WOLF KAHN

By M. Rachael Arauz, Ph.D.

Over a long and generous career, Wolf Kahn produced a remarkable body of paintings and works on paper. He was also a prolific writer and speaker—both about his own practice and about the contemporary art world. His own productive output is almost matched by a profusion of scholarly publications about his work and critical reviews of his exhibitions. I see the daring complexity of Kahn’s formal strategies and his intellectual engagement with historic luminaries and the great artists of his own generation. I see the importance of his brilliant spouse, the artist Emily Mason, and the fascinating balance they created between their urban life in New York City and their seasonal home in Vermont.1 I see an artist deeply committed to the craft of painting, and I see a relentless explorer of materials.

Challenged to find my own path through Kahn’s work, I also see an artist who thrived in the liminal space of not-knowing.2 He asked questions, again and again, of landscapes he knew well, and each time he discovered new possibilities, new secrets, new ideas. Kahn was fascinated by the confrontation of disparate elements in the landscape—meadow and woods, sea and sky, earth and horizon. What happens in the meeting of those edges? I see an artist deeply curious about where we stand in the world, and what we may know, or cannot learn, by looking into the distance ahead.

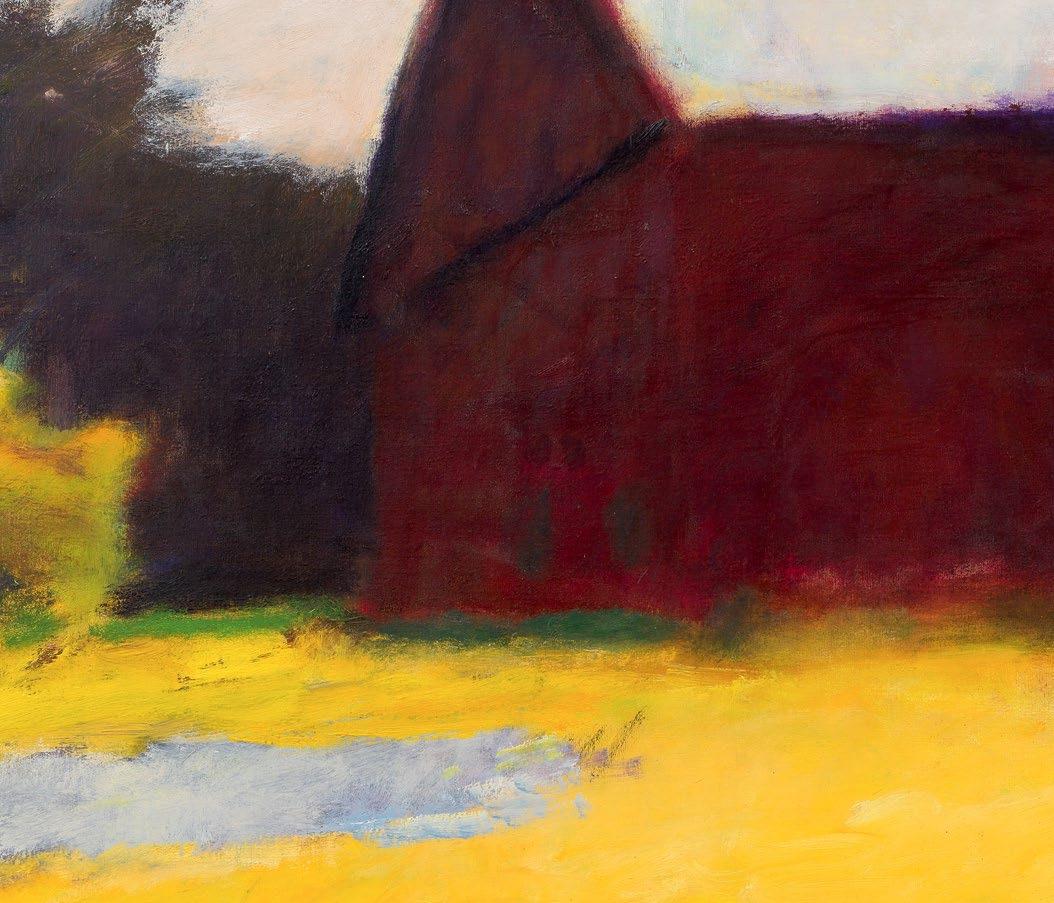

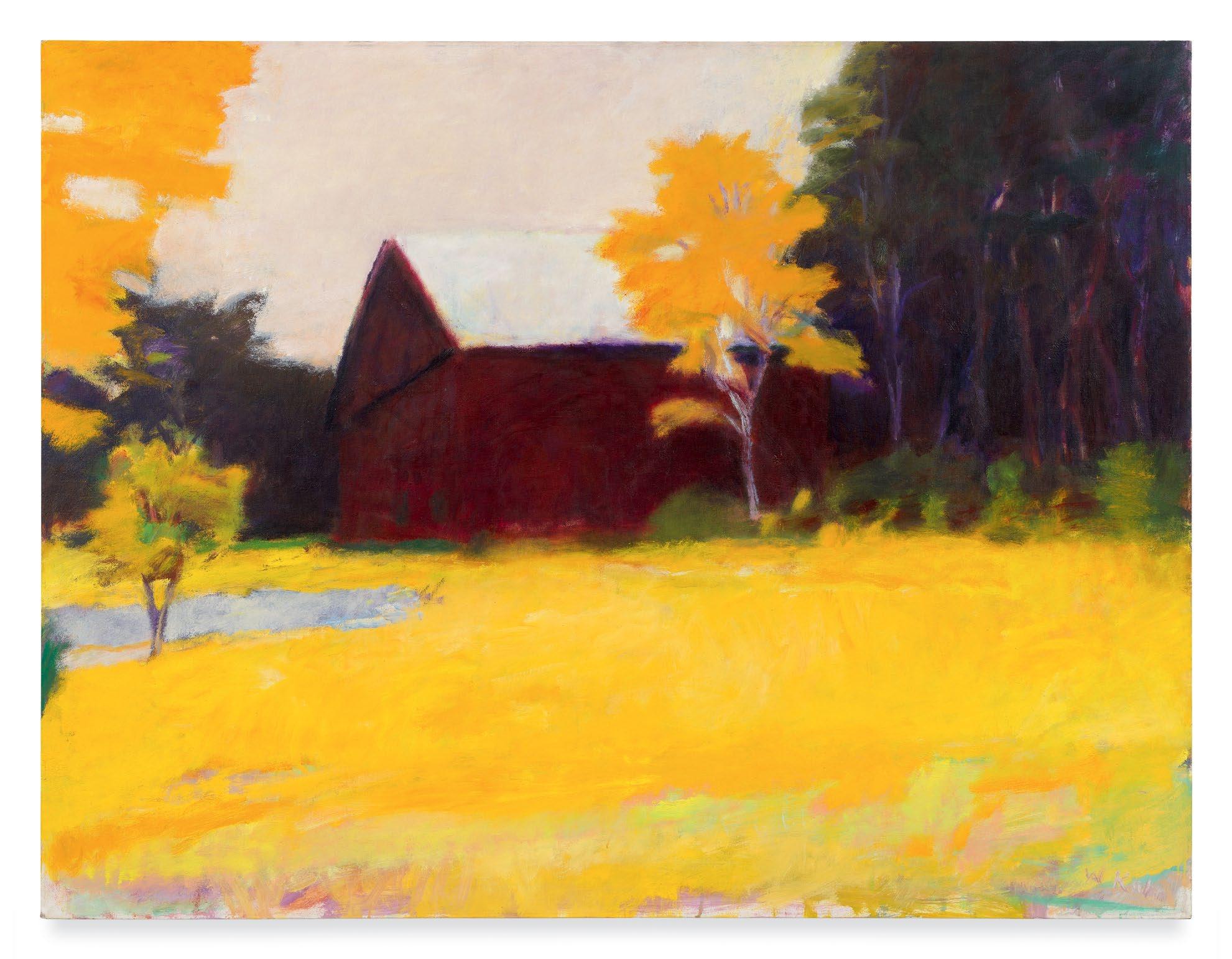

Exploring the enigmatic juncture of field and forest, Kahn often sought out and found the manmade structure of the barn at that soft boundary. During the 1970s and ’80s, paintings of barns defined his incredibly successful mid-career, resulting in some of his most iconic works. Barns became an enduring subject that he would return to throughout his lifetime. Kahn’s 1974 painting

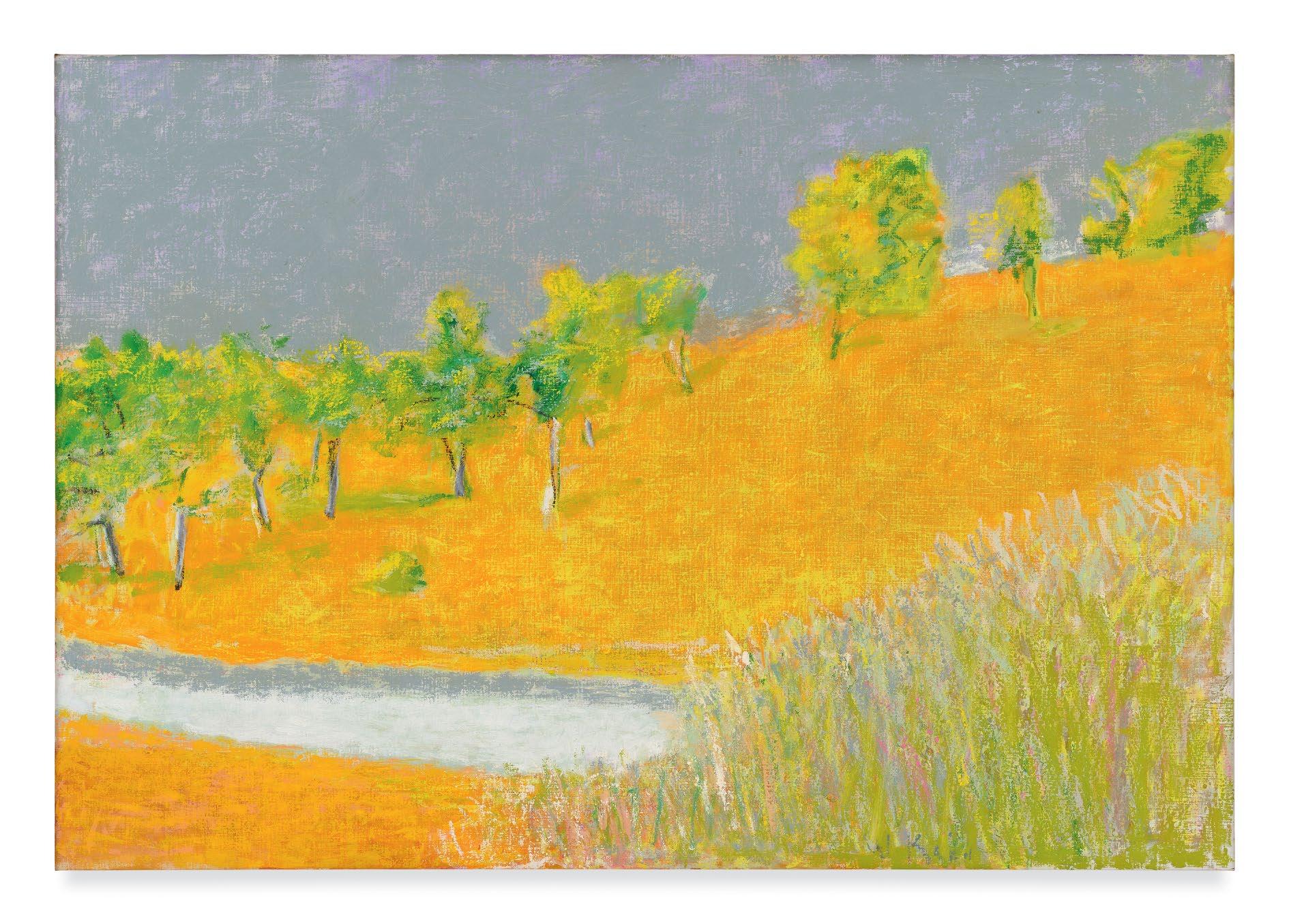

Barn at the Edge of the Woods V exemplifies the array of compositional elements—warm grass, dark woods, bright sky, and a solid building—and the chromatic treatment of light effects that distinguished this theme in his work, even in the early years of its formulation. The simple, descriptive title seems barely worth explication, yet it alerts us to two key considerations: The centrally located barn is the protagonist, and we should pay attention to its specific location. Kahn situates himself, and the viewer, in a late-summer golden meadow that fills the lower half of the canvas. The artist’s active brushstrokes hint at the gentle tones of grasses and flowers across the yellow field. Yet along the bottom edge the depicted space dissolves into paint drips and raw canvas, disrupting the viewer’s secure placement within the landscape. Close in the distance, the titular barn seems oddly compressed between a thick stand of trees on the right and more arboreal

darkness on the left. Ostensibly painted the classic red so common in the New England landscape, this barn’s vibrant identity has been consumed by the tenebrous woods. Kahn renders the structure in deep oxblood and violet hues, with slashes of black to articulate shadows under the eaves. Only a few dark smears of paint hint at a possible entrance to this structure, and there is no overt evidence that it has recently served an agrarian need. Indeed, the setting feels slightly more wild than cultivated, as if the forest has reclaimed the wooden form. In Kahn’s dynamic composition, the woods and the barn meet the meadow’s edge together. The viewer may choose to remain in the sunlight, or move forward into the darkness. Kahn makes no judgment on the merits of either choice—both spaces hold the potential for new questions and new discoveries.

In 1971, as barns began to dominate his paintings, Kahn drafted a short statement to explain their proliferation. He rejected their role as a nostalgic emblem. Instead, he valued their capacity to hold ambiguous dualities—monumental and intimate, confrontational and recessive, “equally part of the life of nature and the life of man.”3 In Kahn’s work, formal strategies such as dramatic lines of perspective, elevated horizons, and the high contrast of sun and shade often destabilize the benign, functional role viewers might expect of barns in their pastoral settings. Stripping away the associative simplicity of barns, Kahn’s emphasis on their planes of light and color liberated them to take on a more enigmatic role in his visual lexicon. With a sly, cryptic wink, he wrote, “A barn implies more than it states.”4 For Kahn, the meeting place of meadow, barn, and woods was both a space of color and geometry, and a space of narrative potential—a space of utilitarian familiarity and a space of conceptual mystery.

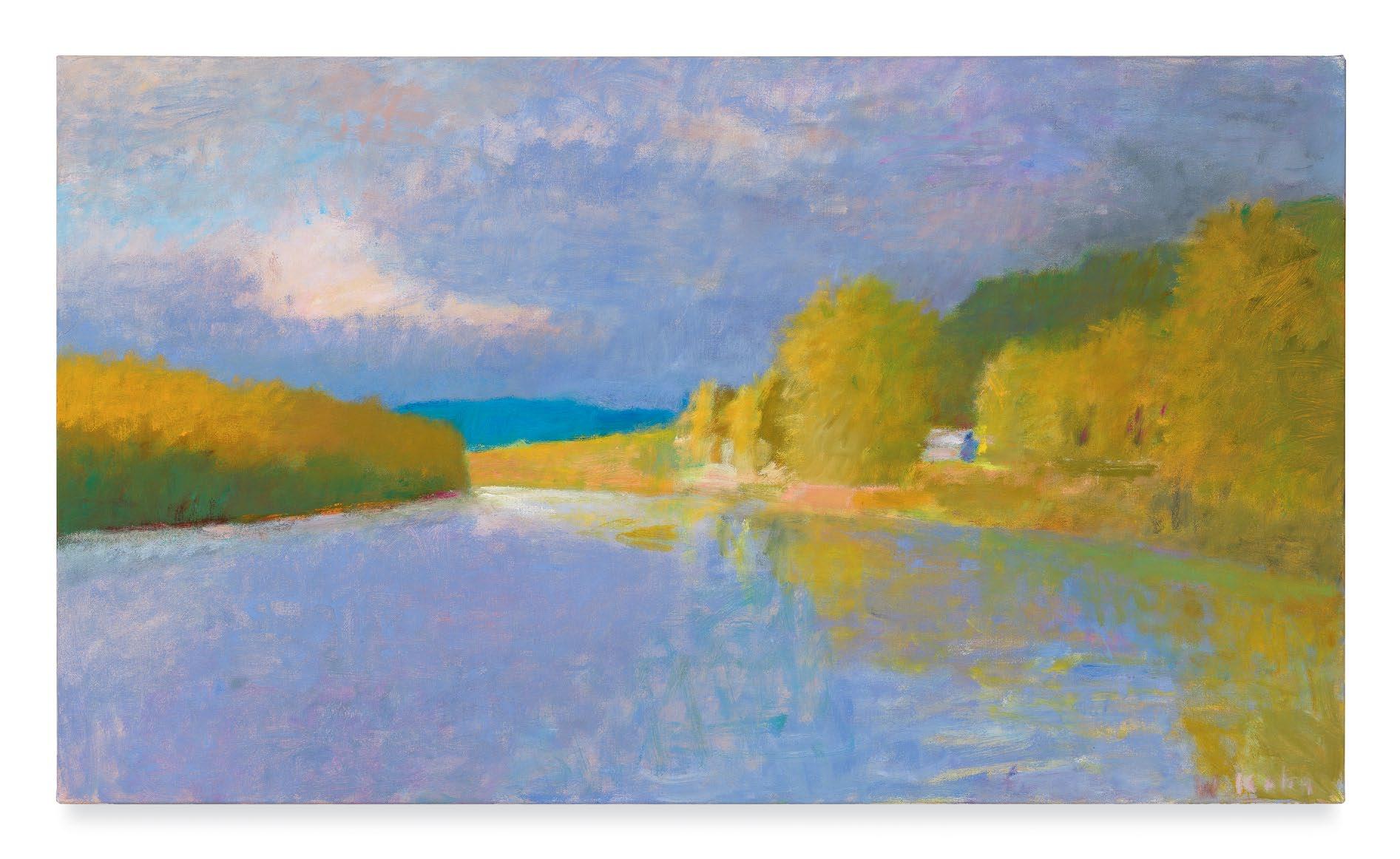

To a certain degree, barns haunt even the paintings where the structure is absent. Kahn traveled internationally, and painted rural architecture and natural subjects in many locations, yet his return to the Vermont landscape each summer provided a reliable challenge to see things in new ways. He was keen to avoid complacency, writing “...habit and the easy ways have to be overcome. I have found a few ways to do this, and one of the most useful is to embrace ambiguity.”5 Years of looking

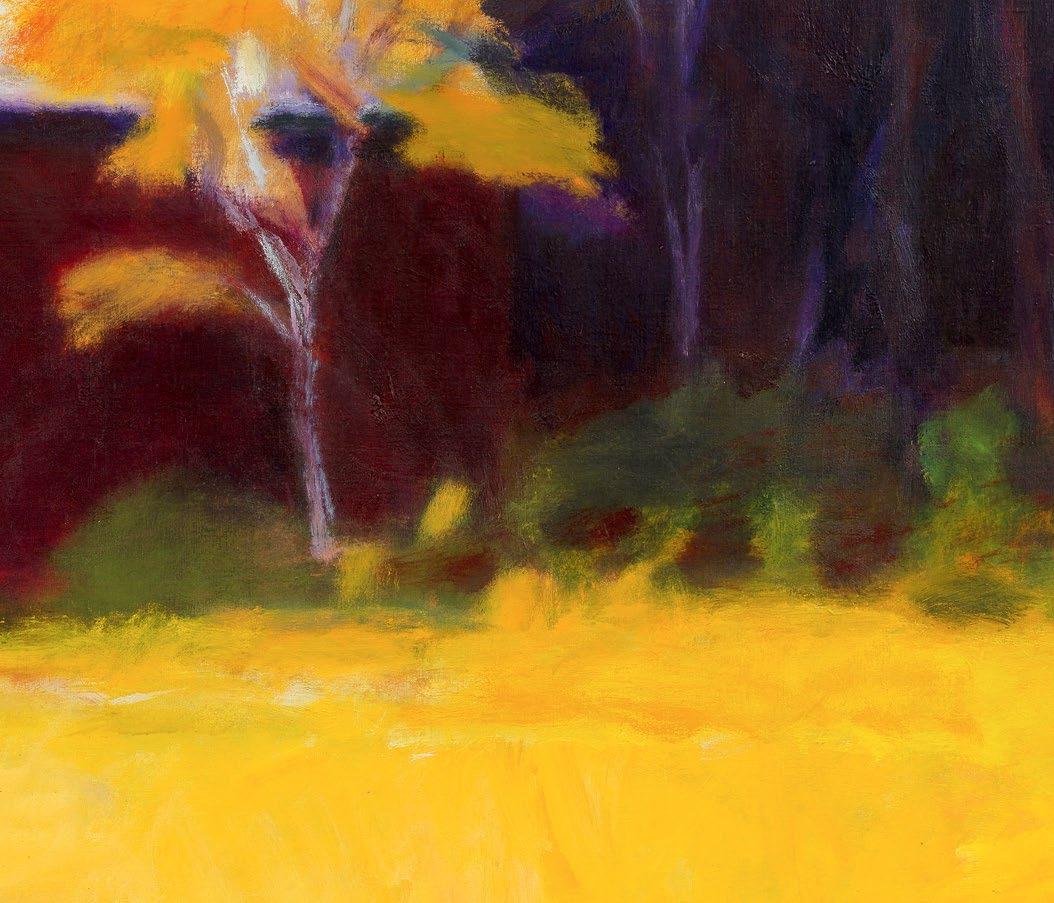

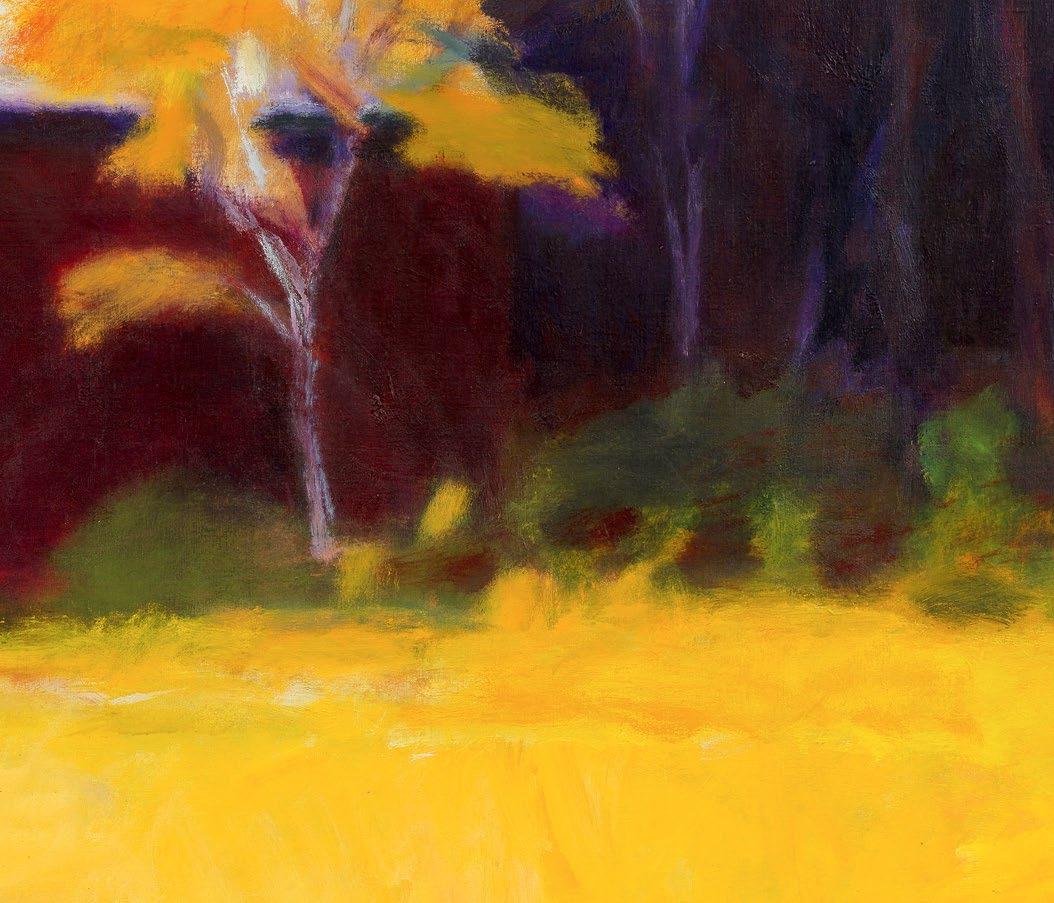

at his seasonal surroundings and asking questions trained him to remain attentive to the strange among the familiar. There is no barn in Back Meadow (2008), yet the laconic title situates the viewer in a specific location—we are at the back of something. A ghost barn lurks behind us, and its absence from the viewer’s purview intensifies the sense that Kahn is alert to the precarious condition of human activity at the edge of wild nature. Citrus yellows define a sloping meadow in the foreground, from which tall dark trees rise and create pools of gray shadow. A warm white sky, almost iridescent with wet touches of ivory, pink, and periwinkle, defines the upper third of the composition and suggests the heat of midsummer. Dark greens and blacks establish a ribbon of woods in the distance that Kahn widens and brings forward to dominate the right edge of the painting as the forest pushes into the meadow.

In Back Meadow, the artist challenges the viewer to reconcile the security of an experience we think we know—gazing upon a meadow—with the strangeness of how he has portrayed his observations. Visible brushstrokes that scrape and swipe across the canvas activate a moving landscape: The trees sway and rustle in a strong wind, the grasses bend and compress. Dots of minty green and small dabs of white pop from among the thick branches, offering confusing, quick glimpses of flickering light. The dark mass of forest contains the meadow and presses it forward, almost to the surface of the canvas and out of the frame’s right edge. Nature is alive in this work, pushing and pulling at whatever fragile perch the artist has found.

I hesitate to make too much of narrative commentary in Kahn’s paintings. His works are most overtly, according to the artist’s own assertions, about chromatic experiments, the physicality of mark-making, and the fusion of plein air immediacy with sensory memory as he painted the rural landscape in his urban studio. They are also beautiful paintings of landscapes he knew intimately and properties he cared for. They are not coded critiques of environmental decay, nor are they celebrations of a conquering eye. Kahn’s constructions of landscape, however, direct the viewer to pay attention to what we think we see and to look again at the hidden spaces where disparate elements meet.

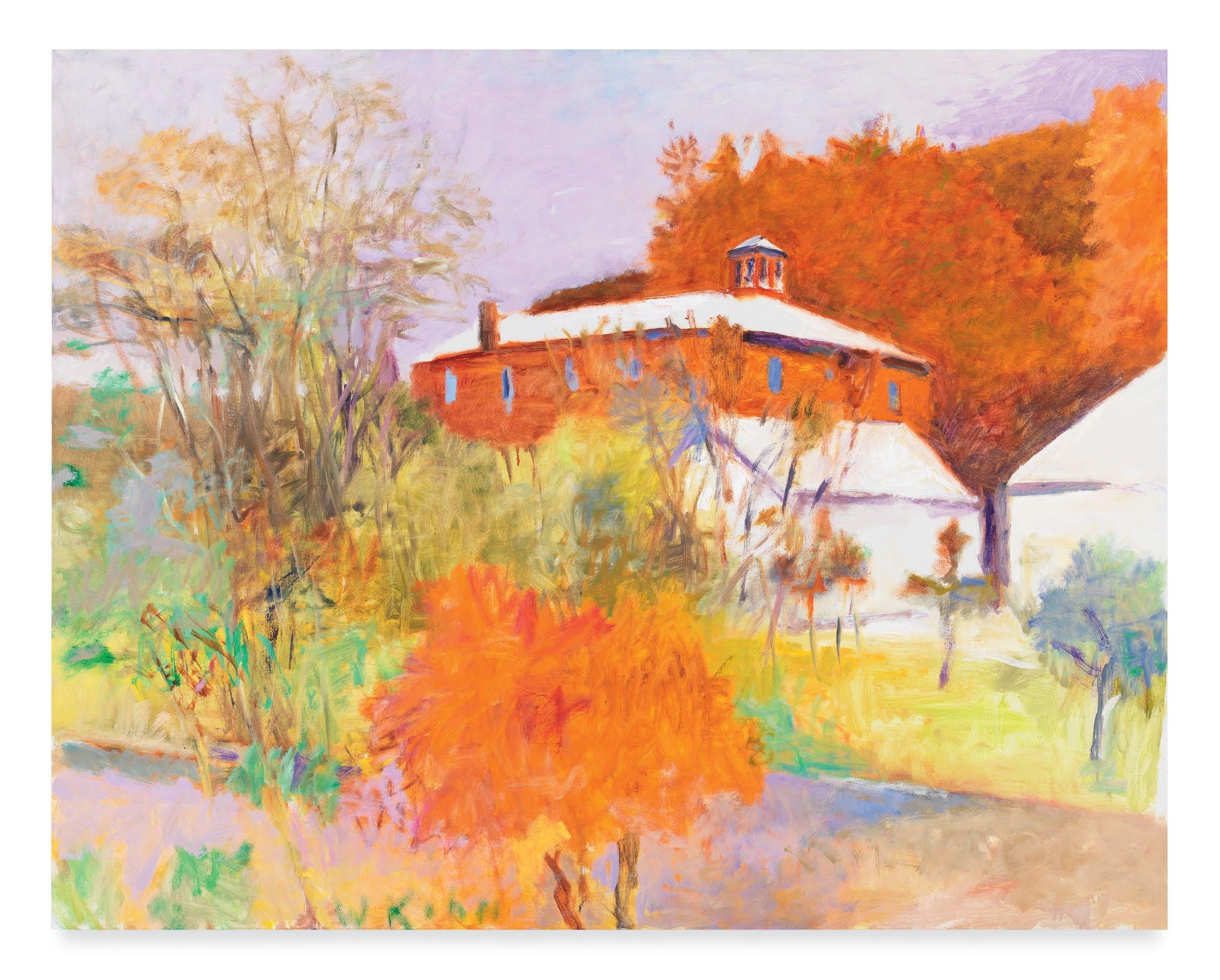

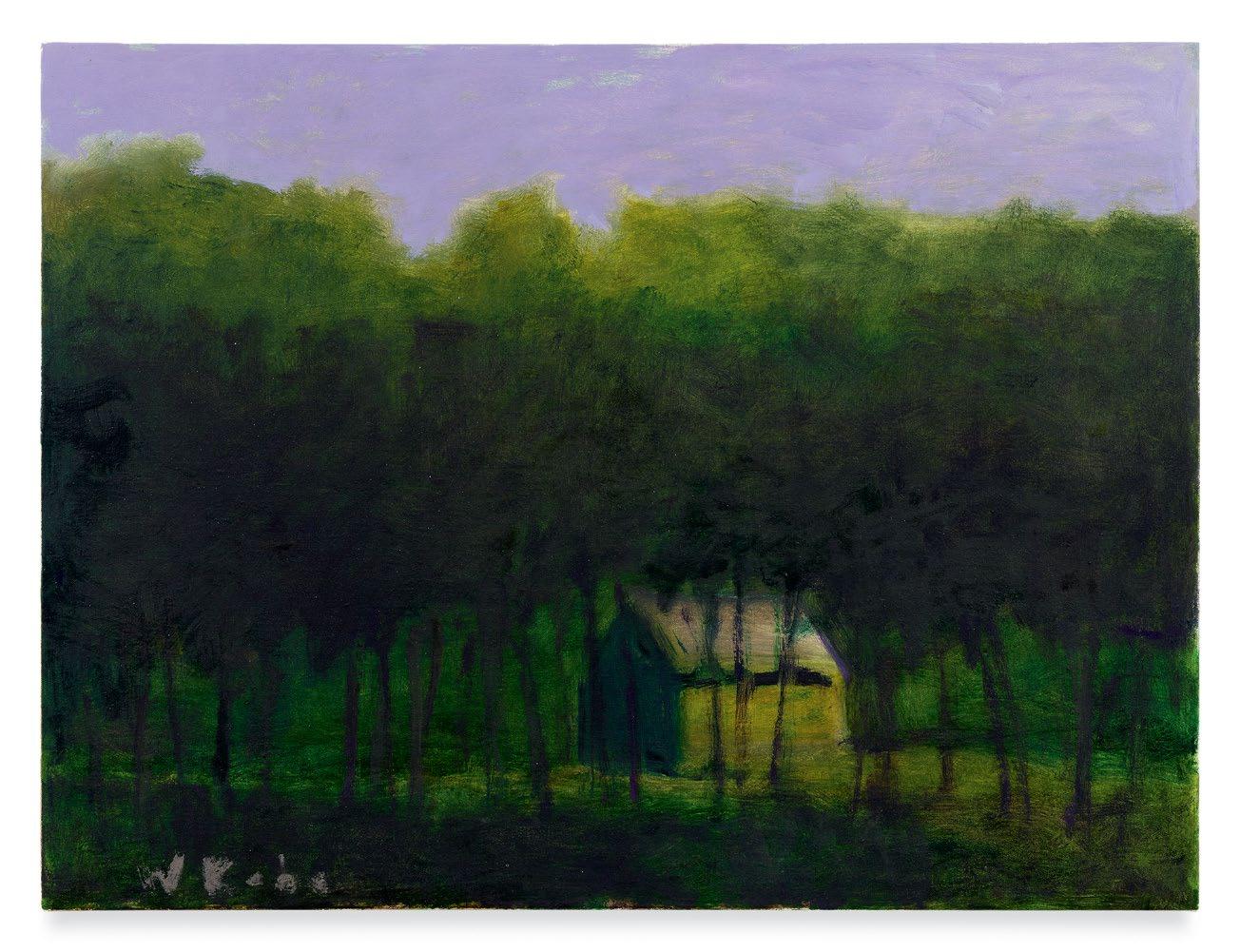

Writing for Kahn’s 2019 exhibition at the Miles McEnery Gallery, the art historian Martica Sawin remarked on Kahn’s “attraction to paradox,” manifest in his capacity to fuse visual perception and the language of abstraction in his works.6 Kahn conceived of an “excluded middle” to describe the physical space in a landscape where he could both observe and invent an ambiguous haze that would disrupt easy habits of reading a landscape. “The near and the far should be where we can comfortably exist, while the excluded middle allows the fantasy to roam,” he explained.7 In Kahn’s 2009 work Barn in the Corner (New Version), his celebrated subject becomes a small, cropped structure, more like a shed or rustic cabin, almost crowded out of the composition in the lower left. An agitated scrim of black and white marks obscures access to the little barn, and the high horizon and dark palette of a wooded landscape loom behind it. A band of warm pink at the sky’s edge sets the scene in the gloaming, those interstitial moments between the clarity of day and the murkiness of nighttime.

Is the viewer also a protagonist in this tangled forest, hoping to reach the barn? Or a remote observer, waiting to see what might transpire in this mysterious setting? Does Kahn seek to suggest adventure, anxiety, or safety in this landscape...or any and all of these things? For the 2009 catalogue that featured this new body of work, Kahn remarked that the series of “barn in the corner” pastels and paintings was “a total invention.”8 Formal strategies such as chromatic contrast, broken brushstrokes, and the odd placement of a familiar motif combine to loosen thematic possibilities. The painting presents a remarkable array of choices—not only the fluent decisionmaking of a dedicated artist at the height of a long career, but also the narrative choices that define how one moves through an experience.

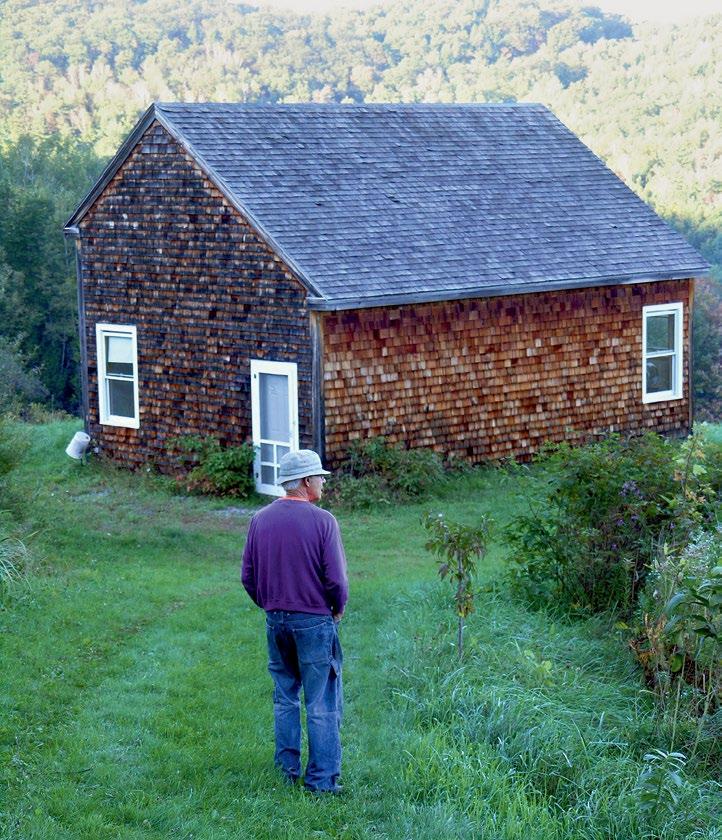

While working on this essay, I was fortunate to spend a summer afternoon walking through the Vermont landscape that Kahn painted for years.9 I was struck by how present he and his wife, Emily, still remain in the community, even though it has been more than five years since they died within three months of each other. Neighbors shared affectionate stories and could still point to

locations on their properties where Kahn stood to sketch. Kahn conveys a sense of solitude and mystery in his landscapes, yet while he was sketching, he might have been only a few yards away from his busy home, or within sight of a farmer harvesting vegetables. The paintings offer a sense of stillness and wonder, and perhaps even unease, that comes from standing alone in a glorious natural setting. But beneath their surface there is also the solace of human connections.

Kahn’s biographical story features a lot of well-deserved success, professional accolades, and familial comfort. His life also included escape from Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport just months before World War II started, the loss of grandparents to the horrors of the concentration camps, and several itinerant years in various households and schools before he was reunited with family. A spare version of his childhood could emphasize abandonment, dislocation, and loss, yet the published narratives, certainly encouraged and approved by Kahn in his lifetime, focus on how the artist felt loved and nurtured by many people. Kahn made choices to soften his narrative, to blur the boundaries between happy memories and their painful edges, to obscure the confusing space between light and dark. His capacity to hold both aspects of life experience was hard-earned and purposeful.

Celebrated for his extraordinary representations of the natural world and his gifted, experimental approach to color and light, he was also highly skilled at observing the shadows. Kahn approached all of his subjects with curiosity and developed formal strategies that enabled the dark edges to bump into beauty and warmth, always with an urgency to generate new questions, to keep looking, to keep going.

Kahn, like his barns, implies more than he states.

Author’s note Thank you to Mara Williams and Ellen McCulloch-Lovell at the Wolf Kahn Foundation, and especially registrar Linda Stewart and archivist Vince Kelley who supported access to both paintings and research materials, and enthusiastically responded to my inquiries. Additional thanks to the artists Dana Clancy, Carly Glovinski, Cristi Rinklin, Claire Sherman, and Joe Wardwell, who spoke with me about Wolf Kahn’s work in the context of their own painting and teaching.

Notes

1. For Kahn’s biography, the leading sources include Justin Spring, Wolf Kahn [Updated Edition] (New York: Abrams, 2011), and the comprehensive chronology in Sasha Nichols, Wolf Kahn: Paintings and Pastels 2010–2020 (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020).

2. I first researched Kahn in the context of the early years of Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, in Deer Isle, Maine, where Kahn taught abstract painting in the summer of 1962. Emily Mason had been among the school’s first scholarship students in 1952, and she remained friends with Haystack’s director, Francis Merritt. Other faculty at Haystack when Kahn was there in 1962 included the ceramic artist Toshiko Takaezu, the fiber artist Jack Lenor Larsen, and the painter Joop Sanders, with whom Kahn led a roundtable discussion about art and craft. During several summers in Deer Isle, Kahn also recalled befriending and acquiring work from the glass artist Marvin Lipofsky and the ceramic artist William Wyman. Rachael Arauz and Diana Greenwold, interview with Wolf Kahn, March 3, 2017, New York, unpublished.

M. Rachael Arauz, Ph.D., is an independent curator of modern and contemporary art, with research interests across media, especially underrecognized artists, movements, and materials. She has organized exhibitions and contributed to museum catalogues in the United States, Mexico, and Europe. She was co-curator of the 2019 exhibition In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969 for the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine.

3. Wolf Kahn, “About Barns,” unpublished statement, 1971. Manuscript in Wolf Kahn Archives, n.p.

4. Ibid.

5. Wolf Kahn, Wolf Kahn Pastels (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), p. 132.

6. Martica Sawin, “Wolf Kahn: Paintings from the 1960s and New York,” in Wolf Kahn [exhibition catalogue] (New York: Miles McEnery Gallery, March 14–April 13, 2019), p. 13.

7. Wolf Kahn Pastels, p. 132.

8. Wolf Kahn Toward the Larger View: A Painter’s Process [exhibition catalogue] (New York: Ameringer Yohe Fine Art, April 23–June 5, 2009), p. 34.

9. Special thanks to Mara Williams for facilitating this visit to Kahn’s studio, home, and surrounding landscape.

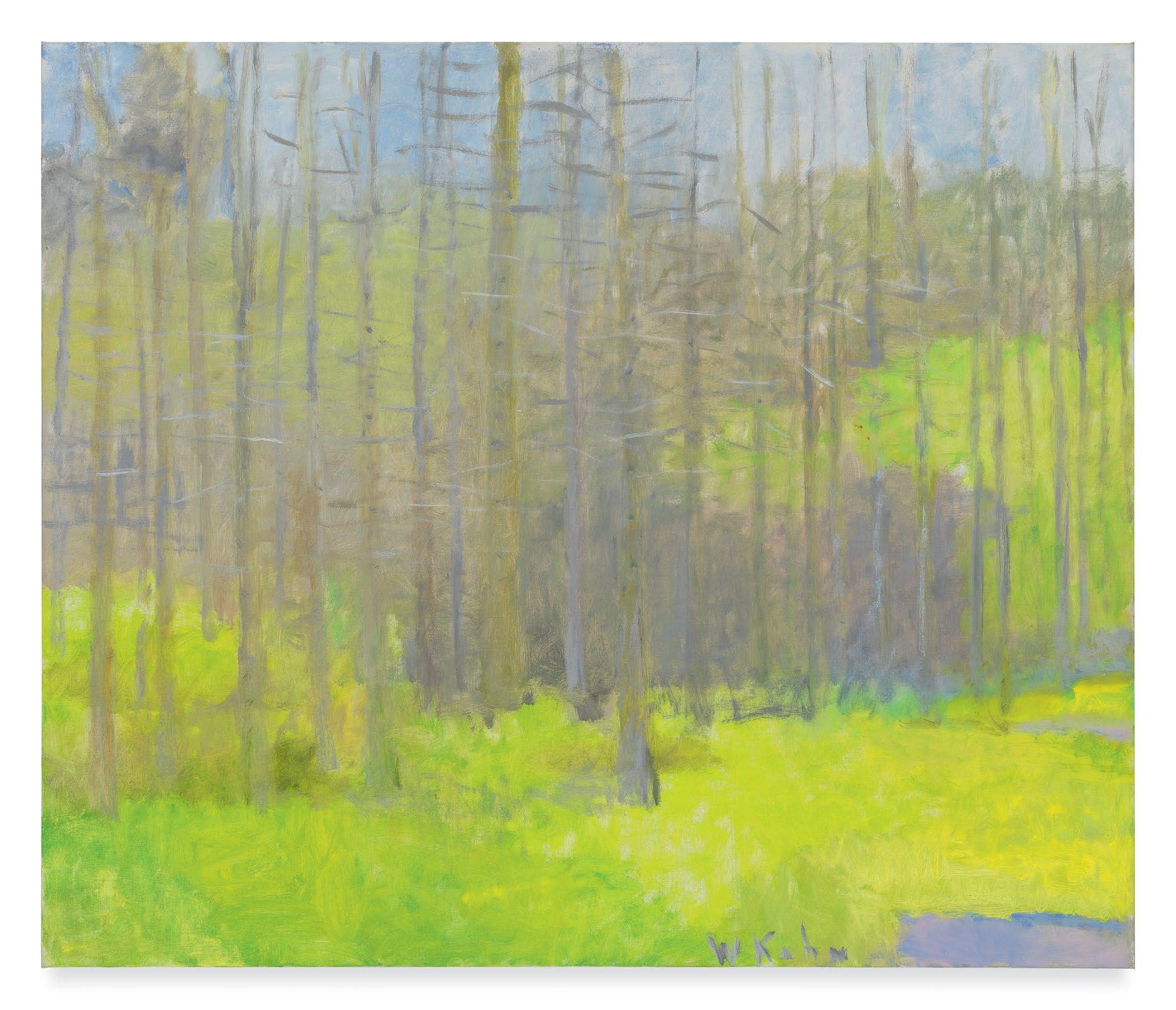

In the Back of the Vermont Studio Center, 2001

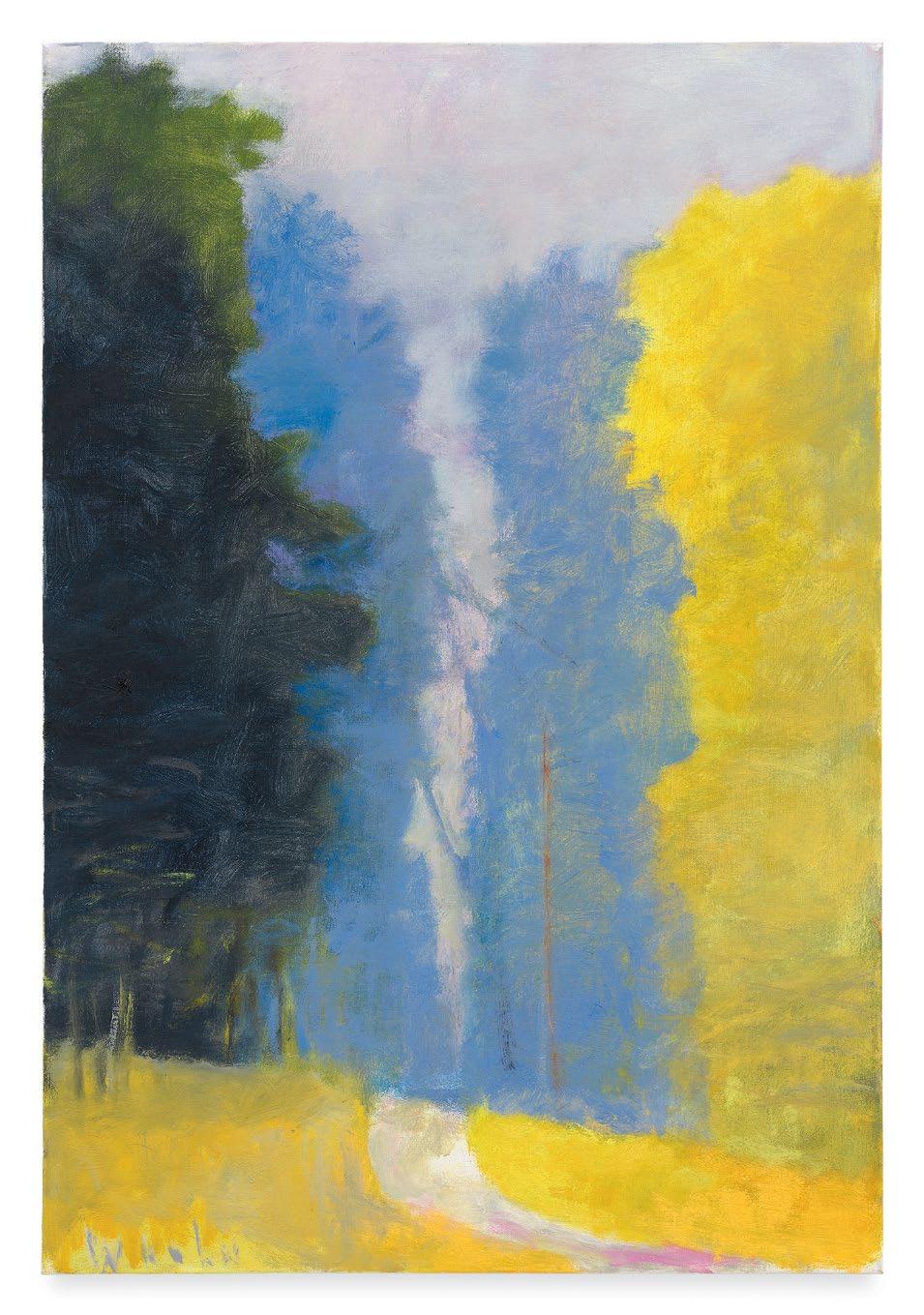

Almost Impenetrable, but not Quite..., 2006

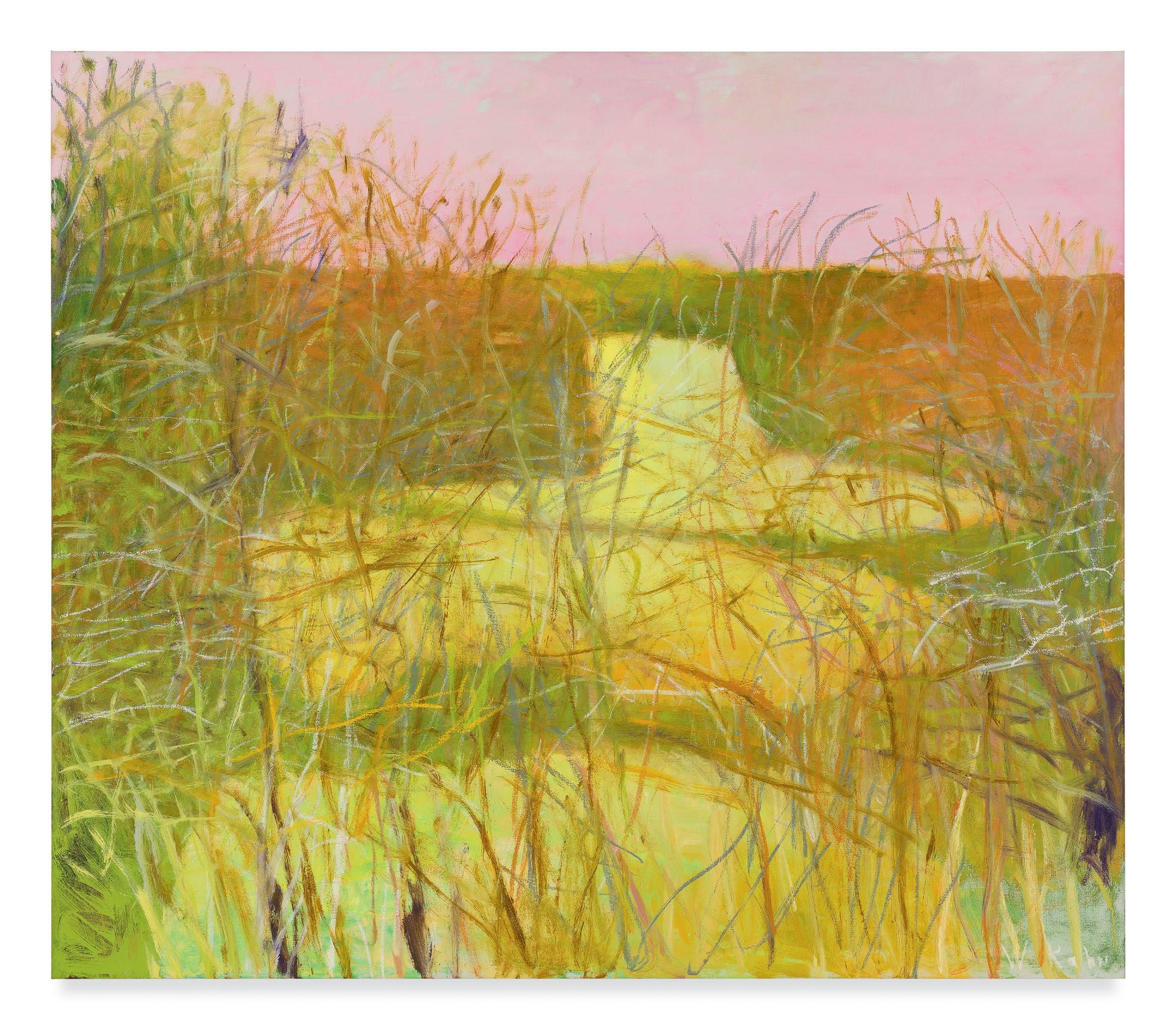

Derived from Late Evening Pastel, 2009

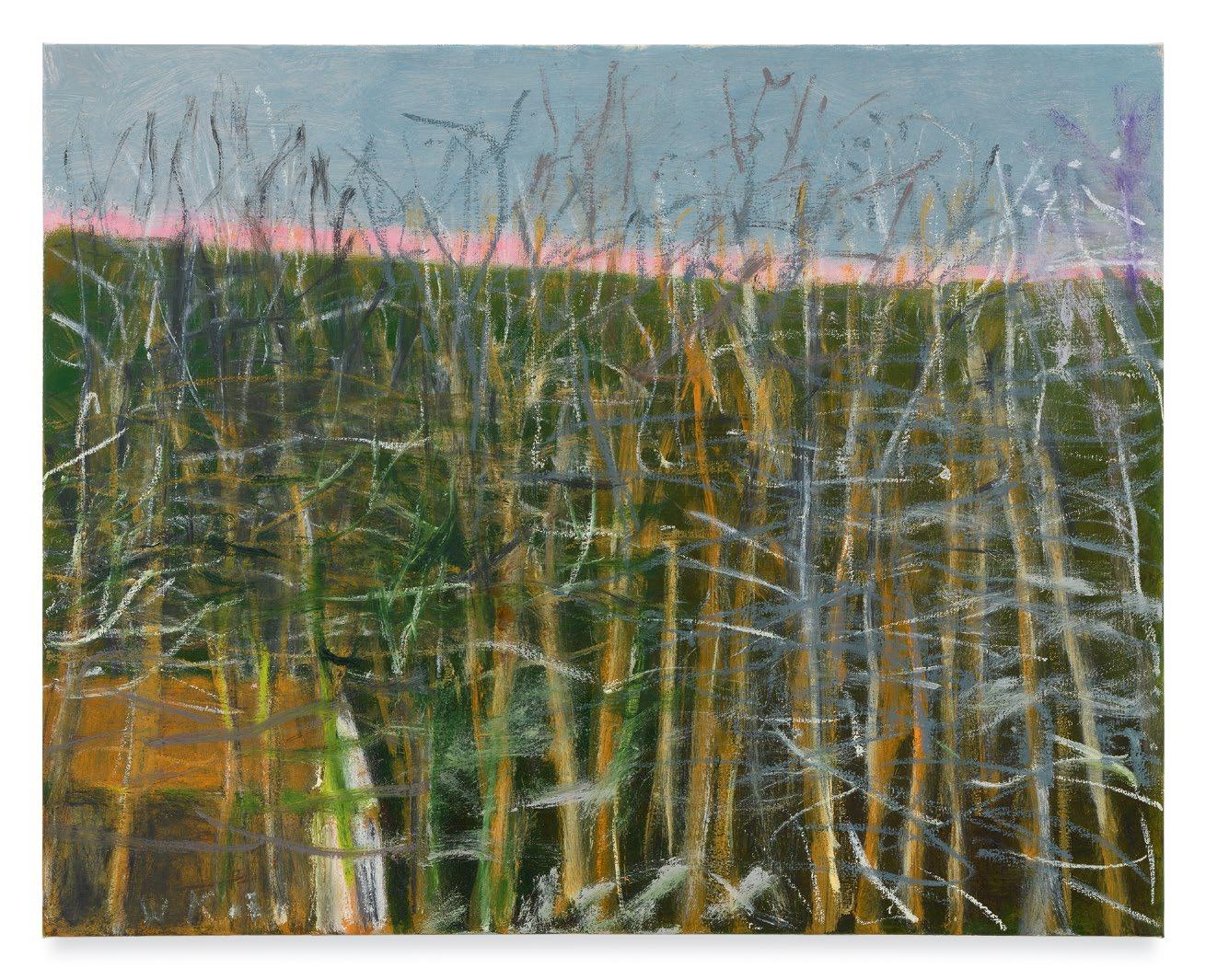

Preference for Green, 2015

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

M. Rachael Arauz, Ph.D., Guest Curator

30 October – 20 December 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery

520 West 21st Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2025 M. Rachael Arauz, Ph.D.

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Special thanks to Mara Williams, Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, and The Wolf Kahn Foundation, Brattleboro, VT

Artwork Images: © 2025 Wolf Kahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY

Image on p. 2: Wolf Kahn in his New York Studio, 2015

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY

Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5326-4

Cover: Barn at the Edge of the Woods V, (detail), 1974