Taming the beast

By Laura King

Lessons observed

Iwas in Alberta the week wildfire decimated parts of Fort McMurray. A handful of firefighters and officers who were supposed to be at the Northern HEAT conference in Peace River had been dispatched to Fort Mac, packing pick-up trucks and answering the call.

Their stories are similar, and remarkable: lack of food and sleep; less-than-perfect command, control and communication.

Which, some argue, was reasonable given the magnitude of the Fort Mac fire and therefore, the response, the number of agencies involved, and the remote and challenging location – one highway in and out.

But given High Level, High River, Slave Lake, Elliot Lake, Lac-Megantic and L’Isle-Verte, the need for broader planning seems crucial and obvious, yet little has changed. As one chief so eloquently put it in conversation this week, lessons from these incidents have been observed, but clearly not learned – the same issues emerging repeatedly in the absence of planned provincial or national responses.

“Nobody really had a great handle on how many firefighters were here [early on], or the resources,” a deputy chief told me over the phone from Fort Mac. “The command structure definitely needed to be formalized.”

While there’s no doubt that those who deployed were needed, the lack of infrastructure (hotels, restaurants) due to the evacuation left fire-

fighters scrambling for food and shelter, just as Can-TF3/HUSAR team members did in Elliot Lake in 2012.

Given Alberta’s experience with wildfire in Slave Lake in 2011 and floods in Calgary and High River in 2013, the expertise of chiefs such as Jamie Coutts and Brian Cornforth, the after-action reports, recommendations, and the well-known science that points to optimum wildfire conditions in May, the lack of preparedness was, to my mind, appalling.

It was never a question of if, but when, a fire bigger than Slave Lake . . . would strike.

Some examples: much of the community was being FireSmarted after the fire; portable kitchens and showers arrived . . . eventually; personnel in the REOC wore respirators for three days until a filtration unit was hooked up to get the smoke out of the building; municipal firefighters and officers lacked an understanding of wildfire behaviour and the role of wildland firefighters. All could have been mitigated with proper planning, co-ordination and co-operation.

Indeed, as Calgary Deputy Chief Allan Ball said in a brief interview from Fort McMurray, had the incident been in Edmonton, for example, things would have happened more quickly. Which is true, but also the point: massive wildfires tend to burn in northern Alberta.

It was never a question of if, but when, a fire bigger than Slave Lake, which threatened more homes and people, would strike.

Our contributors – Slave Lake Chief Jamie Coutts; Cody Zebedee, a volunteer in High River and career captain in Foothills; Chris Fuz Schwab, deputy chief in Smoky Lake; and Dan Verdun, deputy chief with the County of Grande Prairie –wrote compelling stories about their experiences.

Like every other firefighter in Alberta, all four wanted to be in Fort Mac; however, it’s reasonable to conclude that none of them anticipated the conditions, and it’s likely that only Coutts fully understood at the onset the magnitude of the beast. They, like so many, answered the call.

No one died fighting fire in Fort McMurray – although there were close calls.

Only better planning –regional (or provincial) mutual aid similar to that developed by chiefs in northern Alberta in the absence of a government initiative; more structural-protection teams; better understanding by municipal firefighters of weather and wind patterns; full-on FireSmart implementation; an accurate provincial resources list; and a standard incident management system – will ensure no one dies the next time.

@fireincanada facebook.com/CanFirefighter cdnfirefighter.com firehall.com

July 2016 Vol. 39, No. 3 cdnfirefighter.com

EDITOR Laura King lking@annexweb.com 289-259-8077

ASSISTANT EDITOR Maria Church mchurch@annexweb.com 519-429-5184

NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Adam Szpakowski aszpakowski@annexweb.com 289-221-6605

SALES ASSISTANT Barb Comer bcomer@annexweb.com 519-429-5176 or 888-599-2228 ext 235

MEDIA DESIGNER Brooke Shaw

GROUP PUBLISHER Martin McAnulty fire@annexweb.com

PRESIDENT Mike Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

MAILING ADDRESS

P.O. Box 530, 105 Donly Dr. S., Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

For a 1 year subscription (4 issues: January, April, July and October): Canada — $12.00 ($13.56 with HST/QST; $12.60 with GST; GST # 867172652RT0001) USA — $20.00 USD

CIRCULATION

subscribe@firefightingincanada.com 866-790-6070 ext. 206 Fax: 877-624-1940

P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

ISSN 1488 0865 PM 40065710

Occasionally, Canadian Firefighter will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Community to install firefighter sculpture

Twenty firefighters in Fort McMurray, Alta., lost their homes to the mammoth wildfire that destroyed about 10 per cent of the city, but their contributions to help save the other 90 per cent will not likely be forgotten. Timothy Schmalz, a sculptor in Kitchener, Ont., was commissioned to create a sculpture for the Fort McMurray Fire Department weeks before the wildfire, but told media the piece will now serve as a symbol of firefighter bravery in the face of the devastation. The sculpture – a two-metreby-two-metre Maltese cross with images of firefighters – should be completed by September. —

MARIA CHURCH

Fort Mac fire burned:

587,000

5,300

hectares in Saskatchewan (as of June 9)

Collectible coin depicts firefighters

The Canadian Mint has created a collector coin that depicts a firefighter in action to honour the Canadian fire service. The $15 coin, made of silver, was unveiled at the mint’s production facility in Winnipeg in May and is the first of four going into circulation this year to honour Canada’s military and first responders; the other coins depict a police officer, paramedic and infantry soldier. The mint also pledged to donate $10,000 as well as $5 from every coin purchased to the Red Cross Alberta Fires Appeal in Fort McMurray. — MC

firefighters lost their homes in the Fort McMurray wildfire

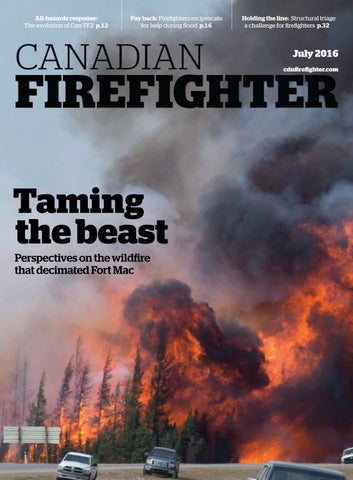

The weather science behind spring wildfires in Alberta

Weeks before wildfire levelled areas of Fort McMurray, wildland fire forced evacuations in Parkland County, west of Edmonton. The month-early start to the wildfire season prompted Lesser Slave Lake Chief Jamie Coutts to tell Fire Fighting in Canada that fire services need to stop looking at the calendar and start looking at conditions. Those conditions, however, are not well understood by all members of fire services.

David Moseley, the lead training officer for Lac La Biche County Fire Rescue, explained in the May 2015 issue of Fire Fighting in Canada that Alberta’s spring wildfires are largely influenced by two factors: weather and fuel.

The perfect weather conditions for wildfire are wind and crossover. The latter occurs when the temperature in degrees Celsius is higher than the percentage of relative humidity. (E.g. 29 C and 20 per cent humidity = crossover

conditions). Wind is common in Alberta in the spring when the weather phenomenon known as an inversion occurs daily. An inversion is a term for when the air on the Earth’s surface cools in the night while a pocket of warmer air sits above it. The inversion breaks down with the morning sun and the cold air is replaced by warm air, rushing in from above.

The trees and grasses that make up northern Alberta’s boreal forest landscape are ideal wildfire fuels. The forest comprises mostly mature conifers, black spruce and jack pine. These two trees are at their driest in the spring and have large crown fuel loads. Dead leaves from the deciduous trembling aspen increase fuel load on the ground, already heavy with dead, dry grasses.

Moseley explained that the combination of fuel and weather creates the perfect conditions for a spark to ignite into an intense, sustained wildland fire. — MC

The firefighter coin is one of four created by the Canadian Mint to honour the country’s first responders and military.

hectares in Alberta (as of June 9)

Voice of experience

Lake chief recounts Day 1 in Fort McMurray

By Jamie Coutts

Editor’s note: Chief Jamie Coutts’ perspective on the fire that ravaged Fort McMurray, burning 10 per cent of the city, is unique. Coutts, chief of the Lesser Slave Regional Fire Service, took his experience from the 2011 fire that decimated 40 per cent of his community to Fort Mac on May 3, with firefighters Ryan Coutts and Patrick McConnell, part of the department’s FireSmart team that was developed post-2011 and is trained in wildland and structural fire fighting, structural protection, ICS 200, emergency preparedness and other disciplines (see Tackling the interface, page 38). Coutts provides a first-hand account of his first 24 hours in Fort McMurray.

We had been watching the Fort McMurray updates on our Alberta Wildfire app for a couple days, keenly aware of the fire’s proximity to the City of Fort McMurray. As the fire grew we started to wonder if anyone would call for our structure-protection trailers or crews. Monday evening, May 2, at 10 p.m., we received a call: “Do you have a structure-protection trailer? How much do you charge per day?” And so the conversation went for about an hour back and forth. I could tell at this point there didn’t seem to be much of a worry; people in Fort McMurray were just trying to look ahead. I called in a couple of the FireSmart crew guys and we got a trailer ready, and rigged up a one-ton with a tank and pump. The call came that the Regional Emergency Operations Centre (REOC) would decide at 7 a.m., and let us know.

At 7 a.m. exactly on May 3 we received a call. The REOC would like us to deliver a trailer to Fort McMurray and drop it off. After that, we would be released to head home. Patrick McConnell, Ryan Coutts and I decided we would pack a bag and take our wildfire gear; we had been down this road before and decided better safe than sorry. We were on the road by 8 a.m. and drove straight to Fort McMurray, listening to broadcasts about the fire and changes from the previous night as we went. There were

so many similarities to the Slave Lake fire in 2011 that we started to talk about what deploying the gear would look like, and what challenges we would face from all the people and organizations involved. We discussed the fact that we would be heading into a situation that people still felt was under control and that we would have to sell our way in.

We arrived at 12:30 p.m. and headed into the REOC: it was like walking into an ant hill – people were everywhere, maps, updates, Smart Boards. We were asked to drop off the trailer and lock it up. Keys would be given to operations and we could go. We went out to the trailer and turned our radios to the Fort McMurray frequency for agriculture and forestry and started listening to the reports. Things were definitely heating up. We went back in and asked to do an orientation with the crews

Slave

Slave Lake Chief Jamie Coutts and two Slave Lake firefighters trained in structural protection worked with other firefighters in the Beacon Hill neighbourhood of Fort McMurray, saving what they could, but forced to let some homes burn – there were “just too many to fight.”

that would be using this equipment. The ops manager said he would call them all up, and we could do the orientation right in the parking lot. Shortly after 1 p.m., about 40 people showed up; we talked briefly about being prepared, having LACES (lookouts, anchors, communications, escape routes, and safety zones), talked about what could be saved and what couldn’t if the fire hit the city, and what the conditions might be like. From there Patrick and Ryan did a quick orientation on equipment, setup, and systems. I saw Fort McMurray Chief Darby Allen walking back into the REOC from outside, caught up to him, introduced myself and said, “You will be under immense political pressure during this event – evacuate, don’t evacuate, priorities will be shifting. Follow your heart, follow your gut and do what you know is right.” We left it there and he went back inside. The media was humming around, and you could tell from the smoke column and radio traffic that things were going sideways. The projected wind at the morning briefing was out of the south east, switching to a stronger wind

out of the south west. We could see outside that the wind would push the fire past the city limits and then slam the whole side of the fire into the southern neighbourhoods. We went back into the REOC and told Assistant Deputy Chief Jody Butz at operations that orientation was done and that the Fort McMurray firefighters were taking the trailer. He thanked us and then Chief Allen asked if we would stick around and discuss some of what Slave Lake had been through and look at some operations with the team. (I didn’t tell him at the time but Patrick, Ryan, and I had talked about this outside, and with conditions the way they were, there was absolutely no way we were going anywhere. We had even put our wildfire gear on already.) We waited inside with one of the deputies for a chance to talk to Chief Allen. The forestry manager, Bernie Schmitte, and the operations chief, Butz, were having a briefing meeting while the deputy chief talked about the layout of the city and the neighbourhoods in front of the fire. As we looked out the second storey window at the fire, I excused myself and headed to the operations briefing. I excused myself again and asked the gentlemen if I could interrupt. I had been watching the conditions and hearing the radio chatter and said that I knew we needed to hurry with structure protection; they handed me a map, listened to the plan, immediately endorsed it, and told us where to go to get more help. We left immediately and headed to Station 1 downtown.

2,400 structures destroyed

At Station 1, fire-service personnel were trying to get organized and keep a helicopter pad free. Firefighters from the city and region were assembling, and gear was being organized. We dumped overnight bags from our one ton, grabbed cases of water (we knew we would need lots) and were assigned another seven firefighters to go with us to meet other firefighters and our structure-protection trailer in Beacon Hill (the first area to be slammed by fire front). Evacuated people were streaming down all lanes as we tried to slowly creep to Beacon Hill. Once we were on Beacon Hill Drive, we tried to find our structure-protection trailer, which was with our friend Dave Tovey from Fort McMurray Fire. We stopped by a park that would provide some distance from where the fire would hit and, along with dozens of Fort Mac firefighters, we started evacuating people (some were still in their houses, others were trying to load motorcycles and campers). The Fort Mac firefighters with us quickly rounded up animals that had been left behind or had been trapped with no owners able to get to them. Then, the set up and fire fight started. The wind picked up, and the sparks started landing. This was the point at which our experience in Slave Lake started to come through for us. It was simple: save the houses that aren’t on fire yet. Hit the spot fires, but once a house goes up, move on –there are just too many to fight. This is an impossible

thought to process when you are a firefighter: we put house fires out, period; so when we are asked or told to let some homes burn so others can be saved, it’s tough to absorb and accept.

Patrick and Ryan left and hooked up with the Fort McMurray crews that had our structure-protection trailer. It was too late to deploy in that area so they fought the fires they could, set up hoses where they could and worked with the Fort Mac crews. I didn’t want to be separated from my guys, but I knew their training and experience was needed where they were. I was lucky to be with a large group of volunteers called in from smaller Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo halls – the new recruit class (five weeks in, I was told) and a few captains and training officers. It was all a little overwhelming and I remember thinking “Were theses the looks on our faces when Slave Lake burned?” I just kept telling them, “Keep up the good work, fight the fires that need to be fought, what you are doing is saving lives and houses; just keep going.” At one point there was an evacuation and we had to work through that; it was very stressful working through the fact that we were safe, yet surrounded by dozens of burning homes. We worked it through command, and were able to stay in the area. (When I went back days later there were houses left right where this group of firefighters had been fighting fires. It was nice to know we won the battle for a few dozen homes.)

After a couple of hours of working in Beacon Hill, I called Patrick and Ryan and we headed up to the REOC. We talked briefly with Chief Allen and Chief Butz about critical infrastructure and what has to be left for a city to survive. Somehow, through all of this, the city crews had kept the water going to most of the hydrants, and dozens of fire departments were on the way to help. We were tasked with protecting the hospital. We went back to Station 1, grabbed a few guys from Albian Sands Fire and headed to the hospital. Short on gear, we talked with people from the hospital, and received help from the security and maintenance staff. We were able to use a small amount of equipment that Albian had brought and hoses from the hospital to get good coverage of the entire roof of the hospital. You could hear, and see, that just like

The cost of recovery:

Insurance industry experts estimate the cost of claims from the Fort McMurray wildfire will total in the billions.

in Slave Lake, this fire had turned into dozens of small battles across a rather huge battlefield.

It was all a little overwhelming and I remember thinking “Were these the looks on our faces when Slave Lake burned?”

Just as we finished getting the roof covered, Capt. Pat Duggan of the Fort McMurray Fire Department came up to the hospital to take command of this area. (Duggan had been married to my cousin, and quickly recognized Ryan and me; funny how small the fire world is. We talked about whether all his family members were out, and they were.) Duggan spotted smoke and fire in a nearby neighbourhood and left with Ryan and Patrick in our one-ton truck: the three of them started that fire fight with a garden hose and a booster reel off the small tank in that one-ton. Duggan quickly called in reinforcements and within minutes had started a fire fight that would last hours and save an entire downtown neighbourhood. From there, we went to a backyard fire with another Fort Mac officer and knocked that down with a garden hose and booster reel again. I was so impressed with the Fort Mac utilities people – all that water being used and yet they somehow kept it going. We went back to the hospital where ash was falling constantly now while the Abasand neighbourhood burned. (Along with half our structure-protection equipment – we didn’t find that out until later). It sounded like a war zone – fireworks from the store going off, propane tanks, oxygen/acetylene torch tanks going off. The smoke was thick and the ash was intense. Duggan called me right then; we talked about the area he was in and hung up. I didn’t get a chance to see him or talk to him again during our time in Fort Mac, but I’m proud to say we worked together. While we waited for trucks to arrive from Slave Lake, we stopped at Station 1 for some water and a bite to eat. As I was walking to the washroom I almost ran smack into a horse. That’s right – a horse. The owners could not get to their trailer so they evacuated with their two horses to the hall. Add that to the list of things I’ve never seen before. At about 11 p.m. our two trucks arrived from Slave Lake. We checked in at Station 1, picked up firefighter Chad Grunow with Fort McMurray Fire, and headed up into Thickwood for our next assignment. (Grunow stayed with our crews through our entire time in Fort Mac, guiding us, saving his beloved city, even letting our firefighters stay with him in his home; a true friend and a heck of a firefighter.) This assignment was to assist with putting out some wildland fires that kept sneaking up to fence lines and starting structural fires. That completed, we assisted in a neighbourhood where about 10 trailers were on fire. From memory, I believe there were crews from Fort Mac and its new recruit class, Syncrude, Albian Sands, Canadian Natural Resources Limited, Slave Lake and Anzac, and I’ve probably missed a few. It was amazing to see all of these people working together trying to save this neighbourhood. This went

on until 4 a.m. ,when we finally headed down to MacDonald Island. We parked our trucks, found cots, and stayed there breathing in thick smoke for a couple hours.

I never thought I’d see something like Slave Lake again – we trained hard, shared the lessons learned and participated in every after-action review we could find to make sure an it wouldn’t happen again. I believe the days, weeks, months and years ahead will be even tougher on the people of Fort McMurray than they were here in Slave Lake (it’s hard to believe but I’m sad to say I’m sure of it), and that the after-action reviews will be gruelling, but always remember this: no one died in Fort McMurray (although there was a tragic loss during the evacuation and those young adults will never be forgotten) and 90 per cent of the city was saved, including all critical infrastructure. The people of Fort McMurray will rebuild. A small piece of my heart will always be with them. As terrible as it was, as scary as it was, there is nowhere on Earth I would rather have been that day than in Fort McMurray, trying to help save a city with my brothers and sisters of the Fort McMurray Fire Department. Chief Allen and Chief Butz were amazing to work with; they listened and respected our views based solely on stories out of Slave Lake. In the days that followed as we took on different roles and different fire fights in the city, we worked with hundreds of firefighters from across the province. It was a different experience from Slave

Lake as we were there to help in a different way – it wasn’t our city burning. The lessons captured this time will be different, will be from another perspective and will no doubt lead to new ideas and solutions.

Looking forward, we need to examine evacuations. (Mandatory needs to mean mandatory, and the RCMP need legislation to enforce the evacuation.) How, and who fights these urban interface fires needs to be reviewed, and the proper training, equipment, and trucks need to be developed and purchased. Unified command between fire services and forestry needs to be solidified and adopted by all. Healthcare follow-up needs to be implemented for all people who stayed behind and came from afar to assist in extinguishing this fire. The toxins from this type of urban interface fire are not fully understood yet.

In July 2011, I wrote in Canadian Firefighter: “The biggest lesson learned is we have to plan farther – when you’re in wildland areas the world is changing, the weather in the world is changing, and we have to plan with that change.”

This outlook has changed the way our whole fire department operates. We were always a stay-ahead department – if one truck is good we send two, if two trucks are good we send three, and we can, because we’re a regional fire service.

We can add extensive FireSmart operations to this now. I had even said if we had 300 fire trucks lined up we could not have stopped Slave Lake because of 100-kilometre-an-hour winds. If we had that many trucks lined up in Fort Mac could we have saved it all? There is no way to know for sure, but I will say these words one more time: get ahead, stay ahead.

THOUSAND

As the wildfire continued to burn, we heard the stories from firefighters involved and critical pieces that were learned from Slave Lake: use of heavy equipment to separate homes saved hundreds, or maybe even thousands of other houses; having water through thick and thin was huge – the utilities people were incredible; transportation folks made sure routes were clear and trucks were fuelled – just amazing. There will always be more to learn, but there were some lessons learned from previous fires.

For our crews here in Slave Lake it had been an active spring with multiple deployments and many busy days; we think of our fellow firefighters in Fort McMurray and hope that they remembered to take care of themselves, and to take care of each other. To Chief Allen, and Chief Butz – remember to go easy on yourselves; you did a great job in an extreme environment.

Jamie Coutts is the fire chief of Lesser Slave Regional Fire Service in Alberta. Contact him at jamie@slavelake.ca and follow him on Twitter @chiefcoutts

The view from the regional emergency operations centre in Fort McMurray, which was itself under an evacuation watch in the early days of the wildfire.

All-hazards response

The evolution of Can-TF2 into a highly specialized support team

Editor’s note: Sue Henry is a deputy chief with the Calgary Emergency Management Agency. Editor Laura King spoke with Henry following the deployment of the all-hazards Canada Task Force 2 to Fort McMurray.

Q. Explain how Canada Task Force 2 was deployed to Fort McMurray.

A. Deployment comes through the provincial emergency operations centre (POC), and they make the request to the Calgary Emergency Management Agency (CEMA).

We started with an advance team. Six members went as an incident management team, to figure out what other support needed to follow.

Over a three- week period, we sent three deployments totaling 180 members, including 22 members from Canada Task Force 4 (from Manitoba). The team consisted of everything from, logistics support and chefs to an incident management team (IMT) and a medical unit. The final deployment returned May 21.

Q. What was CAN-TF2’s role in Fort McMurray?

A. Canada Task Force 2’s role in any disaster response is to support the local community and ensure the local authority succeeds. When we arrived in Fort McMurray CANTF2’s initial role was to provide logistics and support to the incident management team. The team reported to REOC Fire Hall 5 in Fort Mac and started to meet with the local authority and evaluate any of the positions that needed assistance.

The local authority was stretched and there was some confusion about whether it was safe to remain [in the REOC]. Our members were there to help, to prop up the local authority.

Q. How did your members integrate into the REOC?

A. We prefer never to go into a community and take over for the local authority; we prefer to go in and prop them. We play more a mentor role to ensure the local authority is able to continue the response.

Our members filled roles in the incident command team– we had an EOC manager, a deputy, logistics, safety, liaison – as well as many other positions. Many roles were staffed with a member of the local authority and propped up with Can-TF2 members.

Q. Originally CAN-TF2 and the other teams specialized in heavy urban search and rescue, yet you deploy to wildfires. What has changed?

A. When the Joint Emergency Preparedness Program funding ended in 2012, we lost our federal funding. Since then we have shifted to an all-hazards disaster response team to expand our capabilities and expand membership. The team now con-

sists of IMT members, logistics, engineers, communications, building inspectors, rope rescue, canine support. This allowed us to have an all-hazards team that could provide more expertise and co-ordination for the province.

Q. Lessons learned?

A. Absolutely there’s certainly always going to be challenges in responding to a disaster, but the local authority in Fort Mac is amazing; they appreciated our help and assistance and our feedback, and were phenomenal to work with.

We learned the value of relationships and it was reinforced for us yet again, the importance of being dynamic and flexible to certain situations, and to really morph what our team structure looked like in response to what the local authority needed; we go in and figure out how to best help them so we learned importance of that flexibility.

A total of 180 members of Can-TF2, all part of the incident management team, deployed to Fort McMurray over three weeks, assisting local authorities in the regional emergency operations centre.

Q. What was your role in Fort McMurray?

A. I was up there in kind of an interesting role; I went up the second week, working with the EOC manager and deputy manager to provide the link back to Calgary and provide oversight for the team. I was working to support the transition between the local authority and Can-TF2 to ensure the local authority’s needs were met while CAN-TF2 started to demobilize resources.

Q. How is the team structured?

A. The team comprises volunteers from all over Alberta. Team members need to reside within a four-hour radius of Calgary. This allows the team to have a wide breadth of knowledge and skills, from engineers and police to experts in mapping and GIS, medical doctors.

For this deployment there were 180 people deployed to take part in the various roles: 58 per cent were from Calgary and the immediate area; 28 per cent from remainder of Alberta; and 12 per cent from Can-TF4.

When the team first came into existence it really was focused on the heavy urban search and rescue and was mostly firefighters but we’ve really broadened and are able to do that all-hazards focus.

Funding is a combination right now, by the Alberta Emergency Management Agency and the City of Calgary. Of course the federal government has re-announced funding for this year, so we’re crossing our fingers.

Our first full deployment was for the Slave Lake fires in 2011, and then components [of the team were deployed] in 2013 to support floods in High River and in Calgary, and in 2014 after

the September snowstorm that Calgary experienced.

We’ll continue to morph into that all-hazards approach and be able to handle a variety of incidents. There is an incredible wildfire group in Alberta – were not going to become a wildfire-specific team. There was a whole lot of value brought by the team during the flooding in 2013 and the 2011 wildfire – our value is really in the ability to adapt and respond to a variety of events.

We are always looking for people; we’re going through recruiting drive and accepting applications (www.cantf2. com). We’re always looking for new skill sets and individuals willing to volunteer with the team.

Q. Will there be a post-mortem or review of the deployment?

A. We always have a postmortem to ensure we capture lessons learned, identify any gaps in process and determine future training opportunities. CAN-TF2 is part of the Calgary Emergency Management Agency. We continue to be activated [as of May 31] supporting the response because a number of evacuees who are here. Once that’s over we’ll start looking at [a post-mortem] in a number of areas.

Q. What stands out most from your experience in Fort McMurray?

A. I think most of what we’re talking about is the relationship side and getting to know the people around you – meet your utilities workers, meet your wildfire firefighters. You don’t want to be meeting for the fist time at the event.

PAY BACK

High River firefighters reciprocate for help during 2013 floods

By Cody Zebedee

On Tuesday, May 3, we had heard that things in Fort McMurray were getting bad: people were being evacuated and the threat to the city was huge. In the afternoon, I had been talking with one of my captains with the High River Fire Department, Brent McGregor. McGregor had been a training officer in Fort McMurray before moving to High River Fire, and he was concerned about the city and the guys up there as this had been his home for a number of years.

McGregor was talking with the chief about High River Fire going up to help, and he said that High River Fire had been added by the Provincial Operations Centre (PEOC) to the list of resources that were willing to be deployed. I had also called my chief from the Foothills Fire Department about getting us on the list; at that point Chief Jim Smith said he had talked to the PEOC and we had been added.

That night was our regular training in High River and the guys were continually checking social media and other news outlets to watch the situation unfold. All the High River Fire members were anxious to go to aid in this desperate time; we all felt we needed to be there to help as it was our chance to give back for the unwavering support we received in 2013.

We knew what our bothers and sisters to the north were going

though. In 2013 our town was evacuated and a good portion of it was under water. A lot of our members lost their homes, me included; we understood what the responders in Fort Mac were experiencing and the extreme workload ahead. Seeing the news reports and social media posts brought back waves of emotions –not so much that we were going to be directly affected by the fire, but for the people of Fort McMurray and the emergency-services personnel. It is a very helpless feeling – watching something over which you have very little control start to take over your community, damage property and destroy memories. For us in the emergency services, our communities are more than places we live; they are places we are here to protect and serve for our customers, the citizens.

On Wednesday night, May 4, at 18:00, the PEOC called and we were deployed to Fort McMurray. Within minutes, six members from High River Fire were at the station preparing for the 10-hour trip. Within an hour of being notified we were on the road heading north. During this time I was making arrangements with members at my full-time station (Foothills Fire, Heritage Pointe Station) to cover my upcoming shifts; the guys were unreal and without a question they stepped up and my shifts were covered for my next tour. Even though my full-time department was never deployed to

Fort McMurray, members did help by allowing me to have the time off and covering my shifts.

I was very honoured to be selected to head to Fort McMurray with the crew; this was an opportunity for me to pay back all of the support and assistance that my community and fire departments (High River and Foothills) received in 2013. After the flood, I looked back and thought, “How can we ever repay all these people, most of whom I had never met before?”

As we approached Fort McMurray, the smoke became heavy on Highway 63 and we could see where the fire had burned along the highway and where it continued to burn; it was surreal and the guys in the truck became quiet. At around 05:00 on May 5 we pulled into the staging area at MacDonald Island; Deputy Chief Trevor Allan and Capt. McGregor went to check in with the staging manager. Shortly after arriving we were deployed into the Timberlea area, along with firefighters from Cold Lake and Shell Albain Sands, and a Bronto from the Fort McMurray Fire Department. Multiple homes were on fire and homes across the street were becoming exposure fires. We worked alongside these departments for a few hours to contain the fire and keep it from spreading to other homes.

That day we were deployed to multiple areas of Fort McMurray, doing everything from building fires

During floods and fires it is truly amazing to see how departments across the province can come together and work alongside each other to help mitigate a massive disaster.

to wildfires. Driving around the city and seeing the deserted street brought me back to the floods. We had the opportunity during the first day to work with multiple departments from all over Alberta. During the 24 hours we returned to the staging area multiple times to be reassigned and to load up on drinking water and snack foods that were laid out in one of the indoor fields; this was our food for the first day we were deployed. The crew I was with worked until 05:00 the following day with no complaints and, as a collective, we all said we were there to work and help out in any way that we could. After getting to MacDonald Island we found a spot on the floor in the Mac Island rec centre, in one of the children’s indoor play areas, to lay out our sleeping bags and catch a few hours of sleep. Finding a place to sleep was difficult as there were firefighters sleeping

on floors and cots and in hallways – wherever they could find a spot.

When we woke up the crew headed out to our truck, did a quick once over to make sure we were ready for the day, then lined up back in staging to be redeployed. The second day we were sent to different areas of the city to take care of flare ups and spot fires in the trees as well as patrol the downtown area; the fire had burned along the ridge to the east side of the city and there was a concern that it may jump the river. That evening we headed to the Noralta Lodge north of the city where we were able to have a hot shower and a bed for the night. On the way to the lodge the smoke was very heavy, which made driving a bit of a challenge.

In the morning we headed back into the city to the staging area, where we were then deployed to Saprae Creek. We met up with the Saprae Creek area command and

spent the day working around homes (about 11 kilometres east of Fort McMurray) to knock down hot spots and spot fires. Later in the evening we headed back to the Saprae Creek fire hall where a retired RCMP member cooked a steak dinner for the crews; this was the first sit-down, hot meal we had. After leaving Saprae Creek we headed back to staging. Shortly after getting back we were sent to a fire along Highway 63 near Highway 881; we worked to extinguish a fire in the ditch area and then headed down Highway 881 where City of Leduc firefighters were working on a fire in the valley that was threatening some building and fuel storage. We worked alongside Leduc firefighters for the night. After finishing up on Highway 881 we headed back to Mac Island to get some sleep. As we were walking down the hallway in the rec centre, a security guard

High River firefighter Cody Zebedee, who lost his home during the 2013 Alberta flood, deployed to Fort McMurray to assist during the wildfire and says that both incidents reinforce the idea that communities need to have plans in place for large-scale disasters.

More than 2,000 firefighters deployed to Fort Mac from:

stopped to talk and asked us if we had a place to sleep for the night because he knew of an empty room we could use. He took us down to a small classroom and helped us set up a few cots. I don’t think that we could thank him enough for helping us out that night!

The following days we worked around Fort McMurray in different areas on hot spots and spot fires, cleaning up garbage around the staging area along with a crew from Edmonton Fire and unloading semi trailers full of water and supplies. After a long Day 1 – we had not had lunch or supper – we were hungry and tired after arriving in staging; a large semi had arrived and some firefighters from Parkland County were working to unload the supplies. My whole crew jumped in and helped them out to get the job done. Meanwhile a smoking BBQ was 15 feet

away with a hot meal cooking.

On Day 4 our relief crew arrived and we did the hand-over to them.

During our time in Fort McMurray we were able to meet with and talk to some of the FMFD members. You could see how tired these folks were, but they were not stopping and still giving it their all. These members did an outstanding job saving the

majority of the city and keeping everyone safe. Some of them had lost their homes to the fire, but that was not their concern at the time; their concern was stopping the fire from damaging any more of their city. It was good to talk with them and tell them that right now things are bad, but it does

Continued on page 28

High River Capt. Brent McGregor, firefighters Lane Hall, Chris Connell, Cody Zebedee, Deputy Chief Trevor Allan and firefighter John Badduke deployed to Fort McMurray three years after experiencing flooding in their home town, eager to pay back the goodwill that had been extended by firefighters from across the province.

E-Mail:

Notable wildfires

SALMON ARM FIRE, B.C., 1998

Area burned: More than 6,000 hectares

Evacuated: 7,000 people

Damage: More than 40 buildings

HAILEYBURY, ONT., 1922

Area burned: More than 500,000 hectares

Damage: 43 fatalities, $8 million in property damage

Cause: Undetermined

MIRAMICHI FIRE, N.B., SUMMER 1825

Area burned: More than 1 million hectares

Fatalities: Between 150 and 500

Damage: One-third of homes in Fredericton

Cause: Fire ignited when small settler and logging fires grew out of control during a drought

CHELASLIE

RIVER FIRE, B.C.

THE GREAT FIRE, 1919, SASKATCHEWAN AND EASTERN ALBERTA

Area burned: 2.8 million hectares

Damage: 300 people left homeless

Cause: Lightning, low snow levels the previous winter, spring drought and high winds

OKANAGAN PARK FIRE, B.C.

Started: Aug. 16, 2003

Area burned: 26,000 hectares

Cause: lightning

Evacuation: 30,000 people

Damage: 240 homes burned

RICHARDSON BACKCOUNTRY

FIRE, ALTA.

Started: Mid-May

2011

Cause: Human

Largest Canadian fire since 1950

Area burned: 707,648 hectares

COCHRANE, PORCUPINE AND TIMMINS, ONT., 1911

Area burned: 200,000 hectares

Cause: Unknown

On what became known as Black Tuesday, July 11, bush fires converged into a horseshoe-shaped conflagration that wiped out mining camps.

Fatalities: At least 73

MANITOBA, 1989

Area burned: 3.3 million hectares

Evacuated: 24,500

High temperatures, low rainfall and wind combined for one of the worst fire seasons in Manitoba history: 1,147 fires burned almost 10 per cent of the province’s forests. People from 32 communities were evacuated.

Damage: 100 homes

Started: July 8, 2014, contained Oct. 9.

Area burned: 133,098 hectares

WEST

KELOWNA COMPLEX (GLENROSA, ROSE VALLEY, TERRACE MOUNTAIN), B.C.

Started: July 18, 2009

Evacuation: 20,000

Area burned: Almost 10,000 hectares

Cause: Human

Damage: Three homes lost

SLAVE LAKE, ALTA.

Started: May 14, 2011

Area burned: 4,700 hectares

Evacuated: 7,000 people

Damage: 400 homes destroyed, town office, library, six apartment buildings, several churches

MATHESON FIRES, ONTARIO, 1916

Area burned: 500,000 hectares

Damage: 244 fatalities, 49 townships destroyed

Cause: People escaped clearing fire

Worst wildland fire in Ontario’s history

KETCH FIRE, 1958

Largest fire in B.C. history

Area damaged: 225,920 hectares

Loaded with safety, comfort and mobility features for unmatched performance, Flame Fighter® bunker gear offers a variety of custom outer shell fabric, liner system, hardware and pocket options to fit your specific needs. This hard-working gear also includes the following game-changing Starfield LION fire protection technology:

• Patented IsoDri®* moisture management reduces the water absorbtion and helps gear dry faster between runs

• Exclusive Ventilated Trim allows vapor to be released, reducing the risk of scald burns

• Thermashield™ provides an additional layer of liner material in the upper back and shoulders to protect against compression burns

• Move-N-Hance™ crotch gusset increases mobility by reducing bunching, twisting and pulling

• Flex Knee™ for easy, natural movement

• Stay Rite™ sleeve wells integrate the sleeve’s liner into a full-length wristlet so that when you reach, the entire sleeve moves with you

For more information about Flame Fighter bunker gear, contact your Starfield LION sales representative at 1.800.473.5553 or visit us online.

Command, control, communication

Co-operation necessary to ensure smooth response

By Dan Verdun

The County of Grande Prairie in Alberta, in early conversations with Grande Prairie Regional Emergency Partnership (GPREP), had committed personnel for deployment for the incident occurring in Fort McMurray. This commitment was for roles specific to the Incident Management Team (IMT). (GPREP is an emergency response partnership comprising the County of Grande Prairie, the City of Grande Prairie, the Town of Wembley, the Town of Beaverlodge, the Town of Sexsmith and Village of Hythe.)

I attended meetings and conference calls co-ordinated among the Provincial Operations Centre (POC) the M-9 Group (nine of the largest city fire departments in Alberta) and GPREP, during which it was determined that there was a need for personnel. In further meetings with representatives from the GPREP group, both the county and City of Grande Prairie decided to send one person each to be deployed as part of the IMT. Platoon Chief Bart Johnson and I were asked to deploy to the incident. This deployment was confirmed at approximately 12:00 on May 4. We prepared and were on the road at 18:00. A stipulation of this deployment – co-ordinated through the M-9 group – was that we would meet up with Canada Task Force 2 (Can-TF2) and caravan into Fort Mac. Contact information was exchanged and we were on the road to meet with Can-TF2 in Athabasca. At 01:30 and with additional communication, we met with

Areas of growth

Planned accountability systems for all municipalities prior to major incidents; adoption of a standard incident command system; stronger internal communications between the REOC and PEOC to ensure that all sections and site command are on the same page.

personnel from Can-TF2 in Grasslands, where we worked to co-ordinate a place to rest and rehab until our actual deployment into Fort Mac. Approximately one hour later we were provided with a local elementary school gym in which to rest. At 03:30 we caught some sleep until we mustered again at 06:30.

Just before 08:00 we travelled the remaining distance to Fort Mac with Can-TF2. Driving conditions approaching the city were poor; active fires were burning along the route and at times visibility was minimal. As we got closer we observed natural gas risers actively on fire and areas completely consumed. We also noted many abandoned vehicles along the route.

Our entry into Fort Mac was somewhat surreal. Along the highway we encountered RCMP road blocks with an inordinate volume of press, and as we passed we became the fodder for pictures and film.

Somewhere around 11:00 we arrived in Fort Mac at Fire Hall 5. At the hall we participated in a briefing by Can-TF2 during which its members co-ordinated their initial priorities and assignments. We, as part of the IMT, were sent into the hall where the regional emergency operations centre (REOC) was established. We were informed that, based on current conditions, evacuation of this site may occur with short notice.

PHOTO: DAN VERDUN

County of Grande Prairie Deputy Chief Dan Verdun worked in planning in the REOC in Fort McMurray alongside local authorities and members of CAN-TF2.

Observed conditions in the surrounding area were not good. Active fires were burning near our site, both to the west and south. Smoke conditions on arrival were manageable and visibility was fair, but this deteriorated dramatically at night.

We were ushered into the REOC where we signed in and participated in a situation report (sit rep) update. The fire at that time was described as out of control, with many areas of the city still threatened. Although damage was understood, no actual damage assessment had been done at that time due to defensive fire conditions and accessibility issues. The weather forecast was not promising. The overall feeling in the REOC was optimistic but remained realistic. Fort McMurray Fire Chief Darby Allen said a few positive words to conclude the sit rep and provided his priorities for the day.

After the sit rep we were introduced and asked to provide our bios and areas of expertise. Johnson and I said we were comfortable in any role and would facilitate any needs as assigned. We were mustered into a hallway with members of Can-TF2 and waited for assignment. A couple of hours later we were assigned to the planning section and designated shifts; I was given nights. Shifts were 12 hours long, starting at 08:00. I was told to catch a few hours sleep, which I attempted to do in our vehicle.

To see a city of this size without anyone in it other than emergency responders is something I will remember for some time.

I reported for duty at 19:00 for the briefing and assignments. I was introduced to our planning chief, Calgary Police Supt. Ray Robitaille. After more introductions I was assigned as demobilization unit lead. The unit’s initial objectives were to determine the needs of the REOC manager and operations section for the operational cycle and work to complete the tasks from day shift.

For the next days of deployment, my planning section focused on short-term and long-term planning that encompassed everything from evacuation plans for the 25,000 people north of Fort Mac to Alberta Premier Rachel Notley’s visit. We also worked to co-ordinate a damage assessment to get an idea of what was actually lost. Early on we focused on a phased re-entry plan that included restoration of critical infrastructure and getting both businesses and residents back into the city. Planning stayed dynamic and we worked with the REOC manager to stay

Fort McMurray Fire Chief Darby Allen briefs Premier Rachel Notley in the regional emergency operations centre. Continued communications and co-ordination between government groups is crucial.

in front of the incident, amending or modifying plans as required.

On a personal note, Robitaille was extremely professional and well versed in his role and it was my pleasure to work with him and all the planning personnel on my shift.

Working conditions were not the best for the first several days of operations. The REOC was without primary power and potable and non-potable water. Smoke conditions, especially during the evening, were very poor and most personnel were forced to wear air-purifying respirators while on shift. Without power, heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems were non-operational and our ability to control the environment did not exist. Our operations were run using generated power and portable facilities until Day 4 of my deployment.

The task force was able to provide basic requirements to our responders in the form of housing, food, potable water and other basic needs in short order. My hot shower on Day 3 was a welcome relief.

I had the opportunity to drive around the city during my down time; the speed and urgency of the evacuation was apparent in many obvious indicators. I saw abandoned vehicles, businesses not having had the chance to put away exterior displays, and animals (pets) still in their homes. To see a city of this size without anyone in it other than emergency responders is something I will remember for some time. I was deployed for a tour in Slave Lake, Alta., after the wildfires in 2011, and although there were many similarities in damage and impacts to

residents, the sheer scale of Fort McMurray makes this disaster different. Imagine an event that causes more than 80,000 residents and workers to evacuate.

Based on my opinion and observations from my tour I have this to say: I think, for an incident of this scale, it went and continues to go remarkably well. A lot of well-meaning responders did and are doing a lot of work to ensure the safety of the general public and other responders and to minimize the level of potential damage.

I would encourage any municipality to have protocols in place to ensure personnel accountability for safety of responders in a structured manner at the beginning of the incident. I would suggest the incident command system be completely adopted and not modified to suit the needs or perceived needs of the incident. I would finally suggest that internal communications between the REOC and the Provincial Emergency Operations Centre (PEOC) be strengthened and structured to ensure that all sections and site command are on the same page and all needs of the site (boots on the ground) are addressed first and foremost. The entire purpose of the PEOC/REOC initially is to support the responders.

These are my personal observations about areas of growth. The responders with whom I worked and interacted were all exceptional people with no hidden agendas. They, like me, were there to make a positive difference and help a community in need. Some of the people with whom I had the pleasure of working were from Fort McMurray and in some cases, had lost everything, yet they found the resolve to help their community and fellow residents; this to me was very humbling to witness. I do not attempt to detract from the amazing job done in a hectic time by any and all personnel, but, as with any incident, lessons learned will only make us stronger.

As Alberta continues to experience incidents of this scale occur with more regularity we need to ensure continued communications and co-ordination between government groups (incident management teams, both provincial and municipal) to provide professional response. This communication needs to occur previous to these incidents and not when the request to respond occurs. Further, continued training in emergency management for any agency wanting to respond to such incidents is paramount. These are my opinions, but I feel that they will allow us to better respond for the next incident when it occurs.

Dan Verdun is the deputy fire chief of rural operations and training for the County of Grande Prairie Regional Fire Service in Alberta. Verdun began his fire career in 1995 with Union Bay Fire Rescue on Vancouver Island. Employed by Grande Prairie in 2010, Verdun has specialized training in emergency management, fire-service instruction, fire officer and fire prevention programs. He is a fire safety codes officer.

The drive into Fort McMurray was surreal; active fires were burning, at times visibility was minimal; there were natural gas risers actively on fire and many abandoned vehicles.

PHOTO: DAN VERDUN

WILDFIRE

TIMELINE

MAY 1

A fire starts in a remote part of forest southwest of Fort McMurray. Investigators don’t know how it started, but have noted that most spring wildfires are caused by people. A dry, warm spring and trees that are still greening make for lots of fuel. Fire is spotted by helicopter fire patrol. Helicopter begins working the fire immediately. First air tanker arrives 45 minutes later, then three others arrived from Lac la Biche, Peace River and Whitecourt. Two tankers stayed the night in Fort McMurray to be ready to go the next morning

MAY 1, 7:08 P.M.

The Alberta Emergency Alert system warns people who live in Fort McMurray’s Gregoire neighbourhood to prepare to evacuate on short notice.

MAY 1, 10:33 P.M.

A state of local emergency is declared and a mandatory evacuation order is issued for Gregoire as well as for Centennial Trailer Park south of Airport Road.

MAY 6, night

The fire is more than 1,560 square kilometres in size.

MAY 7

The fire is more than 2,000 square kilometres in size and still growing as it spreads east toward the Saskatchewan boundary.

MAY 9

Notley says 2,400 buildings were lost in the fire, but she praises firefighters for saving 25,000 more. Reporters are taken on a tour of devastated neighbourhoods.

MAY 6, morning

The Alberta government says it will provide cash to 80,000 evacuees to help with their immediate needs. Notley says cabinet has approved a payment of $1,250 per adult and $500 per dependant at a cost to the province of $100 million.

MAY 4, 10:23 A.M.

Premier Rachel Notley says the wildfire has destroyed roughly 1,600 structures in the city.

MAY 4, 3:57 P.M.

The Alberta government declares a provincial state of emergency so it can take control of the response.

MAY 6, 6 A.M.

A massive convoy gets underway to move evacuees stranded at oilfield camps north of Fort McMurray through the fire-ravaged community to safe areas south of the oilsands capital. The RCMP and military oversaw the procession of an estimated 1,500 vehicles on Highway 63.

MAY 10

Notley says the fire did not damage any oilsands plants to the north of the city. She says the province and the energy industry are working together to restart oilsands projects as quickly as possible.

MAY 13

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tours the city. He says Canadians have yet to grasp the scope of what happened and the lengths firefighters went to in saving almost 90 per cent of Fort McMurray.

MAY 16

Notley says the air quality in Fort McMurray is at dangerous levels and is hampering efforts to get residents back to their homes. The air quality health index scale is normally one to 10, with 10 being the worst, but the reading that morning was at 38.

Fire officials say the blaze, now at 2,850 square kilometres, remains out of control and a threat as crews deal with hotspots.

MAY 16, 4:45 P.M

Work camps north of Fort McMurray that had been re-populated as the oilsands attempted to restart are cleared again as the wildfire pushes north.

Mandatory evacuation notice for Gregoire is reduced to a voluntary, shelter-in-place notice and people are allowed to return. The 700 residents from the trailer park as well as another neighbourhood, Prairie Creek, remain out of their homes.

MAY 2, during the day

Aircraft drop fire retardant and ground crews work to protect homes. The fire is one-square-kilometre in size. “We are hopeful that we can stop this fire before it gets into town,” says Wood Buffalo fire Chief Darby Allen. The fire is within one kilometre of homes at points, but the wind is pushing it away from the city. The evacuation order for Prairie Creek is lifted in the evening. “All things considered, it is looking good,” says Mayor Melissa Blake.

Overnight on MAY 2 and the morning of MAY 3

The fire grows to 26 square kilometres, but is still moving away from the city. Life in Fort McMurray seems relatively normal. Allen warns people not to let their guard down.

MAY 3

All of Fort McMurray is placed under mandatory evacuation order.

MAY 3, 3:45 P.M.

There’s chaos on the city’s south side as people flee towering walls of orange flame that are charging into neighbourhoods. Residents are told to head either north or south, depending on their location, on the one highway through town. The evacuated trailer park is on fire. Flames are advancing toward a Super 8 motel and a gas station. “People are panicking. It’s gridlock on the roads,” says Carina Van Heerde, a reporter with radio station KAOS.

MAY 18

The wildfire has now scorched more than 3,500 square kilometres as conditions remain dry and windy.

MAY 19

Officials say the threat of the Fort McMurray wildfire has diminished as the flames move into Saskatchewan. Crews have been successful holding the fire back from oilsands facilities and work camps. The blaze has burned 5,000 square kilometres, the same amount of forest as all fires consumed in Alberta in 2015.

MAY 20

Conditions have improved enough for the province to bring in an extra 1,000 firefighters over two weeks to try to gain an upper hand on the fire.

MAY 3, 10:30 A.M.

A change in normal atmospheric conditions, called an inversion, breaks. This, coupled with temperatures in the range of 30 C, low humidity and shifting winds, causes the fire to explode.

MAY 3, 2:25 P.M.

Flames are heading toward the city and huge plumes of smoke are visible. Residents of three south-side neighbourhoods are ordered from their homes. There’s shock at how quickly the situation has deteriorated: “When I got in the shower earlier today the sky was blue. When I got out, the sky was black,” says resident Sandra Hickey.

MAY 24

Oilsands workers begin the process of restarting their projects.

MAY 30

Re-entry remains on track, but Notley says up to 2,000 evacuees will not be able to return until possibly September. She says more than 500 homes and about a dozen apartment complexes that escaped the wildfire in three otherwise heavily damaged neighbourhoods are not safe to be lived in yet; that conclusion was reached with health experts following tests on air, soil, ash and water.

JUNE 1

People in some of the least damaged areas of Fort McMurray are allowed home.

PAY BACK

Continued from page 18

get better with every day that goes by; we in High River learned this and, at the time, it’s very hard to believe things will get better, but they do.

During floods and fires it is truly amazing to see how departments across the province can come together and work alongside each other to help mitigate a massive disaster. A lot of connections were made that will never be forgotten and the camaraderie that all the crews showed was inspiring. Some of the unsung heroes who were very essential to the operations were the water-tender truck drivers who were following the fire trucks to provide us with much needed water where there were no hydrants. These folks worked alongside us, pulling hose, helping in any way they could. Bikers for Veterans and the other people working in the rec centre worked hard to make sure guys had dry socks, making coffee, and finding other supplies to help keep the fire crews going. Bikers for Veterans also had a small barbecue set up and were cooking whatever they could find; these people worked tirelessly for days to make sure the emergency service crews all got something to eat and were taken care of.

Being in Fort McMurray has once again opened my eyes to the fact you never know when a disaster will strike and that we should be prepared. I never would have thought that I would see another disaster of this magnitude in my life but this was the second in three years. I hurt for the people of Fort McMurray who have lost everything, and the people who still have homes but don’t know what they are going to be walking into once they get back.

I was very proud to be with my HRFD family; they were a hard-working, non-stop crew and our two officers made every effort to ensure the safety of our crew. I heard it multiple times from my officers as well as the Fort McMurray officers: “Everyone goes home once this is all over.”

Cody Zebedee is a part-time firefighter with the High River Fire Department and a full-time captain with Foothills Fire Department’s Heritage Pointe Station.

Firefighters Cody Zebedee and John Badduke put out hot spots near Highway 63 and Highway 881 in Fort McMurray.

PHOTO: LANE HALL

GLOVES

Highly dexterous, durable protective barriers remain intact after repeated exposure to high heat.

TURNOUT

GEAR

Gore moisture barriers and liner systems manage heat stress better because they are the most breathable across multiple environments.

BOOTS

Leather boots that include a protective barrier provide better footing and decon more effectively than rubber.

It’s essential to understand what materials go into your gear and how they perform and hold up. To increase your safety and improve gear performance, Gore continues to push the technical capabilities of personal protective equipment. Knowledge is powerful, and the more you know, the safer you are.

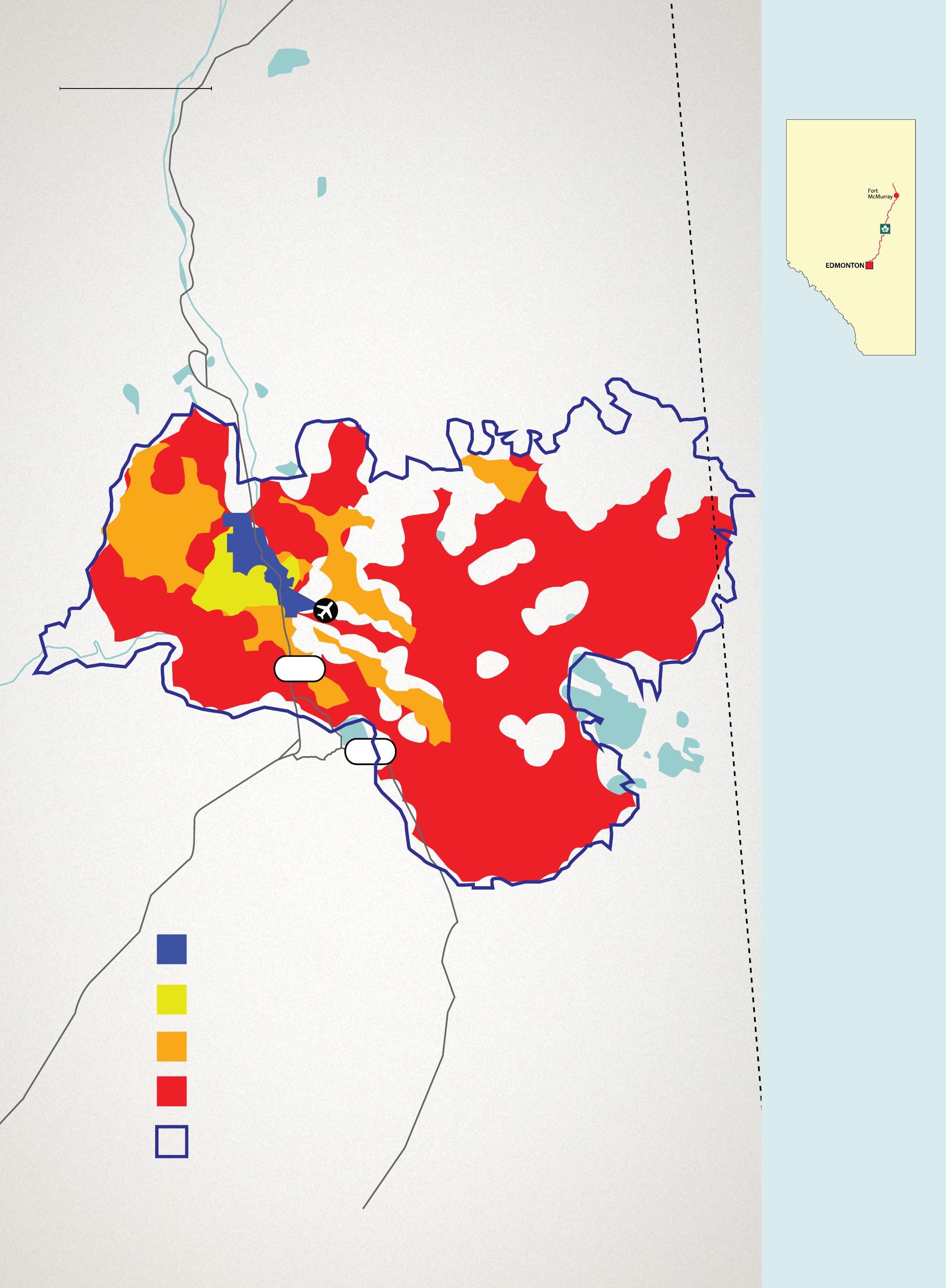

Footprint of a wildfire

587,000 hectares burned

1,000-km perimeter

Resources to fight the Fort McMurray fire included 1,665 wildland firefighters and support staff, 59 helicopters and 194 pieces of heavy equipment.

Resources to fight wildfires across Alberta included 2,794 firefighters, 147 helicopters, 16 tankers, 233 pieces of heavy equipment.

As of June 9 there were 20 active wildfires in Alberta, eight out of control.

As of June 8 the Fort Mac fire was almost 70 per cent contained. At 1600 hours on June 9, the provincial operations centre reverted to operational level 3.

Source: Government of Alberta www.alberta.ca

SHIPPING & TAXES EXTRA

HOLDING THE LINE

Structural triage a challenge for municipal firefighters

Editor Laura King spoke with Chris Fuz Schwab, the deputy chief in Smoky Lake, Alta., after he returned from Fort McMurray. This is an edited transcript of their conversation.

The province contacted our director of emergency management and requested us on Tuesday, the day the fire took off, and we happened to already be at a fire in our own area and couldn’t immediately respond, so the province pretty much ordered us to go to bed and be ready to leave first thing in the morning. We left Wednesday after getting all of our stuff in order – three of our members in a pickup with our structural gear and some food and water and went for the long drive up to Fort Mac.

At first the province asked for fire trucks and the next day just said get manpower here – structurally qualified, NFPA 1001 guys.

Our purpose was strictly structural fire fighting.

Well, we got stopped by RCMP – the highway was shut down. They didn’t want to let us through and we told them pretty well we’re going through. We had respirators with us and we put them on and drove through fire and smoke to get up there. After we passed them and

some RCMP in black SUVs – which is pretty interesting – we reported to command at MacDonald Island and we got into the queue; there was a line up of rigs and trucks that were already there or were just pulling in and we were deployed within the first 10 or 20 minutes.

We were up in the Timberlea neighbourhood; we split up and jumped onto whatever rig we could get on. My two boys went with a private company, Fire Power, and I jumped in with the City of Leduc.

We got to the scene and obviously many homes were already on fire a little ways down the road and we were instructed to set up a defensive line, which we did; there were probably six to eight 38-millimetre lines between houses.

We watched as the fire moved toward us, block by block, house by house by house.

There was another group – several engines and an ARFF truck –that was probably two blocks from us and we were watching the fire come towards us. We were considered the last line – if the guys had to bug out of where the fire was, which did happen . . . We were spraying down houses and trying to buy time to make a proper defensive line. We retreated probably twice, and ended up back up against a row of houses in the backyards. We stayed there the night – I don’t know how many hours we were in that spot. We got back to the station about 9 a.m.

We were watching the houses in front of us burn down one after another. It was fast but in your mind you’re just watching . . . one,

two, three houses.

We got a rest on the scene here and there – you’d see guys that would pull back and would have time to reassess, and guys would be sleeping on their trucks – quick 10-minute power naps. We had a lot of guys up there so we were able to do it safely.

After we held the line on this one specific street, we woke the guys in the morning and looked around and did a quick assessment; our areas were safe. We looked around and saw how far the fire had spread and it was unbelievable. There was no place to sleep so I slept in the box of the truck and my two guys slept in the cab. We grabbed a bite to eat from a biker lady named Betty – a turkey sandwich, the best food I’d ever had. She’s my hero. So we had a quick bite and just gave that lady a hug and got back in the queue. We had about an hour’s sleep.

We were deployed again to the downtown core, looking for spot fires. This was Thursday, when the city was completely encircled – the fire had circled to the east side of the city; there’s a big hill on one side, all forested, and it burned around there and jumped in a couple of spots.

We were just in our pickup trucks – a few departments there; us, St. Paul, Cold Lake and Greenview, all in pickups. I think we did a good job; we found one structure fire – a garage burning and we put that out with limited water and makeshift hand tools (pretty much garden tools that we found in people’s yards).

We did the downtown all day and

all night – I can’t remember what time we got back the next day.

We stayed Thursday and Thursday evening – all downtown. It was like it was snowing downtown, but it was all ash. That’s something that I’ll never forget. We went again for what everyone deemed was our mandatory naptime – which, again, was probably another hour.

Friday we ended up back in the queue and ended up being deployed to Saprae Creek out by the airport, putting out spot fires around homes and prepping yards for the fire to come through for the second time, through this neighbourhood that had been burned out already. But we lucked out – we got the water bombers and planes and helicopters. We were pretty much there at Saprae Creek the entire time until

10-11 p.m., I’m guessing, and then we reported back in and tried to get back in the queue. I think the staging officer noticed us getting back in the queue and said no – mandatory naptime again. And we did nap. I talked to the IC on scene [Parkland County Chief] Brian Cornforth – because we had already been up there for quite a few hours already and asked at what point did

he want replacements – and he said, “What in the heck? You guys are only supposed to be here for 48 hours.” But nobody told us . . .

We stayed overnight just in case; during the daytime there was a lull – we had time to mentally get ready for the evenings; but the evenings, Wednesday and Thursday, when we were there, were pretty scary. It was constant work – moving hose, advan-

We were mentally prepared to go in and put out hot spots; we didn’t realize that we’d be defending neighbourhoods and watching all these houses burn.

Smoky Lake Deputy Chief Chris Fuz Schwab and two firefighters deployed to Fort McMurray on Wednesday, May 4; they spent three days protecting neighbourhoods, setting up defensive lines, putting out spot fires around homes and prepping yards in case the fire returned.

cing lines, backing out, then advancing again, so it was nice to be told sleep was mandatory. When we got back I called ahead and told my DEM we need to sit down for diffusing and we did; we sat down and discussed what happened and our feelings about some of the stuff we had to do on those evenings, which I won’t go into

[While we were in Fort Mac] upstairs in the evacuation centre, where we had been told to get a bite to eat because at that point there was nobody in there, we talked to an evacuee who asked us questions; we were trying not to say anything that would give her false hope

or upset her and, of course, we don’t know everything because we were assigned to an area. That was tough and I think she noticed that . . .

[Back at home] we had just watched hundreds of homes burn. Dealing with it afterwards . . . we thought we had. We had a fire call later on and I didn’t go – I stayed back and while the boys were at a fire we got a phone call for somebody burning in their backyard during the fire ban and I went there and kind of exploded on the guy and then broke down. I don’t remember much about it but that poor ratepayer came up and gave me a big hug after I blew up on him, and my chief

and my DEM got me help and now I’m dealing with it.

My guys too, they’re talking about it and I try to get them also talking about past events too. In my case, it wasn’t just the actual event, even though it was pretty messed up some of the stuff we were witnessing, it was a triggering event, after 13 years.

I’ve always said that we probably have the best CISM groups and we always call in victim services for our guys and we always sit down and talk and low and behold, all it takes is somebody with a little campfire in their backyard and I’m definitely rethinking my approach on CISM now.

We were mentally prepared to go in and put out hot spots; we didn’t realize that we’d be defending neighbourhoods and watching all these houses burn.

The big thing on our defensive line was structural triage – we were not leaving this spot; these houses were staying. We had a back-up plan if we had to bail – we had deck guns set up.

This one captain from Wood Buffalo . . . Archer, he had a house in Saprae Creek that burned and he was in charge of our line. The last time I saw him he was sitting on a lawn chair and his boys were sleeping; that was Thursday morning. We went and told him that it was one hell of a night and he just had this big grin on his face because he was happy we had saved that row of houses. I’d like to shake that man’s hand again.

A lot of times we did what we absolutely had to do in that moment to keep our guys going; it was chaos at times, but boots on the ground and on the attack lies it was organized and everybody did their best.

“Morning after the longest night of my life,” Chris Fuz Schwab wrote with this photo on Facebook on May 7 after holding the line in a neighbourhood in Fort McMurray.

Chris Fuz Schwab and Sheldon James on a break in Fort McMurray, where they protected homes from the raging fire in early May.

Specialized training for a front-line career

With one of the most advanced training facilities in Canada, we challenge you to be the best you can be at our Emergency Training Centre in Vermilion, Alta. From burning buildings to dangerous goods explosions and ambulance transports, with each scenario you work through you develop life-saving skills and gain the confidence you need as an emergency responder.

Choose from:

Emergency Services Technology (diploma)

Specialize in medical or firefighter stream

Firefighter (certificate)

Select face-to-face or online delivery

Tackling the interface

Preparing urban and wildland firefighters to properly handle structural protection

By Jamie Coutts

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the September 2015 edition of Fire Fighting in Canada. It has been updated.

The wildland/urban interface is a tricky area.

I can say from the experience that we had in May 2011 when 40 per cent of Slave Lake was burned by wildfires and another 45 homes lost in the surrounding area, that we were unprepared.

I have spoken across Canada about what happened that day. I like to think that our regional fire department has done phenomenal work to try to get ourselves to a new standard.

The solution, as I see it, is simple: Get firefighters from both sides, who are already the best at what they do, and bridge the training between wildland firefighting and structural firefighting.

In Alberta, we are lucky to have a stateof-the-art wildland training centre in Hinton. We are also lucky to have many qualified schools, and fire departments that provide instruction to become NFPA 1001 structural firefighters.

All agencies try to tackle the wildland/ urban interface problem with some type of training – NFPA 1051 (wildland) or Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (ESRD) 215 sprinkler training – which is tough, because no agency focuses solely on structural

protection during wildfires.

As I stared at 12 Avenue SE in Slave Lake in May 2011 while 35 houses, dozens of campers, and even more vehicles burned around me, I remember thinking: 1. We were never taught to expect anything like this. 2. I will do my best to make sure nothing like this ever happens again. These thoughts were later joined by another: After this happened in Kelowna in 2003, why didn’t we all learn from that?

Since 2011 the Lesser Slave Regional Fire Service has been involved in several projects to better train our firefighters and make our community safer.

The government of Alberta spent $20

million in and around our community to FireSmart the area and make it safer. I can tell you from the grey hair and stress that this has been no easy feat, but I will also say it had to be done, and the pressure to provide accountability was immense.

The project hinged on the seven disciplines within the FireSmart Canada program:

1. Fuel management

2. Education

3. Legislation

4. Development

5. Planning

6. Training

7. Inter-agency co-operation

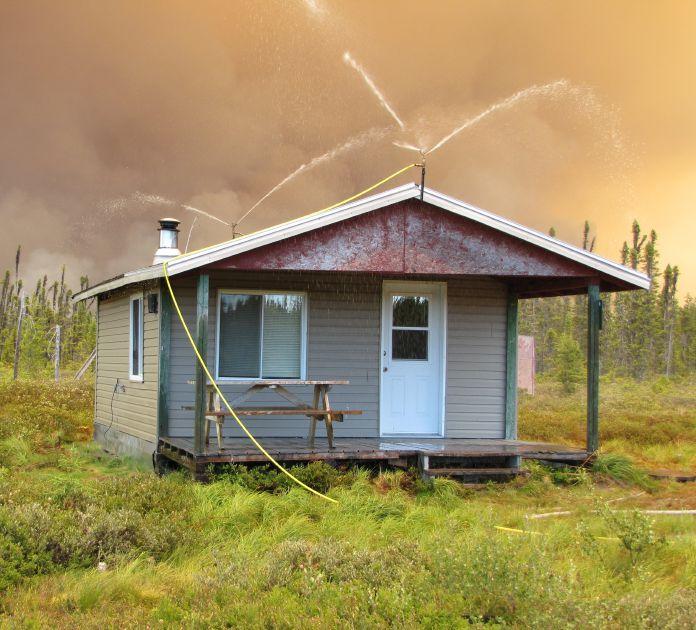

Structural protection sprinklers change conditions around a dwelling. The soaked landscape releases moisture into the air that increases the humidity. Advancing wildfire will bypass the protected property.

Within each discipline there were dozens of projects, committees, meetings and discussions. It would take months for me to tell you all that we learned. Is the FireSmart project done? No. It never is. But I will say that we are headed in the right direction, with the right people, equipment and knowledge. We have tried very hard to share what we have learned and to engage new agencies along the way.

We have a young team of fire-service professionals here that was custom-built after the 2011 fires, as part of the FireSmart program. This FireSmart crew is trained in all aspects of the fire world including:

• Wildland firefighting

• NFPA 1001, structural fire fighting

• NFPA 1002, aerial ops

• NFPA 472 ops, dangerous goods

• Emergency medical responder

• S-215 structural protection

• Search and rescue, basics, team leader, manager, incident leadership

• Basic fire safety codes officer

• Technical rescue, rope, ice, confined space, boat

• Incident command system 200

• Emergency preparedness

• FireSmart, home assessments, vegetation management, heavy equipment use

• Chainsaw faller certification

• Alberta Forestry helicopter attack crew

• Forestry leadership course