WHERE TO GROW IN BENDIGO?

A Suitability Analysis of Potential Urban Growth Area Sites in Greater Bendigo

ABPL90319

GIS in Planning, Design & Development

The University of Melbourne

Prepared by: Alain Nguyen

A Suitability Analysis of Potential Urban Growth Area Sites in Greater Bendigo

ABPL90319

GIS in Planning, Design & Development

The University of Melbourne

Prepared by: Alain Nguyen

The City of Greater Bendigo is a central regional local government area located near Victoria’s geographical center located 150km northwest of the state’s capital Melbourne. With over 119,000 persons living in the area based on recent data from the ABS, it is one of Victoria’s fastest-growing areas outside of the state capital Melbourne. Greater Bendigo is known for its arts and culture scene and is one of Victoria’s early boomtowns.

Today, Bendigo houses significant institutions such as La Trobe University, Bendigo Health and Bendigo Bank. Bendigo itself is also unique, being a city that is encompassed by vast natural landscapes and national forests, providing an outstanding prospect for regional living with the amenities of convenience.

The Greater Bendigo City Council as a major growth corridor in Victoria of which reside in Bendigo proper. This report analyses ascertaining potential sites through land use suitability analysis for urban growth in the Greater Bendigo area through the usage of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and existing spatial data in the area. The main parameter to consider is finding land size that is suitable to 9,000 dwelling units or a total of 18,000 units. It also considers factors such as public transportation, amenities and appropriate land use based on parameters discussed in further detail in the following sections of the report.

Figure 1: Graph of Greater Bendigo’s Population from 2006-20201

Urbanisation is a significant policy challenge for governance authorities over the past few decades. With a global population that is continually rising and the outward expansion of cities, the need to find sound evidence to ensure sustainable development of cities has become prevalent. For example, in Egypt, urban growth and land-use detection have been analysed by Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in a country that sees more unplanned decision making than around agenda policy setting.2 The use of GIS in Egypt presents a unique opportunity because it allows the illustration of data that may not have been possible in previous years and can bettering policy decision making processes about urban and regional planning.34 For land use spatial analysis, a study by Chen in Regina, Canada, showed the invaluable methods of spatial analysis and how data and decision analysis resulted in obtaining viable land use areas for suitability.5 Malczewski in 2004 suggests that GIS is a critical facet in planning itself and the impact of potential decision making in policies. In addition, a

report also in 2004 indicated that spatial data infrastructure could, to some extent can help “local planning”, which was defined around “future-oriented activity” on aspects of planning such as smart growth of urban areas, which is especially relevant to this project. GIS-based analysis for land use suitability is one of the instruments to ascertain decision-making processes to cater to urban and regional planning objectives.

From an Australian context, it seems GIS usage is extensive in the industry, government and academia.6 Indeed, the usage of GIS has been relatively advanced since the beginning of the internet age.7 For example, by using GIS to analyse the Melbourne Metropolitan Area’s “socio-ecological injustices”, the study found that these injustices were a “result of a pronounced presence of polluting” facilities and land usages such as waste treatment and petroleum processing.8 Bendigo itself has seen its land-use suitability be analysed through GIS, with Chen (2016) conducting a weighted overlay analysis on potential urban growth sites in Greater Bendigo.9 However, Duhr et al (2020) warn that this sense of access is not always appropriate for metropolitan planning and analysis of urban planning policy challenges. Usually, it requires specialist manipulation of data to procure the necessary data for any policy goals or decisions. Indeed, from the conceptions of GIS, there has been a development of various platforms and tools ranging from everyday consumption to specialist development such as those used in policy and other disciplines. Thus, the use of GIS is broad, but its definition is underpinned by what planning objectives and policies are in place and its context.

1.id (informed decision), ‘City of Greater Bendigo - Estimated Resident Population (ERP)’, .idcommunity demographic resources - community profle, 2020, https://profile.id.com.au/bendigo/population-estimate.

2 A.A. Belal and F.S. Monghanm, ‘Detecting Urban Growth Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques in Al Gharbiya Governorate, Egypt’ , The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 14, no. 2 (December 2011): 73–79.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibrahim Rizk Hegazy and Mosbeh Rashed Kaloop, ‘Monitoring Urban Growth and Land Use Change Detection with GIS and Remote Sensing Techniques in Daqahlia Governorate Egypt’ , International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 4, no. 1 (June 2015): 117–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsbe.2015.02.005.

5 Jiapei Chen, ‘GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Analysis for Land Use Suitability Assessment in City of Regina’ , Environmental Systems Research 3, no. 13 (2014): 1–10.

6 Stefanie Dühr, Hulya Gilbert, and Stefan Peters, ‘“Evidence- informed” Metropolitan Planning in Australia? Investigating Spatial Data Availability, Integration and Governance’ (Adelaide, South Australia: University of South Australia, July 2020), https://www.unisa.edu.au/contentassets/c7cd69c367ef4d81a0107477a6dac704/ahuri-finalreport_evidence-informed-metropolitan-planning_v310720.pdf.

7 Alister D Nairn, ‘AUSTRALIA’S DEVELOPING GIS INFRASTRUCTURE - ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES FROM A FEDERAL PERSPECTIVE.’ (5th International Seminar on GIS, Seoul, South Korea: Geosciences Australia, 2000), https://www.ga.gov.au/pdf/auslig/gis.pdf.

8 Melissa Pineda-Pinto et al., ‘Mapping Social-Ecological Injustice in Melbourne, Australia: An Innovative Systematic Methodology for Planning Just Cities’ , Land Use Policy 104 (May 2021), http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/460293.

9 Siqing Chen, ‘Land-Use Suitability Analysis for Urban Development in Regional Victoria: A Case Study of Bendigo’ , Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 9, no. 4 (April 2016): 47–58, https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP.

Current policies within the Greater Bendigo revolves around an integrated land use strategy that incorporates the development of Bendigo proper and localities adjacent to it. The Greater Bendigo Local Government Area will see a nearly 40 per cent increase in its population by 2036. The Plan Greater Bendigo Action Plan suggest there will be over 80,000 dwellings by 2050. Currently, the median housing price is approximately $550,000 or more which is comparable to several outer suburbs in Melbourne.10 With a rising population, there needs to be a consideration of expanding beyond the existing urban areas and integrate appropriate sites to manage this population growth. As such, it can be interpreted that any relevant policies to regional planning in Bendigo revolve around a balance between growth and rural integration and heritage The Greater Bendigo Plan acknowledges a need to cater to population growth while developing the area that is responsible, sustainable, and innovative.11 The four pillars of transformation for the Greater Bendigo Plan are:

1. An adaptable and innovative economy: “Improve access to education from an early age, better connect education and employment pathways and facilitate job creation to support a growing region”

2. Healthy and Inclusive Communities: “Strive for inclusive prosperity by facilitating better access to reliable transport, creating strong Aboriginal communities, improving community wellbeing and building social connections”

3. A stronger and more vibrant city centre: “Serve the needs of a growing city and region with diverse employment and services, active and highly valued public spaces, and a diverse residential population”

4. A resourceful and sustainable region: “Be a leader in the implementation of One Planet Living and consider our relationship with the natural environment in all that we do”

In addition, other existing strategies in place include the Integrated Transport and Land Use Strategy (ITLUS)12 and Residential Strategy13 that aims for as mentioned responsible development and progress in Bendigo. These strategies aim to prevent issues pertaining to urban growth such as preventing urban sprawl while providing connection between amenities, people, and places. Like the Plan Greater Bendigo, the strategy has objectives similar such as Compact, Connected, Healthy and Housing Bendigo. The Greater Bendigo Local Government Area, through strategic planning policies such as above, sees a desire to develop into a regional centre that attracts connectivity of productivity between Bendigo and Melbourne. As such, existing projects are in the

10 Zizi Averill, ‘Bendigo Property: COVID-Fuelled Tree Change Pushes up Regional House Prices’ , The Bendigo News, 4 February 2021, https://www.heraldsun.com.au/leader/bendigo/bendigo-property-covidfuelled-tree-change-pushes-upregional-house-prices/news-story/334613e965a7df7d65eefcc11e58df22.

11 City of Greater Bendigo, ‘Plan Greater Bendigo’ (Bendigo, Victoria, 2018), https://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/201801/Plan%20Greater%20Bendigo%20Action%20Plan%20Adopted%20January%202018.pdf.

12 City of Greater Bendigo, ‘Connecting Greater Bendigo: Integrated Transport and Land Use Strategy’, Strategic Planning (Bendigo, Victoria: City of Greater Bendigo, 22 October 2014), https://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/About/DocumentLibrary/connecting-greater-bendigo-integrated-transport-and-land-use-strategy.

13 City of Greater Bendigo, ‘Greater Bendigo Residential Strategy’, Strategic Planning (Bendigo, Victoria, 2015).

pipeline such as the provision of better transportation as well as the identification of activity centres throughout the local government area.

The main objective of this project is to conduct land suitability analysis using GIS and the spatial analysis tools such as weighted overlay analysis from ESRI’s ArcMap. Weighted Overlay analysis has been utilised as it allows the compounding of various spatial data to calculate hypothetical sites. It will take into consideration the current standing policies of the Greater Bendigo Local Government Area such as the Plan Greater Bendigo, ITLUS, Residential Strategy and the various nodes that relate to townships and communities. The project will consolidate a criterion based on these policies and existing literature as a means of potential replicability. Particular attention will be attributed to identified areas of growth or activity potential such as Marong, Elmore, Goornong and Huntly Using the average size of dwellings in Victoria which is 244.8 sq m according to CommSec14. Calculating this size by the intended 18,000 dwelling units, this results in a land mass that equates to over 440 ha.

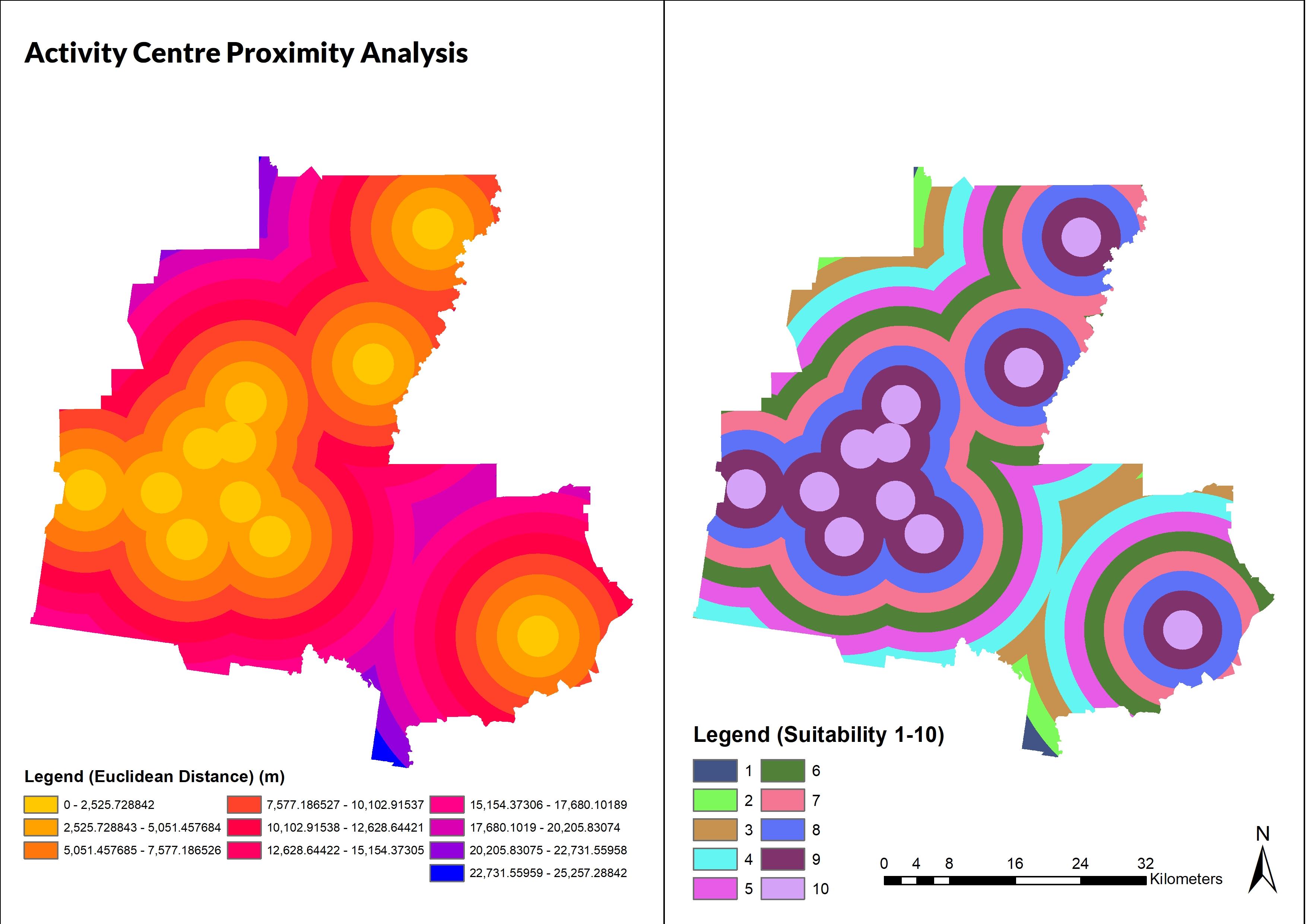

This criterion considers the proximity of amenities within the Greater Bendigo Local Government Area. A consideration of amenities such as supermarkets, proximity to activity centres, education and the Bendigo Central Business District will be the main actors for analysis. Ideally, a potential site should be within 10-20 minutes of these amenities and close enough to the central hub of activity Bendigo proper. The policy desires within Greater Bendigo to develop the area into one that is based on connectivity to activity and opportunity. Indeed, amenities play a role in urban growth and the subsequent investments that come from it.15 Amenities such as education, supermarkets and distance from activity centers are considered

This criterion emphasises the distance and proximation of transport networks such as major roads and public transportation nodes, such as stations on the Bendigo and Echuca Line. It is worth noting that this project will include railway stations that are under construction – Raywood and Goornong as part

14 Commonwealth Securities, ‘Australian Home Size Hits 22-Year Low’, CommSec Home Size Trends Report (Commonwealth Bank of Australia, 16 November 2018), https://www.commsec.com.au/content/dam/EN/ResearchNews/2018Reports/November/ECO_Insights_191118_CommS ec-Home-Size.pdf.

15 Terry Nichols Clark et al., ‘Amenities Drive Urban Growth’ , Journal of Urban Affairs 24, no. 5 (2002): 493–515, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.00134.

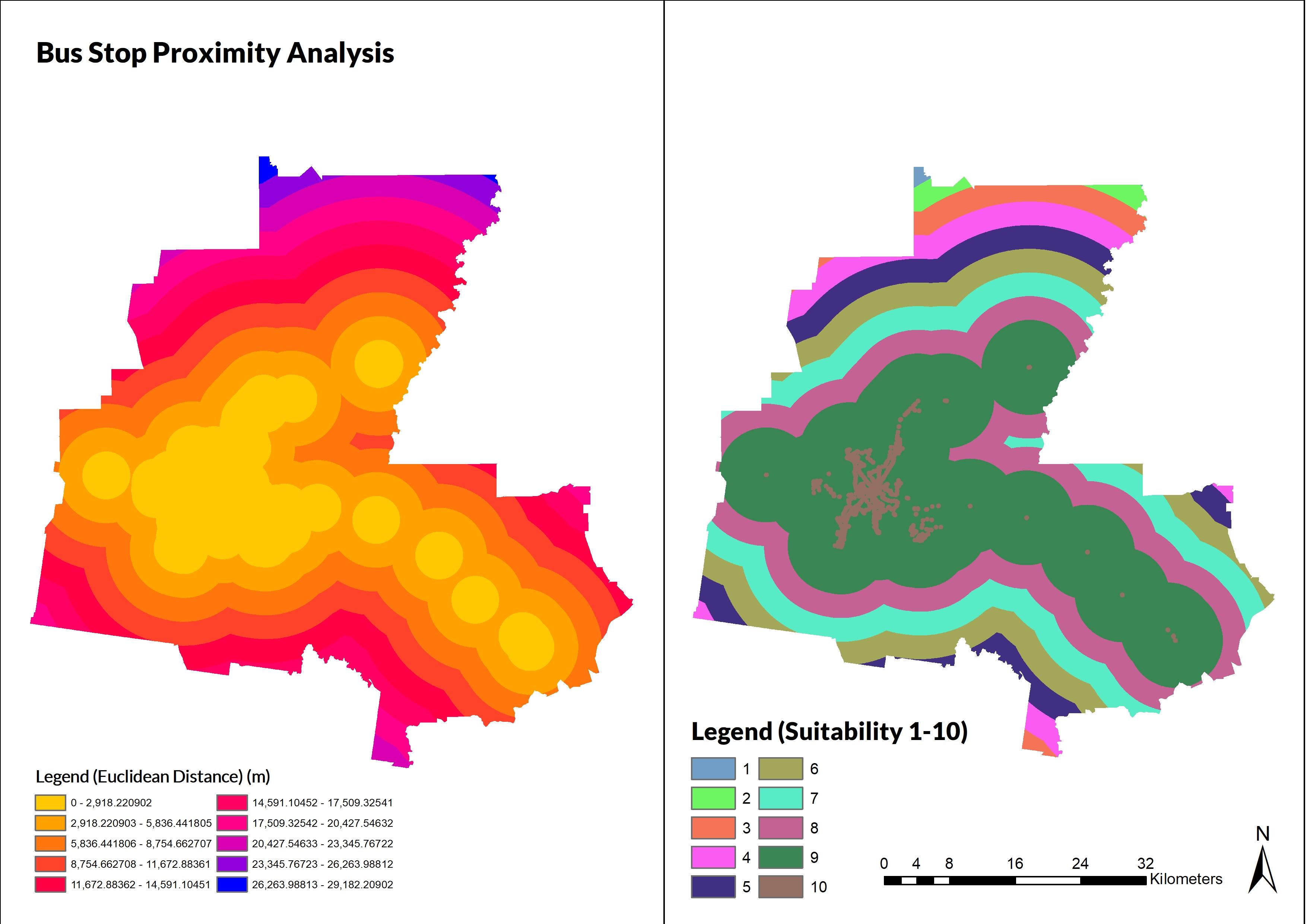

of the rail network. Transit oriented development is based upon key policy interventions and a focus on permeability and accessibility itself rather the extensiveness of transport nodes themselves.16 The requirements are essential because it illustrates the efficacy of integrating a growth area with existing corridors and the potential space for future developments should the need arise. For example, the Greater Bendigo Housing Strategy, Plan Greater Bendigo and Commercial and Residential Strategy all focus on creating transport connectivity akin to transit-oriented development.

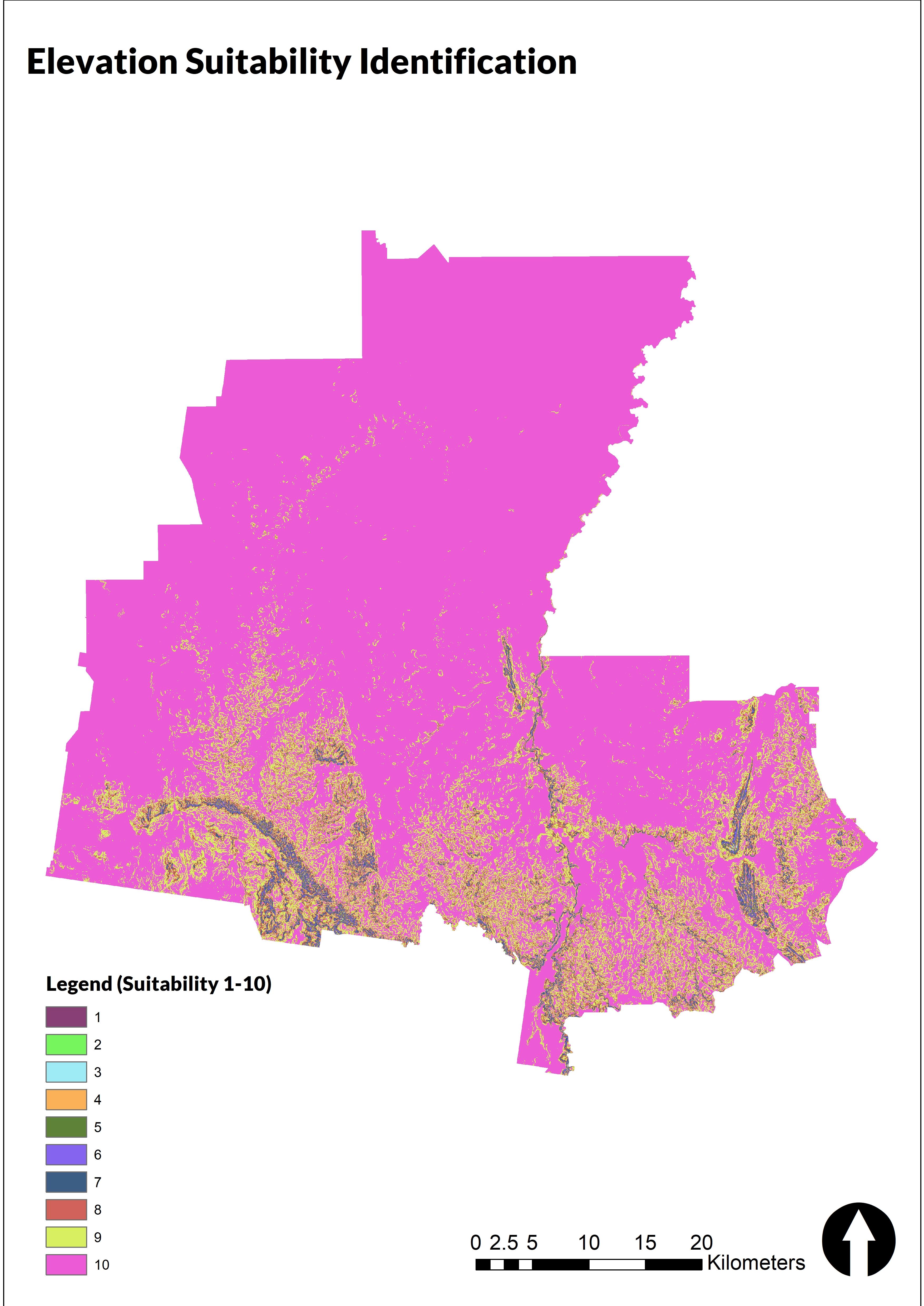

Bendigo is known for its natural landscape and the adjacency to national parks and forested land as well as watercourses that encompass it. It is important to have responsible practices in place to mitigate risk, such as bushfires and the potential damage they may cause; resilience being important in overall planning of a locality and their adjacent areas.17 While the Greater Bendigo Area has multiple parcels of land and masses, there are considerations into potential risk factors and existing land use regulations on what can be used and developed in the area. The concerns of potential risk factors such as bushfire-prone land and floodway as crucial factors in the analysis of suitability for urban growth in Greater Bendigo. Furthermore, other restrictions, such as elevation, zoning, and existing urban areas, will also be considered to ensure that any potential sites are appropriate.

Open space and proximity to community and recreation are vital for the well-being of a locality. A report in 2014 suggests that creating open spaces and recreation is more so about intangible “value based” planning than direct economic implications that result in planning decisions.18 Similarly, in densely populated areas in China for example, open spaces have a correlation with the physical health of residents and communities of varying degree but does alter how the urban landscape is perceived.19 Therefore, this criterion will consider distance and proximity to factors such as healthcare, open spaces, parks, community centres and recreation sites such as swimming pools and sports-related infrastructure.

16 Hollie Lund, ‘Reasons for Living in a Transit-Oriented Development, and Associated Transit Use’ , Journal of the American Planning Association 72, no. 3 (2006): 357–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360608976757.

17 Costanza Gonzalez-Mathiesen et al., ‘Urban Planning: Historical Changes Integrating Bushfire Risk Management in Victoria’ , Australian Journal of Emergency Management 34, no. 3 (July 2019): 60–66.

18 Christopher Ives et al., ‘Planning for Green Open Space in Urbanising Landscapes’, Final Report for the Australian Government Department of Environment (Melbourne, Victoria: National Environment Research Program, Environment Decisions Hub and School of Global, Urban and Social Studies RMIT University, October 2014), https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/25570c73-a276-4efb-82f4-16f802320e62/files/planning-greenopen-space-report.pdf.

19 Han Wang et al., ‘Influence of Urban Green Open Space on Residents’ Physical Activity in China’ , BMC Public Health 19 (2019): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7416-7.

Some literatures suggests that urbanisation and sprawl is a challenge that the planning discipline faces.20 Identified areas of activity in the Residential Strategy, for example, is taken weight here. Places such as Goornong, Heathcote, and Strathfieldsaye are the leading indicators of proximity. They provide distance from established towns and the central areas of Bendigo itself and ensures there is a responsible output of land use and not creating sprawl of Bendigo proper which are represented by an urban and urban growth boundary layer.

20 Onur Şatir, ‘Mapping the Land-Use Suitability for Urban Sprawl Using Remote Sensing and GIS Under Different Scenarios’, in Sustainable Urbanization (IntechOpen, 2016), https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/50491.

Previous sections have elucidated the usage of weighted overlay as the methodology of this project. The analysis itself will be contingent upon a variety of datasets provided both by the course matter and external sources such as Victorian Government Spatial Datamart and others such as AURIN and Google Maps. Many values from these datasets are extracted to create further separate files specific to their usage and for the criterion themselves. Data sources themselves can either come in polygonal shapes, lines or points as well as raster pyramid datasets.

The following figure outlines the input data for the project in ArcGIS. Many were extracted from existing core files relevant to the analysis such as Features of Interest from DELWP and PTV spatial data. The data is put into feature datasets that are relevant to their criteria. The main sources of data came from the Victorian Spatial Datamart and some provided data for the project.21

3: Input Files of the Project

The input data is analysed within a range of metrics that enables ascertaining potential sites for this project. For most parts, the parameters for the multi-criteria weighted overlay analysis is contingent upon a variety of intermediate processes to aggregate the suitability within the boundaries of Greater Bendigo.

While multiple analysis tools are being utilised, they will be standardised upon a scaling of common parameters to ensure there is consistency. A simple 1-10 levelling will be used to indicate the level of suitability with 1 being least suitable to 10 being most suitable. This is dependent on the type of data they are with some requiring a standardised range while others are of a binary-like bool aspect of suitable and non-suitable (1 and 10 instead of 1-10). Scaling is done so beyond the analysis through the process of reclassification of a raster pyramid dataset.

Manipulation of the input data sources relied on the usage of polygonal and raster files. Proximation is based on the Euclidean Distance principle of the length of a line segment between the two points. As such, this is within the domain of meters from certain points and segments. For this project, the length of a line segment precludes a desire for a close gap between nodes in the criteria and the potential site. As such, the usage of the Euclidean Distance is appropriate for criteria that relates to proximity to various nodes such as rail stations, major roads and amenities which can indicate the suitability of potential sites for urban growth. Within

The data analysis will culminate in a weighted overlay analysis on ArcGIS. This tool takes into consideration the data processing based on the criteria set out by the user. The input allows” weighting” the influence of which factors to take into consideration. The analysis will aim to equalise the weight of the data but will take more leeway towards public transportation for example over major roads (which is still important). Further detail will be discussed later in this report.

21 Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), ‘Victorian Spatial Datamart’ , (Government of Victoria, 2020-2021),

As shown in the figures below, it is about being served by multiple identified local, neighborhood and major activity centers within its administrative boundaries. This corridor is having a potential to connect the various townships and Bendigo Proper. It is better to have mixed-use density use and development rather than one influencing than the other.22 Finally, the reclassification of the Euclidean Distance analysis shows the viability of area segments within these boundaries and demarcation of potential sites.

Connection to existing public transportation nodes is important to provide alternative options to motor vehicle usage and reduce environmental pollution.23 While the reality is that regional transportation will be less extensive as metropolitan areas, developing a network that is accessible and connected with various amenities is a key factor in improving the viability of community and residential growth in areas such as Greater Bendigo. As seen in the figures below, this is based on a mix of bus and rail stops and their proximities. Later, the analysis will also show service areas of major transport nodes. As such, this criterion will consider the connectivity to major roads alongside public transportation

22 Junjie Wu, ‘Environmental Amenities, Urban Sprawl, and Community Characteristics’ , Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 52, no. 2 (September 2006): 527–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2006.03.003.

23 Johan Holmgren, ‘The Effect of Public Transport Quality on Car Ownership – A Source of Wider Benefits’ , Research in Transportation Economics 83 (November 2020): 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100957.

This criterion ensures that any potential sites will take into consideration any risk factors from the natural environment such as floodways and land subject to inundation and bushfire prone areas under the bushfire management overlay. As shown in the figure below, these criteria will also aim to respect regulations such as environmental significance and landscape significance overlays as defined by the Greater Bendigo Planning Scheme. Furthermore, it will also ensure that the site will be away from areas that have vegetation protection overlays to protect the flora and fauna of the area.

Using data such as DELWP’s Features of Interest and the Public Park and Recreation Zone, this criterion aims to find an appropriate proximity to open space and recreation centers such as sports facilities. As seen in the figures below, the analysis is there used to illustrate the importance of ensuring these spaces are accessible in providing a neighborhood that has a wide range of access and connections to the communities around them. Like the first criteria, amenities and accessibility remains at the forefront of developing sustainable urban areas.

The challenge of managing growth sustainably is one that is widely discussed to ensure there is no overlap and intensification of areas.24 Similarly, both the Greater Bendigo Local Government Area in the Plan Greater Bendigo document and Chen in 2016 suggests that suitable land use for urban growth should be responsible and integrated within boundaries but not to the point of overexpansion.2526 As seen in the figures below, this criteria will consider the proximity that is close enough to the UGB but not encroaching to avoid over densification and ensure there is more composed growth in the Greater Bendigo area.

24 Christian Gerten, Stefan Fina, and Karsten Rusche, ‘The Sprawling Planet: Simplifying the Measurement of Global Urbanization Trends’ , Frontiers in Environmental Science, 25 September 2019, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00140.

25 Chen, ‘Land-Use Suitability Analysis for Urban Development in Regional Victoria: A Case Study of Bendigo’

26 City of Greater Bendigo, ‘Plan Greater Bendigo’ .

After the reclassification of the relevant datasets into the five criteria, a weighted overlay analysis was undertaken to quantify potential areas in the Greater Bendigo area. Based on the Greater Bendigo Local Government Area’s strategic planning policies as well as the literature examined in this project, criteria were weighted accordingly based on their level of impact and longer-term factors. The highest criteria are the safety and resilience aspect. Because there are considerable amounts of land that is within a Bushfire Management Overlay and proximate to floodway areas, a potential site must ensure that it does not overlap with these factors because they’re likely to cause potential loss not only economically but the risk of human life and communities. Previously, risk analysis was done retroactively rather than in anticipation and recent reforms have shown the trend towards the latter.27 The second most important criteria is around the connectedness of a potential site. As such, weight is given to public transportation networks and amenities such as supermarkets to ensure essential living aspects are accounted for.28 Finally, the remaining criteria are still important and play a complementary role to further quantify a suitable site based on their social and economic benefits.

Total Weight: 30%

Once the weighted overlay analysis was finalized, it went through further revisions to specify potential sites. The resulting raster from the weighted overlay was converted to a polygon so that its scaling can be used on a more flexible level. The first revision after conversion was to erase the polygon from the urban area in case of sites that overlap that wasn’t considered in the weighted overlay analysis itself. Once processed again, the data would go through a final stage of calculating hectares per polygon part to find suitable sites. The average dwelling size in Victoria is 244.8 sq m as mentioned earlier29 and by converting this into hectares and multiplying by 18000 (representing dwelling units), the resulting equation meant there had to be land that was more than 440 ha. The two largest sites and the largest one within the UGB were then extracted.

The identified UGA sites were almost parallel with the Greater Bendigo policies especially the identified activity centres in the Residential Plan.30 For sites within the existing UGB, the areas of Huntly and outward northeastern fringes of the UGB. It is worth mentioning townships such as Marong and Goornong that are outside the UGB that were identified as the most suitable land based on the data manipulation done in ArcMap. These localities are subject to township development and currently have in the pipeline proposals such as railway connections. However, it is worth noting that this has not taken into consideration current zoning provisions yet (which can be subject to change). Furthermore, the Goornong and Marong UGA sites may seem substantially large, but it also intersects with other localities such as Barnadown, Lockwood and Bagshot North and further analysis will potentially reduce the size area.

This project provided a baseline overview of the usage of spatial analysis tools through GIS to illustrate potential urban growth areas in the Greater Bendigo Area. The project while possibly hypothetical and within its parameters shows a procedure in which spatial data can be manipulated for varying levels of analysis. This project utilized Euclidean Distance and Scaling to consider a Weighted Overlay analysis in its objective of corresponding urban growth areas with policies from the Greater Bendigo Local Government Area. Weighted Overlay allows multiple criteria to be put in place and having a degree of control over its influence in an analysis31 The resulting areas such as Marong, Goornong and Elmore highlight the flexibility in regional areas such as this for future growth and investment.

Upon the conclusion of the project analysis, there are a few points that may serve as future guidance for land use suitability analysis and weighted overlays such beyond the parameters of this project. It is recommended that future analysis takes into consideration:

• Longer Term Planning of Land Use and Site Scoping: Addition of Amenities beyond transportation infrastructure

• Other Methods of Analysis Beyond Euclidean Distance and Reclassification such as Network Analysis to Create Service Area Nodes to Calculate the Neighbourhood Drive or Walking Time

• Further refinement and updating of policies to ensure that activity centres and growth areas are continually served by best practices for sustainable and connected growth

Averill, Zizi. ‘Bendigo Property: COVID-Fuelled Tree Change Pushes Up Regional House Prices’. The Bendigo News. 4 February 2021. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/leader/bendigo/bendigoproperty-covidfuelled-tree-change-pushes-up-regional-house-prices/newsstory/334613e965a7df7d65eefcc11e58df22.

Belal, A.A., and F.S. Monghanm. ‘Detecting Urban Growth Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques in Al Gharbiya Governorate, Egypt’. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 14, no. 2 (December 2011): 73–79.

Chen, Jiapei. ‘GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Analysis for Land Use Suitability Assessment in City of Regina’. Environmental Systems Research 3, no. 13 (2014): 1–10.

Chen, Siqing. ‘Land-Use Suitability Analysis for Urban Development in Regional Victoria: A Case Study of Bendigo’. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 9, no. 4 (April 2016): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP.

31 Chen, ‘Land-Use Suitability Analysis for Urban Development in Regional Victoria: A Case Study of Bendigo’ .

City of Greater Bendigo. ‘Connecting Greater Bendigo: Integrated Transport and Land Use Strategy’. Strategic Planning. Bendigo, Victoria: City of Greater Bendigo, 22 October 2014. https://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/About/Document-Library/connecting-greater-bendigointegrated-transport-and-land-use-strategy.

City of Greater Bendigo. ‘Greater Bendigo Residential Strategy’. Strategic Planning. Bendigo, Victoria, 2015.

City of Greater Bendigo. ‘Plan Greater Bendigo’. Bendigo, Victoria, 2018. https://www.bendigo.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/201801/Plan%20Greater%20Bendigo%20Action%20Plan%20Adopted%20January%202018.pdf.

Clark, Terry Nichols, Richard Lloyd, Kenneth K. Wong, and Pushpam Jain. ‘Amenities Drive Urban Growth’. Journal of Urban Affairs 24, no. 5 (2002): 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/14679906.00134.

Commonwealth Securities. ‘Australian Home Size Hits 22-Year Low’. CommSec Home Size Trends Report. Commonwealth Bank of Australia, 16 November 2018. https://www.commsec.com.au/content/dam/EN/ResearchNews/2018Reports/November/EC O_Insights_191118_CommSec-Home-Size.pdf.

Dühr, Stefanie, Hulya Gilbert, and Stefan Peters. ‘“Evidence-informed” Metropolitan Planning in Australia? Investigating Spatial Data Availability, Integration and Governance’. Adelaide, South Australia: University of South Australia, July 2020. https://www.unisa.edu.au/contentassets/c7cd69c367ef4d81a0107477a6dac704/ahuri-finalreport_evidence-informed-metropolitan-planning_v310720.pdf.

Gerten, Christian, Stefan Fina, and Karsten Rusche. ‘The Sprawling Planet: Simplifying the Measurement of Global Urbanization Trends’. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 25 September 2019, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00140.

Gonzalez-Mathiesen, Costanza, Alan March, Justin Leonard, Mark Holland, and Raphael Blanchi. ‘Urban Planning: Historical Changes Integrating Bushfire Risk Management in Victoria’. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 34, no. 3 (July 2019): 60–66.

Hegazy, Ibrahim Rizk, and Mosbeh Rashed Kaloop. ‘Monitoring Urban Growth and Land Use Change Detection with GIS and Remote Sensing Techniques in Daqahlia Governorate Egypt’. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 4, no. 1 (June 2015): 117–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsbe.2015.02.005.

Holmgren, Johan. ‘The Effect of Public Transport Quality on Car Ownership – A Source of Wider Benefits’. Research in Transportation Economics 83 (November 2020): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100957.

.id (informed decision). ‘City of Greater Bendigo - Estimated Resident Population (ERP)’. .idcommunity demographic resources - community profle, 2020. https://profile.id.com.au/bendigo/population-estimate.

Ives, Christopher, Cathy Oke, Benjamin Cooke, Ascelin Gordon, and Sarah Bekessy. ‘Planning for Green Open Space in Urbanising Landscapes’. Final Report for Australian Government Department of Environment. Melbourne, Victoria: National Environment Research Program, Environment Decisions Hub and School of Global, Urban and Social Studies RMIT University, October 2014. https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/25570c73-a276-4efb82f4-16f802320e62/files/planning-green-open-space-report.pdf.

Lund, Hollie. ‘Reasons for Living in a Transit-Oriented Development, and Associated Transit Use’. Journal of the American Planning Association 72, no. 3 (2006): 357–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360608976757.

Nairn, Alister D. ‘AUSTRALIA’S DEVELOPING GIS INFRASTRUCTURE - ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES FROM A FEDERAL PERSPECTIVE.’ Seoul, South Korea: Geosciences Australia, 2000. https://www.ga.gov.au/pdf/auslig/gis.pdf.

Pineda-Pinto, Melissa, Christian A Nygaard, Manoj Chandrabose, and Niki Frantzeskaki. ‘Mapping Social-Ecological Injustice in Melbourne, Australia: An Innovative Systematic Methodology for Planning Just Cities’. Land Use Policy 104 (May 2021). http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/460293.

Şatir, Onur. ‘Mapping the Land-Use Suitability for Urban Sprawl Using Remote Sensing and GIS Under Different Scenarios’. In Sustainable Urbanization. IntechOpen, 2016. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/50491.

Wang, Han, Xiaoling Dai, Jinglan Wu, Xingyi Wu, and Xin Nie. ‘Influence of Urban Green Open Space on Residents’ Physical Activity in China’. BMC Public Health 19 (2019): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7416-7.

Wu, Junjie. ‘Environmental Amenities, Urban Sprawl, and Community Characteristics’. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 52, no. 2 (September 2006): 527–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2006.03.003.