2 minute read

Planning with Resilience

10.. Reed and Lister.

11.. Scott. Planning with Resilience

Advertisement

In discussing the development of ecological resilience theory Reed and Lister compare “systems that attempt to achieve a predictable equilibrium or steady-state condition to systems typically in states of change, adapting to subtle or dramatic changes in inputs, resource and climate. Adaptation, appropriation and flexibility became understood as the hallmarks of “successful” systems. It is now widely accepted (if not fully understood) that an ecosystem’s ability to respond to changing environmental conditions makes persistence possible.”10 Reed and Lister describe in their article past projects and thinking that have considered the application of ecological resilience theories to urban planning and design. However, discussions and previous attempts tend to be abstract and policy oriented. In this case we can see the potential for the development of urban planning and architectural design based on those theories.

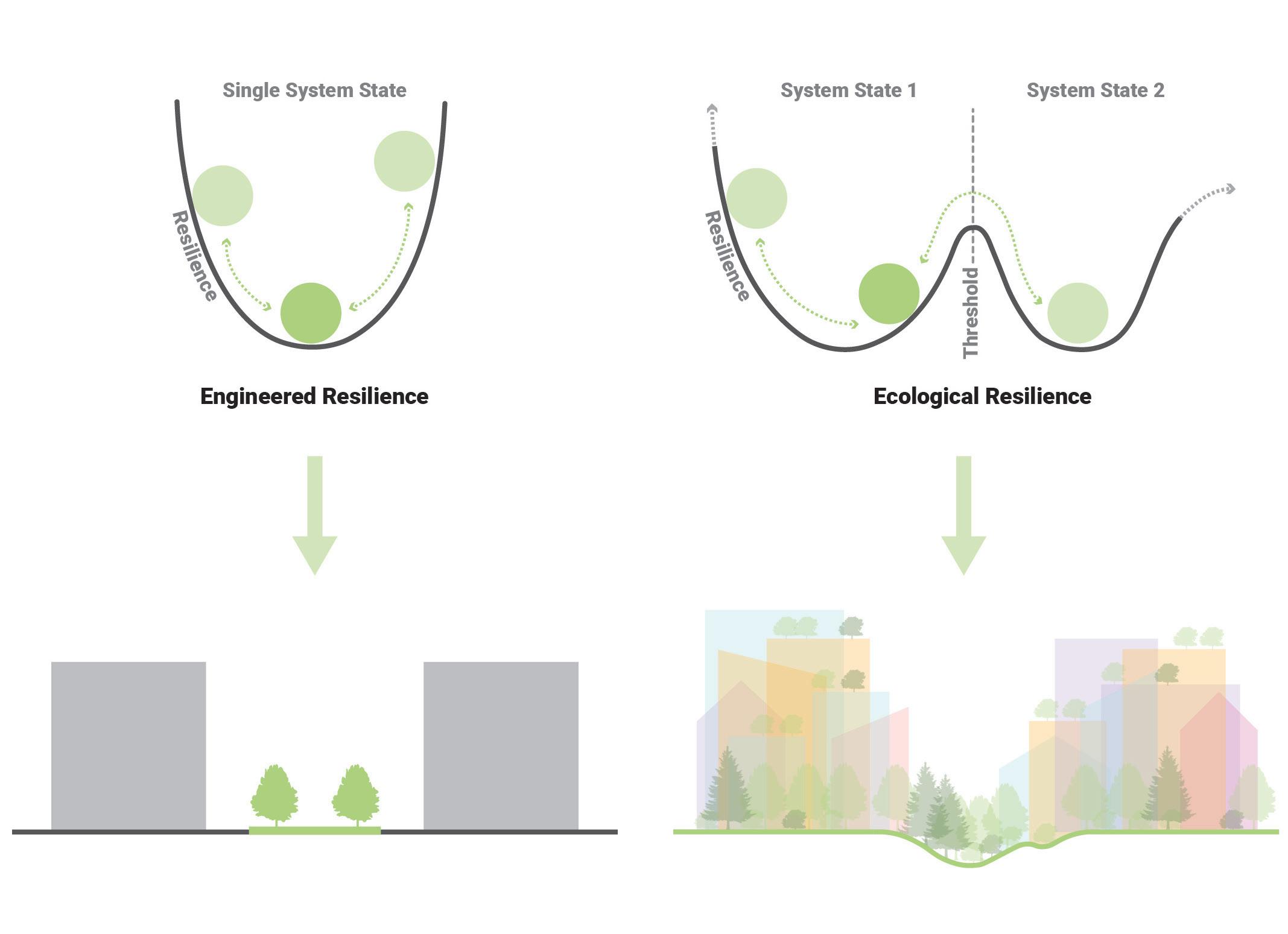

Briefly exploring resilience theory in relation to planning and architecture we can recognize two distinct planning strategies that reflect the difference between engineered and ecological resilience. (Figure 2)

The ordered ideas of modernism, which have contributed largely to the development of North American cities, have a strong affinity with engineered resilience. Modernism is a simple and ordered system of thought that relies on the physical manifestation of a limited set of ecologies, human or otherwise. Order is maintained by removing so-called extraneous or unwanted layers of complexity from the system.11 Urban systems under modernism, especially in its most ideologically pure expression, are maintained within the limits of technology and efficient function. In this understanding, the system exists as a final and ordered state from its inception, and is intended to remain fixed, with a narrow range of variation over time. While so-called high modernism reached its peak in the last century, it can be argued that the basic concepts of modernism continue to pervade our society, from the way we build and manage cities to the way we grow food and organize the systems that maintain our daily lives. A key signal of that reality is the pride of place that we give to efficiency and the related trend towards the concentration of control in ever larger companies.

Planning cities with ecological resilience offers a flexible alternative. Instead of a single system state there are multiple futures for the urban system, all of which are considered stable and viable. With these multiple possibilities a city can be more adaptable, built with multiple latencies within it. Each future is accessible when a tipping point is reached.

While it is possible that a model based on engineered resilience can include both human and non-human ecologies, the tendency until now has been to separate them, as if they were not connected. Ecological resilience is particularly useful because it inherently allows for complex interactions and can therefore allow for non-human ecologies to exist within urban forms. These too can change over time and need not be constrained in the way a traditional park might be for instance. Taking that as a starting point, it is possible to imagine quite complex and open-ended urban forms through ecological resilience.

Reflecting now on the commentary of Bauman, we can see that there is a framework that we can use to include more open-ended long-term planning in the development of our cities. This is an important addition, as Bauman offered more critique than actionable insight.

The use of engineered resilience and ecological resilience in different planning strategies will be expanded upon in the following chapters.

Figure 2. Resilience and planning. Source: By author.