The Journey Home

from the Wilderness In Praise of Park Rangers Lake 22: A Homecoming

from the Wilderness In Praise of Park Rangers Lake 22: A Homecoming

Randy Bott is a fine art landscape photographer based out of Seattle, Washington. He specializes in landscape and infrared photography, including large format limited edition prints and photography workshops. Learn more: randybottphotography.com.

Ethan D’Onofrio was blessed with parents who instilled in him a deep reverence for our place in the natural world. He now provides a range of technical services including consulting on the often-overlooked dangers modern technology poses to our health, and our humanity. He thrives in Hawaii with his wife Shannon. Visit him at donofriocreative.com.

Elizabeth Fischer is a novice mountaineer, ultramarathon runner, and artist and works for the non-profit Recovery Beyond out of Tacoma, WA. She is passionate about healing on all levels—mental, physical, and spiritual—and the transformative power of nature for our well-being.

Cathy Grinstead, born and raised in northern California, spent her summers backpacking in the Sierra. In 2018, she retired from veterinary practice and moved to Bellingham to explore a different part of the world. She enjoys hiking, outrigger paddling, and snow sports, and loves all that Bellingham has to offer!

Beth Hartsoch is a city kid who tries to be brave on outdoor adventures. She wrangles data at her day job and has a mixed record on parenting teenagers, riding bikes, and civic engagement.

Kathy Hastings resides on 1.5 acres of wooded land in Snohomish. After 25 years in art education, she moved to full-time studio work. She particularly enjoys combining digital photography with encaustic (hot wax) techniques. See more of her work at kathyhastings.com.

Bill Hoke came to the Pacific Northwest in 1970 and began a lifetime of climbing and hiking. He’s hiked—primarily solo—more than 1,500 miles in the Olympic Mountains and is the trail editor of the fourth edition of the Olympic Mountains Trail Guide.

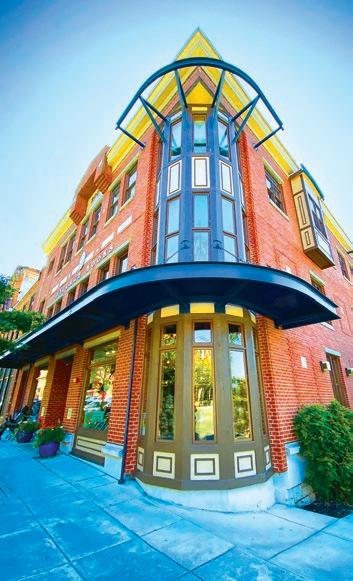

David Johnston is writing a new book about photography and relationships. He redeveloped historic buildings for many years, placing ten buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. He supports the arts and the environment and has created scholarships at WWU, WCC, TESC, and UH. The ocean and forest are his church. Lake 22 is his first book.

Dave Mauro is a forty-year Bellingham resident and author of The Altitude Journals. He has climbed the highest peak on each of the seven continents, yet shamelessly holds out for a closer parking space at Costco. His inspirations include outdoor spaces, the writing of Richard Brautigan, and caffeine.

Eric McRory lives with his wife, Erin Simpson, in Bellingham, WA. He grew up on Lummi Island and— sometimes accompanied by his sixyear-old standard poodle named Rupert—enjoys adventures of all kinds. He owns Northside Dental Care in Bellingham.

John D’Onofrio Publisher/Editor john @ adventuresnw.com

Oksana Brown Accounting accounting @ adventuresnw.com

Jason Rinne Creative Director jason @ adventuresnw.com

Roger Gilman Poetry Editor roger @ adventuresnw.com

John Miles climbed and hiked in the North Cascades for nearly 50 years. He also taught environmental studies at Western Washington University, taking students “into the field” as often as possible, and what a field it was. In retirement, living near Taos, New Mexico, he hikes and skis the Southern Rockies. His latest book is Teaching in the Rain: The Story of North Cascades Institute (2023).

Mike Nolan is a freelance writer living in Port Angeles, WA, where the mountains meet the sea. His writing has appeared in The Seattle Times, Peninsula Daily News, and other publications. Visit him at mikenolanstoryteller.com.

Paul Tolme, the Journalist on the Loose, is an outdoors writer, award-winning environmental journalist, and blogger for Cascade Bicycle Club. He lives with his wife in a Seattle houseboat crammed with bikes, skis, snowboards, kayaks, and paddleboards, but no regrets. His work can be seen at paultolme.com and cascade.org/news.

Catherine Darkenwald Print & Digital Account Manager catherineadventuresnw @ gmail.com

Ethan D’Onofrio Digital Media ethan @ adventuresnw.com Dan Cohen Print & Digital Account Manager dan @ adventuresnw.com

Alicia Jamtaas Copy Editor lish @ adventuresnw.com Cathy Grinstead Social Media cathy @ adventuresnw.com

Alan Sanders

Illustrations alan @ adventuresnw.com

Our public lands are in big trouble.

The funding necessary to maintain (and sustain) them has been mercilessly slashed by the current administration, resulting in a perfect storm: a radical lack of resources concurrent with unprecedented demand. Visitation to our National Parks hit a record 332 million visits in 2024, an increase of 120 million since 1979 (a 64% increase).

The pressure of this ever-increasing usage of our parks, trails, campgrounds, and other recreational facilities has already strained the agencies involved to the breaking point. They have been struggling, underfunded, to maintain roads and trails and repair storm damage.

in the U.S. generated $1.2 trillion in economic output in 2023. This economic driver is now imperiled.

The skeleton crew approach to staff management doesn’t bode well for wildfire season, as the increased number of conflagrations over the last decade has required greater and greater numbers of personnel to manage.

As summer arrives, the situation behooves us all to double down on our responsibility to minimize our impact when visiting our public lands. Bring your garbage home. Use WAG bags when necessary. Be zealously careful with fire. Honor closures. Volunteer. Support recreation-related non-profits with your donations. Make ‘Leave No Trace’ your religion.

To cite a local example, the Deadhorse Road, which provides access to Skyline Divide (one of the most popular trails in the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest), washed out back in November 2021 and remains unrepaired due to a lack of funds. More than three years later, no date has been set to reopen the road. The result is that the ever-increasing throngs of hikers are funneled onto fewer and fewer trails, an outcome that causes damage to those popular routes and the terrain they inhabit.

Now, with previously approved funding withdrawn and employee ranks decimated, it’s a recipe for disaster, threatening the existence of these cherished American resources, our National Parks and Forests themselves.

Make no mistake: Our public lands are the envy of the world. They also produce massive economic benefits, drawing visitors from around the globe and supporting local economies across the country. Domestically, according to the U.S. Department of

By Elisabeth Fischer

In 2011, two mountaineering friends had an audacious idea–get people off the streets and to the summit of Mt. Rainier (also known as “Tahoma”).

Along with a team of committed volunteers, Mike Johnson and Mark Ursino led groups of men and women from the Seattle Union Gospel Mission through a 10-month training program culminating in a successful summit climb of Mt. Rainier. The feature documentary, A New High, released in 2015, captures this story.

In 2016, the Recovery Beyond Paradigm was founded as a 501c3 non-profit foundation to help expand the vision of an outdoor recovery community to support those living in recovery from substance use.

The program has also expanded to include various events ranging from monthly social gatherings open to family and friends to exciting group experiences, including hiking, kayaking, camping, trail walking/running, and more.

In 2019, the name was shortened to Recovery Beyond with a renewed focus to help guide and support those in all paths of recovery who have moved beyond crisis and are wondering, “What’s next?”

Since that first climb, Recovery Beyond has grown to include over 350 active members across Western Washington. Their model is one of “programming with purpose” that allows individuals to start and progress towards an end goal or challenge and focus on positive change.

Volunteering is a foundational component that allows members to incorporate service into their Recovery process. Volunteers provide critical helping hands and skills and can get involved in one of four ways: as an Activity Lead, Activity Helper, First Aid Responder, or Peer Guide.

Recovery Beyond also continues to honor its roots in mountaineering, offering annual guided training from beginner level upwards. In 2024, 12 bold explorers successfully underwent a seven-month training, starting with beginner-level hikes and culminating with an overnight climb and summit of Mt. Adams.

Thanks to a long legacy of dedication, big hearts, and the ongoing generosity of donors, there is no cost to become a member, and activities are free or very low-cost.

Recovery Beyond is passionate about its mission to strengthen connection and recovery through outdoor experiences, keeping the spirit of adventure alive for those choosing a healthier path in life.

More info: www.recoverybp.org

By Cathy Grinstead

As we all know, the first months of the second Trump administration saw widespread cutbacks to US Forest Service (USFS) and National Park Service (NPS) staff and funding.

On March 5, a 45-day temporary stay was issued to block the firings of “probationary” employees of the USFS, and some of these employees have been allowed to return to their jobs with back pay. While it is certainly good news that USFS has reinstated many jobs, the current situation is so volatile that many employees do not feel secure in their positions. State funding is also in jeopardy, with a $12-15 billion funding gap for the next four years.

What does this mean for the Washington Trails Association (WTA)?

In 2024, 44% of WTA’s trail work was done on USFS and NPS projects. WTA needs instruction, coordination, and often pack support from government partners to do this work. With frozen and retracted federal funding, this work cannot be done. Instead, WTA is focusing on local and state projects, delaying federal projects, pausing seasonal hiring, and scaling back capacity.

And for individual hikers? Closed ranger stations and locked gates, fewer maintained trails, locked bathrooms, no trash cans, slower emergency response times, and fewer crews available for wildfire suppression.

What can you do? The first is to join the WTA Trail Action Network (wta.org/TAN) so you can stay informed through emails with opportunities to speak up for trails and public lands. Other essential actions are to leave trails better than you found them, write trip reports (which helps land managers and WTA allocate resources), volunteer for WTA trail work or other opportunities (wta.org/volunteer), and donate to WTA to help fund their programs.

More info: www.wta.org

It was 1963. A local logger by the name of Leon Van Brocklin had been injured on the job. Local loggers, led by Finley Hays, came up with the idea of putting on a show in the village of Deming, WA, and charging a fee of $1.00 to raise some funds for his care. The Deming Logging Show was born.

Now, 62 years later, the tradition of community support continues at the Deming Log Show Grounds on June 14-15. From its humble beginnings, the show has grown into an annual tradition, attracting some 10,000 attendees. But one thing hasn’t changed: all profits generated by the show go to benefit “busted-up loggers.”

More info: www.demingloggingshow.com

The trail that climbs to the top of Table Mountain from the bustling parking lot at Artist Point is a dream come true for hikers who have only a few hours to commune with the Mountain Gods. The climb—zig-zagging up the cliff—is steep and somewhat exposed in places, but it’s only a half mile (600’ of elevation gain), granting access to the top of the table, where a scenic feast awaits. Once on top, it’s easy going across sublime sub-alpine terrain through heather meadows and past shimmering tarns that reflect the surrounding peaks: Shuksan, Baker, the Border Peaks, a who’s who of local monarchs.

Trailhead: Drive WA-542 (the Mt. Baker Highway) 58 miles east from I-5 in Bellingham, bearing right near the Upper Mt. Baker Ski Area Lodge for 2.6 miles to the Artist Point parking lot. Northwest Forest Pass Required.

Spider Gap is a grand Cascadian threshold. Dividing the parklands of Spider Meadows from the ice and tumult of the Lyman Lakes, it’s a compelling place. To get there, you’ll hike 5.5 miles (with several potentially “interesting” stream crossings along the way) up the Phelps Creek Trail (gaining 1500’) to lovely Spider Meadows. Turn left (north) on the Spider Gap Trail and climb another thousand feet in a mile to Larch Knob, an exquisite viewpoint. Fred T. Darvill described it as “one of the most splendid campsites in the North Cascades.” Having camped there myself, I can readily agree. If you pitch your tent on the Knob, you can explore the high divide between the meadows and the glacier at your leisure. There’s no real trail, but the way is obvious enough. Take care not to walk on the vegetation. Take your time. There’s a lot to see.

Trailhead: From Stevens Pass, head east on US-2 for 20 miles, turn north on WA-207, bear right on Chiwawa Loop Rd. Turn left on Chiwawa River Rd. for 22 miles, bear right on FR-6211for 2.3 miles to the trailhead. Northwest Forest Pass Required.

The Kootenays have been an under-the-radar destination for a long time, British Columbia’s best-kept secret. To be sure, a visit to the Kootenays often includes a commitment: long, bumpy 4-wheel drive, high-clearance approaches to the trailheads. The Pedley Pass Trail, near the town of Invermere, is no exception. This 6.5-mile loop features a wild, rugged ridge walk with heart-stopping views out over the Rockies and Purcells and down into the Columbia and Kootenay River Valleys. You’ll climb a well-maintained trail (total elevation gain is 2300’) to the spectacular ridge and then traverse the giddy knife edge. Awe is pretty much guaranteed.

Trailhead: From Invermere, BC take HWY 93/95 south, turn east onto Windermere Loop Rd. Follow for 3.3km, turn left towards Westroc Mine Rd. and immediately turn right onto Westroc Mine Rd. Keep right at the fork at the 8km marker to stay on Westroc Mine Rd. Continue to the trailhead at the 21km marker. 4WD High-Clearance vehicle required.

by John C. Miles. Chuckanut Editions, 2023

Review by Cathy Grinstead

The North Cascades Institute has been a fixture of the northwest Washington landscape since 1986.

In “Teaching in the Rain,” author John C. Miles tells its origin story, a story with so many moving parts it’s a wonder the Institute was established at all. It’s a story of tremendous perseverance, led by its founders Saul Weisberg and Tom Fleischner, and a cast of hundreds, all guided by a desire to share the beauty of the northern Cascades ecosystem.

It began in 1984 as an idea that Saul, Tom, and three friends shared. All had experience in the North Cascades as field biologists, park rangers, and educators. The goal was to create an experiential learning environment involving natural historians, ecologists, geologists, writers, painters, and photographers (with archeologists and historians included later). In 1986, the idea became reality when the National Park Service agreed that the Institute would serve as the non-profit educational arm of North Cascades National Park. The mission statement at that time was “Conserve and restore Northwest environments through education.” Initially, the Institute offered adult trips and classes only. However, in 1989, a stroke of luck occurred when Seattle City Light needed to relicense its hydro project through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Environmental mitigation was required, and education was

deemed an appropriate mitigation response. The team chose the old Diablo resort as the new brick-and-mortar Environmental Learning Center, with construction and renovation partially funded by Seattle City Light.

Once the Learning Center was built, the Institute expanded its programming. Mountain School for Whatcom and Skagit 5th graders moved from tents in the Newhalem campground, and programs for all ages expanded, including lodging and meals for those less inclined to camp. These programs included field seminars, mountain camps, canoe camps, climate change education, watershed education, and stewardship opportunities, among many others. As the Institute gained a reputation for teaching excellence, more and more educators joined the fold, providing top-notch environmental education for all ages.

Miles, a board member of the Institute, details its fascinating story and describes all the people involved in its creation and continued success. He discusses the various challenges facing the Institute, from balancing the differing missions of the Forest Service, the National Park Service, and Seattle City Light, among others, to the COVID pandemic and the particular challenges it created. Throughout it all, the guiding light of Saul Weisberg kept the Institute going. The book is a fascinating and detailed look at how this tremendous institution came to be and how it succeeds today.

“While

Ayear after my dad died, I embarked on a hike into the mountains. My father, James Michael “Jim” Johnston, had asked to have some of his ashes spread at his favorite place, Lake 22, a lake high on the east flank of Mount Pilchuck in the northern Cascades of Washington State. To my dad, it was a very special place, and where he discovered who he was and who he would become. In the truest sense of the words, I was taking him home.

It was on Mount Pilchuck that Jim experienced the first rush of freedom, independence, and deep self-confidence. When he was eleven years old, his parents drove their gold Buick Skylark up the dusty summer mountain roads. Jim sat in back on the edge of the white vinyl seat, surrounded by his camping and fishing gear. His parents dropped him off at the trailhead and he hiked up the mountain to Lake 22. There, he made camp, and went fishing and hunting for the weekend, by himself.

most important container in the whole world. The typed label on the side read:

JAMES MICHAEL JOHNSTON

DOB 2/18/1943

DOD 6/13/2021

think he was. The farther I drove, the nearer to the mountain, the closer I was to him.

I talked to him: I bet when you were a kid, you loved watching these lowlands change into the bigger trees and forests and felt a thrill, a homecoming when you saw Mount Pilchuck.

On June 23, 2022, I set out on my own journey to Lake 22. I’d never been there and I went alone, not by necessity—many of my friends had offered to come with me—but so I could be closer to my dad and feel some of how he felt going there alone.

The funeral home had given us a large wooden urn to hold most of his ashes that would be interred at his gravesite. They also gave us two plastic pill bottles with ashes for spreading where he wanted to be laid to rest. My mom had one, and I had one. That little orange bottle was the

As I drove out through the green fields and rolling pastures of Arlington, I started talking to my dad. He was very far away and very close. I could almost smell the faint comforting smoke of his cigarette drifting back into the car through the partially opened window. This happened thousands of times in my childhood: window rolled down an inch, yellow flare of a match, first drag, smoke swirling, feeling safe, Dad driving our truck.

I wondered if he was listening. I

As I drove, the landscape became less tamed, more wild, and the scattered homes faded into dense forest. I knew my destination, but wasn’t certain of my route. Just outside Verlot, I stopped at the Mountain Loop Store and bought a National Forest Pass and a map.

Ten minutes after leaving the store, I crossed over the Stillaguamish River, an important place for my dad, who had—in his work with the Department of Fish and Wildlife—protected the Stillaguamish from logging and development that would erode its water quality and be detrimental to the fish and habitat of all the nature in those parts. His life had formed a strong current from boyhood enjoyment and soul connection to defending and improving and always loving the region and its waters. I hadn’t understood the connection before that moment.

I followed the river upstream, parked my car near the trailhead, and filled my pack with everything I’d need for the day. My fly-fishing pole was in the same red case I’ve had since age seven, when my dad gave it to me. I took some deep breaths. I started up the mountain. Oh, what a beautiful trail! Radiant green and towering old-growth forest. Babbling streams and wooden footbridges. Ferns poking out of everywhere

by David Johnston

and moss on nearly everything else. Water running over rocks from snow melting above. Summer in full celebratory swing— birds singing, sunlight slanting through cedar boughs. There is a woodsy smell here that sneaks in on smoky motes of pollen, cedar, and cinnamon. Nature has always been my church, my

dad’s greatest gift to me. I was among the trees in a sacred place.

I hiked up the mountain, feeling like I was holding Dad’s hand. Our last time. As I walked, I talked with him and cried and smiled and laughed, and remembered so many things about him. His steadiness. His strength. His love. His critical mind. His big heart wanting to love and be loved.

Pain and love ebbed and flowed as I breathed the forest in and out. I thought of Dad’s deep, omnipresent love for nature and his commitment to it. His love and respect for his parents. His marvelous hands that created so much and put my sister and me to sleep with backrubs. His brilliant mind and powerful control of almost every situation. His art and all that he brought to life artistically. The bronze fish belt buckle that he wore every day. His hour-long pontifications on human history, how to be a leader, so much science and natural-world wonder, and my silent and often-couldn’t-sit-still attendance at these lectures. His raising of me and my sister, his disappointments and criticisms,

and unwavering deep love for us. All he taught me. All of it.

I love you, Dad

The day was warm, sunny, and humid. The effort of hiking made it an intense climb. It was only 3 miles and just 1,300 feet of elevation gain, but I was really sweating. I arrived at a waterfall, 30 feet above a mist-swirling pool, so powerful and loud and an intense rushing full of life, I could only stop and stare. It breathed into me with mist and force and uplifting ions. The clear pool and the spray filled the air around me, and droplets jeweled the heavy-hanging evergreens. The spray settled on my skin: cold, crisp, welcome, and cooling.

And trees! The trees were wonderful to behold. Giant cedar and Douglas fir. Skyrocketing majestic sentinels. Skywalkers. In some places, the trees stood in a circle around me, holding each other with their long, branching arms. This forest was my dad’s first and last church. Conifers in congregation. A fel-

lowship of evergreens.

I know you loved these trees, and they spoke to you like they are speaking to me. The winds through the trees are whispers of ancient wisdom.

Arriving at Lake 22 is like stepping out of the woods onto a different planet. From the dense forest, a sturdy footbridge with log railings crosses the outlet of Lake 22 Creek. A half-circle of vertical mountains striped with countless waterfalls rises majestically.

The sound you hear is not the wind; it is the waterfalls—a spirit-lifting shhhhhhhhhhhhhh, like angels hushing the world to peace. Snow pockets dot the ramparts and give depth and clarity to what feels like too much to take in.

The lake is held by the sharp ridges of the mountain, the strong arms of rock embracing lush mountain meadows. Its surface is still frozen under snow and ice and but there is open water closer to the outlet; bright and sparkling, crystal clear, and mineral green. White floes of

ice six feet long slowly glide toward and under the footbridge, melting as they go, ghostly shapes surrendering one form for another. Water to clouds to rain or snow, to runoff to ocean to evaporation, again and again, as my dad taught me.

I walked around the lake until I found a rock I could jump to out in the water. Later, at home, my son, Henry, looked at the photo of the rock and said that it looked like the skull of a dinosaur.

“It’s definitely a T-Rex,” he said.

I sat on the rock in the lake and talked to Dad.

Where did you set up your campsite the first time you came here by yourself? Were you really only 11 years old? I remember you telling me that when you first arrived you had such a good feeling and thought: ‘Oh this is going to be fun!’

I told my dad how much I missed him, that I loved him, and that I wished we had spent more time together. I said I was sorry for that lost time and hoped we could forgive each other, and ourselves,

for the things that had separated us.

My eyes searched the brilliant blue sky, the shadowed rocky cliffs and mountains, and down into the clear green lake. I said, You always asked me to bring your ashes to Lake 22 and to Mount Pilchuck and help you be part of this place again, to be laid to rest in your first and favorite place, where you felt you became yourself, found yourself. Welcome home, Dad.

I poured a small mound of his precious ashes into my hand and cast them into the lake. Some of his stardust settled gently onto the lake bottom, where small bone fragments were indistinguishable from rocks. Some of his ashes floated in a wide, smoky heart shape, mixing with the snowmelt on the lake’s surface. The image stayed like that. I thought it would dissipate, but it stayed

with me the whole time I sat on that rock. The choir of waterfall angels sang shhhhhhhhhhhh.

I did not want to leave the rock. I felt hugged in warm sunshine and peace of

the mountain and lake—maybe the first time I have ever felt the word serenity. But I had something important I needed to do. Back on the shore, I set up the fly fishing pole Dad gave me 43 years ago and put on a fly that he had tied—choosing

one that looked like the bugs around me and on the lake’s surface—like he taught me. I fished for myself and for my dad. It would have made him happy to see, and maybe he did. I believe he was with me. I didn’t catch any fish but that wasn’t important. It was vital to cast for my dad in memory and love and gratitude for all that he taught me. To fish with Dad one last time.

Wandering back along the lake path, I was about to leave the lake but saw a blooming patch of mountain flowers next to the trail. I had a strong sense that they had been growing there every spring for hundreds of years. I sprinkled some of my father’s ashes around the flowers, saying, Dad you loved flowers so much, and showed me how to see so many plants and animals. I know you would want to be a part of these flowers. As I walked down the mountain,

I spread small amounts of my dad’s ashes into areas where his favorite plants were growing, naming the plants and telling him where he was being given a new home: a grandpa tree stump raising small fir and cedar and huckleberry (he loved his grand children Kaila and Henry so dearly), huge cedar, devil’s club, salmonberry, maple, fern, and a few flowering plants that I wished he was there to identify.

At the foot of the mountain, I spread the last traces of his ashes in Lake 22 Creek, kneeling beside the bridge. Dad, I love you. You’ll be in the Stillaguamish soon. I will see you again. Peace, big spirit.

Arriving at the car, I was tired, aching, blistered, and spent. At the same time, I felt lighter and shifted, peaceful in my heart.

Mount Pilchuck and Lake 22 were always hallowed ground for my dad, and now that I had accompanied him there to his final resting place, it was holy for me as well. I can always come back to his lake, our lake, and say hello to my dad and my memories.

On a snowmelt spring day, you can stand on the wooden bridge above the outlet stream, the beginning of Lake 22 Creek, and as the cold clear water and snow glides under you, and as you look to the wall of mountains at the far side of the lake, you can feel Jim Johnston and hear his voice in the waterfalls and know he is home. And maybe a part of you will be as well.

SATURDAY & SUNDAY

SEPT 27 & 28

Onewarm summer morning in early August of 2005, a small group of grad students from Western Washington University and I gazed across a small lake at one of America’s most spectacular mountain views. The lake was indeed small, really just a tarn, its glass-like surface reflected a perfectly clear upside-down image of Glacier Peak, a gleaming white volcano of powerful symmetry. The mountain was framed in the foreground by spires of subalpine fir. That sunny morning, we had the place and the view to ourselves, rare for such an iconic viewing site. On the other hand possibly not entirely to ourselves. The day before, on the trail close to the lake, we saw bear tracks and watched a large black bear grazing huckleberries. Later, we spied the bear not far from our camp. Our efforts to raise our food out of its reach were laughable, but—full of huckleberries—it left us alone.

The sublime alpine meadows we found ourselves in had once been slated to become an open pit copper mine, thus the name Miners Ridge. As we wandered the ridge, we picked up nuggets of colorful copper lying exposed in small streams.

Thirty-five years before we visited, a renowned writer named John McPhee had visited this place along with a conservationist he profiled in a book titled Encounters With the Archdruid. David Brower, former leader of the Sierra Club and, in the late 1960s, executive director

future generations as wilderness, whether or not it denied the present generation the benefits of the copper lode. Park argued that growing population pressure would ultimately lead to mining the copper, so why wait? Brower thought an open pit mine on Plummer Mountain would be a desecration, and Park insisted that it would not harm the view of Glacier Peak. As to wilderness, Park said, “I don’t agree with that concept of wilderness—to just take a big block of land and say you’re going to keep it for the future. I can’t see it.” Brower’s retort was, “Wilderness was originally a nice place to go to, but that is not what wilderness is for. Wilderness is the bank for the genetic variability of the Earth. We’re wiping out that reserve at a frightening rate. We should draw a line right now. Whatever is wild, leave it wild.”

Our purpose in being there, as part of a long backpack, was to ponder the ideas and realities of public land and wilderness. Image Lake is nestled on Miners Ridge in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, established by the Wilderness Act of 1964. This legislation created a National Wilderness Preservation System and set up a process that has led to nearly 112 million acres of American land being designated as Wilderness over the years. This seems like a lot of land, but it is only 2.7% of the contiguous United States.

of Friends of the Earth, was the “archdruid” of conservation. He hiked to Miners Ridge with McPhee, geologist and mineral engineer Charles Park, and two University of Washington medical students. McPhee arranged this so he could record Brower and Park discussing the prospect of the Kennecott Corporation mining a large copper deposit under Plummer Mountain, a mile east of Image Lake, deep within the Glacier Peak Wilderness. The men spent several days hiking from Holden over Cloudy Pass to Suiattle Pass, across a flank of Plummer Mountain, then on to Image Lake and out the Suiattle River.

The jist of the discussion between Brower and Park was that Brower believed the area should be preserved for

In his account of the interaction of Brower and Park, McPhee brings out the complex nuances of the debate over wilderness. They were having this discussion a scant five years after the passage of the Wilderness Act, which congressionally established 9.1 million acres of wilderness, including the Glacier Peak Wilderness. Over the ensuing sixty years, considerable federally protected wilderness has been added, and no open pit mine has been dug on Miners Ridge. However, in the 21st century, the growth of the Wilderness System has slowed. Pressures on wilderness and all outdoor recreation areas have increased dramatically. It is sobering to think that when the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, the population of the United States was 179 million and is now over 341 million. All outdoor recreation areas, wilder-

ness included, are being hammered by users “loving them to death.”

Since that morning, as we sat by Image Lake gazing at Glacier Peak and reading excerpts from McPhee’s book, I have encountered many who ask, “Why do we need wilderness anyhow?” For me, the Miners Ridge example provides the most definitive answer to this question. What if Kennecott had been permitted to mine there, digging a pit that would likely be at least half a mile from rim to rim?

Road access to the mine would be essential to get equipment in and ore out, likely coming up the Suiattle River. The only other alternative would be up Agnes Creek from the Stehekin Valley or from Holden Village over Cloudy

Pass, all of which would be huge developments slashing into wild and beautiful country.

After camping near Image Lake and

discussing the issue, we continued to Suiattle Pass, camped there, took a day trip over Cloudy Pass to Lyman Lake, and then down Agnes Creek. Everywhere

we went was gorgeous, with trails the only sign of human intrusion. We sat at the toe of the rapidly retreating Lyman Glacier and, on the descent of Agnes Creek, marveled at the ancient forest we experienced on our way to the Stehekin River.

A major industrial development in the heart of the Glacier Peak Wilderness would have more impacts than can be mentioned, but if there were road access into Agnes Creek, would the old-growth timber survive? Same for that in the Suiattle River Valley. I was astonished to learn that there had once been serious consideration of digging a tunnel under Cascade Pass to create road access to Stehekin Village. If there were timber to haul out of Agnes Creek,

might that idea have been revived, outrageous as it seems, as a way to move logs out the Cascade River Road to the mill in Darrington? Where a road goes, so goes development, and this “what if” can go in many directions. Fortunately, the Forest Service, which administers the Glacier Peak Wilderness, conducted this exercise to discuss the impacts and raise many issues. Kennecott could see that permitting such a development would be difficult and even unlikely and slowly and reluctantly relinquished their mining claim, which is another long story.

What stopped them? A region rich in scenic and wildland value designated as wilderness. This example, for me, answers the question of “why wilderness?” If there had been no government-approved wilderness protection of this public land, the copper mine and all its related impacts, whatever they might have been, would be our reality. There would be a Glacier Peak Wilderness, but one bisected by industrial development. Historically, the idea of wilderness, as conceived by Aldo Leopold and others, emerged in response to the threat of rapid roadbuilding and related development through public wildlands. Should there not be some places where wild creatures and those who love them have room to roam? The answer has been a resounding “Yes.” In a recent discussion of the Alpine Lakes region, someone from the Tulalip Tribes asked bluntly, “The animals have nowhere left to go. Where do you want them to go?” Where indeed?

But this story is not over. What Congress approves, Congress can disapprove. Only minor changes have been made to parts of the National Wilderness Preservation System once Congress has approved a wilderness, but this may not always be so. Consider the current situation where an incoming president shouts “drill baby, drill” and does so wherever there might be oil and gas. Charles Park said that the cop-

per under Plummer Mountain would be needed and mined sooner or later. When might that be? Soon? David Brower often said that wilderness protection is never permanent, whether in a national forest, national park, or anywhere in the public domain. The fight to protect it will never end, and when a battle for protection is lost and wilderness developed, it is gone forever or, at the very least, will be very hard to rewild.

I enjoyed the good fortune of traveling to the Glacier Peak Wilderness many times, summiting the peak itself and enjoying it from every direction. Its power to impress and excite never waned. McPhee quoted Charles Park as saying, “How can you ruin a mountain like Glacier Peak? You can’t ruin it.” He added, “A mine would not hurt this country—not with proper housekeeping.” But you can, of course, ruin the experience of it from Image Lake. And “proper housekeeping,” whatever that entails, is very rare in the mining industry. Travel the American Southwest today, and confidence that this industry will ever practice “proper housekeeping” will be dashed.

The upshot of all of this is that there is a great need today to vigilantly protect all parts of the National Wilderness Preservation System and to enlarge it as much as possible. Several generations of persistent and sophisticated Washington wilderness advocates were very successful, and Congress in the 20th century designated much wilderness in the North Cascades, but will it last? We cannot be complacent and take it for granted because powerful interests will leap at every opportunity to challenge the restraint at the heart of the Wilderness Act. The prospect of such a challenge is imminent today. I encourage everyone who can to visit the Glacier Peak Wilderness, see what is at stake, and take up the cause of its protection.

August 11 – 12

Experience an epic 2-day, car-free gravel journey with unique climbs and thrilling descents on the historic Palouse to Cascades Trail, featuring the legendary 2-mile dark tunnel at Snoqualmie Summit. Limited to 200 riders.

cascade.org/iron-horse

JULY 11-13, 2025 BELLINGHAM, WA

By Randy Bott

As the sun set over the mountains south of Mt. Adams, I experienced a quiet, golden moment that sparked a creative awakening. Surrounded by soft light and vivid alpenglow, I realized that a picture on a phone couldn’t capture the beauty before me. That moment marked the beginning of a more profound passion for photography, moving from spontaneous snapshots to a serious pursuit of storytelling through images. It was a turning point, where stillness and nature inspired a lasting creative journey.

See more of Randy Bott’s photography at randybottphotography.com

Visit AdventuresNW. com to view an extended gallery of Randy’s photography

Story by Beth Hartsoch

In September, my husband, Jake, fell to his death on his favorite mountain, the North Twin Sister. My geologist friend Jackie tells me that the Sisters Range is a rare outcropping of the earth’s mantle; the olivine rock a distinctive rusty hue.

Mountains were as necessary as air for Jake, and he’d summited this one dozens of times. Every year, he bought a key to the logging company gate, granting access to five more miles of road, bringing the wild terrain closer to home.

Jake was widely considered to be conservative about risk, and many in our community reacted to the news of his accident with disbelief. How could this have happened to Jake? And–unspoken–if it can happen to Jake, then could it happen to me?

weigh the risks.

Part of being adults, however, is taking responsibility for our choices. Here are the lessons learned as someone with a lot of experience waiting for an adventurer to return home.

gered probate. Another designated our kids, requiring that I open a special type of account for non-spouse beneficiaries, creating extra paperwork.

If you have dependents, buy sufficient life insurance with a reputable company, make sure that premium gets paid, and keep a copy of your policy. Then tell your people where to find these documents.

I was the person who waited for Jake to come home, and over the years, I pushed him to take responsibility for the risks. Between Jake’s adventures, we prepared, and I’ve come to think of this preparation as an act of love, which made our tragedy easier to navigate and less traumatic. We mourn Jake’s loss, but I feel no resentment or regret, and I don’t have to uproot my kids and sell my house.

I don’t want to hyperbolize the risk of adventuring compared with other risks we take: driving on the freeway, owning a swimming pool, sitting on the couch. Adventures deliver physical and mental health benefits, which usually far out-

Jake left a signed durable power of attorney, healthcare directive, and a will. If you are an adult, the first two are a minimum and will relieve your loved ones of having to guess your wishes if you are incapacitated. If you have people who depend on you and/or you have assets, write a will.

Designating beneficiaries on financial accounts makes distribution easier, especially if the beneficiary is your spouse. Jake’s accounts were in good order, but one account with no beneficiary trig-

Don’t put your loved ones in a financial crisis, having to move to different housing, or worse, while they are mourning your death.

Years ago, the first time I stayed up late waiting for Jake to return from some unknown adventure, I was angry when he walked in the door. I had wondered if I should call 911, but I worried I’d just be overreacting and feel silly. I resented the burden of inventing an emergency plan late at night while home alone with our kids.

I remember Jake emphasizing that calling for official Search and Rescue (SAR) should never be plan A. “My friends will find me much faster,” he said. After that day, Jake sent me a text message before each adventure with four points.

1. Destination and planned route

2. Expected return time

3. The time when I should call emergency response

4. Name and phone numbers of people I should call for emergency response

With this simple habit, Jake took responsibility for key decisions around his own search and rescue response.

The morning of his death, Jake’s text to me read, “Biking to n twin. Back 4ish.” It contained only the first two points but was gold that night.

A hiker found Jake’s iPhone 100 meters uphill from the location of his body. Had he been injured but conscious, he still would not have had access to the phone’s satellite SOS feature. Only an inReach device passively transmitting his location at a regular interval would have alerted us that he was stopped and given us his location.

I knew from previous adventures that his friends Peter Lillesve and Ingmar Prokop would be the “who” for emergency response. At 7 pm, I called Ingmar, and we drove to the West Ridge trailhead. We saw no sign of Jake on the drive in but found Jake’s bike at 9 pm at the start of the climber’s trail. We texted Peter from Ingmar’s inReach and asked him to call 911. The message

Birds and Boat Hulls

took 10 minutes to transmit.

Had Jake and I not made an emergency plan, had I just called 911 and waited, or driven to the trailhead alone, or had to stay home with small kids, I can

only imagine the frustration and helplessness I would have felt that night and the regret I might feel now.

Instead, Peter, Ingmar, and I became a team. At midnight, we began the hike in, ready to keep Jake’s spirits, hydration, blood sugar, and body temperature up

through the night with gummy bears, Coke, mini donuts, and sleeping bags.

After reaching the summit at 3 am, Peter returned to our makeshift camp at daybreak and called 911 again. Shortly after, we had our first contact with the SAR deputy, 10 hours after our initial call.

Official SAR practices vary by location, so it’s important to be familiar with your local SAR structure. A rescue is initiated by calling 911 or activating the SOS feature on a satellite emergency notification device (like Garmin inReach). Expect to receive further calls once you make the initial call, so the ability to answer the phone is essential.

Dispatch will ask for GPS coordinates, severity of injury, medical history, familiarity with the terrain, and equipment available on scene.

When Whatcom’s dispatch receives a SAR request, they route it to the SAR sheriff’s deputy on duty. SAR deputies

I’m drawn to the weathered textures I find on the hulls of boats while paddling in a kayak around Fishermen’s Terminal. I often use digital techniques to combine them with my photos of birds. For the finished pieces I use a torch to fuse layers of beeswax with damar (a hardener) onto the mounted prints and then embelish with oil paints, oil pastels and mica powder. See more of Kathy’s work at www.kathyhastings.com

triage requests based on factors like the missing person’s experience level, medical history, familiarity with the terrain, the weather, and the scope of the search area. They may decide against activating a SAR team, but they will call back within an hour. If the SAR deputy hasn’t called, no response is underway. The night we searched for Jake, the deputy declined to activate a SAR team. Unfortunately, we never received this message. At first, this affected our decisions; we assumed we’d talk with SAR before the next step. We decided to hike the West Ridge Trail after the wait passed an hour.

May 25: Fairhaven Festival

July 5: Chicken Festival

Every Saturday, July 5 – Aug 23: Summer Outdoor Movie Series

Jake fell 250 vertical feet and died almost instantly. He did not suffer, and so these lessons can be learned without the nightmares and regret that would have plagued me if he had. Not everyone is so lucky. Work with the people who await your return from adventures to mitigate the risks to their wellbeing. Organize your financial life, communicate your plans, make a SAR plan A, understand how official SAR works, and give your loved ones the gift of knowing how to look for you.

Then go and be alive in the world.

Ingmar Prokop, Peter Lillesve, and Julianna Safstrom contributed to this story.

Get ready for an epic road trip to North Idaho’s Base Camp. Imagine flowers in full-on color parade, lakes and rivers begging for kayaks, and squirrels itching for adventure. You’ll conquer scenic mountain bike trails, superhero hiking paths, rock faces with views so breathtaking you’ll do a double take, and paddle through waters so pristine, they make bottled water jealous. Pack your sunglasses and sense of adventure. Uncover the magic of Idaho, summer-style. Trust me, you’ve never discovered anything this good. Got a camera ready for those epic shots? You’re welcome.

Jenny Reid Art

Story and Photos by Mike Nolan

One of the first things I spot when entering Olympic National Park is the gray shirt, dark forest-green trousers, gold national park badge, and iconic flatbrimmed hat of a park ranger in uniform. I have to wonder: What is it like being a ranger? What makes up their typical day?

On a mission to find out, I call the park office and connect with Jeff Doryland, who discusses park ranger roles with me. “I’m in the facilities department,” Doryland says, “so I work in the administration building. The rangers you’re probably thinking about work at the park entrance, or the Visitor Center, or at campgrounds.”

The National Park employs all rangers; each wears the uniform, but their jobs can be vastly different. There are maintenance staff, interpretive rangers, rangers who work in the Wilderness Information Center, administrative staff, trail maintenance crews, and the list goes on. I decide to follow up on three park ranger roles: backcountry, law enforcement, and interpretive/education.

would tap into my interests: being outdoors, working with the public, speaking to groups. It was very much a traditional park ranger job she portrayed.”

After beginning as an interpreter at Humboldt Redwoods State Park in California, McLean moved to work with students through the NatureBridge program located within Olympic National Park. Over the course of eleven years, he

answers questions.

“People often start by asking me, ‘Where should I go?’ so we discuss how many miles they might want to cover, the elevation gain, crossing streams and rivers, and snow-covered trails. We talk about what they’re capable of and what they would enjoy taking on. The rest of the time, I’m in the field.”

Sometimes visitors remark, “Oh, you get paid to hike around in the park?” Actually, the work involves campsite rehabilitation, helping with search and rescue, and other related duties. “I could be sent anywhere in Olympic National Park. I’ve probably got one of the most broad-based jobs here.”

“I grew up in Alaska and had a high school teacher who was once a park ranger,” Josh McLean says. “She was inspiring, and it sounded like the work

worked part-time and then eventually full-time into a position as a backcountry ranger. His official job title now is “wilderness information assistant.” McLean splits his time between working at the backcountry information counter at the park Visitor Center and actually being in the backcountry.

At the Visitor Center, McLean meets with individuals planning backpacking and hiking trips; he issues permits, gives out bear canisters, goes over maps, and

McLean’s two roles are very much related. McLean does PSAR ( preventive search and rescue) when he’s at the Visitor Center. He’ll ask people if they have experience navigating in rough weather, can find trails in snow-covered areas, and are equipped for ascending steep, rugged terrain. “I need to explain the hazards and try to exercise diplomacy with my questions while emphasizing safety.”

McLean regards this as one of the best parts of his job. “I love talking about the Olympic wilderness and sharing some of my favorite spots. I have the background and experience, and it feels good to use that expertise to enhance someone’s time in the park.”

McLean remembers being at the ranger tent at Royal Lake, which is more than a seven-mile hike into the backcountry. It was raining hard. Around dusk, two hikers in T-shirts and shorts arrived. They looked miserable.

“I helped them find a campsite, but later, both were standing outside my tent. ‘We can’t get our tent pegs into the ground,’ they said, so I came back out and helped them set up their tent. Not long after that, they were back. ‘We can’t get our stove going.’ I came out again and assembled their stove, then got it started.”

The weather cleared the next morning, and McLean was excited to tell them about hiking opportunities.

“You’ve got to do the hike just above the lake,” he told them. “It’s gorgeous.”

“Thanks for your help,” they replied, “but we’re leaving.”

“We’re here to help . . . but I guess sometimes our perceptions and hikers’ perceptions can be a little different,” McLean says. “But the nature of our work is down to that most essential component–to try to help.”

McLean mentions one other backcountry duty: cleaning pit toilets. He does that–a lot. When people see him doing this job, they know he is doing work

of value, work no one else wants to do and work that needs to get done.

“They’re called ‘composter toilets,’ but it’s not as though they magically turn human waste into gardening soil. My tools are a sixty-gallon barrel, a shovel, and a pair of thick rubber gloves. The full barrel gets flown out of the park.”

There are 165,000 backcountry “camper nights” (the number of nights people occupy campsites) a year. The park wouldn’t hold up against the impact of that much use without the backcountry rangers’ help. Human waste can carry pathogens that the park doesn’t want to end up in the watershed, so cleaning toilets is an inarguable service. It all gets back to helping people enjoy the park.

“As rangers, we have a passion for this place. This is our home. We’re in love with the wilderness… and that’s why we do what we do.”

“I’m from the East Coast. I was an English and creative writing major,” Doug Geehan recalls, smiling at the memory. Eventually, after different jobs and a couple of moves, he entered the

Park Ranger Law Enforcement Academy Training Program, which led to seasonal park work in Death Valley. “I loved it!”

Once prospective rangers complete the training program, they’re eligible to apply for seasonal positions with the National Park Service. Most new hires spend two or three years in seasonal employment before finding a permanent park job.

“I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors, but that really grew once I came out west.” Olympic National Park is especially inviting, providing work in dramatically beautiful surroundings, as well as a nice quality of life. And it’s close to town.

Every park is its own place, so law enforcement rangers do different things in different parks. In Olympic National Park, there is no “typical day.” About 50 percent of Geehan’s job involves law enforcement, and the other half involves EMS (emergency medical services), backcountry work, and search and rescue. He also has his wildland firefighting credential.

As trained law-enforcement personnel, these rangers are the legal authority in their jurisdiction. They do investigations ranging from assault to vehicle break-ins to timber theft. But Geehan’s favorite part of the job is search and rescue. “We

work as a team, and when we’re successful, there are just so many positives about it. We found them! and for a moment, you get to be a hero.

“I remember getting a backcountry call when I worked at Sequoia National Park. An extremely fatigued hiker was experiencing altitude sickness.” Geehan’s crew scrambled into a helicopter and went on high alert as they received reports that the hiker was get-

breathing. “We immediately loaded her into the copter and got her on oxygen. Lifting right off, we dropped in elevation, and she started to come around.”

The average national park visitor doesn’t encounter, or even consider, rangers in law-enforcement roles. “The general public is always surprised by us,” Geehan says. “They see us and say, ‘Guns? Body armor?’ Thinking back, I guess I was surprised, too,

action plan for a specific situation. “The work is hard. We take it seriously.”

Taking the helicopter rescue Geehan mentioned as an example, that person would likely have died without the rangers’ intervention. “When things go right, everyone’s glad it worked. Positive public support is reinforcing, but the feeling you get from a successful rescue? That’s amazing.”

“I was in college in Maryland,” Jamie Shurnitski says, “and I started working with the parks through AmeriCorps.”

Elevate your ride. Wing foiling rentals, lessons, and all the gear to help you reach new heights this summer.

love with the job: welcoming visitors and talking with them about what they’d like to see. Olympic is a huge park, and planning can be overwhelming, so Shurnitski’s job is to help visitors get organized and enjoy their time. “I want them to head out excited and prepared.”

But not all of Shurnitski’s work happens at the Visitor Center. During the summer, she guides meadow walks on Hurricane Ridge; in winter, she helps guide snowshoe walks on the ridge. “That’s definitely one of my favorite activities: it’s free, open to anyone, and the snowshoes are provided!” People get to experience winter in a different way. Shurnitski guides people who are usually new to snowshoeing and initially feel out of

their comfort zone, but they’re all doing it together and end up having fun.

Shurnitski also assists with evening campground programs. At the Heart O’ the Hills Campground, which boasts one

of the best preserved old-growth forests in the park, one such program is called “The Secret Language of Trees.” It’s all about how forests communicate. “People are interested, they ask good questions, and they obviously like being here,” Shurnitski says. “It’s one of the times I tell myself, ‘I love this job!’”

Shurnitski also runs the Junior Ranger program. “I meet with youngsters and talk with them about their time here in the park. They’re curious, they share their thoughts, and they always have such good questions. I help them take the ‘Junior Ranger pledge’ and award them their badge. That’s one of the best parts of my day.”

Shurnitski began with the perception that being a park ranger was an

outdoor job, but now she knows it can be a very public role. There is value in both, and her role as an interpretive ranger can directly impact someone’s experience in the backcountry.

“There’s so much to see here. I’ve worked at Olympic for three years, and there are still parts of the park I have yet to see. People initially want to see the whole park in one visit, but that simply can’t be done, so I try to help them slow down and

focus on enjoying one spot.” When they do that, they’ll see things they might otherwise have missed: trees, plants, animals, geologic features. And, of course, they can always come back for more.

Park rangers, regardless of specialty, are dedicated individuals committed to being good stewards. “Whatever

By Bill Hoke

In a few hours of up

Alone

Thinking about tonight

Will there be water

Will I be warm

Will there be others to ignore

Will campfires be allowed I have stick matches

For my small bag of dryer lint

That bursts into

Tentative flame

Set to learn again the Night lessons

Night noises (you better Talk them through)

Left my tent at home

here you must be naked

walking down the river

hiking up to a deserted divide

And just once in your life

Go alone

Go ahead

You will talk to yourself

Go ahead and have that talk

It may take three or four nights

To get this out into the open

I promise you by night five

Just the two of you

Will be getting down to the Nitty gritty.

our role, whatever we do,” explains Jeff Doryland, “we’re all working to support the mission of the park. That is, to preserve—unimpaired—the natural and cultural resources and values of the park system, for this and for future generations to enjoy.”

Parks cannot function without appropriate staff, and President Donald Trump’s recent executive orders eliminating thousands of federal employee jobs threaten park services and access. 1000 National Park Service (NPS) employees have been terminated (alongside 3400 United States Forest Service employees). Parks were already understaffed. Since 2010, the NPS workforce has decreased by 15%. At the same time, park visitation has increased by 16%. We need our National Park

Whenout on a trail, most of us look at the wilderness around us, absorbing the sights, sounds, and smells of the outdoors. Sure, we look at the trail because if we don’t, we’ll trip over a root before we know it. But how many of us look at the trail with “trail eyes”—that critical observation of the trail itself? Knowing how to evaluate problems with the trail, as well as appreciating the many details that go into trail planning, construction, and maintenance, makes you a better hiker and steward of the wilderness around you.

What makes a trail “good”? We can finish a hike and say, “That was a great trail,” but that’s usually based on an overall impression of the hike rather than specific details of the trail. A good trail is designed and maintained with specific users in mind, whether hikers,

bikers, or horse riders. Its degree of difficulty is tailored to a specific skill level of the user. It incorporates features along the trail that enhance our enjoyment of the hike—boulders, trees, views, creeks, vegetation, and undulations—without being an encumbrance to our passage through the terrain. The trail surface is easy on the feet, and the brush and surrounding vegetation have been kept clear of the trail. Erosion and water damage have been mitigated, downed trees and branches removed from the trail, and boardwalks and bridges installed where appropriate. A trail is also good when it is easy on the environment. A good trail should be such an obvious fit for the terrain that it should almost seem like it built itself. It should invite us to follow it.

The details of designing trails are beyond the scope of this discussion, but obviously, a well-designed trail requires less maintenance, which is critical in our era of inadequate and inconsistent

government funding. Sustainability is key. Controlling erosion and water runoff are the two primary structural issues. Still, a trail design is doomed to failure if human nature is not considered since people tend to follow the path of least resistance!

As we hike, if we use our trail eyes to see the subtle and not-so-subtle trail features we pass by, our experience will be enhanced. One of the primary considerations in building and maintaining trails is knowing the trail’s class. There are five classes of trails, categorized by type of user. These range from a Class 1, or minimally developed trail, which may involve route-finding skills to follow, up to Class 5, which is a fully developed trail, likely ADA compliant, whose surface is likely paved or packed gravel. Roots and rocks on the trail surface may not be a problem for a Class 1, 2, or 3 trail but would need removal for a Class 4 or 5 trail, for example. The trail manager would use the designated

class to allocate resources for maintenance and repair.

Trail grade is another major consideration, not only for hiker enjoyment but for sustainability. The average trail grade should be 5-10%, but grades

off since the water will run only a short distance down a trail before it reaches a low point. These can be effective even if hardly noticeable.

exceeding this will, of course, appear in sections. Steeper grades of more than 20% may require steps or be on a rock surface to be manageable for hikers, and grades this steep create a situation where excessive water runoff can create erosion unless mitigated, and be challenging to maintain. When crossing a slope, the trail builder uses the ½ rule, which means keeping the grade at ½ or less of the percent grade of the slope (for example, if a hillside has a 16% grade, the trail should be no more than 8%). Frequent “grade reversals” are of great benefit in controlling water run-

But with new trail eyes, start paying attention to the low areas along a trail with grade reversals, as these can be places where maintenance is frequently needed. Trail crews may dig drains here to direct the water off the trail, and these can become easily filled with debris [Photo A]. Water bars are often used to direct water off the trail, but these are going out of favor since they are more difficult to construct and maintain (you may see a simple log across the trail, but there is often a foundation of rock or gravel that isn’t visible). Other tricks to control water runoff include the cross-trail slope—ideally, the trail slopes down 5% from inside to outside (it should not cause your ankles to roll). This also aids in the “sheet flow” of water down the hillside—when water comes down off a slope, it will hit the trail and run off because of the rolling grade and the out-sloped trail. These trail features are important to improve drainage where water creates mud puddles, so people

don’t enlarge the trail by hiking around them [Photo B].

More complicated trail elements used for wetter areas include turnpikes or puncheons. Turnpikes are sections of the trail raised higher than the

surrounding water table and slightly mounded in the middle. The undersurface of the trail making the mound may be gravel or, heavier mineral soils, or even synthetic materials. There will be siderails made of rock or logs to protect the trail from erosion. The slope of the turnpike surface directs water to the edges of the trails into small rivulets running parallel to the trail. These must be kept empty and free of debris [Photo C]. Trails that are so rutted and deep that hikers no longer use them and instead are creating side trails called cupped trails. These trails

can occur in meadows or areas with softer soils. Repairing them requires turnpikes built on rocky fill to raise the trail, potentially the use of pavers or rocks as well on the surface, and revegetation of the side trails.

Puncheons are another way of traversing boggy areas when draining the trail is not an option. They are wooden walkways that elevate the trail [Photo D].

These have significant maintenance issues as wood has a relatively short lifespan in certain regions. These require careful engineering to construct. Flat pavers or rocks can be placed in wet or chronically muddy areas as well, but these may be hard to find or transport to the area.

For actual water crossings, the class of trail will determine the technique used. Class 1 water crossings may have no structures to aid the crossing or possibly some well-placed boulders or a log. Class 4 and 5 trails will have a wellconstructed permanent structure (logs and handrails), and seasonal bridges are another option for more rugged trails. The designer must first decide if a crossing is needed at all (can the trail continue on the original side?), determine the seasonality of the need for a crossing, and then locate the easiest place to ford the waterway. Maintenance of water crossings is always an issue, and construction is expensive. Culverts can be used for small intermittent streams,

but these can easily become blocked with debris.

Controlling erosion is also key to trail maintenance. Wide turns or switchbacks are critical to trail design and can help control erosion by lessening the trail’s grade. Besides the obvious reason for making it easier to climb a hill, designers must plan carefully to minimize

the temptation of hikers to cut them. Cutting switchbacks is a huge cause of erosion, and they cannot always be successfully repaired [Photo E]. When possible, switchback design should incorporate obstacles in the inner corner (rocks, logs, heavy vegetation) and can be steeply angled or cut a little wider. Rock walls may need to be constructed to stabilize the trail. Sometimes, a slope is so narrow that it may be difficult to use these features. Wide turns are less complicated to construct and maintain, and are easier for horses to navigate.

We don’t often contemplate the trail corridor–the surface, sides, and canopy of the trail–but these areas also require maintenance. Depending on the trail

grade, the trail should ideally be wide enough that your extended arms don’t touch surrounding vegetation (six feet). Tree branches or downed trees across the

trail must be removed for safety, and if horses utilize the trail, a higher canopy is needed. Trail “brushing”—pruning trail edges of vegetation and leaf removal off trails in the fall (heavy leaf fall traps moisture and contributes to mud and erosion)—must be done, especially here in the PNW. Some of these maintenance issues depend on the class of trail.

Developing “trail eyes” will increase our appreciation of the work that trail designers, builders, and trail crews do. These

Know you are appreciated!

Another reason for developing “trail eyes” is to be a link between boots on the ground and land managers. WTA, for example, emphasizes online Trip Reports, which members and nonmembers can complete. These reports are helpful to anyone planning a hike to learn about the current conditions of the trail. However, a well-written trail report will also include information about potential maintenance issues encountered on the trail. WTA will send this information along to the appropriate land managers to determine if repair is needed. (To make a trip report especially useful, include photos with scale and as specific a location as possible.) A very important disclaimer, however, is that learning to read a trail is not an invitation to do the work yourself. Trail building and trail maintenance are complex and require specialized equipment, knowledge, and training, and should not be attempted without volunteering for a supervised trail crew. If trail work sounds like fun to you, though, go to www.wta.org/volunteer/schedule to find

Your mother used to shout, “Go outside and play.” I know. I lived next door and could hear her through four walls and a carefully manicured hedge. Like dogs that join in when they hear another K-9 in the distance, every other mom in the neighborhood followed suit, forming a twilight bark of sorts that was more about moms needing a break than any genuine regard for the health benefits of their progeny.

Sometimes, we do the right thing for the wrong reason. Turns out we were better off for having been forced outside and into a game of stickball. We grew up healthier, eschewing cigarettes and beehive hairdos. We took our bikes into the mountains and invented mountain biking (a marked improvement over lake biking). We combined ping pong paddles and a whiffle ball to create pickleball. A lucky few became professional athletes. It was a lot of wacky fun, but we rarely paused to consider the ancillary benefits that came with it. So, for the sake of those who are outdoors-active and those who are merely outdoors-curious, I offer the

Story by Dave Mauro

following case of what’s in it for you, aside from pleasing your mom.

your Uncle Rick will stop believing a troll lives in the attic, but he will care a lot less.

Studies show that time spent outside improves sleep quality by reinforcing the circadian rhythm, enhances our mood by releasing serotonin and endorphins, and reduces stress by decreasing cortisol levels. Not good enough, you say? They also show that time spent outdoors improves a person’s mental health. That’s not to say

Sunlight has anti-inflammatory properties that can help improve certain skin conditions like acne, psoriasis, and eczema. That’s a fine start to looking good. How about some weight loss? Numerous studies have shown that we tend to burn more calories when engaged in outdoor activities. Alfresco enterprises even improve our posture by strengthening the muscles around the spine. Look at you!

You’re already off to a great start toward solving the world’s problems by feeling great and looking good. After all, you will need to do a lot of persuading to move the levers of government and nature, and who is going to take you seriously if you’re depressed and dressed for rehab? It’s not a heavy lift to suggest you might need a boost to your creativity to tackle the world’s problems. These problems are largely the result of humans all thinking the same way at the same time. You may have guessed this already, but the answer is more time outside. Being

outdoors brings a person to a state of relaxation, and we tend to be most creative when relaxed. It seems self-evident: you will be better equipped to think outside the box by getting outside the box.

The world’s problems are complex. You can’t explain climate change by bringing a snowball to the floor of the Senate. So, you will benefit from increased brain function. Again, with the outdoors. Improved mental focus and the ability to concentrate for extended periods have long been associated with time spent in nature. You don’t have to take my word for it. Just ask John Muir, Leonardo da Vinci, Warren Buffett, or Henry David Thoreau. All have advo -

cated for time spent outdoors to open the higher mind.

In the words of Alan Titchmarsh, “Nature is a masterpiece of beauty, a never-ending source of wonder and inspiration.” As someone who has been to every continent and most corners of each, I can say we live in the most beautiful place on earth. The Pacific Northwest is a magical and unspoiled place. The Puget Sound, mountains, rivers, forests, and farmlands are all easily within reach.

So, listen to your mother. Go outside and play.

Story and Photo by John D’Onofrio

The name beckoned me from the map for years.

Last year, I finally made the circuitous journey to Valhalla Provincial Park, located deep in the magnificent Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia. Getting there required a bit of a commitment: a long (40-kilometer +) bump-and-grind on logging roads from Slocan to reach the lonely trailhead for Drinnon Pass. After some huffing and puffing, climbing across a rockslide, we climbed some more, finally arriving at the crest of the Pass. A sparkling tarn reflected the surrounding peaks—a place of sublime beauty.

We had the place to ourselves – it felt like the North Cascades of 30 years ago.

by Paul Tolme

Forpeople who bike, the Trump administration’s announcement that it was freezing funding for bike lanes, recreational trails, and “green infrastructure” was a nail in the tire of progress.

U.S. Rep. Rick Larsen, D-WA, estimated the decision, if upheld, would result in funding losses “in the double-digit millions” in Washington state alone, as well as increased fatalities.

Bicycles are the most efficient transportation machines ever invented—non-polluting, healthy, affordable, and equitable. Smart leaders from Seattle to Bellingham to Vancouver to Paris and London are investing in bike lanes, cycleways, sidewalks, and safe routes to schools.

But not this White House.

The anti-bike bias coming from DC is why I encourage everyone to ride more than ever this summer. Bicycling is a happy and healthy form of protest in the current political climate.

Below are a few summer rides that I encourage you to join. They are all fundraisers for Cascade Bicycle Club. This Washington state bike advocacy organization is fighting to maintain and increase funding for safer streets and bike trails from Seattle to Spokane. Go to cascade.org/rides-events to sign up.

• Seattle to Portland, July 12-13: Started in 1979, this historic, 206-mile, big group ride can be done in one or two days, with a beer garden festival at the finish and camping at the halfway point.

• Port Townsend Tour, Aug. 1-3: Explore this historic hamlet and the Olympic Peninsula during this fully supported three-day group ride limited to 200 participants, with unique routes each day.

• Iron Horse Gravel, Aug. 11-12: This ride, perfect for gravel newbies and veterans alike, travels up and over Snoqualmie Pass on the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail to Cle Elum. Participants will camp along the Wenatchee River (or stay in a hotel) and bike back to the start on Day Two.

• Revel Revolution, June 29: The new Revel Revolution ride is for women and nonbinary people who seek a welcoming and supportive biking experience amongst friends, new and old. Participants will start and finish at Bellevue College and ride around beautiful Lake Sammamish together, with a finish line celebration.

In addition to biking more, call or email your members of Congress and tell them to fight for safer streets, safe routes to schools, and bikeways that connect our communities.

Join a bike advocacy or transportation safety nonprofit. The League of American Bicyclists, based in Washington, DC, is a great organization that fights for our right to bike.

Together, we can pull the nails and patch the holes that are puncturing our democracy. Let’s Make America Bike Again.

The redesigned Chair One from Helinox raises the bar on superportable, super-comfortable camp seating. Featuring (re)Tension Design, which includes a second tension line to distribute weight around the frame, the new Chair One High-Back provides a lot of back support in a lightweight, packable package. It packs into an 18” x 6” x 4.5” case and weighs a mere 2 lbs, 13 oz, yet can hold 320 lbs. Plus, it has an integrated side pocket.

More Info: helinox.com

The new NeoLoft™ Sleeping Pad from Therm-a-Rest® takes the backpacking sleeping pad to a new level. Weighing 30 oz. and packing down to not much larger than a 1-liter water bottle, it offers 4.6 inches of comfort and an R-Value of 4.7. The TwinLock™ Valve system makes inflation and deflation quick and easy. It’s not the lightest sleeping pad out there, but if you value a good night’s sleep, it’s worth the extra ounces.

More info: cascadedesigns.com

The Two Tent from Gossamer Gear by Chris Gerston

In the world of ultra-light backpacking, you rarely get to use the words superior durability, excellent price, luxurious living space, and lightweight all in one sentence to describe a tent. The Two from Gossamer Gear is all of those and highly recommended for two people.

FIND Adventures Northwest is available free at hundreds of locations region-wide: throughout Whatcom, Skagit, San Juan, and Island counties, at select spots in Snohomish, King, and Pierce counties, and in Leavenworth, the Methow Valley, Spokane, and Wenatchee. The magazine is also available at REI locations across Washington and Oregon as well as at numerous locations in the Vancouver, BC metro area, at races and events, and area visitor centers.

SUBSCRIBE Receive Adventures Northwest via mail anywhere in the US or Canada. Visit AdventuresNW.com/subscribe for subscription info.

ADVERTISE Let Adventures Northwest magazine help you reach a diverse, receptive audience throughout the Pacific Northwest, and be part of one of the most valued and engaging publications in the region. Info is at AdventuresNW.com/advertise or by writing to ads @ AdventuresNW.com.

Specializing in a pub-style menu featuring local oysters, seafood & steaks. We’re well known

Compared to many ultra-light materials, the nylon tent body with a SIL (silicone) nylon finish is durable and offers greater waterproofing. The material is also part of why this tent achieves such a relatively low price ($320). The Two uses trekking poles for structure and allows you to vary the tent’s height. The minimum trekking pole height is 120 cm, but if you have adjustable poles, you can go up to 150 cm, which gives you a very generous living space and two huge vestibules for gear storage and cooking in poor weather. However, this is not a free-standing tent, so you’ll need to use the guy lines and stakes or trees to pitch the tent.