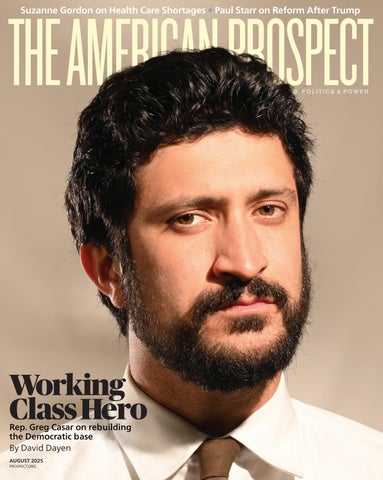

Working Class Hero

By David Dayen

By David Dayen

The American Prospect needs champions who believe in an optimistic future for America and the world, and in TAP’s mission to connect progressive policy with viable majority politics.

You can provide enduring financial support in the form of bequests, stock donations, retirement account distributions and other instruments, many with immediate tax benefits.

Is this right for you? To learn more about ways to share your wealth with The American Prospect, check out Prospect.org/LegacySociety

Your support will help us make a difference long into the future

16 Organizing to Win

Greg Casar wants to do for Democrats what he did for construction workers in Texas. By David Dayen

24 The Illusion of Choice

Republicans say that VA patients can get equivalent private-sector care anywhere in the U.S. Here’s a 50-state reality check. By Suzanne Gordon

32 The Premature Guide to Post-Trump Reform

American history offers three general strategies of repair and renewal. By Paul Starr

40

Nearly everybody wants the NFL’s Commanders back in Washington—but is the price too steep for the struggling city? By Gabrielle Gurley

48 Sugar Rush

Indiana is among several states restricting the purchase of sugary foods with nutrition assistance funds. Is this about health, or punishing poor people? By Emma Janssen

of his second term, Donald Trump essentially completed his legislative agenda for the next four years. That agenda is known as An Act to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, so named after Chuck Schumer, who in an act of boldness that set the political world absolutely ablaze, knocked out Trump’s preferred title, the absurd “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” But despite being only one law, the 2025 budget law is every bit as expansive as the achievements of the last several presidents, maybe combined.

We followed the winding road of this process from origin to final passage at prospect.org. We called it “Trump’s Beautiful Disaster.” But you could also call it the Old Deal. The rollbacks of Medicaid and food assistance and student loans push the country back toward the 1950s, before these Great Society accomplishments were put into law. The huge funding increases for immigration enforcement and the military recall the Reagan-era defense mobilization. The continued flattening and erasing of the income tax, particularly for corporations and the wealthy and their heirs, who can freely pass on dynastic wealth to their progeny, harks back to the era before the 16th Amendment, ratified in 1913.

The ramifications of the Old Deal becoming law will be felt by every American, something we work through in the pages of this issue. The Medicaid cuts, along with the movement toward privatization of the veterans health care system, will exacerbate an existing crisis of medical provider shortages, as Suzanne Gordon outlines for us. Food assistance rollbacks are combining with a new, suspicious interest from red states in what people on that assistance are allowed to buy; Emma Janssen traveled to Indiana to report on that. And the bulking up of Immigration and Customs Enforcement into one of the world’s biggest military units will not only trigger a surge of new surveillance technologies at the border, as James Baratta explains, but will damage America’s home care system, which, as Whitney Wimbish notes, is largely immigrant-led.

And of course, the upheaval of the present will lead to new thinking about the future. Paul Starr outlines proposals for how to dig out of the Trump catastrophe, taking lessons from our history. And I profiled the man who just might organize that renewal: Texas Rep. Greg Casar, the chair of the Progressive Caucus in only his second term in Congress, who is using his labor background to help restore the Democratic Party to its roots defending the working class, which can help prevent the rise of authoritarians who promise the world and deliver nothing.

“Make America Great Again” was always a backward-looking formulation. The future lies in understanding what Trump took away, and building something more appealing to a population desperate for leadership. That’s what we’re chronicling in this issue. – David Dayen

EXECUTIVE EDITOR DAVID DAYEN

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS

ROBERT KUTTNER, PAUL STARR CO-FOUNDER ROBERT B. REICH

EDITOR AT LARGE HAROLD MEYERSON

EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Dayen

SENIOR EDITORS GABRIELLE GURLEY, RYAN COOPER

FOUNDING CO-EDITORS Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr

CO-FOUNDER Robert B. Reich

MANAGING EDITOR AND DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL OPERATIONS

CAITLIN PENZEYMOOG

EDITOR AT LARGE Harold Meyerson

SENIOR EDITOR Gabrielle Gurley

ART DIRECTOR JANDOS ROTHSTEIN

MANAGING EDITOR Ryan Cooper

ASSOCIATE EDITOR SUSANNA BEISER

ART DIRECTOR Jandos Rothstein

STAFF WRITER WHITNEY WIMBISH

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Susanna Beiser

WRITING FELLOWS EMMA JANSSEN, JAMES BARATTA, NAOMI BETHUNE

STAFF WRITER Hassan Kanu

WRITING FELLOW Luke Goldstein

INTERNS BRANDON MALAVE, CHARLIE MCGILL, EYCES TUBBS, ELLA TUMMEL

INTERNS Thomas Balmat, Lia Chien, Gerard Edic, Katie Farthing

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS AUSTIN AHLMAN, MARCIA ANGELL, GABRIEL ARANA, DAVID BACON, JAMELLE BOUIE, JONATHAN COHN, ANN CRITTENDEN, GARRETT EPPS, JEFF FAUX, FRANCESCA FIORENTINI, MICHELLE GOLDBERG, GERSHOM GORENBERG, E.J. GRAFF, JONATHAN GUYER, BOB HERBERT, ARLIE HOCHSCHILD, CHRISTOPHER JENCKS, JOHN B. JUDIS, RANDALL KENNEDY, BOB MOSER, KAREN PAGET, SARAH POSNER, JEDEDIAH PURDY, ROBERT D. PUTNAM, RICHARD ROTHSTEIN, ADELE M. STAN, DEBORAH A. STONE, MAUREEN TKACIK, MICHAEL TOMASKY, PAUL WALDMAN, SAM WANG, WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, JULIAN ZELIZER

PUBLISHER MITCHELL GRUMMON

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Austin Ahlman, Marcia Angell, Gabriel Arana, David Bacon, Jamelle Bouie, Jonathan Cohn, Ann Crittenden, Garrett Epps, Jeff Faux, Francesca Fiorentini, Michelle Goldberg, Gershom Gorenberg, E.J. Graff, Jonathan Guyer, Bob Herbert, Arlie Hochschild, Christopher Jencks, John B. Judis, Randall Kennedy, Bob Moser, Karen Paget, Sarah Posner, Jedediah Purdy, Robert D. Putnam, Richard Rothstein, Adele M. Stan, Deborah A. Stone, Maureen Tkacik, Michael Tomasky, Paul Waldman, Sam Wang, William Julius Wilson, Matthew Yglesias, Julian Zelizer

PUBLISHER Ellen J. Meany

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER MAX HORTEN ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR LAUREN PFEIL

PUBLIC RELATIONS SPECIALIST Tisya Mavuram

ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR Lauren Pfeil

BOARD OF DIRECTORS DAN CANTOR, DAVID DAYEN, REBECCA DIXON, SHANTI FRY, STANLEY B. GREENBERG, MITCHELL GRUMMON, JACOB S. HACKER, AMY HANAUER, JONATHAN HART, DERRICK JACKSON, RANDALL KENNEDY, ROBERT KUTTNER, ELI LUBEROFF, LINDSAY OWENS, MILES RAPOPORT, ADELE SIMMONS, GANESH SITARAMAN, PAUL STARR, MICHAEL STERN, VALERIE WILSON

BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Dayen, Rebecca Dixon, Shanti Fry, Stanley B. Greenberg, Jacob S. Hacker, Amy Hanauer, Jonathan Hart, Derrick Jackson, Randall Kennedy, Robert Kuttner, Ellen J. Meany, Javier Morillo, Miles Rapoport, Janet Shenk, Adele Simmons, Ganesh Sitaraman, Paul Starr, Michael Stern, Valerie Wilson

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR info@prospect.org

PRINT SUBSCRIPTION RATES $60 (U.S. ONLY) $72 (CANADA AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL) CUSTOMER SERVICE 202-776-0730 OR INFO@PROSPECT.ORG

MEMBERSHIPS prospect.org/membership REPRINTS prospect.org/permissions

MEMBERSHIPS PROSPECT.ORG/ MEMBERSHIP

REPRINTS PROSPECT.ORG/PERMISSIONS

VOL. 36, NO. 4. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2025 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Vol. 35, No. 3. The American Prospect (ISSN 1049 -7285) Published bimonthly by American Prospect, Inc., 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. Copyright ©2024 by American Prospect, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without consent. The American Prospect ® is a registered trademark of American Prospect, Inc. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to American Prospect, 1225 Eye St. NW, Ste. 600, Washington, D.C. 20005. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Every digital membership level includes the option to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription. Plus, you’ll have your choice of newsletters, discounts on Prospect merchandise, access to Prospect events, and much more. Find out more at prospect.org/membership

You may log in to your account to renew, or for a change of address, to give a gift or purchase back issues, or to manage your payments. You will need your account number and zip-code from the label:

ACCOUNT NUMBER ZIP-CODE

EXPIRATION DATE & MEMBER LEVEL, IF APPLICABLE

To renew your subscription by mail, please send your mailing address along with a check or money order for $60 (U.S. only) or $72 (Canada and other international) to: The American Prospect 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20005 info@prospect.org | 1-202-776-0730

RYAN

COOPER

Since the early 1980s,

America has seen a consistent budgetary pattern: Republicans blow up the deficit with tax cuts for the rich and military spending, and Democrats subsequently cut down on borrowing with tax hikes and spending cuts.

History is set to repeat again. On July 4, Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act was signed into law. It’s a hyped-up edition of the same old Republican dogma. It contains the largest cuts to Medicaid and SNAP benefits in history, which do not even come close to compensating for giant tax cuts, mostly for the rich. It would increase the national debt by $3.3 trillion by 2034; if we assume that all the tax cuts will be made permanent (a certainty if Republicans have anything to say about it), the total is over $5.5 trillion.

For decades now, Republicans have internalized the idea that “deficits don’t matter,” to quote then-Vice President Dick Cheney. In his day, Cheney was mostly right—neither Reagan’s, Bush’s, nor Trump’s firstterm antics had any directly damaging effect on the broader economy. Inequality skyrocketed, but there were no debt crises. Indeed, Trump’s 2017 cut arguably helped stimulate spending and drive down unemployment, albeit in a highly inefficient manner, in an economy that hadn’t recovered from the Great Recession.

But this time might be different. Key to Cheney’s assumption was not just the fact that Democrats would clean up the mess later, but also the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency. Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, turbulent economic times have reliably led to a flight to the safety of dollars and U.S. government debt. That creates a consistent demand for dollar-based assets, so countries and businesses can settle international transactions, and build up exchange reserves to defend against potential currency crises.

That assumption is now being called into question. Trump’s wildly erratic behavior, abolishing whole federal agencies by fiat and yanking up and down tariffs at random via social media post, has created vast turbulence in the international economy. But instead of a flight to dollar safety, since Trump has taken office, interest rates on 10and 30-year Treasury bonds are up modestly, while the dollar’s value has fallen about 15 percent against the euro, and about 10 percent against the pound and yen.

This suggests that a new economic order is taking shape, after the keystone nation of the global economy decided to elect an unhinged maniac, again. Absent some kind of reckoning with MAGA on par with

President Grant’s all-out assault on the Ku Klux Klan in the 1870s, America will never live this down, and all future administrations will be burdened with Trump’s legacy of lower growth, lower employment, higher inflation, higher interest rates, and a dramatically higher cost of financing the national debt.

Ronald Reagan’s deficits were primarily caused by high interest rates, stemming from the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame inflation. Bill Clinton achieved a short budget surplus in the late 1990s in part from some tax hikes on the rich, but mainly by lucking into a long economic boom. George W. Bush took that surplus and handed it to the rich; but much larger deficits later in his term were caused by the 2008 economic crash, which cratered revenue and required an expensive bailout. Barack Obama passed an inadequate stimulus, but quickly pivoted to austerity by 2010, and subsequently deficits fell, though slowly.

Trump repeated the Bush pattern, except faster. He passed a large tax cut for the rich in 2017, then finished his first term with a pandemic-fueled economic crash, made worse by catastrophic mismanagement. Democrats and Republicans in Congress drew up the CARES Act, by far the most generous policy for the poor and working class in American history, which Trump signed. That and other pandemic rescues drove skyrocketing borrowing.

Biden learned from Obama’s mistakes with a much larger stimulus, which drove the fastest economic recovery from a deep recession in American history. Thereafter deficits fell, but as Biden did not raise taxes much, deficits stabilized at about 6 percent of GDP. As the Fed raised rates to combat rising inflation, interest payments as a share of GDP rose to 3.8 percent by late 2024, the highest level since 1998. In 2024, interest on the debt grew larger than the military budget.

It’s important to emphasize here that the austerity mindset that budgets should be balanced if possible, and every dollar of new spending must be “paid for” with taxes, is both economically illiterate and hugely damaging to the American economy. The Obama pivot was driven in part by a panicked frenzy among the D.C. establishment, even though unemployment was still at 10 percent. Austerity was a major reason why Democrats got killed in the midterms that

year, and why the economy suffered a lost decade of chronically slow growth and high unemployment. The problem with Republican deficits is not so much that they happened, but that they were spent on tax cuts for the rich rather than productive investments in, say, renewable energy.

In addition, as the issuer of the global reserve currency, America has an obligation to provide dollar assets. As Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein argue in their book Trade Wars Are Class Wars , if the government won’t provide them in the form of Treasury bonds, demand for other dollar assets will drive up its value, tanking American exports and widening the trade deficit.

Indeed, the dollar’s reserve status is partly to blame for America’s chronically large trade deficit. As economist Paul Krugman points out, much of these deficits have been financed by foreign investment in the U.S. If those investors lose confidence in America, they might pull back, similar to a “sudden stop” crisis that countries like Argentina and Portugal have faced.

There are built-in shock absorbers in place for a country as critical to the global economy as America. But those guardrails are buckling.

First off, all that foreign investment is denominated in U.S. currency. “That means that a sharp depreciation of the dollar will by itself bring the international investment position back into balance,” economist J.W. Mason said in an interview. Second, America still has the great benefit of borrowing in a currency that it controls. That means the Federal Reserve has control of the interest rate—it can always print money to increase or decrease rates to any level it wishes (at least above zero). “When it comes to sovereign debt in its own currency, the power of a central bank is like that of the God of the Old Testament,” said Mason.

But depreciating the dollar would come at the cost of higher inflation from higher import costs, and a major reduction in investment. And cutting rates, as Trump has called for, conflicts with the Fed’s dual mandate to ensure full employment and price stability. Interest payments are a skyrocketing share of the government budget in part because of the Fed’s rate hikes to fight the inflation of 2022-2024. Chair Jerome Powell cut rates in 2024, but since Trump took office, has hesitated to cut further.

Inflation has persisted at about half a point above the Fed’s 2 percent target. This limits the Fed’s freedom of action.

Trump has regularly attacked Powell for not cutting rates, and might fill the Fed board with toadies to do the job. But rate cuts, combined with other factors, would boost inflation even more. Tariffs are already spiking some prices. New home prices are likely to rise as Trump is deporting so many construction workers. The enormous tax cuts will drive up borrowing, as will the cost of rolling over existing debt, some $14 trillion of which must be refinanced over the next three years. IRS cuts carried out by DOGE , with the obvious goal of preventing audits of wealthy tax cheats, will further cut revenue by an estimated $500 billion this year alone; that’s more money out there to be spent. As a result of all of this, either interest rates will have to stay high, or prices will keep rising.

Weakening demand for the dollar could create a kind of depreciation on its own. But the modest fall in the dollar so far is nothing like a currency flight. Indeed, there is no viable global currency benchmark to replace the dollar, nor one on the horizon. The only realistic candidates are China or the European Union, but China would have to abandon its currency con trol system and open up its capital mar kets so foreigners could get ren minbi, while the EU would have to get over its congeni tal allergy to bor rowing and issue trillions in euro bonds. Neither looks at all likely.

fered from American dominance through sometimes undeserved sanctions, and access to the Fed’s swap lines was highly unfair to poorer nations, by and large using the dollar was a smart move. Now Trump is making that look risky and foolish. How is the world supposed to trust a nation degenerate enough to elect an ultracorrupt lunatic who is tearing up the global trade system designed by and for America itself—twice? If Trump is willing to threaten wars of conquest against two separate NATO allies (Canada and Denmark), who knows who else he might sanction? And even if he is replaced with a Democrat who undoes his policy, they might be replaced by a Trump-like figure again.

So while dollars will continue to be used around the world, I expect a steady erosion in the dollar’s hegemonic status, with a greater share of foreign exchange using a basket of other currencies—the euro, the

Still, the unquestioned faith in the dollar has been shaken, and for good reason. So many countries and institutions were willing to use dollars because America, by and large, was trustworthy. It granted ready access to dollars and took steps to preserve their value. The Fed even acted as a global lender of last resort during the 2008 crash and the pandemic, allowing central banks in the EU, U.K., Switzerland, and Japan to access “swap lines” where they could get dollars by exchanging their own currencies.

Though many people and countries suf-

ery from the pandemic crash, at least in terms of GDP and employment. Almost every country suffered from similar inflation, but American prices stabilized faster, thanks to higher production rather than crushed demand, and growth outstripped that of every other major developed nation.

Trumponomics, by contrast, will produce the opposite: a poorer, weaker America, with structurally higher prices, dedicating a large and growing share of its economy to financing debt created by Republican tax cuts for the rich. And it will all be entirely self-inflicted. n

Now more than ever, the support of readers like you is critical to the Prospect ’s mission to cover what’s at stake. Your tax deductible donations literally keep the Prospect team on the job. Check out all the other benefits online today, because we really can’t do this without you. prospect.org/membership

Dragnet surveillance has bedeviled border communities for years. The rest of America is next.

By James Baratta

Santa Cruz County, Arizona, is the smallest county in the Grand Canyon State, but its location makes it significant. Home to more than 50,000 people, the vast majority of whom identify as Hispanic or Latino, the county is located in the southernmost part of central Arizona and shares a 54-mile stretch of border with the Mexican state of Sonora.

Along this stretch of land is Nogales, the county’s administrative seat and a major port of entry into the United States; millions of people and billions of dollars in trade pass through it every year. Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, are bisected by a demarcation line established by the purchase, six years after the Mexican-American War, of Mexican land by the United States. But the sister cities—collectively referred to as

Ambos Nogales—comprise a single urban area characterized by high levels of crossborder interaction and a common culture.

Today, the line bifurcating Nogales and other border communities is over- and undergirded by a militarized and surveillance-driven security apparatus. The latter established a foothold under the Obama and Biden administrations “as a more humane alternative to other border enforcement methods, such as building walls or putting children in cages,” Petra Molnar, associate director of the Refugee Law Lab at York University, writes in The Walls Have Eyes: Surviving Migration in the Age of Artificial Intelligence . “People will still arrive, but they’re going to take more circuitous routes to try to avoid surveillance, leading to an exponential increase of deaths,” she told the Prospect

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Drones, like the ones being piloted here by Customs and Border Protection officers, are part of the surveillance dragnet at the border.

(CBP) spokesperson denied this, telling the Prospect that “preventing the loss of life is core to our mission, and CBP personnel endeavor to rescue those in distress, a particularly important mission in the harsh environments along the southwest border.”

In 2017, the agency established the Missing Migrant Program, an initiative focused on preventing deaths during attempted border crossings. However, according to CBP’s own data, migration-related deaths in the borderlands surged by 57 percent between October 2021 and September 2022.

Prevention through deterrence has been central to the bipartisan border security project for decades. Today, “the way it manifests itself visibly is just like East Germany,” Santa Cruz County Sheriff David Hathaway said in an interview with the Prospect “Walls don’t just keep people out. They keep people in.”

Walls are but one ingredient in the borderlands’ mix of barriers. In recent years, autonomous surveillance towers, drones, spy blimps, license plate readers, and motionactivated cameras have also been put in place. In the borderlands, no one is free from the ever-expanding surveillance and data collection nexus operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Federal agents have spent years perfecting a range of techniques and technologies that undermine civil liberties, all with the goal of sustaining the surveillance-driven immigration enforcement apparatus. The nearly ubiquitous surveillance has produced what is known as the panopticon effect.

“The panopticon [effect] is, of course, you think that they’re watching you, but they might not be,” Todd Miller, author of Build Bridges, Not Walls: A Journey to a World Without Borders, told the Prospect. “Like in the prison system, a camera could be there, but it might be turned off and no one’s looking, but psychologically, you think people are watching you.”

Nothing screams panopticon quite like CBP ’s Tethered Aerostat Radar System (TARS), semi-stationary blimps providing low-altitude surveillance of the U.S.-Mexico border, Florida Keys, and Puerto Rico. TARS operators relay surveillance data to DHS, law enforcement, and military partners. Since the 2010s, CBP has contracted with British defense contractor QinetiQ and with Peraton—a private equity–owned national-security company based in Virginia—to maintain the program. The agency has dumped hundreds of millions of dollars into TARS. Last year, it also deployed a new aerostat in the Florida Keys amid “upticks in transportation avenues and conveyances for illegal smuggling, fishing, and immigration activities,” according to the agency’s website.

On March 6, the Senate passed the Coast Guard Authorization Act, instructing the U.S. Coast Guard and CBP to procure blimpbased surveillance systems for deployment in additional areas of operation. The move came one day after an aerostat at South Padre Island in Texas broke free and, after drifting hundreds of miles, crash-landed on a ranch property outside Dallas.

Runaway spy blimps aside, license plate readers (LPR s) can also be found throughout the borderlands. These devices, some of which are covert, capture images of license plates and convert those images into data.

CBP uses that data to identify vehicles believed to be linked to cross-border crimes. LPR s also produce real-time alerts to allow CBP and other federal agencies to intercept suspicious vehicles.

For Hathaway, a self-described “big, tall gringo,” LPR s are part and parcel of dragnet surveillance in the borderlands. “I drive in a car with Arizona license plates, but I will get pulled over,” he told the Prospect.

Autonomous surveillance towers installed by CBP in the borderlands are the most visible manifestation of smart border technology to date, with the agency describing them as “a partner that never sleeps, never needs to take a coffee break, never even blinks.” CBP has received more than $700 million in federal funding for its surveillance tower program since 2017. Over the next decade or so, it will spend approximately $68 million to expand the program by upgrading existing towers and constructing hundreds more.

In early April, CBP unveiled plans to integrate machine-learning capabilities into the existing surveillance towers. First reported by The Intercept, modernizing these towers will facilitate automatic detection of anyone and anything moving near the Tucson-area border zone in Arizona. CBP has also tasked Google with operating “a central repository for video surveillance data,” supported by MAGE, a cloud computing platform. As part of the project, CBP is also partnering with IBM and Equitus, which will provide the software needed to collect visual data. That data will be stored on the agency’s Google Cloud.

The CBP spokesperson told the Prospect that technology affords the agency “persistent surveillance of the border region,” which reduces the need for manpower on the border and provides greater coverage to interdict migrant crossings, which have dropped significantly under the Trump administration.

But for residents of border communities, surveillance towers loom not just physically but mentally, creating a sense of perpetual observation while eroding any semblance of privacy. “They’re scanning the whole community and … zooming in on just regular day-to-day people going about their life,” Hathaway said.

On their nightly walks along the border, David and Karen Hathaway see more than just a star-studded sky; they often spot

a CBP -operated Predator B drone flying above. The drone is manufactured by General Atomics, a major defense contractor for the U.S. military. As Miller points out, the very same firms that “have been selling their products to the military now have another branch market for border surveillance.”

In September 2024, Hathaway testified before the House Committee on Homeland Security, telling lawmakers that he and other residents of border communities would prefer not to see their quiet neighborhoods “turned into a police state or a war zone.” During our interview, he reflected on an ordeal his wife had experienced when the two of them were returning home from the Mexican side of the border.

CBP uses facial biometrics for identity verification purposes at land border crossings, snapping pictures of travelers in pedestrian lanes before allowing them to pass through. The agency leverages one-to-one facial recognition technology to compare people’s facial features with the photos in their travel documents. According to CBP’s website, this ostensibly creates a “more seamless, secure, and safer travel experience,” but that wasn’t the case for Karen Hathaway. When she had her picture taken, the matching system spit out a red flag.

Hathaway figured it was an anomaly, as both of them have passports and regularly travel across the border, but the authorities promptly escorted Karen Hathaway to a room where she was detained and had her cellphone taken away. “Eventually that episode ends, but the next time we crossed there was a red flag in the computer that [says] this person has been detained before, so it automatically creates another red flag every time,” he said.

It later occurred to his wife that, in her passport photo, she did not have glasses on. Hathaway told the Prospect she now avoids wearing glasses and tries to mimic the hairstyle from her passport photo prior to re-entry. “I think that’s a real, graphic

Prevention through deterrence has been central to the bipartisan border security project for decades.

demonstration of this kind of surveillance state that’s run amok down here,” he said. Procurement documents reviewed by the Prospect reveal CBP’s intent to expand its error-prone identity verification system to land vehicles with the goal of collecting drivers’ and passengers’ facial biometrics. Dave Maass, director of investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, called the capturing of biometrics that might be used for other purposes later on “a grave concern.” Moreover, given that “lots of people who live in the Mexican cities on the other side have special passes that allow them to cross regularly into the U.S.,” expanding the identity verification system to land vehicles may provide another avenue for CBP to entangle residents of cross-border communities in its technological dragnet.

When CBP seizes electronic devices at the border during questioning or detention, the agency engages in a widely used intelligence practice known as document and media exploitation (DOMEX). This practice involves the scraping and analysis of contents from phones and laptops. The contents of those devices are then combined with data from myriad sources, including government

databases, social media, and other records. There are minimal restrictions on what CBP can extract from electronic devices and how it may use that information. The agency’s own directive indicates that border agents may retain records from seized devices upon establishing probable cause or if “the information relates to immigration, customs, and other enforcement matters.” The bar is equally low for intelligence-sharing with other agencies.

The DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A), which provides intelligence support to CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), “has a mandate as broad as the rest of the department,” said Spencer Reynolds, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice. The civilian intelligence-sharing arm of DHS has gained a reputation for targeting journalists and activists , and running large-scale collection operations in coercive environments like immigrant detention centers and jails.

“The office analyzes contents of phones or laptops seized by agencies like CBP and ICE, comparing them with personal data to create detailed pictures of people, their social networks, and their habits,” Reynolds told the Prospect. “I&A’s risks are particularly

high under an administration that is making good on its promises to go after critics and immigrants.”

In June, ICE released a notice of intent to sole-source a training contract to Magnet Forensics, a digital investigations software development company. Its platform includes Magnet Graykey, a smartphone-cracking software capable of providing “same-day access to the latest iOS and Android devices— often in under one hour,” its website states.

For its part, CBP announced in May plans to renew its contract with Cellebrite, an Israeli digital forensics company with a long-standing history of partnerships with local law enforcement and DHS. Similarly to Graykey, Cellebrite’s flagship tool—the Universal Forensic Extraction Device—allows clients to extract data from a broad range of electronic devices.

Intelligence-sharing is at the heart of I&A’s broad-based mission. It was also the focus of an executive order handed down by President Trump in March. Since then, his administration has been laying the groundwork for a large-scale strategic partnership with Peter Thiel’s Palantir. In recent months, the data analytics software giant

has secured nearly a billion dollars in government contracts and re-ups.

On April 10, ICE disclosed that it had tapped Thiel’s company to develop a prototype for ImmigrationOS, a program designed to track people who are self-deporting and accelerate the agency’s targeting of those it is seeking to deport. Palantir, which began partnering with ICE in the early 2010s, currently operates a case management system for the agency. As 404 Media reported, its database enables ICE “to search for and filter people by hundreds of different, highly specific categories,” ranging from physical characteristics to LPR data.

Three days before ICE revealed its re-up with Palantir, the agency entered into a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The memo shredded taxpayer privacy protections and granted ICE permission to request sensitive information from the IRS on individuals facing deportation. It was a stark departure from IRS best practices, which previously had emphasized neutrality and set a high bar for information-sharing with law enforcement. Prior to the finalization of the memo, top officials at the agency—including former acting IRS commissioner Melanie Krause, a Trump appointee—resigned in protest of the agreement, alleging it would violate taxpayer privacy laws.

On April 11, WIRED exposed Palantir’s collaboration with Elon Musk’s now-discredited Department of Government Efficiency to develop a “mega API” for accessing IRS records and sharing them throughout the federal government. This came after DHS and at least three other agencies had partnered with Palantir for access to its flagship data analytics platform, Foundry.

The idea of centralizing extensive data on all Americans prompted sharp bipartisan pushback . In a June 17 letter to Palantir chief executive officer Alex Karp, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and nine other Democratic lawmakers voiced opposition to the IRS mega-database, describing it as a “surveillance nightmare that raises a host of legal concerns.”

Further opening the floodgates to unprecedented data sharing, the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC)—a lesser-known data broker with a chokehold on the market for information-sharing in the aviation industry—secured a sole-source contract from ICE to provide software services in May, procurement documents seen by the Prospect

On the border, surveillance towers create a sense of perpetual observation while eroding any semblance of privacy.

In recent months, Peter Thiel’s Palantir has secured nearly a billion dollars in government contracts.

show. The U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and CBP have also contracted with ARC, which will sell an assortment of airline passengers’ travel data to ICE for immigration enforcement purposes.

Funding for the border-industrial complex has steadily increased over the past decade, and private-sector partners of all stripes have been eager to cash in. Some, like IBM and Google, are household names, but others are as obscure as they are numerous.

Researchers at the Electronic Frontier Foundation have been tracking the growing number of small-time players making their foray into the industry, documenting hundreds of tech companies that specialize in everything from biometrics to unattended ground sensors (which can detect footsteps).

The chilling effect of border authorities and immigration agents scooping up just about anyone suspected of crimmigration has reverberated across the country. The rise of indiscriminate enforcement activities—CBP raiding places of work and masked ICE agents detaining people at immigration courts and Home Depots—signals a nationwide implementation of the surveillancedriven immigration enforcement apparatus.

“Just because it’s happening at the border doesn’t mean it’s going to stay at the border,” Molnar told the Prospect. “We all need to pay attention to what happens in the border and in migration because it actually impacts all of us.” n

Mass deportations are worsening the staffing crisis in the direct care industry, threatening the lives of the elderly and people with disabilities.

By Whitney Curry Wimbish

Nelly Prieto’s home care clients are already afraid. Who will take care of them if they lose her as a caregiver? What will replace the services she provides? The 18-year home care veteran, patient transporter, and immigrant advocate in Washington state said the answers break her heart: no one, and nothing.

For years, the direct care industry, which provides home and community-based services for the elderly and people with disabilities, has struggled to hire and retain workers, and drew heavily from documented and undocumented immigrants.

But now, thanks to President Trump’s racist regime and mass deportations, that workforce will shrink even more, just as American society is rapidly aging.

For the next five years, 10,000 people will turn 65 years old every day, according to AARP. By 2040, the number of people aged 80 to 85, who are the likeliest to need direct care, will reach 14 million, a 111 percent increase from 2022, according to federal data. If Trump’s deportation policies stand, there won’t be enough caregivers to meet the demand for help.

“A lot of clients really are going to lose their lives,” Prieto told the Prospect. She knows that firsthand. When one of Prie -

to’s clients could no longer use her services because of an insurance change, there was no one else to look after her. “They couldn’t get another provider and my client was left alone. And when she was finally found, she had been left alone for so many days that she was wrapped up in her clothes with her own feces,” Prieto said. The woman was rushed to the hospital. But by then, “she said she didn’t want to live anymore,” and shortly afterward died.

Prieto had cared for the woman for two years. Her voice broke while telling the story.

Advocates, workers, and researchers said the ripple effects of Trump’s deportation

Ten thousand Americans turn 65 years old every day, spiking the need for caregivers who in many cases are immigrants.

policies on the care industry are dire. People who need care but have no one to help them will suffer alone and struggle to maintain their quality of life; some will lose their homes and be driven onto the streets.

Americans 50 years and older are the fastest-growing group of people experiencing homelessness, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. The number of Americans aged 50 or older who are experiencing homelessness is expected to triple in the next five years.

Not only older Americans will feel the pain, said Alison Chandra, a pediatric home health nurse in Utah, who accompanies young clients to school and provides constant care “that keeps them safe and loved at home, instead of in institutions.” She has accompanied one client to school each day since kindergarten and is starting fourth grade with him next year. “I’m the reason why he’s in a class with his peers, with his friends, with his community, where he belongs,” said Chandra, who is also a health care and disability justice advocate. The child could go to an institution. But then he wouldn’t get hugs from his neighbor, or see friends from his church, or just exist as a kid. “What’s better for a child?” she said.

“A lot of the clients, they don’t want to let you go, they don’t know how to get along with another caregiver.”

Without available caregivers, family members will need to look after their elderly and disabled relatives. More Americans every day become part of the “sandwich generation,” raising children while caring for parents (or even the “club sandwich generation” if they have a grandparent or great-grandparent needing care). Family members may find the effort so demanding that they abandon their jobs; but in addition to the economic impact, trying to care for a loved one can be emotionally harrowing, especially for someone without proper training.

“It takes a long time to get to know your client, because every client has different medical issues. If you’re not trained as a home care provider to handle those issues you’re not going to know how,” Prieto said.

As with other industries that rely on immigrants, including construction, farming, hospitality, household work, and meat processing, mass deportations could bring direct care work to a standstill. Documented immigrants make up 28 percent of the overall direct care workers, who provide hands-on personal care to people with disabilities and chronic conditions and the elderly, such as bathing, dressing, and eating. Documented immigrants make up 32 percent of home care workers specifically, who provide that care in people’s homes, said Kezia Scales, vice president of research and evaluation at care industry researcher and advocate PHI.

There’s no definitive data on the number of undocumented workers in the sector.

The American Immigration Council puts the figure at almost 7 percent of the home health aide workforce and 4.4 percent of all

ICE raids and deportations will increase after the GOP budget bill devoted $170 billion to immigration control.

personal care aides, but advocates say the number is likely much higher. Those are the workers most at risk in Trump’s America, Scales said, but Trump is also targeting legal immigrants, revoking immigrants’ right to work, and attacking U.S. citizens, too.

“A lot of immigrant direct care workers would not be directly impacted by deportation orders because they have work authorization, but what we think is very likely is that the broader chilling effect of these incredibly drastic and punitive actions will impact [them] as well because many of them live in households with mixed immigration status,” Scales said. A likely scenario is that workers will leave formal employment and provide care services under the table, which leaves workers and patients alike with fewer protections.

“Generally the widespread fear and uncertainty caused by these deportation orders will make individuals leave the workforce, maybe to go into the gray market where they can work under the radar or leave the workforce all together,” Scales

said. “What we’ll really see is a contraction of the workforce altogether as those with whatever documentation status opt out because it’s just too uncertain.”

It wouldn’t take much to upend the industry, said elder law attorney Harry Margolis, founder of Margolis Bloom & D’Agostino and writer for the Squared Away blog published by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

“The way economics works, you don’t need a huge change to create a huge problem,” Margolis said. “If you cut the availability of caregivers by 10 percent … it’s going to create huge problems.”

The direct care industry is already contending with huge workforce problems. Though direct care added 1.6 million new jobs over the last decade to stand at five million as of 2023, according to PHI, workers don’t stick around for long. Federal data puts the median hourly wage at $16.78; PHI data shows almost 40 percent of caregivers live in low-income households, and almost half rely on Medicaid, cash transfers, nutrition assistance, or other forms of public help.

The days are physically and emotionally demanding, and the job comes with “heavy workloads, scheduling challenges, inadequate supervision, and limited training and career advancement prospects,” PHI said. There is no comprehensive data on care industry turnover, the group said, but assessments of specific jobs give a clue of the sector’s employee retention. Last year, PHI estimated 80 percent turnover in home care. Between 2017 and 2018, the median annual turnover for nursing assistants in nursing homes was almost 100 percent.

“Because these are low-paid, low-technical-skill, high-personal-skill, high-humanskill jobs, they’re staffed by people who don’t have a lot of bargaining power in the economy, and those are often immigrants,” Margolis said. “And if we make it harder for them to be here or harder for them to work … it’s going to be harder and harder to find care when you need it.”

Direct care added 1.6 million new jobs over the last decade, but workers don’t stick around for long.

The industry expects to add more than 860,000 new jobs between 2022 and 2032, the largest growth of any job sector in the country. But workers and advocates say open positions stay unfilled for months, and when someone does get hired, there’s no guarantee that they’ll stay.

“The situation is accelerating because we have more and more people who need the care, and we haven’t figured out how to both increase the supply of workers to meet that need and rationalize services or modernize services in ways that would improve efficiency,” Scales said.

In January, Trump revoked the guidelines that had earlier forbidden ICE to raid “sensitive areas,” leaving those in schools, places of worship, and hospitals and care facilities vulnerable to immigration raids. Immigration advocates also expect a sharp increase in I-9 audits, “silent raids,” in which federal agents check whether employees have work authorization. The two attacks can bleed into each other, said Marisa Díaz, immigration worker justice program director at the National Employment Law Project.

“What we’re seeing is that even in cases where ICE goes to a workplace to initiate an I-9 audit, we’ve seen a trend where they’ll use that to talk to workers and try to arrest them,” Díaz said. Under the last Trump administration, I-9 audits hit a record high of 6,454, quadruple the number under the Obama administration. There will be at least that many again, Díaz expects.

“There are cases that have been reported in Maryland, Arizona, Texas, and Louisiana, where ICE arrived at a workplace with a Notice of Inspection … it’s not a warrant of any kind, it does not give ICE the right to talk to anyone,” Díaz said. “But they use it as an excuse to talk to workers and arrest them on the spot.”

It’s impossible to quantify the effect for patients when they lose a caregiver, especially if the loss is because of a raid, said Sam Brooks, director of public policy at the National Consumer Voice for Quality LongTerm Care.

“We’re concerned, certainly, that workers that are there now will not want to go to work for fear of being caught up in these raids, but it also has a horrible effect on the residents,” Brooks said. “Imagine if police just wantonly came in and took a resident or a worker, imagine how you would feel … the trauma on people getting care there is severe.”

While Chandra, the nurse and advocate in Utah, is not at risk of deportation herself, she has seen the fear among those she’s connected to through the wider medical community via the nonprofit Heterotaxy Connection, an organization focusing on a condition her son has.

“Just speaking to clinicians in our research consortium, their postdoc students are being stopped on the street and questioned,” she said. “It is medicine as a whole that’s being threatened in this country.”

The result is a crisis at all levels of the medical industry, said Dr. Brett Lewis, resident physician at Boston Medical Center, the largest safety-net hospital in the region.

“From my standpoint, everyone is terrified. My patients are forgoing prenatal care because they’re afraid to come in to the clinic, to the hospital because they’re afraid they’re going to be picked up by ICE on the way. They’re afraid to pick up their blood pressure medications. Staff are afraid, certified nursing assistants, custodial staff who are literally making our hospital run are afraid to come in to work,” she said. In Boston, Lewis explained, many patients and employees are Haitian immigrants, and the Trump administration’s revocation of Temporary Protected Status, which allowed Haitians to stay in the U.S. and work, has caused havoc in the health care community.

SEIU Executive Vice President Leslie Frane sees the deadly GOP spending law as creating far more problems for people needing care and the immigrant workforce. Along with Lewis, Prieto, and hundreds of union members, Frane was in Washington, D.C., this summer to fight unsuccessfully against the legislation. It imposes nearly $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid and supercharges Trump’s deportation goals, with $170 billion for immigration control, including tripling Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s budget to nearly $30 billion and adding $45 billion for new detention centers.

“It is no coincidence that when Republicans wanted to find money to fund tax cuts for the wealthy, Medicaid is where they went first,” Frane said. “It’s partly because it’s a big budget item. But, frankly, it’s also because the people who rely on Medicaid for care are working people, poor people, seniors, people with disabilities. They are among the most vulnerable people in our society and they are the people that Republicans consider expendable.” n

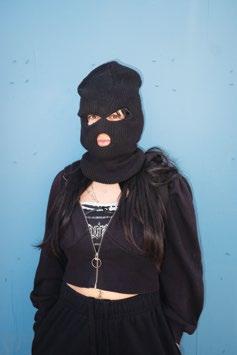

For more than a month, Los Angeles has been under siege from federal operations by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE detained over 1,600 people just in a 16-day stretch in June, inspiring alternating bouts of anger, fear, and protest. President Trump deployed the National Guard and even U.S. Marines to counter demonstrations supporting the city’s immigrants, but community members have not stopped speaking out and confronting ICE raids when they see them.

Rian Dundon is a photographer who spent several days on the ground in Los Angeles taking pictures of scenes throughout the city: the protesters, the Marines, and the vibrant culture of Los Angeles that has shined through in these demonstrations. We present them as a snapshot of life in a city under authoritarian attack by Donald Trump and Stephen Miller.

This story was co-published and supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. Funding has been made possible by The Puffin Foundation. —David Dayen

To see more photos in the series, visit prospect.org/ ICEinLAPhotos.

BY RIAN DUNDON

Clockwise from upper left: A security PSA featuring U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem screens in the arrivals hall of LAX on June 19, 2025.

Protester on Sunset Boulevard, June 21, 2025

U.S. Marines idle outside the Wilshire Federal Building in West Los Angeles, June 22, 2025.

An empty sidewalk in Downtown L.A. the morning of a nearby immigration sting in the Fashion District, where escalating raids have caused business to slow, June 24, 2025.

A handwritten memorial marks the site where three people were arrested in an immigration sting a few hours earlier, Pasadena, June 21, 2025.

Protesters rally outside the Metropolitan Detention Center, June 19, 2025.

By David Dayen

It was 97 degrees outside, and Greg Casar was in a fragrance store, looking for an envelope.

He had marched on that June evening with about 30 workers from two restaurants owned by the mogul Stephen Starr. They stopped first at St. Anselm, a steakhouse in the historic Union Market District in Northeast Washington, D.C., where 85 percent of the workers signed cards seeking union representation and later won an election. But the STARR Restaurant Group argued that the election was void because the Trump administration’s National Labor Relations Board had only two of its five seats filled, one less than a quorum, and therefore could not certify the results.

Casar, a second-term congressmember from Austin, Texas, had visited St. Anselm once before, in February, and the STARR Group’s leadership promised him then that it would honor employee wishes. But St. Anselm and another restaurant, Pastis, not only broke that promise; they started reducing hours, changing work rules, and even firing union-supporting workers. “I haven’t had a raise in two years,” one baker told

Casar at a meetup before the march. “I can barely afford my rent.”

St. Anselm workers had signed a petition demanding wage hikes and union recognition. But the hostess told Casar she was not authorized to accept anything related to the labor dispute. Casar had experienced these indignities from management a million times as a labor organizer. It wasn’t going to deter him.

“Sometimes one of the tactics that our restaurant uses is to make us feel small and powerless,” said Bridget, a baker at St. Anselm. “Having a member of Congress there … makes us feel as if what we’re doing is legitimate.”

Casar suggested that they could seal the petition in an envelope for the hostess to deliver to her superiors. That was deemed acceptable. Now they needed the envelope.

The fragrance store was next door. “A weird fact about me is, really strong perfume gives me a little lightheadedness, I hate it,” Casar said later. “So actually going into there, I was like, I gotta get in and out.” The mission proved unsuccessful. But someone fashioned a sheet of loose-leaf paper

into an envelope, stuck the petition inside, and the hostess took it. Chants of “¡Si se puede!” broke out among the mostly Spanish-speaking workers.

Casar was 1,500 miles from his constituents. It was the hottest day of the year so far in D.C. He was on his own time. There were no TV cameras. I was the only press.

A couple of days later, in his Capitol Hill office, Casar told me the march was “the most fun I had all week, man! … It’s a whole lot better than sitting in a committee hearing.” He believed his presence, as the second-highest ranking Democrat on the House Education and Workforce Committee, could make a difference in the unionization fight. But secondarily, he considered it a way to stay grounded, outside the trappings of power and in solidarity with the kind of people who brought him to Washington. “We need more congressmen and -women,” Casar told me, “who feel more comfortable marching into a fancy D.C. restaurant with a union than mingling inside of one with lobbyists.”

In January, Casar, who is 36 and just three years removed from serving on the Austin City Council, took over as the tenth

chair in the history of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. It was an inauspicious moment to be a leader on the left in Washington. Donald Trump had just swept back into the presidency, winning dramatic gains in many urban precincts represented by many CPC members. Many big liberal cities were under assault from ICE raids and threats to federal funding. Notwithstanding the cautious, business-friendly Kamala

Harris campaign, centrist Democrats had already decided to blame progressives for her loss and every other loss of the past halfcentury, forming new groups and fundraising schemes to steer the party to the right.

What bothered Casar most was waning support for Democrats from working-class voters, something he had seen firsthand on the campaign trail for Harris. He saw it as an existential crisis for the party of the

New Deal and Great Society, predicated on fighting for the common man and woman.

“If we become a party of upper-income people, then I think we’re toast because we become a contradiction in and of ourselves as a party,” he said.

This year, Casar has focused squarely on reviving Democrats’ populist roots, while trusting that such positioning can play across the ideological divide. While the CPC has typ-

Texas is the most dangerous state in the nation for workers, particularly construction workers.

ically tended to its own membership in policy development and political strategy, Casar has pitched frontliners and swing-district members on his anti-oligarchy message.

And the CPC is plotting to introduce what they call the “battleship bill,” a funhousemirror version of the Gingrich Contract with America in 1994, designed to be used for campaigning in every contested district in the 2026 midterms, and as a set of deliverables after taking power. While the specifics have not been finalized, it’s likely to include measures on fighting corruption in D.C., lowering costs at the pharmacy counter, expanding Social Security benefits, and raising taxes on the rich. “It’s a moment where we can actually lead on it but bring the entire caucus along with us,” Casar said.

It’s an audacious strategy, given the low esteem in which Democrats are held by the voting public. The belief that the many cats in the Democratic coalition can be herded toward a singular goal may be even more foolhardy. But organizers focus on what brings people together instead of what drives them apart, and prioritize winning tangible gains over winning an argument. Casar has done this from his earliest years in politics, when he was in the struggle with perhaps the most marginalized people in the entire country—and helping them prevail.

Greg Casar was born in Houston to immigrant parents from Mexico, yet not acquainted with squalor: His father was a physician, and he studied at prep schools. But he grew up amid protests against the Bush administration’s war in Iraq and rallies for comprehensive immigration reform. He entered college at the University of Virginia thinking he wanted to be a teacher, but quickly learned the realities of American life. “So many students in the high schools where we would go in to volunteer teach are getting driven to school in the cars that they’re sleeping in at night with parents,” Casar said. He found a different passion: ensuring everyone had a fair shot.

Organizing for living wages for campus employees later took him back to Texas, as a summer intern with Workers Defense Project, a research outlet and worker center for primarily Latino and immigrant construction workers. Texas is the most dangerous state in the nation for workers—5,165 died on the job throughout the 2010s—and the only state without universal workers’ compensation. Construction work is particularly brutal and disproportionately conducted by Latinos, many of them undocumented.

“Especially in a place like Texas that is notoriously anti-union and anti-immigration, we weren’t going to have the power

to individually shape policy agendas,” said Emily Timm, a co-founder of Workers Defense. So organizers developed coalitions with churches, neighborhood groups, environmentalists—whoever shared their interests. And although worker centers traditionally had standoffish relationships with unions, Workers Defense actively sought them out. “Workers Defense and Greg made a priority to engage in deep conversation and joint organizing that built a powerful force in Austin,” said Rick Levy, president of the Texas AFL- CIO

Timm hired Casar as an intern in 2010, and he jumped into a campaign to secure mandatory rest and water breaks on construction sites. After a worker died from a heart attack a mile from the Workers Defense offices in Austin, the group held a vigil, worked with labor allies, and pressed the city council, sharing stories of accidents and deaths in the Texas heat. By the end of that first summer, Austin had approved the first right-to-water breaks in the South. (In 2023, Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed a law overturning local worker protections, but it was ruled unconstitutional and is now working through appeals courts.)

After graduating, Casar returned to Austin full-time, becoming Workers Defense’s policy director and witnessing the power of

“He’s not just interested in symbolic victories,” said one of Casar’s colleagues. “He’s about what is going to deliver a victory for working people.”

unified working people. “We were organizing sometimes workers that had started a wildcat strike on their own and then came to us to be like, ‘Hey, we all just walked off the job, what do we do next?’” he told me. At weekly Tuesday night meetings, Casar communed with workers, helping them document safety violations and recover stolen wages, with back pay often presented on the spot to raucous applause.

“He really understood how engaging people around working conditions, the most basic economic needs of their day-to-day lives, was such a powerful motivator to bring people together,” Timm said.

A major initiative involved community benefit agreements on projects receiving government subsidies and tax breaks, to ensure that the jobs created would be good jobs. One incident stood out. White Lodging was a developer building a 34-story Marriott near the Austin convention center. In exchange for $3.8 million in tax incentives and fee waivers, White Lodging promised to pay prevailing, union-scale wages to construction workers. But Workers Defense heard from members that they weren’t making these wages.

Casar then discovered that assistant city manager Rudy Garza had signed a secret agreement with White Lodging to pay some workers below prevailing wages, as long as the overall project met “anticipated targeted average wage rates.” Garza left government shortly thereafter and, according to Casar, founded an engineering company that benefited from the hotel project. Workers Defense demanded a meeting with Austin’s mayor

over the secret agreement. “They’re like, ‘Well, we keep our promises that we signed off on this piece of paper,’” Casar said. “We keep our promises to the developer, not we keep our promises to the workers or to the law.”

The outcry led to a city council hearing, where a group of housekeepers showed up wearing “I support White Lodging” stickers. Several of the housekeepers were friends or relatives of the construction workers; Casar talked to the housekeepers in Spanish and found out they were being paid for their time, and were offered higher wages to side with White Lodging. Casar flipped the housekeepers, and unified opposition to undercutting workers.

After two years, the city council revoked White Lodging’s incentive deal. But Casar was frustrated. “This should not have been so damn hard,” he said. His allies thought they needed someone closer to the power, able to organize the council the way they organized workers. One supporter of Casar’s likened it to “salts,” experienced organizers who get hired at workplaces to coordinate unionization efforts. As Casar remembers it, she said to him, “You need to go be our salt on city council.”

Casar’s opportunity arose in 2014 when Austin became the last big city to switch from at-large to geographic districts. Before then, the council “all came from the downtown Austin area, because that area had the greatest voter turnout,” said Steve Adler, who served two terms as Austin’s mayor from 2015 to 2023. That tilted priorities toward business and commercial real estate interests. But only one incumbent was re-elected in 2014; all the downtown councilmembers had to run against one another. Casar won election in predominantly poor, nonwhite District 4, and at 25 became the city’s youngest and likely most leftist councilmember ever.

He approached government work with an organizer mindset. “This world is replete with politicians who are politicians only,” said José Garza, who was executive director at Workers Defense Project at the time. “I quickly realized Greg was a lot more than that. Greg always gave not just Workers Defense but the progressive movement in Austin direction. He gave us guidance. Strategic vision.”

Casar wrote legislation making Austin the first municipality in the South to provide paid sick leave for all workers, while finding lawmakers in other Texas cities to spread the idea. He secured “fair chance” hiring, bringing together labor and criminal justice reformers to ban businesses from asking prospective workers if they had previously been incarcerated. He helped win livingwage increases, including for subcontractors who had historically been left out. The first unions for hotel workers and nurses in Austin were established with his support.

“He’s not just interested in symbolic victories,” Timm said. “He’s about what is going to win and deliver a victory for working people.”

Yet Casar’s initiatives to defy state immigration policy and make Austin a “Freedom City,” end a citywide homeless camping ban, and reallocate police department funds courted controversy in hard-right Texas. Conservatives caricatured his ideas and forced policy reversals. Police budgets were restored by the state legislature; the camping ban was reinstituted by Austin voters; even the paid sick leave ordinance was struck down in the courts.

Adler saw Casar as principled, despite attracting criticism. “He built a reputation for being kind of radical but was not,” he said. “He finds the path to bring along the greatest number of votes and achieve on his values, even if it’s not the path he would take.”

Early on, Adler asked Casar to chair the council’s Planning and Housing Committee. “Everyone told me that was just political suicide,” he told me. “And it felt like it, because we made so many people mad.” On one side were developers wanting to raze neighborhoods and usher in luxury housing; on the other were Not In My Backyard activists opposed to housing stock that disrupted neighborhood character. Casar listened to the fast-growing city’s one million residents, and their need for a better and less expensive place to live.

The showpiece was a bond for acquiring land and building affordable housing, which some city leaders wanted to top out at $100 million. Casar successfully raised that to $250 million, the largest in Texas history, and voters approved it with 73 percent of the vote in 2018. A subsequent transit bond had even more housing funding. He followed that up with an ordinance called “Affordability Unlocked,” which eliminated parking mandates, minimum lot sizes, setbacks, height limits, and other zoning require -

ments, as long as 50 percent of the development project was reserved for affordable units. All affordable housing torn down for new development had to be replaced onefor-one with affordable units. A separate measure enabled more accessory dwelling units on lots throughout the city.

“We broke through with saying we need more housing but at all different levels of income,” Casar said. “But that doesn’t mean that you go and knock down the existing working-class apartments that you have to put a glitzy tower on top of it.”

A broader zoning code rewrite failed in the council and then in the courts. But Casar’s changes did facilitate thousands of new housing units in Austin. In 2022, there were 18 new homes permitted in Austin for every 1,000 residents, more than seven times the rate of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

That last statistic came from the Ezra Klein/Derek Thompson book Abundance , which criticized blue-state housing policy and held up Texas as an alternative. But it rarely gets mentioned that the architect of housing changes in Austin is the head of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. And it certainly doesn’t mention his role in empowering the tenant rights movement in the city.

After helping residents at mobile home parks end forced electricity shutoffs and rescind eviction notices, Casar added funding in the city budget to stand up what would become Building and Strengthening Tenant Action (BASTA , the Spanish word for “Enough!”), which organizes tenant associations across Austin, educating renters on their rights and negotiating solutions with landlords. “It was really that initial support and vision that Greg and his team had that created the project,” said Shoshana Krieger, BASTA’s project director.

Working on housing left Casar with a nuanced assessment of abundance. He agrees with and has demonstrated the importance of increasing state capacity and delivering benefits for constituents quickly and universally. “If you want to add another bathroom into your house because your aging parents are moving in with you, and it takes two years to get done, that is dumb,” he said.

Yet he forcefully rejected “people that want to use abundance framing as an excuse to usher in the 1988 Republican platform into the Democratic platform.” And he named names, going after writer Josh Barro

for saying onstage at the centrist gathering WelcomeFest that abundance necessarily means disempowering unions. “I think we have to become the pro-worker, anti-billionaire party,” Casar said. “And I think there are those folks that want the abundance frame to supersede that.”

On the same June day as WelcomeFest— which Casar prefers to call WalmartFest because of its partial funding from the Walton Foundation—he questioned Education Secretary Linda McMahon, the wrestling family tycoon with a net worth of $3.2 billion, at a House committee hearing. Casar asked McMahon how much she would personally benefit from the Republican budget bill extending the Trump tax cuts. “I’ve not sat down and worked with my accountants,” McMahon replied, and when pressed, she dismissed the “ridiculous line of questioning.”

“I think we have to become the pro-worker, anti-billionaire party,” Casar said.

and relatable to someone working 12 hours a day on a construction site. If Democrats propose universal child care, he said, just cap the cost to a percentage of income, for everyone, without an extra form or a means test, and get it running within a short period of time, unlike the Democrats’ prescription drug price negotiations, which passed in 2022 and whose lower prices don’t begin to come online until 2026.

“No, it’s not ridiculous because here’s what’s important,” Casar countered. “There are families watching at home from my district that could lose their health care … And what it’s paying for is, overwhelmingly, tax cuts for the wealthiest people in the country.” Republican committee chair Tim Walberg (R-MI) tried to halt the questioning, and McMahon bobbed and weaved. But Casar made his point: Billionaires didn’t even know how many millions they would reap from creating devastation among the nation’s poor.

Later that day, Casar made an appearance at the Center for American Progress, discussing how to win back working-class voters. The other panelist was Rep. Nikki Budzinski (D-IL), vice chair for policy at the New Democrat Coalition, the largest caucus in Congress for the party’s moderate wing. In contrast to the leftist-bashing at WelcomeFest, these two representatives from separate poles of the party spent most of the panel agreeing with one another.

“To me it’s not a left-right issue, we’ve got to run directly toward working-class people,” Casar said at the panel. “We’ve got to make their concerns central to who we are as a party, central to our policy, central to the way that we talk about issues.”

Budzinski followed by proposing a “middle of the night” test: The party should prioritize subjects that keep families awake, like grocery prices or child care. Casar supplemented it with a “construction site” test: Those priorities should be explainable

There does seem to be some consensus that Democrats need to rediscover their purpose as a party. “Whether you’re talking about AOC or Vicente Gonzalez, and that’s the entire spectrum of Latino Democrats, both of them believe in economic populism,” said Chuck Rocha, Democratic strategist and former Bernie Sanders adviser. Rocha called it “a uniting thing. It can bring together all sides of the party.”

With his labor organizing background, Casar is seen as someone who can authentically deliver that message. “Greg’s values around that are solid, they didn’t develop after the election,” said Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), Casar’s predecessor as Progressive Caucus chair. Levy, of the Texas AFL- CIO, believes that Democrats allowed an opening to Republicans by straying from workingclass concerns, and marching with unionizing workers, as Casar has done in Austin and Washington, sends an important message. “The way to attract swing voters is not to say, ‘We’ll be your friend, we don’t believe in anything,’” Levy said. “It’s saying, ‘This is the way to make your life better.’”

To suggest that Democrats learned their lesson and now have one voice on economic issues would be far too optimistic. The prescription drug price lag wasn’t due to bureaucracy so much as oligarchy, as Casar acknowledged to me. Democratic allies of the pharmaceutical industry succeeded in delaying the price effects so companies could enjoy a few more years of unfettered profits. Those forces inside the party haven’t

withered away. Some of them congregated at WelcomeFest, up the street from Casar and Budzinski’s less well-attended gathering. Some of them funded the Center for American Progress, where Casar and Budzinski were speaking.

Casar nevertheless insisted that the days of Chuck Schumer happily trading one bluecollar voter for two affluent suburban voters are over. He suggested a generational split: Democrats who came of age through the financial crisis and COVID, who experienced inflation as the culmination of a cost-of-living crisis, who watched their leaders deliver piecemeal reforms that didn’t resonate with the electorate, are ready to cast aside the old politics. “They are young and newer, they’re happy to get uninvited from Big Pharma dinner but win their election campaigning on cutting their profits,” he said.

He doesn’t pivot every political development to the price of eggs. He has forcefully condemned ICE roundups as undermining all Americans’ civil rights. When Trump bombed Iranian nuclear sites, he was among the first to call the strikes illegal. And though Democratic Socialists of America unendorsed his first campaign for Congress for refusing to support the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement in Israel, Casar has supported

a cease-fire in Gaza since the first month of the war, and opposed offensive weapons transfers to Israel.

But he can channel those values into America’s economic divides. At a stop on Bernie Sanders’s “Fighting Oligarchy” tour in McAllen, Texas, Casar marveled at “these right-wing politicians—they eat food cooked by immigrants, they get their fancy cars cleaned by immigrants, they do their corrupt deals in buildings engineered, built, and maintained by immigrants—then they have the gall to turn around and say immigrants are the problem.”

In March, Casar participated in an afternoon of House floor speeches that brought New Dems, Blue Dogs, and progressives together to promote economic patriotism and demand a stronger alternative to Trump. The project reinforced a challenge to the Democratic leadership to shed status quo governance and reinvent the brand. Rep. Chris Deluzio (D-PA), who represents a swing district in and around Pittsburgh, coordinated the speeches. “It’s about taking back the fight for the American dream and opportunity,” Deluzio told me.

Casar’s speech focused on corruption, recalling his past battles in Austin as a labor organizer. “We didn’t win by going on bended knee and begging big corporations

In June, Casar confronted restaurant management in D.C. on behalf of workers fired for seeking a union.

for better treatment. We did it by unifying working people around some basic ideas … and this is what we need the Democratic Party to be all about.”

Jayapal knew of Casar through Local Progress, the network of state and local lawmakers where he served as a co-chair. After his election to Congress in 2022, she installed him as caucus whip. “I wanted somebody who was really grounded in the experience of standing up for working people,” she said. “I felt like he would have a great future.”

The chaotic, dysfunctional Republicanled House of Representatives of 2023-2024 offered no possibility for progressive victories. But Casar did his best to stand out. He pushed the Biden administration to propose nationwide heat safety protections, an echo of his first win at Workers Defense, by holding a thirst strike on the Capitol steps on a scorching July day. Biden’s Department of Labor did propose a rule, but it wasn’t completed before Trump took over.

Casar served on the House Agriculture Committee last year. After learning about 13-year-olds with “glittered school backpacks” working overnight shifts at meatpacking facilities, he proposed an amendment to the farm bill banning companies from federal contracts if they vio -

lated the decades-old ban on child labor. The initial pushback came not from Republicans, but from older committee staff, arguing the amendment would put frontline members in a tough spot with industry. “So then I went and spoke individually with every single member,” Casar explained. “And they all said to me, go ahead and run it, I’ll vote for your amendment.”

At the hearing, Republicans were flustered, voting down the amendment and reduced to arguing that the price of beef would go up if meatpackers couldn’t hire children. The same skittish committee staff told Casar that was the best moment in the markup. “Sometimes in these institutions there’s just built-in hesitancy and built-in caution of not pissing anybody off,” Casar told me. “But if you don’t piss anybody off then you’re probably not doing much.”