Animal-free protein trend comes to fish production

BY LYNN FANTOM

WA representation of the concept of cellular aquaculture. Investmet funds are fueling faux fish innovations Credit: ©uckyo/ Adobe Stock

hen animal nutrition leader Nutreco announced a new partnership with California-based BlueNalu in January, all eyes shifted to the wave of investments pouring into startups in plant- and cell-based seafood. Industry watchers who follow the money continue to pay close attention to this nascent category, tracking to see if it will mirror the trajectory of meat alternatives like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods.

“Next to venture capital funds and national funds (for example, China’s national fund), it is large corporations such as Cargill, Tyson, Merck, Google, UBS, and PHW Group that have already invested in these companies,” says a report about meat substitutes by global consulting firm Kearney.

continued on page 6

The first facility in the US to grow eels to market size wants juvenile eels sourced from Maine waters to stay in Maine

BY TREENA HEIN

ost juvenile eels caught in the US and around the world go to farms in Asia where they are raised to market size. The frozen product then comes back to the US. American Unagi hopes to change that.

Sara Rademaker, founder and president of American Unagi, says eel demand in the US has grown in parallel with the popularity of sushi.

She calls eel the “gateway drug of sushi” because the fish is one of the very few sushi options that are cooked (it is poisonous when eaten raw), making it a fitting introduction to Japanese cuisine.

continued on page 25

Bivalves fit the bill in meeting global appetite for sustainable seafood

Given the subtle surprises of merroir, plump meat and none of the silt found in their bottom-grown wild cousins, plus a host of environmental benefits it’s no wonder consumer appetite for farmed shellfish is increasing.

But these inherent qualities did not do the sales job alone. Strong marketing, industry educational efforts, and operational gains have driven US sales of mollusks to surge 34 percent in the last five years, according to the 2018 Census of Aquaculture recently released by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Aquaculture North America (ANA) has rounded up some of the trends growers are talking about, along with input from scientists and industry experts who gathered for the 40th Milford Aquaculture Seminar in Connecticut in January.

continued on page 12

Publications Mail Agreement #PM40065710

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

In the past, Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis (IHN) has resulted in devastating economic losses to the Canadian salmon industry.1

The success of APEX-IHN® vaccination programs has meant that the risk of IHN is not often spoken about, and yet the potential threat of infection from wild fish remains ever present.

Don’t let IHN become the ‘elephant in the room’, keep protecting your salmon, and your profits, with APEX-IHN®.

But four farming systems identified as potentially transformative have their own challenges

BY LIZA MAYER

New technologies offer “commercial scale solutions” to improve the performance of British Columbia’s farmed salmon industry but investors need clarity and confidence with regard to policy and regulations before making further investments, according to a new government study.

The Aquaculture Act is an important legislative priority,

Bernadette Jordan

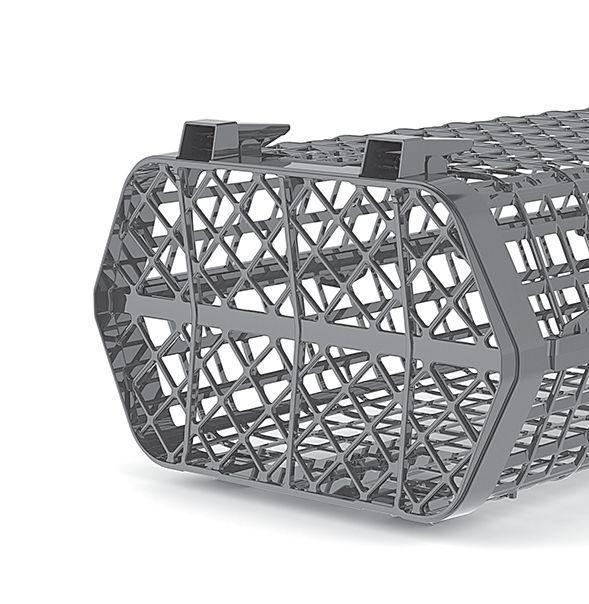

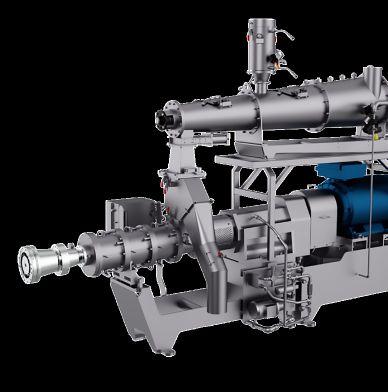

The “Study on the State of Salmon Aquaculture Technology” explored four new production technologies--land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS); hybrid systems; floating closed-containment systems; and offshore systems—all of which have their own challenges, it noted.

Of the four, RAS and hybrid systems are ready for commercial application in BC while the other two still need five to 10 years before they are ready, according to the report.

In term of profitability, the hybrid system is likely more profitable over RAS, said the study, noting that its financial attractiveness and feasibility is already evident as salmon companies are already using it.

As regards capital costs, the expected production costs per kg of salmon from land-based RAS are now about $5 to $6, while costs in the range of $3.5 to $4.5 per kg “are likely” in hybrid but more research is needed, it said.

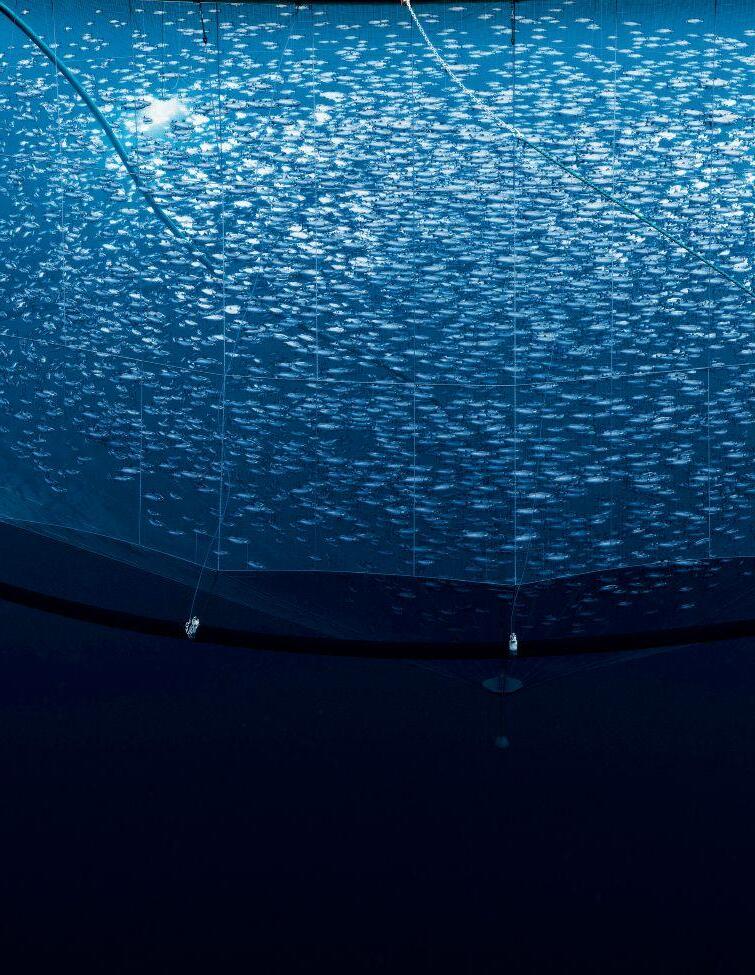

Environmental sustainability, however, is also a major consideration when choosing the ideal production method. In fact, the study attributed the minimal growth of BC salmon farming industry (less than 2 percent per year) from 2000 to 2017 to concerns about open net-pen aquaculture that “were not fully addressed.”

In this regard, both RAS and hybrid both have environmental challenges. RAS’ immense land, energy and water requirements were cited, and very large facilities using sensitive water resources will likely raise concerns among stakeholders, the study said. A hybrid system will have a number of the marine risks seen in conventional farming because the growout phase will remain ocean-based.

Investors need clarity and confidence with regard to policy and regulations before pursuing further investments in BC, the study noted.

The study’s findings, coupled with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s campaign promise in October to transition the province’s salmon open net-pen farming to closed containment by 2025, will be crucial in the policy decisions of the newly installed fisheries minister over the next few months. At stake are BC’s $1.5-billion farmed salmon industry and 7,000 jobs.

“The Aquaculture Act is an important legislative priority that underpins our commitment to create a responsible plan to transition from open net-pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters by 2025. And like any industry, the development of new technologies can play a key role,” Fisheries

BY LIZA MAYER

atalina Sea Ranch, the first and only offshore shellfish farm permitted in US federal waters, has filed for bankruptcy protection.

All assets of the aquaculture operation will be sold pursuant to Bankruptcy Court Approval on March 24, 2020, the California Aquaculture Association announced.

The 100-acre sea ranch is located about six miles off the coast of Huntington Beach, CA. Founded by entrepreneur Phil Cruver, the shellfish aquaculture company won in 2015 the first permit from the US Army Corp of Engineers (USACE) to practice aquaculture for commercial use in federal waters.

All eyes were on the pioneering venture as it navigated a new landscape. In January 2020, the USACE told Aquaculture North America (ANA) that it initiated enforcement action against the company in October 2018 after it encountered installation and maintenance problems that constituted non-compliance with its permit. But by the end of December 2019, “the project’s infrastructure was back in good working order and the company

The study cited the immense land, energy and water requirements of landbased aquaculture. Very large facilities using sensitive water resources will likely raise concerns among stakeholders, it said

Minister Bernadette Jordan told this publication. She also confirmed an earlier statement she made to Seawest News that 2025 is the year she has to come up with a transition plan, and not the deadline to transition the industry to closed-containment.

Jordan assures that “any path forward will include consultations and engagements with the public, environmental organizations, industry, and Provincial and Indigenous partners, ensuring aquaculture is done in the most environmentally sustainable and economically viable way.”

The executive director of the BC Salmon Farmers Association, John Paul Fraser, said the industry looks forward to engaging in a productive conversation with the minister “about how our industry can continue to evolve into the future in a way that allows the industry to continue to thrive, responsibly.”

Finfish aquaculture provides a healthy protein choice for people to eat, and studies have shown it’s also healthy for the planet (see graph), but salmon farmers in BC are committed to make it even healthier for both by having all salmon farms in the province certified to the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC).

An ASC certification verifies that the fish was raised in an environmentally and socially responsible manner. Roughly 60 percent of BC’s farms are currently certified.

BC Salmon Farmers Association Executive Director John Paul Fraser noted that salmon farming in BC has “evolved considerably in recent decades.”

“There’s not enough knowledge out there about the level of technology and innovation that there currently is in BC. That makes aquaculture on our coast quite extraordinary. Investment in new technologies and new ways of doing things allows us to help feed a hungry world in ever-more environmentally-sound ways,” said Fraser.

From 2017-2022 roughly half-a-billion dollars have been allotted towards innovation technology upgrades, and skills training, “the kinds of things that puts BC in a leadership position globally for ocean farming,” he added.

indicates they will be back in compliance with the permit by the end of January,” the USACE said.

In December 2019, a $10-million-dollar wrongful-death claim was filed against Catalina Sea Ranch by the family of a man who died after his fishing boat capsized,

reported The LA Times. The company is being accused of negligence after investigation showed a broken underwater line from its operations wrapped around the boat’s propeller.

Emails and calls to Catalina Sea Ranch were not returned.

Canadian town plans to build ‘business-park on the sea’

Pre-assessed sites will cut down permitting times for potential oyster growers

TArgyle currently has five sites with oyster farming activity by two companies. The town hopes to increase that number with the proposed Aquaculture Development Area

Credit: Municipality of Argyle

he town of Argyle in Nova Scotia, Canada is planning to build a “business park on the sea,” as part of a broader effort to promote oyster aquaculture in its waters.

Acquiring numerous approvals from more than one permitting agency is typical for potential aquaculture lessees anywhere, but under the proposed Aquaculture Development Area (ADA), the sites identified will have already undergone environmental impact assessment, a review by multiple provincial and federal departments, and consultation with stakeholders.

“As Council, we focus on the assets we have in the region, which is ideal conditions for oyster and other aquaculture growth. Our interest in establishing an ADA is to remove some of the barriers of entry in this complex market, supporting new and existing companies in this industry and providing more opportunities for our residents to work, live and play here,” Argyle Warden Danny Muise said.

Charlene LeBlanc, Argyle’s community development officer, said the potential operator wishing to use the space will still have to apply for an aquaculture license and lease from the province.

She noted however that the permitting process would be “much faster and less onerous because the area has already gone through a rigorous assessment for that activity.”

“Biophysical and oceanographic data is available, meaning you will know the average phytoplankton, pH, temperature and salinity, etc of your site. You are aware of what the bottom looks like, the current, proximity to wharves, and three-phase power, where the navigation routes are, and the proximity to lobster fishing gear. The concept is much like shopping for a lot in a business park on land, except it is on water.”

The ADA has yet to be approved but the interest is high, added LeBlanc. “We have been getting calls everyday since we announced it.”

Argyle currently has five sites with oyster farming activity by two companies, and another company soon to receive three leases. Under the proposed ADA, 19 sites have so far been identified. The leases will vary in size, ranging from 4 to 20 hectares.

“Oyster aquaculture is environmentally friendly, and has always been very well received. The lobster fishery has an important presence in our municipality and we value their input and want to avoid their lucrative fishing grounds. Recreational boater routes have also been considered with every site chosen,” LeBlanc said.

— Liza Mayer

The Kona-based research company that helped develop Hawaiian kampachi (Seriola rivoliana) as a new aquaculture species is setting its sights on other finfish, and seaweed.

The company, Kampachi Farms LLC, is also changing its name to Ocean Era LLC as part of its repositioning.

The company will focus on a range of research projects, including improving kampachi diet formulations, selective breeding, cultivation of herbivorous reef fish, and offshore farming of algae for food, feed and biofuel use.

Grieg Seafood of Norway has acquired Grieg Newfoundland, a massive salmon aquaculture operation under construction in eastern Canada.

The Newfoundland operation has 11 licenses for sites in Placentia Bay that are currently approved or in different stages of application. In its first phase, it expects harvest volumes of 15,000 tonnes annually beginning 2022 or 2023, while the second phase expects to see harvest volumes of 33,000 tonnes per year. In the long-term, the harvest potential is around 45,000 tonnes annually.

The acquisition of Grieg Newfoundland will strengthen Grieg Seafood’s exposure in the US market Credit: Grieg Seafood

Grieg Newfoundland also features a recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) facility. It will include hatchery, a smolt facility and three post-smolt modules with potential annual capacity of 7,000 tonnes upon completion.

The Norwegian company paid $66.5 million (NOK 620.5 million) upfront for phase 1. An optional phase 2 additional settlement of up to $100 million (NOK 930 million) will be paid depending on harvest volume milestones to be reached during the first 10 years of operation.

“With close proximity to important markets on the East Coast of the US, this acquisition significantly strengthens our US market exposure and opens up for synergies with existing operations,” says Grieg Seafood CEO Andreas Kvame.

Grieg Seafood has operations in British Columbia.

Avideo game that recently incorporated fish farming into the game’s environs could help spread the word about aquaculture. Terrestrial agriculture and fishing have been staples of the video game Stardew Valley since its release in 2016. But with the game’s most recent update late last year, aquaculture has arrived on the farms “cultivated” by millions of players around the world in the form of fish ponds.

“Stardew Valley’s always had fishing as part of the game but typically you had to go outside of the farm to find a river or the ocean to fish,” says the game’s creator Eric Barone. “But there was nothing related to fishing on the farm itself and I wanted to incorporate that.”

Fish ponds on this Stardew Valley farm have lobster, tuna and sturgeon. The tuna and sturgeon have roe ready to be harvested but the exclamation point indicates that the sturgeon require some attention

While the ponds represent a very simplified iteration of aquaculture (aquatic life are simply thrown in the pond and they begin multiplying), there is a pleasing amount of intricacy. Farmed fish and shellfish may produce roe that can be aged or, in the case of sturgeon roe, processed into caviar. Aquaculture stakeholders lament the fact that children are often taught about farms on land but not about ocean farms. While Barone’s primary focus is always on creating game elements that are fun, he also aims to broaden the player’s understanding of food production methods.

“I hope the game teaches players some things that they might not know about farming,” he said. — Matt Jones

“If we are going to grow offshore aquaculture so we can feed 9 billion people and to be able to move away from reliance on marine animal proteins, we need to be able to do this in a way that is scalable,” said Neil Anthony Sims, marine biologist and CEO of Ocean Era, LLC.

Editor Liza Mayer

Tel: 778-828-6867 lmayer@annexbusinessmedia.com

Advertising Manager Jeremy Thain

Tel: (250) 474-3982

Fax: (250) 478-3979

Toll free in N.A. 1-877-936-2266

jthain@annexbusinessmedia.com

Media Designer Svetlana Avrutin

Audience Development Manager / Subscriptions

Urszula Grzyb

Tel: 416-510-5180

ugrzyb@annexbusinessmedia.com

Fax: 416-510-6875 or 416-442-2191

Aquaculture North America, 815 1st Ave, #93, Seattle, WA, 98104

Regular Contributors: Ruby Gonzalez, John Nickum, Matt Jones, Lynn Fantom

Annex Privacy Officer

Privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com

Tel: 800-668-2384

Group Publisher - Todd Humber

thumber@annexbusinessmedia.com

COO - Scott Jamieson

Mussel farming is heavily dependent on ropes that could end up as marine debris during big storms Credit: CAIA

Project seeks to produce eco-friendly rope for aquaculture

Researchers in the European Union are working on developing biodegradable rope for the aquaculture industry.

Their aim is to replace ropes currently used in aquaculture, which “are nowadays manufactured with 100 percent non-recyclable plastics,” said the group behind the project called “Biogears.”

They said biodegradeable plastic is currently used in the industry but it represents only about 1 percent of the 335 million tonnes of plastic produced annually. “The Biogears project will develop biobased ropes that, although durable and fit-for-purpose, still biodegrade in a shorter time and can be sustainably managed by local composting facilities.”

While the resulting product is aimed at the European aquaculture sector, it will be a much-needed innovation for the rest of the world. Mussel growers are particularly heavily dependent on ropes, which could end up as marine debris during big storms.

Project coordinator Leire Arantzamendi said Biogears hopes to make mussel and seaweed production more eco-friendly. “We will generate three rope prototypes with a highly reduced carbon footprint along the whole value chain. The aim is to develop these as marketable products, whilst minimizing the potential of aquaculture to generate marine litter or release plastic to the sea,” she said.

The EU allocated €945,000 (around $1 million) to the Biogears project, which is set to be completed in 2022.

NWhat if you could increase your stocking densities, improve your fish yields, and decrease your production costs? Our self-contained, turnkey oxygen generators can provide you all of those benefits. With scalable configurations from 113 - 6,363 kg/day you can generate oxygen for as low as 4.4 cents/nm³

ews that plastics are finding their way into our food supply created buzz not too long ago, but help could be at hand.

The Ocean Cleanup, a Netherlands-based nonprofit that developed a garbage collection system for the ocean, says it has successfully captured and collected plastic debris in the so-called Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The patch has the largest accumulation of ocean plastic in the world and is located between Hawaii and California.

“In addition to collecting plainly visible pieces of plastic debris, as well as much larger ghost nets associated with commercial fishing, System 001/B has also successfully captured microplastics as small as 1mm–a feat we were pleasantly surprised to achieve,” said The Ocean Cleanup CEO Boyan Slat, who invented the system in 2012 when he was just 18 years old.

The greatest accumulations of plastics and plastic particles tend to be found in coastal waters, which is also where most shellfish farms are operating. NOAA estimates more than one-third of the shellfish-growing waters of the United States are adversely affected by coastal pollution. Humans are exposed to higher microplastics when eating seafood that are consumed whole, such as shellfish (see ANA May/June 2018, page 10).

The next step for the cleanup mission is to address any design challenges and then start the scale-up to the full fleet in 2021. This year, the first plastic catch will be recycled into sustainable products and sold to help fund the continuation of the cleanup operations.

The pitch for plantbased meat substitutes is similar to that for faux fish—no harm to animals and less taxing on the environment. But there’s one key difference: Doctors recommend eating less red meat, but more fish. That difference strongly suggests lower potential for faux fish.

Now funds are fueling faux fish.

Last year, Tyson invested in New Wave Foods, a producer of plant-based shrimp that is not in the market yet, according to its website, but is served in the Google cafeteria. In January, global grocer Tesco began rolling out a new vegan-friendly tuna product from Good Catch, started by chef brothers who are also creating Tesco’s Wicked Kitchen vegan line.

That’s the pattern. “In addition to their financial support, most large corporations bring along agriculture-,

biotechnology-, and food-related knowledge,” Kearney notes. And they’re hedging their bets as to which sources will meet the world’s growing demand for protein.

CROSSWINDS FOR AQUACULTURE

This interest in fish alternatives comes at a time when aquaculture—“legacy aquaculture,” as some of the new entrants call it—is being buffeted by crosswinds.

Take, for example, the about-face of PM Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government before the latest Canadian election when the party pledged to transition all ocean fish farms in BC to closed containment by 2025 (see related report on page 3). And even land-based aquaculture has become “a complicated space,” as Nordic Aquafarms president Erik Heim diplomatically says. His company has faced “subcultures” opposing projects in both Maine and California. “You have people who just simply hate fish farming and believe that the world should go vegan and that we’re wasting too much food in the first place, so we don’t need any more fish.”

In fact, it was a vegan activist organization behind the undercover videos of a Cooke Aquaculture salmon hatchery in Maine that showed alarming animal abuse, including workers smashing live salmon against a concrete wall. Overall, aquaculture is facing serious concerns revolving around animal rights, the environment, and the increased risk when aquaculture enterprises grow in size. On the coast of Maine, wealthy landowners fought the expansion of an oyster farm lease from 10 to 40 acres, impugning it as “industrial ocean farming.”

“That’s at the core of it: it is difficult to scale up these systems sustainably,” says Jen Lamy of the Good Food Institute (GFI), an alternative-protein advisory and lobby group founded by Bruce Friedrich, a former high-profile PETA activist.

The number of vegetarians in Canada has been growing, from 4 percent of adults in 2003 to 9.4 percent in 2018, according to a survey by Dalhousie University. But, unlike Canada, vegetarianism in the US has been fairly stable over the past 20 years, with 5 percent of adults opting for that identification in a 2018 Gallup poll.

What has been growing, however, is the number of “flexitarians,” whose vegetarian diet occasionally includes meat and fish. Nearly 23 percent of Americans report eating less meat in the past year, Gallup announced in January. Most cite health concerns as the reason.

The food industry has made the flexitarian lifestyle a lot easier: the number of vegetarian food and drink products

doubled between 2009 and 2013, according to Mintel, the global market research agency.

Although the original generation of frozen plant-based seafood, such as Gardein, targeted vegans, fish alternatives have broader appeal as their taste, pricing, and convenience improve. “As plant-based products grow, the number of people interested in them will grow,” says Lamy, GFI’s Sustainable Seafood Initiative Manager.

“Delicious” is frequently heralded as a goal when analysts talk about fish alternatives. For example, Good Catch, which makes a tuna substitute from a six-legume blend flavored with algal oil, adopted the tagline: “Plant Made / Chef Mastered.” This emphasis on taste may well yield the answer on how large the niche category will become.

A NASCENT CATEGORY

Right now, annual sales of fish substitutes at retail in the US are only $9.4 million, representing just 1.2 percent of the $800 million for overall plant-based meat and fish, according to SPINS data released by GFI. But those sales don’t include leading retailers like Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods, or ALDI. Nor restaurants.

Expect sales to increase as companies use the influx of investment dollars to ramp up production and expand distribution.

Good Catch, which raised $10 million last year, is now hiring for a new Ohio production facility and has a relationship with Whole Foods, in addition to multinational grocer Tesco.

Besides the sushi counters at Whole Foods, New Yorkbased Ocean Hugger Foods has been bringing Ahimi, its faux ahi tuna carved from Roma tomatoes, to restaurants and cafeterias. Last April it earned a spot on the menus of Yuzu Sushi, part of MTY Group, one of the largest franchisors in North America’s restaurant industry.

“Our chef and I were thinking about adding vegetarian products and this request also came from customers,” says marketing director Julie Lamothe, adding, “It’s good, tasty.” The sushi alternative is offered at all 68 restaurants of Yuzu Sushi in Quebec and three in New Brunswick.

Restaurant distribution is key for seafood. In the US, consumers spend about two-thirds of their annual expenditures on seafood in restaurants, cafeterias or other types of foodservice businesses, according to NOAA.

WILL FAUX FISH FOLLOW THE PATH OF BEEF?

Investors in the new generation of fish substitutes are betting this category will follow the explosive trajectory of novel meat replacements, like Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, which celebrated its 10th birthday last year with a sizzling IPO.

Plant-based meat sales grew 9.6 percent in the year ended April 2019, smaller than the 25-percent growth a year prior. These new products do not appear to be cannibalizing meat sales, however. In fact, since their introduction, cash receipts for the US beef industry have increased 54 percent, according to the USDA.

The pitch for plant-based meat substitutes is similar to that for faux fish—no harm to animals and less taxing on the environment. But there’s one key difference: Doctors recommend eating less red meat, but more fish. That difference strongly suggests lower potential for faux fish. Close to 25 percent of consumers who avoid eating animalbased protein do so because of health issues versus 16 percent of consumers who do so for environmental issues, according to Mintel.

“Despite the attention and the investments, plant-based fish innovation may face challenges finding a mainstream market who will actually buy it and it may all come down to why. The reality is—other than allergy issues—there is no real health barrier to fish and shellfish consumption and sustainability concerns remain somewhat niche,” says Kaitlin Kamp, food and drink analyst at Mintel.

And the jury is still out on whether the large-scale commercial facilities that will be needed to produce fish substitutes represent less of an environmental threat.

“All food production requires inputs such as food, water, energy, and physical space,” writes David Roberts of

meat sales grew 9.6 percent in the year ended April 2019, smaller than the 25-percent growth a year prior. They appear not to impact meat sales, data from USDA show Credit: Liza Mayer

Sustainable Fish Farming Canada. “The key is to find food production systems that have the highest yields of output for the least amount of inputs.”

Tim Kennedy, president and CEO of the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance, echoed the question about environment impact. “It is hard to assess at this point both what the opportunity is and the environmental issues are [for the fish alternatives]. They will take production resources and space. When you look at environmental efficiencies, will they be friendlier?”

SHOULD FISH FARMERS BE WORRIED?

If the faux fish market mimics that of beef, it will not steal share from aquaculture. “Right now, we see it as a complement—and a very small one,” says Kennedy. However, it may have other impacts. These product innovators, as well as some investors, describe themselves as “market disruptors.”

Part of that disruption will surely come as they promote

their products with iconoclastic language that foretells of the “total collapse of the ocean ecosystem” and announces “No fish were harmed in the making of this product.” For some consumers, it may focus attention on issues that had not been so clearly on their radar.

Seafood farmers should expect some static ahead. Tension is already playing out on another stage: Seafood Expo North America in Boston, North America’s largest seafood trade event. This year organizers barred TUNO, a soy-based protein with a texture like tuna, from the exhibit hall, triggering legal threats from its distributor, Atlantic Natural Foods. Although the event had given Ocean Hugger Foods the green light in 2018, the show has a new policy that restricts the expo to seafood producers.

The situation may be different for RAS, which Blue Ridge Aquaculture sees as the “logical evolution of aquaculture.” Based in Virginia, the company says it is the largest indoor

producer of tilapia in the world, having delivered 4.7 million pounds of live fish to market last year. And it is expanding.

According to business development director Martin Gardner, RAS “addresses a lot of the concerns that may have driven plant-based solutions.”

And Nutreco may agree. Less than two weeks after it took a stake in BlueNalu, it announced an investment in RAS-based Kingfish Zeeland. The funding will help the Dutch yellowtail producer build a much larger RAS facility in Maine by 2021, the third RAS fish farm on the drawing board for the state.

Which brings us back to how companies are hedging their bets. They are exploring many options to feed the future. Some are going it alone; others, in partnership. Maybe aquaculture leaders will come to view faux fish producers as a “frenemy.”

“In my view, to be able to involve the conventional industry is the best path forward,” says Lamy of the Good Food Institute. How that will occur remains to be seen, but this collaborative attitude is striking. After all, 20 years ago, her boss was arrested for throwing fake blood on models wearing fur coats.

The founder of Whole Foods isn’t a fan of plant-based meat because, as he told CNBC last year, “I don’t think eating highly processed food is healthy.” That process, as Beyond Meat and Good Food Institute have described it, takes plant protein and adds binders, fats, natural flavors and colors, as well as nutrients. Then the mixture is shaped using heating, cooling, and pressure.

On the other hand, cell-based meat (like Memphis Meats) and cell-based fish (like BlueNalu’s) are “clean.” That preferred descriptor may signify free from slaughter, environmental degradation, or injury to one’s conscience. But these novel products are also free of the multitude of ingredients in plant-based meat, ingredients that must be processed to get to the end result.

Instead, cell-based meat and fish are grown in labs today, but someday will be produced in large-scale, certified, commercial food facilities. Industry watchers say these products are most like the real thing.

Here’s a highly simplified version of how the process works. Cells are taken from a living animal. They are put in a bioreactor along with cell culture media, which causes them to proliferate. When the lab changes the culture conditions, the cells differentiate into muscle, fat, and connective tissue. They are then given the structure of a fillet or ultimate end-product with 3D materials that act like scaffolding.

A key benefit, proponents say, is that manufacturers only grow what consumers will eat; there’s no waste.

In addition to BlueNalu, which received an investment from Nutreco in January, the startups working on cell-based fish include Wild Type and Finless Foods. All three are based in California.

Although they are all hiring, these companies are early-stage ones—they have made some progress with a regulatory framework, but technical hurdles remain. The big challenge, as the consultants at Kearney see it, is the cost of the molecules that stimulate cells to differentiate. And that, along with other issues related to scaling up, mean they may be five to 10 years away from having fillets on ice at the local fish counter.

– Lynn Fantom

BY MATT JONES

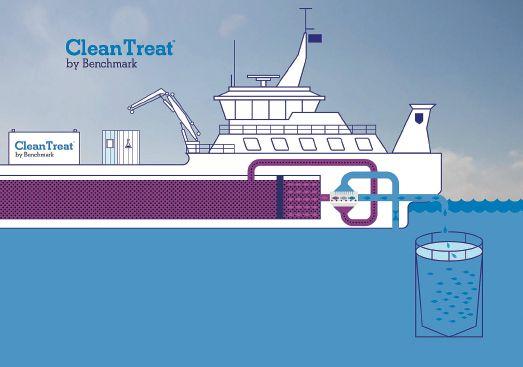

Sea lice are a common challenge in the farmed salmon industry but there is still much to know about them. Dr Shawn Robinson, marine ecologist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ St Andrews Biological Station (SABS) in New Brunswick, has spent much of the past 10 years working towards improving industry understanding of sea lice to inform how to deal with them without the use of chemicals.

One treatment devised at SABS is a warm-water shower to lull the lice into a sleep-like state, causing them to detach from the host. Salmon farmers have been using a thermal water treatment method over the past five or six years and have seen it remove as much as 95 percent of sea lice from the host fish. But while the warm-water bath treatment

had minimal impacts on healthy fish, fish with health issues didn’t do as well, noted Robinson.

“We’ve found that if the fish were really stressed and in poor physiological shape, it pushed them over the edge,” says Robinson.

A related research is selective breeding of sea lice. SABS researcher Hannah Bradford aims to find out if sea lice could develop resistance to warm-water temperatures. She’s growing the fourth generation of sea lice at the lab and plans to raise as many as she can for the length of the project.

Sea lice are a naturally occurring parasite found on marine fish. Biologist Jonathan Day is studying sea lice during larval stage. He is looking at larval distributions of sea lice around farms, and has found that sea lice larvae move closer to shore until they mature and metamorphose into the infective stages. This knowledge

enables scientists to examine the oceanography of the area to get an idea of how far a newly mature sea louse could travel on a tidal excursion.

Day is also examining how sea lice actually attach themselves to their hosts. Robinson says there are notions that “lice jumped on the side of a fish as it swam by.” “That’s probably like you or me trying to get on a plane as it’s taxiing down the runway,” he says.

Day’s research suggests that lice are caught up in a fish’s gills when it draws water into its mouth. Further, when that water is expelled from the gills, it will run down the side of the fish, providing ample opportunities for a louse to attach itself to the fish. Day is nearing the end of a three-year tenure with the lab and is currently preparing a paper on his findings.

Robinson believes that their research will help industry and government in making informed decisions on sea lice, and salmon farming at large.

“If you have no information on a subject that you’re trying to manage, you’re forced into a precautionary approach,” says Robinson. He says taking the most conservative approach possible doesn’t always lead to the best management outcomes.

“By having more information, one can make a much more optimal decision. Those objectives may differ between government and industry, but this type of research is critical in managing our natural resources.”

Cooke Aquaculture Pacific received Washington State approval to farm all-female, sterile (triploid) rainbow trout/steelhead in Puget Sound but the approval comes with strict conditions (see box).

The five-year permit from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) was granted in January after a year of extensive scientific review and public input.

“We heard from a huge number of stakeholders (more than 3,500) on this issue, and we appreciate everyone who took time to make their voice heard as part of this process,” said WDFW deputy director Amy Windrope.

“This permit was approved based on scientific review and is contingent on Cooke complying with strict provisions designed to minimize any risk to native fish species.”

The Canadian company farms Atlantic salmon in the state, but due to the state ban on farming nonnative finfish starting 2025 it sought permission to farm rainbow trout. The approval means it can now stock its existing pens in Puget Sound with rainbow trout once all of its Atlantic salmon have been harvested.

Cooke Aquaculture is in a joint venture with Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe to grow sable fish and rainbow trout, which are Northwest native species. The partners foresee investment in new equipment and technology while supporting local jobs.

Conditions of Cooke’s permit

• Comprehensive escape prevention, response, and report plan;

• Inspection of the net pens’ structural integrity and permit compliance every two years by WDFW-approved marine engineering firm;

• Immediate reports to WDFW of any escaped fish, as well as a unique marking identifying all commercial aquaculture fish;

• Sampling and testing of smolts before being transferred to marine net pens, to ensure that they are free of disease;

• Annual fish health evaluation reports; and

• Tissue sampling for genetic analysis of broodstock by WDFW

By Tom Smith

Tom Smith is the Executive Director of the Aquaculture Association of Nova Scotia. Throughout his career, he has been active in policy development and economic development planning in aquaculture in the province and Canada as Board Member of the Directors of the Nova Scotia Seafood Sector Council, Atlantic Canada Seafood Council, and the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance.

In recent weeks, there’s been a lot of talk about aquaculture, and Nova Scotians deserve to have their questions answered. But without the facts we can’t have an honest conversation. Recent information circulating about the aquaculture industry is inaccurate and fails to recognize it for the safe, sustainable, growth-oriented industry that it is.

For more than 40 years Nova Scotians have supported marine fish farming and recognized that it can coexist with other fisheries on working waterfronts. Fish farms have been operating sustainably with provincial and federal environmental and regulatory approvals and oversight in many coastal communities from Shelburne to Bras d’Or Lake, and from Digby to Halifax County. During this time, we’ve seen export sales in the lobster industry, tourism, and property values all go up in these areas.

Cooke salmon farm in Nova

Aquaculture companies operating in Nova Scotia are regularly audited by international certification programs Credit: AANS

We encourage Nova Scotians and local municipalities to let science

The South Shore of Nova Scotia where fish farming has taken place for many years, shows consistent increases in hotel room sales and tourist visits. According to Nova Scotia Tourism, from 2010 to 2017, South Shore area tourism accommodations room night sales have increased 43 percent, and the province has seen a 15 percent increase over the same period.

Nova Scotia is the gold standard for aquaculture, with regulations that have been updated recently to become the most stringent in the world. We encourage Nova Scotians and local municipalities to let science guide the management and development of the industry.

The Nova Scotia Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture and other federal and provincial agencies perform rigorous science-

based technical reviews and analysis on all aquaculture projects and an Independent Review Board adjudicates projects through a public hearing process.

Aquaculture companies operating in Nova Scotia are regularly audited by international certification programs and performance standards for their entire supply chain – farms, hatcheries, processing plants, and feed. This assures healthy, locally produced foods that are produced through environmentally and socially responsible means, which play a significant role in reducing our carbon footprint.

Marine aquaculture is a responsible, sustainable and innovative means to provide adequate food supply to meet the world’s population growth while helping to reduce the pressure on wild fish stocks. The aquaculture sector is grounded in science and innovation, and our R&D projects drive productivity improvements and new farming technology and processes.

Over the last decade, leading companies have transformed oysters into lifestyle brands—“de rigueur for a warm summer day with a glass of rosé,” as Massachusetts-based Island Creek Oysters president Chris Sherman puts it. This species now accounts for 64 percent of total mollusk sales.

Growers have moved from shucking at a few restaurants to owning their own franchise-extending raw bars, fullservice restaurants, and farm stores. Among leaders, a promotional mix may feature e-commerce, earned media and digital marketing, and events, such as oyster fests, shucking contests, and farm tours. Island Creek, which now supplies 41 states, has appeared at South by Southwest, Art Basel, and the Newport Jazz Festival.

Such marketing created “an awakening of a sleeping demand” for oysters among younger consumers that goes deeper than gastronomical culture, Sherman says. “It’s a product that they can feel good about because of its services rendered to the environment and coastal communities.”

“Environmental mindfulness is more important than ever,” adds Graham Watson, a four-year veteran of California’s Hog Island Oysters who started West Passage Oyster Company in Rhode Island in 2016. Talking about the farm’s tours—offered year-round— he says, “We love bringing people out to talk about the ecosystem and educate them on where their food is grown.”

of

While the number of mollusk farms has grown steadily overall, it’s ballooned in certain states, like Virginia and Maine where the USDA reported increases of 90 and 146 percent respectively from 2013 to 2018. State leases suggest even more robust counts.

“It’s been exponential growth, for sure,” says Hugh Cowperthwaite of Coastal Enterprises Inc (CEI), a Maine nonprofit consulting group.

In Maine, many new farmers have been able to get their feet wet because of the relative ease of acquiring Limited Purposed Aquaculture (LPA) licenses. With no scoping or public hearings, approval is granted in just a few weeks, though it’s limited to certain species, only one year, and a small footprint of under 400 square feet.

1 3 2 5 4

In Mississippi, response to the Department of Marine Resources’ maiden offering of an Oyster Farming Fundamentals course in 2018 has been very good and some of the students have become full-fledged farmers.

Another step forward has come through an initiative of NOAA Fisheries that yielded permitting data on 22 states. Because some states have already solved some problems others are still grappling with (such as having a one-stop permitting website) this compendium is helping foster discussions among states and spur progress, says Kevin Madley of NOAA.

Through non-profit Manomet, the technique of Jordan Kramer (pictured) in growing quahogs is being shared with other farmers. Peer-to-peer mentorship programs are trending up in shellfish aquaculture

To counter the knowledge gap about regulations and more, CEI, in tandem with other Maine aquaculture organizations, offers a free, 12-week course, “Aquaculture in Shared Waters,” which started in January. For the first time in its eight-year history, the program is being live-streamed to a second training location in Maine. The organization taps experienced oyster, mussel, and seaweed growers to speak.

“They lower the bar and reduce the learning curve,” Cowperthwaite says.

Similarly, the Maryland Shellfish Growers Network, supported by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) and other partners, provides a range of resources: a state-wide aquaculture conference, database of financial assistance sources, and promising peer-to-peer mentorship program.

“The best person to learn from is someone who’s already been through it all,” echoes Dr Allison Colden of CBF.

This program, still shy of its two-year anniversary, matches a newcomer with a veteran grower based on geography and cultivation methods. “We had no idea what the reception of the existing farmers would be to new people coming into the industry,” says Colden. “But they’ve been very eager to help…supportive and collegial. At this point, they don’t see them as somebody who’s coming in to knock them out.”

Another service offered free to all members of the Maryland Shellfish Growers Network is technology assistance from specialists in geographic information system (GIS) mapping. To support new lease applications, this tool identifies adjacent land use, as well as regulatory exclusions, salinity, bathymetry, and bottom type.

As farmers seek to boost production, technology can also help. “Five years ago, we were intent on growing the farm to scale, with an expanded lease. That’s a different beast,” admits Abigail Carroll, founder of Nonesuch Oysters in Maine. “An employee begged for Oyster Tracker because it was more user-friendly.”

(L-R) Nate Perry of Pine Point Oyster and Matt Moretti of Bangs Island Mussel operating a scallop washer. Maine’s CEI introduced Japanese technology to local farmers to encourage scallop aquaculture in the state Credit: Coast Enterprises Inc

This software system, launched in 2018, visualizes production, provides activity alerts, and simplifies regulatory reporting. Today, it’s deployed in 10 US states, Prince Edward Island in Canada, and Ireland. “It was a game changer for my team,” says Carroll.

Another example: the ear-hanging technique of growing scallops, developed in Japan and tested in Maine’s waters some three years ago, has been adopted at four Maine farms and will enter a fifth trial this summer. The technology transfer, which includes a significant investment in specialized equipment, is a CEI-sponsored effort to bring that high-value crop to the state.

Branching out to seaweed farming helps shellfish farmers like Steve Bachman diversify income Credit: Magellan Aqua Farms

Another reason shellfish farming is surging is because commercial fishermen—whether they catch lobsters in Maine or blue crabs in Maryland—are turning to aquaculture as a hedge against climate change and regulatory issues. It’s a way to diversify income.

Trials abound: oyster and quahog polyculture in Maine (see story on page 16); bay scallops and Atlantic surf clams in the New Jersey bays traditionally devoted to oysters and hard clams; Atlantic surf clams and blood arks and oysters and seaweed in Massachusetts (see story on page 22).

Bangs Island Mussels, which acquired Calendar Island Mussels last November to meet growing demand for mussels, has been a leader in diversification. In addition to testing sea scallops, this Maine mussel grower is coculturing sea kelp.

It’s a move with another benefit: biodiversity. According to the Island Institute, farmed mussels located near kelp have stronger shells and larger meats.

Phasing out the state’s subsidy for pathogen testing would effectively put us out of business, says Weatherly Bates of Alaska Shellfish Farms Credit: Alaska Shellfish Farms/Corey Arnold

BY LIZA MAYER

Aproposal to end state subsidies for shellfish-pathogen testing will hurt Alaska’s shellfish industry if approved, say the state’s farmers.

Like other oyster growers, Greg and Weatherly Bates send oyster samples to a lab in Anchorage for testing for paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) weekly for half of the year and monthly in the winter. Growers pay for the shipping to the lab and the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) pays the testing fees which DEC estimates to be around $500-$700 per test.

DEC Commissioner Jason Brune proposed to phase out the subsidy after Alaska Governor Michael Dunleavy proposed to cut the $700,000 per year budgeted to DEC for shellfish toxin testing.

Bates, owner of Alaska Shellfish Farms, based in Halibut Cove, AK, estimates that paying for the tests themselves will increase the farm’s operational costs by 50 percent. “The proposal to scrap funding for testing would be catastrophic to our industry. Without subsidy our shellfish industry will end because business in Alaska relies on a narrow margin to operate,” she said.

Oyster growers and geoduck harvesters have been getting the subsidy for the past 10 years. Bates says the health of Alaskans who consume wild shellfish will also be at risk if the proposal is approved.

She explained: “Alaska is the only Coastal State to my knowledge that does not regularly test shellfish for paralytic shellfish toxins despite a long history of illnesses, death and shellfish subsistence in Alaska. The State offers no advise other than ‘know before you dig.’ Our testing saves lives because when we find elevated toxins we notify the public through non-profits and people do not go out and recreationally harvest potentially deadly shellfish.”

Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation (AFDF) executive director Julie Decker says eliminating the subsidy will mean $250,000 of the shellfish industry’s measly $1.5 million annual revenue will go to PSP testing. “That’s a big chunk of the revenue and that’s just for one type of activity. They’ve got other types of expenses,” Decker said.

At the annual conference of the Alaska Shellfish Growers Association in January, a representative from the Office of the Governor heard the shellfish growers’ concern about the proposal.

“After he heard the significant impact it would have on farmers, the representative said that it’s possible that the administration wasn’t clear about the large impact the proposal would have,” said Decker. “So I think there’s going to be a lot of discussion about it throughout the next few months during the legislative session.”

Shellfish growers were talking to their legislative representatives as of press time.

BY MATT JONES

Oyster thefts continue to be a big problem for US farmers. While a handful of cases have attracted significant media attention, many are unreported and some are so sizable that they threaten the existence of the businesses.

In the State of Louisiana, there are no figures available on the number of oyster thefts or the financial losses they represent, but it is a chronic problem exacerbated by challenging logistics, says retired Louisiana Sea Grant researcher and now industry consultant, John Supan.

“All of those thefts occurred in bottom leases,” says Supan. “In many cases, these leases are way out in the marsh so surveillance has to be by vessel. Thieves go when the leaseholder is away; they drop a dredge and steal the oysters. Your only option as a leaseholder is self-policing. You can’t really call a marine enforcement agency; they’re spread too thin. You can’t really call the Sheriff’s Office because very few of them have the resources to put a boat in the water and patrol.”

Supan notes that the thefts occur more frequently when there is a shortage of oysters in the marketplace, as is the case currently. Technology has also helped thieves. Supan has been told stories about thieves coordinating with cell phones and using drones to monitor the readiness of oysters and the presence or absence of the leaseholder at the site.

Nick Collins of Louisiana’s Collins Oyster Company says thefts have been an industry problem for as long as he can remember. He has childhood memories of patrolling the property by boat with his father and grandfather. But he believes the issue is far worse today than it was in the past.

“I’m fourth generation,” says Collins. “I’ve got a quality product. We settle for nothing less. But people don’t care. The thieves’ mindset is ‘I’m a drug addict or I’m starving or whatever, I need money.’ And in the wintertime there’s no work.”

Collins finds himself in a particularly challenging position. His family holds 1,700 acres in leases but only around 300 acres are productive because of the 2010 BP oil spill. Combine that with the thefts and natural predators, he’s wondering whether it might be time to disengage from oyster farming.

for the company to recoup its losses.

“We’re debating it, me and two of my brothers,” says Collins. “We’ve been farmers all our lives. But you’re really facing difficult times each year just to pay for a year’s worth of expenses.”

Last year, Florida’s Pensacola Bay Oyster Company lost more than 30,000 oysters to thieves. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission was able to make four arrests in this case, pursuing charges of grand theft, dealing in stolen property, criminal mischief and misdemeanors related to improper oyster handling. Court proceedings against the accused are still in progress, but there was no way

“They found a bunch of the oysters,” says Pensacola Bay Oyster Co president Donnie McMahon. “But they weren’t sellable at that point because they weren’t traceable. We pretty much lost everything.”

Maryland’s Bill Pfeiffer has been maintaining an oyster lease for the past 20 years and intends to farm oysters into his retirement. In 2018, he found his lease had been dredged and the oysters were gone. He is now exploring potential security measures, including using a beacon that will be hidden among the oysters and sends a signal once moved. A long-range night vision camera is also in his sights, but he acknowledged they could be quite expensive.

bed

Without pest control, growers are forced to abandon beds such as this. Burrowing shrimp undermine the structure that supports the off-bottom gear

OA shrimp-infested oyster bed

yster farms in the single largest oyster growing area in the US face an uncertain future after being left with no pest control option to fight an invasive species.

For years, oyster growers in Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor in Southwest Washington state have fought the burrowing shrimp, a pest that destabilizes the seabed and renders it unusable for oyster farming.

“Burrowing shrimp seem to settle in some areas in greater numbers than others, especially near the estuary and river mouths. Unfortunately one of the areas they seem to recruit to are the locations within the estuaries with the greatest productivity and are obviously of the highest value to the farms,” said David Beugli, executive director of the Willapa Grays Harbor Oyster Growers Association.

Growers say imidacloprid is the only practical way of addressing the pest and has shown to be effective as part of a well managed Integrated Pest Management program. But the chemical has also been the subject of contentious debate and public backlash.

The growers recently gave up the fight to have the Washington State Department of Ecology overturn its 2018 decision to ban imidacloprid because they recognized that the fight could be lengthy and expensive.

“It doesn’t take much to understand the futility of trying to fight an agency with apparently bottomless pockets when you are a small family farm group,” said Brian Sheldon, owner of Northern Oyster Co in Ocean Park.

SMALL FARMERS ARE VULNERABLE

Burrowing shrimp affects most of the farms in the area. But without a way to control them, the smaller farms are more vulnerable.

“The ban is particularly hurtful to smaller farmers because they have limited amount of land available to them and are less vertically integrated. The larger ones will also experience crop shortage but since they have more land available to them, they are able to weather the loss of available growing areas and losses of product better,” said Beugli.

At Northern Oyster Co, Sheldon estimates the farm has lost hundreds of acres to the shrimp over the last four years and could lose more, which would mean reducing plantings and eventually future crops and staff.

“We assess the beds each spring to determine if we can plant seed that season, and we’ve been abandoning beds each year due to shrimp infestation levels. As they infest you lose seed. For the grower it gets to a point where you are losing too much seed, and at that tipping point you are forced to walk away or you lose you investment,” said Sheldon.

For now, the association is trying to secure funding to conduct research on an integrated pest management solution for the problem. The Department of Agriculture has earmarked $650,000 towards burrowing shrimp research in consultation with the departments of Ecology and Natural Resources, and the Willapa-Grays Harbor working group.

— Liza Mayer

• RAS and ow-thru culture facilities from 50-1000 sq meters

• State-of-the-art culture systems

• Business support facilities and networking opportunities

• Assistance in grant writing and identifying funding opportunities

• Plus exceptionally high quality sources of water!

BY LIZA MAYER

Seafood farmers in Maine are exploring the commercial viability of farming quahogs or hard clams in bags placed under floating oyster farms as a supplementary crop.

The technique known as multi-trophic aquaculture will not only address the dwindling harvest of quahogs from the wild caused by Maine’s warming waters, but also protect them from predators and boost farmers’ shellfish harvests without increasing the farm’s footprint.

The method is a departure from the traditional way of farming clams where growers bury clam seeds into the mud and then cover the flats with nets to protect them from predators, particularly green crabs and diving ducks.

“The Gulf of Maine is warming incredibly rapidly. The water temperature is becoming much more suitable for farming quahog in Maine,” says Dr Marissa McMahan, marine fisheries division director at Manomet.

Although a farmer could wait for more than two years before quahogs reach market size, they are much easier to maintain than oysters although Kramer warns one can’t just plant the quahog seeds in bags 20 feet below the water surface and fully forget about them.

Local farmer Jordan Kramer of Winnegance Oyster Farm in New Meadows River, Maine says routinely finding wild quahogs attached to his oyster gear when he hauls them up after winter persuaded him to try farming them.

“Having them in contained culture in the mud below the farm seemed possible because they were growing so well,” he says. In 2017, he started experimenting initially with 20,000 quahogs split among several bags and planted them under two-tiered oyster cages suspended from lines. Those quahogs reached the market in the fall of 2019.

“There’s something like 200,000 in the water now of various sizes. In the coming years, I think a very small farm like my own (1,600 square feet of lease) can have as many as 30,000 clams coming out each year,” he says.

Kramer is speaking from experience. He has lost hundreds of crops, not to predators, but by losing bags when they get buried too deeply in the mud because of drifting debris. “They could still sink too deep in the mud, but pulling them out of the mud once a week or once a month is not a lot of work. It’s tugging on a rope as opposed to air-drying and hand-washing them like one does with oysters. It’s really a lowmaintenance way to farm.”

Not only do farmed quahogs require lower maintenance, they also enjoy a niche market locally. Maine prohibits the harvest of wild quahogs that are less than one inch in thickness; that restriction does not apply to farmed quahogs. “One can sell farmed quahogs below that size. Smaller quahogs are actually very appealing to the raw halfshell market,” says McMahan.

Inspired by Kramer’s success in growing quahogs this way, nonprofit organization Manomet has launched an initiative to explore quahog’s potential as a farmed crop. The organization helps develop scientifically grounded, environmentally sustainable ventures. It has received a $65,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Sea Grant program for the project.

Quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria) aquaculture is an established industry in neighboring Massachusetts but it is only at experimental stage in Maine because local water temperatures were historically too cold for quahog aquaculture.

Kramer is able to sell farmed quahogs for 40 cents apiece at wholesale, whereas wild quahogs are typically sold for 25 cents apiece. By comparison, soft shell clams are sold by the bushel (roughly 50 lbs) from $60 to over $100 depending on the season. Oysters, Maine’s top farmed shellfish produce, fetch $0.75 to over $1 apiece. He says a standalone farm of just quahogs might not be as financially viable than if it were just an auxiliary crop. But that’s one of the things the Manomet project will determine.

“We’re expanding Jordan’s work to three other farmers to see if his method is

replicable in other farms and whether it is economically viable,” says McMahan.

Four farmers, including Kramer, will feed data from their farms to Manomet. “We want to measure growth and environmental variables and from there make recommendations about best practices and give potential farmers a sense of what they’re looking at in terms of investments,” said McMahan.

She hopes this initiative will also help address the biggest challenge Kramer saw as a quahog farmer.

She explains: “One of the real hurdles that we’re working through is the nursery phase, which is how to keep seed that is

one millimeter in size in a containment method where you don’t lose it but there’s also water flow going through so that they don’t die. So that is the single biggest challenge right now.”

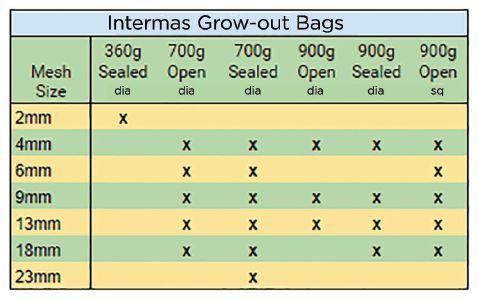

The quahog farmers in the project are using the same type of mesh that oyster growers use. “It’s been it’s been tricky working with seed so small (1 mm),” says Kramer. “They seem to find their way out of the mesh a little bit easier than baby oysters because they’re just so round so they shift a little bit more.”

“We’ve had our hiccups in terms of getting things going in terms of growth and figuring out exactly how to get them to market

‘We’re

Jordan’s work to three other farmers to see if his method

replicable in other farms and whether it is economically viable,’ says Dr Marissa McMahan of Manomet

without too many losses. But really the overhead for it is very inexpensive. I think we’ll see a lot more people experimenting with this technique and tinkering with it to improve it because it really is something you can try without a lot of risk,” he says. Manomet expects the results of the project to become available in the summer of 2021.

Maine oyster farmer balances running a farm with a day job and raising a family

Merritt Island Oysters performs suspended cage culture to grow a sweet and salty oyster that rivals oysters from far more established operations

Credit: Merritt Island Oysters

BY MATT JONES

ordi St. John makes a good living working for a software company based in Washington, DC. But St. John is not just a desk jockey – he spent many years on the water and had previously served as a captain on Windjammers Cruises in Portland. When he noticed increased aquaculture activity on the New Meadows River near his home in West Bath, Maine, he again heard the water’s siren song.

JSt. John allowed himself to be seduced by the water’s call and now he and wife Katrina are owners and operators of Merritt Island Oysters while still holding down their day jobs. In September 2017 they bought their first batch of seed and were able to take about a thousand to market in September, October and November 2018. He gets his hybrid Haskins North East High Survival (NEH) diploid oyster from Muscongus Bay Aquaculture.

“We are doing suspended, floating cages, and I’ve been doing four bag cages just because it’s easy enough to be able to flip them and maintain them as one person,” says St. John.

“We started off with about 20 to 25,000 and then did another 20 to 25,000 more in the spring of 2018. My wife is actually a high school science teacher, so we’ve been doing a few different experiments just in terms of trying to test floating bags versus cages and trying to study water temperatures a little bit and salinity levels.”

St. John says his approach has been to try to keep his bag densities down and to ensure that he flips the cages once a week and allows 24 hours of dry time to keep fallowing down. He decided against using a tumbler and hand culls, and sorts and shakes the oysters himself. These efforts, along with the water quality in the New Meadows River, have helped to produce an impressive product.

Flag Tie Markers

Flag tie markers are another cost-effective way to secure and identify shellfish equipment. They are available in a variety of lengths and marking area sizes to accommodate specific requirements. They can also be hot stamped for identification purposes.

• Lengths from 3” to 18”

• Tensile strength of 120 lbs.

• Available in Blue, Green, Ivory, Orange, Red, Yellow

• Available with blank flags that may be custom printed or Write-on

Cable ties

Cable ties are vastly used in the shellfish industry for securing cages and bags. They are a cost-effective and simple way to ensure equipment is not susceptible to tampering. Available in a wide range of colors, they are also used for identification purposes.

• Lengths from 4” to 60”

• Tensile strengths from 18 lb. to 250 lb.

• Available in 16 different colors, including UV black and fluorescent

• Can be custom printed with company name, date, lot number, etc.

“It’s been amazing how quickly the oysters grew. I think that has a lot to do with the warmer water temperatures last summer,” says St. John. He marvels at their flavor. “They really come out quite sweet and salty. It’s been impressive. I wasn’t necessarily sure that was going to be the case. As you start growing, you hope to find a good site and we kinda got lucky.”

Merritt Island is owned by Bowdoin College of Brunswick, Maine. The college’s Bowdoin Outing Club offers its members a wide range of water activities on the island. St. John says the location has been ideal and the college has been very supportive in his conversations with them during the Limited Purpose Aquaculture (LPA) license application process.

“They’ve been really, really helpful, proactive and excited about things,” says St. John. “And because I’m right up against the island, I don’t have land owners sitting there getting upset about looking at floating cages. I’ve got a college that’s proactive about aquaculture and what that means for the state of Maine, how it’s obviously growing and growing.”

The response to the product has been encouraging. St. John says that at Portland’s annual Harvest on the Harbor festival, their oysters ranked very well in comparison to oysters from far more established companies. They’ve also formed a productive partnership with a Portland oyster bar called the Maine Oyster Company.

The biggest challenge of establishing the operation, in St. John’s view, is trying to balance the desire to grow the business against the limitation of his possible workload.

“Say you’re looking at 50,000 oyster seeds this summer. By doing that, how much more is that going to increase my workload? Working a full time job, I mostly do it on weekends and I can work from home, so I can sneak out here and there to do it. But do I eventually make it a full time operation, this is all I do and really try to expand it?”

While St. John does most of Merritt Island Oyster’s labor himself, he does have some good farm hands – his children, seven-year-old Aislyn and four-year-old Sylvan. That’s part of why they decided to go ahead with the farm, so the entire family could be on the water and have something they could all do together. Aislyn, in particular, has shown some early interest that could someday blossom into a full-blown career on the water.

“When we’re bringing the oysters back, I’ll say ‘hey if you can do this for half an hour, I’ll give you a dollar.’ She literally, as a six-year-old last summer, would just sit down and sort our oysters out by size. Yeah, she’s an entrepreneur, so you never know what will happen there.”

Researchers checking water quality in Chesapeake Bay

Oyster farming’s impact on water quality in Chesapeake Bay is small but important, according to a new study by researchers the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS).

“This important research demonstrates that, while the positive impacts on water quality may be small, just the presence of oyster aquaculture improves the health of the bay,” said Andy Lacatell, Virginia Chesapeake Bay director of The Nature Conservancy, which partially funded the study.

The VIMS team conducted the research as part of a broader aquaculture study initiated by The Nature Conservancy. But conflicting views of oyster aquaculture among locals was also a motivation.

According to the researchers, some stakeholders in Chesapeake Bay are concerned about the negative impacts of oyster farms on viewsheds and sediment nitrogen budgets, while others tout the bivalve’s benefits on the environment as filter feeders.

“Given these questions and the continued growth of the industry, stakeholders need a greater understanding of how oyster farms impact the Bay, whether negative or positive,” said VIMS doctoral student Jessie Turner, who authored the study along with Lisa Kellogg, Grace Massey and Carl Friedrichs.

The researchers set out to measure temperature, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll, turbidity and pH on oyster farms and

in the waters around the farms, and conducted benthic sampling.

“We found differences in water quality and current speed inside and outside the farms but they were minor. The differences we measured between sites and between seasons were typically an order of magnitude greater.”

Their findings suggest there’s room for growth in oyster aquaculture in the Bay, as long as growers continue using “low-density culture with well-spaced cages.”

“Even though we detected no effects in the water column during a single tidal cycle, we know oysters take up nitrogen and phosphorus through feeding and growth, and over time we would thus expect harvesting of farmed oysters to be of benefit to the bay,” Turner said.

The study is different from others in that it was done on a “truly commercial scale,” said Kellogg.

“A lot of the research that had been done before involved researchers simulating an aquaculture farm,” she said. “We were looking for something that was truly at commercial scale to see what those impacts are because I think it’s much easier to extrapolate accurately if you’re working somewhere that has 500 oyster cages instead of five or 10.”

Oysters are the fastest growing segment in Virginia’s shellfish aquaculture industry. Their farm-gate value in 2017 was $15.9 million, data from VIMS show.

The project will give hard clam growers access to strains tolerant to specific barriers in their geographic region

Credit: Tyler Sizemore, Greenwich Time

Acollaborative research effort in the US east coast aims to produce robust quahog stocks through selective breeding to enhance the success of clam farming in the region.

This $1.2-million initiative will enable the breeding of clam stocks that better resist disease and harsh environmental conditions for the benefit of clam farmers in New York State and throughout the region, said the project’s lead researcher, Dr Bassem Allam, of Stony Brook University.

“This will allow us to complete the sequencing of the hard clam genome and to develop innovative genomic selection tools to improve breeding of that species for aquaculture and restoration activities,” Allam said.

The quahog clam is an economically valuable marine resource extensively cultivated in Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia.

At the completion of the project, growers will ultimately have access to strains that can tolerate specific barriers in their geographic region to boost production. “This research will transform the hard clam industry along the entire East Coast, and our Sea Grant and Cooperative Extension partners are eager to transfer this knowledge to the industry and managers in future years,” said NYSG fisheries specialist Antoinette Clemetson.

Shellfish biologists and geneticists and Extension specialists from NYSG, Cornell University, Rutgers University, Stony Brook University, and the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, and industry partners in the five states are part of the initiative.

The collaborative effort involves shellfish biologists and geneticists, Sea Grant and Cornell Cooperative Extension specialists, and industry partners located in the five states where there is significant hard clam aquaculture.

By John Nickum

During the first 20 years of my professional career, I taught courses in aquaculture, environmental conservation, and related aquatic subjects in the Agriculture Colleges of three land grant universities. Discussions with colleagues in animal science, agronomy, and range management frequently involved the relative efficiencies of production and what could be done to promote sustainability.

Shellfish have several advantages in addition to being endothermic. Perhaps most importantly, they obtain their food by filtering organic particles from their environment. Their primary source of energy and nutrition is the base of the food pyramid; they are vegetarians, thus providing an important ecological link between the benthic community and the water column community. The shellfish farmer simply has to locate his/her stocks in clean, productive environments. Shellfish farmers who operate nurseries to start the young animals in captivity do have to maintain algae production systems, but after setting their stock in grow-out habitats, nature provides the food.

My colleagues in the other departments usually acknowledged, albeit grudgingly, the inherent production advantages of rearing aquatic animals for human consumption. They have devoted their professional lives to animals such as cattle, hogs, or poultry so, naturally, they had strong allegiance to their work and the animals on which that work was based.

ranges in temperature. All endothermic animals have optimal temperature ranges within which they thrive and grow best, but they do not “waste” calories and nutrients maintaining specific body temperatures.

Another advantage for the sessile animals used in shellfish culture is they have no “operational costs” for fighting gravity. Oysters, clams, and mussels simply rest on a substrate, filter the water surrounding them, and grow. In contrast, fish, crustaceans, and terrestrial animals use substantial amounts of energy moving about and remaining upright. The lack of motility by shellfish also means that shellfish farmers do not have to spend material and financial resources preventing escapes. Only the larval life stages of these animals are motile. How reproduction is managed varies from location to location and farmer to farmer.

Shellfish farming will probably continue to face challenges in some communities because of this NIMBY mindset.

Among aquatic and marine animals used in various forms of aquaculture, shellfish are inherently efficient. The amount to feed needed to produce a measure of edible flesh for human consumption is substantially lower with these animals than what’s needed to produce an equal measure of beef or pork, or even poultry. Efficient conversion of feed into edible flesh is but one of the advantages of farmed shellfish. The cost of feed is typically the largest single cost to producers in the production of food animals. A primary feed efficiency advantage for fish, crustaceans, and shellfish is their endothermic physiology. None of their feed intake is used to maintain body temperatures above the ambient temperature of their environments. Poultry animals are still relatively efficient in feed utilization despite their high body temperatures; but pigs, cattle, and other mammals used for human food devote substantial portions of their food intake to maintaining their relatively high body temperatures. In contrast fish, crustaceans, and mollusks “go with the flow” in regards to body temperatures. Their physiological systems have evolved to maintain their lives and continue to grow over substantial