The name Mondoluce has long been synonymous with architecturally-designed, residential lighting projects. With access to an array of leading designer brands from around the world, unparalleled industry and application knowledge, we make spaces, simply brilliant.

Contact Mondoluce today on 9321 0101 and embrace the diverse roles that lighting can play for your next project.

The Australian Institute of Architects is the peak body for architecture in Australia representing over 14,500 members globally, committed to raising design standards and positively shaping the places where we live, work and meet.

The Architect is the official publication of the Australian Institute of Architects – WA Chapter. This WA 2025 edition focuses on West Australian homes and community spaces designed by West Australian architects.

Kedela wer kalyakoorl ngalak Wadjak boodjak yaak. Today and always, we stand on the traditional land of the Whadjuk Noongar people.

RAVENSTHORPE CULTURAL PRECINCT

Peter Hobbs Architects, Advanced Timber Concepts, Intensive Fields.

Words: Andrew Boyne 80

ENDURING ARCHITECTURE

22 DELHI STREET

Summerhayes And Associates

Words: Fred Chaney

84

SOCIAL HOUSING

Words: Michelle Blakeley

87

DENSITY DONE WELL?

Words: Jimmy Thompson

EDITOR

Jonathan Speer

MANAGING EDITOR

Emma Adams

EDITORIAL PANEL

Sandy Anghie

Emma Adams

Matthew Sabransky

Ellie Munn

Jonathan Speer

PLANS + DRAWING PREPARATION

Matthew Sabransky

MAGAZINE DESIGN

Peter McDonald

ww.publiccreative.com.au

PRINTING

Advance Press

PUBLISHER

Institute of Architects

WA Chapter 33 Broadway Nedlands WA 6009

T: (08) 6324 3100 architecture.com.au @architects_wa

ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES

wa@architecture.com.au

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

wa@architecture.com.au

COVER IMAGE

Salt Lane at Shoreline by Gresley Abas

Photography: David Deves

SUPPORTING PATRONS

Living Edge

Midland Brick

REGIONAL FOCUS

Words: Sandy Anghie

92

SMALLER HOMES

Matthews McDonald

Architects

Words: Leonie Matthews and Paul McDonald 98

WE ARE THE FUTURE

Words: Ellie Munn

99

MEMBER HONOURS

Warranty: Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

Important Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Institute of Architects. Material should also be seen as general comment and not intended as advice on any particular matter.

No reader should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained herein. Readers should consult professional advisors. The Australian Institute of Architects, its officers, the editor and authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons whatsoever in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by any such persons in reliance whether in whole or in part upon any of the contents of this publication. All photographs are by the respective contributor unless otherwise noted.

ISSN: 2653-1445

This publication has been manufactured responsibly under ISO 14001 environmental management certification and Forest Stewardship Council certification FSC® Mix Certified paper.

A provocation - 100 years later. In 1924, Virginia Woolf wrote:

“On or about December 1910 human nature changed.”

“All human relations shifted,” Woolf continued, “and when human relations change there is at the same time a change in religion, conduct, politics, and literature.”

And so came the fluorescence of what we now call Modernism. The time was associated with a flood of discourse and an extraordinary scale of experimentation in art, architecture, literature, music and indeed all forms of cultural expression as well as some extraordinary scientific developments.

In architecture in those early days of the C20 there was also a flood of transformative experiments often associated with theoretical positions in relation to the social changes and the perceived needs of this new era. In architecture, these were led by figures such as Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Rietveld and so on. They were significantly informed by earlier revolutionary spatial experiments in painting by Cezanne, Picasso, Braque and Mondrian.

And so a new space was invented and there was a reforming of the visual expressions of this new spatial form. These inventions became adopted into a new the style of Modernism and lost much of the interrupt of their spatial composition and whilst much of the social experimentation was initially a failure, the influence remains pervasive still today.

100 years later, many would claim that we are in the midst of similar tectonic social shifts.

But are we seeing a similar level of discourse and purposeful experimentation heralding a direction for architecture commensurate with the changes and challenges increasingly apparent?

Whilst there is plenty being written about climate change, AI, social media driven communication anxiety for the implications, it is fragmented and lacks discursive coherence.

Is there a new architecture of the C21st and if so what is it? And how will these contribute to manifest changes in the urban environment? Should we be seeking out and sharing in a new discourse on architecture and urbanism?

Ross Donaldson WA President Australian Intitute of Architects

The man bent over his guitar, A shearsman of sorts. The day was green

They said, "You have a blue guitar, You do not play things as they are."

The man replied, "Things as they are Are changed upon the blue guitar."

And they said then, "But play you must, A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar Of things exactly as they are."

Wallace Stevens 1936 on cubism

• Designed for double glazing with single glazed options

• Superior energy performance

• Conventional perimeter frames, embedded frames and integrated inline reveals

• U-values as low as 2.2

• Flush glazing lines maximise visible openings

• Australian designed & manufactured

According to population figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Perth was recently identified as Australia’s fastest growing capital city, with a current population of 2.3 million forecast to grow to 2.9 million by 2031 and 3.5 million people by 2050.

These people will need somewhere to live.

Practitioners in Western Australia face immense challenges and exciting opportunities. Rapid urban growth, the imperative of sustainability, and the ongoing housing affordability crisis mean architects play a crucial role in shaping a built environment that is functional, beautiful, and socially and environmentally responsible.

Our unique climate and landscape demand innovative approaches, and, in this edition of The Architect, we examine the ideas, projects, and people driving the future of design in WA, creating spaces that respond to their environment and set new standards for energy efficiency and climate resilience.

As density increases, the design of public spaces, multiresidential developments, and community infrastructure becomes more critical in fostering community. Through case studies and expert insights, we explore how thoughtful design can enhance the way we live, work, and connect.

The WA Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects remains committed to supporting our profession through advocacy, education, and dialogue. The Architect 2025 is an invitation to engage with the ideas shaping our cities and be inspired by the creativity and dedication of our peers.

We look forward to the conversations ahead.

Jonathan Speer Editor

Ross Donaldson

Ross, founder of EPM Experimental and WA Chapter President of the Australian Institute of Architects, led Woods Bagot's global growth as CEO/Chairman (2006-2016). He now lives in Perth, focusing on climate action, teaching, and strategic consulting.

Sandy Anghie

Sandy has experience across diverse fields, combining architecture and planning with legal, finance, commercial and governance skills. She is the immediate past President of the WA Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects.

Doireann de Courcy Mac

Donnel

Doireann, an Irish graduate architect with DKO, is passionate about inclusive urban spaces. A founding member of TYPE.ie and former contributor/editor for various publications, she believes architectural writing and criticism are vital for improving shared spaces.

Jonathan Speer

Jonathan Speer is the Executive Director of the WA Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects. He advocates for resilient, quality design, engaging with built environment stakeholders to support Western Australian architects.

Emilly Barrow

Emilly is a freelance designer and founder of Emly Creative. She works with businesses across Australia's built environment industry, leveraging her marketing and graphics skillsets alongside her degree in Interior Architecture.

Rob Debenham

Rob is a senior architect at Statuo Group with a passion for all aspects of design. Specialising in redefining spaces through innovative design and a focus towards a more sustainable future.

Emma Adams

Emma is the editorial and publishing lead at the Australian Institute of Architects. She is a contributing editor, architectural writer, and researcher with experience in literary archives.

Michelle Blakeley

Michelle leads her own architecture practice developing more efficient living spaces and is founder of My Home housing delivery for people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

Paula Della Gatta

Paula, a 2024 EG Cohen Medallist, is enhancing her affordable housing and civic architecture experience in her current government role. She values workplace culture, collaboration, and advocates for accessible design, with a passion for architecture's impact on human behaviour.

Peter McDonald

Peter is Creative Director at Public, with 30+ years of experience in brand design, publications, signage, and digital media. He's a senior graphic designer dedicated to high quality design solutions.

Andrew Boyne

Andrew Boyne is an Architect at Western Architecture Studio and a PhD Candidate at RMIT University.

Marinda Ergovic

Marinda is an architect and researcher with international experience in London, UK. Marinda has a focus on buildings and their relationship to health and well-being.

Matthew Sabransky

Matthew, completing his Master's, leverages his biomedical background for analytical research and design. Actively supporting industry students, he has been elected President of SONA for 2025.

Fred Chaney Fred, Director of TRCB, is a member of the RAIA WA Honours and ACA WA branch committees. He previously served on the Green Building Council of Australia board and as a professions’ representative with the WA Planning Commission.

Olivia Lomma

Olivia, a Graduate at Plus Architecture, is passionate about adaptive reuse and sustainability. As CoLead of archi-bytes in EmAGN WA, she engages in architectural journalism, advocating for critical conversations in design and the built environment.

Ric Maddren

Ric is an architect at Ha° Architecture in Melbourne, passionate about design and construction. He maintains strong ties to Perth and promotes architectural appreciation locally and across Australia.

Jimmy Thompson

Jimmy, Design Director at MJA Studio, creates context-responsive, heritage-aware designs with whimsy and delight. He deeply cares about people, Perth, humanity, and the positive impact of architecture on occupants and the environment.

Leonie Matthews

Leonie, co-director of Matthews McDonald Architects, has over 30 years of experience as a practitioner, educator, and researcher. Her contributions were recently recognised with her elevation to Fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects.

Trevor Wong Trevor, an architect at Hames Sharley, has diverse project experience in urban planning, commercial, industrial, retail, residential, and mixeduse developments. He is a Picha Studio member, CO-architecture writer, and actively promotes architectural awareness in Perth.

Paul McDonald

Paul, co-director of Matthews McDonald Architects, focuses on residential and community projects. A Curtin University graduate (1988), he worked with several firms, including Howlett and Bailey Architects, before founding MMA in 2001.

Ellie Munn

Ellie is currently pursing her Masters of Architecture whilst working at GHD Design. As the SONA Vice President for Community, she is passionate about supporting students.

Sharaan Muruvaan Sharaan, an architect at COX Architecture, cochairs the RAIA WA Equity Taskforce and serves as a Chapter Councillor. He also teaches at Curtin University, focusing on multi-residential design and promoting equity and innovation in architecture.

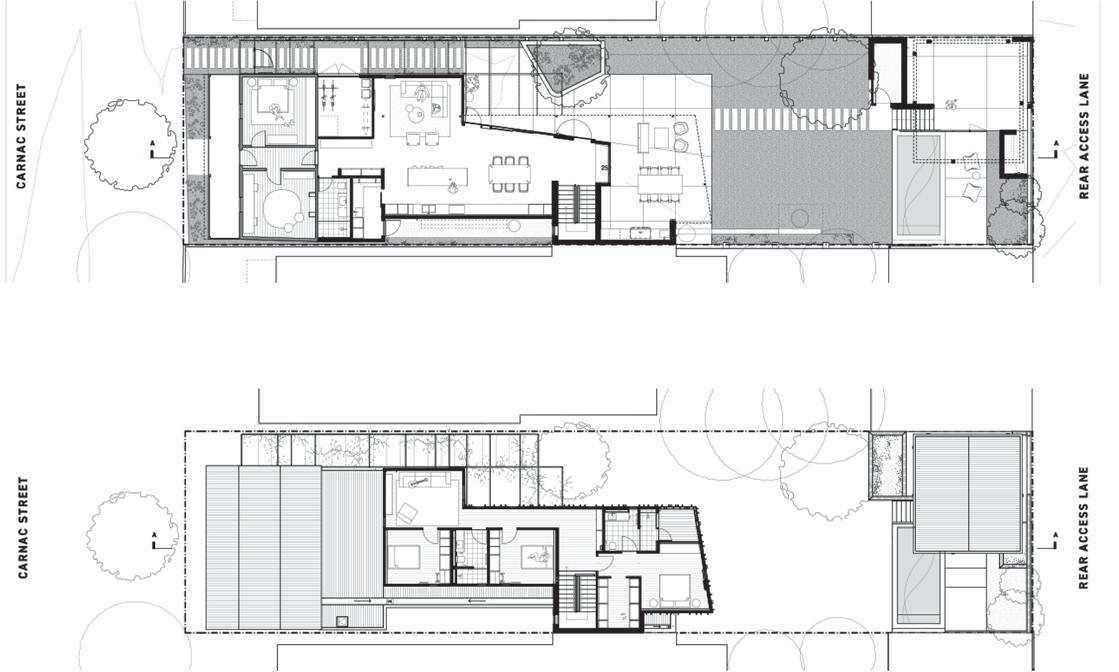

Homes are personal. If we allow them to be, they can adapt to suit our lifestyles and grow with us through different phases of life. White House by Spaceagency speaks volumes about the hidden potential of existing homes, waiting to be unlocked by those willing to preserve character and give old bones a new chance.

Upon arrival, the existing cottage sits humbly in the streetscape of the Carnac Street Precinct in South Fremantle. It is not until you enter the backyard that you experience the addition with its white vertical cladding, serving as a modern interpretation of the heritage facade. Beyond the front fence, which homeowner Clay built from the restored hardwood flooring, the extension interacts with a neighbourhood of shared backyards adorned with art pieces made from repurposed materials, characteristic of Fremantle’s artistic temperament.

White House is a celebration of place, which Spaceagency characterises as an ongoing repair story. As you journey through the house, you are taken through the many repairs the house has undergone throughout its life. A notable architectural feature is the stained-glass door from the existing cottage, acting as the threshold between old and new. Architect Alessia Richards described it as “a nod to the quirkiness of the existing cottage,” which was sanded down just enough to restore, but not taint, its heritage charm.

This charm and the memories embedded in the home have been adopted by Clay and Zoe, and after three years, they found themselves rapidly outgrowing the space as their primary school-aged children approached high school. Given their attachment to the place, the family was adamant they should retain the existing cottage in the home’s renovation.

The renovation was a continuation of the family’s sustainable lifestyle and the ongoing repair story of the heritage cottage. The inclusion of the shipping container was one of Clay’s many ideas to repurpose materials throughout the house. Despite its humble function as a storage space, the shipping container forges a key element in the redesign. Architect Michael Patroni explains that “to Clay, the shipping container represents living in Fremantle” and similar to the heritage stained-glass door, “forms part of the [architectural] punctuation between the old and new house."

What connects the cottage and the addition, deep beyond the surface, is the continuation of the existing structural language of timber-frame construction. Architects Alessia and Michael recounted the poor structural state of the cottage, having seen many phases of life dating back to its use by ironworkers in 1899. It is this continuation of the existing language of the building, that underpins the commitment through the renovation to retain and repair.

Not only is the home sustainable, with the renovation adding another decade to the house’s lifespan to serve the next generation, White House also responds well to the climate with thermal comfort, photovoltaic cells, no gas on site, and thoughtfully curated lighting, all characteristic of Spaceagency’s design approach.

Adaptive reuse can be a lifestyle whereby we re-purpose materials and re-program spaces. White House is ultimately a celebration of place. Clay, Zoe, and their family have grown alongside their home. Heritage or not, our homes have enduring potential. Together with thoughtful design and sustainable practices, we can continue their ongoing repair, extending the lives of our homes as we adapt our own.

ARCHITECT: Spaceagency www.spaceagency.com.au

DESIGN TEAM

Michael Patroni, Alessia Richards, Dimmity Walker

KEY CONSULTANTS

Structural Engineering: WA Structural ESD: Living Building Solutions (LBS) Landscape: Spaceagency Build Surveyor: Resolve Group

BUILDER

Assemble Building Co. Completion date: 04/08/2023

SUSTAINABILITY: Adaptive reuse, alteration and addition – rather than demolition – and well built flexible‚ “loose fit“ spaces are core to the sustainability principles we have employed here. In addition the house is designed to benefit from passive environmental design, orientation and cross ventilation. New work is well insulated and glazing is shaded or screened. Solar powered home. No gas on the site.

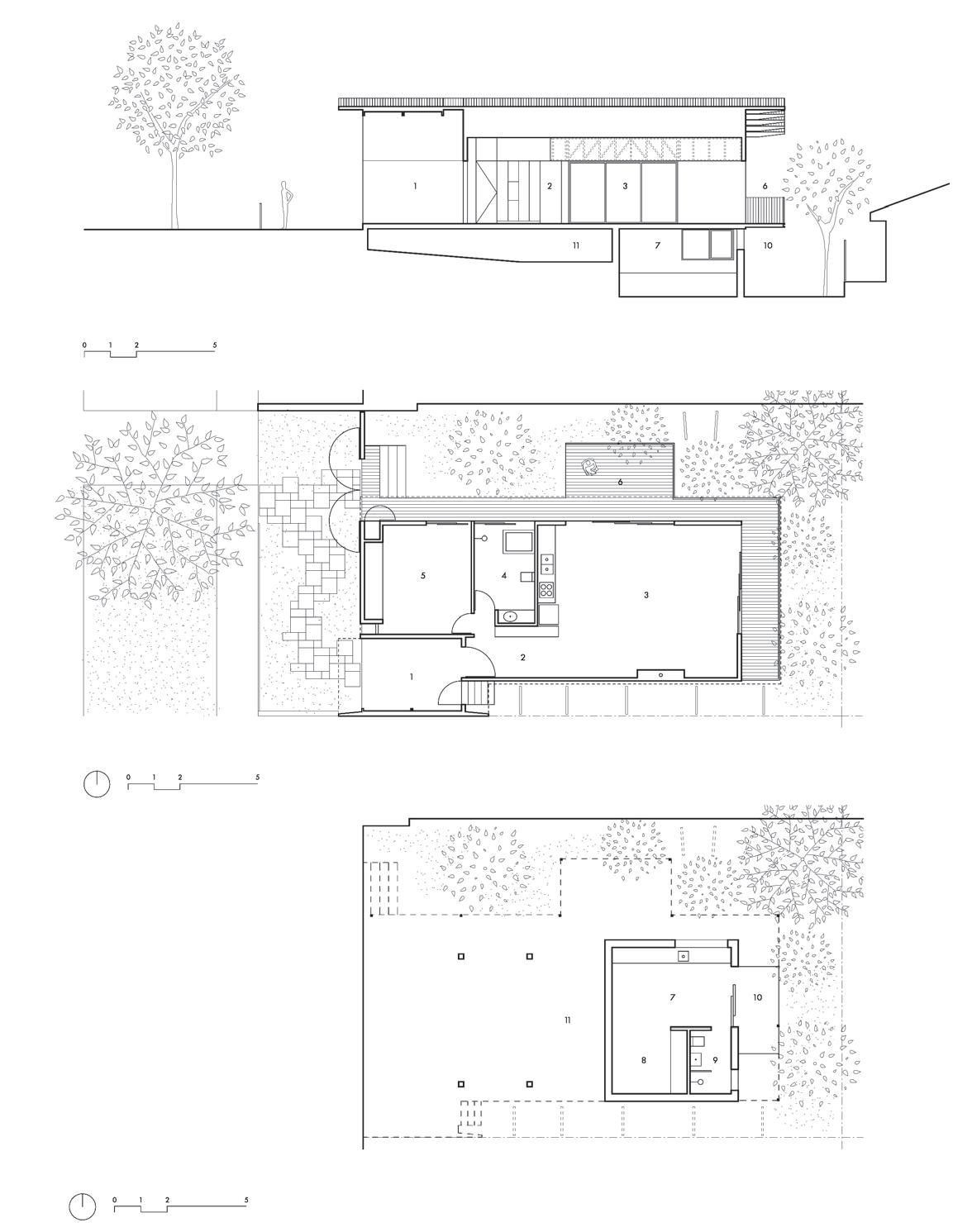

Nestled gently along a teeming, car-laden suburban thoroughfare is a powerful house, that seamlessly integrates with and extends from the landscape of Beaconsfield. Peta’s House by Mt Eyk is an exemplary project that strengthens the emerging paradigm that good design can be aesthetic, innovative, and affordable.

The client, in search of a new home for herself and her charming cat Prince, fell in love with a block that was undesirable for many prospective buyers. Some of the challenges included a heavily sloping site and unfavourable neighbouring conditions. The constraints of the site, although challenging at first, constituted to a robust and intentional design outcome with many opportunities to connect with the surrounding environment.

The design brief was simple: create a space that encapsulates minimalism, simplicity, good design and detail, practicability, and profitability.

When first approaching this architectural marvel, the external public streetscape effortlessly melts into the arrival journey of the home through a progression of landscape, materiality, geometry, and entry loggia. Movement and flow are acknowledged through vertical and horizontal expressed joints of the Barestone, plywood, and Danpalon and for the trained eye, the geometric proportions reveal camouflaged openings into the house.

Access to Peta’s House is extra-ordinary with three distinct entry points at the front. These include a main entrance to the primary home, an entrance to the short-stay accommodation, and entry into to the courtyard space. These entries begin to communicate the use and flexibility of the house.

The experience after arriving through the front door is one of solid/private, light/public. The bedroom and bathroom are at the front of the house, with the kitchen, living, and dining areas flowing through the remainder of the home out into an external courtyard.

The primary dining and living space is flexible in use throughout the differing seasons and is demarked by Peta’s furniture, and her many artworks, and artefacts.

As you move through the house, the spaces seamlessly intertwine and flow into once-imagined views of trees set against vast landscapes, that now act as picturesque backdrops for an abundant courtyard, accompanied by the sounds of birdsong and cicadas.

The client has cleverly created a source of income for herself, while at the same time addressing the housing shortage and giving back to her wider community, by subletting a selfcontained second dwelling, separated from the main house, at the base of the site.

A separate door and entry corridor to the sublet accommodation is located along the southern boundary of Peta’s house. The living spaces, verandahs, and courtyard open to the north, neighbouring a concrete party wall, which serendipitously has become a canvas for nature to flourish.

The courtyard oasis is visible from all openings around the home and accessed by verandahs running north and east, paying homage to 1850s Australian vernacular architecture.

The material palette for Peta’s House is raw, robust, and economical by way of using locally sourced Barestone CFC, Danpalon polycarbonate, concrete blocks, timber, and plywood.

Permeability of space and imaginative use of materials can be further explored through the juxtaposition of the exposed painted timber structure at the entry loggia and the diffused timber truss clad in Danpalon above the kitchen, living, and dining spaces. Used in this way, the materials reinforce the integrity of the design throughout, harmony of the space, functionality, and construction efficiency.

Peta’s House stimulates the conversation around our evolving needs as people and the gravity of having awareness surrounding social, economic, and environmental requirements that also play a significant role as part of the design process.

ARCHITECT: Mt Eyk www.mteyk.com.au

DESIGN TEAM

Emily Van Eyk, Olivia Baljeu

KEY CONSULTANTS

Structural Engineering: Scott Smalley Partnership

ESD: Sustainability WA

Landscape: Supernatural & Peta Walter (client)

BUILDER: White Gum Building. Completion date: 05/05/2023

SITE: AREA: 273m2 Build area: 102m2

SUSTAINABILITY: Key sustainability measures: PV array, orientation, thermal mass, earth berming, passive solar and ventilation.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Cabinetwork: Worldwide Timber Traders. Windows and Doors: Avanti. Exterior cladding: Cemintel Barestone

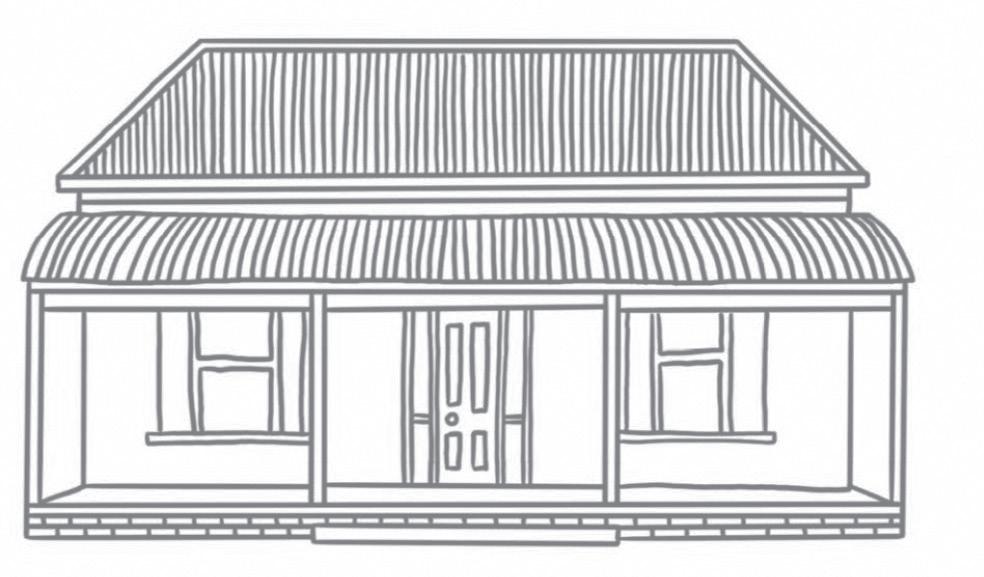

Proclamation House strikes a rare balance, offering spaces that are lavish, yet unpretentious, on a modest lot in leafy Subiaco. With only two bedrooms, State of Kin have designed for intentional living, challenging Australia’s predominant adoration of sprawling houses, meaningfully demonstrating spaces that are tailored for both connection and solitude.

Crafted for multigenerational living, an equilibrium was carefully achieved, balancing privacy and togetherness so the owners could enjoy both independence and connection. The home feels spacious, not by increasing its footprint, but instead ensuring every millimetre is accounted for, and considered with care. This design is evidence that living well doesn’t demand limitless space - it instead requires intention.

A subtle echo of the original cottage reveals itself from the street elevation, preserving its connection to Subiaco, serving as a deliberate nod to the history of the site. The home is patently connected to place, yet undeniably elevated. Set back from the street, a fire pit and garden create a natural buffer, offering the home concealment while also fostering a sense of openness.

The most striking feature of this project is the custom render that envelopes the interior walls throughout. The surface is almost cave-like with a rough, earthy quality that evokes a sense of shelter, protection, and intimacy, as if naturally formed by time and environment. The render is richly worked, offering a tactile and visually engaging finish throughout the entire property.

Architect Ara and interior designer Alessandra revealed how the many challenges faced during the design process led to immensely satisfying outcomes. Alessandra spoke of the arduous task of creating the custom render, a procedure of trial and error to engineer the final remarkable product. The plaster is layered with a variety of materials, including hemp, with intrinsic acoustic and thermal properties. This not only reduces the home’s carbon footprint, but also offers an opportunity to experiment with rich colours, textures, and eco-friendly practices. To accomplish the texture was a process requiring precision and a deep understanding of both material science and design.

The application of the render on interior walls, effortlessly extends into the kitchen culminating in the remarkable centrepiece of the kitchen island. Here, durability and design intersect as the surface was custom engineered to match the walls while also remaining pristine from everyday use. The counter undertook repeated testing to ensure its resistance to oils, spices, and – of course – red wine.

Light pours into enclosed spaces through clever placement of light wells, with each stretching through the home like geological fissure, bathing private spaces in light, and inviting an atmosphere of organic fluidity across private and shared spaces. The mix of texture and light, with each space connecting directly to an ecologically diverse garden, induces a mood of calm comfort and serenity.

Alex and Yackeen, the owners, reflected on the retreat-like aspect of the brief, communicated to the architects. They share they often feel ‘transported away from reality’ as though they ‘could be anywhere in the world’. A year into residency the owners stated that the brief was not only met, but exceeded, a sentiment they have echoed as they continue to admire the design with every passing day.

The seamless passage between indoor and outdoor celebrates Perth’s famous 300 days of sunshine. With its mixture of textured surfaces, rich palette, light wells, and a deep sense of spaciousness, this home feels almost like you're on holiday, every day. It’s the kind of place that’s as unique as its residents, yet somehow still feels like home. The home proclaims itself as the perfect blend of personal and extraordinary.

ARCHITECT: State of Kin

www.stateofkin.com.au

DESIGN TEAM

Architects: Ara Salomone, Jessie Vu Nee Nguyen

Interior design: Alessandra French, Amy Clark

Structural Engineering: Forth Consulting

Landscape: Tristan Peirce Landscape Architecture

Planners: Urbanista

Certifiers: Resolve Group

Energy Efficiency Consultants: Sustainability WA

BUILDER: State of Kin. Completion date: 2023

SITE: Area: 515m2. Build area: 270m2

SUSTAINABILITY: NatHERS rating: 6.7. Key sustainability measures: Achieved a 6.7-star energy rating (Nat HERS) 2020 which exceed the requirement at the time. Installed 9.99kW PV system with 27 x 370W Canadian solar panels. Designed north-facing cantilevers. Implemented protected openings on the east and west sides. No paint at all throughout the project. Utilised hemp render internal finish. Insulator to regulate internal temperatures. Renewable resource. Moisture regulator. Improved indoor air quality, absorbed carbon dioxide. Durable resistant, non toxic. Overall, incorporating hemp render finish internally into a single residential home built in Perth Subiaco can enhance building performance by providing insulation, moisture regulation, sustainability, carbon sequestration, non-toxicity, and durability benefits. These advantages align with sustainable building practices and contribute to the creation of a comfortable, healthy, and environmentally friendly living environment for the homeowners. Equipped with double glazing throughout. Provision made for a car battery. Permeable outdoor paving in designated areas. Prioritised tree retention and future provision for a green roof. Enhanced insulation in cavity brick walls, ceilings, and roof primarily electric appliances (V-Zug). Despite the potential for a larger 4-bedroom, 5-bathroom layout, the ground floor site coverage remains at 48%. However, the building mass is significantly reduced. Walls and window apertures are strategically designed to set the glazing back into the walls, providing improved protection from the sun. Soffit depths are designed to optimise sun exposure, ensuring reduced exposure during summer seasons. Implementing the structural floor as the finishing material throughout to minimise material usage.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Lighting: MLP. Furniture: Mobilia

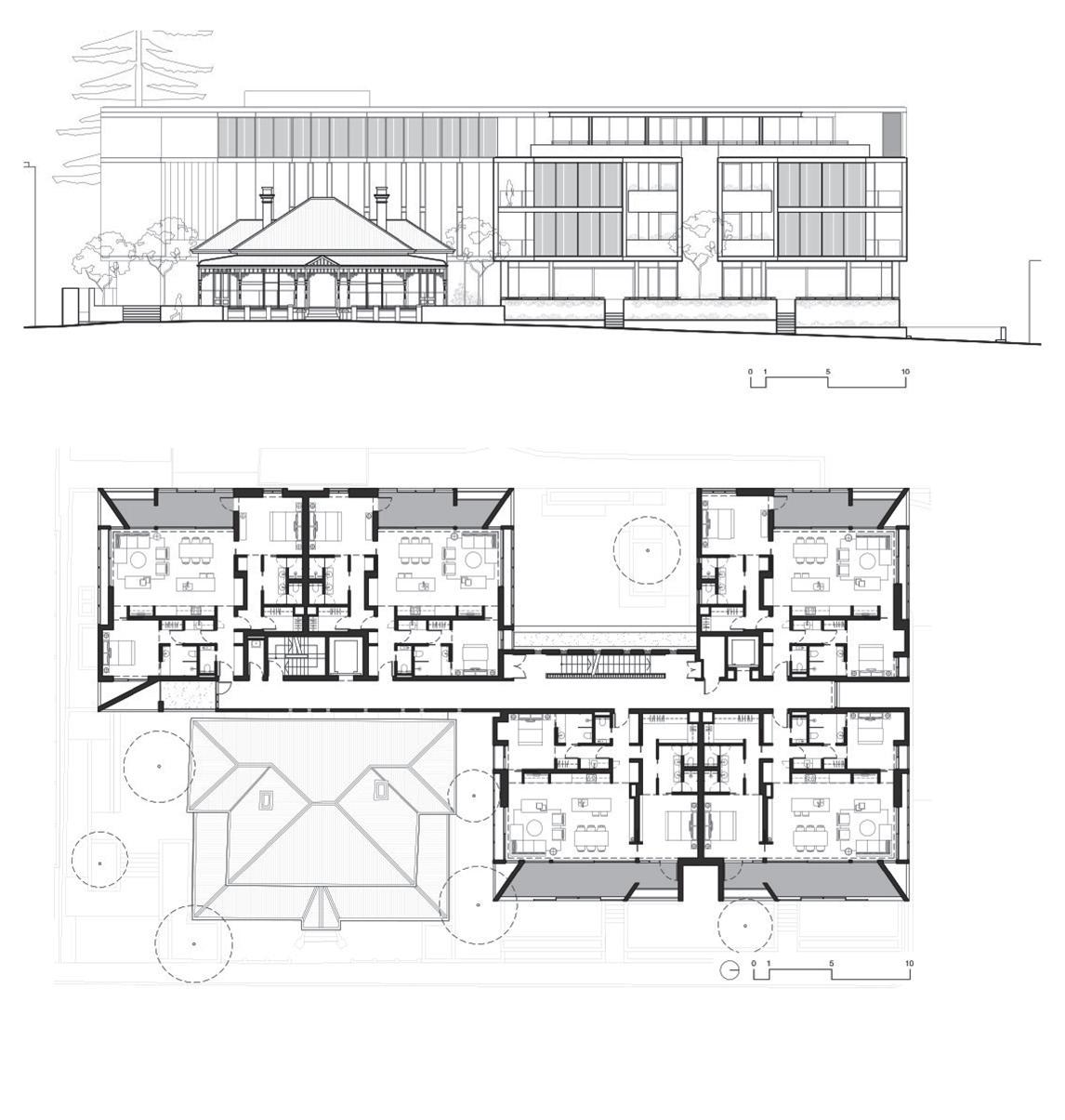

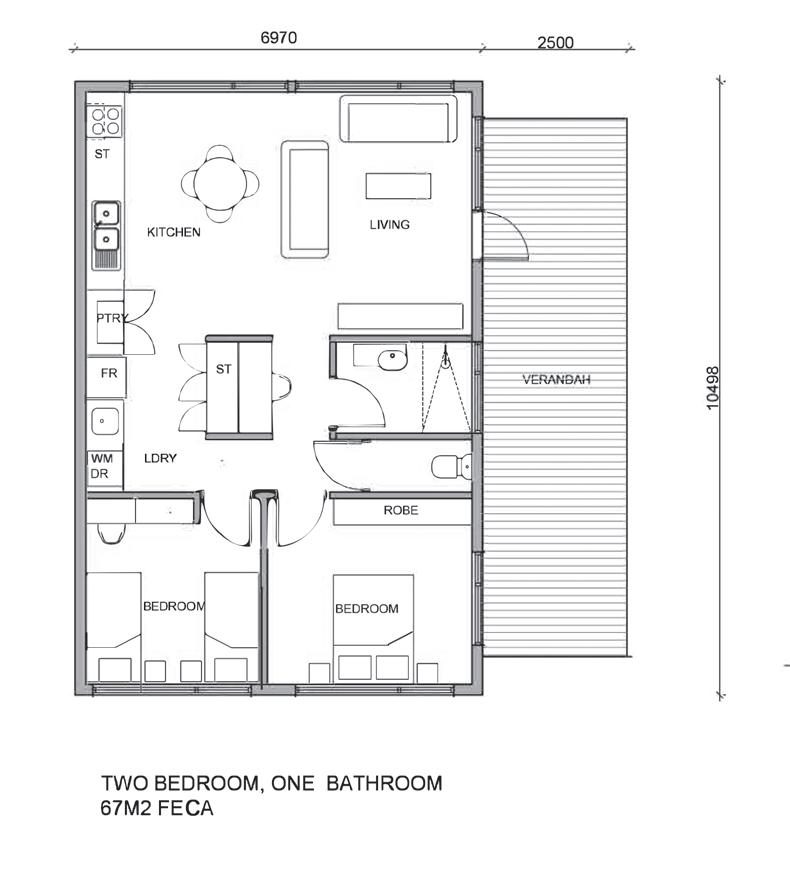

Kiora by KHA is part of the broader master plan for the St. Louis Estate in Claremont, marking the first phase of an independent living development within the estate.

The site holds historical significance, including the heritage-listed Priest’s House on Dean Street, which has been restored and now functions as a library and communal lounge. The name "Kiora" refers to the Māori greeting, "Kia Ora", wishing good health.

The architectural approach is sensitive to the heritage context. The building is carefully sculpted around the preserved Priest’s House, maintaining its historical integrity without overwhelming the original structure. Space is left around the heritage building, ensuring its scale and proportions remain the focal point. From Dean Street, the distinctive roofline of the library is visible within the landscaped garden, creating an immediate sense of place. Kiora rises through a two-story masonry datum, respecting the height context and establishing a strong connection to the streetscape. The upper level is set back, creating a sense of lightness while maintaining visual continuity in the architectural language. These elements are reflected in the material palette, including a brick base, pre-cast concrete, and bronze filigree screening. The materials subtly reference Claremont’s transitional location between the river and coast, grounding the design in its local context.

The entrance to Kiora features a sculptural gesture that serves as a future wayfinding element, linking the development to the broader estate master plan. Its form acts to direct natural light into the interior spaces, with clerestory windows on the upper level bringing light into the corridors. The proportions and materiality of the entrance reinforce the architectural language, grounding the development in both its site context and its relationship with the surrounding heritage elements.

The communal library and lounge area flow into the wellness centre, designed to foster the wellbeing of the community.

This centre supports allied health services and exercise classes, providing an amenity that meets the needs of residents. Kiora offers genuine downsizing options, creating an alternative to larger suburban homes and contributing to the provision of a more balanced housing market in the western suburbs.

Although the development comprises of just 16 apartments, its design conveys a civic sense of scale. Striking, inflected walls at the corners of the façade create opportunities for views and natural light. The apartments on the upper levels reflect a careful focus on scale and proportion. Every apartment is a corner unit, offering dual aspect, cross-ventilated living spaces with generous balconies. These balconies are integrated with planting, creating a seamless connection between indoor and outdoor spaces. Elegant metal screening provides privacy and shading whilst adding animation to the building’s exterior. Every apartment is meticulously crafted, with fluid layouts that avoid dead-end spaces, offering opportunities for spatial connections and a sense of generosity within the homes. The finishes inside the apartments are refined yet robust, reflecting KHA’s commitment to materiality and creating a coherent relationship between interior and exterior spaces. The brickwork from the exterior is echoed within the living spaces, while terrazzo flooring subtly references the concrete finish outside, strengthening the connection between interior and exterior environments.

Kiora sets a new benchmark for independent living developments by blending heritage and modern design. KHA’s thoughtful approach to Claremont’s materiality and streetscape, along with the provision of downsizing options, addresses local housing challenges and contributes to a more balanced market. The building’s refined form and materials, such as masonry and precast concrete, ensure the development respects its surrounding context. Kiora not only meets the needs of its residents but elevates the standard for future developments, demonstrating how a holistic architectural approach can enhance both individual lives and the broader community.

ARCHITECT: KHA

www.kha.studio

DESIGN TEAM: Seán McGivern, Patrick Kosky, Sarah Ashburner, Anna McVey, Lena Lena, Kate Moore, Christopher Shaw, Lucy Bothwell, Gaia

Sebastiani, Lucy Denis, Emily Sullivan, Kendall Onn.

CONSULTANTS

Structural Engineering: BPA Engineering

Electrical Consultant: Floth

Mechanical Consultant: Link Engineering

Hydraulic Consultant: PGD / EDC

ESD: Link Engineering

Landscape: Emerge Associates

Heritage: Griffith Architects

BUILDER: PACT Construction / JAXON Construction

Completion date: March 2023

SITE: Area: 1838m2. Build area: 4472m2

SUSTAINABILITY: NatHERS rating: 7.1 Stars. Key sustainability measures: 30kw PV array. Dual aspect and cross ventilation to all apartments.

KEY SUPPLIERS:

Cabinetwork: Frontline / Artek. Floors: Bernini Stone. Bathrooms: Brodware / Caroma. Furniture: Jardan / Loam / Mobilia. Exterior cladding: Arcadia

PHOTOGRAPHY ROBERT FRITH

COUNTRY WHADJUK NOONGAR

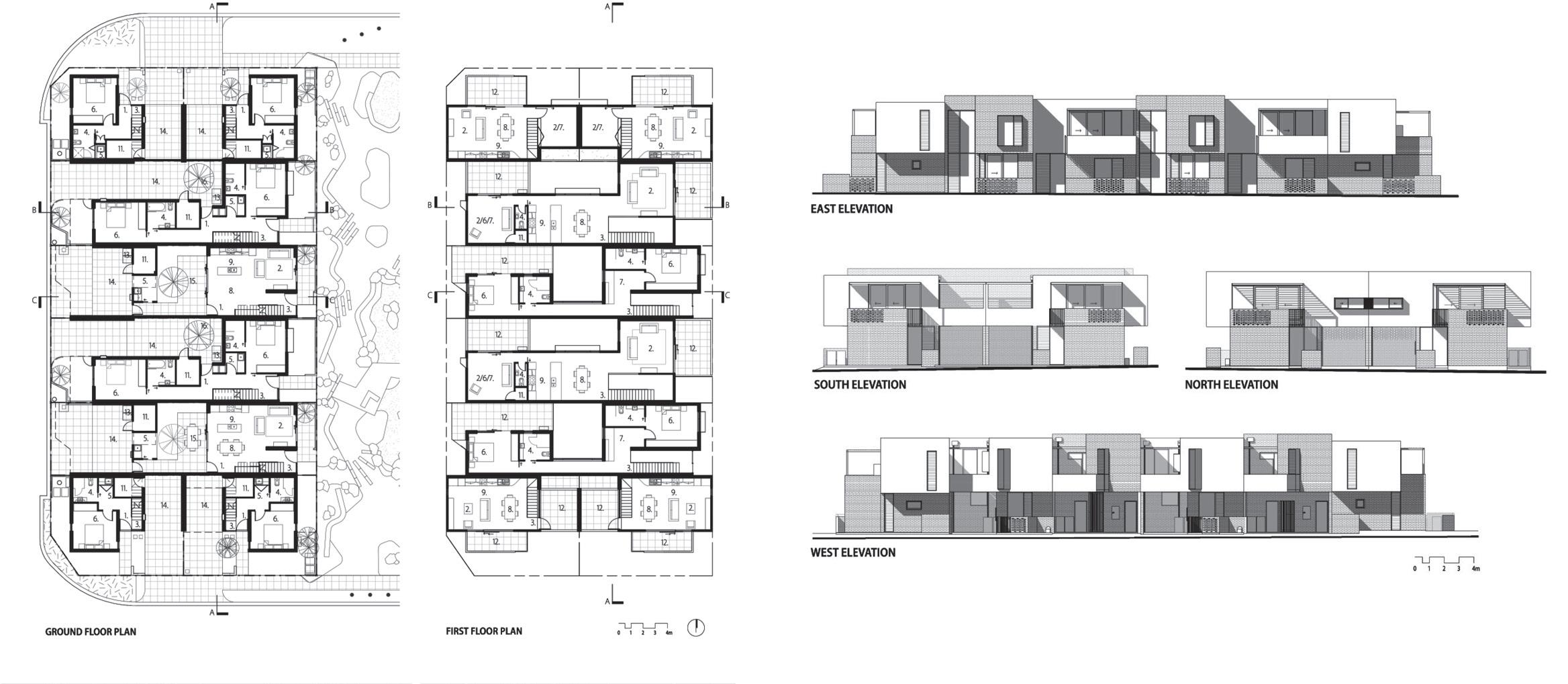

The initial brief for Hope Street Housing by Officer Woods Architects and MDC Architects was two key principles: maximise the yield without being mean, and keep the community sentiment alive. The result is an exemplary project that demonstrates how mediumdensity done right is a viable, sustainable model for infilling suburbia while enriching the urban fabric.

The project comprises of 28 diverse terrace houses and walkup apartments nestled in White Gum Valley, offering flexibility in housing types without compromising on landscape. The design thoughtfully borrows amenity from the site’s established surroundings, while also giving back to the site through generous setbacks, providing deep soil zones for native planting.

Landscaping in urban infill is often sacrificed to features like long driveways, garages, or the unnecessary theatre rooms that prioritise private spaces over shared ones. Too often, these approaches can hinder the interaction with neighbours and the garden. Conversely, the mews typology on Hope Street is one way that provides the density and amenity needed with 100% of dwellings facing north, allowing for housing that is accepted by the community, and delivers a strong, positive return on sustainability.

Jennie Officer, Director of Officer Woods Architects, explains, "The project was driven by the landscape, but it’s the built form that allows for the landscape. To make a project breathe, to feel porous, full of habitat and canopy, the built form must be accommodating and gentle.” Hope Street features water wise planting for both residents and passersby to enjoy, as well as infrastructure for residents to potter in the garden, to add their own spin on things. Something as simple as implementing free standing carports made from scaffolding or steel framing, becomes one’s sculptural canvas for residents to design their own bit of landscape.

Matt Delroy Carr, founder of MDC Architects, commented on the current houses delivered on the market, stating that “the lack of pedestrian interface is because people drive in and out of the back of their houses, but this project doesn’t do that.” The project provides separation with a common driveway through the middle and inviting entry points, leaving room to accommodate landscaping.

Trent Woods, Director of Officer Woods Architects, also touched on the design choice of the carports and common driveway. He said “It's been successful in making a positive, social, interactive and cohesive place because of the built form arrangement where cars aren’t hidden, and garages cease to exist. It also promotes cross-ventilation because the dwellings aren’t obstructed with a storage device for a vehicle.” It is refreshing to see cars not as a hindrance, but rather as a device to enable a development for the better, especially in the context of the global push for carfree cities.

Hope Street Housing serves as a model for density done right; it prioritises landscape, doesn’t dismiss cars, and offers housing flexibility. These elements must be underpinned by the critical component of achieving 100% north-facing orientation for all dwellings. While it seems simple, in conversation with Jennie, Trent and Matt, it is clear that no matter the design, the policy, or codes in place, they all echoed that you need to work with the existing community, the inhabitants of the space, for a project to be accepted, embraced and successful.

ARCHITECTS: Officer Woods Architects and MDC Architects www.officerwoods.com.au www.mdcarchitects.com.au

DESIGN TEAM: Jennie Officer, Trent Woods, Matt Delroy Carr, Olivera Nenadovic, Olivia Webb, Bryan Donnelly, Ryan Berut.

CONSULTANTS

Developer: Salander Property

Structural Engineering: ACCE

Town Planner: Element

ESD: Stantec

Landscape: Aspect Studios

BUILDER: Bruce Construction Design, Completion date: 01/11/2023

SITE: Build area: 28 diverse terrace houses/walk-up apartments with 60% open space

SUSTAINABILITY: 28 new dwellings replaced 5, increasing density and interrelationships of people, streets and landscape. A resilient community is made, providing pleasant spaces for living, working from home, interactions between neighbours/community. Average NatHERS rating of 7.7 stars with many dwellings exceeding 9 stars. All mature trees on site/ verge retained, with 41 new trees planted on site, plus multiple verges. 2kw solar/unit, no gas, heat pumps, LED lighting.

PHOTOGRAPHY JACK LOVEL

COUNTRY WHADJUK NOONGAR

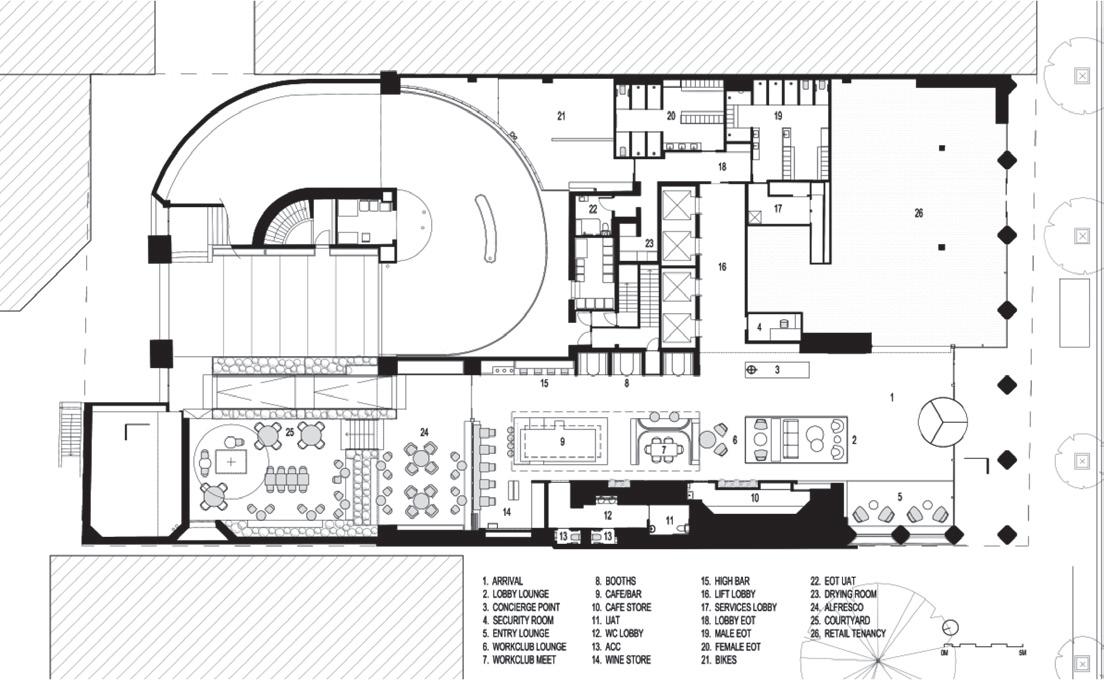

Originally commissioned by Lord Alistair McAlpine and built in 1982, 190 St Georges Terrace is a recognisable modernist icon within the commercial built-form landscape of Perth’s CBD. Its transformation by Donaldson Boshard with Rezen Studio enriches the fabric of the city.

Its symmetrical and balanced brick-and-steel façade sets it apart from typical building forms of the time, asserting itself as a composition that would stand the test of time. Some elements of a building, however, may not have aged as gracefully, necessitating revitalisation to meet the evolving needs of occupants or to align with contemporary trends.

Donaldson Boshard, in collaboration with interior designers Rezen Studio, were tasked with transforming this 40-year-old icon into a reinvigorated, multi-functional space, aiming to move beyond the conventional commercial entry experience. The design emphasised adaptive reuse, sustainability, and respectful treatment of the existing envelope, while accommodating the shifting functional, aesthetic, and comforting the needs of its occupants. As Kristjan Donaldson remarked, the goal was “balancing a sense of activation with a degree of exclusivity.”

The treatment of the existing façade was approached with thoughtful acknowledgment and consideration. Donaldson Boshard’s approach was heavily extracted from the building’s original materials, such as the bronze-finish framing, complementing the terracotta brick. A stone datum was introduced on the external brick columns, establishing a visual plane that extended through the building’s interiors and into the rear courtyard. This datum flowed down and horizontally through the floor finishes, creating a seamless flow through the lobby to the laneway.

Central to the project’s design was the transformation of the previously underutilised rear space into a ‘Living Laneway.’ Once prioritised for vehicle access and parking, this area has been reimagined as a curated landscaped space. The laneway features alcoves with integrated benches, courtyard seating, and outdoor dining areas scattered throughout an abundant outdoor environment. The north-facing orientation ensures plentiful natural light, while the courtyard’s sheltered design provides wind protection, enabling year-round usability.

A cornerstone of the project was the sustainable retention and longevity of existing components. On the surface, historical nods such as the preserved marble St George’s Cross in the dining area symbolise a connection to the building’s past. Beneath the surface, innovative approaches to service upgrades, including a rolled-out strategy for fire sprinkler installation, modernised the infrastructure as a means to avoid compromises on the quality of finishes. Introduced sustainable features included the integration of solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems for the courtyard, and an overhaul of all lighting to LED fixtures, significantly improving the building’s overall environmental performance.

The collaborative efforts of Donaldson Boshard and Rezen Studio are evident in the high quality of the interior spaces. Rezen’s careful curation and material palette prominently feature natural Western Australian materials. The lounge area, complemented by smaller breakout spaces such as benches and nooks, offers occupants opportunities to extend beyond the confines of their offices. The attached café and wine bar further enhance the sense of departure from a typical commercial lobby, creating a more inviting and engaging atmosphere. These amenities are supported by shared meeting spaces and an upgraded endof-trip facility, reinforcing the building’s functional versatility. “We wanted to seamlessly integrate the functionality of retail, hospitality, and office lobby uses, while also inviting the public into the lobby and maintaining a club-like atmosphere for tenants,” Donaldson explained.

The design also reflects the ever-shifting nature of Perth’s commercial landscape. It serves as a successful model for the revitalisation of existing buildings to meet evolving occupant needs while thoughtfully respecting the building’s context and history. OneNinety enriches the fabric of Perth’s CBD, demonstrating how adaptive reuse can breathe new life into the built environment.

ARCHITECT: Donaldson Boshard with Rezen Studio

www.donaldsonboshard.com

www.rezen.com.au

DESIGN TEAM

Grant Boshard – Architect

Kristjan Donaldson – Architect

Carissa Araminta – Architectural Designer

Zenifa Bowring – Lead Interior Designer

Rhys Bowring – Interior Architect

Taylor Sambell – Interior Designer

Jordan Knight – Interior Designer

CONSULTANTS

Developer: Fiveight

Structural Engineering: Forth

Electrical Consultant: BEST Consultants

Mechanical Consultant: LINK

Hydraulic Consultant: Ionic

ESD: Emergen

Landscape: See Design

Interior Design: Rezen Studio

Lighting Design: FPOV

BUILDER: Valtari Completion date: 01/09/2023

SITE: Area: 5200sqm. Build area: 11,000SQM

SUSTAINABILITY: Upcycling and significantly extending the life of an existing building. Upgrading existing 40 yr old building systems to significantly improve efficiency. Upgrading the performance of the ground level building façade. New rooftop solar. Rainwater capture and reduced runoff with rear courtyard planters.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Furniture: Mobilia, Living Edge, Stylecraft, Loam, Designfarm, Remington Matters

PHOTOGRAPHY DAVID DEVES

COUNTRY WHADJUK NOONGAR

Western Australia has long faced challenges with urban sprawl and a lack of highdensity housing models. Recent state government initiatives, including the introduction of new mediumdensity guidelines, aim to address this "Missing

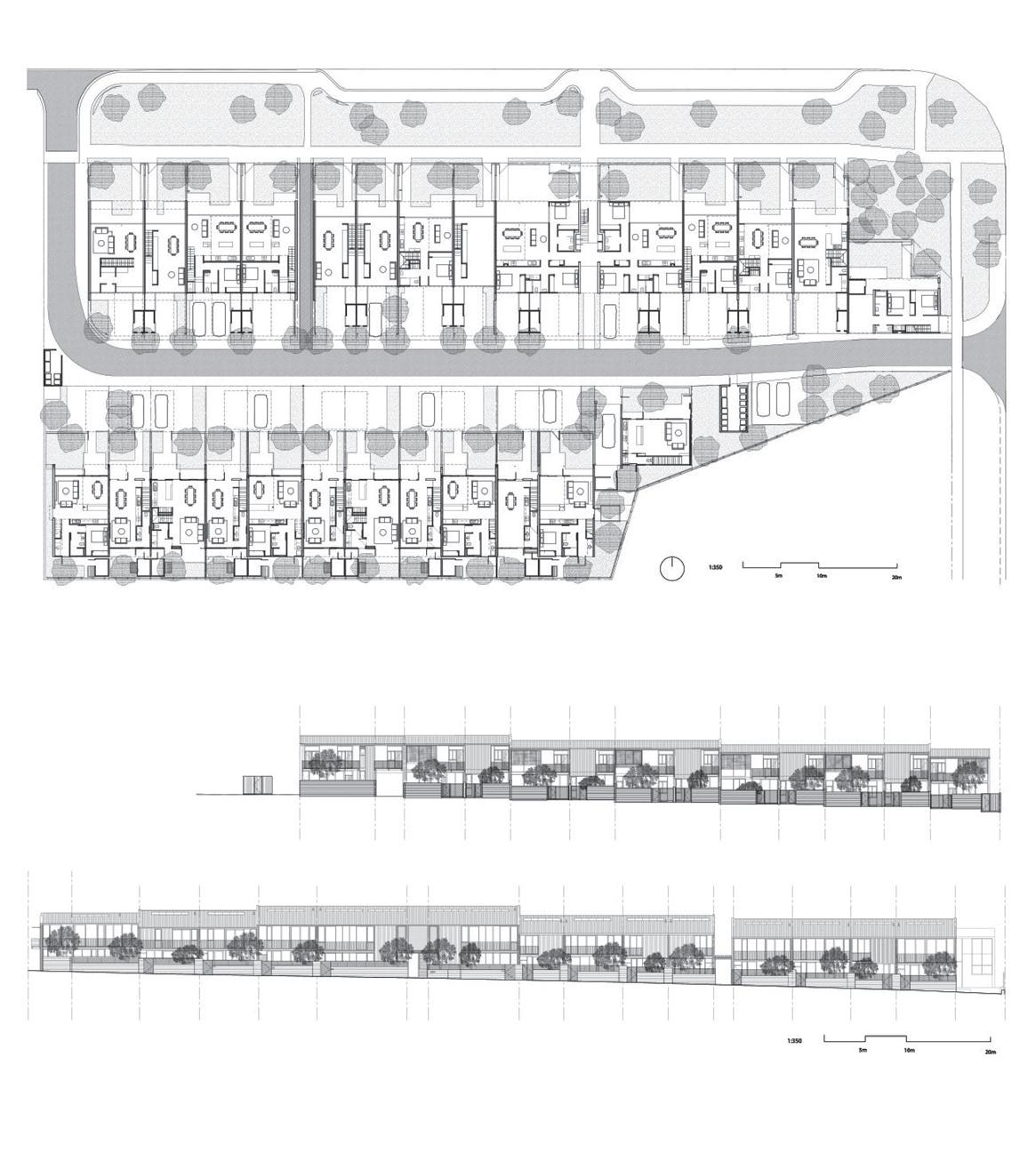

Following a collaborative effort with the Australian Urban Design Research Centre to establish the site’s urban framework, Gresley Abas was commissioned by the State Government through DevelopmentWA to deliver a mediumdensity housing model for a formerly contaminated industrial site near the scenic Coogee beaches, just south of Fremantle.

In the early stages of design, the architect and planner were able to dictate the lot sizes to accommodate a design solution they felt worked best for the dwellings as a collective, an innovative departure from common practice. Philip Gresley highlighted this aspect of the project as a "collaboration of holistic thinking and design that helped us work toward achieving an effective design solution".

Middle"

by delivering better housing choices that reflect the everevolving landscape of Perth and the lifestyles and needs of its communities.

The collaborative process continued through the development of the project with urban planners, landscape architects, engineers, and architects to establish the parameters for an 8-unit row of townhouses, including one, two, and threebedroom dwellings on the 919m² site.

The east-facing public open space adjacent to the townhouses acts as an extension of the private backyards, creating a shared communal garden that connects the residences seamlessly, incorporating mature trees for shading, seating areas, and low lying native coastal vegetation. Composed external wall heights and openings that face the communal garden allow for varying degrees of visibility and privacy, while adding visual interest to the collective envelope.

The external material palette corresponds with its coastal surroundings through a neutral array of brick, render, and concrete, accentuated against dark steel window portals, balcony canopies, and balustrades. Internally, intricate detailing including timber finish joinery and stone floors complement the exteriors coastal aesthetic.

Functionality through passive design principles were key components to the design. Philip Gresley noted "our approach to organising spaces both vertically and horizontally was central to the design, prioritising cross ventilation, natural light access, and a sense of spatial generosity. Ground-floor courtyards provide the intermediate townhouses with sufficient natural light and, in some instances, adjoin external parking bays, seamlessly blending the spaces creating a sense of multi-functionality. Substantial first-floor balconies to all dwellings extend living areas and bedrooms, where thoughtfully placed window awnings and operable louvres allow for optimal access to natural ventilation and natural light.

Beyond the projects strong sustainability focus, Salt Lane offers diversity to the housing market, catering to contemporary lifestyle trends. The one-bedroom dwellings located on 80m2 lots were designed with adaptability in mind, featuring a multiuse space which could function as a studio or home office, which aligned with the emergent work-from-home flexibilities.

The builder, TERRACE, was engaged in an early involvement role to generate innovative solutions for delivery, procurement, and construction including producing working drawings. Gresley Abas collaborated closely with the builder during the documentation and construction phases to ensure key elements such as functionality, access to natural light, and cross-ventilation were carried out as they had intended. Taking lead in delivery, the builder looked to cost-effectiveness and efficiency in construction methodologies, resulting in both an efficient and successful realisation of the project.

Salt Lane sets an exemplar precedent of medium-density living in Western Australia – not only does it address the "Missing Middle" challenge, but it also demonstrates best practices of thoughtfully integrated landscapes, functional and innovatively designed spaces, and considered sustainable approaches. The State Government commended the project as "a fresh take on medium-density living, catering to evolving lifestyle needs while achieving affordability and sustainability."

ARCHITECT: Gresley Abas www.gresleyabas.com.au

DESIGN TEAM: Philip Gresley, Lisa McGann

LANDSCAPE: Emerge Associates

BUILDER: Terrace. Completion date: August 2022

SITE: Site area: 919sqm. Build area: 940 sqm

SUSTAINABILITY: NatHERS rating: 6 Star. Designed with a central courtyard and pulled away from the boundary where possible to enable strong cross ventilation and windows are predominantly louvres to allow for a high percentage of ventilation openings. West facing windows are minimised and shaded to limit solar gain. Ceiling fans incorporated to all bedrooms and living areas. No air conditioning has been provided as part of the development. PV arrays have been incorporated on each dwelling. 5kW on 6 dwellings, and 2KW on the smaller microlots. Hot water service to 2x2 dwellings is Chromagen Midea Heat Pump 170/280L. Instantaneous electric systems for microlots. Materials were chosen to limit the need for applied finishes such as, plywood balustrading, locally sourced face brick as the predominant material at ground, and lightweight construction with timber stud framing on the first floor for good thermal performance and reduced embodied carbon. A Floortech flooring system was used for the first floor, reducing the use of concrete in the construction. Extensive planning and long term visioning was undertaken with Development WA, AUDRC, the architectural team and planners to ensure that the long term planning for the precinct achieved a sustainable, diverse and affordable housing outcome for Coogee, that delivered excellent amenity, with proximity to the beach and public transport links. The development sought to facilitate and encourage pedestrian and bicycle travel, and promote engagement with community through the incorporation of communal landscape spaces and good design. The development also sought to demonstrate innovative, affordable design that was environmnetally responsible in its design, and responsive to climate and site. The design encourages interaction with neighbours and promotes passive surveillance of the landscaped POS and the rear laneway through the incorporation of open carports and balconies overlooking the laneway. Diversity of affordable housing product was also carefully considered, with the incorporation of 4 80m2 microlot sites to supplement the 2x2 and 3x2 sites, addressing this hole in the market for small lot, 1 bed dwellings.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Suppliers are to builders selection.

WORDS ROB DEBENHAM PHOTOGRAPHY DION ROBESON

COUNTRY WHADJUK NOONGAR

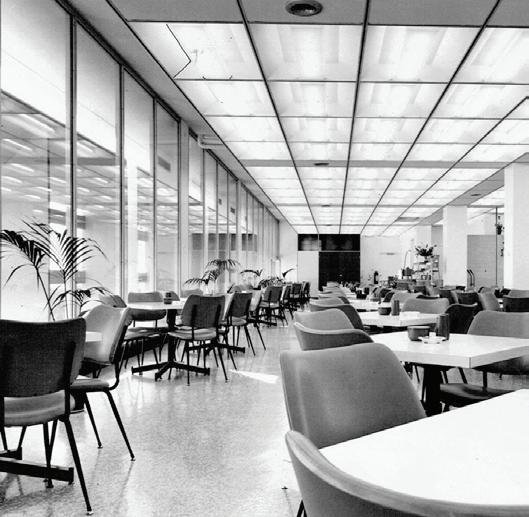

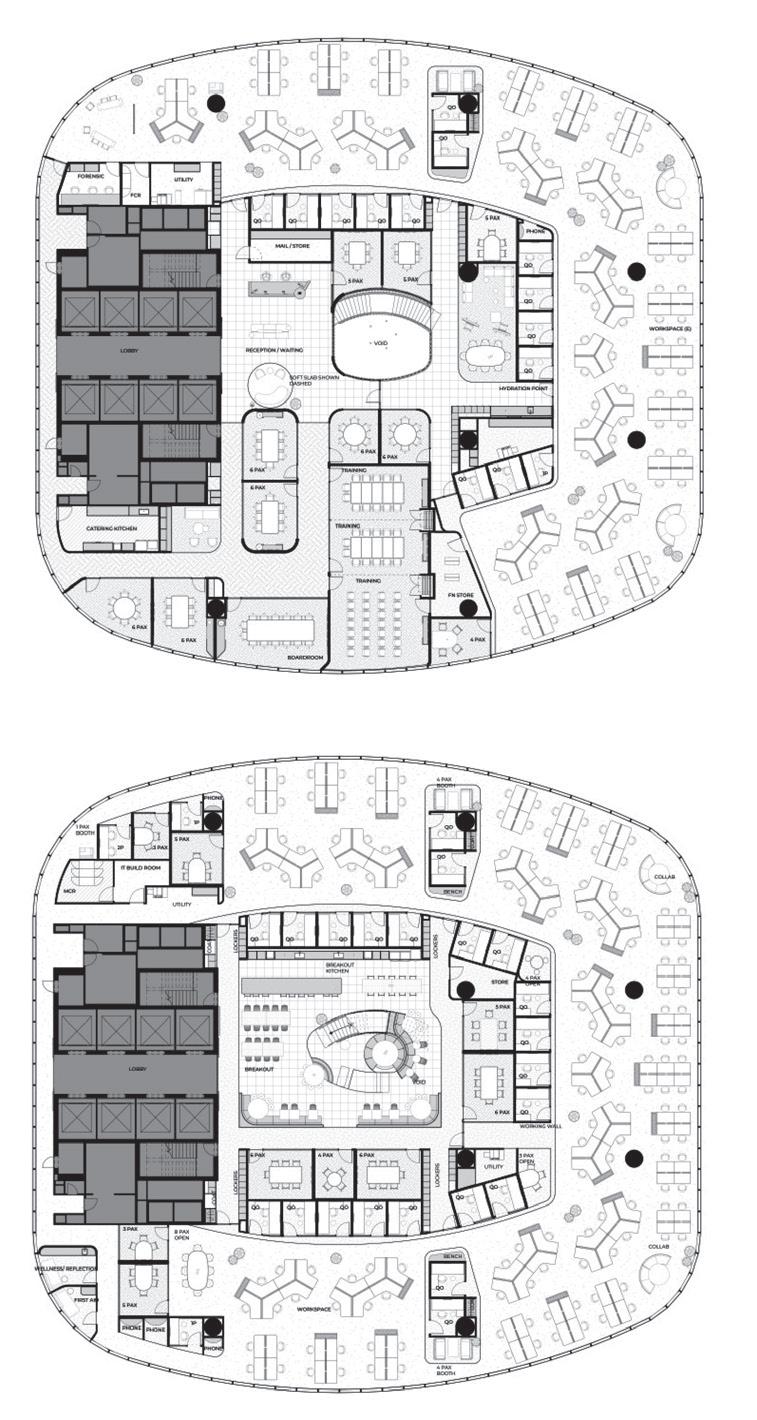

Nestled in the heart of Perth CBD lies the new home for accounting firm BDO, in a recently refurbished office by the talented interior design team at Woods Bagot.

Relocated from Subiaco, BDO now occupies 3,350 square metres split over levels 8 and 9 of the Mia Yellagonga Tower 2.

The design narrative was simple yet effective: ‘The Flip Side’. BDO’s previous office was a regimented and isolated workplace, so the interiors team thought it would be a generous gesture to give back to the staff by designing the opposite. Workstation settings were prioritised to optimise views, natural light and in essence allow a better environment for employee wellbeing.

Careful consideration has been given to hierarchy of settings over the split-level floorplate. The key focus for this was the philosophy of prospect and refuge theory, creating balance and contrast between the active work zones and quiet focus spaces.

“The prospect was defined as all the open areas in the floor plate, whereas the refuge spaces were more intimate, sheltered and quiet,” says Woods Bagot Associate Sara Giunco.

A section of the upper floor is designated to client facing spaces, featuring a concierge desk, boardroom, meeting rooms and a business lounge. To enhance the client experience, a reflective mirrored ceiling tile was selected, making it feel elegant while providing the illusion of higher ceilings.

“We wanted to give some sort of ‘wow’ factor,” says Giunco. “The ceiling gives a sense of volume to the space, and when light moves across it, it gives this beautiful ripple effect, almost like water,” says Giunco.

A large void at the centre of the floorplate helps to visually connect the client floor with the staff breakout and activities spaces, providing visibility and openness and creating the visual heart of the space.

“Creating this void in the centre creates a spacious internal view and visual connection over the split levels,” says Woods Bagot Senior Associate, interior designer Ashleigh Lyford.

The planning principle was based on having communal breakout spaces at the centre and work zones at the perimeter. The central circulation strategy strengthens community and connection within the workplace. The curved feature staircase connects both floors and also acts as a setting to host informal town halls along with formal presentations.

The heightened sense of volume is further enhanced in the breakout space by leaving ceiling services exposed and introducing a sunken lounge.

The workplace component features a variety of work settings, consisting of informal and formal, open and enclosed, and collaborative and focused. This is to ensure all staff are supported with a selection of spaces to suit individual workstyles.

“For the palette, we took inspiration from the colour theory, differentiating the prospect and refuge palettes,” says Giunco.

The prospect spaces are designed to feel transparent and open, with warm, energetic tones in contrast to the refuge spaces, where calm, cool tones take precedence.

Sustainability was a key consideration when it came to all material selections, with materials featuring recycled components where possible.

The success of this project didn’t come without its challenges. The impact of trying to complete this fit-out amid a global pandemic involved strategic rationalisation of the selected materials to maintain design intent and a high level of quality while also meeting the project budget.

“Following a rigorous value engineering process, the client trusted our vision to ensure the overall design intent and quality of the project was maintained,” says Lyford.

Woods Bagot enabled BDO to successfully transition away from the traditional office layout whilst achieving a beautiful fit-out that has set a high standard for workplace design.

ARCHITECT: Woods Bagot www.woodsbagot.com

DESIGN TEAM: Ashleigh Lyford, Sara Giunco, Molly Anderson

CONSULTANTS

Mechanical, Fire, Hydraulic & Electrical, Acoustic Engineering: NDY Structural Engineering: Arup Building Certifier – CBC Project Manager: Property Solve

BUILDER: Dawn Projects. Completion date: January 2022

SITE: 3350 sqm

SUSTAINABILITY: Our approach has been to align to best practice, focusing on materials, people's wellbeing and selecting furniture and finishes that will stand the test of time. Where possible, we have used these principles to guide our approach. Timeless palette to avoid fashion/ trends that require unnecessary refurbishment. Careful consideration of material and sheet size when designing and documenting to minimise waste. Durable and sustainable material selection. Quality furniture and material selection to ensure it will stand the test of time & not go into landfill.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Cabinetwork: Artek Furniture. Carpet: Shaw Contract. Tiles: Imported Ceramics. Furniture: Design Farm, District, Innerspace, Living Edge, Stylecraft, Zenith. System Furniture: District. Wall Finishes: Maharam, Woven Image, Elton Group, Bauwerk. Lighting: Ross Gardam, Modular Lighting.

In the heart of Subiaco, Bob Hawke College Stage 2 stands as a landmark of innovative, communityfocused design. Created by Hassell, this urban school was honoured with the George Temple Poole Award at the 2024 WA Architecture Awards, highlighting its success in addressing the challenges of urban density.

Bob Hawke College Stage 2 exemplifies how thoughtful, highdensity design can create enriching environments for both students and the wider community, setting a benchmark for future educational facilities in Perth’s rapidly growing urban landscape.

With Perth’s population expanding and urban space increasingly limited, solutions for density are essential. Bob Hawke College Stage 2 meets this challenge with a multi-storey, vertical layout that maximises its compact site without compromising quality. The school’s vertical structure fosters a unique, dynamic learning environment where each floor is designed to encourage collaboration and connection among students of all ages. This layered approach includes communal areas and breakout spaces on each level, promoting interaction and creating a campus that feels open and connected despite its compact footprint. Open stairwells and abundant natural light enhance the sense of spaciousness, offering city views that strengthen the connection between students and their urban surroundings.

While Bob Hawke College serves its students, it also functions as a community hub for Subiaco. Hassell designed the school not only as an educational facility but as a versatile space that Subiaco residents can enjoy. Facilities such as sports courts, an auditorium, and public areas are available for community events outside of school hours, reinforcing the bond between the college and its neighbourhood. These shared spaces make the college a lively, inclusive community asset, recognising the value of multi-functional spaces in dense urban areas. By opening its facilities to the public, Bob Hawke College promotes a model of urban development that prioritises community engagement and inclusion.

Bob Hawke College Stage 2’s design is adaptable, recognising that as Perth grows, the school must evolve alongside it. The building’s modular layout allows for potential expansion, ensuring it remains a relevant resource for decades to come. Inside, flexible learning environments can be reconfigured to support various teaching styles and group sizes. Classrooms connect to breakout areas, where students can engage in group work, discussions, or quiet study. This flexibility allows the school to adapt to changing educational needs, supporting students and teachers alike as learning methods evolve.

The George Temple Poole Award celebrates the project's architectural excellence and its success in addressing the challenges of density and community integration. This recognition underscores the project’s role in advancing the conversation around urban density and setting a new standard for educational architecture in Perth.

Bob Hawke College Stage 2 represents density done right. The architects embraced the constraints of a compact site, transforming them into opportunities for innovation. The college’s vertical design, seamless integration with the community, and adaptability for future needs set a benchmark for urban schools. As a critical piece of infrastructure that reflects Subiaco’s community values, Bob Hawke College Stage 2 is more than an award-winning building. It is a blueprint for how educational architecture can meet the demands of density while fostering inclusivity and community engagement.

With its layered design, shared public spaces, and flexible learning environments, Bob Hawke College Stage 2 demonstrates that density can be leveraged to create spaces that are vibrant, inclusive, and designed for future generations. Hassell’s work on this project illustrates how density, when thoughtfully managed, can enhance both the educational experience and the wider urban fabric, proving that architecture has the power to shape communities for the better.

ARCHITECT: Hassell www.hassellstudio.com

DESIGN TEAM: David Gulland, Sophie Bond, Mark Keltie, Matthias

Widjaja, Chris Pratt, Ricky Frazer, Catherine Lindsay, Rachel Tanner, Derek

Tallon, Iain Roy, Renae Basso, Kahla Murphy, John Ducey

Structural and Civil Engineering: Aurecon

Electrical Consultant: Best Consultants

Mechanical Consultant: Stevens McGann Willcock & Copping

Hydraulic Consultant: Hydraulic Design Australia

Fire: Xero Fire & Risk

Acoustic: Gabriels Hearne Farrell

BCA: Philip Chun

ESD: Full Circle Design Services

Town Planning: Successful Projects

Fascades: JMO Facades

BUILDER: PACT Construction Pty Ltd. Completion date: 10/08/2023

SUSTAINABILITY: Appropriate solar orientation and shading elements were carefully considered through the design, including shaded balcony spaces and walkways. The patterned face brick northern façade responds to solar orientation with deep reveals and internal sliding internal whiteboard screens that double as sunscreens when needed. Rainwater is fully retained on site and recharges to existing ground water, using a drainage cell infiltration tank system. Reduced building footprint and planted roof terrace. Transport benefits of the location enhanced with additional bike facilities. Engineering infrastructure reviewed against Greenstar opportunities. PV Array, 30kW additional capacity to existing school array.

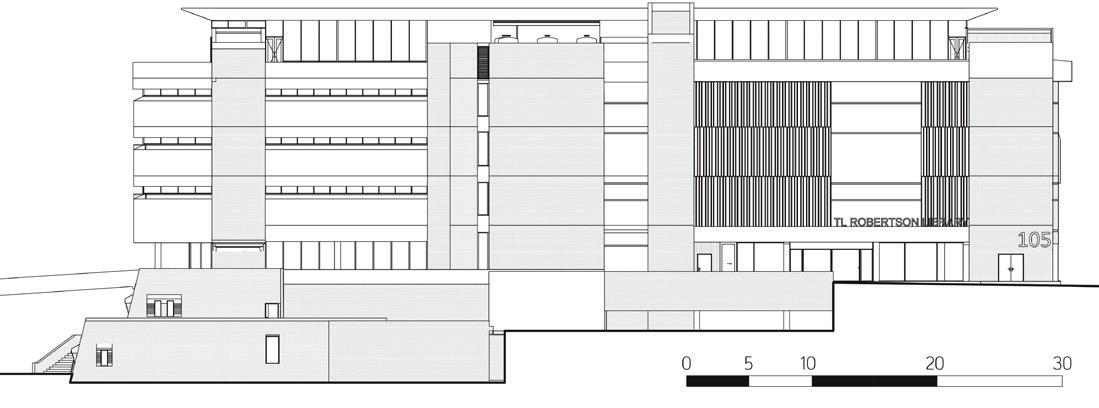

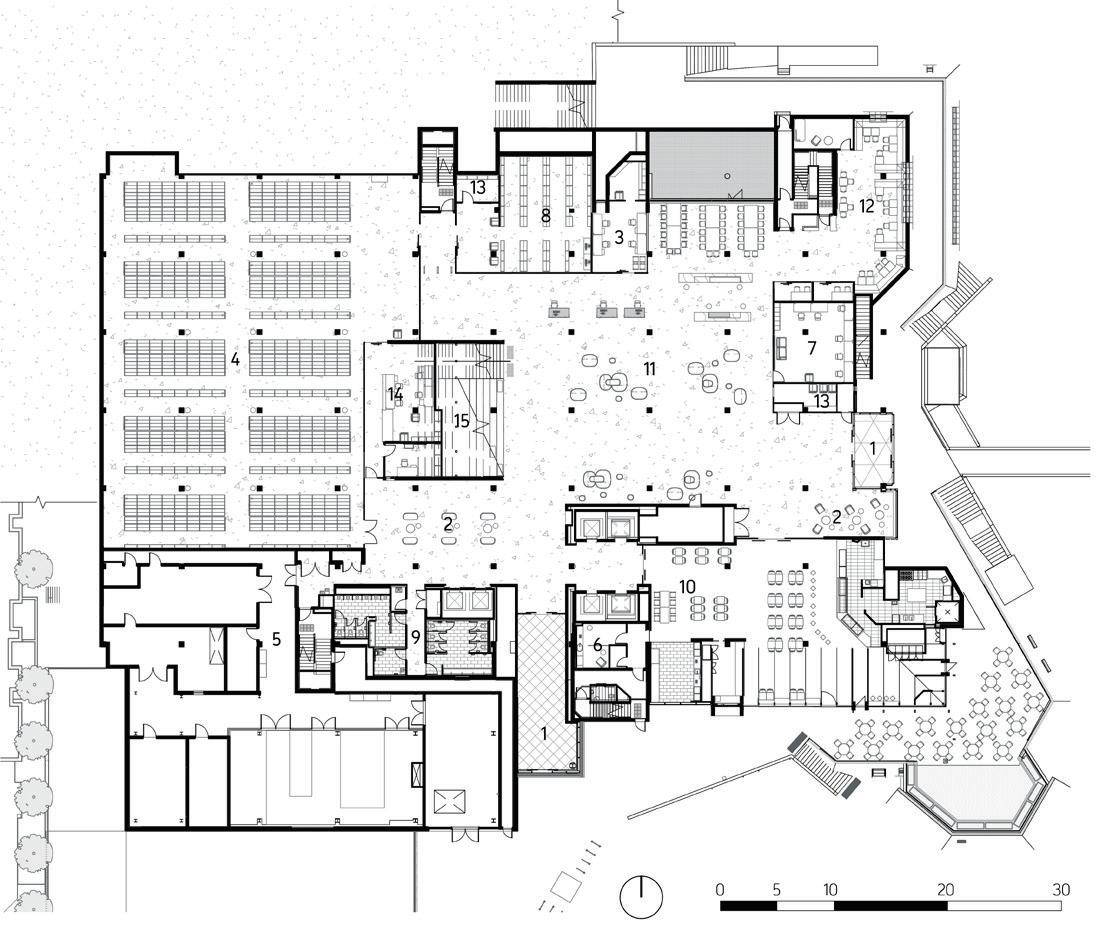

Located in Bentley, the TL Robertson Library has been an iconic landmark of Curtin University since 1972. Positioned in the heart of the precinct, it lacked presence and facilities necessary to meet the evolving demands of the library. Hames Sharley, in partnership with Danish firm Schmidt Hammer Lassen, redefined the building to actively participate with its surroundings, intuitively responding to Curtin's campus and its community.

The redevelopment honours the original brutalist-inspired architecture while challenging typical library functions, highlighting the transformative potential of rethinking spatial typologies. The TL Robertson Library Refurbishment embraces a new era of people-centered, rather than collection-centered, libraries.

An extensive stakeholder engagement process revealed the need for a stronger connection between the library and the urban context of the university. The solution was distinctive, intuitive openings that connected the building, site and the adjacent pine plantation. The design outcome seamlessly integrates with Curtin University’s iconic brutalist architecture, without disrupting its distinctive character. This was achieved using weathering steel, a versatile material that met multiple needs. Its straightforward aesthetic complemented the brutalist design, reinforcing the building’s architectural language without adding unnecessary complexity.

The library's interior transformation focused on creating a flexible, people-centered space that minimised new construction. Space-saving solutions consolidated book collections, unlocking more than 1150 new seats across study zones, from quiet areas to collaborative spaces. This redesign reduced the need for expansion, helping to minimise emissions from new infrastructure.

Public entry points on Levels 2 and 3 serve as arrival zones with new areas like the Makerspace inviting students and the community to engage differently. An expansive atrium connects the main levels, fostering spontaneous interactions. As you move upward, the environment becomes quieter. Level 4 is for group study, while Levels 5 and 6 offer individual study areas, designed to accommodate diverse learning styles.

The redevelopment included an additional level, bringing the project size to 18000sqm. With its panoramic views, Level 7 is an event floor, hosting a range of functions, university gatherings and community events. Surrounded by floor-to-ceiling glass, it provides a surreal experience as visitors find themselves floating among the treetops of Henderson Court's iconic pine trees.

The project is defined by its commitment to adaptive re-use solutions. Rather than starting anew, preserving the existing structure yielded significant environmental benefits. By retaining the original concrete frame, the project minimised the need for new materials like concrete and steel, which contain high carbon footprints. This choice alone saved substantial amounts in embodied carbon.

The adaptive reuse strategy conserves resources while celebrating the library’s bold architectural character. While respecting its brutalist elements, the design introduces warmth through lightweight materials. Stripping away cosmetic finishes revealed the building’s original forms, championing its history and creating more functional, sustainable spaces.

The vertical steel “ribs” on the exterior, inspired by the surrounding pine trees, complement and blend with the campus landscape. Over time, they’ll develop a rust patina, enhancing durability and reducing maintenance. Inside, a restrained palette of natural, low-maintenance finishes was selected for both aesthetics and sustainability, being cost-effective and repurposable.

Other sustainable design methods include passive solar principles, new glazing technology, LED lighting with occupancy sensors, improved insulation and more, further enhance the building's efficiency.

Adaptive re-use projects are challenging, requiring strong commitment from all parties. New construction is often preferred due to the perceived risks, but with collaboration and dedication, adaptive re-use can turn challenges into valuable opportunities. Since its completion, the TL Robertson Library Refurbishment has achieved a 6-Star Green Star as-built rating and has become a recognised benchmark for sustainable architecture, contributing significantly to the roadmap for a responsible future in built environments.

ARCHITECTS: Hames Sharley and Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects in Association

www.hamessharley.com.au

www.shl.dk

DESIGN TEAM: James Edwards, Jerry Cherian, Jessika Hames, Jessica Green, Brigid Salter, Greg Markham, Rob Debenham, Jonathon

Peake, Jane Suckling, Emily Wilson, Jonathan Jones, Rachel Seal, Ruth McCloskey, Cameron Atkins, Amy Tamati, Courtnee Nichols, Elif Tinaztepe, Amber Chambers

BUILDER: Lendlease. Completion date: 21/06/2023

CONSULTANTS

Project Manager: APP

Quantity Surveyor: RLB

Mechanical: Steens Gray & Kelly

Electrical: Norman Disney Young

Hydraulics and Fire: BCA Consultants

ESD and Green Star: Full Circle Design Services

Urban Design / Landscape: UDLA

Façade Consultant: Inhabit

Structural: Stantec

Acoustics/Vibration: Herring Storer

AV and ICT: Arup

BCA: Resolve

Fire Engineering: Strategic Fire Consulting

Wayfinding: Turner Design

Heritage: Pallasis

Feature Lighting: NDY Light

DDA/Accessibility: O’Brien Harrop Access

Wind: Cundall

Vertical Support: Stantec

Access and Maintenance: Altura

Planning Consultant: CLE Planning

Civil: Stantec

Surveyor: Land Surveys

SITE: Build area: 19,238sqm (gross floor area)

SUSTAINABILITY: Key sustainability measures: The refurbishment originally targeted a 5-star Green Star rating, but has since achieved a 6-star Green Star as-built rating. The design responds to the University’s requirement for a flexible facility, fulfilling long-term needs. The project, guided by the University's commitment to sustainability, has revitalised the existing building rather than opting for new construction. This strategic decision not only preserved the architectural heritage but also yielded substantial environmental benefits. By retaining the original structure, the project significantly minimised the demand for new construction materials, particularly concrete and steel, which are notorious for their carbon footprint. The project has increased the building’s utilisation and seating capacity, reducing the need for additional infrastructure on the campus, thereby curbing future construction-related emissions and reducing the University's overall carbon footprint. Solar passive design features and new, energy-efficient services have substantially improved the building’s operational efficiency. Energy-efficient LED lighting has been used throughout with occupancy detection and natural lighting detection devices. Heat load on glazing has been effectively managed, natural lighting improved, and demand for artificial lighting reduced. Materials were selected with consideration for their installation and how they would be repurposed at their end of life if required.

PHOTOGRAPHY MARILYN HOWDEN

COUNTRY WHADJUK NOONGAR

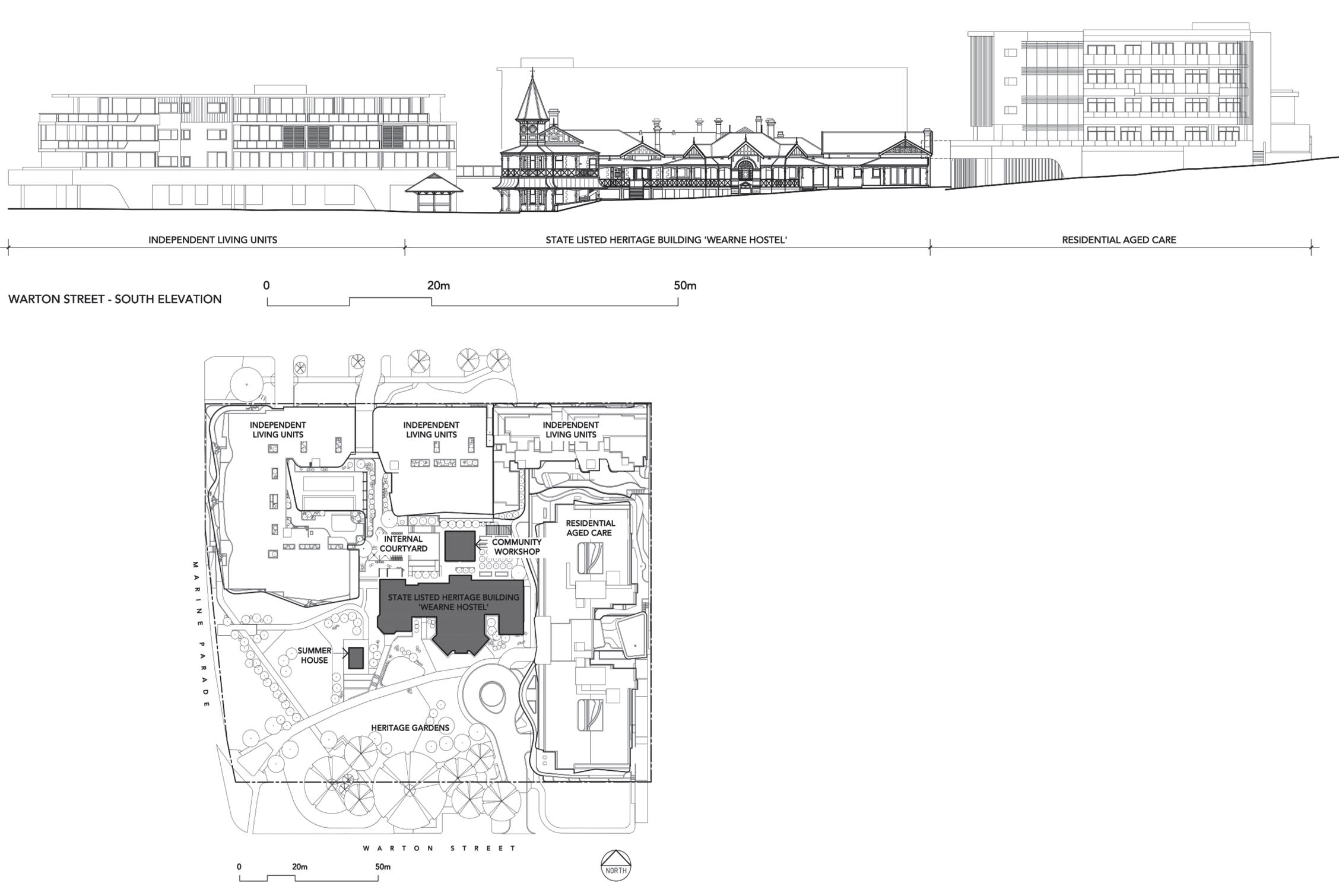

Leaning down the hill toward the ocean, a red-andcream coastal sanctuary nestles in the crook of Curtin Heritage Living Cottesloe Redevelopment. Surrounded by glass modernity, an historic convalescent home, dressed in pretty verandahs and canopies, has been restored and reinstated as the heart of the resident aged-care community. With atmospheric lighting, this project looks as welcoming at night as it is during the day.

Evident in the gardens open to the public, and in the lively restaurant and art gallery greeting the street, this project reflects both a dedication to contemporary place-making and a celebration of the historic fabric of Cottesloe.

On a waterfront site, in a prime location, the generosity of unprogrammed garden in this project is surprising. The arms of the residential blocks extend outwards along the north and east edges of the block, inviting residents and amblers alike into its embrace. Below the picturesque convalescent home, the southwestern corner of the plot remains dedicated to public lawns and landscaped beds. However, this has always been a site of philanthropic architecture. First built between 1897 and 1909, the Ministering Children’s League Convalescent Home opened its doors to provide respite and rejuvenation to its patrons. The success and appeal of this renovation projects prompts the question whether convalescence, this redundant mode of healthcare and recuperation, should be reconsidered in line with twenty-first century ideas of wellness?

The work of the conservation architect is often technical and invisible, making historic spaces safe and accessible by modern standards. The primary move of Griffiths Architects was to reinstate the legibility of the original home. With a number of extensions and reconfigurations from the 1980s and early 2000s to contend with, it had to be deciphered which elements of the original building remained, using historic evidence and onsite investigation. As part of their conservation plan, intrusive additions were discerned and removed, and the features of heritage value retained and restored. Where it was important to the fabric and the understanding of the place, reconstruction was guided by evidence. As an example, the pepper-pot tower had been removed in the past, and that was reinstated using historic documentary and physical evidence.

Over time, the building had been sealed with toxic, damaging paints. Some layers of paint were lead-based and hazardous, others were plastic, sealing in moisture and exacerbating damage to the stone fabric. In several instances punctures had been made along the limestone structure to service smaller rooms. Work to the facade required careful removal of paint, and sourcing appropriate stone to repair and replace previous intrusions.

The selection and replacement of mortar appropriate for the soft limestone was also crucial to the preservation of the original building. While being buffeted by the wind and the waves has been restorative to the residents for the last century, the proximity to the ocean and constant exposure to salt spray has been an issue for the building. The architects worked with a building scientist to find an invisible coating to apply to the facade in order to repel the water, while not sealing the porous limestone fabric.

Internally, the architects organised the demolition of intrusive subdivisions; grand rooms that had in recent years been repurposed as bathrooms and private living spaces. The reinstated spaces were reallocated for communal amenity and rooms for group activity; including a cinema, workspaces, and lounge; emphasising the building as the nucleus of the lot. By removing invasive partitions, a rhythmic flow of spaces was again evident. Through on-site investigations, a grand entrance door, which had been waylaid, was returned to its correct position, and arches along the corridors reinstated.

The master planning exercise for the site in 2016 was crucial to reinstating the essence of the original Heritage Registered scheme. Just as when first erected, the massing of the lot reflects an ambition to support health and wellbeing, welcoming the ocean breeze and bright, clean air. The buildings, the plot, the street, and the community are richer for the architect honouring the historic culture of respite and for restoring the generous architecture of convalescence.

ARCHITECT: Griffiths Architects and Hames Sharley in collaboration www.griffithsarchitects.com.au www.hamessharley.com.au

DESIGN TEAM

Marilyn Howden, Philip Griffiths

CONSULTANTS

Developer: Curtin Heritage Living

Masterplanning: SPH Architecture + Interiors in association with Grounds Kent Architects and Griffiths Architects

Documentation of New Build & Interior Fitout: Hames Sharley

Structural Engineering: Pritchard Francis Consulting

Electrical Consultant: ESC Engineering

Mechanical Consultant: Geoff Hesford Engineering

Hydraulic Consultant: Gravity Hydraulic Solutions

ESD: Full Circle Design Services

Landscape: Hassell

BUILDER: Built. Completion date: January 2024

SITE: Area: 2.0649 ha. Built footprint: Existing Heritage Buildings 1,300m2, New Buidling foot print: 9,142 m2

SUSTAINABILITY: The building’s thermal performance was modeled to demonstrate the existing high thermal mass of the walls combined with higher performance roof and glazing systems satisfied code requirements. Key sustainability measures: Thermal Mass of Limestone walls. Insulation to roof. Double Glazing. Retaining an existing heritage building preserves its embodied energy withing the existing building to reduce the carbon footprint of new construction.

KEY SUPPLIERS: Stone conservation: K&S Restorations. Roof Sheeting: Revolution Roofing. Ceilings: Future Carpentry Ceilings. Door and Window Hardware: Parker Black & Forrest

As I sit down to write this article, the 2024 National Architecture Awards recipients have been released, and I am struck by their homogeneity.

For the most part, the winners are sombre prismatic forms, block, brick, concrete and wood interiors, all shot in overexposed, desaturated photography. I get the feeling that if you were to shuffle the photographs, you’d never be able to reorder them back into their original sets.

It begs the question; what is it that these awards are awarding? And what actually constitutes good architecture?

Across this vast country, can it be possible that the same architectural solutions, by the same practices constitute the best outcomes for all types of architecture, in all contexts and for all building uses, types and constraints?

Is the end-state of all architecture just a shrine for a lonely and meditative architectural aficionado to marvel at texture and shadow? …. I think not.

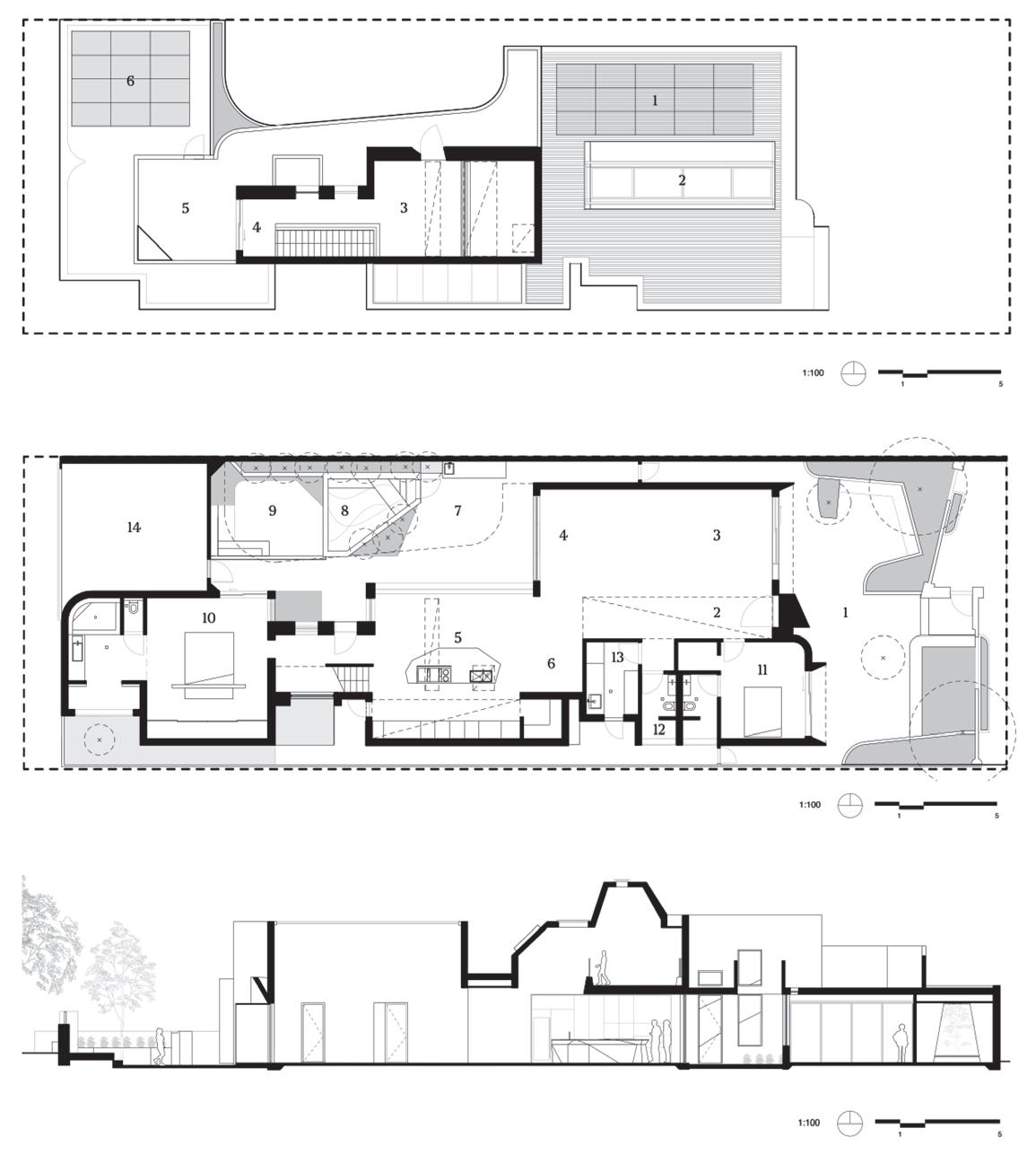

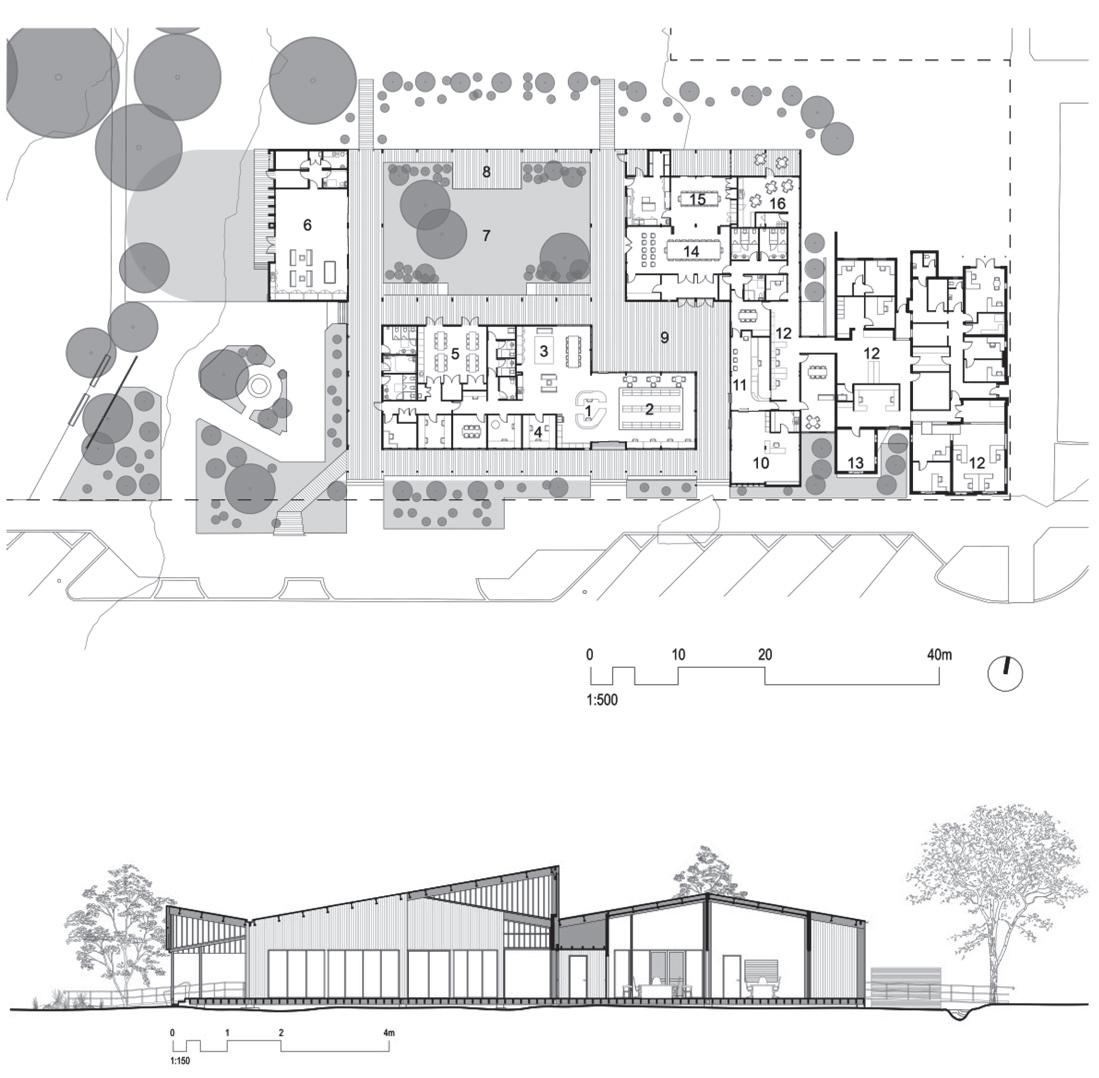

Architecture has real consequences. It affects the way people live their lives, how communities operate, and it has an enormous impact on our environment. If these are legitimate concerns, then the Ravensthorpe Cultural Precinct by Peter Hobbs Architects and Advanced Timber Concepts, with Intensive Fields, offers a different, and useful way forward.

Ravensthorpe is an orange-dirt town on the crest of a rolling hill. It has a few historical brick buildings, a strange

supermarket, and silos painted by Amok Island in enormous Banksia Baxteri. The new community facility was conceived to consolidate community infrastructure and to provide space for local business, but also to diversify the local economy toward tourism as a bolster against the boombust cycle of mining (both the nickel and lithium mines have recently closed).

The building is really a cluster of smaller buildings under a single roof, arranged around a grassed courtyard with a performance stage. The spaces between the buildings, much of which are covered in translucent sheet, allow the whole community to hold events and organically inhabit the facility. Landscaping is planted as a community project.

There is the Council chambers and offices, a library, community business rooms, public toilets and a multi-purpose space. These buildings are all light and bright, and finished sensibly in either wood or plasterboard and white paint.

But it is the integral approach to embodied carbon and economy-inconstruction that drives this design and makes it exemplary. The building is almost completely timber. The primary structure is an LVL portal frame, built on stumps to handle the active clay site, optimised through parametric modelling to minimise timber volumes, and balanced against operational carbon and building

program. Automated manufacturing processes allowed elegant wood-to-wood connections that reduced conventional steel fixings and facilitates future disassembly and reuse of materials. Finished timber is all WA plantation grown Yellow Stringy Bark which was managed by the design team from harvest through to installation. The total result is a reduced environmental footprint and a structure that is appreciated by its community.

If we are to take sustainability seriously, as we so frequently say we do, then building optimisation and carbon minimisation must be a critical part of our design process. The Ravensthorpe Cultural Precinct is a demonstration of a whole-of-project way of thinking, where sustainability issues are placed front and centre of the design. This building does what it sets out to do very well. It is absolutely good architecture.

A PERSONAL REFLECTION. Recipient of the 2024

Award (WA Chapter) 22 Delhi Street has held a mythical place in my imagination for forty years.

I suspect that the building seeped into my consciousness as a once-singular landmark rising above Harold Boas Gardens that also, for a time, held the northern foreground of the West Perth landscape from across the rail line. Its visual dominance has been overtaken by a myriad of lesser commercial and residential buildings that cluster around the park, but 22 Delhi Street remains the architectural ‘pick’ of the precinct.