MAY ‘23

ARCHITECTURE NEW YORK STATE ACCESSIBLE ARCHITECTURE

Access provides individuals with disabilities the ability to use, enjoy, and participate in aspects of daily life and society. Providing equal access means ensuring all individuals can make use of transportation, buildings and facilities. Design professionals can promote equal access by incorporating and integrating accessible and universal design features in a transportation system or building’s design program.

A newer definition of Universal Design is more relevant to all citizens without ignoring people with disabilities. It states that Universal Design is, “a process that enables and empowers a diverse population by improving human performance, health and wellness, and social participation” (Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012). In short, Universal Design makes life easier, healthier, and friendlier for all.

This issue highlights some of the experiences and expertise that has advocated, influenced and ultimately developed solutions that contribute towards a better quality of life for a wide range of individuals.

PAGE 2 | MAY ‘23

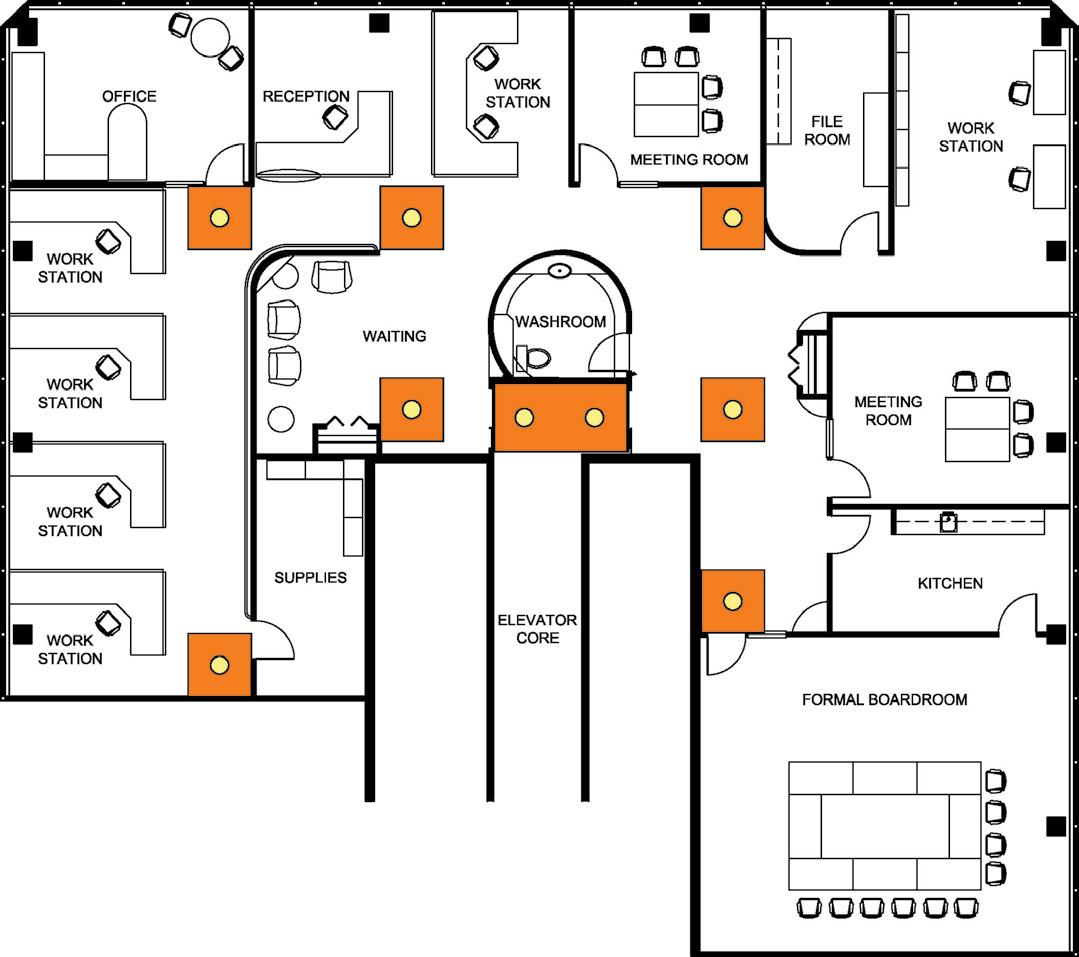

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 3 President’s Letter 4 Executive Vice President’s Letter 5 Supporting Children and Families through Inclusive and Universal Design 6 Kind of Blue: Applying the Principles of DeafSpace at the New Americans’ Pavilion 10 Universal Design: The Limit Does Not Exist 14 More Than Clearance 18 Providing Accessibility to MTA Stations in New York City 20 Five Misconceptions about Fair Housing Act Design and Construction Compliance 24 Fair Housing – What’s your Safe Harbor? 28 A Conversation with Rachel Wiesbrock: A Tireless Advocate for Universal Design and an Accessibility Specialist 30 The Small Things That Matter 34 The Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities An Accessible Office Space 38 Contents 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

PRESIDENT’S LETTER

Spring is all about new beginnings and transformations; it’s a season that symbolizes starting fresh. We’ve come out of the pandemic with new approaches and perspectives on work, life and the communities we serve. As President, I am excited to be a part of initiatives whose outcomes will postively impact and transform our state component thanks to our leadership and our volunteer members.

AIA New York State is especially excited about an initiative that will review how we govern our organization. While AIANYS has been diligent in consistently reviewing strategies, it has been decades since governance was reviewed. This endeavor is not due to any known deficits or problems, this endeavor is to ensure that AIANYS continues to deliver the best services to our membership. To date, the Governance Study Group held six focus group meetings, sent out a comprehensive survey, and provided updates to the board to make certain that we are thorough and inclusive. Stay tuned, we are hoping to have recommendations this summer.

I am also excited to share this impactful issue with you. As problem solvers, architects and design professionals design utilizing both their heads and their hearts. As leaders, we are genuine and empathetic, walking compassionately in the shoes of our many communities. Our colleagues have shared their transformation of spaces as a result of their own personal or professional experiences. They’ve advocated, influenced and developed solutions that contribute towards equal access for all, and a better quality of life for a wide range of individuals.

The landmark Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was created by the federal government with support from the AIA to ensure that public and private facilities were accessible to those with physical impairments. Today, the concepts of accessibility have become second nature to architects, and the buildings we create allow for easier navigation— more importantly independence and dignity—to our disabled citizens. Although our efforts are laudable, the next step is to embrace Universal Design where our buildings are designed to accommodate a variety of abilities; be easy and intuitive to use; communicate necessary information, regardless of sensory abilities; minimize opportunity for error; and be able to accommodate different body sizes, postures and mobility. Along the journey of life, we must not just guarantee independence for the individual reliant upon a wheelchair who needs assistance in mobility, but the young athlete on crutches after surgery; a parent navigating a space with a stroller, bags of groceries and two children, or a neurodivergent child supporting their emotional and educational needs. These types of design features are beneficial to everyone in our society.

Buildings are infrastructure, and if we want to “build back better,” we need to build back with everyone in mind, and universal design is the pathway to that solution. I look forward to continuing to serve the AIA New York State community and I am excited to be a part of the many initiatives we have in place for this year.

Sincerely,

Paul McDonnell, AIA 2023 President | AIA New York State

PAGE 4 | MAY ‘23

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT’S LETTER

The Parallel Between Inclusiveness and Accessible Architecture

In preparing my research for this month’s letter, I came across the website of Ian Fulgar, an architect working in the Philippines. Mr. Fulgar published an article on the site that addresses accessible architecture, not from the perspective of codes and regulations but from the perspective of the inclusive impact of the space. He defines accessibility in architecture as “designing and constructing spaces to be usable by as many individuals as possible, including those with incapacities.” I thought it was interesting that he used what we traditionally think of the purpose of accessible architecture, that of helping to “overcome hurdles in the physical environment,” to true expansion of usage for anyone who wishes to use the building, no matter what.

As important as they are to design, accessible architecture is so much more than wider corridors, curbs and rails. In the true sense, it takes down the barriers of exclusivity and opens its doors to welcome everyone to enter and experience the building. For children, it’s the experience of learning; for workers it’s the experience of employment; for older adults, it’s the experience of an enriched chapter of their life; it’s the experience of living where you want.

Isn’t that what we want in our environment, a space that is open to all of us, without hindrance of prejudice or physical barriers? Inclusiveness is a strong pillar of the American Institute of Architects; one has to be amazed and proud of the depth of influence that architecture and architects have made by applying those principles.

In my travels, whenever someone asks, what is the AIA? I’m truly proud to tell them, The American Institute of Architects, designers of society and the environment.

Have a wonderful summer!

Sincerely,

Georgi Ann Bailey, CAE, Hon. AIA Executive Vice President | AIA New York State

Source: Ian Fulgar, “Accessibility in Architecture and the Role of Social Awareness”, Architecture in the Philippines into New Designs and Land Ventures, April 6, 2022; https://www.ianfulgar.com/ architecture/accessibility-in-architecture-and-the-role-of-social-awareness/

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 5

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES THROUGH INCLUSIVE AND UNIVERSAL DESIGN

by Alexandra Garrity AIA, Architect and Universal Design Specialist, CSArch

When dealing with our youngest and most vulnerable population, it is paramount that designers consider how the built environment impacts users mental, physical, and emotional state. These considerations were at the forefront of the design of the new Family Resource Center in Utica, New York. This resource center is the first of its kind in many ways. Born from a unique and mutually beneficial partnership between ICAN and the Utica Children’s Museum, the Family Resource Center provides a centralized location with access to a variety of traditional and non-traditional services and programs. Located in Utica’s Parkway District, families in the Utica and surrounding regions can receive support, youth and family services, and enjoy all that the Utica Children’s Museum has to offer. Once completed, the Family Resource Center will receive its Innovative Solutions for Universal Design Certification from the University at Buffalo’s Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access, making it the first isUD Certified Children’s Museum in New York State.

Site Considerations

Located on Memorial Parkway, along the path of the Boilermaker road race, the site and existing building chosen for this project are in a location that receives high vehicular and foot traffic from nearby neighborhoods. Due to its location in the Parkway Historical District, the design needed to pay respect to the original building, built in 1969, while also providing a modern space that was accessible to all visitors in the community. In order to provide a welcoming space for guests and

PAGE 6 | MAY ‘23 1

SUPPORTING

improve access for individuals with mobility impairments, a large rotunda was constructed to the rear of the building to serve as the new main entrance to the Family Resource Center and additional exhibit space for the museum.

While providing a set of site stairs and a small ramp to meet ADA requirements and mitigate the 2’-10” change in grade between the parking lot and rotunda floor, the design team worked to redesign the site to create equity between able bodied users and those with mobility impairments. The redesign incorporates two ramps that descend from the most prominent access points off the parking lot, down to each of the main entrances, making them the most convenient paths of travel to access the building. This design change encourages all visitors to use the ramps rather than the stairs and does not ostracize those who would have to use the ramps out of necessity. This site feature makes access to the site more convenient for not only those with mobility issues, but also for parents with strollers, smaller children, and delivery personnel with rolling carts.

Wayfinding and Intuitive Signage

Once inside the building, wayfinding strategies were carefully implemented to direct visitors through the space. Because two very unique programs occupy the building and use one combined entrance, it was important that the wayfinding was simple and intuitive for all users. The design includes ample interior glazing from the entrance vestibule to each of the two different program spaces so it is clear to guests which doors they should use to reach their destination. This glazing is also accompanied by graphic signage that is easy to comprehend without the need to be able to read for young children or those with a language barrier.

The shared elevator for the building posed a unique wayfinding design challenge. Both the ICAN offices and the Utica Children’s Museum have access to the same elevator, but enter and exit from different sides and require access to different floors of the building. Access control systems were implemented to prevent museum visitors from entering an office space, with simple graphics to make the operation of the elevator more intuitive. Using color and simple, easy-to-identify icons, users know exactly which button to push to get to their destination and which way the doors will open.

Within the ICAN office spaces, paint colors and subtle changes in flooring materials help to identify main circulation paths and nodes. Common spaces such as restrooms and reception are located in the same area on both office floors, so navigation is simple and consistent between both floors.

Accommodating Diverse Needs

The modern, open office spaces are supplemented with breakout rooms for individual conversations as well as designated spaces for collaboration. By providing several different types of spaces within the office floors, each staff member can be accommodated whether they work best in a quiet space or in a more open environment.

While the ICAN staff are accommodated in the office spaces, there are still two main groups of visitors that the building needed to consider, each with their own unique set of needs. Visitors to the Utica Children’s Museum may be full of excitement, while visitors to the ICAN offices receiving family services could be in a very different emotional state. The team at ICAN does a great job of providing a safe, comfortable, and nurturing atmosphere within their organization and it is critical that the built environment supports that. Soft, cool tones provide a relaxing space in the Family Services suite complete with soft seating for maximum comfort.

Not only are all bathrooms in the building ADA compliant, but they are generously sized to better serve all users. Each restroom in the Family Services suite is single user, gender

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 7

neutral, and provides features such as full height mirrors and baby changing tables. On the museum side, one of the restrooms was also equipped with an adult changing table to accommodate those with special needs who require additional assistance. The museum space is also equipped with a New Parents room, which provides a peaceful space for a new parent to feed a child in private.

To truly capture the energy embodied in a children’s museum, the design team HandsOn! Studios was contracted to design the exhibits. Their design not only caters to curious and adventurous children with hands on activities and colorful

As the City of Utica continues its revitalization efforts, the new Family Resource Center is slated to become a cornerstone of the community. The unique partnership between ICAN and the Utica Children’s Museum provides the public support and services that promote equity and inclusion. The design of their new shared space ensures that any individual, regardless of physical ability, can partake in their range of services and comfortably engage in all the community has to offer. l

Construction is currently underway on the Utica Children’s Museum. The design of exhibit spaces will be publicly unveiled as it reaches completion in spring 2024.

Alexandra Garrity, AIA

Registered Architect and Universal Design Specialist

An architect and Universal Design Specialist at CSArch, Alex graduated with a Master of Architecture in 2018 from the University at Buffalo’s School of Architecture and Planning. Since joining CSArch, Alex has focused her architectural expertise on her passion in Universal Design to create inspiring spaces that are supportive of all users and abilities. She has worked with ICAN on the

| MAY ‘23

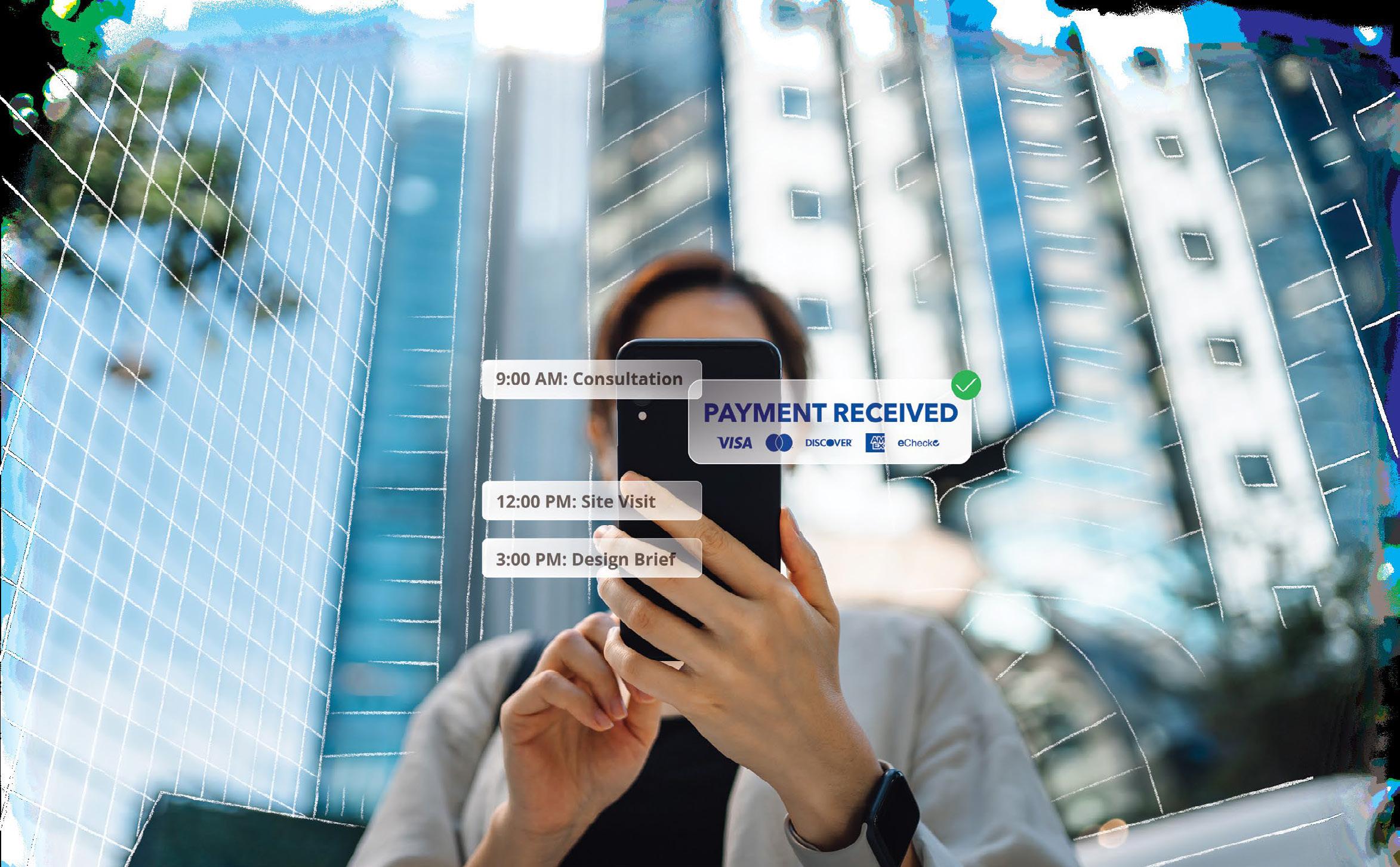

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 9 At ClientPay, we make accepting payments simple, so you can focus on what matters most to your business: your clients. Our user-friendly payment solution allows building and design professionals like you to securely accept credit, debit, and eCheck payments anytime, from anywhere— in the office, online, or even at a project site. ClientPay is a registered agent of Synovus Bank, Columbus, GA., and Fifth Third Bank, N.A., Cincinnati, OH. clientpay.com 866-280-2424 A personalized payment solution built with your clients in mind Make it easy for your clients to pay you 24/7 Enjoy faster, more reliable payments Experience customer support from real people every time you call

KIND OF BLUE: APPLYING THE PRINCIPLES OF DEAFSPACE AT THE NEW AMERICANS’ PAVILION

by David R. Shanks, RA, Co-founder, ASDF

The sign-language interpreter in our design progress meeting on Zoom wore a bright blue dress. It was almost Yves Klein Blue, the kind of blue that flattens most variation in light and shadow when seen on a computer screen. After I complimented her striking dress, the interpreter told me that the color was both a stylistic and a functional choice. Sign-language interpreters, she informed me, are always careful to wear solid-colored clothes and to choose colors that contrast with their skin tone in order to facilitate visual communication with their hands. A major user group for the New Americans’ Pavilion—the project my practice was engaged to design—is a community of refugees and immigrants that are deaf or hard-of-hearing. They call themselves Deaf New Americans, and consideration of their particular needs was an essential part of the design. Sign-language interpretation was necessary during our meetings in order to properly solicit their feedback and ideas.

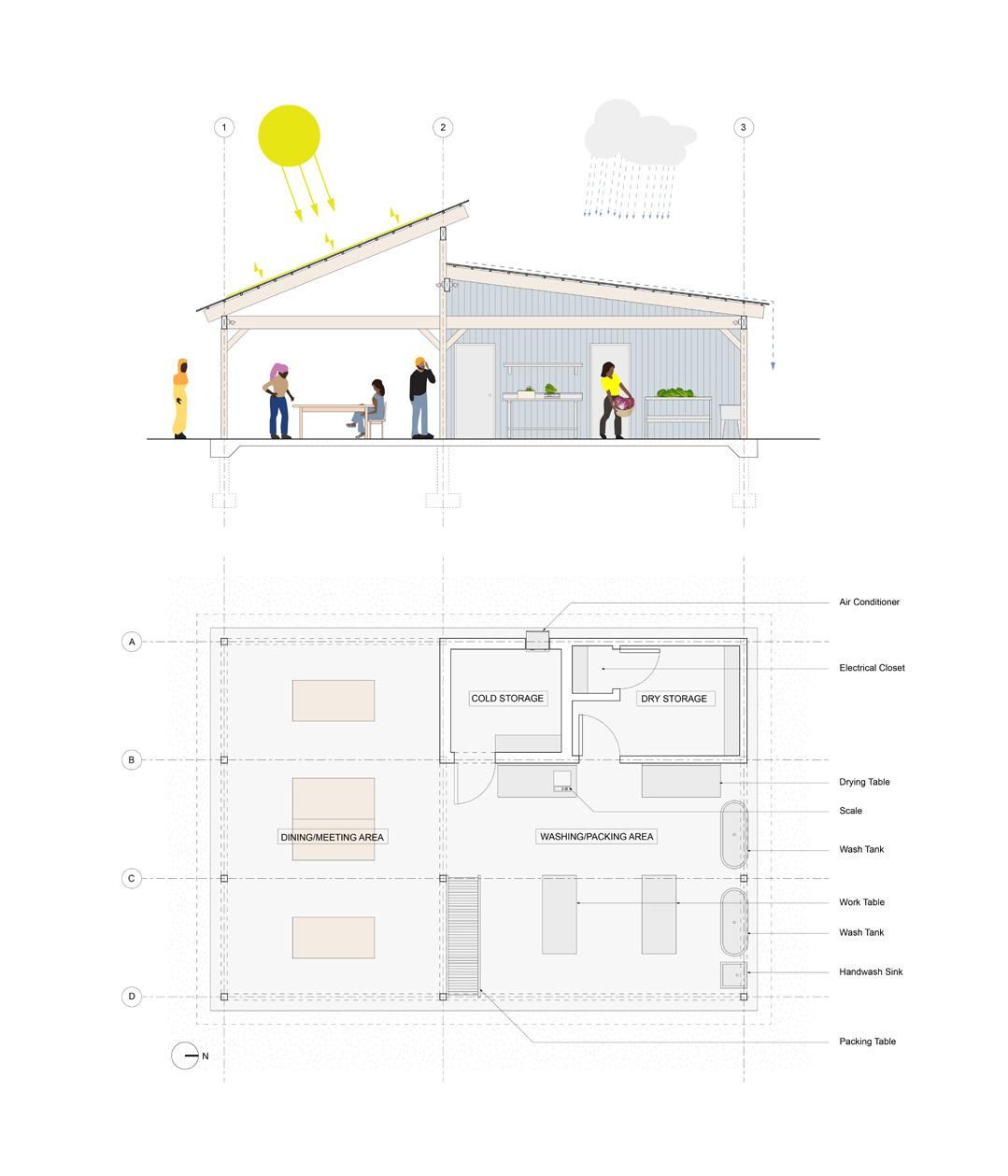

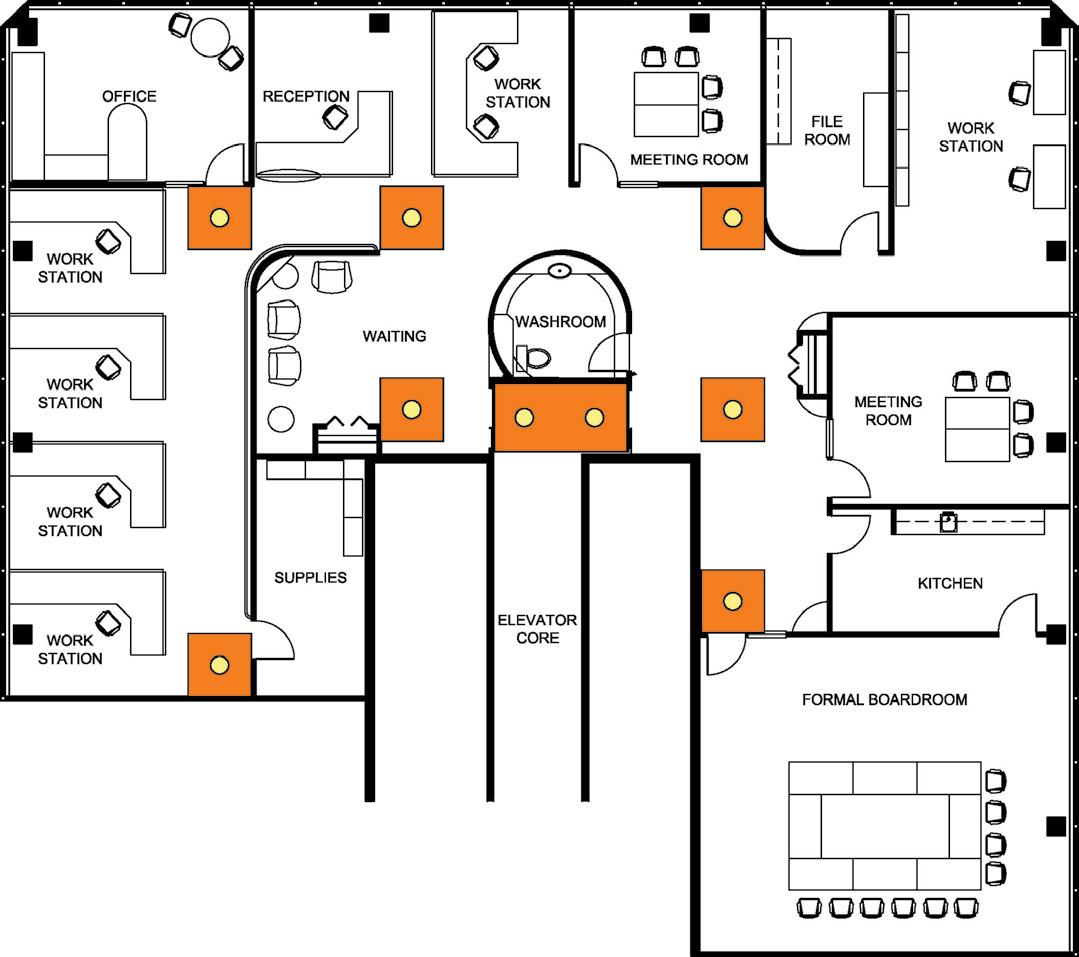

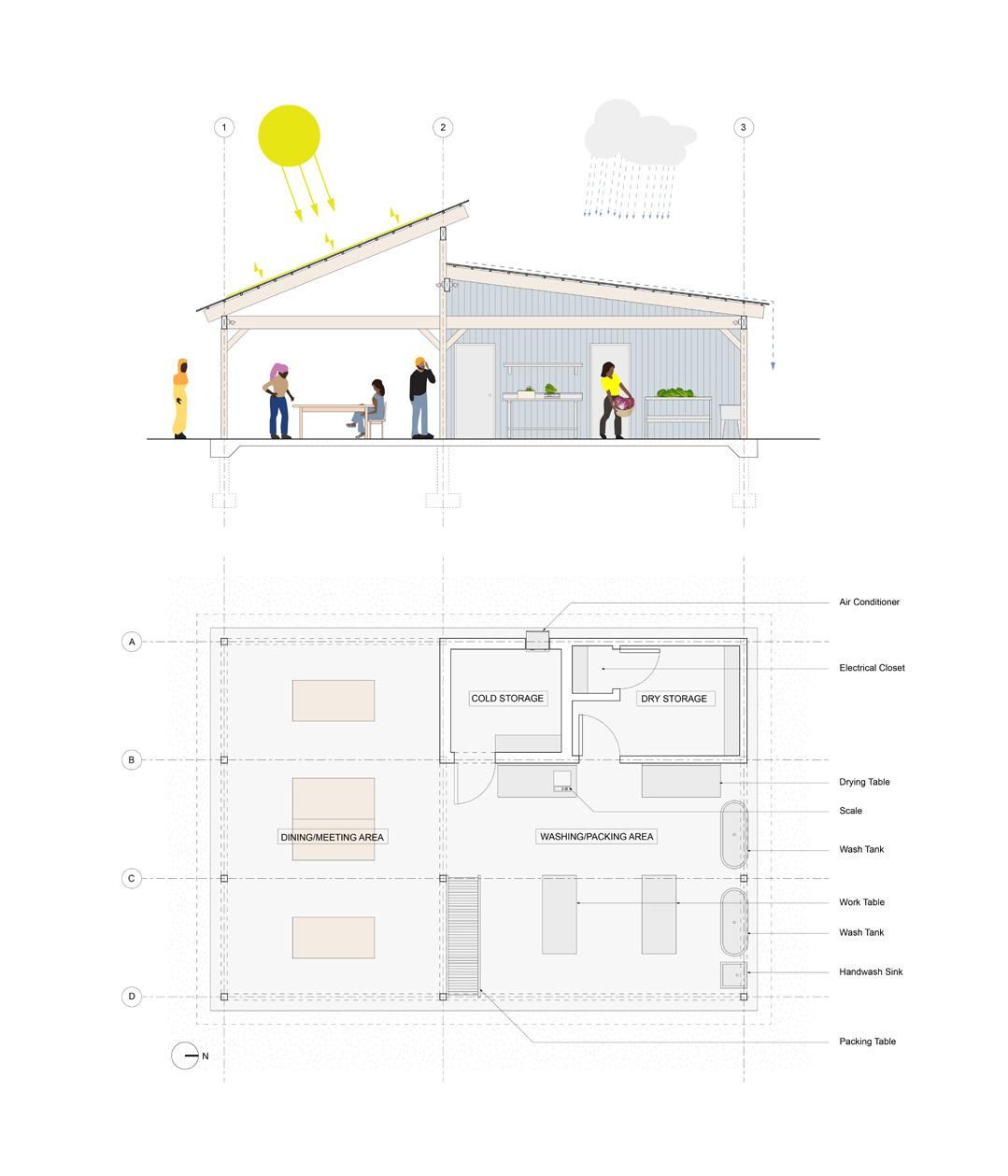

The New Americans’ Pavilion is located at Salt City Harvest Farm (SCHF) near Syracuse, NY. SCHF provides farmland, educational resources, and job training to refugees and immigrants in the Syracuse area, many of whom are deaf. Referencing the local agricultural vernacular, the pavilion is designed as a “double-shed”—the northern space accommodates the functional necessities of the community farm, including washing and packing spaces, refrigeration, and a dry storage enclosure; the southern space hosts more flexible uses of education, dining, and social events. At the seam between the two sheds, the storage enclosure becomes a backdrop for the commu-

PAGE 10 | MAY ‘23

2

The New Americans’ Pavilion, Salt City Harvest Farm (SCHF) near Syracuse, New York

nity functions, which are often conducted either entirely in sign-language or with an interpreter. So, when deciding which color to paint the cladding of the storage enclosure, the needs of the Deaf New Americans were especially relevant. Which color would best facilitate a clear visual environment for sign-language? For people with light skin tones, a dark color creates good contrast, whereas for people with dark skin tones, a light color creates good contrast. The Deaf New Americans are a diverse population, with origins ranging from Nepal to Eritrea to Cambodia, so their skin tones are equally diverse.

Based on my experience with the sign-language interpreter, I proposed a bright blue color for the storage enclosure, which would contrast with a broad spectrum of skin tones. I took inspiration from the bold color palettes of architect Luis Barragan, as well as the work of artist Amanda Williams, whose “Color(ed) Theory” project uses bright colors to draw attention to inequity on Chicago’s South Side. However, when I presented this idea to the Deaf New Americans in a later Zoom meeting, they did not like it very much. The saturated blue color, they told me, would cause visual fatigue if people had to look at such a large area of it for an extended period of time. While the bright color worked well for a dress that appeared in a small square on a computer screen, it would be counterproductive in this architectural application.

So, I went back and did some more research. I learned that a set of principles similar to those that guided the interpreter’s sartorial choices also apply to architectural design for deaf and hard-of-hearing populations. The architect Hansel Bauman founded the DeafSpace project at Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. in 2005. DeafSpace research explores architectural design strategies that produce better experiences for people who are deaf and hard-of-hearing. An important guideline of DeafSpace is to create simple, contrasting backgrounds for sign-language. The colors that researchers recommend are calm shades of either green or blue because they contrast well with a variety of skin tones without causing visual fatigue or distraction. The architectural practice Lewis Tsurumaki Lewis, for example, worked with DeafSpace researchers in the design of the Living and Learning Residence Hall for Gallaudet University, and chose a pale shade of blue for the walls of classroom and social spaces.

On the basis of this research, I purchased some paint samples in a range of blue tones and applied them to a piece of cladding for the Deaf New Americans to review. They were much happier with these colors, and voted amongst themselves to select a cool hue of wood stain called “Polar Blue.” We stained all four sides of the enclosure in this color, which gives the

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 11

Deaf New Americans

Referencing the local agricultural vernacular, the pavilion is designed as a “double-shed.”

completed building a handsome visual identity. The color also produces DeafSpace, a visual environment which accommodates the needs of the Deaf New American community, who have made use of the pavilion for farm-to-table meals, nutritional education programs, holiday celebrations and more. l

David R. Shanks is an architect and an Assistant Professor at Auburn University’s School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture. He is co-founder of the award-winning architectural practice ASDF, which was named among the best new firms in the United States by The Architect’s Newspaper in 2021. David received his M.Arch from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in 2009, and he has practiced in several globally recognized offices, such as Skidmore Owings and Merrill, Gluckman Tang Architects, Preston Scott Cohen, and Office for Metropolitan Architecture. He has exhibited, presented, and published his work both domestically and internationally, in venues such as the Boston Society of Architects, the Biennale di Architettura di Pisa, and the Journal of Architectural Education. From 2018-2020, he served as Architecture Program Director at Syracuse University’s study abroad campus in Florence, Italy. David has been a resident fellow of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust and the MacDowell Colony.

PAGE 12 | MAY ‘23

Blue tone paint samples presented to the Deaf New Americans as options for the pavilion.

The pavilion was stained in “Polar Blue,” which in addition to providing a better experience for the Deaf New Americans, gives the completed building a handsome visual identity.

Make space for dreams come true.

Making your client’s dreams a reality is a complex process with many moving parts. A partner that understands this, and works to streamline your process, can be invaluable. Marvin windows and doors deliver precision, innovation, and quality, and will exceed expectations for service every day—allowing you to make space for distinction, perfection, and everything that matters most to your clients.

marvin.com/architectural-resources

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 13

to get in touch

a

Scan

with

Marvin Expert

Photos courtesy of Spacecrafting

UNIVERSAL DESIGN: THE LIMIT DOES NOT EXIST WHAT CHILDREN’S MUSEUM OF PITTSBURGH MUSEUMLAB TAUGHT US ABOUT UNIVERSAL DESIGN AND ADAPTIVE REUSE PROJECTS

by Danise Levine, AIA, R.A., CAPS Assistant Director, IDEA Center

by Danise Levine, AIA, R.A., CAPS Assistant Director, IDEA Center

Throughout my 23-year architectural career I’ve been involved in many projects. Some were simple and small in scale, while others were larger in scale and more complex. Although they are all memorable for different reasons, there are a few projects that are more notable and invoke a special level of fulfillment and source of pride. The new Museum Lab at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh is one of those projects. I started working on the project in February 2017, and what I anticipated as being just another accessibility/universal design consulting job turned out to be so much more. It was clear from the outset that the team from the Museum was innovative in their thinking. Their goal was to create an environment that would not only encourage learning and creativity, but also would allow equal access and celebrate human diversity. This shared vision and passion is why Museum Lab and the Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDEA Center) became an ideal partnership and the IDEA Center’s new certificate program, innovative solutions for universal design (isUDTM) became the tool for implementing universal design solutions.

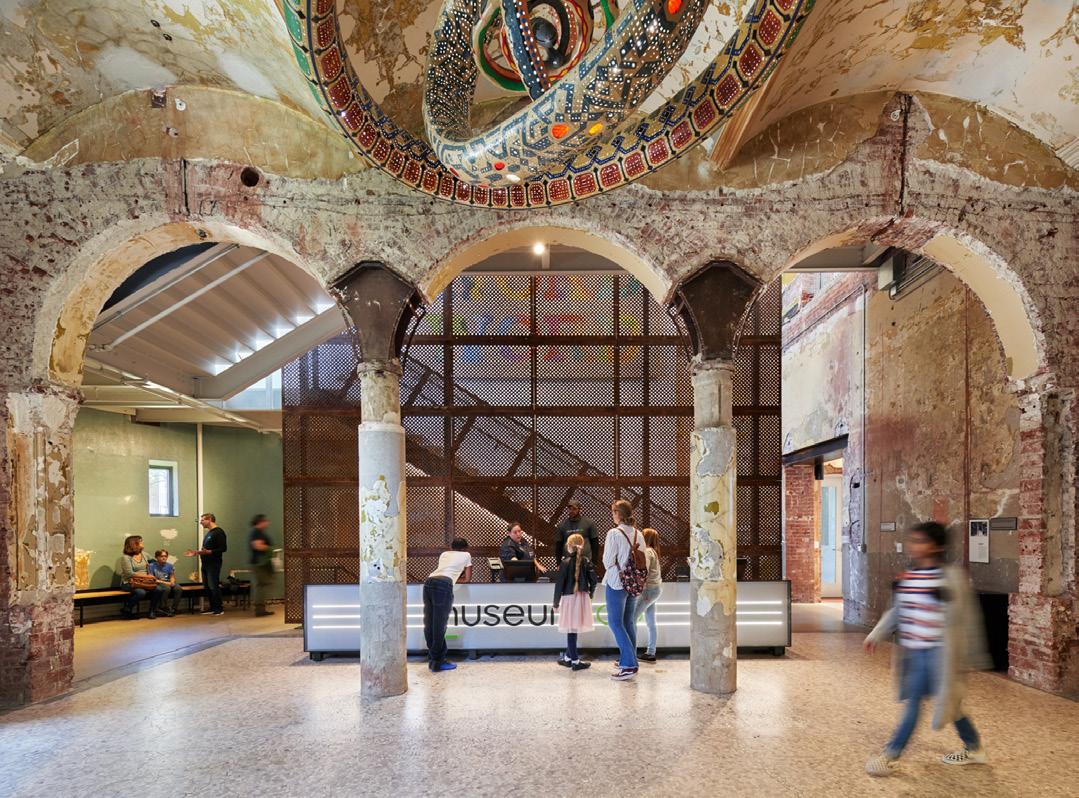

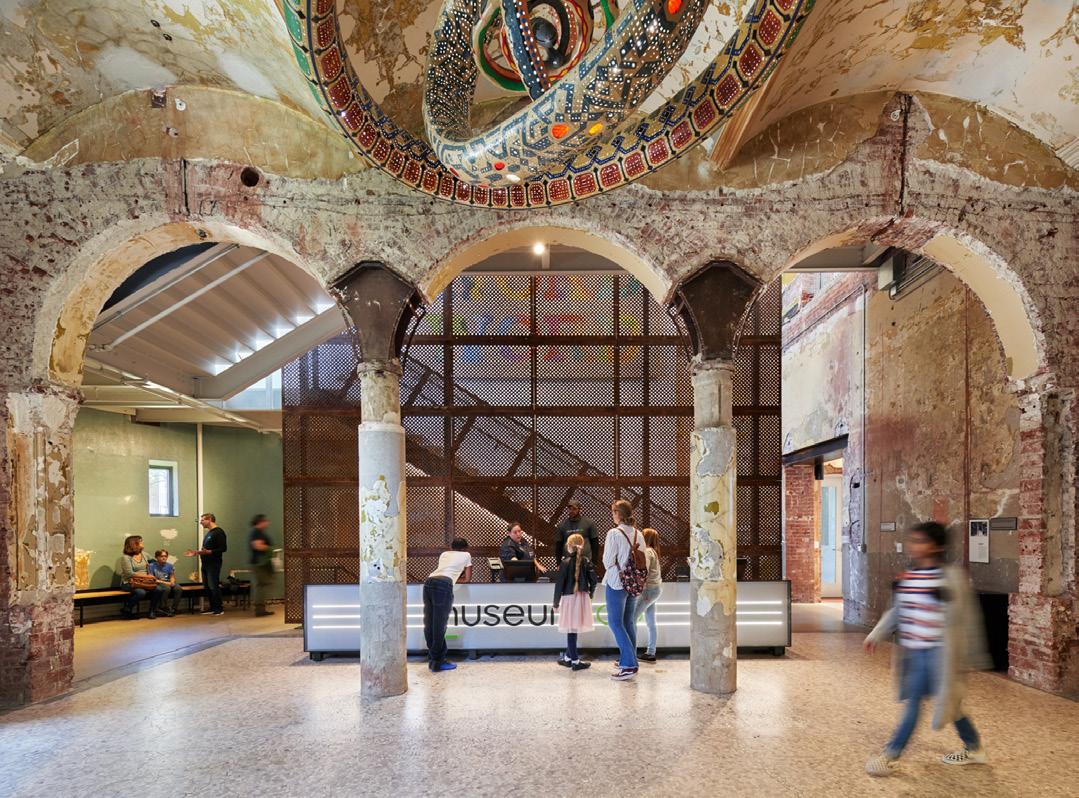

Too often designers and building owners are easily discouraged at the thought of implementing universal design in older, existing buildings because of the perceived costs and challenges involved. This certainly could have been the case with this project based on the conditions I observed firsthand when I made my initial visit to the downtown Pittsburgh site in October 2017. The building had been left vacant since a 2006 lightning strike damaged the roof, and the years of abandonment were obvious in the spalling of the concrete walls, crumbling

PAGE 14 | MAY ‘23 3

MuseumLab. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG | Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

floor tile, and the peeling of painted surfaces. To make matters worse, the building underwent a renovation in the 1970’s, and those repairs were done poorly and masked much of the beauty of the original architecture. Nonetheless, underneath the erosion and cosmetic bandages I could still see traces of a beautiful building with potential. I just didn’t know how the potential was going to translate into success. Those thoughts were quickly erased during a guided tour of the building with the design team. As we walked around the building and explored each space, different members of the team provided details outlining the future plans for each room. Listening to the vision of what was planned and seeing how everyone involved was so engaged and committed, it was truly inspiring. I clearly remember at one point we were standing in the main gallery space, a room that was dim and dusty with a high ceiling, beautiful archways, and towering columns. Although I was trying to focus on what was being said, I couldn’t help but stare down at the original floor tile with the name “Carnegie Library” integrated in the intricate mosaic pattern. I asked if the tile floor was going to remain in place and Chris Cieslak, the Project Director, informed me that it was staying, along with many other features of that spectacular room. It was at that moment that it became very apparent that the Museum Lab design team, including Koning Eizenberg Architecture and PWWG Architects, had fully embraced the exceptional character of the building, and instead of feeling discouraged by limitations of the existing building, they viewed it as an opportunity to preserve the historic integrity of the past and incorporate modern building concepts to accommodate current user needs. One of those modern concepts is universal design and the isUDTM Certification program.

To ensure that universal design was given appropriate attention throughout the entire planning and design process, the design team frequently sent design documents, drawings, specifications, cut sheets, and other materials for my review. It was clear from start to finish that the team was committed to universal design and that every decision they made was thoughtful and had intent. That commitment didn’t just apply to the built environment, but extended to the programming, function

and maintenance of the building after its completion. Those efforts were on full display when I had the honor of attending the Museum Lab grand opening in 2019. Walking into the same building two years after that first visit and seeing what the Museum team had accomplished was awe-inspiring. Although I knew the project was going to be groundbreaking as the largest cultural campus for children in the US and the first museum in the country to receive isUDTM Certification, it was beyond anything I could have ever imagined. It was a thing of pure beauty and purpose. The building was bright, functional and the perfect blend of the old and new. As I walked from room to room, I could see that the universal design solutions were subtly incorporated into the building, which created a more welcoming and inclusive environment for everyone. I believe the most noticeable UD features to visitors were the generous allocation of space in rooms and circulation spaces, along with the comprehensive and consistent wayfinding system, designed by Pentagram, that guides visitors throughout the building. I was particularly drawn to the way the modern, illuminated room signs and corner-mounted directional signage contrasted with the discolored, crumbling brick behind them. They created

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 15

MuseumLab. Compound Ringship by Ryder Henry. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Top & Bottom: MuseumLab. Over View by FreelandBuck. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG.

Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

a certain visual appeal that immediately attracted my attention, as well as others who entered a room or needed guidance in finding their destination. Most of the other UD features throughout the building were cleverly integrated into the overall design. For example, all-gender restrooms are dispersed throughout the building for use by anyone, which among other benefits, provides an opportunity for people with disabilities to receive assistance from someone of a different gender. One particular restroom features an adult changing table that allows caregivers to assist weakened or disabled individuals who may be unable to fully care for themselves. Another feature is the multi-zoned heating and cooling system within the building which enable users to modify room temperature within +/4 degrees to maintain their comfort.

As I continued my way through the museum, I found myself once again back in the middle of the main gallery space (now called the Grable Gallery), standing on that same tile floor I stood on 2 years earlier. It was now brightly lit from the sun streaming through large new windows in the adjacent Studio

Lab and the floor had been polished to shine. Above was a new layered, textured ceiling installation made of laser-cut fabric. I could still see many patched and peeling surfaces, but this time, instead feeling the results of decaying walls around me, I couldn’t help but marvel over the subtle timeline of events everywhere I looked. Instead of trying to restore the building back to its original state, they preserved and celebrated its history. The team was able to create a magnificent space that is welcoming, functional and empowering to all users in their pursuit of learning, creating and playing. It was truly an honor and privilege to be part of this innovative project and work together with a talented and passionate group of people who were not afraid to be innovative and who were committed to creating an inclusive environment for all. l

Danise Levine, AIA, CAPS, is a Registered Architect and a Certified Aging in Place Specialist (CAPS). She is also the Assistant Director of the Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDEA) in Buffalo. During her more than 25-year architectural career she has made an impressive contribution to the fields of accessible and universal design. She aspires to be a change-maker, actively working to change peoples’ lives and alter the way they interact with their environments. Most of her work focuses on problem solving and providing practical solutions to accommodate people of all abilities.

About the IDEA Center:

The IDEA Center is not your ordinary design firm, university research center, or R&D company. It is a globally recognized center of excellence committed to creating and implementing inclusive design policies, practices, environments, and products. We’re a dynamic group of researchers united by our shared values. We’re committed to creating a more inclusive world – for our clients, our team, and our community.

PAGE 16 | MAY ‘23

Top: MuseumLab. Over View by FreelandBuck. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG. Bottom: MuseumLab. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG. Photos © Eric Staudenmaier

Some Big Words by Mia Tarducci. Design Architects: KoningEizenberg; Architect of Record: PWWG. | Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

YOUR SUCCESS DEPENDS ON ANTICIPATING NEEDS AND EXCEEDING EXPECTATIONS. SO DOES OURS.

For over 30 years, Marino\WARE has been committed to providing solutions to customer pain points through a vast selection of quality and innovative cold-formed steel framing products, a knowledgeable sales team, and comprehensive technical services, including pre-design support. Contact

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 17

MarinoWARE.com

Stazzone to

to

Anthony M. Stazzone | Architectural Sales Manager | amstazzone@marinoware.com | c: 908.240.4200 QUALITY SOLUTIONS • High strength-to-mass ratio • Saves time and labor • Superior acoustical performance • Easy and fast to install • Reduces labor and materials • Increases available floor space • Sound control and universal fitting prevent the spread of fire, smoke, and toxic fumes • Faster installation than fire caulk

Anthony

discuss ways we can contribute

your success | amstazzone@marinoware.com

MORE THAN CLEARANCE

by Dominique Haggerty, NCARB, AIA

Inever thought about the relationship between architecture and pain. Our ability as architects to anticipate and perhaps even prevent it through thoughtful and elegant design suddenly became apparent when I gave birth to my daughter via an emergency C-section.

Prior to that moment, I had spent six years specializing in high-rise residential developments at a large prestigious firm in NYC. ADA and accessibility requirements on these projects were strictly observed, albeit in a generic and impersonal way. This is the nature of developments—design has to be for all and no one at the same time, and I have to confess that my younger self only attended to accessibility as a checklist of codes to apply. Fortunately, the firm I worked for championed classical proportions and generous room sizes which aligned well with ADA requirements, and this was my first hint that those things were linked—that the language of spatial and architectural luxury was also the architect’s tools to advocate for universal comfort through design.

My personalized lesson in accessibility came via a 1970s suburban contemporary house that my husband and I purchased in anticipation of our newborn. Our previous accommodation had been an old Victorian farmhouse, and though charming and romantic, refused to provide comfort. It had long and steep staircases, worn-slippery treads, random and sometimes extreme settling of floors, electrical outlets in out of reach locations. It was not family-friendly, it was time to move on.

The newly purchased house on the other hand offered an immediate and unanticipated mercy: it had been custom

designed by local design firm Flemming and Silverman Architects for the original owners’ needs: those of an aging couple. These original design discussions between owner and architect would have predated ADA requirements by at least a decade, and although there is no way of knowing if there had been explicit talks of disability, limited mobility was clearly top of mind and how to ease the body’s quotidian journey through old age.

The house was mostly one level, any stairs always incorporated railings on both sides, including a small set of only three risers. Grab bars had been integrated from the onset at the tubs and the shower stall had a built-in seat; a unique horizontal support, much like a ballet bar, had been installed at the longest stretch of hallway; the kitchen sink and cabinets were shallow reducing the need to lean or reach too far; and the circulation was laid out in a loop around the house to prevent the need to turn around or back out. Yet even with all those well-planned fixtures and layout, evidence of unforeseen challenges remained. Carved in the wood paneling and door jambs along the narrowest halls and pinch points, horizontal rut marks at 4” and 7” above the floor mapped out where a wheelchair would have needed to squeeze by in the latter years of a routine.

Both being designers, my husband and I were certain we would strip away all those artifacts to make way for a cleaner, more youthful and modern aesthetic, but by the time we moved in our daughter’s imminent arrival precluded any renovation plans and everything was left in place. I was in a joyous state of

PAGE 18 | MAY ‘23

4

new parenthood, but also in a state of post-surgical recovery. It took a long time to regain strength and rebuild, and that convalescent time was softened by the new baby and by the people around me who were wonderful to help out. For those moments when I was alone or no one was immediately available to assist, life was not as difficult as it could have been thanks to all the accessible features our house had available.

I always felt confident and in control moving through the space—all of a sudden, every grab bar was put to use as I steadied myself carrying the baby around and going about daily chores, I was quietly thankful to have two railings to go up and down stairs, and the ballet bar came in handy when I had a dizzy spell once, even the shallow kitchen sink and cabinets were unsung gifts to a person with a weakened core who could not lean forward more than a few degrees.

es of dementia; another with Multiple Sclerosis who has built a business informed by her own health journey. Each of these clients are very successful in their fields and defiantly independent—yet what has imprinted in me most through the arc of each project, was the level of support and care that came from their partners as they quietly and imperceptibly adjusted the surroundings to ease their partner’s movements through the day: silverware moved to the working arm’s side, doors held open, chairs brought without having been requested.

Rarely do clients ask for custom modifications to our designs specific to their condition, but taking a cue from their partners, we always considered them and aimed to incorporate elements of accessibility wherever possible. Easily gripped hardware, single handle faucets, railings each side of stairs, and flush sills and transitions are now standard in most of my projects, automation and pneumatically assisted hardware are often suggested, and special attention is placed on the maneuverability of hallways and how well circulation flows throughout a home. As I talk to people about my anecdotes, I am amazed at how many respond with similar mobility issues that they are struggling to manage, from general aging, to arthritis, long Covid, Lyme disease, pregnancy, a broken ankle, etc. Through design, architects can provide beauty but also care and relief as we are asked to steward a person’s experience through a space. This principle is what ADA guidelines and codes have emerged from and it has taken me my own experiences to understand that they serve not as requirements to fulfill, but as reminders to design more kindly for life and the body’s journey now and as it will be in years to come.

All of these accessories were a blessing, yet I still considered them and my limited mobility a temporary condition. When I recovered, my husband and I reopened the case to renovate and remove the grab bars and redundant railings. However, we had to admit they were still used on a regular basis even without a direct disability to service any more: by myself through habit, by our toddler who was enjoying some accelerated autonomy enabled by those grab bars and railings, and by our visiting parents, aunts and uncles, themselves entering their senior years.

Unluckily, five years later I was diagnosed with breast cancer and again found myself in a state of post-surgical recovery— this was a harder and longer convalescence without the joy of a new baby, but I was newly grateful for our house with its thoughtful accessories which buttressed my path to recovery.

I speak of my personal story, but professionally this enlightened my approach to accessibility design as I saw more clearly how its consideration does not need to follow physical injury, it should be ready for it.

Since 2019, I started my own practice focusing on private residences. This allowed me to engage more directly and personally with clients in a way that was not possible through the speculative developments from my corporate days. When talking through each client’s backgrounds and narratives, I was surprised at the prevalence of limited mobility issues that everyone was going through in all its varying forms. I have designed for a person whose arm was paralyzed in a motorcycle accident, his wife who has a hyper-sensitivity to specific vibrations; a paralympic athlete; a matriarch at the beginning stag-

And yes, all of the grab bars and railings in our house remain, anticipating a new need for them in the future whether from us or the next owner that will hopefully appreciate them as I have. l

Dominique Haggerty

is Founding Principal of

DADO

Architecture P.L.L.C., a boutique design firm located in New York’s Hudson Valley that focuses on residential and hospitality projects in New York City and surrounding areas. Prior to starting her own firm she was a lead designer at Robert A.M. Stern Architects. She grew up in Paris and Chicago, and holds a Bachelor of Architecture from The Cooper Union.

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 19

“I speak of my personal story, but professionally this enlightened my approach to accessibility design as I saw more clearly how its consideration does not need to follow physical injury, it should be ready for it.”

5 PROVIDING ACCESSIBILITY TO MTA STATIONS IN NEW YORK CITY

by Nandini B. Sengupta, Urbahn Architects

by Nandini B. Sengupta, Urbahn Architects

Architects are often acknowledged at the ribbon cutting ceremonies of buildings they have designed. Clients praise the look and feel of the building and end-users commend them on how well it serves the function. Those moments are gratifying, but none so much as when a user tells you how his or her life has been changed by what you designed. I recently had the privilege of one such conversation. I was back at a New York City subway station for which we had recently designed accessibility improvements. A middle aged, wheelchair bound person had just descended the elevator and was waiting on the platform for a train. My

hard hat gave me away as an architect. She struck up a conversation, and upon learning that our team had designed the elevator and accessibility for that very station, she thanked me profusely, telling me that her life had been changed by this project. Previously she had to go to an accessible station a mile away to get to work. Her commute was now so much easier! Getting from one place to another is not so straightforward for many of our fellow citizens; providing accessibility for all is a public service that affects the lives of thousands.

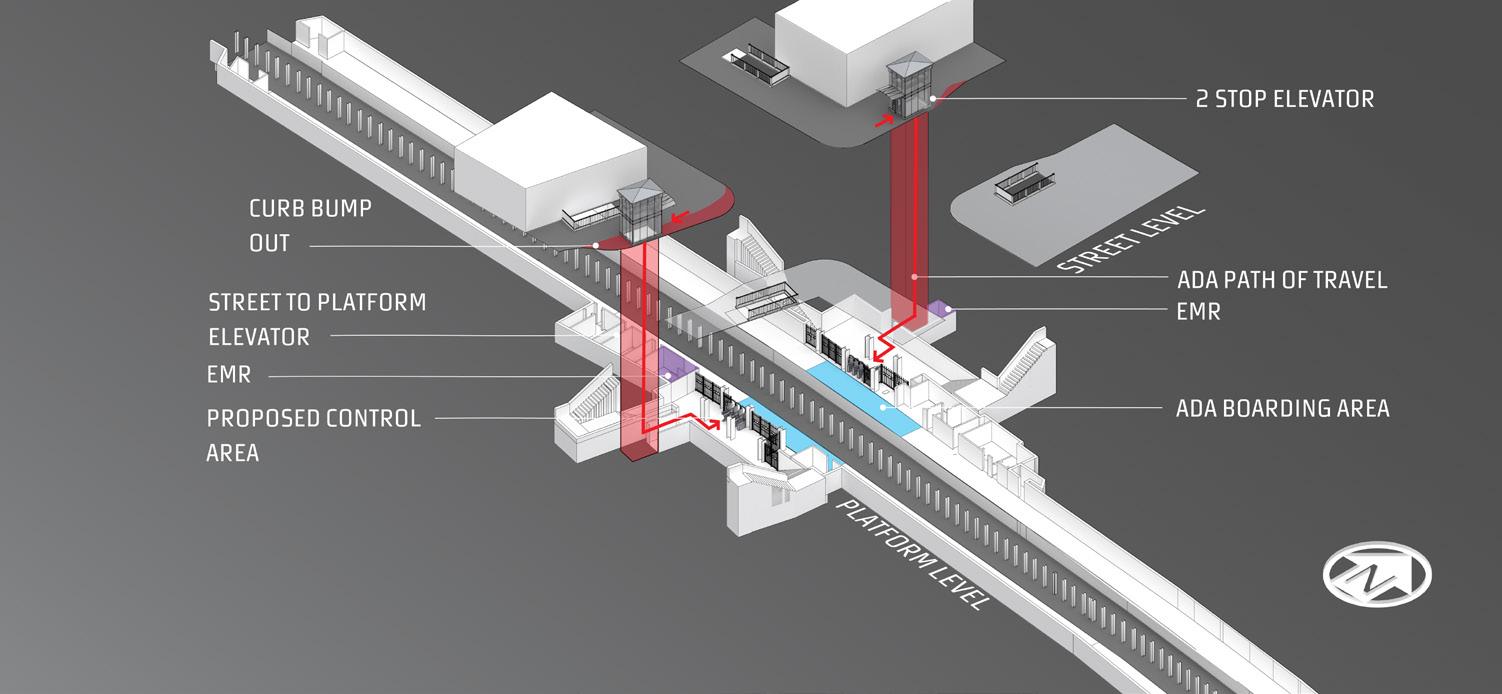

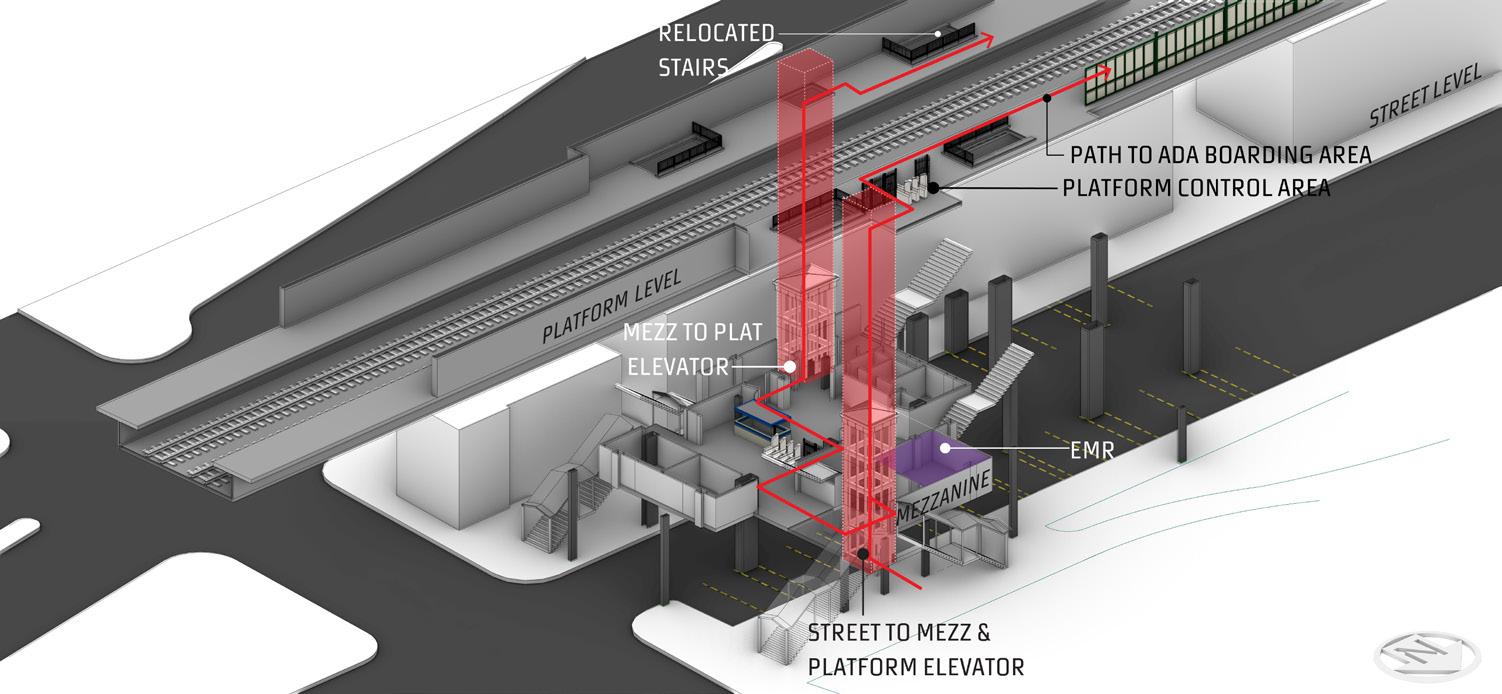

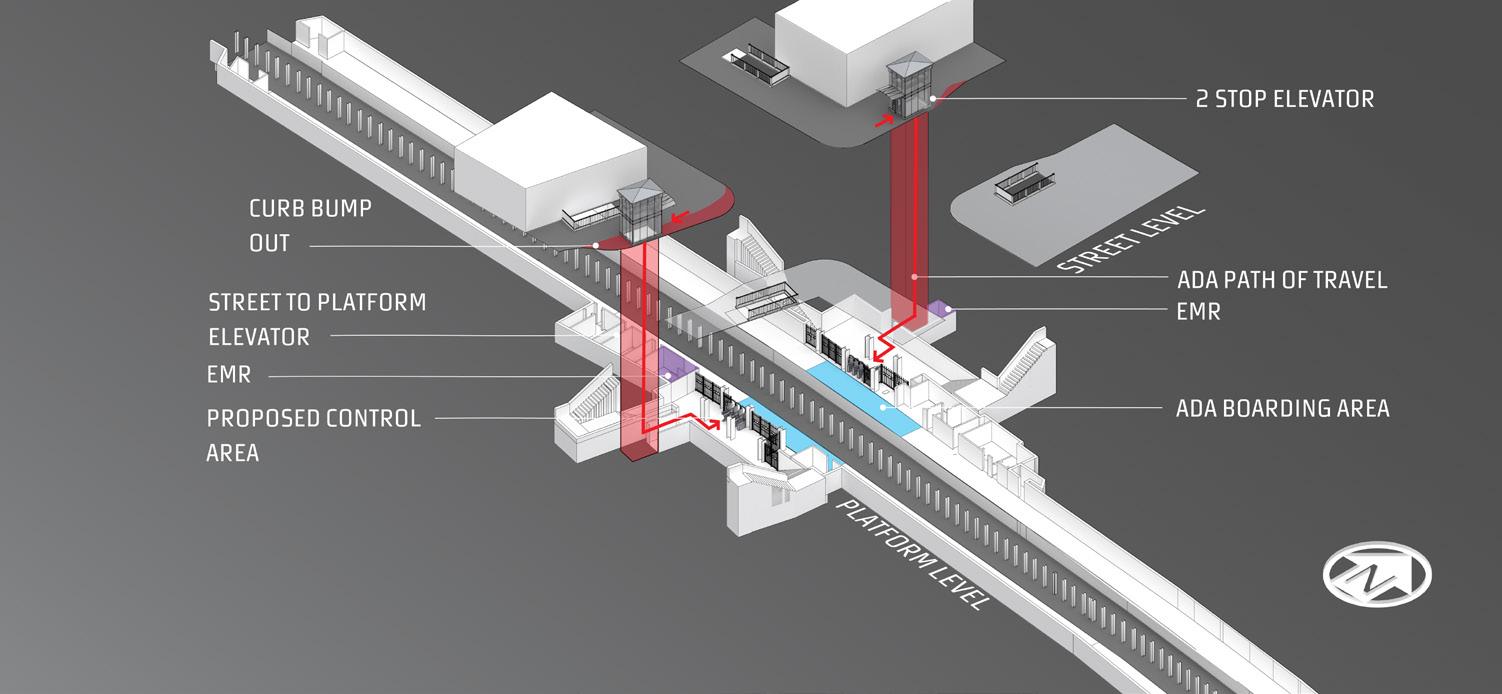

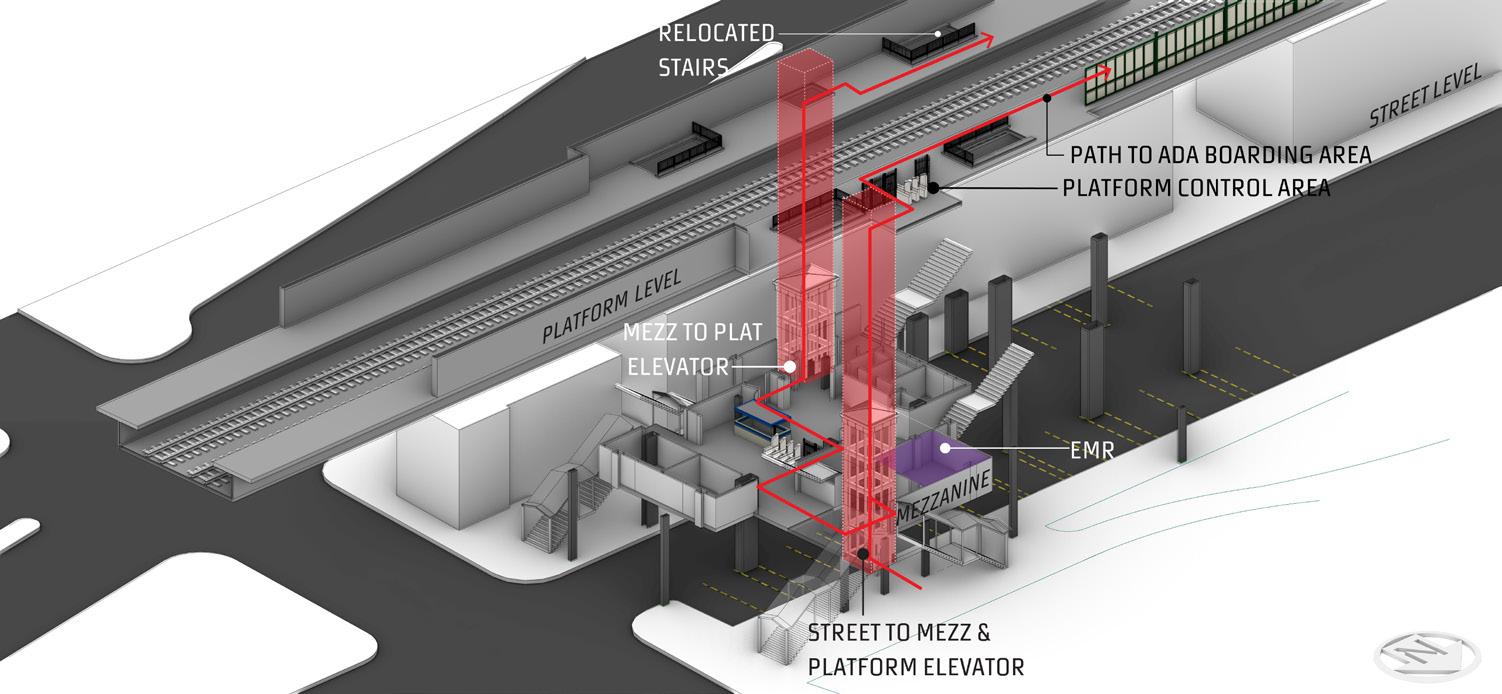

Designers working on station accessibility improvements typically have at their disposal a “kit of parts,” but the specific

PAGE 20 | MAY ‘23

Entrance and elevator headhouse at the 96th Street Broadway Station, Manhattan. Photo: © John Bartelstone

Elevator within the headhouse of the 96th Street Broadway Station, Manhattan. Photo © Wade Zimmerman

solutions invariably require inventiveness to address the specific conditions at and around a station. Altering the built fabric of subway stations in New York City is no simple task. The transit system is the second oldest in the world, with much of the infrastructure dating back between 1904 and 1932. Largely designed and constructed by various private companies, it hosts a range of station configurations—underground running below the streets, open-cut in a trench that cuts through neighborhoods and elevated above the streets and sidewalks. Platform configurations are varied: platforms on the two sides of tracks, island platforms between tracks, combinations of the two, and other variations as well. In many transfer stations, two or more subway lines meet, oftentimes at different levels and odd angles, connected via stairs and a warren of passageways.

Typically, stairs at street corners lead to a mezzanine with fare arrays, and from there into a circulation system that lead to the platforms. Indeed, it is a three-dimensional puzzle that has been designed with consideration for safe access points at street corners, allowing clearances for street utilities in underground stations, allowing clearances for vehicles in elevated stations, while maintaining points of control that separate the “unpaid” side from the “fare paid” side.

Needling an elevator through this maze is no easy task. Architects and engineers should anticipate streets and sidewalks that are densely packed with utilities and other obstructions,

oftentimes placed exactly in the otherwise ideal spot for an elevator. At the street level, elevator kiosks need to allow for the flow of pedestrians on the sidewalk while having adequate clearances from both neighboring buildings and the curb edge. They need to be carefully located to first take the passenger to the unpaid zone of the station. Thereafter, the wheelchair bound passenger passes through an accessible “AFAS” (ADA Farecard Access System) gate. While in a few situations they can get directly onto the platform, in most cases they take another set of elevators to the platforms. This is due to the requirement for the separation of the fare paid side from the unpaid side and/or due to the station configuration, particularly when island platforms are situated above or below the middle of the street, precluding the use of a single elevator shaft from the sidewalk. Complications are many - low headroom situations at mezzanines, utility or structural obstructions above the subway tunnel, low headroom situations above streets - creating challenges in accommodating elevator pits and integrating new elements and systems with a structure that is over a century old.

The Metropolitan Transit Authority is now in the midst of a much needed and ambitious initiative to make 95% of its subway stations accessible by 2045. Over the past few decades and up through the present, Urbahn Architects has been involved in providing innovative design for accessibility at dozens of New York City subway stations. In almost all cases, the elevator shafts and cabs are designed to maximize visibility and security through the extensive use of glass, typically an adaptation of the MTA standard unless a completely customized solution is warranted. At the 96th Street Station on Broadway, the median at the center of the roadway was widened to accommodate a new headhouse from where two elevators were dropped to the island platforms. The widened median was treated as a mini park, with a gently pitched granite ramp and plaza, plantings, and benches. The titanium metal panel roofed station house recalled the curved structure of the nearby 125th Street viaduct. At Eastern Parkway – Brooklyn Museum Station, we complemented the prominent nearby Brooklyn Museum with an elegant glass elevator kiosk that punctuates the station entry point without competing with the historic edifice designed by McKim Meade and White. At the elevated 170th Street Station in the Bronx, a single elevator at a street corner takes passengers up to a mezzanine from where two other elevators convey passengers up to the two side platforms. Within the 120-year-old transit network, accessibility interventions are often made to historic stations,

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 21

Top: ADA path of travel in an elevated station; Bottom: ADA path of travel in an underground station

requiring design sensitivity, either by matching finishes and historic details or clearly distinguishing modern interventions from historic fabric. While new elements can help articulate the entry to the station or become features, the design needs to be compatible with the character of the station and the neighborhood context.

Clearances and tolerances are measured in fractions of an inch in transit projects, and therefore investigation of field conditions needs to be exacting and design documentation must be precise. An architect working on transit stations should recognize that the need for intensive multi-discipline collaboration is even greater than on typical building design projects. These projects call for close coordination with civil, structural, mechanical, electrical, and communications engineers, as well as vertical transportation and other specialty consultants. In developing responsive and innovative accessibility solutions within a transit system that is over a century old, the full design team works together diligently to achieve design and construction excellence. l

Nandini B. Sengupta is a senior associate at Urbahn Architects. Over her 35-year career she has led Urbahn’s Transportation projects, many of them providing accessibility to MTA stations in New York City.

Urbahn Architects is a hundred-person NYC firm providing design services for a range of building types including higher education, K-12, justice, institutional, transportation, and other public sector projects. Since 1990, it has provided design services for accessibility improvements for over 30 stations. In 2022, Urbahn won the Society of American Military Engineers award for its work on providing accessibility to MTA stations.

PAGE 22 | MAY ‘23

New elevator kiosk at the Eastern Parkway-Brooklyn Museum Station, Brooklyn. Photo © Ola WilkPhoto

New glass elevator tower at the 170th Street Station, Bronx. Photo © Ola WilkPhoto

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 23

FIVE MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT FAIR HOUSING ACT DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION COMPLIANCE

by Peter A. Stratton, Managing Director of Accessibility Services, Steven Winter Associates

From “If I comply with the building code, then I comply with the Fair Housing Act” to “Everything is adaptable, so it doesn’t need to work on day one, right?,” accessibility consultants have heard it all.

Here are five of the most common misconceptions about the Fair Housing Act.

1. Following the accessibility requirements of the building code will satisfy the design and construction requirements of the Fair Housing Act (FHA).

Not true. Following the accessibility requirements of the building code may not always satisfy the design and construction requirements of the FHA. Building codes and federal laws are mutually exclusive; a building department or building official is responsible for ensuring compliance with the code —not the law. HUD is responsible for enforcement of the Fair Housing Act—not building codes. Meeting the requirements of one may not always satisfy the requirements of the other. There is only one code, i.e., the International Building Code (IBC), that is a HUD-approved ‘safe harbor’ for compliance with the design and construction requirements of the FHA. Editions of the code after 2018 are not yet approved by HUD as meeting the requirements of the FHA. It is also important to note that any edition of the IBC adopted by a local jurisdiction and edited to fit the context of the local jurisdiction is not a ‘safe harbor’ for compliance with the FHA. The general rule of

PAGE 24 | MAY ‘23

6

thumb is to apply the accessible design and construction requirements of the code and the law and comply with the most stringent provision.

2. Meeting the design and construction requirements of the FHA is not required at the time of design and construction. Because the Fair Housing Act permits adaptability, modifying a feature to accommodate a resident’s particular need is the best way to comply with the FHA.

Not true. Meeting the design and construction requirements of the FHA at the time of design and construction is required. To say that its permissible to meet the requirements by adapting features as needed makes the design and construction requirements of the Act meaningless. Adaptability is permitted by the law, but only after the minimum design and construction requirements are met. And what is permitted to be adapted post construction is included in the technical standards. For example, a forward or parallel approach is required to be provided at a kitchen sink in a dwelling unit. To accommodate the front approach, the base cabinet must be designed to be removable, i.e., adaptable. Adaptability in this case is contemplated by the requirements for usable kitchens. On the other hand, a light switch in a dwelling unit is required by the FHA to be installed below 48 inches above the finished floor. The Act does not permit the light switch to be installed higher and modified as requested. To install a light switch higher than 48 inches above the finish floor is in violation of the design and construction requirements of the FHA. Adaptability in this case is not contemplated or permitted by the requirements for outlets, switches, and environmental controls.

3. The Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines are mandatory.

Not true. The Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines are not mandatory; they are guidelines issued by HUD to help design teams comply with the seven design and construction requirements of the Act. However, in 24 CFR Part 100, published in the Federal Register on October 24, 2008, HUD makes it clear that “In enforcing the design and construction requirements of the Fair Housing Act, a prima facie case may be established by proving a violation of HUD’s Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines. This prima facie case may be rebutted by demonstrating compliance with a recognized, comparable, objective measure of accessibility.” Additionally, there are 15 HUD-approved ‘safe harbors’ for compliance; one of which is the Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines. Although not required, it is highly recommended that design teams use one of the HUD-approved ‘safe harbors.’ As HUD states in 24 CFR Part 100, “…designers and builders who choose to depart from the provisions of a specific safe harbor bear the burden of demonstrating that their actions result in compliance with the Act’s design and construction requirements.”

4. Because the technical standard referenced by the Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines includes criteria for built-in furnishings and equipment, movable non-fixed tables in a residential community room or on a common-use roof deck, for example, are not required to be accessible.

Not true. Although it is true that the technical standard referenced by the Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines includes criteria for built-in furnishings and equipment, it is not true that movable furnishings are not required to be accessible. The over-arching requirement of the Fair Housing Act is equal access. Although the technical standard includes criteria applicable to built-in furnishings, the law itself requires that if table seating is provided as an amenity in a resident community room, then enough seating spaces must be accessible to allow access by people with disabilities. Providing only inaccessible movable tables means that people with disabilities are shut out the enjoyment of the resident amenity and are therefore not provided with equal access.

5. If a multifamily apartment building includes a unit that is set aside for rent on a day-to-day basis by friends and/or family of residents of the apartment building, then as long as that apartment is designed to the requirements applicable to the rest of the dwelling units in the building, then the apartment is in compliance with the Fair Housing Act. Not true. Although the apartment may appear exactly the same as other apartments in the building, because its available to be rented out on a day-to-day basis to friends and family of any resident who lives in the building, it is technically a resident common area, i.e., a common-use amenity available to all residents. As a result, the dwelling unit must comply with the stringent technical criteria applicable to common-use areas. For example, the sink in the kitchen must be designed to be fully accessible, i.e., no base cabinet below, just like the sink in the common-use community room kitchen. Kitchen sinks in the balance of dwelling units in the building are permitted to include a base cabinet below as long as the sinks are served by a compliant parallel approach, which is aligned with the requirements for dwelling unit kitchens. l

Peter Stratton | As the Managing Director of Accessibility Services at Steven Winter Associates, Peter oversees the accessibility consulting business sector and provides leadership to a team of professionals located in the firm’s New York, NY, Washington, DC, Norwalk, CT, and Boston, MA offices.

FEBRUARY ‘23 | PAGE 25

SOPHISTICATED COUNSEL FOR COMPLEX CONSTRUCTION.

Zetlin & De Chiara LLP, one of the country’s leading law firms, has built a reputation on counseling clients through complex issues. Whether negotiating a contract, resolving a dispute, or providing guidance to navigate the construction process, Zetlin & De Chiara is recognized as a “go-to firm for construction.”

PAGE 26 | MAY ‘23 WWW.ZDLAW.COM 801 SECOND AVENUE • NEW YORK, NY

Stainless steel:

- Extremely efficient reflector of solar energy

- Offsets global warming and the heat island effect

- Substantially reduces insulation requirements

Micro Textured Stainless Steel:

- Hydrophobic, naturally cleaning surfaces

- Retains all solar reflectance and energy efficiency indefinitely

- Significantly lower maintenance costs

The

metal made better

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 27

choice

simple.

is

www.rigidized.com

FAIR HOUSING –WHAT’S YOUR SAFE HARBOR?

by Theresa D’Andrea, Senior Accessibility Consultant

ompliance with the accessible design and construction requirements of the Fair Housing Act (FHA), a federal civil rights law, has significantly improved since the early 1990s when the regulations were promulgated. Unfortunately, a quick search of recent news articles will reveal that noncompliance with basic FHA requirements continues to be a problem in newly constructed multifamily projects nationwide. Owners, developers, architects, and others are still cited for noncompliance with the FHA’s seven design and construction requirements even though it has been more than 30 years since those requirements went into effect.

Why Select a Safe Harbor?

Based on our experience, one of the contributing factors in continued noncompliance is the common misconception that following the accessibility requirements of a building code will result in compliance with the FHA. It is important to note that if the accessibility requirements of one of the HUD-approved safe harbors are not incorporated into the design of a multifamily development, and the project complies only with the accessibility requirements of a building code, the risk of noncompliance exists.

CThroughout the 1990s and early 2000s, many building codes fell far short of FHA compliance. For example, many developers relied on compliance with the accessibility requirements of the local code believing that code and FHA requirements were one in the same. Unfortunately, this resulted in widespread noncompliance. To ensure compliance with the accessible design and construction requirements of the FHA and the local code, be sure to comply with both. To avoid the risk of noncompliance, select one of the HUD-approved ‘safe harbors’ and apply its requirements to the entire project. When weighing the requirements of the local code against those of the FHA, follow the most stringent criteria. By implementing this best practice, industry professionals will achieve compliance with the FHA.

What are the Safe Harbors?

Before March 8, 2021, there were ten HUD-approved safe harbors for FHA compliance:

1. HUD Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines published on March 6, 1991 and the Supplemental Notice to Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines: Questions and Answers about the Guidelines, published on June 28, 1994;

2. HUD Fair Housing Act Design Manual;

3. ANSI A117.1 (1986), used with the Fair Housing Act, HUD’s regulations, and the Guidelines;

4. CABO/ANSI A117.1 (1992), used with the Fair Housing Act, HUD’s regulations, and the Guidelines;

PAGE 28 | MAY ‘23

7

5. ICC/ANSI A117.1 (1998), used with the Fair Housing Act, HUD’s regulations, and the Guidelines;

6. Code Requirements for Housing Accessibility 2000 (CRHA);

7. International Building Code 2000 as amended by the 2001 Supplement to the International Codes;

8. International Building Code 2003, on the condition that the ICC publish and distribute a statement that indicates that “the ICC interprets Section 1104.1, and specifically the exception to Section1104.1, to be read together with Section 1107.4, and that the Code requires an accessible pedestrian route from site arrival points to accessible building entrances, unless site impracticality applies. Exception 1 to Section 1107.4 is not applicable to site arrival points for any Type B dwelling units because site impracticality is addressed under Section 1107.7”

9. ICC/ANSI A117.1 (2003), used with the Fair Housing Act, HUD’s regulations, and the Guidelines; and,

10. The 2006 International Building Code (loose leaf format only)

In the December 8, 2020 edition of the Federal Register, HUD published a final rule adopting additional safe harbors that can be used to demonstrate compliance with the design and construction requirements of the FHA. This is a long-awaited update and an important step toward bringing building code and FHA requirements together for designers. As of March 8, 2021, the following additional safe harbors have been approved by HUD:

11. ICC A117.1-2009

12. The 2009 International Building Code

13. The 2012 International Building Code

14. The 2015 International Building Code

15. The 2018 International Building Code

The New Safe Harbors

The final rule published in the December 8, 2020 edition of the Federal Register states that HUD has reviewed the updated editions of the IBC and found that it “found that the accessibility provision of these IBC editions [2009, 2012, 2015, and 2018] are consistent with the requirements in the Act, HUD’s regulations, and the Guidelines.” HUD also clarified that it “… did not find any provision [in the additional safe harbors] that it believes provides less accessibility than what is required in the Act, the regulations, and the Guidelines,” and that “to ensure compliance with the Act, covered entities must select one safe harbor; once a safe harbor document has been selected, the building in question must comply with all the provisions in that document that address the Fair Housing Act design and construction requirements to ensure the full benefit of the safe harbor.”

HUD’s clarifications implied that where provisions of a safe harbor exceed the design and construction requirements of the Act, they do not need to be met as a matter of FHA compliance; they need to be met as a matter of building code compliance. Many Type A unit criteria included in the ICC

A117.1 technical standard exceed baseline FHA requirements. For example, a 30-inch wide work surface is required in Type A units, but not required by the FHA. In this case, the lack of the 30-inch wide work surface would violate the code, but not the FHA. The only way to understand provisions of the safe harbors that exceed the Act is to read each in the context of the requirements of the Act itself, HUD’s implementing regulations, and the Fair Housing Act Accessibility Guidelines. Only when baseline FHA requirements are understood, then safe harbor requirements that exceed baseline FHA requirements will be brought to light.

Section 101 of the ICC A117.1 standard states that Type B criteria are designed to be consistent with the dwelling unit requirements of the FHA. Baseline FHA requirements do not stipulate that maneuvering clearance is required on the dwelling unit side of the unit entry door, but the interior side of a Type B dwelling unit entry door is subject to maneuvering clearance requirements under ICC A117.1 2009. Despite Section 101 and its clarification that Type B units are designed to align with FHA requirements, maneuvering clearance on the interior side of the dwelling unit entry door exceeds baseline FHA requirements. Although compliance with Type B requirements at the entry door is required as a matter of demonstrating compliance with the code where Type B units are required, compliance to the same extent is not required by the FHA.

Selecting a Safe Harbor

Despite what the recently approved safe harbors allow, HUD continues to evaluate properties to the baseline requirements of the FHA Guidelines, which requires exactly 18 inches between the toilet centerline and the side wall. However, if a designer can demonstrate compliance with one of the recently approved safe harbors, which permits a range of between 16 and 18 inches versus 18 inches exactly, then compliance is achieved.

The best advice is to comply with the selected safe harbor in its entirety despite there being subtle differences between each. In the end, HUD will identify violations of the Act by demonstrating noncompliance with the Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines. It is up to the designer to refute allegations of noncompliance by demonstrating full compliance with any of the currently HUD-approved safe harbors. If you can do that, then you’re golden! l

in

complex scoping and technical requirements of federal, state, and local laws and codes governing accessibility compliance. She conducts plan reviews and field inspections and provides training and technical support to project teams throughout design and construction.

FEBRUARY ‘23 | PAGE 29

Theresa D’Andrea | As a Senior Accessibility Consultant at Steven Winter Associates, Theresa has specialized expertise

the

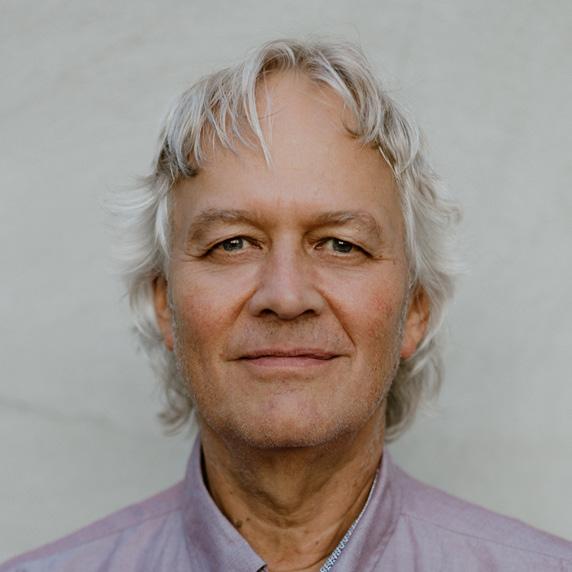

A CONVERSATION WITH RACHEL WIESBROCK:

A TIRELESS ADVOCATE FOR UNIVERSAL DESIGN AND AN ACCESSIBILITY SPECIALIST

by Tannia Chavez, Intl. Assoc. AIA

by Tannia Chavez, Intl. Assoc. AIA

A Conversation with Rachel Wiesbrock: a tireless advocate for Universal Design and an Accessibility Specialist at LCM Architects. Rachel shares her vision for a more equitable world in which architects must allow all users to experience the natural progression of space in the same way.

As an Accessibility Specialist at LCM Architects, Rachel Wiesbrock brings a passion for integrating inclusive design into all aspects of the built environment. Her personal journey with a disability gives her a unique awareness of physical barriers, and as an architectural designer, she has the technical knowledge to contribute thoughtful solutions to remediate those inequities. While pursuing her degree, she worked for architecture firms performing ADA compliance plan reviews, completing survey reports and remediation recommendations for existing buildings, and creating Revit models. Since joining LCM, Rachel supports project teams for a variety of client types, from education to healthcare.

Rachel channels her energy and talent into organizations that reflect her commitment to accessibility progress. She was a leader in the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS), focusing on nationwide accessibility education and promoting equitable design approaches. She is AIA Illinois’ State and Territory Associate Representative (STAR) and serves on their Emerging Professionals Committee.

PAGE 30 | MAY ‘23

8

Rachel Wiesbrock, 2023 - 2024 AIA Illinois STAR

Tannia Chavez, Intl. Assoc. AIA

Rachel Wiesbrock, Assoc. AIA

1. When did you become interested in architecture?

At a young age, I remember telling my family that my favorite classes were math and art, so my grandpa suggested becoming an architect. In high school, I learned more about what architects do and started looking for colleges with architecture programs. Unfortunately, I did not know what NAAB and all the accreditation programs were, but I ended up luckily in a five-year program at IIT (Illinois Institute of Technology).

2. When did you learn that becoming an Accessibility Specialist was an option within the profession?

Well, I grew up in Spring Grove, Illinois, where the population is a little over 5,000 people. I don’t remember having multi-story buildings, so accessibility was not a word in my vocabulary growing up. It was really through college that I learned more about it.

3. How did you become an advocate for accessibility in architecture?

I used my experience to bring awareness that architectural solutions must support equity, and I started advocating through my Film Class elective in 2018. I did an exposure piece video of my campus to show some of the challenges I went through to access the different buildings. Shortly after, I became one of the four inaugural members of the AIAS Advocates Program and chose accessibility as my advocacy topic when I applied. I felt the need to start the conversation about accessibility with students.

At the 2019 AIAS Leadership Summit, I presented a video (AIAS Advocates Program 2019) as part of my keynote speech.

4. Tell me more about this experience.

The AIAS (American Institute of Architecture Students) hosts annual conferences in different cities. Three years ago, it took place in Toronto, and with the support of another student, Kathryn Platt from Northeastern University (who was doing her thesis on universal design). We hosted an info session that

turned into a design charette. The goal was to allow users to perceive a public space as fully accessible.

Twenty-five students reimagined the space without diminishing someone’s experience with architecture because of their physical disabilities. It was amazing to see so much enthusiasm and light bulbs turning on! This experience fueled my passion to continue advocating.

5. How do you feel when a place is not accessible?

My perspective has evolved over time. It does bring a lot of psychological and sociological impact. I do not want to stereotype either, but most of the time, people with disabilities feel like a burden to their loved ones and prefer to stay home. I normally google the place in advance to make sure I can visit it. Of course, it is disappointing when the website claims to be accessible, and it turns out not to be. These days, the adult in me feels a bit more frustrated than sad that after 33 years of ADA existence, I feel like most people only see it as a checkbox minimum at the end of a design process, and it is way more than that. It has an emotional and mental effect on a person with disabilities—society needs to understand more about this topic and what are the tangible stepping stones.

6. How do you feel when a place is fully inclusive?

It feels amazing! (smiles). I do applaud the progress that is being made in designing more buildings with a natural progression of space. I get to enjoy the grand entrance with everyone else instead of going around the dark corner to find the elevator.

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 31

2019 AIAS Advocates Program

2019 AIAS Advocates Program

7. How did you become an accessibility Specialist?

I started my career at Stantec as an Architectural Intern. This opportunity opened my eyes to the fact that if spaces were accessibly designed, it allowed me to choose if I wanted to use my crutches, wheelchair, or walk around. Making me realize how my unique experience translates into architecture.

Last year, I became part of LCM Architects. My team provides plan reviews on ADA barriers that need to be addressed to achieve accessibility. We also do traditional architecture and FHA. One of the main reasons I joined the firm is their extra empathy for accessibility. Everyone in the firm is driven to design accessible and equitable places. I have not only learned a lot about the technical background of ADA, but they have inspired me to pick up my advocacy efforts. My eyes are more technical now. LCM has given me a great foundation; I immediately notice if it’s a just minimum requirement that was met or a universal design.

Now, I dream of the day that ADA designs become completely equitable and the “norm” instead of an additive process to design.

8. How do you define Universal Design?

I would say it’s not only the consideration and execution of full inclusion within the built environment but especially a true and genuine effort for all users to feel welcomed and encouraged to experience any physical space.

9. What is your vision for a world that promotes inclusiveness?

We must start with exposure to younger crowds. The sooner we can introduce children to the vast differences that humans have, the more naturally accepted differences will become - that there is no “normal.” People are generally afraid to

confront/acknowledge things they don’t know so awareness is paramount if we want to redefine the social “norms” when addressing disabilities.

10. What inspires you to give more to the architectural world?

People with disabilities because they are not the problem. The problem is that society needs to be open-minded and account for them naturally to support their thriving. From time to time, I have thoughts about my childhood years from seven to eleven years old when I attended summer camp through the Great Lakes Adaptive Sports Association (GLASA). The camp was so well adapted for children with physical and cognitive disabilities. Children were always encouraged to have fun by being active and participating in group activities.

My drive is to be the voice of those who don’t dare to talk or don’t have the means to do it. I want to advocate so others can have the opportunities that I have because all we need is to embrace our uniqueness and recognize that Inclusive Design is real! l

Rachel Wiesbrock, Assoc. AIA brings a unique perspective to the architectural field. Her experience as a person with a physical disability has fueled her passion for universal, inclusive, and accessible design. Rachel is currently an accessibility specialist at LCM Architects, something she has been dreaming about for the past five years.

While pursuing her Bachelor of Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), she was a leader in the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS), focusing on nationwide accessibility education and promoting equitable design approaches. She is AIA Illinois’ State and Territory Associate Representative (STAR) and serves on their Emerging Professionals Committee.

ACCESS//ability (a short video made for the 2019 AIAS Advocates Program)” - https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=AItNlMzx4OQ&authuser=0

PAGE 32 | MAY ‘23

2023 AIA National Associates Committee Annual Meeting, St. Louis, Missouri.

With Jack Catlin, FAIA (Co-Founder and Partner at LCM Architects). LCM holiday party, December 2022.

MAY ‘23 | PAGE 33 FUNCTION MEETS DESIGN Architect | CRSA Project | BYU Banyan Café, Designer | Rachel Bangerter AGSstainless.com | 888-842-9492 Beauty, Strength and Safety. When you specify 100% offsite fabrication for your project’s railing system, you can depend on delivering consistently high-quality results because no onsite modification is needed. To learn more about this project, read an Interview with Rachel Bangerter, Interior Designer, CRSA Architects

THE SMALL THINGS THAT MATTER

by Matthew Hume, NCARB, AIA CEO, Hume Construction, Inc.

Iam a proud father of three daughters. My youngest was diagnosed with Achondroplasia (dwarfism) a couple of months before birth. My wife and I were a little scared because we did not know what to expect. We also knew there would be some challenges our daughter, my wife and I would have to face together. Andrew Solomon describes a lot of these challenges in his book “Far from the Tree,” a must read for any parent or anyone for that matter. My daughter just recently turned 12. The things we have learned and the challenges we have overcome have all drastically improved our lives and made us realize that the small things really matter... a lot!

Architectural design does not usually consider short stature. When we designed and built our house in 2015, I wanted to address this issue. The challenge was this; How do I design a home that works for all of us? I thought about it and talked with other members of the LPA (Little People of America) community. I decided to focus on the subtle changes I could make within our home that anyone of average height might overlook but would make a world of difference to my daughter. I wanted us all to be comfortable there. I didn’t want the house to feel cumbersome and out of scale for her or the rest of our family. I began by identifying all the aspects of the house design were I had flexibility to make modifications and still meet residential building code. The following are some of the subtle modifications that made a big difference.

Light switches. Standard height is 42” off the floor so light switches can be placed over other obstacles such as furniture and countertops while maintaining this standard dimension. What this means for little people is they often need a stick to operate the light switch. Can you imagine not being able to reach a light switch and having to use a stick? There was an existing 3-car garage where we built our house. We have to keep a custom made stick by the door so she can operate that switch. Good luck trying to find the switch in the dark right? In our new house, I placed all the switches at 36” off the floor. Six inches lower than the standard. For my daughter, this means no stick. The rest of us don’t even notice the difference in the placement of the switch. Most door hardware is placed at this height so it feels pretty natural.

Window sill height and type. We placed all our window sills at 24” or lower. Everyone enjoys the natural light that windows provide regardless of their positioning in the space but (as you know) windows are also a portal to the outside, strategically placed to provide views. The average height for an adult with dwarfism is 46”. This means a window sill at 36” or greater provides nothing more than natural light. Forget the view. In our home, we have enjoyed the lower sill height. Not only can our daughter see out the windows but we still maintain a view from a seated position. She doesn’t need to be lifted to see out the window as deer pass through the yard. We also decided to use casement type windows so she could easily operate them and we all would maintain an unobstructed view (no middle sash or mullions).

PAGE 34 | MAY ‘23

9