ADVOCATE

impar ity, rttiality, experience and intervention are thefoundation of w necessary to be a good mediator. I possess these traits,and will bring the table to assist in resolving your

interve wha Integr

STEVEWWAALLACE Mediator, Lawyer

expert ecognized by L *R

” dispute them to t is

swallace@dolden.com OR tioswallace@wallacemedia cialinsu c e eading s L Canada experience earsof 30+ Y One of ’ thear aof commer

ons.com ance litiga a tion. Practitioner ur rs in

tions.cowallacemedia

Advi ts s & Trus tate Senior Es x No appointment of Ale the d t please t is ncentra Trus Co Local presence.

604 992 2595 saace@dodeco O om t. British Columbia marke

About Concentra Trust y. rs of attorne powe , and es s, committe state including trusts, e of ad range a bro cuss x to dis ntact Ale Co

ing the erv r s iso y, LL.B. as rthe announce to ational reach. nt. nt manageme investme r trust rs fo nt manage estme nt inv pende rming inde perfo rk with high- wo tration. We r adminis unde assets f s $36 billion o ersee ars and ov for 70+ ye ss in busine en t company that has be d national trus gulate rally re fede a mpany, is Bank co t, an Equitable ncentra Trus Co

6.668.1203 (P ex.northey@eqbank.ca nior Estates & Trusts Advisor

equ

Sen Al uitablebank.ca/concentra-trust

OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVES

LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, K.C. President

Brook Greenberg, K.C. First Vice President

Lindsay R. LeBlanc, K.C. Second Vice President

Don Avison, K.C.

Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

BENCHERS

APPOINTED BENCHERS

Simran Bains

Paul A.H. Barnett

Sasha Hobbs

ELECTED BENCHERS

Aleem Bharmal, K.C.

Tanya Chamberlain

Nikki Charlton

Jennifer Chow, K.C.

Christina J. Cook

Cheryl S. D’Sa, K.C.

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, K.C.

Tim Delaney

Brian Dybwad

Brook Greenberg, K.C.

Ravi Hira, K.C.

Lindsay R. LeBlanc, K.C.

James A.S. Legh

Dr. Jan Lindsay

Michèle Ross

Natasha Tony

Benjamin Levine

Jaspreet Singh Malik

Jay Michi

Georges Rivard

Gurminder Sandhu, K.C.

Thomas L. Spraggs

Barbara Stanley, K.C.

James Struthers

Michael F. Welsh, K.C.

Kevin B. Westell

Jonathan Yuen

Gaynor C. Yeung

BRITISH COLUMBIA BAR ASSOCIATIONS

ABBOTSFORD & DISTRICT

Kirsten Tonge, President

CAMPBELL RIVER

Ryan A. Krasman, President

CHILLIWACK & DISTRICT

Nicholas Cooper, President

COMOX VALLEY

Michael McCubbin

Shannon Aldinger

COWICHAN VALLEY

Jeff Drozdiak, President

FRASER VALLEY

Michael Jones, President

KAMLOOPS

Jeanine Ball, President

KELOWNA

Tom Fellhauer, K.C., President

KOOTENAY

Dana Romanick, President

NANAIMO CITY

Kristin Rongve, President

NANAIMO COUNTY

Lisa M. Low, President

NEW WESTMINSTER

Mylene de Guzman, President

NORTH FRASER

Lyle Perry, President

NORTH SHORE

Adam Soliman, President

PENTICTON

Ryu Okayama, President

CANADIAN BAR ASSOCIATION

BRITISH COLUMBIA BRANCH

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Scott Morishita

President

Lee Nevens

First Vice President

Mylene de Guzman

Second Vice President

Judith Janzen

Finance & Audit Committee Chair

Dan Melnick

Young Lawyers Representative

Rupinder Gosal

Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Representative

Michelle Casavant

Aboriginal Lawyers Forum Representative

Patricia Blair

Director at Large

Adam Munnings

Director at Large

Randolph W. Robinson

Director at Large

Sarah Klinger Director at Large

ELECTED MEMBERS OF CBABC PROVINCIAL COUNCIL

PORT ALBERNI

Christina Proteau, President

PRINCE GEORGE

Marie Louise Ahrens, President

PRINCE RUPERT

Bryan Crampton, President

QUESNEL

Karen Surcess, President

SALMON ARM

Dennis Zachernuk, President

SOUTH CARIBOO COUNTY

Angela Amman, President

SURREY

Peter Buxton, K.C., President

VANCOUVER

Executive

Heather Doi President

Sean Gallagher Vice President

Zachary Rogers

Secretary Treasurer

Niall Rand Past President

VERNON

Chelsea Kidd, President

VICTORIA

Sofia Bakken, President

CARIBOO

Nathan Bauder

Jon Duncan

Nicholas Maviglia

KOOTENAY

Jamie Lalonde

Christopher Trudeau

NANAIMO

Phil Dwyer

Patricia Blair

Ben Kingstone

PRINCE RUPERT

Emily Beggs

VANCOUVER

Joseph Cuenca

Bahareh Danael

Nicole Garton

Diane Gradley

Graham Hardy

Lisa Jean Helps

Bruce McIvor

Heather McMahon

Heather Mathison

VICTORIA

J. Berry Hykin

Cherolyn Knapp

Kimberley Nusbaum

WESTMINSTER

Manpreet K. Mand

Daniel Moseley

Matthew Somers

Sarah Weber

YALE

Mark Brade

Laurel Hogg

Aachal Soll

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF BLACK LAWYERS (B.C.)

Cecilia Barnes, President

FEDERATION OF ASIAN CANADIAN LAWYERS (B.C.)

Fiona Wong, President INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION (B.C.)

Michael McDonald, President

SOUTH ASIAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Hardeep S. Gill, President

ASSOCIATION DES JURISTES D’EXPRESSION FRANÇAISE DE LA COLOMBIE-BRITANNIQUE (AJEFCB)

Sandra Mandanici, President

ADVOCATE

“Of interest to the lawyer and in the lawyer’s interest”

Published six times each year by the Vancouver Bar Association

Established 1943

ISSN 0044-6416

GST Registration #R123041899

Annual Subscription Rate

$36.75 per year (includes GST)

Out-of-Country Subscription Rate $42 per year (includes GST)

Audited Financial Statements Available to Members

EDITOR: D. Michael Bain, K.C.

ASSISTANT EDITOR: Ludmila B. Herbst, K.C.

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD:

Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., K.C.

Carolyn MacDonald

David Roberts, K.C.

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Mary Saunders

The Honourable Alexander Wolf

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS:

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Jon Sigurdson Lily Zhang

BUSINESS MANAGER: Lynda Roberts

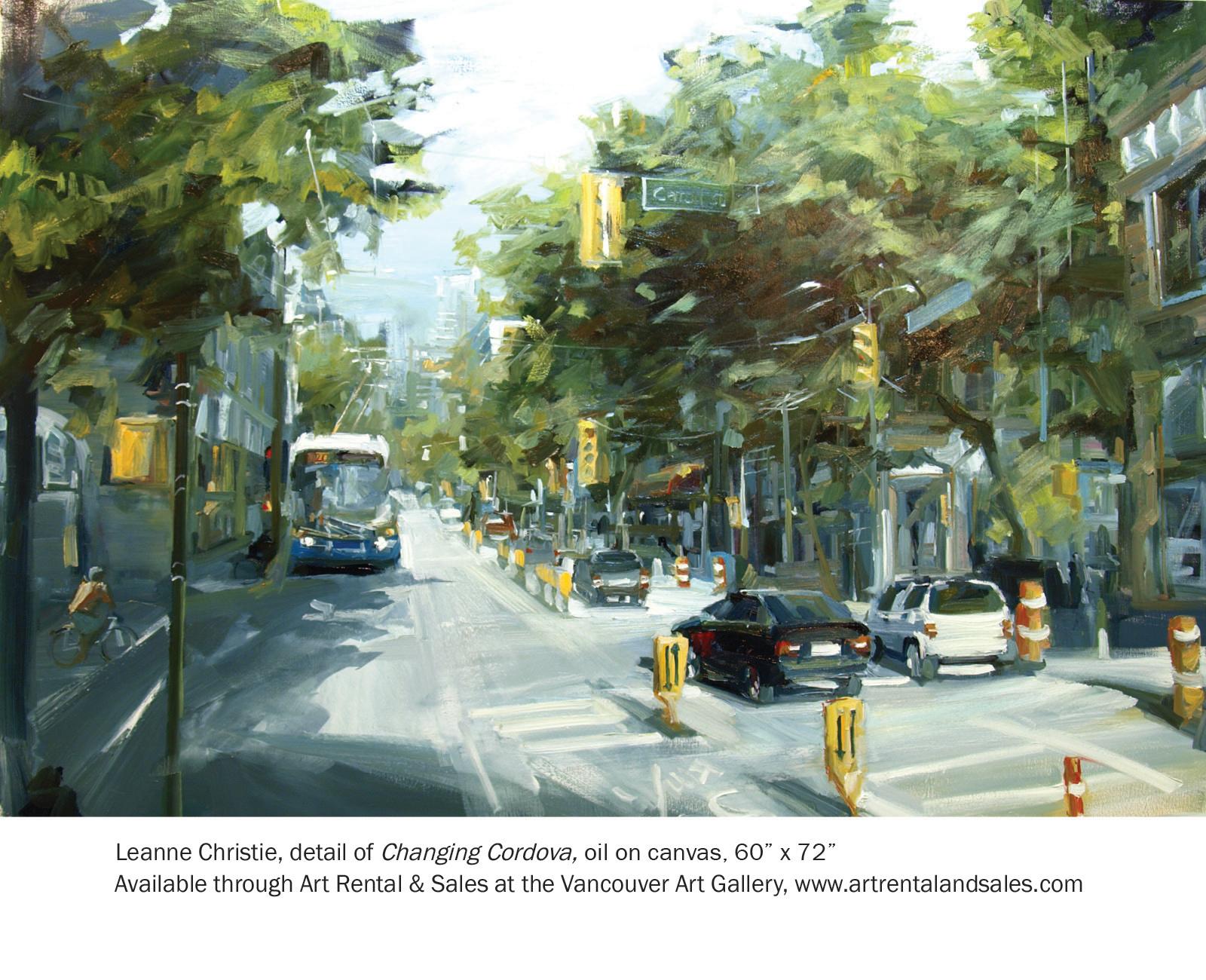

COVER ARTIST: David Goatley

COPY EDITOR: Connor Bildfell

EDITORIAL OFFICE:

#1918 – 1030 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Y3 Telephone: 604-696-6120

E-mail: <mbain@hhbg.ca>

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE: 709 – 1489 Marine Drive West Vancouver, B.C. V7T 1B8

Telephone: 604-987-7177

E-mail: <info@the-advocate.ca>

WEBSITE: <www.the-advocate.ca>

VOL. 82 PART 3 MAY 2024

On the Front Cover: Freya Kodar By

Katie McGroartySome Things Change, Some Things Don’t: Gang Violence in Vancouver Then (1955) and Now (2024) – Part I: The Process By

Joseph C. Bellows, K.C.Bill 48 and Online Platform Workers in British Columbia: A Brief Comment By

Fife OgundeEverywhere But After By Eric

KroshusSpot the Lawyer: The Answer By Joseph C. Bellows, K.C.

Frankenstein’s Folly: A Lesson in How to Avoid Scorch-the-Earth Litigation By

Leslie PallesonON THE FRONT COVER

Freya Kodar is the dean of UVic Law. Read about the legal legacy she follows and the legacy she is building now at p. 337; periodic and elemental perhaps?

We are a firm ofconsulting economists who specialize in providing litigation support services to legal professionals across western Canada. Our economic reports are supported by knowledgeable staffwith extensive experience in providing expert testimony.

We offer the following services in the area ofloss assessment:

Past and future loss ofemployment income

Past and future loss ofhouseholdservices

Past and future loss offinancial support (wrongful death)

Class action valuations

Future cost ofcare valuations

Loss ofestate claims (Duncan claims in Alberta)

Income tax gross-ups

Management fees

Pension valuations

Future income loss and future cost of care multipliers

The Litigation Support Group

Business Valuations

• Matrimonial disputes

• Shareholder disputes

• Minority oppression actions

• Tax and estate planning

• Acquisitions and divestitures

Personal Injury Claims

• Income loss claims

• Wrongful death claims

Economic Loss Claims

• Breach of contract

• Loss of opportunity

Business Insurance Claims

• Business interruption

• Construction claims

Forensic Accounting

• Accounting investigations

• Fraud investigations

ENTRE NOUS

One of our unfortunate colleagues recently found herself in the middle of a maelstrom created by the invention of two cases by ChatGPT, a prominent artificial intelligence (“AI”) system. The mistake was caught before the court application for which ChatGPT had invented the cases was heard, and the court recognized the involved lawyer’s efforts to correct the error, sincere apology and manifest regret.1

In light of examples such as the above, courts and regulators are increasingly urging or requiring lawyers who make use of generative AI (the form to which this editorial relates) for the purpose of legal research and preparation of attendant legal arguments to do so with care, to make known to opposing counsel and the court that AI has been used, and to verify that the citations and statements that AI generates are accurate.2 However, at least some of those courts and regulators still assume that, as long as the appropriate improvements and safeguards are put in place, AI may well be ultimately as useful in the underlying legal research and the drafting of submissions as in such tasks as document production and processing, court administration and streamlining case management.3

Undoubtedly it is important to explore the use of AI to ease burdens on overburdened judicial systems, and to improve efficiencies and reduce costs in the legal system as a whole. Perhaps all could benefit from use of AI’s organizational and predictive abilities to comb through millions of documents, streamline scheduling and provide further means of interacting with the courts and other tribunals. However, we should at least pause before assuming AI is of automatic benefit in legal research and the drafting of submissions, or that its benefits outweigh the costs.

Now, we anticipate some readers will dismiss out of hand the cautious note expressed in the preceding paragraph. Those readers may say that it is

in lawyers’ financial self-interest (as well as a boost to their egos) to carve out this realm from further AI incursion: lawyers want clients to pay them for hours of human work when, were those lawyers prepared to admit it, a machine could do the same or better in a fraction of the time and (assuming the per-use cost of a quality AI system were reasonable) a fraction of the cost.

But let us think about that. When it comes to legal research and the drafting of submissions, (1) is there a problem with the human form of those exercises that can be, or needs to be, solved; (2) if there is, is AI a potential solution to that problem; and (3) if AI is a potential solution, is AI better than other potential solutions?

Is there, in fact, a problem, now, with human legal research and submission drafting? Arguably there are at least two problems. One is that these exercises take a lot of human time (and consume the resources of clients who pay for that time, as well as distracting from other tasks). The second arguable problem is that the legal research rarely results in certainty in terms of output (that is, there is often some ambiguity left at the end of the exercise). What, if anything, can AI do about those issues?

Turning first to the question of time: will using AI for legal research and submission drafting save time? Well of course, AI may spit out an initial result faster than a human can (assuming a computer has not crashed and that internet access is available—otherwise the human able to use a library catalogue and physical books, digests and law reports takes the lead). Does the swifter production of the initial work product itself mean the use of AI saves time? No, it does not—and bear with us on this.

First, let’s not overstate how long human research on most legal topics does or should actually take. (That is, even if AI takes seconds or minutes at most, the human equivalent is in most cases not days, weeks or months, but minutes or hours—just ask the registrars and judges who, when assessing court costs, are reluctant to entertain the thought that lawyers reasonably spend all that much time on any given research task.) That the disparity in time spent (machine vs. human) is less than one might think is because what actually needs to be researched to come to a conclusion on the state of B.C. law is quite limited. It is not the millions upon millions of documents that AI is known for absorbing and generating predictions from. It is, rather, an enactment or two, and—given the principles of vertical and horizontal stare decisis4—ideally a Supreme Court of Canada case, perhaps one or two B.C. Court of Appeal cases, and perhaps a few more B.C. Supreme Court cases. Existing shortcuts for finding those enactments or cases, other than AI, include (1) secondary sources that humans have gen-

erated5 and (2) recent cases in which helpful judges have summarized leading authorities.

We rarely think of research in this limited way anymore because of the vast quantity of resources, over and above those listed in the prior paragraph, that the internet has made available to us. That quantity—and the varied quality—instill panic in many of us. There are millions upon millions of documents we could access, globally, touching on many topics. Given we know that, statistically, something must be out there in some jurisdiction bearing on what we are researching, it is often difficult to resist the temptation to search for it, or avoid a nagging sense of guilt for not doing so. However, a much more limited subset of that available pool of material actually consists of binding authority that needs to be consulted, other than when trying to construct more complex arguments relying on policy or merely persuasive authority to effect a change in, or clarification of, our own jurisdiction’s existing law. We otherwise do not need either a human or AI to churn through the enormous database of at best tangentially relevant material that is the “internet” to come up with an answer to a B.C. question.

Second, while in most cases the immediate work product may be generated more quickly by AI than by a human, receipt of the immediate output is not the end of the exercise: the clock does not stop running at that point. After AI generates its work product, human time is going to be consumed by taking certain extra steps that the human doing their own research and writing would not need to take.

One of those extra steps is checking the AI work product to make sure it is accurate. This “human-in-the-loop” verification is now being urged or even required by courts that contemplate some use of AI for legal research and submission drafting.6 The requirement for human verification likely flows as well from existing standards of professional conduct requiring that lawyers not misrepresent the law to the court and that they take responsibility for (supervise) work that is done in their office.7

It is not, of course, that a lawyer can be careless in doing their own legal research (and can avoid embarrassment or worse by saying “I may be wrong, but at least I was human”). However, in the course of doing their own research, the lawyer is already doing the tasks that checking AI work product would involve: looking at and reading the cases and other sources on which they wish to rely. It is a combined exercise, not a two-step exercise.

The exercise of checking the AI work product is not, in most cases, simply a matter of minutes—rather, it could be a matter of hours. Recent news coverage has made clear that AI is capable of (1) inventing case citations

that look very much like actual case citations, with convincing-looking party names, dates and the names of actual law reports or other sources, (2) inventing passages from those phantom cases, and (3) reporting its results in a way that sounds both coherent and confident. In order to verify the accuracy of the AI work product, a diligent human actually has to find each cited source (if it even exists), read it through, and then think about it.

Where AI generates a form of written submission in which case or other citations are not included and sources are not otherwise identified, the human reviewer must also puzzle through to try to identify what might have been the inputs that generated the answer—questions that the human who had done the underlying research would not have. If the underlying inputs cannot be determined, concerns about potential bias in AI’s selection of a subset of potential sources, or its failure to recognize a bias in dominant sources, may not be resolvable.

There is an additional extra step, that a human author does not need to take, that comes with using AI to generate submissions. Even if the problem of AI systems “hallucinating” footnoted cases were a short-term one that programmers could ultimately fix, the fact remains that counsel taking a case to court would inevitably need to adjust the emphasis and nuance in the text of an AI-generated submission to fit with the facts of their case, their pleaded claims or defences, and their personal style.

A third way in which AI may cause extra time to be spent on a case does not arise in every case, but does in those cases where things go wrong (perhaps in part because not enough time was devoted to the verification and adjustment above). If a mistake AI causes is not caught in time, a lawyer may later need to spend an enormous amount of time and mental energy on fixing or ameliorating the situation in the courts, in the press and before a regulator.

Fourth, say AI performs its job thoroughly and does not, in fact, invent cases. Rather, it finds cases from around the world supporting propositions that the lawyer from whom it has received its mission wants to argue, and it creates elegant-sounding written submissions about those propositions for the court to consider. Thoroughly impressed with AI, lawyers then use it to generate articles, blog posts and case comments (more to post on LinkedIn and firm websites). Next time another lawyer tasks either AI or a human with finding the law on an issue, those AI-generated sources come up in the search and are so attractive that they get cited. Legal arguments get longer, books of authorities get bigger, and more court time is spent on hearing submissions. This may be the price of getting the law right, or it may simply facilitate the spending of time and money on issues that do not

matter, or on which a party is ultimately not going to succeed anyway when core binding law is deferred to.

If it is not AI that can reduce the time spent on legal research and submission drafting (and on the larger litigation into which those exercises may be slotted), what can? Well, perhaps time and cost savings might instead be achieved more effectively through courts setting (or enforcing) shorter deadlines on parties, capping the length of submissions or the number of authorities that may be cited, and encouraging preliminary motions to strike out or otherwise resolve distracting, legally complex claims or arguments.

As referenced earlier, the other “problem” that we often associate with the present state of legal research is a sense of uncertainty: it is difficult to emerge from a legal research exercise with full confidence that the correct answer has been found. Even if AI might not save time, is the use of AI for legal research and generating submissions a means of providing us with the certainty we seek?

We suggest it is not. Uncertainty is not an issue that stems from the fact a human, rather than a machine (once its results are human-verified), has done the research. Rather, it stems from what is being researched: law, which is inherently uncertain. Enactments contain words that are subject to interpretation, cases rarely deal with the whole of any issue, what is found in any given enactment or case may be subject to competing enactments or foundational constitutional requirements and principles, and over time it may evolve.

The fact AI rather than a human does the legal research should not make the outcome any less uncertain. AI is, after all (or so we hope), basing its research on the same categories of sources that human researchers consult: primary sources (enactments, cases) and secondary sources. Although AI may find and process those sources more quickly, in theory it should be looking at the same things as a human would be—other than where AI invents a case that a human would not find. As it is the sources from which, by their nature, uncertainty stems, AI should not actually be generating more certain results. If AI generates arguments that sound more confident than a human researcher might sound in reporting on the results of their research, that is not necessarily a good thing—rather, AI’s confidence might mask problems that a lawyer advising the client or taking a case to court should know about.

Think about all the technologies and innovations that were supposed to make our lives easier that have just caused us to spend more time fretting at our computers, interacting with our IT departments (for those of us fortunate enough to have one) and feeling discombobulated. All we ask is that

before we assume AI is the solution to embrace, we think about the problem we are trying to address, whether the issue is inherent or solvable, and whether there are alternatives.

Still not convinced there is reason for concern about using AI in legal research and submission drafting? Or more concerned by arguments not identified above? Write and tell us—this is an important conversation for us all to engage in.

ENDNOTES

1. Zhang v Chen, 2024 BCSC 285.

2. See, for example, the Federal Court’s December 20, 2023 Notice to the Parties and the Profession regarding “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Court Proceedings”, reproduced in “Court Notices and Directions” (2024) 82 Advocate 245 at 252–54. In that notice, the court said it expects parties to proceedings before it “to inform it, and each other, if they have used artificial intelligence to create or generate new content in preparing a document” that they file. It also “urge[d] caution when using legal references or analysis created or generated by AI” in submitted documents, noting that “[w]hen referring to jurisprudence, statutes, policies, or commentaries … , it is crucial to use only well-recognized and reliable sources. These include official court websites, commonly referenced commercial publishers, or trusted public services such as CanLII”. Further, the court referred to the concept of “[h]uman in the loop”, stating that “[t]o ensure accuracy and trustworthiness, it is essential to check documents and material generated by AI” and “urg[ing] verification of any AI-created content in these documents”. The notice “does not apply to AI that lacks the creative ability to generate new content. For example, this Notice does not apply to AI that only follows pre-set instructions, including programs such as system automation, voice recognition, or document editing. It bears underscoring that this Notice only applies to content that was created or generated by AI”.

3. See also the Federal Court’s companion “Interim Principles and Guidelines on the Court’s Use of Artificial Intelligence”, also of December 20, 2023: ibid at 255–57. This document suggests that, at least as properly monitored, regulated or evolved, AI could ultimately provide valuable assistance in legal research, just as it could for the performance of

administrative tasks, “streamlining aspects of case management” and assisting in translating text.

4. R v Kang, 2019 BCSC 2109 at paras 42–47; R v Comeau, 2018 SCC 15 at para 26.

5. Although bearing in mind that some of those human authors are optimistic or sloppy and their footnotes need to be checked as well, to ensure the cited cases or other sources actually stand for the propositions for which they are cited.

6. For example, as noted earlier, the Federal Court’s December 20, 2023 Notice to the Parties and the Profession regarding “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Court Proceedings”, supra note 2, refers to the concept of “[h]uman in the loop”, stating that “[t]o ensure accuracy and trustworthiness, it is essential to check documents and material generated by AI” and “urg[ing] verification of any AI-created content in these documents”.

7. Rule 2.1-2(c) of the BC Code of Professional Conduct provides that “[a] lawyer should not attempt to deceive a court or tribunal by … misstating … law”, and r 6.1-1 provides that “[a] lawyer has complete professional responsibility for all business entrusted to him or her and must directly supervise staff and assistants to whom the lawyer delegates particular tasks and functions”. The Law Society of British Columbia practice resource entitled “Guidance on Professional Responsibility and Generative AI”, prepared in October 2023, provides on p. 4: “Although Code rule 6.1-1 was intended to cover human-tohuman supervision, it provides an important reminder that lawyers are ultimately responsible for all work product they oversee, whether it be produced by non-lawyer staff or technology-based solutions”. See online: <www.lawsociety.bc.ca/Website/media /Shared/docs/practice/resources/Professionalresponsibility-and-AI.pdf>.

ON THE FRONT COVER

FREYA KODAR

By Katie McGroarty

Growing up in Toronto with librarian parents, Freya’s first job at her local library felt familiar. Her love for reading and research could easily have led her to follow them into a life as a librarian or archivist. Yet, amidst these familiar surroundings, Freya discovered a different passion—one that would guide her towards a journey in law and advocacy, and influence the leadership style she would come to embrace throughout her career. It will be no surprise to those who know her that Freya was a Girl Guide and a Pathfinder. What may be more surprising is that she is an amateur violist.

While the decision to take up the viola in junior high school was largely driven by practicalities (the challenges of lugging the cello up and down the subway stairs, and around the snowy streets of Toronto), Freya came to appreciate its tone and the role that the viola plays in orchestras and ensembles. It may not take centre stage, but it is undeniably essential to an orchestra’s harmony. Freya’s next chapter would mirror her early experiences as a viola player, providing a quietly supportive role in helping others and effecting change, often from behind the scenes.

Although Freya’s aspirations for a legal career did not fully materialize until university, early signs of her interest in law began to emerge. A visit from a female lawyer to a Girl Guide meeting sparked her curiosity about the law and legal practice. Later, as a teenager, Freya took steps to advocate for greater political rights for youth. Writing a letter to then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, she asked for the minimum voting age to be lowered to 16. While the effort did not lead to the kind of change she envisioned, these early experiences would foreshadow Freya’s future in law and hint at her later contributions to legal academia and leadership.

After high school, Freya headed east to Montreal to attend McGill University. It was 1986, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was now entrenched in the constitution and the courts were giving meaning to its content. Freya would complete a B.A. degree in political science. Outside the classroom, she was an elected member of the McGill Student Council, supported gender-neutral language initiatives on campus, helped to form the McGill Coalition Against Sexual Assault and sat on the university’s Senate Committee on Women. Freya’s commitment to feminism and equality, which she embraced at McGill, has been a constant in her life. Law, for her, is a means to advance equality, a philosophy that has guided her career choices and advocacy efforts.

While at McGill, Freya was discovering the rich body of feminist research and advocacy within the legal academy, particularly around discussions of formal and substantive equality. While she had not seriously considered a legal career, through this scholarship, she realized that law could be an important instrument for social change. After spending a year in Quebec City completing a Certificate in French as a Second Language at Laval University, she headed to law school.

As it turns out, Freya was not the only one in her family to see law as a means to advance equality. In 1916, her great-great aunt Isabel Ross MacLean Hunt was the first woman to receive a bachelor of laws degree from the University of Manitoba, and in 1918, the first woman in Western Canada to establish a law office. She would go on to be the first woman in Manitoba to be appointed Queen’s Counsel. In 1983 she was awarded a Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Person Case for her role in improving the status of women in the legal field in Canada.

In choosing to apply to UVic Law, Freya was drawn to its progressive spirit. At the time, Maureen Maloney, Q.C. (as she then was), was the dean, the first female law dean in British Columbia, something that reflected the type of representation Freya wanted to see in law school. After receiving her acceptance, it was the invitation (sent in the mail!) to the annual “Dean’s Barbeque” that confirmed that UVic Law was the type of place Freya wanted to be. In the invite, students were expressly invited to bring their “partners” and children. This recognition of diverse relationships and childcare responsibilities was something that was unusual at that time.

In her first year, Freya remembers her introductory Legal Process class as a place that fostered an environment where students could respectfully disagree—something she recalls Professor Gerry Ferguson as embracing, even if he remembers her class as being among the most opinionated and vocal Legal Process classes he taught. While debate was encouraged, Freya

made sure that there was space for everyone to speak. Her classmate Deborah Hull remembers Freya standing up when a classmate was speaking over others, and not giving some the opportunity to join. Ensuring that everyone’s voices were heard has been an indelible part of Freya’s personality, from her first years in law school until now. Though she may see herself as a background supporter, her colleagues and friends all speak to her quiet integrity, and her ability to effectively challenge the status quo through her strong, non-confrontational demeanour.

At UVic Law, Freya continued her pursuit of equality and commitment to feminism, bringing a feminist perspective to her academic work, and taking courses with Hester Lessard, Lisa Philipps and Margot Young. During her first year, the Law Society of British Columbia’s Gender Bias Committee, chaired by Ted Hughes, Q.C., was examining gender bias in the legal profession and the justice system. As a member of the UVic chapter of the National Association of Women and the Law (“NAWL”), Freya, along with her peers, conducted a survey of female students about their law school experiences. She was part of the group of NAWL members who presented their findings to the Gender Bias Committee when it visited the law school.

After graduating with the Class of ’95, where she shared the William R. McIntyre Award (the graduating class prize for academic excellence, community service and student leadership), Freya articled with the Legal Services Society, with time at the poverty law, criminal law and family law clinics. After working as a staff lawyer for Vancouver’s Legal Services Society and the Langley Legal Assistance Centre, and as a program director at the Law Foundation of British Columbia, she decided to return to school to explore questions that she felt she was not able to address through practice.

Freya completed an LL.M. at Osgoode Hall Law School, under the supervision of Mary Condon. Her thesis, “Corporate Law, Pension Law and the Transformative Potential of Pension Fund Investment Activism”, explored the ways in which pension law and corporate law principles and practices permit or constrain unions from using their pension fund investments to respond to, or influence, corporate behaviour.

Law school positions were scarce in the early 2000s, but an opportunity at UVic Law emerged, providing a chance for Freya return to an institution that resonated with her values and research. The collaborative teaching approach and a focus on social justice aligned with her vision for legal education, so she, her partner Ken and her four-month-old son all made the trip to Victoria to participate in the interview process. When she was offered the position, the fact that UVic accommodated her family responsibilities during the interview process and acknowledged the diverse responsibilities

applicants may have outside of work helped Freya and Ken decide to pack up and head back to the place where she had started her legal education.

Freya joined the faculty in 2005 and recalls her first couple of years as a time of hectic adjustments. She remembers the students in her first classes as generous and kind while she juggled long hours, childcare and the seemingly endless cycle of preparation that comes with being a new teacher. Seeing others on campus struggle to find childcare within an overburdened system, she quickly became involved in a university coalition that encouraged spaces to be opened on campus. Even in her first years, Freya’s commitment to fostering a supportive environment for both faculty and students would be one early example of how she would use her inclusive spirit to help advocate for those around her. Now with 20 years of teaching experience, Freya still loves getting to teach first-year students as they start to think and see the world through a new lens and learn the language of law. She values being able to witness the next generations of law students reacting to a changed perspective, and getting to see where their legal education takes them.

In her research, Freya has focused on questions of income and financial inequality across the life course and has been published in a range of scholarly media. She undertakes this work with attention to marginalization, particularly in the construction of gender and family relations. Freya also teaches in the areas of consumer law, pensions, torts, and disability and the law, where she brings a feminist perspective to both her classroom and scholarly pursuits. Most recently, she has been one of the co-authors of Law and Disability in Canada: Cases and Materials, the first Canadian textbook on law and disability.

Her transition to administrative roles, particularly as Associate Dean Administration and Research from 2016 to 2021, allowed Freya to explore the intricacies of problem solving for a large, influential institution, while supporting her colleagues to advance the types of change needed in the legal landscape. Her role extended beyond the classroom, involving responses to critical situations like the COVID-19 pandemic and the introduction of the joint J.D./J.I.D. degree program in Canadian Common Law (J.D.) and Indigenous Legal Orders (J.I.D.).

When reflecting on her contributions, colleagues Sarah Morales, Associate Professor, and Ruth Young, Director of Indigenous Initiatives, liken Freya’s presence to the Moon in Coast Salish stories—a symbol of transformation, guidance and protection. The Moon is often talked about as being a different version of itself everyday, and like the Moon, Freya is both a transformer and one who is open to being transformed. Her leadership style

embodies these qualities, providing steady guidance while remaining open to change and the evolving needs of faculty, staff and students. Despite her reluctance to seek the spotlight, Freya’s dedication to the faculty, its people and the land is unwavering, something her colleagues see as positioning her as an ideal leader to guide UVic Law into its next chapter.

While she may have never aspired to the position of dean, Freya’s commitment to serving the institution led her to embrace the opportunity, and on July 1, 2023, she started as dean of UVic Law. Freya’s tenure so far has been marked by a dedication to service, where her leadership style aligns with a “lead from behind” philosophy. Overcoming initial hesitations, she embraced the role to facilitate crucial developments within the school, focusing on the collaborative, inclusive and socially conscious aspects of legal education. Her works stems from a personal commitment to bettering the world around her and she is recognized for having the unique ability to listen and understand the school’s obligations to the territories they live on and work with. While the Sun may take centre stage, it is the Moon in the background that helps the stars shine brighter—a role that Freya embodies through her leadership and commitments to students, staff, faculty and the land.

As dean of law, Freya’s priorities are rooted in tangible outcomes. She leads the faculty through planning and curriculum reform processes, emphasizing the need for ongoing growth, inclusion and relevance. With an exemplary record of teaching and research, implementing equity, diversity and reconciliation initiatives, and supporting faculty, staff and student success, Freya has a reputation of balancing both strategy and tackling real-world issues. As she leads the faculty, her focus remains on creating inclusive spaces, providing steady guidance while being open to transformation, change and the needs of those she works alongside. With the completion of the expansion to the Fraser Building, which will house the (provisionally named) National Centre for Indigenous Laws, Freya anticipates celebrating the faculty’s upcoming 50th anniversary in a transformative space that embodies its commitment to equity, justice and reconciliation.

Freya’s journey mirrors the changing landscape of legal education, activism and leadership. Her experiences, from McGill to UVic, from the viola section to the dean’s office, show a dedication to social justice, equality and the influence of legal education. As she leads the UVic Faculty of Law, Freya demonstrates the impact the law can have on shaping a more equitable and just society.

SOME THINGS CHANGE, SOME THINGS DON’T: GANG VIOLENCE IN VANCOUVER THEN (1955) AND NOW (2024)

PART I: THE PROCESS

By Joseph C. Bellows, K.C.After a Vancouver jury convicted multiple people accused of gang violence, the trial judge remarked, “We are only too familiar in this city with violence between rival gangs. We have crimes of violence which endanger the peace and security of the whole community.” Was this the sentiment of a judge who presided over a trial in 1955 or a trial that completed in the fall of 2023?

Gang prosecutions in British Columbia are notorious. The historical present would include the 1995 prosecution of Bindy Johal and four others, formally charged with two counts of first-degree murder, and the subsequent conviction of the tainted juror Gillian Guess, who had a personal relationship with one of the accused during the trial.

Since then, a great many prosecutions have taken place in the province with multiple accused persons associated with recognized gangs, including the Hells Angels, The Greeks, The Red Scorpions, The UN, The Brothers Keepers and others. Invariably the core causation of the conflict involves some aspect of seeking to control lucrative drug trafficking activities.

Gang violence in support of the drug trade is not a new phenomenon, nor is the prosecution of those involved in that violence. But the scope and dimensions of the trial process then and now are profoundly different. This article does not purport to compare present legal principles and evidentiary standards to those accepted in the 1950s. This article only chronicles differences in process, scope and the dimensions of comparable trials. For this comparison, I have chosen one of the most sensational criminal prosecutions of the 1950s in which the accused persons were represented by the two pre-eminent barristers of the day, the Honourable Angelo E. Branca, Q.C., described as the “Gladiator of the Courts”, and Hugh McGivern, Q.C., one of the province’s best-known defence counsel.1

Five men (Robert Tremblay, Luciene Mayers, Charles Talbot, Marcel Frenette and James Malgren) were charged with the attempted murder, on June 11, 1955, of Thomas Kinna. The motive was one recognizable in today’s trials. Kinna was beaten almost to death after he “hi-jacked a small quantity of drugs”, believed to be just ten capsules of heroin with a market value of $40. City Prosecutor Stewart McMorran charged in Police Court that “a four-man gang was dispatched from Montreal to organize the drug, bootlegging and prostitution rackets in Vancouver into one large ring directed from the east”. Four men were sent here from Montreal and were “to organize the city’s illegal rackets among them”. James (Jimmy) Malgren was born in Vancouver, had local knowledge and joined the four. The City Prosecutor alleged that Kinna was a drug addict and pusher who obtained 200 caps of heroin from Bert Lawrence, Chick Morgan and Tom West “without payment” and that the beating was a reprisal for that theft.

Shortly after midnight on June 11, 1955, Kinna was lured to the False Creek flats with two men for a drug “fix”. He was attacked and savagely beaten with a three-quarter inch diameter iron bar. He was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital at 10 a.m. that morning in critical condition suffering fractures to both legs, bruising to his back and head and substantial loss of blood.

Among many remarkable differences between gang prosecutions then and now are how quickly bail was dealt with and how quickly the matter came to trial. The accused persons were arrested within days of the offence. Each had a serious criminal record. Tremblay’s record dated from 1939 and included three months’ incarceration for assault in 1944 and carrying a concealed weapon and possession of burglary tools in 1946. Frenette had been convicted of breaking and entering in 1943. Mayers’ criminality began in 1924 and included convictions for breaking and entry, theft, armed robbery (for which he received a sentence of eight years’ incarceration), illegal possession of burglary tools, possession of opium and passing counterfeit money. Talbot’s record started in 1934 and included possession of opium, possession of stolen goods, attempted shop breaking and armed robbery (for which he received a sentence of seven years’ incarceration). Malgren’s record started in 1946 and included five years for armed robbery, three months for inflicting bodily harm and ten years for an offence under the Narcotics Act. Bail was dealt with in the Kinna case within two months and each man was detained.

A preliminary inquiry was conducted and by September 7, 1955 the accused persons had been committed for trial. On September 8, 1955, ten exhibits entered at the preliminary inquiry were transferred to “SCR Locker” (the Supreme Court Locker) and on September 9, 1955 the registry

received the five warrants of committal. On October 12, 1955 an order was made for the attendance of R. Gordon to testify for the Crown.

The trial commenced before Justice Manson with a jury in Assize Court in Vancouver on October 17, 1955, so within four months of the arrests. As my colleagues at the bar will attest, having bail dealt with, a preliminary inquiry conducted and a jury trial commence within four months of arrests being made is remarkable compared to the present day. Currently, it is not unusual for a client, if an allegation is serious, not even to find representation within four months of their arrest. Defence counsel would not contemplate a bail hearing before receiving substantial disclosure from the Crown, organizing sureties and preparing a reasonable “release package” to form part of their submissions. With exceptions, it is not unusual for counsel not to be in a position to make an application for release before three to five months after their client’s arrest. Even more remarkable is that the trial of five accused persons commenced before a jury within four months of their arrests. With exceptions, given the competing calendars of defence counsel, the Crown and the availability of court time, today it would not be unusual for a trial to be set down a year after bail was dealt with. In a serious case, with multiple accused, it is not uncommon for a trial date in Supreme Court to be 12 to 18 months after an arrest.

Of course, the form of the indictment today is different than it was in the 1950s, as reflected below:

1955 THAT at the City of Vancouver, in the County and Province aforesaid, on or about the eleventh day of June, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and fifty-five, they, the said ROBERT TREMBLAY, MARCEL FRENETTE, LUCIENE MAYERS, CHARLES TALBOT and JAMES B. MALGREN, did unlawfully attempt to murder THOMAS KINNA, against the form of the Statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace of our Lady the Queen, her Crown and Dignity.

2024 Robert Tremblay, Marcel Frenette, Luciene Mayers, Charles Talbot and James B. Malgren on or about (date), in the City of Vancouver, Province of British Columbia did attempt to commit the murder of Thomas Kinna, contrary to Section 239(1)(b) of the Criminal Code

The 1955 indictment also included a count of “intent to wound” and a count of “assault causing bodily harm” and was personally signed by the Attorney General, Robert W. Bonner. Today, a direct indictment is prepared by trial counsel, then reviewed and, if approved, signed by the Assistant Deputy Attorney General.

On the first day of trial, the entire jury panel was exhausted by noon and the judge instructed the sheriff to summon 15 more potential “jury men”

during the noon hour adjournment. Such a person is referred to as a “talesman”. Black’s Law Dictionary describes a talesman “as a person summoned to act as a juror from among by-standers in the court. A person summoned as one of the tales added to a jury.” This required sheriffs to leave the courthouse and stop and take 15 individuals off the street and into court to form part of the jury panel. This procedure for summoning a talesman is still available today, although jury pools are large enough that the use of the procedure is rare.

After jury selection, the Crown called Dr. E.W. Fink, who testified that he had known Kinna “since he was born”. He testified that Kinna arrived at Vancouver General Hospital in critical condition and in severe shock. He confirmed that Kinna was a drug addict and that he administered “a quarter gram of morphine every four hours for the first four days”.

Kinna began his evidence on October 18, 1955. The trial judge allowed an application by counsel to have the jury “take a view” and the entire court including judge, court staff, counsel, jury and the five accused persons reconvened on the False Creek Flats. “Thomas Kinna … limped ahead of a curious procession that wound its way … along a scrub-tangled path beside railroad tracks …”. This procedure is available and is allowed in the court’s discretion. My only experience was when defence counsel made an application that the jury view a portion of Dunsmuir Street between Howe and Granville Streets in downtown Vancouver where a shooting had occurred.

For trial, the Crown had requested the medical records of Kinna from Vancouver General Hospital. The hospital refused to provide them. The Crown relayed this information to the judge, who indicated that he was going to have “no nonsense” from the hospital and threatened a bench warrant if the records were not produced forthwith. When the records were brought later in the day, the Chief Medical Record Librarian still refused to provide them to the Crown until court resumed. This difficulty with having hospitals produce medical records persisted until the Criminal Code amendment authorizing peace officers to seek a production order.

On October 19, 1955, Branca sought a mistrial, advising the judge that the day before the Vancouver Province had published the name and address of each of the jurors. Branca alleged that this was “contempt of the most profound type”. Justice Manson agreed, dismissed the jury, ordered a new trial and ordered the publisher and editor of the newspaper to appear in court to show cause why they should not be cited for contempt. On October 20, 1955, the contempt was confirmed and a fine of $1,208.40 imposed.

In terms of a record of proceedings, all of the above matters are represented by 11 lines of handwritten notations found in a leather-bound vol-

The new trial commenced before Justice Clyne on December 12, 1955, at 11:04 a.m. Branca represented Frenette, Talbot and Mayers. He used all 12 of his peremptory challenges for each of his three clients. McGivern represented Malgren and Tremblay. He did not use any of his challenges for either client. The Crown stood aside six of the jury panel. The jury was excused and ordered to return on December 19, 1955, at 11 a.m.

On that day, Mr. Hefferman opened to the jury at 12:08 p.m. His opening was eight minutes long. Although brevity is encouraged in Crown openings, this was very brief indeed. I have no doubt that present defence counsel would endorse the brevity.

Three witnesses were called on the first day of trial. The direct examination by the Crown and cross-examination by both defence counsel of Allan Jackson took approximately five minutes. The direct examination and cross-examination of Constable William Eades took approximately 28 minutes, and the direct examination and cross-examination of Edwin Henry Funk took 21 minutes. No admissions of fact were filed during the trial and the remarkably fast pace of examining witnesses continued. On the third day of the trial, the direct examination and cross-examination of John Pukish took ten minutes and the evidence of John Wardrop took six minutes. On the fourth day of trial, the “railway policeman”, Constable Harold McDonald (who found Kinna), took nine minutes. The two main witnesses for the Crown were the victim Thomas Kinna and Robert Gordon. Their evidence took approximately one day.

Only 17 exhibits were filed at trial, two of which were photographs. Today’s police disclosure often includes several hundred photographs from which the Crown selects and tenders many dozens.

The Crown closed its case at 11:30 a.m. on the fifth day of trial, December 16, 1955. During the trial, several voir dires were conducted in the absence of the jury. Taking this into account, with the jury’s absence for other matters, the evidence of 12 witnesses was heard over the period of approximately three and a half days. Given the seriousness of the offence and the number of accused, this was an unusually quick trial which, today, certainly would have taken several weeks, if for no other reason than each accused would have separate representation. The Crown’s closing argument, on December 16, took 48 minutes, McGivern’s closing was 51 minutes and Branca’s closing was 85 minutes. Counsel strive for this sort of brevity in closing arguments, but it is seldom realized today.

The judge’s charge, at 86 minutes, was exceptionally brief. It would undoubtedly take much more time today, given the number of accused and the special warnings the judge would have to include in his remarks regarding the unsavory nature of the Crown’s two main witnesses.

The jury found each of the accused persons guilty of attempted murder. This was after the jury had deliberated for 100 minutes. This is unheard of in trials today, especially given the number of counts and multiple accused.

The sentencing of the accused persons took place on December 19, 1955, four days after their conviction. As will be discussed in a later part of this article, defence counsel today would never represent more than one accused person in a multi-accused prosecution. Regardless, in this case, it seems a daunting task to prepare submissions and materials for this sentencing in such a short period of time.

On December 19, 1955, Branca’s submissions on behalf of Talbot, Frenette and Mayers took approximately five minutes. McGivern’s submissions in relation to Malgren and Tremblay followed, beginning at 10:59 a.m. There is no record as to the duration of his remarks. Justice Clyne was informed of the criminal records of each of the accused and he sentenced each man to 20 years’ incarceration.

At the beginning of this article, I posed the question whether the trial judge’s remarks were made at the conclusion of a trial in 1955 or the fall of 2023. The remarks relate to the trial discussed here, in 1955. In imposing sentence, the judge stated that “citizens are heartily sick of constantly increasing gang violence and will not permit this type of crime to plague what used to be a comparatively peaceful place.”

Some things change, some things don’t.

Part II of this article, “Substantive Differences”, will follow in a later issue of the Advocate.

ENDNOTE

1. The description of this case is based on considerable research, including through the Provincial Archives and materials in the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal criminal registries.

BILL 48 AND ONLINE PLATFORM WORKERS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: A BRIEF COMMENT

By Fife OgundeOn November 16, 2023, the government of British Columbia announced a proposal for new employment standards for platform workers.1 These proposed amendments are designed to ensure that platform workers are regarded as employees under British Columbia’s Employment Standards Act and Worker’s Compensation Act 2 In the words of the Minister of Labour, “the workers who appear at the touch of a button to drive us home or deliver our dinner deserve to be treated fairly”.3 The proposed amendments are expected to come into effect early 2024.

The announcement has met with mixed reactions. The BC Federation of Labour, for example, considered the plan as “not going far enough” and also expressed concerns about drivers and delivery workers not being guaranteed pay for the time spent waiting for the next assignment.4 Platform workers in British Columbia have regarded it as a starting point, but also note that the proposed minimum wage standard is insufficient to cover operating costs and provide for families.5

HISTORY OF GIG WORKER PROTECTION IN BRITISH COLUMBIA

Of all the Canadian provinces, gig work6 has been most prevalent in British Columbia.7 A 2018 survey of independent workers showed that gig workers preferred self-employment and the flexibility and freedom provided by the gig economy.8 Income instability and lack of access to employer benefits were identified as the biggest disadvantages to independent gig work.9 In 2019, United Food and Commercial Workers International Union filed a complaint against Lyft Canada Inc. for a declaration that Lyft and Uber Drivers are “dependent contractors” and therefore employees under British Columbia’s Labour Relations Code. This application was dismissed.10 In October 2021, three Uber drivers fired after alleged conflicts with passengers filed a complaint against Uber at the British Columbia Labour Relations Board.11

In October 2022, the Ministry of Labour initiated a public engagement to review and propose appropriate employment standards and other protection for app-based ride-sharing and food delivery workers. In April 2023, researchers conducted a study on precarious work in British Columbia. According to the study, half of B.C. workers lacked access to “standard jobs” and thirty-seven per cent of workers were in “precarious employment”.12 The analysis concluded that British Columbia’s system of labour law and employment standards did not guarantee employer-provided benefits coverage, adequate income, certainty of work hours or a voice at work for many workers.13 Included in the recommendations was the need for addressing misclassification of employees as independent contractors and setting a floor of a minimum set of rights for workers not considered employees. 14 Before the introduction of the proposed amendments, companies, including those with only incidental relationships, have expressed concerns with the proposal. DoorDash, a food delivery company, claimed that most of its workers would stop working on the platform if they could not choose their hours.15

PLATFORM WORKERS AS EMPLOYEES?

One of the major challenges with recognizing platform workers as employees and platforms as employers under the proposed amendments is the fact that most platform workers do not provide service on one delivery platform. More than two-thirds of those who completed the survey indicated working on only food-delivery platforms, with seventeen per cent indicating that they worked only on ride-sharing platforms.16 More than half of the workers indicated working on multiple platforms, with fifteen per cent claiming they worked on three to five platforms.17 In such cases, defining a platform operator as the employer of the platform worker becomes more problematic. In instances where a worker is present on multiple applications, it is less clear what platform bears the responsibility for maintaining minimum standards.

Another challenge, albeit a lesser one, is the fact that not all platform workers can be truly classed as employees. There are still categories of platform workers that are independent contractors.18 Even in the ride-hailing and food delivery sectors, some platform workers are more dependent on platform labour than others.19 Determining these categories of workers is in itself a challenge as more often than not, platform work is subsumed into the “gig economy”, which is a diverse economy containing various categories of workers.20 The Greater Vancouver Board of Trade points out this difficulty with respect to British Columbia, using it as a basis to argue for a “measured, cautious and precise approach” to regulating ride-sharing

and food delivery platforms.21 The Board of Trade further argued that providing platform workers with the same protection as employees could lead to undesirable outcomes such as lost income, higher cost of services and reduction in value of the gig economy.22 While there may be questions regarding the veracity of such arguments, the point here is that the wording of the legislation essentially covers all categories of platform workers when in truth the problems it aims to solve are principally located in two sectors: ride-share and food delivery. It is workers in these areas that formed the bulk of public engagement before the development of these proposed amendments. The all-inclusive definition may end up creating new interpretation and application problems, especially when other categories of platform workers outside ride-share and food delivery seek to enforce employment rights without being properly classed as employees.

Summarily, it is important to understand the aim sought to be achieved, which is protecting vulnerable workers. Not all workers have the same level of dependence on the gig economy, but for heavily dependent workers at least, the risks associated with the gig economy necessitate a certain degree of legislative protection. This is not in dispute, even by platforms. Are all platform workers employees? This is a more difficult question to answer based on the diversity in the structure and operation of platforms. There are features of the relationship between digital platforms and platform workers that closely resemble the traditional employment relationship—e.g., control over workers’ access and usage. Other features suggest an independent contractor relationship e.g. flexibility in work hours and workers’ provision of work tools. Unequivocal resolution of this question has proven difficult, particularly in the courts. By presuming an employment relationship for platform workers, particularly for minimum wage, legislative intervention provides much-needed clarity in the regulation of platform work. Will some platform workers look more like independent contractors than others? Yes. Will all benefit from minimum standards of employment? Yes. Will a presumption of employment impose additional standards of employment on ride-hailing and food-delivery companies? Yes? Is it necessary? Based on existing research, yes. On this basis, the proposal can be considered a step in the right direction. To the possibility of the amendments covering more categories of workers than intended, it may be best to say, “We will cross that bridge when we get there.”

ENDNOTES

1. See British Columbia, “Fairness Coming for Gig Workers” (16 November 2023), online: <news.gov. bc.ca/releases/2023LBR0030-001799>.

2. See Bill 48, Labour Statutes Amendment Act, 2023, SBC 2023, c 44.

3. See supra note 1.

4. See Bethany Lindsay, “B.C. Proposes Minimum Pay Standards and Workers’ Compensation for App Based Gig Workers”, CBC News, (16 November 2023), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-

columbia/labour-standards-app-based-gig-workers -bc-1.7030885>.

5. Ibid

6. While the gig economy and the platform economy tend to overlap and are referred to interchangeably, they are not the same. Not all gig work is connected to the platform economy. See Carolyn Ali, “What is the Difference Between the Gig Economy and the Platform Economy?” University of British Columbia (19 January 2023), online: <https://beyond.ubc.ca/ what-is-the-difference-between-the-gig-economyand-the-platform-economy/>.

7. Statistics Canada, “Study: Measuring the Gig Economy in Canada Using Administrative Data” (16 December 2019), , online: https://www150.stat can.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/191216/dq1912 6deng.htm>.

8. “Independents’ Day: Why Gig Work is Taking Hold in BC”, Vancity (August 2018), online: <www.van city.com/SharedContent/documents/pdfs/News/ Vancity-Report-Gig-Economy-2018.pdf>.

9. Ibid.

10. See Lyft Canada Inc v United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, Local 1518, 2020 BCLRB 35 (CanLII).

11. See Jon Hernandez, “B.C. Uber Drivers Say They Were Fired for Refusing Unsafe Work, File Labour Complaint”, CBC News, (8 October 2021), online: <www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/b-cuber-drivers-say-they-were-fired-for-refusingunsafe-work-file-labour-complaint-1.6203671>.

12. Iglika Ivanova and Kendra Strauss, But is it a Good Job? Understanding Employment Precarity in BC, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, April 2023, online: <policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/

uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2023/04/BC %20Good%20Job%20report%20final%20web. pdf>.

13. Ibid

14. Ibid at 57.

15. Zak Vescera, “BC Moves Closer to Gig Worker Protection Laws” (11 August 2023), The Tyee, online: <thetyee.ca/News/2023/08/11/BC-MovesCloser-Gig-Worker-Protections-Laws/>.

16. See British Columbia “App-Based Ride Hail & FoodDelivery Work in British Columbia: What We Heard”, <engage.govbc.ca/app/uploads/sites/ 121/2023/04/What-We-Heard-Report-GigWorkers -1.pdf>.

17. Ibid

18. See Carolyn Ali, “Working in the Gig Economy? What You Don’t Know Might Hurt You”, University of British Columbia (19 January 2023), online: <beyond.ubc.ca/working-in-the-gig-economywhat-you-dont-know-might-hurt-you/>.

19. Studies show that the level of dependence on platforms may also influence their response to losing platform work. See Youngrong Lee, “After a Global Platform Leaves: Understanding the Heterogeneity of Gig Workers Through Capital Mobility” (2023) 49:1 Critical Sociology 23.

20. Online: https://www.boardoftrade.com/files/ advocacy/2023-gig-economy/gig-economy-mar2023.pdf#view=FitV

21. See “A Path Forward for the Gig Economy in British Columbia” (March 2023), Greater Vancouver Board of Trade, online: <www.boardoftrade.com/files/ advocacy/2023-gig-economy/gig-economy/mar2023.pdf#view=FitV>.

22. Ibid

EVERYWHERE BUT AFTER*

By Eric KroshusDeath was lonely. For some time he’d suspected as much, but it wasn’t until he paused to watch the coda of a plum-purple dusk outside an alpine village that he accepted the gnawing emptiness in his stomach for what it was. He stood perfectly still as the last light dissolved into night, and then he stood longer still in the inky black, feeling stinging shards of snow falling sideways on the freshly roused wind. Then, he decided that he couldn’t face the long journey ahead, alone through the serrated dark, and so he turned back toward town.

He wandered the empty streets covered in fresh snow tinted apricot by the soft glow of latticed lanterns lining the street like a string of incandescent Fabergé eggs. Death sensed the muffled thrum of conversation nearby, and so he bent his trajectory in that direction. The murmur of interwoven voices grew into a hum, and as he drew nearer, he noticed a globule of honeyed light oozing out of an unshuttered window and onto the street. Death meant only to glance through the window as he strode past, but as he approached the window, it was as if he actually were wading through honey. He slowed to a stroll, then a crawl, then to a pace most generously described as idling.

Death knew he wasn’t welcome, but he couldn’t help but linger in the light. He watched as barrel-shaped men gripped vast flagons of mead, amber liquid splashing onto rough oak tables as the men tipped their heads back and sprayed great geysers of laughter across the room. Later, through a different window, he saw a few adults clustered around a bronzed turkey, scratching their heads and giving it dubious pokes like weekend mechanics around an open hood. Through another, he saw an old couple huddled together on a couch, watching a movie from their youth.

Each window revealed a different scene, though the ratio remained the same: fellowship inside, Death outside. Alone. Apart . Still, as he gazed through each frosted window, Death sometimes felt the separation flicker, and though he still ached with loneliness, he smiled. If he lingered undetected for several minutes, the flicker lingered too, a warm glow expanding,

* This story won first place in the 2023 Advocate Short Fiction Competition.

invigorated as if by a glassblower’s breath and then fashioned into a fragile glass animal which would keep Death company for a time. More often, someone would spot him immediately, screaming or rushing over to slam the shutter in his face. Mostly, he was conspicuously ignored, as if even a glance at his face was too horrifying to risk. Death was used to such reactions, but each time he felt lonelier still, pulling his hood tighter as he slunk away.

After another slammed shutter, Death decided he’d overstayed even his unwelcome in the village. The once roaring wind was now tamed, reduced to nothing more than a meek flutter. Plump snowflakes fell like languid confetti. His duty lay elsewhere: it was time to go.

At the edge of town, Death stopped for a break near a home tucked away within a grove of cedars. Like a minnow drawn to an angler fish’s glowing lure, Death mindlessly drifted toward the feeble light flickering through a single unshuttered window. As he drew near, he saw that the light was cast by a handful of paraffin candles. He peered inside: subdued people clothed in black sat on low stools, speaking in hushed tones. A golden retriever was curled on a mat by the wood fire. Black sheets were draped over the walls in several places, covering what Death suspected were mirrors.

A few people glanced in his direction, but Death sensed neither fear nor hostility in their eyes. He wasn’t a welcomed guest, but his presence was accepted. As Death surveyed the room, he noticed a boy of around seven staring at him. Seeing that he’d been spotted, the boy walked toward Death without breaking his gaze.

“Did you know my grandma?” the boy asked. Death nodded. “Come in then – we’re sitting shiva. There’s lots of food and it’s warm inside. You can pet Akiva if you want, he’s by the fire,” he added with great seriousness.

From then on, Death had a friend. Although his duty drew him away frequently, he returned to the village as often as he could. He lived for the days he and the boy wandered about town with Akiva, transforming the village into their own secret world. Or they’d hike through alpine meadows, reveling in the fresh air, marveling at the delicate flowers which bloomed in the midst of indifferent granite. Sometimes, they’d merely throw a stick for Akiva, delighting in his delight at the most simple of pleasures.

Death was happy. He didn’t even mind when the boy asked him to lower his hood so he could see his face. Death always politely declined—although he’d never seen it himself, he was afraid to show the boy the face everyone else was too scared to even glance at. As their friendship deepened, Death forgot the feeling of loneliness, and although he knew it was silly precisely because of who he was, Death secretly hoped their friendship would never end.

After seven years, it did. Every quarter, Death received a list of names to cross out before the next season. As he scanned the new list absentmindedly, a name suddenly leapt off the page. Death looked away and then back again, praying he’d misread the name even though he knew he hadn’t.

The next three months, Death returned to the village as much as possible. Each time, he avoided his unavoidable duty, putting it off until the next time, and when the next time came and went, he always convinced himself he needed just one more next time to savour.

As the final leaf fell from the boy’s favourite aspen tree, the next times ran out. Death knew he could no longer avoid his duty, but he could make the end peaceful, and so he found a quiet spot in the forest near the boy’s home. He laid down a soft blanket of pine needles at the edge of a stream dancing with flecks of golden light, and then he waited for the boy.

Soon, Death heard the boy calling out “Akiva, where are you?” A minute later, the boy entered the clearing, smiling and waving once he spotted Death. Death began to shake, and he thought he might be sick. The boy took a few more steps and his smile vanished.

“Akiva!” he screamed, rushing toward the spot where the dog lay. He cradled Akiva in his arms, tears streaming down his face. Death looked away, unable to bear the pain.

“What have you done?” the boy sobbed.

Death searched desperately for something to say, but his mind was blank. He wanted to tell the boy he was sorry, to explain that he had no choice, but his rehearsed lines now escaped him. Instead, he bowed his head, too ashamed of what he was to face his friend.

“You take Akiva, but you can’t even look at me?” the boy cried. Death pulled his hood tighter. “I don’t need to see your face to know what you are,” the boy said. “You’re a coward, and I never want to see you again!”

As the years passed, Death continued to fulfill his duty—from this there was no escape—but the shame from that night was seared into him. It was not just a stain on his character—his character was a stain on the world. He was the worm at the core of life, and he always had been. Death was lonely again.

The boy, beneath his anger, was also lonely. But as the weeks passed, the past’s sting lessened and the future’s glimmering promise pulled him back into the rush of life. Moment by moment, day by day—and then suddenly, all at once—the boy became a man. He went to college possessed of thrillingly vague notions of becoming a doctor which vanished when they came face to face with a cadaver. After wandering through diverse fields in search of a major, he stumbled into anthropology. He learned about tablets

of clay and paintings in caves, carbon dating and polyandrous mating, burial sites and the afterlife and of course, he examined pottery shard after pottery shard. He learned, in short, everything that it was to be human, and then in the summer of his junior year, he fell in love. The following spring, as the frozen river thawed and Caribbean blue eggshells cracking like ice heralded new life, the world seemed unbounded and eternal. Then, in quick succession, his heart was broken, and he graduated to find the six-figure job market for anthropologists wanting. He was adrift, working variously as a tutor, a tour guide and a minor league mascot named Odin, all the while trying and failing to envision what his life might look like at the impossibly old age of forty. The next fall, he went to law school.

Although he never forgave Death, he never entirely forgot him. Months would pass without a thought to his old friend, and then, in a quiet moment after a raucous night out, he would remember Death. During one such fit of nostalgia, he got a memento mori tattoo. His parents warned him that he’d regret the tattoo when he was older, but he knew they were wrong: he regretted it immediately. Afterwards, if he ever found himself shirtless near a mirror, he averted his eyes, and soon the avoidance was so instinctual that he often forgot he even had a tattoo.

At first, he dabbled in wills and estates, but he soon shifted into corporate insolvency, where he built a reputation as a tough but fair advocate. The law fascinated him. He pictured it as a mural on the ceiling of an enormous dome upon which was painted all the drama of human life. And yet the law existed beyond any single life, like an ever-evolving Sistine Chapel. His job was to repair it, touch it up here and there, and then occasionally extend his little corner of the law. As he climbed the stairs to his office every morning, he imagined himself as Michelangelo, humbly ascending his ladder for a day’s work.

He married, made partner, had kids. Forty became a harsh reality then a wistful memory. He bought his son his own golden retriever with the point of one ear folded down like a wink. The ink on his tattoo faded and his skin sagged and folded until the tattoo became truly invisible. His children grew up, moved out, started families of their own, and then, while she was pulling radishes out of the moist dirt on a pleasant Tuesday afternoon, his wife died.

Although his work was done, Death stayed for the funeral. He wanted to apologize to his old friend, but he couldn’t find the right moment, and so he stayed in town while the old man sat shiva, lingering outside his window, waiting. On the fourth day as the sun started to set, the old man stood up abruptly and strode outside to confront Death.

“You’ve taken Akiva, my parents, my friends,” he spat, “and now you’ve taken my wife before she could watch her grandchildren grow.”

“I-I-I,” Death stammered.

“And still, you won’t take off your hood! You take everything from me, but you won’t look me in the face!”

Death bowed his head. “I’m sorry,” he whispered, but the old man wasn’t listening.

“I guess it doesn’t matter,” he sneered, “I’ve always known what you are.”

He was right, Death thought, he was a coward. Death turned away, but as he began to leave, he heard a sob. He looked back and saw that the old man, the only person who’d ever shown him any kindness, was crying. A flood of compassion rushed over him, and so Death reached up with trembling hands and took hold of his hood.

As his hood fell away, there was a glint of light and the old man gasped and staggered backward. There, staring back at him, was his own face. Death reached to pull his hood back up—what a horrible mistake he’d made—but the old man asked Death to wait, and so he did.

He approached Death slowly, and the face staring back at him—his own face—grew larger. He paused, stroking his chin in thought, and the face staring back at him did the same. It’s a reflection, he whispered, but why? He leaned forward toward Death, and as he examined his reflection, his eyes tracing the endless hieroglyphics of his wrinkled skin, it all made sense.

Death had been by his side all along. He was not Death, but he was nothing without him. The lined face staring back at him was fashioned not just from his past, which already belonged to Death, but from each potential past he’d discarded in choosing his future at every point throughout his entire life. Death wasn’t just waiting at the end, he was present for this moment and this moment and this moment and every moment wherein the man died and was born again, over and over. Death was not an executioner—he was a sculptor. And so all those times he’d raged at Death, he’d been raging at himself. And every time he ignored Death, he’d been denying his own true nature.

All this made perfect sense to the old man, but when he tried to explain it to Death his words sounded garbled, and he knew that Death did not understand. You are a mirror, and every separate part of life is reflected in your face, the old man kept repeating to no avail. Then, possessed by an idea, he rushed back inside and flung away a black cloth which had been covering a fulllength mirror. There were gasps as he pulled the mirror off the wall, and then the old man carried it back outside trailed by a wake of bewildered faces.

He placed the mirror against the house and then turned toward Death, motioning for him to come closer. Once they were standing side by side, he

explained that once Death looked into the mirror, he would understand his true nature. Although Death was afraid, he nodded, and then, on the count of three, they both spun around and looked into the mirror.

For a whole minute, both of them stood still in stunned silence. Both of them saw the old man in the mirror, but neither could see Death reflected. And then, all at once, they both understood. The old man smiled at Death, and Death smiled back.

SPOT THE LAWYER: THE ANSWER

By Joseph C. Bellows, K.C.In the March issue of the Advocate (2024) 82 Advocate 199–200, you were invited to identify my classmates from a 50-year-old photograph taken of us in first-year law school (1971). How did you do?

The “who’s who” is found in the legend on the following page. So young…

ANSWER KEY