Lawyer The Arkansas

CYBER THREATS?

At Pinnacle IT, we recognize the distinctive challenges encountered by law firms, and our mission is to equip your organization with state-of-the-art technology solutions that will revolutionize your operations. With our profound understanding of the legal industry and unwavering dedication to excellence, we stand as your trusted partner in transforming your IT landscape.

Count on us to streamline your firm’s processes, enhance data security, optimize workflow efficiency, and deliver innovative solutions tailored to meet the specific demands of your legal practice. With our support, you can focus on providing exceptional legal services while relying on a robust and secure IT infrastructure to propel your success.

PUBLISHER

Arkansas Bar Association

Phone: (501) 375-4606

www.arkbar.com

EDITOR

Anna K. Hubbard

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Karen K. Hutchins

PROOFREADER

Cathy Underwood

EDITORIAL BOARD

Caroline R. Boch

Turquoise Early

William Taylor Farr

Abigail Grimes

Jim L. Julian

Tory Hodges Lewis

Drake Mann

Tyler D. Mlakar, Chair

Michael A. Thompson

Brett D. Watson

Amie Schoeppel Wilcox

David H. Williams

Nicole M. Winters

OFFICERS

President

Jamie Jones Walsworth

President-Elect

Representative Carol Dalby

Immediate Past President

Kristin L. Pawlik

Secretary

Glen Hoggard

Treasurer

Marc P. Martinez

Parliamentarian

Brent J. Eubanks

YLS Chair

Samuel W. Mason

BAR ASSOCIATION STAFF

Executive Director

Karen K. Hutchins

Director of Operations

Kristen Frye

Finance Administrator/CPA

Staci Clark

Publications Director

Anna K. Hubbard

Executive Administrative Assistant

Michele Glasgow

Office & Data Administrator

Cynthia Barnes

Professional Development Coordinator

Lisa McCormick

Information Technology Specialist

Rachel Henderson

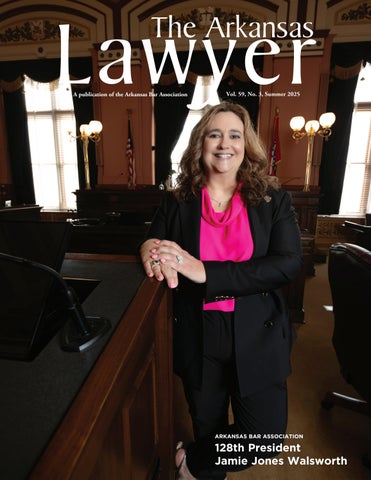

2025-2026 Arkansas Bar Association President Jamie Jones Walsworth By Anna K. Hubbard

Arkansas Bar Association Legislative Committee Report By Glen Hoggard

Artificial Intelligence in the Natural State By W. Taylor Farr

The Arkansas Uniform Trust Decanting Act: A New Chapter in Modern Trust Modification By Erin E. Behring

Act 975: Original Jurisdication in the Court of Appeals By Houston Downes

One Word, Big Impact: Strengthening UPL Enforcement Through Act 110 By Meagan Davis

Converting Damages to Reimbursement: Act 28's Insult to Injury Law By Brian G. Brooks

Act 28 Marks a Major Change in Claim Value

Adoption of Market-Based Sourcing in Arkansas Highlights Tax Risks for Firms in Other States

The Arkansas Lawyer (USPS 546-040) is published quarterly by the Arkansas Bar Association. Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, Arkansas. POSTMASTER: send address changes to The Arkansas Lawyer, 1401 W. Capitol Ave., Suite 170, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201. Subscription price to nonmembers of the Arkansas Bar Association $35.00 per year. Any opinion expressed herein is that of the author, and not necessarily that of the Arkansas Bar Association or The Arkansas Lawyer. Contributions to The Arkansas Lawyer are welcome and should be sent to Anna Hubbard, Editor, ahubbard@arkbar. com. All inquiries regarding advertising should be sent to Editor, The Arkansas Lawyer, at the above address. Copyright 2025, Arkansas Bar Association. All rights reserved.

Lawyer

Advertise in the next issue of The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

President: Jamie Jones Walsworth; President-Elect: Representative Carol Dalby; Immediate Past President: Kristin L. Pawlik

Secretary: Glen Hoggard; Treasurer: Marc P. Martinez

Parliamentarian: Brent J. Eubanks; YLS Chair: Samuel W. Mason

Trustees:

District A1: Elizabeth Esparza, Samuel W. Mason, William M. Prettyman, Lindsey C. Vechik

District A2-A3: Payton C. Bentley, Evelyn E. Brooks, Jason M. Hatfield, Christopher M. Hussein, Michelle Rene’ Jaskolski, Sarah C. Jewell, George Rozzell, Russell B. Winburn

District A4: Kelsey K. Bardwell, Craig L. Cook, Brinkley B. Cook-Campbell, Dusti Standridge

District B: Brooke Blackwell, Randall L. Bynum, Mark Kelly Cameron, Thomas M. Carpenter, Tim J. Cullen, Bob Edwards, John A. Ellis, Bobby Forrest, Joseph Gates, Michael K. Goswami, Steven P. Harrelson, Michael M. Harrison, Jim Jackson, Anton L. Janik, Jr., Victoria Leigh, Skye Martin, Kathleen M. McDonald, J. Cliff McKinney II, Jeremy M. McNabb, Molly M. McNulty, Meredith S. Moore, John Ogles, Casey Rockwell, Lauren Spencer, Aaron L. Squyres, Caitlin C. Stepina, Danyelle J. Walker, Patrick D. Wilson

District C5: William A. Arnold, Joe A. Denton, John T. Henderson, Brett D. Watson

District C6: Bryce Cook, Paul N. Ford, Jeffrey W. Puryear, Paul D. Waddell

District C7: Kandice A. Bell, Robert G. Bridewell, Sterling T. Chaney, Ledly Jennings

District C8: Meagan E. Davis, Amy Freedman, John S. Stobaugh, Joshua R. Thane

Ex-officio Members: Judge David McCormick, Judge Chaney W. Taylor, Vicki S. Vasser, Dean Cynthia Nance, Dean Colin Crawford, Glen Hoggard, Eddie H. Walker, Jr., Karen K. Hutchins

2025 Annual Award Recipients

The Arkansas Bar Association held its 127th Annual Meeting June 11–13, 2025, at Oaklawn Resort in Hot Springs. During the awards luncheon on June 13, 127th President Kristin L. Pawlik presented this year’s recognitions, Chief Justice Karen R. Baker delivered the State of the Judiciary Address, and Jamie Jones Walsworth was sworn in as the Association’s 128th President. The program also included a special passing of the gavel ceremony led by ArkBar past presidents in attendance, symbolizing the continuity of leadership and service within the Association.

Thank you to everyone who joined us in celebrating this special event—and to our generous sponsors, listed on the inside front cover of this issue, for their support of the 127th Annual Meeting. Special thanks to Annual Meeting CoChairs Will Ogles and Chris Hussein for their leadership and hard work in making the event a success.

Mark your calendars and join us next year, June 10–12, 2026, back at Oaklawn!

Margaret King Davis, Mock Trial Committee

Chris Hussein, Co-Chair of the 127th Annual Meeting

J. Cliff McKinney II, 2025 ArkBar Legislative Package

Adrienne M. Griffis, Mock Trial Committee

Adam Jackson, Mock Trial Committee

Anthony McMullen, Mock Trial Committee

Presidential Awards of Excellence

Stuart P. Miller, Exceptional Commitment

Young Lawyer Awards

G. S. Brant Perkins, Treasurer

Denise R. Hoggard, Personnel Committee

Frank LaPorteJenner, Young Lawyers Section

William J. Ogles, CoChair of the 127th Annual Meeting

Maurice Cathey Award

Tyler Mlakar, The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

Samuel W. Mason, Judith Ryan Gray Service Award

Frank LaPorteJenner, Frank C. Elcan Leadership Award

Glen Hoggard, Legislation Committee Chair

Meredith Lowry, AI Task Force Chair

Aaron Squyres, Political Speech and Activities TF Chair

Charles Carpenter Memorial Award

Legislation Awards

D. Wilson, Board of Trustee

Senator Tyler Dees Representative Matthew Brown

Pictured from left to right: Will Ogles, Annual Meeting Co-Chair; Kristin L. Pawlik, 127th President of the Arkansas Bar Association; and Chris Hussein, Annual Meeting Co-Chair.

Golden Gavel Awards

Patrick

Oyez! Oyez!

Appointments and Elections

Brett Watson of Searcy was recently appointed to the Arkansas Judicial Discipline and Disability Commission. Frank Arey was recently appointed to the Federal Advisory Committee for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

Word About Town

Gordon and Rees has hired Senior Counsel Zachary Wilson and associates Matthew Haley and Marcos Perez. The firm is continuing its growth in Arkansas and has expanded its space in the Simmons Tower Building. Quattlebaum, Grooms & Tull PLLC announced that MiKayla B. Jayroe has joined the law firm as an associate in the firm’s Northwest Arkansas office. Wilson & Associates, an affiliate of The Wilson Law Group, is pleased to announce the launch of its new Family and Business Solutions practice area and the addition of attorney Katie Griffin who will be leading the practice. Arvest Wealth Management recently promoted Katie Pipkin to vice president, Regional Trust Manager, overseeing trust services in Central Arkansas and the River Valley.

Send your oyez to ahubbard@arkbar.com

Michele Glasgow Celebrates 25 Years with ArkBar and Announces Retirement

On June 26, the Arkansas Bar Association recognized Executive Administrative Assistant Michele Glasgow for reaching an extraordinary milestone—25 years of service. Michele is known for her dependability, organizational skills, and commitment to supporting our members.

In her role, Michele has supported Association leadership and worked closely with committees, helping to keep projects and initiatives on track. Her knowledge of the organization and consistent presence have made her a go-to resource for colleagues and members alike.

“Michele’s work as Executive Administrative Assistant has made her invaluable to the association leadership,” said Executive Director Karen Hutchins. “She cultivated knowledge of the Association’s governance structure and acquired a unique ability to master various technology systems. Michele’s loyalty to the association as well as her diligence in serving our members and the public was unwavering throughout her career. Her service was particularly evident in her exceptional support of the Mock Trial Committee.”

As Michele celebrates this milestone, she is also preparing for a new chapter, her retirement this October. While her expertise and sense of humor will be greatly missed, the Association is grateful for her years of service and wishes her the very best in retirement.

Jenna Adams Devin Bates Christy Bjornson Dr. Riva Brown Hon. Tjuana B Manning

Hon. Cathi Compton Nate Coulter Charlie Cunningham Jennifer Donaldson Seth Hampton

Shelly Joyner Meredith Lowry Hon. Melanie Martin Candace McCown Cliff McKinney

Abtin Mehdizadegan David Slade Stephanie Vardaman Jillian Wilson Robbie Wilson

From Connection to Collaboration

If I have a focus for the year, it would be connections—connections between our members, connections between the bench and the bar, and connections between the bar and the public. Martin Luther King, Jr. said “whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality.” Connections thus speak directly to the mission of the Arkansas Bar Association— to support attorneys; advance the practice of law; advocate for the legal profession; foster professionalism, civility, and integrity; and protect the rule of law.

1. Supporting our attorneys: Connecting our lawyers by engagement in section membership and fostering professionalism, civility, and integrity. ArkBar conducted a survey a few years ago, and one of the conclusions made from the data is that the most satisfied member is the member who is engaged in a substantive section. Section members have a shared interest in the law, which allows members to focus on and naturally integrate the current trends, ethical issues, and shared expectations of their area of law. Engaging with others who have shared interests and with whom you practice humanizes others and encourages courtesy and civility even when engaging in the adversarial system. Sections further create a collaborative culture by creating opportunities for collegial dialogue, mutual learning and mentoring.

We will make section engagement and revitalization a priority. Sections are active engines for cultivating civility and professionalism, and supporting increased connections and relationships in your

Jamie Jones Walsworth is the President of the Arkansas Bar Association. She is a partner at Friday, Eldredge & Clark, LLP in Little Rock.

practice of law. If you are interested in being involved in a section, please let me know and I will assist you in plugging into section leadership.

2. Advancing the practice of law and the legal profession: Connecting through technology. Whether you are a solo practitioner in South Arkansas, a prosecutor in Northeast Arkansas, a big firm lawyer in Central Arkansas, or an in-house lawyer in Northwest Arkansas, keeping up with the latest trends in the law can be daunting. ArkBar has long had case law updates available through our podcast, but we have now launched ArkBar On Air: President’s Mic. This is a monthly podcast designed to connect all lawyers in the state to explore local issues and national legal trends. Our first two episodes are available now for download! Our first episode features a discussion about the Arkansas Supreme Court’s proposed rules on Artificial Intelligence, and the role the ArkBar AI Task Force played. Please reach out if you have a topic idea, or would like to recommend a guest.

3. Advocating for the legal profession and protecting the Rule of Law: As lawyers, we have been educated to understand the value of the Rule of Law and the value that the legal profession brings to our society. The general public does not always understand these principles. How lawyers behave publicly certainly influences the value of our profession. Actions indeed speak louder than words. ArkBar is uniquely situated in that it can provide education on the issues that are hotly debated—it can provide necessary context and education for the public to reach a conclusion. In June,

the Board of Trustees approved a Task Force on Public Education, chaired by Judge Brent Eubanks.

In addition, modeling behavior for the next generation of lawyers gives back to our profession, and creates a generation valuing the legal profession and the Rule of Law. ArkBar has long been involved with showing off our grand profession through the Mock Trial Program. While this program greatly benefits the high school students participating by exposing students to the legal profession and teaching them public speaking, critical thinking and argument skills, it also benefits the legal profession. Mock Trial builds a pipeline of motivated and skilled future lawyers, a true talent incubator. Mock Trial also encourages legal literacy in the students and their families, fostering a respect for the Rule of Law and informed civic participation. The lawyers, judges, and legal professionals volunteering crucially build bridges between the legal community and the public and improve the perceptions of the legal profession. Mock Trial needs several volunteers to continue to grow this program—coaching (volunteers can even coach via Zoom to underrepresented or rural communities), serving as a judge at the tournament, teaching at our upcoming Mock Trial programming in January, and sponsoring a team so they can afford materials. Contact me if you are interested in helping.

ArkBar hopes that you will continue your membership, and encourage others to join, the only organization that supports all the lawyers in the state. We really are better lawyers when we work together. ■

Leading Boldly. Serving Proudly. Let’s

Do This!

Let’s get this year started off right! What could be better for the Young Lawyers Section than having it comprised of some of the brightest and most hard-working and steadfast young lawyers in the state? I’ll tell you what could be better: having those same members and executives eager to serve the Bar, the practice, and, most importantly, the hard-working citizens of our beautiful state. Arkansas is in luck because that is what our Young Lawyers Section and Executive Council is comprised of this year!

So, what is the Section going to do this year? The simple answer is: the Young Lawyers Section is going to do whatever we can to help engage new lawyers, promote our services across the state, and have just enough fun to keep us young. We have books

to finish and distribute, we have clinics to help those in need, we have networking events across the state, and we have much, much more. To start off, members of the Executive Council were at both law schools’ orientations: Fayetteville on August 12 and Little Rock on August 20. We passed out some swag, mini tri-highlighters to help “highlight their journey,” and let students know that ArkBar is here to support them from 1L to JD. As this year progresses, more details will be provided of what is to come. After all, a good book is never finished in the first chapter.

However, as we all know, none of this could be possible without the outpouring of support from those behind the scenes. The Young Lawyers Section is grateful to the Bar

Samuel W. Mason is the Chair of the Young Lawyers Section. Sam is a trial attorney at the Oliver Law Firm in Rogers.

and its administration and staff who work to guide and promote the Section across the state of Arkansas. Personally, I am grateful to the staff for keeping the Section and me on track and providing us with the tools to do the absolute best job possible for those who rely on our services. Without their help, the Section would not be what it is.

In conclusion, the Young Lawyers Section is blessed to have an outstanding Executive Council for the 2025-2026 term; with a combination of our seasoned executive members and new executive members, this will be a year filled with progress and fun. You’ve probably realized by now that I am not someone who enjoys fitting the mold, so I’m asking y’all to hold on tight and enjoy the ride with me. Let’s do this! ■

Leading with Connection

Arkansas Bar Association 128th President Jamie Jones Walsworth

ArkBar President Jamie Jones Walsworth brings intentionality, energy, and heart to her role—fostering trust, building community, and finding common ground in the legal profession.

By Anna K. Hubbard

The Power of Connection

For Jamie Jones Walsworth, leadership always comes back to one thing: connection. It drives everything from her daily interactions to her long-term priorities for the legal community. On June 13, 2025, she stood before her colleagues at the Arkansas Bar Association’s Annual Meeting in Hot Springs and took the oath as the Association’s 128th President, continuing the leadership and commitment to service she’s brought to the Association for years.

In her remarks leading up to Jamie’s swearing-in, Immediate Past President Kristin Pawlik said:

“She has been an invaluable resource for this association for years. She is a consummate professional, a fierce advocate, and a trained volunteer. She knows how to get things done, and our association is so very, very fortunate to have her stepping into this role at this time with her strategic vision, thoughtfulness, and intentionality.”

From the moment she took the podium, Jones made it clear that building community would be the heart of her presidency. Whether it’s bringing lawyers together across the state, building trust within the profession, or finding common ground in moments of disagreement, she believes that strengthening those ties is imperative to the legal profession, as well as to the health of our communities.

“Mr. Rogers famously said that ‘the connections we make in the course of a life, maybe that’s what heaven is,’” Jones shares.

“I believe that connecting with our community is incredibly important to our human experience, and to the betterment of society. It’s hard to ignore the good in people if you feel a connection to them. But it’s incredibly easy to focus only on the bad and the points of disagreement when we lose that connection.”

For Jones, connection isn’t just a leadership philosophy, it’s woven into her own life story. In the last year, she reconnected with her high school sweetheart, Rick Walsworth, someone she hadn’t seen in decades. That reconnection sparked a joyful new chapter in her life, and the two recently married.

Photo: Mike Pirnique

Rebuilding Civility in the Profession

Jones believes the legal profession has a vital role in rebuilding the civility and connection that have eroded in recent years. COVID, she notes, played a part. “We became more isolated. People stopped engaging, and that hurt us, not just as organizations, but as a society.”

She sees the impact not only in declining membership across professional associations, but also in a cultural shift: a growing tendency to focus on the negative. “We’ve become too quick to find the bad in people. But people aren’t simply good or bad, they’re nuanced.”

For lawyers, she argues, recognizing that nuance is essential. Advocating fiercely in the courtroom, she says, doesn’t have to come at the expense of respect outside of it. In fact, it can make attorneys more effective. “Civility and connection go hand in hand. The more we engage with each other, the harder it is to lose sight of our shared humanity.”

By creating space for respectful debate, she hopes to restore connection and model the kind of thoughtful dialogue lawyers are uniquely positioned to lead.

She notes that while technology has made it easier than ever to stay in touch, it has also made it easier to lose the personal, human side of relationships. “We’re often communicating more, but connecting less,” she says.

To help close that gap, Jones launched ArkBar On Air: The President’s Mic, a podcast designed to bridge the geographic and generational divides within Arkansas’s legal community. “Our state is heavily rural,” she explains. “For lawyers in small towns, it’s hard to make it to events in Central or

Northwest Arkansas. I’m hopeful this is a way to connect us all—quickly and efficiently.”

Featuring timely conversations with legal professionals from across the state, the podcast offers a platform for sharing expertise, engaging in thoughtful debate, and amplifying the work of ArkBar’s sections. “The most satisfied members are those who are engaged in a substantive section,” Jones says, citing findings from an extensive membership study she chaired a few years ago. “This is one more way to support that connection, to educate, and to create space for dialogue around the issues that matter most.”

Rooted in Resilience

Jones credits much of her career path to early encouragement and opportunity. “I didn’t grow up with a lot of built-in advantages,” she says. “If I wanted something, I had to work hard for it.”

As a teenager in Rogers, she already knew she wanted to be a lawyer—even if she could barely speak in front of a classroom. “I was so shy I had to record my book reports alone in a separate room,” she recalls. Programs like Teen Court and high school drama helped her find her voice, but she found her calling as a litigator when the Benton County Bar Association sponsored her attendance of a teen legal program in Washington, D.C. through Duke University. “That was a turning point,” she says. “I’m not sure I’d be a lawyer today if they hadn’t believed in me.”

That belief took her to the University of Kansas School of Law, where she served as managing editor of the Kansas Law Review, graduating in 2003 with the highest score on

the Arkansas Bar Exam that year. She earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology, magna cum laude, from the University of Arkansas in 2000, where she was recognized as the Top Psychology Student of the Year Her early colleagues quickly recognized both her legal talent and her character. “I had the great privilege to work with Jamie at the Friday Firm and am proud to call her a friend,” says U.S. Magistrate Judge Edie Ervin. “Jamie is a talented lawyer and smart as a whip. Her equally important gifts include stellar communication skills, a commitment to service, and genuine kindness, all of which will make her an excellent Arkansas Bar President.”

From the start of her legal career, Jones immersed herself in service to the Arkansas Bar Association—serving as a tenured delegate in the House of Delegates, on the Board of Trustees, and as a member of the Board of Governors. She has chaired and served on numerous committees and task forces, including work in legal research, membership value, jurisprudence and law reform, strategic governance, and legislation. Her commitment to service also extends to the Arkansas Bar Foundation, where she is a two-term former member of the Board of Directors and continues to serve as a Fellow, and to national leadership through the Federation of Defense & Corporate Counsel, where she holds leadership roles and was recognized in 2021 for her leadership. She is also a past president of the Arkansas Association of Defense Counsel, and in 2017 Arkansas Business named her to its “40 Under 40” list.

From left to right: Jamie and Arden (Photo: Vincent Jackson); Jamie and Rick (Photo: Lizzy Yates); Jamie (Photo: Mike Pirnique).

The Friday Firm Legacy

That commitment to service only deepened when Jones joined Friday, Eldredge & Clark LLP in Little Rock, where she is now a partner in the litigation practice group and serves on the Firm’s Management Committee. Bar involvement and community engagement are woven into the fabric of the Friday Firm, and from her first day, she was immersed in that culture.

During law school, then-managing partner Buddy Sutton invited her to a lunch interview. They talked about college football for three hours. “Mr. Sutton then flew me down a few weeks later to meet with the firm, and when they offered me the job, I accepted immediately,” she recalls. “The Friday Firm encourages you to be engaged, not just in your practice, but in the profession.”

Jones says she has been “raised” by the lawyers and staff at the firm, who valued her voice from day one. “Even as a brand-new lawyer, I was expected to have an opinion and be part of the discussion, and my colleagues with decades of experience would stop and listen, explaining where I was wrong or validating when I was right,” she says.

She credits mentors like Fred Ursery and Kevin Crass for modeling what it means to lead with purpose. “Fred basically told me I was going to be president of the Bar,” she laughs.

Ursery, a longtime colleague, remembers her early days well:

“Jamie joined the Friday law firm in 2003. She chose to be in the litigation section, which gave me the opportunity to work with her. I knew she would be a good writer because she had been the editor of the law review. Then Jamie and I tried several jury

trials together and she demonstrated the attributes of a good trial lawyer. Shortly after she joined the firm, I served as President of the Arkansas Bar and encouraged her to participate in bar activities. She handled a number of projects and was active in numerous civic efforts alongside her bar work. As the old saying goes, ‘If you want something done, give it to a busy person.’ She has the energy of three people. I would always want her on my team. I have no doubt she will do a great job as our Bar President.”

Jamie recalls that their shared love of animals helped them connect early on. “Not long after I started, I ran into Fred and his wife, Sharon, at the pet store. I was there picking up something for my dog and ended up adopting a kitten on the spot. When Fred realized I was an animal lover too, he started using me more in his cases,” she laughs, adding, “I was very lucky to gain him as a mentor, and frankly, a best friend.”

Crass, also a member of the Friday Firm Management Committee, echoes Ursery’s praise:

“From the time Jamie joined our firm, she was a self-starter with a drive to excel. If you gave her an assignment, you could count on a high-quality response. She also brought a high level of enthusiasm to become a go-to lawyer, and it did not take her long to reach that goal. At the same time, she took on leadership roles in the firm, the bar, and the community. I honestly don’t know how she has the time to do it all, especially given her commitment to her daughter. I am very proud of her, and I believe the Arkansas Bar Association will continue to benefit from her leadership.”

Jamie says her years working alongside Crass have shaped how she sees her role in

the community. “Kevin does a lot of business and class action litigation, so I worked closely with him from the start. He never had to tell me to be engaged in the community; it was something I learned by watching him. Community is important to Kevin, and how he spends his time makes that obvious. It’s given him a broader perspective that I think makes him a better problem-solver, and I’ve tried to carry that lesson forward in my own work.”

Her election as ArkBar President also continues a proud tradition for the Friday Firm. Three of her predecessors—founding member Herschel H. Friday (1976–77), Fred Ursery (2004–05) and Jim Simpson (2013–14)—once held the same role, continuing the firm’s long history of service and deep connection to the Association.

A Lesson in Service

Jones’s commitment to service reaches far beyond the legal profession. She is the Immediate Past Chair of the Board of Directors for the American Heart Association, Central Arkansas (2023–2025), and immediate Past President of the National Charity League, Little Rock Chapter. Her past community leadership includes board roles with the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, the Junior League of Little Rock, and the Little Rock Chamber of Commerce’s Leadership Greater Little Rock.

She hopes her daughter, Arden, grows up with that same sense of empathy and responsibility. “I want her to always include service to others in her life,” she says. “It’s important not to get so isolated in your thinking that you believe only your perspective matters.”

Motherhood, she adds, has made her a better lawyer and leader. “You look at the world differently and consider issues from the perspective of others. It’s a reminder that I am but a part of a larger community and I have responsibilities that go beyond my personal wishes for the world.”

When Arden looks back on these years, Jones hopes she remembers: “That I would listen to others before I make a decision. That she can do anything. That being a mom, or a wife, or a lawyer is part of who I am—but I am the collective of all my roles.”

Jamie is intentional about modeling that approach. “I very much subscribe to the John

Jamie receives the gavel from ArkBar Past Presidents (Photo: Mike Pirnique)

Wesley philosophy: ‘Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, at all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.’” By including Arden in her work and volunteer life, she hopes to share both her values and a real-world example of serving others.

A Love of Reading

For Jones, another form of connection, and a way to recharge, comes through books. Known for her thoughtful and candid book reviews on social media, she once read as many as 15 books a month. While she may not post or read quite that volume these days, she still averages a couple of books a week.

“I’ve always been a big reader,” she says. “For me, it’s an important part of my mental well-being. It helps me turn my brain off at night from all the obligations and stress I have going on. It gives my mind a break from whatever I was problem-solving that day.”

What began as a personal outlet evolved into a surprising way to connect with others. Friends encouraged her to start posting recommendations, and soon people she barely knew were stopping her in the grocery store to talk about a book she had reviewed. At a national legal conference, two women she’d never met rushed up to greet her, exclaiming, “You’re JJ Reads a Lot!”

“That’s the great thing about books,” Jones says. “They let you see the world from a different perspective for a while. And they give you something to share with people you might not otherwise connect with.” Jamie is excited to launch the ArkBar Presidential Book Club as a way to connect members and engage in meaningful conversation.

The Role of the Bar Today

With the rise of national CLE providers, some offering free or low-cost content, Jones sees a clear distinction in what the Arkansas Bar Association offers. “We provide content that’s specific to practice in Arkansas, and often presented by the judges our members appear before. Nothing takes the place of hearing directly from the judge who’s going to be on the bench in your upcoming case.”

At a time when public trust in the legal system is under strain, Jones sees the Bar Association as uniquely positioned to help restore confidence. “We can educate the

public on hot topics in the legal community without taking an opinion,” she said. “We can increase public perception in a positive way of lawyers, judges, and the legal community.”

To that end, she announced the formation of a Public Education Task Force, chaired by Judge Brent Eubanks, to explore new opportunities for community outreach and civic education. The Task Force is already working with the New Civic Education Center on several upcoming projects. She has appointed a CLE Task Force, chaired by Michelle Jaskolski, to help the Association stay responsive to the changing needs of Arkansas lawyers. “We’re proud to be a leader in Arkansas-specific CLE,” she said, “but we also know the market is evolving.”

Looking ahead, she encouraged members to mark their calendars for the 2026 Annual Meeting, scheduled for June 10–12. Judge Shawn Johnson of Pulaski County and Judge Joe Volpe of the Eastern District of Arkansas are already hard at work planning what promises to be a meaningful and forwardlooking gathering.

Johnson brings both community focus and experience from other member-driven organizations, including his leadership in Cub Scouts. “He’s extremely communityoriented, and I think we share that desire to be connected to the community,” Jones says. “He’s already bringing great ideas, and he and Judge Volpe are certainly willing to flip the script a little bit and try new things.”

In Johnson’s words: “Today, social media and the tech-driven strategies for navigating our daily lives—e.g., on-demand television, instant Google answers, ChatGPT, and the social-media algorithms, etc.—are creating pressures and anxieties in our society. While they may make some things more efficient, they also make us over-busy and overstimulated and prevent us from joining in community activities like more people have done in past eras. It thus isolates us into our own echo chambers. Hence, choosing community and helping our friends and neighbors is needed now more than ever.

“In guiding the planning of next year’s annual meeting, Jamie is embracing solutions to this very concern. As lawyers, we are called to serve not only our clients but our communities. Next year’s annual meeting will focus on encouraging lawyers to serve

their communities and to care for themselves in the process. Jamie’s appreciation for innovation and change is inspiring. All members of the Arkansas Bar should get ready for a great, updated experience (yes, an ‘experience!’) at the 2026 annual meeting.”

Looking Ahead

As she steps into this next chapter of leadership, Jamie brings the same intentionality, energy, and belief in people that have defined her journey so far. She knows leadership isn’t about checking boxes, it’s about listening first, building trust, and making decisions with clarity.

“I used to think that to be a leader, you had to be a certain age or meet a certain criterion,” she reflects. “Now, I realize that leadership comes in many ages and experience levels. It’s about processing information effectively, owning your decisions, and surrounding yourself with people who will challenge and support you.”

For her, the most rewarding moments are the connections she’s built, bridging differences in background, perspective, and practice area to find common ground. “You do not become forceful until you listen to your team,” she says. “I rely on a diverse group of individuals to give me the data and perspective I need to lead.”

And to the next generation of lawyers just starting out, her advice is simple and lasting: “Surround yourself with great people—they’ll make you look good.” ■

Jamie announces the launch of her President’s Mic Podcast. (Photo: Vincent Jackson)

By Glen Hoggard

Arkansas Bar Association Legislative Committee Report

The Arkansas Legislature adjourned sine die, Monday, May 5, 2025, drawing to a close the 95th Regular Session of the General Assembly. I offer this report to the Bar membership regarding the results of this Session and the Arkansas Bar’s participation in it.

One of the significant aims of the Arkansas Bar Association is Legislative Advocacy on behalf of the legal profession and the fair administration of justice. The Bar has established a detailed process to both advocate for bills sponsored by the Association, as well as to review legislation introduced by others.

It was my high honor this session to serve as Chair of the Committee, concluding my tenth year of service on ArkBar Legislation. This report is authored from my perspective as Chair and certainly is not intended to represent the opinions of the entire Committee.

Glen

Hoggard has served as the Chair of Arkansas Bar Association's Legislation Committe.

Starting a year before the current Legislative Session, ArkBar’s Jurisprudence Committee solicited and reviewed legislative proposals for the purpose of including those proposals in the Bar’s legislative package. Jurisprudence selected five pieces of legislation for introduction to the General Assembly. Four of the five proposals were submissions of the Uniform Law Commission. The fifth proposal was the result of a joint Committee of the Association’s Real Estate and Natural Resources Sections.

The five bills were all passed and enacted into law under the Governor’s signature. The bill and act numbers, along with a brief description are:

HB 1736 & HB 1746: both ULC bills and both amending Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code, one bill adopting the 2018 promulgated amendments and one the 2022 amendments; they are now Acts 603 and 997, respectively.

HB 1737: from the Title Standards Committee, amending the Transmitting Utility Act, this bill enacted a process for filing multi-county liens with the Secretary of State’s office on conduit and fiber optic installations in public rights of way; now Act 584.

HB 1739: adopting the Electronic Materials Act, this ULC submission was proposed and supported by our two law school’s law librarians. It creates a process for a public record of electronic materials, such as state agency rules and regulations. Now Act 814.

HB 1749: adopting the Uniform Trust Decanting Act, this ULC submission was passed without opposition. It permits the pouring over of a Trust’s Assets into a new Trust with modified Trust provisions and is now Act 680.

The Committee adopted positions on eight pieces of Legislation and two Joint Resolutions (proposed state constitutional amendments). The Committee observes a mandate of only advocating on legislation that either directly affects the legal profession or that addresses the fair administration of justice. Those bills, our position, and the result are shown below.

HB 1204: neutral; this bill limited the manner in which healthcare costs could be presented to a jury in an injury action. Now Act 28.

HB 1282: support; made the payment of benefits to anyone soliciting a case for an attorney illegal as the unauthorized practice of law. Now Act 110.

HB 1468: oppose; established a new process for claims against home improvement companies, home builders, and suppliers with new timelines and ADR processes. Now Act 558.

HB 1533: oppose; established a Decentralized Unincorporated Nonprofit Association regimen. Died in House Committee.

HB 1656: oppose; amended the law regarding oil and gas royalty calculation. The Committee opposed because the bill attempted to alter existing contracts via legislative enactment. After being defeated in Senate Committee, the bill was significantly amended at the very end of the Session and passed. Now Act 1024.

HB 1679: opposed, then support as amended. The bill amended the ULC

Anatomical Gift Act, a prior legislative proposal sponsored by ArkBar. Following significant negotiations with the Sponsor and the bill’s interested parties, amendments were adopted that satisfied the major concerns. Now Act 861.

HB 1832: opposed: made the Court of Appeals the court of original jurisdiction for facial constitutional challenges to state and federal statutes. This bill seeks to amend rules promulgated under Amendment 80 to the AR Constitution. Amendment 80 was a significant legislative and electoral effort by ArkBar that was passed in 2000. The Committee voted to oppose, believing Amendment 80 cannot be altered by a legislative action. The bill’s sponsor did agree to amend the bill to set a November 1st effective date to permit the adoption of rules and processes for implementation. Now Act 975.

SB 629: oppose; created an exemption to the statute on the unauthorized practice of law and allowed certain corporate entities to be represented by a corporate officer in eviction actions. Died in House Committee.

HJR 1015 and SJR 13: oppose; these

proposed constitutional amendments mandated or permitted, respectively, the use of political party labels in judicial elections. Amendment 80 made judicial elections nonpartisan. Joined by the Judicial Council, President Pawlik offered Committee testimony opposing the amendments. Both died in their respective Committees.

There were numerous other bills where the Committee made inquiries to the Bar’s Sections and members of expertise in their field. There were numerous bills where concerns or requests for changes were expressed to Legislators and those requests were honored.

In all, it was a highly successful year for Bar Association legislative advocacy. Special thanks to Rep. Matt Brown, a practicing attorney from Conway, for sponsoring the Bar package and to the members of Government Consulting for their lobbying advocacy and intelligence on behalf of the Bar. The 11 members of the Legislation Committee are to be commended for their efforts and service to the Bar Association. It was a privilege to serve with this outstanding and distinguished group. ■

261 Peninsula Dr - Lake Hamilton, Hot Springs

Artificial Intelligence in the Natural State

By W. Taylor Farr

W. Taylor Farr is an Assistant Professor of Law at William H. Bowen School of Law. He also serves as an attorney advisor in the Clerk's Office of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. His comments do not necessarily reflect the views of his employers.

Acouple of issues ago, The Arkansas Lawyer covered how generative artificial intelligence is shaping our profession, from our practices to our ethical obligations to the education of our future colleagues. Thus, it seems fitting that we discuss briefly how generative artificial intelligence is making its way into our statutory law.1 From this author’s review, it appears 13 bills were introduced this legislative session that contained the phrase “artificial intelligence.” On one hand, this is not a surprisingly high number given the technology’s grasp on the current zeitgeist—in fact, some may find it surprisingly low. But consider that the phrase has been in our lexicon since the 1960s and has not once appeared in Arkansas statutes.2 Of the 13 bills that were introduced, only four passed.3

My Input, My Output. Arkansas appears to be an early mover in enacting Act 927,4 which delineates the ownership rights to trained models and generated content. In short, it prescribes that the person who provides the data to train the model owns the resulting model and the person who prompts the program owns the resulting content. The caveats? Ownership rights do not attach if the data was obtained, or the content was generated, in violation of existing intellectual property rights.5 And if the prompter is working at the behest of his or her employer, the employer owns the output.

Deep “Franks.” Act 1596 amends the Frank Broyles Publicity Rights Protection Act of 2016, Ark. Code Ann. § 4-75-1101 et seq. (the Frank Broyles Act), which establishes a property right in, and prohibits another’s commercial use of, an “individual’s name, voice, signature, photograph, [and] likeness.” 7 Act 159 simply clarifies that the Frank Broyles Act captures any appropriation of an individual’s likeness, photograph, and voice created through artificial intelligence. While explicit language in statutes is generally preferred, it is unclear whether this language gives any more bite to the prior version of the Frank Broyles Act. Its previous terms likely encompassed such creations anyway.8

Government Guidelines. Act 8489 amends Ark. Code Ann. § 25-1-128 and in part requires public entities to “[c]reate an artificial intelligence and automated decision tool policy” that requires a human to exercise independent judgment in making the final decision for the entity whenever such tools are used. Of particular note, Act 848 defines the ever-changing technology by appropriating language similar to the language Congress adopted in 2021: “[A] machine-based system that can, based on a given set of humandefined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing a real or virtual environment.”10

Child Pornography. Act 97711 amends the Arkansas Protection of Children Against Exploitation Act of 1979 to criminalize the creation of child pornography through the use of artificial intelligence. Defendants have historically challenged these types of statutes on First Amendment grounds with varying success.12 But courts have been reluctant to wholly strike down similar laws, recognizing the harms children suffer when they are used in the creation of such content or are the subject thereof.13 To protect Act 977 from First Amendment attacks, the legislature carved out depictions that are “drawing[s], cartoon[s], sculpture[s], or painting[s]” and criminalized only instances where the

depiction is “indistinguishable from the image of a child,” considerations analogous to those which courts outside of Arkansas have relied upon in finding similar statutes constitutional.14

In Memoriam. Though each of the following were “only a bill,” it is worth highlighting the proposed legislation that died at the end of the session or was withdrawn to see what type of artificialintelligence laws might be on the horizon. The legislature proposed bills to restrict certain artificial-intelligence use in the healthcare industry,15 develop artificialintelligence literacy goals in schools,16 prohibit deepfakes in election-related content17 and in sexually explicit content involving adults,18 and protect children while online.19

In conclusion, this legislative session was an interesting microcosm of our nation’s broader conversation on artificial intelligence.20 What will be more fascinating is observing whether such artificial-intelligence legislation is merely in vogue or is the start of a persisting trend of states seeking to directly regulate an exponentially evolving technology.

Endnotes:

1. Significantly more could be said about how generative artificial intelligence is affecting our substantive law, but that topic is for another article for another day.

2. And, based on this author’s review, it has not appeared even in proposed legislation.

3. Five died at the end of the session. Four were withdrawn, two of which appear to have been withdrawn in order to introduce similar legislation.

4. 2025 Ark. Acts 927.

5. These rights are currently being litigated. For example, three book authors sued Anthropic PBC, the creator of Claude, after the company used their works to train its models. In short, Anthropic obtained over seven million pirated copies of books from online libraries. However, seeking a morelegal approach, Anthropic later purchased millions of books, ripped them apart, scanned them, and copied them for training purposes. The United States District Court for the Northern District of California recently granted partial summary judgment in favor of

Anthropic, finding that its “print-to-digital” copying of the purchased books and its use of such copies to train the large language model supporting Claude were permissible under the fair-use doctrine. See generally Bartz v. Anthropic PBC, ___ F. Supp. 3d ___, 2025 WL 1741691 (N.D. Cal. June 23, 2025). However, it denied summary judgment with regard to Anthropic’s download and retention of the pirated copies, noting that no amount of subsequent transformation could bless Anthropic’s initial download and retention as permissible fair use. See id.

6. 2025 Ark. Acts 159.

7. Ark. Code Ann. § 4-75-1104 (2016).

8. Indeed, anecdotally, the author used the prior version of the Frank Broyles Act to successfully remove an artificial-intelligencegenerated deepfake video of a client from an internet platform. Act 159 may illustrate a broader phenomenon in our profession: it seems that many are racing to pass artificialintelligence specific rules and regulations even when current rules or regulations adequately account for the technology. Maybe such movers are uncomfortable with how a court might approach the topic or simply want certainty in the law.

9. 2025 Ark. Acts 848.

10. See for comparison 15 U.S.C. § 9401. It will be interesting to see if this definition will need to evolve with the technology. What happens when artificial intelligence agents begin defining their own objectives based on trends they observe in the provided data?

11. 2025 Ark. Acts 977.

12. See, e.g., Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 535 U.S. 234 (2002) (holding that virtual child pornography enjoys First Amendment protection).

13. See, e.g., United States v. Anderson, 759 F.3d 891 (8th Cir. 2014) (holding that, while morphed child pornography—that is, an image of a minor’s face superimposed on an adult’s body engaged in sexually explicit conduct—was protected by the First Amendment, the criminal prohibition of defendant’s conduct was constitutional when it was narrowly drawn to serve the government’s compelling interest of protecting an identifiable minor).

14. See Ashcroft, 535 U.S. at 234 (noting that “pornography depicting actual children can be proscribed” (emphasis added)); Brasse v. State, 333 A.3d 593, 609, 610 (Md. App. Ct.

2025) (“To the extent that images are created by artificial intelligence using an actual child’s face, the same concerns involved with morphing exist. Such images, to the extent that they are indistinguishable from an actual and identifiable child, implicate the interests of an actual child, who is subject to the type of reputational and emotional harm that justifies their exclusion from protection under the First Amendment.” (emphasis added)); see also State v. Fingal, 666 N.W.2d 420, 425 (Minn. Ct. App. 2003) (finding Minnesota’s computer-generated child-pornography prohibition constitutional under the First Amendment because under the statute the “visual depiction must be of an identifiable minor, not a virtual child” (emphasis added)). On the other hand, it is not readily apparent that—like these other statutes—Act 977’s language criminalizes only depictions of an actual, identifiable child. “Child” is simply defined as “any person under eighteen (18) years of age,” Ark. Code Ann. § 5-27-302, without an explicit requirement that the child be identifiable.

15. See, e.g., H.B. 1297, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025); H.B. 1816, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025).

16. See H.B. 1283, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025).

17. See H.B. 1041, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025).

18. See H.B. 1823, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025).

19. See, e.g., H.B. 1726, 95th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2025).

20. The conversation was almost cut short. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act initially contained a 10-year moratorium on most state regulation of artificial intelligence. See H.R. 1, 119th Cong. § 43201(c) (as passed by House, May 22, 2025). In the end, Congress removed the moratorium, leaving the states to individually regulate the technology. See H.R. 1, 119th Cong. (2025) (enacted). On one hand, this allows more experimentation within artificial-intelligence regulation among the states. On the other, it may simply shift the regulatory power to the most aggressive states, forcing artificial-intelligence companies to build their programs in ways that are compliant with the most stringent state laws. ■

The Arkansas Uniform Trust Decanting Act: A New Chapter in Modern Trust Modification

By Erin E. Behring

Erin E. Behring, J.D., LL.M., is a senior trust officer at Regions Bank in Little Rock and manages a wide variety of accounts specializing in complex family matters.

Erin does not practice law for Regions Bank or its subsidiaries. Rather, the information and observations presented in this column are hers alone, are general in nature, and should not be considered legal, accounting or tax advice from Behring, Regions or any related entity.

The concept of decanting has been around since 1940 when a Florida court in Phipps v. Palm Beach Trust Co. held that “the power vested in a trustee to create an estate in fee includes the power to create or appoint any estate less than a fee unless the donor indicates a contract intent.”1 Arkansas made its first attempt at decanting with the approval of Act 293 (“2023 Act”)2 and earlier this year in April 2025, the Uniform Trust Decanting Act 680 (“2025 Act”) was adopted. This legislative update represents a significant step forward in the flexibility and administration of irrevocable trusts. Arkansas law has become more aligned with a growing national trend of offering trustees clearer, more comprehensive authority to modify trust structures and conform with the Uniform Law Commission’s version.

This article will examine the 2023 Act and compare it to the newly enacted 2025 Act, discuss issues that have arisen in other jurisdictions, and highlight practical considerations for attorneys and trustees in navigating trust decanting.

I. Decanting as a Tool of Trust Modification

The concept of trust “decanting” takes its name from the act of pouring wine from one vessel into another, leaving the sediment behind. In the legal context, decanting refers to a trustee’s authority to distribute assets (all or part) of an existing irrevocable trust into a new trust with different terms without approval. Decanting allows trustees to adjust the terms of an irrevocable trust, often to fix drafting errors, consolidate trusts, address tax concerns, clarify ambiguities, or accommodate beneficiary needs. While traditionally the modification of irrevocable trusts required court approval or the consent of all beneficiaries, decanting provides a nonjudicial alternative that is more flexible and cost-effective.

II. Act 293 (2023): Arkansas’s First Foray into Decanting

Decanting has been allowed in Arkansas since 2023 when Act 293 was approved and later codified as Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818.3 While scant in nature compared to the later-adopted 2025 Act, coming in at barely six pages, it did set up a basic framework for a trustee to make changes to a trust. The 2023 Act gave trustees authority to decant irrevocable trusts, provided they had discretion over income or principal distributions.4 This authority is seen as an exercise of a limited/nongeneral power of appointment rather than a power to modify.5 The 2023 Act does allow for beneficiaries to be excluded, but adds some protection in not allowing

any to be added to the new trust.6 The 2023 Act also specifically protects the tax status of certain trusts by limiting decanting where the original trust has utilized a marital deduction or charitable deduction, or where there is a grantor-retained annuity trust interest.7 Under the 2023 Act, notice is not specifically required, with the statute stating, “a trustee may give notice.”8 The statute does explicitly allow for the second trust to be considered special needs.9

While the 2023 Act represented progress, it was narrow in scope. It offered limited guidance on making changes in the administration of the trust, lacked provisions addressing potential tax consequences, and did not distinguish between degrees of trustee discretion.

III. The Arkansas Uniform Decanting Act (2025): Expanded Authority and Clearer Guidelines § 28-78-101

Earlier this year Arkansas adopted a version of the Uniform Trust Decanting Act drafted by the Uniform Law Commission.10 This legislation provides a more comprehensive statutory framework for decanting. It is much more robust than the 2023 Act and offers clear direction to Arkansas trustees.

Under the 2025 Act the trustee is empowered with the authority to modify the original trust if they have discretion only over principal.11 This is a significant difference from the 2023 Act, which as noted above allows for the trustee to decant if they have discretion over income or principal. The 2025 Act applies to primarily an irrevocable trust12 administered under Arkansas law unless expressly prohibited by the trust instrument or for trusts held solely for charitable purposes.13 The 2025 Act specifically requires the trustee to act in accordance with the original trust’s intended purpose.14 As in the 2023 Act, there is no implied duty to exercise the decanting power.15

Another major difference between the two decanting statutes is that notice is required under the 2025 Act.16 The statute has specific and detailed requirements for the form of the notice and a default 60-day notice period.17 The 2025 Act limits decanting when attempting to change compensation, add liability/indemnification language, and modify trustee removal provisions.18

The 2025 Act makes a distinction between limited and expanded discretionary authority and directly affects what aspects of the trust may be modified in the decanting process.19 Expanded authority requires discretionary language such as “sole” or “absolute trustee discretion.” This expanded authority allows the trustee to make a number of changes, including: eliminate one or more current beneficiaries (but not add); change the standard for distributions; add spendthrift provisions; and change administrative provisions.20 Limited refers to the very common ascertainable standard language of health, education, maintenance, or support (“HEMS” standard). When this language is present, the trustee can make administrative changes but is required to retain “substantially similar” interests for the beneficiaries when making modifications.21 These discretionary authority distinctions are a significant departure from the 2023 Act, which allowed the trustee to make extensive modifications.

While the 2023 Act mentioned the ability of decanting to cover special needs trusts, the 2025 Act provides more details and particulars.22 There are also much broader provisions for the protection of charitable interests.23 The 2025 Act adds additional limitations on modifications where the original trust includes Irrevocable Life Insurance Trusts utilizing Crummey notices, Generation-skipping trusts, S Corporation Stock, qualified benefits, or Grantor Trusts.24 Man’s best friend was not forgotten in the 2025 Act, specifically allowing for decanting into a new trust to add for care of animals.25 The Act allows for the second trust to have a different duration with some limitations on the rule against perpetuities.26 The 2025 Act also includes a savings clause and directions on later-discovered property.27

IV. Act

293 vs. the New Uniform Decanting Act

Feature 2023 Act (§ 28-73-818) 2025 Act (§ 28-78-101)

Trustee Authority Principal or Income Principal only Trustee Discretion No distinction Differentiated: limited vs. expanded

Notice Requirements Trustee may give notice Required

Tax considerations Silent Explicit protections Beneficiary Elimination Allowed Allowed

V. Experiences from Other Jurisdictions

Although this author is unaware of any Arkansas cases discussing or challenging decanting, there are plenty of other states that have experienced the pitfalls and issues that can arise.28 Trustee’s authority to decant has been a major litigation issue. In a 2017 Massachusetts case the court held that the power to decant does not need to be expressly stated in trust.29 The court looked to the discretionary authority the trustee had over the income and principal and the trustee’s “full power to take any steps and do any acts which he may deem necessary or proper.” In this case the trustee decanted the assets of a trust to a spendthrift trust outside the reach of the beneficiary’s spouse and the court surprisingly upheld the decanting as valid even though it defeated his marital support obligation. Caution should be taken in utilizing this

Landex Research, Inc.

PROBATE RESEARCH

Missing and Unknown Heirs Located No Expense to the Estate

Endnotes:

1. Phipps v. Palm Beach Trust Company, 142 Fla. 782, 196 So. 299 (1940).

2. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818.

3. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818.

4. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(c)(1).

5. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(k).

6. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(c)(1).

7. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(d).

8. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(h)(1).

9. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-73-818(s).

10. ULC “The Uniform Trust Decanting Act” (2015 and 2018).

11. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-102(3).

12. Revocable trusts where consent of a trustee or an adverse party is required may also be decanted.

13. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-103.

14. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-104(a).

15. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-104(b).

16. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-107.

17. Ark. Code Ann. §§ 28-78-107 and -110.

18. Ark. Code Ann. §§ 28-78-115–118.

19. Ark. Code Ann. §§ 28-78-111–112.

20. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-111.

21. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-112(c)(2).

22. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-113.

23. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-114.

practice as an attempt to defeat creditor claims.

The ability to decant into a special needs trust has also been challenged. For instance, the New York Attorney General argued that the new trust was a self-settled trust requiring payback provisions that a third-party trust does not require.30 The court in the case upheld that since the beneficiary’s withdrawal right had not vested the principal of the original trust was not a countable asset of the beneficiary and, therefore, the new second trust was not a countable asset of the beneficiary.

VI. Practical Considerations for Arkansas Trustees and Attorneys

Arkansas attorneys and trustees now have a number of options at their disposal when wanting or needing to make modifications to a trust document. Determining the trustee’s discretionary authority is the first step in determining which statute or modification route best fits the situation. This determination will then set out the ground rules—whether sparse or detailed—on the notice and

documentation required. Decanting could be a minefield for even the knowledgeable estate planning attorney and careful attention should be paid to the proper authority, limitations, and tax implications. If decanting does not fit within the needs or circumstances at play, there are always the more time-tested avenues of modifications that can be utilized: nonjudicial modifications (settlor is living and consent of everyone), judicial modifications (settlor deceased and consent of all beneficiaries) and nonjudicial settlement agreements (consent of all interested parties).

Conclusion

The adoption of the two Arkansas decanting statutes reflects a broader national trend toward greater flexibility in trust administration. Trustees are now empowered to update irrevocable trusts to make necessary changes. However, as with any powerful tool, attorneys and trustees are advised to carefully plan and execute trust decanting to avoid unintended legal or tax consequences.

24. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-119(b).

25. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-123.

26. Ark. Code Ann. § 28-78-120.

27. Ark. Code Ann. §§ 28-78-122 and -126.

28. Sour Grapes: When Decanting Gives Rise to Litigation, Chambers and Partners, https://chambers.com/articles/sour-grapeswhen-decanting-gives-rise-to-litigation.

29. Ferri v. Powell-Ferri, 72 N.E.3d 541, 546 (Mass. 2017).

30. Kroll v. New York State Dep’t of Health, 143 A.D.3d 716, 719–20 (N.Y. App. Div. 2016). ■

Act 975 Original Jurisdication in the Court of Appeals

By Houston Downes

Act 975 of 2025 grants the Arkansas Court of Appeals exclusive original jurisdiction over all facial challenges under the United States Constitution and Arkansas Constitution to acts passed by the General Assembly, provisions of the Arkansas Code, and administrative rules and regulations.1 This legislation has the potential to dramatically change the landscape of constitutional litigation in state court—if it stands. This change is set to take effect on November 1, 2025,2 which gives us time to consider three main questions. First, why the shift? Second, is Act 975 constitutional? And third, assuming this law will go into effect, what would that mean for a lawsuit with both a facial and an as-applied challenge?

Why?

The “why” for Act 975 depends on who you ask, but we’ll settle for the reasons offered by its sponsors: Representative Matthew Shepherd and Senator Bart Hester.

During the floor debate in the House of Representatives, Rep. Shepherd focused on fairness for Arkansas voters—Pulaski County receives an outsized number of constitutional challenges to statutes, and therefore, Pulaski County voters receive an outsized influence on who has the power to enjoin the enforcement of laws passed by the General Assembly.3 Senator Hester echoed these points during Senate floor debate, and he also stated his belief that the Court of Appeals would be less likely to have its rulings overturned by the Arkansas Supreme Court.4

Houston Downes is a litigation associate at Quattlebaum, Grooms & Tull PLLC.

Is Act 975 Constitutional?

Maybe. But the weight of the arguments seems to lean toward “no.”

Article 4, Section 2 of the Arkansas Constitution ensures the separation of powers by prohibiting the legislative, executive, and judicial “departments”5 from exercising “any power belonging to either of the others except in the instances hereinafter expressly directed or permitted.” Amendment 80 draws the line between the legislative and judicial branch—and a few provisions stick out as applicable here.

Sections 5 and 10

Amendment 80, Section 5 states that “[t]here shall be a Court of Appeals which may have divisions thereof as established by Supreme Court rule. The Court of Appeals shall have such appellate jurisdiction as the Supreme Court shall by rule determine and shall be subject to the general superintending control of the Supreme Court.”6 The term “appellate” plays a key role.

On one hand, Section 5 could be read as a constitutional requirement that the Court of Appeals have only appellate jurisdiction. After all, expressio unius est exclusio alterius, right? The expression of one term may be interpreted to exclude others. The Arkansas Supreme Court recently applied this canon of construction when it determined that Amendment 91’s specific provision

to fund “four-lane” highways meant the money could not be used for six-lane highways.7 Similarly, Amendment 80 uses the terms “appellate” and “original” with intention. Section 2 provides the Supreme Court with “[s]tatewide appellate jurisdiction,” “original jurisdiction” over various matters, and “[o]nly such other original jurisdiction as provided by this Constitution.”8 Section 6(a) establishes Circuit Courts as “the trial courts of original jurisdiction of all justiciable matters not otherwise assigned pursuant to this Constitution.”9 Section 7(a) establishes the district courts as courts of “limited jurisdiction,” and Section 7(b) provides:

The jurisdictional amount and the subject matter of civil cases that may be heard in the District Courts shall be established by Supreme Court rule. District Courts shall have original jurisdiction, concurrent with Circuit Courts, of misdemeanors, and shall also have such other criminal jurisdiction as may be provided pursuant to Section 10 of this Amendment.10

The designations of “original” and “appellate” seem carefully chosen and Section 5 is not a likely exception. Perhaps, then, the Court of Appeals has only appellate jurisdiction as a constitutional matter.

On the other hand, Section 10 states that “[t]he General Assembly shall have the power to establish jurisdiction of all courts and venue of all actions therein, unless otherwise provided in this Constitution.”11 The General Assembly’s ability to assign “jurisdiction” may be broadly interpreted to include original and appellate jurisdiction, if not otherwise allocated. And Section 5 does not explicitly prohibit the Court of Appeals from having original jurisdiction. This might open the door for Act 975 to take effect.

Nevertheless, it may be legally significant that the provision creating district courts’ original jurisdiction over criminal matters specifically invokes the General Assembly’s authority to expand it under Section 10. Such an invocation could be required when altering the original or appellate jurisdiction

of a court mentioned in Amendment 80. Otherwise, why would the drafters have mentioned it there?

Section 3

Amendment 80, Section 3, provides that “[t]he Supreme Court shall prescribe the rules of pleading, practice and procedure for all courts.”12 However, Act 975 provides that the procedure of facial challenges in the Court of Appeals “will conform to that prevailing in bench trials in circuit court.”13 It also states additional requirements related to pleadings, fees, summons, and time to file a responsive pleading.14 While Amendment 80 allows the General Assembly to amend or annul Supreme Court rules made pursuant to Section 5, 6(B), 7(B), 7(D), and 8 with a two-thirds vote of each house, it allows no similar power to alter rules made pursuant to Section 3.15 So the purely procedural rules are almost certainly unconstitutional.16 However, they may be severable from the rest of the statute, in which case, the law would survive.17

Section 3 does beg one more question, though: If the Arkansas Supreme Court is the sole source of procedural rules, can the General Assembly use Section 10 to alter jurisdiction in a way that forces the Arkansas Supreme Court to make new procedural rules? Doing so could present additional separation of powers issues under Article 4.

Constitutional Conclusion

This is certainly not an exhaustive constitutional analysis, and the outcome of a constitutional challenge is not immediately clear to me. Nevertheless, I find it compelling that Section 5 mentions only appellate jurisdiction for the Court of Appeals.

Where Do I File?

Under Act 975, if a client wants to challenge a statute with both facial and as-applied claims, it seems like the case would have to split in half, with the as-applied challenge going to circuit court and the facial challenge going to the Court of Appeals. Act 975 is silent on original jurisdiction for as-applied challenges, and Amendment 80, Section 5 only permits the Arkansas Supreme Court to make rules related to the appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals. Therefore, it seems that

the Court of Appeals is left without the original jurisdiction to hear as-applied challenges, and the Arkansas Supreme Court is without authority to grant it. So where would you file constitutional challenges to Arkansas laws and regulations? Until there is more guidance, probably federal court, if possible.

Endnotes:

1. Act 975, §§ 2, 5.

2. Act 975, § 6.

3. Ark. H.R. Deb. on H.B. 1832, 95th General Assemb. (Apr. 9, 2025), https://sg001-harmony.sliq. net/00284/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/ PowerBrowserV2/20250409/-1/31050?med iaStartTime=20250409141207.

4. Ark. S. Deb. on H.B. 1832, 95th General Assemb. (Apr. 15, 2025), https://sg001-harmony.sliq. net/00284/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/ PowerBrowserV2/20250415/-1/31106?med iaStartTime=20250415153305.

5. Ark. Const. art. IV, § 1 divides Arkansas government into “departments” rather than “branches.”

6. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 5 (emphasis added).

7. Buonauito v. Gibson, 2020 Ark. 352, at 8, 609 S.W.3d 381, 386.

8. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 2(d).

9. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 6(a).

10. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 7(a), (b).

11. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 10.

12. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 3.

13. Act 975, § 2.

14. Act 975, § 2.

15. Ark. Const. amend. LXXX, § 9.

16. See Johnson v. Rockwell Automation, Inc., 2009 Ark. 241, at 6–7, 308 S.W.3d 135, 140.

17. See U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Hill, 316 Ark. 251, 268–69, 872 S.W.2d 349, 358 (1994), aff'd sub nom. U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779 (1995) (conducting a severability analysis that considered whether an unconstitutional portion of a provision was functionally independent from the constitutional portions and whether the provision would have been enacted without the unconstitutional portion). ■

One Word, Big Impact: Strengthening UPL Enforcement Through Act 110

By Meagan Davis

In the legal world, a single word can change everything. That truth is on full display in Act 110 of 2025, which amended Arkansas Code Annotated § 16-22-501(a), the state’s central statute concerning the unauthorized practice of law (UPL). The change—seemingly minor—swaps the phrase “intent to obtain a direct economic benefit” with “intent to obtain any economic benefit.” This shift strengthens the state’s ability to protect Arkansans from the harm caused by unlicensed legal practice.

The unauthorized practice of law remains a significant concern throughout Arkansas, as vulnerable individuals across the state seek help following accidents or personal injury. Prior challenges in enforcing the statute revealed a loophole created by the original “direct economic benefit” language, which limited the ability of prosecutors and courts to hold certain unlicensed practitioners accountable. Act 110 addresses this issue with a targeted amendment that enhances public protection.

The UPL Committee receives numerous complaints annually regarding various suspected forms of unauthorized practice. It is important to note that this code section is limited to those acts that constitute a criminal unauthorized practice of law. When a complaint comes to the committee implicating a violation of this code section, “[t]he Committee may also refer cases to the appropriate prosecutor, the United States Attorney, the Attorney General of the State of Arkansas, or other appropriate authorities for investigation and possible prosecution or action.”1

The Problem: “Direct” Economic Benefit Created a Loophole

Meagan Davis is a partner at Maddox & Davis PLLC and a member of the Arkansas Supreme Court Committee on the Unauthorized Practice of Law

Before the amendment, Arkansas law required proof that an unlicensed individual acted “with intent to obtain a direct economic benefit” to be charged with unauthorized practice. The qualifier “direct” created confusion and limited enforcement in several cases. Questions arose about whether an economic benefit had to come immediately and directly or if indirect compensation—such as payment routed through a third party—was sufficient to trigger liability.

This ambiguity became apparent in a recent Sebastian County case. Daniel Shue, Prosecuting Attorney for the county, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee about the proposed legislation. He explained that two individuals were operating as “runners” for chiropractors by soliciting accident victims and providing legal advice regarding settlement timing and waiver signing. These actions clearly constituted the unauthorized practice of law. However, because these individuals received payment indirectly from the chiropractor rather than directly from insurance proceeds, the judge questioned whether the existing statute applied. While the individuals were charged and convicted, the case exposed a potential problem in the law’s language.

Rep. Jay Richardson, one of the bill’s house sponsors, provided similar testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, highlighting the need for legislative action to clarify and strengthen the statute. He stated this change was needed to help prevent similar issues in the future.

From the perspective of the UPL Committee, lawyers whose clients engage in activities that previously fell within these statutory gray areas should read the new law carefully and counsel their clients accordingly. The statutory revision enacted by Act 110 expands the range of conduct that may constitute criminal unauthorized practice, thereby broadening the circumstances under which the committee may refer matters to an appropriate law enforcement entity for further investigation and/or enforcement.

The Legislative Response: Expanding Protection for the Public

Act 110’s key amendment replaces “direct economic benefit” with “any economic benefit,” eliminating the ambiguity that previously hindered enforcement. This change ensures that individuals cannot avoid liability simply because their economic gain comes indirectly, through intermediaries, or via complex business arrangements.

Representative John Maddox, another of the bill’s house sponsors, described the amendment’s purpose succinctly:

This amendment isn’t about expanding the law—it’s about closing a loophole. We want to make sure people who are exploiting Arkansans with unlicensed legal services can be held accountable, no matter how they try to profit.