REFEREED PROCEEDINGS OF THE 5th WIL AFRICA CONFERENCE 2024

Published by:

Available Online: www.sasce.net

ISBN: 978-0-7961-8633-1(e-book)

Proceedings Editor: Lia Marus BA (UCT) | MA (Wits), PDM (Wits Business School), LLB (Unisa) www.liamarus.com

The publisher grants permission and encourages authors to archive the final unaltered published proceedings in their institutional repositories, distribute directly to a third party, and on their personal websites. The authors and readers of this proceedings publication can distribute an unlimited number of printed and electronic copies of the unaltered version of this proceedings publication on the condition that it is the unaltered original version as published here and that distribution is at no commercial gain.

Publication Information

Title: WIL Africa Conference Proceedings

ISBN: 978-0-7961-8633-1(e-book)

Format: Online https://sasce.net/ Date of publication: 30 August 2025

CONFERENCE COMMITTEES

CHAIRS OF CONFERENCE COMMITTEE

Dr Fundiswa R. Nofemela

Prof Lalini Reddy

CONFERENCE COMMITTEE

Naleli Q Wasa – SASCE

David Haarhoff– Cape Peninsula University of Technology

Bronwyn Abrahams – Cape Peninsula University of Technology

Matseke Moloantoa – SASCE

CONFERENCE ABSTRACT REVIEW COMMITTEE

Prof Chris Winberg

Prof Lalini Reddy

Ass Prof James Garraway

CHAIR OF THE PROCEEDINGS REVIEW BOARD

Prof JN Nduna (SASCE Research Pillar Lead)

REVIEW BOARD

Prof Chris Winberg, Cape Peninsula University of Technology

Dr Themba Msukwini, Durban University of Technology

Prof Lalini Reddy, Cape Peninsula University of Technology

Dr Princess Thulile Duma, Mangosuthu University of Technology

Dr Moeti Kgware, Durban University of Technology

Dr Siphiwe Gumede, Mangosuthu University of Technology

Dr Joseph Mesuwini, Wits University

Dr Thobeka Makhathini, Mangosuthu University of Technology

Prof Arthur Maphanga, Walter Sisulu University

A/Prof James Garraway, Cape Peninsula University of Technology

All papers were independently, double-blind peer reviewed by two members of the Review Board. All papers published in these proceedings were presented at the 5th WIL Africa Conference, 2024, Century City Conference Centre, Cape Town

Publication Information

Title: WIL Africa Conference Proceedings

ISBN: 978-0-7961-8633-1(e-book) Format: Online https://sasce.net/ Date of publication: 30 August 2025

https://sasce.net/

BUILDING STRONG COLLABORATIONS FOR WORKINTEGRATED LEARNING: THE CASE OF A UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN KWAZULU-NATAL

Hlubi Zamandaba, C

Nofemela Fundiswa, R

Mangosuthu University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) combines academic instruction with practical experience, facilitated through collaborations among institutions, Employers, and other Stakeholders. These partnerships strengthen employability outcomes and skill development (Ferrández-Berrueco et al., 2016). The Employer engagement strategy, which is led by the Cooperative Education Directorate at the institution, serves as an exemplary model of sustainable Stakeholder collaboration. This paper examines a university of technology’s Employer Engagement Program through a descriptive case study, drawing on the Sustainable Relationship Framework (Flemming et al., 2018) with its emphasis on Compatibility, Communication, and Commitment. The study highlights best practices that have rebuilt Stakeholder trust and enhanced the institution’s reputation.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The Sustainable Relationship Framework

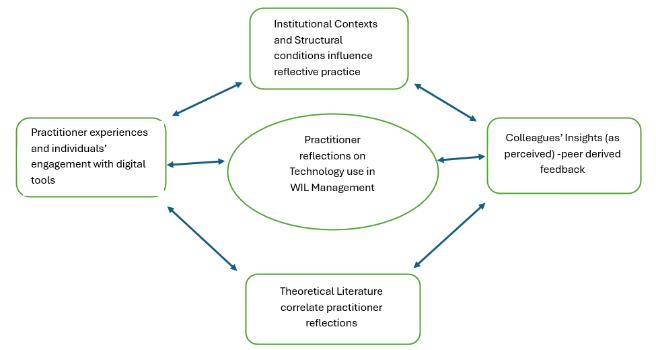

Effective Stakeholder engagement underpins all elements of a successful WIL programme Flemming et al. (2018) propose the Sustainable Relationships Framework, which is centred on Compatibility, Communication, and Commitment (“the three Cs”) as pillars for enduring WIL relationships. Figure 1 below depicts a graphical representation of the framework.

Figure 1: The Sustainable Relationship Framework, Flemming et al, 2018

Effective Stakeholder management is widely recognised as being central in successful project execution and organisational governance. It is thus critical for communication to be strategic, as it is not just a conduit for information exchange but also as a mechanism for building trust, managing expectations, and coordinating collaborative relationships.

‘Compatibility’ refers to the strategic and operational alignment between educational institutions and industry partners. It entails the shared vision between the institution and Employers, the extent to which the institution acknowledges Stakeholders, and the reciprocity that exists among them.

‘Commitment’ in WIL Stakeholder management refers to the sustained dedication of all Stakeholders particularly institutions and Employers - to upholding its principles, responsibilities, and practices. It is not merely a contractual obligation but a strategic and ethical stance that ensures continuity, quality,

and trust. It is evidenced through the extent to which expectations of both Stakeholders are considered as well as how reputational considerations are managed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Importance of effective Stakeholder management in Work-Integrated Learning

Recent literature underscores the pivotal role of effective Stakeholder management in enhancing the quality and impact of Work-Integrated Learning (WIL). Wait and Govender (2016) advocate for a transdisciplinary model that includes government, industry, and education institutions, highlighting the need for clearly defined roles to ensure mutual benefit and policy alignment. Similarly, University West (2023) emphasises strategic collaboration to support lifelong learning and promote quality frameworks for WIL delivery. Fleming et al. (2018) present a sustainability-focused framework anchored in three essential pillars: communication, commitment, and compatibility that serve as guiding principles for enduring Stakeholder engagement. Rook and Sloan (2020) further reveal the complexity of Stakeholder perspectives on employability and graduate attributes, noting the importance of shared definitions and the integration of Stakeholder feedback into curriculum design. Collectively, these studies reinforce that effective Stakeholder management is not only instrumental for operational success but also essential for ensuring relevance, reciprocity, and systemic improvement in WIL practice.

Communication and Expectation Management

The literature consistently affirms that communication is not a peripheral activity but a core strategic function that underpins Stakeholder engagement across sectors and contexts. Jenny et al. (2017) highlight communication as a mechanism for expectation alignment, trust-building, and continuous improvement in university-industry engagement.

The emphasis on communication across multiple Stakeholder management theories provides a foundational lens through that strong collaborations in Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) can be built and sustained. Stakeholder theory, as articulated by Freeman (1984), situates interest alignment as critical to long-term success and positions communication as a prerequisite for identifying and negotiating those interests within WIL partnerships. Building on this, Grunig and Hunt’s (1984) Excellence Theory advocates for two-way symmetrical communication, which is instrumental in fostering institutional understanding and legitimacy among WIL Stakeholders. Empirical insights from Alqaisi (2018) and Bourne (2016) further reinforce that the absence of inadequacy of structured communication leads to disengagement and dissatisfaction, which are conditions that directly undermine collaborative initiatives in WIL settings. Trust - identified by Khan, Skibniewski, and Cable (2023) and reinforced by Rajhans (2018) - arises from transparent, consistent communication and acts as a foundation for durable Stakeholder relationships. Together, these insights highlight the role of strategic communication in aligning Stakeholders while promoting trust, clarity, and sustainable collaboration in WIL.

Compatibility

The consideration of compatibility in WIL Stakeholder management involves evaluating the “why” behind WIL placements and ensures that learning objectives are context-sensitive and aligned with institutional goals (Young et al. (2024). It ensures that both parties share a common purpose and can collaborate effectively to deliver meaningful WIL experiences.

Recognition and Reciprocity

According to Ferrández-Berrueco et al. (2016), reciprocal recognition promotes Stakeholder loyalty. Freeman et al. (2007) emphasises the importance of recognising Stakeholder contributions and fostering

the institutional respect. Recognition practices can be both formal and informal recognition and reinforce Stakeholder commitment and trust. In the case of WIL Placements, institutions may offer awards or public acknowledgment, while Employers may provide testimonials or future placements. Stakeholder Reciprocity surpasses corporate responsibility to include Stakeholder duties such as loyalty, fairness, and constructive engagement. Fassin (2012) argues that reciprocity is not just transactional but ethical, fostering loyalty and long-term engagement.

Vision Alignment

Compatibility begins with an institutional understanding of the goals of WIL, whether it is enhancing employability, developing specific skills, or contributing to industry innovation. Sachs & Rowe (2016) emphasise that alignment of institutional and industry visions is foundational to sustainable WIL partnerships. According to Fleming, McLachlan & Pretti (2018), compatibility begins with shared values and long-term commitment to WIL goals. They posit that Institutions and Employers must co-own the vision for student development and employability.

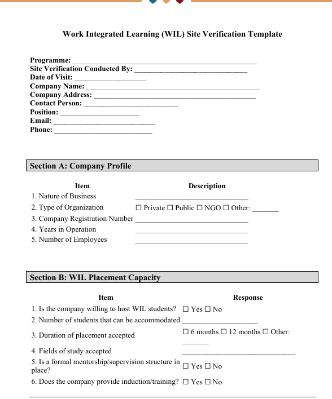

Provision of Learning and Worksite Verification

It is critical in a Stakeholder relationship to ensure that learning environment is suitable. This means that the host organisation must offer a worksite that meets academic and developmental criteria including mentorship, exposure to relevant tasks, as well as safety. Flemming et al. (2018) recommend formalised verification protocols to maintain quality assurance and compatibility. To achieve this, institutions must conduct site visits and audits to ensure compliance with learning standards and workplace readiness.

Commitment

Commitment, particularly in Work-Integrated Learning Stakeholder management, is critical for managing risk (Effeney, 2020). Further, the University of Pretoria’s WIL Policy (2024) provides an example of an institution’s commitment to WIL Stakeholder management through mandated agreements that explicitly delineate the obligations of the university, placement site, and student thereby institutionalising and reinforcing collaborative intent. When combined with principles of communication and trust, such formal structures become essential for sustaining effective Stakeholder engagement in WIL.

Expectations of all Parties

Expectations regarding supervision, feedback, assessment, and duration must be clearly defined and agreed upon. These are determined using Stakeholder matrices or MoUs to help document and align expectations. Advisory boards and feedback sessions allow for recalibration of expectations over time. In this regard, the South African Council on Higher Education (CHE) emphasises the critical role that advisory structures play in curriculum alignment, Stakeholder engagement, and quality assurance in WIL programmes (CHE, 2011).

Reputational Considerations

Compatibility includes addressing how each party is perceived especially if the Employer has never hosted students before. Additionally, discussions around past collaborations, institutional strengths, and student preparedness help build trust. Reputational management also entails ensuring that the host company does not exploit students and that the university prepares the students adequately for the world of work. Cameron et al. (2019) proposes managing intellectual property, student conditions, and host organisations as a form of risk mitigation in WIL.

METHODOLOGY

This descriptive case study synthesises multiple qualitative sources to evaluate the institution’s application of the Sustainable Relationship Framework (see Table 1, below) It was chosen for its capability to provide in-depth description and understanding of the case within its own world, its issues, interpretations, and settings (Stake,2005). The research design entailed:

Table 1: Research Design

Domain Purpose

Commitment To provide evidence of engagement events

Evidence of Employer engagement activities

To show evidence of feedback from Stakeholders

To show evidence of external endorsements

Compatibility Evidence of spelled-out and documented commitments

Evidence of Stakeholder recognition

Communication To gain insights on how trust and coordination is operationalized

To review engagements between the university and external Stakeholders

Institutional evidence Review Source

Review of event photos, including WIL Imbizo sessions, Employer awards, and MoU signings, to contextualise Stakeholder engagement.

Review of Employer satisfaction surveys, WIL Imbizo reports, and Stakeholder Excellence awards to show meeting of expectations

Visual evidence

Annual WIL Imbizo report Feedback

Incorporation of findings from the CHE Institutional Audit (2023) and the IFC Employability Assessment (2024), highlighting external endorsement of the institution’s Employer engagement.

Review of documents pertaining to MoUs and Site Verifications to show meeting of expectations;

WIL Partner Excellence Awards concept document

Analysis of MoUs, Advisory Board policy, site verification forms student placement records, and partner recognition protocols.

Examination of email exchanges between placement officers, mentors, and lecturers to gauge expectation management and communication dynamics.

External evaluations

Contracts

Awards Concept document and award images

Institutional document review

Correspondence analysis

This multi-source approach provided triangulated insights into Stakeholder trust, compatibility mechanisms, and institutional commitment.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Commitment

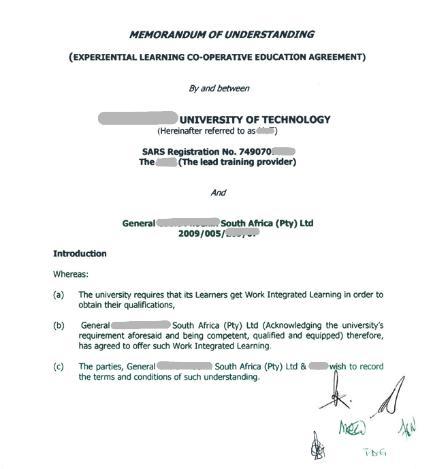

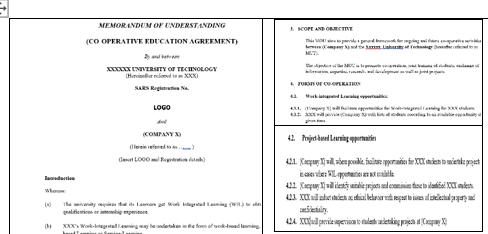

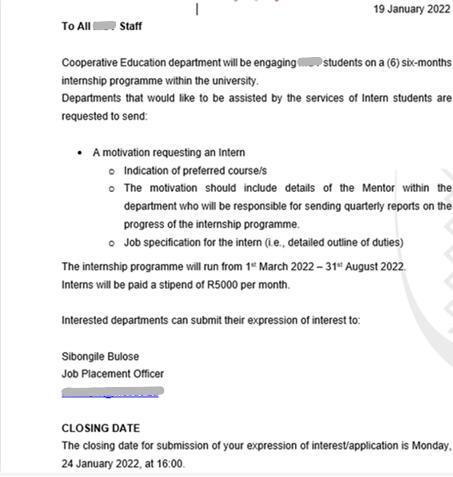

The Institution’s commitment to Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) is firmly embedded in structured governance and ongoing Stakeholder engagement practices. This commitment is formalised through Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) Document reviews showed several MoUs that stipulate forms of cooperation between the Institution and the host company as well as scope covered by the MoU, see figure 2.

Figure 2 : MoU extract showing parties to the Mou, scope and signature page

Beyond contractual frameworks, the Institution conducts Employer satisfaction surveys on a triennial basis to determine, quantitatively, the host Employer’s level of satisfaction with the institution’s WIL students. The Employer Satisfaction Survey Report is compiled and sent to Employers. An extract of an Employer Satisfaction Survey Report is provided below (Figure 3).

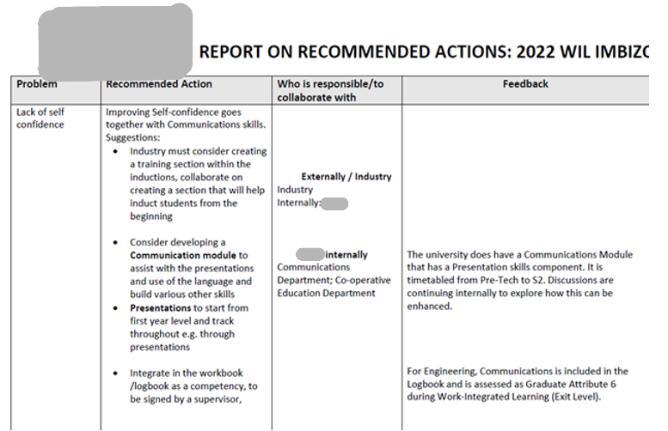

This is complemented by annual engagement reviews facilitated through the WIL Imbizo Symposium. Analysis showed that the discussions in the WIL Imbizo encompass concerns from industry,

Figure 3: Extract from the Employer satisfaction survey report

recommended actions as well as responsibilities. These further show reports by the institution on annual progress in improvements (Figure 4)

Figure 4:Extract from WIL Imbizo2022 report

These feedback mechanisms are not merely ceremonial. They function as strategic dialogue platforms. Employer recommendations arising from both the surveys and the Imbizo discussions are systematically communicated to academic faculties and incorporated into institutional improvement plans. This process enables evidence-based enhancements that align academic provision with evolving industry expectations.

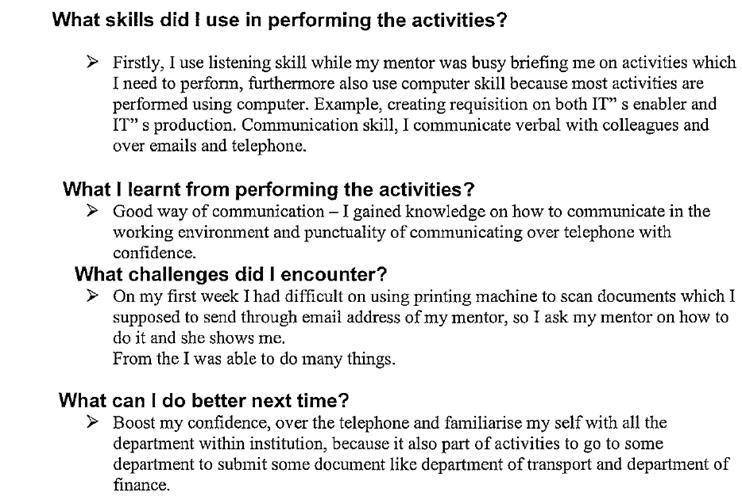

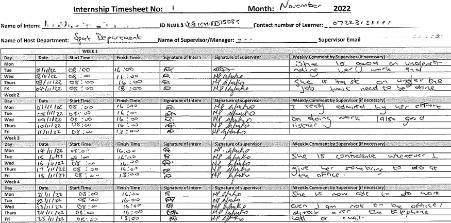

The evidence examined highlights student support initiatives such as placement tracking through quarterly reflection reports from both students and host supervisors, regular site verification visits by academic staff, and structured mentorship coordination as examples of the institution’s commitment to sustaining the integrity and effectiveness of employer relationships. These measures facilitate continuous quality assurance and reinforce the reliability of institutional partnerships.

The impact of this multi-layered commitment is evidenced by tangible outcomes: heightened Employer Loyalty, recurring referrals, and active advocacy from industry Stakeholders. Such Stakeholder endorsement has directly contributed to a notable increase in WIL placement rates across disciplines. The institution’s strategic engagement was validated externally by the 2024 Institutional Audit conducted by the Council on Higher Education (CHE), which affirmed its growing reputation and Stakeholder trust. These commendations were further substantiated by the Employability Assessment carried out by the International Finance Corporation (IFC)), reinforcing the credibility and scalability of the institution’s WIL model.

Compatibility

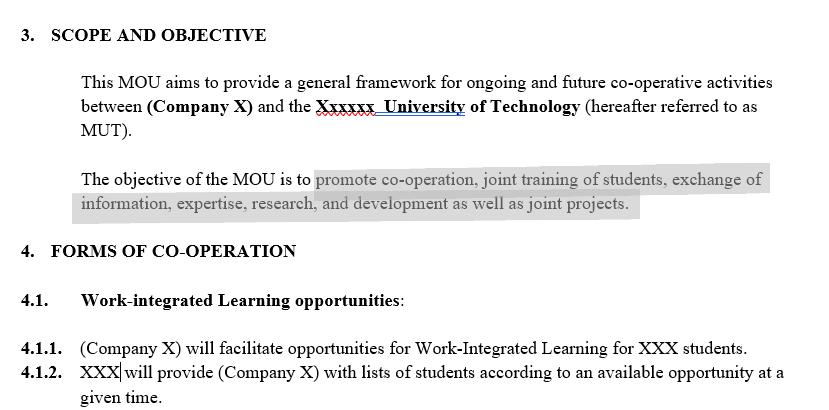

Compatibility at the Institution is cultivated through structured agreements and collaborative vetting processes that ensure mutual alignment between the university and its Employer partners. Central to this process are Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs), which formally articulate the roles, expectations, and responsibilities of both parties (Figure 5). These documents serve not only as legal instruments but as strategic tools for operational synergy. Compatibility is further reinforced through pre-placement consultations where the institution engages in detailed discussions with potential hosts to determine their capacity to meet the academic outcomes of the respective qualifications.

5:

showing cover, roles, expectations and responsibilities

As part of its quality assurance measures, the Institution conducts site verification visits for new Employer partners. These assessments evaluate the learning environment's adequacy, focusing on aspects such as:

1. Alignment between workplace tasks and learning outcomes,

2. Availability and ratio of qualified mentors to students,

3. Suitability and safety of infrastructure, including machinery-to-student ratios, and

4. Supervisory structures and workplace readiness for student engagement.

Figure 6: Site Verification Form

Strategic alignment is strengthened through dialogues on reciprocal interests, such as opportunities for collaborative research, skills development, and institutional visibility. Where applicable, these mutual interests are codified within the MoU to ensure shared value and sustained collaboration.

Figure

MoU Snip

Figure

MoU snip: Areas of collaboration

To address reputational considerations, the Institution proactively presents its student preparation strategy during initial Stakeholder discussions. These engagements highlight academic rigour, workplace readiness modules, and experiential learning components, thereby instilling confidence in the Institution's capacity to produce well-prepared graduates. Simultaneously, the Institution assesses the Employer's familiarity with its programmes and history of engagement, identifying potential misconceptions or gaps in understanding that may require attention. This dual exchange facilitates trust-building and mutual reputational assurance.

In addition to operational practices, the Institution actively promotes recognition and reciprocity through a biennial Employer Partner Excellence Awards ceremony. This initiative acknowledges Employers who exemplify excellence in WIL collaboration, based on a set criterion and through certificates and awards trophies. (Figure 8)

By institutionalising both strategic engagement and formal recognition mechanisms, the University sustains high levels of compatibility and trust with its Employer partners, thereby strengthening the overall impact of its WIL programme.

Communication

Effective communication underpins the Institution’s engagement strategy and channels include daily operational emails, Stakeholder advisory boards, and the annual WIL Imbizo

7:

Figure 8: Stakeholder Excellence Awards

Institutional document review:

A review of documents revealed that the University has a Stakeholder Advisory Board Policy as well as a Standard Operating Procedure document that guides implementation of the policy. This stipulates having WIL as a standing agenda item thus providing space for discussions around advances in WIL curriculum matters as well as concerns that industry may have. Further, the document review showed that that MoUs that the university signs with Stakeholders spell out responsibilities of each party as well as expectations.

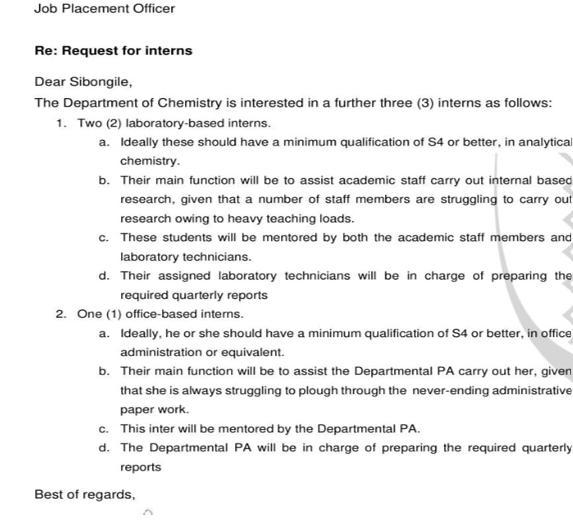

Correspondence analysis

The analysis of correspondence showed frequent emails between the Job Placement Officers. These ranged from initial discussions on the establishment of a partnership to jointly addressing student behaviour issues. The correspondence between the University and the Employers shows that there is frequent engagement.

CONCLUSION

The Employer Engagement Programme detailed in this paper is an example of a strategically embedded approach to Work-Integrated Learning (WIL), underpinned by the principles of Communication, Commitment, and Compatibility. Through a combination of formal agreements, structured feedback mechanisms, and recognition protocols, the Institution under review has cultivated an ecosystem of trust and reciprocity with its Employer partners.

This case study demonstrates that sustainable WIL partnerships do not arise by chance, but are intentionally designed, shaped through continuous dialogue, and sustained by shared accountability. Practices such as site verification audits, Stakeholder advisory boards, and the WIL Imbizo symposium, reflect a maturity in Stakeholder Engagement that aligns with global best practices.

The model shows that when Stakeholder Relationships are based on strategic alignment and mutual recognition, WIL can move from being a compliance-driven activity into a transformative educational experience that enhances employability, institutional credibility, and societal impact. It also offers a blueprint for other institutions navigating the complexities of university-industry collaboration in the African Higher Education context.

The external validations from the Council on Higher Education and the International Finance Corporation further affirm the scalability and replicability of this approach. As the demand for futureready graduates intensifies, institutions must adopt frameworks that not only meet accreditation standards but also foster innovation, inclusivity, and long-term value creation.

The author concludes that this study contributes to the growing body of evidence that effective Stakeholder management is the cornerstone of impactful WIL. By institutionalizing the “Three Cs” and embedding them into operational practice, the institution under review has positioned itself as a leader in co-operative education, one that others can learn from, adapt, and build upon.

REFERENCES

Alqaisi, B. (2018). Communication Challenges in Stakeholder Management. Journal of Business and Communication, 24(3), 215–228.

Bourne, L. (2016). Stakeholder Relationship Management: A Maturity Model for Organisational Implementation. Routledge.

Cameron, C., Orrell, J., & Bloomfield, R. (2019). Graduate Employability and Work-Integrated Learning: Crossing the Threshold of Student Experience. Springer.

Council on Higher Education (CHE). (2023). Work-Integrated Learning: Good Practice Guide https://www.che.ac.za/publications/work-integrated-learning-good-practice-guide

Effeney, G. (2020). Risk Management in Work-Integrated Learning Partnerships. Australian Journal of Experiential Learning, 7(1), 48–59.

Fassin, Y. (2012). Stakeholder Management, Reciprocity and Stakeholder Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(1), 83–96.

Ferrández-Berrueco, R., Kekale, T., & Devins, D. (2016). A Framework for Work-Based Learning: Basic Pillars and Their Interactions. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 6(1), 35–54.

Flemming, J., McLachlan, K., & Pretti, T. J. (2018). Successful Work-Integrated Learning Relationships: A Framework for Sustainability. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 19(4), 321–335.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Publishing.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation, and Success. Yale University Press.

Grunig, J. E., & Hunt, T. (1984). Managing Public Relations. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Jenny, F., Neil, J., & Haigh, N. (2017). Examining the Intentions of Work-Integrated Learning. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 7(2), 198–210.

Khan, S. Z., Skibniewski, M. J., & Cable, J. (2023). Trust as a Catalyst in Stakeholder Relationships International Journal of Strategic Project Management, 12(1), 112–129.

Rajhans, K. (2018). Effective Communication Management: A Key to Stakeholder Relationship and Project Success. International Journal of Business and Management, 3(2), 32–42.

Sachs, J., Rowe, A., & Wilson, M. (2016). Good Practice Report Work Integrated Learning (WIL) Department of Education and Training.

Sunnemark, F., Berglund, K., & Lindberg, M. (2023). Co-Creation and Academic Capitalism in WIL. WorkIntegrated Learning Journal, 28(2), 101–120.

University of Pretoria (2024). Work-Integrated Learning Policy https://www.up.ac.za/media/shared/1/ZP_Files/s5148_24-work-integrated-learningpolicy.zp258511.pdf

Walker, A., & Marr, J. (2001). Stakeholder Engagement: A Pathway to Sustainable Value. Business & Society Review, 106(3), 335–348.

Young, M., Pham, Q., & Daniels, H. (2024). Contextual Alignment in WIL Placements: Exploring the ‘Why’. Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(1), 56–73.

CHALLENGES AND PERCEPTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS IN RELATION TO WORKPLACE LEARNING AT A SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY

Nduna Nothemba, J

Cape Peninsula University of Technology

INTRODUCTION

The internationalisation of higher education has led to increasing enrolments of international students in undergraduate programmes globally. In Southern Africa, 16 countries that formed a regional intergovernmental organisation, called the Southern African Development Community (SADC), encourages education institutions to reserve at least 5% of admissions for international students in undergraduate degrees. These degrees demand the integration of academic instruction with real-world experiences through workplace learning opportunities (Gribble, Blackmore & Rahimi, 2015). These expect international students to gain workplace experience (Patrick et al., 2009; Billett, 2014; Jackson, 2015). However, existing research indicates that international graduates struggle to find work experience and this prevents them from entering professional fields (Jackson, 2013; Blackmore et al., 2014). A lack of funding is noted by Gribble, Blackmore & Rahimi (2015) as a contributing factor to the challenges of international students’ workplace learning.

International students have mentioned unpaid work as one of the ways in which they have been subject to discrimination (Tran, & Soejatminah, 2018; Junankar et al. 2004; Syed 2008). To address this issue, some studies suggests that WIL should be exempt from wage payment if it is part of a course of education or training (Stewart and Owens 2013), thereby positioning it outside of equality and fair work regulatory boundaries (Gribble, Blackmore & Rahimi, 2015).

Although the SADC Protocol on Education and Training provides a regional framework that supports the provision of workplace learning for international students (SADC, 1977), it does not have a detailed guideline document for funding WIL. Hence such funding becomes a cause for concern for international students.

AIM AND OBJECTIVES

This paper presents the challenges of international students in relation to their workplace learning with the purpose of developing an understanding of how WIL should be planned and implemented for international students.

The objectives are to:

1) Present the challenges and perceptions of international students in relation to their workplace learning opportunities,

2) Highlight the responses and attempts made by a University of Technology to address the concerns raised by international students, and

3) Stimulate debate to find solutions to South African challenges in relation to providing workplace learning opportunities to international students.

To achieve the above objectives, the following three research questions were posed:

1. What are international students’ challenges and perceptions of their workplace learning opportunities in South Africa?

2. How did the University WIL management team and workplace officials respond to address such challenges?

3. What can be done to improve the South African provision of workplace learning opportunities to international students?

OVERVIEW OF LITERATURE

The paper is set against the general literature on Work Integrated Learning, legislative frameworks that relate to the provision of WIL for international students in higher education, as well as challenges relating to WIL placements and funding.

Work Integrated Learning

Globally, Work Integrated Learning (WIL) is viewed as a cornerstone of the higher education curriculum and an educational strategy that provides students with real-life work experiences (Zegwaard & Pretti, 2023). Such experiences enable students with the opportunity to apply academic and technical skills as well as help students to develop employability skills (Jackson, 2013).

The studies indicate that WIL can take various forms such as work placements, industry projects internships, co-ops, apprenticeships, service-learning, and non-placement models, such as simulated work environments. Although some studies (Groenewald et al., 2011; Rowe & Zegwaard, 2017; McRae & Johnston, 2016; Kaider, Hains-Wesson, and Young, 2017) propose a shared understanding of the meaning of each term, these are used inconsistently in practice (Zegwaard et al., 2023)

This paper focuses on work placements that are highly recommended by the South African White Paper on Post School Education and Training (PSET) (2014). It is aligned with studies on the practice of WIL that attribute the challenges to the complex nature of WIL that traverses work and university spaces (Jackson, 2013; Rook, 2017) The paper highlights the challenges of work placements for international students in relation to the expected role of higher education institutions that are documented in the South African Higher Education Qualifications Sub Framework (HEQSF) (2012: 49):

“Where the entire WIL component or part of it takes the form of workplace-based learning, it is the responsibility of the institutions that offer programmes requiring credits for such learning, to place students into appropriate workplaces. Such workplace-based learning must be properly structured, properly supervised and assessed. “

The above statement indicates that educational institutions must place their local and international students and create an enabling environment for these students to participate in hosting workplaces.

Legislative framework for WIL international students in higher education

Global studies and agreements (UNESCO, 2005; ILO 2020; Leask & Carroll, 2011; Gribble, Blackmore & Rahimi 2015) highlight legislative frameworks that relate to the provision of WIL for international students in higher education. These include international agreements, policies and protocols that guide institutions and policymakers.

The Southern African and Regional Frameworks include the SADC Protocol on Education and Training (1997) that emphasise collaboration for placement opportunities across SADC countries. The SADC Qualifications Framework (SADCQF) supports WIL mobility and comparability of qualifications and facilitates recognition of internships and placements across countries. In South Africa, the Higher Education Act (No. 101 of 1997) supports the offering of workplace learning as part of academic programmes. The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) Policy Framework for Internationalisation (2017) encourages inclusive participation of international students in WIL programmes. In addition, the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training (DHET 2014) emphasises workplace-based learning as a core strategy to improve graduate employability and calls for better coordination between institutions, employers, and government, including in the context of international students. A Good Practice Guide for Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) in University Education that was published by Universities South Africa and DHET in 2016 also contains sections on supporting diverse student needs including international participants. This paper supports the reviewed literature and responds to global and national calls to provide international students with appropriate workplace learning opportunities.

CHALLENGES

The challenge of funding international students for their workplace learning has been documented by several studies (Marginson et al. 2010; Trice 2003; Harman 2003; Lee and Rice 2007; DomininguezWhitehead and Sing, 2015; Wall, Tran, & Soejatminah, 2018):

“International students with limited financial support find it necessary to take up part-time work. However, their situation in this regard can be further complicated by student visa stipulations, which not uncommonly restrict the number of hours students may engage in paid employment” (Domininguez-Whitehead and Sing, 2015: 82).

Some authors suggest that WIL should be exempt from wage payment if it is part of a course of education or training (Stewart and Owens 2013), while others suggest a “multipronged approach which hinges on cooperation between international students, universities, employers, and government”. (Gribble, et al., 2015: 16).

An overview of the challenges is relevant for this study as it focuses on the challenges of international students in relation to their work placements in a South African context.

METHODOLOGY

Qualitative research approaches were used to understand the challenges, opinions, or experiences (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) of international students in relation to their work placements. Research was conducted in three phases. The first involved data-gathering on students’ challenges through an analysis of email messages that raised their concerns in relation to their workplace learning. The email correspondence was followed by focus group interviews that were conducted with 11 mechanical engineering students who were placed in a company in Bellville, Cape Town. The use of focus group interviews allowed the researchers to gain a deeper understanding of students’ concerns, capture diverse perspectives on their experiences and uncover insights that might not be revealed through individual interviews (Nyumba, et al., 2018; Lauri 2019; Taherdoost, 2021).

During the second phase, a group meeting was convened to uncover an explanation from the Head of Department, the WIL Coordinator, four staff members of an institutional WIL Centre and two workplace supervisors as to why the placement of international students was a challenge. The use of group meetings is supported by Goodall and Barnards (2015), who indicate that group meetings serve to generate in-depth data on a topic. The use of focus groups in phase 1, and a meeting in phase 2, was appropriate for the study as the purpose was not to generalise the findings. For both phases 1 and 2, purposive sampling was used to select participants with knowledge and experience (Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim, 2016) of the challenges relating to work placements.

Qualitative data analysis was used to code and transform data on the challenges into a set of meaningful, cohesive categories. The process of summarising and representing data was carried out to provide a systematic account of the recorded information and to enable researchers to classify, organise and interpret data. Thematic analysis was employed as it is considered a popular method for analysing qualitative data (Strauss & Corbin 1990; Bowen, Rose & Pilkington 2017; Lerigo-Sampson, 2022).

RESEARCH FINDINGS

An analysis of email messages and responses to focus group interviews revealed the following perceptions, concerns, and challenges of international students:

• Students wanted stipends for travelling and buying food.

• “We are starving here and there is no transport. How are we going to survive?”

• Students felt that they could not perform well in the workplace because they were not treated fairly.

“As we are working with our colleagues, next to each other, our performance is not adequate as we are still treated unfairly … we cannot work and study while hungry and without transport”

• Students indicated that they were not prepared or informed about workplace learning challenges. “ (Name of the institution) should have been open to us before we came to study here.”

• Students believed that the institution was discriminating against them deliberately. “The WIL manager sent a letter for only South African students … We come from the same institution and study same subjects … We think we shouldn’t be discriminated the way it has been done.”

• Students stated that they had done everything to make the institution aware that they faced workplace learning challenges. “We have approached everyone concerned with the matter, no one heard us and that is why we approached the Office of the Vice Chancellor.”

Responses of the university management team and workplace officials

• The explanation that was given as to why the placement of international students was a challenge was that the South African legislation and strategies do not favour international students. Examples that were cited in this regard were:

• The Broad Base Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) incentives that encourage employers to host South African students rather than international students.

• The SETAs that prioritise South Africans in all their strategies.

• The following explanation was also given:

• The professional body (the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA) is not accepting campus-based workplace learning, especially for students doing P2.

• The admission of international students into courses that have a compulsory workplace learning component in their first year of study increases numbers of international students that will face workplace learning challenges in their second and third year of study.

• International students demanded work placements to satisfy the requirements of their qualification as well as funding.

The responses from the WIL management team and workplace representatives indicated the following attempts made to address the concerns raised by international students:

1. Several meetings were held with university management, workplace officials, international students, and the Student Representative Council (SRC).

2. To provide financial support, the university decided to utilise the Teaching Development Grant (TDG) to train international WIL students as mentors but the mentoring programme was not taken beyond the training as no first-year students took advantage of the offer to be mentored.

3. After the challenge of international students was referred to the national WIL task team of a national association for the Universities of Technology, it was indicated that “apart from the international students for whom WIL placements are problematic, there are also large numbers of local students experiencing similar problems” (Extract from SATN Board minutes). This issue remained unresolved.

DISCUSSION

From the research findings, workplace learning for international students is an unresolved issue that could hinder students from completing their qualifications. The economic climate is also not favourable for some of the workplaces to pay students for their workplace learning, although they are willing to host them. In addition, SETA grants only cater for South African students.

Placing international students within the university may not be acceptable to some professional bodies. Although placing international students in their countries of origin could be the best option, it could be a challenge for the WIL coordinators to conduct workplace approvals, as well as to monitor and assess WIL students especially if there are many students in different programmes who are placed in their countries of origin. In addition, it could be difficult for the WIL coordinators to deal with insurance issues and attend to students who might become injured during their workplace learning if students are in their countries of origin.

With all these challenges, education institutions must comply with the South African legislative framework which states that: “It is the responsibility of the institutions that offer programmes requiring credits for workplace learning, to place students into appropriate workplaces” (HEQSF, 2012: 49). These challenges confirm the findings of global studies that highlight the challenges of international students in relation to workplace learning. Such studies include Herman (2011) who notes that international students from other African countries have raised concerns with issues relating to discrimination and xenophobia in South Africa.

The following questions are raised to stimulate debate and encourage more attempts to formulate clear guidelines:

1. Who should be responsible for funding the WIL component of international students?

2. How should international students be placed, monitored, and assessed?

3. What must be done to improve the South African provision of workplace learning opportunities for international students?

RECOMMENDATIONS

- International students should not be admitted at diploma level.

- If admitted, students should sign a contract and be made aware of the risk by including the constraints relating to their placement in the admission booklet.

- The option of “at-home” workplace learning should be added as a requirement for those international students who wish to be admitted to courses that have a compulsory workplace learning component.

- WIL guidelines should be included in the SADC Protocol on Education and Training.

CONCLUSION

This paper highlights the challenges and perceptions of international students in South Africa and indicates that the problem remains unresolved, although attempts were made to address such challenges. The paper therefore calls for clear legislative guidelines for planning and implementing workplace learning for international students. Such guidelines could be developed through a collaborative and inclusive process that allows a dialogue or robust discussions between workplaces, universities, and international partners. It is concluded that providing international students with access to discipline-related work experience is emerging as a critical issue for South African universities.

REFERENCES

Billett, S. (2014). Integrating learning experiences across tertiary education and practice settings: A socio-personal account. Educational Research Review, 12, 1–13. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1747938X1400003

Blackmore, J., Gribble, C., & Rahimi, M. (2014). Mobility matters: Researching the student experience of international mobility. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(4), 686–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841650

Bowen, G. A., Rose, R. K., & Pilkington, L. (2017). Enhancing student engagement through qualitative methods. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2016.1226853

Domínguez-Whitehead, Y., & Sing, N. (2015). International students in the South African higher education system: A review of pressing challenges. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(3), 77–95. https://journals.co.za › doi › pdf › EJC182455

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Gribble, C., Rahimi, M., & Blackmore, J. (2016). International students and post-study employment: The impact of university and host community engagement on the employment outcomes of international students in Australia. In Cultural Studies and Transdisciplinarity in Education (pp. 15–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2601-0_2

Groenewald, T., Drysdale, M. T. B., Chiupka, C., & Johnston, N. (2011). Towards a definition and models of practice for cooperative and work-integrated education. In R. K. Coll & K. E. Zegwaard (Eds.), International handbook for cooperative and work-integrated education: International perspectives of theory, research, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 17–24). Lowell, MA: World Association for Cooperative Education

Herman, C. (2011). Elusive equity in doctoral education in South Africa. Journal of Education and Work, 24(1–2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.534773

International Labour Office. 2017. Quality Apprenticeships: A Guide for Policy Makers. ILO Toolkit for Quality Apprenticeships, Vol. 1. Geneva: International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/skills/pubs/WCMS_607466/lang en/index.htm

Jackson, D. (2013). Student perceptions of the importance of employability skill provision in business undergraduate programs. Journal of Education for Business, 88(5), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.697928

Junankar, P. N., Paul, S., & Yasmeen, R. (2004). Are Asian migrants discriminated against in the labour market? Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper, No. 487. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228689994

Kaider, F., Hains-Wesson, R., & Young, K. (2017). Enhancing graduate employability attributes through a work-integrated learning curriculum. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), 971–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1262829

Lauri, M. A. (2019). Focus groups: Between theory and practice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-17-00054

Leask, B., & Carroll, J. (2011). Moving beyond ‘wishing and hoping’: Internationalisation and student experiences of inclusion and engagement. Higher education research & development, 30(5), 647-659. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.598454

Paul, S., Junankar, P. N. (Raja), & Yasmeen, W. (2004). Are Asian migrants discriminated against in the labour market? A case study of Australia (IZA Discussion Paper No. 1167). Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). https://hdl.handle.net/10419/20406

Tisdell, E. J., Merriam, S. B., & Stuckey-Peyrot, H. L. (2025). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 111900361X

Nyumba, T. O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860

Patrick, C.-J., Peach, D., Pocknee, C., Webb, F., Fletcher, M., & Pretto, G. (2008). The WIL (Work Integrated Learning) Report: A national scoping study (Australian Learning and Teaching Council Final Report). Brisbane, QLD: Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/216185/

Rowe, A. D., & Zegwaard, K. E. (2017). Developing graduate employability skills and attributes: Curriculum enhancement through work-integrated learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 18(2), 87–99. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10289/11267

Southern African Development Community (SADC). (1997, September 8). Protocol on Education and Training (entered into force July 31, 2000). Retrieved from https://www.sadc.int/document/protocoleducation-training-1997/

Stewart, A., & Owens, R. (2013). Experience or exploitation? The nature, prevalence and regulation of unpaid work experience, internships and trial periods in Australia. Fair Work Ombudsman. Retrieved from https://www.fairwork.gov.au/sites/default/files/migration/763/UW-complete-report.pdf

Stewart, A., & Owens, R. (2013). Experience or exploitation? The nature, prevalence and regulation of unpaid work experience, internships and trial periods in Australia. Fair Work Ombudsman. Retrieved from https://www.fairwork.gov.au/sites/default/files/migration/763/UW-complete-report.pdf

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques Sage Publications. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/mono/basics-of-qualitative-research/toc

Syed, J. (2008). Employment prospects for skilled migrants: A relational perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 18(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.12.001

Taherdoost, H. (2021). Data Collection Methods and Tools for Research; A Step-by-Step Guide to Choose Data Collection Technique for Academic and Business Research Projects International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 10(1), 10–38. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4178676

Tran, L. T., & Soejatminah, S. (2017). Integration of work experience and learning for international students: From harmony to inequality. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(3), 261-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316687012

UNESCO. (2005). Guidelines for Quality Provision in Cross-border Higher Education https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000389910

Zegwaard, K. E., & Pretti, T. J. (2023). Future directions for advancing work-integrated learning pedagogy: The International Handbook of Work Integrated, Learning 3rd Edition, United Kingdom, Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003156420-42

Zegwaard, K. E., & Pretti, T. J. (2023) Future directions for advancing work-integrated learning pedagogy. In The Routledge International Handbook of Work-Integrated Learning (3rd ed., pp. 593–606). Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003156420-42 https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003156420-42

CHALLENGES ENCOUNTERED BY CPUT PRE-SERVICE TVET TEACHER DURING THE WORK INTEGRATED LEARNING –

Vimbelo Siphokazi

INDUSTRY-BASED IN THE WESTERN CAPE

Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Educational institutions and workplaces are no longer seen as isolated for pre-employment preparations and continuing workforce development (Choy, Warvik, & Lindberg, 2018). This is evident in South Africa’s policy framework for TVET colleges. South Africa’s policy TVET frameworks require that the Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) element of programmes include WIL in appropriate ‘industry settings’ to ensure that TVET lecturers develop expertise in both teaching their subjects and preparing their students for the demands of the workplace (Taylor & Van der Bijl, 2028).

Similar to Malaysia, the country strengthened policy guidance and regulatory frameworks for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), improving governance and programme implementation to support economic transformation and sustainable development (Ismail et al., 2028). According to this Malaysian study, transformation requires that TVET educators be well prepared to face the challenges of globalisation, enabling them to remain competitive. The study argues that developing competencies ensures that quality TVET educators produce competent TVET graduates capable of meeting the requirements of industries and professional bodies (Ismail et al., 2018). Similarly, the South African Policy on Professional Qualifications for lecturers in TVET provides a framework of professional qualifications for lecturers in the TVET system, which requires Work-Integrated Learning placements in education and industry settings (Van der Bijle, 2021). However, a few years ago South Africa had no established convention of industry placement for vocational lecturers, which prompted the introduction of a professional qualification for TVET lecturers: the Advanced Diploma in Technical and Vocational Teaching (ADTVT) (Van der Bijl, 2021). In 2021, the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) began enrolling both prospective TVET lecturers and those already employed in the sector without a professional qualification. The ADTVT is an NQF Level 7 qualification, with entry requirements set at NQF Level 6. Among the modules offered is Work-Integrated Learning, which consists of two components: Teaching Practice (already established in the Faculty of Education) and an industry-based component. This study focuses on the WIL-industry-based component. An ADTVT is the programme this study used to investigate the challenges pre-service teachers experienced during the WIL-Industry-based experience. Thus, this study will address the following research questions. 1. What challenges did mathematics and engineering science pre-service teachers experience during their WIL-Industry-based?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Work-Integrated Learning in TVET Teaching

There is an increasing gap between industry expectations and the content taught by TVET lecturers (Mesuwini & Mokoena, 2023). At the same time, TVET plays a pivotal role in producing skilled graduates by shaping their professional competencies through pedagogical practices and exposure to WIL (Mesuwini & Mokoena, 2023). Work-Integrated Learning (WIL) involves learning in and from the workplace through industry exposure, interactions, and teamwork (Batholmeus & Prop, 2019; Mesuwini, Thaba-Nkadimene & Kgomotlokoa, 2021). It is a component of teacher education as it enhances lecturers’ potential to integrate theory with practice (Mesuwini et al., 2023). Moreover, WIL

was introduced to address the lack of work experience among TVET lecturers and to equip them with the industry skills needed for effective teaching (Mesuwini & Mokoena, 2023). All these studies show the significance of WIL in teaching. The primary and common significance is integrating the industrybased experience into teaching. However, most of these studies focus more on TVET lecturers who are already in the system, not on the pre-service TVET teachers, and also highlight the expectations of TVET teachers.

Expectations of TVET lecturers

The demand in educational institutions in the 21st century is constantly changing. Central to these evolutionary changes are the teacher's expectations. Teachers are expected to initiate innovative teaching strategies, which often come with various challenges (Ndebele, Legg-Jack & Tabe, 2023). Furthermore, lecturers are expected to demonstrate how their newly acquired knowledge and skills are applied to prepare students for the changes of the 21st century (Magadza & Mampane, 2024).

However, several studies have shown that traditional teaching still dominates TVET colleges. For example, there are concerns about the pedagogies employed by TVET college lecturers, particularly regarding teaching mathematics (Vimbelo & Bayaga, 2023). Most TVET lecturers rely heavily on traditional approaches where there is a lack of real-life examples (Vimbelo & Bayaga, 2023). Similarly, TVET college education is exam-oriented and lecturers often rely on a teacher-centred approach to impart concepts such as geometry to students abstractly (Madimabe, Bunmi, & Cias, 2020). Consequently, this leads to the deterioration of educational standards in the subject (Madimabe, Bunmi, & Cias, 2020; Magadza & Mampane, 2024). Thus, industry exposure helps teachers be creative and use practical teaching approaches that include real-life examples.

Preparation of Pre -Service TVET teachers

Pre-service teachers are particularly important today, as they will become the future educators responsible for shaping and developing students’ knowledge and skills (Napanoy, Gayagay & Tuazon, 2021). However, several studies have shown that TVET programmes do not sufficiently prepare preservice teachers for sustainability (Chinedu et al., 2019; Diao & Hu, 2022). Insufficient preparation for sustainability limits the TVE programmes’ prospects (Diao & Hu, 2022), and the preparedness level of the preservice TVET teachers is critical to the success of vocational education (Estubio & Sarsale, 2024).

Therefore, there is a critical need to equip preservice teachers with the competencies required for teaching. For example, another study focused on developing the technological competencies of preservice teachers (Tondeur et al., 2025). Pre-service teachers should be able to align their teaching with industry (Estubio, 2024). Supporting and preparing pre-service teachers involves knowing the needs and expectations of TVET lecturers as well as the challenges pre-service teachers face (Napanoy, Gayagay & Tuazon, 2021).

Challenges Faced by Pre-Service TVET Teachers in Industry-Based WIL

Some TVET teachers in the developing world face challenges in becoming effective educators (Ismail, Nopiah & Rasul, 2028). These challenges differ with studies conducted, and some are similar, as indicated below:

2. Individual differences among students, supervisors, and peers, as well as a lack of facilities, preparation, and training, contribute to the difficulties pre-service teachers encounter (Napanoy, Gayagay & Tuazon, 2021).

3. Other challenges include insufficient supervision from both industry personnel and colleges, limited opportunities for hands-on engagement with expensive machinery, and weak industry induction processes (Mesuwini & Mokoena, 2023).

4. Additional studies point to disinterest, low motivation, and inadequate industrial experience among vocational lecturers (Ismail, Nopiah & Rasul, 2018). Although these findings focus on lecturers rather than pre-service teachers, many of the challenges are still relevant, as pre-service teachers are preparing to become TVET lecturers, and some are already employed in such roles. There are recommendations from different scholars, such as strengthening collaboration with stakeholders (Cabreros & Barbacena, 2024), the need to enhance awareness among company owners regarding their crucial role in contributing to TVET education and ensuring the cultivation of a future workforce with high competence (Philogene, Zhiyuan & Nyoni, 2024). The effectiveness of TVET is contingent upon robust collaborations between TVET institutions and the industrial sector. Unfortunately, existing collaborations fall short of being effective in addressing the dynamic changes in the current labour market, particularly concerning the practical sides (Philogene, Zhiyuan, & Nyoni, 2024)

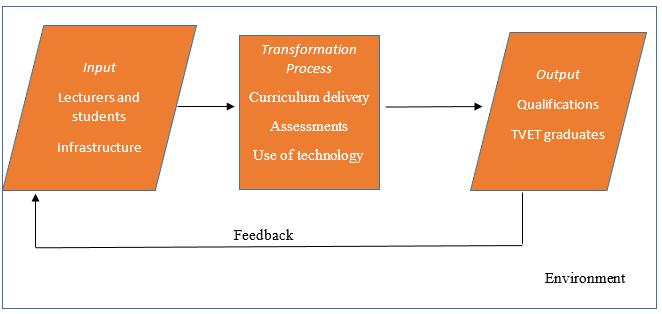

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The study found situated learning theory to be an appropriate and relevant theory. This theory is a process of social participation in everyday situations rather than the acquisition of knowledge by individuals (Pengiran & Besar, 2018). Situated Learning Theory holds that effective education requires learning embedded in authentic contexts of practice, wherein students engage in increasingly more complex tasks within social communities (Pengiran & Besar, 2018). It is within a community of practice as shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Model of Situated Learning Theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

The model shows the community of practice, which consists of two experts. One is the Institution, in this case, the University, that has sent these preservice teachers to Expert 2 (Industry). These experts (University and Industry) are expected to interact with each other and thereafter, each support the novices (preservice teachers). The pre-service learn from their interactions with the experts and gain opportunities to develop personally, professionally, and intellectually (Lave & Wenger, 1991). They learn as they participate in the industry. It can be concluded that learning occurs through participation as an “apprenticeship.” Situation Learning Theory emphasises the relevance of integrating new ideas and human actions into teaching; hence, it is appropriate for this study. Pre-service teachers were engaged in more complex, practical tasks requiring them to think about the mathematics and engineering science they will teach. Their teacher-educators prepared them in the classroom, and now they are out in the WIL industry to acquire practical knowledge. They will then apply the knowledge acquired in their classrooms (Pengiran & Besar, 2018).

Novice

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The study followed a qualitative approach as it is non-numerical and explores, discovers, and describes the experiences of pre-service teachers (Brodsky et al., 2016). The data collected from the WIL- industry assignment given to eight pre-service teachers teaching mathematics and engineering sciences during the WIL - industry session. The assignment focused on the challenges pre-service TVET teachers experienced during the WIL-Industry-based and how they will integrate the industry-based experience into their teaching. However, this paper focuses on the first part of the assignment the challenges experienced in order to improve the future placement of student teachers. Content analysis was used to examine the data.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Communication breakdown

However, this paper focuses on the first part of the assignment examining the difficulties encountered to inform improvements in the future placement of student teachers. Content analysis was used to examine the data. “The host organisation did not know about the work-integrated learning for mathematics students”. Many factors can cause communication breakdowns. In this case, there was a limited partnership or relationship. There was no formalised and effective partnership between the host organisation and the ADTVT programme administrators. One can argue that the challenge began with poor planning, as it was not done thoroughly enough to establish partnerships. Partnerships and collaborations are encouraged by the pre-service teachers and scholars (Cabreros & Barbacena, 2024; Napanoy, Gayagay & Tuazon, 2021). “Partnerships or collaborations are expected to be in place between the university and the host organisation.”

Lack of support

The findings also showed no existing training programme for mathematics WIL teachers. It was their first time for the company to host mathematics teachers. Those mentioned that the University did not define the learning outcomes and assessment criteria for the host organisation, resulting in their inability to evaluate these teachers properly. Hence, scholars such as Philogene, Zhiyuan, and Nyoni (2024) argue that company owners need to enhance awareness regarding their crucial role in preparing these pre-service teachers.

Lack or insufficient supervision

Furthermore, the findings show that there were no dedicated supervisors or mentors. “I did have a dedicated WIL mentor who could come and review my training.” Some students were assigned to different supervisors who would get confused about what to do and how to mentor them. This finding calls for a proper induction for the mentors by the universities so that they know what is expected of them. Situated Learning Theory emphasises learning through relationships and interactions. Pre-service teachers might see this practice of working with different supervisors as a challenge. However, Situated Learning Theory emphasises learning within the community of practice, which consists of many experts, not just one (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Working under pressure

One student reported that he had not encountered significant difficulties during his placement. However, he did note instances where his supervisor overlooked the fact that the training formed part of his studies rather than regular employment, which at times resulted in being assigned additional work. “I had to multitask because I am still a worker at the end of the day.” The student went further to support the findings above of mentors who do not know the expectations and said, “My supervisor gave me a project, but the instructions were not clear and did not make sense to me, and I had trouble seeing the bigger

picture.” Supervisors who gave them unclear instructions require what has been recommended above: a proper induction with the mentors or supervisors. Another challenge arose from the shift system, as students were assigned to different mentors who each applied their own strategies, leading to confusion. Despite this, students valued the experience and noted that they would seek to integrate their WIL-industry exposure into their teaching. They further observed that the experience would enable them to draw on real-life examples when teaching mathematics and engineering science, rather than presenting these subjects in an abstract manner.

IMPLICATION OF THE STUDY

Many institutions have introduced the Advanced Diploma in Technical and Vocational Teaching, within which WIL forms a core component. The findings of this study can assist higher education institutions offering TVET professional programmes including the one where this research was conducted to reflect on pre-service teachers’ experiences of WIL and to identify ways of strengthening its delivery. The study will also contribute to the TVET teaching pedagogy as TVET lecturers are expected to integrate industry experience into their teaching. The TVET college will gain an understanding of those challenges. The findings have helped the institution improve communication with the host and clarify expectations.

CONCLUSION

The challenges faced by pre-service TVET teachers during industry-based WIL are multifaceted and significant. In particular, communication breakdowns and inadequate supervision arose because some mentors were uncertain of expectations, especially in companies hosting mathematics and engineering science students for the first time. Hence, this study recommends establishing partnerships with companies and providing orientation or induction for mentors to ensure clarity about their roles when hosting pre-service TVET teachers. Collaboration between educational institutions and industry partners is therefore essential for aligning expectations and enhancing the experiential learning process.

REFERENCES

Batholmeus, P., & Pop, C. (2019). Enablers of Work-Integrated Learning in Technical Vocational Education and Training Teacher Education. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 20(2), 147159.

binti Pengiran, P. H. S. N., & Besar, H. (2018). Situated learning theory: The key to effective classroom teaching?. HONAI, 1(1).

Brodsky, A. E., Buckingham, S. L., Scheibler, J. E., & Mannarini, T. (2016). Introduction to qualitative approaches. Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, 13-22.

Chinedu, C. C., Wan Mohamed, W. A., Ajah, A. O., & Tukur, Y. A. (2019). Prospects of a technical and vocational education program in preparing pre-service teachers for sustainability: a case study of a TVE program in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Curriculum Perspectives, 39(1), 33-46.

Choy, S., Wärvik, G. B., & Lindberg, V. (2018). Integration between school and work: Developments, conceptions and applications. In Integration of vocational education and training experiences: Purposes, practices and principles (pp. 3-18). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Diao, J., & Hu, K. (2022). Preparing TVET teachers for sustainable development in the information age: Development and application of the TVET teachers’ teaching competency scale. Sustainability, 14(18), 11361.

Govender, S., & Dhurumraj, T. (2024). Opening up TVET lecturer professional learning and development through work integrated learning in South Africa. Open Learning as a Means of Advancing Social Justice, 338.

Estubio, M., & Sarsale, M. (2024). Exploring the Preparedness and Competence Level of Pre-service TVET Teachers Using Knowledge, Skills, and Attitude Model. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 16(3), 201-215.

Ismail, A., Hassan, R., Bakar, A. A., Hussin, H., Hanafiah, M. A. M., & Asary, L. H. (2018). The development of TVET educator competencies for quality educator. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 10(2).

Lave, J. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

Madimabe, M. P., Bunmi, I. O., & Cias, T. T. (2020). Indigenous knowledge as an alternative pedagogy to improve student performance in the teaching and learning of mathematical Geometry in TVET College. Proceedings of ADVED, 2020(6th).

Magadza, I., & Mampane, J. (2024). Experiences of adult educators in selecting appropriate teaching methods in engineering courses at TVET colleges in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 1-12.

Mesuwini, J., & Mokoena, S. P. (2023). TVET lecturer work-integrated learning: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(8), 415-440.

Mesuwini, J., Thaba-Nkadimene, K. L., & Kgomotlokoa, L. (2021). Nature of TVET lecturer learning during work integrated learning: A South African perspective. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 13(4), 106-117.

Mesuwini, J., Thaba-Nkadimene, K. L., Mzindle, D., & Mokoena, S. (2023). Work-integrated learning experiences of South African technical and vocational education and training lecturers. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 24(1), 83-97.

Napanoy, J. B., Gayagay, G. C., & Tuazon, J. R. C. (2021). Difficulties encountered by pre-service teachers: basis of a pre-service training program. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 9(2), 342-349.

Oosthuizen, L. J., Spencer, J., & Chigano, A. (2022). Work-integrated learning for lecturers at a TVET college in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(3), 214-230.

Philogene, M., Zhiyuan, S., & Nyoni, P. (2024). Teacher professionalism development in TVET system: Preparedness, In-Service trainings and challenges. Journal Evaluation in Education (JEE), 5(3), 107-117.

Rohanai, R., Othman, H., Paimin, A. N., Ismail, A., & Razali, S. S. (2024). Exploring Teaching Strategies for Work-based Learning in TVET Practices: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 16(3), 88-100.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (2013). Reflections on problem solving theory and practice. The Mathematics Enthusiast, 10(1), 9-34.

Sibisi, P. N. (2024). Work-Integrated Learning: A TVET Experience. In Technical and Vocational Teaching in South Africa: Practice, Pedagogy and Digitalisation (pp. 143-162). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Taylor, V., & van der Bijl, A. (2018). Work-integrated learning for TVET lecturers: Articulating industry and college practices. Journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training, 1(1), 126-145.

Tondeur, J., Trevisan, O., Howard, S. K., & van Braak, J. (2025). Preparing preservice teachers to teach with digital technologies: An update of effective SQD-strategies. Computers & Education, 105262.

Van der Bijl, A. J. (2021). Integrating the world of work into initial TVET teacher education in South Africa. Journal of Education and Research, 11(1), 13-28.

Vimbelo, S., & Bayaga, A. (2023). Current pedagogical practices employed by a technical vocational education and training College’s mathematics lecturers. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(4), 305-321.

STRIDES TOWARDS A FUTURE-PROOF TVET ELECTRICAL TRADE THEORY N2 CURRICULUM: A SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT

Mesuwini Joseph

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Ganya Elison S.

Majuba TVET College, Newcastle, South Africa

Mlotshwa Sanele J

Majuba TVET College, Newcastle, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The government aims to produce approximately 30,000 artisans annually in line with the National Development Plan 2030. However, a review of supply and demand reveals that 19% of these qualified artisans remain unemployed (Mzabalazo Advisory Services, 2022). The qualifications offered by Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges should equip students with the skills necessary to enhance their employability. If the issue of artisan unemployment is not adequately addressed, it may undermine the credibility of TVET colleges as institutions of higher learning and diminish their appeal as institutions of choice. In particular, the TVET curriculum must be aligned with the evolving needs of the labour market and broader society (Lolwana et al., 2015). It should focus on cultivating the skills, knowledge, and attitudes that enable students to become adaptable, competent, and responsive to the demands of a dynamic employment landscape. The evolving global economies are characterised by enormous technological changes that are fuelled by the ubiquitous presence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which has brought about automation and technological changes that have impacted on the way people live their lives and interact with each other (Barrow et al., 2020a). These digital technologies have resulted in proliferation of new job opportunities however, these changes also disrupted some existing industries and in the process, rendering other jobs obsolete (Dumitru & Halpern, 2023). The current digitalised labour market demands artisans who possess an appreciation of Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies, including Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, the Internet of Things (IoT), and Virtual Reality (CEDEFOP, 2018). The TVET curriculum needs to incorporate the concept of 4IR technologies and how this can be used to solve problems in the industry to mitigate the skills obsolescence (CEDEFOP, 2018; Mesuwini, 2022). A TVET curriculum that is responsive to the needs of its students and environmental factors future-proofs it from obsolescence and enhances its graduates employability (Kana & Letaba, 2024a) Therefore, it is vital for TVET colleges to periodically revise their curricula to ensure that both their qualifications and the artisans they produce remain relevant and do not become obsolete. In 2020, DHET revised a number of Report 191 Engineering programmes. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the future-proof merit of the recently revised Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) N2 curriculum through subject matter experts’ perceptions.

Report 191 (NATED) Engineering and Business programmes in South Africa are nationally recognised technical and vocational qualifications offered at TVET colleges (Mabunda & Frick, 2020). The authors focus on developing practical and theoretical skills in business and engineering fields. The programmes span from N1 to N6 levels, with N1 to N3 providing foundational knowledge and N4 to N6 offering advanced, career-oriented training (Booyens, 2012). After completing N6, students gain eligibility for a National Diploma after completing 18 months of relevant industry experience. These programmes are designed to address industry-specific skills shortages by preparing students for pathways such as

apprenticeships, internships, direct employment, or further studies in engineering and related technical fields.

Problem Statement

The DHET is making steady progress in producing a sizeable number of artisans in line with the target set out in the National Development Plan for 2030 (Mzabalazo Advisory Services, 2022). However, a contradiction appears to exist while 19% of qualified artisans across all trades were unemployed, there are still ongoing claims of an artisan shortage (Mzabalazo Advisory Services, 2022). For instance, there was a report of a shortage of welder artisans, whereas there are unemployed welders. This may suggest that the quality of qualified artisans is inadequate, and that they lack the skills required to meet the specific needs of certain industrial sectors (Nkwanyane et al., 2020). This study will evaluate the futureproof merit of the recently revised Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) N2 curriculum through subject matter experts’ perceptions. This study is important as it will give feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the revised curriculum and provide recommendations on future-proofing the Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) N2 curriculum.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the future-proof merit of the recently revised Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) N2 curriculum.

Research Question

To what extent does the recently revised Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) N2 curriculum align with future industry demands?

LITERATURE REVIEW

While there appears to be limited research specifically focused on future-proofing the TVET Electrical Trade Theory (ETT) curriculum, relevant studies were reviewed to provide contextual background and inform the discussion. In a study aimed at strengthening the long-term relevance of bioscience students’ enterprise skills, the Future Ready Ideas Lab was employed to cultivate enterprising behaviours among students (Barrow et al., 2020b). The study successfully addressed the issue of the importance of developing students’ skills to remain relevant in ever-changing global economies.

In South Africa, a study examining the transition to the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) focused specifically on rural-based tertiary institutions (Yende, 2021). The findings highlighted that rapidly evolving digital technologies demand a radical review of existing curricula to ensure students are equipped with the skills needed to navigate complex technological systems. The revised curriculum should integrate concepts such as the Internet of Things (IoT), automation, and artificial intelligence to enable students to adapt to ongoing industrial and technological advancements.