5 | Resistance is better than tolerance

Breeding for verticillium resistance prevents the spread of the pathogen.

By Rosalie I. Tennison

Controlling beetles with

By Rosalie I. Tennison

DISEASES

Fusarium resistance in potatoes

By Mo Oishi

Adding longevity to soil health

By Julienne Isaacs

8 | Breeding out glycoalkaloids

A Canadian project employs new genetic tools to speed up potato breeding.

By Treena Hein

20 | Hitting a moving target

Keeping potato crops free of the PVY virus is a matter of good management, but resistant varieties are on the way.

By Treena Hein

JAY BRADSHAW | PRESIDENT, SYNGENTA CANADA INC.

Delivering sustainable food production is one of our biggest collective challenges and opportunities. Nowhere is that more evident than in the potato sector, with its focus on increasing marketable yield in a sustainable way. Syngenta is committed to working with you with this objective in mind. While much of our focus in this area is driven by research and development to generate yield and quality-enhancing crop production technologies and practices, we’re also undertaking numerous activities that support a sustainable agriculture and food production system.

This includes support for and partnerships with organizations across Canada for on-farm biodiversity and productivity initiatives. Examples include our work with rural landowners to support Maritime small marsh restoration, where over 200 projects restored 700 hectares over the past decade. A similar project in Saskatchewan focused on protecting waterways and native habitats. And on Prince Edward Island specifically, Syngenta is working with watershed organizations, area residents, farmers and fishermen to restore streams, reduce field run-off and improve biodiversity.

Our commitment in this area is not new. Recently, however, we formalized it with the launch of The Good Growth Plan (www.GoodGrowthPlan.com), which outlines six commitments to address critical global challenges with respect to feeding a growing population by 2020. These commitments include specific goals for increasing the average productivity of major global crops by 20 per cent without using more land, water or inputs, and enhancing biodiversity on five million acres of farmland.

Ambitious initiatives such as these require strong localized efforts to maintain and encourage thriving native ecosystems – for this, we thank you for all of the stewardship efforts you undertake and wish you all the best for the upcoming season.

This early spring edition of Potatoes in Canada, sponsored by Syngenta, includes an updated Potato Pest Control Guide. The guide provides comparative charts on products and the various diseases, insects and weeds they control. Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

POTATOES IN CANADA MARCH 2014 EDITOR

Kleer

www.topcropmanager.com

Breeding for verticillium resistance prevents the spread of the pathogen.

By Rosalie I. Tennison

Savvy growers know that when a potato plant begins to die, harvest is close at hand. However, the presence of verticillium wilt in the field can cause early plant senescence and, with that, the concern that the tubers would not be mature enough to harvest, resulting in low yields and economic losses. Researchers at Lethbridge and Fredericton have been researching how verticillium wilt induces does not kill the plant or damage the tubers, it merely encourages it to die earlier. This can mess with production schedules and allow the verticillium pathogen to enter the soil.

“Early dying can result in a 30 per cent yield reduction, so it is not desired. The plant dies early in response to the pathogens Verticillium dahliae and albo-atrum that cause verticillium wilt,” explains Dr. Helen Tai of the Potato Research Centre in Fredericton. “Verticillium wilt is a soil-borne disease, and when the plant dies the pathogen continues to proliferate on the dead tissue and make its way to the soil.”

The researchers began studying how resistant and tolerant plants responded to the pathogen and how each affected the plant’s maturity and the incidence of verticillium in the soil. What they learned was that resistant and tolerant plants appeared the same with infection. However, resistant plants protected the soil from verticillium whereas tolerant plants were infected at a high level, which results in high levels of the pathogen entering the soil.

“If the plant can tolerate high levels of the pathogen, you can get more verticillium in the soil,” Tai explains. “Plants that

resist the pathogen keep the amount low and they won’t respond by dying early.”

“Resistance prevents proliferation of the pathogen, whereas tolerance actually increases the levels of the pathogen,” adds Dr. Lawrence Kawchuk, the lead researcher at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, Alta. Kawchuk discovered the genetic marker that indicates resistance making it possible for plant breeders to breed for resistance more efficiently.

“The resistance is being transferred by various breeding programs and the new varieties should be available in a few years,” Kawchuk continues.

The differences between tolerance and resistance prove the value of using genetic markers to identify resistance, Tai explains. There is also a difference between the genetic makeup of verticillium strains, so it is important to breed resistance to the strain that causes the most problems.

“Verticillium has varying levels of infection geographically and there are genetic variations within verticillium species,” Tai explains. Therefore, researchers are also working to identify the geographic variances and to develop potato plants with resistance to different verticillium strains.

by Rosalie I. Tennison

Keeping the pesky Colorado Potato Beetle (CPB) under control is a fulltime job for growers. With bugs developing resistance to pesticides a constant worry, researchers are looking for alternative ways to control the bugs. The most sensible idea is to create a plant that beetles don’t want to eat. The potato is a member of one of the largest group of plants on earth and is a relative of eggplant, peppers and, surprisingly, petunia – the pretty flowers we grow in window boxes. However, while CPB munch on the potato plant, they ignore the petunias growing along the fence row.

Scientists who study potatoes know that the CPB does not like many of its wild relatives, so researchers started there to determine which species could be crossed with potatoes to create a plant that is less palatable to CPB. The researchers at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Potato Research Centre in Fredericton determined that metabolites in the plant’s leaves repulsed the beetles. Then, they considered how to get the metabolite into or onto the potato plant. The idea of developing a spray was dismissed as too complex because the product would have to be sun-tolerant, rain resistant and immune to other weather conditions. The spray option was not deemed economical in comparison to commercial pesticide products.

“This work has been ongoing for 15 years,” admits Dr. Yvan Pelletier, who recently retired from AAFC and who worked on the search for metabolites to breed into potatoes that would take the bite out of CPB. “This is a worthwhile endeavour, but it takes time.” He says the team finally determined that the wild potato (Solanum oplocense) is the plant most likely to succeed when it comes to helping domesticated potatoes resist CPB. This wild cousin of the potato can be used with a traditional breeding technique to make the garden variety potato less tasty for CPB.

One of Pelletier’s colleagues, Dr. Helen Tai, has been working to isolate the metabolite and the biochemical pathways that control the metabolite’s production in leaves. She says the process of getting the potato to produce CPB resistance metabolites is done by old-fashioned breeding, which is not too difficult. “We crosspollinate the potato and wild plant by putting pollen from the wild plant on the emasculated potato plants,” Tai explains. “We chose Solanum oplocense (wild potato) because it has resistance and will cross with potato.” After the cross is completed, she continues, there are some progeny you want and some you don’t. At that point, the team selected the progeny that had the resistance yet still had the ability to develop

<LEFT: Researchers know that the Colorado Potato Beetle ignores many of its wild relatives, and are determining which species could be bred with potatoes to deter the pest.

<LEFT: Scientists are using oldfashioned breeding methods to produce CPB resistance metabolites.

BOTTOM: Colorado Potato Beetle females can have a prolific life cycle, laying as many as 800 eggs, making control a constant priority for potato growers.

tubers under northern, long day growing conditions.

“We don’t want to change the potato radically,” comments Pelletier. “We are working on small changes that will make the plant resistant to beetles.”

Tai says determining how to identify and detect the metabolites is part of the process in developing new varieties with CPB resistance. The strategy would involve crossing current favourite varieties with potatoes that have already been crossed with Solanum oplocense so that they carry the CPB resistance, then the resistance metabolite is used to screen the progeny. Using the metabolite will save a lot of time and money in screening for CPB resistance. The research is aimed at getting more potato varieties with CPB resistance to the potato industry and the consumer at a faster rate.

Pelletier says the current progress is being made with beetle resistance in table stock potatoes and he sees a niche opportunity for the organic market.

“There is so much that has to be done in order to ensure the resulting variety is suitable for Canada’s growing conditions,” adds Pelletier. “You have to ensure you get the tuber size wanted, that the maturity of the plants meets our growing needs and that the plants develop properly. We are close to developing our first variety, that would have compatibility with organic growing systems because that market needs products produced without pesticides.”

Meanwhile, Tai continues her work in developing metabolite selection tools for selecting potatoes that the beetles don’t like, which would help the breeders develop varieties for industrial processing. “CPB also develops resistance to pesticides making those products ineffective,” she says. “Our development of CPB resistant potato lines will be a resource that will provide an additional way to avoid CPB-induced crop losses.”

Unsaid by either researcher is how much the development of CPB resistance in potatoes could protect the environment as there would be less and less need for pesticides as more and more varieties would have the metabolite in their makeup.

To make an impact on pesticide use, breeding for CPB resistance alone is not enough. Dr. Tai says that the challenge is getting the CPB resistance in combination with traits in potatoes that are suited to the chipping or frying industries, which make up the majority of the potato utilization in Canada. Without these other traits, breeding for CPB resistance is like going to the moon: we know we can do it, but why bother if we don’t need to go? The development of the metabolite screening tool for breeding is a way forward to more efficient selection of potatoes that are tastier for us and less tasty for the CPB.

by Treena Hein

Depending on the variety, environmental conditions and handling practices, potatoes may contain high levels of toxic and bitter substances called steroidal glycoalkaloids (SGAs). SGAs are naturally produced in both foliage and tubers (in the green parts of the potato) as a defence against animals, insects and fungi attack. The common glycoalkaloids found in potato plants are solanine and chaconine, with solanine being the more toxic of the two. The production of solanine in potatoes is thought to provide protection from the Colorado potato beetle, potato leafhopper and wireworms.

Of the major food products, potatoes are of most concern in terms of human food safety because glycoalkaloids as a residual level of these compounds are almost always present. SGAs are not destroyed during cooking or frying. In fact, the Lenape potato variety was removed as an option for commercial cultivation in Canada and the United States, as it contained unacceptably high levels of SGAs.

These substances affect the human central nervous system and have disruptive effects on cell membrane integrity, affect-

ing the digestive system and more. Most people who ingest SGAs at a level to cause health concerns experience only mild gastrointestinal effects, beginning within about eight to 12 hours of consumption and disappearing within a day or two. Effects can range from nausea and vomiting and headaches to hallucinations and paralysis. Some studies have also linked SGAs to birth defects in humans and breeding problems in animals.

Some sources state that potato vines (which contain solanine) can be a valuable ruminant livestock feed when fed just after harvest, as they are not toxic at that point. Harvesting the vines also helps to control disease, but the costs involved in harvest may not make it a worthwhile practice.

Although breeding efforts over the years have resulted in the release of potato varieties that result in the lowest-

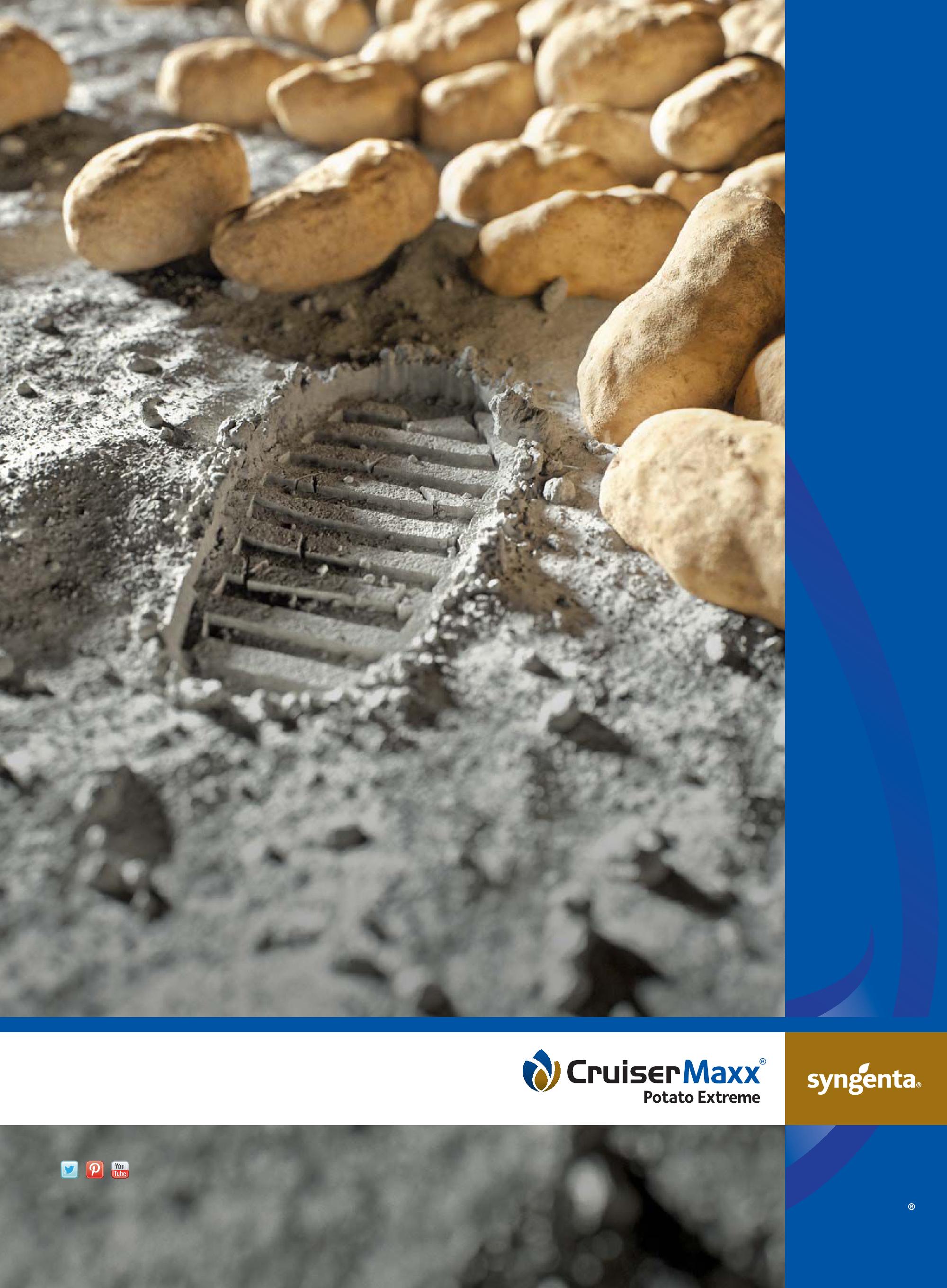

ABOVE: Researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Charlottetown are analyzing potato seedlings and tubers to find the ones carrying genes that result in very low SGA production.

ever production levels of SGAs, a great deal of effort, time, energy and resources are still deployed to minimize SGA formation during storage – and in turn, in processed potato end-products. Thus, a new Canadian project using cutting-edge genetic tools is aiming to develop, in a short period of time, new cultivars to contain levels not exceeding 20 mg/100 g fresh weight, which is the current internationally accepted maximum.

The research is headed by Dr. Bourlaye Fofana, a geneticist specialized in plant molecular physiology and genomics at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Crops and Livestock Research Centre (CLRC) in Charlottetown, P.E.I., and includes Dr. Benoit Bizimungu (potato breeder, AAFC-Fredericton, N.B.), Dr. Jason McCallum (phytochemist, AAFC-Charlottetown), David Main (biologist, AAFC-Charlottetown), Dr. Helen Tai (molecular biologist, AAFC-Fredericton), and Dr. Lawrence Kawchuk (plant pathologist, AAFC-Lethbridge, Alta.).

“We are working on complementary aspects of potato crop improvement (genetics and genomics, chemistry, pathology, breeding, and agronomy) using innovative approaches for accelerating the breeding of potato cultivars free of glycoalkaloid content,” Fofana explains.

Using genetic techniques and tools, the scientists are analyzing thousands of potato seedlings and tubers generated

from true seeds to find the ones carrying genes that result in very low SGA production. “The approach involves inducing mutations in genes of true potato seeds (harvested from potato fruits, which look like tomatoes) obtained from selected germplasm,” Fofana explains. “We’ve treated approximately 4,000 true potato seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate, a compound that induces random mutations in the genetic material.”

The team is then characterizing the 2,500 surviving mutagenized lines for their ability to produce tubers and their SGA production levels. Next-generation sequencing technologies and extensive bioinformatics analysis are being used to identify lines carrying mutations in targeted genes.

The selected lines will be evaluated later for other useful traits such as disease resistance and agronomic traits related to yield, tuber shape, flesh and skin colour, maturity date and so on. If necessary, the team will treat more true potato seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate. “We expect to pinpoint about 100 candidates for the breeding program that within five years, will result in potatoes low or free of glycoalkaloids,” says Fofana. To his knowledge, no similar studies using the same approach to breed out glycoalkaloids are occurring elsewhere in the world.

Fofana was born and grew up in Cote d’Ivoire, Africa. He was trained in

agricultural sciences and biological engineering at the Gembloux Agricultural University in Belgium and obtained graduate degrees in plant molecular genetics. After his Ph.D. graduation, Fofana joined a research group at Laval University in Quebec, holding a postdoctoral fellow position and working on cucumber defence mechanisms. In 2002, he obtained a National Research Council postdoctoral position at the AAFC Cereal Research Centre in Winnipeg, working on flax and wheat functional genomics. From 2006 to 2007, Fofana worked as a term researcher at AAFC-Winnipeg in wheat genomics. Since 2008, he has been at CLRC in Charlottetown, focusing on wild rose, flax and potato genomics. Fofana’s current research group is composed of a postdoctoral fellow, a graduate student and a co-op student.

“Diversity of life on Earth has fascinated me since elementary school,” he says. “The question I used to ask my brothers was, ‘Why are there so many different insects, animals and plants?’ The response lies in genetics, of course. It is fascinating to study how a change of a ‘single letter’ in the genetic code of a living organism can make huge morphological difference, or an important difference in the ability of a plant to produce a particular metabolite, even if the plant is not visually different from its counterparts.”

Fofana says the challenge for him in genetics is “to understand the factors leading naturally to changes of genetic material, and how these factors can be controlled to human advantage.” His work in meeting this challenge by producing glycoalkaloid-free potatoes is sure to provide significant advantage for the Canadian potato industry, at home and worldwide.

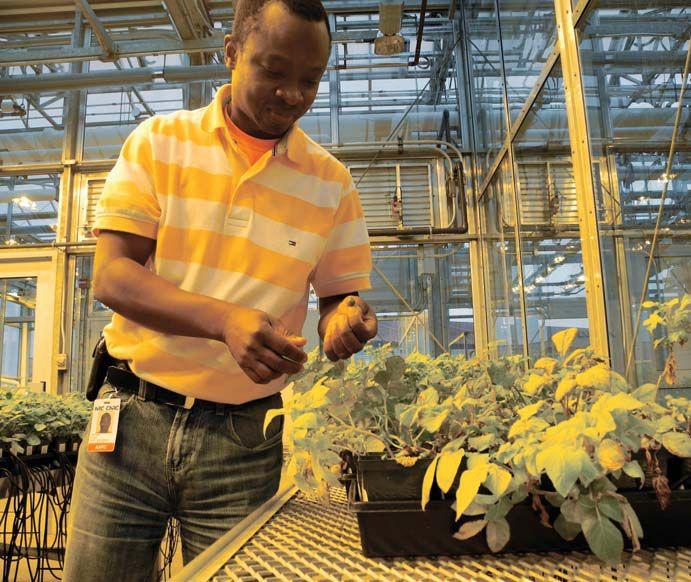

Diseasemanagement productsManufacturer/supplierCommonname

Chemicalgroup(Rotate groupstomanage resistance)(Check labelfordetails) Resistance grouping*

ACROBAT®50WPBASFdimethomorphcarboxylicacideamine40A/G412

AllegroSyngentafluazinampyridinamine29G1424

BravoZNSyngentachlorothalonilchloronitrileM5A/G148

CABRIO®PLUSBASFPyraclostrobin&Metiramstrobilurin&dithiocarbanate11&M2A/G312

CANTUS™BASFboscalidanilid7A/G3012

Copper53WUAPcoppersulphateinorganicM1G148

CoppersprayUAPcopperoxychlorideinorganicM1G148

CoppercideWPUAPcopperhydroxideinorganicM1G1

Curzate60DFDuPontcymoxanilacetamide27G824

DithaneRainshieldFungicideDowAgroSciencesmancozebdithiocarbamateM3A/G1Dry Echo720SipcamAgrochlorothalonilchloronitrileM5A/G148

Echo90DFSipcamAgrochlorothalonilchloronitrileM5A/G148

Gavel75DFGowanAgroCanadazoxamide/mancozebbenzimidazole/dithiocarbamateM22A/G348

HEADLINE®BASFpyraclostrobinstrobilurin11A/G312 Kocide2000DuPontcopperhydroxideinorganicMG1dry

LanceWDGBASFboscalidanilid7A/G304

LunaTranquilityBayerCropSciencefluopyram,pyrimethanilpyridinyl-ethylbenzamides,anilino-pyrimadine7,9A/G712 ManzatePro-StickUPImancozebdithiocarbamateM3A/G124 ParasolWGNufarm/EngageAgrocopperhydroxideinorganicM1124 ParasolflowableNufarm/EngageAgrocopperhydroxideinorganicM1G124 Penncozeb75DFUAPmancozebdithiocarbamateM3A/G124

PhostrolEngageAgro mono-anddibasicsodium, potassium,andammonium phosphites phosphonate33A/G112

POLYRAM®DFBASFmetiramdithiocarbamateM2A/G1Dry

QuadrisTopSyngentaazoxystrobin&difenoconozolestrobilurin&dithiocarbanate11A/G1412

QuadrisSyngentaazoxystrobinstrobilurin11IF90dry

RampartUAPphosphorousacidphosphonates33Postharvest

RanmanISK/FMCcyazofamidcyanoimidazole21G712

ReasonBayerCropSciencefenamidoneimidazolinone11A/G14dry RevusSyngentamandipropamidcarboxylicacidamine40A1412

RidomilGold480SLSyngentametalaxyl-macylamine4IF9012 RidomilGold/BravoSyngentametalaxyl-m/chlorothalonilacylamine/chloronitrile4,M5A/G12

ScalaSCBayerCropSciencepyrimethanilanilino-pyrimadine9A/G712

SerenadeSOILBayerCropScienceQST713strainofdriedBacillussubtilisbacillussp.44IF00

SerenadeMAXBayerCropScienceQST713strainofdriedBacillussubtilisbacillussp.44A/G00

Tanos50DFDuPontfamoxadone/cymoxaniloxazolidinedione/acetimide11,27G1424

TattooCBayerCropSciencepropamocarb/chlorothalonilcarbamate/chloronitrile28,M5G748

Torrent400SCISK/EngageAgrocyazofamidcyanoimidazole21G712

VertisanDuPontpenthiopyradSDHIIIA/G7

ZAMPRO™BASFdimethomorph/ametoctradincarboxylicacidamine/pyrimidylamine40,45A/G412

Important: The Potatoes in Canada Potato PestControltablesareaguideonly.Itishighly recommendedthatgrowersrefertolocal provincialguidesandlabels.

5-103•Reducestuberblight.

7-106to10•Protectsagainstfoliarandtuberlateblight,controlofwhite mould.Donotapplymorethan4L/haperseason.

7-10••Applyasthebasetoafungicideprogramaloneorin combinationwithspecialtyfungicides.

7-143••AgCelencebenefits.

144•Mayalsobeappliedthroughsprinklerorpivotirrigation.TankmixwithaprotectantforLateblightcontrol.

7-1010••Applywhenplantsare12to18centimetreshigh.

7-1010••Startapplicationswhenplantsare12to18centimetreshigh.

7-10••Startapplicationswhenplantsare15centimetreshightilharvest.

5-74•Useonlyastank-mixwithManzatePro-Stick.Kickback-upto 72hours.Donotapplymorethan150Ha/day.

5-10••

7-1012•••Cropre-entryrestriction.

7-1012••Cropre-entryrestriction.

76••Highlyeffectiveandlongresidualcontroloflateblightand tuberrot.

5-143••AgCelencebenefits.

7-10••

144•Uniquemodeofactionforearlyblightprotection.Mayalso beappliedthroughsprinklerorpivotirrigation.

7-144-5•Alsoregisteredtocontrolbrownleafspot,whilemoldand suppressionofblackdot.

5-10••

7-10••

7-10••Reducesprayintervalto5-6daysifhighlateblightpressure. 7-147•SIn-furrow(pinkrotonly),foliarandpostharvestuses.Consult labelforvarioustank-mixpartners.

5-10••Contains14.4%Zinc.

7-143••

TwoMOAagainsttargetedfoliardiseaseswithnoriskof increasingresistanceofsoilbornediseaseswiththeuseof Quadrisin-furrow.Alsocontrolsblackspotandbrownspot.

Applyina6-8inchbanddirectlyoverseedpiecesinfurrow. Useinaprogramwithseedtreatmentsandpost-harvest solutions.

1••Applyasasinglesprayorrinseafterharvestandpriorto storage. 76•Lateblightandlateblighttuberrotcontrol.

7-106••UseonlyasatankmixwithDithaneorBravo.

7-104•Applyearlytoprotectagainstlatebight,thenwhendiseasethreatens.

1••Makeanin-furrowapplicationor2foliarapplications.

143•••••Make2foliarapplications.Bravoprovidesprotectionagainst lateblightstrainswhichmayberesistanttoRidomilGold.

7-146•Uniquemodeofactionforearlyblightprotection.Useasa tank-mixwithBravo.

7-10N/ASSSS SerenadeSOILisanewbiologicalfungicidethatprotects againstsoildiseaseslikerhizoctoniaandpythiumandis exemptfromtolerances.

7-10N/ASSerenadeMAXisabiologicalfungicidethatprotectsagainst earlyblight&whitemoldandisexemptfromtolerances.

12,243••

Famoxadone-sameresistancegroupasstrobilurins-rotate withnon-strobilurins.LateBlightKickback-upto72hours.Do notapplymorethan100Ha/day.

7-143•Systemicfungicideforhighlyeffectivecontroloflateblight.

76•Lateblightandlateblighttuberrotcontrol.Tankmixingwitha non-ionicororganosiliconesurfactantisrecommended. 72SS

5-103•Lateblightandtuberblightcontrol.

Potato Pest Control 2013 Application timing

Weedcontrolproducts (Notregisteredin allprovinces.Some processorsdonot acceptuseofall products.) Manufacturer/ supplierChemical group

Pre-plant burndownPre-emergence burndown Pre-plant soil incorporated Post-plant soil incorporatedPre-emergence surface appliedFoliarappliedDesiccantVarietycautionsin someprovinces

AimECFMC/Nufarm14•• ArrowMANACanadaLtd.1• BoundaryLQDSyngenta15,5•Belleisle,Tobique, Superior

Broadleaf weed tank-mix partners (group)

Grassy weed tank-mix partners (group)

*Tank-mixesnot registeredinall provinces

*Tank-mixesnot registeredinall provinces

ChateauWDGValentCanada14•

DualIIMagnumSyngenta15•••SuperiorLinuron(7),Patoran(7), Sencor(5),Afesin(7) Glyphosatevarious9•• GramoxoneSyngenta22•RussettBurbank,CherokeeLinuron(7),Sencor(5) LoroxDF,LoroxL, Linuron480 Novasource/ LovelandProducts7•Sencor(5)

OutlookBASF15•Sencor(5)Linuron(7)Linuron(7)

PoastUltraBASF1• PrismSGDuPont2• RegloneSyngenta22• Select/CenturionBayerCropScience1• SencorBayerCropScience5••••SeelabelLinuron(7) DualII Magnum(15), Linuron(7), TricorUPI5••••RefertolabelReferTricorlabel TitusPRODuPont2,5•Refertolabel VentureLSyngenta1•Sencor(5)

NOTES:*Conditionsapply:Checkprovincialguidesorproductlabelsfordetailsandspecificweedcontrolratings.Some provincialguidesincludecontrolratingsnotshown.Sometank-mixesmaynotberegisteredinallprovinces:additiveeffects andantagonismmayalsooccur.Someproductsandtank-mixesareonlyrecommendedforcertainvarieties.Various formulationsmaybeavailableandadditionalapplicationratesmayberecommended.**Dandelionnotonlabelforsome glyphosates.Somepotatoprocessorsdonotapproveuseofsomeproducts.

Grassy weeds VolunteersBroadleaf weeds Perennial weeds Barnyard grass Foxtail, green Foxtail, yellow Wild oats Vol. barley Vol. corn Vol. flax Vol. canola/mustard

sunflowers Vol. wheatBuckwheat, wild Catch fly, night flowering ChickweedCleaversCockleburFlixweedHempnettleKochiaLady’s thumb Lamb’s quarters Mallow, round-leaved Mustard, wildNightshadesPigweed, red root Pigweed, prostrate PurslaneRagweedRussianthistleShepherd’s purse Smart weed, annual StinkweedDandelionQuackgrassSowthistle,perennialThistle, Canada Warnings

AimECHerbicidecanbeapplied onlyonetimepergrowingseason.

Applyafterhilling,beforeground crack;donotapplytoredskinned potatoes.

Minimum5centimetresofsoil mustbecoveringthevegetative portionofthepotatoplantattime ofapplication.Requiresirrigation toensureactivationpriorto emergence.Donotapplyator postemerge.

evening/cloudy/stressed.

Applyafterplantingbutnoton emergedpotatoes.Outlookalso controlsGroup2and5resistant PigweedandEBNightshade,Fall Panicum,Crabgrass(Smoothand Large)andOldWitchGrass.Outlook alsosuppressesYellowNutsedge.

Ssuppression only

Important: The Potatoes in Canada PotatoPestControltablesareaguide only.Itishighlyrecommendedthatgrowersrefertolocalprovincialguides andlabelsaswellaswithprocessorsandpackers.

Donotapplyduringperiodsof extremedroughtorexcessive moisture.

Notonmucksoils/totalapplied restriction**nottriazineresistant lamb’squarters.

Notonmucksoils/totalapplied restriction**nottriazineresistant lamb’squarters.

application/90daystoharvest.

Potato growers measure success at the end of the season by three measurement key factors: crop quality, yields and storability. Many factors go into maximizing marketable yield – from seed quality, to fertility, crop management and other components. That’s what prompted Syngenta to look at optimizing disease management to help to maintain the health of potato crops all season. We call it Performance+™.

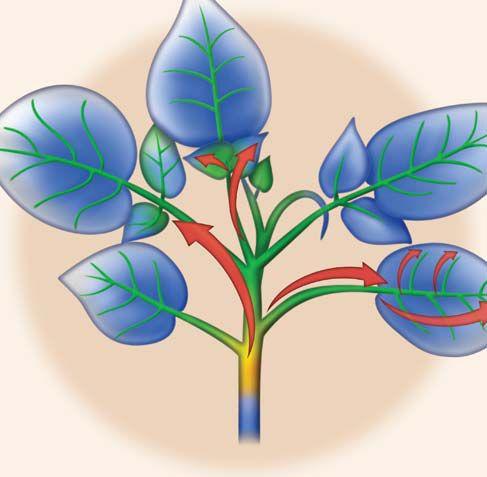

Once potatoes emerge, mitigating in-season disease pressure is important for maximizing crop performance. When plants are small, growers should take the opportunity to protect the stems with an application of Quadris Top® fungicide. This is the time to target early blight, brown spot1 and black dot1, which primarily impact yield. Growers should target black dot with two of their first three fungicide applications to optimize coverage on the stems. A third application in August, when hot, dry weather is about to break, will target early blight and brown spot. The active ingredients in Quadris Top, with translaminar and xylem-systemic movement, provide protection to the entire plant.

Xylem-systemic movement: Azoxystrobin moves quickly through the xylem of the plant (its water conducting system), providing protection to the entire plant, including new areas of growth.

This is also an excellent time to start protecting plants against late blight. Revus fungicide is a late blight specialist, ranked best in class in EuroBlight results three years in a row. A translaminar fungicide, Revus moves throughout the leaf from the base to the tip and from the upper surface to the underside, protecting areas of the plant that contact-only fungicides typically miss. Apply Revus just prior to row closure for the best defense against late blight, and then continue applications throughout the season when disease threatens. Remember that applying a translaminar product will provide longer and better protection, especially in highly active weather. In fact, Revus can provide you with trusted late blight protection for up to 10 days!

Continue to protect your plants throughout the season –apply Bravo® ZN fungicide alone to bridge the gap between sprays, or apply in a tank-mix, if required, to broaden your disease spectrum.

White mould becomes a concern later in the season. The spores often land on flower petals and, when the petals fall, they infect potato plants from the bottom up. White mould draws nutrients from the stems of potato plants, resulting in reduced yield. To prevent white mould damage, apply Allegro® fungicide at first bloom (10%) or just prior to row closure, whichever comes first. Make a second application two weeks later if rain and

humidity remain high. In addition to white mould, Allegro is also very effective for late blight control. Consider a tank-mix with Ridomil Gold® 480SL fungicide for two modes of action to mitigate yield loss in-field and financial loss in storage. Ridomil Gold moves very quickly in the plant to protect against susceptible pink rot and late blight strains.2

Protecting the crop from disease right through harvest is important to defend potato plants from foliar diseases. Continue with Bravo ZN for broad-spectrum protection and switch to Allegro to help guard against tuber blight prior to harvest (14-day PHI). Allegro inhibits the formation and movement of late blight spores, effectively limiting the spread of foliar late blight and stopping zoospores from infecting daughter tubers in the soil.

Performance+ integrates the use of Syngenta fungicides to create the most complete disease management solution from planting to harvest, thereby promoting healthy tubers going into storage.

Speak with your retailer or your Syngenta Representative to learn more about Performance+.

nc Pe anglwhhoin ce+ rformance+ glewhenchoosingyour

Consider the disease triangle when choosing your fungicide. Understanding how each disease behaves, which diseases are more likely to be present at the same time and the environmental conditions that are conducive to disease development in your crops will allow you to tackle the key diseases that threaten to rob you of marketable yield.

that disease. Always read and follow label directions. Bravo®, Performance+™, Quadris®, Quadris Top®, Revus®, Ridomil Gold® and the Syngenta logo are trademarks of a Syngenta Group Company. Allegro® is a trademark of ISK Biosciences Corporation. © 2014 Syngenta.

Insectmanagement products Manufacturer/ supplierCommonname Chemicalgroup (rotategroupsto manageresistance)Applicationtiming

Actara240SCSyngentathiamethoxamneonicitinoidPlantingSG12

Actara240SCSyngentathiamethoxamthianicotinylFA/G712

Admire240FBayerCropScienceimidaclopridchloronicotinylPlantingSIF24 Admire240F(Alsosee SeedPieceTreatments)BayerCropScienceimidaclopridchloronicotinylSeedpieceSG

Agri-mekSyngentaabamectinavermectinsFA/G14

Alias240ECMANACanadaLtd.imidaclopridchloronicotinylPlantingSG24 Alias240ECMANACanadaLtd.imidaclopridchloronicotinylFG724 Alias240ECMANACanadaLtd.imidaclopridchloronicotinylSeedpieceSG Ambush500ECAmVac/EngageAgropermethrinpyrethroidFA/G1dry Assail70WPEngageAgroacetamipridneonicitinoidFG712 Beleaf50SGISK/FMCflonicamidpyridinecarboxamideFG712 CloserSCDowAgroSciencessulfoxaforsulfoxaminesFA/G712 Clutch50WDGValentCanadaclothianidinneonicitinoidPlantingSG12 Clutch50WDGValentCanadaclothianidinneonicitinoidFA/G1412 ConceptBayerCropScienceimidacloprid+ deltamethrin neonicitinoid+ pyrethroidFoliarFA/G712

CoragenDuPontchlorantraniliproleanthranilicdiamideFA/G1 Cygon480ECIPCO/CheminovadimethoateorganophosphateF7 Decis5ECBayerCropSciencedeltamethrinpyrethroidSeelabelFA/G112 DelegateWGDowAgroSciencesspinetoramspinosynegghatch/smalllarvaeFG712

DibromECUAPnaledorganophosphateFA/G448

EntrustSCDowAgroSciencesspinosadspinosynegghatch/smalllarvaeFG712

ExirelDuPontcyantraniliproleanthranilicdiamideFA/G712 Fulfill50WGSyngentapymetrozinepyridineazomethinesFA/G1412

FyfanonCheminovamalathionFA/G3 Grapple/Grapple2CheminovaimidaclopridchloronicotinylPlantingSG24 Grapple/Grapple2CheminovaimidaclopridchloronicotinylFG724

Grapple/Grapple2CheminovaimidaclopridchloronicotinylSeedpieceSG

Imidan70WPInstapakGowanAgroCanadaphosmetFG7

Lagon480EUAPdimethoateorganophosphateFG7 LannateToss-N-GoDuPontmethomylcarbamateFG3

LorsbanDowAgroScienceschlorpyrifosorganophosphateFG724

Malathion85EUAPmalathionorganophosphateFA/G3

Matador120ECSyngentacyhalothrin-lambdapyrethroidFA/G724

MinectoDuoSyngentacyantraniliproleand thiamethoxam diamide+ neonicotinoidPlantingSG12

Movento240SCBayerCropSciencespirotetramattetronic/tetramicacidderivativesFoliarFA/G712hours NufosCheminovachlorpyrifosorganophosphateSG724 Orthene75SPUAPacephateorganophosphateFG2124 Perm-upUnitedPhosphorusInc.permethrinpyrethroidFA/G112 Pounce384ECFMC/UAPpermethrinpyrethroidFA/G1 Pyrifos15GUAPchlorpyrifosorganophosphatePlanting/In-furrowSG70 Pyrinex480ECMANACanadaLtd.chlorpyrifosorganophosphateFG7 Rimon10ECChemturanovaluronbenzoylphenylureaegghatch/smalllarvaeFG14

Ripcord400ECENGAGEAgrocypermethrinpyrethroidFA/G7dry SevinXLRNovaSource/TKIcarbarylcarbamateFA/G712

Important: The Potatoes in Canada PotatoPestControl tablesareaguideonly.Itishighly recommendedthatgrowersrefer tolocalprovincialguidesandlabels.

Usethehighrateontheseed orin-furrowforlongerresidual, especiallywhenpestpressureis high.

Donotfollowasoilapplied group4withafoliarapplication ofActaraoranyothergroup4 insecticide.

Maximumseasonaluserate500 mLl/haforCPB;pHofwater between6and8forbestcontrol.

Applicationcausesaphidstostop feedingafterexposureandhelps reducethespreadofviruses.

Targetlateseasonpestsincluding fleabeetleandEuropeancorn borer.

TwoMOAforresistance managementandextended residualcontrol.

Makefirstapplicationwhen thresholdisbuilding,thena secondapplication7dayslater. Alsocontrolspotatopsyllids.

Important: The Potatoes in Canada PotatoPestControltablesareaguideonly.Itishighlyrecommendedthatgrowersrefertolocalprovincial guidesandlabelsandconsultwithprocessorsandpackers.

Insectmanagement products

Manufacturer/ supplier(willnot appear)Commonname

Chemicalgroup (rotategroupsto manageresistance)Applicationtiming Soil/foliar applied Aerial/ ground

Silencer120ECMANACanadaLtd.cyhalothrin-lambdapyrethroidFA/G724

Success480SCDowAgroSciencesspinosadspinosynegghatch/smalllarvaeFG712 Thimet15GAmVac/EngageAgrophorateorganophosphatePlantingSG90 ThionexECUAPendosulfanchlorinatedcyclodieneFG55days TitanBayerCropScienceclothianidinchloronicotinylPlantingSIF UP-Cyde2.5ECUnitedPhosphorusInc.cypermethrinFA/G712 VydateLDuPontoxamylcarbamateFG772 Warhawk480ECUAPchlorpyrifosorganophosphateFG724

Seedpiece treatments Manufacturer/ supplierCommonnameChemicalgroup

Actara240SCSyngentathiamethoxamthianicontinyl 380-488mL/ ha(upto24.4 mL/100kg)

Admire240BayerCropScienceimidaclopridchloronicotinyl26-39mL/100kg••••

Alias240MANACanadaLtd.imidaclopridchloronicotinyl26-39mL/100kg••••

CruiserMaxxD PotatoSyngenta thiamethoxam +fludioxonil+ difenoconazole thianicontinyl+ phenylpyrrole+triazole

Seelabelfor Actararates,65-130 mL/100kgMaximD

CruiserMaxxPotato ExtremeSyngenta thiamethoxam +fludioxonil+ difenoconazole thianicontinyl+ phenylpyrrole+triazole 20mL/100kg seed

Grapple/Grapple2Cheminovaimidaclopridchloronicotinyl26-39mL/100kg••••

HeadsUpPlant Protectant HeadsUpPlant Protectant/ Engage saponinsof Chenopodium quinoa notclassified(plant based) 1gHeadsUp per1Lwater,1L solution/100-264kg

SolanMZNoracConcepts/Engagemancozebethylenebisdithiocarbamate250

MaximDSyngentafludioxonil+difenoconazolephenylpyrrole+triazole65-130mL/100kg

MaximMZSyngentafludioxonil+ mancozeb

phenylpyrrole +ethylene bisdithiocarbamate

500g/100kg seed

MaximPSPSyngentafludioxonilphenylpyrrole500g/100kgseed

MaximLiquidPSPSyngentafludioxonilphenylpyrrole5.2mL/100kg

Penncozeb80WPUPImancozebdithiocarbamateRefertolabel

PM223GlobalProteinProductszeinproductnone135g/100kg

Polyram16DFBASFmetiramdithiocarbamate225-325 PSPT16%UAPmancozebdithiocarbamate500g/100kg

SenatorPSPTEngageAgrothiophanate-methylbenzimidazole250

TitanBayerCropScienceclothianidinchloronicotinyl10.4-20.8mL/100kg••••S

TitanEmestoBayerCropScience clothianidin +penflufen/ prothioconazole

chloronicotinyl/SDHI/ triazole

Titan: 15.6mL/100kg EmestoSilver: 20mL/100kg

TubersealNoracConcepts/Engagemancozebdithiocarbamate250

VerimarkDuPontcyantraniliproleanthranilicdiamide45ml/100kg••

In-storage seed treatment

MertectSyngentathiabendazolebenzimidazole88mL/1000kg

Days between applications

73(2aerial)•••••

7-102••

Important: The Potatoes in Canada PotatoPestControl tablesareaguideonly.Itishighly recommendedthatgrowersrefer tolocalprovincialguidesandlabels.

Maximumseasonaluserate 249ml/haforCPB;pHofwater between6and8forbestcontrol.

74•••••RegisteredforusetillDec31,2016. 1•• Thehigherrateisrecommended whenextendedlengthofcontrol isneeded.

3(2aerial)••••Re-entryperiod. 2••••• 1Soilapp3-7daysbeforeplanting forcutwormcontrol.

Important: The Potatoes in Canada PotatoPestControltablesareaguideonly.Itis highlyrecommendedthatgrowersrefertolocalprovincialguidesandlabels Usethehighrateontheseedorin-furrowforlongerresidual,especiallywhenpest pressureishigh.

FordiseasecontroladdtreatmentfollowingapplicationofAdmire240. DonotuseanotherGroup4foliarinsecticideinsameyear.

••••Aco-packofActara240SCandMaximD,ControlsracesofFusariumspp. Determinedtoberesistanttofludioxonilandorthiophanate-methyl.

S•••Premixconcentratedformulationforcontroloftargetinsectsanddiseases. FordiseasecontroladdtreatmentfollowingapplicationofGrapple.

SSTreatonlythoseseedpiecesneededforimmediateuseandplanting.Mustbe appliedtogerminatingseedpotatoes.S=suppressiononly.

•Plantassoonaspossibleaftertreatment.Usesecondapplicationforcutseed.

ControlsracesofFusariumspp.Determinedtoberesistanttofludioxonilandor thiophanate-methyl.Useinco-ordinationwithActaraorMinectoDuotoprotect againstinsectpests.

••••TwoMOAeffectivelycontrolsracesofFusariumspp.Determinedtoberesistant tofludioxonilandorthiophanate-methyl.

••••UseanotherapprovedproductwhereresistancetoFusariumisaconcern.

Apply100gramsper100kgofpotatoseedpiecesforthecontroloffusarium seedpiecedecay.Applythoroughlytocoatthesurfaceofwholeorcutseed pieceswithdust.Iftreatedwholeseediscutmakeasecondapplicationto protectthecutsurface.Plantassoonaspossibleaftertreatment.Ifcutseedis notplantedimmediately,storeinawell-ventilatedlocationtopermitcutsurface todry.Donotusesurplustreatedseedpiecesforfoodorfeed.

Quicklydriesandsealscutsurfacesandprotectsseedsinwet,coldsoils Plantassoonaspossibleaftertreatment.Usesecondapplicationforcutseed.

•Plantassoonaspossibleaftertreatment.Usesecondapplicationforcutseed.

•••Treatcutpieceswithinsixhours.DonotuseafterMertectusedinstorage. Forwirewormsuppressionandextendedresidualcontrolofabove-groundpests,use higherrate.

•••Forwirewormsuppressionandextendedresidualcontrolofabove-groundpests,use highrateofTitan.

•Plantassoonasposssibleaftertreatment.Usesecondapplicationforcutseed.

Keeping potato crops free of the PVY virus is a matter of good management, but resistant varieties are on the way.

by Treena Hein

Any Canadian potato farmer knows well the half dozen major viral diseases that can damage their potato crops. The PVY group is one of the most destructive.

PVY occurs worldwide and mutations occur regularly, so new strains are being created on an ongoing basis. The virus is spread in the field by aphids from infected plants to uninfected plants. Those with the virus rapidly lose vitality and produce fewer and smaller potatoes. A severe strain of PVY called PVYNTN can also cause potato tuber necrotic ringspot disease on some cultivars such as Yukon Gold, AC Chaleur and Cherokee, making them unmarketable. There is no cure, so planting clean seed is paramount.

However, within a few years, potato growers in Canada and beyond will be able to access varieties with extreme resistance to PVY. This is thanks to the hard work of potato breeder Agnes Murphy and her colleagues, such as virologist Dr. Xianzhou Nie, at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Potato Research Centre (PRC) in Fredericton, N.B. They are studying strains of the virus, as well as potato plant genes that confer resistance to these strains, with world-renowned methods they created themselves.

“There are many strains of the virus that now exist, with varying characteristics and properties,” says Nie. “We have to stay on top of what strains exist because different potato varieties respond differently to each of them.” His updates on the latest strains are provided to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and to farmers, so they can do a better job at spotting symptoms of the virus in the field.

“PVY is a very complex virus,” notes Nie. “It can be categorized into potato- and non-potato groups, and within those that infect potatoes, at least five strains have been recognized to date.” The most common ones are PVYO (ordinary strain), PVYN

ABOVE: Dr. Xianzhou Nie, virologist at AAFC’s Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, is studying strains of PVY in order to determine resistant varieties.

Managing the growing risk of fungicide-resistant dry rot.

by Mo Oishi

When growers from across Canada sent tubers to be tested for Fusarium dry rot, many of them received an unpleasant surprise. The testing found that a substantial proportion of the samples were contaminated with fungicide-resistant Fusarium.

The tests were part of a study conducted by Dr. Rick Peters of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Prince Edward Island. What’s concerning about these Fusarium samples is that they were resistant to thiabendazole and fludioxonil, active ingredients in some of the most routinely used potato seed treatments and fungicides.

“It became quite an issue here in Eastern Canada for some growers’ operations,” Peters says. “It moved onto the front burner when we saw some of the really serious losses right from the get-go, when growers were planting their crop. In some cases, it caused significant issues with seed decay and stand development, obviously resulting in yield suppression.”

Peters’ research, which was funded by the Prince Edward Island Department of Agriculture and Forestry and the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund, found that potatoes from Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick are most likely to host resistant Fusarium strains. But that doesn’t mean that western producers can rest easy; potatoes from all provinces as far west as Alberta had resistant strains.

“There’s perhaps a higher incidence in the east versus the west,” Peters says. “We’ve been doing these surveys for over a decade now and you can see the incidence increasing over time and really becoming national in scope. So we have seen pretty much a national spread of this resistance phenomenon across the country.”

Dr. Rick Peters’ 2012 survey found five species of Fusarium that cause seed decay and dry rot.

In his most-recent 2012 seed survey, Peters found five species of Fusarium that cause seed decay and dry rot. Of these species, the large majority of isolates of Fusarium sambucinum was resistant to either thiabendazole or fludioxonil, with several isolates being resistant to both active ingredients. This is troubling because F. sambucinum is the most common cause of dry rot. And when it came to resistance to fludioxonil, all but one of the 165 isolates of the species Fusarium oxysporum were resistant to the fungicide.

What does this mean to growers? If you rely on either fludioxonil (Maxim) or thiabendazole (Mertect) alone, it’s time to transition your seed care and post-harvest programs to other products, says Jennifer Foster, field development biologist at Syngenta Canada Inc. Foster notes seed care products containing difenoconazole (Cruiser Maxx Potato Extreme, Maxim D), prothioconazole (Titan Emesto) or mancozeb (Tuberseal, Maxim MZ) are good alternatives to fludioxonil-only products.

It’s the higher adoption of mancozeb products in the west that explains, in part, the lower apparent incidence of resistance in the region, says Peters. Resistant strains of Fusarium may be common on the prairies, but might be masked by agronomic practices.

While alternative seed treatments can help combat resistance in the short term, Foster notes that on their own, they aren’t a sustainable long-term solution without broader diseaseand resistance-management practices.

Fusarium is both seed and soil borne. Given the fact that the seed is the primary source of infection and the complexity of managing the disease in the soil, Foster says, controlling the disease on the seeds is the most feasible approach.

The fungus can spread between tubers during seed cutting, handling or during planting. Seeds inoculated with fungicideresistant Fusarium will produce a patchy potato field with poor vigour. The infected seeds spread inoculum to the surrounding soil, where it infects other tubers through wounds in the skin. And so the cycle continues.

To manage the spread of disease before planting, check your seed potatoes for signs of dry rot, including shrivelled tubers with lesions on the outside and light to dark brown dry rot with cavities filled with fine mycelium strands on the inside. Remove any diseased tubers.

It’s also important that the cut seed be given the opportunity to heal quickly. To speed this process, warm the tubers before cutting them. Also, be sure to keep your cutting equipment sharp, and clean it often and thoroughly with a disinfectant. After the seeds have been cut and treated with an appropriate seed treatment, store them in well-aerated bins for no longer than 10 days. And, as far as possible, ensure the seeds are planted into soil at a temperature that will promote rapid germination.

After harvest, the tubers are also at risk. The disease spreads when tubers are bruised or wounded during harvest and handling and come into contact with contaminated soil or equipment. So here again, prompt wound healing is important in minimizing disease spread and optimizing storage longevity and quality. Healing can be promoted by providing proper aeration, followed by storage in lower temperatures.

Peters advises against relying on just one mode of action, regardless of the disease. At the same time, he says, it’s important not to reject some active ingredients outright. For instance, Fusarium may be resistant to fludioxonil, but this active ingredient is still a powerful agent against silver and black scurf, and stem and stolon canker. So it’s still a viable disease control tool; however, it needs to be combined with other chemistry appropriate for the control of resistant Fusarium.

Overall, Peters warns against over-reliance on just fungicides and seed treatments in disease control. “There’s starting to be a laundry list of resistant pathogens,” he says. “It’s becoming an issue in a lot of areas of potato production. So we have to be conscious that these new products aren’t put at risk of resistance too. That’s what makes these integrated cultural practices so important.”

Growing potatoes in rotation without conservation management practices dramatically reduces yields long term.

by Julienne Isaacs

A12-year irrigated rotation study near Vauxhall, Alta., which set out to examine the impact of rotation length and conventional (CONV) and conservation (CONS) management practices for potatoes, sugar beets, beans and soft wheat, has concluded that growing crops without conservation management practices may result in reduced yields and diminished soil quality.

The study, led by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researcher Frank Larney, was initiated in 2000 after meetings with various key players in Alberta, including the Alberta Pulse Growers, the Potato Growers of Alberta and Rogers Sugar/Lantic Inc., along with growers from around the province.

“We had buy-in from growers very early on. We used those meetings to plan the experiment and come up with the crops we wanted to include, [as well as the] sequence we wanted to grow them in,” says Larney.

The CONS rotations used in the study were built around four

specific management practices: direct seeding and reduced tillage where possible; fall-seeded cover cropping (fall rye); feedlot manure compost applications; and where beans occurred in the rotation, solid-seeding narrow-row beans versus seeding conventional wide-row beans.

Six rotations were used in the study (see Table 1) with each of the 26 phases appearing each year, and replicated four times in total.

Larney explains that CONS practices were chosen with

TOP: In September 2011, wheat phases [except the second one of 5CONS, P-W-SB-W-B], as well as the oat phase from the sixyear rotation (6CONS) were sampled (0-7.5 cm) to explore rotation and management practices effects on soil aggregates and organic matter.

INSET: Overall, CONS practices increased potato yield by seven per cent, with this number increasing for rotations of longer than four years.

Conservation practices used over the 12-year study included composted beef cattle manure as a substitute for inorganic

direct input from growers and were thus highly practical in nature. For example, the compost practice was chosen because, he says, “a lot of irrigated land is closely associated with the feedlot industry in southern Alberta, so the use of composted manure to replace some of the chemical fertilizer inputs seemed obvious.”

Additionally, Larney and his team chose to use narrow-row solid-seeding management for beans because, when the study began, only a single Alberta grower was using the technique. Estimates revealed at the Irrigated Crop Production Update meeting in Lethbridge in late January show that in 2013, 15 per cent of bean growers were solid-seeding in narrow rows. “It’s a management practice that’s set up to protect soil quality and reduce the risk of erosion,” says Larney.

The researchers chose to include rye as a fall-seeded cover crop because there was interest from growers.

The study’s results show that growing potatoes in rotation (potatoes-beans-wheat) without the use of CONS practices is not recommended due to declines in yield of between 12 and 18 per cent over the long term. Overall, CONS practices increased potato yield by seven per cent, with this number increasing for rotations longer than four years. CONS practices also improved soil quality parameters such as organic carbon, microbial biomass and soil aggregate stability.

Larney says that once the rotation plots had been established, many researchers used the study to investigate a variety of research concerns. Populations of weeds, insects and nematodes, respectively, were measured over time, and soil microbiologists examined microbiological indicators of soil quality. “I also did some measurements on various soil quality indicators, like soil organic matter, and looked at effects of rotations on nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil profile,” says Larney.

Key among the findings was the positive impact of CONS practices on soil health. “The soil microbiology indicators were quite consistent,” says Larney. “All but one of 10 indicators showed positive effects of CONS on biological indicators of soil health.”

The chief indicator of soil quality is soil organic carbon. The study was set up to compare CONV and CONS practices in three-year rotations, as well as CONV and CONS practices in four-year rotations. In the three-year rotation comparison, there was a 17 per cent increase in soil organic carbon in the top 30 centimetres of soil at the end of 12 years.

In the four-year rotation comparison, there was a 23 per cent increase in soil organic carbon in the top 30 centimetres of soil after 12 years. “The main driver of those increases was the compost application, because that’s how we were putting carbon back into the soil,” says Larney.

Overall, the study highlights the importance of maintaining good management practices in order to protect soil health in the long-term – a lesson that is already well understood by Prairie growers, according to Larney. “Soil organic matter content can decline, and if there’s no effort made to replenish that by adding manure or compost or reducing tillage or growing cover crops, you can run into problems with reduced soil organic matter, which, in turn, leads to problems with soil erosion, or general soil degradation.”

Growers face frequent temptation to tighten up rotations, but if organic matter is not returned to the soil, soil quality will decline, and this will ultimately impact yields. “Farmers should be aware of their soil organic matter levels,” says Larney. “They can test soil organic matter or carbon, and if these levels look like they’re low, growers can look at using compost as a way of increasing them.

“You have to balance the economic returns with the environmental effects that you want. You want to keep your soil in good condition and productive.”

Continued from page 5

Once resistant varieties are available, growers can ensure the resistance can remain effective longer by following good cultural practices. “Continue traditional management practices, such as recommended rotations and monitoring the crop for verticillium wilt,” Kawchuk suggests.

“Use rotation crops to reduce verticillium in the soil and grow the resistant varieties that are available now, if possible,” Tai adds.

Meanwhile, as breeders work to transfer the gene discovered by Kawchuk into commercial cultivars to give growers better protection from verticillium wilt, growers must continue using cultural practices to minimize the increase of the pathogen in the soil. Kawchuk and his colleagues currently have four clones in which the verticillium resistant gene was identified, but he says it will be a few years before a commercially viable variety will be available for growers to plant.

(tobacco necrosis strain), PVYN:O (N:O strain) and PVYNTN (potato tuber necrosis strain). “PVYO and PVYN are the conventional strains, and from which PVYN:O and PVYNTN have emerged due to natural genome recombination processes,” Nie explains. “PVYO causes symptoms ranging from mosaic to leaf drop and plant death in potato, depending on cultivars, and mosaic on tobacco. PVYN causes severe venial/petiole necrosis on tobacco plants, but mild symptoms on most potato cultivars.” Both PVYN:O and PVYNTN cause severe symptoms on tobacco plants, and mild to severe mosaic on most potato cultivars. PVYNTN also causes potato tuber necrotic ringspot disease in several varieties.

Being able to differentiate between these existing PVY strains means you must have a reliable diagnostic method. Nie and colleague Dr. Rudra Singh were the first researchers in the world to develop this over 2002 and 2003, and their technique is now used commonly around the globe. “It is a polymerase chain reaction-based approach methodology that amplifies a part of the virus genome under the direction of two primers that are specific to the virus strain you are targeting,” Nie explains. “The amplified DNA fragment is then detected after electrophoresis in an agarose gel, and visualized using an image analysis system.”

Previous methods for differentiating PVY strains were not as effective, relying on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). “Our polymerase chain reaction-based method targets the virus genome sequence directly and therefore can detect and differentiate different strains of PVY more effectively,” Nie says. Their method is not only used widely to survey and characterize PVY in potatoes, but also to detect and identify new strains.

Transmission of the disease by aphids – the only insect known to be capable of transmission of PVY – is also a

Another concern raised is the probability of the verticillium pathogen developing tolerance to the potato resistance gene, allowing a stronger strain of the pathogen to become prevalent. Kawchuk suggests breeding resistance into a plant is not the same as control by a pesticide in which the disease can develop tolerance to the product. “Tomato breeders used verticillium resistance for 50 years before a new race emerged that could overcome the resistance,” he says. “This would indicate that verticillium resistance should be effective in potato for many decades.”

Verticillium is such a large problem for potato growers that other means of control, such as soil fumigation, are continuing to be studied. However, the development of resistant, rather than tolerant, potato varieties may prove to be the most effective way to minimize the effects of the pathogen on the plant and in the soil.

concern, and Nie works with entomologists at the PRC to understand it more thoroughly. PVY is transmitted when the aphids feed, carried from plant to plant through sticking to aphid mouthparts. “Green peach aphid is the most effective vector of PVY,” Nie notes. “Nevertheless, many other species of aphid – both potato-colonizing and non-potato-colonizing species – can transmit PVY during the aphid’s dispersal phase when they are in search of new hosts.” Farmers may be able to prevent some of the insects from carrying the virus to uninfected plants by spraying the crop with mineral oil, but planting clean seed is the best management practice and diseaseprevention strategy.

However, growers will have another strategy soon enough. Researchers at the Potato Research Centre are hard at work developing new potato varieties that are resistant to the virus. “There are two types of resistance to PVY,” Nie says. “These are called hypersensitive resistance (HR) and extreme resistance (ER), and different sets of potato genes produce them.” HR is strain-specific (typically to PVYO), whereas ER is broadspectrum, effective to all strains of PVY. In 2013, the PRC released two new potato selections (AR2013-08 and AR2013-14) with extreme resistance to PVY, and they are now being tested by industry potato evaluators. The test is done in the greenhouse by mechanically inoculating the selections with PVY, followed by graft-inoculation with the virus to test for extreme resistance, Nie explains.

There are now also several promising lines at PRC with extreme resistance to PVY that are currently being evaluated. “To put all desirable traits – a cultivar with extreme PVY resistance and acceptable agronomic and economic characteristics – into a single variety selection is a tremendously challenging job,” he says. “However, to be optimistic, it will likely be available in the next several years.”

Two powerful active ingredients with different modes of action for effective resistance management. Quadris Top® fungicide provides protection for your crop with two active ingredients that work together to more effectively protect against disease for improved plant performance.