FOCUS ON SHELLFISH

FOCUS ON SHELLFISH

Closure of oyster farm in coastal park put oyster farmers on edge

FOCUS ON SHELLFISH

BY AARON ORLOWSKI

FOCUS ON SHELLFISH

he eviction of Drakes Bay Oyster Co’s California shellfish farm from Point Reyes National Seashore in December 2014 left oyster farmers up and down the Pacific Coast nervous about their own fates.

But the rancorous battle that preceded the shutdown has yielded several valuable lessons for shellfish farmers in California and aquaculturists across the country, Drakes Bay owner Kevin Lunny tells Aquaculture North America (ANA)

Since closing down the farm, the National Park Service has wasted no time in dismantling eight decades worth of oyster farming equipment, beginning in January 2015 by removing nine commercial buildings and nearly 6,000 square feet of asphalt and concrete. All told, the Park Service will remove five

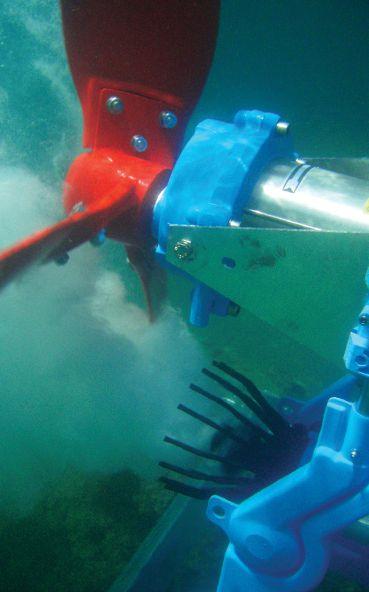

Mussels and seaweed thriving under the nets offer added value

continued on page 14

Workers approach racks of oysters. Hog Island Oyster Co was launched in 1983 in Tomales Bay

Biologist believes that knowledge about sea lice at larval stage may hold key to stopping re-infestation in salmon farms

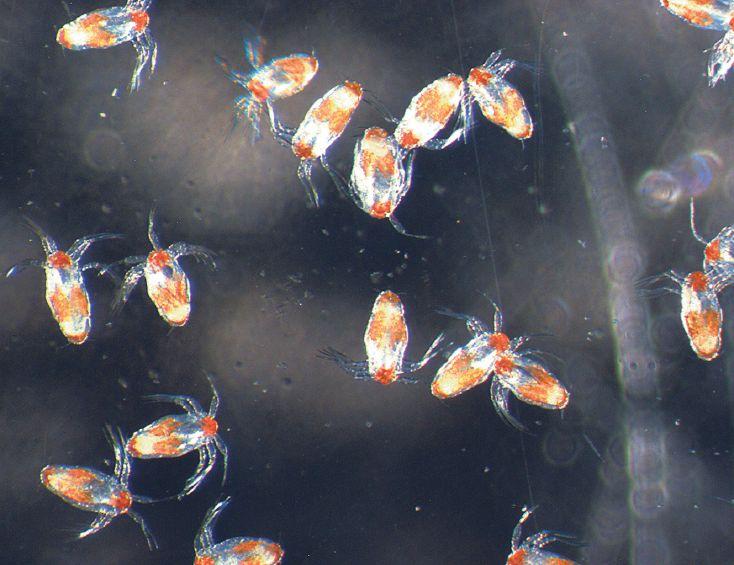

ea lice have long been a research focus at Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO) St Andrews Biological Station (SABS). Recently, studies have focused on the ecology of their early life history stages, non-chemical methods to reduce their incidence, and genetic selection of sea-lice-resistant Atlantic salmon. These elements have been, or are being studied, in an attempt to combat sea lice outbreaks in near-shore ocean caged fish.

Current treatment methods used by industry are mostly aimed at combating the adult stage of sea lice once they have infested the salmon. This is done by killing, removing and/or collecting the attached parasites. However, by the time the salmon are treated, the female sea lice carrying the egg strings (known as gravids) have already had ample opportunity to produce eggs. These viable eggs can hatch and the subsequent larvae may become the next generation to possibly re-infest the salmon farms.

BY LIZA MAYER

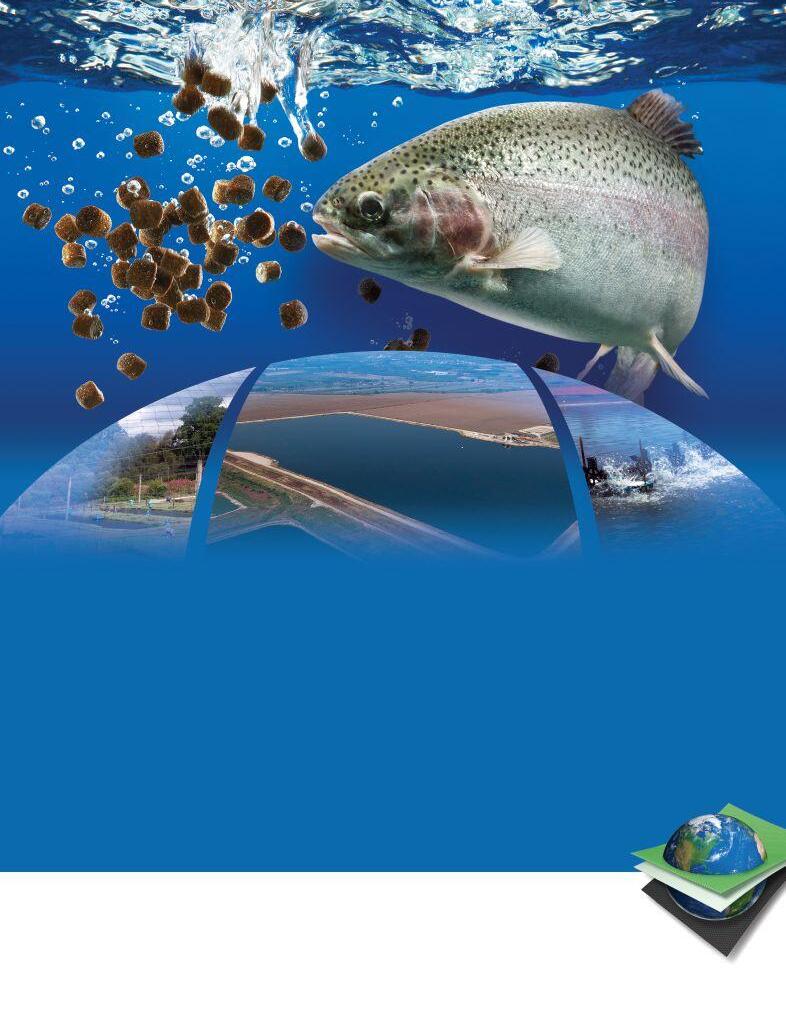

An aquaculture project in New Hampshire that raises steelhead trout in net pens at the mouth of the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire is enabling the local community to enjoy fresh, locally grown fish.

A joint project between the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and New Hampshire Sea Grant, the project raises 350 to 400 fish in two nets on a floating platform 500 yards off the shores of New Castle, New Hampshire.

Michael Chambers holds up long length of sugar kelp seaweed grown in the IMTA raft. The kelp is sold locally to restaurants and breweries to make beer

Project head Dr Michael Chambers said the steelhead trout has been the most successful species raised by the university. The species is hardier and grows faster — from 150 grams to around 2 kg in seven months — than cod, haddock, and halibut, he told WSCH News.

Recent increased consumer interest in eating locally sourced food bodes well for the project. Orders from local markets range from 30-50 fish per week come harvest time beginning November, to the time the cages are empty in January, Chambers told Aquaculture North America (ANA). “The UNH steelhead trout is seasonal so customers look forward to them when they are available. Customers like the fact that they are grown locally

on page 8

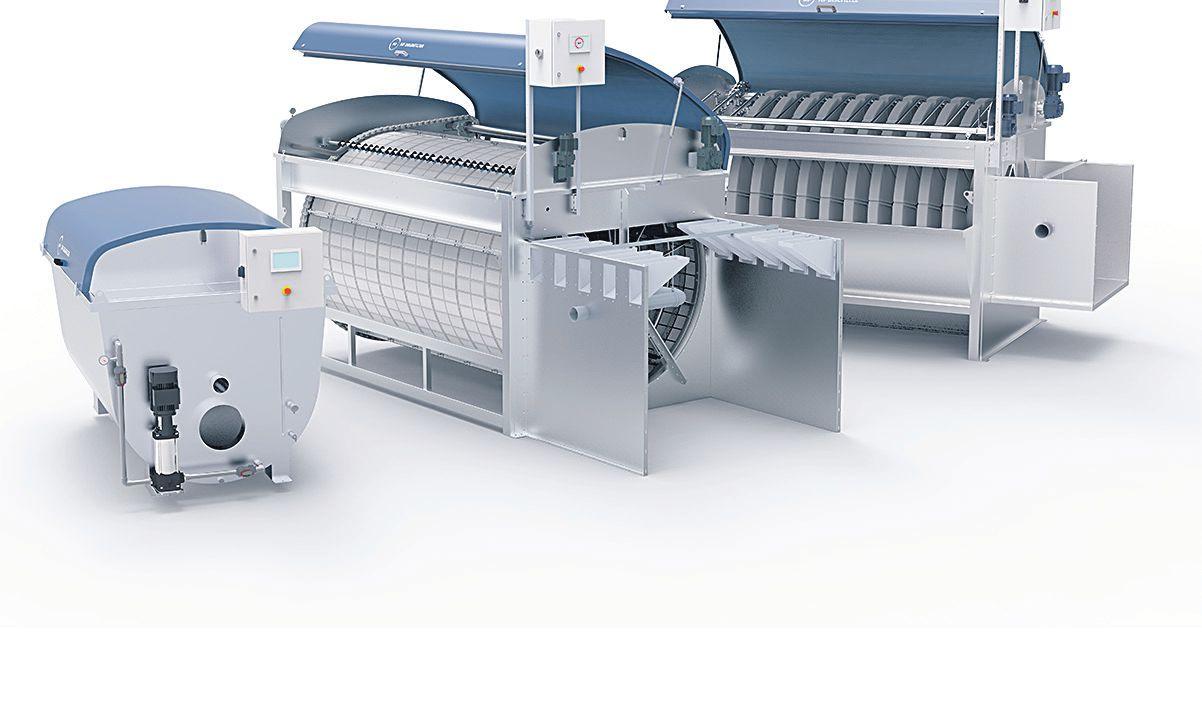

Today’s modern aquaculture farmer needs a partner that is able to help with the scope and variety of challenges they face every day. That is why Pentair AES has assembled a team of experts with diverse backgrounds in aquaculture, biological and technological engineering that is grounded in decades of research and commercial industry application experience. We help our customers run successful operations by providing the design expertise they need, a responsive service team and the largest selection of equipment and supplies in the industry. Trust in a team that’s here to help you—ASK US!

anada could aim to boost its aquaculture exports to $2.6 billion and its global market share from 0.2 percent to 0.6 percent by 2027 to help it achieve a strong and sustained long-term economic growth, says an economic advisory council.

In 2015, Canada’s volume of exports for all aquaculture products was over 100,000 tonnes, which by volume was just under $770 million, according to the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance (CAIA), citing official trade data.

The Advisory Council on Economic Growth, created by Finance Minister Bill Morneau in March 2016, said the industry could achieve this target “by adopting a new, forward-looking Canadian Aquaculture Act” as well as adopting an economicdevelopment strategy that reforms “illadapted traditional fisheries regulations.” Examples of regulations that need streamlining are those that stifle or deter investments in assets such as aquaculture systems, and complex permitting processes, said the council. It added that doing so will create opportunities for provincial, regional, and aboriginal stakeholders.

British Columbians processing farmed salmon. An advisory panel says Canada could aim to boost its aquaculture exports to $2.6 billion by 2027 from roughly $770 million in 2015

The recommendations are part of the council’s second wave of proposals that it presented to the Canadian government in February. Aside from recommendations that would galvanize agriculture — under which aquaculture is a sub-category — the council also offered recommendations on other growth sectors, such as manufacturing, energy, and health care and life sciences.

Commenting on the proposals, CAIA Executive Director Ruth Salmon said: “Today the Finance Minister’s Economic Council laid out a responsible and sustainable goal for aquaculture in Canada, and we are committed to working with all stakeholders to seize this unique opportunity. Working together we can continue to produce fresh, healthy, and sustainable farmed seafood, and create new jobs and opportunity across Canada.”

Overfishing and increased consumption have reportedly depleted local resources of some of China’s favorite seafood species, thus beginning January 1, China has claimed to have cut tariffs on a number of imported marine products to ensure “supplies remain plentiful” and prices are in check.

Among the seafood that have seen a reduction in import tariffs include:

• Tuna down from 12 to six percent

• Ribbonfish/hairtail down from 10 to five percent

• Arctic shrimp down from five to two percent

• Cod down from 10 to five percent

• “Flat fish” (which includes flounder and sole) down from 12 to 2 percent

• Lobster down from 15 to 10 percent

• Geoduck down from 15 to 10 percent

• Shrimp (Pandalus borealis) down from 5 to 2 percent

The tariff reduction is expected to boost Canada’s trade with China, which is its second largest export market for seafood following the United States. Since 2013, exports to China have increased by 46 percent from $338.5 million (C$443 million) in to $493.6 million (C$646 million) in 2015, according to the

The tariff reduction is expected to boost Canada’s trade with China

Credit: Craftsy.com

Canada Seafood Market report by Islandbanki Research. In the first 10 months of 2016, Canada’s seafood export to that country reached $484.5 million (C$634 million), of which $166.5 million (C$218 million), or roughly 35 percent, was from Nova Scotia.

Blue Ridge Aquaculture is investing $3.2 million to expand its operations in Henry County, Virginia, which its president and CEO Bill Martin considers a significant step in the company’s growth plans.

Blue Ridge, said to be the world’s largest producer of indoor-raised tilapia, produces 4 million pounds of the fish a year using recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and ships between 10,000 and 20,000 pounds of live tilapia each day.

Martin said the expansion will create five new jobs and help maintain the company’s leadership position in the industry.

Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe approved a $50,000 grant from the Governor’s Agriculture and Forestry Industries Development (AFID) Fund to assist with the project, which Henry County is matching with local funds, according to a statement from the Governor’s Office.

Blue Ridge was also awarded a grant from the Virginia Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission. In addition, the company is receiving a Real Property Investment Grant through the Virginia

Enterprise Zone Program, administered by the Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development.

“I applaud Blue Ridge Aquaculture’s continued investment in Henry County and their expansion speaks to the highquality seafood and marketplace success of the company,” said McAuliffe.

Virginia is the nation’s third largest seafood producer and the largest on America’s Atlantic coast. The state is ranked 10th nationally in aquaculture production.

joins

wenty-five global companies, including Cermaq, have committed to an initiative to speed up change in global food systems so everyone can access healthy, enjoyable diets that are produced responsibly.

TThe group launched the program, called FReSH, at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland in January. It will catalyze change across the food systems, taking into account local eating patterns.

The program underscores the role the private sector plays in making healthy and sustainable diets accessible. Companies are invited to join the program.

“We are excited about the FReSH program which brings aquaculture into the WBCSD programs. Aquaculture will definitely play an important role to reach the objective of ensuring healthy diets for all based on food that is produced responsibly within planetary boundaries,” says Wenche Grønbrekk, Head of Sustainability and Risk, Cermaq.

Aquaculture will definitely play an important role to reach the objective of ensuring healthy diets for all, says Wenche Grønbrekk, Head of Sustainability and Risk, Cermaq

Editor Liza Mayer Tel: 778.828.6867 liza.mayer@capamara.com

Subscription Services Deirdre Chettleburgh Tel: (250) 478-3975 deirdre@capamara.com Tollfree 1-800-661-0368

Advertising Department Jeremy Thain Tel: (250) 474.3982 Fax: (250) 478-3979 Toll free in N.A. 1.877.936.2266 jeremy@capamara.com

Art Department James Lewis Tel: (709) 754-5059 Fax: (709) 754-5067 james@capamara.com

Content Manager Deirdre Chettleburgh Tel: (250) 478-3975 deirdre@capamara.com

Accounts Debbi Moyen Tel. (250)474-3935 dmoyen@capamara.com

Publisher Peter Chettleburgh Tel: (250) 478-3973 Fax: (250) 478-3979 peter@capamara.com

Regular Contributors: Quentin Dodd, Ruby Gonzalez, Erich Luening, John Nickum, Matt Jones, Tom Walker, Amanda Bibby

United States Mailing Address Aquaculture North America, 815 1st Ave, #93, Seattle, WA, 98104 Canadian Mailing Address Aquaculture North America 4623 William Head Road, Victoria, BC, Canada, V9C 3Y7 ISSN 1922-4117 (GST# 897422788RT)

Postage paid at Vancouver, BC Aquaculture North America is published by Capamara Communications Inc.

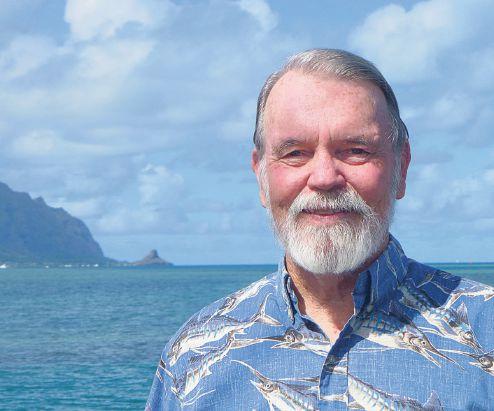

The decision to expand fish farming into federal waters around Hawaii and other Pacific islands could help the US meet its seafood demand but there are hurdles in the path of potential investors

BY MATT JONES

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is beginning the early stages of work towards opening up federal waters in the Pacific Ocean to aquaculture operations but some are concerned that developing regulations before an industry is established may prevent growth.

The Magnuson-Stevens Conservation and Management Act of 1976 defines a relationship between fisheries councils and service districts: councils develop and amend fisheries management plans while the fisheries service issues regulations and implement those plans. Since 2008, the Western Pacific Fishery Council has sought to engage in aquaculture in federal waters in strategically, says David O’Brien, deputy director of NOAA’s Fisheries and Aquaculture program.

“The council looked at this and said, ‘this is a great opportunity, a way to create seafood locally, let’s pursue this,’” says O’Brien. “The way they did this is to work with the fisheries services and they developed a programmatic assessment of the area to help inform any future decisions about what areas are suitable for aquaculture, what areas are not suitable, what species are likely to grow, what methods could be allowed – a whole range of things.”

O’Brien says that the council decided the best way to proceed was through a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process.

“It’s a wide-ranging law that applies to all federal agencies which look at potential environmental and economic impacts of federal action,” says O’Brien. “It can also be used as a planning tool, which is what the council wants to do.”

This past August, the fisheries service issued a notice of intent to prepare a programmatic environmental impact statement under NEPA. This was followed by a

The current process is putting “the cart before the horse” and regulating an industry to the point where it may never develop.

~ John Ericsson, Gulf Marine Institute of Technology CEO

60-day public comment period, which closed at the end of October. That information will be used as the basis for a draft of an environmental impact statement, which is scheduled to be published in the spring, followed by another public comment period and a final statement in the fall.

The effort has drawn some comparison to the process undertaken to open up waters in the Gulf of Mexico for aquaculture operations. The process of using the councils and the Magnuson-Stevens Act are analogous, however O’Brien notes some key differences between both efforts.

“The Gulf went first and the Pacific council is going second,” said O’Brien. “No one had ever done this before; it was a brand new operation. To their credit, both the council and the folks in the fisheries service down in the south east were pioneers. The Western-Pacific and other regions that may want to follow have the enormous benefit of having a road map to follow. One thing they’ve done in the Gulf that was pretty god was the co-ordination among federal agencies in the Gulf, but, in retrospect, it could have been a bit tighter. In the Western-Pacific, they were earlier [than the Gulf] in bringing in partners from the Army Corps of Engineers and the EPA and the Coast Guard into the process and getting them involved in the earlier planning stages. It will make it easier down the road.”

BIG HURDLES

However, there are still concerns about the process, with some seeing hurdles on the path of potential investors. For one, there is the question of permit versus lease.

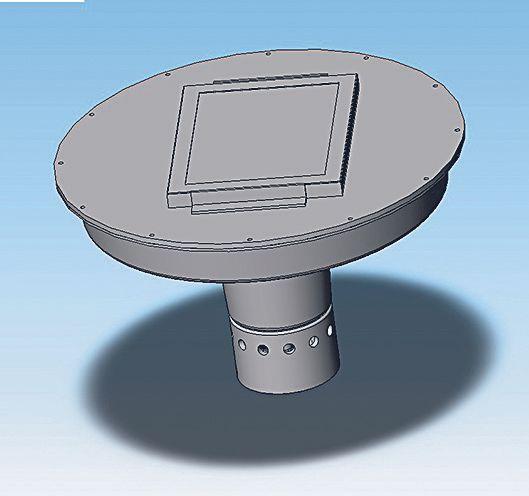

John Corbin, president of the Aquaculture Planning & Advocacy LLC. He says the acceptance of open-ocean aquaculture may also require next-generation technology to move it forward

“A permit is not the same as a lease,” says Corbin. “If you look at all the coastal states that have aquaculture, I believe virtually all of them use a lease as the vehicle to give people access to the public resource. Does a permit really offer adequate, exclusive-use controls and does it offer adequate property rights and property protections to justify an investor investing, say, $10 million or $15 million to create a commercial-scale project in the Pacific Ocean? I think that’s a question that has not been answered.”

O’Brien of NOAA says that the issue of “lease versus permit” has indeed been raised in past discussions on this topic. While a lease may offer more certainty when

continued on page 6

lays groundwork continued from page 5

attempting to secure financing from a bank or an investor, logistically it may not be applicable.

“The reality is that even if we wanted to, with the Magnuson-Stevens Act, we don’t have the authority to issue leases,” says O’Brien. “We have the authority to issue permits. From a legal standpoint, we wouldn’t have that option using Magnuson-Stevens.”

John Ericsson, Gulf Marine Institute of Technology CEO and managing director, participated in drafting the rules for offshore farming in the Gulf of Mexico. He believes that the current process is putting “the cart before the horse” and regulating an industry to the point where it may never develop.

“Usually regulations are the result of an industry starting, going through the infancy stages and then things get big enough in scale, issues come up and need to be attended to; it is trial, error and experience,” says Ericsson. “But in this case it’s just the opposite. They took 12 years to develop the rules for an infant sea farming industry before there was anything to regulate.”

Ericsson points to the example of aquaculture industries in Greece and the Mediterranean, where the industry grew over 30 years, beginning with mom-andpop operators and caged systems, and evolved into a multi-million dollar industry owned by public companies with hundreds of net-pen systems. Looking at the startup costs and the time and effort necessary to get a permit, he wonders if there is an inducement for smaller operators.

“There’s no protection once you get a federal permit to do sea farming in the Gulf of Mexico,” says Ericsson. “Somebody can go and get some judge to impose a cease-and-desist order while you’ve got millions of dollars invested and years in an offshore sea farming operation. There’s no protection for the business other than through the courts because there are no provisions to protect the operators from possible interference. The way the regulations are, there’s no real stopgap to protect the operator from what the federal regulators can do to shut your farm down and put you in bankruptcy.”

The process for revocation, suspension or modification of a permit is based on compliance with permit conditions, which falls under the same process used for commercial fishing licences, O’Brien notes. One of the overall objectives for NOAA in this process is to work on permitting efficiency in both state and federal waters. He also acknowledges that while regulations can be a burden to overcome, so can the lack of regulations.

“If you look at federal waters specifically, there has been an absence of clarity on regulating aquaculture in federal

David O’Brien, deputy director of NOAA’s Fisheries Aquaculture program, says the next opportunity for public comment on the plan to open up federal waters in the Pacific Ocean to aquaculture is scheduled this spring

waters until last year when we published rules for the Gulf of Mexico fisheries management plan for aquaculture,” O’Brien says. “The absence of that regulatory certainty in places like the Gulf of Mexico has been an obstacle for development. Very few people applied for a permit for aquaculture in federal waters because of the lack of regulatory certainty. People tend to think of regulation as restrictive, but I think in this case the lack of regulatory structure has been restrictive. We’re trying to fix that, by using Magnuson-Stevens in this case, to develop that regulatory process so people will know what the rules are with a degree of certainty before they go investing a lot of money.”

John Corbin, president of the Aquaculture Planning & Advocacy LLC, and the former manager of Hawaii’s state aquaculture program, Corbin acknowledges that while most people in the region recognize that aquaculture would be a positive for economic development and diversification, the process may be too difficult for any local projects to start up. The widespread acceptance of open-ocean aquaculture, he says, may also require nextgeneration technology to move it forward.

“I think it’s a long-range venture because I think we need next-generation technology to really utilize the exclusive economic zone for aquaculture,” says Corbin. “We need a demonstration of technology, we need commercially successful projects that will probably come from Europe and other places before it occurs here in the United States.”

Blue Ridge Aquaculture says move would also result in ‘significant unintended consequences’

The world’s largest producer of indoor-raised tilapia is alarmed over the US government’s plan to consider the inclusion of various species of tilapia and their strains to the List of Injurious Wildlife.

In a December letter to Craig Martin, Chief of the US Wildlife Fish Service (USFWS), Virginia-based Blue Ridge Aquaculture said the plan, if implemented, would force the company to immediately close its business.

The plan, if implemented, would force Blue Ridge Aquaculture to immediately close its business, says president and CEO Bill Martin

The Atlantic Canada Fish Farmers Association (ACFFA) has sounded alarm over the 33-percent increase in workers’ compensation insurance premiums that employers in New Brunswick, Canada will have to pay beginning this year.

WorkSafeNB, the government agency responsible for occupational health and safety, recently announced it is raising the average assessment rate for employers from $1.11 per $100 in 2016 to $1.48 in 2017, or by 33 percent, because of “recent benefit policy changes and a declining funding position.” This is the first rate increase since 2010.

“Increasing claim costs, mainly as a result of changes to benefit policies coupled with a slight increase in accident frequency, have led to a reduction in WorkSafeNB’s funding position,” the agency said.

While acknowledging that fish farmers work in varying and challenging conditions and “safe and healthy work environments are imperative,” the Atlantic Canada Fish Farmers Association said it is also important to have “a functional workers’ compensation system in place that balances the needs of employees and employers.”

Susan Farquharson, the association’s executive director, believes the rate hike “will have an immediate and significant impact on the budgets of both big and small companies and subsequently the entire provincial economy.”

support provincial economic development, while operating under these unknowns?” she wrote in the association’s website.

“The system we have in place now that allows for such sudden, unplanned and disruptive increases is simply not acceptable, professional or productive. New Brunswick businesses need stability and predictability in order to survive and thrive.”

“The Injurious Wildlife petition completely threatens our entire business. If such a petition is approved, all of our research and development work will come to a stop, and our progress towards a more environmental sustainable food source will come to an end,” wrote Bill Martin, president and CEO of Blue Ridge Aquaculture.

Inclusion in the injurious wildlife list would mean the movement of the species across state lines, or their importation, would become illegal and a direct violation of the US Lacey Act. Penalties, both monetary and prison sentences await.

Martin noted that tilapia is a species that is already established in US waterways. To prevent the establishment of a species that is already established in US waters by adding it to the Injurious Wildlife list is not only “futile” but will also have “significant unintended consequences.”

“It will encourage overseas production and reward farmers that raise food using unsustainable methods. It will shut down farmers in America using sustainable methods and extinguish a developing and important US industry,” Martin wrote.

Instead, he said the USFWS should look at tropical fish intended for the hobbyist and aquarium industry, which he described as posing the “greatest threat.” The aquarium industry is not reliant on specific species, and substitutes could satisfy the demand; a flexibility that aquaculturists do not enjoy, he noted. “We urge the US Wildlife Fish Service to recognize the difference between the aquarium trade and aquaculture used for food production,” he said. (See Floaters & Sinkers on page 10 for more on the Injurious Wildlife petition.)

— Liza Mayer

“WorkSafeNB’s warning that subsequent rate hikes are likely for the foreseeable future is alarming as well. How can companies operating in New Brunswick plan and

She urged the New Brunswick provincial government to work with WorkSafeNB and New Brunswick businesses, including those in aquaculture, “to act quickly to find a solution that works for both employers and employees.”

— Liza Mayer

Innovations in Water Monitoring

Reduce operational costs and gain better visibility into changing conditions with the Aqua TROLL® 400 Multiparameter Probe and the Con TROLL® PRO Process Controller. Accurate and reliable sensors let you optimize pond conditions to protect your investment and increase your ROI.

• Measure salinity, pH, ORP, optical dissolved oxygen, temperature, level, and more

• Low-maintenance and compact probe

• Integrate with Con TROLL PRO, PLC, or wireless options to automatically run aerators and pumps only when needed, reducing energy costs

Improve feed-conversion ratios, minimize sh stress, and reduce sh disease and mortality with consistent water quality monitoring.

In-Situ Ad – Aquaculture North America Size: 6.84” x 5” print: 4-color / CMYK SCD# 17INST212 / Date: January 2017 Learn

continued from cover

and have no antibiotics or hormones,” said Chambers, who is Extension Specialist-Aquaculture, at UNH Cooperative Extension.

At Seaport Fish Company in Rye, New Hampshire, customers buy out the fish as soon as it’s stocked in the cooler, reported WSCH News. “There’s no real aquaculture to speak of around here so seeing a product that is raised in New Hampshire and raised in the ocean in New Hampshire is an exciting thing,” Rich Pettigrew, owner of Seaport Fish, was quoted as saying.

Evan Mallet, owner of Black Trumpet Bistro in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, also buys trout from the project. “It has a better flavor than you would find in a

freshwater fish like a rainbow trout...,” he told WSCH. Restaurants get to buy the fish at wholesale price, while at retail the fish sells for $16 per pound.

Steelhead trout are not the only produce from the floating farm. Mussels and seaweed thrive under the nets — thanks to the ammonia and phosphorus that the fish give off — opening up other business opportunities.

“The project provides eight-month old mussels to a group of fishermen (Isle of Shoals Mariculture) that are culturing mussels on submerged longlines offshore New

Hampshire. It takes 16 months to bring mussels to market at 55-60mm so this is a way for us to help seed new aquaculture companies,” Chambers told ANA

The kelp is sold locally to restaurants and breweries to make beer. “Kelp is a grown throughout the year and harvested in the spring and summer,” added Chambers.

Building on the project’s success in New Hampshire, Chambers hopes to expand the project with additional culture sites and IMTA rafts. “Maine could be an early adopter of the technology and has many areas along their coast for this type of aquaculture,” he said.

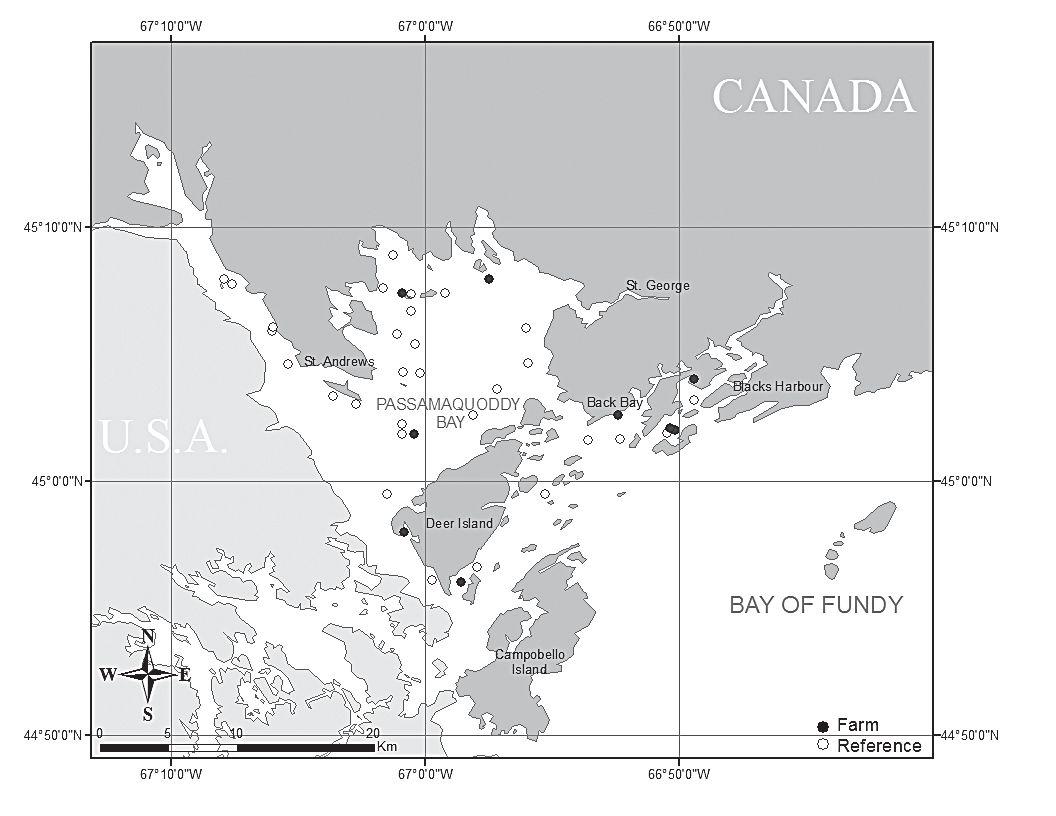

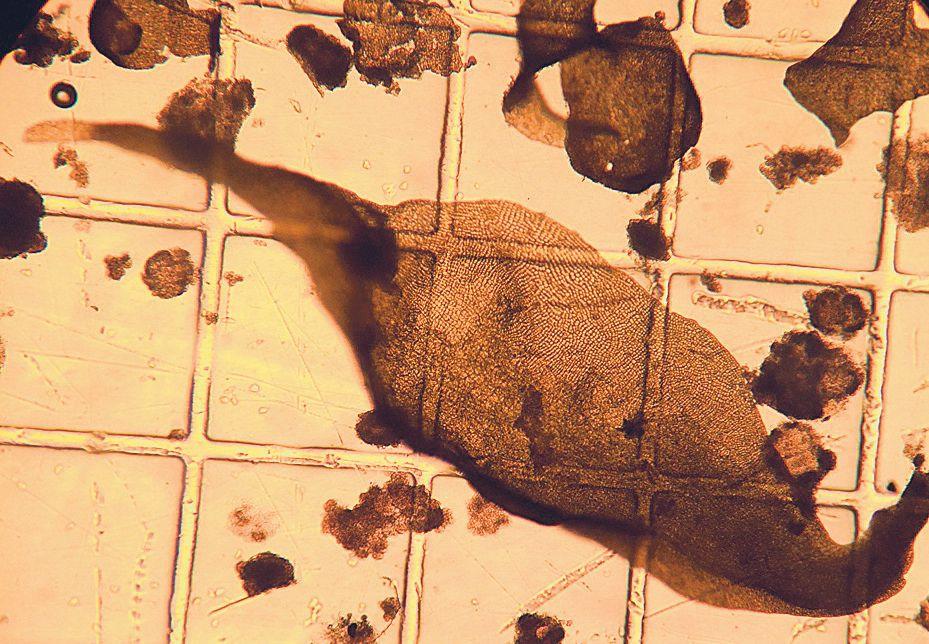

What remains unknown is what happens to the larvae once the eggs hatch. This information is crucial in order to develop strategies to “short-circuit” the life cycle of the sea louse on farms. Until recently, it was thought that early sea lice larval stages were passive and drifted away with tides and currents. However, these free-swimming larvae have been shown to be active swimmers (up to 20 metres per hour) and continue to be found mostly in close proximity to salmon farms (albeit in low densities). These results also agree with the few available larval sea lice studies from scientists in other salmon-producing countries.

With funding under DFO’s Program for Aquaculture Regulatory Research (PARR), Emily Nelson, a biologist at SABS hopes to help crack the code as to how and where these larvae go and how they survive until the stage when they are able to attach to their host.

“We now believe that these microscopic larvae are not passive, are capable of swimming and must have some mechanism that allows them to stay near farms to re-infest the fish. If we can discover where these larvae are, the potential exists to selectively target the larval stages, before they become infective on the salmon,” Nelson said.

Nelson has spent the past 18 months sampling the water in and around salmon aquaculture sites in southwest New Brunswick. She is looking for the microscopic larval stage of sea lice using submersible pumps and vertical plankton tows. This sampling will continue throughout the year to capture the rise and fall of sea lice densities on salmon farms and – for comparative purposes – at reference sites away from the sea cages.

Knowing what happens to the larvae once the eggs hatch is crucial in order to develop strategies to “short-circuit” the life cycle of the sea louse on farms

“Larvae are able to survive on their own for two life history stages – nauplius and copepodid – before they need to attach to a host or fish,” Nelson said.

The plankton tows allow her to concentrate the microscopic life from up to 4 m3 of water and take it back to the Biological Station for viewing and counting under a microscope. Here, the number and stage of larval sea lice are recorded into her database.

While the samples to date have revealed some interesting larvae distribution trends in being found in close proximity to the cages, Nelson says that it is too early to conclude too much on the implications of the work. This is due to the amount of work remaining such as counting previously collected samples, another six months of field work, and the subsequent analysis of data.

In addition to this study, a sea lice hatchery has been developed at SABS where Nelson and Dr Shawn Robinson are researching energy consumption of the early life stages of sea lice. This will address risk-related questions such as: how long can larvae survive before they need to attach to a host? And at what nutritional level are they too weak to infect a host?

DFO hopes the findings from these and other studies will provide a better understanding of the reproductive cycle of this parasite whose outbreaks can result in significant commercial losses. This information, along with factors such as water temperatures and currents will be used to develop a model to provide biologically-based information. With this information, better management measures can be implemented to reduce the incidence of sea lice infestations in the salmon farming industry. An improved understanding of the sea lice life cycle will also enable scientists to better understand potential impacts on wild Atlantic salmon.

“Our goal is to better understand how sea lice are remaining at sites to ultimately develop ways to reduce their severity and frequency on salmon. Any way that we can intervene in the reproductive cycle of this parasite is good for the fish and good for the farmers,” said Nelson.

To further this goal, she said the St Andrews Biological Station is also setting up an international network with other larval sea lice ecologists to facilitate research studies in the field so that problems can be resolved more timely and effectively.

ust as “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” defining “injurious wildlife” is often very subjective. Regulations based on subjective evaluations and decisions are often wrong and are certain to be controversial, even when respect and trust between those regulated and the regulator are high. Such respect and trust between American aquaculturists and the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has been rare in recent years. This somewhat harsh statement has grown increasingly accurate in recent years as the USFWS has morphed from a fish and wildlife resource conservation and management agency into an environmental regulatory and species protection organization.

Injurious wildlife regulations have received considerable attention from aquaculturists since September 2015 when the USFWS issued a proposal to list 10 species of freshwater fish and one crayfish as injurious wildlife. The species named in that proposal did not include any that are commonly produced by American fish farmers; however, several species produced in Asia and Europe were included in the proposal. The act of including these cultured species brought US aquaculturists to full alert.

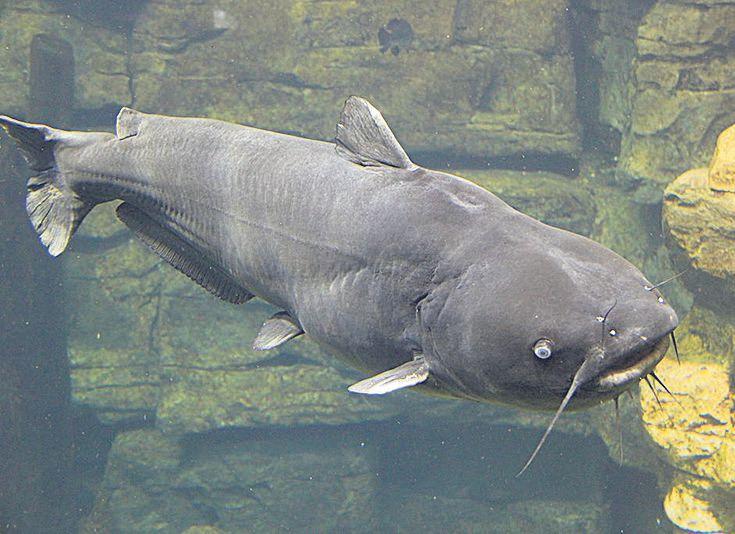

A final rule listing all the proposed additions to the injurious wildlife list was published on September 30, 2016. The same day, a private non-governmental organization, the Center for Invasive Species Prevention (CISP) announced that they had submitted a petition to UFWS to list 43 species as Injurious Wildlife. The CISP list included the blue catfish, koi, grass carp, guppy, three species of tilapia (blue, Nile, Mozambique), flathead catfish, and red shiner. The USFWS does not have to adopt the CISP petition; however, the petition was based on findings produced by the Ecological Risk Screening Summary (ERSS) developed and used by the USFWS. Including fish produced by aquaculture in the petition, especially the tilapia, brought US aquaculturists to full alert and into action to oppose it (see page 7 for news of Blue Ridge Aquaculture’s reaction).

The Lacey Act, which provides the statutory authority for injurious wildlife designations and enforcement actions,

Blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) and Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) are among the farmed fish species that are on the proposed list of injurious wildlife

has a long and contentious relationship with American fish farmers. Injurious wildlife actions were not a primary consideration when the Lacey Act was enacted in 1900. Only three species were designated at that time; none of which were fish. The Lacey Act provides substantial fines, and can include jail time for violations that involve transportation of wildlife across jurisdictional boundaries

BY JOHN G. NICKUM

if the wildlife was taken, or owned, in violation of State or Federal regulations. In the current situation, this means that possession or transport of a species designated as injurious wildlife would be considered a violation of the Lacey Act.

At this point, readers may be asking which characteristics and/or factors cause a species to be identified as injurious. The primary consideration is the probable negative effects on wildlife resources (species) or ecosystems, through competition for food and habitats, habitat degradation and destruction, predation, hybridization, and/or pathogen transfer. The potential for the species to survive, reproduce, spread, and become established (the probability to colonize) is also a highly important consideration; as is the probability of release or escape from holding or rearing facilities. Potential harm to humans or human activities caused by either the species directly, or human actions to control or eradicate them is yet another consideration.

The ERSS used by the USFWS is essentially a “quick and dirty” system used to make tentative evaluations and was never intended to be used by non-governmental organizations as a basis for petitions. An unwritten pseudo-principle that is prevalent within the USFWS and many environmental organizations is the belief that all non-native species should be considered to be injurious. The pseudoscience beliefs extend to firm convictions that any departure from the ecosystem species structures that existed in North America prior to European colonization is dangerous, and in the words of some zealots, “downright evil.” The individuals espousing these beliefs frequently quote the green pop-culture “Precautionary Principle” (actually a legal concept that developed in Europe) as a reason to take no risks whatsoever. The advocates of these so-called principles fail to understand that the balance of nature is much more a matter of détente than warm, fuzzy state of “kumbaya” among the species making up a natural ecosystem.

American aquaculture associations, especially the National Aquaculture Association, led by its President Jim Parsons and Executive Director, Paul Zajicek, have reacted quickly with science-based arguments and realistic economic projections to the CISP petition. Given CISP’s stated goals if implanting injurious wildlife regulations “more forcefully, or better yet, replacing the outmoded law with one that assesses potential risks before animals are imported” there is little hope for negotiated settlements. CISP is working its contacts in Congress to increase the USFWS staff and budget for injurious wildlife designations and enforcement. CISP states that its goal is prevention of potentially injurious wildlife, rather than control after the fact.

While I agree that a few non-native species have become injurious to American interests, native species, and ecosystems, I suggest that future classifications of injurious species must be based on full environmental reviews, preferably an Environmental Impact Statement, but, at least a formal Environmental Impact Assessment. A screening tool is not adequate.

Also, the USFWS needs to return to the aquaculture motto it adopted 25 years ago, “Help Aquaculture Grow.” That goal can be accomplished without sacrificing sciencebased species and ecosystem management.

Additional details on the issue can be found at USFWS website: www.fws.gov/injuriouswildlife/11-freshwaterspecies.html and at the CISP website: www.cisp.us

Early-detection method raises flag that problem is developing

BY MATT JONES

Aresearch effort from the University of Glasgow in Scotland has discovered a new diagnostic test that can detect salmonid alphavirus infections, which cause pancreas disease. The new test – called the selective precipitation reaction (SPR) – may be a significant game-changer for detection of symptoms of pancreas disease, and other ailments that cause muscle damage, by enabling testing to be done on-site on live samples. The research was performed in partnership with BioMar Ltd and Marine Harvest Ltd.

Like many scientific discoveries, the new diagnostic test was developed almost by accident; then-University of Scotland PhD student Mark Braceland had been studying different ways of looking at individual proteins and markers when he came across a precipitation reaction which occurred with samples from infected fish, but did not occur in healthy fish.

“We were using a methodology that we can use in any species, for a protein called cellular plasmid,” says Dr David Eckersall, a professor of veterinary biochemistry at the University of Glasgow, who worked on the research with Braceland. “We applied this to the samples of salmon with pancreas disease and we found a very big response.”

The response was so large that it was a biological impossibility. Braceland and Eckersall found they were getting interference in the methodology of the precipitation reaction. When they realized what that strange result meant, they started to unravel the mystery.

“It’s nothing to do with the salmonid alphavirus, which is the agent involved in pancreas disease,” says Braceland. “What it’s really detecting is the pathological damage that’s elicited by that disease. In essence, it’s allowing us to identify, nondestructively, pathological damage. Right now, the only real established method for doing that is hepatopathology, which is also destructive. That really restricts how often farmers are looking for signs of pathology. Or they have to do it on already dead fish, so times when that really occurs is when mortality rates start to increase on a farm, but I would argue that you’re missing the boat by that point. You’re reducing the efficacy of the disease mitigation strategy you would have.”

Dr David Eckersall, professor of veterinary biochemistry at the University of Glasgow, helped develop a new diagnostic test that can detect the symptoms of pancreas disease quicker and non-destructively

viral infections, but functional feeds have been shown to be effective in reducing the pathological damage caused by infections. However, that relies on the identification of an issue before it becomes too big to try to mitigate.

“Its main benefit is that it can determine early on that there’s a problem,” says Eckersall. “The current methodologies, my understanding is that normally a tissue sample would have to be sent to a laboratory which could take a few days to analyze the result. This test is very cheap and we’re hoping to have it in a format that could actually be used on the fish farm side, so they can get an early warning that there’s a problem developing. Then you could use specific tests to really confirm what the problem is, but it could be an early detection system.”

Dr Mark Braceland began the work that developed the new diagnostic test while at the University of Glasgow

The goal is to have a routine test that can be used in labs that run health methodology assessments of salmon on farms. Eckersall says the test is simple enough that he expects it could be developed into a format where it could be applied on a fish farm.

“The actual technology isn’t very difficult, so given the right sort of conditions and resources, we should be able to develop it into something that would be very simple to carry out on a fish farm.”

Braceland points out that aquaculture producers are limited in how they can treat

“The potential is pretty good,” says Braceland. “It can be carried out in the field. If something is flagged, it can be sent to a lab and the reaction can be quantified. This will allow us to monitor stocks more efficiently to see earlier warning signs of when a disease is developing within a stock, which can only help.”

•

BY ERICH LUENING

ar from the coast of the US State of South Carolina, known for its own wild shrimp fishery, a young couple of entrepreneurs are farming their first shrimp on land using a biofloc recirculation system in a rented warehouse.

Located in the northern part of the state in a town called Greenville, near the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Urban Seas Aquaculture owner and founder Valeska Minkowski hopes to be selling Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) this spring to restaurants in the region.

Minkowski has always been aware of where her food comes from and how it’s harvested.

“I decided on shrimp specifically because it’s one of those species I love to eat personally, so it was more for selfish reasons at first,” she told Aquaculture North America (ANA). “We know farming shrimp inshore isn’t good for reasons like high bacteria rates and antibiotics use and fishing for wild shrimp has its own set of issues. I thought the most sustainable way would be to grow them on land using a recirculation system.”

Armed with a PhD in fisheries and aquatic sciences she had a leg up on most start-up aquaculture entrepreneurs, but she only had taken a few aquaculture related classes in all her time at school.

“Aquaculture 101 mentioned recirculation systems as one of the ways to farm fish on land,” she said. “We decided to go that route.”

She works the new shrimp farm with her husband Austin, who is a materials engineer during his day job, but a full partner in his wife’s business venture.

Urban Seas joins a small but growing recirculation shrimp aquaculture sector in the US. There are a handful of closed system farms producing shrimp for the huge domestic market in the country.

Shrimp aquaculture in the States has traditionally occurred in inland waters among mangroves or man-made ponds primarily in the south of the country which takes up acres of land or miles of inland coasts, causing more than a few environmental concerns.

Domestic production fails to meet the massive consumer demand for shrimp, also called scampi, or prawn, so much of the shrimp making it on plates in the US are imported from Latin America or Southeast Asia, where labor, environmental, and chemical use concerns flood those industries, according to international food safety organizations.

In 2015, the US imported 585,826 metric tons (MTs) of shrimp from overseas while only exporting 18,367 MTs from the wild fishery, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports that in the same year only 17 MTs of farmed shrimp were exported. This clearly shows a massive trade deficit when it comes to shrimp that’s existed for years.

The Minkowskis hope to add to those domestic production numbers one harvest at a time.

“I hope when we get further along we will be able to hire more staff,” she said, adding that other family members help when they can. “We’ve got eight tanks total. Four up and running and we add a tank every two weeks as the shrimp continue their growth stages.”

She said she gave this endeavor three years to take off. “Then we’ll take it to a bigger place, building and expanding without necessarily renting space.”

For now, she gets her post-larval shrimp at three days old from a shrimp hatchery in Florida. “Maybe, as part of the three year plan we may expand and take that part on ourselves too.”

feed for fish with 100-percent plant origin has been developed and is being tested in farmed rainbow trout.

A researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Dr Luis Héctor Hernández Hernández, developed the feed, which consists of a mixture of pellets that concentrate soy protein, spirulina microalgae powder, yeast, proteases, lipids, vitamins and minerals, according to the Mexican news agency, Notimex.

Being plant-based, phosphorus is reduced by 50-75 per cent, thus it is friendlier to the environment. It is also said to be less expensive than feed made with fishmeal.

“It is a diet of vegetable origin, which does not use fish to feed fish; it seeks to be ecological and competitive on a commercial level, especially for rainbow trout aquaculture farms, from fingerling to juvenile fish,” FIS quoted Hernandez as saying.

The feed has already been tested experimentally and can also be used for carp and tilapia. A new composition is sought for crustaceans such as shrimp and prawns, which could be ready in three years, the news agency said.

S food technology multinational Ralco Aquaculture is preparing to begin construction of a shrimp production facility in the spring of 2018.

An economic impact study that the company commissioned to the University of Minnesota found that construction of a nine-acre facility would result in $14.5 million of labor income and support an estimated 330 jobs. Once the facility is constructed it will continue to generate an estimated $23 million annually in economic activity and provide employment directly and indirectly for 124 people, Ralco said in a statement.

The company, based in Minnesota, uses trū Shrimp Systems that utilize the Tidal Basin technology, created by Texas A&M University, which it says produces shrimp as naturally and safely as possible.

The fully integrated shrimp company also plans to construct two shrimp hatcheries, which will provide enough young shrimp to continuously stock

as many as three shrimp production facilities. The company forecasts that the production of one facility will exceed 50 percent of the current US shrimp aquaculture production.

The company added that it is also looking at constructing a processing facility, distribution sales & marketing, and hatchery in Marshall and Lyon County.

trū Shrimp President and CEO Michael Ziebell said trū Shrimp is an opportunity for people from the Midwest to invest in the Midwest.

“We are building the trū Shrimp company on the idea that the people of the upper Midwest are the first to invest in a Harbor [shrimp production facility] and the trū Shrimp company. We are not going to the coasts or Wall Street for investment money, but invite the agriculture community of the upper Midwest to invest here and allow that money to grow and provide a return to everybody,” Ziebell said.

Drakes Bay shutdown

continued from cover

miles of wooden oyster racks and 500 tons of marine debris that once supported an operation that grew roughly

The closure of Drakes Bay resulted from a unique confluence of circumstances — most crucially the farm’s location in Point Reyes National Seashore.

An oyster farm was first established in 1935, and it wasn’t until 1962 that President John F Kennedy designated the area a national seashore. A decade later, the family operating the oyster farm sold the land to the federal government and signed a 40-year lease to farm oysters. In the mid-2000s, Lunny bought the permit and rebranded the farm “Drakes Bay Oyster Co.”

Workers at Hog Island Oyster Co harvest oysters in Tomales Bay. Hog Island co-founder John Finger suggests taking regulators and legislators out on the water to clear up misconceptions about oyster farming’s impact on the environment

It will be difficult for California to regain the oyster production it lost when Drakes Bay closed, given the hurdles to starting an oyster farm in the state. Lunny says he doesn’t want to give up oystering, but has yet to find a new place to launch anew. Prospective oyster farmers must contend with a thicket of regulations and permits from multiple government agencies such as the US Army Corps of Engineers and the California Coastal Commission.

“It’s not an easy business to find a place and get started,” Lunny says. “Most oyster farms have people. They’re successful. They’re not turning over. And we’re not seeing expansion in California.”

But the lease expired in 2012, and the Interior Department, which manages the land, decided against renewing. The resulting legal battles pitted Lunny and his allies in the local farming and food community against wilderness advocates. Environmentalists that normally would be allies turned into enemies.

Lunny wishes he could have avoided those battles. The first lesson he offers for shellfish growers is to stay vigilant about standing up for the facts, he says. “Don’t be sure that completely false claims that are repeated and repeated won’t become truth,” he says. “Nip those things in the bud.”

Lunny says that regulators relied on dodgy science and dubious studies about the negative environmental impacts of oystering to justify closing the shellfish farm while allowing other commercial operations — cattle ranches — to renew their leases.

“To decide to renew without a reason would have been in violation of the law. They had to create a reason to not renew,” Lunny says.

Lunny’s second lesson is to establish working relationships with people that might initially oppose shellfish farming, especially local environmental groups. Have a respectful dialogue, and listen to their concerns. Work with them, whether they’re worried about plastic on the beach or bright lights and loud noises disrupting wildlife.

“Go out and see them, talk to them, take them out on the bay. Create a platform where these things can be discussed. They aren’t your enemy,” he says.

Do the same with elected officials, who might not be

educated about shellfish farming, Lunny says. “Make sure you’re available.”

Lunny’s third lesson is that shellfish farmers must hold each other accountable. If there’s a polluting shellfish farmer, it’s up to the community of shellfish farmers to work together to correct them.

Other California oyster farmers have garnered similar lessons from the Drakes Bay incident.

John Finger, who launched Hog Island Oyster Co in 1983 in Tomales Bay, just north of Drakes Bay, says that oyster farmers need to be more proactive about documenting the positive environmental effects of shellfish farming. Oyster farmers observe first-hand how their farms bolster the growth of eelgrass, an important habitat for juvenile fish. But official scientific results to confirm what farmers know from experience haven’t caught up. Vetted scientific studies are needed.

Oyster farmers also need to engage with policymakers at all levels, from Washington, DC to local planning commissions. That could mean taking regulators and legislators out on the water to see oyster operations and clear up misconceptions.

“People will paint it as industrial farming and it’s really not,” Finger says.

For over 30 years oyster growers worldwide have trusted our S1000 Oyster Tray and S4000 nursery tray, to produce the highest quality half-shell oyster for today's demanding consumers. Featuring our 6061 T-6 aluminum suspender pole which stands up to the harshest of salt water environments.

Phone: 604-926-1050

Fax: 604-926-1055

Cell: 604-833-5311

darksea@shaw.ca

Hog Island Oyster Co worker lifts a wire rack of oysters out of the water at Tomales Bay. Co-founder John Finger says starting an oyster farm in California today is much harder than it was when he launched Hog Island three decades ago

Finger agrees. When he launched his farm more than three decades ago, he started with $500 in his pocket. At the time, it was easier to open a shellfish farm on the West Cost than the East Coast. These days, it’s the opposite, and West Coast permitting costs have soared, he says.

“We’re not getting a lot of new farms on the West Coast because the permitting process is so onerous. For someone to do what I did 30 years ago and start a small farm is just not feasible,” says Finger, who added that demand for his company’s Tomales Bay oysters has increased substantially since neighboring Drakes Bay Oyster Co was shut down in December 2014.

The California Shellfish Initiative, an effort to increase shellfish farming that the Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association is spearheading, could help grow the industry in California.

There are other signs of progress in California, says Margaret Barrette, the executive director of the PCSGA. Elsewhere in the state, active farms are still growing oysters in Humboldt Bay, Tomales Bay and Morro Bay. Coalitions are working to make permitting more efficient and develop new technologies.

“There are some exciting things that are happening in California,” says Barrette. “Whether Drakes Bay was unique or telling of what we might see more of, I don’t think we know. Though it certainly remains on everyone’s mind as far as what can happen.”

The University of Southern Mississippi (USM) plans to acquire an existing hatchery and aquaculture facility that will enable it to lead oyster restoration efforts in the state of Mississippi.

In a project proposed by Governor Phil Bryant, the state will provide $7.7 million in funding from requested BP oil-spill settlement dollars for USM to acquire the Aqua Green hatchery facility and farm, located in Perkinston, Mississippi.

The Aqua Green facility incorporates nine structures, with a combined footprint of approximately 99,000 square feet on more than 47 acres of land. It serves as a land-based aquaculture research, hatchery and nursery center. Capable of yearround operation, Aqua Green has the ability to maintain appropriate salinity levels, recirculate artificial seawater and recapture salt for reuse.

Funding for acquisition of the facility will also support renovations for expanded oyster aquaculture research and production, teaching and student research needs, and integration and expansion of other USM aquaculture programs, such as blue crabs, finfish and shrimp, at the facility.

The university’s ultimate goal is to meet the Governor’s Oyster Restoration and Resiliency Council’s recommendation to produce 10 billion oyster larvae annually.

BY ERICH LUENING

Shellfish farmers on the island of Martha’s Vineyard in the US State of Massachusetts have begun commercial kelp farming pilot projects in the hopes of diversifying their products and introducing homegrown seaweed to the regional markets.

In the waters around the island located off Cape Cod, which juts off the state into the Atlantic Ocean like a bent arm, shellfish farmers have applied for permits over the last year or so to pilot a commercial sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) farming project led by shellfish biologist and hatchery manger of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group (MVSG), Amandine Surier-Hall. Among these farmers are Dan and Greg Martino, owners of Cottage City Oysters, and local fisherman and shellfish farmer Stanley Larsen.

Surier-Hall told Aquaculture North America (ANA) that she sees the island as playing a dual role in the development of kelp farming in the state.

“Right now, it is leading the kelp movement by having the first experimental lines in Massachusetts waters,” she explained. “Later the Vineyard could become a resource for growers if the stateowned Hughes Hatchery in Oak Bluffs [a town on the island] becomes a regional kelp seed stock nursery.”

As co-director of the MVSG she was also responsible for finding the funding for the kelp project and partnering with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI), which is just a ferry ride away on the mainland, to source the sugar kelp seed. WHOI has been conducting scientific research into various seaweed species for a number of years.

Cottage City Oysters was one of the first shellfish farmers to take part in both the scientific and commercial programs on the island.

The Martinos obtained permits for oyster farming about four years ago and now look to seaweed as a way to supplement the shellfish business, which has a different harvesting season than sugar kelp. Before they were allowed to farm kelp, they worked with local scientists on the best time, place and methods to grow kelp off Martha’s Vineyard.

“Amandine got the grant for researching sugar kelp for commercial growing,” Dan Martino said over a cup of coffee one January afternoon. “Last year we learned off our mistakes and this year the next run is growing better so far.”

MISTAKES PART OF SCIENCE

The first season of the project had mixed results.

The seaweed grew at their site but not at all to market size either because of water quality or some type of predation, SurierHall explained.

At the mussel farm on the western side of the island, Stanley Larsen also experimented with growing sugar kelp as part of the project and found similar results — the kelp did not grow to adequate market size.

Surier-Hall admits that hurdles and mistakes are part of doing good science in testing different methods, locations, and water quality.

Martino agrees. “One of the great things is we have learned a lot about our water quality at the site because that’s part of the science being done as part of the project,” he said.

As part of the deal with WHOI, the institute supplied the farmers with the kelp and collected data as it grew. That data was passed along to biologists, like SurierHall on the Vineyard, and David Bailey, a hatchery manager at WHOI, who works with the Martinos and Larsen.

Off the shores of Menemsha Harbor on another side of the island, Larsen grows his mussels on a five-acre site one-mile offshore where there are five 300-foot ropes hanging in 70 to 100 feet of water. This is the first mussel farm in Martha’s Vineyard. It was started by fisherman Al Gale six years ago, but worked by Larsen for the past year in a grant leased to him by the state.

Larsen has been working with another WHOI scientist, Scott Lindell, who planted sugar kelp above Larsen’s mussels. “We got a grant from the USDA [US Department of Agriculture] to work with shellfish farmers to do some double cropping,” Lindell said. “Diversification is a good thing,” he told The Martha’s Vineyard Times in December.

Sugar kelp is attached to ropes that hang above the mussel lines. The species of seaweed need to be in the sunlit portion of the water column. Unlike other species, sugar kelp is a winter crop; farmers plant it in November and December and harvest it in April and May.

POTENTIAL GROWTH

Since 2012, Massachusetts has been experimenting with seaweed farming and now has a small stake in this fledgling US industry. Worldwide, the seaweed market is about $5.5 billion.

Massachusetts seaweed farming is dwarfed by its New England cousin, the State of Maine, where wild harvesting and farming of seaweed has been a commercial success for years.

According to The University of Maine Sea Grant, sugar kelp was the first commercial kelp crop to be cultivated in Maine in 2010, with other native species under development since then.

Maine commercial seaweed farmers such as Ocean Approved and Maine Fresh Sea Farms are farming or harvesting as many as ten different species. All are edible and nutritious, although some more than others have been favored as food. These seaweeds, or “sea greens” as some refer to them, have been used for everything from fertilizing gardens to animal feed, to perhaps most consistently, in a financial sense, as a thickening agent for foods like puddings and ice creams.

Massachusetts seaweed farming is still in its early stages compared to Maine, but researchers and shellfish growers are willing to try it as a supplemental harvest to their regular shellfish farming even if there are some hurdles along the way.

“Maybe it’s a carbon or nitrogen deficiency,” Martino said about last year’s crop. “Even if it doesn’t become sixfeet long there is a market for baby kelp. It’s more tender and sweeter so there is even a chance for that market to open up.”

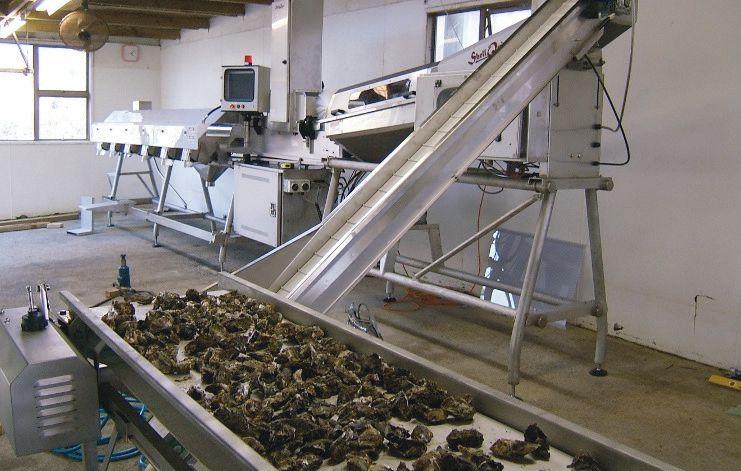

Crassostrea virginica, the Eastern Oyster, being sorted by shellfish growers

Oyster farmer tending to cages in Chesapeake Bay

BY HEATHER WEIDENHOFT

ot only are oysters a tasty treat packed with iron and omega 3, but researchers are hoping this powerful filtering dynamo will also help clean up one of the most important US waterways.

Recent studies are focusing on developing recommendations for addressing some of the problems caused by eutrophication, or nutrient overload, in Chesapeake Bay. The deteriorating water quality levels in and near the bay have long been on the government’s radar and a concern for fishermen and shellfish growers in that area. At the end of 2016, a special panel of aquaculture scientists from the NOAA Northeast Fisheries

Panel releases initial findings on using oysters to reduce nutrient load in Chesapeake Bay

Science Center, the Oyster Recovery Partnership, and the University of Maryland approved the “Oyster Best Management Practices” to develop ways that oysters may be used to reduce nutrients, in particular nitrogen and phosphorous, in order to meet the EPA’s water quality standards. The panel has just finished the first stage of approving best management practices (BMPs) for the uptake of nitrogen and phosphorus into oyster tissue.

OYSTERS AS FILTERING MEDIUM

Oysters gather food by filtering nutrients out of the water, and when harvested the nutrients absorbed in their tissues — including nitrogen — are removed from the environment. How effective they are at this process can

Excessive nitrogen and phosphorus are making their way into the waterways and have dramatically increased the nutrient load in Chesapeake Bay over the last two centuries due to human habitation and agriculture near the watershed.

In small doses, nitrogen and phosphorus stimulate the growth of algae and aquatic plants that are the basis for a healthy ecosystem. In large amounts, those same nutrients can cause an overstimulation of plant growth, which leads to harmful algal blooms and low oxygen conditions.

The economic loss due to eutrophication, or nutrient overload, doesn’t end with shellfish.

Researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science have found concrete evidence that the low oxygen conditions, called “dead zones,” have direct impact on the distribution and abundance of demersal fish like white perch, Atlantic croaker, striped bass and summer flounder living and feeding near the bottom of the Bay. The study was authored by Andre Buchheister, who notes: “This is the first study to document that chronically low levels of dissolved oxygen in Chesapeake Bay can reduce the number and catch rates of fish species on a large scale.”

The water quality degradation has not gone unnoticed. Despite extensive restoration efforts during the prior 25 years, in 2010 the EPA was prompted into action by insufficient progress and established the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), a measure of accountability to ensure major changes are made to educe pollution and restore clean water to the region’s most important watershed.

be measured by applying the Farm Aquaculture Resource Management (FARM) model, which estimates the impact of shellfish nutrient removal through growth, harvest and shellfish production. Already used in 14 locations across nine countries and four continents, the model estimated an overall annual amount of nitrogen removed by shellfish from those locations between 105 to 1,356 pounds per acre. The estimates can be counted towards reaching the TMDL requirements for Chesapeake Bay and given as “credits” for counties that agree to use approved BMPs and work with the shellfish industry to help clean up their nearshore environment. “The novel part of this project is engaging with new industry partners and joining with the aquaculture community for help in this large-scale clean-up,” Suzanne Bricker of NOAA told Aquaculture North America (ANA)

RESULTS ARE CYCLIC

In a perfect scenario, the proposed biofiltration project would create its own sustainable loop: Increased aquaculture leads to increased water quality, and vice versa. From this loop could emerge a new sustainable source of seafood, and the results from previous FARM models have already created a conversation between growers and regulators interested in using shellfish filtration to address eutrophication issues on a worldwide level. With so many positives (good for consumers, good for economy, good for the environment, good for wild oysters) it seems likely the panel recommendations will have far reaching implications. Panel discussions will continue into late 2017, when BMPs addressing the evaluation of oyster shells and burial of their biodeposits into sediments can be given a denitrification value for further credits to oyster growers. Julie Rose, also at NOAA, says, “The approach of biofiltration isn’t new, but the visionary aspect of Chesapeake Bay’s BMPs are addressing nitrogen in waters with a much broader application than ever before and providing a framework of policy that other states can use.”

Amid challenges posed by predators and the unpredictable environment, the company succeeds in producing tasty, grit-free bivalves

BY TOM WALKER

Ason-and-pop partnership is cultivating mussels suspended in rafts floating in the waters of the Casco Bay, in the Gulf of Maine, guided by the principles of environmental sustainability. “My father and I have both been interested in aquaculture for a long time, but what attracted us to Bangs Island Mussels was that it fit with our values of harmony with the environment,” says co-owner Matt Moretti. “We wanted to do aquaculture in a way that didn’t hurt nature around it, and potentially help the environment too.”

‘Many of the restaurants put our name on the menu and it helps with sales. People have come to realize that the brand means quality and a method of production they can get behind,’ ~ Matt Moretti

“Mussel farming is all that,” says Moretti. “It’s the most sustainable and lowimpact way of producing food I have ever heard of. They’re a filter for the ocean. We don’t add chemicals, we don’t use freshwater, we don’t have a lot of waste, everything is reusable like our lines, and the rafts will last for decades.”

“It has been a dream of mine to get some IMTA (integrated multi-trophic aquaculture) going,” says Moretti. “Recent studies show that kelp culture alongside shellfish culture can actually benefit both. The kelp get extra nutrients that they need from the mussels and mussels get a Ph buffering effect from

The company has been around since 1999 and Matt and his father Gary, purchased it six years ago. “We bought it from the original owner which is actually somewhat rare in Maine, as opposed to starting your own farm,” he says. “It speaks to the evolution of the industry in that it is older and more mature and becoming more valuable.”

“It was operating at a pretty small scale so we made it our mission to grow as quickly as we can,” Moretti explains. “Dad and I reinvested everything we could into the company and we grew the business to where it is today.”

They started with three rafts, one lease site, a barge and a skiff. Now they have 10 rafts, two lease sites, the barge and a larger lobster boat. “In the beginning it was myself and one employee with my dad helping out,” says Moretti. “Now we have grown to three full-time employees and about six part-time.”

The two sites with a total of 3.66 acres in Casco Bay, northeast of Portland Maine, are leased from the state. The 10 rafts are 40-by-40 foot square. Each raft can hold 400 long lines, 35-feet long. “The sites are actually quite small for the amount of mussels you can produce,” says Moretti. Each raft is wrapped in protective netting to keep out the voracious eider ducks. “They can eat their body weight in mussels in a single day,” Moretti says.

“We have managed to squeeze in two kelp long lines on the site and we will be putting in a scallop long line in the next couple of weeks,” Moretti says. “We have actually been doing kelp for about five years. It’s a great example of a high-quality delicious food we can produce, that doesn’t impact the ocean.”

Recently, a number of Maine growers had the opportunity to go to Japan to study scallop-farming (A story on the efforts to bring the Japanese earhanging technique to Maine appeared in Aquaculture North America, September/ October 2016, page 1.) “I learned all about the ear hanging [method] and we are pretty hopeful we can adapt their methods to the Maine environment and grow the scallop industry here,” says Moretti.

continued from page 19

The scallops, like the mussels, are a natural set. “People have been using a natural set in Maine probably for 25 years,” Moretti points out. “We have an abundant natural resource and we have never had to go the hatchery route.” There is some research work being done with mussel hatcheries in the area, he adds.

“Because of the timing of mussel farming we are actually increasing the natural resource,” Moretti explains. Mussels mature and spawn before they are large enough to harvest. “We can collect seed on our lease sites underneath our rafts well protected from the elements and predators that would affect them in a more open environment.”

Scallop seed is collected further offshore with a permit. “It works a similar way, in that you collect the seed and protect it and you have a much higher survival rate than you would in the wild,” says Moretti. “And it is certainly not impacting the wild population.”

“We work pretty closely with our governing body, the Department of Marine Resources,” says Moretti. “It’s a good relationship. Both sides are trying to make things better for the industry.”

Aquaculture is still quite small in Maine, Moretti says. “There is a lot of excitement around aquaculture right now. There are a lot of growers starting out, particularly in oysters and kelp. Aquaculture is certainly a way of supporting economic improvement in less affluent communities on the coast.”

Current harvest is 200,000 pounds a year, with an 18-month grow-out. “We just added three new rafts, so we will see how it turns out when we are going full scale,” Moretti says. “Right now we are harvesting about two times a week. In the summer we might pick it up to three times a week.”

He says they have a few different distributor/ wholesalers with about eight customers in total. Most sales are direct to restaurants, although there are a few retail stores that carry Bangs Island Mussels. “We have the Bangs Island brand name and I think it’s pretty strong. It’s a part of what we do,” Moretti says. “I understand many of the restaurants put our name on the menu and it helps with sales. We are not just mussels from Maine. People have come to realize that the brand means quality and a method of production they can get behind.”

BY TOM WALKER

laska, the United States’ top producer of wild seafood, is just in its infancy when it comes to farming it. Current and prospective farmers are looking at the technology and equipment used in Maine, where farming of shellfish and seaweed have been a commercial success for years.

The Pacific Shellfish Institute (PSI) based in Washington State is helping to grow the Alaska shellfish and seaweed industries.

“The Pacific Shellfish Institute was involved in phase 1 of the Alaska Mariculture Initiative,” explains Julie Decker of the Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation. “PSI felt that a good next step would be to help existing growers to become more profitable in what they are currently doing with oysters and help them diversify into different species.”

Mariculture in Alaska is considered to be producing only a fraction of its potential, with 95 percent of the $1-million industry coming from sales of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Blue mussels (Mytilus trossolus) and a small amount of seaweed are the other species currently being raised. The Alaska Mariculture Diversification Innovation and Technology Transfer project received Sea Grant funding to help expand the industry. PSI is a collaborator and sub-contractor on this project.

The project has targeted current and prospective farmers through workshops and an Alaska Shellfish Growers conference in 2015 and 2016. They have also coordinated the distribution of seaweed seed and cultivation materials and new oyster growout gear in exchange for growers testing the gear, keeping records and sharing their results.

last year,” says Hudson. “Some got in the water, some not.”

“We do have some lessons learned already,” says Hudson. “One site in the Ketchikan area where they deployed floating Vexar bags found the wind and the waves just too much for it. They had a lot of their gear break apart. It won’t work at his site.”

“But the same bags work really well in Jakolof Bay up in the Homer area,” says Hudson. “There is not as much of a fetch towards the corner of the bay that a farmer

is working in and the floating bags are working beautifully.”

Hudson says they were concerned about local sea otters chewing the floats. “It’s not something they have to deal with in the north east but so far it has not been a problem,” she says.

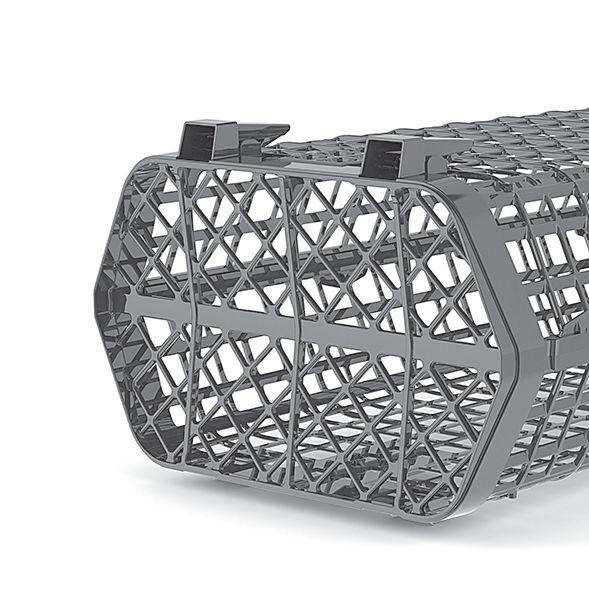

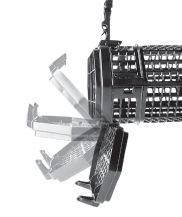

“The Seapa baskets are suspended just below the water and they work great,” adds Hudson. “I know the folks who have been working with them are pleased. They are easy to handle, open and dump, and easy to monitor growth.”

PSI provides technical assistance and advice on best culture practices of oyster and kelp species, and works to connect Alaska with specialists on the East coast.

“The growing conditions in Maine and Alaska are quite similar,” explains PSI Executive Director Bobbi Hudson, from her office in Olympia, Washington.

“Maine has deep rocky shorelines with big tides. Neither area is suitable for beach culture. And Maine is really expanding their seaweed industry.”

Traditionally, Alaska oyster growers have used lantern nets, says Hudson. “But they are difficult to work with and are labor-intensive. A lot of growers have switched over to ‘Mexican style’ trays, hanging from buoys.”

Growers were interested in trying something else and they started looking out of state. “Vexar bags seemed like something to try but they didn’t just want to go out and buy it themselves,” Hudson says. “So this was an opportunity to access funding and try it out and experiment, at no cost to them.”

“We were able to purchase some Vexar bags, with the closed cell foam and the bouys already attached, from Maine. Trucking across the country was cheap but barging it up to Alaska was not,” she adds.

Each grower in the program received 44 five-inch-deep Vexar boxes with foam floats, 44 three-inch-deep Vexar bags with floats, and 22 Seapa baskets. “We didn’t get the gear distributed until mid summer

Endowed with seafood infrastructure and a rich coastline, the United States’ biggest producer of wild seafood is looking to expand its stake in mariculture

BY TOM WALKER

hy not Alaska? That’s a question that Alaska shellfish and seaweed growers are starting to ask themselves. The $6-billion seafood industry in the state produces more seafood than the rest of the US combined. Indeed, if Alaska were a country it would be in the top 10 for seafood production, yet almost all of that comes from the wild fishery.

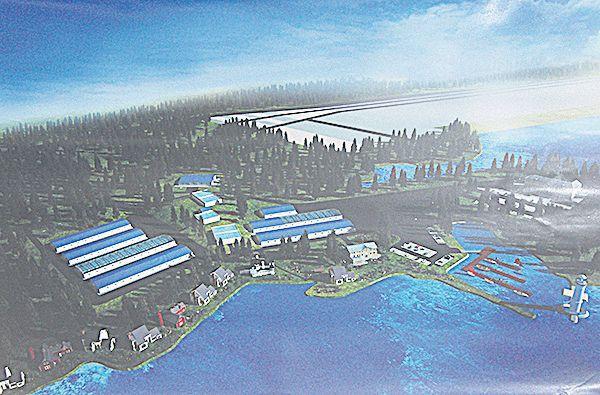

Industry organizers see a lot of potential for mariculture in Alaska. “We are aiming to grow the current industry from $1 million to $1billion over the next 30 years,” says Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation (AFDF) Executive Director Julie Decker, from her office in Wrangell, Alaska.

“Our organization represents the traditional seafood industry and we focus on research and development,” says Decker. “So it gives a different look at what mariculture can be.” AFDF has been leading the Alaska Mariculture Initiative over the last three years.

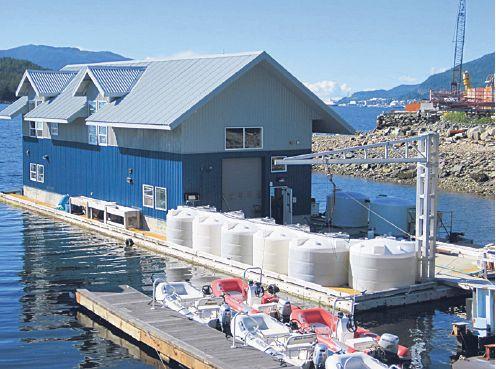

OceansAlaska hatchery facility in Ketchikan, Alaska. The non-profit aims to expand mariculture and enhance wild stock for oysters, geoducks, sea cucumbers and kelp in Alaska by making commercial quantities of seed available

The goal is to grow Alaska’s mariculture industry from $1 million currently to $1billion over the next 30 years, says Julie Decker, AFDF Executive Director

“We developed the Initiative and NOAA funded it with a grant,” says Decker. She explains that what began as a two-year project with a steering committee to contact stakeholders, hold some workshops and come up with a plan, has continued to grow. “The state manages these resources, so we knew from the beginning we would have to have them on board,” she says. “We met with the Governor and asked that he consider supporting the initiative. He was happy that we had a long-term vision to grow the industry and he set up the task force.”

Governor Walker established the Alaska Mariculture Task Force in February 2016, with a directive to present