Can AI

TheAcostaInstituteisalearningandresearchhub fosteringinnovationattheintersectionofhealingcenterededucation,contemplativesocialscienceandslow workthroughthefacilitationofonlinecourses,trainings, workshops,lecturesandinternationalsummits.This documentwasdesignedbySteveSaintFleur,Creative Director,andAngelAcostaattheinstitute’sStudio–a collaborationbetweenCultureTouchandtheAcosta Instituteservingasacreativehubwherestorytelling, design,andeducationintersecttoharnessthepowerof creativity,technology,andcontemplativepractices.To learnmoreaboutourwork,visitacostainstitute.com.

Tolearnmoreaboutourwork,visitacostainstitute.com.

By Angel Acosta

By Matt Klein

By Susanna Raj

By Sará King

By Tim Leberecht

By Angel Acosta

By Matt Klein

By Susanna Raj

By Sará King

By Tim Leberecht

Inspired by a collaboration between the House of Beautiful Business and the Acosta Institute, this inaugural volume explores some responses to the timely and timeless question—"Can AI Heal Us?" We find ourselves at a unique crossroads–surrounded by our devices and the Internet of Things. Artificial Intelligence and its exponential growth has the capacity to both heal and harm us. The urgency of the moment cannot be overstated, as we stand on the precipice of an era of unprecedented change.

In essence, our quest for healing has ancient roots, predating modern medicine and transcending national, ethnic, and cultural boundaries. From shamanic rituals to robotic surgery, the impulse to restore health—whether physical, emotional, societal or even spiritually—is intrinsically human. Yet, as we move forward into an age where AI has the potential to either amplify our healing efforts or exacerbate our existing wounds, we must ask–what does it mean for something inherently human to be augmented or even replaced by artificial intelligence?

Etched into the passenger side of many vehicle mirrors, the phrase "objects in the mirror are closer than they appear" serves as a cautionary reminder that the distance between one’s car and any observable object in the mirror is actually much shorter than it appears to be. On a metaphorical level, the phrase speaks to the deceptive nature of perspective. We invite readers to orient towards the question of whether artificial intelligence can heal us with a sense of urgency and gentle curiosity. The real consequences related to this question might be closer and more urgent than we realize. As one of the leading thinkers in the field, Kate Crawford reminds us that the “extractive mining that leaves an imprint on the planet, the mass capture of data, and the profoundly unequal and increasingly exploitative labor practices that sustain” this industry point towards our desperate need to recalibrate.

In this inaugural issue, our contributing authors offer a variety of perspectives, illuminating the intricate interplay between technology and ethics, the shifting paradigms of healing in the context of AI, and the socio-economic repercussions that ripple through our digital lives. We don’t arrive at definitive answers nor do we claim this to be an exhaustive exploration. Instead, we embark on a kaleidoscopic journey to find inspiration, challenge one another, and dance within the tension of a provocative inquiry. Our hope is that this Volume 1. serves as a seed that will ignite more intentional conversation.

We extend a heartfelt thank you to the House of Beautiful Business for being such a gracious and intellectually robust partner in this work. We are bound by our shared vision of a life-centered economy, which respects the intangibles that make life meaningful—joy, creativity, and connection.

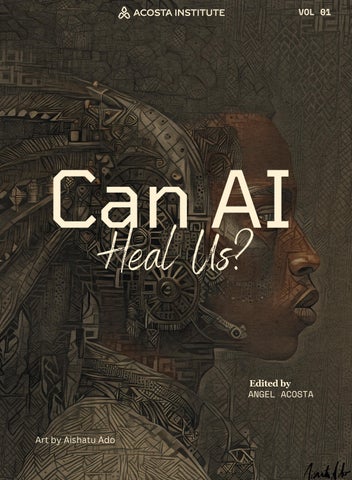

We appreciate Drisana McDaniel, our senior researcher, for her support with this precious document. Lastly, we are honored to grace the cover of this magazine with work of Aishatu Ado, who is a peace technologist, artist, storyteller, public speaker, and entrepreneur, advocating for social justice within technology by forging new digital pathways for peace. As you turn these pages, We invite you to consider your own role in shaping the answer to the question– "Can AI Heal Us?."

It's a question that deserves our fullest attention and our most spirited debate.

By: Matt Klein

By: Matt Klein

But thankfully, in a moment of stale institutional regurgitation, we’re witnessing a swell of colorful bottoms-up creations.

When we analyze our entertainment charts, we find the old keeps winning.

Until 2020, roughly 25% of the topgrossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, remakes, reboots, or cinematic universe expansions. Since 2010, it’s been over half. Most recently, it’s closer to 100%.

This summer, The Wall Street Journal rejoiced that finally a box office hit wasn’t a part of an existing franchise. What they failed to mention was that Barbie is over half a century old.

As for TV, about a third of the most viewed shows are spin offs of other shows in the Top 30 (ex: CSI vs. CSI: Miami) or multiple broadcasts of the same show.

In the 1950s, a little over half of authors in the Top 10 had been there before. These days, it’s closer to 75%.

In the late 1990s, 75% or less of best selling video games were franchise installments. Since 2005, it’s been above 75% annually, and similar to film, now often 100%.

And as for music, the number of unique artists cracking the Top 100 is shrinking. With fewer and fewer artists making the charts, each of those artists are now charting 1.5x to 2x as many songs per year.

Spotify is witnessing 70,000 tracks uploaded every day. YouTube is uploading 30,000 hours of new content every hour. Nearly 3M unique podcasts currently exist. Twitch is broadcasting +7.5M streamers, both indie game releases and play are growing year over year, and roughly 4M books are published annually in the U.S. — nearly half of those self-published, a +250% increase over just five years.

With creative tools democratized, gatekeepers ignored, and paths toward monetization clearer, never before have we seen so many accept the invitation to make.

The result is more diverse representation, seemingly personalized content for each of our tastes and interests, and the ability to not just consume, but make culture.

The thing is, we face a problem:

Despite the fact that more people are creating, their work is not easily breaking through. Check the charts.

his is in part because we lack effective platform features for discoverability, we’re desperate for the medicinal effects of nostalgia, and black-box algorithms both determine reach and are programmed to segment us into predictable buckets rather than service our unique needs. Most of all, institutions aren’t incentivized to take risks. Instead they rely upon the formula once it’s cracked.

We’re seemingly getting less creative.

Psychologist Adam Mastroianni coined this pattern in entertainment “The Cultural Oligopoly” while strategist Alex Murrell broadened its scope, calling our moment “The Age of Average.” He draws our attention to visual support that sameness is pervasive across interior design, architecture, car manufacturing, city planning, logo typography, branding or “blanding,” and the “Instagram Face.”

Homogeneity is omnipresent as culture is colonized on a global scale. But while the average has always had the largest share and plays an important role, AI is poised to worsen our creative predicament.

As AI tools become cheaper, faster and easier to use, creators will continue to flock to them – as many already have.This won’t help, but worsen our uniformity and at risk creative ecosystem.

Presented with the most powerful technology ever devised, many reflexively mash up old IP.

No different than the studios we critique for their unoriginality, we too are regurgitating. Fandom, sure. But this approach is not creative, but reductive and uninspiring. We can finally escape franchises yet choose to instead double down.

That we're so bullish on AI, something dependent upon the past, to help us chart our future is ironic.

At this rate: The future is the past. It’s a trap.

Consider when new AI-generated content –based upon the dusty past – is inputted back into the model? It’s a recursion – a hall of mirrors.

When we summon AI, we must not forget its default setting is to revert to the mean. It forecasts what should come next, seeking out the average or most readily available – not necessarily what’s “best” or most creative or innovative. It’s optimized for familiarity.

It’s not intelligent as much as it is impressive at mimicking the ordinary with mass amounts of pre-existing human-generated information. Only when it regurgitates back the past, does it appear “human.”

When images of Harry Potter characters in the style of Wes Anderson went viral, AI and its creator were applauded. “This right here is the future,” one proclaimed.

This phenomenon is already a norm across our media ecosystem. We react to reactions. It’s a norm to see a Tweet of a TikTok, which uses a screenshot text message as its background. Beneath it is a chain of replies.

Our entertainment should provoke us, confronting us with new characters, narratives and feelings. Being open to what’s foreign is what strengthens our empathy and understanding of the world. This discomfort is invaluable.

We need "net-new" ideas, not ones built off the backs of the past. Sarcastic, gray, ambiguous, surreal, sophisticated, unexpected ideas.

Yes, everything is a remix and we must learn from the past, but we need not repeat it out of convenience.

In the act of mindlessly drawing upon the old, AI charms us with the ability to bypass the messy creative process. The bitter blocks, frustrating strains and awkward tensions required to get to net-new. But it’s this work, which pushes and stretches us – the work which helps us grow and conjure net-new.

AI , itself, is not what will bring the demise of humanity, but instead the unquestioned belief that it’s the answer for each of our creative challenges.

Since we must learn to live with, and not against this magic, AI should be seen as only half of an effective creative solution. The second part is to interrogate, challenge, turn over, inverse and seek out what’s not offered to us.

Then, still, our human superpowers may remain intact.

To be honest, when I heard the question “Can AI heal us?” it made me snicker and roll my eyes. Annoyed a bit at both the naivety and inherent danger of the narrative behind such a question – but I took a moment to pause and ponder at my own reaction. Yes, that goes contrary to the religion of everyone working in tech, where one must act fast, to fail fast, to succeed fast –in essence to never ever dare to pause or you will lose.

I paused and asked what if I had replaced the word AI to art, or music, playing, cooking, reading, or gardening in that question, would it still offend me the same way?

“Can Art heal us”?

That sounds sweet – I would have gleefully consumed that question and clicked on that article or attended that conference where this was the title.

So, you can say I’m prejudiced. Heavily. Yes, I agree. Rightfully so I would argue, coming from the tribe of AI ethics and inclusive AI practitioners, I’m aware of the consequences of giving more power to something that is now mindlessly allowed to redefine our future –even if it’s in the form of a question. Yet, I paused to assess why those other words do not offend me. They all signify an action that involves a strategy to engage others, to build connections.

You can’t do art in isolation. Well, maybe you can but you still need supplies and inspiration that comes from outside, and you do (no matter how hard we artists deny it) want your art to be seen and valued and appreciated. Gardening? You must work with nature, so you must put some effort in understanding her or you need to connect to those who do understand her to get the job done. (Ask all the orchids I killed so far, and they will tell you).

Founder & CEO of AI4Nomads, cognitive science and AI ethics researcherSame goes for cooking, not done in isolation either in its process or purpose. Nothing in that list of words excludes connections and community, either with us or others or with the larger universe. But if I replace that list with ‘Can Excel heal us, ’ or ‘Can PowerPoint heal us, ’ or “Can Shovels and Rakes heal us?, 'Can Brushes and Paint heal us ’ , ‘Can Pots and Pans heal us’? ...etc., you can see it sounds absurd and does look a little bit like a marketing copy for a product.

Tools and technology will not heal us. What we do with them, will. If you are assuming or auto completing my next sentence to say, ‘Do not revere things, even if they create the value of healing,’ I would say your prediction model is overfitting and needs more data! I come from India originally, where we literally have a day and a festival to worship tools. The festival of Ayuda Pooja in Hinduism is about venerating the tools and tech we use. Yes, it’s a big deal there.

Raised as a Christian, where the ideology differed in not worshiping what we created but to worship the one who created us; I never participated in the celebrations. Nevertheless, nor culture nor religion will allow you to recede safely into another dimension by choice. They layer

on you like lotion until you absorb some of it into your skin. It’s a blessing and a curse (but the curse part is not the scope of this article).

If raised in a society that worships tools, then you will learn by default to not dishonor or disrespect the things we use You cannot walk over or step on any book whether it was the Bible or Vogue magazine. Even today if I step over a page or paper on the street by accident, internally a little voice goes “oh I’m sorry ”” Although I don’t know whom I’m apologizing to. I was raised to take care of what I owned, including what I created.

That still resonates with me. I don’t do Pooja to my tools and tech, (my iPhone may disagree given how religiously I clean it, but it doesn’t know that that’s post Covid-19 trauma) but I respect their purpose in adding value to my life.

Ayuda Pooja is about the victory of knowledge over ignorance. The equipment that allows one to use knowledge to diminish the power of ignorance must be given respect. That’s the crux. The tool that empowers you to heal a hurt deserves respect. AI could be one such device at our disposal. Could have been. It is not.

That being said. AI is not a mere tool. Not a mere tech. As far as I know, my PowerPoint never jumped out of my PC and went to discriminate against a minority couple who is looking for housing loans, or wrongly accused someone of a crime, or extended the sentencing for jail time for others based on how they looked. My paint brushes never walked over and marked my neighbor’s house to lower their home value based on their race, income, and education level – or color- coded the college applicants’ chance of admission based on race.

AI is unlike any of these. It has done all those things with its algorithms. Only in Disney movies do the teacups and door knobs have a life of their own, with the ability to predict, react and execute Now we have AI. We have a leash on it, yes, but the leash is not in our hands. Those who have it,do not wish to yank it back, even when we tell them that it has bitten many.

Humans have managed to create something that can do a lot more harm than good. Not our first rodeo either in this area – we did create incredibly stupid things like atomic bombs; nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons...the list goes on. Sometimes what we create have no good use whatsoever – except to feed our insecurities like societal belief systems such as casteism and racism.

We have proved over and over again that indifference does not reside outside us as a force to be reckoned with but inside us through our inventions and intentions. AI is one more invention of ours. It has the power to win over ignorance, but as any entrepreneur including yours truly will tell you; you need to make sure your product is addressing a pain point before deploying it as a solution.

The product in its current form adds to the pain points of the customer instead of reducing them. And it depletes, destroys energy, both natural and human energy, disproportionately for the value it adds. Healing? What healing? Healing starts when hurting stops. The hurting has not stopped. What does not kill you, may make you stronger but it certainly, certainly, most certainly will not heal you.

Nothing can heal us from the harms that come from developing tech in a non-introspective space where we live 24/7/ now. Invention without the right intention is destructive. Can AI act with good intention when we have not paused long enough to design it for that purpose?

Pause and think about that.

If you still ask me “Can AI heal us?” –, since I’m a construct science advocate – - I would say define your constructs first, for both your noun and your verb. Who is hurt, who is the hurter and who needs healing? Which is which here? Is it “Can WE heal us?” Since we made AI?

Who is we? You and me? Let’s define where we begin and where we end; the limits of ourselves. Let’s go from there. If I need to be healed from what you did and you need to be healed from what I did, then what we created is not a salve but an irritant. That is where we are now. The alarms are blaring. Don’t run. For there is no clear exit. Stand still. It’s the only way out.

Pause. And. Think. About that.

As a neuroscientist, I am sometimes asked if I receive pushback for talking about love and loving-awareness in my research. Love as an act, a presence, a skill, a relational orientation, and an intention to be actively cultivated is not a phenomenon that we can measure holistically in any quantitative sense. However, many of our greatest discoveries in science in the past decade in the fields of quantum physics, quantum computing, astrophysics, and cosmology have come from teams of dedicated scientists testing theories that are decades, if not over a century old, until one day they find a data point that begins to confirm what their models alluded to the possibility of all along. In some ways, I look at the process of researching well-being, social justice, and even love in a similar light.

We cannot say that we know as a whole what these phenomena are, but we have caught glimpses in our models that these realities are possible, and therefore, we have hope that our combined creativity, imagination, collaborative abilities, and technological innovations will shed light on these future collective realities.

Perhaps because I was trained academically in the social sciences during my undergraduate career –-- exploring and getting degrees in Linguistics, AfricanAmerican Studies, and Political Science before I pursued Neuroscience –- that my mind is oriented towards including phenomena that are qualitative, subjective, and felt in nature towards the goal of creating interdisciplinary spaces where the ineffable and the objective flow naturally into an everevolving story line together.

I am convinced that a critical part of doing science that is innovative is grappling with the theoretical, the liminal, or the things which we cannot say for certainty exist in the same way for everyone, but that we intuit are necessary components of the picture of human consciousness that we are attempting to give shape and voice to.

There is this aspect of exploration and adventure that occurs at the very edges of the human imagination which I love about my profession. So with that in mind, I talk about love and loving-awareness not as phenomena that I purport to be an expert in, but rather as “North Stars” to exemplify a way of being towards ourselves and one another that I think encapsulate what it might mean to live in a state of individual and collective well-being. The central thesis I operate with is that the more that we learn to love ourselves and to express this love in our relationships with one another, the greater the health, vitality, authentic care, and well-being we will all experience.

A central aspect of cultivating this love I am speaking of, in the way that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of agape, is to consciously cultivate awareness of self. By this I mean it is all too easy to move through life on auto-pilot, moving from a place of emotional and behavioral reactivity that aims to blunt or ignore the enormous information coming from our internal experience of self, and that reacts to external stimuli either by running, fighting, appeasing, or fawning to ensure that we survive. That is called operating from the autonomic nervous system’s trauma response.

" We are beings who live at the nexus of the dreams of our ancestors and the memories of our descendants " .

This is, of course, a simplification of the complexity that is actually happening within our daily experience of life, but it also describes what life in “survival mode” feels like, which thousands of people have described to me in my trauma-healing work and research. People tell me that they sometimes feel they are grasping from moment to moment for a feeling of true belonging, connectivity, and empathy in their homes and workplaces, but instead feel quite depleted from the non-stop expectation that they perform some semblance of perfection and productivity while the world is literally burning down around us. This can produce feelings of great cognitive dissonance.

We know that interconnection and interdependence are our birthright, but it can feel so mystifying why it seems too hard to get there, and why violence and separation of all kinds seem so persistent. The idea that those on the front lines of developing Artificial Intelligence might not find intergenerational trauma healing work to be as important as the technological innovations that they are driven to create

The people identifying the data sets that inform large language models, images or video repositories, or other complex human artifacts which are of value to the creation of Artificial Intelligence cannot create technological advancements that support collective liberation and healing if they are disconnected from that journey themselves – a journey which would involve connecting with communities that probably look and feel very different culturally and socioeconomically from their own.

Our world is moving at such a frighteningly fast pace, and it feels impossible to move at the speed of capitalism every day. The frenetic energy of work, and the labor that is required to make a basic living can seem untenable to a person who also wants to experience rest, rejuvenation, slowing down, connecting with oneself, others, and the environment - all of the things we need to be supported in doing to experience greater well-being.

The conscious cultivation of awareness – or the application of awareness-based practices that teach us how to pay attention to our own experience as a witness, and therefore subject of life rather than as an object that

Our capacity to gently encourage and guide our attention back to our body in the present moment and sense into what we are thinking, feeling, emoting, remembering, or how our bodies are moving in space relative to other bodies and objects is a super power which should not be taken for granted. In that space we can begin to tap into our capacity to be empowered to know our own experience as valid and real. We live in a world where we now have to constantly question the “realness” and authenticity of the stimuli that we encounter. Perhaps the ability to know our own sense of self as real might be one of the greatest gifts we can now give ourselves.

I want to emphasize here that I don’t believe that cultivating awareness of self in the present moment is enough to move towards healing or well-being. You can become as aware as you want of what is happening inside of you, as well as in the world, and not be motivated to act towards the benefit of anyone other than yourself. Meaning, the skill of being aware can reach the wall of the self, and go no farther. I am passionate about exploring the question of what loving-awareness is, and how we can build it as a skill set individually and collectively, because then we can consciously turn towards emotional states such as gratitude, acceptance, lovingkindness, compassion, and relational practices like forgiveness, and see how their application in the context of cultivating awareness may be integral to our ability to bring healing to our own hearts, as well as to local and global communities.

Towards the aim of supporting the development of loving-awareness, I am exploring the development of what I call “contemplative technology” – or technology that aids in the development of contemplative practices – as well as how we keep track of our relationship to individual and collective well-being. I see certain forms of AI as a technology that can really aid humans in communicating about our experiences of systemic oppression, a process which not only validates those experiences as real, but could also provide some kind of system of understanding the linkages between the complexity of human identity as it continues shifting over time, as well as providing responsive and compassionate communication and feedback in terms of what kinds of contemplative and/or embodied practices and digital or IRL wellbeing supports might be available for us to explore together.

Technology is increasingly important to every aspect of how humans live their lives and connect to an experience of “aliveness” and holistic well-being, though I want to also acknowledge the existence of an everwidening digital divide between those with easy access to technology (either in its development, production or in its use) and those who remain without. My research on the “Science of Social Justice” was actually fostered and developed as a part of an NIHsponsored post-doctoral fellowship in Neurology at Oregon Health Science University, which is a hospital and a medical school, and so in some ways, I conducted very unconventional research that was sponsored by a conventional, government entity.

It is important for the public to know that novel approaches to healing are being given support by some of the highest institutions of science and medicine, though of course, we are always in need of greater support to make sure that current and future generations of scientists know that this kind of work is valuable and will be funded. “The Science of Social Justice" (SSJ) is defined as the study of the intersectional biopsychosocial impact of the psychological (mental), embodied (physiological), and relational (relationship-based) intergenerational trauma that has resulted from centuries of systemic and institutionalized oppression for marginalized populations here in the U.S. In other words, it is the scientific study of how systemic oppression has a combined physiological, emotional, and psychological impact on individuals and communities. This theory posits that the creative development and use of contemplative and embodied practices, which are biopsychosocial interventions,

can be grounded in the investigation of how well-being relates to our identities in order to explore the nuanced relationship between identity and our experience of health and well-being. This can allow scientists and well-being practitioners to explore how to heal intergenerational trauma as manifests in both individual and a term that I have coined: "collective nervous systems", to support a return to holistic health for individuals and communities. Though this theory gained a lot of traction quickly within my local community where I created it, I realized very quickly that it would not be of much use to the broader global community if it was not more accessible outside of the boundaries of the scientific community.

I needed to translate this theoretical framework into something applied and accessible, so I decided that turning it into a contemplative technology was the best way to go about that. The “Systems-Based Awareness Map” (SBAM) is a theoretical map of human awareness that I developed to give a visual representation to the Science of Social Justice, because from both a research and praxis oriented point of view, it was immensely helpful to construct a 2dimensional means of describing the relationship between internal and external awareness as they relate to well-being, both individually and collectively, when attempting to envision how the development of loving-awareness might assist in healing the intergenerational trauma that is linked to systemic oppression. The contemplative technology I am currently developing is the 3dimensional, AI-integrated version of the (SBAM) that I described above, that is intended to be a very personalized platform for digital and IRL well-being support.

(SBAM) through my company, MindHeart Collective, with support from the Mobius Collective, a non-profit that is stewarding the development of what we term “Liberatory Technology”. This work is being done outside of academia deliberately, which allows me greater latitude to be conscientious about applying ethical data sovereignty practices and building liberatory tech principles and foundations (authored by my colleague Davion “Zi” Ziere) into every stage of the product design, as well as into how we are seeking to influence the tech ecosystem overall. Incorporating technology into my research and design efforts made most sense because of my desire that the (SBAM) be capable of integrating with the wide variety of tools for digital biomarker measurement, in order to capture the kind of psychophysiological data that is so relevant to how well-being scientists, and particularly neuroscientists understand biopsychosocial measures of health and wellbeing.

It is important to note here that when I am using this term “social justice”, I am being very specific in how I am defining it. By “social” I mean “the relational field of our interbeing” as Thich Nat Hahn might describe our fundamental interdependence as humans.

action”. Defining justice in this way grounds the experience of justice in the experience of the body, and our capacity to develop awareness of ourselves in a way that is fundamentally oriented towards love. Of course, I am aware that there is no universal definition of what “love” is, but I feel for certain that most humans agree that when love is expressed, it is non-harming and non-violent in nature, and is the most powerful force of harnessing feeling of belonging, safety, and interconnection that humans have the capacity to connect to in our internal experience of self and other. As I have stated previously, when lovingawareness is put into action from a societal point of view, we just might see this as an exploration of what collective healing might look like.

However, I am also aware that what I am describing, for me, yet again, a North Star –I don’t believe we have ever experienced collective healing on our planet, otherwise we would not be facing the polycrisis of climate change, war, pandemics, and technologically-exacerbated structural violence that we continue to face today.

The (SBAM) technology is meant to be for anybody with a body who is interested in the intersection of their identity and their wellbeing, or who is interested in understanding how their awareness of “self” changes over time. It is also for those interested in visualizing their individual relationship to collective well-being, who may want support in understanding what kinds of social action they can partake in that would support well-being and the development of loving-awareness in digital and real world communities. In that way, it is meant to provide care for anyone interested in this kind of interface. I also like to say that this a a lifetime technology, so I am really looking at what it would mean for a person to be able to track the development of their awareness over a lifetime, and then, if they choose, to be able to share this information with their loved ones or others who they think would benefit from having access.

I have even thought about what it would mean if people decided to share an artifact of the history of the development of their awareness over a lifetime, as a sort of time capsule of awareness with family members who are descendants – so, what would it mean for ancestors to be able to share this kind of information as an archive if they so choose, and how would that change the way we relate to our ancestors if we could get to know them on that level?

The research component could only be conducted with the data that people voluntarily decide they would like to share for the betterment of the platform as well as for the betterment of our understanding of the relationship between loving-awareness and individual and collective well-being. Data sovereignty is extraordinarily important to how I am conceptualizing ways to empower users who contribute their data to the platform. We would store all user data on the blockchain, so that each user has full ownership of their data of awareness. The (SBAM) could be considered to be a digital phenotyping technology, at least in part, so having the capacity to decide what is done with that data is of great important especially for marginalized communities who have historically not been asked permission, have been experimented upon, or who have been extracted from for profits by others in the big tech industry.

I once read a quote by Peter Thiel that says that technology is any new and better way of doing things. But many of the things that make life more convenient for some are experienced as extractive, harmful, and even violent to others. I think that is powerful distinction to keep in mind.

The motivation and intention to develop ways of being as well as technology that supports aliveness, eco-systems of trust, holistic well-being, wholeness, and loving-awareness are huge factors that influence the development of liberatory technology. My partners at Mobius, Aden Van Noppen and Davion “Zi” Ziere, have been instrumental in co-presencing what Liberatory Technology is and how we think it is different from traditional approaches to building technology. But beyond this, we feel it is important that the people developing liberatory technology are themselves seeking to understand how the embodiment of liberation feels individually and collectively. The consciousness of the technologist is fundamentally imbued in the technology they create. I don’t think technology is somehow separate from us; it is us.

While seeking to embody liberation, is it important to recognize the places in society that are suffering from systemic inequality and where pain, domination, and violence of all kinds exists. This approach to understanding individual and collective liberation is rooted in a fundamental compassion for all beings, and a recognition that some are experiencing suffering and lack more disproportionately than others due to historical and socio-economic forces such as racialized capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, the continued vestiges of imperialism, forces of colonization, and other methods of systematizing disenfranchisement. So building liberatory technology has to do with how we are embodying liberation and simultaneously actively identifying the social, cultural and environmental resources and healing practices that exist individually and collectively; and also asking how technology such as AI can support and elevate these for the greatest accessibility, while simultaneously being truthful about the pain points that exist, and asking what this same technology can do to potentially alleviate or lessen those.

I hope that researchers, technologists and entrepreneurs who are interested in supporting healing, and in understanding the relationship between social justice (as I have defined it) and well-being, will find that my framework helps them to better understand the extraordinary complexity of human health, identity, and our capacity to transform our collective intergenerational trauma into post-traumatic growth. We are at an incredible inflection point right now as a species, and all of our actions to heal ourselves and the planet with have immense repercussions for all of our children and grandchildren. I understand that our capacity to develop greater lovingawareness just might make the difference between our capacity to survive as a species, or not. Businesses are collectives of people with immense power to leverage for societal change and transformation. I wonder what it would mean for business entities and other institutions to develop their very own Systems-Based Awareness Maps - if they had a way of visualizing their own collective nervous system, and noticing both what they are collectively aware of, as well as their blind spots – how might they be able to co-create business ecosystems that reflect healing, collective well-being, and lovingawareness-in-action?

It is also my intention that my framework encourages greater interdisciplinary scientific work, as well as more lovecentered business practices, because it lies at the intersection of so many fields of practice and inquiry that support this.

Businesses are collectives who are trying to do the work of complexity science, in many ways, because the complexity of human awareness is precisely what they have to navigate and understand, in order to thrive and make a contribution to human society.

Technology is developing with greater complexity at an exponential rate, much faster than human biology, psychology, or even relationships have had time to catch up with. It makes sense to me that science, technology, and business sectors need to collaborate to serve the purpose of helping us to better understand ourselves, and to evolve our most positive traits and behaviors, rather than inspiring further disconnection, confusion, pain and suffering. I also believe that my personal practice of embodying healing and liberation through the cultivation of interconnection, compassion, loving-awareness, empathy, and belonging as a scientist, technologist and entrepreneur will create an invitation for others to walk with me and my partners at Mobius Collective on this path where the “how we be”, and “what we make,”are not considered to be separate.

The dream: AI will exponentially enhance our productivity and creativity. It will optimize everything that can be optimized, freeing us humans up to do work that truly matters. It will lead to new breakthroughs in science, scale up mental health services, detect and cure cancer, and more. It will finally enable humanity to realize its full potential.

The nightmare: present and future harm. Estimates suggest AI will eliminate 300 million jobs worldwide, with 18 percent of work to be automated, overproportionally affecting knowledge workers in advanced economies. AI will destroy the very fabric of our societies as we know it, threaten the core of our work-based identities, exacerbate social divisions and discrimination, blur the lines between truth and fiction, unleash unprecedented waves of propagandistic misinformation, impose a dominant, allencompassing, all-knowing universal operating system, an aiOS, on us, start wars, and ultimately, as AI morphs into AGI, go HAL or M3GAN-style rogue and extinguish the human race

“Reality hitting us in the face” Eliezer

Yudkowsky is sure about the latter: “We’re all going to die,” he declared on the TED stage. The founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute delivered his dystopian outlook straight into the astonished faces of the 1,800 attendees of the TED conference in Vancouver, many of whom are staunch tech-optimists who only think of positive outcomes, of “making the world a better place,” when they hear “Possibility” the theme of this year’s program.

Listening to the TED talks in Vancouver it became clear to me why many outside Silicon Valley aren’t enthusiastic about AI. As a doomsayer, Yudkowsky seemed to already be in a state of grief. The enthusiasts, on the other hand, suffer from the Zuckerberg problem: they are not very compelling. None of the AI creators on the TED stage seemed particularly trustworthy. Their concern came across as casual perhaps something to do with the obvious commercial incentives.

It’s like we haven’t learned anything from history, and the new ostentatious enlightenment the AI masters exhibit is just the same old disruptivism.

When Greg Brockman, president, chairman, and co-founder of Open AI, advocates putting AI out in the world as a form of live lab to learn by “reality hitting us in the face,” as he did in Vancouver, it sounds an awful lot like the Zuckerbergian “ move fast and break things.” At least Zuckerberg was the known enemy, dorky somehow in his alltoo-obvious world conquest guised as connecting-the-world idealism. The Open AI founders, however, and other AI pioneers such as Tom Graham, founder of deep fake video tech firm Metaphysic, are more elusive and their organizations more opaque. The reason they cite for forging ahead with AI development, no matter what, is usually along the lines of ‘it can be a huge upside to humanity, and if we don’t explore it, others (read: bad actors) will do it.’

Robert Oppenheimer’s famous adage comes to mind: “Technology happens because it is possible.” Oppenheimer, of course, is the physicist who led the Manhattan Project and is known as “the father of the atomic bomb ”

“Mysticism to honor the unintelligible” So what shall we do? The one thing, it seems, that everyone can agree on is that no one has a clue where this is all headed, not even the makers of ChatGPT themselves, as Sam Altman, of OpenAI, readily admits. Obviously, I don’t have a clue either, and it is for this very reason that I’m more comfortable with a mystical rather than a materialist view. The mystical view is more expansive and accounts for a wider option set. Asking for empirical evidence is not very useful for phenomena that appear to exceed our cognitive apparatus. When humans no longer fully comprehend the direction and speed of advances in AI development, when the territory has outgrown the map, as Yudkowsky argues, then the only ones still holding the key to the black box, to the cathedral, are the priests, not the scientists.

Stephen Wolfram of Wolfram Alpha contends that the success of ChatGPT suggests that “ we can expect there to be major new implicit ‘laws of language’ and effectively ‘laws of thought’ out there to discover.”

Let’s look at the four criteria William James established for mystical experiences: passivity, transiency, ineffability, and “noetic quality”: “states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect. They are illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance [and] carry with them a curious sense of authority.”

The most ordinary universal human experience that matches James’ criteria is dreaming. From hallucinating to dreaming To date, no one really knows why we dream. Despite extensive research and myriad theories, a rational explanation is still missing. That, of course, does make sense, as dreams are the realm of the irrational, defying our very attempt to make sense of them.

In 2020 the Dutch neuroscientist Erik Hoel presented a new theory: the so-called “overfitted brain hypothesis.” He suggested we view “dreams as a form of purposefully corrupted input likely derived from noise injected into the hierarchical structure of the brain.” In layman’s terms, and grossly oversimplified, this means that our brains tend to get overwhelmed by daytime information and are prone to taking it at face value as the equally weighted, accurate representation of the world. Dreams, Hoel postulated, insert an intentional distraction that helps the brain zoom out and generalize (basically, seeing the forest again despite all the trees): “Dreams are there to keep you from becoming too fitted to the model of the world.”

Understanding, at least the basics, of how dreaming works, matters to how we think about AI.

In contrast, in light of the Generative AI “shock,” we now widely use the term “hallucinate” dismissively when we describe an AI system giving us implausible or overtly inaccurate information (for instance, Microsoft’s Bing claimed that Google’s Bard had been shut down, incorrectly citing a news story.)

But what if hallucinating, as a core quality of dreams, is actually desirable? AI systems mimic the deep neural networks of our brains, so AI developers have recently started to apply Hoel’s “overfitted brain hypothesis” to AI systems, suggesting that hallucinating dreaming is a feature, not a bug when it comes to preventing AI from “overfitting” in other words, suffering from bias due to its conditioning by existing data.

You could even argue that dreaming will become the main generative power of generative AI as deep neural networks advance.

As early as 2015, Google (with Deep Dream) and others began to feed neural networks with input that makes them spin out surreal imagery,kind of like an AI that is having hallucinations after taking psychedelics.

It is striking that media coverage frequently speaks of AI “dreaming up ” images or proteins to describe generative AI’s exponential creative power. And it seems to be an apt metaphor as ever more powerful AI models will generate an abundance of creative options that seem to have sprung from some sort of subconscious exceeding the human intellect. Transformer networks, the “T” in Generative Pre-trained Transformer Networks, better known as GPT, are already superior to so-called Convolutional Neural Networks and Recurrent Neural Networks, since they apply a fast-evolving set of mathematical techniques, called attention or selfattention, to detect ways in which even distant data in a series influence and depend on one another.

This means that they understand context immediately; they process data and learn “everything, everywhere, all at once. ” It sounds as if they’re dreaming.

There’s another reason dreaming might become the new MO of AI. Mark Rolston, cofounder and chief creative officer of argodesign, predicts “ephemeral AI” that will eventually render mobile apps obsolete and serve users by creating AI on the fly, super-tailored to their needs Like dreams, these kinds of AI apps will be “transient” and extremely contextaware, and they will run in the background, not always clearly indicating which purpose they serve, seemingly tapping from and serving as our subconscious. Initially, we will still understand their raison d’etre, but increasingly, they will puzzle us, simply because they know more about us than we are able to express (“ineffability”), relegating us to “passive” users. Yet they will direct us with absolute authority (“noetic quality”).

“It’s the end of explanations, a great increase in reality is here.” No matter how you look at it, AI will further blur the lines between reality and dream, and create entirely new worlds, as fiction does. But fiction won’t only be the end product it will be the starting point. Imagine a whole new genre called co-fiction: humans writing with AI co-authors who do not understand what they are saying and are occasionally hallucinatory.

The human (yes, we need to get used to this qualifier) author and TED speaker K AlladoMcDowell, who established the Artists + Machine Intelligence program at Google AI, welcomes this confusion: “It’s the end of explanations, a great increase in reality is here,” they proclaim

Allado-McDowell collaborated with GPT-3 for their book Pharmako K, a hybrid creation, in which they describe the hallucinatory effect the AI has had on their thinking, blurring the lines between the two notions of authorship. Rather than just switching back and forth, with a clear line of demarcation, the two minds enmesh with each other in a symbiotic act of cocreation.

Joy and sorrow Speaking of life, it is perhaps not a coincidence that the rise of AI in public discourse corresponds with a rise in conversations about death.

And it is perhaps not a coincidence either that after having lost a loved one recently, I began to read more poetry — the manifestation of absence; the more “noetic,” the better — and exchange regular letters (without the help of ChatGPT, delivered via email)

ArtbyAishatuAdoTo another human living in another city, in a communion of the grief both of us have been carrying with us, and beyond it. The old-fashioned asynchronous form of correspondence gives us time to listen and to think, without interruption, judgment, or expectation (aside from a reply).

If there ever was a form of nonviolent communication, it’s this. The writing is not entirely agenda-less, but it is aimless. It is not transactional as it has no goals. When I told a friend of mine about the letters, he observed: “You are not writing to each other; you are each writing to yourself.” I protested and insisted ours was a true dialogue, to which he gently replied: “Exactly. You serve as windows into each other’s soul precisely because you write to yourselves first. If you simply wrote to the other, you would merely project onto one another, but you wouldn’t have the same intimate connection.”

It occurred to me that this is exactly the difference between AI and humans (and journalists and artists, for that matter).

AI would never write to it itself or for itself. AI writes to serve, to convey information, for the benefit of the reader; it is never aimless, it cannot reflect, it cannot reveal, there are no windows because there is no interior. Ironically, writers who primarily write for others will be replaced by AI; writers who write for themselves will not.

AI autocompletes, it will always fill in the blank after the last word, but we humans are unique experts at filling in the blank before the last word. We don’t dream to___; we chase the ____dream. We imagine, we make choices, often poor ones. To borrow from Leonard Cohen, we are the flaw in our plans through which life comes in.

We can embrace joy as “unmasked sorrow,” as Kahlil Gibran, the Lebanese poet, put it in his poem Joy and Sorrow. We can write the story of our life. We can forgive ourselves, even preemptively. We can appreciate that “we are all dying,” as death doula Alua Arthur reminds us, so we can “stop the diet and eat that cake!”

We can ask AI to craft a strategy to solve our grief. But as humans, we recognize that grief is not a problem to be solved. Grief is how we experience life. It is the strategy.

Weinviteyoutodeepenyourexplorationwithourcuratedset ofquestions.Thesequestionsaredesignedtoengageyouin multidimensionalthinkingintermsofartificialintelligence Theyserveasspringboardsforpersonalreflectionorbroader discussion,aimingtostimulatebothyouremotional, intellectualandethicalengagementwiththecorequestion: "CanAIHealUs?"

To what extent should we rely on AI for mental and emotional support?

How can we ensure AI contributes to societal healing rather than exacerbating existing inequalities?

Do you believe AI can ever fully replicate or replace human medical expertise?

How can we instill ethics and accountability in AI, especially in its role in healthcare and well-being?

Kate Crawford describes AI as "a form of exercising power and a way of seeing " How can we democratize this power?

Should AI be designed to have ethical and meaningful goals? How would you envision such a computational ecosystem?

If natural intelligence evolves over time, what does that imply for the "evolution" of artificial intelligence? Can AI ever achieve a form of adaptability similar to biological evolution?

Bayo Akomolafe asks us to reconsider 'natural intelligence.' How might our perceptions of intelligence itself change if AI begins to demonstrate creativity, empathy, or even what we might term 'wisdom'?

As AI systems become more sophisticated, will there be a shift in how we define what is uniquely "human"? What are the existential implications of this potential shift?

Weinviteyoutodeepenyourexplorationwithourcuratedset ofquestions.Thesequestionsaredesignedtoengageyouin multidimensionalthinkingintermsofartificialintelligence Theyserveasspringboardsforpersonalreflectionorbroader discussion,aimingtostimulatebothyouremotional, intellectualandethicalengagementwiththecorequestion: "CanAIHealUs?"

To what extent should we rely on AI for mental and emotional support?

How can we ensure AI contributes to societal healing rather than exacerbating existing inequalities?

Do you believe AI can ever fully replicate or replace human medical expertise?

How can we instill ethics and accountability in AI, especially in its role in healthcare and well-being?

Kate Crawford describes AI as "a form of exercising power and a way of seeing." How can we democratize this power?

Should AI be designed to have ethical and meaningful goals? How would you envision such a computational ecosystem?

Tim Leberecht is a German-American author and entrepreneur, and the co-founder and co-CEO of the House of Beautiful Business, a global think tank and community with the mission to make humans more human and business more beautiful.

Sará King is a Mother, a neuroscientist, political and learning scientist, medical anthropologist, social entrepreneur, public speaker, and certified yoga and meditation instructor, and the CEO of Mindheart Collective.

Matt Klein is the foremost published cultural theorist and strategist, currently Head of Global Foresight at Reddit and Resident Futurist with Hannah Grey VC. A Webby Award-winning writer for his publication ZINE, Klein studies technology and the unspoken trends defining our future.

Angel Acosta has worked to bridge the fields of leadership, social justice, and mindfulness for over a decade. He is currently the Director of the Garrison Institute Fellowship Program and the Chief Curator at the Acosta Institute.

Susanna Raj is the CEO & Founder of AI4NOMADS, a Partnerships Lead for Women in AI USE, AI Ethics Advisory Board Member at the Institute for Experiential AI at Northeastern University, Program Chair and Co-Founder of Global South in AI Affinity at NEURIPS and Board Member at DATAETHICS4ALLl.

AcollaborationbetweenCultureTouchandtheAcostaInstitute servingasacreativehubwherestorytelling,design,and educationintersecttoharnessthepowerofcreativity, technology,andcontemplativepractices.

TheAcostaInstituteisalearningandresearchhub fosteringinnovationattheintersectionofhealingcenterededucation,contemplativesocialscienceand slowworkthroughthefacilitationofonlinecourses, trainings,workshops,lecturesandinternational summits.ThisdocumentwasdesignedbySteveSaint Fleur,CreativeDirector,andAngelAcostaatthe institute’sStudio–acollaborationbetweenCulture TouchandtheAcostaInstituteservingasacreative hubwherestorytelling,design,andeducation intersecttoharnessthepowerofcreativity, technology,andcontemplativepractices.Tolearn moreaboutourwork,visitacostainstitute.com.

Tolearnmoreaboutourwork,visit acostainstitute.com.