VERTICAL FARMING

The rebirth of an old technique PG. 14

yourTracingbeer

NEW TECH ALLOWS BREWERS TO IDENTIFY THE FARM THAT PRODUCED THE MALT BARLEY PG.20

+ REGULATORY AFFAIRS PG. 22 THE PATH FORWARD FOR SUPPLEMENTED FOODS

The rebirth of an old technique PG. 14

NEW TECH ALLOWS BREWERS TO IDENTIFY THE FARM THAT PRODUCED THE MALT BARLEY PG.20

+ REGULATORY AFFAIRS PG. 22 THE PATH FORWARD FOR SUPPLEMENTED FOODS

Fabbri Automatic Stretch Wrappers produce low-cost, highly attractive packages that make your products look fresh and “just packed”.

n Uses stretch film to overwrap fresh food products in preformed trays

n Produces tight, over-the-flange, wrinkle-free pack ages with securely sealed bottoms

n Handles a wide range of tray sizes with no changeovers to reduce downtime and increase production.

n Up to 75 packs per minute

JULY/AUGUST 2021 • VOL. 81, I006

Reader Service Print and digital subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Anita Madden, Audience Development Manager Tel: 416-510-5183 Fax: 416-510-6875 Email: amadden@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

ED ITOR | Nithya Caleb ncaleb@annexbusinessmedia.com 437-220-3039

MEDIA SALES MANAGER | Kim Barton kbarton@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5246

MEDIA DESIGNER | Alison Keba akeba@annexbusinessmedia.com

ACCOUNT COORDINATOR | Alice Chen achen@annexbusinessmedia.com 416-510-5217

VP/GROUP PUBLISHER | Diane Kleer dkleer@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO | Scott Jamieson sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com

Publication Mail Agreement No. 40065710

Subscription rates

Canada 1-year – $84.95 per year Canada 2-year – $124.95 Single Issue – $15.00

United States/Foreign – $159.95 All prices in CAD funds

Occasionally, Food in Canada will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe could be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our Audience Development in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Officer Privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com 800-668-2384

No part of the editorial content of this publication can be reprinted without the publisher’s written permission @2021 Annex Business Media. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

Mailing address

Annex Business Media

111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1 Tel: 416-442-5600 Fax: 416-442-2230

ISSN 1188-9187 (Print) ISSN 1929-6444 (Online)

Funded by the Government of Canada. Financé par le gouvernement du Canada.

In early summer, I attended the virtual Future Food-Tech’s Alternative Proteins Summit. It focused on three key pillars of alternative proteins: plant-based, cell-based, and microbial fermentation, and brought together CPG leaders, entrepreneurs, investors, ingredient developers, retailers and food service providers to unpack the possibilities of new technologies.

In his keynote address, Marco Bertacca, CEO of Quorn Foods, urged attendees to imagine the possibility of creating protein from waste. He made a convincing case for the same.

In his opening remarks, Bertacca focused on world hunger. He mentioned the United Nations believes it is almost impossible to achieve zero hunger by 2030.

“We have to openly acknowledge that the global food system is broken,” he said. The stats are indeed staggering. In 2019, 690 million people went hungry, an increase of 60 million in five years. The pandemic has left another 130 million people in chronic hunger.

However, the issue facing food industry leaders is not just hunger. Bertacca went on to highlight the fact that around two billion people are obese, and 460 million are underweight. He emphasized that all of this is happening while ⅓ of the food produced for human consumption is wasted globally. This is equivalent to 1.3 billion tonnes per year.

“While no single company, government or individual will be able to fix the food system by themselves, a global and collective effort will,” stressed Bertacca. “There is an urgent need for mankind to adopt alternative protein sources in a huge scale. We are looking to produce enough alternative protein to reduce our overall reliance on planet’s damaging animal protein.”

According to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture. Recently, Kings College London has estimated that every year, arable farming produces eight billion tonnes of carbohydrate waste.

“If we can find a way to ferment that carbohydrate and make microproteins, we would produce the same amount of protein that we would get from five billion cows, three times more cows than we currently have on the planet. Even if we could achieve a fraction of this, it would be a game changer. We could produce a superprotein to feed the world as well as reduce the carbon footprint created by food production,” said Bertacca.

One of the highlights of the summit was Future Food-Tech’s Innovation Challenges with Quorn Foods and Roquette. NotCo and Umiami won the contest. The Quorn Foods’ challenge

Nithya Caleb

was “technologies that help to achieve a whole muscle food experience.”

Roquette asked for “plant-based products offering new gastronomic experiences to the consumer.”

NotCo uses AI technology to replicate animal protein and develop plant-based products. Umiami is developing a unique technology to texturize plant proteins.

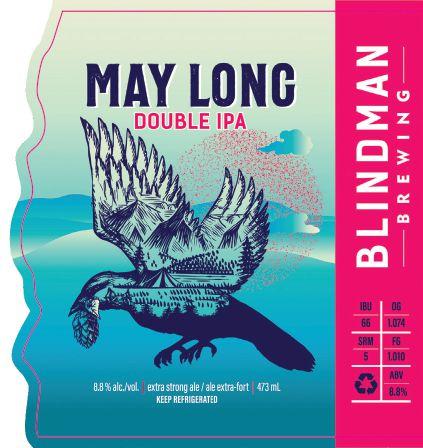

Bertacca’s address and the overall summit inspired us to highlight some technologies that can address food security in a sustainable manner. Vertical farming is becoming popular; you can pick a bunch of freshly and locally (in the store itself) grown greens from a grocery story. Why is this age-old technique being resurrected? Find out on pg 14. Another interesting initiative is the world’s first fully traceable beer. Blindman Brewing and Grain Discovery collaborated to build an end-to-end digital system to trace Canadian grown malt barley through every stage of the value chain, from the field to a customer’s glass. Check out pg 20 for details. While labelling wars rage around the world, Canada has launched a certification program for plant-based products. Read about it on pg 18. On pg 24, we discuss the need for food products to be apportioned precisely and packaged correctly.

Nithya Caleb ncaleb@annexbusinessmedia.com

Nabati Foods Global, Inc., completes the construction of a new manufacturing facility in Edmonton. It is five times larger than the company’s current plant. The extra square footage will enable the company to house its full R&D department and expand its team by 150 per cent to 15 members. Additionally, the facility will be able to produce 1.2 million pounds of plant-based cheese and 1 million pounds of plant-based meat. This additional capacity will also give Nabati the ability to put additional resources into product development.

In May, JBS U.S.A. was the target of an organized cybersecurity attack, affecting some of the servers supporting its North American and Australian IT systems.

The company took immediate action, suspended all affected systems, notified authorities and activated the company’s global network of IT professionals and third-party experts to resolve the situation. Production was shut down for a few days at some facilities of both JBS U.S.A. and Pilgrim.

In June, JBS U.S.A. announced that it paid the equivalent of $11 million in ransom. “This was a very difficult decision to make for our company and for me personally,” said Andre Nogueira, CEO, JBS U.S.A. “However, we felt this decision had to be made to prevent any potential risk for our customers.”

New sheep milk processing centre opens near Toronto Ovino is a new venture that houses more than 2000 sheep. It employs state-ofthe-art feeding, bedding and milking automation technologies. The sheep are fed and bedded by electrically powered TKS feeding and bedding machines that hang on the ceiling and travel along structural steel rails.

The sheep are milked twice a day in a rotary parlour that can milk up to 1000 sheep per hour. The sheep milk is then processed on-farm to produce fresh sheep milk and sheep yogurt.

grow for a national agrifood sustainability index

Momentum is building to establish Canada’s first agri-food sustainability index. A private–public coalition of 34 diverse partners has released the “Business Case for Establishing the National Index on Agri-Food Performance.”

The index would be housed in a newly proposed Centre for Agri-Food Benchmarking, a neutral and authoritative body with shared private–public leadership and governance. The centre would enable stakeholders to collaborate and prepare an integrated picture of sustainability from farm to retail. Its work would be based on science-driven and verified indicators and be informed by sectoral benchmarking work and national statistics.

The coalition now seeks feedback from stakeholders and to broaden its representation as well as identify the optimum path to financially support the project by the fall. The intent is to publish the index by late 2022. For more information and to share feedback, email David McInnes, co-ordinator, Nation-

al Index on Agri-Food Performance Project, at daviddmcinnes@gmail.com.

Weston Foods announces its Suppliers of the Year, recognizing suppliers that exemplify the North American bakery’s value of commitment and went beyond expectations. Each year, the company selects four award recipients, one for each of its four procurement towers of commodities, ingredients, indirect procurement and packaging. This year the awards went to P&H Milling Group, Port Royal Mills, Gforce Custom Fabrications & Installation, Inc., and E.B. Box Company.

New $1.9M project to develop a plant-based seafood line

Protein Industries Canada is co-investing in a project with New School Foods and Liven Proteins to develop plant-based seafood products. The project will focus on developing a whole muscle, plantbased fish filet that emulates the texture, taste and cooking experience of fish.

> Kerry releases new dairy-free flavours in its Big Train product family of hot and cold beverage mixes for use by foodservice operators. Fortified with Kerry’s GanedenBC30—a probiotic ingredient that helps support digestive and immune health—the four new non-dairy flavours are horchata, caramel latte, latte and mocha.

> C-P Flexible Packaging (C-P) unveils a Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI)-certified compostable coffee pod lidding film designed for single-serve coffee makers. C-P’s proprietary compostable lidding allows several prongs to puncture the coffee pod without tearing, allowing multiple streams of hot water to saturate coffee grounds—extracting more aroma and flavour.

> Cinnamon specialists Royal Polak Spices , a wholly owned subsidiary of Barentz International B.V., have launched their products in North America. Royal Polak’s ingredients include all varieties of Cassia and Zeylanicum cinnamon. Cinnamon blends are available with Kosher, Halal, Organic and Fair-Trade certifications.

This co-investment will allow New School Foods to expand its research and development efforts by partnering with additional universities and private laboratories, allowing them to more quickly and successfully achieve their product development goals. It will also accelerate Liven’s development of protein ingredients through its precision fermentation platform, and will enable the company to bring these ingredients to the marketplace.

The Kemin Flour Tortilla Guide is a new downloadable performance resource, complete with troubleshooting checklist, to help tortilla manufacturers resolve common performance challenges.

In the guide, Kemin Food Technologies – Americas examines 12 of the most common tortilla manufacturing problems and features various solutions to each challenge. Manufacturers can use the guide to easily search and find the needed remedy for any number of issues with which they might be struggling.

Several associations have formed the Canadian Food Industry Collaborative Alliance, and developed a framework for industry leaders to develop a Canadian Food Industry Code of Practice.

The members of the alliance represent thousands of small, medium and large businesses in the Canadian food supply chain. The alliance believes there must be just one code of practice throughout the country administered uniformly to ensure consistency.

While the proposal does not prescribe the contents of a code of practice, it describes the framework for a collaborative and inclusive process through which industry stakeholders will design a code of practice and oversight framework that meets the unique needs of Canada’s food system.

> Lassonde names Claire Bara as president of its Canadian subsidiary, A. Lassonde, Inc. In her new role, Bara will lead the commercial activities of this subsidiary, which develops, manufactures and markets ready-to-drink juices and drinks and fruit-based snacks for the Canadian market.

> Daiya Foods names finance veteran Melissa Lee as chief financial officer for the company. Originally from Canada, Lee returns following three years in the United States, where she most recently held an executive leadership role as vice-president, Corporate FP&A, with Walmart Inc.

> Outcast Foods , a Canadian food technology company that rescues cast off produce and upcycles it into supplements and other ingredients, hires Miriam Zitner as vice-president, business development. She will help lead the company’s North American expansion and help Outcast scale its plant-based technology.

> PSSI , a food safety and contract sanitation provider, appoints Doug White to the newly created position of COO. White will lead the company’s ongoing operational growth focusing on operational excellence, continuous improvement and driving PSSI strategy. He was previously senior vice-president of operations for the Western Region. In that role, he led PSSI’s operational partnerships for more than 100 food processing plants across the U.S. and Canada.

> Epogee , a developer of EPG, an ingredient technology that eliminates most calories from fat, appoints Brent Campbell as their new sales director. Campbell brings more than 20 years of sales experience and considerable expertise in palm oil sustainability, sourcing and supply chain initiatives. Most recently, Campbell was key account director for Tate & Lyle’s food and beverage solutions division and has also worked with ingredient companies such as AAK USA and Golden Brands.

> Teasdale Latin Foods appoints Tim O’Connor as CEO. He brings a wealth of food industry leadership in addition to deep financial and operational expertise. Most recently O’Connor served as CEO of Richelieu Foods, Inc., a manufacturer of retail private label frozen and deli pizza in the U.S., from 2013 to 2019. He previously served as their CFO from 2011 to 2013.

Sweets from the Earth, a vegan baking company, acquires Shockingly Healthy, a plant-based superfood-focused bakery promoting body-benefiting, whole food dessert bars.

Marc Kadonoff, vice-president of Sweets from the Earth, said, “The addition of Shockingly Healthy to the Sweets from the Earth family brings complementary and innovative baked goods to our current lineup. We expect to continue the innovation and R&D to bring delicious legume-based desserts and confectionary to the Canadian and US marketplace”. The acquisition of Shockingly Healthy fits into the Sweets from the Earth mission to connect more people to real food, as well as the commitment to growing healthier plantbased communities.

Gericke USA, Somerset, N.J., has launched a hygienic sack tipping station suitable for discharging bulk materials in sanitary processing environments. Developed for food, nutrition and other manufacturers requiring FDA-compliant equipment, the Gericke sanitary sack tipping station features stainless steel construction machined as a smooth, monobloc unit with rounded corners and a fully polished interior. Designed to control combustible dust and support worker safety, the ergonomic sanitary sack tipping station enables powders and other bulk solids in bags, sacks, totes and bins to be safely emptied and transferred into storage or into the process without allowing fine particles into the work environment.

The sanitary sack tipping station integrates with pneumatic conveying systems, sifters, mixers, lump breakers and other equipment. www.gerickegroup.com

Cargill joins with Frontline International to develop the Kitchen Controller, an end-to-end, automated oil management system.

The Kitchen Controller system simplifies cooking oil management by automating the oil filtering and replacement process. At the heart of the system, a fry vat sensor gathers oil quality data. The data is then analyzed by the Kitchen Controller proprietary software and fed to a touchscreen pad. Kitchen staff use the green, yellow and red onscreen indicators on the touchpad to take action with the oil. This helps to ensure consistency and quality of fried foods, and also improves profitability.

www.kitchencontrollersystem.com

Sterling Systems releases batching automation app Sterling Systems & Controls, Inc., announces availability of its automation application module for the batching of solids and liquids, such as for ingredient batching in feed and recipe batching in baking and food. The Sterling Systems BatchPro-SA batching automation and control application is expected to eliminate error, ensure lot and material traceability, and optimize throughput and profitability. www.sterlingcontrols.com

Dynatrol CL-10GH CIP, a Teflon-coated liquid level switch is the latest addition to the Dynatrol line of high, intermediate and low point level detectors for liquids or slurries. It is suitable for applications that may include fruit and vegetable juices, plant-based waters, fructose, corn syrup, sugar liquor, soybean and other

vegetable oils and slurries. The detector provides rugwged construction with a sensitive transmission of vibration energy.

The CL-10GH liquid level switch has no moving parts, floats, diaphragms or packing glands. It can be installed in almost any position of a vessel or pipe.

www.dynatrolusa.com

A line of bag dump stations from process equipment manufacturer Volkmann captures bulk materials discharged from bags and stages the powders, granules, tablets and/or pellets for transfer into storage or directly into a production process. Installed with a companion pneumatic vacuum conveying system, the bag dumping stations help control dust, stop product loss and prevent product contamination while reducing labour-intensive, manual bag hauling and emptying into mixers, vessels and other equipment. Dangerous, ambient dust is virtually eliminated.

Featuring the RNT-180 standard model bag station and the RNT-CON Rip-and-Tip dump station for dust-free, high containment, the line of modular sack tipping stations may be configured to meet FDA requirements for sanitary processing and to ATEX requirements for explosive atmospheres, as well as for non-regulated environments. The line of bag unloading stations includes stainless steel construction and may be filled with HEPA filtration, integrated glove box, dust hood, empty bag compactor and a wide range of other equipment as custom options. www.volkmannusa.com

Ron Wasik

Food allergies affect over three million Canadians and 50 per cent of households. Consumers with food allergies and those that purchase products on their behalf (family, friends, schools, daycares, etc.) depend on having complete, easy-to-understand and accurate labelling that they can trust.

Deciding what to eat is complicated for consumers with food allergies. The challenge is to assess what might be in a product, as indicated by the precautionary allergen label (PAL), or the “may contain” statement. For some people, “may contain” means the product likely has the said ingredient, and others may assume it is not the case and that manufacturers are attempting to cover legal liability. Yet, research has shown that in some cases where PAL is used, there is no detectable level of the allergen. In other instances, the amount of an allergen was found to be at a level that would require it to be listed as an ingredient, but instead, was listed in a PAL statement. Based on this research, some consumers may be unnecessarily limiting food choices, while others may take unnecessary risks.

Allergen management in the food industry is usually integrated into a company’s food safety program. While clear regulations exist on the labelling of priority allergens (eggs, milk, mustard, peanuts, crustaceans and molluscs, fish, sesame seeds, soy, sulphites, tree nuts, wheat and triticale) as ingredients, food processors can exercise considerable discretion when declaring any of these allergens if they had inadvertently entered the product. This has led to the overuse of PAL and rendered “may

contain” confusing. At the same time, food allergen labelling generates the largest percentage of food recalls, accounting for approximately 35 per cent of the total.

To help consumers and Canada’s food industry address these issues, Food Allergy Canada, in collaboration with Université Laval, Que., Maple Leaf Foods and Health Canada, is working with the food industry, academia, healthcare and government to develop the following resources:

• Voluntary, consensus-based industry guidelines on allergen risk management using a risk-based approach following the Codex risk analysis framework (i.e. identify, assess, prevent/control, communicate).

• Guidance on the application of precautionary allergen labelling in order to make this a useful and meaningful tool that consumers with food allergies can trust.

• Training tools for all levels of manufacturers.

• Consumer education framework.

Funding for this initiative is being provided through Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

This collective effort aims to advance food safety practices and to make “may contain” statements meaningful.

For consumers, this means greater confidence in the safety of the products they are purchasing.

For food manufacturers, this means enabling safe food choices through industry-informed allergen risk management practices and accurate labelling with the lowest levels of risk, while providing product options that are suitable for the maximum number of consumers.

Food Allergy Canada and Université Laval are reaching out to the food industry to better understand their current approach to managing allergens and the use of precautionary allergen labelling. They have developed a survey geared toward food manufacturers/ processors who create prepackaged food products for the Canadian market. To access the survey, please visit www. surveymonkey.com/r/L6BJWMT. After the survey is completed, all participants will receive a summary report. By participating in the survey, you will contribute toward the development of voluntary industry guidelines that support food safety and labelling practices in Canada. The findings will also help inform the next phase of the project, which will focus on the development of industry training and resources to support the rollout of the guidelines. Additionally, the survey also allows participants to provide recommendations/feedback to regulators regarding the support needed by industry, as it pertains to allergen risk management.

This collaborative initiative will help the food industry maintain and build public trust and consumer confidence in food products. It will also have a long-lasting impact on the safety of food products and enable consumers to make informed, safe food choices. If you are interested in learning more about this initiative, please reach out to project manager Beatrice Povolo at bpovolo@foodallergycanada.ca.

Dr. R.J. (Ron) Wasik, PhD, MBA, CFS, is president of RJW Consulting Canada. Contact him at rwasik@rjwconsultingcanada.com.

When a shipment is rejected at the border, the clock starts ticking as storage fees accumulate and delays risk disrupting carefully planned logistics. Finding the right solution often involves co-ordinating with multiple providers and regulators to determine the root cause and fix the issue.

When foods are imported into Canada, CFIA receives commercial import data electronically from Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) via the CBSA’s Single Window Initiative (SWI) – Integrated Import Declaration (IID). SWI streamlines the sharing of commercial import data between the import community and the Government of Canada. Participating government departments and agencies rely on IID data to validate import information and to ensure requirements are being met.

The information conveyed through SWI is intended to satisfy a variety of legislative regimes. As such, service options must accommodate complex and, sometimes, disparate regulatory requirements.

Two recent issues demonstrate the importance of co-ordination among regulators and the import community.

As food distribution becomes increasingly global, so do the legal entities involved in delivering food to Canadians. Whether due to tax, commercial or residency requirements, there are many legal reasons why the Importer of Record declared for customs purposes may be a different legal entity than the SFC Licenced Importer. However, current IID data fields do not provide a method by which to declare an SFC Licenced Importer specifically. This lack of functionality presents an issue as

Laura

When a shipment is rejected at the border, the clock starts ticking as storage fees accumulate and delays risk disrupting carefully planned logistics.

the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR) require importers to declare the name and address of the SFC Licensed Importer as well as the licence number. In cases where the Importer of Record and the SFC Licensed Importer are different entities, there is no way to communicate this information via IID. Further, the discrepancy has been noted by CFIA as a possible non-compliance (i.e. erroneously suggesting the wrong SFC licence number had been declared).

The CFIA has taken action to address this issue, and is in the process of reviewing IID data fields to determine how best to capture the name and address of the SFC Licenced Importer. In the meantime, CFIA has confirmed the declaration of the SFC licence number will be sufficient to allow CFIA to access the associated name and address of the SFC Licensed Importer for the purpose of SFCR

Last December, our colleague Dr. JonPaul Powers wrote in this column about the confusion and delays experienced by importers of natural health products (NHPs) whose shipments were being automatically rejected at the border for

failure to enter an SFC licence. The import issues arose due to the Automated Import Reference System (AIRS) linking certain HS codes with the requirement for an SFC licence. In fact, the system was not implemented in a manner that recognized that in some cases, the same HS code can apply to a food or an NHP. Specifically, when there is a regulatory jurisdictional overlap in relation to an HS code, the SWI system necessitates the import requirements be satisfied for all applicable programs. For NHPs, this meant forcing the declaration of an SFC licence, even though the import of an NHP, a subset of drugs, must occur via a site licence, not a food licence.

Resolving this issue involved co-ordination with both Health Canada and CFIA. Requests were made to add affected HS codes to Health Canada’s Regulated Commodities Data Element Matching Criteria for NHPs, and CFIA updated AIRS to include an “Other End Use” exemption such that the other government department regulating the goods can be identified.

Moving forward, Health Canada intends to co-ordinate with CBSA and CFIA to ensure exemption codes are available for any potentially new overlapping HS codes added to the Data Matching tables. Industry is encouraged to reach out and bring affected HS codes to Health Canada’s attention.

Rejected shipments lead to delays and costs. This increases the pressure on busi nesses to implement a “quick fix” rather than investigate and resolve the root cause. However, certain actions can trigger unin tended legal consequences.

Laura Gomez and Gladys Osien are lawyers in the Ottawa offices of Gowling WLG, specializing in food and drug regulatory law. Contact them at laura.gomez@gowlingwlg. com and gladys.osien@gowlingwlg.com.

Cher Mereweather

oday, I want to talk about fruits and vegetables, but not the shiny, perfectly graded and meticulously displayed apples, oranges and greens adorning the shelves of produce sections from coast to coast.

Instead I want to talk about ugly vegetables—contorted carrots, blemished broccoli angular asparagus and knobby potatoes.

Those of you who regularly read this column know how passionate I am about food waste, or rather, about preventing and repurposing it.

Twenty-two per cent of food waste happens at the farm. Nearly $2.88 billion of nutrient-rich produce is ploughed under or sent to compost or animal feed every year.

The reasons for this waste are complex, but in my experience, they are often connected to the fact that Mother Nature doesn’t always produce perfectly formed produce.

In Spring, I was part of a masterclass that

of how companies are using empathy, purpose and emotional connection to transcend almost all other drivers of business and build movements based on a common cause and a yearning to connect.

After a year-and-a-half of lockdown, it would appear that we all mostly want to connect and to belong again.

As I was digesting these insights, my mind kept wandering back to food waste. How could we learn from this and build a movement around waste? How could we create empathy around waste?

It’s hard to get emotionally connected to waste in a food processing plant (the language of SOPs and HACCP doesn’t really do it for most people), but what about fruit and vegetables at farm level?

Elsewhere in the world, the ugly vegetable movement has had notable successes. Startups, such as Misfits Market or Imperfect Foods, are rescuing ugly produce and selling it to customers at a significant

However, it feels like we have been slower on the uptake here in Canada. Perhaps the leader nationally is Loblaws, whose Naturally Imperfect range reaches across both the fresh and frozen produce categories. But even there, the products are marketed under the No Name brand, and positioned for price, not value. There is little emotional connection or empathy to be had about a plain yellow bag of potatoes, even if you do get a few more for your

What if we could see ugly produce as a real marketing opportunity? One that is very much grounded in a post-COVID world, where purpose, sustainability and empathy are increasingly shaping how we live, and how

The Ontario potato grower, Brenn-B, has done just that. Shawn, Chris and Nicki Brenn are the fifth generation to farm potatoes near Hamilton, Ont. Each year, their team plants, tends and harvests over 800 acres, producing for many of Canada’s mainstream retailers. Every year they have seconds and smalls that just don’t make the grade for retail or processing.

Until last year, these would go to animal feed. Until, that is, our team at Provision, in partnership with Sherpa Creative helped the Brenns launch B-Yourself, their new brand of perfectly imperfect potatoes sold at Sobeys.

The first thing you spot on the bright orange B-Yourself bags are the ugly potatoes, sassily dressed up with hand-drawn wigs and glasses to look like characters out of a Pixar cartoon. Each character has a little word bubble next to them, proclaiming that they “only have eyes for you”, or asking you to “love your imperfections, just like I love mine”.

Turn the bag over and out jumps the copy: “Mother Nature doesn’t always grow supermodel spuds. But that doesn’t make them any less loveable or worthy of your dinner table. So, B-Yourself, and come celebrate the imperfections that make us who we are”.

Celebrating our imperfections, encouraging consumers to be themselves, creating emotional connections in a world which is yearning for them…this is how we should be marketing ugly fruits and vegetables. This is how we should be engaging consumers in creating awareness, and (dare I say it) a movement around food waste based on inspiration and empathy, not on bland bags and a promise of more spud for your buck.

So, I call out to all farmers, producers, restaurateurs and retailers—let your ugly produce become a source of creativity, where the pressure of being perfect can be replaced by the desire to simply connect, over a good meal, with people we really care for.

Cher Mereweather, CEO of Provision Coalition, Inc., is a food industry sustainability expert based in Canada

Birgit Blain

ales of organic products are growing, but does organic make sense for your brand? There are many factors to consider before launching an organic line.

Fresh categories represent the most frequently purchased organic products. Fresh fruits and vegetables top the list, and are experiencing phenomenal growth, followed by meat and poultry; dairy; and breads and grains.

Six packaged food categories represent over 20 per cent market share, led by baby food; infant and toddler snacks; and infant cereal. Broad leaf bagged vegetables; soya, rice and alternative beverages; and dried fruit complete the list.

Although some CPG categories show impressive percentage growth, it’s critical to examine the dollar sales on which it’s based, to reveal a more accurate picture.

Conventional foods dominate most CPG categories. What percentage of sales and dollars does organic represent? Is the category over or under indexed? Analyzing the overall category and the role organics play will expose white space opportunities.

Is it advisable to expand a conventional line with organic offerings? Will it generate incremental sales for the brand and retailers, or cannibalize existing sales?

How do regulatory requirements impact products, processes and the business as a whole?

Displaying the Canada Organic logo or making an “organic” claim on food sold inter-provincially, exported and imported requires certification under the Canadian Organic Standard. Products must have minimum 95 per cent organic content.

Additionally, ingredients, food additives and processing aids must comply with the Permitted Substances Lists.

Are the required organic ingredients readily available? It’s critical to ensure there is ample supply, especially since organic agricultural inputs can be more susceptible to environmental threats. Further, an alternate source of supply is a necessary safety net against supply interruptions and cost increases.

Organics are more aligned with environmentally conscious packaging. What packaging format and materials are most appropriate for the product? Does it require changes to the packaging process and equipment?

Some of our clients insisted on using organic ingredients, only to price themselves out of the market. Price is a top driver of buying decisions. Ingredient cost is a big factor that will drive up the cost of goods and SRP.

Myriad surveys claim consumers are willing to pay more for organics, but how much more? Is it dollars or cents? That’s an important distinction. The SRP must be within the threshold to garner sales.

Competition is tough from store brands such as President’s Choice that price organics more affordably, compared to specialty brands.

It’s critical to know what makes your target consumer tick. Who is the organic shopper? Do they shop your category and what drives their purchase decisions? Determine where organic ranks on their decision tree; it varies by category. Are organic buyers a viable target to achieve sales and profit

goals or do they represent a small segment of shoppers?

Canadian consumers are becoming increasingly mistrustful of organic claims. Does your brand have a compelling point of difference or rely solely on organic? Does organic align with your brand positioning or necessitate development of a new brand?

Increasing food prices are putting pressure on strained wallets. Canadians are price conscious and have become cautious spenders. Is this the right time to launch a premium offering?

The above list of considerations is by no means exhaustive. Thorough research culminating in a sound strategic plan sets the stage for success.

As a CPG food consultant, Birgit Blain transforms food into retail-ready products. Her experience includes 17 years with Loblaw Brands and President’s Choice. Contact her via email at birgit@bbandassoc.com or learn more at www.bbandassoc.com.

Attend the one event that has it all! PACK EXPO Las Vegas and co-located Healthcare Packaging EXPO will be the most comprehensive packaging and processing event this year.

NOTHING COMPARES TO LIVE, FACE-TO-FACE CONNECTIONS!

Be there and get your all-access pass to:

New technology and full-scale machinery

Sustainable solutions and materials

Crossover applications from 40+ vertical markets

70+ FREE educational sessions

Invaluable in-person networking

Learn about our health and safety commitment by visiting: packexpolasvegas.com/packready

A perfect storm of conditions has breathed life into an old technique

— BY MARK CARDWELL —

As innovations go, growing baby kale and micro radishes indoors without the use of soil likely wouldn’t be on most people’s top-10 list. However, for Barry Murchie, who leads Canada’s largest commercial vertical farming operation, the proprietary process and cutting-edge technology being used to grow small leafy green produce at his company’s fully automated facility in Guelph, Ont., is the greatest thing since sliced bread.

“We’ve done tremendously well and learned so much about the vertical farming industry,” said Murchie, president and CEO of GoodLeaf Farms, a wholly owned subsidiary of Truro, N.S.-based TruLeaf Sustainable Agriculture. “This is a major pioneering effort.”

Opened in July 2020 with a production capacity of nearly 500,000 kgs, the 4,200- m2 GoodLeaf plant meets what Murchie says is growing demand and interest from national, regional and local food retailers across the Greater Toronto Area.

A long-time senior executive with Canadian agri-food giant McCain, which is the largest shareholder in GoodLeaf, Murchie is now leading his company to new frontiers.

This summer, GoodLeaf will begin building two more plants—one near Montreal and another at a still-unnamed location in Western Canada—as part of a McCain-driven plan to build a national network of vertical farms for year-round production of micro- and baby greens for local markets.

“Vertical farming is more efficient, more sustainable and a better way to grow food,” said Murchie. “It’s a tremendous opportunity to bring technology into agriculture and to help ensure global food security.”

Vertical farming—the notion and practice of rowing crops in stacked, upright layers in buildings, old mines or even shipping containers through the use of specialized LED lighting and soilless farming techniques like hydroponics, aquaponics, aquaculture and aeroponics—is not new.

Driven by a space-age need to survive on distant planets and a humanitarian desire to end hunger, provide food security and reduce the environmental impacts of traditional agriculture, vertical farming has attracted the attention of scientists, food companies and starry-eyed entrepreneurs since the phrase was first coined in the 1990s.

However, the vast majority of early vertical farming operations were scuppered by the harsh realities of high energy costs associated with the technology at the heart of their production systems and low revenues from agriculture commodities driven by the lowest price point.

“They simply couldn’t compete,” said Mark Lefsrud, an associate professor at Montreal’s McGill University and one of Canada’s

leading experts in greenhouse technology and urban agriculture.

“Even today, it costs a lot more to grow lettuce and other produce in a climate-controlled environment here in Canada than it does to truck it in every day from Florida, California, the southern U.S. and even Mexico, like we do now.”

However, Lefsrud says a perfect storm of conditions has given the vertical farming industry new life in recent years. Those conditions include the development of better and cheaper lighting and hydroponic equipment (the result of R&D in the legal cannabis sector), massive amounts of investment capital (roughly $1.8 billion USD into startups between 2014 and November 2020, according to Financial Times) and increased consumer and government demand for locally grown produce and food security as a result of the pandemic, which disrupted supply chains.

In Canada, roughly a dozen commercial vertical farms are now in operation or planning to either expand existing operations and/ or open new ones.

According to a March 2020 report from Ontario’s Greenbelt Foundation, half of those farms are operating in Ontario and all of them are growing leafy greens.

One of those businesses, Elevate Farms, formerly known as Intravision Greens, can grow up to 454,000 kgs a year of lettuce, arugula, basil and other leafy greens at its nearly 2,000-m2 flagship plant in Welland.

The company, which also has farming facilities in New Jersey and New Zealand, is currently working on a $15-million deal it signed a year ago with Whitehorse-based North Star Agriculture to develop and build cost-effective vertical farming facilities in the Yukon and other isolated First Nations and northern communities that are dependent on costly imported produce.

Elevate founder and CEO Amin Jadavji, who calls his company one of the most advanced farming solutions in the world in terms of both labour per kilogram and electricity per kilogram of production—two key industry metrics—said the northern facilities will bring more food security and nutrition to “particularly isolated and vulnerable regions of Canada.”

$3.1 BILLION

More than USD 3 billion invested worldwide in vertical farms.

Vertical farms have also popping up outside Canada. In the U.S., which represents roughly one-third of the US$3.1 billion invested worldwide in vertical farms (according to the Ontario Greenbelt Foundation report), a showcase facility called 80 Acres Farms opened to great fanfare in Hamilton, Ohio, in January.

Dubbed a ‘reference design’ for potential partners and governments worldwide, the $30-million, 5,800m2 facility can produce some 10 million servings of leafy green produce a year close to consumers, cutting transportation time and costs while improving freshness.

In Europe, the first phase of what will soon be that continent’s largest vertical farm went into operation in Copenhagen in December.

Built by Nordic Harvest, a Danish start-up with Taiwanese partners—a consortium that also plans to build the world’s biggest indoor farm in Abu Dhabi— the facility has a production capacity of 200 tons of organic salads and herbs a year, an output that will quintuple when the facility expands in two upcoming phases to 14 floors and 7,000 m2

“Vertical farming is very sexy and trendy right now, like cannabis was a few years ago,” said Derek Schulze, a former commercial greenhouse grower who now teaches at Ontario’s Niagara College. “It all sounds great, having these fresh finished products at the end of a modern manufacturing process. But it’s all being driven by engineers, not agronomists, and plants are living things, not widgets or potato chips.”

Schulze pointed to a 2019 report on indoor agriculture by the World Wildlife Fund-U.S. It suggests that while vertical farming has exciting potential, it “remains a nascent, disparate industry with several risks that must be addressed before it can achieve scale.”

Challenges range from the acquisition and mastery of the automation and technology required to grow produce in confined spaces to the control of variables like energy costs, climate, plant genetics and systemic external and internal diseases.

The industry is also currently restricted almost exclusively to the production of non-flowering leafy greens due to technological constraints and agricultural retail market realities.

However, proponents of vertical farming believe the industry has a bright future. McGill’s Lefsrud, for example, says innovations under development will allow more types of produce to be grown indoors at more competitive prices.

“We’re never going to grow oranges or kiwis or mangos or other tropical plants here. It just doesn’t make economic or practical sense,” he said. “But I fully expect that vertical farms will soon be growing all types of temperate crops.”

500,000 KG

The 4,200- m 2 GoodLeaf plant in Guelph, Ont., can produce nearly 500,000 kg of small green leafy produce.

Despite the headlines, vertical farming remains a niche sector in the field of ‘controlled environment agriculture’ (also known as ‘indoor plant environment’), which includes greenhouses and hoop houses.

According to various sources, the worldwide vertical farming industry currently accounts for about 30 hectares, an area equivalent to about 50 football fields in size. That pales in comparison to the half-million hectares of greenhouses growing produce and the roughly 50 million hectares of farmland used to grow produce.

Despite all the hopes and hoopla over vertical farming, many indoor agriculture experts say food companies in the sector have a hard to row to hoe before they reach profitability.

Lefsrud estimates that in 20 years time, 20 per cent of all produce sold in Canada will be grown locally indoors. “There’s talk of going up to 50 per cent, but not in the short term,” he said. “There are even export opportunities for places like Quebec, where energy costs are much lower than Ontario or the U.S.”

For his part, Abraham Gusman, president of UpCulture and Rvest, a Montreal-based collective of farmers that is in the planning stages of a large vertical farm to produce lettuce for the local market, says the potential is limitless.

“It’s extremely exciting to grow food indoors yearround using hydroponic and aeroponic technologies,” said Gusman. “We’re trying to understand Mother Nature and all of the elements that intertwine in this beautiful dance. The demand is there. Consumers are looking for locally grown food products.”

While labelling battles rage across the Atlantic, a certification program has been launched in Canada — BY

TREENA HEIN

—

Wherever you live in Canada, it’s common to see products labelled as “dairy alternative”, “dairyfree”, “plant-based”, “Chick’n”, “Chickun”, “Bacun”, “Cheeze” and “plant butter”.

Indeed, the number of plantbased products that are similar in taste, appearance (and in some cases, nutritional content) to meat, poultry and dairy products is exploding. According to a recent Fior Markets report, the global vegan “butter” market is expected to grow to USD1.77 billion by 2026.

Dairy alternatives in particular, including milks made from crops such as soybeans, rice and oats, various nuts and even microalgae, are a fast-growing segment. Starbucks recently sold out of oat milk at many of its U.S. locations. Baskin Robbins has launched several oat milk ice creams, and Quebec-based dairy firm Liberté has also launched a “dairy-free coconut,” yogurt-type product in three flavours.

Similarly, the France-based maker of the famous Laughing Cow, Babybel and Boursin cheeses has recently launched “Boursin Dairy-Free Cheese Spread Alternative, Garlic & Herbs” and “Laughing Cow Blends” wedges, which mix cheese with plantbased protein from chickpeas and more. Saputo has purchased Bute Island Foods in Scotland, a manufacturer of dairy alternative

by 2026.

cheese products under the award-winning vegan Sheese brand. Additionally, another Canadian firm called Future of Cheese is about to launch organic plant-based butter and plant-based versions of cream cheese and other popular cheeses.

Start-ups, along with major meat companies such as Cargill are offering many meat alternative products.

With any new product category, there will be labelling issues that must be addressed. The use of common names such as milk on plant-based beverages is a contentious issue in both Europe and the U.S.

Further, a new study from Cornell University found “consumers are no more likely to think that plant-based products come from an animal if the product’s name incorporates words traditionally associated with animal products [such as milk, cheese or burger] than if it does not.” The researchers conclude that “omitting words traditionally associated with animal products from the names of plant-based products actually

causes consumers to be significantly more confused about the taste and uses of these products.”

Lindsay Sutton, sales manager at Lovingly Made Ingredients in Calgary (a producer of plant-based protein and starches) echoes these findings. “I support that the industry be open to allowing plant-based cheese, dairy and meat be called just that,” she says. “I would say that consumers are fully aware that, for instance, cashew cheese is not made from dairy. They are not being fooled.”

Ahmad Yehya, CEO and co-founder of Nabati Foods Global in Edmonton (maker of dairy-free cheesecakes, ‘Nabati Cheeze’ and plant-based meats), agrees. “I think that this is completely fine because otherwise, how will a consumer know what the product is supposed to replace?”

In terms of national legislation, Leslie Ewing, executive director of Plant-Based Foods of Canada (PBFC), a division of Food, Health & Consumer Products of Canada, explains that right now, the use of common names like butter, cheese, meat and milk to identify plant-based foods is prohibited in Canada. For its part, PBFC has recommended Health Canada re-evaluate requirements on the use of common names for plant-based food products, and qualifiers are included where appropriate. “The label would clearly indicate that the product is plantbased, vegan or vegetarian by using terms like plantmilk, soy-milk, plant-butter or soy burger,” says Ewing.

PBFC has also recommended Health Canada repeal section B.01.100 (1)-(4) of the Food and Drug Regulations, which require that plant-based products be identified as simulated. PBFC views this as redundant and confusing to the consumer as “these products clearly communicate they do not contain meat by using designations such as plant-based.”

When asked for its desired labelling framework for plant-based products, the Canadian Meat Council (CMC) states it “advocates for accurate and truthful labelling of [these] products, while supporting enforcement of fair labelling by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). CMC encourages consumer choice and welcomes competitive markets. Plant-based products designed to mimic real meat must face the same stringent regulatory requirements as livestock agriculture.”

Dairy Processors of Canada said it expects all products, dairy or otherwise, to adhere to labelling regulations.

The Canadian Poultry and Egg Processors Council echoes these comments. “Plant-based products should be labelled to clearly distinguish them from meat, poultry and egg products. This, for example, means that the name or descriptor of any plant-based product should be part of its common name and clearly indicate it is a simulated meat and/or a plant-based product.”

In November 2020, CFIA consulted with consumers and industry on proposed guidelines “that explain the regulations for simulated meat and poultry products.” A ‘What We Heard’ report summarizing the feedback…is expected to be posted in the coming months.

CFIA will also use the consultation feedback to update its guidelines for simulated meat and poultry products and other plant-based foods that are not intended to substitute meat or poultry. “The consultation on proposed guidelines for simulated meat and poultry products will also inform a possible second phase of further clarifications to guidelines on plantbased products that are intended to substitute for dairy and egg, at a later date.”

Regarding the appearance of plant-based alternative products—for example, plant ‘butter’ that looks very similar in shape, size and packaging to a rectangle pound of cow milk butter—CFIA notes the guidelines to come “will not address packaging specifically, but rather the overall representation of the food product.”

CFIA adds that “labelling information must not be false or misleading. This includes ensuring foods are accurately represented and not mistaken with other foods.”

In early May, PBFC announced dozens of products carrying the Certified Plant Based seal are starting to appear on Canadian grocery store shelves. PBFC had commissioned international consulting firm Nielsen to conduct a study that revealed consumers are looking for assurance products claiming to be plant-based do not contain ingredients from animal-based sources.

This certification protocol is owned by the U.S.based Plant-Based Foods Association. They worked with PBFC to create the Canadian version, which encompasses plant-based alternatives to meat, poultry, egg, dairy and seafood products. NSF International serves as the third-party certifying agency.

“We want to make it easy for Canadian consumers to confidently identify plant-based products,” says Ewing, “as the plant-based food industry continues to grow and new products enter the market.”

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration is examining federal labelling issues for plant-based products. Meanwhile, legislatures of North Carolina, Maryland and Wisconsin have passed laws to restrict use of the word “milk” to milk from animals. In mid-May 2021, Texas passed a law, which defines “beef” and “chicken” as “any edible portion of a formerly live…cattle/ chicken carcass,” and declares that products labelled “meat” cannot contain lab-grown, cell-cultured, insect or plant-based food products.”

Meanwhile in the European Union, dairy producers and associations convinced legislators to prohibit the use of terms such as “almond milk” or “vegan cheese” on the labels of products mimicking dairy. In late 2020, an amendment to the law (known as the ‘dairy ban’) was passed to make it even stricter. At the same time, however, legislators rejected an amendment to forbid vegan food producers from using terms like “burger.”

A new agri-technology traces the entire process of beer manufacturing

— BY JENNIFER D’AGOSTINO —

It all starts with a seed, specifically a barley seed. Barley is an important crop for Canadians. According to the Canadian Grain Commission, Western Canada produced over 7 million tonnes of barley in 2017. From there, seeds make their way to farmers and maltsters across Canada, then to brewers where they mash, boil, ferment and package their beer for consumers. What if all of this was traceable? What if consumers could trace all the hard work that goes into the supply chain that puts the can of beer in their hands?

Luckily, late last year Grain Discovery came up with a system to answer those very questions. Connecting seed growers, farmers and brewers, their agri-technology traces the entire process of beer manufacturing. First launched in 2020, Grain Discovery connects seed growers to farmers, and farmers to brewers and their products. With this system, producers are able to pinpoint where their barley grains end-up.

“We wanted to create the feedback loop within the supply chain, and create an easy way for the data to flow through legacy systems,” said Rory O’Sullivan, founder and CEO of Grain Discovery. “We can share how the malt performs in the brewing process, and farmers and growers can get intel on how well their products work.”

The system doesn’t replace the legacy systems, but rather works with it to create

a way for everyone in the supply chain to gain access to certain information about the product. Growers, farmers and brewers can access a certain subset of information through an app. Growers can learn which barley seed performed well, while brewers can pinpoint exactly where their malt barley originates.

Before this technology was developed data was trapped within each producer’s computer. With the introduction of traceability everyone in the supply chain can have access to the data they need, creating a transparent and accessible process.

While Grain Discovery’s aim is to open lines of communication within the blockchain, they also developed this technology out of necessity. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) updated the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations

(SFCR) to state that anyone who makes products with an alcohol content of 0.5 per cent or above, must have a traceability process in place.

Implemented earlier this year, breweries had to get to work to make sure their systems are traceable. Blindman Brewing, based in central Alberta, has worked closely with the Grain Discovery Team. When setting up for the new traceability regulation, there was a lot of learning to be done.

“This system is truly live, it’s every batch, every day,” explains Kirk Zembal of Blindman Brewing. “The is the first time permission blocking has ever been done. This system allows for certainty in the blockchain, and we have all information, and can take it a step further and provide it to our customers as well.”

Starting in May of this year, Blindman Brewing introduced a tracking system for their customers that consists of a QR code label or a lot number on their beer can that can be plugged into their website. With a quick scan or lot number input, consumers have access to the entire blockchain. And it’s not just consumers that are curious about where their beer came from, but growers are curious where their crop ends up.

“Barley variety developers work a long time on different barley varieties, they have to breed and cross-breed and do a lot of experimenting. Then when it goes out into the world, they don’t know where it’s going,” said Zembal. “Now they can see how well their particular variety of barley is doing. It’s all being captured and shared.”

There are other benefits to traceability as well, including health and safety. If there is a recall on any product, food safety officials can trace the recalled ingredient to the specific farm, thus making the recall system more efficient and accurate for both producers and consumers.

Traceability also has lasting impacts on the economy. The beer industry has a substantial impact on the Canadian economy. According to StatsCanada, it contributes $13.6 billion to Canada’s GDP. However, breweries report a negative net profit. By adding traceability to their beers, breweries can offer extra value to their customers because of the extra information and connection it inherently provides. These higher premiums would then drive higher value throughout the malt barley supply chain.

With traceability growers also have a way to showcase their sustainable farming practices, which can help boost the export market in Canada. It will give farmers, growers and breweries the edge they need to remain competitive on the global market.

Beer isn’t the only industry that’s getting involved in traceability. Seafood and product industries are reaping the benefits as well. Seattle-based Dynamic Sys-

tems, have developed a technology called Simba that not only helps track the blockchain, but it can also track waste during processing. This will help food processors find any inefficiencies in their process.

“Simba keeps track of all their inventory, both raw materials and finished goods. We take it through production and give the producers information of how much they produced during the day,” said Alison Falco of Dynamic Systems. “We track efficiencies, and inventory reports that can help people understand what they’re selling. They can also upload all this data to their financial reports.”

The people at Dynamic Systems work closely with food producers to implement Simba on their factory floor. Working with suppliers, they write up a document with all the required tracking information, including weight, colour and where the ingredients came from, among other descriptors.

“We’ll configure the system so that it is easy for them to select the attributes they want and then deliver the software,” said Falco. “They receive some training, make any adjustments if needed, then the software workstations are delivered and installed on the plant floor.”

Thanks to Simba, suppliers can track their product all the way back to the fishermen in British Columbia with a simple barcode.

With regulations and industry trends on the rise, traceability is the way of the future and is sure to have a lasting impact across all food industries.

Gary Gnirss

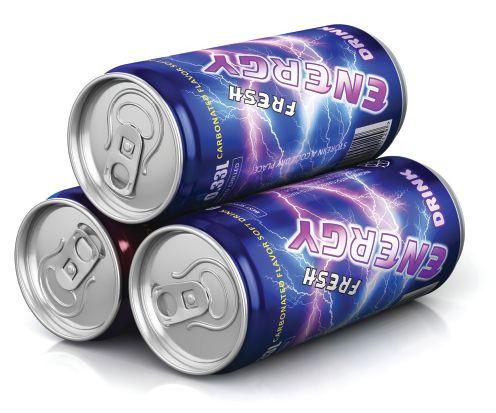

Health Canada is drafting regulations for supplemented food. While the framework has been in the making for decades, it became necessary due to the gap created by the 2004 Natural Health Products Regulations (NHPR). Natural health products (NHP) are not foods. They are regulated under the Food And Drugs Act (FDA) as a type of therapeutic product. In the case of foods subject to the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR), there are prohibitions on adding vitamins, minerals and amino acids to foods, except as provided for. Food manufacturers migrated their products to NHPR to overcome obstacles. The result was an uncomfortable expansion of NHPtype foods. Now, the two (food and NHPs) have converged as supplemented foods. Around 2008, Health Canada took action to differentiate food and NHPs. The chief difference is that NHPs are consumed as a dosage, whereas foods are taken ad libitum (as you wish). There had also been a prior, but failed attempt in the mid 2000s by Health Canada to add flexibility to food fortification. To overcome the obstacles in food regulations, Health Canada accepted temporary marketing authorizations (TMAs) for various foods, such as caffeinated energy drinks and supplemented food.

Supplemented food is expected to emerge as a separate category subject to a unique regulatory framework. They will even have nutrition facts table similar to the ones for conventional food, but with the additional “supplemented with” information. A supplemented food contains added vitamins, minerals, amino

acids, herbal and/or bioactive ingredients that are outside the scope of current food regulations. Twelve categories are currently being proposed. These will be included in the List of Permitted Supplemented Food Categories, which is to be incorporated by reference (IbR) by FDR. Among the 12 are caffeinated energy drinks, ice pops, juices and smoothies, candies and chocolate confections. The permitted ingredients and their amounts will be highlighted in the List of Permitted Supplement Ingredients, which is also to be IbR. IbR documents can be more efficiently updated by Health Canada. Rules about making new submissions to Health Canada will be outlined in FDR.

Health Canada is not known for making things easy. Certain added supplemented ingredients and/or the amounts thereof, if exceeded on a serving or daily bases, will trigger cautionary statements like, “Do not drink more than X containers daily”. Many foods subject to TMAs are already required to include cautionary statements. There is a new requirement for a “Supplemented Food Caution Identifier”, details of which will be in its own IbR Directory. The supplemented food identifier is chock-full of details including height of the exclamation mark, all of which vary depending on the area of the principal display surface of the prepackaged food. It is important to note novel foods and food additives would still require premarket submissions. For example, carbonated beverages with less than 150 ppm of caffeine will be governed as a conventional food where caffein is a food additive. Energy drinks with higher levels of caffeine will be governed as supplemented foods. There is a need to differentiate these on the

basis of amounts, as traditional caffeinated drinks like cola would need to be labelled as a supplemented food.

There are also prohibitions in representing foods for health purposes outside of what might be considered suitable to their nutritive or dietary role. Health Canada historically has been a tight gatekeeper on claims, and this is expected to continue. Health Canada has noted premarket notification for Schedule A.1 (FDA) claims will continue. This is also true for conventional foods. Nutrient function claims, as with conventional foods, also do not require a premarket notification. Health Canada may accommodate certain other claims without a requirement for premarket notification. Claims for ingredients that trigger cautionary statements will likely be subject to restrictions to avoid conflicts with the cautionary messaging.

Products that are currently subject to a TMA, with few exceptions, will be permitted to be sold under their current label, even with the former ingredients list and nutrition facts table, until the end of the proposed transition period.

New products must conform to the new rules once finalized. Health Canada is looking at a transition period of three years but will align with their new Food Labelling Co-ordination Policy, which is also being finalized. That proposed policy is targeting January 1, 2026, as a co-ordinated compliance date.

If final rules are not out by the end of 2021, Health Canada is expected to extend current TMAs.

Gary Gnirss is a partner and president of Legal Suites Inc., specializing in regulatory software and services. Contact him at president@legalsuites.com.

Three reasons to consider replacing weighing systems with precision optical counting machines — BY CREMER —

To avoid costly and reputation-damaging errors, food products must be apportioned precisely and packaged correctly. A common practice is to pack by weight. Unfortunately, some companies utilizing this long-embraced technique may also be weighing down their profit margins and brand reputations.

Precision optical counting guarantees 100 per cent accuracy—an exacting portion control leads to satisfied consumers and an upward trending ROI. Let’s explore a trifecta of ways counting improve profit margins, point-of-purchase marketing and production operations.

The value of an exact count

For food companies that sell largecontainer quantities, fast and accurate sorting, quantity apportionment and packing methods are essential for efficiency and quality control. From an end-of-line standpoint, among the most important decisions is whether to pack by weight or product count.

While some production lines utilize weighers to pack pieces by individual weight, problems can arise when using this technique. Typically, inaccurate quantities can result from products not being exactly the same weight. For example, frozen chicken nuggets. With these and similar items (fish sticks, etc.), there are generally small weight variances from piece to piece. Packing according to a total weight with products that have weight

variations frequently leads to over or undercounts. While the effect is minimal in small quantities, such individually minor discrepancies become major when multiplied by thousands or even millions.

The resulting sizable miscalculation can cause profitability issues. Undercounting shortchanges customers and causes dissatisfaction, decreasing sales by diminishing brand loyalty. Overcounting simply gives product away for nothing. The former impacts sales, the latter sell-ability, since you can’t sell something you’re handing out as a freebie.

For products with slightly varying weights, packaging apportionment on a per-piece basis is the most efficient, cost-effective method. Optical counting guarantees the contents count is 100 per cent accurate for both wholesale and retail packages, preventing product loss and avoiding wastage via over- or under-filling.

Eliminating product giveaway is the most cost-saving notch on a counting machine’s belt. It’s not uncommon for packs of 20 products—frozen meatballs, for example—to have an extra in nearly every package. This is because food companies err on the side of too much versus too little, to avoid customer blowback from packages that have, say, 19 meatballs instead of 21. In food, more is less—less complaints, anyway.

However, more is also more: as more money is lost to overcounts. Multiply a five per cent attrition rate, and revenue lost to overage adds up fast. So, while replacing a traditional weighing system with precision counting equipment might seem like an onerous expense, money saved by eliminating product waste results in a quickly recouped infrastructure investment. Simply put, counters pay for themselves quickly,

then keep making money for every extra product they don’t give away gratis.

As for undercounts, the advantage counting brings is obvious: no more complaints from customers who purchased a 20-count package with 19 items. Considering each official complaint represents exponentially more disappointed customers—most don’t bother to complain, they simply stop buying the product—the salvaged brand reputation and customer loyalty translates directly to bolstered profitability.

Counting also helps customers envision exactly what is in the package before making a purchase.

Let’s say someone is planning a party, and buying everyone’s favourite festive food: chicken wings. They know approximately how many people will attend the event, and about how many wings the average guest will eat.

Our party planner gets to the chicken wing freezer and sees three brands. Two bags are labeled “10 lb,” and the other “50 pieces.”

Now, unless the party planner knows how much the average chicken wing weighs, this shopping experience (and many others like it) plays out in numbers, not weight. The combined weight of the package’s contents is far less useful than knowing exactly how many products the package contains. This is especially relevant when a package is on the larger side—the bigger the package, the more nebulous total weight becomes.

Listing product count also gives customers information on how frequently to purchase that product, providing easier-to-track insight as to when they may be “running low.” No one ever says, “I only have three ounces of breakfast sausages left.”

Counting systems also offer direct benefits for production facilities. Counting allows

for elevated control over inventory, and provides ample production data to compare between different stages of the line. For example, a company would be able to ensure the number of pieces filled matches the number of pallets in the truck. This allows the supply chain process to be as precise as possible from the point of origin to the warehouse.

Counting machines have additional features that make them an attractive option for company’s prioritizing efficiency and conserving floor space. They are:

• Smaller footprint, same output: More compact than weighing equipment, counters save floor space especially for longer production lines.

• Reduced system height: Counting machines are shorter, reducing overall

system heights, which is ideal for lowceiling spaces where there is often no room to position a weigher directly over a packing machine.

• Lower drop heights: With counters being shorter than weighers, they offer the benefit of lower drop heights. The farther up products are dropped, the more room there is for error, less accurate counts and possible damage from increased-velocity impact.

• Less mechanics to clean/maintain: Counters have lower maintenance with less parts to clean and maintain. They have clean lanes and product separation, meaning less possibilities for product to become wedged in tight spaces. Here, adverse hygiene issues can come into play.

Carol Zweep

Packaging is a crucial part of any product, designed to entice consumers to make a purchase and convey relevant information. It also provides protection and facilitates transportation and storage throughout the supply chain. In the industry, we are experiencing an unprecedented push for innovation as consumers, package converters and government programs push for more sustainable solutions.

Earlier this year, a group of businesses, NGOs and government organizations launched the Canada Plastics Pact to establish a united front against plastics pollution. This platform encourages reusable, recyclable or compostable plastic, metal, glass or fibre packaging.

The packaging industry continues to evolve and innovate to find more sustainable solutions, transforming a creative idea into practical reality. This can result in changes to not only design, graphics and messaging, but also to material choices and functionality.

Diageo is the first to create a 100 per cent plastic-free, paper-based spirits bottle for its Johnnie Walker Black Label Scotch whisky. Traditionally packaged in glass bottles, Diageo has created an attractive bottle from sustainably sourced pulp that is fully recyclable. Developed by Pulpex, this patented technology is expected to become cheaper than glass bottles and, in the future, be capable of holding carbonated and hot-fill products. The ability to customize shapes and to use embossing and sustainable colour pigments and labels shows great potential for this new technology.

FruchtBar, a German food company, is also making the switch to recyclable

packaging for its baby food pouches. Originally made from non-recyclable multi-layer laminated materials, the company is transitioning to a monolayer recyclable pouch with the help of Gualapack. Another recent shift came from John B. Sanfilippo & Son, which transitioned its non-recyclable composite can for nut products to a recyclable PET canister (SmartCan from Ring Container Technologies).

World Centric has developed a tree-free, plant-based and compostable pizza boxes. Nabob and Maxwell House developed a zero-waste solution for coffee pods. All the pod components including lids, rings and filter, along with the used coffee grounds are compostable. Also, the bag holding the coffee pods is also compostable and the carton can be recycled.

containers to drop-off locations where participating restaurants wash and reuse them. This program will eliminate the large volume of single-use takeout containers.

Another innovation is giving consumers the ability to eat the package instead of throwing it away. Leading this trend is Notpla, which has created a seaweed-based edible capsule for drinks called Ooho. These pods – filled with sport drinks and energy gel – can be consumed by runners while on the go and eliminate the need for plastic bottles and disposable cups.

Sustainable packaging can reduce environmental impact and meet consumer demand for eco-friendly options.

Reusable packaging is making a resurgence with companies like Loop, which delivers name-brand products in reusable glass and metal containers to customers’ doors and, once emptied, picks the containers up for reuse and refill.

In the Netherlands, a pilot program called SharePack is partnering with restaurants to provide reusable delivery containers. Customers can return the

A relatively new innovation on the scene is digital watermarking technology, which enables a much higher sorting and recycling capture rate for packaging and helps reduce waste. Digimarc technology works by modifying the pixels of the packaging to carry an imperceptible code that is undetectable to the consumer but can be picked up by cameras, such as one installed on a sorting line at a waste management facility. Digimarc has been used for Procter & Gamble’s Lenor fabric softener but can be utilized in food packaging as well.

Ultimately, sustainable packaging can reduce environmental impact and meet consumer demand for eco-friendly options. We are seeing encouraging innovations in this space that are pioneering new, and better, ways to tackle the problem of reducing waste. Whether through thoughtful research, developmental testing, pilot evaluations or scale-up exercises, there is a surge in new possibilities that can all contribute to the success of an innovative packaging solution for the future.

Carol Zweep is senior packaging lead for NSF Canada. Contact her at czweep@nsf.org.