ADVOC A TE

SEPTEMBER 2023

VOL. 81 PART 5 THE

THE ADVOCAT E 641 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 642 THE ADVOCAT E

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 THE ADVOCAT E 643

OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVES

LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Christopher McPherson, K.C. President

Don Avison, K.C.

Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

BENCHERS

APPOINTED BENCHERS

Paul A.H. Barnett

Sasha Hobbs

Dr. Jan Lindsay

ELECTED BENCHERS

Kim Carter

Tanya Chamberlain

Jennifer Chow, K.C.

Christina J. Cook

Cheryl S. D ’Sa

Tim Delaney

Lisa H. Dumbrell

Brian Dybwad

Brook Greenberg, K.C.

Katrina Harry, K.C.

Lindsay R. LeBlanc

Geoffrey McDonald

CANADIAN BAR ASSOCIATION

BRITISH COLUMBIA BRANCH

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Aleem S. Bharmal, K.C.

President

Scott Morishita

First Vice President

Lee Nevens

Second Vice President

Judith Janzen

Finance & Audit Committee Chair

Michèle Ross

Natasha Tony

Guangbin Yan

Steven McKoen, K.C.

Paul Pearson

Georges Rivard

Kelly Harvey Russ

Gurminder Sandhu

Thomas L. Spraggs

Barbara Stanley, K.C.

Michael F. Welsh, K.C.

Kevin B. Westell

Sarah Westwood, K.C.

Gaynor C. Yeung

BRITISH COLUMBIA BAR ASSOCIATIONS

ABBOTSFORD & DISTRICT

Kirsten Tonge, President

CAMPBELL RIVER

Ryan A. Krasman, President

CHILLIWACK & DISTRICT

Nicholas Cooper, President

COMOX VALLEY

Michael McCubbin

Shannon Aldinger

COWICHAN VALLEY

Jeff Drozdiak, President

FRASER VALLEY

Michael Jones, President

KAMLOOPS

Kelly Melnyk, President

KELOWNA

Tom Fellhauer, K.C., President

KOOTENAY

Dana Romanick, President

NANAIMO CITY

Kristin Rongve, President

NANAIMO COUNTY

Lisa M. Low, President

NEW WESTMINSTER

Mylene de Guzman, President

NORTH FRASER

Lyle Perry, President

NORTH SHORE

Adam Soliman, President

PENTICTON

Ryu Okayama, President

PORT ALBERNI

Christina Proteau, President

PRINCE GEORGE

Marie Louise Ahrens, President

PRINCE RUPERT

Bryan Crampton, President

QUESNEL

Karen Surcess, President

SALMON ARM

Dennis Zachernuk, President

SOUTH CARIBOO COUNTY

Angela Amman, President

SURREY

Peter Buxton, K.C., President

VANCOUVER

Executive

Niall Rand President

Heather Doi

Vice President

Zachary Rogers Secretary Treasurer

Jason Newton

Past President

VERNON

Chelsea Kidd, President

VICTORIA

Marlisa H. Martin, President

Dan Melnick

Young Lawyers Representative

Rupinder Gosal

Equality and Diversity Representative

Randolph W. Robinson

Aboriginal Lawyers Forum Representative

Patricia Blair

Director at Large

Adam Munnings

Director at Large

Mylene de Guzman

Director at Large

Sarah Klinger

Director at Large

ELECTED MEMBERS OF CBABC PROVINCIAL COUNCIL

CARIBOO

Nathan Bauder

Jon Duncan

Nicholas Maviglia

KOOTENAY

Jamie Lalonde

Christopher Trudeau

NANAIMO

Johanna Berry

Patricia Blair

Ben Kingstone

PRINCE RUPERT

Emily Beggs

VANCOUVER

Joseph Cuenca

Bahareh Danael

Nicole Garton

Diane Gradley

Graham Hardy

Lisa Jean Helps

Bruce McIvor

Heather McMahon

Heather Mathison

VICTORIA

J. Berry Hykin

Cherolyn Knapp

Kimberley Nusbaum

WESTMINSTER

Manpreet K. Mand

Daniel Moseley

Matthew Somers

Sarah Weber

YALE

Mark Brade

Laurel Hogg

Aachal Soll

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF BLACK LAWYERS (B.C.)

Zahra Jimale, President

FEDERATION OF ASIAN CANADIAN LAWYERS (B.C.)

Fiona Wong, President

INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION (B.C.)

Michael McDonald, President

SOUTH ASIAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Anita Atwal, President

ASSOCIATION DES JURISTES D’EXPRESSION FRANÇAISE DE LA COLOMBIE-BRITANNIQUE (AJEFCB)

Sandra Mandanici, President

644 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, K.C. First Vice President Brook Greenberg, K.C. Second Vice President

“Of interest to the lawyer and in the lawyer’s interest”

Published six times each year by the Vancouver Bar Association

Established 1943

ISSN 0044-6416

GST Registration #R123041899

Annual Subscription Rate $36.75 per year (includes GST)

Out-of-Country Subscription Rate $42 per year (includes GST)

Audited Financial Statements Available to Members

EDITOR:

D. Michael Bain, K.C.

ASSISTANT EDITOR:

Ludmila B. Herbst, K.C.

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD:

Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., K.C.

Carolyn MacDonald

David Roberts, K.C.

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Mary Saunders

The Honourable Alexander Wolf

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS:

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Jon Sigurdson

Lily Zhang

BUSINESS MANAGER:

Lynda Roberts

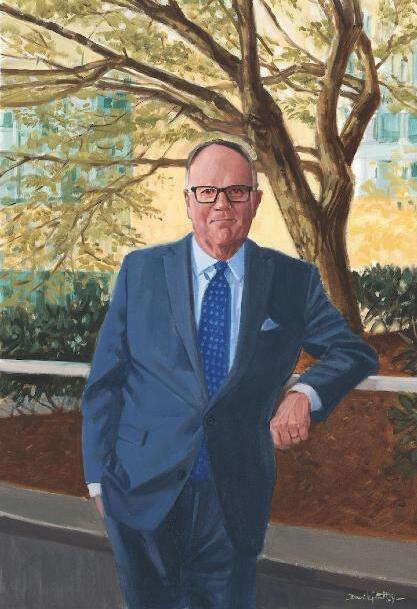

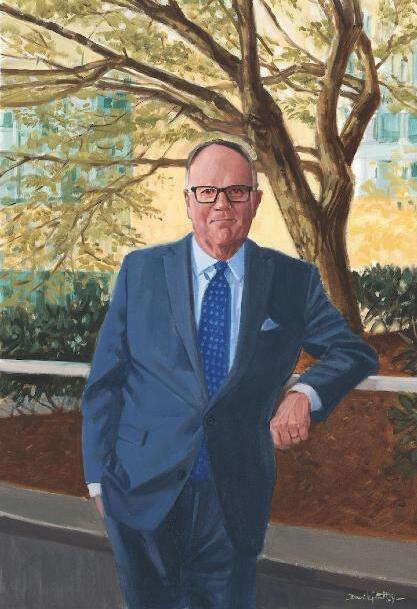

COVER ARTIST: David Goatley

COPY EDITOR: Connor Bildfell

EDITORIAL OFFICE:

#1918 – 1030 West Georgia Street

Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Y3

Telephone: 604-696-6120

E-mail: <mbain@the-advocate.ca>

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE: 709 – 1489 Marine Drive West Vancouver, B.C. V7T 1B8

Telephone: 604-987-7177

E-mail: <info@the-advocate.ca>

WEBSITE: <www.the-advocate.ca>

ON THE

COVER

Read about the judicial accomplishments of Chief Justice Robert Bauman – quickly, if you’d like to do so while he remains in that role!

– starting on page 655 of this issue.

FRONT

ADVOCATE

THE VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2 023 Entre Nous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 649 On the Front Cover: The Honourable Chief Justice Robert Bauman By the Honourable Jon Sigurdson 655 Credit Card Fees Aren’t Indirect Taxation – and Even If They Feel Like It, It Doesn’t Matter Anyway By David Ross 667 Addressing Indigenous Cultural Safety in the Legal Profession By Christopher McPherson, K.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 675 Changes in the B.C. Provincial Court May Surprise You By the Honourable Chief Judge Melissa Gillespie 677 Wish Without Precedent By Jan Crerar 685 Further Adventures of a Deputy Judge of the Yukon By the Honourable Marion Allan, K.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 691 The Crown’s Duty to Determine, Recognize and Respect Aboriginal Title—Part I – Existence of the Duty By Tim Dickson 699 The Wine Column 709 News from BC Law Institute 717 LAPBC Notes 721 A View from the Centre 723 Announcing the 2024 Advocate Short Fiction Competition 729 UVic Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 731 TRU Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 739 Nos Disparus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 743 New Judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 751 New Judicial Justices 755 New Registrar 767 Classified 771 Legal Anecdotes and Miscellanea 773 From Our Back Pages 779 Bench and Bar 783 Contributors 799

646 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

THE ADVOCAT E 647 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

648 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

“One big step for OceanGate, one huge leap for ocean exploration.”

—Stockton Rush, founder of OceanGate, emerging from a 4,000 metre “validation dive” in 2018

Stockton Rush’s appropriation of Neil Armstrong’s famous words from the 1969 moon landing (“one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”) was not so much a celebration of an incredible scientific achievement as it was a bid to create a sound bite to promote his brand, OceanGate. In a December 2018 press release, OceanGate, the Everett, WA-based company that produced manned submersible vessels for underwater exploration, boasted that its founder, Mr. Rush, had completed a solo 4,000 metre “validation dive” that “completely validate[s] OceanGate’s innovative engineering and the construction of Titan’s carbon fiber and titanium hull, it also means that all systems are GO for the 2019 Titanic Survey Expedition”. That exploration dive to the wreck of the Titanic was delayed until 2021 when Titan descended 3,800 metres to the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean six times. In 2022, it performed another seven successful dives to the Titanic. On June 18, 2023, Titan’s first dive of the year to the wreck ended with a catastrophic implosion instantly killing Stockton Rush and his four passengers: Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a French deep-sea explorer and Titanic expert; Hamish Harding, a British billionaire; Shahzada Dawood, a Pakistani-British billionaire; and Mr. Dawood’s 19-year-old son, Suleman Dawood.

The implosion itself, which occurred only one hour and forty-five minutes into the dive, was not reported for several days and only after a massive search and rescue effort was undertaken by the U.S. and Canadian Coast

Guards, naval vessels from both countries, the U.S. Air National Guard and the Royal Canadian Airforce. Research vessels flying French and Guernsey flags also joined in on the massive search covering some 25,000 square km. Worldwide media attention, however, focused exhaustively on the rescue effort with the suspected amount of oxygen left in the tiny submersible being counted down live on television in a somewhat macabre fashion. At one point “underwater noises” were picked up giving false hope to those holding out for a miraculous rescue. On June 22, a debris field of the Titan was found about 500 metres northeast of the bow of the Titanic at the bottom of the ocean. A “catastrophic loss of the pressure chamber” was suspected as the cause of the wreckage. All lives aboard were lost in a mercifully brief microsecond that would have been too quick for the brain to process.

The intense fascination that the world still has with the sinking of the “unsinkable” Titanic more than 100 years ago likely fueled the scrutiny given to the rescue mission as it unfolded live around the world. The coverage and attention were reminiscent of the 2018 Tham Luang cave rescue mission in which a group of 12 junior football players and their 25-year-old assistant coach were trapped in a cave due to heavy rain and the 18-day search and rescue mission was successful (although one of the rescuers drowned). The world likes a (mostly) happy ending. Sadly, for the owner and passengers on Titan the ending was unimaginably bleak—images of a life support system slowly depleting over several hours gave way to the obliteration of lives in a microsecond—at the bottom of the North Atlantic.

Perversely, the entire ordeal might well have been avoided altogether. The “validation dive” that Stockton Rush proudly championed had been designed “to assess the integrity of the hull on OceanGate’s patent-pending Real Time Monitoring system (RTM) that monitors acoustic emissions from the carbon fiber structure”. This sounds impressive, but it does not actually say anything about the structural integrity capabilities of the hull itself. It merely boasts of a patent-pending system that assessed hull integrity. In an email to Rush in April 2019, one of Titan’s passengers on earlier testing in the Bahamas, Karl Stanley, an expert in submersibles, complained of a large cracking sound he had heard during the test dives:

What we heard, in my opinion, sounded like a flaw/defect in one area being acted on by the tremendous pressures and being crushed/damaged. From the intensity of the sounds, the fact that they never totally stopped at depth, and the fact that there were sounds at about 300 feet that indicated a relaxing of stored energy would indicate that there is an area of the hull that is breaking down/getting spongy.

Meanwhile, an employee of OceanGate—the director of operations, David Lochridge—had delivered an inspection report on the Titan sub-

650 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

mersible (then named Cyclops 2) to Mr. Rush in January 2019. The preamble of his report stated:

With Cyclops 2 (Titan) being handed off from Engineering to Operations in the coming weeks, now is the time to properly address items that may pose a safety risk to personnel. Verbal communication for the key items I have addressed in my attached document have been dismissed on several occasions, so I feel now I must make this report so there is an official record in place.

The report detailed the safety concerns Mr. Lochridge had previously tried to bring to the company’s attention including a lack of proper testing performed on the hull of the Titan and visible flaws and weaknesses in the carbon fibre hull. Mr. Lochridge specifically noted that any detection system would not function in sufficient time to give the occupants of the vessel sufficient warning to deal with an imminent hull breach. At a meeting the day following his report, Mr. Lochridge learned that the view port at the forward of the submersible was only built to a certified pressure of 1,300 metres and not the 4,000 metre depth to which the submersible would be taking paying passengers. Lochridge was appalled and encouraged OceanGate to use a classification agency to certify the suitability of the vessel for its intended purposes. OceanGate, however, was having none of it. Rush viewed regulations as a hinderance to innovation and he fired Lochridge with immediate effect and gave the four-year employee ten minutes to clear out his desk.

Part of Lochridge’s report expressed this startling concern: The paying passengers would not be aware, and would not be informed, of this experimental design, the lack of non-destructive testing of the hull, or that hazardous flammable materials were being used within the submersible.

Earlier still, in March 2018, 38 members of the Marine Technology Society sent a joint letter to OceanGate and addressed “Dear Stockton”. The letter was sent on behalf of those “who have collectively expressed unanimous concern regarding the development of TITAN and the planned Titanic Expedition”. Among the many concerns expressed about the design and suitability of the submersible to dive to the depths necessary to reach the Titanic, the letter referenced the risk assessment protocols of a certification company named DNV and stated:

Your marketing material advertises that the TITAN design will meet or exceed the DNV-GL safety standards, yet it does not appear that OceanGate has the intention of following DNV-GL class rules. Your representation is, at minimum, misleading to the public and breaches an industry-wide professional code of conduct we all endeavour to uphold.

THE ADVOCAT E 651 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

While Stockton Rush forged ahead with his launching of Titan without DNV-GL certification or the rigorous testing urged upon him by others, he does not appear to have ignored the criticism entirely. To the contrary, he appears to have intentionally looked for legal loopholes that would allow him to exploit the lack of certification, proper safety testing and potential liability to paying passengers. In fact, he appears to have gone to great lengths to shield himself (and his company) from the inevitable lawsuits that might occur should the technology fail (as he had been expressly warned it would).

The liability waiver he required his paying passengers to sign (US$250,000 per person) started with a preamble that confirmed OceanGate was registered in the Bahamas, would embark from Newfoundland, Canada, participants would travel “for the most part aboard non-United States flagged vessels” and the expedition itself would be “largely conducted in international waters”. These acknowledgments were crucial because in international waters, no government has jurisdiction on the high seas. Instead, it is the law of the flag flown by the vessel that governs what happens on that vessel. Titan , however, was an unregistered submersible, launched from a Canadian registered (and flag flying) vessel in international waters—essentially it was cargo that was lifted off the registered vessel. Titan flew no flag of its own, had not been certified by any organization, was not registered and had deemed its passengers “mission specialists” rather than passengers—all efforts to avoid liability should something go wrong. What’s more, the waiver of liability included the following:

I have been informed about the nature of the Expedition and the risks it presents including that:

. . . a portion of the Expedition will be conducted inside an experimental submersible vessel that will dive 3,800 meters to the shipwreck of the Titanic. The experimental submersible vessel has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body and is constructed of materials that have not been widely used for manned submersibles. As of the date of this Release, the experimental submersible vessel has conducted fewer than 90 dives and 13 of those dives reached the depth of the Titanic. When diving below the ocean surface this vessel will be subject to extreme pressure and any failure of the vessel while I am aboard could cause me severe injury, disability, emotional trauma, other harm and/or death.

Of course the document went on to release, waive and forever discharge OceanGate (and everyone and everything associated with them) “from all liabilities, actions, claims, demands, costs, losses or expenses which I or my heirs, distributees, guardians, legal representatives, next of kin, members of my family (including minor children), or assignees may have against the

652 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

Released Parties on account of injury to myself or my property, or resulting in my death, arising out of or in any way connected with my participation in the Expedition”. The release was governed by the laws of the Bahamas to be resolved by the courts of the Bahamas.

There is something almost chilling about the attention given to avoiding potential liability. In an interview after the disaster, Karl Stanley, who had dived in the Titan, rhetorically asked: “Who was the last person to murder two billionaires at once, and have them pay for the privilege?” He described Rush as definitely knowing “it was going to end like this”. Rush certainly appears to have had a complete disregard for safety, preferring to make boastful claims and operate outside of the restrictions that a regulated industry might have imposed. His endeavours would probably have taken longer and would have likely been more costly. But it is not clear what more anyone could have done to prevent Stockton Rush from pursuing his dangerous and ultimately lethal scheme. An entire industry had warned him.

OceanGate did find itself from time to time in court concerning the Titanic wreckage site itself. A judge sitting on the U.S. District Court in Norfolk, Virginia has overseen cases involving access to the wreckage of the Titanic for over two decades. In April 2023, a consultant for OceanGate notified the court of the company’s intention to undertake its survey expedition in the summer of 2023. Remarkably, the consultant went on to invite the judge, Rebecca Beach Smith, to join the party: “If you would like to personally participate in [the] 2023 Titanic Survey Expedition, you are more than welcome to do so as a guest of OceanGate Expeditions”. In her reply, the judge wrote: “I thank you for the invitation to participate in the 2023 Titanic Survey Expedition, and perhaps, if another expedition occurs in the future, I will be able to do so. That opportunity would be quite informative and present a first ‘eyes on’ view of the wreck site by the Court”. As judicial decisions go, this was a good one.

One of the final news postings on OceanGate’s now defunct website ran with the headline: “Can You Build a Carbon Fiber Adventure Sub From Home?” That post is now gone. Only a sparse holding page exists now. Beneath the registered trademark for OceanGate are the words: “OceanGate has suspended all exploration and commercial operations.” In the end, Titan’s dive was not a giant leap for ocean exploration. Experts claim it may well have set the industry back decades.

THE ADVOCAT E 653 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 654 THE ADVOCAT E

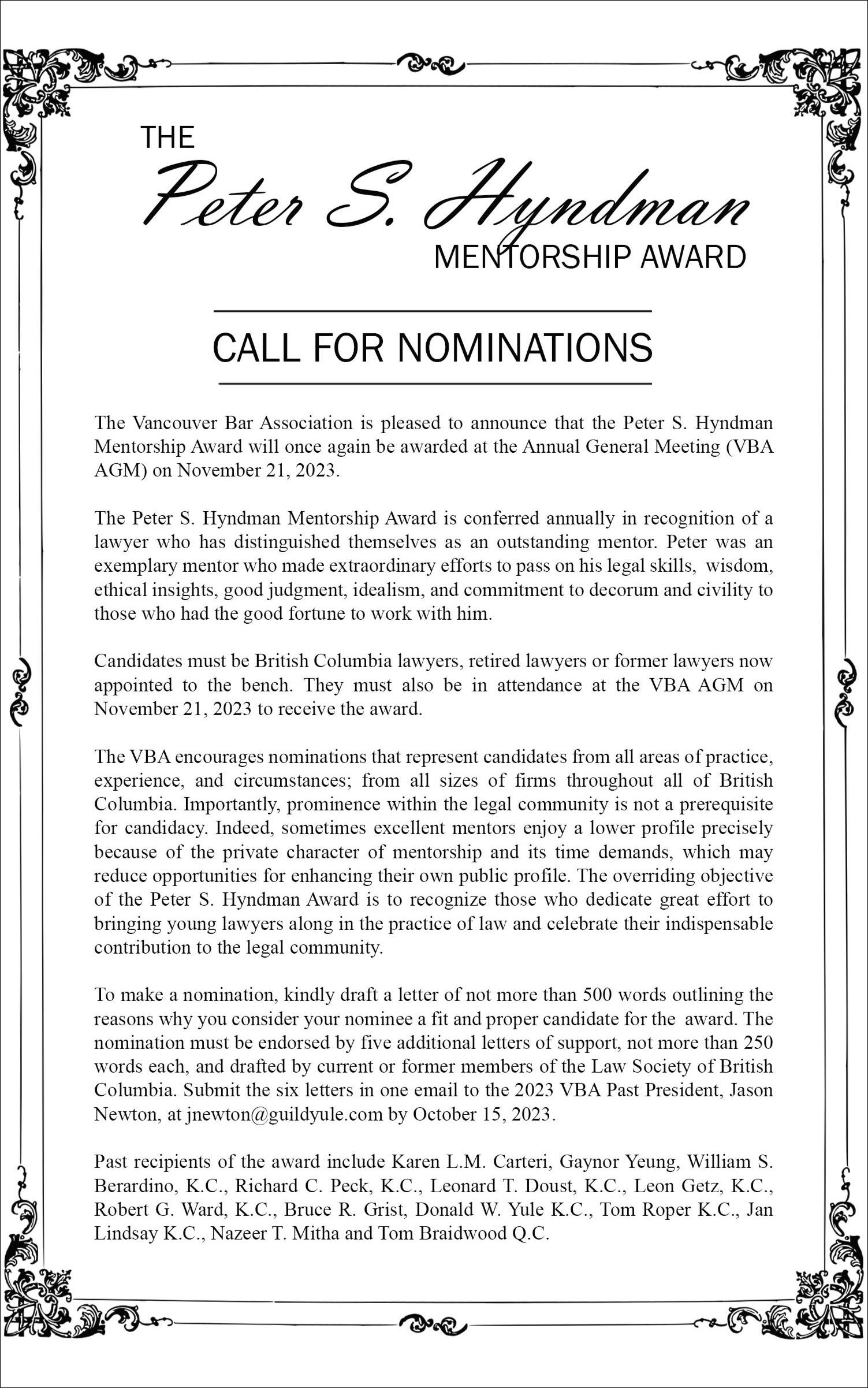

ON THE FRONT COVER

THE HONOURABLE CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERT BAUMAN

By the Honourable Jon Sigurdson*

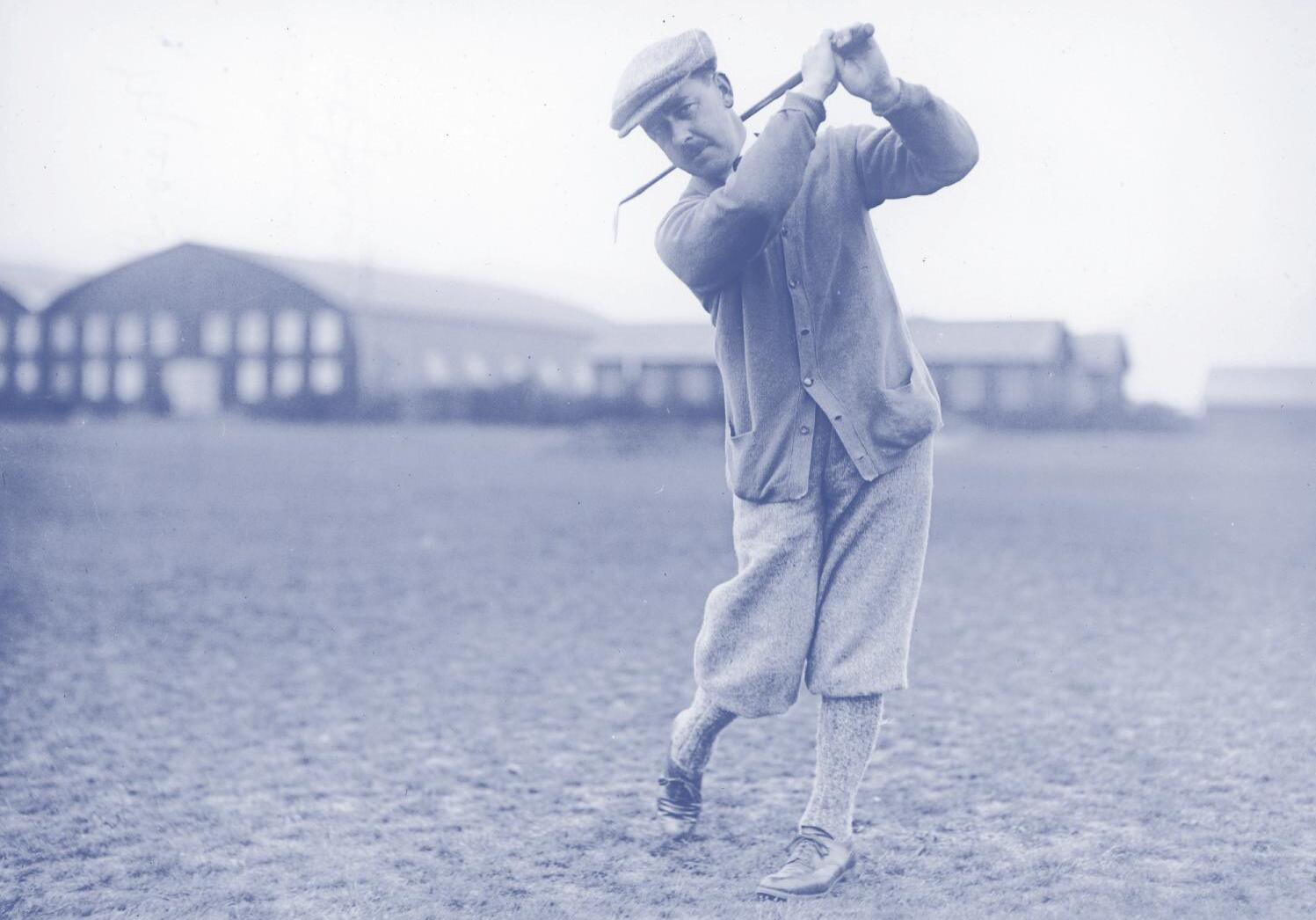

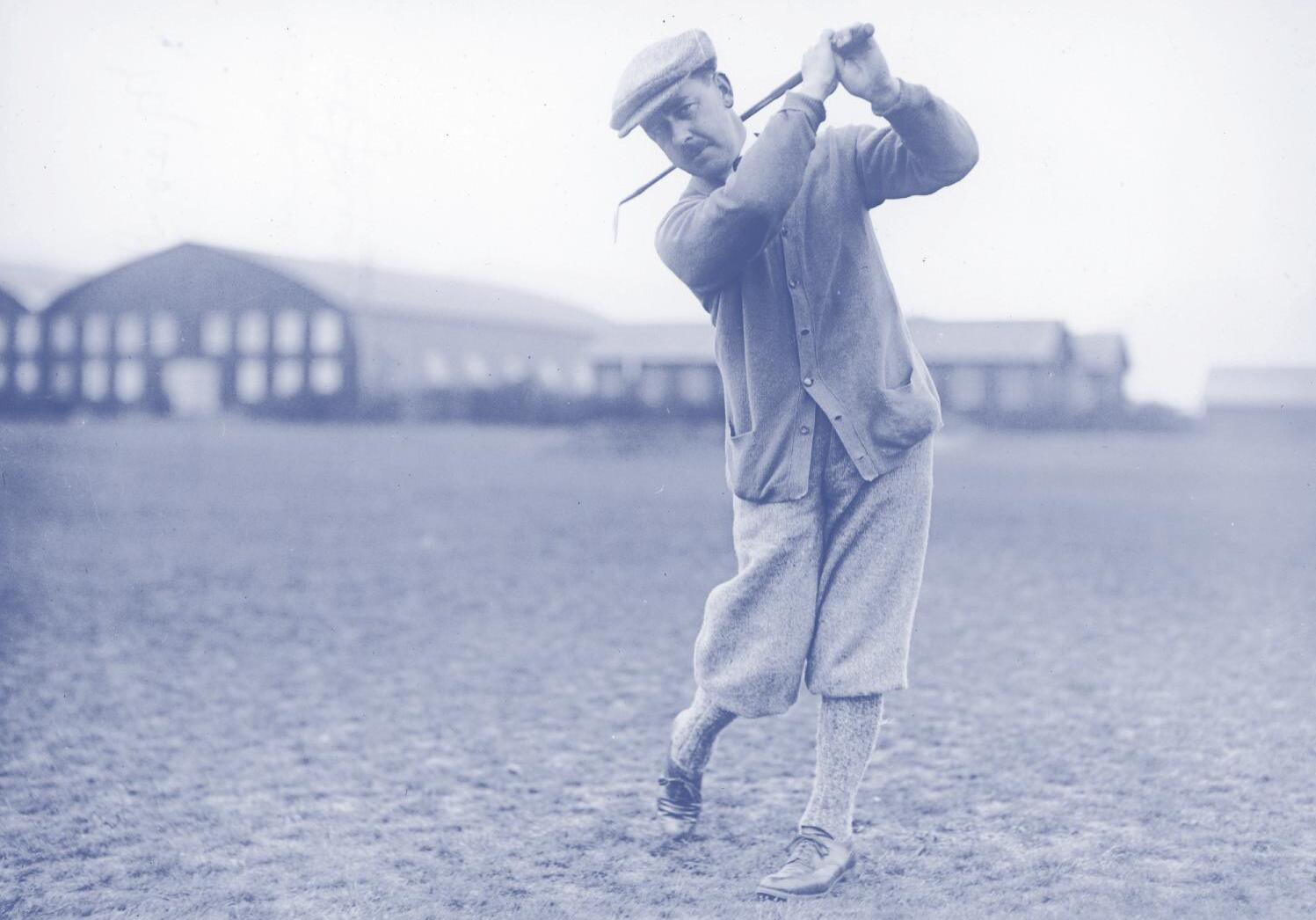

On October 1, 2023, Chief Justice Bauman will retire. This article recognizes his time and contributions as chief justice of the Courts of Appeal of British Columbia and the Yukon, previously as chief justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia and as a sitting judge on those courts. His portrait graces the cover of what will be the last issue of the Advocate during his tenure.

Robert (Bob) J. Bauman has been a judge for almost three decades and has served as chief justice for 14 of those years, with four on the trial court and the remainder, since 2013, on the Court of Appeal. Perhaps surprisingly, there have been only three other judges in British Columbia’s history who have served as the chief justice of both courts. In chronological order, they are Sherwood Lett (1955–1964), Nathan Nemetz (1973–1988) and Allan McEachern (1979–2001). In terms of length of service, Chief Justice McEachern was the longest serving, but—without having counted days—it appears that Chief Justice Nemetz inched Bob out for longevity and would be entitled to receive the silver medal.

There is really no need for deep disappointment. Anyone who has had longer than the briefest conversation with Bob will know two important facts: he received the silver medal from his law school and it was the University of Toronto.

In this article, I move far away from his law school days and focus on Bob’s time as a judge and as chief justice of the B.C. Supreme Court and then

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 THE ADVOCAT E 655

* The author thanks the people who helped him with this article, including Trevor Bant, Julia Riddle, Sally Rudolf and many others.

of the two appellate courts. In the latter capacity, he is the spokesperson for the appeal courts on many issues concerning the administration of justice. Given the size of the British Columbia courts, the nature of the work the judges of each court do and the places where the courts sit, the roles of chief justice of the trial court and chief justice of the appeal court are quite different. (I was unable to obtain a printable quote from Chief Justice Hinkson when I asked him which role was more onerous.)

By using the “point first” and concise writing style that Bob is famous for, let me put my conclusion up front. In the view of the profession, the public and his colleagues on both the trial and appellate courts, Bob has served with great distinction both as a jurist and as a spokesperson on the important issues affecting the justice system.

Now some necessary background before I expand on those points.

I met Bob when he joined Bull, Housser and Tupper in the early ’80s. We became friends. I was appointed to the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1994 and he was appointed two years later. After that, during his career, I was mostly only visible in his rear-view mirror. When we first met, I found a lot of people underestimated him, but I felt proud that I could always see his true potential: I could see him as a retired person.

Our loyal and dedicated readers will recall that Bob was first on the front cover of the Advocate in 20101 to recognize his appointment as the 15th chief justice of the Supreme Court. For those who do not have that cover article fresh in their minds, I will briefly review the salient facts. He was born and raised in Toronto and Montreal, attended Loyola High School and College, obtained a history degree at Western University, went to the University of Toronto for his law degree and met Sue Hadgraft during first year. They married, he graduated with the silver medal (has this been mentioned already?), he articled with Wilson King in Prince George and became a partner and he later formed Wilson Bauman with his partner Galt Wilson to practise municipal law. Bob and Sue had two boys, Rob and Dave, and in the early ’80s moved to Vancouver. Bob joined Bull, Housser and Tupper and became a partner, specializing in municipal, regulatory and administrative law. As is well known by Bob’s colleagues and friends, he has had staunch support and wise counsel from Sue now for some 50 years. He is enormously proud of his two sons, who have pursued careers outside the law (in business) to great success. The sons married Angela and Ashley respectively, and the family now includes a much-adored grandson, Jackson.

Bob became a Supreme Court judge in 1996 and in 2008 was appointed to the Court of Appeal. He went back to the Supreme Court as its chief justice in 2009, then back to the Court of Appeal as its chief justice in 2013. He

656 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

retained his sense of humour through all these moves and translations. He maintained his golf game only through the strategic use of the “Leaf Rule”, a common law rule he developed that you do not count a lost ball penalty stroke if the ball could possibly be under a fallen leaf.

Bob is very particular about structure and design, so let me describe where I am going next. In the remainder of this article, I will first set out some observations about the way he approaches and hears matters that come before him in court, then turn to his jurisprudence (and jurisprudential legacy) and then discuss his role as a chief justice. In preparing this article, I have consulted widely with former law firm colleagues, justices of both trial and appellate courts, law clerks and friends.

Turning first to his approach in court, in what feel like times of increasing incivility and bullying in our society, the value of courts resolving contentious disputes calmly, respectfully and firmly cannot be overstated. No one has been a better exemplar of civility than Bob. He is widely known for his calm, relaxed and respectful approach to lawyers and litigants alike. He manages to display a firm grasp of the issues in the case while, with a light touch, he moves the proceedings along briskly.

A leading Vancouver counsel described him in these two phrases: “Smart, principled and guided by the rule of law” and “kind, funny and fair, but always in control.” Another barrister who has been a leader of the bar for many years put it this way: “Obviously, the Chief is held in the highest regard by the profession.” Another, somewhat less senior, counsel described her meeting with Bob this way: “I remember the first time I met Chief Justice Bauman at a social occasion (bar function). He was, of course, as he was in court, extremely intelligent, articulate and quick. However, what I had not expected was that he was also extremely humble, down-to-earth, funny and dare I say ‘cool’. We are extremely fortunate to have had his exceptional leadership of our courts over the past 14 years. I am sure his keen sense of humour came in handy at times.”

Civility has many aspects. Sitting as a judge in the Court of Appeal is different from being a trial judge. An appellate judge must work with their colleagues in preparing for and hearing the case and then deliberating on the proper decision. I spoke with several of Bob’s fellow appellate judges, and they unanimously told me that he approaches deliberations and engagement with his colleagues in the same open-minded and respectful manner as he is known for in the courtroom. A colleague described him as “the epitome of collegiality. He is always ready to listen to the views of others, and the first to acknowledge when someone has made a good point or written well. He presents his own views quietly, but firmly, remaining open to

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 THE ADVOCAT E 657

being persuaded of a different approach.” Another colleague said that “sitting with the Chief on a division hearing reveals a person who demonstrates the same traits both before, during and after the hearing itself as he does in his other professional obligations. He is thoughtful, respectful to a tee to the views of his colleagues and if/when he has a different viewpoint, is courteous yet firm in his opinion. He also has a sense of humour, which he will use to his advantage if the situation warrants it. I find him to be very fair with counsel but, again, will be respectful while remaining firm to ensure that the proper regard is given to the court and the administration of justice, which is fundamental to him.” Another colleague said that he asks fewer questions than others on the panel and put it this way: “When he does ask a question, it is pointed and illustrates that he has completely grasped the issue … He is polite and respectful to all who appear, counsel as well as selfrepresented litigants. He uses plain language to address self-represented litigants and tries to make them comfortable in the process. He presides over the courtroom in a firm but fair manner.”

Maya Angelou famously said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Bob shows the value of applying that insight to the art of judging. When new judges wonder about how to conduct themselves in court, judicial educators advise them to look to the judges they admire and conduct themselves that way. Recognizing that judges bring their own unique personalities and strengths to the courtroom, there is much to emulate in Bob’s approach to judging.

Judges, whether puisne judges or chief justices, first and foremost are appointed to hear and decide cases. Judges are of course remembered by their judgments and sometimes by only a few of their judgments. What about Bob’s decisions? Bob has always enjoyed writing and analyzing legal problems. In a reflective moment, he would probably confess to always having wanted to be a judge because he enjoyed the analysis and writing that come with the job. Working with his clerks (not always agreeing with them, but always engaging) has been a highlight of his career, in part because of the opportunity to hear a point of view that differs from his own.

For most practical purposes, the Court of Appeal is the court of last resort in British Columbia, but sometimes cases go to the Supreme Court of Canada and sometimes even Bob is found daydreaming of the days when there was a possible further appeal to the Privy Council. However, Bob is realistic and understood from his early days as a student working in the forest industry in northern British Columbia that occasionally the chips will fall.

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023 658 THE ADVOCAT E

One of the strengths of Bob’s judgment writing is his placement of the facts and the dispute in their full and proper context. All trial judges know that viewing the evidence in its context, particularly its proper chronological sequence, is crucial to understanding the case. Bob has a particular longstanding love of timelines.

His boyhood and lifelong friend David Covo, now a professor of architecture at McGill, was visiting Bob many years ago and saw him painstakingly taping the long edges of eight or ten sheets together to make a larger document, a continuous strip that could be folded back, accordion-style, to a single 8 ½ by 14 “book”. The first few pages had been divided with a single horizontal line just above the centre and the spaces above and below the line were covered with notes. Bob had invented a format for his bench notes that organized the narrative of the trial along a horizontal line, drawn freehand and marked with the key dates in sequence from left to right. According to Covo: “In fact, the Chief had re-invented one of the earliest forms of what we now recognize as a book, the second step in the transformation from a continuous scroll to a bound sequence of separate pages, a Chinese invention that spread throughout Asia and remains in use all over the world as a sketchbook … I have been keeping him supplied with various versions, mostly Chinese, of what I now regard as a wonderful point of intersection in our professional trajectories.”

THE ADVOCAT E 659 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

Examples of Chief Justice Bauman’s timeless timeline style

Let me now discuss the jurisprudence emanating from this thoughtful judge and his carefully scotch-taped sheets of legal foolscap.

Bob has authored important decisions on municipal law,2 the health care system, 3 Yukon’s treaty obligations, 4 commercial arbitration, 5 tribunal standing and costs in judicial review proceedings,6 civil forfeiture,7 search warrants and s. 8 of the Charter, 8 contracts,9 damages for loss of housekeeping capacity,10 class proceedings,11 the proper approach to summary judgment,12 Treaty 8,13 stare decisis in constitutional cases,14 the open court principle,15 civil procedure,16 s. 96 of the Constitution Act, 1867, 17 family law,18 the criminal prohibition of polygamy,19 solicitor-client privilege,20 inferential reasoning in criminal cases,21 legislative competence over taxation,22 criminal sentencing,23 health profession regulation,24 election spending, 25 notarial practice, 26 property assessment, 27 fraudulent misrepresentation,28 freedom of religion,29 civil contempt,30 public interest immunity31 and McBarge.32

The Chief Justice’s approach to judgment writing and decision making was accurately summarized by Trevor Bant, his former law clerk, who later clerked at the Supreme Court of Canada, worked at Hunter Litigation Chambers and presently is counsel for the Ministry of Attorney General. He said this:

In my view, the Chief Justice’s jurisprudence has three main characteristics.

First, his decisions are animated by practical judgment and common sense. His reasons seek to explain why the result makes sense, in addition to why it follows from the facts and law. He often uses phrases like “To proceed from ‘common sense’ to a more legalistic approach […]”[33] or “the result which appeals to our common sense is supported by a traditional legal (some would say an overly technical, or tortured) analysis”[34] or “it happily accords with common sense”.[35] This practical approach dovetails with his accessible writing style (plain language, point first, mostly short sentences, mostly short paragraphs). Most of his decisions do not require legal training to understand.

Second, his decisions reflect a concern for institutional competence and a humility about the judicial role. He was not timid about developing the law in appropriate cases,[36] nor about granting constitutional remedies when required,[ 37 ] but he was cautious about intruding into matters within the responsibility of the legislature or executive. He often emphasized, when deciding a challenge to legislation or government action, that he was not passing judgment on its policy merits or wisdom.[38]

Finally, his decisions convey his compassion and empathy for litigants and witnesses. He writes with an awareness that litigants are people, not fact patterns. When summarizing the evidence, he captures witnesses’ personalities. When he finds himself compelled to reach a result that may be difficult or upsetting to a litigant, he does so with sensitivity. Here is

660 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

just one example, from one of his early decisions, after he has concluded that two persons were not “spouses” within the meaning of family law: That conclusion should not be viewed, in any way, as demeaning of the love between these two people. It rather reflects an application of the law. At law, human relationships sometimes must be placed on a continuum which ranges from “single and dating” to “meaningfully involved” to “marriage-like”. The placement, in any given case, by definition, is arbitrary even if it is principled.[39]

To give the reader some tangible idea of Bob’s approach to decision making, let me refer to a few examples.

In West Moberly First Nations v. British Columbia, the B.C. Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal from an order granting declaratory relief about the location of the western boundary of Treaty 8.40 The location of the boundary was in issue, but there was a more fundamental issue about whether any declaration about the boundary should be granted. Given that the rights conferred by Treaty 8 are not entirely clear, a declaration about the boundary within which those rights may be exercised would not obviously have the practical effect that is typically required for a court to grant declaratory relief. In concluding that declaratory relief was appropriate, the Chief Justice set out an important but restrained role for the court in advancing reconciliation. Noting the practical realities of Aboriginal rights and title litigation, which frequently involve immense expense and time, the Chief Justice rejected an all-or-nothing approach to declaratory relief in these cases. In essence, he held that the court does not need to resolve every issue; instead, the court can play a more modest role in resolving some issues and creating space for others to be resolved outside the litigation process.

In Rosas v. Toca, the Court of Appeal developed the common law of contractual modification.41 When the parties to a contract agree to vary its terms, the court held the variation should be enforceable even if there is no fresh consideration. Rosas is an example of the Chief Justice’s commitment to practical judgment and common sense. When the law seems to lead to a result that is unjust, that is a cue to look more closely at the law and, in an appropriate case, develop the law incrementally in the common law tradition. His colourful introductory paragraph sets the stage: It has been famously said that “hard cases make bad law”; sometimes, however, hard cases make new law. Or, at least, they very much encourage the court to do so lest we give credence to Mr. Bumble’s lament in Oliver Twist: “If the law supposes that…the law is a ass”.42

His reasons in Rosas are notable for their marriage of practical, commonsense reasoning with scholarly reflections on a wide range of case law and

THE ADVOCAT E 661 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

academic commentary from across the common law world. His ultimate reason for concluding the law must develop would be understandable to anyone: “To do otherwise would be to let the doctrine of consideration work an injustice”.43

I turn now to Bob’s role in leading the Court of Appeal and speaking for that court. The traits that make him such a good judge are ones that allow him to excel as chief justice.

The Court of Appeal in British Columbia consists of a chief justice and 14 other justices as well as supernumerary justices. I am informed by Court of Appeal members that Bob brings the same respectful tone to the administration of the court as he does to the courtroom. Court meetings are collegial and democratic. Decisions are made by consensus after all points of view are heard. Bob’s famous sense of humour helps the court run collegially but efficiently.

The chief justice has extensive duties outside hearing cases and being responsible for the administration of the court. One of the chief justice’s roles is to be the spokesperson for the court on serious issues affecting the administration of justice. These can include public education, interaction with the government, the maintenance of the physical plant and generally the representation of the judiciary on all matters related to the administration of justice.

The chief justice has multitudinous roles and responsibilities. As a wise person said, “A lot of the Chief’s work is like housework: there is a great deal of it and it is only noticed when it is not done well.” I will touch on some of those lesser-known duties at the end of this piece but will start with a few of the chief justice’s more significant initiatives.

It became clear during Bob’s tenure that the cost and complexity of the system of civil justice were acting as impediments to many Canadians’ ability to exercise their legal rights in civil and family matters. This was a serious national issue. Following the report of the pan-Canadian committee called Access to Civil and Family Justice: A Roadmap for Change, key members of the B.C. justice system, including Bob, established the BC Access to Justice Committee. Bob chaired that committee and led the discussion in that group about which initiatives should be pursued and how.

He also established a blog to speak to the important issues, a key one being the need for culture change in the profession, particularly in the area of family law. He encouraged people to take a fresh look at the issues, to become involved and to focus attention on the access to justice movement that is taking place in British Columbia. He proved to be a man of this century when his blog received a Clawbie (a Canadian Law Blog Award) in

662 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

2019. By then, Clawbies were in their 15th year and recognized every form of digital publishing in the Canadian legal community.

The Honourable Thomas Cromwell described Bob’s involvement this way: “Chief Justice Bauman was not only an enthusiastic supporter of the work of the Action Committee on Access to Justice, he was a strong leader of the work in British Columbia to react to our 2013 report and of the B.C. efforts to make tangible improvements in access to justice in the province. His encouragement, personable manner and availability to attend and speak at access to justice events were models for how a chief justice can engage with this vital issue and encourage everyone in the system—and beyond—to strive for change.”

Throughout his tenure as chief justice, Bob has recognized the importance of the traditions of the bar while reminding the bar and the courts that change is needed to build a better justice system that will serve the interests of the public. He has worked in the family law collaborative initiative with various people who are not, as he put it, usually in the tent, including children and health professionals.

Bob has taken a leadership role in ensuring that the courts of British Columbia are truly open. His commitment to the access to justice issue has led to some candid comments on the challenges and issues of making the courts truly open to the public. During his tenure, he made himself available for interviews, public comments and appearances on open-line radio programs. He believes that the better information and education the public receives about the courts, the greater confidence the public will have in the courts’ decisions. For example, he recently participated in a Twitter Town Hall, a Provincial Court initiative headed by Chief Judge Gillespie, who continued the initiative started by Chief Judge Crabtree. Bob described it this way:

Social media has become such an important means for people to get information, and it’s a platform underused by the judiciary, including my own court, admittedly. In particular, Twitter is a useful way of creating dialogue, within appropriate bounds, and providing a route for members of the public and bar to educate and inform judges about their concerns.

Bob recognized that having open courts means that the public must truly have access to those courts. This became a major challenge during the pandemic. One senior counsel commented, “Importantly, Chief Justice Bauman led with more than his writing. His response to COVID was amazing.

I argued a number of early video appeals that would have gone into the abyss without the Court of Appeal’s quick and effective response to the shut-down. My clients and the system were extremely well served by Chief Justice Bauman’s leadership at this critical time (dare I call him a technological progressive).”

THE ADVOCAT E 663 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

Bob has addressed the important issues facing Canada and the legal community. A crucial issue facing this country is reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Speaking at the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice in 2021 on the subject of Indigenous peoples and the law, Bob noted that it was almost a decade earlier that Chief Justice Finch, his predecessor, had presented a paper entitled “A Duty to Learn” and said: Chief Justice Finch called on members of the largely non-Indigenous legal community to admit uncertainty and hold ourselves ready to learn about Indigenous legal orders, to divest ourselves of pre-existing certainties as to the nature of the law. He encouraged us to protect the interests of all Canadians by making space for a pluralistic legal and cultural landscape. Most importantly, Chief Justice Finch reminded people like myself that it is we, as strangers and newcomers, who must find our role within the Indigenous legal orders themselves. ….

Sometimes, it can be daunting for an outsider like myself to think of the sheer diversity of Indigenous languages and traditions. How will I ever feel like I’m starting to get the full picture, when there is simply so much to learn and so much, which by virtue of my background, I may never understand? It is truly humbling. I have been advised, and take comfort in the advice, that I need only to take things moment by moment, case by case, and truly listen. Listen to the real stories of those Indigenous writers and researchers who have expert knowledge and lived the experience of Indigenous culture. Listen to the counter-stories. Listen, question, recognize the truth and act.

Bob recognized that the rule of law and a healthy and open justice system are not just Canadian issues but require careful attention around the world, and he devoted time to making an international contribution. Between 2015 and 2021, as part of a delegation from the National Judicial Institute, he visited Ukraine on a number of occasions and participated in judicial education programs in Zaporizhzhia, Odesa and Kyiv.

While Bob could be accused of being forward thinking and alive to the challenges facing the justice system in the future, he is at heart a traditionalist. He believes that an independent judiciary and an independent bar are crucial to a fair and proper justice system.

Our chief justice also has a flair for design—just ask him. His interest in design had an important consequence: he cherished and has worked hard to maintain our world-famous Robson Square courthouse designed by Arthur Erickson.

The tasks of the chief justice are too numerous and diverse to properly catalogue. I could report on the respect he has earned from colleagues across the country serving on the Canadian Judicial Council, for a signifi-

664 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

cant time as its vice-chair, or the hours he has spent on committees to consider the appointment of King’s Counsel or the award of the Order of British Columbia, or showing up to many, many meetings and events in the legal community and in the wider community.

On behalf of the public and the legal community, thank you, Bob, for the wonderful work you have done in maintaining and building a justice system that is fair, open, just and focused on meeting the needs of the community it is meant to serve.

ENDNOTES

1. (2010) 68 Advocate 335.

2. Community Association of New Yaletown v Vancouver (City), 2015 BCCA 227; Society of Fort Langley Residents for Sustainable Development v Langley (Township), 2014 BCCA 271; Western Forest Products Inc v Capital Regional District, 2009 BCCA 356; Martin v City of Vancouver, 2006 BCSC 1260; Denman Island Loc Trust v 4064 Investments Ltd, 2000 BCSC 1618; 417489 BC Ltd v Scana Holdings Ltd, 1998 CanLII 6770 (BCSC).

3. Cambie Surgeries Corporation v British Columbia (Attorney General) , 2022 BCCA 245 [ Cambie Surgeries].

4. The First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v Yukon, 2015 YKCA 18 [Nacho Nyak Dun].

5. Boxer Capital Corporation v JEL Investments Ltd , 2015 BCCA 24.

6. 18320 Holdings Inc v Thibeau, 2014 BCCA 494.

7. British Columbia (Director of Civil Forfeiture) v Qin, 2020 BCCA 244.

8. R v Ling, 2009 BCCA 70.

9. Rosas v Toca, 2018 BCCA 191.

10. Kim v Lin, 2018 BCCA 77.

11. Trotman v WestJet Airlines Ltd , 2022 BCCA 22; Jiang v Peoples Trust Company, 2017 BCCA 119; Samos Investments Inc v Pattison, 2001 BCSC 1790.

12. Beach Estate v Beach, 2019 BCCA 277.

13. West Moberly First Nations v British Columbia, 2020 BCCA 138 [West Moberley].

14. R v MB, 2016 BCCA 476.

15. R v Moazami, 2020 BCCA 350.

16. Smithe Residences Ltd v 4 Corners Properties Ltd., 2020 BCCA 227.

17. Trial Lawyers Association of British Columbia v British Columbia (Attorney General), 2022 BCCA 163.

18. AB v CD, 2020 BCCA 11; British Columbia Birth Registration No 2004-59-020158 (Re), 2014 BCCA 137.

19. 2011 BCSC 1588.

20. British Columbia (Auditor General) v British Columbia (Attorney General), 2013 BCSC 98.

21. R v Rai, 2019 BCCA 377.

22. Vander Zalm v British Columbia, 2010 BCSC 1320 [Vander Zalm].

23. R v Chambers, 2014 YKCA 13.

24. Scott v College of Massage Therapists of British Columbia, 2016 BCCA 180.

25. Heed v The Chief Electoral Officer of BC, 2011 BCSC 1181.

26. Law Society of BC v Gravelle, 1998 CanLII 3215 (BCSC).

27. Assessor of Area #01 – Capital v Nav Canada , 2016 BCCA 71.

28. Catalyst Pulp and Paper Sales Inc v Universal Paper Export Company Ltd, 2009 BCCA 307.

29. Trinity Western University v The Law Society of British Columbia, 2016 BCCA 423.

30. HEABC v Facilities Subsector Bargaining Association, 2004 BCSC 762.

31. Provincial Court Judges’ Association of British Columbia v British Columbia (Attorney General) , 2018 BCCA 394.

32. McDonald’s Restaurants of Canada Ltd v British Columbia, 1999 CanLII 6957 (BCSC).

33. R v Chambers, 2014 YKCA 13 at para 52.

34. R v VPS, 2001 BCSC 619 at para 85.

35. R v DLW, 2015 BCCA 169 at para 69.

36. See e.g. Rosas, supra note 9.

37. See e.g. Nacho Nyak Dun, supra note 4.

38. See e.g. Cambie Surgeries, supra note 3 at paras 14–15; Vander Zalm, supra note 22 at para 49.

39. Huyer v Bourgeois, 1998 CanLII 5330 at para 8 (BCSC).

40. West Moberly, supra note 13.

41. Rosas, supra note 9.

42. Ibid at para 1.

43. Ibid at para 4.

THE ADVOCAT E 665 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

THE LANCE FINCH MEMORIAL FUND AT TRU CALL

FOR DONATIONS

Chief Justice Finch loved the law and devoted many hours as a lawyer and judge to mentoring students, in particular in the area of oral and written advocacy. Chief Justice Bauman has stated: “Lance always commanded the respect of the legal profession in our province and his legacy of significant jurisprudence was acknowledged across Canada. He was a good colleague, a good friend, and a great judge.”

In figuring out how best to honour Chief Justice Finch’s legacy, TRU, Judy Finch (and the Finch family), the judiciary, and members of the bar decided on the establishment of a dedicated endowment in Lance’s name that can be used to advance the development of essential advocacy skills and to provide mooting opportunities to students at B.C.’s newest law school.

Since it was founded eleven years ago, TRU Law at Thompson Rivers University has taken its rightful place as a mooting competitor. Supported by 26 coaches, close to 200 students have mooted against teams from Canada, the USA, Germany, Estonia and Afghanistan. Fifteen TRU mooters have been chosen as clerks in the British Columbia Courts, the Alberta Court of Appeal, the Tax Court and the Federal Court of Canada. This endowment fund will help to ensure that law students develop the communication skills and confidence needed to become skillful advocates and leaders, whether in the courtroom or boardroom. Individuals, law firms, and businesses that wish to donate can do so by contacting Sarah Sandholm, Director of Development at TRU Law by email <ssandholm@tru.ca> or phone 250-377-6122.

Individuals can also give online: <tru.ca/giving>

Thank you for your generous consideration,

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE: Peter Senkpiel, Thomas Cromwell O.C., Robert McDiarmid K.C., & Frank Quinn K.C.

666 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

CREDIT CARD FEES AREN’T INDIRECT TAXATION – AND EVEN IF THEY FEEL LIKE IT, IT DOESN’T MATTER ANYWAY

By David Ross*

We love credit cards, but consumers in Canada have long been shielded from the actual cost of using them. But now, when you buy a pair of new, fast cross-country skis, you may need to think twice before using your credit card, because the merchant may add a surcharge for the privilege. Until recently, Canadian merchants were prohibited by the payment card network operators (“PCNOs”) from charging surcharges to recover the extra costs associated with accepting credit cards.1

At the same time, the 2023 federal budget proposes to amend the Excise Tax Act2 (“ETA”) to exclude PCNOs’ services to the banks from the definition of “financial services”, making them again subject to GST and HST, after a 2021 Federal Court of Appeal decision found them to be exempt financial services.3

Now that these costs are being separately passed on to consumers, are they a form of indirect taxation? And does it matter in HST provinces, since provinces cannot, constitutionally, impose indirect taxation?

The counterintuitive answer to both questions is “no”. Even if the tax on a PCNO’s services to the banks is reflected in higher fees charged by the bank and then ultimately passed on to consumers, the tax remains a direct tax on the final consumer of the PCNO’s services: the bank. And, because the HST is imposed by Canada and not the participating provinces, the distinction between direct and indirect taxation does not matter, because Canada may impose all forms of tax.

BACKGROUND

How Do Credit Cards Work?

This paper will focus on Visa, but similar conclusions can be drawn about other PCNOs.

THE ADVOCAT E 667

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

* The author would like to thank Zvi Halpern Shavim of Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP for his helpful comments. Any mistakes are the author’s alone.

Visa operates what it calls a “four-party” model.4 An issuer (e.g., a Canadian financial institution, like a bank) issues a credit card to consumers, agreeing to provide the consumer credit on certain terms and conditions.

The consumer presents the card to a merchant to purchase something. The merchant accepts the card and sends the transaction data to a payment processor or acquirer. The acquirer is a third-party provider of processing services that connects merchants to Visa’s network and may also provide the equipment to do so (e.g., point of sale terminals) and technical support to merchants.

The acquirer in turn immediately sends the transaction data to Visa (or other PCNO like Mastercard). Visa contacts the issuer—the bank—through its network to confirm whether the transaction is authorized or not. The issuer’s acceptance (or not) is then communicated back to Visa, then to the acquirer, and finally to the merchant, and the transaction completes. The issuer provides the consumer credit for the purchase, and then collects payment under the credit agreement monthly. At the end of each day, Visa coordinates settlement of payments between issuers and acquirers, and acquirers are responsible for settling with their merchants.5

What Is GST/HST Again?

Every recipient of a “taxable supply” made in Canada must pay, to Canada, a five per cent tax (GST) on the consideration for the supply.6 In participating provinces, the recipient must pay an additional tax to Canada at the specified rate for that province.7 Together, those taxes are the HST. A “taxable supply” is any supply made in the course of commercial activity.8

There are two major exceptions: “exempt supplies” and “zero-rated supplies”. Zero-rated supplies are specific taxable supplies, but the tax rate is zero. 9 Exempt supplies are not taxable supplies because the supply of exempt supplies is not “commercial activity”.10 The primary difference is that a supplier of zero-rated supplies can claim input tax credits on its inputs; a supplier of exempt supplies cannot.11

Exempt supplies are those listed in Schedule V of the ETA. One of the most important exempt supplies is financial services.12

“Financial services” are defined in s. 123(1) of the ETA to include:

(i) any service provided pursuant to the terms and conditions of any agreement relating to payments of amounts for which a credit card voucher or charge card voucher has been issued

but do not include “a prescribed service”:

(a) the transfer, collection or processing of information, and

(b) any administrative service, including an administrative service in relation to the payment or receipt of dividends, interest, principal,

668 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

claims, benefits or other amounts, other than solely the making of the payment or the taking of the receipt.13

Who Pays Whom for What in a Typical Credit Card Transaction?

Visa charges the issuers for access to its network and for the settlement and clearing services it provides between issuers and acquirers.14

Issuers in turn charge acquirers interchange reimbursement fees for use of the payment network. Visa sets default interchange fees for the issuers to charge acquirers, but issuers may negotiate different deals with acquirers.15 The standard Visa interchange fee on consumer credit cards increases based on the type of card used. In Canada, the fee is 1.45 per cent for classic, gold and platinum cards; 1.70 per cent for an Infinite card; and 2.45 per cent for a Visa Infinite Privilege card.16

Issuers in turn charge merchants a fee called a merchant discount rate (“MDR”), which is usually a percentage of each credit card transaction and may be higher or lower depending on the type of card used and the associated interchange fee.17 The MDR is either billed separately or deducted from the amount the acquirer remits to the merchant in settlement of consumers’ purchases.

The merchant charges the consumer for the items purchased and, if it chooses, a surcharge for the use of the credit card.

Merchants can add surcharges by brand (e.g., the same surcharge for all Visas) or by product (e.g., higher surcharges for more expensive cards like Infinite or Infinite Privilege cards).

Per Visa’s rules, a merchant must:

• disclose the surcharge to the consumer and give the consumer an opportunity to cancel the transaction without penalty;

• make it clear the surcharge is being charged by the merchant and not Visa;

• provide 30 days’ notice to its acquirer of its intention to add a surcharge (and the acquirer must notify Visa); and

• not charge more than its average effective MDR for accepting the card brand or specific card product.18

In Quebec, merchants cannot add surcharges because all charges must be incorporated into the advertised price of a product, except for Quebec sales tax and the GST.19

WHAT IS TAXABLE IN A TYPICAL CREDIT CARD TRANSACTION?

Where’s the tax?

THE ADVOCAT E 669 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

• Visa’s charge to the issuers is (again) a taxable supply, subject to GST/HST.

• The interchange fee that the issuers charge the acquirers is an exempt financial service.20

• The MDR that the issuers charge merchants is an exempt financial service.21

• The surcharge that merchants may charge customers is also an exempt financial service.

For a long time, the PCNOs’ services were considered an administrative service and therefore not financial services, and GST/HST applied. In 2021, the Federal Court of Appeal found that Visa’s service to issuers was not administrative, and was an exempt financial service.22 The court reasoned that Visa’s services were more than administrative; rather, they were essential to the issuers’ ability to issue credit cards that would be widely accepted, without individually building enormously expensive payment networks and investigating and underwriting every merchant using the network.23

In response, the 2023 federal budget indicates that Canada will overrule the decision and exclude PCNOs’ services from the definition of financial services.24 As a result, PCNOs’ services will, again, be taxable supplies, and issuers will need to pay GST/HST, and PCNOs will need to collect GST/HST, on the fees charged by PCNOs like Visa to issuers like the banks.

Why Is the Merchant’s Surcharge Exempt?

CRA considers that a merchant’s separate surcharge for accepting a credit card is an exempt financial service, notwithstanding its connection with the supply of the merchant’s goods or services, and the potential that the two supplies are a single supply of the merchant’s goods or services.25

The Supreme Court of Canada has endorsed the following test for whether single or separate supplies exist:

The test … is whether, in substance and reality, the alleged separate supply is an integral part, integrant or component of the overall supply.

… [O]ne should look at the degree to which the services alleged to constitute a single supply are interconnected, the extent of their interdependence and intertwining, whether each is an integral part or component of a composite whole.26

There are at least two identifiable supplies in a consumer/merchant transaction: the good or service that merchant is providing (e.g., a pair of cross-country skis) and access to the Visa payment network. They are not a single supply because supplying skis is not dependent on access to the

670 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

Visa payment network. The customer can pay the merchant many ways: with cash, cheque, bank draft, barter or a form of electronic payment with lower fees.

So, a merchant would charge the price and collect GST/HST on the sale of the skis and charge the surcharge for accepting a credit card as a payment method, but not collect GST/HST on the surcharge.

It is important for the merchant to separate the charge for the skis and the surcharge. Otherwise, s. 138 of the ETA might apply to the “incidental” provision of financial services in connection with the main supply of taxable goods. Section 138 applies when two (or more) supplies are supplied together for a single price, deeming the “incidental” supplies to form part of the other supply. In this case, it could deem the payment service to be part of the taxable supply of skis.

Section 139 would also not deem the entire supply to be a financial service, as the surcharge will never constitute more than fifty per cent of the consideration for the total supply. Section 139 applies to deem a mixed supply of financial services and other supplies to be a financial service when, among other conditions, the consideration for the financial service is more than fifty per cent of the total consideration. If credit card surcharges were that high, payment networks would quickly go out of business.

IS THE TAX ON VISA’S SERVICES AN INDIRECT TAX?

Because the issuers do not resell Visa’s services but rather incorporate them into their own credit card products, the issuers are the final consumer of Visa’s services, and the tax on Visa’s services is direct, even though the issuers may recoup the cost by charging higher interchange fees, acquirers may recoup that cost by charging a higher MDR and merchants may recoup that cost by charging a higher surcharge.

Constitutionally, Canada may raise money by any mode or system of taxation,27 while the provinces are restricted to direct taxation within the province.28

Canadian courts rely on John Stuart Mill’s definition of direct and indirect taxation:

A direct tax is one which is demanded from the very person who it is intended or desired should pay it. Indirect taxes are those which are demanded from one person in the expectation and intention that he should indemnify himself at the expense of another.29

Sales taxes on a final consumer of a good or service have been held to be direct taxes, even if the consumer might recoup the cost of the tax by other means.

THE ADVOCAT E 671

VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

In Air Canada v. British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada considered airlines’ challenge of British Columbia’s gasoline tax, imposed when a consumer of gasoline purchased fuel in the province. La Forest J. said:

[T]he generally accepted test of what constitutes a direct tax has been that of John Stuart Mill: “A direct tax is one which is demanded from the very persons who it is intended or desired should pay it.” That person is clearly identified … as the ultimate consumer of the gasoline; there is no passing on of the tax to others, whatever may be the opportunities of recouping the amount of the tax by other means (a very different thing).30

An issuer is likely in the same position regarding the tax on Visa’s services as the airlines were regarding the gasoline tax. The issuers rely on Visa’s service when they issue credit cards and provide credit, but Visa’s services are merely another, albeit important, input consumed by the issuer in providing credit cards just like fuel is an input consumed in providing air travel. The issuer is therefore the final consumer of Visa’s services; the tax is not indirect even if the issuers set higher interchange fees to recover the cost of the tax, and even if they cannot recover that cost through an input tax credit because their own supply of credit card services is an exempt supply.

Does It Matter if It Is Indirect?

If the tax on Visa’s services were indirect, the provinces could not impose it themselves. But the GST, and the HST, are federal taxes, not provincial taxes, so the constitutional distinction between a direct and indirect tax is irrelevant.

The provincial portion of the HST is legally imposed by and paid to Canada under s. 165(2) of the ETA. However, Canada and each participating province have entered a sales tax harmonization agreement under the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act 31 where the province agrees to Canada imposing a particular rate in its province under the ETA and agrees to harmonize its tax base with Canada’s so that HST is collected on the same things. Canada agrees to administer the tax and remit the province’s share under the formula agreed to with the province.32 The agreement is implemented by Canada collecting HST under the ETA.

Even if the tax on Visa’s services were an indirect tax, participating provinces could still benefit by participating in the HST regime.

CONCLUSION

You may curse the surcharge the next time you buy skis. You may even try to pay with gold nuggets to avoid it. But do not challenge the constitutionality of the tax lurking in the background. And maybe say “no” when the bank offers to upgrade your basic card from 20 years ago.

672 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

ENDNOTES

1. The 2017 settlement of class action lawsuits against the major PCNOs—Visa, Mastercard, etc.—forced them to allow Canadian merchants to add surcharges to credit card payments, starting October 6, 2022. Previously, the PCNOs’ Canadian terms of service prohibited surcharges. See Cindy Y Zhang, Guillaume Talbot-Lachance & Luca Vita, “Credit Card Surcharges in Canada: What You Need to Know”, Borden Ladner Gervais (10 November 2022), online: <www.blg.com/en/insights/2022/ 11/credit-card-surcharges-in-canada-what-youneed-to-know>. See also Visa, Annual Report 2022 (2022) at 29 [2022 Visa Annual Report], online: <s29.q4cdn.com/385744025/files/doc_down loads/2022/Visa-Inc-Fiscal-2022-Annual-Report. pdf>.

2. Excise Tax Act, RSC 1985, c E-15 [ETA].

3. Canada, Department of Finance, Budget 2023: Tax Measures: Supplementary Information (2023) at 45, online: <www.budget.canada.ca/2023/pdf/tm-mf2023-en.pdf>; Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce v Canada, 2021 FCA 10 [CIBC].

4. 2022 Visa Annual Report, supra note 1 at 17–18.

5. CIBC, supra note 3 at para 17.

6. ETA, supra note 2, s 165(1).

7. Ibid, s 165(2).

8. Ibid, s 123(1).

9. Ibid, s 165(3).

10. Ibid, s 123(1).

11. Input tax credits, a refund of the GST paid on inputs, can only be claimed based on the proportion of supplies made by the claimant that were in the course of “commercial activity”. This excludes the makers of exempt supplies, or at least excludes the portion of their activity that is making exempt supplies like financial services rather than other, taxable supplies. See ETA, supra note 2, ss 141.01, 141.02, 169, 225(1).

12. ETA, supra note 2, Schedule V, Part VII.

13. Financial Services and Financial Institutions (GST/ HST) Regulations, SOR/91-26, s 4(1).

14. Ibid

15. 2022 Visa Annual Report, supra note 1 at 18–19.

16. Visa, “Visa Canada Interchange Reimbursement Fees” (April 2021) at 5, online: <www.visa.ca/content /dam/VCOM/regional/na/canada/Support/ Documents/visa-canada-interchange-rates-april2021.pdf>.

17. Canada, Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, “How Card Payments Work: Overview for Merchants” (February 2017), online: <www.canada.ca /en/financial-consumer-agency/services/merchants /overview-card-payment.html>; Canada, Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, “Glossary: Payment Card Industry” (October 2022), sub verbo “merchant discount rate”, online: <www.canada.ca/en/ financial-consumer-agency/services/merchants/ glossary.html#mdr>.

18. Visa, Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules (15 October 2022) at 357–61, 900, online: <www.visa.ca/content/dam/VCOM/download/ about-visa/visa-rules-public.pdf>.

19. Consumer Protection Act, CQLR c P-40.1, s 224(c).

20. ETA, supra note 2, s 123(1), sub verbo “financial service” (“any service provided pursuant to … any agreement relating to payments of amounts for which a credit card voucher … has been issued”). See also Canada Revenue Agency, “ABM Services”, GST/HST Info Sheet GI-006 (December 2006), online: <www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/ services/forms-publications/publications/gi-006/ services.html>.

21. Ibid

22. CIBC, supra note 3.

23. Ibid at para 63.

24. Supra note 3.

25. Canada Revenue Agency, ”Application of the GST/HST to Credit Card Surcharges”, GST/HST Info Sheet GI-200 (March 2023), online: <www.canada. ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications /publications/gi-200/application-gst-hst-creditcard-surcharges.html>.

26. Calgary (City) v Canada, 2012 SCC 20 at paras 35–36.

27. The Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3, s 91(3).

28. Ibid, s 92(2).

29. Peter W Hogg, Constitutional Law of Canada, 5th ed (Scarborough: Carswell, 2007) at 858.

30. Air Canada v British Columbia, [1989] 1 SCR 1161 at 1186.

31. RSC 1985, c F-8, Part III.1.

32. See e.g. the Comprehensive Integrated Tax Coordination Agreement Between the Government of Canada and the Government of Prince Edward Island, signed in November 2012.

THE ADVOCAT E 673 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

674 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

ADDRESSING INDIGENOUS CULTURAL SAFETY IN THE LEGAL PROFESSION

By Christopher McPherson, K.C.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its report and 94 Calls to Action to further reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.1 To date, only 13 Calls to Action have been completed. Three crucial Calls to Action that seek to create equity for Indigenous peoples in the legal system—50, 51 and 52—remain in progress.

The importance of ensuring Indigenous cultural safety within the legal system cannot be overstated. The legal system has devastating effects on Indigenous claimants and communities when their safety is not prioritized. Motivated by the need to acknowledge the Law Society of British Columbia’s role in perpetuating the colonial legal system, we established the Indigenous Engagement in Regulatory Matters (“IERM”) Task Force in 2021 to review our processes and make recommendations to improve our ability to effectively engage, address and accommodate Indigenous complainants and witnesses.

The IERM Task Force drafted a report2 that contains key recommendations to address systemic barriers experienced by Indigenous complainants and witnesses, and proposes solutions to establish and maintain culturally safe and trauma-informed regulatory processes. The recommendations include taking steps to build relationships, gain trust and become more proactive in preventing harm to the public, particularly Indigenous individuals. Benchers unanimously approved the recommendations at their July 2023 meeting and the Law Society has begun the process of implementing them.

In addition, the Law Society created the Indigenous Intercultural Course3 in 2022 in response to Call to Action 27, which called on law societies to create skills-based training for lawyers in Indigenous intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights and anti-racism. This free course, which is mandatory for all practising lawyers in British Columbia, provides information about the history of Indigenous-Crown relations, the history and legacy of residential schools and how discriminatory legislation and policies imposed on Indigenous peoples created the issues that the Law Society of British Columbia seeks to address.

THE ADVOCAT E 675 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

The course has received feedback about the positive impact it has had on lawyers and law firms, as well as valuable suggestions for improvement. However, the majority of B.C. lawyers have still not completed it. We urge those who have not completed the course to take the time to go through the materials and reflect on the role that reconciliation plays in their own legal practice, as soon as possible.

The legal profession still has a long way to go when it comes to repairing the harm caused by colonialism, including the discriminatory laws and policies that have been imposed on Indigenous peoples. We at the Law Society are hopeful that, by following the recommendations of the IERM report, boosting lawyer competency through the Indigenous Intercultural Course and continuing to make learning, cultural safety and reconciliation a priority of the organization, we can work toward a safe, equitable, supportive and inclusive legal system in British Columbia.

ENDNOTES

1. For further background, see “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada”, online: <www.rcaanccirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060 525#chp2> and “Delivering on Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action”, online: <www. rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524494530110/1557 511412801>.

2. Online: <www.lawsociety.bc.ca/Website/media/ Shared/docs/publications/reports/Indigenous EngagementTF-2023.PDF>.

3. For more information, see Law Society of British Columbia, “Indigenous Intercultural Course”, online: <www.lawsociety.bc.ca/support-and-resources-forlawyers/professional-development/indigenousintercultural-course/>.

676 THE ADVOCAT E VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

CHANGES IN THE B.C. PROVINCIAL COURT MAY SURPRISE YOU

By the Honourable Chief Judge Melissa Gillespie

When courts reduced operations in 2020 to protect court users and staff from COVID-19, the Provincial Court of British Columbia was determined that its response to the pandemic be not just timely and effective, but also enduring. The intense pressures of the pandemic prompted us to re-think the way the court operated while it required government to accelerate its Digital Transformation Strategy. The resulting advances our court has made and their lasting impact on access to justice may surprise you!

PREVENTING INCREASED BACKLOGS

Among the Provincial Court’s most notable achievements is coming out of the pandemic without significant escalation of our case backlog. In March 2022, our overall provincial weighted1 time to trial delays were generally similar to 2019’s pre-COVID-19 rates, although some individual court locations did experience increases, which we addressed with early judicial appointments for anticipated retirements.

VIRTUAL FRONT-END PROCEDURES

One of the ways the Provincial Court avoided crippling backlogs was by modifying and expanding front-end procedures to support early resolution in criminal, civil and family cases. During the pandemic, we used Microsoft Teams to conduct virtual case conferences. When health measures limiting in-person proceedings resulted in some trials being adjourned, we were able to assign those judges and court staff to increase the number of frontend conferences being held.

These virtual conferences provided flexibility and improved access to justice, including for vulnerable people, those in remote communities and those self-isolating due to COVID-19. Convenient and cost-saving for many litigants and lawyers, they also enabled the court to use judicial resources effectively since a judge located anywhere in British Columbia could preside virtually. Because of virtual conferences’ positive impact on access to

THE ADVOCAT E 677 VOL. 81 PART 5 SEPTEMBER 2023

justice, we have made attending them remotely the default method of attendance, subject to a judge ordering otherwise.

In criminal cases with trial time estimates of a certain length,2 a judge meets virtually with both counsel for a pre-trial case management conference to determine if an early resolution is possible and, if not, what admissions might be made to make efficient use of court time. Results indicate these conferences have led to a high file resolution rate, thereby saving many days of trial time and reducing delays.

Small claims settlement and trial conferences were converted from inperson to virtual proceedings in May 2020. Although remote attendance continues to be the default method of attending these conferences, parties can apply to appear in person.3 Documents for conferences can be submitted by e-mail.

EARLY RESOLUTION OF FAMILY LAW ACT CASES