We’re All About YOU! Vancouver • New Westminster • Victoria Tel: 604-659-8600 • Toll Free: 800-553-1936 • info@wcts.com • wcts.com The reason we exist... our mission... is to support your practice. Full stop. West Coast is proud to be considered a preeminent resource for Process Serving, Registry and Research Services in British Columbia’s legal community. Proudly serving the legal profession since 1969

THE ADVOCATE 161 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 atinCelebr OUR NEW PARTNERSng S H Assurance Partner Audit and (UK), CIA A PA MAHASE ARESHM CPA, FCCA ax Partner Ta A, CGA CP ARD CHANG HOWWA T WWW.DAVIDSON-CO.C O M

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 162 THE ADVOCATE ( csconomi PhD E rotiationssuppoNeg + c C pecifi s S ’ & Canada ed as an exper Qualifi DRED + T UBC, 1982) rt:valuesofoffers bunalri laims T Court upreme BLEWET t in BC S ons Expert Opini + aluations miEcono c V + tio cConsulStrategi ta + f d e o lu c va miEcono + onsforcomPIDopini + teroffers and coun ns amages mmercialfishers 60449997615 ed ww 4 999 7615 win@gocounterpoint.com w.gocounterpoint.com To book a mediation please contact Anna Pelzer at apelzer@guildyule.com

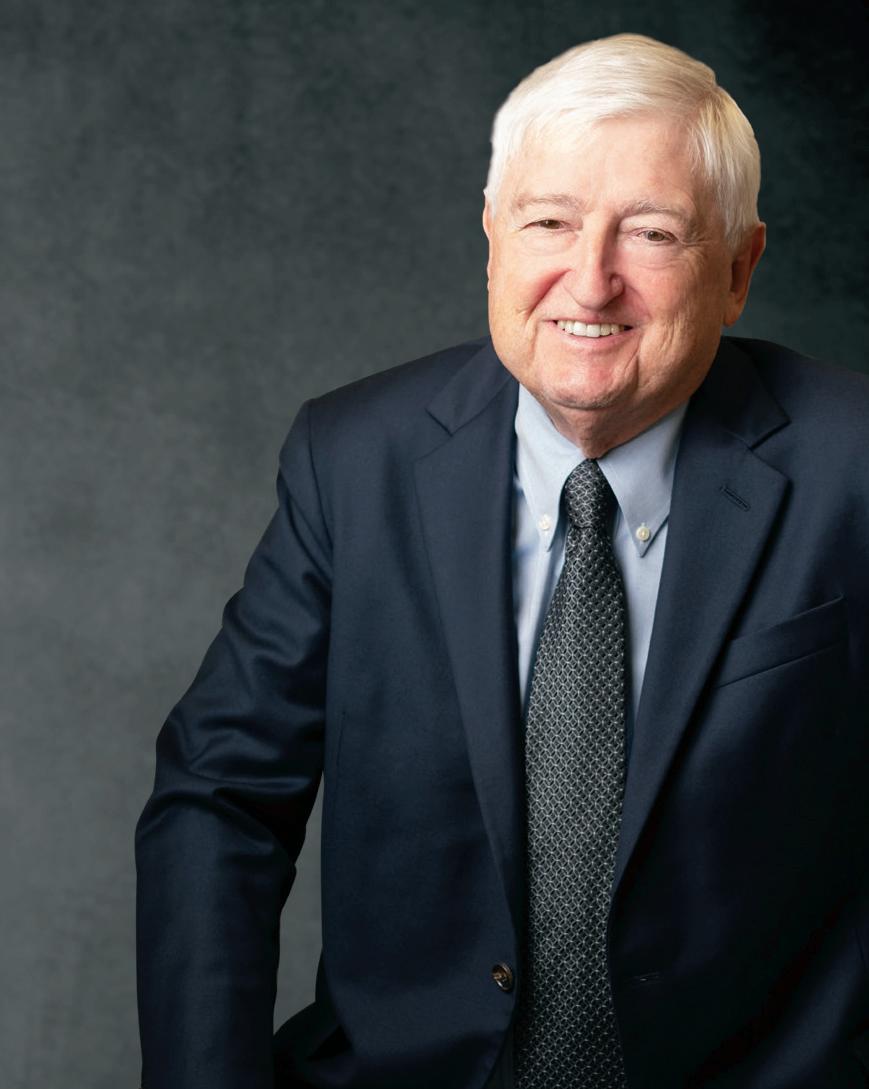

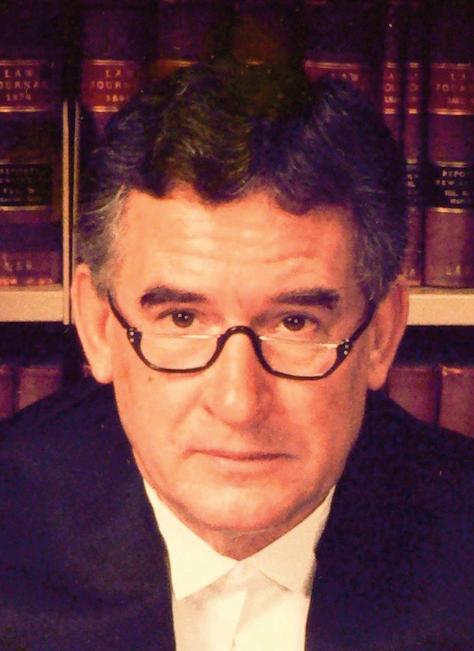

•21-year judicial career: 9 years on the BC Court of Appeal, 12 years as a Supreme Court Judge.

•Presided over all manner of cases including criminal, civil and family claims.

•27 years as a leading litigator, has appeared in all courts of British Columbia and the Supreme Court of Canada.

•Effective and respected decision-maker.

Immediately available to assist with arbitration, mediation, and other forms of dispute resolution with an emphasis on commercial and insurance disputes.

| rgoepel@watsongoepel.com

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 THE ADVOCATE 163

Richard Goepel, K.C. 604.642.5651

FORWARD

CONFIDENCE watsongoepel.com

MOVE

WITH

Mediation, Arbitration & Dispute Resolution Services

OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVES

LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Christopher McPherson, K.C. President

Don Avison, K.C.

Chief Executive Officer and Executive Director

BENCHERS

APPOINTED BENCHERS

Paul A.H. Barnett

Sasha Hobbs

Dr. Jan Lindsay

ELECTED BENCHERS

Kim Carter

Tanya Chamberlain

Jennifer Chow, K.C.

Cheryl S. D’Sa

Tim Delaney

Lisa H. Dumbrell

Brian Dybwad

Brook Greenberg, K.C.

Katrina Harry

Lindsay R. LeBlanc

Geoffrey McDonald

Steven McKoen, K.C.

Michèle Ross

Natasha Tony

Guangbin Yan

Jacqueline McQueen, K.C.

Paul Pearson

Georges Rivard

Kelly Harvey Russ

Gurminder Sandhu

Thomas L. Spraggs

Barbara Stanley, K.C.

Michael F. Welsh, K.C.

Kevin B. Westell

Sarah Westwood

Gaynor C. Yeung

CANADIAN BAR ASSOCIATION

BRITISH COLUMBIA BRANCH

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Aleem S. Bharmal, K.C.

President

Scott Morishita

First Vice President

Lee Nevens

Second Vice President

Judith Janzen

Finance & Audit Committee Chair

Dan Melnick

Young Lawyers Representative

Rupinder Gosal

Equality and Diversity Representative

Randolph W. Robinson

Aboriginal Lawyers Forum Representative

Patricia Blair

Director at Large

Adam Munnings

Director at Large

Mylene de Guzman

Director at Large

Sarah Klinger

Director at Large

ELECTED MEMBERS OF CBABC PROVINCIAL COUNCIL BRITISH COLUMBIA BAR ASSOCIATIONS

ABBOTSFORD & DISTRICT

Kirsten Tonge, President

CAMPBELL RIVER

Ryan A. Krasman, President

CHILLIWACK & DISTRICT

Nicholas Cooper, President

COMOX VALLEY

Michael McCubbin

Shannon Aldinger

COWICHAN VALLEY

Jeff Drozdiak, President

FRASER VALLEY

Michael Jones, President

KAMLOOPS

Kelly Melnyk, President

KELOWNA

Taylor-Marie Young, President

KOOTENAY

Dana Romanick, President

NANAIMO CITY

Kristin Rongve, President

NANAIMO COUNTY

Lisa M. Low, President

NEW WESTMINSTER

Mylene de Guzman, President

NORTH FRASER

Lyle Perry, President

NORTH SHORE

Adam Soliman, President

PENTICTON

Ryu Okayama, President

PORT ALBERNI

Christina Proteau, President

PRINCE GEORGE

Marie Louise Ahrens, President

PRINCE RUPERT

Bryan Crampton, President

QUESNEL

Karen Surcess, President

SALMON ARM

Dennis Zachernuk, President

SOUTH CARIBOO COUNTY

Angela Amman, President

SURREY

Peter Buxton, K.C., President

VANCOUVER Executive

Niall Rand President

Heather Doi Vice President

Zachary Rogers Secretary Treasurer

Jason Newton Past President

VERNON

Christopher Hart, President

VICTORIA

Marlisa H. Martin, President

CARIBOO

Nathan Bauder

Susan Grattan

Nicholas Maviglia

KOOTENAY

Andrew Bird

Christopher Trudeau

NANAIMO

Johanna Berry

Patricia Blair

Kevin Simonett

PRINCE RUPERT

Sara Hopkins

VANCOUVER

Kyle Bienvenu

Karey Brooks

Joseph Cuenca

Bahareh Danael

Graham Hardy

Lisa Jean Helps

Judith Janzen

Heather Mathison

Scott Morishita

VICTORIA

Sarah Klinger

Dan Melnick

Paul Pearson

WESTMINSTER

Anouk Crawford

Mylene de Guzman

Daniel Moseley

Greg Palm

YALE

Rachel LaGroix

Michael Sinclair

Kylie Walman

CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF BLACK LAWYERS (B.C.)

Zahra Jimale, President

FEDERATION OF ASIAN CANADIAN LAWYERS (B.C.)

Steven Ngo, President

INDIGENOUS BAR ASSOCIATION (B.C.)

Michael McDonald, President

SOUTH ASIAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

Anita Atwal, President

ASSOCIATION DES JURISTES D’EXPRESSION FRANÇAISE DE LA COLOMBIE-BRITANNIQUE (AJEFCB)

Sandra Mandanici, President

164 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

Jeevyn Dhaliwal, K.C. First Vice President Brook Greenberg, K.C. Second Vice President

“Of

Published six times each year by the Vancouver Bar Association

Established 1943

ISSN 0044-6416

GST Registration #R123041899

Annual Subscription Rate

$36.75 per year (includes GST)

Out-of-Country Subscription Rate $42 per year (includes GST)

Audited Financial Statements Available to Members

EDITOR:

D. Michael Bain, K.C.

ASSISTANT EDITOR:

Ludmila B. Herbst, K.C.

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD:

Anne Giardini, O.C., O.B.C., K.C.

Carolyn MacDonald

David Roberts, K.C.

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Mary Saunders

The Honourable Alexander Wolf

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS:

Peter J. Roberts, K.C.

The Honourable Jon Sigurdson

Lily Zhang

BUSINESS MANAGER: Lynda Roberts

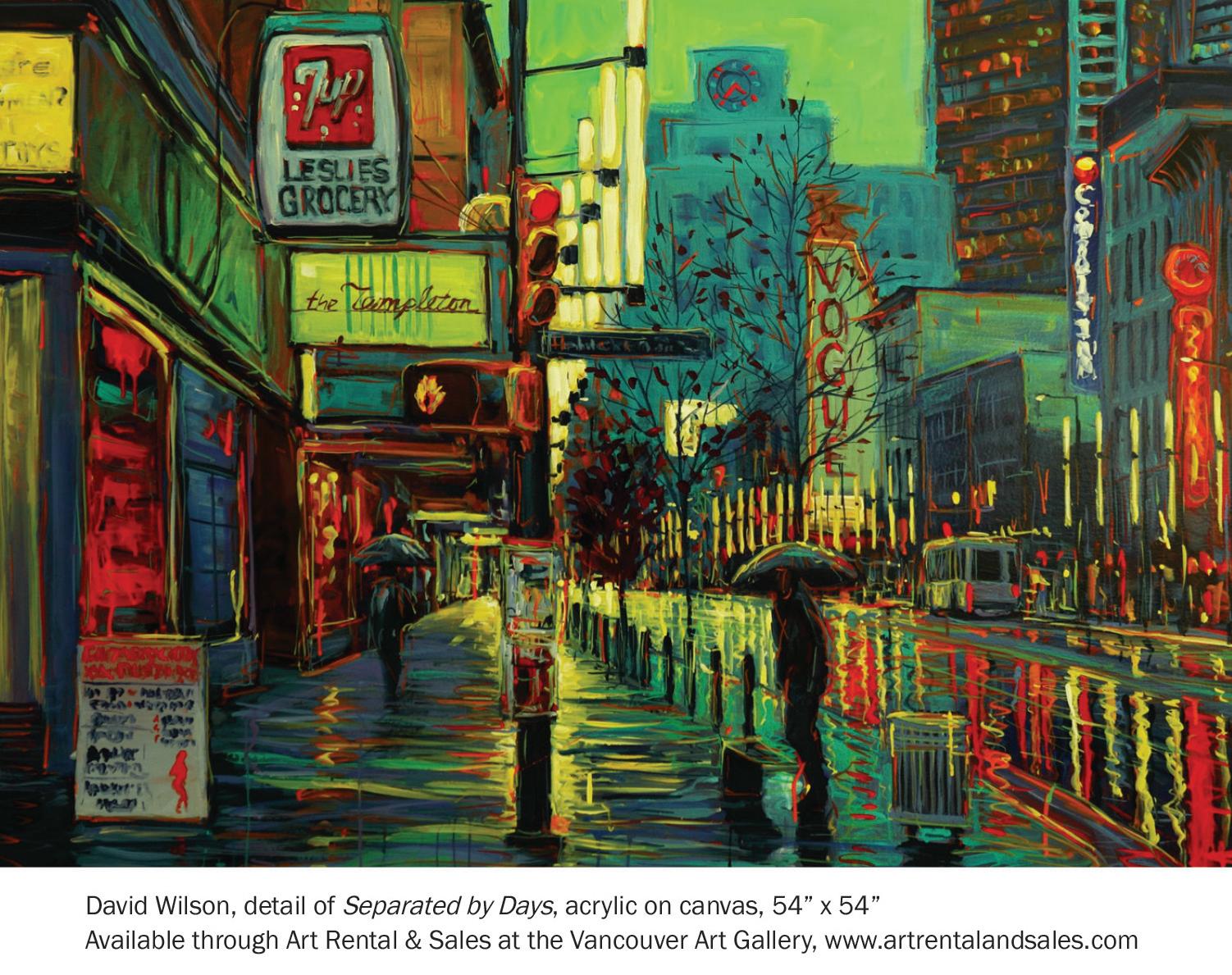

COVER ARTIST: David Goatley

COPY EDITOR: Connor Bildfell

EDITORIAL OFFICE:

#1918 – 1030 West Georgia Street

Vancouver, B.C. V6E 2Y3

Telephone: 604-696-6120

E-mail: <mbain@the-advocate.ca>

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE: 709 – 1489 Marine Drive

West Vancouver, B.C. V7T 1B8

Telephone: 604-987-7177

E-mail: <info@the-advocate.ca>

WEBSITE: <www.the-advocate.ca>

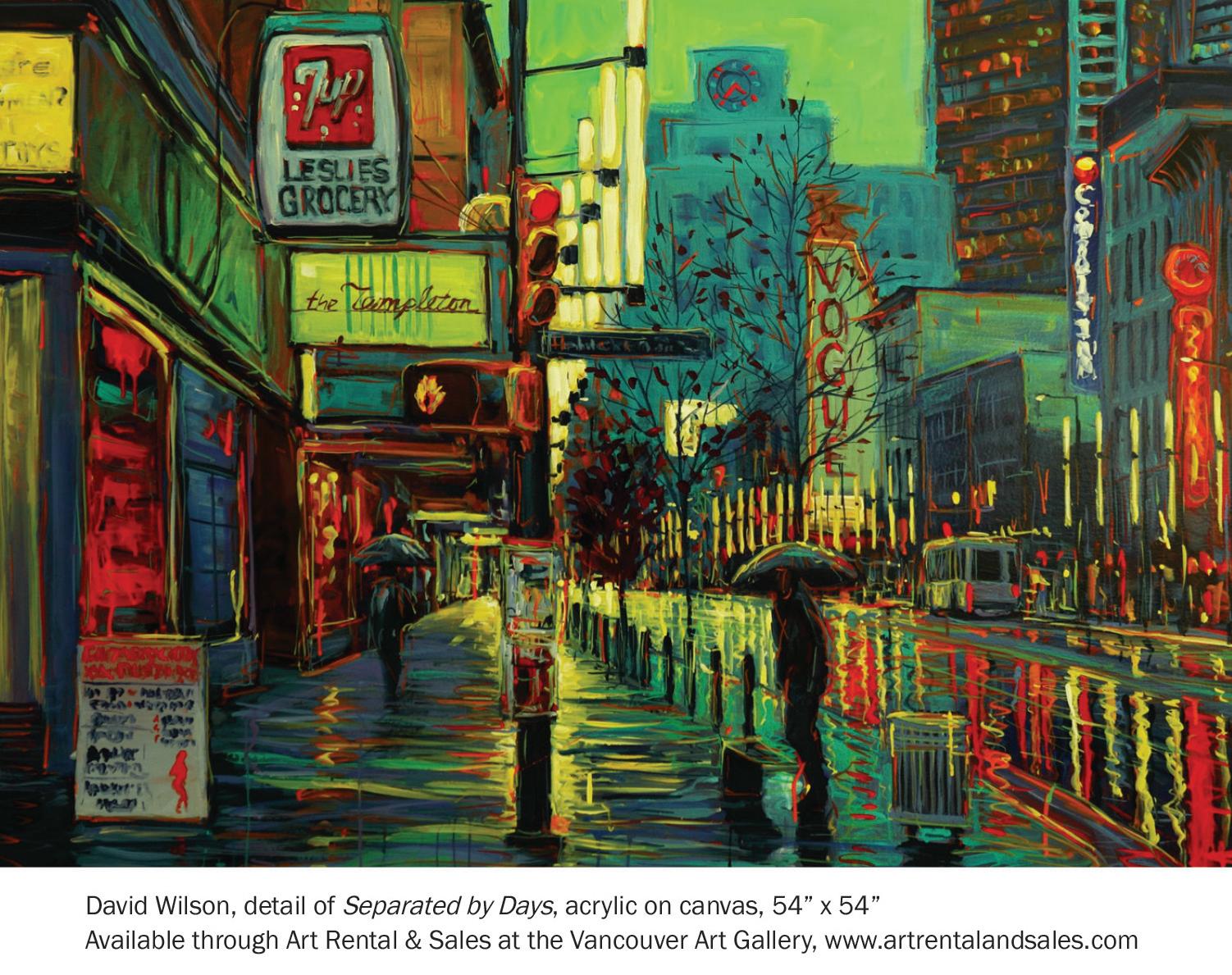

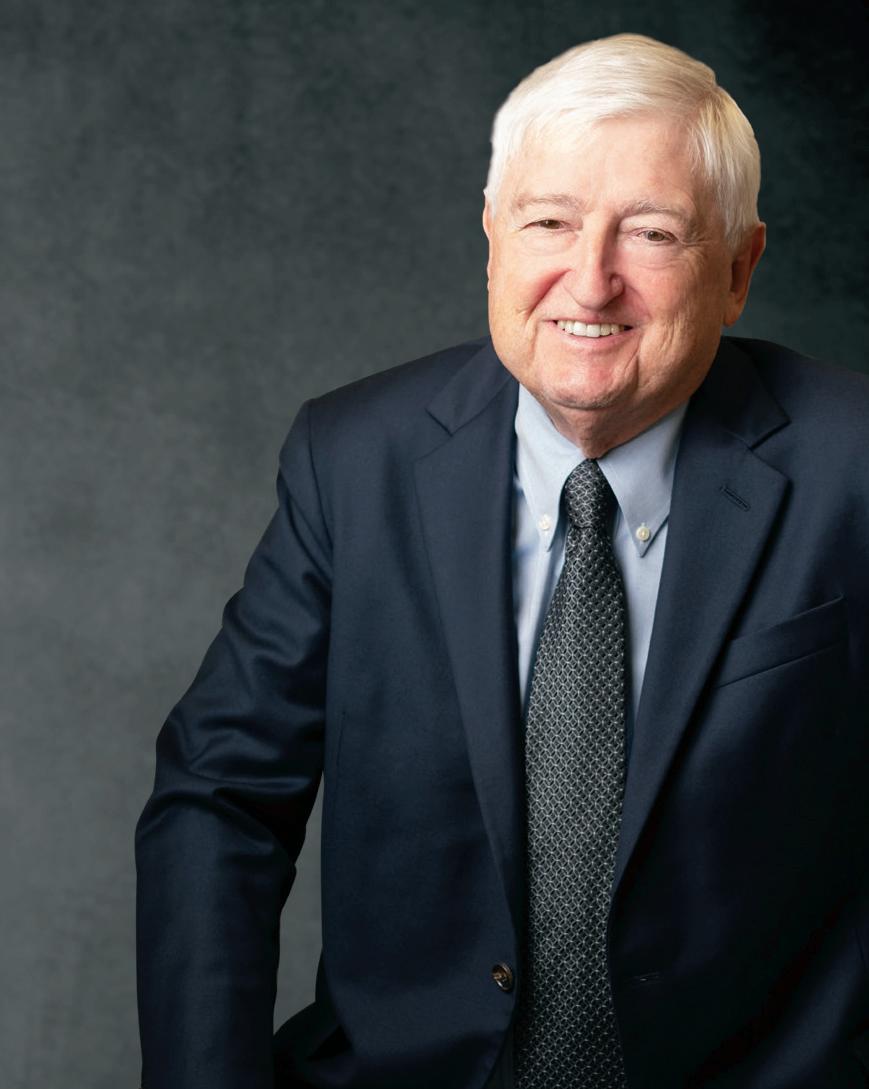

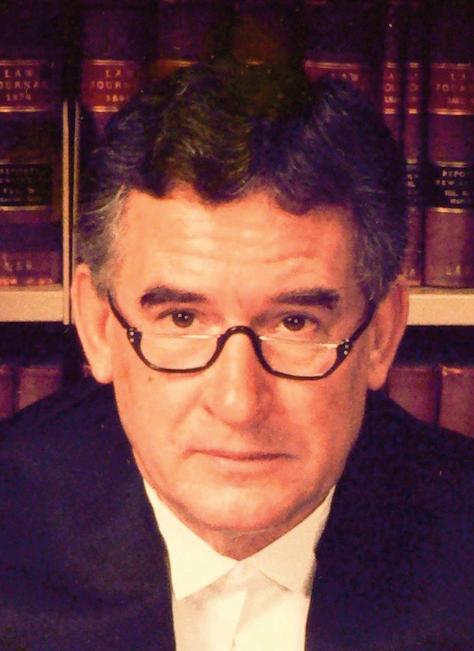

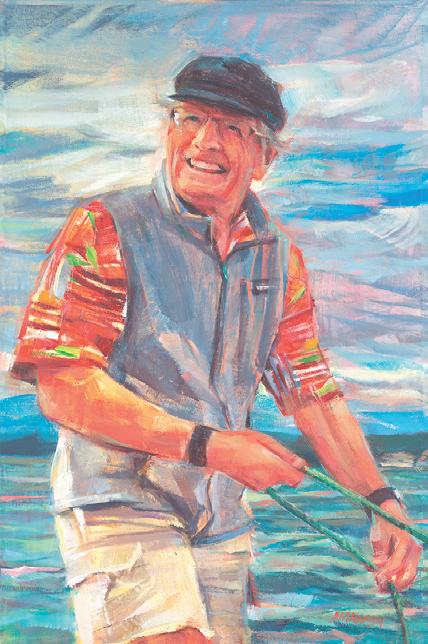

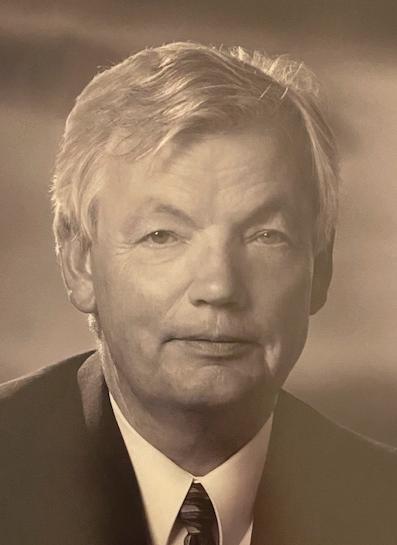

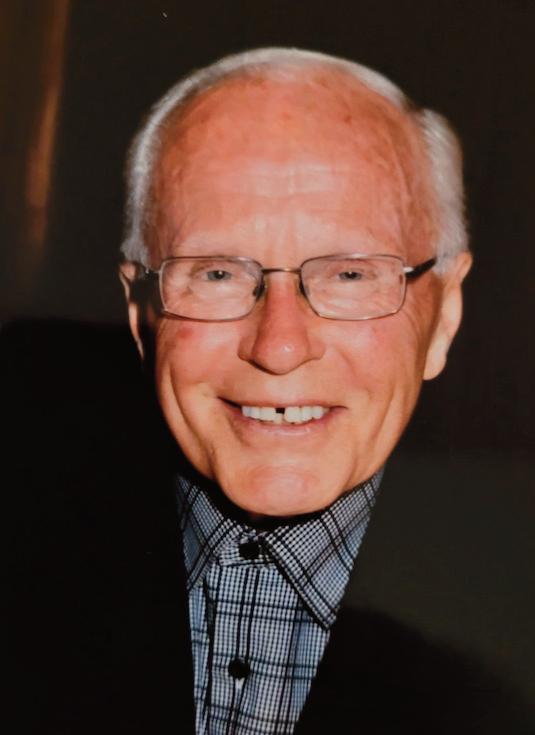

ON THE FRONT COVER

165

The late Christopher Harvey, Q.C., is depicted on this issue’s cover in a portrait painted by his widow, Anne-Marie Harvey. Chris is shown in his happy place … pulling up prawn traps. Read his amazing story on page 177.

ADVOCATE

interest to the

and

the

THE

2023 Entre Nous . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169 On the Front Cover: Christopher Harvey, Q.C. By Gavin Hume, K.C., and Timothy Harvey . . . . . . . . . . . 177 Surreptitious Recordings

Civilians in Criminal Trials: Are They Constitutional? By Robert Diab . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 Disallowance is the Paladin of the Rights and Freedoms in the Canadian Charter By Darrell W. Roberts, K.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197

By Bruce Woolley, K.C. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209 Is Time Really of the Essence? Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Contract Law By David Wotherspoon and Jaclyn Vanstone . . . . . . . . . . . 215 The Wine Column . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223 News from BC Law Institute . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235 LAP Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239 A View from the Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243 Announcing the 2023 Advocate Short Fiction Competition . . . 251 Peter A. Allard School of Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253 TRU Law Faculty News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 259 Nos Disparus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263 New Judges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281 Classified . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295 Legal Anecdotes and Miscellanea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297 From Our Back Pages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 303 Bench and Bar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309 Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 319

lawyer

in

lawyer’s interest”

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH

by

The Solicitor’s Legal Opinions Committee (Fondly Known as “SLOC”)

We are a firm ofconsulting economists who specialize in providing litigation support services to legal professionals across western Canada. Our economic reports are supported by knowledgeable staffwith extensive experience in providing expert testimony.

PETAConsultants Ltd.

We offer the following services in the area ofloss assessment:

Past and future loss ofemployment

income

Past and future loss ofhouseholdservices

Past and future loss offinancial support

(wrongful death)

Class action valuations

Future cost ofcare valuations

DARREN BENNING PRESIDENT

info@petaconsultants.com

T. 604.681.0776

F. 604.662.7183

Suite 301,1130 West Pender Street

Vancouver,B.C.Canada V6E 4A4

Loss ofestate claims (Duncan claims in Alberta)

Income tax gross-ups

Management fees

Pension valuations

Future income loss and future cost of care multipliers

166 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

Malpractice

Tel: 604.685.2361 Toll Free: 1.888.333.2361 Email: info@pacificmedicallaw.ca www.pacificmedicallaw.ca

Medical

is all we do

A FOUNDING MEMBER OF BILA

ECONOMIC DAMAGES SINCE

QUANTIFYING

1983

Built on Trust, Backed by Results

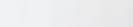

Jeff Davis has been entrusted with the investment portfolios of legal professionals in British Columbia and Alberta for 20 years. Attuned to your needs, he understands that the demands of being a successful lawyer often result in a lack of time to manage your own investments. At Odlum Brown, Jeff develops investment strategies that are conflict-free and focused on creating and preserving the wealth and legacy of his clients. For over two decades, the results of the highly regarded Odlum Brown Model Portfolio have been a testament to the quality of our advice.

Jeff Davis, B.Comm, CIM Vice President, Director Portfolio Manager

Jeff Davis, B.Comm, CIM Vice President, Director Portfolio Manager

THE ADVOCATE 167 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 a l s · ors t olici S rss& e t is i Bar · paany al & Com os G p r r TION TA EE CONSUL FR 604.591.8187 www.wcblawyers.com Wo r kSafeBC Appe B.A., LL.B. sal j Go Sar 7AStreet,Surrey,BC3916304-93 Centre 2 City M1V3T0

COMPOUND ANNUAL RETURNS (Including reinvested dividends, as of January 15, 2023) 1 YEAR3 YEAR5 YEAR10 YEAR20 YEARINCEPTION1 Odlum Brown Model Portfolio2 -2.9%14.3%11.1%14.0%12.6%14.0% S&P/TSX Total Return Index -5.6%13.1%9.7%9.0%9.1%8.5% Let us make a case for adding value to your portfolio; contact Jeff today at 604-844-5404 or jdavis@odlumbrown.com. Visit odlumbrown.com/jdavis for more information. 1 December 15, 1994. 2 The Odlum Brown Model Portfolio is a hypothetical all-equity portfolio that was established by the Odlum Brown Equity Research Department on December 15, 1994 with a hypothetical investment of $250,000. It showcases how we believe individual security recommendations may be used within the context of a client portfolio. The Model also provides a basis with which to measure the quality of our advice and the effectiveness of our disciplined investment strategy. Trades are made using the closing price on the day a change is announced. Performance figures do not include any allowance for fees. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Member-Canadian Investor Protection Fund

168 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

ENTRE NOUS P

eering into the windows of the local polling station (a repurposed community centre gymnasium) during the last municipal election, a cute youngster of kindergarten vintage watched adults collect, mark and drop off their ballots. Those of us who caught sight of the child while shuffling around the facility may have patted ourselves on the back for setting a good example, inspiring a future voter.

It is a good thing the curious youngster could not compare the number of voters who passed through the gymnasium against the number eligible to vote. With some exceptions, voter turnout in the 2022 municipal election was not inspiring at all.1 It was far worse than even in the most recent (2021) federal election (62.6 per cent) and the most recent (2020) provincial election (51.76 per cent of eligible, and 53.86 per cent of registered, voters). Voter turnout for the 2022 municipal election in each of Vancouver and Victoria was just under 37 per cent, and just over 30 per cent in Kelowna and Kamloops. Prince George and Dawson Creek were in the 25–26 per cent range.

It is possible, we suppose, that members of the legal profession were disproportionately represented among the voters in federal, provincial and municipal elections. One might expect educated citizens with a knowledge of voting rights and relatively flexible schedules to be among the groups that are the most able to vote and the most interested in doing so. However, given how few lawyers use their opportunities to vote within their own regulatory body elections, it seems unlikely that their turnout in other elections exceeds that of the general population—well, unless, having voted in disproportionate numbers in other elections, by the time of Law Society elections their energy has been so exhausted that they can no longer do so.

The Legal Profession Act and the Law Society Rules provide for the election by members in good standing of benchers and the second vice-president (who is to become first vice-president and then president), and for there to be resolutions of general meetings of the society. However,

THE ADVOCATE 169 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

province-wide, most of us do not actually take up in practice the voting opportunities provided.

The most recent election held within the Law Society was the November 2022 bencher by-election in Vancouver county (where the majority of lawyers in British Columbia practise). Only 17.9 per cent of those eligible to do so turned out. This was not an aberration: the figure is comparable to the July 2021 Vancouver county by-election, where turnout was 19.2 per cent.

Can this low turnout be explained by the fact that each of these by-elections was simply held to elect one bencher? Not necessarily. And indeed, it is important to remember that five of the province’s nine electoral districts have only one bencher each. The counties of Vancouver (13), New Westminster (3), Victoria (2) and Cariboo (2), each of which is its own electoral district, are the exceptions.2 The district with the best turnout in the November 2021 general election was Kamloops, at 61.4 per cent, though only one bencher was being elected. Kamloops still had a very respectable turnout of 56.4 per cent to elect one bencher in its June 2021 by-election.

At 28.3 per cent, the Vancouver county turnout was indeed better for the November 2021 general election, where 11 benchers were to be elected, than for its own recent one-bencher by-elections. However, it remained far from impressive.

Do we do better in terms of voter turnout at the Law Society’s annual general meetings? No—indeed, we seem to do worse, by and large. The resolution on which the most total votes were cast at the June 2022 annual general meeting related to the appointment of auditors. Counting all of the votes in favour and opposed as well as abstentions, the total was 2,924—representing well under a quarter of eligible voters.3 Only 44 of those 2,924 votes were cast at the meeting rather than as part of advanced voting.

The low turnout in Law Society elections is particularly striking given the efforts that have been made to make voting easy for us. No trudging to a polling station, or even putting the ballot in an envelope and mailing it in, is required. Instead, given provision for voting by electronic means, we do not even have to leave our desks to do it—we can simply click on certain selections online. We can take the few minutes required at the time of our choosing, rather than during the limited window of a meeting. And given the level of education that got us into the profession, it is not as though we cannot read and process the information provided to equip us to vote.

Are the online missives we receive about voting, whether from the Law Society or on behalf of bencher candidates, lost in the sea of other emails we receive? Well, maybe we overlook some of these emails, but surely it would not be possible to overlook all. Further, even without being told on

170 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

each occasion, most of us should have a sense of the timing of bencher elections, for example. The Law Society Rules provide that elections for the office of bencher in all districts must be held on November 15 of each oddnumbered year. In addition, we can safely guess that a by-election will follow a bencher’s appointment to the other bench.

Low voter turnout is also evident in bencher elections in Ontario. Commentators on the phenomenon there have speculated that, for example, eligible voters might be too fearful of the Law Society of Ontario to engage with it even through voting, or alternatively that, confident of avoiding any negative interaction with the Law Society in the course of their own practice, they do not mind by whom the regulator will be run. Neither of these explanations seems especially flattering either to the Law Society of Ontario or to lawyers themselves. Surely even if those regulated are not concerned about unpleasant personal scenarios such as disciplinary proceedings being brought against them, they should recognize that legal regulators have broader mandates. Legal professionals should still have some level of engagement with and interest in the broader public interest objectives that legal regulators must pursue.

It may be that we do not vote in the context of the Law Society of British Columbia because we think the public interest would be well served by passage of any of the resolutions put forward at any given time, or the election of any of the candidates who run for office. Indeed, given the pool of eligible bencher candidates is limited to those members in good standing at the time of nomination, it would be difficult to say that any of those individuals is other than qualified and well meaning. Our comments here do not arise out of unease with any substantive outcome of any given election.

Assume for the moment, then—to take the most aggressive assumption— that all potential electoral outcomes are equally fine and any nuances are entirely immaterial. Would there still be downsides if substantial numbers of those eligible to vote do not in fact vote?

Yes, there would be. First, not voting sends a bad message to those who put themselves or their positions forward to be voted on. Imagine you are nominated to be a candidate for bencher, and make all the efforts required to participate in the election. Or imagine you submit a resolution to a general meeting, and make all the efforts required to do so. The vast majority of your colleagues then promptly shows no interest whatsoever in the exercise that you have participated in—the exercise is met with the equivalent of a blank stare. If your candidacy or resolution nonetheless triumphs among those who voted—though on the assumption that all outcomes are equal this seems just to be a fluke—that fact may somewhat overcome any

THE ADVOCATE 171 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

sting. However, it is not exactly a buoyant basis either on which to proceed with bencher duties or to energize anyone else to try again.

Second, not voting at least arguably sends a bad message about our commitment to the organization in which voting opportunities are provided. The structure of the Law Society involves elected (as well as other) benchers and voted-on resolutions. A good turnout is an indication to anyone watching that we care about the Law Society’s continued existence. The Code of Professional Conduct does not address voting specifically, but section 2.2-2 does state: “A lawyer has a duty to uphold the standards and reputation of the legal profession and to assist in the advancement of its goals, organizations and institutions.” From the fact that the majority of members do not even click their mouse a few times every one or two years during Law Society elections, an observer might extrapolate that we would be just as happy not to have the Law Society at all.

Is that too alarmist a reading? Maybe low voter turnout could be interpreted, not as implicit criticism of or indifference to the regulator, but as a sign that most members are sufficiently content with its performance to mean they feel no need to intervene. However, any occasion for voting inherently gives rise at least to the potential for some change to the status quo, via replacement of benchers or the making of new resolutions.

Further and in any event, not voting at least sends a message that as members we do not feel we need to continue to have voting input into the regulator or its governance. If we do not engage in the election of benchers, for example, one might conclude that we would be just as, or more, content to see them all appointed. There is always the risk of losing that which is unused, and of having someone else, by other means, step in to make the decisions we do not seem interested in making. As regulatory reform looms in some form, we do not have the luxury of much time to correct the impression that on each occasion of low turnout we create and entrench, if that impression is wrong.

What if the impression is not wrong? What if—and we do not think this is accurate, but say for the moment that it is—most of us do not vote because we really do not care about or for the Law Society, either at all or as its governance is structured now? If that is the case, that is all the more reason for its members to be active, not passive. Maybe we should be exercising our votes within the Law Society in an effort to implement reforms, or exercising our votes in provincial elections to constitute a legislative assembly prepared to overhaul the Law Society’s governing statute even more dramatically than the present government seems to contemplate. Neither of these alternatives is one for which we advocate, but if you do, that is a position to be articulated and debated, not extrapolated from disengagement.

172 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

But let us come back to the original assumption we made as the underpinning for the discussion above: that all electoral outcomes within the Law Society are equally good. Surely this is not actually, however, the case.

Perhaps all bencher candidates, for example, do fall within an acceptable range given the nature of what makes them eligible for nomination. However, is it truly the case that no one of them is better suited to serving as bencher than another? Not everyone is as attuned to the public interest lens through which the Law Society must act.

And is it truly the case that the distinction between passing and not passing a particular resolution makes no difference? Benchers are not bound to implement resolutions other than in some circumstances, but at least symbolically they have some importance even if the referendum needed to enforce them does not occur.

If one electoral outcome could better advance the objectives of the Law Society and another could do so less well, or not at all, how can we then justify not voting?

Perhaps we say to ourselves that while there may logically be some difference between outcomes, who am I, as a potential voter who has not read over the background materials, to judge which one is best? However, surely most of us, most of the time—admittedly not always—can remedy that perceived shortcoming by taking the time to do some further reading. In addition, why should those of us alert to the existence of our own potential shortcomings leave the outcome to be decided by more confident colleagues who may vote without having perceived or remedied any informational deficits of their own?

Or perhaps we do reach a point at which we identify the bencher candidate we prefer, or whether we prefer that a given resolution be defeated or passed, but assume the majority of those who choose to vote will have the same views we do. As such, we may assume that their votes will get us the result we want even if we do not vote as well.

Not only does this approach deny our preferred candidate or side the courtesy of knowing that we liked them too, but it may backfire in terms of outcome. By assuming that the majority is aligned with us and will carry the day, we may jeopardize the outcome we prefer. Of course, we may be wrong about what the majority wants. Further, even if the majority does hold the same preferences we do, this may extend not simply to sharing our preference for the substantive outcome, but also to sharing our preference for not voting. If everyone were to decline to vote where the outcome they prefer seems likely, and those mobilized to vote are the ones who seek the contrary, the contrary may in fact result.

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 THE ADVOCATE 173

Maybe our plan is to hold voting in reserve until matters reach the point at which results do start turning against our preferences: at that point, and only at that point, would we step in by exercising our right to vote. However, once benchers we do not like serve out their two-year terms and resolutions we do not like are (potentially) implemented, it may be too late to change course; it is not as though the next election will be directly on the heels of the one in which we did not use our chance to participate. Further, this theory of voting as a last resort turns on its head the fact that voting should be the norm and default, not the exception, given how the Law Society is structured.

Not voting also brings with it an opportunity cost in terms of our sense of community. Voting in the same election is one of the few opportunities that lawyers have to act as a collective for a shared purpose. While for the most part today we cannot visibly see each other casting our ballots, we do have a tangible manifestation of the tallied number of members who engaged in the exercise. Voting is an affirmation that we are part of the same community and fosters a bond that ultimately may help in advancing the objectives that as a profession we should further.

We do not go as far as saying that voting in Law Society elections should be compulsory. Our sense is that compulsion is not required to improve voter turnout in a measurable way. We would like to think that many of us would vote if we paused to think more about why it is important to do so, or at least got into the habit of doing so. We do hope that some part of this editorial will resonate even with those who do not historically vote in each election or at all, and that they might remember to do so the next time they get a chance.

So speaking to one and all of us (and yes, if there is any finger-wagging, it would sometimes be in the mirror), please vote. Even those of us disinclined to serve as bencher, submit resolutions or debate them should gain some understanding of the candidates and issues, and take the far-fromonerous further step of voting.

Can we move the needle in saying this? We will look to the next Law Society elections to find out.

ENDNOTES

1. Voting statistics are always nuanced and not precisely comparable: the numerators and denominators that together lead to a voter turnout percentage can differ. This editorial is intended to capture the magnitude rather than nuances.

2. The county of Yale has two benchers, but over two electoral districts: one bencher for the Kamloops district and one bencher for the Okanagan district.

3. Members in good standing are eligible to vote. According to page 12 of the Law Society’s 2021 Annual Report, 16,135 were registered with the Law Society, with 13,487 of those being practising lawyers. The others fell within the “non-practising” or “retired” categories.

174 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

THE ADVOCATE 175 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 176 THE ADVOCATE LEGAL SERVICES mcquarrie.com PASSION. TRUST. EXPERTISE. RESULTS. McQuarrie Hunter LLP Suite 1500 13450 102 Avenue Surrey BC V3T 5X3 Email: info@mcquarrie.com Phone: 604.581.7001 Toll-free: 1.877.581.7001 Fax: 604.581.7110 CONTACT MCQUARRIE AT 604.581.7001 MCQUARRIE.COM

ON THE FRONT COVER

CHRISTOPHER HARVEY, Q.C.

By Gavin Hume, K.C., and Timothy Harvey

On September 2, 2022, Christopher Harvey, Q.C., passed away peacefully in Lions Gate Hospital. It was highly unexpected, given Chris’s youthful vigour and irrepressible joie de vivre through 80 years of life, 54 as a practising barrister. Chris loved that, as a barrister, he embodied the rich history of the common law, and he charged himself with helping to pass its knowledge and traditions on to the next generation of lawyers. He authored dozens of articles and columns for the Advocate and served as editor from 2008 to 2013. He considered that period a glowing highlight of his career.

It might seem incongruous that Christopher Harvey, once the boy racing plywood outboards in Prince Rupert Harbour, then a man working nine consecutive seasons on the high-earning fleet of the Halibut Capital of the World, would consider any other vocation than fishing. And yet, with a mind as sharp as a filleting knife, Chris carved out a magnificent career as British Columbia’s foremost legal champion of the fishing industry.

A sixth-generation Canadian born in Nanaimo into a nation at war on Dominion Day of 1942, to an artist mother, Ruth Harvey (formerly Hornsby, raised in Prince George), Chris was steeped from his boyhood in the legal history of British Columbia. His father was the Honourable James “Jim” Teetzel Harvey, M.B.E., Q.C. Jim returned from distinguished wartime service to a family now three children strong (Chris, Peter and Gail) and resumed partnership in Prince Rupert’s leading law firm.1 Brown & Harvey, with the Honourable T.W. (Tommy) Brown, was formed upon Jim’s arrival in Prince Rupert in 1931, prior to which he practised in Prince George, Smithers and Hazelton. Jim accepted an appointment as a County Court judge of Prince Rupert in 1962. It was British Columbia’s largest judi-

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 THE ADVOCATE 177

cial county, requiring him to travel the northwestern quarter of the province, holding court from the town of Atlin2 to his lakeside lawn near Smithers.3 He held the post until retirement in 1977, but occupied the second courthouse chambers as an advisor to the bench until his passing in 1999. Judge Harvey had a solemn veneer but an active sense of humour, the latter rubbing off in no small measure on his son.

Chris’s grandfather James Albert Harvey, K.C., also loomed large in the family history. He arrived by rail from Ontario to the mining-boom Kootenays in 1897 with his wife Lillian, a favourite sister of Justice James Vernal Teetzel, K.C., of the Ontario High Court who had been made Q.C. in the Victorian era’s waning days. J.V. posted letters to Lillian detailing a family history reaching back to Alexandrew McQueen, a Scottish highlander who battled for the British on the Plains of Abraham before putting down roots in Ontario, two generations before James Albert’s own grandfather set sail from Ireland to New Brunswick. Chris never met his grandfather, but it was James Albert who set the family on its course in British Columbia. Grand-father, father and son combined for 120 years at the bench and bar.

In 1907, Jim was born and James Albert was made K.C. He moved his family from Cranbrook to Vancouver in 1909, forming Taylor and Harvey with S.S. Taylor, K.C. James Albert played a role in the 1910 first sitting of Victoria’s new B.C. Court of Appeal,4 and also served as director of the Bank of Vancouver alongside Lieutenant-Governor T.W. Paterson. He and Lillian raised Jim and his four sisters in a classic mansion in Vancouver’s West End. James Albert passed away in 1918 in the aftermath of a stock market crash that devastated his fortune. He had only his personal law library to bequeath to Jim, who left university after one year for financial reasons.

“I went to sea on a merchant vessel, and I soon received a proposition,” Jim explained to his grandson Tim in his final decade of life. “I had a choice between a career in rum-running or going ashore to study law.” Wisely, Jim chose a five-year articling program at the Vancouver Law School.

Upon completing a B.A. in English and philosophy from McGill in 1965, Chris faced a similar decision between land and sea. Long university vacations had allowed him to fish halibut from Hecate Strait to the Aleutian Islands with skippers Foster Husoy and Sid Dickens. Chris felt drawn to earn his living from the sea—a life of high adventure on his own terms. The legal profession, on the other hand, would mean working in the great shadow cast by his father from the bench of Prince Rupert. But his sagacious Pop suggested a third option: as they scanned the world in the family home overlooking Prince Rupert harbour, glass in hand, he suggested, “Why not go to where the common law began: London, England?”

178 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

Decision made: London in the swinging ’60s was irresistible. Chris would be joined by Dorothy Armitage, whom he had met at McGill and would marry in Paris in 1968. Dorothy would be the mother of all four of Chris’s sons.

Chris breezed through a three-year law course and exams in only two years in the Middle Temple of the Inns of Court School of Law, which had trained barristers since the 14th century. His eldest son, Crane Charles Harvey, was born two months before courses commenced in September 1966. The family’s financial sustenance required Chris to continue working the summer halibut season, despite the length of travel by transatlantic steamer and rail. Chris continued the routine into his early years as a working barrister in London. He would instruct his chambers clerk not to schedule cases during his annual fishing trip. The clerk commended Chris’s choice of aristocratic sport. He imagined a fly rod, tweed jacket and Scottish trout, not a slime-spattered mackinaw and an iron gaff on the heaving decks of a ship at sea. The misconception kept Chris smiling for years.

At the Inns of Court, Chris took an immediate love for a legal profession struggling to bring the law into the modern world. The leader in this was a hero of all law students: Lord Alfred Thomas Denning, Master of the Rolls. He was at the height of his powers and held court every day. Between law classes, Chris would make his way into Lord Denning’s court, slip into the back row and observe the best of the British barristers pitch their cases, refined down to about 15 minutes. Lord Denning would ask what was their best point in the appeal. They all tried to dodge it. Lord Denning, in the kindest possible way, pressed for the answer. When he got it, he would say, “Well, if that is your best point, I don’t think we have to hear your other points.” The young law student in the back row could not help but be overwhelmed by the process, especially the magic that made every loser in Lord Denning’s court feel as though he had won.

In Lord Denning, Chris had found a father figure in law, and in Tom Denning, a friend. He continued to visit Tom at his home in Whitchurch, Hampshire until he passed in 1999 at the age of 100.

Chris developed qualities in himself that he admired as the strengths of Lord Denning’s character: forthright efficiency, and the evocative power of clear, earthy language and his peerless knowledge of the common law. “Like most of his judicial innovations,” Chris wrote, “his protection of individual rights … found its roots in the common law tradition. He went as far back as the Magna Carta, which he frequently cited.” Chris would also invoke the Great Charter for the length of his career.

In a 1968 letter, Chris recounts an evening spent dining in the Middle Temple’s great Elizabethan Hall. It remains one of London’s finest medieval

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 THE ADVOCATE 179

structures, having survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 (fought with beer from the Temple cellar) and both World Wars. Under its famous hammerbeam roof, Chris observed a typical Middle Temple evening: We had a super after-dinner speech from the Solicitor-General … he was talking about the rule of law and the commonwealth; about defending Sheik Abdullah in Karachi, Kenyatta et al in Nairobi. On the 14, Francis Chichester is to be made an Honorary Master of the Bench and will be seated at Drake’s table (from the Golden Hind) amid champagne toasts etc.

Chris then shared a moment of understanding with an observer: There was a Nigerian fellow sipping port and looking about; he was there for the first time, so I asked him what he thought of it all: “Nonsense, all nonsense.” Really it was, but that’s life. Everybody knows that.

This so-called nonsense was something Chris grew to love about the legal community. In about 2002, he was a founding member of the Trafalgar Day Club led by the SSCC (officially, the “Shadowy Secret Central Committee”) that must, for reasons evident, remain unnamed. The members are a group of friends who are lawyers, judges and others with links to Russell and DuMoulin who continue to meet annually on Trafalgar Day to enjoy camaraderie, good wine and “lectures” on such topics as Britain’s naval victories.

In England in the late 1960s, Chris found creative ways to augment and stretch his halibut finances. He used his Ford Cortina as an unregistered taxi in the theatre district, shopped for groceries on the basis of protein per pound and rationed all supplies with exacting parsimony. For the rest of his life, Chris would continue his habit of calculated rationing with everything from toilet paper (only five squares permitted5) to pocket diaries.6 Old habits die hard.

In 1967, he conceived the Middle Templar magazine as a publishing venture in the model of the Advocate. An article in the first edition extolled the virtues of Lord Denning as Master of the Rolls. “Sales were a great success at £2 per copy. We sold 450 copies in 1½ days and made a great walloping profit,” Chris wrote in a hand-typed letter to Dorothy dated February 1968.

Immediately I sent one off to support my application at University College … University C accepted me, but I have learned that the threat of veto from the Higher Degrees sub-committee is a real one! The Head of UC Law Dept is holding my application for the most propitious moment. He is very well known, and solidly on my side ...

The veto never came. Chris distinguished himself as a legal scholar, earning a master of laws degree and a doctor of laws degree from University College, London in 1970 and 1975, respectively. In 1975, Chris produced a 670-page doctoral dissertation on the history of law relating to pollution of

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 180 THE ADVOCATE

rivers and the development of the law of nuisance from ancient to modern times.7 His 1970 master’s thesis entitled “The Duty Concept in Negligence: Liability for Infringement of an Economic Interest” was thought by Chris’s father to be relevant to a case then before the B.C. Supreme Court, Rivtow Marine Ltd. v. Washington Iron Works (1970). Judge Harvey forwarded a copy to the presiding judge, the Honourable Justice J.G. Ruttan, who made reference to Chris’s thesis in his judgment. The case went on to the Supreme Court of Canada, and the thesis was recast as an article in the Canadian Bar Review in 1972, 8 subsequently referred to in nine Canadian decisions between 1976 and 2006.

While in his master’s program, Chris found a place in a leading set of common law chambers as pupil. The pupil’s role was to tag along behind his pupil master, appearing in court dressed in the normal wig and gown, but with no other role to play—just observe and learn. After the first six months, the pupil is deemed sufficiently qualified to appear in court on his own. That assumption was put to the test when in August 1968—less than three years since opening his first law book—Chris found himself as prosecuting counsel in the Old Bailey.

The previous case was a murder case: “Not guilty,” said the jury. “He was damned lucky” commented one elderly lady to another in the gallery before they crossed their arms and settled down to see what the next case had to offer. Their judgment may have been that Chris’s prosecution stumbled more than once. Fair challenges were made to all the evidence Chris had to offer. As Chris said, “Justice was done: acquittals all around.” The two elderly ladies, no doubt, had seen better performances.

Being Canadian conferred the advantage of being memorable: “Give this next brief to that Canadian chap who did a good job on short notice.” Before long, Chris had the beginnings of a small but growing practice. The best of it, he later recalled, was “the fascination of working in a system that had changed little since Dickensian times.”

In his final days at Lions Gate Hospital, his blood oxygen running low, Chris continued to write. He produced this description of the quotidian rhythms of life as a young barrister:

[He would] pick up his brief for the next day, quickly review to see if he needed to take a book, check the British Rail times, plan when to arrive at King’s Cross, Paddington or one of the other London railway stations to arrive in time for court. The next morning, having read the brief thoroughly on the train, he would arrive at his destination, hand in the ticket stub and ask, “Where’s the crown court?” “Up the road, Gov, just past the gaol, can’t miss it.” After trudging up the hill, barrister’s bag over the shoulder, finding his instructing solicitor waiting, they discuss the case. The gowned barrister sweeps into court, doors held open for him.

THE ADVOCATE 181 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

The accused is in the dock, having been brought up from “below”. Chris argues strenuously that the jury cannot convict for whatever defence reasons apply. The jury disagree and convict. The judge determines sentence with little input from counsel, being unnecessary because the sentencing principles are well known. Sentence given is then followed by the order, “take the convict down.” Down he goes, step by step from inside the dock. Walking back to the train Chris notices a small arched, barred, completely dirt-covered window, the top half moon up against the sidewalk, and realises that the other side of that window is “down”.

Then back to chambers hoping there will be a brief waiting to similarly occupy the next day. How not to like that?

By 1975, England was economically the “sick man of Europe”. Coal miners and government were in open battle for control of the country; Maggie Thatcher was not yet on the horizon. Chris reluctantly informed his fellow barristers in chambers that the time had come to return to his Canadian roots. At his farewell party, Chris received a curious gift: “a painting with ‘chambers’ on one side and our neighbours, the Knights Templars, on the other, lying in sarcophagi, crossed legs over a dog, a note of date of death 1170”.9, 10

The family’s canary yellow Morgan was loaded onto one of the last transAtlantic steamers at Tilbury docks. Next stop: Port of Montreal. A crosscountry drive brought the family to Vancouver. For the Prince Rupert fisherman-turned-lawyer, it was a triumphant return. Crane, however, would return to England for two more years at a boarding school near London, where at age nine, he was thriving.

Chris was treated generously by the Vancouver bar. Ladner Downs saw him through a year of Law Society requirements, and in 1976 he was taken in by what he found to be the best litigation firm in Vancouver. Working at Russell and DuMoulin (now Fasken) with counsel including Douglas McK. Brown, Q.C., the Honourable D.M.M. Goldie, Q.C., and the Honourable Allan McEachern, he felt he was back in England. The quality of counsel work was just as high.

Chris developed a diverse and unique scope of practice. Gavin Hume, K.C., summarizes it well in an article discussing Chris’s “retirement” of 2013 in the Advocate (although, as Hume points out, one couldn’t use the word “retirement” and “Chris Harvey” in the same sentence). Chris carried on a robust practice into his 80th year; in August 2022, on a laptop in Lions Gate Intensive Care Unit, he continued to conduct billable hours.

The range of issues covered in his cases illustrates his breadth and depth of knowledge of the law, and includes marine, fishing and aquaculture, aboriginal (including several leading cases in the Supreme Court of Canada), marine insurance, libel, slander, helicopter and hot air balloon incidents, the defence of various charges under the Fisheries Act, Customs Act and Railway Act, international maritime boundary issues, interpreta-

182 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

tion of wills, First Nations elections issues, expropriation, patents and trademark cases … Marketing boards dealing with [cheese], chicken, turkey, eggs, tomatoes and potatoes all felt the sting of his arguments.11

Chris was naturally drawn to the defence of fishermen and fisheries, and in his own words, “never turned down a case from a fisherman in trouble”. In 2010, he was a natural choice to represent the Westcoast Trollers Area G Association, United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union in the Cohen Commission, which investigated the decline of sockeye salmon in the Fraser River. Chris’s cross-examinations revealed a parallel decline in the quality of sockeye salmon fisheries management.

Chris was appointed Queen’s Counsel in 1990. Moving to MacKenzie Fujisawa in 2003, he worked with Thomas Braidwood, Q.C., and a host of exemplary barristers, most closely with Chris Watson and Ian Knapp. Knapp described the great advantage Chris drew from his impressive breadth and depth of knowledge of the law:

One of Chris’s great regrets about our modern profession is that too many lawyers specialized at too early a stage in their careers, preventing them from seeing the bigger picture of cases and broader dimensions of our law. Chris, for his part, had a remarkable knowledge of the law. He often out-manoeuvred his opponents by drawing on principles of law which they had never even considered, due to excessive specialization.

Chris believed firmly in the cab-rank rule, and as a result he often took cases no other lawyer wanted. He argued them vigorously. In Knapp’s words, “His method of rapidly ascertaining the essential issues in a case and then focusing with laser-like precision on those points made his preparations efficient, reduced trial times and kept clients’ bills under control.”

One of Chris’s cab-rank cases had him represent the Nicola Valley Rod and Gun Club respecting what was viewed as the appropriation of public lakes by private interests. He had no real expectation of full payment for these cases, beyond perhaps a fishing rod and a few good lunches, but he drew immense satisfaction from battling to protect access to public rights of way and public lakes. After a decisive B.C. Supreme Court victory in Douglas Lake Cattle Company v. Nicola Valley Fish and Game Club (2018), the outcome was overturned in 2021 by the B.C. Court of Appeal in what Chris described as a “very strange ruling about trespassing on [public] water”. Chris felt that justice would have been restored had the Supreme Court of Canada not declined to hear an appeal. For the public right of access to be restored will now take a new case before the courts, and a judge who will not allow precedent to stand in the way of justice.

Chris never lost sight of how efficiency in Lord Denning’s court contributed to the accessibility of justice. He used his final “Entre Nous” edito-

THE ADVOCATE 183 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

rial12 to address the need for “serious pruning” to the modern rules of court, lamenting “roadblock after roadblock” placed in the way of the modern litigant. Until 1979, a much simpler set of rules had remained essentially unchanged from the English rules of 1883. They featured “stripped-down pleadings and limited discovery” and were contained in a single slender volume, the B.C. Supreme Court Rules of 1912, that emphasized brevity, avoiding “unnecessary prolixity” and requiring counsel to state “as concisely as possible the contentions to be urged”.

If we are serious about access to justice, we should throw out the existing civil rules and return to a rule book with nothing but the essentials … our trial and pre-trial procedures, like most things in life, have developed an excess of appendages and fluff … We should abolish the current civil rules and start over. They have been an unmitigated disaster.

Chris’s personal brand of accessible justice involved conveying himself to clients and courthouses up and down the coast in the open-topped, 23’ highspeed boat he operated from June 1987 until June 2022, just two weeks shy of his 80th birthday. A one-off custom vessel, the boat was modelled after the famous Miami Vice speedboat but constructed of aluminum. It featured a sealed deck that was entirely above the waterline, allowing it to self-drain if swamped by any amount of water. The boat was an extension of Chris’s own essence: pure efficiency and durability, with no unnecessary frills that would impact performance. He named her the Northern Freedom, which combined two concepts that meant a lot to him. It was also the name of a client’s ship that was lost at sea, the subject of one of Chris’s infamous civil jury trials.

Chris put together an impressive string of 33 annual summer voyages over a 34-year span in the Northern Freedom, with only one season lost to COVID restrictions. Passengers recall how Chris created the impression of disaster narrowly averted, while exuding calm enjoyment in the most intolerable conditions. Chris’s risk tolerance was evidence of his high confidence in the Northern Freedom as a ship, and in himself as ship’s captain. When a passenger asked with a hint of concern about the apparent nonexistence of a backup engine, Chris would gesture casually to the Sea Clipper canoe strapped to the vessel’s side. The passenger was left to reflect that they were the backup engine.

Volume one of the Northern Freedom’s log books13 opens with the comment “fine dark lager – on tap” made in Silva Bay on June 26, 1987. The vessel’s maiden voyage under Chris’s captaincy paused on Savary Island, then continued northwest to Bella Bella, where, rather boldly, Chris, two sons and a dog turned west into the open Pacific. His calculation of the Northern Freedom’s compass deviation must have been slightly off, as they would

184 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

have missed the islands entirely and continued westward toward Japan had a fortuitous break in the clouds not allowed Matthew, age ten, to sight a hump on the northern horizon. “Is that an island or a cloud?” his sons debated as Chris swung the bow almost 90° to starboard. At 7 p.m., a full five hours since leaving the mainland, they came abeam of Cape St. James on Kunghit Island, having consumed half of the ship’s 100 gallons of fuel. They would need both luck and fair seas to make it back to Bella Bella, so they dropped anchor between the fjord-like walls of Luxana Bay, unstrapped the canoe and set off to explore the archipelago by paddle.

“In a different world several months later, I found myself cross-examining a fishery officer in a trial in Prince Rupert,” Chris wrote in an unpublished chronicle of the adventure.

He expressed the opinion that a VHF transmission from a fishery patrol vessel at the south end of the Charlottes could be heard in Dixon Entrance. “Where was the vessel?” “Luxana Bay on Kunghit Island.” “Luxana Bay! ... but there are huge mountains around all sides of Luxana Bay.” I could see him wondering how a dumb lawyer from Vancouver could possibly have known that.

For the Northern Freedom’s first decade, Chris’s crew often consisted of his children Matthew, Timothy and Jonathan, and by the mid-nineties, his new bride Anne-Marie, who was soon to serve as the Advocate’s cover artist (1999–2012). In more recent times, many of his grandchildren joined his adventures. Anne-Marie married Chris in a beautiful full-moon ceremony on Savary Island in August 1997, with Gavin Hume as best man. Chris had purchased the land on Savary in 1979 and barged a 1930s house up the coast from West Vancouver behind a client’s fishing vessel. He called the island home his “sanctuary” and spent the opening and closing of each summer on Savary, book-ending his annual adventure north.

Chris and Anne-Marie would spend weeks on these expeditions exploring remote stretches of British Columbia’s coastline, looking for crescent beaches and fishing holes, dipping in hot springs and paddling up river estuaries to watch grizzly bears. On the exposed outer coast, while Anne-Marie painted, Chris would canoe solo in tidal whitewater caused by ocean swells roiling around rocky outcrops. He found it altogether delightful, a sort of canoe ballet, until, inevitably, a wave spilled him onto the barnacles and all but snapped the canoe’s gunwale.

Chris would eventually motor up to a community dock and pull a carefully folded suit and leather briefcase from below the Northern Freedom’s decks, to appear respectable, if well-weathered, in the courthouse of places like Masset or Prince Rupert. He would emerge from the wilderness on

THE ADVOCATE 185 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

schedule, despite his journeys invariably featuring a healthy measure of misadventure: cold-water swimming to change a damaged propellor, or paddling half a day by canoe to fill a few milk jugs with fuel.

Once in court, Chris would drive to the heart of the issue in a way that all but forced the opposition to concede. There was a case involving the crab fishery near Penelakut Island; as one would expect, the best crabbing was right along a boundary with the closed area. Chris’s clients did well by setting traps close alongside the line. On one occasion, before they managed to raise the traps from the ocean floor and scan the barcodes to transmit their position, the ship had drifted across the boundary and into the closed region. Ian Knapp recalls how Chris reduced the issue in dispute to one simple question when seeking leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal: “What is fishing?”

“Chris’s opponent was left in the unenviable position of having to explain to the court that it would be of no assistance to the bench and the bar to know what the law considers to be ‘fishing.’ Needless to say, Chris was granted leave to appeal.”

Many of Chris’s cases cited the provisions of the Magna Carta. In R. v. Gladstone (1996), the Supreme Court of Canada accepted Chris’s argument that the Magna Carta guaranteed a common law right to fish for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal alike. His November 1996 article, “The Abolition of the Public Right of Fishery Proposed by Bill C-62”, was cited in Canadian senate debate and reprinted in the Advocate in June 1997. Chris opened with the words: “Bill C-62, the proposed new Fisheries Act … contains provisions … designed to abrogate the public right of access to the fishery, a right that has existed in the common law since the Magna Carta, 1215.” He described the abuses of King John that gave rise to the Magna Carta: the king would clear the public from fishing grounds and grant exclusive access to his favoured groups—precisely what the proposed Canadian legislation would allow, rolling back the law by eight centuries.

Besides enshrining the rights of trial by jury and habeas corpus, the Charter, in a lesser-known passage, prevented the monarch from establishing any new exclusive fisheries in tidal waters. This, the forty-seventh provision of the Magna Carta developed into what became known in English law as the “public right to fish”.

Chris wrote this on the heels of Chief Justice Antonio Lamer’s pronouncement that owing to the Magna Carta, “subjects of the Crown are entitled as of right not only to navigate but to fish in the high seas and tidal waters alike”. It was the “unquestioned law”.14

Nevertheless, some lawyers have questioned whether an archaic charter, inscribed on sheepskin parchment in medieval England, could possibly

186 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

hold water in modern times. Knapp recalled one such occasion during “one of his last, great cases”, when Chris was in court to make an application to certify a class proceeding on behalf of geoduck fishermen in British Columbia, who were claiming compensation for the closure of several large areas of the coast to fishing. “As one would expect, an important part of Chris’s argument involved the Magna Carta and the public right to fish.”

During a break, one of the counsel acting for DOJ jovially suggested that Magna Carta was not the law of the land. Chris’s response was elegant. He marched her down the hall of the courthouse to where a copy of that document hangs prominently, and asked her: “Why, if it is not part of the law of the land, is it hanging on the walls of our courts?”

Chris was widely appreciated and his loss is felt heavily in the legal profession, in coastal communities and in the fishing industry, which carried his lifetime loyalty. Chris enjoyed working with First Nations—above all, the fishing community of Lax Kw’alaams, formerly Port Simpson, north of Prince Rupert. In a moving letter read aloud at his Celebration of Life, the Lax Kw’alaams Band pledged to launch a fishing vessel bearing his name on its hull—both to honour Chris, and to send a clear message to Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Their final summer expedition together to Prince Rupert was meant to be the opening of a new chapter of coastal navigation for Chris and Anne-Marie. It was the first lengthy voyage on their new ship, a stately but workmanlike dual-engine jet boat with an aluminum hull and a proud West Coast design that resoundingly echoed the commercial fishing vessels Chris worked as a younger man. They named her Wanderingspirit, the name given to Chris as an honourary member of the Salt River First Nation.15 Chris was inordinately pleased to have Anne-Marie on board again. In recent years, she had lost her enthusiasm for being rattled about in the Northern Freedom. Their faithful white giant of a dog, Pip, rounded out the crew.

Wanderingspirit steered into the Port of Prince Rupert just as Chris’s last great legal victory bore fruit. He had managed to “pry open a salmon fishery” that the minister had seemed determined to permanently close. With just hours to respond to an injunction application that Chris had filed on behalf of the Lax Kw’alaams Band, the minister, perhaps coincidentally, had opened the Skeena River fishery. In his last days, low oxygen affecting his vision but not his memories, the final words of prose Chris ever wrote were these:

Chris and Anne-Marie had the profound satisfaction of seeing gillnetters streaming out of Prince Rupert harbour, all shapes and sizes, a seemingly never-ending stream, for an opening the next day. An industry that is essential to the survival of local coastal communities was preserved from

THE ADVOCATE 187 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

effective government expropriation … Seeing that, in the form of a stream of gillnetters heading to their favourite fishing spots, was very satisfying. One little camping boat going into harbour and hundreds of gillnetters streaming out …

He closed with an exhortation to a younger generation of barristers to continue with his battle, to carry forth the banner handed down from those knights and rebel barons who laid the foundations of modern justice: When necessary, I marshalled the historical weapons buried well down in the common law toolbox … There are competent junior barristers to pick up the pieces and run with them. My dying wish is that they will follow my example and find ways in that toolbox to protect a way of life that communities rely on but governments would simply eliminate.

Chris lived and loved intensely. Predeceased by his parents and brother Peter, and survived by his sister Gail, four sons, three stepsons, twelve grandchildren, and his beloved wife Anne-Marie, Chris will be remembered for the immeasurable impact he made on those people and causes he cared most about.

ENDNOTES

1. The Honourable JT Harvey’s military career is summarized in “Welcome Home” (1945) 3 Advocate 186 at 188.

2. The Honourable JT Harvey, “Meditations in the Atlin Vault” (1964) 22 Advocate 133 at 133–36.

3. The Honourable JT Harvey was well known for his habit of holding court on his summer cottage lawn, a practice noted in “Nos Disparus” (1999) 57 Advocate 597 at 597–600.

4. Discussed in greater detail in (2010) 68 Advocate, an edition marking the centennial of the BC Court of Appeal.

5. Gavin Hume, Best Man’s Speech (Savary Island), Wedding of Chris and Anne-Marie, Savary Island.

6. Chris was generous but let nothing go to waste. He was known for keeping his calendar in a distinctive leather-bound pocket diary manufactured in London, and gifted them to many lawyers on an annual basis. He would then ascertain over the course of the year who was in the habit of using them; only those able to produce their London Diary upon request would remain on the list for resupply.

7. His doctoral dissertation ultimately led to a contribution on the history of nuisance in a chapter in The Law of Nuisance by Gregory S. Pun and Margaret I Hall, as reported by Gavin Hume in (2013) 71 Advocate 568.

8. Chris Harvey, “Economic Losses and Negligence: The Search for a Just Solution” (1972) 50 Can Bar Rev 580.

9. This rather cryptic painting described by Chris in his Life Notes, written in his final days, concerns the origins of the Magna Carta and English common law.

The Inner and Middle Temples stand beside the Temple Church, built by the Knights Templars in the late 12th century on land purchased on the banks of the Thames to be their stronghold in England. Among the Templars “lying in sarcophagi” is the early lawmaker William Marshal, First Earl of Pembroke, who was chief negotiator of the Magna Carta on behalf of King John in meetings held within Temple Church. As regent following John’s death, Marshal reissued an amended Magna Carta in 1216 and 1217 under his own seal, on terms favourable to the barons.

10. The “date of death 1170” denotes the murder of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, by four knights of the realm. The murder removed an obstacle to King Henry II’s reorganization of England’s administration of justice. The king abolished church courts, implemented jury trials and introduced a system of writs that ended the practice of trial by combat to settle land disputes. Though his intent was to consolidate power in the royal court, these actions established enduring legal traditions.

11. Gavin Hume, QC, “On the Front Cover: Christopher Harvey, Q.C.” (2013) 71 Advocate 657 at 659.

12. “Entre Nous” (2013) 71 Advocate 649.

13. The log books, which remain aboard the Northern Freedom, contain records of the joys, mishaps, friendships, events and places experienced, diligently recorded alongside engine hours, compass bearings and travel times from June 1987 to June 2022.

14. R v Gladstone, [1996] 2 SCR 723 at para 67.

15. The Salt River First Nation was another of Chris’s Indigenous clients, located in Alberta.

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 188 THE ADVOCATE

THE ADVOCATE 189 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 190 THE ADVOCATE Suite 700 – 1177 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6E 2K3 Telephone: 604.687.4544 • Facsimile: 604.687.4577 • www.bmmvaluations.com Vern Blair: 604.697.5276 • Rob Mackay: 604.697.5201 • Gary Mynett: 604.697.5202 Kiu Ghanavizchian: 604.697.5297 • Farida Sukhia: 604.697.5271 Lucas Terpkosh: 604.697.5286 • Sunny Sanghera: 604.697.5294 Business Valuations • Matrimonial disputes • Shareholder disputes • Minority oppression actions • Tax and estate planning • Acquisitions and divestitures Personal Injury Claims • Income loss claims • Wrongful death claims Economic Loss Claims • Breach of contract • Loss of opportunity Business Insurance Claims • Business interruption • Construction claims Forensic Accounting • Accounting investigations • Fraud investigations

The Litigation Support Group

Left to Right: Kiu Ghanavizchian, Sunny Sanghera, Gary Mynett, Lucas Terpkosh, Vern Blair, Rob Mackay, Farida Sukhia

SURREPTITIOUS RECORDINGS BY CIVILIANS IN CRIMINAL TRIALS: ARE THEY CONSTITUTIONAL?

By Robert Diab

It is not a criminal offence in Canada to surreptitiously record a conversation to which you are a party. In some provinces, making such a recording may be tortious.1 Whether or not it is legal, the act can be invasive and unfair. Yet, for decades, criminal courts across Canada have admitted into evidence recordings that a complainant has surreptitiously made of their conversation with the accused. Prosecutors have had to satisfy a common law test to establish that a recording is accurate and more probative than prejudicial.2 Crown counsel have assumed they were otherwise fair game under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and courts have agreed.3

But the law is changing. Recent decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada (the “Court”) have put the building blocks in place for a court to recognize that police or Crown receipt of a surreptitious recording from a thirdparty civilian, with the intention of using it for prosecutorial purposes, constitutes a search or seizure under s. 8 of the Charter and would require a warrant to render it reasonable. At least one superior court has done so, in a case involving a civilian who made an unlawful recording of a conversation to which she was not a party.4 The reasoning should apply to any surreptitious recording, including those in which the complainant is a party and gives the recording to police.

One might ask: What would be the point? What mischief on the part of the state would this seek to avoid? Would a warrant not be a mere formality?

I argue that there are compelling reasons to recognize a privacy interest in surreptitious recordings under the Charter. Doing so would better protect everyone’s privacy without precluding the Crown from using a recording to obtain a conviction.

THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA’S DISTASTE FOR SURREPTITIOUS RECORDING

In 1974, Parliament added a framework to the Criminal Code for lawful wire-

THE ADVOCATE 191 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

tapping.5 A cornerstone of that framework is the offence of “intercepting” a private communication with a device 6 One exception explicitly carved out of the offence is for persons who intercept a conversation with the consent of one party.7 In R. v. Duarte, 8 the Court held that police cannot circumvent the requirement to obtain a warrant by obtaining an informant’s consent to record a conversation they are about to have with a target. While the Charter does not protect us from the risk of speaking to a “tattletale”, Justice La Forest reasoned, the risk of our interlocutor “making a permanent electronic record” is a risk of a “different order of magnitude”.9 The concern in that case was not just that the state might obtain such a recording, but that such a recording might be made.

The Court’s other cases dealing with surreptitious recording— R. v. Wong, 10 R. v. Araujo, 11 and R. v. Fliss12—concern whether police are authorized to make a recording or what use may be made of the fruit of a recording they made unlawfully. None deal with the status or use that police might make of a recording by an independent civilian. The Court has, however, dealt with a number of related issues.

These issues can be approached in terms of two broader questions: Do police conduct a search or seizure on receipt or review of evidence from an independent party? And does a person have a reasonable expectation of privacy in a surreptitious recording that a civilian volunteers? I take each issue in turn before addressing the rationale for a warrant requirement.

POLICE RECEIPT ON THIRD-PARTY DISCLOSURE

The Court has not decided whether police conduct a seizure when an independent civilian brings them evidence or a search when police proceed to review it. However, the Court has consistently held that where police ask for or receive an item in which the claimant has a reasonable expectation of privacy, police conduct a seizure upon receipt of it or a search on review of it if they act with an investigative purpose.

In R. v. Dyment, 13 a doctor took a vial of blood from an accused for medical purposes after a car accident and without his knowledge. Discovering that the accused had been drinking, the doctor decided to turn over the sample to police. Setting out the majority’s reasons on point, La Forest J. held: “If I were to draw the line between a seizure and a mere finding of evidence, I would draw it logically and purposefully at the point at which it can reasonably be said that the individual had ceased to have a privacy interest in the subjectmatter allegedly seized.”14 The officer’s receipt of the sample constituted a seizure because the accused retained a privacy interest in the sample when the officer received it.15 The warrantless seizure was unreasonable.16

192 THE ADVOCATE VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

In R. v. Colarusso,17 following a motor vehicle accident involving a fatality in which alcohol was suspected, hospital staff took a blood sample and, with an officer’s assistance, a urine sample. The accused consented to samples being taken for “medical purposes”.18 At the coroner’s behest, the officer delivered the samples to a forensic lab for storage. A majority of the Court held that the officer conducted an unreasonable seizure because he intended “from the outset” to make use of the samples for a prosecutorial purpose to which the accused had not consented.19

In R. v. Cole, 20 a school principal gave police a teacher’s board-issued laptop containing nude pictures of a student. The Court held that the principal was authorized to seize the laptop for administrative purposes, but the accused retained a reasonable privacy interest in the laptop since he was permitted some personal use of it. Police receipt of it for a criminal investigative purpose constituted a seizure. Justice Fish held that police may have been authorized to take custody of it temporarily, for safekeeping, while obtaining a warrant.21 Holding on to it at length and reviewing its contents without a warrant was unreasonable.22

In R. v. Spencer, 23 police asked an internet service provider to disclose subscriber information attached to an internet protocol address implicated in a child pornography investigation. The Court held that subscriber information attracts a privacy interest, given what it may reveal about online activity. In light of this interest, police conducted a search in asking for and receiving the accused’s subscriber information from the service provider— a search requiring some form of authorization to be reasonable.24

In R. v. Marakah, 25 the Court held that the accused retained a reasonable expectation of privacy in texts that police seized from a recipient’s phone when investigating firearms offences. In obiter, Chief Justice McLachlin considered how the holding might be applied where “police access text messages volunteered by a third party”.26 If the accused were held to retain a privacy interest in the exchange, she held, s. 8 would be engaged and “police officers will be aware that they should not look at the text messages in question prior to obtaining a warrant”.27

PRIVACY WITHOUT CONTROL

The section above shows how the Court has consistently found a search or seizure where police take or receive an item from a third party in which the accused retains a privacy interest. That being the case, does an accused have a reasonable privacy interest in a surreptitious recording a civilian turns over? The Court’s holdings in Marakah and R. v. Reeves28 suggest that an accused person does have such an interest and it would not be waived by another party’s voluntary disclosure.

THE ADVOCATE 193 VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023

Marakah established that text messages can engage a high privacy interest, given how much personal information can be gleaned from them,29 and that a sender can retain privacy in a message despite not having control over it in the recipient’s hands. As Chief Justice McLachlin held, a sender still exerts “meaningful control over the information they send by text message by making choices about how, when, and to whom they disclose the information”.30 As a result, she held, “the risk that a recipient could disclose an electronic conversation does not negate a reasonable expectation of privacy in an electronic conversation”.31

In Cole and Reeves, the Court rejected the third-party consent doctrine.32 The school board in Cole owned the laptop the principal turned over to police. The Court held that the board’s consent could not authorize police to seize or search the device. Third-party consent would entail police interference with a person’s privacy interest “on the basis of a consent that is not voluntarily given by the rights holder, and not necessarily based on sufficient information in his or her hands to make a meaningful choice”.33 In Reeves, a spouse consented to police seizing the family computer alleged to contain evidence of her partner’s possession of child pornography. Citing Cole, the Court held that police could not rely on the spouse’s consent, despite her having a shared or “overlapping” interest in the device.34 Justice Karakatsanis, for the majority, wrote: “[w]e are not required to accept that our friends and family can unilaterally authorize police to take things that we share”.35

An accused would have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the subject matter of a surreptitious recording—the conversation itself—on the basis of their assumption that it was private and confidential in nature, and the assumption being objectively reasonable.36 Provincial privacy law and criminal cases in which recordings are tendered (recognizing a prejudice to the accused and to the administration of justice) would support this finding.37 And as Cole, Marakah and Reeves have established, the accused would retain their privacy interest in the recording despite the complainant’s consent to provide it to police or Crown. Police or Crown taking custody of the recording or proceeding to review with a prosecutorial purpose would engage s. 8 and require a warrant to be reasonable.38

WHY BOTHER WITH A WARRANT?

One might ask: What possible purpose does insisting on a warrant serve here? By the time a civilian has made a recording and described its illicit content to police, has the damage not already been done? What mischief on the part of the state would we avoid by insisting that police obtain a warrant?

VOL. 81 PART 2 MARCH 2023 194 THE ADVOCATE

In a number of cases, the Court has affirmed that even if police know what an item contains, on the basis of what a third party has told them, an accused may still retain a privacy interest in the item against the state.39 The need to obtain a warrant in these cases is not a formality, because the Court recognizes a significant difference between a third party violating a person’s privacy and the state doing so. Holding the state to a higher standard protects everyone’s privacy in at least two important ways.

In Reeves, Justice Karakatsanis held that “[w]hen police seize a computer, they not only deprive individuals of control over intimate data in which they have a reasonable expectation of privacy, they also ensure that such data remains preserved and thus subject to potential future state inspection”.40 This is true of a surreptitious recording. State possession of it deprives a person of control over the fate and possible dissemination of it. Insisting police obtain a warrant here would mean that police would have to report the seizure of a recording to a justice and comply with post-seizure requirements in the Criminal Code, including the provisions for returning or destroying the evidence in the event of a stay or after the proceeding has ended.41

Justice Karakatsanis provided a broader rationale in Reeves that also applies here. The requirement that police obtain a warrant to render a search presumptively reasonable “more accurately accords with the expectations of privacy Canadians attach to their use of personal home computers and encourages more predictable policing”.42 As the Court held in Hunter v. Southam Inc. , predictable policing and protecting privacy are both supported in turn by clear rules and objective standards that help to avoid unreasonable searches before they occur.43