REWILDING BIJLMER

@regenerative.landscape

@regenerative.landscape

we allocate 10% of the money investing in buildings into transforming the public space of Bijlmer ?

Every now and then walking in the Zandkasteel, I can see a group of investors wearing neat suits looking at the interiors of this former ING office building turning into a residential flat. I can’t stop wondering why people only invest in buildings, but no one is interested in investing in public spaces?

Public space encourages flourishing at the individual, neighbourhood, community and even nation level. If we invest in public spaces, we could make a difference in areas ranging from mental health to social justice. Public spaces impact so many things from the informal economy, environmental sustainability to health, recreation, play, creativity, and resilience.

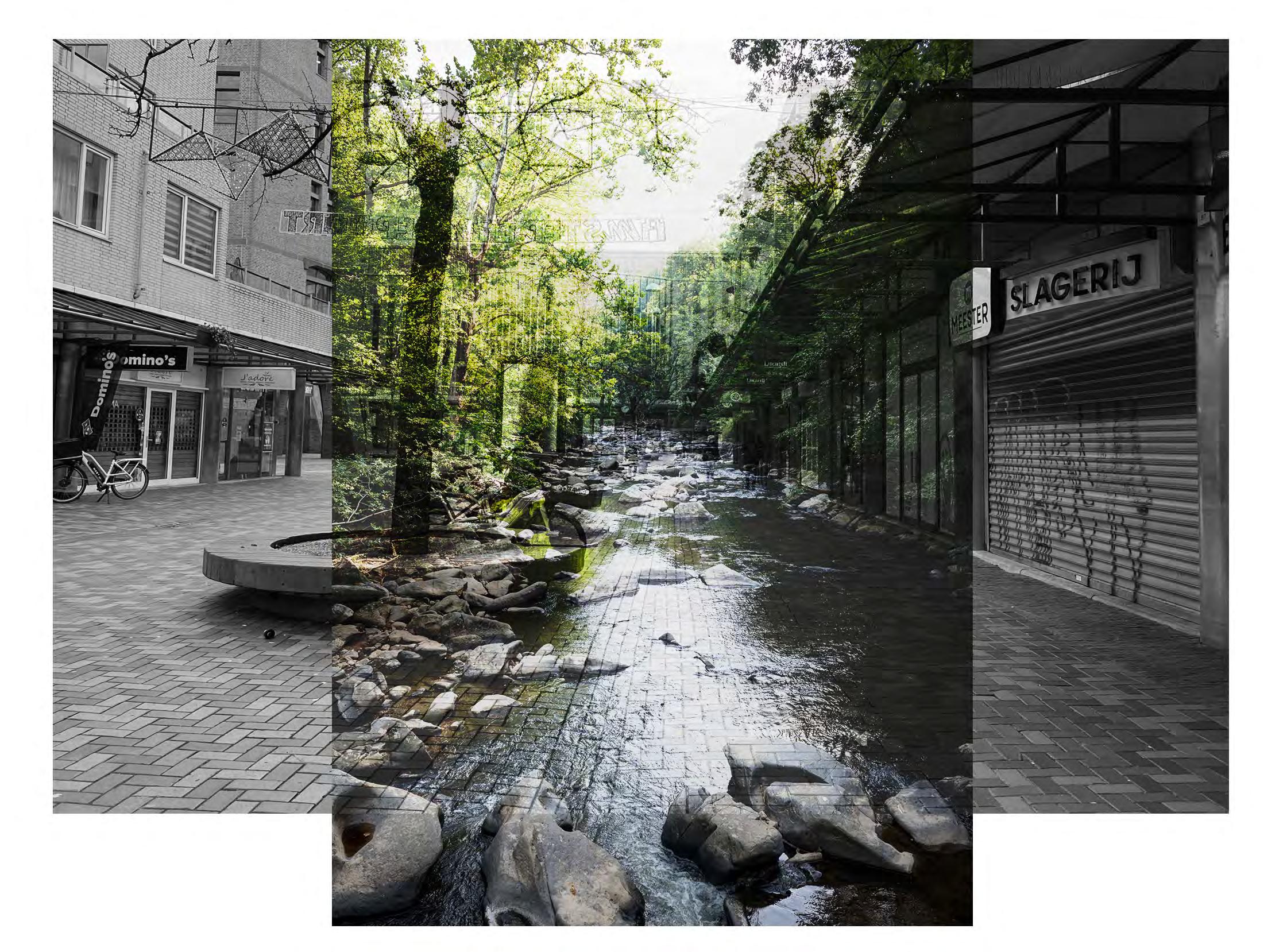

The essence of the area of Bijlmer is Bijlmerplein, the heart of Amsterdam Poort. Bijlmer is changing rapidly, so is Bijlmerplein. The lights of the newly opened Hawaii Pokebowl restaurant are especially bright in the evening to showcase its arrival and the upcoming JD retail store is waiting for its opening. But that’s it? Is this what the local community needs or maybe more the investors want? What if we allocate 10% of the money busy transforming bank buildings into transforming the public space of Bijlmer?

Gentrification is not only happening in Amsterdam Noord, NieuweWest, but also happening rapidly in Zuid-Oost. But there is much less quality and attention on the public space of Zuid-Oost. The investors might smile at the increase in the housing price, the woz value and the rental price. But are residents who live here pleased about the transformation? As a resident of Zandkasteel, as a daily pedestrian of Bijlmerplein, as a citizen that deeply care about the community, and as a landscape architect and urban thinker, I think Bijlmer so as Bijlmerplein needs a new imagination that is beyond the perspectives of the investors, the bankers and the bureaucrats.

Bijlmer deserves better public space than carelessly placed trash bins

what if we transformed it into forest ?

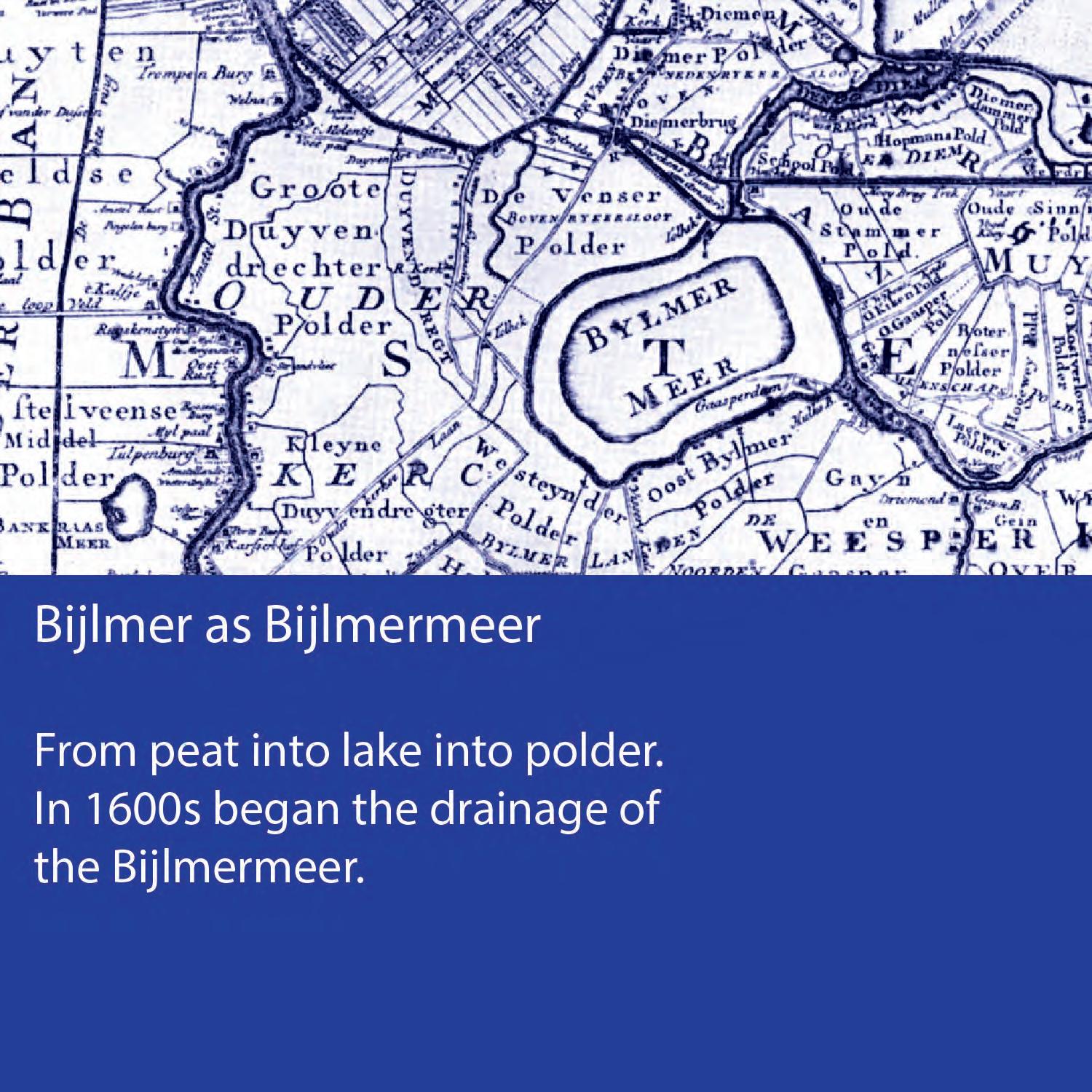

If we want to reimagine Bijlmer, first we need to know its past. Where does Bijlmer come from? Bijlmer is at Amsterdam Zuidoost, covering about six square kilometers (6 km2). It’s an extremely diverse area. Bijlmer is a home to approximately 85,000 people of more than 150 nationalities, among them only 20% were born in the Netherlands. Many new arrivals like me didn’t know that Bijlmer is a short version of Bijlmermeer.

‘Meer’ in Dutch means lake, so Bijlmermeer translates to Bijlmer lake.

According the book Ridders in de Bijlmer (Knights in Bijlmer), the Bijlmer transformed from peat into lake into polder, then got intentionally flooded (for instance as defence system), was reclaimed as polder again, flooded again, was reclaimed once more and was eventually used for agriculture until 1965 when they decided it was time for the largest urban sprawl in Dutch history”. The author of the book concluded that one thing that runs through the history of Bijlmer is water. area population nationalities

6 km2

85,000

150

none Dutch born

80%

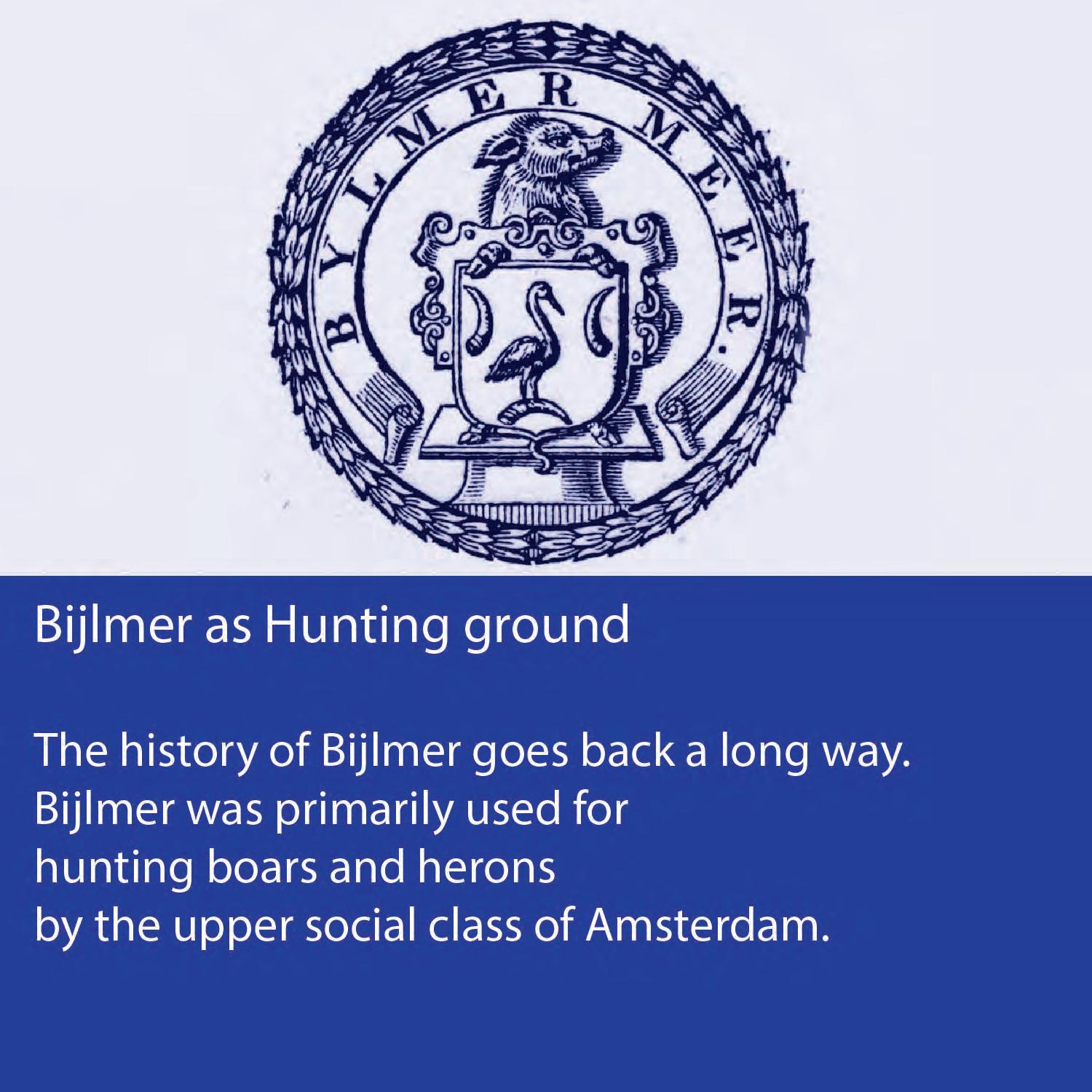

The history of Bijlmer goes back a long way. It already appears on a map from 1525. It’s an area with a lot of water. Back then, the area of Bijlmer was primarily used for hunting boars and herons by the upper social class of Amsterdam who lived here in their manors. This past was reflected in the Crest of Bijlmer. Now, if you walk around Bijlmer, you no longer see boars, but every now and then you might still encounter herons, one of Bijlmer’s earliest residents.

In 1622, the States of Holland approved the drainage of the Bijlmermeer. It took four years to fully dry the polder, but the peat soil turned out to be less fertile than expected, and was only usable during the summer months. Many farmlands in the Netherlands still face similar issues today, with soil that is not very fertile.

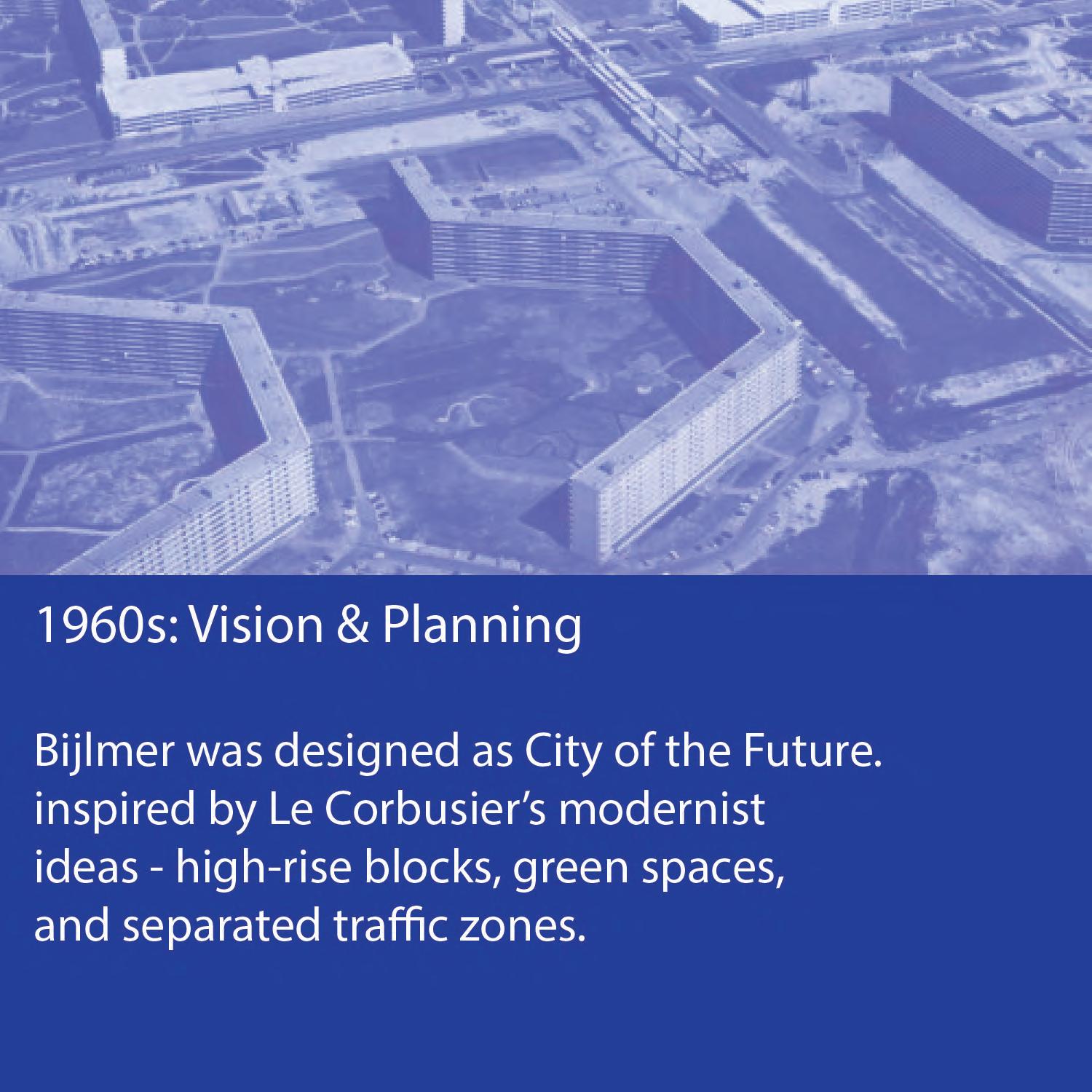

After the second world war, there was a great shortage of houses. Between 1950 and 1960, the Dutch population grew from 10 million to 11 million. Building new houses was an important priority in the 1960s. City of Amsterdam developed urban development plans in 1962 to house 100,000 people in Amsterdam-Zuidoost (even in 2024 Bijlmer never reached this number of residents). The target group was mainly white dutch middle class family who wanted to leave the dirty, busy city. At that time Jordaan in Amsterdam was known for the small, crowded and rotted apartments where many people lived in cramped rooms. It’s hard to imagine it now because Jordaan is one of the most expensive neighbourhoods in the city.

This utopian plan was known as “City of the future”. It’s a testground of the lofty ideas of the CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture) on a grand scale. CIAM envisioned cities as functionally zoned, efficiently organized spaces with standardized housing, separated transportation systems, and open green areas. Modernist idea was taken really far in Bijlmer.

Le Corbusier envisioned modern cities where cars played a central role in transportation, often proposing elevated highways and separating pedestrians from vehicles. This vision was brought into reality in Bijlmer that roads were elevated to separate traffic, with the ground designated for pedestrians and the sky for cars. 31 very wide 10 storey concrete towers were built in the shape of honeycomb with large green spaces between them.

It was once a dream house for many white Dutch middle class. There was a long waiting list and interviews to get an apartment in this city of the future. But after they moved in, this future dream crashed, shops were not built, no school for children and the promised metro line connection was delayed. Due to lack of money, the outdoor space was designed much more simply than previously thought (every landscape architect is familiar with this story :) People started to move out of Bijlmer and the waiting list disappeared really fast.

Completely in the mid 70s, many of the 13000 apartments of these 31 concrete towers were unoccupied. The idea fell apart when no one who could afford to live in the Bijlmer actually wanted to live there.

In 1975 Suriname became independent. It’s estimated that more than a quarter of the country around 100,000 people moved to the Netherlands from Suriname. Back then, there were at least 3000 people at least per month coming to the Netherlands from Suriname. Surinames weren’t technically immigrants. They were Dutch citizens who grew up speaking Dutch and learning the history of the Netherlands at School. They thought they would be welcomed in the Netherlands but the country offered nothing more than a space in Amsterdam-Zuidoost that everyone else wanted to forget.

White Dutch people didn’t want to live in the Bijlmer which increasingly attracted people who couldn’t afford housing anywhere else or who were discriminated against elsewhere. Overtime thousands of Dutch Caribbeans, gay individuals and immigrants from Turkey, Morocco, Ghana and various other African nations came to the Netherlands for work. Bijlmer eventually became the first black-majority neighbourhood in the country.

In the 1980s, there was a lot of heroin trading in the city centre of Amsterdam. The city council wanted to put an end to this by cleaning up the streets of the city centre. This forced the drug dealers and addicts to move to the outskirts, including the Zuidoost. Bijlmer’s empty parking garages and isolated streets made it an ideal spot for drug dealers, leading to a significant rise in crime. During this time Bijlmer was often described as the most dangerous neighbourhood in Europe.

Finally beginning in the mid-1990s, a large urban renewal of the Bijlmer began. Over the next 15 years, the high-rise concrete towers were demolished and replaced with a tighter layout of mid-height buildings, ranging from one to five stories. These new structures gave each apartment its own garden and a sense of ownership over a section of the street.

The redevelopment also introduced loosely zoned spaces for shops and businesses, allowing for lively and organic markets. Elevated roads were partially removed, bringing cars and pedestrians back to ground level. It’s an approach that opposes the modernist idea of separating functions and traffic.

This urban renewal was combined with targeted efforts to improve education and employment opportunities for the Dutch-born children of migrants. As a result, the secondgeneration Surinamese now have university education and income levels similar to those of ethnic Dutch and their children.

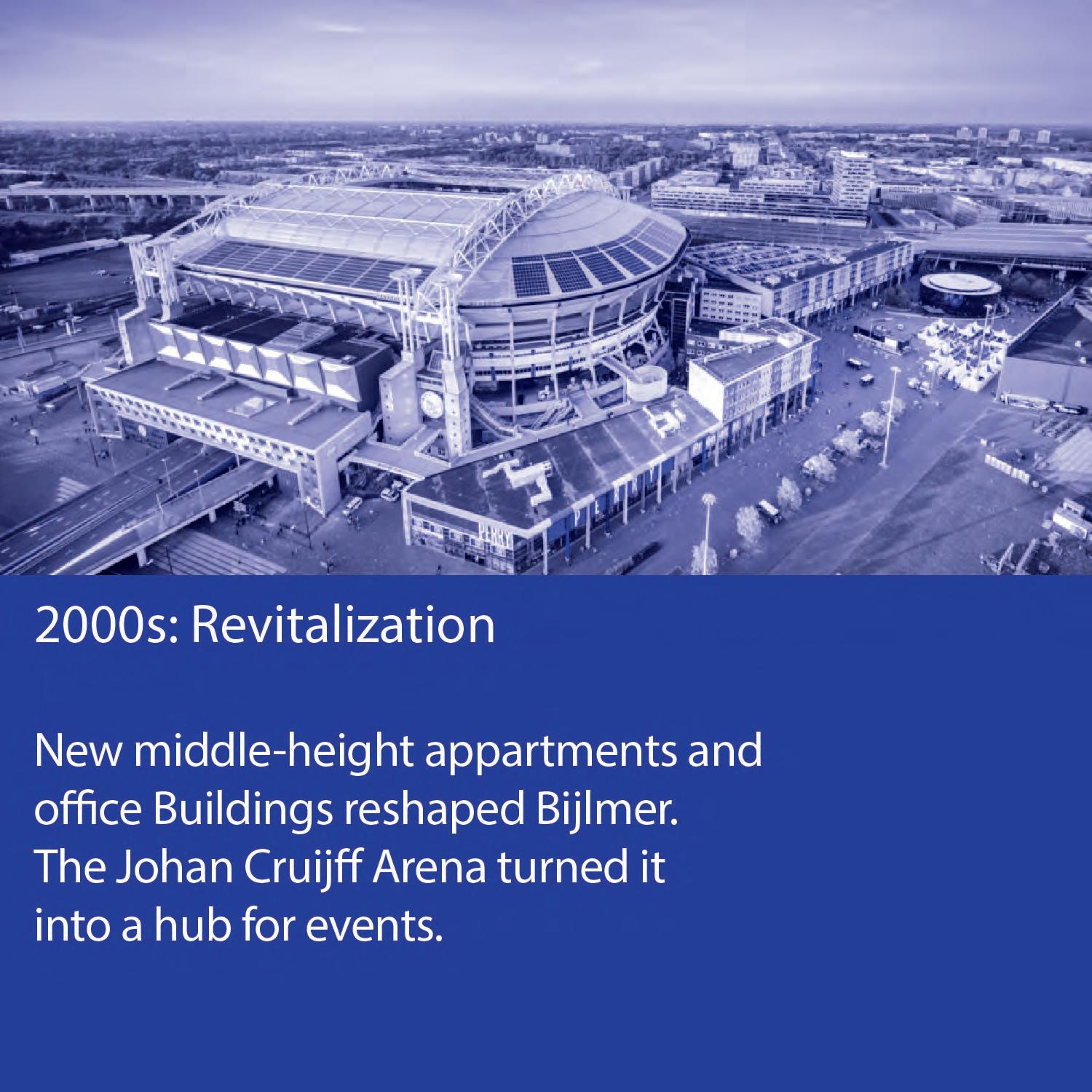

Bijlmer is also well known for the Bijlmer Arena, now called the Johan Cruijff Arena, which has significantly altered the dynamics of the area. Completed in 1996, the stadium quickly became a hub of activity, regularly attracting large crowds for Ajax football matches, with one or two games per week during the football season. Beyond football, the arena functions as a multi-use venue for concerts and other major events throughout the year, which brings large, temporary influxes of people to the area. This surge in foot traffic brought new challenges for the use of Bijlmer’s public spaces, as the community must manage the balance between daily life and event-driven crowds.

However, this surge in human activity has also impacted the local biodiversity. The Common Terns (visdiefjes) that used to nest near the arena are now under pressure, with their breeding grounds disappearing due to development. Moreover, larger gull species have begun to dominate the area, driving the Common Terns away. The rapid urbanization and increasing human presence around the arena have thus had a significant effect not only on the local economy but also on the surrounding wildlife, leading to challenges for certain bird species in maintaining their habitat.

Bijlmer nowadays has vivid dynamics that change throughout the day, week, and year.

From Monday to Friday, between 8AM and 5PM, Bijlmerplein is like a central business district. Large numbers of employees from major corporations such as ING and Vattenfall flood into the area in the morning, much like factory workers, and gradually leave around 5 PM. Bijlmer already began attracting businesses in the 1990s as part of the urban renewal plan. When ING moved its headquarters to Bijlmer in 2012, it marked a turning point for the area’s development. The relocation of this big financial institution attracted more businesses and investment, setting the stage for Bijlmer to evolve into a significant business hub.

This influx of corporate presence and wealth transformed the landscape of the area and contributed to gentrification in Bijlmer. It brought economic vitality and infrastructure improvements. However, the rise in property

values and increased demand for office space displaced many long-time residents and small businesses. The modern office complexes and high-end facilities created a sharp contrast with the surrounding neighbourhoods, where lower-income communities, largely consisting of immigrants and ethnic minorities, struggled to keep up with rising rents.

This transformation intensified social injustices, as the benefits of the economic boom were not equally shared. While the business sector thrived and new developments flourished, many local residents found fewer job opportunities within these corporations, and faced increased marginalisation.

Over time, Bijlmer shifted from being a predominantly residential, multicultural area to a mixed business and residential district, further widening the gap between the corporate world and the everyday lives of its long-established local community. The needs of the local residents often remain sidelined in favour of corporate interests.

philosophy

1. City is an Organism

City is a Machine

2. Design for Experience

Design for Function

3. Design for Minority

Design for the Wealthy & Powerful

4. Weaving nature into Urban fabric

Segregation of Nature and Nature

4. Bottom Up, Participatory apparoch

Top-Down, Paternalistic Approach

5. Celebrate the diversity

One metric that fit all

City is a Machine

1. City is an Organism

City is a living being.

It’s constantly evolving.

Room for spontaneity for creativity.

Room for chaos.

It’s not just about how we think it’s also about how we feel ?

Can we design the landscape that is more sensual?

That is soft.

We walk in Bijlmer like we are eating a cake. It’s soft and the air smells sweet.

Design for the Wealthy & Powerful

Minority is not just about people

But also about the animals.

Design for the homeless, they can rest on the benches.

Design for the elderly they can gather and chat.

Design for kids where they can play.

Design for women where they feel safe and bright.

Top-Down, Paternalistic Approach

4. Bottom Up, Participatory apparoch

Panel discussion. Community engagement.

We gather and we share our experience and what we want in our daily space.

We Dance We Sing.

One metric that fit all

5. Celebrate the diversity

There is no such a thing as a metric that fit all.

Celebrate the difference. Celebrate the diverity.

visionary, utopia, yet ignorant of the ecosystem, at that time nobody were concerned about the loss of the habitat for the animals.

Bijlmermeer plan in the 1960s was arrogant. It’s the architecture for architect. Sadly this kind of space is repeated like IJburg. The modernist architects want to plan the city like a machine. City is not a machine.

It’s a very masculine plan that wants to control everything, plan everything. They didn’t forsee the delay of facilities.

We don’t want our cities to function as well organized machines.

Yes, we want our apartments to be quiet and our cities to be safe, but we also enjoy the spontaneity and chaos of traditional cities.

Car running on the road, traffic separated.

But where are the people?

People live in the highrise like barbylon sky city.

But what about the streets?

The modernist architect said the ground is for everyone, but why it turns out that the ground become the drug dealing place, why no one wants to hang out there?

From spatial perspective, it’s a failure of dimensions.

From social perspective, lost of private ownership leads to the loss of the quality of the public space.

Even the planned parking lots were mostly vacant and turns into a perfect palces for drug dealing.

It’s programmatic but no experiential, not sensual.

It’s hard, very hard.

Paved roads, concrete blocks, artificial forests. While underneath the pavement, it’s a swap. There are millions of wells underneath.

But no matter how the ecosystems are going to restore themselves, whether we like it or not.