ADVOCATE

LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Lisa Hamilton, Q.C. President

Christopher McPherson, Q.C. First Vice President

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, Q.C. Second Vice President

Don Avison, Q.C. Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

Paul A.H. Barnett Sasha Hobbs Dr. Jan Lindsay

Kim Carter Tanya Chamberlain Jennifer Chow, Q.C. Cheryl S. D’Sa Lisa H. Dumbrell Brian Dybwad Brook Greenberg, Q.C. Katrina Harry Lindsay R. LeBlanc Geoffrey McDonald Steven McKoen, Q.C.

Michèle Ross Natasha Tony Guangbin Yan

Jacqueline McQueen, Q.C. Paul Pearson

Georges Rivard Kelly Harvey Russ Gurminder Sandhu Thomas L. Spraggs Barbara Stanley, Q.C. Michael F. Welsh, Q.C. Kevin B. Westell Sarah Westwood Gaynor C. Yeung

BRITISH COLUMBIA BAR ASSOCIATIONS

ABBOTSFORD & DISTRICT Kirsten Tonge, President CAMPBELL RIVER Ryan A. Krasman, President CHILLIWACK & DISTRICT Nicholas Cooper, President

COMOX VALLEY Michael McCubbin Shannon Aldinger

COWICHAN VALLEY Jeff Drozdiak, President

FRASER VALLEY Michael Jones, President KAMLOOPS Kelly Melnyk, President KELOWNA Taylor-Marie Young, President KOOTENAY Dana Romanick, President

NANAIMO CITY Kristin Rongve, President

NANAIMO COUNTY Lisa M. Low, President

NEW WESTMINSTER Mylene de Guzman, President

NORTH FRASER Lyle Perry, President

NORTH SHORE Lesley Midzain, President

PENTICTON Ryu Okayama, President

PORT ALBERNI Christina Proteau, President

PRINCE GEORGE Marie Louise Ahrens, President

PRINCE RUPERT Bryan Crampton, President

QUESNEL Karen Surcess, President SALMON ARM Dennis Zachernuk, President

SOUTH CARIBOO COUNTY Angela Amman, President

SURREY Gordon Kabanuk, President VANCOUVER Executive Jason Newton President Niall Rand Vice President Zachary Rogers Secretary Treasurer Samantha Chang Past President VERNON Christopher Hart, President

VICTORIA

Marlisa H. Martin, President

BRITISH COLUMBIA BRANCH

Aleem S. Bharmal, Q.C. President Scott Morishita First Vice President Lee Nevens Second Vice President Judith Janzen

Finance & Audit Committee Chair Dan Melnick

Young Lawyers Representative

TBD Equality and Diversity Representative Randolph W. Robinson Aboriginal Lawyers Forum Representative Patricia Blair Director at Large Adam Munnings Director at Large Mylene de Guzman Director at Large Sarah Klinger Director at Large

CARIBOO Nathan Bauder Susan Grattan Nicholas Maviglia

KOOTENAY Andrew Bird Christopher Trudeau

NANAIMO Johanna Berry Patricia Blair Kevin Simonett

PRINCE RUPERT Sara Hopkins VANCOUVER Kyle Bienvenu Karey Brooks Joseph Cuenca Bahareh Danael Graham Hardy

Lisa Jean Helps Judith Janzen Heather Mathison Scott Morishita

VICTORIA Sarah Klinger Dan Melnick Paul Pearson

WESTMINSTER Anouk Crawford Mylene De Guzman Daniel Moseley Greg Palm

Rachel LaGroix Michael Sinclair Kylie Walman

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF BLACK LAWYERS (B.C.)

Zahra Jimale, President

FEDERATION OF ASIAN CANADIAN LAWYERS (B.C.)

Hasan Alum, President INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION (B.C.)

Michael McDonald, President

SOUTH ASIAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Rupinder Gosal, President

ASSOCIATION DES JURISTES D’EXPRESSION FRANÇAISE DE LA COLOMBIE-BRITANNIQUE (AJEFCB)

Sandra Mandanici, President

THE

“Of interest to the lawyer and in the lawyer’s interest”

Published six times each year by the Vancouver Bar Association

Established 1943 ISSN 0044-6416 GST Registration #R123041899 Annual Subscription Rate $36.75 per year (includes GST)

Out-of-Country Subscription Rate $42 per year (includes GST)

Audited Financial Statements Available to Members

EDITOR: D. Michael Bain, Q.C.

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Ludmila B. Herbst, Q.C.

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., Q.C. Christopher Harvey, Q.C. Carolyn MacDonald David Roberts, Q.C. Peter J. Roberts, Q.C. The Honourable Mary Saunders The Honourable Alexander Wolf

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Samantha Chang Peter J. Roberts, Q.C. The Honourable Jon Sigurdson BUSINESS MANAGER: Lynda Roberts

COVER ARTIST: David Goatley COPY EDITOR: Connor Bildfell

EDITORIAL OFFICE: #1918 – 1030 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Y3 Telephone: 604-696-6120 E-mail: <mbain@the-advocate.ca>

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE: 709 – 1489 Marine Drive West Vancouver, B.C. V7T 1B8 Telephone: 604-987-7177

E-mail: <info@the-advocate.ca>

WEBSITE: <www.the-advocate.ca>

Entre Nous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 649

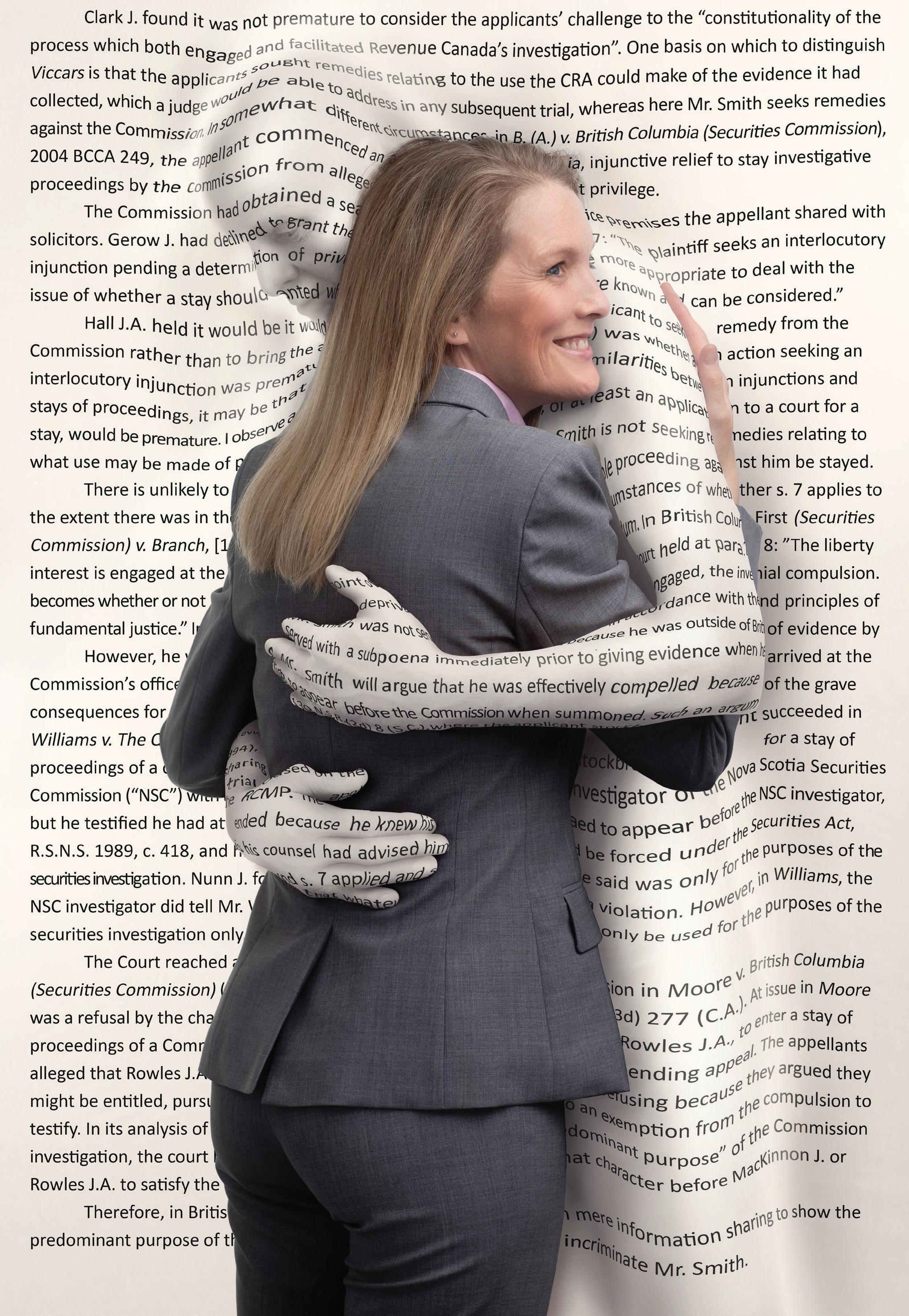

On the Front Cover: Perry Ehrlich

By D. Michael Bain, Q.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 655

Ukraine and the Unfinished Crime of Aggression By Jeffrey J. Smith . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 661

The Canadian Legal Genealogy of Terra Nullius – Sub Nom.: Is It Too Late to Send Terra Nullius Back to Australia (and Would They Even Take It)? Part I By Sarah Pike . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 671

The Litigator and Mental Health By the Honourable George R. Strathy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 681

Blockchain for Bloodfeuds By Eric Kroshus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 697

The Wine Column . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 703

News from BC Law Institute . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 713

LAP Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 717

A View from the Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 719 Announcing the 2023 Advocate Short Fiction Competition . . . 723 Peter A. Allard School of Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 725

TRU Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 727

Nos Disparus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 731

New Judges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 745

New Master . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 761

Letters to the Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 765

Classified . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 769

Legal Anecdotes and Miscellanea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 771

From Our Back Pages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 779

Bench and Bar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 783 Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 799

With a tip of his hat, Richmond’s very own Perry Ehrlich graces this month’s front cover. Find out about how this Yorkton, Saskatchewan kid came to Lulu Island and became not only an impressive solicitor but also a showstopping impresario!

firm ofconsulting economists

litigation

following services

area

This long-standing Notary Public firm (with staff Notary) provides the notarization of many documents, conveyancing of real estate transactions, the preparation of personal planning documents such as Wills, enduring Power of Attorneys, etc. The office also provides executor services for estates as either full executor, or partial executor, or by way of a joint executor. A purchaser can take advantage of approx. 200 Will files, where the current Notary Public is named as Executor or Co-executor with the rights to assign that role. These files are anticipated to provide significant future billings.

The staff Notary supports current business demands across all practice areas. As well, with the established conveyancing and administration services team, the business is well-positioned for further growth and development within the metro Vancouver marketplace.

I had three discussions with the President that I can recall … and … I made it clear I did not agree with the idea of saying the election was stolen and putting out this stuff which I told the President was bullshit. … You can’t live in a world where the incumbent administration stays in power based on its view unsupported by specific evidence that there was fraud in the election.

—William S. Barr, former attorney general of the United StatesWhen William Barr testified before the select committee charged with investigating the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol,1 he did not mince words. The fact that he had to resort to profanity is entirely forgivable. We use profanity either when we do not personally have the vocabulary to express ourselves, or when there simply are no words that exist to adequately describe a situation. Barr called Trump’s ridiculous positioning about a “rigged” and “fraudulent” election—a perverse attempt to remain in the White House— exactly what it was: bullshit. He called it a number of other things too (maybe there was vocabulary for it after all) including “completely bullshit,” “absolute rubbish,” “idiotic,” “bogus,” “stupid,” “crazy,” “crazy stuff,” “complete nonsense,” and “a great disservice to the country.”

Barr was merely saying what anyone with even a modicum of knowledge about democracy and how democracy ought to work has been thinking for years now. It was strange, however, to hear it coming from a man who so regularly backed up the former president when he took other audacious and ridiculous positions. If The Washington Post is to be believed, it racked

up more than 30,000 false or misleading statements made by Donald Trump during his presidency. The attorney general was not exactly rushing to correct the record in every instance. While it is perhaps telling that Barr’s memoir is titled One Damn Thing After Another, it is troubling that whereas he testified that the “bullshit” was one of the reasons he decided to resign, his resignation letter makes no reference to it. Instead, he praised the president for the “unprecedented achievements you have delivered for the American people”.

The more important part of Barr’s testimony quoted above, though, is the part that talks about the inability to live in a world where positions unsupported by evidence hold any sway whatsoever. As members of the legal profession, do any of us need to be convinced of this fact? Together with scientists (and the professions science informs), lawyers are among those usually completely obsessed with the notion that evidence is necessary to support, advance and sustain a position. Judges rely on experts to opine on matters outside of the judicial area of knowledge, so that an informed and principled decision can be made, but they will not permit an expert to merely opine without an evidentiary foundation. Our entire system of criminal and civil justice is dependent upon reason, intellect, wisdom and, above all, evidence. Indeed, we have entire courses and textbooks dedicated to the law of evidence.

Evidence, and the ability to synthesize it, scrutinize it, analyze it and accept or reject it, are at the very core of almost every analysis a lawyer does. Why, then, does it seem to go out the window when people talk about emotionally charged topics or political viewpoints? It would be easy enough to wade into one or more of the controversial topics plaguing the legal profession at the moment, but for fear of these thoughts getting lost in the topic itself and someone entirely missing the point, let us turn to something not exactly disputed any more: the complete lack of evidence of weapons of mass destruction used to justify the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Those of us who watched the build-up to that war (unless we were walking around draped in flags or perhaps holding shares in a company that manufactures bombs) were fairly skeptical about the claimed justifications for that war. The stated intent to “disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, to end Saddam Hussein’s support for terrorism, and to free the Iraqi people” seemed to lack only one thing: evidence. If you are going to claim that a world leader is developing weapons of mass destruction and poses an immediate threat to his neighbours and the world community, surely the burden is on you to produce the evidence of such a claim. One ought to have, for example, evidence of weapons of mass destruction readily at hand.

Instead of evidence, though, there was only rhetoric. For example, FBI director Robert Mueller claimed: “Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program poses a clear threat to our national security, a threat that will certainly increase in the event of future military action against Iraq. Baghdad has the capability and, we presume, the will to use biological, chemical, or radiological weapons against US domestic targets”. White House press secretary Ari Fleisher claimed: “We have high confidence that they have weapons of mass destruction. That is what this war was about and it is about. And we have high confidence it will be found.”

We presume. High confidence. No evidence.

It was terrifying to think of such things back then. It was upsetting. The pictures painted were ominous. President George Bush warned in October 2002: “America must not ignore the threat gathering against us. Facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.” Except that there wasn’t any clear evidence. None. Not any. In fact, after an exhaustive search led by a team of more than 1,400 members, no evidence of Iraqi weapons programs was found. The conclusion of the investigation was that Iraq had destroyed all major stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction and ceased production in 1991 when sanctions were imposed by the United Nations.

Yet, 12 years after Iraq destroyed its prohibited weapons, the United Kingdom relied on a “sexed-up” dossier in which Prime Minister Tony Blair claimed that “this document discloses that [Saddam Hussein’s] military planning allows for some of the [weapons of mass destruction] to be ready within 45 minutes of an order to use them.” This then led to headlines in the press claiming “Brits 45mins from doom” and “Mad Saddam ready to attack: 45 minutes from a chemical war.” And yet, there was not one shred of reliable evidence to support such statements.

The result, of course, was not simply hysteria in the media and an anxious populace; the result was an illegal war in the Middle East that lasted at least eight years and resulted in about half a million deaths. That’s a staggering and sobering result when it was actually clear all along that there was no evidence to support what was being claimed. The point was not that Saddam Hussein was a bad man (he was) or a brutal dictator (he was). The point was that the stated premise for the war—weapons of mass destruction—did not exist. In the case of the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, where very angry people demanded the hanging of the vice president for refusing to reverse the results of a democratic election, nothing less than U.S. democracy was hanging precariously in the balance. And it was the president egging them on based on falsehoods!

We live in strange times. There is a lot of upset about. There is a lot of anger. There are often calls for destruction, deconstruction and civil and sometimes not-so-civil protest or disobedience. The next time people—even lawyers—are getting worked up about something, maybe ask whether there is an evidentiary basis for what is being said. Perhaps there is only rhetoric designed to exploit emotions and create a frenzy for some political purpose. Frankly, if it’s the latter, it’s bullshit.

1. The select committee has rather imaginatively been named “The United States House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United

States Capitol”. It has a website: <january6th. house.gov/>.

By D. Michael Bain, Q.C.

By D. Michael Bain, Q.C.

Her name was Lulu. She was a showgirl. Lulu Sweet was a member of the Potter Troupe, an American Music Hall theatre troupe that performed in Victoria and New Westminster in the mid-1860s. Something of a triple threat, Lulu was introduced in the press at the time as “the beautiful Juvenile Actress, Songstress and Danseuse”. One of the many Royal Engineers stationed in New Westminster at the time (in fact the Commander of said engineers and first Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia), Richard Moody, was travelling with Lulu and her mother on a boat from New Westminster to Victoria, and as they passed a large island in the Fraser River, Lulu asked what the name of the island was. “By Jove!” Moody exclaimed, “I’ll name it after you!” Lulu Island is still so named after that young performer, although today it is more commonly referred to by the city that occupies most of it: Richmond, B.C. It has also been the home of Perry Ehrlich for more than 40 years, where he has raised a family and developed a thriving solicitor’s practice. It seems somehow fitting, though, that Perry should live and work on an island named after a showgirl, because Lulu Island is where, for the past nearly 30 years, Perry has nurtured the musical theatre skills of literally thousands of young people between the ages of 9 and 19 through his programs for youth: Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance!, Sound Sensation and ShowStoppers.

Perry grew up in Yorkton, Saskatchewan. His mother is a second-generation Canadian and his father is a survivor of the concentration camp at Auschwitz. His parents met and fell in love in Winnipeg, where Perry’s father travelled to after the war. They settled in Yorkton, where they ran a dry-cleaning business. The Ehrlichs had three sons: Perry (the eldest),

Howard and Brent. Two of these boys would go on to become well-regarded lawyers with practices in British Columbia: Perry and Howard.1

While still a boy in Yorkton, Perry knew of Nancy Morrison2 (16 years older than him) and her father, William, who was “like royalty” in Yorkton because he was a lawyer. Perry notes that at the time in small-town Saskatchewan, if you were a doctor or a lawyer, you were a somebody. The law partially appealed to him as a career calling because he grew up in the era of Perry Mason, a popular fictional lawyer who had the same first name as him and was based on a real lawyer with the same last name as him.3 Being in a courtroom appealed to Perry, who had shown an early interest in performance and was intrigued by the theatricality of the courtroom. More significantly, though, the law rang true to Perry because it involved human communication and caring about people.

Perry’s parents were not especially musical. Although his mother’s father had been a cantor (the singer at the synagogue), Perry says that when he sang “O Canada” with his parents, it was always in three-part harmony only because neither of his parents could stay in tune. He took piano lessons from an early age and entered the Yorkton Music Festival competitions. At eight years old, he came in second, singing a song called “Fishing” (first place went to David MacIntyre, who went on to teach musical composition at SFU). The comment on the adjudication form (which Perry still has) reads: “You weren’t the best voice here, but you sang the song with such a degree of truth I could tell you love fishing and you communicated it.” In fact, Perry hates fishing.

Perry’s father did not make much money, and as a child of a holocaust survivor, Perry was all too aware that he needed to seize any opportunities he had. As he told me: “When you grow up as the child of a holocaust survivor who lost his entire family and didn’t have the luxury of a good life or an education or any food on the table, you realize: ‘My father didn’t have this opportunity; I have this opportunity.’ You make the most of it. It wasn’t demanded; it was expected.”

As a result, Perry entered law school at the age of 20 with only two years of university education behind him. He financed his legal tuition ($400 per year) by selling carpets and playing piano. He graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with an LL.B. in 1976 at the age of 23. While at university, he entered another musical competition called “I Can Hear Canada Singing” for which he won a case of beer. In his final year of law school, he was the musical director of the school’s Legal Follies production. That year, Perry and others penned a legal parody of Fiddler on the Roof restyled as Fiddling with the Truth

Having spent previous summers in British Columbia visiting his grandparents, and realising that The Piano Stylings of Perry Ehrlich at the Holiday Inn would only take him so far, Perry headed west to look for articles—not an easy prospect at the time for someone with a law degree with “Sask” on it. The policy at the time was for law firms to hire B.C. students first. He finally secured a position, but unfortunately, a month before the job was to start, the lawyer got cited by the Law Society and the job evaporated. Perry, being rather tenacious, managed to find another position where he was offered substantially less than the going rate and was required to do all his own typing (this was in 1976). Perry seized the opportunity.

After articling, Perry got a job with Barry Kerfoot, who had just left Cumming Richards (now Richards Buell Sutton). He let Perry loose with all his clients. Barry was a great mentor who guided Perry and gave him confidence. The first few years, though, were tough. Perry ran criminal trials, contested divorce cases, finalized conveyances, handled complicated trust agreements and advised on s. 85 rollovers. There was nothing he did not do. It was trial by fire.

Helping him through these tumultuous years was the woman who has been Perry’s wife now for over 45 years, Marilyn. In 1980, Marilyn’s aunt, Rosalee Hardin, a probation officer in Richmond, knew a lawyer named Danny Zack who worked with his childhood friend, Larry Kahn, and another lawyer, Soren Hammerberg, practising family law and civil litigation. They were looking for someone to start up a business law practice with them. Rosalee told Marilyn, who told Perry, and against all the naysayers who told Perry that moving away from Vancouver was “professional suicide”, he seized the opportunity. Perry joined Kahn Zack Hammerberg, and he and Marilyn moved to Lulu Island.

Perry and Marilyn had two daughters. Lisa was born in 1982, and Mandy arrived in 1987. By then, Perry had become a partner. Starting with 13 corporate records, he was growing the business (to almost 1,000 eventually) and growing with his clients. For example, someone might come in for a simple notarization, then perhaps a lease. The next time they came in, they needed a share purchase agreement, or were engaged in a merger or buyout. Perry also developed a personal wills and estates practice. His solicitor practice grew with his clients, and he became part of the business team of multiple businesses including Costco Wholesale Canada, Keg Restaurants Ltd. and Shoppers Drug Mart. By that time, the firm had its current name— Kahn Zack Ehrlich Lithwick—and Perry was outside counsel for a number of growing companies.

Perry’s partners encouraged a work-life balance that enabled a presence in the community that humanized what they did. Larry Kahn was involved

in minor sports and hockey coaching. Danny Zack was active in Maccabi Canada, an organization devoted to developing Jewish identity and future leaders through sport. Perry, meanwhile, had enrolled his daughter Lisa in a summer musical theatre program. There were things that Perry liked about the program, and things he did not. He therefore set about designing a program that he would want his own kids to be in.

Initially, Perry founded a show choir for teens called Sound Sensation in 1994 together with Simon Isherwood, who ran a drama program at Notre Dame Secondary School. Sound Sensation performed at the World Figure Skating Championship and started a Canada Day performance tradition at Canada Place that has continued for nearly 30 years.

Perry had previously witnessed musical programs focused on competition and creating stars. He saw only a few who might be elevated and many who were defeated. He therefore wanted to create a program where the ultimate goal was not to create musical theatre professionals, but to help young people develop their self-esteem, work collaboratively, learn to focus and benefit from a sense of accomplishment. Perry wanted to set young people up for success.

To these ambitious ends, Perry approached the Jewish Community Centre in Vancouver about establishing a musical theatre program for kids aged 9-19. While he feels it was no different than the father who wants to coach his kids in sports, Perry actually set about creating the entire league, developing the rules of the game they would be playing and populating the pitch with coaches and mentors to develop the various skills necessary for the kids to become the best players.

Perry assembled an impressive list of educators, actors, musicians and choreographers as his “faculty”. He took on the role of overall director, which has evolved over the years to “impresario”. His initial goal with Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! was to get 25 kids to sign up so as to break even. He got 72. Do not let the title of “impresario” fool you. Perry is the heart of Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! He is the person who puts fire into the bellies of the young performers. Perry is all about positivity and energy. He invites kids to go all in, to believe in themselves and also in one another. He invites them to overcome whatever shortcomings they may think they have and to commit to the event they are staging.

With a ratio of one faculty member to ten students, Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! is a safe environment for young people. Perry wants to pass on what he knows, and what he knows is that hard work and dedication pay off. He comes from a time “when dinosaurs ruled the earth,” he says, so he is “no nonsense.” You will not find a smartphone or iPad in sight during

rehearsals. You will also not find a parent. Perry is very strict about building self-reliance among his performers. The kids are not coddled, and they navigate the program on their own, not through a meddling parent.

Students are taught to develop their performance skills as well as their life skills. One of the first lessons Perry teaches the kids is that “if you’re not ten minutes early, you’re already ten minutes late.” More recently, he has found that he needs to teach kids eye contact, as they are too often engaged with screens rather than one another. He does not tolerate laziness or slackers. “When you make a commitment,” he tells me, “you keep it. By building the commitments, that’s how you build strength. Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! is about building community.” To his students, who willingly give up their screens for the experience (it’s the parents who complain, as they need to get in touch with their precious darlings), Perry is affectionately known as “Uncle Perry!”

The irony about the “no stars” approach of Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! is that, inevitably, stars do shine. His students have gone on to perform professionally on almost every stage in British Columbia and on many stages beyond, including on Broadway and in film and television. Even long after his daughters came and went from the program and grew into adults, Perry took such joy in what he was doing that he continued Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! Also, Sound Sensation evolved into ShowStoppers, a teenage glee choir “before Glee was even in the womb,” as Perry notes. That choir belts out a colourful, high-energy show for crowds across the province. Showstoppers have performed with the Universal Gospel Choir, The Nylons, Foreigner and—much to Perry’s delight—even Barry Manilow. “Her name was Lola. She was a showgirl.”

The transformative nature of what Perry’s programs accomplish should not be underestimated. Kids might go into his program at age 9 and leave at age 19—or they might start later, at 16. Either way, they emerge not only having evolved through the incredible growth spurt of puberty, but as fully formed human beings with confidence, enthusiasm, friendships and a realization that accomplishment comes through hard work and commitment. What’s more, they know how to sing and dance!

Some of those singers and dancers have gone on to become all types of professionals, including lawyers—even an international lawyer in Washington, D.C. For his efforts, Perry has received an Ovation! Award4 for outstanding long-time contribution to the theatre community. The award is given to “a member of the community who has contributed more than 10 years to the development, promotion and continuation of musical theatre in the lower mainland”. In 2008, the Canadian Bar Association, BC Branch hon-

oured Perry with a Community Service Award, “the highest honour provided by the CBABC in recognition of community involvement and contributions outside of the practise of law”.

Perry’s ability to mentor young people extends to his mentoring of other lawyers. Inevitably, through word of mouth, Perry gets asked to mentor articling students and young lawyers who may need direction in what they are doing. His mentees are referred to him by the Law Society and by other lawyers. “These are kids who are trying to find themselves,” he tells me: Every single lawyer says they’re working too hard, they’re taken for granted, they don’t know when they have to work late or on weekends, they have no life. So many of them are sucked into the downtown mentality. What I tell them is what people of my generation say: sometimes the best thing that can happen is you take a risk. You’re attractive, you’re bright, you’re personable. Let’s assume you have brains and know how to do the work. The most important thing you have to do is care about what you do. We’ve got to get back to a place where it is less about the money we make and the documents we produce, and more about values, morals and caring.

Perry often recommends taking on a practice outside of the downtown core in a place where young lawyers can be more involved in their communities. He also notes that we are very lucky in the legal profession. Unlike doctors looking to change direction, if we want to do environmental law, estate law, employment law or indeed any area of legal practice, we do not need to formally retrain and get certificates. We have opportunities. We can seize them. Just as he encourages young kids, Perry encourages young lawyers.

Perry was special counsel to RBC for many years and was once invited to a huge reception in Toronto. In the corner of the room was a young woman playing the harp. Perry stopped to listen to her for a while. At an appropriate moment, he approached her and said: “I feel really sorry for you. I’m listening to you and you are terrific! I wish the people here would shut up and listen to you.” The woman looked at him and paused before speaking: “Thanks so much, Uncle Perry. I knew you were listening. I was in Gotta Sing! Gotta Dance! year two.” Alas, her name was neither Lola nor Lulu, but she was a showgirl!

1. Howard Ehrlich was a highly regarded labour and employment lawyer at Davis & Co. and Bull Housser & Tupper who tragically died at age 57 from lung cancer. His life was celebrated in the Nos Disparus section of this magazine at (2016) 74 Advocate 180.

2. While we strive for diversity in the Advocate, this means two kids from Yorkton, Saskatchewan have been on our covers in the past four months. The Hon-

ourable Nancy Morrison features on our May 2022 cover.

3. Jake Ehrlich was a lawyer from Brooklyn who was born in 1900. He was known as “The Master” and coined the phrase “Never plead guilty.” He is said to be the inspiration for Erle Stanley Gardner’s fictional defence lawyer, Perry Mason.

4. Musical theatre people love exclamation marks!

Russia’s further invasion and occupation of Ukraine in 2022 will predictably have far-reaching consequences for global order and the shaping of international law, not least the progress of international criminal law. Whatever the problems of resolving a conflict in Europe exceptional for its depravity and horror, international criminal law has been shown to be an inadequate deterrent even as it offers the promise of justice in the aftermath of hostilities. The suggestion that a kind of end of history had arrived in recent years for international criminal law can be dismissed: war in Ukraine will reveal new demands of it, some urgent.

It is fittingly ironic that war in Ukraine has brought renewed discussion of how the international crime of aggression is being implemented. The city of present-day Lviv in the west of the country is where the idea of making aggression a crime can be traced, by the education there of two lawyers who shaped the Nuremburg trials following the Second World War: Hersch Lauterpacht and Raphael Lemkin.1 Until now, their legacy in defining a modern international criminal law, one that includes aggression as the “supreme international crime ... in that it contains the accumulated evil of the whole”, has remained incomplete.2

International criminal law (“ICL”) can be understood as those precepts binding on individual persons for the avoidance of specific wrongful acts during armed conflict and its aftermath. ICL is the adjunct to an international humanitarian law (“IHL”) directed to the protection of persons (and, to an extent, their cultural heritage, natural resources and environment) during hostilities and occupation. ICL was, until recent decades, without a coordinating framework for its definition (i.e., a treaty for its more certain codification and uniform implementation among states). This can be seen in the criminal tribunals created by the UN Security Council for, among other situations, Rwanda and Yugoslavia in the 1990s, each with initially uncertain definitions of crimes, jurisdiction and forms of accessory and contributing liability. ICL as defined by the 1949 Geneva Conventions (and

their 1977 additional protocols) and the 1998 Rome Statute treaty for the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) consists of four general categories: (1) genocide; (2) crimes against humanity; (3) war crimes; and (4) the crime of aggression.3 The comprehensive codification of ICL is now the Rome Statute together with its subordinate guiding criteria known as the “elements” of crimes. The Rome Statute increasingly supersedes earlier ICL sources including customary law definitions, such as that for the crime of aggression that was conceived in the Nuremburg trials.

In reviewing this developmental landscape, two other things are usefully noted. First, because states are best equipped to respond to criminal acts, member countries of the Rome Statute agreed they would be required to adopt the treaty’s crimes into their national criminal systems most often by legislation, and preferably first prosecute individual perpetrators. Under the principle known as complementarity, the ICC is meant as a court of second recourse, by reference to it of criminal acts from the UN Security Council in particular cases or when states cannot or will not act. Second, while ICL is directed to the wrongful conduct of individuals, it overlaps in definition and its actuating circumstances with state responsibility—i.e., the corporate liability of countries—for the same acts. The current stateagainst-state proceedings in the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) by Ukraine against Russia, and The Gambia against Myanmar (Burma) for alleged acts of genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention, are examples.4

After World War II, states meeting in the UN General Assembly began to consider improved norms to secure international peace. The work began in 1950 with a proposal to define aggression, which was referred by the General Assembly to the International Law Commission for study.5 In 1967, the General Assembly resumed the work of developing guidance for the Security Council about which acts of states should qualify as aggression.6 Various suggestions—all concerned with state and not individual responsibility— began to take form. The central matter for agreement was responsibility for unlawful attack and invasion of another state. A consensus definition culminated in a 1974 UN General Assembly resolution.7 Aggression would include “military occupation, however temporary” after attack and “any annexation by the use of force”.8 The General Assembly agreed that cases of state aggression would be something for the Security Council to assess and declare. There was no codified crime to hold individuals to account and as yet no legislation in the legal systems of the few states interested in such a project.9 Despite the 1974 advance, the General Assembly’s guidance went without application even in obvious situations such as East Timor’s occupa-

tion and annexation from 1975 until 1999. However, the General Assembly’s work was the basis toward defining aggression as a crime in the aftermath of Rwanda and Yugoslavia.

Even when the Rome Statute had been negotiated, with many states immediately joining it in 1998, there was not yet agreement over acts that would constitute aggression by individuals involved in the unlawful use of force against other states. Aggression is not like the long-understood crimes, even genocide, that make up ICL. On the one hand, the crime of aggression is concerned with the liability of the highest officials of a state. On the other hand, it is about acts that initiate unlawful war or result in its perpetuation through annexation and occupation, in contrast to acts during the course of hostilities. It is for this reason that an eventual negotiation of the crime for inclusion in the Rome Statute—reached by ICC member states in 2010 and which for the ICC came into effect in 2018—would exclude individuals responsible for simply following such direction, even if the direction had been obviously unlawful. Moreover, in the negotiation of a definition among Rome Statute countries, a cautious approach was taken, with state accession to be by express act (i.e., in addition to any original joining of the treaty). The result is that only 43 ICC member states to date have acceded to the crime of aggression, Sweden and Italy being the latest in January 2022. Only when seven-eighths of member states have accepted the crime will it become binding on all. Until then, the ICC will not have jurisdiction— unless by specific reference of the UN Security Council—over the nationals of all other states (both Rome Statute members and states yet to join, including their territories). Canada is typical among developed Western states and much of the Global South in not yet expressly acceding to the crime. Thus, the crime of aggression is far from complete in its implementation. Finally, consistent with the established principle against retroactivity of newly codified crimes in the ICC and national legal systems alike, the crime of aggression does not apply to situations occurring before the crime entered in effect for the ICC in 2018 or the 43 states that have acceded to it since 2010.

Criminalizing aggression has been politically fraught. A first reason for this is that criminalizing aggression is meant to preserve the international order by prohibiting what can be called constitutional violations of the essential principles of the UN Charter.10 The international order for peace and security is violated when a state uses armed force unlawfully against the territorial integrity of other states or the political independence of peoples.11 Of course, history is replete with instances of this occurring. A head of state or government (and sometimes other high officials) who directs acts of aggression—including bombardment, blockade, invasion and occupation—contrary to the UN Charter will be culpable. Criminalizing aggression

gives form to moral condemnation, deterrence and the prospect of punishment for something that has long been done. Criminalizing aggression is also politically contentious because of the similarity of the definition of the crime to that of state responsibility, in situations where international law may preferably be directed to wrongful corporate conduct, as in the genocide examples of Russia and Myanmar (Burma) cited above. Finally, the crime of aggression can take the pursuit of justice against individual perpetrators outside the purview of the UN Security Council. This is a democratization by sometimes wresting away the Security Council’s power to direct a response—or to remain passive—in cases of international conflict. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that none of the permanent five veto-wielding member states of the Security Council show interest in acceding to the crime of aggression.12 Among the five, only the United Kingdom and France are otherwise ICC member states.

No state currently engaged in a case of apparent aggression has acceded to the Rome Statute codification of the crime.13 Contemporary cases of conduct arguably amounting to aggression are those where the states responsible have not joined the Rome Statute or, if they are member states, have not expressly acceded to the crime of aggression. Member states that have acceded to the 2010 codification of aggression and (as required by the Rome Statute) have adopted it into their domestic legal regimes can exercise jurisdiction with respect to the crime by anyone as realized within their territories and otherwise their nationals extraterritorially.14 What this means is that Spain has been the only state with jurisdiction over current acts of aggression, following its 2014 accession to the Rome Statute codification of the crime. This jurisdiction is the result of Spain’s continuing responsibility for criminal law, confirmed by domestic appeals cases in 2014 and 2015, for its former colony of Western Sahara which is unlawfully occupied by Morocco.15 No other case seems actionable, whether in the ICC or the courts of aggression-acceding ICC member states, including (to name a few) Russia’s presence in Georgia, that of Saudi Arabia (and others) in Yemen16 and perhaps that of the United Kingdom by its overholding colonial possession of the Chagos Islands.17 In addition, Ukraine has not invoked application of the crime of aggression to acts committed (and continuing) by all individuals regardless of nationality within its territory by invoking ICC jurisdiction, explained below.18

The definition of “aggression” in the Rome Statute, uniquely because of the nature of the crime and its implications for international relations, was done in three parts, namely: (1) as Article 8bis of the Rome Statute; (2) as the

amplifying criteria known as “elements” for each codified crime in the Rome Statute; and (3) the so-called “Kampala Understandings”, which culminated negotiation of the crime of aggression in 2010 among ICC member states. The three are consistent with each other; however, the non-binding Kampala Understandings are meant to be strongly persuasive of a high threshold for states and ICC alike to invoke the crime. No transient act of unlawful use of force would seem to qualify.

Article 8bis of the Rome Statute requires the following to be established in order to prove that the crime of aggression has been committed. The key modifier is “manifest”:

(1) For the purpose of this Statute, “crime of aggression” means the planning, preparation, initiation or execution, by a person in a position to effectively exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.

(2) For the purpose of paragraph 1, “act of aggression” means the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State, or in any manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations. Any of the following acts, regardless of a declaration of war, shall, in accordance with United Nations General Assembly resolution 3314 (XXIX) of 14 December 1974, qualify as an act of aggression:

(a) The invasion or attack by the armed forces of a State of the territory of another State, or any military occupation, however temporary, resulting from such invasion or attack, or any annexation by the use of force of the territory of another State or part thereof …19

Meanwhile, the elements also provide nuance in identifying wrongful conduct:

Elements [of aggression]

1. The perpetrator planned, prepared, initiated or executed an act of aggression.

2. The perpetrator was a person in a position to effectively exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of the State which committed the act of aggression.

3. The act of aggression – the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations – was committed.

4. The perpetrator was aware of the factual circumstances that established that such a use of armed force was inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations.

5. The act of aggression, by its character, gravity and scale, constituted a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.

6. The perpetrator was aware of the factual circumstances that established such a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.20

Next, the Kampala Understandings are useful in assuring states of the orderly implementation of the crime. Understandings 1 and 2 provide that the ICC is to exercise jurisdiction over cases referred to the ICC by the UN Security Council. Understanding 3 addresses the timing of the ICC’s jurisdiction over the crime, to begin July 17, 2018.21 (As noted, there can be no retroactive jurisdiction by either states or the ICC.) Understandings 4 and 5 respond to concerns that the crime should not result in a cause of action in national courts against the states of alleged perpetrators.22 Understandings 6 and 7 clarify the test of individual responsibility to meet Article 8bis of the Rome Statute:

6. It is understood that aggression is the most serious and dangerous form of the illegal use of force; and that a determination whether an act of aggression has been committed requires consideration of all the circumstances of each particular case, including the gravity of the acts concerned and their consequences, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

7. It is understood that in establishing whether an act of aggression constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations, the three components of character, gravity and scale must be sufficient to justify a “manifest” determination. No one component can be significant enough to satisfy the manifest standard by itself.

Understanding 6 demands a high degree of culpability at a level of specific intent mens rea because of the disapproval of the organized international community for “serious and dangerous ... illegal use of force”. Understanding 6 further confirms that the “post-aggression” acts of occupation and annexation must be shown to have involved the use of force.

It follows that four things need to be established in order to prove the crime of aggression: (1) the personal: the individual who is being prosecuted must be shown to have “exercised control” over the use of armed force at the highest levels of state; (2) the mode of wrongful conduct: the use of armed force must be under the perpetrator’s control; (3) the nature of the violation: it must be shown that force was used “against the sovereignty, territory or political independence of another State” or otherwise “inconsistent with” the UN Charter; and (4) the degree of violation: the character, gravity and scale of force must be shown to be a manifest violation of the UN Charter. Where the four requirements are made out, no defence would seem to be possible. Self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter avoids the crime by making the use of force lawful. Meanwhile, the Kampala Understandings eliminate de minimis use of force as a qualifying wrongful behaviour. Where

force is said to have been unlawful, a violation must be shown as overt in each of its character, gravity and scale.

It is arguable that there may be acceptable uses of minimal force in humanitarian intervention situations. Force could be tolerable in the delivery of humanitarian relief to a state unable or unwilling to give approval. The threshold for an individual senior official’s liability is the degree of gravity as prescribed by Article 8bis and Understanding 7. A second type of permissible situation, where there is no loss of life or damage to civil infrastructure, could be the deterrence of threatened violence by a targeted state against part of its population in circumstances where there is no selfdefence interest on the part of the attacking state. Missile strikes by the United States against alleged chemical weapons sites in Syria in 2017 and 2018 could arguably have met this justification.23

The conflict in Ukraine offers lessons for understanding the crime of aggression and the challenges of its prosecution. These challenges arise despite the fact that the requirements of the definition are likely met. A more obvious act of aggression, both at the level of a state and in criminal behavioural terms as one directed by individuals, is difficult to imagine. Who are such individuals? They include Russia’s president Vladimir V. Putin and defence minister General Sergei Shoigu. The available record is less clear about ostensibly involved members of Russia’s government, including prime minister Mikhail Mishustin and foreign minister Sergey Lavrov. Of course, the scope of “ordinary” ICL crimes is now extensive seven months into an illegal war and occupation, and will surely extend to officials across the Russian government and armed forces.

There is no ambiguity about the nature and seriousness of the armed conflict and a continuing occupation in Ukraine since February 24, 2022. The extensive thresholds to invoke the crime of aggression that resulted from compromise on the way to codification in 2010 are readily met in the case of Ukraine. The character, gravity and scale of territorial transgression are manifold. Further, no justification, including any claim of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter, seems credible. One of Russia’s stated objectives in the first days of the war, to eliminate Ukraine as a state, demonstrates the peril of the circumstances.24 In the following months, this has been reinforced by Russia’s disregard of the ICJ’s provisional measures order that directed Russia to “immediately suspend the military operations that it had commenced on 24 February 2022 in the territory of Ukraine”.25 The adequacy of aggression’s definition for circumstances that are less clear-cut can await future reconsideration.

It will not be a UN Security Council, absent a significant change of government in Moscow (and the cooperation or at least the abstention of China), that will refer to the ICC those responsible for aggression in Ukraine for investigation and possible prosecution. Pursuing the crime will have to fall to states, which means, for the time being, Ukraine. However, Ukraine has yet to accede to the Rome Statute. It remains in a sort of halfway adoption of the Rome Statute, in 2013 invoking a specific-cases jurisdiction of the ICC for war crimes and crimes against humanity.26 Joining the Rome Statute in the ordinary course will come with advantages beyond the symbolic, including better coordination of the complementarity of prosecutions between Ukraine’s courts and the ICC, and perhaps a more credible Ukrainian influence for adoption of the Rome Statute by all states. In addition, if Ukraine were to accede to and legislate for the crime of aggression, that would mean jurisdiction for the crime over citizens and, crucially, all responsible for its manifestation within Ukraine. The rule against nonretroactivity is, sadly, not much of a concern: aggression continues through the unlawful use of force and by an occupation, together with the annexation of Crimea and (it seems imminently at the time of writing) Ukraine’s eastern provinces in the Donbas region.

The history of ICL has been one of incremental progress, with significant development following major conflicts. In the aftermath of hostilities, there will be much work in Ukraine’s (and other) criminal courts to be done.27 We may yet see ICL, with the prosecution of aggression, return to a place of its origin in trials held at Lviv.

1. Philippe Sands recounts the story in his acclaimed East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity” (London: Alfred A Knopf, 2016).

2. International Military Tribunal (Nuremburg) Judgment of 1 October 1946, at 25 (“[t]o initiate a war of aggression, therefore, is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole”).

3. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (17 July 1998) 2187 UNTS 90 (in force 1 July 2002) [Rome Statute]. One hundred and twenty-three states are members of—that is, have ratified or acceded to—the Rome Statute, including Canada. The “original” international crime—maritime piracy—is defined in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Acts of terrorism arguably amount to international crimes as a matter of modern-era treaties (and state practice) concerned with international aviation and maritime transport and other activities. See the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (12 August 1949) 75

UNTS 287 (21 October 1950) (Fourth Geneva Convention), and its Protocols I and II Additional to the Geneva Conventions (8 June 1977) at 1125 UNTS 3 and 1125 UNTS 609, respectively. See also Hague Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its Annex, Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land (18 October 1907) 187 CTS 227 (in force 26 January 1910).

4. See the order of the International Court of Justice of 16 March 2022 in Allegations of Genocide under the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine/Russia), General List No 182, and the court’s judgment of July 22, 2022 in Allegations of Genocide under the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (The Gambia/Myanmar), General List No 178.

5. In 1951 and 1954, the International Law Commission proposed definitions of aggression.

6. See UN General Assembly Resolution 2330 (XXII) 18 December 1967 (“[n]eed to expedite the drafting of a definition of aggression in light of the present international situation”). The impetus to define aggres-

sion does not appear to have emerged at the time from a particular conflict.

7. See “Report of the Special Committee on the Question of Defining Aggression (25 April – 30 May 1973)”, UN Doc A/9019. By this time, aggression was being proposed to include the use of force “against the sovereignty, territorial integrity or political independence of another State”. Self-determination in the colonial context of non-self-governing peoples was provided for, with use of force permissible in order to resist “alien domination”.

8. UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (14 December 1974), Annex, “Definition of Aggression”, Article 3 (“[a]ny of the following acts, regardless of a declaration of war, shall … qualify as an act of aggression: … invasion or attack … or any military occupation, or any annexation by the use of force”).

9. This is reflected in the maxim nullum crimen sine lege, codified as Article 22 of the Rome Statute

10. Article 2(4) of the Charter of the United Nations (26 June 1945) 1 UNTS XVI (in force 24 October 1945) [UN Charter] provides that “[t]he [UN] Organization and its Members, in pursuit of the Purposes [of the UN] stated in Article 1, shall act in accordance with the following principles … All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations”.

11. The criminalization of unlawful use of force is extensive in the Rome Statute. Article 8bis(2) prohibits almost all extraterritorial use of force without the justifications of UN Security Council authorization or self-defence, from bombardment and blockade to the use of mercenary forces against another state.

12. See Steven W Becker, “The Objections of Larger Nations to the International Criminal Court” (2010) 81 Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal 47.

13. Rome Statute, supra note 3, art 15bis(5) (“[i]n respect of a state that is not a party to this Statute, the Court shall not exercise its jurisdiction over the crime of aggression when committed by that State’s nationals or on its territory”).

14. There appears to be no instance of a non-ICC state legislating the crime of aggression. ICC states that accede to Rome Statute aggression are required to domestically legislate the crime within a year.

15. See JJ Smith, “A Four-Fold Evil? The Crime of Aggression and the Case of Western Sahara” (2020) 20 International Criminal Law Review 492.

16. See Tom Ruys & Luca Ferro, “Weathering the Storm: Legality and Legal Implications of the Saudi-Led Military Intervention in Yemen” (2016) 65 International & Comparative Law Quarterly 61.

17. Mauritius claims the islands have been subject to “unlawful colonial administration”. See the argu-

ments of Mauritius to the International Court of Justice in Legal Consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 (Request for Advisory Opinion), “Written Statement of Mauritius” (1 March 2018) at 251ff, online: <www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/169/169-201 80301-WRI-05-00-EN.pdf>.

18. Neither Ukraine nor Russia is a Rome Statute member state. However, with the invasion of the Crimea and conflicts in its eastern provinces, Ukraine put itself within the jurisdiction of the ICC under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute for crimes in its territory effective from November 21, 2013. No claim of aggression was made. See International Criminal Court – Office of the Prosecutor, Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2019 (5 December 2019) at 66: <www.icc-cpi.int/itemsDocuments/ 191205-rep-otp-PE.pdf>.

19. Rome Statute, supra note 3.

20. Elements, Rome Statute, supra note 3. Element 1 of the crime of aggression provides that more than one person may fulfill the criterion of directing or controlling a state’s use of force.

21. Understanding 3, Jurisdiction ratione temporis (“[i]t is understood that in case of article 13, paragraph (a) or (c), the Court may exercise its jurisdiction only with respect to crimes of aggression committed after a decision in accordance with article 15 bis, paragraph 3, is taken, and one year after the ratification or acceptance of the amendments by thirty States Parties, whichever is later”).

22. In other words, the immunity of states is to be preserved when prosecuting aggression in national legal systems.

23. However, consider the threshold prescription of Article 8bis(2)(b) prohibiting “bombardment … or the use of any weapons by a State against the territory of another State”.

24. For the rationale of Russia’s would-be incorporation of Ukraine, see Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” (12 July 2021), first published on the website of The Kremlin, online: <e.wikisource.org/wiki/On_the_Historical_Unity_of _Russians_and_Ukrainians>.

25. Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine v Russian Federation), supra note 4.

26. Supra note 18.

27. The war in Ukraine will predictably be the most documented in history with overwhelming evidence amassed. See e.g. the website of Bellingcat, the international consortium of “researchers, investigators and citizen journalists”, online: <www.bellingcat. com>.

… When Europeans arrived in the South Pacific in the land that is now Australia and New Zealand, [1] they regarded it as terra nullius or “nobody’s land.” They simply ignored the fact that Indigenous Peoples had been living in these lands for thousands of years, with their own cultures and civilizations. For the newcomers, the land was theirs to colonize; this narrative was also applied in Canada.

Law Society of British Columbia, Indigenous Intercultural Course, announced January 26, 2022, Module 3.1.2

The doctrine of terra nullius (that no one owned the land prior to European assertion of sovereignty) never applied in Canada, as confirmed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44 at para. 69, per Chief Justice McLachlin.

Which of these seemingly opposite statements is true? Both? Neither?

In 2007, Australian historian Andrew Fitzmaurice published “The Genealogy of Terra Nullius” as part of his contribution to the Australian “history wars”, debates concerning the historiography of British colonization of

* I thank Hamar Foster, Q.C., Stephanie McHugh, Dr. S. Ronald Stevenson and Dr. Timothy Brook for their reviews and helpful feedback on drafts of this article. Any errors are mine, as are the views I express.

Australia and its effect on Indigenous peoples.3 The present article, published in two parts, adapts and extends Fitzmaurice’s framework to the Canadian legal context showing, I hope, that neither the Law Society’s nor the Chief Justice’s statement is entirely correct.

In Part I of this article, I examine the international and Australian use of the term terra nullius in legal and non-legal contexts. In Part II, which will be published in a later issue of the Advocate, I will trace the Canadian jurisprudential adoption of the term. To the date of writing, Canadian judges have referenced terra nullius in only 17 decisions; the treatment has been substantive in only seven. Tellingly, the first mention of the term was in May 1993, a year after the High Court of Australia’s lengthy discussion of terra nullius in its groundbreaking Aboriginal title decision, Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2). 4 I will conclude Part II by briefly examining the interface and friction between Indigenous and settler legal systems in 19th-century British Columbia, suggesting that this is where we should focus our attention if we are to properly understand our legal pasts and present and to craft a legal future.

In the last 30 years, terra nullius—meaning, literally, “land belonging to no one”5 or “land without owners”6—has come into wide usage in reference to British colonization.7 However, as Fitzmaurice and others have shown, terra nullius is valid only as a shorthand; it is not an accurate description of a legal or political doctrine employed in the justification of the British empire.8 One scholar terms it a “neologistic loan expression” whose “fascination is in being so widely misunderstood, a casualty of the conjunction of legal, political, and historical attitudes toward the past”.9

Terra nullius emerged as an international law concept only toward the end of the 19th century.10 Although similar to the Roman law terms res nullius and territorium nullius, terra nullius has a distinct meaning and genesis.11

By applying terra nullius anachronistically, we obscure two complex histories: (1) the comparatively recent history of terra nullius as it was used to discuss European expansion; and (2) the older history of how ideas of occupation were used to justify empire.12

Following the term’s sporadic appearances, Britain and Venezuela applied terra nullius in an 1899 arbitration concerning a long-simmering conflict over three former Dutch colonies in Guiana.13 Then, early in the 20th century, terra nullius secured a place in the international law lexicon.14 In 1909, French foreign affairs official Camille Piccioni used it in an article

about sovereignty over Spitzbergen, an island within the Arctic circle over which no sovereignty had been established.15 He used the term to refer not to a place that was uninhabited—he knew it was inhabited—but to territory that states had agreed would remain in common.16

Over successive decades, terra nullius continued to be used in discussions concerning the polar regions.17 Its prominence in these debates brought it to the attention of the Columbia University Joint Seminar in International Law (the “Columbia Seminar”), established by law professor Philip Jessup and others in the 1930s and concerned primarily with the doctrine of occupation. 18 Among other questions, the scholars considered whether the International Court of Justice’s reference to terra nullius in a 1933 decision concerning a dispute between Norway and Denmark over East Greenland19—the court had used the term to refer to a land that was unpeopled— could be extended beyond the polar context. They wondered whether terra nullius could explain previous centuries’ colonial expansionism.20

The students in the Columbia Seminar began to publish works arguing that terra nullius could indeed be used to understand the justifications of empire in the previous 400 years.21 In one book, the students took the meaning of terra nullius that had emerged from the polar regions debate—that is, “land not under any sovereignty”22—and extended it, determining that they would retain the term even to describe lands inhabited by Indigenous peoples: The presence of a savage population, of aborigines, or of nomadic tribes engaged in hunting and fishing, was generally disregarded by Europeans. For the purposes of this volume, therefore, insofar as any status of sovereignty is concerned, the existence of such a population will not exclude these lands from our definition of terra nullius. 23

It was the Columbia Seminar that delivered terra nullius to Australia. In addition to publishing, Columbia Seminar members wrote to scholars in settler societies asking them whether the assertion of sovereignty over terra nullius—according to the seminar’s definition—could explain the colonial settlement of their countries.24 As part of this project, Philip Jessup wrote to eminent Australian historian Sir Ernest Scott in 1939, asking if Australia had been terra nullius—again, according to their definition—at the time of British occupation. Scott quite easily concluded that it had, which he reported in two papers, including “Taking Possession of Australia – The Doctrine of ‘Terra Nullius’ (No-Man’s Land)”.25

In the paper, Scott wrote:

I was induced to write this paper by receiving some inquiries from Professor Philip C. Jessup, of the Department of International Law, University of Columbia. He informed me that he had been working with a seminar of advanced students on the subject of “Terra Nullius,” which has been defined as land not under any sovereignty. It is, therefore, land of which a sovereign state may consider itself at liberty to take possession. We may put

the point more simply if we say that “Terra Nullius” is No-man’s-land. In the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Portugal, Spain, Holland, England and France took possession of such territory in Asia, Africa, America and Australasia, by performing certain symbolic acts, which I shall describe presently.

Little regard was paid to the rights of original inhabitants by any of the colonizing peoples. Generally, they considered that they were acting righteously in introducing the Christian religion to lands previously heathen.26

Having gained a foothold in Australia in the 1930s, terra nullius largely lay dormant there for nearly another half-century. Finally, in 1977, it arose again in a court case in which an Indigenous man, Paul Coe, argued that Aboriginal people continued to hold sovereignty in Australia.27 Coe sought to leverage a recent International Court of Justice decision concerning the Western Sahara and amend his statement of claim to assert that “[t]he proclamations by Captain James Cook, Captain Arthur Phillip and others and the settlement which followed the said proclamations and each of them wrongfully treated the continent now known as Australia as terra nullius whereas it was occupied by the sovereign aboriginal nation as set out in paragraphs 5A, 6A and 7A hereof”.28

Australia’s highest court, however, dismissed Coe’s appeal, refusing him permission to file the amended pleading. The majority concluded that if there were serious legal questions to be decided about “what rights the aboriginal people of this country have, or ought to have, in the lands of Australia[,] … the resolution of such questions by the courts will not be assisted by imprecise, emotional or intemperate claims”.29 Thus, no court ever dealt with Coe’s claim on its merits.

Just three years later, Eddie Mabo and others filed a claim on behalf of the Meriam people of the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait, part of the Australian state of Queensland, arguing that they still held “native title” to their lands. The Mabo plaintiffs did not use terra nullius to attack British sovereignty over Australia, as Coe had proposed to do. Instead, they ultimately successfully argued that “the doctrine of terra nullius” had prevented Australian common law from recognizing Aboriginal title.

Justice Brennan, whose judgment can be considered the majority judgment, referred repeatedly to “the enlarged notion of terra nullius”—which, he explained, was an international law principle that justified “the acquisition of inhabited territory by occupation on behalf of the acquiring sovereign”. 30 The previous international law principle, according to Justice

Brennan, had allowed such acquisition only where the land was truly “desert” and “uninhabited”. 31 In refusing to enforce the contemporary results of this allegedly historical doctrine—the “enlarged notion of terra nullius”—Justice Brennan was explicit that his court could modify the common law to account for the inequities history had left in Australian society: Although our law is the prisoner of its history, it is not now bound by decisions of courts in the hierarchy of an Empire then concerned with the development of its colonies. … [T]he law of this country is entirely free of Imperial control. The law which governs Australia is Australian law. … Increasingly since 1968 … the common law of Australia has been substantially in the hands of this Court. Here rests the ultimate responsibility of declaring the law of the nation. … The peace and order of Australian society is built on the legal system. It can be modified to bring it into conformity with contemporary notions of justice and human rights … [N]o [previous] case can command unquestioning adherence if the rule it expresses seriously offends the values of justice and human rights (especially equality before the law) which are aspirations of the contemporary Australian legal system. If a postulated rule of the common law expressed in earlier cases seriously offends those contemporary values, the question arises whether the rule should be maintained and applied. Whenever such a question arises, it is necessary to assess whether the particular rule is an essential doctrine of our legal system and whether, if the rule were to be overturned, the disturbance to be apprehended would be disproportionate to the benefit flowing from the overturning.32

In this manner, Justice Brennan overruled historical precedent in a way not often seen in the common law world. He refused to follow older judgments that had been based on “the enlarged notion of terra nullius”: “the Court can overrule the existing authorities, discarding the distinction between inhabited colonies that were terra nullius and those which were not. … The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by a policy which has no place in the contemporary law of this country”.33

In the result, six out of seven members of the High Court agreed that Australian common law should reject “the notion that, when the Crown acquired sovereignty over territory which is now part of Australia it thereby acquired the absolute beneficial ownership of the land therein”.34 The court thus took the British Crown’s sovereignty as a given—indeed, it concluded that the acquisition of sovereignty by a country could not be challenged in municipal (i.e., national) courts, as it is a matter of international law35—but accepted that “the antecedent rights and interests in land possessed by the indigenous inhabitants of the territory survived the change in sovereignty” and now constitute “a burden on the radical title of the Crown”.36

After the High Court’s decision, it became “repeated wisdom that in Mabo, the High Court ‘rejected’ or ‘reversed’ the ‘doctrine of terra nullius’,

which had held that in 1788 Australia was ‘nobody’s land’”.37 But how had the High Court come to take the terra nullius hook?

The Mabo court referred several times to Australian historian Henry Reynolds’s book The Law of the Land as a source of historical fact and an explanation of the doctrine of terra nullius . Justice Toohey’s judgment referred explicitly to Reynolds’s “attack” on terra nullius 38 In the book, published five years before the High Court’s decision, Reynolds had set out to “challenge[] the legal and moral assumptions underlying the European occupation of Aboriginal Australia”.39 In fact, he had written the book “‘as an argument that lawyers could follow’ and with a judicial audience in mind”.40

In the first chapter, “Who Was in Possession?”, Reynolds wrote that “[t]he doctrine underlying the traditional view of settlement was that before 1788 Australia was terra nullius, a land belonging to no-one”.41 In his last chapter, Reynolds determined that terra nullius lay—and lies—at the heart of the Indigenous land issue in Australia. He distinguished British sovereignty from “[t]he claim to all the property”, concluding that “[p]ractice in other parts of the world suggested that negotiations should have been conducted prior to the purchase of land”. He laid the failure to do so at the doorstep of terra nullius:

The situation in Australia may have arisen from the mistaken belief that the country was largely uninhabited and therefore literally a terra nullius The idea was soon discredited. The law, however, continued to work on that assumption in face of everything that happened after 1788. Terra nullius is still at the heart of the Australian legal system. While it remains there the gap will yawn between jurisprudence and historical reality. There will never be a real accommodation between black and white. Australia will continue to be an imperial nation where the indigenous people are ruled by a legal system which enfolds old injustice.42

Upon the release of Mabo and for many years afterward, Australian historians and lawyers criticized the Mabo court’s anachronistic reference to terra nullius and its related reliance on Reynolds’s book.43 Today, commentators almost universally acknowledge that terra nullius was not used in the 18th and 19th centuries to justify the dispossession of Australian Indigenous peoples.44

Nonetheless, they also acknowledge that the Mabo court’s and Reynolds’s use of the term was shorthand for something real:

[W]hile the term terra nullius was not used to justify dispossession in Australia, it was produced by the legal tradition that dominated questions of the justice of ‘occupation’ at the time that Australia was colonised. Terra nullius is a product of the history of dispossession and the larger history of European expansion.45

Australian historian Bain Attwood concluded that Reynolds “undoubtedly” had used the term terra nullius metaphorically “to register the racism that Aborigines and their supporters saw as integral to the British colonization of the continent and the dispossession and destruction of its indigenous peoples”.46 Similarly, Australian lawyer David Ritter noted that the term “emotively connoted the historical reality of how Aboriginal people had been treated”.47 Recently, Australian legal academic Shane Chalmers acknowledged that terra nullius was not used in the 19th century in reference to Australian colonization, but that he nonetheless continued “to use the term here anachronistically, not as a legal-doctrinal concept, nor as an historical concept, but as a discursive concept that expresses the denial of Indigenous land rights in Australia and that has been used in the struggle by Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders against the ongoing colonisation of their country”.48

But there was even more to it than this.49 In fact, there had been a domestic common law corollary to the (later) international law concept of terra nullius : land acquired by settlement that was “desert and uncultivated”. 50 According to the common law, this kind of colonized land attracted English laws of real property ownership, since it was assumed that no land law or tenure existed in the colony at the time of its annexation by the Crown.51 Britain had applied this categorization to the Australian colonies. Reading Justice Brennan’s judgment, one can see his conflation of terra nullius and the status of land and law in a settled colony.52 By the “enlarged notion of terra nullius ”, Justice Brennan appears to have intended to describe the imperial treatment of inhabited lands as uninhabited lands, for the purposes of law, in a colony established by settlement. For the majority in Mabo, this “enlargement” had been improperly based on assumptions that the Indigenous inhabitants were too “low in the scale of social organization” to have legal systems and interests in land that ought to be recognized by British common law.53

Australian judges had routinely applied the English common law rule relating to settled colonies. In Milirrpum in 1970, in an action claiming Aboriginal title under the common law, a judge of the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory rejected the government’s argument that the Indigenous plaintiffs could not have had “law”. Of the government’s position, the judge said, “I do not find myself much impressed by this line of argument”,54 and concluded:

I am very clearly of opinion, upon the evidence, that the social rules and customs of the plaintiffs cannot possibly be dismissed as lying on the