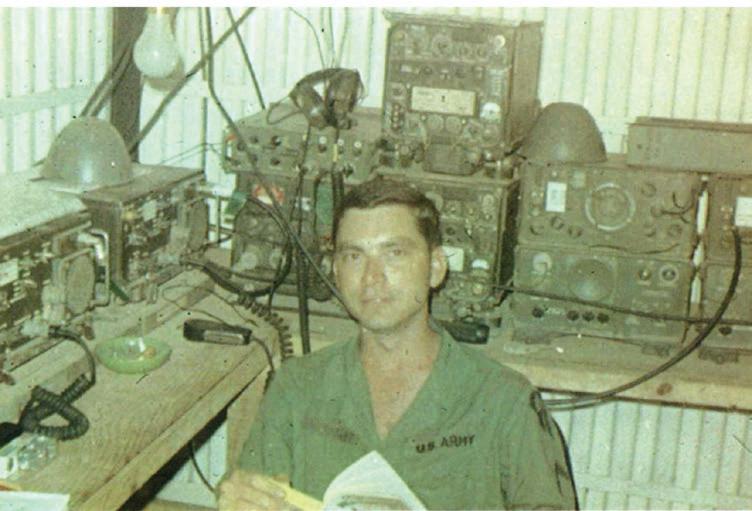

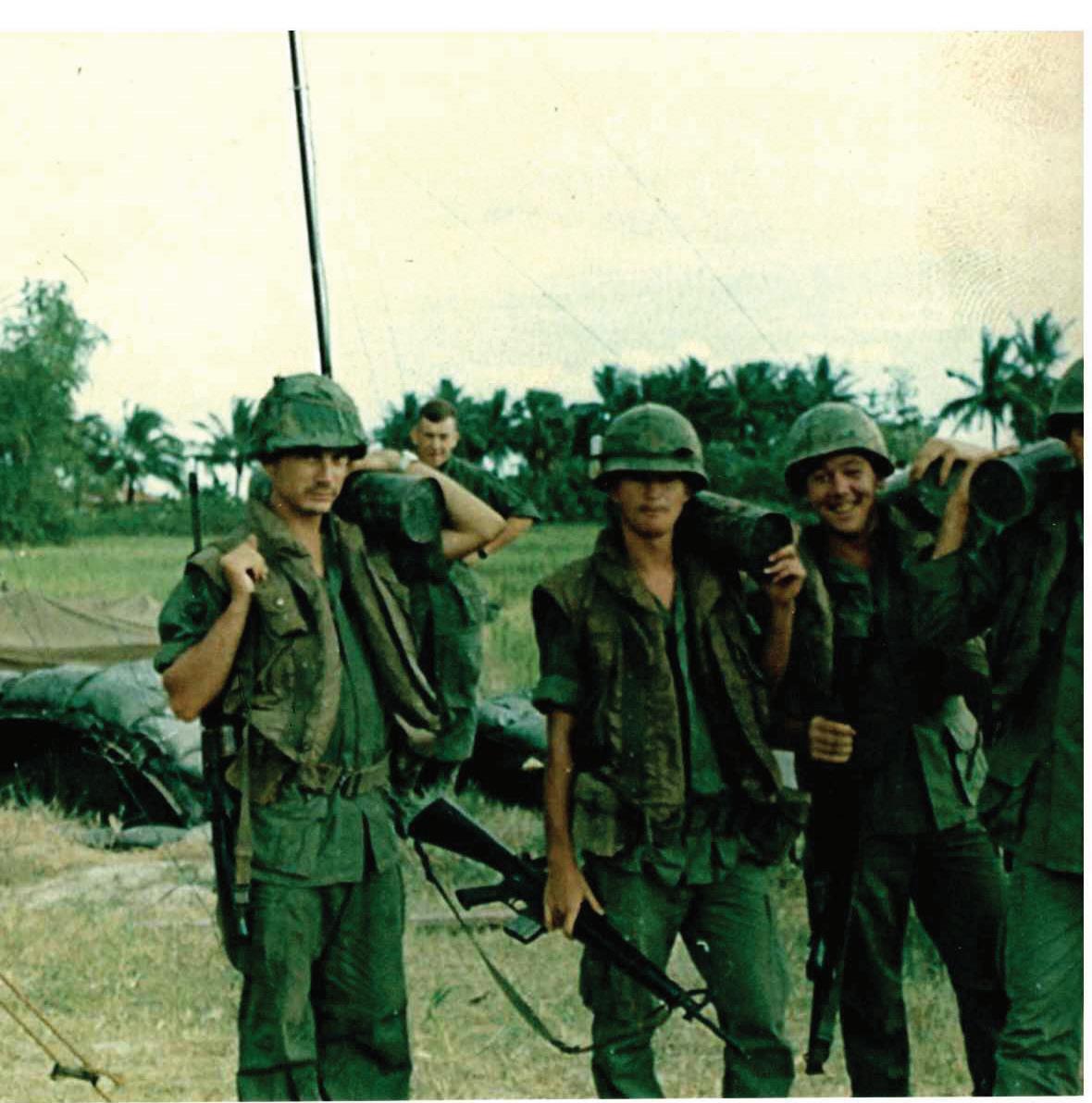

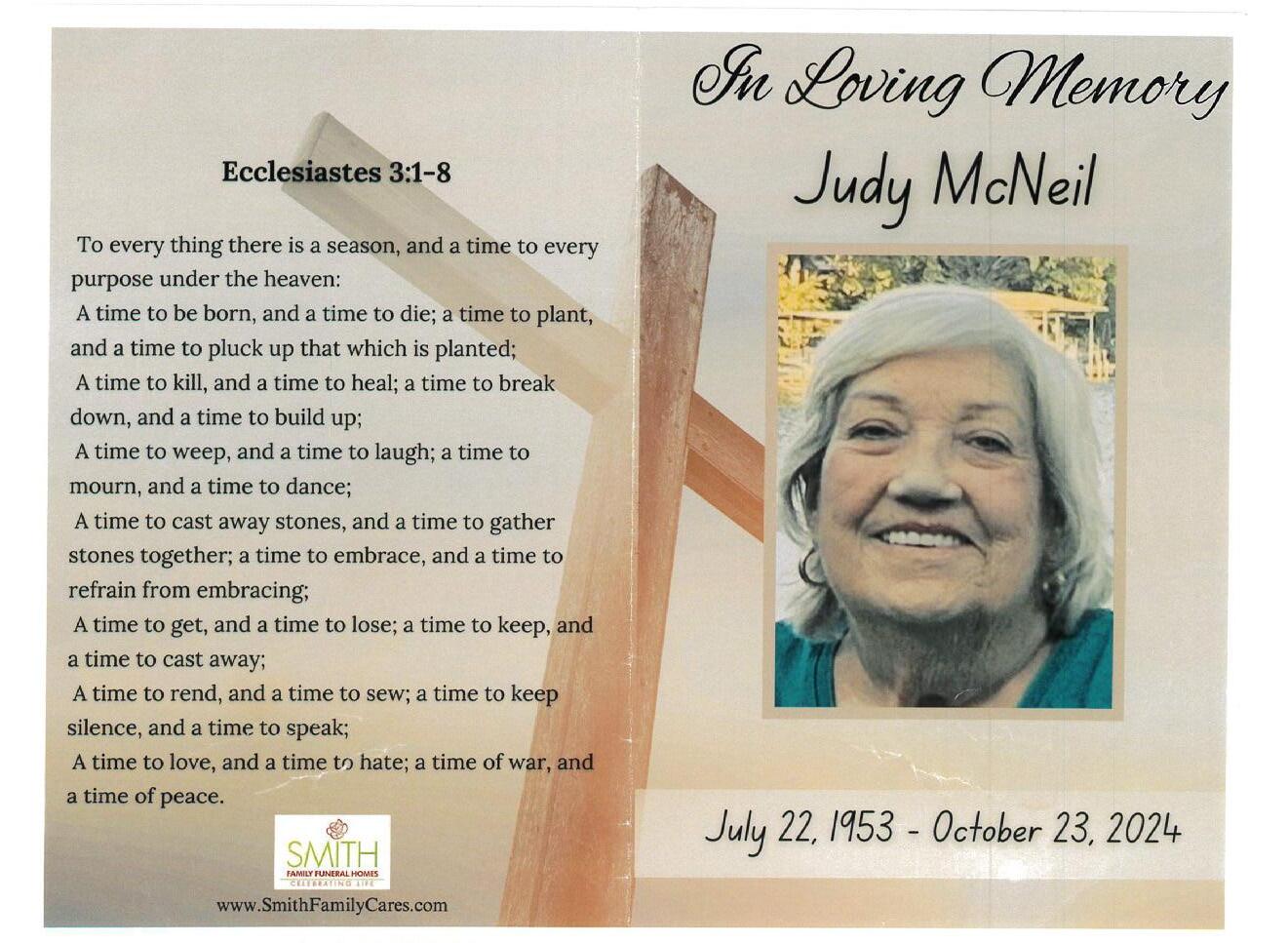

Specialist 5 (E-5) Fred Ursery 6th Battalion/77th Artillery in Cu Chi and Can Tho, Vietnam March

1, 1968-April 1, 1969

By Fred Ursery

“At the time I served there were about 500,000 troops there. Over 58,000 people were killed; that figure includes 592 Arkansans.”

Fred Ursery is Of Counsel with Friday, Eldredge & Clark in Little Rock. He served in the Vietnam War in 1968-1969.

When asked if I would write an article about my Vietnam service for the Fall issue of this magazine, which features members who have served in the military, I was honored and agreed to do so. By the next day I regretted my decision. However, I thought this might be an opportunity to tell some and remind others what this chapter in our history was like. And to recognize the many veterans who served. At the time I served there were about 500,000 troops there. Over 58,000 people were killed; that figure includes 592 Arkansans.

Yogi Berra is quoted as saying, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” So I can provide a bird’s-eye view of what I saw for whatever relevance it has to the bigger picture.

I graduated from law school in May of 1967. I was 25 years old and single. This was at the height of the Vietnam war. The military draft was in effect. This was before the draft lottery. I had been deferred by my local draft board through college and law school. Most of the men in my law school class were in the same boat. Everyone was scrambling to figure out what to do about the draft. Most people decided to take the bar exam first and then deal with the draft. No one was looking for a job.

Fortunately, I passed the Arkansas Bar in July of 1967. I then moved to the draft problem. My local draft board informed me that I would be drafted in December. There were very few law job opportunities for a July-to-December stint. I decided to go ahead and sign up for the military and get it out of the way. I tried to join the National Guard but at that point all of the units in the state were full and there were long waiting lists for any vacancies. I thought that since I was a lawyer I would just join the Army and sign up to be a member of the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. I learned that every newly-graduated lawyer in the country had the same idea. I was told that if I signed up for five years I would then be considered for a legal position. The military needed a lot of people, but it did not need many lawyers.

I was told that I could apply to join either the Infantry, Armor or Artillery. I chose the Artillery because it sounded like the lesser of three evils. I signed up for two years. In August of 1967 I was sworn in and put on a Greyhound bus for a ride to Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, for basic training. I was with a busload of other recruits. Most of the other people were just out of high school, so I was about seven years older than everyone else. We arrived at basic training, got our heads shorn,

and began eight weeks of physical training. It was an abrupt change to go from law school to the demands of a drill sergeant. I did have the sense to conceal that I was a lawyer.

After basic training, I was sent to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, for eight weeks of advanced training to learn how to be an artilleryman. After I completed my artillery training I was offered the opportunity to go to Officer Candidate School. At the end of my first 10 months in the Army, I would be a 2nd Lt. However, those first 10 months would not count toward my two-year commitment. I would have to serve two years and 10 months. I declined the opportunity and decided to serve my two years as an enlisted man.

At the end of my artillery training, I received my orders to go to Vietnam. These were the same orders received by 99% of my fellow soldiers. I arrived in Vietnam on March 1, 1968, just four days shy of my 26th birthday and several weeks after the Tet Offensive.

I was a PFC and I was sent to join the 6th Battalion/77th Artillery in Cu Chi, Vietnam. The Battalion was part of the 25th Infantry Division. Cu Chi was located about 30 miles northwest of Saigon. I was a replacement for someone who had served his one-year tour of duty

and rotated home. I soon learned that everyone’s main pre-occupation was to count off the days until your one-year tour of duty was over. In July of 1968 our battalion was transferred to Can Tho, Vietnam. It is located in the southern part of the country in the Mekong Delta

Our battalion was a 105-howitzer unit. A 105 howitzer could fire rounds that would go up to seven miles away. These rounds were fired in support of our infantry forces.

Fortunately, I was not assigned to the tough and dirty job of actually loading and firing the howitzer. I became a radio operator and was given the task of receiving the fire mission requests from the infantry and giving that information to our men so they could deliver the requested artillery fire. That was more nerve-racking than it sounds because we had to also keep track of where our troops and helicopters were located so we would not inadvertently shoot them.

When we were in Cu Chi, we were often attacked by Viet Cong (VC) mortars and rockets. Some of these landed nearby but most did not. We later learned that the VC had an elaborate system of tunnels under Cu Chi. The VC would come out and fire and then retire to the safety of the tunnels.

1968 was the deadliest year of the war. There were 16,899 Americans killed. May

“1968 was the deadliest year of the war. There were 16,899 Americans killed. May of 1968 was the deadliest month of the war. There were 2,169 killed.”

of 1968 was the deadliest month of the war. There were 2169 killed. When I was at Cu Chi our unit was located across from the 25th Infantry morgue, and there was a constant stream of trucks with Red Crosses on the side delivering dead bodies.

Since I had gone to law school, I was one of the oldest men in the unit. Most of the men were recent high school graduates, although there were some college graduates. When the men found out I was a lawyer I was given the nickname “Perry Mason.” After awhile, as new men rotated into the unit, many of the men actually thought that was my name.

I recall the saddest occasion for me during my tour. One of our helicopters crashed and all six of the people on board were killed. I knew all of them.

Malaria was also a problem. We were given pills to take about every two weeks which supposedly prevented malaria. However, the pills caused severe stomach aches. Many of the men acted as if they were taking the pill and then spit it out. One of the men in our unit died from malaria.

One of the more gruesome memories I have is that one of our men was riding in the back of a jeep in a field with his legs dangling over the back. The jeep hit a landmine and blew his leg sky high. The medic instructed us to go search for his leg.

Fortunately I was not the one who found it. The man bled to death before the medevac helicopter arrived.

On one occasion I was driving a truck in a convoy and the vehicle right ahead of me hit a road mine. The VC road mines were not as powerful as the ones today, and the men only sustained shrapnel wounds.

1968 was an eventful year back in the U.S. as well. One of my relatives gave me a subscription to the Arkansas Gazette which was delivered to me in Vietnam. Shortly after I arrived I read about LBJ’s decision not to run for re-election, the next month MLK was killed, and then

RFK was assassinated. The troops in Vietnam were beginning to wonder what was going on at home.

Most people do not ask me questions about my Vietnam service and that is fine with me. It is usually the younger people like my grandson who will go to the heart of the issue and ask, “How many people did you shoot?” He was disappointed when I told him none.

Most of my experience with “combat” was when our positions would receive sporadic rocket and mortar fire. On one rare occasion my unit was directly attacked at night by the VC. I could actually hear them hollering but never saw them. Our men were able to lower our howitzers and fire at them at point blank range with beehive rounds. We were also able to secure the assistance of a Cobra helicopter gunship which arrived and used its awesome firepower. A friend of mine told me that he counted over 50 VC bodies the next morning. I took his word for it. He did show me a pair of sandals made out of cut up tire treads that he had taken off one of the VC. My only involvement in this incident was watching the Cobra gunship in action.

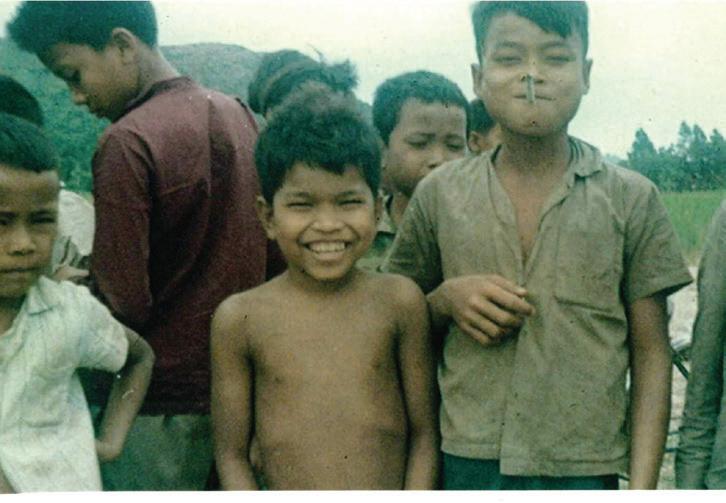

My most vivid memories of Vietnam are the children. Whenever we were out in the field, the children would appear out of nowhere and want to eat our C-rations and smoke the cigarettes which were included. The C-rations were not that good anyway, but it was impossible to eat

with a young kid asking for your food. The most popular item in the C-rations was the canned peaches. The only problem was that, as soon as you opened the can, the flies descended on the syrup. When I arrived in Vietnam I was issued an M-16 automatic rifle. I spent a lot of time taking it apart and cleaning it. Fortunately, I never had to use it. One of my Vietnam veteran friends said recently on Facebook: “I was glad when the government took my automatic rifle from me.”

I ended up serving 13 months in Vietnam. The Army had a rule that if you returned to the U.S. with six months or less left on your two years you would be discharged. I made the bet that one additional month in Vietnam would not be as bad as six months in Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. I returned to the U.S. and was discharged as a Specialist 5 (E-5), which was the equivalent of a sergeant, on April Fool’s Day 1969. On May 1, 1969, I joined the Friday Firm. The main benefit I get today for my service is free hearing aids from the VA.

I know that a number of the current members of our association served in Vietnam. Some were wounded and many were decorated for their service. They are recognized elsewhere in this edition. I hope that this article will help remind our members of this difficult time in our history and the terrible loss of life. ■

Unraveling the Facts. Delivering the Truth.

What We Offer

Expert Testimony: Unbiased, clear, and professional expert testimony in court to support your legal cases

Forensic Investigations: Comprehensive analysis of accidents, mechanical failures, product defects, and more.

Detailed Reports: Thorough and scientifically backed reports that stand up to legal scrutiny

Consultation Services: Collaborate with attorneys to develop a sound legal strategy with solid engineering expertise.

Why Choose Us?

Years of Experience: Our team of forensic engineers brings years of hands-on experience in the field.

Credibility in Court: Trusted by top law firms for delivering concise, accurate, and compelling testimony that juries and judges can understand

Timely & Professional Service: We work diligently to meet your deadlines while maintaining the highest quality standards

Expert Witness Testimony

Mechanical Equipment Failures

VAR- Accident Reconstruction

Agriculture Accidents and Equipment

HVAC Fires & Product Liability

UALR William H. Bowen School of Law Veterans Legal Services Clinic

By Professor Rebecca Feldmann

The Veterans Legal Services Clinic (VLSC) is the newest of the six in-house clinics at the University of Arkansas - Little Rock (UALR) William H. Bowen School of Law (Bowen). The VLSC, and the clinical program more broadly, embody Bowen’s commitment to its core values of access to justice, public service, and professionalism. The idea for a clinic at Bowen that would cater exclusively to the needs of Arkansas veterans was the brainchild of Bowen graduate Simon Kelly, now a veterans disability lawyer with Rob Levine Law.1 In 2019, the law school received the funding that would make Kelly’s dream a reality.2

After meeting with community partners and assessing the needs of the population the clinic intended to serve, the VLSC began taking applications from veterans in the Fall of 2020. The first class of VLSC students began working with their clients in January 2021. Since that time, the VLSC has provided trauma-informed advocacy for veterans who have endured service-related injuries, while providing law students a service-oriented learning experience. To date, 52 students have taken the clinic. As Kelly envisioned, the students work, under the supervision of a licensed and VA-accredited attorney, to help veterans navigate the VA compensation process. Additionally, clinic students help correct errors or injustice in their discharge paperwork, based on changes in military policy surrounding the treatment of mental health conditions.

I. The VLSC’s Services

The VLSC serves veterans in three ways—through our in-house clinic, through our Pro Bono Program, and through resources we provide on our website.

A. In-house Clinic

Rebecca Feldmann is the Director of the Veterans Legal Services Clinic at the William H. Bowen School of Law.

The VLSC’s in-house clinic serves both to provide much-needed legal assistance to Arkansas veterans and to give Bowen students a critical, hands-on learning experience. In our in-house clinic, we provide trauma-informed advocacy on behalf of veterans with disabilities related to their service, helping them navigate the VA appeals process. Additionally, we represent veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health conditions who received a less than fully honorable discharge as a result of behaviors associated with that condition. The clinic helps these veterans apply to the Department of Defense (DoD) boards to upgrade their discharge status and make any other necessary corrections to their military records, based on policy guidance issued by the DoD beginning in 2014.3

Under the supervision of a VA-accredited attorney, students in the clinic work on discharge upgrades and VA disability claim appeals for veterans with PTSD, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or another mental health condition related to their service. The clinic focuses on providing traumainformed advocacy to its clients, who include survivors of military sexual trauma (MST). For these veterans, having representation can make a world of difference in their ability to access life-altering benefits.

So-called “bad paper”—i.e., less than fully honorable discharges from the military— frequently co-occur with military-related trauma, such as PTSD, MST, and TBI.4 And veterans with bad paper are more likely to experience homelessness, more likely to have a substance use disorder, more likely to commit suicide, and more likely to experience incarceration.5 Thus, a core part of the clinic’s mission, since its inception, has been to serve those individuals whose less than fully honorable discharges coincided with an in-service traumatic event. In doing so, our clinic has worked in conjunction with community partners like the VA Day Treatment Center to both provide direct services to eligible

RELATIONSHIPS ARE OUR FOUNDATION

We partner with attorneys, CPAs and other financial advisors to help their clients achieve philanthropic goals. The Foundation provides expertise and tools to maximize tax benefits while achieving the greatest impact for local programs. The process is easy, flexible and efficient. Arkansas Community Foundation: engaging people, connecting resources and inspiring solutions to build Arkansas communities.

must meet a minimum number of yearly CLE requirements, as detailed at 38 C.F.R. § 14.629(b)(iii)-(iv) (2023). To assist attorneys with this requirement, VLSC provides free CLE opportunities for its volunteers. For example, each year since 2021, we have partnered with the Attorney General’s office and the Arkansas Army National Guard, Office of Legal Assistance to provide CLEs on topics specifically impacting veterans. In addition, the VLSC regularly hosts symposia, which provide volunteers the opportunity to receive CLE credit, practical advice related to veterans’ law, and an opportunity to network.7 We are excited to partner with even more Arkansas lawyers to expand our services to veterans across the state in the years to come!

More information about the Veterans Legal Services Clinic can be found at https:// ualr.edu/law/clinical-programs/veterans-legalservices-clinic/. To volunteer, you can fill out the form at https://docs.google.com/forms/d/ e/1FAIpQLSePkUSnqbABFnBKNl7mxsv6o VtXpprHzs9q9FOMrtFRmJE7Ng/viewform or contact Zach Baumgarten, VLSC Pro Bono Program Director, at zjbaumgarten@ ualr.edu. For other questions, you can contact the VLSC Director, Rebecca Feldmann, at rlfeldmann@ualr.edu.

Endnotes:

1. Tracy Courage, Bowen School of Law announces new Veterans Legal Services Clinic, University of Arkansas at Little Rock (Aug. 20, 2019), https://ualr.edu/newsarchive/2019/08/20/veterans-legal-clinic/; Rob Levine Law, Attorneys, https://roblevine. com/department/attorneys/.

2. Tracy Courage, Bowen School of Law announces new Veterans Legal Services Clinic, University of Arkansas at Little Rock (Aug. 20, 2019), https://ualr.edu/newsarchive/2019/08/20/veterans-legal-clinic/; John Moritz, Law school gets veterans clinic Arkansas Democrat Gazette (Aug. 21, 2019), https://www.arkansasonline.com/ news/2019/aug/21/law-school-gets-veteransclinic-2019082/.

3. See Memorandum from Chuck Hagel, Sec'y of Def., U.S. Dep't of Def., to Sec'ys of the Mil. Dep'ts attach. 2 (Sept. 3, 2014), https://arba.army.pentagon.mil/documents/ SECDEF%20Guidance%20to%20 BCMRs%20re%20Vets%20Claiming%20 PTSD.pdf (“Hagel Memo”); Memorandum

from Brad Carson, Acting Under Sec'y of Def. for Pers. & Readiness, U.S. Dep't of Def., to Sec'ys of the Mil. Dep'ts 1 (Feb. 24, 2016), https://afrba-portal.cce.af.mil/app/ assets/2016-Carson-Memo-24-Feb-2016.pdf (“Carson Memo”); Memorandum from A.M. Kurta, Acting Under Sec'y of Def. for Pers. & Readiness, U.S. Dep't of Def., to Sec'ys of the Mil. Dep'ts 1 (Aug. 25, 2017), https:// dod.defense.gov/portals/1/documents/pubs/ clarifying-guidance-to-military-dischargereview-boards.pdf (“Kurta Memo”); Memorandum from Robert L. Wilkie, Under Sec'y of Def., U.S. Dep't of Def., to Sec'ys of the Mil. Dep'ts 1 (July 25, 2018), https:// afrba-portal.cce.af.mil/app/assets/2018Wilkie-Memo-25-Jul-2018-DRB-Guidance. pdf (“Wilkie Memo”).

4. See Hugh McLean, Discharged and Discarded: The Collateral Consequences of a Less-than-Honorable Military Discharge, 121 Colum. L. Rev. 2203, 2205–06 (2021); Randall B. Williamson, GAO-17-260, DOD Health: Actions Needed to Ensure PostTraumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury Are Considered in Misconduct Separations 12, U.S. Gov't Accountability

Off. (2017); Swords to Plowshares, Veterans and Bad Paper Fact Sheet (June 2015), available at swords-to-plowshares.org.

5. Underserved: How the VA Wrongfully Excludes Veterans with Bad-Paper Discharges 21–22, Veterans Legal Clinic, Legal Svcs. Ctr. of Harvard Law Sch. (2016), available at swords-to-plowshares.org.

6. The VA’s Office of General Counsel provides the application for accreditation, as well as detailed instructions about how to apply, on its website. Accreditation, Discipline, & Fees Program, U.S. Dept. of Veterans Aff., Office of General Counsel, https:// www.va.gov/ogc/accreditation.asp (Sept. 17, 2024); How to Apply for VA Accreditation as An Attorney or Claims Agent, U.S. Dept. of Veterans Aff., VA Accreditation Program, https://www.va.gov/OGC/docs/ Accred/HowtoApplyforAccreditation.pdf.

7. See 2023 Veterans Legal Services Clinic Symposium, UALR William H. Bowen School of Law, https://ualr.edu/law/ clinical-programs/veterans-legal-servicesclinic/2023-veterans-legal-services-clinicsymposium/. ■

Legislative Hearings: Playing by the Right Rules

By Frank Arey and Emily White

Frank Arey opened an appellate practice in Little Rock after serving 16 years as Arkansas Legislative Audit's legal counsel.

Emily White currently serves as legal counsel for Arkansas Legislative Audit.

Legislative committee hearings might feel familiar to attorneys. Committee chairs preside more or less in compliance with known rules, calling witnesses and recognizing legislators for questions. Witnesses testify and provide documents; on rare occasions they might be under subpoena, and they may swear an oath prior to testifying. Legislators pose questions in pursuit of relevant information.

This familiarity can be deceptive. As one expert observed about congressional investigations, legislative committees utilize a “legal process with unique and explicit rules and procedures.”1 Most hearings don’t reveal the very real differences between legislative and judicial rules and procedures. But sometimes those differences matter—and they can be substantial. For example, witnesses don’t have a right to counsel, evidentiary privileges are not applicable in legislative proceedings, and relevance is a much broader concept when applied to legislative inquiries.

This article’s goal is to illustrate some differences between legislative and judicial rules and procedures. The context is presumed to be hearings involving legislative oversight or legislative investigations. Examples include an attorney appearing before the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee with a client involved in an audit finding, or with a contractor involved in a transaction under review by the Joint Performance Review Committee. Law from other jurisdictions will be cited where Arkansas law does not yet address an issue. At the end of this article there are suggested resources for further study.

Witnesses do not have the right to have an attorney present. Your legislative witness client does not have the right to your presence. A legislative hearing is not a trial. Your client is a witness, not a party.

An 1885 decision of the Court of Appeals of New York expounds on this observation. A legislative committee pressed contempt charges against a witness; he defended his actions, in part, with a claim “that the committee refused to recognize his right to be attended by counsel….”2 But the appellate court was “of opinion that he had no constitutional or legal right to the aid of counsel on such examination.”3

“Take advantage of applicable resources to prepare for legislative hearings. There are resources available to interested attorneys.”

But here [the witness] was not on trial, nor was he a party, but he was a mere witness … and there was no trial pending against anyone. As well might a witness, examined before a grand jury conducting an investigation of a charge against another person, with a view to his indictment, claim the right to be attended by counsel. We do not think that a mere witness has that right.4

As the Supreme Court of New York stated, “a witness has no right to counsel … in a legislative inquiry….”5 Nonetheless, attorneys may be present and participate in Arkansas legislative proceedings—to some degree—as a matter of legislative grace. Committee chairs have the discretion to permit such participation.6 Committee rules can also permit attorney participation. At this writing, the rules of Arkansas’s Legislative Joint Auditing Committee provide: “A witness may be accompanied by counsel of the witness’s own choosing, who may advise the witness as to the witness’s rights, subject to reasonable limitations … to prevent obstruction or interference with the orderly conduct of the hearing.”7

Attorney participation, if allowed, can be very limited. Attorneys should not expect to do more than advise their clients

during legislative proceedings. Because legislative investigations are not trials potentially resulting in criminal sanctions, the Sixth Amendment confrontation right does not apply, and witnesses do not have the right to cross-examine others or to present evidence in their own behalf.8 Legislative rules or the committee’s discretion will govern the order of testimony and the ability to make opening or closing statements, offer evidence, or cross-examine other witnesses.9 Your ability to answer for your client is at the chair’s discretion.

If permitted to advise a client under examination, attorneys should avoid “coaching” that witness.10 Legislators are generally more interested in hearing from witnesses, not their attorneys, in the authors’ experience.

Attorneys will need to gauge whether a particular hearing requires a higher level of preparation, even if their role is likely to be limited. Most hearings won’t require extensive participation by an attorney. But there are instances when a witness might benefit from counsel’s advice about matters such as the privilege against selfincrimination, whistleblower protection, or perjury charges arising out of the witness’s testimony.11 On these occasions, to paraphrase Brendan Sullivan’s retort during the Iran-Contra hearings, the attorney isn’t there to be a potted plant.12

The Arkansas General Assembly makes its own rules. Ark. Const. art. V, § 12, provides that “[e]ach house shall have power to determine the rules of its proceedings….” This provision authorizes the General Assembly to determine the propriety and effect of any action taken in the exercise of any power, transaction of any business, or performance of any duty.13 For example, although the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act requires open meetings of governing bodies, the “rules of proceedings” provision likely makes any legislative decision to close a committee meeting nonjusticiable.14

Attorneys participating in legislative proceedings must be familiar with legislative rules. Rules applicable in judicial proceedings don’t apply unless adopted by the General Assembly. Legislatures “have the last word on their proceedings” so that “[c]ourt-made rules of evidence do not govern; most striking, legislative hearings need not conform to rules against hearsay.”15

Although it does not refer to the “rules of proceedings” provision, a 2014 decision of the Arkansas Supreme Court provides an example of this principle at work.16 A trial court found the defendant guilty of criminal contempt for not complying with the Legislative Auditor’s subpoena. The defendant appealed, arguing among other points that the subpoena was defective for noncompliance with Ark. R. Civ. P. 45(d).

The Supreme Court rejected this argument, noting that the Code section authorizing the subpoena “does not reference any other applicable procedural rules” and that the defendant wanted the court to “read a requirement into the statute that the legislature has not intended.”17 Thus, legislative subpoenas need not comply with judicial rules governing subpoenas unless the General Assembly expressly assents. Legislative rules are subject to constitutional provisions.18 Otherwise, the rulemaking power of the General Assembly is plenary, whether or not it subsequently complies with those rules.

Subject to the restrictions imposed by the constitution each branch of the legislature is free to adopt any rules it thinks desirable. It follows, both as a matter of logic and as a matter of law, that each house is equally free to determine the extent to which it will adhere to its self-imposed regulations.19

Attorneys should be familiar with legislative rules of proceedings, even if they are not meticulously followed.

Evidentiary privileges do not apply in legislative proceedings. Attorneys must carefully consider how their clients’ evidentiary privileges might be affected if those clients testify in a legislative proceeding.20 Evidentiary privileges that protect the disclosure of communications made in certain confidential relationships— such as the attorney-client or spousal relationships—are set forth in rules of evidence adopted by the Arkansas Supreme Court and are only applicable in judicial proceedings.21 The court stated in a different context:

[T]he attorney-client privilege, A.R.E. Rule 502, is an evidentiary rule limited to court proceedings. A.R.E. Rule 101. It has no application outside of court proceedings and, therefore, cannot create an exception to a substantive act.22

Because evidentiary privileges are judicial rules adopted by the judiciary for judicial proceedings, they are not applicable in legislative proceedings unless adopted by the General Assembly or recognized at a chair’s or committee’s discretion.23 The General Assembly sets its own rules of proceedings.24 Any judicial attempt to impose nonconstitutional rules in legislative proceedings, such as the use of evidentiary privileges, would be contrary to separation of powers principles.25

Relevance is a much broader concept in legislative proceedings. A legislative committee can obtain information when (1) the subject of the committee’s investigation is proper for legislative inquiry, and (2) the information is relevant to that subject.26 Attorneys should leave the judicial understanding of relevance outside the committee hearing room.

A judicial inquiry relates to a case, and the evidence to be admissible must be measured by the narrow limits of the pleadings. A legislative inquiry anticipates all possible cases which may arise thereunder and the evidence admissible must be responsive to the scope of the inquiry, which generally is very broad.27

One Massachusetts opinion cautions that “too rigid or exacting an approach” to relevance could unduly impede a legislative inquiry, and that past cases applied a “plainly irrelevant” standard to test relevance in legislative investigations.28 This broader approach to relevance can matter if a witness chooses not to answer a question because it is not pertinent or relevant to the legislative inquiry. This is one possible defense to contempt charges: a witness can only be found in contempt for refusing to answer a question if the testimony sought is pertinent and material to the subject of the legislative inquiry.29 A broader conception of relevance may well lessen the availability of this particular defense by making it more difficult to argue impertinence or immateriality.

Take advantage of applicable resources to prepare for legislative hearings. There are resources available to interested attorneys. Simply watching hearings of the committee you will appear before can be instructive—just as attorneys should know the judges they appear before, they should know the committee, too. Archived hearings can be found on the Arkansas General Assembly’s website.30 In addition to specific committee rules, attorneys may want to consult Mason’s Manual of Legislative Procedure, published by the National Conference of State Legislatures— in the absence of applicable rules, Arkansas’s legislative committees may consult this volume.31 A pair of law review articles may also be helpful for starting research.32 Legislative staff assigned to the committee your client will appear before are a valuable resource.

Conclusion. Most legislative hearings will not justify an attorney’s presence. Yet, problematic issues arise often enough33 to caution that attorneys with clients testifying before legislative committees should at least consider whether their presence is necessary. And to do that effectively requires an appreciation of the differences between legislative and judicial rules and procedures.

The personal opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. They are not official positions of the Arkansas General Assembly or its committees, members, or staff.

Endnotes:

1. James Hamilton, Robert F. Muse, and Kevin R. Amer, Congressional Investigations: Politics and Process, 44 American Crim. L. Rev. 1115, 1117 (2007).

2. People ex rel. McDonald v. Keeler, 2 N.E. 615, 626 (N.Y. 1885).

3. Id.

4. Id.

5. In re Withrow, 28 N.Y.S.2d 223, 228 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1941).

6. National Conference of State Legislatures, Mason’s Manual of Legislative Procedure §§ 611, 638 (2020) (hereinafter Mason’s Manual).

7. Legislative Joint Auditing Committee, Rules of the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee V.G.3 (2018); cf. Congressional

Research Service, RL30240, Congressional Oversight Manual 41 (2022) (hereinafter Oversight Manual) (while the Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of counsel may not apply, congressional rules may afford witnesses a limited form of that right).

8. See In re Withrow, 28 N.Y.S.2d at 228 (“a witness has no legal right … to cross-examine his accusers in a legislative inquiry”); cf. United States v. Fort, 443 F.2d 670, 678–82 (D.C. Cir. 1970) (explaining Sixth Amendment’s inapplicability to routine congressional investigations).

9. James Willard Hurst, The Legislative Branch and the Supreme Court, 5 U. Ark. Little Rock L.J. 487, 496 (1982); cf. Oversight Manual, 40–41 (witnesses at congressional hearings have no right to make an opening statement, offer evidence, or cross-examine others, but a committee can permit this at its discretion).

10. Cf. Oversight Manual, 41 (noting congressional committee rules to prevent “coaching”).

11. An Arkansas-based example can be found in John Diamond, Please Delete (2015). After two witnesses gave conflicting testimony to the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee while under oath, a prosecuting attorney announced that he would review the matter; ultimately, he decided not to pursue perjury charges for lack of jurisdiction. Id. at 211–12, 224–28, 235, 253–54. One of the witnesses may have had an attorney present – but this is an example of when legal advice was appropriate.

12. Quoted in Lance Cole and Stanley M. Brand, Congressional Investigations and Oversight 308 (2011).

13. See Mason’s Manual, § 3, para. 2. 14. John J. Watkins et al., The Arkansas Freedom of Information Act § 2.02[b] (6th ed. 2017); see Mason’s Manual, § 15, para. 4 (stating general rule).

15. Hurst, supra note 9, at 496.

16. Valley v. Pulaski Co. Circ. Ct., Third Div., 2014 Ark. 112, 431 S.W.3d 916.

17. Id. at 9, 431 S.W.3d at 922.

18. Mason’s Manual, §§ 2, para. 3, 6, para. 2. 19. Bradley Lumber Co. v. Cheney, 226 Ark. 857, 859, 295 S.W.2d 765, 766–67 (1956).

20. Guidance relating to congressional investigations may be useful. See, e.g.,

James Cole et al., Exploring Every Avenue: The Dilemma Posed by Attorney-Client Assertions in Congress, 8 Appalachian J. Law 157 (2009) (exploring attorney options). The United States Supreme Court’s dicta in its 2020 Trump v. Mazars opinion, regarding evidentiary privileges and congressional proceedings, is best read as suggesting that these privileges are not waived by disclosure in such proceedings. Trump v. Mazars USA, 140 S. Ct. 2019, 2032 (2020); David Rapallo, House Rules: Congress and the Attorney-Client Privilege, 100 Wash. U. L. Rev. 455, 506–15 (2022) (advancing a “charitable” reading of Mazars that “complying with mandatory demands from Congress does not constitute a general waiver of the privilege in separate judicial proceedings”). The Congressional Oversight Manual rejects reading Mazars as permitting common-law privileges to impede the congressional power of inquiry. Oversight Manual, 59–61.

21. See Ark. R. Evid. art. V (setting forth evidentiary privileges); Ark. R. Evid. 101 (“These rules govern proceedings in the courts of this State….”); Morton Gitelman, Commentary: How the Arkansas Supreme Court Raised the Dead, 1987 Ark. L. Notes 93 (discussing adoption of the rules of evidence).

22. McCambridge v. Little Rock, 298 Ark. 219, 226, 766 S.W.2d 909, 912 (1989).

23. See Hurst, supra note 9, at 496 (“[c]ourt-made rules of evidence do not govern” in legislative proceedings); cf. Edward J. Imwinkelried, Evidentiary Foundations § 7.02 (11th ed. 2020) (“[I]n a large number of states and in federal practice, the privileges recognized by the courts do not apply to hearings conducted by legislative committees.”).

24. Ark. Const. art. V, § 12.

25. Ark. Const. art. IV, § 2 (no members of one department of government can exercise any power belonging to either of the other two departments); cf. Michael D. Bopp & DeLisa Lay, The Availability of Common Law Privileges for Witnesses in Congressional Investigations, 35 Harv. J. L. & Pub. Pol’y 897, 932 (2012) (“[B]ecause the courts cannot dictate the rules of Congress’s proceedings, parties must realize that the discretion to compel production of privileged material lies with Congress.”).

26. This rule is explored further in D. Franklin Arey, III, Legislative Oversight Proceedings of the Arkansas General Assembly: Issues and Procedures, 45 U. Ark. Little Rock L. Rev. 593, 606–10 (2023).

27. Townsend v. United States, 95 F.2d 352, 361 (D.C. Cir. 1938).

28. Ward v. Peabody, 405 N.E.2d 973, 978, 978 n.5 (Mass. 1980).

29. See Mason’s Manual, § 801, para. 4. 30. https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/.

31. See, e.g., Legislative Joint Auditing Committee, Rules of the Legislative Joint Auditing Committee V.A (2018) (“Except as otherwise specified by these rules,” the committee’s proceedings shall conform to applicable Senate and House rules, “together with Mason’s Manual of Legislative Procedure.”).

32. See Hurst, supra note 9; Arey, supra note 26.

33. Examples include Diamond, supra note 11; Michael R. Wickline, Shoffner, aide tell panel different stories, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Sept. 18, 2012; Neal Early, Lawmakers call for audit of Augusta after accusations of misused funds, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Aug. 12, 2023. ■

By Brenda Stallings

Juvenile Circuit Court 101

"The

purpose of Juvenile Circuit Court is rehabilitation."

Brenda Stallings is a Deputy Public Defender in Little Rock. She is also an Adjunct Professor at William H. Bowen School of Law.

Many attorneys tend to shy away from Juvenile Court, often citing that cases rarely reach closure, it can be inconvenient, and the procedural rules differ from Criminal Circuit Court. Juvenile Court is, indeed, a unique court within the legal system. Although it is not classified as a specialty court, many practitioners would likely refer to it as such. Why? Juvenile Circuit Court operates under its own set of rules, as outlined in the Arkansas Children and Family Laws Annotated Code1 (The Code). The Code, which I often describe as the “Bible” of Juvenile Circuit Court, serves as the authoritative source that governs our purpose and dictates what can and cannot be done in juvenile cases. I never attend court without it. Due to these specialized rules and timelines, Juvenile Circuit Court closely resembles a specialty court within the Arkansas judicial system.

This article will provide a brief overview of the key differences between Juvenile Circuit Court and Criminal Circuit Court, including the types of cases handled, the court’s purpose and goals, the roles of the parties involved, and the distinct terminology, rules, and timelines that characterize Juvenile Circuit Court.

Attorneys will find that Juvenile Circuit Court is more informal than Criminal Circuit Court. The informalities may include things such as not having to stand when speaking, having a smaller courtroom and having bean bags in the courtroom for smaller children to sit on. The informality does not lessen the seriousness of the court, the cases, or the possible consequences to neglectful parents or delinquent children. The informalities also do not change the fact that the rules of evidence and criminal procedure still apply.

The purpose of Juvenile Circuit Court is rehabilitation 2 This purpose is significantly different from the purpose of Criminal Circuit Court. Criminal Circuit Court is more akin to retributive punishment. The goal of Juvenile Circuit Court is “to assure that all juveniles brought to the attention of the courts receive the guidance, care and control, preferably in each juvenile’s own home when the juvenile’s health and safety are not at risk, that will best serve the emotional, mental and physical welfare of the juvenile and the best interest of the state.”3

There are four basic types of juvenile cases in Juvenile Circuit Court: dependency-neglect, delinquency, Family in Need of Services (FINS), and truancy. Dependency-neglect cases are where the child is the victim either from abuse, abandonment, neglect and the like or where the parents are no longer available and there is no caretaker available. Delinquency cases are where a juvenile has been charged criminally for violating an Arkansas criminal law.4 Status offense case means these cases are applicable to children from birth to 18 years of age. FINS cases and truancy cases are status offense cases. FINS are cases where the parent/guardian or

“Juvenile Circuit Court proceedings are both intricate and of significant importance. It is essential to approach these cases with the utmost respect and diligence.”

the child needs services of the court. These cases traditionally focus on the child being habitually disobedient, skipping school or leaving home without permission; however, a child can and may bring a FINS case upon their parent/guardian for services for the family. Truancy cases are brought when a child between the ages of 5-17 is not regularly attending school. Arkansas law mandates school attendance.5 Children between the ages of 5-17 must attend public, private, charter, parochial or homeschool.6 If a child fails to attend school regularly, the school may send information to the prosecutor’s office for a truancy petition to be filed against the child and parent.

Juvenile Circuit Court uses terminology that may be unfamiliar to attorneys who don’t routinely practice in juvenile court: Adjudication means trial; a not true plea means not guilty; a true plea means guilty; a true plea or admission to the charges means the juvenile is delinquent, and delinquent means guilty. Once a juvenile is found delinquent, the judge will enter a disposition which means sentence. Dispositional alternatives are the various sentencing options in Juvenile Circuit Court. Structured Assessment for Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) is the risk and needs assessment which is ordered for the purpose of disposition.7 An Extended

Juvenile Jurisdication (EJJ) offender is a juvenile that is subject to the jurisdiction and protections of Juvenile Circuit Court but could be sentenced to the Department of Corrections, if the court deems the juvenile is not amenable to rehabilitation.8

An Attorney ad litem is an attorney who is appointed to represent the best interest of the juvenile in dependency-neglect cases.9 Juveniles historically didn’t have the same constitutional rights as adults. Fiftyseven years ago, the Supreme Court of the United States decided In Re Gault, 10 which changed the trajectory of juvenile court in every state. In Re Gault gave juveniles the right to counsel, the right to notice of charges to the parent and child, the right to confront witnesses and the right against self-incrimination.11

Juveniles who have been charged as adults are afforded the right to have a transfer hearing from Criminal Circuit Court to Juvenile Circuit Court. The Criminal Circuit Court case may be transferred to Juvenile Circuit Court or designated as an EJJ offender case.12 An EJJ offender designation allows Juvenile Circuit Court to conduct the court hearings and attempt rehabilitation of the juvenile, if the juvenile is found delinquent. If the court deems the juvenile is not amenable to rehabilitation, the juvenile could be sentenced to the Department of Corrections.13

One thing that is distinctive about Juvenile Circuit Court is that juveniles are not afforded a jury trial in their delinquency cases. The United States Supreme Court has stated that a right of a juvenile to a jury trial is not constitutional.14 The right to a jury trial is a statutory right determined by each state. In Arkansas, EJJ offenders are afforded the right to a jury trial.15 However, if the EJJ offender is found delinquent, the sentence phase is not conducted by the jury but by the Juvenile Circuit Court Judge.16

In juvenile delinquency cases, the State must prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt, the same as in Criminal Circuit Court.17 All appeals must be made in the time and manner provided by the Arkansas Rules of Appellate Procedure.18 As stated, the Rules of Evidence and Criminal Procedure apply in Juvenile Circuit Court. The burden of knowing the Arkansas Children and Family Laws Annotated and the Rules of Evidence and Criminal Procedure can be daunting to a new attorney or one who doesn’t practice in Juvenile Circuit Court often. I always suggest that attorneys learn the timelines that are applicable to Juvenile Circuit Court.

Time Constraints

In Juvenile Circuit Court, the rules regarding notice to parents, filing of the

charging petition, detention hearings, and detainment are significantly different from Criminal Circuit Court.

The intake officer has 24 hours to determine if the juvenile will be detained.19 Unlike in Criminal Circuit Court there is no bond hearing; juveniles are detained and have a detention hearing or they are released with a citation.20 When a juvenile is detained (taken into custody), the officer shall make every effort to notify the parents/ guardians of the juvenile’s detainment.21 Detainment is mandatory if the alleged charges deal with a gun or firearm.22

Once a juvenile is detained, a juvenile judge must hold a detention hearing within 72 hours of detention or, if the 72 hours ends on the weekend or holiday, on the next business day.23 “If no delinquency petition is filed within 24 hours after a detention hearing or 96 hours ends on a Saturday, Sunday or a holiday, at the close of the next business day, after an alleged delinquent juvenile is taken into custody, whichever is sooner, the alleged delinquent juvenile shall be discharged from custody, detention, or shelter care.”24

If a juvenile is detained after the detention hearings, the Court shall hold an adjudication, absent a waiver or continuance for good cause, no later than 14 days from the date of the detention.25

If a juvenile is adjudicated delinquent and the juvenile judge detained the juvenile, a disposition hearing shall be held within 14 days of the adjudication.26

A SAVRY assessment must be submitted to the parties seven days before the disposition hearing.27

The court shall conduct a transfer hearing within 30 days if the juvenile is detained and no longer than 90 days from the date of the motion to transfer.28

Burdens of Proof

The burdens of proof are different depending on the type of hearing held. The burden of proof in a detention hearing is clear and convincing evidence to determine if the juvenile should be released or detained.29 The burden of proof during an adjudication case is proof beyond a reasonable doubt.30 The burden of proof in a transfer hearing or termination of parental rights is clear and convincing evidence.31

The burden of proof is preponderance of the evidence in a dependency-neglect case, FINS case, EJJ designation hearing, probation revocation hearing, and to impose an adult sentence in an EJJ case.32

Who are the Players?

Who are the players in Juvenile Circuit Court and what roles do they play? The various parties include the juvenile, parents/ guardians, probation officer, defense attorney, prosecuting attorney, and attorney ad litem (addressed in the next section). Juveniles are the central characters. Juvenile Circuit Court can have jurisdiction over a juvenile in a FINS case from birth until 18 years of age;33 in truancy cases from 5-17 years of age;34 in dependency-neglect cases from birth to 18 years of age;35 and in delinquency cases from 10-18 years of age.36 In both dependency-neglect and delinquency cases, Juvenile Circuit Courts can extend jurisdiction up to the age of 21; however, a juvenile shall not under any circumstances remain under the court’s jurisdiction past 21 years of age.37

In Juvenile Circuit Court, the juvenile is the client. This can be difficult for a parent/ guardian or caretaker to understand. The relationship between the lawyer and juvenile is confidential. The lawyer works for and represents the child. This does not always sit well with parents. Parents usually feel they should have a bigger role in the decisionmaking process between the lawyer and the child. Parents can become emotional about the court process for various reasons: perhaps every time they come to court, they are losing wages; perhaps they don’t feel they should be punished for their child’s wrongdoing; perhaps they themselves have been traumatized and need therapy; or perhaps they are suffering from stress, grief, or a myriad of possible issues. It is important to be patient and thoroughly explain the court process to both the parents and the juvenile. Additionally, take the time to clearly outline your role and ethical responsibilities to them.

A parent/guardian or custodian must be present at all court appearances. The courts will usually call the parent as a witness to testify to historical aspects of the child’s life and the family dynamics. Juvenile Circuit Court is confidential; however, the judge

routinely allows close family members (grandparents, stepparents, siblings) to observe the court proceedings.