With an eye to the future, using nature-based solutions to meet the challenges of the present: thinking, working, living together.

In-Between Vol. 3

In-between landscape

Vol. 3

LAND

December 2023

Publisher

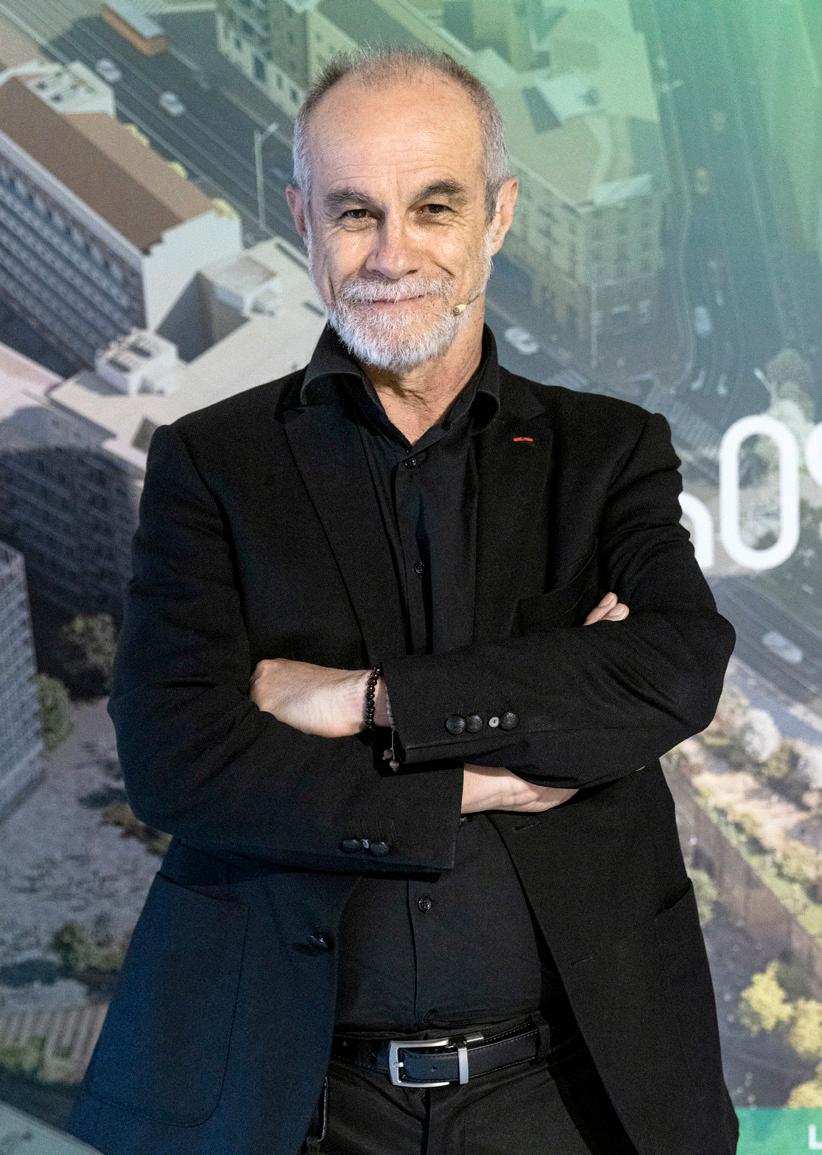

Andreas Kipar

Concept

Andrea Küpfer

Editing

Andrea Küpfer

Henning Klüver

Design

Tim Santore

Art

Thomas Schönauer

Unless otherwise stated, all images copyrights are held by LAND

landsrl.com

IN-BETWEEN SPACES OPEN FUTURE AND CONCRETE STEPS

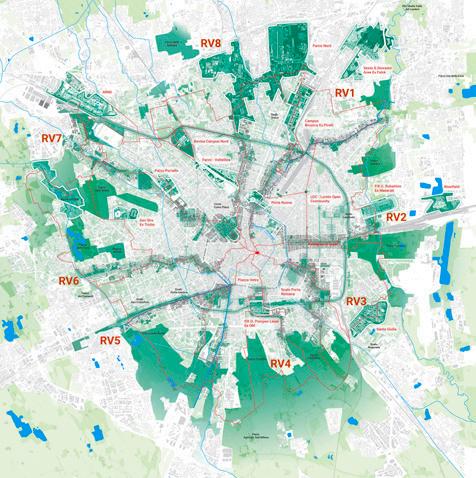

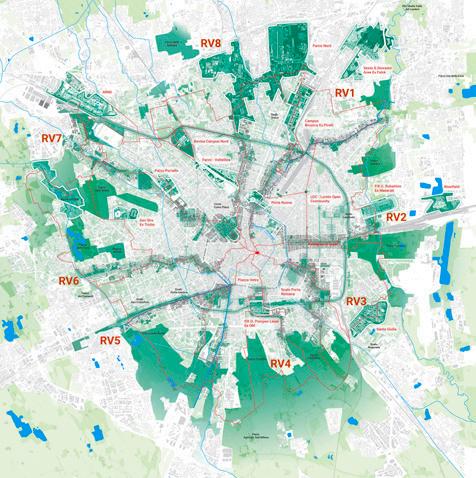

It’s all about the inbetween. With the third edition of the LANDmagazine, we make space for a dialectic between an open future and the forwardlooking steps we‘ve taken towards a productive relationship with nature. We are driven by the momentum of what we’ve learned and our experience with Raggi Verdi, the 'Green Rays' we developed twenty years ago for Milan, which in the meantime have become an internationally successful model for connecting open spaces and natural areas. Learning steps, rays in a transformation process where undefined, fluid styles of urban and rural cultivation have increasingly passed muster as social and peopleoriented processes in everyday consulting and planning.

The first chapter, 'Thinking Together', addresses fundamental questions about the relationship between nature and people and methods for scientifically verifying interactions with landscape and making developments measurable. In the second chapter, 'Working Together', we pursue concrete projects in close dialogue with clients. And in the third chapter, 'Living Together', we address everyday and design issues, particularly in urban spaces.

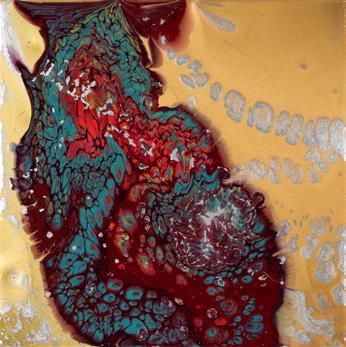

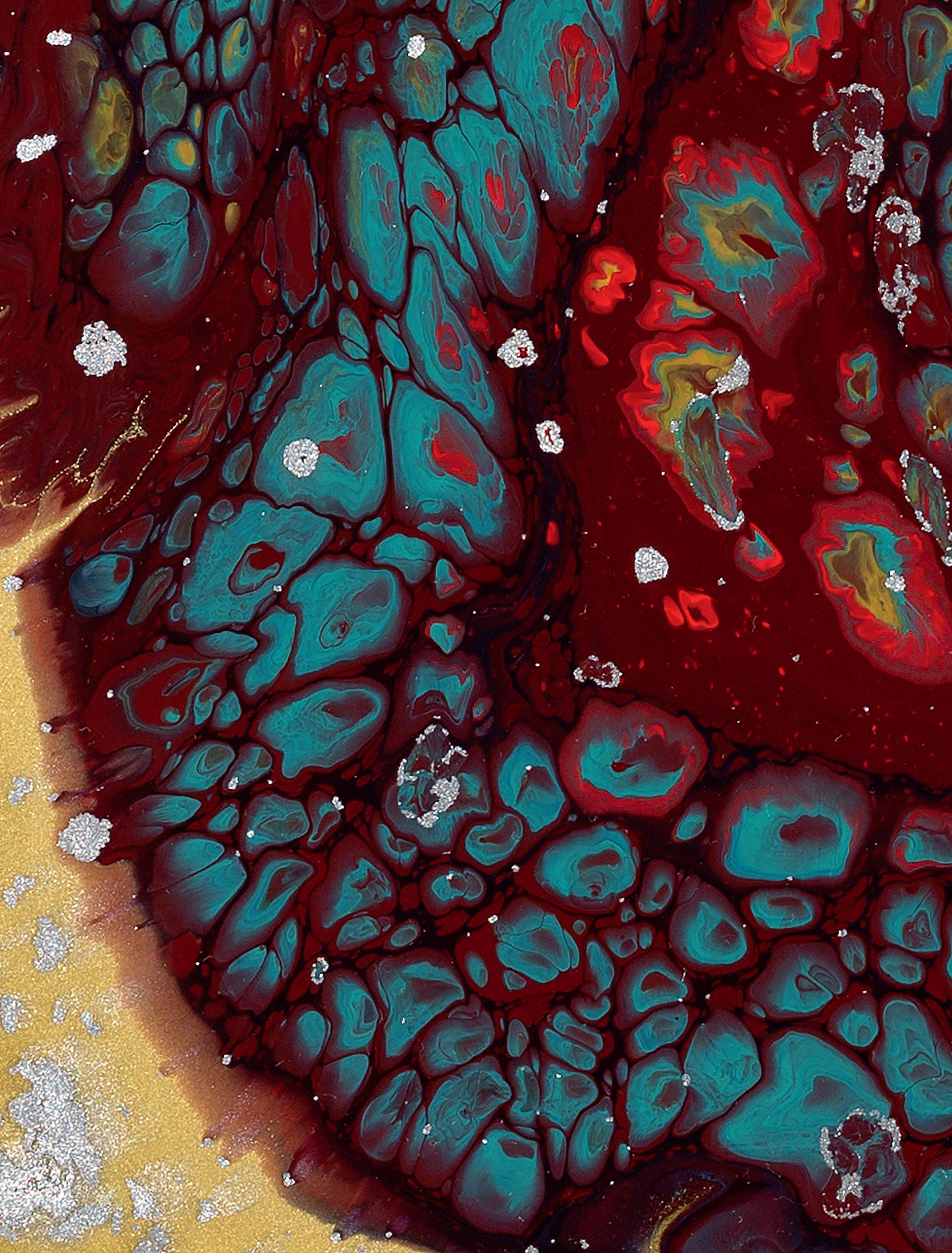

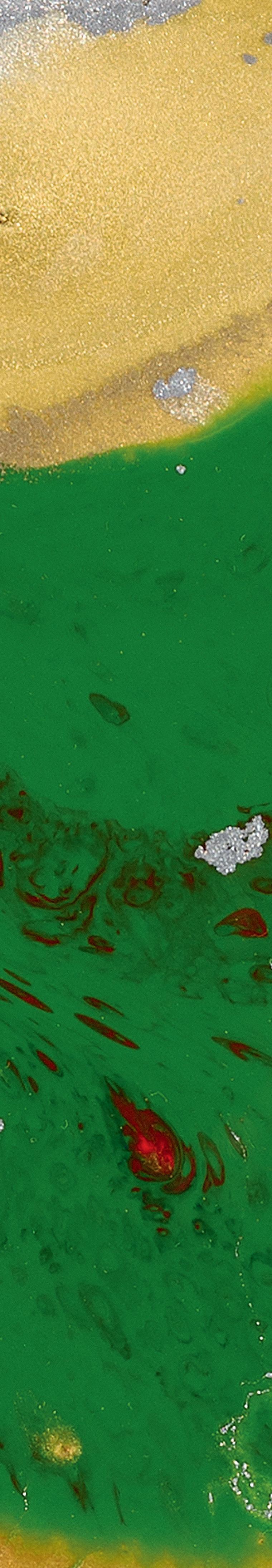

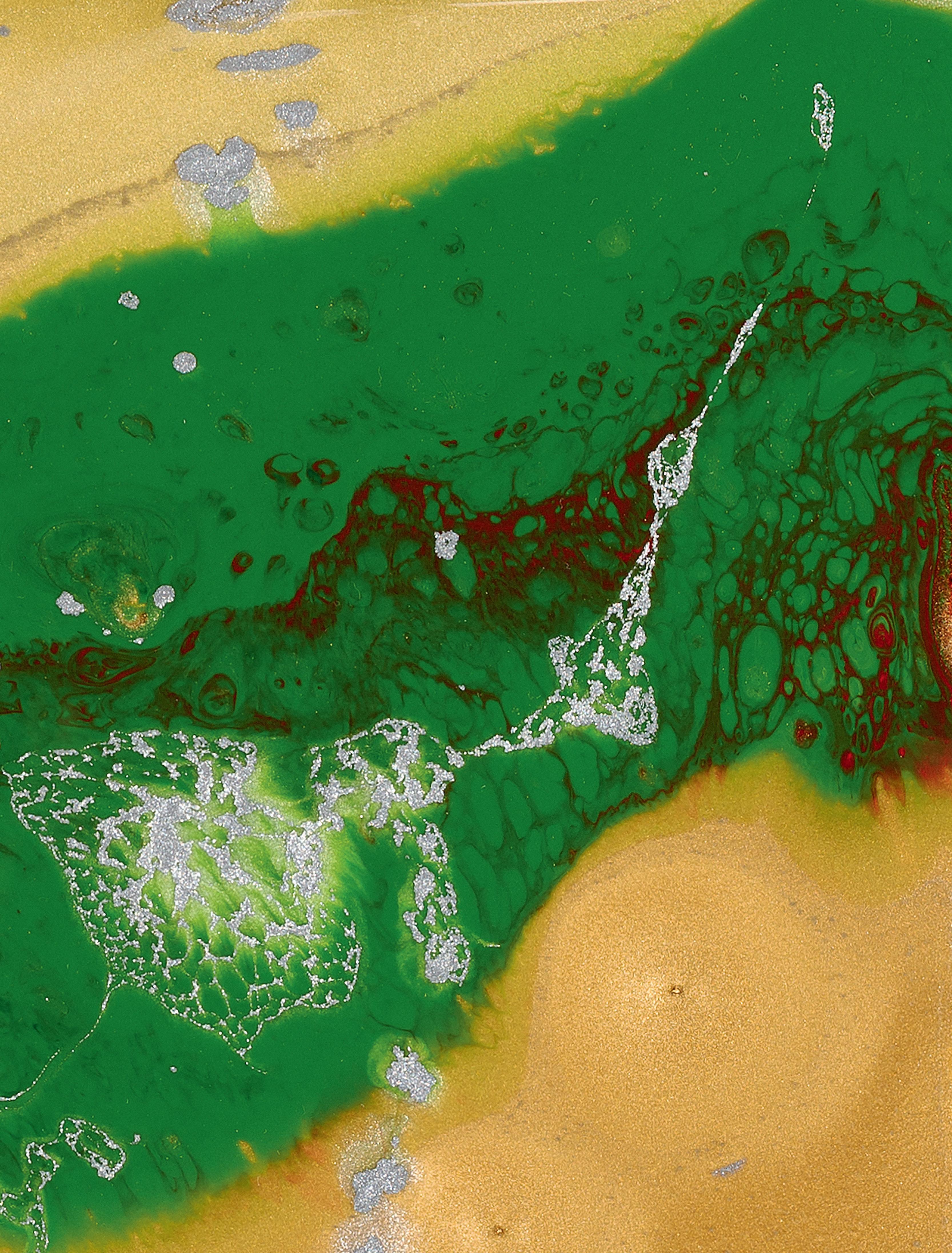

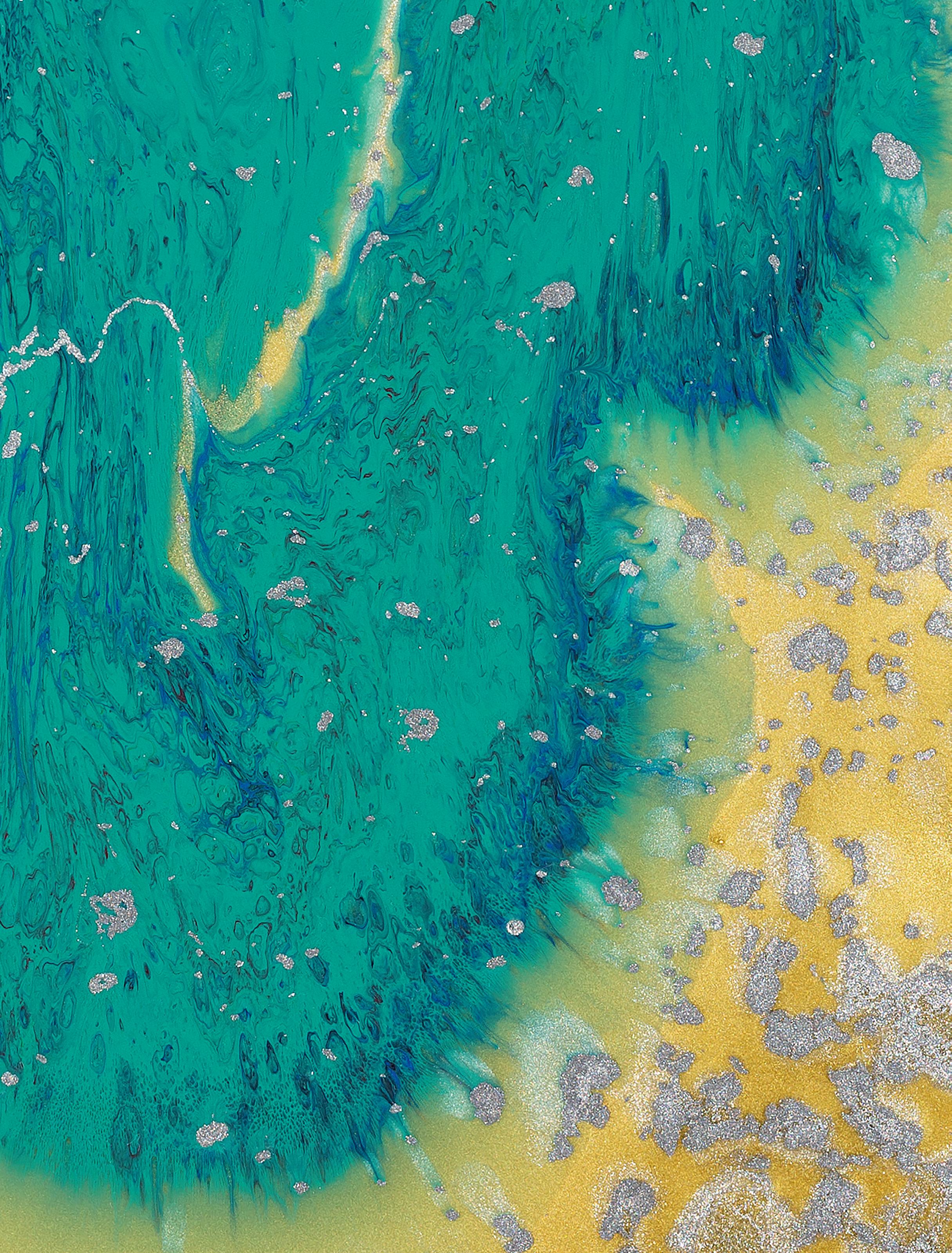

It‘s all coming into focus: as we move into the future, we’re increasingly leaving clear boundaries behind. They’re becoming permeable, creating new spaces within our awareness. Aesthetic, ethicsbased thinking is driving us forward. It’s a sensibility that‘s also expressed in the artistic works of our companion and friend Thomas Schönauer. A selection of his CT (Computer Tomography) paintings introduce the individual chapters of this LANDmagazine, excerpts that reflect the fluidity and permeability of landscape, but also its permanence.

Working, living, and thinking together is what sets us apart. Established in Milan over thirty years ago, today we feel at home in many places: Düsseldorf, Lugano, and more recently also Vienna and Montreal, where our company is experiencing dynamic growth in response to the challenges of socioecological transformation. As we break up the old, we’re making new space for our targeted message: reconnecting people with nature!

Andreas Kipar

THINKING TOGETHER

08

The tension between distance and identity

Volker Demuth

14

Milan as a laboratory City of knowledge, research, and culture

O

16

Tools and methods

Meeting the UN Sustainable Development Goals

Andrea Balestrini

WORKING TOGETHER

22

28

Between energy and future Edison

Ilaria Congia, Beatrice Magagnoli, Benedetta Falcone and Ilaria Giubellino

N

Passion for nature Vibram

Martina Erba and Matteo Pedaso

36

Everything is landscape

AgriPark Fellbach (IBA'27)

Kristina Knauf and Anna-Lena Bauer

LAND SCAPE

C

T40

46

N55

50

The new centrality of landscape Directors of LAND

58

ERethink your landscape Next generation dreams Giuliana Bonifati

62

Green rays Wunderkammer

Raggi Verdi 20 years

process in

The transformation

cities Uwe Schneidewind

Value to the region IBSA

Federico Scopinich and Davide Caspani

TOGETHER

Collective resilience Kristina Knauf LIVING

THINKING TOGETHER

Creating future landscape

Nature and landscape: a complex relationship. There is no landscape without humans, who shape the natural world but have long trampled it underfoot. Lucius Burckhardt, the Swiss founder of strollology, said that humans have two ways of approaching nature: "Through science or through poetry." Science develops methods for identifying natural processes and making future landscapes more resilient. Poetry develops approaches to provide landscapes with an aesthetic and social framework that makes people feel secure. Even though, according to Burckhardt, we're not going to be able to "replant the Garden of Eden."

Talk of climate change and its ecological and social consequences has now become a mantra. Yet we must tirelessly seek new ways to cultivate urban and rural areas. We need to change the way we think, and we've begun to take joint action despite all the doomsday talk. "Reconnecting people with nature" has become a clear battle cry for designing future landscapes. Because what's at stake is our relationship with nature and quality of life worldwide – including our own front yards. For us and for future generations.

06

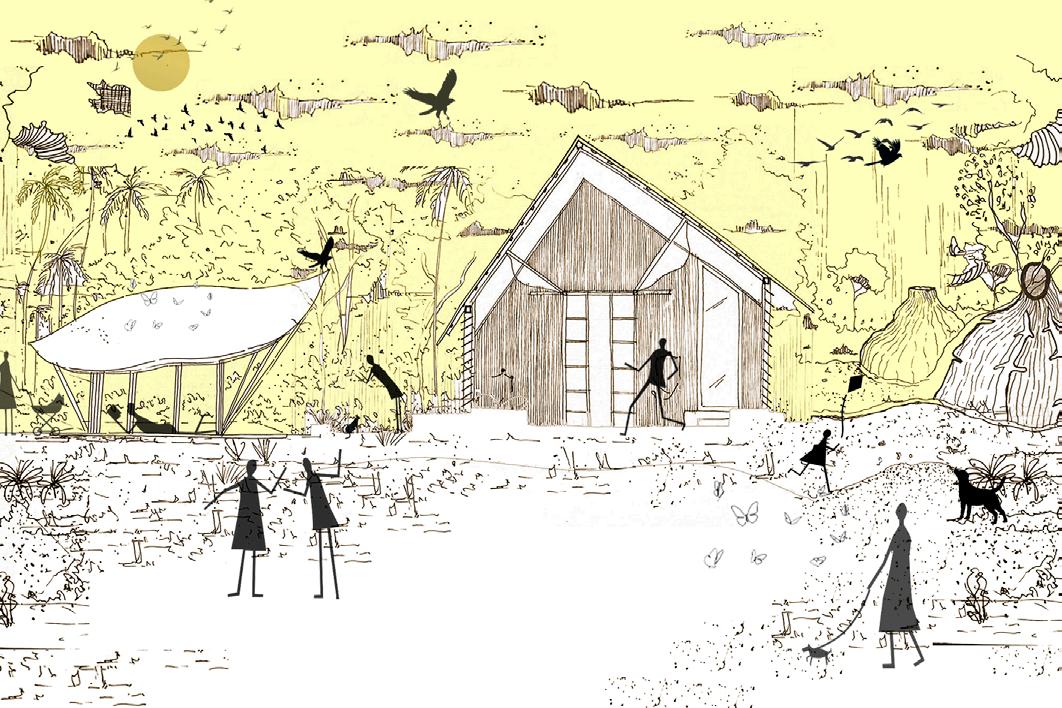

Original and detail: Thomas Schönauer CTPainting (1) Thinking together

THE TENSION BETWEEN DISTANCE AND IDENTITY RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN LIFE AND LANDSCAPE

08

A discussion with the writer Volker Demuth

Thinking together

Landscape is moving to center stage – KruppPark Essen © Photo Johannes Kassenberg

Landscape's attraction and rebirth in our society, individual responsibility in the climate crisis, land consumption, the relationship between town and country, and the tasks of our civilization: explorations of the writer Volker Demuth, whose essay collection "Unruhige Landschaften"1 was recently published.

The author, born in 1961, studied philosophy, literature and history at the universities of Oxford and Tübingen. For several years he was a professor of media theory (giving up his chair in 2004), and he now lives as a freelance writer in Berlin and the Uckermark district. The text is a compilation of excerpts from a radio broadcast with Volker Demuth for Deutschlandfunk2

What's alluring about landscape?

What importance does landscape have today?

Unlike Nature, which was ideally thought of as an independent "thinginitself" (to Hegel it was "otherness" par excellence), landscape is an enormously multifaceted system of references, a bewildering sphere of relationships. The shift from a Naturelike "thinginitself" to landscape as a form of relationship presupposes a sensual, emotional, and cognitive encounter. We smell landscapes, listen for their sound, feel their temperature and the wind flowing through them, their moisture on our skin, we see the atmosphere of their light and the interplay of their shapes and forms. And we become aware of this concentrated, dense sensuality in a culturally formed, unmistakable way. Nature as a thinginitself, or the abstract notion of it, transforms into the experience of landscape only when there is an aesthetic encounter.

Far out and difficult to see through the relentless advance of urban agglomeration, landscape is surreptitiously moving to center stage. For the first time in history, all landscapes on Earth are exposed to human influence and civilization. We're no longer confronted by the alien, the natural, in landscapes; instead, we encounter ourselves, our own human imprint, our selfmade mess, our own advancing specters. Each of us is party to the landscape in which we live and through which we move, we're all complicit.

Where does this human imprint of ours lead?

Uninhabited or sparsely inhabited landscapes account for ninetyseven percent of the Earth's land surface, with half the world's population concentrated on just one percent of the land. Yet humans now cast a shadow over every landscape on the planet, even the most remote. This is increasingly evident as landscapes are visibly and ever more seriously impacted by fire, drought, and flooding. Indeed, the media now bombards us daily with images of devastating typhoons, clearcut rainforests, dwindling polar ice and melting glaciers, encroaching deserts, and vast inland lakes silting up.

1 Volker Demuth: Unruhige Landschaften. Ästhetik und Ökologie. Würzburg 2022

2 Unruhige Landschaften. Von der Neuerfindung von Kultur und Natur. A broadcast by the national German radio Deutschlandfunk (Cologne) August 22nd, 2021

And our reaction to it?

Signs of a coming disaster? Thinking together

But isn't that schizophrenic?

The economic systems of disaster have become a lucrative and global demonstration of our time. But media presentations mislead us when they suggest that we can expect the apocalypse at some more or less distant point in the future. The apocalypse isn't some sudden event, it's a period of time. It's not something that's going to happen, it's something that is.

Our lifestyles are characterized by a latemodern inconsistency. Even in our mobile environments with their urban nomadism, where every day we're out and about in the city, moving through countless metropolises year after year, we feel a growing desire to immerse ourselves in natural landscapes when we go on vacation, to gently sink back into something we deeply desire. When we can, we travel to idyllic Caribbean beaches, go hiking in the Andes, rafting on Nepalese rivers. At the same time, on our mobile screens, we're witnessing the Arctic cryosphere melting away as we await the impending, apocalyptic demise of huge swaths of the planet.

It seems that most of us have grown used to compartmentalizing landscape into two sections: one that offers an experience, a sort of wellness space, a green area where we can kick back, replenish our stressed out psyches, and experience Nature when we get sick of civilization; and the other a space that we use, that we exploit, to make as much money as possible. While one space – the romanticized idyll – is to be protected and preserved, the other is ruthlessly exploited, ravaged and plundered. The schizophrenia is obvious. It's comparable to the almost insatiable desire for powerful off road vehicles, now that transport infrastructure has finally removed all obstacles and paved every back road. The loss of wild landscape is obscured by this symbolic pretension and transformed into technical consumption, into simulation.

Is landscape consumption increasing in all directions?

Since industrialization first began in the 1700s, we have expanded arable land fivefold, and pastureland has increased from two percent to one quarter of the earth's surface today. Not to mention our increasingly congested urban areas and road systems. Furthermore, land consumption and soil sealing continue to attack landscapes, devouring a landscape area approximately the size of Frankfurt every year in Germany alone.

We now know that the cultivation of natural areas and the urbanization of cultural landscapes generally destroys ninety percent of the original organisms living there.

10

So

what do we do?

Since we can't just deny responsibility for the collapse of more and more landscape habitats, the unavoidable conclusion is that a universal landscape policy must be developed. Because the threats and increasing risks to landscapes are politicizing even lands that until recently were considered beyond politics: glacier lakes, grasslands, shifting sand dunes, frog ponds.

Climate change, environmental degradation, and continued world population growth have transformed the once promising future into a fearfilled vision. Melancholy, once an expression of sadness for past loss, has now shifted direction: we now mourn the future.

»WE MUST ABANDON THE NOTION THAT LANDSCAPES BEGIN AT THE EDGE OF CITIES. THEY BEGIN IN THE CITY, IN EVERY HOME.«

Volker Demuth, © Photo Thomas Warnack

How can we restore the future?

First of all, it's clearly difficult to create an inner connection to landscapes that have been abused. Their deleterious structure refuses to become part of our identity. Consequently, communal and individual life disassociates from the landscape. For this reason as well, it's essential to build balanced landscapes that consider the interests of all living beings and topographic features. This requires a very delicate touch to preserve the fine spatial balances of nonhuman life, and a radical slowdown in landscape tempo, thus allowing biological balances to be reestablished and natural spaces to be maintained in a state of active tranquility, with changes occurring gradually over time to allow living organisms to make the necessary modifications and adaptations.

Moreover, we can no longer get around the need to bring the tense relationship between town and country into the landscape. This task includes using expanded urban areas and the frayed edges of cities to create new hybrid forms of urbanrural life that, aided by digital technologies, can lead to local solutions for organizing work and life, with a more placecentered lifestyle that can restore our firm sense of responsibility for where we live.

Do town and country create unity through multiplicity?

Technical infrastructure such as power lines, photovoltaic plants, pipelines, water supply, communication networks and server parks form the technosphere of sprawling urbanism. But the basis for the diversity of life on the surface is what's underground. Every day, countless soil organisms are buried under asphalt, concrete and cobblestones in landscapes in order to meet the city's metabolic needs. We must abandon the notion that landscapes begin at the edge of cities. They begin in the city, in every home, every office. With the awareness that the production of food and other essential items must not be jeopardized, balanced and intact landscapes filled with diverse life are among the most basic of human needs, especially when we consider that all species, genes, and ecosystems are interconnected. Perhaps we've finally reached the point where people increasingly recognize this, where it becomes clear that as humans, we always have a relationship to landscape and certain places. Because landscapes create places for us, they become stages for actualizing space, or more precisely, for localizing our lives. A historical, political and mental topography is formed within them. In short, landscape is an experiential and narrative space where we encounter ourselves and others, in the tension between distance and identity.

12

Thinking together

What does this mean for our way of life?

But aren't we on the way to recognizing this in many places?

We need to introduce a more fundamental change and thus redefine the meaning of the word progress. Indeed, as balanced landscapes, broadly speaking, embody precious symbiotic relationships and commodities, they inevitably become the scene of a revolution that arises from within themselves – from soil, plants, animals, air, and water : a revolution in the human way of life.

Through the landscape, the civilization of arrogance and presumption looks itself in the face, injured, unreconciled. It may be that the civilizational sickness that confronts us in the landscape has become so obvious that it's sparked a growing demand for new cultural approaches to it. But what's certain is that in this planetary age, now more than ever landscapes are not just the private property of the few. Rather, as resources for the future, they will have to be protected as a public good much more extensively than before. Such a systemic change, however, also places responsibility on society as a whole, and thus on each individual. If nothing else, it brings other consumption patterns into the discussion, as well as an ambitious modesty in which "more and more" isn't good enough. And it means considering new forms of a landscapeusing economy, which could include legal provisions, incentives and institutional directives to guide reform, and social participation that could breathe new life into the model of the commons, of communal landscape ownership.

Landscape at the center of society...

So there are good reasons, which are in our own interest, to let the landscape renaissance become a velvet landscape revolution. Nothing is remote in the global world. The Arctic and the Amazon jungle aren't somewhere else, they're not far away. They're here, under our feet. Our present civilization can no longer postpone its duty to renaturalize denatured urban areas and regenerate degenerated landscapes.

Compilation and questions: Henning Klüver (Translated from the German original)

PIECES OF A GREAT MOSAIC MILAN AS A LABORATORY FOR URBAN AND SCIENTIFIC DEVELOPMENT

More than a financial metropolis: Milan is a constantly evolving city of knowledge, research, and culture. About 200,000 students attend the eight universities in this Lombard city. New campuses (MIND, Bovisa) are under construction. And the MUSA project is implementing a program for the city and the region's transition to environmental, economic, and social sustainability.

Planning for the future remains incomplete without knowledge and its implementation, without research and its networking. This is even more true for Milan, Italy's economic and cultural engine, where an urban transformation has been underway for several years. In 2016, one year after Expo 2015, which in many ways represented a sort of turning point for Milan, the philosopher Salvatore Veca (father of Expo's "Milan Charter") expressed a dream: "Milan as an international city of knowledge."

Milan has an extraordinary wealth of universities, research organizations, and cultural institutions, starting with its eight universities. At present, about 200,000 students attend the city's universities, almost as many as in Paris. A little less than one tenth of them comes from abroad, a figure which is nevertheless less than the European average. Course offerings continue to increase: at Milanese universities, one course in three is international, and education in English is double the national average (22%).

»A strong point of MUSA is the multiplicity of approaches, which helps provide a systemic response: from streng thening human capital to research conducted in synergy with industrial players, from actions aimed at economic growth in the local area to the active participation of communities.«

Giovanna Iannantuoni Rector – University of Milano-Bicocca

Universities are expanding, moving, transferring. At present there are two large campus projects. The new campus of the University of Milan, about 190,000 square meters in the MIND (Milan Innovation District) area, will accommodate more than 23,000 persons, including instructors, researchers, and students. And in the Bovisa district, where the Politecnico has already transferred several faculties, the North Campus is emerging on 32 hectares of land, based on a master plan from Studio RPBW (Renzo Piano), for which LAND handled the green portion.

14

Thinking together

»Development of technologies for economic and circular sustainability, and promotion of high tech entrepreneurship: these are the two main objectives of the Politecnico di Milano within the MUSA ecosystem.«

Donatella Sciuto

Rector

– Politecnico di Milano

Finally, Salvatore Veca's dream of Milan as a "city of knowledge, research and culture" seems to be coming true in an innovative way. Universities, institutions, and the business world, all united in a partnership of scientific and industrial excellence, are transforming Milan's metropolitan area into a true ecosystem of innovation for urban regeneration. This, in a nutshell, is the MUSA (Multilayered Urban Sustainable Action) project, which was presented at the University of MilanoBicocca, one of the four universities in Milan (along with the Politecnico, Bocconi, and the state University of Milan), which is participating in this program for the city's transition to environmental, economic and social sustainability.

»MUSA is a challenge and invitation to innovation and collaboration, creating new scenarios destined to transform the very concept of the university and its relationships with local economic, political and social organizations.«

Elio Franzini

Rector – University of Milan

There are six spokes, or areas of MUSA intervention: urban regeneration; big and open data in the life sciences; deep tech – entrepreneurship and technology transfer; economic impact and sustainable finance; sustainable fashion, luxury and design; innovation for sustainable and inclusive societies. These six macroissues will be

the foundation for achieving concrete projects aimed at changing the face of the city : from waste management to green mobility, from creation of an incubation and acceleration center for startups to optimization of big data for the health and wellbeing of citizens. The true ambition, as repeated by the rector of Bicocca, Giovanna Iannantuoni, is to make the MUSA model "replicable at the national and European level."

»MUSA brings together universities, companies, and institutions so they can work at the local level to make Milan an increasingly sustainable and inclusive city, through the efforts of almost a thousand researchers.«

Francesco Billari, Rector – Bocconi University

Milan is a constantly evolving city of knowledge Bicocca area

© Photo Giovanni Nardi

Thinking together

TOOLS AND METHODS

From meeting sustainability goals to assessing climate-related vulnerability.

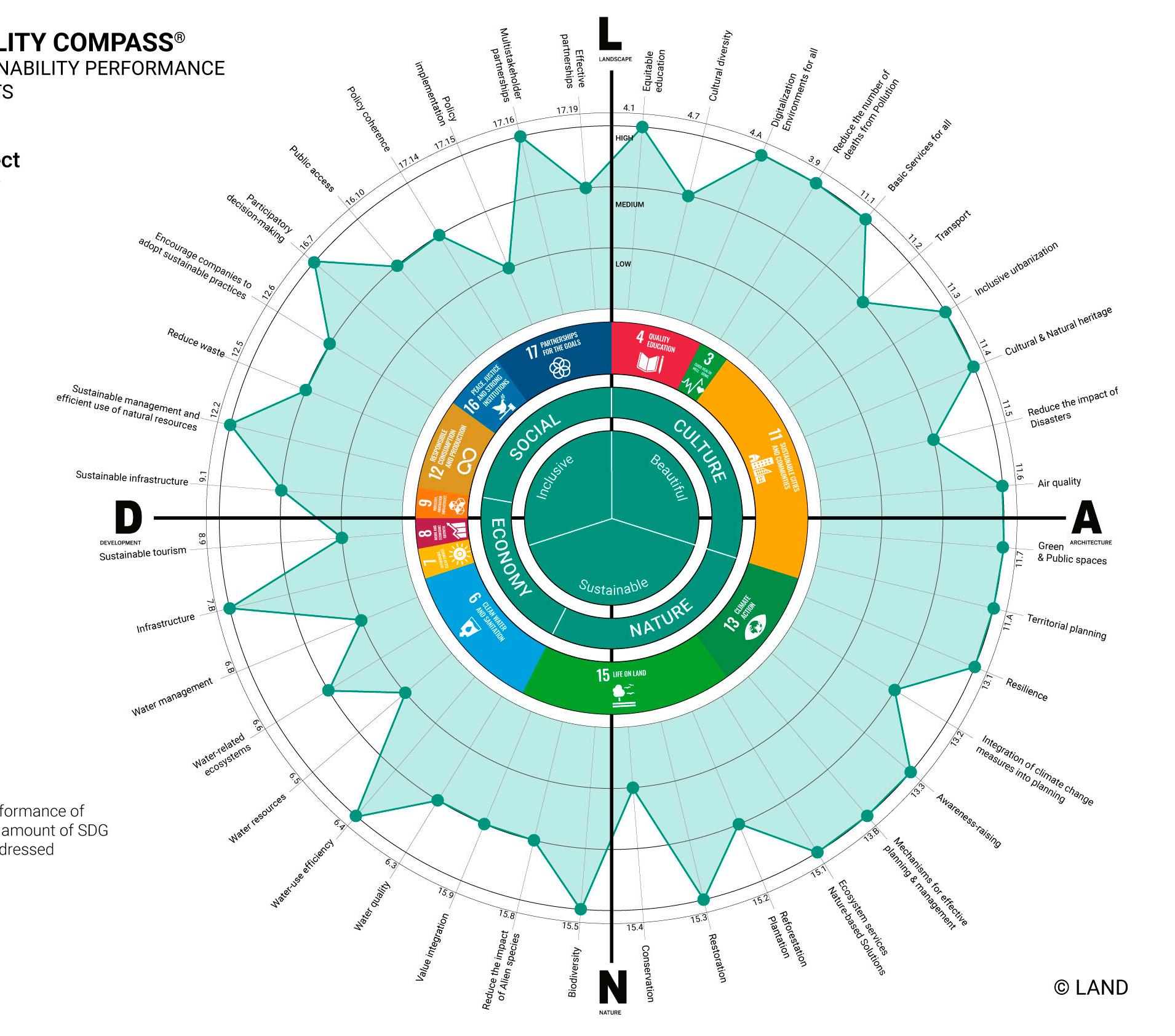

Landscape design reflects the specific culture of a society and is steered by its relevance and benefits for the people who live the places we conceive. In this era of climate emergency, health concerns, and social segregation, landscape design must be even more ethically justified. From this standpoint, LAND is engaged in achieving technical solutions using tools, methods, and models conceived by its LAND Research Lab®, which ensure an ethical impact as well. These efforts are then brought into project and planning approaches, accompanied by consultation with designers and clients.

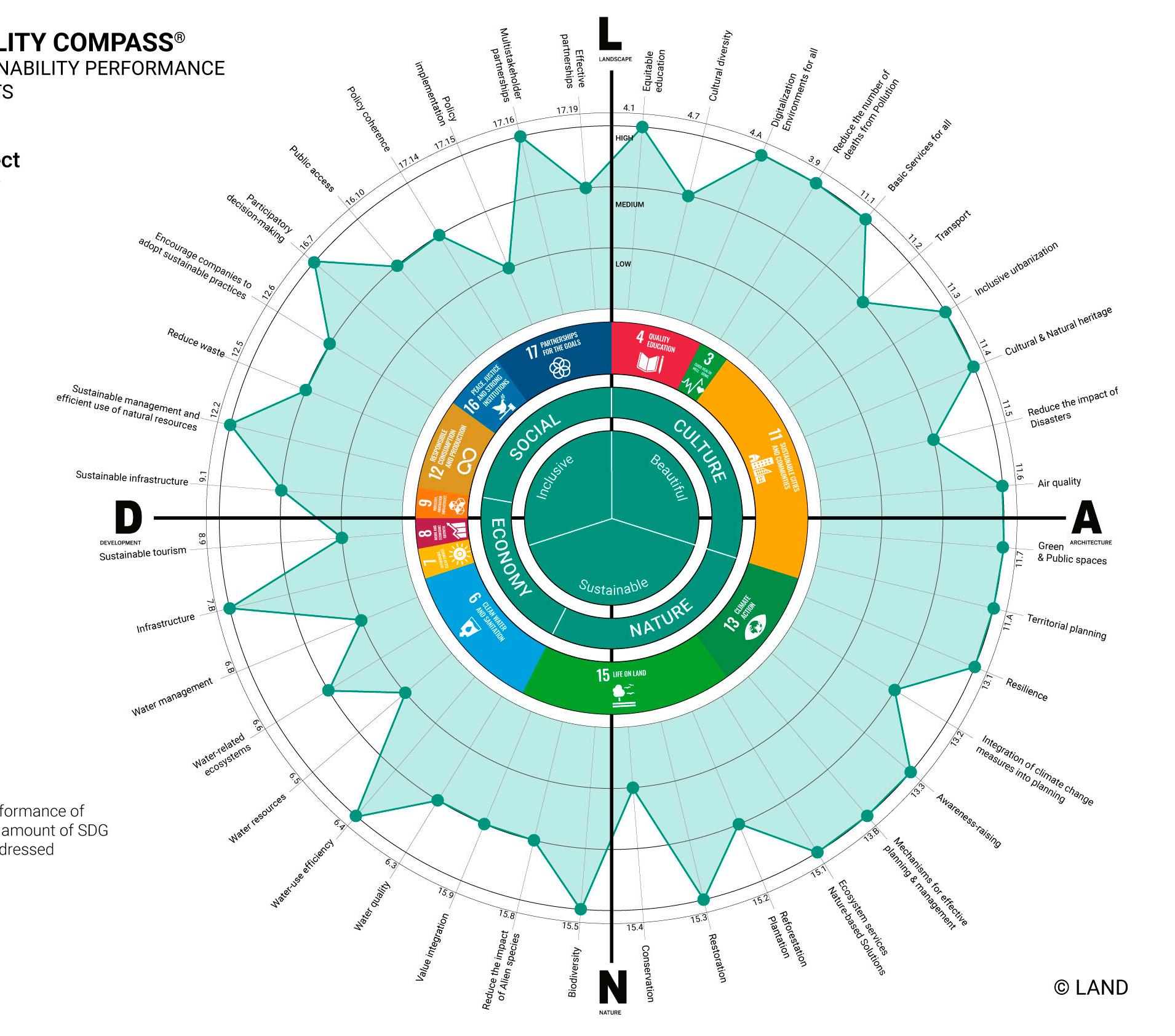

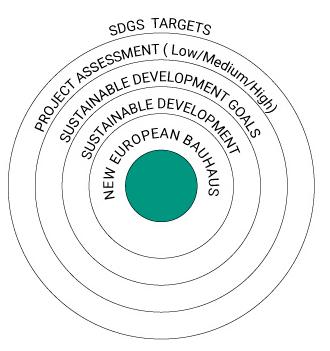

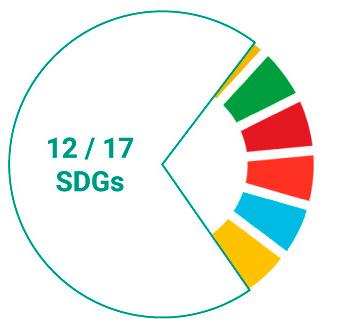

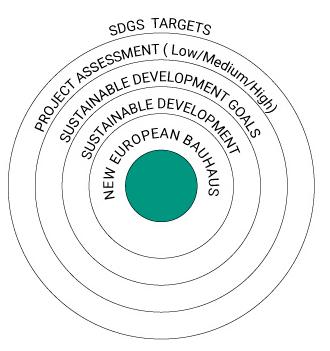

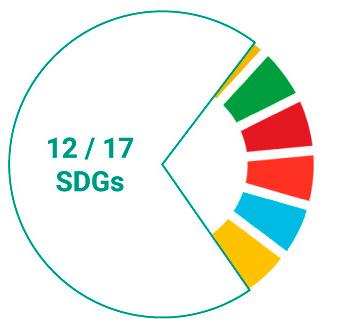

Among those challenges, the increasing pressure of climate change led LAND to seek a way to measure the extent to which its own projects meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN Agenda 2030. LAND's Sustainability Compass® shows how a landscape project approaches SDGs through its actions and in combination with New European Bauhaus’ principles (inclusivity, aesthetics, sustainability). The assessment pursued by the Compass estimates on a (so far) qualitative basis on the extent to which the SDGs' subgoals are met. This tool can be used to identify, further hone or validate project objectives according to their development phase.

The Compass becomes an even more complete tool if supported by LIM landscape information modelling®, a proprietary method that LAND created to quantify landscape ecosystem services.

0 low moderate high very high 1 16

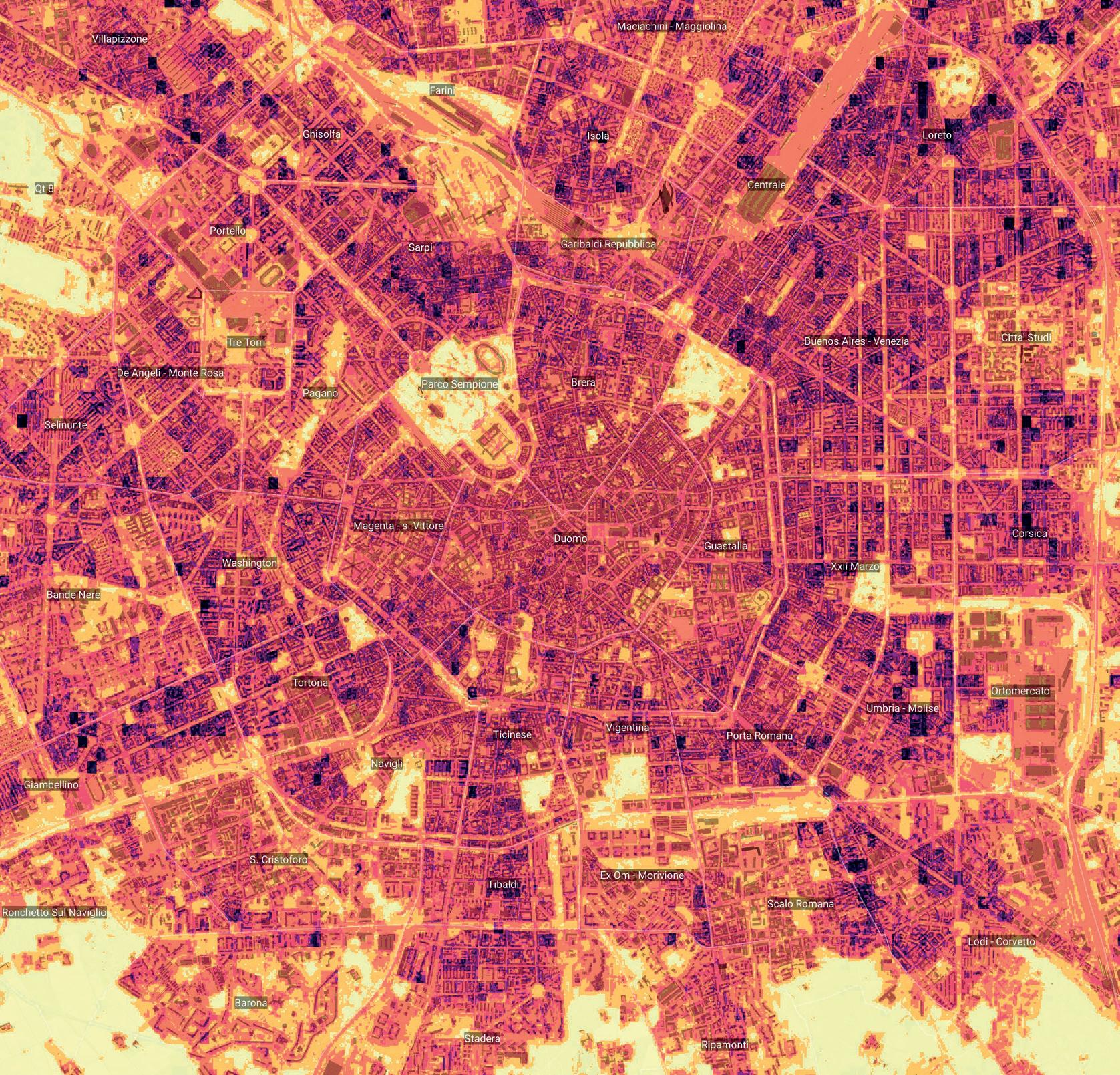

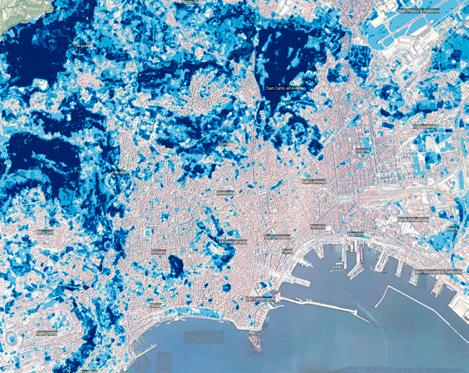

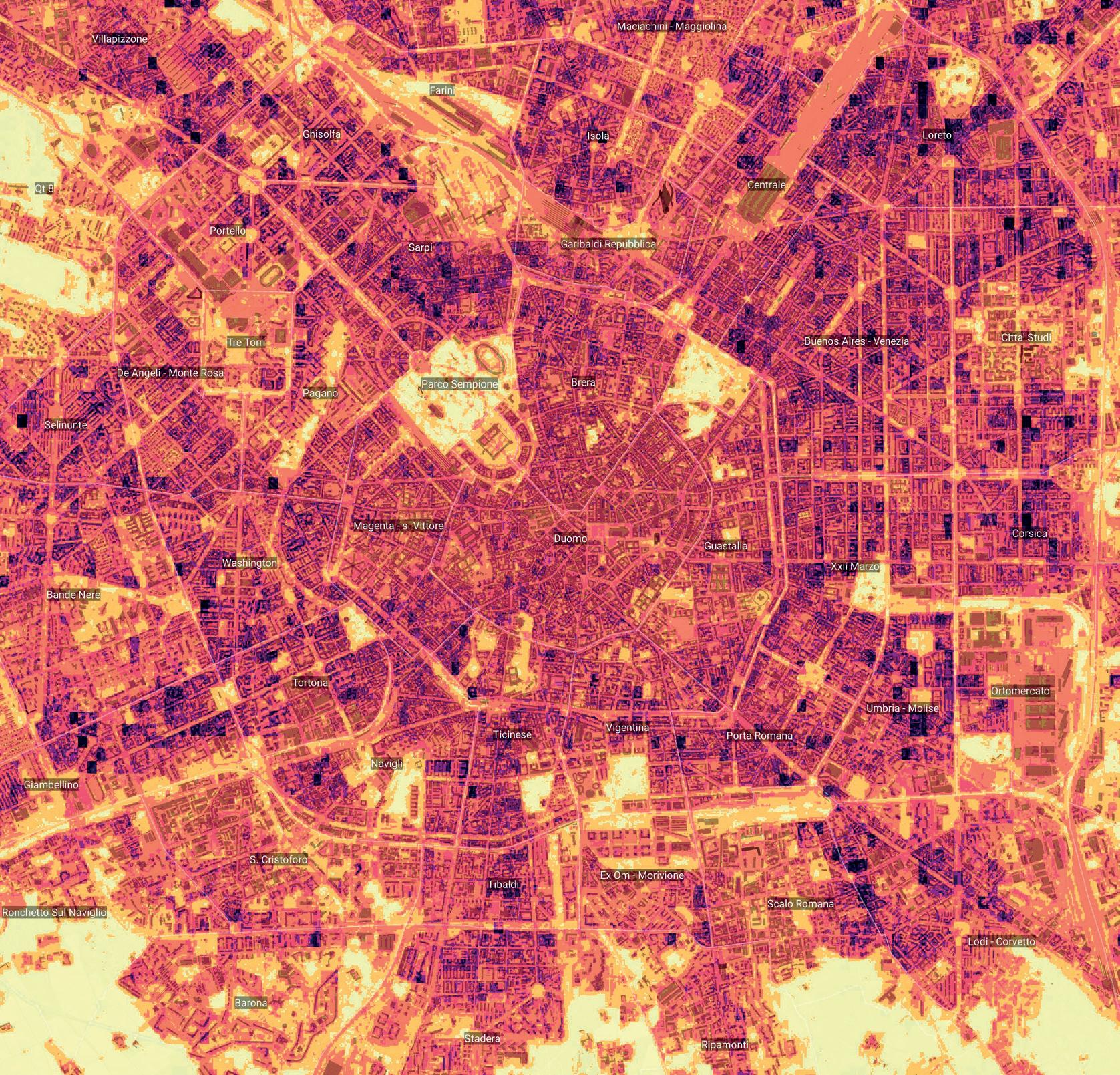

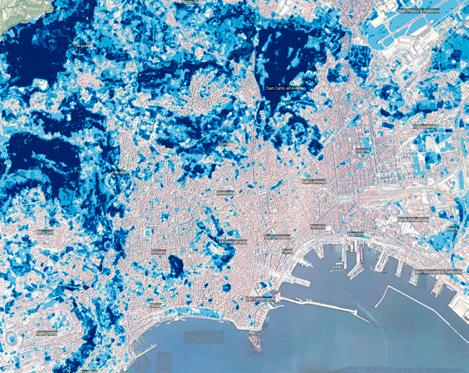

Milan case study from UrbAlytics project: Heatwave Potential Risk (HPR) index based on Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) averaged over summer months 20182022 from Sentinel 2 imagery.

0 low moderate high very high 100

Milan case study from UrbAlytics project: Microclimatic Performance Index (MPI) of urban vegetation calculated on 20 classes of Green Infrastructures taking into account land cover and tree canopy density.

LIM is a databased process that assesses positive environmental impacts produced by vegetation. Specific predictions can be provided for all tree species, for example in terms of carbon sequestration, reduction of ozone concentration, or oxygen production. LIM's innovativeness is based on its ability to envision future development scenarios for vegetation and communicate these data in graphic, comprehensible form. Nonetheless, ecosystem services can also be quantified on broader land surfaces, especially when vegetation data is not accurate or not available.

For this purpose, LAND added an additional measurement tool to the international standard of natural capital accounting (NCA). The EU defines natural capital accounting as "a tool to measure the changes in the stock and condition of natural capital (ecosystems) at a variety of scales and to integrate the flow and value of ecosystem services into accounting and reporting systems in a standard way." (See "Natural Capital Accounting" box). Through its own NCA assessment, LAND endorses the implementation of climate adaptation strategies and naturebased solutions to enhance livability conditions in cities (for example, by developing green/blue infrastructure for climate mitigation like the Green Rays in Milan). To this end, during the past year UrbAlytics was developed to detect urban heating impacts within the AI4Copernicus project, a research initiative funded by the European Commission.

UrbAlytics aims to combine artificial intelligence with satellite observation of Earth to produce information that can support urban planners and decisionmakers in terms of mitigation and adaptation to the urban heat island (UHI) effect. Thanks to the joint expertise of partners Latitudo 40 (Naples) and LAND Research Lab®, the ecosystem services provided by blue and green infrastructure were assessed and a set of naturebased solutions for climate adaptation and mitigation of extreme heat was proposed.

LAND SUSTAINABILITY COMPASS ®

ASSESSMENT OF SUSTAINABILITY PERFORMANCE OF A LAND PROJECT (EXAMPLE)

Structure and methodology

Commitment to the goals of Agenda 2030

LANDSCAPE

SUSTAINABILITY SCORE

The score delivers the overall performance of the project assessed on the total amount of SDG targets that can potentially be addressed

18

During the project, pilot applications were tested in the cities of Naples and Milan. The result was a heat risk assessment map that considers the severity of events, exposure of vulnerable age groups, and vulnerability due to urban morphology and surface materials in the UHI. The municipality involved – the city governments of Milan and Naples – have already expressed interest in using the maps and data generated within UrbAlytics for their climate adaptation plans.

Beyond analyzing data and exploring the new opportunities of artificial intelligence, landscape architects are called to examine perceptions, desires and barriers regarding public spaces and their social use. This mission resulted in the development of Anatomy of Public Space, a self financed research project promoted by an interdisciplinary collaboration between LAND Research Lab®, Park Plus, and Fondazione Transform Transport ETS.

The project aims to study public space from the different perspectives of the working group’s three components (architecture, landscape, mobility) in order to present a multidimensional narrative of the role of public space in contemporary cities. The connection between the different components of public space and the human body is meant to define new perspectives from which to view public space through a multisectoral lens. The project was presented at several public festivals and was directly discussed with citizens at open workshops.

In the ecological transition, landscape architects play a crucial role in translating people's expectations, environmental requirements, and public interests into a novel design approach that is more just and naturepositive. Digital tools and methods support the process with data and interoperable resources; nevertheless, they must be integrated with the relationships and needs of people and ecosystems, which ultimately shape our landscapes.

NATURAL CAPITAL ACCOUNTING

Naples case study from UrbAlytics project: Heatwave Potential Risk index at urban scale

Naples case study from UrbAlytics project: Microclimatic Performance Index of urban vegetation

Text: Andrea Balestrini, LAND

Based on the UN’s SEEA Ecosystem Accounting framework, LAND’s approach to natural capital accounting (NCA) is aimed at analyzing specific areas, using different scales and both public and private property, to quantify natural capital in terms of extension, state of health, and benefits provided by ecosystems. In particular, ecosystem services are services that natural systems generate for the environment and thus for human beings.

Assessing natural capital from an ecosystemic perspective makes it possible to analyze landscapes and organize data on habitats within a particular spatial area by tracking changes in resources and connecting environmental information to human activity.

This important process becomes quite significant in meeting one of the challenges that LAND faces every day : making sustainability and the impacts of its landscape projects visible and measurable. LAND’s NCA makes it possible to quantify the project’s performance based on environmental parameters related to greenery management, water management, climate change mitigation, and air quality, which are provided by the LIM database. In so doing, evaluations based on different timeframes, both present and forecasted, support the decisionmaking process and link planning decisions to the medium and longterm goals set out in the UN Agenda 2030, European Green Deal, and other policies such as the EU Biodiversity Strategy and the recently approved Nature Restoration Law.

In promoting the management and improvement of natural capital, LAND’s NCA supports clients in achieving their ESGbased goals, accessing to funding opportunities (e.g. the PNRR, Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan), and meeting compliance with environmental sustainability certifications.

Text: Matteo Pedaso, LAND

WORKING TOGETHER

Creating best practice

The word of the future is "gifts." What gifts do we bring as people, as companies or institutions, as landscape, as space? The concept of productive landscape conceives space as a network of relationships and new productivity. Because the landscape is a diplomat that structures public space, creates a stronger bond between people and nature, and enables a healthier life.

From the productive landscape perspective, landscape is no longer considered something passive that we either exploit or protect. Instead, it's something active that puts innovation in the service of sustainability. Naturebased planning and working together is an opportunity for epochal transformation that we must not squander, precisely because we are responsible for the future. It's not "back to nature," but "forward to nature," where humans and creation are inseparably linked.

20 Working together

Original and detail: Thomas Schönauer CTPainting (2)

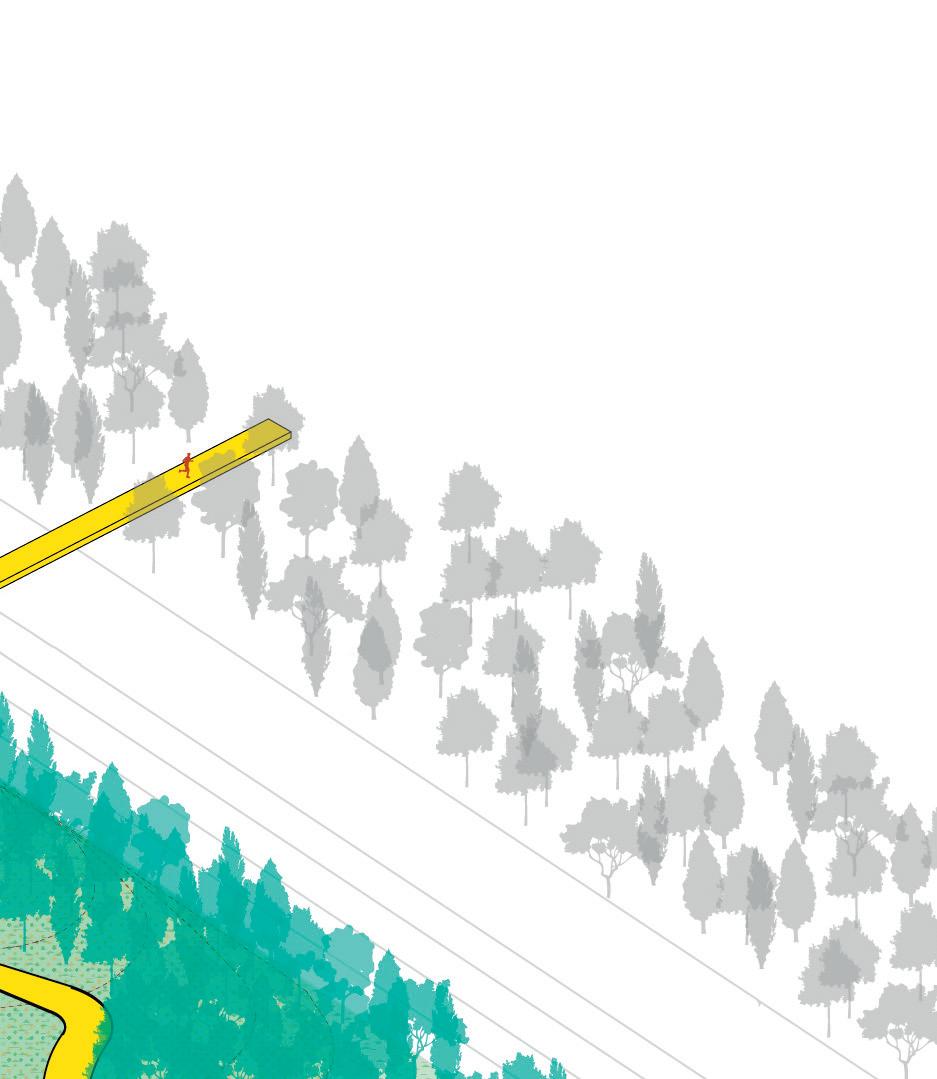

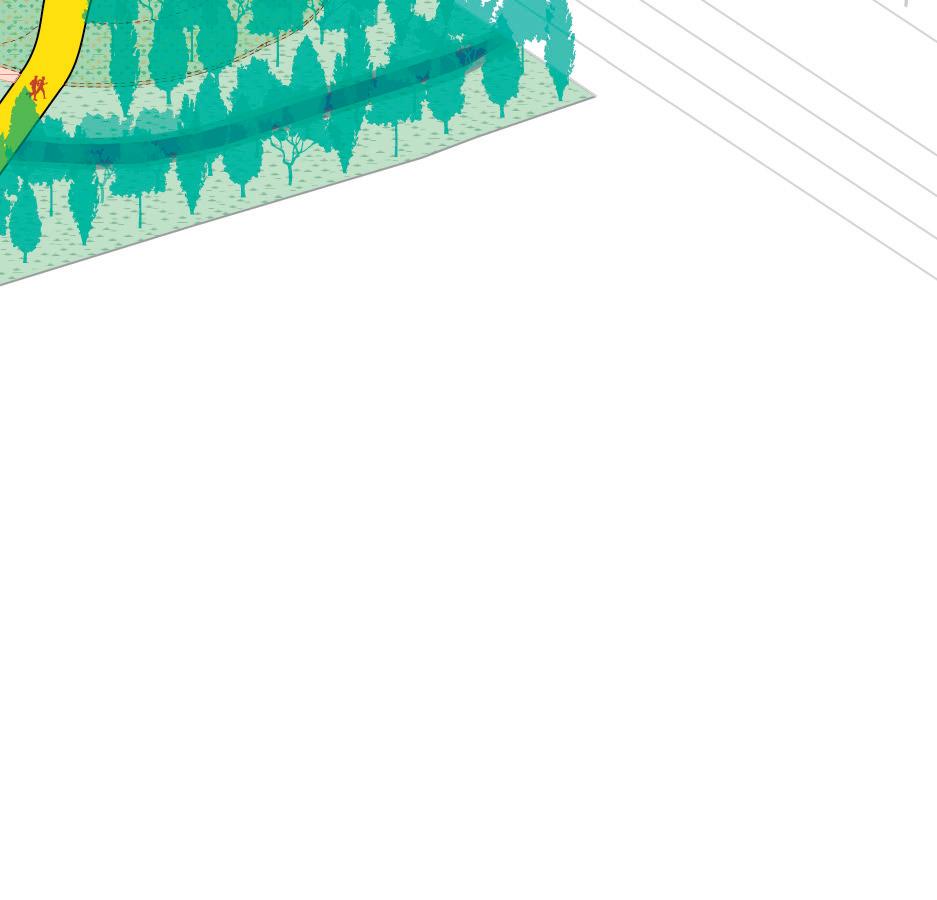

PASSION FOR NATURE

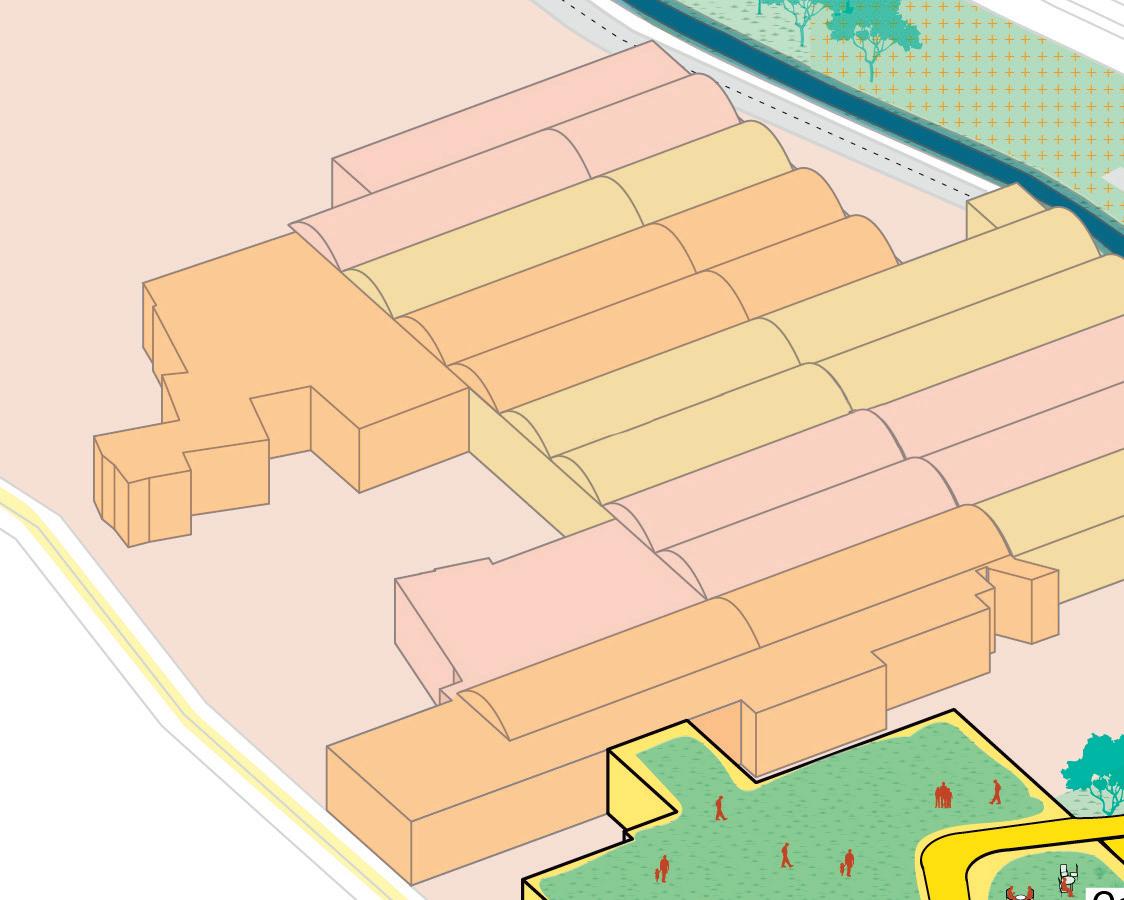

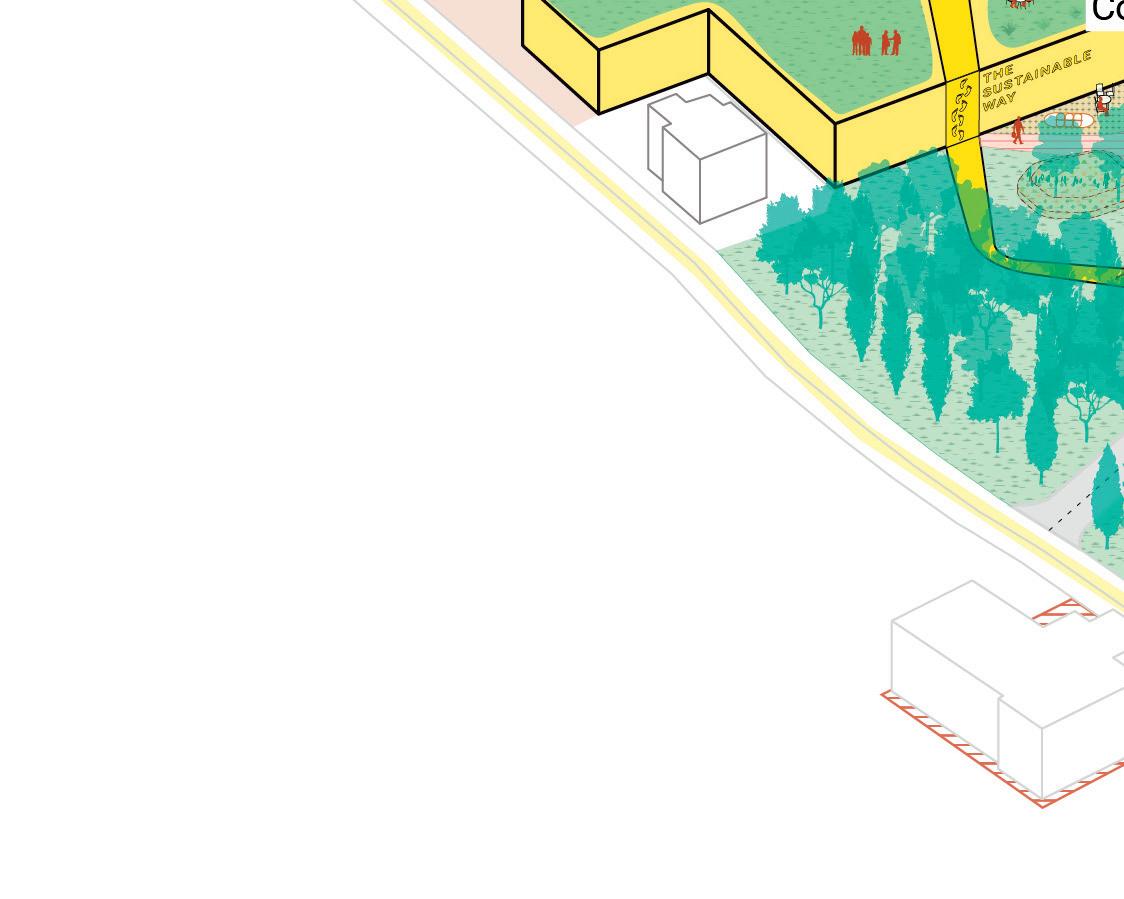

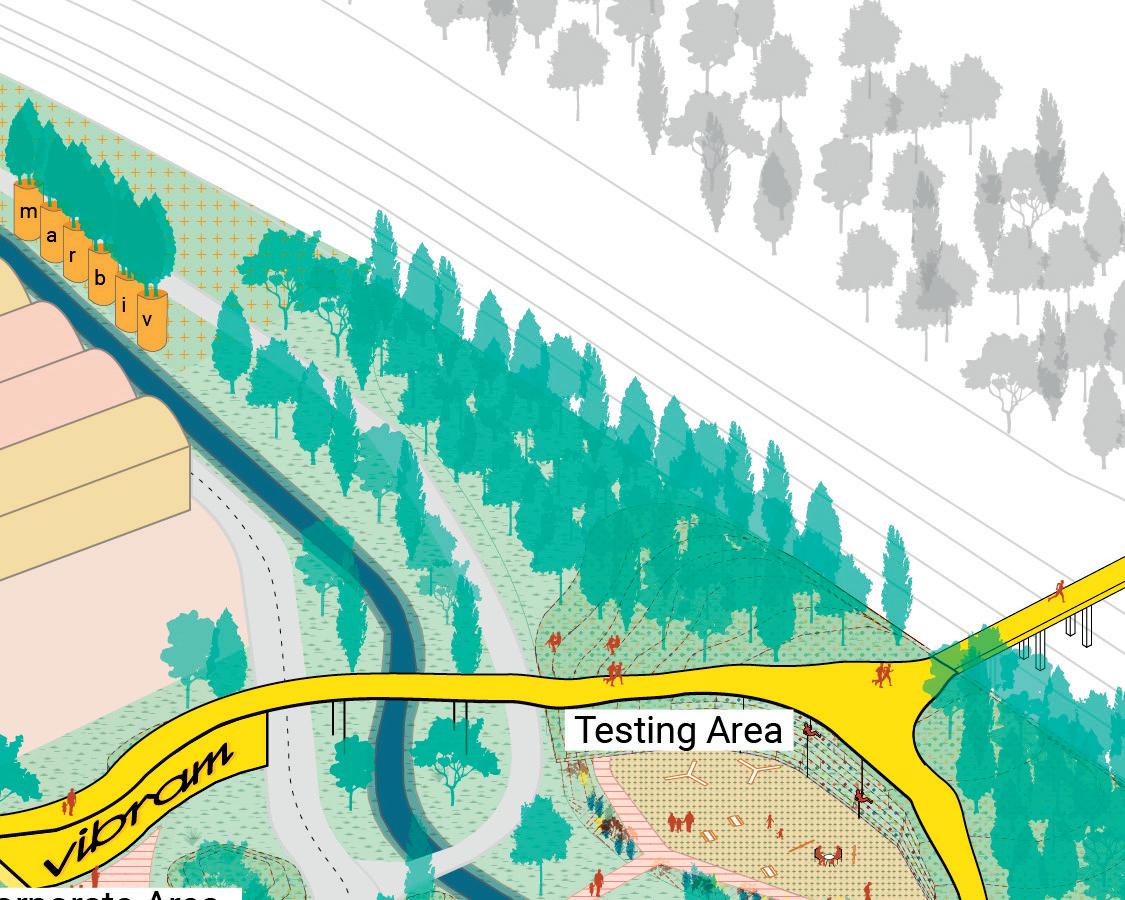

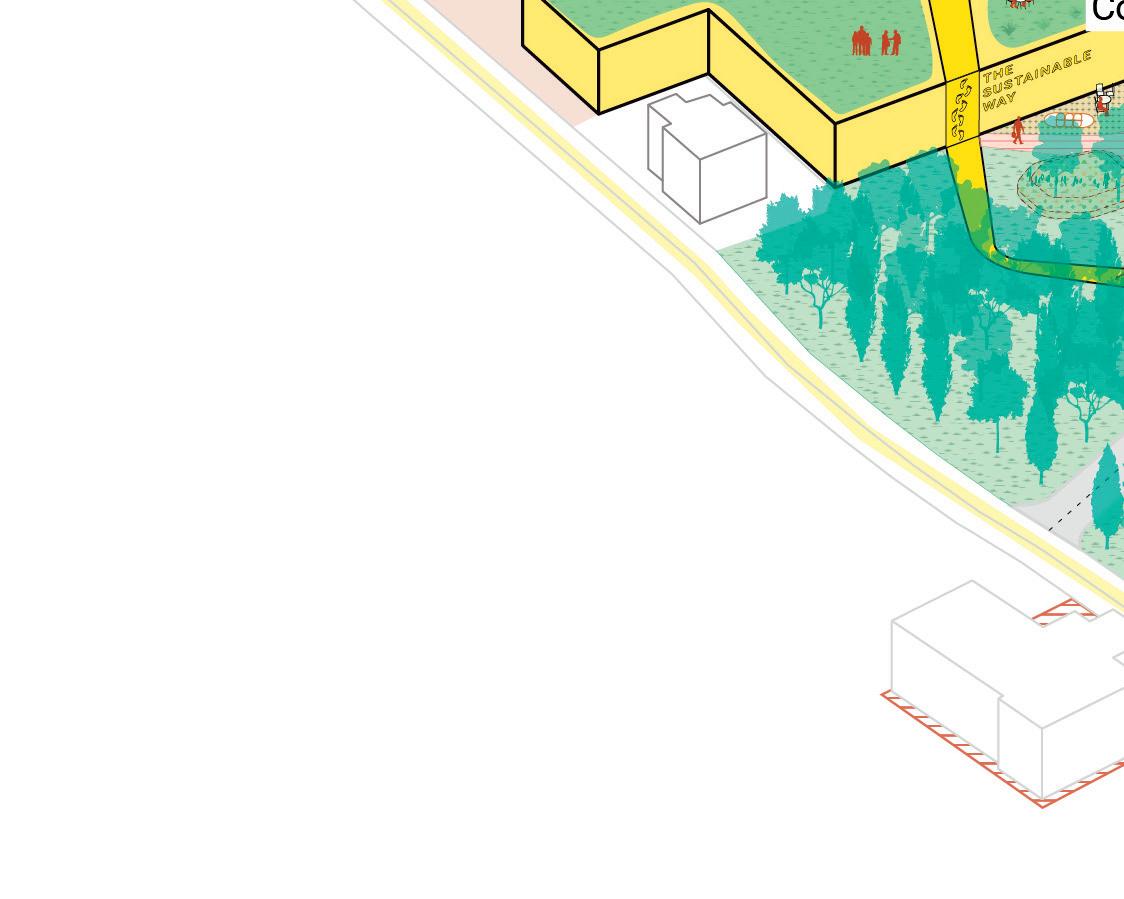

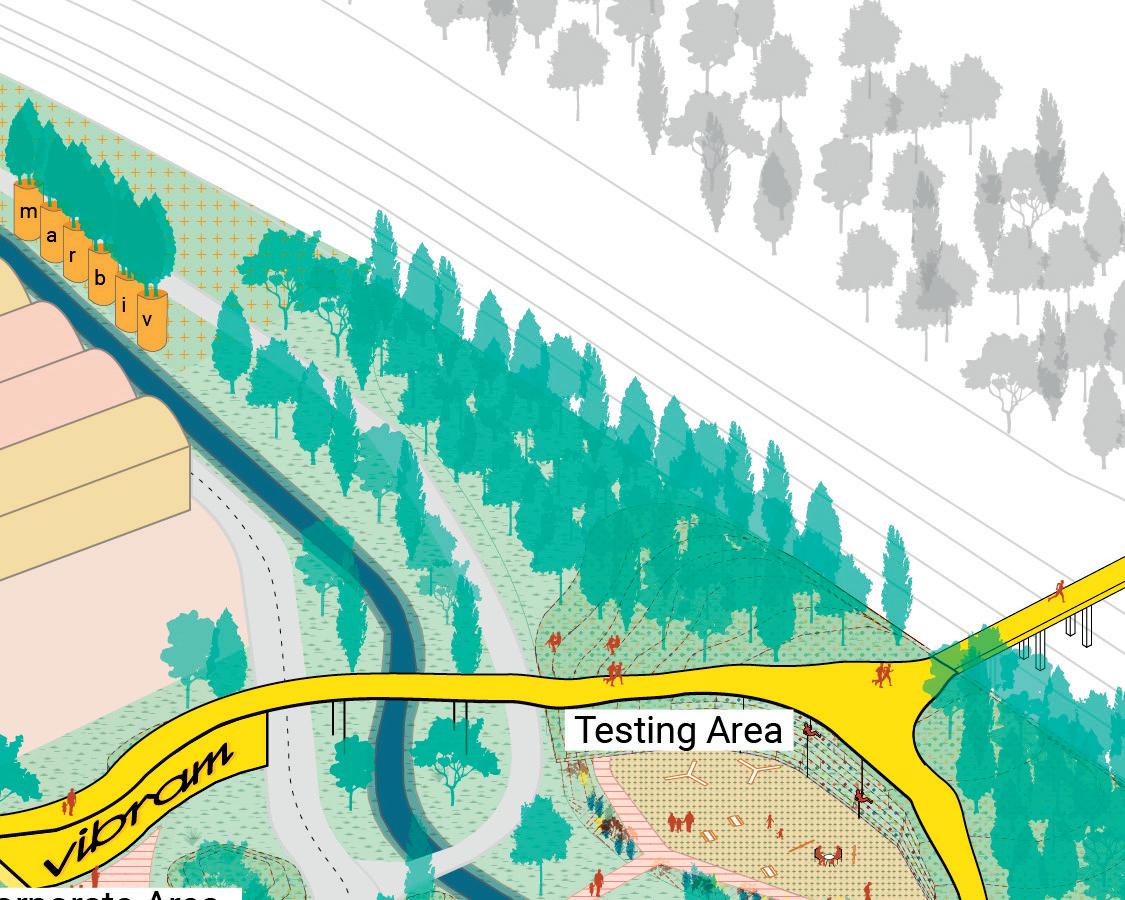

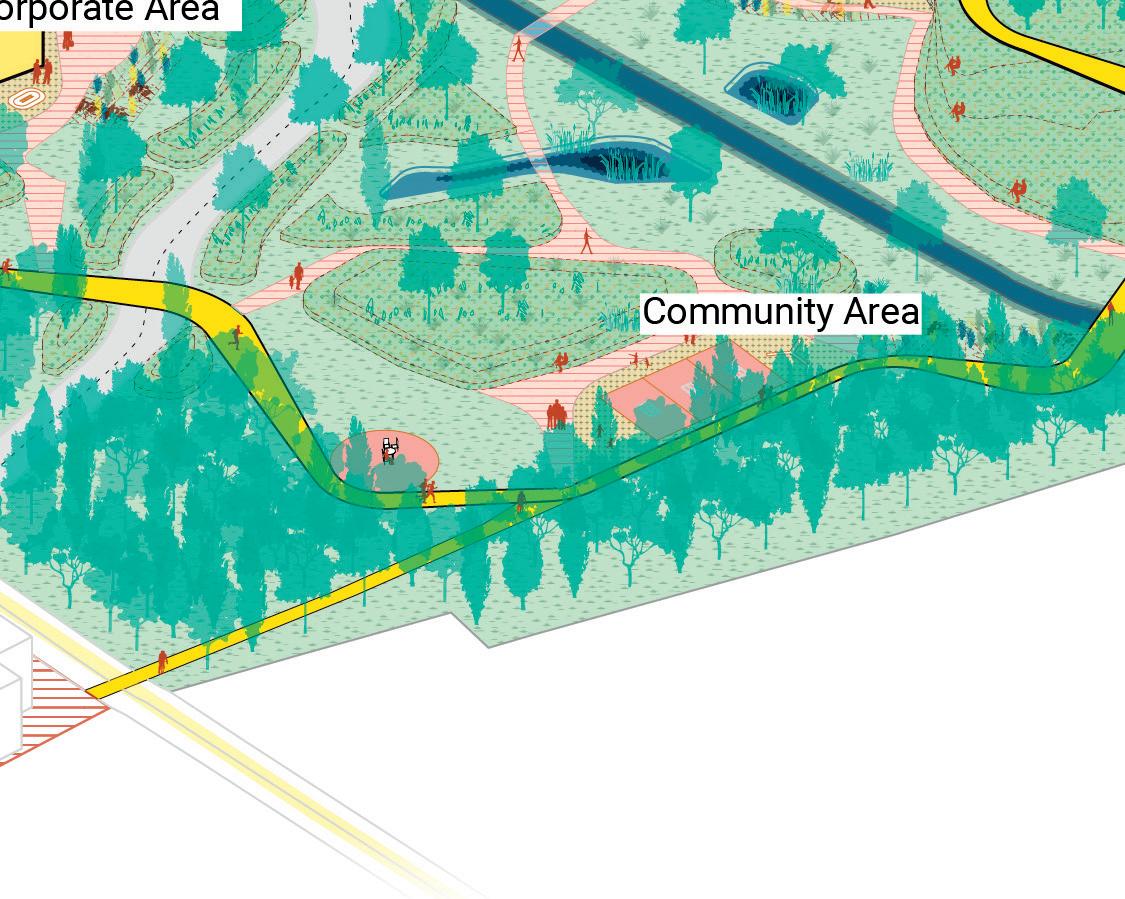

Vibram, a corporate leader in high performance rubber soles, wants to transform its Albizzate headquarters into a productive landscape.

The story begins with Vitale Bramani (19001970), a mountaineer and alpine guide from Milan who left his mark not only on Italian mountaineering, but also on international entrepreneurship. In 1935, during an ascent to Punta Rasica in Val Bregaglia (Sondrio), he lost six companions when a sudden change in weather and inadequate equipment made it impossible for them to get back to the shelter, resulting in their death from frostbite and exposure. Following this tragic event, Vitale Bramani sought solutions to increase safety in the mountains: his ingenious idea was to replace heavy iron studs in boots with robust rubber lugs. Thus the first Carrarmato sole was created in 1937.

22

Working together

In 1947, the first production plant was opened in Gallarate, followed by the one in Albizzate (province of Varese) ten years later, which is still today company headquarters. For over 80 years, the yellow octagon that identifies Vibram all over the world has been synonymous with quality, performance, safety, and innovation in the footwear industry. Vibram produces over 40 million soles a year for outdoor activities, recreation, work, fashion, orthopedics and repairs. It dedicates more than a million kilometers to testing, is present in 120 countries, and has production and research sites and offices in the USA, China, Japan, Brazil, and Italy.

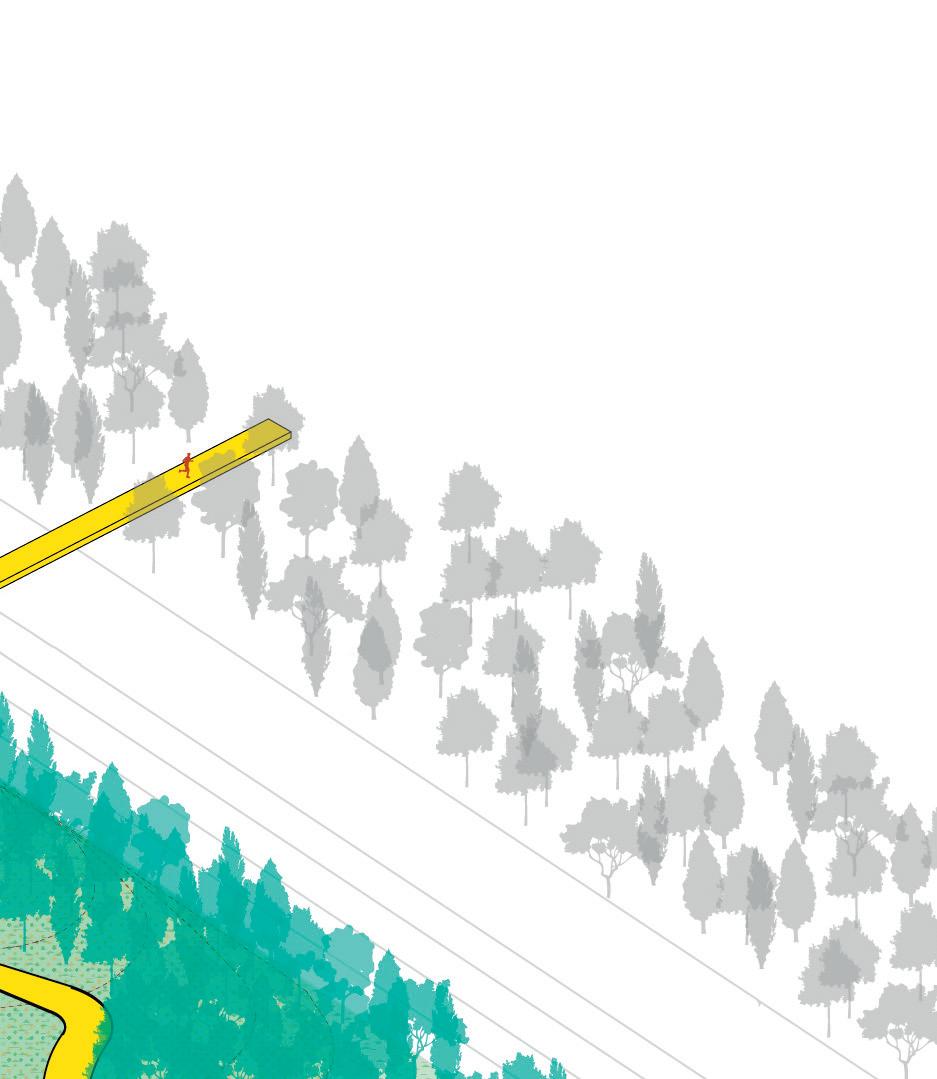

Now the Albizzate headquarters will be expanded with new buildings. LAND was hired to prepare a master plan to integrate production and administration buildings into the natural environment. With an eye to sustainable development, the landscape will become the star of the entire structure, benefiting employees and the people who live in the surrounding area.

The landscape project aims to become a key element of the new industrial complex – Vibram production plants (Albizzate)

INTEGRATING WITH LANDSCAPE

A conversation with Paolo Manuzzi, Global General Manager of Vibram, on the role of nature.

The subject of productive landscapes, unifying the nature aspect with the productive aspect, is a major gamble for Italy and Europe. Vibram is a brand with local roots but great visibility and international breadth, and thus is the perfect entity to talk about its relationship with nature.

Paolo Manuzzi (PM): "Vibram was established as a result of strong ties to nature; the founder, Vitale Bramani, loved the mountains and was an avid climber during the 1930s. A mountaineer without today's technical instruments, because his materials and equipment were certainly not cutting edge. A search for the best performing, safest equipment for moving around in nature resulted in the idea of a new type of rubber sole, which made history in mountain shoes."

What's your commitment to sustainability today?

PM: "For us, nature has been part of our DNA all the way back to our founder. If there were no meadows and mountains, Vibram would have no reason to exist. We're very attentive to the environment, which we consider to be a key factor. Even the decision to locate north of Milan was no coincidence: it was near the Alps, we could work near our beloved mountains.

We're trying to pass on this passion for nature. As far back as the 1990s, we decided to produce compounds that could reduce waste or be reused, to diminish the environmental impact of production. Over the years, thanks to our research and development department, we've created another innovative petrolfree solution made of over 90% natural ingredients, where the unique and original colors of this compound are 100% derived from natural pigments, from plants and organic agricultural byproducts.

The entire process was achieved without the use of solvents or chemical products, a factor that underscores Vibram's constant commitment to responsible and more sustainable high performing products.

"Reconnecting people with nature" is our mission. The exact same thing is part of your DNA, your thoughts, your actions, and this reinforces the idea of this union. So what drove you to call us? Why a landscape designer?

PM: "One of our goals is harmony and integration with the landscape, not to create ecomonsters. And secondly because we want a green landscape, not normal architecture that proposes an aesthetically beautiful building. We'd like something that could also serve the community, employees. Emersion in nature, in beauty, is important to improve the environment and stimulate all of us, and our collaborators."

Is this something you're doing for yourselves, or is it also for the local community?

PM: "For ourselves, to expand, but certainly also for the community. The project idea is to have a public area that the community can use: an environment that can connect people, can make them feel good; this helps promote the brand and develop the company."

The experience you're creating, to further integrate the plant with nature and with its landscape, is it something you want to export to other plants in the world? Or maybe this has already happened to some extent?

PM: "It's already happened to some extent. It's a philosophy, like the commitment to make a good shoe sole. Nature is that tree, it has to stay where it is, we need to have green, we need a place where people can enjoy the surroundings, the landscape. The approach has been identical in our plants from China to America."

24

Working together

Are you able to get your neighbors involved, other companies, to popularize this approach?

PM: "We're trying with other companies too, but it's hard. Right now we're in discussions with a neighboring company to create a pathway in the surrounding woods. The pathway would impact a Vibram area at the back, an area of theirs, and would run through several communities with the goal of improving, enhancing and preserving these areas. We're having a hard time because this involves institutions as well, with whom we have to have conversations. But the idea is to offer a path in the woods for our employees and for the entire community."

Questions by Martina Erba and Matteo Pedaso, LAND. The conversation took place in May 2023 at Vibram's head office in Albizzate.

Soles for the right step: Paolo Manuzzi (left), Martina Erba and Matteo Pedaso in dialogue

Greenery signs in the manufacturing area

plant

A MASTER KEY IN GREEN AND BLUE

dei Laghi highway

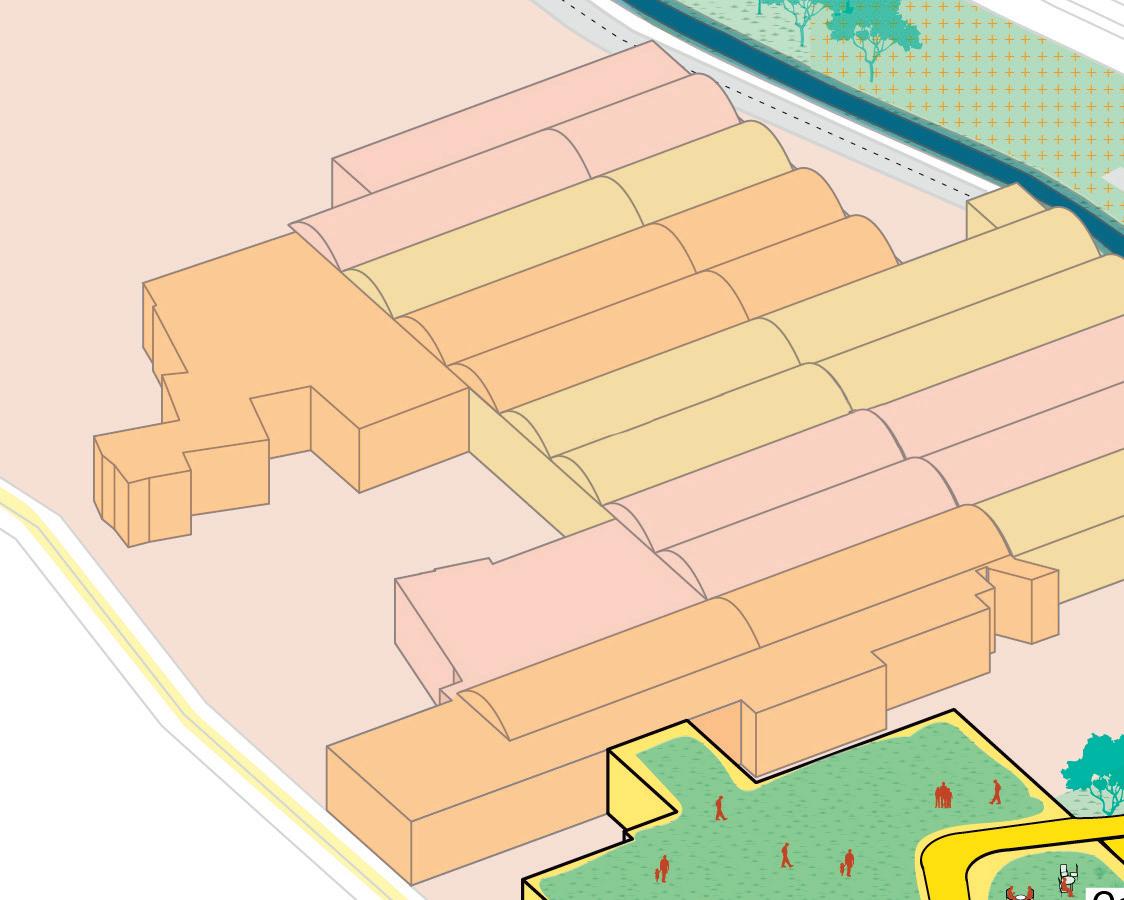

Strategic: Green infrastructure in the LAND masterplan

Vibram headquarters in Albizzate: a new component of the productive landscape.

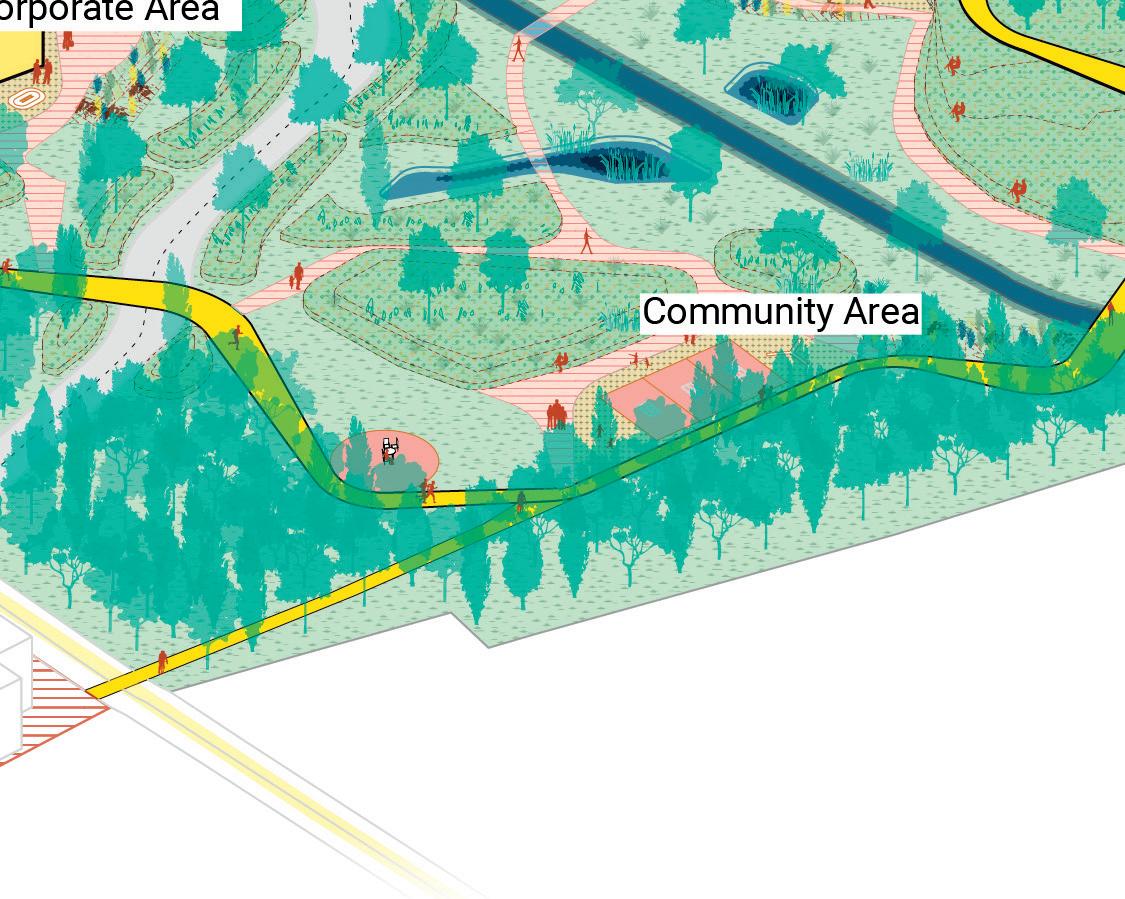

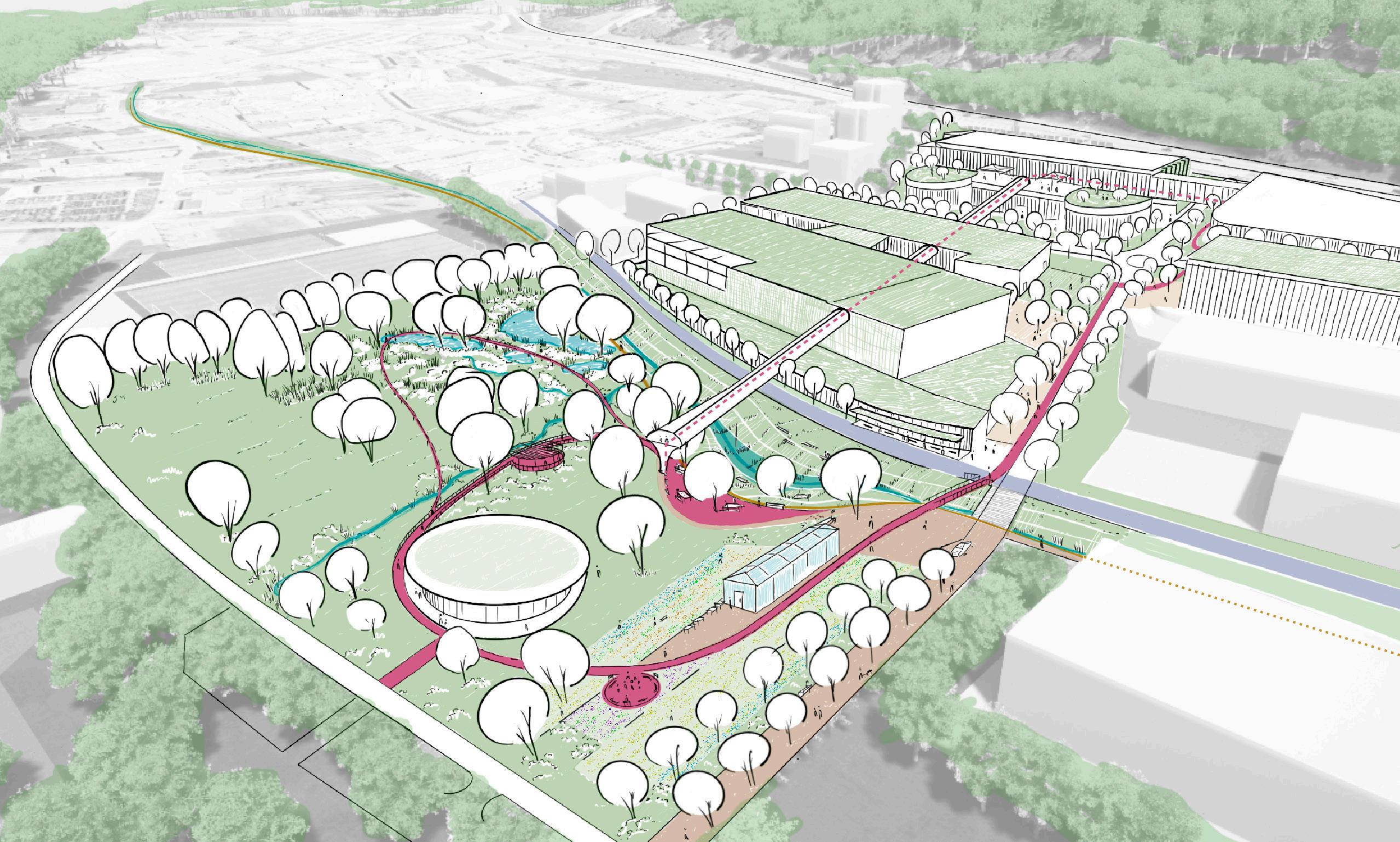

The project for Vibram's headquarters in Albizzate emerged from a desire to make sustainability visible and measurable through an approach that considers the landscape a driver of development consonant with European New Bauhaus principles and the objectives of the United Nations' 2030 Agenda. At the same time, the project is intended to create a showcase that clearly expresses Vibram's personality, using a company image consonant with its mountaineering and outdoor spirit.

Thus, the goal of the project is to open up the area, to create a showcase that's accessible to visitors and the community, consonant with company principles. For this reason, the landscape project aims to become a key element of the new industrial complex that can harmonize and unify infrastructural, cultural, functional, and natural aspects.

The proposed master plan includes green infrastructure strategies that can connect the system of open spaces to the new industrial structure, thus creating an integrated architecture and landscape design. Nature becomes an element that can define and characterize the various areas, creating on one hand a recognizable green master key that can determine access points and screen production areas, and on the other introducing natural elements and biodiversity to the center of the Park with a synergistic relationship to the existing waterway, in order to create a true greenblue infrastructure. The addition of a Vibram experiential pathway, winding through the Park along different levels, is intended to help visitors discover the company units that enliven these open spaces and to itself become a landmark and iconic element of the Albizzate headquarters.

Thus, Vibram's head office becomes a new component of the productive landscape: a polarity that can work with and for the local community while creating new ways for public and private areas to interact with each other, encouraging social cohesion between the company and the local community.

Text: Martina Erba, LAND

26

Arno waterway

Vibram

Autostrada

together

Elementary school

Working

MEASURING NATURAL CAPITAL

In order to make the effectiveness of a landscape design concrete and verifiable, it is increasingly necessary to measure its performance in terms of both quality (improved livability and usability of spaces, accessibility, type of use, etc.) and above all quantity, by measuring the performance of natural capital in terms of the supply of ecosystem services. That is, how much the green systems included in the design (trees, shrubs, fields, wetlands, etc.) improve the preconstruction situation from the environmental standpoint.

The principal indicators that could be measured in the project for the New Vibram Headquarters through natural capital accounting primarily regard three factors, which are increasingly important to guarantee the safety and livability of open spaces:

Water Management: soil permeability indices, surface runoff avoided (m³/year);

Climate change mitigation: sequestration and storage of CO2 (kg/year), tree coverage (m²);

Air quality: removal of SO2 (g/year); removal of O3 (g/year); removal of NO2 (g/year); removal of PM 2.5 (g/year); production of oxygen (kg/year).

Application of natural capital accounting by LAND permits an assessment of the ecosystem benefits resulting from the project scenario, with a "before/after" comparison and dynamic measurement at 0.5 years, 15 years, and 30 years.

Text: Matteo Pedaso, LAND

Between traffic artery, hilly terrain, and residential area – Vibram headquarters

THE LANDSCAPE, SUSPENDED BETWEEN ENERGY AND FUTURE

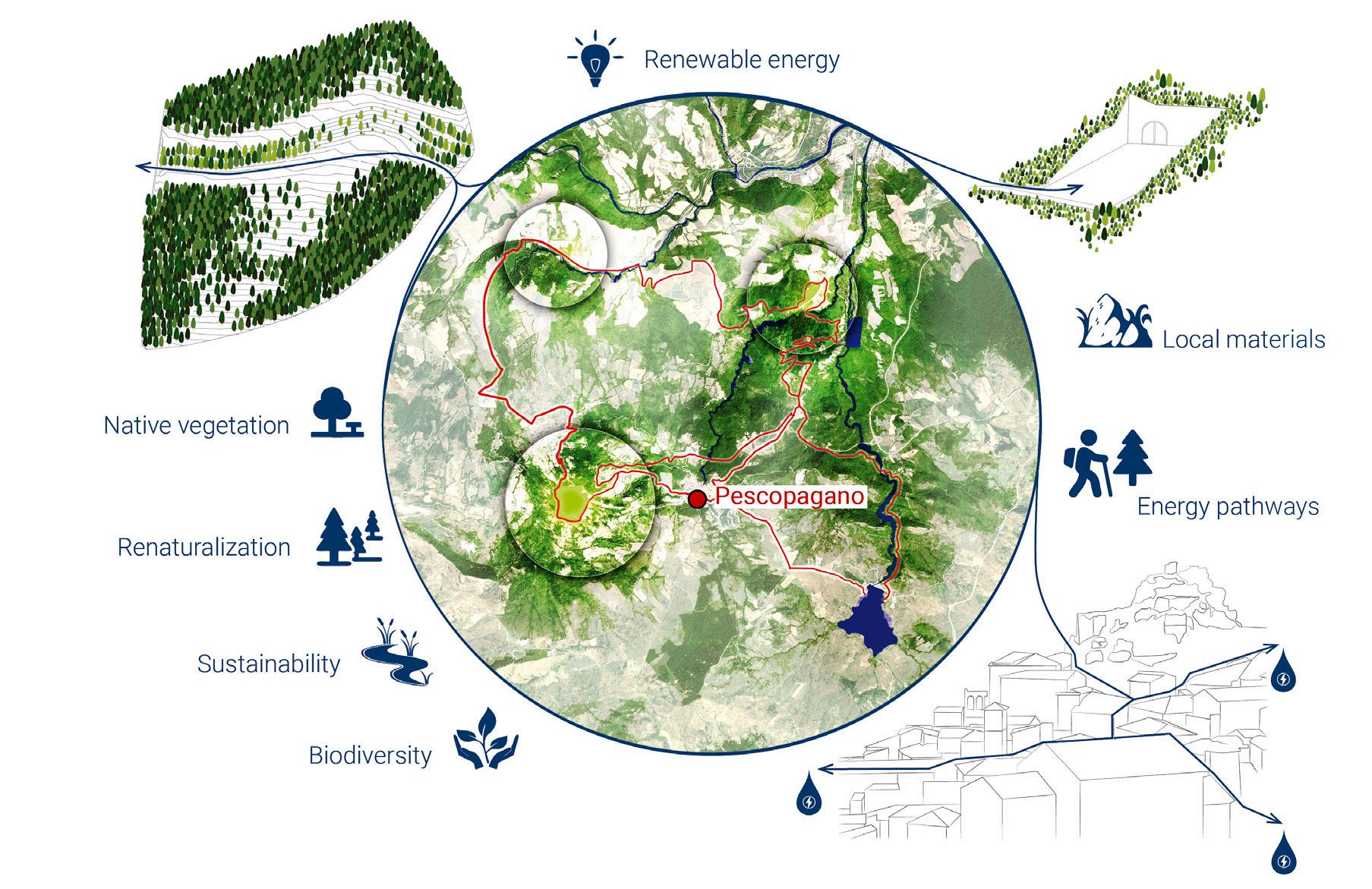

Edison and the transformation processes in close contact with energy and nature.

Edison is an Italian corporate leader in the energy market, with activities that include the supply, production, and sale of electrical energy, natural gas, and energy services. The company was formally established in Milan in January 1884. The partnership between Edison and LAND began in 2020 with one objective: to identify innovative and replicable models of new productive landscapes, capable of activating management processes and raising awareness in the regions where Edison has energy facilities or is planning to build new ones. Attention to the landscape, in terms of its natural, energy, population, and cultural components, offers a concrete opportunity to create a corporate development strategy that shifts the logic of land transformation to sustainable models, focusing on the intelligent use of environmental resources in synergy with energy production systems.

28

Working together

»We support programs designed to create social value in local areas in order to contribute to improving quality of life.«

Nicola Monti, CEO Edison

View of the Edison wind farm at Volturino (FG), Italy

FOLLOWING EACH OTHER: INNOVATIVE MODELS FOR PRODUCTIVE LANDSCAPES

Excerpts of a conversation between Barbara Terenghi (Executive Vice President of Sustainability and CEO's Office Director of Edison) and Andreas Kipar. Moderated by Ilaria Congia.

Edison is the oldest energy company in Europe. In the 140 years of Edison's history, what has changed about your way of doing energy and your approach to the landscape and region where you have a presence?

Barbara Terenghi (BT): "The energy world has changed a lot: over recent decades it's had to face challenges related to various issues, especially in the modern world we're part of and the developed countries we live in. Decarbonization is a very challenging issue, as is digitalizing the energy world. And last but not least is the aspect of energy deployment, the forms of production and consumption that emerge, evolve, and become more widespread. For this reason, over the last seven or eight years, Edison has decided to leave the hydrocarbon production and exploration sector; we're no longer an oil and gas company, we've moved toward energy transition, including renewable energy, where we've decided to allocate increasing investments, creating solutions that are of greater value to customers from the standpoint of decarbonization as well as energy efficiency."

Keeping in mind this evolving dimension of the energy world, we know that we're now going through quite a difficult economic, ecological and climate situation where it's increasingly urgent for us to rediscover the primordial relationship between humans, nature and energy. And we know that we can initiate this process of redi

scovery primarily by developing new productive landscapes. When can a landscape be considered productive?

Andreas Kipar (AK): "Let me follow up on what Barbara Terenghi just said: tradition and transformation over time. Productivity is now returning to center stage as the landscape itself is able to 'provide stimulation.' We all come from a time when more than anything else, landscape was a beautiful aspect of the past that was supposed to be preserved. To change this approach, three extraordinary events had to happen: first the pandemic, then the war and the consequent energy crisis, and then the climate issue, which was already there but is now evolving and becoming more urgent every summer.

Today we find ourselves in a dimension where landscape is back in the picture, often taking the form of an energy landscape. I see a lot of parallels with attitudes from the time when Edison was founded: electric power plants were something to be proud of, they were the future, like trains were in the field of mobility. More recently, there was sometimes a desire to reject, to almost hide power plants. Today energy has become something to be proud of again. The ethical dimension of renewables must necessarily also produce new aesthetic forms. When a landscape stimulates the desire to explore, then it's already productive."

30

Working together

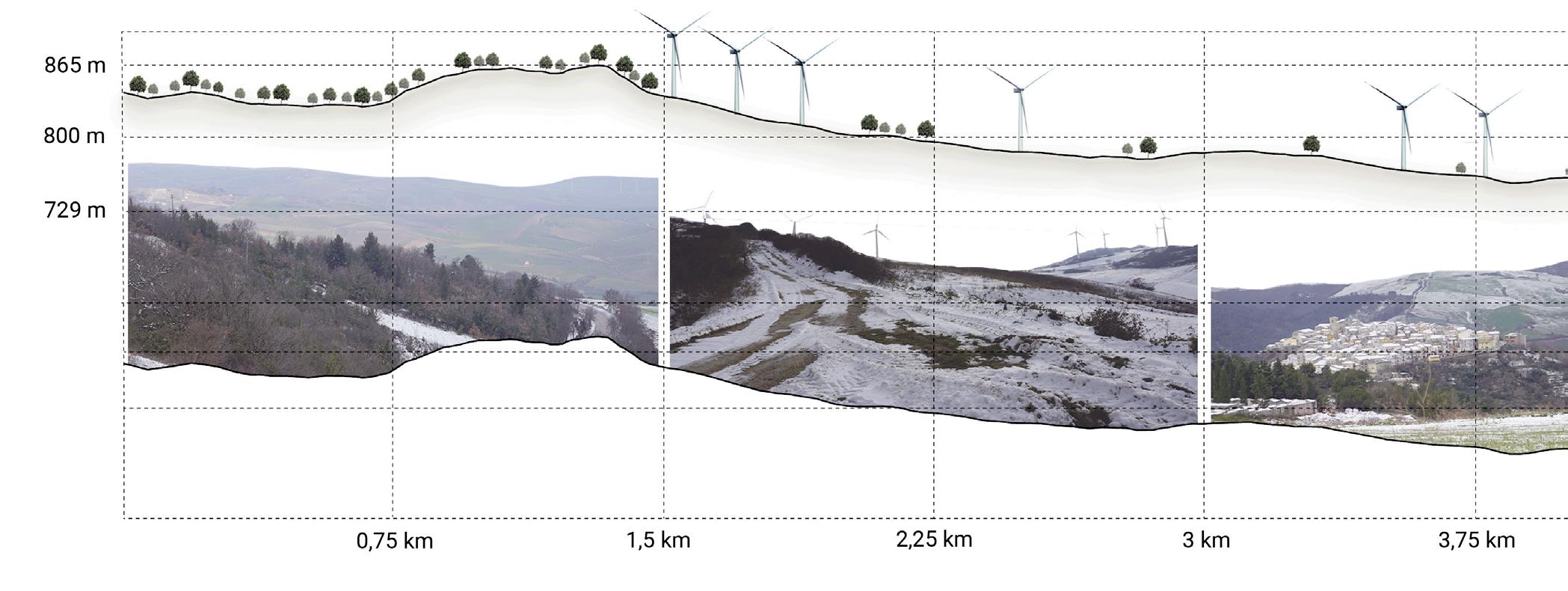

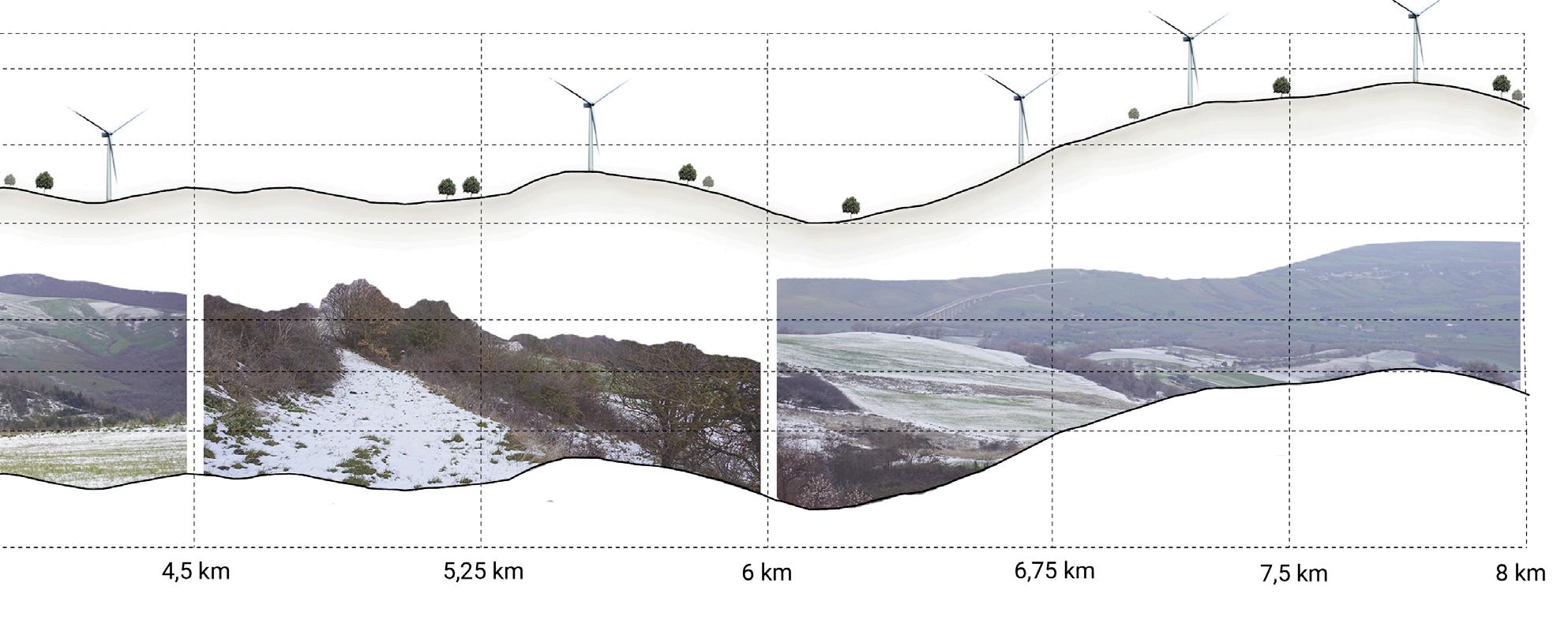

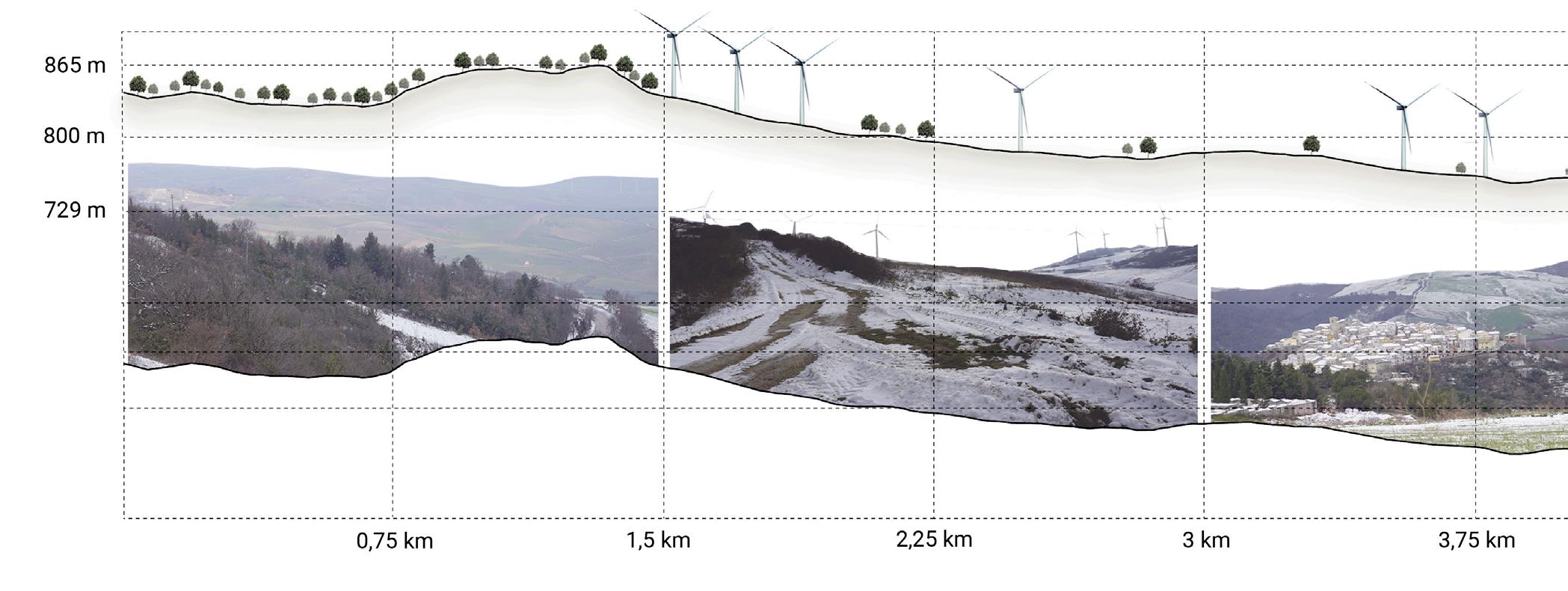

Altitude profile of one of the Energy Pathways along the Edison wind farms in Volturino and Volturara Appula (FG), Italy

What steps is Edison taking to contribute to both Italian and European decarbonization goals?

BT: "Edison is strongly committed to and involved in decarbonization, which also encompasses energy security and the economic sustainability of energy spending. These are the three legs of a hypothetical triangle that needs to be balanced. In particular, in 2021 we made a public commitment to multiyear sustainability goals to 2030, and we also want to contribute to reducing emissions for our customers. We really wanted to take advantage of one of our companies, Edison Next, which is focusing on these issues, with selfgeneration of renewable energy and assistance to industrial customers and public administrations in moving toward decarbonization and innovative energy models.

We're very aware of this issue, and we're also part of a global group that's making these carbon neutral targets a fundamental commitment, with the goal of reaching carbon neutrality in 2050. So we've got the best road map for our energy mix and that of the country."

What strategic role could natural capital play, not only in your mission and in managing your processes, but in your future investment plans as well?

BT: "First of all, we see that natural capital is becoming more and more crucial in the developments that energyclimate plans contemplate, including at the country level. There's more attention to the country's environmental and energy policies broadly speaking, so the issue of natural capital, expectations related to the

landscape on one hand and nature on the other, are also increasingly relevant. Restore Nature, a European Union law, will certainly be implemented in Italy as well. Obviously, it won't prevent development of new renewable energy, however companies will have to comply with it and make it the basis for advanced development. Natural capital has become part of the industrial development equation, and now it's not just something nice to have, but is one of the rules of the game."

From the perspective of landscape and landscape architecture, what opportunities can we seize as we quantify natural capital, that is make it concrete, make it tangible, make it measurable?

AK: "Energy, which championed industrial development, is now championing the transition to a new era. In terms of natural capital, landscape is once again the moderator, because in the end, all our actions become visible. Landscape as human being. Closeness to communities isn't achieved through the territory but through landscapes. Identity lies there.

When we talk about energy landscapes, we mean quantitative energy landscapes; we've seen and we're well aware of the extent of your facilities; this is the starting point for exploring new territories, for understanding how to act with energy that's become a driver again, this time in terms of sustainability. The landscape becomes productive again, and at the same time, society itself assumes a productive dimension around energy landscapes, this is the most important aspect."

Edison and LAND have been solid partners for a few years now. What new perspectives has LAND brought to your company and your processes?

BT: "Having a partner with international experience has been crucial for us, because they can be brought into projects that we consider strategic, and above all enable their realization. This leads to the dimension of implementation, where things happen, and helps advance a message in regional and local contexts in order to raise awareness of why the energy work we want to achieve improves that territory, and allows us to highlight our mission.

The other element I find in LAND is the dimension of vision, a new vision of natural capital, which then enters the dimension of productive landscape to which the energy theme is attached."

To conclude: Andreas Kipar, what is LAND learning from a player like Edison?

AK: "Collaboration arises from trust and necessity. When we join forces, the credibility you've gained in the region over 140 years also increases the credibility of landscape culture, something we could not accomplish alone. Let's always

remember that fundamentally, we are the landscape, because even when a landscape is formed by private parties, it always becomes public again. This is a process that we're now cultivating together, and it leads us to many environments, settings, regions.

Let's not forget that together we're also creating new forms of work for the next generation, jobs that are no longer the classic socially useful ones, but those that promote and assist in the restoration of nature. The sum of all this means energy. Today we're learning together how to follow a path, and tomorrow we can also learn together how to create a partnership model that ennobles those who follow it."

BT: "You think you're following us, while at the same time we think we're following you. Each of us has faith in the path that the other is forging. That's how it works, and I think that's how it's supposed to work."

AK: "We take turns. This is a good conclusion, a symbol of reciprocity."

The conversation took place in July 2023 at Edison’s head office in Milan.

32

Working together

Barbara Terenghi (Edison) in front of Ilaria Congia and Andreas Kipar (LAND)

THE NEW FRONTIERS OF RES (RENEWABLE ENERGY SYSTEMS)

HYDROELECTRIC: A KEY ROLE

The first power plants in Italy in the late 1800s, built along the river Adda, ushered in Italy's process of electrification, guaranteeing economic development and the growth of the entire nation. Now we stand at a complex moment in history, marked by a sharp transition, as we lay the foundations for a new paradigm to undergird a society that will be very different, including in terms of energy.

Today, hydroelectric is the primary programmable renewable energy source, capable of guaranteeing a balance between supply and demand by stabilizing the national electric grid and preventing potential breakdowns. In addition, it plays an important role in regulating water, which has become an increasingly pressing issue over recent years as extreme weather conditions become more common, from periods of drought to very heavy rainfall over just a few hours. These issues have made this area particularly strategic.

WIND: SYNERGY

The relationship between wind farms, the land, and their maintenance is one of the thorniest issues we have faced over recent years as an energy operator.

Due to the very nature of wind energy, wind farms are primarily concentrated in southern Italy. For years, working closely and synergistically with local institutions and communities, we have been committed to identifying plant management models that make them compatible with the local landscape and can guarantee the rise of a local economic sector specialized in their maintenance. Thus, wind energy as not just a renewable energy infrastructure, but as a true driver of economic, social, and cultural development for local areas.

AGRIVOLTAIC: BETTING ON INTEGRATION

Today, agrivoltaic represents an opportunity. Like every renewable energy plant, it needs to be appropriately integrated into the local area so that it can become an occasion for sustainable economic and environmental development. In particular, the advantages of groundmounted photovoltaic systems include the ability to repurpose uncultivated or even abandoned agricultural land. The possibility of integrating the production of electrical energy through photovoltaic systems along with agricultural or livestock use makes the land more profitable. The energy and ecological transition is based on numerous technologies, some more traditional, some more innovative. Agrivoltaic is certainly one of the latter, and is as necessary as the former in order to achieve the goals we've set ourselves for the near future.

Text: Marco Stangalino, Director of the Power Asset Division of Edison

Hydroelectric, Wind, and Agrivoltaic

This is how it all began: historic waterworks on the Adda River. Photo © Edison

ENERGY PATHWAYS

To experience and explore new energy landscapes means making them an integral part of the experience of using a region. Thus, the "Energy Pathways" format becomes a concrete tool for linking natural and cultural assets with existing and planned hydroelectric, wind, and photovoltaic facilities in Italy.

This format is characterized by a series of interventions aimed at the enhancement, redevelopment, and improvement of existing slow mobility routes, generating a multiplecircuit model that can provide access to the landmarks of the cities concerned, drawing in local governments, citizens, and stakeholders. In addition, the identified pathways include scattered rest areas, new plantings, and a system of signs and coordinated communication that makes these interventions clearly recognizable.

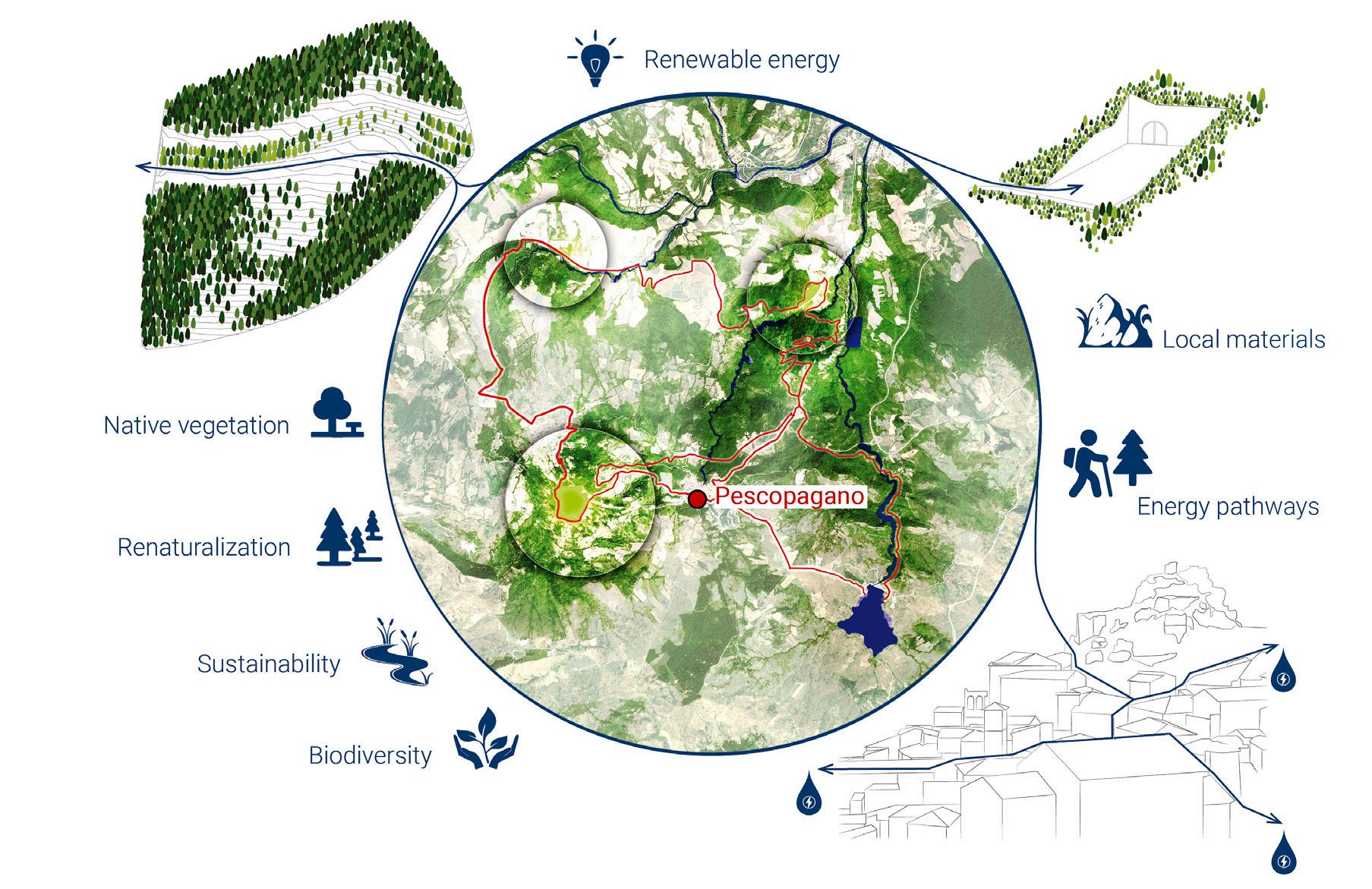

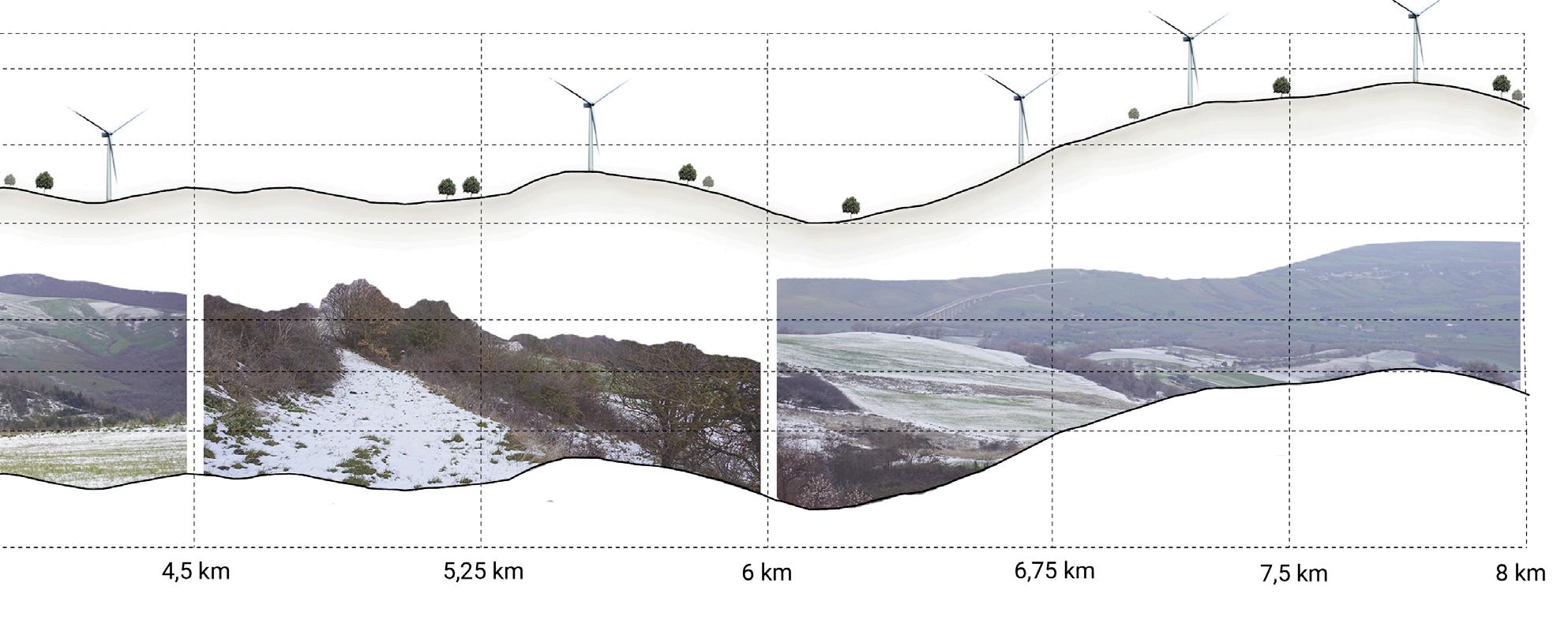

Masterplan for Pescopagano pumpedstorage hydro power plant conceiving landscape as an active value that has the potential to become a prime place for innovation

INSERTING THE PESCOPAGANO PUMPED-STORAGE HYDROPOWER PLANT INTO THE LANDSCAPE

The project in Pescopagano (PZ) is a pioneer of similar projects that Edison is advancing in southern Italy. It provides for the creation of a new downstream reservoir connected to the existing Lake Saetta via underground waterways. The landscaping plan conceives the landscape as an active value that has the potential to become a prime place for innovation.

Following an examination of the region's propensities and particular features, the facility's aboveground works are minimized through the use of local colors and natural materials, forms that follow the shape of the land, renaturalization of degraded areas, and the use of local vegetation, integrating the project into its sensitive surroundings. The "Energy Pathways" format, applied as a way to offset impact, makes the plant an activator of new local synergies, rekindling the energy of the region.

Text: Benedetta Falcone, Ilaria Giubellino, Beatrice Magagnoli, LAND

34

Working together

CREATING VALUE FOR LOCAL REGIONS

Two questions for Elena Guarnone, Head of Sustainability

What learnings and challenges are involved as you seek to measure natural capital and develop innovative and replicable models of approach in your company processes?

"The methodological and legal framework for natural capital is complex and detailed. The mitigation hierarchy includes a series of steps: anticipate, avoid, minimize, and in case of residual impact, balance the risks and impact to nature. The applicable international frameworks and EU laws being adopted focus on the goals of No Net Loss or Net Gain of biodiversity.

Companies must reckon with increased environmental sensitivity and a broader vision of sustainability, yet must also employ an approach for their business activities and processes that achieves clear governance of the issue.

In this regard, measuring the effects of your actions, using best practices, identifying models that are innovative yet replicable (like new productive landscapes where energy plays an increasingly important role), and creating synergy with stakeholders in your places of operation, become indispensable tools to effectively and positively contribute to natural capital."

Edison's presence in Italy, in terms of electrical generation facilities, primarily involves domestic areas, affecting a significant part of the country. What actions is Edison taking to improve the local environment?

"Strengthened by its strong and in some cases historic presence in Italy, and firmly embedded in the local socioeconomic fabric, Edison is committed to maintaining and continuously reinforcing solid relationships with local stakeholders. With an eye to creating shared value, the company approach to relationships with the local region and its communities is based on: listening to needs and expectations, developing shared solutions and enabling local development, supporting various types of local initiatives, promoting an energy culture for communities, bringing in local suppliers, and protecting and safeguarding the local region.

In 2022, 60% of the communities in which Edison operates through electricitygenerating sites were involved in local projects through sociocultural, educational, environmental, and athletic initiatives in about 2/3 of the Regions. Along with that, solidarity energy sustainability initiatives were launched in collaboration with third sector organizations for Solidarity Energy Communities, through the Banco dell’Energia Foundation Philanthropic Entity and Edison EOS Foundation."

Landscape as an asset for the next generation: LANDTeam at work

Ilaria Congia with Elena Guarnone, Head of Sustainability at Edison on the right

Living together

EVERYTHING IS LANDSCAPE

The future of building and living together is traditionally the focus of an International Building Exhibition (IBA). This is also so for the Stuttgart 2027 urban region, which was set up by the governing bodies of the city and region of Stuttgart jointly with the University of Stuttgart and the BadenWürttemberg Chamber of Architects, to be implemented by a team led by Andreas Hofer (ETH Zurich). But profound shifts in society and the economy due to the climate crisis demand a change in the way we deal with natural resources; this will have drastic consequences for the future of building and living together and will demand a new way of thinking.

IBA'27 confronts this process of change jointly with project sponsors by introducing a twofold paradigm shift. Firstly, the development of cities and regions is no longer the task of architects and urbanists alone, but a process guided by society; and secondly, the cultural separation that used to divide urban space and

36

The productive city at the center of IBA'27 in Stuttgart.

landscape is disappearing. Everything is landscape: the productive landscape is what shapes our coexistence. As a consequence, the IBA reveals new perspectives on how to handle outdoor and peripheral areas, to replace the outdated image of a functionally separated city with a hybrid city of built, open, and natural spaces. This includes a series of projects related to the "productive city," such as the "Agriculture meets Manufacturing" project developed by LAND as part of the Fellbach AgriPark, which focuses on urban agriculture.

IBA'27: Fellbach AgriPark connects the city and the countryside

Living together

»Here in Stuttgart in particular, the boundaries between city and country are complex and often blurred; it's an agglomeration. In the metropolitan area, which has both very rural and very urban corners, we may be able to create something like an identity for the region.«

Andreas Hofer, Director IBA'27

LEARNING TO LIVE WITH THE LANDSCAPE AGAIN:

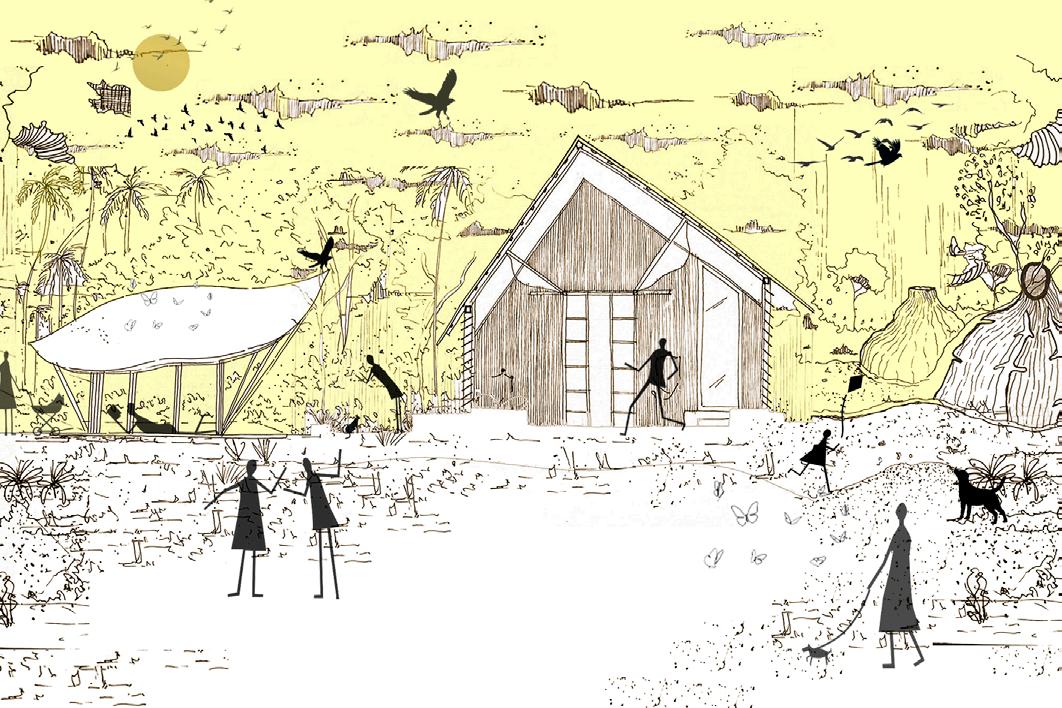

The "Fellbach Agripark" case study in the "IBA'27 – Productive Urban Landscapes" research study.

IBA'27 in the Stuttgart metro area addresses futureoriented approaches to building and living together, especially in terms of the climate crisis. Its focus is on resilient solutions for buildings, landscapes, and planning processes, with the importance of landscape and ecosystem services taking center stage. LAND's research study "Productive Urban Landscapes – Learning to Live with Nature Again" explores the potential of landscape in the Stuttgart metro area. It identifies areas of transformation, potential ecosystem services, and players who can empower sustainable change in managing agricultural land and urban areas through new forms of collaboration. Based on this analysis, LAND has developed a toolbox of measures to promote a symbiotic coexistence of nature and people in urban fringes and to support new collaboration models for farmers and citymakers.

These measures were further elaborated using the city of Fellbach as a case study. LAND developed the Agripark concept here, building on the findings of the IBA research study and an intensive participation process with farmers, as well as experts from the research, business, planning, financial, legal and administrative world. The Fellbach Agripark unifies previously separate agricultural, industrial, and commercial areas into a cohesive experimental field approximately 280 hectares in size. Innovative solutions for the productive urban landscape will be developed jointly with the IBA "Agriculture meets Manufac

Text: Kristina Knauf, LAND

turing" project of about 110 hectares of land in the heart of the Agripark. The focus is on three field laboratory situations: the Agrimarket, the Agrilab, and the AgriReserve, where different players develop integrated transformation concepts for soils and buildings in order to increase resilience and the production of ecosystem services on site. Dialoguing with farmers plays a central role here, examining the production potential of soils in terms of climate resilience and nature regeneration, as well as the resulting new agricultural business models. The Fellbach Agripark aims to integrate (eco)productive, nature based solutions in both urban areas and on agricultural land, and to demonstrate sustainable transformation models. At the same time, open and recreational spaces are planned for residents and visitors.

Similar field labs at universities, such as Center Smart Industrial Agriculture at RWTHAachen, develop methods to promote resourceregenerating cultivation. As part of IBA'27, the Agripark complements these approaches and, through the special spatial development frameworks the IBAstatus offers, demonstrates sustainable thinking, planning, and business models in the context of an existing city. The Agripark could thus serve as a cuttingedge example to inspire other regions and cities to create a future of (renewed) productiveness and climate resilience, living in harmony with the landscape.

38

UNDER DISCUSSION

Communication to resolve conflicts of interest.

The Fellbach project for a productive urban landscape uses a holistic approach that impacts various areas. For this purpose, administrative, research, business, and planning representatives were interviewed, with their responses to objections from agriculture. Here are some of their opinions, propositions, and arguments.

Agriculture's tasks are no longer merely economic (food production), but in urban areas are instead much more infrastructural. Agricultural parks may be able to perform agriculture's infrastructural tasks as well as a cultural one.

Planner

We urgently need to think about technical feasibility. One major problem is technical regulations, which are not interconnected. We also need to think about the technical interconnection of cities to surrounding areas.

Economy

We need to find ways to unify energy supply, landscape protection, and soil conservation. That peripheral area between urban and rural spaces will play an important role here.

Administration

Solutions should be considered locally and developed using local expertise and resources. It's essential to get key players involved (from agriculture and industry).

Economy

Ownership structures are often a major hurdle – solutions must be found that are agreeable to the owners.

Research

We have no planning security –land development in particular is a major problem.

Agriculture

Regional planning must make a shift from restrictive to reactive regional planning. For example, a sort of reward system for municipalities could be introduced, in which municipalities that cooperate receive more funding.

Administration

Quantitative comparisons of areas aren't an indication of quality, but quality is still essential to convey the concept. In many areas, we lack parameters for making qualitative comparisons. So far, there have been no concrete implementations of actual productive urban agriculture. Innovative approaches can be set up through showrooms, test rooms, or field tests, which can demonstrate the feasibility of these concepts and make them tangible.

Research

All interviewees agree that creating a productive urban landscape will depend on whether the project can be successfully communicated to the many different stakeholders. Ultimately, individuals now need the courage to implement such concepts and thereby set a positive example.

Compared to industry, we always come out on the short end.

Agriculture

Conflicts over land are exacerbated by complicated ownership issues.

Economy

Area participants

Research: Christiane Gebhardt, Steffen Braun

Planning: Rolf Messerschmidt, Joachim Eble

Economy : Holger Haas, Alexander Schmidt

Administration: Phillip Schwarz, Detlef Kurth

Text and compilation of quotations by Anna-Lena Bauer, LAND

RESTORING VALUE TO THE REGION

The IBSA pharmaceutical group and its new CorPharma industrial district as an example of sustainable urban hub regeneration for Pian Scairolo (Lugano).

IBSA, Institut Biochimique SA, is a Swiss multinational pharmaceutical company that was founded in Lugano in 1945. Forty years later, in 1985, it was acquired by the Italian businessman Arturo Licenziati, whose efforts and dedication transformed a small Swiss laboratory into the pharmaceutical group it is today: a multinational active in ten therapeutic areas, operating in more than ninety countries on five continents, with eighteen subsidiaries in Europe, China, and the United States. Technology and Innovation, Culture and Education, Communication and Sustainability are milestones along IBSA's path as it undertakes to restore value to the regions and communities in which it operates, in a responsible, ethical, and sustainable manner.

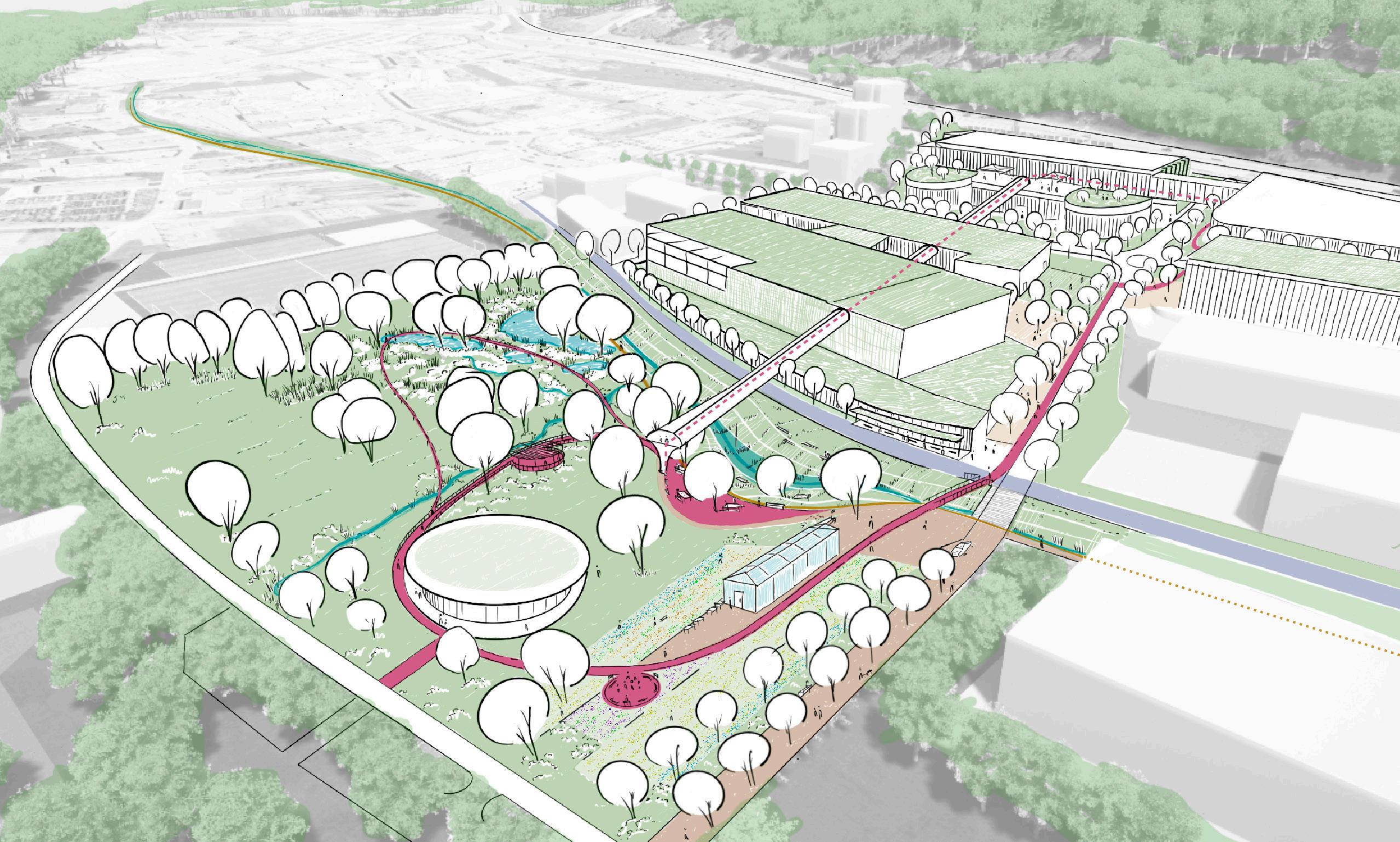

This is particularly evident in IBSA's headquarters in Pian Scairolo, between the municipalities of Lugano and Collina d'Oro, where LAND is involved in designing a district plan related to the development of IBSA's new CorPharma industrial district, starting with the cosmos production facility.

40

Working together

Aerial photo of Pian Scairolo in relation to the Luganese territorial surroundings – © IBSA | Beppe Raso

SOURCE OF INSPIRATION

IBSA – CorPharma District: an opportunity to reorganize and develop the landscape

IBSA is an innovative multinational pharmaceutical company attentive to sustainability and environmental impact. Its head office is in the Swiss canton of Ticino, in Pian Scairolo south of Lugano, where IBSA's new headquarters will be built. LAND is part of a team of experts that's creating a "PQ4 District Plan" to develop and improve the area.

The masterplan becomes an opportunity to reorganize and develop the valley's landscape as a pilot project within the strategic plan for revitalizing Pian Scairolo. The site will become part of the landscape fabric and environmental system, strengthening and improving the existing network of open spaces, environmental connections, and slow mobility in an area that for decades has been impacted by unplanned development. This is an opportunity to implement a series of naturebased solutions applied to construction (green walls and roofs) and the wider surroundings, such as renaturalizing the Roggia Scairolo stream and developing quality open spaces, using a climate adaptation approach.

A public path links headquarters buildings to the green areas west of Roggia Scairolo, where various functional areas open to the public are proposed: an exhibition greenhouse with a landscape of medicinal herbs, an educational laboratory with its open areas; a series of meeting places that not only cross existing wetlands, but also connect visitors to the area's natural features and highlight its ties to water.

The primary goals is to restore the area's natural identity, balancing it with the practical necessities of a production site in an area that's already quite densified. Pian Scairolo, once a source of inspiration for the novels and paintings of Herman Hesse, must also rediscover its natural calling through private development, in the form of qualitative elements connected to the environment and the surrounding landscape.

Text: Davide Caspani, LAND

The master plan as an opportunity to connect spatial planning and industrial development.

Sketch by Pier Paolo Hurle, LAND

A CULTURAL CHANGE

Excerpts from a conversation with Christophe Direito, Sr ESG & Real Estate Manager for the IBSA group, on IBSA's transformation in the context of redeveloping Lugano's Pian Scairolo district.

Pian Scairolo is a corridor, a very narrow valley, with a variety of shared uses. The masterplan for the new IBSA headquarters aims to reconcile the company's production needs by finding a balance between built areas and outdoor spaces, in line with the region's identity and regional planning dynamics.

Christophe Direito (CD): "Pian Scairolo is now included in the design of greater Lugano, a vision that contemplates the innovative principle of nine constellations. This is a process that comes from afar : over the years, we made the necessary adjustments and gradually perfected it, balancing the rules, planning, and our vision. Ticino has become increasingly disorganized over time, and today there are efforts to restore order. IBSA's message is that it can be done."

In your "pillars," you talk about a "new humanism of healthcare" and in general the importance of "taking care" of people. How is this reflected in planning a new campus? What are the drivers that pushed you to invest in sustainability?

CD: "Certainly the far sightedness of an entrepreneur whose work began in Ticino and was successful there. Even though we've also expanded abroad, the intention was to remain in this region, as a way to give back. The first pillar of sustainability is care for the person. We're a pharmaceutical company, so our mission is to provide effective products to care for patients. The rest follows: if I provide care for people, I necessarily provide care for nature, the landscape."

It's a dual theme: firstly the regeneration of a region, the connection with a region; and secondly the quality of spaces for workers in the new IBSA division. Someone who works at IBSA can use a green area and quality spaces you won't find anywhere else in Pian Scairolo. What does it mean to IBSA to be part of this place and the dynamics set out in the intermunicipal Pian Scairolo Planning?

CD: "Considering how district plans are developed, the private sector needs to act as a driver. Our President and CEO Arturo Licenziati intuited that investments were necessary to make this vision a reality. So we worked at dialoguing on multiple fronts: with Collina d'Oro (where we're going forward with the green park), with Lugano, with CIPPS (the Intermunicipal Pian Scairolo Planning Commission), and with cantonal authorities. IBSA's strong point has always been dialogue, which has produced synergy and in the end has led to a cultural change. For an entrepreneur of Mr. Licenziati's generation, imagining a public use green area on private land wasn't a given. But the intention of an enlightened client can activate the necessary processes and drive their realization."

This experience of the CorPharma project, the sustainable district serving the community, which in the Pian Scairolo urban hub also envisages an educational and instructional landscape, could it become an exportable product for IBSA? Can it be replicated in other facilities, in Italy and the world?

CD: "Absolutely. When I came to IBSA, I tried to understand the distinctive elements of the group. Through the impetus of Arturo Licenziati, we brought healthcare and beauty everywhere. If you go to the head office, or to our Italian subsidiary in Lodi or the French one in Atibes, or the IBSA facilities in China, you'll find all the fine details of the IBSA personality, which integrates with local territorial identity."

42

Working together

There's a growing trend to design industrial areas with a focus on the quality of private spaces and strong ties to the local region. What are your suggestions for other companies?

CD: "Planning is a process, a path. I think that the key point is to understand the reality of the local area. And to engage in dialogue. Because if I don't understand what the planner wants, what the municipality, the community want, what the dynamics are, if I don't consider all the pros and cons, everything gets more complicated. And then identity: involvement at the local level. And, as Arturo Licenziati says, we do things well and beautifully; that's how they become something of value. Because someone who walks in, who passes through or looks around, understands that we're doing something we believe in, they notice the care for the surroundings, for nature and the landscape. First you need to pay attention, and then you need to make it tangible."

Questions by Federico Scopinich and Davide Caspani, LAND. The conversation took place in July 2023 at IBSA headquarters in Lugano.

»We are also transforming the company and making major investments to improve our manufacturing capabilities while reducing our environmental footprint: we are working to implement a sciencebased decarbonization process in line with the pharmaceutical industry. The recent opening of our new manufacturing facility in Lugano, cosmos, is an example of our efforts to return value to the communities and environment in which we live and operate.«

Arturo Licenziati, President and CEO of IBSA

Source: IBSA Sustainability Report

Federico Scopinich, Christophe Direito and Davide Caspani (from left to right)

Relations with the Lugano Maglia Verde of the Pian Scairolo Masterplan and the PQ4 IBSA District Plan – LAND

Federico Scopinich, Christophe Direito and Davide Caspani (from left to right)

Relations with the Lugano Maglia Verde of the Pian Scairolo Masterplan and the PQ4 IBSA District Plan – LAND

LIVING TOGETHER

Creating better urban spaces

For a long time, our prime focus was on cities, which pushed urban boundaries and interlocked with other cities in metropolitan areas. Now the reverse is occurring: it‘s the landscape that’s conquering urban space in a congenial mix with nature like yeast in bread dough. Now, when we rebuild a city, what we envisage is no longer the old city’s purely functional image, but a hybrid of built, open, and natural space.

These new urban landscapes are geared to the future. We can produce better within them, they‘re more flexible, they’re resilient, they’re climateadaptive. They make room for wilderness in the city and continued creative use –and room for empathy, social identity, and community. Because the new urban landscapes are based on people and their needs. To improve quality of life under the constraints of climate change, we need nature with its vegetative power, we need healthy air, healthy water, healthy soil. Old structures must be broken up like sealed and overbuilt ground.

44

Living together

Original and detail: Thomas Schönauer CTPainting (3)

ACCELERATING COLLECTIVE RESILIENCE

Strategies for adapting to climate change in the urban landscape.

Climate adaptation requires a cultural change that goes beyond purely technical solutions. This does not mean going backwards, but rather rethinking the Western approach and relearning sustainable practices. Modern technologies, digital tools, and local traditions can drive the development of flexible and effective strategies for adapting to climate change. Projects like Sea2City Vancouver and the IBA'27 study make the value of nature increasingly clear in dealing with mounting climate stress and natural disasters in urban areas. Instead of seeing greenery as simply decorative, people are becoming

more aware that it acts as a catalyst for sustainable transitions, including social change. A new "wildness" in our cities gradually changes our image of beauty in urban spaces. This cultural change requires communication and acceptance, and also creates new opportunities to collectively make our environment more diverse, resilient, and inclusive. To create the necessary synergies between stakeholders and systems, new integrated governance, financing, planning, and cooperation models are urgently needed. Moreover, resilience planning should not be seen as a series of isolated projects, but rather

46

Living together

Flowing: city and nature © Photo Nicola Colella

»A new "wildness" in our cities gradually changes the image of beauty in urban spaces. This cultural change requires communication and acceptance, and also creates new opportunities.«

Kristina Knauf, LAND

a continuous, integrated process in which the effectiveness of measures is constantly monitored, evaluated, and optimized even after implementation. This requires planners and designers to change their roles and forms of expertise. At LAND, we develop the necessary digital tools and knowhow to do this.

From Vision to Execution

Resilience planning drives gradual changes in our environment and society by using very broad planning horizons. Therefore, it is essential to develop strong visions for the future with all stakeholders. I'm happy to share my experience in this with the LAND team. Our Düsseldorf team's many years of experience in concept design and execution planning also enable us to translate clear visions for climate resilient cities into