Jury Evaluation Report

Jury Evaluation Report

Design Competition

Helsinki, Finland

September 2025

The jury report for the international design competition for a new museum building for the Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki provides an overview of the competition, which was held in two stages between April 2024 and September 2025. The publication also includes evaluations of all 624 entries accepted into the competition and sets out instructions for the further development of the winning entry.

The design competition was organised by the Real Estate Company ADM together with the Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design, in collaboration with the City of Helsinki and the Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA).

Publication Title Jury Evaluation Report: Design Competition for the New Museum of Architecture and Design, Helsinki, Finland

Editors

Reetta Turtiainen

Heini Lehtinen

Jussi Vuori

Translation and Proofreading

Silja Kudel

Visual Identity hasan & partners

Graphic Layout

Salla Bedard

Images

Anni Koponen

Sami Saastamoinen

Publication Date 11 September 2025

Place of Publication Helsinki, Finland

Print Run 400 (1st edition)

ISBN 978-952-5195-63-7 EAN 9789525195637

Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki 2025

A decades-old dream is finally coming true: a new Museum of Design and Architecture is coming to town. At long last, Helsinki will host a museum where architecture and design will provide a roadmap for exploring our homes, cities and societies, a place to engage critically and creatively with our past, present and future. A museum where Finland’s rich design heritage – from Aalto to Angry Birds, from Art Nouveau to hockey jerseys, from Nokia to nano pulp, from baby boxes to smart clothes – will come to life. A museum that will draw people together and immerse them in new experiences and encounters.

The project was launched just before the pandemic, when the City of Helsinki and the Finnish government committed to making this vision a reality. Two of the world’s oldest institutions in their respective fields – the Design Museum, founded in 1873, and the Museum of Finnish Architecture, established in the 1950s – were to be united, and a new building would be created that would enable the museum to achieve its full potential.

By spring 2021, with a shared commitment and framework in place, a concrete plan for implementation started to take form. As part of this work – which has involved countless museum visitors, professionals and experts from Finland and abroad – the competition brief for the new museum building was developed. Alongside the city’s and the state’s decisions on funding, a group of private foundations joined in as founding partners. Their early commitment has been an essential and inspiring expression of trust in the future, and in the role of cultural institutions as critical building blocks of our society and economy.

The competition was launched in April 2024. Its aim was to identify a design solution as well as a team capable of realizing the new national Museum of Architecture and Design. A total of 624 entries were accepted to the competition from all over the world. In December 2024 the jury selected five finalists for the second stage. Today, as we announce the results, the next phase begins: Developing the winning proposal into an executable plan. Again, we invite our audiences and stakeholders to be part of this work.

Our goal is clear: To create a leading cultural institution – a museum where everyone can experience the relevance of architecture and design for their lives – a place of repose, calmness and rest for some; a site of social life, fun and inspiration for many; a space for deep reflection on urgent societal questions for others. The new building is not an end in itself. It is simply a platform for the museum to fulfil its mission and a point of departure for the society to explore and debate its possible tomorrows. This is a proud and transformative moment. At a time when cultural institutions across the world are under increasing pressure, Finland is investing in the cultural heritage that weaves communities together.

We wish to thank the jury and all the experts that supported the jury’s work for your careful and valuable input. We extend our heartfelt thanks to each design team that participated in the competition. Warmest congratulations to the winners.

With gratitude to our founders and founding partners we look forward to creating a museum that belongs not only to Helsinki and Finland, but to the world.

Helsinki, 11 September 2025

Kaarina Gould

CEO,

Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design

Mikko Aho

Architect SAFA

Chair

of the Jury Vice Chair of Real Estate Company ADM

The design competition was organised to select a proposal for a new building for the Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki. The aim of the design competition is to realise the new museum building in Helsinki based on the winning entry.

In addition to determining the overall architectural concept, the competition also served as a procurement process for selecting the principal designer, as well as the designers responsible for structures, foundations, HVAC, and electrical systems.

The museum site is located in the emerging Makasiiniranta district in Helsinki’s South Harbour. The building will sit on the waterfront of the historic city centre in an area of national heritage value. Both the museum and the Makasiiniranta district are part of the buffer zone of the World Heritage site of the Suomenlinna Sea Fortress.

To organise the design competition, the ADM Real Estate Company partnered with the Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design. The competition was arranged in collaboration with the City of Helsinki and the Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA). ADM, owned jointly by the City of Helsinki and the State of Finland, was founded specifically to develop and build the new museum of architecture and design.

Schedule

Stage 1

15 April–29 August 2024

Stage 2

10 February–6 June 2025

The competition brief and its appendices were made available on the competition website1. Participants were advised to monitor the website throughout the competition period, as all competition-related notifications were published there.

An English-language competition seminar was held as a webcast on 24 April 2024. A separate guided site visit was not organised, as the area is freely accessible to the public.

During Stage 1, competitors had the opportunity to submit questions related to the competition. Questions had to be submitted by 2:00 pm on 12 May 2024 via the competition website. A total of 633 questions were received by the deadline. All questions and the organisers’ responses were published on the competition website in two parts, on 9 May and 9 June 2024.

During Stage 2, a total of 45 questions were submitted by the five finalist teams by 31 March 2025. Responses were provided on 16 April 2025.

By the deadline, the competition received 634 proposals with complete status and 137 with incomplete status.

During Stage 1, digital 3D models were requested from 21 entries to support the jury’s decision-making. These models were placed within a large digital model of the city to give a clearer understanding of how each proposal might fit into its location.

A total of 624 proposals that met the competition brief’s programme requirements were accepted for evaluation. All five finalist teams submitted their proposals by 6 June 2025, and these were accepted for evaluation.

All 624 accepted proposals from Stage 1 were published on 12 September 2024 in an online gallery for public viewing. In addition, digital 3D-models of all five finalists were available for the public.

On 18 December 2024, the five proposals accepted for Stage 2 were published on the Kerrokantasi (Voice Your Opinion) online platform for public viewing and commenting until 31 January 2025. A total of 1,412 comments were received. Stage 2 proposals were also available on the same platform between 17 June and 31 July 2025.

Feedback from public engagement is presented in more detail in Chapter 3.1.

The jury convened on the following dates:

28 March 2024

9 September 2024

24–25 October 2024

14 November 2024

5 December 2024

11 December 2024

18 June 2025

15 July 2025

13–14 August 2025

27 August 2025

1 www.admuseo.fi/competition

In addition, evaluation progressed through numerous meetings of smaller working groups with various experts. The results of the competition were announced at an event held on Thursday, 11 September 2025, at Helsinki City Hall.

Stage 1 of the competition (15 April–29 August 2024) was open to individuals and design teams with the following eligibility criteria.

The lead designer must present the following personal qualifications:

• A completed university level master’s degree in architecture

• Confirm that they have the right to practise as an architect in their country of residence

• The person must be a resident of a European Union country or of a country that is party to The Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA 2012)

The design team might also contain members from countries that do not fall under the scope of the European Union and its procurement legislation. No separate registration was needed, but the participant must ensure the validity of the given information by accepting the terms when submitting the competition entry. The competition organiser verified the given information from the teams selected for Stage 2 of the competition.

Design teams behind the entries that were selected for Stage 2 had the opportunity to supplement the teams prior to the beginning of Stage 2. In addition to the lead designer as described in the requirements for Stage 1, the design teams selected for Stage 2 must have included the following experts:

• At least one member of the design team must have obtained qualifications to the level required in Finland to act as a principal designer 1–3

• At least one member of the design team must have obtained qualifications to the level required in Finland to act as a corresponding building designer 1

• Corresponding structural designer (structural engineer) with qualifications that meet the level required in Finland for executing the task 1–3

• Corresponding foundation structures designer (structural engineer) with qualifications that meet the level required in Finland for executing the task.1–3 The organiser reserves the right not to deem this role mandatory during the competition.

• Corresponding HVAC designer (mechanical engineer) with qualifications that meet the level required in Finland for executing the task 1–3 at least regarding the design of ventilation or water and sewerage equipment

• Corresponding electrical designer (electrical engineer) with the experience required in Finland for executing the task

These experts were required to have good Finnish language proficiency.

1 Required level of qualification: exceptionally difficult / poikkeuksellisen vaativa (PV), YM1/601/2015

2 Find more information on qualification requirements: FISE, Certifications and Application Instructions, Designers

3 Find more information on equivalence of qualifications and work experience outside of Finland: RTY Topten 120 f 05, Application of foreign qualifications and work experience in assessing the competence of a responsible person, Regulations and Guidelines (in Finnish)

Jury of the design competition for the new museum for architecture and design consisted of a chair of a jury and 12 jury members.

Chair of the Jury

Mikko Aho, Architect SAFA, Vice Chair of Real Estate Company ADM

Vice-chair of the Jury

Juha Lemström, Architect SAFA, Chair of Real Estate Company ADM

Members of the Jury

Gus Casely-Hayford, Director, V&A East Beatrice Galilee, Architect, Executive Director, The World Around

Kaarina Gould, CEO, Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design

Salla Hoppu, Architect SAFA, Team Manager, City of Helsinki

Beate Hølmebakk, Architect, Professor, Partner, Manthey Kula Architects

Riitta Kaivosoja, Master of Laws with Court Training; Director General, Ministry of Education and Culture, Department for Art and Cultural Policy (until June 2025)

Matti Kuittinen, Architect, Associate Professor, Aalto University

Miklu Silvanto, Designer, Entrepreneur, Oura; Member of the Board, Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki

Anni Sinnemäki, Vice Chair for Helsinki City Council; Deputy Mayor for Urban Environment (until June 2025), City of Helsinki

Members of the Jury Appointed by the Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA)

Sari Nieminen, Architect SAFA, Architect Office

Sari Nieminen

Hannu Tikka, Architect SAFA, Professor, APRT Architects

Competition Secretary

Jussi Vuori, Architect SAFA, JADA Oy

Among the members of the jury, Mikko Aho, Juha Lemström, Beatrice Galilee, Salla Hoppu, Beate Hølmebakk, Matti Kuittinen, Sari Nieminen and Hannu Tikka served as professional members, as defined in the competition rules of the Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA). In accordance with SAFA’s competition rules, professional members hold the majority of votes.

A diverse group of specialists—from museum and urban design experts to education, accessibility and environmental sustainability professionals—contributed to the design process. All finalist teams were given the opportunity to consult with these specialists and integrate their input into their proposals. Detailed information on public and expert engagement can be found in Part4:ReimaginingArchitecturalCompetitions.

The following specialists contributed their expertise during Stage 1, Stage 2, and the interim period between these stages.

Architecture and Design Museum

Erkki Izarra, Director of Communications and Marketing

Carina Jaatinen, Director of Content and Programs

Emmi Jouslehto, Chief Technology Officer

Arja-Liisa Kaasinen, Director, Public Engagement

Pilvi Kalhama, Museum Director (from 4 August 2025)

Petteri Kummala, PhD, Head of Research

Piia Lehtinen, Head of Partnerships

Hanna Mutanen, Director, Business Development

Minna Moberg, Head of Customer Service

Aino Pisilä, Head of Technical Services

Suvi Saloniemi, Head of Exhibitions

Mari Sundell, Customer Experience Manager

Maija Tanninen-Mattila, Museum Director (until 31 July 2025)

Susanna Thiel, Head of Collections

Reetta Turtiainen, Project Manager

In addition, the entire staff of the Architecture and Design Museum took part in the process, providing valuable input and comments on the competition entries.

City of Helsinki, Urban Environment Division

Anu Haahla, Senior Specialist, Strategic Urban Planning

Kati Immonen, Senior Specialist, Strategic Urban Planning

Mirva Koskinen, Team Manager

Anu Lamminpää, Leading Landscape Architect

Valtteri Lankiniemi, Senior Specialist, Strategic Urban Planning

Tuula Töyrylä, Project Manager, Strategic Urban Planning

Sakari Mentu, Architect

Taneli Nissinen, Leading Traffic Engineer

Alpo Tani, Senior Specialist

Haahtela

Tuuli Härkönen, M.Sc. (Tech.)

Lotta Kuisma, B.Sc. (Tech.)

Tiina Luhtanen, M.Sc. (Tech.)

Markus Mikkola, M.Sc. (Arch.)

Miska Särkkälä, M.Sc. (Tech.), M.Sc. (Econ.)

Maria Tepponen, M.Sc.(Tech.), B.Eng.

Sustera

Eveliina Kostiainen, Consultant

Sami Nevala, Team Lead

Specialists Participating Thematic Workshops

Thematic workshops were held between Stage 1 and Stage 2.

Peggy Bauer, Managing Director, Kaupunkitilat

Juha Hakola, Chief Superintendent / Head of the Department on International Affairs, Helsinki Police Department

Aava Harjola, Pedagogical Expert / Childhood and Education Division, City of Helsinki

Tiina Hörkkö, Area Manager / Youth, Culture and Leisure, City of Helsinki

Niina Kilpelä, Senior Architect / Sustainable Construction and Housing Department, Ministry of the Environment

Riitta Koukku, Teacher, Helsinki Vocational College (Stadin AO)

Leena Lassila, Director, Visitor and Talent Attraction, Helsinki Partners

Anniina Lavikainen, Development Manager, Kuuloliitto ry / Finnish Hearing Association

Melina Lukkarinen, Pedagogical Expert / Childhood and Education Division, City of Helsinki

Kari Lämsä, Head of Unit Partnerships, Facilities and Customer Services. Helsinki City Library Oodi

Eija-Liisa Markkula, Cultural Services for the Visually Impaired

Pirjetta Mulari, Chief of Children’s Culture, Director of Annantalo Arts Centre

Jaana Räsänen, Principal, Arkki School of Architecture for Children and Youth

Sari Salovaara, Senior Expert, Culture for All Tuttu Sillanpää, Head Art Teacher, Helsinki Upper Secondary School of Visual Arts

Santeri Sihvonen, Executive Manager, Finnish Skateboarding Association

Johanna Vuori-Karvia, Executive Manager, Autismiyhdistys PAUT ry

External Museum Specialists

The museum specialists participated in the specialist reviews during Stage 1 and in the discussions with the competition teams. These museum specialists were independent from the competition’s organisers.

Sevra Davis, Director / Architecture, Design, Fashion, British Council

Antto Melasniemi, Restaurateur

Arja Miller, Director, HAM / Helsinki Art Museum

Stuba Nikula, CEO, Events Helsinki

Tiina Ritvala, Associate Professor, Aalto University

Petri Ryöppy, Exhibition Manager, The Finnish Nature Centre Haltia

Jorma Saarikko, CEO, Pro AV Saarikko

Henrik Spangelo Svalheim, Director of Administration, Munch Museet

Other Contributing Specialists

These specialists contributed to the competition at various stages of the process. The secretary of the competition and all appointed experts were excluded from the decision-making process.

Tommi Laitio, Urban Strategist, Founder, Convivencia Urbana

Kieran Long, Museum Director, Amos Rex

Tomi Nikander, Project Manager, The National Museum of Finland

6

Participation and Co-Creation

Text Tommi Laitio

In the anonymous design competition for the new Museum of Architecture and Design in Helsinki we used co-creation on an unprecedented scale. We like to think our goal was to make the jury’s work more difficult by making all finalist designs as good as possible.

Finland lives and breathes design and architecture. The Finnish design tradition is a globally known brand, a source of national pride and one of the main reasons to travel to Finland. So when in 2022, the Government of Finland and the City of Helsinki, together with philanthropic partners, made the decision to establish the Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design with the intention of building a new world-class museum, the expectations could not be higher.

Combining architecture and design into one museum had been decades in the making. In the concept for the new museum, the ambition was nothing short of democratizing the tools of design and architecture, while raising awareness on how design can be used for creating more sustainable futures. The selected plot is part of Helsinki’s iconic skyline with the Presidential Palace, City Hall and the two cathedrals. The €150 million endowment for the museum would be made at a time when most museums, artists and arts institutions were facing austerity measures. Not to mention that this was not any museum but that of design and architecture.

Therefore, getting this right in terms of process and result was critical.

The discussions with the Finnish architect community made it clear that every architect in Finland and beyond would want to win the project. Simultaneously, we knew that both the Association of Architects and the public funders required that the project would follow the 150year Finnish tradition of anonymous, two-stage competition. In a two-stage competition, the jury chooses the finalists and the competition organization provides them with a development grant for their final submission. The

works would compete anonymously, meaning that the jury and the commissioning organization would learn the identities of the designers only after the winner had been chosen. Due to regulations, the competition would need to be EU-wide and a public procurement process.

There’s a lot of reasons to be proud of the competition tradition. Most notable Finnish architects have made their breakthroughs in anonymous competitions. An anonymous competition is what has resulted in many of Finland’s iconic buildings, like Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium (1933) and Helsinki’s Central Library Oodi (Ala Architects 2018). Ideally, an anonymous competition removes bias from the competition. The work speaks for itself regardless whether the architect is a seasoned professional or straight out of school.

Simultaneously we were doing something incredibly complicated. The museum building is part of a larger development of the harbour area, which requires immense amounts of coordination. The project’s public funding creates a moral obligation for public engagement and co-creation. Stakeholder engagement is needed to improve the design but also to build advocacy and legitimacy for the project. Also, the museum staff has tremendous and critical expertise, which would be foolish to ignore.

So we needed a competition process that would build on ambitions that first seem to be in direct contradiction: doing things together and doing things anonymously. We needed an innovative way to bring more views and expertise into the process, while securing a firewall between the competition jury and the design teams. Breaks in the firewall could result in lawsuits, delays, decrease in public trust or even an obligation to disquality and redo the entire competition.

Step 1. Supporting the Selection of Finalists

There is a strong precedent and an expectation that the competition needs an approval from the Finnish Association of Architects’s (SAFA) competition committee, which also appoints two members to the jury. After months of negotiation, we agreed on an enhanced version of the traditional two-stage competition.

We knew from recent anonymous and international competitions for Helsinki’s Central Library Oodi (544 entries) and Helsinki’s Guggenheim Museum (1715 entries) that it was likely that the first stage would attract a flood of entries. There was no intentional goal to achieve a record-high number of applications and intentional decisions were made to manage this. The entry was limited to 12 pages, focusing on the building’s concept, exterior and its connection to the cityscape. The competition was limited only to graduated architects.

The expectation of a flood was not misplaced. The competition attracted 624 entries. An online gallery of all the proposals opened to the public during Helsinki Design Week in September 2024.

The jury undertook the extensive labour of reviewing the entries with the first milestop being a semifinalist list: 20–30 works that best met the ambitious demands set in the competition brief.

It is common practice that as the jury moves from semifinalists to finalists, their deliberation is supported with expert reviews by urban planners, structural engineers, and economists.

We wanted to go further. Considering the ambitions set for the museum experience, we saw it as crucial that expertise on museum operations and urban culture would be elevated to the same level of importance as knowledge in financial planning, structural engineering or architecture. We recruited a group of internationally recognized urban culture and museum experts not affiliated with the competition organization. Their task was similar to that of engineers, architects and urban planners: to give detailed feedback based on their fields of expertise, such as exhibition design, museum logistics, city events, food and beverage, and customer experience. They commented on things such as how well the technical spaces functioned for moving large objects, the feasibility of audiovisual experiences inside and and on the museum, how the workshop spaces would function for children and how well the design demonstrated an understanding of the critical role of the library and resource center for research. As the independent facilitator for the entire engagement process, I then summarized this feedback into short briefs for the jury.

The jury announced the five finalists on December 18th, 2024. Upon agreeing to the terms of the second phase of the competition, such as adding various technical expertise to the design teams, each of the finalists received 50,000 euros to develop their final submission.

The five first pages of each of the finalist entries were published on the City of Helsinki’s engagement platform for review and commentary. The discussion online was lively, critical and demonstrated a high level of understanding of architecture. Many of the comments focused on criticizing individual entries or calling for “wow” architecture. Reading some of the comments raised questions whether the online platform might have also functioned as a channel for anger and frustration for those architects and other design professionals who had put hundreds and hundreds of hours into their submission only to receive a negative decision. Looking back, there could have been a clearer communication effort from the competition organization to explain that the winning museum would not be selected based on the current material but now the teams would have months to develop or even radically change their entry based on the feedback they received from the jury.

Normally the teams develop their proposal based on written feedback from the jury. Again, we wanted to go further. We decided to do something that had never been done at this scale in Finland: to provide expert consultation on the functionality and experience to all the finalist teams.

In January 2025, four expert groups reviewed the finalist designs and provided feedback on each of them. The identities of the designers were not disclosed to these experts.

The four groups of experts were selected based on the museum’s concept and they were:

• The museums’ staff

• Teachers and other educators

• Urban culture professionals such as police, skateboarders, youth work event organizers, and tourism experts

• Accessibility experts

All of the experts had the same assignment: review the works individually and participate in a four-hour workshop in Helsinki. In the workshop, each entry received the same amount of time for review. As the independent facilitator for the entire process, it was my responsibility to ensure that each entry was treated fairly and to capture the feedback and suggestions into a report. Next to these stakeholder workshops, we also gathered feedback from technical and structural experts.

We designed the process with great respect for the mastery and craft of architects. The goal was not to redesign the entries but to support the design intent and provide practical feedback on functionality and experience. Rather than ranking or comparing the entries, we started fresh with each entry. In our preparatory sessions, I described our ambition as making the jury’s work more difficult by supporting all of the five finalist designs to be as good as possible.

Unlike engineers or architects, most of the people we invited do not work with floor plans or circulation diagrams on a daily basis. During our planning phase, we regularly faced doubt and skepticism whether these professionals would be able to be objective. Looking back, I am glad we stood our ground.

While a teacher or a skateboarder does not work with CAD images, they do know a lot about needs and spaces. From our first preparatory sessions to the actual review workshops, we received regular affirmation that we have made the right decision. These professionals showed up prepared, in time and with a clear sense of respect and integrity. One of the early educators verbalized something we witnessed in all the workshops: the power of recognition. She said:”I feel really honoured that we and our kids are recognized as important like this. That our experience is brought in at this stage and not only when we need to fix something that really does not work.”

Even when I have done most of my career in public spaces, I learned so much from these professionals.We discussed issues like the need for calming spaces for visitors on the spectrum or for a toddler having a hissy fit. An educator explained how easy access to restrooms from children’s workshop spaces defines the adult-to-child ratio in the group and therefore the cost of the visit. We learned how the museum’s library goes far beyond books

to drawings and models and how designers or researchers often spend days or weeks working on a particular material. We talked about how in this museum an exhibition can consist of valuable items in vitrines but it can also be a noisy and messy process or a big machine. We discussed how the museum’s business model depends on event spaces that provide spectacular city views and can be used outside the opening hours. Something that really stuck with me was an educator who explained how a view, a wall, an elevator or a door, actually the entire museum building, is a pedagogical object beyond the exhibitions. Another note that will stay with me forever was the emphasis of an accessibility advocate on how important it is that people with special needs can move through the museum with their company rather than being sent around the corner for an elevator.

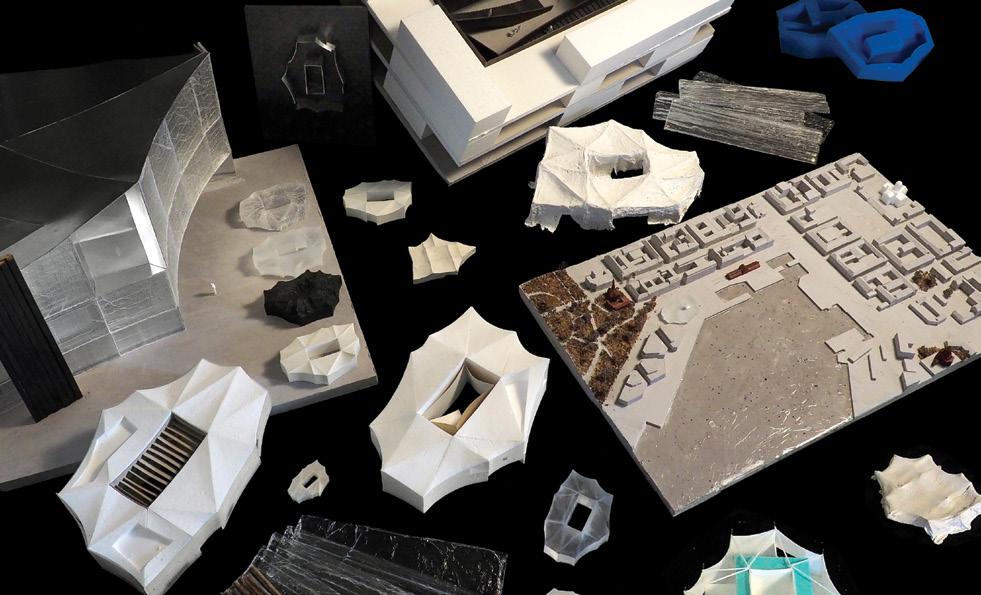

As a result of this engagement, we as the competition organization and I as the facilitator, improved our capacity for inclusive engagement. We learned how to use Braille printers for floor plans, how tiny 3D-prints helped blind experts but were actually beneficial for everyone.

After the workshops, we packaged the feedback with Project Manager Reetta Turtiainen and Competition Secretary Jussi Vuori. This feedback was integrated into reports with the standard technical feedback, structural feedback, and financial analysis. Each team received an extensive package of general feedback as well as detailed feedback on their submission. The level and amount of detailed feedback was way beyond a standard competition.

As the second round of consultation, each team was given an opportunity to see the building site in Helsinki and receive three hours of in-person consultation from recognized experts in themes like museum pedagogy, exhibition design, food and beverage, public-private partnerships, museum operations, curation, audiovisual design and events. While a substantial financial investment, we saw this as a way to increase the quality of final submissions and an equity investment in an international competition. We designed the process with the assumption that at least some of the teams would be from abroad and many of them might not have had the time, money or means to come to Helsinki in the first stage of the competition.

Each workshop followed an identical format:

• Presentation of the entry and first reflections on the jury’s feedback (20 min)

• Expert conversation on the strengths and challenges of the entry with no interjection from the design team (30 min)

• Break (15 min)

• Dialogue between the design team and the experts, focused on the issues the design team wished to discuss (90 min)

• Visit to the museum site

When designing this process, we took the questions of anonymity and confidentiality very seriously. All of the experts received training on the importance of confidentiality and signed non-disclosure agreements and received training on the importance of confidentiality. We made it clear in the adcance communication and in the beginning of the workshop that the experts were familiar with the competition program but were not representatives of the jury and would have no say in choosing the winner. The design teams received a stipend for travel but arranged their own travel and accommodation. The jury was not informed of the place and time of the workshops. The experts, myself included, only learned the identities of the designers as we shook hands on the morning of the workshop to prevent curious googling or other information gathering. As the facilitator, I emphasized that the teams

has responsibility to make sure that they used the experts in a way that benefited their process and that they had full discretion on how and how much of the feedback they would eventually incorporate into their design. As a way to promote anonymity, we did not do written documentation of the workshops and nothing of the discussion was reported to the jury.

We were doing many things differently and faced concerns and critique along the way. Therefore, we wanted to learn from the process. The anonymous feedback gathered after the workshops demonstrated that we are on the right track. On a scale of one to five, the workshop experience received an 4,7/5 average and a 5/5 median score. The usefulness of the workshops for them now and for future competitions received an 4,6/5 average and a 5/5 median score. A clear majority of the architects would recommend using such a format in future competitions.

The most rewarding feedback was the acknowledgement of valuable expertise beyond tradition. One of the lead architects wrote that they felt that the experts were able to make valuable contributions without disrupting the project. The architect felt that the experts were trying to go along with the concept behind the project as much as possible. Another architect said that the reactions from the experts were valuable and strengthened their own presumptions and that they received valuable

ideas and inspiration for further development. Several of the designers appreciated the level of preparation that the experts had done to understand their specific design.

The feedback also demonstrates that many of the finalists, like us, see great value in the tradition of an anonymous competition. While the usefulness of the engagement was ranked high, some did raise concerns about ensuring the anonymity of the process. As one of the designers said, “If anonymity can be secured, then this is quite an efficient system.”

We take this concern seriously and took conscious choices to secure anonymity. Simultaneously, it is worth noting that already in the traditional competitions we have had urban planners, structural engineers, and financial analysts reviewing the designs or even meet with the teams in the final stages of the competition. Broadening the circle of expertise beyond finances, design and engineering demonstrates respect and builds legitimacy. Broadening the circle of valuable expertise sends an important

message to disability advocates, curators, skateboarders, restaurateurs, the police, researchers, teachers, and arts educators that we need them and their expertise to create thriving public spacesis critical in creating a great museum. Our experience confirms our assumption that a teacher, an conference planner or a disability advocate can provide the same level of integrity, confidentiality, expertise and unbiased review as an engineer.

I spent a decade as an executive for the City of Helsinki, in charge of large capital investment decisions for instance for libraries, museums, recreation centers and libraries. Looking back, I would have loved this as a standard for procurement.

What proved to be critical was how the role of the experts was framed. They approached the designs with respect and saw their contributions as consultation rather than critique or ranking.Those who met the teams had an arm’s length distance to the commissioning organization.

As a sign of success, most of the experts could see the opportunities in all of the finalists.

The benefits are clear for the commissioning organization. This kind of engagement can help the design teams avoid mistakes that would work against an otherwise stellar concept. As a simple example, If you do not work with museums or children every day, you probably won’t think about where to put 50 rucksacks when a group of enthusiastic and maybe soaked kindergarteners enter a museum but not solving that might destroy your lobby experience completely.

The competition was a public procurement process. Procurement is a field in urgent need of innovation. Our experiment shows that we can find a balance between anonymity and engagement with careful design. Engagement practices can save us from a lot of frustration and conflict later in the process. Fixing something like the location of the service lift or the access to the toilets from workshop spaces is a lot cheaper and easier at this stage of the competition.

The competition teams have until the 6th of June to submit their final submissions. On June 17, the developed entries will be published for public comments in Voice Your Opinion platform hosted by the city of Helsinki. The winner will be announced in September 2025.

The announcement of the winner kicks off a new stage in co-creation and engagement. As a major investment for the city and the country, the engagement will be essential for the legitimacy of the project. It will pose a test to the winning architects to navigate the often contradictory hopes and dreams of thousands of stakeholders and the public, the budget and structural limitations of the project

while holding onto their original architectural concept. The current practices of an anonymous architectural competition do not take the designers´ capability and willingness for collaboration and co-creation into account.

I hope that such stakeholder engagement and co-design will become the norm in a few years in the development for major buildings. The engagement in Helsinki´s Central Library Oodi is earlier proof that a deep understanding of needs and collaboration can create conditions for worldclass results. When done well, engagement improves the likelihood of innovation and legitimacy. And what organisation would be better in charting new standards for design than a Museum of Architecture and Design?

Key stakeholders and user groups played a central role in shaping the overall vision and concept for the new museum. Participatory engagement and co-creation are not only integral to the new museum’s envisaged programming and operations, but were also meaningfully incorporated into the design competition itself. Given the anonymous nature of the public procurement process, a tailored approach was developed to enable dialogue between user groups and the competing design teams.

In September 2024, key visuals from all 624 entries evaluated in Stage 1 of the competition were published in an online gallery, launched as part of Helsinki Design Week. To accompany the launch, the Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design organised an event where the museum’s international advisory group presented and discussed the future of museums and broader creative industries. The online gallery was open from 12 September to 29 November 2024.

The jury undertook the substantial task of reviewing all the entries, with the first major milestone being the selection of the 22 semifinalists—those entries that responded most successfully to the ambitious competition brief. At this stage, it is standard practice for jury deliberations to be supported by expert reviews from professionals such as urban planners, structural engineers, and economists. Considering the brief’s high aspirations for the museum experience, it was also crucial to elevate expertise in museum operations and urban culture to the same level of importance as knowledge in financial planning, structural engineering or architecture.

To support a small team from the Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki organisation, a group of internationally recognised experts in urban culture and museum practices—independent from the competition’s organisers—was invited to join the review process. Their role—mirroring that of engineers, architects and urban

planners—was to give detailed feedback rooted in their fields of expertise, which included exhibition design, museum logistics, city events, food and beverage services, and customer experience. This feedback was summarised as concise briefs to inform the jury’s decision-making.

On 18 December 2024, when the jury announced the entries selected for Stage 2 of the competition, the five finalist entries were published on the Kerro kantasi (Voice Your Opinion) platform hosted by the City of Helsinki. From 18 December to 31 January 2025, the public was invited to discuss and comment on the five entries. In total, 1,412 comments were submitted. The public comments on each entry were compiled and shared with the competition teams as part of the Stage 2 materials, to support further development of their proposals.

Alongside this public feedback process, a series of expert workshops was arranged to gather input for the further refinement of instructions and guidelines provided to the competition teams. In January 2025, four expert groups reviewed the finalist designs and provided feedback on each of them. The identities of the designers were not disclosed to these experts. The four groups of experts were selected based on the museum’s conceptual vision, and included the following:

• Museum staff

• Teachers and other educators

• Urban culture professionals, such as police officers, skateboarders, youth workers, event organisers, and tourism experts

• Accessibility experts

All the experts followed the same protocol: first, they reviewed the proposals individually, then participated in a four-hour workshop in Helsinki. In the workshop, each entry was allotted equal time for discussion. The workshops were facilitated by independent urban strategist Tommi Laitio, who ensured that each entry received fair and equal treatment and that all feedback and suggestions were documented in a report. Alongside these stakeholder workshops, feedback was also gathered from technical and structural experts.

The process was designed carefully. The goal was not to redesign the entries but to support the original design intent and provide practical feedback focusing on functionality and user experience.

After the workshops, the feedback was compiled into reports, including standard technical evaluations, structural reviews, and financial analysis. Each finalist team received an extensive package containing both general guidance and detailed, proposal-specific recommendations.

Based on the detailed recommendations and guidelines they received, the finalist teams were expected to refine their overall design direction to better align with the needs of future museum users. In Stage 2, the teams were specifically asked to reflect on how the received expert feedback would inform the evolution of their design proposals. To support this refinement process, each team was invited to visit the museum site in Helsinki. They also received three hours of in-person consultation with recognised experts in fields including museum pedagogy, exhibition design, food and beverage services, public-private partnerships, museum operations, curation, audiovisual design and event planning. This process aimed to both raise the quality of the final submissions and serve as an equity investment in an international competition, recognising that at least some of the teams would be from abroad and may not have had the time or resources to visit Helsinki during Stage 1.

Each workshop followed an identical format:

• Presentation of the entry and initial reflections on the jury’s feedback (20 minutes)

• Expert discussion on the strengths and challenges of the entry, without input from the design team (30 minutes)

• Break (15 minutes)

• Dialogue between the design team and the experts, focused on issues the design team wished to explore (90 minutes)

• Visit to the museum site

Anonymity and confidentiality were carefully safeguarded throughout this process. All of the contributing experts received training on the importance of confidentiality and signed non-disclosure agreements. It was clearly communicated—both in advance and at the start of the workshops—that the experts were familiar with the competition brief but were not part of the jury and played no role in the selection process. The jury was not informed of the place and time of the workshops. The experts and the facilitator learned the identities of the designers only on the morning of the workshop. The facilitator emphasised that it was each team’s responsibility to make the most of the expert input in a way that supported their own design process. They had full discretion over how, and to what extent, they would eventually incorporate the feedback into their design. To preserve anonymity, there was no formal documentation of the workshops, and no reports were shared with the jury.

Following the final submission of the refined entries, materials from the five finalist teams were published on 17 June 2025. As during Stage 1, the proposals were published on the Kerrokantasi (Voice Your Opinion) platform, inviting the public to discuss and comment on the entries. The public engagement process ran until 31 July 2025, during which a total of 1,032 comments were received. A summary of the public feedback was presented to the jury to support their evaluation and selection of the winner.

The design competition was presented at Architecture and Design Museum from 2021–2024. In the exhibition room, museum visitors had a chance to leave ideas, comments and feedback for the new museum of architecture and design.

Competition Brief

The competition brief was published on 15 April 2024 at the design competition website1. The competition materials consisted of the brief itself and 15 appendices. In addition to outlining the competition format and technical requirements, the brief described the goals and the envisioned functions of the new museum, as well as the background and context of the overall museum project. The following chapters summarise key information about the new Museum of Architecture and Design, including details about the proposed building, the competition site, design guidelines and the space groups and functions.

1 www.admuseo.fi/competition

The vision for the new museum for architecture and design is to create an inspiring destination that is easily accessible to everyone—a human-scale museum that welcomes both Helsinki residents and visitors of all ages. It will offer something for everyone—a place of calm, rest and reflection for some; a hub of social activity, fun, and creativity for others; and also a platform for deep engagement with urgent societal issues.

In spring 2021, the Finnish Government and the City of Helsinki launched a joint initiative—developed in collaboration with the Design Museum and the Museum of Finnish Architecture—to merge these two institutions into a new national museum of architecture and design. This initiative was built on a feasibility study published in 2018, and a concept study released in 2019, commissioned by the State of Finland and the City of Helsinki. Both studies confirmed the relevance of establishing a museum that reflects Finland’s global significance in architecture and design. The 2019 concept study specifically recommended organising an international architectural competition to find the team capable of bringing this vision to life.

In April 2022, the State of Finland and the City of Helsinki established the Foundation for the Finnish Museum of Architecture and Design—an institution dedicated to realising the vision for a new, national museum. In August 2022, the ADM Real Estate Company was formed to lead the museum’s construction project, including the organisation of an international design competition for the new museum building.

The operational organisation for the new museum was formed in January 2024 through the merger of the Museum of Finnish Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki. Both institutions previously held national responsibility for preserving, researching and showcasing Finnish architecture and design—work that the new museum for architecture and design will proudly continue. The new museum building is set to open in 2030.

The new museum for architecture and design brings together the globally and nationally significant collections of its two predecessor institutions. The collections span a wide selection of items from early crafts, Art Nouveau and the golden age of Finnish modernism to contemporary design innovations. Altogether, the collections represent the work of approximately 5,500 designers and design groups. As the museum collections are stored in a dedicated facility outside Helsinki, the new museum building will include only limited space for collection management.

The new museum for architecture and design is dedicated to offering a broad, inclusive programme of exhibitions, events, and experiences that celebrate the stories of creators and communities from diverse backgrounds. A key objective of the museum is to support the transition to a more sustainable future. In addition to hosting a varied programme of exhibitions, the museum will include spaces for various public events, hand-on learning, a library, a museum shop, and restaurant and café services. All of the museum’s programming and services will be designed with diverse user groups in mind. Design and architecture will be explored through experimentation, observation and dialogue. For professionals and students, the museum will provide a meeting place for critical discussion and skill-building, fostering a more inclusive, equitable and sustainable professional space. For lovers of Nordic architecture and design, the museum’s collections offer rich opportunities for endless exploration. Overall, the museum will serve as a dynamic meeting point for art, research and design, offering multisensory experiences that engage visitors on many levels.

The museum’s services and programmes will be delivered not only in the new museum building, but also across Finland, internationally, and via digital platforms. Its financing is built on several pillars: income from the museum foundation’s endowment, government grants, admission fees, and revenues from food, beverage and retail services. As detailed in the Architecture and Design Museum Helsinki's business plan, all supporting services—including food and beverage—are considered integral to the museum’s concept and profile, and are operated by the museum itself. Unusually for its Nordic context, the museum’s financial model includes a high degree of self-financing, projected at 58%.

The collections span a wide selection of items from early crafts, Art Nouveau and the golden age of Finnish modernism to contemporary design innovations.

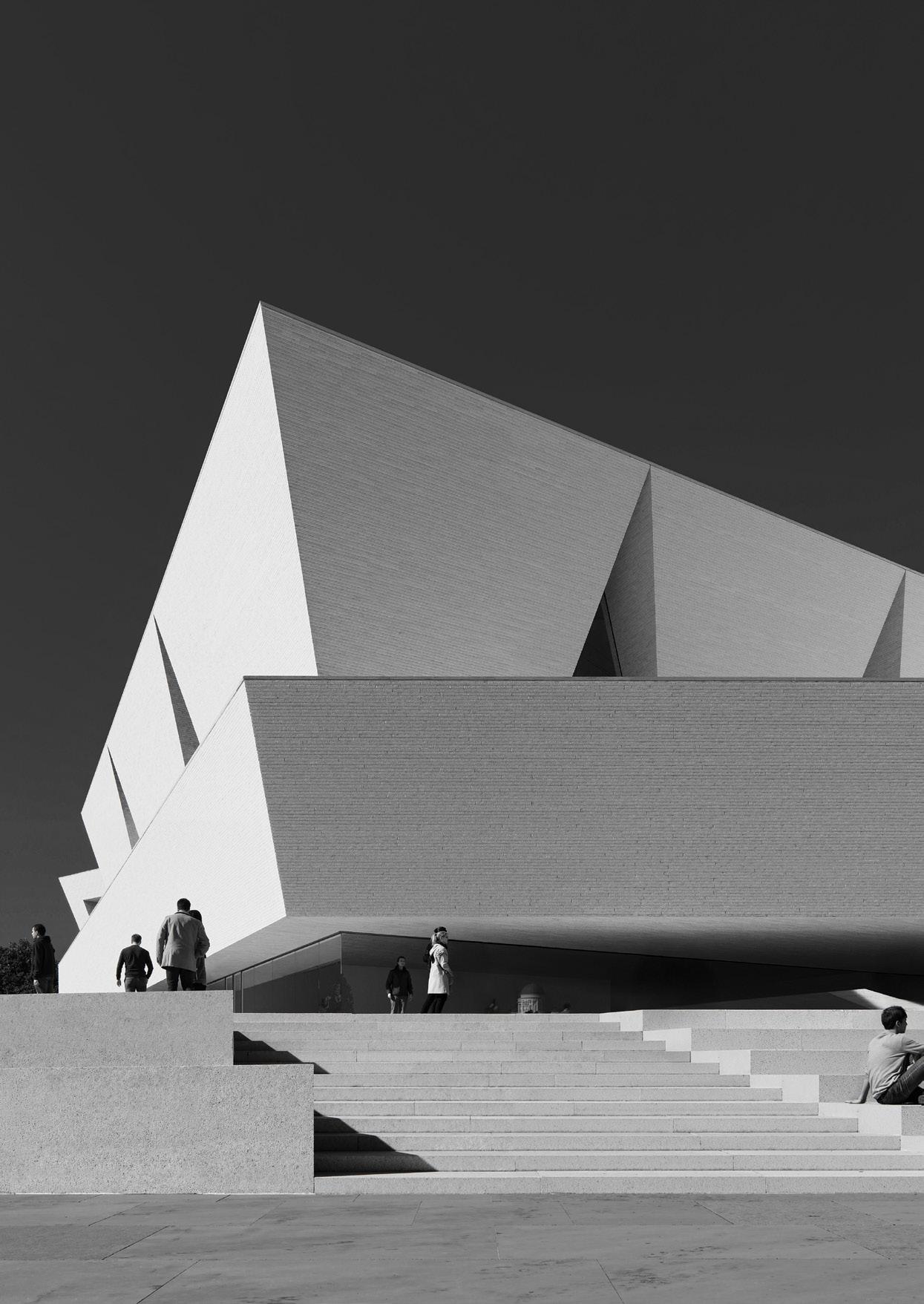

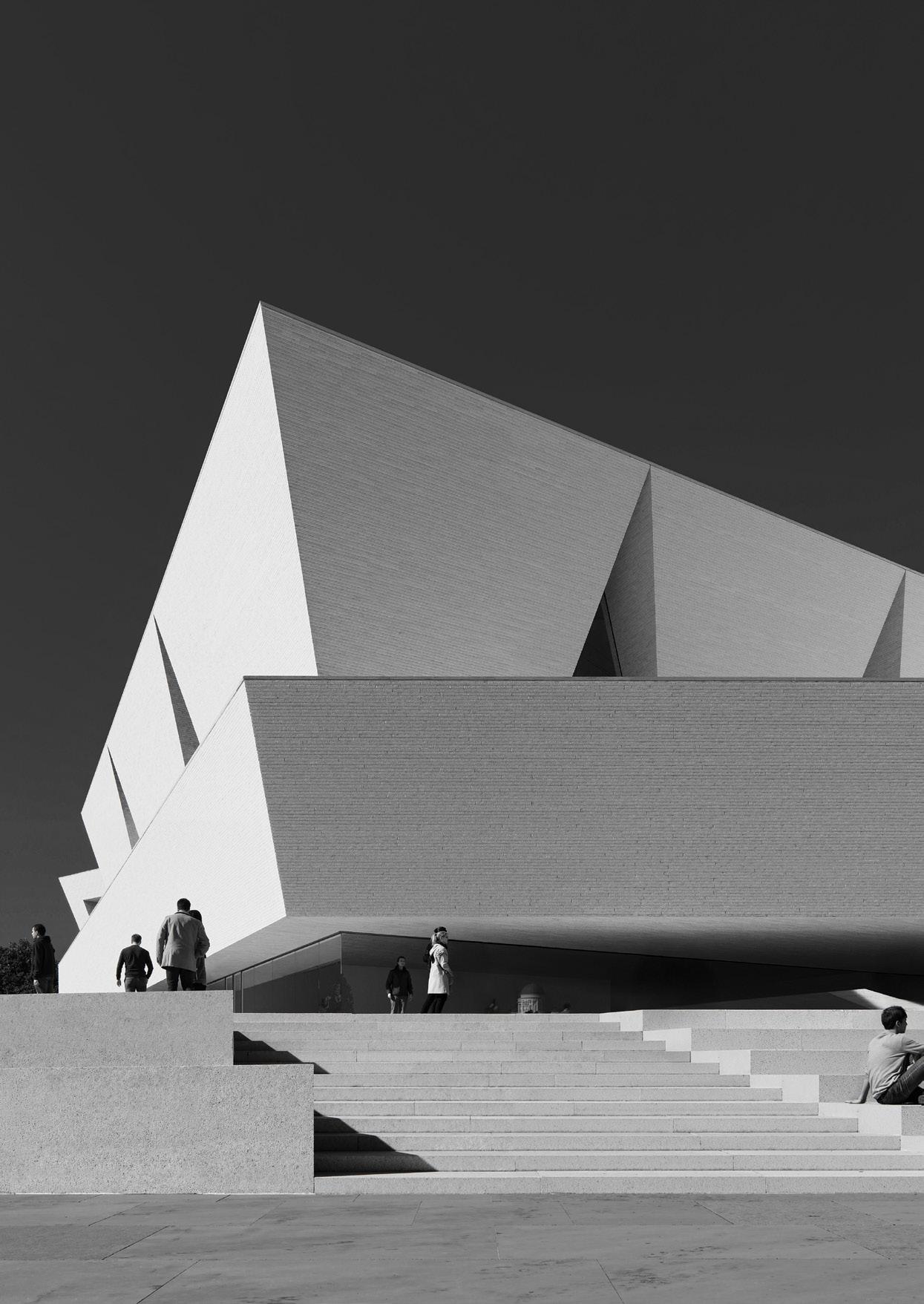

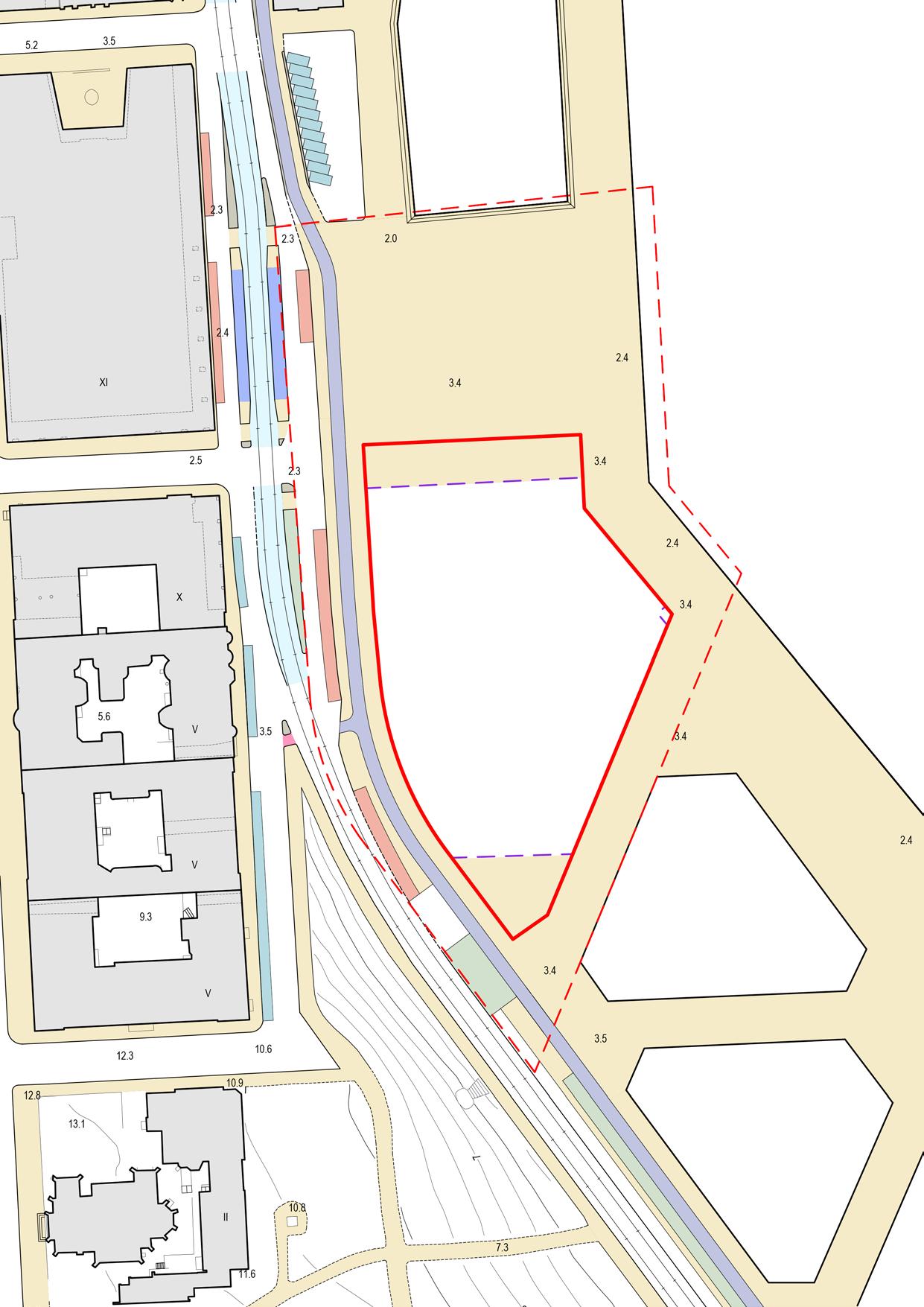

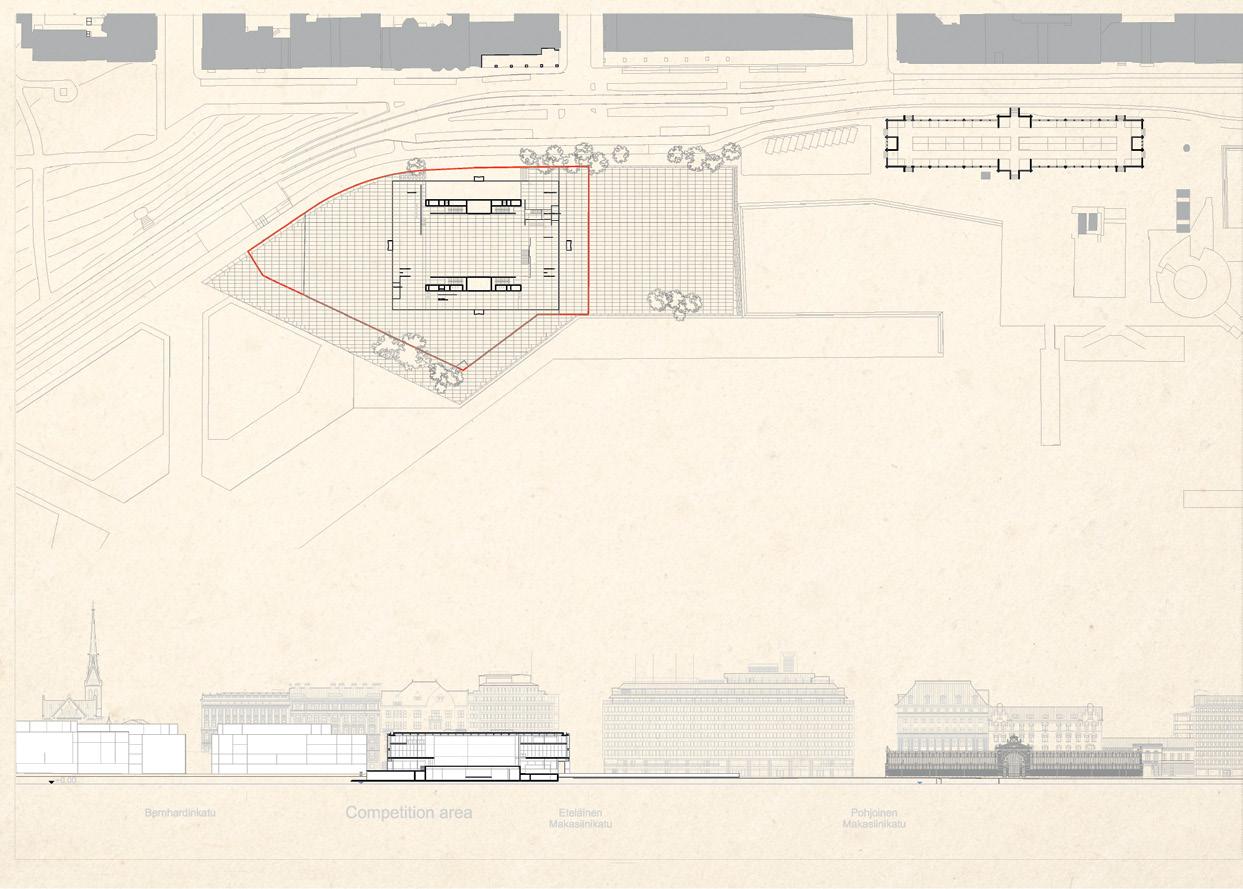

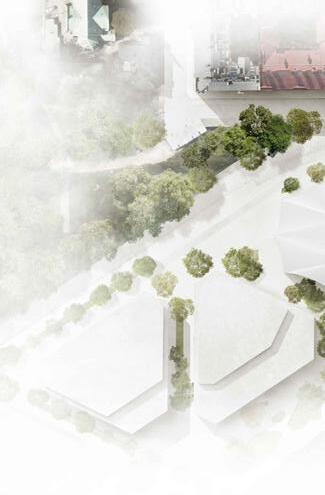

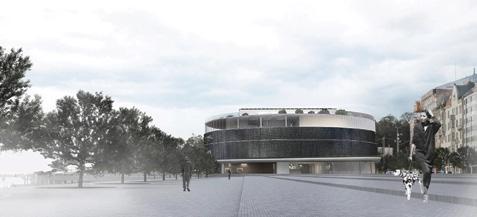

The building site for the new museum is in the developing Makasiiniranta district, in Helsinki's South Harbour. The museum building will be located on the waterfront of Helsinki’s historic city centre, an area of national cultural and historical value. The museum site and the Makasiiniranta district are part of a buffer zone of the World Heritage property of the Suomenlinna Sea Fortress.

As part of Helsinki's South Harbour area, the building location is part of the city’s national landscape and a nationally significant, culturally valuable environment. The location is central, carries symbolic value and is part of the maritime waterfront of Helsinki’s historical centre. The competition site contains many important characteristics of the culturally historical environment, as well as iconic city views that need to be embraced by competition entries.

Today, the area is used primarily for the Port’s terminal operations and parking, but the building location and

its surrounding area will drastically change, as the current harbour area will be transformed into a vibrant area as part of the city centre. The area will be a part of the pedestrian centre and will be developed as an area of high-quality public outdoor spaces, urban seaside squares with multiple functions. The area will be a part of the seaside trail around the southern shores of Helsinki, the conditions of which will be improved.

To find partners for the development and implementation of the whole Makasiiniranta, the City of Helsinki organised the two-stage international quality and concept competition in 2021–2022. The competition’s winning entry Saaret functions as a starting point for the detailed planning and the new museum building will become part of the overall plan. Saaret includes an events square located on the north side of the museum, where larger events and the museum's exhibition activities can be held. On the south side of the museum, four new urban blocks are indicated, containing offices and hotels with a variety of business and service spaces on their ground floors. These support the urban character and appeal of the shoreline route and pedestrian area. Service, working and cultural spaces are planned to be located in the Olympia terminal and port house, which are protected buildings built for the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games. Further planning of the winning entry Saaret is currently under way.

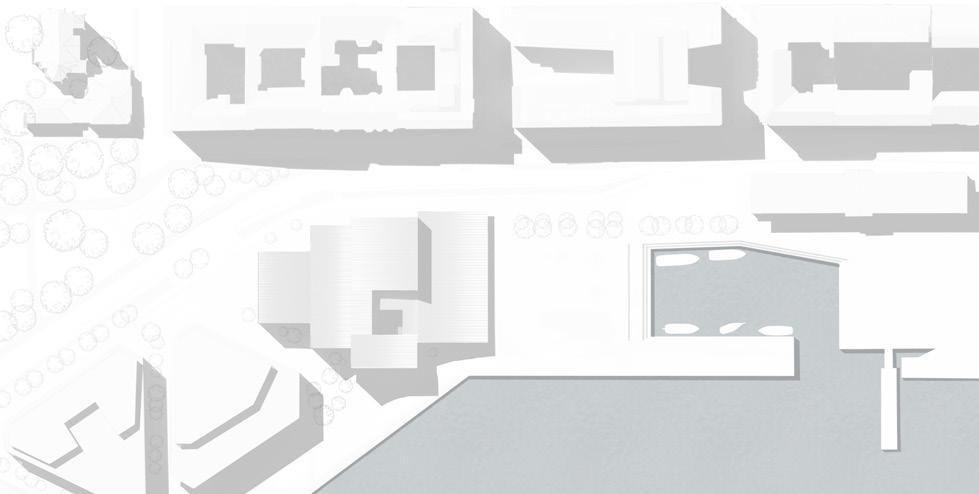

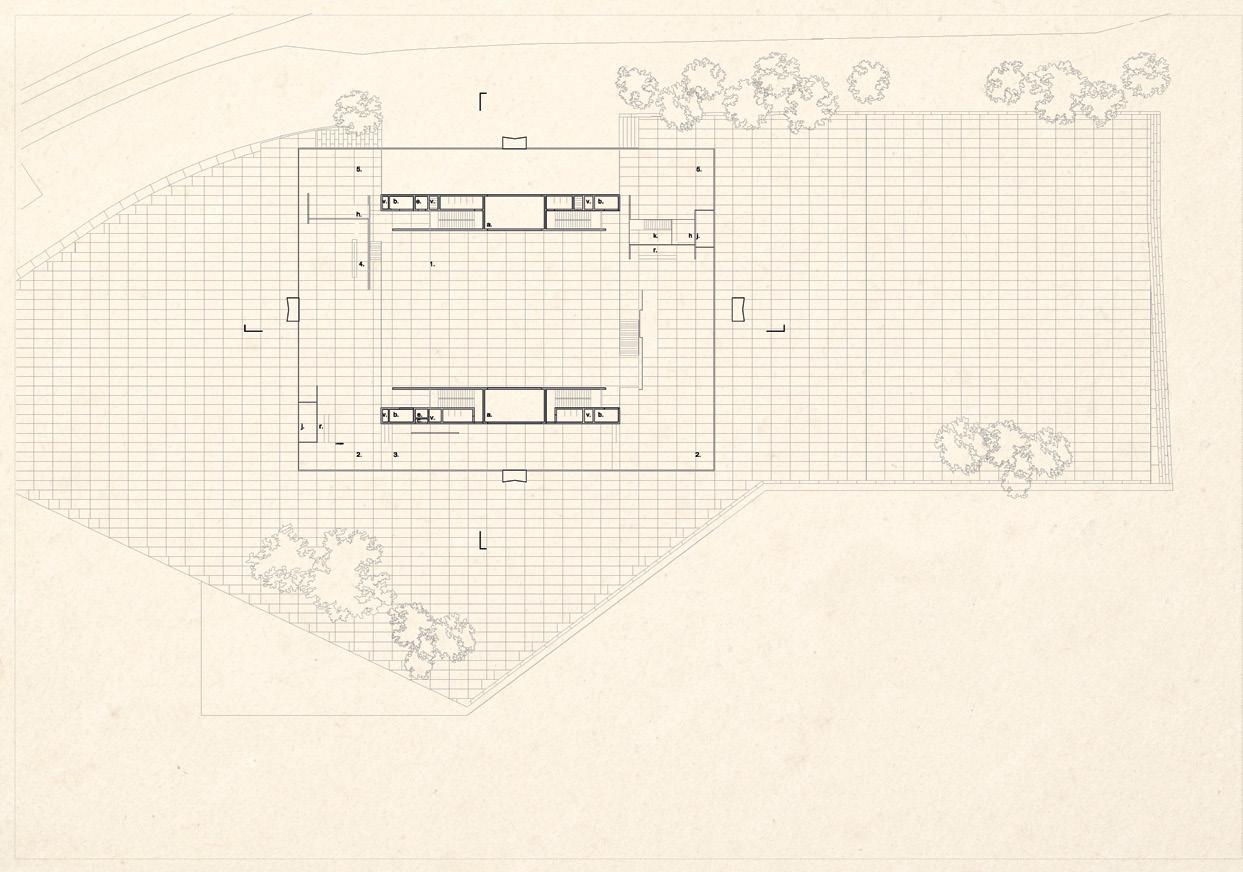

The site of the museum building is in the current harbour area east of Laivasillankatu and south of the envisioned extension of Eteläinen Makasiinikatu. It will change city views of the South Harbour area, Helsinki's Old Market Hall and the park area on Tähtitorninvuori hill. The competition area is around 5,300 m2. The 5,300 m2 comprises the area required by the museum building and associated fixed structures such as entrance awnings, staircases and other similar structures. Indicative building area is around 4,500 m2. Pick-up and drop-off traffic, as well as traffic areas for pedestrians and bicycles, are not part of the planned site for the museum building.

Makasiinikatu

Eteläinen Makasiinikatu

Creating a centrally-located new museum of architecture and design in Helsinki calls for a building of high architectural quality. The museum’s architectural identity should be innovative and surprising, while also respecting and integrating with the cityscape.

While the project’s construction goals are ambitious, the building project has a set budget, and thus its design must be realised in balance with economic considerations and other equally relevant project priorities. While user experience and programmatic needs are central to this project, practical construction strategies, sensible spaces, and an arresting, but contextual form for the building’s city-facing appearance are equally important considerations. With an overwhelming concern for the environment, the construction process and building materials should be sustainable, mitigating harmful effects and promoting the longevity of the structure.

Of paramount importance is the creation of a welcoming building with cutting-edge spaces that allow for novel presentation of collections, temporary installations and exhibitions, as well as surprising and meaningful events, experiences and encounters that encourage visits and re-visits to the museum.

The competition brief presented architectural design guidelines divided in four categories as well as the objectives for the climate-resilient building.

It is a core ambition for the new museum for architecture and design to be a place, inside and out, that is welcoming, open and universally and equally accessible. The museum spaces will feel warm, social and functional and help lower the threshold for potential visitors to the museum.

From out-of-town visitors wanting to experience Finnish design to students, families and professionals looking for an inspiring place to meet, work and study, the museum should invite people from all walks of life to gather, socialise, relax and explore. The new museum will be a central piece of the new urban fabric forming on Helsinki’s central waterfront. Its architecture should invite people in and facilitate the institution’s social impact. The building design should be attractive when approached from every direction and closed facades should be kept to a minimum. In short, the building should aspire to be an outstanding neighbourthat contributes to the area’s urban and social qualities.

1. The building and its spaces create an inclusive and welcoming atmosphere for all kinds of museum users, allowing for new encounters between the institution and its different visitor groups.

2. Spatial sanctuaries inside and outside the museum encourage museum users to linger, reflect, sit, lie down and recharge the mind and body.

3. By integrating natural elements throughout the museum grounds and building, the spaces become tranquil oases in the urban environment.

4. The design of the building embraces holistic accessibility where the museum’s users, regardless of their culture, socioeconomic status, gender, age, size, ability, or disability have the possibility to experience the building to its fullest potential.

The new museum building will have a strong identity in its architecture, programmes and public spaces. This will be centred on our vision and concept that reframes what a design museum can offer to society. The building has the potential to become a symbol of the city, distinctive in the image of Helsinki both from land and water. Its architectural elements should help frame views in new ways, revealing fresh angles and perspectives to visitors of the surrounding urban context and the museum’s content.

1. The building seamlessly integrates with the cityscape and urban waterfront in terms of scale, massing and orientation, and respects the cultural, historic and environmental values of the national landscape of maritime Helsinki and the buffer zone of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

2. The building design, including its immediate outdoor and public areas, makes connections with the city and the Baltic Sea.

3. Starting before entering the museum and continuing inside, the building creates a unique spatial experience that is itself an expression of the possibilities of architecture as an artistic field and as a generator of public life.

4. Spaces throughout the building are not neutral but use architectural means to create moments of drama as well as calmness and reflection. The design of the building is elegant but avoids exaggeration.

The new museum will be a place for making, learning new skills and sharing experiences. It will invite both professionals and the public alike to engage with each other, explore the tools of architecture and design and imagine new futures together. The building design should allow visitors to move from seeing to doing. Our vision is not for traditional museum spaces where reverence and contemplation are primary. The spaces should have the atmosphere of a shared workshop, less pristine than traditional museum spaces and adaptable for many different kinds of activity. Throughout the building, visitors should be invited to participate and create. The building design should generate ideas for programmes and activities that push the boundaries of what can be experienced in a museum of architecture and design.

1. The museum building invites its users to boost their creative confidence by encouraging them to make, test, touch and embrace the chaos and creativity of the imaginative process.

2. Spaces mix programmes and juxtapose activities, triggering curiosity and unexpected resonances.

3. The building offers everyday spaces where past and future converge – where children, teenagers and adults alike can dream, build and express their imaginations.

4. The building provokes new ideas by blurring boundaries between processes, revealing behindthe-scenes activities and creating interfaces between professionals, the museum staff and the general public.

We imagine a building that enables us to mix different museum activities, from the practical to the visual, the small to the large, from workshops and talks to performances, vernissages and the opening galas of major city festivals. These things will occur around artistic installations and museum collection objects.

We imagine a series of spaces that are free to enter without a ticket, which can accommodate a variety of potential programmes on various scales. This zone might include entrance lobbies, outdoor spaces, event and conference spaces, project and workshop spaces, a library and resource centre, the shop and the cafe/restaurant. Emphasis should be placed on reconfigurable spaces that can generate a vibrant atmosphere, perhaps augmented with temporary or mobile infrastructure (for data, power, light, audio etc.) that can be repositioned within and beyond the museum’s walls.

Finally, the museum is being created for the long term, and future museum practices in the fields of architecture and design are unpredictable. We want the museum future-proofed and flexible enough to adapt to future demands of the museum, its public and the artists we work with.

1. Using outdoor and indoor spaces will enable a mix of programmes and events on varying scales, from exhibitions and events to festivals and performance, generating a vibrant atmosphere and motivating repeat visits.

2. Versatility and adaptability for unpredictable futures is key. Adaptable infrastructure should allow for spaces to be reconfigured in the future.

3. Public areas of the museum should be optimised for hybrid programming that brings together different audience groups at different times of the day and year. A vibrant public area that can be visited without a ticket should be in constant transformation, providing a new experience for returning visitors.

When designing the museum building, the building is seen as part of a larger ecosystem and urban context. Design choices should be studied from the perspective of environmental impact, and solutions that enhance the positive carbon handprint of the building should be looked for. By acting wisely, the functional quality and usability of the building can be increased while simultaneously reducing costs and the carbon footprint within reasonable limits. It is recommended that building design would utilise strategies of regenerative design.

Based on the previous studies, a decision has been made to construct a new museum building in order to better serve the museum’s and its users’ needs, as well as enlivening the city centre in Helsinki. Thus, the museum bears a significant burden of responsibility to not only deliver the project avoiding unnecessary harm, but to also produce added environmental value and mitigate the climate crisis.

During the initial planning of the project, the aim was to find solutions to reduce the carbon footprint of the building. As examples, optimising the needed space for different functionalities and planning the service and maintenance traffic to be above ground level, the carbon

footprint of the project has been reduced by almost half.

However, these decisions are not sufficient in isolation. The general focus should be on achieving energy efficiency and hitting environmental targets while minimising the carbon footprint in an economical manner.

A primary concern is that the design should seek solutions that are not only environmentally friendly, but also durable and financially sustainable over the building's lifetime. The goal is that the building meets the requirements of the EU taxonomy with the focus on climate mitigation, as well as attaining the Building Information Foundation RTS environmental assessment method level 4/5. The level corresponds roughly to LEED Platinum and BREEAM Excellent. The building's carbon footprint without foundation works must be below the level of an energy-efficient and high-quality reference building built to a high standard, which is a maximum of 15.4 kgCO2e/m², as assessed according to the practice of the city of Helsinki. The E-value of the building is a maximum of 84 kWh/m² (regulatory level 135 kWh/m²). As the planning progresses, the targets will be always reconsidered in relation to tightening regulations and laws and opportunities that arise from accumulated knowledge and technological development.

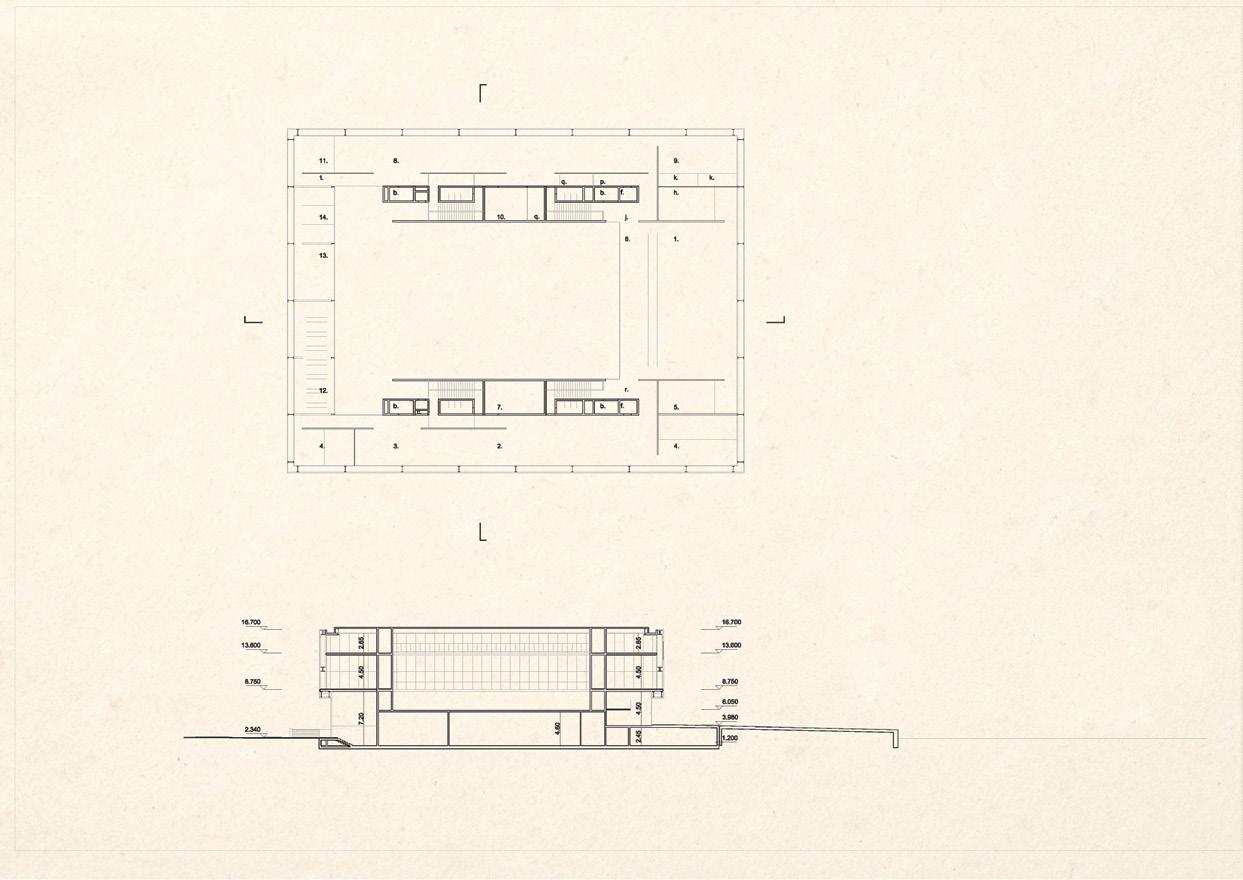

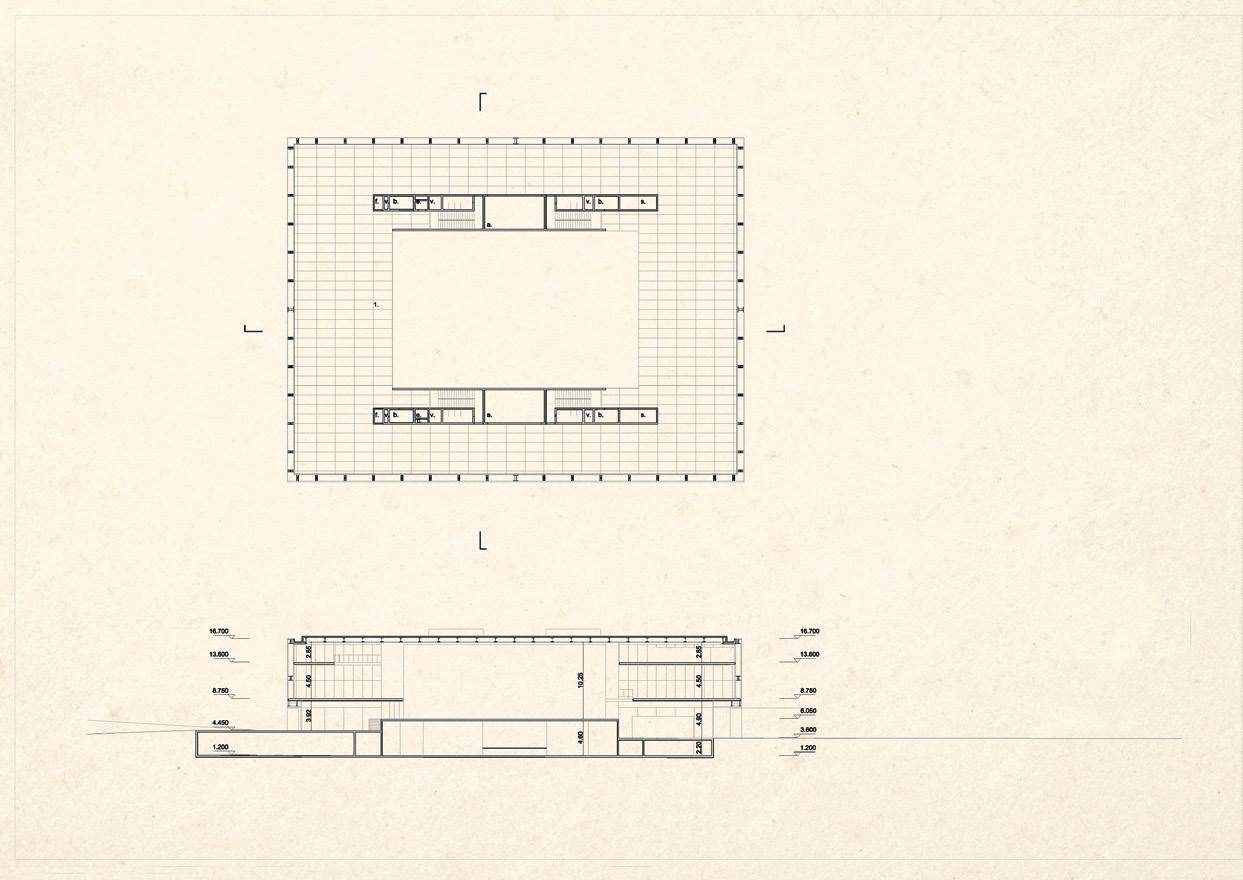

In Stage 1, the spatial programme provided to participants was presented at a higher level, including detailed explanations of the different spatial requirements. For Stage 2, the teams received a more detailed spatial programme.

The total net floor area (NFA) of the museum is 6,600 m2 and the estimated gross floor area (GFA) of the building is approximately 10,050 m2. Approximately half of this area consists of public areas for museum visitors. The museum is expected to welcome around half a million visitors annually, of which 380,000 will purchase a museum ticket. Public

The net floor area is the theoretical floor area of rooms and spaces needed for different functions. The area of corridors, stairwells, technical spaces, flues or structures is not included in the net floor area. ² Gross floor area (GFA) m² The total floor area contained within the building measured to the external face of the external walls.

Galleries (approx. 2,250 m²)

Entrance Spaces and Lobbies

~750 m²

Event and Conference Spaces ~560 m²

Project and Workshop Spaces ~230 m²

Library and Resource Center ~200 m²

Shop Facilities ~200 m²

Café and Restaurant ~250 m²

Additional Function – Space Proposed by the Competition Participant ~100 m²

Offices and Employee Facilities (approx. 400 m²)

Museum Logistics Spaces ~650 m²

Technical Workshops ~410 m²

Main Kitchen ~200 m²

Event and Retail Support Areas, Storage, and Lockers ~400 m²

Facility Services ~255 m²

Compartmented Circulation Spaces ~410 m²

Spaces for Technical Installations ~970 m²

Spaces for ventilation, heat and water, electricity and IT, as well as technical closets. PUBLIC AREAS 4,540 m² (all areas presented as

Flexible and adaptable gallery spaces that can be divided into a maximum of five different galleries. While distinct, the exhibition spaces should still form a naturally flowing whole, but do not have to be located on the same floor level.

Supports visitor orientation and basic needs of the visit (information, restrooms, cloakrooms etc.). Based on the visitor target, the museum will be visited by approximately 1,400 visitors per day on average, increasing to 3,000–4,000 on busy days. Peak hour footfall is estimated to be at 600 people, in which case the museum has to prepare for 1,000 simultaneous visitors.

Multipurpose spaces for internal and external events and gatherings of different sizes, including space for a small bar. Different spaces serve small gatherings of daily meetings between a few people up to cocktail parties of 400 persons.

Adaptable workshop spaces designed for collaborative learning and hands-on activities employing various methods, techniques and materials. Total capacity of the spaces is approximately 60 people.

Provides easy access to most frequently used archive items and knowledge. The area should include spaces for a public reading room, office rooms for researchers and a staff working area for information service, book maintenance, logistics and digitalisation. The library should have reservation for approximately 100 metres of book shelves.

Facilities for a relaxed shopping experience with a good visibility from the entrance hall and a separate entrance from the street/square/promenade. Facilities include a main retail shop and a smaller, flexible pop-up space (approx. 50 m2) for special projects or visitors exiting temporary exhibitions.

Welcoming and flexible space that caters both museum visitors and visitors not entering the gallery spaces to enjoy a menu that changes according to seasons and time. The capacity should be for 140 people seated.

Space reserved for participants to envision a use that supports the architectural concept and the functional goals of the new museum.

An activity-based office for 80 people.

Space to securely manage arriving and departing museum objects.

Technical workshops that include spaces for working with wood, painting, framing and tasks requiring AV / electrical work.

Kitchen to serve cafe-restaurant and event catering.

Supporting spaces that support museum organisation operations within the building.

Total net floor area (NFA): 6,600 m²

TECHNICAL SPACES OF THE BUILDING – 1,635 m²

Cleaning centres and storage, recycling and bicycle storage.

Emergency exit routes serving also internal circulation.

Total estimated gross floor area of the building (GFA): 10,050 m²

The competition entries were evaluated based on a comprehensive assessment where the jury paid attention to several predetermined criteria.

Evaluations are based on the following criteria:

Architectural quality and integration with the cityscape and urban structure

Does the proposed design create a new attractive, architecturally unique destination in Helsinki’s historic waterfront, while being respectful of the cultural and environmental values of the surrounding city scape and urban structure?

Building concept and its added value for the museum’s mission

How does the proposal leverage both indoor and outdoor spaces to host diverse programmes and events, ensuring a dynamic atmosphere that encourages repeat visits? Does the concept bring added value to the museum’s ambitious mission of rethinking the civic role of a museum?

Feel and look

Does the building create a unique spatial experience that is itself an expression of the possibilities of architecture and design as generators of public life, triggering curiosity and expressing its users’ imaginations?

Functionality, flow, and flexibility

How does the proposal meet the changing functional, cultural, and social needs of museum operations and users and create public areas optimized for hybrid programming to engage diverse audience groups, prioritizing holistic accessibility for individuals of diverse backgrounds, abilities, and needs?

Sustainability

Does the proposal prioritize energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and carbon footprint reduction in a cost-effective manner, while ensuring durability and financial viability over the building's lifespan?

Feasibility and project costs

How feasible it is to develop the concept to meet practical constraints of cost, time, and other resources without compromising its original identity and qualities?

In Stage 1, the primary focus of the evaluation was on the integration with the surrounding cityscape and the overall concept, functionality, and architecture of the work. The jury emphasised the identity of the work and how the building feels and looks. Further development potential of the entry was more important than flawless details. The entries selected for Stage 2 must had great development potential, also from the perspectives of cost and scope, to meet the project’s targets.

In addition to the aspects above, greater emphasis was placed on the technical functionality and feasibility of the plan in Stage 2. Among the finalists, the jury commissioned analyses and comparisons of scope and cost, as well as the necessary technical and functional studies for the best competition entries, which served as a basis for decision-making.

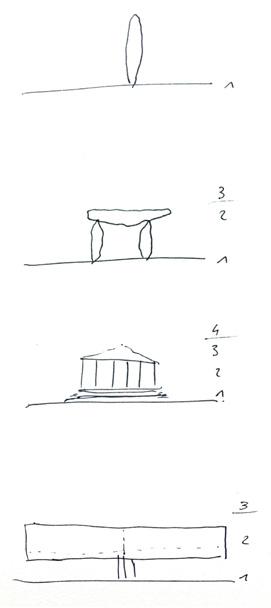

Central Helsinki has evolved on a peninsula at the edge of the outer archipelago, where a grid of orthogonally planned urban blocks merges with the surrounding maritime landscape. The site’s character is defined not only by the surrounding urban fabric, but also by the intimate natural features of the archipelago and the open sea horizon. The fortified islands just offshore form part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and a designated buffer zone—extending to the future museum site at Makasiiniranta—has been established to protect this heritage. This buffer zone has informed the assessed requirements on the form and height of the new museum building.

The site itself lies within a former harbour zone, at a point where iconic landscape views converge: the Market Square and Helsinki Cathedral rising behind it, Katajanokka and the Uspenski Cathedral across the bay, and Tähtitorninmäki Park to the south.

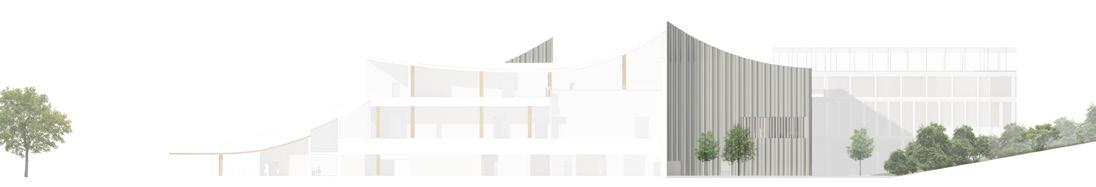

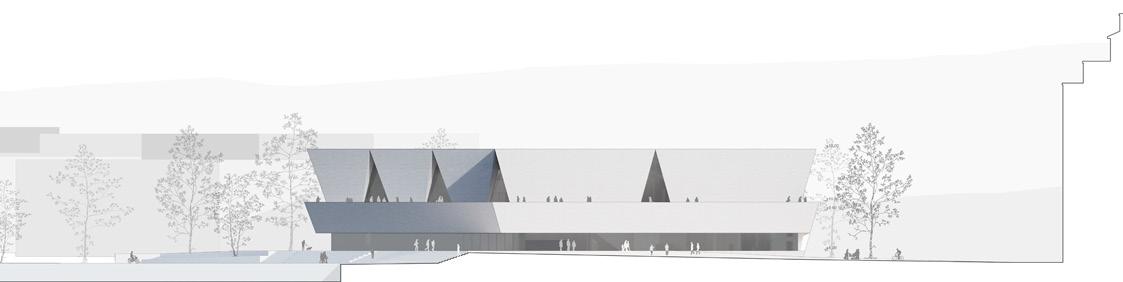

The competition brief outlines clear requirements for integrating the new building into the former harbour zone. Its height is to remain below that of the surrounding historical urban blocks, preserving the visual prominence of Helsinki Cathedral and Uspenski Cathedral—both of which stand out as key landmarks when approaching the Market Square from the sea. The objective was not to introduce a third landmark, but to complement the existing cityscape. This aspect of the design challenge proved particularly demanding. In some entries, the visualisations— especially those embedded in oblique aerial views or waterfront perspectives—appeared to underrepresent the actual scale of the proposal compared with the other submitted materials.

In addition to evaluating each proposal accepted into the competition, the jury also provided an overview of how the participating teams approached the design brief.

The most successful proposals demonstrated a particular attentiveness to the calibration of interior ceiling heights, ensuring that spatial quality was achieved within the constraints of the permitted external building volume.

Several proposals, while architecturally strong, were ultimately deemed unsuited to this specific site, given its location within Helsinki’s historically sensitive archipelagic cityscape.

The view from Tähtitorninmäki Park towards the Market Square is a vital element of the city’s historical identity. Visitors regularly climb the hill to admire the view— an iconic panorama that has been immortalised by many of Finland’s foremost painters. In designing the new museum building, this cultural heritage and the associated open view corridors should be treated with sensitivity and respect.

Several proposals demonstrated an ambition to merge the new building with the park landscape of Tähtitorninmäki in the background. Some envisaged the entire site as reforested, with particularly ambitious concepts featuring tall trees planted even atop of the museum’s roof. However, such solutions would substantially increase structural loads due to the need for deep growing substrates, which runs counter to the principles of sustainable construction. Furthermore, the existing harbour quay structures and their piled foundations limit the feasibility of planting trees in the ground surrounding the building.

Certain entries proposed a direct connection between the museum and Tähtitorninmäki Park via a bridge creating a seamless link to the hilltop. However, a defining characteristic of any scenic viewpoint is the physical act of ascending to it. In this case, the existing park path already offers a natural and accessible route. The approximately seven-metre-high rock face—a prominent feature of the local topography—marks a clear boundary between the park and the harbour zone. The museum site lies entirely within the latter.

As the museum’s roofscape will be visible from the hilltop of Tähtitorninmäki Park, particular sensitivity should be shown in the selection of roofing materials and the placement of any technical equipment on the roof.

The New Building as a Continuation of the Market Square’s Pedestrian Axis along the Waterfront

The competition brief specifies that the new museum must be easily accessible and welcoming to people of all ages and backgrounds. While many proposals commendably addressed the experiential aspects of visitor interaction with the building, a significant number of entries exhibited an overly formal, inward-looking architectural identity typical of traditional art museums. Proposals that placed the museum atop a raised plinth or grassy mound created a sense of separation from the waterfront promenade, effectively isolating the building as a detached “island” that undermines the museum’s inclusive ambitions.

The currently estimated maximum flood level is +3.4 metres above sea level, which generally dictated the placement of the entrance level in the submitted designs. To avoid expensive and unsustainable waterproofing solutions, the lowest acceptable internal floor level has been defined at +1.2 to +1.5 metres above sea level. At present, the site’s existing ground level is approximately +2 metres above sea level.

The optimal location for the main entrance is on the northern façade, facing the Market Square. Comparative analysis of the proposals affirmed that configurations featuring a staircase flanked by accessibility ramps leading to the main entrance is not a functional solution. Instead, the pedestrian area in front of the museum should be gently elevated, creating a sloped approach beginning at +1.8 at the southern end of Vironallas harbour basin.

In addition to the new waterfront promenade, the existing pavement along Laivasillankatu—directly adjacent to the museum site—is expected to remain a busy pedestrian thoroughfare. Proposals featuring solid, closed façades along this street were generally regarded as a missed opportunity to engage passers-by. Furthermore, turning space for articulated lorries cannot be accommodated on the building’s western side. As a result, all servicing functions must be planned for the building’s southern end.

The competition brief outlined an ambitious vision to establish a museum that will help re-define what museums can be in the future. The core challenge was to create a space that supports world-class exhibition-making, accommodates diverse and unconventional public programmes, serves as a communal gathering place, and advances the museum’s broader civic mission.