Francesca Borgo and Ruth Ezra

A“These people say material, but they mean work.”1

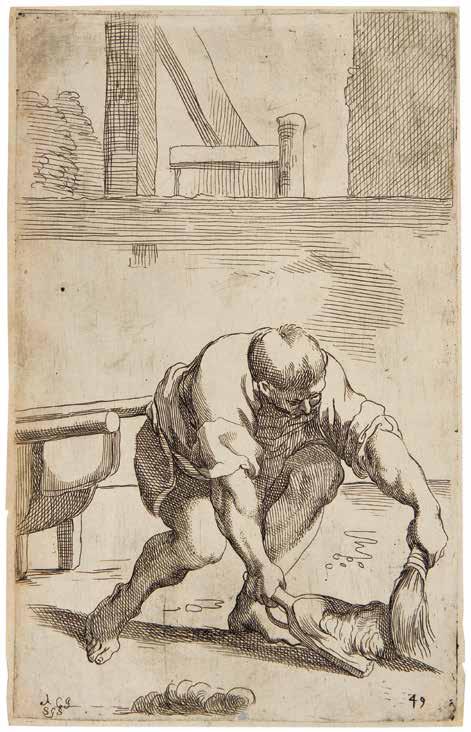

round 1490 to 1495, when the Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli portrayed Saint Augustine in his study on a small panel now at the Uffizi, he forgot to take out the trash. Used-up pens and shredded documents litter the painting’s foreground (figs. 1 and 1.1). Their detailed rendering tells a step-by-step story of material vicissitude. The quills were tempered, sharpened and re-sharpened, exhausted, discarded; the sheets were first inscribed with ink, then crumpled and torn to pieces.

Due to their location, shape, and arrangement, these scraps can only be characterized as waste. Scattered in an ostensibly random disposition on the stone floor just beneath the saint’s platform desk, they had but a short distance to fall, clearly thrown from the writer’s perch. And indeed, to judge by the three worn-down pens that lie among the refuse, Augustine has been writing and rewriting for quite some time, and with some effort. While a nib had to be sharpened frequently, a quill, once cut, could last several days, even weeks. Recutting and scraping were specialized skills worth cultivating.2

Early modern economies of thrift encouraged the pursuit of virtuosity in maintenance work, as in the case of quills.3 In 1601 the Englishman Philemon Holland boasted of translating all of Plutarch’s Moralia with a single gray goose feather.4 There was no such virtue to be won by advertising

1. “Diese Leute sagen Material und meinen die Arbeit.” Translated in Loos, “Building Materials,” 115.

2. Finlay, Western Writing Implements, 8–12; Clemens and Graham, Introduction, 18. For pen trials, see Clemens and Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies, 45. For instructions on quill sharpening, see Cennini, Craftsman’s Handbook, 8; Neudörffer, Ein Gesprechbüchlein zweyer schüler

3. Werrett, Thrifty Science, 109–128; Barker, “Maintenance Work”; Ryley, Re-Using Manuscripts; Woodward, “ ‘Swords into Ploughshares.’ ” Erratic supply chains also played their part. The best goose feathers were a seasonal harvest, plucked in the spring. Shortages occurred, as in Venice in 1433, an episode Ambrogio Traversari recounts in his letters. In Florence at the same time, bundles remained comparatively numerous; see Finlay, Western Writing Implements, 2.

4. “With One Sole Pen I writ this book,/ Made of a Grey Goose Quill,/ A Pen it was when it I took,/ and a Pen I leave it still,” cited in Fuller, History of the Worthies, 3:181. The rhyme appears elsewhere, with the book in question being Pliny the Elder’s Natural History or Camden’s Britannia, a

Borgo and Ruth Ezra

fare no better. One notable exception comes from research into the late Titian, where technical analysis revealed his at times baffling parsimony. The aging artist, loath to waste materials even once flush, repeatedly adapted and expanded unsold canvas supports to undergird new commissions.25

Economic and cultural historians characterize the early modern period as a golden age for recycling across Europe.26 A rising person-to-resource ratio, coupled with religious reforms that praised work and technological change that accelerated it, ensured that there was “no limit to the ingenuity of [early moderns] in their exploitation of natural resources and agricultural by-products,” at least as Donald Woodward imagines it.27 Brian Clapp, too, judges the recombination of by-products as “relatively more common in pre-industrial economies than they are [today].”28 The reuse practices of the period were not just born out of necessity or scarcity, though, but also dictated by cultural expectations and norms; they would, in turn, become central to the development of the experimental sciences, as the emerging field of maintenance and repair studies teaches.29 Colonization and the push toward industrialization eventually changed things.30 To return to Augustine’s recut pen, a culture of maintenance work, codified in sixteenth-century calligraphy manuals, would by the nineteenth century give way to a culture of obsolescence—as much the product of abundance as incompetence.31 If quills never go out of stock, why learn how to repair them?

25. Dunkerton and Spring, “Titian after 1540,” 10.

26. Neumann, “Vormoderne Recycling-Mentalität?”; Reith, “Recycling im späten Mittelalter”; Walsham, “Recycling the Sacred”; Stöger and Reith, “Western Recycling in a Long-term Perspective”; Woodward, “ ‘Swords into Ploughshares.’ ” For responses to resource constraints elsewhere, such as Tokugawa Japan (1603–1867), see Richards, The Unending Frontier, ch. 5. For equally frugal attitudes to workshop waste and the economic situation of craftspeople with regard to materials in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, see Cutler, “The Right Hand’s Cunning,” 978; for medieval labor crises and waste, see Johnson, “The Poetics of Waste.”

27. Woodward, “Straw, Bracken and the Wicklow Whale,” 44.

28. The term “by-product” applied to the early modern period is strictly speaking an anachronism, as it has only been in English usage since 1857. Desrochers, “Invisible Hand,” 350; Clapp, Environmental History of Britain, 223. Clapp defines by-products more nearly as that which “arise[s] when complex materials, often but not always of organic origin, are broken down into their constituent parts, or recombine in a new way,” 220.

29. Casson and Welch, “Histories and Futures,” 36. For the need to “make use” as a motivation for experiment, see Werrett, “Food, Thrift, and Experiment,” 228; Werrett, Thrifty Science; Young and Coeckelbergh, Maintenance and Philosophy of Technology. See also Margócsy and Brazelton, “Techniques of Repair,” and the website https://themaintainers.org/.

30. For the emergence of a “Cornucopian Scarcity” mindset from the seventeenth century onward, and the related emergence of capitalism in early modern Europe, see Jonsson and Wennerlind, Scarcity, 8–9.

31. Finlay, Western Writing Implements, 10. For the relationship of obsolescence and expendability

Fanmaker’s waste, London,

The intensity of salvage (meaning reuse in the same activity) and loop-closing (meaning inter-trade feedback) across the early modern world has left few of the period’s by-products extant today. Those that do surface, such as a cache of fan-making supplies from seventeenth-century London, tend to be declared failures: the struts were over- or under-cut, hence discarded (fig. 2).32 But what makes us so sure that, if workshop waste comes up in aggregate, it must have fallen down in the same quantity, produced by the same hand, or even in one go?33 Maybe early modern craftspeople, like twenty-first-century scientists, kept at least some of their null results around for reference, offering up the too-thick and the too-thin as cautionary tales for their apprentices to study.34

to modernity, see Packard, The Waste Makers; Tischleder and Wasserman, “Thinking out of Sync.”

32. Egan, “Archaeological Evidence,” 61, 65; Egan and Jeffries, “London, Capital of Empire,” 63.

33. Egan, “Archaeological Evidence,” 47–48.

34. Brazil, “Illuminating ‘the Ugly Side of Science.’”

must be rendered invisible: collected, contained, sorted, stored, and classified. This is all part of the labor wastework demands.

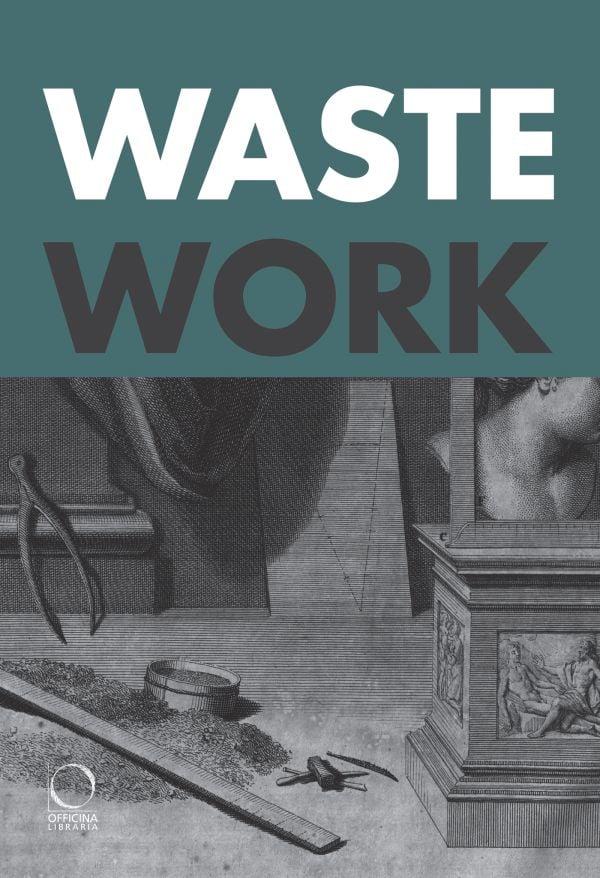

Waste and labor come together even more transparently in another series of popular images: the depictions of itinerant tradesmen drawn by Annibale Carracci during the late 1580s and printed in Rome in 1646 by Lodovico Grignani, when titles were first added.81 There is a wasteworker among the group of tradesmen, and he is labeled cariolaro da mondezza (fig. 11).82 The word mondezza identifies both the cleanliness that results from his work (from the Latin mundus) as well as its exact opposite, the dirt and filth taken away in the process. In early modern Europe, refuse left to linger in civic squares was believed to pose a significant threat to public health, contaminating the air with disease-inducing miasmas. Although urban waste disposal was not yet a clearly delineated public function, municipalities could still rely on sanctioned street cleaners. Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Venice, these grew to be increasingly specialized professions. Cleaners were appointed to clear drains (gattolieri), dredge canals (cava rii), or collect rubbish (scoazeri or nettadori). Working at dawn or during nighttime, these workers came equipped with the tools of removal required: shovels, brooms, baskets, and barrels.83

Carracci’s mondizaro fares significantly worse than the other eighty characters in the series. More a beggar than a salesman, he is the only one who appears not just barefoot but with bare knees and elbows as well. As if to reiterate that his is a business of the ground, the domain of waste, he is the only figure in the group not depicted in an erect posture. Instead, he crouches on the floor with bent head, his attention trained on the formless mass he is collecting rather than meeting his potential buyers at eye level. Unlike his companions—all street vendors loaded with trinkets and wares—he brings nothing and sells nothing, consigned to removing materials with his barrel. His is a work, a livelihood, of subtraction rather than addition, and something of the pressure and expectations of this diminution has rubbed off on his scarcely clad figure. Reduced to the point of invisibility, the mondizaro’s trade only becomes noticeable when it breaks down, as with Work,” 699, and for “workaday mess that is present but under control,” 701.

81. Carracci, Diverse Figure

82. On the series, see McTighe, “Perfect Deformity.” See also Brambilla, Ritratto, where the wasteworker is labeled mondizaro

83. See Crawshaw, Cleaning Up Renaissance Italy, 133–157. For wasteworkers outside Venice, see Reid, Paris Sewers and Sewermen; Stuart, Defiled Trades, 102–104.

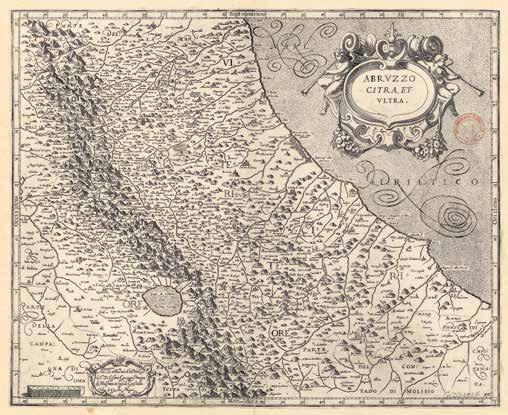

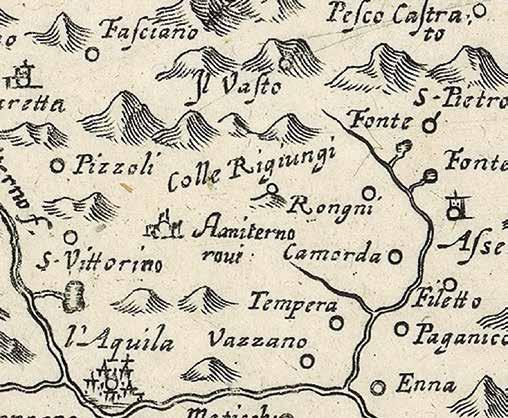

and settlements were scarce, for example the Valle del Vasto or Valle del Guasto in Italy’s Apennine Mountains (figs. 1 and 1.1). In medieval contexts, vasto or guasto was often used interchangeably with the word deserto, meaning an empty place, one whose harsh environmental conditions made it threatening to human survival. Thus, in the medieval and early modern periods, people might travel to and through the waste, and at times they might even dwell in it for periods of time, but more often than not they would avoid it altogether, or at least not linger any longer than was strictly necessary.

But if waste was a place, what kind of place was it, exactly? Across medieval and early modern texts, waste has an inconsistent identity. It can be a dry expanse of parched earth, a swampy morass of mud and stagnant water, or a vertiginous pile of forbidding peaks. It can be completely barren, or choked with thick and impenetrable brambles. It can pose as the haunt of savage animals, demons, and other fierce natural and supernatural creatures, or it

can appear to be devoid of all forms of life. Thus, across these early texts, waste appears as a category of land that is characterized not by consistent physical qualities but rather by the absence of comfort and safety. In other words, waste tends to be defined not so much by what it is or what it has, but by what it lacks. This association of waste with a kind of emptiness and absence is key to the term’s potential for abstraction. And this abstraction meant that waste became a term that could be applied to a wide range of places, united primarily by their hostility to human existence.

Despite this inconsistent ecological identity, however, waste nevertheless has played a consistent role in Western thought: its definition resides not so much in what it is but in what it does. The waste’s lacks (of food and water, of cities and towns) and its wild creatures (savage animals and demons) make it a challenging, threatening, and dangerous place. Although the waste may appear in many guises, it consistently stands for a space that is posited as

Stefano della Bella, closely resembles his father’s scenery for the Tempio della Pace in Il giudizio di Paride, while the younger Parigi’s set for the Nozze degli dei (1637), featuring a ruined street front set ablaze, almost exactly replicates his father’s Palazzo della Fama from the previously cited performance. Such visual citations register the complex dynamics and tensions of reuse, adaptation, and innovation in early modern machine theater. They reveal the ways that stage designers turned practical limitations of theatrical design into creative opportunities, building, in the process, a sort of visual legacy. By reproducing stage sets, costumes, and design elements in promotional prints, scenographers stitched together a material and cultural repertoire of ideas, images, and techniques handed down and developed from one generation of collaborators to the next. Their reuse and reproduction of stage materials crafted a sort of intergenerational network of collaborators and ensured that, even if a spectacle was not repeated, the memory of their “ingenious devices” would be maintained over time.

As with the 1554 destruction of the Florentine paradise machinery, the destruction of scenic repertoires also signaled the reverse phenomenon: an

intentional erasure of the material memory, comprising both iconographies and techniques, associated with a designer. In perhaps the most notorious and egregious example of the deliberate rejection of stage materials, the scenographer Gaspare Vigarini chose not to take over the warehouse of the Grande Salle du Petit-Bourbon in 1660. Located in the Louvre, the theater, formerly directed by the opera designer Giacomo Torelli, was being destroyed to expand the palatial residence.39 Torelli’s rival, Vigarini, was given the first pick of its holdings, comprising set dressings, stage machinery, costumes, and drop cloths. Instead, he chose to burn it to the ground. According to the diarist La Grange, “[h]e made these decorations be burned, ay to the very least, in order that nothing should remain of the invention of his predecessor, The Sieur Torelli, whose memory he wished to bury in oblivion.”40

Like the Confraternity of Sant’Agnese, Vigarini made clear how cultural memory was intimately tied to the continual use of ingenious things. From the informal storage of stage machinery in church attics to the development of elaborate administrative units responsible for inventorying, moving, supervising, and maintaining stage machines over decades and even centuries, the early modern reuse of theatrical designs illuminates the unique ways material and intellectual practices intersected backstage. For early modern scenographers who pursued innovation over repetition, working with the materials and machines invented by another entailed a historical collaboration. Their adaptations and citations of existing materials and ideas challenged an increasingly prevailing tendency to value the scenographer’s output as a singular intellectual contribution, revealing instead a deep complicity in working together to craft an artistic tradition.

39. On the rivalry between Torelli and Vigarini, see de La Gorce, “Torelli et les Vigarini”; Jarrard, “Gaspare Vigarini.”

40. “A Parisian Theater,” 474.

classical origins for emerging genre imagery of kitchens, markets, and even brothels in the Roman writer Pliny the Elder’s term “rhyparography,” or the painting of quotidian objects.3 Yet, as Norman Bryson has observed, the designation of rhyparography could also be “an insult: ‘rhyparographer’ means painter of rhyparos, literally of waste or filth; the association is with things that are physically and morally unclean.”4

Through a close reading of The Crying Bride, this essay considers what the emerging field of waste studies can contribute to reexamining early modern Netherlandish art and genre imagery in particular. I contend that the content and function of early sixteenth-century Netherlandish genre scenes of Folly, see Erasmus, Moriae encomium, 78–153.

3. Pliny recounted the success of the painter Piraeicus, whose humble imagery delighted viewers and fetched high prices. Pliny, Natural History 35.112, 9:342–345. For the reception of this anecdote in Renaissance art, see also McHam, Pliny, 50, 156, 242.

4. Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked, 136.

come most fully into focus when we see them as rhyparography in the sense of depictions of “waste” or “filth.” The theme of waste inherent to the classical roots of genre painting takes on especially charged gendered and classbased connotations, connecting to period ideas about aging and procreation. Furthermore, in works of superb artistic quality such as Van Hemessen’s The Crying Bride, rhyparography functions beyond the level of iconography. A deluxe oil-on-panel painting, its humor depends on the inherent tension between its “low” subject and its refined technique.

In analyzing how class and gender shape rhyparography as artistic “waste” or “filth,” I draw on the literary historian Susan Morrison’s characterization of “wasteways” as the investigation of cultural meaning and practices surrounding waste.5 Dirt and waste are social designations given to certain types of matter. Dirt is famously defined by the anthropologist Mary Douglas as

5. Morrison, The Literature of Waste, 2. A play on “foodways.”

Peeter Baltens,

1540–1584.

Van Hemessen’s The Crying Bride is both the earliest extant version of this scene in Netherlandish art and the version that deviates most fully from the eventual standard type.18 The bridal procession is reduced to a minimum.19 The bride is surrounded by two men, one of whom is much younger than her and one of whom is significantly older. Almost life-sized, the three figures are shown in a portrait-like format, at bust length and closely cropped. Scholars have come up with a range of answers about the relationship between the figures, yet their precise connections remain ambiguous.20 The candle is missing, even though

18. Renger, “Tränen in der Hochzeitsnacht,” 154–155.

19. Van Hemessen’s The Bagpipe Player and Merry Woman is comparable to The Crying Bride in terms of scale as well as content. One of the best versions of this popular composition is preserved in Brussels at the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts. The other is in a private collection (sold at Christie’s New York, Old Masters, 10 June 2022). Nevertheless, in my view it is unlikely that The Bagpipe Player and Merry Woman was intended as a pendant to The Crying Bride, especially since the former places the figures against a dark background rather than in a defined interior. For The Bagpipe Player and Merry Woman as a multivalent genre subject in its own right, see most recently Cagol and Peterlini, “Der segnende Dudelsackspieler.”

20. Renger, “Tränen in der Hochzeitsnacht,” with summary of interpretations by previous scholars

3. Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dirty Bride or the Marriage of Mopsus and Nisa, 1570. Engraving, 22.2 x 28.9 cm. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

the chamber pot is prominent. Above all, the bride is older than usual and, as will become clear, conforms to the role of de vuile bruid (the dirty bride).

Originating in vernacular plays, the figure of the dirty bride derives from a corruption of het vuile bruidspaar (the dirty bride and groom) in which the woman is singled out. The dirty bride figure has clear associations with Carnival. She appears in vernacular Shrove Tuesday plays, including those about the battle between barren winter and fertile spring.21 In a print of the subject designed by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, viewers are actually witness to a group of Carnival actors performing a play featuring the dirty bride for donations (fig. 3).22 The actor playing the dirty bride wears a wedding dress of pelts and rags, and her at 155. See also Wallen, Jan van Hemessen, 64–66 and cat. no. 22, primarily following Renger’s analysis (Renger’s essay was originally published in 1977). Most recently, see Henneke, “Ritueel in beeld,” 121–127, and for a different interpretation of the relationship between the three figures, see Ubl, “Van hoerenhuis tot hoofse liefde,” 163–165.

21. Henneke, “Ritueel in beeld,” 125–127.

22. Orenstein, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 246–248.

barred Jews from strazzaria in 1498, but in 1515 they negotiated a license to deal in used goods with the Council of Ten.26 This agreement notwithstanding, Venice’s Jews faced recriminations from the city’s Christian rag merchants, who had long opposed official recognition of Jewish activity in that area.27 That dispute reveals a longstanding tension between the stereotypes of social filthiness as voiced by authors like Garzoni and the realities of an indispensable waste-focused trade that states and merchants both vied to protect.28 Rags were themselves riches: reliably profitable as a desired raw material. Given the legislative attention and mercantile conflict that rags drew over the centuries, the key agents, labor relations, and trade frameworks in the centuries before 1700 deserve further research to reveal the economic and social mechanisms that accompanied their growth. Here I echo Renzo Sabbatini’s recent call for greater attention in the history of papermaking to the people involved and not only the product.29

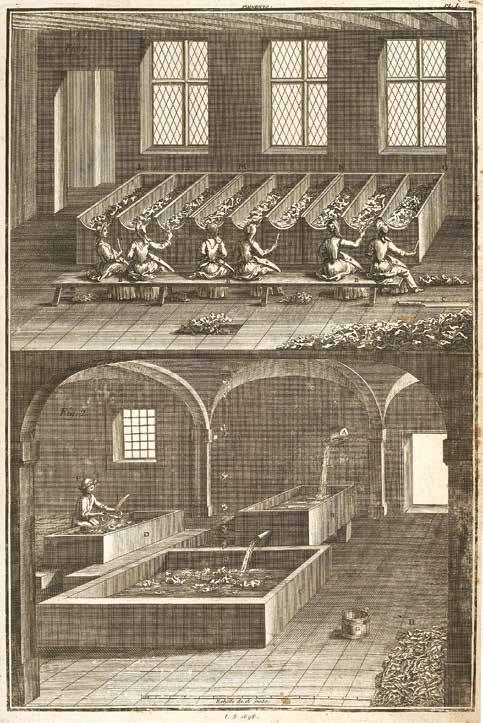

The paper mill was the temple where artisans performed the transubstantiation of mundane linens into fresh white paper. Somewhere onsite, covered sheds housed bales of rags to protect them from the elements. A 1588 inventory of a mill outside Vicenza describes 4,000 pounds of white rags and 2,500 more of dark ones awaiting processing.30 Workers, often women, removed all stitching, ripping the seams and then cutting the fabric into small squares (fig. 3). Those scraps were then moistened and fermented to further their disintegration. Days later, once hot to the touch and caked in mushrooms, the rotten rags were then hand-washed and dumped into troughs or “vat-holes” worked over by mechanical stamping hammers whose up-and-down motion was actioned by cams on an axle turned by a watermill. Once reduced to paste, the fibers were soaked in limewater, then purged and diluted in water to produce the milky liquid through which the vatman drew his wire-mesh form to extract a sheet of paper, ready to be pressed, hung, dried, and sized.31

26. On the prohibition, see Jacoby, “Les juifs à Venise,” 200. For the concession of rights to work in strazzaria, see Sanudo, Diarii, 20:339, 354.

27. Segre, Preludio al Ghetto di Venezia, 515–519. It is worth noting the apparent activity of Jews in papermaking in fourteenth-century Treviso. See Möschter, “Gli ebrei a Treviso,” 74.

28. Jewish merchants continued to trade in rags into the nineteenth century. See Ciuffetti, “Mercanti ebrei.”

29. Sabbatini, “The Civilization.”

30. “Le cartiere di Dueville e Vivaro in un documento del 1588,” appendix to Simeone, “Le origine della produzione cartaria,” 12–14, at 12.

31. See Fahy, “Paper Making.” For mushrooms growing atop the fermented rags, see Hunter, Papermaking, 154.

3. Engraver L. S., Selection and unseaming of different qualities of rags; shredder and fermenting trough, 1698. Republished in Jérôme de La Lande, Art de faire le papier (Paris, 1761).

of depicting an eruption alongside moonlight and water. As I have discussed, such images were also deeply marked by the practices and consequences of industrial mining. Michel Serres once observed that Turner’s paintings, especially those depicting the operations of steam power, replicate the effects of combustion in their conversion of pigmented materiality into light and energy.20 Turner’s vortex-like landscapes featuring steam ships bear witness to the early stages of what Nathan Hensley describes as the suicidal inferno of fossil capitalism.21 His eruption scenes could themselves be understood as portrayals of the combustive protocols of industrial modernity. Silhouetted in the right foreground of the painting, a modest rowboat contrasts the explosive power of the distant eruption with the declining importance of traditional sources of energy and labor.

Rather than return to the space of the mine, I will close by looking outward to the broader extractive stakes of this image. Whereas Turner’s later portrayal of the eruption of Vesuvius illuminates the foreground and midground of the surrounding landscape, his painting of La Soufrière shrouds much of the environment in obscurity. In practical terms, the artist would not have known what St. Vincent looked like. Having never visited the Caribbean, Turner based his painting on a sketch made by Hugh Perry Keane, a British planter and enslaver who was on the island during the eruption. If Turner was more attentive than most to the conditions of “fossil capital,” this painting encodes an awareness of additional geographies of extraction and exploitation, other spatial axes along which the imperatives of European economic interests were operating.

In the years separating Volaire’s painting of Vesuvius and Turner’s painting of La Soufrière, volcanic eruptions had become a pervasive metaphor for the events of the French Revolution and other political uprisings. An eruption signaled not only the dramatic reversal of existing political hierarchies and the collective power of “the people,” but it also indicated the conversion of a seemingly inert topographical formation (that is, a mountain) into an explosive source of destruction.22 In one famous example, Sylvain Maréchal’s play The Last Judgment of Kings (1793) imagines the monarchs of Europe stranded on a volcanic island whose eruption at the end of the play kills them all. An

20. Serres, “Turner Translates Carnot.”

21. Hensley, Action without Hope, “Introduction.”

22. See Miller, “Mountain, Become a Volcano”; McCallam, “The Volcano.” Miller has written an important account of how natural history metaphors structured peoples’ understanding and experience of the French Revolution. Miller, A Natural History of Revolution

inscription on a rock on the stage read, “For a neighbor, it is better to have/ a volcano than a king.”23 The Indigenous Caribs of St. Vincent had lost their second major war against the British during the closing years of the French Revolution.24 St. Vincent, at the time of Turner’s painting, had both a volcano and a king. Its tobacco, coffee, cotton, indigo, cocoa, and sugar plantations, worked by enslaved Africans, were a major source of economic value for British landowners and for the nation. Turner pictures not the valuable plantations that covered the topographical surface of the island but only the explosive power rising up from beneath it. Turner’s painting of La Soufrière evokes the possibility of other paroxysms, other powerful forces that were both set in motion by and posed an imminent threat to European extractive capitalism at the turn of the nineteenth century.

23. Maréchal, Le Jugement, 1.

24. On the importance of Indigenous resistance on Saint Vincent, see Kim, “The Caribs of St. Vincent.”