The American Prospect needs champions who believe in an optimistic future for America and the world, and in TAP’s mission to connect progressive policy with viable majority politics.

You can provide enduring financial support in the form of bequests, stock donations, retirement account distributions and other instruments, many with immediate tax benefits.

Is this right for you? To learn more about ways to share your wealth with The American Prospect, check out Prospect.org/LegacySociety

Your support will help us make a difference long into the future

51 Ryan Cooper on Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water

How plutonomy, premiumization, and social media squeeze the middle class By

The Historic Reversal of Cultural Affordability By Paul

AI’s real contribution to humanity could be maximizing corporate profit by preying on personal data to raise prices. In fact, it’s already happening. By David Dayen

Regulatory capture is at the root of the affordability crisis in electricity. Public power could offer a way out.

By James Baratta

Middlemen, our economy’s most shadowy characters, sit in between buyers and sellers and get rich in the process. It can even be a matter of life or death.

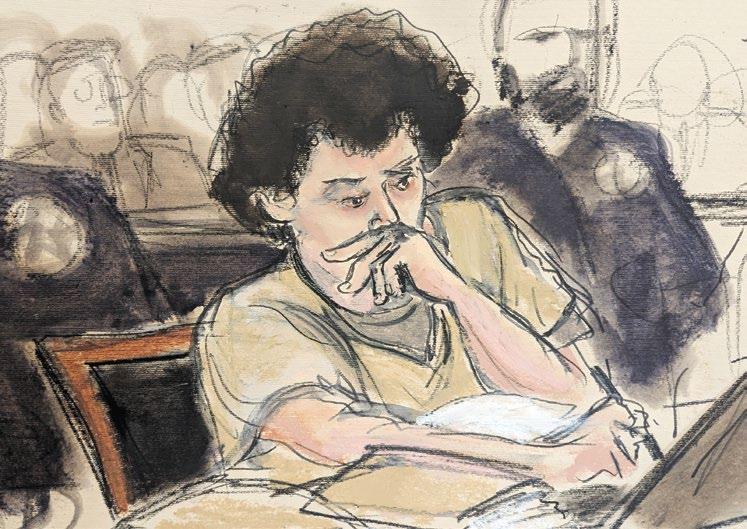

55 Adam M. Lowenstein on Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley and Stealing the Future: Sam Bankman-Fried, Elite Fraud, and the Cult of Techno-Utopia

58 Rhoda Feng on The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity 61 A.A. Dowd on Sinners 64 Parting Shot: A Breakup Letter to Capitalism By Francesca Fiorentini

Extreme weather and changes in seasonal patterns are fundamentally altering the landscape, in cities and in farming communities. You’re going to pay for it.

We’re in an affordability crisis because workers aren’t being paid at the same levels they earned in the past.

How unemployment in the Trump era shapes Black women’s lives when maternal care and food choices are in the mix By Naomi

Bethune

, election results

reinforced our instincts that the cost of living is the subject of greatest concern in America right now. Zohran Mamdani came out of nowhere by stressing on a minute-by-minute basis that New York City needed to be a more affordable place to live. On the other end of the Democratic ideological spectrum, Mikie Sherrill and Abigail Spanberger targeted their campaigns at high electricity, health care, and housing prices, and trounced Republican opponents by double digits.

Every candidate I’ve talked to who is running next year has listed affordability as their main concern. But this slogan, while compelling to the broad mass of people who feel like they’re running to stand still in this economy, lacks specificity. Why are we in an affordability crisis? What is causing it? What policies can help us out of it?

My view is that affordability is a cumulative problem. The recent post-pandemic inflation galvanized a long-standing sense that the middle-class lifestyle was moving out of reach for a lot of people. People have been struggling with health care costs for decades; they called it the Affordable Care Act for a reason. Student loans swelled as states stopped providing inexpensive higher education to residents. The average age of a first-time homebuyer is now 40, and the average age of any homebuyer went from 39 to 59 over the last 15 years.

Elizabeth Warren talked about this more than 20 years ago in the book she co-authored called The Two-Income Trap. The stay-at-home mother used to be a key safety net for families; if trouble emerged, she could go to work. Now, that second income is necessary for survival, and child care expenses—which used to be covered in the stay-at-home-mom age—are responsible for the poverty of 134,000 families a year.

Inflation since the pandemic just added costs for retail goods like groceries onto family budgets that were already stressed. The need for community after lockdowns sent the cost of experiences soaring. And corporate profits surged after the pandemic and have stayed at that level since.

In this issue, we wanted to pull out the more endemic drivers behind these trends, to look beyond Donald Trump’s contribution or other short-term factors. We started from the premise that if you don’t understand why things are getting unaffordable, you won’t be able to fix it.

I think what we’ve reported gives policymakers the potential to form a comprehensive affordability agenda. It would involve policies that boost wages and rebalance the relationship between corporations and their workers. It would simplify markets to prevent intermediaries from excessive profit-taking. It would boost public investment and public provisioning and prevent abuses of market power that lead to high prices. It would restore consumer protections to stop us from being trapped and surveilled. It would deal with disruptions from a warming planet to our typical growing patterns.

I hope this issue helps you understand both deeper causes and prospective remedies, and that affordability can become more than just a political buzzword. —David Dayen

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITORS GABRIELLE GURLEY, RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

MANAGING EDITOR AND DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL OPERATIONS

CAITLIN PENZEYMOOG

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

STAFF WRITER WHITNEY WIMBISH

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOWS EMMA JANSSEN, JAMES BARATTA, NAOMI BETHUNE

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS BRANDON MALAVE, CHARLIE MCGILL, EYCES TUBBS, ELLA TUMMEL

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, JULIAN ZELIZER

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER MAX HORTEN ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR LAUREN PFEIL

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAN CANTOR, DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, ELI LUBEROFF, LINDSAY OWENS, MILES RAPOPORT, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL)

CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/ MEMBERSHIP

REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

VOL. 36, NO. 6. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285)

Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2025 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

By Robert Kuttner

Prices have been rising across the economy in ways that are both visible and opaque. There are short-term drivers of inflation due to President Trump’s mismanagement of the economy. But the deeper drivers result from the degradation of capitalism.

For example, the lethal combination of digital technology and tech monopolies picks your pocket in countless ways. Instead of technical advances leading to greater convenience and lower cost, as they logically should, they create strategies for opportunistic price hikes.

When Amazon uses its deep knowledge of consumer preferences to rig markets and undermine competitors, higher prices are passed along. When HP makes it illegal or impossible for consumers to use cheaper non-HP cartridges in their printers, it can charge exorbitant prices. If you are prohibited from repairing your own car or your own iPhone, or as a farmer, prohibited from sav-

ing seed for next year’s planting, that invites monopoly profits built on higher prices. Costs rise because the rules are rigged.

It isn’t just the increasing cost of health insurance, but the tax on your time when a health system of byzantine complexity requires you to waste hours to get a simple referral or get a claim paid. Middlemen and algorithms, both in the business of denying claims, are a direct cost to the system and a source of rising out-of-pocket prices to patients. If insurance doesn’t pay, you do. These middlemen also function as a drain on doctor time and thus a tax on doctors’ incomes, as well as a debasement of medical services

In this special issue of the Prospect, we take stock of several hidden drivers of rising costs. David Dayen explores all the ways that technology allows sellers of any product that uses the internet to take advantage of surveillance capitalism to personalize prices

and charge more than the market price that would be produced by ordinary supply and demand. It’s another case of monopoly pricing power, facilitated by invasive technology.

As Emma Janssen writes, plutocracy is a driver of the affordability crisis. The top 10 percent of income earners now do close to half of the spending, by some estimates. This has led to “premiumization,” where airline seats, concert tickets, and even staple goods are priced for wealthier people because they are the primary buyers. That in turn drives prices higher for everyone else, as anyone who buys a ticket to a concert or a sporting event appreciates. Antitrust policy has thus far failed to curb obvious abuses by middlemen ticket sellers. Paul Starr writes in a sidebar that these trends invert the 20th-century pattern of affordable culture, beginning with nickel movie tickets and cheap bleacher seats.

As the concert ticket example shows,

middlemen are drivers of the affordability crisis. As Whitney Curry Wimbish writes, across the economy, from pharmaceuticals to real estate to meatpacking and more, middlemen sit in between suppliers and customers and squeeze out a layer of profit for themselves, taking advantage of their knowledge of industries and typically concentrated control of the supply chain.

Regulatory capture, as James Baratta points out, is another source of price increases. Baratta’s focus is on electricity rates, and the failure of state public utility commissions to protect ratepayers from extractive price hikes based on dubious economic models used by utility companies. There is an even more subtle and insidious version of regulatory capture, in which regulations themselves are used to enforce industry’s anti-competitive strategies.

As Cory Doctorow observes in his indispensable book Enshittification (reviewed in

our October issue), far more sinister than traditional regulatory capture is regulatory fusion , in which industry designs laws and rules to thwart competition and raise profits. Using provisions of the industrywritten 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, Apple makes it a copyright violation for technicians to use non-Apple parts for most repairs to Apple products. The preposterous doctrine is that if an inferior non-Apple part caused the product to fail, that could reduce consumer confidence in Apple’s brand. There is even a name for this doctrine: tarnishment.

Trump’s contribution to rising prices adds to these long-term abuses. Eric Winograd, a senior vice president at AllianceBernstein, calculates that Trump’s tariffs have added about one percentage point to the core inflation rate, though other estimates that account for Trump’s numerous exemptions

of various products and industries put the number at 0.6 to 0.7 percent.

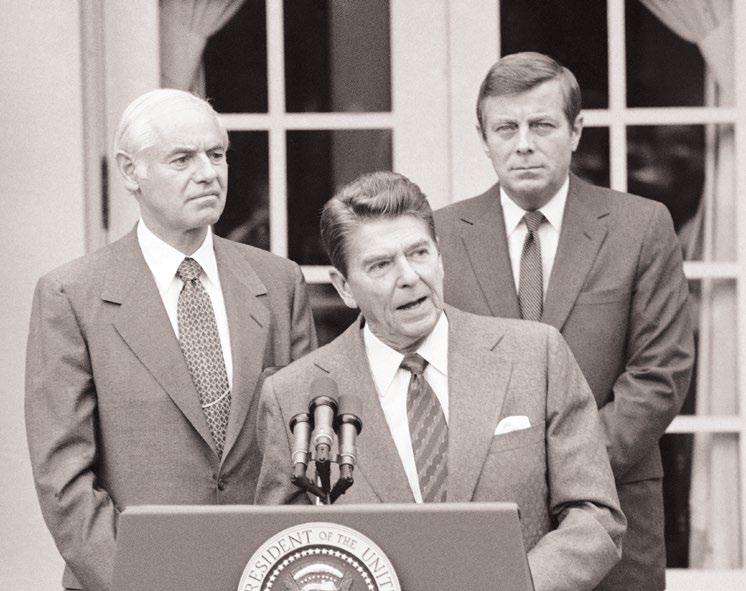

But tariffs are only the beginning of Trump’s impact on prices. The remedy for opportunistic price hikes in so many sectors is the resurrection of antitrust. Internet innovators grew from purveyors of ingenuity and user convenience into extractive monopolies largely because antitrust enforcement ceased to exist from late in the Carter administration until Joe Biden’s appointments of some of the smartest students of abuses and their remedies: Lina Khan at the FTC, Jonathan Kanter at the Justice Department, Rohit Chopra at the CFPB, and Tim Wu (whose latest book is reviewed in these pages) as competition policy chief at the White House.

These agencies had just gotten serious about reversing four decades of corporate market power when the antitrust revolution was reversed by Trump. As antitrust

enforcement has been aborted, private equity companies have been buying up traditionally local firms in order to use market power to raise prices, in sectors as diverse as pest control operations, HVAC companies, and veterinary practices

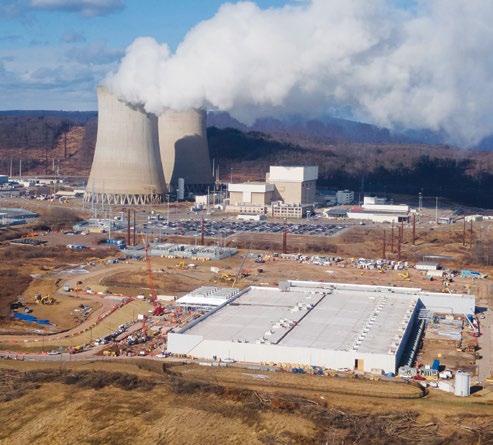

In addition, Trump’s shutting down of Biden’s industrial policies has raised prices. Electric power costs have lately risen far faster than the general rate of inflation. Trump’s policy of killing renewable-energy projects, in order to raise profits for oil and gas companies, contributes to this price rise, by taking away power that might otherwise come onto the grid and alleviate demand. So does the failure to regulate the extensive use of electric power by data centers used by tech companies.

There was a time when we needed to shift to solar and wind in order to help address climate change. But now that renewables are cheaper than most fossil fuels, we need to make that shift because it saves money. Instead, Trump promotes more costly oil and gas.

It is hard to quantify precisely how much all of Trump’s policies taken together have added to price inflation, but a very conservative estimate would be about two percentage points. That may not sound like a lot, but it is the difference between a baseline inflation rate of 2.5 percent and a rate of 4.5 percent. And that difference is not just a hidden tax on consumers. It has knock-on effects.

With inflation at 2.5 percent, the Federal Reserve is willing to reduce interest rates in order to reduce unemployment. But when price increases approach 4 percent, the Fed worries more about inflation. At a time when unemployment rates are rising, policies that raise prices tie the Fed’s hands. This paradoxically could make things more unaffordable for low-income workers, if a loose job market keeps wages from rising.

It’s not clear whether there will be any more rate cuts in the near future, and there may even be rate increases. A Fed policy of tighter money means that people pay more for their mortgage loans, their credit card debt, their student loans, and consumers pay more when small businesses pay more for credit.

Trump’s cuts in programs such as SNAP and Medicaid are another form of indirect price hikes; even worse, they are price hikes that hit the poor. If your food stamp allotment is reduced, you have to pay more out of pocket in order to eat. If your Medicaid

Higher

is cut, you pay out of pocket or do without. The failure to address climate change, and Trump’s reversal of long-standing policies aimed at preserving the environment, also add to costs. As destructive storms become more severe and frequent, the costs of recovery and of homeowner insurance relentlessly rise, some borne by consumers directly and some by taxpayers. This natural-world aspect of hidden inflation is addressed in another of our special articles, by Gabrielle Gurley.

Some years ago, there was a debate among economists and policymakers about whether the Consumer Price Index should be adjusted downward to reflect improvements in quality. A 2020 car was simply a better car than a 1980 car, so some of the nominal price inflation actually represented a superior product. Likewise coffee: In 1970, a cup of coffee only cost a dime, but the swill was undrinkable. Coffee today is a lot more expensive, but it is palatable. In practice, the Bureau of Labor Statistics did some minor revisions to adjust for quality improvements. Today, we might need to do the reverse. We are paying more money for products and services whose quality has deteriorated. And in many cases, the deterioration has been deliberate. Indeed, the business model of the tech giants is to systematically degrade the quality of products and services. Products are needlessly complex from the perspective of the consumer, but the complexity adds to the surveillance. Same

with tech services. This is the essence of what Doctorow calls enshittification. Doctorow tells the story of how Google deliberately slowed down its search process in order to make more time for its system to festoon the search results with annoying ads that embody everything that Google knows about the user’s buying habits.

In conventional economics, wages and prices are two different aspects of the economy. But whether people can afford to live decently is a function of what they earn applied to what they have to pay to live. The same technology that allows tech monopolists to gouge consumers enables them to treat workers like serfs and evade the protections of labor law. As Harold Meyerson writes in his piece, the cost of living is higher because earnings are lower. And earnings are lower because of both the weakening of the labor movement and the sidelining of the National Labor Relations Board.

In addition, tech allows employers to double down on the old practice of denying that workers are payroll employees protected by labor laws. From Uber drivers and UPS contractors to chicken farmers and fast-food workers, the company controls and monitors every aspect of the work, but the employer pretends that the workers are independent contractors. This represents a toxic marriage of app technology and market power. The effect is to batter down earnings.

And as Naomi Bethune writes, all of the predations tend to hit racial and ethnic minorities harder, because African Americans and Latinos are more economically

vulnerable to begin with. Trump’s war on DEI only increases the vulnerability.

Even apart from the predations of extractive and invasive capitalism, other sources of the relentless rise in prices are the result of policy failures that predate the abuses of surveillance capitalism and Donald Trump by decades.

Housing is out of reach for so many Americans because America has failed to build enough houses. Houses were cheap after World War II mainly because cheap farmland was being converted to suburbia, with the help of federal highway and mortgage policies. The cheap land is gone, and homebuilder consolidation has distorted markets. Trump’s tariffs have caused a rise in building costs, and his proposal to privatize the secondary mortgage market would make financing more expensive.

Housing tax breaks are tilted toward more expensive homes, and toward homeowners over renters. The sheer purchasing power of the oligarchy also bids up prices. Local regulatory barriers also raise costs, but many zoning restrictions also reflect the political power of oligarchs, who don’t want riffraff in their neighborhoods.

The bipartisan failure to regulate new financial scams such as subprime mortgages added to the pressure on housing. Millions of homeowners, disproportionately Black and Hispanic, lost their homes in the wake of the subprime collapse. Congress passed legislation to allow for mortgage refinancing for duped homeowners, but

the Obama administration failed to carry it out. You might think that scads of vacant and foreclosed houses would lead to lower prices via the law of supply and demand. But the same regulatory failure led private equity companies to swoop in, buy houses, and jack up prices and rents, while making homebuilders reluctant to build the additional units we need.

Public policy has also failed to produce an adequate supply of affordable rental housing. The rental housing that we do subsidize is done in wildly inefficient ways, for the convenience and profit of landlords and developers. Our failure to have a true socialhousing sector reflects power imbalances between oligarchs and ordinary citizens.

The cost of higher education is out of sight because legislators, Republican and Democrat alike, permitted universities to inflate costs via the student loan program, and then piled debt onto generations of students and graduates. State legislatures compounded the damage by reducing direct appropriations to public universities that were free to state residents until a generation ago, substituting tuition and fees. It now costs more to attend a state university than what a private university cost when I was a student.

Health care costs also keep rising because the United States has failed to adopt an efficient program of universal public health insurance, as every other major country has done. To compound the damage, policymakers have allowed a plague of for-profit middlemen to take over hospitals, nursing homes, and doctors’ practices. In many hos-

pitals, people of means hire private nurses because the hospital’s own nursing staff is so stretched thin and overworked by costcutting aimed at siphoning profits. A hidden price hike, if you can afford it. If the U.S. had a universal nonprofit insurance system, it would save about 6 percent of GDP. That’s $1.2 trillion a year.

There was a time when the abuses of capitalism were relatively straightforward and transparent. Large corporations sought to combine into monopolies. The remedy was enactment and enforcement of antitrust laws. Corporations tried to pay their workers as little as possible and to break their unions. The remedy was the Wagner Act, guaranteeing workers the right to organize and join unions. Bankers tried to swindle investors for their own enrichment. The remedy was tougher banking and securities laws, prohibiting conflicts of interest. Corporations tried to cheat consumers with tricky terms and shoddy products. The remedy was the proconsumer legislation of the 1960s and 1970s.

But today’s corporate and financial abuses are hidden in a web of algorithms and apps, reinforced by regulations that actually help tech companies cheat consumers rather than protect them. It takes a complex, deeply knowledgeable, and radical critique of capitalism as currently practiced to get serious about remedies. That does not describe about half of the current Democratic Party, which is on the take from these same industries.

One of the many tragedies of Joe Biden was that he was a feeble spokesman for his own good policies. He hired the most knowledgeable people in the country to revive antitrust and apply it to new abuses. But Biden did poorly at narrating the significance of these policies to ordinary Americans coping with rising prices. As I’ve written elsewhere, many of these policies and people reflected the work of Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who was a superb narrator of what they meant and why we needed them. But we ended up with the soul of Elizabeth Warren in the feckless persona of Joe Biden.

If we can make the heroic assumption that Trump will not be president forever, and that there will be an opportunity to pick up where Biden and Warren left off, America’s next leaders will need to be even more radical in their understanding and remediation of capitalism, which has become even more debased since Trump took office. n

By Emma Janssen

We are living in a new Gilded Age. The first, from roughly 1870 to 1890, was marked by dramatic inequality: Wealthy monopolists like bank tycoons and railroad barons saw their fortunes boom as the country industrialized, while the poor, particularly in the post-Reconstruction South, continued to suffer. A cast of corrupt men controlled the flow of capital and political power, shaping the country around their will. Thus it was not a golden age, but a gilded one—a veneer of prosperity hiding the real economic and social rot below.

Today, with a president obsessed with gold and material wealth, the Second Gilded Age metaphors write themselves; just look at the literally gilded add-ons to the Oval Office. Tens of millions of Americans rely on government food and medical assistance that Republicans have voted to cut; some Americans use “buy now, pay later” apps to pay for their rent and groceries; and wages can’t keep up with inflation. But the wealthy are doing just fine. The stock market is up 48 percent since 2022; luxury-brand purchases are holding strong; and Elon Musk is about to get a $1 trillion pay package. Our country is dramatically unequal, and it’s only getting worse.

The rich have a gravitational pull on the economy, dragging it in their direction. According to economic researchers at Moody’s Analytics, the top 10 percent of Americans earners are now doing almost half of the spending. Even those economists who dispute this specific number concede that the wealthiest Americans are doing an outsized amount of consumer spending. The wealth of the top 10 percent is up to $113 trillion, up $5 trillion just between April and July, according to Federal Reserve data. The top 1 percent holds $52 trillion in wealth, a new record.

That matters for several reasons. First, it produces an unclear picture of the economy. Even though the majority of Americans are feeling the squeeze of inflation and rising unemployment, the ultra-wealthy are doing well enough to keep spending, which makes it look like everyone has kept spending.

If you stop looking at averages and check the wealth of who’s actually spending, you can better understand the economic realities for the majority of Americans: There’s one line steadily going up, and another going down. That’s why some call ours a “K-shaped” economy—two lines headed in opposite directions. Others call it a plu-

tonomy, a portmanteau of “plutocrat” and “economy,” signaling the disproportional power of the ultra-wealthy over our entire financial system.

There’s another reason that this wealth and spending inequality matters: It makes things more expensive for everyone.

Corporations know that the wealthy have a distortionary impact on the economy, as they continue to spend while everyone else flounders. Citigroup executives coined the term “plutonomy” almost exactly 20 years ago in a memo sent to investors. The bankers didn’t coin the term as an intellectual exercise; the goal was to curate stocks accordingly. Identifying the country’s “plutonomy” was a way to marshal the movers of American capitalism, giving them a framework to continue making money. Corporations have taken note. If wealthy consumers are responsible for the lion’s share of spending, the logic goes, companies might as well raise their prices—the primary buyers can afford it.

“If you can come up with something that [rich people will] regard as special, you can really make a lot of money selling to

Companies like Dyson cater their products to wealthier customers who do more of the spending.

them,” said Robert Frank , a professor of management and economics at Cornell. “So, a lot of the ingenuity in the economy gets directed to things that we would think of as less than essential.”

That’s the idea behind premiumization, a marketing trend that encourages companies to brand their products as high-end and sell them to wealthier consumers. A Forbes article describes premiumization as a “strategic move by consumer brands to elevate product offerings and charge higher prices.” The push for premiumization is largely driven by demand—wealthier consumers have more money to spend and are looking for “premium” ways to spend it—but it is also spurred on by inflation, which pushes companies to justify price hikes with a shiny exterior.

“If I tell you that I raised your price … because I need to increase my profitability, you’re probably just going to go away,” said Z. John Zhang, a professor of marketing at the University of Pennsylvania. “But if I tell you that I raised my price because … I pro -

duced a better product for you, that sounds like a better message.”

Michael Rapino, the CEO of Live Nation, the owner of the loathed, fee-grabbing event ticketing operator Ticketmaster, was blunt about this in an interview with The New York Times ’ Andrew Ross Sorkin. “I think music has been underappreciated,” he said. “It’s like a badge of honor to spend 70 grand for a Knicks courtside [seat], they beat me up if we charge $800 for Beyoncé … we have a lot of runway left.”

Once you learn the term, it’s hard not to see premiumization everywhere. Demand for new luxury goods is outstripped only by demand for used luxury goods from websites like The RealReal. Apple and Dyson (maker of $1,000 vacuums as well as $400 hair dryers) have long embraced premium aesthetics to sell their products, but so have more surprising companies: WD-40, the company that makes the eponymous lubricant, found that they could charge more by selling cans with “smart straws” that spray the oil in both a stream and a mist.

Airplanes are becoming premiumization delivery systems, with seats that were once considered basic economy now sold as premium because they are in the front of the plane. The half-decent seat pitch (referring to the distance between your seat and the seat in front of you) that was once standard has now become a luxury that passengers will pay for to avoid the even more cramped seats in the back. Some first-class “suites” now have doors, caviar service, and even free pajamas.

Changes to Disney resorts reveal premiumization in perhaps its most concentrated form. Whereas traveling to Disneyland or Disney World was once a rite of passage for the middle class, visitors now shell out for access to the front of the line for rides; those booking a guide or staying at a Disney property get priority. (Until 2021, that FastPass service was free, as long as patrons returned to the ride in a specific time window.) There’s a lounge in Disney’s EPCOT that has a $179-per-person prix fixe snack and champagne; Disney’s Grand

Social media has ratcheted up the status competition, making the clothes we wear and the weddings we throw visible to everyone we know.

a measure of the average change over time in prices Americans pay for a new car with roughly similar features. That data tells us that, between 1980 and 2025, the price of a new car doubled. But when you look at what consumers are actually spending on new cars, it’s now somewhere around six times as much as it was in 1980. Are today’s cars three times better than they were in 1980? Maybe. But if consumers don’t actually need cars that are three times as good, and are buying them anyway, it points to two possible reasons: They’re paying for the status of the car, or premium options are the majority of what’s for sale.

to more wealth and consumption in an hour of scrolling than some of their grandparents ever saw in a lifetime. Just take the social media hubbub around ultra-wealthy Anant Ambani’s Mumbai wedding in 2024 or the TikTok-fueled tween obsession with Drunk Elephant, a skin care brand that will run you $72 for a moisturizer. The $250 billion influencer industry is selling their lifestyles to us, whether or not we can afford them.

Floridian hotel on the resort grounds has a Michelin-starred restaurant; there’s a secret Club 33 in the theme parks that is invitation-only. Instead of providing a common experience, Disney caters to the rich, putting a velvet rope around the most American vacation there is.

An increase in costs and luxuries doesn’t just affect wealthy spenders. Middle-class Americans see the same advertisements, watch the same influencer vlogs, and thus feel pressure to make the same purchases. And sometimes it’s not just psychological pressure, but simple logistics: If the only hair dryer at your beauty supply store is a Dyson, and you need a hair dryer, you will end up paying more.

J.W. Mason , an associate professor of economics at John Jay College at the City University of New York, compares this to a kind of premiumization that some companies turned to during World War II, when the country put caps on the price of goods to manage runaway inflation. The price controls were quite effective at slowing massive inflation, but some companies found a clever way around the caps by only stocking high-end items, so they could say they didn’t raise their prices, but still charge a premium. While today’s businesses aren’t responding to the same artificial price caps, consumers are feeling something similar when their only options are premium-ized and marked up.

We can see some evidence that consumers are responding to premiumization by buying more expensive versions of the same products. Using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, I looked at the Consumer Price Index for new vehicles, yielding

Another good example is weddings. Within just a few years, event planners have noticed a steep rise in couples wanting to tie the knot away from home. Market research confirms it: The destination wedding industry grew by $7 billion between 2022 and 2023. By 2027, the industry will be worth more than $78 billion. “If what people are buying isn’t just the material thing, but the kind of status and display that goes with it, then people may feel that they have to buy more expensive versions,” said Mason.

This jostling for status has a real economic impact. A study of U.K. consumers found that around 40 percent of Brits had been invited to a destination wedding in the past year, and the average cost of attendance lands around $2,500. Of those who attended, over 30 percent put the travel expenses on their credit cards. Others used buy now, pay later services or even took out loans.

It’s a natural thing to feel the pressure of “keeping up with the Joneses,” but that becomes a lot harder in a plutonomy, when the Joneses are really, really rich. It’s also harder to tune out the lifestyles of our neighbors now that they’re all over our phones. Social media has ratcheted up the status competition, making the clothes we wear and the weddings we throw visible to everyone we know, and often to thousands of strangers too. It’s a digital form of the upsell: Instead of the fast-food clerk asking if you want fries with that, thousands of people streaming through your feed are telling you to take that vacation, go to that five-star hotel, and live your best life. We’re living in the FOMO economy.

In the early days of Facebook and Instagram, users could keep up with how their friends were living; now, with TikTok’s boom and algorithms designed to push content from strangers, users are exposed

Frank, who wrote the 2013 book Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class, was careful to note that the blame for our plutonomy shouldn’t fall on consumers, whether it be the wealthy who are indulging in luxuries or the middle- and working-class people who feel pressure to spend more than they have. The wealthy “do what everybody does who has more money: They spend more, they build bigger, they buy faster, they travel farther,” he said. “That’s not a moral indictment of them. I mean, that’s what poor people do when they get more money. That’s what middle-class people do when they get more. Rich people do that too,” he said.

If anyone should be blamed for our rapidly increasing consumer inequality, Frank argues, it’s policymakers who refuse to tax the wealthy. “When [the wealthy] just bid up the prices of penthouse apartments, there’s only so many of them with views of Central Park to go around,” he said. If the government taxed the exorbitantly wealthy, “all that money that went into that could have been used to buy things that are actually useful for everybody.”

To Mike Pierce, the executive director of debtor advocacy group Protect Borrowers, corporate America deserves much of the blame, too. When speaking about plutonomy and premiumization, “it’s really easy to tell a story about how people are living beyond their means,” Pierce said. “But the real story here is about big financial companies seeing that precarity, that vulnerability, and trying to get rich off of it.”

The middle class is taught, through carefully designed marketing and social media, to identify more with the rich than the poor. This class misalignment keeps them striving for the upward mobility our economic mythology promises them, even though so many are just one medical emergency or car crash away from poverty.

“The people in the middle aren’t resentful of the lifestyles of the rich,” Frank said. “They want to see pictures and footage of

mansions and yachts. They think, usually incorrectly, they’ll be rich someday. What’s it going to be like?”

On October 29, Chipotle, purveyors of burritos and slop bowls, had a difficult earnings call. CEO Scott Boatwright described the “consumer headwinds” the company has been experiencing as consumers who make below $100,000 per year have stopped eating out. The executives offered a succinct explanation: Everyone who isn’t wealthy is feeling the weight of unemployment, student loan repayments, and slow wage growth. These low- to middle-class consumers account for 40 percent of Chipotle’s sales, so losing them threatens their whole business model. Chipotle is not alone. Other fast-casual chains are seeing depressed sales. Walmart, Kohl’s, and discount store Dollar General have noticed their lowestearning customers spending less and less. Growing numbers of back-to-school shopping families have struggled to outfit their kids this year. Americans making over $100,000 a year have seen their consumer sentiment climb in 2025, while those under $100,000 are gloomy.

If Chipotle is missing a major chunk of its customer base, it’s likely they’ll be forced to raise the prices for everyone else to make up for it. Maybe they’ll use premiumization to justify those price hikes (special guacamole or healthful tortillas, perhaps). Regardless of their strategy, low- and middle-class consumers lose. If prices go up, eating out at Chipotle becomes less of a casual weekday lunch and more of a once-in-a-while treat. And, generalizing this conclusion to other goods and services not of the burrito bowl variety, it’s clear that the goalposts of a comfortable middle-class lifestyle have just moved further back.

Pierce took a second lesson from the Chipotle earnings call. “It’s downstream from that moment when the C-suite is finally waking up to the fact that people can’t afford the stuff they’re selling,” he said. “They haven’t been able to afford the stuff they’re selling for a while now, and easy access to debt is masking that sickness in the economy.”

Indeed, wide-open access to lines of credit is one tool that has emerged to keep Americans spending like influencers—or even just staying afloat—despite economic trouble. With the proliferation of “buy now, pay later” companies like Klarna and

is one tool that has emerged to keep Americans spending like influencers.

“We know that inequality is psychologically discomforting to people,” said Bernstein. “If you’re a billionaire, and the person you think you’re competing with is a trillionaire, you feel like you’re falling behind … I think for most middle-class people, falling behind means falling behind on the rent.”

Affirm, which allow consumers to put purchases on credit and pay off their debt over a number of weeks, Americans can keep buying what they always have, even if they don’t actually have the money in hard cash.

While the majority of buy now, pay later purchases are for general “stuff,” like furniture and clothing, an alarming number of Americans are using these debt services for absolute essentials. A quarter of buy now, pay later users have used the services to pay their rent, according to a poll commissioned by Protect Borrowers and Groundwork Collaborative. One in three have used it to pay for medical or dental care. Perhaps most harrowingly, nearly 40 percent have used buy now, pay later to make a payment on another debt, such as a credit card payment.

Those numbers are a stark reminder that middle- and working-class Americans aren’t greedy or overindulgent; instead, they are just trying to live in accordance with the model set by generations past, where a meal out or a new sweater didn’t require taking on debt. In our new Gilded Age, that’s a much harder prospect.

These Americans “go to work every day, they bring home the paycheck that they command in our economy, and it just doesn’t go far enough,” said Pierce. “And so, they’re figuring out how to live the same kind of life that their parents lived, and to do that often involves a tremendous amount of consumer debt.”

Jared Bernstein, former chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Biden, emphasized to me that for increasing numbers of Americans, the issue isn’t whether they can afford a destination wedding or a new car. Instead, it’s whether they can put food on the table while also paying off student loans and the electricity bill.

Whether they’re taking on debt to buy the products and experiences social media markets as the trappings of a good middle-class life, or taking on debt just to make rent, those in the middle are feeling the squeeze of an economy by and for the wealthy. Our ideas of how to live and what to buy are often warped, as if in a funhouse mirror, by the ultra-rich and the companies that design products toward them.

Soon, Pierce told me, he thinks people will start to miss their buy now, pay later payments en masse. Those companies are directly linked to consumer bank accounts, so people will start getting charged overdraft fees if they don’t have enough when “pay later” becomes “pay now.” Pierce sees the buy now, pay later economy as a house of cards threatening collapse as debt catches up with consumers.

I asked him if he worries about the shifting goalposts of middle-class life—the idea that we need luxury cars and new clothes and destination weddings to keep up with the wealthy. He agreed that our plutonomy is psychologically destructive, but fears something far worse.

“I certainly do worry about what it means for the American dream and the way people think about their role in the economy if this keeps up,” he said. “But I worry more about what it means if people don’t actually have any agency in that position, and at some point Wall Street pulls the rug right out from under them.”

Those of us who are “too poor to afford life, but too high-income to get help,” as Elizabeth Pancotti, managing director of policy and advocacy at Groundwork Collaborative, put it, are caught between a plutonomy that pushes prices higher and a lower class that, under the Trump administration, is rapidly having the social safety net pulled out from under them.

“You really get squeezed by both sides by this phenomenon of prices going up as things get luxurious, and you don’t get any help from the bottom,” she said. “And I think that window is expanding as our social safety net shrinks as the wealthy get even richer.” n

“Everyone is a V.I.P.” was the motto of the Disney theme parks for decades after the opening of Disneyland in 1955. A broad middle class could afford a trip to a Disney park, and visitors had equal access to the attractions once they were there.

Unfortunately, America is a long way from that middleclass ideal today.

Disney and other companies now make more money from people with high incomes, and they tailor their services accordingly. So much for the old Disney theme song: “When you wish upon a star / Makes no difference who you are.”

The original Disney vision reflected a long history of popular cultural affordability that once set America apart. At the time of the American Revolution and during the first half of the 19th century, European countries levied stamp taxes on newspapers, to raise their prices and block the growth of a cheap working-class press that might cause trouble. In contrast, as I showed in my book The Creation of the Media , Americans didn’t just revolt against the British stamp taxes; their new government subsidized newspapers and later magazines through below-cost postal rates. (Low-cost “media mail” rates for books and periodicals exist to this day, though they are much less significant than they once were.) In the 1830s and 1840s, a revolution of cheap print brought a popularly oriented “penny press.” That development initially had more to do with the popular politics of Jacksonian America than with technological advances in printing technology. Entre -

preneurs developed faster presses to satisfy a market the partisan papers pioneered.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a series of low-cost innovations in popular culture. As working people had more discretionary income and free time, showmen found they could make money based on what historian David Nasaw calls a “new calculus of public entertainment”—lower prices and larger audiences. The new venues had to be cheap but respectable. Like the penny papers, some were named for their low price, from dime museums and penny arcades to nickelodeons, the first popular venues for movies.

Free public elementary and secondary education, public libraries, land grant colleges with low tuition, and the 20th century’s mass media—including free, over-the-air radio and television—all fit into this tradition. New Deal programs supported artists, musicians, writers, and actors and left cultural legacies across the country. Public broadcasting and the early vision of the internet as a cornucopia of free culture also aimed to fulfill the old ideals that originally motivated cheap postal rates for publications.

The economist William Baumol raised a famous caution about cultural afford -

ability. The costs of cultural production, according to “Baumol’s law,” necessarily rise relative to other goods because productivity in culture cannot keep pace. His illustration was a live musical performance, which will always take musicians the same time. That’s true but of limited relevance to what has been happening lately.

How commercially produced culture is designed and priced depends on the distribution of income. In a society where the top 5 or 10 percent have gotten richer and dominate consumer spending, many companies unsurprisingly have reoriented their business. Management consultant Daniel Currell wrote in The New York Times in August that “Disney’s ethos began to change in the 1990s as it increased its luxury offerings, but only after the economic shock of the pandemic did the company seem to more fully abandon any pretense of being a middle-class institution.”

As a consultant, Currell says he saw “industry after industry” use data analytics “to shift their focus to the big spenders” in their customer base. “Whereas in the 1970s and before, the revenue driving corporate profits came from the middle class, by the 1990s it was clear that the big money was at the top.”

A different political leadership might resist these tendencies. Not only might it use taxes and other measures to ensure that the gains from economic growth are more widely shared; it might also find new ways to do what earlier generations did in making culture and education more affordable. Today, however, the Trump administration is not just cutting back but eliminating federal support of the arts and education, supposedly for populist reasons. It’s popular access that will suffer.

Americans don’t need to do anything unprecedented to respond to current trends and policies. They just need to remember a great American tradition of making culture affordable.

—Paul Starr

AI’s real contribution to humanity could be maximizing corporate profit by preying on personal data to raise prices. In fact, it’s already happening.

By David Dayen

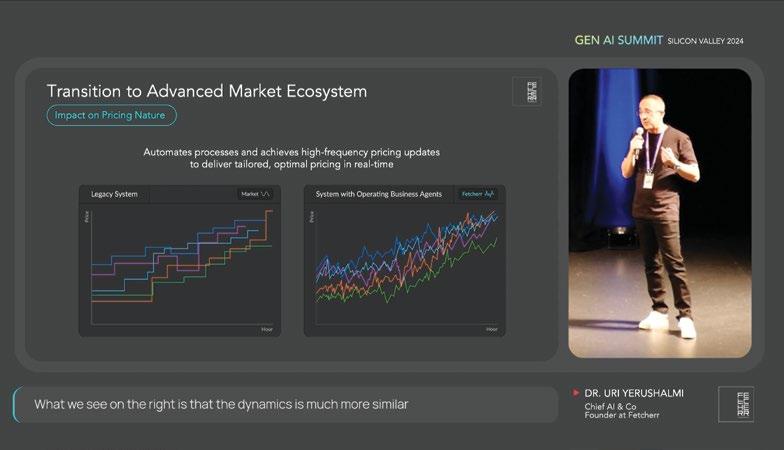

Earlier this year, a slightly balding man in spectacles, a black T-shirt, and bright hightop sneakers gave a presentation about how his computer can predict what you want to buy. His name is Dr. Uri Yerushalmi, co-founder and chief artificial intelligence officer of Fetcherr, an Israeli-based pricing consultant used by a half dozen airlines around the world.

“While most of us in the AI community have been focusing on building models that are generating either text or image, in Fetcherr we have been focusing during the last five years on building large market models,” Yerushalmi said. Trained on years of market data—prices, orders, competitors, regulation, stock prices, even the weather— Fetcherr’s “business agents” aim to simulate market dynamics, assist pricing analysts, and even automatically price tickets.

One presentation slide stuck out. It showed price fluctuations before the use of Fetcherr’s system and after. In the before graph, prices are relatively static and straight. After Fetcherr, the jagged lines pulse with staccato rhythms. “The dynamic is much more similar to dynam-

ics in NASDAQ or capital markets where the prices change much more frequently,” said Yerushalmi, “because every time something in the market changes, there is an immediate response.”

Yerushalmi once ran AI for a high-speed stock trading firm. He approaches pricing like a science experiment, engaging in constant real-time testing and tweaking to maximize corporate profits. Fetcherr boasts of delivering annual “revenue uplift” of over 10 percent. The guinea pigs for these tests, the ones being separated from their cash, are you and me.

AI can depict you as an anime character. It can respond half-intelligently to questions about the Franco-Prussian War or concentrations of sulfur in the upper atmosphere. It can delight and distract and maybe help you get work done. But none of that is as prized by corporate America as its data-driven approach to the previously conjectural world of pricing.

“That’s the use case they don’t want you to talk about. That’s why we’re building all these data centers,” said Lee Hepner, senior legal counsel for the American Eco -

nomic Liberties Project. “As we have built social media platforms that shape the flow of information across society, now we are building the platforms that control the flow of money.”

Technology-fueled pricing is more widespread than once thought, presenting serious policy challenges in an age where affordability is on everyone’s minds. AI bots are colluding with one another, anticipating consumer choices, and accumulating surplus—that is, transferring wealth—for the businesses that employ them. It’s part of why corporate profits hit record highs after the pandemic and have stayed there.

The public recoils at the thought of seeing prices tick up based on when they like to get lunch or what device they’re using. When Delta, which employs Fetcherr as a pricing agent, announced on an earnings call this summer that up to 20 percent of its flights would be priced using AI by the end of the year, the outcry was so intense that the company claimed its critics were peddling “misinformation.”

Policymakers and advocates have united to crack down on some tactics, winning real legislative victories from coast to coast. But every step government takes can be countered by AI price-setters. How can consumers keep up?

“What worries me is that it will become hyperefficient to price discriminate and to charge more in ways that ordinary people will not be able to combat,” said Doha Mekki, the top deputy at the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division under Joe Biden. “And it will make a very bad cost-of-living crisis even worse.”

A year ago, I wrote about what I termed surveillance pricing: companies offering individualized prices based on personal data. The idea was that a business equipped with granular information about demographics, purchase history, social and financial interactions, or even medical status could exploit a customer’s willingness to pay. Uber could charge more when a rider booked on a company credit card; people aren’t as pricesensitive when someone else is paying. Delta could jack up fares after learning that a traveler needs to attend a funeral; desperation could translate into opportunity.

I couldn’t be certain how many businesses

used surveillance pricing. The proliferation of third-party pricing consultants touting “digital pricing transformations” seemed like a strong indicator. But concealment was key to the strategy, to minimize the anger generated by charging different prices to different people. For instance, when a reporter at SFGate logged in to hotel booking platforms using his regular IP address in high-wage San Francisco, he received a quote of $829 a night. But when he used a virtual private network set up to originate from Phoenix or Kansas City, prices were more than $500 less. Without a public price, it takes research to understand if someone is being ripped off.

A month after my report, Lina Khan’s Federal Trade Commission announced an investigation into surveillance pricing, seeking information from eight third-party consultants. The agency only had a short time to conduct the study before the changeover of power in Washington. But days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, it issued “research summaries” of the work done thus far. (Trump’s FTC has yet to finish the study.)

Stephanie Nguyen, the FTC ’s chief technologist under Khan, told me those eight pricing consultants were working with

over 250 clients, suggesting broad reach across the economy. Services included individually targeted pricing, segmentation of customers based on their profiles, and ranking tools that alter what products people see atop a web page or search. A customer clicking on fast shipping, for example, suggests an urgency that would lead them to tolerate higher prices. The key to surveillance pricing is data. Nguyen and Sam Levine, the FTC ’s former head of the Bureau of Consumer Protection, recently wrote a paper about how customers deliver that data when they sign up for loyalty programs. Enticed by promised discounts and concierge treatment, customers consent to data collection that allows companies to build intricate social graphs; one customer profile created by the grocery chain Kroger stretched to 62 pages. The discounts often aren’t maintained or are curtailed, loyalty card fees expand over time, and the more loyal a customer, the more data is collected and the more they pay over time, according to the report.

One case study is the McDonald’s app, which has 185 million users and provides seamless access on smartphones, our per-

sonal data-spewing machines. According to a recent earnings call, after downloading the app, a customer goes from 10.5 annual McDonald’s visits on average to 26. McDonald’s clearly wants its customers on the app. Its popular Monopoly game gives out stickers on the packaging of items like Big Macs and fries; you collect the right ones to win big prizes. But this year, instead of filling out a physical game board, Monopoly pieces now must be scanned into the app.

“This is about taxing people who don’t turn over their data, and manipulating people who do,” Levine said. “Do we really want a world in which you will have to pay a premium if you want to shop anonymously?”

Surveillance pricing is just one technology that companies use to set prices. Surge pricing accelerates supply and demand to raise prices when more people want the product or service. Subscription pricing offers products for a monthly fee, a steady stream of revenue from absent-minded customers that can feature deceptive sign-ups and impossible cancellation policies. Trump’s FTC sued Uber for a subscription service that takes as many as 23 screens and 32 actions to cancel;

Amazon Prime’s cancellation policy, the subject of a separate FTC settlement that cost the company $2.5 billion, was internally nicknamed “Iliad Flow,” like the tortuous war Odysseus waged in the Greek epic.

Electronic shelf tags at Walmart and other grocers have triggered fears of endlessly changing prices while you shop. FIFA has confirmed use of differential pricing for World Cup events based on demand, something New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani has criticized. “They can become a tool for pure extraction and leave everybody paying what they shouldn’t,” said Kevin Erickson of the Future of Music Coalition, which monitors event ticketing.

One of the most insidious uses of technology is on the wage side. An issue brief from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth focused on how companies are using personal data to set worker pay, something first seen in the ride-hailing industry. Twenty AI consultants offer surveillance wage services to clients in logistics, manufacturing, retail, finance, education, transportation, technology, and health care, which is “the new Uber in a lot

of ways,” said Veena Dubal, a law professor at the University of California and coauthor of the report.

The AI systems can adjust worker pay in real time, and offer different wages to people doing the same work. They can adjust wages based on performance data, customer feedback, and even factors off the job, such as “predictive analytics that attempt to determine a worker’s potential tolerance for low pay,” the report notes. Most of these wagesetting practices are opaque to workers or their bargaining representatives.

“This is becoming normalized,” Dubal said. “It fundamentally undermines the well-worn and very American idea that hard work should result in higher pay.”

The result of these strategies is that supply and demand no longer solely determines price, as in textbook economics. AI-based pricing has become more critical than sale volume or product quality. Customers seeking a fair deal are simply outworked, unable to avoid being targeted. “There used to be moments where you really blew it, you had to buy a last-minute airline ticket and they’ve got you,” said

Tim Wu, former competition policy chief in the Biden White House. “That’s really daily life now.”

Consumers used to benefit from what economists would call imperfect information. The uncertainty of defining the optimal price, and the ability in open markets for new businesses to undercut competitors, gave consumers a fighting chance to get a deal, or just to manage their life without being tracked and prodded. Technology eliminates that information inefficiency. “What these technologies are about is eliminating all risk for the shareholder,” Hepner said. “There’s no more error. It is a well-oiled extraction machine.”

Even advocates have been surprised by the furiousness of the response to technologyaided pricing. As post-pandemic inflation swelled, AI trickery was a tangible, easy-tounderstand depiction of an economy rigged against ordinary people, and the lack of transparency and unpredictability vexed consumers. “It was hiding in plain sight and everyone has found it and you just can’t unsee it,” said Lindsay Owens, executive director of the Groundwork Collaborative.

Politicians looking for anti-inflation messaging rode the wave of constituent anger. Sen. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ) challenged Delta’s palpable glee over surveillance pricing in an earnings call, and when Delta responded that they wouldn’t actually target customers using their personal data, Gallego didn’t let up. After all, Delta’s president Glen Hauenstein said on the earnings call that “to get [travelers] the right offer in your hand at the right time” is the “Holy Grail,” which sure sounds like surveillance pricing. “Delta is telling their investors one thing, and then turning around and telling the public another,” Gallego said in a statement.

House Democrats proposed a bill to ban surveillance pricing and surveillance wagesetting. So-called “drip pricing,” where junk

Supply and demand no longer solely determines price, as in textbook economics.

fees are added during a sale, was effectively banned in event ticketing and hotel stays by an FTC rule finalized in May. But with GOP control of Washington, the real action has moved to the states. Surveillance pricing bans were introduced in California, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, and Minnesota; surge pricing bans for grocery stores and restaurants were introduced in New York and Maine. By July, 24 states had seen bills introduced over some form of technologyaided pricing, according to a tracker from Consumer Reports.

In a major win this year, the nation’s two largest blue states explicitly banned algorithmic price-fixing, a tactic famously used by RealPage, which aggregated data from landlords across a city and recommended coordinated rent hikes. Joe Biden’s Justice Department sued RealPage, reaching settlements with corporate landlords vowing to end the practice. But data aggregators like Agri Stats and PotatoTrac already do this for meat and produce, and states wanted to prevent tech-enabled collusion from expanding. Advocates were pushing on an open door; housing is the biggest monthly expense people have. “When RealPage came out, it quickly mapped onto something people feel viscerally,” said Samantha Gordon, chief advocacy officer at TechEquity, which lobbied on the California tech pricing bills. Moreover, since price-fixing is illegal when human beings enter a smoke-filled room and collude, extending that to algorithmic collusion made sense to lawmakers.

That was the concept behind California’s AB 325, which states that “common pricing algorithms,” whether informed through public or nonpublic competitor data, violate the Cartwright Act, California’s antitrust law. The law lowers the evidence standard to prove an algorithmic pricing conspiracy. It also prohibits anyone from distributing a pricing tool that coerces the setting of a recommended price, protecting small businesses along with consumers, explained Hepner, who was active in drafting the bill. “We saw mom-and-pop businesses swept up into these pricing schemes,” he said. “If you want to get the buy box on Amazon, you have to use their smart pricing tool. You have to give up independent decision-making authority to participate in the economy.”

After seven rounds of amendments, AB 325 passed and Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) signed it in October. Days later, Gov. Kathy Hochul (D-NY) signed S.7882, another pro -

hibition on coordinated price-fixing via software, though limited to rental housing. The New York law also blocks landlords from using algorithms to set “lease renewal terms, ideal occupancy levels, or other lease terms and conditions.” Cities like Jersey City, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Seattle have enacted similar citywide collusion bans, and 51 algorithmic price-fixing bills were introduced nationwide in just the 2025 legislative session. It’s “a potentially very powerful first step in tilting some of this economy back in favor of consumers,” Hepner said.

Surveillance pricing bills have not seen the same success, though their failure revealed critical information. In California, AB 446, which would have banned pricing based on personal data, was held back, giving sponsors time to build support next year. That’s because businesses across the economy, even ones not suspected of surveillance pricing, swarmed Sacramento to defend their practices. “It was fascinating over the course of that legislative process to see the opposition come out and openly say, ‘Hey, we’re actually doing this, you mean we can’t do this anymore?’” Hepner told me. Some economists allege that tech pricing crackdowns threaten discounts and other potential benefits for consumers. But it’s hard to believe that companies would hire the most sophisticated engineers to figure out how to reduce their revenues. As Nguyen told me, the argument to preserve discounts boils down to this: “You can have privacy or low prices, but you can’t have both.”

A modest breakthrough came in New York, which passed a disclosure law requiring that relevant transactions include a pop-up stating: “This price was set by an algorithm using your personal data.” The National Retail Federation sued to block the law, but in October, a federal judge dismissed the case, ruling that the disclaimer “is plainly factual.”

Advocates believe that the legal victory will give policymakers permission to revisit the topic. But the fierce pushback showed that AI-based pricing was no longer a speculative harm. “So many companies and industries trying to kill [surveillance pricing bans] told us everything we need to know on why everything is getting more and more expensive,” Gordon concluded.

RealPage got the message as well. As the price-fixing bills worked their way through statehouses, the company announced it was acquiring Livble, a

property management software tool. With Livble integrated into their platform, RealPage said, residents could subdivide rental payments into installments based on real-time cash flow landlords can see. In other words, RealPage was trying out surveillance pricing.

These technological shifts from one scheme to the next make it difficult for policymakers to stay ahead of the curve. For example, Lyft, one of the early adopters of surge pricing, reacted to rider anger about the service being more expensive precisely when they needed it most by moving to something called Price Lock, a subscription-based pricing tool that caps fares on targeted routes—for a monthly fee.

Another tactic involves redefining basic terms. When Delta claimed it would not use personal data, it added that it was merely “enhanc[ing] our existing fare pricing processes” with AI. “The lack of regulations about this and the way people’s data can be collected and used allows them to play around with what they are calling personal data and use,”

said Ben Winters, director of AI and privacy at the Consumer Federation of America. This forces policymakers to think more broadly, even on the outer edges of the possible. “I do worry that we’re always going to be chasing the companies,” said Sam Levine. “I think companies need to advertise a price publicly that’s available to all consumers … there should be a basic principle to advertise a price and it’s deceptive to charge more than that.”

Levine’s testimony to Congress this summer hits on another option: limiting collection of personal data, rather than just its usage. “‘Surveillance pricing’ is only possible because of how companies collect, share, and weaponize our personal data,” he told lawmakers, while arguing that relying on outdated tools to safeguard privacy risked further abuse.

Consumer protection and anti-monopoly experts are warming to this idea of cutting the data off at the source. Companies, after all, provide a full road map of what they collect in the privacy policies almost nobody reads. Levine and Nguyen’s loyalty

program paper documents privacy policies, finding that rental car giant Hertz admits to collecting demographic and behavioral data, Home Depot tracks Wi-Fi usage inside their stores, and Macy’s captures customer driver’s licenses. Much of this data is sold to third-party data brokers, who share it with other businesses. A data minimization standard could prevent use of personal information for pricing, Winters suggested. Mekki added that antitrust law recognizes that antitrust remedies often call for disgorgement of whatever gives companies an unfair advantage in the marketplace. Applied to surveillance pricing, that would argue for destroying the data allowing them to price-set. “If you can be forced to give up money or property, it stands to reason that you need to give up data,” she said.

The bipartisan American Privacy Rights Act introduced last year would have limited collection of certain kinds of data and given people the ability to opt out of having their data used to target them or sold to third parties. But this is at least the third major com-

The best way to get at surveillance pricing might not be to go after the data, but rather those who receive, share, and process it.

data with. Data sales could be considered unfair or deceptive under state consumer protection laws. And even when customers consent to having their data collected, they may not be consenting to transferring that data to third parties. “State enforcers should be thinking, under what circumstances is it lawful for companies to share personal data with pricing consultants?” Levine said.

economic silos,” Hepner said. “You cannot comparison shop anymore. You cannot predict what a price is supposed to be anymore.”

prehensive privacy bill in the internet era that’s gone nowhere in Congress; too many companies are invested in the surveillance economy to let it be legislated out of existence.

“This is a textbook example of people not getting what they want,” said Wu, whose recent book The Age of Extraction highlights Big Tech platform-ization multiplying across the economy. “Is there anyone in America who wants less privacy or thinks it’s fine, or really wants targeted ads? The constituency is zero … In 20 years of privacy laws, there hasn’t been a single vote. This is not even a conspiracy. The tech industry lobbyists specialize in one thing: killing privacy laws.”

Some states have fared better, with a dozen passing limitations on data collection or letting consumers opt out of targeted ads or sale of personal data. California updated its policy this legislative session by passing AB 566, which allows internet users to opt out of data collection at the browser level, rather than having to go website by website.

But practically all privacy legislation has carve-outs for “bona fide loyalty programs,” giving companies an escape hatch under the guise of offering discounts. Even given that, however, loyalty programs are not exempt from “excessive” collection under these statutes that is not reasonably necessary. Maryland recently finalized a privacy law that prevents companies from conditioning loyalty programs on the sale of data, despite industry pushback.

The best way to get at this activity might not be to go after the data, but rather those who receive, share, and process it. That includes companies acting as data brokers by selling and trading data, and the thirdparty pricing consultants they share the

Under Lina Khan, the FTC made headway by looking at these agglomerations of data as unfair practices, and subsequently prohibiting the sale of sensitive data, like when someone visits an abortion clinic. Today’s FTC has walked away from this enforcement, but their past work outlines a path for states to argue that targeted pricing is similarly unfair.

AI pricing won’t look the same in five years as it does now, but we have hints of where it’s going. That’s why the role of Fetcherr is more interesting than Delta’s meandering explanations for how it uses AI. Airlines have been at the forefront of every pricing innovation of the past 30 years, from junk fees to differential pricing to loyalty programs. What’s the next frontier?

Fetcherr, which closed $90 million in funding in 2024 and another $42 million this year, tells you right on its website: “hyperpersonalization at scale.” (Or at least, it used to tell you that, before it scrubbed this section.) “We’re talking about understanding each customer as an individual, optimizing every interaction for maximum value,” the now-redacted section states, detailing how its AI model uses data points like “customer lifetime value, past purchase behaviors, and the real-time context of each booking inquiry” to give each passenger their own product bundle at a bespoke price. The goal isn’t just a pleasant customer experience—it’s “revenue growth.” Robby Nissan, a Fetcherr co-founder, has said publicly that its AI systems can “manipulat[e] the market in order to gain more profit.” There’s not a lot of mystery here.

There are other airline pricing consultants, like Peter Thiel–backed FLYR and PROS and Air Price IQ. But the pitch is the same: maximizing travelers’ willingness to pay by analyzing reams of data. If you want to see the dystopia of perfect information accurately predicting exactly how much you’ll pay for a service, just book a flight this Christmas. “It’s a very real example of how AIbased pricing schemes put consumers into

This is facilitated by a concentrated economy where markets aren’t as open to alternatives to AI-optimized schemes. But AI pricing may shrink choice even further. For example, Delta recently stopped flying from LAX to London Heathrow Airport, despite the popularity of the route. Virgin Atlantic still makes the LAX-Heathrow trip; it’s a joint venture partner with Delta, and perhaps as important, both of them use Fetcherr. Was canceling the route an AI-enabled suggestion to benefit another client? We will never know.

Large market models running millions of price tests with thousands of input signals could short-circuit restrictions on surveillance pricing or data minimization. If it’s all just simulations, after all, is it really using personal data?

Another future is glimpsed in the rise of AI agents that shop for you. Chat GPT users will soon be able to link their PayPal accounts for instant purchases based on chatbot recommendations. Walmart has partnered with OpenAI for e-commerce as well. Autonomous bots with a linked bank account could even shop on their own, something a new AI agent lobby is trying to facilitate in Washington.

There’s little transparency on how products are recommended, how prices are derived, or whether AI agents will act in the interest of consumers or the retailers they’re partnering with. “You’re delegating purchasing power to one algorithm to interface with another,” said Ben Winters. “You’re getting people signed up into these systems where they have no control.”

But there’s also a brighter future possible, one where the backlash to nonstop data collection and pricing subterfuge accelerates, and people simply demand a fair price. Polling shows that the public is deeply skeptical that AI will work in their favor. Consumers may not have much control, but they do hold the dollars companies need to thrive, and they can withhold them from companies that treat them poorly.

“I think it’s possible that this is headed back to cost-based pricing,” said Owens, whose book Gouged about the new era of pricing releases next year. “It’s the way companies priced for decades … There is a world where the outcome is transparent, public, predictable pricing.” n

Regulatory capture is at the root of the affordability crisis in electricity. Public power could offer a way out.

By James Baratta

Electricity is a public good, dating back to when rural electrification was a pressing need for the nation during the New Deal era. Yet control over this essential service today rests largely in the hands of private monopolies known as investor-owned utilities (IOUs), which provide power to nearly 70 percent of utility customers in the U.S. These monopolies are regulated at the state level by public utility commissions, which are responsible for setting rates. Utilities must justify any rate increases and convince regulators of the need for their actions. But 2025 may be the year that this regulatory framework collapses under its own contradictions