PILE UP YOUR PROFITS

Protect your potatoes AND your profits.

MANA Canada offers four products to protect your potato crop and maximize your production, utilizing the same actives that you already rely on. MANA Canada is the right choice for providing optimum control of grassy weeds and pests like Colorado potato beetles, leafhoppers and aphids.

Support choice: ask for MANA Canada products by name.

MANAGER

5 | Wireworms on the rise

Although advances in control options have been made, the quest for a “silver bullet”

Controlling disease in storage by Julienne Isaacs

selections by Treena Hein

Andrew

12 | Not glyphosate ready

Proactive management may help growers get a handle on late blight next year. By

Rosalie I. Tennison

Rosalie I. Tennison

More than just a number by Julienne Isaacs

24 | Tillage radishes

This cover crop can provide important benefits to potato farmers.

By Treena Hein

A sunny forecast by Stefanie Croley, Editor

PHOTO

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITOR

A SUNNY FORECAST

It has been a tough few months for Canada’s potato producers.

A harsh winter – even by Canadian standards – was the first contributing factor. Nearly the entire country felt the effects of an extended deep freeze, during which temperatures set records for consecutive days below zero. A spring storm dumped up to 53 centimetres of snow in parts of Atlantic Canada in late-March. And across Canada, meteorologists called this one of the coldest and snowiest winters in several years – decades, even, in some parts of the country.

Just as we thought warmer times were on the horizon, April brought some disappointing news to growers in both Eastern and Western Canada. With unfavourable weather conditions continuing in Prince Edward Island, some potato farmers were forced to delay planting. Grower David MacLeod told CBC News that he only managed to plant a few acres of potatoes during the last half of the month, as the wet, cold weather that continued into spring delayed his timing.

And in Manitoba, mid-April saw contract talks deteriorate between the province’s potato producers and processors. Cavendish, Simplot and McCain Foods have cut some farmers entirely from their contract list, and volume agreements are below last year’s numbers.

But the summer’s forecast looks to be positive, sprinkled with new strategies, innovation and growth for the industry, with much of this new light coming from the winter’s conferences and seminars. I travelled to Brandon, Man., in late-January to attend the Manitoba Potato Production Days conference, during which researchers from across Canada and the United States met to discuss spraying strategies, pest and disease issues and control, and best management practices. It was a jam-packed two days, filled with presentations and conversations with producers, but the keynote speaker offered a different take on potatoes to the crowd.

Shimona Mehta, the director of client development for the market research firm NPD Group’s Canadian foodservice division, presented interesting statistics on consumer food choices to attendees. Mehta revealed several factors that drive food choice, but the number 1 factor consumers look for in choosing meals is taste, and French fries are the number 1 item served at Canadian restaurants – good news for the potato producer. Ironically enough, shortly after my trip to Manitoba, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) released two new chipping varieties – another positive move toward maintaining a vibrant potato industry in Canada (read more about the new varieties on page 16).

And in February, Dr. Bob Vernon with AAFC met potato producers in Prince Edward Island to discuss new wireworm control strategies and to provide an update on his continued research of the pest. We spoke further with Vernon, as well as AAFC’s Dr. Christine Noronha, and other researchers, about new strategies to control wireworm, on page 5.

If you didn’t get to Brandon for the Manitoba Potato Production Days – or Charlottetown for the International Potato Technology Expo, or Guelph for the Ontario Potato Conference – not to worry. We’ve followed up with researchers on several topics to provide you the information you need as we move into summer. From looking at the effects of glyphosate on potatoes (page 12) to the relationship between the physiological age and yield of seed potatoes (page 20), new research is abundant across North America and in our pages.

As the growing season continues, we’d love to hear about the challenges and successes you’ve found so far. Send me a note or give me a call, and we’ll see you in the fields.

Crop Manager West - 9 issuesFebruary, March, Mid-March, April, June, September, October, November and December1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East - 7 issuesFebruary, March, April, September, October, November and December - 1 Year - $45.00 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada - 4 issues - Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter 1 Year - $16 CDN plus tax All of the above - $80.00 Cdn. plus tax

www.topcropmanager.com

PESTS AND DISEASES

WIREWORMS ON THE RISE

Although advances in control options have been made, the quest for a “silver bullet” continues.

by Carolyn King

Potato growers in Prince Edward Island are struggling with escalating wireworm populations. And wireworm problems are on the rise in some other parts of Canada too, impacting potatoes and many other crops. As well, Thimet 15G, the main insecticide for wireworm control in potatoes, is scheduled to be phased out in 2015. So researchers are working on strategies to keep these serious pests at bay, while looking for a “silver bullet” to provide longer-lasting control.

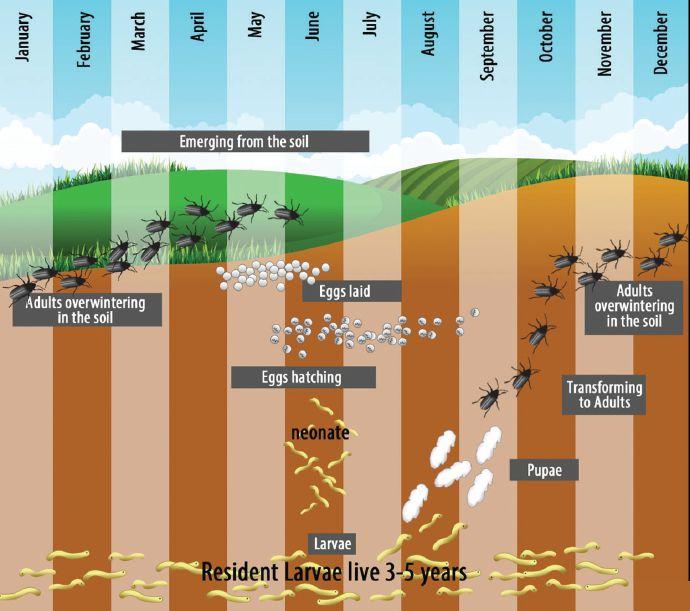

Wireworms are the soil-dwelling larvae of beetles in the Elateridae family, called click beetles. Canada has about 30 wireworm species of economic importance. In most species, the beetles lay eggs in the soil in the spring. A few weeks later, the larvae hatch. The larval stage lasts about four or five years, depending on the species. Then the larvae pupate and emerge from the soil as adults in the spring.

In potato crops, wireworms rise to near the soil surface in the spring to feed on the seed pieces. In the summer, they go deeper to escape hot, dry conditions. As cooler, moister conditions return in late summer, they rise up again and tunnel into the daughter tubers, reducing the marketable yield. The tunnels can also be entry points for potato pathogens. As winter approaches, the larvae descend again to avoid the cold.

Wireworm control is plagued with challenges. For instance, the 30 pest species differ from each other in ways that affect control practices, such as their susceptibility to some insecticides. Because the larvae are

hidden in the soil, it is difficult to know how many species, if any, are in a field.

Each generation of wireworms can cause problems in a field for several years. If their preferred crops of cereals and grasses aren’t available, they can feed on other crops. They can go for long periods without food. And they can move to escape unfavourable conditions. As well, because wireworms feed several times during a season, the length of time an insecticide remains effective can be an issue.

P.E.I. situation

“Wireworms have been a localized problem in P.E.I. for many years. But in the last few years the populations have increased to the point where the problem is really out of hand,” says Dr. Christine Noronha with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Charlottetown.

She started working on wireworms in P.E.I. in 2004 when a grower in Queens County told her he was having a lot of problems with the pest. Since then, she has been using click beetle pheromone traps to get a better understanding of their distribution on the Island. “Initially, we just surveyed in areas where we knew the problem was bad. But we started getting more and more reports of problems in new areas. So we did a major survey across the province in 2009 and a follow-up survey

PHOTO COURTESY

OF DR. CHRISTINE NORONHA, AAFC.

TOP: Wireworm populations have greatly increased in Prince Edward Island over the last few years.

in 2012,” she explains.

The 2009 and 2012 surveys were joint efforts of AAFC and the P.E.I. Department of Agriculture and Forestry. In 2009, they placed 60 traps in fields across all three counties. In 2012, they placed traps in those same fields and additional fields, setting out 85 traps.

“Our results show more fields were infested in 2012 than in 2009. In 2009 some pockets didn’t have any problems; we don’t have any such pockets now. Also the numbers of beetles caught in 2012 were much higher than in 2009, in spite of taking into account the additional traps. Queens County had the highest change in population, with about an eight-fold increase,” says Noronha.

Populations of Agriotes sputator, the most damaging wireworm species in P.E.I., increased in all three counties.

P.E.I. has several wireworm species, and typically at least two species in a field. The pheromone traps are for the three European species found in P.E.I. – Agriotes sputator, Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus – because those are the only ones for which pheromones are available for purchase.

“One big reason why P.E.I. is having such problems with wireworms is the spread of those European species,” says Dr. Bob Vernon, who leads AAFC’s national wireworm research effort, which is based at Agassiz, B.C.

“Agriotes sputator is known as the potato

wireworm because it is a very bad pest of potatoes. The sputator beetle flies quite well so it can invade new areas rapidly, moving about half a kilometre per year. Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus beetles move primarily by walking, so they invade new areas more slowly. These three species, and especially sputator, have gained a foothold in parts of P.E.I. and are expanding their range and increasing their numbers.”

According to Vernon, another key reason for the increasing problems in P.E.I. is that potato rotations in the province often include cereals and other grassy crops. He says, “Such rotations are good for soil conservation, but they favour the spread of wireworms.”

In P.E.I., the European beetles tend to spread out from non-farmed grassy verges into nearby fields, preferring to lay their eggs in cereals, grasses or pasture. He notes, “If that generation of larvae emerges as adults when a really favourable crop, such as barley or hay, is in the field, they’ll stay and lay all of their eggs there. So the wireworm population in the field will increase by 200 times because that’s about the number of eggs that each female of these European species lays.”

Vernon believes a third reason for the wireworm population boom is the gradual breakdown of long-lasting residues of organochlorine insecticides, which used to be widely used in Canada and around the world. “When applied to the soil, organochlorines did a very good job of killing wireworms, but

those insecticides persist in the soil for a long time. For instance, Dr. Fred Wilkinson determined that a single application of heptachlor in the soil would kill wireworm larvae for 13 years,” says Vernon.

Depending on the products and how often they were applied to a field, the residues could be sufficient to kill newly hatched larvae in that field for many years. “So wireworms almost worldwide became a problem of the past because of the organochlorines. But those insecticides have been banned for years, so the soils are losing those residues. And now the fields are wide open for wireworm populations to start to explode,” he says.

A look at the rest of Canada

“The organochlorines were a silver bullet –we didn’t have to worry about the wireworm species because they killed every wireworm species. But some of the newer insecticides are more effective on certain species than others, so we need to know which species are in an area to know if a particular insecticide will work,” explains Vernon. “And to make things more complicated, many fields have more than one species; they can have up to five species.”

So Vernon’s research team is working on the daunting task of conducting Canada’s first-ever national wireworm species survey. Like P.E.I., Nova Scotia has native species as well as the three European species, which

PHOTO COURTESY OF DR. CHRISTINE NORONHA, AAFC.

Noronha has developed a rotational strategy, using buckwheat (shown here) or brown mustard that reduces tuber damage by about 80 per cent or more.

are causing problems in many crops. In New Brunswick, wireworms do not appear to be a major problem so far.

“Wireworm problems in Quebec and Ontario are starting to increase. We’ve just finished a three-year study with the Quebec government, so we have a good idea of the species in Quebec; they don’t have the European species yet. We’ll be doing the same type of survey in Ontario in 2014,” says Vernon.

The researchers have identified the primary species on the Prairies. “We’re seeing a huge build-up of some wireworm populations in places like Alberta. Prairie farmers used lindane [Vitavax] as a cereal seed treatment. It killed about 70 per cent of the existing wireworms and about 80 per cent of the baby wireworms in that cereal crop. So they used lindane once every three or four years and that kept the populations under control,” he says.

“Now that lindane is banned, farmers have replaced it with newer insecticides. For example, the neonicotinoids just put wireworms into a coma from which they recover fully. So you can get a good crop stand, but you have new egg laying in that cereal crop and you’re not killing any wireworms in that field. So you have a constant increase in wireworms.”

Cereals are often key crops in Prairie rotations, including potato rotations, so lindane was an important tool.

Prairie potato growers are using Thimet 15G for wireworm control. “In potatoes east of the Rocky Mountains we have basically one insecticide that will reduce wireworm damage by about 90 per cent, and that is Thimet 15G,” says Vernon. Usually Thimet works well, but he says it can be overwhelmed

when wireworm populations are enormous. Vernon’s research team has good information on the B.C. wireworm species, which include native species as well as Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus. Although B.C. does not have Thimet, Vernon has developed an effective strategy for B.C. potato growers. It combines a neonicotinoid seed treatment (clothianidin, Titan) and an in-furrow spray with chlorpyrifos (Pyrinex). However, clothianidin is not quite as effective on some wireworm species in other parts of Canada, and chlorpyrifos cannot be used on potatoes that will be sold into the U.S. because no minimum residue levels have been established for the U.S.

Searching for a new silver bullet

For many years, Vernon and his colleagues at AAFC have tested virtually every insecticide that has come along for its effects on wireworms in various crops. This research shows neonicotinoid and pyrethroid products can protect the crop they are applied on, but he wants to find something like lindane that also protects the following crops in the rotation.

“We are always looking for a new silver bullet, for something that will effectively kill wireworms, not just knock them out, like the neonicotinoids, or repel them, like the pyrethroids.”

The irony is that Vernon has already found a silver bullet.

“Our big hope was fipronil. It is registered in the United States on potatoes for wireworm control and it was registered on corn. We found that fipronil kills all species of wireworms very effectively. And we came up with a strategy to put it on cereal

crop seed. This strategy combined very low amounts of fipronil – less than one gram of fipronil per hectare – with low amounts of a neonicotinoid. The neonicotinoid gave us an exceptional crop stand and the fipronil eradicated the existing wireworm populations, including the baby wireworms produced that year. So with one application of this blend, we could inexpensively control wireworms for three to four years, just like lindane. And it was even more effective than lindane with 60 times less insecticide,” explains Vernon.

“Whether or not that strategy ever sees the light of day is up to the chemical industry to either bring fipronil into Canada or not. That has not happened yet, and it may not happen.”

AAFC has been working with Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) to find options for controlling wireworms, including alternatives to Thimet 15G (phorate), which is to be phased out due to environmental concerns.

“In 2006, under a joint Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada/Health Canada Pesticide Risk Reduction Program, the pesticide risk reduction strategy for wireworm was developed and centered on the need to find lower risk replacement pesticide products and practices for the control of wireworm in Canadian agriculture,” says Margherita Conti, director general of PMRA’s value assessment and re-evaluation directorate.

“In 2008 . . . the PMRA initiated a transition trategy for phorate to address this loss of an older chemistry and to promote the transition toward reduced risk pest control options. There are continuing consultations with researchers, growers and grower associations, processors, provincial specialists and

Courtesy of Dr. Christine Noronha - AAFC

Rotation effects on wireworm damage in potatoes, P.E.I.

Courtesy of Dr. Christine Noronha – AAFC

pesticide companies towards the goal of finding replacement products. To date, chlorpyrifos has been registered for wireworm control in B.C., and clothianidin has been registered for suppression of wireworm in potatoes.”

Thimet was previously scheduled to be phased out by 2012, but that deadline was extended. Currently, the last date of use of Thimet 15G by growers and users is set for August 1, 2015. “Any extension would have to consider the outcome and timeline of the ongoing review of a potential replacement,” Conti notes. “There has been an application received by the PMRA to register bifenthrin [Capture] for control of wireworm on potatoes. There has not been a decision made at this time [April 2014] to extend the registration of Thimet.”

She adds, “The PMRA is aware of the critical nature of the wireworm situation in Canada. Consultations are continuing with researchers in AAFC, provincial officials and other stakeholders regarding the wireworm situation.”

Next steps

Over the next four years, with funding through Growing Forward 2, Vernon, Noronha and their colleagues are expanding their work on wireworms, including options for hot spots with huge populations.

Noronha has developed a rotational strategy for P.E.I. potato growers. Her re-

search shows that growing either brown mustard or buckwheat for two years before growing potatoes can reduce tuber damage by about 80 per cent or more.

When brown mustard plants are disked into the soil, a natural chemical in the plant breaks down to form isothiocyanate, which acts like a fumigant to kill wireworms. As well, brown mustard roots have natural chemicals that are toxic to wireworms. The mechanism causing buckwheat’s effect on wireworms is unknown at present. Both crops control all of the wireworm species found in P.E.I.’s agricultural areas.

Noronha and her provincial colleagues are talking with P.E.I. growers about this strategy and how to implement it. For growers in severely affected areas, the approach is to grow two crops per season of either brown mustard or buckwheat, and to do that for two years in a row. “Because brown mustard and buckwheat are both shortseason crops, the farmers have to grow two crops a year. They plant the crop in June. At the end of July, before the crop has gone to seed, they disk it into the soil, and then they plant the second crop. Any wireworms that didn’t die with the first crop are targeted with the second crop. The growers leave the crop standing over the winter for soil conservation cover,” explains Noronha. The growers repeat those steps for another year, then in the third year they plant potatoes.

For the strategy to work effectively, the control crops can’t set seed. So the farmers have the costs of growing the control crops but they are not earning any money from them.

She suggests potato growers with severe infestations use Thimet along with the rotational strategy: “Hopefully that will bring some of the populations down to manageable levels.” The rotation also provides an option for growers if Thimet is no longer available.

For P.E.I. growers who are just beginning to have wireworm problems, she recommends planting brown mustard in August, before planting potatoes in the following year. Growers who don’t have a wireworm problem so far can use the same approach, but they only need to plant a control crop once in while.

Noronha and her P.E.I. colleagues are working on various other wireworm projects, including another provincial survey to be conducted in 2016.

Vernon is continuing his insecticide efficacy studies to find a lindane-like substitute that can be used on cereal crops to provide wireworm control for several years.

He’s also adding a new focus to his research: killing the beetles before they can lay their eggs. This approach would not control the larvae already living in a field. It is aimed at areas where wireworm populations are exploding.

Vernon and his colleagues are working on a variety of methods to kill the beetles. For instance, he is using pheromone traps to time field spraying of an insecticide, such as a pyrethroid or a botanical spray like pyrethrin. One of Vernon’s colleagues, Todd Kabaluk, is evaluating methods to apply Metarhizium anisopliae to kill the beetles. This fungus is highly lethal to click beetles and does not harm the key beneficial insect species they have tested. The researchers are also investigating environmentally safe ways to control the beetle populations in grassy verges, such as using botanical sprays or mass trapping and mating disruption.

“This insect has been a nightmare,” says Vernon. “Farmers are losing crops, and the problem is going to get worse. If we had access to products that other countries have access to already, we would not have a wireworm problem today. It’s very discouraging to have to look at spraying fields to pre-emptively control beetles just in the hope that you can slow them down.”

STORAGE

CONTROLLING DISEASE IN STORAGE

Do’s and don’ts for post-harvest pesticide application.

by Julienne Isaacs

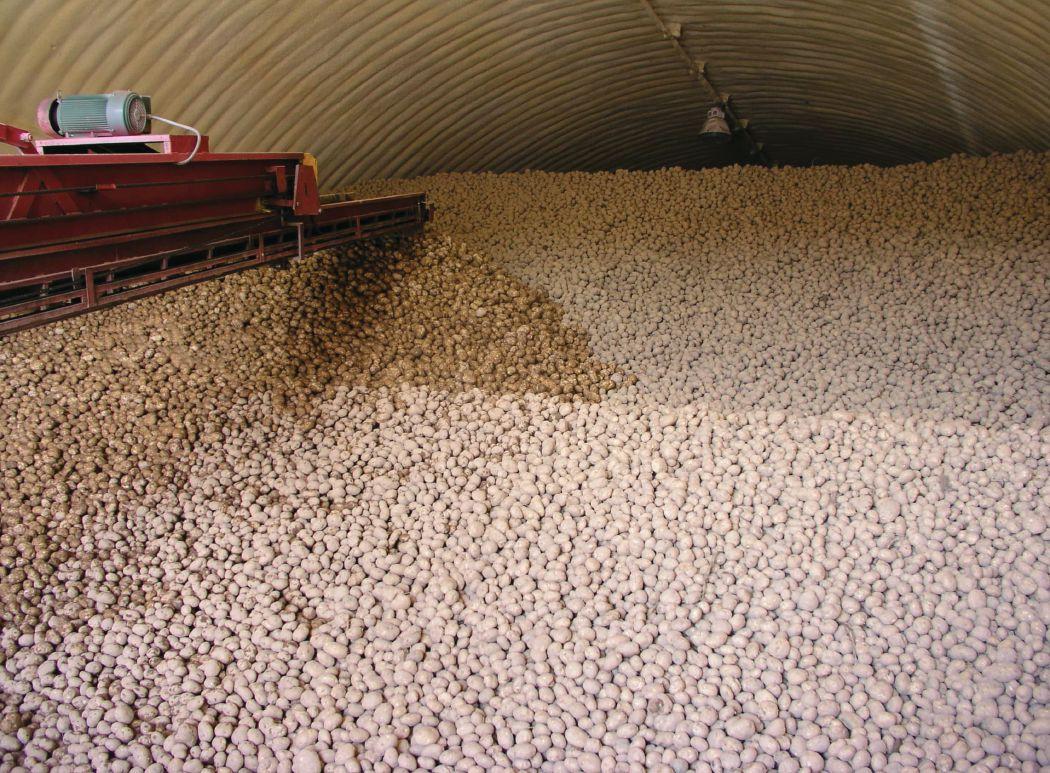

Asolution for growers hoping to control the spread of disease in storage is the application of phosphorous acid postharvest, according to crops specialist Steven Johnson.

Johnson, an extension professor at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, delivered a presentation on phosphorous acid and its uses in potato post-harvest situations to a packed room at this year’s Manitoba Potato Production Days, held in Brandon, Man., from January 28 to 30.

Johnson’s research for this presentation was concerned with the damage that can occur to tubers during several stages of the harvest and storage process – and the impact this can have on disease control, as damage offers an entry point for pathogens.

“Skinning or wounds provide easy access for two devastating potato tuber pathogens: Phytophthora infestans, the causal agent of late blight, and Phytophthora erythroseptica, the causal agent of pink rot,” Johnson says. The two diseases are responsible for massive losses in potato production systems.

Both pathogens, but especially P. infestans, spread rapidly in the field, but tuber-to-tuber contact can also cause the pathogen to spread dur-

ing mechanical harvesting and tuber unloading and transfer procedures. But Johnson says a post-harvest phosphorous application may help mitigate this problem.

“Phosphorous acid, sometimes called phosphonate or phosphite, is generally formulated as mono- and di-basic sodium or potassium salts, or an ammonium salt of phosphite,” he explains. Phosphorous acid is often confused with phosphate, but it differs from phosphate in its mode of action. While phosphate is a nutritional source that, when used as fertilizer, quickly assimilates into plant compounds on uptake, phosphorous acid is not a nutritional source, and does not become assimilated into plant compounds.

“Phosphorous acid moves in the phloem and limits the growth of some oomycetes, including P. infestans and P. erythroseptica,” Johnson explains. “Phosphorous acid has also been shown to induce and enhance natural defense reactions in plants, often called systemic acquired re-

TOP: Applying phosphorous acid post-harvest may prevent the spread of disease in storage.

INSET: Johnson and his team designed a sprayer to maximize spraying area.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF STEVEN JOHNSON.

In examining whether reduced-carrier volumes would prove as effective as full-carrier volumes with the same amount of active ingredient, phosphorous acid treatments were applied at 24 ounces per ton (left), 32 ounces per ton (right) and other levels of the recommended carrier rate of 64 ounces per ton. Johnson says late blight control started to break down at one-quarter of the recommended carrier rate.

sistance or SAR. Phosphorous acid has systemic properties within the plant and tuber, but the exact mode of action of phosphorous acid is not conclusively established.”

Research findings

In a study examining the efficacy of post-harvest applications of phosphorous acid in controlling P. infestans and P. erythroseptica on potatoes headed into storage, treatments applied to the potatoes included an untreated check, and potatoes treated with Agclor 310, Oxidate, Phostrol, ProPhyt, and Rampart, respectively – the latter three being phosphorous acid materials. Rates used, per hundredweight, were 0.48 ounces of Agclor 310, 1.5 ounces of Oxidate, 12.8 ounces of Phostrol, 12.8 and 25.6 ounces of ProPhyt and 12.8 ounces of Rampart. All materials in the study were applied at the rate of 64 ounces per ton of potatoes. The potatoes in the study were handled as they would be during typical harvesting procedures.

The first research question posed by the study was: how long does it take after exposure to inoculum before treatment with phosphorous acid proves ineffective? One and three hours post-exposure were chosen as phosphorous acid application timings, in order to simulate a time frame for potential tuber-to-tuber spread during post-harvest handling. The data showed that phosphorous acid treatments provided complete control over the spread of disease.

A second research question addressed whether phosphorous acid treatments could be applied at lower-than-recommended rates. Studies were performed over two years with the same parameters as for the previous research question. According to Johnson, treatments were applied at full, half or one-quarter of the labeled rates, which is 12.8 ounces per ton.

“Looking at one or three hours after inoculation, late blight control

started to break down at one-quarter of the labelled rates of either phosphorous acid,” he says. “In both years, all the phosphorous acid materials provided excellent control when used at the full labelled rate.”

Finally, a third research question examined whether reduced-carrier volumes would prove as effective as full-carrier volumes with the same amount of active ingredient. The same phosphorous acid treatments were applied at full, half or one-quarter of the recommended carrier rate of 64 ounces per ton. “Bear in mind that with 12.8 ounces of phosphorous acid in 16 ounces of carrier, there is not a lot of carrier,” Johnson says.

“As in the reduced phosphorous acid rate trial, late blight control started to break down at one-quarter of the 64-ounce recommended carrier rate.”

Johnson also notes the importance of coverage in applying phosphorous acid treatments. Ideally, potatoes should be treated while they are tumbling onto a transfer belt. Solution applied to the belt aids coverage, he says, but growers should ensure the belt is damp, but not dripping, to aid distributing material.

Also key to application is proper use of all materials. “Improper application of phosphorous acid may result in crop injury, monetary loss or poor disease control,” Johnson says. “It is essential to calibrate application equipment precisely and apply the correct rate of material in the proper volume of carrier.”

Johnson and his team designed a special applicator to address the concern of proper coverage, with nozzles on swivel bodies facing forward and backward, to maximize exposure to treatment.

The bottom line, Johnson says, is that phosphorous acid is extremely effective against P. infestans and P. erythroseptica, and it is an excellent control against tuber-to-tuber spread when applied correctly.

It’s written in the soil. The Hot Potatoes® Rewards Program is back! The more eligible purchases you make in 2014 and 2015, the more Hot Potatoes reward points you earn. At the end of the season, your points can be redeemed for a cash rebate, a heart-thumping European adventure, or maybe even both. Learn more and find new bonus offers at Hot-Potatoes.ca or call 1 877-661-6665

NOT GLYPHOSATE READY

It turns out even inadvertent contact can damage potatoes.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

When everything has been done correctly and there is no visible reason why a potato crop is substandard, it could be glyphosate damage.

Growers who purchase seed from reputable providers, manage pests and diseases properly, and follow a good fertility program are sometimes puzzled – this occurs when they have poor emergence, multiple sprouting underground and/or a poor crop at harvest (and know they can’t blame the weather). Research completed at the University of Idaho suggests the problem could be due to glyphosate damage.

Dr. Pam Hutchinson, a potato cropping systems weed scientist at the university’s Aberdeen Research and Extension Center, says herbicide carryover in the mother crop can affect the daughter crop. This could explain some crop failures. The problem lies with identifying how the carryover occurred, so growers need to be diligent in their spray practices and be aware of what their neighbours are doing.

While herbicide damage can occur from any product that is not registered for potatoes, Hutchinson focused her attention on glyphosate. “With the introduction of glyphosate-tolerant sugar beets, I began to wonder about drift or poor spray tank clean-out and damage to the mother crop plus carry over in the seed,” she says. “I set up a trial in potatoes with different rates of glyphosate applied at different times of plant development.” She made applications at the small plant stage, tuber formation and tuber bulking. She stored the resulting tubers and planted them the following year.

Hutchinson says the most damage to the mother crop plants occurred when the plants were sprayed when small (10 centimetres tall), and the least amount of damage was observed when the tubers were bulking in the latter stages of crop development. “We saw no indication of injury at bulking that could be noticed unless you knew that glyphosate had been applied and had a check plot for comparison,” she comments.

However, the tables turned the following year when the daughter tubers were planted. The mother crop plants that had damage at the earlier spray times developed healthy tubers. Problems emerged from the tubers harvested from plants that showed no damage at the later spray times.

“We had multiple sprouting from those daughter tubers and in some cases we had only 20 per cent emergence of the tubers that had been sprayed during the later time period,” Hutchinson

Dr. Pam Hutchinson found that greatest injury to the

was from glyphosate applied at

No injury was found at the mid-bulking stage.

explains. “Growers may not notice the damage on the mother crop, but they could still have it.”

Hutchinson says her findings will be of particular interest to seed potato growers, but growers of table or processing varieties will want to understand why their crop may have failed or feel confident that the crop they are selling is undamaged.

As a systemic product, glyphosate will work down to the tubers in the ground causing damage, especially during the bulking period. She says glyphosate damage is rarely detected in tubers, so a problem may go unidentified. The only indication of damage may be small defects in the tubers that have to be looked for, such as the bud end folding in. If the tubers are intended for consumption

PHOTOS COURTESY OF DR. PAM HUTCHINSON.

Ranger Russet mother crop

hooking.

The year after glyphosate was applied to the mother crop, the Ranger Russet daughter tubers were examined at the hooking and mid-bulking stages. Daughter tubers from mother plants treated with 1/16X at hooking stage were planted in the plot on the left, and plants emerged from 16 out of 20 tubers with no foliar damage. On the right plot, 20 daughter tubers from mother plants treated with 1/16X at mid-bulking stage were planted, with stunted plants emerging from two tubers. Although injury was greatest to the mother crop at hooking, daughter tuber emergence the next year was fine, but this was not so with daughter tubers harvested from the mid-bulking application mother crop.

and are stored, the herbicide will break down to acceptable Health Canada levels and will pose no threat. However, seed potatoes may pass the problem on causing damage in the following crop.

How does this happen? Growers who are diligent in their crop production and yet learn they have glyphosate damage in their crop may be scratching their heads. But, Hutchinson says the damage can come from unconsidered sources. For example, she says a neighbour may spray for late-season weed control and to desiccate a cereal crop and drift will occur onto the potato crop in the next field. Poorly cleaned sprayers could also be the culprits.

“Growers need to be aware if glyphosate is being used near their potato crop and they need to be diligent in cleaning their sprayers from tank to nozzle,” Hutchinson advises. “Consider having a sprayer that is dedicated only for potato use and will never have product in it that is not registered for potatoes.” She also suggests talking to neighbours about cropping intentions, so they will be aware that a potato crop in close proximity to their fields may be sprayed with products damaging to potatoes.

“This isn’t just about glyphosate; I have seen damage from other herbicides,” notes Hutchinson. However, her research focused on glyphosate, and the extent or effect of damage from other products has not been proven.

Hutchinson says the next question was whether the damage could continue into the third or granddaughter potato crop. After growing out the granddaughter crop, no discernable damage was noted. The issues were with the daughter crop if it failed to emerge

and produce an acceptable yield.

“The take home message in all this is to be aware of the herbicides that could come in contact with your seed potato crop,” she cautions. For example, if a seed grower goes away during the period when the crop is bulking and a neighbour sprays a cereal crop with glyphosate and there is drift, the damage may not be noticed. But, if that potato crop is sold for seed to a commercial grower who ends up with yield loss and damage due to the affected seed, the reason for the failure will not be apparent. Who would be liable for the failure? Assuming it’s possible to determine what caused it.

Hutchinson’s research shows that potatoes are susceptible to glyphosate even at the smallest amounts. She says the main point is that “a high level of damage to the mother crop doesn’t mean daughter tubers will be affected when planted the following year.” But, timing is everything, she adds, and at mid-bulking the glyphosate will move to the developing daughter tubers.

Even though potatoes are a sturdy, dependable crop, they are not without their weaknesses, and growers need to be aware of the challenges facing their crop. Therefore, growers should continue to do everything possible to ensure a healthy, high-yielding crop, and now, complete sprayer cleaning and guarding against drift need to be added to the list of things to do.

WHAT MATTERS MOST?

Keller Farms is the largest irrigated farm in Canada. Globally, our products feed millions; locally, our business helps employ thousands. Syngenta is a huge part of my operation. The research they do around the world helps us to keep growing here.

Mark Keller, owner/farmer, Keller & Sons Farming Ltd., Carberry, MB growing here.

Visit SyngentaFarm.ca or contact our Customer Resource Centre at 1-

NEW SELECTIONS

AAFC is offering two new chipping potato varieties.

by Treena Hein

Canadians love their potato chips. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) reports that the potato chips industry in Canada is expected to increase to $1.7 billion by the end of 2016. That’s why those within the AAFC breeding program have been hard at work on two new chip varieties, released in February 2014 for the potato industry to evaluate.

These two newbies are among 15 other new potato selections, including varieties best suited for French fry production and fresh market. They have all been released through AAFC’s Accelerated Release Program, which offers potato industry entrepreneurs of any size the opportunity to evaluate front-runners coming out of early selection trials.

Agnes Murphy, AAFC research scientist at the Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, N.B., says, in terms of the need among growers for better chip selections, it’s always present and steady. “Growers and processors are always keen to try new chip selections, especially if they offer a competitive edge by reducing the cost of production through better yields and

lessening the need for inputs,” Murphy says. “There are exacting requirements for manufacturing chips, and traits associated with that must be combined with improved agronomic traits and low rates of defects for any of the new selections to succeed.”

The two new chip selections (see sidebar for details) were all produced using classical breeding methods. Murphy explains that this entails choosing parents each year according to specific objectives and traits the plants may confer to their progeny. “Parents may be cultivars or breeding selections that have been well-characterized for numerous traits such as yielding potential, shape, tuber culinary qualities, skin and flesh colour, disease and pest resistance,” she says.

The parents are grown in greenhouses or growth chambers to produce flowers, which are used for the first step in breeding – the hybridizations. Pollen from the parents (those chosen to serve as male parents) is collected and applied the female

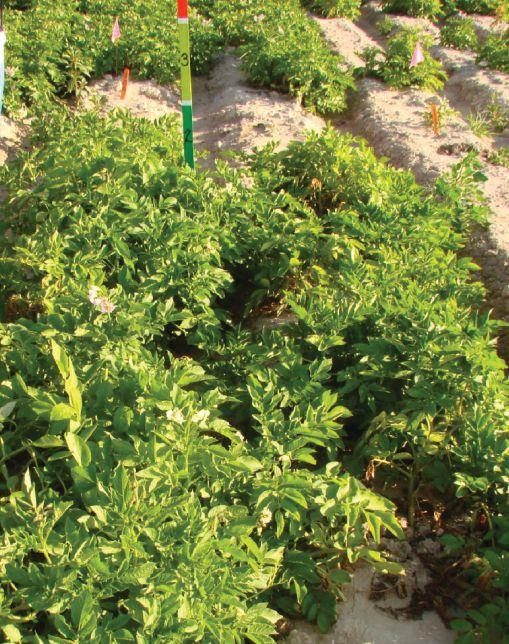

ABOVE: The AR2014 varieties were launched at an event in February through AAFC’s Accelerated Release Program.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JOHN MORRISON, AAFC.

stigma (flower part). If the fertilization is successful, small fruit (berries that look like miniature green tomatoes) will form that can contain several hundred botanical seeds. Murphy points out that not every cross combination is successful and that there are a number of barriers that may prevent fertilization. But in cases where it is successful, the next step involves extracting the botanical seeds (also called TPS for true botanical seed to differentiate them from the seed tubers) from the berries and adding them to the seed inventory.

“Then each year, TPS are sown in greenhouses as you would bedding plants,” Murphy says. “Each seed that grows will produce a potato plant that may form small tubers. One small tuber is collected from each separate plant and kept for planting to the field the following year in what is referred to as the first field generation.” From then on the plants are multiplied vegetatively and evaluated for adaptation and for the traits that are important for each end-use category (chip, French fry or fresh market).

Most of the 15 AAFC selections on offer have had five or six years of evaluation, which includes agronomic and culinary performance and disease and pest challenges. “Modern molecular technologies and tools are applied wherever feasible to assist with evaluation,” says Murphy.

“Each year, a series of adaptation trials are conducted nationally at sites across the country. There are usually 40 or more selections plus reference checks included in the trials. The data collected from the trial sites are analyzed and reviewed carefully to identify the selections that will advance to the Accelerated Release Program (ARP) process.”

Farmer involvement

Growers who wish to evaluate these ARP selections had to contact AAFC by the end of February. Samples of these selections from the AR2014 series are offered to growers or associations on a non-exclusive basis for up to two years of field evaluation. “So, there may be multiple evaluators in different regions participating in Phase 1 each year,” Murphy explains. “After that, in Phase 2, the selections are offered for exclusive field testing for up to three more years based on a competitive bidding process. At any point in Phase 2, if the performance is promising, the right’s holder may negotiate a license with AAFC and variety registration may proceed. All the assessments are performed by the grower or grower’s agent.”

Having the farmers on board means all the hard work of developing these chip varieties under the ARP will continue on schedule. “Potato breeding and cultivar development is absolutely a team effort with lots of people contributing along the way in greenhouse, fields and laboratories,” Murphy notes. “People directly involved include technicians, farm staff, trial collaborators at national trial sites and data managers. Behindthe-scenes administrative staff facilitate the day-to-day operations and provide communications support and more. Dr. Benoit Bizimungu and I are very fortunate to have such a dedicated and highly competent group working with us.”

Murphy says she loves participating in the quest for improved varieties. “There is a continuum in potato breeding that appeals to me,” she says. “The current offerings of selections build on years of contributions made by our predecessors while blending in exciting research advances being made by our colleagues.”

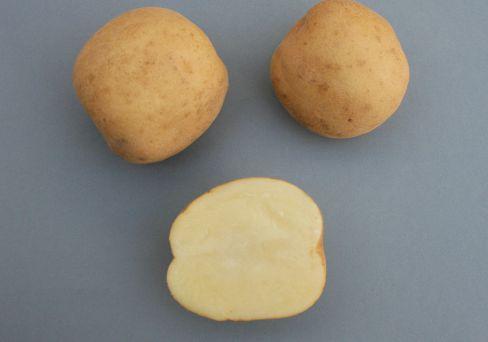

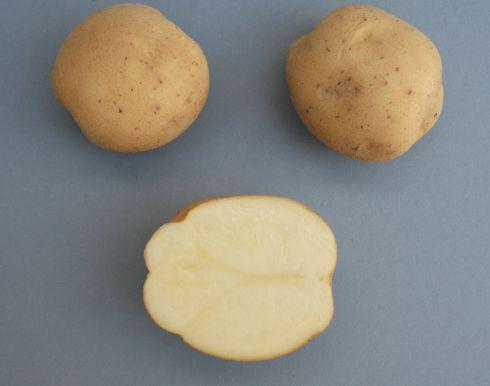

AGRICULTURE AND AGRI-FOOD CANADA’S NEW CHIP POTATO SELECTIONS

AR2014-02 F09020 (Brodick x CS7232-4) chip variety is a round potato with flaky light yellow skin, cream coloured flesh, and good chip colour. It offers potato growers a higher-yielding chip potato, with fewer internal imperfections that can reduce chip quality.

AR2014-03 FV15559-79 (Andover x F87031) chip variety is also a round selection with slightly flaky buff skin, creamy flesh, very good chip colour and resistance to PVX. It does better than other chip varieties in cold storage, prolonging shelf life and reducing the need for chemical treatment to control disease that can occur in storage.

Both the new selections have a molecular marker associated with a gene that provides resistance to golden nematode pathotype, Ro1. Murphy says this pest is a quarantine pest and not all widespread, so resistance is useful basically only for areas where it occurs or for export seed markets. Some well-known chipping cultivars such as Atlantic are resistant to golden nematode while others are not, and having the marker is an add-on benefit. For more, see http://www.inspection.gc.ca/plants/plant-protection/ nematodes-other/potato-cyst-nematodes/eng/1336742692 502/1336742884627

EARLY BLIGHT MANAGEMENT

Grow a strong plant and then protect it for better yield.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

No question that early blight is a yield robber, but, with careful management, most growers can prevent losses. An independent potato researcher has some useful advice on how to manage early blight even more effectively, but it requires planning.

Dr. Jeff Miller of Miller Research LLC in Idaho says of the different ways growers can manage early blight infections, the best is to keep fertility at optimum levels right from the beginning. “Fertility management can reduce early blight problems effectively,” he says. “But, it has to be done properly.”

“Too high levels of fertility can cause problems in crop yield,” Miller explains. “So, manage fertility for optimum production and then use fungicides for control of early blight.”

However, the greatest concern about this strategy is overuse of a limited number of fungicides, which could lead to resistance development. Miller says there are some fungicides that are showing early blight resistance in the midwestern United States and that resistance could show up in Canadian fields in the near future. “We are recommending that growers use a tank mix for early blight management to help reduce the development of resistance,” says Miller. “Use two chemistries at the high end of the label rate to ensure resistance doesn’t develop.” He adds that if growers start early to control early blight, they can sometimes get late blight control as well.

Currently, the most effective fungicides for early blight are in Group 7. Of these, boscalid (sold as Cantus in Canada) has proven most effective, but resistance to this product is developing, perhaps due to injudicious use. However, while losing its effectiveness on early blight due to resistance issues, boscalid remains effective on white mould. Therefore, a tank mix with boscalid along with another product effective on early blight from another chemical group should control both.

When a new chemistry is introduced, such as fluopyram + pyrimethanil (sold as Luna Tranquility), which is effective on both early blight and white mould, growers need to use it frugally to minimize resistance development. Despite being a Group 7 chemistry, there has been no recorded resistance to Luna Tranquility, which means it could be a good tank mix choice with another chemistry, Miller says. He suggests tank mixing with a protectant fungicide, such as one based on chlorothalonil or mancozeb. “When we have an effective product we need to use it carefully to ensure its continuance,” Miller comments.

Miller says Group 3 chemistries have good activity on early blight, but not on white mould. Again, tank mixing a Group 3 and a Group 7 should provide the control needed and ensure the longevity and effectiveness of the chemistries. Group 11 strobilurin chemistry products, while registered for early blight control, do not get a vote of confidence from Miller because of fungicide resistance in the early blight pathogen. He says he would not recommend using them because the risk is too great.

Miller recommends the “protectant approach” for optimum disease management, particularly for early blight control. “I would always begin my early blight management with good fertility,” he concludes. “Then, my next step would be to choose an effective fungicide and apply it early in my planned program at row closure and then 10 to 14 days later. After that, I would switch to other products used as protectants. My first products would be strong on early blight.” He likens this approach to using sunscreen on your skin. It’s not effective if you put it on after you have been out in the sun for several minutes, but it is highly effective if it is put on before sun exposure occurs.

“Too high levels of fertility can cause problems in crop yield,” Miller explains.

“So, manage fertility for optimum production and then use fungicides for control of early blight.”

“If you wait until you see early blight before you begin control, it is already too late,” Miller says. “You have to plan your early blight management when the crop is in the ground beginning with fertility and then continue with the protectant approach before early blight becomes a yield reducing problem.”

While most growers understand the importance of rotating chemistries to prevent resistance development, tank mixing two different chemistries and then switching to a mixture of two other chemistries may be a new approach. It could be one that proves most effective as growers begin to plan the management for their latest potato crop.

MORE THAN JUST A NUMBER

Increasing yield potential through seed potato age.

by Julienne Isaacs

There are countless factors at play that influence potato yields from year to year, and growers constantly face the challenge of ensuring they maximize their chosen varieties’ yield potential.

Recent research, however, has illuminated a new way to think about yield – namely, in relation to the seed potatoes’ physiological age, or the functional life expectancy of the potato. According to Rick Knowles, a professor in Washington State University’s department of horticulture, determining seed potatoes’ physiological age prior to planting can help commercial potato growers increase yield potential.

The older the physiological age of a seed potato lot, says Knowles, the more plant emergence and establishment speeds up, the greater the increase in stem numbers and tuber set, and the greater the decrease in apical dominance, or the inhibition of lateral bud development. Ultimately, greater physiological age results in a trend toward smaller-sized tubers.

There is a direct relationship between the seed lot’s degree of apical dominance – the stem numbers per seedpiece – and the

number of tubers, or the tuber set, per hill, says Knowles. The more tubers there are beneath each potato plant, the more competition for resources and the smaller the tubers.

The overall effect of physiological age on yield has a lot to do with the length of the growing season. In longer growing seasons, Knowles explains, moderate differences in physiological age between seed lots of the same cultivar likely won’t have a significant effect on overall yield – but differences in age could dramatically impact tuber size distribution.

“In a long growing season area where the crop can fully complete its annual lifecycle, the greater number of smaller average size tubers from an older seed lot will equal the overall weight of the fewer, but larger, tubers produced by a younger seed lot – and the overall yields will be comparable,” he says.

In shorter growing seasons, by contrast, an older seed lot might

ABOVE: In a longer growing season, Dr. Rick Knowles has found the greater number of smaller tubers from an older seed lot will equal the overall weight of the fewer, but larger, tubers produced by a younger seed lot, with comparable yields overall.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF DR. RICK KNOWLES.

produce higher yields than younger seed lots, because more time during short growing seasons is devoted to tuber bulking.

Knowles and his team performed several experiments that proved these results in two ways. First, they produced seed of different physiological ages and compared the resulting effects on growth, development and yield in short and long growing season areas. They also compared the yield potentials of commercial seed lots produced in areas with either short or long growing seasons in side-by-side trials.

Controlling physiological aging

According to Knowles, the age of seed potatoes can be manipulated through the accumulation of heat units. “Allowing seed to accumulate degree days above 4 C base temperature during the maturation period and during storage will advance the physiological age of a seed lot,” he says.

Additionally, growers can control the period of maturation and the amount of time that tubers are exposed to temperatures above 4 C in storage.

“Prolonging the initial wound healing period at the beginning of storage or instituting and/or extending the warm-up period toward the end of storage prior to moving the seed through distribution channels will contribute to advancing the physiological age of a seed lot,” says Knowles.

Respiration is also key to the aging process of seed tubers in storage. In higher temperatures, seed respiration rates increase, and this accelerates aging. Higher temperatures also speed up changes in growth hormones in the buds that allow potatoes to sprout. One of these hormones, auxin, says Knowles, controls

the degree of apical dominance in the potatoes, or the number of stems – and when temperatures increase age the number of stems also increases.

“More stems results in greater tuber set and more tubers,” explains Knowles. “The increased numbers of tubers compete for a limited amount of resources that can be supplied by the plant, thus resulting in a smaller average size of tubers.”

Minimizing respiration is therefore important in preserving the quality of seed potatoes in storage, and slowing respiration through cooling slows the rate of aging and prolongs postharvest life.

Knowles believes that greater control over the physiological age of seed potatoes will allow growers to manipulate tuber set and size development, and this will eventually pay off. “The various end-use markets – seed, fresh, process – differ in their tuber size class requirements, which is reflected in contracts,” he says. “Hence, growers can add value to a crop by controlling tuber size distribution to supply greater yields of the more lucrative tuber size classes in relation to market needs.”

Manipulating seed physiological age is not the only technique for controlling tuber size distribution, but it’s a potentially powerful one. Growers should be aware of their seed lot’s physiological age before planting – this way they can make informed decisions about in-row seed spacing. “Consistency in how seed is produced and handled will translate into consistent physiological age in terms of stem numbers from year to year,” says Knowles. This will provide opportunities to control tuber set and size development via other techniques such as spacing or treatments with growth regulators.

Knowles and his team conducted several experiments to prove their results, including producing seed of different physiological ages.

CRUSH

Turn the lights out on unwanted pests. Delegate™ delivers rapid knockdown of CPB. And once they’re hit, they don’t get back up. Tough on chewing pests, easy on beneficials. Try Delegate and see for yourself. Visit dowagro.ca.

COVER CROPS

TILLAGE RADISHES

This cover crop can provide important benefits to potato farmers.

by Treena Hein

Like other cover crops, tillage radishes can offer many important benefits, especially to soil health. However, how this crop is used is critical to maximizing the benefits it can potentially provide to potato farmers.

Tillage radishes have been found to be effective in controlling winter annual weeds and capturing nitrogen. When they decompose quickly in the spring, the roots release a great deal of nutrients (especially nitrogen) into the upper portion of the soil, which then may be available to the next crop (however, the foliage can disintegrate quickly in the late fall after several hard frosts).

Further, the holes left by the decomposed radish taproots provide excellent water infiltration and soil aeration benefits. The decomposition also obviously increases soil organic matter (OM), boosting yield to crops that follow in the long-term with repeated use. The taproots have a potential depth of three feet and size of several inches across at the top. The plants keep grow-

ing until temperatures of -10 C or colder are reached for three or four days in a row.

The radishes must be planted in August so that they can grow to a large size and good depth, therefore growing them after main-crop potatoes are harvested is perhaps not the best option. Planting them in late-summer, after another crop in the rotation and before potatoes, may provide growers with the best benefits – most importantly, better potato yields in the long-term due to better soil health.

The need to plant them in mid-August in Canada is confirmed by recent studies done by Dr. Robert Coffin and his colleagues. Coffin, a P.E.I.-based potato industry consultant, worked with Erica MacDonald (Paradigm Precision/A&L Canada Laboratories in

TOP: The taproots of a tillage radish compared to the fibrous roots of an oilseed radish. The decomposed radish taproots provide great water infiltration and soil aeration benefits.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF DR. ROBERT COFFIN.

P.E.I.), Jennifer Roper (Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources) and Brian Beaton (P.E.I. Department of Agriculture). In mid-March, Coffin presented the group’s results on tillage radish growth – as well as how it and two other Brassica cover crops could play a role in soil nitrogen management in potato rotations – at the 2014 North East Potato Technology Forum in Fredericton, N.B.

The team planted Indian hot mustard, oilseed radish and tillage radish (using branded variety Tillage Radish) at four different times (August 14, August 21, September 13 and October 12) in Green Bay, P.E.I., in 2011. “Planting at the two later dates gave very limited plant and root growth for all three Brassica crops,” Coffin notes. “Large tap roots of six to 10 inches in the tillage radish were only formed from August seeding.”

Benefits

How might planting tillage radishes following another crop in the rotation boost potato yields? This is an important question. Coffin says that some growers in P.E.I. are currently not grossing enough pay yields to cover potato production and storage costs. Cover crops such as radishes may help mitigate some of the factors leading to declining yields, such as soil compaction, reduced organic matter content and crop pests. “Soil health is beginning to be a very important topic amongst famers,” Coffin notes.

Some P.E.I. potato fields have OM levels as low as one to two per cent. “To maximize yields, that should be doubled,” Coffin says. Soils with lower OM levels can limit root growth, and also have reduced water-holding capacity.” Tillage radishes have

been shown to build up organic matter over the long term, reduce compaction and also may assist with crop pest populations. These pests include those that affect potatoes and other crops in the rotation, whether wheat, oats, barley, mixed grain, oilseeds or others.

“There are numerous claims that some Brassica crops (mustard, rapeseed and radish) can reduce populations of nematodes, wireworms, Verticillium fungi and some types of weeds,” Coffin explains. “Most Brassica crops contain glucosinolates in plant tissues, and when you chop the foliage and/or disk the plants into the soil, there is often a release of compounds (isothiocyanates) from the glucosinolates that can kill or inactivate some crop pests.”

Tillage radishes, along with other cover crops, may also help with mitigating nutrient release into soil. Nutrient release – nitrogen in particular – is a big concern on P.E.I. as 100 per cent of drinking water is from wells. “There are increasing concentrations of nitrate in groundwater in areas of intensive agriculture,” Coffin says. “What’s more, the Russet Burbank variety accounts for approximately 60 per cent of our potato acreage and is usually fertilized with a higher rate of nitrogen fertilizer than other varieties, and some farmers have been trying additional fertilizer to boost yields.”

The use of cover crops has been suggested as a method to absorb and hold the residual nitrogen. While the late potato harvest (Russet Burbank in mid-October) does not allow for significant growth of some cover crops planted at that point in time, tillage radishes can still absorb at least some nitrogen. However,

A healthy taproot and plant of tillage radish in mid-October before killing frosts.

Coffin and his team found that radishes planted at any point can release nitrogen after a few hard frosts in the late-fall as the leaves and roots quickly disintegrate. “It’s been suggested that winter rye planted with them might pick up the nitrogen they release and carry it through to the spring, helping to reduce leaching,” he notes. At this stage, though, “more study is needed.”

Like Coffin, Anne Verhallen sees the potential in using tillage radishes with rye. “Radish leaves disappear to nothing as the spring progresses, so oat and rye will protect the soil a bit better in the freeze-thaw and rainstorms of that season,” says the soil management (horticultural crops) specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food (OMAF) and Ministry of Rural Affairs. Indeed, Verhallen recommends mixing cover crops for a variety of reasons – not the least of which is because different plants in the mixture do better or poorer in different areas of the fields. “Mixtures are a good opportunity, and there are a lot of commercial mixtures available now,” she notes.

In terms of the specific benefits of tillage radish, Verhallen confirms that they are heavy nitrogen scavengers and excellent at weed control, but that growers should never expect spectacular results the year after, in terms of nitrogen available to the crop that follows. She notes that multiple-year studies conducted at the University of Guelph’s Ridgetown Campus, during OMAF field trials in the Woodstock, Ont., area and by Michigan State

University have shown that nitrogen release by disintegrating radishes can come too early to benefit the next crop (in these studies, that was corn). “It’s long-term benefits that you are after with tillage radishes,” Verhallen notes.

“They must be used with care,” she adds. “Tillage radishes won’t do everything for you, but do provide improved water infiltration, and improved soil aggregation and soil organism activity around the root in the rhyzosphere and around the tap root.”

Coffin plans to continue research in 2014 with the Tillage Radish brand of radishes to document performance under P.E.I. conditions.

For more

Verhallen recommends checking out the Midwest Cover Crop Selector Tool (which includes Ontario) at www.mccc.msu.edu/ selectorINTRO.html

There is another cover crop decision tool at http://covercrops. cals.cornell.edu/decision-tool.php and more good information here: http://plantcovercrops.com/

Visit the agronomy section of www.potatoesincanada.com for more cover crop research.

Tillage radishes must be planted in August so that they can grow to a large size (like the 10-inch one shown here, which was planted mid-August).

TITUS™ PRO: THE STRAIGHTEST PATH TO A CLEANER FIELD.

Introducing new DuPont™ Titus™ PRO herbicide for potatoes. As a convenient co-pack, Titus™ PRO brings together rimsulfuron and metribuzin to deliver exceptional postemergent control of all kinds of grassy and broadleaf weeds. By combining two modes of action, Titus™ PRO is also a valuable resistance management tool and keeps your re-cropping options exible. One case treats 40 acres. One try and you’re sold. Questions? Call 1-800-667-3925 or visit cropprotection.dupont.ca