Greenville & Hockessin L I F E

• Chris Lemole: The film producer next door • The Brandywine Valley you don’t know • Q & A with Dr. Judith Provencal, Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory

• Chris Lemole: The film producer next door • The Brandywine Valley you don’t know • Q & A with Dr. Judith Provencal, Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory

In this edition of Greenville & Hockessin Life, writer Ken Mammarella offers readers a look at the Brandywine Valley you don’t know. The Brandywine Valley is famous for its beauty, its history and its industries, Mammarella writes, but there is a lot to uncover while exploring the lesser-known elements along the Brandywine River.

In this edition, we also introduce readers to Chris Lemole, the film producer next door. Lemole has produced a dozen films, including one that earned four Oscar nominations. Now, he’s doing that work from Centreville.

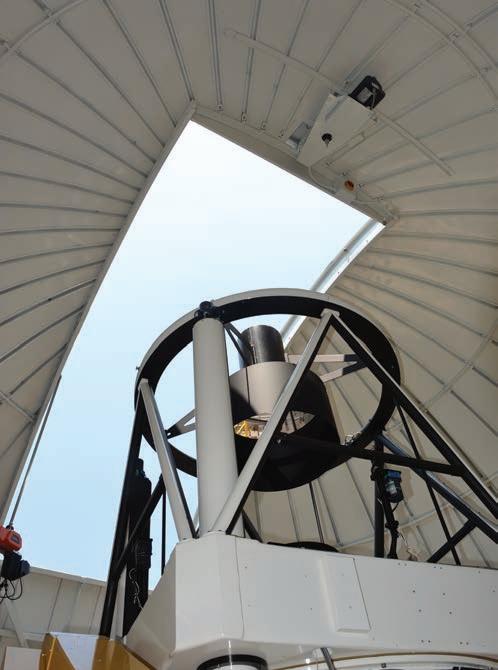

Greenville & Hockessin Life recently met with Dr. Judith Provencal, the resident astronomer at the Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory in Greenville, to discuss her early moments behind a telescope, the Observatory’s recent acquisition of a 1.3-meter MCAO telescope, and what we can continue to learn from our observation and study of the skies above us.

The Centreville Layton School helps students who have “struggled in school somewhere else.” We offer an in-depth look at how this school’s unique approach to educating students makes it a destination for students not only from northern Delaware, southeastern Pennsylvania and northeastern Maryland, but also from Delaware below the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal and in southern New Jersey.

We also introduce readers to Alyssa Andress and her Editorial Candle Co. Over the last five years, Alyssa has been making scents of memories and places. The concept and its fragrances are now in thousands of homes.

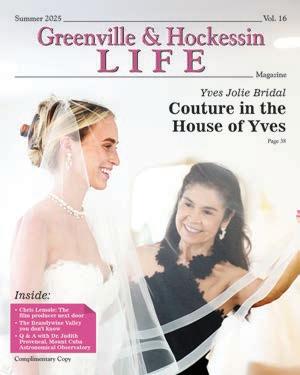

In the Greenville & Hockessin Life Photo Essay, we shine a spotlight on Yves Jolie Bridal.

We hope you enjoy the stories and photos in this edition of Greenville & Hockessin Life as much as we enjoyed working on them. We always welcome comments and suggestions for future stories, and we look forward to bringing you the next edition of the magazine in the fall. In the meantime, have a great summer!

Sincerely,

Avery Lieberman Eaton averyl@chestercounty.com

Stone Lieberman stone@chestercounty.com

Steve Hoffman, Editor editor@chestercounty.com

‘struggled

By Ken Mammarella Contributing Writer

Centreville Layton School “teaches children who learn differently,” it says on the school’s website. Its reputation for that approach draws students to its 23-acre location, just north of Centreville, not only from northern Delaware, southeastern Pennsylvania and northeastern Maryland, but also from Delaware below the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal and an hour away in southern New Jersey.

“What we do is valued, and there are not a lot of other schools that provide the type of education that we provide,” said Head of School Richard Taubar, who started 25 years ago as a third-grade teacher and has devoted his career to the Centreville School, which in 2014 merged with Layton Preparatory School, and the combined school.

Continued on Page 10

Continued from Page 8

“They’ve all struggled in school somewhere else, with dyslexia, ADHD or whatever their conditions are,” he said. “They’ve fallen through the cracks.”

The website (centrevillelayton.org) says the 100 or so students, in pre-K through 12th grade, “may face challenges in one or more of the following areas: language processing difficulties; dyslexia; difficulties with spelling, reading, writing, and math; fine and gross motor skill delays; executive functioning disorder; social skills; anxiety; receptive and expressive language disorders; peer relationships; school-related apprehension” and attention issues such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

For some students, their issues are identified and addressed, with students then mainstreamed into larger private, parochial and public schools. For others, their issues are identified later, and families choose Centreville Layton to address these issues. For some students, they receive their entire education at Centreville Layton.

“Our main focus is academics,” Taubar said, noting a curriculum focused on problem solving and critical thinking, but there are also elements engineered for socialization. “We try to create an environment as focused as possible for each student. We can’t offer everything that large schools can, but students are more likely to be involved in activities like theater, government and sports.”

Centreville School was founded in 1974 as the Delaware Learning Center, a formative play program for children with learning differences. The school gradually expanded into a pre-kindergarten through eighth-grade program that moved to its Kennett Pike location in 1984.

Layton Prep opened in 2005 with a class consisting primarily of ninth-graders before expanding to serve all high school grades. It was in the New Castle Corporate Commons before moving to the Centreville School campus in 2012.

The Kennett Pike campus today features the main building, part of which dates back to 1934; the annex, which is nicknamed “the mansion”; and the gym, which was built in 2019-20. The old, smaller gym, was then con-

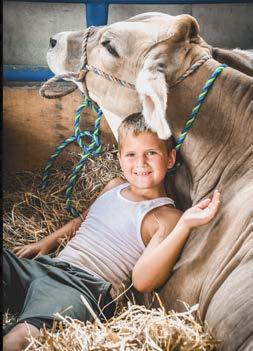

verted into a multipurpose room that every day serves as the lunchroom and at times an art gallery, dance hall and a performance space, with a raised stage. There’s also a barn, which during a visit at the end of the 2024-25 school year housed a pig named Boris and a rooster.

Outdoors, there’s a playground, a certified bird habitat, some trails and a creek – that’s why boots in one vestibule await younger students ready to splash and explore.

Classrooms sport lots of specialized things to enhance learning, such as art supplies in two art rooms, a wide range of musical instruments and 3-D printers. On this day, Thomas Mendola, the academic innovation coordinator, was printing hearts, and he said that he introduces students as young as kindergartners to computer-aided design.

Continued on Page 12

Continued from Page 11

Upper School teacher Alicia Latham had multiple enhancements in her classroom, including six chicks, a yellow crested gecko named King Louis (sent home during the summer and the two-week winter and spring breaks) and a hydroponic garden nurturing strawberries and a tomato plant.

The hallways and staircases that connect the warren of spaces in the main building are put to use as display areas for lots of student artworks and many inspirational thoughts and quotations.

Centreville Layton has a staff of 40, Taubar said. It has a 5:1 student-teacher ratio, and the average class size is eight in the middle and upper schools, but some classes mix students in different grades with similar abilities. Sometimes, older students have formally helped younger students, say as reading buddies, he added.

The school website lists tuition as $32,750 pre-K through eighth grade and $36,000 ninth through 12th grade, with need-based financial support available. That tuition is higher than Sanford and sometimes higher and sometimes lower than Tatnall.

Continued on Page 14

Continued from Page 12

Students appreciate the school’s approach.

“People are nice, and you don’t feel judged,” said Shyanne Gregor, a 12th-grader this fall from Coatesville, Pa., who said that she likes the small classes and “how everyone works together.”

Tyler D’Amico, a seventh-grader from the Newark area, started at Centreville Layton when he was in second grade and hopes to transition out for high school.

“I’ve progressed a lot,” he said of the work on his learning disability. “You get more help, and teachers give you ways to solve problems and the tools you need, and everyone is willing to be friends.”

Continued on Page 16

Continued from Page 14

Librarian Loredana Hansen enrolled two children in the school. Melania, who graduated this year, and her brother Christian, a ninth-grader who said that he enjoys the school’s academic style, in contrast to the “stress from piles of homework” he endured at his previous school.

“People struggle, but Centreville Layton is the world. It helps you mature.”

“The thing that Centreville taught me the most is thinking outside the box,” alumnus Peter Harris said in a fundraising video for the school. “In life sometimes when we think a little differently, it’s stigmatized, but quite often I think that’s the greatest gift, and being able to leverage that, Centreville has taught me that.”

To learn more about Centreville Layton School, visit www.centrevillelayton.org.

By Ken Mammarella Contributing Writer

The dozen-plus films that Chris Lemole has produced include Mudbound, a 2017 film that earned four Oscar nominations, and The Peanut Butter Falcon, the No. 1 independent movie of 2019.

Since the end of 2019, Lemole has been living in Centreville and producing movies, including Easy’s Waltz, an upcoming release starring Al Pacino, Vince Vaughn and Shania Twain.

“I needed to get out of L.A.,” he said. “It was incredibly hard to raise our five sons in the city. I was unhappy with the quality of life and the crime. I had made only two films in California (Zombeavers and Fool’s Paradise), and realized I could do my job from anywhere and fly in for meetings.”

He moved to be close to where he grew up (Northeast Philadelphia) to be near his parents – Gerald M., a retired doctor and ChristianaCare executive, and Emily Jane – and other family members.

He and his wife, Sonya, have a screening room he’s never used to screen a film. Their sons, ranging from elementary

school to high school, enjoy it for video games. Family members do watch films together that “give them a solid base in storytelling,” including classics he enjoyed when younger (such as E.T., The Goonies and The Black Stallion), The Peanut Butter Falcon (“They love the story,” about a dreamer with Down syndrome), mature fare (such as Goodfellas, Casino and Tombstone) but not yet Mudbound (“such a heavy film” focused on racism and post-traumatic stress disorder).

This summer, Lemole’s oldest will get his first taste of the business at the Vancouver shooting location for his next production. Lemole is committed to his family: “I have a two-week rule,” he said, referring to the maximum time that he can be away on location. And to his work: “I read scripts every night in bed,” he said, including scripts for movies he has admired and new scripts he might abandon midway. “And I’ll read books we’re looking at. At 10 most nights, I’m on the phone.”

Sometimes, the commitment is simultaneous: On this year’s family spring break trip, he spent six hours a day working the phone.

Continued on Page 20

“This is what I’m mainly doing on set. I’m doing emails on my phone,” Centreville film producer Chris Lemole explains. “This was the last night of shooting on Easy’s Waltz on the roof of the El Cortez Casino. Hence the safety jacket.”

Besides spending time with his family, Lemole also enjoys golfing, surfing and following all Philadelphia sports teams, particularly the Eagles.

“We want the game in the background, and we’re watching very closely, but it’s a wonderful kind of vehicle to get us all together and talk about life,” he said.

Lemole started college at Bryn Athyn College and transferred to Villanova University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in history and a law degree. He moved across the country to form his own identity and career that began with a three-year “boot camp” experience with United Talent Agency.

“After closing the door on many different positions within the biz, I decided that producing was what I wanted to do,” he told a Bryn Athyn audience in 2019. “Film is a medium that joins the human experience, where we can relate to one another and share similar emotions. Conversely, film can expose the audience to new ideas. … Producing

allowed me to find the stories that excited me and find the most impactful way to tell them.” As he said in the interview: “I love having my fingerprints all over the film.”

Lemole started producing with 2011’s From the Head, written and directed by his brother-in-law, George Griffith.

In 2013, Lemole and Tim Zajaros founded Armory Films, “nurturing distinctive stories into groundbreaking films,” according to Armory’s site. Lemole figures he devotes two years to making a movie. “If I’m going to live with it that long, I want it to have a meaning or a message and it strikes a chord,” he said. “We just make films we like.”

“Chris Lemole is one of the best people I know,” said Michael Schwartz, one of the directors and writers of The Peanut Butter Falcon. “He’s fun to be around, inspiring, and can be trusted to fight for what he believes in. My directing partner Tyler [Nilson] and I had the privilege of getting to know Chris working on our first movie The Peanut Butter Falcon together. It was a risky movie to make, but Chris understood what we were trying to do and the mark we

were trying to leave on the world.

“He put his full weight behind us as artists and when no distribution company wanted to put out that movie he doubled down on his gut belief that we, along with our cast and crew, had made something people wanted to see. That movie went on to become the highest grossing platform release of the year.

“I owe my entire career as an artist to Chris but even more importantly he’s a true friend. When I lived close by I would watch football with him every Sunday in the fall— ‘Go Birds.’ Seeing him as a father and a husband is just as impressive as seeing him as a film producer. The way you do anything is the way you do everything.”

Continued on Page 22

Continued from Page 21

In 2021, Lemole, Zajaros and Don Handfield founded Thunder Comics, which has nurtured multiple worlds and many characters that could become movie franchises.

“We believe stories are real estate,” they wrote on Thunder Comics’ site. “Intellectual property is the next gold rush.”

A film can credit multiple people as different types of producers, he said, noting that some get the designation by attaching talent or funding. As the producer, Lemole compares himself to “the sheriff of the town who decides which projects are made and with whom.”

“Much of my time is spent wondering and worrying about how I’m going to solve the five problems in front of me, knowing that five more serious ones are coming down the pike,” he said. “How do we get out of this alive while making the best film possible? It’s not for the faint of heart.”

“The system is broken,” he said of how films are distributed and hence money flows. “And I see opportunity in chaos.” That’s an interesting observation by someone nicknamed “Captain Chaos” by his family.

Moviemaking has moved to many jurisdictions beyond Hollywood, enticed by tax credits and other incentives. He’s been working with Gov. Matt Meyer and others to legislate tax credits to encourage more movies to be made in Delaware.

“I’d love to make a movie and stay in my own bed,” he said.

Continued on Page 24

Continued from Page 22

Ten inside-Hollywood terms that movie producer Chris Lemole used in his interview with Greenville & Hockessin Life or in a 2019 talk at Bryn Athyn College, where he started college:

COVERAGE: A commissioned summary of a script that might encourage potential producers to read it themselves.

CREATIVE: A noun referring to someone who makes a movie special through their creativity.

DISTRO: Short for the distribution of a movie, or one of the biggest tasks that he doesn’t handle.

•Prepared Meats•All Natural

•Catering

•Certified

•Boar’s Head Gourmet Deli Meats

•Honey Glazed Sliced Ham

•Homemade Sausage

•Homemade Prepared Salads

DOWNSTREAM WINDOWS: Money-making opportunities after a movie is shown at first-run theaters. Consumers used to buy DVDs, but they’re no longer a significant thing in this age of streaming.

HEAT: The buzz coming from the talent attached to a project.

LOCKED: Finalized.

MEZZ POSITION: Financing for a film that’s between senior debt and equity for recouping investments (yes, it’s

complicated). The term is from the mezzanine, between the best seats in a theater and the more distant seats in the balcony.

POST: Short for post-production, or the work needed after principal shooting ends.

PRE: Short for pre-production.

2X: Generally, how much more money is spent marketing a movie over making it. Lemole pronounced it “two ex,” noting the ratio is changing in the age of influencers.

By Ken Mammarella Contributing Writer

The Brandywine Valley is famous for its beauty, its history and its industries, as these writers have eloquently noted.

“God with His Hand Divine must have patterned after Heaven when He made the old Brandywine,” Christian C. Sanderson writes in a poem quoted by Elizabeth Humphrey and Michael Kahn, in Brandywine.

“The Brandywine … certainly ranks as one of the most historic rivers in the United States,” Bruce Mowday writes in a postcard collection titled Along the Brandywine. That includes the influential Battle of Brandywine on Sept. 11, 1777, the largest single-day engagement of the American Revolution.

“In terms of game-changing innovation, the Brandywine Valley at Wilmington was effectively the Silicon Valley of its day,” W. Barksdale Maynard writes in The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait, a well-researched and beautifully written book.

Let’s take a journey exploring lesser-known elements along the Brandywine, thanks to these books: The Brandywine, by Henry Seidel Canby; Red Men on the Brandywine, by C.A. Weslager; and other research.

Continued on Page 30

Continued from Page 28

The Brandywine River has had a bewildering number of names over the centuries.

The local Native Americans called it Wawaset, Wawa and Wawasan. That eventually led to places like Wawaset Park, a planned community in Wilmington that’s on the National Register of Historic Places, and Wawa, a community in Delaware County made famous as the site of the first dairy of the Wawa convenience store chain. “Wawaset” means “near the winding bend,” according to the University of Delaware Water Resources Center. The Wawa logo is a Canada goose, even though experts say some Native Americans used “we’we” for the snow goose.

The Lenape – who themselves had multiple names, including the Lenni Lenape and eventually the Delaware – may have also called it Tankapanicum, Tankopanicum or Trancopanican, meaning “rushing waters.” The name

was resurrected for an orchestra founded by Alfred I. du Pont that’s the earliest ancestor of the Delaware Symphony. That name means “stream of little tubers,” referring to ground nuts found nearby.

Another Lenape name for the waterway, according to Weslager, was Sitakonk or Sittakunck. The waterway was also called Suspecough, meaning “at the muddy pond,” according to the center.

The Lenape and William Penn in 1685 signed a treaty about using the Brandywine and its banks, but European colonists increasingly encroached on the Lenape reservation. The area’s last Lenape, called Hannah Freeman, died in 1802. Tribal members moved west, perhaps repeating “allummeuchtummen,” which means “go away weeping.” The Lenape – who only numbered 300 to 500 when the Europeans arrived, Weslager estimates – have re-established a community near Cheswold.

The Swedes who were the first Europeans to colonize its banks called it Fiskielkjilenin, the center says, meaning “fish stream” and anglicized as Fishkill.

Shad was likely that fish. “American shad was without doubt a major food source for the Lenape due to its abundance and migratory behavior which made it easy to catch,” writes the Brandywine River Restoration Trust, which wants to bring back the shad to the Brandywine. “During the spring migration they were so plentiful that the river was said to be ‘boiling’ with shad.”

Multiple stories compete for the derivation of the

Brandywine name.

The boring but probably true one is that it was named for Andren Braindwine (or Brandwyn, sources vary), who in 1670 bought (or sold, sources vary) 200 acres on the creek. The English who followed anglicized the name. One evocative one is that it came from the wreck of a Dutch ship carrying brandy (“there is no historical proof,” Weslager sniffs). The center suggests one more: it’s named after brannvin, a Swedish potato liquor.

Finally, there is no consensus whether the Brandywine is a creek or a river.

Two families have had huge influence on the Brandywine Valley, in both its industry and its beauty. The story of the du Ponts – gunpowder, chemicals, thousands of jobs, lots of financial support for local culture and many stately properties since opened to the public –is well-known.

Less so is the story of the Bancrofts, particularly the visionary William Poole Bancroft.

“It was Bancroft’s vision of preserved green space, accessible to all people, regardless of class or wealth, that allowed for the preservation of the Brandywine Valley that we know today,” the National Park Service writes.

John Bancroft, a Quaker cabinetmaker, moved to the area in 1831, and his brother, Joseph, followed, setting up a cotton mill. Joseph’s son, William Poole Bancroft, helped form Wilmington’s parks commission and headed the group for 19 years. He donated the land for Rockford Park, and was also a force behind Brandywine, Judy Johnson, Kosciusko and Haynes parks, all in Wilmington. In the 1880s, he also retained Frederick

Law Olmsted, the most highly regarded landscape architect in the country, to look at the park situation in Wilmington. In 1901, Bancroft “set out to preserve the unmatched beauty of the lower Brandywine Valley for residents and future generations to enjoy,” according to Woodlawn Trustees, the group that he created. “It is the only example of a community planning experiment in the United States that established an entity to ensure its goals were achieved long-term.”

He and his trustees have built hundreds of units of affordable housing in The Flats and the East Side sections of Wilmington, created open space for the community to enjoy in Beaver Valley (acreage that’s now the dominant part of First State National Historical Park) and donated money to buy a farm that became Brandywine Creek State Park. Over the years, Woodlawn Trustees has raised money to perpetuate this philanthropy by selling land abutting the west side of Concord Pike, north of Wilmington.

Continued from Page 31

“It would be hard to take in even a fraction of what the [Brandywine] Valley has to offer in a single day,” Lisa Foderaro writes in a New York Times travel column. “Better to stay the weekend and savor the region at the unhurried pace of the Brandywine River itself.”

The Brandywine Valley’s first tourists date back to at least 1780, when the Marquis de Lafayette – who experienced his first Revolutionary War action at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777 – revisited the site.

Part of the beauty comes from all the nearby gardens started by the du Ponts, going back to Éleuthère Irénée himself, who trained as a botanist.

The beauty and tranquility were recognized by many artists, some united as the Brandywine school. It’s a realistic style of illustration, but it was briefly a real-life school along the Brandywine.

The school was founded by Wilmington native Howard Pyle, who in 1898 and 1899 taught at Turner’s Mill in Chadds Ford and hosted gatherings at Painter’s Folly, his nearby home. Pyle rented the property from his uncle, Samuel Painter, whose name lives on as Painter’s Crossing.

Pyle’s goal “was to found a great artistic movement for the nation … rooted in love indigenous rural landscapes,” Maynard writes. His legacy lives on with the “modern conception of knights and pirates” (think Disney swashbucklers), and his death led to the formation of the Delaware Art Museum.

One of Pyle’s students was N.C. Wyeth, whose son Andrew was maybe even more influential. Grandson Jamie Wyeth and other artists continue the tradition.

Continued on Page 34

from Page 34

Continued from Page 32

Important organizations helping to protect the beauty of the area include the Brandywine Valley Authority, founded in 1945 as America’s first watershed protection organization.

The Brandywine Conservancy followed in 1967, focused on preserving the land, water, natural and cultural resources of the Brandywine-Christina watershed. Its museum opened in 1971 in an old mill on the Brandywine, with the Wyeths and other local artists prominent in its collection.

In 2017, a group now called the Brandywine River Restoration Trust formed to bring back the shad to the river, who were made unwelcome by dams that were built as early as 1720.

The conservation and recreation is united in the Brandywine Creek Greenway, an initiative of the conservancy. “The Greenway boasts over 36,000 acres of protected open space, one National Historical Park, one state Scenic

Byway, three major state parks, over 40 municipal parks and 69 miles of trails and sidewalks,” the conservancy says.

The conservancy is also working on a 22-mile recreational route called the Brandywine Water Trail.

And a significant trend in American interior design began in the 1920s at Dower House, the oldest continuously inhabited house in West Chester, less than four miles from where the east and west branches of the Brandywine meet in Lenape.

Joseph Hergesheimer was considered an “important” writer in the 1920s but is largely forgotten today, Maynard writes. His 1926 book, From an Old House helped turn antique collecting into a great contemporary mania. As Hergesheimer wrote, the book ended the days “where you could find a colonial ladder-back chair for 15 cents, sitting cobwebby on some farmhouse porch.”

The Brandywine Valley’s unusual geography – convenient water power from its steep drop and yet easy access to the Delaware River and shipping to points beyond – attracted a lot of entrepreneurs.

At the Pennsylvania-Delaware line, the Brandywine digs a channel through granite “and in less than four miles, it descends 120 feet, in a mad rush to the Delaware River and on out to the sea,” Joseph Frazier Wall writes in Alfred I. du Pont: the Man and His Family, in an excerpt featured atop Hagley Museum’s landing page for its Delaware’s Industrial Brandywine project.

“No industrial planner could have designed a better terrain for 18th-century industry, for the river has its fall line immediately above its broad, sluggish estuary,” he continues. “This felicitous union of fall-line power and tidewater transportation within a stretch of only four miles was highly attractive to the proto-industrialists of the 18th century.”

Another cool Hagley page is its Brandywine Oral History Project, featuring interviews done as early as 1954 with 150 people who lived and worked in the Brandywine Valley.

Flour, paper, textile and gunpowder dominated the mills – numbering more than 100 by 1800.

“Brandywine Mills” was a brand for flour, set up after the Revolutionary War after various mills agreed to inspections to insure quality. The price of wheat and flour was determined on the Brandywine at the end of the 18th cen-

tury “because of the efficiency and quality of the product,” Mowday writes. Brandywine was also the name of a cornmeal, Maynard writes.

A condo complex on the mouth of the Brandywine honors that legacy with its Superfine Lane address, named for the high-quality flour ground there.

Continued on Page 36

Continued from Page 35

By 1787, brothers Thomas and Joshua Gilpin set up Delaware’s first paper mill. In 1816, Thomas patented a machine to make continuous-roll paper, and a year later set up America’s first paper-making machine. A mill near Rockland was reportedly the nation’s largest papermaker about the time of the Civil War, Maynard writes.

“Brandywine” was a brand of paper, famed for its cheapness and whiteness.

In 1790, Oliver Evans received America’s third patent for inventing machinery to improve moving grain and flour through the mill.

In 1794, Jacob Broom set up Delaware’s first cotton mill. He moved operations upriver and, after a disastrous fire, sold

his land to the du Ponts.

In 1802, E. I. du Pont set up that famous gunpowder facility. Making gunpowder was the ninth business proposal for the du Ponts. Their first was creating a utopian community called Pontiana, probably in Virginia. But they didn’t raise all the money that they needed; speculation made land prices high; and the du Ponts, as foreigners, couldn’t buy land in America. They faced the same legal issue in Delaware at first, so E.I.’s brother Victor applied early for U.S. citizenship. Making gunpowder was a tough business; hence the DuPont Co. insistence on safety, a philosophy that continued for centuries. That said, going “across the creek” meant to be killed in an explosion.

The mills declined with the development of steam power, the popularity of the turbine over the water wheel, roller mills replacing grist stones, an increasingly erratic water flow from deforestation upstream and export limits during World War I. The mills’ legacy lives on as buildings converted to other uses and the names of so many roads. Ditto for the entrepreneurial families.

“The log cabin, which became such a powerful folk symbol in our politics and represents the coming to power of the West in the nation, began at the mouth of the Brandywine,” Weslager writes. Credit the Swedes and Finns who started arriving in 1638.

The Conestoga wagon, another icon of America’s westward push, was developed in Pennsylvania’s Lancaster County to ship grain under a canvas cover to Wilmington’s port, he continues.

In 1830, the Bush & Lobdell foundry started, and “it

helped pioneer modern techniques, such as research and development and even the hiring of traveling salesmen,” Maynard writes.

“In the decade before the Civil War, Wilmington led the nation in iron shipbuilding,” Richard Urban writes in “The City That Launched a Thousand Ships” (albeit mostly on the nearby Christiana River).

And finally, there’s the Brandywine tomato, flavorful and delicate. The 1890 Johnson & Stokes seed catalog says it was named by Thomas H. Brinton of Chadds Ford, “who has probably grown and tested more varieties of tomatoes than any other person in the United States.” In September of 1888, he describes his discovery, in a note excerpted on padutchcompanion.com. “I am pleased with it. It is certainly a magnificent, new, most valuable and distinct variety, and worthy of the name Brandywine after that most beautiful of all streams, which flows near our Quaker village.”

|Greenville & Hockessin Life Photo Essay|

|Greenville

& Hockessin Life Photo Essay|

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 39

When a woman ascends the stairs of Yves Jolie Bridal, nestled in the Shops of Centreville, she’s greeted by a gallery of stunning photographs—brides glowing in their gowns, each image curated from within this intimate studio.

At the top, she and her party are welcomed by owner Linda Ives and guided through a deeply personal experience—one designed to merge elegance and emotion into a singular statement: her story of timeless beauty.

A self-described “nomad, military girl, educator, protocol and etiquette buff,” Ives was serving as an Army protocol officer in Hawaii at age 23 when her friend Amara enlisted her help as wedding coordinator, maid of honor, and dress shopper. Together, they found the dress—the one that made Amara absolutely radiate. That experience didn’t immediately launch Ives into bridal fashion, but it was a glimpse into the kind of joy she would one day create for others.

It reflected a truth about her spirit—one now woven into every consultation, every fitting, and every connection she forms with her brides at Yves Jolie Bridal.

“My nature is very nurturing,” she said. “I’m a caretaker, and I receive so much joy from helping others connect with their inner beauty. I’ve always wanted people to feel like the best version of themselves.”

Opened last fall, Yves Jolie Bridal is the creative culmination of Ives’ multifaceted path— from Army officer to educator to lifelong lover of fashion and the arts. The shop is, in many ways, a love letter to both beauty and purpose.

“This place is a living work of art,” she says. “Between the designers I’ve chosen and the women I get to work with—what a joyful profession! I’m caring for people during one of the most beautiful times of their lives. It brings together everything I love: art, fashion, and human connection.”

The boutique carries gowns by nearly a dozen of the world’s most celebrated bridal designers, forming a global symphony of styles. Each selection becomes part of a bride’s narrative — a creative vision brought to life on her walk down the aisle.

Destiny, it seems, has a way of biding its time… until it doesn’t.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 43

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 41

Then, all at once, it insists.

Yves Jolie Bridal is the realization of a dream long held in Ives’ heart: to become a working artist in her own right.

“From the moment I signed the lease last fall, I felt like a little woodland creature with a giant straw backpack,” she says, smiling. “Every person who’s supported this dream has been like an acorn in my basket; and now my basket is so full. When you combine your gifts from God with your true passion, there truly is no greater happiness.”

Yves Jolie Bridal is located at 5714 Kennett Pike in the Shops of Centreville. To learn more, visit www. yvesjoliebridal.com or call (484) 639-3774.

Over the last five years, Alyssa Andress and her Editorial Candle Co. have been making scents of memories and places.

The concept and its fragrances are now in thousands of

By Richard L. Gaw Staff Writer

It is a Sunday morning, and as you arrive in the kitchen of your home, the intoxicating scent of freshly brewed coffee, made by someone else in your family, is enfolding the room in the way a blanket serves as a canopy of warmth and protection.

It is an Autumn afternoon, and you trudge through an apple orchard plucking fruit off of trees, and there is a familiarity in the October air – with its bittersweet pungency - that reminds you that this is a season of quiet surrender to the winter ahead.

You gracefully hug the shoreline like a dancer on a stage as the waves voraciously crash against the rocks, and you inhale the sea salt brine that seems to have a language of its own that melts you within the tenderness of the moment.

You want to flip the catalog open. You want to turn the pages, see the photographs, close off all potential interference and become intoxicated by every moment’s fragrance.

For the last five years, through her online company Editorial Candle Co., Alyssa Andress has been bottling those aromas of your life in the form of candles that for her customers have become quiet embers of memory and rejuvenation.

Continued on Page 46

Continued from Page 44

“I have always been a storyteller of some sort,” Andress said from her home near Greenville, where in addition to her work with Editorial Candle Co., she is a fiction writer. “Storytelling is where my heart lives.”

COVID-19 was wrong for more reasons that can possibly be counted, yet within that nearly two-year fog of isolation, it spawned millions of side hustles and part-time occupations and reintroduced new passions that had been for too long relegated to inapproachable daydreams. Andress and her husband were living in Media, Pa. in March of 2020, here she soon began a job at Philadelphia Style magazine. Two weeks later – after the world shut down on March 13 - the publication’s staff were asked to work from home. Two weeks later, the entire department was furloughed.

“I was looking for an outlet that would allow me to be creative,” Andress said. “I was buying a lot of candles but didn’t have any income, so I thought about perhaps buy-

ing some wax and making candles on my own. From the start, I knew that I wanted to create an editorial aspect.”

During that incubation period, two definitive scents emerged.

“I knew that I wanted to name one candle “Edge of Seventeen,’” said Andress, who grew up in Berwick, Pa. “I was in this era of my life when I listened a lot to Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac and wanted to capture that essence. I also wanted to capture the scene of my Nanna’s home. The fragrances of her home at Christmas time were very specific, filled with chestnuts and pinecones. I called the candle ‘One Eleven Center Street,’ which was her home’s address.”

Andress began to source fragrances, oils and other

Editorial Candles come in many names and fragrances.

materials from candle resource companies, and took the next four months to experiment. Eventually, the two candles that first emerged were joined with other names that included “Montauk & Monterey,” a seascape scent that combines citrus with cedar, violet, jasmine and sea salt; “Nights on Vinyl,” that conjures up the feeling of relaxing on a leather couch, infusing cedarwood, leather and sandalwood; and “A Bushel & A Peck,” reminiscent of apple gathering in the Autumn and made of fresh greens and juice.

The company’s inventory has now grown to include “Breakfast for Dinner,” “Dancing in the Kitchen,” “Auroras & Sad Prose,” “Sweet Nothings,” “Mulled Nostalgia,” “Sailor’s Delight,” “Biker Jacket,” “Afternoon Delight,” “On the Clothesline,” “Kuh-Laire,” “Grand Carousel,” “Curiouser & Curiouser,” “By Any Other Name,” “Tomato/ Tomato,” “Dark & Stormy,” “Summer Lovin’,’” “Ghost Stories,” “Lavender Haze” and “Solar Flare.”

“Often, I start with the story, and I write out the description of the candle first and tie the scent of the candles I choose into the name,” Andress said. “I often

pull from literature and pop culture. For instance, I named “Curiouser & Curiouser” after the book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. “Wednesday in a Café” is a lyric from a Taylor Swift song and so many are pulled from my life. “Dancing in the Kitchen” and “Breakfast for Dinner” come from the experiences that we all have.”

In between her work with an agency to promote the work of companies and organizations to boost the economy of Philadelphia, Andress fills her weeknights and weekends with developing new candle scents, pouring candles, filling online and made-to-order requests and showcasing her work at artisan markets in Delaware and nearby Chester County. Editorial Candle Co. products can also be found in shops near Pittsburgh and Berwick, and Andress said that she is prioritizing showcasing her products at shops in northern Delaware.

Continued on Page 48

Continued from Page 47

Editorial Candle Co. also offers lowercase., a quarterly subscription box that pairs stories with scents to transform one’s reading experience. Each box features a newly released book, an exclusive candle, a bookmark, and a customized playlist of songs selected by Andress, all designed to transport the reader beyond the pages and into the heart of the story.

“The idea for lowercase. came from my love of reading,” Andress said, who pointed to a shelf full of books that takes up an entire wall of her home. “It was natural for me to do a book-candle-music combination. So far, I have offered literary fiction, literary fiction with a touch of romance, and a package that has a touch of magical realism to it.”

If there is a happy problem in Andress’s life, it is coordinating the balancing effect of managing the growth of a successful business with the obligations of a full-time job. The sales of Editorial Candle Co. have reached more than 20 states, developed an online presence, achieved product placement with online influencers, boosted by appearances at locations like the Kennett Creamery and the Brandywine Park Farmers Market and a powerful word-of-mouth

Continued on Page 50

Continued from Page 48

network of friends and customers. While Andress said that she would welcome the opportunity to expand her company in the future, she said that it is crucial that it always remain beholden to its original mission.

“The goal of Editorial Candle Co. has always been to connect everyone to places and moments that are special to them, because everyone has a story to tell and the story I am telling with these candles is something that everyone can relate to,” she said. “Whether it is the aroma of a grandmother’s house or smelling coffee on a Sunday morning, there is a place – and a candle - for everyone here.”

To learn more about Editorial Candle Co., visit www.editorialcandle.com or email editorialcandle@gmail.com.

To contact Staff Writer Richard L. Gaw, email rgaw@chestercounty.com.

“The moment I opened the box my entire apartment smelled incredible. I didn’t even need to light it to experience this perfect, cozy scent. I loved it so much I immediately bought one for a friend. Do yourself a favor and get yourself one.”

An Editorial Candle Co. customer from Media, Pa.

Hockessin

Greenville & Hockessin Life recently met with Dr. Judith Provencal, the resident astronomer at the Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory in Greenville, to discuss her early moments behind a telescope, the Observatory’s recent acquisition of a 1.3-meter MCAO telescope, and what we can continue to learn from our observation and study of the skies above us.

Greenville & Hockessin Life: Take me back to the time and place where you first looked through a telescope. How old were you?

Provencal: I think I was about ten years old when I first looked through a telescope. I had a little telescope as a child growing up in Kittery, Maine, but that was not the first telescope that I remember looking through. My cousin had a little telescope that I contributed about $50 to purchase. My allowance was about twenty-five cents a week, so it took a long time to save up. My parents paid the rest as a Christmas present.

Do you remember what you saw?

Jupiter and its four moons. Back in the days before light pollution, I could see the Milky Way when I was a kid. My parents thought I was nuts, but I would take my telescope out in the winter, set it up and be out there in the snow, so that I could see the sky.

Was there a moment that crystallized your decision to pursue the study of astronomy – a specific minute of your life that said, “Go in the direction of the stars?”

I don’t remember a specific moment, so I suspect that my interest has always been there. I have to admit that I picked my college – Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts – not on the basis of its astronomy program, but because they had horses on campus, where you could take riding lessons. Away from my research and teaching, I am a horse addict and I still own a horse.

You began working at the University of Delaware as a post-doctoral student in 1994 under the esteemed Dr. Harry Shipman. What did you learn from Dr. Shipman, and in what ways do you still incorporate his tutelage in your study today?

Continued on Page 54

Continued from Page 53

Harry was more of a theorist than an observer, and I am more of an observer than a theorist, so we made a good team. When I first came to Delaware, we were studying a binary star known as Procyon B. It had a white dwarf star companion orbiting around it, and we wanted to get the orbital period of the white dwarf accurately in order to determine its mass and radius. There wasn’t much empirical evidence to support the white dwarf mass radius relation theory.

We used the Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS), the Wide Field Planetary Camera (WFPC2), and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) – instruments that are all attached to the Hubble Space telescope - to observe Procyon B.

The rule for the Faint Object Spectrograph was, ‘Thou shall not point the telescope at anything bright,’ because you could damage the instrument, but Procyon B, right next to it, was very bright, so in order to avoid that light and focus on the white dwarf, we had to have an accurate placement. We ended up locating the white dwarf with the WFPC2 instrument, but because science is crazy, you find things out that you would never predict. Our WFPC2 data showed that the white dwarf had a core made of iron, and supposedly, all white dwarfs are made of carbon and oxygen. We published our paper saying that Procyon B had an iron core.

A few years later, we got better observations using STIS and found out that the white dwarf was a different type than what we expected it to be. When we figured this out, our analysis supported the white dwarf mass radius relation that we were trying to prove. It took a lot of steps to get to that result! Harry taught me to always work towards getting better data to improve our knowledge.

Describe Harry’s infectious curiosity and how it influenced you.

I had met Harry before, but until I began at the University of Delaware, I didn’t know how enthusiastic he was about astronomy. The thing about Harry that I remember most was that he loved teaching. He loved research, but it was more important to him that his students were learning. Harry would take his classes and divide them into groups and assign them projects and at the end of each project they would get back together and discuss their results.

He had so much energy. He would run around the class and check on how everyone was doing. Being able to observe that has influenced me as teacher.

What do you enjoy most about teaching and research? I love those moments when a student of mine figures something out. When I am doing my own research and I get a result, I love that moment when I realize that no one else knows this data except me.

Less than one year ago, a 1.3-meter MCAO telescope was installed at the Cuba Astronomical Observatory. Talk about why the Observatory was seeking to add this technology to its inventory, and what its key purpose will be in the years ahead.

The whole process began about nine years ago. Our 24-inch telescope – still here at the Observatory – was installed in the 1960s but has 1960s technology. We then began thinking about why we need a more modern telescope. I began traveling around different observatories that had telescopes that were close to what we were looking to buy and began talking with them.

In 2020, we started the construction of the building, and the ground was very rocky which required a special machine to get rid of the rocks. The building was completed in 2022, which was delayed because of COVID-19, and the telescope arrived in June of 2024.

When the MCAO is ready – hopefully this fall – it will give students the hands-on ability to use it. This telescope will enable us to see objects that are much fainter in the sky than we could see before.

Continued on Page 56

Continued from Page 54

The 1.3-meter MCAO telescope puts the Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory in a bigger ballgame, yes? Absolutely. It will be the largest working research telescope on the East Coast.

The Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory remains a vital center for astronomical research, drawing thousands of curious minds to classes and workshops there every year. What continues to drive the Observatory forward?

For me, it is training the next generation of astronomers. It is important that the next generation understand where the data comes from, and that is what this new telescope will do. We may discover some new and fantastic thing, and who knows, we might – but it’s not guaranteed. What is guaranteed is being able to teach that next generation.

What needs to be done to encourage more young women to enter the field of astronomy?

When I was a graduate student, a professor told me that I was the first woman he’d ever had as a graduate student, and I was the only woman in my group. “How do I treat you?” he asked. I told him that he should treat me no differently than any of my male colleagues.

We need more places like Mt. Cuba that encourage young women to nurture their interest. If they have the interest, they will have the motivation. I would encourage them to continue to be stubborn, and to never give up.

contours and craters.

We had a young person at the Observatory named Jackson recently who was looking at the moon through the telescope lens during a public event. One of our teachers asked him, “Do you see the moon?” He kept telling her that he had not yet. Afterward, he told the teacher that he had seen the moon, “but I just didn’t want to tell you because I wanted to keep looking.”

Jackson started coming to the Observatory when he was about five years old, and he is still coming here.

There is a sense of curiosity that leads someone to a telescope lens, and for many, it happens again and again. What is it like for you to introduce someone to a telescope viewing for the first time or someone to a telescope for the thousandth time? I am sure it’s an experience that never grows old, yes?

It’s been fifty years since I first looked through a telescope, and I still love looking at Jupiter and Saturn. The best moments are looking at the moon because when you look at the moon through the telescope, you can see all its

What can we as humans continue to learn from our observation and study of outer space? How will looking up to the skies help us live better lives here on Earth?

Every time we have a new telescope or new technology, we learn something new, every time. Right now, the Webb telescope is teaching us more about the early history of the universe, and how galaxies are formed. The other new development in astronomical research is the search for other Earth-like planets. There are a couple of space missions whose focus is to find planets like ours.

That may be the greatest question that continues to drive human curiosity: Is there life on other planets? I think it would be a vast waste of space if we were the only source of life. There are 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, and just beyond that, the Andromeda Galaxy is twice as large and there are easily another hundred billion galaxies out there, and that’s a lot of stars. It would be a statistical anomaly if we were the only planet that has developed some kind of life.

What is your favorite spot in either Greenville or Hockessin?

The Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory. I have an office at the University of Delaware, but when I really need to get some particular kind of research done, I come to the Observatory because no one knocks on my door. I also like the Hockessin Bookshelf.

You organize a dinner party and can invite anyone – famous or not, living or not. Who would you want to see around that table?

For astronomical reasons, I would invite my colleague in Texas, Mike Montgomery. He’s a theorist, and he’s constantly coming up with new ideas. I love the way he thinks, and he’s wonderful to talk to. It would be nice if Harry Shipman could come back and sit around that table. Another person I would like to invite would be Rosa Parks, because I want to know how she managed to have the guts to do what she did.

What items can always be found in your refrigerator? Yogurt and homemade vegetable soup.

The Mount Cuba Astronomical Observatory is located at 1610 Hillside Mill Road, Wilmington, Del. 19807. Office hours are Mon-Fri from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. by appointment only. To learn more about special events, public nights and other programs, visit www.mountcuba.org.

~ Richard L. Gaw

Recently, Contributing Writer Gabbie Burton joined Chase Wilkinson of Wild Birds Unlimited on a bird walk through became a new and profound appreciation for what had once

By Gabbie Burton Contributing Writer

When I feel nostalgic and search for memories of my earlier life, my senses light up. I see the black soles of my feet from running around barefoot through the summer. I smell the peculiar odor of a brand-new dance costume.

I hear the call of a bird, whose name I never cared to learn but who I know well. It is a bird that you all know well, too. They sound like waking up too early during summer break, an alarm clock that I either love or loathe depending on just how early their warbling coo roused me, and that I mistook for an owl for many years. If you haven’t already guessed what bird I’m talking about, this bird is a Mourning Dove, a childhood companion I fear that I have ignored for too long. Similarly, after my recent magazine assignment to walk through Auburn Valley State Park with Charles Shattuck and Chase Wilkinson from Wild Birds Unlimited in Hockessin, I now realize that the Mourning Dove is not the only bird I’ve thus far overlooked.

“Everyone can learn how to bird,” Shattuck said. “It’s not that hard.”

Shattuck has owned the Hockessin Wild Birds Unlimited for 25 years and revealed he only got into birding after acquiring the store, having no prior affinity for the hobby. The store – located in the heart of Hockessin - has become a primary spot for all things birding, selling products for outdoor birds and bird watchers including feeders, feed, bird houses and other accessories. In addition, he and his team, including Wilkinson, supervise nearby bird houses and gourds in local parks – 57 in total.

For our walk in early June, we took a peek at some of those bird houses. A nest of four baby Bluebirds occupied a bird house near the Dew Point Brewing Company, the start

of our journey. The mom and dad flew anxiously nearby as Shattuck opened the box to reveal the siblings huddled next to each other.

“A lot of people think you can’t touch a baby bird because it will get rejected by the parents, but that’s not true,” he clarified. “These birds can’t smell it.”

This was just one of the many lessons Shattuck and Wilkinson would impart upon me. Quickly, seemingly just every few seconds, Wilkinson was recognizing nearly every bird call I didn’t even know I was hearing, and both were pointing to identify who was making the noise from the trees. First, it was the Bluebirds, then the Catbirds - a seasonal guest to the region - then the Wrens, a yearlong neighbor.

While I was playing catch up to the scenery and squawks, Shattuck and Wilkinson’s extensive birding knowledge left me wondering, what is it about these birds that inspire so many people to be so captivated by them?

For many - like my childhood sound bath memories of birds calling outside my home - it also comes back to nostalgia. Shattuck described how when people realize the native bird populations that were once abundant in the region in their youth have since decreased, they want to do something about it. Shattuck cited development and pesticides as some of the reasons for declining bird populations, both in the past and still today.

“Development leads to bird deaths,” Shattuck said. “You have to do something for what you displace, and people don’t realize that when you start taking down trees it’s probably someone’s house.”

Continued from Page 59

Dead trees, which may be an eyesore to some, provide a lovely and safe home for some species of birds. Clearing open and forested land for housing developments not only take the homes of the birds but introduce an additional threat to their survival in the form of windows. Birding is a step in the right direction to rectify this impact, according to Shattuck. A simple house, gourd or feeder in a backyard can help not only the birds but the owner and the surrounding ecosystems as well.

“It’s beneficial for both you and the birds, and it keeps people calm,” he said. “People want to do something to save the planet. Maybe this isn’t saving the planet, but it’s a start.”

Shattuck explained how some birds, such as Purple Martins, are entirely dependent on human provided housing. Without provided housing, the Martins and other birds can’t eat plants or seeds that are later dispersed through their feces, spreading more plants to more places.

Threats to bird populations are not limited to development. Invasive species such as the European Starling and

House Sparrow can threaten the Martins or other birds as they compete for nests. Starlings have been known to kick birds out of their nests to steal for themselves and the Sparrows will go far as to attack and kill native birds when looking for nesting sites. Checking up on birdhouses and Purple Martin gourds are imperative to ensure these surprisingly violent species don’t harm the birds these protections are aimed to help.

When asked their favorite birds - Starlings and House Sparrows were now out of the equation - both Shattuck and Wilkinson hesitated for an answer. Shattuck settled on the Purple Martin, due to the close nature of the bird-human relationship.

“Maybe just a Robin,” Wilkinson decided. “I shouldn’t say ‘Just a Robin,’ because when you walk the trails this often, you see the same birds but they’re all special and they’re all pretty.”

This sentiment struck a chord with me. Just after this moment we saw a deer off our path and, ironically, my excitement over the creature seemed to catch my guides off

guard, as it is “just” a deer. While the deer and the Robin may be mundane to most, that doesn’t inherently make them any less special or any less pretty.

Although I could appreciate the mundaneness of a deer, I realized that I haven’t spent a lot of my life offering the

same grace to birds, and that just because they are common doesn’t mean I should ignore them. Near the end of our walk, I became so acutely aware of just how many birds I was hearing that there is a strong possibility that I will begin

to acknowledge these sounds when I step outside. “Whenever you go outside, are you thinking about all the different bird calls?” I ask.

“Every time I leave the house, I notice it,” Wilkinson confirmed.

I realize this concert of bird calls is something nearly forgotten to my ears, making me all the more aware. Does it always sound like this outside and I’ve just been missing it? I wondered. I haven’t heard this many birds in a long time. In reality, I have always heard them. I just wasn’t listening to them. That tiny fraction of effort to acknowledge their presence was all it takes.

As I listened through my walk with Shattuck and Wilkinson, I concluded that it isn’t just the Mourning Dove who makes me nostalgic. Something about all the bird calls reminds me of when I was a kid. The noise of my inner world grew louder than the world around me as I grew up, and I stopped listening to the birds. Admittedly, I stopped listening to nature in general.

I always thought bird watching was a hobby reserved for those much older, and that engaging in it would feel profoundly uncool and, frankly, my unfair perception was that I would be bored to be partaking in the activity. However, I found the opposite to be true. The floods of bird calls filling my ears and the stillness to watch them fly made me feel younger. Being on that walk with Shattuck and Wilkinson

Continued on Page 64

Continued from Page 62

became for me a simple moment to reconnect with a part of nature that has for too long existed entirely in the background of my life.

“Birding is something that unites generations,” Shattuck said. “Children are fascinated by it and for senior citizens, they want to know that life is perpetual and it’s still out there…just outside the window.”

Wild Birds Unlimited is located at 7411 Lancaster Pike, P.O. Box 249, Hockessin, Del. 19707.

To learn more about birding, providing backyard homes for birds and bird walks in the area, visit the Wild Birds Unlimited website at www.wbu.com, or call (302) 239-9071.

To contact Contributing Writer Gabbie Burton, email gburton@chestercounty.com.